Europa es un continente [t] ubicado completamente en el hemisferio norte y mayormente en el hemisferio oriental . Limita con el océano Ártico al norte, el océano Atlántico al oeste, el mar Mediterráneo al sur y Asia al este. Europa comparte la masa continental de Eurasia con Asia, y de Afro-Eurasia con Asia y África . [10] [11] Se considera comúnmente que Europa está separada de Asia por la divisoria de aguas de los montes Urales , el río Ural , el mar Caspio , el Gran Cáucaso , el mar Negro y la vía fluvial del estrecho del Bósforo . [12]

Europa cubre alrededor de 10,18 millones de km2 ( 3,93 millones de millas cuadradas), o el 2% de la superficie de la Tierra (6,8% del área terrestre), lo que la convierte en el segundo continente más pequeño (usando el modelo de siete continentes ). Políticamente, Europa está dividida en unos cincuenta estados soberanos , de los cuales Rusia es el más grande y poblado , abarcando el 39% del continente y comprendiendo el 15% de su población. Europa tenía una población total de alrededor de 745 millones (alrededor del 10% de la población mundial ) en 2021; la tercera más grande después de Asia y África. [2] [3] El clima europeo se ve afectado por las corrientes cálidas del Atlántico, como la Corriente del Golfo , que producen un clima templado , templando los inviernos y veranos, en gran parte del continente. Más lejos del mar, las diferencias estacionales son más notorias produciendo climas más continentales .

La cultura europea consiste en una gama de culturas nacionales y regionales, que forman las raíces centrales de la civilización occidental más amplia , y juntas comúnmente hacen referencia a la antigua Grecia y la antigua Roma , particularmente a través de sus sucesores cristianos , como raíces cruciales y compartidas. [13] [14] A partir de la caída del Imperio Romano de Occidente en 476 d. C., la consolidación cristiana de Europa a raíz del Período de Migración marcó la Edad Media posclásica europea . El Renacimiento italiano difundió en el continente un nuevo interés humanista en el arte y la ciencia que condujo a la era moderna . Desde la Era de los Descubrimientos , liderada por España y Portugal , Europa jugó un papel predominante en los asuntos globales con múltiples exploraciones y conquistas en todo el mundo. Entre los siglos XVI y XX, las potencias europeas colonizaron en varias ocasiones América , casi toda África y Oceanía , y la mayor parte de Asia.

La Ilustración , la Revolución Francesa y las Guerras napoleónicas moldearon el continente cultural, política y económicamente desde finales del siglo XVII hasta la primera mitad del siglo XIX. La Revolución Industrial , que comenzó en Gran Bretaña a finales del siglo XVIII, dio lugar a un cambio económico, cultural y social radical en Europa occidental y, finalmente, en el resto del mundo. Ambas guerras mundiales comenzaron y se libraron en gran medida en Europa, lo que contribuyó a un declive del dominio de Europa occidental en los asuntos mundiales a mediados del siglo XX, cuando la Unión Soviética y los Estados Unidos tomaron prominencia y compitieron por el dominio en Europa y a nivel mundial. [15] La Guerra Fría resultante dividió a Europa a lo largo de la Cortina de Hierro , con la OTAN en el oeste y el Pacto de Varsovia en el este . Esta división terminó con las Revoluciones de 1989 , la caída del Muro de Berlín y la disolución de la Unión Soviética , lo que permitió que la integración europea avanzara significativamente.

La integración europea ha avanzado institucionalmente desde 1948 con la fundación del Consejo de Europa , y significativamente a través de la realización de la Unión Europea (UE), que representa hoy a la mayoría de Europa. [16] La Unión Europea es una entidad política supranacional que se encuentra entre una confederación y una federación y se basa en un sistema de tratados europeos . [17] La UE se originó en Europa occidental, pero se ha expandido hacia el este desde la disolución de la Unión Soviética en 1991. La mayoría de sus miembros han adoptado una moneda común, el euro , y participan en el mercado único europeo y una unión aduanera . Un gran bloque de países, el Espacio Schengen , también ha abolido las fronteras internas y los controles de inmigración. Las elecciones populares regulares tienen lugar cada cinco años dentro de la UE; se consideran las segundas elecciones democráticas más grandes del mundo después de las de la India . La UE es la tercera economía más grande del mundo.

El topónimo Evros fue utilizado por primera vez por los antiguos griegos para referirse a su provincia más septentrional, que lleva el mismo nombre en la actualidad. El río principal de la zona, Evros (hoy Maritsa ), fluye a través de los fértiles valles de Tracia [18] , que también se llamaba Europa, antes de que el término significara continente [19] .

En la mitología griega clásica , Europa ( griego antiguo : Εὐρώπη , Eurṓpē ) era una princesa fenicia . Una opinión es que su nombre deriva de los elementos griegos antiguos εὐρύς ( eurús ) 'ancho, amplio', y ὤψ ( ōps , gen. ὠπός , ōpós ) 'ojo, cara, semblante', por lo que su compuesto Eurṓpē significaría 'de mirada amplia' o 'de aspecto amplio'. [20] [21] [22] [23] Amplia ha sido un epíteto de la Tierra misma en la religión protoindoeuropea reconstruida y la poesía dedicada a ella. [20] Una visión alternativa es la de Robert Beekes , quien ha argumentado a favor de un origen preindoeuropeo para el nombre, explicando que una derivación de eurus daría como resultado un topónimo diferente de Europa. Beekes ha localizado topónimos relacionados con el de Europa en el territorio de la antigua Grecia y localidades como la de Europos en la antigua Macedonia . [24]

Se ha intentado relacionar Europa con un término semítico para designar el oeste , que puede ser el acadio erebu, que significa «bajar, ponerse» (dicho del sol), o el fenicio ereb , que significa «atardecer, oeste», [25] que está en el origen del árabe maghreb y del hebreo ma'arav . Martin Litchfield West afirmó que «fonológicamente, la coincidencia entre el nombre de Europa y cualquier forma de la palabra semítica es muy pobre», [26] mientras que Beekes considera improbable una conexión con las lenguas semíticas. [24]

La mayoría de los principales idiomas del mundo utilizan palabras derivadas de Eurṓpē o Europa para referirse al continente. El chino, por ejemplo, utiliza la palabra Ōuzhōu (歐洲/欧洲), que es una abreviatura del nombre transliterado Ōuluóbā zhōu (歐羅巴洲) ( zhōu significa "continente"); un término similar derivado de chino, Ōshū (欧州), también se usa a veces en japonés, como en el nombre japonés de la Unión Europea, Ōshū Rengō (欧州連合) , a pesar de que el katakana Yōroppa (ヨーロッパ) se usa más comúnmente. En algunas lenguas turcas, el nombre originalmente persa Frangistan ("tierra de los francos ") se usa casualmente para referirse a gran parte de Europa, además de nombres oficiales como Avrupa o Evropa . [27]

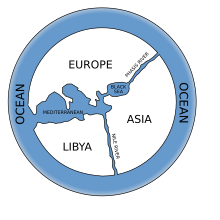

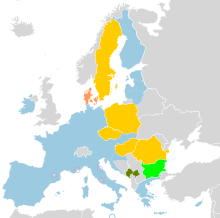

Mapa interactivo de Europa que muestra uno de los límites continentales más utilizados [u]

Clave: azul : estados que se extienden a lo largo de la frontera entre Europa y Asia ; verde : países que no están geográficamente en Europa, pero que están estrechamente asociados con el continente

La definición predominante de Europa como término geográfico se ha utilizado desde mediados del siglo XIX. Se considera que Europa está limitada por grandes masas de agua al norte, oeste y sur; los límites de Europa al este y noreste suelen ser los montes Urales , el río Ural y el mar Caspio ; al sureste, los montes del Cáucaso , el mar Negro y las vías fluviales que conectan el mar Negro con el mar Mediterráneo . [28]

Las islas generalmente se agrupan con la masa continental más cercana, por lo que Islandia se considera parte de Europa, mientras que la cercana isla de Groenlandia generalmente se asigna a América del Norte , aunque políticamente pertenece a Dinamarca. Sin embargo, existen algunas excepciones basadas en diferencias sociopolíticas y culturales. Chipre es el más cercano a Anatolia (o Asia Menor), pero se considera parte de Europa políticamente [29] y es un estado miembro de la UE. Malta fue considerada una isla del noroeste de África durante siglos, pero ahora también se considera parte de Europa. [30] "Europa", como se usa específicamente en inglés británico , también puede referirse exclusivamente a Europa continental . [31]

El término "continente" suele implicar la geografía física de una gran masa de tierra completamente o casi completamente rodeada de agua en sus fronteras. Antes de la adopción de la convención actual que incluye las divisorias montañosas, la frontera entre Europa y Asia había sido redefinida varias veces desde su primera concepción en la antigüedad clásica , pero siempre como una serie de ríos, mares y estrechos que se creía que se extendían una distancia desconocida al este y al norte desde el mar Mediterráneo sin la inclusión de ninguna cadena montañosa. El cartógrafo Herman Moll sugirió en 1715 que Europa estaba delimitada por una serie de vías fluviales parcialmente unidas dirigidas hacia los estrechos turcos y el río Irtysh que desemboca en la parte superior del río Ob y el océano Ártico . En contraste, el límite oriental actual de Europa se adhiere parcialmente a los montes Urales y del Cáucaso, lo que es algo arbitrario e inconsistente en comparación con cualquier definición clara del término "continente".

La división actual de Eurasia en dos continentes refleja las diferencias culturales, lingüísticas y étnicas entre Oriente y Occidente , que varían en un espectro más que en una línea divisoria nítida. La frontera geográfica entre Europa y Asia no sigue ninguna frontera estatal y ahora solo sigue unos pocos cuerpos de agua. Turquía se considera generalmente un país transcontinental dividido completamente por agua, mientras que Rusia y Kazajstán solo están divididos parcialmente por vías navegables. Francia, los Países Bajos, Portugal y España también son transcontinentales (o más propiamente, intercontinentales, cuando se trata de océanos o grandes mares) en el sentido de que sus principales áreas terrestres están en Europa, mientras que partes de sus territorios están ubicadas en otros continentes separados de Europa por grandes masas de agua. España, por ejemplo, tiene territorios al sur del mar Mediterráneo —a saber, Ceuta y Melilla— que son partes de África y comparten una frontera con Marruecos. Según la convención actual, Georgia y Azerbaiyán son países transcontinentales donde las vías navegables han sido completamente reemplazadas por montañas como división entre continentes.

El primer uso registrado de Eurṓpē como término geográfico se encuentra en el Himno homérico a Apolo de Delos , en referencia a la costa occidental del mar Egeo . Como nombre para una parte del mundo conocido, se utilizó por primera vez en el siglo VI a. C. por Anaximandro y Hecateo . Anaximandro colocó el límite entre Asia y Europa a lo largo del río Fasis (el moderno río Rioni en el territorio de Georgia ) en el Cáucaso, una convención que Heródoto todavía seguía en el siglo V a. C. [32] Heródoto mencionó que el mundo había sido dividido por personas desconocidas en tres partes: Europa, Asia y Libia (África), con el Nilo y el Fasis formando sus límites, aunque también afirma que algunos consideraban el río Don , en lugar del Fasis, como el límite entre Europa y Asia. [33] La frontera oriental de Europa fue definida en el siglo I por el geógrafo Estrabón en el río Don. [34] El Libro de los Jubileos describe los continentes como las tierras dadas por Noé a sus tres hijos; Europa se define como la que se extiende desde las Columnas de Hércules en el Estrecho de Gibraltar , que la separa del Noroeste de África , hasta el Don, que la separa de Asia. [35]

La convención recibida por la Edad Media y que sobrevive en el uso moderno es la de la era romana utilizada por autores de la era romana como Posidonio , [36] Estrabón , [37] y Ptolomeo , [38] quienes tomaron el Tanais (el moderno río Don) como límite.

El Imperio romano no le dio una identidad fuerte al concepto de divisiones continentales. Sin embargo, tras la caída del Imperio romano de Occidente , la cultura que se desarrolló en su lugar , vinculada al latín y a la iglesia católica, comenzó a asociarse con el concepto de "Europa". [39] El término "Europa" se utilizó por primera vez para una esfera cultural en el Renacimiento carolingio del siglo IX. A partir de ese momento, el término designó la esfera de influencia de la Iglesia occidental , en oposición tanto a las iglesias ortodoxas orientales como al mundo islámico .

Una definición cultural de Europa como las tierras de la cristiandad latina se fusionó en el siglo VIII, lo que significa el nuevo condominio cultural creado a través de la confluencia de las tradiciones germánicas y la cultura cristiano-latina, definida en parte en contraste con Bizancio y el Islam , y limitada al norte de Iberia , las Islas Británicas, Francia, Alemania occidental cristianizada, las regiones alpinas y el norte y centro de Italia. [40] [41] El concepto es uno de los legados duraderos del Renacimiento carolingio : Europa a menudo [ dudoso - discutir ] figura en las cartas del erudito de la corte de Carlomagno, Alcuino . [42] La transición de Europa a ser un término cultural además de geográfico llevó a que las fronteras de Europa se vieran afectadas por consideraciones culturales en Oriente, especialmente relacionadas con áreas bajo influencia bizantina, otomana y rusa. Tales cuestiones se vieron afectadas por las connotaciones positivas asociadas con el término Europa por sus usuarios. Tales consideraciones culturales no se aplicaron a las Américas, a pesar de su conquista y asentamiento por estados europeos. En cambio, el concepto de “civilización occidental” surgió como una forma de agrupar a Europa y estas colonias. [43]

La cuestión de definir un límite oriental preciso de Europa surge en el período moderno temprano, cuando la extensión oriental de Moscovia comenzó a incluir el norte de Asia . A lo largo de la Edad Media y hasta el siglo XVIII, la división tradicional de la masa continental de Eurasia en dos continentes, Europa y Asia, siguió a Ptolomeo, con el límite siguiendo los estrechos turcos , el mar Negro , el estrecho de Kerch , el mar de Azov y el Don (antiguo Tanais ). Pero los mapas producidos durante los siglos XVI al XVIII tendían a diferir en cómo continuar el límite más allá de la curva del Don en Kalach-na-Donu (donde está más cerca del Volga, ahora unido a él por el canal Volga-Don ), en un territorio no descrito en ningún detalle por los geógrafos antiguos.

En torno a 1715, Herman Moll elaboró un mapa que mostraba la parte norte del río Ob y el río Irtysh , un importante afluente del Ob, como componentes de una serie de vías navegables parcialmente unidas que marcaban la frontera entre Europa y Asia desde los estrechos turcos y el río Don hasta el océano Ártico. En 1721, elaboró un mapa más actualizado y más fácil de leer. Sin embargo, su propuesta de ceñirse a los ríos principales como línea de demarcación nunca fue aceptada por otros geógrafos que empezaban a alejarse de la idea de las fronteras fluviales como únicas divisiones legítimas entre Europa y Asia.

Cuatro años después, en 1725, Philip Johan von Strahlenberg fue el primero en apartarse de la clásica frontera del Don. Trazó una nueva línea a lo largo del Volga , siguiendo el Volga hacia el norte hasta el recodo de Samara , a lo largo de Obshchy Syrt (la divisoria de aguas entre los ríos Volga y Ural ), luego al norte y al este a lo largo de esta última vía fluvial hasta su nacimiento en los montes Urales . En este punto, propuso que las cadenas montañosas podrían incluirse como límites entre continentes como alternativas a las vías fluviales cercanas. En consecuencia, trazó la nueva frontera hacia el norte a lo largo de los montes Urales en lugar de los ríos Ob e Irtysh, cercanos y paralelos. [44] Esto fue respaldado por el Imperio ruso e introdujo la convención que eventualmente sería aceptada comúnmente. Sin embargo, esto no vino sin críticas. Voltaire , escribiendo en 1760 sobre los esfuerzos de Pedro el Grande para hacer que Rusia fuera más europea, ignoró toda la cuestión de los límites con su afirmación de que ni Rusia, Escandinavia, el norte de Alemania ni Polonia eran parte completa de Europa. [39] Desde entonces, muchos geógrafos analíticos modernos como Halford Mackinder han declarado que ven poca validez en los Montes Urales como límite entre continentes. [45]

Los cartógrafos siguieron discrepando sobre el límite entre el bajo Don y Samara hasta bien entrado el siglo XIX. El atlas de 1745 publicado por la Academia Rusa de Ciencias indica que el límite sigue el Don más allá de Kalach hasta Serafimovich antes de cortar hacia el norte hacia Arkhangelsk , mientras que otros cartógrafos de los siglos XVIII y XIX, como John Cary , siguieron la prescripción de Strahlenberg. Al sur, la depresión de Kuma-Manych fue identificada alrededor de 1773 por un naturalista alemán, Peter Simon Pallas , como un valle que una vez conectaba el mar Negro y el mar Caspio, [46] [47] y posteriormente fue propuesta como un límite natural entre continentes.

A mediados del siglo XIX, había tres convenciones principales: una que seguía el Don, el canal Volga-Don y el Volga; la otra que seguía la depresión Kuma-Manych hasta el Caspio y luego el río Ural; y la tercera que abandonaba por completo el Don y seguía la cuenca del Gran Cáucaso hasta el Caspio. La cuestión todavía se trataba como una "controversia" en la literatura geográfica de la década de 1860, y Douglas Freshfield defendía el límite de la cresta del Cáucaso como el "mejor posible", citando el apoyo de varios "geógrafos modernos". [48]

En Rusia y la Unión Soviética , el límite a lo largo de la depresión de Kuma-Manych fue el más comúnmente utilizado ya en 1906. [49] En 1958, la Sociedad Geográfica Soviética recomendó formalmente que el límite entre Europa y Asia se trazara en los libros de texto desde la bahía de Baydaratskaya , en el mar de Kara , a lo largo del pie oriental de los montes Urales, siguiendo luego el río Ural hasta las colinas de Mugodzhar , y luego el río Emba ; y la depresión de Kuma-Manych, [50] colocando así el Cáucaso completamente en Asia y los Urales completamente en Europa. [51] La Flora Europaea adoptó un límite a lo largo de los ríos Terek y Kuban , hacia el sur desde el Kuma y el Manych, pero todavía con el Cáucaso completamente en Asia. [52] [53] Sin embargo, la mayoría de los geógrafos de la Unión Soviética favorecían el límite a lo largo de la cresta del Cáucaso, [54] y esto se convirtió en la convención común a finales del siglo XX, aunque el límite Kuma-Manych siguió utilizándose en algunos mapas del siglo XX.

Algunos consideran que la separación de Eurasia en Asia y Europa es un residuo del eurocentrismo : "En cuanto a diversidad física, cultural e histórica, China y la India son comparables a toda la masa continental europea, no a un solo país europeo. [...]." [55]

Durante los 2,5 millones de años que duró el Pleistoceno , se produjeron numerosas fases frías llamadas glaciaciones ( Edad de hielo cuaternaria ), o avances significativos de las capas de hielo continentales, en Europa y América del Norte, a intervalos de aproximadamente 40.000 a 100.000 años. Los largos períodos glaciares estuvieron separados por interglaciares más templados y más cortos que duraron unos 10.000-15.000 años. El último episodio frío del último período glaciar terminó hace unos 10.000 años. [57] La Tierra se encuentra actualmente en un período interglaciar del Cuaternario, llamado Holoceno . [58]

El Homo erectus georgicus , que vivió hace aproximadamente 1,8 millones de años en Georgia , es el homínido más antiguo que se ha descubierto en Europa. [59] Otros restos de homínidos, que datan de aproximadamente 1 millón de años, se han descubierto en Atapuerca , España . [60] El hombre de Neandertal (llamado así por el valle de Neandertal en Alemania ) apareció en Europa hace 150.000 años (hace 115.000 años ya se encuentra en el territorio de la actual Polonia [61] ) y desapareció del registro fósil hace unos 40.000 años, [62] siendo su refugio final la península Ibérica. Los neandertales fueron suplantados por los humanos modernos ( cromañones ), que parecen haber aparecido en Europa hace unos 43.000 a 40.000 años. [63] Sin embargo, también hay evidencia de que el Homo sapiens llegó a Europa hace unos 54.000 años, unos 10.000 años antes de lo que se creía anteriormente. [64] Los primeros yacimientos de Europa que datan de hace 48.000 años son Riparo Mochi (Italia), Geissenklösterle (Alemania) e Isturitz (Francia). [65] [66]

El Neolítico europeo , marcado por el cultivo de cosechas y la cría de ganado, el aumento del número de asentamientos y el uso generalizado de la cerámica, comenzó alrededor del 7000 a. C. en Grecia y los Balcanes , probablemente influenciado por prácticas agrícolas anteriores en Anatolia y Oriente Próximo . [67] Se extendió desde los Balcanes a lo largo de los valles del Danubio y el Rin ( cultura de la cerámica lineal ) y a lo largo de la costa mediterránea ( cultura cardial ). Entre el 4500 y el 3000 a. C., estas culturas neolíticas de Europa central se desarrollaron más hacia el oeste y el norte, transmitiendo habilidades recién adquiridas en la producción de artefactos de cobre. En Europa occidental, el Neolítico no se caracterizó por grandes asentamientos agrícolas, sino por monumentos de campo, como recintos con calzadas , túmulos funerarios y tumbas megalíticas . [68] El horizonte cultural de la cerámica cordada floreció en la transición del Neolítico al Calcolítico . Durante este período se construyeron monumentos megalíticos gigantes , como los templos megalíticos de Malta y Stonehenge , en toda Europa occidental y meridional. [69] [70]

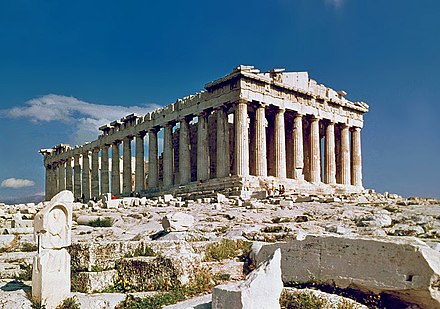

Las poblaciones nativas modernas de Europa descienden en gran medida de tres linajes distintos: [71] cazadores-recolectores mesolíticos , descendientes de poblaciones asociadas con la cultura paleolítica epigravetiense ; [56] agricultores europeos primitivos neolíticos que migraron de Anatolia durante la Revolución Neolítica hace 9000 años; [72] y pastores de la estepa yamna que se expandieron a Europa desde la estepa póntico-caspia de Ucrania y el sur de Rusia en el contexto de las migraciones indoeuropeas hace 5000 años. [71] [73] La Edad del Bronce europea comenzó c. 3200 a. C. en Grecia con la civilización minoica en Creta , la primera civilización avanzada en Europa. [74] Los minoicos fueron seguidos por los micénicos , que colapsaron repentinamente alrededor de 1200 a. C., marcando el comienzo de la Edad del Hierro europea . [75] La colonización de la Edad del Hierro por los griegos y los fenicios dio lugar a las primeras ciudades mediterráneas . La Italia y Grecia de la Edad del Hierro temprana , alrededor del siglo VIII a. C., dieron lugar gradualmente a la Antigüedad clásica histórica, cuyo comienzo a veces se data en 776 a. C., el año de los primeros Juegos Olímpicos . [76]

La antigua Grecia fue la cultura fundadora de la civilización occidental. La cultura democrática y racionalista occidental a menudo se atribuye a la antigua Grecia. [77] La ciudad-estado griega, la polis , fue la unidad política fundamental de la Grecia clásica. [77] En 508 a. C., Clístenes instituyó el primer sistema democrático de gobierno del mundo en Atenas . [78] Los ideales políticos griegos fueron redescubiertos a fines del siglo XVIII por filósofos e idealistas europeos. Grecia también generó muchas contribuciones culturales: en filosofía , humanismo y racionalismo con Aristóteles , Sócrates y Platón ; en historia con Heródoto y Tucídides ; en verso dramático y narrativo, comenzando con los poemas épicos de Homero ; [79] en drama con Sófocles y Eurípides ; en medicina con Hipócrates y Galeno ; y en ciencia con Pitágoras , Euclides y Arquímedes . [80] [81] [82] En el transcurso del siglo V a. C., varias de las ciudades-estado griegas finalmente frenarían el avance persa aqueménida en Europa a través de las guerras greco-persas , consideradas un momento crucial en la historia mundial, [83] ya que los 50 años de paz que siguieron se conocen como la Edad de Oro de Atenas , el período seminal de la antigua Grecia que sentó muchos de los cimientos de la civilización occidental.

A Grecia le siguió Roma , que dejó su huella en el derecho , la política , el lenguaje , la ingeniería , la arquitectura , el gobierno y muchos otros aspectos clave de la civilización occidental. [77] Hacia el año 200 a. C., Roma había conquistado Italia y durante los dos siglos siguientes conquistó Grecia , Hispania ( España y Portugal ), la costa norteafricana , gran parte de Oriente Medio , la Galia ( Francia y Bélgica ) y Britania ( Inglaterra y Gales ).

Los romanos, que se expandieron desde su base en el centro de Italia a partir del siglo III a. C., se expandieron gradualmente hasta gobernar toda la cuenca mediterránea y Europa occidental a finales del milenio. La República romana terminó en el 27 a. C., cuando Augusto proclamó el Imperio romano . Los dos siglos siguientes se conocen como la pax romana , un período de paz, prosperidad y estabilidad política sin precedentes en la mayor parte de Europa. [84] El imperio continuó expandiéndose bajo emperadores como Antonino Pío y Marco Aurelio , que pasaron un tiempo en la frontera norte del Imperio luchando contra las tribus germánicas , pictas y escocesas . [85] [86] El cristianismo fue legalizado por Constantino I en 313 d. C. después de tres siglos de persecución imperial . Constantino también trasladó permanentemente la capital del imperio de Roma a la ciudad de Bizancio (la actual Estambul ), que pasó a llamarse Constantinopla en su honor en 330 d. C. El cristianismo se convirtió en la única religión oficial del imperio en el año 380 d. C., y en el año 391-392 d. C. el emperador Teodosio prohibió las religiones paganas. [87] A veces se considera que esto marca el fin de la antigüedad; alternativamente, se considera que la antigüedad termina con la caída del Imperio romano de Occidente en el año 476 d. C.; el cierre de la pagana Academia platónica de Atenas en el año 529 d. C.; [88] o el surgimiento del Islam a principios del siglo VII d. C. Durante la mayor parte de su existencia, el Imperio bizantino fue una de las fuerzas económicas, culturales y militares más poderosas de Europa. [89]

Durante la decadencia del Imperio Romano , Europa entró en un largo período de cambio que surgió de lo que los historiadores llaman la " Era de las Migraciones ". Hubo numerosas invasiones y migraciones entre los ostrogodos , visigodos , godos , vándalos , hunos , francos , anglos , sajones , eslavos , ávaros , búlgaros , vikingos , pechenegos , cumanos y magiares . [84] Pensadores renacentistas como Petrarca se referirían más tarde a esto como la "Edad Oscura". [90]

Las comunidades monásticas aisladas eran los únicos lugares donde se podían resguardar y recopilar los conocimientos escritos acumulados previamente; aparte de esto, sobreviven muy pocos registros escritos. Gran parte de la literatura, la filosofía, las matemáticas y otras ideas del período clásico desaparecieron de Europa occidental, aunque se conservaron en Oriente, en el Imperio bizantino. [91]

Mientras que el Imperio romano en Occidente siguió decayendo, las tradiciones romanas y el Estado romano se mantuvieron fuertes en el Imperio Romano de Oriente , predominantemente de habla griega , también conocido como el Imperio bizantino . Durante la mayor parte de su existencia, el Imperio bizantino fue la fuerza económica, cultural y militar más poderosa de Europa. El emperador Justiniano I presidió la primera edad de oro de Constantinopla: estableció un código legal que forma la base de muchos sistemas legales modernos, financió la construcción de Santa Sofía y puso a la iglesia cristiana bajo el control del Estado. [92]

A partir del siglo VII, cuando los bizantinos y los persas sasánidas vecinos se vieron gravemente debilitados debido a las prolongadas, seculares y frecuentes guerras bizantino-sasánidas , los árabes musulmanes comenzaron a hacer incursiones en territorio históricamente romano, tomando el Levante y el norte de África y haciendo incursiones en Asia Menor . A mediados del siglo VII, tras la conquista musulmana de Persia , el Islam penetró en la región del Cáucaso . [93] Durante los siglos siguientes, las fuerzas musulmanas tomaron Chipre , Malta , Creta , Sicilia y partes del sur de Italia . [94] Entre 711 y 720, la mayoría de las tierras del Reino visigodo de Iberia quedaron bajo el dominio musulmán , salvo pequeñas áreas en el noroeste ( Asturias ) y regiones en gran parte vascas en los Pirineos . Este territorio, bajo el nombre árabe Al-Andalus , pasó a formar parte del creciente califato omeya . El fallido segundo asedio de Constantinopla (717) debilitó a la dinastía omeya y redujo su prestigio. Los omeyas fueron derrotados por el líder franco Carlos Martel en la batalla de Poitiers en 732, lo que puso fin a su avance hacia el norte. En las regiones remotas del noroeste de Iberia y los Pirineos medios , el poder de los musulmanes en el sur apenas se sintió. Fue aquí donde se sentaron las bases de los reinos cristianos de Asturias , León y Galicia y desde donde comenzaría la reconquista de la península Ibérica. Sin embargo, no se haría ningún intento coordinado para expulsar a los moros . Los reinos cristianos se centraron principalmente en sus propias luchas de poder internas. Como resultado, la Reconquista duró la mayor parte de ochocientos años, período en el que una larga lista de Alfonsos, Sanchos, Ordoños, Ramiros, Fernandos y Bermudos lucharían contra sus rivales cristianos tanto como contra los invasores musulmanes.

Durante la Edad Oscura, el Imperio Romano de Occidente cayó bajo el control de varias tribus. Las tribus germánicas y eslavas establecieron sus dominios sobre Europa occidental y oriental, respectivamente. [95] Finalmente, las tribus francas se unieron bajo Clodoveo I. [ 96] Carlomagno , un rey franco de la dinastía carolingia que había conquistado la mayor parte de Europa occidental, fue ungido " Sacro Emperador Romano " por el Papa en 800. Esto condujo en 962 a la fundación del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico, que finalmente se centró en los principados alemanes de Europa central. [97]

En Europa central y oriental se crearon los primeros estados eslavos y se adoptó el cristianismo ( hacia el año 1000 d. C.) . El poderoso estado eslavo occidental de Gran Moravia extendió su territorio hasta los Balcanes, alcanzando su mayor extensión territorial bajo Svatopluk I y provocando una serie de conflictos armados con Francia Oriental . Más al sur, los primeros estados eslavos del sur surgieron a finales del siglo VII y VIII y adoptaron el cristianismo : el Primer Imperio Búlgaro , el Principado Serbio (más tarde Reino e Imperio ) y el Ducado de Croacia (más tarde Reino de Croacia ). Al este, la Rus de Kiev se expandió desde su capital en Kiev para convertirse en el estado más grande de Europa en el siglo X. En 988, Vladimir el Grande adoptó el cristianismo ortodoxo como religión del estado. [98] [99] Más al este, la Bulgaria del Volga se convirtió en un estado islámico en el siglo X, pero finalmente fue absorbida por Rusia varios siglos después. [100]

El período comprendido entre el año 1000 y 1250 se conoce como la Alta Edad Media , seguido por la Baja Edad Media hasta aproximadamente el año 1500.

Durante la Alta Edad Media la población de Europa experimentó un importante crecimiento, que culminó con el Renacimiento del siglo XII . El crecimiento económico, unido a la falta de seguridad en las rutas comerciales continentales, posibilitó el desarrollo de importantes rutas comerciales a lo largo de la costa de los mares Mediterráneo y Báltico . La creciente riqueza e independencia adquirida por algunas ciudades costeras otorgaron a las Repúblicas Marítimas un papel protagonista en el panorama europeo.

La Edad Media en el continente estuvo dominada por los dos escalones superiores de la estructura social: la nobleza y el clero. El feudalismo se desarrolló en Francia en la Alta Edad Media y pronto se extendió por toda Europa. [103] Una lucha por la influencia entre la nobleza y la monarquía en Inglaterra condujo a la redacción de la Carta Magna y al establecimiento de un parlamento . [104] La principal fuente de cultura en este período provino de la Iglesia Católica Romana . A través de los monasterios y las escuelas catedralicias , la Iglesia fue responsable de la educación en gran parte de Europa. [103]

.jpg/440px-Philip_II_and_Tancred_meeting_in_Messina_-_British_Library_Royal_MS_16_G_vi_f350r_(detail).jpg)

El papado alcanzó el apogeo de su poder durante la Alta Edad Media. Un cisma entre Oriente y Occidente en 1054 dividió religiosamente al antiguo Imperio romano, quedando la Iglesia ortodoxa oriental en el Imperio bizantino y la Iglesia católica romana en el antiguo Imperio romano occidental. En 1095, el papa Urbano II convocó una cruzada contra los musulmanes que ocupaban Jerusalén y Tierra Santa . [105] En Europa, la Iglesia organizó la Inquisición contra los herejes. En la península Ibérica , la Reconquista concluyó con la caída de Granada en 1492 , poniendo fin a más de siete siglos de dominio islámico en el suroeste de la península. [106]

En el este, un Imperio bizantino resurgente recuperó Creta y Chipre de los musulmanes y reconquistó los Balcanes. Constantinopla fue la ciudad más grande y más rica de Europa desde el siglo IX hasta el XII, con una población de aproximadamente 400.000 habitantes. [107] El Imperio se debilitó tras la derrota en Manzikert , y se debilitó considerablemente por el saqueo de Constantinopla en 1204 , durante la Cuarta Cruzada . [108] [109] [110] [111] [112] [113] [114] [115] [116] Aunque recuperaría Constantinopla en 1261, Bizancio cayó en 1453 cuando Constantinopla fue tomada por el Imperio otomano . [117] [118] [119]

En los siglos XI y XII, las constantes incursiones de tribus nómadas turcas , como los pechenegos y los cumanos-kipchaks , provocaron una migración masiva de poblaciones eslavas a las regiones más seguras y boscosas del norte, y detuvieron temporalmente la expansión del estado de la Rus hacia el sur y el este. [120] Como muchas otras partes de Eurasia , estos territorios fueron invadidos por los mongoles . [121] Los invasores, que se conocieron como tártaros , eran en su mayoría pueblos de habla turca bajo soberanía mongola. Establecieron el estado de la Horda de Oro con sede en Crimea, que más tarde adoptó el Islam como religión, y gobernó el sur y el centro de Rusia actual durante más de tres siglos. [122] [123] Después del colapso de los dominios mongoles, los primeros estados rumanos (principados) surgieron en el siglo XIV: Moldavia y Valaquia . Anteriormente, estos territorios estaban bajo el control sucesivo de los pechenegos y los cumanos. [124] Desde el siglo XII hasta el siglo XV, el Gran Ducado de Moscú creció desde un pequeño principado bajo el dominio mongol hasta el estado más grande de Europa, derrocando a los mongoles en 1480 y finalmente convirtiéndose en el Zarato de Rusia . El estado se consolidó bajo Iván III el Grande e Iván el Terrible , expandiéndose constantemente hacia el este y el sur durante los siglos siguientes.

La Gran Hambruna de 1315-1317 fue la primera crisis que azotaría a Europa a finales de la Edad Media. [125] El período entre 1348 y 1420 fue testigo de la mayor pérdida. La población de Francia se redujo a la mitad. [126] [127] La Gran Bretaña medieval se vio afectada por 95 hambrunas, [128] y Francia sufrió los efectos de 75 o más en el mismo período. [129] Europa fue devastada a mediados del siglo XIV por la Peste Negra , una de las pandemias más mortíferas de la historia de la humanidad que mató a unos 25 millones de personas solo en Europa, un tercio de la población europea en ese momento. [130]

La peste tuvo un efecto devastador en la estructura social de Europa; indujo a la gente a vivir el momento, como lo ilustra Giovanni Boccaccio en El Decamerón (1353). Fue un duro golpe para la Iglesia católica romana y condujo a una mayor persecución de judíos , mendigos y leprosos . [131] Se cree que la peste regresó en cada generación con diferente virulencia y mortalidad hasta el siglo XVIII. [132] Durante este período, más de 100 epidemias de peste arrasaron Europa. [133]

El Renacimiento fue un período de cambio cultural que se originó en Florencia y luego se extendió al resto de Europa. El surgimiento de un nuevo humanismo estuvo acompañado por la recuperación del conocimiento clásico griego y árabe olvidado de las bibliotecas monásticas , a menudo traducido del árabe al latín . [134] [135] [136] El Renacimiento se extendió por Europa entre los siglos XIV y XVI: vio el florecimiento del arte , la filosofía , la música y las ciencias , bajo el patrocinio conjunto de la realeza , la nobleza, la Iglesia católica romana y una clase mercantil emergente. [137] [138] [139] Los mecenas en Italia, incluida la familia Medici de banqueros florentinos y los Papas en Roma , financiaron a prolíficos artistas del quattrocento y cinquecento como Rafael , Miguel Ángel y Leonardo da Vinci . [140] [141]

Las intrigas políticas dentro de la Iglesia a mediados del siglo XIV causaron el Cisma de Occidente . Durante este período de cuarenta años, dos papas, uno en Aviñón y otro en Roma, reclamaron el gobierno de la Iglesia. Aunque el cisma finalmente se curó en 1417, la autoridad espiritual del papado había sufrido mucho. [142] En el siglo XV, Europa comenzó a extenderse más allá de sus fronteras geográficas. España y Portugal, las mayores potencias navales de la época, tomaron la delantera en la exploración del mundo. [143] [144] La exploración llegó al hemisferio sur en el Atlántico y al extremo sur de África. Cristóbal Colón llegó al Nuevo Mundo en 1492, y Vasco da Gama abrió la ruta oceánica hacia el Este uniendo los océanos Atlántico e Índico en 1498. El explorador nacido en Portugal Fernando de Magallanes llegó a Asia hacia el oeste a través de los océanos Atlántico y Pacífico en una expedición española, lo que resultó en la primera circunnavegación del globo , completada por el español Juan Sebastián Elcano (1519-1522). Poco después, los españoles y portugueses comenzaron a establecer grandes imperios globales en América , Asia, África y Oceanía. [145] Francia, los Países Bajos e Inglaterra pronto siguieron en la construcción de grandes imperios coloniales con vastas posesiones en África, América y Asia. En 1588, una armada española fracasó en su intento de invadir Inglaterra. Un año después, Inglaterra intentó invadir España sin éxito , lo que permitió a Felipe II de España mantener su capacidad de guerra dominante en Europa. Este desastre inglés también permitió a la flota española conservar su capacidad para hacer la guerra durante las siguientes décadas. Sin embargo, otras dos armadas españolas fracasaron en su intento de invadir Inglaterra ( la 2.ª Armada Española y la 3.ª Armada Española ). [146] [147] [148] [149]

El poder de la Iglesia se debilitó aún más por la Reforma protestante en 1517 cuando el teólogo alemán Martín Lutero clavó sus Noventa y cinco tesis criticando la venta de indulgencias en la puerta de la iglesia. Posteriormente fue excomulgado en la bula papal Exsurge Domine en 1520 y sus seguidores fueron condenados en la Dieta de Worms de 1521 , que dividió a los príncipes alemanes entre las religiones protestante y católica romana. [151] Las luchas religiosas y la guerra se extendieron con el protestantismo. [152] El saqueo de los imperios de las Américas permitió a España financiar la persecución religiosa en Europa durante más de un siglo. [153] La Guerra de los Treinta Años (1618-1648) paralizó el Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico y devastó gran parte de Alemania , matando entre el 25 y el 40 por ciento de su población. [154] Después de la Paz de Westfalia , Francia alcanzó el predominio dentro de Europa. [155] La derrota de los turcos otomanos en la batalla de Viena en 1683 marcó el final histórico de la expansión otomana en Europa . [156]

El siglo XVII en Europa central y partes de Europa oriental fue un período de decadencia general ; [157] la región experimentó más de 150 hambrunas en un período de 200 años entre 1501 y 1700. [158] Desde la Unión de Krewo (1385), Europa central y oriental estuvo dominada por el Reino de Polonia y el Gran Ducado de Lituania . La hegemonía de la vasta Mancomunidad polaco-lituana había terminado con la devastación provocada por la Segunda Guerra del Norte ( Diluvio ) y los conflictos posteriores; [159] el propio estado se dividió y dejó de existir a fines del siglo XVIII. [160]

Desde los siglos XV al XVIII, cuando los kanatos en desintegración de la Horda de Oro fueron conquistados por Rusia, los tártaros del Kanato de Crimea atacaban con frecuencia las tierras eslavas orientales para capturar esclavos . [161] Más al este, la Horda Nogai y el Kanato kazajo atacaban con frecuencia las zonas de habla eslava de la Rusia y Ucrania contemporáneas durante cientos de años, hasta la expansión y conquista rusa de la mayor parte del norte de Eurasia (es decir, Europa del Este, Asia Central y Siberia).

El Renacimiento y los Nuevos Monarcas marcaron el inicio de una Era de Descubrimiento, un período de exploración, invención y desarrollo científico. [162] Entre las grandes figuras de la revolución científica occidental de los siglos XVI y XVII estuvieron Copérnico , Kepler , Galileo e Isaac Newton . [163] Según Peter Barrett, "Es ampliamente aceptado que la 'ciencia moderna' surgió en la Europa del siglo XVII (hacia el final del Renacimiento), introduciendo una nueva comprensión del mundo natural". [134]

La Guerra de los Siete Años puso fin al "viejo sistema" de alianzas en Europa . En consecuencia, cuando la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos se convirtió en una guerra mundial entre 1778 y 1783, Gran Bretaña se encontró con la oposición de una fuerte coalición de potencias europeas y sin ningún aliado importante. [164]

La Ilustración fue un poderoso movimiento intelectual durante el siglo XVIII que promovía el pensamiento científico y basado en la razón. [165] [166] [167] El descontento con el monopolio de la aristocracia y el clero sobre el poder político en Francia resultó en la Revolución Francesa y el establecimiento de la Primera República como resultado de la cual la monarquía y muchos de los nobles perecieron durante el reinado inicial del terror . [168] Napoleón Bonaparte llegó al poder después de la Revolución Francesa y estableció el Primer Imperio Francés que, durante las Guerras Napoleónicas , creció hasta abarcar grandes partes de Europa antes de colapsar en 1815 con la Batalla de Waterloo . [169] [170] El gobierno napoleónico resultó en una mayor difusión de los ideales de la Revolución Francesa, incluido el del estado nación , así como la adopción generalizada de los modelos franceses de administración , derecho y educación . [171] [172] [173] El Congreso de Viena , convocado después de la caída de Napoleón, estableció un nuevo equilibrio de poder en Europa centrado en las cinco " Grandes Potencias ": el Reino Unido, Francia, Prusia , Austria y Rusia. [174] Este equilibrio se mantendría hasta las Revoluciones de 1848 , durante las cuales los levantamientos liberales afectaron a toda Europa excepto Rusia y el Reino Unido. Estas revoluciones fueron finalmente sofocadas por elementos conservadores y resultaron pocas reformas. [175] El año 1859 vio la unificación de Rumania, como estado-nación, a partir de principados más pequeños. En 1867, se formó el imperio austrohúngaro ; 1871 vio las unificaciones de Italia y Alemania como estados-nación a partir de principados más pequeños. [176]

En paralelo, la cuestión oriental se volvió más compleja desde la derrota otomana en la guerra ruso-turca (1768-1774) . Como la disolución del Imperio otomano parecía inminente, las grandes potencias lucharon por salvaguardar sus intereses estratégicos y comerciales en los dominios otomanos. El Imperio ruso se benefició de la decadencia, mientras que el Imperio de los Habsburgo y Gran Bretaña percibieron que la preservación del Imperio otomano era lo mejor para sus intereses. Mientras tanto, la Revolución serbia (1804) y la Guerra de Independencia griega (1821) marcaron el comienzo del fin del dominio otomano en los Balcanes , que terminó con las Guerras de los Balcanes en 1912-1913. [177] El reconocimiento formal de los principados independientes de facto de Montenegro , Serbia y Rumania se produjo en el Congreso de Berlín en 1878.

La Revolución Industrial comenzó en Gran Bretaña en la última parte del siglo XVIII y se extendió por toda Europa. La invención e implementación de nuevas tecnologías resultó en un rápido crecimiento urbano, empleo masivo y el surgimiento de una nueva clase trabajadora. [178] Siguieron reformas en las esferas social y económica, incluidas las primeras leyes sobre el trabajo infantil , la legalización de los sindicatos , [179] y la abolición de la esclavitud . [180] En Gran Bretaña, se aprobó la Ley de Salud Pública de 1875 , que mejoró significativamente las condiciones de vida en muchas ciudades británicas. [181] La población de Europa aumentó de aproximadamente 100 millones en 1700 a 400 millones en 1900. [182] La última gran hambruna registrada en Europa occidental, la Gran Hambruna de Irlanda , causó la muerte y la emigración masiva de millones de irlandeses. [183] En el siglo XIX, 70 millones de personas abandonaron Europa en migraciones a varias colonias europeas en el extranjero y a los Estados Unidos. [184] La revolución industrial también condujo a un gran crecimiento demográfico, y la proporción de la población mundial que vivía en Europa alcanzó un pico de poco más del 25% alrededor del año 1913. [185] [186]

Dos guerras mundiales y una depresión económica dominaron la primera mitad del siglo XX. La Primera Guerra Mundial se libró entre 1914 y 1918. Comenzó cuando el archiduque Francisco Fernando de Austria fue asesinado por el nacionalista yugoslavo [187] Gavrilo Princip . [188] La mayoría de las naciones europeas se vieron arrastradas a la guerra, que se libró entre las potencias de la Entente ( Francia , Bélgica , Serbia , Portugal, Rusia , el Reino Unido y más tarde Italia , Grecia , Rumania y los Estados Unidos) y las potencias centrales ( Austria-Hungría , Alemania , Bulgaria y el Imperio otomano ). La guerra dejó más de 16 millones de civiles y militares muertos. [189] Más de 60 millones de soldados europeos fueron movilizados entre 1914 y 1918. [190]

Rusia se vio inmersa en la Revolución rusa , que derrocó a la monarquía zarista y la reemplazó por la Unión Soviética comunista , [191] lo que llevó también a la independencia de muchas antiguas gobernaciones rusas , como Finlandia , Estonia , Letonia y Lituania , como nuevos países europeos. [192] Austria-Hungría y el Imperio otomano colapsaron y se dividieron en naciones separadas, y muchas otras naciones vieron sus fronteras redefinidas. El Tratado de Versalles , que puso fin oficialmente a la Primera Guerra Mundial en 1919, fue duro con Alemania, a quien le atribuyó plena responsabilidad por la guerra e impuso fuertes sanciones. [193] El exceso de muertes en Rusia durante el transcurso de la Primera Guerra Mundial y la Guerra Civil Rusa (incluida la hambruna de posguerra ) ascendió a un total combinado de 18 millones. [194] En 1932-1933, bajo el liderazgo de Stalin , las confiscaciones de grano por parte de las autoridades soviéticas contribuyeron a la segunda hambruna soviética que causó millones de muertes; [195] Los kulaks supervivientes fueron perseguidos y muchos de ellos enviados a los gulags para realizar trabajos forzados . Stalin también fue responsable de la Gran Purga de 1937-38, en la que la NKVD ejecutó a 681.692 personas; [196] millones de personas fueron deportadas y exiliadas a zonas remotas de la Unión Soviética. [197]

.jpg/440px-Mussolini_and_Hitler_1940_(retouched).jpg)

Las revoluciones sociales que arrasaron Rusia también afectaron a otras naciones europeas después de la Gran Guerra : en 1919, con la República de Weimar en Alemania y la Primera República Austriaca ; en 1922, con el gobierno fascista de partido único de Mussolini en el Reino de Italia y en la República Turca de Atatürk , adoptando el alfabeto occidental y el secularismo estatal . La inestabilidad económica, causada en parte por las deudas contraídas en la Primera Guerra Mundial y los "préstamos" a Alemania, causó estragos en Europa a fines de la década de 1920 y en la de 1930. Esto, y el desplome de Wall Street de 1929 , provocaron la Gran Depresión mundial . Ayudados por la crisis económica, la inestabilidad social y la amenaza del comunismo, se desarrollaron movimientos fascistas en toda Europa que colocaron a Adolf Hitler en el poder de lo que se convirtió en la Alemania nazi . [203] [204]

En 1933, Hitler se convirtió en el líder de Alemania y comenzó a trabajar para lograr su objetivo de construir la Gran Alemania. Alemania se expandió nuevamente y recuperó el Sarre y Renania en 1935 y 1936. En 1938, Austria se convirtió en parte de Alemania después del Anschluss . Después del Acuerdo de Munich firmado por Alemania, Francia, el Reino Unido e Italia, más tarde en 1938 Alemania anexó los Sudetes , que era una parte de Checoslovaquia habitada por alemanes étnicos. A principios de 1939, el resto de Checoslovaquia se dividió en el Protectorado de Bohemia y Moravia , controlado por Alemania y la República Eslovaca . En ese momento, el Reino Unido y Francia preferían una política de apaciguamiento .

Con las tensiones en aumento entre Alemania y Polonia sobre el futuro de Danzig , los alemanes se volvieron hacia los soviéticos y firmaron el Pacto Mólotov-Ribbentrop , que permitió a los soviéticos invadir los estados bálticos y partes de Polonia y Rumania. Alemania invadió Polonia el 1 de septiembre de 1939, lo que llevó a Francia y el Reino Unido a declarar la guerra a Alemania el 3 de septiembre, abriendo el Teatro Europeo de la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [205] [206] [207] La invasión soviética de Polonia comenzó el 17 de septiembre y Polonia cayó poco después. El 24 de septiembre, la Unión Soviética atacó los países bálticos y, el 30 de noviembre, Finlandia, a la última de las cuales le siguió la devastadora Guerra de Invierno para el Ejército Rojo. [208] Los británicos esperaban desembarcar en Narvik y enviar tropas para ayudar a Finlandia, pero su objetivo principal en el desembarco era rodear a Alemania y cortar a los alemanes de los recursos escandinavos. Casi al mismo tiempo, Alemania trasladó tropas a Dinamarca. La Guerra Falsa continuó.

En mayo de 1940, Alemania atacó a Francia a través de los Países Bajos. Francia capituló en junio de 1940. En agosto, Alemania había comenzado una ofensiva de bombardeo contra el Reino Unido , pero no logró convencer a los británicos de que se rindieran. [209] En 1941, Alemania invadió la Unión Soviética en la Operación Barbarroja . [210] El 7 de diciembre de 1941, el ataque de Japón a Pearl Harbor atrajo a los Estados Unidos al conflicto como aliados del Imperio británico y otras fuerzas aliadas . [211] [212]

_(B&W).jpg/440px-Yalta_Conference_(Churchill,_Roosevelt,_Stalin)_(B&W).jpg)

Después de la asombrosa Batalla de Stalingrado en 1943, la ofensiva alemana en la Unión Soviética se convirtió en una continua retirada. La Batalla de Kursk , que implicó la batalla de tanques más grande de la historia, fue la última gran ofensiva alemana en el Frente Oriental . En junio de 1944, las fuerzas británicas y estadounidenses invadieron Francia en los desembarcos del Día D , abriendo un nuevo frente contra Alemania. Berlín finalmente cayó en 1945 , poniendo fin a la Segunda Guerra Mundial en Europa. La guerra fue la más grande y destructiva en la historia de la humanidad, con 60 millones de muertos en todo el mundo . [213] Más de 40 millones de personas en Europa habían muerto como resultado de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, [214] incluyendo entre 11 y 17 millones de personas que perecieron durante el Holocausto . [215] La Unión Soviética perdió alrededor de 27 millones de personas (en su mayoría civiles) durante la guerra, aproximadamente la mitad de todas las bajas de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [216] Al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Europa tenía más de 40 millones de refugiados . [217] [218] [219] Varias expulsiones posteriores a la guerra en Europa central y oriental desplazaron a un total de unos 20 millones de personas. [220]

La Primera Guerra Mundial, y especialmente la Segunda Guerra Mundial, disminuyeron la eminencia de Europa Occidental en los asuntos mundiales. Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el mapa de Europa fue rediseñado en la Conferencia de Yalta y dividido en dos bloques, los países occidentales y el bloque comunista del Este, separados por lo que más tarde Winston Churchill llamó una " Cortina de Hierro ". Estados Unidos y Europa Occidental establecieron la alianza de la OTAN y, más tarde, la Unión Soviética y Europa Central establecieron el Pacto de Varsovia . [221] Los puntos calientes particulares después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial fueron Berlín y Trieste , por lo que el Territorio Libre de Trieste , fundado en 1947 con la ONU, se disolvió en 1954 y 1975, respectivamente. El bloqueo de Berlín en 1948 y 1949 y la construcción del Muro de Berlín en 1961 fueron una de las grandes crisis internacionales de la Guerra Fría . [222] [223] [224]

Las dos nuevas superpotencias , Estados Unidos y la Unión Soviética, se vieron envueltas en una Guerra Fría que duró cincuenta años, centrada en la proliferación nuclear . Al mismo tiempo, la descolonización , que ya había comenzado después de la Primera Guerra Mundial, resultó gradualmente en la independencia de la mayoría de las colonias europeas en Asia y África. [15]

En la década de 1980, las reformas de Mijail Gorbachov y el movimiento Solidaridad en Polonia debilitaron el sistema comunista, que hasta entonces era rígido. La apertura de la Cortina de Hierro en el Picnic Paneuropeo puso en marcha una reacción en cadena pacífica, al final de la cual se derrumbaron el bloque del Este , el Pacto de Varsovia y otros estados comunistas , y terminó la Guerra Fría. [226] [227] [228] Alemania se reunificó, después de la caída simbólica del Muro de Berlín en 1989 y los mapas de Europa Central y Oriental se rediseñaron una vez más. [229] Esto hizo posible las antiguas relaciones culturales y económicas previamente interrumpidas, y ciudades anteriormente aisladas como Berlín , Praga , Viena , Budapest y Trieste volvieron a estar en el centro de Europa. [203] [230] [231] [232]

La integración europea también creció después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. En 1949 se fundó el Consejo de Europa , tras un discurso de Sir Winston Churchill , con la idea de unificar Europa [16] para alcanzar objetivos comunes. Incluye a todos los estados europeos excepto Bielorrusia , Rusia [233] y la Ciudad del Vaticano . El Tratado de Roma de 1957 estableció la Comunidad Económica Europea entre seis estados de Europa occidental con el objetivo de una política económica unificada y un mercado común. [234] En 1967, la CEE, la Comunidad Europea del Carbón y del Acero y Euratom formaron la Comunidad Europea , que en 1993 se convirtió en la Unión Europea . La UE estableció un parlamento , un tribunal y un banco central , e introdujo el euro como moneda unificada. [235] Entre 2004 y 2013, más países de Europa Central comenzaron a unirse, expandiendo la UE a 28 países europeos y convirtiendo una vez más a Europa en un importante centro económico y político de poder. [236] Sin embargo, el Reino Unido se retiró de la UE el 31 de enero de 2020, como resultado de un referéndum de junio de 2016 sobre la membresía en la UE . [237] El conflicto ruso-ucraniano , que ha estado en curso desde 2014, se intensificó abruptamente cuando Rusia lanzó una invasión a gran escala de Ucrania el 24 de febrero de 2022, marcando la mayor crisis humanitaria y de refugiados en Europa desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial [238] y las guerras yugoslavas . [239]

Europa constituye la quinta parte occidental de la masa continental de Eurasia . [28] Tiene una mayor proporción de costa a masa continental que cualquier otro continente o subcontinente. [240] Sus fronteras marítimas consisten en el océano Ártico al norte, el océano Atlántico al oeste y el Mediterráneo, los mares Negro y Caspio al sur. [241] El relieve terrestre en Europa muestra una gran variación dentro de áreas relativamente pequeñas. Las regiones del sur son más montañosas, mientras que al moverse hacia el norte el terreno desciende desde los altos Alpes , los Pirineos y los Cárpatos , a través de tierras altas montañosas, hasta las amplias y bajas llanuras del norte, que son vastas en el este. Esta extensa llanura se conoce como la Gran Llanura Europea y en su corazón se encuentra la Llanura del Norte de Alemania . También existe un arco de tierras altas a lo largo de la costa noroeste, que comienza en las partes occidentales de las islas de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda, y luego continúa a lo largo de la columna montañosa cortada por fiordos de Noruega.

Esta descripción es simplificada. Subregiones como la península Ibérica y la península italiana contienen sus propias características complejas, al igual que la propia Europa central continental, donde el relieve contiene muchas mesetas, valles fluviales y cuencas que complican la tendencia general. Subregiones como Islandia , Gran Bretaña e Irlanda son casos especiales. La primera es una tierra en sí misma en el océano norte que se considera parte de Europa, mientras que las segundas son áreas de tierras altas que alguna vez estuvieron unidas al continente hasta que el aumento del nivel del mar las separó.

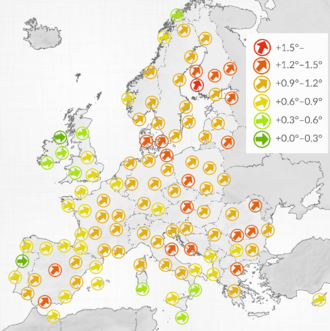

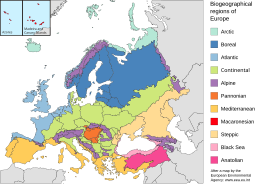

Europa se encuentra principalmente en la zona de clima templado del hemisferio norte, donde la dirección predominante del viento es del oeste . El clima es más suave en comparación con otras áreas de la misma latitud alrededor del mundo debido a la influencia de la Corriente del Golfo , una corriente oceánica que transporta agua cálida desde el Golfo de México a través del Océano Atlántico hasta Europa. [242] La Corriente del Golfo recibe el apodo de "la calefacción central de Europa", porque hace que el clima de Europa sea más cálido y húmedo de lo que sería de otra manera. La Corriente del Golfo no solo transporta agua cálida a la costa de Europa, sino que también calienta los vientos predominantes del oeste que soplan a través del continente desde el Océano Atlántico.

Por lo tanto, la temperatura media durante todo el año en Aveiro es de 16 °C (61 °F), mientras que en la ciudad de Nueva York, que está casi en la misma latitud y bordea el mismo océano, es de tan solo 13 °C (55 °F). Berlín (Alemania), Calgary (Canadá) e Irkutsk, en el extremo sureste de Rusia, se encuentran aproximadamente en la misma latitud; las temperaturas de enero en Berlín son en promedio alrededor de 8 °C (14 °F) más altas que las de Calgary y son casi 22 °C (40 °F) más altas que las temperaturas promedio en Irkutsk. [242]

También son de particular importancia las grandes masas de agua del mar Mediterráneo , que igualan las temperaturas medias anuales y diarias. Las aguas del Mediterráneo se extienden desde el desierto del Sahara hasta el arco alpino en su parte más septentrional del mar Adriático, cerca de Trieste . [243]

En general, Europa no sólo es más fría hacia el norte que hacia el sur, sino que también se enfría más desde el oeste hacia el este. El clima es más oceánico en el oeste y menos en el este. Esto se puede ilustrar con la siguiente tabla de temperaturas medias en lugares que se encuentran aproximadamente en las latitudes 64, 60, 55, 50, 45 y 40. Ninguno de ellos se encuentra a gran altitud; la mayoría están cerca del mar.

[245] Es notable cómo las temperaturas medias del mes más frío, así como las temperaturas medias anuales, descienden de oeste a este. Por ejemplo, Edimburgo es más cálido que Belgrado durante el mes más frío del año, aunque Belgrado se encuentra unos 10° de latitud más al sur.

La historia geológica de Europa se remonta a la formación del Escudo Báltico (Fennoscandia) y el cratón sármata , ambos hace unos 2.250 millones de años, seguidos por el escudo Volgo-Uralia , los tres juntos dando lugar al cratón de Europa del Este (≈ Baltica ) que se convirtió en parte del supercontinente Columbia . Hace unos 1.100 millones de años, Baltica y Arctica (como parte del bloque Laurentia ) se unieron a Rodinia , volviéndose a dividir hace unos 550 millones de años para reformarse como Baltica. Hace unos 440 millones de años, Euramérica se formó a partir de Baltica y Laurentia; una unión posterior con Gondwana dio lugar a la formación de Pangea . Hace unos 190 millones de años, Gondwana y Laurasia se separaron debido al ensanchamiento del océano Atlántico. Finalmente, y muy poco después, la propia Laurasia se dividió de nuevo, en Laurentia (América del Norte) y el continente euroasiático. La conexión terrestre entre ambos continentes persistió durante un tiempo considerable, a través de Groenlandia , lo que dio lugar al intercambio de especies animales. Desde hace unos 50 millones de años, el aumento y la disminución del nivel del mar han determinado la forma actual de Europa y sus conexiones con continentes como Asia. La forma actual de Europa data de finales del período Terciario , hace unos cinco millones de años. [251]

La geología de Europa es enormemente variada y compleja y da lugar a la amplia variedad de paisajes que se encuentran en todo el continente, desde las Tierras Altas de Escocia hasta las llanuras onduladas de Hungría. [252] La característica más significativa de Europa es la dicotomía entre las tierras altas y montañosas del sur de Europa y una vasta llanura norte parcialmente submarina que se extiende desde Irlanda en el oeste hasta los montes Urales en el este. Estas dos mitades están separadas por las cadenas montañosas de los Pirineos y los Alpes / Cárpatos . Las llanuras del norte están delimitadas en el oeste por las montañas escandinavas y las partes montañosas de las Islas Británicas. Los principales cuerpos de agua poco profundos que sumergen partes de las llanuras del norte son el mar Céltico , el mar del Norte , el complejo del mar Báltico y el mar de Barents .

La llanura septentrional contiene el antiguo continente geológico del Báltico y, por lo tanto, puede considerarse geológicamente como el "continente principal", mientras que las tierras altas periféricas y las regiones montañosas del sur y el oeste constituyen fragmentos de varios otros continentes geológicos. La mayor parte de la geología más antigua de Europa occidental existía como parte del antiguo microcontinente Avalonia .

Los animales y las plantas de Europa, que han convivido con pueblos agrícolas durante milenios, se han visto profundamente afectados por la presencia y las actividades humanas. Con excepción de Fennoscandia y el norte de Rusia, en la actualidad quedan pocas zonas de naturaleza intacta en Europa, salvo varios parques nacionales .

La principal cubierta vegetal natural de Europa es el bosque mixto . Las condiciones para el crecimiento son muy favorables. En el norte, la Corriente del Golfo y la Deriva del Atlántico Norte calientan el continente. El sur de Europa tiene un clima cálido pero suave. Hay frecuentes sequías estivales en esta región. Las crestas montañosas también afectan las condiciones. Algunas de ellas, como los Alpes y los Pirineos , están orientadas de este a oeste y permiten que el viento transporte grandes masas de agua desde el océano hacia el interior. Otras están orientadas de sur a norte ( Montañas Escandinavas , Dinárides , Cárpatos , Apeninos ) y debido a que la lluvia cae principalmente en el lado de las montañas que está orientado hacia el mar, los bosques crecen bien en este lado, mientras que en el otro lado, las condiciones son mucho menos favorables. Pocos rincones de la Europa continental no han sido pastoreados por el ganado en algún momento, y la tala del hábitat forestal preagrícola causó alteraciones en los ecosistemas vegetales y animales originales.

Posiblemente entre el 80 y el 90 por ciento de Europa estuvo alguna vez cubierta de bosques. [253] Se extendía desde el mar Mediterráneo hasta el océano Ártico. Aunque más de la mitad de los bosques originales de Europa desaparecieron a través de siglos de deforestación , Europa todavía tiene más de una cuarta parte de su superficie terrestre como bosque, como los bosques latifoliados y mixtos , la taiga de Escandinavia y Rusia, las selvas tropicales mixtas del Cáucaso y los bosques de alcornoques en el Mediterráneo occidental. Durante los últimos tiempos, la deforestación se ha ralentizado y se han plantado muchos árboles. Sin embargo, en muchos casos, las plantaciones de monocultivos de coníferas han reemplazado al bosque natural mixto original, porque estos crecen más rápido. Las plantaciones ahora cubren vastas áreas de tierra, pero ofrecen hábitats más pobres para muchas especies que habitan en los bosques europeos y que requieren una mezcla de especies de árboles y una estructura forestal diversa. La cantidad de bosque natural en Europa occidental es solo del 2-3% o menos, mientras que en su Rusia occidental es del 5-10%. El país europeo con el menor porcentaje de superficie forestal es Islandia (1%), mientras que el país con más bosques es Finlandia (77%). [254]

En la Europa templada predominan los bosques mixtos con árboles de hoja ancha y coníferas. Las especies más importantes en Europa central y occidental son el haya y el roble . En el norte, la taiga es un bosque mixto de abetos , pinos y abedules ; más al norte, en Rusia y en el extremo norte de Escandinavia, la taiga da paso a la tundra a medida que nos acercamos al Ártico. En el Mediterráneo se han plantado muchos olivos , que se adaptan muy bien a su clima árido; el ciprés mediterráneo también se planta ampliamente en el sur de Europa. La región mediterránea semiárida alberga mucho bosque de matorrales. Una estrecha lengua de pastizales euroasiáticos ( la estepa ) de este a oeste se extiende hacia el oeste desde Ucrania y el sur de Rusia y termina en Hungría y atraviesa la taiga hacia el norte.

La glaciación durante la última edad de hielo y la presencia humana afectaron a la distribución de la fauna europea . En cuanto a los animales, en muchas partes de Europa la mayoría de los animales grandes y las especies de depredadores superiores han sido cazados hasta su extinción. El mamut lanudo se extinguió antes del final del Neolítico . Hoy en día, los lobos ( carnívoros ) y los osos ( omnívoros ) están en peligro de extinción. Una vez se encontraron en la mayor parte de Europa. Sin embargo, la deforestación y la caza hicieron que estos animales se retiraran cada vez más. En la Edad Media, los hábitats de los osos se limitaban a montañas más o menos inaccesibles con suficiente cobertura forestal. Hoy en día, el oso pardo vive principalmente en la península de los Balcanes , Escandinavia y Rusia; también persiste un pequeño número en otros países de Europa (Austria, Pirineos, etc.), pero en estas áreas las poblaciones de osos pardos están fragmentadas y marginadas debido a la destrucción de su hábitat. Además, se pueden encontrar osos polares en Svalbard , un archipiélago noruego muy al norte de Escandinavia. El lobo , el segundo mayor depredador de Europa después del oso pardo, se puede encontrar principalmente en Europa central y oriental y en los Balcanes, con un puñado de manadas en algunas zonas de Europa occidental (Escandinavia, España, etc.).

Otros carnívoros incluyen el gato montés europeo , el zorro rojo y el zorro ártico , el chacal dorado , diferentes especies de martas , el erizo europeo , diferentes especies de reptiles (como serpientes como víboras y culebras de collar) y anfibios, así como diferentes aves ( búhos , halcones y otras aves rapaces).

Entre los herbívoros europeos más importantes se encuentran los caracoles, las larvas, los peces, diversas aves y mamíferos como roedores, ciervos, corzos, jabalíes y, entre otros, marmotas, gamuzas y otros animales de montaña. También contribuyen a la biodiversidad una serie de insectos como la pequeña mariposa de orejas de tortuga. [257]

Las criaturas marinas también son una parte importante de la flora y fauna europeas. La flora marina está compuesta principalmente por fitoplancton . Los animales importantes que viven en los mares europeos son el zooplancton , los moluscos , los equinodermos , diferentes crustáceos , calamares y pulpos , peces, delfines y ballenas .

La biodiversidad está protegida en Europa a través del Convenio de Berna del Consejo de Europa , que también ha sido firmado por la Comunidad Europea y estados no europeos.

El mapa político de Europa se deriva en gran medida de la reorganización de Europa tras las guerras napoleónicas en 1815. La forma de gobierno predominante en Europa es la democracia parlamentaria , en la mayoría de los casos en forma de república ; en 1815, la forma de gobierno predominante todavía era la monarquía . Las once monarquías restantes de Europa [258] son constitucionales .

La integración europea es el proceso de integración política, jurídica, económica (y en algunos casos social y cultural) de los estados europeos que han llevado a cabo las potencias que patrocinan el Consejo de Europa desde el final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial . La Unión Europea ha sido el foco de la integración económica en el continente desde su fundación en 1993. Más recientemente, se ha establecido la Unión Económica Euroasiática como contraparte que comprende a los antiguos estados soviéticos.

27 Estados europeos son miembros de la Unión Europea político-económica, 26 de la zona libre de fronteras Schengen y 20 de la unión monetaria Eurozona . Entre las organizaciones europeas más pequeñas se encuentran el Consejo Nórdico , el Benelux , la Asamblea Báltica y el Grupo de Visegrado .

Los países menos democráticos de Europa son Bielorrusia , Rusia y Turquía en 2024 según los índices de democracia V-Dem . [259]

Esta lista incluye todos los países soberanos reconocidos internacionalmente que caen incluso parcialmente dentro de cualquier definición geográfica o política común de Europa .

Entre los Estados mencionados se encuentran varios países independientes de facto con un reconocimiento internacional limitado o nulo . Ninguno de ellos es miembro de la ONU:

Varias dependencias y territorios similares con amplia autonomía también se encuentran dentro o cerca de Europa. Esto incluye Åland (un condado autónomo de Finlandia), dos territorios autónomos del Reino de Dinamarca (aparte de Dinamarca propiamente dicha), tres Dependencias de la Corona y dos Territorios Británicos de Ultramar . Svalbard también está incluido debido a su estatus único dentro de Noruega, aunque no es autónomo. No se incluyen los tres países del Reino Unido con poderes delegados y las dos Regiones Autónomas de Portugal , que a pesar de tener un grado único de autonomía, no son en gran medida autónomas en asuntos que no sean los asuntos internacionales. Las áreas con poco más que un estatus fiscal único, como las Islas Canarias y Heligoland , tampoco están incluidas por este motivo.

Como continente, la economía de Europa es actualmente la más grande de la Tierra y es la región más rica en términos de activos bajo gestión, con más de 32,7 billones de dólares en comparación con los 27,1 billones de dólares de América del Norte en 2008. [261] En 2009, Europa siguió siendo la región más rica. Sus 37,1 billones de dólares en activos bajo gestión representaron un tercio de la riqueza mundial. Fue una de varias regiones donde la riqueza superó su pico de fin de año anterior a la crisis. [262] Al igual que con otros continentes, Europa tiene una gran brecha de riqueza entre sus países. Los estados más ricos tienden a estar en el noroeste y el oeste en general, seguidos de Europa central , mientras que la mayoría de las economías de Europa oriental y sudoriental todavía están resurgiendo del colapso de la Unión Soviética y la desintegración de Yugoslavia .

El modelo del plátano azul fue diseñado como una representación geográfica económica del respectivo poder económico de las regiones, que luego se desarrolló hasta convertirse en el plátano dorado o la estrella azul. El comercio entre Oriente y Occidente, así como hacia Asia, que se había visto perturbado durante mucho tiempo por las dos guerras mundiales, las nuevas fronteras y la Guerra Fría, aumentó drásticamente después de 1989. Además, hay un nuevo impulso de la Iniciativa del Cinturón y la Ruta de China a través del Canal de Suez hacia África y Asia. [263]

La Unión Europea, entidad política compuesta por 27 estados europeos, comprende el área económica única más grande del mundo. Diecinueve países de la UE comparten el euro como moneda común. Cinco países europeos se ubican entre las diez mayores economías nacionales del mundo en PIB (PPA) . Esto incluye (clasificaciones según la CIA ): Alemania (6), Rusia (7), el Reino Unido (10), Francia (11) e Italia (13). [264]

Algunos países europeos son mucho más ricos que otros. El más rico en términos de PIB nominal es Mónaco , con 185.829 dólares per cápita (2018), y el más pobre es Ucrania , con 3.659 dólares per cápita (2019). [265]

En conjunto, el PIB per cápita de Europa es de 21.767 dólares estadounidenses según una evaluación del Fondo Monetario Internacional de 2016. [266]

El capitalismo ha sido dominante en el mundo occidental desde el fin del feudalismo. [272] Desde Gran Bretaña, se extendió gradualmente por toda Europa. [273] La Revolución Industrial comenzó en Europa, específicamente en el Reino Unido a fines del siglo XVIII, [274] y el siglo XIX vio a Europa Occidental industrializarse. Las economías se vieron perturbadas por la Primera Guerra Mundial, pero a principios de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, se habían recuperado y tuvieron que competir con la creciente fuerza económica de los Estados Unidos. La Segunda Guerra Mundial, nuevamente, dañó gran parte de las industrias de Europa.

Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la economía del Reino Unido estaba en ruinas, [275] y continuó sufriendo un declive económico relativo en las décadas siguientes. [276] Italia también estaba en malas condiciones económicas, pero recuperó un alto nivel de crecimiento en la década de 1950. Alemania Occidental se recuperó rápidamente y duplicó la producción con respecto a los niveles anteriores a la guerra en la década de 1950. [277] Francia también protagonizó una notable recuperación disfrutando de un rápido crecimiento y modernización; más tarde, España, bajo el liderazgo de Franco , también se recuperó y la nación registró un enorme crecimiento económico sin precedentes a partir de la década de 1960 en lo que se llama el milagro español . [278] La mayoría de los estados de Europa central y oriental quedaron bajo el control de la Unión Soviética y, por lo tanto, eran miembros del Consejo de Asistencia Económica Mutua (COMECON). [279]

Los estados que mantuvieron un sistema de libre mercado recibieron una gran cantidad de ayuda de los Estados Unidos bajo el Plan Marshall . [280] Los estados occidentales se movieron para vincular sus economías, proporcionando la base para la UE y aumentando el comercio transfronterizo. Esto los ayudó a disfrutar de economías en rápida mejora, mientras que los estados del COMECON luchaban en gran parte debido al costo de la Guerra Fría . Hasta 1990, la Comunidad Europea se amplió de 6 miembros fundadores a 12. El énfasis puesto en resucitar la economía de Alemania Occidental llevó a que superara al Reino Unido como la economía más grande de Europa.

Con la caída del comunismo en Europa Central y Oriental en 1991, los estados post-socialistas sometieron a medidas de terapia de choque para liberalizar sus economías e implementar reformas de libre mercado.

Después de que Alemania Oriental y Occidental se reunificaron en 1990, la economía de Alemania Occidental atravesó dificultades, ya que tuvo que apoyar y reconstruir en gran medida la infraestructura de Alemania Oriental, mientras que esta última experimentó un desempleo masivo repentino y una caída en picada de la producción industrial .

En el cambio de milenio, la UE dominaba la economía de Europa, y en ella se encontraban las cinco mayores economías europeas de la época: Alemania, el Reino Unido, Francia, Italia y España. En 1999, 12 de los 15 miembros de la UE se unieron a la eurozona , reemplazando sus monedas nacionales por el euro .

Las cifras publicadas por Eurostat en 2009 confirmaron que la eurozona había entrado en recesión en 2008. [282] Afectó a gran parte de la región. [283] En 2010, surgieron temores de una crisis de deuda soberana [284] en algunos países de Europa, especialmente Grecia, Irlanda, España y Portugal. [285] Como resultado, los principales países de la eurozona tomaron medidas, especialmente para Grecia. [286] La tasa de desempleo de la UE-27 fue del 10,3% en 2012. Para los de 15 a 24 años fue del 22,4%. [287]

La población de Europa era de unos 742 millones en 2023 según estimaciones de la ONU. [2] [3] Esto es un poco más de una novena parte de la población mundial. [v] La densidad de población de Europa (el número de personas por área) es la segunda más alta de cualquier continente, detrás de Asia. La población de Europa está disminuyendo lentamente actualmente, aproximadamente un 0,2% por año, [289] porque hay menos nacimientos que muertes . Esta disminución natural de la población se reduce por el hecho de que más personas migran a Europa desde otros continentes que viceversa.

Europa meridional y Europa occidental son las regiones con mayor número medio de personas mayores del mundo. En 2021, el porcentaje de personas mayores de 65 años fue del 21% en Europa occidental y Europa meridional, frente al 19% en toda Europa y el 10% en el mundo. [290] Las proyecciones sugieren que para 2050 Europa alcanzará el 30%. [291] Esto se debe a que la población ha estado teniendo hijos por debajo del nivel de reemplazo desde la década de 1970. Las Naciones Unidas predicen que Europa disminuirá su población entre 2022 y 2050 en un −7%, sin cambios en los movimientos migratorios. [292]

Según una proyección de población de la División de Población de las Naciones Unidas, la población de Europa podría reducirse a entre 680 y 720 millones de personas en 2050, lo que representaría el 7% de la población mundial en ese momento. [293] En este contexto, existen disparidades significativas entre regiones en relación con las tasas de fertilidad . El número promedio de hijos por mujer en edad fértil es de 1,52, muy por debajo de la tasa de reemplazo. [294] La ONU predice una disminución constante de la población en Europa central y oriental como resultado de la emigración y las bajas tasas de natalidad. [295]