La frontera estadounidense , también conocida como el Viejo Oeste y popularmente conocida como el Salvaje Oeste , abarca la geografía, la historia, el folclore y la cultura asociados con la ola de expansión estadounidense en América del Norte continental que comenzó con los asentamientos coloniales europeos a principios del siglo XVII y terminó con la admisión de los últimos territorios occidentales contiguos como estados en 1912. Esta era de migración y asentamiento masivos fue particularmente alentada por el presidente Thomas Jefferson después de la Compra de Luisiana , dando lugar a la actitud expansionista conocida como " destino manifiesto " y la " Tesis de la Frontera " de los historiadores. Las leyendas, los eventos históricos y el folclore de la frontera estadounidense, conocida como el mito de la frontera , se han incrustado en la cultura de los Estados Unidos tanto que el Viejo Oeste, y el género de los medios de comunicación del oeste específicamente, se ha convertido en una de las características definitorias de la identidad nacional estadounidense.

Los historiadores han debatido extensamente sobre cuándo comenzó la era fronteriza, cuándo terminó y cuáles fueron sus subperíodos clave. [3] Por ejemplo, los historiadores a veces usan el subperíodo del Viejo Oeste para referirse al tiempo desde el final de la Guerra Civil estadounidense en 1865 hasta cuando el Superintendente del Censo, William Rush Merriam , declaró que la Oficina del Censo de los EE. UU. dejaría de registrar los asentamientos fronterizos occidentales como parte de sus categorías censales después del Censo de los EE. UU . de 1890. [6] [7] [10] [11] Sin embargo, sus sucesores continuaron la práctica hasta el Censo de 1920. [ 1] [2]

Otros, incluida la Biblioteca del Congreso y la Universidad de Oxford , a menudo citan puntos diferentes que se remontan a principios del siglo XX; típicamente dentro de las primeras dos décadas, antes de la entrada estadounidense en la Primera Guerra Mundial . [4] [12] Un período conocido como "La Guerra Civil Occidental de Incorporación" duró desde la década de 1850 hasta 1919. Este período incluyó eventos históricos sinónimos del arquetipo del Viejo Oeste o "Salvaje Oeste", como el conflicto violento que surgió de los asentamientos invasores en tierras fronterizas, la remoción y asimilación de nativos, la consolidación de la propiedad en grandes corporaciones y el gobierno, el vigilantismo y el intento de hacer cumplir las leyes a los delincuentes. [13]

En 1890, el superintendente del censo, William Rush Merriam, afirmó: "Hasta 1880 inclusive, el país tenía una frontera de asentamiento, pero en la actualidad el área no colonizada ha sido tan dividida por cuerpos aislados de asentamiento que difícilmente puede decirse que haya una línea fronteriza. En la discusión de su extensión, su movimiento hacia el oeste, etc., por lo tanto, ya no puede tener un lugar en los informes del censo". [14] A pesar de esto, el censo estadounidense posterior de 1900 continuó mostrando la línea fronteriza hacia el oeste, y sus sucesores continuaron con la práctica. [1] [15] Sin embargo, para el censo estadounidense de 1910 , la frontera se había reducido a áreas divididas sin una línea singular de asentamiento hacia el oeste. [16] Se cita una afluencia de colonos agrícolas en las primeras dos décadas del siglo XX, que ocuparon más superficie que las concesiones de propiedad en todo el siglo XIX, por haber reducido significativamente las tierras abiertas. [17]

Una frontera es una zona de contacto en el borde de una línea de asentamiento. El teórico Frederick Jackson Turner fue más allá y sostuvo que la frontera fue el escenario de un proceso definitorio de la civilización estadounidense: "La frontera", afirmó, "promocionó la formación de una nacionalidad compuesta para el pueblo estadounidense". Teorizó que era un proceso de desarrollo: "Este renacimiento perenne, esta fluidez de la vida estadounidense, esta expansión hacia el oeste... proporciona las fuerzas que dominan el carácter estadounidense". [18] Las ideas de Turner desde 1893 han inspirado a generaciones de historiadores (y críticos) a explorar múltiples fronteras estadounidenses individuales, pero la frontera popular se concentra en la conquista y el asentamiento de tierras de los nativos americanos al oeste del río Mississippi , en lo que ahora es el Medio Oeste , Texas , las Grandes Llanuras , las Montañas Rocosas , el Suroeste y la Costa Oeste .

En la segunda mitad del siglo XIX y principios del siglo XX, desde la década de 1850 hasta la de 1910, el Oeste de los Estados Unidos (especialmente el Suroeste ) recibió una enorme atención popular . Estos medios solían exagerar el romance, la anarquía y la violencia caótica de la época para lograr un mayor efecto dramático. Esto inspiró el género cinematográfico del Oeste , junto con programas de televisión , novelas , cómics , videojuegos , juguetes infantiles y disfraces.

Como definen Hine y Faragher, "la historia de la frontera cuenta la historia de la creación y defensa de las comunidades, el uso de la tierra, el desarrollo de cultivos y hoteles y la formación de estados". Explican: "Es una historia de conquista, pero también de supervivencia, persistencia y fusión de pueblos y culturas que dieron origen y continuidad a los Estados Unidos". [19] El propio Turner enfatizó repetidamente cómo la disponibilidad de "tierra libre" para iniciar nuevas granjas atrajo a los pioneros estadounidenses: "La existencia de un área de tierra libre, su recesión continua y el avance de los asentamientos estadounidenses hacia el oeste explican el desarrollo estadounidense". [20]

Mediante tratados con naciones extranjeras y tribus nativas , compromisos políticos, conquistas militares, el establecimiento de la ley y el orden, la construcción de granjas, ranchos y pueblos, la señalización de senderos y la excavación de minas, y la atracción de grandes migraciones de extranjeros, Estados Unidos se expandió de costa a costa, cumpliendo la ideología del Destino Manifiesto. En su "Tesis de la Frontera" (1893), Turner teorizó que la frontera era un proceso que transformaba a los europeos en un nuevo pueblo, los estadounidenses, cuyos valores se centraban en la igualdad, la democracia y el optimismo, así como en el individualismo , la autosuficiencia e incluso la violencia.

La frontera es el margen de territorio no desarrollado que comprendería los Estados Unidos más allá de la línea fronteriza establecida. [21] [22] La Oficina del Censo de los EE. UU. designó territorio fronterizo como tierra generalmente desocupada con una densidad de población de menos de 2 personas por milla cuadrada (0,77 personas por kilómetro cuadrado). La línea fronteriza era el límite exterior del asentamiento europeo-estadounidense en esta tierra. [23] [24] Comenzando con los primeros asentamientos europeos permanentes en la Costa Este , se ha movido constantemente hacia el oeste desde el siglo XVII hasta el siglo XX (décadas) con movimientos ocasionales hacia el norte hasta Maine y New Hampshire, hacia el sur hasta Florida y hacia el este desde California hasta Nevada.

También aparecen bolsas de asentamientos mucho más allá de la línea fronteriza establecida, particularmente en la Costa Oeste y el interior profundo, con asentamientos como Los Ángeles y Salt Lake City respectivamente. El " Oeste " era el área recientemente colonizada cerca de esa frontera. [25] Por lo tanto, partes del Medio Oeste y el Sur de Estados Unidos , aunque ya no se consideran "occidentales", tienen una herencia fronteriza junto con los estados occidentales modernos. [26] [27] Richard W. Slatta, en su visión de la frontera, escribe que "los historiadores a veces definen el Oeste estadounidense como tierras al oeste del meridiano 98 o 98° de longitud oeste ", y que otras definiciones de la región "incluyen todas las tierras al oeste de los ríos Mississippi o Missouri". [28]

Llave: Estados Territorios Zonas en disputa Otros países

En la era colonial , antes de 1776, el oeste era una prioridad para los colonos y los políticos. La frontera estadounidense comenzó cuando los ingleses se establecieron en Jamestown , Virginia, en 1607. En los primeros días de la colonización europea en la costa atlántica, hasta aproximadamente 1680, la frontera era esencialmente cualquier parte del interior del continente más allá del borde de los asentamientos existentes a lo largo de la costa atlántica. [29]

Los patrones de expansión y asentamiento de los ingleses , franceses , españoles y holandeses fueron bastante diferentes. Sólo unos pocos miles de franceses emigraron a Canadá; estos habitantes se asentaron en aldeas a lo largo del río San Lorenzo , construyendo comunidades que se mantuvieron estables durante largos períodos. Aunque los comerciantes de pieles franceses se extendieron ampliamente por los Grandes Lagos y la región del medio oeste, rara vez se asentaron. El asentamiento francés se limitó a unas pocas aldeas muy pequeñas como Kaskaskia, Illinois [30], así como a un asentamiento más grande alrededor de Nueva Orleans . En lo que ahora es el estado de Nueva York, los holandeses establecieron puestos de comercio de pieles en el valle del río Hudson, seguidos de grandes concesiones de tierra a ricos terratenientes patronos que trajeron agricultores arrendatarios que crearon aldeas compactas y permanentes. Crearon un asentamiento rural denso en el norte del estado de Nueva York, pero no avanzaron hacia el oeste. [31]

Las áreas del norte que estaban en la etapa de frontera en 1700 generalmente tenían malas instalaciones de transporte, por lo que la oportunidad de agricultura comercial era baja. Estas áreas permanecieron principalmente en la agricultura de subsistencia y, como resultado, en la década de 1760 estas sociedades eran altamente igualitarias , como lo explicó el historiador Jackson Turner Main:

La sociedad fronteriza típica, por lo tanto, era aquella en la que las distinciones de clase se reducían al mínimo. El especulador rico, si había alguno, por lo general se quedaba en casa, de modo que normalmente no había ningún rico residente. La clase de los pobres sin tierra era pequeña. La gran mayoría eran terratenientes, la mayoría de los cuales también eran pobres porque empezaban con poca propiedad y todavía no habían desbrozado mucha tierra ni habían adquirido las herramientas agrícolas y los animales que un día los harían prósperos. Pocos artesanos se establecieron en la frontera, excepto aquellos que ejercían un oficio para complementar su ocupación principal, la agricultura. Podía haber un tendero, un ministro y tal vez un médico; y había varios trabajadores sin tierra. Todos los demás eran agricultores. [32]

En el sur, las zonas fronterizas que carecían de transporte, como la región de los Apalaches , seguían basándose en la agricultura de subsistencia y se parecían al igualitarismo de sus homólogas del norte, aunque tenían una clase alta más numerosa de propietarios de esclavos. Carolina del Norte era representativa. Sin embargo, las zonas fronterizas de 1700 que tenían buenas conexiones fluviales se transformaron cada vez más en agricultura de plantación. Llegaban hombres ricos, compraban las buenas tierras y las trabajaban con esclavos. La zona ya no era "fronteriza". Tenía una sociedad estratificada que comprendía una poderosa nobleza blanca terrateniente de clase alta, una pequeña clase media, un grupo bastante grande de agricultores blancos sin tierra o arrendatarios y una creciente población de esclavos en la base de la pirámide social. A diferencia del norte, donde eran comunes las pequeñas ciudades y hasta los pueblos, el sur era abrumadoramente rural. [33]

Los asentamientos coloniales costeros dieron prioridad a la propiedad de la tierra para los agricultores individuales y, a medida que la población crecía, se dirigieron hacia el oeste en busca de nuevas tierras de cultivo. [34] A diferencia de Gran Bretaña, donde un pequeño número de terratenientes poseían la mayor parte de la tierra, la propiedad en Estados Unidos era barata, fácil y generalizada. La propiedad de la tierra trajo consigo un grado de independencia, así como el derecho a voto para los cargos locales y provinciales. Los asentamientos típicos de Nueva Inglaterra eran bastante compactos y pequeños, de menos de una milla cuadrada. El conflicto con los nativos americanos surgió de cuestiones políticas, a saber, quién gobernaría. [35] Las primeras áreas fronterizas al este de los Apalaches incluían el valle del río Connecticut, [36] y el norte de Nueva Inglaterra (que fue un movimiento hacia el norte, no hacia el oeste). [37]

Los colonos de la frontera a menudo relacionaban incidentes aislados con conspiraciones indígenas para atacarlos, pero estos carecían de una dimensión diplomática francesa después de 1763, o de una conexión española después de 1820. [38]

La mayoría de las fronteras experimentaron numerosos conflictos. [39] La Guerra Francesa e India estalló entre Gran Bretaña y Francia, con los franceses compensando su pequeña base de población colonial alistando partidas de guerra nativas como aliados. La serie de grandes guerras que se extendieron a partir de las guerras europeas terminó en una victoria completa para los británicos en la Guerra de los Siete Años en todo el mundo . En el tratado de paz de 1763 , Francia cedió prácticamente todo, ya que las tierras al oeste del río Misisipi, además de Florida y Nueva Orleans, pasaron a España. De lo contrario, las tierras al este del río Misisipi y lo que ahora es Canadá pasaron a Gran Bretaña. [ cita requerida ]

A pesar de las guerras, los estadounidenses se desplazaban a través de los Apalaches hacia el oeste de Pensilvania, lo que hoy es Virginia Occidental y áreas del Territorio de Ohio , Kentucky y Tennessee. En los asentamientos del sur a través de Cumberland Gap , su líder más famoso fue Daniel Boone . [40] El joven George Washington promovió asentamientos en Virginia Occidental en tierras que el gobierno real le había otorgado a él y a sus soldados en pago por su servicio en tiempos de guerra en la milicia de Virginia. Los asentamientos al oeste de los Apalaches fueron restringidos brevemente por la Proclamación Real de 1763 , que prohibía el asentamiento en esta área. El Tratado de Fort Stanwix (1768) reabrió la mayoría de las tierras occidentales para que los colonos se establecieran. [41]

La nación estaba en paz después de 1783. Los estados dieron al Congreso el control de las tierras occidentales y se desarrolló un sistema eficaz para la expansión de la población. La Ordenanza del Noroeste de 1787 abolió la esclavitud en el área al norte del río Ohio y prometió la condición de estado cuando un territorio alcanzara un umbral de población, como lo hizo Ohio en 1803. [ 42] [43]

El primer gran movimiento al oeste de los Apalaches se originó en Pensilvania, Virginia y Carolina del Norte tan pronto como terminó la Guerra de la Independencia en 1781. Los pioneros se alojaban en cobertizos rústicos o, como mucho, en cabañas de troncos de una sola habitación. Al principio, el principal suministro de alimentos provenía de la caza de ciervos, pavos y otros animales abundantes.

Ataviado con el típico atuendo de la frontera, pantalones de cuero, mocasines, gorro de piel y camisa de caza, y ceñido con un cinturón del que colgaban un cuchillo de caza y una bolsa de perdigones —todos ellos de fabricación casera—, el pionero presentaba un aspecto singular. En poco tiempo abrió en el bosque un terreno o claro en el que cultivó maíz, trigo, lino, tabaco y otros productos, incluso frutas. [44]

En pocos años, los pioneros añadieron cerdos, ovejas y vacas, y tal vez adquirieron un caballo. Las pieles de animales fueron sustituidas por ropas tejidas a mano. Los pioneros, más inquietos, se sintieron insatisfechos con la vida demasiado civilizada y se desarraigaron de nuevo para trasladarse 50 o 100 millas (80 o 160 km) más al oeste.

La política agraria de la nueva nación era conservadora y prestaba especial atención a las necesidades de los colonos del Este. [45] Los objetivos que ambos partidos perseguían en la era 1790-1820 eran hacer crecer la economía, evitar la fuga de los trabajadores cualificados que necesitaba el Este, distribuir la tierra de forma inteligente, venderla a precios que fueran razonables para los colonos pero lo suficientemente altos como para pagar la deuda nacional, sanear los títulos legales y crear una economía occidental diversificada que estuviera estrechamente interconectada con las áreas colonizadas con un riesgo mínimo de un movimiento separatista. Sin embargo, en la década de 1830, el Oeste se estaba llenando de ocupantes ilegales que no tenían títulos legales, aunque es posible que hubieran pagado dinero a los colonos anteriores. Los demócratas jacksonianos favorecían a los ocupantes ilegales prometiéndoles un acceso rápido a tierras baratas. Por el contrario, Henry Clay estaba alarmado por la "chusma sin ley" que se dirigía al Oeste y que estaba socavando el concepto utópico de una comunidad republicana de clase media estable y respetuosa de la ley. Mientras tanto, los sureños ricos buscaban oportunidades para comprar tierras de alta calidad para establecer plantaciones de esclavos. El movimiento Free Soil de la década de 1840 exigía tierras de bajo costo para los agricultores blancos libres, una posición promulgada como ley por el nuevo Partido Republicano en 1862, ofreciendo granjas gratuitas de 160 acres (65 ha) a todos los adultos, hombres y mujeres, negros y blancos, nativos o inmigrantes. [46]

Después de ganar la Guerra de la Independencia (1783), los colonos estadounidenses llegaron en masa al oeste. En 1788, los pioneros estadounidenses del Territorio del Noroeste establecieron Marietta, Ohio , como el primer asentamiento estadounidense permanente en el Territorio del Noroeste . [47]

En 1775, Daniel Boone abrió un camino para la Compañía Transilvania desde Virginia a través de Cumberland Gap hasta el centro de Kentucky. Más tarde se alargó hasta llegar a las cataratas del Ohio en Louisville . El Wilderness Road era empinado y accidentado, y solo se podía recorrer a pie o a caballo, pero era la mejor ruta para miles de colonos que se mudaban a Kentucky . [48] En algunas áreas tuvieron que enfrentarse a ataques nativos. Solo en 1784, los nativos mataron a más de 100 viajeros en el Wilderness Road. Kentucky en ese momento se había despoblado: estaba "vacío de aldeas indias". [49] Sin embargo, a veces pasaban grupos de asalto. Uno de los interceptados fue el abuelo de Abraham Lincoln , a quien le arrancaron el cuero cabelludo en 1784 cerca de Louisville. [50]

La Guerra de 1812 marcó la confrontación final entre las principales fuerzas británicas y nativas que luchaban para detener la expansión estadounidense. El objetivo de la guerra británica incluía la creación de un estado de barrera indígena bajo los auspicios británicos en el Medio Oeste que detendría la expansión estadounidense hacia el oeste. Las milicias fronterizas estadounidenses bajo el mando del general Andrew Jackson derrotaron a los creeks y abrieron el suroeste, mientras que la milicia bajo el mando del gobernador William Henry Harrison derrotó a la alianza nativo-británica en la batalla del Támesis en Canadá en 1813. La muerte en batalla del líder nativo Tecumseh disolvió la coalición de tribus nativas hostiles. [51] Mientras tanto, el general Andrew Jackson puso fin a la amenaza militar nativa en el sudeste en la batalla de Horseshoe Bend en 1814 en Alabama. En general, los hombres de la frontera lucharon contra los nativos con poca ayuda del ejército de los EE. UU. o del gobierno federal. [52]

Para poner fin a la guerra, los diplomáticos estadounidenses negociaron con Gran Bretaña el Tratado de Gante , firmado a finales de 1814. Rechazaron el plan británico de establecer un estado indígena en territorio estadounidense al sur de los Grandes Lagos. Explicaron la política estadounidense respecto de la adquisición de tierras indígenas:

Los Estados Unidos, si bien tienen la intención de no adquirir nunca tierras de los indios de otra manera que no sea pacíficamente y con su libre consentimiento, están plenamente decididos a recuperar progresivamente y en proporción a lo que su creciente población pueda requerir, del estado de naturaleza y a poner en cultivo toda porción del territorio contenido dentro de sus límites reconocidos. Al proveer de esta manera al sustento de millones de seres civilizados, no violarán ningún dictado de justicia o humanidad, pues no sólo darán a los pocos miles de salvajes dispersos en ese territorio un equivalente suficiente por cualquier derecho que puedan ceder, sino que siempre les dejarán la posesión de tierras más de las que puedan cultivar y más que adecuadas para su subsistencia, comodidad y disfrute mediante el cultivo. Si esto es un espíritu de engrandecimiento, los abajo firmantes están dispuestos a admitir, en ese sentido, su existencia; pero deben negar que proporcione la más mínima prueba de una intención de no respetar los límites entre ellos y las naciones europeas, o de un deseo de invadir los territorios de Gran Bretaña. [...] No supondrán que ese Gobierno admitirá, como base de su política hacia los Estados Unidos, un sistema de frenar el crecimiento natural de sus territorios, con el fin de preservar un desierto perpetuo para los salvajes. [53]

A medida que los colonos iban llegando, los distritos fronterizos se convirtieron primero en territorios, con una legislatura elegida y un gobernador designado por el presidente. Luego, cuando la población alcanzó los 100.000 habitantes, el territorio solicitó la condición de estado. [54] Los colonos solían abandonar las formalidades legalistas y el sufragio restrictivo que favorecían las clases altas del este y adoptar más democracia y más igualitarismo. [55]

En 1810, la frontera occidental había llegado al río Misisipi . San Luis, Misuri , era la ciudad más grande de la frontera, la puerta de entrada para los viajes hacia el oeste y un importante centro comercial para el tráfico del río Misisipi y el comercio interior, pero permaneció bajo control español hasta 1803.

Thomas Jefferson se consideraba un hombre de frontera y estaba muy interesado en expandir y explorar el Oeste. [56] La Compra de Luisiana de Jefferson en 1803 duplicó el tamaño de la nación a un costo de $15 millones, o alrededor de $0,04 por acre ($305 millones en dólares de 2023, menos de 42 centavos por acre). [57] Los federalistas se opusieron a la expansión, pero los jeffersonianos saludaron la oportunidad de crear millones de nuevas granjas para expandir el dominio de los terratenientes ; la propiedad fortalecería la sociedad republicana ideal, basada en la agricultura (no en el comercio), gobernada a la ligera y promoviendo la autosuficiencia y la virtud, además de formar la base política para la democracia jeffersoniana . [58]

Francia recibió un pago por su soberanía sobre el territorio en términos del derecho internacional. Entre 1803 y la década de 1870, el gobierno federal compró la tierra a las tribus nativas que entonces la poseían. Los contables y los tribunales del siglo XX han calculado el valor de los pagos realizados a los nativos, que incluían pagos futuros en efectivo, alimentos, caballos, ganado, suministros, edificios, educación y atención médica. En términos de efectivo, el total pagado a las tribus en el área de la Compra de Luisiana ascendió a unos 2.600 millones de dólares, o casi 9.000 millones de dólares en dólares de 2016. Se pagaron sumas adicionales a los nativos que vivían al este del Mississippi por sus tierras, así como pagos a los nativos que vivían en partes del oeste fuera de la Compra de Luisiana. [59]

Incluso antes de la compra, Jefferson estaba planeando expediciones para explorar y cartografiar las tierras. Encargó a Lewis y Clark que "exploraran el río Misuri y su curso principal, ya que, por su curso y comunicación con las aguas del océano Pacífico, el río Columbia, el río Oregón, el río Colorado o cualquier otro río pueden ofrecer la comunicación más directa y practicable a través del continente para el comercio". [60] Jefferson también encargó a la expedición que estudiara las tribus nativas de la región (incluida su moral, idioma y cultura), el clima, el suelo, los ríos, el comercio comercial y la vida animal y vegetal. [61]

Los empresarios, en particular John Jacob Astor, aprovecharon rápidamente la oportunidad y expandieron las operaciones de comercio de pieles al noroeste del Pacífico . El " Fort Astoria " de Astor (más tarde Fort George), en la desembocadura del río Columbia, se convirtió en el primer asentamiento blanco permanente en esa zona, aunque no fue rentable para Astor. Fundó la American Fur Company en un intento de romper el control que tenía el monopolio de la Compañía de la Bahía de Hudson sobre la región. En 1820, Astor se había hecho cargo de los comerciantes independientes para crear un monopolio rentable; dejó el negocio como multimillonario en 1834. [62]

A medida que la frontera se desplazaba hacia el oeste, los tramperos y cazadores se adelantaron a los colonos en busca de nuevos suministros de pieles de castor y otras pieles para enviarlas a Europa. Los cazadores fueron los primeros europeos en gran parte del Viejo Oeste y formaron las primeras relaciones de trabajo con los nativos americanos en el Oeste. [63] [64] Aportaron un amplio conocimiento del terreno del Noroeste, incluido el importante Paso Sur a través de las Montañas Rocosas centrales. Descubierto alrededor de 1812, más tarde se convirtió en una ruta importante para los colonos hacia Oregón y Washington. Sin embargo, en 1820, un nuevo sistema de "encuentros de brigadas" enviaba a los hombres de la compañía en "brigadas" a través del país en largas expediciones, evitando a muchas tribus. También alentó a los "tramperos libres" a explorar nuevas regiones por su cuenta. Al final de la temporada de recolección, los tramperos se "encontraban" y entregaban sus productos a cambio de un pago en los puertos fluviales a lo largo del río Verde , el Alto Misuri y el Alto Misisipi. San Luis era la ciudad de encuentro más grande. Sin embargo, en 1830, las modas cambiaron y los sombreros de castor fueron reemplazados por sombreros de seda, lo que puso fin a la demanda de pieles estadounidenses caras. Así terminó la era de los hombres de montaña , los tramperos y los exploradores como Jedediah Smith , Hugh Glass , Davy Crockett , Jack Omohundro y otros. El comercio de pieles de castor prácticamente cesó en 1845. [65]

Hubo un amplio acuerdo sobre la necesidad de colonizar los nuevos territorios rápidamente, pero el debate se polarizó sobre el precio que el gobierno debería cobrar. Los conservadores y los whigs, representados por el presidente John Quincy Adams , querían un ritmo moderado que cobrara a los recién llegados lo suficiente para pagar los costos del gobierno federal. Los demócratas, sin embargo, toleraron una lucha salvaje por la tierra a precios muy bajos. La resolución final llegó en la Ley de Homestead de 1862, con un ritmo moderado que les dio a los colonos 160 acres gratis después de trabajar en ellos durante cinco años. [66]

El afán de lucro privado dominó el movimiento hacia el oeste, [67] pero el gobierno federal desempeñó un papel de apoyo en la obtención de tierras mediante tratados y el establecimiento de gobiernos territoriales, con gobernadores designados por el presidente. El gobierno federal adquirió primero territorio occidental mediante tratados con otras naciones o tribus nativas. Luego envió topógrafos para cartografiar y documentar la tierra. [68] En el siglo XX, las burocracias de Washington administraban las tierras federales, como la Oficina General de Tierras de los Estados Unidos en el Departamento del Interior, [69] y, después de 1891, el Servicio Forestal en el Departamento de Agricultura. [70] Después de 1900, la construcción de presas y el control de inundaciones se convirtieron en preocupaciones importantes. [71]

El transporte era un tema clave y el Ejército (especialmente el Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército) recibió la responsabilidad total de facilitar la navegación en los ríos. El barco de vapor, utilizado por primera vez en el río Ohio en 1811, hizo posible viajar de manera económica utilizando los sistemas fluviales, especialmente los ríos Misisipi y Misuri y sus afluentes. [72] Las expediciones del Ejército por el río Misuri entre 1818 y 1825 permitieron a los ingenieros mejorar la tecnología. Por ejemplo, el barco de vapor del Ejército " Western Engineer " de 1819 combinó un calado muy bajo con una de las primeras ruedas de popa. En 1819-1825, el coronel Henry Atkinson desarrolló barcos de quilla con ruedas de paletas accionadas manualmente. [73]

El sistema postal federal desempeñó un papel crucial en la expansión nacional. Facilitó la expansión hacia el Oeste al crear un sistema de comunicación económico, rápido y conveniente. Las cartas de los primeros colonos proporcionaban información y estímulo para alentar una mayor migración hacia el Oeste, ayudaban a las familias dispersas a mantenerse en contacto y brindar ayuda neutral, ayudaban a los empresarios a encontrar oportunidades comerciales y posibilitaban las relaciones comerciales regulares entre los comerciantes y el Oeste y los mayoristas y fábricas del Este. El servicio postal también ayudó al Ejército a expandir el control sobre los vastos territorios occidentales. La amplia circulación de periódicos importantes por correo, como el New York Weekly Tribune , facilitó la coordinación entre los políticos de diferentes estados. El servicio postal ayudó a integrar áreas ya establecidas con la frontera, creando un espíritu de nacionalismo y proporcionando una infraestructura necesaria. [74]

El ejército asumió desde el principio la misión de proteger a los colonos a lo largo de los Senderos de Expansión hacia el Oeste , una política que fue descrita por el Secretario de Guerra de los EE. UU. , John B. Floyd , en 1857: [75]

Una línea de puestos que corra paralela sin fronteras, pero cerca de las viviendas habituales de los indios, situados a distancias convenientes y en posiciones adecuadas, y ocupados por infantería, ejercería una restricción saludable sobre las tribus, que sentirían que cualquier incursión de sus guerreros sobre los asentamientos blancos se encontraría con una rápida represalia en sus propios hogares.

En aquella época se debatió sobre el tamaño óptimo de los fuertes, y Jefferson Davis , Winfield Scott y Thomas Jesup defendían la idea de que los fuertes fueran más grandes pero menos numerosos que el de Floyd. El plan de Floyd era más caro, pero contaba con el apoyo de los colonos y del público en general, que preferían que los militares permanecieran lo más cerca posible. La zona fronteriza era enorme e incluso Davis admitió que "la concentración habría expuesto partes de la frontera a las hostilidades de los nativos sin ninguna protección". [75]

El gobierno y la empresa privada enviaron a muchos exploradores al Oeste. En 1805-1806, el teniente del ejército Zebulon Pike (1779-1813) dirigió un grupo de 20 soldados para encontrar las cabeceras del Misisipi. Más tarde exploró los ríos Rojo y Arkansas en territorio español, llegando finalmente al río Grande . A su regreso, Pike avistó el pico en Colorado que lleva su nombre . [76] El mayor Stephen Harriman Long (1784-1864) [77] dirigió las expediciones a Yellowstone y Missouri de 1819-1820, pero su categorización en 1823 de las Grandes Llanuras como áridas e inútiles llevó a que la región recibiera una mala reputación como el "Gran Desierto Americano", lo que desalentó el asentamiento en esa área durante varias décadas. [78]

En 1811, los naturalistas Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859) y John Bradbury (1768-1823) viajaron por el río Misuri documentando y dibujando la vida vegetal y animal. [79] El artista George Catlin (1796-1872) pintó cuadros precisos de la cultura nativa americana. El artista suizo Karl Bodmer hizo paisajes y retratos atractivos. [80] John James Audubon (1785-1851) es famoso por clasificar y pintar en minuciosos detalles 500 especies de aves, publicadas en Birds of America . [81]

El más famoso de los exploradores fue John Charles Frémont (1813-1890), oficial del ejército en el Cuerpo de Ingenieros Topográficos. Demostró un talento para la exploración y un genio en la autopromoción que le valió el sobrenombre de "Pionero del Oeste" y lo llevó a la nominación presidencial del nuevo Partido Republicano en 1856. [82] Lideró una serie de expediciones en la década de 1840 que respondieron a muchas de las preguntas geográficas pendientes sobre la región poco conocida. Cruzó las Montañas Rocosas por cinco rutas diferentes y cartografió partes de Oregón y California. En 1846-1847, jugó un papel en la conquista de California. En 1848-1849, Frémont fue asignado para localizar una ruta central a través de las montañas para el ferrocarril transcontinental propuesto, pero su expedición terminó casi en un desastre cuando se perdió y quedó atrapada por una fuerte nevada. [83] Sus informes mezclaban la narración de una aventura emocionante con datos científicos e información práctica detallada para los viajeros. Captó la imaginación del público e inspiró a muchos a dirigirse al oeste. Goetzman dice que fue "monumental en su amplitud, un clásico de la literatura exploratoria". [84]

Mientras las universidades aparecían en todo el noreste, había poca competencia en la frontera occidental para la Universidad de Transilvania , fundada en Lexington, Kentucky, en 1780. Contaba con una facultad de derecho además de sus programas de pregrado y de medicina. Transilvania atraía a jóvenes políticamente ambiciosos de todo el suroeste, incluidos 50 que se convirtieron en senadores de los Estados Unidos, 101 representantes, 36 gobernadores y 34 embajadores, así como Jefferson Davis, el presidente de la Confederación. [85]

La mayoría de los pioneros mostraron poco compromiso con la religión hasta que comenzaron a aparecer evangelistas itinerantes y a producir "resurrecciones". Los pioneros locales respondieron con entusiasmo a estos eventos y, en efecto, desarrollaron sus religiones populistas, especialmente durante el Segundo Gran Despertar (1790-1840), que incluía reuniones de campamento al aire libre que duraban una semana o más y que introdujeron a muchas personas a la religión organizada por primera vez. Una de las reuniones de campamento más grandes y famosas tuvo lugar en Cane Ridge, Kentucky , en 1801. [86]

Los bautistas locales establecieron pequeñas iglesias independientes: los bautistas renunciaron a la autoridad centralizada; cada iglesia local se fundó sobre el principio de independencia de la congregación local. Por otra parte, los obispos de los metodistas, bien organizados y centralizados, asignaron a los itinerantes a áreas específicas durante varios años, para luego trasladarlos a nuevos territorios. Se formaron varias denominaciones nuevas, de las cuales la más grande fue la de los Discípulos de Cristo . [87] [88] [89]

Las iglesias orientales establecidas tardaron en satisfacer las necesidades de la frontera. Los presbiterianos y los congregacionalistas, que dependían de ministros bien educados, no contaban con personal suficiente para evangelizar la frontera. En 1801, elaboraron un Plan de Unión para combinar recursos en la frontera. [90] [91]

El historiador Mark Wyman llama a Wisconsin un "palimpsesto" de capas y capas de pueblos y fuerzas, cada una de las cuales imprime influencias permanentes. Identificó estas capas como múltiples "fronteras" a lo largo de tres siglos: la frontera de los nativos americanos, la frontera francesa, la frontera inglesa, la frontera del comercio de pieles, la frontera minera y la frontera maderera. Finalmente, la llegada del ferrocarril trajo consigo el fin de la frontera. [92]

Frederick Jackson Turner creció en Wisconsin durante su última etapa fronteriza y, en sus viajes por el estado, pudo ver las capas de desarrollo social y político. Uno de los últimos estudiantes de Turner, Merle Curti, utilizó un análisis profundo de la historia local de Wisconsin para poner a prueba la tesis de Turner sobre la democracia. La opinión de Turner era que la democracia estadounidense "implicaba una amplia participación en la toma de decisiones que afectaban a la vida en común, el desarrollo de la iniciativa y la autosuficiencia y la igualdad de oportunidades económicas y culturales. Por lo tanto, también implicaba la americanización de los inmigrantes". [93] Curti descubrió que, entre 1840 y 1860, en Wisconsin los grupos más pobres ganaron rápidamente en propiedad de la tierra y, a menudo, ascendieron a liderazgo político a nivel local. Descubrió que incluso los jóvenes trabajadores agrícolas sin tierra podían obtener pronto sus granjas. Por lo tanto, la tierra gratuita en la frontera creó oportunidades y democracia, tanto para los inmigrantes europeos como para los viejos yanquis. [94]

Entre los años 1770 y 1830, los pioneros se trasladaron a las nuevas tierras que se extendían desde Kentucky hasta Alabama y Texas. La mayoría eran agricultores que se desplazaban en grupos familiares. [95]

El historiador Louis Hacker muestra lo derrochadora que fue la primera generación de pioneros: eran demasiado ignorantes para cultivar la tierra adecuadamente y, cuando se agotó la fertilidad natural de la tierra virgen, vendieron todo y se trasladaron al oeste para intentarlo de nuevo. Hacker describe lo que ocurrió en Kentucky alrededor de 1812:

Se vendían granjas de diez a cincuenta acres desbrozados, con casas de troncos, huertos de melocotoneros y, a veces, de manzanos, cercados con vallas y con abundante madera en pie para leña. La tierra estaba sembrada de trigo y maíz, que eran los alimentos básicos, mientras que el cáñamo [para hacer cuerdas] se cultivaba en cantidades cada vez mayores en los fértiles lechos de los ríos... Sin embargo, en general, era una sociedad agrícola sin habilidad ni recursos. Cometía todos los pecados que caracterizan a la agricultura despilfarradora e ignorante. No se sembraban semillas de pasto para heno y, como resultado, los animales de la granja tenían que buscar su propio sustento en los bosques; no se permitía que los campos estuvieran cubiertos de pasto; se plantaba un solo cultivo en el suelo hasta que la tierra se agotaba; el estiércol no se devolvía a los campos; solo se cultivaba una pequeña parte de la granja, mientras que el resto se dejaba con árboles. Los instrumentos de cultivo eran rudimentarios y torpes y muy pocos, muchos de ellos fabricados en la granja. Es evidente por qué el colono de la frontera norteamericana se desplazaba continuamente. No era su miedo a un contacto demasiado estrecho con las comodidades y restricciones de una sociedad civilizada lo que lo impulsaba a una actividad incesante, ni simplemente la posibilidad de venderla con beneficios a la próxima oleada de colonos; era la pérdida de tierras lo que lo impulsaba a continuar. El hambre era el acicate. La ignorancia del agricultor pionero, sus inadecuadas instalaciones para el cultivo, sus limitados medios de transporte lo obligaban a cambiar de escenario con frecuencia. Sólo podía tener éxito con un suelo virgen. [96]

Hacker añade que la segunda oleada de colonos recuperó la tierra, reparó los daños y practicó una agricultura más sostenible. El historiador Frederick Jackson Turner exploró la cosmovisión y los valores individualistas de la primera generación:

Lo que objetaban era la existencia de obstáculos arbitrarios, de limitaciones artificiales a la libertad de cada miembro de esta gente de la frontera para desarrollar su carrera sin temor ni favoritismo. A lo que se oponían instintivamente era a la cristalización de las diferencias, a la monopolización de las oportunidades y a la fijación de ese monopolio por el gobierno o por las costumbres sociales. El camino debe estar abierto. El juego debe jugarse de acuerdo con las reglas. No debe haber ninguna restricción artificial a la igualdad de oportunidades, ninguna puerta cerrada a los capaces, nada que detenga el juego libre antes de que se juegue hasta el final. Más que eso, había un sentimiento no formulado, tal vez, pero muy real, de que el mero éxito en el juego, mediante el cual los hombres más capaces podían alcanzar la preeminencia, no daba a los exitosos ningún derecho a mirar por encima del hombro a sus vecinos, ningún derecho adquirido para afirmar la superioridad como una cuestión de orgullo y para disminuir el derecho y la dignidad iguales de los menos exitosos. [97]

El Destino Manifiesto era la controvertida creencia de que Estados Unidos estaba predestinado a expandirse desde la costa atlántica hasta la costa pacífica, y los esfuerzos que se hicieron para hacer realidad esa creencia. El concepto apareció durante la época colonial, pero el término fue acuñado en la década de 1840 por una revista popular que editorializó: "el cumplimiento de nuestro destino manifiesto... extenderse por el continente asignado por la Providencia para el libre desarrollo de nuestros millones que se multiplican anualmente". A medida que la nación crecía, el "Destino Manifiesto" se convirtió en un grito de guerra para los expansionistas del Partido Demócrata. En la década de 1840, las administraciones de Tyler y Polk (1841-1849) promovieron con éxito esta doctrina nacionalista. Sin embargo, el Partido Whig , que representaba los intereses comerciales y financieros, se opuso al Destino Manifiesto. Los líderes Whig como Henry Clay y Abraham Lincoln pidieron profundizar la sociedad a través de la modernización y la urbanización en lugar de la simple expansión horizontal. [98] A partir de la anexión de Texas, los expansionistas obtuvieron la ventaja. John Quincy Adams , un Whig antiesclavista, consideró que la anexión de Texas en 1845 fue "la peor calamidad que jamás me haya sucedido a mí y a mi país". [99]

Para ayudar a los colonos a trasladarse hacia el oeste, en la década de 1840 se utilizaron las "guías" para emigrantes, que incluían información sobre las rutas proporcionadas por los comerciantes de pieles y las expediciones de Frémont, y prometían tierras de cultivo fértiles más allá de las Montañas Rocosas. [nb 1]

México se independizó de España en 1821 y se apoderó de las posesiones del norte de España que se extendían desde Texas hasta California. Las caravanas estadounidenses comenzaron a entregar mercancías a la ciudad mexicana de Santa Fe a lo largo del Camino de Santa Fe , a lo largo de un viaje de 870 millas (1400 km) que duraba 48 días desde Kansas City, Missouri (entonces conocida como Westport). Santa Fe también era el punto de partida del "Camino Real" (la Carretera del Rey), una ruta comercial que transportaba productos manufacturados estadounidenses hacia el sur hasta lo más profundo de México y devolvía plata, pieles y mulas hacia el norte (no debe confundirse con otro "Camino Real" que conectaba las misiones en California). Un ramal también corría hacia el este cerca del Golfo (también llamado el Viejo Camino de San Antonio ). Santa Fe se conectaba con California a través del Viejo Camino Español . [100] [101]

Los gobiernos español y mexicano atrajeron a colonos estadounidenses a Texas con términos generosos. Stephen F. Austin se convirtió en un "empresario", recibiendo contratos de los funcionarios mexicanos para traer inmigrantes. Al hacerlo, también se convirtió en el comandante político y militar de facto de la zona. Sin embargo, las tensiones aumentaron después de un intento fallido de establecer la nación independiente de Fredonia en 1826. William Travis , liderando el "partido de la guerra", abogó por la independencia de México, mientras que el "partido de la paz" liderado por Austin intentó obtener más autonomía dentro de la relación actual. Cuando el presidente mexicano Santa Anna cambió de alianzas y se unió al partido conservador centralista, se declaró dictador y ordenó a los soldados que entraran en Texas para reducir la nueva inmigración y los disturbios. Sin embargo, la inmigración continuó y 30.000 anglosajones con 3.000 esclavos se establecieron en Texas en 1835. [102] En 1836, estalló la Revolución de Texas . Después de las pérdidas en El Álamo y Goliad , los tejanos ganaron la decisiva Batalla de San Jacinto para asegurar la independencia. En San Jacinto, Sam Houston , comandante en jefe del ejército texano y futuro presidente de la República de Texas, gritó: "¡Recuerden El Álamo! ¡Recuerden Goliad!". El Congreso de los Estados Unidos se negó a anexar Texas, estancado por disputas polémicas sobre la esclavitud y el poder regional. De este modo, la República de Texas siguió siendo una potencia independiente durante casi una década antes de ser anexada como el 28.º estado en 1845. Sin embargo, el gobierno de México consideraba a Texas como una provincia fugitiva y afirmó su propiedad. [103]

México se negó a reconocer la independencia de Texas en 1836, pero Estados Unidos y las potencias europeas sí lo hicieron. México amenazó con la guerra si Texas se unía a Estados Unidos, lo que hizo en 1845. Los negociadores estadounidenses fueron rechazados por un gobierno mexicano en crisis. Cuando el ejército mexicano mató a 16 soldados estadounidenses en territorio en disputa, la guerra estaba al caer. Los whigs como el congresista Abraham Lincoln denunciaron la guerra, pero fue bastante popular fuera de Nueva Inglaterra. [104]

La estrategia mexicana era defensiva; la estrategia estadounidense era una ofensiva de tres frentes, utilizando un gran número de soldados voluntarios. [105] Las fuerzas terrestres tomaron Nuevo México con poca resistencia y se dirigieron a California, que rápidamente cayó ante las fuerzas terrestres y navales estadounidenses. Desde la base estadounidense principal en Nueva Orleans, el general Zachary Taylor dirigió fuerzas hacia el norte de México, ganando una serie de batallas que siguieron. La Marina de los EE. UU. transportó al general Winfield Scott a Veracruz . Luego marchó con su fuerza de 12.000 hombres al oeste hasta la Ciudad de México, ganando la batalla final en Chapultepec. Las conversaciones sobre la adquisición de todo México se desvanecieron cuando el ejército descubrió que los valores políticos y culturales mexicanos eran tan ajenos a los de Estados Unidos. Como preguntó el Cincinnati Herald , ¿qué haría Estados Unidos con ocho millones de mexicanos "con su adoración de ídolos, superstición pagana y razas mestizas degradadas?" [106]

El Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo de 1848 cedió los territorios de California y Nuevo México a los Estados Unidos por 18,5 millones de dólares (que incluían la asunción de reclamaciones contra México por parte de los colonos). La Compra de Gadsden en 1853 añadió el sur de Arizona, que era necesario para una ruta ferroviaria a California. En total, México cedió medio millón de millas cuadradas (1,3 millones de km 2 ) e incluyó los futuros estados de California, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, Nuevo México y partes de Colorado y Wyoming, además de Texas. La gestión de los nuevos territorios y el tratamiento de la cuestión de la esclavitud provocaron una intensa controversia, en particular sobre la Cláusula Wilmot , que habría prohibido la esclavitud en los nuevos territorios. El Congreso nunca la aprobó, sino que resolvió temporalmente la cuestión de la esclavitud en el Oeste con el Compromiso de 1850. California entró en la Unión en 1850 como estado libre; las otras áreas siguieron siendo territorios durante muchos años. [107] [108]

El nuevo estado creció rápidamente a medida que los inmigrantes llegaban en masa a las fértiles tierras algodoneras del este de Texas. [109] Los inmigrantes alemanes comenzaron a llegar a principios de la década de 1840 debido a las presiones económicas, sociales y políticas negativas en Alemania. [110] Con sus inversiones en tierras algodoneras y esclavos, los plantadores establecieron plantaciones de algodón en los distritos orientales. La zona central del estado fue desarrollada más por agricultores de subsistencia que rara vez poseían esclavos. [111]

Texas, en sus días del Salvaje Oeste, atraía a hombres que podían disparar con precisión y poseían entusiasmo por la aventura, "por la fama masculina, el servicio patriótico, la gloria marcial y las muertes significativas". [112]

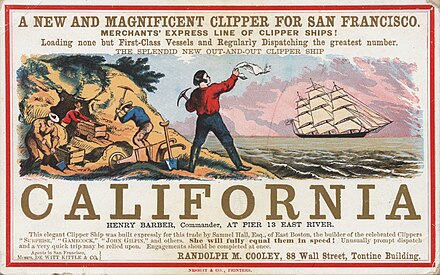

En 1846, unos 10.000 californianos (hispanos) vivían en California, principalmente en ranchos de ganado en lo que hoy es el área de Los Ángeles. Unos cientos de extranjeros estaban dispersos en los distritos del norte, incluidos algunos estadounidenses. Con el estallido de la guerra con México en 1846, Estados Unidos envió a Frémont y una unidad del ejército estadounidense , así como fuerzas navales, y rápidamente tomó el control. [113] Cuando la guerra estaba terminando, se descubrió oro en el norte y la noticia pronto se extendió por todo el mundo.

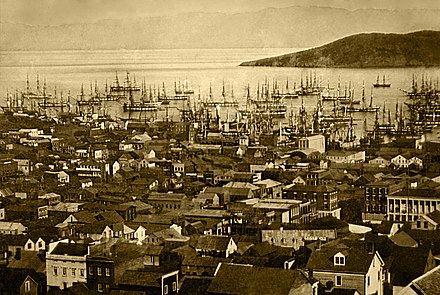

Miles de "los del 49" llegaron a California navegando alrededor de Sudamérica (o tomando un atajo a través de Panamá, un país asolado por enfermedades), o recorriendo a pie la ruta de California. La población se disparó hasta más de 200.000 personas en 1852, principalmente en los distritos auríferos que se extendían hasta las montañas al este de San Francisco.

En San Francisco, la vivienda era escasa y los barcos abandonados cuyas tripulaciones se dirigían a las minas solían convertirse en alojamientos temporales. En los propios yacimientos de oro, las condiciones de vida eran primitivas, aunque el clima templado resultaba atractivo. Los suministros eran caros y la comida escasa; las dietas típicas consistían principalmente en carne de cerdo, frijoles y whisky. Estas comunidades transitorias, predominantemente masculinas y sin instituciones establecidas, eran propensas a altos niveles de violencia, embriaguez, blasfemias y comportamiento impulsado por la avaricia. Sin tribunales ni agentes de la ley en las comunidades mineras para hacer cumplir las reclamaciones y la justicia, los mineros desarrollaron su propio sistema legal ad hoc, basado en los "códigos mineros" utilizados en otras comunidades mineras del extranjero. Cada campamento tenía sus propias reglas y a menudo impartía justicia por votación popular, a veces actuando de manera justa y a veces ejerciendo justicieros; los nativos americanos (indios), los mexicanos y los chinos generalmente recibían las sentencias más duras. [114]

La fiebre del oro cambió radicalmente la economía de California y trajo consigo una serie de profesionales, entre ellos especialistas en metales preciosos, comerciantes, médicos y abogados, que se sumaron a la población de mineros, taberneros, jugadores y prostitutas. Un periódico de San Francisco afirmó: "El país entero... resuena con el sórdido grito del oro! ¡Oro! ¡Oro! ¡Oro! mientras el campo queda a medio sembrar, la casa a medio construir y todo se descuida, salvo la fabricación de palas y picos". [115] Más de 250.000 mineros encontraron un total de más de 200 millones de dólares en oro en los cinco años que duró la fiebre del oro de California. [116] [117] Sin embargo, a medida que llegaban miles, cada vez menos mineros hicieron fortuna, y la mayoría acabó exhausta y arruinada.

Los bandidos violentos solían atacar a los mineros, como en el caso de Jonathan R. Davis, que mató a once bandidos sin ayuda de nadie. [118] Los campamentos se extendieron al norte y al sur del río American y al este, hacia las Sierras . En pocos años, casi todos los mineros independientes fueron desplazados cuando las minas fueron compradas y administradas por compañías mineras, que luego contrataron a mineros asalariados con salarios bajos. A medida que el oro se volvió más difícil de encontrar y más difícil de extraer, los prospectores individuales dieron paso a cuadrillas de trabajo remunerado, habilidades especializadas y maquinaria minera. Sin embargo, las minas más grandes causaron un mayor daño ambiental. En las montañas, predominaba la minería de pozos, que producía grandes cantidades de desechos. A partir de 1852, al final de la fiebre del oro de 1849, hasta 1883, se utilizó la minería hidráulica . A pesar de que se obtuvieron enormes ganancias, cayó en manos de unos pocos capitalistas, desplazó a numerosos mineros, grandes cantidades de desechos ingresaron en los sistemas fluviales y causaron un gran daño ecológico al medio ambiente. La minería hidráulica terminó cuando la protesta pública por la destrucción de tierras de cultivo condujo a la ilegalización de esta práctica. [119]

Las áreas montañosas del triángulo que va desde Nuevo México hasta California y Dakota del Sur contenían cientos de yacimientos mineros de roca dura, donde los buscadores descubrieron oro, plata, cobre y otros minerales (así como algo de carbón de roca blanda). De la noche a la mañana surgieron campamentos mineros temporales; la mayoría se convirtieron en pueblos fantasmas cuando se agotaron los minerales. Los buscadores se dispersaron y buscaron oro y plata a lo largo de las Montañas Rocosas y en el suroeste. Pronto se descubrió oro en Colorado , Utah, Arizona, Nuevo México, Idaho, Montana y Dakota del Sur (en 1864). [120]

El descubrimiento de la veta Comstock , que contenía grandes cantidades de plata, dio lugar a las ciudades en auge de Virginia City , Carson City y Silver City en Nevada . La riqueza proveniente de la plata, más que la del oro, impulsó la maduración de San Francisco en la década de 1860 y ayudó al ascenso de algunas de sus familias más ricas, como la de George Hearst . [121]

Para llegar a las nuevas y ricas tierras de la Costa Oeste, había tres opciones: algunos navegaban alrededor del extremo sur de Sudamérica durante un viaje de seis meses, algunos emprendieron el peligroso viaje a través del istmo de Panamá, pero otros 400.000 caminaron hasta allí en una ruta terrestre de más de 2.000 millas (3.200 km); sus caravanas de carretas generalmente partían de Missouri. Se movían en grandes grupos bajo la dirección de un capataz experimentado, llevando su ropa, suministros agrícolas, armas y animales. Estas caravanas de carretas seguían ríos importantes, cruzaban praderas y montañas y, por lo general, terminaban en Oregón y California. Los pioneros generalmente intentaban completar el viaje durante una sola estación cálida, generalmente durante seis meses. En 1836, cuando se organizó la primera caravana de carretas de migrantes en Independence, Missouri , se había despejado un sendero de carretas hasta Fort Hall, Idaho . Los senderos se despejaron cada vez más hacia el oeste, hasta llegar finalmente al valle de Willamette en Oregón. Esta red de caminos para carros que conducían al noroeste del Pacífico se denominó posteriormente Camino de Oregón . La mitad oriental de la ruta también fue utilizada por viajeros del Camino de California (desde 1843), el Camino Mormón (desde 1847) y el Camino de Bozeman (desde 1863) antes de desviarse hacia sus destinos separados. [122]

En la "Carretera de carretas de 1843", entre 700 y 1.000 emigrantes se dirigieron a Oregón; el misionero Marcus Whitman encabezó las carretas en el último tramo. En 1846, se completó la carretera Barlow alrededor del monte Hood, proporcionando una ruta de carretas accidentada pero transitable desde el río Misuri hasta el valle de Willamette: alrededor de 3.200 km (2.000 millas). [123] Aunque la dirección principal de viaje en las primeras rutas de carretas era hacia el oeste, la gente también usaba la Ruta de Oregón para viajar hacia el este. Algunos lo hacían porque estaban desanimados y derrotados. Algunos regresaban con bolsas de oro y plata. La mayoría regresaba para recoger a sus familias y trasladarlas de regreso al oeste. Estos "regresos" eran una importante fuente de información y entusiasmo sobre las maravillas y promesas (y peligros y decepciones) del lejano Oeste. [124]

No todos los emigrantes llegaron a su destino. Los peligros de la ruta terrestre eran numerosos: mordeduras de serpientes, accidentes de carros, violencia de otros viajeros, suicidio, desnutrición, estampidas, ataques nativos, una variedad de enfermedades ( disentería , fiebre tifoidea y cólera estaban entre las más comunes), exposición, avalanchas, etc. Un ejemplo particularmente conocido de la naturaleza traicionera del viaje es la historia de la desafortunada expedición Donner , que quedó atrapada en las montañas de Sierra Nevada durante el invierno de 1846-1847. La mitad de las 90 personas que viajaban con el grupo murieron de hambre y exposición, y algunos recurrieron al canibalismo para sobrevivir. [125] Otra historia de canibalismo presentó a Alferd Packer y su viaje a Colorado en 1874. También hubo frecuentes ataques de bandidos y salteadores de caminos , como los infames hermanos Harpe que patrullaban las rutas fronterizas y atacaban a los grupos de migrantes. [126] [127]

En Misuri e Illinois, la animosidad entre los colonos mormones y los lugareños creció, lo que reflejaría los de otros estados como Utah años después. La violencia finalmente estalló el 24 de octubre de 1838, cuando las milicias de ambos lados se enfrentaron y se produjo una matanza masiva de mormones en el condado de Livingston 6 días después. [128] Se presentó una orden de exterminio mormón durante estos conflictos, y los mormones se vieron obligados a dispersarse. [129] Brigham Young , que buscaba abandonar la jurisdicción estadounidense para escapar de la persecución religiosa en Illinois y Misuri, llevó a los mormones al valle del Gran Lago Salado , propiedad en ese momento de México pero no controlado por ellos. Un centenar de asentamientos rurales mormones surgieron en lo que Young llamó " Deseret ", que gobernó como una teocracia. Más tarde se convirtió en el Territorio de Utah. El asentamiento de Young en Salt Lake City sirvió como centro de su red, que también se extendió a los territorios vecinos. El comunalismo y las prácticas agrícolas avanzadas de los mormones les permitieron tener éxito. [130] Los mormones a menudo vendían bienes a las caravanas de carros que pasaban por allí y llegaron a acuerdos con las tribus nativas locales porque Young decidió que era más barato alimentar a los nativos que luchar contra ellos. [131] La educación se convirtió en una alta prioridad para proteger al grupo asediado, reducir la herejía y mantener la solidaridad grupal. [132]

Tras el fin de la guerra entre México y Estados Unidos en 1848, México cedió Utah a los Estados Unidos. Aunque los mormones de Utah habían apoyado los esfuerzos de Estados Unidos durante la guerra, el gobierno federal, impulsado por las iglesias protestantes, rechazó la teocracia y la poligamia. Fundado en 1852, el Partido Republicano era abiertamente hostil hacia la Iglesia de Jesucristo de los Santos de los Últimos Días (Iglesia SUD) en Utah por la práctica de la poligamia, considerada por la mayoría del público estadounidense como una afrenta a los valores religiosos, culturales y morales de la civilización moderna. Los enfrentamientos rayaron en la guerra abierta a finales de la década de 1850, cuando el presidente Buchanan envió tropas. Aunque no se libraron batallas militares y las negociaciones llevaron a una retirada, la violencia se intensificó y hubo varias víctimas. [133] Después de la Guerra Civil, el gobierno federal tomó sistemáticamente el control de Utah, la Iglesia SUD fue legalmente desincorporada en el territorio y los miembros de la jerarquía de la iglesia, incluyendo a Young, fueron removidos sumariamente y excluidos de prácticamente todos los cargos públicos. [134] Mientras tanto, el exitoso trabajo misionero en los EE. UU. y Europa trajo una avalancha de conversos mormones a Utah. Durante este tiempo, el Congreso se negó a admitir a Utah en la Unión como un estado y la estadidad significaría el fin del control federal directo sobre el territorio y el posible ascenso de políticos elegidos y controlados por la Iglesia SUD a la mayoría, si no todos, los cargos electos federales, estatales y locales del nuevo estado. Finalmente, en 1890, el liderazgo de la iglesia anunció que la poligamia ya no era un principio central, a partir de entonces un compromiso. En 1896, Utah fue admitido como el estado número 45 con los mormones divididos entre republicanos y demócratas. [135]

El gobierno federal proporcionó subsidios para el desarrollo del correo y la entrega de mercancías, y en 1856, el Congreso autorizó mejoras en las carreteras y un servicio de correo terrestre a California. El nuevo servicio de trenes de carretas comerciales transportaba principalmente mercancías. En 1858, John Butterfield (1801-1869) estableció un servicio de diligencias que iba de San Luis a San Francisco en 24 días a lo largo de una ruta del sur. Esta ruta fue abandonada en 1861 después de que Texas se uniera a la Confederación, a favor de los servicios de diligencias establecidos a través de Fort Laramie y Salt Lake City , un viaje de 24 días, con Wells Fargo & Co. como el principal proveedor (inicialmente utilizando el antiguo nombre "Butterfield"). [136]

William Russell, con la esperanza de obtener un contrato gubernamental para un servicio de entrega de correo más rápido, inició el Pony Express en 1860, reduciendo el tiempo de entrega a diez días. Instaló más de 150 estaciones a unas 15 millas (24 km) de distancia.

En 1861, el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Telégrafos de Concesión de Tierras, que financió la construcción de las líneas telegráficas transcontinentales de Western Union. Hiram Sibley , director de Western Union, negoció acuerdos exclusivos con los ferrocarriles para que instalaran líneas telegráficas a lo largo de sus derechos de paso. Ocho años antes de que se inaugurara el ferrocarril transcontinental, el primer telégrafo transcontinental unió Omaha, Nebraska, con San Francisco el 24 de octubre de 1861. [137] El Pony Express terminó en tan solo 18 meses porque no podía competir con el telégrafo. [138] [139]

Constitucionalmente, el Congreso no podía tratar la esclavitud en los estados, pero tenía jurisdicción en los territorios occidentales. California rechazó por unanimidad la esclavitud en 1850 y se convirtió en un estado libre. Nuevo México permitió la esclavitud, pero rara vez se vio allí. Kansas estaba fuera de los límites de la esclavitud por el Compromiso de 1820. Los elementos del suelo libre temían que si se permitía la esclavitud, los plantadores ricos comprarían las mejores tierras y las trabajarían con cuadrillas de esclavos, dejando pocas oportunidades para que los hombres blancos libres tuvieran granjas. Pocos plantadores sureños estaban interesados en Kansas, pero la idea de que la esclavitud fuera ilegal allí implicaba que tenían un estatus de segunda clase que era intolerable para su sentido del honor y parecía violar el principio de los derechos de los estados . Con la aprobación de la extremadamente controvertida Ley Kansas-Nebraska en 1854, el Congreso dejó la decisión en manos de los votantes en el terreno en Kansas. En todo el Norte, se formó un nuevo partido importante para luchar contra la esclavitud: el Partido Republicano , con numerosos occidentales en puestos de liderazgo, sobre todo Abraham Lincoln de Illinois. Para influir en la decisión territorial, los elementos antiesclavistas (también llamados "Jayhawkers" o "Free-soilers") financiaron la migración de colonos políticamente decididos. Pero los defensores de la esclavitud contraatacaron con colonos proesclavistas de Missouri. [140] El resultado fue la violencia en ambos bandos; en total, 56 hombres habían sido asesinados cuando la violencia disminuyó en 1859. [141] En 1860, las fuerzas proesclavistas tenían el control, pero Kansas solo tenía dos esclavos. Las fuerzas antiesclavistas tomaron el poder en 1861, cuando Kansas se convirtió en un estado libre. El episodio demostró que un compromiso democrático entre el Norte y el Sur sobre la esclavitud era imposible y sirvió para acelerar la Guerra Civil. [142]

A pesar de su gran territorio, el oeste trans-Mississippi tenía una población pequeña y su historia de guerra ha sido en gran medida subestimada en la historiografía de la Guerra Civil estadounidense. [143]

La Confederación participó en varias campañas importantes en el Oeste. Sin embargo, Kansas, una importante zona de conflicto que precedió a la guerra, fue escenario de una sola batalla, en Mine Creek . Pero su proximidad a las líneas confederadas permitió que las guerrillas pro-confederadas, como los Raiders de Quantrill , atacaran los bastiones de la Unión y masacraran a los residentes. [144]

En Texas, los ciudadanos votaron para unirse a la Confederación; los alemanes pacifistas fueron ahorcados. [145] Las tropas locales tomaron el arsenal federal en San Antonio, con planes de apoderarse de los territorios del norte de Nuevo México, Utah y Colorado, y posiblemente California. La Arizona Confederada fue creada por ciudadanos de Arizona que querían protección contra las incursiones apaches después de que las unidades del Ejército de los Estados Unidos se retiraran. La Confederación luego se propuso obtener el control del Territorio de Nuevo México. El general Henry Hopkins Sibley fue asignado para la campaña y, junto con su Ejército de Nuevo México , marchó directamente hacia el Río Grande en un intento de tomar la riqueza mineral de Colorado y California. El Primer Regimiento de Voluntarios descubrió a los rebeldes, e inmediatamente advirtieron y se unieron a los yanquis en Fort Union. Pronto estalló la Batalla de Glorieta Pass , y la Unión puso fin a la campaña confederada y el área al oeste de Texas permaneció en manos de la Unión. [146] [147]

Misuri , un estado fronterizo del sur donde la esclavitud era legal, se convirtió en un campo de batalla cuando el gobernador secesionista, en contra del voto de la legislatura, condujo tropas al arsenal federal en San Luis ; recibió la ayuda de fuerzas confederadas de Arkansas y Luisiana. El gobernador de Misuri y parte de la legislatura estatal firmaron una Ordenanza de Secesión en Neosho, formando el gobierno confederado de Misuri y la Confederación controlando el sur de Misuri. Sin embargo, el general de la Unión Samuel Curtis recuperó San Luis y todo Misuri para la Unión. El estado fue escenario de numerosas incursiones y guerra de guerrillas en el oeste. [148]

Después de 1850, el ejército estadounidense estableció una serie de puestos militares a lo largo de la frontera, diseñados para detener la guerra entre tribus nativas o entre nativos y colonos. A lo largo del siglo XIX, los oficiales del ejército generalmente desarrollaron sus carreras en funciones de mantenimiento de la paz, pasando de un fuerte a otro hasta su jubilación. La experiencia real en combate era poco común para cualquier soldado. [149]

The most dramatic conflict was the Sioux war in Minnesota in 1862 when Dakota tribes systematically attacked German farms to drive out the settlers. For several days, Dakota attacks at the Lower Sioux Agency, New Ulm, and Hutchinson killed 300 to 400 white settlers. The state militia fought back and Lincoln sent in federal troops. The ensuing battles at Fort Ridgely, Birch Coulee, Fort Abercrombie, and Wood Lake punctuated a six-week war, which ended in an American victory. The federal government tried 425 Natives for murder, and 303 were convicted and sentenced to death. Lincoln pardoned the majority, but 38 leaders were hanged.[150]

The decreased presence of Union troops in the West left behind untrained militias; hostile tribes used the opportunity to attack settlers. The militia struck back hard, most notably by attacking the winter quarters of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, filled with women and children, at the Sand Creek massacre in eastern Colorado in late 1864.[151]

Kit Carson and the U.S. Army in 1864 trapped the entire Navajo tribe in New Mexico, where they had been raiding settlers and put them on a reservation.[152] Within the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, conflicts arose among the Five Civilized Tribes, most of which sided with the South being slaveholders themselves.[153]

In 1862, Congress enacted two major laws to facilitate settlement of the West: the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railroad Act. The result by 1890 was millions of new farms in the Plains states, many operated by new immigrants from Germany and Scandinavia.

With the war over and slavery abolished, the federal government focused on improving the governance of the territories. It subdivided several territories, preparing them for statehood, following the precedents set by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. It standardized procedures and the supervision of territorial governments, taking away some local powers, and imposing much "red tape", growing the federal bureaucracy significantly.[154]

Federal involvement in the territories was considerable. In addition to direct subsidies, the federal government maintained military posts, provided safety from Native attacks, bankrolled treaty obligations, conducted surveys and land sales, built roads, staffed land offices, made harbor improvements, and subsidized overland mail delivery. Territorial citizens came to both decry federal power and local corruption, and at the same time, lament that more federal dollars were not sent their way.[155]

Territorial governors were political appointees and beholden to Washington so they usually governed with a light hand, allowing the legislatures to deal with the local issues. In addition to his role as civil governor, a territorial governor was also a militia commander, a local superintendent of Native affairs, and the state liaison with federal agencies. The legislatures, on the other hand, spoke for the local citizens and they were given considerable leeway by the federal government to make local law.[156]

These improvements to governance still left plenty of room for profiteering. As Mark Twain wrote while working for his brother, the secretary of Nevada, "The government of my country snubs honest simplicity but fondles artistic villainy, and I think I might have developed into a very capable pickpocket if I had remained in the public service a year or two."[157] "Territorial rings", corrupt associations of local politicians and business owners buttressed with federal patronage, embezzled from Native tribes and local citizens, especially in the Dakota and New Mexico territories.[158]

In acquiring, preparing, and distributing public land to private ownership, the federal government generally followed the system set forth by the Land Ordinance of 1785. Federal exploration and scientific teams would undertake reconnaissance of the land and determine Native American habitation. Through treaties, the land titles would be ceded by the resident tribes. Then surveyors would create detailed maps marking the land into squares of six miles (10 km) on each side, subdivided first into one square mile blocks, then into 160-acre (0.65 km2) lots. Townships would be formed from the lots and sold at public auction. Unsold land could be purchased from the land office at a minimum price of $1.25 per acre.[159]

As part of public policy, the government would award public land to certain groups such as veterans, through the use of "land script". The script traded in a financial market, often at below the $1.25 per acre minimum price set by law, which gave speculators, investors, and developers another way to acquire large tracts of land cheaply.[160] Land policy became politicized by competing factions and interests, and the question of slavery on new lands was contentious. As a counter to land speculators, farmers formed "claims clubs" to enable them to buy larger tracts than the 160-acre (0.65 km2) allotments by trading among themselves at controlled prices.[161]

In 1862, Congress passed three important bills that transformed the land system. The Homestead Act granted 160 acres (0.65 km2) free to each settler who improved the land for five years; citizens and non-citizens including squatters and women were all eligible. The only cost was a modest filing fee. The law was especially important in the settling of the Plains states. Many took a free homestead and others purchased their land from railroads at low rates.[162][163]

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 provided for the land needed to build the transcontinental railroad. The land was given the railroads alternated with government-owned tracts saved for free distribution to homesteaders. To be equitable, the federal government reduced each tract to 80 acres (32 ha) because of its perceived higher value given its proximity to the rail line. Railroads had up to five years to sell or mortgage their land, after tracks were laid, after which unsold land could be purchased by anyone. Often railroads sold some of their government acquired land to homesteaders immediately to encourage settlement and the growth of markets the railroads would then be able to serve. Nebraska railroads in the 1870s were strong boosters of lands along their routes. They sent agents to Germany and Scandinavia with package deals that included cheap transportation for the family as well as its furniture and farm tools, and they offered long-term credit at low rates. Boosterism succeeded in attracting adventurous American and European families to Nebraska, helping them purchase land grant parcels on good terms. The selling price depended on such factors as soil quality, water, and distance from the railroad.[164]

The Morrill Act of 1862 provided land grants to states to begin colleges of agriculture and mechanical arts (engineering). Black colleges became eligible for these land grants in 1890. The Act succeeded in its goals to open new universities and make farming more scientific and profitable.[165]

In the 1850s, the U.S. government sponsored surveys that charted the remaining unexplored regions of the West in order to plan possible routes for a transcontinental railroad. Much of this work was undertaken by the Corps of Engineers, Corps of Topographical Engineers, and Bureau of Explorations and Surveys, and became known as "The Great Reconnaissance". Regionalism animated debates in Congress regarding the choice of a northern, central, or southern route. Engineering requirements for the rail route were an adequate supply of water and wood, and as nearly-level route as possible, given the weak locomotives of the era.[166]

Proposals to build a transcontinental failed because of Congressional disputes over slavery. With the secession of the Confederate states in 1861, the modernizers in the Republican party took over Congress and wanted a line to link to California. Private companies were to build and operate the line. Construction would be done by unskilled laborers who would live in temporary camps along the way. Immigrants from China and Ireland did most of the construction work. Theodore Judah, the chief engineer of the Central Pacific surveyed the route from San Francisco east. Judah's tireless lobbying efforts in Washington were largely responsible for the passage of the 1862 Pacific Railroad Act, which authorized construction of both the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific (which built west from Omaha).[167] In 1862 four rich San Francisco merchants (Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins) took charge, with Crocker in charge of construction. The line was completed in May 1869. Coast-to-coast passenger travel in 8 days now replaced wagon trains or sea voyages that took 6 to 10 months and cost much more.

The road was built with mortgages from New York, Boston, and London, backed by land grants. There were no federal cash subsidies, But there was a loan to the Central Pacific that was eventually repaid at six percent interest. The federal government offered land-grants in a checkerboard pattern. The railroad sold every-other square, with the government opening its half to homesteaders. The government also loaned money—later repaid—at $16,000 per mile on level stretches, and $32,000 to $48,000 in mountainous terrain. Local and state governments also aided the financing.

Most of the manual laborers on the Central Pacific were new arrivals from China.[168] Kraus shows how these men lived and worked, and how they managed their money. He concludes that senior officials quickly realized the high degree of cleanliness and reliability of the Chinese.[169] The Central Pacific employed over 12,000 Chinese workers, 90% of its manual workforce. Ong explores whether or not the Chinese railroad workers were exploited by the railroad, with whites in better positions. He finds the railroad set different wage rates for whites and Chinese and used the latter in the more menial and dangerous jobs, such as the handling and the pouring of nitroglycerin.[170] However the railroad also provided camps and food the Chinese wanted and protected the Chinese workers from threats from whites.[171]

Building the railroad required six main activities: surveying the route, blasting a right of way, building tunnels and bridges, clearing and laying the roadbed, laying the ties and rails, and maintaining and supplying the crews with food and tools. The work was highly physical, using horse-drawn plows and scrapers, and manual picks, axes, sledgehammers, and handcarts. A few steam-driven machines, such as shovels, were used. The rails were iron (steel came a few years later), weighed 700 lb (320 kg) and required five men to lift. For blasting, they used black powder. The Union Pacific construction crews, mostly Irish Americans, averaged about two miles (3 km) of new track per day.[172]

Six transcontinental railroads were built in the Gilded Age (plus two in Canada); they opened up the West to farmers and ranchers. From north to south they were the Northern Pacific, Milwaukee Road, and Great Northern along the Canada–U.S. border; the Union Pacific/Central Pacific in the middle, and to the south the Santa Fe, and the Southern Pacific. All but the Great Northern of James J. Hill relied on land grants. The financial stories were often complex. For example, the Northern Pacific received its major land grant in 1864. Financier Jay Cooke (1821–1905) was in charge until 1873 when he went bankrupt. Federal courts, however, kept bankrupt railroads in operation. In 1881 Henry Villard (1835–1900) took over and finally completed the line to Seattle. But the line went bankrupt in the Panic of 1893 and Hill took it over. He then merged several lines with financing from J.P. Morgan, but President Theodore Roosevelt broke them up in 1904.[173]