Los árabes ( árabe : عَرَب , DIN 31635 : ʿarab , pronunciación árabe : [b] [ˈʕɑ.rɑb] ), también conocido comopueblo árabe(الشَّعْبَ الْعَرَبِيّ), es ungrupo étnico[c]que habita principalmente en elmundo árabeenAsia occidentalyel norte de África. Unadiáspora árabeestá presente en varias partes del mundo.[74]

Los árabes han estado en el Creciente Fértil durante miles de años. [75] En el siglo IX a. C., los asirios hicieron referencias escritas a los árabes como habitantes del Levante , Mesopotamia y Arabia . [76] A lo largo del Antiguo Cercano Oriente , los árabes establecieron civilizaciones influyentes a partir del 3000 a. C. en adelante, como Dilmun , Gerrha y Magan , desempeñando un papel vital en el comercio entre Mesopotamia y el Mediterráneo . [77] Otras tribus prominentes incluyen a Madián , ʿĀd y Thamud mencionados en la Biblia y el Corán . Más tarde, en 900 a. C., los qedaritas disfrutaron de estrechas relaciones con los estados cananeos y arameos cercanos , y su territorio se extendió desde el Bajo Egipto hasta el Levante Sur. [78] Desde 1200 a. C. hasta 110 a. C., surgieron reinos poderosos como Saba , Lihyan , Minaean , Qataban , Hadhramaut , Awsan y Homerite en Arabia. [79] Según la tradición abrahámica , los árabes son descendientes de Abraham a través de su hijo Ismael . [80]

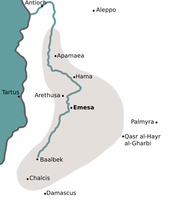

Durante la antigüedad clásica , los nabateos establecieron su reino con Petra como capital en 300 a. C., [81] para 271 d. C., el Imperio palmireno con la capital Palmira , liderado por la reina Zenobia , abarcaba Siria Palestina , Arabia Pétrea y Egipto , así como grandes partes de Anatolia . [82] Los árabes itureos habitaron Líbano , Siria y el norte de Palestina ( Galilea ) durante los períodos helenístico y romano. [83] Osroene y Hatran eran reinos árabes en la Alta Mesopotamia alrededor de 200 d. C. [84] En 164 d. C., los sasánidas reconocieron a los árabes como " Arbayistán ", que significa "tierra de los árabes", [85] ya que eran parte de Adiabene en la Alta Mesopotamia. [86] Los árabes emesenos gobernaron en 46 a. C. Emesa ( Homs ), Siria . [87] Durante la Antigüedad tardía , los tanújidas , salíjidas , lájmíes , kinda y gasánidas eran tribus árabes dominantes en el Levante, Mesopotamia y Arabia; abrazaron predominantemente el cristianismo . [88]

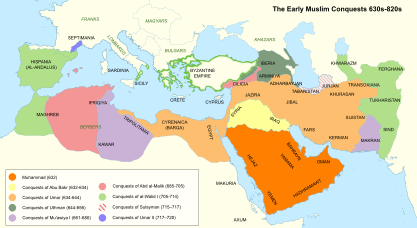

Durante la Edad Media , el Islam fomentó una vasta unión árabe, lo que llevó a importantes migraciones árabes al Magreb , el Levante y territorios vecinos bajo el dominio de imperios árabes como el rashidun , el omeya , el abasí y el fatimí , lo que en última instancia condujo a la decadencia de los imperios bizantino y sasánida . En su apogeo, los territorios árabes se extendieron desde el sur de Francia hasta el oeste de China , formando uno de los imperios más grandes de la historia . [89] La Gran Revuelta Árabe a principios del siglo XX ayudó a desmantelar el Imperio Otomano , lo que en última instancia condujo a la formación de la Liga Árabe el 22 de marzo de 1945, con su Carta respaldando el principio de una " patria árabe unificada ". [90]

Los árabes desde Marruecos hasta Irak comparten un vínculo común basado en la etnicidad, el idioma , la cultura , la historia , la identidad , la ascendencia , el nacionalismo , la geografía , la unidad y la política , [91] que le dan a la región una identidad distintiva y la distinguen de otras partes del mundo musulmán . [92] También tienen sus propias costumbres, literatura , música , danza , medios de comunicación , comida , vestimenta , sociedad, deportes , arquitectura , arte y mitología . [93] Los árabes han influenciado y contribuido significativamente al progreso humano en muchos campos, incluyendo la ciencia , la tecnología , la filosofía , la ética , la literatura , la política , los negocios , el arte , la música , la comedia , el teatro, el cine , la arquitectura , la comida , la medicina y la religión . [94] Antes del Islam , la mayoría de los árabes seguían la religión semítica politeísta , mientras que algunas tribus adoptaron el judaísmo o el cristianismo y unos pocos individuos, conocidos como los hanifs , seguían una forma de monoteísmo . [95] Actualmente, alrededor del 93% de los árabes son musulmanes , mientras que el resto son principalmente cristianos árabes , así como grupos árabes de drusos y baháʼís . [96]

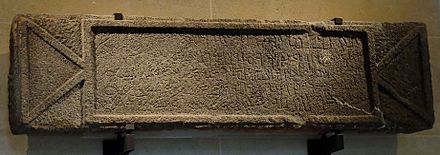

El primer uso documentado de la palabra árabe en referencia a un pueblo aparece en los Monolitos Kurkh , un registro en lengua acadia de la conquista asiria de Aram (siglo IX a. C.). Los Monolitos usaban el término para referirse a los beduinos de la península arábiga bajo el reinado del rey Gindibu , que lucharon como parte de una coalición opuesta a Asiria . [97] Entre el botín capturado por el ejército del rey asirio Salmanasar III en la batalla de Qarqar (853 a. C.) se encuentran 1000 camellos de « Gîndibuʾ el Arbâya » o «[el hombre] Gindibu perteneciente a los árabes » ( ar-ba-aa es una nisba adjetival del sustantivo ʿArab ). [97]

La palabra relacionada ʾaʿrāb se utiliza para referirse a los beduinos en la actualidad, en contraste con ʿArab que se refiere a los árabes en general. [98] Ambos términos se mencionan alrededor de 40 veces en inscripciones sabeas preislámicas . El término ʿarab ('árabe') aparece también en los títulos de los reyes himyaritas desde la época de 'Abu Karab Asad hasta MadiKarib Ya'fur. Según la gramática sabea, el término ʾaʿrāb se deriva del término ʿarab . El término también se menciona en los versículos coránicos , refiriéndose a las personas que vivían en Medina y podría ser un préstamo del sur de Arabia al idioma coránico. [99]

La indicación más antigua que sobrevive de una identidad nacional árabe es una inscripción hecha en una forma arcaica del árabe en 328 d. C. usando el alfabeto nabateo , que se refiere a Imru' al-Qays ibn 'Amr como 'Rey de todos los árabes'. [100] [101] Heródoto se refiere a los árabes en el Sinaí, el sur de Palestina y la región del incienso (sur de Arabia). Otros historiadores griegos antiguos como Agatárquides , Diodoro Sículo y Estrabón mencionan a los árabes que vivían en Mesopotamia (a lo largo del Éufrates ), en Egipto (el Sinaí y el Mar Rojo), el sur de Jordania (los nabateos ), la estepa siria y en el este de Arabia (el pueblo de Gerrha ). Las inscripciones que datan del siglo VI a. C. en Yemen incluyen el término 'árabe'. [102]

La versión árabe más popular sostiene que la palabra árabe proviene de un padre epónimo llamado Ya'rub , que supuestamente fue el primero en hablar árabe. Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani tenía otra opinión; afirma que los árabes eran llamados gharab ('occidentales') por los mesopotámicos porque los beduinos residían originalmente al oeste de Mesopotamia; el término luego se corrompió y se convirtió en árabe .

Otra opinión es la de al-Masudi , que sostiene que la palabra árabe se aplicó inicialmente a los ismaelitas del valle del Arabá . En la etimología bíblica, árabe (hebreo: arvi ) proviene del origen desértico de los beduinos que originalmente describía ( arava significa 'desierto').

La raíz ʿ-rb tiene varios significados adicionales en las lenguas semíticas (entre ellos, «oeste», «puesta de sol», «desierto», «mezclado», «comerciante» y «cuervo») y son «comprensibles», ya que todos ellos tienen distintos grados de relevancia para el surgimiento del nombre. También es posible que algunas formas fueran metatéticas a partir de ʿ-BR , «moviéndose» (árabe: ʿ-BR , «atravesando») y, por lo tanto, se alega que eran «nómadas». [103]

El árabe es una lengua semítica que pertenece a la familia de las lenguas afroasiáticas . La mayoría de los estudiosos aceptan que la « península Arábiga » ha sido aceptada durante mucho tiempo como la Urheimat (patria lingüística) original de las lenguas semíticas . [104] [105] [106] [107] Algunos estudiosos investigan si sus orígenes están en el Levante . [108] Los antiguos pueblos de habla semítica vivieron en el antiguo Cercano Oriente , incluido el Levante, Mesopotamia y la península Arábiga desde el tercer milenio a. C. hasta el final de la antigüedad. El protosemita probablemente llegó a la península Arábiga en el cuarto milenio a. C., y sus lenguas hijas se extendieron desde allí, [109] mientras que el árabe antiguo comenzó a diferenciarse del semítico central a principios del primer milenio a. C. [110] El semítico central es una rama de la lengua semítica que incluye el árabe, el arameo , el cananeo , el fenicio , el hebreo y otros. [111] [112] Los orígenes del protosemítico pueden estar en la península arábiga, y la lengua se extendió desde allí a otras regiones. Esta teoría propone que los pueblos semíticos llegaron a Mesopotamia y otras áreas desde los desiertos al oeste, como los acadios que entraron en Mesopotamia alrededor de finales del cuarto milenio a. C. [109] Se cree que los orígenes de los pueblos semíticos incluyen varias regiones: Mesopotamia , el Levante, la península arábiga y el norte de África . Algunos opinan que el semítico puede haberse originado en el Levante alrededor del 3800 a. C. y posteriormente se extendió al Cuerno de África alrededor del 800 a. C. desde Arabia, así como al norte de África. [113] [114]

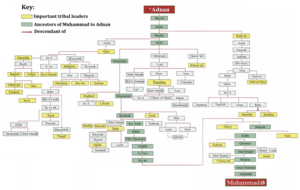

Según las tradiciones árabe -islámicas-judías , Ismael , hijo de Abraham y Agar , fue el «padre de los árabes». [115] [116] [117] [118] [119] El libro del Génesis narra que Dios prometió a Agar engendrar de Ismael doce príncipes y convertir a sus descendientes en una « gran nación» . [120] [121 ] [122] [123] [124] [125] Ismael fue considerado el antepasado del profeta islámico Mahoma , el fundador del Islam . Las tribus del centro-oeste de Arabia se autodenominaban «el pueblo de Abraham y la descendencia de Ismael». [126] Ibn Jaldún , un erudito árabe del siglo VIII, describió a los árabes como de origen ismaelita. [127]

El Corán menciona que Ibrahim (Abraham) y su esposa Hajar (Agar) tuvieron un hijo profético llamado Ismael, a quien Dios le concedió un favor por encima de las demás naciones. [128] Dios le ordenó a Ibrahim que llevara a Hajar e Ismael a La Meca , donde oró para que se les proporcionara agua y frutas. Hajar corrió entre las colinas de Safa y Marwa en busca de agua, y un ángel se les apareció y les proporcionó agua. Ismael creció en La Meca. Más tarde se le ordenó a Ibrahim que sacrificara a Ismael en un sueño, pero Dios intervino y lo reemplazó con una cabra. Ibrahim e Ismael luego construyeron la Kaaba en La Meca, que originalmente fue construida por Adán . [129]

Según el libro samaritano Asaṭīr añade: [130] : 262 "Y después de la muerte de Abraham, Ismael reinó veintisiete años; Y todos los hijos de Nebaot gobernaron durante un año en la vida de Ismael; Y durante treinta años después de su muerte desde el río de Egipto hasta el río Éufrates ; y edificaron La Meca ." [131] Josefo también enumera a los hijos y afirma que ellos "... habitan las tierras que están entre el Éufrates y el Mar Rojo , cuyo nombre es Nabathæa . [132] [133] El Targum Onkelos anota ( Génesis 25:16 ), describiendo la extensión de sus asentamientos: Los ismaelitas vivían desde Hindekaia ( India ) hasta Chalutsa (posiblemente en Arabia), al lado de Mizraim (Egipto), y desde el área alrededor de Arturo ( Asiria ) hacia el norte. Esta descripción sugiere que los ismaelitas eran un grupo ampliamente disperso con presencia en una porción significativa del antiguo Cercano Oriente. [134] [135]

Los nómadas de Arabia se han estado extendiendo a través de las franjas desérticas de la Media Luna Fértil desde al menos el año 3000 a. C., pero la primera referencia conocida a los árabes como un grupo distinto proviene de un escriba asirio que registra una batalla en el año 853 a. C. [136] [137] La historia de los árabes durante el período preislámico en varias regiones, incluida Arabia, el Levante, Mesopotamia y Egipto. Los árabes fueron mencionados por sus vecinos, como las inscripciones reales asirias y babilónicas del siglo IX al VI a. C., que mencionan al rey de Qedar como rey de los árabes y rey de los ismaelitas. [138] [139] [140] [141] De los nombres de los hijos de Ismael, los nombres "Nabat, Kedar, Abdeel, Dumah, Massa y Teman" se mencionan en las inscripciones reales asirias como tribus de los ismaelitas. Jesur fue mencionado en inscripciones griegas en el siglo I a. C. [142] También hay registros del reinado de Sargón que mencionan vendedores de hierro a personas llamadas árabes en Huzaza en Babilonia , lo que provocó que Sargón prohibiera dicho comercio por temor a que los árabes pudieran usar el recurso para fabricar armas contra el ejército asirio. La historia de los árabes en relación con la Biblia muestra que eran una parte importante de la región y desempeñaron un papel en las vidas de los israelitas. El estudio afirma que la nación árabe es una entidad antigua y significativa; sin embargo, destaca que los árabes carecían de una conciencia colectiva de su unidad. No inscribieron su identidad como árabes ni afirmaron la propiedad exclusiva sobre territorios específicos. [143]

Magan , Midian y ʿĀd son todas tribus o civilizaciones antiguas que se mencionan en la literatura árabe y tienen raíces en Arabia. Magan ( árabe : مِجَانُ , Majan ), conocida por su producción de cobre y otros metales, la región fue un importante centro comercial en la antigüedad y se menciona en el Corán como un lugar donde Musa ( Moisés ) viajó durante su vida. [144] [145] Midian ( árabe : مَدْيَن , Madyan ), por otro lado, era una región ubicada en la parte noroeste de Arabia, la gente de Midian es mencionada en el Corán por haber adorado ídolos y haber sido castigada por Dios por su desobediencia. [146] [147] Moisés también vivió en Midian por un tiempo, donde se casó y trabajó como pastor. Los ʿĀd ( árabe : عَادَ , ʿĀd ), como se mencionó anteriormente, eran una antigua tribu que vivía en el sur de Arabia, la tribu era conocida por su riqueza, poder y tecnología avanzada, pero finalmente fueron destruidos por una poderosa tormenta de viento como castigo por su desobediencia a Dios . [148] Se considera a los ʿĀd como una de las tribus árabes originales. [149] [150] El historiador Heródoto proporcionó amplia información sobre Arabia, describiendo las especias , el terreno , el folclore , el comercio , la vestimenta y las armas de los árabes. En su tercer libro, mencionó a los árabes (Άραβες) como una fuerza a tener en cuenta en el norte de la península Arábiga justo antes de la campaña de Cambises contra Egipto. Otros autores griegos y latinos que escribieron sobre Arabia incluyen a Teofrasto , Estrabón , Diodoro Sículo y Plinio el Viejo . El historiador judío Flavio Josefo escribió sobre los árabes y su rey, mencionando su relación con Cleopatra , la reina de Egipto. El tributo pagado por el rey árabe a Cleopatra fue recaudado por Herodes , el rey de los judíos, pero el rey árabe más tarde se volvió lento en sus pagos y se negó a pagar sin más deducciones. Esto arroja algo de luz sobre las relaciones entre los árabes, los judíos y Egipto en ese momento. [151] Geshem el árabe era un hombre árabe que se oponíaNehemías en la Biblia hebrea ( Neh . 2:19 , 6:1 ). Probablemente era el jefe de la tribu árabe "Gushamu" y fue un gobernante poderoso con influencia que se extendió desde el norte de Arabia hasta Judá. Los árabes y los samaritanos hicieron esfuerzos para obstaculizar la reconstrucción de los muros de Jerusalén por parte de Nehemías . [152] [153] [154]

,_Petra,_Jordan.jpg/440px-Al-Khazneh_(The_Treasury),_Petra,_Jordan.jpg)

El término " sarracenos " era un término utilizado en los primeros siglos, tanto en escritos griegos como latinos , para referirse a los "árabes" que vivían en y cerca de lo que los romanos designaron como Arabia Petraea (Levante) y Arabia Deserta (Arabia). [155] [156] Los cristianos de Iberia usaban el término moro para describir a todos los árabes y musulmanes de esa época. Los árabes de Medina se referían a las tribus nómadas de los desiertos como los A'raab, y se consideraban sedentarios, pero eran conscientes de sus estrechos vínculos raciales. Hagarenos es un término ampliamente utilizado por los primeros siríacos , griegos y armenios para describir a los primeros conquistadores árabes de Mesopotamia, Siria y Egipto, se refiere a los descendientes de Agar, que le dio un hijo llamado Ismael a Abraham en el Antiguo Testamento. En la Biblia, los hagarenos son referidos como "ismaelitas" o "árabes". [157] Las conquistas árabes del siglo VII fueron una conquista repentina y dramática liderada por ejércitos árabes, que rápidamente conquistaron gran parte del Medio Oriente, el norte de África y España. Fue un momento significativo para el Islam , que se veía a sí mismo como el sucesor del judaísmo y el cristianismo. [158] El término ʾiʿrāb tiene la misma raíz que se refiere a las tribus beduinas del desierto que rechazaron el Islam y resistieron a Mahoma. ( Corán 9:97 ) El Kebra Nagast del siglo XIV dice: "Y por lo tanto, los hijos de Ismael se convirtieron en reyes sobre Tereb , y sobre Kebet , y sobre Nôbâ , y Sôba , y Kuergue , y Kîfî, y Mâkâ , y Môrnâ , y Fînḳânâ , y 'Arsîbânâ , y Lîbâ , y Mase'a , porque eran la descendencia de Sem ". [159]

La limitada cobertura histórica local de estas civilizaciones significa que la evidencia arqueológica, los relatos extranjeros y las tradiciones orales árabes se basan en gran medida en la reconstrucción de este período. Las civilizaciones prominentes en ese momento incluyeron la civilización Dilmun , que fue un importante centro comercial [162] que en el apogeo de su poder controlaba las rutas comerciales del Golfo Pérsico . [162] Los sumerios consideraban a Dilmun como tierra santa . [163] Dilmun es considerada como una de las civilizaciones antiguas más antiguas del Medio Oriente . [164] [165] que surgió alrededor del cuarto milenio a. C. y duró hasta el 538 a. C. Gerrha era una antigua ciudad de Arabia Oriental , en el lado oeste del Golfo, Gerrha fue el centro de un reino árabe desde aproximadamente el 650 a. C. hasta aproximadamente el 300 d. C. Thamud , que surgió alrededor del primer milenio a. C. y duró hasta aproximadamente el 300 d. C. Los textos protoárabes o del norte de Arabia , que datan de principios del primer milenio a. C. , ofrecen una imagen más clara del surgimiento de los árabes. Los más antiguos están escritos en variantes de la escritura musnad epigráfica del sur de Arabia , incluidas las inscripciones hasaeas del siglo VIII a. C. de Arabia Saudita oriental y los textos tamúdicos que se encuentran por toda la península Arábiga y el Sinaí .

Los qedaritas eran una antigua confederación tribal árabe en gran parte nómada centrada en el Wādī Sirḥān en el desierto sirio . Eran conocidos por su estilo de vida nómada y por su papel en el comercio de caravanas que unía la península arábiga con el mundo mediterráneo . Los qedaritas expandieron gradualmente su territorio a lo largo de los siglos VIII y VII a. C., y para el siglo VI a. C., se habían consolidado en un reino que cubría una gran área en el norte de Arabia, el sur de Palestina y la península del Sinaí . Los qedaritas fueron influyentes en el antiguo Cercano Oriente , y su reino jugó un papel significativo en los asuntos políticos y económicos de la región durante varios siglos. [166]

Saba ( árabe : سَبَأٌ Saba ) es un reino mencionado en la Biblia hebrea ( Antiguo Testamento ) y el Corán , aunque el sabeo era una lengua del sur de Arabia y no árabe. Saba aparece en las tradiciones judías , musulmanas y cristianas , cuyo linaje se remonta a Qahtan hijo de Hud , uno de los antepasados de los árabes, [167] [168] [169] Saba fue mencionada en inscripciones asirias y en los escritos de escritores griegos y romanos . [170] Una de las antiguas referencias escritas que también hablaban de Saba es el Antiguo Testamento, que afirmaba que el pueblo de Saba suministraba incienso, especialmente incienso, a Siria y Egipto y les exportaba oro y piedras preciosas. [171] La reina de Saba, que viajó a Jerusalén para interrogar al rey Salomón , con una gran caravana de camellos que llevaban regalos de oro , piedras preciosas y especias , [172] cuando llegó, quedó impresionada por la sabiduría y la riqueza del rey Salomón, y le planteó una serie de preguntas difíciles. [173] El rey Salomón pudo responder a todas sus preguntas, y la reina de Saba quedó impresionada por su sabiduría y su riqueza. (1 Reyes 10)

.jpg/440px-Dhamar_Ali_Yahbur_(bust).jpg)

Los sabeos son mencionados varias veces en la Biblia hebrea . En el Corán , [174] se los describe como Sabaʾ ( سَبَأ , que no debe confundirse con Ṣābiʾ , صَابِئ ), [168] [169] o como Qawm Tubbaʿ (árabe: قَوْم تُبَّع , lit. 'Pueblo de Tubbaʿ'). [175] [176] Eran conocidos por su próspera economía comercial y agrícola, que se basaba en el cultivo de incienso y mirra, estas resinas aromáticas de gran valor se exportaban a Egipto, Grecia y Roma , lo que hizo que los sabeos fueran ricos y poderosos, también comerciaban con especias, textiles y otros bienes de lujo. La presa de Maʾrib fue uno de los mayores logros de ingeniería del mundo antiguo y proporcionó agua a la ciudad de Maʾrib y a las tierras agrícolas circundantes. [177] [178] [170]

Lihyan, también llamado Dadān o Dedan, fue un poderoso y altamente organizado reino árabe antiguo que desempeñó un papel cultural y económico vital en la región noroccidental de la península arábiga y utilizó el idioma dadanítico . [179] Los lihyanitas eran conocidos por su avanzada organización y gobierno, y desempeñaron un papel importante en la vida cultural y económica de la región. El reino estaba centrado alrededor de la ciudad de Dedan (la actual Al Ula ) y controlaba un gran territorio que se extendía desde Yathrib en el sur hasta partes del Levante en el norte. [180] [179] Las genealogías árabes consideran que los Banu Lihyan eran ismaelitas y usaban el idioma dadanítico . [181]

El reino de Ma'in era un antiguo reino árabe con un sistema de monarquía hereditaria y un enfoque en la agricultura y el comercio . [182] Las fechas propuestas van desde el siglo XV a. C. hasta el siglo I d. C. Su historia ha sido registrada a través de inscripciones y libros clásicos griegos y romanos, aunque las fechas exactas de inicio y fin del reino aún se debaten. El pueblo Ma'in tenía un sistema de gobierno local con consejos llamados "Mazood", y cada ciudad tenía su propio templo que albergaba a uno o más dioses. También adoptaron el alfabeto fenicio y lo usaron para escribir su idioma. El reino finalmente cayó en manos del pueblo árabe sabeo . [183] [184]

Qataban fue un antiguo reino ubicado en el sur de Arabia , que existió desde principios del primer milenio a. C. hasta finales del siglo I o II d. C. [186] [186] [187] Se convirtió en un estado centralizado en el siglo VI a. C. con dos polos gobernantes de co-reyes. [186] [188] Qataban expandió su territorio, incluida la conquista de Ma'in y campañas exitosas contra los sabeos. [187] [185] [189] Desafió la supremacía de los sabeos en la región y libró una guerra exitosa contra Hadramawt en el siglo III a. C. [185] [190] El poder de Qataban declinó en los siglos siguientes, lo que llevó a su anexión por Hadramawt y Ḥimyar en el siglo I d. C. [191] [187] [185] [ 186] [192] [185]

El Reino de Hadramaut era conocido por su rico patrimonio cultural , así como por su ubicación estratégica a lo largo de importantes rutas comerciales que conectaban Oriente Medio , el sur de Asia y África oriental . [193] El Reino se estableció alrededor del siglo III a. C. y alcanzó su apogeo durante el siglo II d. C., cuando controlaba gran parte del sur de la península Arábiga. El reino era conocido por su impresionante arquitectura , en particular sus distintivas torres, que se usaban como torres de vigilancia, estructuras defensivas y hogares para familias adineradas. [194] La gente de Hadramaut era experta en agricultura, especialmente en el cultivo de incienso y mirra. Tenían una fuerte cultura marítima y comerciaban con la India, África oriental y el sudeste asiático. [195] Aunque el reino decayó en el siglo IV, Hadramaut siguió siendo un centro cultural y económico. Su legado todavía se puede ver hoy. [196]

El antiguo reino de Awsān (siglos VIII-VII a. C.) fue, de hecho, uno de los pequeños reinos más importantes de Arabia del Sur , y su capital, Ḥajar Yaḥirr, fue un importante centro de comercio en el mundo antiguo. Es fascinante aprender sobre la rica historia de esta región y el patrimonio cultural que se ha conservado a través de los sitios arqueológicos como Ḥajar Asfal. La destrucción de la ciudad en el siglo VII a. C. por el rey y Mukarrib de Saba' Karab El Watar es un evento significativo en la historia de Arabia del Sur. Destaca la compleja dinámica política y social que caracterizaba a la región en ese momento y las luchas de poder entre diferentes reinos y gobernantes. La victoria de los sabeos sobre Awsān también es un testimonio del poderío militar y la destreza estratégica de los sabeos, que fueron uno de los reinos más poderosos e influyentes de la región. [197]

El reino himyarita o himyar fue un antiguo reino que existió desde alrededor del siglo II a. C. hasta el siglo VI d. C. Su centro era la ciudad de Zafar , que se encuentra en el actual Yemen. Los himyaritas eran un pueblo árabe que hablaba una lengua del sur de Arabia y eran conocidos por su destreza en el comercio y la navegación, [198] controlaban la parte sur de Arabia y tenían una economía próspera basada en la agricultura, el comercio y el comercio marítimo, eran expertos en irrigación y terrazas, lo que les permitía cultivar cosechas en el ambiente árido. Los himyaritas se convirtieron al judaísmo en el siglo IV d. C., y sus gobernantes llegaron a ser conocidos como los "reyes de los judíos", esta conversión probablemente estuvo influenciada por sus conexiones comerciales con las comunidades judías de la región del Mar Rojo y el Levante, sin embargo, los himyaritas también toleraban otras religiones, incluido el cristianismo y las religiones paganas locales. [198]

Los nabateos eran árabes nómadas que se asentaron en un territorio centrado alrededor de su capital, Petra, en lo que hoy es Jordania. [199] [200] Sus primeras inscripciones estaban en arameo , pero gradualmente cambiaron al árabe y, dado que tenían escritura, fueron ellos quienes hicieron las primeras inscripciones en árabe. El alfabeto nabateo fue adoptado por los árabes del sur y evolucionó hacia la escritura árabe moderna alrededor del siglo IV. Esto está atestiguado por las inscripciones safaíticas (que comienzan en el siglo I a. C.) y los numerosos nombres personales árabes en las inscripciones nabateas . Desde aproximadamente el siglo II a. C., unas pocas inscripciones de Qaryat al-Faw revelan un dialecto que ya no se considera protoárabe , sino árabe preclásico . Se han encontrado cinco inscripciones siríacas que mencionan a los árabes en Sumatar Harabesi , una de las cuales data del siglo II d. C. [201] [202]

Los primeros registros de árabes en Palmira datan de finales del primer milenio a. C. [203] Los soldados del jeque Zabdibel, que ayudaron a los seléucidas en la batalla de Rafia (217 a. C.), fueron descritos como árabes; Zabdibel y sus hombres no fueron identificados como palmirenos en los textos, pero el nombre "Zabdibel" es un nombre palmireno, lo que lleva a la conclusión de que el jeque era oriundo de Palmira. [204] Después de la batalla de Edesa en el 260 d. C., la captura de Valeriano por parte del rey sasánida Sapor I fue un golpe significativo para Roma y dejó al imperio vulnerable a futuros ataques. Zenobia pudo capturar la mayor parte del Cercano Oriente, incluidos Egipto y partes de Asia Menor. Sin embargo, su imperio duró poco, ya que Aureliano pudo derrotar a los palmirenos y recuperar los territorios perdidos. Los palmirenos recibieron ayuda de sus aliados árabes, pero Aureliano también pudo aprovechar sus propias alianzas para derrotar a Zenobia y su ejército. En definitiva, el Imperio palmireno duró solo unos pocos años, pero tuvo un impacto significativo en la historia del Imperio romano y del Oriente Próximo.

La mayoría de los eruditos identifican a los itureos como un pueblo árabe que habitó la región de Iturea, [205] [206] [207] [208] emergió como una potencia prominente en la región después de la decadencia del Imperio seléucida en el siglo II a. C., desde su base alrededor del Monte Líbano y el valle de Beqaa , llegaron a dominar vastas extensiones de territorio sirio , [209] y parecen haber penetrado en partes del norte de Palestina hasta Galilea . [83] Los tanújidas eran una confederación tribal árabe que vivió en la península Arábiga central y oriental durante los períodos antiguos tardíos y medievales tempranos. Como se mencionó anteriormente, eran una rama de la tribu Rabi'ah , que era una de las tribus árabes más grandes en el período preislámico. Eran conocidos por su destreza militar y desempeñaron un papel importante en el período islámico temprano, luchando en batallas contra los imperios bizantino y sasánida y contribuyendo a la expansión del imperio árabe. [210]

Los árabes osroene , también conocidos como abgaridas , [211] [212] [213] estuvieron en posesión de la ciudad de Edesa en el antiguo Cercano Oriente durante un período significativo de tiempo. Edesa estaba ubicada en la región de Osroene, que era un antiguo reino que existió desde el siglo II a. C. hasta el siglo III d. C. Establecieron una dinastía conocida como los abgaridas, que gobernaron Edesa durante varios siglos. El gobernante más famoso de la dinastía fue Abgar V , de quien se dice que mantuvo correspondencia con Jesucristo y se cree que se convirtió al cristianismo . [214] Los abgaridas desempeñaron un papel importante en la historia temprana del cristianismo en la región, y Edesa se convirtió en un centro de aprendizaje y erudición cristianos . [215] El Reino de Hatra era una antigua ciudad situada en la región de Mesopotamia , fundada en el siglo II o III a. C. y floreció como un importante centro de comercio y cultura durante el Imperio parto . Los gobernantes de Hatra eran conocidos como la dinastía Arsácida, que era una rama de la familia gobernante parta. Sin embargo, en el siglo II d. C., la tribu árabe de Banu Tanukh tomó el control de Hatra y estableció su propia dinastía. Los gobernantes árabes de Hatra asumieron el título de "malka", que significa rey en árabe, y a menudo se referían a sí mismos como el "Rey de los árabes". [216]

Los osroeni y hatrans eran parte de varios grupos o comunidades árabes en la alta Mesopotamia, que también incluían a los árabes de Adiabene , que era un antiguo reino en el norte de Mesopotamia , su ciudad principal era Arbela ( Arba-ilu ), donde Mar Uqba tenía una escuela, o la vecina Hazzah, por cuyo nombre los árabes posteriores también llamaron a Arbela. [217] [218] Esta elaborada presencia árabe en la alta Mesopotamia fue reconocida por los sasánidas , que llamaron a la región Arbayistán , que significa "tierra de los árabes", está atestiguada por primera vez como provincia en la inscripción de la Ka'ba-ye Zartosht del segundo rey de reyes sasánida ( shahanshah ) Shapur I ( r. 240-270 ), [219] que fue erigida en c. 262. [220] [86] Los emesenos fueron una dinastía de reyes-sacerdotes árabes que gobernaron la ciudad de Emesa (hoy Homs , Siria) en la provincia romana de Siria desde el siglo I d.C. hasta el siglo III d.C. La dinastía es notable por producir una serie de sumos sacerdotes del dios El-Gabal , que también fueron influyentes en la política y la cultura romanas . El primer gobernante de la dinastía emesena fue Sampsiceramus I , que llegó al poder en el año 64 d.C. Fue sucedido por su hijo, Jámblico , a quien le siguió su propio hijo, Sampsiceramus II . Bajo Sampsiceramus II, Emesa se convirtió en un reino cliente del Imperio romano , y la dinastía se vinculó más estrechamente con las tradiciones políticas y culturales romanas. [221]

Los gasánidas , los lájmidas y los kinditas fueron la última gran migración de árabes preislámicos que salieron del Yemen hacia el norte. Los gasánidas aumentaron la presencia semítica en la entonces helenizada Siria , la mayoría de los semitas eran pueblos arameos. Se asentaron principalmente en la región de Hauran y se extendieron al Líbano moderno , Palestina y Jordania . Los griegos y los romanos se referían a toda la población nómada del desierto del Cercano Oriente como Arabi. Los romanos llamaban a Yemen " Arabia Félix ". [222] Los romanos llamaban a los estados nómadas vasallos dentro del Imperio romano Arabia Petraea , en honor a la ciudad de Petra , y llamaban a los desiertos no conquistados que bordeaban el imperio al sur y al este Arabia Magna .

Los lájmidas como dinastía heredaron su poder de los tanújidas , la región media del Tigris alrededor de su capital Al-Hira . Terminaron aliándose con los sasánidas contra los gasánidas y el Imperio bizantino . Los lájmidas disputaron el control de las tribus de Arabia Central con los kinditas, y los lájmidas acabaron destruyendo el Reino de Kinda en 540 tras la caída de su principal aliado Himyar . Los sasánidas persas disolvieron la dinastía lájmida en 602, quedando bajo reyes títeres, entonces bajo su control directo. [223] Los kinditas emigraron de Yemen junto con los gasánidas y los lájmidas, pero fueron rechazados en Bahréin por la tribu Abdul Qais Rabi'a . Regresaron al Yemen y se aliaron con los himyaritas, quienes los instalaron como un reino vasallo que gobernaba Arabia Central desde "Qaryah Dhat Kahl" (la actual Qaryat al-Faw). Gobernaron gran parte de la península arábiga del norte y centro del país, hasta que fueron destruidos por el rey lájmida Al-Mundhir y su hijo 'Amr .

Los gasánidas eran una tribu árabe del Levante a principios del siglo III. Según la tradición genealógica árabe, se los consideraba una rama de la tribu azd . Lucharon junto a los bizantinos contra los sasánidas y los lájmidas árabes. La mayoría de los gasánidas eran cristianos, se convirtieron al cristianismo en los primeros siglos y algunos se fusionaron con comunidades cristianas helenizadas. Después de la conquista musulmana del Levante, pocos gasánidas se convirtieron al cristianismo y la mayoría siguió siendo cristiana y se unió a las comunidades melquitas y siríacas en lo que ahora es Jordania, Palestina, Siria y Líbano. [224] Los salihids eran foederati árabes en el siglo V, eran cristianos fervientes y su período está menos documentado que los períodos anteriores y posteriores debido a la escasez de fuentes. La mayoría de las referencias a los salihids en fuentes árabes derivan del trabajo de Hisham ibn al-Kalbi , y el Tarikh de Ya'qubi se considera valioso para determinar la caída de los salihids y los términos de su enfrentamiento con los bizantinos. [225]

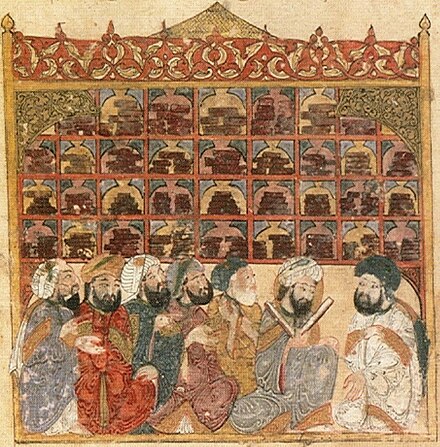

Durante la Edad Media , la civilización árabe floreció y los árabes hicieron contribuciones significativas a los campos de la ciencia , las matemáticas , la medicina , la filosofía y la literatura , con el surgimiento de grandes ciudades como Bagdad , El Cairo y Córdoba , se convirtieron en centros de aprendizaje, atrayendo a eruditos, científicos e intelectuales. [226] [227] Los árabes forjaron muchos imperios y dinastías, en particular, el Imperio Rashidun, el Imperio Omeya, el Imperio Abasí, el Imperio Fatimí, entre otros. Estos imperios se caracterizaron por su expansión, logros científicos y florecimiento cultural, extendiéndose desde España hasta la India . [226] La región fue vibrante y dinámica durante la Edad Media y dejó un impacto duradero en el mundo. [227]

El ascenso del Islam comenzó cuando Mahoma y sus seguidores emigraron de La Meca a Medina en un evento conocido como la Hégira . Mahoma pasó los últimos diez años de su vida involucrado en una serie de batallas para establecer y expandir la comunidad musulmana. De 622 a 632, dirigió a los musulmanes en un estado de guerra contra los mecanos. [228] Durante este período, los árabes conquistaron la región de Basora , y bajo el liderazgo de Umar , establecieron una base y construyeron una mezquita allí. Otra conquista fue Madián , pero debido a su duro entorno, los colonos finalmente se mudaron a Kufa . Umar derrotó con éxito las rebeliones de varias tribus árabes, trayendo estabilidad a toda la península arábiga y unificándola. Bajo el liderazgo de Uthman , el imperio árabe se expandió a través de la conquista de Persia , con la captura de Fars en 650 y partes de Khorasan en 651. [229] La conquista de Armenia también comenzó en la década de 640. Durante este tiempo, el Imperio Rashidun extendió su dominio sobre todo el Imperio sasánida y más de dos tercios del Imperio romano de Oriente . Sin embargo, el reinado de Ali ibn Abi Talib , el cuarto califa, se vio empañado por la Primera Fitna , o Primera Guerra Civil Islámica, que duró todo su gobierno. Después de un tratado de paz con Hassan ibn Ali y la supresión de los primeros disturbios jariyitas , Muawiyah I se convirtió en el califa. [230] Esto marcó una transición significativa en el liderazgo. [229] [231]

Tras la muerte de Mahoma en el año 632, los ejércitos de Rashidun lanzaron campañas de conquista, estableciendo el Califato , o Imperio Islámico, uno de los mayores imperios de la historia . Fue más grande y duró más que el anterior imperio árabe Tanukhids de la reina Mawia o el Imperio árabe de Palmira . El estado de Rashidun era un estado completamente nuevo y a diferencia de los reinos árabes de su siglo como los himyaritas , los lájmíes o los gasánidas .

Durante la era Rashidun, la comunidad árabe se expandió rápidamente, conquistando muchos territorios y estableciendo un vasto imperio árabe, que está marcado por el reinado de los primeros cuatro califas, o líderes, de la comunidad árabe. [232] Estos califas son Abu Bakr , Umar , Uthman y Ali , quienes son conocidos colectivamente como los Rashidun, que significa "correctamente guiados". La era Rashidun es significativa en la historia árabe e islámica, ya que marca el comienzo del imperio árabe y la expansión del Islam más allá de la Península Arábiga. Durante este tiempo, la comunidad árabe enfrentó numerosos desafíos, incluidas divisiones internas y amenazas externas de los imperios vecinos. [232] [233]

Bajo el liderazgo de Abu Bakr, la comunidad árabe sofocó con éxito una rebelión de algunas tribus que se negaban a pagar el Zakat , o caridad islámica. Durante el reinado de Umar ibn al-Khattab, el imperio árabe se expandió significativamente, conquistando territorios como Egipto, Siria e Irak . El reinado de Uthman ibn Affan estuvo marcado por la disidencia interna y la rebelión, que finalmente condujo a su asesinato. Ali, el primo y yerno de Muhammad , sucedió a Uthman como califa, pero enfrentó la oposición de algunos miembros de la comunidad islámica que creían que no había sido nombrado legítimamente. [232] A pesar de estos desafíos, la era Rashidun es recordada como una época de gran progreso y logros en la historia árabe e islámica, los califas establecieron un sistema de gobierno que enfatizaba la justicia y la igualdad para todos los miembros de la comunidad islámica. También supervisaron la compilación del Corán en un solo texto y difundieron las enseñanzas y principios árabes en todo el imperio. En general, la era Rashidun desempeñó un papel crucial en la configuración de la historia árabe y continúa siendo venerada por los musulmanes de todo el mundo como un período de liderazgo y orientación ejemplares. [234]

En 661, el califato de Rashidun cayó en manos de la dinastía omeya y Damasco se estableció como la capital del imperio. Los omeyas estaban orgullosos de su identidad árabe y patrocinaron la poesía y la cultura de la Arabia preislámica. Establecieron ciudades de guarnición en Ramla , Raqqa , Basora , Kufa , Mosul y Samarra , todas las cuales se convirtieron en ciudades importantes. [235] El califa Abd al-Malik estableció el árabe como idioma oficial del califato en 686. [236] El califa Umar II se esforzó por resolver el conflicto cuando llegó al poder en 717. Rectificó la disparidad, exigiendo que todos los musulmanes fueran tratados como iguales, pero sus reformas previstas no surtieron efecto, ya que murió después de solo tres años de gobierno. Para entonces, el descontento con los omeyas se había extendido por la región y se produjo un levantamiento en el que los abasíes llegaron al poder y trasladaron la capital a Bagdad .

Los omeyas expandieron su imperio hacia el oeste y arrebataron el norte de África a los bizantinos. Antes de la conquista árabe, el norte de África había sido conquistado o colonizado por varios pueblos, entre ellos los púnicos , los vándalos y los romanos. Después de la revolución abasí , los omeyas perdieron la mayor parte de sus territorios, con excepción de Iberia.

Su última posesión se conoció como el Emirato de Córdoba . No fue hasta el gobierno del nieto del fundador de este nuevo emirato que el estado entró en una nueva fase como el Califato de Córdoba . Este nuevo estado se caracterizó por una expansión del comercio, la cultura y el conocimiento, y fue testigo de la construcción de obras maestras de la arquitectura de al-Ándalus y de la biblioteca de Al-Ḥakam II , que albergaba más de 400.000 volúmenes. Con el colapso del estado omeya en 1031 d. C., Al-Ándalus se dividió en pequeños reinos . [237]

Los abasíes eran descendientes de Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib , uno de los tíos más jóvenes de Mahoma y del mismo clan Banu Hashim . Los abasíes lideraron una revuelta contra los omeyas y los derrotaron en la batalla de Zab, poniendo fin de manera efectiva a su dominio en todas las partes del Imperio con la excepción de al-Andalus. En 762, el segundo califa abasí al-Mansur fundó la ciudad de Bagdad y la declaró capital del califato. A diferencia de los omeyas, los abasíes tenían el apoyo de súbditos no árabes. [235] La Edad de Oro islámica fue inaugurada a mediados del siglo VIII por la ascensión del califato abasí y el traslado de la capital de Damasco a la recién fundada ciudad de Bagdad . Los abasíes estaban influenciados por los preceptos coránicos y hadices como "La tinta del erudito es más sagrada que la sangre de los mártires", que enfatizaban el valor del conocimiento.

Durante este período, el Imperio árabe se convirtió en un centro intelectual para la ciencia, la filosofía, la medicina y la educación, ya que los abasíes defendieron la causa del conocimiento y establecieron la " Casa de la Sabiduría " ( árabe : بيت الحكمة ) en Bagdad. Las dinastías rivales como los fatimíes de Egipto y los omeyas de al-Ándalus también fueron importantes centros intelectuales con ciudades como El Cairo y Córdoba rivalizando con Bagdad . [238] Los abasíes gobernaron durante 200 años antes de perder su control central cuando las wilayas comenzaron a fracturarse en el siglo X; después, en la década de 1190, hubo un resurgimiento de su poder, que fue terminado por los mongoles , que conquistaron Bagdad en 1258 y mataron al califa Al-Musta'sim . Los miembros de la familia real abasí escaparon de la masacre y recurrieron a El Cairo, que se había separado del gobierno abasí dos años antes; Los generales mamelucos tomaron el lado político del reino mientras los califas abasíes se dedicaban a actividades civiles y continuaban patrocinando la ciencia, las artes y la literatura.

El califato fatimí fue fundado por al-Mahdi Billah , descendiente de Fátima , hija de Mahoma, y fue un imperio chiita que existió desde el año 909 hasta el 1171 d. C. El imperio tenía su base en el norte de África, con su capital en El Cairo , y en su apogeo controlaba un vasto territorio que incluía partes de lo que hoy es Egipto , Libia , Túnez , Argelia , Marruecos , Siria y Palestina . El estado fatimí tomó forma entre los kutama , en el oeste del litoral norteafricano, en Argelia, conquistando en 909 Raqqada , la capital aglabí . En 921 los fatimíes establecieron la ciudad tunecina de Mahdia como su nueva capital. En 948 trasladaron su capital a Al-Mansuriya , cerca de Kairuán en Túnez, y en 969 conquistaron Egipto y establecieron El Cairo como la capital de su califato.

Los fatimíes eran conocidos por su tolerancia religiosa y logros intelectuales, establecieron una red de universidades y bibliotecas que se convirtieron en centros de aprendizaje en el mundo islámico . También promovieron las artes, la arquitectura y la literatura, que florecieron bajo su patrocinio. Uno de los logros más notables de los fatimíes fue la construcción de la mezquita Al-Azhar y la Universidad Al-Azhar en El Cairo. Fundada en 970 d.C., es una de las universidades más antiguas del mundo y sigue siendo un importante centro de aprendizaje islámico hasta el día de hoy. Los fatimíes también tuvieron un impacto significativo en el desarrollo de la teología y la jurisprudencia islámicas . Eran conocidos por su apoyo al Islam chií y su promoción de la rama ismailí del Islam chií. A pesar de sus muchos logros, los fatimíes enfrentaron numerosos desafíos durante su reinado. Estaban constantemente en guerra con los imperios vecinos, incluido el califato abasí y el Imperio bizantino . También enfrentaron conflictos internos y rebeliones, que debilitaron su imperio con el tiempo. En 1171, el califato fatimí fue conquistado por la dinastía ayubí , liderada por Saladino . Aunque la dinastía fatimí llegó a su fin, su legado continuó influyendo en la cultura y la sociedad árabe-islámica durante los siglos siguientes. [239]

Entre 1517 y 1918, los otomanos derrotaron al sultanato mameluco en El Cairo y acabaron con el califato abasí en las batallas de Marj Dabiq y Ridaniya . Entraron en el Levante y Egipto como conquistadores y derribaron el califato abasí después de que perdurara durante muchos siglos. En 1911, intelectuales y políticos árabes de todo el Levante formaron al-Fatat ("la Sociedad de Jóvenes Árabes "), un pequeño club nacionalista árabe, en París. Su objetivo declarado era "elevar el nivel de la nación árabe al nivel de las naciones modernas". En los primeros años de su existencia, al-Fatat pidió una mayor autonomía dentro de un estado otomano unificado en lugar de la independencia árabe del imperio. Al-Fatat fue sede del Congreso Árabe de 1913 en París, cuyo propósito era discutir las reformas deseadas con otros individuos disidentes del mundo árabe. [240] Sin embargo, cuando las autoridades otomanas tomaron medidas enérgicas contra las actividades y los miembros de la organización, al-Fatat pasó a la clandestinidad y exigió la completa independencia y unidad de las provincias árabes. [241]

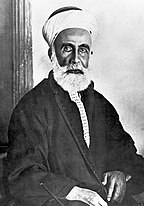

La Revuelta Árabe fue un levantamiento militar de las fuerzas árabes contra el Imperio Otomano durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, que comenzó en 1916, liderado por el jerife Hussein bin Ali , el objetivo de la revuelta era obtener la independencia de las tierras árabes bajo el dominio otomano y crear un estado árabe unificado. La revuelta fue provocada por una serie de factores, incluido el deseo árabe de una mayor autonomía dentro del Imperio Otomano, el resentimiento hacia las políticas otomanas y la influencia de los movimientos nacionalistas árabes. La Revuelta Árabe fue un factor significativo en la eventual derrota del Imperio Otomano . La revuelta ayudó a debilitar el poder militar otomano y atar a las fuerzas otomanas que podrían haber sido desplegadas en otros lugares. También ayudó a aumentar el apoyo a la independencia y el nacionalismo árabe, lo que tendría un impacto duradero en la región en los años venideros. [242] [243] La derrota del Imperio y la ocupación de parte de su territorio por las potencias aliadas después de la Primera Guerra Mundial , el Acuerdo Sykes-Picot tuvo un impacto significativo en el mundo árabe y su gente. El acuerdo dividió los territorios árabes del Imperio Otomano en zonas de control para Francia y Gran Bretaña, ignorando las aspiraciones del pueblo árabe a la independencia y la autodeterminación. [244]

La Edad de Oro de la Civilización Árabe, conocida como la « Edad de Oro Islámica », se remonta tradicionalmente al siglo VIII y al siglo XIII. [245] [246] [247] Se dice tradicionalmente que este período terminó con el colapso del califato abasí debido al asedio de Bagdad en 1258. [248] Durante este tiempo, los eruditos árabes hicieron contribuciones significativas en campos como las matemáticas, la astronomía, la medicina y la filosofía. Estos avances tuvieron un profundo impacto en los eruditos europeos durante el Renacimiento . [249]

Los árabes compartieron sus conocimientos e ideas con Europa , incluidas las traducciones de textos árabes. [250] Estas traducciones tuvieron un impacto significativo en la cultura de Europa , lo que llevó a la transformación de muchas disciplinas filosóficas en el mundo latino medieval . Además, los árabes hicieron innovaciones originales en varios campos, incluidas las artes, la agricultura , la alquimia , la música y la cerámica , y los nombres tradicionales de estrellas como Aldebarán , términos científicos como alquimia (de donde también química ), álgebra , algoritmo , etc. y nombres de productos básicos como azúcar , alcanfor , algodón , café , etc. [251] [252] [253] [254]

De los eruditos medievales del Renacimiento del siglo XII , que se habían centrado en estudiar obras griegas y árabes de ciencias naturales, filosofía y matemáticas, en lugar de dichos textos culturales. Los lógicos árabes, sobre todo Averroes , habían heredado las ideas griegas después de haber invadido y conquistado Egipto y el Levante . Sus traducciones y comentarios sobre estas ideas se abrieron camino a través del Occidente árabe hasta Iberia y Sicilia , que se convirtieron en centros importantes para esta transmisión de ideas. Desde el siglo XI al XIII, muchas escuelas dedicadas a la traducción de obras filosóficas y científicas del árabe clásico al latín medieval se establecieron en Iberia, sobre todo la Escuela de Traductores de Toledo . Este trabajo de traducción de la cultura árabe, aunque en gran parte no planificado y desorganizado, constituyó una de las mayores transmisiones de ideas de la historia. [255]

Durante el Renacimiento timúrida, que abarcó finales del siglo XIV, el siglo XV y principios del XVI, hubo un importante intercambio de ideas, arte y conocimiento entre diferentes culturas y civilizaciones. Los eruditos, artistas e intelectuales árabes desempeñaron un papel en este intercambio cultural, contribuyendo a la atmósfera intelectual general de la época. Participaron en varios campos, incluida la literatura, el arte, la ciencia y la filosofía. [256] A finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, surgió el Renacimiento árabe , también conocido como Nahda, un movimiento cultural e intelectual. El término "Nahda" significa "despertar" o "renacimiento" en árabe y se refiere a un período de renovado interés en la lengua, la literatura y la cultura árabes. [257] [258] [259]

El período moderno de la historia árabe se refiere al período de tiempo que va desde finales del siglo XIX hasta la actualidad. Durante este tiempo, el mundo árabe experimentó importantes cambios políticos , económicos y sociales. Uno de los eventos más significativos del período moderno fue el colapso del Imperio Otomano, el fin del dominio otomano condujo al surgimiento de nuevos estados-nación en el mundo árabe. [260] [261]

En caso de éxito de la revolución árabe y de victoria de los aliados en la Primera Guerra Mundial , Sharif Hussein debía poder establecer un Estado árabe independiente que abarcara la península Arábiga y la Media Luna Fértil, incluidos Irak y el Levante. Su objetivo era convertirse en el «rey de los árabes» en este Estado, pero la revolución árabe sólo logró algunos de sus objetivos, entre ellos la independencia del Hiyaz y el reconocimiento de Sharif Hussein como su rey por parte de los aliados. [262]

El nacionalismo árabe surgió como un movimiento importante a principios del siglo XX, con muchos intelectuales, artistas y líderes políticos árabes que buscaban promover la unidad y la independencia del mundo árabe. [264] Este movimiento ganó impulso después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , lo que llevó a la formación de la Liga Árabe y la creación de varios nuevos estados árabes. El panarabismo surgió a principios del siglo XX y tenía como objetivo unir a todos los árabes en una sola nación o estado. Enfatizó en una ascendencia, cultura, historia, idioma e identidad compartidas y buscó crear un sentido de identidad y solidaridad panárabes. [265] [266]

Las raíces del panarabismo se remontan al movimiento del Renacimiento árabe o Al-Nahda de finales del siglo XIX, que supuso un renacimiento de la cultura, la literatura y el pensamiento intelectual árabes. El movimiento hizo hincapié en la importancia de la unidad árabe y la necesidad de resistir el colonialismo y la dominación extranjera. Una de las figuras clave en el desarrollo del panarabismo fue el estadista e intelectual egipcio Gamal Abdel Nasser , que lideró la revolución de 1952 en Egipto y se convirtió en presidente del país en 1954. Nasser promovió el panarabismo como un medio para fortalecer la solidaridad árabe y resistir al imperialismo occidental. También apoyó la idea del socialismo árabe , que buscaba combinar el panarabismo con los principios socialistas. Otros líderes árabes , como Hafiz al-Assad , Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr , Faisal I de Irak , Muammar Gaddafi , Saddam Hussein , Gaafar Nimeiry y Anwar Sadat , realizaron intentos similares . [267]

Muchas uniones propuestas tenían como objetivo crear una entidad árabe unificada que promovería la cooperación y la integración entre los países árabes. Sin embargo, las iniciativas enfrentaron numerosos desafíos y obstáculos, incluidas divisiones políticas, conflictos regionales y disparidades económicas. [268] La República Árabe Unida (RAU) fue una unión política formada entre Egipto y Siria en 1958, con el objetivo de crear una estructura federal que permitiera a cada estado miembro conservar su identidad e instituciones. Sin embargo, en 1961, Siria se había retirado de la RAU debido a diferencias políticas, y Egipto continuó llamándose RAU hasta 1971, cuando se convirtió en la República Árabe de Egipto . En el mismo año en que se formó la RAU, se estableció otra unión política propuesta, la Federación Árabe , entre Jordania e Irak , pero colapsó después de solo seis meses debido a las tensiones con la RAU y la Revolución del 14 de julio . En 1958 también se creó una confederación llamada Estados Árabes Unidos , que incluía a la RAU y al Reino Mutawakkilite de Yemen , pero se disolvió en 1961. [269] Los intentos posteriores de crear una unión política y económica entre los países árabes incluyeron la Federación de Repúblicas Árabes , que fue formada por Egipto, Libia y Siria en la década de 1970, pero se disolvió después de cinco años debido a desafíos políticos y económicos. Muammar Gaddafi, el líder de Libia, también propuso la República Árabe Islámica con Túnez, con el objetivo de incluir a Argelia y Marruecos , [270] en cambio se formó la Unión del Magreb Árabe en 1989. [271]

Durante la segunda mitad del siglo XX, muchos países árabes experimentaron agitación política y conflictos, incluidas revoluciones. El conflicto árabe-israelí sigue siendo un problema importante en la región y ha dado lugar a tensiones constantes y brotes periódicos de violencia. En los últimos años, el mundo árabe se ha enfrentado a nuevos desafíos, incluidas las desigualdades económicas y sociales, los cambios demográficos y el impacto de la globalización . [272] La Primavera Árabe fue una serie de levantamientos y protestas a favor de la democracia que se extendieron por varios países del mundo árabe en 2010 y 2011. Los levantamientos fueron provocados por una combinación de quejas políticas, económicas y sociales y exigían reformas democráticas y el fin del régimen autoritario. Si bien las protestas resultaron en la caída de algunos líderes autoritarios de larga data, también llevaron a conflictos continuos e inestabilidad política en otros países. [273]

La identidad árabe se define independientemente de la identidad religiosa y es anterior a la expansión del Islam , con reinos cristianos árabes y tribus judías árabes atestiguadas históricamente . Hoy, sin embargo, la mayoría de los árabes son musulmanes, con una minoría que se adhiere a otras religiones, principalmente el cristianismo , pero también los drusos y los baháʼís . [274] [275] La descendencia paterna se ha considerado tradicionalmente la principal fuente de afiliación en el mundo árabe cuando se trata de la pertenencia a un grupo étnico o clan . [276]

La identidad árabe está determinada por una serie de factores, entre ellos la ascendencia, la historia, el idioma, las costumbres y las tradiciones. [277] La identidad árabe ha sido determinada por una rica historia que incluye el ascenso y la caída de imperios , la colonización y la agitación política. A pesar de los desafíos que enfrentan las comunidades árabes, su herencia cultural compartida ha ayudado a mantener un sentido de unidad y orgullo por su identidad. [278] Hoy en día, la identidad árabe continúa evolucionando a medida que las comunidades árabes navegan por paisajes políticos, sociales y económicos complejos. A pesar de esto, la identidad árabe sigue siendo un aspecto importante del tejido cultural e histórico del mundo árabe, y continúa siendo celebrada y preservada por comunidades de todo el mundo . [279]

Las tribus árabes prevalecen en la Península Arábiga, Mesopotamia, el Levante, Egipto, el Magreb, la región de Sudán y el Cuerno de África. [280] [278] [281]

Los árabes del Levante se dividen tradicionalmente en tribus Qays y Yaman . La distinción entre Qays y Yaman se remonta a la era preislámica y se basaba en afiliaciones tribales y ubicaciones geográficas; incluyen Banu Kalb , Kinda , Ghassanids y Lakhmids . [282] Los Qays estaban formados por tribus como Banu Kilab , Banu Tayy , Banu Hanifa y Banu Tamim , entre otros. Los Yaman, por otro lado, estaban compuestos por tribus como Banu Hashim , Banu Makhzum , Banu Umayya y Banu Zuhra , entre otros.

También hay muchas tribus árabes indígenas de Mesopotamia (Irak) e Irán, incluso desde mucho antes de la conquista árabe de Persia en 633 d. C. [283] El grupo más grande de árabes iraníes son los árabes ahwazi , incluidos Banu Ka'b , Bani Turuf y la secta Musha'sha'iyyah . Grupos más pequeños son los nómadas Khamseh en la provincia de Fars y los árabes en Khorasan . Como resultado de la migración árabe de siglos de duración al Magreb , varias tribus árabes (incluidos Banu Hilal , Banu Sulaym y Maqil ) también se establecieron en el Magreb y formaron las subtribus que existen hasta la actualidad. Los Banu Hilal pasaron casi un siglo en Egipto antes de mudarse a Libia , Túnez y Argelia , y otro siglo después se mudaron a Marruecos . [284]

Según las tradiciones árabes, las tribus se dividen en diferentes divisiones llamadas cráneos árabes, que se describen en la costumbre tradicional de fuerza, abundancia, victoria y honor. Varias de ellas se ramificaron, y luego se convirtieron en tribus independientes (subtribus). La mayoría de las tribus árabes descienden de estas tribus principales. [285] [286] [287] [288] [289]

Son: [287]

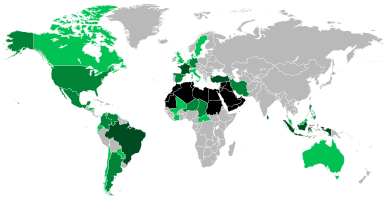

El CIA Factbook (2014) estima que el número total de árabes que viven en los países árabes es de 366 millones . El número estimado de árabes en países fuera de la Liga Árabe se estima en 17,5 millones, lo que arroja un total cercano a los 384 millones. El mundo árabe se extiende alrededor de 13.000.000 kilómetros cuadrados (5.000.000 millas cuadradas), desde el océano Atlántico en el oeste hasta el mar Arábigo en el este y desde el mar Mediterráneo en el norte hasta el Cuerno de África y el océano Índico en el sureste.

La diáspora árabe se refiere a los descendientes de los inmigrantes árabes que, voluntariamente o como refugiados, emigraron de sus tierras nativas en países no árabes, principalmente en África Oriental , América del Sur , Europa , América del Norte , Australia y partes del sur de Asia , el sudeste de Asia , el Caribe y África Occidental . Según la Organización Internacional para las Migraciones , hay 13 millones de migrantes árabes de primera generación en el mundo, de los cuales 5,8 millones residen en países árabes. Los expatriados árabes contribuyen a la circulación de capital financiero y humano en la región y, por lo tanto, promueven significativamente el desarrollo regional. En 2009, los países árabes recibieron un total de 35.100 millones de dólares estadounidenses en remesas y las remesas enviadas a Jordania , Egipto y Líbano desde otros países árabes son entre un 40 y un 190 por ciento superiores a los ingresos comerciales entre estos y otros países árabes. [299] La comunidad libanesa de 250.000 personas en África Occidental es el grupo no africano más grande de la región. [300] [301] Los comerciantes árabes han operado durante mucho tiempo en el sudeste asiático y a lo largo de la costa swahili de África oriental . Zanzíbar alguna vez estuvo gobernada por árabes omaníes . [302] La mayoría de los indonesios , malayos y singapurenses prominentes de ascendencia árabe son personas hadhrami con orígenes en el sur de Arabia en la región costera de Hadramawt . [303]

Hay millones de árabes viviendo en Europa , principalmente concentrados en Francia (alrededor de 6.000.000 en 2005 [304] ). La mayoría de los árabes en Francia son del Magreb , pero algunos también provienen de las áreas del Mashreq del mundo árabe. Los árabes en Francia forman el segundo grupo étnico más grande después de los franceses . [305] En Italia , los árabes llegaron por primera vez a la isla meridional de Sicilia en el siglo IX. Las sociedades modernas más grandes de la isla provenientes del mundo árabe son los tunecinos y los marroquíes, que representan el 10,9% y el 8% respectivamente de la población extranjera de Sicilia, que en sí misma constituye el 3,9% de la población total de la isla. [306] La población árabe moderna de España asciende a 1.800.000, [307] [308] [309] [310] y ha habido árabes en España desde principios del siglo VIII, cuando la conquista musulmana de Hispania creó el estado de Al-Andalus. [311] [312] [313] Árabes En Alemania, la población árabe asciende a más de 1.401.950. [314] [315] en el Reino Unido entre 366.769 [316] y 500.000, [317] y en Grecia entre 250.000 y 750.000 [318] ). Además, Grecia es el hogar de personas de países árabes que tienen el estatus de refugiados (por ejemplo, refugiados de la guerra civil siria ). [319] En los Países Bajos 180.000, [38] y en Dinamarca 121.000. Otros países también albergan poblaciones árabes, entre ellos Noruega , Austria , Bulgaria , Suiza , Macedonia del Norte , Rumania y Serbia . [320] A finales de 2015, Turquía tenía una población total de 78,7 millones, y los refugiados sirios representaban el 3,1% de esa cifra según estimaciones conservadoras. Los datos demográficos indicaron que anteriormente el país tenía entre 1.500.000 [321] y 2.000.000 de residentes árabes, [12] la población árabe de Turquía representa ahora entre el 4,5 y el 5,1% de la población total, o aproximadamente entre 4 y 5 millones de personas. [12] [322]

La inmigración árabe a los Estados Unidos comenzó en grandes cantidades durante la década de 1880, y hoy en día, se estima que 3,7 millones de estadounidenses tienen algún origen árabe. [14] [323] [324] Los árabes estadounidenses se encuentran en todos los estados, pero más de dos tercios de ellos viven en solo diez estados, y un tercio vive en Los Ángeles , Detroit y la ciudad de Nueva York específicamente. [14] [325] La mayoría de los árabes estadounidenses nacieron en los EE. UU., y casi el 82% de los árabes que residen en los EE. UU. son ciudadanos. [326] [327] [328] [329]

Los inmigrantes árabes comenzaron a llegar a Canadá en pequeñas cantidades en 1882. Su inmigración fue relativamente limitada hasta 1945, momento a partir del cual aumentó progresivamente, particularmente en la década de 1960 y en adelante. [330] Según el sitio web "Who are Arab Canadians ", Montreal , la ciudad canadiense con la mayor población árabe, tiene aproximadamente 267.000 habitantes árabes. [331]

América Latina tiene la mayor población árabe fuera del mundo árabe . [332] América Latina alberga entre 17 y 25 a 30 millones de personas de ascendencia árabe, lo que es más que cualquier otra región de diáspora en el mundo. [333] [334] Los gobiernos brasileño y libanés afirman que hay 7 millones de brasileños de ascendencia libanesa . [335] [336] Además, el gobierno brasileño afirma que hay 4 millones de brasileños de ascendencia siria . [335] [7] [337] [338] [339] [340] Otras grandes comunidades árabes incluyen Argentina (alrededor de 3.500.000 [15] [341] [342] )

El matrimonio interétnico en la comunidad árabe, independientemente de la afiliación religiosa, es muy alto; la mayoría de los miembros de la comunidad tienen solo un padre que tiene etnia árabe. [343] Colombia (más de 3.200.000 [344] [345] [346] ), Venezuela (más de 1.600.000), [25] [347] México (más de 1.100.000), [348] Chile (más de 800.000), [349] [350] [351] y América Central , particularmente El Salvador y Honduras (entre 150.000 y 200.000). [352] [31] [32] Los haitianos árabes (257.000 [353] ), un gran número de los cuales viven en la capital , se concentran, la mayoría de las veces, en áreas financieras donde la mayoría de ellos establecen negocios. [354]

En 1728, un oficial ruso describió a un grupo de nómadas árabes que poblaban las costas del Caspio de Mughan (en la actual Azerbaiyán ) y hablaban una lengua mixta turco-árabe. [355] Se cree que estos grupos emigraron al Cáucaso Sur en el siglo XVI. [356] La edición de 1888 de la Encyclopædia Britannica también mencionó un cierto número de árabes que poblaban la Gobernación de Bakú del Imperio ruso . [357] Conservaron un dialecto árabe al menos hasta mediados del siglo XIX, [358] hay casi 30 asentamientos que aún mantienen el nombre árabe (por ejemplo, Arabgadim , Arabojaghy , Arab-Yengija , etc.). Desde la época de la conquista árabe del Cáucaso Sur , se produjo en Daguestán una continua migración árabe a pequeña escala desde varias partes del mundo árabe . La mayoría de ellos vivían en el pueblo de Darvag, al noroeste de Derbent . El último de estos relatos data de la década de 1930. [356] La mayoría de las comunidades árabes en el sur de Daguestán sufrieron una turquización lingüística , por lo que hoy en día Darvag es un pueblo de mayoría azerí . [359] [360]

Según la Historia de Ibn Jaldún , los árabes que alguna vez estuvieron en Asia Central fueron asesinados o huyeron de la invasión tártara de la región, dejando solo a los locales. [361] Sin embargo, hoy en día muchas personas en Asia Central se identifican como árabes. La mayoría de los árabes de Asia Central están completamente integrados en las poblaciones locales y, a veces, se llaman a sí mismos como los locales (por ejemplo, tayikos , uzbekos ), pero usan títulos especiales para mostrar su origen árabe, como Sayyid , Khoja o Siddiqui . [362]

Solo hay dos comunidades en la India que afirman tener ascendencia árabe: los chaush de la región del Decán y los chavuse de Gujarat . [364] [365] Estos grupos descienden en gran medida de inmigrantes hadhrami que se asentaron en estas dos regiones en el siglo XVIII. Sin embargo, ninguna de las dos comunidades habla todavía árabe, aunque los chaush han visto una reinmigración al este de Arabia y, por lo tanto, una readopción del árabe. [366] En el sur de Asia , donde la ascendencia árabe se considera prestigiosa, algunas comunidades tienen mitos de origen que afirman tener ascendencia árabe. Varias comunidades que siguen la madhab shafi'i (en contraste con otros musulmanes del sur de Asia que siguen la madhab hanafi ) afirman descender de comerciantes árabes como los musulmanes konkani de la región de Konkan , los mappilla de Kerala y los labbai y marakkar de Tamil Nadu y unos pocos grupos cristianos en la India que afirman y tienen raíces árabes están situados en el estado de Kerala . [367] Los biradri iraquíes del sur de Asia pueden tener registros de sus antepasados que emigraron de Irak en documentos históricos. Los moros de Sri Lanka son el tercer grupo étnico más grande de Sri Lanka , constituyendo el 9,23% de la población total del país. [368] Algunas fuentes rastrean la ascendencia de los moros de Sri Lanka a los comerciantes árabes que se establecieron en Sri Lanka en algún momento entre los siglos VIII y XV. [369] [370] [371] Hay alrededor de 118.866 árabes indonesios [372] de ascendencia hadrami en el censo indonesio de 2010. [373]

Los afroárabes son individuos y grupos de África que son de ascendencia árabe parcial. La mayoría de los afroárabes habitan la costa swahili en la región de los Grandes Lagos africanos , aunque algunos también pueden encontrarse en partes del mundo árabe. [374] [375] Un gran número de árabes emigraron a África occidental , particularmente Costa de Marfil (hogar de más de 100.000 libaneses), [376] Senegal (aproximadamente 30.000 libaneses), [377] Sierra Leona (aproximadamente 10.000 libaneses en la actualidad; alrededor de 30.000 antes del estallido de la guerra civil en 1991), Liberia y Nigeria . [378] Desde el final de la guerra civil en 2002, los comerciantes libaneses se han restablecido en Sierra Leona. [379] [380] [381] Los árabes del Chad ocupan el norte de Camerún y Nigeria (donde a veces se les conoce como shuwa), y se extienden como un cinturón a través de Chad y hasta Sudán, donde se les llama la agrupación baggara de grupos étnicos árabes que habitan la parte del Sahel de África . Hay 171.000 en Camerún , 150.000 en Níger [382] ) y 107.000 en la República Centroafricana . [383]

Los árabes son en su mayoría musulmanes con una mayoría sunita y una minoría chiita , con la excepción de los ibadíes , que predominan en Omán . [384] Los cristianos árabes generalmente siguen iglesias orientales como las iglesias ortodoxa griega y católica griega , aunque también existe una minoría de seguidores de la iglesia protestante . [385] También hay comunidades árabes formadas por drusos y baháʼís . [386] [387] Históricamente, también hubo poblaciones considerables de judíos árabes en todo el mundo árabe.

Antes de la llegada del Islam , la mayoría de los árabes seguían una religión pagana con una serie de deidades, entre ellas Hubal , [388] Wadd , Allāt , [389] Manat y Uzza . Unos pocos individuos, los hanifs , aparentemente habían rechazado el politeísmo en favor del monoteísmo no afiliado a ninguna religión en particular. Algunas tribus se habían convertido al cristianismo o al judaísmo. Los reinos cristianos árabes más destacados fueron los reinos gasánida y lájmida . [390] Cuando el rey himyarita se convirtió al judaísmo a finales del siglo IV, [391] las élites del otro reino árabe destacado, los kinditas , al ser vasallos himyritas, aparentemente también se convirtieron (al menos en parte). Con la expansión del Islam, los árabes politeístas se islamizaron rápidamente y las tradiciones politeístas desaparecieron gradualmente. [392] [393]

En la actualidad, el Islam sunita predomina en la mayoría de las zonas, sobre todo en el Levante, el norte de África, el oeste de África y el Cuerno de África. El Islam chiita predomina en Bahréin y el sur de Irak , mientras que el norte de Irak es mayoritariamente sunita. Existen importantes poblaciones chiitas en Líbano , Yemen , Kuwait , Arabia Saudita , [394] el norte de Siria y la región de Al-Batinah en Omán . También hay un pequeño número de musulmanes ibadíes y no confesionales . [384] La comunidad drusa se concentra en el Levante. [395]

El cristianismo tuvo una presencia destacada en la Arabia preislámica entre varias comunidades árabes, incluido el pueblo bahraní de Arabia Oriental , la comunidad cristiana de Najran , en partes de Yemen y entre ciertas tribus del norte de Arabia como los gasánidas , los lájmíes , los taghlib , los banu amela , los banu judham , los tanújidas y los tayy . En los primeros siglos cristianos, Arabia era conocida a veces como Arabia hereje , debido a que era "bien conocida como un caldo de cultivo para las interpretaciones heterodoxas del cristianismo". [396] Los cristianos representan el 5,5% de la población de Asia occidental y el norte de África. [397] En el Líbano, los cristianos representan aproximadamente el 40,5% de la población. [398] En Siria, los cristianos representan el 10% de la población. [399] Los cristianos en Palestina representan el 8% y el 0,7% de las poblaciones, respectivamente. [400] [401] En Egipto, los cristianos representan aproximadamente el 10% de la población. En Irak, los cristianos constituyen el 0,1% de la población. [402]

En Israel, los cristianos árabes constituyen el 2,1% (aproximadamente el 9% de la población árabe). [403] Los cristianos árabes constituyen el 8% de la población de Jordania . [404] La mayoría de los árabes de América del Norte y del Sur son cristianos, [405] al igual que aproximadamente la mitad de los árabes en Australia, que provienen particularmente del Líbano, Siria y Palestina. Un miembro bien conocido de esta comunidad religiosa y étnica es San Abo , mártir y santo patrón de Tbilisi , Georgia . [406] Los cristianos árabes también viven en ciudades cristianas santas como Nazaret , Belén y el Barrio Cristiano de la Ciudad Vieja de Jerusalén y muchos otros pueblos con lugares cristianos sagrados.

La cultura árabe está marcada por una larga y rica historia que abarca miles de años, desde el océano Atlántico en el oeste hasta el mar Arábigo en el este, y desde el mar Mediterráneo en el norte hasta el Cuerno de África y el océano Índico en el sureste. Las diversas religiones que los árabes han adoptado a lo largo de su historia y los diversos imperios y reinos que han gobernado y liderado la civilización árabe han contribuido a la etnogénesis y la formación de la cultura árabe moderna. La lengua , la literatura , la gastronomía , el arte , la arquitectura , la música , la espiritualidad , la filosofía y el misticismo son parte del patrimonio cultural de los árabes. [407]

El árabe es una lengua semítica de la familia afroasiática . [408] La primera evidencia de la aparición de la lengua aparece en los registros militares del año 853 a. C. Hoy en día se ha desarrollado ampliamente como lengua franca para más de 500 millones de personas. También es una lengua litúrgica para 1.700 millones de musulmanes . [409] [410] El árabe es uno de los seis idiomas oficiales de las Naciones Unidas , [411] y es venerado en el Islam como el idioma del Corán . [409] [412]

El árabe tiene dos registros principales. El árabe clásico es la forma de la lengua árabe utilizada en los textos literarios de las épocas omeya y abasí (siglos VII al IX). Se basa en los dialectos medievales de las tribus árabes . El árabe estándar moderno (MSA) es el descendiente directo utilizado hoy en día en todo el mundo árabe por escrito y en el habla formal, por ejemplo, discursos preparados, algunas emisiones de radio y contenido no relacionado con el entretenimiento, [413] mientras que el léxico y el estilo del árabe estándar moderno son diferentes del árabe clásico . También hay varios dialectos regionales del árabe hablado coloquial que varían mucho entre sí y de las formas formales escritas y habladas del árabe. [414]

La mitología árabe comprende las antiguas creencias de los árabes. Antes del Islam, la Kaaba de La Meca estaba cubierta de símbolos que representaban a una miríada de demonios, genios, semidioses o simplemente dioses tribales y otras deidades diversas que representaban la cultura politeísta de la época preislámica. Se ha inferido de esta pluralidad un contexto excepcionalmente amplio en el que la mitología podía florecer. [415] [416]

Las bestias y demonios más populares de la mitología árabe son Bahamut , Dandan , Falak , Ghoul , Hinn , Jinn , Karkadann , Marid , Nasnas , Qareen , Roc , Shadhavar , Werehyena y otras criaturas variadas que representaban el ambiente profundamente politeísta del preislámico. [417]

El símbolo más destacado de la mitología árabe es el genio o genio. [418] Los genios son seres sobrenaturales que pueden ser buenos o malos. [419] [420] No son puramente espirituales, sino que también son de naturaleza física, pudiendo interactuar de manera táctil con personas y objetos y, del mismo modo, ser objeto de acciones. Los genios , los humanos y los ángeles constituyen las creaciones inteligentes conocidas de Dios . [421]

Los necrófagos también aparecen en la mitología como monstruos o espíritus malignos asociados con los cementerios y que consumen carne humana. [422] [423] En el folclore árabe, los necrófagos pertenecían a una clase diabólica de genios y se decía que eran descendientes de Iblīs, el príncipe de las tinieblas en el Islam. Eran capaces de cambiar de forma constantemente, pero siempre conservaban las pezuñas de burro . [424]

El Corán , el principal libro sagrado del Islam , tuvo una influencia significativa en la lengua árabe y marcó el comienzo de la literatura árabe. Los musulmanes creen que fue transcrito en el dialecto árabe de los Quraysh , la tribu de Mahoma . [425] [426] A medida que el Islam se expandía, el Corán tuvo el efecto de unificar y estandarizar el árabe. [425]

El Corán no sólo es la primera obra de extensión significativa escrita en el idioma, sino que también tiene una estructura mucho más complicada que las obras literarias anteriores, con sus 114 suwar (capítulos) que contienen 6.236 ayat (versos). Contiene preceptos , narraciones , homilías , parábolas , mensajes directos de Dios, instrucciones e incluso comentarios sobre cómo debe recibirse y entenderse el Corán. También es admirado por sus capas de metáforas, así como por su claridad, una característica que se menciona en An-Nahl , la decimosexta sura.

Al-Jahiz (nacido en 776, en Basora - diciembre de 868/enero de 869) fue un prosista árabe y autor de obras literarias, teología mutazilí y polémicas político-religiosas. Fue un erudito destacado del califato abasí, y su canon incluye doscientos libros sobre diversos temas, entre ellos gramática árabe , zoología , poesía, lexicografía y retórica . De sus escritos, solo sobreviven treinta libros. Al-Jāḥiẓ fue también uno de los primeros escritores árabes en sugerir una revisión completa del sistema gramatical de la lengua, aunque esto no se llevaría a cabo hasta que su colega lingüista Ibn Maḍāʾ se ocupó del asunto doscientos años después. [427]

Hay un pequeño remanente de poesía preislámica , pero la literatura árabe surge predominantemente en la Edad Media , durante la Edad de Oro del Islam . [428] Imru' al-Qais fue un rey y poeta en el siglo VI, fue el último rey de Kindite . Es uno de los mejores poetas árabes hasta la fecha, y a veces se lo considera el padre de la poesía árabe . [429] Kitab al-Aghani de Abul-Faraj fue llamado por el historiador del siglo XIV Ibn Khaldun el registro de los árabes. [430] El árabe literario se deriva del árabe clásico , basado en el lenguaje del Corán tal como fue analizado por los gramáticos árabes a partir del siglo VIII. [431]

Una gran parte de la literatura árabe anterior al siglo XX se presenta en forma de poesía , e incluso la prosa de este período está llena de fragmentos de poesía o se presenta en forma de saj o prosa rimada. [432] El ghazal o poema de amor tenía una larga historia, siendo a veces tierno y casto y otras veces bastante explícito. [433] En la tradición sufí, el poema de amor adquiriría una importancia más amplia, mística y religiosa .