Los palestinos ( árabe : الفلسطينيون , romanizado : al-Filasṭīniyyūn ) son un grupo etnonacional árabe nativo de la región de Palestina . [34] [35] [36] [37]

En 1919, los musulmanes palestinos y los cristianos palestinos constituían el 90 por ciento de la población de Palestina, justo antes de la tercera ola de inmigración judía y el establecimiento de la Palestina del Mandato Británico después de la Primera Guerra Mundial . [38] [39] La oposición a la inmigración judía estimuló la consolidación de una identidad nacional unificada , aunque la sociedad palestina todavía estaba fragmentada por diferencias regionales, de clase, religiosas y familiares. [40] [41] La historia de la identidad nacional palestina es un tema controvertido entre los académicos. [42] [43] Para algunos, el término " palestino " se utiliza para referirse al concepto nacionalista de un pueblo palestino por parte de los árabes palestinos desde finales del siglo XIX y en el período anterior a la Primera Guerra Mundial, mientras que otros afirman que la identidad palestina abarca la herencia de todas las épocas desde los tiempos bíblicos hasta el período otomano . [37] [44] [45] Después de la Declaración de Independencia de Israel , la expulsión palestina de 1948 y más aún después del éxodo palestino de 1967 , el término "palestino" evolucionó hacia un sentido de futuro compartido en forma de aspiraciones a un Estado palestino . [37]

Fundada en 1964, la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina es una organización paraguas para los grupos que representan al pueblo palestino ante los estados internacionales. [46] La Autoridad Nacional Palestina , establecida oficialmente en 1994 como resultado de los Acuerdos de Oslo , es un organismo administrativo provisional nominalmente responsable de la gobernanza en los centros de población palestinos en Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza. [47] Desde 1978, las Naciones Unidas han observado un Día Internacional de Solidaridad con el Pueblo Palestino cada año . Según el historiador británico Perry Anderson , se estima que la mitad de la población de los territorios palestinos son refugiados, y que colectivamente han sufrido aproximadamente 300 mil millones de dólares estadounidenses en pérdidas de propiedad debido a las confiscaciones israelíes, a precios de 2008-2009. [48]

A pesar de varias guerras y éxodos , aproximadamente la mitad de la población palestina del mundo continúa residiendo en el territorio de la antigua Palestina Mandataria , que ahora abarca Israel y los territorios palestinos ocupados de Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza . [49] En Israel propiamente dicho, los palestinos constituyen casi el 21 por ciento de la población como parte de sus ciudadanos árabes . [50] Muchos son refugiados palestinos o palestinos desplazados internamente , incluidos más de 1,4 millones en la Franja de Gaza, [2] más de 870.000 en Cisjordania, [51] y alrededor de 250.000 en Israel propiamente dicho. De la población palestina que vive en el extranjero, conocida como diáspora palestina , más de la mitad son apátridas , carecen de ciudadanía legal en cualquier país. [52] 2,3 millones de la población de la diáspora están registrados como refugiados en la vecina Jordania , la mayoría de los cuales tienen ciudadanía jordana; [6] [53] más de un millón viven entre Siria y Líbano , y alrededor de 750.000 viven en Arabia Saudita , y Chile alberga la mayor concentración de diáspora palestina (alrededor de medio millón) fuera del mundo árabe .

El topónimo griego Palaistínē (Παλαιστίνη), que es el origen del árabe Filasṭīn (فلسطين), aparece por primera vez en la obra del historiador griego del siglo V a. C. Heródoto , donde denota de manera general [54] la tierra costera desde Fenicia hasta Egipto . [55] [56] Heródoto también emplea el término como etnónimo , como cuando habla de los "sirios de Palestina" o "sirios palestinos", [57] un grupo étnicamente amorfo que distingue de los fenicios. [58] [59] Heródoto no hace distinción entre los habitantes de Palestina. [60]

La palabra griega refleja una antigua palabra del Mediterráneo oriental y Oriente Próximo que se usaba como topónimo o etnónimo . En el antiguo Egipto, se ha conjeturado que Peleset/Purusati [61] se refiere a los " Pueblos del Mar ", en particular a los filisteos . [62] [63] Entre las lenguas semíticas , el acadio Palaštu (variante Pilištu ) se usa para referirse a la Filistea del siglo VII y sus, por entonces, cuatro ciudades-estado. [64] La palabra cognada del hebreo bíblico Plištim , suele traducirse como filisteos . [61]

Cuando los romanos conquistaron la región en el siglo I a. C., utilizaron el nombre de Judea para la provincia que cubría la mayor parte de la región. Al mismo tiempo, el nombre de Siria Palestina continuó siendo utilizado por historiadores y geógrafos para referirse al área entre el mar Mediterráneo y el río Jordán , como en los escritos de Filón , Josefo y Plinio el Viejo . A principios del siglo II d. C., Siria Palestina se convirtió en el nombre administrativo oficial en una medida vista por los académicos como un intento del emperador Adriano de disociar a los judíos de la tierra como castigo por la revuelta de Bar Kokhba . [65] [66] [67] Jacobson sugirió que el cambio se racionalizara por el hecho de que la nueva provincia era mucho más grande. [68] A partir de entonces, el nombre se inscribió en monedas y, a partir del siglo V, se mencionó en textos rabínicos . [65] [69] [70] La palabra árabe Filastin se ha utilizado para referirse a la región desde la época de los primeros geógrafos árabes medievales . Parece haber sido utilizada como sustantivo adjetival árabe en la región desde el siglo VII. [71]

En tiempos modernos, la primera persona que se autodescribió a los árabes de Palestina como "palestinos" fue Khalil Beidas en 1898, seguido por Salim Quba'in y Najib Nassar en 1902. Después de la Revolución de los Jóvenes Turcos de 1908 , que flexibilizó las leyes de censura de prensa en el Imperio Otomano, se fundaron docenas de periódicos y publicaciones periódicas en Palestina, y el término "palestino" se expandió en su uso. Entre ellos estaban los periódicos Al-Quds , Al-Munadi , Falastin , Al-Karmil y Al-Nafir, que utilizaron el término "Filastini" más de 170 veces en 110 artículos entre 1908 y 1914. También hicieron referencias a una "sociedad palestina", una "nación palestina" y una "diáspora palestina". Los autores de los artículos incluían palestinos árabes cristianos y musulmanes, emigrantes palestinos y árabes no palestinos. [72] [73] El periódico cristiano árabe palestino Falastin se había dirigido a sus lectores como palestinos desde su creación en 1911 durante el período otomano. [74] [75]

Durante el período del Mandato Británico de Palestina , el término "palestino" se utilizó para referirse a todas las personas que residían allí, independientemente de su religión o etnia , y a quienes las autoridades del Mandato Británico concedieron la ciudadanía se les concedió la "ciudadanía palestina". [76] Otros ejemplos incluyen el uso del término Regimiento de Palestina para referirse al Grupo de la Brigada de Infantería Judía del Ejército Británico durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, y el término "Talmud Palestino", que es un nombre alternativo del Talmud de Jerusalén , utilizado principalmente en fuentes académicas.

Tras la creación del Estado de Israel en 1948 , el uso y la aplicación de los términos «Palestina» y «palestino» por parte de los judíos palestinos y dirigidos a ellos prácticamente dejaron de utilizarse. Por ejemplo, el periódico en inglés The Palestine Post , fundado por judíos en 1932, cambió su nombre en 1950 a The Jerusalem Post . El término «judíos árabes» puede incluir a los judíos de ascendencia palestina y ciudadanía israelí, aunque algunos judíos árabes prefieren que se les llame « judíos mizrajíes» . Los ciudadanos árabes no judíos de Israel con ascendencia palestina se identifican a sí mismos como árabes o palestinos. [77] Estos israelíes árabes no judíos incluyen, por tanto, a aquellos que son palestinos por herencia pero israelíes por ciudadanía. [78]

La Carta Nacional Palestina , modificada por el Consejo Nacional Palestino de la OLP en julio de 1968, definió a los "palestinos" como "aquellos ciudadanos árabes que, hasta 1947, residieron normalmente en Palestina, independientemente de si fueron expulsados de ella o permanecieron allí. Cualquiera nacido, después de esa fecha, de padre palestino, ya sea en Palestina o fuera de ella, también es palestino". [79] Obsérvese que "ciudadanos árabes" no es específico de una religión, e incluye no sólo a los musulmanes de habla árabe de Palestina, sino también a los cristianos árabes y otras comunidades religiosas de Palestina que en ese momento eran de habla árabe, como los samaritanos y los drusos . Por lo tanto, los judíos de Palestina también estaban/están incluidos, aunque limitados sólo a "los judíos [de habla árabe] que habían residido normalmente en Palestina hasta el comienzo de la invasión sionista [preestatal] ". La Carta también establece que "Palestina, con las fronteras que tenía durante el Mandato Británico, es una unidad territorial indivisible". [79] [80]

Los orígenes de los palestinos son complejos y diversos. Según el historiador palestino Nazmi Al-Ju'beh, al igual que en otras naciones árabes, la identidad árabe de los palestinos, basada en gran medida en la afiliación lingüística y cultural , es independiente de la existencia de cualquier origen árabe real. [81] A los palestinos a veces se los describe como indígenas. [34] En un contexto de derechos humanos , la palabra indígena puede tener diferentes definiciones; la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de la ONU utiliza varios criterios para definir este término. [82] Según el Grupo de Trabajo Internacional para Asuntos Indígenas , los "pueblos indígenas de Palestina son los beduinos Jahalin, al-Kaabneh, al-Azazmeh, al-Ramadin y al-Rshaida". [83]

Palestina ha sufrido muchos trastornos demográficos y religiosos a lo largo de la historia. Durante el segundo milenio a. C. , estuvo habitada por los cananeos , pueblos de habla semítica que practicaban la religión cananea . [84] La mayoría de los palestinos comparten un fuerte vínculo genético con los antiguos cananeos. [85] [86] Los israelitas surgieron más tarde como una consecuencia de la civilización cananea del sur , y los judíos y los samaritanos israelitas acabaron formando la mayoría de la población de Palestina durante la antigüedad clásica , [87] [88] [89] [90] [91] [92] Sin embargo, la población judía de Jerusalén y sus alrededores en Judea , y la población samaritana de Samaria , nunca se recuperaron por completo como resultado de las guerras judeo-romanas y las revueltas samaritanas respectivamente. [93]

En los siglos siguientes, la región experimentó disturbios políticos y económicos , conversiones masivas al cristianismo (y la posterior cristianización del Imperio romano ) y la persecución religiosa de minorías. [94] [95] La inmigración de cristianos, la emigración de judíos y la conversión de paganos, judíos y samaritanos contribuyeron a la formación de una mayoría cristiana en la Palestina tardorromana y bizantina . [96] [97] [98] [99]

En el siglo VII, los árabes Rashiduns conquistaron el Levante ; más tarde fueron sucedidos por otras dinastías árabes musulmanas, incluidos los omeyas , los abasíes y los fatimíes . [100] Durante los siguientes siglos, la población de Palestina disminuyó drásticamente, de un estimado de 1 millón durante los períodos romano y bizantino a aproximadamente 300.000 a principios del período otomano. [101] [102] Con el tiempo, la población existente adoptó la cultura y el idioma árabes y muchos se convirtieron al Islam . [97] Se cree que el asentamiento de árabes antes y después de la conquista musulmana jugó un papel en la aceleración del proceso de islamización. [103] [104] [105] [106] Algunos eruditos sugieren que para la llegada de los cruzados , Palestina ya era abrumadoramente musulmana, [107] [108] mientras que otros afirman que fue sólo después de las Cruzadas que los cristianos perdieron su mayoría, y que el proceso de islamización masiva tuvo lugar mucho más tarde, tal vez durante el período mameluco . [103] [109]

Durante varios siglos durante el período otomano, la población de Palestina disminuyó y fluctuó entre 150.000 y 250.000 habitantes, y fue solo en el siglo XIX que comenzó a ocurrir un rápido crecimiento demográfico. [110] Este crecimiento fue ayudado por la inmigración de egipcios (durante los reinados de Muhammad Ali e Ibrahim Pasha ) y argelinos (después de la revuelta de Abdelkader El Djezaïri ) en la primera mitad del siglo XIX, y la posterior inmigración de argelinos, bosnios y circasianos durante la segunda mitad del siglo. [111] [112]

Muchos aldeanos palestinos afirman tener vínculos ancestrales con tribus árabes de la Península Arábiga que se asentaron en Palestina durante o después de la conquista musulmana del Levante . [113] Algunas familias palestinas, en particular en las regiones de Hebrón y Nablus , afirman tener ascendencia judía y samaritana respectivamente, preservando costumbres y tradiciones culturales asociadas. [114] [115] [116]

Estudios genéticos indican una afinidad genética entre los palestinos y otros grupos árabes y semíticos en Oriente Medio y el norte de África . [117] [118] Investigaciones recientes sugieren una continuidad genética entre los palestinos modernos y las antiguas poblaciones levantinas, evidenciada por su agrupamiento con la población de la Edad de Bronce de Canaán . [119] Se han observado variaciones entre palestinos musulmanes y cristianos . [120] Además, hay indicios dentro de las poblaciones palestinas de flujo genético materno desde el África subsahariana , posiblemente vinculado a migraciones históricas o al comercio árabe de esclavos . [121] Los estudios genéticos también han demostrado una relación genética entre palestinos y judíos . [122] [123] [124] Un estudio de 2023 que examinó los genomas completos de las poblaciones mundiales encontró que las muestras palestinas se agrupaban en el "grupo genómico de Oriente Medio", que incluía muestras como muestras de samaritanos , beduinos , jordanos , judíos iraquíes y judíos yemeníes . [125]

Los académicos no están de acuerdo en el momento y las causas que se produjeron tras el surgimiento de una identidad nacional distintivamente palestina entre los árabes de Palestina. Algunos sostienen que se remonta a la revuelta de los campesinos en Palestina en 1834 (o incluso al siglo XVII), mientras que otros sostienen que no surgió hasta después del período del Mandato Palestino. [42] [126] El historiador jurídico Assaf Likhovski afirma que la opinión predominante es que la identidad palestina se originó en las primeras décadas del siglo XX, [42] cuando se cristalizó entre la mayoría de los editores, cristianos y musulmanes, de los periódicos locales un deseo embrionario de autogobierno entre los palestinos frente a los temores generalizados de que el sionismo condujera a un Estado judío y al despojo de la mayoría árabe. [127] El término en sí, Filasṭīnī, fue introducido por primera vez por Khalīl Beidas en una traducción de una obra rusa sobre Tierra Santa al árabe en 1898. Después de eso, su uso se extendió gradualmente de modo que, en 1908, con la relajación de los controles de censura bajo el gobierno otomano tardío, varios corresponsales musulmanes, cristianos y judíos que escribían para periódicos comenzaron a usar el término con gran frecuencia para referirse al 'pueblo palestino' ( ahl/ahālī Filasṭīn ), 'palestinos' ( al-Filasṭīnīyūn ), los 'hijos de Palestina' ( abnā' Filasṭīn ) o a la 'sociedad palestina' ( al-mujtama' al-filasṭīnī ). [128]

Cualesquiera que sean los diferentes puntos de vista sobre el momento, los mecanismos causales y la orientación del nacionalismo palestino, a principios del siglo XX se puede encontrar una fuerte oposición al sionismo y evidencia de una floreciente identidad nacionalista palestina en el contenido de los periódicos en lengua árabe en Palestina, como Al-Karmil (fundado en 1908) y Filasteen (fundado en 1911). [129] Filasteen centró inicialmente su crítica del sionismo en el fracaso de la administración otomana para controlar la inmigración judía y la gran afluencia de extranjeros, explorando más tarde el impacto de las compras de tierras sionistas en los campesinos palestinos ( árabe : فلاحين , fellahin ), expresando una creciente preocupación por la desposesión de tierras y sus implicaciones para la sociedad en general. [129]

El libro de 1997 del historiador Rashid Khalidi , La identidad palestina: la construcción de la conciencia nacional moderna, se considera un "texto fundacional" sobre el tema. [130] Señala que los estratos arqueológicos que denotan la historia de Palestina (que abarca los períodos bíblico , romano , bizantino , omeya , abasí , fatimí , cruzado , ayubí , mameluco y otomano ) forman parte de la identidad del pueblo palestino moderno, tal como la han llegado a entender durante el último siglo. [45] Al señalar que la identidad palestina nunca ha sido exclusiva, y que "el arabismo, la religión y las lealtades locales" desempeñan un papel importante, Khalidi advierte contra los esfuerzos de algunos defensores extremos del nacionalismo palestino por leer "anacrónicamente" en la historia una conciencia nacionalista que, de hecho, es "relativamente moderna". [131] [132]

Khalidi sostiene que la identidad nacional moderna de los palestinos tiene sus raíces en los discursos nacionalistas que surgieron entre los pueblos del imperio otomano a fines del siglo XIX y que se agudizaron tras la demarcación de las fronteras de los estados-nación modernos en Medio Oriente después de la Primera Guerra Mundial . [132] Khalidi también afirma que, si bien el desafío planteado por el sionismo jugó un papel en la configuración de esta identidad, "es un grave error sugerir que la identidad palestina surgió principalmente como una respuesta al sionismo". [132]

Por el contrario, el historiador James L. Gelvin sostiene que el nacionalismo palestino fue una reacción directa al sionismo. En su libro The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War (El conflicto entre Israel y Palestina: Cien años de guerra), afirma que «el nacionalismo palestino surgió durante el período de entreguerras en respuesta a la inmigración y el asentamiento sionistas ». [134] Gelvin sostiene que este hecho no hace que la identidad palestina sea menos legítima: «El hecho de que el nacionalismo palestino se desarrollara más tarde que el sionismo y, de hecho, en respuesta a él, no disminuye en modo alguno la legitimidad del nacionalismo palestino ni lo hace menos válido que el sionismo. Todos los nacionalismos surgen en oposición a algún «otro». ¿Por qué, si no, habría necesidad de especificar quién eres? Y todos los nacionalismos se definen por aquello a lo que se oponen». [134]

David Seddon escribe que “la creación de la identidad palestina en su sentido contemporáneo se formó esencialmente durante la década de 1960, con la creación de la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina”. Sin embargo, añade que “la existencia de una población con un nombre reconociblemente similar (“los filisteos”) en tiempos bíblicos sugiere un grado de continuidad a lo largo de un largo período histórico (de la misma manera que “los israelitas” de la Biblia sugieren una larga continuidad histórica en la misma región)”. [135]

Baruch Kimmerling y Joel S. Migdal consideran que la rebelión de los campesinos de 1834 en Palestina constituyó el primer acontecimiento formativo del pueblo palestino. De 1516 a 1917, Palestina estuvo gobernada por el Imperio otomano, salvo una década entre 1830 y 1840, cuando un vasallo egipcio de los otomanos, Muhammad Ali , y su hijo Ibrahim Pasha lograron separarse con éxito del liderazgo otomano y, conquistando territorio que se extendía desde Egipto hasta el norte de Damasco, afirmaron su propio gobierno sobre la zona. La llamada rebelión de los campesinos de los árabes palestinos fue precipitada por las fuertes demandas de reclutas. Los líderes locales y los notables urbanos estaban descontentos con la pérdida de los privilegios tradicionales, mientras que los campesinos eran muy conscientes de que el reclutamiento era poco más que una sentencia de muerte. A partir de mayo de 1834, los rebeldes tomaron muchas ciudades, entre ellas Jerusalén , Hebrón y Nablus , y se desplegó el ejército de Ibrahim Pasha, que derrotó a los últimos rebeldes el 4 de agosto en Hebrón. [136] Benny Morris sostiene que, no obstante, los árabes de Palestina siguieron formando parte de un movimiento panárabe o, alternativamente, panislamista nacional más amplio . [137] Walid Khalidi sostiene lo contrario, escribiendo que los palestinos en la época otomana eran "muy conscientes de la singularidad de la historia palestina..." y "aunque orgullosos de su herencia y ascendencia árabes, los palestinos se consideraban descendientes no sólo de los conquistadores árabes del siglo VII, sino también de pueblos indígenas que habían vivido en el país desde tiempos inmemoriales, incluidos los antiguos hebreos y los cananeos antes que ellos". [138]

Zachary J. Foster argumentó en un artículo de Foreign Affairs de 2015 que "basándose en cientos de manuscritos, registros de tribunales islámicos, libros, revistas y periódicos del período otomano (1516-1918), parece que el primer árabe en utilizar el término "palestino" fue Farid Georges Kassab, un cristiano ortodoxo radicado en Beirut ". Explicó además que el libro de Kassab de 1909, Palestina, helenismo y clericalismo, señaló de pasada que "los otomanos palestinos ortodoxos se llaman a sí mismos árabes, y de hecho son árabes", a pesar de describir a los hablantes árabes de Palestina como palestinos en el resto del libro". [139]

Bernard Lewis sostiene que los árabes de la Palestina otomana no se opusieron a los sionistas como nación palestina, ya que el concepto mismo de una nación de ese tipo era desconocido para los árabes de la zona en ese momento y no surgió hasta mucho después. Incluso el concepto de nacionalismo árabe en las provincias árabes del Imperio otomano "no había alcanzado proporciones significativas antes del estallido de la Primera Guerra Mundial". [44] Tamir Sorek, un sociólogo , sostiene que "aunque una identidad palestina distinta se remonta al menos a mediados del siglo XIX (Kimmerling y Migdal 1993; Khalidi 1997b), o incluso al siglo XVII (Gerber 1998), no fue hasta después de la Primera Guerra Mundial que una amplia gama de afiliaciones políticas opcionales se volvió relevante para los árabes de Palestina". [126]

El historiador israelí Efraim Karsh sostiene que la identidad palestina no se desarrolló hasta después de la guerra de 1967, porque el éxodo y la expulsión de los palestinos habían fracturado la sociedad hasta tal punto que era imposible reconstruir una identidad nacional. Entre 1948 y 1967, los jordanos y otros países árabes que acogieron a refugiados árabes de Palestina/Israel silenciaron toda expresión de identidad palestina y ocuparon sus tierras hasta las conquistas israelíes de 1967. La anexión formal de Cisjordania por Jordania en 1950 y la posterior concesión de la ciudadanía jordana a sus residentes palestinos frenaron aún más el crecimiento de una identidad nacional palestina al integrarlos en la sociedad jordana. [140]

La idea de un Estado palestino único, distinto de sus vecinos árabes, fue rechazada en un principio por los representantes palestinos. El Primer Congreso de Asociaciones Musulmanas-Cristianas (en Jerusalén , febrero de 1919), que se reunió con el propósito de seleccionar un representante árabe palestino para la Conferencia de Paz de París , adoptó la siguiente resolución: "Consideramos a Palestina como parte de la Siria árabe, ya que nunca ha estado separada de ella en ningún momento. Estamos conectados con ella por vínculos nacionales, religiosos, lingüísticos , naturales, económicos y geográficos". [141]

Un Estado palestino independiente no ha ejercido soberanía plena sobre la tierra en la que los palestinos han vivido durante la era moderna. Palestina fue administrada por el Imperio Otomano hasta la Primera Guerra Mundial, y luego supervisada por las autoridades del Mandato Británico. Israel se estableció en partes de Palestina en 1948, y a raíz de la Guerra árabe-israelí de 1948 , Cisjordania fue gobernada por Jordania y la Franja de Gaza por Egipto , y ambos países continuaron administrando estas áreas hasta que Israel las ocupó en la Guerra de los Seis Días . El historiador Avi Shlaim afirma que la falta de soberanía de los palestinos sobre la tierra ha sido utilizada por los israelíes para negar a los palestinos sus derechos a la autodeterminación. [142]

Hoy en día, el derecho del pueblo palestino a la libre determinación ha sido afirmado por la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas , la Corte Internacional de Justicia [143] y varias autoridades israelíes [144] . Un total de 133 países reconocen a Palestina como Estado. [145] Sin embargo, la soberanía palestina sobre las zonas reclamadas como parte del Estado palestino sigue siendo limitada, y las fronteras del Estado siguen siendo un punto de disputa entre palestinos e israelíes.

Las primeras organizaciones nacionalistas palestinas surgieron al final de la Primera Guerra Mundial . [146] Surgieron dos facciones políticas. al-Muntada al-Adabi , dominada por la familia Nashashibi , militaba por la promoción de la lengua y la cultura árabes, por la defensa de los valores islámicos y por una Siria y Palestina independientes. En Damasco , al-Nadi al-Arabi , dominada por la familia Husayni , defendía los mismos valores. [147]

El artículo 22 del Pacto de la Sociedad de Naciones confirió un estatus legal internacional a los territorios y pueblos que habían dejado de estar bajo la soberanía del Imperio Otomano como parte de un "encargo sagrado de civilización". El artículo 7 del Mandato de la Sociedad de Naciones requirió el establecimiento de una nueva nacionalidad palestina separada para los habitantes. Esto significaba que los palestinos no se convertían en ciudadanos británicos y que Palestina no era anexada a los dominios británicos. [148] El documento del Mandato dividía a la población en judíos y no judíos, y Gran Bretaña, la Potencia Mandataria, consideraba que la población palestina estaba compuesta por grupos religiosos, no nacionales. En consecuencia, los censos gubernamentales de 1922 y 1931 categorizarían a los palestinos confesionalmente como musulmanes, cristianos y judíos, sin la categoría de árabes. [149]

Los artículos del Mandato mencionaban los derechos civiles y religiosos de las comunidades no judías de Palestina, pero no su estatus político. En la conferencia de San Remo se decidió aceptar el texto de esos artículos, aunque se incluyó en las actas de la conferencia un compromiso de la Potencia Mandataria de que esto no implicaría la renuncia a ninguno de los derechos que hasta entonces habían disfrutado las comunidades no judías de Palestina. En 1922, las autoridades británicas sobre la Palestina Mandataria propusieron un proyecto de constitución que habría otorgado a los árabes palestinos representación en un Consejo Legislativo con la condición de que aceptaran los términos del mandato. La delegación árabe palestina rechazó la propuesta por considerarla "totalmente insatisfactoria", señalando que "el pueblo de Palestina" no podía aceptar la inclusión de la Declaración Balfour en el preámbulo de la constitución como base para las discusiones. Además, cuestionaron la designación de Palestina como una "colonia británica del más bajo orden". [150] Los árabes intentaron que los británicos volvieran a ofrecer un establecimiento jurídico árabe aproximadamente diez años después, pero sin éxito. [151]

Después de que el general británico Louis Bols leyera la Declaración Balfour en febrero de 1920, unos 1.500 palestinos se manifestaron en las calles de Jerusalén. [152]

Un mes después, durante los disturbios de Nebi Musa de 1920, las protestas contra el dominio británico y la inmigración judía se tornaron violentas y Bols prohibió todas las manifestaciones. Sin embargo, en mayo de 1921, estallaron más disturbios antijudíos en Jaffa y decenas de árabes y judíos murieron en los enfrentamientos. [152]

Después de los disturbios de Nebi Musa de 1920 , la conferencia de San Remo y el fracaso de Faisal en establecer el Reino de la Gran Siria , una forma distintiva de nacionalismo árabe palestino echó raíces entre abril y julio de 1920. [153] [154] Con la caída del Imperio Otomano y la conquista francesa de Siria , junto con la conquista y administración británica de Palestina, el ex alcalde pan-sirianista de Jerusalén , Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni , dijo: "Ahora, después de los recientes acontecimientos en Damasco , tenemos que efectuar un cambio completo en nuestros planes aquí. El sur de Siria ya no existe. Debemos defender Palestina". [155]

El conflicto entre los nacionalistas palestinos y varios tipos de panarabistas continuó durante el Mandato británico, pero estos últimos fueron cada vez más marginados. Dos líderes destacados de los nacionalistas palestinos fueron Mohammad Amin al-Husayni , Gran Mufti de Jerusalén, designado por los británicos, e Izz ad-Din al-Qassam . [152] Después del asesinato del jeque Izz ad-Din al-Qassam por los británicos en 1935, sus seguidores iniciaron la revuelta árabe de 1936-39 en Palestina , que comenzó con una huelga general en Jaffa y ataques a instalaciones judías y británicas en Nablus . [152] El Comité Superior Árabe convocó a una huelga general a nivel nacional, el no pago de impuestos y el cierre de los gobiernos municipales, y exigió el fin de la inmigración judía y la prohibición de la venta de tierras a los judíos. A finales de 1936, el movimiento se había convertido en una revuelta nacional y la resistencia creció durante 1937 y 1938. En respuesta, los británicos declararon la ley marcial , disolvieron el Alto Comité Árabe y arrestaron a los funcionarios del Consejo Supremo Musulmán que estaban detrás de la revuelta. En 1939, 5.000 árabes habían muerto en los intentos británicos de sofocar la revuelta; más de 15.000 resultaron heridos. [152]

En noviembre de 1947, la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas adoptó el Plan de Partición , que dividía el mandato de Palestina en dos estados: uno de mayoría árabe y otro de mayoría judía. Los árabes palestinos rechazaron el plan y atacaron áreas civiles judías y objetivos paramilitares. Tras la declaración de independencia de Israel en mayo de 1948, cinco ejércitos árabes (Líbano, Egipto, Siria, Irak y Transjordania) acudieron en ayuda de los árabes palestinos contra el recién fundado Estado de Israel . [156]

Los árabes palestinos sufrieron una derrota tan importante al final de la guerra que el término que utilizan para describirla es Nakba (la "catástrofe"). [157] Israel tomó el control de gran parte del territorio que habría sido asignado al estado árabe si los árabes palestinos hubieran aceptado el plan de partición de la ONU. [156] Junto con una derrota militar, cientos de miles de palestinos huyeron o fueron expulsados de lo que se convirtió en el Estado de Israel. Israel no permitió que los refugiados palestinos de la guerra regresaran a Israel. [158]

Después de la guerra, hubo una pausa en la actividad política palestina. Khalidi atribuye esto a los traumáticos acontecimientos de 1947-49, que incluyeron la despoblación de más de 400 ciudades y pueblos y la creación de cientos de miles de refugiados. [159] 418 aldeas habían sido arrasadas, 46.367 edificios, 123 escuelas, 1.233 mezquitas, 8 iglesias y 68 santuarios sagrados, muchos de ellos con una larga historia, destruidos por las fuerzas israelíes. [160] Además, los palestinos perdieron entre 1,5 y 2 millones de acres de tierra, aproximadamente 150.000 hogares urbanos y rurales y 23.000 estructuras comerciales como tiendas y oficinas. [161] Estimaciones recientes del costo para los palestinos de las confiscaciones de propiedades por parte de Israel a partir de 1948 han concluido que los palestinos han sufrido una pérdida neta de 300 mil millones de dólares en activos. [48]

Las partes del Mandato Británico de Palestina que no pasaron a formar parte del recién declarado Estado de Israel fueron ocupadas por Egipto o anexadas por Jordania. En la Conferencia de Jericó del 1 de diciembre de 1948, 2.000 delegados palestinos apoyaron una resolución que pedía "la unificación de Palestina y Transjordania como un paso hacia la unidad árabe plena". [162] Durante lo que Khalidi llama los "años perdidos" que siguieron, los palestinos carecieron de un centro de gravedad, divididos como estaban entre estos países y otros como Siria, Líbano y otros lugares. [163]

En la década de 1950, una nueva generación de grupos y movimientos nacionalistas palestinos comenzó a organizarse clandestinamente, saliendo a la escena pública en la década de 1960. [164] La élite palestina tradicional que había dominado las negociaciones con los británicos y los sionistas en el Mandato, y que fue considerada en gran medida responsable de la pérdida de Palestina, fue reemplazada por estos nuevos movimientos cuyos reclutas generalmente provenían de entornos pobres y de clase media y a menudo eran estudiantes o graduados recientes de universidades de El Cairo , Beirut y Damasco. [164] La potencia de la ideología panarabista propuesta por Gamal Abdel Nasser —popular entre los palestinos para quienes el arabismo ya era un componente importante de su identidad [165] — tendió a oscurecer las identidades de los estados árabes separados que subsumía. [166]

Desde 1967, los palestinos de Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza han vivido bajo ocupación militar, creando, según Avram Bornstein, una carcelalización de su sociedad . [167] Mientras tanto, el panarabismo ha decaído como aspecto de la identidad palestina. La ocupación israelí de la Franja de Gaza y Cisjordania desencadenó un segundo éxodo palestino y fracturó a los grupos políticos y militantes palestinos, impulsándolos a renunciar a las esperanzas residuales en el panarabismo. Se agruparon cada vez más en torno a la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina (OLP), que se había formado en El Cairo en 1964. El grupo creció en popularidad en los años siguientes, especialmente bajo la orientación nacionalista del liderazgo de Yasser Arafat . [168] El nacionalismo palestino secular dominante se agrupó bajo el paraguas de la OLP, cuyas organizaciones constituyentes incluyen a Fatah y al Frente Popular para la Liberación de Palestina , entre otros grupos que en ese momento creían que la violencia política era la única manera de "liberar" Palestina. [45] Estos grupos dieron voz a una tradición surgida en la década de 1960 que sostiene que el nacionalismo palestino tiene raíces históricas profundas, con defensores extremos que leen una conciencia e identidad nacionalista palestina en la historia de Palestina durante los últimos siglos, e incluso milenios, cuando tal conciencia es de hecho relativamente moderna. [169]

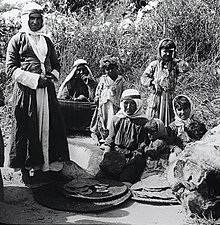

La batalla de Karameh y los acontecimientos de Septiembre Negro en Jordania contribuyeron a aumentar el apoyo palestino a estos grupos, en particular entre los palestinos en el exilio. Al mismo tiempo, entre los palestinos de Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza, un nuevo tema ideológico, conocido como sumud , representó la estrategia política palestina adoptada popularmente a partir de 1967. Como concepto estrechamente relacionado con la tierra, la agricultura y la identidad indígena , la imagen ideal del palestino que se planteaba en ese momento era la del campesino (en árabe, fellah ) que se quedaba en su tierra y se negaba a irse. Una estrategia más pasiva que la adoptada por los fedayines palestinos , el sumud proporcionó un importante subtexto a la narrativa de los combatientes, "al simbolizar la continuidad y las conexiones con la tierra, con el campesinado y un modo de vida rural". [170]

En 1974, la OLP fue reconocida como el único representante legítimo del pueblo palestino por los estados-nación árabes y se le concedió el estatus de observador como movimiento de liberación nacional por las Naciones Unidas ese mismo año. [46] [171] Israel rechazó la resolución, calificándola de "vergonzosa". [172] En un discurso ante el Knesset , el viceprimer ministro y ministro de Asuntos Exteriores Yigal Allon expuso la opinión del gobierno de que: "Nadie puede esperar que reconozcamos a la organización terrorista llamada OLP como representante de los palestinos, porque no lo hace. Nadie puede esperar que negociemos con los jefes de bandas terroristas, que a través de su ideología y acciones, intentan liquidar el Estado de Israel". [172]

En 1975, las Naciones Unidas establecieron un órgano subsidiario, el Comité para el ejercicio de los derechos inalienables del pueblo palestino , para recomendar un programa de aplicación que permitiera al pueblo palestino ejercer la independencia nacional y sus derechos a la libre determinación sin interferencia externa, la independencia nacional y la soberanía, y regresar a sus hogares y propiedades. [173]

La Primera Intifada (1987-1993) fue el primer levantamiento popular contra la ocupación israelí de 1967. Seguida por la proclamación del Estado de Palestina por parte de la OLP en 1988 , estos acontecimientos sirvieron para reforzar aún más la identidad nacional palestina. Después de la Guerra del Golfo en 1991, las autoridades kuwaitíes presionaron por la fuerza a casi 200.000 palestinos para que abandonaran Kuwait . [174] La política que en parte condujo a este éxodo fue una respuesta al alineamiento del líder de la OLP Yasser Arafat con Saddam Hussein .

Los Acuerdos de Oslo , el primer acuerdo de paz provisional entre israelíes y palestinos, se firmaron en 1993. Se había previsto que el proceso durara cinco años y terminara en junio de 1999, cuando comenzó la retirada de las fuerzas israelíes de la Franja de Gaza y la zona de Jericó. La expiración de este plazo sin que Israel reconociera al Estado palestino y sin que se pusiera fin de manera efectiva a la ocupación fue seguida por la Segunda Intifada en 2000. [175] [176] La segunda intifada fue más violenta que la primera. [177] La Corte Internacional de Justicia observó que, dado que el gobierno de Israel había decidido reconocer a la OLP como representante del pueblo palestino, su existencia ya no era un problema. La Corte observó que el Acuerdo Provisional entre Israel y Palestina sobre Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza del 28 de septiembre de 1995 también se refería varias veces al pueblo palestino y a sus "derechos legítimos". [178] Según Thomas Giegerich , con respecto al derecho del pueblo palestino a formar un Estado soberano e independiente, "el derecho de libre determinación otorga al pueblo palestino colectivamente el derecho inalienable de determinar libremente su estatus político, mientras que Israel, habiendo reconocido a los palestinos como un pueblo separado, está obligado a promover y respetar este derecho de conformidad con la Carta de las Naciones Unidas". [179]

Tras los fracasos de la Segunda Intifada, está surgiendo una generación más joven a la que le importa menos la ideología nacionalista que el crecimiento económico. Esto ha sido una fuente de tensión entre algunos de los dirigentes políticos palestinos y los profesionales del sector empresarial palestino que desean la cooperación económica con los israelíes. En una conferencia internacional celebrada en Bahréin, el empresario palestino Ashraf Jabari dijo: "No tengo ningún problema en trabajar con Israel. Es hora de seguir adelante... La Autoridad Palestina no quiere la paz. Les dijeron a las familias de los empresarios que los busca [la policía] por participar en el taller de Bahréin". [180]

En ausencia de un censo exhaustivo que incluya a todas las poblaciones de la diáspora palestina y a las que han permanecido dentro de lo que era el Mandato Británico de Palestina , es difícil determinar las cifras exactas de población. La Oficina Central Palestina de Estadísticas (PCBS) anunció a fines de 2015 que el número de palestinos en todo el mundo a fines de 2015 era de 12,37 millones, de los cuales el número que aún residía dentro de la Palestina histórica era de 6,22 millones. [189] En 2022, Arnon Soffer estimó que en el territorio de la antigua Palestina Mandataria (que ahora abarca Israel y los territorios palestinos de Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza ), hay una población palestina de 7,503 millones, lo que representa el 51,16% de la población total. [190] [191] Dentro de Israel propiamente dicho, los palestinos constituyen casi el 21 por ciento de la población como parte de sus ciudadanos árabes . [50]

En 2005, el Grupo de Investigación Demográfica Estadounidense-Israelí (AIDRG) realizó una revisión crítica de las cifras y la metodología de la PCBS. [192] En su informe, [193] afirmaron que varios errores en la metodología y las suposiciones de la PCBS inflaron artificialmente las cifras en un total de 1,3 millones. Las cifras de la PCBS se cotejaron con una variedad de otras fuentes (por ejemplo, las tasas de natalidad declaradas basadas en suposiciones sobre la tasa de fertilidad para un año determinado se cotejaron con las cifras del Ministerio de Salud palestino, así como con las cifras de matriculación escolar del Ministerio de Educación seis años después; las cifras de inmigración se cotejaron con las cifras recogidas en los cruces fronterizos, etc.). Entre los errores denunciados en su análisis figuraban: errores en la tasa de natalidad (308.000), errores en la inmigración y la emigración (310.000), falta de contabilización de la migración a Israel (105.000), doble contabilización de los árabes de Jerusalén (210.000), contabilización de antiguos residentes que ahora viven en el extranjero (325.000) y otras discrepancias (82.000). Los resultados de su investigación también se presentaron ante la Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos el 8 de marzo de 2006. [194]

El estudio fue criticado por Sergio DellaPergola , un demógrafo de la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén. [195] DellaPergola acusó a los autores del informe de AIDRG de no entender los principios básicos de la demografía debido a su falta de experiencia en el tema, pero también reconoció que no tuvo en cuenta la emigración de palestinos y cree que debe examinarse, así como las estadísticas de natalidad y mortalidad de la Autoridad Palestina. [196] También acusó a AIDRG de uso selectivo de datos y múltiples errores sistemáticos en su análisis, afirmando que los autores asumieron que el registro electoral palestino estaba completo a pesar de que el registro es voluntario, y utilizaron una tasa de fertilidad total irrealista (una abstracción estadística de nacimientos por mujer) para volver a analizar esos datos en un "error circular típico". DellaPergola estimó que la población palestina de Cisjordania y Gaza a fines de 2005 era de 3,33 millones, o 3,57 millones si se incluye Jerusalén Oriental. Estas cifras son apenas inferiores a las cifras oficiales palestinas. [195] La Administración Civil Israelí estimó el número de palestinos en Cisjordania en 2.657.029 en mayo de 2012. [197] [198]

El estudio de AIDRG también fue criticado por Ian Lustick , quien acusó a sus autores de múltiples errores metodológicos y de una agenda política. [199]

En 2009, a petición de la OLP, “Jordania revocó la ciudadanía a miles de palestinos para impedirles permanecer permanentemente en el país”. [200]

Muchos palestinos se han establecido en los Estados Unidos, particularmente en el área de Chicago. [201] [202]

En total, se estima que 600.000 palestinos residen en América. La emigración palestina a América del Sur comenzó por razones económicas anteriores al conflicto árabe-israelí, pero continuó creciendo después. [203] Muchos emigrantes eran del área de Belén . Los que emigraron a América Latina eran principalmente cristianos. La mitad de los de origen palestino en América Latina viven en Chile . [10] El Salvador [204] y Honduras [205] también tienen poblaciones palestinas sustanciales. Estos dos países han tenido presidentes de ascendencia palestina ( Antonio Saca en El Salvador y Carlos Roberto Flores en Honduras). Belice , que tiene una población palestina más pequeña, tiene un ministro palestino : Said Musa . [206] Schafik Jorge Handal , político salvadoreño y ex líder guerrillero , era hijo de inmigrantes palestinos. [207]

En 2006, había 4.255.120 palestinos registrados como refugiados en el Organismo de Obras Públicas y Socorro de las Naciones Unidas (OOPS). Esta cifra incluye a los descendientes de los refugiados que huyeron o fueron expulsados durante la guerra de 1948, pero excluye a los que han emigrado desde entonces a zonas fuera del ámbito de competencias del OOPS. [187] Según estas cifras, casi la mitad de todos los palestinos son refugiados registrados. En estas cifras se incluyen los 993.818 refugiados palestinos en la Franja de Gaza y los 705.207 refugiados palestinos en Cisjordania, que proceden de ciudades y pueblos que ahora se encuentran dentro de las fronteras de Israel. [208]

Las cifras del OOPS no incluyen a unas 274.000 personas, o 1 de cada 5,5 de todos los residentes árabes de Israel, que son refugiados palestinos desplazados internamente . [209] [210]

Los campos de refugiados palestinos en Líbano, Siria, Jordania y Cisjordania están organizados según el pueblo o lugar de origen de la familia de refugiados. Una de las primeras cosas que aprenden los niños que nacen en los campos es el nombre de su pueblo de origen. David McDowall escribe que “[...] el anhelo por Palestina impregna a toda la comunidad de refugiados y es abrazado con más fervor por los refugiados más jóvenes, para quienes el hogar sólo existe en la imaginación”. [211]

La política israelí para impedir que los refugiados regresaran a sus hogares fue formulada inicialmente por David Ben Gurion y Joseph Weitz , director del Fondo Nacional Judío, y fue adoptada formalmente por el gabinete israelí en junio de 1948. [212] En diciembre de ese año, la ONU adoptó la resolución 194 , que resolvió "que a los refugiados que deseen regresar a sus hogares y vivir en paz con sus vecinos se les debe permitir hacerlo lo antes posible, y que se debe pagar una compensación por la propiedad de aquellos que elijan no regresar y por la pérdida o daño a la propiedad que, según los principios del derecho internacional o en equidad, deben ser reparados por los gobiernos o autoridades responsables". [213] [214] [215] A pesar de que gran parte de la comunidad internacional, incluido el presidente estadounidense Harry Truman, insistió en que la repatriación de los refugiados palestinos era esencial, Israel se negó a aceptar el principio. [215] En los años intermedios, Israel se ha negado sistemáticamente a cambiar su posición y ha introducido más legislación para impedir que los refugiados palestinos regresen y reclamen sus tierras y propiedades confiscadas. [214] [215]

De conformidad con una resolución de la Liga Árabe de 1965, la mayoría de los países árabes se han negado a conceder la ciudadanía a los palestinos, argumentando que sería una amenaza a su derecho a regresar a sus hogares en Palestina. [214] [216] En 2012, Egipto se desvió de esta práctica al conceder la ciudadanía a 50.000 palestinos, en su mayoría de la Franja de Gaza. [216]

Los palestinos que viven en el Líbano se ven privados de sus derechos civiles básicos. No pueden poseer viviendas ni tierras y no pueden ejercer como abogados, ingenieros o médicos. [217]

La mayoría de los palestinos son musulmanes, [218] la gran mayoría de los cuales son seguidores de la rama sunita del Islam , [219] con una pequeña minoría de Ahmadiyya . [220] Los cristianos palestinos representan una minoría significativa del 6%, y pertenecen a varias denominaciones, seguidos por comunidades religiosas mucho más pequeñas, incluyendo drusos y samaritanos . Los judíos palestinos -considerados palestinos por la Carta Nacional Palestina adoptada por la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina (OLP) que los definió como aquellos "judíos que normalmente habían residido en Palestina hasta el comienzo de la invasión sionista "- hoy se identifican como israelíes [221] (con la excepción de unos pocos individuos). Los judíos palestinos abandonaron casi universalmente cualquier identidad de ese tipo después del establecimiento de Israel y su incorporación a la población judía israelí , que originalmente estaba compuesta por inmigrantes judíos de todo el mundo.

Hasta finales del siglo XIX, el sincretismo intercultural entre símbolos y figuras islámicas y cristianas en la práctica religiosa era común en el campo palestino, donde la mayoría de las aldeas no tenían mezquitas o iglesias locales. [222] Los días festivos populares, como el Jueves de Muertos , eran celebrados tanto por musulmanes como por cristianos y los profetas y santos compartidos incluían a Jonás , quien es venerado en Halhul como un profeta bíblico e islámico, y San Jorge , quien es conocido en árabe como al-Khdir . Los aldeanos rendían tributo a los santos patronos locales en maqams - habitaciones individuales abovedadas a menudo ubicadas a la sombra de un antiguo algarrobo o roble ; muchas de ellas tienen sus raíces en tradiciones judías, samaritanas, cristianas y, a veces, paganas. [223] Los santos, tabú según los estándares del Islam ortodoxo, mediaban entre el hombre y Dios, y los santuarios a los santos y hombres santos salpicaban el paisaje palestino. [222] Ali Qleibo, un antropólogo palestino , afirma que esta evidencia construida constituye "un testimonio arquitectónico de la sensibilidad religiosa palestina cristiana/musulmana y sus raíces en las antiguas religiones semíticas ". [222]

Hasta la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, la religión como elemento constitutivo de la identidad individual ocupó un lugar menor en la estructura social palestina. [222] Jean Moretain, un sacerdote que escribió en 1848 que un cristiano en Palestina se distinguía "solamente por el hecho de pertenecer a un clan particular. Si una determinada tribu era cristiana, entonces un individuo sería cristiano, pero sin conocimiento de lo que distinguía su fe de la de un musulmán". [222]

Las concesiones otorgadas a Francia y otras potencias occidentales por el Sultanato Otomano tras la Guerra de Crimea tuvieron un impacto significativo en la identidad cultural religiosa palestina contemporánea. [222] La religión se transformó en un elemento "constitutivo de la identidad individual/colectiva de conformidad con los preceptos ortodoxos", y formó un elemento fundamental en el desarrollo político del nacionalismo palestino. [222]

El censo británico de 1922 registró 752.048 habitantes en Palestina, de los cuales 660.641 eran árabes palestinos (árabes musulmanes y cristianos), 83.790 judíos palestinos y 7.617 personas pertenecientes a otros grupos. El desglose porcentual correspondiente es el siguiente: 87% de árabes musulmanes y cristianos y 11% de judíos. [224]

Bernard Sabella, de la Universidad de Belén, estima que el 6% de la población palestina en todo el mundo es cristiana y que el 56% de ellos vive fuera de la Palestina histórica. [225] Según la Sociedad Académica Palestina para el Estudio de Asuntos Internacionales , la población palestina de Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza es 97% musulmana y 3% cristiana. La gran mayoría de la comunidad palestina en Chile sigue el cristianismo, en gran parte ortodoxo oriental y algunos católicos romanos , y de hecho el número de cristianos palestinos en la diáspora solo en Chile excede el número de los que han permanecido en su patria. [226] San Jorge es el santo patrón de los cristianos palestinos. [227]

Los drusos se convirtieron en ciudadanos israelíes y los varones drusos sirven en las Fuerzas de Defensa de Israel , aunque algunos individuos se identifican como "drusos palestinos". [228] Según Salih al-Shaykh, la mayoría de los drusos no se consideran palestinos: "su identidad árabe emana principalmente de la lengua común y su contexto sociocultural, pero está separada de cualquier concepción política nacional. No está dirigida a los países árabes ni a la nacionalidad árabe ni al pueblo palestino, y no expresa compartir ningún destino con ellos. Desde este punto de vista, su identidad es Israel, y esta identidad es más fuerte que su identidad árabe". [229]

También hay unos 350 samaritanos que llevan documentos de identidad palestinos y viven en Cisjordania, mientras que un número aproximadamente igual vive en Holon y tiene ciudadanía israelí. [230] Los que viven en Cisjordania también están representados en la legislatura de la Autoridad Nacional Palestina. [230] Los palestinos se refieren comúnmente a ellos como los "judíos de Palestina", y mantienen su propia identidad cultural única. [230]

Los judíos que se identifican como judíos palestinos son pocos, pero incluyen a los judíos israelíes que forman parte del grupo Neturei Karta , [231] y a Uri Davis , un ciudadano israelí y autodenominado judío palestino (que se convirtió al Islam en 2008 para casarse con Miyassar Abu Ali) que sirve como miembro observador en el Consejo Nacional Palestino . [232]

Bahá'u'lláh , fundador de la Fe Bahá'í , pasó sus últimos años en Acre , que entonces formaba parte del Imperio Otomano. Permaneció allí durante 24 años, donde se erigió un santuario en su honor. [233] [234]

Según la PCBS, en 2016 había aproximadamente 4.816.503 palestinos en los territorios palestinos [update], de los cuales 2.935.368 vivían en Cisjordania y 1.881.135 en la Franja de Gaza. [181] Según la Oficina Central de Estadísticas de Israel , en 2013 había 1.658.000 ciudadanos árabes de Israel. [235] Ambas cifras incluyen a los palestinos en Jerusalén Oriental.

En 2008, Minority Rights Group International estimó que el número de palestinos en Jordania era de unos 3 millones. [236] La UNRWA estimó su número en 2,3 millones en 2024. [update][ 6]

El árabe palestino es un subgrupo del dialecto árabe levantino más amplio . Antes de la conquista islámica del siglo VII y la arabización del Levante, las principales lenguas habladas en Palestina, entre las comunidades predominantemente cristianas y judías , eran el arameo , el griego y el siríaco . [237] El árabe también se hablaba en algunas áreas. [238] El árabe palestino, al igual que otras variaciones del dialecto levantino , exhibe influencias sustanciales en el léxico del arameo. [239]

El árabe palestino tiene tres subvariantes principales: rural, urbano y beduino. La pronunciación del Qāf sirve como shibboleth para distinguir entre los tres principales subdialectos palestinos: la variedad urbana tiene un sonido [Q], mientras que la variedad rural (hablada en los pueblos alrededor de las ciudades principales) tiene una [K] para la [Q]. La variedad beduina de Palestina (hablada principalmente en la región sur y a lo largo del valle del Jordán) utiliza una [G] en lugar de [Q]. [240]

Barbara McKean Parmenter ha señalado que a los árabes de Palestina se les atribuye la preservación de los nombres de lugares semíticos originales de muchos sitios mencionados en la Biblia, como lo documentó el geógrafo estadounidense Edward Robinson en el siglo XIX. [241]

Los palestinos que viven o trabajan en Israel generalmente también pueden hablar hebreo moderno , al igual que algunos que viven en Cisjordania y la Franja de Gaza.

.jpg/440px-Secretary_Kerry_Speaks_With_Palestinian_Youth_in_Bethlehem_(10708795753).jpg)

Según un informe de 2014 del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo , la tasa de alfabetización de Palestina era del 96,3% , lo que es elevado en comparación con los estándares internacionales. Existe una diferencia de género en la población mayor de 15 años: el 5,9% de las mujeres se consideran analfabetas en comparación con el 1,6% de los hombres. [242] El analfabetismo entre las mujeres ha disminuido del 20,3% en 1997 a menos del 6% en 2014. [242]

Los intelectuales palestinos, entre ellos May Ziadeh y Khalil Beidas , eran parte integral de la intelectualidad árabe. [ ¿Cuándo? ] Los niveles educativos entre los palestinos han sido tradicionalmente altos. En la década de 1960, Cisjordania tenía un porcentaje más alto de su población adolescente matriculada en la educación secundaria que el Líbano. [243] Claude Cheysson , Ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de Francia bajo la primera presidencia de Mitterrand , sostuvo a mediados de los años ochenta que, "incluso hace treinta años, (los palestinos) probablemente ya tenían la élite educada más grande de todos los pueblos árabes". [244]

Entre los aportes a la cultura palestina se encuentran figuras de la diáspora como Edward Said y Ghada Karmi , ciudadanos árabes de Israel como Emile Habibi y jordanos como Ibrahim Nasrallah . [245] [246]

En el siglo XIX y principios del XX, hubo algunas familias palestinas bien conocidas, que incluían la familia Khalidi , la familia al-Husayni , la familia Nashashibi , la familia Tuqan , la familia Nusaybah , la familia Qudwa , el clan Shawish , la familia Shurrab , la familia Al-Zaghab, la familia Al-Khalil , la dinastía Ridwan , la familia Al-Zeitawi, el clan Abu Ghosh , la familia Barghouti , el clan Doghmush , la familia Douaihy , el clan Hilles , la familia Jarrar y la familia Jayyusi . Desde que comenzaron varios conflictos con los sionistas, algunas de las comunidades han abandonado Palestina posteriormente. El papel de las mujeres varía entre los palestinos, existiendo opiniones tanto progresistas como ultraconservadoras. Otros grupos de palestinos, como los beduinos del Néguev o los drusos, pueden ya no identificarse como palestinos por razones políticas. [247]

Ali Qleibo, antropólogo palestino , ha criticado la historiografía musulmana por atribuir el origen de la identidad cultural palestina a la llegada del Islam en el siglo VII. Al describir el efecto de esa historiografía, escribe:

Se niegan los orígenes paganos . Por ello, los pueblos que poblaron Palestina a lo largo de la historia han renunciado discursivamente a su propia historia y religión al adoptar la religión, el idioma y la cultura del Islam. [222]

Algunos eruditos y exploradores occidentales que cartografiaron y estudiaron Palestina durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX llegaron a la conclusión de que la cultura campesina de la gran clase fellahin mostraba características de culturas distintas a la del Islam, [248] y estas ideas influirían en los debates del siglo XX sobre la identidad palestina que llevaron a cabo etnógrafos locales e internacionales. Las contribuciones de las etnografías "nativistas" producidas por Tawfiq Canaan y otros escritores palestinos y publicadas en The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society (1920-1948) estuvieron impulsadas por la preocupación de que la "cultura nativa de Palestina", y en particular la sociedad campesina, estuviera siendo socavada por las fuerzas de la modernidad . [249] Salim Tamari escribe que:

Implícito en su erudición (y hecho explícito por el propio Canaan) había otro tema, a saber, que los campesinos de Palestina representan —a través de sus normas populares... la herencia viva de todas las culturas antiguas acumuladas que habían aparecido en Palestina (principalmente la cananea, la filistea, la hebrea , la nabatea , la sirio-aramea y la árabe). [249]

La cultura palestina está estrechamente relacionada con las de los países del Levante cercanos, como Líbano, Siria y Jordania, y con las del mundo árabe. Las contribuciones culturales en los campos del arte , la literatura , la música , la indumentaria y la cocina expresan las características de la experiencia palestina y muestran signos de origen común a pesar de la separación geográfica entre los territorios palestinos , Israel y la diáspora. [250] [251] [252]

Al-Quds Capital de la Cultura Árabe es una iniciativa de la UNESCO en el marco del Programa de Capitales Culturales para promover la cultura árabe y fomentar la cooperación en la región árabe. El evento inaugural se celebró en marzo de 2009.

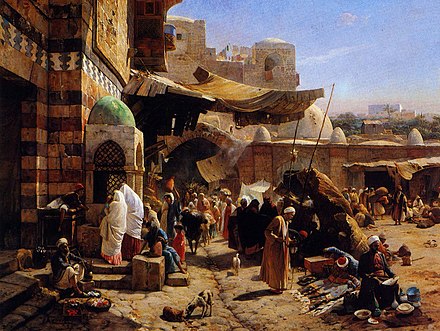

Palestine's history of rule by many different empires is reflected in Palestinian cuisine, which has benefited from various cultural contributions and exchanges. Generally speaking, modern Syrian-Palestinian dishes have been influenced by the rule of three major Islamic groups: the Arabs, the Persian-influenced Arabs and the Turks.[253] The Arabs who conquered Syria and Palestine had simple culinary traditions primarily based on the use of rice, lamb and yogurt, as well as dates.[254] The already simple cuisine did not advance for centuries due to Islam's strict rules of parsimony and restraint, until the rise of the Abbasids, who established Baghdad as their capital. Baghdad was historically located on Persian soil and henceforth, Persian culture was integrated into Arab culture during the 9th–11th centuries and spread throughout central areas of the empire.[253]

There are several foods native to Palestine that are well known in the Arab world, such as, kinafe Nabulsi, Nabulsi cheese (cheese of Nablus), Ackawi cheese (cheese of Acre) and musakhan. Kinafe originated in Nablus, as well as the sweetened Nabulsi cheese used to fill it.[citation needed] Another very popular food is Palestinian Kofta or Kufta.[255]

Mezze describes an assortment of dishes laid out on the table for a meal that takes place over several hours, a characteristic common to Mediterranean cultures. Some common mezze dishes are hummus, tabouleh,baba ghanoush, labaneh, and zate 'u zaatar, which is the pita bread dipping of olive oil and ground thyme and sesame seeds.[256]

Entrées that are eaten throughout the Palestinian territories, include waraq al-'inib – boiled grape leaves wrapped around cooked rice and ground lamb. Mahashi is an assortment of stuffed vegetables such as, zucchinis, potatoes, cabbage and in Gaza, chard.[257]

Similar to the structure of Palestinian society, the Palestinian field of arts extends over four main geographic centers: the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Israel, the Palestinian diaspora in the Arab world, and the Palestinian diaspora in Europe, the United States and elsewhere.[258]

Palestinian cinematography, relatively young compared to Arab cinema overall, receives much European and Israeli support.[259] Palestinian films are not exclusively produced in Arabic; some are made in English, French or Hebrew.[260] More than 800 films have been produced about Palestinians, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and other related topics.[citation needed] Examples include Divine Intervention and Paradise Now.

A wide variety of handicrafts, many of which have been produced in the area of Palestine for hundreds of years, continue to be produced today. Palestinian handicrafts include embroidery and weaving, pottery-making, soap-making, glass-making, and olive-wood and Mother of Pearl carvings, among others.[261][262]

Foreign travelers to Palestine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries often commented on the rich variety of costumes among the area's inhabitants, and particularly among the fellaheen or village women. Until the 1940s, a woman's economic status, whether married or single, and the town or area they were from could be deciphered by most Palestinian women by the type of cloth, colors, cut, and embroidery motifs, or lack thereof, used for the robe-like dress or "thoub" in Arabic.[263]

New styles began to appear in the 1960s. For example, the "six-branched dress" named after the six wide bands of embroidery running down from the waist.[264] These styles came from the refugee camps, particularly after 1967. Individual village styles were lost and replaced by an identifiable "Palestinian" style.[265] The shawal, a style popular in the West Bank and Jordan before the First Intifada, probably evolved from one of the many welfare embroidery projects in the refugee camps. It was a shorter and narrower fashion, with a western cut.[266]

Palestinian literature forms part of the wider genre of Arabic literature. Unlike its Arabic counterparts, Palestinian literature is defined by national affiliation rather than territorially. For example, Egyptian literature is the literature produced in Egypt. This too was the case for Palestinian literature up to the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, but following the Palestinian Exodus of 1948 it has become "a literature written by Palestinians" regardless of their residential status.[267][268]

Contemporary Palestinian literature is often characterized by its heightened sense of irony and the exploration of existential themes and issues of identity.[268] References to the subjects of resistance to occupation, exile, loss, and love and longing for homeland are also common.[269] Palestinian literature can be intensely political, as underlined by writers such as Salma Khadra Jayyusi and novelist Liana Badr, who have mentioned the need to give expression to the Palestinian "collective identity" and the "just case" of their struggle.[270] There is also resistance to this school of thought, whereby Palestinian artists have "rebelled" against the demand that their art be "committed".[270] Poet Mourid Barghouti for example, has often said that "poetry is not a civil servant, it's not a soldier, it's in nobody's employ."[270] Rula Jebreal's novel Miral tells the story of Hind al-Husseini's effort to establish an orphanage in Jerusalem after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Deir Yassin massacre,[271][272] and the establishment of the state of Israel.

Since 1967, most critics have theorized the existence of three "branches" of Palestinian literature, loosely divided by geographic location: 1) from inside Israel, 2) from the occupied territories, 3) from among the Palestinian diaspora throughout the Middle East.[273]

Hannah Amit-Kochavi recognizes only two branches: that written by Palestinians from inside the State of Israel as distinct from that written outside (ibid., p. 11).[267] She also posits a temporal distinction between literature produced before 1948 and that produced thereafter.[267] In a 2003 article published in Studies in the Humanities, Steven Salaita posits a fourth branch made up of English language works, particularly those written by Palestinians in the United States, which he defines as "writing rooted in diasporic countries but focused in theme and content on Palestine."[273]

Poetry, using classical pre-Islamic forms, remains an extremely popular art form, often attracting Palestinian audiences in the thousands. Until 20 years ago, local folk bards reciting traditional verses were a feature of every Palestinian town.[274] After the 1948 Palestinian exodus and discrimination by neighboring Arab countries, poetry was transformed into a vehicle for political activism.[157] From among those Palestinians who became Arab citizens of Israel after the passage of the Citizenship Law in 1952, a school of resistance poetry was born that included poets including Mahmoud Darwish, Samih al-Qasim, and Tawfiq Zayyad.[274] The work of these poets was largely unknown to the wider Arab world for years because of the lack of diplomatic relations between Israel and Arab governments. The situation changed after Ghassan Kanafani, another Palestinian writer in exile in Lebanon, published an anthology of their work in 1966.[274] Palestinian poets often write about the common theme of a strong affection and sense of loss and longing for a lost homeland.[274] Among the new generation of Palestinian writers, the work of Nathalie Handal an award-winning poet, playwright, and editor has been widely published in literary journals and magazines and has been translated into twelve languages.[275]

Palestinian folklore is the body of expressive culture, including tales, music, dance, legends, oral history, proverbs, jokes, popular beliefs, customs, and comprising the traditions (including oral traditions) of Palestinian culture. There was a folklorist revival among Palestinian intellectuals such as Nimr Sirhan, Musa Allush, Salim Mubayyid, and the Palestinian Folklore Society during the 1970s. This group attempted to establish pre-Islamic (and pre-Hebraic) cultural roots for a re-constructed Palestinian national identity. The two putative roots in this patrimony are Canaanite and Jebusite.[249] Such efforts seem to have borne fruit as evidenced in the organization of celebrations including the Qabatiya Canaanite festival and the annual Music Festival of Yabus by the Palestinian Ministry of Culture.[249]

Traditional storytelling among Palestinians is prefaced with an invitation to the listeners to give blessings to God and the Prophet Mohammed or the Virgin Mary as the case may be, and includes the traditional opening: "There was, or there was not, in the oldness of time..."[274][276] Formulaic elements of the stories share much in common with the wider Arab world, though the rhyming scheme is distinct. There are a cast of supernatural characters: djinns who can cross the Seven Seas in an instant, giants, and ghouls with eyes of ember and teeth of brass. Stories invariably have a happy ending, and the storyteller will usually finish off with a rhyme like: "The bird has taken flight, God bless you tonight", or "Tutu, tutu, finished is my haduttu (story)."[274]

Palestinian music is well known throughout the Arab world.[278] After 1948, a new wave of performers emerged with distinctively Palestinian themes relating to dreams of statehood and burgeoning nationalist sentiments. In addition to zajal and ataaba, traditional Palestinian songs include: Bein Al-dawai, Al-Rozana, Zarif – Al-Toul, and Al-Maijana, Dal'ona, Sahja/Saamir, Zaghareet. Over three decades, the Palestinian National Music and Dance Troupe (El Funoun) and Mohsen Subhi have reinterpreted and rearranged traditional wedding songs such as Mish'al (1986), Marj Ibn 'Amer(1989) and Zaghareed (1997).[279] Ataaba is a form of folk singing that consists of four verses, following a specific form and meter. The distinguishing feature of ataaba is that the first three verses end with the same word meaning three different things, and the fourth verse serves as a conclusion. It is usually followed by a dalouna.

Reem Kelani is one of the foremost researchers and performers in the present day of music with a specifically Palestinian narrative and heritage.[280] Her 2006 debut solo album Sprinting Gazelle – Palestinian Songs from the Motherland and the Diaspora comprised Kelani's research and an arrangement of five traditional Palestinian songs, whilst the other five songs were her own musical settings of popular and resistance poetry by the likes of Mahmoud Darwish, Salma Khadra Jayyusi, Rashid Husain and Mahmoud Salim al-Hout.[281] All the songs on the album relate to 'pre-1948 Palestine'.

Palestinian hip hop reportedly started in 1998 with Tamer Nafar's group DAM.[282] These Palestinian youth forged the new Palestinian musical subgenre, which blends Arabic melodies and hip hop beats. Lyrics are often sung in Arabic, Hebrew, English, and sometimes French. Since then, the new Palestinian musical subgenre has grown to include artists in the Palestinian territories, Israel, Great Britain, the United States and Canada.

.jpg/440px-DJ_Khaled_2012_(cropped).jpg)

Borrowing from traditional rap music that first emerged in New York in the 1970s, "young Palestinian musicians have tailored the style to express their own grievances with the social and political climate in which they live and work." Palestinian hip hop works to challenge stereotypes and instigate dialogue about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[283] Palestinian hip-hop artists have been strongly influenced by the messages of American rappers. Tamar Nafar says, "When I heard Tupac sing 'It's a White Man's World' I decided to take hip hop seriously".[284] In addition to the influences from American hip hop, it also includes musical elements from Palestinian and Arabic music including "zajal, mawwal, and saj" which can be likened to Arabic spoken word, as well as including the percussiveness and lyricism of Arabic music.

Historically, music has served as an integral accompaniment to various social and religious rituals and ceremonies in Palestinian society (Al-Taee 47). Much of the Middle-Eastern and Arabic string instruments utilized in classical Palestinian music are sampled over Hip-hop beats in both Israeli and Palestinian hip-hop as part of a joint process of localization. Just as the percussiveness of the Hebrew language is emphasized in Israeli Hip-hop, Palestinian music has always revolved around the rhythmic specificity and smooth melodic tone of Arabic. "Musically speaking, Palestinian songs are usually pure melody performed monophonically with complex vocal ornamentations and strong percussive rhythm beats".[285] The presence of a hand-drum in classical Palestinian music indicates a cultural esthetic conducive to the vocal, verbal and instrumental percussion which serve as the foundational elements of Hip-hop. This hip hop is joining a "longer tradition of revolutionary, underground, Arabic music and political songs that have supported Palestinian Resistance".[284] This subgenre has served as a way to politicize the Palestinian issue through music.

The Dabke, a Levantine Arab folk dance style whose local Palestinian versions were appropriated by Palestinian nationalism after 1967, has, according to one scholar, possible roots that may go back to ancient Canaanite fertility rites.[286] It is marked by synchronized jumping, stamping, and movement, similar to tap dancing. One version is performed by men, another by women.

Although sport facilities did exist before the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight, many such facilities and institutions were subsequently shut down. Today there remains sport centers such as in Gaza and Ramallah, but the difficulty of mobility and travel restrictions means most Palestinian are not able to compete internationally to their full potential. However, Palestinian sport authorities have indicated that Palestinians in the diaspora will be eligible to compete for Palestine once the diplomatic and security situation improves.

En suma, los árabes y palestinos, arribados al país a finales del siglo XIX, dominan hoy en día la economía del país, y cada vez están emergiendo como actores importantes de la clase política hondureña y forman, después de Chile, la mayor concentración de descendientes de palestinos en América Latina, con entre 150,000 y 200,000 personas.

Palestinians (similar to the Samaritans and some of the Druze), highlighting their primarily indigenous origin

Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement. The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some "other". Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose. As we have seen, Zionism itself arose in reaction to anti-Semitic and exclusionary nationalist movements in Europe. It would be perverse to judge Zionism as somehow less valid than European anti-Semitism or those nationalisms. . . Furthermore, Zionism itself was also defined by its opposition to the indigenous Palestinian inhabitants of the region. Both the "conquest of land" and the "conquest of labor" slogans that became central to the dominant strain of Zionism in the Yishuv originated as a result of the Zionist confrontation with the Palestinian "other".

'the Syrians called Palestinians', at the time of Herodotus were a mixture of Phoenicians, Philistines, Arabs, Egyptians, and perhaps also other peoples. . . Perhaps the circumcised 'Syrians called Palestinians' are the Arabs and Egyptians of the Sinai coast; at the time of Herodotus there were few Jews in the coastal area.

The thesis that a great "migration of the Sea Peoples" occurred ca. 1200 B.C. is supposedly based on Egyptian inscriptions, one from the reign of Merneptah and another from the reign of Ramesses III. Yet in the inscriptions themselves such a migration nowhere appears. After reviewing what the Egyptian texts have to say about 'the sea peoples', one Egyptologist (Wolfgang Helck) recently remarked that although some things are unclear, "eins ist aber sicher: Nach den ägyptischen Texten haben wir es nicht mit einer "Völkerwanderung" zu tun." ("one thing is clear: according to the Egyptian texts, we are not dealing here with a 'Völkerwanderung' [migration of peoples as in 4th–6th-century Europe].") Thus the migration hypothesis is based not on the inscriptions themselves but on their interpretation.

In an effort to wipe out all memory of the bond between the Jews and the land, Hadrian changed the name of the province from Judaea to Syria-Palestina, a name that became common in non-Jewish literature.

It seems clear that by choosing a seemingly neutral name – one juxtaposing that of a neighboring province with the revived name of an ancient geographical entity (Palestine), already known from the writings of Herodotus – Hadrian was intending to suppress any connection between the Jewish people and that land.

That year, Al-Karmil was founded in Haifa 'with the purpose of opposing Zionist colonization...' and in 1911, Falastin began publication, referring to its readers, for the first time, as 'Palestinians'.

As befitted its name, Falastin regularly discussed questions to do with Palestine as if it were a distinct entity and, in writing against the Zionists, addressed its readers as 'Palestinians'.

In this sense, the emergence of ancient Israel is viewed not as the cause of the demise of Canaanite culture but as its upshot.

Despite the long regnant model that the Canaanites and Israelites were people of fundamentally different culture, archaeological data now casts doubt on this view. The material culture of the region exhibits numerous common points between Israelites and Canaanites in the Iron I period (c. 1200–1000 BCE). The record would suggest that the Israelite culture largely overlapped with and derived from Canaanite culture... In short, Israelite culture was largely Canaanite in nature. Given the information available, one cannot maintain a radical cultural separation between Canaanites and Israelites for the Iron I period.

The emergence of a second Jewish population peak can be posited toward the time of the construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem during the Hasmonean period (3rd-2nd century B.C.E.). This new peak, variously estimated, and here cautiously put at around 4.5 million people during the first century B.C.E.