Baltimore [a] es la ciudad más poblada del estado estadounidense de Maryland . Con una población de 585.708 habitantes en el censo de 2020 , es la 30.ª ciudad más poblada de Estados Unidos . [15] Baltimore fue designada ciudad independiente por la Constitución de Maryland [b] en 1851, y es la ciudad independiente más poblada de la nación. En 2020 [update], la población del área metropolitana de Baltimore era de 2.838.327 habitantes, la vigésima área metropolitana más grande del país. [16] Cuando se combina el área estadística combinada (CSA) de Washington-Baltimore tenía una población en 2020 de 9.973.383 habitantes, la tercera más grande del país. [16] Aunque la ciudad no está ubicada dentro o bajo la jurisdicción administrativa de ningún condado del estado, es parte de la región central de Maryland, junto con el condado circundante que comparte su nombre .

La tierra que hoy es Baltimore fue utilizada como terreno de caza por los paleoindios . A principios del siglo XVII, los susquehannock comenzaron a cazar allí. [17] La gente de la provincia de Maryland estableció el puerto de Baltimore en 1706 para apoyar el comercio de tabaco con Europa, y estableció la ciudad de Baltimore en 1729. Durante la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos , el Segundo Congreso Continental , huyendo de Filadelfia antes de su caída ante las tropas británicas , trasladó sus deliberaciones a Henry Fite House en West Baltimore Street desde diciembre de 1776 hasta febrero de 1777, lo que permitió que Baltimore sirviera brevemente como capital de la nación , antes de regresar a Filadelfia en marzo de 1777. La batalla de Baltimore fue fundamental durante la guerra de 1812 , que culminó con el fallido bombardeo británico de Fort McHenry , durante el cual Francis Scott Key escribió un poema que se convertiría en " The Star-Spangled Banner ", designado como himno nacional en 1931. [18] Durante el motín de Pratt Street de 1861 , la ciudad fue el escenario de algunos de los primeros actos de violencia asociados con la Guerra Civil estadounidense .

El ferrocarril de Baltimore y Ohio , el más antiguo del país, se construyó en 1830 y consolidó el estatus de Baltimore como centro de transporte, brindando a los productores del Medio Oeste y los Apalaches acceso al puerto de la ciudad . El Inner Harbor de Baltimore fue el segundo puerto de entrada principal para los inmigrantes a los EE. UU. y un importante centro manufacturero . [19] Después de un declive en la industria manufacturera importante, la industria pesada y la reestructuración de la industria ferroviaria , Baltimore ha cambiado a una economía orientada a los servicios . El Hospital y la Universidad Johns Hopkins son los principales empleadores. [20] Baltimore es el hogar de los Baltimore Orioles de las Grandes Ligas de Béisbol y los Baltimore Ravens de la Liga Nacional de Fútbol .

Muchos barrios de Baltimore tienen una rica historia. La ciudad alberga algunos de los primeros distritos históricos del Registro Nacional del país, incluidos Fell's Point , Federal Hill y Mount Vernon . Baltimore tiene más estatuas y monumentos públicos per cápita que cualquier otra ciudad del país. [21] Casi un tercio de los edificios (más de 65 000) están designados como históricos en el Registro Nacional , más que cualquier otra ciudad de EE. UU. [22] [23] Baltimore tiene 66 distritos históricos del Registro Nacional y 33 distritos históricos locales. [22] Los registros históricos del gobierno de Baltimore se encuentran en los Archivos de la Ciudad de Baltimore .

El área de Baltimore había estado habitada por nativos americanos desde al menos el décimo milenio a. C. , cuando los paleoindios se establecieron por primera vez en la región. [24] Se han identificado un sitio paleoindio y varios sitios arqueológicos del período Arcaico y del período Woodland en Baltimore, incluidos cuatro del período Woodland tardío . [24] En diciembre de 2021, se encontraron varios artefactos nativos americanos del período Woodland en Herring Run Park en el noreste de Baltimore, que datan de hace entre 5000 y 9000 años. El hallazgo siguió a un período de inactividad en los hallazgos arqueológicos de la ciudad de Baltimore que había persistido desde la década de 1980. [25] Durante el período Woodland tardío, la cultura arqueológica conocida como el complejo Potomac Creek residió en el área desde Baltimore al sur hasta el río Rappahannock en la actual Virginia . [26]

La ciudad debe su nombre a Cecil Calvert, segundo barón de Baltimore , [27] un noble inglés, miembro de la Cámara de los Lores irlandesa y propietario fundador de la provincia de Maryland . [28] [29] Los Calvert tomaron el título de barones de Baltimore de Baltimore Manor , una finca de plantación inglesa que se les concedió en el condado de Longford , Irlanda . [29] [30] Baltimore es una anglicización del nombre irlandés Baile an Tí Mhóir , que significa "ciudad de la casa grande". [29]

A principios del siglo XVII, la zona inmediata de Baltimore estaba escasamente poblada, si es que había alguna, por nativos americanos. El área del condado de Baltimore al norte era utilizada como terreno de caza por los susquehannock que vivían en el valle inferior del río Susquehanna . Este pueblo de habla iroquesa "controlaba todos los afluentes superiores del Chesapeake", pero "se abstenía de mucho contacto con los powhatan en la región del Potomac " y al sur de Virginia. [31] Presionada por los susquehannock, la tribu piscataway , un pueblo de habla algonquina , se quedó bastante al sur del área de Baltimore y habitó principalmente la orilla norte del río Potomac en lo que ahora son los condados de Charles y Prince George del sur en las áreas costeras al sur de Fall Line . [32] [33] [34]

La colonización europea de Maryland comenzó en serio con la llegada del barco mercante The Ark que transportaba a 140 colonos a la isla de San Clemente en el río Potomac el 25 de marzo de 1634. [35] Luego, los europeos comenzaron a establecerse en el área más al norte, en lo que ahora es el condado de Baltimore . [36] Dado que Maryland era una colonia, las calles de Baltimore recibieron nombres para mostrar lealtad a la madre patria, por ejemplo, las calles King, Queen, King George y Caroline. [37] La sede original del condado , conocida hoy como Old Baltimore, estaba ubicada en Bush River dentro del actual Aberdeen Proving Ground . [38] [39] [40] Los colonos participaron en guerras esporádicas con los susquehannock, cuyo número disminuyó principalmente debido a nuevas enfermedades infecciosas, como la viruela , endémica entre los europeos. [36] En 1661, David Jones reclamó el área conocida hoy como Jonestown en la orilla este del arroyo Jones Falls . [41]

La Asamblea General colonial de Maryland creó el puerto de Baltimore en el antiguo Whetstone Point, ahora Locust Point , en 1706 para el comercio del tabaco . La ciudad de Baltimore, en el lado oeste de las cataratas Jones, se fundó el 8 de agosto de 1729, cuando el gobernador de Maryland firmó una ley que permitía "la construcción de una ciudad en el lado norte del río Patapsco". Los topógrafos comenzaron a trazar el trazado de la ciudad el 12 de enero de 1730. En 1752, la ciudad tenía solo 27 casas, incluida una iglesia y dos tabernas. [37] Jonestown y Fells Point se habían establecido al este. Los tres asentamientos, que cubrían 60 acres (24 ha), se convirtieron en un centro comercial y en 1768 fueron designados como sede del condado. [42]

La primera imprenta fue introducida en la ciudad en 1765 por Nicholas Hasselbach , cuyo equipo se utilizó más tarde en la impresión de los primeros periódicos de Baltimore, The Maryland Journal y The Baltimore Advertiser , publicados por primera vez por William Goddard en 1773. [43] [44] [45]

Baltimore creció rápidamente en el siglo XVIII, sus plantaciones producían granos y tabaco para las colonias productoras de azúcar del Caribe . Las ganancias provenientes del azúcar fomentaron el cultivo de caña en el Caribe y la importación de alimentos por parte de los plantadores de la zona. [46] Como Baltimore era la sede del condado, en 1768 se construyó un palacio de justicia para servir tanto a la ciudad como al condado. Su plaza era un centro de reuniones y debates comunitarios.

Baltimore estableció su sistema de mercado público en 1763. [47] El mercado de Lexington , fundado en 1782, es uno de los mercados públicos más antiguos que siguen funcionando de forma continua en los Estados Unidos en la actualidad. [48] El mercado de Lexington también fue un centro de tráfico de esclavos. Los esclavos negros eran vendidos en numerosos sitios del centro de la ciudad, y las ventas se anunciaban en The Baltimore Sun. [ 49] Tanto el tabaco como la caña de azúcar eran cultivos que requerían mucha mano de obra.

En 1774, Baltimore estableció el primer sistema de correos en lo que luego sería Estados Unidos, [50] y la primera compañía de agua autorizada en la nación recién independizada, Baltimore Water Company, en 1792. [51] [52]

Baltimore desempeñó un papel importante en la Revolución estadounidense . Los líderes de la ciudad, como Jonathan Plowman Jr., llevaron a muchos residentes a resistirse a los impuestos británicos y los comerciantes firmaron acuerdos en los que se negaban a comerciar con Gran Bretaña. [53] El Segundo Congreso Continental se reunió en la Casa Henry Fite desde diciembre de 1776 hasta febrero de 1777, convirtiendo a la ciudad en la capital de los Estados Unidos durante este período. [54]

Baltimore, Jonestown y Fells Point se incorporaron como la ciudad de Baltimore en 1796-1797.

La ciudad siguió siendo parte del condado circundante de Baltimore y continuó sirviendo como su sede desde 1768 hasta 1851, después de lo cual se convirtió en una ciudad independiente . [57]

La batalla de Baltimore contra los británicos en 1814 inspiró el himno nacional de los Estados Unidos, " The Star-Spangled Banner ", y la construcción del Monumento a la Batalla , que se convirtió en el emblema oficial de la ciudad. Comenzó a tomar forma una cultura local distintiva y se desarrolló un horizonte único salpicado de iglesias y monumentos. Baltimore adquirió su apodo de "La ciudad monumental" después de una visita a Baltimore en 1827 por parte del presidente John Quincy Adams . En una función vespertina, Adams dio el siguiente brindis: "Baltimore: la ciudad monumental. Que los días de su seguridad sean tan prósperos y felices como los días de sus peligros han sido difíciles y triunfantes". [58] [59]

Baltimore fue pionera en el uso de iluminación a gas en 1816, y su población creció rápidamente en las décadas siguientes, con el desarrollo concomitante de la cultura y la infraestructura. La construcción de la Carretera Nacional financiada por el gobierno federal , que más tarde se convirtió en parte de la Ruta 40 de EE. UU. , y el ferrocarril privado Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B. & O.) hicieron de Baltimore un importante centro de transporte y fabricación al conectar la ciudad con los principales mercados del Medio Oeste . En 1820, su población había alcanzado los 60.000 habitantes y su economía había pasado de basarse en las plantaciones de tabaco al aserradero , la construcción naval y la producción textil . Estas industrias se beneficiaron de la guerra, pero se trasladaron con éxito al desarrollo de infraestructuras durante los tiempos de paz. [60]

Baltimore tuvo uno de los peores disturbios del Sur antes de la guerra en 1835, cuando las malas inversiones llevaron al motín bancario de Baltimore . [61] Fueron estos disturbios los que llevaron a que la ciudad fuera apodada "Mobtown". [62] Poco después, la ciudad creó la primera facultad de odontología del mundo, el Baltimore College of Dental Surgery , en 1840, y compartió la primera línea telegráfica del mundo , entre Baltimore y Washington, DC , en 1844.

Maryland, un estado esclavista con un apoyo popular limitado a la secesión , especialmente en los tres condados del sur de Maryland, siguió siendo parte de la Unión durante la Guerra Civil estadounidense , tras la votación de 55 a 12 de la Asamblea General de Maryland contra la secesión. Más tarde, la ocupación estratégica de la ciudad por parte de la Unión en 1861 aseguró que Maryland no volvería a considerar la secesión. [63] [64] La capital de la Unión, Washington, DC, estaba bien situada para impedir la comunicación o el comercio de Baltimore y Maryland con la Confederación . Baltimore experimentó algunas de las primeras bajas de la Guerra Civil el 19 de abril de 1861, cuando los soldados del Ejército de la Unión en ruta desde la estación de President Street a Camden Yards se enfrentaron con una turba secesionista en el motín de Pratt Street .

En medio de la Larga Depresión que siguió al Pánico de 1873 , la compañía de ferrocarril de Baltimore y Ohio intentó reducir los salarios de sus trabajadores, lo que provocó huelgas y disturbios en la ciudad y más allá . Los huelguistas se enfrentaron a la Guardia Nacional , dejando 10 muertos y 25 heridos. [65] Los inicios del trabajo del movimiento de asentamiento en Baltimore se hicieron a principios de 1893, cuando el reverendo Edward A. Lawrence se alojó con su amigo Frank Thompson, en una de las viviendas de los Winans , estableciéndose poco después la Casa Lawrence en 814-816 West Lombard Street. [66] [67]

El 7 de febrero de 1904, el Gran Incendio de Baltimore destruyó más de 1.500 edificios en 30 horas, y dejó más de 70 manzanas del centro de la ciudad calcinadas. Los daños se estimaron en 150 millones de dólares de 1904. [68] A medida que la ciudad se reconstruía durante los dos años siguientes, las lecciones aprendidas del incendio llevaron a mejoras en los estándares de los equipos de extinción de incendios. [69]

El abogado de Baltimore Milton Dashiell abogó por una ordenanza que prohibiera a los afroamericanos mudarse al barrio de Eutaw Place en el noroeste de Baltimore. Propuso reconocer los bloques residenciales de mayoría blanca y los bloques residenciales de mayoría negra y evitar que la gente se mudara a viviendas en dichos bloques donde serían una minoría. El Consejo de Baltimore aprobó la ordenanza y se convirtió en ley el 20 de diciembre de 1910, con la firma del alcalde demócrata J. Barry Mahool . [70] La ordenanza de segregación de Baltimore fue la primera de su tipo en los Estados Unidos. Muchas otras ciudades del sur siguieron con sus propias ordenanzas de segregación, aunque la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos falló en contra de ellas en Buchanan v. Warley (1917). [71]

La ciudad creció en área mediante la anexión de nuevos suburbios de los condados circundantes hasta 1918, cuando la ciudad adquirió partes del condado de Baltimore y el condado de Anne Arundel . [72] Una enmienda constitucional estatal, aprobada en 1948, requirió una votación especial de los ciudadanos en cualquier área de anexión propuesta, previniendo efectivamente cualquier expansión futura de los límites de la ciudad. [73] Los tranvías permitieron el desarrollo de áreas de vecindarios distantes como Edmonson Village, cuyos residentes podían viajar fácilmente al trabajo en el centro. [74]

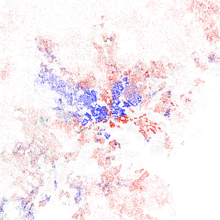

Impulsada por la migración desde el sur profundo y por la suburbanización blanca , el tamaño relativo de la población negra de la ciudad creció del 23,8% en 1950 al 46,4% en 1970. [75] Alentadas por las técnicas de destrucción de terrenos , las áreas blancas recientemente pobladas rápidamente se convirtieron en barrios totalmente negros, en un proceso rápido que fue casi total en 1970. [76]

El motín de Baltimore de 1968 , que coincidió con levantamientos en otras ciudades , siguió al asesinato de Martin Luther King Jr. el 4 de abril de 1968. El orden público no se restableció hasta el 12 de abril de 1968. El levantamiento de Baltimore le costó a la ciudad unos 10 millones de dólares (88 millones de dólares estadounidenses en 2024). Se ordenó el envío de un total de 12.000 soldados de la Guardia Nacional de Maryland y tropas federales a la ciudad. [77] La ciudad experimentó desafíos nuevamente en 1974 cuando maestros, trabajadores municipales y oficiales de policía realizaron huelgas. [78]

A principios de la década de 1970, el centro de Baltimore, conocido como Inner Harbor, había sido descuidado y estaba ocupado por una colección de almacenes abandonados. El apodo de "Charm City" surgió de una reunión de anunciantes de 1975 que buscaban mejorar la reputación de la ciudad. [79] [80] Los esfuerzos para reurbanizar el área comenzaron con la construcción del Centro de Ciencias de Maryland , que se inauguró en 1976, el Baltimore World Trade Center (1977) y el Centro de Convenciones de Baltimore (1979). Harborplace , un complejo urbano de venta minorista y restaurantes, abrió sus puertas en la costa en 1980, seguido por el Acuario Nacional , el destino turístico más grande de Maryland, y el Museo de Industria de Baltimore en 1981. En 1995, la ciudad abrió el Museo de Arte Visionario Americano en Federal Hill. Durante la epidemia de VIH/SIDA en los Estados Unidos , el funcionario del Departamento de Salud de la Ciudad de Baltimore, Robert Mehl, persuadió al alcalde de la ciudad para que formara un comité para abordar los problemas alimentarios. La organización benéfica Moveable Feast, con sede en Baltimore, surgió de esta iniciativa en 1990. [81] [82] [83]

En 1992, el equipo de béisbol Baltimore Orioles se mudó del Memorial Stadium al Oriole Park en Camden Yards , ubicado en el centro de la ciudad cerca del puerto. El Papa Juan Pablo II celebró una misa al aire libre en Camden Yards durante su visita papal a los Estados Unidos en octubre de 1995. Tres años después, el equipo de fútbol Baltimore Ravens se mudó al M&T Bank Stadium junto a Camden Yards. [84]

Baltimore ha tenido una alta tasa de homicidios durante varias décadas, alcanzando su pico máximo en 1993 y nuevamente en 2015. [85] [86] Estas muertes han tenido un costo especialmente severo dentro de la comunidad negra. [87] Después de la muerte de Freddie Gray en abril de 2015, la ciudad experimentó grandes protestas y atención de los medios internacionales, así como un enfrentamiento entre jóvenes locales y la policía que resultó en una declaración de estado de emergencia y un toque de queda. [88]

Baltimore ha visto la reapertura del Teatro Hippodrome en 2004, [89] la apertura del Museo Reginald F. Lewis de Historia y Cultura Afroamericana de Maryland en 2005, y el establecimiento del Museo Nacional Eslavo en 2012. El 12 de abril de 2012, Johns Hopkins celebró una ceremonia de dedicación para marcar la finalización de uno de los complejos médicos más grandes de los Estados Unidos, el Hospital Johns Hopkins en Baltimore, que cuenta con la Torre de Cuidados Intensivos y Cardiovasculares Sheikh Zayed y el Centro Infantil Charlotte R. Bloomberg. El evento, celebrado en la entrada de la instalación de 1,6 millones de pies cuadrados de 1.100 millones de dólares, honró a los numerosos donantes, incluido el jeque Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan , primer presidente de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos , y Michael Bloomberg . [90] [91]

En septiembre de 2016, el Ayuntamiento de Baltimore aprobó un acuerdo de emisión de bonos por 660 millones de dólares para el proyecto de reurbanización de Port Covington , valorado en 5500 millones de dólares y promovido por el fundador de Under Armour, Kevin Plank, y su empresa inmobiliaria Sagamore Development. Port Covington superó al proyecto de Harbor Point como el mayor acuerdo de financiación con incremento de impuestos en la historia de Baltimore y uno de los proyectos de reurbanización urbana más grandes del país. [92] Se prevé que el desarrollo de la zona costera, que incluye la nueva sede de Under Armour, así como tiendas, viviendas, oficinas y espacios de fabricación, cree 26 500 puestos de trabajo permanentes con un impacto económico anual de 4300 millones de dólares. [93] Goldman Sachs invirtió 233 millones de dólares en el proyecto de reurbanización. [94]

.jpg/440px-Wreckage_from_Key_Bridge_Collapse_(240326-A-SE916-9511).jpg)

En las primeras horas del 26 de marzo de 2024, el puente Francis Scott Key de 2,6 km de largo de la ciudad , que constituía una parte sureste de la Baltimore Beltway , fue golpeado por un barco portacontenedores y se derrumbó por completo . Se lanzó una importante operación de rescate con las autoridades estadounidenses intentando rescatar a las personas en el agua. [95] Ocho trabajadores de la construcción, que estaban trabajando en el puente en ese momento, cayeron al río Patapsco . [96] Dos personas fueron rescatadas del agua, [97] y los cuerpos de las seis restantes fueron encontrados el 7 de mayo. [98] El reemplazo del puente se estimó en mayo de 2024 a un costo cercano a los $ 2 mil millones para una finalización en el otoño de 2028. [99]

Baltimore se encuentra en el centro-norte de Maryland, sobre el río Patapsco , cerca de su desembocadura en la bahía de Chesapeake . La ciudad está situada en la línea de caída entre la meseta de Piedmont y la llanura costera del Atlántico , que divide a Baltimore en "ciudad baja" y "ciudad alta". La elevación de la ciudad varía desde el nivel del mar en el puerto hasta los 480 pies (150 m) en la esquina noroeste cerca de Pimlico . [6]

Según el censo de 2010, la ciudad tiene una superficie total de 239 km² (92,1 millas cuadradas ) , de las cuales 210 km² (80,9 millas cuadradas ) son tierra y 29 km² (11,1 millas cuadradas ) son agua. [100] La superficie total es 12,1 por ciento agua.

Baltimore está prácticamente rodeada por el condado de Baltimore, pero es políticamente independiente de él. Limita al sur con el condado de Anne Arundel .

Baltimore exhibe ejemplos de cada período de la arquitectura a lo largo de más de dos siglos, y obras de arquitectos como Benjamin Latrobe , George A. Frederick , John Russell Pope , Mies van der Rohe e IM Pei .

Baltimore es una ciudad rica en edificios de gran importancia arquitectónica de distintos estilos. La Basílica de Baltimore (1806-1821) es un diseño neoclásico de Benjamin Latrobe y una de las catedrales católicas más antiguas de los Estados Unidos. En 1813, Robert Cary Long Sr. construyó para Rembrandt Peale la primera estructura importante de los Estados Unidos diseñada expresamente como museo. Restaurada, ahora es el Museo Municipal de Baltimore, o popularmente conocido como el Museo Peale .

La Escuela Libre McKim fue fundada y dotada por John McKim. El edificio fue construido por su hijo Isaac en 1822 según un diseño de William Howard y William Small. Refleja el interés popular por Grecia cuando la nación estaba asegurando su independencia y un interés académico por los dibujos recientemente publicados de las antigüedades atenienses.

La Torre Phoenix Shot (1828), de 71,40 m de altura, fue el edificio más alto de los Estados Unidos hasta la época de la Guerra Civil y es una de las pocas estructuras de este tipo que quedan. [101] Se construyó sin el uso de andamios exteriores. El Sun Iron Building, diseñado por RC Hatfield en 1851, fue el primer edificio con fachada de hierro de la ciudad y fue un modelo para toda una generación de edificios del centro de la ciudad. La Iglesia Presbiteriana Brown Memorial , construida en 1870 en memoria del financiero George Brown , tiene vidrieras de Louis Comfort Tiffany y ha sido llamada "uno de los edificios más importantes de esta ciudad, un tesoro de arte y arquitectura" por la revista Baltimore . [102] [103]

La sinagoga de Lloyd Street, de estilo neogriego , construida en 1845, es una de las sinagogas más antiguas de los Estados Unidos . El hospital Johns Hopkins , diseñado por el teniente coronel John S. Billings en 1876, fue un logro considerable para su época en cuanto a disposición funcional y protección contra incendios.

El World Trade Center de I. M. Pei (1977) es el edificio pentagonal equilátero más alto del mundo, con 123 m (405 pies) de altura.

En el área de Harbor East se han agregado dos nuevas torres cuya construcción ha finalizado: una torre de 24 pisos que es la nueva sede mundial de Legg Mason y un complejo hotelero Four Seasons de 21 pisos.

Las calles de Baltimore están organizadas en un patrón de cuadrícula y radios, alineadas con decenas de miles de casas adosadas . La mezcla de materiales en la fachada de estas casas adosadas también le da a Baltimore su aspecto distintivo. Las casas adosadas son una mezcla de revestimientos de ladrillo y piedra de forma, esta última una tecnología patentada en 1937 por Albert Knight. John Waters caracterizó la piedra de forma como "el poliéster del ladrillo" en un documental de 30 minutos, Little Castles: A Formstone Phenomenon . [104] En The Baltimore Rowhouse , Mary Ellen Hayward y Charles Belfoure consideraron la casa adosada como la forma arquitectónica que define a Baltimore como "quizás ninguna otra ciudad estadounidense". [105] A mediados de la década de 1790, los desarrolladores comenzaron a construir barrios enteros de casas adosadas de estilo británico, que se convirtieron en el tipo de casa dominante de la ciudad a principios del siglo XIX. [106]

Oriole Park at Camden Yards es un parque de béisbol de las Grandes Ligas , que abrió sus puertas en 1992 y fue construido como un parque de béisbol de estilo retro . Junto con el Acuario Nacional, Camden Yards ha ayudado a revitalizar el área de Inner Harbor, que antes era un distrito exclusivamente industrial lleno de almacenes en ruinas, y se ha convertido en un distrito comercial animado lleno de bares, restaurantes y establecimientos minoristas.

Tras un concurso internacional, la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de Baltimore otorgó el primer premio a la firma alemana Behnisch Architekten por su diseño, que fue seleccionado para la nueva sede de la facultad. Tras la inauguración del edificio en 2013, el diseño ganó otros honores, incluido el premio ENR National "Best of the Best". [107]

El recientemente rehabilitado Teatro Everyman de Baltimore fue galardonado por Baltimore Heritage en la Celebración de Premios a la Preservación de 2013. El Teatro Everyman recibirá un Premio a la Reutilización Adaptativa y al Diseño Compatible como parte de la ceremonia de premios a la preservación histórica de 2013 de Baltimore Heritage. Baltimore Heritage es la organización sin fines de lucro de Baltimore dedicada a la preservación histórica y arquitectónica, que trabaja para preservar y promover los edificios y vecindarios históricos de Baltimore. [108]

Baltimore está dividido oficialmente en nueve regiones geográficas: Norte, Noreste, Este, Sureste, Sur, Suroeste, Oeste, Noroeste y Central, y cada distrito es patrullado por un respectivo Departamento de Policía de Baltimore . La Interestatal 83 y Charles Street hasta Hanover Street y Ritchie Highway sirven como línea divisoria este-oeste y Eastern Avenue hasta la Ruta 40 como línea divisoria norte-sur; sin embargo, Baltimore Street es la línea divisoria norte-sur para el Servicio Postal de los Estados Unidos . [120]

El centro de Baltimore, originalmente llamado Middle District, [121] se extiende al norte del Inner Harbor hasta el borde del parque Druid Hill . El centro de Baltimore ha servido principalmente como un distrito comercial con oportunidades residenciales limitadas; sin embargo, entre 2000 y 2010, la población del centro creció un 130 por ciento a medida que las antiguas propiedades comerciales fueron reemplazadas por propiedades residenciales. [122] Sigue siendo la principal zona comercial y distrito de negocios de la ciudad, incluye los complejos deportivos de Baltimore: Oriole Park en Camden Yards , M&T Bank Stadium y Royal Farms Arena ; y las tiendas y atracciones en el Inner Harbor: Harborplace , el Centro de Convenciones de Baltimore , el Acuario Nacional , el Centro de Ciencias de Maryland , Pier Six Pavilion y Power Plant Live . [120]

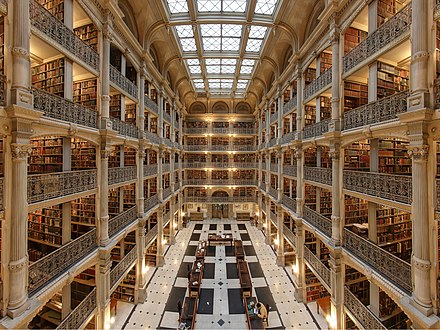

La Universidad de Maryland, Baltimore , el Centro Médico de la Universidad de Maryland y el Mercado de Lexington también se encuentran en el distrito central, así como el Hipódromo y muchos clubes nocturnos, bares, restaurantes, centros comerciales y varias otras atracciones. [120] [121] La parte norte de Central Baltimore, entre el centro y el parque Druid Hill, alberga muchas de las oportunidades culturales de la ciudad. Maryland Institute College of Art , el Peabody Institute (conservatorio de música), George Peabody Library , Enoch Pratt Free Library – Central Library, la Lyric Opera House , el Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall , el Walters Art Museum , el Maryland Center for History and Culture y su Enoch Pratt Mansion, y varias galerías se encuentran en esta región. [123]

En este distrito se encuentran varios barrios históricos y notables: Govans (1755), Roland Park (1891), Guilford (1913), Homeland (1924), Hampden , Woodberry , Old Goucher (el campus original de Goucher College ) y Jones Falls . A lo largo del corredor de York Road en dirección norte se encuentran los grandes barrios de Charles Village , Waverly y Mount Washington . El distrito de arte y entretenimiento Station North también se encuentra en North Baltimore. [124]

El sur de Baltimore, una zona mixta industrial y residencial, está formada por la península "Old South Baltimore" debajo del Inner Harbor y al este de las vías de la antigua línea Camden del ferrocarril B&O y la calle Russell en el centro de la ciudad. Es una zona costera con diversidad cultural, étnica y socioeconómica, con barrios como Locust Point y Riverside alrededor de un gran parque del mismo nombre. [125] Justo al sur del Inner Harbor, el histórico barrio de Federal Hill , es el hogar de muchos profesionales, pubs y restaurantes. Al final de la península se encuentra el histórico Fort McHenry , un parque nacional desde el final de la Primera Guerra Mundial, cuando se derribó el antiguo hospital del ejército de los EE. UU. que rodeaba las almenas en forma de estrella de 1798. [126]

Al otro lado del puente de Hanover Street hay zonas residenciales como Cherry Hill . [127]

Northeast es principalmente un barrio residencial, hogar de la Universidad Estatal Morgan , delimitada por la línea de la ciudad de 1919 en sus límites norte y este, Sinclair Lane , Erdman Avenue y Pulaski Highway al sur y The Alameda al oeste. También en esta cuña de la ciudad en la calle 33 se encuentra la escuela secundaria Baltimore City College , la tercera escuela secundaria pública activa más antigua de los Estados Unidos, fundada en el centro de la ciudad en 1839. [128] Al otro lado de Loch Raven Boulevard se encuentra el antiguo sitio del antiguo Memorial Stadium, sede de los Baltimore Colts , Baltimore Orioles y Baltimore Ravens , ahora reemplazado por un complejo deportivo y de viviendas de la YMCA . [129] [130] Lake Montebello se encuentra en el noreste de Baltimore. [121]

Ubicado debajo de Sinclair Lane y Erdman Avenue , sobre Orleans Street , East Baltimore está compuesto principalmente por barrios residenciales. Esta sección de East Baltimore alberga el Hospital Johns Hopkins , la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Johns Hopkins y el Centro Infantil Johns Hopkins en Broadway . Los barrios notables incluyen: Armistead Gardens , Broadway East , Barclay , Ellwood Park , Greenmount y McElderry Park . [121]

Esta área fue el lugar de rodaje de Homicide: Life on the Street , The Corner y The Wire . [131]

El sureste de Baltimore, ubicado debajo de Fayette Street , bordeando el Inner Harbor y la rama noroeste del río Patapsco al oeste, la línea de la ciudad de 1919 en sus límites orientales y el río Patapsco al sur, es un área industrial y residencial mixta. Patterson Park , el "mejor patio trasero de Baltimore", [132] así como el Highlandtown Arts District y el Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center se encuentran en el sureste de Baltimore. The Shops at Canton Crossing abrió en 2013. [133] El vecindario de Canton , está ubicado a lo largo de la principal costa de Baltimore. Otros vecindarios históricos incluyen: Fells Point , Patterson Park , Butchers Hill , Highlandtown , Greektown , Harbor East , Little Italy y Upper Fell's Point . [121]

Northwestern está delimitada por la línea del condado al norte y al oeste, Gwynns Falls Parkway al sur y Pimlico Road al este, es el hogar del hipódromo de Pimlico , el Hospital Sinai y la sede de la NAACP . Sus vecindarios son en su mayoría residenciales y están atravesados por Northern Parkway . El área ha sido el centro de la comunidad judía de Baltimore desde después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Los vecindarios notables incluyen: Pimlico , Mount Washington , Cheswolde y Park Heights . [134]

West Baltimore se encuentra al oeste del centro de la ciudad y del bulevar Martin Luther King Jr. y está delimitado por Gwynns Falls Parkway, Fremont Avenue y West Baltimore Street . El distrito histórico Old West Baltimore incluye los barrios de Harlem Park , Sandtown-Winchester , Druid Heights , Madison Park y Upton . [135] [136] Originalmente un barrio predominantemente alemán, en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, Old West Baltimore albergaba a una parte importante de la población negra de la ciudad. [135]

Se convirtió en el barrio más grande para la comunidad negra de la ciudad y su centro cultural, político y económico. [135] La Universidad Estatal de Coppin , el centro comercial Mondawmin y Edmondson Village se encuentran en este distrito. Los problemas de delincuencia de la zona han proporcionado material para series de televisión, como The Wire . [137] Las organizaciones locales, como Sandtown Habitat for Humanity y el Comité de Planificación de Upton, han estado transformando de manera constante partes de áreas anteriormente deterioradas de West Baltimore en comunidades limpias y seguras. [138] [139]

El suroeste de Baltimore está delimitado por la línea del condado de Baltimore al oeste, West Baltimore Street al norte y Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard y Russell Street/Baltimore-Washington Parkway (Maryland Route 295) al este. Los barrios notables del suroeste de Baltimore incluyen: Pigtown , Carrollton Ridge , Ridgely's Delight , Leakin Park , Violetville , Lakeland y Morrell Park . [121]

El Hospital St. Agnes en las avenidas Wilkens y Caton [121] está ubicado en este distrito con la vecina Cardinal Gibbons High School , que es el antiguo sitio del alma mater de Babe Ruth , St. Mary's Industrial School. [ cita requerida ] A través de este segmento de Baltimore corrían los inicios de la histórica National Road , que se construyó a partir de 1806 a lo largo de Old Frederick Road y continuó hacia el condado en Frederick Road hasta Ellicott City, Maryland . [ cita requerida ] Otros lados en este distrito son: Carroll Park , uno de los parques más grandes de la ciudad, la mansión colonial Mount Clare y Washington Boulevard , que data de los días anteriores a la Guerra de la Independencia como la ruta principal para salir de la ciudad hacia Alexandria, Virginia , y Georgetown en el río Potomac . [ cita requerida ]

Baltimore limita con las siguientes comunidades, todas ellas lugares designados por el censo no incorporados .

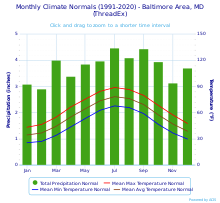

Baltimore tiene un clima subtropical húmedo ( Cfa ) en la clasificación climática de Köppen , con veranos cálidos, inviernos fríos y un pico de precipitación anual en verano. [140] [141] Baltimore es parte de las zonas de rusticidad de plantas del USDA 7b y 8a. [142] Los veranos son normalmente cálidos, con tormentas eléctricas ocasionales al final del día. Julio, el mes más cálido, tiene una temperatura media de 80,3 °F (26,8 °C). Los inviernos varían de fríos a suaves, pero varían, con nevadas esporádicas: enero tiene un promedio diario de 35,8 °F (2,1 °C), [143] aunque las temperaturas alcanzan los 50 °F (10 °C) con bastante frecuencia, y ocasionalmente pueden caer por debajo de los 20 °F (−7 °C) cuando las masas de aire del Ártico afectan el área. [143] Según Vox , los inviernos se están calentando más rápido que los veranos. [141]

La primavera y el otoño son suaves, siendo la primavera la estación más lluviosa en términos de número de días de precipitación. Los veranos son calurosos y húmedos, con una media diaria en julio de 27,1 °C (80,7 °F). [143] La combinación de calor y humedad da lugar a tormentas eléctricas ocasionales. Una brisa de bahía del sudeste procedente de Chesapeake suele producirse en las tardes de verano cuando el aire caliente se eleva sobre las zonas del interior. Los vientos predominantes del suroeste que interactúan con esta brisa, así como con el UHI de la ciudad propiamente dicha, pueden exacerbar gravemente la calidad del aire. [144] [145] A finales del verano y principios del otoño, la trayectoria de los huracanes o sus remanentes puede provocar inundaciones en el centro de Baltimore, a pesar de que la ciudad está muy alejada de las zonas típicas de marejadas ciclónicas costeras . [146]

La nevada estacional media es de 48 cm (19 pulgadas). [147] Varía mucho según el año: en algunas estaciones solo se ven acumulaciones mínimas de nieve, mientras que en otras se ven varias tormentas del noreste importantes . [c] Debido a la isla de calor urbana (UHI) reducida en comparación con la ciudad propiamente dicha y a la distancia de la bahía de Chesapeake, que se modera, las zonas periféricas e interiores del área metropolitana de Baltimore suelen ser más frescas, especialmente por la noche, que la ciudad propiamente dicha y las ciudades costeras. Por lo tanto, en los suburbios del norte y el oeste, las nevadas invernales son más significativas y algunas áreas tienen un promedio de más de 76 cm (30 pulgadas) de nieve por invierno. [149]

No es raro que se forme una línea de lluvia y nieve en el área metropolitana. [150] En algunos inviernos, en la zona se producen lluvias heladas y aguanieve, ya que el aire cálido se impone al aire frío en los niveles bajos y medios de la atmósfera. Cuando el viento sopla desde el este, el aire frío se bloquea contra las montañas del oeste y el resultado es lluvia helada o aguanieve.

Al igual que todo Maryland , Baltimore corre el riesgo de sufrir mayores impactos del cambio climático . Históricamente, las inundaciones han arruinado casas y casi han matado a gente, especialmente en los barrios de ingresos bajos de mayoría negra, y han causado atascos en las aguas residuales, dado el deterioro actual del sistema de agua de Baltimore. [151]

Las temperaturas extremas varían desde -22 °C (-7 °F) el 9 de febrero de 1934 y el 10 de febrero de 1899 , [d] hasta 42 °C (108 °F) el 22 de julio de 2011. [152] [153] En promedio, se producen temperaturas de 38 °C (100 °F) o más durante tres días al año, 32 °C (90 °F) o más durante 43 días, y hay nueve días en los que la máxima no alcanza el punto de congelación. [143]

Ver o editar datos gráficos sin procesar.

Baltimore alcanzó una población máxima de 949.708 en el censo de EE. UU. de 1950. En cada censo de diez años desde entonces, la ciudad ha perdido población, con su población del censo de 2020 en 585.708. En 2011, la entonces alcaldesa Stephanie Rawlings-Blake dijo que uno de sus objetivos era aumentar la población de la ciudad, mejorando los servicios de la ciudad para reducir la cantidad de personas que abandonan la ciudad y aprobando una legislación que protegiera los derechos de los inmigrantes para estimular el crecimiento. [163] Baltimore es identificada como una ciudad santuario . [164] En 2019, el entonces alcalde Jack Young dijo que Baltimore no ayudaría a los agentes de ICE con las redadas de inmigración. [165]

La población de la ciudad de Baltimore disminuyó de 620.961 en 2010 a 585.708 en 2020, lo que representa una caída del 5,7%. En 2020, Baltimore perdió más población que cualquier otra ciudad importante de los Estados Unidos . [166] [7] [167]

La gentrificación ha aumentado desde el censo de 2000, principalmente en el este de Baltimore, el centro y la zona central de Baltimore, con un 14,8% de las áreas censales que han experimentado un crecimiento de los ingresos y una apreciación del valor de las viviendas a un ritmo superior al de la ciudad en general. Muchos de los barrios en proceso de gentrificación, pero no todos, son zonas predominantemente blancas que han experimentado una renovación de los hogares de ingresos bajos a los de ingresos altos. Estas zonas representan la expansión de las zonas gentrificadas existentes o la actividad en torno al Inner Harbor, el centro o el campus de Johns Hopkins Homewood. [168] En algunos barrios del este de Baltimore, la población hispana ha aumentado, mientras que tanto la población blanca no hispana como la población negra no hispana han disminuido. [169]

Después de la ciudad de Nueva York , Baltimore fue la segunda ciudad de los Estados Unidos en alcanzar una población de 100.000 habitantes. [170] [171] Desde los censos de EE. UU. de 1820 a 1850, Baltimore fue la segunda ciudad más poblada, [171] [172] antes de ser superada por Filadelfia y la entonces independiente Brooklyn en 1860, y luego ser superada por San Luis y Chicago en 1870. [173] Baltimore estuvo entre las 10 ciudades con mayor población en los Estados Unidos en todos los censos hasta el de 1980. [174] Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Baltimore tenía una población cercana al millón, hasta que la población comenzó a caer después del censo de 1950.

En el censo de 2010 [update], la población de Baltimore era 63,7% negra , 29,6% blanca (6,9% alemana , 5,8% italiana , 4% irlandesa , 2% estadounidense , 2% polaca , 0,5% griega ), 2,3% asiática (0,54% coreana , 0,46% india , 0,37% china , 0,36% filipina , 0,21% nepalí , 0,16% paquistaní ) y 0,4% nativa americana y nativa de Alaska. Entre las razas, el 4,2% de la población es de origen hispano, latino o español (1,63% salvadoreña , 1,21% mexicana , 0,63% puertorriqueña , 0,6% hondureña ). [15]

Según el censo de 2020, el 8,1% de los residentes entre 2016 y 2020 eran personas nacidas en el extranjero. [175] Las mujeres constituían el 53,4% de la población. La edad media era de 35 años, con un 22,4% de menores de 18 años, un 65,8% de entre 18 y 64 años y un 11,8% de 65 años o más. [15]

Baltimore tiene una gran población caribeña-estadounidense , siendo los grupos más numerosos los jamaiquinos y los trinitenses . La comunidad jamaiquina de Baltimore se concentra principalmente en el barrio de Park Heights , pero generaciones de inmigrantes también han vivido en el sudeste de Baltimore. [181]

En 2005, aproximadamente 30.778 personas (6,5%) se identificaron como homosexuales, lesbianas o bisexuales . [182] En 2012, se legalizó el matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo en Maryland , que entró en vigor el 1 de enero de 2013. [183]

Entre 2016 y 2020, el ingreso familiar promedio fue de $52,164 y el ingreso per cápita promedio fue de $32,699, en comparación con los promedios nacionales de $64,994 y $35,384, respectivamente. [175] En 2009, el ingreso familiar promedio fue de $42,241 y el ingreso per cápita promedio fue de $25,707, en comparación con el ingreso nacional promedio de $53,889 por hogar y $28,930 per cápita. [15]

En 2009, el 23,7% de la población vivía por debajo del umbral de pobreza, en comparación con el 13,5% a nivel nacional. [15] En el censo de 2020, el 20% de los residentes de Baltimore vivían en la pobreza, en comparación con el 11,6% a nivel nacional. [175]

La vivienda en Baltimore es relativamente barata para ciudades grandes y cercanas a la costa de su tamaño. El precio de venta medio de las viviendas en Baltimore en diciembre de 2022 fue de 209.000 dólares, frente a los 95.000 dólares de 2012. [184] [185] A pesar del desplome de los precios de la vivienda a finales de la década de 2000, y junto con las tendencias nacionales, los residentes de Baltimore todavía se enfrentaban a un aumento lento del alquiler, que subió un 3% en el verano de 2010. [186] El valor medio de las unidades de vivienda ocupadas por sus propietarios entre 2016 y 2020 fue de 242.499 dólares. [175]

La población sin hogar de Baltimore está aumentando de forma constante. En 2011 superó las 4.000 personas. El aumento de la cantidad de jóvenes sin hogar fue especialmente grave. [187]

En 2015, la esperanza de vida en Baltimore era de 74 a 75 años, en comparación con el promedio de los EE. UU. de 78 a 80. Catorce vecindarios tenían una esperanza de vida más baja que Corea del Norte . La esperanza de vida en Downtown/Seton Hill era comparable a la de Yemen . [188]

En 2015, el 25% de los adultos en Baltimore no declaró ninguna afiliación religiosa. El 50% de la población adulta de Baltimore son protestantes . [h] El catolicismo es la segunda afiliación religiosa más grande, constituyendo el 15% de la población, seguido por el judaísmo (3%) y el islam (2%). Alrededor del 1% se identifica con otras denominaciones cristianas . [189] [190] [191]

En 2010, el 91% (526.705) de los residentes de Baltimore de cinco años o más hablaban solo inglés en casa. Cerca del 4% (21.661) hablaba español. Otros idiomas, como las lenguas africanas , el francés y el chino, son hablados por menos del 1% de la población. [192]

Baltimore, que en el pasado fue una ciudad predominantemente industrial, con una base económica centrada en el procesamiento de acero, el transporte marítimo, la fabricación de automóviles (General Motors Baltimore Assembly ) y el transporte, experimentó una desindustrialización , que costó a los residentes decenas de miles de empleos de baja cualificación y altos salarios. [193] Baltimore ahora depende de una economía de servicios de bajos salarios , que representa el 31% de los empleos de la ciudad. [194] [195] A principios del siglo XX, Baltimore era el principal fabricante estadounidense de whisky de centeno y sombreros de paja . Lideró la refinación de petróleo crudo, que llegaba a la ciudad por oleoducto desde Pensilvania. [196] [197] [198]

En marzo de 2018, la tasa de desempleo de Baltimore era del 5,8%. [199] En 2012, una cuarta parte de los residentes de Baltimore y el 37% de los niños de Baltimore vivían en la pobreza. [200] Se espera que el cierre en 2012 de una importante planta siderúrgica en Sparrows Point tenga un mayor impacto en el empleo y la economía local. [201] En 2013, 207.000 trabajadores viajaban a la ciudad de Baltimore cada día. [202] El centro de Baltimore es el principal activo económico de la ciudad de Baltimore y la región, con 29,1 millones de pies cuadrados de espacio de oficina. El sector tecnológico está creciendo rápidamente, ya que el área metropolitana de Baltimore ocupa el octavo lugar en el Informe de talento tecnológico de CBRE entre las 50 áreas metropolitanas de EE. UU. por su alta tasa de crecimiento y número de profesionales tecnológicos. [203] En 2013, Forbes clasificó a Baltimore en el cuarto lugar entre los "nuevos puntos calientes tecnológicos" de Estados Unidos. [204]

La ciudad alberga el Hospital Johns Hopkins . Otras grandes empresas de Baltimore son Under Armour , [205] BRT Laboratories , Cordish Company , [206] Legg Mason , McCormick & Company , T. Rowe Price y Royal Farms . [207] Una refinería de azúcar propiedad de American Sugar Refining es uno de los íconos culturales de Baltimore. Las organizaciones sin fines de lucro con sede en Baltimore incluyen Lutheran Services in America y Catholic Relief Services .

A mediados de 2013, casi una cuarta parte de los empleos en la región de Baltimore estaban relacionados con la ciencia, la tecnología, la ingeniería y las matemáticas, un hecho atribuido en parte a las extensas escuelas de pregrado y posgrado de la ciudad; en este recuento se incluyeron expertos en mantenimiento y reparación. [208]

El centro del comercio internacional de la región es el World Trade Center de Baltimore . Alberga la Administración Portuaria de Maryland y las oficinas centrales en EE. UU. de las principales líneas navieras. Baltimore ocupa el noveno lugar en valor total en dólares de carga y el decimotercero en tonelaje de carga para todos los puertos de EE. UU. En 2014, la carga total que se movió a través del puerto totalizó 29,5 millones de toneladas, por debajo de los 30,3 millones de toneladas en 2013. El valor de la carga que pasó por el puerto en 2014 llegó a $52,5 mil millones, por debajo de los $52,6 mil millones en 2013. El Puerto de Baltimore genera $3 mil millones en salarios y sueldos anuales, además de sustentar 14.630 empleos directos y 108.000 empleos relacionados con el trabajo portuario. En 2014, el puerto generó más de $300 millones en impuestos. [209]

El puerto da servicio a más de 50 transportistas marítimos, que realizan cerca de 1.800 visitas anuales. Entre todos los puertos de Estados Unidos, Baltimore es el primero en cuanto a tráfico de automóviles, camiones ligeros, maquinaria agrícola y de construcción, así como de productos forestales importados, aluminio y azúcar. El puerto es el segundo en exportaciones de carbón. La industria de cruceros del puerto de Baltimore, que ofrece viajes durante todo el año en varias líneas, sustenta más de 500 puestos de trabajo y aporta más de 90 millones de dólares anuales a la economía de Maryland. El crecimiento en el puerto continúa con los planes de la Administración del Puerto de Maryland de convertir el extremo sur de la antigua fábrica de acero en una terminal marítima, principalmente para envíos de automóviles y camiones, y para nuevos negocios previstos que llegarán a Baltimore después de la finalización del proyecto de ampliación del Canal de Panamá . [209]

La historia y las atracciones de Baltimore la han convertido en un destino turístico popular. En 2014, la ciudad recibió a 24,5 millones de visitantes, que gastaron 5200 millones de dólares. [210] El Centro de Visitantes de Baltimore, que es operado por Visit Baltimore , está ubicado en Light Street en el Inner Harbor. Gran parte del turismo de la ciudad se centra alrededor del Inner Harbor, y el Acuario Nacional es el principal destino turístico de Maryland. La restauración del puerto de Baltimore lo ha convertido en "una ciudad de barcos", con varios barcos históricos y otras atracciones en exhibición y abiertas al público. El USS Constellation , el último buque de la era de la Guerra Civil a flote, está atracado en la cabecera del Inner Harbor; el USS Torsk , un submarino que tiene el récord de inmersiones de la Armada (más de 10 000); y el guardacostas WHEC-37 , el último buque de guerra estadounidense superviviente que estuvo en Pearl Harbor durante el ataque japonés el 7 de diciembre de 1941, y que se enfrentó a aviones Zero japoneses durante la batalla. [211]

También está atracado el buque faro Chesapeake , que durante décadas marcó la entrada a la bahía de Chesapeake; y el faro Seven Foot Knoll, el faro de pilotes enroscados más antiguo que aún se conserva en la bahía de Chesapeake, que una vez marcó la desembocadura del río Patapsco y la entrada a Baltimore. Todas estas atracciones son propiedad de la organización Historic Ships in Baltimore y están a su cargo . El Inner Harbor también es el puerto base del Pride of Baltimore II , el barco "embajador de buena voluntad" del estado de Maryland, una reconstrucción de un famoso barco Baltimore Clipper . [211]

Otros destinos turísticos incluyen lugares deportivos como Oriole Park en Camden Yards , M&T Bank Stadium y Pimlico Race Course , Fort McHenry , los vecindarios de Mount Vernon , Federal Hill y Fells Point , Lexington Market , Horseshoe Casino y museos como el Museo de Arte Walters , el Museo de Industria de Baltimore , el lugar de nacimiento y museo de Babe Ruth , el Centro de Ciencias de Maryland y el Museo del Ferrocarril B&O .

Baltimore ha sido históricamente una ciudad portuaria de clase trabajadora, a veces llamada "ciudad de barrios". Comprende 72 distritos históricos designados [212] tradicionalmente ocupados por distintos grupos étnicos. Hoy en día, los más notables son tres áreas del centro a lo largo del puerto: el Inner Harbor, frecuentado por turistas debido a sus hoteles, tiendas y museos; Fells Point, que alguna vez fue un lugar de entretenimiento favorito para los marineros, pero que ahora ha sido remodelado y aburguesado (y aparece en la película Sleepless in Seattle ); y Little Italy , ubicada entre las otras dos, donde se encuentra la comunidad italoamericana de Baltimore y donde creció la presidenta de la Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos, Nancy Pelosi .

Further inland, Mount Vernon is the traditional center of cultural and artistic life of the city. It is home to a distinctive Washington Monument, set atop a hill in a 19th-century urban square, that predates the monument in Washington, D.C. by several decades. Baltimore has a significant German American population,[213] and was the second-largest port of immigration to the United States behind Ellis Island in New York and New Jersey. Between 1820 and 1989, almost 2 million who were German, Polish, English, Irish, Russian, Lithuanian, French, Ukrainian, Czech, Greek and Italian came to Baltimore, mostly between 1861 and 1930. By 1913, when Baltimore was averaging forty thousand immigrants per year, World War I closed off the flow of immigrants. By 1970, Baltimore's heyday as an immigration center was a distant memory. There was a Chinatown dating back to at least the 1880s, which consisted of 400 Chinese residents. A local Chinese-American association remains based there, with one Chinese restaurant as of 2009.

Beer making thrived in Baltimore from the 1800s to the 1950s, with over 100 old breweries in the city's past.[214] The best remaining example of that history is the old American Brewery Building on North Gay Street and the National Brewing Company building in the Brewer's Hill neighborhood. In the 1940s the National Brewing Company introduced the nation's first six-pack. National's two most prominent brands, were National Bohemian Beer colloquially "Natty Boh" and Colt 45. Listed on the Pabst website as a "Fun Fact", Colt 45 was named after running back #45 Jerry Hill of the 1963 Baltimore Colts and not the .45 caliber handgun ammunition round. Both brands are still made today, albeit outside of Maryland, and served all around the Baltimore area at bars, as well as Orioles and Ravens games.[215] The Natty Boh logo appears on all cans, bottles, and packaging. Merchandise featuring him can be found in shops in Maryland, including several in Fells Point.

Each year the Artscape takes place in the city in the Bolton Hill neighborhood, close to the Maryland Institute College of Art. Artscape styles itself as the "largest free arts festival in America".[citation needed] Each May, the Maryland Film Festival takes place in Baltimore, using all five screens of the historic Charles Theatre as its anchor venue. Many movies and television shows have been filmed in Baltimore. Homicide: Life on the Street was set and filmed in Baltimore, as well as The Wire. House of Cards and Veep are set in Washington, D.C. but filmed in Baltimore.[216]

Baltimore has cultural museums in many areas of study. The Baltimore Museum of Art and the Walters Art Museum are internationally renowned for their collections of art. The Baltimore Museum of Art has the largest holding of works by Henri Matisse in the world.[217] The American Visionary Art Museum has been designated by Congress as America's national museum for visionary art.[218] The National Great Blacks In Wax Museum is the first African American wax museum in the country, featuring more than 150 life-size and lifelike wax figures.[51]

Baltimore is known for its Maryland blue crabs, crab cake, Old Bay Seasoning, pit beef, and the "chicken box". The city has many restaurants in or around the Inner Harbor. The most known and acclaimed are the Charleston, Woodberry Kitchen, and the Charm City Cakes bakery featured on the Food Network's Ace of Cakes. The Little Italy neighborhood's biggest draw is the food. Fells Point also is a foodie neighborhood for tourists and locals and is where the oldest continuously running tavern in the country, "The Horse You Came in on Saloon", is located.[219]

Many of Baltimore's upscale restaurants are found in Harbor East. Five public markets are located across Baltimore. The Baltimore Public Market System is the oldest continuously operating public market system in the United States.[220] Lexington Market is one of the longest-running markets in the world and the longest running in the country, having been around since 1782. The market continues to stand at its original site. Baltimore is the last place in America where one can still find arabbers, vendors who sell fresh fruits and vegetables from a horse-drawn cart that goes up and down neighborhood streets.[221] Food- and drink-rating site Zagat ranked Baltimore second in a list of the 17 best food cities in the US in 2015.[222]

Baltimore city, along with its surrounding regions, is home to a unique local dialect known as the Baltimore dialect. It is part of the larger Mid-Atlantic American English group and is noted to be very similar to the Philadelphia dialect.[223][224]

The so-called "Bawlmerese" accent is known for its characteristic pronunciation of its long "o" vowel, in which an "eh" sound is added before the long "o" sound (/oʊ/ shifts to [ɘʊ], or even [eʊ]).[225] It adopts Philadelphia's pattern of the short "a" sound, such that the tensed vowel in words like "bath" or "ask" does not match the more relaxed one in "sad" or "act".[223]

Baltimore native John Waters parodies the city and its dialect extensively in his films. Most are filmed in Baltimore, including the 1972 cult classic Pink Flamingos, as well as Hairspray and its Broadway musical remake.

Baltimore has four state-designated arts and entertainment districts: The Pennsylvania Avenue Black Arts and Entertainment District, Station North Arts and Entertainment District, Highlandtown Arts District, and the Bromo Arts & Entertainment District.[226][227][228]

The Baltimore Office of Promotion and The Arts, a non-profit organization, produces events and arts programs as well as managing several facilities. It is the official Baltimore City Arts Council. BOPA coordinates Baltimore's major events, including New Year's Eve and July 4 celebrations at the Inner Harbor, Artscape, which is America's largest free arts festival, Baltimore Book Festival, Baltimore Farmers' Market & Bazaar, School 33 Art Center's Open Studio Tour, and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Parade.[229]

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is an internationally renowned orchestra, founded in 1916 as a publicly funded municipal organization. Its most recent music director was Marin Alsop, a protégé of Leonard Bernstein's. Centerstage is the premier theater company in the city and a regionally well-respected group. The Lyric Opera House is the home of Lyric Opera Baltimore, which operates there as part of the Patricia and Arthur Modell Performing Arts Center. Shriver Hall Concert Series, founded in 1966, presents classical chamber music and recitals featuring nationally and internationally recognized artists.[230]

The Baltimore Consort has been a leading early music ensemble for over twenty-five years. The France-Merrick Performing Arts Center, home of the restored Thomas W. Lamb-designed Hippodrome Theatre, has afforded Baltimore the opportunity to become a major regional player in the area of touring Broadway and other performing arts presentations. Renovating Baltimore's historic theatres has become widespread throughout the city. Renovated theatres include the Everyman, Centre, Senator, and most recently Parkway Theatre. Other buildings have been reused. These include the former Mercantile Deposit and Trust Company bank building, which is now The Chesapeake Shakespeare Company Theater.

Baltimore has a wide array of professional (non-touring) and community theater groups. Aside from Center Stage, resident troupes in the city include The Vagabond Players, the oldest continuously operating community theater group in the country, Everyman Theatre, Single Carrot Theatre, and Baltimore Theatre Festival. Community theaters in the city include Fells Point Community Theatre and the Arena Players Inc., which is the nation's oldest continuously operating African American community theater.[231] In 2009, the Baltimore Rock Opera Society, an all-volunteer theatrical company, launched its first production.[232]

Baltimore is home to the Pride of Baltimore Chorus, a three-time international silver medalist women's chorus, affiliated with Sweet Adelines International. The Maryland State Boychoir is located in the northeastern Baltimore neighborhood of Mayfield.

Baltimore is the home of non-profit chamber music organization Vivre Musicale. VM won a 2011–2012 award for Adventurous Programming from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers and Chamber Music America.[233]

The Peabody Institute, located in the Mount Vernon neighborhood, is the oldest conservatory of music in the United States.[234] Established in 1857, it is one of the most prestigious in the world,[234] along with Juilliard, Eastman, and the Curtis Institute. The Morgan State University Choir is also one of the nation's most prestigious university choral ensembles.[235] The city is home to the Baltimore School for the Arts, a public high school in the Mount Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore. The institution is nationally recognized for its success in preparation for students entering music (vocal/instrumental), theatre (acting/theater production), dance, and visual arts.

In 1981, Baltimore hosted the first International Theater Festival, the first such festival in the country. Executive producer Al Kraizer staged 66 performances of nine shows by international theatre companies, including from Ireland, the United Kingdom, South Africa and Israel.[236] The festival proved to be expensive to mount, and in 1982 the festival was hosted in Denver, called the World Theatre Festival,[237] at the Denver Center for Performing Arts, after the city had asked Kraizer to organize it.[238]

In June 1986, the 20th Theatre of Nations, sponsored by the International Theatre Institute, was held in Baltimore, the first time it had been held in the U.S.[239]

Baltimore has a long and storied baseball history, including its distinction as the birthplace of Babe Ruth in 1895. The original 19th century Baltimore Orioles were one of the most successful early franchises, featuring numerous hall of famers during its years from 1882 to 1899. As one of the eight inaugural American League franchises, the Baltimore Orioles played in the AL during the 1901 and 1902 seasons. The team moved to New York City before the 1903 season and was renamed the New York Highlanders, which later became the New York Yankees. Ruth played for the minor league Baltimore Orioles team, which was active from 1903 to 1914. After playing one season in 1915 as the Richmond Climbers, the team returned the following year to Baltimore, where it played as the Orioles until 1953.[citation needed]

The team currently known as the Baltimore Orioles has represented Major League Baseball locally since 1954 when the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore. The Orioles advanced to the World Series in 1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1979 and 1983, winning three times (1966, 1970 and 1983), while making the playoffs all but one year (1972) from 1969 through 1974.[240]

In 1995, local player (and later Hall of Famer) Cal Ripken Jr. broke Lou Gehrig's streak of 2,130 consecutive games played, for which Ripken was named Sportsman of the Year by Sports Illustrated magazine.[citation needed] Six former Orioles players, including Ripken (2007), and two of the team's managers have been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Since 1992, the Orioles' home ballpark has been Oriole Park at Camden Yards, which has been hailed as one of the league's best since it opened.[241]

Prior to a National Football League team moving to Baltimore, there had been several attempts at a professional football team prior to the 1950s, which were blocked by the Washington team and its NFL friends. Most were minor league or semi-professional teams. The first major league to base a team in Baltimore was the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), which had a team named the Baltimore Colts. The AAFC Colts played for three seasons in the AAFC (1947, 1948, and 1949), and when the AAFC folded following the 1949 season, moved to the NFL for a single year (1950) before going bankrupt.

In 1953, the NFL's Dallas Texans folded. Its assets and player contracts were purchased by an ownership team headed by Baltimore businessman Carroll Rosenbloom, who moved the team to Baltimore, establishing a new team also named the Baltimore Colts. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Colts were one of the NFLs more successful franchises, led by Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Johnny Unitas who set a then-record of 47 consecutive games with a touchdown pass. The Colts advanced to the NFL Championship twice (1958 & 1959) and Super Bowl twice (1969 & 1971), winning all except Super Bowl III in 1969. After the 1983 season, the team left Baltimore for Indianapolis in 1984, where they became the Indianapolis Colts.

The NFL returned to Baltimore when the former Cleveland Browns moved to Baltimore to become the Baltimore Ravens in 1996. Since then, the Ravens won a Super Bowl championship in 2000 and 2012, seven AFC North division championships (2003, 2006, 2011, 2012, 2018, 2019 and 2023), and appeared in five AFC Championship Games (2000, 2008, 2011, 2012 and 2023).[242]

Baltimore also hosted a Canadian Football League franchise, the Baltimore Stallions for the 1994 and 1995 seasons. Following the 1995 season, and ultimate end to the Canadian Football League in the United States experiment, the team was sold and relocated to Montreal.

The first professional sports organization in the United States, The Maryland Jockey Club, was formed in Baltimore in 1743. Preakness Stakes, the second race in the United States Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing, has been held every May at Pimlico Race Course in Baltimore since 1873.

College lacrosse is a common sport in the spring, as the Johns Hopkins Blue Jays men's lacrosse team has won 44 national championships, the most of any program in history. In addition, Loyola University won its first men's NCAA lacrosse championship in 2012.

The Baltimore Blast are a professional arena soccer team that play in the Major Arena Soccer League at the SECU Arena on the campus of Towson University. The Blast have won nine championships in various leagues, including the MASL. A previous entity of the Blast played in the Major Indoor Soccer League from 1980 to 1992, winning one championship. The Baltimore Kings, a Baltimore Blast affiliate,[243] joined MASL 3 in 2021 to begin play in 2022.[244]

FC Baltimore 1729 was a semi-professional soccer club in the NPSL league, with the goal of bringing a community-oriented competitive soccer experience to Baltimore. Their inaugural season started on May 11, 2018, and they played their home games at CCBC Essex Field. Baltimore City F.C. is an Eastern Premier Soccer League club that plays since 2023 at Middle Branch Fitness Center in Cherry Hill.

The Baltimore Blues were a semi-professional rugby league club which began competition in the USA Rugby League in 2012.[245] The Baltimore Bohemians were an American soccer club which competed in the USL Premier Development League, the fourth tier of the American Soccer Pyramid. Their inaugural season started in the spring of 2012.

The Baltimore Grand Prix debuted along the streets of the Inner Harbor section of the city's downtown on September 2–4, 2011. The event played host to the American Le Mans Series on Saturday and the IndyCar Series on Sunday. Support races from smaller series were also held, including Indy Lights. After three consecutive years, on September 13, 2013, it was announced that the event would not be held in 2014 or 2015 due to scheduling conflicts.[246]

The athletic equipment company Under Armour is also based in Baltimore. Founded in 1996 by Kevin Plank, a University of Maryland alumnus, the company's headquarters are located in Tide Point, adjacent to Fort McHenry and the Domino Sugar factory. The Baltimore Marathon is the flagship race of several races. The marathon begins at Camden Yards and travels through many diverse neighborhoods of Baltimore, including the scenic Inner Harbor waterfront area, historic Federal Hill, Fells Point, and Canton, Baltimore. The race then proceeds to other important focal points of the city such as Patterson Park, Clifton Park, Lake Montebello, the Charles Village neighborhood, and the western edge of downtown. After winding through 42.195 kilometres (26.219 mi) of Baltimore, the race ends at virtually the same point at which it starts.

The Baltimore Brigade were an Arena Football League team based in Baltimore that, from 2017 to 2019, played at Royal Farms Arena. In 2019, the team ceased operations along with the rest of the league.

Baltimore has over 4,900 acres (1,983 ha) of parkland.[247] The Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks manages the majority of parks and recreational facilities in the city, including Patterson Park, Federal Hill Park, and Druid Hill Park.[248] The city is home to Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, a coastal star-shaped fort best known for its role in the War of 1812. As of 2015[update], The Trust for Public Land, a national land conservation organization, ranks Baltimore 40th among the 75-largest U.S. cities.[247]

Baltimore is an independent city, and not part of any county. For most governmental purposes under Maryland law, Baltimore City is treated as a county-level entity. The United States Census Bureau uses counties as the basic unit for presentation of statistical information in the United States, and treats Baltimore as a county equivalent for those purposes.

Baltimore has been a Democratic stronghold for over 150 years, with Democrats dominating every level of government. In virtually all elections, the Democratic primary is the real contest.[249] As of the 2020 elections, registered Democrats outnumbered registered Republicans by almost 10-to-1.[250] No Republican has been elected to the City Council since 1939. The city's last Republican mayor, Theodore McKeldin, left office in 1967. No Republican candidate since then has received 25 percent or more of the vote. In the 2016 and 2020 mayoral elections, the Republicans were pushed into third place by write-in and independent candidates, respectively. The last Republican candidate for president to win the city was Dwight Eisenhower in his successful reelection bid in 1956.

The city hosted the first six Democratic National Conventions, from 1832 through 1852, and hosted the DNC again in 1860, 1872, and 1912.[251]

Brandon Scott is the current mayor of Baltimore. He was elected in 2020 and took office on December 8, 2020.

Scott succeeded Jack Young, who took office on May 2, 2019. Young had been the president of the Baltimore City Council when Mayor Catherine Pugh was accused of a self-dealing book-sales arrangement. He became acting mayor on April 2 when she took a leave of absence, then mayor upon her resignation.[253][254]

Pugh, a Democrat, won the 2016 mayoral election with 57.1% of the vote and took office on December 6, 2016.[255]

Stephanie Rawlings-Blake assumed the office of Mayor on February 4, 2010, when predecessor Dixon's resignation became effective.[256] Rawlings-Blake had been serving as City Council President at the time. She was elected to a full term in 2011, defeating Pugh in the primary election and receiving 84% of the vote.[257]

Sheila Dixon became the first female mayor of Baltimore on January 17, 2007. As the former City Council President, she assumed the office of Mayor when former Mayor Martin O'Malley took office as Governor of Maryland.[258] On November 6, 2007, Dixon won the Baltimore mayoral election. Mayor Dixon's administration ended less than three years after her election, the result of a criminal investigation that began in 2006 while she was still City Council President. She was convicted on a single misdemeanor charge of embezzlement on December 1, 2009. A month later, Dixon made an Alford plea to a perjury charge and agreed to resign from office; Maryland, like most states, does not allow convicted felons to hold office.[259][260]

Grassroots pressure for reform, voiced as Question P, restructured the city council in November 2002, against the will of the mayor, the council president, and the majority of the council. A coalition of union and community groups, organized by the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), backed the effort.[261]

Baltimore City Council is made up of 14 single-member districts and one elected at-large council president.[262][263]

The Baltimore City Police Department is the current primary law enforcement agency serving Baltimore citizens. It was founded 1784 as a "Night City Watch" and day Constables system and later reorganized as a City Department in 1853, with a later reorganization under State of Maryland supervision in 1859, with appointments made by the Governor of Maryland after a period of civic and elections violence with riots in the later part of the decade. Campus and building security for the city's public schools is provided by the Baltimore City Public Schools Police, established in the 1970s.

In the four-year span of 2011 to 2015, 120 lawsuits were brought against Baltimore police for alleged brutality and misconduct. The Freddie Gray settlement of $6.4 million exceeds the combined total settlements of the 120 lawsuits, as state law caps such payments.[264]

Maryland Transportation Authority Police under the Maryland Department of Transportation, originally established as the "Baltimore Harbor Tunnel Police" when opened in 1957, is the primary law enforcement agency on the Fort McHenry Tunnel Thruway on I-95 and the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel Thruway, which goes underneath the northwestern branch of Patapsco River, and Interstate 395, which has three ramp bridges crossing the middle branch of the Patapsco River that are under MdTA jurisdiction, and have limited concurrent jurisdiction with the Baltimore Police Department under a memorandum of understanding.

Law enforcement on the fleet of transit buses and transit rail systems serving Baltimore is the responsibility of the Maryland Transit Administration Police, which is part of the Maryland Transit Administration of the state Department of Transportation. The MTA Police also share jurisdiction authority with the Baltimore City Police, governed by a memorandum of understanding.[265]

As the enforcement arm of the Baltimore circuit and district court system, the Baltimore City Sheriff's Office, created by state constitutional amendment in 1844, is responsible for the security of city courthouses and property, service of court-ordered writs, protective and peace orders, warrants, tax levies, prisoner transportation and traffic enforcement. Deputy Sheriffs are sworn law enforcement officials, with full arrest authority granted by the constitution of Maryland, the Maryland Police and Correctional Training Commission and the Sheriff of Baltimore.[266]

The United States Coast Guard, operating out of their shipyard and facility (since 1899) at Arundel Cove on Curtis Creek, (off Pennington Avenue extending to Hawkins Point Road/Fort Smallwood Road) in the Curtis Bay section of southern Baltimore City and adjacent northern Anne Arundel County. The U.S.C.G. also operates and maintains a presence on Baltimore and Maryland waterways in the Patapsco River and Chesapeake Bay. "Sector Baltimore" is responsible for commanding law enforcement and search & rescue units as well as aids to navigation.

_and_Franklintown_Road_in_Baltimore_City,_Maryland.jpg/440px-2016-05-11_18_45_30_Baltimore_City_Police_Car_at_the_intersection_of_Franklin_Street_(U.S._Route_40)_and_Franklintown_Road_in_Baltimore_City,_Maryland.jpg)

Baltimore is considered one of the most dangerous cities in the U.S.[267] Experts say an emerging gang presence and heavy recruitment of adolescent boys into these gangs, who are statistically more likely to get serious charges reduced or dropped, are major reasons for the sustained crime crises in the city.[268][269] Overall reported crime dropped by 60% from the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s, but homicides and gun violence remain high and far exceed the national average.[270]

The worst years for crime in Baltimore overall were from 1993 to 1996, with 96,243 crimes reported in 1995. Baltimore's 344 homicides in 2015 represented the highest homicide rate in the city's recorded history—52.5 per 100,000 people, surpassing the record ratio set in 1993—and the second-highest for U.S. cities behind St. Louis and ahead of Detroit. Of Baltimore's 344 homicides in 2015, 321 (93.3%) of the victims were African-American.[270]

Drug use and deaths by drug use, particularly drugs used intravenously, such as heroin, are a related problem which has impaired Baltimore for decades. Among cities greater than 400,000, Baltimore ranked 2nd in its opiate drug death rate in the United States. The DEA reported that 10% of Baltimore's population – about 64,000 people – are addicted to heroin, most of which is trafficked into the city from New York.[271][272][273][274][275]

In 2011, Baltimore police reported 196 homicides, the lowest number in the city since 197 homicides in 1978, and far lower than the peak homicide count of 353 slayings in 1993. City leaders at the time credited a sustained focus on repeat violent offenders and increased community engagement for the continued drop, reflecting a nationwide decline in crime.[276][277]

In August 2014, Baltimore's new youth curfew law went into effect. It prohibits unaccompanied children under age 14 from being on the streets after 9 p.m. and those aged 14–16 from being out after 10 p.m. during the week and 11 p.m. on weekends and during the summer. The goal is to keep children out of dangerous places and reduce crime.[278]

Crime in Baltimore reached another peak in 2015 when the year's tally of 344 homicides was second only to the record 353 in 1993, when Baltimore had about 100,000 more residents. The killings in 2015 were on pace with recent years in the early months of 2015, but skyrocketed after the unrest and rioting of late April following the killing of Freddie Gray by police. In five of the next eight months, killings topped 30–40 per month. Nearly 90 percent of 2015's homicides resulted from shootings, renewing calls for new gun laws. In 2016, there were 318 murders in the city.[279] This total marked a 7.56 percent decline in homicides from 2015.