Bob Dylan (legalmente Robert Dylan ; [3] nacido Robert Allen Zimmerman , 24 de mayo de 1941) es un cantautor estadounidense. A menudo considerado uno de los mejores compositores de la historia, [4] [5] [6] Dylan ha sido una figura importante en la cultura popular a lo largo de sus 60 años de carrera. Saltó a la fama en la década de 1960, cuando canciones como " The Times They Are a-Changin' " (1964) se convirtieron en himnos de los movimientos por los derechos civiles y contra la guerra . Inicialmente modeló su estilo en las canciones folk de Woody Guthrie , [7] el blues de Robert Johnson [8] y lo que él llamó las "formas arquitectónicas" de las canciones country de Hank Williams , [9] Dylan agregó técnicas líricas cada vez más sofisticadas a la música folk de principios de la década de 1960, infundiéndole "el intelectualismo de la literatura y la poesía clásicas". [4] Sus letras incorporaron influencias políticas, sociales y filosóficas, desafiando las convenciones de la música pop y apelando a la creciente contracultura . [10]

Dylan nació y creció en el condado de St. Louis, Minnesota . Después de su álbum debut homónimo de canciones folclóricas tradicionales en 1962, hizo su gran avance con The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (1963). El álbum incluía " Blowin' in the Wind " y " A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall ", que adaptaban las melodías y el fraseo de canciones folclóricas más antiguas. Lanzó el políticamente cargado The Times They Are a-Changin' y el más abstracto e introspectivo Another Side of Bob Dylan en 1964. En 1965 y 1966, Dylan generó controversia entre los puristas del folk cuando adoptó la instrumentación de rock amplificada eléctricamente , y en el espacio de 15 meses grabó tres de los álbumes de rock más influyentes de la década de 1960: Bringing It All Back Home , Highway 61 Revisited y Blonde on Blonde . Cuando Dylan pasó del folk acústico y la música blues al rock, la mezcla se volvió más compleja. Su sencillo de seis minutos " Like a Rolling Stone " (1965) amplió los límites comerciales y creativos de la música popular. [11] [12]

En julio de 1966, un accidente de motocicleta provocó que Dylan se retirara de las giras. Durante este período, grabó una gran cantidad de canciones con miembros de The Band , que anteriormente lo habían respaldado en giras. Estas grabaciones se lanzaron más tarde como The Basement Tapes en 1975. A fines de la década de 1960 y principios de la de 1970, Dylan exploró la música country y los temas rurales en John Wesley Harding (1967), Nashville Skyline (1969) y New Morning (1970). En 1975, lanzó Blood on the Tracks , que muchos vieron como un regreso a la forma. A fines de la década de 1970, se convirtió en un cristiano renacido y lanzó tres álbumes de música gospel contemporánea antes de regresar a su idioma más familiar basado en el rock a principios de la década de 1980. Time Out of Mind (1997) de Dylan marcó el comienzo de un renacimiento de su carrera. Desde entonces, ha publicado cinco álbumes aclamados por la crítica con material original, el más reciente Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020). También grabó una trilogía de álbumes que cubren el Great American Songbook , especialmente canciones cantadas por Frank Sinatra , y un álbum que suaviza su material de rock temprano en una sensibilidad americana más suave , Shadow Kingdom (2023). Dylan ha estado de gira continuamente desde finales de la década de 1980 en lo que se ha conocido como Never Ending Tour . [13]

Desde 1994, Dylan ha publicado nueve libros de pinturas y dibujos , y su obra ha sido expuesta en importantes galerías de arte. Ha vendido más de 125 millones de discos, [14] convirtiéndolo en uno de los músicos con mayores ventas de la historia . Ha recibido numerosos premios , entre ellos la Medalla Presidencial de la Libertad , diez premios Grammy , un Globo de Oro y un premio Óscar . Dylan ha sido incluido en el Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll , el Salón de la Fama de los Compositores de Nashville y el Salón de la Fama de los Compositores . En 2008, la Junta del Premio Pulitzer le otorgó una mención especial por "su profundo impacto en la música popular y la cultura estadounidense, marcado por composiciones líricas de extraordinario poder poético". En 2016, Dylan fue galardonado con el Premio Nobel de Literatura . [15]

Bob Dylan nació como Robert Allen Zimmerman ( en hebreo : שבתאי זיסל בן אברהם Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham ) [1] [16] [17] en el St. Mary's Hospital el 24 de mayo de 1941, en Duluth, Minnesota , [18] y se crió en Hibbing, Minnesota , en la cordillera Mesabi al oeste del Lago Superior . Los abuelos paternos de Dylan, Anna Kirghiz y Zigman Zimmerman, emigraron de Odessa en el Imperio ruso (ahora Odesa , Ucrania) a los Estados Unidos, después de los pogromos contra los judíos de 1905. [19] Sus abuelos maternos, Florence y Ben Stone, eran judíos lituanos que habían llegado a los Estados Unidos en 1902. [19] Dylan escribió que la familia de su abuela paterna era originaria del distrito de Kağızman de la provincia de Kars en el noreste de Turquía. [20]

El padre de Dylan, Abram Zimmerman, y su madre, Beatrice "Beatty" Stone, formaban parte de una pequeña y unida comunidad judía. [21] [22] [23] Vivieron en Duluth hasta que Dylan tenía seis años, cuando su padre contrajo polio y la familia regresó a la ciudad natal de su madre, Hibbing, donde vivieron durante el resto de la infancia de Dylan, y su padre y sus tíos paternos tenían una tienda de muebles y electrodomésticos. [23] [24]

A principios de la década de 1950, Dylan escuchó el programa de radio Grand Ole Opry y escuchó las canciones de Hank Williams . Más tarde escribió: “El sonido de su voz me atravesó como una vara eléctrica”. [9] Dylan también quedó impresionado por la forma de cantar de Johnnie Ray : “Fue el primer cantante cuya voz y estilo, supongo, me enamoró por completo… Me encantaba su estilo, quería vestirme como él también”. [25] Cuando era adolescente, Dylan escuchó rock and roll en estaciones de radio que transmitían desde Shreveport y Little Rock . [26]

Dylan formó varias bandas mientras asistía a la Hibbing High School . En los Golden Chords, interpretó versiones de canciones de Little Richard [27] y Elvis Presley . [28] Su interpretación de " Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay " de Danny & the Juniors en el concurso de talentos de su escuela secundaria fue tan fuerte que el director cortó el micrófono. [29] En 1959, el anuario de la escuela secundaria de Dylan llevaba la leyenda "Robert Zimmerman: unirse a 'Little Richard ' ". [27] [30] Ese año, como Elston Gunnn, realizó dos fechas con Bobby Vee , tocando el piano y aplaudiendo. [31] [32] [33] En septiembre de 1959, Dylan se inscribió en la Universidad de Minnesota . [34] Viviendo en la casa de la fraternidad judía Sigma Alpha Mu , Dylan comenzó a actuar en el Ten O'Clock Scholar, una cafetería a pocas cuadras del campus, y se involucró en el circuito de música folk de Dinkytown . [35] [36] Su enfoque en el rock and roll dio paso a la música folk estadounidense , como explicó en una entrevista de 1985:

Lo que pasa con el rock'n'roll es que, de todos modos, para mí no era suficiente... Había frases pegadizas y ritmos que te impulsaban... pero las canciones no eran serias o no reflejaban la vida de una manera realista. Sabía que cuando me metí en la música folk, era algo más serio. Las canciones están llenas de más desesperación, más tristeza, más triunfo, más fe en lo sobrenatural, sentimientos mucho más profundos. [37]

Durante este período, comenzó a presentarse como "Bob Dylan". [38] En sus memorias, escribió que consideró adoptar el apellido Dillon antes de ver inesperadamente poemas de Dylan Thomas y decidir sobre la ortografía del nombre de pila. [39] [a 1] En una entrevista de 2004, dijo: "Nacemos, ya sabes, con los nombres equivocados, los padres equivocados. Quiero decir, eso pasa. Te llamas a ti mismo como quieres llamarte. Esta es la tierra de los libres". [40]

En mayo de 1960, Dylan abandonó la universidad al final de su primer año. En enero de 1961, viajó a la ciudad de Nueva York para tocar y visitar a su ídolo musical Woody Guthrie [41] en el Hospital Psiquiátrico Greystone Park . [42] Guthrie había sido una revelación para Dylan e influyó en sus primeras actuaciones. Escribió sobre el impacto de Guthrie: "Las canciones en sí mismas tenían el alcance infinito de la humanidad en ellas... [Él] era la verdadera voz del espíritu estadounidense. Me dije a mí mismo que iba a ser el mayor discípulo de Guthrie". [43] Además de visitar a Guthrie, Dylan se hizo amigo de su protegido Ramblin' Jack Elliott . [44]

A partir de febrero de 1961, Dylan tocó en clubes alrededor de Greenwich Village , entablando amistad y recogiendo material de cantantes de folk, incluidos Dave Van Ronk , Fred Neil , Odetta , los New Lost City Ramblers y los músicos irlandeses Clancy Brothers y Tommy Makem . [45] En septiembre, el crítico de The New York Times, Robert Shelton, impulsó la carrera de Dylan con una reseña muy entusiasta de su actuación en Gerde's Folk City : "Bob Dylan: un estilista distintivo de canciones folk". [46] Ese mes, Dylan tocó la armónica en el tercer álbum de la cantante folk Carolyn Hester , lo que llamó la atención del productor del álbum , John Hammond , [47] quien contrató a Dylan para Columbia Records . [48] El álbum debut de Dylan, Bob Dylan , lanzado el 19 de marzo de 1962, [49] [50] consistía en material tradicional de folk, blues y gospel con solo dos composiciones originales, " Talkin' New York " y " Song to Woody ". El álbum vendió 5000 copias en su primer año, apenas alcanzando el punto de equilibrio. [51]

En agosto de 1962, Dylan cambió su nombre a Bob Dylan, [a 2] y firmó un contrato de representación con Albert Grossman . [52] Grossman siguió siendo el representante de Dylan hasta 1970, y era conocido por su personalidad a veces conflictiva y su lealtad protectora. [53] Dylan dijo: "Era algo así como una figura del Coronel Tom Parker ... se podía oler que venía". [36] La tensión entre Grossman y John Hammond llevó a este último a sugerirle a Dylan que trabajara con el productor de jazz Tom Wilson , quien produjo varias pistas para el segundo álbum sin crédito formal. Wilson produjo los siguientes tres álbumes que grabó Dylan. [54] [55]

Dylan hizo su primer viaje al Reino Unido entre diciembre de 1962 y enero de 1963. [56] Había sido invitado por el director de televisión Philip Saville para aparecer en Madhouse on Castle Street , que Saville dirigía para BBC Television . [57] Al final de la obra, Dylan interpretó « Blowin' in the Wind », una de sus primeras representaciones públicas. [57] Mientras estaba en Londres, Dylan actuó en clubes folk londinenses, incluidos el Troubadour , Les Cousins y Bunjies . [56] [58] También aprendió material de artistas del Reino Unido, incluido Martin Carthy . [57]

Con el lanzamiento de su segundo álbum, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan , en mayo de 1963, Dylan había comenzado a hacerse un nombre como cantautor. Muchas canciones del álbum fueron etiquetadas como canciones de protesta , inspiradas en parte por Guthrie e influenciadas por las canciones de actualidad de Pete Seeger . [59] « Oxford Town » fue un relato de la terrible experiencia de James Meredith como el primer estudiante negro en inscribirse en la Universidad de Mississippi . [60] La primera canción del álbum, «Blowin' in the Wind», derivó en parte su melodía de la canción tradicional de esclavos «No More Auction Block», [61] mientras que su letra cuestionaba el status quo social y político. La canción fue ampliamente grabada por otros artistas y se convirtió en un éxito para Peter, Paul and Mary . [62] « A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall » se basó en la balada folk « Lord Randall ». Con sus premoniciones apocalípticas, la canción ganó resonancia cuando se desarrolló la Crisis de los Misiles de Cuba unas semanas después de que Dylan comenzara a interpretarla. [63] [a 3] Ambas canciones marcaron una nueva dirección en la composición de canciones, mezclando un flujo de conciencia , un ataque lírico imaginista con una forma folclórica tradicional. [64]

Las canciones de Dylan sobre temas de actualidad hicieron que se lo considerara más que un simple compositor. Janet Maslin escribió sobre Freewheelin ' :

Éstas fueron las canciones que establecieron a [Dylan] como la voz de su generación, alguien que entendía implícitamente cuán preocupados se sentían los jóvenes estadounidenses acerca del desarme nuclear y el creciente Movimiento por los Derechos Civiles : su mezcla de autoridad moral y no conformidad fue quizás el más oportuno de sus atributos. [65] [a 4]

Freewheelin ' también incluía canciones de amor y blues surrealistas . El humor era una parte importante de la personalidad de Dylan, [66] y la variedad de material del álbum impresionó a los oyentes, incluidos los Beatles . George Harrison dijo sobre el álbum: "Simplemente lo tocamos, simplemente lo desgastamos. El contenido de las letras de las canciones y simplemente la actitud, fue increíblemente original y maravilloso". [67]

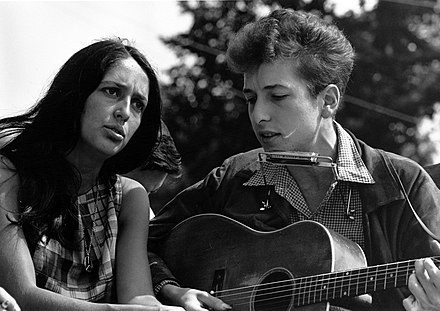

El tono áspero de Dylan inquietó a algunos, pero atrajo a otros. La autora Joyce Carol Oates escribió: «Cuando escuchamos por primera vez esta voz cruda, muy joven y aparentemente sin entrenamiento, francamente nasal, como si el papel de lija pudiera cantar, el efecto fue dramático y electrizante». [68] Muchas de las primeras canciones llegaron al público a través de versiones más agradables de otros intérpretes, como Joan Baez , que se convirtió en la defensora y amante de Dylan. [69] Baez influyó en la prominencia de Dylan al grabar varias de sus primeras canciones e invitarlo al escenario durante sus conciertos. [70] Otros que tuvieron éxitos con las canciones de Dylan a principios de la década de 1960 incluyeron a los Byrds , Sonny & Cher , los Hollies , la Association , Manfred Mann y los Turtles .

« Mixed-Up Confusion », grabado durante las sesiones de Freewheelin' con una banda de acompañamiento, fue lanzado como el primer sencillo de Dylan en diciembre de 1962, pero luego fue retirado rápidamente. En contraste con las interpretaciones acústicas en su mayoría solistas del álbum, el sencillo mostró una voluntad de experimentar con un sonido rockabilly . Cameron Crowe lo describió como «una mirada fascinante a un artista folk con su mente vagando hacia Elvis Presley y Sun Records ». [71]

En mayo de 1963, el perfil político de Dylan aumentó cuando abandonó The Ed Sullivan Show . Durante los ensayos, el jefe de prácticas de programación de la cadena de televisión CBS le había dicho a Dylan que " Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues " era potencialmente difamatorio para la John Birch Society . En lugar de cumplir con la censura, Dylan se negó a aparecer. [72]

Dylan y Baez fueron destacados en el movimiento por los derechos civiles, cantando juntos en la Marcha en Washington el 28 de agosto de 1963. Dylan interpretó " Only a Pawn in Their Game " y " When the Ship Comes In ". [73]

El tercer álbum de Dylan, The Times They Are a-Changin' , reflejó un Dylan más politizado. [74] Las canciones a menudo tomaban como tema historias contemporáneas, con " Only a Pawn in Their Game " abordando el asesinato del trabajador de derechos civiles Medgar Evers , y la brechtiana " The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll " la muerte de la camarera de hotel negra Hattie Carroll a manos del joven socialité blanco William Zantzinger. [75] " Ballad of Hollis Brown " y " North Country Blues " abordaban la desesperación engendrada por el colapso de las comunidades agrícolas y mineras. Este material político fue acompañado por dos canciones de amor personales, " Boots of Spanish Leather " y " One Too Many Mornings ". [76]

A finales de 1963, Dylan se sintió manipulado y limitado por los movimientos populares y de protesta. [77] Al aceptar el " Premio Tom Paine " del Comité de Libertades Civiles de Emergencia poco después del asesinato de John F. Kennedy , un Dylan ebrio cuestionó el papel del comité, caracterizó a los miembros como viejos y calvos, y afirmó ver algo de él mismo y de cada hombre en el asesino de Kennedy, Lee Harvey Oswald . [78]

Another Side of Bob Dylan , grabada en una sola velada el 9 de junio de 1964, [79] tenía un tono más ligero. El humor de Dylan resurgió en « I Shall Be Free No. 10 » y «Motorpsycho Nightmare». « Spanish Harlem Incident » y « To Ramona » son apasionadas canciones de amor, mientras que « Black Crow Blues » y « I Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met) » sugieren el rock and roll que pronto dominaría la música de Dylan. « It Ain't Me Babe », en apariencia una canción sobre el amor rechazado, ha sido descrita como un rechazo al papel de portavoz político que se le impuso. [80] Su nueva dirección fue señalada por dos largas canciones: la impresionista " Chimes of Freedom ", que plantea un comentario social contra un paisaje metafórico en un estilo caracterizado por Allen Ginsberg como "cadenas de imágenes destellantes", [a 5] y " My Back Pages ", que ataca la seriedad simplista y arrogante de sus propias canciones temáticas anteriores y parece predecir la reacción que estaba a punto de encontrar por parte de sus antiguos campeones. [81]

En la segunda mitad de 1964 y principios de 1965, Dylan pasó de ser compositor de canciones folk a estrella de la música pop folk-rock . Sus vaqueros y camisas de trabajo fueron reemplazados por un vestuario de Carnaby Street , gafas de sol de día y de noche y botas puntiagudas "Beatle ". Un reportero de Londres señaló "Un pelo que haría que los dientes de un peine se pusieran de punta. Una camisa llamativa que atenuaría las luces de neón de Leicester Square . Parece un cacatúa desnutrido ". [82] Dylan comenzó a discutir con los entrevistadores. Cuando se le preguntó sobre una película que planeaba mientras estaba en el programa de televisión de Les Crane , le dijo a Crane que sería una "película de terror de vaqueros". Cuando se le preguntó si interpretaba al vaquero, Dylan respondió: "No, interpreto a mi madre". [83]

.jpg/440px-Dont_Look_Back_-_Bob_Dylan_(1967_film_poster).jpg)

El álbum de Dylan de finales de marzo de 1965 Bringing It All Back Home fue otro salto, [84] presentando sus primeras grabaciones con instrumentos eléctricos, bajo la guía del productor Tom Wilson. [85] El primer sencillo, " Subterranean Homesick Blues ", le debía mucho a " Too Much Monkey Business " de Chuck Berry ; [86] sus letras de libre asociación se describen como un regreso a la energía de la poesía beat y como un precursor del rap y el hip-hop . [87] La canción fue provista de un video musical temprano, que abrió la presentación de cine vérité de DA Pennebaker de la gira británica de Dylan de 1965, Dont Look Back . [88] En lugar de hacer mímica, Dylan ilustró la letra arrojando tarjetas con palabras clave al suelo. Pennebaker dijo que la secuencia fue idea de Dylan, y ha sido imitada en videos musicales y anuncios. [89]

La segunda cara de Bringing It All Back Home contenía cuatro canciones largas en las que Dylan se acompañaba a sí mismo con guitarra acústica y armónica. [90] « Mr. Tambourine Man » se convirtió en una de sus canciones más conocidas cuando The Byrds grabaron una versión eléctrica que alcanzó el número uno en los EE. UU. y el Reino Unido. [91] [92] « It's All Over Now, Baby Blue » y « It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding) » fueron dos de las composiciones más importantes de Dylan. [90] [93]

En 1965, como cabeza de cartel del Newport Folk Festival , Dylan realizó su primer set eléctrico desde la escuela secundaria con un grupo de improvisación que incluía a Mike Bloomfield en la guitarra y Al Kooper en el órgano. [94] Dylan había aparecido en Newport en 1963 y 1964, pero en 1965 fue recibido con vítores y abucheos y abandonó el escenario después de tres canciones. Una versión dice que los abucheos eran de los fanáticos del folk a los que Dylan había alejado al aparecer, inesperadamente, con una guitarra eléctrica. Murray Lerner , quien filmó la actuación, dijo: "Creo absolutamente que estaban abucheando a Dylan por tocar con una guitarra eléctrica". [95] Una versión alternativa afirma que los miembros de la audiencia estaban molestos por el sonido deficiente y un set corto. [96] [97]

La actuación de Dylan provocó una respuesta hostil del establishment de la música folk. [98] [99] En la edición de septiembre de Sing Out!, Ewan MacColl escribió: "Nuestras canciones y baladas tradicionales son creaciones de artistas extraordinariamente talentosos que trabajan dentro de disciplinas formuladas a lo largo del tiempo... '¿Pero qué hay de Bobby Dylan?' gritan los adolescentes indignados... Sólo un público completamente acrítico, nutrido con la papilla acuosa de la música pop, podría haber caído en semejantes tonterías de décima categoría". [100] El 29 de julio, cuatro días después de Newport, Dylan estaba de vuelta en el estudio en Nueva York, grabando " Positively 4th Street ". La letra contenía imágenes de venganza y paranoia, [101] y ha sido interpretada como un desprecio de Dylan hacia antiguos amigos de la comunidad folk que había conocido en clubes a lo largo de West 4th Street . [102]

En julio de 1965, el sencillo de seis minutos de Dylan « Like a Rolling Stone » alcanzó el número dos en la lista estadounidense. En 2004 y en 2011, Rolling Stone lo incluyó como número uno en « Las 500 mejores canciones de todos los tiempos ». [11] [103] Bruce Springsteen recordó haber escuchado la canción por primera vez: «ese disparo de caja sonó como si alguien hubiera abierto de una patada la puerta de tu mente». [104] La canción abrió el siguiente álbum de Dylan, Highway 61 Revisited , llamado así por la carretera que conducía desde el Minnesota de Dylan hasta el semillero musical de Nueva Orleans . [105] Las canciones estaban en la misma línea que el exitoso sencillo, condimentadas con la guitarra de blues de Mike Bloomfield y los riffs de órgano de Al Kooper. « Desolation Row », respaldada por una guitarra acústica y un bajo discreto, [106] ofrece la única excepción, con Dylan aludiendo a figuras de la cultura occidental en una canción descrita por Andy Gill como «una epopeya de entropía de 11 minutos, que toma la forma de un desfile felliniano de grotescos y rarezas con un gran elenco de personajes célebres». [107] El poeta Philip Larkin , que también reseñó jazz para The Daily Telegraph , escribió: «Me temo que robé Highway 61 Revisited (CBS) de Bob Dylan por curiosidad y me encontré bien recompensado». [108]

.jpg/440px-Bob-Dylan-arrived-at-Arlanda-surrounded-by-twenty-bodyguards-and-assistants-391770740297_(cropped).jpg)

Para promocionar el álbum, Dylan fue contratado para dos conciertos en Estados Unidos con Al Kooper y Harvey Brooks de su equipo de estudio y Robbie Robertson y Levon Helm , antiguos miembros de la banda de acompañamiento de Ronnie Hawkins, The Hawks . [109] El 28 de agosto en el Forest Hills Tennis Stadium, el grupo fue abucheado por una audiencia todavía molesta por el sonido eléctrico de Dylan. La recepción de la banda el 3 de septiembre en el Hollywood Bowl fue más favorable. [110]

Desde el 24 de septiembre de 1965, en Austin, Texas, Dylan realizó una gira de seis meses por Estados Unidos y Canadá, respaldado por los cinco músicos de los Hawks que se hicieron conocidos como The Band . [111] Aunque Dylan y los Hawks conocieron audiencias cada vez más receptivas, sus esfuerzos en el estudio fracasaron. El productor Bob Johnston convenció a Dylan de grabar en Nashville en febrero de 1966 y lo rodeó de músicos de sesión de primer nivel. Ante la insistencia de Dylan, Robertson y Kooper vinieron de la ciudad de Nueva York para tocar en las sesiones. [112] Las sesiones de Nashville produjeron el álbum doble Blonde on Blonde (1966), que presenta lo que Dylan llamó "ese sonido fino y salvaje del mercurio". [113] Kooper lo describió como "tomar dos culturas y unirlas con una gran explosión": los mundos musicales de Nashville y del "hipster neoyorquino por excelencia" Bob Dylan. [114]

El 22 de noviembre de 1965, Dylan se casó discretamente con la ex modelo Sara Lownds , de 25 años . [115] Algunos amigos de Dylan, incluido Ramblin' Jack Elliott, dicen que, inmediatamente después del evento, Dylan negó que estuviera casado. [115] La escritora Nora Ephron hizo pública la noticia en el New York Post en febrero de 1966 con el titular "¡Silencio! Bob Dylan está casado". [116]

Dylan realizó una gira por Australia y Europa en abril y mayo de 1966. Cada espectáculo se dividió en dos. Dylan actuó en solitario durante la primera mitad, acompañándose con guitarra acústica y armónica. En la segunda, respaldado por los Hawks, tocó música amplificada eléctricamente. Este contraste provocó a muchos fanáticos, que abuchearon y aplaudieron lentamente . [117] La gira culminó en una estridente confrontación entre Dylan y su público en el Manchester Free Trade Hall en Inglaterra el 17 de mayo de 1966. [118] Una grabación de este concierto fue lanzada en 1998: The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966. En el clímax de la velada, un miembro del público, enojado por el acompañamiento eléctrico de Dylan, gritó: " ¡Judas !" a lo que Dylan respondió: "No te creo... ¡Eres un mentiroso!" Dylan se volvió hacia su banda y dijo: "¡Tócala jodidamente fuerte!". [119]

Durante su gira de 1966, Dylan fue descrito como exhausto y actuando "como si estuviera en un viaje de la muerte". [120] DA Pennebaker, el cineasta que acompañó la gira, describió a Dylan como "tomando mucha anfetamina y quién sabe qué más". [121] En una entrevista de 1969 con Jann Wenner , Dylan dijo: "Estuve de gira durante casi cinco años. Me agotó. Estaba drogado, muchas cosas... solo para seguir adelante, ¿sabes?" [122]

El 29 de julio de 1966, Dylan estrelló su motocicleta, una Triumph Tiger 100 , cerca de su casa en Woodstock, Nueva York . Dylan dijo que se rompió varias vértebras del cuello. [123] Las circunstancias del accidente no están claras ya que no se llamó a ninguna ambulancia al lugar y Dylan no fue hospitalizado. [123] [124] Los biógrafos de Dylan han escrito que el accidente le ofreció la oportunidad de escapar de las presiones que lo rodeaban. [123] [125] Dylan estuvo de acuerdo: "Había tenido un accidente de motocicleta y me había lastimado, pero me recuperé. La verdad es que quería salir de la carrera de ratas". [126] Hizo muy pocas apariciones públicas y no volvió a salir de gira durante casi ocho años. [124] [127]

Una vez que Dylan estuvo lo suficientemente bien como para reanudar su trabajo creativo, comenzó a editar la película de DA Pennebaker de su gira de 1966. Se mostró un corte preliminar a ABC Television, pero lo rechazaron por incomprensible para el público en general. [128] La película, titulada Eat the Document en copias piratas , se ha proyectado desde entonces en algunos festivales de cine. [129] Aislado de la mirada del público, Dylan grabó más de 100 canciones durante 1967 en su casa de Woodstock y en el sótano de la casa cercana de los Hawks, " Big Pink ". [130] Estas canciones se ofrecieron inicialmente como demos para que otros artistas las grabaran y fueron éxitos para Julie Driscoll , los Byrds y Manfred Mann. El público escuchó estas grabaciones cuando Great White Wonder , la primera " grabación pirata ", apareció en las tiendas de la Costa Oeste en julio de 1969, que contenía material de Dylan grabado en Minneapolis en 1961 y siete canciones de Basement Tapes. Este disco dio origen a una pequeña industria en la publicación ilícita de grabaciones de Dylan y otros grandes artistas del rock. [131] Columbia lanzó una selección de Basement en 1975 llamada The Basement Tapes .

A finales de 1967, Dylan volvió a grabar en estudio en Nashville, [132] acompañado por Charlie McCoy en el bajo, [132] Kenny Buttrey en la batería [132] y Pete Drake en la guitarra de acero. [132] El resultado fue John Wesley Harding , un disco de canciones cortas inspiradas temáticamente en el Oeste americano y la Biblia . La estructura y la instrumentación escasas, con letras que tomaban en serio la tradición judeocristiana , se alejaron del trabajo anterior de Dylan. [133] Incluía « All Along the Watchtower », famosamente versionada por Jimi Hendrix . [37] [a 6] Woody Guthrie murió en octubre de 1967, y Dylan hizo su primera aparición en vivo en veinte meses en un concierto conmemorativo celebrado en el Carnegie Hall el 20 de enero de 1968, donde fue respaldado por The Band. [134]

Nashville Skyline (1969) contó con músicos de Nashville, un Dylan de voz suave, un dueto con Johnny Cash y el sencillo « Lay Lady Lay ». [136] Variety escribió: «Dylan definitivamente está haciendo algo que se puede llamar canto. De alguna manera ha logrado agregar una octava a su rango». [137] Durante una sesión de grabación, Dylan y Cash grabaron una serie de duetos, pero solo su versión de « Girl from the North Country » apareció en el álbum. [138] [139] El álbum influyó en el género naciente del country rock . [4]

En 1969, Dylan recibió la invitación para escribir canciones para Scratch , la adaptación musical de Archibald MacLeish de « The Devil and Daniel Webster ». MacLeish inicialmente elogió las contribuciones de Dylan, escribiéndole «Esas canciones tuyas me han estado atormentando y emocionando», pero las diferencias creativas llevaron a Dylan a abandonar el proyecto. Algunas de las canciones fueron grabadas más tarde por Dylan en una forma revisada. [140] En mayo de 1969, Dylan apareció en el primer episodio de The Johnny Cash Show , donde cantó un dueto con Cash en «Girl from the North Country» e interpretó solos de «Living the Blues» y « I Threw It All Away ». Dylan viajó a Inglaterra para encabezar el cartel en el Festival de la Isla de Wight el 31 de agosto de 1969, después de rechazar propuestas para aparecer en el Festival de Woodstock más cerca de casa. [141]

A principios de la década de 1970, los críticos acusaron a Dylan de ser variado e impredecible. Greil Marcus preguntó "¿Qué es esta mierda?" al escuchar por primera vez Self Portrait , lanzado en junio de 1970. [142] [143] Fue un LP doble que incluía pocas canciones originales y fue mal recibido. [144] En octubre de 1970, Dylan lanzó New Morning , considerado un regreso a la forma. [145] La canción principal era de la desafortunada colaboración de Dylan con MacLeish, [140] y "Day of the Locusts" fue su relato de recibir un título honorario de la Universidad de Princeton el 9 de junio de 1970. [146] En noviembre de 1968, Dylan coescribió " I'd Have You Anytime " con George Harrison; [147] Harrison grabó esa canción y " If Not for You " de Dylan para su álbum All Things Must Pass . Olivia Newton-John versionó "If Not For You" en su álbum debut y " The Man in Me " apareció de forma destacada en la película The Big Lebowski (1998).

Tarantula , un libro de poesía en prosa de formato libre, había sido escrito por Dylan durante un estallido creativo en 1964-65. [148] Dylan archivó su libro durante varios años, aparentemente inseguro de su estatus, [149] hasta que de repente le informó a Macmillan a fines de 1970 que había llegado el momento de publicarlo. [150] El libro atrajo críticas negativas, pero los críticos posteriores han sugerido sus afinidades con Finnegans Wake y A Season In Hell . [151]

Entre el 16 y el 19 de marzo de 1971, Dylan grabó con Leon Russell en Blue Rock , un pequeño estudio en Greenwich Village. Estas sesiones dieron como resultado « Watching the River Flow » y una nueva grabación de « When I Paint My Masterpiece ». [152] El 4 de noviembre de 1971, Dylan grabó « George Jackson », que lanzó una semana después. Para muchos, el sencillo fue un sorprendente regreso al material de protesta, en duelo por el asesinato de George Jackson, miembro de las Panteras Negras, en la prisión estatal de San Quentin . [153] La aparición sorpresa de Dylan en el Concierto de Harrison para Bangladesh el 1 de agosto de 1971 atrajo la cobertura de los medios, ya que sus apariciones en vivo se habían vuelto raras. [154]

En 1972, Dylan se unió a la película de Sam Peckinpah Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid , proporcionando la banda sonora e interpretando a "Alias", un miembro de la pandilla de Billy. [155] A pesar del fracaso de la película en taquilla, " Knockin' on Heaven's Door " se convirtió en una de las canciones más versionadas de Dylan. [156] [157] Ese mismo año, Dylan protestó por la medida de deportar a John Lennon y Yoko Ono , que habían sido condenados por posesión de marihuana , enviando una carta al Servicio de Inmigración de Estados Unidos que decía en parte: "Hurra por John y Yoko. Déjenlos quedarse y vivir aquí y respirar. El país tiene mucho espacio. ¡Dejen que John y Yoko se queden!" [158]

Dylan comenzó 1973 firmando con un nuevo sello, Asylum Records de David Geffen , cuando su contrato con Columbia Records expiró. [160] Su siguiente álbum, Planet Waves , fue grabado en el otoño de 1973, utilizando a The Band como su grupo de apoyo mientras ensayaban para una gran gira. [161] El álbum incluía dos versiones de «Forever Young» , que se convirtió en una de sus canciones más populares. [162] Como lo describió un crítico, la canción proyectaba «algo himnario y sincero que hablaba del padre en Dylan», [163] y Dylan dijo: «La escribí pensando en uno de mis hijos y sin querer ser demasiado sentimental». [37] Columbia Records lanzó simultáneamente Dylan , una colección de tomas descartadas de estudio, ampliamente interpretada como una respuesta grosera a la firma de Dylan con un sello discográfico rival. [164]

En enero de 1974, Dylan, respaldado por The Band, se embarcó en una gira norteamericana de 40 conciertos, su primera gira en siete años. Un álbum doble en vivo, Before the Flood , fue lanzado por Asylum Records. Pronto, según Clive Davis , Columbia Records envió un mensaje diciendo que "no escatimarían nada para traer a Dylan de vuelta al redil". [165] Dylan tuvo dudas sobre Asylum, descontento porque Geffen había vendido solo 600.000 copias de Planet Waves a pesar de millones de solicitudes de entradas sin cumplir para la gira de 1974; [166] regresó a Columbia Records, que reeditó sus dos álbumes de Asylum. [167]

Después de la gira, Dylan y su esposa se distanciaron. Llenó tres pequeños cuadernos con canciones sobre relaciones y rupturas, y grabó el álbum Blood on the Tracks en septiembre de 1974. [168] [169] Dylan retrasó el lanzamiento del álbum y volvió a grabar la mitad de las canciones en Sound 80 Studios en Minneapolis con la ayuda de producción de su hermano, David Zimmerman. [170] Lanzado a principios de 1975, Blood on the Tracks recibió críticas mixtas. En NME , Nick Kent describió los "acompañamientos" como "a menudo tan basura que suenan como simples tomas de práctica". [171] En Rolling Stone , Jon Landau escribió que "el disco ha sido hecho con la típica chapuza". [171] Con los años, los críticos llegaron a verlo como una de las obras maestras de Dylan. En Salon , el periodista Bill Wyman escribió:

Blood on the Tracks es su único álbum impecable y el mejor producido; las canciones, cada una de ellas, están construidas de manera disciplinada. Es su álbum más amable y más consternado, y parece, en retrospectiva, haber logrado un equilibrio sublime entre los excesos plagados de logorrea de su producción de mediados de los años 60 y las composiciones conscientemente simples de sus años posteriores al accidente. [172]

A mediados de 1975, Dylan defendió al boxeador Rubin "Hurricane" Carter , encarcelado por triple asesinato, con su balada " Hurricane " defendiendo la inocencia de Carter. A pesar de su duración (más de ocho minutos), la canción fue lanzada como sencillo, alcanzando el puesto 33 en la lista Billboard de Estados Unidos , y se interpretó en cada fecha de 1975 de la siguiente gira de Dylan, la Rolling Thunder Revue . [a 7] [173] La gira, que duró hasta finales de 1975 y nuevamente hasta principios de 1976, contó con alrededor de cien artistas y seguidores de la escena folk de Greenwich Village, entre ellos Ramblin' Jack Elliott, T-Bone Burnett , Joni Mitchell , [174] [175] David Mansfield , Roger McGuinn , Mick Ronson , Ronee Blakely , Joan Baez y Scarlet Rivera , a quien Dylan descubrió caminando por la calle, con el estuche de su violín a la espalda. [176] La gira incluyó el lanzamiento en enero de 1976 del álbum Desire . Muchas de las canciones de Desire presentan un estilo narrativo similar a un diario de viaje , influenciado por el nuevo colaborador de Dylan, el dramaturgo Jacques Levy . [177] [178] La mitad de 1976 de la gira fue documentada por un especial de concierto de televisión, Hard Rain , y el LP Hard Rain .

La gira de 1975 con la Revue sirvió de telón de fondo para la película de Dylan Renaldo and Clara , una narrativa extensa mezclada con imágenes de conciertos y reminiscencias. El actor y dramaturgo Sam Shepard acompañó a la Revue y se desempeñó como guionista, pero gran parte de la película fue improvisada. Estrenada en 1978, recibió críticas negativas, a veces mordaces. [179] [180] Más tarde en el año, una edición de dos horas, dominada por las actuaciones del concierto, fue lanzada más ampliamente. [181] En noviembre de 1976, Dylan apareció en el concierto de despedida de la Band con Eric Clapton , Muddy Waters , Van Morrison , Neil Young y Joni Mitchell. La película de 1978 de Martin Scorsese del concierto, The Last Waltz , incluyó la mayor parte del repertorio de Dylan. [182]

En 1978, Dylan se embarcó en una gira mundial de un año , realizando 114 espectáculos en Japón, el Lejano Oriente, Europa y América del Norte, para una audiencia total de dos millones de personas. Dylan reunió una banda de ocho miembros y tres coristas. Los conciertos en Tokio en febrero y marzo fueron lanzados como el álbum doble en vivo Bob Dylan at Budokan . [183] Las críticas fueron mixtas. Robert Christgau le otorgó al álbum una calificación de C +, [184] mientras que Janet Maslin lo defendió: "Estas últimas versiones en vivo de sus viejas canciones tienen el efecto de liberar a Bob Dylan de los originales". [185] Cuando Dylan llevó la gira a los EE. UU. en septiembre de 1978, la prensa describió el aspecto y el sonido como un "Las Vegas Tour". [186] La gira de 1978 recaudó más de 20 millones de dólares, y Dylan le dijo al Los Angeles Times que tenía deudas porque "tuve un par de años malos. Puse mucho dinero en la película, construí una casa grande... y cuesta mucho divorciarse en California". [183] En abril y mayo de 1978, Dylan llevó a la misma banda y vocalistas a Rundown Studios en Santa Mónica , California, para grabar un álbum de material nuevo, Street-Legal . [187] Fue descrito por Michael Gray como "después de Blood On The Tracks , posiblemente el mejor disco de Dylan de la década de 1970: un álbum crucial que documenta un período crucial en la propia vida de Dylan". [188] Sin embargo, tenía un sonido y una mezcla pobres (atribuidos a las prácticas de estudio de Dylan), lo que enturbió el detalle instrumental hasta que un lanzamiento en CD remasterizado en 1999 restauró algunas de las fortalezas de las canciones. [189] [190]

A finales de los años 1970, Dylan se convirtió al cristianismo evangélico , [191] [192] realizando un curso de discipulado de tres meses dirigido por la Asociación de Iglesias Vineyard . [193] [194] Lanzó tres álbumes de música gospel contemporánea . Slow Train Coming (1979) contó con la participación del guitarrista de Dire Straits Mark Knopfler y fue producido por el veterano productor de R&B Jerry Wexler . Wexler dijo que Dylan había tratado de evangelizarlo durante la grabación. Él respondió: "Bob, estás tratando con un ateo judío de 62 años. Hagamos un álbum". [195] Dylan ganó el premio Grammy a la mejor interpretación vocal masculina de rock por la canción " Gotta Serve Somebody ". Cuando estuvo de gira a finales de 1979 y principios de 1980, Dylan no tocaba sus obras más antiguas y seculares, y pronunció declaraciones de su fe desde el escenario, como:

Hace años decían que yo era un profeta. Yo solía decir: "No, yo no soy un profeta", y ellos decían: "Sí, tú eres un profeta". Yo decía: "No, yo no soy". Solían decir: "Seguro que eres un profeta". Solían convencerme de que yo era un profeta. Ahora salgo y digo que Jesucristo es la respuesta. Ellos dicen: "Bob Dylan no es un profeta". Simplemente no pueden soportarlo. [196]

El cristianismo de Dylan era impopular entre algunos fans y músicos. [197] John Lennon, poco antes de ser asesinado , grabó «Serve Yourself» en respuesta a «Gotta Serve Somebody». [198] En 1981, Stephen Holden escribió en The New York Times que «ni la edad (ahora tiene 40 años) ni su muy publicitada conversión al cristianismo renacido han alterado su temperamento esencialmente iconoclasta». [199]

A finales de 1980, Dylan realizó breves conciertos anunciados como "Una retrospectiva musical", en los que reincorporó al repertorio canciones populares de los años 60. Su segundo álbum cristiano, Saved (1980), recibió críticas mixtas, descritas por Michael Gray como "lo más parecido a un álbum posterior que Dylan haya hecho jamás, Slow Train Coming II e inferior". [200] Su tercer álbum cristiano fue Shot of Love (1981). [201] El álbum incluía sus primeras composiciones seculares en más de dos años, mezcladas con canciones cristianas. La letra de "Every Grain of Sand" recuerda a " Auguries of Innocence " de William Blake . [202] Elvis Costello escribió que " Shot of Love puede que no sea tu disco favorito de Bob Dylan, pero podría contener su mejor canción: 'Every Grain of Sand'". [203]

La recepción de las grabaciones de Dylan de los años 1980 fue variada. Gray criticó los álbumes de Dylan de los años 1980 por su descuido en el estudio y por no publicar sus mejores canciones. [204] Infidels (1983) contrató a Knopfler nuevamente como guitarrista principal y también como productor; las sesiones dieron como resultado varias canciones que Dylan dejó fuera del álbum. Las más consideradas de estas fueron « Blind Willie McTell », que era a la vez un tributo al músico de blues epónimo y una evocación de la historia afroamericana , [205] «Foot of Pride» y « Lord Protect My Child ». Estas tres canciones fueron lanzadas más tarde en The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991 . [206]

Entre julio de 1984 y marzo de 1985, Dylan grabó Empire Burlesque . [207] Arthur Baker , que había remezclado éxitos de Bruce Springsteen y Cyndi Lauper , fue contratado para realizar la ingeniería y la mezcla del álbum. Baker dijo que sintió que lo habían contratado para hacer que el álbum de Dylan sonara "un poco más contemporáneo". [207] En 1985, Dylan cantó en el sencillo de ayuda a la hambruna de USA for Africa " We Are the World ". También se unió a Artists United Against Apartheid , prestando su voz para su sencillo " Sun City ". [208] El 13 de julio de 1985, apareció en el concierto Live Aid en el estadio JFK de Filadelfia. Respaldado por Keith Richards y Ronnie Wood , interpretó una versión irregular de "Ballad of Hollis Brown", una historia de pobreza rural, y luego dijo a la audiencia mundial: "Espero que algo del dinero... tal vez puedan tomar un poco de él, tal vez... uno o dos millones, tal vez... y usarlo para pagar las hipotecas de algunas de las granjas y, los granjeros aquí, le deben a los bancos". [209] Sus comentarios fueron ampliamente criticados como inapropiados, pero inspiraron a Willie Nelson a organizar un concierto, Farm Aid , para beneficiar a los granjeros estadounidenses endeudados. [210]

En octubre de 1985, Dylan lanzó Biograph , un box set que incluía 53 temas, 18 de ellos inéditos. Stephen Thomas Erlewine escribió: «Históricamente, Biograph es importante no por lo que hizo por la carrera de Dylan, sino por establecer el box set, completo con éxitos y rarezas, como una parte viable de la historia del rock». [211] Biograph también contenía notas de Cameron Crowe en las que Dylan hablaba de los orígenes de algunas de sus canciones. [212]

En abril de 1986, Dylan hizo una incursión en el rap cuando añadió voces al verso de apertura de «Street Rock» en el álbum Kingdom Blow de Kurtis Blow . [213] El siguiente álbum de estudio de Dylan, Knocked Out Loaded (1986), contenía tres versiones (de Junior Parker , Kris Kristofferson y el himno gospel « Precious Memories »), más tres colaboraciones (con Tom Petty , Sam Shepard y Carole Bayer Sager ), y dos composiciones en solitario de Dylan. Un crítico escribió que «el disco sigue demasiados desvíos para ser consistentemente convincente, y algunos de esos desvíos serpentean por caminos que son indiscutiblemente callejones sin salida. En 1986, Dylan no se esperaba del todo que tuviera discos tan desiguales, pero eso no los hizo menos frustrantes». [214] Fue el primer álbum de Dylan desde su debut en 1962 que no logró entrar en el Top 50. [215] Algunos críticos han llamado a la canción que Dylan coescribió con Shepard, " Brownsville Girl ", una obra maestra. [216]

En 1986 y 1987, Dylan realizó una gira con Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers , compartiendo voces con Petty en varias canciones cada noche. Dylan también realizó una gira con Grateful Dead en 1987, lo que resultó en el álbum en vivo Dylan & The Dead , que recibió críticas negativas; Erlewine dijo que era "posiblemente el peor álbum de Bob Dylan o Grateful Dead". [217] Dylan inició lo que se llamó Never Ending Tour el 7 de junio de 1988, tocando con una banda de respaldo que incluía al guitarrista GE Smith . Dylan continuaría de gira con una banda pequeña y cambiante durante los siguientes 30 años. [218] En 1987, Dylan protagonizó la película Hearts of Fire de Richard Marquand , en la que interpretó a Billy Parker, una estrella de rock fracasada que se convierte en granjero de pollos cuya amante adolescente ( Fiona ) lo deja por una sensación de synth-pop inglesa hastiada ( Rupert Everett ). [219] Dylan también contribuyó con dos canciones originales para la banda sonora: «Night After Night» y «Had a Dream About You, Baby», así como una versión de «The Usual» de John Hiatt . La película fue un fracaso comercial y de crítica. [220]

Dylan fue incluido en el Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll en enero de 1988. Bruce Springsteen, en su introducción, declaró: "Bob liberó tu mente de la misma manera que Elvis liberó tu cuerpo. Nos mostró que el hecho de que la música fuera innatamente física no significaba que fuera antiintelectual". [104] Down in the Groove (1988) se vendió incluso peor que Knocked Out Loaded . [221] Gray escribió: "El título en sí mismo socava cualquier idea de que pueda haber trabajo inspirado en él. Aquí hubo una devaluación aún mayor de la noción de un nuevo álbum de Bob Dylan como algo significativo". [222] La decepción crítica y comercial de ese álbum fue seguida rápidamente por el éxito de los Traveling Wilburys , un supergrupo que Dylan cofundó con George Harrison, Jeff Lynne , Roy Orbison y Tom Petty. A fines de 1988, su Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 alcanzó el número tres en la lista de álbumes de EE. UU., [221] presentando canciones descritas como las composiciones más accesibles de Dylan en años. [223] A pesar de la muerte de Orbison en diciembre de 1988, los cuatro restantes grabaron un segundo álbum en mayo de 1990, Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3. [ 224]

Dylan terminó la década con una nota alta de crítica con Oh Mercy , producido por Daniel Lanois . Gray elogió el álbum como "Atentamente escrito, vocalmente distintivo, musicalmente cálido e inflexiblemente profesional, este conjunto cohesivo es lo más cercano a un gran álbum de Bob Dylan en la década de 1980". [222] " Most of the Time ", una composición sobre un amor perdido, apareció de manera destacada en la película High Fidelity (2000), mientras que " What Was It You Wanted " ha sido interpretada tanto como un catecismo como un comentario irónico sobre las expectativas de los críticos y los fanáticos. [225] La imaginería religiosa de "Ring Them Bells" impactó a algunos críticos como una reafirmación de la fe. [226]

La década de 1990 de Dylan comenzó con Under the Red Sky (1990), un cambio radical respecto del álbum Oh Mercy . Contenía varias canciones aparentemente simples, entre ellas «Under the Red Sky» y «Wiggle Wiggle». El álbum estaba dedicado a «Gabby Goo Goo», un apodo para la hija de Dylan y Carolyn Dennis , Desiree Gabrielle Dennis-Dylan, que tenía cuatro años. [227] Entre los músicos que participaron en el álbum se encontraban George Harrison, Slash , David Crosby , Bruce Hornsby , Stevie Ray Vaughan y Elton John . El disco recibió críticas negativas y se vendió mal. [228] En 1990 y 1991, Dylan fue descrito por sus biógrafos como un bebedor empedernido, lo que perjudicó sus actuaciones en el escenario. [229] [230] En una entrevista con Rolling Stone , Dylan desestimó las acusaciones de que beber estaba interfiriendo con su música: "Eso es completamente inexacto. Puedo beber o no beber. No sé por qué la gente asociaría beber con algo que hago, realmente". [231]

La profanación y el remordimiento fueron temas que Dylan abordó cuando recibió un premio Grammy a la trayectoria de manos de Jack Nicholson en febrero de 1991. [232] El evento coincidió con el inicio de la Guerra del Golfo y Dylan tocó " Masters of War "; la revista Rolling Stone calificó su actuación de "casi ininteligible". [233] Pronunció un breve discurso: "Mi padre me dijo una vez: 'Hijo, es posible que te vuelvas tan profano en este mundo que tu propia madre y tu propio padre te abandonen. Si eso sucede, Dios creerá en tu capacidad para enmendar tus propios caminos ' ". [232] [234] Esta fue una paráfrasis del comentario del rabino ortodoxo del siglo XIX Samson Raphael Hirsch sobre el Salmo 27. [235] El 16 de octubre de 1992, se celebró el trigésimo aniversario del álbum debut de Dylan con un concierto en el Madison Square Garden , bautizado como "Bobfest" por Neil Young y con la participación de John Mellencamp , Stevie Wonder , Lou Reed , Eddie Vedder , Dylan y otros. Fue grabado como el álbum en vivo The 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration . [233]

En los años siguientes Dylan volvió a sus raíces con dos álbumes que versionaban canciones tradicionales de folk y blues: Good as I Been to You (1992) y World Gone Wrong (1993), respaldado únicamente por su guitarra acústica. [236] Muchos críticos y fans notaron la tranquila belleza de la canción «Lone Pilgrim», [237] escrita por un maestro del siglo XIX. En agosto de 1994, tocó en Woodstock '94 ; Rolling Stone calificó su actuación de «triunfante». [233] En noviembre, Dylan grabó dos shows en vivo para MTV Unplugged . Dijo que su deseo de interpretar canciones tradicionales fue rechazado por los ejecutivos de Sony que insistieron en éxitos. [238] El álbum resultante, MTV Unplugged , incluyó «John Brown» , una canción inédita de 1962 sobre cómo el entusiasmo por la guerra termina en mutilación y desilusión. [239]

Con una colección de canciones supuestamente escritas mientras estaba encerrado por la nieve en su rancho de Minnesota, [240] Dylan reservó tiempo de grabación con Daniel Lanois en los Criteria Studios de Miami en enero de 1997. Las sesiones de grabación posteriores estuvieron, según algunos relatos, cargadas de tensión musical. [241] Antes del lanzamiento del álbum, Dylan fue hospitalizado con pericarditis potencialmente mortal , provocada por histoplasmosis . Su gira europea programada fue cancelada, pero Dylan se recuperó rápidamente y salió del hospital diciendo: "Realmente pensé que vería a Elvis pronto". [242] Volvió a la carretera a mediados de año y actuó ante el Papa Juan Pablo II en la Conferencia Eucarística Mundial en Bolonia , Italia. El Papa invitó a la audiencia de 200.000 personas a una homilía basada en "Blowin' in the Wind" de Dylan. [243]

En septiembre, Dylan lanzó el nuevo álbum producido por Lanois, Time Out of Mind . Con sus amargas evaluaciones del amor y reflexiones morbosas, la primera colección de canciones originales de Dylan en siete años fue muy aclamada. Alex Ross lo llamó "un emocionante regreso a la forma". [244] " Cold Irons Bound " le valió a Dylan otro Grammy a la Mejor Interpretación Vocal de Rock Masculina, y el álbum le valió su primer Premio Grammy al Álbum del Año . [245] El primer sencillo del álbum, " Not Dark Yet ", ha sido llamado una de las mejores canciones de Dylan [246] y " Make You Feel My Love " fue versionada por Billy Joel , Garth Brooks , Adele y otros. Elvis Costello dijo: "Creo que podría ser el mejor disco que ha hecho". [247]

En 2001, Dylan ganó un premio Óscar a la mejor canción original por « Things Have Changed », escrita para la película Wonder Boys . [249] «Love and Theft» se lanzó el 11 de septiembre de 2001. Grabado con su banda de gira, Dylan produjo el álbum bajo el alias de Jack Frost. [250] Los críticos notaron que Dylan estaba ampliando su paleta musical para incluir rockabilly , western swing , jazz y música lounge . [251] El álbum ganó el premio Grammy al mejor álbum de folk contemporáneo . [252] La controversia se produjo cuando The Wall Street Journal señaló similitudes entre las letras del álbum y el libro de Junichi Saga Confesiones de un Yakuza . Saga no estaba familiarizado con el trabajo de Dylan, pero dijo que se sentía halagado. Al escuchar el álbum, Saga dijo de Dylan: «Sus líneas fluyen de una imagen a la siguiente y no siempre tienen sentido. Pero tienen una gran atmósfera». [253] [254]

En 2003, Dylan revisó las canciones evangélicas de su período cristiano y participó en el proyecto Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs of Bob Dylan . Ese año, Dylan lanzó Masked & Anonymous , que coescribió con el director Larry Charles bajo el alias Sergei Petrov. [255] Dylan protagonizó a Jack Fate, junto a un elenco que incluía a Jeff Bridges , Penélope Cruz y John Goodman . La película polarizó a los críticos. [256] En The New York Times , AO Scott la calificó como un "lío incoherente"; [257] algunos la trataron como una obra de arte seria. [258] [259]

En 2004, Dylan publicó la primera parte de sus memorias, Chronicles: Volume One . Desconcertando las expectativas, [260] Dylan dedicó tres capítulos a su primer año en la ciudad de Nueva York en 1961-1962, ignorando virtualmente la mitad de la década de 1960 cuando su fama estaba en su apogeo, mientras dedicaba capítulos a los álbumes New Morning (1970) y Oh Mercy (1989). El libro alcanzó el número dos en la lista de libros de no ficción de tapa dura de The New York Times en diciembre de 2004 y fue nominado para un Premio Nacional del Libro . [261]

El documental de Dylan No Direction Home de Martin Scorsese se emitió el 26 y 27 de septiembre de 2005 en BBC Two en el Reino Unido y como parte de American Masters en PBS en los EE. UU. [262] Cubre el período desde la llegada de Dylan a Nueva York en 1961 hasta su accidente de motocicleta en 1966, presentando entrevistas con Suze Rotolo , Liam Clancy , Joan Baez, Allen Ginsberg, Pete Seeger, Mavis Staples y el propio Dylan. La película ganó un premio Peabody [263] y un premio Columbia-duPont . [264] La banda sonora que acompaña al documental presenta canciones inéditas de los primeros años de Dylan. [265]

La carrera de Dylan como presentador de radio comenzó el 3 de mayo de 2006, con su programa semanal, Theme Time Radio Hour , en XM Satellite Radio . Tocaba canciones con un tema en común, como «Weather», «Weddings», «Dance» y «Dreams». [266] [267] Los discos de Dylan abarcaban desde Muddy Waters hasta Prince , LL Cool J y The Streets . El programa de Dylan fue elogiado por la amplitud de sus selecciones musicales [268] y por sus chistes, historias y referencias eclécticas. [269] [270] En abril de 2009, Dylan transmitió el programa número 100 de su serie de radio; el tema fue «Goodbye» y se despidió con « So Long, It's Been Good to Know Yuh » de Woody Guthrie. [271]

Dylan lanzó Modern Times en agosto de 2006. A pesar de un cierto engrosamiento de la voz de Dylan (un crítico de The Guardian caracterizó su canto en el álbum como "un estertor catarral" [272] ), la mayoría de los críticos elogiaron el álbum, y muchos lo describieron como la última entrega de una exitosa trilogía, que abarca Time Out of Mind y "Love and Theft" . [273] Modern Times entró en las listas de éxitos de Estados Unidos en el número uno, lo que lo convirtió en el primer álbum de Dylan en alcanzar esa posición desde Desire de 1976. [274] The New York Times publicó un artículo que exploraba las similitudes entre algunas de las letras de Dylan en Modern Times y el trabajo del poeta de la Guerra Civil Henry Timrod . [275] Modern Times ganó el premio Grammy al Mejor Álbum de Folk Contemporáneo y Dylan ganó el premio a la Mejor Interpretación Vocal de Rock Solista por "Someday Baby". [276] Modern Times fue nombrado Álbum del Año por Rolling Stone [277] y Uncut . [278] El mismo día que se lanzó Modern Times , la iTunes Music Store lanzó Bob Dylan: The Collection , una caja digital que contenía todos sus álbumes (773 pistas), junto con 42 pistas raras e inéditas. [279]

El 1 de octubre de 2007, Columbia Records lanzó la retrospectiva en triple CD Dylan , antologando toda su carrera bajo el logo Dylan 07. [280] La sofisticación de la campaña de marketing de Dylan 07 fue un recordatorio de que el perfil comercial de Dylan había aumentado considerablemente desde la década de 1990. Esto se hizo evidente en 2004, cuando Dylan apareció en un anuncio de televisión de Victoria's Secret . [281] En octubre de 2007 , participó en una campaña multimedia para el Cadillac Escalade 2008. [282] [283] En 2009 dio el respaldo de más alto perfil de su carrera hasta la fecha, apareciendo con el rapero will.i.am en un anuncio de Pepsi que debutó durante el Super Bowl XLIII . El anuncio se abrió con Dylan cantando el primer verso de "Forever Young" seguido de will.i.am haciendo una versión hip hop del tercer y último verso de la canción. [284]

The Bootleg Series Vol. 8 – Tell Tale Signs fue lanzado en octubre de 2008, tanto como un set de dos CD como una versión de tres CD con un libro de tapa dura de 150 páginas. El set contiene actuaciones en directo y tomas descartadas de álbumes de estudio seleccionados desde Oh Mercy hasta Modern Times , así como contribuciones a la banda sonora y colaboraciones con David Bromberg y Ralph Stanley . [285] El precio del álbum (el set de dos CD salió a la venta por 18,99 dólares y la versión de tres CD por 129,99 dólares) provocó quejas sobre el "empaquetado de imitación". [286] [287] El lanzamiento fue ampliamente aclamado por los críticos. [288] La abundancia de tomas alternativas y material inédito le sugirió a un crítico que este volumen de tomas descartadas antiguas "se siente como un nuevo disco de Bob Dylan, no solo por la asombrosa frescura del material, sino también por la increíble calidad de sonido y la sensación orgánica de todo aquí". [289]

Dylan lanzó Together Through Life el 28 de abril de 2009. En una conversación con el periodista musical Bill Flanagan, Dylan explicó que se originó cuando el director francés Olivier Dahan le pidió que proporcionara una canción para su película My Own Love Song . Inicialmente tenía la intención de grabar una sola canción, "Life Is Hard", pero "el disco tomó su propia dirección". [290] Nueve de las diez canciones del álbum están acreditadas como coescritas por Dylan y Robert Hunter . [291] El álbum recibió críticas en gran medida favorables, [292] aunque varios críticos lo describieron como una adición menor al canon de Dylan. [293] En su primera semana de lanzamiento, el álbum alcanzó el número uno en la lista Billboard 200 en los EE. UU., lo que convirtió a Dylan, a los 67 años de edad, en el artista de mayor edad en debutar en el número uno de esa lista. [294]

Dylan's Christmas in the Heart fue lanzado en octubre de 2009, e incluía clásicos navideños como « Little Drummer Boy », « Winter Wonderland » y « Here Comes Santa Claus ». [295] Edna Gundersen escribió que Dylan estaba «revisitando estilos navideños popularizados por Nat King Cole , Mel Tormé y los Ray Conniff Singers ». [296] Las regalías de Dylan del álbum fueron donadas a las organizaciones benéficas Feeding America en los EE. UU., Crisis en el Reino Unido y el Programa Mundial de Alimentos . [297] El álbum recibió críticas generalmente favorables. [298] En una entrevista publicada en The Big Issue , Flanagan le preguntó a Dylan por qué había interpretado las canciones con un estilo sencillo, y él respondió: «No había otra forma de tocarlas. Estas canciones son parte de mi vida, como las canciones folk. También tienes que tocarlas de forma directa». [299]

El volumen 9 de la serie Bootleg de Dylan, The Witmark Demos , se publicó el 18 de octubre de 2010. Comprendía 47 grabaciones de demostración de canciones grabadas entre 1962 y 1964 para los primeros editores musicales de Dylan: Leeds Music en 1962 y Witmark Music de 1962 a 1964. Un crítico describió el conjunto como "una mirada cordial del joven Bob Dylan cambiando el negocio de la música y el mundo, una nota a la vez". [300] En el agregador crítico Metacritic , el álbum tiene una puntuación de 86, lo que indica "aclamación universal". [301] En la misma semana, Sony Legacy lanzó Bob Dylan: The Original Mono Recordings , un box set que presentaba los ocho primeros álbumes de Dylan, desde Bob Dylan (1962) hasta John Wesley Harding (1967), en su mezcla mono original en formato CD por primera vez. El conjunto iba acompañado de un folleto con un ensayo de Greil Marcus. [302] [303]

El 12 de abril de 2011, Legacy Recordings lanzó Bob Dylan in Concert – Brandeis University 1963 , grabado en la Brandeis University el 10 de mayo de 1963, dos semanas antes del lanzamiento de The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan . La cinta fue descubierta en el archivo del escritor musical Ralph J. Gleason , y la grabación lleva notas de Michael Gray, quien dice que captura a Dylan "desde mucho antes de que Kennedy fuera presidente y los Beatles aún no habían llegado a Estados Unidos. No lo revela en ningún gran momento, sino dando una actuación como sus sets de clubes de folk de la época ... Esta es la última actuación en vivo que tenemos de Bob Dylan antes de que se convierta en una estrella". [304]

En el 70.º cumpleaños de Dylan, tres universidades organizaron simposios sobre su obra: la Universidad de Maguncia , [305] la Universidad de Viena , [306] y la Universidad de Bristol [307] invitaron a críticos literarios e historiadores culturales a presentar ponencias sobre aspectos de la obra de Dylan. Otros eventos, incluidas bandas tributo, debates y cantos sencillos, tuvieron lugar en todo el mundo, como informó The Guardian : "Desde Moscú hasta Madrid, Noruega hasta Northampton y Malasia hasta su estado natal de Minnesota, los autoconfesos 'Bobcats' se reunirán hoy para celebrar el 70.º cumpleaños de un gigante de la música popular". [308]

El 35.º álbum de estudio de Dylan, Tempest , fue lanzado el 11 de septiembre de 2012. [309] El álbum incluye un tributo a John Lennon, « Roll On John », y la canción principal es una canción de 14 minutos sobre el hundimiento del Titanic . [310] En Rolling Stone , Will Hermes le dio a Tempest cinco de cinco estrellas, escribiendo: «Líricamente, Dylan está en la cima de su juego, bromeando, dejando caer juegos de palabras y alegorías que evaden las lecturas fáciles y citando las palabras de otras personas como un rapero de estilo libre en llamas». [311]

El volumen 10 de la serie Bootleg de Dylan, Another Self Portrait (1969–1971) , fue lanzado en agosto de 2013. [312] El álbum contenía 35 temas inéditos, incluyendo tomas alternativas y demos de las sesiones de grabación de Dylan de 1969-1971 durante la realización de los álbumes Self Portrait y New Morning . El box set también incluía una grabación en vivo de la actuación de Dylan con The Band en el Festival de la Isla de Wight en 1969. Thom Jurek escribió: "Para los fans, esto es más que una curiosidad, es una adición indispensable al catálogo". [313] Columbia Records lanzó un box set que contenía los 35 álbumes de estudio de Dylan, seis álbumes de grabaciones en vivo y una colección de material que no es de álbumes ( Sidetracks ) como Bob Dylan: Complete Album Collection: Vol. Uno , en noviembre de 2013. [314] [315] Para publicitar el box set, se lanzó un video innovador de "Like a Rolling Stone" en el sitio web de Dylan. El video interactivo, creado por la directora Vania Heymann , permitió a los espectadores cambiar entre 16 canales de televisión simulados, todos con personajes que hacen playback de la letra. [316] [317]

Dylan apareció en un anuncio del automóvil Chrysler 200 que se emitió durante el Super Bowl de 2014. En él, dice que "Detroit hizo automóviles y los automóviles hicieron Estados Unidos... Así que dejen que Alemania fabrique su cerveza, dejen que Suiza fabrique su reloj, dejen que Asia ensamble su teléfono. Nosotros fabricaremos su automóvil". El anuncio de Dylan fue criticado por sus implicaciones proteccionistas , y la gente se preguntó si se había " vendido ". [318] [319] The Lyrics: Since 1962 fue publicado por Simon & Schuster en el otoño de 2014. El libro fue editado por el crítico literario Christopher Ricks , Julie Nemrow y Lisa Nemrow y ofrecía versiones variantes de las canciones de Dylan, extraídas de tomas descartadas y presentaciones en vivo. Una edición limitada de 50 libros, firmados por Dylan, tenía un precio de $5,000. "Es el libro más grande y más caro que hemos publicado, hasta donde yo sé", dijo Jonathan Karp, presidente y editor de Simon & Schuster. [320] [321] Una edición completa de Basement Tapes, canciones grabadas por Dylan y The Band en 1967, fue lanzada como The Bootleg Series Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete en noviembre de 2014. El álbum incluía 138 pistas en una caja de seis CD; el álbum de 1975 The Basement Tapes contenía solo 24 pistas del material que Dylan y The Band habían grabado en sus casas en Woodstock, Nueva York en 1967. Posteriormente, más de 100 grabaciones y tomas alternativas habían circulado en discos piratas. Las notas de la funda son del autor Sid Griffin . [322] [323] The Basement Tapes Complete ganó el premio Grammy al mejor álbum histórico . [324] La caja obtuvo una puntuación de 99 en Metacritic. [325]

En febrero de 2015, Dylan lanzó Shadows in the Night , que incluye diez canciones escritas entre 1923 y 1963, [326] [327] que han sido descritas como parte del Great American Songbook . [328] Todas las canciones habían sido grabadas por Frank Sinatra , pero tanto los críticos como el propio Dylan advirtieron contra ver el disco como una colección de "versiones de Sinatra". [326] [329] Dylan explicó: "No me veo haciendo versiones de estas canciones de ninguna manera. Han sido versionadas lo suficiente. Enterradas, de hecho. Lo que mi banda y yo estamos haciendo básicamente es descubrirlas. Sacándolas de la tumba y llevándolas a la luz del día". [330] Los críticos elogiaron los acompañamientos instrumentales moderados y la calidad del canto de Dylan. [328] [331] El álbum debutó en el número uno en la lista de álbumes del Reino Unido en su primera semana de lanzamiento. [332] The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966 , que consiste en material inédito de los tres álbumes que Dylan grabó entre enero de 1965 y marzo de 1966 ( Bringing It All Back Home , Highway 61 Revisited y Blonde on Blonde ), se lanzó en noviembre de 2015. El conjunto se lanzó en tres formatos: una versión "Best Of" de 2 CD, una "edición Deluxe" de 6 CD y una "Edición de coleccionista" limitada de 18 CD. En el sitio web de Dylan, la "Edición de coleccionista" se describió como que contenía "cada nota grabada por Bob Dylan en el estudio en 1965/1966". [333] [334] The Best of the Cutting Edge entró en la lista Billboard Top Rock Albums en el número uno el 18 de noviembre, según sus ventas de la primera semana. [335]

Dylan lanzó Fallen Angels , descrito como "una continuación directa del trabajo de 'descubrir' el Gran Cancionero que comenzó en Shadows In the Night ", en mayo. [336] El álbum contenía doce canciones de compositores clásicos como Harold Arlen , Sammy Cahn y Johnny Mercer , once de las cuales habían sido grabadas por Sinatra. [336] Jim Farber escribió en Entertainment Weekly : "De manera reveladora, [Dylan] ofrece estas canciones de amor perdido y querido no con una pasión ardiente sino con la nostalgia de la experiencia. Ahora son canciones de memoria, entonadas con un sentido presente de compromiso. Lanzadas solo cuatro días antes de su 75 cumpleaños, no podrían ser más apropiadas para su edad". [337] Las grabaciones en vivo de 1966 , que incluyen todas las grabaciones conocidas de la gira de conciertos de Dylan de 1966, se lanzaron en noviembre de 2016. [338] Las grabaciones comienzan con el concierto en White Plains, Nueva York, el 5 de febrero de 1966, y terminan con el concierto en el Royal Albert Hall de Londres el 27 de mayo. [339] [340] El New York Times informó que la mayoría de los conciertos "nunca se habían escuchado en ninguna forma", y describió el conjunto como "una adición monumental al corpus". [341]

En marzo de 2017, Dylan lanzó un álbum triple de 30 grabaciones más de canciones clásicas estadounidenses, Triplicate . El 38.º álbum de estudio de Dylan se grabó en los estudios Capitol de Hollywood y presenta a su banda de gira. [342] Dylan publicó una larga entrevista en su sitio web para promocionar el álbum, y se le preguntó si este material era un ejercicio de nostalgia.

¿Nostálgico? No, yo no diría eso. No es un viaje al pasado ni añorar los buenos tiempos ni los buenos recuerdos de lo que ya no existe. Una canción como 'Sentimental Journey' no es una canción de antaño, no emula el pasado, es alcanzable y realista, está en el aquí y ahora. [343]

Los críticos elogiaron la minuciosidad de la exploración de Dylan del Gran Cancionero Americano, aunque, en opinión de Uncut , "A pesar de todos sus encantos fáciles, Triplicate trabaja su punto hasta el borde de la exageración. Después de cinco álbumes llenos de canciones alegres, esto se siente como un punto y final gordo en un capítulo fascinante". [344] El siguiente volumen de la Bootleg Series de Dylan revisó su período cristiano "Born Again" de 1979 a 1981, descrito por Rolling Stone como "un tiempo intenso y tremendamente controvertido que produjo tres álbumes y algunos de los conciertos más conflictivos de su larga carrera". [345] Al revisar el box set The Bootleg Series Vol. 13: Trouble No More 1979–1981 , que comprende 8 CD y 1 DVD, [345] Jon Pareles escribió en The New York Times :

Décadas después, lo que se percibe sobre todo en estas grabaciones es el fervor inconfundible de Dylan, su sentido de misión. Los álbumes de estudio son moderados, incluso tentativos, comparados con lo que las canciones se convirtieron en la gira. La voz de Dylan es clara, cortante y siempre improvisada; trabajando con el público, era enfático, comprometido, a veces provocativamente combativo. Y la banda se lanza a la música. [346]

Trouble No More incluye un DVD de una película dirigida por Jennifer Lebeau que consta de imágenes en vivo de las actuaciones gospel de Dylan intercaladas con sermones pronunciados por el actor Michael Shannon .

En abril de 2018, Dylan hizo una contribución al EP recopilatorio Universal Love , una colección de canciones de boda reinventadas para la comunidad LGBT . [347] El álbum fue financiado por MGM Resorts International y las canciones están destinadas a funcionar como "himnos de boda para parejas del mismo sexo". [348] Dylan grabó la canción de 1929 " She's Funny That Way ", cambiando el pronombre de género a "He's Funny That Way". La canción fue grabada previamente por Billie Holiday y Frank Sinatra. [348] [349] Ese mismo mes, The New York Times informó que Dylan estaba lanzando Heaven's Door, una gama de tres whiskies . El Times describió la empresa como "la entrada del Sr. Dylan en el floreciente mercado de licores de marca de celebridades, el último giro en la carrera de un artista que ha pasado cinco décadas confundiendo las expectativas". [350] Dylan ha estado involucrado tanto en la creación como en la comercialización de la gama; El 21 de septiembre de 2020, Dylan resucitó Theme Time Radio Hour con un especial de dos horas con el tema de "Whiskey". [351] El 2 de noviembre de 2018, Dylan lanzó More Blood, More Tracks como el volumen 14 de la serie Bootleg. El conjunto comprende todas las grabaciones de Dylan para Blood On the Tracks y se publicó como un solo CD y también como una edición de lujo de seis CD. [352]

En 2019, Netflix lanzó Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story de Martin Scorsese , anunciada como "parte documental, parte película de concierto, parte sueño febril". [353] [354] La película recibió críticas en gran parte positivas, pero causó confusión porque mezclaba material documental filmado durante la Rolling Thunder Revue en el otoño de 1975 con personajes e historias ficticias, y escenas de Renaldo y Clara de Dylan , que también mezclaban realidad y ficción. [355] [356] Coincidiendo con el estreno de la película, Columbia Records lanzó el box set The Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings . El set incluye cinco actuaciones completas de Dylan de la gira y cintas recientemente descubiertas de los ensayos de la gira de Dylan. [357] El box set recibió una puntuación total de 89 en Metacritic, lo que indica "aclamación universal". [358] La siguiente entrega de la serie Bootleg de Dylan, Bob Dylan (con Johnny Cash) – Travelin' Thru, 1967 – 1969: The Bootleg Series Vol. 15 , se lanzó el 1 de noviembre. El conjunto incluye tomas descartadas de los álbumes de Dylan John Wesley Harding y Nashville Skyline , y canciones que Dylan grabó con Johnny Cash en Nashville en 1969 y con Earl Scruggs en 1970. [359] [360]

El 26 de marzo de 2020, Dylan lanzó « Murder Most Foul », una canción de diecisiete minutos que gira en torno al asesinato de Kennedy , en su canal de YouTube. [361] Dylan publicó una declaración: «Esta es una canción inédita que grabamos hace un tiempo y que te puede resultar interesante. Mantente a salvo, mantente observador y que Dios esté contigo». [362] Billboard informó el 8 de abril que «Murder Most Foul» había encabezado la lista de ventas de canciones digitales de Billboard Rock, la primera vez que Dylan había conseguido una canción número uno en una lista pop con su propio nombre. [363] Tres semanas después, el 17 de abril de 2020, Dylan lanzó otra canción nueva, « I Contain Multitudes ». [364] [365] El título es del poema de Walt Whitman « Song of Myself ». [366] El 7 de mayo, Dylan lanzó un tercer sencillo, « False Prophet », acompañado de la noticia de que las tres canciones aparecerían en un próximo álbum doble.

Rough and Rowdy Ways , el 39.º álbum de estudio de Dylan y su primer álbum de material original desde 2012, fue lanzado el 19 de junio con críticas favorables. [367] Alexis Petridis escribió: "A pesar de toda su desolación, Rough and Rowdy Ways bien podría ser el conjunto de canciones más consistentemente brillante de Bob Dylan en años: los fanáticos pueden pasar meses desentrañando las letras más complicadas, pero no necesitas un doctorado en Dylanología para apreciar su singular calidad y poder". [368] Rob Sheffield escribió: "Mientras el mundo sigue tratando de celebrarlo como una institución, inmovilizarlo, incluirlo en el canon del Premio Nobel, embalsamar su pasado, este vagabundo siempre sigue haciendo su próximo escape. En Rough and Rowdy Ways , Dylan está explorando un terreno que nadie más ha alcanzado antes, pero sigue avanzando hacia el futuro". [369] El álbum obtuvo una puntuación de 95 en Metacritic, lo que indica "aclamación universal". [367] En su primera semana de lanzamiento, Rough and Rowdy Ways alcanzó el número uno en la lista de álbumes del Reino Unido, convirtiendo a Dylan en "el artista de mayor edad en alcanzar el número uno de material nuevo y original". [370]

En diciembre de 2020, se anunció que Dylan había vendido todo su catálogo de canciones a Universal Music Publishing Group , [371] incluidos tanto los ingresos que recibe como compositor como su control de los derechos de autor. Universal, una división del conglomerado de medios francés Vivendi , cobrará todos los ingresos futuros de las canciones. [372] El New York Times afirmó que Universal había comprado los derechos de autor de más de 600 canciones y que el precio se "estimó en más de 300 millones de dólares", [372] aunque otros informes sugirieron que la cifra estaba más cerca de los 400 millones de dólares. [373]

En febrero de 2021, Columbia Records lanzó 1970 , un conjunto de tres CD de grabaciones de las sesiones de Self Portrait y New Morning , incluida la totalidad de la sesión que Dylan grabó con George Harrison el 1 de mayo de 1970. [374] [375] El 80 cumpleaños de Dylan se conmemoró con una conferencia virtual, Dylan@80, organizada por el Instituto de Estudios de Bob Dylan de la Universidad de Tulsa . El programa contó con diecisiete sesiones durante tres días impartidas por más de cincuenta académicos, periodistas y músicos internacionales. [376] Se publicaron varias biografías y estudios nuevos de Dylan. [377] [378]

En julio de 2021, la plataforma de transmisión en vivo Veeps presentó una actuación de 50 minutos de Dylan, Shadow Kingdom: The Early Songs of Bob Dylan . [379] Filmada en blanco y negro con un aspecto de cine negro , [380] Dylan interpretó 13 canciones en un club con público. [379] [381] La actuación fue revisada favorablemente, [381] [380] y un crítico sugirió que la banda de acompañamiento se parecía al estilo del musical Girl from the North Country . [382] La banda sonora de la película se lanzó en formatos de 2 LP y CD en junio de 2023. [383] En septiembre, Dylan lanzó Springtime in New York: The Bootleg Series Vol. 16 (1980-1985) , publicado en formatos de 2 LP, 2 CD y 5 CD. Incluía ensayos, grabaciones en vivo, tomas descartadas y tomas alternativas de Shot of Love , Infidels y Empire Burlesque . [384] En The Daily Telegraph , Neil McCormick escribió: "Estas sesiones pirata nos recuerdan que el peor período de Dylan sigue siendo más interesante que los momentos de mayor interés de la mayoría de los artistas". [385] Springtime in New York recibió una puntuación total de 85 en Metacritic. [386]

El 7 de julio de 2022, Christie's , Londres, subastó una grabación de 2021 de Dylan cantando "Blowin' in the Wind". El disco estaba en un innovador medio de grabación "único en uno", con la marca Ionic Original, que el productor T Bone Burnett afirmó que "supera la excelencia y profundidad sonoras por las que es famoso el sonido analógico, al mismo tiempo que cuenta con la durabilidad de una grabación digital". [387] [388] La grabación se vendió por £ 1,482,000 libras esterlinas, equivalentes a $ 1,769,508. [389] [390] En noviembre, Dylan publicó The Philosophy of Modern Song , una colección de 66 ensayos sobre canciones de otros artistas. The New Yorker lo describió como "un libro de ensayos rico, lleno de riffs, divertido y completamente atractivo". [391] Otros críticos elogiaron la perspectiva ecléctica del libro, [392] mientras que algunos cuestionaron sus variaciones de estilo y la escasez de compositoras. [393]