Apolo [a] es una de las deidades olímpicas de la religión clásica griega y romana y de la mitología griega y romana . Apolo ha sido reconocido como un dios del tiro con arco, la música y la danza, la verdad y la profecía, la curación y las enfermedades, el Sol y la luz, la poesía y más. Uno de los dioses griegos más importantes y complejos, es hijo de Zeus y Leto , y hermano gemelo de Artemisa , diosa de la caza. Se le considera el dios más bello y se le representa como el ideal del kouros (efebo, o un joven atlético e imberbe). Apolo es conocido en la mitología etrusca de influencia griega como Apulu . [3]

Como deidad patrona de Delfos ( Apolo Pitio ), Apolo es un dios oracular , la deidad profética del Oráculo de Delfos y también la deidad de la purificación ritual. Sus oráculos eran consultados a menudo para obtener orientación en diversos asuntos. En general, se lo consideraba el dios que brinda ayuda y aleja el mal, y se lo conoce como Alexicacus , el "que aparta el mal".

La medicina y la curación están asociadas con Apolo, ya sea a través del propio dios o a través de su hijo Asclepio . Apolo liberó a la gente de las epidemias, pero también es un dios que podía traer mala salud y plagas mortales con sus flechas. La invención del tiro con arco se atribuye a Apolo y a su hermana Artemisa. A Apolo se lo describe generalmente portando un arco de plata o de oro y un carcaj de flechas de plata o de oro.

Como dios de la mousike , [b] Apolo preside toda la música, las canciones, la danza y la poesía. Es el inventor de la música de cuerdas y el compañero frecuente de las Musas, actuando como su líder de coro en las celebraciones. La lira es un atributo común de Apolo. La protección de los jóvenes es una de las facetas mejor atestiguadas de su personaje de culto panhelénico. Como kourotrophos , Apolo se preocupa por la salud y la educación de los niños, y preside su paso a la edad adulta. El cabello largo, que era prerrogativa de los niños, se cortaba al llegar a la mayoría de edad ( ephebeia ) y se dedicaba a Apolo. El propio dios es representado con el pelo largo y sin cortar para simbolizar su eterna juventud.

Apolo es una importante deidad pastoral, y era el patrón de los pastores y los ganaderos. La protección de los rebaños, los rebaños y los cultivos contra enfermedades, plagas y depredadores eran sus principales deberes rústicos. Por otra parte, Apolo también fomentaba la fundación de nuevas ciudades y el establecimiento de constituciones civiles, se asocia con el dominio sobre los colonos y era el dador de leyes. Sus oráculos se consultaban a menudo antes de establecer leyes en una ciudad. Apolo Agieo era el protector de las calles, los lugares públicos y las entradas de las casas. [ cita requerida ]

En tiempos helenísticos, especialmente durante el siglo V a. C., como Apolo Helios llegó a ser identificado entre los griegos con Helios , la personificación del Sol. [4] Aunque las obras teológicas latinas de al menos el siglo I a. C. identificaron a Apolo con Sol , [5] [6] no hubo una fusión entre los dos entre los poetas latinos clásicos hasta el siglo I d. C. [7]

Apolo ( ático , jónico y griego homérico : Ἀπόλλων , Apollōn ( GEN Ἀπόλλωνος ); dórico : Ἀπέλλων , Apellōn ; arcadocipriota : Ἀπείλων , Apeilōn ; eólico : Ἄπλουν , Aploun ; latín : Apollō )

El nombre Apolo —a diferencia del nombre más antiguo relacionado Paean— no se encuentra generalmente en los textos lineales B ( griego micénico ), aunque hay una posible atestación en la forma lacunosa ]pe-rjo-[ (Lineal B: ] 𐀟𐁊 -[) en la tablilla KN E 842, [8] [9] [10] aunque también se ha sugerido que el nombre podría en realidad leerse " Hiperión " ([u]-pe-rjo-[ne]). [11]

La etimología del nombre es incierta. La ortografía Ἀπόλλων ( pronunciada [a.pól.lɔːn] en ático clásico ) había casi reemplazado a todas las demás formas a principios de la era común , pero la forma dórica , Apellon ( Ἀπέλλων ), es más arcaica, ya que deriva de un * Ἀπέλjων anterior . Probablemente sea un cognado del mes dórico Apellaios ( Ἀπελλαῖος ), [12] y las ofrendas apellaia ( ἀπελλαῖα ) en la iniciación de los jóvenes durante el festival familiar apellai ( ἀπέλλαι ). [13] [14] Según algunos estudiosos, las palabras se derivan de la palabra dórica apella ( ἀπέλλα ), que originalmente significaba "muro", "cerca para animales" y más tarde "asamblea dentro de los límites de la plaza". [15] [16] Apella ( Ἀπέλλα ) es el nombre de la asamblea popular en Esparta, [15] correspondiente a la ecclesia ( ἐκκλησία ). RSP Beekes rechazó la conexión del teónimo con el sustantivo apellai y sugirió una protoforma pregriega * Apal y un . [17]

Varios ejemplos de etimología popular están atestiguados por autores antiguos. Así, los griegos asociaban con mayor frecuencia el nombre de Apolo con el verbo griego ἀπόλλυμι ( apollymi ), "destruir". [18] Platón en Cratilo conecta el nombre con ἀπόλυσις ( apolysis ), "redención", con ἀπόλουσις ( apolousis ), "purificación", y con ἁπλοῦν ( [h]aploun ), "simple", [19] en particular en referencia a la forma tesalia del nombre, Ἄπλουν , y finalmente con Ἀειβάλλων ( aeiballon ), "siempre disparando". Hesiquio relaciona el nombre Apolo con el dórico ἀπέλλα ( apella ), que significa «asamblea», de modo que Apolo sería el dios de la vida política, y también da la explicación σηκός ( sekos ), «redil», en cuyo caso Apolo sería el dios de los rebaños y las manadas. [20] En la antigua lengua macedonia πέλλα ( pella ) significa «piedra», [21] y algunos topónimos pueden derivar de esta palabra: Πέλλα ( Pella , [22] la capital de la antigua Macedonia ) y Πελλήνη ( Pellēnē / Pellene ). [23]

La forma hitita Apaliunas ( d x-ap-pa-li-u-na-aš ) está atestiguada en la carta Manapa-Tarhunta . [24] El testimonio hitita refleja una forma temprana * Apeljōn , que también puede deducirse de la comparación del Ἀπείλων chipriota con el Ἀπέλλων dórico . [25] El nombre del dios lidio Qλdãns /kʷʎðãns/ puede reflejar un /kʷalyán-/ anterior a la palatalización, la síncope y el cambio de sonido pre-lidio *y > d. [26] Nótese la labiovelar en lugar de la labial /p/ que se encuentra en el Ἀπέλjων predórico y el Apaliunas hitita .

Una etimología luvita sugerida para Apaliunas hace de Apolo "El de la Trampa", tal vez en el sentido de "Cazador". [27]

El epíteto principal de Apolo era Febo ( / ˈf iː b ə s / FEE -bəs ; Φοῖβος , Phoibos pronunciación griega: [pʰó͜i.bos] ), literalmente "brillante". [28] Tanto los griegos como los romanos lo usaban con mucha frecuencia para referirse al papel de Apolo como dios de la luz. Al igual que otras deidades griegas, se le aplicaban otros epítetos que reflejaban la variedad de roles, deberes y aspectos que se le atribuían al dios. Sin embargo, aunque Apolo tiene una gran cantidad de apelativos en la mitología griega, solo aparecen unos pocos en la literatura latina .

El lugar de nacimiento de Apolo fue el monte Cinto en la isla de Delos .

Delfos y Actium fueron sus principales lugares de culto. [32] [33]

-testo_e_photo_Paolo_Villa-nB08_Cortile-Statua_di_Apollo_-_scultura_Arte_Manierista_-_parete_di_rampicanti_-_Kodak_EktachromeElite_100_5045_EB_100.jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Apolo era venerado en todo el Imperio Romano . En las tierras tradicionalmente celtas , se lo consideraba con mayor frecuencia un dios del sol y de la curación. A menudo se lo equiparaba con dioses celtas de carácter similar. [49]

Apolo es considerado el más helénico (griego) de los dioses olímpicos . [58] [59] [60]

Los centros de culto de Apolo en Grecia, Delfos y Delos , datan del siglo VIII a. C. El santuario de Delos estaba dedicado principalmente a Artemisa , la hermana gemela de Apolo. En Delfos, Apolo era venerado como el matador de la monstruosa serpiente Pitón . Para los griegos, Apolo era el más griego de todos los dioses, y a través de los siglos adquirió diferentes funciones. En la Grecia arcaica era el profeta , el dios oracular que en tiempos más antiguos estaba relacionado con la "curación". En la Grecia clásica era el dios de la luz y de la música, pero en la religión popular tenía una fuerte función de alejar el mal. [61] Walter Burkert discernió tres componentes en la prehistoria del culto a Apolo, a los que denominó "un componente griego dórico-noroccidental, un componente cretense-minoico y un componente sirio-hitita". [62]

En la época clásica, su principal función en la religión popular era alejar el mal, y por ello se le llamaba "apotropaios" ( ἀποτρόπαιος , "evitar el mal") y "alexikakos" ( ἀλεξίκακος "alejar el mal"; del v. ἀλέξω + n. κακόν ). [64] Apolo también tenía muchos epítetos relacionados con su función como sanador. Algunos ejemplos de uso común son "paion" ( παιών , literalmente "sanador" o "ayudante") [65] "epikourios" ( ἐπικούριος , "socorrista"), "oulios" ( οὔλιος , "sanador, funesto") [66] y "loimios" ( λοίμιος , "de la plaga"). En escritores posteriores, la palabra "paion", generalmente escrita "Paean", se convierte en un mero epíteto de Apolo en su calidad de dios de la curación . [67]

Apolo en su aspecto de "sanador" tiene una conexión con el dios primitivo Peán ( Παιών-Παιήων ), que no tenía un culto propio. Peán sirve como sanador de los dioses en la Ilíada , y parece haberse originado en una religión pre-griega. [68] Se sugiere, aunque no está confirmado, que está conectado con la figura micénica pa-ja-wo-ne (Lineal B: 𐀞𐀊𐀺𐀚 ). [69] [70] [71] Peán era la personificación de las canciones sagradas cantadas por los "médicos videntes" ( ἰατρομάντεις ), que se suponía que curaban las enfermedades. [72]

Homero utiliza el sustantivo Peón para designar tanto a un dios como a su característico canto de acción de gracias y triunfo apotropaico . [73] Tales cantos se dirigían originalmente a Apolo y después a otros dioses: a Dioniso , a Apolo Helios , al hijo de Apolo, Asclepio , el sanador. Alrededor del siglo IV a. C., el peán se convirtió simplemente en una fórmula de adulación; su objeto era implorar protección contra la enfermedad y la desgracia o dar gracias después de que se hubiera brindado dicha protección. Fue de esta manera que Apolo había sido reconocido como el dios de la música. El papel de Apolo como el matador de la Pitón llevó a su asociación con la batalla y la victoria; por lo tanto, se convirtió en costumbre romana que un ejército cantara un peán en marcha y antes de entrar en batalla, cuando una flota salía del puerto y también después de que se hubiera obtenido una victoria.

En la Ilíada , Apolo es el sanador bajo los dioses, pero también es el portador de enfermedades y muerte con sus flechas, similar a la función del dios védico de la enfermedad, Rudra . [74] Envía una plaga ( λοιμός ) a los aqueos . Sabiendo que Apolo puede prevenir una recurrencia de la plaga que envió, se purifican en un ritual y le ofrecen un gran sacrificio de vacas, llamado hecatombe . [75]

El Himno homérico a Apolo describe a Apolo como un intruso procedente del norte. [76] La conexión con los dorios que habitaban en el norte y su festival de iniciación apellai se refuerza con el mes Apellaios en los calendarios del noroeste griego. [77] El festival familiar estaba dedicado a Apolo ( dórico : Ἀπέλλων ). [78] Apellaios es el mes de estos ritos, y Apellon es el "megistos kouros" (el gran Kouros). [79] Sin embargo, solo puede explicar el tipo dórico del nombre, que está conectado con la palabra macedonia antigua "pella" ( Pella ), piedra . Las piedras desempeñaban un papel importante en el culto al dios, especialmente en el santuario oracular de Delfos ( Omphalos ). [80] [81]

George Huxley consideró que la identificación de Apolo con la deidad minoica Paiawon, adorada en Creta, se originó en Delfos. [82] En el Himno homérico , Apolo aparece como un delfín que lleva a los sacerdotes cretenses a Delfos, lugar al que evidentemente trasladan sus prácticas religiosas. Apolo Delphinios o Delphidios era un dios del mar adorado especialmente en Creta y en las islas. [83] La hermana de Apolo , Artemisa , que era la diosa griega de la caza, se identifica con Britomartis (Diktynna), la «señora de los animales» minoica. En sus primeras representaciones estaba acompañada por el «amo de los animales», un dios de la caza que empuñaba un arco y cuyo nombre se ha perdido; es posible que algunos aspectos de esta figura hayan sido absorbidos por el más popular Apolo. [84]

Durante mucho tiempo se ha asumido en la erudición que Apolo no tenía un origen griego. [12] El nombre de la madre de Apolo, Leto , tiene origen lidio y era venerada en las costas de Asia Menor . El culto oracular inspirador probablemente se introdujo en Grecia desde Anatolia , que es el origen de la Sibila y donde se originaron algunos de los santuarios oraculares más antiguos. Presagios, símbolos, purificaciones y exorcismos aparecen en antiguos textos asirio - babilónicos . Estos rituales se extendieron al imperio de los hititas y de allí a Grecia. [85]

Homero describe a Apolo del lado de los troyanos , luchando contra los aqueos , durante la Guerra de Troya . Se le describe como un dios terrible, en el que los griegos confiaban menos que en otros dioses. El dios parece estar relacionado con Apalunas , un dios tutelar de Wilusa ( Troya ) en Asia Menor, pero la palabra no está completa. [86] Las piedras encontradas frente a las puertas de la Troya homérica eran los símbolos de Apolo. Un origen anatoliano occidental también puede verse reforzado por referencias al culto paralelo de Artimus ( Artemisa ) y Qλdãns , cuyo nombre puede estar relacionado con las formas hitita y dórica, en los textos lidios supervivientes . [87] Sin embargo, estudiosos recientes han puesto en duda la identificación de Qλdãns con Apolo. [88]

Los griegos le dieron el nombre de ἀγυιεύς agyieus como dios protector de los lugares públicos y las casas que aleja el mal y su símbolo era una piedra cónica o columna. [89] Sin embargo, mientras que normalmente los festivales griegos se celebraban en la luna llena , todas las fiestas de Apolo se celebraban el séptimo día del mes, y el énfasis dado a ese día ( sibutu ) indica un origen babilónico . [90]

El Rudra védico tiene algunas funciones similares a las de Apolo. El terrible dios es llamado "el arquero" y el arco también es un atributo de Shiva . [91] Rudra podía traer enfermedades con sus flechas, pero era capaz de liberar a la gente de ellas y su Shiva alternativo es un dios médico sanador. [92] Sin embargo, el componente indoeuropeo de Apolo no explica su fuerte asociación con presagios, exorcismos y un culto oracular.

Apolo tenía dos lugares de culto que tenían una influencia muy amplia, algo inusual entre las deidades olímpicas: Delos y Delfos . En la práctica del culto, Apolo de Delos y Apolo pitio (el Apolo de Delfos) eran tan distintos que ambos podían tener santuarios en la misma localidad. [60] Licia era sagrada para el dios, ya que este Apolo también era llamado licio. [93] [94] El culto a Apolo ya estaba plenamente establecido cuando comenzaron las fuentes escritas, alrededor del 650 a. C. Apolo se volvió extremadamente importante para el mundo griego como deidad oracular en el período arcaico , y la frecuencia de nombres teofóricos como Apolodoro o Apolonio y ciudades llamadas Apolonia dan testimonio de su popularidad. Se establecieron santuarios oraculares a Apolo en otros sitios. En los siglos II y III d. C., los de Dídima y Claros pronunciaron los llamados "oráculos teológicos", en los que Apolo confirma que todas las deidades son aspectos o sirvientes de una deidad suprema que todo lo abarca . "En el siglo III, Apolo cayó en el silencio. Juliano el Apóstata (359-361) intentó revivir el oráculo de Delfos, pero fracasó." [12]

Apolo tenía un famoso oráculo en Delfos y otros notables en Claros y Dídima . Su santuario oracular en Abae en Fócida , donde llevaba el epíteto toponímico Abaeus ( Ἀπόλλων Ἀβαῖος , Apollon Abaios ), era lo suficientemente importante como para ser consultado por Creso . [95] Sus santuarios oraculares incluyen:

Los oráculos también fueron dados por los hijos de Apolo.

.jpg/440px-The_Temple_of_Apollo_Epikourios_at_Bassae,_east_colonnade,_Arcadia,_Greece_(14087181020).jpg)

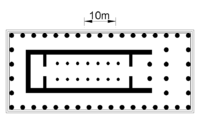

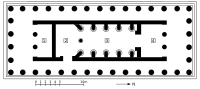

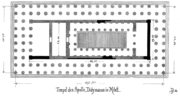

En Grecia y en las colonias griegas se dedicaron numerosos templos a Apolo, que muestran la expansión del culto a Apolo y la evolución de la arquitectura griega, que se basaba principalmente en la corrección de las formas y en las relaciones matemáticas. Algunos de los primeros templos, especialmente en Creta , no pertenecen a ningún orden griego. Parece que los primeros templos peripétreos eran estructuras rectangulares de madera. Los diferentes elementos de madera se consideraban divinos y sus formas se conservaron en los elementos de mármol o piedra de los templos de orden dórico . Los griegos utilizaban tipos estándar porque creían que el mundo de los objetos era una serie de formas típicas que podían representarse en varios casos. Los templos debían ser canónicos y los arquitectos intentaban alcanzar esta perfección estética. [97] Desde los primeros tiempos se observaron estrictamente ciertas reglas en los edificios peripétreos y prostilos rectangulares. Los primeros edificios se construyeron de forma estrecha para sostener el techo y, cuando cambiaron las dimensiones, se hicieron necesarias algunas relaciones matemáticas para mantener las formas originales. Esto probablemente influyó en la teoría de los números de Pitágoras , quien creía que detrás de la apariencia de las cosas estaba el principio permanente de las matemáticas. [98]

El orden dórico dominó durante los siglos VI y V a.C., pero existía un problema matemático con respecto a la posición de los triglifos, que no podía resolverse sin cambiar las formas originales. El orden fue casi abandonado por el orden jónico , pero el capitel jónico también planteaba un problema insoluble en la esquina de un templo. Ambos órdenes fueron abandonados por el orden corintio gradualmente durante la época helenística y bajo Roma.

Los templos más importantes son:

En los mitos, Apolo es hijo de Zeus , el rey de los dioses, y Leto , su esposa anterior [135] o una de sus amantes. Apolo aparece a menudo en los mitos, obras de teatro e himnos, ya sea directa o indirectamente a través de sus oráculos. Como hijo favorito de Zeus, tenía acceso directo a la mente de Zeus y estaba dispuesto a revelar este conocimiento a los humanos. Una divinidad más allá de la comprensión humana, aparece tanto como un dios benéfico como un dios iracundo.

Leto, embarazada de Zeus, vagó por muchas tierras con la intención de dar a luz a Apolo, pero todas las tierras la rechazaron por miedo. Al llegar a Delos, Leto pidió a la isla que la albergara y que, a cambio, su hijo traería fama y prosperidad a la isla. Delos le reveló entonces que se rumoreaba que Apolo era el dios que "dominaría en gran manera entre los dioses y los hombres en toda la fértil tierra". Por esta razón, todas las tierras estaban temerosas y Delos temía que Apolo la rechazara una vez que naciera. Al oír esto, Leto juró sobre el río Estigia que si se le permitía dar a luz en la isla, su hijo honraría a Delos más que a todas las demás tierras. Con esta seguridad, Delos aceptó ayudar a Leto. Todas las diosas, excepto Hera, también acudieron en ayuda de Leto.

Sin embargo, Hera había engañado a Ilitía , la diosa del parto, para que se quedara en el Olimpo, por lo que Leto no pudo dar a luz. Las diosas convencieron a Iris para que fuera a buscar a Ilitía ofreciéndole un collar de ámbar de 8,2 m de largo. Iris obedeció y convenció a Ilitía para que entrara en la isla. Así, agarrada a una palmera, Leto finalmente dio a luz después de nueve días y nueve noches de trabajo de parto, con Apolo "saltando" del vientre de su madre. Las diosas lavaron al recién nacido, lo cubrieron con una prenda blanca y le ataron bandas de oro. Como Leto no podía alimentarlo, Temis , la diosa de la ley divina, lo alimentó con néctar y ambrosía . Al probar la comida divina, el niño se liberó de las ataduras que lo sujetaban y declaró que sería el maestro de la lira y el arco, e interpretaría la voluntad de Zeus para la humanidad. Luego comenzó a caminar, lo que hizo que la isla se llenara de oro. [136]

La isla de Delos solía ser Asteria , una diosa que saltó a las aguas para escapar de los avances de Zeus y se convirtió en una isla flotante con el mismo nombre. Cuando Leto se quedó embarazada, le dijeron a Hera que el hijo de Leto sería más querido para Zeus que Ares. Enfurecida por esto, Hera vigiló los cielos y envió a Ares e Iris para evitar que Leto diera a luz en la tierra. Ares, estacionado sobre el continente, e Iris, sobre las islas, amenazaron todas las tierras y les impidieron ayudar a Leto.

Cuando Leto llegó a Tebas, Apolo, ya en estado fetal, profetizó desde el vientre de su madre que en el futuro castigaría a una mujer calumniosa de Tebas ( Níobe ), por lo que no quería nacer allí. Leto fue entonces a Tesalia y buscó la ayuda de las ninfas fluviales, hijas del río Peneo. Aunque al principio se mostró temeroso y reacio, Peneo decidió más tarde dejar que Leto diera a luz en sus aguas. No cambió de opinión ni siquiera cuando Ares emitió un sonido aterrador y amenazó con arrojar los picos de las montañas al río. Pero la propia Leto declinó su ayuda y se marchó, ya que no quería que él sufriera por su causa.

Después de haber sido rechazado en varias tierras, Apolo volvió a hablar desde el vientre materno, pidiendo a su madre que mirara la isla flotante que tenía frente a ella y expresando su deseo de nacer allí. Cuando Leto se acercó a Asteria, todas las demás islas huyeron. Pero Asteria recibió a Leto sin ningún temor a Hera. Caminando por la isla, se sentó contra una palmera y le pidió a Apolo que naciera. Durante el parto, los cisnes dieron siete vueltas alrededor de la isla, una señal de que más tarde Apolo tocaría la lira de siete cuerdas. Cuando Apolo finalmente "saltó" del vientre de su madre, las ninfas de la isla cantaron un himno a Ilitía que se escuchó hasta los cielos. En el momento en que Apolo nació, toda la isla, incluidos los árboles y las aguas, se volvió de oro. Asteria bañó al recién nacido, lo envolvió y lo alimentó con su leche materna. La isla había echado raíces y más tarde se llamó Delos.

Hera ya no estaba enojada, pues Zeus había logrado calmarla; y no guardaba rencor contra Asteria, ya que Asteria había rechazado a Zeus en el pasado. [137]

Píndaro es la fuente más antigua que explícitamente menciona a Apolo y Artemisa como gemelos. Aquí también se afirma que Asteria es la hermana de Leto. Queriendo escapar de los avances de Zeus, se arrojó al mar y se convirtió en una roca flotante llamada Ortigia hasta que nacieron los gemelos. [138] Cuando Leto pisó la roca, cuatro pilares con bases de adamantina se levantaron de la tierra y sostuvieron la roca. [139] Cuando nacieron Apolo y Artemisa, sus cuerpos brillaron radiantemente y se entonó un cántico por Ilitía y Láquesis , una de las tres Moiras . [140]

Despreciando los avances de Zeus, Asteria se transformó en un pájaro y saltó al mar. De ella surgió una isla que fue llamada Ortigia. [141] Cuando Hera descubrió que Leto estaba embarazada del hijo de Zeus, decretó que Leto solo podía dar a luz en un lugar donde no brillara el sol. Durante este tiempo, el monstruo Pitón también comenzó a acosar a Leto con la intención de matarla, porque había previsto que su muerte llegaría a manos de la descendencia de Leto. Sin embargo, por orden de Zeus, Bóreas se llevó a Leto y la confió a Poseidón . Para protegerla, Poseidón la llevó a la isla Ortigia y la cubrió con olas para que el sol no brillara sobre ella. Leto dio a luz agarrada a un olivo y en adelante la isla se llamó Delos. [142]

Otras variaciones del nacimiento de Apolo incluyen:

Eliano afirma que Leto tardó doce días y doce noches en viajar desde Hiperbórea hasta Delos. [143] Leto se transformó en loba antes de dar a luz. Esta es la razón por la que Homero describe a Apolo como el "dios nacido de lobo". [144] [145]

Libanio escribió que ni la tierra ni las islas visibles recibirían a Leto, pero por voluntad de Zeus, Delos se hizo visible y así recibió a Leto y a los niños. [146]

Según Estrabón, los Curetes ayudaron a Leto creando fuertes ruidos con sus armas y asustando así a Hera, ocultaron el parto de Leto. [147]

Teognis escribió que la isla estaba llena de fragancia ambrosial cuando nació Apolo, y la Tierra rió de alegría. [148]

En algunas versiones, Artemisa nació primero y posteriormente ayudó en el nacimiento de Apolo. [149] [150]

Aunque en algunos relatos el nacimiento de Apolo fijó la isla flotante de Delos a la tierra, hay relatos de que Apolo aseguró Delos al fondo del océano poco tiempo después. [151] [152]

Esta isla se convirtió en sagrada para Apolo y fue uno de los principales centros de culto del dios. Apolo nació el séptimo día ( ἑβδομαγενής , hebdomagenes ) [153] del mes de Targelión —según la tradición de Delos— o del mes de Bisios —según la tradición de Delfos. El séptimo y el vigésimo, los días de la luna nueva y llena, siempre fueron considerados sagrados para él. [20]

Hiperbórea , la tierra mística de la eterna primavera, veneraba a Apolo por encima de todos los dioses. Los hiperbóreos siempre cantaban y bailaban en su honor y organizaban los juegos píticos . [154] Allí, un vasto bosque de hermosos árboles era llamado "el jardín de Apolo". Apolo pasaba los meses de invierno entre los hiperbóreos, [155] [156] dejando su santuario en Delfos al cuidado de Dioniso. Su ausencia del mundo causaba frío y esto se marcaba como su muerte anual. No se emitieron profecías durante este tiempo. [157] Regresó al mundo durante el comienzo de la primavera. El festival de Teofanía se celebró en Delfos para celebrar su regreso. [158]

Sin embargo, Diodoro Silculus afirma que Apolo visitaba Hiperbórea cada diecinueve años. Este período de diecinueve años era llamado por los griegos el "año de Metón", el período de tiempo en el que las estrellas volvían a sus posiciones iniciales. Y que al visitar Hiperbórea en esa época, Apolo tocaba la cítara y bailaba continuamente desde el equinoccio de primavera hasta la salida de las Pléyades (constelaciones). [159]

Hiperbórea también fue el lugar de nacimiento de Leto. Se dice que Leto llegó a Delos desde Hiperbórea acompañado de una manada de lobos. A partir de entonces, Hiperbórea se convirtió en el hogar de invierno de Apolo y los lobos se convirtieron en sagrados para él. Su íntima conexión con los lobos es evidente por su epíteto Lyceus , que significa parecido a un lobo . Pero Apolo también era el matador de lobos en su papel de dios que protegía a los rebaños de los depredadores. El culto hiperbóreo a Apolo lleva las marcas más fuertes de Apolo siendo adorado como el dios del sol. Los elementos chamánicos en el culto de Apolo a menudo se relacionan con su origen hiperbóreo, y también se especula que se originó como un chamán solar. [160] [161] Chamanes como Abaris y Aristeas también eran seguidores de Apolo, que provenía de Hiperbórea.

En los mitos, las lágrimas de ámbar que Apolo derramó cuando murió su hijo Asclepio se mezclaron con las aguas del río Erídano, que rodeaba Hiperbórea. Apolo también enterró en Hiperbórea la flecha que había usado para matar a los cíclopes . Más tarde le dio esta flecha a Abaris. [162]

Mientras crecía, Apolo fue cuidado por las ninfas Coritalia y Aletea , la personificación de la verdad. [163] Febe , su abuela, le dio el santuario oracular de Delfos a Apolo como regalo de cumpleaños. [164]

A los cuatro años, Apolo construyó una base y un altar en Delos usando los cuernos de las cabras que cazaba su hermana Artemisa. Como aprendió el arte de la construcción cuando era joven, llegó a ser conocido como Arquégetes ( el fundador de ciudades ) y guió a los hombres para construir nuevas ciudades. [165] Para mantener al niño entretenido, las ninfas de Delos corrían alrededor del altar golpeándolo y luego, con las manos atadas a la espalda, mordían una rama de olivo. Más tarde se convirtió en costumbre que todos los marineros que pasaban por la isla hicieran lo mismo. [166]

De su padre Zeus, Apolo recibió una diadema de oro y un carro tirado por cisnes. [167] [168]

En sus primeros años, cuando Apolo pasaba su tiempo pastoreando vacas, fue criado por las Thriae , quienes lo entrenaron y mejoraron sus habilidades proféticas. [169] También se decía que el dios Pan lo había instruido en el arte profético. [170] También se dice que Apolo inventó la lira y, junto con Artemisa, el arte del tiro con arco. Luego enseñó a los humanos el arte de la curación y el tiro con arco. [171]

Poco después de dar a luz a sus gemelos, Leto huyó de Delos por temor a Hera. Al llegar a Licia, sus crías habían bebido toda la leche de su madre y lloraban pidiendo más para saciar su hambre. La exhausta madre intentó beber de un lago cercano, pero algunos campesinos licios se lo impidieron . Cuando les rogó que la dejaran saciar su sed, los altivos campesinos no solo la amenazaron, sino que también revolvieron el barro del lago para ensuciar las aguas. Enfadada por esto, Leto los convirtió en ranas. [172]

En una versión ligeramente variada, Leto tomó a sus hijos y cruzó a Licia, donde intentó bañarlos en un manantial que encontró allí, pero los pastores locales la echaron. Después de eso, unos lobos encontraron a Leto y la guiaron hasta el río Xantos, donde Leto pudo bañar a sus hijos y saciar su sed. Luego regresó al manantial y convirtió a los pastores en ranas. [173]

-François_Gaspard_Adam-Große_Fontäne-Sanssouci_Steffen_Heilfort.JPG/440px-7003.Apollo_mit_dem_getöteten_Python(1752)-François_Gaspard_Adam-Große_Fontäne-Sanssouci_Steffen_Heilfort.JPG)

Pitón , una serpiente-dragón ctónica , era hija de Gea y guardiana del Oráculo de Delfos . En el himno de Calímaco a Delos, Apolo fetal prevé la muerte de Pitón a manos de él. [166]

En el himno homérico a Apolo, Pitón era un dragón hembra y la nodriza del gigante Tifón , que Hera había creado para derrocar a Zeus. Se la describía como un monstruo aterrador y una "plaga sangrienta". Apolo, en su afán por establecer su culto, se encontró con Pitón y la mató con una sola flecha disparada desde su arco. Dejó que el cadáver se pudriera bajo el sol y se declaró a sí mismo la deidad oracular de Delfos. [174] Otros autores dicen que Apolo mató al monstruo usando cien flechas [175] [176] o mil flechas. [177]

Según Eurípides, Leto había llevado a sus gemelos a los acantilados del Parnaso poco después de darlos a luz. Al ver al monstruo allí, Apolo, todavía un niño llevado en brazos de su madre, saltó y mató a Pitón. [178] Algunos autores también mencionan que Pitón fue asesinada por mostrar afectos lujuriosos hacia Leto. [179] [180]

En otro relato, Pitón persiguió a Leto, embarazada, con la intención de matarla porque su muerte estaba destinada a llegar a manos del hijo de Leto. Sin embargo, tuvo que detener la persecución cuando Leto quedó bajo la protección de Poseidón. Después de su nacimiento, Apolo, de cuatro días de edad, mató a la serpiente con el arco y las flechas que le había regalado Hefesto y vengó el mal causado a su madre. Luego, el dios puso los huesos del monstruo asesinado en un caldero y lo depositó en su templo. [181]

Esta leyenda también se narra como el origen del grito " Hië paian ". Según Ateneo, Pitón atacó a Leto y sus gemelos durante su visita a Delfos. Tomando a Artemisa en sus brazos, Leto trepó a una roca y gritó a Apolo que disparara al monstruo. El grito que soltó, "ιε, παῖ" ("Dispara, muchacho"), más tarde se alteró ligeramente como "ἰὴ παιών" ( Hië paian ), una exclamación para alejar los males. [182] Calímaco atribuye el origen de esta frase a los habitantes de Delfos, que lanzaron el grito para animar a Apolo cuando el joven dios luchó con Pitón. [183]

Estrabón ha registrado una versión ligeramente diferente, en la que Pitón era en realidad un hombre cruel y sin ley, también conocido por el nombre de "Drakon". Cuando Apolo estaba enseñando a los humanos a cultivar frutas y civilizarse, los habitantes del Parnaso se quejaron al dios sobre Pitón. En respuesta a sus súplicas, Apolo mató al hombre con sus flechas. Durante la lucha, los parnasianos gritaron "Hië paian" para animar al dios. [184]

Continuando con su victoria sobre Pitón, el himno homérico describe cómo el joven dios estableció su adoración entre los humanos. Mientras Apolo reflexionaba sobre qué tipo de hombres debería reclutar para que lo sirvieran, vio un barco lleno de mercaderes o piratas cretenses. Tomó la forma de un delfín y saltó a bordo del barco. Cada vez que los desprevenidos miembros de la tripulación intentaban arrojar al delfín por la borda, el dios sacudía el barco hasta que la tripulación se sometía. Apolo creó entonces una brisa que dirigió el barco a Delfos. Al llegar a la tierra, se reveló como un dios y los inició como sus sacerdotes. Les instruyó para que protegieran su templo y mantuvieran siempre la rectitud en sus corazones. [185]

Alceo narra el siguiente relato: Zeus, que había adornado a su hijo recién nacido con una diadema de oro, también le proporcionó un carro tirado por cisnes y encargó a Apolo que visitara Delfos para establecer sus leyes entre el pueblo. Pero Apolo desobedeció a su padre y se fue a la tierra de Hiperbórea . Los habitantes de Delfos cantaban continuamente himnos en su honor y le rogaban que volviera con ellos. El dios regresó solo después de un año y luego llevó a cabo las órdenes de Zeus. [167] [186]

En otras variantes, el santuario de Delfos fue simplemente entregado a Apolo por su abuela Febe como regalo, [164] o la propia Temis lo inspiró a ser la voz oracular de Delfos. [187]

Sin embargo, en muchos otros relatos, Apolo tuvo que superar ciertos obstáculos antes de poder establecerse en Delfos. Gea entró en conflicto con Apolo por matar a Pitón y reclamar el oráculo de Delfos para sí mismo. Según Píndaro, ella intentó desterrar a Apolo al Tártaro como castigo. [188] [189] Según Eurípides, poco después de que Apolo tomara la propiedad del oráculo, Gea comenzó a enviar sueños proféticos a los humanos. Como resultado, la gente dejó de visitar Delfos para obtener profecías. Preocupado por esto, Apolo fue al Olimpo y suplicó a Zeus. Zeus, admirando las ambiciones de su joven hijo, le concedió su petición poniendo fin a las visiones oníricas. Esto selló el papel de Apolo como la deidad oracular de Delfos. [190]

Como Apolo había cometido un crimen de sangre, también tuvo que ser purificado. Pausanias ha registrado dos de las muchas variantes de esta purificación. En una de ellas, tanto Apolo como Artemisa huyeron a Sición y se purificaron allí. [191] En la otra tradición que había prevalecido entre los cretenses, Apolo viajó solo a Creta y fue purificado por Carmanor . [192] En otro relato, el rey argivo Crotopo fue quien realizó los ritos de purificación en Apolo solo. [193]

Según Aristótoo y Eliano, Apolo fue purificado por voluntad de Zeus en el valle de Tempe . [194] Aristótoo continuó el relato, diciendo que Apolo fue escoltado de regreso a Delfos por Atenea. Como muestra de gratitud, más tarde construyó un templo para Atenea en Delfos, que sirvió como umbral para su propio templo. [195] Al llegar a Delfos, Apolo convenció a Gea y Temis para que le entregaran la sede del oráculo. Para celebrar este evento, otros inmortales también honraron a Apolo con regalos: Poseidón le dio la tierra de Delfos, las ninfas de Delfos le regalaron la cueva de Coricio y Artemisa envió a sus perros a patrullar y salvaguardar la tierra. [196]

Otros también han dicho que Apolo fue exiliado y sometido a servidumbre bajo el rey Admeto como un medio de castigo por el asesinato que había cometido. [197] Fue cuando estaba sirviendo como pastor de vacas bajo Admeto que ocurrió el robo del ganado por parte de Hermes. [198] [199] Se decía que la servidumbre había durado un año, [200] [201] o un gran año (un ciclo de ocho años), [202] [203] o nueve años. [204]

Plutarco, sin embargo, menciona una variante en la que Apolo no fue purificado en Tempe ni desterrado a la Tierra como sirviente durante nueve años, sino que fue expulsado a otro mundo durante nueve largos años. El dios que regresó fue purificado y purificado, convirtiéndose así en un «verdadero Febo, es decir, claro y brillante». Entonces se hizo cargo del oráculo de Delfos, que había estado bajo el cuidado de Temis en su ausencia. [205] A partir de entonces, Apolo se convirtió en el dios que se purificó a sí mismo del pecado del asesinato, hizo que los hombres tomaran conciencia de su culpa y los purificó. [206]

Los juegos Píticos también fueron establecidos por Apolo, ya sea como juegos funerarios para honrar a Pitón [181] [207] o para celebrar su propia victoria. [208] [209] [177] La Pitia era la suma sacerdotisa de Apolo y su portavoz a través de la cual daba profecías.

Ticio fue otro gigante que intentó violar a Leto, ya fuera por su propia voluntad cuando ella se dirigía a Delfos [210] [211] o por orden de Hera. [212] Leto llamó a sus hijos, quienes al instante mataron al gigante. Apolo, todavía un niño, le disparó con sus flechas. [213] [214] En algunos relatos, Artemisa también se unió a él en la protección de su madre atacando a Ticio con sus flechas. [215] [216] Por este acto, fue desterrado al Tártaro y allí fue clavado al suelo de roca y tendido en un área de 9 acres (36.000 m 2 ), mientras una pareja de buitres se daban un festín diario con su hígado [210] o su corazón. [211]

Otro relato recogido por Estrabón dice que Ticio no era un gigante, sino un hombre sin ley a quien Apolo mató a petición de los residentes. [184]

_of_King_Admetus,_1780–1800_(CH_18122047).jpg/440px-Drawing,_Apollo_Guards_the_Herds_(or_Flocks)_of_King_Admetus,_1780–1800_(CH_18122047).jpg)

Admeto era el rey de Feras , conocido por su hospitalidad. Cuando Apolo fue exiliado del Olimpo por matar a Pitón, sirvió como pastor a las órdenes de Admeto, que entonces era joven y soltero. Se dice que Apolo mantuvo una relación romántica con Admeto durante su estancia. [156] Tras completar sus años de servidumbre, Apolo regresó al Olimpo como dios.

Como Admeto había tratado bien a Apolo, el dios le concedió grandes beneficios a cambio. Se dice que la mera presencia de Apolo hizo que el ganado diera a luz gemelos. [217] [156] Apolo ayudó a Admeto a ganar la mano de Alcestis , la hija del rey Pelias , [218] [219] domando un león y un jabalí para que tiraran del carro de Admeto. Estuvo presente durante su boda para dar sus bendiciones. Cuando Admeto enfureció a la diosa Artemisa al olvidarse de darle las ofrendas debidas, Apolo acudió al rescate y calmó a su hermana. [218] Cuando Apolo se enteró de la muerte prematura de Admeto, convenció o engañó a las Parcas para que permitieran que Admeto viviera más allá de su tiempo. [218] [219]

Según otra versión, o quizás algunos años después, cuando Zeus mató al hijo de Apolo, Asclepio, con un rayo por resucitar a los muertos, Apolo en venganza mató a los Cíclopes , que habían fabricado el rayo para Zeus. [217] Apolo habría sido desterrado al Tártaro por esto, pero su madre Leto intervino y, recordándole a Zeus su antiguo amor, le suplicó que no matara a su hijo. Zeus accedió y condenó a Apolo a un año de trabajos forzados una vez más bajo Admeto. [217]

El amor entre Apolo y Admeto fue un tema favorito de poetas romanos como Ovidio y Servio .

El destino de Níobe fue profetizado por Apolo mientras aún estaba en el vientre de Leto. [156] Níobe era la reina de Tebas y esposa de Anfión . Mostró arrogancia cuando se jactó de ser superior a Leto porque tenía catorce hijos ( Níobides ), siete varones y siete mujeres, mientras que Leto tenía solo dos. Además, se burló de la apariencia afeminada de Apolo y de la apariencia masculina de Artemisa. Leto, insultada por esto, dijo a sus hijos que castigaran a Níobe. En consecuencia, Apolo mató a los hijos de Níobe y Artemisa a sus hijas. Según algunas versiones del mito, entre los Níobides, Cloris y su hermano Amiclas no fueron asesinados porque rezaron a Leto. Anfión, al ver a sus hijos muertos, se suicidó o fue asesinado por Apolo después de jurar venganza.

Niobe, desolada, huyó al monte Sípilo, en Asia Menor , y se convirtió en piedra mientras lloraba. Sus lágrimas formaron el río Aqueloo . Zeus había convertido en piedra a todos los habitantes de Tebas, por lo que nadie enterró a las Niobidas hasta el noveno día después de su muerte, cuando los propios dioses las sepultaron.

Cuando Cloris se casó y tuvo hijos, Apolo concedió a su hijo Néstor los años que éste le había quitado a los Nióbides. Así, Néstor pudo vivir tres generaciones. [220]

,_Troppa_(attr.)_-_Laomedon_Refusing_Payment_to_Poseidon_and_Apollo_-_17th_c.jpg/440px-Sandrart_(attributed),_Troppa_(attr.)_-_Laomedon_Refusing_Payment_to_Poseidon_and_Apollo_-_17th_c.jpg)

En una ocasión, Apolo y Poseidón sirvieron a las órdenes del rey troyano Laomedonte, de acuerdo con las palabras de Zeus. Apolodoro afirma que los dioses acudieron voluntariamente al rey disfrazados de humanos para poner freno a su arrogancia. [221] Apolo protegió el ganado de Laomedonte en los valles del monte Ida, mientras Poseidón construía las murallas de Troya. [222] Otras versiones hacen que tanto Apolo como Poseidón fueran los constructores de la muralla. En el relato de Ovidio, Apolo completa su tarea tocando sus melodías con su lira.

En las odas de Píndaro , los dioses tomaron como ayudante a un mortal llamado Éaco . [223] Cuando se terminó el trabajo, tres serpientes se lanzaron contra la muralla, y aunque las dos que atacaron las secciones de la muralla construidas por los dioses cayeron muertas, la tercera se abrió paso hacia la ciudad a través de la parte de la muralla construida por Éaco. Apolo profetizó inmediatamente que Troya caería a manos de los descendientes de Éaco, los Eacidae (es decir, su hijo Telamón se unió a Heracles cuando asedió la ciudad durante el gobierno de Laomedonte. Más tarde, su bisnieto Neoptólemo estuvo presente en el caballo de madera que conduce a la caída de Troya).

Sin embargo, el rey no sólo se negó a pagar a los dioses el salario que les había prometido, sino que amenazó con atarles los pies y las manos y venderlos como esclavos. Enfadado por el trabajo no pagado y los insultos, Apolo contagió la ciudad con una peste y Poseidón envió al monstruo marino Ceto . Para liberar a la ciudad de ella, Laomedonte tuvo que sacrificar a su hija Hesione (que más tarde sería salvada por Heracles ).

Durante su estancia en Troya, Apolo tuvo una amante llamada Ourea, que era una ninfa e hija de Poseidón. Juntos tuvieron un hijo llamado Íleo, a quien Apolo amaba entrañablemente. [224]

Apolo se puso del lado de los troyanos durante la Guerra de Troya librada por los griegos contra los troyanos.

Durante la guerra, el rey griego Agamenón capturó a Criseida , la hija de Crises , el sacerdote de Apolo , y se negó a devolverla. Enfadado por ello, Apolo disparó flechas infectadas con la plaga al campamento griego. Exigió que devolvieran a la muchacha, y los aqueos (griegos) accedieron, provocando indirectamente la ira de Aquiles , que es el tema de la Ilíada .

Apolo, que recibió la égida de Zeus, entró en el campo de batalla siguiendo las órdenes de su padre y causó gran terror en el enemigo con su grito de guerra. Hizo retroceder a los griegos y destruyó a muchos de los soldados. Se le describe como "el agitador de ejércitos" porque reunió al ejército troyano cuando se estaba desmoronando.

Cuando Zeus permitió que los demás dioses se involucraran en la guerra, Poseidón provocó a Apolo a un duelo. Sin embargo, Apolo se negó a luchar contra él, diciendo que no lucharía contra su tío por el bien de los mortales.

_MET_80355.jpg/440px-Diomedes_prevented_by_Apollo_from_pursuing_Aeneas_(%3F)_MET_80355.jpg)

Cuando el héroe griego Diomedes hirió al héroe troyano Eneas , Afrodita intentó rescatarlo, pero Diomedes también la hirió. Apolo envolvió a Eneas en una nube para protegerlo. Repelió los ataques que Diomedes le lanzó y le dio al héroe una severa advertencia para que se abstuviera de atacar a un dios. Eneas fue llevado a Pérgamo, un lugar sagrado en Troya , donde fue curado.

Tras la muerte de Sarpedón , hijo de Zeus, Apolo rescató el cadáver del campo de batalla por deseo de su padre y lo limpió. Luego se lo entregó al Sueño ( Hipnos ) y a la Muerte ( Tánatos ). Apolo también había convencido una vez a Atenea de que detuviera la guerra ese día, para que los guerreros pudieran hacer sus necesidades por un rato.

El héroe troyano Héctor (que, según algunos, era el propio hijo del dios con Hécuba [225] ) fue favorecido por Apolo. Cuando resultó gravemente herido, Apolo lo curó y lo animó a tomar sus armas. Durante un duelo con Aquiles, cuando Héctor estaba a punto de perder, Apolo lo escondió en una nube de niebla para salvarlo. Cuando el guerrero griego Patroclo intentó entrar en el fuerte de Troya, fue detenido por Apolo. Al animar a Héctor a atacar a Patroclo, Apolo le quitó la armadura al guerrero griego y rompió sus armas. Patroclo finalmente fue asesinado por Héctor. Por último, después de la muerte predestinada de Héctor, Apolo protegió su cadáver del intento de Aquiles de mutilarlo creando una nube mágica sobre el cadáver, protegiéndolo de los rayos del sol .

Apolo guardó rencor contra Aquiles durante toda la guerra porque Aquiles había asesinado a su hijo Tenes antes de que comenzara la guerra y había asesinado brutalmente a su hijo Troilo en su propio templo. Apolo no solo salvó a Héctor de Aquiles, sino que también lo engañó disfrazándose de guerrero troyano y alejándolo de las puertas. Frustró el intento de Aquiles de mutilar el cadáver de Héctor.

Finalmente, Apolo provocó la muerte de Aquiles al dirigir una flecha disparada por Paris hacia el talón de Aquiles . En algunas versiones, el propio Apolo mató a Aquiles disfrazándose de Paris.

Apolo ayudó a muchos guerreros troyanos, entre ellos Agenor , Polidamante y Glauco , en el campo de batalla. Aunque favorecía enormemente a los troyanos, Apolo estaba obligado a seguir las órdenes de Zeus y sirvió a su padre lealmente durante la guerra.

Apolo Kurótrofo es el dios que cuida y protege a los niños y jóvenes, especialmente a los varones. Supervisa su educación y su paso a la edad adulta. Se dice que la educación se originó a partir de Apolo y las Musas . Muchos mitos lo muestran como el que entrena a sus hijos. Era una costumbre que los niños cortaran y dedicaran su cabello largo a Apolo después de llegar a la edad adulta.

Quirón , el centauro abandonado , fue acogido por Apolo, quien lo instruyó en medicina, profecía, tiro con arco y más. Quirón se convertiría más tarde en un gran maestro.

Asclepio, durante su infancia, adquirió de su padre muchos conocimientos relacionados con las artes medicinales. Sin embargo, más tarde fue confiado a Quirón para que continuara su formación.

Anio , hijo de Apolo y Reo , fue abandonado por su madre poco después de su nacimiento. Apolo lo crió y lo educó en las artes mánticas. Anio se convirtió más tarde en sacerdote de Apolo y rey de Delos.

Yamo era hijo de Apolo y Evadne . Cuando Evadne se puso de parto, Apolo envió a las Moiras para ayudar a su amante. Después de que el niño nació, Apolo envió serpientes para alimentar al niño con un poco de miel. Cuando Yamo alcanzó la edad de la educación, Apolo lo llevó a Olimpia y le enseñó muchas artes, incluida la capacidad de entender y explicar los lenguajes de los pájaros. [226]

Idmón fue educado por Apolo para ser vidente. Aunque previó su muerte, que le sucedería en su viaje con los Argonautas , aceptó su destino y murió con valentía. Para conmemorar la valentía de su hijo, Apolo ordenó a los beocios que construyeran una ciudad alrededor de la tumba del héroe y lo honraran. [227]

Apolo adoptó a Carno , el hijo abandonado de Zeus y Europa . Crió al niño con la ayuda de su madre Leto y lo educó para que fuera vidente.

Cuando su hijo Melaneo llegó a la edad de casarse, Apolo le pidió a la princesa Estratónice que fuera la esposa de su hijo y la sacó de su casa cuando ella aceptó.

Apolo salvó a un pastorcillo (de nombre desconocido) de morir en una gran cueva profunda, gracias a los buitres. En agradecimiento, el pastor le construyó a Apolo un templo con el nombre de Vulturio. [228]

Inmediatamente después de su nacimiento, Apolo exigió una lira e inventó el peán , convirtiéndose así en el dios de la música. Como cantor divino, es el patrón de poetas, cantantes y músicos. Se le atribuye la invención de la música de cuerdas. Platón dijo que la capacidad innata de los humanos para deleitarse con la música, el ritmo y la armonía es el don de Apolo y las Musas. [229] Según Sócrates , los antiguos griegos creían que Apolo es el dios que dirige la armonía y hace que todas las cosas se muevan juntas, tanto para los dioses como para los humanos. Por esta razón, se le llamó Homopolon antes de que el Homo fuera reemplazado por A. [230] [231] La música armoniosa de Apolo liberó a las personas de su dolor y, por lo tanto, como Dioniso, también se le llama el liberador. [ 156] Se creía que los cisnes, que se consideraban los más musicales entre los pájaros, eran los "cantantes de Apolo". Son los pájaros sagrados de Apolo y actuaron como su vehículo durante su viaje a Hiperbórea . [156] Eliano dice que cuando los cantantes cantaban himnos a Apolo, los cisnes se unían al canto al unísono. [232]

.jpg/440px-Parnassus,_Andrea_Appiani_(1811).jpg)

Entre los pitagóricos , el estudio de las matemáticas y la música estaban vinculados al culto a Apolo, su deidad principal. [233] [234] [235] Su creencia era que la música purifica el alma, así como la medicina purifica el cuerpo. También creían que la música estaba sujeta a las mismas leyes matemáticas de la armonía que la mecánica del cosmos, evolucionando hacia una idea conocida como la música de las esferas . [236]

Apolo aparece como compañero de las Musas , y como Musagetes ("líder de las Musas") las dirige en la danza. Pasan su tiempo en el Parnaso , que es uno de sus lugares sagrados. Apolo es también el amante de las Musas y por ellas se convirtió en el padre de músicos famosos como Orfeo y Lino .

A menudo se encuentra a Apolo deleitando a los dioses inmortales con sus canciones y música en la lira . [237] En su papel como dios de los banquetes, siempre estaba presente para tocar música en las bodas de los dioses, como el matrimonio de Eros y Psique , Peleo y Tetis . Es un invitado frecuente de las Bacanales , y muchas cerámicas antiguas lo representan a gusto entre las ménades y los sátiros. [238] Apolo también participó en concursos musicales cuando otros lo desafiaron. Fue el vencedor en todos esos concursos, pero tendía a castigar severamente a sus oponentes por su arrogancia .

_at_Hadrian's_Villa,_Ny_Carlsberg_Glyptoteket_(12233881783).jpg/440px-Detail_of_the_statue_of_Apollo_holding_the_kithara,_from_the_Temple_of_Venus_(Casino_Fede)_at_Hadrian's_Villa,_Ny_Carlsberg_Glyptoteket_(12233881783).jpg)

La invención de la lira se atribuye a Hermes o al propio Apolo. [239] Se han hecho distinciones según las cuales Hermes inventó una lira hecha de caparazón de tortuga, mientras que la lira que inventó Apolo era una lira normal. [240]

Los mitos cuentan que el infante Hermes robó varias vacas de Apolo y las llevó a una cueva en el bosque cerca de Pilos , borrando sus huellas. En la cueva, encontró una tortuga y la mató, luego le quitó las entrañas. Utilizó uno de los intestinos de la vaca y el caparazón de la tortuga e hizo su lira .

Al descubrir el robo, Apolo se enfrentó a Hermes y le pidió que le devolviera el ganado. Cuando Hermes actuó como si fuera inocente, Apolo llevó el asunto a Zeus. Zeus, al ver lo sucedido, se puso del lado de Apolo y le ordenó a Hermes que devolviera el ganado. [241] Hermes comenzó entonces a tocar música con la lira que había inventado. Apolo se enamoró del instrumento y se ofreció a intercambiar el ganado por la lira. Por lo tanto, Apolo se convirtió en el maestro de la lira.

Según otras versiones, Apolo había inventado él mismo la lira, cuyas cuerdas rompió en señal de arrepentimiento por el castigo excesivo que había infligido a Marsias . La lira de Hermes sería, por tanto, una reinvención. [242]

En cierta ocasión, Pan tuvo la audacia de comparar su música con la de Apolo y desafiar al dios de la música a un concurso. El dios de la montaña Tmolo fue elegido como árbitro. Pan tocó su flauta y con su rústica melodía se dio una gran satisfacción a sí mismo y a su fiel seguidor, Midas , que estaba presente. Entonces, Apolo golpeó las cuerdas de su lira. Era tan hermoso que Tmolo inmediatamente le otorgó la victoria a Apolo y todos quedaron satisfechos con el fallo. Sólo Midas disintió y cuestionó la justicia del premio. Apolo no quería soportar más un par de orejas tan depravadas y las convirtió en orejas de burro.

Marsias era un sátiro que fue castigado por Apolo por su arrogancia . Había encontrado un aulos en el suelo, tirado después de ser inventado por Atenea porque le hacía hinchar las mejillas. Atenea también había puesto una maldición sobre el instrumento, que decía que quien lo cogiera sería severamente castigado. Cuando Marsias tocó la flauta, todos se pusieron frenéticos de alegría. Esto llevó a Marsias a pensar que era mejor que Apolo, y desafió al dios a un concurso musical. El concurso fue juzgado por las Musas , o las ninfas de Nisa . Atenea también estuvo presente para presenciar el concurso.

Marsias se burló de Apolo por "llevar el pelo largo, por tener un rostro hermoso y un cuerpo terso, por su habilidad en tantas artes". [243] También dijo:

«Su cabello [de Apolo] es suave y está formado en mechones y bucles que caen sobre su frente y cuelgan ante su rostro. Su cuerpo es hermoso de pies a cabeza, sus miembros resplandecen, su lengua da oráculos y es igualmente elocuente en prosa o en verso, propongan lo que quieran. ¿Qué hay de sus ropas tan finas en textura, tan suaves al tacto, resplandecientes de púrpura? ¿Qué hay de su lira que destella oro, reluce blanco con marfil y reluce con gemas del arco iris? ¿Qué hay de su canción, tan astuta y tan dulce? No, todos estos atractivos no se adaptan a nada más que al lujo. ¡A la virtud solo traen vergüenza!» [243]

Las Musas y Atenea rieron entre dientes ante este comentario. Los concursantes acordaron turnarse para mostrar sus habilidades y la regla era que el vencedor podía "hacer lo que quisiera" con el perdedor.

Según un relato, después de la primera ronda, las Nisíadas los consideraron iguales . Pero en la siguiente ronda, Apolo decidió tocar su lira y agregar su melodiosa voz a su actuación. Marsias argumentó en contra de esto, diciendo que Apolo tendría una ventaja y acusó a Apolo de hacer trampa. Pero Apolo respondió que, dado que Marsias tocaba la flauta, que necesitaba aire soplado desde la garganta, era similar a cantar, y que o bien ambos deberían tener la misma oportunidad de combinar sus habilidades o ninguno de ellos debería usar la boca en absoluto. Las ninfas decidieron que el argumento de Apolo era justo. Apolo entonces tocó su lira y cantó al mismo tiempo, hipnotizando al público. Marsias no pudo hacer esto. Apolo fue declarado ganador y, enojado con la altivez de Marsias y sus acusaciones, decidió desollar al sátiro. [244]

.jpg/440px-Marsyas_Flayed_by_the_Order_of_Apollo_-_Charles_André_van_Loo_(1735).jpg)

Según otra versión, Marsias desafinó su flauta en un momento dado y aceptó su derrota. Por vergüenza, se asignó a sí mismo el castigo de ser desollado por un saco de vino. [245] Otra variación es que Apolo tocó su instrumento al revés. Marsias no podía hacer esto con su instrumento. Entonces las Musas, que eran los jueces, declararon a Apolo ganador. Apolo colgó a Marsias de un árbol para desollarlo. [246]

Apolo desolló vivo a Marsias en una cueva cerca de Celenae en Frigia por su arrogancia al desafiar a un dios. Luego entregó el resto de su cuerpo para un entierro apropiado [247] y clavó la piel desollada de Marsias en un pino cercano como lección para los demás. La sangre de Marsias se convirtió en el río Marsias. Pero Apolo pronto se arrepintió y, afligido por lo que había hecho, rompió las cuerdas de su lira y la arrojó. La lira fue descubierta más tarde por las Musas y los hijos de Apolo, Lino y Orfeo . Las Musas arreglaron la cuerda central, Lino la cuerda golpeada con el dedo índice y Orfeo la cuerda más baja y la siguiente. Se la devolvieron a Apolo, pero el dios, que había decidido alejarse de la música por un tiempo, dejó la lira y las flautas en Delfos y se unió a Cibeles en sus peregrinajes hasta Hiperbórea . [244] [248]

Cíniras era un gobernante de Chipre , amigo de Agamenón . Cíniras prometió ayudar a Agamenón en la guerra de Troya, pero no cumplió su promesa. Agamenón maldijo a Cíniras. Invocó a Apolo y le pidió al dios que vengara la promesa rota. Apolo entonces tuvo un concurso de lira con Cíniras y lo derrotó. O bien Cíniras se suicidó cuando perdió, o fue asesinado por Apolo. [249] [250]

Apolo funciona como patrón y protector de los marineros, una de las funciones que comparte con Poseidón . En los mitos, se lo ve ayudando a los héroes que le rezan para tener un viaje seguro.

Cuando Apolo avistó un barco de marineros cretenses que estaba atrapado en una tormenta, rápidamente asumió la forma de un delfín y guió su barco a salvo a Delfos. [251]

Cuando los argonautas se enfrentaron a una terrible tormenta, Jasón rezó a su patrón, Apolo, para que los ayudara. Apolo usó su arco y su flecha dorada para arrojar luz sobre una isla, donde los argonautas pronto se refugiaron. Esta isla fue rebautizada como " Anaphe ", que significa "Él lo reveló". [252]

Apolo ayudó al héroe griego Diomedes a escapar de una gran tempestad durante su viaje de regreso a casa. Como muestra de gratitud, Diomedes construyó un templo en honor a Apolo bajo el epíteto de Epibaterio ("el embarcador"). [253]

Durante la guerra de Troya, Odiseo llegó al campamento troyano para devolver a Chriseis, la hija de Crises , el sacerdote de Apolo , y llevó muchas ofrendas a Apolo. Complacido con esto, Apolo envió suaves brisas que ayudaron a Odiseo a regresar sano y salvo al campamento griego. [254]

Arión era un poeta que fue raptado por unos marineros por los ricos premios que poseía. Arión les pidió que le dejaran cantar por última vez, a lo que los marineros accedieron. Arión comenzó a cantar una canción en alabanza a Apolo, pidiendo la ayuda del dios. En consecuencia, numerosos delfines rodearon el barco y cuando Arión saltó al agua, los delfines lo llevaron sano y salvo.

Apolo desempeñó un papel fundamental en toda la Guerra de Troya. Se puso del lado de los troyanos y envió una terrible plaga al campamento griego, lo que indirectamente provocó el conflicto entre Aquiles y Agamenón . Mató a los héroes griegos Patroclo , Aquiles y numerosos soldados griegos. También ayudó a muchos héroes troyanos, el más importante de los cuales fue Héctor . Después del final de la guerra, Apolo y Poseidón juntos limpiaron los restos de la ciudad y los campamentos.

Estalló una guerra entre los brigos y los tesprotos, que contaban con el apoyo de Odiseo . Los dioses Atenea y Ares acudieron al campo de batalla y tomaron partido. Atenea ayudó al héroe Odiseo mientras Ares luchaba junto a los brigos. Cuando Odiseo perdió, Atenea y Ares se batieron en duelo directo. Para detener la lucha de los dioses y el terror creado por su batalla, Apolo intervino y detuvo el duelo entre ellos. [255] [256]

Cuando Zeus sugirió que Dioniso derrotara a los indios para ganarse un lugar entre los dioses, Dioniso declaró la guerra a los indios y viajó a la India junto con su ejército de bacantes y sátiros . Entre los guerreros estaba Aristeo , el hijo de Apolo. Apolo armó a su hijo con sus propias manos y le dio un arco y flechas y le colocó un fuerte escudo en el brazo. [257] Después de que Zeus instó a Apolo a unirse a la guerra, fue al campo de batalla. [258] Al ver a varias de sus ninfas y a Aristeo ahogándose en un río, los llevó a un lugar seguro y los curó. [259] Enseñó a Aristeo artes curativas más útiles y lo envió de regreso para ayudar al ejército de Dioniso.

Durante la guerra entre los hijos de Edipo , Apolo favoreció a Anfiarao , un vidente y uno de los líderes de la guerra. Aunque entristecido por el destino del vidente, Apolo hizo que las últimas horas de Anfiarao fueran gloriosas "iluminando su escudo y su yelmo con un resplandor estelar". Cuando Hipseo intentó matar al héroe con una lanza, Apolo dirigió la lanza hacia el auriga de Anfiarao. Entonces, el propio Apolo reemplazó al auriga y tomó las riendas en sus manos. Desvió muchas lanzas y flechas lejos de ellos. También mató a muchos de los guerreros enemigos como Melaneo , Antífo , Eción, Polites y Lampo . Por último, cuando llegó el momento de la partida, Apolo expresó su dolor con lágrimas en los ojos y se despidió de Anfiarao, que pronto fue engullido por la Tierra. [260]

Apolo mató a los gigantes Pitón y Ticio, que habían atacado a su madre Leto.

Durante la gigantomaquia , Apolo y Hércules cegaron al gigante Efialtes disparándole en los ojos, Apolo disparándole en el izquierdo y Hércules en el derecho. [261] También mató a Porfirión , el rey de los gigantes, usando su arco y sus flechas. [262]

Los alóadas , es decir, Otis y Efialtes, eran gigantes gemelos que decidieron declarar la guerra a los dioses. Intentaron asaltar el monte Olimpo apilando montañas y amenazaron con llenar el mar de montañas e inundar la tierra firme. [263] Incluso se atrevieron a pedir la mano de Hera y Artemisa en matrimonio. Enfadado por esto, Apolo las mató disparándoles flechas. [264] Según otra historia, Apolo las mató enviando un ciervo entre ellos; cuando intentaron matarlo con sus jabalinas, accidentalmente se apuñalaron el uno al otro y murieron. [265]

Forbas era un rey gigante y salvaje de Flegias , al que se describía como de rasgos porcinos. Quería saquear Delfos para hacerse con sus riquezas. Se apoderó de los caminos que conducían a Delfos y comenzó a hostigar a los peregrinos. Capturó a los ancianos y a los niños y los envió a su ejército para pedir rescate por ellos. Retó a los hombres jóvenes y robustos a un combate de boxeo, pero cuando los venció les cortó la cabeza. Colgó las cabezas cortadas de un roble. Finalmente, Apolo llegó para poner fin a esta crueldad. Entró en un combate de boxeo con Forbas y lo mató de un solo golpe. [266]

En los primeros Juegos Olímpicos , Apolo derrotó a Ares y se convirtió en el vencedor en la lucha libre. Superó a Hermes en la carrera y obtuvo el primer puesto. [267]

Apolo divide los meses en verano e invierno. [268] Viaja a lomos de un cisne hasta la tierra de los hiperbóreos durante los meses de invierno, y la ausencia de calor en invierno se debe a su partida. Durante su ausencia, Delfos estaba bajo el cuidado de Dioniso , y no se daban profecías durante los inviernos.

Perifas era un rey ático y sacerdote de Apolo. Era noble, justo y rico. Cumplía con todas sus obligaciones con justicia. Por eso la gente le tenía mucho cariño y empezó a honrarlo tanto como a Zeus. En un momento dado, adoraron a Perifas en lugar de Zeus y le levantaron santuarios y templos. Esto molestó a Zeus, que decidió aniquilar a toda la familia de Perifas. Pero como era un rey justo y un buen devoto, Apolo intervino y pidió a su padre que perdonara la vida a Perifas. Zeus consideró las palabras de Apolo y accedió a dejarlo vivir. Pero metamorfoseó a Perifas en águila y convirtió al águila en el rey de las aves. Cuando la esposa de Perifas le pidió a Zeus que la dejara quedarse con su marido, Zeus la convirtió en un buitre y cumplió su deseo. [269]

Molpadia y Partenos eran hermanas de Reo , un antiguo amante de Apolo. Un día, se les encargó vigilar la jarra de vino ancestral de su padre, pero se quedaron dormidas mientras realizaban esta tarea. Mientras dormían, la jarra de vino fue rota por los cerdos que tenía su familia. Cuando las hermanas despertaron y vieron lo que había sucedido, se arrojaron por un acantilado por miedo a la ira de su padre. Apolo, que pasaba por allí, las atrapó y las llevó a dos ciudades diferentes en Quersoneso, Molpadia a Cástabo y Partenos a Bubasto. Las convirtió en diosas y ambas recibieron honores divinos. El nombre de Molpadia fue cambiado a Hemithea tras su deificación. [270]

Prometeo era el titán que fue castigado por Zeus por robar el fuego. Fue atado a una roca, donde cada día enviaba un águila para que se comiera el hígado de Prometeo, que luego volvería a crecer durante la noche para ser comido nuevamente al día siguiente. Al ver su difícil situación, Apolo suplicó a Zeus que liberara al bondadoso titán, mientras Artemisa y Leto estaban detrás de él con lágrimas en los ojos. Zeus, conmovido por las palabras de Apolo y las lágrimas de las diosas, finalmente envió a Hércules para liberar a Prometeo. [271]

Después de que Heracles (entonces llamado Alcides) sufriera una locura y matara a su familia, trató de purificarse y consultó al oráculo de Apolo. Apolo, a través de la Pitia, le ordenó que sirviera al rey Euristeo durante doce años y que completara las diez tareas que el rey le encomendara. Solo entonces Alcides sería absuelto de su pecado. Apolo también lo rebautizó como Heracles. [272]

Para completar su tercera tarea, Heracles tuvo que capturar a la cierva de Cerinea , una cierva consagrada a Artemisa, y traerla de vuelta con vida. Después de perseguir a la cierva durante un año, el animal finalmente se cansó y cuando intentó cruzar el río Ladón, Heracles la capturó. Mientras la recuperaba, se enfrentó a Apolo y Artemisa, quienes se enojaron con Heracles por este acto. Sin embargo, Heracles calmó a la diosa y le explicó su situación. Después de mucho suplicar, Artemisa le permitió tomar la cierva y le dijo que la devolviera más tarde. [273]

Después de ser liberado de su servidumbre a Euristeo, Heracles tuvo un conflicto con Ifito, un príncipe de Ecalia, y lo asesinó. Poco después, contrajo una terrible enfermedad. Consultó el oráculo de Apolo una vez más, con la esperanza de librarse de la enfermedad. Sin embargo, la Pitia se negó a dar ninguna profecía. Enfadado, Heracles agarró el trípode sagrado y comenzó a alejarse, con la intención de iniciar su propio oráculo. Sin embargo, Apolo no toleró esto y detuvo a Heracles; se produjo un duelo entre ellos. Artemisa se apresuró a apoyar a Apolo, mientras que Atenea apoyó a Heracles. Pronto, Zeus lanzó su rayo entre los hermanos combatientes y los separó. Reprendió a Heracles por este acto de violación y le pidió a Apolo que le diera una solución a Heracles. Apolo entonces ordenó al héroe que sirviera a Ónfale , reina de Lidia, durante un año para purificarse.

Después de su reconciliación, Apolo y Heracles fundaron juntos la ciudad de Gythion. [274]

Hace mucho tiempo, había tres tipos de seres humanos: masculinos, descendientes del sol; femeninos, descendientes de la tierra; y andróginos, descendientes de la luna. Cada ser humano era completamente redondo, con cuatro brazos y cuatro piernas, dos caras idénticas en lados opuestos de una cabeza con cuatro orejas, y todo lo demás a juego. Eran poderosos y rebeldes. Otis y Efialtes incluso se atrevieron a escalar el monte Olimpo .

Para poner freno a su insolencia, Zeus ideó un plan para humillarlos y mejorar sus modales en lugar de destruirlos por completo. Los cortó a todos en dos y le pidió a Apolo que hiciera las reparaciones necesarias, devolviendo a los humanos la forma individual que todavía tienen ahora. Apolo giró sus cabezas y cuellos hacia sus heridas, juntó su piel a la altura del abdomen y cosió la piel en el medio. Esto es lo que hoy llamamos ombligo . Suavizó las arrugas y dio forma al pecho. Pero se aseguró de dejar algunas arrugas en el abdomen y alrededor del ombligo para que recordaran su castigo. [275]

"Mientras Zeus los iba cortando uno tras otro, le ordenó a Apolo que girara la cara y la mitad del cuello... También se le ordenó a Apolo que curara sus heridas y compusiera sus formas. Entonces Apolo giró la cara y tiró de la piel de los lados por todo lo que en nuestro idioma se llama vientre, como las bolsas que se encogen, e hizo una boca en el centro [del vientre] que sujetó con un nudo (el mismo que se llama ombligo); también moldeó el pecho y eliminó la mayoría de las arrugas, de manera muy similar a como un zapatero alisa el cuero sobre una horma; dejó algunas arrugas, sin embargo, en la región del vientre y el ombligo, como un recuerdo del estado primigenio.

Se creía que Leukatas era una roca de color blanco que sobresalía de la isla de Leukas hacia el mar. Estaba presente en el santuario de Apolo Leukates. Se creía que un salto desde esta roca ponía fin a los anhelos de amor. [276]

En cierta ocasión, Afrodita se enamoró profundamente de Adonis , un joven de gran belleza que más tarde murió accidentalmente a causa de un jabalí. Con el corazón roto, Afrodita vagó en busca de la roca de Leukas. Cuando llegó al santuario de Apolo en Argos, le confió su amor y su dolor. Apolo la llevó a la roca de Leukas y le pidió que se arrojara desde lo alto de la roca. Ella lo hizo y se liberó de su amor. Cuando buscó la razón detrás de esto, Apolo le dijo que Zeus, antes de tomar otra amante, se sentaría en esta roca para liberarse de su amor por Hera. [207]

Otra historia cuenta que un hombre llamado Nireo, que se enamoró de la estatua de Atenea, se acercó a la roca y saltó para hacer sus necesidades. Después de saltar, cayó en la red de un pescador, en la que, cuando lo sacaron, encontró una caja llena de oro. Luchó con el pescador y tomó el oro, pero Apolo se le apareció en la noche en un sueño y le advirtió que no se apropiara del oro que pertenecía a otros. [207]

Entre los leucedios existía la costumbre ancestral de arrojar desde esta roca a un criminal todos los años durante el sacrificio que se realizaba en honor de Apolo para evitar el mal. Sin embargo, un grupo de hombres se apostaba alrededor de la roca para atrapar al criminal y sacarlo de las fronteras para exiliarlo de la isla. [277] [207] Esta era la misma roca desde la que, según una leyenda, Safo dio su salto suicida. [276]

En cierta ocasión, Hera , por despecho, incitó a los Titanes a guerrear contra Zeus y arrebatarle su trono. En consecuencia, cuando los Titanes intentaron escalar el monte Olimpo , Zeus, con la ayuda de Apolo, Artemisa y Atenea , los derrotó y los arrojó al Tártaro. [278]

Se dice que Apolo fue el amante de las nueve Musas y, al no poder elegir a una de ellas, decidió permanecer soltero. Fue padre de Coribantes con la musa Talía . [279] Con Calíope , tuvo a Himeneo , Ialemo , Orfeo [280] y Lino . Alternativamente, se decía que Lino era hijo de Apolo y Urania o Terpsícore .

En las Grandes Eoiae atribuidas a Hesoideo, Escila es la hija de Apolo y Hécate. [281]

Cirene era una princesa tesalia a la que Apolo amaba. En su honor, construyó la ciudad de Cirene y la nombró gobernante. Más tarde, Apolo le concedió longevidad al convertirla en ninfa. La pareja tuvo dos hijos: Aristeo e Idmón .

Evadne era una ninfa hija de Poseidón y amante de Apolo. Tuvieron un hijo, Iamos . Durante el parto, Apolo envió a Ilitía , la diosa del parto, para que la ayudara.

Reo , una princesa de la isla de Naxos, era amada por Apolo. Por cariño hacia ella, Apolo convirtió a sus hermanas en diosas. En la isla de Delos, le dio a Apolo un hijo llamado Anio . Como no quería tener el niño, le confió el infante a Apolo y se fue. Apolo crió y educó al niño por su cuenta.

Ourea, hija de Poseidón , se enamoró de Apolo cuando él y Poseidón servían al rey troyano Laomedonte . Ambos se unieron el día en que se construyeron las murallas de Troya . Ella le dio a Apolo un hijo, a quien Apolo llamó Íleo, en honor a la ciudad donde nació, Ilión ( Troya ). Íleo era muy querido por Apolo. [282]

Thero , hija de Phylas , una doncella tan hermosa como los rayos de la luna, fue amada por el radiante Apolo, y ella lo amó a él a cambio. A través de su unión, se convirtió en la madre de Querón, quien era famoso como "el domador de caballos". Más tarde construyó la ciudad de Queronea . [283]

Hiria o Tiria era la madre de Cicno . Apolo convirtió a la madre y al hijo en cisnes cuando saltaron a un lago e intentaron suicidarse. [284]

Hécuba era la esposa del rey Príamo de Troya , y Apolo tuvo con ella un hijo llamado Troilo . Un oráculo profetizó que Troya no sería derrotada mientras Troilo alcanzara la edad de veinte años con vida. Fue emboscado y asesinado por Aquiles , y Apolo vengó su muerte matando a Aquiles. Después del saqueo de Troya, Apolo llevó a Hécuba a Licia. [285]

Coronis era hija de Flegias , rey de los lápitas . Estando embarazada de Asclepio , Coronis se enamoró de Isquis , hijo de Élato , y durmió con él. Cuando Apolo se enteró de su infidelidad por sus poderes proféticos o gracias a su cuervo que le informó, envió a su hermana, Artemisa, a matar a Coronis. Apolo rescató al bebé abriendo el vientre de Coronis y se lo entregó al centauro Quirón para que lo criara.

Dríope , hija de Dríope, fue embarazada por Apolo en forma de serpiente y dio a luz a un hijo llamado Anfiso. [286]

En la obra de Eurípides, Ion , Apolo engendró a Ion con Creúsa , esposa de Juto . Utilizó sus poderes para ocultar el embarazo de su hija a su padre. Más tarde, cuando Creúsa dejó que Ion muriera en la naturaleza, Apolo le pidió a Hermes que salvara al niño y lo llevara al oráculo de Delfos , donde fue criado por una sacerdotisa.

Apolo amó y raptó a una ninfa oceánica, Melia . Su padre , Océano, envió a uno de sus hijos, Cánto , a buscarla, pero Cánto no pudo recuperarla de Apolo, por lo que quemó el santuario de Apolo. En represalia, Apolo disparó y mató a Cánto. [287]

_-_Apollo_e_Giacinto,_inc._da_Annibale_Carracci,_-1675-.jpg/440px-Cesio,_Carlo_1626_-_1686)_-_Apollo_e_Giacinto,_inc._da_Annibale_Carracci,_-1675-.jpg)

Jacinto (o Jacinto), un príncipe espartano hermoso y atlético , era uno de los amantes favoritos de Apolo. [288] La pareja estaba practicando el lanzamiento del disco cuando un disco lanzado por Apolo fue desviado por el celoso Céfiro y golpeó a Jacinto en la cabeza, matándolo instantáneamente. Se dice que Apolo estaba lleno de dolor. A partir de la sangre de Jacinto, Apolo creó una flor que lleva su nombre como monumento a su muerte, y sus lágrimas tiñeron los pétalos de la flor con la interjección αἰαῖ , que significa ay . [289] Más tarde resucitó y fue llevado al cielo. El festival Hyacinthia era una celebración nacional de Esparta, que conmemoraba la muerte y el renacimiento de Jacinto. [290]

Otro amante masculino fue Cipariso , un descendiente de Heracles . Apolo le dio un ciervo domesticado como compañero, pero Cipariso lo mató accidentalmente con una jabalina mientras dormía en la maleza. Cipariso estaba tan triste por su muerte que le pidió a Apolo que dejara que sus lágrimas cayeran para siempre. Apolo le concedió la petición convirtiéndolo en el ciprés que lleva su nombre, que se decía que era un árbol triste porque la savia forma gotitas como lágrimas en el tronco. [291]

Admeto , rey de Feras, también era amante de Apolo. [292] [293] Durante su exilio, que duró uno o nueve años, [294] Apolo sirvió a Admeto como pastor. La naturaleza romántica de su relación fue descrita por primera vez por Calímaco de Alejandría, quien escribió que Apolo estaba "ardiente de amor" por Admeto. [156] Plutarco menciona a Admeto como uno de los amantes de Apolo y dice que Apolo sirvió a Admeto porque lo adoraba. [295] El poeta latino Ovidio en su Ars Amatoria dijo que, aunque era un dios, Apolo abandonó su orgullo y se quedó como sirviente por amor a Admeto. [296] Tibulo describe el amor de Apolo por el rey como servitium amoris (esclavitud de amor) y afirma que Apolo se convirtió en su sirviente no por la fuerza sino por elección. También hacía queso y se lo servía a Admeto. Sus acciones domésticas causaban vergüenza a su familia. [297]

¡Oh, cuántas veces se sonrojaba su hermana (Diana) al encontrar a su hermano mientras llevaba un ternero joven por los campos!... A menudo Latona se lamentaba cuando veía los cabellos despeinados de su hijo, que eran admirados incluso por Juno, su madrastra... [298]

Cuando Admeto quiso casarse con la princesa Alcestis , Apolo le proporcionó un carro tirado por un león y un jabalí que había domesticado. Esto satisfizo al padre de Alcestis y permitió que Admeto se casara con su hija. Además, Apolo salvó al rey de la ira de Artemisa y también convenció a las Moiras de posponer una vez más la muerte de Admeto.

Branchus , un pastor, se encontró un día con Apolo en el bosque. Cautivado por la belleza del dios, lo besó. Apolo correspondió a su afecto y, queriendo recompensarlo, le otorgó habilidades proféticas. Sus descendientes, los Branchides, fueron un influyente clan de profetas. [299]

Otros amantes masculinos de Apolo incluyen:

Apolo engendró muchos hijos, tanto de mujeres mortales y ninfas como de diosas. Sus hijos crecieron y se convirtieron en médicos, músicos, poetas, videntes o arqueros. Muchos de sus hijos fundaron nuevas ciudades y se convirtieron en reyes.

Asclepio es el hijo más famoso de Apolo. Sus habilidades como médico superaban a las de Apolo. Zeus lo mató por resucitar a los muertos, pero a petición de Apolo, resucitó como dios. Aristeo fue puesto bajo el cuidado de Quirón después de su nacimiento. Se convirtió en el dios de la apicultura, la elaboración de quesos, la cría de animales y más. Finalmente se le concedió la inmortalidad por los beneficios que otorgó a la humanidad. Los coribantes eran semidioses danzantes que chocaban con sus lanzas.

Los hijos de Apolo que participaron en la Guerra de Troya incluyen a los príncipes troyanos Héctor y Troilo , así como a Tenes , el rey de Ténedos , los tres fueron asesinados por Aquiles en el transcurso de la guerra.

Los hijos de Apolo que se convirtieron en músicos y bardos incluyen a Orfeo , Lino , Ialemo , Himeneo , Filamón , Eumolpo y Eleutero . Apolo engendró tres hijas, Apolonis , Boristenis y Cefiso , que formaron un grupo de musas menores, las "Musa Apolónides". [308] Se las apodó Nete, Mese e Hipate por las cuerdas más agudas, medias y graves de su lira. [ cita requerida ] Femonoe fue una vidente y poeta que fue la inventora del hexámetro.

Apis , Idmón , Yamo , Tenero , Mopso , Galeo , Telmeso y otros fueron videntes dotados. Anio , Piteo e Ismeno vivieron como sumos sacerdotes. La mayoría de ellos fueron entrenados por el propio Apolo.

Árabe , Delfo , Dríope , Mileto , Tenes , Epidauro , Ceos , Licoras , Siro , Piso , Marato , Megaro , Pátaro, Acrafeo , Cicón , Querón y muchos otros hijos de Apolo, bajo la guía de sus palabras, fundaron ciudades epónimas.