Texas ( / ˈtɛk sə s / TEK-səss,localmente también/ ˈ t ɛ k s ɪ z / TEK-siz;[8] español:TexasoTejas,[b] pronunciado[ˈtexas]) es elestadode laregióncentro-surEstados Unidos. Limita conLuisianaal este,Arkansasal noreste,Oklahomaal norte,Nuevo Méxicoal oeste yuna frontera internacionalcon losestados mexicanosdeChihuahua,Coahuila,Nuevo LeónyTamaulipasal sur y suroeste. Texas tiene una costa en elGolfo de Méxicoal sureste. Con una superficie de 268 596 millas cuadradas (695 660 km2), y con más de 30 millones de residentes en 2023,[10][11][12]es el segundo estado más grande tanto poráreacomopoblación.

Texas es apodado el Estado de la Estrella Solitaria por su antiguo estatus como república independiente. La Estrella Solitaria se puede encontrar en la bandera del estado de Texas y en el sello del estado de Texas. [13] España fue el primer país europeo en reclamar y controlar el área de Texas. Después de una colonia de corta duración controlada por Francia, México controló el territorio hasta 1836, cuando Texas ganó su independencia, convirtiéndose en la República de Texas . En 1845, Texas se unió a los Estados Unidos como el estado número 28. [14] La anexión del estado desencadenó una cadena de eventos que llevaron a la Guerra México-Estadounidense en 1846. Después de la victoria de los Estados Unidos, Texas siguió siendo un estado esclavista hasta la Guerra Civil estadounidense , cuando declaró su secesión de la Unión a principios de 1861 antes de unirse oficialmente a los Estados Confederados de América el 2 de marzo. Después de la Guerra Civil y la restauración de su representación en el gobierno federal, Texas entró en un largo período de estancamiento económico.

Históricamente, cinco industrias principales dieron forma a la economía de Texas antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial : ganado, bisontes, algodón, madera y petróleo. [15] Antes y después de la Guerra Civil, la industria ganadera, que Texas llegó a dominar, fue un importante motor económico y creó la imagen tradicional del vaquero tejano. A finales del siglo XIX, el algodón y la madera se convirtieron en industrias importantes a medida que la industria ganadera se volvió menos lucrativa. En última instancia, el descubrimiento de importantes depósitos de petróleo ( Spindletop en particular) inició un auge económico que se convirtió en la fuerza impulsora de la economía durante gran parte del siglo XX. Texas desarrolló una economía diversificada y una industria de alta tecnología a mediados del siglo XX. A partir de 2022 [update], tiene la mayor cantidad de sedes de empresas Fortune 500 (53) en los Estados Unidos. [16] [17] Con una creciente base industrial, el estado es líder en muchas industrias, incluido el turismo , la agricultura , los petroquímicos , la energía , las computadoras y la electrónica , la industria aeroespacial y las ciencias biomédicas . Texas ha liderado los ingresos por exportaciones estatales en Estados Unidos desde 2002 y tiene el segundo producto estatal bruto más alto .

El área metropolitana de Dallas-Fort Worth y el área metropolitana de Houston son la cuarta y quinta región urbana más poblada del país , respectivamente. Su capital es Austin . Debido a su tamaño y a sus características geológicas, como la falla de Balcones , Texas contiene diversos paisajes comunes tanto a las regiones del sur como del suroeste de los EE. UU . [18] La mayoría de los centros de población se encuentran en áreas de antiguas praderas , pastizales , bosques y costa . De este a oeste, el terreno varía desde pantanos costeros y bosques de pinos hasta llanuras onduladas y colinas escarpadas, pasando por el desierto y las montañas del Big Bend .

El nombre Texas , basado en la palabra Caddo táy:shaʼ ( /tə́jːʃaʔ/ ) 'amigo', fue aplicado, en la ortografía Tejas o Texas , [19] [20] [21] [1] por los españoles a los propios Caddo , específicamente a la Confederación Hasinai . [22]

Durante el dominio colonial español , en el siglo XVIII, la zona era conocida como Nuevas Filipinas (' Nuevas Filipinas ') y Nuevo Reino de Filipinas ('Nuevo Reino de Filipinas'), [23] o como provincia de los Tejas ('provincia de las Tejas '), [24] más tarde también provincia de Texas (o de Tejas ), ('provincia de Texas'). [25] [23] Fue incorporada como provincia de Texas al Imperio Mexicano en 1821, y declarada república en 1836. La Real Academia Española reconoce ambas grafías, Tejas y Texas , como formas en español del nombre. [26]

La pronunciación inglesa con /ks/ no es etimológica, contrariamente al valor histórico de la letra x ( / ʃ / ) en la ortografía española . Las etimologías alternativas del nombre propuestas a fines del siglo XIX conectaron el nombre Texas con la palabra española teja , que significa 'teja', y el plural tejas se usa para designar los asentamientos de los pueblos indígenas . [27] Un mapa de la década de 1760 de Jacques-Nicolas Bellin muestra un pueblo llamado Teijas en el río Trinity , cerca del sitio de la moderna Crockett . [27]

Texas se encuentra entre dos esferas culturales importantes de la América del Norte precolombina : las áreas del suroeste y de las llanuras . Los arqueólogos han descubierto que tres culturas indígenas principales vivieron en este territorio y alcanzaron su apogeo de desarrollo antes del primer contacto europeo. Estas fueron: [28] los pueblos ancestrales de la región superior del Río Grande , centrados al oeste de Texas; la cultura misisipiana , también conocida como constructores de montículos , que se extendió a lo largo del valle del río Misisipi al este de Texas; y las civilizaciones de Mesoamérica , que se centraron al sur de Texas. La influencia de Teotihuacan en el norte de México alcanzó su punto máximo alrededor del año 500 d. C. y declinó entre los siglos VIII y X.

Cuando los europeos llegaron a la región de Texas, las familias lingüísticas presentes en el estado eran caddoana, atakapán , atabascana, coahuilteca y utoazteca, además de varias lenguas aisladas como la tonkawa . Los pueblos utoaztecas puebloan y jumano vivían cerca del río Grande en la parte occidental del estado y las tribus apaches de habla atabascana vivían en todo el interior. Los caddo, agricultores y constructores de montículos, controlaban gran parte de la parte noreste del estado, a lo largo de las cuencas de los ríos Rojo , Sabine y Neches . [29] [30] Los pueblos atakapán como los akokisa y los bidai vivían a lo largo de la costa noreste del Golfo; los karankawa vivían a lo largo de la costa central. [31] Al menos una tribu de coahuiltecanos , los aranama , vivía en el sur de Texas. Todo este grupo cultural, centrado principalmente en el noreste de México , ahora está extinto.

Ninguna cultura era dominante en todo el actual Texas, y muchos pueblos habitaban el área. [32] Las tribus nativas americanas que han vivido dentro de los límites del actual Texas incluyen a los alabama , apache , atakapan , bidai , caddo , aranama , comanche , choctaw , coushatta , hasinai , jumano , karankawa , kickapoo , kiowa , tonkawa y wichita . [33] [34] Muchos de estos pueblos migraron desde el norte o el este durante el período colonial, como los choctaw , alabama-coushatta y delaware . [29]

La región estuvo controlada principalmente por los españoles hasta la Revolución de Texas . Estaban más interesados en las relaciones con los caddo, que eran, como los españoles, un pueblo agrícola y sedentario. Se abrieron varias misiones españolas en territorio caddo, pero la falta de interés en el cristianismo entre los caddo significó que pocos se convirtieron. Situados entre la Luisiana francesa y la Texas española, los caddo mantuvieron relaciones con ambos, pero eran más cercanos con los franceses. [35] Después de que España tomó el control de Luisiana, la mayoría de las misiones en el este de Texas fueron cerradas y abandonadas. [36] Estados Unidos obtuvo Luisiana después de la Compra de Luisiana de 1803 y comenzó a convencer a las tribus de que se autosegregaran de los blancos moviéndose hacia el oeste; frente a un desbordamiento de pueblos nativos en Missouri y Arkansas, pudieron negociar con los caddo para permitir que varios pueblos desplazados se establecieran en tierras no utilizadas en el este de Texas. Estos incluían a los muscogee , houma choctaw , lenape y mingo seneca , entre otros, que llegaron a ver a los caddoanos como salvadores. [37] [38]

El temperamento de las tribus nativas americanas afectó el destino de los exploradores y colonos europeos en esa tierra. [39] Las tribus amistosas enseñaron a los recién llegados cómo cultivar cultivos locales, preparar alimentos y cazar animales salvajes . Las tribus guerreras resistieron a los colonos. [39] Los tratados anteriores con los españoles prohibían a cualquiera de los dos lados militarizar a su población nativa en cualquier conflicto potencial entre las dos naciones. Varios brotes de violencia entre nativos americanos y tejanos comenzaron a extenderse en el preludio de la Revolución de Texas. Los tejanos acusaron a las tribus de robar ganado. Si bien no se encontraron pruebas, [29] los que estaban a cargo de Texas en ese momento intentaron culpar públicamente y castigar a los Caddo, con el gobierno de los EE. UU. tratando de mantenerlos bajo control. Los Caddo nunca recurrieron a la violencia debido a la situación, excepto en casos de defensa propia. [37]

En la década de 1830, Estados Unidos había redactado la Ley de Remoción de los Indios, que se utilizó para facilitar el Sendero de las Lágrimas. Temiendo represalias, los agentes indígenas de todo el este de Estados Unidos intentaron convencer a todos los pueblos indígenas de que se desarraigaran y se mudaran al oeste. Esto incluía a los Caddo de Luisiana y Arkansas. Después de la Revolución de Texas, los tejanos optaron por hacer las paces con los pueblos indígenas, pero no honraron los reclamos o acuerdos de tierras anteriores. [ cita requerida ] El primer presidente de Texas, Sam Houston , tenía como objetivo cooperar y hacer las paces con las tribus nativas, pero su sucesor, Mirabeau B. Lamar , adoptó una postura mucho más hostil. La hostilidad hacia los nativos por parte de los tejanos blancos impulsó el movimiento de la mayoría de las poblaciones nativas hacia el norte, a lo que se convertiría en el Territorio Indio (la actual Oklahoma). [29] [37] Solo los alabama-coushatta permanecerían en las partes de Texas sujetas al asentamiento blanco, aunque los comanches continuarían controlando la mayor parte de la mitad occidental del estado hasta su derrota en las décadas de 1870 y 1880. [40]

El primer documento histórico relacionado con Texas fue un mapa de la Costa del Golfo , creado en 1519 por el explorador español Alonso Álvarez de Pineda . [41] Nueve años después, el explorador español náufrago Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca y su cohorte se convirtieron en los primeros europeos en lo que hoy es Texas. [42] [43] Cabeza de Vaca informó que en 1528, cuando los españoles desembarcaron en la zona, "la mitad de los nativos murieron de una enfermedad de los intestinos y nos culparon". [44] Cabeza de Vaca también hizo observaciones sobre la forma de vida de los nativos Ignaces de Texas. [c] [46] Francisco Vázquez de Coronado describió otro encuentro con nativos en 1541. [d] [48]

La expedición de Hernando de Soto entró en Texas por el este, buscando una ruta hacia México. Pasaron por tierras Caddo, pero regresaron al llegar al río Daycao (posiblemente el Brazos o Colorado), más allá del cual los pueblos nativos eran nómadas y no tenían provisiones agrícolas para alimentar a la expedición. [49] [50]

Las potencias europeas ignoraron la zona hasta que se establecieron allí accidentalmente en 1685. Los cálculos erróneos de René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle dieron como resultado que estableciera la colonia de Fort Saint Louis en la bahía de Matagorda en lugar de a lo largo del río Mississippi . [51] La colonia duró solo cuatro años antes de sucumbir a las duras condiciones y a los nativos hostiles. [52] Un pequeño grupo de sobrevivientes viajó hacia el este a las tierras de los Caddo, pero La Salle fue asesinado por miembros de la expedición descontentos. [53]

En 1690, las autoridades españolas, preocupadas por la amenaza que Francia representaba para la competencia, construyeron varias misiones en el este de Texas entre los caddo. [54] Después de la resistencia de los caddo, los misioneros españoles regresaron a México. [55] Cuando Francia comenzó a colonizar Luisiana , en 1716 las autoridades españolas respondieron fundando una nueva serie de misiones en el este de Texas. [56] Dos años más tarde, crearon San Antonio como el primer asentamiento civil español en la zona. [57]

Las tribus nativas hostiles y la distancia de las colonias españolas cercanas desalentaron a los colonos a mudarse a la zona. Era una de las provincias menos pobladas de Nueva España. [59] En 1749, el tratado de paz español con los apaches lipán enfureció a muchas tribus, [60] incluidas las comanches, tonkawas y hasinai. [61] Los comanches firmaron un tratado con España en 1785 y más tarde ayudaron a derrotar a las tribus lipán apache y karankawa. [62] [63] Con numerosas misiones establecidas, los sacerdotes lideraron una conversión pacífica de la mayoría de las tribus. A fines del siglo XVIII, solo unas pocas tribus nómadas no se habían convertido. [64]

Cuando Estados Unidos compró Luisiana a Francia en 1803, las autoridades estadounidenses insistieron en que el acuerdo también incluía a Texas. La frontera entre Nueva España y Estados Unidos finalmente se estableció en 1819 en el río Sabine , la frontera moderna entre Texas y Luisiana. [65] Ávidos de nuevas tierras, muchos colonos estadounidenses se negaron a reconocer el acuerdo. Varios filibusteros levantaron ejércitos para invadir el área al oeste del río Sabine. [66] Marcado por la Guerra de 1812 , algunos hombres que habían escapado de los españoles, poseían (Viejas) Filipinas habían inmigrado y también habían pasado por Texas (Nuevas Filipinas) [67] y llegaron a Luisiana, donde los exiliados filipinos ayudaron a los Estados Unidos en la defensa de Nueva Orleans contra una invasión británica , con filipinos en el asentamiento de Saint Malo ayudando a Jean Lafitte en la Batalla de Nueva Orleans . [68]

En 1821, la Guerra de Independencia de México incluyó el territorio de Texas, que pasó a ser parte de México. [69] Debido a su baja población, el territorio fue asignado a otros estados y territorios de México ; el territorio central era parte del estado de Coahuila y Tejas , pero otras partes de la actual Texas eran parte de Tamaulipas , Chihuahua o el Territorio Mexicano de Santa Fe de Nuevo México . [70]

Con la esperanza de que más colonos redujeran las incursiones comanches casi constantes, el Texas mexicano liberalizó sus políticas de inmigración para permitir inmigrantes de fuera de México y España. [71] Grandes franjas de tierra fueron asignadas a empresarios , quienes reclutaron colonos de los Estados Unidos, Europa y el interior de México, principalmente los colonos de Austin, los Old Three Hundred , se establecieron a lo largo del río Brazos en 1822. [72] La población de Texas creció rápidamente. En 1825, Texas tenía alrededor de 3.500 personas, la mayoría de ascendencia mexicana. [73] Para 1834, la población había crecido a alrededor de 37.800 personas, con solo 7.800 de ascendencia mexicana. [74]

Muchos inmigrantes violaron abiertamente la ley mexicana, especialmente la prohibición de la esclavitud . Combinado con los intentos de Estados Unidos de comprar Texas, las autoridades mexicanas decidieron en 1830 prohibir la inmigración continua desde los Estados Unidos. [75] Sin embargo, la inmigración ilegal de los Estados Unidos a México continuó aumentando la población de Texas. [76] Las nuevas leyes también exigían la aplicación de derechos de aduana, lo que enfureció tanto a los ciudadanos mexicanos nativos ( tejanos ) como a los inmigrantes recientes. [77] Los disturbios de Anáhuac en 1832 fueron la primera revuelta abierta contra el gobierno mexicano, coincidiendo con una revuelta en México contra el presidente de la nación. [78] Los texanos se pusieron del lado de los federalistas contra el gobierno y expulsaron a todos los soldados mexicanos del este de Texas. [79] Se aprovecharon de la falta de supervisión para agitar por una mayor libertad política. Los texanos se reunieron en la Convención de 1832 para discutir la solicitud de la condición de estado independiente, entre otros temas. [80] Al año siguiente, los tejanos reiteraron sus demandas en la Convención de 1833. [ 81]

En México, las tensiones entre federalistas y centralistas continuaron. A principios de 1835, los texanos cautelosos formaron Comités de Correspondencia y Seguridad. [82] El malestar estalló en un conflicto armado a fines de 1835 en la Batalla de Gonzales . [83] Esto desencadenó la Revolución de Texas . Los texanos eligieron delegados para la Consulta , que creó un gobierno provisional. [84] El gobierno provisional pronto colapsó debido a las luchas internas, y Texas no tuvo un gobierno claro durante los primeros dos meses de 1836. [85]

El presidente mexicano Antonio López de Santa Anna dirigió personalmente un ejército para poner fin a la revuelta. [86] El general José de Urrea derrotó a toda la resistencia texana a lo largo de la costa, culminando en la masacre de Goliad . [87] Las fuerzas de López de Santa Anna, después de un asedio de trece días , abrumaron a los defensores texanos en la Batalla de El Álamo . Las noticias de las derrotas provocaron pánico entre los colonos de Texas. [88]

Los delegados texanos recién elegidos para la Convención de 1836 firmaron rápidamente una declaración de independencia el 2 de marzo, formando la República de Texas . Después de elegir a los funcionarios interinos, la Convención se disolvió. [89] El nuevo gobierno se unió a los demás colonos de Texas en el Runaway Scrape , huyendo del ejército mexicano que se acercaba. [88]

Después de varias semanas de retirada, el ejército texano comandado por Sam Houston atacó y derrotó a las fuerzas de López de Santa Anna en la batalla de San Jacinto . [90] López de Santa Anna fue capturado y obligado a firmar los Tratados de Velasco , poniendo fin a la guerra. [91] La Constitución de la República de Texas prohibía al gobierno restringir la esclavitud o liberar esclavos, y exigía que las personas libres de ascendencia africana abandonaran el país. [92]

Las batallas políticas se desataron entre dos facciones de la nueva República. La facción nacionalista, liderada por Mirabeau B. Lamar , abogó por la independencia continua de Texas, la expulsión de los nativos americanos y la expansión de la República hasta el océano Pacífico . Sus oponentes, liderados por Sam Houston, abogaron por la anexión de Texas a los Estados Unidos y la coexistencia pacífica con los nativos americanos. El conflicto entre las facciones fue ejemplificado por un incidente conocido como la Guerra de los Archivos de Texas . [93] Con un amplio apoyo popular, Texas solicitó por primera vez la anexión a los Estados Unidos en 1836, pero su condición de país esclavista provocó que su admisión fuera controvertida y fue rechazada inicialmente. Esta condición, y la diplomacia mexicana en apoyo de sus reclamos sobre el territorio, también complicaron la capacidad de Texas para formar alianzas extranjeras y relaciones comerciales. [94]

Los indios comanches constituyeron la principal oposición de los nativos americanos a la República de Texas, que se manifestó en múltiples incursiones en los asentamientos . [95] México lanzó dos pequeñas expediciones a Texas en 1842. La ciudad de San Antonio fue capturada dos veces y los tejanos fueron derrotados en batalla en la masacre de Dawson . A pesar de estos éxitos, México no mantuvo una fuerza de ocupación en Texas y la república sobrevivió. [96] La caída del precio del algodón de la década de 1840 deprimió la economía del país. [94]

Texas fue finalmente anexada cuando el expansionista James K. Polk ganó las elecciones de 1844. [ 97] El 29 de diciembre de 1845, el Congreso de los Estados Unidos admitió a Texas en los EE. UU. [98] Después de la anexión de Texas, México rompió relaciones diplomáticas con los Estados Unidos. Mientras que Estados Unidos afirmó que la frontera de Texas se extendía hasta el Río Grande, México afirmó que era el Río Nueces dejando el Valle del Río Grande bajo la soberanía texana en disputa. [98] Si bien la antigua República de Texas no pudo hacer cumplir sus reclamos fronterizos, Estados Unidos tenía la fuerza militar y la voluntad política para hacerlo. El presidente Polk ordenó al general Zachary Taylor que se dirigiera al sur hacia el Río Grande el 13 de enero de 1846. Unos meses más tarde, las tropas mexicanas derrotaron a una patrulla de caballería estadounidense en el área en disputa en el Asunto Thornton , lo que inició la Guerra México-Estadounidense . Las primeras batallas de la guerra se libraron en Texas: el Asedio de Fort Texas , la Batalla de Palo Alto y la Batalla de Resaca de la Palma . Después de estas victorias decisivas, Estados Unidos invadió territorio mexicano, poniendo fin a los combates en Texas. [99]

El Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo puso fin a la guerra de dos años. A cambio de 18.250.000 dólares, México entregó a Estados Unidos el control indiscutible de Texas, cedió la Cesión Mexicana en 1848, la mayor parte de la cual hoy se llama el Suroeste de Estados Unidos, y las fronteras de Texas se establecieron en el Río Grande. [99]

El Compromiso de 1850 fijó los límites de Texas en su posición actual: Texas cedió sus reclamos sobre la tierra que más tarde se convertiría en la mitad del actual Nuevo México , [100] un tercio de Colorado y pequeñas porciones de Kansas , Oklahoma y Wyoming al gobierno federal, a cambio de asumir la asunción de $ 10 millones de la deuda de la antigua república. [100] El Texas de la posguerra creció rápidamente a medida que los inmigrantes llegaban en masa a las tierras de algodón del estado. [101] También trajeron o compraron esclavos afroamericanos, cuyo número se triplicó en el estado entre 1850 y 1860, de 58.000 a 182.566. [102]

Texas volvió a entrar en guerra después de las elecciones de 1860. Durante este tiempo, los negros comprendían el 30 por ciento de la población del estado y estaban abrumadoramente esclavizados. [103] Cuando Abraham Lincoln fue elegido, Carolina del Sur se separó de la Unión; otros cinco estados del Sur Profundo siguieron rápidamente la misma estrategia. Una convención estatal que consideraba la secesión se inauguró en Austin el 28 de enero de 1861. El 1 de febrero, por una votación de 166 a 8, la convención adoptó una Ordenanza de Secesión . Los votantes de Texas aprobaron esta Ordenanza el 23 de febrero de 1861. Texas se unió a los recién creados Estados Confederados de América el 4 de marzo de 1861, ratificando la Constitución permanente de los Estados Confederados de América el 23 de marzo. [1] [104]

No todos los texanos estaban a favor de la secesión inicialmente, aunque muchos de ellos apoyarían más tarde la causa sureña. El unionista más notable de Texas fue el gobernador del estado, Sam Houston . Para no agravar la situación, Houston rechazó dos ofertas del presidente Lincoln de enviar tropas de la Unión para mantenerlo en el cargo. Después de negarse a jurar lealtad a la Confederación, Houston fue depuesto. [105]

Aunque estaba lejos de los principales campos de batalla de la Guerra Civil estadounidense , Texas contribuyó con un gran número de soldados y equipo. [106] Las tropas de la Unión ocuparon brevemente el puerto principal del estado, Galveston. La frontera de Texas con México era conocida como la "puerta trasera de la Confederación" porque el comercio se producía en la frontera, evitando el bloqueo de la Unión. [107] La Confederación rechazó todos los intentos de la Unión de cerrar esta ruta, [106] pero el papel de Texas como estado de suministro quedó marginado a mediados de 1863 después de la captura de la Unión del río Misisipi . La batalla final de la Guerra Civil se libró en Palmito Ranch , cerca de Brownsville, Texas, y vio una victoria confederada. [108] [109]

Texas cayó en la anarquía durante dos meses entre la rendición del Ejército del Norte de Virginia y la asunción de la autoridad por el general de la Unión Gordon Granger . La violencia marcó los primeros meses de la Reconstrucción . [106] El Juneteenth conmemora el anuncio de la Proclamación de la Emancipación en Galveston por el general Gordon Granger, casi dos años y medio después del anuncio original. [110] [111] El presidente Johnson, en 1866, declaró restaurado el gobierno civil en Texas. [112] A pesar de no cumplir con los requisitos de la Reconstrucción, el Congreso reanudó la admisión de representantes electos de Texas en el gobierno federal en 1870. La volatilidad social continuó mientras el estado luchaba con la depresión agrícola y los problemas laborales. [113]

Al igual que la mayor parte del Sur, la economía de Texas quedó devastada por la guerra. Sin embargo, dado que el estado no había dependido tanto de los esclavos como otras partes del Sur, pudo recuperarse más rápidamente. La cultura en Texas durante el siglo XIX posterior exhibió muchas facetas de un territorio fronterizo. El estado se hizo famoso como un refugio para personas de otras partes del país que querían escapar de las deudas, las tensiones de la guerra u otros problemas. "Se fue a Texas" era una expresión común para quienes huían de la ley en otros estados. Sin embargo, el estado también atrajo a muchos empresarios y otros colonos con intereses más legítimos. [114]

La industria ganadera siguió prosperando, aunque gradualmente se volvió menos rentable. El algodón y la madera se convirtieron en industrias importantes que generaron nuevos auges económicos en varias regiones. Las redes ferroviarias crecieron rápidamente, al igual que el puerto de Galveston, a medida que se expandía el comercio. La industria maderera se expandió rápidamente y fue la industria más grande de Texas antes del siglo XX. [115]

En 1900, Texas sufrió el desastre natural más mortífero en la historia de Estados Unidos durante el huracán de Galveston . [116] El 10 de enero de 1901, se encontró el primer pozo petrolero importante en Texas, Spindletop , al sur de Beaumont . Más tarde se descubrieron otros campos cercanos en el este de Texas , el oeste de Texas y bajo el golfo de México . El " boom petrolero " resultante transformó a Texas. [117] La producción de petróleo promedió tres millones de barriles por día en su pico en 1972. [118]

En 1901, la legislatura estatal dominada por los demócratas aprobó un proyecto de ley que exigía el pago de un impuesto electoral para votar, lo que privó de sus derechos a la mayoría de los negros y a muchos blancos y latinos pobres . Además, la legislatura estableció las primarias blancas , asegurando que las minorías fueran excluidas del proceso político formal. El número de votantes se redujo drásticamente y los demócratas aplastaron la competencia de los partidos republicano y populista. [119] [120] El Partido Socialista se convirtió en el segundo partido más grande en Texas después de 1912, [121] coincidiendo con un gran resurgimiento socialista en los Estados Unidos durante las feroces batallas en el movimiento obrero y la popularidad de héroes nacionales como Eugene V. Debs . La popularidad de los socialistas pronto disminuyó después de su vilipendio por parte del gobierno federal por su oposición a la participación de Estados Unidos en la Primera Guerra Mundial . [122] [123]

La Gran Depresión y el Dust Bowl asestaron un doble golpe a la economía del estado, que había mejorado significativamente desde la Guerra Civil. Los migrantes abandonaron las secciones más afectadas de Texas durante los años del Dust Bowl. Especialmente a partir de este período, los negros abandonaron Texas en la Gran Migración para conseguir trabajo en el norte de los Estados Unidos o California y escapar de la segregación. [103] En 1940, Texas estaba compuesta por un 74% de blancos , un 14,4% de negros y un 11,5% de hispanos. [124]

La Segunda Guerra Mundial tuvo un impacto dramático en Texas, ya que el dinero federal se utilizó para construir bases militares, fábricas de municiones, campos de detención y hospitales del ejército; 750.000 tejanos se marcharon para servir; las ciudades estallaron con nueva industria; y cientos de miles de agricultores pobres abandonaron los campos en busca de trabajos de guerra mucho mejor pagados, para nunca volver a la agricultura. [125] [126] Texas fabricó el 3,1 por ciento del total de armamentos militares de los Estados Unidos producidos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, ocupando el undécimo lugar entre los 48 estados. [127]

Texas modernizó y amplió su sistema de educación superior durante la década de 1960. El estado creó un plan integral para la educación superior, financiado en gran parte por los ingresos del petróleo, y un aparato estatal central diseñado para gestionar las instituciones estatales de manera más eficiente. Estos cambios ayudaron a que las universidades de Texas recibieran fondos federales para investigación. [128]

A partir de mediados del siglo XX, Texas comenzó a transformarse de un estado rural y agrícola a uno urbano e industrializado. [129] La población del estado creció rápidamente durante este período, con grandes niveles de migración desde fuera del estado. [129] Como parte del Sun Belt , Texas experimentó un fuerte crecimiento económico, particularmente durante la década de 1970 y principios de la de 1980. [129] La economía de Texas se diversificó, disminuyendo su dependencia de la industria petrolera . [129] Para 1990, los hispanos y latinoamericanos superaron a los negros para convertirse en el grupo minoritario más grande. [129] Texas tiene la población negra más grande con más de 3,9 millones. [130]

A finales del siglo XX, el Partido Republicano reemplazó al Partido Demócrata como el partido dominante en el estado. [129] A principios del siglo XXI, las áreas metropolitanas, incluidas Dallas-Fort Worth y el Gran Austin, se convirtieron en centros del Partido Demócrata de Texas en las elecciones estatales y nacionales a medida que las políticas liberales se volvían más aceptadas en las áreas urbanas. [131] [132] [133] [134]

Desde mediados de la década de 2000 hasta 2019, Texas recibió una afluencia de reubicaciones comerciales y sedes regionales de empresas en California . [135] [136] [137] [138] Texas se convirtió en un destino importante para la migración a principios del siglo XXI y fue nombrado el estado más popular para mudarse durante tres años consecutivos. [139] Otro estudio en 2019 determinó la tasa de crecimiento de Texas en 1000 personas por día. [140]

Durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en Texas , el primer caso confirmado del virus en Texas se anunció el 4 de marzo de 2020. [141] El 27 de abril de 2020, el gobernador Greg Abbott anunció la fase uno de reapertura de la economía. [142] En medio de un aumento de los casos de COVID-19 en el otoño de 2020, Abbott se negó a promulgar más cierres. [143] [144] En noviembre de 2020, Texas fue seleccionado como uno de los cuatro estados para probar la distribución de la vacuna COVID-19 de Pfizer. [145] Hasta el 2 de febrero de 2021, había habido más de 2,4 millones de casos confirmados en Texas, con al menos 37.417 muertes. [146]

Del 13 al 17 de febrero de 2021, el estado enfrentó una importante emergencia climática cuando la tormenta invernal Uri azotó el estado, así como la mayor parte del sureste y medio oeste de los Estados Unidos. [147] [148] El uso de energía históricamente alto en todo el estado provocó que la red eléctrica del estado se sobrecargara y ERCOT (el principal operador de la red de interconexión de Texas ) declaró una emergencia y comenzó a implementar apagones rotativos en todo Texas, lo que provocó una crisis energética . [149] [150] [151] Más de 3 millones de tejanos se quedaron sin electricidad y más de 4 millones estaban bajo avisos de hervir el agua. [152]

Texas es el segundo estado más grande de los EE. UU. por área, después de Alaska , y el estado más grande dentro de los Estados Unidos contiguos , con 268,820 millas cuadradas (696,200 km 2 ). Si fuera un país independiente, Texas sería el 39.º más grande . [153] Ocupa el puesto 26 a nivel mundial entre las subdivisiones de países por tamaño .

Texas se encuentra en la parte central sur de los Estados Unidos. El río Grande forma una frontera natural con los estados mexicanos de Chihuahua , Coahuila , Nuevo León y Tamaulipas al sur. El río Rojo forma una frontera natural con Oklahoma y Arkansas al norte. El río Sabine forma una frontera natural con Luisiana al este. El Panhandle de Texas tiene una frontera oriental con Oklahoma a 100° O , una frontera norte con Oklahoma a 36°30' N y una frontera occidental con Nuevo México a 103° O. El Paso se encuentra en el extremo occidental del estado a 32° N y el río Grande. [ 100]

Con 10 regiones climáticas , 14 regiones de suelo y 11 regiones ecológicas distintas , la clasificación regional se vuelve complicada con las diferencias en suelos, topografía, geología, precipitaciones y comunidades de plantas y animales. [154] Un sistema de clasificación divide a Texas, en orden de sureste a oeste, en lo siguiente: llanuras costeras del Golfo , tierras bajas interiores, grandes llanuras y provincia de cuenca y cordillera. [155]

La región de las llanuras costeras del Golfo rodea el Golfo de México en la sección sureste del estado. La vegetación en esta región consiste en densos bosques de pinos. La región de las tierras bajas interiores consiste en tierras boscosas suavemente onduladas a montañosas y es parte de un bosque más grande de pinos y frondosas. La región de Cross Timbers y Caprock Escarpment son parte de las tierras bajas interiores. [155]

La región de las Grandes Llanuras en el centro de Texas se extiende a través de la franja norte del estado y Llano Estacado hasta la región montañosa del estado cerca de Lago Vista y Austin . Esta región está dominada por praderas y estepas . El "Lejano Oeste de Texas" o la región " Trans-Pecos " es la provincia de cuenca y cordillera del estado. Esta área, la más variada de las regiones, incluye colinas de arena, la meseta de Stockton , valles desérticos, laderas montañosas boscosas y pastizales desérticos. [156]

Texas tiene 3.700 arroyos con nombre y 15 ríos importantes, [157] [158] siendo el río Grande el más grande. Otros ríos importantes son el Pecos , el Brazos , el Colorado y el río Rojo . Si bien Texas tiene pocos lagos naturales, los tejanos han construido más de cien embalses artificiales . [159]

El tamaño y la historia única de Texas hacen que su afiliación regional sea discutible; puede considerarse un estado del sur o del suroeste, o ambos. La vasta diversidad geográfica, económica y cultural dentro del propio estado impide una fácil categorización de todo el estado como una región reconocida de los Estados Unidos . Los extremos notables van desde el este de Texas , que a menudo se considera una extensión del sur profundo , hasta el lejano oeste de Texas , que generalmente se reconoce como parte del suroeste interior . [160]

Texas es la parte más meridional de las Grandes Llanuras, que termina al sur contra la Sierra Madre Occidental plegada de México. La corteza continental forma un cratón mesoproterozoico estable que cambia a lo largo de un amplio margen continental y una corteza de transición hasta convertirse en la verdadera corteza oceánica del Golfo de México. Las rocas más antiguas de Texas datan del Mesoproterozoico y tienen alrededor de 1.600 millones de años. [161]

Este margen existió hasta que Laurasia y Gondwana colisionaron en el subperíodo Pensilvánico para formar Pangea . [162] Pangea comenzó a romperse en el Triásico , pero la expansión del fondo marino para formar el Golfo de México ocurrió solo a mediados y finales del Jurásico . La línea de costa se desplazó nuevamente al margen oriental del estado y el margen pasivo del Golfo de México comenzó a formarse. Hoy en día, de 9 a 12 millas (14 a 19 km) de sedimentos están enterrados debajo de la plataforma continental de Texas y una gran proporción de las reservas de petróleo restantes de EE. UU. están aquí. La incipiente cuenca del Golfo de México estaba restringida y el agua de mar a menudo se evaporaba por completo para formar gruesos depósitos de evaporita de la era Jurásica. Estos depósitos de sal formaron diapiros de domo de sal y se encuentran en el este de Texas a lo largo de la costa del Golfo. [163]

Los afloramientos del este de Texas consisten en sedimentos del Cretácico y Paleógeno que contienen importantes depósitos de lignito del Eoceno . Los sedimentos del Misisipiense y Pensilvánico en el norte; los sedimentos del Pérmico en el oeste; y los sedimentos del Cretácico en el este, a lo largo de la costa del Golfo y en la plataforma continental de Texas contienen petróleo. Las rocas volcánicas del Oligoceno se encuentran en el extremo oeste de Texas en el área de Big Bend . Un manto de sedimentos del Mioceno conocido como la formación Ogallala en la región de las altas llanuras occidentales es un acuífero importante . [164] Ubicado lejos de un límite tectónico de placas activo , Texas no tiene volcanes y pocos terremotos. [165]

Texas es el hogar de 65 especies de mamíferos, 213 especies de reptiles y anfibios, incluida la rana arbórea verde americana , y la mayor diversidad de aves de los Estados Unidos: 590 especies nativas en total. [166] Se han introducido al menos 12 especies y ahora se reproducen libremente en Texas. [167]

Texas alberga varias especies de avispas , incluida una gran cantidad de Polistes exclamans , [168] y es un terreno importante para el estudio de Polistes annularis . [169]

Durante la primavera, las flores silvestres de Texas, como la flor estatal, el lupino azul , adornan las carreteras de todo el estado. Durante la administración Johnson, la primera dama, Lady Bird Johnson , trabajó para atraer la atención hacia las flores silvestres de Texas. [170]

El gran tamaño de Texas y su ubicación en la intersección de múltiples zonas climáticas le confieren al estado un clima muy variable. El Panhandle del estado tiene inviernos más fríos que el norte de Texas, mientras que la Costa del Golfo tiene inviernos suaves. Texas tiene amplias variaciones en los patrones de precipitación. El Paso, en el extremo occidental del estado, tiene un promedio de 8,7 pulgadas (220 mm) de lluvia anual, [171] mientras que partes del sureste de Texas tienen un promedio de hasta 64 pulgadas (1600 mm) por año. [172] Dallas, en la región del centro norte, tiene un promedio más moderado de 37 pulgadas (940 mm) por año. [173]

La nieve cae varias veces cada invierno en el Panhandle y las áreas montañosas del oeste de Texas, una o dos veces al año en el norte de Texas y una vez cada pocos años en el centro y este de Texas. La nieve cae al sur de San Antonio o en la costa solo en circunstancias excepcionales. Cabe destacar la tormenta de nieve de la víspera de Navidad de 2004 , cuando cayeron 150 mm de nieve tan al sur como Kingsville , donde la temperatura máxima promedio en diciembre es de 65 °F. [174]

Las temperaturas nocturnas de verano varían desde los 14 °C en las montañas del oeste de Texas hasta los 27 °C en Galveston. [175] [176]

La siguiente tabla consta de promedios de agosto (generalmente el mes más cálido) y enero (generalmente el más frío) en ciudades seleccionadas en varias regiones del estado.

Las tormentas eléctricas azotan Texas con frecuencia, especialmente las partes este y norte del estado. El Tornado Alley cubre la sección norte de Texas. El estado experimenta la mayor cantidad de tornados en los Estados Unidos, un promedio de 139 al año. Estos azotan con mayor frecuencia el norte de Texas y el Panhandle. [178] Los tornados en Texas generalmente ocurren en abril, mayo y junio. [179]

Algunos de los huracanes más destructivos en la historia de los EE. UU. han impactado a Texas. Un huracán en 1875 mató a unas 400 personas en Indianola , seguido de otro huracán en 1886 que destruyó la ciudad. Estos eventos permitieron que Galveston asumiera el cargo de principal ciudad portuaria. El huracán Galveston de 1900 posteriormente devastó esa ciudad, matando a unas 8.000 personas o posiblemente hasta 12.000 en el desastre natural más mortífero en la historia de los EE. UU. [116] En 2017, el huracán Harvey tocó tierra en Rockport como un huracán de categoría 4, causando daños significativos allí. Sus cantidades sin precedentes de lluvia sobre el área metropolitana de Houston resultaron en inundaciones generalizadas y catastróficas que inundaron cientos de miles de hogares. Harvey finalmente se convirtió en el huracán más costoso del mundo, causando un estimado de $ 198.6 mil millones en daños, superando el costo del huracán Katrina . [180]

Otros huracanes devastadores en Texas incluyen el huracán Galveston de 1915 , el huracán Audrey en 1957, el huracán Carla en 1961, el huracán Beulah en 1967, el huracán Alicia en 1983, el huracán Rita en 2005 y el huracán Ike en 2008. Las tormentas tropicales también han causado su parte de daños: Allison en 1989 y nuevamente durante 2001 , Claudette en 1979 y la tormenta tropical Imelda en 2019. [181] [182] [183]

No existe una barrera física sustancial entre Texas y la región polar . Aunque es inusual, es posible que masas de aire ártico o polar penetren en Texas, [184] [185] como ocurrió durante la tormenta invernal norteamericana del 13 al 17 de febrero de 2021. [186] [187] Por lo general, los vientos predominantes en América del Norte empujarán las masas de aire polares hacia el sureste antes de que lleguen a Texas. Debido a que tales intrusiones son raras y, tal vez, inesperadas, pueden resultar en crisis como la crisis energética de Texas de 2021 .

A partir de 2017 [update], Texas emitió la mayor cantidad de gases de efecto invernadero en los EE. UU. [ 188] A partir de 2017, [update]el estado emite alrededor de 1,600 mil millones de libras (707 millones de toneladas métricas) de dióxido de carbono anualmente. [188] Como estado independiente, Texas se ubicaría como el séptimo mayor productor mundial de gases de efecto invernadero. [189] Las causas de las vastas emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero del estado incluyen la gran cantidad de plantas de energía de carbón del estado y las industrias de refinación y fabricación del estado. [189] En 2010, hubo 2,553 "eventos de emisión" que vertieron 44,6 millones de libras (20,200 toneladas métricas) de contaminantes en el cielo de Texas. [190]

El estado tiene tres ciudades con poblaciones superiores a un millón: Houston, San Antonio y Dallas. [195] Estas tres se encuentran entre las 10 ciudades más pobladas de los Estados Unidos. A partir de 2020, seis ciudades de Texas tenían poblaciones superiores a 600.000. Austin, Fort Worth y El Paso se encuentran entre las 20 ciudades más grandes de EE. UU . . Texas tiene cuatro áreas metropolitanas con poblaciones superiores a un millón: Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington , Houston-Sugar Land-The Woodlands , San Antonio-New Braunfels y Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos . Las áreas metropolitanas de Dallas-Fort Worth y Houston suman alrededor de 7,5 millones y 7 millones de residentes a partir de 2019, respectivamente. [196]

Tres autopistas interestatales —la I-35 al oeste (de Dallas–Fort Worth a San Antonio, con Austin en el medio), la I-45 al este (de Dallas a Houston) y la I-10 al sur (de San Antonio a Houston)— definen la región del Triángulo Urbano de Texas . La región de 60.000 millas cuadradas (160.000 km2 ) contiene la mayoría de las ciudades y áreas metropolitanas más grandes del estado, así como 17 millones de personas, casi el 75 por ciento de la población total de Texas. [197] Houston y Dallas han sido reconocidas como ciudades del mundo . [198] Estas ciudades están repartidas por todo el estado. [199]

A diferencia de las ciudades, los asentamientos rurales no incorporados, conocidos como colonias, a menudo carecen de infraestructura básica y están marcados por la pobreza. [200] La oficina del Procurador General de Texas declaró, en 2011, que Texas tenía alrededor de 2.294 colonias y estima que alrededor de 500.000 personas vivían en ellas. El condado de Hidalgo , a partir de 2011, tiene el mayor número de colonias. [201] Texas tiene el mayor número de personas viviendo en colonias de todos los estados. [200]

Texas tiene 254 condados , más que cualquier otro estado. [202] Cada condado funciona según el sistema de Tribunal de Comisionados, que consta de cuatro comisionados elegidos (uno de cada uno de los cuatro distritos del condado, divididos aproximadamente según la población) y un juez del condado elegido en general de todo el condado. El gobierno del condado funciona de manera similar a un sistema de alcalde-consejo "débil" ; el juez del condado no tiene autoridad de veto, pero vota junto con los demás comisionados. [203] [204]

Aunque Texas permite que las ciudades y los condados celebren "acuerdos interlocales" para compartir servicios, el estado no permite gobiernos consolidados de ciudad y condado , ni tampoco tiene gobiernos metropolitanos . A los condados no se les concede el estatus de autonomía ; sus poderes están estrictamente definidos por la ley estatal. El estado no tiene municipios: las áreas dentro de un condado están incorporadas o no incorporadas. Las áreas incorporadas son parte de un municipio. El condado proporciona servicios limitados a las áreas no incorporadas y a algunas áreas incorporadas más pequeñas. Los municipios se clasifican como ciudades de "ley general" o "autonomía". [205] Un municipio puede elegir el estatus de autonomía una vez que supera los 5000 habitantes con la aprobación de los votantes. [206]

Texas también permite la creación de "distritos especiales", que proporcionan servicios limitados. El más común es el distrito escolar , pero también puede incluir distritos hospitalarios, distritos de colegios comunitarios y distritos de servicios públicos. Las elecciones municipales, de distritos escolares y de distritos especiales son no partidistas , [207] aunque la afiliación partidaria de un candidato puede ser bien conocida. Las elecciones de condado y estatales son partidistas. [208]

La población residente de Texas fue de 29.145.505 en el censo de 2020 , un aumento del 15,9% desde el censo de 2010. [ 210] [211] En el censo de 2020, la población asignada de Texas era de 29.183.290. [212] El programa de Estimación de la población de Texas de 2023 estimó que la población era de 30.503.301 el 1 de julio de 2023. [213] En 2010, Texas tenía una población censada de 25.145.561. [214] Texas es el segundo estado más poblado de los Estados Unidos después de California y el único otro estado de los EE. UU. que supera una población total estimada de 30 millones de personas al 2 de julio de 2022. [215] [216]

En 2015, Texas tenía 4,7 millones de residentes nacidos en el extranjero, aproximadamente el 17% de la población y el 21,6% de la fuerza laboral del estado. [217] Los principales países de origen de los inmigrantes texanos fueron México (55,1% de los inmigrantes), India (5%), El Salvador (4,3%), Vietnam (3,7%) y China (2,3%). [217] De los residentes inmigrantes, el 35,8 por ciento eran ciudadanos estadounidenses naturalizados . [217] A partir de 2018, la población aumentó a 4,9 millones de residentes nacidos en el extranjero o el 17,2% de la población del estado, frente a los 2.899.642 en 2000. [218]

En 2014, se estimó que había 1,7 millones de inmigrantes indocumentados en Texas, lo que representa el 35% de la población inmigrante total de Texas y el 6,1% de la población total del estado. [217] Además de la población nacida en el extranjero del estado, otros 4,1 millones de tejanos (el 15% de la población del estado) nacieron en los Estados Unidos y tenían al menos un padre inmigrante. [217]

Según las estimaciones de 2019 de la Encuesta sobre la Comunidad Estadounidense , 1.739.000 residentes eran inmigrantes indocumentados, una disminución de 103.000 desde 2014 y un aumento de 142.000 desde 2016. De la población inmigrante indocumentada, 951.000 han residido en Texas desde menos de 5 hasta 14 años. Se estima que 788.000 vivieron en Texas entre 15 y 19 años y 20 años o más. [219]

El Valle del Río Grande de Texas ha sido testigo de una importante migración desde el otro lado de la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México . Durante la crisis de 2014 , muchos centroamericanos , incluidos menores no acompañados que viajaban solos desde Guatemala , Honduras y El Salvador , llegaron al estado, lo que abrumó los recursos de la Patrulla Fronteriza por un tiempo. Muchos buscaron asilo en los Estados Unidos. [220] [221]

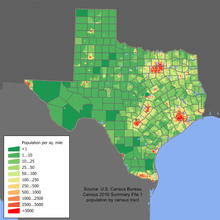

La densidad de población de Texas en 2010 es de 96,3 personas por milla cuadrada (37,2 personas/km 2 ), que es ligeramente superior a la densidad de población promedio de los EE. UU. en su conjunto, de 87,4 personas por milla cuadrada (33,7 personas/km 2 ). En contraste, mientras que Texas y Francia tienen un tamaño geográfico similar, el país europeo tiene una densidad de población de 301,8 personas por milla cuadrada (116,5 personas/km 2 ). Dos tercios de todos los tejanos viven en áreas metropolitanas importantes como Houston.

Según el Informe Anual de Evaluación de Personas sin Hogar de 2022 de HUD , se estima que había 24.432 personas sin hogar en Texas. [222] [223]

En 2019, los blancos no hispanos representaban el 41,2% de la población de Texas, lo que refleja un cambio demográfico nacional. [225] [226] [227] Los negros constituían el 12,9%, los indios americanos y nativos de Alaska el 1,0%, los asiático-americanos el 5,2%, los nativos hawaianos y otros isleños del Pacífico el 0,1%, alguna otra raza el 0,2% y dos o más razas el 1,8%. Los hispanos o latinoamericanos de cualquier raza constituían el 39,7% de la población estimada. [228]

En el censo de 2020, la composición racial y étnica del estado era 42,5% blanca (39,8% blanca no hispana), 11,8% negra, 5,4% asiática, 0,3% indígena americana y nativa de Alaska, 0,1% nativa hawaiana y de otras islas del Pacífico, 13,6% de alguna otra raza, 17,6% de dos o más razas y 40,2% hispano y latinoamericano de cualquier raza. [229] [230]

En 2010, el 49% de todos los nacimientos fueron hispanos; el 35% fueron blancos no hispanos; el 11,5% fueron negros no hispanos y el 4,3% fueron asiáticos/isleños del Pacífico. [231] Según datos de la Oficina del Censo de los EE. UU. publicados en febrero de 2011, por primera vez en la historia reciente, la población blanca de Texas está por debajo del 50% (45%) y los hispanos crecieron al 38%. Entre 2000 y 2010, la población total creció un 20,6%, pero los hispanos y latinoamericanos crecieron un 65%, mientras que los blancos no hispanos crecieron solo un 4,2%. [232] Texas tiene la quinta tasa más alta de nacimientos de adolescentes en la nación y una pluralidad de estos son de hispanos o latinos. [233] [234] A partir de 2022, los hispanos y latinos de cualquier raza reemplazaron a la población blanca no hispana como la mayor proporción de la población del estado. [235]

Texas tiene la segunda mayor proporción de mexicano-estadounidenses en los EE. UU., lo que representa el 32,2% de la población total y el 80% de la población hispana del estado. [236] Además de los mexicanos, las ascendencias autodeclaradas más grandes en el estado en 2022 eran alemanas (8,1%), inglesas (7,9%), irlandesas (5,8%), las que se identificaban como estadounidenses (4,6%), italianas (1,9%), indias (1,9%), salvadoreñas ( 1,4%), escocesas (1,3%), vietnamitas (1,1%), chinas (1%), puertorriqueñas (0,9%), polacas (0,9%), hondureñas (0,8%), filipinas (0,8%) y escocesas-irlandesas (0,7%). [237] [238] [239]

El acento o dialecto más común hablado por los nativos en todo Texas a veces se conoce como inglés tejano , en sí mismo una subvariedad de una categoría más amplia de inglés estadounidense conocida como inglés sureño estadounidense . [241] [242] El idioma criollo se habla en algunas partes del este de Texas. [243] En algunas áreas del estado, particularmente en las grandes ciudades, el inglés estadounidense occidental y el inglés estadounidense general son cada vez más comunes. El inglés chicano , debido a una creciente población hispana, está muy extendido en el sur de Texas, mientras que el inglés afroamericano es especialmente notable en áreas históricamente minoritarias del Texas urbano.

Según las estimaciones de la Encuesta sobre la Comunidad Estadounidense de 2020, el 64,9 % de la población hablaba solo inglés y el 35,1 % hablaba un idioma distinto del inglés. [244] Aproximadamente el 30 % de la población total hablaba español. En 2021, aproximadamente 50 546 tejanos hablaban francés o una lengua criolla francesa. 49 565 residentes hablaban alemán y otras lenguas germánicas occidentales; 37 444 hablaban ruso, polaco y otras lenguas eslavas; 31 673 hablaban coreano; 86 370 hablaban chino; 92 410 hablaban vietnamita; 40 124 hablaban tagalo; y 47 170 hablaban árabe. [245]

En el censo de 2010, el 65,8% (14.740.304) de los residentes de Texas de 5 años o más hablaban solo inglés en casa, mientras que el 29,2% (6.543.702) hablaba español , el 0,8 por ciento (168.886) vietnamita y el 0,6% (122.921) de la población mayor de cinco años hablaba chino (que incluye cantonés y mandarín ). [240] Otros idiomas hablados incluyen alemán (incluido el alemán de Texas ) por el 0,3% (73.137), tagalo con el 0,3% (64.272) hablantes y francés (incluido el francés cajún ) por el 0,3% (55.773) de los tejanos. [240] Según se informa, el cherokee es la lengua nativa americana más hablada en Texas. [246] En total, el 34,2% (7.660.406) de la población de Texas de cinco años de edad o más hablaba en casa un idioma distinto del inglés en 2006. [240]

Con la llegada de las sociedades misioneras católicas españolas y protestantes estadounidenses, [248] las religiones y tradiciones espirituales indígenas de los indios americanos disminuyeron. Desde entonces, el Texas colonial y actual se ha convertido en un estado predominantemente cristiano, con un 75,5% de la población que se identifica como tal según el Public Religion Research Institute en 2020. [249]

Entre su población cristiana mayoritaria, la denominación cristiana más grande hasta 2014 ha sido la Iglesia Católica , según el Pew Research Center con el 23% de la población, aunque los protestantes constituían colectivamente el 50% de la población cristiana en 2014; [250] en el estudio de 2020 del Public Religion Research Institute, la membresía de la Iglesia Católica aumentó hasta abarcar el 28% de la población que se identifica con una creencia religiosa o espiritual. [249] En el estudio de 2020 de la Association of Religion Data Archives , había 5.905.142 católicos en el estado. [251] Las jurisdicciones católicas más grandes de Texas son la Arquidiócesis de Galveston-Houston —la primera y más antigua diócesis de la Iglesia latina en Texas [252] —las diócesis de Dallas y Fort Worth , y la Arquidiócesis de San Antonio .

Al ser parte del Cinturón Bíblico , fuertemente conservador en lo social , [253] los protestantes en su conjunto disminuyeron al 47% de la población en el estudio de 2020 del Instituto de Investigación de Religión Pública. El protestantismo evangélico predominantemente blanco disminuyó al 14% de la población cristiana protestante. Los protestantes tradicionales , en cambio, constituían el 15% de los protestantes de Texas. Las iglesias protestantes dominadas por hispanos o latinoamericanos y el protestantismo históricamente negro o afroamericano crecieron hasta un colectivo del 13% de la población protestante.

Los protestantes evangélicos eran el 31% de la población en 2014, y los bautistas eran la tradición evangélica más grande (14%); [250] según el estudio de 2014, constituían el segundo grupo protestante tradicional más grande detrás de los metodistas (4%). Los cristianos protestantes no denominacionales e interconfesionales eran el segundo grupo evangélico más grande (7%), seguidos de los pentecostales (4%). Los bautistas evangélicos más grandes del estado eran la Convención Bautista del Sur (9%) y los bautistas independientes (3%). Las Asambleas de Dios de EE. UU. fueron la denominación pentecostal evangélica más grande en 2014. Entre los protestantes tradicionales , la Iglesia Metodista Unida fue la denominación más grande (4%) y las Iglesias Bautistas Americanas de EE. UU. comprendían el segundo grupo protestante tradicional más grande (2%).

Según el Pew Research Center en 2014, las denominaciones cristianas afroamericanas históricamente más grandes del estado eran la Convención Bautista Nacional (EE. UU.) y la Iglesia de Dios en Cristo . Los metodistas negros y otros cristianos representaban menos del 1 por ciento cada uno de la demografía cristiana. Otros cristianos representaban el 1 por ciento de la población cristiana total, y los ortodoxos orientales y orientales formaban menos del 1 por ciento de la población cristiana en todo el estado. La Iglesia de Jesucristo de los Santos de los Últimos Días es el grupo cristiano no trinitario más grande en Texas junto con los Testigos de Jehová . [250]

Entre su población protestante, la Asociación de Archivos de Datos de Religión determinó en 2020 que los bautistas del sur sumaban 3.319.962; los protestantes no denominacionales 2.405.786 (incluidas las iglesias cristianas y las iglesias de Cristo , y las iglesias de Cristo en total 2.758.353); y los metodistas unidos 938.399 como los grupos protestantes más numerosos en el estado. [251] Los bautistas en total (bautistas del sur, asociados bautistas estadounidenses , bautistas estadounidenses, bautistas del evangelio completo , bautistas generales , bautistas de libre albedrío , bautistas nacionales, bautistas nacionales de América , bautistas misioneros nacionales , bautistas primitivos nacionales y bautistas nacionales progresistas ) sumaban 3.837.306; Los metodistas dentro del Metodismo Unido, la AME , AME Zion , CME y la Iglesia Metodista Libre sumaban 1.026.453 tejanos.

El mismo estudio tabuló 425.038 pentecostales repartidos entre las Asambleas de Dios, la Iglesia de Dios (Cleveland) y la Iglesia de Dios en Cristo. Los pentecostales no trinitarios o unitarios sumaban 7.042 entre la Iglesia del Camino Bíblico de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo , COOLJC , y las Asambleas Pentecostales del Mundo . Otros cristianos, incluidos los ortodoxos orientales y orientales, sumaban 55.329 en total, y los episcopalianos sumaban 134.318, aunque la Iglesia Católica Anglicana , la Iglesia Anglicana en América , la Iglesia Anglicana en América del Norte , la Provincia Anglicana de América y la Santa Iglesia Católica de Rito Anglicano tenían una presencia colectiva en 114 iglesias. [254]

Las religiones no cristianas representaron el 4% de la población religiosa en 2014 y el 5% en 2020 según el Pew Research Center y el Public Religion Research Institute. [250] [249] Los seguidores de muchas otras religiones residen predominantemente en los centros urbanos de Texas. El judaísmo, el islam y el budismo empataron como la segunda religión más grande en 2014 y 2020. En 2014, el 18% de la población del estado no estaba afiliada a ninguna religión. De los no afiliados en 2014, se estima que el 2% eran ateos y el 3% agnósticos ; en 2020, el Public Religion Research Institute señaló que los grupos no cristianos más grandes eran los irreligiosos (20%), el judaísmo (1%), el islam (1%), el budismo (1%) y el hinduismo , y otras religiones con menos del 1 por ciento cada uno.

En 1990, la población islámica era de unos 140.000 habitantes y cifras más recientes sitúan el número actual de musulmanes entre 350.000 y 400.000 en 2012. [255] La Asociación de Archivos de Datos Religiosos estimó que había 313.209 musulmanes en 2020. [251] Texas es el quinto estado con mayor población musulmana en 2014. [256] La población judía era de alrededor de 128.000 en 2008. [257] En 2020, la población judía creció a más de 176.000. [258] Según el estudio de 2020 de ARDA, había 43 sinagogas de Jabad ; 17.513 judíos conservadores ; 8.110 judíos ortodoxos ; y 31.378 judíos reformistas . En 2004, en Texas vivían alrededor de 146.000 seguidores de religiones como el hinduismo y el sijismo. [259] En 2020, había 112.153 hindúes y 20 gurdwaras sijs; 60.882 tejanos se adherían al budismo .

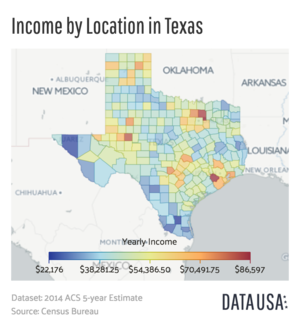

En 2024, Texas tenía un producto estatal bruto (GSP) de 2,664 billones de dólares, el segundo más alto de los EE. UU. [260] Su GSP es mayor que el PIB de Brasil , la octava economía más grande del mundo. [261] El estado ocupa el puesto 22 entre los estados de EE. UU. con un ingreso familiar medio de 64 034 dólares, mientras que la tasa de pobreza es del 14,2 %, lo que convierte a Texas en el estado con la 14.ª tasa de pobreza más alta (en comparación con el 13,15 % a nivel nacional). La economía de Texas es la segunda más grande de cualquier subdivisión de país a nivel mundial, detrás de California .

La gran población de Texas, la abundancia de recursos naturales, las ciudades prósperas y los principales centros de educación superior han contribuido a una economía grande y diversificada. Desde que se descubrió petróleo, la economía del estado ha reflejado el estado de la industria petrolera . En los últimos tiempos, los centros urbanos del estado han aumentado de tamaño, y en 2005 albergaban a dos tercios de la población. El crecimiento económico del estado ha provocado la expansión urbana y sus síntomas asociados. [262]

En mayo de 2020, durante la pandemia de COVID-19 , la tasa de desempleo del estado era del 13 por ciento. [263]

En 2010, la revista Site Selection clasificó a Texas como el estado más favorable para las empresas, en parte debido al Texas Enterprise Fund de tres mil millones de dólares del estado . [264] Texas tiene el mayor número de sedes de empresas Fortune 500 en los Estados Unidos a partir de 2022. [16] [17] En 2010, había 346.000 millonarios en Texas, la segunda población más grande de millonarios en la nación. [f] [265] En 2018, el número de hogares millonarios aumentó a 566.578. [266]

Texas tiene fama de tener impuestos bajos. [267] Según la Tax Foundation , las cargas impositivas estatales y locales de los tejanos son las séptimas más bajas a nivel nacional; los impuestos estatales y locales cuestan $3,580 per cápita, o el 8,4 por ciento de los ingresos de los residentes. [268] Texas es uno de los siete estados que carecen de un impuesto estatal sobre la renta . [268] [269]

Instead, the state collects revenue from property taxes (though these are collected at the county, city, and school district level; Texas has a state constitutional prohibition against a state property tax) and sales taxes. The state sales tax rate is 6.25 percent,[268][270] but local taxing jurisdictions (cities, counties, special purpose districts, and transit authorities) may also impose sales and use tax up to 2 percent for a total maximum combined rate of 8.25 percent.[271]

Texas is a "tax donor state"; in 2005, for every dollar Texans paid to the federal government in federal income taxes, the state got back about $0.94 in benefits.[268] To attract business, Texas has incentive programs worth $19 billion per year (2012); more than any other U.S. state.[272][273]

Texas has the most farms and the highest acreage in the United States. The state is ranked No. 1 for revenue generated from total livestock and livestock products. It is ranked No. 2 for total agricultural revenue, behind California.[274] At $7.4 billion or 56.7 percent of Texas's annual agricultural cash receipts, beef cattle production represents the largest single segment of Texas agriculture. This is followed by cotton at $1.9 billion (14.6 percent), greenhouse/nursery at $1.5 billion (11.4 percent), broiler chickens at $1.3 billion (10 percent), and dairy products at $947 million (7.3 percent).[275]

Texas leads the nation in the production of cattle, horses, sheep, goats, wool, mohair and hay.[275] The state also leads the nation in production of cotton which is the number one crop grown in the state in terms of value.[274][276][277] The state grows significant amounts of cereal crops and produce.[274] Texas has a large commercial fishing industry. With mineral resources, Texas leads in creating cement, crushed stone, lime, salt, sand and gravel.[274] Texas throughout the 21st century has been hammered by drought, costing the state billions of dollars in livestock and crops.[278]

Ever since the discovery of oil at Spindletop, energy has been a dominant force politically and economically within the state.[279] If Texas were its own country it would be the sixth-largest oil producer in the world according to a 2014 study.[280]

The Railroad Commission of Texas regulates the state's oil and gas industry, gas utilities, pipeline safety, safety in the liquefied petroleum gas industry, and surface coal and uranium mining. Until the 1970s, the commission controlled the price of petroleum because of its ability to regulate Texas's oil reserves. The founders of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) used the Texas agency as one of their models for petroleum price control.[281]

As of January 1, 2021, Texas has proved recoverable petroleum reserves of about 15.6 billion barrels (2.48×109 m3) of crude oil (44% of the known U.S. reserves) and 9.5 billion barrels (1.51×109 m3) of natural gas liquids.[282][283] The state's refineries can process 5.95 million barrels (946,000 m3) of oil a day.[282][283] The Port Arthur Refinery in Southeast Texas is the largest refinery in the U.S.[282] Texas is also a leader in natural gas production at 28.8 billion cubic feet (820,000,000 m3) per day, some 32% of the nation's production.[284] Texas has 102.4 trillion cubic feet (2.90×1012 m3) of gas reserves which is 23% of the nation's gas reserves.[282][283] Many petroleum companies are based in Texas such as: ConocoPhillips,[285] EOG Resources, ExxonMobil,[286] Halliburton,[287] Hilcorp, Marathon Oil,[288] Occidental Petroleum,[289] Valero Energy,[290] and Western Refining.[291]

According to the Energy Information Administration, Texans consume, on average, the fifth most energy (of all types) in the nation per capita and as a whole, following behind Wyoming, Alaska, Louisiana, North Dakota, and Iowa.[282]

Unlike the rest of the nation, most of Texas is on its own alternating current power grid, the Texas Interconnection. Texas has a deregulated electric service. Texas leads the nation in total net electricity production, generating 437,236 MWh in 2014, 89% more MWh than Florida, which ranked second.[292][293]

The state is a leader in renewable energy commercialization; it produces the most wind power in the nation.[282][294] In 2014, 10.6% of the electricity consumed in Texas came from wind turbines.[295] The Roscoe Wind Farm in Roscoe, Texas, is one of the world's largest wind farms with a 781.5 megawatt (MW) capacity.[296] The Energy Information Administration states the state's large agriculture and forestry industries could give Texas an enormous amount of biomass for use in biofuels. The state also has the highest solar power potential for development in the U.S.[282]

With large universities systems coupled with initiatives like the Texas Enterprise Fund and the Texas Emerging Technology Fund, a wide array of different high tech industries have developed in Texas. The Austin area is nicknamed the "Silicon Hills" and the north Dallas area the "Silicon Prairie". Many high-tech companies are located in or have their headquarters in Texas (and Austin in particular), including Dell, Inc.,[297] Borland,[298] Forcepoint,[299] Indeed.com,[300] Texas Instruments,[301] Perot Systems,[302] Rackspace and AT&T.[303][304][305]

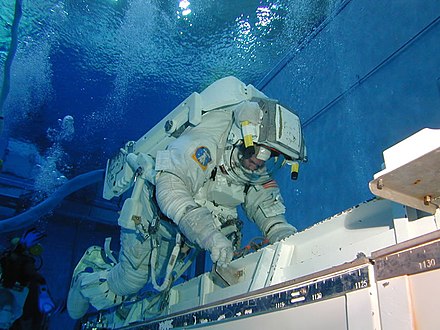

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (NASA JSC) is located in Southeast Houston. Both SpaceX and Blue Origin have their test facilities in Texas.[306][307] Fort Worth hosts both Lockheed Martin's Aeronautics division and Bell Helicopter Textron.[308][309] Lockheed builds the F-16 Fighting Falcon, the largest Western fighter program, and its successor, the F-35 Lightning II in Fort Worth.[310]

Texas's affluence stimulates a strong commercial sector consisting of retail, wholesale, banking and insurance, and construction industries. Examples of Fortune 500 companies not based on Texas traditional industries are AT&T, Kimberly-Clark, Blockbuster, J. C. Penney, Whole Foods Market, and Tenet Healthcare.[311]

Nationally, the Dallas–Fort Worth area, home to the second shopping mall in the United States, has the most shopping malls per capita of any American metropolitan statistical area.[312]

Mexico, the state's largest trading partner, imports a third of the state's exports because of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). NAFTA has encouraged the formation of maquiladoras on the Texas–Mexico border.[313]

Historically, Texas culture comes from a blend of mostly Southern (Dixie), Western (frontier), and Southwestern (Mexican/Anglo fusion) influences, varying in degrees of such from one intrastate region to another. A popular food item, the breakfast burrito, draws from all three, having a soft flour tortilla wrapped around bacon and scrambled eggs or other hot, cooked fillings. Adding to Texas's traditional culture, established in the 18th and 19th centuries, immigration has made Texas a melting pot of cultures from around the world.[314][315]

Texas has made a strong mark on national and international pop culture. The entire state is strongly associated with the image of the cowboy shown in westerns and in country western music. The state's numerous oil tycoons are also a popular pop culture topic as seen in the hit TV series Dallas.[316]

The internationally known slogan "Don't Mess with Texas" began as an anti-littering advertisement. Since the campaign's inception in 1986, the phrase has become "an identity statement, a declaration of Texas swagger".[317]

"Texas-sized" describes something that is about the size of the U.S. state of Texas,[318][319] or something (usually but not always originating from Texas) that is large compared to other objects of its type.[320][321][322] Texas was the largest U.S. state until Alaska became a state in 1959. The phrase "everything is bigger in Texas" has been in regular use since at least 1950.[323]

.jpg/440px-ZZ_Top_on_the_Pyramid_Stage_at_Glastonbury_2016_IMG_8527_(27374417884).jpg)

Houston is one of only five American cities with permanent professional resident companies in all the major performing arts disciplines: the Houston Grand Opera, the Houston Symphony Orchestra, the Houston Ballet, and The Alley Theatre.[324] Known for the vibrancy of its visual and performing arts, the Houston Theater District ranks second in the country in the number of theater seats in a concentrated downtown area, with 12,948 seats for live performances and 1,480 movie seats.[324]Founded in 1892, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, also called "The Modern", is Texas's oldest art museum. Fort Worth also has the Kimbell Art Museum, the Amon Carter Museum, the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, the Will Rogers Memorial Center, and the Bass Performance Hall downtown. The Arts District of Downtown Dallas has arts venues such as the Dallas Museum of Art, the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center, the Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House, the Trammell & Margaret Crow Collection of Asian Art, and the Nasher Sculpture Center.[325]

The Deep Ellum district within Dallas became popular during the 1920s and 1930s as the prime jazz and blues hotspot in the Southern United States. The name Deep Ellum comes from local people pronouncing "Deep Elm" as "Deep Ellum".[326] Artists such as Blind Lemon Jefferson, Robert Johnson, Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter, and Bessie Smith played in early Deep Ellum clubs.[327]

Austin, The Live Music Capital of the World, boasts "more live music venues per capita than such music hotbeds as Nashville, Memphis, Los Angeles, Las Vegas or New York City".[328] The city's music revolves around the nightclubs on 6th Street; events like the film, music, and multimedia festival South by Southwest; the longest-running concert music program on American television, Austin City Limits; and the Austin City Limits Music Festival held in Zilker Park.[329]

Since 1980, San Antonio has evolved into "The Tejano Music Capital Of The World".[330] The Tejano Music Awards have provided a forum to create greater awareness and appreciation for Tejano music and culture.[331]

Within the "Big Four" professional leagues, Texas has two NFL teams (the Dallas Cowboys and the Houston Texans), two MLB teams (the Houston Astros and the Texas Rangers),[332][333] three NBA teams (the San Antonio Spurs, the Houston Rockets, and the Dallas Mavericks), and one NHL team (the Dallas Stars). The Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex is one of only thirteen American metropolitan areas that host sports teams from all the "Big Four" professional leagues. Outside of the "Big Four", Texas also has a WNBA team (the Dallas Wings), three Major League Soccer teams (Austin FC, Houston Dynamo FC and FC Dallas), and one NWSL team (the Houston Dash).[citation needed]

Collegiate athletics have deep significance in Texas culture, especially football. The state has twelve Division I-FBS schools, the most in the nation. Four of the state's schools claim at least one national championship in football: the Texas Longhorns, the Texas A&M Aggies, the TCU Horned Frogs, and the SMU Mustangs.[334][335][336][337] According to a survey of Division I-A coaches, the rivalry between the University of Oklahoma and the University of Texas at Austin, the Red River Shootout, ranks the third-best in the nation.[338] The TCU Horned Frogs and SMU Mustangs also share a rivalry and compete annually in the Battle for the Iron Skillet. A fierce rivalry, the Lone Star Showdown, also exists between the state's two largest universities, Texas A&M University and the University of Texas at Austin. The athletics portion of the Lone Star Showdown rivalry has been put on hold after the Texas A&M Aggies joined the Southeastern Conference.[339]

The University Interscholastic League (UIL) organizes most primary and secondary school competitions. Events organized by UIL include contests in athletics (the most popular being high school football) as well as artistic and academic subjects.[340]

Texans also enjoy rodeo. The world's first rodeo was hosted in Pecos, Texas.[341] The annual Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo is the largest rodeo in the world. The Southwestern Exposition and Livestock Show in Fort Worth is the oldest continuously running rodeo incorporating many of the state's most historic traditions into its annual events. Dallas hosts the State Fair of Texas each year at Fair Park.[342]

Texas Motor Speedway hosts annual NASCAR Cup Series and IndyCar Series auto races since 1997. Since 2012, Austin's Circuit of the Americas plays host to a round of the Formula 1 World Championship.[343]

The Panther City Lacrosse Club is a professional lacrosse team in the National Lacrosse League. They have played local matches at Dickies Arena in Fort Worth, Texas since their inaugural 2021–2022 season.[344]

The second president of the Republic of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, is the Father of Texas Education. During his term, the state set aside three leagues in each county for public schools. An additional 50 leagues of land set aside for the support of two universities would later become the basis of the state's Permanent University Fund.[345] Lamar's actions set the foundation for a Texas-wide public school system.[346]

Between 2006 and 2007, Texas spent $7,275 per pupil, ranking it below the national average of $9,389. The pupil/teacher ratio was 14.9, below the national average of 15.3. Texas paid instructors $41,744, below the national average of $46,593. The Texas Education Agency (TEA) administers the state's public school systems. Texas has over 1,000 school districts; all districts except the Stafford Municipal School District are independent from municipal government and many cross city boundaries.[347] School districts have the power to tax their residents and to assert eminent domain over privately owned property. Due to court-mandated equitable school financing, the state has a tax redistribution system called the "Robin Hood plan" which transfers property tax revenue from wealthy school districts to poor ones.[348] The TEA has no authority over private or homeschooling activities.[349]

Students in Texas take the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) in primary and secondary school. STAAR assess students' attainment of reading, writing, mathematics, science, and social studies skills required under Texas education standards and the No Child Left Behind Act. The test replaced the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) test in the 2011–2012 school year.[350]

Generally prohibited in the Western world, school corporal punishment is not unusual in the more conservative, rural areas of the state,[351][352][353] with 28,569 public school students paddled at least one time,[g] according to government data for the 2011–2012 school year.[354] The rate of school corporal punishment in Texas is surpassed only by Mississippi, Alabama, and Arkansas.[354]

.jpg/440px-University_of_Texas_at_Austin_August_2019_30_(Littlefield_Fountain_and_Main_Building).jpg)

The state's two most widely recognized flagship universities are The University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University, ranked as the 21st[355] and 41st[356] best universities in the nation according to 2020's latest Center for World University Rankings report, respectively. Some observers[357] also include the University of Houston and Texas Tech University as tier one flagships alongside UT Austin and A&M.[358][359] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board ranks the state's public universities into three distinct tiers:[360]

Texas's alternative affirmative action plan, Texas House Bill 588, guarantees Texas students who graduated in the top 10 percent of their high school class automatic admission to state-funded universities. This does not apply to The University of Texas at Austin, which automatically admits Texas students who graduated in the top 6 percent of their high school class.[363] The bill encourages demographic diversity while attempting to avoid problems stemming from the Hopwood v. Texas (1996) case.[364]

Thirty-six public universities exist in Texas, of which 32 belong to one of the six state university systems.[365][366] Discovery of minerals on Permanent University Fund land, particularly oil, has helped fund the rapid growth of the state's two largest university systems: the University of Texas System and the Texas A&M System. The four other university systems: the University of Houston System, the University of North Texas System, the Texas State System, and the Texas Tech System are not funded by the Permanent University Fund.[367]