La historia de Europa se divide tradicionalmente en cuatro períodos de tiempo: la Europa prehistórica (antes de aproximadamente el 800 a. C.), la antigüedad clásica (800 a. C. a 500 d. C.), la Edad Media (500-1500 d. C.) y la era moderna (desde el 1500 d. C.).

Los primeros humanos modernos europeos tempranos aparecen en el registro fósil hace unos 48.000 años, durante la era Paleolítica . La agricultura sedentaria marcó la era Neolítica , que se extendió lentamente por Europa desde el sureste hasta el norte y el oeste. El período Neolítico posterior vio la introducción de la metalurgia temprana y el uso de herramientas y armas a base de cobre, y la construcción de estructuras megalíticas , como lo ejemplifica Stonehenge . Durante las migraciones indoeuropeas , Europa vio migraciones desde el este y el sureste. El período conocido como antigüedad clásica comenzó con el surgimiento de las ciudades-estado de la antigua Grecia . Más tarde, el Imperio Romano llegó a dominar toda la cuenca mediterránea . El Período de Migración del pueblo germánico comenzó a fines del siglo IV d. C. e hizo incursiones graduales en varias partes del Imperio Romano.

La caída del Imperio Romano de Occidente en el año 476 d. C. marca tradicionalmente el inicio de la Edad Media. Si bien el Imperio Romano de Oriente continuaría durante otros 1000 años, las antiguas tierras del Imperio de Occidente se fragmentarían en varios estados diferentes. Al mismo tiempo, los primeros eslavos comenzaron a establecerse como un grupo distinto en las partes central y oriental de Europa. El primer gran imperio de la Edad Media fue el Imperio franco de Carlomagno , mientras que la conquista islámica de Iberia estableció Al-Andalus . La era vikinga vio una segunda gran migración de pueblos nórdicos . Los intentos de recuperar el Levante de los estados musulmanes que lo ocupaban hicieron de la Alta Edad Media la era de las Cruzadas , mientras que el sistema político del feudalismo llegó a su apogeo. La Baja Edad Media estuvo marcada por grandes descensos demográficos, ya que Europa estaba amenazada por la peste bubónica , así como por las invasiones de los pueblos mongoles de la estepa euroasiática . Al final de la Edad Media, hubo un período de transición, conocido como el Renacimiento .

La Europa moderna temprana se suele fechar a finales del siglo XV. Los cambios tecnológicos como la pólvora y la imprenta cambiaron la forma en que se realizaba la guerra y cómo se preservaba y difundía el conocimiento. La Reforma vio la fragmentación del pensamiento religioso, lo que llevó a guerras religiosas . La Era de la Exploración condujo a la colonización , y la explotación de la gente y los recursos de las colonias trajo recursos y riqueza a Europa occidental. Después de 1800, la Revolución Industrial trajo acumulación de capital y rápida urbanización a Europa occidental, mientras que varios países pasaron del gobierno absolutista a regímenes parlamentarios. La Era de la Revolución vio cómo los sistemas políticos establecidos desde hacía mucho tiempo se trastocaban y se volcaban. En el siglo XX, la Primera Guerra Mundial condujo a una reestructuración del mapa de Europa a medida que los grandes imperios se dividían en estados-nación . Los problemas políticos persistentes conducirían a la Segunda Guerra Mundial , durante la cual la Alemania nazi perpetró el Holocausto . La posterior Guerra Fría vio a Europa dividida por la Cortina de Hierro en estados capitalistas y comunistas, muchos de ellos miembros de la OTAN y el Pacto de Varsovia , respectivamente. Los imperios coloniales que quedaban en Occidente fueron desmantelados . En las últimas décadas se produjo la caída de las dictaduras que aún quedaban en Europa occidental y una integración política gradual que dio lugar a la Comunidad Europea , más tarde a la Unión Europea . Después de las revoluciones de 1989 , todos los estados comunistas europeos hicieron la transición al capitalismo. El siglo XXI comenzó con la incorporación gradual de la mayoría de ellos a la UE . Paralelamente, Europa sufrió la Gran Recesión y sus secuelas , la crisis migratoria europea y la invasión rusa de Ucrania .

El Homo erectus emigró de África a Europa antes de la aparición de los humanos modernos. El Homo erectus georgicus , que vivió hace aproximadamente 1,8 millones de años en Georgia , es el primer homínido descubierto en Europa. [2] La primera aparición de personas anatómicamente modernas en Europa se ha datado en el 45.000 a. C., lo que se conoce como los primeros humanos modernos europeos . Algunas culturas de transición desarrolladas localmente ( Uluzziense en Italia y Grecia, Altmühliense en Alemania, Szeletiense en Europa Central y Châtelperroniense en el suroeste) utilizan tecnologías claramente del Paleolítico superior en fechas muy tempranas.

BisonsPoursuivisParDesLions.jpg/440px-18_PanneauDesLions(PartieDroite)BisonsPoursuivisParDesLions.jpg)

Sin embargo, el avance definitivo de estas tecnologías lo realiza la cultura Auriñaciense , originaria del Levante (Ahmariano) y Hungría (primer Auriñaciense pleno). Hacia el 35.000 a. C., la cultura Auriñaciense y su tecnología se habían extendido por la mayor parte de Europa. Los últimos neandertales parecen haberse visto obligados a retirarse a la mitad sur de la península Ibérica . Hacia el 29.000 a. C. apareció una nueva tecnología/cultura en la región occidental de Europa: el Gravetiense . Se ha teorizado que esta tecnología/cultura llegó con las migraciones de personas procedentes de los Balcanes (véase Kozarnika ).

Alrededor de 16.000 a. C., Europa fue testigo de la aparición de una nueva cultura, conocida como Magdaleniense , posiblemente arraigada en el antiguo Gravetiense. Esta cultura pronto reemplazó al área Solutrense y al Gravetiense de principalmente Francia, España, Alemania, Italia, Polonia, Portugal y Ucrania. La cultura de Hamburgo prevaleció en el norte de Europa en el XIV y XIII milenio a. C. como lo hizo el Creswelliano (también llamado Magdaleniense tardío británico) poco después en las Islas Británicas . Alrededor de 12.500 a. C., terminó la glaciación de Würm . La cultura Magdaleniense persistió hasta c. 10.000 a. C., cuando evolucionó rápidamente en dos culturas microlitistas : Azilian ( Federmesser ), en España y el sur de Francia , y luego Sauveterrian , en el sur de Francia y Tardenoisian en Europa Central, mientras que en el norte de Europa el complejo Lyngby sucedió a la cultura de Hamburgo con la influencia del grupo Federmesser también.

La evidencia de asentamiento permanente data del octavo milenio a. C. en los Balcanes. El Neolítico llegó a Europa central en el sexto milenio a. C. y partes del norte de Europa en el quinto y cuarto milenio a. C. Las poblaciones indígenas modernas de Europa descienden en gran medida de tres linajes distintos: cazadores-recolectores mesolíticos , un derivado de la población de Cro-Magnon , agricultores europeos primitivos que migraron de Anatolia durante la Revolución Neolítica y pastores yamna que se expandieron a Europa en el contexto de la expansión indoeuropea . [3] Las migraciones indoeuropeas comenzaron en el sudeste de Europa alrededor de c. 4200 a. C. a través de las áreas alrededor del mar Negro y la península de los Balcanes . En los siguientes 3000 años, las lenguas indoeuropeas se expandieron por Europa.

En esta época, en el quinto milenio a. C., se desarrolló la cultura de Varna . Entre los años 4700 y 4200 a. C., floreció la ciudad de Solnitsata , considerada la ciudad prehistórica más antigua de Europa. [4] [5]

La primera civilización alfabetizada conocida en Europa fue la civilización minoica que surgió en la isla de Creta y floreció aproximadamente desde el siglo XXVII a. C. hasta el siglo XV a. C. [6]

Los minoicos fueron reemplazados por la civilización micénica que floreció durante el período comprendido aproximadamente entre 1600 a. C., cuando la cultura heládica en la Grecia continental se transformó bajo las influencias de la Creta minoica, y 1100 a. C. Las principales ciudades micénicas fueron Micenas y Tirinto en Argólida, Pilos en Mesenia, Atenas en el Ática, Tebas y Orcómeno en Beocia, y Yolco en Tesalia. En Creta , los micénicos ocuparon Cnosos . También aparecieron sitios de asentamiento micénicos en Epiro , [7] [8] Macedonia , [9] [10] en islas del mar Egeo , en la costa de Asia Menor , el Levante , [11] Chipre [12] e Italia. [13] [14] Se han encontrado artefactos micénicos mucho más allá de los límites del mundo micénico.

A diferencia de los minoicos, cuya sociedad se beneficiaba del comercio, los micénicos avanzaron mediante la conquista. La civilización micénica estaba dominada por una aristocracia guerrera . Alrededor de 1400 a. C., los micénicos extendieron su control a Creta, el centro de la civilización minoica, y adoptaron una forma de la escritura minoica (llamada Lineal A ) para escribir su forma primitiva de griego en Lineal B.

La civilización micénica pereció con el colapso de la civilización de la Edad del Bronce en las orillas orientales del mar Mediterráneo. El colapso se atribuye comúnmente a la invasión dórica , aunque también se han propuesto otras teorías que describen desastres naturales y cambios climáticos. [ cita requerida ] Cualquiera que sea la causa, la civilización micénica había desaparecido después del LH III C , cuando los sitios de Micenas y Tirinto fueron nuevamente destruidos y perdieron su importancia. Este final, durante los últimos años del siglo XII a. C., se produjo después de un lento declive de la civilización micénica, que duró muchos años antes de extinguirse. El comienzo del siglo XI a. C. abrió un nuevo contexto, el de la protogeometría, el comienzo del período geométrico, la Edad Oscura griega de la historiografía tradicional.

El colapso de la Edad del Bronce puede verse en el contexto de la historia tecnológica que vio la lenta difusión de la tecnología del trabajo del hierro desde las actuales Bulgaria y Rumania en los siglos XIII y XII a. C. [15]

La cultura de los túmulos y la posterior cultura de los campos de urnas de Europa central fueron parte del origen de las culturas romana y griega . [16]

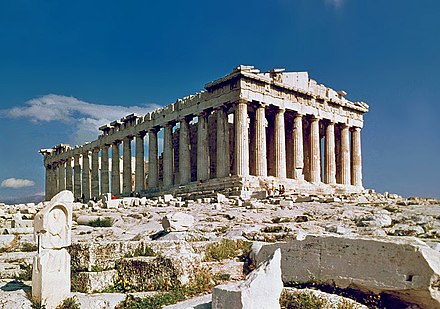

La Antigüedad clásica , también conocida como era clásica, período clásico, edad clásica o simplemente antigüedad, [17] es el período de la historia cultural entre el siglo VIII a. C. y el siglo V d. C. que comprende las civilizaciones entrelazadas de la antigua Grecia y la antigua Roma conocidas juntas como el mundo grecorromano , centradas en la cuenca del Mediterráneo . Es el período durante el cual la antigua Grecia y la antigua Roma florecieron y tuvieron una gran influencia en gran parte de Europa , el norte de África y Asia occidental . [18] [19]

La civilización helénica fue un conjunto de ciudades-estado o polis con diferentes gobiernos y culturas que lograron notables desarrollos en el gobierno, la filosofía, la ciencia, las matemáticas, la política, los deportes, el teatro y la música.

Las ciudades-estado más poderosas eran Atenas , Esparta , Tebas , Corinto y Siracusa . Atenas era una poderosa ciudad-estado helénica y se gobernaba a sí misma con una forma temprana de democracia directa inventada por Clístenes ; los ciudadanos de Atenas votaban sobre la legislación y los proyectos de ley ejecutivos. Atenas fue la cuna de Sócrates , [20] Platón y la Academia Platónica .

Las ciudades-estado helénicas establecieron colonias en las costas del mar Negro y el mar Mediterráneo ( Asia Menor , Sicilia y el sur de Italia en la Magna Grecia ). A finales del siglo VI a. C., las ciudades-estado griegas de Asia Menor se habían incorporado al Imperio persa , mientras que este último había logrado avances territoriales en los Balcanes (como Macedonia , Tracia , Peonia , etc.) y también en Europa del Este. Durante el siglo V a. C., algunas de las ciudades-estado griegas intentaron derrocar el dominio persa en la Revuelta Jónica , que fracasó. Esto provocó la primera invasión persa de la Grecia continental . En algún momento durante las subsiguientes guerras greco-persas , concretamente durante la segunda invasión persa de Grecia , y precisamente después de la batalla de las Termópilas y la batalla de Artemisio , casi toda Grecia al norte del istmo de Corinto había sido invadida por los persas, [21] pero las ciudades-estado griegas alcanzaron una victoria decisiva en la batalla de Platea . Con el final de las guerras greco-persas, los persas finalmente se vieron obligados a retirarse de sus territorios en Europa. Las guerras greco-persas y la victoria de las ciudades-estado griegas influyeron directamente en todo el curso posterior de la historia europea y marcarían su tono posterior. Algunas ciudades-estado griegas formaron la Liga de Delos para continuar luchando contra Persia, pero la posición de Atenas como líder de esta liga llevó a Esparta a formar la rival Liga del Peloponeso . Se produjeron las guerras del Peloponeso y la Liga del Peloponeso salió victoriosa. Posteriormente, el descontento con la hegemonía espartana condujo a la Guerra de Corinto y a la derrota de Esparta en la Batalla de Leuctra . Al mismo tiempo, en el norte gobernaba el reino tracio odrisio entre el siglo V a. C. y el siglo I d. C.

Las luchas internas helénicas dejaron vulnerables a las ciudades-estado griegas, y Filipo II de Macedonia unió las ciudades-estado griegas bajo su control. El hijo de Filipo II, conocido como Alejandro Magno , invadió la vecina Persia , derrocó e incorporó sus dominios, además de invadir Egipto y llegar hasta la India, aumentando el contacto con las personas y culturas de estas regiones que marcaron el comienzo del período helenístico .

Tras la muerte de Alejandro Magno , su imperio se dividió en varios reinos gobernados por sus generales, los diádocos . Los diádocos lucharon entre sí en una serie de conflictos llamados las Guerras de los Diádocos . A principios del siglo II a. C., solo quedaban tres reinos principales: el Egipto ptolemaico , el Imperio seléucida y Macedonia . Estos reinos difundieron la cultura griega a regiones tan lejanas como Bactria . [22]

Gran parte del saber griego fue asimilado por el naciente Estado romano a medida que se expandía desde Italia, aprovechando la incapacidad de sus enemigos para unirse: el único desafío al ascenso romano vino de la colonia fenicia de Cartago , y sus derrotas en las tres Guerras Púnicas marcaron el inicio de la hegemonía romana . Primero gobernada por reyes , luego como república senatorial (la República Romana ), Roma se convirtió en un imperio a finales del siglo I a. C., bajo Augusto y sus sucesores autoritarios.

El Imperio Romano tenía su centro en el Mediterráneo, controlando todos los países de sus costas; la frontera norte estaba marcada por los ríos Rin y Danubio . Bajo el emperador Trajano (siglo II d. C.) el imperio alcanzó su máxima expansión, controlando aproximadamente 5.900.000 km² ( 2.300.000 millas cuadradas) de superficie terrestre, incluyendo Italia , Galia , Dalmacia , Aquitania , Britania , Bética , Hispania , Tracia , Macedonia , Grecia , Moesia , Dacia , Panonia , Egipto, Asia Menor , Capadocia , Armenia , Cáucaso , África del Norte, Levante y partes de Mesopotamia . La Pax Romana , un período de paz, civilización y un gobierno centralizado eficiente en los territorios sometidos, terminó en el siglo III, cuando una serie de guerras civiles socavaron la fuerza económica y social de Roma.

En el siglo IV, los emperadores Diocleciano y Constantino lograron frenar el proceso de decadencia al dividir el imperio en una parte occidental con capital en Roma y una parte oriental con capital en Bizancio, o Constantinopla (hoy Estambul). Constantinopla es generalmente considerada como el centro de la " civilización ortodoxa oriental ". [23] [24] Mientras que Diocleciano persiguió severamente al cristianismo , Constantino declaró el fin oficial de la persecución de los cristianos patrocinada por el estado en 313 con el Edicto de Milán , preparando así el escenario para que la Iglesia se convirtiera en la iglesia estatal del Imperio romano alrededor de 380.

El Imperio Romano había sido atacado repetidamente por ejércitos invasores del norte de Europa y en 476, Roma finalmente cayó . Rómulo Augusto , el último emperador del Imperio Romano de Occidente , se rindió al rey germánico Odoacro .

Cuando el emperador Constantino reconquistó Roma bajo la bandera de la cruz en el año 312, poco después promulgó el Edicto de Milán en el año 313 (precedido por el Edicto de Serdica en el año 311), declarando la legalidad del cristianismo en el Imperio romano. Además, Constantino trasladó oficialmente la capital del Imperio romano de Roma a la ciudad griega de Bizancio , a la que rebautizó Nova Roma (más tarde se la llamó Constantinopla , «ciudad de Constantino»).

Teodosio I , que había hecho del cristianismo la religión oficial del Imperio romano , sería el último emperador en presidir un Imperio romano unificado, hasta su muerte en 395. El imperio se dividió en dos mitades: el Imperio romano de Occidente con centro en Rávena y el Imperio romano de Oriente (que más tarde se denominaría Imperio bizantino ) con centro en Constantinopla. El Imperio romano fue atacado repetidamente por tribus hunas , germánicas , eslavas y otras tribus "bárbaras" (véase: Período de migraciones ), y en 476 finalmente la parte occidental cayó en manos del jefe hérulo Odoacro .

La autoridad romana en la parte occidental del imperio se había derrumbado y, como consecuencia de ello, se había producido un vacío de poder; la organización central, las instituciones, las leyes y el poder de Roma se habían desmoronado, lo que dio lugar a que muchas zonas quedaran abiertas a la invasión de tribus migratorias. Con el tiempo, surgieron el feudalismo y el señorío , que establecían la división de la tierra y el trabajo, así como una amplia, aunque desigual, jerarquía de leyes y protección. Estas jerarquías localizadas se basaban en el vínculo de la gente común con la tierra que trabajaba y con un señor, que proporcionaría y administraría tanto la ley local para resolver las disputas entre los campesinos como la protección frente a los invasores externos.

Las provincias occidentales pronto serían dominadas por tres grandes potencias: primero, los francos ( dinastía merovingia ) en Francia ( 481-843 d. C.), que cubrían gran parte de la actual Francia y Alemania; segundo, el reino visigodo (418-711 d. C.) en la península Ibérica (España moderna); y tercero, el reino ostrogodo (493-553 d. C.) en Italia y partes de los Balcanes occidentales. Los ostrogodos fueron reemplazados más tarde por el reino de los lombardos (568-774 d. C.). Aunque estas potencias cubrían grandes territorios, no tenían los grandes recursos y la burocracia del imperio romano para controlar regiones y localidades; más poder y responsabilidades se dejaron a los señores locales. Por otro lado, también significó más libertad, particularmente en áreas más remotas.

En Italia, Teodorico el Grande inició la romanización cultural del nuevo mundo que había construido. Hizo de Rávena un centro de la cultura artística romano-griega y su corte fomentó un florecimiento de la literatura y la filosofía en latín . En Iberia, el rey Chindasvinto creó el Código visigodo . [25]

En la parte oriental, el estado dominante era el resto del Imperio Romano de Oriente.

En el sistema feudal surgieron nuevos príncipes y reyes, el más poderoso de los cuales fue sin duda el gobernante franco Carlomagno . En el año 800, Carlomagno, reforzado por sus enormes conquistas territoriales, fue coronado emperador de los romanos por el papa León III , consolidando su poder en Europa occidental. El reinado de Carlomagno marcó el comienzo de un nuevo Imperio Romano Germánico en Occidente, el Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico . Fuera de sus fronteras, se estaban reuniendo nuevas fuerzas. La Rus de Kiev estaba delimitando su territorio, estaba creciendo una Gran Moravia , mientras que los anglos y los sajones estaban asegurando sus fronteras.

Durante el siglo VI, el Imperio romano de Oriente se vio envuelto en una serie de conflictos mortales, primero con el Imperio persa sasánida (véase Guerras romano-persas ), seguido por el ataque del naciente califato islámico ( Rashidun y Omeya ). Hacia el año 650, las provincias de Egipto , Palestina y Siria se perdieron ante las fuerzas musulmanas , seguidas por Hispania y el sur de Italia en los siglos VII y VIII (véase Conquistas musulmanas ). La invasión árabe desde el este se detuvo después de la intervención del Imperio búlgaro (véase Han Tervel ).

La Edad Media se fecha comúnmente desde la caída del Imperio Romano de Occidente (o por algunos estudiosos, antes de eso) en el siglo V hasta el comienzo del período moderno temprano en el siglo XVI, marcado por el surgimiento de los estados nacionales , la división del cristianismo occidental en la Reforma , el surgimiento del humanismo en el Renacimiento italiano y los comienzos de la expansión europea en el extranjero que permitió el intercambio colombino . [26] [27]

Muchos consideran que el emperador Constantino I (reinó entre 306 y 337) fue el primer « emperador bizantino ». Fue él quien trasladó la capital imperial en 324 desde Nicomedia a Bizancio , que se volvió a fundar como Constantinopla o Nova Roma (« Nueva Roma »). [28] La ciudad de Roma no había servido como capital desde el reinado de Diocleciano (284-305). Algunos datan los inicios del Imperio en el reinado de Teodosio I (379-395) y la suplantación oficial del cristianismo de la religión pagana romana , o después de su muerte en 395, cuando el imperio se dividió en dos partes, con capitales en Roma y Constantinopla. Otros lo sitúan aún más tarde, en 476, cuando Rómulo Augústulo , considerado tradicionalmente el último emperador occidental, fue depuesto, dejando así la autoridad imperial exclusiva al emperador en el Oriente griego . Otros apuntan a la reorganización del imperio en la época de Heraclio (c. 620) cuando los títulos y usos latinos fueron reemplazados oficialmente por versiones griegas. En cualquier caso, el cambio fue gradual y hacia 330, cuando Constantino inauguró su nueva capital, el proceso de helenización y creciente cristianización ya estaba en marcha. En general, se considera que el Imperio terminó después de la caída de Constantinopla ante los turcos otomanos en 1453. La plaga de Justiniano fue una pandemia que afligió al Imperio bizantino, incluida su capital Constantinopla , en los años 541-542. Se estima que la plaga de Justiniano mató a unos 100 millones de personas. [29] [30] Hizo que la población de Europa cayera alrededor del 50% entre 541 y 700. [31] También puede haber contribuido al éxito de las conquistas musulmanas . [32] [33] Durante la mayor parte de su existencia, el Imperio bizantino fue una de las fuerzas económicas, culturales y militares más poderosas de Europa, y Constantinopla fue una de las ciudades más grandes y ricas de Europa. [34]

La Alta Edad Media abarca aproximadamente cinco siglos, desde el año 500 hasta el año 1000. [35]

En el este y sudeste de Europa se formaron nuevos estados dominantes: el Kanato Ávaro (567-después de 822), la Antigua Gran Bulgaria (632-668), el Kanato Jázaro (c. 650-969) y la Bulgaria del Danubio (fundada por Asparuh en 680) que rivalizaban constantemente con la hegemonía del Imperio bizantino.

A partir del siglo VII, la historia bizantina se vio muy afectada por el ascenso del Islam y los califatos . Los árabes musulmanes invadieron por primera vez el territorio históricamente romano bajo Abu Bakr , primer califa del califato Rashidun , que entró en la Siria romana y la Mesopotamia romana . Como los bizantinos y los vecinos sasánidas estaban severamente debilitados por el momento, entre las razones más importantes estaban las prolongadas, duraderas y frecuentes guerras bizantino-sasánidas , que incluyeron la culminante Guerra bizantino-sasánida de 602-628 , bajo Omar , el segundo califa, los musulmanes derrocaron por completo el Imperio persa sasánida y conquistaron decisivamente Siria y Mesopotamia, así como la Palestina romana , el Egipto romano y partes de Asia Menor y el norte de África romano . A mediados del siglo VII d. C., tras la conquista musulmana de Persia , el Islam penetró en la región del Cáucaso , de la que partes pasarían a formar parte permanente de Rusia. [36] Esta tendencia, que incluyó las conquistas de las fuerzas musulmanas invasoras y, por ende, la expansión del Islam, continuó bajo los sucesores de Omar y bajo el Califato Omeya , que conquistó el resto del norte de África mediterráneo y la mayor parte de la península Ibérica . Durante los siglos siguientes, las fuerzas musulmanas pudieron tomar más territorio europeo, incluidos Chipre , Malta, Creta y Sicilia y partes del sur de Italia . [37]

La conquista musulmana de Hispania comenzó cuando los moros invadieron el reino visigodo cristiano de Hispania en 711, bajo el mando del general bereber Tariq ibn Ziyad . Desembarcaron en Gibraltar el 30 de abril y avanzaron hacia el norte. A las fuerzas de Tariq se unieron al año siguiente las de su superior árabe, Musa ibn Nusair . Durante la campaña de ocho años, la mayor parte de la península Ibérica quedó bajo dominio musulmán, salvo pequeñas zonas en el noroeste ( Asturias ) y regiones en gran parte vascas en los Pirineos . En 711, la Hispania visigoda se vio debilitada porque se vio inmersa en una grave crisis interna provocada por una guerra de sucesión al trono. Los musulmanes aprovecharon la crisis de la sociedad hispanovisigoda para llevar a cabo sus conquistas. Este territorio, bajo el nombre árabe de Al -Andalus , pasó a formar parte del imperio omeya en expansión.

El segundo asedio de Constantinopla (717) terminó sin éxito tras la intervención de Tervel de Bulgaria y debilitó a la dinastía omeya y mermó su prestigio. En 722 don Pelayo formó un ejército de 300 soldados astures , para enfrentarse a las tropas musulmanas de Munuza. En la batalla de Covadonga , los astures derrotaron a los árabes-moros, que decidieron retirarse. La victoria cristiana marcó el inicio de la Reconquista y el establecimiento del Reino de Asturias , cuyo primer soberano fue don Pelayo. Los conquistadores pretendían continuar su expansión en Europa y avanzar hacia el noreste a través de los Pirineos, pero fueron derrotados por el líder franco Carlos Martel en la batalla de Poitiers en 732. Los omeyas fueron derrocados en 750 por los abasíes , [38] y, en 756, los omeyas establecieron un emirato independiente en la península Ibérica. [39]

El Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico surgió alrededor del año 800, cuando Carlomagno, rey de los francos y parte de la dinastía carolingia , fue coronado por el papa como emperador. Su imperio, con sede en la actual Francia, los Países Bajos y Alemania, se expandió a la actual Hungría, Italia, Bohemia , Baja Sajonia y España. Él y su padre recibieron ayuda sustancial de una alianza con el papa, que quería ayuda contra los lombardos . [40] Su muerte marcó el comienzo del fin de la dinastía, que se derrumbó por completo en 888. La fragmentación del poder condujo a una semiautonomía en la región, y se ha definido como un punto de partida crítico para la formación de estados en Europa. [41]

Al este, Bulgaria se estableció en 681 y se convirtió en el primer país eslavo . [ cita requerida ] El poderoso Imperio búlgaro fue el principal rival de Bizancio por el control de los Balcanes durante siglos y desde el siglo IX se convirtió en el centro cultural de la Europa eslava. El Imperio creó la escritura cirílica durante el siglo IX d. C., en la Escuela Literaria de Preslav , y experimentó la Edad de Oro de la prosperidad cultural búlgara durante el reinado del emperador Simeón I el Grande (893-927). Dos estados, Gran Moravia y Rus de Kiev , surgieron entre los pueblos eslavos respectivamente en el siglo IX. A finales del siglo IX y del siglo X, el norte y el oeste de Europa sintieron el creciente poder e influencia de los vikingos que atacaban, comerciaban, conquistaban y se asentaban rápida y eficientemente con sus avanzados barcos marítimos como los barcos largos . Los vikingos habían dejado una influencia cultural en los anglosajones y los francos , así como en los escoceses . [42] Los húngaros saquearon la Europa continental, los pechenegos atacaron Bulgaria, los estados rusos y los estados árabes . En el siglo X se establecieron reinos independientes en Europa central, incluidos Polonia y el recién establecido Reino de Hungría . El Reino de Croacia también apareció en los Balcanes. El período posterior, que finalizó alrededor del año 1000, vio un mayor crecimiento del feudalismo , que debilitó al Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico.

En Europa del Este, la Bulgaria del Volga se convirtió en un estado islámico en 921, después de que Almış I se convirtiera al Islam bajo los esfuerzos misioneros de Ahmad ibn Fadlan . [43]

La esclavitud en el período medieval temprano había desaparecido casi por completo en Europa occidental alrededor del año 1000 d. C., reemplazada por la servidumbre . Persistió más tiempo en Inglaterra y en áreas periféricas vinculadas al mundo musulmán, donde la esclavitud continuó floreciendo. Las reglas de la Iglesia suprimieron la esclavitud de los cristianos. La mayoría de los historiadores sostienen que la transición fue bastante abrupta alrededor del año 1000, pero algunos ven una transición gradual desde aproximadamente el año 300 hasta el año 1000. [44]

En 1054 se produjo el cisma Este-Oeste entre las dos sedes cristianas restantes: Roma y Constantinopla (la actual Estambul).

La Alta Edad Media de los siglos XI, XII y XIII muestra un rápido aumento de la población de Europa, lo que provocó un gran cambio social y político con respecto a la era anterior. Hacia 1250, el robusto aumento de la población benefició enormemente a la economía, alcanzando niveles que no volvería a verse en algunas zonas hasta el siglo XIX. [45]

A partir del año 1000, Europa occidental fue testigo de las últimas invasiones bárbaras y se organizó políticamente mejor. Los vikingos se habían establecido en Gran Bretaña, Irlanda, Francia y otros lugares, mientras que los reinos cristianos nórdicos se desarrollaban en sus países de origen escandinavos. Los magiares habían cesado su expansión en el siglo X y, hacia el año 1000, el Reino Apostólico Católico Romano de Hungría fue reconocido en Europa central. Con la breve excepción de las invasiones mongolas , cesaron las incursiones bárbaras importantes.

La soberanía búlgara fue restablecida con el levantamiento antibizantino de los búlgaros y valacos en 1185. Los cruzados invadieron el Imperio bizantino, capturaron Constantinopla en 1204 y establecieron su Imperio latino . Kaloyan de Bulgaria derrotó a Balduino I , emperador latino de Constantinopla , en la batalla de Adrianópolis el 14 de abril de 1205. El reinado de Iván Asen II de Bulgaria condujo a la máxima expansión territorial y el de Iván Alejandro de Bulgaria a una Segunda Edad de Oro de la cultura búlgara . El Imperio bizantino fue restablecido por completo en 1261.

En el siglo XI, las poblaciones al norte de los Alpes comenzaron a asentarse en nuevas tierras. Grandes bosques y pantanos de Europa fueron talados y cultivados. Al mismo tiempo, los asentamientos se trasladaron más allá de los límites tradicionales del Imperio franco hacia nuevas fronteras en Europa, más allá del río Elba , triplicando el tamaño de Alemania en el proceso. Los cruzados fundaron colonias europeas en el Levante , la mayor parte de la península Ibérica fue conquistada a los musulmanes y los normandos colonizaron el sur de Italia, todo ello como parte del importante patrón de aumento de la población y reasentamiento.

La Alta Edad Media produjo muchas formas diferentes de obras intelectuales, espirituales y artísticas . Las más famosas son las grandes catedrales como expresiones de la arquitectura gótica , que evolucionó a partir de la arquitectura románica . Esta época vio el surgimiento de los estados-nación modernos en Europa occidental y el ascenso de las famosas ciudades-estado italianas , como Florencia y Venecia . Los influyentes papas de la Iglesia católica llamaron a ejércitos voluntarios de toda Europa a una serie de cruzadas contra los turcos selyúcidas , que ocupaban Tierra Santa . El redescubrimiento de las obras de Aristóteles llevó a Tomás de Aquino y otros pensadores a desarrollar la filosofía de la escolástica .

Después del cisma de Oriente y Occidente , el cristianismo occidental fue adoptado por los reinos recién creados de Europa central: Polonia , Hungría y Bohemia . La Iglesia católica romana se desarrolló como una gran potencia, lo que llevó a conflictos entre el Papa y el emperador. El alcance geográfico de la Iglesia católica romana se expandió enormemente debido a las conversiones de reyes paganos (Escandinavia, Lituania , Polonia, Hungría), la Reconquista cristiana de Al-Ándalus y las Cruzadas. La mayor parte de Europa era católica romana en el siglo XV.

Los primeros signos del renacimiento de la civilización en Europa occidental comenzaron a aparecer en el siglo XI cuando se reanudó el comercio en Italia, lo que llevó al crecimiento económico y cultural de ciudades-estado independientes como Venecia y Florencia ; al mismo tiempo, comenzaron a formarse estados-nación en lugares como Francia, Inglaterra, España y Portugal, aunque el proceso de su formación (generalmente marcado por la rivalidad entre la monarquía, los señores feudales aristocráticos y la iglesia) en realidad tomó varios siglos. Estos nuevos estados-nación comenzaron a escribir en sus propias lenguas vernáculas culturales, en lugar del latín tradicional . Figuras notables de este movimiento incluirían a Dante Alighieri y Christine de Pizan . El Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico , basado esencialmente en Alemania e Italia, se fragmentó aún más en una miríada de principados feudales o pequeñas ciudades-estado, cuya sujeción al emperador era solo formal.

El siglo XIV, cuando el Imperio mongol llegó al poder, a menudo se llama la Era de los Mongoles . Los ejércitos mongoles se expandieron hacia el oeste bajo el mando de Batu Khan . Sus conquistas occidentales incluyeron casi toda la Rus de Kiev (excepto Nóvgorod , que se convirtió en vasallo), [46] y la Confederación Kipchak-Cuman . Bulgaria , Hungría y Polonia lograron seguir siendo estados soberanos. Los registros mongoles indican que Batu Khan estaba planeando una conquista completa de las potencias europeas restantes, comenzando con un ataque invernal a Austria, Italia y Alemania, cuando fue llamado de regreso a Mongolia tras la muerte del Gran Khan Ögedei . La mayoría de los historiadores creen que solo su muerte impidió la conquista completa de Europa. [ cita requerida ] Las áreas de Europa del Este y la mayor parte de Asia Central que estaban bajo el dominio directo de los mongoles se conocieron como la Horda de Oro . Bajo Uzbeg Khan , el Islam se convirtió en la religión oficial de la región a principios del siglo XIV. [47] Los invasores mongoles, junto con sus súbditos, en su mayoría turcos, eran conocidos como tártaros . En Rusia, los tártaros gobernaron los diversos estados de la Rus mediante vasallaje durante más de 300 años.

En el norte de Europa, Conrado de Mazovia entregó Chełmno a los Caballeros Teutónicos en 1226 como base para una cruzada contra los antiguos prusianos y el Gran Ducado de Lituania . Los Hermanos de la Espada de Livonia fueron derrotados por los lituanos, por lo que en 1237 Gregorio IX fusionó el resto de la orden con la Orden Teutónica como la Orden Livona . A mediados de siglo, los Caballeros Teutónicos completaron su conquista de los prusianos antes de convertir a los lituanos en las décadas posteriores. La orden también entró en conflicto con la Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental de las Repúblicas de Pskov y Nóvgorod . En 1240, el ejército ortodoxo de Nóvgorod derrotó a los suecos católicos en la Batalla del Neva y, dos años más tarde, derrotó a la Orden de Livonia en la Batalla del Hielo . La Unión de Krewo en 1386, que supuso dos cambios importantes en la historia del Gran Ducado de Lituania: la conversión al catolicismo y el establecimiento de una unión dinástica entre el Gran Ducado de Lituania y la Corona del Reino de Polonia, marcó tanto la mayor expansión territorial del Gran Ducado como la derrota de los Caballeros Teutónicos en la Batalla de Grunwald en 1410.

La Baja Edad Media abarcó los siglos XIV y XV. [48] Alrededor de 1300, siglos de prosperidad y crecimiento europeos se detuvieron. Una serie de hambrunas y plagas, como la Gran Hambruna de 1315-1317 y la Peste Negra , mataron a personas en cuestión de días, reduciendo la población de algunas áreas a la mitad, ya que muchos sobrevivientes huyeron. Kishlansky informa:

La despoblación provocó que la mano de obra escaseara; los supervivientes estaban mejor pagados y los campesinos podían librarse de algunas de las cargas del feudalismo. También hubo malestar social; Francia e Inglaterra experimentaron graves levantamientos campesinos, incluidas la Jacquerie y la Rebelión de los Campesinos . La unidad de la Iglesia católica se hizo añicos por el Gran Cisma . En conjunto, estos acontecimientos se han denominado la Crisis de la Baja Edad Media . [50]

A partir del siglo XIV, el mar Báltico se convirtió en una de las rutas comerciales más importantes . La Liga Hanseática , una alianza de ciudades comerciales, facilitó la absorción de vastas áreas de Polonia, Lituania y Livonia para el comercio con otros países europeos. Esto alimentó el crecimiento de estados poderosos en esta parte de Europa, incluidos Polonia-Lituania, Hungría, Bohemia y Moscovia más tarde. El final convencional de la Edad Media suele asociarse con la caída de la ciudad de Constantinopla y del Imperio bizantino ante los turcos otomanos en 1453. Los turcos hicieron de la ciudad la capital de su Imperio otomano , que duró hasta 1922 e incluyó Egipto, Siria y la mayor parte de los Balcanes. Las guerras otomanas en Europa marcaron una parte esencial de la historia del continente.

Un avance clave del siglo XV fue la aparición de la imprenta de tipos móviles alrededor de 1439 en Maguncia, [51] basándose en el impulso proporcionado por la introducción previa del papel desde China a través de los árabes en la Alta Edad Media. [52] La adopción de la tecnología en todo el continente a una velocidad deslumbrante durante la parte restante del siglo XV marcaría el comienzo de una revolución y en 1500 más de 200 ciudades de Europa tenían prensas que imprimían entre 8 y 20 millones de libros. [51]

El período moderno temprano abarca los siglos entre la Edad Media y la Revolución Industrial , aproximadamente de 1500 a 1800, o desde el descubrimiento del Nuevo Mundo en 1492 hasta la Revolución Francesa en 1789. El período se caracteriza por el aumento de la importancia de la ciencia y el progreso tecnológico cada vez más rápido , la política cívica secularizada y el estado nacional. Las economías capitalistas comenzaron su auge, y el período moderno temprano también vio el surgimiento y el predominio de la teoría económica del mercantilismo . Como tal, el período moderno temprano representa el declive y la eventual desaparición, en gran parte de la esfera europea, del feudalismo , la servidumbre y el poder de la Iglesia católica. El período incluye el Renacimiento , la Revolución científica , la Reforma protestante , la desastrosa Guerra de los Treinta Años , la colonización europea de las Américas y la caza de brujas europea .

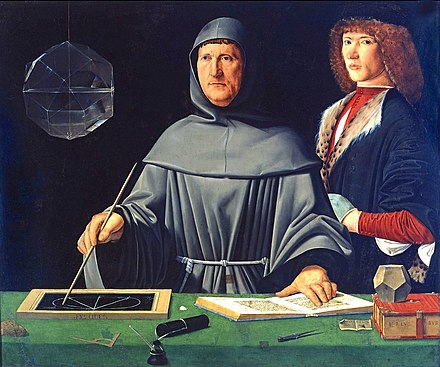

A pesar de estas crisis, el siglo XIV también fue una época de grandes avances en las artes y las ciencias. Un renovado interés por la Grecia y la Roma antiguas condujo al Renacimiento italiano , un movimiento cultural que afectó profundamente la vida intelectual europea en el período moderno temprano. Comenzó en Italia y se extendió al norte, oeste y centro de Europa durante un desfase cultural de unos dos siglos y medio; su influencia afectó a la literatura, la filosofía, el arte, la política, la ciencia, la historia, la religión y otros aspectos de la investigación intelectual. Los humanistas vieron su recuperación de un gran pasado como un Renacimiento, un renacimiento de la civilización misma. [53] También se establecieron precedentes políticos importantes en este período. Los escritos políticos de Nicolás Maquiavelo en El Príncipe influyeron en el absolutismo y la realpolitik posteriores. También fueron importantes los numerosos mecenas que gobernaron estados y utilizaron el arte del Renacimiento como signo de su poder.

La revolución científica tuvo lugar en Europa a partir de la segunda mitad del Renacimiento, y la publicación de Nicolás Copérnico de 1543 De revolutionibus orbium coelestium ( Sobre las revoluciones de las esferas celestes ) suele citarse como su inicio.

.jpg/440px-Cantino_planisphere_(1502).jpg)

Hacia el final de este período, comenzó una era de descubrimientos. El crecimiento del Imperio otomano , que culminó con la caída de Constantinopla en 1453, cortó las posibilidades comerciales con Oriente. Europa occidental se vio obligada a descubrir nuevas rutas comerciales, como sucedió con el viaje de Colón a las Américas en 1492 y la circunnavegación de la India y África por parte de Vasco da Gama en 1498.

Las numerosas guerras no impidieron que los estados europeos exploraran y conquistaran amplias porciones del mundo, desde África hasta Asia y las recién descubiertas Américas. En el siglo XV, Portugal lideró la exploración geográfica a lo largo de la costa de África en busca de una ruta marítima hacia la India, seguido por España cerca del final del siglo XV, dividiendo su exploración del mundo según el Tratado de Tordesillas en 1494. [54] Fueron los primeros estados en establecer colonias en América y puestos comerciales europeos (fábricas) a lo largo de las costas de África y Asia, estableciendo los primeros contactos diplomáticos europeos directos con los estados del sudeste asiático en 1511, China en 1513 y Japón en 1542. En 1552, el zar ruso Iván el Terrible conquistó dos importantes kanatos tártaros , el Kanato de Kazán y el Kanato de Astracán . El viaje de Yermak en 1580 condujo a la anexión del Kanato tártaro de Siberia a Rusia, y los rusos poco después conquistarían el resto de Siberia , expandiéndose de forma constante hacia el este y el sur durante los siglos siguientes. Las exploraciones oceánicas pronto fueron seguidas por las de Francia, Inglaterra y los Países Bajos, que exploraron las rutas comerciales portuguesas y españolas en el océano Pacífico, llegando a Australia en 1606 [55] y a Nueva Zelanda en 1642.

Con el desarrollo de la imprenta , nuevas ideas se extendieron por toda Europa y desafiaron las doctrinas tradicionales en ciencia y teología. Simultáneamente, la Reforma bajo el alemán Martín Lutero cuestionó la autoridad papal. La datación más común de la Reforma comienza en 1517, cuando Lutero publicó Las noventa y cinco tesis , y concluye en 1648 con el Tratado de Westfalia que puso fin a años de guerras religiosas europeas . [56]

Durante este período, la corrupción en la Iglesia Católica provocó una fuerte reacción en la Reforma Protestante. Ganó muchos seguidores, especialmente entre los príncipes y reyes que buscaban un estado más fuerte poniendo fin a la influencia de la Iglesia Católica. También comenzaron a surgir otras figuras además de Martín Lutero , como Juan Calvino , cuyo calvinismo tuvo influencia en muchos países, y el rey Enrique VIII de Inglaterra, que se separó de la Iglesia Católica en Inglaterra y fundó la Iglesia Anglicana . Estas divisiones religiosas provocaron una ola de guerras inspiradas e impulsadas por la religión, pero también por los ambiciosos monarcas de Europa Occidental, que se estaban volviendo más centralistas y poderosos.

La Reforma protestante también dio lugar a un fuerte movimiento de reforma en la Iglesia católica llamado Contrarreforma , que tenía como objetivo reducir la corrupción, así como mejorar y fortalecer el dogma católico. Dos grupos importantes de la Iglesia católica que surgieron de este movimiento fueron los jesuitas , que ayudaron a mantener a España, Portugal, Polonia y otros países europeos dentro del redil católico, y los Oratorianos de San Felipe Neri , que atendieron a los fieles en Roma, restaurando su confianza en la Iglesia de Jesucristo que subsistía sustancialmente en la Iglesia de Roma. Aun así, la Iglesia católica se vio algo debilitada por la Reforma, partes de Europa ya no estaban bajo su influencia y los reyes de los países católicos restantes comenzaron a tomar el control de las instituciones de la iglesia dentro de sus reinos.

A diferencia de muchos países europeos de la época, la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania fue notablemente tolerante con el movimiento protestante, al igual que el Principado de Transilvania . También se mostró cierto grado de tolerancia en la Hungría otomana . Si bien seguían imponiendo el predominio del catolicismo, continuaron permitiendo que las grandes minorías religiosas mantuvieran su fe, tradiciones y costumbres. La Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania se dividió entre católicos, protestantes, ortodoxos, judíos y una pequeña población musulmana.

Otro desarrollo fue la idea de la "superioridad europea". Hubo un movimiento de algunos, como Montaigne , que consideraban a los no europeos como un pueblo mejor, más natural y primitivo. Se fundaron servicios de correos en toda Europa, lo que permitió una red interconectada de intelectuales humanísticos en toda Europa, a pesar de las divisiones religiosas. Sin embargo, la Iglesia Católica Romana prohibió muchas obras científicas importantes; esto condujo a una ventaja intelectual para los países protestantes, donde la prohibición de libros se organizó regionalmente. Francis Bacon y otros defensores de la ciencia trataron de crear unidad en Europa centrándose en la unidad en la naturaleza. 1 [ ancla rota ] En el siglo XV, al final de la Edad Media, aparecieron poderosos estados soberanos, construidos por los Nuevos Monarcas que centralizaban el poder en Francia, Inglaterra y España. Por otro lado, el Parlamento de la Mancomunidad Polaca-Lituana creció en poder, arrebatando derechos legislativos al rey polaco. El nuevo poder estatal fue impugnado por los parlamentos de otros países, especialmente Inglaterra. Surgieron nuevos tipos de estados que eran acuerdos de cooperación entre gobernantes territoriales, ciudades, repúblicas agrícolas y caballeros.

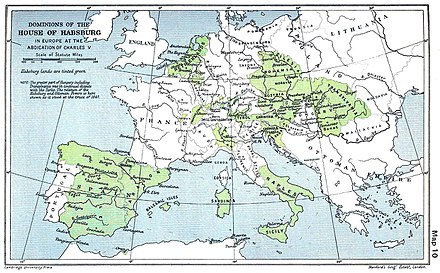

Los reinos ibéricos pudieron dominar la actividad colonial en el siglo XVI. Los portugueses forjaron el primer imperio global en los siglos XV y XVI, mientras que durante el siglo XVI y la primera mitad del siglo XVII, la corona de Castilla (y la Monarquía Hispánica en general, incluido Portugal desde 1580 hasta 1640) se convirtió en el imperio más poderoso del mundo. El dominio español en América fue cada vez más desafiado por los esfuerzos coloniales británicos , franceses , holandeses y suecos de los siglos XVII y XVIII. Las nuevas formas de comercio y la expansión de los horizontes hicieron necesarias nuevas formas de gobierno , derecho y economía.

La expansión colonial continuó en los siglos siguientes (con algunos reveses, como las exitosas guerras de independencia en las colonias británicas americanas y luego más tarde Haití , México , Argentina , Brasil y otras en medio de la agitación europea de las Guerras Napoleónicas ). España tenía el control de gran parte de América del Norte, toda América Central y gran parte de América del Sur, el Caribe y Filipinas ; Gran Bretaña tomó la totalidad de Australia y Nueva Zelanda, la mayor parte de la India y grandes partes de África y América del Norte; Francia tenía partes de Canadá y la India (casi la totalidad de la cual perdió ante Gran Bretaña en 1763 ), Indochina , grandes partes de África y las islas del Caribe; los Países Bajos obtuvieron las Indias Orientales (ahora Indonesia ) e islas en el Caribe; Portugal obtuvo Brasil y varios territorios en África y Asia; y más tarde, potencias como Alemania, Bélgica, Italia y Rusia adquirieron más colonias. [ cita requerida ]

Esta expansión ayudó a la economía de los países que los poseían. El comercio floreció, debido a la pequeña estabilidad de los imperios. A fines del siglo XVI, la plata americana representaba una quinta parte del presupuesto total de España. [57] [58] La colonia francesa de Saint-Domingue fue una de las colonias europeas más ricas del siglo XVIII, y operaba con una economía de plantación impulsada por el trabajo esclavo . Durante el período de dominio francés, los cultivos comerciales producidos en Saint-Domingue comprendían el treinta por ciento del comercio total francés, mientras que sus exportaciones de azúcar representaban el cuarenta por ciento del mercado atlántico. [59] [60]

El siglo XVII fue una época de crisis. [61] [62] Muchos historiadores han rechazado la idea, mientras que otros la promueven como una valiosa perspectiva de la guerra, la política, la economía, [63] e incluso el arte. [64] La Guerra de los Treinta Años (1618-1648) centró la atención en los horrores masivos que las guerras podían traer a poblaciones enteras. [65] La década de 1640 en particular vio más colapsos estatales en todo el mundo que cualquier período anterior o posterior. [61] [62] La Mancomunidad Polaca-Lituana , el estado más grande de Europa, desapareció temporalmente. Además, hubo secesiones y levantamientos en varias partes del imperio español, el primer imperio global del mundo. En Gran Bretaña, toda la monarquía Estuardo ( Inglaterra , Escocia , Irlanda y sus colonias norteamericanas ) se rebeló. La insurgencia política y una serie de revueltas populares rara vez igualadas sacudieron los cimientos de la mayoría de los estados de Europa y Asia. A mediados del siglo XVII se produjeron más guerras en todo el mundo que en casi cualquier otro período de la historia registrada. En todo el hemisferio norte , a mediados del siglo XVII se registraron índices de mortalidad casi sin precedentes.

El gobierno "absoluto" de poderosos monarcas como Luis XIV (gobernó Francia entre 1643 y 1715), [66] Pedro el Grande (gobernó Rusia entre 1682 y 1725), [67] María Teresa (gobernó las tierras de los Habsburgo entre 1740 y 1780) y Federico el Grande (gobernó Prusia entre 1740 y 1786), [68] produjo poderosos estados centralizados, con ejércitos fuertes y burocracias poderosas, todos bajo el control del rey. [69]

Durante la primera parte de este período, el capitalismo (a través del mercantilismo) fue reemplazando al feudalismo como la principal forma de organización económica, al menos en la mitad occidental de Europa. La expansión de las fronteras coloniales dio lugar a una revolución comercial . El período se destaca por el auge de la ciencia moderna y la aplicación de sus hallazgos a las mejoras tecnológicas, que impulsaron la Revolución Industrial después de 1750.

La Reforma tuvo efectos profundos en la unidad de Europa. No sólo las naciones se dividieron entre sí por su orientación religiosa, sino que algunos estados se desgarraron internamente por luchas religiosas, fomentadas ávidamente por sus enemigos externos. Francia sufrió este destino en el siglo XVI en la serie de conflictos conocidos como las Guerras de religión francesas , que terminaron en el triunfo de la dinastía borbónica . Inglaterra se estableció bajo Isabel I en un anglicanismo moderado . Gran parte de la Alemania actual estaba formada por numerosos pequeños estados soberanos bajo el marco teórico del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico , que se dividió aún más a lo largo de líneas sectarias trazadas internamente. La Mancomunidad Polaca-Lituana es notable en esta época por su indiferencia religiosa e inmunidad general a las luchas religiosas europeas.

La Guerra de los Treinta Años se libró entre 1618 y 1648 en Alemania y sus zonas vecinas, y en ella participaron la mayoría de las grandes potencias europeas, excepto Inglaterra y Rusia, [70] en la que se enfrentaron en su mayor parte católicos y protestantes. El principal impacto de la guerra fue la devastación de regiones enteras arrasadas por los ejércitos forrajeros. Episodios de hambruna y enfermedades generalizadas, y la ruptura de la vida familiar, devastaron a la población de los estados alemanes y, en menor medida, a los Países Bajos , la Corona de Bohemia y partes del norte de Italia, al tiempo que llevaron a la bancarrota a muchas de las potencias regionales implicadas. Entre una cuarta parte y una tercera parte de la población alemana pereció por causas militares directas o por enfermedades y hambruna, así como por nacimientos postergados. [71]

Después de la Paz de Westfalia , que puso fin a la guerra a favor de que las naciones decidieran su propia lealtad religiosa, el absolutismo se convirtió en la norma del continente, mientras que partes de Europa experimentaron con constituciones prefiguradas por la Guerra Civil Inglesa y, en particular, la Revolución Gloriosa . El conflicto militar europeo no cesó, pero tuvo efectos menos perturbadores en las vidas de los europeos. En el noroeste avanzado, la Ilustración dio una base filosófica a la nueva perspectiva, y la continua difusión de la alfabetización, posibilitada por la imprenta , creó nuevas fuerzas seculares en el pensamiento.

Desde la Unión de Krewo, Europa central y oriental estuvo dominada por el Reino de Polonia y el Gran Ducado de Lituania . En los siglos XVI y XVII, Europa central y oriental fue un escenario de conflicto por la dominación del continente entre Suecia , la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania (involucrada en una serie de guerras, como el Levantamiento de Jmelnitski , la Guerra Ruso-Polaca , el Diluvio Universal , etc.) y el Imperio Otomano . Este período vio un declive gradual de estas tres potencias que finalmente fueron reemplazadas por nuevas monarquías absolutistas ilustradas: Rusia, Prusia y Austria (la monarquía de los Habsburgo ). A principios del siglo XIX se habían convertido en nuevas potencias, habiéndose dividido Polonia entre ellas, y Suecia y Turquía habían experimentado pérdidas territoriales sustanciales ante Rusia y Austria respectivamente, así como empobrecimiento.

La Guerra de Sucesión Española (1701-1715) fue una importante guerra con Francia a la que se opuso una coalición de Inglaterra, los Países Bajos, la monarquía de los Habsburgo y Prusia. El duque de Marlborough comandó la victoria inglesa y holandesa en la batalla de Blenheim en 1704. La cuestión principal era si Francia, bajo el rey Luis XIV, tomaría el control de las extensas posesiones de España y, por lo tanto, se convertiría en la potencia dominante, o se vería obligada a compartir el poder con otras naciones importantes. Después de los éxitos aliados iniciales, la larga guerra produjo un punto muerto militar y terminó con el Tratado de Utrech , que se basó en un equilibrio de poder en Europa. El historiador Russell Weigley sostiene que las muchas guerras casi nunca lograron más de lo que costaron. [72] El historiador británico GM Trevelyan sostiene:

Federico el Grande , rey de Prusia entre 1740 y 1786, modernizó el ejército prusiano , introdujo nuevos conceptos tácticos y estratégicos, libró guerras mayoritariamente exitosas ( Guerras de Silesia , Guerra de los Siete Años) y duplicó el tamaño de Prusia. [74] [75]

Rusia libró numerosas guerras para lograr una rápida expansión hacia el este (es decir, Siberia , el Lejano Oriente , el sur, el mar Negro, el sudeste y Asia central). Rusia contaba con un ejército grande y poderoso , una burocracia interna muy grande y compleja y una corte espléndida que rivalizaba con París y Londres. Sin embargo, el gobierno vivía muy por encima de sus posibilidades y se apoderó de las tierras de la Iglesia , dejando a la religión organizada en una condición débil. A lo largo del siglo XVIII, Rusia siguió siendo "un país pobre, atrasado, abrumadoramente agrícola y analfabeto". [76]

La Ilustración fue un poderoso y extendido movimiento cultural de intelectuales que comenzó a fines del siglo XVII en Europa y que enfatizaba el poder de la razón en lugar de la tradición; era especialmente favorable a la ciencia (especialmente la física de Isaac Newton) y hostil a la ortodoxia religiosa (especialmente la de la Iglesia Católica). [77] Buscaba analizar y reformar la sociedad usando la razón, desafiar las ideas basadas en la tradición y la fe, y hacer avanzar el conocimiento a través del método científico . Promovió el pensamiento científico, el escepticismo y el intercambio intelectual. [78] La Ilustración fue una revolución en el pensamiento humano. Esta nueva forma de pensar consistía en que el pensamiento racional comienza con principios claramente establecidos, utiliza la lógica correcta para llegar a conclusiones, prueba las conclusiones frente a la evidencia y luego revisa los principios a la luz de la evidencia. [78]

Los pensadores de la Ilustración se opusieron a la superstición. Algunos de ellos colaboraron con los déspotas ilustrados , gobernantes absolutistas que intentaron imponer por la fuerza algunas de las nuevas ideas sobre el gobierno en la práctica. Las ideas de la Ilustración ejercieron una influencia significativa en la cultura, la política y los gobiernos de Europa. [79]

La Revolución científica, que se originó en el siglo XVII, fue impulsada por los filósofos Francis Bacon , Baruch Spinoza , John Locke , Pierre Bayle , Voltaire , Francis Hutcheson , David Hume y el físico Isaac Newton . [80] Los príncipes gobernantes a menudo respaldaron y fomentaron estas figuras e incluso intentaron aplicar sus ideas de gobierno en lo que se conoció como absolutismo ilustrado . La Revolución científica está estrechamente vinculada a la Ilustración, ya que sus descubrimientos anularon muchos conceptos tradicionales e introdujeron nuevas perspectivas sobre la naturaleza y el lugar del hombre en ella. La Ilustración floreció hasta aproximadamente 1790-1800, momento en el que la Ilustración, con su énfasis en la razón, dio paso al Romanticismo , que puso un nuevo énfasis en la emoción; una Contrailustración comenzó a ganar protagonismo.

En Francia, la Ilustración se basó en los salones y culminó en la gran Encyclopédie (1751-72). Estas nuevas corrientes intelectuales se extenderían a los centros urbanos de toda Europa, en particular Inglaterra, Escocia, los estados alemanes, los Países Bajos, Polonia, Rusia, Italia, Austria y España, así como a las colonias estadounidenses de Gran Bretaña . Los ideales políticos de la Ilustración influyeron en la Declaración de Independencia de los Estados Unidos , la Carta de Derechos de los Estados Unidos , la Declaración de los Derechos del Hombre y del Ciudadano de Francia y la Constitución polaco-lituana del 3 de mayo de 1791. [ 81]

Norman Davies ha argumentado que la masonería fue una fuerza poderosa en nombre del liberalismo y las ideas de la Ilustración en Europa, desde aproximadamente 1700 hasta el siglo XX. Se expandió rápidamente durante la Era de la Ilustración , llegando prácticamente a todos los países de Europa. [82] El gran enemigo de la masonería era la Iglesia Católica Romana, de modo que en países con un gran elemento católico, como Francia, Italia, Austria, España y México, gran parte de la ferocidad de las batallas políticas implican la confrontación entre partidarios de la Iglesia versus masones activos. [83] [84] Los movimientos totalitarios y revolucionarios del siglo XX , especialmente los fascistas y comunistas , aplastaron a los masones. [85]

The "long 19th century", from 1789 to 1914 saw the drastic social, political and economic changes initiated by the Industrial Revolution, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Following the reorganisation of the political map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Europe experienced the rise of Nationalism, the rise of the Russian Empire and the peak of the British Empire, as well as the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Finally, the rise of the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire initiated the course of events that culminated in the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

The Industrial Revolution saw major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, and transport impacted Britain and subsequently spread to the United States and Western Europe. Technological advancements, most notably the utilization of the steam engine, were major catalysts in the industrialisation process. It started in England and Scotland in the mid-18th century with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of coal as the main fuel. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. The introduction of steam power (fuelled primarily by coal) and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity.[86] The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world.[87]

Historians R.R. Palmer and Joel Colton argue:

The era of the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic wars was a difficult time for monarchs. Tsar Paul I of Russia was assassinated; King Louis XVI of France was executed, as was his queen Marie Antoinette. Furthermore, kings Charles IV of Spain, Ferdinand VII of Spain and Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden were deposed as were ultimately the Emperor Napoleon and all of the relatives he had installed on various European thrones. King Frederick William III of Prussia and Emperor Francis II of Austria barely clung to their thrones. King George III of Great Britain lost the better part of the First British Empire.[89]

The American Revolution (1775–1783) was the first successful revolt of a colony against a European power. It rejected aristocracy and established a republican form of government that attracted worldwide attention.[90] The French Revolution (1789–1804) was a product of the same democratic forces in the Atlantic World and had an even greater impact.[91] French historian François Aulard says:

French intervention in the American Revolutionary War had nearly bankrupted the state. After repeated failed attempts at financial reform, King Louis XVI had to convene the Estates-General, a representative body of the country made up of three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. The third estate, joined by members of the other two, declared itself to be a National Assembly and created, in July, the National Constituent Assembly. At the same time the people of Paris revolted, famously storming the Bastille prison on 14 July 1789.

At the time the assembly wanted to create a constitutional monarchy, and over the following two years passed various laws including the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the abolition of feudalism, and a fundamental change in the relationship between France and Rome. At first the king agreed with these changes and enjoyed reasonable popularity with the people. As anti-royalism increased along with threat of foreign invasion, the king tried to flee and join France's enemies. He was captured and on 21 January 1793, having been convicted of treason, he was guillotined.

On 20 September 1792 the National Convention abolished the monarchy and declared France a republic. Due to the emergency of war, the National Convention created the Committee of Public Safety to act as the country's executive. Under Maximilien de Robespierre, the committee initiated the Reign of Terror, during which up to 40,000 people were executed in Paris, mainly nobles and those convicted by the Revolutionary Tribunal, often on the flimsiest of evidence. Internal tensions at Paris drove the Committee towards increasing assertions of radicalism and increasing suspicions. A few months into this phase, more and more prominent revolutionaries were being sent to the guillotine by Robespierre and his faction, for example Madame Roland and Georges Danton. Elsewhere in the country, counter-revolutionary insurrections were brutally suppressed. The regime was overthrown in the coup of 9 Thermidor (27 July 1794) and Robespierre was executed. The regime which followed ended the Terror and relaxed Robespierre's more extreme policies.

Napoleon Bonaparte was France's most successful general in the Revolutionary wars. In 1799 on 18 Brumaire (9 November) he overthrew the government, replacing it with the Consulate, which he dominated. He gained popularity in France by restoring the Church, keeping taxes low, centralizing power in Paris, and winning glory on the battlefield. In 1804 he crowned himself Emperor. In 1805, Napoleon planned to invade Britain, but a renewed British alliance with Russia and Austria (Third Coalition), forced him to turn his attention towards the continent, while at the same time the French fleet was demolished by the British at the Battle of Trafalgar, ending any plan to invade Britain. On 2 December 1805, Napoleon defeated a numerically superior Austro-Russian army at Austerlitz, forcing Austria's withdrawal from the coalition (see Treaty of Pressburg) and dissolving the Holy Roman Empire. In 1806, a Fourth Coalition was set up. On 14 October Napoleon defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, marched through Germany and defeated the Russians on 14 June 1807 at Friedland. The Treaties of Tilsit divided Europe between France and Russia and created the Duchy of Warsaw.

On 12 June 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia with a Grande Armée of nearly 700,000 troops. After the measured victories at Smolensk and Borodino Napoleon occupied Moscow, only to find it burned by the retreating Russian army. He was forced to withdraw. On the march back his army was harassed by Cossacks, and suffered disease and starvation. Only 20,000 of his men survived the campaign. By 1813 the tide had begun to turn from Napoleon. Having been defeated by a seven nation army at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, he was forced to abdicate after the Six Days' Campaign and the occupation of Paris. Under the Treaty of Fontainebleau he was exiled to the island of Elba. He returned to France on 1 March 1815 (see Hundred Days), raised an army, but was finally defeated by a British and Prussian force at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815 and exiled to the small British island of Saint Helena.

Roberts finds that the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, from 1793 to 1815, caused 4 million deaths (of whom 1 million were civilians); 1.4 million were French.[93]

Outside France the Revolution had a major impact. Its ideas became widespread. Roberts argues that Napoleon was responsible for key ideas of the modern world, so that, "meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances, and so on-were protected, consolidated, codified, and geographically extended by Napoleon during his 16 years of power."[94]

Furthermore, the French armies in the 1790s and 1800s directly overthrew feudal remains in much of western Europe. They liberalised property laws, ended seigneurial dues, abolished the guild of merchants and craftsmen to facilitate entrepreneurship, legalised divorce, closed the Jewish ghettos and made Jews equal to everyone else. The Inquisition ended as did the Holy Roman Empire. The power of church courts and religious authority was sharply reduced and equality under the law was proclaimed for all men.[95]

France conquered Belgium and turned it into another province of France. It conquered the Netherlands, and made it a client state. It took control of the German areas on the left bank of the Rhine River and set up a puppet Confederation of the Rhine. It conquered Switzerland and most of Italy, setting up a series of puppet states. The result was glory and an infusion of much needed money from the conquered lands. However the enemies of France, led by Britain, formed a Second Coalition in 1799 (with Britain joined by Russia, the Ottoman Empire and Austria). It scored a series of victories that rolled back French successes, and trapped the French Army in Egypt. Napoleon slipped through the British blockade in October 1799, returning to Paris, where he overthrew the government and made himself the ruler.[96][97]

Napoleon conquered most of Italy in the name of the French Revolution in 1797–99. He split up Austria's holdings and set up a series of new republics, complete with new codes of law and abolition of feudal privileges. Napoleon's Cisalpine Republic was centered on Milan; Genoa became a republic; the Roman Republic was formed as well as the small Ligurian Republic around Genoa. The Neapolitan Republic was formed around Naples, but it lasted only five months. He later formed the Kingdom of Italy, with his brother as King. In addition, France turned the Netherlands into the Batavian Republic, and Switzerland into the Helvetic Republic. All these new countries were satellites of France, and had to pay large subsidies to Paris, as well as provide military support for Napoleon's wars. Their political and administrative systems were modernized, the metric system introduced, and trade barriers reduced. Jewish ghettos were abolished. Belgium and Piedmont became integral parts of France.[98]

Most of the new nations were abolished and returned to prewar owners in 1814. However, Artz emphasizes the benefits the Italians gained from the French Revolution:

Likewise in Switzerland the long-term impact of the French Revolution has been assessed by Martin:

The greatest impact came in France itself. In addition to effects similar to those in Italy and Switzerland, France saw the introduction of the principle of legal equality, and the downgrading of the once powerful and rich Catholic Church. Power became centralized in Paris, with its strong bureaucracy and an army supplied by conscripting all young men. French politics were permanently polarized – new names were given, "left" and "right" for the supporters and opponents of the principles of the Revolution.

By the 19th century, governments increasingly took over traditional religious roles, paying much more attention to efficiency and uniformity than to religiosity. Secular bodies took control of education away from the churches, abolished taxes and tithes for the support of established religions, and excluded bishops from the upper houses. Secular laws increasingly regulated marriage and divorce, and maintaining birth and death registers became the duty of local officials. Although the numerous religious denominations in the United States founded many colleges and universities, that was almost exclusively a state function across Europe. Imperial powers protected Christian missionaries in African and Asian colonies.[101] In France and other largely Catholic nations, anti-clerical political movements tried to reduce the role of the Catholic Church. Likewise briefly in Germany in the 1870s there was a fierce Kulturkampf (culture war) against Catholics, but the Catholics successfully fought back. The Catholic Church concentrated more power in the papacy and fought against secularism and socialism. It sponsored devotional reforms that gained wide support among the churchgoers.[102]

The political development of nationalism and the push for popular sovereignty culminated with the ethnic/national revolutions of Europe. During the 19th century nationalism became one of the most significant political and social forces in history; it is typically listed among the top causes of World War I.[103][104] Most European states had become constitutional monarchies by 1871, and Germany and Italy merged many small city-states to become united nation-states. Germany in particular increasingly dominated the continent in economics and political power. Meanwhile, on a global scale, Great Britain, with its far-flung British Empire, unmatched Royal Navy, and powerful bankers, became the world's first global power. The sun never set on its territories, while an informal empire operated through British financiers, entrepreneurs, traders and engineers who established operations in many countries, and largely dominated Latin America. The British were especially famous for financing and constructing railways around the world.[105]

Napoleon's conquests of the German and Italian states around 1800–1806 played a major role in stimulating nationalism and demand for national unity.[106]

In the German states east of Prussia Napoleon abolished many of the old or medieval relics, such as dissolving the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.[107] He imposed rational legal systems and his organization of the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806 promoted a feeling of German nationalism. In the 1860s it was Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck who achieved German unification in 1870 after the many smaller states followed Prussia's leadership in wars against Denmark, Austria and France.[108]

Italian nationalism emerged in the 19th century and was the driving force for Italian unification or the "Risorgimento". It was the political and intellectual movement that consolidated different states of the Italian Peninsula into the single state of the Kingdom of Italy in 1860. The memory of the Risorgimento is central to both Italian nationalism and Italian historiography.[109]

For centuries the Orthodox Christian Serbs were ruled by the Muslim-controlled Ottoman Empire. The success of the Serbian revolution (1804–1817) against Ottoman rule in 1817 marked the foundation of modern Principality of Serbia. It achieved de facto independence in 1867 and finally gained recognition in the Berlin Congress of 1878. The Serbs developed a larger vision for nationalism in Pan-Slavism and with Russian support sought to pull the other Slavs out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[110][111] Austria, with German backing, tried to crush Serbia in 1914 but Russia intervened, thus igniting the First World War in which Austria dissolved into nation states.[112]

In 1918, the region of Vojvodina proclaimed its secession from Austria-Hungary to unite with the pan-Slavic State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs; the Kingdom of Serbia joined the union on 1 December 1918, and the country was named Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. It was renamed Yugoslavia, which was never able to tame the multiple nationalities and religions and it flew apart in civil war in the 1990s.

The Greek drive for independence from the Ottoman Empire inspired supporters across Christian Europe, especially in Britain. France, Russia and Britain intervened to make this nationalist dream become reality with the Greek War of Independence (1821-1829/1830).[113]

Bulgarian modern nationalism emerged under Ottoman rule in the late 18th and early 19th century. An autonomous Bulgarian Exarchate was established in 1870/1872 for the diocese of Bulgaria as well as for those, wherein at least two-thirds of Orthodox Christians were willing to join it. The April Uprising in 1876 indirectly resulted in the re-establishment of Bulgaria in 1878.

In the 1790s, Germany, Russia and Austria partitioned Poland. Napoleon set up the Duchy of Warsaw, igniting a spirit of Polish nationalism. Russia took it over in 1815 as Congress Poland with the tsar as King of Poland. Large-scale nationalist revolts erupted in 1830 and 1863–64 but were harshly crushed by Russia, which tried to Russify the Polish language, culture and religion. The collapse of the Russian Empire in the First World War enabled the major powers to reestablish an independent Second Polish Republic, which survived until 1939. Meanwhile, Poles in areas controlled by Germany moved into heavy industry but their religion came under attack by Bismarck in the Kulturkampf of the 1870s. The Poles joined German Catholics in a well-organized new Centre Party, and defeated Bismarck politically. He responded by stopping the harassment and cooperating with the Centre Party.[114][115]

After the War of the Spanish Succession, the assimilation of the Crown of Aragon by the Castilian Crown through the Decrees of Nova planta was the first step in the creation of the Spanish nation state, through the imposition of the political and cultural characteristics of the dominant ethnic group, in this case the Castilians, over those of other ethnic groups, who became national minorities to be assimilated.[116][117] Since the political unification of 1714, Spanish assimilation policies towards Catalan-speaking territories (Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, part of Aragon) and other national minorities have been a historical constant.[118][119][120] The nationalization process accelerated in the 19th century, in parallel to the origin of Spanish nationalism, the social, political and ideological movement that tried to shape a Spanish national identity based on the Castilian model, in conflict with the other historical nations of the State. These nationalist policies, sometimes very aggressive,[121][122][123][124] and still in force,[125][126][127][128] are the seed of repeated territorial conflicts within the State.

An important component of nationalism was the study of the nation's heritage, emphasizing the national language and literary culture. This stimulated, and was in turn strongly supported by, the emergence of national educational systems. Latin gave way to the national language, and compulsory education, with strong support from modernizers and the media, became standard in Germany and eventually other West European nations. Voting reforms extended the franchise. Every country developed a sense of national origins – the historical accuracy was less important than the motivation toward patriotism. Universal compulsory education was extended to girls at the elementary level. By the 1890s, strong movements emerged in some countries, including France, Germany and the United States, to extend compulsory education to the secondary level.[129][130]

After the defeat of revolutionary France, the great powers tried to restore the situation which existed before 1789. The 1815 Congress of Vienna produced a peaceful balance of power among the European empires, known as the Metternich system. The powerbase of their support was the aristocracy.[131] However, their reactionary efforts were unable to stop the spread of revolutionary movements: the middle classes had been deeply influenced by the ideals of the French revolution, and the Industrial Revolution brought important economical and social changes.[132]

Radical intellectuals looked to the working classes for a base for socialist, communist and anarchistic ideas. Widely influential was the 1848 Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.[133]