Massachusetts ( / ˌ m æ s ə ˈ tʃ uː s ɪ t s / ,/- z ɪ t s / MASS-ə-CHOO-sits, -zits;Massachusett:Muhsachuweesut [məhswatʃəwiːsət]), oficialmente laMancomunidad de Massachusetts,[b]es unestadoen laNueva Inglaterradelnoreste de los Estados Unidos. Limita con elocéano Atlánticoyel golfo de Maineal este,ConnecticutyRhode Islandal sur,Nuevo HampshireyVermontal norte, yNueva Yorkal oeste. Massachusetts es elsexto estado más pequeño por área terrestre. Con más de siete millones de residentes en 2020,[nota 1]es el estado más poblado de Nueva Inglaterra, eldecimosexto más pobladodel país y eltercero más densamente poblado, después deNueva Jerseyy Rhode Island.

Massachusetts fue un sitio de colonización inglesa temprana . La colonia de Plymouth fue fundada en 1620 por los peregrinos del Mayflower . En 1630, la colonia de la bahía de Massachusetts , que tomó su nombre del pueblo indígena de Massachusett , también estableció asentamientos en Boston y Salem. En 1692, la ciudad de Salem y las áreas circundantes experimentaron uno de los casos más infames de histeria colectiva de Estados Unidos , los juicios de brujas de Salem . [43] A fines del siglo XVIII, Boston se hizo conocida como la "Cuna de la Libertad" [44] por la agitación que luego condujo a la Revolución estadounidense . En 1786, la Rebelión de Shays , una revuelta populista liderada por veteranos descontentos de la Guerra de la Independencia de Estados Unidos , influyó en la Convención Constitucional de los Estados Unidos . [45] Originalmente dependiente de la agricultura , la pesca y el comercio , [46] Massachusetts se transformó en un centro manufacturero durante la Revolución industrial . [47] Antes de la Guerra Civil estadounidense , el estado era un centro para los movimientos abolicionista , de templanza , [48] y trascendentalista [49] . [50] Durante el siglo XX, la economía del estado pasó de la manufactura a los servicios ; [51] y en el siglo XXI, Massachusetts se ha convertido en el líder mundial en biotecnología , [52] y también sobresale en inteligencia artificial , [53] ingeniería , educación superior , finanzas y comercio marítimo . [54]

La capital y ciudad más poblada del estado , así como su centro cultural y financiero , es Boston . Otras ciudades importantes son Worcester , Springfield y Cambridge . Massachusetts también alberga el núcleo urbano de Greater Boston , el área metropolitana más grande de Nueva Inglaterra y una región profundamente influyente en la historia estadounidense , la academia y la economía de la investigación . [55] Massachusetts tiene una reputación de progresismo social y político ; [56] convirtiéndose en el único estado de EE. UU. con una ley de derecho a refugio , y el primer estado de EE. UU., y una de las primeras jurisdicciones del mundo en reconocer legalmente el matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo . [57] Boston es considerado un centro de la cultura y el activismo LGBT en los Estados Unidos. La Universidad de Harvard en Cambridge es la institución de educación superior más antigua de los Estados Unidos , [58] con la mayor dotación financiera de cualquier universidad del mundo. [59] Tanto Harvard como el MIT , también en Cambridge, se clasifican perennemente como las instituciones académicas más respetadas o entre las más respetadas del mundo. [60] Los estudiantes de las escuelas públicas de Massachusetts se ubican entre los mejores del mundo en cuanto a rendimiento académico. [61]

Massachusetts es el estado con mayor nivel educativo [62] y uno de los más desarrollados y ricos de EE. UU., ocupando el primer lugar en porcentaje de población de 25 años o más con título de licenciatura o título avanzado , primero tanto en el Índice de Desarrollo Humano de EE. UU. como en el Índice de Desarrollo Humano estándar , primero en ingreso per cápita y, a partir de 2023, primero en ingreso medio . [62] En consecuencia, Massachusetts generalmente se ubica como el estado número uno de EE. UU. [63], así como el estado más caro para vivir. [64]

La colonia de la bahía de Massachusetts recibió su nombre de la población indígena , los massachusett o muhsachuweesut, cuyo nombre probablemente deriva de una palabra wôpanâak muswachasut , segmentada como mus(ây) "grande" + wach "montaña" + -s "diminutivo" + - ut "locativo". [65] Esta palabra se ha traducido como "cerca de la gran colina", [66] "por las colinas azules", "en la pequeña gran colina" o "en la cordillera de colinas", en referencia a las Colinas Azules , es decir, la Gran Colina Azul , ubicada en el límite de Milton y Cantón . [67] [68] Massachusett también ha sido representada como Moswetuset . Esto proviene del nombre de Moswetuset Hummock (que significa "colina con forma de punta de flecha") en Quincy , donde el comandante de la colonia de Plymouth, Myles Standish (un oficial militar inglés contratado) y Squanto (un miembro de la banda Patuxet del pueblo Wamponoag , que desde entonces ha muerto debido a enfermedades contagiosas traídas por los colonizadores) se encontraron con el jefe Chickatawbut en 1621. [69] [70]

Aunque la designación "Commonwealth" forma parte del nombre oficial del estado, no tiene implicaciones prácticas en los tiempos modernos, [71] y Massachusetts tiene la misma posición y poderes dentro de los Estados Unidos que otros estados. [72] John Adams puede haber elegido la palabra en 1779 para el segundo borrador de lo que se convirtió en la Constitución de Massachusetts de 1780 ; a diferencia de la palabra "estado", la palabra " commonwealth " tenía la connotación de una república en ese momento. Esto contrastaba con la monarquía contra la que luchaban las antiguas colonias durante la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos . El nombre "Estado de la Bahía de Massachusetts" apareció en el primer borrador, que finalmente fue rechazado. También se eligió para incluir las "Islas del Cabo" en referencia a Martha's Vineyard y Nantucket : de 1780 a 1844, se las consideraba entidades adicionales y separadas confinadas dentro de la Commonwealth. [73]

Massachusetts fue habitada originalmente por tribus de la familia lingüística algonquina , entre ellas los wampanoag , los narragansett , los nipmuc , los pocomtuc , los mahican y los massachusett . [74] [75] Si bien el cultivo de cosechas como la calabaza y el maíz era una parte importante de su dieta, la gente de estas tribus cazaba , pescaba y buscaba en el bosque la mayor parte de su comida. [74] Los aldeanos vivían en cabañas llamadas wigwams , así como en casas comunales . [75] Las tribus estaban dirigidas por ancianos masculinos o femeninos conocidos como sachems . [76]

A principios del siglo XVII, los colonizadores europeos provocaron epidemias en suelos vírgenes como viruela , sarampión , gripe y quizás leptospirosis en lo que ahora se conoce como la región noreste de los Estados Unidos. [77] [78] Entre 1617 y 1619, una enfermedad que probablemente fue la viruela mató aproximadamente al 90% de los nativos americanos de la Bahía de Massachusetts . [79]

Los primeros colonizadores ingleses en la Colonia de la Bahía de Massachusetts desembarcaron con Richard Vines y pasaron el invierno en Biddeford Pool cerca de Cape Porpoise (después de 1820 el estado de Maine) en 1616. Los puritanos llegaron a Plymouth en 1620. Esta fue la segunda colonia inglesa permanente en la parte de América del Norte que luego se convirtió en los Estados Unidos, después de la Colonia de Jamestown . El "Primer Día de Acción de Gracias" fue celebrado por los puritanos después de su primera cosecha en el " Nuevo Mundo " y duró tres días. Pronto fueron seguidos por otros puritanos, que colonizaron la Colonia de la Bahía de Massachusetts —ahora conocida como Boston— en 1630. [80]

Los puritanos creían que la Iglesia de Inglaterra necesitaba una mayor reforma siguiendo las líneas calvinistas protestantes , y sufrieron acoso debido a las políticas religiosas del rey Carlos I y de eclesiásticos de alto rango como William Laud , que se convertiría en el arzobispo de Canterbury de Carlos , a quien temían que estuviera reintroduciendo elementos "romanos" en la iglesia nacional. [81] Decidieron colonizar Massachusetts, con la intención de establecer lo que consideraban una sociedad religiosa "ideal". [82] La colonia de la bahía de Massachusetts fue colonizada bajo una carta real, a diferencia de la colonia de Plymouth, en 1629. [83] Tanto la disidencia religiosa como el expansionismo dieron como resultado la fundación de varias colonias nuevas, poco después de Plymouth y la bahía de Massachusetts, en otras partes de Nueva Inglaterra. La bahía de Massachusetts desterró a disidentes como Anne Hutchinson y Roger Williams debido al conflicto religioso y político. En 1636, Williams colonizó lo que ahora se conoce como Rhode Island , y Hutchinson se unió a él allí varios años después. La intolerancia religiosa continuó, y entre quienes se opusieron a esto más tarde en ese siglo estaban los predicadores cuáqueros ingleses Alice y Thomas Curwen , quienes fueron azotados públicamente y encarcelados en Boston en 1676. [84] [85]

En 1641, Massachusetts se había expandido significativamente hacia el interior. La Mancomunidad adquirió el asentamiento de Springfield en el valle del río Connecticut , que recientemente había estado en disputa con sus administradores originales, la Colonia de Connecticut , y se había desvinculado de ellos . [86] Esto estableció la frontera sur de Massachusetts en el oeste. [87] Sin embargo, este se convirtió en territorio en disputa hasta 1803-04 debido a problemas de topografía, lo que dio lugar al moderno Southwick Jog . [88]

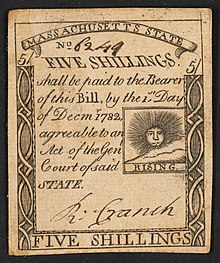

En 1652, el Tribunal General de Massachusetts autorizó al platero de Boston John Hull a producir monedas locales en denominaciones de chelines, seis peniques y tres peniques para abordar la escasez de monedas en la colonia. [89] Antes de ese momento, la economía de la colonia había dependido completamente del trueque y la moneda extranjera, incluidas las monedas inglesas, españolas, holandesas, portuguesas y falsificadas. [90] En 1661, poco después de la restauración de la monarquía británica , el gobierno británico consideró que la Casa de la Moneda de Boston era traidora. [91] Sin embargo, la colonia ignoró las demandas inglesas de cesar las operaciones hasta al menos 1682, cuando expiró el contrato de Hull como maestro de la ceca y la colonia no se movió para renovar su contrato o nombrar un nuevo maestro de la ceca. [92] La acuñación fue un factor que contribuyó a la revocación de la carta de la Colonia de la Bahía de Massachusetts en 1684. [93]

En 1691, las colonias de la bahía de Massachusetts y Plymouth se unieron (junto con el actual Maine , que anteriormente había estado dividido entre Massachusetts y Nueva York ) en la provincia de la bahía de Massachusetts . [94] Poco después, llegó el primer gobernador de la nueva provincia, William Phips . También se llevaron a cabo los juicios de brujas de Salem , donde varios hombres y mujeres fueron ahorcados por presunta brujería . [95]

El terremoto más destructivo conocido hasta la fecha en Nueva Inglaterra ocurrió el 18 de noviembre de 1755, causando daños considerables en todo Massachusetts. [96] [97]

Massachusetts fue un centro del movimiento de independencia de Gran Bretaña . Los colonos de Massachusetts habían tenido durante mucho tiempo relaciones incómodas con la monarquía británica, incluida una rebelión abierta bajo el Dominio de Nueva Inglaterra en la década de 1680. [94] Las protestas contra los intentos británicos de gravar las colonias después de que la Guerra franco-india terminara en 1763 llevaron a la Masacre de Boston en 1770, y el Motín del té de Boston de 1773 aumentó las tensiones. [98] En 1774, las Leyes Intolerables apuntaron a Massachusetts con castigos para el Motín del té de Boston y redujeron aún más la autonomía local, aumentando la disidencia local. [99] La actividad antiparlamentaria de hombres como Samuel Adams y John Hancock , seguida de represalias por parte del gobierno británico, fueron una razón principal para la unidad de las Trece Colonias y el estallido de la Revolución estadounidense en 1775. [100]

.jpg/440px-Official_Presidential_portrait_of_John_Adams_(by_John_Trumbull,_circa_1792).jpg)

Las batallas de Lexington y Concord , libradas en Massachusetts en 1775, dieron inicio a la Guerra de Independencia de los Estados Unidos . [101] George Washington , más tarde el primer presidente del futuro país, se hizo cargo de lo que se convertiría en el Ejército Continental después de la batalla. Su primera victoria fue el asedio de Boston en el invierno de 1775-76, después del cual los británicos se vieron obligados a evacuar la ciudad. [102] El evento todavía se celebra en el condado de Suffolk solo cada 17 de marzo como el Día de la Evacuación . [103]

En la costa, Salem se convirtió en un centro de corso . Aunque la documentación es incompleta, durante la Guerra de Independencia de los Estados Unidos se otorgaron alrededor de 1700 patentes de corso , emitidas por cada viaje. Casi 800 barcos fueron comisionados como corsarios, a los que se les atribuyó la captura o destrucción de unos 600 barcos británicos. [104]

El bostoniano John Adams , conocido como el "Atlas de la Independencia", [105] estuvo muy involucrado tanto en la separación de Gran Bretaña como en la Constitución de Massachusetts , que efectivamente (los casos Elizabeth Freeman y Quock Walker según la interpretación de William Cushing ) convirtieron a Massachusetts en el primer estado en abolir la esclavitud. David McCullough señala que una característica igualmente importante fue la colocación por primera vez de los tribunales como una rama co-igual separada del ejecutivo. [106] (La Constitución de Vermont , adoptada en 1777, representó la primera prohibición parcial de la esclavitud entre los estados. Vermont se convirtió en un estado en 1791, pero no prohibió completamente la esclavitud hasta 1858 con la Ley de Libertad Personal de Vermont. La Ley de Abolición Gradual de Pensilvania de 1780 [107] convirtió a Pensilvania en el primer estado en abolir la esclavitud por estatuto - la segunda colonia inglesa en hacerlo; la primera había sido la Colonia de Georgia en 1735.) Más tarde, Adams estuvo activo en los primeros asuntos exteriores estadounidenses y sucedió a Washington como el segundo presidente de los Estados Unidos . Su hijo, John Quincy Adams , también de Massachusetts, [108] se convertiría en el sexto presidente de la nación.

Entre 1786 y 1787, un levantamiento armado liderado por el veterano de la Guerra de la Independencia Daniel Shays , ahora conocido como la Rebelión de Shays , causó estragos en todo Massachusetts y, en última instancia, intentó apoderarse de la Armería federal de Springfield . [45] La rebelión fue uno de los principales factores en la decisión de redactar una constitución nacional más fuerte para reemplazar los Artículos de la Confederación . [45] El 6 de febrero de 1788, Massachusetts se convirtió en el sexto estado en ratificar la Constitución de los Estados Unidos . [109]

En 1820, Maine se separó de Massachusetts y entró en la Unión como el estado número 23 debido a la ratificación del Compromiso de Misuri . [110]

Durante el siglo XIX, Massachusetts se convirtió en un líder nacional en la Revolución Industrial estadounidense , con fábricas alrededor de ciudades como Lowell y Boston que producían textiles y zapatos, y fábricas alrededor de Springfield que producían herramientas, papel y textiles. [111] [112] La economía del estado se transformó de una basada principalmente en la agricultura a una industrial, haciendo uso inicialmente de la energía hidráulica y más tarde de la máquina de vapor para impulsar las fábricas. Los canales y los ferrocarriles se utilizaban en el estado para transportar materias primas y productos terminados. [113] Al principio, las nuevas industrias atraían mano de obra de los yanquis en las granjas de subsistencia cercanas, aunque más tarde dependieron de la mano de obra inmigrante de Europa y Canadá. [114] [115]

Aunque Massachusetts fue la primera colonia esclavista, ya que la esclavitud se remontaba a principios del siglo XVII, el estado se convirtió en un centro de actividad progresista y abolicionista (antiesclavista) en los años previos a la Guerra Civil estadounidense . Horace Mann hizo del sistema escolar del estado un modelo nacional. [116] Henry David Thoreau y Ralph Waldo Emerson , ambos filósofos y escritores del estado, también hicieron importantes contribuciones a la filosofía estadounidense. [117] Además, los miembros del movimiento trascendentalista dentro del estado enfatizaron la importancia del mundo natural y la emoción para la humanidad. [117]

Aunque en Massachusetts existió una oposición significativa al abolicionismo desde el principio, lo que dio lugar a disturbios antiabolicionistas entre 1835 y 1837, [118] las opiniones abolicionistas aumentaron gradualmente durante las décadas siguientes. [119] [120] Los abolicionistas John Brown y Sojourner Truth vivieron en Springfield y Northampton, respectivamente, mientras que Frederick Douglass vivió en Boston y Susan B. Anthony en Adams . Las obras de estos abolicionistas contribuyeron a las acciones de Massachusetts durante la Guerra Civil. Massachusetts fue el primer estado en reclutar, entrenar y armar un regimiento negro con oficiales blancos , el 54.º Regimiento de Infantería de Massachusetts . [121] En 1852, Massachusetts se convirtió en el primer estado en aprobar leyes de educación obligatoria . [122]

Aunque el mercado de valores de Estados Unidos había sufrido fuertes pérdidas la última semana de octubre de 1929, el martes 29 de octubre se recuerda como el comienzo de la Gran Depresión. La Bolsa de Valores de Boston , arrastrada al torbellino de ventas de pánico que acosó a la Bolsa de Valores de Nueva York, perdió más del 25 por ciento de su valor en dos días de operaciones frenéticas. La BSE, que tenía casi 100 años en ese momento, había ayudado a recaudar el capital que había financiado muchas de las fábricas, ferrocarriles y empresas de la Commonwealth. " [123] El gobernador de Massachusetts, Frank G. Allen, nombró a John C. Hull como el primer Director de Valores de Massachusetts. [124] [125] [126] Hull asumiría el cargo en enero de 1930, y su mandato terminaría en 1936. [127]

Con la salida de varias empresas manufactureras, la economía industrial del estado comenzó a declinar a principios del siglo XX. En la década de 1920, la competencia del sur y el medio oeste de Estados Unidos , seguida de la Gran Depresión , provocó el colapso de las tres principales industrias de Massachusetts: textiles, zapatería y mecánica de precisión. [128] Este declive continuaría hasta la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Entre 1950 y 1979, el número de residentes de Massachusetts involucrados en la fabricación de textiles disminuyó de 264.000 a 63.000. [129] El cierre en 1969 de la Armería de Springfield , en particular, estimuló un éxodo de empleos bien remunerados del oeste de Massachusetts, que sufrió mucho al desindustrializarse durante los últimos 40 años del siglo. [130]

Massachusetts fabricó el 3,4 por ciento del armamento militar total de los Estados Unidos producido durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial , ocupando el décimo lugar entre los 48 estados. [131] Después de la guerra mundial, la economía del este de Massachusetts se transformó de una basada en la industria pesada a una economía basada en los servicios . [132] Los contratos gubernamentales, la inversión privada y las instalaciones de investigación llevaron a un clima industrial nuevo y mejorado, con un desempleo reducido y un aumento del ingreso per cápita. La suburbanización floreció y, en la década de 1970, el corredor de la Ruta 128 / Interestatal 95 estaba salpicado de empresas de alta tecnología que reclutaban a graduados de las muchas instituciones de educación superior de élite de la zona. [133]

En 1987, el estado recibió fondos federales para el Proyecto de Túnel/Arteria Central. Comúnmente conocido como "el Big Dig ", fue, en ese momento, el proyecto de autopista federal más grande jamás aprobado. [134] El proyecto incluía convertir la Arteria Central , parte de la Interestatal 93 , en un túnel bajo el centro de Boston, además del desvío de varias otras autopistas importantes. [135] [ verificación fallida ] El proyecto a menudo fue controvertido, con numerosas denuncias de corrupción y mala gestión, y con un precio inicial de $ 2.5 mil millones que aumentó a una cuenta final de más de $ 15 mil millones. No obstante, el Big Dig cambió la cara del centro de Boston [134] y conectó áreas que alguna vez estuvieron divididas por una autopista elevada. Gran parte de la antigua Arteria Central elevada fue reemplazada por la Vía Verde Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy . El proyecto también mejoró las condiciones del tráfico a lo largo de varias rutas. [134] [135]

La familia Kennedy fue prominente en la política de Massachusetts del siglo XX. Los hijos del empresario y embajador Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. incluyeron a John F. Kennedy , quien fue senador y presidente de los Estados Unidos antes de su asesinato en 1963; Ted Kennedy , senador desde 1962 hasta su muerte en 2009; [136] y Eunice Kennedy Shriver , cofundadora de las Olimpiadas Especiales . [137] En 1966, Massachusetts se convirtió en el primer estado en elegir directamente a un afroamericano para el Senado de los Estados Unidos con Edward Brooke . [138] George HW Bush , 41.º presidente de los Estados Unidos (1989-1993), nació en Milton en 1924. [139]

Otros políticos notables de Massachusetts a nivel nacional incluyeron a Joseph W. Martin Jr. , Presidente de la Cámara de Representantes (de 1947 a 1949 y luego nuevamente de 1953 a 1955) y líder de los republicanos de la Cámara de Representantes desde 1939 hasta 1959 (donde fue el único republicano en servir como Presidente entre 1931 y 1995), [140] John W. McCormack , Presidente de la Cámara de Representantes en la década de 1960, y Tip O'Neill , cuyo servicio como Presidente de la Cámara de Representantes de 1977 a 1987 fue el mandato continuo más largo en la historia de los Estados Unidos. [141]

El 17 de mayo de 2004, Massachusetts se convirtió en el primer estado de los EE. UU. en legalizar el matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo . Esto siguió a la decisión del Tribunal Supremo Judicial de Massachusetts en el caso Goodridge v. Department of Public Health en noviembre de 2003, que determinó que la exclusión de las parejas del mismo sexo del derecho a un matrimonio civil era inconstitucional. [57]

En 2004, el senador de Massachusetts John Kerry , que ganó la nominación demócrata a la presidencia de los Estados Unidos, perdió ante el actual presidente George W. Bush . Ocho años después, el exgobernador de Massachusetts Mitt Romney (el candidato republicano) perdió ante el actual presidente Barack Obama en 2012. Otros ocho años después, la senadora de Massachusetts Elizabeth Warren se convirtió en la favorita en las primarias demócratas para las elecciones presidenciales de 2020. Sin embargo, más tarde suspendió su campaña y respaldó al candidato presunto Joe Biden . [142]

Dos bombas de ollas a presión explotaron cerca de la línea de meta del Maratón de Boston el 15 de abril de 2013, alrededor de las 2:49 pm hora local ( EDT ). Las explosiones mataron a tres personas e hirieron a unas 264 más. [143] La Oficina Federal de Investigaciones (FBI) identificó más tarde a los sospechosos como los hermanos Dzhokhar Tsarnaev y Tamerlan Tsarnaev . La persecución que siguió terminó el 19 de abril cuando miles de agentes de la ley registraron un área de 20 cuadras de la cercana Watertown . Dzhokhar dijo más tarde que estaba motivado por creencias islámicas extremistas y que aprendió a construir dispositivos explosivos en Inspire , la revista en línea de Al Qaeda en la Península Arábiga . [144]

El 8 de noviembre de 2016, Massachusetts votó a favor de la Iniciativa de Legalización de la Marihuana de Massachusetts , también conocida como Pregunta 4. [145]

Massachusetts es el séptimo estado más pequeño de los Estados Unidos . Está ubicado en la región de Nueva Inglaterra , en el noreste de los Estados Unidos . Tiene una superficie de 27 340 km² (10 555 millas cuadradas ) , de los cuales el 25,7 % es agua. Varias bahías grandes dan forma distintiva a su costa. Boston es la ciudad más grande, en el punto más interno de la bahía de Massachusetts y en la desembocadura del río Charles . [ cita requerida ]

A pesar de su pequeño tamaño, Massachusetts cuenta con numerosas regiones topográficamente distintivas. La gran llanura costera del océano Atlántico en la sección oriental del estado contiene el Gran Boston , junto con la mayor parte de la población del estado, [55] así como la distintiva península de Cape Cod . Al oeste se encuentra la región rural montañosa del centro de Massachusetts y, más allá de ella, el valle del río Connecticut . A lo largo de la frontera occidental del oeste de Massachusetts se encuentra la parte más elevada del estado, los Berkshires , que forman una parte del extremo norte de los montes Apalaches . [ cita requerida ]

El Servicio de Parques Nacionales de los Estados Unidos administra una serie de sitios naturales e históricos en Massachusetts . [146] Junto con doce sitios, áreas y corredores históricos nacionales, el Servicio de Parques Nacionales también administra la Costa Nacional de Cape Cod y el Área Recreativa Nacional de las Islas del Puerto de Boston . [146] Además, el Departamento de Conservación y Recreación mantiene una serie de parques , senderos y playas en todo Massachusetts. [147]

El bioma principal del interior de Massachusetts es el bosque templado caducifolio . [148] Aunque gran parte de Massachusetts había sido talada para la agricultura, dejando solo rastros de bosque antiguo en lugares aislados, el crecimiento secundario se ha regenerado en muchas áreas rurales a medida que se han abandonado las granjas. [149] Los bosques cubren alrededor del 62% de Massachusetts. [150] Las áreas más afectadas por el desarrollo humano incluyen el área metropolitana de Boston en el este y el área metropolitana de Springfield en el oeste, aunque esta última incluye áreas agrícolas en todo el valle del río Connecticut. [151] Hay 219 especies en peligro de extinción en Massachusetts. [152]

Varias especies prosperan en Massachusetts, un estado cada vez más urbanizado. Los halcones peregrinos utilizan las torres de oficinas de las grandes ciudades como zonas de anidación, [153] y la población de coyotes , cuya dieta puede incluir basura y animales atropellados, ha aumentado en las últimas décadas. [154] También se encuentran ciervos de cola blanca , mapaches , pavos salvajes y ardillas grises orientales en todo Massachusetts. En las zonas más rurales de la parte occidental de Massachusetts, han regresado mamíferos más grandes como los alces y los osos negros , en gran medida debido a la reforestación tras el declive regional de la agricultura. [155]

Massachusetts se encuentra a lo largo de la ruta migratoria del Atlántico , una ruta importante para las aves acuáticas migratorias a lo largo de la costa este. [156] Los lagos en el centro de Massachusetts proporcionan hábitat para muchas especies de peces y aves acuáticas, pero algunas especies como el colimbo común se están volviendo raras. [157] Una población significativa de patos de cola larga invernan frente a Nantucket . Las pequeñas islas y playas costeras son el hogar de charranes rosados y son áreas de reproducción importantes para el chorlito playero amenazado localmente . [158] Las áreas protegidas como el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Monomoy proporcionan un hábitat de reproducción crítico para las aves playeras y una variedad de vida silvestre marina, incluida una gran población de focas grises . Desde 2009, ha habido un aumento significativo en el número de tiburones blancos avistados y marcados en las aguas costeras de Cape Cod . [159] [160] [161]

Las especies de peces de agua dulce en Massachusetts incluyen lubina , carpa , bagre y trucha , mientras que las especies de agua salada como el bacalao del Atlántico , el eglefino y la langosta americana pueblan las aguas costeras. [162] Otras especies marinas incluyen focas comunes , las ballenas francas del Atlántico Norte en peligro de extinción , así como ballenas jorobadas , rorcuales de aleta , ballenas minke y delfines de lados blancos del Atlántico . [163]

El barrenador europeo del maíz , una plaga agrícola importante, se encontró por primera vez en América del Norte cerca de Boston, Massachusetts, en 1917. [164]

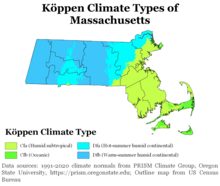

La mayor parte de Massachusetts tiene un clima continental húmedo , con inviernos fríos y veranos cálidos. Las áreas costeras del extremo sureste son la amplia zona de transición a los climas subtropicales húmedos . Los veranos cálidos a calurosos hacen que el clima oceánico sea poco común en esta transición, y solo se aplica a las áreas costeras expuestas, como en la península del condado de Barnstable . El clima de Boston es bastante representativo del estado, caracterizado por máximas de verano de alrededor de 81 °F (27 °C) y máximas de invierno de 35 °F (2 °C), y es bastante húmedo. Las heladas son frecuentes durante todo el invierno, incluso en las áreas costeras debido a los vientos interiores predominantes. Boston tiene un clima relativamente soleado para una ciudad costera en su latitud, con un promedio de más de 2600 horas de sol al año.

El cambio climático en Massachusetts afectará tanto a los entornos urbanos como rurales, incluida la silvicultura, la pesca, la agricultura y el desarrollo costero. [166] [167] [168] Se proyecta que el noreste se calentará más rápido que las temperaturas medias globales; para 2035, según el Programa de Investigación del Cambio Global de los EE. UU., se proyecta que el noreste "será más de 3,6 °F (2 °C) más cálido en promedio que durante la era preindustrial". [168] En agosto de 2016, la EPA informa que Massachusetts se ha calentado más de dos grados Fahrenheit, o 1,1 grados Celsius. [169]

Los cambios de temperatura también provocan cambios en los patrones de precipitaciones y la intensificación de los episodios de precipitación. Por ello, la precipitación media en el noreste de Estados Unidos ha aumentado un diez por ciento entre 1895 y 2011, y el número de episodios de precipitaciones intensas ha aumentado un setenta por ciento durante ese período. [169] Estos patrones de precipitación aumentados se concentran en el invierno y la primavera. El aumento de las temperaturas, junto con el aumento de las precipitaciones, dará lugar a un derretimiento más temprano de la nieve y, por consiguiente, a un suelo más seco en los meses de verano. [170]

El cambio climático en Massachusetts provocará un cambio significativo en el entorno construido y los ecosistemas del estado. Sólo en Boston , los costos de las tormentas relacionadas con el cambio climático se traducirán en daños de entre 5.000 y 100.000 millones de dólares. [169]

Las temperaturas más cálidas también afectarán la migración de las aves y la floración de la flora. Con estos cambios, se espera que las poblaciones de ciervos aumenten, lo que resultará en una disminución de la maleza que la fauna más pequeña utiliza como camuflaje. Además, el aumento de las temperaturas aumentará el número de casos de enfermedad de Lyme notificados en el estado. Las garrapatas pueden transmitir la enfermedad una vez que las temperaturas alcanzan los 45 grados, por lo que los inviernos más cortos aumentarán la ventana de transmisión. Estas temperaturas más cálidas también aumentarán la prevalencia de los mosquitos tigre asiáticos , que a menudo transmiten el virus del Nilo Occidental . [169]

Para luchar contra este cambio, la Oficina Ejecutiva de Energía y Asuntos Ambientales de Massachusetts ha delineado un camino para descarbonizar la economía del estado. El 22 de abril de 2020, Kathleen A. Theoharides, Secretaria de Energía y Asuntos Ambientales del estado, publicó una Determinación de límites de emisiones estatales para 2050. En su carta, Theoharides enfatiza que a partir de 2020, la Commonwealth ha experimentado daños a la propiedad atribuibles al cambio climático por más de $60 mil millones. Para garantizar que la Commonwealth experimente un calentamiento no mayor a 1.5 °C de los niveles previos a la industrialización, el estado trabajará para alcanzar dos objetivos para 2050: lograr emisiones netas cero y reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero en un 85 por ciento en general. [171]

El estado de Massachusetts ha desarrollado una plétora de incentivos para fomentar la implementación de energía renovable y electrodomésticos y equipos domésticos eficientes. El programa Mass Save, creado en colaboración con el estado por varias empresas que suministran electricidad y gas en Massachusetts, ofrece a los propietarios e inquilinos incentivos monetarios para modernizar sus hogares con equipos de calefacción, ventilación y aire acondicionado eficientes y otros electrodomésticos. Los electrodomésticos como calentadores de agua, aires acondicionados, lavadoras y secadoras y bombas de calor son elegibles para recibir reembolsos con el fin de incentivar el cambio. [172]

El concepto de Mass Save fue creado en 2008 con la aprobación de la Ley de Comunidades Verdes de 2008, durante el mandato de Deval Patrick como gobernador . El objetivo principal de la Ley de Comunidades Verdes era reducir el consumo de combustibles fósiles en el Estado y fomentar nuevas tecnologías más eficientes. Entre otros, un resultado de esta ley fue un requisito para que los administradores de programas de servicios públicos invirtieran en el ahorro de energía, en lugar de comprar y generar energía adicional cuando fuera económicamente factible. En Massachusetts, once administradores de programas, incluidos Eversource , National Grid , Western Massachusetts Electric , Cape Light Compact, Until y Berkshire Gas, poseen conjuntamente los derechos de este programa, junto con el Departamento de Recursos Energéticos de Massachusetts (DOER) y el Consejo Asesor de Eficiencia Energética (EEAC). [173]

El Servicio de Ingresos del Estado ofrece incentivos para la instalación de paneles solares . Además del crédito federal de energía renovable residencial , los residentes de Massachusetts pueden ser elegibles para un crédito fiscal de hasta el 15 por ciento del proyecto. [174] Una vez instalados, los paneles son elegibles para la medición neta . [175] Algunos municipios ofrecerán hasta $1.20 por vatio, hasta el 50 por ciento del costo del sistema en paneles fotovoltaicos de 25 kW o menos. [176] El Departamento de Recursos Energéticos de Massachusetts también ofreció financiamiento a bajo interés y tasa fija con apoyo crediticio para residentes de bajos ingresos hasta el 31 de diciembre de 2020. [177]

Como parte de los esfuerzos del Departamento de Recursos Energéticos de Massachusetts para incentivar el uso de energía renovable , se creó la iniciativa Massachusetts Offers Rebates for Electric Vehicles (MOR-EV). Con este incentivo, los residentes pueden calificar para un incentivo provisto por el estado de hasta $2,500 para la compra o arrendamiento de un vehículo eléctrico , o $1,500 para la compra o arrendamiento de un vehículo híbrido enchufable . [178] Este reembolso está disponible además de los créditos fiscales ofrecidos por el Departamento de Energía de los Estados Unidos para la compra de vehículos eléctricos e híbridos enchufables. [179]

Para los residentes que reúnen los requisitos de ingresos, Mass Save se ha asociado con las Agencias del Programa de Acción Comunitaria de Massachusetts y la Red de Asequibilidad de Energía para Personas de Bajos Ingresos (LEAN, por sus siglas en inglés) para ofrecer a los residentes asistencia con mejoras en sus hogares que resulten en un uso más eficiente de la energía. Los residentes pueden calificar para un reemplazo de su sistema de calefacción, instalación de aislamiento, electrodomésticos y termostatos si cumplen con los requisitos de ingresos proporcionados en el sitio web de Mass Save. Para los residentes de edificios residenciales de 5 o más familias, existen beneficios adicionales restringidos por ingresos disponibles a través de LEAN. Si al menos el 50 por ciento de los residentes del edificio califican como de bajos ingresos, están disponibles mejoras de eficiencia energética como las disponibles a través de Mass Save. Las estructuras residenciales operadas por organizaciones sin fines de lucro, operaciones con fines de lucro o autoridades de vivienda pueden aprovechar estos programas. [180]

A fines de 2020, la administración del gobernador de Massachusetts, Charlie Baker, publicó una hoja de ruta de descarbonización para alcanzar emisiones netas de gases de efecto invernadero cero para 2050. El plan exige importantes inversiones en energía eólica marina y solar. También exigiría que todos los automóviles nuevos que se vendan en el estado sean de cero emisiones ( eléctricos o propulsados por hidrógeno ) para 2035. [181] [182]

En el censo de EE. UU. de 2020 , Massachusetts tenía una población de más de 7 millones, un aumento del 7,4 % desde el censo de Estados Unidos de 2010. [ 185] [186] En 2015, se estimó que Massachusetts era el tercer estado más densamente poblado de EE. UU ., con 871,0 personas por milla cuadrada, [187] detrás de Nueva Jersey y Rhode Island . En 2014, Massachusetts tenía 1 011 811 residentes nacidos en el extranjero o el 15 % de la población. [187] En julio de 2023, se estima que la población es de 7 001 399. [5]

La mayoría de los residentes de Massachusetts viven en el área metropolitana de Boston, también conocida como Greater Boston , que incluye Boston y sus alrededores cercanos, pero que también se extiende a Greater Lowell y Worcester . El área metropolitana de Springfield , también conocida como Greater Springfield, también es un importante centro de población. Demográficamente, el centro de población de Massachusetts se encuentra en la ciudad de Natick . [188] [189]

Al igual que el resto del noreste de los Estados Unidos , la población de Massachusetts ha seguido creciendo a finales del siglo XX y principios del XXI. Massachusetts es el estado de más rápido crecimiento de Nueva Inglaterra y el 25.º estado de más rápido crecimiento de los Estados Unidos. [190] El crecimiento de la población ha sido impulsado principalmente por la calidad de vida relativamente alta y un gran sistema de educación superior. [190]

La inmigración extranjera también es un factor en el crecimiento de la población del estado, lo que hace que la población del estado continúe creciendo a partir del censo de 2010 (particularmente en las ciudades de entrada de Massachusetts , donde los costos de vida son más bajos). [191] [192] El cuarenta por ciento de los inmigrantes extranjeros eran de América Central o del Sur , según un estudio de la Oficina del Censo de 2005, y muchos del resto eran de Asia . Muchos residentes que se han establecido en Greater Springfield afirman tener ascendencia puertorriqueña . [191] Muchas áreas de Massachusetts mostraron tendencias de población relativamente estables entre 2000 y 2010. [192] Boston exurbano y las áreas costeras crecieron más rápidamente, mientras que el condado de Berkshire en el extremo occidental de Massachusetts y el condado de Barnstable en Cape Cod fueron los únicos condados que perdieron población a partir del censo de 2010. [ 192] En 2018, los principales países de origen de los inmigrantes de Massachusetts fueron China , República Dominicana , Brasil , India y Haití . [193]

Por sexo, en 2014 el 48,4% eran hombres y el 51,6% mujeres. En cuanto a la edad, el 79,2% tenía más de 18 años y el 14,8% tenía más de 65 años. [187]

Según el Informe Anual de Evaluación de Personas sin Hogar de 2022 de HUD , se estima que había 15.507 personas sin hogar en Massachusetts . [194] [195]

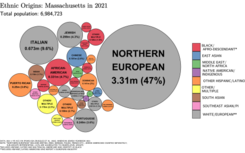

El grupo étnico más numeroso del estado, los blancos no hispanos, ha disminuido del 95,4% en 1970 al 67,6% en 2020. [187] [198] En 2011, los blancos no hispanos estuvieron involucrados en el 63,6% de todos los nacimientos, [199] mientras que el 36,4% de la población de Massachusetts menor de 1 año pertenecía a minorías (al menos uno de los padres que no era blanco no hispano). [200] Una de las principales razones de esto es que los blancos no hispanos en Massachusetts registraron una tasa de fertilidad total de 1,36 en 2017, la segunda más baja del país después del vecino Rhode Island. [201]

Tan tarde como 1795, la población de Massachusetts era casi 95% de ascendencia inglesa. [202] A principios y mediados del siglo XIX, grupos de inmigrantes comenzaron a llegar a Massachusetts en grandes cantidades; primero desde Irlanda en la década de 1840; [203] hoy los irlandeses y parte irlandeses son el grupo de ascendencia más grande en el estado con casi el 25% de la población total. Otros llegaron más tarde desde Quebec, así como lugares de Europa como Italia, Portugal y Polonia. [204] A principios del siglo XX, un número cada vez mayor de afroamericanos emigraron a Massachusetts , aunque en cantidades algo menores que muchos otros estados del norte. [205] Más tarde en el siglo XX, la inmigración desde América Latina aumentó considerablemente. Más de 156.000 chino-estadounidenses se establecieron en Massachusetts en 2014, [206] y Boston alberga un Chinatown en crecimiento que alberga líneas de autobús de propiedad china muy transitadas hacia y desde Chinatown, Manhattan en la ciudad de Nueva York . Massachusetts también tiene grandes poblaciones dominicanas , puertorriqueñas , haitianas , caboverdianas y brasileñas . [207] South End de Boston y Jamaica Plain son pueblos gay , al igual que la cercana Provincetown, Massachusetts en Cape Cod. [208]

El grupo de ascendencia más grande en Massachusetts son los irlandeses (22,5% de la población), que viven en cantidades significativas en todo el estado, pero forman más del 40% de la población a lo largo de la costa sur en los condados de Norfolk y Plymouth (en ambos condados en general, los estadounidenses de origen irlandés comprenden más del 30% de la población). Los italianos forman el segundo grupo étnico más grande del estado (13,5%), pero forman una pluralidad en algunos suburbios al norte de Boston y en algunas ciudades de los Berkshires. Los estadounidenses de origen inglés , el tercer grupo más grande (11,4%), forman una pluralidad en algunas ciudades occidentales. Los franceses y los canadienses franceses también forman una parte significativa (10,7%), [209] con poblaciones considerables en los condados de Bristol, Hampden y Worcester, junto con el condado de Middlesex, especialmente concentrados en las áreas que rodean Lowell y Lawrence. [210] [211] Lowell es el hogar de la segunda comunidad camboyana más grande de la nación. [212] Massachusetts también es el hogar de una pequeña comunidad de greco-estadounidenses , que según la Encuesta sobre la Comunidad Estadounidense son 83.701 de ellos dispersos a lo largo del estado (1,2% de la población total del estado). [213] También hay varias poblaciones de nativos americanos en Massachusetts. La tribu Wampanoag mantiene reservas en Aquinnah en Martha's Vineyard y en Mashpee en Cape Cod, con un proyecto de recuperación de la lengua nativa en curso desde 1993, mientras que los Nipmuc mantienen dos reservas reconocidas por el estado en la parte central del estado, incluida una en Grafton . [214]

Massachusetts ha evitado muchas formas de conflicto racial vistas en otras partes de los EE. UU., pero ejemplos como los exitosos resultados electorales de los nativistas (principalmente anticatólicos ) Know Nothings en la década de 1850, [215] las controvertidas ejecuciones de Sacco y Vanzetti en la década de 1920, [216] y la oposición de Boston al transporte en autobús para la desegregación en la década de 1970. [217]

Composición racial y étnica histórica

Massachusetts – Composición racial y étnica

( NH = No hispano )

Nota: el censo de los EE. UU. considera a los hispanos/latinos como una categoría étnica. Esta tabla excluye a los latinos de las categorías raciales y los asigna a una categoría separada. Los hispanos/latinos pueden ser de cualquier raza.

Las variedades más comunes del inglés americano hablado en Massachusetts, aparte del inglés americano general , son el dialecto occidental de Massachusetts, rótico, distinto del inglés cot -caught , y el dialecto oriental de Massachusetts, no rótico, fusionado y cot-caught (conocido popularmente como "acento de Boston"). [221]

En 2010, el 78,93% (4.823.127) de los residentes de Massachusetts de 5 años o más hablaban inglés en casa como primera lengua , mientras que el 7,50% (458.256) hablaba español, el 2,97% (181.437) portugués , el 1,59% (96.690) chino (que incluye cantonés y mandarín ), el 1,11% (67.788) francés, el 0,89% (54.456) criollo francés , el 0,72% (43.798) italiano, el 0,62% (37.865) ruso y el 0,58% (35.283) de la población mayor de 5 años hablaba vietnamita como lengua principal . En total, el 21,07% (1.287.419) de la población de Massachusetts de 5 años o más hablaba una primera lengua distinta del inglés. [187] [222]

Autoidentificación religiosa, según la Encuesta de valores estadounidenses de 2022 del Public Religion Research Institute [223]

Massachusetts fue fundada y colonizada por puritanos brownistas en 1620, [81] y poco después por otros grupos de separatistas / disidentes , no conformistas e independientes de la Inglaterra del siglo XVII . [224] La mayoría de la gente de Massachusetts hoy en día sigue siendo cristiana . [187] Los descendientes de los puritanos pertenecen a muchas iglesias diferentes; en la línea directa de herencia están las diversas iglesias congregacionalistas , la Iglesia Unida de Cristo y las congregaciones de la Asociación Unitaria Universalista . La sede de la Asociación Unitaria Universalista , ubicada durante mucho tiempo en Beacon Hill , ahora se encuentra en South Boston . [225] [226] Muchos descendientes puritanos también se dispersaron a otras denominaciones protestantes. Algunos se desafiliaron junto con los católicos romanos y otros grupos cristianos a raíz de la secularización moderna . [227]

Según el estudio de Pew de 2014, los cristianos representaban el 57% de la población del estado, y los protestantes representaban el 21% de ellos. Los católicos romanos representaban el 34% y ahora predominan debido a la inmigración masiva de países y regiones principalmente católicos, principalmente Irlanda, Italia, Polonia, Portugal, Quebec y América Latina. Tanto las comunidades protestantes como las católicas romanas han estado en declive desde finales del siglo XX, debido al aumento de la irreligiosidad en Nueva Inglaterra . Es la región más irreligiosa del país, junto con el oeste de los Estados Unidos ; sin embargo, a modo de comparación y contraste, en 2020, el Public Religion Research Institute determinó que el 67% de la población era cristiana, lo que refleja un ligero aumento de la religiosidad. [228] Una importante población judía emigró a las áreas de Boston y Springfield entre 1880 y 1920. Los judíos representan el 3% de la población. Mary Baker Eddy hizo que la Iglesia Madre de la Ciencia Cristiana de Boston sirviera como sede mundial de este nuevo movimiento religioso . También se pueden encontrar budistas , paganos , hindúes , adventistas del séptimo día , musulmanes y mormones . El Templo Satánico tiene su sede en Salem. El Centro Kripalu en Stockbridge , el Templo de Meditación Shaolin en Springfield y el Centro de Meditación Insight en Barre son ejemplos de centros religiosos no abrahámicos en Massachusetts. Según datos de 2010 de The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), las denominaciones individuales más grandes son la Iglesia Católica con 2.940.199 seguidores; la Iglesia Unida de Cristo con 86.639 seguidores; y la Iglesia Episcopal con 81.999 seguidores. [229]

En 2014, el 32% de la población se identificó como no religiosa; [230] en un estudio independiente de 2020, el 23% de la población se identificó como irreligiosa y el 67% de la población se identificó como cristiana (incluido el 26% como protestantes blancos y el 20% como católicos blancos). [228] A partir de 2022, una pluralidad de habitantes de Massachusetts eran irreligiosos , [228] y el estado se considera parte del Cinturón Sin Iglesia . [231]

Lo que hoy es Massachusetts estuvo habitado originalmente por los wampanoag, los nipmuc, los massachusett, los pocumtuc, los nauset, los pennacook y algunas tribus más. [232] [233] Algunas de estas tribus todavía están representadas entre la población del estado actual.

Las tribus nativas americanas más grandes de Massachusetts según el censo de 2010 se enumeran en la siguiente tabla: [234]

En 2018, el sistema educativo general de Massachusetts fue clasificado como el mejor entre los cincuenta estados de EE. UU. por US News & World Report . [236] Massachusetts fue el primer estado de América del Norte en exigir a los municipios que designaran a un maestro o establecieran una escuela secundaria con la aprobación de la Ley de Educación de Massachusetts de 1647, [237] y las reformas del siglo XIX impulsadas por Horace Mann sentaron gran parte de las bases para la educación pública universal contemporánea [238] [239] que se estableció en 1852. [122] Massachusetts alberga la escuela más antigua en existencia continua en América del Norte ( The Roxbury Latin School , fundada en 1645), así como la escuela primaria pública más antigua del país ( The Mather School , fundada en 1639), [240] su escuela secundaria más antigua ( Boston Latin School , fundada en 1635), [241] su internado más antiguo en funcionamiento continuo ( The Governor's Academy , fundada en 1763), [242] su universidad más antigua ( Harvard University , fundada en 1636), [243] y su universidad femenina más antigua ( Mount Holyoke College , fundada en 1837). [244] Massachusetts también alberga la escuela secundaria privada de mayor rango en los Estados Unidos, Phillips Academy en Andover, Massachusetts , que fue fundada en 1778. [245]

En 2012, el gasto público per cápita de Massachusetts para escuelas primarias y secundarias fue el octavo del país, con 14.844 dólares. [246] En 2013, Massachusetts obtuvo la puntuación más alta de todos los estados en matemáticas y la tercera más alta en lectura en la Evaluación Nacional del Progreso Educativo . [247] Los estudiantes de las escuelas públicas de Massachusetts se sitúan entre los primeros del mundo en rendimiento académico. [61]

Massachusetts es el hogar de 121 instituciones de educación superior. [248] La Universidad de Harvard y el Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts , ambos ubicados en Cambridge , se ubican constantemente entre las mejores universidades privadas y universidades en general del mundo. [249] Además de Harvard y el MIT, varias otras universidades de Massachusetts se ubican entre las 50 mejores a nivel de pregrado a nivel nacional en las clasificaciones ampliamente citadas de US News & World Report : Tufts University (#27), Boston College (#32), Brandeis University (#34), Boston University (#37) y Northeastern University (#40). Massachusetts también alberga tres de las cinco mejores universidades de artes liberales de US News & World Report: Williams College ( #1), Amherst College (#2) y Wellesley College (#4). [250] También alberga la universidad católica de artes liberales más antigua, College of the Holy Cross (#33). [251] Boston Architectural College es la universidad privada de diseño espacial más grande de Nueva Inglaterra . La Universidad pública de Massachusetts (apodada UMass ) cuenta con cinco campus en el estado, con su campus insignia en Amherst , que inscribe a más de 25.000 estudiantes. [252] [253]

A partir de 2021, Massachusetts tiene el porcentaje más alto de adultos mayores de 25 años con un título de licenciatura (46,62 %) y un título de posgrado (21,27 %) de cualquier estado del país.

La Oficina de Análisis Económico de los Estados Unidos estima que el producto bruto estatal de Massachusetts en 2020 fue de $584 mil millones. [254] El ingreso personal per cápita en 2012 fue de $53,221, lo que lo convierte en el tercer estado más alto de la nación. [255] A partir de enero de 2023, el salario mínimo general del estado de Massachusetts es de $15.00 por hora, mientras que el salario mínimo para los trabajadores con propinas es de $6.75 por hora, con una garantía de que los empleadores pagarán la diferencia si el salario por hora de un empleado con propinas no cumple o excede el salario mínimo general. [256] Este salario estaba programado para aumentar a un mínimo general de $15.00 por hora y un mínimo para los trabajadores con propinas de $6.75 por hora en enero de 2023, como parte de una serie de enmiendas al salario mínimo aprobadas en 2018 que vieron el salario mínimo aumentar lentamente cada enero hasta 2023. [257]

En 2015, doce empresas Fortune 500 estaban ubicadas en Massachusetts: Liberty Mutual , Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company , TJX Companies , General Electric , Raytheon , American Tower , Global Partners , Thermo Fisher Scientific , State Street Corporation , Biogen , Eversource Energy y Boston Scientific . [258] La lista de CNBC de "Los mejores estados para los negocios en 2023" ha reconocido a Massachusetts como el decimoquinto mejor estado de la nación para los negocios, [259] y por segundo año consecutivo en 2016 el estado fue clasificado por Bloomberg como el estado más innovador de Estados Unidos. [260] Según un estudio de 2013 de Phoenix Marketing International, Massachusetts tenía el sexto mayor número de millonarios per cápita en los Estados Unidos, con una proporción del 6,73 por ciento. [261] Los multimillonarios que viven en el estado incluyen líderes pasados y presentes (y familiares relacionados) de empresas locales como Fidelity Investments , New Balance , Kraft Group , Boston Scientific y la antigua Continental Cablevision . [262]

Massachusetts tiene tres zonas de comercio exterior : la Autoridad Portuaria de Massachusetts de Boston, el Puerto de New Bedford y la Ciudad de Holyoke. [263] El Aeropuerto Internacional Boston-Logan es el aeropuerto más transitado de Nueva Inglaterra, con un total de 33,4 millones de pasajeros en 2015 y un rápido crecimiento del tráfico aéreo internacional desde 2010. [264]

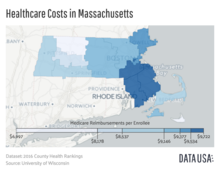

Los sectores vitales para la economía de Massachusetts incluyen la educación superior, la biotecnología , la tecnología de la información , las finanzas, la atención médica, el turismo, la manufactura y la defensa. El corredor de la Ruta 128 y el Gran Boston siguen siendo un importante centro de inversión de capital de riesgo , [265] y la alta tecnología sigue siendo un sector importante. En los últimos años, el turismo ha jugado un papel cada vez más importante en la economía del estado, siendo Boston y Cape Cod los principales destinos. [266] Otros destinos turísticos populares incluyen Salem , Plymouth y Berkshires . Massachusetts es el sexto destino turístico más popular para los viajeros extranjeros. [267] En 2010, la Comisión de Grandes Lugares de Massachusetts publicó '1,000 Grandes Lugares de Massachusetts' que identificó 1,000 sitios en todo el estado para resaltar las diversas atracciones históricas, culturales y naturales. [268]

Si bien la manufactura representó menos del 10% del producto bruto estatal de Massachusetts en 2016, la Commonwealth ocupó el puesto 16 en la nación en producción manufacturera total en los Estados Unidos. [269] Esto incluye una amplia gama de productos manufacturados, como dispositivos médicos, productos de papel, productos químicos y plásticos especiales, equipos de telecomunicaciones y electrónica y componentes mecanizados. [270] [271]

Las más de 33.000 organizaciones sin fines de lucro de Massachusetts emplean a una sexta parte de la fuerza laboral del estado. [272] En 2007, el gobernador Deval Patrick firmó la ley de un feriado estatal, el Día de Concientización sobre las Organizaciones sin Fines de Lucro. [273]

En febrero de 2017, US News & World Report clasificó a Massachusetts como el mejor estado de los Estados Unidos en base a 60 parámetros, entre ellos atención médica, educación, delincuencia, infraestructura, oportunidades, economía y gobierno. Massachusetts ocupó el primer puesto en educación, el segundo en atención médica y el quinto en gestión de la economía. [274]

En 2012, había 7.755 granjas en Massachusetts que abarcaban un total de 523.517 acres (2.120 km 2 ), con un promedio de 67,5 acres (27,3 hectáreas) cada una. [275] Los productos de invernadero , floricultura y césped , incluido el mercado ornamental , representan más de un tercio de la producción agrícola del estado. [276] [277] Los productos agrícolas particulares de destacar también incluyen arándanos rojos , maíz dulce y manzanas que también son grandes sectores de producción. [277] El cultivo de frutas es una parte importante de los ingresos agrícolas del estado, [278] y Massachusetts es el segundo estado productor de arándanos más grande después de Wisconsin . [279]

Según cómo se calcule, la carga impositiva estatal y local en Massachusetts se ha estimado entre los estados de EE. UU. y Washington DC como la 21.ª más alta (11,44 % o $6163 por año para un hogar con un ingreso medio nacional) [280] o la 25.ª más alta en general con impuestos corporativos por debajo del promedio (39.º más alto), impuestos sobre la renta personal por encima del promedio (13.º más alto), impuestos sobre las ventas por encima del promedio (18.º más alto) e impuestos sobre la propiedad por debajo del promedio (46.º más alto). [281] En la década de 1970, la Commonwealth se clasificó como un estado con impuestos relativamente altos, lo que le valió el apodo peyorativo de "Taxachusetts". A esto le siguió una ronda de limitaciones impositivas durante la década de 1980, un período conservador en la política estadounidense, incluida la Proposición 2½ . [282]

A partir del 1 de enero de 2020, Massachusetts tiene un impuesto a la renta personal de tasa fija del 5,00%, [283] después de un referéndum de los votantes de 2002 para eventualmente reducir la tasa al 5,0% [284] según lo enmendado por la legislatura. [285] Existe una exención fiscal para los ingresos por debajo de un umbral que varía de un año a otro. La tasa del impuesto a la renta corporativa es del 8,8%, [286] y la tasa del impuesto a las ganancias de capital a corto plazo es del 12%. [287] Una disposición inusual permite a los contribuyentes pagar voluntariamente a la tasa del impuesto a la renta del 5,85% anterior al referéndum, lo que hacen entre mil y dos mil contribuyentes por año. [288]

El estado impone un impuesto a las ventas del 6,25% [286] sobre las ventas minoristas de bienes personales tangibles, excepto comestibles, ropa (hasta $175,00) y publicaciones periódicas. [289] El impuesto a las ventas se cobra sobre la ropa que cuesta más de $175,00, por el monto que exceda los $175,00. [289] Massachusetts también cobra un impuesto al uso cuando los bienes se compran en otros estados y el vendedor no remite el impuesto a las ventas de Massachusetts; los contribuyentes informan y pagan esto en sus formularios de impuestos sobre la renta o formularios dedicados, aunque hay montos de "puerto seguro" que se pueden pagar sin sumar las compras reales (excepto las compras superiores a $1000). [289] No existe un impuesto a la herencia y el impuesto al patrimonio de Massachusetts está limitado a la recaudación del impuesto al patrimonio federal. [287]

El mercado de generación de electricidad de Massachusetts se hizo competitivo en 1998, lo que permitió a los clientes minoristas cambiar de proveedor sin cambiar de empresa de servicios públicos. [290] En 2018, Massachusetts consumió 1.459 billones de BTU , [291] lo que lo convirtió en el séptimo estado más bajo en términos de consumo de energía per cápita, y el 31 por ciento de esa energía provino de gas natural . [291] En 2014 y 2015, Massachusetts fue clasificado como el estado más eficiente energéticamente de los Estados Unidos [292] [293] mientras que Boston es la ciudad más eficiente, [294] pero tuvo el cuarto precio promedio más alto de electricidad minorista residencial de cualquier estado. [291] En 2018, la energía renovable representó aproximadamente el 7,2 por ciento de la energía total consumida en el estado, ocupando el puesto 34. [291]

Massachusetts cuenta con 10 organizaciones regionales de planificación metropolitana y tres organizaciones de planificación no metropolitana que cubren el resto del estado; [295] la planificación estatal está a cargo del Departamento de Transporte de Massachusetts . El transporte es la principal fuente de emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero por sector económico en Massachusetts. [296]

La Autoridad de Transporte de la Bahía de Massachusetts (MBTA), también conocida como "The T", [297] opera el transporte público en forma de sistemas de metro, [298] autobús, [299] y ferry [300] en el área metropolitana de Boston .

Fifteen other regional transit authorities provide public transportation in the form of bus services in the rest of the state.[301] Four heritage railways are also in operation:

Amtrak operates several inter-city rail lines in Massachusetts. Boston's South Station serves as the terminus for three lines, namely the high-speed Acela Express, which links to cities such as Providence, New Haven, New York City, and eventually Washington DC; the Northeast Regional, which follows the same route but includes many more stops, and also continues further south to Newport News in Virginia; and the Lake Shore Limited, which runs westward to Worcester, Springfield, and eventually Chicago.[306][307] Boston's other major station, North Station, serves as the southern terminus for Amtrak's Downeaster, which connects to Portland and Brunswick in Maine.[306]

Outside of Boston, Amtrak connects several cities across Massachusetts, along the aforementioned Acela, Northeast Regional, Lake Shore Limited, and Downeaster lines, as well as other routes in central and western Massachusetts. The Hartford Line connects Springfield to New Haven, operated in conjunction with the Connecticut Department of Transportation, and the Valley Flyer runs a similar route but continues further north to Greenfield. Several stations in western Massachusetts are also served by the Vermonter, which connects St. Albans, Vermont to Washington DC.[306]

Amtrak carries more passengers between Boston and New York than all airlines combined (about 54% of market share in 2012),[308] but service between other cities is less frequent. There, more frequent intercity service is provided by private bus carriers, including Peter Pan Bus Lines (headquartered in Springfield), Greyhound Lines, OurBus, BoltBus and Plymouth and Brockton Street Railway. Various Chinatown bus lines depart for New York from South Station in Boston.[309]

MBTA Commuter Rail services run throughout the larger Greater Boston area, including service to Worcester, Fitchburg, Haverhill, Newburyport, Lowell, and Kingston.[310] This overlaps with the service areas of neighboring regional transportation authorities. As of the summer of 2013 the Cape Cod Regional Transit Authority in collaboration with the MBTA and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) is operating the CapeFLYER providing passenger rail service between Boston and Cape Cod.[311][312]

Most ports north of Cape Cod are served by Boston Harbor Cruises, which operates ferry services in and around Greater Boston under contract with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Several routes connect the downtown area with Hingham, Hull, Winthrop, Salem, Logan Airport, Charlestown, and some of the islands located within the harbor. The same company also operates seasonal service between Boston and Provincetown.[313]

On the southern shore of the state, several different passenger ferry lines connect Martha's Vineyard to ports along the mainland, including Woods Hole, Hyannis, New Bedford, and Falmouth, all in Massachusetts, as well as North Kingstown in Rhode Island, Highlands in New Jersey, and New York City in New York.[314] Similarly, several different lines connect Nantucket to ports including Hyannis, New Bedford, Harwich, and New York City.[315] Service between the two islands is also offered. The dominant companies serving these routes include SeaStreak, Hy-Line Cruises, and The Steamship Authority, the latter of which regulates all passenger services in the region and is also the only company permitted to offer freight ferry services to the islands.[316]

Other ferry connections in the state include a water taxi connecting various points in Fall River,[317] seasonal ferry service connecting Plymouth to Provincetown,[318] and a service between New Bedford and Cuttyhunk.[319]

As of 2018, a number of freight railroads were operating in Massachusetts, with Class I railroad CSX being the largest carrier, and another Class 1, Norfolk Southern serving the state via its Pan Am Southern joint partnership. Several regional and short line railroads also provide service and connect with other railroads.[320] Massachusetts has a total of 1,110 miles (1,790 km) of freight trackage in operation.[321][322]

Boston Logan International Airport served 33.5 million passengers in 2015 (up from 31.6 million in 2014)[264] through 103 gates.[323][324] Logan, Hanscom Field in Bedford, and Worcester Regional Airport are operated by Massport, an independent state transportation agency.[324] Massachusetts has 39 public-use airfields[325] and more than 200 private landing spots.[326] Some airports receive funding from the Aeronautics Division of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation and the Federal Aviation Administration; the FAA is also the primary regulator of Massachusetts air travel.[327]

There are a total of 36,800 miles (59,200 km) of interstates and other highways in Massachusetts.[328] Interstate 90 (I-90, also known as the Massachusetts Turnpike), is the longest interstate in Massachusetts. The route travels 136 mi (219 km) generally west to east, entering Massachusetts at the New York state line in the town of West Stockbridge, and passes just north of Springfield, just south of Worcester and through Framingham before terminating near Logan International Airport in Boston.[329] Other major interstates include I-91, which travels generally north and south along the Connecticut River; I-93, which travels north and south through central Boston, then passes through Methuen before entering New Hampshire; and I-95, which connects Providence, Rhode Island with Greater Boston, forming a partial loop concurrent with Route 128 around the more urbanized areas before continuing north along the coast into New Hampshire.[330]

I-495 forms a wide loop around the outer edge of Greater Boston. Other major interstates in Massachusetts include I-291, I-391, I-84, I-195, I-395, I-290, and I-190. Major non-interstate highways in Massachusetts include U.S. Routes 1, 3, 6, and 20, and state routes 2, 3, 9, 24, and 128. A great majority of interstates in Massachusetts were constructed during the mid-20th century, and at times were controversial, particularly the intent to route I-95 northeastwards from Providence, Rhode Island, directly through central Boston, first proposed in 1948. Opposition to continued construction grew, and in 1970 Governor Francis W. Sargent issued a general prohibition on most further freeway construction within the I-95/Route 128 loop in the Boston area.[331] A massive undertaking to bring I-93 underground in downtown Boston, called the Big Dig, brought the city's highway system under public scrutiny for its high cost and construction quality.[134]

.jpg/440px-Boston_-Massachusetts_State_House_(48718911666).jpg)

Massachusetts has a long political history; earlier political structures included the Mayflower Compact of 1620, the separate Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies, and the combined colonial Province of Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Constitution was ratified in 1780 while the Revolutionary War was in progress, four years after the Articles of Confederation was drafted, and eight years before the present United States Constitution was ratified on June 21, 1788. Drafted by John Adams, the Massachusetts Constitution is the oldest functioning written constitution in continuous effect in the world.[332][333][334] It has been amended 121 times, most recently in 2022.[335]

Massachusetts politics since the second half of the 20th century have generally been dominated by the Democratic Party, and the state has a reputation for being the most liberal state in the country.[336] In 1974, Elaine Noble became the first openly lesbian or gay candidate elected to a state legislature in US history.[337] The state's 12th congressional district elected the first openly gay member of the United States House of Representatives, Gerry Studds, in 1972[338] and in 2004, Massachusetts became the first state to allow same-sex marriage.[57] In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state to approve a law that provided for nearly universal healthcare.[339][340] Massachusetts has a pro-sanctuary city law.[341]

In a 2020 study, Massachusetts was ranked as the 11th easiest state for citizens to vote in.[342]

The Government of Massachusetts is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. The governor of Massachusetts heads the executive branch, while legislative authority vests in a separate but coequal legislature. Meanwhile, judicial power is constitutionally guaranteed to the independent judicial branch.[343]

As chief executive, the governor is responsible for signing or vetoing legislation, filling judicial and agency appointments, granting pardons, preparing an annual budget, and commanding the Massachusetts National Guard.[344] Massachusetts governors, unlike those of most other states, are addressed as His/Her Excellency.[344] The governor is Maura Healey and the incumbent lieutenant governor is Kim Driscoll. The governor conducts the affairs of state alongside a separate Governor's Council made up of the lieutenant governor and eight separately elected councilors.[344] The council is charged by the state constitution with reviewing and confirming gubernatorial appointments and pardons, approving disbursements out of the state treasury, and certifying elections, among other duties.[344]

Aside from the governor and Governor's Council, the executive branch also includes four independently elected constitutional officers: a secretary of the commonwealth, an attorney general, a state treasurer, and a state auditor. The commonwealth's incumbent constitutional officers are respectively William F. Galvin, Andrea Campbell, Deb Goldberg and Diana DiZoglio, all Democrats. In accordance with state statute, the secretary of the commonwealth administers elections, regulates lobbyists and the securities industry, registers corporations, serves as register of deeds for the entire state, and preserves public records as keeper of the state seal.[345] Meanwhile, the attorney general provides legal services to state agencies, combats fraud and corruption, investigates and prosecutes crimes, and enforces consumer protection, environment, labor, and civil rights laws as Massachusetts chief lawyer and law enforcement officer.[346] At the same time, the state treasurer manages the state's cash flow, debt, and investments as chief financial officer, whereas the state auditor conducts audits, investigations, and studies as chief audit executive in order to promote government accountability and transparency and improve state agency financial management, legal compliance, and performance.[347][348]

The Massachusetts House of Representatives and Massachusetts Senate comprise the legislature of Massachusetts, known as the Massachusetts General Court.[344] The House consists of 160 members while the Senate has 40 members.[344] Leaders of the House and Senate are chosen by the members of those bodies; the leader of the House is known as the Speaker while the leader of the Senate is known as the President.[344] Each branch consists of several committees.[344] Members of both bodies are elected to two-year terms.[349]

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (a chief justice and six associates) are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Governor's Council, as are all other judges in the state.[344]

Federal court cases are heard in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, and appeals are heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit.[350]

The Congressional delegation from Massachusetts is entirely Democratic.[351] The Senators are Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey while the Representatives are Richard Neal (1st), Jim McGovern (2nd), Lori Trahan (3rd), Jake Auchincloss (4th), Katherine Clark (5th), Seth Moulton (6th), Ayanna Pressley (7th), Stephen Lynch (8th), and Bill Keating (9th).[352]

In U.S. presidential elections since 2012, Massachusetts has been allotted 11 votes in the electoral college, out of a total of 538.[353] Like most states, Massachusetts's electoral votes are granted in a winner-take-all system.[354]

For more than 70 years, Massachusetts has shifted from a previously Republican-leaning state to one largely dominated by Democrats; the 1952 victory of John F. Kennedy over incumbent Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. is seen as a watershed moment in this transformation. His younger brother Edward M. Kennedy held that seat until his death from a brain tumor in 2009.[355] Since the 1950s, Massachusetts has gained a reputation as being a politically liberal state and is often used as an archetype of modern liberalism, hence the phrase "Massachusetts liberal".[356]

Massachusetts is one of the most Democratic states in the country. Democratic core concentrations are everywhere, except for a handful of Republican leaning towns in the Central and Southern parts of the state. Until recently, Republicans were dominant in the Western and Northern suburbs of Boston, however both areas heavily swung Democratic in the Trump era. The state as a whole has not given its Electoral College votes to a Republican in a presidential election since Ronald Reagan carried it in 1984, and not a single county has voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1988 . Additionally, Massachusetts provided Reagan with his smallest margins of victory in both the 1980[357] and 1984 elections.[358] Massachusetts had been the only state to vote for Democrat George McGovern in the 1972 presidential election. In 2020, Biden received 65.6% of the vote, the best performance in over 50 years for a Democrat.[359]

Democrats have an absolute grip on the Massachusetts congressional delegation; there are no Republicans elected to serve at the federal level. Both Senators and all nine Representatives are Democrats; only one Republican (former Senator Scott Brown) has been elected to either house of Congress from Massachusetts since 1994. Massachusetts is the most populous state to be represented in the United States Congress entirely by a single party.[360]

As of the 2018 elections, the Democratic Party holds a super-majority over the Republican Party in both chambers of the Massachusetts General Court (state legislature). Out of the state house's 160 seats, Democrats hold 127 seats (79%) compared to the Republican Party's 32 seats (20%), an independent sits in the remaining one,[361] and 37 out of the 40 seats in the state senate (92.5%) belong to the Democratic Party compared to the Republican Party's three seats (7.5%).[362] Both houses of the legislature have had Democratic majorities since the 1950s.[363]

Despite the state's Democratic-leaning tendency, Massachusetts has generally elected Republicans as Governor: only two Democrats (Deval Patrick and Maura Healey) have served as governor since 1991, and among gubernatorial election results from 2002 to 2022, Republican nominees garnered 48.4% of the vote compared to 45.7% for Democratic nominees.[365] These have been considered to be among the most moderate Republican leaders in the nation;[366][367] they have received higher net favorability ratings from the state's Democrats than Republicans.[368]

A number of contemporary national political issues have been influenced by events in Massachusetts, such as the decision in 2003 by the state Supreme Judicial Court allowing same-sex marriage[369] and a 2006 bill which mandated health insurance for all Massachusetts residents.[340] In 2008, Massachusetts voters passed an initiative decriminalizing possession of small amounts of marijuana.[370] Voters in Massachusetts also approved a ballot measure in 2012 that legalized the medical use of marijuana.[371] Following the approval of a ballot question endorsing legalization in 2016, Massachusetts began issuing licenses for the regulated sale of recreational marijuana in June 2018. The licensed sale of recreational marijuana became legal on July 1, 2018; however, the lack of state-approved testing facilities prevented the sale of any product for several weeks.[372] However, in 2020, a ballot initiative to implement Ranked-Choice Voting failed, despite being championed by many progressives.[373]

Massachusetts is one of the most pro-choice states in the Union. A 2014 Pew Research Center poll found that 74% of Massachusetts residents supported the right to an abortion in all/most cases, making Massachusetts the most pro-choice state in the United States.[374]

In 2020, the state legislature overrode Governor Charlie Baker's veto of the ROE Act, a controversial law that codified existing abortion laws in case the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, dropped the age of parental consent for those seeking an abortion from 18 to 16, and legalized abortion after 24 weeks, if a fetus had fatal anomalies, or "to preserve the patient's physical or mental health."[375]

The 2023 American Values Atlas by Public Religion Research Institute found that same-sex marriage is supported near-universally by Massachusettsans.[376]

There are 50 cities and 301 towns in Massachusetts, grouped into 14 counties.[377] The fourteen counties, moving roughly from west to east, are Berkshire, Franklin, Hampshire, Hampden, Worcester, Middlesex, Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk, Bristol, Plymouth, Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket. Eleven communities which call themselves "towns" are, by law, cities since they have traded the town meeting form of government for a mayor-council or manager-council form.[378]

Boston is the state capital in Massachusetts. The population of the city proper is 692,600,[379] and Greater Boston, with a population of 4,873,019, is the 11th largest metropolitan area in the nation.[380] Other cities with a population over 100,000 include Worcester, Springfield, Lowell, Cambridge, Brockton, Quincy, New Bedford, and Lynn. Plymouth is the largest municipality in the state by land area, followed by Middleborough.[377]