Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier OM ( / ˈl ɒr ə n s ˈk ɜːr ə ˈl ɪ v i eɪ / LORR -ənss KUR ə- LIV -ee-ay ; 22 de mayo de 1907 - 11 de julio de 1989) fue un actor y director inglés . Él y sus contemporáneos Ralph Richardson y John Gielgud formaron un trío de actores masculinos que dominaron el escenario británico de mediados del siglo XX. También trabajó en películas a lo largo de su carrera, interpretando más de cincuenta papeles cinematográficos. Al final de su carrera tuvo un éxito considerable en papeles televisivos.

La familia de Olivier no tenía conexiones teatrales, pero su padre, un clérigo, decidió que su hijo debía convertirse en actor. Después de asistir a una escuela de arte dramático en Londres, Olivier aprendió su oficio en una sucesión de trabajos de actuación durante finales de la década de 1920. En 1930 tuvo su primer éxito importante en el West End en Private Lives de Noël Coward , y apareció en su primera película. En 1935 actuó en una célebre producción de Romeo y Julieta junto a Gielgud y Peggy Ashcroft , y a finales de la década era una estrella establecida. En la década de 1940, junto con Richardson y John Burrell , Olivier fue codirector del Old Vic , convirtiéndolo en una compañía muy respetada. Allí, sus papeles más celebrados incluyeron Ricardo III de Shakespeare y Edipo de Sófocles .

En la década de 1950, Olivier era un actor y representante independiente, pero su carrera teatral estaba en crisis hasta que se unió a la vanguardista English Stage Company en 1957 para interpretar el papel principal en The Entertainer , un papel que más tarde interpretó en una película . De 1963 a 1973 fue el director fundador del Teatro Nacional de Gran Bretaña , dirigiendo una compañía residente que fomentó a muchas futuras estrellas. Sus propios papeles allí incluyeron el papel principal en Otelo (1965) y Shylock en El mercader de Venecia (1970).

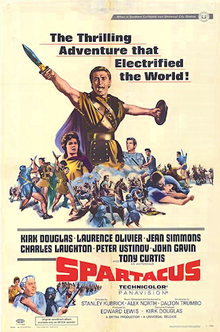

Entre las películas de Olivier se encuentran Cumbres borrascosas (1939), Rebeca (1940) y una trilogía de películas de Shakespeare como actor/director: Enrique V (1944), Hamlet (1948) y Ricardo III (1955). Sus películas posteriores incluyeron Espartaco (1960), Las sandalias del pescador (1968), La huella (1972), Maratón de hombres (1976) y Los muchachos del Brasil (1978). Sus apariciones en televisión incluyeron una adaptación de La luna y seis peniques (1960), Largo viaje hacia la noche (1973), Amor entre ruinas (1975), La gata sobre el tejado de zinc (1976), Retorno a Brideshead (1981) y El rey Lear (1983).

Olivier recibió entre otros honores el título de caballero (1947), un título nobiliario vitalicio (1970) y la Orden del Mérito (1981). Por su trabajo en pantalla recibió dos premios Óscar , dos premios de la Academia Británica de Cine , cinco premios Emmy y tres Globos de Oro . El auditorio más grande del Teatro Nacional lleva su nombre y se le conmemora en los Premios Laurence Olivier , que otorga anualmente la Sociedad de Teatro de Londres . Se casó tres veces: con las actrices Jill Esmond de 1930 a 1940, Vivien Leigh de 1940 a 1960 y Joan Plowright desde 1961 hasta su muerte.

Olivier nació en Dorking , Surrey, el más joven de los tres hijos de Agnes Louise ( née Crookenden) y el reverendo Gerard Kerr Olivier. [1] Tenía dos hermanos mayores: Sybille y Gerard Dacres "Dickie". [2] Su tatarabuelo era de ascendencia hugonote francesa , y Olivier provenía de una larga línea de clérigos protestantes. [a] Gerard Olivier había comenzado una carrera como maestro de escuela, pero a los treinta años descubrió una fuerte vocación religiosa y fue ordenado sacerdote de la Iglesia de Inglaterra . [4] Pertenecía a la alta iglesia , el ala ritualista del anglicanismo y era conocido como "Padre Olivier". A algunas congregaciones anglicanas no les gustaba este estilo, [4] y los únicos puestos eclesiásticos que se le ofrecían eran temporales, generalmente sustituyendo a los titulares regulares en su ausencia. Esto significó una existencia nómada y durante los primeros años de Laurence, nunca vivió en un lugar el tiempo suficiente como para hacer amigos. [5]

En 1912, cuando Olivier tenía cinco años, su padre consiguió un puesto permanente como rector adjunto en St Saviour's, Pimlico . Ocupó el puesto durante seis años y por fin pudo llevar una vida familiar estable. [6] Olivier era devoto de su madre, pero no de su padre, a quien consideraba un padre frío y distante, [7] aunque aprendió mucho de él en el arte de la interpretación. De joven, Gerard Olivier había considerado una carrera en el teatro y era un predicador dramático y eficaz. Olivier escribió que su padre sabía "cuándo bajar la voz, cuándo vociferar sobre los peligros del infierno, cuándo poner una mordaza, cuándo ponerse de repente sentimental... Los rápidos cambios de humor y de actitud me absorbieron, y nunca los he olvidado". [8]

En 1916, después de asistir a una serie de escuelas preparatorias, Olivier aprobó el examen de canto para ser admitido en la escuela coral de All Saints, Margaret Street , en el centro de Londres. Su hermano mayor ya era alumno y Olivier se fue adaptando gradualmente, aunque se sentía algo así como un extraño. [9] El estilo de culto de la iglesia era (y sigue siendo) anglocatólico , con énfasis en el ritual, las vestimentas y el incienso. [10] La teatralidad de los servicios atrajo a Olivier, [b] y el vicario alentó a los estudiantes a desarrollar un gusto por el drama secular y religioso. [12] En una producción escolar de Julio César en 1917, la actuación de Olivier, de diez años, como Bruto impresionó a una audiencia que incluía a Lady Tree , la joven Sybil Thorndike y Ellen Terry , quien escribió en su diario: "El niño pequeño que interpretó a Bruto ya es un gran actor". [13] Más tarde recibió elogios en otras producciones escolares, como María en Noche de Reyes (1918) y Katherine en La fierecilla domada (1922). [14]

De All Saints, Olivier pasó a la St Edward's School de Oxford , de 1921 a 1924. [15] No dejó gran huella hasta su último año, cuando interpretó a Puck en la producción de la escuela de El sueño de una noche de verano ; su actuación fue un tour de force que le ganó popularidad entre sus compañeros. [16] [c] En enero de 1924, su hermano dejó Inglaterra para trabajar en la India como plantador de caucho. Olivier lo extrañaba mucho y le preguntó a su padre cuándo podría seguirlo. Recordó en sus memorias que su padre le respondió: "No seas tan tonto, no vas a la India, vas a subir al escenario". [18] [d]

En 1924, Gerard Olivier, un hombre habitualmente frugal, le dijo a su hijo que debía obtener no solo la admisión a la Escuela Central de Oratoria y Arte Dramático , sino también una beca con una bolsa de estudio para cubrir sus gastos de matrícula y manutención. [20] La hermana de Olivier había sido estudiante allí y era la favorita de Elsie Fogerty , la fundadora y directora de la escuela. Olivier especuló más tarde que fue sobre la base de esta conexión que Fogerty acordó otorgarle la beca. [20] [e]

Una de las contemporáneas de Olivier en la escuela fue Peggy Ashcroft , quien observó que era "bastante grosero, ya que sus mangas eran demasiado cortas y su cabello estaba erizado, pero era intensamente vivaz y muy divertido". [22] Según admitió él mismo, no era un estudiante muy concienzudo, pero a Fogerty le agradaba y más tarde dijo que él y Ashcroft se destacaban entre sus muchos alumnos. [23]

Después de dejar la Central School en 1925, Olivier trabajó para pequeñas compañías teatrales; [24] su primera aparición en el escenario fue en un sketch llamado The Unfailing Instinct en el Brighton Hippodrome en agosto de 1925. [25] [26] Más tarde ese año, fue contratado por Sybil Thorndike (la hija de un amigo del padre de Olivier) y su esposo Lewis Casson como actor de papeles secundarios, suplente y asistente de dirección de escena para su compañía de Londres. [24] Olivier modeló su estilo de actuación en el de Gerald du Maurier , de quien dijo: "Parecía murmurar en el escenario, pero tenía una técnica tan perfecta. Cuando comencé, estaba tan ocupado haciendo un du Maurier que nadie escuchó una palabra de lo que dije. Los actores shakespearianos que uno veía eran unos jamones terribles como Frank Benson ". [27] La preocupación de Olivier por hablar con naturalidad y evitar lo que él llamaba "cantar" los versos de Shakespeare fue causa de mucha frustración al principio de su carrera, ya que los críticos criticaban regularmente su forma de hablar. [28]

En 1926, por recomendación de Thorndike, Olivier se unió a la Birmingham Repertory Company . [29] Su biógrafo Michael Billington describe la compañía de Birmingham como "la universidad de Olivier", donde en su segundo año se le dio la oportunidad de interpretar una amplia gama de papeles importantes, incluido Tony Lumpkin en She Stoops to Conquer , el papel principal en Uncle Vanya y Parolles en All's Well That Ends Well . [30] Billington agrega que el compromiso condujo a "una amistad de por vida con su compañero actor Ralph Richardson que tendría un efecto decisivo en el teatro británico". [1]

Mientras interpretaba el papel protagónico juvenil en Bird in Hand en el Royalty Theatre en junio de 1928, Olivier comenzó una relación con Jill Esmond , la hija de los actores Henry V. Esmond y Eva Moore . [31] Olivier contó más tarde que pensó que "ella sin duda sería una excelente esposa... No era probable que yo lo hiciera mejor a mi edad y con mi historial mediocre, así que rápidamente me enamoré de ella". [32]

En 1928, Olivier creó el papel de Stanhope en Journey's End de R. C. Sherriff , en la que obtuvo un gran éxito en su único estreno nocturno de domingo. [33] Se le ofreció el papel en la producción del West End al año siguiente, pero lo rechazó a favor del papel más glamoroso de Beau Geste en una adaptación teatral de la novela de PC Wren de 1929 del mismo nombre. Journey's End se convirtió en un éxito duradero; Beau Geste fracasó. [1] El Manchester Guardian comentó: "El Sr. Laurence Olivier hizo lo mejor que pudo como Beau, pero se merece y obtendrá mejores papeles. El Sr. Olivier se va a hacer un gran nombre". [34] Durante el resto de 1929, Olivier apareció en siete obras, todas las cuales duraron poco. Billington atribuye esta tasa de fracaso a las malas decisiones de Olivier en lugar de a la mera mala suerte. [1] [f]

En 1930, con su inminente matrimonio en mente, Olivier ganó algo de dinero extra con pequeños papeles en dos películas. [38] En abril viajó a Berlín para filmar la versión en inglés de The Temporary Widow , una comedia policial con Lilian Harvey , [g] y en mayo pasó cuatro noches trabajando en otra comedia, Too Many Crooks . [40] Durante el trabajo en la última película, por la que le pagaron £ 60, [h] conoció a Laurence Evans, quien se convirtió en su representante personal. [38] A Olivier no le gustaba trabajar en el cine, al que desestimó como "este pequeño medio anémico que no podía soportar grandes actuaciones", [42] pero financieramente era mucho más gratificante que su trabajo en el teatro. [43]

Olivier y Esmond se casaron el 25 de julio de 1930 en All Saints, Margaret Street, [44] aunque en cuestión de semanas ambos se dieron cuenta de que habían cometido un error. Olivier escribió más tarde que el matrimonio fue "un error bastante craso. Insistí en casarme por una patética mezcla de impulsos religiosos y animales... Ella me había admitido que estaba enamorada de otra persona y que nunca podría amarme tan completamente como yo desearía". [45] [i] [j] Olivier contó más tarde que después de la boda no llevó un diario durante diez años y nunca volvió a practicar la religión, aunque consideró que esos hechos eran "mera coincidencia", sin relación con las nupcias. [48]

En 1930, Noël Coward eligió a Olivier para interpretar a Victor Prynne en su nueva obra Private Lives , que se estrenó en el nuevo Phoenix Theatre de Londres en septiembre. Coward y Gertrude Lawrence interpretaron los papeles principales, Elyot Chase y Amanda Prynne. Victor es un personaje secundario, junto con Sybil Chase; el autor los llamó "títeres adicionales, bolos de madera ligera, que solo se derriban y se vuelven a levantar repetidamente". [49] Para convertirlos en esposos creíbles para Amanda y Elyot, Coward estaba decidido a que dos intérpretes extraordinariamente atractivos interpretaran los papeles. [50] Olivier interpretó a Victor en el West End y luego en Broadway ; Adrianne Allen fue Sybil en Londres, pero no pudo ir a Nueva York, donde el papel lo interpretó Esmond. [51] Además de darle a Olivier, de 23 años, su primer papel exitoso en el West End, Coward se convirtió en una especie de mentor. A fines de la década de 1960, Olivier le dijo a Sheridan Morley :

Noël me dio un sentido del equilibrio, del bien y del mal. Me hacía leer; antes yo no leía nada. Recuerdo que me dijo: "Bien, muchacho, Cumbres borrascosas , De la servidumbre humana y El cuento de las viejas de Arnold Bennett . Eso basta, son tres de los mejores. Léelos". Y lo hice. ... Noël también hizo algo inestimable: me enseñó a no reírme en el escenario. Una vez ya me habían despedido por hacerlo, y casi me despiden del Birmingham Rep. por la misma razón. Noël me curó; al intentar hacerme reír escandalosamente, me enseñó a no ceder a la risa. [k] Mi gran triunfo llegó en Nueva York, cuando una noche logré hacer reír a Noël en el escenario sin reírme yo también". [53]

En 1931, RKO Pictures le ofreció a Olivier un contrato de dos películas por 1000 dólares semanales; [l] discutió la posibilidad con Coward, quien, molesto, le dijo a Olivier "No tienes integridad artística, ese es tu problema; así es como te abaratas". [55] Aceptó y se mudó a Hollywood, a pesar de algunas dudas. Su primera película fue el drama Friends and Lovers , en un papel secundario, antes de que RKO lo prestara a Fox Studios para su primer papel protagonista, un periodista británico en una Rusia bajo la ley marcial en The Yellow Ticket , junto a Elissa Landi y Lionel Barrymore . [56] El historiador cultural Jeffrey Richards describe el aspecto de Olivier como un intento de Fox Studios de producir una semejanza de Ronald Colman , y el bigote, la voz y los modales de Colman están "perfectamente reproducidos". [57] Olivier regresó a RKO para completar su contrato con el drama de 1932 Westward Passage , que fue un fracaso comercial. [58] La incursión inicial de Olivier en el cine estadounidense no le había proporcionado el éxito que esperaba; desilusionado con Hollywood, regresó a Londres, donde apareció en dos películas británicas, Perfect Understanding con Gloria Swanson y No Funny Business , en la que también apareció Esmond. Se sintió tentado a volver a Hollywood en 1933 para aparecer junto a Greta Garbo en Queen Christina , pero fue reemplazado después de dos semanas de rodaje debido a la falta de química entre los dos. [59]

Los papeles teatrales de Olivier en 1934 incluyeron a Bothwell en La reina de Escocia de Gordon Daviot , que fue solo un éxito moderado para él y para la obra, pero que le llevó a un importante contrato con la misma dirección ( Bronson Albery ) poco después. Mientras tanto, tuvo un gran éxito interpretando una versión apenas disfrazada del actor estadounidense John Barrymore en Theatre Royal de George S. Kaufman y Edna Ferber . Su éxito se vio viciado por la fractura de tobillo que sufrió dos meses después de la presentación, en una de las acrobacias atléticas con las que le gustaba animar sus actuaciones. [60]

El señor Olivier estaba veinte veces más enamorado de Peggy Ashcroft que el señor Gielgud, pero el señor Gielgud recitaba la mayor parte de la poesía mucho mejor que el señor Olivier... Sin embargo, debo decirlo: el fuego de la pasión del señor Olivier llevó adelante la obra, algo que el señor Gielgud no logró del todo.

Herbert Farjeon sobre los Romeos rivales [61]

En 1935, bajo la dirección de Albery, John Gielgud representó Romeo y Julieta en el New Theatre , coprotagonizada por Peggy Ashcroft, Edith Evans y Olivier. Gielgud había visto a Olivier en La reina de Escocia , detectó su potencial y le dio un gran paso adelante en su carrera. Durante las primeras semanas de la obra, Gielgud interpretó a Mercutio y Olivier a Romeo , después de lo cual intercambiaron papeles. [m] La producción rompió todos los récords de taquilla para la obra, con 189 representaciones. [n] Olivier se enfureció con los anuncios después de la primera noche, que elogiaron la virilidad de su actuación pero criticaron ferozmente su forma de hablar de los versos de Shakespeare, contrastándolos con la maestría de su coprotagonista de la poesía. [o] La amistad entre los dos hombres fue espinosa, por parte de Olivier, durante el resto de su vida. [64]

En mayo de 1936, Olivier y Richardson dirigieron y protagonizaron conjuntamente una nueva pieza de J. B. Priestley , Bees on the Boatdeck . Ambos actores obtuvieron excelentes críticas, pero la obra, una alegoría de la decadencia de Gran Bretaña, no atrajo al público y cerró después de cuatro semanas. [65] Más tarde, ese mismo año, Olivier aceptó una invitación para unirse a la compañía Old Vic . El teatro, en una ubicación poco elegante al sur del Támesis , había ofrecido entradas económicas para ópera y teatro bajo la dirección de su propietaria Lilian Baylis desde 1912. [66] Su compañía de teatro se especializaba en las obras de Shakespeare, y muchos actores principales habían aceptado grandes recortes en sus salarios para desarrollar sus técnicas shakespearianas allí. [p] Gielgud había estado en la compañía desde 1929 hasta 1931 y Richardson desde 1930 hasta 1932. [68] Entre los actores a los que Olivier se unió a fines de 1936 estaban Edith Evans , Ruth Gordon , Alec Guinness y Michael Redgrave . [69] En enero de 1937, Olivier tomó el papel principal en una versión sin cortes de Hamlet en la que una vez más su interpretación del verso fue comparada desfavorablemente con la de Gielgud, quien había interpretado el papel en el mismo escenario siete años antes con enorme aclamación. [q] Ivor Brown de The Observer elogió el "magnetismo y musculatura" de Olivier, pero extrañó "el tipo de patetismo tan ricamente establecido por el Sr. Gielgud". [72] El crítico de The Times encontró la actuación "llena de vitalidad", pero a veces "demasiado ligera ... el personaje se le escapa al Sr. Olivier". [73]

Después de Hamlet , la compañía presentó La duodécima noche en lo que el director, Tyrone Guthrie , resumió como "una producción mía mala e inmadura, con Olivier escandalosamente divertido como Sir Toby y un jovencísimo Alec Guinness escandalosamente y más divertido como Sir Andrew ". [74] Enrique V fue la siguiente obra, presentada en mayo para conmemorar la coronación de Jorge VI . Pacifista como era entonces, Olivier era tan reacio a interpretar al rey guerrero como Guthrie a dirigir la pieza, pero la producción fue un éxito y Baylis tuvo que extender la obra de cuatro a ocho semanas. [75]

Tras el éxito de Olivier en las producciones teatrales de Shakespeare, hizo su primera incursión en Shakespeare en el cine en 1936, como Orlando en Como gustéis , dirigida por Paul Czinner , "una producción encantadora aunque ligera", según Michael Brooke de Screenonline del British Film Institute (BFI) . [76] Al año siguiente, Olivier apareció junto a Vivien Leigh en el drama histórico Fuego sobre Inglaterra . Había conocido a Leigh brevemente en el Savoy Grill y luego nuevamente cuando ella lo visitó durante la presentación de Romeo y Julieta , probablemente a principios de 1936, y los dos habían comenzado un romance en algún momento de ese año. [77] De la relación, Olivier dijo más tarde que "no pude evitarlo con Vivien. Ningún hombre podría. Me odiaba a mí mismo por engañar a Jill, pero ya la había engañado antes, pero esto era algo diferente. Esto no fue solo por lujuria. Este fue un amor que realmente no pedí, pero me sentí atraído". [78] Mientras su relación con Leigh continuó, mantuvo un romance con la actriz Ann Todd , [79] y posiblemente tuvo un breve romance con el actor Henry Ainley , según el biógrafo Michael Munn . [80] [r]

En junio de 1937, la compañía Old Vic aceptó una invitación para representar Hamlet en el patio del castillo de Elsinor , donde Shakespeare situó la obra. Olivier consiguió el papel de Leigh para sustituir a Cherry Cottrell como Ofelia . Debido a las lluvias torrenciales, la representación tuvo que trasladarse del patio del castillo al salón de baile de un hotel local, pero la tradición de representar Hamlet en Elsinor se estableció, y a Olivier le siguieron, entre otras, Gielgud (1939), Redgrave (1950), Richard Burton (1954), Christopher Plummer (1964), Derek Jacobi (1979), Kenneth Branagh (1988) y Jude Law (2009). [85] De vuelta en Londres, la compañía representó Macbeth , con Olivier en el papel principal. La estilizada producción de Michel Saint-Denis no gustó mucho, pero Olivier tuvo algunas buenas críticas entre las malas. [86] Al regresar de Dinamarca, Olivier y Leigh les contaron a sus respectivas esposas sobre el asunto y que sus matrimonios habían terminado; Esmond se mudó de la casa conyugal y se fue a vivir con su madre. [87] Después de que Olivier y Leigh hicieran una gira por Europa a mediados de 1937, regresaron a proyectos cinematográficos separados ( A Yank at Oxford para ella y The Divorce of Lady X para él) y se mudaron juntos a una propiedad en Iver , Buckinghamshire. [88]

Olivier regresó al Old Vic para una segunda temporada en 1938. Para Otelo interpretó a Yago , con Richardson en el papel principal. Guthrie quería experimentar con la teoría de que la villanía de Yago está impulsada por un amor reprimido por Otelo . [89] Olivier estaba dispuesto a cooperar, pero Richardson no; el público y la mayoría de los críticos no lograron detectar la supuesta motivación del Yago de Olivier, y el Otelo de Richardson parecía poco potente. [90] Después de ese fracaso comparativo, la compañía tuvo un éxito con Coriolanus protagonizada por Olivier en el papel principal. Las críticas fueron elogiosas, mencionándolo junto a grandes predecesores como Edmund Kean , William Macready y Henry Irving . El actor Robert Speaight lo describió como "la primera actuación incontestablemente grandiosa de Olivier". [91] Esta fue la última aparición de Olivier en un escenario de Londres durante seis años. [91]

En 1938, Olivier se unió a Richardson para filmar el thriller de espías Q Planes , estrenado al año siguiente. Frank Nugent , el crítico de The New York Times , pensó que Olivier "no era tan bueno" como Richardson, pero era "bastante aceptable". [92] A fines de 1938, atraído por un salario de $50,000, el actor viajó a Hollywood para interpretar el papel de Heathcliff en la película de 1939 Cumbres borrascosas , junto a Merle Oberon y David Niven . [93] [s] En menos de un mes, Leigh se unió a él, explicando que su viaje fue "en parte porque Larry está allí y en parte porque tengo la intención de conseguir el papel de Scarlett O'Hara ", el papel en Lo que el viento se llevó para el que finalmente fue elegida. [94] Olivier no disfrutó haciendo Cumbres borrascosas , y su enfoque de la actuación cinematográfica, combinado con su aversión por Oberon, provocó tensiones en el set. [95] El director, William Wyler , era un duro capataz, y Olivier aprendió a eliminar lo que Billington describió como "el caparazón de teatralidad" al que era propenso, reemplazándolo con "una realidad palpable". [1] La película resultante fue un éxito comercial y de crítica que le valió una nominación al Oscar al Mejor Actor y creó su reputación en la pantalla. [96] [t] Caroline Lejeune , escribiendo para The Observer , consideró que "el rostro oscuro y melancólico de Olivier, su estilo abrupto y cierta arrogancia fina hacia el mundo en su interpretación son perfectos" en el papel, [98] mientras que el crítico de The Times escribió que Olivier "es una buena encarnación de Heathcliff... lo suficientemente impresionante en un plano más humano, diciendo sus líneas con verdadera distinción, y siempre romántico y vivo". [99]

Después de regresar brevemente a Londres a mediados de 1939, la pareja regresó a Estados Unidos, Leigh para filmar las tomas finales de Lo que el viento se llevó y Olivier para prepararse para el rodaje de Rebecca de Alfred Hitchcock , aunque la pareja esperaba aparecer en ella juntos. [100] En cambio, Joan Fontaine fue seleccionada para el papel de la Sra. de Winter, ya que el productor David O. Selznick pensó que no solo era más adecuada para el papel, sino que era mejor mantener separados a Olivier y Leigh hasta que se concretaran sus divorcios. [101] Olivier siguió a Rebecca con Orgullo y prejuicio , en el papel del Sr. Darcy . Para su decepción, Elizabeth Bennet fue interpretada por Greer Garson en lugar de Leigh. Recibió buenas críticas por ambas películas y mostró una presencia en pantalla más segura que en sus primeros trabajos. [102] En enero de 1940, a Olivier y Esmond se les concedió el divorcio. En febrero, a raíz de otra petición de Leigh, su marido también solicitó la disolución del matrimonio. [103]

En el escenario, Olivier y Leigh protagonizaron Romeo y Julieta en Broadway. Fue una producción extravagante, pero un fracaso comercial. [104] En The New York Times, Brooks Atkinson elogió la escenografía pero no la actuación: "Aunque la señorita Leigh y el señor Olivier son jóvenes guapos, apenas actúan sus papeles". [105] La pareja había invertido casi todos sus ahorros en el proyecto, y su fracaso fue un duro golpe financiero. [106] Se casaron en agosto de 1940, en el rancho San Ysidro en Santa Bárbara . [107]

La guerra en Europa llevaba ya un año en marcha y estaba yendo mal para Gran Bretaña. Después de su boda, Olivier quiso ayudar al esfuerzo bélico. Telefoneó a Duff Cooper , el Ministro de Información de Winston Churchill , con la esperanza de conseguir un puesto en el departamento de Cooper. Cooper le aconsejó que se quedara donde estaba y hablara con el director de cine Alexander Korda , que estaba basado en los EE. UU. a instancias de Churchill, con conexiones con la inteligencia británica. [108] [u] Korda, con el apoyo y la participación de Churchill, dirigió That Hamilton Woman , con Olivier como Horatio Nelson y Leigh en el papel principal . Korda vio que la relación entre la pareja era tensa. Olivier estaba cansado de la sofocante adulación de Leigh, y ella bebía en exceso. [109] La película, en la que la amenaza de Napoleón era paralela a la de Hitler , fue vista por los críticos como "mala historia pero buena propaganda británica", según el BFI. [110]

La vida de Olivier estaba amenazada por los nazis y los simpatizantes proalemanes. Los dueños del estudio estaban tan preocupados que Samuel Goldwyn y Cecil B. DeMille le brindaron apoyo y seguridad para garantizar su seguridad. [111] Al finalizar el rodaje, Olivier y Leigh regresaron a Gran Bretaña. Había pasado el año anterior aprendiendo a volar y había completado casi 250 horas cuando dejó Estados Unidos. Tenía la intención de unirse a la Real Fuerza Aérea, pero en su lugar hizo otra película de propaganda, 49th Parallel , narró piezas cortas para el Ministerio de Información y se unió a la Fleet Air Arm porque Richardson ya estaba en el servicio. Richardson se había ganado una reputación por estrellar aviones, que Olivier eclipsó rápidamente. [112] Olivier y Leigh se instalaron en una cabaña a las afueras de RNAS Worthy Down , donde estaba destinado con un escuadrón de entrenamiento; Noël Coward visitó a la pareja y pensó que Olivier parecía infeliz. [113] Olivier pasó gran parte de su tiempo participando en transmisiones y haciendo discursos para levantar la moral, y en 1942 fue invitado a hacer otra película de propaganda, The Demi-Paradise , en la que interpretó a un ingeniero soviético que ayuda a mejorar las relaciones británico-rusas. [114]

En 1943, a instancias del Ministerio de Información, Olivier comenzó a trabajar en Enrique V. Originalmente no tenía intención de asumir las funciones de director, pero terminó dirigiendo y produciendo, además de asumir el papel principal. Fue asistido por un interno italiano, Filippo Del Giudice , que había sido liberado para producir propaganda para la causa aliada. [115] Se tomó la decisión de filmar las escenas de batalla en Irlanda neutral, donde era más fácil encontrar a los 650 extras. John Betjeman , el agregado de prensa de la embajada británica en Dublín, jugó un papel clave de enlace con el gobierno irlandés para hacer los arreglos adecuados. [116] La película se estrenó en noviembre de 1944. Brooke, que escribe para el BFI, considera que "llegó demasiado tarde en la Segunda Guerra Mundial para ser un llamado a las armas como tal, pero formó un poderoso recordatorio de lo que Gran Bretaña estaba defendiendo". [117] La música de la película fue escrita por William Walton , "una banda sonora que se ubica entre las mejores de la música cinematográfica", según el crítico musical Michael Kennedy . [118] Walton también proporcionó la música para las siguientes dos adaptaciones shakespearianas de Olivier, Hamlet (1948) y Ricardo III (1955). [119] Enrique V fue recibida calurosamente por los críticos. El crítico de The Manchester Guardian escribió que la película combinaba "el nuevo arte de la mano con el viejo genio, y ambos magníficamente de una sola mente", en una película que funcionó "triunfalmente". [120] El crítico de The Times consideró que Olivier "interpreta a Enrique en una nota alta y heroica y nunca hay peligro de una grieta", en una película descrita como "un triunfo del arte cinematográfico". [121] Hubo nominaciones al Oscar para la película, incluyendo Mejor Película y Mejor Actor, pero no ganó ninguna y Olivier recibió en cambio un "Premio Especial". [122] No quedó impresionado y más tarde comentó que "ésta fue mi primera derrota absoluta y lo consideré como tal". [123]

Durante toda la guerra, Tyrone Guthrie se había esforzado por mantener en funcionamiento la compañía del Old Vic, incluso después de que los bombardeos alemanes de 1942 dejaran el teatro casi en ruinas. Una pequeña compañía realizó giras por las provincias, con Sybil Thorndike a la cabeza. En 1944, cuando la marea de la guerra estaba cambiando, Guthrie consideró que era hora de restablecer la compañía en una base de Londres e invitó a Richardson a dirigirla. [124] Richardson puso como condición para aceptar que él compartiría la actuación y la dirección en un triunvirato. Inicialmente propuso a Gielgud y Olivier como sus colegas, pero el primero declinó, diciendo: "Sería un desastre, tendrías que pasar todo tu tiempo como árbitro entre Larry y yo". [125] [v] Finalmente se acordó que el tercer miembro sería el director de escena John Burrell . Los gobernadores del Old Vic se acercaron a la Marina Real para asegurar la liberación de Richardson y Olivier; Los señores del mar consintieron, como dijo Olivier, "con una rapidez y una falta de renuencia que fueron positivamente perjudiciales". [127]

El triunvirato consiguió el New Theatre para su primera temporada y reclutó una compañía. A Thorndike se unieron, entre otros, Harcourt Williams , Joyce Redman y Margaret Leighton . Se acordó abrir con un repertorio de cuatro obras: Peer Gynt , Arms and the Man , Ricardo III y Tío Vania . Los papeles de Olivier fueron el moldeador de botones, Sergio, Ricardo y Astrov; Richardson interpretó a Peer, Bluntschli, Richmond y Vania. [128] Las primeras tres producciones fueron aclamadas por los críticos y el público; Tío Vania tuvo una recepción mixta, aunque The Times consideró que Astrov de Olivier era "un retrato muy distinguido" y Vania de Richardson "la combinación perfecta de absurdo y patetismo". [129] En Ricardo III , según Billington, el triunfo de Olivier fue absoluto: "tanto que se convirtió en su actuación más imitada y cuya supremacía no fue cuestionada hasta que Antony Sher interpretó el papel cuarenta años después". [1] En 1945, la compañía realizó una gira por Alemania, donde fue vista por miles de militares aliados; también actuó en el teatro Comédie-Française de París, siendo la primera compañía extranjera en recibir ese honor. [130] El crítico Harold Hobson escribió que Richardson y Olivier rápidamente "hicieron del Old Vic el teatro más famoso del mundo anglosajón". [131]

La segunda temporada, en 1945, incluyó dos funciones dobles. La primera consistió en Enrique IV, partes 1 y 2. Olivier interpretó al guerrero Hotspur en la primera y al vacilante juez Shallow en la segunda. [w] Recibió buenas críticas, pero por consenso general la producción perteneció a Richardson como Falstaff . [133] En la segunda función doble fue Olivier quien dominó, en los papeles principales de Edipo Rey y El Crítico . En las dos obras de un acto, su cambio de tragedia y horror abrasadores en la primera mitad a comedia farsa en la segunda impresionó a la mayoría de los críticos y miembros de la audiencia, aunque una minoría sintió que la transformación del héroe cegado por la sangre de Sófocles al vanidoso y ridículo Sr. Puff de Sheridan "olía a un cambio rápido en un music hall". [134] Después de la temporada de Londres, la compañía representó tanto las funciones dobles como El tío Vania en una presentación de seis semanas en Broadway. [135]

La tercera y última temporada londinense bajo el triunvirato fue en 1946-47. Olivier interpretó al Rey Lear y Richardson tomó el papel principal en Cyrano de Bergerac . Olivier hubiera preferido que los papeles se invirtieran, pero Richardson no quiso intentar interpretar a Lear. [136] El Lear de Olivier recibió críticas buenas pero no sobresalientes. En sus escenas de decadencia y locura hacia el final de la obra, algunos críticos lo encontraron menos conmovedor que sus mejores predecesores en el papel. [137] El influyente crítico James Agate sugirió que Olivier usó su deslumbrante técnica escénica para disfrazar una falta de sentimiento, una acusación que el actor rechazó firmemente, pero que se hizo a menudo a lo largo de su carrera posterior. [138] Durante la representación de Cyrano , Richardson fue nombrado caballero , para la envidia no disimulada de Olivier. [139] El hombre más joven recibió el galardón seis meses después, momento en el que los días del triunvirato estaban contados. El alto perfil de los dos actores estrella no los hizo muy queridos por el nuevo presidente de la junta de gobernadores del Old Vic, Lord Esher . Tenía ambiciones de ser el primer director del Teatro Nacional y no tenía intención de dejar que los actores lo dirigieran. [140] Guthrie lo alentó, ya que, tras haber instigado el nombramiento de Richardson y Olivier, había llegado a resentir sus títulos de caballero y su fama internacional. [141]

En enero de 1947, Olivier comenzó a trabajar en su segunda película como director, Hamlet (1948), en la que también interpretó el papel principal. La obra original fue recortada en gran medida para centrarse en las relaciones, en lugar de la intriga política. La película se convirtió en un éxito crítico y comercial en Gran Bretaña y en el extranjero, aunque Lejeune, en The Observer , la consideró "menos efectiva que el trabajo teatral [de Olivier] ... Dice las líneas noblemente y con la caricia de alguien que las ama, pero anula su propia tesis al no dejar nunca, ni por un momento, la impresión de un hombre que no puede tomar una decisión; aquí, uno siente más bien, que hay un actor-productor-director que, en cualquier circunstancia, sabe exactamente lo que quiere y lo consigue". [142] Campbell Dixon , el crítico de The Daily Telegraph, pensó que la película era "brillante ... una de las obras maestras del teatro se ha convertido en una de las mejores películas". [143] Hamlet se convirtió en la primera película no estadounidense en ganar el Premio de la Academia a la Mejor Película , mientras que Olivier ganó el Premio al Mejor Actor. [144] [145] [x]

En 1948, Olivier dirigió a la compañía Old Vic en una gira de seis meses por Australia y Nueva Zelanda. Interpretó a Ricardo III, Sir Peter Teazle en The School for Scandal de Sheridan y a Antrobus en The Skin of Our Teeth de Thornton Wilder , apareciendo junto a Leigh en las dos últimas obras. Mientras Olivier estaba de gira por Australia y Richardson estaba en Hollywood, Esher rescindió los contratos de los tres directores, que se dijo que habían "dimitido". [147] Melvyn Bragg en un estudio de 1984 sobre Olivier, y John Miller en la biografía autorizada de Richardson, ambos comentan que la acción de Esher retrasó la creación de un Teatro Nacional durante al menos una década. [148] Mirando hacia atrás en 1971, Bernard Levin escribió que la compañía Old Vic de 1944 a 1948 "fue probablemente la más ilustre que se haya reunido nunca en este país". [149] El Times dijo que los años del triunvirato fueron los mejores en la historia del Old Vic; [150] como lo expresó The Guardian , "los gobernadores los despidieron sumariamente en pos de un espíritu de compañía más mediocre". [151]

.jpg/440px-Sir_Laurence_Olivier_and_Vivien_Leigh_on_holiday_in_Queensland_(3190855694).jpg)

Al final de la gira australiana, tanto Leigh como Olivier estaban exhaustos y enfermos, y él le dijo a un periodista: "Puede que no lo sepas, pero estás hablando con un par de cadáveres andantes". Más tarde comentaría que "perdió a Vivien" en Australia, [152] una referencia al romance de Leigh con el actor australiano Peter Finch , a quien la pareja conoció durante la gira. Poco después, Finch se mudó a Londres, donde Olivier lo audicionó y lo puso bajo un contrato de largo plazo con Laurence Olivier Productions . El romance de Finch y Leigh continuó intermitentemente durante varios años. [153] [154]

Aunque era de conocimiento público que el triunvirato del Old Vic había sido despedido, [155] se negaron a hablar del asunto en público, y Olivier incluso acordó actuar una última temporada en Londres con la compañía en 1949, como Ricardo III, Sir Peter Teazle y Coro en su propia producción de Antígona de Anouilh con Leigh en el papel principal. [1] Después de eso, fue libre de embarcarse en una nueva carrera como actor-representante. En asociación con Binkie Beaumont, montó el estreno en inglés de Un tranvía llamado deseo de Tennessee Williams , con Leigh en el papel central de Blanche DuBois. La obra fue condenada por la mayoría de los críticos, pero la producción fue un éxito comercial considerable y llevó a que Leigh fuera elegida para interpretar a Blanche en la versión cinematográfica de 1951 . [156] Gielgud, que era un amigo devoto de Leigh, dudaba de que Olivier fuera prudente al dejarla desempeñar el exigente papel de la heroína mentalmente inestable: "[Blanche] se parecía mucho a ella, en cierto modo. Debe haber sido un esfuerzo terrible hacerlo noche tras noche. Ella temblaba, estaba pálida y bastante angustiada al final". [157]

Creo que ahora soy un buen director. Dirigí el teatro St. James durante ocho años, pero no lo hice nada bien. Cometí un error tras otro, pero me atrevo a decir que esos errores me enseñaron algo.

Olivier hablando con Kenneth Tynan en 1966 [12]

La productora creada por Olivier alquiló el teatro St James's . En enero de 1950 produjo, dirigió y protagonizó la obra en verso Venus Observed de Christopher Fry . La producción fue popular, a pesar de las malas críticas, pero la costosa producción no ayudó mucho a las finanzas de Laurence Olivier Productions. Después de una serie de fracasos de taquilla, [y] la compañía equilibró sus cuentas en 1951 con producciones de César y Cleopatra de Shaw y Antonio y Cleopatra de Shakespeare , que los Olivier interpretaron en Londres y luego llevaron a Broadway. Algunos críticos pensaron que Olivier estaba por debajo de sus expectativas en ambos papeles, y algunos sospecharon que actuaba deliberadamente por debajo de su fuerza habitual para que Leigh pudiera parecer su igual. [159] Olivier descartó la sugerencia, considerándola un insulto a su integridad como actor. En opinión del crítico y biógrafo W. A. Darlington , simplemente no fue elegido para los papeles de César y Antonio, ya que encontró aburrido al primero y débil al segundo. Darlington comenta: "Olivier, a mediados de sus cuarenta, cuando debería haber estado mostrando sus poderes en su apogeo, parecía haber perdido el interés en su propia actuación". [160] Durante los siguientes cuatro años, Olivier pasó gran parte de su tiempo trabajando como productor, presentando obras en lugar de dirigirlas o actuar en ellas. [160] Sus presentaciones en el St James's incluyeron temporadas de la compañía de Ruggero Ruggeri presentando dos obras de Pirandello en italiano, seguidas de una visita de la Comédie-Française interpretando obras de Molière , Racine , Marivaux y Musset en francés. [161] Darlington considera una producción de 1951 de Otelo protagonizada por Orson Welles como la mejor de las producciones de Olivier en el teatro. [160]

Mientras Leigh rodaba Un tranvía en 1951, Olivier se unió a ella en Hollywood para filmar Carrie , basada en la controvertida novela Sister Carrie ; aunque la película estuvo plagada de problemas, Olivier recibió cálidas críticas y una nominación al BAFTA . [162] Olivier comenzó a notar un cambio en el comportamiento de Leigh, y más tarde contó que "encontraba a Vivien sentada en la esquina de la cama, retorciéndose las manos y sollozando, en un estado de grave angustia; naturalmente trataba desesperadamente de darle algo de consuelo, pero durante algún tiempo estaba inconsolable". [163] Después de unas vacaciones con Coward en Jamaica, ella parecía haberse recuperado, pero Olivier escribió más tarde: "Estoy seguro de que... [los médicos] debieron haberse tomado algunas molestias para decirme qué le pasaba a mi esposa; que su enfermedad se llamaba depresión maníaca y lo que eso significaba: un ir y venir cíclico posiblemente permanente entre las profundidades de la depresión y la manía salvaje e incontrolable". [164] También contó los años de problemas que había experimentado debido a la enfermedad de Leigh, escribiendo: "a lo largo de su posesión por ese monstruo extrañamente malvado, la depresión maníaca, con sus espirales mortales cada vez más apretadas, ella conservó su propia astucia individual: una capacidad para disfrazar su verdadera condición mental de casi todos, excepto de mí, por quien difícilmente se podía esperar que se tomara la molestia". [165]

En enero de 1953, Leigh viajó a Ceilán (hoy Sri Lanka) para filmar Elephant Walk con Peter Finch. Poco después de comenzar el rodaje, sufrió una crisis nerviosa y regresó a Gran Bretaña, donde, entre períodos de incoherencia, le dijo a Olivier que estaba enamorada de Finch y que había estado teniendo una aventura con él; [166] se recuperó gradualmente durante un período de varios meses. Como resultado de la crisis nerviosa, muchos de los amigos de los Olivier se enteraron de sus problemas. Niven dijo que había estado "bastante, bastante loca", [167] y, en su diario, Coward expresó la opinión de que "las cosas habían estado mal y empeorando desde 1948 o por ahí". [168]

Para la temporada de la Coronación de 1953, Olivier y Leigh protagonizaron en el West End la comedia ruritana de Terence Rattigan , El príncipe durmiente . Se presentó durante ocho meses [169] pero fue ampliamente considerada como una contribución menor a la temporada, en la que otras producciones incluyeron a Gielgud en Venice Preserv'd , Coward en The Apple Cart y Ashcroft y Redgrave en Antony and Cleopatra . [170] [171]

Olivier directed his third Shakespeare film in September 1954, Richard III (1955), which he co-produced with Korda. The presence of four theatrical knights in the one film—Olivier was joined by Cedric Hardwicke, Gielgud and Richardson—led an American reviewer to dub it "An-All-Sir-Cast".[172] The critic for The Manchester Guardian described the film as a "bold and successful achievement",[173][174] but it was not a box-office success, which accounted for Olivier's subsequent failure to raise the funds for a planned film of Macbeth.[172] He won a BAFTA award for the role and was nominated for the Best Actor Academy Award, which Yul Brynner won.[175][176]

In 1955 Olivier and Leigh were invited to play leading roles in three plays at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford. They began with Twelfth Night, directed by Gielgud, with Olivier as Malvolio and Leigh as Viola. Rehearsals were difficult, with Olivier determined to play his conception of the role despite the director's view that it was vulgar.[177] Gielgud later commented:

Somehow the production did not work. Olivier was set on playing Malvolio in his own particular rather extravagant way. He was extremely moving at the end, but he played the earlier scenes like a Jewish hairdresser, with a lisp and an extraordinary accent, and he insisted on falling backwards off a bench in the garden scene, though I begged him not to do it. ... But then Malvolio is a very difficult part.[178]

The next production was Macbeth. Reviewers were lukewarm about the direction by Glen Byam Shaw and the designs by Roger Furse, but Olivier's performance in the title role attracted superlatives.[179] To J. C. Trewin, Olivier's was "the finest Macbeth of our day"; to Darlington it was "the best Macbeth of our time".[180][181] Leigh's Lady Macbeth received mixed but generally polite notices,[180][182][183] although to the end of his life Olivier believed it to have been the best Lady Macbeth he ever saw.[184]

In their third production of the 1955 Stratford season, Olivier played the title role in Titus Andronicus, with Leigh as Lavinia. Her notices in the part were damning,[z] but the production by Peter Brook and Olivier's performance as Titus received the greatest ovation in Stratford history from the first-night audience, and the critics hailed the production as a landmark in post-war British theatre.[186] Olivier and Brook revived the production for a continental tour in June 1957; its final performance, which closed the old Stoll Theatre in London, was the last time Leigh and Olivier acted together.[181]

Leigh became pregnant in 1956 and withdrew from the production of Coward's comedy South Sea Bubble.[187] The day after her final performance in the play she miscarried and entered a period of depression that lasted for months.[188] In the same year Olivier directed and co-starred with Marilyn Monroe in a film version of The Sleeping Prince, retitled The Prince and the Showgirl. Although the filming was challenging because of Monroe's behaviour, the film was appreciated by the critics.[189]

During the production of The Prince and the Showgirl, Olivier, Monroe and her husband, the American playwright Arthur Miller, went to see the English Stage Company's production of John Osborne's Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court. Olivier had seen the play earlier in the run and disliked it, but Miller was convinced that Osborne had talent, and Olivier reconsidered. He was ready for a change of direction; in 1981 he wrote:

I had reached a stage in my life that I was getting profoundly sick of—not just tired—sick. Consequently the public were, likely enough, beginning to agree with me. My rhythm of work had become a bit deadly: a classical or semi-classical film; a play or two at Stratford, or a nine-month run in the West End, etc etc. I was going mad, desperately searching for something suddenly fresh and thrillingly exciting. What I felt to be my image was boring me to death.[190]

Osborne was already at work on a new play, The Entertainer, an allegory of Britain's post-colonial decline, centred on a seedy variety comedian, Archie Rice. Having read the first act—all that was completed by then—Olivier asked to be cast in the part. He had for years maintained that he might easily have been a third-rate comedian called "Larry Oliver", and would sometimes play the character at parties. Behind Archie's brazen façade there is a deep desolation, and Olivier caught both aspects, switching, in the words of the biographer Anthony Holden, "from a gleefully tacky comic routine to moments of the most wrenching pathos".[191] Tony Richardson's production for the English Stage Company transferred from the Royal Court to the Palace Theatre in September 1957; after that it toured and returned to the Palace.[192] The role of Archie's daughter Jean was taken by three actresses during the various runs. The second of them was Joan Plowright, with whom Olivier began a relationship that endured for the rest of his life.[aa] Olivier said that playing Archie "made me feel like a modern actor again".[194] In finding an avant-garde play that suited him, he was, as Osborne remarked, far ahead of Gielgud and Ralph Richardson, who did not successfully follow his lead for more than a decade.[195][ab] Their first substantial successes in works by any of Osborne's generation were Alan Bennett's Forty Years On (Gielgud in 1968) and David Storey's Home (Richardson and Gielgud in 1970).[197]

Olivier received another BAFTA nomination for his supporting role in 1959's The Devil's Disciple.[176] The same year, after a gap of two decades, Olivier returned to the role of Coriolanus, in a Stratford production directed by the 28-year-old Peter Hall. Olivier's performance received strong praise from the critics for its fierce athleticism combined with an emotional vulnerability.[1] In 1960 he made his second appearance for the Royal Court company in Ionesco's absurdist play Rhinoceros. The production was chiefly remarkable for the star's quarrels with the director, Orson Welles, who according to the biographer Francis Beckett suffered the "appalling treatment" that Olivier had inflicted on Gielgud at Stratford five years earlier. Olivier again ignored his director and undermined his authority.[198] In 1960 and 1961 Olivier appeared in Anouilh's Becket on Broadway, first in the title role, with Anthony Quinn as the king, and later exchanging roles with his co-star.[1]

Two films featuring Olivier were released in 1960. The first—filmed in 1959—was Spartacus, in which he portrayed the Roman general, Marcus Licinius Crassus.[199] His second was The Entertainer, shot while he was appearing in Coriolanus; the film was well received by the critics, but not as warmly as the stage show had been.[200] The reviewer for The Guardian thought the performances were good, and wrote that Olivier "on the screen as on the stage, achieves the tour de force of bringing Archie Rice ... to life".[201] For his performance, Olivier was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.[202] He also made an adaptation of The Moon and Sixpence in 1960, winning an Emmy Award.[203]

The Oliviers' marriage was disintegrating during the late 1950s. While directing Charlton Heston in the 1960 play The Tumbler, Olivier divulged that "Vivien is several thousand miles away, trembling on the edge of a cliff, even when she's sitting quietly in her own drawing room", at a time when she was threatening suicide.[204] In May 1960 divorce proceedings started; Leigh reported the fact to the press and informed reporters of Olivier's relationship with Plowright.[205] The decree nisi was issued in December 1960, which enabled him to marry Plowright in March 1961.[206] A son, Richard, was born in December 1961; two daughters followed, Tamsin Agnes Margaret—born in January 1963—and actress Julie-Kate, born in July 1966.[207]

In 1961 Olivier accepted the directorship of a new theatrical venture, the Chichester Festival. For the opening season in 1962 he directed two neglected 17th-century English plays, John Fletcher's 1638 comedy The Chances and John Ford's 1633 tragedy The Broken Heart,[208] followed by Uncle Vanya. The company he recruited was forty strong and included Thorndike, Casson, Redgrave, Athene Seyler, John Neville and Plowright.[208] The first two plays were politely received; the Chekhov production attracted rapturous notices. The Times commented, "It is doubtful if the Moscow Arts Theatre itself could improve on this production."[209] The second Chichester season the following year consisted of a revival of Uncle Vanya and two new productions—Shaw's Saint Joan and John Arden's The Workhouse Donkey.[210] In 1963 Olivier received another BAFTA nomination for his leading role as a schoolteacher accused of sexually molesting a student in the film Term of Trial.[176]

At around the time the Chichester Festival opened, plans for the creation of the National Theatre were coming to fruition. The British government agreed to release funds for a new building on the South Bank of the Thames.[1] Lord Chandos was appointed chairman of the National Theatre Board in 1962, and in August Olivier accepted its invitation to be the company's first director. As his assistants, he recruited the directors John Dexter and William Gaskill, with Kenneth Tynan as literary adviser or "dramaturge".[211] Pending the construction of the new theatre, the company was based at the Old Vic. With the agreement of both organisations, Olivier remained in overall charge of the Chichester Festival during the first three seasons of the National; he used the festivals of 1964 and 1965 to give preliminary runs to plays he hoped to stage at the Old Vic.[212]

The opening production of the National Theatre was Hamlet in October 1963, starring Peter O'Toole and directed by Olivier. O'Toole was a guest star, one of occasional exceptions to Olivier's policy of casting productions from a regular company. Among those who made a mark during Olivier's directorship were Michael Gambon, Maggie Smith, Alan Bates, Derek Jacobi and Anthony Hopkins. It was widely remarked that Olivier seemed reluctant to recruit his peers to perform with his company.[213] Evans, Gielgud and Paul Scofield guested only briefly, and Ashcroft and Richardson never appeared at the National during Olivier's time.[ac] Robert Stephens, a member of the company, observed, "Olivier's one great fault was a paranoid jealousy of anyone who he thought was a rival".[214]

In his decade in charge of the National, Olivier acted in thirteen plays and directed eight.[215] Several of the roles he played were minor characters, including a crazed butler in Feydeau's A Flea in Her Ear and a pompous solicitor in Maugham's Home and Beauty; the vulgar soldier Captain Brazen in Farquhar's 1706 comedy The Recruiting Officer was a larger role but not the leading one.[216]

Apart from his Astrov in the Uncle Vanya, familiar from Chichester, his first leading role for the National was Othello, directed by Dexter in 1964. The production was a box-office success and was revived regularly over the next five seasons.[217] His performance divided opinion. Most of the reviewers and theatrical colleagues praised it highly; Franco Zeffirelli called it "an anthology of everything that has been discovered about acting in the past three centuries."[218] Dissenting voices included The Sunday Telegraph, which called it "the kind of bad acting of which only a great actor is capable ... near the frontiers of self-parody";[219] the director Jonathan Miller thought it "a condescending view of an Afro Caribbean person".[220] The burden of playing this demanding part at the same time as managing the new company and planning for the move to the new theatre took its toll on Olivier. To add to his load, he felt obliged to take over as Solness in The Master Builder when the ailing Redgrave withdrew from the role in November 1964.[221][ad] For the first time Olivier began to suffer from stage fright, which plagued him for several years.[224] The National Theatre production of Othello was released as a film in 1965, which earned four Academy Award nominations, including another for Best Actor for Olivier.[225]

During the following year Olivier concentrated on management, directing one production (The Crucible), taking the comic role of the foppish Tattle in Congreve's Love for Love, and making one film, Bunny Lake is Missing, in which he and Coward were on the same bill for the first time since Private Lives.[226] In 1966, his one play as director was Juno and the Paycock. The Times commented that the production "restores one's faith in the work as a masterpiece".[227] In the same year Olivier portrayed the Mahdi, opposite Heston as General Gordon, in the film Khartoum.[228]

In 1967 Olivier was caught in the middle of a confrontation between Chandos and Tynan over the latter's proposal to stage Rolf Hochhuth's Soldiers. As the play speculatively depicted Churchill as complicit in the assassination of the Polish prime minister Władysław Sikorski, Chandos regarded it as indefensible. At his urging the board unanimously vetoed the production. Tynan considered resigning over this interference with the management's artistic freedom, but Olivier himself stayed firmly in place, and Tynan also remained.[229] At about this time Olivier began a long struggle against a succession of illnesses. He was treated for prostate cancer and, during rehearsals for his production of Chekhov's Three Sisters he was hospitalised with pneumonia.[230] He recovered enough to take the heavy role of Edgar in Strindberg's The Dance of Death, the finest of all his performances other than in Shakespeare, in Gielgud's view.[231]

Olivier had intended to step down from the directorship of the National Theatre at the end of his first five-year contract, having, he hoped, led the company into its new building. By 1968 because of bureaucratic delays construction work had not even begun, and he agreed to serve for a second five-year term.[232] His next major role, and his last appearance in a Shakespeare play, was as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, his first appearance in the work.[ae] He had intended Guinness or Scofield to play Shylock, but stepped in when neither was available.[234] The production by Jonathan Miller, and Olivier's performance, attracted a wide range of responses. Two different critics reviewed it for The Guardian: one wrote "this is not a role which stretches him, or for which he will be particularly remembered"; the other commented that the performance "ranks as one of his greatest achievements, involving his whole range".[235][236]

In 1969 Olivier appeared in two war films, portraying military leaders. He played Field Marshal French in the First World War film Oh! What a Lovely War, for which he won another BAFTA award,[176] followed by Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding in Battle of Britain.[237] In June 1970 he became the first actor to be created a peer for services to the theatre.[238][239] Although he initially declined the honour, Harold Wilson, the incumbent prime minister, wrote to him, then invited him and Plowright to dinner, and persuaded him to accept.[240]

After this Olivier played three more stage roles: James Tyrone in Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night (1971–72), Antonio in Eduardo de Filippo's Saturday, Sunday, Monday and John Tagg in Trevor Griffiths's The Party (both 1973–74). Among the roles he hoped to play, but could not because of ill-health, was Nathan Detroit in the musical Guys and Dolls.[241] In 1972 he took leave of absence from the National to star opposite Michael Caine in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's film of Anthony Shaffer's Sleuth, which The Illustrated London News considered to be "Olivier at his twinkling, eye-rolling best";[242] both he and Caine were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor, losing to Marlon Brando in The Godfather.[243]

The last two stage plays Olivier directed were Jean Giradoux's Amphitryon (1971) and Priestley's Eden End (1974).[244] By the time of Eden End, he was no longer director of the National Theatre; Peter Hall took over on 1 November 1973.[245] The succession was tactlessly handled by the board, and Olivier felt that he had been eased out—although he had declared his intention to go—and that he had not been properly consulted about the choice of successor.[246] The largest of the three theatres within the National's new building was named in his honour, but his only appearance on the stage of the Olivier Theatre was at its official opening by the Queen in October 1976, when he made a speech of welcome, which Hall privately described as the most successful part of the evening.[247]

Olivier spent the last 15 years of his life securing his finances and dealing with deteriorating health,[1] which included thrombosis and dermatomyositis, a degenerative muscle disorder.[248][249] Professionally, and to provide financial security, he made a series of advertisements for Polaroid cameras in 1972, although he stipulated that they must never be shown in Britain; he also took a number of cameo film roles, which were in "often undistinguished films", according to Billington.[250] Olivier's move from leading parts to supporting and cameo roles came about because his poor health meant he could not get the necessary long insurance for larger parts, with only short engagements in films available.[251]

Olivier's dermatomyositis meant he spent the last three months of 1974 in hospital, and he spent early 1975 slowly recovering and regaining his strength. When strong enough, he was contacted by the director John Schlesinger, who offered him the role of a Nazi torturer in the 1976 film Marathon Man. Olivier shaved his pate and wore oversized glasses to enlarge the look of his eyes, in a role that the critic David Robinson, writing for The Times, thought was "strongly played", adding that Olivier was "always at his best in roles that call for him to be seedy or nasty or both".[252] Olivier was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and won the Golden Globe of the same category.[253][254]

In the mid-1970s Olivier became increasingly involved in television work, a medium of which he was initially dismissive.[1] In 1973 he provided the narration for a 26-episode documentary, The World at War, which chronicled the events of the Second World War, and won a second Emmy Award for Long Day's Journey into Night (1973). In 1975 he won another Emmy for Love Among the Ruins.[203] The following year he appeared in adaptations of Tennessee Williams's Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Harold Pinter's The Collection.[255] Olivier portrayed the Pharisee Nicodemus in Franco Zeffirelli's 1977 miniseries Jesus of Nazareth. In 1978 he appeared in the film The Boys from Brazil, playing the role of Ezra Lieberman, an ageing Nazi hunter; he received his eleventh Academy Award nomination. Although he did not win the Oscar, he was presented with an Honorary Award for his lifetime achievement.[256]

Olivier continued working in film into the 1980s, with roles in The Jazz Singer (1980), Inchon (1981), The Bounty (1984) and Wild Geese II (1985).[257] He continued to work in television; in 1981 he appeared as Lord Marchmain in Brideshead Revisited, winning another Emmy, and the following year he received his tenth and last BAFTA nomination in the television adaptation of John Mortimer's stage play A Voyage Round My Father.[176] In 1983 he played his last Shakespearean role as Lear in King Lear, for Granada Television, earning his fifth Emmy.[203] He thought the role of Lear much less demanding than other tragic Shakespearean heroes: "No, Lear is easy. He's like all of us, really: he's just a stupid old fart."[258] When the production was first shown on American television, the critic Steve Vineberg wrote:

Olivier seems to have thrown away technique this time—his is a breathtakingly pure Lear. In his final speech, over Cordelia's lifeless body, he brings us so close to Lear's sorrow that we can hardly bear to watch, because we have seen the last Shakespearean hero Laurence Olivier will ever play. But what a finale! In this most sublime of plays, our greatest actor has given an indelible performance. Perhaps it would be most appropriate to express simple gratitude.[259]

The same year he also appeared in a cameo alongside Gielgud and Richardson in Wagner, with Burton in the title role;[260] his final screen appearance was as an elderly wheelchair-using soldier in Derek Jarman's 1989 film War Requiem.[261]

After being ill for the last 22 years of his life, Olivier died of renal failure on 11 July 1989 aged 82 at his home in the village of Ashurst, near Steyning, West Sussex. His cremation was held three days later;[262] a memorial service was held in Westminster Abbey in October that year, where his ashes were later buried in Poets' Corner.[249][263]

Olivier was appointed Knight Bachelor in the 1947 Birthday Honours for services to the stage and to films.[264] A life peerage as Baron Olivier, of Brighton in the County of Sussex, followed in the 1970 Birthday Honours for services to the theatre.[265][266] Olivier was later appointed to the Order of Merit in 1981.[267] He also received honours from foreign governments. In 1949, he was made Commander of the Danish Order of the Dannebrog; France appointed him Officier, Legion of Honour, in 1953; the Italian government created him Grande Ufficiale, Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, in 1953; and in 1971 he was granted the Order of Yugoslav Flag with Golden Wreath.[268]

From academic and other institutions, Olivier received honorary doctorates from Tufts University in Massachusetts (1946), Oxford (1957) and Edinburgh (1964). He was also awarded the Danish Sonning Prize in 1966, the Gold Medallion of the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities in 1968; and the Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts in 1976.[268][269][af]

For his work in films, Olivier received four Academy Awards: an honorary award for Henry V (1947), a Best Actor award and one as producer for Hamlet (1948), and a second honorary award in 1979 to recognise his lifetime of contribution to the art of film. He was nominated for nine other acting Oscars and one each for production and direction.[270][271] He also won two British Academy Film Awards out of ten nominations,[ag] five Emmy Awards out of nine nominations,[ah] and three Golden Globe Awards out of six nominations.[ai] He was nominated once for a Tony Award (for best actor, as Archie Rice) but did not win.[203][273]

In February 1960, for his contribution to the film industry, Olivier was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame, with a star at 6319 Hollywood Boulevard;[274] he is included in the American Theater Hall of Fame.[275] In 1977, Olivier was awarded a British Film Institute Fellowship.[276]

In addition to the naming of the National Theatre's largest auditorium in Olivier's honour, he is commemorated in the Laurence Olivier Awards, bestowed annually since 1984 by the Society of London Theatre.[268] In 1991, Gielgud unveiled a memorial stone commemorating Olivier in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey.[277] In 2007, the centenary of Olivier's birth, a life-sized statue of him was unveiled on the South Bank, outside the National Theatre;[278] the same year the BFI held a retrospective season of his film work.[279]

Olivier's acting technique was minutely crafted, and he was known for changing his appearance considerably from role to role. By his own admission, he was addicted to extravagant make-up,[280] and unlike Richardson and Gielgud, he excelled at different voices and accents.[281][aj] His own description of his technique was "working from the outside in";[283] he said, "I can never act as myself, I have to have a pillow up my jumper, a false nose or a moustache or wig ... I cannot come on looking like me and be someone else."[280] Rattigan described how at rehearsals Olivier "built his performance slowly and with immense application from a mass of tiny details".[284] This attention to detail had its critics: Agate remarked, "When I look at a watch it is to see the time and not to admire the mechanism. I want an actor to tell me Lear's time of day and Olivier doesn't. He bids me watch the wheels go round."[285]

.jpg/440px-Laurence_Olivier_(borders_removed).jpg)

Tynan remarked to Olivier, "you aren't really a contemplative or philosophical actor";[12] Olivier was known for the strenuous physicality of his performances in some roles. He told Tynan this was because he was influenced as a young man by Douglas Fairbanks, Ramon Navarro and John Barrymore in films, and Barrymore on stage as Hamlet: "tremendously athletic. I admired that greatly, all of us did. ... One thought of oneself, idiotically, skinny as I was, as a sort of Tarzan."[12][ak] According to Morley, Gielgud was widely considered "the best actor in the world from the neck up and Olivier from the neck down."[287] Olivier described the contrast thus: "I've always thought that we were the reverses of the same coin ... the top half John, all spirituality, all beauty, all abstract things; and myself as all earth, blood, humanity."[12]

Olivier, a classically trained actor, was known to have been distrustful of method acting. In his memoir, On Acting, he exhorts actors to "have Stanislavski with you in your study or in your limousine... but don't bring him onto the film set."[288] During production of The Prince and the Showgirl, he quarrelled with Marilyn Monroe, who was trained under Lee Strasberg's method, over her acting process.[289] Similarly, an anecdote casts him as offering Dustin Hoffman, enduring physical travails while playing in Marathon Man, a curt suggestion: "why don't you just try acting?"[290][291] Hoffman disputes the details of this account, which he claims was distorted by a journalist: he had been up all night at the Studio 54 nightclub for personal rather than professional reasons and Olivier, who understood this, was joking.[292][293]

Together with Richardson and Gielgud, Olivier was internationally recognised as one of the "great trinity of theatrical knights"[294] who dominated the British stage during the middle and later decades of the 20th century.[295] In an obituary tribute in The Times, Bernard Levin wrote, "What we have lost with Laurence Olivier is glory. He reflected it in his greatest roles; indeed he walked clad in it—you could practically see it glowing around him like a nimbus. ... no one will ever play the roles he played as he played them; no one will replace the splendour that he gave his native land with his genius."[296] Billington commented:

[Olivier] elevated the art of acting in the twentieth century ... principally by the overwhelming force of his example. Like Garrick, Kean, and Irving before him, he lent glamour and excitement to acting so that, in any theatre in the world, an Olivier night raised the level of expectation and sent spectators out into the darkness a little more aware of themselves and having experienced a transcendent touch of ecstasy. That, in the end, was the true measure of his greatness.[1]

After Olivier's death, Gielgud reflected, "He followed in the theatrical tradition of Kean and Irving. He respected tradition in the theatre, but he also took great delight in breaking tradition, which is what made him so unique. He was gifted, brilliant, and one of the great controversial figures of our time in theatre, which is a virtue and not a vice at all."[297]

Olivier said in 1963 that he believed he was born to be an actor,[298] but his colleague Peter Ustinov disagreed; he commented that although Olivier's great contemporaries were clearly predestined for the stage, "Larry could have been a notable ambassador, a considerable minister, a redoubtable cleric. At his worst, he would have acted the parts more ably than they are usually lived."[299] The director David Ayliff agreed that acting did not come instinctively to Olivier as it did to his great rivals. He observed, "Ralph was a natural actor, he couldn't stop being a perfect actor; Olivier did it through sheer hard work and determination."[300] The American actor William Redfield had a similar view:

Ironically enough, Laurence Olivier is less gifted than Marlon Brando. He is even less gifted than Richard Burton, Paul Scofield, Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud. But he is still the definitive actor of the twentieth century. Why? Because he wanted to be. His achievements are due to dedication, scholarship, practice, determination and courage. He is the bravest actor of our time.[301]

In comparing Olivier and the other leading actors of his generation, Ustinov wrote, "It is of course vain to talk of who is and who is not the greatest actor. There is simply no such thing as a greatest actor, or painter or composer".[302] Nonetheless, some colleagues, particularly film actors such as Spencer Tracy, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, came to regard Olivier as the finest of his peers.[303] Peter Hall, though acknowledging Olivier as the head of the theatrical profession,[304] thought Richardson the greater actor.[220] Olivier's claim to theatrical greatness lay not only in his acting, but as, in Hall's words, "the supreme man of the theatre of our time",[305] pioneering Britain's National Theatre.[213] As Bragg identified, "no one doubts that the National is perhaps his most enduring monument".[306]