Corea del Sur , [c] oficialmente la República de Corea ( ROK ), [d] es un país del este de Asia . Constituye la parte sur de la península de Corea y limita con Corea del Norte a lo largo de la Zona Desmilitarizada de Corea ; aunque también reclama la frontera terrestre con China y Rusia . [e] La frontera occidental del país está formada por el Mar Amarillo , mientras que su frontera oriental está definida por el Mar de Japón . Corea del Sur afirma ser el único gobierno legítimo de toda la península y las islas adyacentes . Tiene una población de 51,96 millones, de los cuales la mitad vive en el Área Capital de Seúl , la novena área metropolitana más poblada del mundo . Otras ciudades importantes son Busan , Daegu e Incheon .

La península de Corea estuvo habitada desde el Paleolítico Inferior . Su primer reino aparece registrado en los registros chinos a principios del siglo VII a. C. Después de la unificación de los Tres Reinos de Corea en Silla y Balhae a finales del siglo VII, Corea fue gobernada por la dinastía Goryeo (918-1392) y la dinastía Joseon (1392-1897). El Imperio coreano (1897-1910) que le sucedió fue anexado en 1910 al Imperio del Japón . El dominio japonés terminó tras la rendición de Japón en la Segunda Guerra Mundial , tras lo cual Corea se dividió en dos zonas : una zona norte , que fue ocupada por la Unión Soviética , y una zona sur , que fue ocupada por los Estados Unidos . Después de que fracasaran las negociaciones sobre la reunificación , la zona sur se convirtió en la República de Corea en agosto de 1948, mientras que la zona norte se convirtió en la República Popular Democrática de Corea comunista al mes siguiente.

En 1950, una invasión norcoreana dio inicio a la Guerra de Corea , que terminó en 1953 después de extensos combates que involucraron al Comando de las Naciones Unidas liderado por Estados Unidos y al Ejército Popular Voluntario de China con asistencia soviética . La guerra dejó 3 millones de coreanos muertos y la economía en ruinas . La autoritaria Primera República de Corea liderada por Syngman Rhee fue derrocada en la Revolución de Abril de 1960. Sin embargo, la Segunda República no logró controlar el fervor revolucionario. El golpe de Estado del 16 de mayo de 1961 liderado por Park Chung Hee puso fin a la Segunda República, señalando el inicio de la Tercera República en 1963. La devastada economía de Corea del Sur comenzó a despegar bajo el liderazgo de Park, registrando uno de los aumentos más rápidos en el PIB per cápita promedio . A pesar de carecer de recursos naturales, la nación se desarrolló rápidamente para convertirse en uno de los Cuatro Tigres Asiáticos basados en el comercio internacional y la globalización económica , integrándose dentro de la economía mundial con la industrialización orientada a la exportación . La Cuarta República se estableció después de la Restauración de Octubre de 1972, en la que Park ejerció el poder absoluto. La Constitución de Yushin declaró que el presidente podía suspender los derechos humanos básicos y nombrar a un tercio del parlamento. La represión de la oposición y el abuso de los derechos humanos por parte del gobierno se hicieron más severos en este período. Incluso después del asesinato de Park en 1979, el gobierno autoritario continuó en la Quinta República liderada por Chun Doo-hwan , que tomó violentamente el poder mediante dos golpes de Estado y reprimió brutalmente el Levantamiento de Gwangju . La Lucha Democrática de Junio de 1987 puso fin al gobierno autoritario , formando la actual Sexta República. El país ahora se considera una de las democracias más avanzadas de Asia continental y oriental.

Corea del Sur mantiene una república presidencial unitaria bajo la constitución de 1987 con una legislatura unicameral, la Asamblea Nacional . Se considera una potencia regional y un país desarrollado , con su economía clasificada como la decimocuarta más grande del mundo por PIB nominal y la decimocuarta más grande por PIB ajustado por PPA . Sus ciudadanos disfrutan de una de las velocidades de conexión a Internet más rápidas del mundo y las redes ferroviarias de alta velocidad más densas . El país es el noveno exportador y el noveno importador más grande del mundo . Sus fuerzas armadas están clasificadas como uno de los ejércitos más fuertes del mundo, con el segundo ejército permanente más grande del mundo por personal militar y paramilitar . En el siglo XXI, Corea del Sur ha sido reconocida por su cultura pop de influencia mundial, particularmente en música , dramas televisivos y cine , un fenómeno conocido como la Ola Coreana . Es miembro del Comité de Asistencia para el Desarrollo de la OCDE , el G20 , el IPEF y el Club de París .

El nombre Corea es un exónimo , aunque se deriva de un nombre histórico de reino, Goryeo ( romanización revisada ) o Koryŏ ( McCune–Reischauer ). Goryeo fue el nombre acortado adoptado oficialmente por Goguryeo en el siglo V [11] [12] [13] y el nombre de su estado sucesor del siglo X, Goryeo. [14] [15] Los comerciantes árabes y persas que visitaban el lugar pronunciaban su nombre como "Korea". [16] El nombre moderno de Corea aparece en los primeros mapas portugueses de 1568 de João vaz Dourado como Conrai [17] y más tarde, a finales del siglo XVI y principios del siglo XVII, como Corea (Korea) en los mapas de Teixeira Albernaz de 1630. [18]

El Reino de Goryeo se hizo conocido por primera vez por los occidentales cuando Afonso de Albuquerque conquistó Malaca en 1511 y describió a los pueblos que comerciaban con esta parte del mundo conocidos por los portugueses como los Gores . [19] A pesar de la coexistencia de las grafías Corea y Korea en publicaciones del siglo XIX, algunos coreanos creen que el Japón Imperial , en la época de la ocupación japonesa, estandarizó intencionalmente la ortografía de Korea , haciendo que Japón apareciera primero alfabéticamente. [20] [21]

Después de que Goryeo fuera reemplazado por Joseon en 1392, Joseon se convirtió en el nombre oficial de todo el territorio, aunque no fue aceptado universalmente. El nuevo nombre oficial tiene su origen en el antiguo reino de Gojoseon (2333 a. C.). En 1897, la dinastía Joseon cambió el nombre oficial del país de Joseon a Daehan Jeguk ( Imperio coreano ). El nombre Daehan (Gran Han) deriva de Samhan (Tres Han), refiriéndose a los Tres Reinos de Corea , no a las antiguas confederaciones en el sur de la península de Corea. [22] [23] Sin embargo, el nombre Joseon todavía era ampliamente utilizado por los coreanos para referirse a su país, aunque ya no era el nombre oficial. Bajo el dominio japonés , los dos nombres Han y Joseon coexistieron.

Tras la rendición de Japón en 1945, se adoptó la "República de Corea" ( 대한민국 /大韓民國, IPA : /ˈtɛ̝ːɦa̠n.min.ɡuk̚/ ; ) como el nombre legal en inglés para el nuevo país. Sin embargo, no es una traducción directa del nombre coreano. [24] Como resultado, los surcoreanos a veces usan el nombre coreano "Daehan Minguk" como metonimia para referirse a la etnia coreana (o " raza ") en su conjunto, en lugar de solo al estado surcoreano. [25] [24]

La península de Corea estuvo habitada desde el Paleolítico Inferior . [27] [28]

Según la mitología fundacional de Corea , la historia de Corea comienza con la fundación de Joseon (también conocida como " Gojoseon " o "Antiguo Joseon", para diferenciarla de la dinastía del siglo XIV) en 2333 a. C. por el legendario Dangun . [29] [30] Gojoseon fue mencionado en registros chinos a principios del siglo VII. [31] Gojoseon se expandió hasta controlar la península de Corea del Norte y partes de Manchuria . Gija Joseon supuestamente fue fundada en el siglo XII a. C., pero su existencia y papel han sido controvertidos en la era moderna. [30] [32] En 108 a. C., la dinastía Han derrotó a Wiman Joseon e instaló cuatro comandancias en la península de Corea del Norte. Tres de las comandancias cayeron o se retiraron hacia el oeste en unas pocas décadas. Como la comandancia Lelang fue destruida y reconstruida en esta época, el lugar se movió gradualmente hacia Liaodong. [ aclaración necesaria ] Por lo tanto, su fuerza disminuyó y solo sirvió como centro comercial hasta que fue conquistada por Goguryeo en 313. [33] [34] [35]

A partir de alrededor del año 300 a. C., el pueblo yayoi de habla japonesa de la península de Corea entró en las islas japonesas y desplazó o se mezcló con los habitantes originales de Jōmon . [36] La patria lingüística de los protocoreanos se encuentra en algún lugar del sur de Siberia / Manchuria , como la zona del río Liao o la zona del río Amur . Los protocoreanos llegaron a la parte sur de la península de Corea alrededor del año 300 a. C., reemplazando y asimilando a los hablantes de japonés y probablemente causando la migración yayoi . [37]

Durante el período de los Proto-Tres Reinos , los estados de Buyeo , Okjeo , Dongye y Samhan ocuparon toda la península de Corea y el sur de Manchuria. De ellos surgieron los Tres Reinos de Corea : Goguryeo , Baekje y Silla .

Goguryeo, el más grande y poderoso de ellos, era un estado altamente militarista [38] y compitió con varias dinastías chinas durante sus 700 años de historia. Goguryeo experimentó una época dorada bajo Gwanggaeto el Grande y su hijo Jangsu , [39] [40] [41] [42] quienes sometieron a Baekje y Silla durante sus respectivos reinados, logrando una breve unificación de los Tres Reinos y convirtiéndose en la potencia más dominante en la península de Corea. [43] [44] Además de disputar el control de la península de Corea, Goguryeo tuvo muchos conflictos militares con varias dinastías chinas, más notablemente la Guerra Goguryeo-Sui , en la que Goguryeo derrotó a una enorme fuerza que se dice que contaba con más de un millón de hombres. [45]

Baekje fue una potencia marítima, [46] a veces llamada la " Fenicia del Este de Asia". [47] Su capacidad marítima fue fundamental para la difusión del budismo en todo el Este de Asia y la expansión de la cultura continental a Japón. [48] [49] Baekje fue una vez una gran potencia militar en la península de Corea, especialmente durante la época de Geunchogo , [50] pero fue derrotada críticamente por Gwanggaeto el Grande y declinó. [ cita requerida ] Silla era la más pequeña y débil de las tres, pero utilizó pactos y alianzas oportunistas con los reinos coreanos más poderosos, y eventualmente con la China Tang , para su beneficio. [51] [52]

En 676, la unificación de los Tres Reinos por parte de Silla dio lugar al período de los Estados del Norte y del Sur , en el que Balhae controlaba las partes septentrionales de Goguryeo, y gran parte de la península de Corea estaba bajo el control de Silla Posterior . Las relaciones entre Corea y China se mantuvieron relativamente pacíficas durante este tiempo. Balhae fue fundada por un general de Goguryeo y se formó como un estado sucesor de Goguryeo. Durante su apogeo, Balhae controlaba la mayor parte de Manchuria y partes del Lejano Oriente ruso y se lo denominaba el «país próspero del este». [53]

Silla tardía era un país rico, [54] y su capital metropolitana de Gyeongju [55] creció hasta convertirse en la cuarta ciudad más grande del mundo. [56] [57] [58] [59] Experimentó una edad de oro del arte y la cultura, [60] [61] [62] [63] ejemplificada por monumentos como Hwangnyongsa , Seokguram y la Campana Emille . También continuó el legado marítimo y la destreza de Baekje, y durante los siglos VIII y IX dominó los mares del este de Asia y el comercio entre China, Corea y Japón, más notablemente durante la época de Jang Bogo . Además, la gente de Silla creó comunidades de ultramar en China en la península de Shandong y la desembocadura del río Yangtze . [64] [65] [66] [67] Sin embargo, Silla se debilitó más tarde debido a conflictos internos y al resurgimiento de los estados sucesores Baekje y Goguryeo , que culminaron en el período de los Tres Reinos Posteriores a fines del siglo IX.

El budismo floreció durante esta época. Muchos budistas coreanos ganaron gran fama entre los círculos budistas chinos [68] y contribuyeron en gran medida al budismo chino . [69] Entre los ejemplos de budistas coreanos importantes de este período se incluyen Woncheuk , Wonhyo , Uisang , Musang , [70] [71] [72] [73] y Kim Gyo-gak . Kim era un príncipe de Silla cuya influencia hizo del monte Jiuhua una de las Cuatro Montañas Sagradas del budismo chino. [74]

.jpg/440px-창덕궁_전경_(2012).jpg)

En 936, los Tres Reinos Posteriores fueron unificados por Wang Geon , un descendiente de la nobleza de Goguryeo, [75] quien estableció Goryeo como el estado sucesor de Goguryeo. [14] [15] [76] [77] Balhae había caído ante el Imperio Khitan en 926, y una década después el último príncipe heredero de Balhae huyó al sur a Goryeo, donde fue recibido calurosamente e incluido en la familia gobernante por Wang Geon, unificando así las dos naciones sucesoras de Goguryeo. [78] Al igual que Silla, Goryeo era un estado altamente cultural e inventó la imprenta de tipos móviles de metal . [26] Después de derrotar al Imperio Khitan, que era el imperio más poderoso de su tiempo, [79] [80] en la Guerra Goryeo-Khitan , Goryeo experimentó una época dorada que duró un siglo, durante la cual se completó la Tripitaka Koreana y ocurrieron importantes avances en la impresión y publicación. Esto promovió la educación y la difusión del conocimiento sobre filosofía, literatura, religión y ciencia. Hacia el año 1100, había 12 universidades que formaban eruditos notables. [81] [82]

Sin embargo, las invasiones mongolas en el siglo XIII debilitaron enormemente el reino. Goryeo nunca fue conquistado por los mongoles, pero exhausta después de tres décadas de lucha, la corte coreana envió a su príncipe heredero a la capital Yuan para jurar lealtad a Kublai Khan , quien aceptó y casó a una de sus hijas con el príncipe heredero coreano. [83] De ahí en adelante, Goryeo continuó gobernando Corea, aunque como aliado tributario de los mongoles durante los siguientes 86 años. Durante este período, las dos naciones se entrelazaron ya que todos los reyes coreanos posteriores se casaron con princesas mongolas, [83] y la última emperatriz de la dinastía Yuan fue una princesa coreana. A mediados del siglo XIV, Goryeo expulsó a los mongoles para recuperar sus territorios del norte, conquistó brevemente Liaoyang y derrotó las invasiones de los Turbantes Rojos . Sin embargo, en 1392, el general Yi Seong-gye , a quien se le había ordenado atacar China, dio vuelta a su ejército y dio un golpe de estado.

Yi Seong-gye declaró el nuevo nombre de Corea como "Joseon" en referencia a Gojoseon, y trasladó la capital a Hanseong (uno de los antiguos nombres de Seúl ). [84] Los primeros 200 años de la dinastía Joseon estuvieron marcados por la paz y vieron grandes avances en la ciencia [85] [86] y la educación, [87] así como la creación del Hangul por Sejong el Grande para promover la alfabetización entre la gente común. [88] La ideología predominante de la época era el neoconfucianismo , que estaba personificado por la clase seonbi : nobles que dejaron pasar puestos de riqueza y poder para llevar vidas de estudio e integridad. Entre 1592 y 1598, Japón bajo el mando de Toyotomi Hideyoshi lanzó invasiones a Corea , pero el avance fue detenido por las fuerzas coreanas (sobre todo la Armada Joseon dirigida por el almirante Yi Sun-sin y su famoso " barco tortuga ") con la ayuda de milicias del ejército justo formadas por civiles coreanos y tropas chinas de la dinastía Ming . [89] A través de una serie de exitosas batallas de desgaste, las fuerzas japonesas finalmente se vieron obligadas a retirarse y las relaciones entre todas las partes se normalizaron. Sin embargo, los manchúes se aprovecharon del estado debilitado por la guerra de Joseon e invadieron en 1627 y 1637 y luego continuaron conquistando la desestabilizada dinastía Ming. Después de normalizar las relaciones con la nueva dinastía Qing , Joseon experimentó un período de paz de casi 200 años. Los reyes Yeongjo y Jeongjo en particular lideraron un nuevo renacimiento de la dinastía Joseon durante el siglo XVIII. [90] [91]

En el siglo XIX, Joseon comenzó a experimentar dificultades económicas y levantamientos generalizados, incluida la Revolución Campesina Donghak . Las familias políticas reales habían obtenido el control del gobierno, lo que llevó a una corrupción masiva y al debilitamiento del estado. [ cita requerida ] Además, el estricto aislacionismo del gobierno de Joseon que le valió el título de " reino ermitaño " se volvió cada vez más ineficaz debido a la creciente invasión de potencias como Japón, Rusia y los Estados Unidos. Esto se ejemplifica con el Tratado Joseon-Estados Unidos de 1882 , en el que se obligó a este último a abrir sus fronteras.

A finales del siglo XIX, Japón se convirtió en una importante potencia regional tras ganar la Primera Guerra Sino-Japonesa contra la China Qing y la Guerra Ruso-Japonesa contra el Imperio Ruso . En 1897, el rey Gojong, el último rey de Corea , proclamó a Joseon como el Imperio Coreano . Sin embargo, Japón obligó a Corea a convertirse en su protectorado en 1905 y la anexó formalmente en 1910. Lo que siguió fue un período de asimilación forzada, en el que se suprimió la lengua, la cultura y la historia coreanas. [92] Esto condujo a las protestas del Movimiento del 1 de Marzo en 1919 y la posterior fundación de grupos de resistencia en el exilio, principalmente en China. Entre los grupos de resistencia se encontraba el Gobierno Provisional de la República de Corea . [93]

Hacia el final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , Estados Unidos propuso dividir la península de Corea en dos zonas de ocupación: una zona estadounidense y una zona soviética . Dean Rusk y Charles H. Bonesteel III sugirieron el paralelo 38 como línea divisoria, ya que colocaba a Seúl bajo control estadounidense. Para sorpresa de Rusk y Bonesteel, los soviéticos aceptaron su propuesta y acordaron dividir Corea. [94]

A pesar de las intenciones de liberar una península unificada en la Declaración de El Cairo de 1943 , las crecientes tensiones entre la Unión Soviética y los Estados Unidos llevaron a la división de Corea en dos entidades políticas en 1948: Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur.

En el Sur, Estados Unidos designó y apoyó al ex jefe del Gobierno Provisional de Corea Syngman Rhee como líder. Rhee ganó las primeras elecciones presidenciales de la recién declarada República de Corea en mayo de 1948. En el Norte, los soviéticos respaldaron a un ex guerrillero antijaponés y activista comunista, Kim Il-sung , quien fue nombrado primer ministro de la República Popular Democrática de Corea en septiembre. [96]

En octubre, la Unión Soviética declaró al gobierno de Kim Il-sung soberano tanto del norte como del sur. La ONU declaró al gobierno de Rhee como "un gobierno legítimo que tiene control efectivo y jurisdicción sobre esa parte de Corea donde la Comisión Temporal de la ONU sobre Corea pudo observar y consultar" y el gobierno "basado en elecciones que fueron observadas por la Comisión Temporal", además de una declaración de que "este es el único gobierno de ese tipo en Corea". [97] Ambos líderes participaron en la represión autoritaria de los oponentes políticos. [98] Corea del Sur solicitó apoyo militar a los Estados Unidos, pero se le negó, [99] y el ejército de Corea del Norte fue fuertemente reforzado por la Unión Soviética. [100] [101]

El 25 de junio de 1950, Corea del Norte invadió Corea del Sur, lo que desencadenó la Guerra de Corea , el primer gran conflicto de la Guerra Fría , que continuó hasta 1953. En ese momento, la Unión Soviética había boicoteado a la ONU, perdiendo así sus derechos de veto . Esto permitió a la ONU intervenir en una guerra civil cuando se hizo evidente que las fuerzas superiores de Corea del Norte unificarían todo el país. La Unión Soviética y China respaldaron a Corea del Norte, con la posterior participación de millones de tropas chinas . Después de un flujo y reflujo que vio a ambos lados enfrentar la derrota con pérdidas masivas entre los civiles coreanos tanto en el norte como en el sur, la guerra finalmente llegó a un punto muerto. Durante la guerra, el partido de Rhee promovió el Principio de un solo pueblo , un esfuerzo por construir una ciudadanía obediente a través de la homogeneidad étnica y apelaciones autoritarias al nacionalismo . [102]

El armisticio de 1953 , que nunca fue firmado por Corea del Sur, dividió la península a lo largo de la zona desmilitarizada cerca de la línea de demarcación original. Nunca se firmó ningún tratado de paz, lo que resultó en que los dos países permanecieran técnicamente en guerra. Aproximadamente 3 millones de personas murieron en la Guerra de Corea, con una cifra proporcional de muertes civiles mayor que la Segunda Guerra Mundial o la Guerra de Vietnam , lo que la convirtió en uno de los conflictos más mortíferos de la era de la Guerra Fría. [103] [104] Además, prácticamente todas las principales ciudades de Corea fueron destruidas por la guerra. [105]

En 1960, un levantamiento estudiantil (la " Revolución de Abril ") condujo a la dimisión del presidente autocrático Syngman Rhee. A esto le siguieron 13 meses de inestabilidad política, ya que Corea del Sur estaba dirigida por un gobierno débil e ineficaz. Esta inestabilidad se rompió con el golpe de Estado del 16 de mayo de 1961 encabezado por el general Park Chung Hee . Como presidente, Park supervisó un período de rápido crecimiento económico impulsado por las exportaciones, reforzado por la represión política . Bajo el mando de Park, Corea del Sur asumió un papel activo en la guerra de Vietnam. [106]

Park fue duramente criticado como un dictador militar despiadado, que en 1972 extendió su mandato creando una nueva constitución , que le dio al presidente amplios poderes (casi dictatoriales) y le permitió postularse para un número ilimitado de mandatos de seis años. La economía coreana se desarrolló significativamente durante el mandato de Park. El gobierno desarrolló el sistema nacional de autopistas , el sistema de metro de Seúl y sentó las bases para el desarrollo económico durante su mandato de 17 años, que terminó con su asesinato en 1979.

Los años posteriores al asesinato de Park estuvieron marcados nuevamente por la agitación política, ya que los líderes de la oposición previamente reprimidos hicieron campaña para postularse a la presidencia en el repentino vacío político. En 1979, el general Chun Doo-hwan encabezó el golpe de estado del 12 de diciembre . Tras el golpe de estado, Chun planeó llegar al poder mediante varias medidas. El 17 de mayo, Chun obligó al Gabinete a expandir la ley marcial a toda la nación, que anteriormente no se había aplicado a la isla de Jejudo . La ley marcial ampliada cerró las universidades, prohibió las actividades políticas y restringió aún más la prensa. La asunción de Chun a la presidencia a través de los eventos del 17 de mayo desencadenó protestas en todo el país exigiendo democracia; estas protestas se centraron particularmente en la ciudad de Gwangju , a la que Chun envió fuerzas especiales para reprimir violentamente el Movimiento de Democratización de Gwangju . [107]

Chun creó posteriormente el Comité de Política de Emergencia de Defensa Nacional y tomó la presidencia de acuerdo con su plan político. Chun y su gobierno mantuvieron a Corea del Sur bajo un régimen despótico hasta 1987, cuando un estudiante de la Universidad Nacional de Seúl , Park Jong-chul , fue torturado hasta la muerte. [108] El 10 de junio , la Asociación de Sacerdotes Católicos por la Justicia reveló el incidente, lo que encendió la Lucha Democrática de Junio en todo el país. Finalmente, el partido de Chun, el Partido de la Justicia Democrática , y su líder, Roh Tae-woo , anunciaron la Declaración del 29 de junio , que incluía la elección directa del presidente. Roh ganó las elecciones por un estrecho margen contra los dos principales líderes de la oposición, Kim Dae-jung y Kim Young-sam . Seúl fue sede de los Juegos Olímpicos en 1988 , ampliamente considerados como exitosos y un impulso significativo para la imagen global y la economía de Corea del Sur. [109]

Corea del Sur fue invitada formalmente a convertirse en miembro de las Naciones Unidas en 1991. La transición de Corea de la autocracia a la democracia moderna estuvo marcada en 1997 por la elección de Kim Dae-jung, quien juró como octavo presidente de Corea del Sur el 25 de febrero de 1998. Su elección fue significativa dado que en años anteriores había sido un preso político condenado a muerte (más tarde conmutada por exilio). Ganó en el contexto de la crisis financiera asiática de 1997 , donde siguió el consejo del FMI para reestructurar la economía y la nación pronto recuperó su crecimiento económico, aunque a un ritmo más lento. [110]

En junio de 2000, como parte de la " Política del Sol " de compromiso del presidente Kim Dae-jung , se celebró una cumbre Norte-Sur en Pyongyang , la capital de Corea del Norte. [111] Más tarde ese año, Kim recibió el Premio Nobel de la Paz "por su trabajo por la democracia y los derechos humanos en Corea del Sur y en Asia Oriental en general, y por la paz y la reconciliación con Corea del Norte en particular". [112] Sin embargo, debido al descontento entre la población por los enfoques infructuosos hacia el Norte bajo las administraciones anteriores y, en medio de las provocaciones norcoreanas, en 2007 se eligió un gobierno conservador encabezado por el presidente Lee Myung-bak , ex alcalde de Seúl . [113] Mientras tanto, Corea del Sur y Japón organizaron conjuntamente la Copa Mundial de la FIFA 2002. [ 114] Sin embargo, las relaciones entre Corea del Sur y Japón se deterioraron más tarde debido a las reclamaciones conflictivas de soberanía sobre las rocas de Liancourt . [115]

En 2010, se produjo una escalada de ataques por parte de Corea del Norte. En marzo de 2010, el buque de guerra surcoreano ROKS Cheonan se hundió y murieron 46 marineros surcoreanos, presuntamente por un submarino norcoreano. En noviembre de 2010, la isla de Yeonpyeong fue atacada por una importante andanada de artillería norcoreana, en la que murieron 4 personas. La falta de una respuesta contundente a estos ataques tanto por parte de Corea del Sur como de la comunidad internacional (el informe oficial de la ONU se negó a nombrar explícitamente a Corea del Norte como autor del hundimiento del Cheonan ) provocó un enfado considerable en el público surcoreano. [117]

Corea del Sur vivió otro hito en 2012 con la elección de la primera presidenta Park Geun-hye y su asunción del cargo. Hija del expresidente Park Chung Hee, ejerció una política conservadora. [118] La administración de la presidenta Park Geun-hye fue acusada formalmente de corrupción, soborno y tráfico de influencias por la participación de su amiga íntima Choi Soon-sil en asuntos de Estado. A esto le siguieron una serie de manifestaciones públicas masivas a partir de noviembre de 2016, [119] y fue destituida de su cargo. [120] Tras las consecuencias del impeachment y la destitución de Park, se celebraron elecciones y Moon Jae-in del Partido Demócrata ganó la presidencia, asumiendo el cargo el 10 de mayo de 2017. [121] Su mandato vio una mejora de la relación política con Corea del Norte, una creciente divergencia en la alianza militar con los Estados Unidos y la exitosa celebración de los Juegos Olímpicos de Invierno en Pyeongchang . [122] En abril de 2018, Park Geun-hye fue sentenciada a 24 años de prisión por abuso de poder y corrupción. [123] La pandemia de COVID-19 ha afectado a la nación desde 2020. Ese mismo año, Corea del Sur registró más muertes que nacimientos, lo que resultó en una disminución de la población por primera vez en la historia. [124]

En marzo de 2022, Yoon Suk Yeol , candidato del partido conservador opositor Partido del Poder Popular , ganó unas elecciones reñidas contra el candidato del Partido Demócrata por el margen más estrecho de la historia. Yoon prestó juramento el 10 de mayo de 2022. [125]

.jpg/440px-Korea_(MODIS_2015-05-17).jpg)

Corea del Sur ocupa la parte sur de la península de Corea , que se extiende unos 1100 km (680 mi) desde el continente asiático continental y oriental. Esta península montañosa está flanqueada por el mar Amarillo al oeste y el mar de Japón al este. Su extremo sur se encuentra en el estrecho de Corea y el mar de China Oriental . El país, incluidas todas sus islas, se encuentra entre las latitudes 33° y 39° N , y las longitudes 124° y 130° E. Su área total es de 100 410 kilómetros cuadrados (38 768,52 millas cuadradas). [6]

Corea del Sur se puede dividir en cuatro regiones generales: una región oriental de altas cadenas montañosas y estrechas llanuras costeras; una región occidental de amplias llanuras costeras, cuencas fluviales y colinas onduladas; una región suroccidental de montañas y valles; y una región sudoriental dominada por la amplia cuenca del río Nakdong . [126] Corea del Sur alberga tres ecorregiones terrestres: los bosques caducifolios de Corea del Centro , los bosques mixtos de Manchuria y los bosques siempreverdes de Corea del Sur . [127] El terreno de Corea del Sur es principalmente montañoso, la mayor parte del cual no es cultivable . Las tierras bajas , ubicadas principalmente en el oeste y sureste, representan solo el 30% de la superficie terrestre total. Corea del Sur tiene 20 parques nacionales y lugares naturales populares como los campos de té de Boseong , el parque ecológico de la bahía de Suncheon y Jirisan . [128]

Cerca de 3.000 islas, en su mayoría pequeñas y deshabitadas, se encuentran frente a las costas occidental y meridional de Corea del Sur. La provincia de Jeju está a unos 100 kilómetros (62 millas) de la costa sur de Corea del Sur. Es la isla más grande del país, con una superficie de 1.845 kilómetros cuadrados (712 millas cuadradas). Jeju es también el sitio del punto más alto de Corea del Sur: Hallasan , un volcán extinto , alcanza los 1.950 metros (6.400 pies) sobre el nivel del mar . Las islas más orientales de Corea del Sur incluyen Ulleungdo y Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo/Takeshima), mientras que Marado y Socotra Rock son las islas más meridionales de Corea del Sur. [126]

Corea del Sur tiende a tener un clima continental húmedo y un clima subtropical húmedo , y se ve afectado por el monzón del este de Asia , con precipitaciones más intensas en verano durante una corta temporada de lluvias llamada jangma (장마), que comienza a fines de junio y dura hasta fines de julio. En Seúl, el rango de temperatura promedio de enero es de −7 a 1 °C (19 a 34 °F), y el rango de temperatura promedio de agosto es de 22 a 30 °C (72 a 86 °F). Las temperaturas invernales son más altas a lo largo de la costa sur y considerablemente más bajas en el interior montañoso. [130] El verano puede ser incómodamente caluroso y húmedo, con temperaturas que superan los 30 °C (86 °F) en la mayor parte del país. Corea del Sur tiene cuatro estaciones distintas: primavera, verano, otoño e invierno. La primavera generalmente dura desde fines de marzo hasta principios de mayo, el verano desde mediados de mayo hasta principios de septiembre, el otoño desde mediados de septiembre hasta principios de noviembre y el invierno desde mediados de noviembre hasta mediados de marzo.

Las precipitaciones se concentran en los meses de verano, de junio a septiembre. La costa sur está sujeta a tifones de finales de verano que traen fuertes vientos, lluvias torrenciales y, a veces, inundaciones. La precipitación media anual varía de 1.370 milímetros (54 pulgadas) en Seúl a 1.470 milímetros (58 pulgadas) en Busan.

Durante los primeros 20 años del auge del crecimiento de Corea del Sur, se hizo poco esfuerzo para preservar el medio ambiente. [131] La industrialización y el desarrollo urbano descontrolados han dado lugar a la deforestación y la destrucción continua de humedales como la llanura mareal de Songdo. [132] Sin embargo, ha habido esfuerzos recientes para equilibrar estos problemas, incluido un proyecto de crecimiento verde de cinco años de 84 mil millones de dólares dirigido por el gobierno que tiene como objetivo impulsar la eficiencia energética y la tecnología verde. [133]

La estrategia económica basada en el medio ambiente es una reforma integral de la economía de Corea del Sur, que utiliza casi el dos por ciento del PIB nacional. La iniciativa de ecologización incluye esfuerzos como una red nacional de bicicletas, energía solar y eólica, reducción de la dependencia de los vehículos de petróleo, respaldo al horario de verano y uso extensivo de tecnologías respetuosas con el medio ambiente como los LED en la electrónica y la iluminación. [134] El país, uno de los más conectados del mundo, planea construir una red nacional de próxima generación que será diez veces más rápida que las instalaciones de banda ancha, con el fin de reducir el consumo de energía. [134]

El programa estándar de cartera renovable con certificados de energía renovable se extenderá desde 2012 hasta 2022. [135] Los sistemas de cuotas favorecen a los grandes generadores integrados verticalmente y a las empresas eléctricas multinacionales, aunque sólo sea porque los certificados suelen estar denominados en unidades de un megavatio-hora. También son más difíciles de diseñar e implementar que una tarifa de alimentación . [136] En 2012 se instalaron alrededor de 350 microunidades residenciales de cogeneración . [137] En 2017, Corea del Sur fue el séptimo mayor emisor de emisiones de carbono del mundo y el quinto mayor emisor per cápita. El presidente Moon Jae-in se comprometió a reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero a cero en 2050. [138] [139]

El agua del grifo de Seúl se volvió recientemente segura para beber, y los funcionarios de la ciudad la etiquetaron como " Arisu " en un intento de convencer al público. [140] También se han realizado esfuerzos con proyectos de forestación . Otro proyecto multimillonario fue la restauración de Cheonggyecheon , un arroyo que atraviesa el centro de Seúl y que anteriormente había sido pavimentado por una autopista. [141] Un desafío importante es la calidad del aire, con la lluvia ácida, los óxidos de azufre y las tormentas anuales de polvo amarillo como problemas particulares. [131] Se reconoce que muchas de estas dificultades son el resultado de la proximidad de Corea del Sur a China, que es un importante contaminante del aire. [131] Corea del Sur tuvo una puntuación media del Índice de Integridad del Paisaje Forestal de 2019 de 6,02/10, lo que la ubica en el puesto 87 a nivel mundial de 172 países. [142]

Corea del Sur es miembro del Protocolo Ambiental Antártico , Tratado Antártico , Tratado de Biodiversidad , Protocolo de Kioto (formando el Grupo de Integridad Ambiental (EIG), en relación con la CMNUCC , [143] con México y Suiza), Desertificación , Especies en Peligro de Extinción , Modificación Ambiental , Residuos Peligrosos , Derecho del Mar , Vertidos Marinos , Tratado de Prohibición Completa de los Ensayos Nucleares (no en vigor), Protección de la Capa de Ozono , Contaminación por Buques , Maderas Tropicales 83 , Maderas Tropicales 94 , Humedales y Caza de Ballenas . [144]

La estructura del gobierno de Corea del Sur está determinada por la Constitución de la República de Corea . Como muchos estados democráticos, [145] Corea del Sur tiene un gobierno dividido en tres poderes: ejecutivo , judicial y legislativo . Los poderes ejecutivo y legislativo operan principalmente a nivel nacional, aunque varios ministerios del poder ejecutivo también llevan a cabo funciones locales. El poder judicial opera tanto a nivel nacional como local. Los gobiernos locales son semiautónomos y contienen órganos ejecutivos y legislativos propios. Corea del Sur es una democracia constitucional.

La constitución ha sido revisada varias veces desde su primera promulgación en 1948, en el momento de la independencia. Sin embargo, ha conservado muchas características generales y, con la excepción de la efímera Segunda República de Corea , el país siempre ha tenido un sistema presidencial con un jefe ejecutivo independiente. [146] Según su constitución actual, el estado a veces se denomina Sexta República de Corea . La primera elección directa también se celebró en 1948.

Aunque Corea del Sur experimentó una serie de dictaduras militares desde la década de 1960 hasta la de 1980, desde entonces se ha convertido en una democracia liberal exitosa . Hoy, el CIA World Factbook describe la democracia de Corea del Sur como una "democracia moderna en pleno funcionamiento", [147] mientras que el Índice de Democracia de The Economist la clasifica como una "democracia plena", ocupando el puesto 24 de 167 países en 2022. [148] Según los índices de democracia V-Dem, Corea del Sur es en 2023 el tercer país democrático más electoral de Asia . [149] Corea del Sur ocupa el puesto 33 en el Índice de Percepción de la Corrupción (6.º en la región de Asia y el Pacífico ), con una puntuación de 63 sobre 100. [150]

Las principales divisiones administrativas de Corea del Sur son once provincias , [f] tres provincias autónomas especiales , seis ciudades metropolitanas (ciudades autónomas que no forman parte de ninguna provincia), una ciudad especial y una ciudad autónoma especial .

a Romanización revisada ; b Véase Nombres de Seúl ; c Mayo de 2018 [update].; [151] d Áreas que pertenecen al territorio bajo la Constitución de la República de Corea pero que no han sido recuperadas.

Corea del Sur es miembro de las Naciones Unidas desde 1991, cuando se convirtió en estado miembro al mismo tiempo que Corea del Norte. El 1 de enero de 2007, el ex ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de Corea del Sur, Ban Ki-moon, se desempeñó como Secretario General de la ONU de 2007 a 2016. Corea del Sur ha desarrollado vínculos con la Asociación de Naciones del Sudeste Asiático como miembro de la ASEAN más tres , un organismo de observadores, y de la Cumbre de Asia Oriental (EAS). En noviembre de 2009, Corea del Sur se unió al Comité de Asistencia para el Desarrollo de la OCDE , lo que marcó la primera vez que un ex país receptor de ayuda se unió al grupo como miembro donante. Corea del Sur fue sede de la Cumbre del G-20 en Seúl en noviembre de 2010, un año en el que Corea del Sur y la Unión Europea concluyeron un acuerdo de libre comercio (TLC) para reducir las barreras comerciales. Corea del Sur firmó un acuerdo de libre comercio con Canadá y Australia en 2014, y otro con Nueva Zelanda en 2015. Corea del Sur y Gran Bretaña acordaron extender un período de aranceles bajos o nulos al comercio bilateral de productos con partes de la Unión Europea en octubre de 2023. [152]

Tanto Corea del Norte como Corea del Sur reclaman soberanía total sobre toda la península y las islas periféricas. [153] A pesar de la animosidad mutua, los esfuerzos de reconciliación han continuado desde la separación inicial entre Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur. Figuras políticas como Kim Koo trabajaron para reconciliar a los dos gobiernos incluso después de la Guerra de Corea. [154] Con una animosidad de larga data después de la Guerra de Corea de 1950 a 1953, Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur firmaron un acuerdo para buscar la paz. [155] El 4 de octubre de 2007, Roh Moo-Hyun y el líder norcoreano Kim Jong-il firmaron un acuerdo de ocho puntos sobre cuestiones de paz permanente, conversaciones de alto nivel, cooperación económica, renovación de los servicios ferroviarios, viajes por carretera y aéreos, y un equipo de animación olímpico conjunto. [155]

A pesar de la Política Sunshine y los esfuerzos de reconciliación, el progreso se complicó por las pruebas de misiles de Corea del Norte en 1993 , 1998 , 2006 , 2009 y 2013. A principios de 2009, las relaciones entre Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur eran muy tensas; se había informado de que Corea del Norte había desplegado misiles, [156] puso fin a sus antiguos acuerdos con Corea del Sur, [157] y amenazó a Corea del Sur y a los Estados Unidos con no interferir en el lanzamiento de un satélite que había planeado. [158] Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur todavía están técnicamente en guerra (ya que nunca firmaron un tratado de paz después de la Guerra de Corea) y comparten la frontera más fortificada del mundo. [159]

_01.jpg/440px-Vladimir_Putin_and_Moon_Jae-in_(2017-09-06)_01.jpg)

Históricamente, Corea tenía estrechas relaciones con las dinastías de China, y algunos reinos coreanos eran miembros del sistema tributario imperial chino . Los reinos coreanos también gobernaron sobre algunos reinos chinos, incluido el pueblo kitán y los manchúes antes de la dinastía Qing y recibieron tributos de ellos. [160] En los tiempos modernos, antes de la formación de Corea del Sur, los combatientes por la independencia de Corea trabajaron con soldados chinos durante la ocupación japonesa. Sin embargo, después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la República Popular China abrazó el maoísmo mientras que Corea del Sur buscó relaciones estrechas con los Estados Unidos. La República Popular China ayudó a Corea del Norte con mano de obra y suministros durante la Guerra de Corea, y después de ella, la relación diplomática entre Corea del Sur y la República Popular China cesó casi por completo. Las relaciones se descongelaron gradualmente y Corea del Sur y la República Popular China restablecieron relaciones diplomáticas formales el 24 de agosto de 1992. Los dos países buscaron mejorar las relaciones bilaterales y levantaron el embargo comercial de cuarenta años, [161] y las relaciones entre Corea del Sur y China han mejorado constantemente desde 1992. [161] La República de Corea rompió relaciones oficiales con la República de China (Taiwán) al obtener relaciones oficiales con la República Popular China, que no reconoce la soberanía de Taiwán . [162] China se ha convertido en el mayor socio comercial de Corea del Sur con diferencia, enviando el 26% de las exportaciones surcoreanas en 2016 por valor de 124.000 millones de dólares, así como 32.000 millones de dólares adicionales en exportaciones a Hong Kong . [163] Corea del Sur es también el cuarto socio comercial más importante de China, con 93.000 millones de dólares de importaciones chinas en 2016. [164]

Tras la Guerra de Corea, la relación de la Unión Soviética con Corea del Norte se redujo hasta la disolución de la Unión Soviética . Desde la década de 1990, ha habido un mayor comercio y cooperación entre las dos naciones.

Corea y Japón han tenido relaciones difíciles desde la antigüedad, pero también un intercambio cultural significativo, con Corea actuando como puerta de entrada entre Asia Oriental y Japón. Las percepciones contemporáneas de Japón todavía están definidas en gran medida por la colonización de Corea por parte de Japón durante 35 años en el siglo XX, que generalmente se considera en Corea del Sur como muy negativa . No hubo lazos diplomáticos formales entre Corea del Sur y Japón directamente después de la independencia al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945. Corea del Sur y Japón finalmente firmaron el Tratado de Relaciones Básicas entre Japón y la República de Corea en 1965 para establecer lazos diplomáticos. Japón es hoy el tercer socio comercial más importante de Corea del Sur, con el 12% ($ 46 mil millones) de las exportaciones en 2016. [163]

Los problemas de larga data, como los crímenes de guerra japoneses contra civiles coreanos, la reescritura negacionista de los libros de texto japoneses que relatan las atrocidades japonesas durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, las disputas territoriales sobre las rocas de Liancourt , conocidas en Corea del Sur como "Dokdo" y en Japón como "Takeshima", [165] y las visitas de políticos japoneses al Santuario Yasukuni , en honor a los japoneses (civiles y militares) muertos durante la guerra, siguen perturbando las relaciones entre Corea y Japón. Las rocas de Liancourt fueron los primeros territorios coreanos en ser colonizados por la fuerza por Japón en 1905. Aunque fueron devueltos nuevamente a Corea junto con el resto de su territorio en 1951 con la firma del Tratado de San Francisco, Japón no se retracta de sus afirmaciones de que las rocas de Liancourt son territorio japonés. [166] En 2009, en respuesta a las visitas del Primer Ministro Junichiro Koizumi al Santuario Yasukuni, el Presidente Roh Moo-hyun suspendió todas las conversaciones cumbre entre Corea del Sur y Japón en 2009. [167] Una cumbre entre los líderes de las naciones finalmente se celebró el 9 de febrero de 2018, durante los Juegos Olímpicos de Invierno celebrados en Corea. [168] Corea del Sur pidió al Comité Olímpico Internacional (COI) que prohibiera la bandera japonesa del Sol Naciente en los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 2020 en Tokio, [169] [170] y el COI dijo en una declaración que "los estadios deportivos deben estar libres de cualquier manifestación política. Cuando surgen preocupaciones en el momento de los juegos, las analizamos caso por caso". [171]

La Unión Europea (UE) y Corea del Sur son socios comerciales importantes, y han negociado un acuerdo de libre comercio durante muchos años desde que Corea del Sur fue designada como socio prioritario del TLC en 2006. El acuerdo de libre comercio se aprobó en septiembre de 2010 y entró en vigor el 1 de julio de 2011. [172] Corea del Sur es el décimo socio comercial más importante de la UE, y la UE se ha convertido en el cuarto destino de exportación más importante de Corea del Sur. El comercio de la UE con Corea del Sur superó los 90 mil millones de euros en 2015 y ha disfrutado de una tasa de crecimiento promedio anual del 9,8% entre 2003 y 2013. [173]

La UE ha sido el mayor inversor extranjero en Corea del Sur desde 1962, y representó casi el 45% de todas las entradas de IED a Corea en 2006. Sin embargo, las empresas de la UE tienen problemas importantes para acceder y operar en el mercado surcoreano debido a las estrictas normas y requisitos de prueba para productos y servicios que a menudo crean barreras al comercio. Tanto en sus contactos bilaterales regulares con Corea del Sur como a través de su TLC con Corea, la UE está tratando de mejorar la situación geopolítica actual. [173]

Una relación estrecha con los Estados Unidos comenzó directamente después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, cuando Estados Unidos administró temporalmente Corea durante tres años (principalmente en el Sur, mientras que la Unión Soviética participaba en Corea del Norte). Al estallar la Guerra de Corea en 1950, las fuerzas estadounidenses fueron enviadas para defenderse de una invasión de Corea del Norte en el Sur y posteriormente lucharon como el mayor contribuyente de tropas de la ONU . La participación de los Estados Unidos fue fundamental para evitar la casi derrota de la República de Corea a manos de las fuerzas del norte, así como para luchar por las ganancias territoriales que definen a la nación surcoreana en la actualidad.

Tras el armisticio, Corea del Sur y Estados Unidos acordaron un "Tratado de Defensa Mutua", en virtud del cual un ataque a cualquiera de las partes en el área del Pacífico provocaría una respuesta de ambas. [174] En 1967, Corea del Sur cumplió con el tratado de defensa mutua enviando un gran contingente de tropas de combate para apoyar a Estados Unidos en la guerra de Vietnam . Las dos naciones tienen fuertes vínculos económicos, diplomáticos y militares, aunque a veces han discrepado con respecto a las políticas hacia Corea del Norte y con respecto a algunas de las actividades industriales de Corea del Sur que involucran el uso de tecnología nuclear o de cohetes. También hubo un fuerte sentimiento antiamericano durante ciertos períodos, que se ha moderado en gran medida en la actualidad. [175]

Las dos naciones también comparten una estrecha relación económica, siendo Estados Unidos el segundo socio comercial más importante de Corea del Sur, recibiendo 66 mil millones de dólares en exportaciones en 2016. [163] En 2007, se firmó un acuerdo de libre comercio conocido como el Tratado de Libre Comercio entre la República de Corea y los Estados Unidos entre Corea del Sur y los Estados Unidos, pero su implementación formal se retrasó repetidamente, a la espera de la aprobación de los órganos legislativos de los dos países. El 12 de octubre de 2011, el Congreso de los Estados Unidos aprobó el acuerdo comercial con Corea del Sur, que llevaba mucho tiempo estancado. [176] Entró en vigor el 15 de marzo de 2012. [177]

_broadside_view.jpg/440px-ROKS_Sejong_the_Great_(DDG_991)_broadside_view.jpg)

La tensión no resuelta con Corea del Norte ha llevado a Corea del Sur a asignar el 2,6% de su PIB y el 13,2% de todo el gasto gubernamental a su ejército (porcentaje del gobierno en el PIB: 14,967%), al tiempo que mantiene el reclutamiento obligatorio para los hombres. [178] En consecuencia, las Fuerzas Armadas de la República de Corea son una de las fuerzas armadas permanentes más grandes y poderosas del mundo, con una dotación de personal reportada de 3.600.000 en 2022 (500.000 activos y 3.100.000 de reserva). [179]

El ejército de Corea del Sur está formado por el Ejército (ROKA), la Armada (ROKN), la Fuerza Aérea (ROKAF) y el Cuerpo de Marines (ROKMC), además de fuerzas de reserva. Muchas de estas fuerzas se concentran cerca de la Zona Desmilitarizada de Corea. Todos los varones surcoreanos están obligados constitucionalmente a servir en el ejército, normalmente durante 18 meses. [180] Además, el Aumento Coreano del Ejército de los Estados Unidos es una rama del Ejército de la República de Corea que está formada por personal alistado coreano que se incorpora al Octavo Ejército de los Estados Unidos. En 2010, Corea del Sur gastó 1,68 billones de wones en un acuerdo de reparto de costes con los EE.UU. para proporcionar apoyo presupuestario a las fuerzas estadounidenses en Corea, además del presupuesto de 29,6 billones de wones para su propio ejército.

De vez en cuando, Corea del Sur ha enviado sus tropas al extranjero para ayudar a las fuerzas estadounidenses. Ha participado en la mayoría de los conflictos importantes en los que Estados Unidos se ha visto involucrado en los últimos 50 años. Corea del Sur envió 325.517 tropas para luchar en la Guerra de Vietnam , con una fuerza máxima de 50.000. [181] En 2004, Corea del Sur envió 3.300 tropas de la División Zaytun para ayudar a la reconstrucción en el norte de Irak , y fue el tercer mayor contribuyente a las fuerzas de la coalición después de Estados Unidos y Gran Bretaña. [182] A partir de 2001, Corea del Sur había desplegado 24.000 tropas en la región de Oriente Medio para apoyar la guerra contra el terrorismo .

.jpg/440px-해군_독도함_(7438321572).jpg)

Hasta hace poco, el derecho a la objeción de conciencia no se reconocía en Corea del Sur. En los años anteriores a la creación del derecho a la objeción de conciencia, más de 400 hombres eran encarcelados en cualquier momento por negarse a realizar el servicio militar por razones políticas o religiosas. [183] El 28 de junio de 2018, el Tribunal Constitucional de Corea del Sur declaró inconstitucional la Ley de Servicio Militar y ordenó al gobierno que permitiera que los objetores de conciencia pudieran realizar formas civiles de servicio militar. [ 184] El 1 de noviembre de 2018, el Tribunal Supremo de Corea del Sur legalizó la objeción de conciencia como base para rechazar el servicio militar obligatorio. [185]

Estados Unidos ha estacionado un contingente sustancial de tropas para defender a Corea del Sur. Hay aproximadamente 28.500 efectivos militares estadounidenses estacionados en Corea del Sur, [186] la mayoría de ellos cumpliendo misiones de un año sin acompañamiento. Las tropas estadounidenses, que son principalmente unidades terrestres y aéreas, están asignadas a las Fuerzas de los Estados Unidos en Corea y principalmente asignadas al Octavo Ejército , la Séptima Fuerza Aérea y las Fuerzas Navales de Corea . Están estacionadas en instalaciones en Osan , Kunsan , Yongsan, Dongducheon , Sungbuk, Camp Humphreys y Daegu , así como en Camp Bonifas en el Área de Seguridad Conjunta DMZ .

En la cima de la cadena de mando de todas las fuerzas de Corea del Sur, incluidas las fuerzas estadounidenses y todo el ejército surcoreano, se encuentra un mando de las Naciones Unidas plenamente operativo : si se produjera una escalada repentina de la guerra entre Corea del Norte y Corea del Sur, Estados Unidos asumiría el control de las fuerzas armadas surcoreanas en todas las maniobras militares y paramilitares. Existe un acuerdo de largo plazo entre Estados Unidos y Corea del Sur de que Corea del Sur debería asumir eventualmente el liderazgo de su propia defensa. Esta transición a un mando surcoreano ha sido lenta y a menudo pospuesta, aunque actualmente está programada para ocurrir en la década de 2020. [187]

La economía mixta de Corea del Sur [188] [189] [190] es la 13.ª mayor economía del mundo en términos de PIB nominal y la 14.ª mayor en términos de PIB por paridad de poder adquisitivo [191] , lo que la identifica como una de las principales economías del G20 . Es un país desarrollado con una economía de altos ingresos y es el país miembro más industrializado de la OCDE. Marcas surcoreanas como LG Electronics y Samsung son famosas a nivel internacional y le han ganado a Corea del Sur reputación por su electrónica de calidad y otros productos manufacturados. [192] Corea del Sur se convirtió en miembro de la OCDE en 1996. [193]

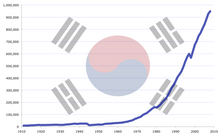

Su inversión masiva en educación ha llevado al país del analfabetismo masivo a una importante potencia tecnológica internacional. La economía nacional del país se beneficia de una fuerza laboral altamente calificada y se encuentra entre los países más educados del mundo con uno de los porcentajes más altos de sus ciudadanos con un título de educación superior. [194] La economía de Corea del Sur fue una de las de más rápido crecimiento del mundo desde principios de la década de 1960 hasta fines de la década de 1990, y todavía era uno de los países desarrollados de más rápido crecimiento en la década de 2000, junto con Hong Kong, Singapur y Taiwán, los otros tres tigres asiáticos . [195] Registró el aumento más rápido del PIB per cápita promedio en el mundo entre 1980 y 1990. [196] Los surcoreanos se refieren a este crecimiento como el Milagro del río Han . [197] La economía de Corea del Sur depende en gran medida del comercio internacional y, en 2014, Corea del Sur fue el quinto mayor exportador y el séptimo mayor importador del mundo. Además, el país tiene una de las mayores reservas de divisas del mundo . [198]

A pesar del alto potencial de crecimiento de la economía y la aparente estabilidad estructural, el país sufre daños en su calificación crediticia en el mercado de valores debido a la beligerancia de Corea del Norte en tiempos de profundas crisis militares, lo que tiene un efecto adverso en sus mercados financieros. [199] [200] El Fondo Monetario Internacional elogia la resiliencia de la economía frente a varias crisis económicas, citando la baja deuda estatal y las altas reservas fiscales que se pueden movilizar rápidamente para abordar emergencias financieras. [201] Aunque se vio gravemente perjudicado por la crisis financiera asiática de 1997 , el país logró una rápida recuperación y posteriormente triplicó su PIB. [202]

Además, Corea del Sur fue uno de los pocos países desarrollados que logró evitar una recesión durante la crisis financiera mundial de 2007-08. [203] Su tasa de crecimiento económico alcanzó el 6,2% en 2010 (el crecimiento más rápido en ocho años después de un crecimiento significativo del 7,2% en 2002), [204] una marcada recuperación de las tasas de crecimiento económico del 2,3% en 2008 y del 0,2% en 2009 durante la Gran Recesión . La tasa de desempleo también se mantuvo baja en 2009, en el 3,6%. [205]

Corea del Sur tiene una red de transporte tecnológicamente avanzada que consiste en ferrocarriles de alta velocidad, autopistas, rutas de autobús, servicios de ferry y rutas aéreas que atraviesan el país. Korea Expressway Corporation opera las autopistas de peaje y los servicios de transporte en ruta. Korail proporciona servicios de tren a las principales ciudades de Corea del Sur. Se están reconectando dos líneas ferroviarias, Gyeongui y Donghae Bukbu Line , a Corea del Norte. El sistema ferroviario de alta velocidad coreano, KTX , proporciona un servicio de alta velocidad a lo largo de Gyeongbu y Honam Line . Las principales ciudades tienen sistemas de tránsito rápido urbano. [206] Hay terminales de autobuses exprés disponibles en la mayoría de las ciudades. [207]

El aeropuerto más grande y de mayor tamaño es el Aeropuerto Internacional de Incheon , que atendió a 58 millones de pasajeros en 2016. [208] Otros aeropuertos internacionales son Gimpo , Busan y Jeju . También hay muchos aeropuertos que se construyeron como parte del auge de la infraestructura, pero que apenas se utilizan. [209] También hay muchos helipuertos . [210] La aerolínea nacional Korean Air atendió a más de 26 millones de pasajeros, incluidos casi 19 millones de pasajeros internacionales en 2016. [211] Una segunda aerolínea, Asiana Airlines, también atiende tráfico nacional e internacional. En conjunto, las aerolíneas surcoreanas atienden 297 rutas internacionales. [212] Las aerolíneas más pequeñas, como Jeju Air , ofrecen servicio doméstico con tarifas más bajas. [213]

Corea del Sur es el quinto mayor productor de energía nuclear del mundo y el tercero más grande de Asia en 2010. [update][ 214] Suministrando el 45% de su producción de electricidad, la investigación nuclear es muy activa con investigaciones sobre una variedad de reactores avanzados, incluyendo un pequeño reactor modular, un reactor de transmutación rápida de metal líquido y un diseño de generación de hidrógeno de alta temperatura . También se han desarrollado localmente tecnologías de producción de combustible y manejo de desechos. También es miembro del proyecto ITER . [215]

Corea del Sur es un exportador emergente de reactores nucleares , habiendo concluido acuerdos con los Emiratos Árabes Unidos para construir y mantener cuatro reactores nucleares avanzados, [216] con Jordania para un reactor nuclear de investigación, [217] [218] y con Argentina para la construcción y reparación de reactores nucleares de agua pesada. [219] [220] En 2010 [update], Corea del Sur y Turquía están en negociaciones sobre la construcción de dos reactores nucleares. [221] Corea del Sur también se está preparando para presentar una oferta para la construcción de un reactor nuclear de agua ligera para Argentina. [220]

Corea del Sur no puede enriquecer uranio ni desarrollar tecnología tradicional de enriquecimiento de uranio por su cuenta, debido a la presión política de los EE. UU., [222] a diferencia de la mayoría de las grandes potencias nucleares, como Japón, Alemania y Francia, competidores en el mercado nuclear internacional. Este impedimento al emprendimiento industrial nuclear autóctono de Corea del Sur ha provocado ocasionales disputas diplomáticas entre los dos aliados. Si bien tiene éxito en la exportación de su tecnología nuclear generadora de electricidad y reactores nucleares, no puede capitalizar el mercado de instalaciones de enriquecimiento nuclear y refinerías , lo que le impide expandir aún más su nicho de exportación. Corea del Sur ha buscado tecnologías únicas como el piroprocesamiento para sortear estos obstáculos y buscar una competencia más ventajosa. [223] Recientemente, los EE. UU. se han mostrado cautelosos ante el floreciente programa nuclear, que Corea del Sur insiste en que será solo para uso civil. [214]

Corea del Sur es el segundo país del continente asiático mejor clasificado en el Índice de preparación para la interconexión en red del Foro Económico Mundial , después de Singapur, un indicador para determinar el nivel de desarrollo de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación de un país. Corea del Sur ocupa el noveno puesto a nivel mundial. [224]

En 2019, más de 17 millones de turistas extranjeros visitaron Corea del Sur. [225] El turismo surcoreano está impulsado por muchos factores, incluida la prominencia de la cultura pop coreana, como la música pop surcoreana y los dramas televisivos , conocidos como la Ola Coreana o Hallyu , que han ganado popularidad en todo el este de Asia. El Instituto de Investigación Hyundai informó que la Ola Coreana tiene una influencia directa en el fomento de la inversión extranjera directa de regreso al país a través de la demanda de productos y la industria del turismo. [226] Entre los países del este de Asia, China fue el más receptivo, invirtiendo $ 1.4 mil millones en Corea del Sur, con gran parte de la inversión dentro de su sector de servicios, un aumento de siete veces desde 2001.

Según un análisis del economista Han Sang-Wan, un aumento del 1% en las exportaciones de contenido cultural coreano impulsa las exportaciones de bienes de consumo un 0,083%, mientras que un aumento del 1% en las exportaciones de contenido pop coreano a un país produce un aumento del 0,019% en el turismo. [226]

El sistema de pensiones de Corea del Sur fue creado para proporcionar beneficios a las personas que llegan a la vejez, a las familias y a las personas afectadas por la muerte de su sustentador principal, y con el propósito de estabilizar el estado de bienestar de la nación . [227] La estructura se basa principalmente en los impuestos y está relacionada con los ingresos. [228] El sistema está dividido en cuatro categorías que distribuyen beneficios a los participantes a través de planes de pensiones nacionales, de personal militar, gubernamentales y de maestros de escuelas privadas. [229] El plan nacional de pensiones es el principal sistema de bienestar que proporciona subsidios a la mayoría de las personas. La elegibilidad para el plan nacional de pensiones no depende de los ingresos, sino de la edad y la residencia, donde están cubiertos aquellos entre las edades de 18 y 59 años. [230] Cualquier persona menor de 18 años es dependiente de alguien que está cubierto o bajo una exclusión especial donde se le permiten disposiciones alternativas. [231] El sistema nacional de pensiones se divide en cuatro categorías de personas aseguradas: los asegurados en el lugar de trabajo, los asegurados individuales, los asegurados voluntariamente y los asegurados voluntarios y continuos. Un sistema de pensiones de vejez cubre a las personas de 60 años o más durante el resto de su vida, siempre que hayan cumplido previamente con el mínimo de 20 años de cobertura de pensión nacional. [231]

.jpg/440px-LG전자,_깜빡임_없는_55인치_3D_OLED_TV_공개(2).jpg)

El desarrollo científico y tecnológico en Corea del Sur no se produjo en un principio debido en gran medida a cuestiones más urgentes, como la división de Corea y la Guerra de Corea que se produjo justo después de su independencia. No fue hasta la década de 1960, bajo la dictadura de Park Chung Hee, cuando la economía de Corea del Sur creció rápidamente gracias a la industrialización y a las corporaciones chaebol como Samsung , LG y SK . Desde la industrialización de la economía de Corea del Sur, el país ha centrado su atención en las corporaciones basadas en la tecnología, que han sido apoyadas por el desarrollo de infraestructuras por parte del gobierno.

Corea del Sur lidera la OCDE en graduados en ciencias e ingeniería. [232] De 2014 a 2019, el país ocupó el primer lugar entre los países más innovadores en el Índice de Innovación de Bloomberg . [233] Ocupó el sexto lugar en el Índice de Innovación Global en 2024. [234] Corea del Sur hoy es conocida como una plataforma de lanzamiento de un mercado móvil maduro que permite a los desarrolladores cosechar los beneficios de un mercado donde existen muy pocas restricciones tecnológicas. Existe una tendencia creciente a la invención de nuevos tipos de medios o aplicaciones, utilizando la infraestructura de Internet 4G y 5G en Corea del Sur. Corea del Sur tiene las infraestructuras para satisfacer una alta densidad de población y cultura; esto, junto con los altos ingresos, permite a las nuevas empresas tecnológicas exclusivamente surcoreanas alcanzar valoraciones de mil millones de dólares o más, un pico generalmente reservado para las nuevas empresas que crecen en varios países. [235]

El gasto total en investigación y desarrollo aumentó de aproximadamente el 3,9% del producto interno bruto (PIB) en 2013 a más del 4,9% en 2022 y, por lo tanto, fue el segundo más alto del mundo, solo detrás de Israel, que gastó el 5,9%. En 2023, el gobierno anunció un recorte del gasto de aproximadamente el 11% para 2024 y la intención de trasladar recursos a nuevas iniciativas, como los esfuerzos para construir cohetes, realizar investigaciones biomédicas y desarrollar innovaciones biotecnológicas al estilo estadounidense. [236]

Tras los ciberataques de la primera mitad de 2013, que afectaron a sitios web del gobierno, de medios de comunicación, de estaciones de televisión y de bancos, el gobierno nacional se comprometió a formar a 5.000 nuevos expertos en ciberseguridad para 2017. El gobierno de Corea del Sur culpó a Corea del Norte de estos ataques, así como de los incidentes ocurridos en 2009, 2011 y 2012, pero Pyongyang niega las acusaciones. [237] El gobierno de Corea del Sur mantiene un enfoque de amplio alcance en la regulación de contenidos específicos en línea e impone un nivel sustancial de censura sobre el discurso relacionado con las elecciones y sobre muchos sitios web que el gobierno considera subversivos o socialmente dañinos. [238] [239]

Corea del Sur ha enviado 10 satélites desde 1992, todos ellos utilizando cohetes extranjeros y plataformas de lanzamiento en el extranjero, en particular el Arirang-1 en 1999 y el Arirang-2 en 2006 como parte de su asociación espacial con Rusia. [240] El Arirang-1 se perdió en el espacio en 2008, después de nueve años en servicio. [241] En abril de 2008, Yi So-yeon se convirtió en la primera coreana en volar al espacio, a bordo del Soyuz TMA-12 ruso . [242] [243]

En junio de 2009, se completó el primer puerto espacial de Corea del Sur, el Centro Espacial Naro , en Goheung , provincia de Jeolla del Sur . [244] El lanzamiento de Naro-1 en enero de 2013 fue un éxito, después de dos intentos fallidos anteriores. [245]

Los esfuerzos para construir un vehículo de lanzamiento espacial autóctono se han visto empañados por la persistente presión política de los Estados Unidos, que durante muchas décadas habían obstaculizado los programas de desarrollo de cohetes y misiles autóctonos de Corea del Sur [246] por temor a su posible conexión con programas clandestinos de misiles balísticos militares, que Corea insistió muchas veces que no violaban las directrices de investigación y desarrollo estipuladas por los acuerdos entre Estados Unidos y Corea sobre la restricción de la investigación y el desarrollo de tecnología de cohetes. [247] Corea del Sur ha buscado la asistencia de países extranjeros como Rusia a través de compromisos MTCR para complementar su tecnología de cohetes doméstica restringida. Los dos vehículos de lanzamiento KSLV-I fallidos se basaron en el Módulo de Cohete Universal , la primera etapa del cohete ruso Angara , combinado con una segunda etapa de combustible sólido construida por Corea del Sur.

El 21 de octubre de 2021 se lanzó con éxito el KSLV-2 Nuri y Corea del Sur se convirtió en un país con su propia tecnología de proyectiles espaciales. [248]

La robótica ha sido incluida en la lista de los principales proyectos nacionales de investigación y desarrollo desde 2003. [249] En 2009, el gobierno anunció planes para construir parques temáticos de robots en Incheon y Masan con una combinación de financiación pública y privada. [250] En 2005, el Instituto Coreano Avanzado de Ciencia y Tecnología ( KAIST ) desarrolló el segundo robot humanoide caminante del mundo , HUBO . Un equipo del Instituto Coreano de Tecnología Industrial desarrolló el primer androide coreano , EveR-1 en mayo de 2006. [251] EveR-1 ha sido reemplazado por modelos más complejos con movimiento y visión mejorados. [252] [253]

En febrero de 2010 se anunciaron planes para crear robots asistentes que enseñen inglés para compensar la escasez de profesores, y en 2013 se instalarán robots en la mayoría de los centros preescolares y jardines de infancia. [254] La robótica también se incorpora al sector del entretenimiento; el Festival de Juegos de Robots de Corea se celebra todos los años desde 2004 para promover la ciencia y la tecnología robótica. [255]

Desde la década de 1980, el gobierno ha invertido en el desarrollo de una industria biotecnológica nacional. [256] El sector médico representa una gran parte de la producción, incluida la producción de vacunas contra la hepatitis y antibióticos . La investigación y el desarrollo en genética y clonación han recibido una atención cada vez mayor, con la primera clonación exitosa de un perro, Snuppy en 2005, y la clonación de dos hembras de una especie en peligro de extinción de lobos grises por la Universidad Nacional de Seúl en 2007. [257] El rápido crecimiento de la industria ha dado lugar a importantes vacíos en la regulación de la ética, como lo puso de relieve el caso de mala conducta científica que involucró a Hwang Woo-Suk . [258]

Desde finales de 2020, SK Bioscience Inc. (una división de SK Group ) produce una parte importante de la vacuna Vaxzevria (también conocida como vacuna COVID-19 de AstraZeneca), bajo licencia de la Universidad de Oxford y AstraZeneca , para su distribución mundial a través del mecanismo COVAX, dependiente del hospicio de la OMS . Un acuerdo reciente con Novavax amplía su producción de una segunda vacuna a 40 millones de dosis en 2022, con una inversión de 450 millones de dólares en instalaciones nacionales y extranjeras. [259]

Corea del Sur tenía una población estimada de aproximadamente 51,7 millones en 2022. [260] [261] A pesar de que su población se ha más que duplicado desde 1960, [262] la tasa de natalidad de Corea del Sur se convirtió en la más baja del mundo en 2009, [263] con una tasa anual de aproximadamente 9 nacimientos por cada 1000 personas. [264] La fertilidad experimentó un modesto aumento después, [265] pero cayó a un nuevo mínimo mundial en 2017, [266] con menos de 30.000 nacimientos al mes por primera vez desde que comenzaron los registros, [267] y menos de 1 hijo por mujer en 2018. [268] En consecuencia, en 2020, el país registró más muertes que nacimientos, lo que resultó en la primera disminución de la población desde que comenzaron los registros modernos. [269] [270] En 2021, la tasa de fertilidad se situó en apenas 0,81 hijos por mujer, [271] muy por debajo de la tasa de reemplazo de 2,1, y se redujo aún más hasta 0,78 en 2022 y 0,72 en 2023, la más baja del mundo. En consecuencia, Corea del Sur tiene la disminución más pronunciada de la población en edad de trabajar entre las naciones de la OCDE , [272] y se prevé que la proporción de personas de 65 años o más supere el 20% en 2025 y se acerque al 45% en 2050. [273]

Corea del Sur es conocida por su densidad de población, que se estimó en 514,6 por kilómetro cuadrado (1333/mi²) en 2022, [260] más de 10 veces el promedio mundial.

La mayoría de los surcoreanos viven en áreas urbanas luego de una rápida migración desde el campo durante la rápida expansión económica del país en los años 1970 a 1990. [274] Aproximadamente la mitad de la población ( 24,5 millones ) se concentra en el Área de la Capital Nacional de Seúl , lo que la convierte en la segunda área metropolitana más grande del mundo; otras ciudades importantes incluyen Busan ( 3,5 millones ), Incheon ( 3,0 millones ), Daegu ( 2,5 millones ), Daejeon ( 1,4 millones ), Gwangju ( 1,4 millones ) y Ulsan ( 1,1 millones ). [275]

.jpg/440px-Korea_Chuseok_31logo_(8046078268).jpg)

La población ha sido moldeada por la migración internacional. Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la división de la península de Corea, alrededor de cuatro millones de personas de Corea del Norte cruzaron la frontera hacia Corea del Sur. Esta tendencia de entrada neta se revirtió en los siguientes 40 años debido a la emigración, especialmente hacia América del Norte a través de los Estados Unidos y Canadá. La población total de Corea del Sur en 1955 era de 21,5 millones [276] , que se duplicaría con creces hasta alcanzar los 50 millones en 2010. [262]

Corea del Sur es considerada una de las sociedades étnicamente más homogéneas del mundo, y los coreanos étnicos representan aproximadamente el 96% de la población total. Es difícil calcular cifras precisas, ya que las estadísticas no registran la etnia, dado que muchos inmigrantes son étnicamente coreanos y algunos ciudadanos surcoreanos no son étnicamente coreanos. [277]

El porcentaje de extranjeros ha estado creciendo rápidamente desde finales de la década de 1990. [278] En 2016 [update], Corea del Sur tenía 1.413.758 residentes extranjeros, el 2,75% de la población; [277] sin embargo, muchos de ellos son coreanos étnicos con ciudadanía extranjera. Por ejemplo, los inmigrantes de China (RPC) representan el 56,5% de los extranjeros, pero aproximadamente el 70% de los ciudadanos chinos en Corea son Joseonjok ( 조선족 ), ciudadanos de la RPC de etnia coreana. [279] Además, alrededor de 43.000 profesores de inglés de países de habla inglesa residen temporalmente en Corea. [280] Corea del Sur tiene una de las tasas más altas de crecimiento de la población nacida en el extranjero, con alrededor de 30.000 residentes nacidos en el extranjero que obtienen la ciudadanía surcoreana cada año desde 2010.

Un gran número de coreanos étnicos viven en el extranjero, a veces en barrios étnicos coreanos también conocidos como Koreatowns . Las cuatro poblaciones diásporicas más grandes se encuentran en China (2,3 millones), Estados Unidos (1,8 millones), Japón (0,85 millones) y Canadá (0,25 millones).

En correspondencia con su desarrollo socioeconómico, Corea del Sur ha experimentado un aumento dramático en la esperanza de vida , de 79,10 años en 2008 [281] (que ocupaba el puesto 34.º en el mundo ), [282] a 83,53 años en 2024, la quinta más alta de cualquier país o territorio.

El coreano es el idioma oficial de Corea del Sur y la mayoría de los lingüistas lo clasifican como una lengua aislada . Incorpora una cantidad significativa de palabras prestadas del chino. El coreano utiliza un sistema de escritura indígena llamado Hangul , creado en 1446 por el rey Sejong , para proporcionar una alternativa conveniente a los caracteres chinos clásicos Hanja que eran difíciles de aprender y no se adaptaban bien al idioma coreano. Corea del Sur todavía utiliza algunos caracteres chinos Hanja en áreas limitadas, como los medios impresos y la documentación legal.

El idioma coreano en Corea del Sur tiene un dialecto estándar conocido como dialecto de Seúl , con otros cuatro dialectos ( Chungcheong , Gangwon , Gyeongsang y Jeolla ) y un idioma ( Jeju ) en uso en todo el país. Casi todos los estudiantes surcoreanos de hoy aprenden inglés a lo largo de su educación. [284] [285]

Religión en Corea del Sur (censo de 2015) [286] [4]

Según los resultados del censo de 2015, más de la mitad de la población de Corea del Sur (56,1%) se declaró no afiliada a ninguna organización religiosa . [286] En una encuesta de 2012, el 52% se declaró "religioso", el 31% dijo que "no era religioso" y el 15% se identificó como " ateo convencido ". [287] De las personas que están afiliadas a una organización religiosa, la mayoría son cristianos y budistas . Según el censo de 2015, el 27,6% de la población eran cristianos (el 19,7% se identificaron como protestantes, el 7,9% como católicos romanos) y el 15,5% eran budistas. [286] Otras religiones incluyen el Islam (130.000 musulmanes, en su mayoría trabajadores migrantes de Pakistán y Bangladesh, pero incluyendo unos 35.000 musulmanes coreanos [288] ), la secta local del budismo won y una variedad de religiones indígenas, incluido el cheondoísmo (una religión confucianizante ), el jeungsanismo , el daejongismo , el daesun jinrihoe y otros. La libertad de religión está garantizada por la constitución y no hay religión estatal . [289] En general, entre los censos de 2005 y 2015, ha habido un ligero descenso del cristianismo (del 29% al 27,6%), un marcado descenso del budismo (del 22,8% al 15,5%) y un aumento de la población no afiliada (del 47,2% al 56,9%). [286]

El cristianismo es la religión organizada más grande de Corea del Sur, y representa más de la mitad de todos los seguidores de organizaciones religiosas surcoreanas. En la actualidad, hay aproximadamente 13,5 millones de cristianos en Corea del Sur; alrededor de dos tercios de ellos pertenecen a iglesias protestantes y el resto a la Iglesia católica. [286] El número de protestantes se había estancado durante las décadas de 1990 y 2000, pero aumentó hasta un nivel máximo durante la década de 2010. Los católicos romanos aumentaron significativamente entre las décadas de 1980 y 2000, pero disminuyeron a lo largo de la década de 2010. [286] El cristianismo, a diferencia de otros países del este de Asia, encontró terreno fértil en Corea en el siglo XVIII y, a fines del siglo XVIII, persuadió a una gran parte de la población, ya que la monarquía en decadencia lo apoyó y abrió el país a un proselitismo generalizado como parte de un proyecto de occidentalización. La debilidad del sindo coreano, que, a diferencia del sintoísmo japonés y el sistema religioso de China , nunca se desarrolló hasta convertirse en una religión nacional de alto estatus, [290] combinada con el estado empobrecido del budismo coreano (después de 500 años de supresión a manos del estado de Joseon, en el siglo XX estaba prácticamente extinto) dejó vía libre a las iglesias cristianas. La similitud del cristianismo con las narrativas religiosas nativas se ha estudiado como otro factor que contribuyó a su éxito en la península. [291] La colonización japonesa de la primera mitad del siglo XX fortaleció aún más la identificación del cristianismo con el nacionalismo coreano , ya que los japoneses cooptaron al sindo coreano nativo en el sintoísmo imperial nipón que intentaron establecer en la península. [292] La cristianización generalizada de los coreanos tuvo lugar durante el sintoísmo estatal, [292] después de su abolición, y luego en la Corea del Sur independiente cuando el gobierno militar recién establecido apoyó al cristianismo y trató de expulsar por completo al sindo nativo.

.jpg/440px-KOCIS_Korea_YeonDeungHoe_20130511_05_(8733836165).jpg)

Entre las denominaciones cristianas, el presbiterianismo es la más numerosa. Alrededor de nueve millones de personas pertenecen a una de las cien iglesias presbiterianas diferentes; las más grandes son la Iglesia Presbiteriana HapDong , la Iglesia Presbiteriana TongHap y la Iglesia Presbiteriana Koshin . Corea del Sur es también la segunda nación que más misioneros envía, después de Estados Unidos. [293]