Kerala ( inglés: / ˈ k ɛr ə l ə / /KERR-ə-lə), llamadoKeralamenmalayalam(malayalam:[keːɾɐɭɐm] ), es unestadoen lacosta de Malabardela India.[15]Se formó el 1 de noviembre de 1956, tras la aprobación de laLey de Reorganización de los Estados, combinandomalayalamde las antiguas regiones deCochin,Malabar,South CanarayTravancore.[16][17]Con una extensión de 38.863 km²(15.005 millas cuadradas), Kerala es el 21.ºestado indio más grande por área. Limita conKarnatakaal norte y noreste,Tamil Nadual este y al sur, y elmar de Lakshadweep[18]al oeste. Con 33 millones de habitantes según elcenso de 2011, Kerala es el13.º estado indio más grande por población. Está dividido en 14distritosy su capital esThiruvananthapuram.El malabares el idioma más hablado y también es el idioma oficial del estado.[19]

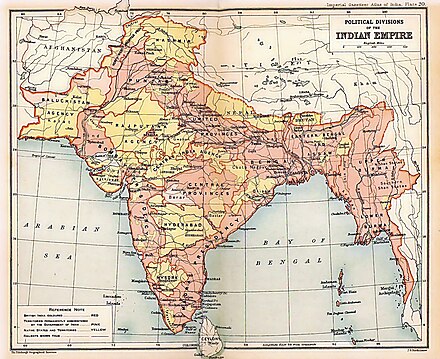

La dinastía Chera fue el primer reino importante con sede en Kerala. El reino Ay en el sur profundo y el reino Ezhimala en el norte formaron los otros reinos en los primeros años de la Era Común (EC) . La región había sido un importante exportador de especias desde 3000 a. C. [20] La prominencia de la región en el comercio se observó en las obras de Plinio , así como en el Periplo alrededor del año 100 d . C. En el siglo XV, el comercio de especias atrajo a los comerciantes portugueses a Kerala y allanó el camino para la colonización europea de la India. En el momento del movimiento de independencia de la India a principios del siglo XX, había dos estados principescos importantes en Kerala: Travancore y Cochin . Se unieron para formar el estado de Thiru-Kochi en 1949. La región de Malabar , en la parte norte de Kerala, había sido parte de la provincia de Madrás de la India británica , que más tarde se convirtió en parte del estado de Madrás después de la independencia. Después de la Ley de Reorganización de los Estados de 1956 , el estado moderno de Kerala se formó fusionando el distrito de Malabar del estado de Madrás (excluyendo el taluk de Gudalur del distrito de Nilgiris , las islas Lakshadweep , Topslip , el bosque de Attappadi al este de Anakatti), el taluk de Kasaragod (ahora distrito de Kasaragod ) en el sur de Canara , y el antiguo estado de Thiru-Kochi (excluyendo cuatro taluks del sur del distrito de Kanyakumari y los taluks de Shenkottai). [17]

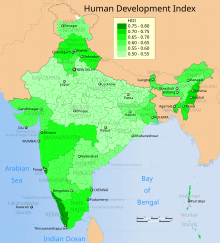

Kerala tiene la tasa de crecimiento poblacional positiva más baja de la India, 3,44%; el Índice de Desarrollo Humano (IDH) más alto, 0,784 en 2018 (0,712 en 2015); la tasa de alfabetización más alta , 96,2% en la encuesta de alfabetización de 2018 realizada por la Oficina Nacional de Estadística de la India; [8] la esperanza de vida más alta, 77,3 años; y la proporción de sexos más alta , 1.084 mujeres por cada 1.000 hombres. Kerala es el estado menos empobrecido de la India según el panel de Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible de NITI Aayog y el Manual de Estadísticas sobre la Economía India del Banco de la Reserva de la India . [21] [22] Kerala es el segundo estado importante más urbanizado del país con un 47,7% de población urbana según el Censo de la India de 2011 . [23] El estado encabezó el país en alcanzar los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible según el informe anual de NITI Aayog publicado en 2019. [24] El estado tiene la mayor exposición mediática en la India con periódicos publicados en nueve idiomas, principalmente malabar y, a veces, inglés . El hinduismo es practicado por más de la mitad de la población, seguido del islam y el cristianismo .

En 2019-20, la economía de Kerala fue la octava más grande de la India con ₹ 8,55 billones (US$ 100 mil millones) en producto interno bruto estatal (GSDP) y un producto interno estatal neto per cápita de ₹ 222,000 (US$ 2,700). [25] En 2019-20, el sector terciario contribuyó con alrededor del 65% al GSVA del estado , mientras que el sector primario contribuyó solo con el 8%. [26] El estado ha sido testigo de una emigración significativa, especialmente a los estados árabes del Golfo Pérsico durante el auge del Golfo de la década de 1970 y principios de la de 1980, y su economía depende significativamente de las remesas de una gran comunidad de expatriados malayos . La producción de pimienta y caucho natural contribuye significativamente a la producción nacional total. En el sector agrícola, el coco , el té , el café , el anacardo y las especias son importantes. El estado está situado entre el mar Arábigo al oeste y las cadenas montañosas de los Ghats occidentales al este. La costa del estado se extiende por 595 kilómetros (370 millas), y alrededor de 1,1 millones de personas en el estado dependen de la industria pesquera, que contribuye con el 3% de los ingresos del estado. Nombrado como uno de los diez paraísos del mundo por National Geographic Traveler , [27] Kerala es uno de los destinos turísticos más destacados de la India, con playas de arena bordeadas de cocoteros , remansos , estaciones de montaña , turismo ayurvédico y vegetación tropical como sus principales atracciones.

La palabra Kerala se registra por primera vez como Keralaputo ('hijo de Chera [s]') en una inscripción en roca del siglo III a. C. dejada por el emperador Maurya Ashoka (274-237 a. C.), uno de sus edictos relacionados con el bienestar. [28] En ese momento, uno de los tres estados de la región se llamaba Cheralam en tamil clásico: Chera y Kera son variantes de la misma palabra. [29] La palabra Cheral se refiere a la dinastía más antigua conocida de reyes de Kerala y se deriva de la antigua palabra tamil para 'lago'. [30] Keralam puede provenir del tamil clásico cherive-alam 'declive de una colina o ladera de una montaña' [31] o chera alam 'tierra de los Cheras'.

Una etimología popular deriva Kerala de la palabra malayalam kera 'cocotero' y alam 'tierra'; por lo tanto, 'tierra de cocos', [32] que es un apodo para el estado utilizado por los lugareños debido a la abundancia de cocoteros. [33]

El texto sánscrito más antiguo que menciona a Kerala como Cherapadha es el texto védico tardío Aitareya Aranyaka . Kerala también se menciona en el Ramayana y el Mahabharata , las dos epopeyas hindúes. [34] El Skanda Purana menciona el cargo eclesiástico del Thachudaya Kaimal , al que se hace referencia como Manikkam Keralar , sinónimo de la deidad del templo Koodalmanikyam . [35] [36] El mapa comercial grecorromano Periplus Maris Erythraei se refiere a Kerala como Celobotra . [37]

En los círculos de comercio exterior, Kerala también se llamaba Malabar . Anteriormente, el término Malabar también se había utilizado para designar a Tulu Nadu y Kanyakumari, que se encuentran contiguos a Kerala en la costa suroeste de la India, además del estado moderno de Kerala. [38] [39] Los habitantes de Malabar eran conocidos como Malabars . Hasta la llegada de la Compañía de las Indias Orientales , el término Malabar se utilizaba como nombre general para Kerala, junto con el término Kerala . [16] Desde la época de Cosmas Indicopleustes (siglo VI d. C.), los marineros árabes solían llamar a Kerala Male . Sin embargo, el primer elemento del nombre ya está atestiguado en la Topografía escrita por Cosmas Indicopleustes . Esta menciona un emporio de pimienta llamado Male , que claramente dio su nombre a Malabar ('el país de Male'). Se cree que el nombre Male proviene de la palabra dravidiana Mala ('colina'). [40] [41] Al-Biruni (973–1048 d. C. ) es el primer escritor conocido que llamó a este país Malabar . [16] Autores como Ibn Khordadbeh y Al-Baladhuri mencionan los puertos de Malabar en sus obras. [42] Los escritores árabes habían llamado a este lugar Malibar , Manibar , Mulibar y Munibar . Malabar recuerda a la palabra Malanad que significa la tierra de las colinas . [43] Según William Logan , la palabra Malabar proviene de una combinación de la palabra dravídica Mala (colina) y la palabra persa / árabe Barr (país/continente). [44]

Según el clásico Sangam Purananuru , el rey Chera Senkuttuvan conquistó las tierras entre Kanyakumari y el Himalaya . [45] A falta de enemigos dignos, sitió el mar arrojando su lanza en él. [45] [46] Según la obra de mitología hindú del siglo XVII Keralolpathi , las tierras de Kerala fueron recuperadas del mar por el sabio guerrero con hacha Parashurama , el sexto avatar de Vishnu (por lo tanto, Kerala también se llama Parashurama Kshetram 'La Tierra de Parashurama' en la mitología hindú). [47] Parashurama arrojó su hacha a través del mar, y el agua retrocedió hasta donde llegó. Según el relato legendario, esta nueva área de tierra se extendía desde Gokarna hasta Kanyakumari . [48] La tierra que surgió del mar estaba llena de sal y no era apta para ser habitada; Entonces Parashurama invocó al Rey Serpiente Vasuki , quien escupió veneno sagrado y convirtió el suelo en una tierra verde fértil y exuberante. Por respeto, Vasuki y todas las serpientes fueron designados como protectores y guardianes de la tierra. PT Srinivasa Iyengar teorizó que Senguttuvan puede haberse inspirado en el relato legendario de Parashurama, que fue traído por los primeros colonos arios. [49]

Otro personaje puránico mucho más antiguo asociado con Kerala es Mahabali , un asura y un rey justo prototípico, que gobernó la tierra desde Kerala. Ganó la guerra contra los Devas , llevándolos al exilio. Los Devas suplicaron ante el Señor Vishnu , quien tomó su quinta encarnación como Vamana y empujó a Mahabali al inframundo para aplacar a los Devas. Existe la creencia de que, una vez al año durante el festival de Onam , Mahabali regresa a Kerala. [50] El Matsya Purana , uno de los más antiguos de los 18 Puranas , [51] [52] utiliza las montañas Malaya como escenario de la historia de Matsya , la primera encarnación de Vishnu, y Manu , el primer hombre y el rey de la región. [53] [54]

Poovar se identifica a menudo con la región bíblica de Ofir , conocida por su riqueza. [55]

La leyenda de Cheraman Perumals es la tradición medieval asociada con los Cheraman Perumals (literalmente los reyes Chera ) de Kerala. [56] La validez de la leyenda como fuente de historia generó mucho debate entre los historiadores del sur de la India. [57] La leyenda fue utilizada por los cacicazgos de Kerala para la legitimación de su gobierno (la mayoría de las principales casas de jefes en la Kerala medieval rastrearon su origen hasta la asignación legendaria por parte de los Perumal). [58] [59] Según la leyenda, Rayar , el señor de los Cheraman Perumal en un país al este de los Ghats , invadió Kerala durante el gobierno del último Perumal. Para hacer retroceder a las fuerzas invasoras, los Perumal convocaron a la milicia de sus jefes (como Udaya Varman Kolathiri , Manichchan y Vikkiran de Eranad ). Los Eradis (jefes de Eranad) aseguraron a los Cheraman Perumal que tomarían un fuerte establecido por los Rayar . [60] La batalla duró tres días y Rayar finalmente evacuó su fuerte (y fue tomado por las tropas de Perumal). [60] Luego, el último Cheraman Perumal dividió Kerala o reino Chera entre sus jefes y desapareció misteriosamente. La gente de Kerala nunca más escuchó noticias de él. [56] [58] [59] A los Eradis de Nediyiruppu , que más tarde llegaron a ser conocidos como los Zamorins de Kozhikode , que fueron dejados de lado durante la asignación de la tierra, se les concedió la espada de Cheraman Perumal (con el permiso de "morir, matar y apoderarse"). [59] [60]

Una parte sustancial de Kerala, incluidas las tierras bajas costeras occidentales y las llanuras de las tierras altas, puede haber estado bajo el mar en la antigüedad. Se han encontrado fósiles marinos en un área cerca de Changanassery , lo que respalda la hipótesis. [61] Los hallazgos arqueológicos prehistóricos incluyen dólmenes de la era neolítica en el área de Marayur del distrito de Idukki , que se encuentran en las tierras altas orientales hechas por los Ghats occidentales . Se los conoce localmente como "muniyara", derivado de muni ( ermitaño o sabio ) y ara (dolmen). [62] Los grabados rupestres en las cuevas de Edakkal , en Wayanad, datan de la era neolítica alrededor del 6000 a. C. [63] [64] Los estudios arqueológicos han identificado sitios mesolíticos , neolíticos y megalíticos en Kerala. [65] Los estudios apuntan al desarrollo de la antigua sociedad de Kerala y su cultura a partir del Paleolítico , pasando por el Mesolítico, el Neolítico y el Megalítico. [66] Los contactos culturales extranjeros han ayudado a esta formación cultural; [67] Los historiadores sugieren una posible relación con la civilización del valle del Indo durante la Edad del Bronce tardía y la Edad del Hierro temprana . [68]

Kerala ha sido un importante exportador de especias desde 3000 a. C., según los registros sumerios y todavía se lo conoce como el "Jardín de las Especias" o como el "Jardín de las Especias de la India". [69] [70] : 79 Las especias de Kerala atrajeron a los antiguos árabes , babilonios , asirios y egipcios a la costa de Malabar en el tercer y segundo milenio a. C. Los fenicios establecieron comercio con Kerala durante este período. [71] Los árabes y fenicios fueron los primeros en ingresar a la costa de Malabar para comerciar especias . [71] Los árabes en las costas de Yemen , Omán y el Golfo Pérsico deben haber hecho el primer viaje largo a Kerala y otros países orientales . [71] Deben haber traído la canela de Kerala al Medio Oriente . [71] El historiador griego Heródoto (siglo V a. C.) registra que en su época la industria de la canela como especia estaba monopolizada por los egipcios y los fenicios. [71]

En la literatura Sangam se señala que el rey Chera Uthiyan Cheralathan gobernó la mayor parte de Kerala moderna desde su capital en Kuttanad , [72] [73] y controló el puerto de Muziris , pero su extremo sur estaba en el reino de Pandyas , [74] que tenía un puerto comercial a veces identificado en fuentes occidentales antiguas como Nelcynda (o Neacyndi ) en Quilon . [75] Tyndis era un importante centro de comercio, solo superado por Muziris , entre Cheras y el Imperio Romano . [76] Los reinos menos conocidos de Ays y Mushikas se encontraban al sur y al norte de las regiones de Chera, respectivamente. [77] [78] Plinio el Viejo (siglo I d.C.) afirma que el puerto de Tyndis estaba ubicado en la frontera noroeste de Keprobotos . [79] La región de Malabar del Norte , que se encuentra al norte del puerto de Tyndis , fue gobernada por el reino de Ezhimala durante el período Sangam . [16] El puerto de Tyndis , que estaba en el lado norte de Muziris , como se menciona en los escritos grecorromanos, estaba en algún lugar alrededor de Kozhikode . [16] Su ubicación exacta es un tema de disputa. [16] Las ubicaciones sugeridas son Ponnani , Tanur , Beypore - Chaliyam - Kadalundi - Vallikkunnu y Koyilandy . [16]

Los comerciantes de Asia occidental y Europa meridional establecieron puestos y asentamientos costeros en Kerala. [80] La conexión israelí (judía) con Kerala comenzó en 573 a. C. [81] [82] [83] Los árabes también tenían vínculos comerciales con Kerala, desde antes del siglo IV a. C., ya que Heródoto (484-413 a. C.) señaló que los bienes traídos por los árabes desde Kerala se vendían a los israelíes [judíos hebreos] en Edén. [84] En el siglo IV, los cristianos knanaya o sudistas también emigraron de Persia y vivieron junto a la comunidad cristiana siríaca primitiva conocida como los cristianos de Santo Tomás, que remontan sus orígenes a la actividad evangelizadora del apóstol Tomás en el siglo I. [85] [86]

.jpg/440px-Quilon_Syrian_copper_plates_(9th_century_AD).jpg)

Un segundo reino Chera (c. 800-1102), también conocido como dinastía Kulasekhara de Mahodayapuram (actual Kodungallur ), fue establecido por Kulasekhara Varman , [88] que gobernó sobre un territorio que comprendía todo el Kerala moderno y una parte más pequeña del Tamil Nadu moderno. Durante la primera parte del período Kulasekara, la región sur desde Nagercoil hasta Thiruvalla fue gobernada por reyes Ay , que perdieron su poder en el siglo X, haciendo de la región una parte del imperio Kulasekara. [89] [90] Bajo el gobierno de Kulasekhara, Kerala fue testigo de un período de desarrollo del arte, la literatura, el comercio y el movimiento Bhakti del hinduismo. [91] Una identidad keralita , distinta de los tamiles , se volvió lingüísticamente separada durante este período alrededor del siglo VII. [92] El origen del calendario malayalam se remonta al año 825 d. C. [93] [94] [95] Para la administración local, el imperio se dividió en provincias bajo el gobierno de Naduvazhis , y cada provincia comprendía una serie de Desams bajo el control de jefes, llamados Desavazhis . [91] El festival Mamankam , que era el festival nativo más grande, se celebraba en Tirunavaya cerca de Kuttippuram , en la orilla del río Bharathappuzha . [43] [16] Athavanad , la sede de Azhvanchery Thamprakkal , que también era considerado como el jefe religioso supremo de los brahmanes Nambudiri de Kerala, también se encuentra cerca de Tirunavaya. [43] [16]

Sulaiman al-Tajir , un comerciante persa que visitó Kerala durante el reinado de Sthanu Ravi Varma (siglo IX d. C.), registra que había un amplio comercio entre Kerala y China en ese momento, con base en el puerto de Kollam . [96] Varios relatos extranjeros han mencionado la presencia de una considerable población musulmana en las ciudades costeras. Escritores árabes como Al-Masudi de Bagdad (896-956 d. C.), Muhammad al-Idrisi (1100-1165 d. C.), Abulfeda (1273-1331 d. C.) y Al-Dimashqi (1256-1327 d. C.) mencionan las comunidades musulmanas en Kerala. [97] Algunos historiadores asumen que los mappilas pueden considerarse como la primera comunidad musulmana nativa y establecida en el sur de Asia . [98] [99] La mención más antigua conocida sobre los musulmanes de Kerala se encuentra en las placas de cobre sirias de Quilon . [87]

.jpg/440px-Calicut_1572_(cropped).jpg)

Las inhibiciones, causadas por una serie de guerras Chera-Chola en el siglo XI, resultaron en el declive del comercio exterior en los puertos de Kerala. Además, las invasiones portuguesas en el siglo XV causaron que dos religiones importantes, el budismo y el jainismo , desaparecieran del país. Se sabe que los Menons en la región Malabar de Kerala eran originalmente fuertes creyentes del jainismo . [100] El sistema social se fracturó con divisiones en líneas de castas . [101] Finalmente, la dinastía Kulasekhara fue subyugada en 1102 por el ataque combinado de Pandyas posteriores y Cholas posteriores . [89] Sin embargo, en el siglo XIV, Ravi Varma Kulashekhara (1299-1314) del reino de Venad del sur pudo establecer una supremacía de corta duración sobre el sur de la India.

Después de su muerte, en ausencia de un poder central fuerte, el estado se dividió en 30 pequeños principados en guerra; los más poderosos de ellos eran el reino de Zamorin de Kozhikode en el norte, Kollam en el extremo sur, Kochi en el sur y Kannur en el extremo norte. El puerto de Kozhikode tenía la posición económica y política superior en Kerala, mientras que Kollam (Quilon), Kochi y Kannur (Cannanore) se limitaban comercialmente a papeles secundarios. [102] El Zamorin de Calicut era originalmente el gobernante de Eranad , que era un principado menor ubicado en las partes del norte del actual distrito de Malappuram . [16] [103] El Zamorin se alió con comerciantes árabes y chinos y utilizó la mayor parte de la riqueza de Kozhikode para desarrollar su poder militar. Kozhikode se convirtió en el reino más poderoso de la región de habla malayalam durante la Edad Media . [104] [103]

En el apogeo de su reinado, los zamorines de Kozhikode gobernaron una región desde Kollam ( Quilon ) en el sur hasta Panthalayini Kollam ( Koyilandy ) en el norte. [104] [103] Ibn Battuta (1342-1347), que visitó la ciudad de Kozhikode seis veces, ofrece los primeros atisbos de la vida en la ciudad. [105] Ma Huan (1403 d. C.), el marinero chino que formaba parte de la flota imperial china bajo el mando de Cheng Ho ( Zheng He ) [106] afirma que la ciudad es un gran emporio comercial frecuentado por comerciantes de todo el mundo. Abdur Razzak (1442-1443), Niccolò de' Conti (1445), Afanasy Nikitin (1468-1474), Ludovico di Varthema (1503-1508) y Duarte Barbosa dieron testimonio de que la ciudad era uno de los principales centros comerciales del subcontinente indio , donde se podían ver comerciantes de diferentes partes del mundo. [107] [108]

El rey Deva Raya II (1424-1446) del Imperio Vijayanagara conquistó la totalidad del actual estado de Kerala en el siglo XV. [103] Derrotó al Zamorin de Kozhikode, así como al gobernante de Kollam alrededor de 1443. [103] Fernão Nunes dice que el Zamorin tuvo que pagar tributo al rey del Imperio Vijayanagara. [103] Más tarde, Kozhikode y Venad parecen haberse rebelado contra sus señores Vijayanagara, pero Deva Raya II sofocó la rebelión. [103] A medida que el poder Vijayanagara disminuyó durante los siguientes cincuenta años, el Zamorin de Kozhikode volvió a cobrar importancia en Kerala. [103] Construyó un fuerte en Ponnani en 1498. [103]

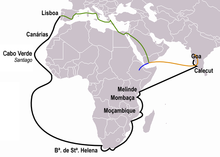

El monopolio del comercio marítimo de especias en el mar Arábigo permaneció en manos de los árabes durante la Alta y Baja Edad Media . Sin embargo, el dominio de los comerciantes de Oriente Medio fue desafiado en la Era Europea de los Descubrimientos . Después de la llegada de Vasco Da Gama a Kappad , Kozhikode en 1498, los portugueses comenzaron a dominar el transporte marítimo oriental, y en particular el comercio de especias. [a] [110] [111] [112] Tras el descubrimiento de la ruta marítima desde Europa hasta Malabar en 1498, los portugueses comenzaron a expandir sus territorios y gobernaron los mares entre Ormus y la costa de Malabar y al sur hasta Ceilán . [113] [114] Establecieron un centro comercial en Tangasseri en Quilon durante 1502 según la invitación de la entonces Reina de Quilon para iniciar el comercio de especias desde allí. [115]

El gobernante del Reino de Tanur , que era vasallo del Zamorin de Calicut , se puso del lado de los portugueses contra su señor en Kozhikode. [16] Como resultado, el Reino de Tanur ( Vettathunadu ) se convirtió en una de las primeras colonias portuguesas en la India. Sin embargo, las fuerzas de Tanur bajo el rey lucharon por el Zamorin de Calicut en la Batalla de Cochin (1504) . [43] Sin embargo, la lealtad de los comerciantes de Mappila en la región de Tanur todavía permaneció bajo el Zamorin de Calicut . [116] Los portugueses aprovecharon la rivalidad entre el Zamorin y el rey de Kochi aliado con Kochi. Cuando Francisco de Almeida fue nombrado virrey de la India portuguesa en 1505, su sede se estableció en Fort Kochi ( Fort Emmanuel ) en lugar de en Kozhikode. Durante su reinado, los portugueses lograron dominar las relaciones con Kochi y establecieron algunas fortalezas en la costa de Malabar. [117] Sin embargo, los portugueses sufrieron reveses por los ataques de las fuerzas zamorinas en el sur de Malabar ; especialmente por los ataques navales bajo el liderazgo de los almirantes de Kozhikode conocidos como Kunjali Marakkars , que los obligaron a buscar un tratado. A los Kunjali Marakkars se les atribuye la organización de la primera defensa naval de la costa india. [118] Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan , considerado el padre de la literatura malayalam moderna , nació en Tirur ( Vettathunadu ) durante el período portugués. [43] [16]

En 1571, los portugueses fueron derrotados por las fuerzas de Zamorin en la batalla de la fortaleza de Chaliyam . [119] Una insurrección en el puerto de Quilon entre los árabes y los portugueses condujo al final de la era portuguesa en Quilon . La línea musulmana de Ali Rajas del reino de Arakkal , cerca de Kannur , que eran vasallos de los Kolathiri , gobernaron las islas Lakshadweep . [120] El fuerte de Bekal cerca de Kasaragod , que también es el fuerte más grande del estado, fue construido en 1650 por Shivappa Nayaka de Keladi . [121] Los portugueses fueron expulsados por la Compañía Holandesa de las Indias Orientales , que durante los conflictos entre Kozhikode y Kochi , obtuvo el control del comercio. [122] La llegada de los británicos a la costa de Malabar se remonta al año 1615, cuando un grupo bajo el liderazgo del capitán William Keeling llegó a Kozhikode, utilizando tres barcos. [16] Fue en estos barcos que Sir Thomas Roe fue a visitar a Jahangir , el cuarto emperador mogol , como enviado británico . [16] En 1664, el municipio de Fort Kochi fue establecido por los holandeses de Malabar , convirtiéndolo en el primer municipio del subcontinente indio , que se disolvió cuando la autoridad holandesa se debilitó en el siglo XVIII. [123]

Los holandeses a su vez se vieron debilitados por las constantes batallas con Marthanda Varma de la familia real de Travancore , y fueron derrotados en la batalla de Colachel en 1741. [124] Un acuerdo, conocido como "Tratado de Mavelikkara", fue firmado por los holandeses y Travancore en 1753, según el cual los holandeses estaban obligados a desprenderse de toda participación política en la región. [125] [126] [127] En el siglo XVIII, el rey de Travancore Sree Anizham Thirunal Marthanda Varma anexó todos los reinos hasta Cochin a través de conquistas militares, lo que resultó en el ascenso de Travancore a la preeminencia en Kerala. [128] El gobernante de Kochi pidió la paz con Anizham Thirunal y las partes norte y centro-norte de Kerala ( distrito de Malabar ), junto con Fort Kochi , Tangasseri y Anchuthengu en el sur de Kerala, quedaron bajo el dominio británico directo hasta que la India se independizó . [129] [130] Travancore se convirtió en el estado dominante en Kerala al derrotar al poderoso Zamorin de Kozhikode en la batalla de Purakkad en 1755. [131]

En 1761, los británicos capturaron Mahé y el asentamiento fue entregado al gobernante de Kadathanadu . [132] Los británicos devolvieron Mahé a los franceses como parte del Tratado de París de 1763. [132] En 1779, estalló la guerra anglo-francesa, lo que resultó en la pérdida francesa de Mahé . [132] En 1783, los británicos acordaron devolver a los franceses sus asentamientos en la India, y Mahé fue entregada a los franceses en 1785. [132] En 1757, para resistir la invasión del Zamorin de Kozhikode , el Raja de Palakkad buscó la ayuda de Hyder Ali de Mysore . [103] En 1766, Hyder Ali derrotó al Zamorin de Kozhikode, un aliado de la Compañía de las Indias Orientales en ese momento, y absorbió a Kozhikode en su estado. [103] Los estados principescos más pequeños en las partes norte y centro-norte de Kerala ( región de Malabar ), incluidos Kolathunadu , Kottayam , Kadathanadu , Kozhikode , Tanur , Valluvanad y Palakkad , se unificaron bajo los gobernantes de Mysore y se convirtieron en parte del Reino más grande de Mysore . [133] Su hijo y sucesor, Tipu Sultan , lanzó campañas contra la expansión de la Compañía Británica de las Indias Orientales , lo que resultó en dos de las cuatro Guerras Anglo-Mysore . [134] [135] Tipu finalmente cedió el Distrito Malabar y Kanara del Sur a la compañía en la década de 1790 como resultado de la Tercera Guerra Anglo-Mysore y el posterior Tratado de Seringapatam ; ambos fueron anexados a la Presidencia de Bombay (que también había incluido otras regiones en la costa occidental de la India) de la India británica en los años 1792 y 1799, respectivamente. [136] [137] [138]

A finales del siglo XVIII, todo Kerala cayó bajo el control de los británicos, ya sea administrados directamente o bajo soberanía . [139] Inicialmente, los británicos tuvieron que sufrir resistencia local contra su gobierno bajo el liderazgo de Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja , que tenía apoyo popular en la región de Thalassery - Wayanad . [16] [140] [141] [142] [143]

Después de que la India se dividió en 1947 en India y Pakistán , Travancore y Kochi , parte de la Unión de la India, se fusionaron el 1 de julio de 1949 para formar Travancore-Cochin . [144] El 1 de noviembre de 1956, el taluk de Kasargod en el distrito de Kanara del Sur de Madrás, el distrito de Malabar de Madrás (excluyendo las islas de Lakshadweep ) y Travancore-Cochin, sin cuatro taluks del sur y el taluk de Sengottai (que se unió a Tamil Nadu), se fusionaron para formar el estado de Kerala bajo la Ley de Reorganización de los Estados . [17] [145] [146] Un gobierno dirigido por los comunistas bajo EMS Namboodiripad resultó de las primeras elecciones para la nueva Asamblea Legislativa de Kerala en 1957. [146] Fue uno de los primeros gobiernos comunistas electos en cualquier lugar . [147] [148] [149] Su gobierno implementó reformas agrarias y educativas que a su vez redujeron la desigualdad de ingresos en el estado. [150]

El estado está encajado entre el mar de Lakshadweep y los Ghats occidentales . Situado entre las latitudes norteñas 8°18' y 12°48' y las longitudes orientales 74°52' y 77°22', [151] Kerala experimenta un clima de selva tropical húmeda con algunos ciclones. El estado tiene una costa de 590 km (370 mi) [152] y el ancho del estado varía entre 11 y 121 kilómetros (7 y 75 mi). [153] Geográficamente, Kerala se puede dividir en tres regiones climáticamente distintas: las tierras altas orientales; terreno montañoso accidentado y fresco, las tierras medias centrales; colinas onduladas, y las tierras bajas occidentales; llanuras costeras. [70] : 110 Las formaciones geológicas precámbricas y pleistocenas componen la mayor parte del terreno de Kerala. [154] [155] Una inundación catastrófica en Kerala en 1341 CE modificó drásticamente su terreno y en consecuencia afectó su historia; también creó un puerto natural para el transporte de especias. [156] La región oriental de Kerala consiste en altas montañas, gargantas y valles profundos inmediatamente al oeste de la sombra de lluvia de los Ghats occidentales . [70] : 110 41 de los ríos que fluyen hacia el oeste de Kerala, [157] y 3 de los que fluyen hacia el este se originan en esta región. [158] [159] Los Ghats occidentales forman una pared de montañas interrumpida solo cerca de Palakkad ; por lo tanto también conocido como Pal ghat , donde se rompe el Palakkad Gap . [160] Los Ghats occidentales se elevan en promedio a 1.500 metros (4.900 pies ) sobre el nivel del mar , [161] mientras que los picos más altos alcanzan alrededor de 2.500 metros (8.200 pies). [162] Anamudi en el distrito de Idukki es el pico más alto del sur de la India, está a una altitud de 2.695 m (8.842 pies). [163] La cadena montañosa de los Ghats occidentales es reconocida como uno de los ocho "puntos calientes" del mundo en cuanto a diversidad biológica y está incluida en la lista de sitios Patrimonio de la Humanidad de la UNESCO . [164] Se considera que los bosques de la cadena son más antiguos que las montañas del Himalaya. [164] Las cataratas de Athirappilly , que están situadas en el fondo de las cadenas montañosas de los Ghats occidentales, también se conocen como el Niágara de la India . [165] Está ubicada en el río Chalakudy y es la catarata más grande del estado. [165] Wayanad es la única Meseta en Kerala. [166] Las regiones orientales en los distritos de Wayanad , Malappuram ( valle de Chaliyar en Nilambur ) y Palakkad ( valle de Attappadi ), que juntos forman parte de la Reserva de la Biosfera de Nilgiri y una continuación de la meseta de Mysore , son conocidas por sus yacimientos de oro naturales , junto con los distritos adyacentes de Karnataka . [167] En el cinturón costero de Kerala se encuentran minerales como la ilmenita , la monacita , el torio y el titanio . [168] El cinturón costero de Karunagappally en Kerala es conocido por la alta radiación de fondo de la arena de monacita que contiene torio . En algunos panchayats costeros, los niveles medios de radiación exterior son más de 4 mGy/año y, en ciertas ubicaciones de la costa, llegan a 70 mGy/año. [169]

El cinturón costero occidental de Kerala es relativamente plano en comparación con la región oriental, [70] : 33 y está atravesado por una red de canales salobres interconectados, lagos, estuarios , [170] y ríos conocidos como los remansos de Kerala . [171] Kuttanad , también conocido como el cuenco de arroz de Kerala , tiene la altitud más baja de la India , y también es uno de los pocos lugares del mundo donde el cultivo se realiza por debajo del nivel del mar. [172] [173] El lago más largo del país , Vembanad , domina los remansos; se encuentra entre Alappuzha y Kochi y tiene unos 200 km2 ( 77 millas cuadradas) de superficie. [174] Alrededor del ocho por ciento de las vías fluviales de la India se encuentran en Kerala. [175] Los 44 ríos de Kerala incluyen el Periyar ; 244 kilómetros (152 millas), Bharathapuzha ; 209 kilómetros (130 mi), Pamba ; 176 kilómetros (109 mi), Chaliyar ; 169 kilómetros (105 mi), Kadalundipuzha ; 130 kilómetros (81 mi), Chalakudipuzha ; 130 kilómetros (81 mi), Valapattanam ; 129 kilómetros (80 mi) y el río Achankovil ; 128 kilómetros (80 mi). La longitud media de los ríos es de 64 kilómetros (40 mi). Muchos de los ríos son pequeños y se alimentan enteramente de la lluvia monzónica. [176] Como los ríos de Kerala son pequeños y carecen de delta , son más propensos a los efectos ambientales. Los ríos se enfrentan a problemas como la extracción de arena y la contaminación. [177] El estado experimenta varios peligros naturales como deslizamientos de tierra, inundaciones y sequías. El estado también se vio afectado por el tsunami del Océano Índico de 2004 , [178] y en 2018 recibió la peor inundación en casi un siglo. [179] En 2024, Kerala experimentó sus peores deslizamientos de tierra de la historia. [180]

Con alrededor de 120-140 días de lluvia al año, [181] : 80 Kerala tiene un clima tropical húmedo y marítimo influenciado por las fuertes lluvias estacionales del monzón de verano del suroeste y el monzón de invierno del noreste . [182] Alrededor del 65% de la lluvia ocurre de junio a agosto correspondiente al monzón del suroeste, y el resto de septiembre a diciembre correspondiente al monzón del noreste. [182] Los vientos cargados de humedad del monzón del suroeste, al llegar al punto más al sur de la península india , debido a su topografía, se dividen en dos ramas; la "rama del mar Arábigo" y la "rama de la bahía de Bengala". [183] La "rama del mar Arábigo" del monzón del suroeste golpea primero los Ghats occidentales, [184] convirtiendo a Kerala en el primer estado de la India en recibir lluvia del monzón del suroeste. [185] [186] La distribución de los patrones de presión se invierte en el monzón del noreste, durante esta estación los vientos fríos del norte de la India recogen la humedad de la Bahía de Bengala y la precipitan en la costa este de la India peninsular. [187] [188] En Kerala, la influencia del monzón del noreste se ve solo en los distritos del sur. [189] La precipitación media de Kerala es de 2923 mm (115 pulgadas) anuales. [190] Algunas de las regiones bajas más secas de Kerala promedian solo 1250 mm (49 pulgadas); las montañas del distrito oriental de Idukki reciben más de 5000 mm (197 pulgadas) de precipitación orográfica : la más alta del estado. En el este de Kerala, prevalece un clima tropical húmedo y seco más seco. Durante el verano, el estado es propenso a vientos huracanados, marejadas ciclónicas, lluvias torrenciales relacionadas con ciclones, sequías ocasionales y aumentos del nivel del mar. [191] : 26, 46, 52 La temperatura media diaria oscila entre 19,8 °C y 36,7 °C. [192] Las temperaturas medias anuales oscilan entre 25,0 y 27,5 °C en las tierras bajas costeras y entre 20,0 y 22,5 °C en las tierras altas orientales. [191] : 65

La mayor parte de la biodiversidad se concentra y protege en los Ghats occidentales . Tres cuartas partes de la superficie terrestre de Kerala estaba cubierta de espesos bosques hasta el siglo XVIII. [193] En 2004 [update], más del 25% de las 15.000 especies de plantas de la India se encuentran en Kerala. De las 4.000 especies de plantas con flores , 1.272 son endémicas de Kerala, 900 son medicinales y 159 están amenazadas . [194] : 11 Sus 9.400 km 2 de bosques incluyen bosques tropicales húmedos siempreverdes y semi-siempreverdes (elevaciones bajas y medias: 3.470 km 2 ), bosques tropicales húmedos y secos caducifolios (elevaciones medias: 4.100 km 2 y 100 km 2 , respectivamente) y bosques montañosos subtropicales y templados ( shola ) (elevaciones más altas: 100 km 2 ). En total, el 24% de Kerala está cubierto de bosques. [194] : 12 Cuatro de los humedales del mundo incluidos en la lista de la Convención de Ramsar ( el lago Sasthamkotta , el lago Ashtamudi , los humedales Thrissur-Ponnani Kole y los humedales Vembanad-Kol) se encuentran en Kerala, [195] así como 1455,4 km2 de la vasta Reserva de la Biosfera de Nilgiri y 1828 km2 de la Reserva de la Biosfera de Agasthyamala . [196] Sometida a una extensa tala para el cultivo en el siglo XX, [197] : 6–7 gran parte de la cubierta forestal restante está ahora protegida de la tala rasa . [198] Las montañas de barlovento del este de Kerala albergan bosques húmedos tropicales y bosques secos tropicales , que son comunes en los Ghats occidentales. [199] [200] La plantación de teca más antigua del mundo, 'Conolly's Plot', se encuentra en Nilambur . [201]

La fauna de Kerala es notable por su diversidad y altas tasas de endemismo: incluye 118 especies de mamíferos (1 endémica), 500 especies de aves , 189 especies de peces de agua dulce, 173 especies de reptiles (10 de ellas endémicas) y 151 especies de anfibios (36 endémicas). [202] Estos están amenazados por la extensa destrucción del hábitat, incluida la erosión del suelo, los deslizamientos de tierra, la salinización y la extracción de recursos. En los bosques, sonokeling , Dalbergia latifolia , anjili , mullumurikku , Erythrina y Cassia se encuentran entre las más de 1000 especies de árboles en Kerala. Otras plantas incluyen bambú , pimienta negra silvestre, cardamomo silvestre , la palma de ratán cálamo y la hierba vetiver aromática, Vetiveria zizanioides . [194] : 12 El elefante indio , el tigre de Bengala , el leopardo indio , el tahr de Nilgiri , la civeta palmera común y las ardillas gigantes canosas también se encuentran en los bosques. [194] : 12, 174–75 Los reptiles incluyen la cobra real , la víbora , la pitón y el cocodrilo de las marismas . Las aves de Kerala incluyen el trogón de Malabar , el cálao grande , el zorzal risueño de Kerala , el darter y el miná de las colinas del sur . En los lagos, humedales y vías fluviales, se encuentran peces como el kadu , el barbo torpedo de línea roja y el choottachi ; cromuro naranja — Etroplus maculatus . [203] [194] : 163–65 Recientemente, una especie de tardígrado (oso de agua) recién descrita recolectada de la costa de Vadakara en Kerala lleva el nombre del estado de Kerala; Stygarctus keralensis . [204]

Los 14 distritos del estado se distribuyen en seis regiones: Malabar del Norte (extremo norte de Kerala), Malabar del Sur (centro norte de Kerala), Kochi (centro de Kerala), Travancore del Norte , Travancore Central (sur de Kerala) y Travancore del Sur (extremo sur de Kerala). Los distritos que sirven como regiones administrativas a efectos fiscales se subdividen a su vez en 27 subdivisiones de ingresos y 77 taluks , que tienen poderes fiscales y administrativos sobre los asentamientos dentro de sus fronteras, incluido el mantenimiento de los registros locales de tierras. Los taluks de Kerala se subdividen a su vez en 1.674 aldeas de ingresos. [206] [207] Desde las enmiendas 73 y 74 a la Constitución de la India , las instituciones de gobierno local funcionan como el tercer nivel de gobierno, que constituye 14 Panchayats de distrito , 152 Panchayats de bloque , 941 Panchayats de grama , 87 municipios , seis corporaciones municipales y un municipio . [208] Mahé , una parte del territorio de la unión india de Puducherry , [209] aunque a 647 kilómetros (402 millas) de distancia de él, [210] es un enclave costero rodeado por Kerala en todos sus accesos terrestres. El distrito de Kannur rodea Mahé en tres lados con el distrito de Kozhikode en el cuarto. [211]

En 1664, el municipio de Fort Kochi fue establecido por los holandeses Malabar , convirtiéndolo en el primer municipio del subcontinente indio , que se disolvió cuando la autoridad holandesa se debilitó en el siglo XVIII. [123] Los municipios de Kozhikode , Palakkad , Fort Kochi , Kannur y Thalassery fueron fundados el 1 de noviembre de 1866 [140] [141] [142] [143] del Imperio Británico de la India , lo que los convirtió en los primeros municipios modernos del estado de Kerala. El municipio de Thiruvananthapuram nació en 1920. Después de dos décadas, durante el reinado de Sree Chithira Thirunal , el municipio de Thiruvananthapuram se convirtió en corporación el 30 de octubre de 1940, convirtiéndose en la corporación municipal más antigua de Kerala. [212] La primera Corporación Municipal fundada después de la independencia de la India , así como la segunda Corporación Municipal más antigua del estado, está en Kozhikode en el año 1962. [213] Hay seis corporaciones municipales en Kerala que gobiernan Thiruvananthapuram , Kozhikode , Kochi , Kollam , Thrissur y Kannur . [214] La Corporación Municipal de Thiruvananthapuram es la corporación más grande de Kerala, mientras que el área metropolitana de Kochi, llamada Kochi UA, es la aglomeración urbana más grande. [215] Según una encuesta realizada por la firma de investigación económica Indicus Analytics en 2007, Thiruvananthapuram , Kozhikode , Kochi , Kollam y Thrissur se encuentran entre las "mejores ciudades de la India para vivir"; la encuesta utilizó parámetros como la salud, la educación, el medio ambiente, la seguridad, las instalaciones públicas y el entretenimiento para clasificar las ciudades. [216]

El estado está gobernado por un sistema parlamentario de democracia representativa . Kerala tiene una legislatura unicameral . La Asamblea Legislativa de Kerala , también conocida como Niyamasabha, consta de 140 miembros que son elegidos por períodos de cinco años. [217] El estado elige a 20 miembros para la Lok Sabha , la cámara baja del Parlamento indio, y a 9 miembros para la Rajya Sabha , la cámara alta. [218]

El Gobierno de Kerala es un organismo elegido democráticamente en la India con el gobernador como su jefe constitucional y es designado por el presidente de la India por un período de cinco años. [219] El líder del partido o coalición con mayoría en la Asamblea Legislativa es designado como ministro principal por el gobernador, y el consejo de ministros es designado por el gobernador siguiendo el consejo del ministro principal. [219] El gobernador sigue siendo un jefe ceremonial del estado, mientras que el ministro principal y su consejo son responsables de las funciones gubernamentales diarias. El consejo de ministros está formado por los ministros del gabinete y los ministros de estado (MoS). La Secretaría encabezada por el secretario principal asiste al consejo de ministros. El secretario principal es también el jefe administrativo del gobierno. Cada departamento gubernamental está encabezado por un ministro, que es asistido por un secretario principal adicional o un secretario principal , que suele ser un funcionario del Servicio Administrativo Indio (IAS), el secretario principal adicional/secretario principal actúa como jefe administrativo del departamento al que está asignado. Cada departamento también cuenta con funcionarios con rango de Secretario, Secretario Especial, Cosecretario, etc., que asisten al Ministro y al Secretario Principal Adicional .

Cada distrito tiene un administrador de distrito designado por el gobierno llamado recaudador de distrito para la administración ejecutiva. Las autoridades auxiliares conocidas como panchayats , para las cuales se celebran elecciones de órganos locales periódicamente, gobiernan los asuntos locales. [220] El poder judicial está formado por el Tribunal Superior de Kerala y un sistema de tribunales inferiores. [221] El Tribunal Superior, ubicado en Kochi, [222] tiene un Presidente de la Corte Suprema junto con 35 jueces permanentes y doce jueces pro tempore adicionales a partir de 2021. [223] El tribunal superior también escucha casos del Territorio de la Unión de Lakshadweep[update] . [224] [225]

En Kerala, los órganos de gobierno local como Panchayats, Municipios y Corporaciones han existido desde 1959. Sin embargo, una importante iniciativa de descentralización comenzó en 1993, alineándose con las enmiendas constitucionales del gobierno central. [226] La Ley de Panchayati Raj de Kerala y la Ley de Municipios de Kerala se promulgaron en 1994, estableciendo un sistema de tres niveles para el gobierno local. [227] Este sistema incluye Gram Panchayat, Block Panchayat y District Panchayat. [228] Las leyes definen poderes claros para estas instituciones. [226] Para las áreas urbanas, la Ley de Municipios de Kerala sigue un sistema de un solo nivel, equivalente a Gram Panchayat. Estos órganos reciben importantes poderes administrativos, legales y financieros para asegurar una descentralización efectiva. [229] Actualmente, el gobierno estatal asigna alrededor del 40% del desembolso del plan estatal a los gobiernos locales. [230] Kerala fue declarado el primer estado digital de la India en 2016 y, según la Encuesta de Corrupción de la India de 2019 de Transparencia Internacional , se considera el estado menos corrupto de la India. [231] [232] El Índice de Asuntos Públicos de 2020 designó a Kerala como el estado mejor gobernado de la India. [233]

Kerala alberga dos alianzas políticas importantes: el Frente Democrático Unido (UDF), liderado por el Congreso Nacional Indio ; y el Frente Democrático de Izquierda (LDF), liderado por el Partido Comunista de la India (Marxista) (CPI(M)). A partir de las elecciones de la Asamblea Legislativa de Kerala de 2021 , el LDF es la coalición gobernante; Pinarayi Vijayan del Partido Comunista de la India (Marxista) es el Ministro Principal, mientras que VD Satheesan del Congreso Nacional Indio es el Líder de la Oposición . Según la Constitución de la India , Kerala tiene un sistema parlamentario de democracia representativa ; se concede sufragio universal a los residentes. [234][update]

Después de la independencia, el estado fue manejado como una economía de bienestar socialdemócrata . [237] El "fenómeno Kerala" o " modelo de desarrollo Kerala " de desarrollo humano muy alto y en comparación bajo desarrollo económico ha sido resultado de un fuerte sector de servicios. [191] : 48 [238] : 1 En 2019-20, el sector terciario contribuyó con alrededor del 63% del GSVA del estado , en comparación con el 28% del sector secundario y el 8% del sector primario . [26] En el período entre 1960 y 2020, la economía de Kerala fue cambiando gradualmente de una economía agraria a una basada en servicios. [26]

El sector de servicios del estado , que representa alrededor del 63% de sus ingresos, se basa principalmente en la industria hotelera , el turismo , el Ayurveda y los servicios médicos, la peregrinación, la tecnología de la información , el transporte , el sector financiero y la educación . [239] Las principales iniciativas del sector industrial incluyen el Astillero Cochin , la construcción naval, la refinería de petróleo, la industria del software, las industrias minerales costeras, [168] el procesamiento de alimentos, el procesamiento de productos marinos y los productos a base de caucho. El sector primario del estado se basa principalmente en cultivos comerciales . [240] Kerala produce una cantidad significativa de la producción nacional de cultivos comerciales como el coco , el té , el café , la pimienta , el caucho natural , el cardamomo y el anacardo en la India. [240] El cultivo de cultivos alimentarios comenzó a reducirse desde la década de 1950. [240]

La economía de Kerala depende significativamente de los emigrantes que trabajan en países extranjeros , principalmente en los estados árabes del Golfo Pérsico , y las remesas contribuyen anualmente con más de una quinta parte del PBI. [241] El estado fue testigo de una emigración significativa durante el auge del Golfo de los años 1970 y principios de los años 1980. En 2012, Kerala todavía recibía las remesas más altas de todos los estados: US$11.3 mil millones, que era casi el 16% de los US$71 mil millones de remesas al país. [242] En 2015, los depósitos NRI en Kerala se han disparado a más de ₹ 1 lakh crore (US$12 mil millones), lo que equivale a una sexta parte de todo el dinero depositado en cuentas NRI, que asciende a aproximadamente ₹ 7 lakh crore (US$84 mil millones). [243] El distrito de Malappuram tiene la mayor proporción de hogares emigrantes en el estado. [26] Un estudio encargado por la Junta de Planificación del Estado de Kerala sugirió que el estado busque otras fuentes confiables de ingresos, en lugar de depender de las remesas para financiar sus gastos. [244]

En marzo de 2002, el sector bancario de Kerala comprendía 3341 sucursales locales: cada sucursal atendía a 10.000 personas, cifra inferior al promedio nacional de 16.000; el estado tiene la tercera penetración bancaria más alta entre los estados indios. [245] El 1 de octubre de 2011, Kerala se convirtió en el primer estado del país en tener al menos una instalación bancaria en cada aldea. [246] El desempleo en 2007 se estimó en un 9,4%; [247] los problemas crónicos son el subempleo , la baja empleabilidad de los jóvenes y una baja tasa de participación laboral femenina de sólo el 13,5%, [248] : 5, 13 como lo era la práctica de Nokku kooli , "salarios por mirar". [249] En 1999-2000, las tasas de pobreza rural y urbana cayeron al 10,0% y al 9,6%, respectivamente. [250]

El presupuesto del estado de 2020-2021 fue de ₹ 1,15 lakh crore (US$ 14 mil millones). [251] Los ingresos fiscales del gobierno estatal (excluyendo las partes del fondo fiscal de la Unión) ascendieron a ₹ 674 mil millones (US$ 8,1 mil millones) en 2020-21; frente a ₹ 557 mil millones (US$ 6,7 mil millones) en 2019-20. Sus ingresos no fiscales (excluyendo las partes del fondo fiscal de la Unión) del Gobierno de Kerala alcanzaron los ₹ 146 mil millones (US$ 1,7 mil millones) en 2020-2021. [251] Sin embargo, la alta proporción de impuestos de Kerala con respecto al GSDP no ha aliviado los déficits presupuestarios crónicos y los niveles insostenibles de deuda gubernamental, que han afectado a los servicios sociales. [252] En 2006 se observó un total récord de 223 hartals , lo que resultó en una pérdida de ingresos de más de 20 mil millones de rupias (240 millones de dólares estadounidenses). [253] El aumento del 10% del PIB de Kerala es un 3% más que el PIB nacional. En 2013, el gasto de capital aumentó un 30% en comparación con el promedio nacional del 5%, los propietarios de vehículos de dos ruedas aumentaron un 35% en comparación con la tasa nacional del 15%, y la relación profesor-alumno aumentó un 50% de 2:100 a 4:100. [254]

El Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board es una institución financiera propiedad del gobierno en el estado para movilizar fondos para el desarrollo de infraestructura desde fuera de los ingresos estatales, con el objetivo de un desarrollo general de la infraestructura del estado. [255] [256] En noviembre de 2015, el Ministerio de Desarrollo Urbano seleccionó siete ciudades de Kerala para un programa de desarrollo integral conocido como la Misión Atal para el Rejuvenecimiento y la Transformación Urbana (AMRUT). [257] Se declaró un paquete de ₹ 2,5 millones (US$ 30.000) para cada una de las ciudades para desarrollar un plan de mejora del nivel de servicio (SLIP), un plan para un mejor funcionamiento de los organismos urbanos locales en las ciudades de Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, Alappuzha, Kochi, Thrissur, Kozhikode y Palakkad. [258] El Grand Kerala Shopping Festival (GKSF) comenzó en 2007, cubriendo más de 3000 puntos de venta en las nueve ciudades de Kerala con enormes descuentos fiscales, reembolsos de IVA y una gran variedad de premios. [259] Lulu International Mall en Thiruvananthapuram es el centro comercial más grande de la India. [260]

A pesar de sus muchos logros, Kerala enfrenta muchos desafíos, como altos niveles de desempleo que afectan desproporcionadamente a las mujeres educadas, un alto grado de exposición global y un medio ambiente muy frágil. [261]

Las industrias tradicionales que fabrican artículos de fibra de coco , telares manuales y artesanías emplean a alrededor de un millón de personas. [262] Kerala suministra el 60% de la producción mundial total de fibra de coco blanca. La primera fábrica de fibra de coco de la India se estableció en Alleppey en 1859-60. [263] El Instituto Central de Investigación de Fibra de Coco se estableció allí en 1959. Según el censo de 2006-2007 de SIDBI , hay 1.468.104 micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas en Kerala que emplean a 3.031.272 personas. [264] [265] El KSIDC ha promovido más de 650 empresas manufactureras medianas y grandes en Kerala, creando empleo para 72.500 personas. [266] Un sector minero del 0,3% del PBI implica la extracción de ilmenita , caolín , bauxita , sílice , cuarzo , rutilo , circón y silimanita . [267] Otros sectores importantes son el turismo , el sector médico, el sector educativo , la banca, la construcción naval , la refinería de petróleo , la infraestructura, la manufactura, los huertos domésticos , la cría de animales y la subcontratación de procesos comerciales .

_fruits.jpg/440px-Black_Pepper_(Piper_nigrum)_fruits.jpg)

El cambio más importante en la agricultura de Kerala ocurrió en la década de 1970, cuando la producción de arroz cayó debido a la mayor disponibilidad de arroz en toda la India y la menor disponibilidad de mano de obra. [268] En consecuencia, la inversión en la producción de arroz disminuyó y una gran parte de la tierra se desplazó al cultivo de cultivos arbóreos perennes y cultivos estacionales. [269] [270] La rentabilidad de los cultivos cayó debido a la escasez de mano de obra agrícola, el alto precio de la tierra y el tamaño antieconómico de las explotaciones agrícolas. [271] Sólo el 27,3% de las familias de Kerala dependen de la agricultura para su sustento, que es también la tasa correspondiente más baja en la India. [272]

Kerala produce el 97% de la producción nacional de pimienta negra [273] y representa el 85% del caucho natural del país. [274] [275] El coco , el té , el café , el anacardo y las especias, incluido el cardamomo, la vainilla , la canela y la nuez moscada , son los principales productos agrícolas. [70] : 74 [276] [277] [278] [279] [280] Alrededor del 80% de los granos de anacardo de calidad de exportación de la India se preparan en Kollam . [281] El cultivo comercial clave es el coco y Kerala ocupa el primer lugar en el área de cultivo de coco en la India. [282] Alrededor del 90% del cardamomo total producido en la India proviene de Kerala. [26] India es el segundo mayor productor de cardamomo en el mundo. [26] Aproximadamente el 20% del café total producido en la India proviene de Kerala. [240] El principal producto agrícola es el arroz, con variedades cultivadas en extensos arrozales. [283] Los huertos familiares constituyen una parte importante del sector agrícola. [284]

Con 590 kilómetros (370 millas ) de franja costera, [285] 400.000 hectáreas de recursos de aguas continentales [286] y aproximadamente 220.000 pescadores activos, [287] Kerala es uno de los principales productores de pescado de la India. [288] Según informes de 2003-04, alrededor de 11 lakh (1,1 millones) de personas se ganan la vida con la pesca y actividades conexas, como el secado, el procesamiento, el envasado, la exportación y el transporte de pescado. El rendimiento anual del sector se estimó en 608.000 toneladas en 2003-04. [289] Esto contribuye a alrededor del 3% de la economía total del estado. En 2006, alrededor del 22% del rendimiento total de la pesca marina india provino de Kerala. [290] Durante el monzón del suroeste, se desarrolla un banco de lodo suspendido a lo largo de la costa, que a su vez conduce a la calma del agua del océano, lo que aumenta la producción de la industria pesquera. Este fenómeno se llama localmente chakara . [291] [292] Las aguas proporcionan una gran variedad de peces: especies pelágicas ; 59%, especies demersales ; 23%, crustáceos , moluscos y otros para el 18%. [290] Alrededor de 1050.000 (1.050 millones) de pescadores extraen una captura anual de 668.000 toneladas según una estimación de 1999-2000; 222 aldeas pesqueras se encuentran a lo largo de la costa de 590 kilómetros (370 millas). Otras 113 aldeas pesqueras salpican el interior.

Kerala tiene 331.904 kilómetros (206.236 millas) de carreteras, lo que representa el 5,6% del total de la India. [26] [293] Esto se traduce en unos 9,94 kilómetros (6,18 millas) de carreteras por cada mil personas, en comparación con un promedio de 4,87 kilómetros (3,03 millas) en el país. [26] [293] Las carreteras en Kerala incluyen 1.812 kilómetros (1.126 millas) de carreteras nacionales; el 1,6% del total de la nación, 4.342 kilómetros (2.698 millas) de carreteras estatales; el 2,5% del total de la nación, 27.470 kilómetros (17.070 millas) de carreteras de distrito; el 4,7% del total de la nación, 33.201 kilómetros (20.630 millas) de carreteras urbanas (municipales); 6,3% del total de la nación y 158.775 kilómetros (98.658 mi) de caminos rurales; 3,8% del total de la nación. [294] Kottayam tiene la máxima longitud de caminos entre los distritos de Kerala , mientras que Wayanad representa el mínimo. [295] La mayor parte de la costa oeste de Kerala es accesible a través de la NH 66 (anteriormente NH 17 y 47); y el lado oriental es accesible a través de carreteras estatales. [296] Recientemente se anunciaron nuevos proyectos para carreteras de montaña y costeras bajo KIIFB . [297] La Carretera Nacional 66, con el tramo de carretera más largo (1.622 kilómetros (1.008 mi)) conecta Kanyakumari con Mumbai ; Entra en Kerala a través de Talapady en Kasargod y pasa por Kannur , Kozhikode , Malappuram , Guruvayur , Kochi , Alappuzha , Kollam , Thiruvananthapuram antes de entrar en Tamil Nadu . [296] El distrito de Palakkad generalmente se conoce como la Puerta de Kerala, debido a la presencia de la Brecha de Palakkad en los Ghats occidentales, a través de la cual las partes norte ( Malabar ) y sur (Travancore) de Kerala están conectadas con el resto de la India a través de carreteras y ferrocarriles. El puesto de control más grande del estado, Walayar , está en NH 544 , en la ciudad fronteriza entre Kerala y Tamil Nadu , a través del cual una gran cantidad de transporte público y comercial llega a los distritos norte y central de Kerala. [298]

El Departamento de Obras Públicas es responsable de mantener y expandir el sistema de carreteras estatales y las principales carreteras de distrito. [299] El Proyecto de Transporte del Estado de Kerala (KSTP), que incluye el Proyecto de Información y Gestión de Carreteras basado en SIG (RIMS), es responsable de mantener y expandir las carreteras estatales en Kerala. También supervisa algunas carreteras de distrito importantes. [300] [301] El tráfico en Kerala ha estado creciendo a una tasa del 10-11% cada año, lo que resulta en un alto tráfico y presión en las carreteras. La densidad del tráfico es casi cuatro veces el promedio nacional, lo que refleja la alta población del estado. El total anual de accidentes de tráfico de Kerala está entre los más altos del país. Los accidentes son principalmente el resultado de las carreteras estrechas y la conducción irresponsable. [302] Las carreteras nacionales en Kerala están entre las más estrechas del país y seguirán siendo así en el futuro previsible, ya que el gobierno estatal ha recibido una exención que permite carreteras nacionales estrechas. En Kerala, las carreteras tienen 45 metros (148 pies) de ancho. En otros estados, las carreteras nacionales están separadas por niveles, tienen 60 metros (200 pies) de ancho y un mínimo de cuatro carriles, así como autopistas con acceso controlado de 6 u 8 carriles. [303] [304] La Autoridad Nacional de Carreteras de la India (NHAI) ha amenazado al gobierno del estado de Kerala con que dará mayor prioridad a otros estados en el desarrollo de carreteras, ya que ha faltado compromiso político para mejorar las carreteras en Kerala. [305] En 2013 [update], Kerala tenía la tasa de accidentes de tráfico más alta del país, y la mayoría de los accidentes mortales se producían a lo largo de las carreteras nacionales del estado. [306]

La Corporación de Transporte por Carretera del Estado de Kerala (KSRTC) es una corporación de transporte por carretera de propiedad estatal. Es uno de los servicios de transporte público en autobús más antiguos del país. Sus orígenes se remontan al Departamento de Transporte por Carretera del Estado de Travancore, cuando el gobierno de Travancore encabezado por Sri Chithra Thirunnal decidió establecer un sistema de transporte público por carretera en 1937.

La corporación está dividida en tres zonas (Norte, Centro y Sur), con sede en Thiruvananthapuram (capital de Kerala). El servicio diario programado ha aumentado de 1.200.000 kilómetros (750.000 millas) a 1.422.546 kilómetros (883.929 millas), [307] utilizando 6.241 autobuses en 6.389 rutas. En la actualidad, la corporación tiene 5.373 autobuses que circulan en 4.795 horarios. [308] [309]

La Corporación de Transporte Urbano por Carretera de Kerala (KURTC) se formó bajo la KSRTC en 2015 para gestionar los asuntos relacionados con el transporte urbano. [295] Se inauguró el 12 de abril de 2015 en Thevara . [310]

La zona ferroviaria del sur de los ferrocarriles indios opera todas las líneas ferroviarias del estado que conectan la mayoría de las ciudades y pueblos principales, excepto los de los distritos montañosos de Idukki y Wayanad . [311] La red ferroviaria del estado está controlada por dos de las seis divisiones del Ferrocarril del Sur ; la división ferroviaria de Thiruvananthapuram con sede en Thiruvananthapuram y la división ferroviaria de Palakkad con sede en Palakkad . [312] Thiruvananthapuram Central (TVC) es la estación de tren más concurrida del estado. [313] Las principales estaciones de tren de Kerala son:

La primera línea ferroviaria del estado se construyó de Tirur a Chaliyam ( Kozhikode ), con la estación de tren más antigua en Tirur , pasando por Tanur , Parappanangadi , Vallikkunnu y Kadalundi . [314] [315] El ferrocarril se extendió de Tirur a Kuttippuram a través de Tirunavaya en el mismo año. [315] Se extendió nuevamente de Kuttippuram a Shoranur a través de Pattambi en 1862, lo que resultó en el establecimiento de la estación de tren Shoranur Junction , que también es el cruce ferroviario más grande del estado. [315] El principal transporte ferroviario entre Chaliyam - Tirur comenzó el 12 de marzo de 1861, [315] desde Tirur - Shoranur en 1862, [315] desde la sección del puerto de Shoranur-Cochin en 1902, desde Kollam-Sengottai el 1 de julio de 1904, Kollam-Thiruvananthapuram el 4 de enero de 1918, desde Nilambur- Shoranur en 1927, de Ernakulam -Kottayam en 1956, de Kottayam-Kollam en 1958, de Thiruvananthapuram-Kanyakumari en 1979 y de la sección Thrissur-Guruvayur en 1994. [316] La línea Nilambur-Shoranur es una de las líneas ferroviarias de vía ancha más cortas de la India . [317] Se estableció en la era británica para el transporte de teca de Nilambur y laterita de Angadipuram al Reino Unido a través del puerto de Kozhikode . [317] La presencia de Palakkad Gap en los Ghats occidentales hace que la estación de tren de Shoranur Junction sea importante, ya que conecta la costa suroeste de la India ( Mangalore ) con la costa sureste ( Chennai ). [318]

El metro de Kochi es el sistema de metro de la ciudad de Kochi. Es el único sistema de metro de Kerala. La construcción comenzó en 2012, y la primera fase se instaló con un costo estimado de ₹ 51.81 mil millones (US$ 620 millones). [319] [320] El metro de Kochi utiliza trenes Metropolis de 65 metros de largo construidos y diseñados por Alstom . [321] [322] [323] Es el primer sistema de metro en la India que utiliza un sistema de control de trenes basado en comunicaciones (CBTC) para señalización y telecomunicaciones. [324] En octubre de 2017, el metro de Kochi fue nombrado el "Mejor proyecto de movilidad urbana" en la India por el Ministerio de Desarrollo Urbano , como parte de la Conferencia Internacional de Movilidad Urbana de la India (UMI) organizada por el ministerio todos los años. [325]

Kerala tiene cuatro aeropuertos internacionales:

El aeropuerto de Kollam , establecido bajo la presidencia de Madrás, pero cerrado desde entonces, fue el primer aeropuerto de Kerala. [326] Kannur tenía una pista de aterrizaje utilizada para la aviación comercial desde 1935, cuando las aerolíneas Tata operaban vuelos semanales entre Mumbai y Thiruvananthapuram, con escalas en Goa y Kannur. [327] El aeropuerto internacional de Trivandrum, administrado por la Autoridad Aeroportuaria de la India , es uno de los aeropuertos existentes más antiguos del sur de la India. El aeropuerto internacional de Calicut , inaugurado en 1988, es el segundo aeropuerto existente más antiguo de Kerala y el más antiguo de la región de Malabar . [328] El aeropuerto internacional de Cochin es el más transitado del estado y el séptimo más transitado del país. También es el primer aeropuerto del mundo que funciona completamente con energía solar [329] y ha ganado el codiciado premio Champion of the Earth , el máximo honor medioambiental instituido por las Naciones Unidas . [330] El Aeropuerto Internacional de Cochin es también el primer aeropuerto indio en ser incorporado como una compañía pública limitada ; fue financiado por casi 10.000 indios no residentes de 30 países. [331] Además de los aeropuertos civiles, Kochi tiene un aeropuerto naval llamado INS Garuda . El aeropuerto de Thiruvananthapuram comparte instalaciones civiles con el Comando Aéreo del Sur de la Fuerza Aérea de la India . Estas instalaciones son utilizadas principalmente por personalidades del gobierno central que visitan Kerala.

Kerala tiene un puerto principal, cuatro puertos intermedios y 13 puertos menores , 4 de los cuales tienen instalaciones de control de inmigración. [332] [333] El puerto principal del estado está en Kochi , que tiene un área de 8,27 km 2 . [334] El puerto marítimo internacional de Vizhinjam , que actualmente está clasificado como puerto intermedio, es un próximo puerto importante en construcción. [334] Otros puertos intermedios incluyen Beypore , Kollam y Azheekal . [334] Los puertos restantes están clasificados como menores, que incluyen Manjeshwaram , Kasaragod , Nileshwaram , Kannur , Thalassery , Vadakara , Ponnani , Munambam , Manakodam, Alappuzha , Kayamkulam , Neendakara y Valiyathura . [334] El Instituto Marítimo de Kerala tiene su sede en Neendakara , que también tiene un subcentro adicional en Kodungallur . [334] El estado tiene numerosos remansos , que se utilizan para la navegación interior comercial . Los servicios de transporte son proporcionados principalmente por embarcaciones nacionales y buques de pasajeros. Hay 67 ríos navegables en el estado, mientras que la longitud total de las vías navegables interiores es de 1.687 kilómetros (1.048 millas). [335] Las principales limitaciones a la expansión de la navegación interior son; la falta de profundidad en las vías navegables causada por la sedimentación, la falta de mantenimiento de los sistemas de navegación y protección de los bancos, el crecimiento acelerado del jacinto de agua , la falta de terminales modernas para embarcaciones interiores y la falta de un sistema de manipulación de carga.

The 616 kilometres (383 mi) long West-Coast Canal is the longest waterway in state connecting Kasaragod to Poovar.[310] It is divided into five sections: 41 kilometres (25 mi) long Kasaragod-Nileshwaram reach, 188 kilometres (117 mi) long Nileshwaram-Kozhikode reach, 160 kilometres (99 mi) Kozhikode-Kottapuram reach, 168 kilometres (104 mi) long National Waterway 3 (Kottapuram-Kollam reach), and 74 kilometres (46 mi) long Kollam-Vizhinjam reach.[26] The Conolly Canal, which is a part of West-Coast Canal, connects the city of Kozhikode with Kochi through Ponnani, passing through the districts of Malappuram and Thrissur. It begins at Vadakara.[336] It was constructed in the year 1848 under the orders of then District collector of Malabar, H. V. Conolly, initially to facilitate movement of goods to Kallayi Port from hinter lands of Malabar through Kuttiady and Korapuzha river systems.[336] It was the main waterway for the cargo movement between Kozhikode and Kochi through Ponnani, for more than a century.[336] Other important waterways in Kerala include the Alappuzha-Changanassery Canal, Alappuzha-Kottayam-Athirampuzha Canal, and Kottayam-Vaikom Canal.[334]

Kochi Water Metro (KWM) is an integrated ferry transport system serving the Greater Kochi region in Kerala, India. It is the first water metro system in India and the first integrated water transport system of this size in Asia, which connects Kochi's 10 island communities with the mainland through a fleet of 78 battery-operated electric hybrid boats plying along 38 terminals and 16 routes spanning 76 kilometres.[337] It is integrated with the Kochi Metro and serves as a feeder service to the suburbs along the rivers where transport accessibility is limited.[338]

Kerala is home to 2.8% of India's population; with a density of 859 persons per km2, its land is nearly three times as densely settled as the national average of 370 persons per km2.[340] As of 2011[update], Thiruvananthapuram is the most populous city in Kerala.[341] In the state, the rate of population growth is India's lowest, and the decadal growth of 4.9% in 2011 is less than one third of the all-India average of 17.6%.[340] Kerala's population more than doubled between 1951 and 1991 by adding 15.6 million people to reach 29.1 million residents in 1991; the population stood at 33.3 million by 2011.[340] Kerala's coastal regions are the most densely settled with population of 2022 persons per km2, 2.5 times the overall population density of the state, 859 persons per km2, leaving the eastern hills and mountains comparatively sparsely populated.[342] Kerala is the second-most urbanised major state in the country with 47.7% urban population according to the 2011 Census of India.[23] Around 31.8 million Keralites are predominantly Malayali.[340] The state's 321,000 indigenous tribal Adivasis, 1.1% of the population, are concentrated in the east.[343]: 10–12

There is a tradition of matrilineal inheritance in Kerala, where the mother is the head of the household.[344] As a result, women in Kerala have had a much higher standing and influence in the society. This was common among certain influential castes and is a factor in the value placed on daughters. Christian missionaries also influenced Malayali women in that they started schools for girls from poor families.[345] Opportunities for women such as education and gainful employment often translate into a lower birth rate,[346] which in turn, make education and employment more likely to be accessible and more beneficial for women. This creates an upward spiral for both the women and children of the community that is passed on to future generations. According to the Human Development Report of 1996, Kerala's Gender Development Index was 597; higher than any other state of India. Factors, such as high rates of female literacy, education, work participation and life expectancy, along with favourable sex ratio, contributed to it.[347]

Kerala's sex ratio of 1.084 (females to males) is higher than that of the rest of India; it is the only state where women outnumber men.[238]: 2 While having the opportunities that education affords them, such as political participation, keeping up to date with current events, reading religious texts etc., these tools have still not translated into full, equal rights for the women of Kerala. There is a general attitude that women must be restricted for their own benefit. In the state, despite the social progress, gender still influences social mobility.[348][349][350]

Kerala has been at the forefront of LGBT issues in India.[351] Kerala is one of the first states in India to form a welfare policy for the transgender community. In 2016, the Kerala government introduced free sex reassignment surgery through government hospitals.[352][353][354] Queerala is one of the major LGBT organisations in Kerala. It campaigns for increased awareness of LGBT people and sensitisation concerning healthcare services, workplace policies and educational curriculum.[355] Since 2010, Kerala Queer Pride has been held annually across various cities in Kerala.[356]

In June 2019, the Kerala government passed a new order that members of the transgender community should not be referred to as the "third gender" or "other gender" in government communications. Instead, the term "transgender" should be used. Previously, the gender preferences provided in government forms and documents included male, female, and other/third gender.[357][358]

In the 2021 Mathrubhumi Youth Manifesto Survey conducted on people aged between 15 and 35, majority (74.3%) of the respondents supported legislation for same-sex marriage while 25.7% opposed it.[359]

Under a democratic communist local government, Kerala has achieved a record of social development much more advanced than the Indian average.[361] As of 2015[update], Kerala has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.770, which is in the "high" category, ranking it first in the country.[7] It was 0.790 in 2007–08[362] and it had a consumption-based HDI of 0.920, which is better than that of many developed countries.[362] Comparatively higher spending by the government on primary level education, health care and the elimination of poverty from the 19th century onwards has helped the state maintain an exceptionally high HDI;[363][364] the report was prepared by the central government's Institute of Applied Manpower Research.[365][366] However, the Human Development Report 2005, prepared by Centre for Development Studies envisages a virtuous phase of inclusive development for the state since the advancement in human development had already started aiding the economic development of the state.[363] Kerala is also widely regarded as the cleanest and healthiest state in India.[367]

According to the 2011 census, Kerala has the highest literacy rate (94%) among Indian states. In 2018, the literacy rate was calculated to be 96%. In the Kottayam district, the literacy rate was 97%.[368][9][369] The life expectancy in Kerala is 74 years, among the highest in India as of 2011[update].[370] Kerala's rural poverty rate fell from 59% (1973–1974) to 12% (1999–2010); the overall (urban and rural) rate fell 47% between the 1970s and 2000s against the 29% fall in overall poverty rate in India.[371] By 1999–2000, the rural and urban poverty rates dropped to 10.0% and 9.6%, respectively.[250] The 2013 Tendulkar Committee Report on poverty estimated that the percentages of the population living below the poverty line in rural and urban Kerala are 9.1% and 5.0%, respectively.[372] These changes stem largely from efforts begun in the late 19th century by the kingdoms of Cochin and Travancore to boost social welfare.[373][374] This focus was maintained by Kerala's post-independence government.[191][375]: 48

Kerala has undergone a "demographic transition" characteristic of such developed nations as Canada, Japan, and Norway.[238]: 1 In 2005, 11.2% of people were over the age of 60.[375] In 2023, the BBC reported on the problems and benefits which have arisen from migration away from Kerala, focussing on the village of Kumbanad.[376]

In 2004, the birthrate was low at 18 per 1,000.[377] According to the 2011 census, Kerala had a total fertility rate (TFR) of 1.6. All district except Malappuram district had fertility rate below 2. Fertility rate is highest in Malappuram district (2.2) and lowest in Pathanamthitta district (1.3).[378] In 2001, Muslims had the TFR of 2.6 as against 1.5 for Hindus and 1.7 for Christians.[379] The state also is regarded as the "least corrupt Indian state" according to the surveys conducted by CMS Indian Corruption Study (CMS-ICS)[380] Transparency International (2005)[381] and India Today (1997).[382] Kerala has the lowest homicide rate among Indian states, with 1.1 per 100,000 in 2011.[383] In respect of female empowerment, some negative factors such as higher suicide rate, lower share of earned income, child marriage,[384] complaints of sexual harassment and limited freedom are reported.[347] The child marriage is lower in Kerala. The Malappuram district has the highest number of child marriage and the number of such cases are increasing in Malappuram. The child marriages are particularly higher among the Muslim community.[385][386] In 2019, Kerala recorded the highest child sex abuse complaints in India.[387]

In 2015, Kerala had the highest conviction rate of any state, over 77%.[388] Kerala has the lowest proportion of homeless people in rural India, <0.1%,[389] and the state is attempting to reach the goal of becoming the first "Zero Homeless State", in addition to its acclaimed "Zero landless project", with private organisations and the expatriate Malayali community funding projects for building homes for the homeless.[390] The state was also among the lowest in the India State Hunger Index next only to Punjab. In 2015 Kerala became the first "complete digital state" by implementing e-governance initiatives.[391]

Kerala is a pioneer in implementing the universal health care program.[392] The sub-replacement fertility level and infant mortality rate are lower compared to those of other states, estimated from 12[191][377]: 49 to 14[393]: 5 deaths per 1,000 live births; as per the National Family Health Survey 2015–16, it has dropped to 6.[394] According to a study commissioned by Lien Foundation, a Singapore-based philanthropic organisation, Kerala is considered to be the best place to die in India based on the state's provision of palliative care for patients with serious illnesses.[395] However, Kerala's morbidity rate is higher than that of any other Indian state—118 (rural) and 88 (urban) per 1,000 people. The corresponding figures for all India were 55 and 54 per 1,000, respectively as of 2005[update].[393]: 5 Kerala's 13.3% prevalence of low birth weight is higher than that of many first world nations.[377] Outbreaks of water-borne diseases such as diarrhoea, dysentery, hepatitis, and typhoid among the more than 50% of people who rely on 3 million water wells is an issue worsened by the lack of sewers.[396]: 5–7 As of 2017, the state has the highest number of diabetes patients and also the highest prevalence rate of the disease in India.[397]