La teología cristiana es la teología –el estudio sistemático de lo divino y la religión– de la creencia y la práctica cristianas . [1] Se concentra principalmente en los textos del Antiguo Testamento y del Nuevo Testamento , así como en la tradición cristiana . Los teólogos cristianos utilizan la exégesis bíblica , el análisis racional y la argumentación. Los teólogos pueden emprender el estudio de la teología cristiana por diversas razones, como por ejemplo:

La teología cristiana ha permeado gran parte de la cultura occidental no eclesiástica , especialmente en la Europa premoderna , aunque el cristianismo es una religión mundial .

La teología cristiana varía significativamente entre las principales ramas de la tradición cristiana: católica , ortodoxa y protestante . Cada una de esas tradiciones tiene sus propios enfoques singulares respecto de los seminarios y la formación ministerial.

La teología sistemática, como disciplina de la teología cristiana, formula una explicación ordenada, racional y coherente de la fe y las creencias cristianas. [9] La teología sistemática se basa en los textos sagrados fundacionales del cristianismo, al tiempo que investiga el desarrollo de la doctrina cristiana a lo largo de la historia, en particular a través de los concilios ecuménicos de la iglesia primitiva (como el Primer Concilio de Nicea ) y la evolución filosófica . Inherente a un sistema de pensamiento teológico es el desarrollo de un método, que puede aplicarse tanto de manera amplia como particular. La teología sistemática cristiana normalmente explorará:

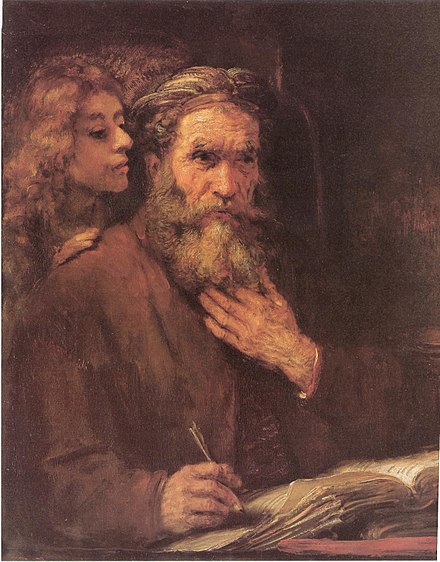

La revelación es la revelación o el descubrimiento, o el hacer evidente algo a través de una comunicación activa o pasiva con Dios, y puede originarse directamente de Dios o a través de un agente, como un ángel . [10] A una persona a la que se reconoce que ha experimentado dicho contacto a menudo se la llama [¿ por quién? ] profeta . El cristianismo generalmente considera que la Biblia es revelada o inspirada de manera divina o sobrenatural. Tal revelación no siempre requiere la presencia de Dios o de un ángel. Por ejemplo, en el concepto que los católicos llaman locución interior , la revelación sobrenatural puede incluir simplemente una voz interior escuchada por el receptor.

Tomás de Aquino (1225-1274) describió por primera vez dos tipos de revelación en el cristianismo: la revelación general y la revelación especial . [11]

La Biblia contiene muchos pasajes en los que los autores afirman que su mensaje tiene inspiración divina o informan de los efectos que dicha inspiración ha tenido en otras personas. Además de los relatos directos de la revelación escrita (como cuando Moisés recibió los Diez Mandamientos escritos en tablas de piedra), los profetas del Antiguo Testamento afirmaron con frecuencia que su mensaje era de origen divino al introducir la revelación con la siguiente frase: “Así dice el Señor” (por ejemplo, 1 R 12:22-24; 1 Cr 17:3-4; Jer 35:13; Ez 2:4; Zac 7:9; etc.). La Segunda Epístola de Pedro afirma que “ninguna profecía de la Escritura... fue traída jamás por voluntad humana, sino que los santos hombres de Dios hablaron siendo inspirados por el Espíritu Santo” [12]. La Segunda Epístola de Pedro también implica que los escritos de Pablo son inspirados (2 P 3:16).

Muchos cristianos citan un versículo de la carta de Pablo a Timoteo, 2 Timoteo 3:16-17, como evidencia de que «toda Escritura es inspirada por Dios y útil...». Aquí San Pablo se refiere al Antiguo Testamento, ya que Timoteo conocía las Escrituras desde la «infancia» (versículo 15). Otros ofrecen una lectura alternativa para el pasaje; por ejemplo, el teólogo CH Dodd sugiere que «probablemente se deba traducir» como: «Toda Escritura inspirada también es útil...». [13] Una traducción similar aparece en la New English Bible , en la Revised English Bible y (como una alternativa con nota al pie) en la New Revised Standard Version . La Vulgata latina puede leerse así. [14] Sin embargo, otros defienden la interpretación «tradicional»; Daniel B. Wallace dice que la alternativa «probablemente no es la mejor traducción». [15]

Algunas versiones modernas de la Biblia en inglés traducen theopneustos como "inspirado por Dios" ( NVI ) o "inspirado por Dios" ( ESV ), evitando la palabra inspiración , que tiene la raíz latina inspīrāre - "soplar o respirar en". [16]

El cristianismo generalmente considera que las colecciones de libros conocidas como la Biblia tienen autoridad y fueron escritas por autores humanos bajo la inspiración del Espíritu Santo . Algunos cristianos creen que la Biblia es inerrante (totalmente libre de errores y contradicciones, incluidas las partes históricas y científicas) [17] o infalible (inerrante en cuestiones de fe y práctica, pero no necesariamente en cuestiones de historia o ciencia). [18] [ necesita cita para verificar ] [19] [20] [21] [22]

Algunos cristianos infieren que la Biblia no puede decir que es divinamente inspirada y que también es errática o falible. Porque si la Biblia fuera divinamente inspirada, entonces, al ser divina la fuente de inspiración, no estaría sujeta a falibilidad o error en lo que se produce. Para ellos, las doctrinas de la inspiración divina, la infalibilidad y la inerrancia están inseparablemente unidas. La idea de la integridad bíblica es un concepto adicional de infalibilidad, al sugerir que el texto bíblico actual es completo y sin errores, y que la integridad del texto bíblico nunca ha sido corrompida o degradada. [17] Los historiadores [ ¿cuáles? ] señalan, o afirman, que la doctrina de la infalibilidad de la Biblia fue adoptada [ ¿cuándo? ] cientos de años después de que se escribieron los libros de la Biblia. [ disputado (por: atribución errónea de referencia) – discutir ] [23]

El contenido del Antiguo Testamento protestante es el mismo que el canon de la Biblia hebrea , con cambios en la división y el orden de los libros, pero el Antiguo Testamento católico contiene textos adicionales, conocidos como los libros deuterocanónicos . Los protestantes reconocen 39 libros en su canon del Antiguo Testamento, mientras que los católicos romanos y los cristianos orientales reconocen 46 libros como canónicos. [ cita requerida ] Tanto los católicos como los protestantes utilizan el mismo canon del Nuevo Testamento de 27 libros.

Los primeros cristianos utilizaron la Septuaginta , una traducción al griego koiné de las escrituras hebreas. Posteriormente, el cristianismo aprobó varios escritos adicionales que se convertirían en el Nuevo Testamento. En el siglo IV, una serie de sínodos , en particular el Sínodo de Hipona en el año 393 d. C., produjo una lista de textos igual al canon de 46 libros del Antiguo Testamento que los católicos usan hoy (y el canon de 27 libros del Nuevo Testamento que todos usan). Una lista definitiva no provino de ningún concilio ecuménico temprano . [24] Alrededor del año 400, Jerónimo produjo la Vulgata , una edición latina definitiva de la Biblia, cuyo contenido, por insistencia del obispo de Roma , concordaba con las decisiones de los sínodos anteriores. Este proceso estableció efectivamente el canon del Nuevo Testamento, aunque existen ejemplos de otras listas canónicas en uso después de esta época. [ cita requerida ]

Durante la Reforma protestante del siglo XVI, algunos reformadores propusieron diferentes listas canónicas del Antiguo Testamento. Los textos que aparecen en la Septuaginta pero no en el canon judío cayeron en desgracia y finalmente desaparecieron de los cánones protestantes. Las Biblias católicas clasifican estos textos como libros deuterocanónicos, mientras que los contextos protestantes los etiquetan como apócrifos .

En el cristianismo , Dios es el creador y preservador del universo . Dios es el único poder supremo del universo, pero es distinto de él. La Biblia nunca habla de Dios como impersonal, sino que se refiere a él en términos personales : que habla, ve, oye, actúa y ama. Se entiende que Dios tiene voluntad y personalidad y es un ser todopoderoso , divino y benévolo . En las Escrituras se le representa como alguien que se preocupa principalmente por las personas y su salvación. [25]

Muchos teólogos reformados distinguen entre los atributos comunicables (aquellos que los seres humanos también pueden tener) y los atributos incomunicables (aquellos que pertenecen sólo a Dios). [26]

Algunos atributos que se le atribuyen a Dios en la teología cristiana [27] son:

Algunos cristianos creen que el Dios al que adoraba el pueblo hebreo de la era precristiana siempre se había revelado a través de Jesús , pero que esto nunca fue evidente hasta que nació Jesús (véase Juan 1 ). Además, aunque el Ángel del Señor habló a los Patriarcas y les reveló a Dios, algunos creen que siempre fue sólo a través del Espíritu de Dios que les concedió el entendimiento que los hombres pudieron percibir más tarde que Dios mismo los había visitado.

Esta creencia fue evolucionando gradualmente hasta llegar a la formulación moderna de la Trinidad , que es la doctrina de que Dios es una sola entidad ( Yahvé ), pero que existe una trinidad en el ser único de Dios, cuyo significado siempre ha sido debatido. Esta misteriosa "Trinidad" ha sido descrita como hipóstasis en el idioma griego ( subsistencias en latín ) y "personas" en inglés. No obstante, los cristianos enfatizan que solo creen en un Dios.

La mayoría de las iglesias cristianas enseñan la Trinidad, en contraposición a las creencias monoteístas unitarias. Históricamente, la mayoría de las iglesias cristianas han enseñado que la naturaleza de Dios es un misterio , algo que debe revelarse mediante una revelación especial en lugar de deducirse mediante una revelación general .

Las tradiciones cristianas ortodoxas (católica, ortodoxa oriental y protestante) siguen esta idea, que fue codificada en 381 y alcanzó su pleno desarrollo a través del trabajo de los Padres Capadocios . Consideran a Dios como una entidad trina, llamada Trinidad, que comprende las tres "Personas"; Dios Padre , Dios Hijo y Dios Espíritu Santo , descritos como "de la misma sustancia" ( ὁμοούσιος ). Sin embargo, la verdadera naturaleza de un Dios infinito se describe comúnmente como más allá de toda definición, y la palabra "persona" es una expresión imperfecta de la idea.

Algunos críticos sostienen que, debido a la adopción de una concepción tripartita de la deidad, el cristianismo es una forma de triteísmo o politeísmo . Este concepto data de las enseñanzas arrianas que afirmaban que Jesús, al haber aparecido más tarde en la Biblia que su Padre, tenía que ser un dios secundario, menor y, por lo tanto, distinto. Para los judíos y los musulmanes , la idea de Dios como una trinidad es herética : se considera similar al politeísmo . Los cristianos afirman abrumadoramente que el monoteísmo es central para la fe cristiana, ya que el propio Credo de Nicea (entre otros) que da la definición cristiana ortodoxa de la Trinidad comienza con: "Creo en un solo Dios".

En el siglo III, Tertuliano afirmó que Dios existe como el Padre, el Hijo y el Espíritu Santo, las tres personas de una misma sustancia. [32] Para los cristianos trinitarios, Dios Padre no es en absoluto un dios separado de Dios Hijo (de quien Jesús es la encarnación) y el Espíritu Santo, las otras hipóstasis (Personas) de la Deidad cristiana . [32] Según el Credo de Nicea, el Hijo (Jesucristo) es "eternamente engendrado del Padre", lo que indica que su relación divina Padre-Hijo no está ligada a un evento dentro del tiempo o la historia humana.

En el cristianismo , la doctrina de la Trinidad afirma que Dios es un ser que existe, simultánea y eternamente , como una morada mutua de tres Personas: el Padre, el Hijo (encarnado como Jesús) y el Espíritu Santo (o Holy Ghost). Desde el cristianismo primitivo, la salvación de uno ha estado muy estrechamente relacionada con el concepto de un Dios trino, aunque la doctrina trinitaria no se formalizó hasta el siglo IV. En esa época, el emperador Constantino convocó el Primer Concilio de Nicea , al que fueron invitados a asistir todos los obispos del imperio. El papa Silvestre I no asistió, pero envió a su legado . El concilio, entre otras cosas, decretó el Credo Niceno original.

Para la mayoría de los cristianos, las creencias sobre Dios están consagradas en la doctrina del trinitarismo , que sostiene que las tres personas de Dios juntas forman un solo Dios. La visión trinitaria enfatiza que Dios tiene una voluntad y que Dios el Hijo tiene dos voluntades, divina y humana, aunque estas nunca están en conflicto (ver Unión hipostática ). Sin embargo, este punto es disputado por los cristianos ortodoxos orientales, quienes sostienen que Dios el Hijo tiene solo una voluntad de divinidad y humanidad unificadas (ver Miafisitismo ).

La doctrina cristiana de la Trinidad enseña la unidad del Padre , el Hijo y el Espíritu Santo como tres personas en una sola Deidad . [33] La doctrina afirma que Dios es el Dios Trino, que existe como tres personas , o en el griego hipóstasis , [34] pero un solo ser. [35] La personalidad en la Trinidad no coincide con la comprensión occidental común de "persona" tal como se usa en el idioma inglés: no implica un "centro individual, autorrealizado de libre albedrío y actividad consciente". [36] : 185-186. Para los antiguos, la personalidad "era en cierto sentido individual, pero siempre en comunidad también". [36] : p.186 Se entiende que cada persona tiene una esencia o naturaleza idéntica, no meramente naturalezas similares. Desde principios del siglo III [37] la doctrina de la Trinidad se ha establecido como "el único Dios existe en tres Personas y una sustancia , Padre, Hijo y Espíritu Santo". [38]

El trinitarismo, la creencia en la Trinidad, es una característica del catolicismo , la ortodoxia oriental y oriental , así como de otras sectas cristianas prominentes que surgieron de la Reforma protestante , como el anglicanismo , el metodismo , el luteranismo , el bautismo y el presbiterianismo . El Diccionario Oxford de la Iglesia Cristiana describe la Trinidad como "el dogma central de la teología cristiana". [38] Esta doctrina contrasta con las posiciones no trinitarias que incluyen el unitarismo , la unicidad y el modalismo . Una pequeña minoría de cristianos sostiene puntos de vista no trinitarios, que en gran medida se enmarcan en el unitarismo .

La mayoría de los cristianos, si no todos, creen que Dios es espíritu, [39] un ser increado, omnipotente y eterno, creador y sustentador de todas las cosas, que obra la redención del mundo por medio de su Hijo, Jesucristo. Con este trasfondo, la creencia en la divinidad de Cristo y del Espíritu Santo se expresa como la doctrina de la Trinidad , [40] que describe la única ousia (sustancia) divina que existe como tres hipóstasis (personas) distintas e inseparables: el Padre , el Hijo ( Jesucristo el Logos ) y el Espíritu Santo . [41]

La mayoría de los cristianos consideran que la doctrina trinitaria es un principio fundamental de su fe. Los no trinitarios suelen sostener que Dios, el Padre, es supremo; que Jesús, aunque sigue siendo el Señor y Salvador divino, es el Hijo de Dios ; y que el Espíritu Santo es un fenómeno similar a la voluntad de Dios en la Tierra. Los tres santos están separados, pero aún se considera que el Hijo y el Espíritu Santo tienen su origen en Dios Padre.

El Nuevo Testamento no tiene el término “Trinidad” y en ningún lugar se habla de la Trinidad como tal. Sin embargo, algunos enfatizan que el Nuevo Testamento sí habla repetidamente del Padre, el Hijo y el Espíritu Santo para “obligar a una comprensión trinitaria de Dios”. [42] La doctrina se desarrolló a partir del lenguaje bíblico utilizado en pasajes del Nuevo Testamento como la fórmula bautismal en Mateo 28:19 y hacia fines del siglo IV era ampliamente aceptada en su forma actual.

En muchas religiones monoteístas , a Dios se le llama el padre, en parte debido a su interés activo en los asuntos humanos, de la manera en que un padre se interesaría por sus hijos que dependen de él y, como padre, responderá a la humanidad, a sus hijos, actuando en su mejor interés. [43] En el cristianismo, a Dios se le llama "Padre" en un sentido más literal, además de ser el creador y sustentador de la creación, y el proveedor de sus hijos. [44] Se dice que el Padre está en una relación única con su hijo unigénito ( monogenes ), Jesucristo , lo que implica una familiaridad exclusiva e íntima: "Nadie conoce al Hijo sino el Padre, y nadie conoce al Padre sino el Hijo y aquel a quien el Hijo quiera revelarlo". [45]

En el cristianismo, la relación de Dios Padre con la humanidad es la de un padre con sus hijos —en un sentido nunca antes visto— y no sólo la de creador y sustentador de la creación, y proveedor de sus hijos, su pueblo. Así, a los seres humanos, en general, se les llama a veces hijos de Dios . Para los cristianos, la relación de Dios Padre con la humanidad es la de Creador y seres creados, y en ese sentido es el padre de todos. El Nuevo Testamento dice, en este sentido, que la idea misma de familia, dondequiera que aparezca, deriva su nombre de Dios Padre, [46] y, por tanto, Dios mismo es el modelo de la familia.

Sin embargo, existe un sentido "legal" más profundo en el que los cristianos creen que son hechos partícipes de la relación especial entre Padre e Hijo, a través de Jesucristo como su esposa espiritual . Los cristianos se llaman a sí mismos hijos adoptivos de Dios. [47]

En el Nuevo Testamento, Dios Padre tiene un papel especial en su relación con la persona del Hijo, donde se cree que Jesús es su Hijo y su heredero. [48] Según el Credo de Nicea , el Hijo (Jesucristo) es "eternamente engendrado por el Padre", lo que indica que su relación divina Padre-Hijo no está ligada a un evento dentro del tiempo o la historia humana. Véase Cristología . La Biblia se refiere a Cristo, llamado " El Verbo ", como presente al principio de la creación de Dios, [49] no una creación en sí misma, sino igual en la personalidad de la Trinidad.

En la teología ortodoxa oriental , Dios Padre es el "principium" ( principio ), la "fuente" u "origen" tanto del Hijo como del Espíritu Santo, lo que da un énfasis intuitivo a la trilogía de personas; en comparación, la teología occidental explica el "origen" de las tres hipóstasis o personas como estando en la naturaleza divina, lo que da un énfasis intuitivo a la unidad del ser de Dios. [ cita requerida ]

La cristología es el campo de estudio dentro de la teología cristiana que se ocupa principalmente de la naturaleza, la persona y las obras de Jesucristo , considerado por los cristianos como el Hijo de Dios . La cristología se ocupa del encuentro de lo humano ( Hijo del Hombre ) y lo divino ( Dios el Hijo o Palabra de Dios ) en la persona de Jesús .

Las consideraciones principales incluyen la Encarnación , la relación de la naturaleza y la persona de Jesús con la naturaleza y la persona de Dios, y la obra salvífica de Jesús. Como tal, la cristología generalmente se preocupa menos por los detalles de la vida de Jesús (lo que hizo) o de las enseñanzas que por quién o qué es él. Ha habido y hay varias perspectivas de quienes afirman ser sus seguidores desde que la iglesia comenzó después de su ascensión. Las controversias se centraron en última instancia en si una naturaleza humana y una naturaleza divina pueden coexistir en una persona y cómo. El estudio de la interrelación de estas dos naturalezas es una de las preocupaciones de la tradición mayoritaria.

En el Nuevo Testamento se encuentran enseñanzas sobre Jesús y testimonios sobre lo que él logró durante su ministerio público de tres años . Las enseñanzas bíblicas centrales sobre la persona de Jesucristo pueden resumirse en que Jesucristo fue y es por siempre completamente Dios (divino) y completamente humano en una persona sin pecado al mismo tiempo, [50] y que a través de la muerte y resurrección de Jesús , los humanos pecadores pueden reconciliarse con Dios y, por lo tanto, se les ofrece la salvación y la promesa de vida eterna a través de su Nuevo Pacto . Si bien ha habido disputas teológicas sobre la naturaleza de Jesús, los cristianos creen que Jesús es Dios encarnado y " verdadero Dios y verdadero hombre " (o ambos completamente divino y completamente humano). Jesús, habiéndose convertido en completamente humano en todos los aspectos, sufrió los dolores y las tentaciones de un hombre mortal, pero no pecó. Como completamente Dios, derrotó a la muerte y resucitó a la vida nuevamente. Las Escrituras afirman que Jesús fue concebido por el Espíritu Santo y nació de su madre virgen María sin un padre humano. [51] Los relatos bíblicos del ministerio de Jesús incluyen milagros , predicación, enseñanza, sanidad , muerte y resurrección . El apóstol Pedro, en lo que se ha convertido en una famosa proclamación de fe entre los cristianos desde el siglo I, dijo: "Tú eres el Cristo, el Hijo de Dios viviente". [52] La mayoría de los cristianos ahora esperan la Segunda Venida de Cristo cuando creen que él cumplirá las profecías mesiánicas restantes .

Cristo es el término español para el griego Χριστός ( Khristós ) que significa " el ungido ". [53] Es una traducción del hebreo מָשִׁיחַ ( Māšîaḥ ), generalmente transliterado al español como Mesías . La palabra a menudo se malinterpreta como el apellido de Jesús debido a las numerosas menciones de Jesucristo en la Biblia cristiana . De hecho, la palabra se usa como título , de ahí su uso recíproco común Cristo Jesús , que significa Jesús el Ungido o Jesús el Mesías. Los seguidores de Jesús llegaron a ser conocidos como cristianos porque creían que Jesús era el Cristo, o Mesías, profetizado en el Antiguo Testamento , o Tanaj .

Las controversias cristológicas llegaron a su punto álgido en torno a las personas de la Divinidad y su relación entre sí. La cristología fue una preocupación fundamental desde el Primer Concilio de Nicea (325) hasta el Tercer Concilio de Constantinopla (680). En este período, las opiniones cristológicas de varios grupos dentro de la comunidad cristiana más amplia dieron lugar a acusaciones de herejía y, con poca frecuencia, a la persecución religiosa posterior . En algunos casos, la cristología única de una secta es su principal característica distintiva; en estos casos es común que la secta sea conocida por el nombre dado a su cristología.

Las decisiones tomadas en el Primer Concilio de Nicea y ratificadas nuevamente en el Primer Concilio de Constantinopla , después de varias décadas de controversias en curso durante las cuales la obra de Atanasio y los Padres Capadocios fueron influyentes. El lenguaje utilizado fue que el único Dios existe en tres personas (Padre, Hijo y Espíritu Santo); en particular se afirmó que el Hijo era homoousios (de una misma sustancia) con el Padre. El Credo del Concilio de Nicea hizo declaraciones sobre la plena divinidad y plena humanidad de Jesús, preparando así el camino para la discusión sobre cómo exactamente lo divino y lo humano se unen en la persona de Cristo (Cristología).

Nicea insistió en que Jesús era totalmente divino y también humano, pero no aclaró cómo una persona podía ser a la vez divina y humana, ni cómo lo divino y lo humano estaban relacionados dentro de esa persona. Esto condujo a las controversias cristológicas de los siglos IV y V de la era cristiana.

El Credo de Calcedonia no puso fin a todo el debate cristológico, pero sí aclaró los términos utilizados y se convirtió en un punto de referencia para todas las demás cristologías. La mayoría de las principales ramas del cristianismo —catolicismo , ortodoxia oriental , anglicanismo , luteranismo y reforma— suscriben la formulación cristológica de Calcedonia, mientras que muchas ramas del cristianismo oriental —ortodoxia siria , iglesia asiria , ortodoxia copta , ortodoxia etíope y apostolicismo armenio— la rechazan.

Según la Biblia, la segunda Persona de la Trinidad, debido a su relación eterna con la primera Persona (Dios como Padre), es el Hijo de Dios . Los trinitarios lo consideran coigual al Padre y al Espíritu Santo. Es todo Dios y todo humano : el Hijo de Dios en cuanto a su naturaleza divina, mientras que en cuanto a su naturaleza humana es del linaje de David. [54] [55] El núcleo de la autointerpretación de Jesús fue su "conciencia filial", su relación con Dios como hijo con padre en un sentido único [25] (ver la controversia del Filioque ). Su misión en la tierra resultó ser la de permitir a las personas conocer a Dios como su Padre, lo que los cristianos creen que es la esencia de la vida eterna . [56]

Dios Hijo es la segunda persona de la Trinidad en la teología cristiana. La doctrina de la Trinidad identifica a Jesús de Nazaret como Dios Hijo, unido en esencia pero distinto en persona con respecto a Dios Padre y Dios Espíritu Santo (la primera y tercera personas de la Trinidad). Dios Hijo es coeterno con Dios Padre (y el Espíritu Santo), tanto antes de la Creación como después del Fin (véase Escatología ). Por lo tanto, Jesús siempre fue "Dios Hijo", aunque no se reveló como tal hasta que también se convirtió en el "Hijo de Dios" a través de la encarnación . "Hijo de Dios" llama la atención sobre su humanidad, mientras que "Dios Hijo" se refiere de manera más general a su divinidad, incluida su existencia preencarnada. Por lo tanto, en la teología cristiana, Jesús siempre fue Dios Hijo, [57] aunque no se reveló como tal hasta que también se convirtió en el Hijo de Dios a través de la encarnación .

La frase exacta "Dios el Hijo" no se encuentra en el Nuevo Testamento. El uso teológico posterior de esta expresión refleja lo que llegó a ser la interpretación estándar de las referencias del Nuevo Testamento, entendidas como implicando la divinidad de Jesús, pero la distinción de su persona con la del único Dios al que llamó su Padre. Como tal, el título se asocia más con el desarrollo de la doctrina de la Trinidad que con los debates cristológicos . Hay más de 40 lugares en el Nuevo Testamento donde a Jesús se le da el título de "el Hijo de Dios", pero los eruditos no consideran que esta sea una expresión equivalente. "Dios el Hijo" es rechazado por los antitrinitarios, que ven esta inversión del término más común para Cristo como una perversión doctrinal y como una tendencia hacia el triteísmo .

Mateo cita a Jesús diciendo: «Bienaventurados los pacificadores, porque ellos serán llamados hijos de Dios» (5:9). Los evangelios continúan documentando una gran cantidad de controversias sobre la identidad de Jesús como Hijo de Dios, de una manera única. Sin embargo, el libro de los Hechos de los Apóstoles y las cartas del Nuevo Testamento registran las enseñanzas tempranas de los primeros cristianos, aquellos que creían que Jesús era el Hijo de Dios, el Mesías, un hombre designado por Dios, así como Dios mismo. Esto es evidente en muchos lugares, sin embargo, la primera parte del libro de Hebreos aborda el tema en un argumento deliberado y sostenido, citando las escrituras de la Biblia hebrea como autoridades. Por ejemplo, el autor cita el Salmo 45:6 como dirigido por el Dios de Israel a Jesús.

La descripción que hace el autor de Hebreos de Jesús como la representación exacta del Padre divino tiene paralelos en un pasaje de Colosenses .

El evangelio de Juan cita extensamente a Jesús en relación con su Padre celestial. También contiene dos famosas atribuciones de divinidad a Jesús.

Las referencias más directas a Jesús como Dios se encuentran en varias cartas.

La base bíblica para las declaraciones trinitarias posteriores en los credos es la fórmula del bautismo primitivo que se encuentra en Mateo 28.

El docetismo (del verbo griego parecer ) enseñaba que Jesús era completamente divino y que su cuerpo humano era solo ilusorio. En una etapa muy temprana, surgieron varios grupos docetistas; en particular, las sectas gnósticas que florecieron en el siglo II d. C. tendían a tener teologías docetistas. Las enseñanzas docetistas fueron atacadas por San Ignacio de Antioquía (principios del siglo II), y parecen ser el blanco de las epístolas canónicas de Juan (las fechas son discutidas, pero van desde fines del siglo I entre los eruditos tradicionalistas hasta fines del siglo II entre los eruditos críticos).

El Concilio de Nicea rechazó las teologías que descartaban por completo cualquier humanidad en Cristo, afirmando en el Credo Niceno la doctrina de la Encarnación como parte de la doctrina de la Trinidad , es decir, que la segunda persona de la Trinidad se encarnó en la persona de Jesús y fue plenamente humana.

En los primeros siglos de la historia cristiana también hubo grupos que se situaron en el otro extremo del espectro, argumentando que Jesús era un mortal común y corriente. Los adopcionistas enseñaban que Jesús nació plenamente humano y fue adoptado como Hijo de Dios cuando Juan el Bautista lo bautizó [58] debido a la vida que vivió . Otro grupo, conocido como los ebionitas , enseñaba que Jesús no era Dios, sino el profeta humano Moshiach (mesías, ungido) prometido en la Biblia hebrea .

Algunas de estas opiniones podrían describirse como unitarismo (aunque ese es un término moderno) por su insistencia en la unicidad de Dios. Estas opiniones, que afectaban directamente la manera en que uno entendía la Divinidad, fueron declaradas herejías por el Concilio de Nicea. A lo largo de gran parte del resto de la historia antigua del cristianismo, las cristologías que negaban la divinidad de Cristo dejaron de tener un impacto importante en la vida de la iglesia.

El arrianismo afirmaba que Jesús era divino, pero enseñaba que, no obstante, era un ser creado ( hubo [un tiempo] en que no [existía] ), y, por lo tanto, era menos divino que Dios Padre. La cuestión se reducía a un ápice; el arrianismo enseñaba Homo i ousia —la creencia de que la divinidad de Jesús es similar a la de Dios Padre— en oposición a Homoousia —la creencia de que la divinidad de Jesús es la misma que la de Dios Padre—. Los oponentes de Arrio incluyeron además en el término arrianismo la creencia de que la divinidad de Jesús es diferente de la de Dios Padre ( Heteroousia ).

El arrianismo fue condenado por el Concilio de Nicea, pero siguió siendo popular en las provincias del norte y el oeste del imperio y continuó siendo la opinión mayoritaria en Europa occidental hasta bien entrado el siglo VI. De hecho, incluso la leyenda cristiana del bautismo de Constantino en su lecho de muerte incluye a un obispo que, según la historia registrada, era arriano.

En la era moderna, varias denominaciones han rechazado la doctrina nicena de la Trinidad, incluidos los Cristadelfianos y los Testigos de Jehová . [59]

Los debates cristológicos posteriores al Concilio de Nicea buscaron dar sentido a la interacción de lo humano y lo divino en la persona de Cristo, al tiempo que defendían la doctrina de la Trinidad. Apolinar de Laodicea (310-390) enseñó que en Jesús, el componente divino tomó el lugar del nous humano ( pensamiento , que no debe confundirse con thelis , que significa intención ). Sin embargo, esto fue visto como una negación de la verdadera humanidad de Jesús, y la visión fue condenada en el Primer Concilio de Constantinopla .

Posteriormente, Nestorio de Constantinopla (386-451) inició una visión que efectivamente separó a Jesús en dos personas: una divina y otra humana; el mecanismo de esta combinación se conoce como hipóstasis , y contrasta con la hipóstasis , la visión de que no hay separación. La teología de Nestorio fue considerada herética en el Primer Concilio de Éfeso (431). Aunque, como se ve en los escritos de Babai el Grande , la cristología de la Iglesia de Oriente es muy similar a la de Calcedonia, muchos cristianos ortodoxos (particularmente en Occidente) consideran que este grupo es la perpetuación del nestorianismo ; la moderna Iglesia asiria de Oriente ha rechazado en ocasiones este término, ya que implica la aceptación de toda la teología de Nestorio.

Varias formas de monofisismo enseñaron que Cristo tenía una sola naturaleza: que la divina se había disuelto ( eutiquianismo ), o que la divina se había unido con la humana como una sola naturaleza en la persona de Cristo ( miafisitismo ). Un notable teólogo monofisita fue Eutiques ( c. 380-456 ). El monofisismo fue rechazado como herejía en el Concilio de Calcedonia en 451, que afirmó que Jesucristo tenía dos naturalezas (divina y humana) unidas en una persona, en unión hipostática (véase Credo calcedoniano ). Mientras que el eutiquianismo fue suprimido hasta el olvido por los calcedonios y los miafisitas, los grupos miafisitas que disintieron de la fórmula calcedonia han persistido como la Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental .

A medida que los teólogos continuaron buscando un compromiso entre la definición calcedonia y los monofisitas , se desarrollaron otras cristologías que rechazaban parcialmente la humanidad plena de Cristo. El monotelismo enseñaba que en la persona única de Jesús había dos naturalezas, pero solo una voluntad divina. Estrechamente relacionado con esto está el monoenergismo , que sostenía la misma doctrina que los monotelitas, pero con diferente terminología. Estas posiciones fueron declaradas herejía por el Tercer Concilio de Constantinopla (el Sexto Concilio Ecuménico , 680-681).

La encarnación es la creencia en el cristianismo de que la segunda persona de la divinidad cristiana , también conocida como Dios Hijo o el Logos (Verbo), "se hizo carne" cuando fue concebida milagrosamente en el vientre de la Virgen María . La palabra encarnar deriva del latín (in=en o dentro, caro, carnis=carne) que significa "hacer carne" o "convertirse en carne". La encarnación es una enseñanza teológica fundamental del cristianismo ortodoxo (niceno) , basada en su comprensión del Nuevo Testamento . La encarnación representa la creencia de que Jesús, que es la segunda hipóstasis no creada del Dios trino , tomó un cuerpo y una naturaleza humanos y se convirtió en hombre y Dios . En la Biblia su enseñanza más clara está en Juan 1:14: "Y el Verbo se hizo carne, y habitó entre nosotros". [60]

En la Encarnación, tal como se define tradicionalmente, la naturaleza divina del Hijo se unió, pero no se mezcló, con la naturaleza humana [61] en una sola Persona divina, Jesucristo , que era a la vez «verdaderamente Dios y verdaderamente hombre». La Encarnación se conmemora y celebra cada año en Navidad , y también se puede hacer referencia a la Fiesta de la Anunciación ; en Navidad y en la Anunciación se celebran «diferentes aspectos del misterio de la Encarnación». [62]

Este es un aspecto central de la fe tradicional de la mayoría de los cristianos. A lo largo de los siglos se han propuesto puntos de vista alternativos sobre el tema (véase Los ebionitas y el Evangelio según los hebreos ) (véase más adelante), pero todos fueron rechazados por los principales organismos cristianos .

En las últimas décadas, una doctrina alternativa conocida como " Unicidad " ha sido adoptada entre varios grupos pentecostales (ver más abajo), pero ha sido rechazada por el resto de la cristiandad .

En la era cristiana primitiva , existía un considerable desacuerdo entre los cristianos sobre la naturaleza de la Encarnación de Cristo. Si bien todos los cristianos creían que Jesús era en verdad el Hijo de Dios , se discutía la naturaleza exacta de su filiación, junto con la relación precisa de " Padre ", "Hijo" y " Espíritu Santo " a la que se hace referencia en el Nuevo Testamento. Aunque Jesús era claramente el "Hijo", ¿qué significaba esto exactamente? El debate sobre este tema se extendió sobre todo durante los primeros cuatro siglos del cristianismo, en el que participaron cristianos judíos , gnósticos , seguidores del presbítero Arrio de Alejandra y seguidores de San Atanasio el Grande , entre otros.

Finalmente, la Iglesia cristiana aceptó la enseñanza de San Atanasio y sus aliados, de que Cristo era la encarnación de la segunda persona eterna de la Trinidad , que era completamente Dios y completamente hombre simultáneamente. Todas las creencias divergentes fueron definidas como herejías . Esto incluía el docetismo , que decía que Jesús era un ser divino que tomó apariencia humana pero no carne; el arrianismo , que sostenía que Cristo era un ser creado; y el nestorianismo , que sostenía que el Hijo de Dios y el hombre, Jesús, compartían el mismo cuerpo pero conservaban dos naturalezas separadas . La creencia de la Unicidad sostenida por ciertas iglesias pentecostales modernas también es vista como herética por la mayoría de los organismos cristianos convencionales.

Las definiciones más ampliamente aceptadas de la Encarnación y la naturaleza de Jesús que la Iglesia cristiana primitiva hizo en el Primer Concilio de Nicea en 325, el Concilio de Éfeso en 431 y el Concilio de Calcedonia en 451. Estos concilios declararon que Jesús era a la vez completamente Dios: engendrado, pero no creado por el Padre; y completamente hombre: tomó su carne y naturaleza humana de la Virgen María . Estas dos naturalezas, humana y divina, estaban hipostáticamente unidas en la única persona de Jesucristo. [63]

El vínculo entre la Encarnación y la Expiación dentro del pensamiento teológico sistemático es complejo. Dentro de los modelos tradicionales de la Expiación, como la Sustitución , la Satisfacción o el Christus Victor , Cristo debe ser Divino para que el Sacrificio de la Cruz sea eficaz, para que los pecados humanos sean "eliminados" o "vencidos". En su obra La Trinidad y el Reino de Dios , Jürgen Moltmann diferenció entre lo que llamó una Encarnación "fortuita" y una "necesaria". La última da un énfasis soteriológico a la Encarnación: el Hijo de Dios se hizo hombre para poder salvarnos de nuestros pecados. El primero, por otro lado, habla de la Encarnación como un cumplimiento del Amor de Dios , de su deseo de estar presente y vivir en medio de la humanidad, de "caminar en el jardín" con nosotros.

Moltmann favorece la encarnación "fortuita" principalmente porque considera que hablar de una encarnación "necesaria" es hacerle una injusticia a la vida de Cristo . El trabajo de Moltmann, junto con otros teólogos sistemáticos, abre caminos para la cristología de la liberación .

En resumen, esta doctrina afirma que dos naturalezas, una humana y otra divina, están unidas en la única persona de Cristo. El Concilio enseñó además que cada una de estas naturalezas, la humana y la divina, era distinta y completa. Esta visión es a veces llamada diofisita (que significa dos naturalezas) por quienes la rechazan.

La unión hipostática (del griego sustancia) es un término técnico de la teología cristiana empleado en la cristología convencional para describir la unión de dos naturalezas, la humanidad y la divinidad, en Jesucristo. Una breve definición de la doctrina de las dos naturalezas puede darse como: "Jesucristo, que es idéntico al Hijo, es una persona y una hipóstasis en dos naturalezas: una humana y una divina". [64]

El Primer Concilio de Éfeso reconoció esta doctrina y afirmó su importancia, afirmando que la humanidad y la divinidad de Cristo se hacen una según la naturaleza y la hipóstasis en el Logos .

El Primer Concilio de Nicea declaró que el Padre y el Hijo son de la misma sustancia y coeternos. Esta creencia se expresó en el Credo Niceno.

Apolinar de Laodicea fue el primero en utilizar el término hipóstasis al intentar comprender la Encarnación . [65] Apolinar describió la unión de lo divino y lo humano en Cristo como una sola naturaleza y con una sola esencia: una sola hipóstasis.

El nestoriano Teodoro de Mopsuestia fue en la dirección opuesta, argumentando que en Cristo había dos naturalezas ( diofisita ) (humana y divina) y dos hipóstasis (en el sentido de "esencia" o "persona") que coexistían. [66]

El Credo de Calcedonia coincidía con Teodoro en que había dos naturalezas en la Encarnación . Sin embargo, el Concilio de Calcedonia también insistió en que se utilizara hipóstasis tal como estaba en la definición trinitaria: para indicar la persona y no la naturaleza como en el caso de Apolinar.

Así, pues, el Concilio declaró que en Cristo hay dos naturalezas, cada una de las cuales conserva sus propias propiedades y juntas están unidas en una sola subsistencia y en una sola persona. [67]

Como se considera que la naturaleza precisa de esta unión desafía la comprensión humana finita, la unión hipostática también se conoce con el término alternativo de "unión mística".

Las Iglesias ortodoxas orientales , que habían rechazado el credo de Calcedonia, eran conocidas como monofisitas porque sólo aceptaban una definición que caracterizara al Hijo encarnado como poseedor de una sola naturaleza. La fórmula calcedonia de "dos naturalezas" se consideraba derivada de la cristología nestoriana y afín a ella . [68] Por el contrario, los calcedonios veían a los ortodoxos orientales como tendientes al monofisismo eutiquiano . Sin embargo, los ortodoxos orientales han especificado en el diálogo ecuménico moderno que nunca han creído en las doctrinas de Eutiques, que siempre han afirmado que la humanidad de Cristo es consustancial con la nuestra, y por ello prefieren el término "miafisita" para referirse a sí mismos (una referencia a la cristología ciriliana, que utilizaba la frase "mia physis tou theou logou sesarkomene").

En los últimos tiempos, los líderes de las Iglesias Ortodoxa Oriental y Ortodoxa Oriental han firmado declaraciones conjuntas en un intento de trabajar por la reunificación.

Aunque la ortodoxia cristiana sostiene que Jesús era plenamente humano, la Epístola a los Hebreos , por ejemplo, afirma que Cristo era “santo y sin maldad” (7:26). La cuestión relativa a la impecabilidad de Jesucristo se centra en esta aparente paradoja. ¿Ser plenamente humano requiere que uno participe en la “caída” de Adán , o podría Jesús existir en un estado “no caído” como lo hicieron Adán y Eva antes de la “caída”, según Génesis 2-3?

El escritor evangélico Donald Macleod sugiere que la naturaleza sin pecado de Jesucristo implica dos elementos. “Primero, Cristo estaba libre de pecado actual” [69] . Al estudiar los evangelios no hay ninguna referencia a que Jesús orara por el perdón de los pecados ni a que los confesara. La afirmación es que Jesús no cometió pecado, ni se le podía probar que era culpable de pecado; no tenía vicios. De hecho, se le cita preguntando: “¿Puede alguno de ustedes probar que soy culpable de pecado?” en Juan 8:46. “Segundo, estaba libre de pecado inherente (“ pecado original ” o “ pecado ancestral ”)”. [69]

La tentación de Cristo que se muestra en los evangelios confirma que fue tentado. De hecho, las tentaciones fueron genuinas y de una intensidad mayor que la que normalmente experimentan los seres humanos. [70] Experimentó todas las frágiles debilidades de la humanidad. Jesús fue tentado por el hambre y la sed, el dolor y el amor de sus amigos. Así, las debilidades humanas podían engendrar tentaciones. [71] Sin embargo, MacLeod señala que "un aspecto crucial en el que Cristo no era como nosotros es que no fue tentado por nada dentro de sí mismo". [71]

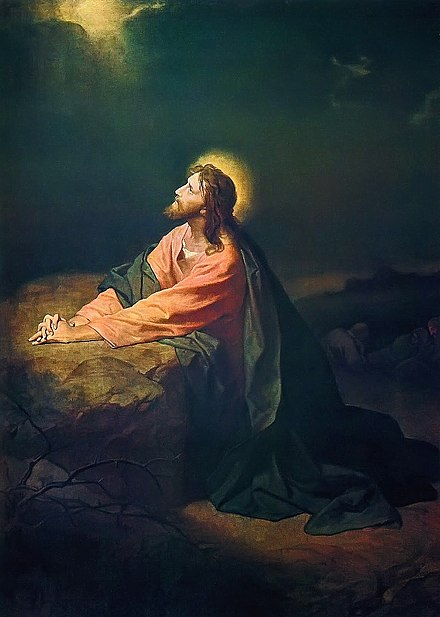

Las tentaciones que Cristo enfrentó se centraron en su persona e identidad como el Hijo encarnado de Dios. MacLeod escribe: “Cristo podía ser tentado a través de su condición de hijo”. La tentación en el desierto y nuevamente en Getsemaní ejemplifica este ámbito de tentación . Con respecto a la tentación de realizar una señal que afirmara su condición de hijo arrojándose desde el pináculo del templo, MacLeod observa: “La señal era para sí mismo: una tentación de buscar seguridad, como si dijera: ‘La verdadera cuestión es mi propia condición de hijo. Debo olvidar todo lo demás y a todos los demás y todo servicio posterior hasta que eso esté claro ’ ” . [72] MacLeod coloca esta lucha en el contexto de la encarnación: “… se ha convertido en un hombre y debe aceptar no solo la apariencia sino la realidad”. [72]

La comunión de atributos ( Communicatio idiomatum ) de las naturalezas divina y humana de Cristo se entiende, según la teología calcedonia, como que ambas existen juntas sin que ninguna prevalezca sobre la otra. Es decir, ambas se conservan y coexisten en una sola persona. Cristo tenía todas las propiedades de Dios y de la humanidad. Dios no dejó de ser Dios para convertirse en hombre. Cristo no era mitad Dios y mitad humano. Las dos naturalezas no se mezclaron en una nueva tercera clase de naturaleza. Aunque independientes, actuaron en completo acuerdo; cuando una naturaleza actuaba, también lo hacía la otra. Las naturalezas no se mezclaron, fusionaron, se infundieron entre sí ni se reemplazaron entre sí. Una no se convirtió en la otra. Permanecieron distintas (pero actuaron de común acuerdo).

El Evangelio según Mateo y el Evangelio según Lucas sugieren un nacimiento virginal de Jesucristo. Algunos hoy en día hacen caso omiso de esta "doctrina" a la que se adhieren la mayoría de las denominaciones del cristianismo o incluso la rechazan. Esta sección analiza las cuestiones cristológicas en torno a la creencia o no en el nacimiento virginal.

Un nacimiento no virginal parecería requerir alguna forma de adopcionismo , ya que una concepción y un nacimiento humanos parecerían producir un Jesús completamente humano, con algún otro mecanismo necesario para que Jesús sea divino también.

Un nacimiento no virginal parecería apoyar la plena humanidad de Jesús. William Barclay afirma: “El problema supremo del nacimiento virginal es que indudablemente diferencia a Jesús de todos los hombres; nos deja con una encarnación incompleta”. [73]

Barth habla del nacimiento virginal como del signo divino «que acompaña e indica el misterio de la encarnación del Hijo». [74]

Donald MacLeod [75] ofrece varias implicaciones cristológicas de un nacimiento virginal:

La discusión sobre si las tres personas distintas en la Deidad de la Trinidad eran mayores, iguales o menores en comparación también fue, como muchas otras áreas de la cristología primitiva, un tema de debate. En los escritos de Atenágoras de Atenas ( c. 133-190 ) encontramos una doctrina trinitaria muy desarrollada. [76] [77] En un extremo del espectro estaba el modalismo , una doctrina que afirmaba que las tres personas de la Trinidad eran iguales hasta el punto de borrar sus diferencias y distinciones. En el otro extremo del espectro estaban el triteísmo , así como algunas opiniones radicalmente subordinacionistas , las últimas de las cuales enfatizaban la primacía del Padre de la Creación sobre la deidad de Cristo y la autoridad de Jesús sobre el Espíritu Santo. Durante el Concilio de Nicea, los obispos modalistas de Roma y Alejandría se alinearon políticamente con Atanasio; mientras que los obispos de Constantinopla (Nicomedia), Antioquía y Jerusalén se pusieron del lado de los subordinacionistas como punto medio entre Arrio y Atanasio.

Teólogos como Jürgen Moltmann y Walter Kasper han caracterizado las cristologías como antropológicas o cosmológicas. Estas también se denominan "cristología desde abajo" y "cristología desde arriba", respectivamente. Una cristología antropológica comienza con la persona humana de Jesús y trabaja a partir de su vida y ministerio hacia lo que significa para él ser divino; mientras que una cristología cosmológica trabaja en la dirección opuesta. Partiendo del Logos eterno, una cristología cosmológica trabaja hacia su humanidad. Los teólogos suelen empezar por un lado o por el otro y su elección inevitablemente colorea la cristología resultante. Como punto de partida, estas opciones representan enfoques "diversos pero complementarios"; cada uno plantea sus propias dificultades. Tanto la cristología "desde arriba" como la "desde abajo" deben llegar a un acuerdo con las dos naturalezas de Cristo: humana y divina. Así como la luz puede percibirse como una onda o como una partícula, así Jesús debe ser pensado en términos tanto de su divinidad como de su humanidad. No se puede hablar de "o esto o aquello", sino que se debe hablar de "ambos y". [78]

Las cristologías desde arriba parten del Logos, la segunda Persona de la Trinidad, establecen su eternidad, su acción en la creación y su filiación económica. La unidad de Jesús con Dios se establece mediante la Encarnación, cuando el Logos divino asume una naturaleza humana. Este enfoque era común en la iglesia primitiva, por ejemplo, San Pablo y San Juan en los Evangelios. La atribución de plena humanidad a Jesús se resuelve afirmando que las dos naturalezas comparten mutuamente sus propiedades (un concepto denominado communicatio idiomatum ). [79]

Las cristologías desde abajo parten del ser humano Jesús como representante de la nueva humanidad, no del Logos preexistente. Jesús vive una vida ejemplar, a la que aspiramos en la experiencia religiosa. Esta forma de cristología se presta al misticismo, y algunas de sus raíces se remontan al surgimiento del misticismo de Cristo en Oriente en el siglo VI, pero en Occidente floreció entre los siglos XI y XIV. Un teólogo reciente, Wolfhart Pannenberg, sostiene que el Jesús resucitado es el "cumplimiento escatológico del destino humano de vivir en proximidad a Dios". [80]

La fe cristiana es inherentemente política porque la lealtad a Jesús como Señor resucitado relativiza todo gobierno y autoridad terrenales. A Jesús se lo llama “Señor” más de 230 veces en las epístolas de Pablo solamente, y es por lo tanto la principal confesión de fe en las epístolas paulinas. Además, NT Wright sostiene que esta confesión paulina es el núcleo del evangelio de salvación. El talón de Aquiles de este enfoque es la pérdida de la tensión escatológica entre esta era presente y el gobierno divino futuro que está por venir. Esto puede suceder cuando el estado coopta la autoridad de Cristo, como fue a menudo el caso en la cristología imperial. Las cristologías políticas modernas buscan superar las ideologías imperialistas. [81]

La resurrección es quizás el aspecto más controvertido de la vida de Jesucristo. El cristianismo se apoya en este punto de la cristología, tanto como respuesta a una historia particular como respuesta confesional. [82] Algunos cristianos afirman que, debido a que resucitó, el futuro del mundo cambió para siempre. La mayoría de los cristianos creen que la resurrección de Jesús trae la reconciliación con Dios (2 Corintios 5:18), la destrucción de la muerte (1 Corintios 15:26) y el perdón de los pecados para los seguidores de Jesucristo.

Después de que Jesús murió y fue enterrado, el Nuevo Testamento afirma que se apareció a otros en forma corporal. Algunos escépticos dicen que sus apariciones solo fueron percibidas por sus seguidores en mente o espíritu. Los evangelios afirman que los discípulos creyeron haber presenciado el cuerpo resucitado de Jesús y eso condujo al comienzo de la fe. Anteriormente se habían escondido por temor a la persecución después de la muerte de Jesús. Después de ver a Jesús, proclamaron con valentía el mensaje de Jesucristo a pesar del tremendo riesgo. Obedecieron el mandato de Jesús de reconciliarse con Dios mediante el arrepentimiento (Lucas 24:47), el bautismo y la obediencia (Mateo 28:19-20).

Jesucristo, el Mediador de la humanidad, cumple los tres oficios de Profeta, Sacerdote y Rey . Eusebio , de la iglesia primitiva, elaboró esta triple clasificación, que durante la Reforma desempeñó un papel sustancial en la cristología luterana escolástica y en la cristología de Juan Calvino [83] y Juan Wesley [84] .

La pneumatología es el estudio del Espíritu Santo . Pneuma (πνεῦμα) es la palabra griega para " aliento ", que describe metafóricamente un ser o influencia no material. En la teología cristiana, la pneumatología se refiere al estudio del Espíritu Santo . En el cristianismo , el Espíritu Santo (o Espíritu Santo) es el Espíritu de Dios . Dentro de las creencias cristianas dominantes (trinitarias), es la tercera persona de la Trinidad . Como parte de la Deidad , el Espíritu Santo es igual a Dios Padre y a Dios Hijo . La teología cristiana del Espíritu Santo fue la última pieza de la teología trinitaria en desarrollarse por completo.

Dentro del cristianismo convencional (trinitario), el Espíritu Santo es una de las tres personas de la Trinidad que conforman la única sustancia de Dios. Como tal, el Espíritu Santo es personal y, como parte de la Deidad , es plenamente Dios, coigual y coeterno con Dios Padre e Hijo de Dios . [85] [86] [87] Es diferente del Padre y del Hijo en que procede del Padre (o del Padre y del Hijo ) como se describe en el Credo de Nicea . [86] Su santidad se refleja en los evangelios del Nuevo Testamento [88] que proclaman la blasfemia contra el Espíritu Santo como imperdonable .

La palabra inglesa proviene de dos palabras griegas: πνευμα ( pneuma , espíritu) y λογος ( logos , enseñanza acerca de). La pneumatología normalmente incluiría el estudio de la persona del Espíritu Santo y las obras del Espíritu Santo. Esta última categoría normalmente incluiría las enseñanzas cristianas sobre el nuevo nacimiento , los dones espirituales (charismata), el bautismo en el Espíritu , la santificación , la inspiración de los profetas y la morada de la Santísima Trinidad (que en sí misma cubre muchos aspectos diferentes). Diferentes denominaciones cristianas tienen diferentes enfoques teológicos.

Los cristianos creen que el Espíritu Santo conduce a las personas a la fe en Jesús y les da la capacidad de vivir un estilo de vida cristiano . El Espíritu Santo habita dentro de cada cristiano, siendo el cuerpo de cada uno su templo. [89] Jesús describió al Espíritu Santo [90] como paracletus en latín , derivado del griego . La palabra se traduce de diversas formas como Consolador, Consejero, Maestro, Abogado, [91] guiando a las personas en el camino de la verdad. Se cree que la acción del Espíritu Santo en la vida de uno produce resultados positivos, conocidos como el Fruto del Espíritu Santo . El Espíritu Santo permite a los cristianos, que todavía experimentan los efectos del pecado, hacer cosas que nunca podrían hacer por sí mismos. Estos dones espirituales no son habilidades innatas "desbloqueadas" por el Espíritu Santo, sino habilidades completamente nuevas, como la capacidad de expulsar demonios o simplemente el habla atrevida. A través de la influencia del Espíritu Santo, una persona ve más claramente el mundo que lo rodea y puede usar su mente y su cuerpo de maneras que exceden su capacidad anterior. Una lista de dones que pueden ser otorgados incluye los dones carismáticos de profecía , lenguas , sanidad y conocimiento. Los cristianos que sostienen una perspectiva conocida como cesacionismo creen que estos dones fueron otorgados solo en tiempos del Nuevo Testamento. Los cristianos casi universalmente están de acuerdo en que ciertos " dones espirituales " todavía están vigentes hoy, incluyendo los dones de ministerio, enseñanza, generosidad, liderazgo y misericordia. [92] La experiencia del Espíritu Santo a veces se conoce como ser ungido .

Después de su resurrección , Cristo dijo a sus discípulos que serían « bautizados con el Espíritu Santo» y recibirían poder de este acontecimiento, [93] promesa que se cumplió en los acontecimientos relatados en el segundo capítulo de los Hechos. En el primer Pentecostés , los discípulos de Jesús estaban reunidos en Jerusalén cuando se oyó un fuerte viento y aparecieron lenguas de fuego sobre sus cabezas. Una multitud multilingüe escuchó hablar a los discípulos, y cada uno de ellos los oyó hablar en su lengua materna .

Se cree que el Espíritu Santo desempeña funciones divinas específicas en la vida del cristiano o de la iglesia, entre ellas:

También se cree que el Espíritu Santo está activo especialmente en la vida de Jesucristo , permitiéndole cumplir su obra en la tierra. Algunas de las acciones particulares del Espíritu Santo son:

Los cristianos creen que el “ fruto del Espíritu ” consiste en características virtuosas engendradas en el cristiano por la acción del Espíritu Santo. Son las que se enumeran en Gálatas 5:22-23: “Mas el fruto del Espíritu es amor , gozo , paz , paciencia , benignidad , bondad , fe , mansedumbre y templanza .” [100] La Iglesia Católica Romana añade a esta lista la generosidad , la modestia y la castidad . [101]

Los cristianos creen que el Espíritu Santo da "dones" a los cristianos. Estos dones consisten en habilidades específicas otorgadas al cristiano individual. [95] Con frecuencia se los conoce por la palabra griega para don, Charisma , de la cual se deriva el término carismático . El Nuevo Testamento proporciona tres listas diferentes de tales dones que van desde los sobrenaturales (curación, profecía, lenguas ) pasando por los asociados con llamamientos específicos (enseñanza) hasta los que se esperan de todos los cristianos en algún grado (fe). La mayoría considera que estas listas no son exhaustivas, y otros han compilado sus propias listas. San Ambrosio escribió sobre los siete dones del Espíritu Santo derramados sobre un creyente en el bautismo: 1. Espíritu de sabiduría; 2. Espíritu de entendimiento; 3. Espíritu de consejo; 4. Espíritu de fortaleza; 5. Espíritu de conocimiento; 6. Espíritu de piedad; 7. Espíritu de santo temor . [102]

Es sobre la naturaleza y ocurrencia de estos dones, particularmente los dones sobrenaturales (a veces llamados dones carismáticos), que existe el mayor desacuerdo entre los cristianos con respecto al Espíritu Santo.

Una de las opiniones es que los dones sobrenaturales fueron una dispensación especial para las eras apostólicas, otorgados debido a las condiciones únicas de la iglesia en ese momento, y que son extremadamente raramente otorgados en el tiempo presente. [103] Esta es la opinión de algunos en la Iglesia Católica [87] y muchos otros grupos cristianos tradicionales. La opinión alternativa, adoptada principalmente por las denominaciones pentecostales y el movimiento carismático, es que la ausencia de los dones sobrenaturales se debió a la negligencia del Espíritu Santo y su obra por parte de la iglesia. Aunque algunos grupos pequeños, como los montanistas , practicaron los dones sobrenaturales, eran raros hasta el crecimiento del movimiento pentecostal a fines del siglo XIX. [103]

Los creyentes en la relevancia de los dones sobrenaturales a veces hablan de un bautismo del Espíritu Santo o de una llenura del Espíritu Santo que el cristiano necesita experimentar para recibir esos dones. Muchas iglesias sostienen que el bautismo del Espíritu Santo es idéntico a la conversión, y que todos los cristianos son, por definición, bautizados en el Espíritu Santo. [103]

Y dijo Dios: Sea la luz; y fue la luz. Y vio Dios que la luz era buena; y separó Dios la luz de las tinieblas. Y llamó Dios a la luz Día, y a las tinieblas llamó Noche. Y fue la tarde y la mañana un día. Génesis 1:3-5

Los distintos autores del Antiguo y Nuevo Testamento nos ofrecen una visión de su visión de la cosmología . El cosmos fue creado por Dios por orden divina, según el relato más conocido y completo de la Biblia, el de Génesis 1.

Sin embargo, dentro de este amplio entendimiento hay una serie de puntos de vista sobre cómo exactamente debe interpretarse esta doctrina.

Es un principio de la fe cristiana (católica, ortodoxa oriental y protestante) que Dios es el creador de todas las cosas de la nada y ha hecho a los seres humanos a imagen de Dios , quien por inferencia directa es también la fuente del alma humana . En la cristología calcedonia , Jesús es la Palabra de Dios , que era en el principio y, por lo tanto, es increada, y por lo tanto es Dios , y en consecuencia idéntico al Creador del mundo ex nihilo .

Roman Catholicism uses the phrase special creation to refer to the doctrine of immediate or special creation of each human soul. In 2004, the International Theological Commission, then under the presidency of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, published a paper in which it accepts the current scientific accounts of the history of the universe commencing in the Big Bang about 15 billion years ago and of the evolution of all life on earth including humans from the micro organisms commencing about 4 billion years ago.[104] The Roman Catholic Church allows for both a literal and allegorical interpretation of Genesis, so as to allow for the possibility of Creation by means of an evolutionary process over great spans of time, otherwise known as theistic evolution.[dubious – discuss] It believes that the creation of the world is a work of God through the Logos, the Word (idea, intelligence, reason and logic):

The New Testament claims that God created everything by the eternal Word, Jesus Christ his beloved Son. In him

Christian anthropology is the study of humanity, especially as it relates to the divine. This theological anthropology refers to the study of the human ("anthropology") as it relates to God. It differs from the social science of anthropology, which primarily deals with the comparative study of the physical and social characteristics of humanity across times and places.

One aspect studies the innate nature or constitution of the human, known as the nature of mankind. It is concerned with the relationship between notions such as body, soul and spirit which together form a person, based on their descriptions in the Bible. There are three traditional views of the human constitution– trichotomism, dichotomism and monism (in the sense of anthropology).[106]

The semantic domain of Biblical soul is based on the Hebrew word nepes, which presumably means "breath" or "breathing being".[107] This word never means an immortal soul[108] or an incorporeal part of the human being[109] that can survive death of the body as the spirit of dead.[110] This word usually designates the person as a whole[111] or its physical life. In the Septuagint nepes is mostly translated as psyche (ψυχή) and, exceptionally, in the Book of Joshua as empneon (ἔμπνεον), that is "breathing being".[112]

The New Testament follows the terminology of the Septuagint, and thus uses the word psyche with the Hebrew semantic domain and not the Greek,[113] that is an invisible power (or ever more, for Platonists, immortal and immaterial) that gives life and motion to the body and is responsible for its attributes.

In Patristic thought, towards the end of the 2nd century psyche was understood in more a Greek than a Hebrew way, and it was contrasted with the body. In the 3rd century, with the influence of Origen, there was the establishing of the doctrine of the inherent immortality of the soul and its divine nature.[114] Origen also taught the transmigration of the souls and their preexistence, but these views were officially rejected in 553 in the Fifth Ecumenical Council. Inherent immortality of the soul was accepted among western and eastern theologians throughout the middle ages, and after the Reformation, as evidenced by the Westminster Confession.

The spirit (Hebrew ruach, Greek πνεῦμα, pneuma, which can also mean "breath") is likewise an immaterial component. It is often used interchangeably with "soul", psyche, although trichotomists believe that the spirit is distinct from the soul.

The body (Greek σῶμα soma) is the corporeal or physical aspect of a human being. Christians have traditionally believed that the body will be resurrected at the end of the age.

Flesh (Greek σάρξ, sarx) is usually considered synonymous with "body", referring to the corporeal aspect of a human being. The apostle Paul contrasts flesh and spirit in Romans 7–8.

The Bible teaches in the book of Genesis the humans were created by God. Some Christians believe that this must have involved a miraculous creative act, while others are comfortable with the idea that God worked through the evolutionary process.

The book of Genesis also teaches that human beings, male and female, were created in the image of God. The exact meaning of this has been debated throughout church history.

Christian anthropology has implications for beliefs about death and the afterlife. The Christian church has traditionally taught that the soul of each individual separates from the body at death, to be reunited at the resurrection. This is closely related to the doctrine of the immortality of the soul. For example, the Westminster Confession (chapter XXXII) states:

The question then arises: where exactly does the disembodied soul "go" at death? Theologians refer to this subject as the intermediate state. The Old Testament speaks of a place called sheol where the spirits of the dead reside. In the New Testament, hades, the classical Greek realm of the dead, takes the place of sheol. In particular, Jesus teaches in Luke 16:19–31 (Lazarus and Dives) that hades consists of two separate "sections", one for the righteous and one for the unrighteous. His teaching is consistent with intertestamental Jewish thought on the subject.[116]

Fully developed Christian theology goes a step further; on the basis of such texts as Luke 23:43 and Philippians 1:23, it has traditionally been taught that the souls of the dead are received immediately either into heaven or hell, where they will experience a foretaste of their eternal destiny prior to the resurrection. (Roman Catholicism teaches a third possible location, Purgatory, though this is denied by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox.)

Some Christian groups which stress a monistic anthropology deny that the soul can exist consciously apart from the body. For example, the Seventh-day Adventist Church teaches that the intermediate state is an unconscious sleep; this teaching is informally known as "soul sleep".

In Christian belief, both the righteous and the unrighteous will be resurrected at the last judgment. The righteous will receive incorruptible, immortal bodies (1 Corinthians 15), while the unrighteous will be sent to hell. Traditionally, Christians have believed that hell will be a place of eternal physical and psychological punishment. In the last two centuries, annihilationism has become popular.

The study of the Blessed Virgin Mary, doctrines about her, and how she relates to the Church, Christ, and the individual Christian is called Mariology. Catholic Mariology is the Marian study specifically in the context of the Catholic Church. Examples of Mariology include the study of and doctrines regarding her Perpetual Virginity, her Motherhood of God (and by extension her Motherhood/Intercession for all Christians), her Immaculate Conception, and her Assumption into heaven.

Most descriptions of angels in the Bible describe them in military terms. For example, in terms such as encampment (Gen.32:1–2), command structure (Ps.91:11–12; Matt.13:41; Rev.7:2), and combat (Jdg.5:20; Job 19:12; Rev.12:7).

Its specific hierarchy differs slightly from the Hierarchy of Angels as it surrounds more military services, whereas the Hierarchy of angels is a division of angels into non-military services to God.

Cherubim are depicted as accompanying God's chariot-throne (Ps.80:1). Exodus 25:18–22 refers to two Cherub statues placed on top of the Ark of the Covenant, the two cherubim are usually interpreted as guarding the throne of God. Other guard-like duties include being posted in locations such as the gates of Eden (Gen.3:24). Cherubim were mythological winged bulls or other beasts that were part of ancient Near Eastern traditions.[117]

This angelic designation might be given to angels of various ranks. An example would be Raphael who is ranked variously as a Seraph, Cherub, and Archangel .[118] This is usually a result of conflicting schemes of hierarchies of angels.

It is not known how many angels there are but one figure given in Revelation 5:11 for the number of "many angels in a circle around the throne, as well as the living creatures and the elders" was "ten thousand times ten thousand", which would be 100 million.

In most of Christianity, a fallen angel is an angel who has been exiled or banished from Heaven. Often such banishment is a punishment for disobeying or rebelling against God (see War in Heaven). The best-known fallen angel is Lucifer. Lucifer is a name frequently given to Satan in Christian belief. This usage stems from a particular interpretation, as a reference to a fallen angel, of a passage in the Bible (Isaiah 14:3–20) that speaks of someone who is given the name of "Day Star" or "Morning Star" (in Latin, Lucifer) as fallen from heaven. The Greek etymological synonym of Lucifer, Φωσφόρος (Phosphoros, "light-bearer").[119][120] is used of the morning star in 2 Peter 1:19 and elsewhere with no reference to Satan. But Satan is called Lucifer in many writings later than the Bible, notably in Milton's Paradise Lost (7.131–134, among others), because, according to Milton, Satan was "brighter once amidst the host of Angels, than that star the stars among."

Allegedly, fallen angels are those which have committed one of the seven deadly sins. Therefore, are banished from heaven and suffer in hell for all eternity. Demons from hell would punish the fallen angel by ripping out their wings as a sign of insignificance and low rank.[121]

Christianity has taught Heaven as a place of eternal life, in that it is a shared plane to be attained by all the elect (rather than an abstract experience related to individual concepts of the ideal). The Christian Church has been divided over how people gain this eternal life. From the 16th to the late 19th century, Christendom was divided between the Catholic view, the Eastern Orthodox view, the Coptic view, the Jacobite view, the Abyssinian view and Protestant views. See also Christian denominations.

Heaven is the English name for a transcendental realm wherein human beings who have transcended human living live in an afterlife. in the Bible and in English, the term "heaven" may refer to the physical heavens, the sky or the seemingly endless expanse of the universe beyond, the traditional literal meaning of the term in English.

Christianity maintains that entry into Heaven awaits such time as, "When the form of this world has passed away." (*JPII) One view expressed in the Bible is that on the day Christ returns the righteous dead are resurrected first, and then those who are alive and judged righteous will be brought up to join them, to be taken to heaven. (I Thess 4:13–18)

Two related and often confused concepts of heaven in Christianity are better described as the "resurrection of the body", which is exclusively of biblical origin, as contrasted with the "immortality of the soul", which is also evident in the Greek tradition. In the first concept, the soul does not enter heaven until the last judgement or the "end of time" when it (along with the body) is resurrected and judged. In the second concept, the soul goes to a heaven on another plane such as the intermediate state immediately after death. These two concepts are generally combined in the doctrine of the double judgement where the soul is judged once at death and goes to a temporary heaven, while awaiting a second and final physical judgement at the end of the world.(*" JPII, also see eschatology, afterlife)

One popular medieval view of Heaven was that it existed as a physical place above the clouds and that God and the Angels were physically above, watching over man. Heaven as a physical place survived in the concept that it was located far out into space, and that the stars were "lights shining through from heaven".

Many of today's biblical scholars, such as N. T. Wright, in tracing the concept of Heaven back to its Jewish roots, see Earth and Heaven as overlapping or interlocking. Heaven is known as God's space, his dimension, and is not a place that can be reached by human technology. This belief states that Heaven is where God lives and reigns whilst being active and working alongside people on Earth. One day when God restores all things, Heaven and Earth will be forever combined into the New Heavens and New Earth[122] of the World to Come.

Religions that teach about heaven differ on how (and if) one gets into it, typically in the afterlife. In most, entrance to Heaven is conditional on having lived a "good life" (within the terms of the spiritual system). A notable exception to this is the 'sola fide' belief of many mainstream Protestants, which teaches that one does not have to live a perfectly "good life," but that one must accept Jesus Christ as one's Lord and Saviour, and then Jesus Christ will assume the guilt of one's sins; believers are believed to be forgiven regardless of any good or bad "works" one has participated in.[123]

Many religions state that those who do not go to heaven will go to a place "without the presence of God", Hell, which is eternal (see annihilationism). Some religions believe that other afterlives exist in addition to Heaven and Hell, such as Purgatory. One belief, universalism, believes that everyone will go to Heaven eventually, no matter what they have done or believed on earth. Some forms of Christianity believe Hell to be the termination of the soul.

Various saints have had visions of heaven (2 Corinthians 12:2–4). The Eastern Orthodox concept of life in heaven is described in one of the prayers for the dead: "...a place of light, a place of green pasture, a place of repose, whence all sickness, sorrow and sighing are fled away."[124]

The Church bases its belief in Heaven on some main biblical passages in the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures (Old and New Testaments) and collected church wisdom. Heaven is the Realm of the Blessed Trinity, the angels[125] and the saints.[126]

The essential joy of heaven is called the beatific vision, which is derived from the vision of God's essence. The soul rests perfectly in God, and does not, or cannot desire anything else than God. After the Last Judgment, when the soul is reunited with its body, the body participates in the happiness of the soul. It becomes incorruptible, glorious and perfect. Any physical defects the body may have laboured under are erased. Heaven is also known as paradise in some cases. The Great Gulf separates heaven from hell.

Upon dying, each soul goes to what is called "the particular judgement" where its own afterlife is decided (i.e. Heaven after Purgatory, straight to Heaven, or Hell.) This is different from "the general judgement" also known as "the Last judgement" which will occur when Christ returns to judge all the living and the dead.

The term Heaven (which differs from "The Kingdom of Heaven" see note below) is applied by the biblical authors to the realm in which God currently resides. Eternal life, by contrast, occurs in a renewed, unspoilt and perfect creation, which can be termed Heaven since God will choose to dwell there permanently with his people, as seen in Revelation 21:3. There will no longer be any separation between God and man. The believers themselves will exist in incorruptible, resurrected and new bodies; there will be no sickness, no death and no tears. Some teach that death itself is not a natural part of life, but was allowed to happen after Adam and Eve disobeyed God (see original sin) so that mankind would not live forever in a state of sin and thus a state of separation from God.

Many evangelicals understand this future life to be divided into two distinct periods: first, the Millennial Reign of Christ (the one thousand years) on this earth, referred to in Revelation 20:1–10; secondly, the New Heavens and New Earth, referred to in Revelation 21 and 22. This millennialism (or chiliasm) is a revival of a strong tradition in the Early Church[127] that was dismissed by Saint Augustine of Hippo and the Roman Catholic Church after him.

Not only will the believers spend eternity with God, they will also spend it with each other. John's vision recorded in Revelation describes a New Jerusalem which comes from Heaven to the New Earth, which is seen to be a symbolic reference to the people of God living in community with one another. 'Heaven' will be the place where life will be lived to the full, in the way that the designer planned, each believer 'loving the Lord their God with all their heart and with all their soul and with all their mind' and 'loving their neighbour as themselves' (adapted from Matthew 22:37–38, the Great Commandment)—a place of great joy, without the negative aspects of earthly life. See also World to Come.

Purgatory is the condition or temporary punishment[33] in which, it is believed, the souls of those who die in a state of grace are made ready for Heaven. This is a theological idea that has ancient roots and is well-attested in early Christian literature, while the poetic conception of purgatory as a geographically situated place is largely the creation of medieval Christian piety and imagination.[33]

The notion of purgatory is associated particularly with the Latin Church of the Catholic Church (in the Eastern Catholic Churches it is a doctrine, though often without using the name "Purgatory"); Anglicans of the Anglo-Catholic tradition generally also hold to the belief.[citation needed] John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, believed in an intermediate state between death and the final judgment and in the possibility of "continuing to grow in holiness there."[128][129] The Eastern Orthodox Churches believe in the possibility of a change of situation for the souls of the dead through the prayers of the living and the offering of the Divine Liturgy,[130] and many Eastern Orthodox, especially among ascetics, hope and pray for a general apocatastasis.[131] A similar belief in at least the possibility of a final salvation for all is held by Mormonism.[132] Judaism also believes in the possibility of after-death purification[133] and may even use the word "purgatory" to present its understanding of the meaning of Gehenna.[134] However, the concept of soul "purification" may be explicitly denied in these other faith traditions.

Hell in Christian beliefs, is a place or a state in which the souls of the unsaved will suffer the consequences of sin. The Christian doctrine of Hell derives from the teaching of the New Testament, where Hell is typically described using the Greek words Gehenna or Tartarus. Unlike Hades, Sheol, or Purgatory it is eternal, and those damned to Hell are without hope. In the New Testament, it is described as the place or state of punishment after death or last judgment for those who have rejected Jesus.[135] In many classical and popular depictions it is also the abode of Satan and of Demons.[136] Such is not the case in the Book of Revelation, where Satan is thrown into Hell only at the end of Christ's millennium long reign on this Earth.[137]

Hell is generally defined as the eternal fate of unrepentant sinners after this life.[138] Hell's character is inferred from biblical teaching, which has often been understood literally.[138] Souls are said to pass into Hell by God's irrevocable judgment, either immediately after death (particular judgment) or in the general judgment.[138] Modern theologians generally describe Hell as the logical consequence of the soul using its free will to reject the will of God.[138] It is considered compatible with God's justice and mercy because God will not interfere with the soul's free choice.[138]