El pensamiento evolutivo , el reconocimiento de que las especies cambian con el tiempo y la comprensión percibida de cómo funcionan estos procesos, tiene raíces en la antigüedad, en las ideas de los antiguos griegos , romanos , chinos , Padres de la Iglesia , así como en la ciencia islámica medieval . Con los inicios de la taxonomía biológica moderna a fines del siglo XVII, dos ideas opuestas influyeron en el pensamiento biológico occidental : el esencialismo , la creencia de que cada especie tiene características esenciales que son inalterables, un concepto que se había desarrollado a partir de la metafísica aristotélica medieval y que encajaba bien con la teología natural ; y el desarrollo del nuevo enfoque antiaristotélico de la ciencia moderna : a medida que avanzaba la Ilustración , la cosmología evolutiva y la filosofía mecanicista se extendieron de las ciencias físicas a la historia natural . Los naturalistas comenzaron a centrarse en la variabilidad de las especies; el surgimiento de la paleontología con el concepto de extinción socavó aún más las visiones estáticas de la naturaleza . A principios del siglo XIX, antes del darwinismo , Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) propuso su teoría de la transmutación de las especies , la primera teoría de la evolución completamente formada .

En 1858, Charles Darwin y Alfred Russel Wallace publicaron una nueva teoría evolutiva, explicada en detalle en El origen de las especies (1859) de Darwin. La teoría de Darwin, originalmente llamada descendencia con modificación, se conoce contemporáneamente como darwinismo o teoría darwiniana. A diferencia de Lamarck, Darwin propuso una descendencia común y un árbol ramificado de la vida , lo que significa que dos especies muy diferentes podrían compartir un ancestro común. Darwin basó su teoría en la idea de la selección natural : sintetizó una amplia gama de evidencia de la cría de animales , la biogeografía , la geología , la morfología y la embriología . El debate sobre el trabajo de Darwin llevó a la rápida aceptación del concepto general de evolución, pero el mecanismo específico que propuso, la selección natural, no fue ampliamente aceptado hasta que fue revivido por los avances en biología que ocurrieron durante la década de 1920 a 1940. Antes de esa época, la mayoría de los biólogos consideraban que otros factores eran responsables de la evolución. Las alternativas a la selección natural sugeridas durante el "eclipse del darwinismo " (c. 1880 a 1920) incluían la herencia de características adquiridas ( neolamarckismo ), un impulso innato al cambio ( ortogénesis ) y mutaciones repentinas de gran magnitud ( saltacionismo ). La genética mendeliana , una serie de experimentos del siglo XIX con variaciones de la planta del guisante redescubierta en 1900, fue integrada con la selección natural por Ronald Fisher , JBS Haldane y Sewall Wright durante las décadas de 1910 a 1930, y dio como resultado la fundación de la nueva disciplina de la genética de poblaciones . Durante las décadas de 1930 y 1940, la genética de poblaciones se integró con otros campos biológicos, lo que dio como resultado una teoría de la evolución ampliamente aplicable que abarcó gran parte de la biología: la síntesis moderna .

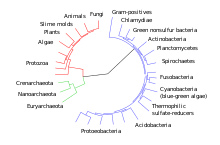

Tras el establecimiento de la biología evolutiva , los estudios de mutación y diversidad genética en poblaciones naturales, combinados con la biogeografía y la sistemática , condujeron a sofisticados modelos matemáticos y causales de la evolución. La paleontología y la anatomía comparada permitieron reconstrucciones más detalladas de la historia evolutiva de la vida . Después del surgimiento de la genética molecular en la década de 1950, se desarrolló el campo de la evolución molecular , basado en secuencias de proteínas y pruebas inmunológicas, y que más tarde incorporó estudios de ARN y ADN . La visión de la evolución centrada en los genes cobró importancia en la década de 1960, seguida de la teoría neutral de la evolución molecular , lo que desató debates sobre el adaptacionismo , la unidad de selección y la importancia relativa de la deriva genética frente a la selección natural como causas de la evolución. [2] A finales del siglo XX, la secuenciación del ADN condujo a la filogenética molecular y a la reorganización del árbol de la vida en el sistema de tres dominios por Carl Woese . Además, los factores recientemente reconocidos de simbiogénesis y transferencia horizontal de genes introdujeron aún más complejidad en la teoría evolutiva. Los descubrimientos en biología evolutiva han tenido un impacto significativo no sólo en las ramas tradicionales de la biología, sino también en otras disciplinas académicas (por ejemplo: antropología y psicología ) y en la sociedad en general. [3]

.jpg/440px-Anaximander_Mosaic_(cropped,_with_sundial).jpg)

Se sabe que las propuestas de que un tipo de animal , incluso los humanos , podrían descender de otros tipos de animales se remontan a los filósofos griegos presocráticos . Anaximandro de Mileto ( c. 610 - c. 546 a. C. ) propuso que los primeros animales vivieron en el agua, durante una fase húmeda del pasado de la Tierra , y que los primeros antepasados terrestres de la humanidad deben haber nacido en el agua y solo pasaron parte de su vida en la tierra. También argumentó que el primer humano de la forma conocida hoy debe haber sido hijo de un tipo diferente de animal (probablemente un pez), porque el hombre necesita una lactancia prolongada para vivir. [5] [6] [4] A fines del siglo XIX, Anaximandro fue aclamado como el "primer darwinista", pero esta caracterización ya no es comúnmente aceptada. [7] La hipótesis de Anaximandro podría considerarse "evolución" en cierto sentido, aunque no darwiniano. [7]

Empédocles argumentó que lo que llamamos nacimiento y muerte en los animales son solo la mezcla y separación de elementos que causan las innumerables "tribus de cosas mortales". [8] En concreto, los primeros animales y plantas eran como partes disjuntas de las que vemos hoy, algunas de las cuales sobrevivieron uniéndose en diferentes combinaciones, y luego entremezclándose durante el desarrollo del embrión, [a] y donde "todo resultó como lo habría hecho si hubiera sido a propósito, allí las criaturas sobrevivieron, al ser compuestas accidentalmente de una manera adecuada". [9] Otros filósofos que se volvieron más influyentes en ese momento, incluidos Platón , Aristóteles y miembros de la escuela estoica de filosofía , creían que los tipos de todas las cosas, no solo de los seres vivos, estaban fijados por diseño divino. [10] [11]

El biólogo Ernst Mayr llamó a Platón "el gran antihéroe del evolucionismo" [10] porque promovió la creencia en el esencialismo, también conocido como la teoría de las Formas . Esta teoría sostiene que cada tipo natural de objeto en el mundo observado es una manifestación imperfecta del ideal, forma o "especie" que define ese tipo. En su Timeo , por ejemplo, Platón hace que un personaje cuente una historia según la cual el Demiurgo creó el cosmos y todo lo que hay en él porque, siendo bueno y, por lo tanto, "libre de celos, deseaba que todas las cosas fueran lo más parecidas a Él que pudieran ser". El creador creó todas las formas de vida concebibles, ya que "sin ellas el universo estaría incompleto, porque no contendría todos los tipos de animales que debería contener, si ha de ser perfecto". Este " principio de plenitud " —la idea de que todas las formas de vida potenciales son esenciales para una creación perfecta— influyó mucho en el pensamiento cristiano . [11] Sin embargo, algunos historiadores de la ciencia han cuestionado cuánta influencia tuvo el esencialismo de Platón en la filosofía natural al afirmar que muchos filósofos después de Platón creían que las especies podrían ser capaces de transformación y que la idea de que las especies biológicas eran fijas y poseían características esenciales inmutables no se volvió importante hasta el comienzo de la taxonomía biológica en los siglos XVII y XVIII. [12]

Aristóteles, el filósofo griego más influyente en Europa , fue alumno de Platón y también es el primer historiador natural cuyo trabajo se ha conservado con verdadero detalle. Sus escritos sobre biología fueron el resultado de su investigación sobre la historia natural en la isla de Lesbos y sus alrededores , y han sobrevivido en forma de cuatro libros, generalmente conocidos por sus nombres en latín , De anima ( Sobre el alma ), Historia animalium ( Historia de los animales ), De generatione animalium ( Generación de los animales ) y De partibus animalium ( Sobre las partes de los animales ). Las obras de Aristóteles contienen observaciones precisas, encajadas en sus propias teorías de los mecanismos del cuerpo. [13] Sin embargo, para Charles Singer , "Nada es más notable que los esfuerzos [de Aristóteles] por [exhibir] las relaciones de los seres vivos como una scala naturae ". [13] Esta scala naturae , descrita en Historia animalium , clasificaba a los organismos en relación con una "escalera de la vida" o "gran cadena del ser" jerárquica pero estática, ubicándolos según su complejidad de estructura y función, con organismos que mostraban mayor vitalidad y capacidad de movimiento descritos como "organismos superiores". [11] Aristóteles creía que las características de los organismos vivos mostraban claramente que tenían lo que él llamaba una causa final , es decir, que su forma se adaptaba a su función. [14] Rechazó explícitamente la visión de Empédocles de que las criaturas vivientes podrían haberse originado por casualidad. [15]

Otros filósofos griegos, como Zenón de Citium , el fundador de la escuela estoica de filosofía, coincidieron con Aristóteles y otros filósofos anteriores en que la naturaleza mostraba claras evidencias de haber sido diseñada para un propósito; esta visión se conoce como teleología . [16] El filósofo escéptico romano Cicerón escribió que se sabía que Zenón sostenía la visión, central para la física estoica, de que la naturaleza está principalmente "dirigida y concentrada... para asegurar para el mundo... la estructura mejor adaptada para la supervivencia". [17]

Los antiguos pensadores chinos , como Zhuang Zhou ( c. 369 – c. 286 a. C. ), un filósofo taoísta , expresaron ideas sobre el cambio de las especies biológicas. Según Joseph Needham , el taoísmo niega explícitamente la fijeza de las especies biológicas y los filósofos taoístas especularon que las especies habían desarrollado diferentes atributos en respuesta a diferentes entornos. [18] El taoísmo considera que los humanos, la naturaleza y los cielos existen en un estado de "transformación constante" conocido como el Tao , en contraste con la visión más estática de la naturaleza típica del pensamiento occidental. [19]

El poema De rerum natura de Lucrecio ofrece la mejor explicación que se conserva de las ideas de los filósofos epicúreos griegos. Describe el desarrollo del cosmos, la Tierra, los seres vivos y la sociedad humana a través de mecanismos puramente naturalistas, sin ninguna referencia a la participación sobrenatural . De rerum natura influiría en las especulaciones cosmológicas y evolutivas de los filósofos y científicos durante y después del Renacimiento . [20] [21] Esta visión contrastaba fuertemente con las opiniones de los filósofos romanos de la escuela estoica, como Séneca el Joven y Plinio el Viejo, que tenían una visión fuertemente teleológica del mundo natural que influyó en la teología cristiana . [16] Cicerón informa que la visión peripatética y estoica de la naturaleza como una agencia preocupada básicamente por producir vida "mejor adaptada para la supervivencia" se daba por sentado entre la élite helenística . [17]

En consonancia con el pensamiento griego anterior, el filósofo cristiano del siglo III y Padre de la Iglesia Orígenes de Alejandría argumentó que la historia de la creación en el Libro del Génesis debería interpretarse como una alegoría de la caída de las almas humanas lejos de la gloria de lo divino, y no como un relato histórico literal: [22] [23]

¿Quién, en efecto, que tenga entendimiento, supondrá que el primer día, el segundo día, el tercer día, la tarde y la mañana, existieron sin sol, luna y estrellas? ¿Y que el primer día también fue, por así decirlo, sin cielo? ¿Y quién es tan necio como para suponer que Dios, a la manera de un labrador, plantó un paraíso en Edén, hacia el este, y colocó en él un árbol de vida, visible y palpable, de modo que quien probara el fruto con los dientes corporales obtenía la vida? ¿Y que uno era partícipe del bien y del mal al masticar lo que se tomaba del árbol? Y si se dice que Dios caminaba en el paraíso por la tarde y que Adán se escondía bajo un árbol, no supongo que alguien dude de que estas cosas indican figurativamente ciertos misterios, ya que la historia tuvo lugar en apariencia y no literalmente.

— Orígenes, Sobre los primeros principios IV.16

Gregorio de Nisa escribió:

La Escritura nos informa que la Deidad procedió por una especie de avance gradual y ordenado a la creación del hombre . Después de que se sentaron las bases del universo, como registra la historia, el hombre no apareció en la tierra de inmediato, sino que la creación de los animales lo precedió, y las plantas los precedieron. De este modo, la Escritura muestra que las fuerzas vitales se mezclaron con el mundo de la materia según una gradación; primero se infundieron en la naturaleza insensible; y en continuación de esto avanzaron hacia el mundo sensible; y luego ascendieron a los seres inteligentes y racionales (énfasis añadido). [9]

Henry Fairfield Osborn escribió en su obra sobre la historia del pensamiento evolutivo, De los griegos a Darwin (1894):

Entre los Padres cristianos, el movimiento hacia una interpretación parcialmente naturalista del orden de la Creación fue iniciado por Gregorio de Nisa en el siglo IV, y fue completado por Agustín en los siglos IV y V. ...[Gregorio de Nisa] enseñó que la Creación era potencial. Dios impartió a la materia sus propiedades y leyes fundamentales. Los objetos y las formas completas del Universo se desarrollaron gradualmente a partir de material caótico. [24]

En el siglo IV d. C., el obispo y teólogo Agustín de Hipona siguió el ejemplo de Orígenes y sostuvo que los cristianos debían leer el relato de la creación del Génesis de manera alegórica. En su libro De Genesi ad litteram ( Sobre el significado literal del Génesis ), prologa su relato con lo siguiente:

En todos los libros sagrados debemos tener en cuenta las verdades eternas que se enseñan, los hechos que se narran, los acontecimientos futuros que se predicen y los preceptos o consejos que se dan. En el caso de una narración de acontecimientos, surge la cuestión de si todo debe tomarse sólo según el sentido figurado, o si debe exponerse y defenderse también como un registro fiel de lo que sucedió. Ningún cristiano se atrevería a decir que la narración no debe tomarse en sentido figurado. Pues San Pablo dice: Ahora bien, todo lo que les sucedió era simbólico (1 Cor 10,11). Y explica la afirmación del Génesis: Y serán dos en una sola carne (Ef 5,32) como un gran misterio con referencia a Cristo y a la Iglesia (26) .

Más tarde, diferencia entre los días de la narrativa de la creación de Génesis 1 y los días de 24 horas que experimentan los humanos (argumentando que "sabemos que [los días de la creación] son diferentes del día ordinario con el que estamos familiarizados") [27] antes de describir lo que podría llamarse una forma temprana de evolución teísta : [28] [29]

Las cosas que [Dios] había creado potencialmente... [surgieron] en el curso del tiempo en diferentes días según sus diferentes especies... [y] el resto de la tierra [estaba] llena de sus diversas especies de criaturas, [que] produjeron sus formas apropiadas a su debido tiempo. [30]

Agustín utilizó el concepto de rationes seminales para fusionar la idea de la creación divina con el desarrollo posterior. [31] Esta idea de que «las formas de vida se habían transformado ‘lentamente a lo largo del tiempo ’ » impulsó al padre Giuseppe Tanzella-Nitti, profesor de teología en la Pontificia Universidad Santa Croce de Roma, a afirmar que Agustín había sugerido una forma de evolución. [32] [33]

Henry Fairfield Osborn escribió en De los griegos a Darwin (1894):

Si la ortodoxia de Agustín hubiera seguido siendo la enseñanza de la Iglesia, el establecimiento final de la evolución habría llegado mucho antes de lo que lo hizo, ciertamente durante el siglo XVIII en lugar del XIX, y la amarga controversia sobre esta verdad de la naturaleza nunca habría surgido. ... Claramente, como la creación directa o instantánea de animales y plantas parecía enseñarse en el Génesis, Agustín lo interpretó a la luz de la causalidad primaria y el desarrollo gradual de lo imperfecto a lo perfecto de Aristóteles. Este maestro tan influyente transmitió así a sus seguidores opiniones que se ajustan estrechamente a las opiniones progresistas de los teólogos de la actualidad que han aceptado la teoría de la evolución. [34]

En Una historia de la guerra de la ciencia con la teología en la cristiandad (1896), Andrew Dickson White escribió sobre los intentos de Agustín de preservar el antiguo enfoque evolutivo de la creación de la siguiente manera:

Durante siglos, una doctrina ampliamente aceptada había sido la de que el agua, la suciedad y la carroña habían recibido poder del Creador para generar gusanos, insectos y una multitud de animales más pequeños; y esta doctrina había sido especialmente bien recibida por San Agustín y muchos de los padres, ya que liberaba al Todopoderoso de crear, a Adán de nombrar y a Noé de vivir en el arca con estas innumerables especies despreciadas. [35]

En De Genesi contra Manichæos , de Agustín , sobre el Génesis, dice: «Suponer que Dios formó al hombre del polvo con manos corporales es muy infantil... Dios no formó al hombre con manos corporales ni sopló sobre él con garganta y labios». Agustín sugiere en otra obra su teoría del desarrollo posterior de los insectos a partir de carroña, y la adopción de la antigua teoría de la emanación o evolución, mostrando que «ciertos animales muy pequeños pueden no haber sido creados en el quinto y sexto día, sino que pueden haberse originado más tarde a partir de materia en putrefacción». En relación con De Trinitate ( Sobre la Trinidad ) de Agustín, White escribió que Agustín «desarrolla extensamente la opinión de que en la creación de los seres vivos hubo algo así como un crecimiento, que Dios es el autor último, pero trabaja a través de causas secundarias; y finalmente argumenta que ciertas sustancias están dotadas por Dios con el poder de producir ciertas clases de plantas y animales». [36]

Agustín implica que, cualquiera que sea la demostración de la ciencia, la Biblia debe enseñar:

Por lo general, incluso un no cristiano sabe algo sobre la tierra, los cielos y los demás elementos de este mundo, sobre el movimiento y la órbita de las estrellas... Ahora bien, es una cosa vergonzosa y peligrosa para un infiel oír a un cristiano, presumiblemente dando el significado de las Sagradas Escrituras, hablar tonterías sobre estos temas; y debemos tomar todos los medios para evitar una situación tan embarazosa, en la que la gente muestra la gran ignorancia de un cristiano y se ríe de ello con desprecio. La vergüenza no es tanto que se ridiculice a un individuo ignorante, sino que la gente fuera de la familia de la fe piense que nuestros escritores sagrados sostenían tales opiniones y, para gran pérdida de aquellos por cuya salvación trabajamos, los escritores de nuestras Escrituras son criticados y rechazados como hombres sin letras. [37]

Aunque las ideas evolucionistas griegas y romanas se extinguieron en Europa occidental después de la caída del Imperio romano , no se perdieron para los filósofos y científicos islámicos (ni para el Imperio bizantino, culturalmente griego ). En la Edad de Oro islámica de los siglos VIII al XIII, los filósofos exploraron ideas sobre la historia natural. Estas ideas incluían la transmutación de lo inerte a lo vivo: "de mineral a planta, de planta a animal y de animal a hombre". [38]

En el mundo islámico medieval, el erudito al-Jāḥiẓ escribió su Libro de los animales en el siglo IX. Conway Zirkle , escribiendo sobre la historia de la selección natural en 1941, dijo que un extracto de esta obra era el único pasaje relevante que había encontrado de un erudito árabe. Aportó una cita que describe la lucha por la existencia, citando una traducción al español de esta obra: "Todo animal débil devora a los más débiles que él mismo. Los animales fuertes no pueden escapar de ser devorados por otros animales más fuertes que ellos. Y en este aspecto, los hombres no se diferencian de los animales, unos respecto de otros, aunque no lleguen a los mismos extremos. En resumen, Dios ha dispuesto a unos seres humanos como causa de vida para otros, y, del mismo modo, ha dispuesto a estos últimos como causa de la muerte de los primeros". [39] Al-Jāḥiẓ también escribió descripciones de cadenas alimentarias . [40]

Algunos de los pensamientos de Ibn Jaldún , según algunos comentaristas, anticipan la teoría biológica de la evolución. [41] En 1377, Ibn Jaldún escribió la Muqaddimah en la que afirmaba que los humanos se desarrollaron a partir del «mundo de los monos», en un proceso por el cual «las especies se vuelven más numerosas». [41] En el capítulo 1 escribe: «Este mundo con todas las cosas creadas en él tiene un cierto orden y una construcción sólida. Muestra nexos entre causas y cosas causadas, combinaciones de algunas partes de la creación con otras y transformaciones de algunas cosas existentes en otras, en un patrón que es a la vez notable e interminable». [42]

La Muqaddimah también afirma en el capítulo 6:

Allí explicamos que toda la existencia en (todos) sus mundos simples y compuestos está dispuesta en un orden natural de ascenso y descenso, de modo que todo constituye un continuo ininterrumpido. Las esencias al final de cada etapa particular de los mundos están por naturaleza preparadas para ser transformadas en la esencia adyacente a ellas, ya sea por encima o por debajo de ellas. Así sucede con los elementos materiales simples; así sucede con las palmeras y las vides, (que constituyen) el último estadio de las plantas, en su relación con los caracoles y los mariscos, (que constituyen) el estadio (más bajo) de los animales. También sucede con los monos, criaturas que combinan en sí mismas la inteligencia y la percepción, en su relación con el hombre, el ser que tiene la capacidad de pensar y reflexionar. La preparación (para la transformación) que existe en uno y otro lado, en cada etapa de los mundos, se indica cuando (hablamos de) su conexión. [43]

Aunque la mayoría de los teólogos cristianos sostenían que el mundo natural formaba parte de una jerarquía inmutable y diseñada, algunos teólogos especulaban que el mundo podría haberse desarrollado a través de procesos naturales. Tomás de Aquino expuso la idea inicial de Agustín de Hipona sobre la evolución teísta.

El día en que Dios creó el cielo y la tierra, creó también toda planta del campo, no realmente, sino “antes de que brotara en la tierra”, es decir, potencialmente... Todas las cosas no fueron distinguidas y adornadas juntas, no por falta de poder de parte de Dios, como si requiriera tiempo para trabajar, sino para que se pudiera observar el debido orden en la institución del mundo. [38]

Él vio que la autonomía de la naturaleza era un signo de la bondad de Dios, y no detectó ningún conflicto entre un universo creado divinamente y la idea de que el universo se había desarrollado con el tiempo a través de mecanismos naturales. [44] Sin embargo, Aquino cuestionó las opiniones de aquellos (como el antiguo filósofo griego Empédocles) que sostenían que tales procesos naturales demostraban que el universo podría haberse desarrollado sin un propósito subyacente. Aquino sostuvo más bien que: "Por lo tanto, es claro que la naturaleza no es nada más que un cierto tipo de arte, es decir, el arte divino, impreso en las cosas, por el cual estas cosas son movidas hacia un fin determinado. Es como si el constructor de barcos fuera capaz de dar a las maderas aquello por lo que se moverían para tomar la forma de un barco". [45]

En la primera mitad del siglo XVII, la filosofía mecanicista de René Descartes fomentó el uso de la metáfora del universo como una máquina, un concepto que llegaría a caracterizar la revolución científica . [46] Entre 1650 y 1800, algunos naturalistas, como Benoît de Maillet , produjeron teorías que sostenían que el universo, la Tierra y la vida se habían desarrollado mecánicamente, sin guía divina. [47] En contraste, la mayoría de las teorías contemporáneas de la evolución, como las de Gottfried Leibniz y Johann Gottfried Herder , consideraban la evolución como un proceso fundamentalmente espiritual . [48] En 1751, Pierre Louis Maupertuis se inclinó hacia un terreno más materialista . Escribió sobre modificaciones naturales que ocurren durante la reproducción y se acumulan a lo largo de muchas generaciones, produciendo razas e incluso nuevas especies, una descripción que anticipó en términos generales el concepto de selección natural. [49]

Las ideas de Maupertuis se oponían a la influencia de los primeros taxónomos como John Ray . A finales del siglo XVII, Ray había dado la primera definición formal de una especie biológica, que describió como caracterizada por características esenciales inmutables, y afirmó que la semilla de una especie nunca podría dar lugar a otra. [12] Las ideas de Ray y otros taxónomos del siglo XVII estaban influenciadas por la teología natural y el argumento del diseño. [50]

La palabra evolución (del latín evolutio , que significa "desenrollarse como un pergamino") se utilizó inicialmente para referirse al desarrollo embriológico ; su primer uso en relación con el desarrollo de las especies se produjo en 1762, cuando Charles Bonnet la utilizó para su concepto de " preformación ", en el que las hembras portaban una forma en miniatura de todas las generaciones futuras. El término adquirió gradualmente un significado más general de crecimiento o desarrollo progresivo. [51]

Más tarde, en el siglo XVIII, el filósofo francés Georges-Louis Leclerc, conde de Buffon , uno de los principales naturalistas de la época, sugirió que lo que la mayoría de la gente denominaba especies eran en realidad variedades bien marcadas, modificadas a partir de una forma original por factores ambientales. Por ejemplo, creía que los leones, tigres, leopardos y gatos domésticos podrían tener un ancestro común. Además, especuló que las aproximadamente 200 especies de mamíferos conocidas en ese momento podrían haber descendido de tan solo 38 formas animales originales. Las ideas evolutivas de Buffon eran limitadas; creía que cada una de las formas originales había surgido a través de la generación espontánea y que cada una estaba formada por "moldes internos" que limitaban la cantidad de cambio. Las obras de Buffon, Histoire naturelle (1749-1789) y Époques de la nature (1778), que contienen teorías bien desarrolladas sobre un origen completamente materialista de la Tierra y sus ideas que cuestionaban la fijeza de las especies, fueron extremadamente influyentes. [52] [53] Otro filósofo francés, Denis Diderot , también escribió que los seres vivos podrían haber surgido primero a través de la generación espontánea, y que las especies siempre estaban cambiando a través de un proceso constante de experimentación donde nuevas formas surgían y sobrevivían o no basadas en prueba y error; una idea que puede considerarse una anticipación parcial de la selección natural. [54] Entre 1767 y 1792, James Burnett, Lord Monboddo , incluyó en sus escritos no solo el concepto de que el hombre había descendido de los primates, sino también que, en respuesta al medio ambiente, las criaturas habían encontrado métodos para transformar sus características en largos intervalos de tiempo. [55] El abuelo de Charles Darwin, Erasmus Darwin , publicó Zoonomia (1794-1796) que sugería que "todos los animales de sangre caliente han surgido de un filamento vivo". [56] En su poema Temple of Nature (1803), describió el surgimiento de la vida desde diminutos organismos que vivían en el barro hasta toda su diversidad moderna. [57]

En 1796, Georges Cuvier publicó sus hallazgos sobre las diferencias entre los elefantes vivos y los encontrados en el registro fósil . Su análisis identificó a los mamuts y mastodontes como especies distintas, diferentes de cualquier animal vivo, y puso fin de manera efectiva a un largo debate sobre si una especie podía extinguirse. [59] En 1788, James Hutton describió procesos geológicos graduales que operaban de manera continua a lo largo del tiempo . [60] En la década de 1790, William Smith comenzó el proceso de ordenar los estratos de roca examinando fósiles en las capas mientras trabajaba en su mapa geológico de Inglaterra. Independientemente, en 1811, Cuvier y Alexandre Brongniart publicaron un influyente estudio de la historia geológica de la región alrededor de París, basado en la sucesión estratigráfica de capas de roca. Estos trabajos ayudaron a establecer la antigüedad de la Tierra. [61] Cuvier abogó por el catastrofismo para explicar los patrones de extinción y sucesión faunística revelados por el registro fósil.

El conocimiento del registro fósil continuó avanzando rápidamente durante las primeras décadas del siglo XIX. En la década de 1840, los contornos de la escala de tiempo geológica se estaban volviendo claros, y en 1841 John Phillips nombró tres eras principales, basadas en la fauna predominante de cada una: el Paleozoico , dominado por invertebrados marinos y peces, el Mesozoico , la era de los reptiles, y la actual era Cenozoica de los mamíferos. Esta imagen progresiva de la historia de la vida fue aceptada incluso por geólogos ingleses conservadores como Adam Sedgwick y William Buckland ; sin embargo, al igual que Cuvier, atribuyeron la progresión a repetidos episodios catastróficos de extinción seguidos de nuevos episodios de creación. [62] A diferencia de Cuvier, Buckland y algunos otros defensores de la teología natural entre los geólogos británicos hicieron esfuerzos para vincular explícitamente el último episodio catastrófico propuesto por Cuvier con el diluvio bíblico . [63] [64]

Entre 1830 y 1833, el geólogo Charles Lyell publicó su obra de varios volúmenes Principles of Geology (Principios de geología ), que, basándose en las ideas de Hutton, proponía una alternativa uniformista a la teoría catastrófica de la geología. Lyell afirmaba que, en lugar de ser el producto de acontecimientos cataclísmicos (y posiblemente sobrenaturales), las características geológicas de la Tierra se explican mejor como resultado de las mismas fuerzas geológicas graduales observables en la actualidad, pero que actúan durante períodos de tiempo inmensamente largos. Aunque Lyell se oponía a las ideas evolucionistas (incluso cuestionaba el consenso de que el registro fósil demuestra una verdadera progresión), su concepto de que la Tierra fue moldeada por fuerzas que actuaron gradualmente durante un período prolongado, y la inmensa edad de la Tierra asumida por sus teorías, influirían fuertemente en futuros pensadores evolucionistas como Charles Darwin. [65]

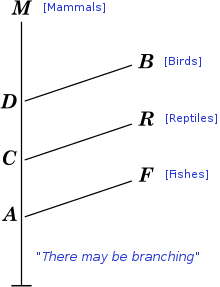

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck propuso, en su Philosophie zoologique de 1809, una teoría de la transmutación de las especies ( transformisme ). Lamarck no creía que todos los seres vivos compartieran un ancestro común, sino que las formas simples de vida se creaban continuamente por generación espontánea. También creía que una fuerza vital innata impulsaba a las especies a volverse más complejas con el tiempo, avanzando por una escalera lineal de complejidad que estaba relacionada con la gran cadena del ser. Lamarck reconoció que las especies se adaptaban a su entorno. Lo explicó diciendo que la misma fuerza innata que impulsaba una complejidad creciente causaba que los órganos de un animal (o una planta) cambiaran en función del uso o desuso de esos órganos, al igual que el ejercicio afecta los músculos. Argumentó que estos cambios serían heredados por la siguiente generación y producirían una adaptación lenta al medio ambiente. Fue este mecanismo secundario de adaptación a través de la herencia de características adquiridas lo que se conocería como lamarckismo e influiría en las discusiones sobre la evolución hasta el siglo XX. [67] [68]

A radical British school of comparative anatomy that included the anatomist Robert Edmond Grant was closely in touch with Lamarck's French school of Transformationism. One of the French scientists who influenced Grant was the anatomist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, whose ideas on the unity of various animal body plans and the homology of certain anatomical structures would be widely influential and lead to intense debate with his colleague Georges Cuvier. Grant became an authority on the anatomy and reproduction of marine invertebrates. He developed Lamarck's and Erasmus Darwin's ideas of transmutation and evolutionism, and investigated homology, even proposing that plants and animals had a common evolutionary starting point. As a young student, Charles Darwin joined Grant in investigations of the life cycle of marine animals. In 1826, an anonymous paper, probably written by Robert Jameson, praised Lamarck for explaining how higher animals had "evolved" from the simplest worms; this was the first use of the word "evolved" in a modern sense.[69][70]

In 1844, the Scottish publisher Robert Chambers anonymously published an extremely controversial but widely read book entitled Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. This book proposed an evolutionary scenario for the origins of the Solar System and of life on Earth. It claimed that the fossil record showed a progressive ascent of animals, with current animals branching off a main line that leads progressively to humanity. It implied that the transmutations lead to the unfolding of a preordained plan that had been woven into the laws that governed the universe. In this sense it was less completely materialistic than the ideas of radicals like Grant, but its implication that humans were only the last step in the ascent of animal life incensed many conservative thinkers. The high profile of the public debate over Vestiges, with its depiction of evolution as a progressive process, would greatly influence the perception of Darwin's theory a decade later.[71][72]

Ideas about the transmutation of species were associated with the radical materialism of the Enlightenment and were attacked by more conservative thinkers. Cuvier attacked the ideas of Lamarck and Geoffroy, agreeing with Aristotle that species were immutable. Cuvier believed that the individual parts of an animal were too closely correlated with one another to allow for one part of the anatomy to change in isolation from the others, and argued that the fossil record showed patterns of catastrophic extinctions followed by repopulation, rather than gradual change over time. He also noted that drawings of animals and animal mummies from Egypt, which were thousands of years old, showed no signs of change when compared with modern animals. The strength of Cuvier's arguments and his scientific reputation helped keep transmutational ideas out of the mainstream for decades.[73]

In Great Britain, the philosophy of natural theology remained influential. William Paley's 1802 book Natural Theology with its famous watchmaker analogy had been written at least in part as a response to the transmutational ideas of Erasmus Darwin.[75] Geologists influenced by natural theology, such as Buckland and Sedgwick, made a regular practice of attacking the evolutionary ideas of Lamarck, Grant, and Vestiges.[76][77] Although Charles Lyell opposed scriptural geology, he also believed in the immutability of species, and in his Principles of Geology, he criticized Lamarck's theories of development.[65] Idealists such as Louis Agassiz and Richard Owen believed that each species was fixed and unchangeable because it represented an idea in the mind of the creator. They believed that relationships between species could be discerned from developmental patterns in embryology, as well as in the fossil record, but that these relationships represented an underlying pattern of divine thought, with progressive creation leading to increasing complexity and culminating in humanity. Owen developed the idea of "archetypes" in the Divine mind that would produce a sequence of species related by anatomical homologies, such as vertebrate limbs. Owen led a public campaign that successfully marginalized Grant in the scientific community. Darwin would make good use of the homologies analyzed by Owen in his own theory, but the harsh treatment of Grant, and the controversy surrounding Vestiges, showed him the need to ensure that his own ideas were scientifically sound.[70][78][79]

It is possible to look through the history of biology from the ancient Greeks onwards and discover anticipations of almost all of Charles Darwin's key ideas. As an example, Loren Eiseley has found isolated passages written by Buffon suggesting he was almost ready to piece together a theory of natural selection, but states that such anticipations should not be taken out of the full context of the writings or of cultural values of the time which made Darwinian ideas of evolution unthinkable.[80]

When Darwin was developing his theory, he investigated selective breeding and was impressed[81] by John Sebright's observation that "A severe winter, or a scarcity of food, by destroying the weak and the unhealthy, has all the good effects of the most skilful selection" so that "the weak and the unhealthy do not live to propagate their infirmities."[82] Darwin was influenced by Charles Lyell's ideas of environmental change causing ecological shifts, leading to what Augustin de Candolle had called a war between competing plant species, competition well described by the botanist William Herbert. Darwin was struck by Thomas Robert Malthus' phrase "struggle for existence" used of warring human tribes.[83][84]

Several writers anticipated evolutionary aspects of Darwin's theory, and in the third edition of On the Origin of Species published in 1861 Darwin named those he knew about in an introductory appendix, An Historical Sketch of the Recent Progress of Opinion on the Origin of Species, which he expanded in later editions.[85]

In 1813, William Charles Wells read before the Royal Society essays assuming that there had been evolution of humans, and recognising the principle of natural selection. Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace were unaware of this work when they jointly published the theory in 1858, but Darwin later acknowledged that Wells had recognised the principle before them, writing that the paper "An Account of a White Female, part of whose Skin resembles that of a Negro" was published in 1818, and "he distinctly recognises the principle of natural selection, and this is the first recognition which has been indicated; but he applies it only to the races of man, and to certain characters alone."[86]

Patrick Matthew wrote in his book On Naval Timber and Arboriculture (1831) of "continual balancing of life to circumstance. ... [The] progeny of the same parents, under great differences of circumstance, might, in several generations, even become distinct species, incapable of co-reproduction."[87] Darwin implies that he discovered this work after the initial publication of the Origin. In the brief historical sketch that Darwin included in the third edition he says "Unfortunately the view was given by Mr. Matthew very briefly in scattered passages in an Appendix to a work on a different subject ... He clearly saw, however, the full force of the principle of natural selection."[88]

However, as historian of science Peter J. Bowler says, "Through a combination of bold theorizing and comprehensive evaluation, Darwin came up with a concept of evolution that was unique for the time." Bowler goes on to say that simple priority alone is not enough to secure a place in the history of science; someone has to develop an idea and convince others of its importance to have a real impact.[89] Thomas Henry Huxley said in his essay on the reception of On the Origin of Species:

The suggestion that new species may result from the selective action of external conditions upon the variations from their specific type which individuals present—and which we call "spontaneous," because we are ignorant of their causation—is as wholly unknown to the historian of scientific ideas as it was to biological specialists before 1858. But that suggestion is the central idea of the 'Origin of Species,' and contains the quintessence of Darwinism.[90]

The biogeographical patterns Charles Darwin observed in places such as the Galápagos Islands during the second voyage of HMS Beagle caused him to doubt the fixity of species, and in 1837 Darwin started the first of a series of secret notebooks on transmutation. Darwin's observations led him to view transmutation as a process of divergence and branching, rather than the ladder-like progression envisioned by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and others. In 1838 he read the new sixth edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population, written in the late 18th century by Thomas Robert Malthus. Malthus' idea of population growth leading to a struggle for survival combined with Darwin's knowledge on how breeders selected traits, led to the inception of Darwin's theory of natural selection. Darwin did not publish his ideas on evolution for 20 years. However, he did share them with certain other naturalists and friends, starting with Joseph Dalton Hooker, with whom he discussed his unpublished 1844 essay on natural selection. During this period he used the time he could spare from his other scientific work to slowly refine his ideas and, aware of the intense controversy around transmutation, amass evidence to support them. In September 1854 he began full-time work on writing his book on natural selection.[79][91][92]

Unlike Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, influenced by the book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, already suspected that transmutation of species occurred when he began his career as a naturalist. By 1855, his biogeographical observations during his field work in South America and the Malay Archipelago made him confident enough in a branching pattern of evolution to publish a paper stating that every species originated in close proximity to an already existing closely allied species. Like Darwin, it was Wallace's consideration of how the ideas of Malthus might apply to animal populations that led him to conclusions very similar to those reached by Darwin about the role of natural selection. In February 1858, Wallace, unaware of Darwin's unpublished ideas, composed his thoughts into an essay and mailed them to Darwin, asking for his opinion. The result was the joint publication in July of an extract from Darwin's 1844 essay along with Wallace's letter. Darwin also began work on a short abstract summarising his theory, which he would publish in 1859 as On the Origin of Species.[93]

By the 1850s, whether or not species evolved was a subject of intense debate, with prominent scientists arguing both sides of the issue.[95] The publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species fundamentally transformed the discussion over biological origins.[96] Darwin argued that his branching version of evolution explained a wealth of facts in biogeography, anatomy, embryology, and other fields of biology. He also provided the first cogent mechanism by which evolutionary change could persist: his theory of natural selection.[97]

One of the first and most important naturalists to be convinced by Origin of the reality of evolution was the British anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley. Huxley recognized that unlike the earlier transmutational ideas of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, Darwin's theory provided a mechanism for evolution without supernatural involvement, even if Huxley himself was not completely convinced that natural selection was the key evolutionary mechanism. Huxley would make advocacy of evolution a cornerstone of the program of the X Club to reform and professionalise science by displacing natural theology with naturalism and to end the domination of British natural science by the clergy. By the early 1870s in English-speaking countries, thanks partly to these efforts, evolution had become the mainstream scientific explanation for the origin of species.[97] In his campaign for public and scientific acceptance of Darwin's theory, Huxley made extensive use of new evidence for evolution from paleontology. This included evidence that birds had evolved from reptiles, including the discovery of Archaeopteryx in Europe, and a number of fossils of primitive birds with teeth found in North America. Another important line of evidence was the finding of fossils that helped trace the evolution of the horse from its small five-toed ancestors.[98] However, acceptance of evolution among scientists in non-English speaking nations such as France, and the countries of southern Europe and Latin America was slower. An exception to this was Germany, where both August Weismann and Ernst Haeckel championed this idea: Haeckel used evolution to challenge the established tradition of metaphysical idealism in German biology, much as Huxley used it to challenge natural theology in Britain.[99] Haeckel and other German scientists would take the lead in launching an ambitious programme to reconstruct the evolutionary history of life based on morphology and embryology.[100]

Darwin's theory succeeded in profoundly altering scientific opinion regarding the development of life and in producing a small philosophical revolution.[101] However, this theory could not explain several critical components of the evolutionary process. Specifically, Darwin was unable to explain the source of variation in traits within a species, and could not identify a mechanism that could pass traits faithfully from one generation to the next. Darwin's hypothesis of pangenesis, while relying in part on the inheritance of acquired characteristics, proved to be useful for statistical models of evolution that were developed by his cousin Francis Galton and the "biometric" school of evolutionary thought. However, this idea proved to be of little use to other biologists.[102]

Charles Darwin was aware of the severe reaction in some parts of the scientific community against the suggestion made in Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation that humans had arisen from animals by a process of transmutation. Therefore, he almost completely ignored the topic of human evolution in On the Origin of Species. Despite this precaution, the issue featured prominently in the debate that followed the book's publication. For most of the first half of the 19th century, the scientific community believed that, although geology had shown that the Earth and life were very old, human beings had appeared suddenly just a few thousand years before the present. However, a series of archaeological discoveries in the 1840s and 1850s showed stone tools associated with the remains of extinct animals. By the early 1860s, as summarized in Charles Lyell's 1863 book Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, it had become widely accepted that humans had existed during a prehistoric period—which stretched many thousands of years before the start of written history. This view of human history was more compatible with an evolutionary origin for humanity than was the older view. On the other hand, at that time there was no fossil evidence to demonstrate human evolution. The only human fossils found before the discovery of Java Man in the 1890s were either of anatomically modern humans or of Neanderthals that were too close, especially in the critical characteristic of cranial capacity, to modern humans for them to be convincing intermediates between humans and other primates.[105]

Therefore, the debate that immediately followed the publication of On the Origin of Species centered on the similarities and differences between humans and modern apes. Carolus Linnaeus had been criticised in the 18th century for grouping humans and apes together as primates in his ground breaking classification system.[106] Richard Owen vigorously defended the classification suggested by Georges Cuvier and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach that placed humans in a separate order from any of the other mammals, which by the early 19th century had become the orthodox view. On the other hand, Thomas Henry Huxley sought to demonstrate a close anatomical relationship between humans and apes. In one famous incident, which became known as the Great Hippocampus Question, Huxley showed that Owen was mistaken in claiming that the brains of gorillas lacked a structure present in human brains. Huxley summarized his argument in his highly influential 1863 book Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature. Another viewpoint was advocated by Lyell and Alfred Russel Wallace. They agreed that humans shared a common ancestor with apes, but questioned whether any purely materialistic mechanism could account for all the differences between humans and apes, especially some aspects of the human mind.[105]

In 1871, Darwin published The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, which contained his views on human evolution. Darwin argued that the differences between the human mind and the minds of the higher animals were a matter of degree rather than of kind. For example, he viewed morality as a natural outgrowth of instincts that were beneficial to animals living in social groups. He argued that all the differences between humans and apes were explained by a combination of the selective pressures that came from our ancestors moving from the trees to the plains, and sexual selection. The debate over human origins, and over the degree of human uniqueness continued well into the 20th century.[105]

The concept of evolution was widely accepted in scientific circles within a few years of the publication of Origin, but the acceptance of natural selection as its driving mechanism was much less widespread. The four major alternatives to natural selection in the late 19th century were theistic evolution, neo-Lamarckism, orthogenesis, and saltationism. Alternatives supported by biologists at other times included structuralism, Georges Cuvier's teleological but non-evolutionary functionalism, and vitalism.

Theistic evolution was the idea that God intervened in the process of evolution, to guide it in such a way that the living world could still be considered to be designed. The term was promoted by Charles Darwin's greatest American advocate Asa Gray. However, this idea gradually fell out of favor among scientists, as they became more and more committed to the idea of methodological naturalism and came to believe that direct appeals to supernatural involvement were scientifically unproductive. By 1900, theistic evolution had largely disappeared from professional scientific discussions, although it retained a strong popular following.[108][109]

In the late 19th century, the term neo-Lamarckism came to be associated with the position of naturalists who viewed the inheritance of acquired characteristics as the most important evolutionary mechanism. Advocates of this position included the British writer and Darwin critic Samuel Butler, the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, and the American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. They considered Lamarckism to be philosophically superior to Darwin's idea of selection acting on random variation. Cope looked for, and thought he found, patterns of linear progression in the fossil record. Inheritance of acquired characteristics was part of Haeckel's recapitulation theory of evolution, which held that the embryological development of an organism repeats its evolutionary history.[108][109] Critics of neo-Lamarckism, such as the German biologist August Weismann and Alfred Russel Wallace, pointed out that no one had ever produced solid evidence for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Despite these criticisms, neo-Lamarckism remained the most popular alternative to natural selection at the end of the 19th century, and would remain the position of some naturalists well into the 20th century.[108][109]

Orthogenesis was the hypothesis that life has an innate tendency to change, in a unilinear fashion, towards ever-greater perfection. It had a significant following in the 19th century, and its proponents included the Russian biologist Leo S. Berg and the American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn. Orthogenesis was popular among some paleontologists, who believed that the fossil record showed a gradual and constant unidirectional change.

Saltationism was the idea that new species arise as a result of large mutations. It was seen as a much faster alternative to the Darwinian concept of a gradual process of small random variations being acted on by natural selection, and was popular with early geneticists such as Hugo de Vries, William Bateson, and early in his career, Thomas Hunt Morgan. It became the basis of the mutation theory of evolution.[108][109]

The rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's laws of inheritance in 1900 ignited a fierce debate between two camps of biologists. In one camp were the Mendelians, who were focused on discrete variations and the laws of inheritance. They were led by William Bateson (who coined the word genetics) and Hugo de Vries (who coined the word mutation). Their opponents were the biometricians, who were interested in the continuous variation of characteristics within populations. Their leaders, Karl Pearson and Walter Frank Raphael Weldon, followed in the tradition of Francis Galton, who had focused on measurement and statistical analysis of variation within a population. The biometricians rejected Mendelian genetics on the basis that discrete units of heredity, such as genes, could not explain the continuous range of variation seen in real populations. Weldon's work with crabs and snails provided evidence that selection pressure from the environment could shift the range of variation in wild populations, but the Mendelians maintained that the variations measured by biometricians were too insignificant to account for the evolution of new species.[110][111]

When Thomas Hunt Morgan began experimenting with breeding the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, he was a saltationist who hoped to demonstrate that a new species could be created in the lab by mutation alone. Instead, the work at his lab between 1910 and 1915 reconfirmed Mendelian genetics and provided solid experimental evidence linking it to chromosomal inheritance. His work also demonstrated that most mutations had relatively small effects, such as a change in eye color, and that rather than creating a new species in a single step, mutations served to increase variation within the existing population.[110][111]

The Mendelian and biometrician models were eventually reconciled with the development of population genetics. A key step was the work of the British biologist and statistician Ronald Fisher. In a series of papers starting in 1918 and culminating in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, Fisher showed that the continuous variation measured by the biometricians could be produced by the combined action of many discrete genes, and that natural selection could change gene frequencies in a population, resulting in evolution. In a series of papers beginning in 1924, another British geneticist, J. B. S. Haldane, applied statistical analysis to real-world examples of natural selection, such as the evolution of industrial melanism in peppered moths, and showed that natural selection worked at an even faster rate than Fisher assumed.[112][113]

The American biologist Sewall Wright, who had a background in animal breeding experiments, focused on combinations of interacting genes, and the effects of inbreeding on small, relatively isolated populations that exhibited genetic drift. In 1932, Wright introduced the concept of an adaptive landscape and argued that genetic drift and inbreeding could drive a small, isolated sub-population away from an adaptive peak, allowing natural selection to drive it towards different adaptive peaks. The work of Fisher, Haldane and Wright founded the discipline of population genetics. This integrated natural selection with Mendelian genetics, which was the critical first step in developing a unified theory of how evolution worked.[112][113]

In the early 20th century, most field naturalists continued to believe that alternative mechanisms of evolution such as Lamarckism and orthogenesis provided the best explanation for the complexity they observed in the living world. But as the field of genetics continued to develop, those views became less tenable.[114] Theodosius Dobzhansky, a postdoctoral worker in Thomas Hunt Morgan's lab, had been influenced by the work on genetic diversity by Russian geneticists such as Sergei Chetverikov. He helped to bridge the divide between the foundations of microevolution developed by the population geneticists and the patterns of macroevolution observed by field biologists, with his 1937 book Genetics and the Origin of Species. Dobzhansky examined the genetic diversity of wild populations and showed that, contrary to the assumptions of the population geneticists, these populations had large amounts of genetic diversity, with marked differences between sub-populations. The book also took the highly mathematical work of the population geneticists and put it into a more accessible form. In Britain, E. B. Ford, the pioneer of ecological genetics, continued throughout the 1930s and 1940s to demonstrate the power of selection due to ecological factors including the ability to maintain genetic diversity through genetic polymorphisms such as human blood types. Ford's work would contribute to a shift in emphasis during the course of the modern synthesis towards natural selection over genetic drift.[112][113][115][116]

The evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr was influenced by the work of the German biologist Bernhard Rensch showing the influence of local environmental factors on the geographic distribution of sub-species and closely related species. Mayr followed up on Dobzhansky's work with the 1942 book Systematics and the Origin of Species, which emphasized the importance of allopatric speciation in the formation of new species. This form of speciation occurs when the geographical isolation of a sub-population is followed by the development of mechanisms for reproductive isolation. Mayr also formulated the biological species concept that defined a species as a group of interbreeding or potentially interbreeding populations that were reproductively isolated from all other populations.[112][113][117]

In the 1944 book Tempo and Mode in Evolution, George Gaylord Simpson showed that the fossil record was consistent with the irregular non-directional pattern predicted by the developing evolutionary synthesis, and that the linear trends that earlier paleontologists had claimed supported orthogenesis and neo-Lamarckism did not hold up to closer examination. In 1950, G. Ledyard Stebbins published Variation and Evolution in Plants, which helped to integrate botany into the synthesis. The emerging cross-disciplinary consensus on the workings of evolution would be known as the modern synthesis. It received its name from the 1942 book Evolution: The Modern Synthesis by Julian Huxley.[112][113]

The modern synthesis provided a conceptual core—in particular, natural selection and Mendelian population genetics—that tied together many, but not all, biological disciplines: developmental biology was one of the omissions. It helped establish the legitimacy of evolutionary biology, a primarily historical science, in a scientific climate that favored experimental methods over historical ones.[118] The synthesis also resulted in a considerable narrowing of the range of mainstream evolutionary thought (what Stephen Jay Gould called the "hardening of the synthesis"): by the 1950s, natural selection acting on genetic variation was virtually the only acceptable mechanism of evolutionary change (panselectionism), and macroevolution was simply considered the result of extensive microevolution.[119][120]

The middle decades of the 20th century saw the rise of molecular biology, and with it an understanding of the chemical nature of genes as sequences of DNA and of their relationship—through the genetic code—to protein sequences. Increasingly powerful techniques for analyzing proteins, such as protein electrophoresis and sequencing, brought biochemical phenomena into the realm of the synthetic theory of evolution. In the early 1960s, biochemists Linus Pauling and Emile Zuckerkandl proposed the molecular clock hypothesis (MCH): that sequence differences between homologous proteins could be used to calculate the time since two species diverged. By 1969, Motoo Kimura and others provided a theoretical basis for the molecular clock, arguing that—at the molecular level at least—most genetic mutations are neither harmful nor helpful and that mutation and genetic drift (rather than natural selection) cause a large portion of genetic change: the neutral theory of molecular evolution.[121] Studies of protein differences within species also brought molecular data to bear on population genetics by providing estimates of the level of heterozygosity in natural populations.[122]

From the early 1960s, molecular biology was increasingly seen as a threat to the traditional core of evolutionary biology. Established evolutionary biologists—particularly Ernst Mayr, Theodosius Dobzhansky, and George Gaylord Simpson, three of the architects of the modern synthesis—were extremely skeptical of molecular approaches, especially their connection (or lack thereof) to natural selection. The molecular-clock hypothesis and the neutral theory were particularly controversial, spawning the neutralist-selectionist debate over the relative importance of mutation, drift and selection, which continued into the 1980s without a clear resolution.[123][124]

In the mid-1960s, George C. Williams strongly critiqued explanations of adaptations worded in terms of "survival of the species" (group selection arguments). Such explanations were largely replaced by a gene-centered view of evolution, epitomized by the kin selection arguments of W. D. Hamilton, George R. Price and John Maynard Smith.[125] This viewpoint would be summarized and popularized in the influential 1976 book The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins.[126] Models of the period seemed to show that group selection was severely limited in its strength; though newer models do admit the possibility of significant multi-level selection.[127]

In 1973, Leigh Van Valen proposed the term "Red Queen," which he took from Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll, to describe a scenario where a species involved in evolutionary arms races would have to constantly change to keep pace with the species with which it was co-evolving. Hamilton, Williams and others suggested that this idea might explain the evolution of sexual reproduction: the increased genetic diversity caused by sexual reproduction would help maintain resistance against rapidly evolving parasites, thus making sexual reproduction common, despite the tremendous cost from the gene-centric point of view of a system where only half of an organism's genome is passed on during reproduction.[128][129]

Contrary to the expectations of the Red Queen hypothesis, Hanley et al. found that the prevalence, abundance and mean intensity of mites was significantly higher in sexual geckos than in asexuals sharing the same habitat.[130] Furthermore, Parker, after reviewing numerous genetic studies on plant disease resistance, failed to find a single example consistent with the concept that pathogens are the primary selective agent responsible for sexual reproduction in their host.[131] At an even more fundamental level, Heng[132] and Gorelick and Heng[133] reviewed evidence that sex, rather than enhancing diversity, acts as a constraint on genetic diversity. They considered that sex acts as a coarse filter, weeding out major genetic changes, such as chromosomal rearrangements, but permitting minor variation, such as changes at the nucleotide or gene level (that are often neutral) to pass through the sexual sieve. The adaptive function of sex remains a major unresolved issue. The competing models to explain the adaptive function of sex were reviewed by Birdsell and Wills.[134] A principal alternative view to the Red Queen hypothesis is that sex arose, and is maintained, as a process for repairing DNA damage, and that genetic variation is produced as a byproduct.[135][136]

The gene-centric view has also led to an increased interest in Charles Darwin's idea of sexual selection,[137] and more recently in topics such as sexual conflict and intragenomic conflict.

W. D. Hamilton's work on kin selection contributed to the emergence of the discipline of sociobiology. The existence of altruistic behaviors has been a difficult problem for evolutionary theorists from the beginning.[138] Significant progress was made in 1964 when Hamilton formulated the inequality in kin selection known as Hamilton's rule, which showed how eusociality in insects (the existence of sterile worker classes) and other examples of altruistic behavior could have evolved through kin selection. Other theories followed, some derived from game theory, such as reciprocal altruism.[139] In 1975, E. O. Wilson published the influential and highly controversial book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis which claimed evolutionary theory could help explain many aspects of animal, including human, behavior. Critics of sociobiology, including Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin, claimed that sociobiology greatly overstated the degree to which complex human behaviors could be determined by genetic factors. They also claimed that the theories of sociobiologists often reflected their own ideological biases. Despite these criticisms, work has continued in sociobiology and the related discipline of evolutionary psychology, including work on other aspects of the altruism problem.[140][141]

One of the most prominent debates arising during the 1970s was over the theory of punctuated equilibrium. Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould proposed that there was a pattern of fossil species that remained largely unchanged for long periods (what they termed stasis), interspersed with relatively brief periods of rapid change during speciation.[142][143] Improvements in sequencing methods resulted in a large increase of sequenced genomes, allowing the testing and refining of evolutionary theories using this huge amount of genome data.[144] Comparisons between these genomes provide insights into the molecular mechanisms of speciation and adaptation.[145][146] These genomic analyses have produced fundamental changes in the understanding of evolutionary history, such as the proposal of the three-domain system by Carl Woese.[147] Advances in computational hardware and software allow the testing and extrapolation of increasingly advanced evolutionary models and the development of the field of systems biology.[148] One of the results has been an exchange of ideas between theories of biological evolution and the field of computer science known as evolutionary computation, which attempts to mimic biological evolution for the purpose of developing new computer algorithms. Discoveries in biotechnology now allow the modification of entire genomes, advancing evolutionary studies to the level where future experiments may involve the creation of entirely synthetic organisms.[149]

Microbiology was largely ignored by early evolutionary theory due to the paucity of morphological traits and the lack of a species concept in microbiology, particularly amongst prokaryotes.[150] Now, evolutionary researchers are taking advantage of their improved understanding of microbial physiology and ecology, produced by the comparative ease of microbial genomics, to explore the taxonomy and evolution of these organisms.[151] These studies are revealing unanticipated levels of diversity amongst microbes.[152][153]

One important development in the study of microbial evolution came with the discovery in Japan in 1959 of horizontal gene transfer.[154] This transfer of genetic material between different species of bacteria came to the attention of scientists because it played a major role in the spread of antibiotic resistance.[155] More recently, as knowledge of genomes has continued to expand, it has been suggested that lateral transfer of genetic material has played an important role in the evolution of all organisms.[156] These high levels of horizontal gene transfer have led to suggestions that the family tree of today's organisms, the so-called "tree of life," is more similar to an interconnected web.[157][158]

The endosymbiotic theory for the origin of organelles sees a form of horizontal gene transfer as a critical step in the evolution of eukaryotes.[159][160] The endosymbiotic theory holds that organelles within the cells of eukorytes such as mitochondria and chloroplasts had descended from independent bacteria that came to live symbiotically within other cells. It had been suggested in the late 19th century when similarities between mitochondria and bacteria were noted, but largely dismissed until it was revived and championed by Lynn Margulis in the 1960s and 1970s; Margulis was able to make use of new evidence that such organelles had their own DNA that was inherited independently from that in the cell's nucleus.[161]

In the 1980s and 1990s, the tenets of the modern evolutionary synthesis came under increasing scrutiny. There was a renewal of structuralist themes in evolutionary biology in the work of biologists such as Brian Goodwin and Stuart Kauffman,[162] which incorporated ideas from cybernetics and systems theory, and emphasized the self-organizing processes of development as factors directing the course of evolution. The evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould revived earlier ideas of heterochrony, alterations in the relative rates of developmental processes over the course of evolution, to account for the generation of novel forms, and, with the evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin, wrote an influential paper in 1979 suggesting that a change in one biological structure, or even a structural novelty, could arise incidentally as an accidental result of selection on another structure, rather than through direct selection for that particular adaptation. They called such incidental structural changes "spandrels" after an architectural feature.[163] Later, Gould and Elisabeth Vrba discussed the acquisition of new functions by novel structures arising in this fashion, calling them "exaptations."[164]

Molecular data regarding the mechanisms underlying development accumulated rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s. It became clear that the diversity of animal morphology was not the result of different sets of proteins regulating the development of different animals, but from changes in the deployment of a small set of proteins common to all animals.[165] These proteins became known as the "developmental-genetic toolkit."[166] Such perspectives influenced the disciplines of phylogenetics, paleontology and comparative developmental biology, and spawned the new discipline of evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo).[167]

One of the tenets of population genetics is that macroevolution (the evolution of phylogenic clades at the species level and above) was solely the result of the mechanisms of microevolution (changes in gene frequency within populations) operating over an extended period of time. During the last decades of the 20th century some paleontologists raised questions about whether other factors, such as punctuated equilibrium and group selection operating on the level of entire species and even higher level phylogenic clades, needed to be considered to explain patterns in evolution revealed by statistical analysis of the fossil record. Some researchers in evolutionary developmental biology suggested that interactions between the environment and the developmental process might have been the source of some of the structural innovations seen in macroevolution, but other evo-devo researchers maintained that genetic mechanisms visible at the population level are fully sufficient to explain all macroevolution.[168][169][170]

Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression or cellular phenotype caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence. By the first decade of the 21st century it was accepted that epigenetic mechanisms were a necessary part of the evolutionary origin of cellular differentiation.[171] Although epigenetics in multicellular organisms is generally thought to be involved in differentiation, with epigenetic patterns "reset" when organisms reproduce, there have been some observations of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. This shows that in some cases nongenetic changes to an organism can be inherited; such inheritance may help with adaptation to local conditions and affect evolution.[172] Some have suggested that in certain cases a form of Lamarckian evolution may occur.[173]

The idea of an extended evolutionary synthesis extends the 20th-century modern synthesis to include concepts and mechanisms such as multilevel selection theory, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, niche construction and evolvability—though several different such syntheses have been proposed, with no agreement on what exactly would be included.[174][175][176][177]

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin's metaphysical Omega Point theory, found in his book The Phenomenon of Man (1955),[178] describes the gradual development of the universe from subatomic particles to human society, which he viewed as its final stage and goal, a form of orthogenesis.[179]

The Gaia hypothesis proposed by James Lovelock holds that the living and nonliving parts of Earth can be viewed as a complex interacting system with similarities to a single organism.[180][181] The Gaia hypothesis has also been viewed by Lynn Margulis[182] and others as an extension of endosymbiosis and exosymbiosis.[183] This modified hypothesis postulates that all living things have a regulatory effect on the Earth's environment that promotes life overall.

The mathematical biologist Stuart Kauffman suggested that self-organization may play roles alongside natural selection in three areas of evolutionary biology: population dynamics, molecular evolution, and morphogenesis.[162] However, Kauffman does not take into account the essential role of energy in driving biochemical reactions in cells, as proposed by Christian de Duve and modelled mathematically by Richard Bagley and Walter Fontana. Their systems are self-catalyzing but not simply self-organizing as they are thermodynamically open systems relying on a continuous input of energy.[184]

An admirable application of this well-ordered liberty appears in his thesis on the simultaneous creation of the universe, and the gradual development of the world under the action of the natural forces which were placed in it. ... Is Augustine, therefore, an Evolutionist?

The concept of rationes seminales allows Augustine to affirm that, in one sense, creation is completed simultaneously, once and for all (Gn. litt. 5.23.45), and yet that there is a real history of interaction between creator and creation, not just the playing out of a foreordained necessity.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link){{cite book}}: |journal= ignored (help)