La invasión de Irak de 2003 [b] fue la primera etapa de la Guerra de Irak . La invasión comenzó el 20 de marzo de 2003 y duró poco más de un mes, [24] incluyendo 26 días de importantes operaciones de combate, en las que una fuerza combinada liderada por los Estados Unidos de tropas de los Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido, Australia y Polonia invadió la República de Irak . Veintidós días después del primer día de la invasión, la ciudad capital de Bagdad fue capturada por las fuerzas de la coalición el 9 de abril después de la Batalla de Bagdad que duró seis días . Esta primera etapa de la guerra terminó formalmente el 1 de mayo cuando el presidente estadounidense George W. Bush declaró el "fin de las principales operaciones de combate" en su discurso de Misión Cumplida , [25] después de lo cual se estableció la Autoridad Provisional de la Coalición (CPA) como el primero de varios gobiernos de transición sucesivos que condujeron a la primera elección parlamentaria iraquí en enero de 2005. Las fuerzas militares estadounidenses permanecieron más tarde en Irak hasta la retirada en 2011. [26]

La coalición envió 160.000 tropas a Irak durante la fase inicial de invasión, que duró del 19 de marzo al 1 de mayo. [27] Alrededor del 73% o 130.000 soldados eran estadounidenses, con unos 45.000 soldados británicos (25%), 2.000 soldados australianos (1%) y unos 200 comandos polacos del JW GROM (0,1%). Treinta y seis países más estuvieron involucrados en sus secuelas. En preparación para la invasión, 100.000 tropas estadounidenses se reunieron en Kuwait el 18 de febrero. [27] Las fuerzas de la coalición también recibieron apoyo de los Peshmerga en el Kurdistán iraquí .

Según el presidente estadounidense George W. Bush y el primer ministro británico Tony Blair , la coalición tenía como objetivo "desarmar a Irak de armas de destrucción masiva [ADM], poner fin al apoyo de Saddam Hussein al terrorismo y liberar al pueblo iraquí", a pesar de que el equipo de inspección de la ONU dirigido por Hans Blix había declarado que no había encontrado evidencia de la existencia de ADM justo antes del inicio de la invasión. [28] [29] Otros ponen un énfasis mucho mayor en el impacto de los ataques del 11 de septiembre , en el papel que esto jugó en el cambio de los cálculos estratégicos de EE. UU. y el surgimiento de la agenda de la libertad. [30] [31] Según Blair, el detonante fue el fracaso de Irak de aprovechar una "oportunidad final" para desarmarse de supuestas armas nucleares, químicas y biológicas que los funcionarios estadounidenses y británicos llamaron una amenaza inmediata e intolerable para la paz mundial. [32]

En una encuesta de CBS de enero de 2003, el 64% de los estadounidenses había aprobado una acción militar contra Irak; sin embargo, el 63% quería que Bush encontrara una solución diplomática en lugar de ir a la guerra, y el 62% creía que la amenaza del terrorismo dirigido contra los EE. UU. aumentaría debido a la guerra. [33] La invasión fue firmemente opuesta por algunos aliados de larga data de los EE. UU., incluidos los gobiernos de Francia, Alemania y Nueva Zelanda. [34] [35] [36] Sus líderes argumentaron que no había evidencia de armas de destrucción masiva en Irak y que invadir ese país no estaba justificado en el contexto del informe de la UNMOVIC del 12 de febrero de 2003. Alrededor de 5.000 ojivas químicas , proyectiles o bombas de aviación fueron descubiertos durante la guerra de Irak, pero estos habían sido construidos y abandonados anteriormente en el gobierno de Saddam Hussein antes de la Guerra del Golfo de 1991. Los descubrimientos de estas armas químicas no respaldaron la lógica de invasión del gobierno. [37] [38] En septiembre de 2004, Kofi Annan , entonces Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas , calificó la invasión de ilegal según el derecho internacional y dijo que era una violación de la Carta de las Naciones Unidas . [39]

El 15 de febrero de 2003, un mes antes de la invasión, hubo protestas en todo el mundo contra la guerra de Irak , incluida una manifestación de tres millones de personas en Roma, que el Libro Guinness de los Récords catalogó como la manifestación contra la guerra más grande de la historia . [40] Según el académico francés Dominique Reynié , entre el 3 de enero y el 12 de abril de 2003, 36 millones de personas en todo el mundo participaron en casi 3.000 protestas contra la guerra de Irak. [41]

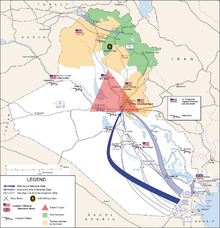

La invasión fue precedida por un ataque aéreo contra el Palacio Presidencial en Bagdad el 20 de marzo de 2003. Al día siguiente, las fuerzas de la coalición lanzaron una incursión en la Gobernación de Basora desde su punto de concentración cerca de la frontera entre Irak y Kuwait. Mientras las fuerzas especiales lanzaban un asalto anfibio desde el Golfo Pérsico para asegurar Basora y los campos petrolíferos circundantes, el principal ejército de invasión se trasladó al sur de Irak, ocupando la región y participando en la Batalla de Nasiriyah el 23 de marzo. Los ataques aéreos masivos en todo el país y contra el mando y control iraquíes sumieron al ejército defensor en el caos e impidieron una resistencia efectiva. El 26 de marzo, la 173.ª Brigada Aerotransportada fue lanzada desde el aire cerca de la ciudad norteña de Kirkuk , donde unió fuerzas con los rebeldes kurdos y luchó en varias acciones contra el Ejército iraquí , para asegurar la parte norte del país.

El grueso de las fuerzas de la coalición continuó su avance hacia el corazón de Irak y se encontró con poca resistencia. La mayor parte del ejército iraquí fue derrotado rápidamente y la coalición ocupó Bagdad el 9 de abril. Se produjeron otras operaciones contra sectores del ejército iraquí, incluida la captura y ocupación de Kirkuk el 10 de abril y el ataque y captura de Tikrit el 15 de abril. El presidente iraquí Saddam Hussein y la dirección central se escondieron mientras las fuerzas de la coalición completaban la ocupación del país. El 1 de mayo, el presidente George W. Bush declaró el fin de las principales operaciones de combate: esto puso fin al período de invasión y comenzó el período de ocupación militar . Saddam Hussein fue capturado por las fuerzas estadounidenses el 13 de diciembre.

Las hostilidades de la Guerra del Golfo fueron suspendidas el 28 de febrero de 1991, con un alto el fuego negociado entre la coalición de la ONU e Irak. [42] Estados Unidos y sus aliados intentaron mantener a Saddam bajo control con acciones militares como la Operación Southern Watch , que fue llevada a cabo por la Fuerza de Tarea Conjunta del Sudoeste de Asia (JTF-SWA) con la misión de monitorear y controlar el espacio aéreo al sur del paralelo 32 (ampliado al paralelo 33 en 1996), así como utilizando sanciones económicas. Se reveló que un programa de armas biológicas (BW) en Irak había comenzado a principios de la década de 1980 con ayuda involuntaria [43] [44] de los EE. UU. y Europa en violación de la Convención sobre Armas Biológicas (BWC) de 1972. Los detalles del programa de BW -junto con un programa de armas químicas- salieron a la luz después de la Guerra del Golfo (1990-91) a raíz de las investigaciones realizadas por la Comisión Especial de las Naciones Unidas (UNSCOM) que había sido encargada del desarme de posguerra del Irak de Saddam. La investigación concluyó que el programa no había continuado después de la guerra. Los EE. UU. y sus aliados mantuvieron entonces una política de " contención " hacia Irak. Esta política implicó numerosas sanciones económicas por parte del Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU ; la aplicación de zonas de exclusión aérea iraquíes declaradas por los EE. UU. y el Reino Unido para proteger a los kurdos en el Kurdistán iraquí y a los chiítas en el sur de los ataques aéreos del gobierno iraquí; e inspecciones continuas. Helicópteros y aviones militares iraquíes impugnaron regularmente las zonas de exclusión aérea. [45] [46]

En octubre de 1998, la destitución del gobierno iraquí se convirtió en una política exterior oficial de Estados Unidos con la promulgación de la Ley de Liberación de Irak . Promulgada tras la expulsión de los inspectores de armas de la ONU el agosto anterior (después de que algunos habían sido acusados de espiar para Estados Unidos), la ley proporcionó 97 millones de dólares a las "organizaciones de oposición democrática" iraquíes para "establecer un programa de apoyo a la transición a la democracia en Irak". [47] Esta legislación contrastaba con los términos establecidos en la Resolución 687 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas , que se centraba en las armas y los programas de armas y no hacía mención del cambio de régimen. [48] Un mes después de la aprobación de la Ley de Liberación de Irak, Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido lanzaron una campaña de bombardeo de Irak llamada Operación Zorro del Desierto . La lógica expresa de la campaña era obstaculizar la capacidad del gobierno de Saddam Hussein para producir armas químicas, biológicas y nucleares, pero el personal de inteligencia estadounidense también esperaba que ayudara a debilitar el control de Saddam sobre el poder. [49]

Con la elección de George W. Bush como presidente en 2000 , Estados Unidos adoptó una política más agresiva hacia Irak. La plataforma de campaña del Partido Republicano en las elecciones de 2000 exigía la "plena implementación" de la Ley de Liberación de Irak como "punto de partida" de un plan para "eliminar" a Saddam. [50] Después de dejar la administración de George W. Bush , el secretario del Tesoro Paul O'Neill dijo que se había planeado un ataque a Irak desde la investidura de Bush y que la primera reunión del Consejo de Seguridad Nacional de Estados Unidos incluyó una discusión sobre una invasión. O'Neill luego se retractó, diciendo que estas discusiones eran parte de una continuación de la política exterior puesta en marcha por primera vez por la administración Clinton . [51]

A pesar del interés declarado de la administración Bush en invadir Irak, no hubo muchos movimientos formales hacia una invasión hasta los ataques del 11 de septiembre . Por ejemplo, la administración preparó la Operación Desert Badger para responder agresivamente si algún piloto de la Fuerza Aérea era derribado mientras volaba sobre Irak, pero esto no sucedió. El Secretario de Defensa Donald Rumsfeld desestimó los datos de interceptación de la Agencia de Seguridad Nacional (NSA) disponibles al mediodía del día 11 que apuntaban a la culpabilidad de Al Qaeda , y a media tarde ordenó al Pentágono que preparara planes para atacar Irak. [52] Según los asistentes que estaban con él en el Centro de Comando Militar Nacional ese día, Rumsfeld pidió: "la mejor información rápidamente. Juzguen si es lo suficientemente buena para atacar a Saddam Hussein al mismo tiempo. No sólo a Osama bin Laden ". [53] Un memorando escrito por Rumsfeld en noviembre de 2001 considera una guerra en Irak. [54] La lógica de la invasión de Irak como respuesta al 11 de septiembre ha sido ampliamente cuestionada, ya que no hubo cooperación entre Saddam Hussein y Al Qaeda . [55]

El 20 de septiembre de 2001, Bush se dirigió a una sesión conjunta del Congreso (transmitida en directo al mundo en forma simultánea) y anunció su nueva " Guerra contra el Terror ". Este anuncio fue acompañado por la doctrina de la acción militar "preventiva", posteriormente denominada Doctrina Bush . Algunos funcionarios del gobierno de los Estados Unidos hicieron acusaciones de una conexión entre Saddam Hussein y Al Qaeda, afirmando que existía una relación altamente secreta entre Saddam y la organización militante islamista radical Al Qaeda desde 1992 hasta 2003, específicamente a través de una serie de reuniones en las que supuestamente participaba el Servicio de Inteligencia Iraquí (IIS). Algunos asesores de Bush favorecían una invasión inmediata de Irak, mientras que otros abogaban por la creación de una coalición internacional y la obtención de la autorización de las Naciones Unidas. [56] Bush finalmente decidió buscar la autorización de la ONU, aunque todavía se reservaba la opción de invadir sin ella. [57]

El general David Petraeus recordó en una entrevista su experiencia durante el período anterior a la invasión, afirmando que "cuando nos estábamos preparando para lo que se convirtió en la invasión de Irak, la opinión predominante era que íbamos a tener una lucha larga y dura hasta Bagdad, y que realmente iba a ser difícil tomar Bagdad. El camino hacia el despliegue, que fue un camino muy comprimido para la 101 División Aerotransportada, comenzó con un seminario sobre operaciones militares en terreno urbano, porque se consideraba que ese era el evento decisivo para derribar el régimen en Irak y encontrar y destruir las armas de destrucción masiva". [58]

Aunque ya se había hablado de tomar medidas contra Irak, la administración Bush esperó hasta septiembre de 2002 para pedir que se tomaran medidas, y el jefe de gabinete de la Casa Blanca, Andrew Card, dijo: "Desde un punto de vista de marketing, no se introducen nuevos productos en agosto". [59] Bush comenzó a exponer formalmente ante la comunidad internacional su argumento a favor de una invasión de Irak en su discurso del 12 de septiembre de 2002 ante la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas . [60]

El Reino Unido estuvo de acuerdo con las acciones estadounidenses, mientras que Francia y Alemania criticaron los planes de invadir Irak y abogaron por continuar con la diplomacia y las inspecciones de armas. Después de un debate considerable, el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU adoptó una resolución de compromiso, la Resolución 1441 del Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU , que autorizó la reanudación de las inspecciones de armas y prometió "graves consecuencias" en caso de incumplimiento. Los miembros del Consejo de Seguridad, Francia y Rusia, dejaron en claro que no consideraban que estas consecuencias incluyeran el uso de la fuerza para derrocar al gobierno iraquí. [61] Tanto el embajador de los EE. UU. ante la ONU, John Negroponte , como el embajador del Reino Unido, Jeremy Greenstock , confirmaron públicamente esta interpretación de la resolución, asegurando que la Resolución 1441 no preveía "automaticidad" ni "desencadenantes ocultos" para una invasión sin una mayor consulta al Consejo de Seguridad. [62]

La Resolución 1441 dio a Iraq "una última oportunidad para cumplir con sus obligaciones de desarme" y estableció inspecciones por parte de la Comisión de las Naciones Unidas de Vigilancia, Verificación e Inspección (UNMOVIC) y el Organismo Internacional de Energía Atómica (OIEA). Saddam aceptó la resolución el 13 de noviembre y los inspectores regresaron a Iraq bajo la dirección del presidente de la UNMOVIC, Hans Blix, y el Director General del OIEA, Mohamed El Baradei . En febrero de 2003, el OIEA "no encontró pruebas ni indicios plausibles de la reanudación de un programa de armas nucleares en Iraq"; el OIEA concluyó que ciertos artículos que podrían haber sido utilizados en centrifugadoras de enriquecimiento nuclear, como tubos de aluminio, estaban de hecho destinados a otros usos. [63] La UNMOVIC "no encontró pruebas de la continuación o reanudación de programas de armas de destrucción masiva" ni cantidades significativas de artículos prohibidos. La UNMOVIC supervisó la destrucción de una pequeña cantidad de ojivas de cohetes químicos vacías, 50 litros de gas mostaza que habían sido declarados por el Iraq y sellados por la UNSCOM en 1998, y cantidades de laboratorio de un precursor del gas mostaza, junto con unos 50 misiles Al-Samoud de un diseño que el Iraq afirmó que no excedía el alcance permitido de 150 km, pero que habían recorrido hasta 183 km en pruebas. Poco antes de la invasión, la UNMOVIC declaró que se necesitarían "meses" para verificar el cumplimiento por parte del Iraq de la resolución 1441. [64] [65] [66]

En octubre de 2002, el Congreso de Estados Unidos aprobó la Resolución sobre Irak , que autorizaba al presidente a "utilizar todos los medios necesarios" contra Irak. En enero de 2003, los estadounidenses encuestados se mostraron ampliamente a favor de una mayor diplomacia en lugar de una invasión. Sin embargo, más tarde ese año, los estadounidenses comenzaron a estar de acuerdo con el plan de Bush. El gobierno de Estados Unidos emprendió una elaborada campaña de relaciones públicas internas para promocionar la guerra entre sus ciudadanos. La abrumadora mayoría de los estadounidenses creía que Saddam tenía armas de destrucción masiva: el 85% así lo afirmó, aunque los inspectores no habían descubierto esas armas. De los que pensaban que Irak tenía armas secuestradas en algún lugar, aproximadamente la mitad respondió que dichas armas no se encontrarían en combate. En febrero de 2003, el 64% de los estadounidenses apoyaba la adopción de medidas militares para derrocar a Saddam del poder. [33]

Los equipos de la División de Actividades Especiales (SAD) de la Agencia Central de Inteligencia , compuestos por oficiales de operaciones paramilitares y soldados del 10.º Grupo de Fuerzas Especiales , fueron las primeras fuerzas estadounidenses en entrar en Irak, en julio de 2002, antes de la invasión principal. Una vez en el terreno, se prepararon para la posterior llegada de las Fuerzas Especiales del Ejército de los EE. UU. para organizar a los Peshmerga kurdos . Este equipo conjunto (llamado Elemento de Enlace del Norte de Irak (NILE)) [67] se combinó para derrotar a Ansar al-Islam , un grupo con vínculos con Al Qaeda, en el Kurdistán iraquí. Esta batalla fue por el control del territorio que estaba ocupado por Ansar al-Islam. Fue llevada a cabo por Oficiales de Operaciones Paramilitares de SAD y el 10.º Grupo de Fuerzas Especiales del Ejército. Esta batalla resultó en la derrota de Ansar y la captura de una instalación de armas químicas en Sargat. [67] Sargat fue la única instalación de su tipo descubierta en la guerra de Irak. [68] [69]

Los equipos del SAD también llevaron a cabo misiones tras las líneas enemigas para identificar objetivos de liderazgo. Estas misiones condujeron a los ataques aéreos iniciales contra Saddam y sus generales. Aunque el ataque contra Saddam no logró matarlo, efectivamente terminó con su capacidad de comandar y controlar sus fuerzas. Los ataques contra los generales iraquíes tuvieron más éxito y degradaron significativamente la capacidad del comando iraquí para reaccionar y maniobrar contra la fuerza de invasión liderada por los EE. UU. [67] [70] Los oficiales de operaciones del SAD convencieron con éxito a oficiales clave del ejército iraquí para que entregaran sus unidades una vez que comenzaron los combates. [68]

Turquía, miembro de la OTAN, se negó a permitir que las fuerzas estadounidenses cruzaran su territorio hacia el norte de Irak . Por lo tanto, los equipos conjuntos de las fuerzas especiales del ejército y del SAD y los Peshmerga constituyeron toda la fuerza del norte contra el ejército iraquí. Se las arreglaron para mantener a las divisiones del norte en su lugar en lugar de permitirles ayudar a sus colegas contra la fuerza de la coalición liderada por los EE. UU. que venía del sur. [71] Cuatro de estos oficiales de la CIA fueron galardonados con la Estrella de Inteligencia por sus acciones. [68] [69]

En el discurso sobre el Estado de la Unión de 2003 , el presidente Bush dijo que "sabemos que Irak, a finales de los años 1990, tenía varios laboratorios móviles de armas biológicas". [72] El 5 de febrero de 2003, el Secretario de Estado de los Estados Unidos, Colin Powell, se dirigió a la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas , continuando los esfuerzos de Estados Unidos para obtener la autorización de la ONU para una invasión. Su presentación ante el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU contenía una imagen generada por computadora de un "laboratorio móvil de armas biológicas". Sin embargo, esta información se basaba en afirmaciones de Rafid Ahmed Alwan al-Janabi, con el nombre en código "Curveball" , un emigrante iraquí que vivía en Alemania y que más tarde admitió que sus afirmaciones habían sido falsas.

Powell también presentó afirmaciones falsas en las que se afirmaba que Irak tenía vínculos con Al Qaeda . Como seguimiento de la presentación de Powell, Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido, Polonia, Italia, Australia, Dinamarca, Japón y España propusieron una resolución que autorizara el uso de la fuerza en Irak, pero Canadá, Francia y Alemania, junto con Rusia, instaron firmemente a que se continuara con la diplomacia. Ante la posibilidad de perder la votación y de vetar a Francia y Rusia, Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido, Polonia, España, Dinamarca, Italia, Japón y Australia finalmente retiraron su resolución. [73] [74]

La oposición a la invasión se consolidó en la protesta mundial contra la guerra del 15 de febrero de 2003 , que atrajo entre seis y diez millones de personas en más de 800 ciudades, la mayor protesta de su tipo en la historia de la humanidad según el Libro Guinness de los Récords Mundiales . [ cita requerida ] [40]

El 16 de marzo de 2003, el primer ministro español José María Aznar , el primer ministro del Reino Unido Tony Blair , el presidente de los Estados Unidos George W. Bush y el primer ministro de Portugal José Manuel Durão Barroso como anfitrión se reunieron en las Azores para discutir la invasión de Irak y la posible participación de España en la guerra, así como el comienzo de la invasión. Este encuentro fue extremadamente controvertido en España, incluso ahora sigue siendo un punto muy sensible para el gobierno de Aznar. [75] Casi un año después, Madrid sufrió el peor ataque terrorista en Europa desde el atentado de Lockerbie , motivado por la decisión de España de participar en la guerra de Irak, lo que llevó a algunos españoles a acusar al primer ministro de ser responsable. [76]

En marzo de 2003, Estados Unidos, el Reino Unido, Polonia, Australia, España, Dinamarca e Italia comenzaron a prepararse para la invasión de Irak , con una serie de medidas militares y de relaciones públicas . En su discurso a la nación del 17 de marzo de 2003, Bush exigió que Saddam y sus dos hijos, Uday y Qusay , se rindieran y abandonaran Irak, dándoles un plazo de 48 horas. [77]

El 18 de marzo de 2003, la Cámara de los Comunes del Reino Unido celebró un debate sobre la posibilidad de ir a la guerra, en el que la moción del gobierno fue aprobada por 412 votos a favor y 149 en contra . [78] La votación fue un momento clave en la historia de la administración de Blair , ya que el número de parlamentarios del gobierno que se rebelaron contra la votación fue el mayor desde la derogación de las Leyes del Maíz en 1846. Tres ministros del gobierno dimitieron en protesta por la guerra: John Denham , Lord Hunt de Kings Heath y el entonces líder de la Cámara de los Comunes, Robin Cook . En un apasionado discurso ante la Cámara de los Comunes tras su dimisión, dijo: «Lo que me ha llegado a preocupar es la sospecha de que si los 'sicarios' de Florida hubieran ido en sentido contrario y Al Gore hubiera sido elegido, ahora no estaríamos a punto de enviar tropas británicas a la acción en Irak». Durante el debate, se afirmó que el Fiscal General había informado de que la guerra era legal en virtud de resoluciones anteriores de la ONU.

En diciembre de 2002, un representante del jefe de la inteligencia iraquí, el general Tahir Jalil Habbush al-Tikriti , se puso en contacto con el ex jefe del Departamento Antiterrorista de la CIA, Vincent Cannistraro, y le dijo que Saddam "sabía que había una campaña para vincularlo con el 11 de septiembre y demostrar que tenía armas de destrucción masiva". Cannistraro añadió que "los iraquíes estaban dispuestos a satisfacer esas preocupaciones. Informé de la conversación a los altos niveles del Departamento de Estado y me dijeron que me hiciera a un lado y que ellos se encargarían del asunto". Cannistraro afirmó que la administración de George W. Bush "rechazó" todas las ofertas realizadas porque permitían a Saddam permanecer en el poder, un resultado considerado inaceptable. Se ha sugerido que Saddam Hussein estaba dispuesto a exiliarse si se le permitía quedarse con 1.000 millones de dólares. [79]

El asesor de seguridad nacional del presidente egipcio Hosni Mubarak , Osama El-Baz , envió un mensaje al Departamento de Estado de Estados Unidos en el que afirmaba que los iraquíes querían discutir las acusaciones de que el país tenía armas de destrucción masiva y vínculos con Al Qaeda. Irak también intentó llegar a Estados Unidos a través de los servicios de inteligencia sirios, franceses, alemanes y rusos.

En enero de 2003, el libanés-estadounidense Imad Hage se reunió con Michael Maloof, de la Oficina de Planes Especiales del Departamento de Defensa de Estados Unidos . Hage, residente en Beirut , había sido reclutado por el departamento para ayudar en la guerra contra el terrorismo . Informó de que Mohammed Nassif, un colaborador cercano del presidente sirio Bashar al-Assad , había expresado su frustración por las dificultades de Siria para ponerse en contacto con los Estados Unidos y había intentado utilizarlo como intermediario. Maloof organizó una reunión de Hage con el civil Richard Perle , entonces jefe de la Junta de Política de Defensa . [80] [81]

En enero de 2003, Hage se reunió con el jefe de operaciones exteriores de la inteligencia iraquí, Hassan al-Obeidi. Obeidi le dijo a Hage que Bagdad no entendía por qué los habían atacado y que no tenían armas de destrucción masiva. Luego le hizo una oferta a Washington para que enviara 2.000 agentes del FBI para confirmarlo. Además, ofreció concesiones petroleras, pero no llegó a obligar a Saddam a renunciar al poder, sugiriendo en cambio que podrían celebrarse elecciones en dos años. Más tarde, Obeidi sugirió que Hage viajara a Bagdad para mantener conversaciones; él aceptó. [80]

Más tarde ese mes, Hage se reunió con el general Habbush y el viceprimer ministro iraquí Tariq Aziz . Se le ofreció máxima prioridad a las empresas estadounidenses en derechos petroleros y mineros, elecciones supervisadas por la ONU, inspecciones estadounidenses (con hasta 5.000 inspectores), entregar al agente de Al Qaeda Abdul Rahman Yasin (bajo custodia iraquí desde 1994) como señal de buena fe, y dar "pleno apoyo a cualquier plan estadounidense" en el proceso de paz israelí-palestino . También deseaban reunirse con funcionarios estadounidenses de alto rango. El 19 de febrero, Hage envió por fax a Maloof su informe del viaje. Maloof informa haber llevado la propuesta a Jaymie Duran. El Pentágono niega que Wolfowitz o Rumsfeld, los jefes de Duran, estuvieran al tanto del plan. [80]

El 21 de febrero, Maloof informó a Duran en un correo electrónico que Richard Perle deseaba reunirse con Hage y los iraquíes si el Pentágono lo autorizaba. Duran respondió: "Mike, estoy trabajando en esto. Mantén esto bajo control". El 7 de marzo, Perle se reunió con Hage en Knightsbridge y le manifestó que quería seguir investigando el asunto con gente de Washington (ambos reconocieron la reunión). Unos días después, le informó a Hage que Washington se negaba a permitirle reunirse con Habbush para discutir la oferta (Hage declaró que la respuesta de Perle fue "que el consenso en Washington era que no se podía hacer"). Perle le dijo a The Times : "El mensaje fue 'Dígales que los veremos en Bagdad'". [82]

Según el general Tommy Franks , los objetivos de la invasión eran: "Primero, acabar con el régimen de Saddam Hussein. Segundo, identificar, aislar y eliminar las armas de destrucción masiva de Irak. Tercero, buscar, capturar y expulsar a los terroristas de ese país. Cuarto, reunir toda la información que podamos sobre las redes terroristas. Quinto, reunir toda la información que podamos sobre la red mundial de armas ilícitas de destrucción masiva. Sexto, poner fin a las sanciones y prestar inmediatamente ayuda humanitaria a los desplazados y a muchos ciudadanos iraquíes necesitados. Séptimo, asegurar los yacimientos y recursos petrolíferos de Irak, que pertenecen al pueblo iraquí. Y por último, ayudar al pueblo iraquí a crear las condiciones para una transición hacia un autogobierno representativo". [83]

Durante todo el año 2002, la administración Bush insistió en que la eliminación de Saddam del poder para restablecer la paz y la seguridad internacionales era un objetivo primordial. Las principales justificaciones declaradas para esta política de "cambio de régimen" fueron que la continua producción de armas de destrucción masiva por parte de Iraq y sus conocidos vínculos con organizaciones terroristas , así como las continuas violaciones por parte de Iraq de las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas, constituían una amenaza para los Estados Unidos y la comunidad mundial.

En octubre de 2002, George W. Bush dijo que "la política declarada de los Estados Unidos es la de un cambio de régimen... Sin embargo, si Saddam cumpliera todas las condiciones de las Naciones Unidas, las condiciones que he descrito muy claramente en términos que todo el mundo pueda entender, eso en sí mismo indicaría que el régimen ha cambiado". [84] Citando informes de ciertas fuentes de inteligencia, Bush declaró el 6 de marzo de 2003 que creía que Saddam no estaba cumpliendo con la Resolución 1441 de la ONU . [85]

Las principales acusaciones fueron: que Saddam poseía o estaba intentando producir armas de destrucción masiva , que Saddam Hussein había utilizado en lugares como Halabja , [86] [87] poseía y hacía esfuerzos por adquirir, particularmente considerando dos ataques previos a las instalaciones de producción de armas nucleares de Bagdad por parte de Irán e Israel que supuestamente habían pospuesto el progreso del desarrollo de armas; y, además, que tenía vínculos con terroristas, específicamente al-Qaeda.

El 5 de febrero de 2003 , el Secretario de Estado norteamericano Colin Powell presentó en detalle ante el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas la justificación general de la administración Bush para la invasión de Irak . En resumen, afirmó:

Sabemos que Saddam Hussein está decidido a conservar sus armas de destrucción masiva; está decidido a fabricar más. Teniendo en cuenta la historia de agresión de Saddam Hussein... teniendo en cuenta lo que sabemos de sus vínculos terroristas y teniendo en cuenta su determinación de vengarse de quienes se le oponen, ¿deberíamos correr el riesgo de que algún día no utilice esas armas en el momento, el lugar y la forma que él elija, en un momento en que el mundo está en una posición mucho más débil para responder? Estados Unidos no quiere ni puede correr ese riesgo para el pueblo estadounidense. Dejar a Saddam Hussein en posesión de armas de destrucción masiva durante unos meses o años más no es una opción, no en un mundo posterior al 11 de septiembre. [88]

En septiembre de 2002, Tony Blair declaró, en respuesta a una pregunta parlamentaria, que "un cambio de régimen en Irak sería algo maravilloso. Ése no es el propósito de nuestra acción; nuestro propósito es desarmar a Irak de armas de destrucción masiva..." [89]. En noviembre de ese año, Blair añadió que "en lo que respecta a nuestro objetivo, es el desarme, no el cambio de régimen; ése es nuestro objetivo. Ahora bien, creo que el régimen de Saddam es un régimen muy brutal y represivo, creo que causa un daño enorme al pueblo iraquí... así que no tengo ninguna duda de que Saddam es muy malo para Irak, pero por otro lado tampoco tengo ninguna duda de que el propósito de nuestro desafío a las Naciones Unidas es el desarme de las armas de destrucción masiva, no es un cambio de régimen". [90]

En una conferencia de prensa celebrada el 31 de enero de 2003, Bush reiteró una vez más que el único detonante de la invasión sería el fracaso de Irak en desarmarse: "Saddam Hussein debe comprender que si no se desarma, por el bien de la paz, nosotros, junto con otros, iremos a desarmar a Saddam Hussein". [91] Hasta el 25 de febrero de 2003, la postura oficial seguía siendo que la única causa de la invasión sería el fracaso en desarmarse. Como Blair dejó claro en una declaración a la Cámara de los Comunes: "Detesto su régimen. Pero incluso ahora puede salvarlo cumpliendo la exigencia de la ONU. Incluso ahora, estamos dispuestos a dar el paso adicional para lograr el desarme de forma pacífica". [92]

En septiembre de 2002, la administración Bush dijo que los intentos de Irak de adquirir miles de tubos de aluminio de alta resistencia apuntaban a un programa clandestino de enriquecimiento de uranio para bombas nucleares. Powell, en su discurso ante el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU justo antes de la guerra, se refirió a los tubos de aluminio. Sin embargo, un informe publicado por el Instituto para la Ciencia y la Seguridad Internacional en 2002 informó que era muy improbable que los tubos pudieran utilizarse para enriquecer uranio. Powell admitió más tarde que había presentado un caso inexacto ante las Naciones Unidas sobre las armas iraquíes, basándose en fuentes erróneas y en algunos casos "deliberadamente engañosas". [93] [94] [95]

La administración Bush afirmó que el gobierno de Saddam había tratado de comprar uranio concentrado de Níger . [96] El 7 de marzo de 2003, los Estados Unidos presentaron documentos de inteligencia como prueba al Organismo Internacional de Energía Atómica . Estos documentos fueron desestimados por el OIEA como falsificaciones, con la coincidencia en esa opinión de expertos externos. En ese momento, un funcionario estadounidense declaró que la evidencia fue presentada al OIEA sin conocimiento de su procedencia y calificó los errores como "más probablemente debidos a la incompetencia que a la malicia".

Desde la invasión, las declaraciones del gobierno de los Estados Unidos sobre los programas de armas iraquíes y sus vínculos con Al Qaeda han sido desacreditadas, [97] aunque se encontraron armas químicas en Irak durante el período de ocupación. [98] Si bien el debate sobre si Irak tenía la intención de desarrollar armas químicas, biológicas y nucleares en el futuro sigue abierto, no se han encontrado armas de destrucción masiva en Irak desde la invasión a pesar de las inspecciones exhaustivas que duraron más de 18 meses. [99] En El Cairo, el 24 de febrero de 2001, Colin Powell había predicho lo mismo, diciendo: "[Saddam] no ha desarrollado ninguna capacidad significativa con respecto a las armas de destrucción masiva. Es incapaz de proyectar poder convencional contra sus vecinos". [100]

Otra justificación incluía la supuesta conexión entre el régimen de Saddam Hussein y el de organizaciones terroristas como Al-Qaeda que habían atacado a Estados Unidos durante los ataques terroristas del 11 de septiembre de 2001 .

Aunque nunca hizo una conexión explícita entre Irak y los ataques del 11 de septiembre, la administración de George W. Bush insinuó repetidamente un vínculo, creando así una falsa impresión para el público estadounidense. El testimonio del gran jurado en los juicios por el atentado del World Trade Center de 1993 citó numerosos vínculos directos de los atacantes con Bagdad y el Departamento 13 del Servicio de Inteligencia iraquí en ese ataque inicial que marcó el segundo aniversario para reivindicar la rendición de las fuerzas armadas iraquíes en la Operación Tormenta del Desierto . Por ejemplo, The Washington Post ha señalado que,

Aunque no declararon explícitamente la culpabilidad iraquí en los ataques terroristas del 11 de septiembre de 2001, funcionarios de la administración sí insinuaron en varias ocasiones la existencia de un vínculo. A fines de 2001, Cheney dijo que estaba "bastante bien confirmado" que el cerebro del ataque, Mohamed Atta, se había reunido con un alto funcionario de inteligencia iraquí. Más tarde, Cheney calificó a Irak como "la base geográfica de los terroristas que nos han estado atacando durante muchos años, pero sobre todo el 11 de septiembre". [101]

Steven Kull, director del Programa de Actitudes Políticas Internacionales (PIPA) de la Universidad de Maryland , observó en marzo de 2003 que "la administración ha logrado crear la sensación de que existe alguna conexión [entre el 11 de septiembre y Saddam Hussein]". Esto ocurrió después de que una encuesta del New York Times / CBS mostrara que el 45% de los estadounidenses creía que Saddam Hussein estaba "personalmente involucrado" en las atrocidades del 11 de septiembre. Como observó entonces The Christian Science Monitor , aunque "fuentes conocedoras de la inteligencia estadounidense dicen que no hay pruebas de que Saddam haya desempeñado un papel en los ataques del 11 de septiembre, ni de que haya estado o esté ayudando actualmente a Al Qaeda... la Casa Blanca parece estar alentando esta falsa impresión, ya que busca mantener el apoyo estadounidense a una posible guerra contra Irak y demostrar seriedad de propósitos al régimen de Saddam". El CSM continuó informando que, si bien los datos de las encuestas recogidas "inmediatamente después del 11 de septiembre de 2001" mostraban que sólo el 3 por ciento había mencionado a Irak o a Saddam Hussein, las actitudes "se habían transformado" en enero de 2003, y una encuesta de Knight Ridder mostraba que el 44 por ciento de los estadounidenses creía que "la mayoría" o "algunos" de los secuestradores del 11 de septiembre eran ciudadanos iraquíes. [102]

La BBC también ha señalado que, si bien el presidente Bush "nunca acusó directamente al ex líder iraquí de tener algo que ver con los ataques a Nueva York y Washington", "asoció repetidamente las dos cosas en los discursos pronunciados desde el 11 de septiembre", añadiendo que "miembros de alto rango de su administración han mezclado de manera similar las dos cosas". Por ejemplo, el informe de la BBC cita a Colin Powell en febrero de 2003, quien afirmó: "Hemos sabido que Irak ha entrenado a miembros de Al Qaeda en la fabricación de bombas, venenos y gases letales. Y sabemos que después del 11 de septiembre, el régimen de Saddam Hussein celebró con regocijo los ataques terroristas contra Estados Unidos". El mismo informe de la BBC también señaló los resultados de una encuesta de opinión reciente, que sugería que "el 70% de los estadounidenses creen que el líder iraquí estuvo personalmente involucrado en los ataques". [103]

También en septiembre de 2003, The Boston Globe informó que "el vicepresidente Dick Cheney, ansioso por defender la política exterior de la Casa Blanca en medio de la violencia en curso en Irak, sorprendió a los analistas de inteligencia e incluso a miembros de su propia administración esta semana al no desestimar una afirmación ampliamente desacreditada: que Saddam Hussein podría haber jugado un papel en los ataques del 11 de septiembre". [104] Un año después, el candidato presidencial John Kerry afirmó que Cheney seguía "engañando intencionalmente al público estadounidense al establecer un vínculo entre Saddam Hussein y el 11 de septiembre en un intento de hacer que la invasión de Irak sea parte de la guerra global contra el terrorismo". [105]

Desde la invasión, las afirmaciones de vínculos operativos entre el régimen iraquí y al Qaeda han sido en gran medida desacreditadas por la comunidad de inteligencia, y el propio Secretario Powell admitió más tarde que no tenía pruebas. [97]

En octubre de 2002, unos días antes de que el Senado de Estados Unidos votara la Resolución sobre la Autorización para el Uso de la Fuerza Militar contra Irak , se informó a unos 75 senadores en una sesión a puertas cerradas de que el gobierno iraquí tenía los medios para lanzar armas biológicas y químicas de destrucción masiva mediante vehículos aéreos no tripulados (UAV) que podían ser lanzados desde barcos frente a la costa atlántica de Estados Unidos para atacar ciudades de la costa este de ese país . Colin Powell sugirió en su presentación ante las Naciones Unidas que los UAV eran transportados fuera de Irak y podían ser lanzados contra Estados Unidos.

De hecho, Irak no tenía una flota de vehículos aéreos no tripulados ofensivos ni capacidad para instalarlos en barcos. [106] La flota de vehículos aéreos no tripulados de Irak estaba formada por menos de un puñado de anticuados drones de entrenamiento checos. [107] En ese momento, había una vigorosa disputa dentro de la comunidad de inteligencia sobre si las conclusiones de la CIA sobre la flota de vehículos aéreos no tripulados de Irak eran exactas. La Fuerza Aérea de los Estados Unidos negó rotundamente que Irak poseyera alguna capacidad ofensiva de vehículos aéreos no tripulados. [108]

Otras justificaciones utilizadas en diversas ocasiones incluyeron la violación iraquí de las resoluciones de la ONU, la represión del gobierno iraquí a sus ciudadanos y las violaciones iraquíes del alto el fuego de 1991. [28]

A medida que se debilitaban las pruebas que respaldaban las acusaciones estadounidenses y británicas sobre las armas de destrucción masiva iraquíes y sus vínculos con el terrorismo, algunos partidarios de la invasión han ido cambiando cada vez más su justificación hacia las violaciones de los derechos humanos cometidas por el gobierno de Saddam . [109] Sin embargo, importantes grupos de derechos humanos como Human Rights Watch han argumentado que creen que las preocupaciones por los derechos humanos nunca fueron una justificación central para la invasión, ni creen que la intervención militar fuera justificable por razones humanitarias, sobre todo porque "las matanzas en Irak en ese momento no eran de la naturaleza excepcional que justificaría tal intervención". [110]

La Resolución de Autorización para el Uso de la Fuerza Militar contra Irak de 2002 fue aprobada por el Congreso con un 98% de votos a favor de los republicanos en el Senado y un 97% a favor en la Cámara de Representantes. Los demócratas apoyaron la resolución conjunta con un 58% y un 39% en el Senado y la Cámara de Representantes respectivamente. [111] [112] La resolución afirma la autorización de la Constitución de los Estados Unidos y del Congreso para que el Presidente luche contra el terrorismo antiestadounidense. Citando la Ley de Liberación de Irak de 1998 , la resolución reiteró que debería ser política de los Estados Unidos eliminar el régimen de Saddam Hussein y promover un reemplazo democrático.

La resolución "apoyó" y "alentó" los esfuerzos diplomáticos del Presidente George W. Bush para "hacer cumplir estrictamente, a través del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas, todas las resoluciones pertinentes del Consejo de Seguridad relativas a Irak" y "obtener una acción rápida y decisiva del Consejo de Seguridad para asegurar que Irak abandone su estrategia de demora, evasión e incumplimiento y cumpla rápida y estrictamente con todas las resoluciones pertinentes del Consejo de Seguridad relativas a Irak". La resolución autorizó al Presidente Bush a utilizar las Fuerzas Armadas de los Estados Unidos "como determine que sea necesario y apropiado" para "defender la seguridad nacional de los Estados Unidos contra la amenaza continua que plantea Irak; y hacer cumplir todas las resoluciones pertinentes del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas relativas a Irak".

La legalidad de la invasión de Irak según el derecho internacional ha sido cuestionada desde su inicio en varios frentes, y varios partidarios destacados de la invasión en todos los estados invasores han puesto en duda pública y privadamente su legalidad. Los gobiernos de Estados Unidos y Gran Bretaña han sostenido que la invasión fue completamente legal porque se dio a entender que contaba con la autorización del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas . [113] Expertos legales internacionales, incluida la Comisión Internacional de Juristas , un grupo de 31 destacados profesores de derecho canadienses, y el Comité de Abogados sobre Política Nuclear, con sede en Estados Unidos, han denunciado este razonamiento. [114] [115] [116]

El jueves 20 de noviembre de 2003, un artículo publicado en The Guardian afirmó que Richard Perle , un miembro de alto rango del Comité Asesor de Política de Defensa de la administración , admitió que la invasión era ilegal pero aún así justificada. [117] [118]

El Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas ha aprobado casi 60 resoluciones sobre el Iraq y Kuwait desde la invasión iraquí de Kuwait en 1990. La más pertinente a esta cuestión es la Resolución 678 , aprobada el 29 de noviembre de 1990. Autoriza a "los Estados miembros que cooperan con el Gobierno de Kuwait ... a utilizar todos los medios necesarios" para (1) aplicar la Resolución 660 del Consejo de Seguridad y otras resoluciones que piden el fin de la ocupación iraquí de Kuwait y la retirada de las fuerzas iraquíes del territorio kuwaití y (2) "restaurar la paz y la seguridad internacionales en la zona". La Resolución 678 no ha sido rescindida ni anulada por resoluciones posteriores y, después de 1991, no se ha acusado al Iraq de invadir Kuwait ni de amenazar con hacerlo.

La Resolución 1441 fue la más destacada durante el período previo a la guerra y constituyó el principal telón de fondo del discurso del Secretario de Estado Colin Powell ante el Consejo de Seguridad un mes antes de la invasión. [119] Según una comisión de investigación independiente creada por el gobierno de los Países Bajos, la Resolución 1441 de la ONU "no puede interpretarse razonablemente (como hizo el gobierno holandés) como una autorización a los Estados miembros individuales para utilizar la fuerza militar para obligar a Irak a cumplir con las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad". En consecuencia, la comisión holandesa concluyó que la invasión de 2003 violó el derecho internacional. [120]

Al mismo tiempo, los funcionarios de la administración Bush presentaron un argumento jurídico paralelo utilizando las resoluciones anteriores, que autorizaban el uso de la fuerza en respuesta a la invasión de Kuwait por parte de Irak en 1990. Según ese razonamiento, al no desarmarse y someterse a inspecciones de armas, Irak estaba violando las Resoluciones 660 y 678 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas , y Estados Unidos podía obligar legalmente a Irak a cumplir con esas resoluciones por medios militares.

Los críticos y defensores del fundamento jurídico basado en las resoluciones de la ONU argumentan que el derecho legal de determinar cómo hacer cumplir sus resoluciones corresponde únicamente al Consejo de Seguridad, no a las naciones individuales, y que, por lo tanto, la invasión de Irak no fue legal según el derecho internacional y violó directamente el Artículo 2(4) de la Carta de la ONU.

En febrero de 2006, Luis Moreno Ocampo , fiscal principal de la Corte Penal Internacional , informó que había recibido 240 comunicaciones separadas sobre la legalidad de la guerra, muchas de las cuales se referían a la participación británica en la invasión. [121] En una carta dirigida a los denunciantes, el Sr. Moreno Ocampo explicó que sólo podía considerar cuestiones relacionadas con la conducta durante la guerra y no con su legalidad subyacente como un posible crimen de agresión porque todavía no se había adoptado ninguna disposición que "definiera el crimen y estableciera las condiciones bajo las cuales la Corte puede ejercer jurisdicción con respecto a él". En una entrevista de marzo de 2007 con The Sunday Telegraph , Moreno Ocampo alentó a Irak a inscribirse en la corte para que pudiera presentar casos relacionados con presuntos crímenes de guerra. [122]

El congresista de Ohio, Dennis Kucinich, celebró una conferencia de prensa en la tarde del 24 de abril de 2007, en la que reveló la Resolución 333 de la Cámara de Representantes y los tres artículos de acusación contra el vicepresidente Dick Cheney . Acusó a Cheney de manipular las pruebas del programa de armas de Irak, engañar al público sobre la conexión de Irak con Al Qaeda y amenazar con una agresión contra Irán en violación de la Carta de las Naciones Unidas .

En noviembre de 2002, el presidente George W. Bush, que visitaba Europa para una cumbre de la OTAN , declaró que "si el presidente iraquí Saddam Hussein decide no desarmarse, Estados Unidos liderará una coalición de los dispuestos a desarmarlo". [123] A partir de entonces, la administración Bush utilizó brevemente el término coalición de los dispuestos para referirse a los países que apoyaron, militar o verbalmente, la acción militar en Irak y la posterior presencia militar en Irak después de la invasión desde 2003. La lista original preparada en marzo de 2003 incluía 49 miembros. [124] De esos 49, sólo seis además de los EE. UU. aportaron tropas a la fuerza de invasión (el Reino Unido, Australia, Polonia, España, Portugal y Dinamarca), y 33 proporcionaron una cierta cantidad de tropas para apoyar la ocupación después de que se completó la invasión. Seis miembros no tienen ejército, lo que significa que retuvieron tropas por completo.

Un informe del Comando Central de los Estados Unidos, del Comandante del Componente Aéreo de las Fuerzas Combinadas, indicó que, al 30 de abril de 2003, se habían desplegado 466.985 efectivos estadounidenses para la invasión de Irak. Entre ellos se encontraban: [8]

Elemento de fuerzas terrestres: 336.797 efectivos

Elemento de las fuerzas aéreas: 64.246 efectivos

Elemento de las fuerzas navales: 63.352 efectivos

Aproximadamente 148.000 soldados de los Estados Unidos, 50.000 soldados británicos, 2.000 soldados australianos y 194 soldados polacos de la unidad de fuerzas especiales GROM fueron enviados a Kuwait para la invasión. [9] La fuerza de invasión también fue apoyada por combatientes peshmerga kurdos iraquíes , cuyo número se estima en más de 70.000. [10] En las últimas etapas de la invasión, 620 tropas del grupo de oposición Congreso Nacional Iraquí fueron desplegadas en el sur de Irak. [2]

Canadá contribuyó discretamente con algunos recursos militares para la campaña, como personal de la Real Fuerza Aérea Canadiense que tripuló aviones estadounidenses en misiones en Irak para entrenar con las plataformas, y once tripulantes canadienses que tripularon aviones AWACS . [125] [126] Las Fuerzas Armadas Canadienses tenían barcos, aviones y 1.200 efectivos de la Marina Real Canadiense en la desembocadura del Golfo Pérsico para ayudar a apoyar la Operación Libertad Duradera , y un cable informativo secreto de EE. UU. señaló que a pesar de las promesas públicas de los funcionarios canadienses de que estos activos no se utilizarían en apoyo de la guerra en Irak, "también estarán disponibles para proporcionar servicios de escolta en el Estrecho y, de lo contrario, serán discretamente útiles para el esfuerzo militar". [127] Sin embargo, el Departamento de Defensa Nacional emitió una orden a los comandantes navales de no hacer nada en apoyo de la operación liderada por Estados Unidos, y no se sabe si esta orden alguna vez se rompió. [127] Eugene Lang , jefe de gabinete del entonces ministro de defensa John McCallum , declaró que es "bastante posible" que las fuerzas canadienses apoyaran indirectamente la operación estadounidense. [127] Según Lang, el ejército de Canadá abogó firmemente por involucrarse en la guerra de Irak en lugar de la guerra en Afganistán, y Canadá decidió principalmente mantener sus activos en el Golfo para mantener buenas relaciones con Estados Unidos. [127] Después de la invasión, el general de brigada Walter Natynczyk , del ejército canadiense , sirvió como comandante general adjunto del Cuerpo Multinacional - Irak , que comprendía 35.000 soldados estadounidenses en diez brigadas repartidas por Irak. [128]

Los planes para abrir un segundo frente en el norte se vieron gravemente obstaculizados cuando Turquía se negó a utilizar su territorio para tales fines. [129] En respuesta a la decisión de Turquía, Estados Unidos lanzó varios miles de paracaidistas de la 173.ª Brigada Aerotransportada al norte de Irak, un número significativamente menor que la 4.ª División de Infantería de 15.000 efectivos que Estados Unidos originalmente había planeado desplegar en el frente norte. [130]

.jpg/440px-Kurdish-inhabited_area_by_CIA_(1992).jpg)

Los equipos paramilitares de la División de Actividades Especiales (SAD) de la CIA y del MI6 ( Escuadrón E ) entraron en Irak en julio de 2002 antes de la invasión de 2003. Una vez en el terreno, se prepararon para la posterior llegada de las fuerzas militares estadounidenses y británicas. Los equipos de la SAD se combinaron entonces con las Fuerzas Especiales del Ejército de los EE. UU. para organizar a los Peshmerga kurdos . Este equipo conjunto se combinó para derrotar a Ansar al-Islam , un aliado de Al Qaeda, en una batalla en la esquina noreste de Irak. El lado estadounidense fue llevado a cabo por oficiales paramilitares de la SAD y el 10º Grupo de Fuerzas Especiales del Ejército . [67] [68] [69]

Los equipos del SAD también llevaron a cabo misiones especiales de reconocimiento de alto riesgo tras las líneas iraquíes para identificar objetivos de alto nivel. Estas misiones condujeron a los ataques iniciales contra Saddam Hussein y sus generales clave. Aunque los ataques iniciales contra Saddam no lograron matar al dictador o a sus generales, sí lograron poner fin de manera efectiva a la capacidad de mando y control de las fuerzas iraquíes. Otros ataques contra generales clave tuvieron éxito y degradaron significativamente la capacidad del comando para reaccionar y maniobrar contra la fuerza de invasión liderada por Estados Unidos que venía del sur. [67] [69]

El MI6 llevó a cabo la Operación Llamamiento Masivo , una campaña para difundir en los medios de comunicación historias sobre las armas de destrucción masiva de Irak y aumentar el apoyo a la invasión. El MI6 también sobornó a muchos de los aliados más cercanos de Saddam para que le entregaran información y datos de inteligencia.

Los oficiales de operaciones del SAD también lograron convencer a oficiales clave del ejército iraquí de que entregaran sus unidades una vez que comenzaran los combates y/o de que no se opusieran a la fuerza de invasión. [68] Turquía , miembro de la OTAN, se negó a permitir que su territorio se utilizara para la invasión. Como resultado, los equipos conjuntos del SAD/SOG y las Fuerzas Especiales del Ejército de los EE. UU. y los Peshmerga kurdos constituyeron toda la fuerza del norte contra las fuerzas gubernamentales durante la invasión. Sus esfuerzos mantuvieron al 5.º Cuerpo del ejército iraquí en su lugar para defenderse de los kurdos en lugar de moverse para enfrentar a la fuerza de la coalición.

Según el general Tommy Franks , April Fool , un oficial estadounidense que trabajaba encubierto como diplomático, fue abordado por un agente de inteligencia iraquí . April Fool luego vendió a Irak planes de invasión falsos y "de alto secreto" proporcionados por el equipo de Franks. Este engaño llevó al ejército iraquí a desplegar fuerzas importantes en el norte y el oeste de Irak en previsión de ataques por Turquía o Jordania , que nunca tuvieron lugar. Esto redujo en gran medida la capacidad defensiva en el resto de Irak y facilitó los ataques reales a través de Kuwait y el Golfo Pérsico en el sudeste.

El número de personal en el ejército iraquí antes de la guerra era incierto, pero se creía que estaba mal equipado. [131] [132] El Instituto Internacional de Estudios Estratégicos estimó que las fuerzas armadas iraquíes contaban con 389.000 ( ejército iraquí 350.000, marina iraquí 2.000, fuerza aérea iraquí 20.000 y defensa aérea 17.000), los fedayines paramilitares Saddam 44.000, la Guardia Republicana 80.000 y las reservas 650.000. [133]

Otra estimación cifra el número de efectivos del Ejército y la Guardia Republicana en entre 280.000 y 350.000 y de 50.000 a 80.000, respectivamente, [ cita requerida ] y los paramilitares en entre 20.000 y 40.000. [ cita requerida ] Se calcula que había trece divisiones de infantería , diez divisiones mecanizadas y blindadas , así como algunas unidades de fuerzas especiales . La Fuerza Aérea y la Armada iraquíes desempeñaron un papel insignificante en el conflicto.

Durante la invasión, voluntarios extranjeros viajaron a Irak desde Siria y participaron en los combates, generalmente dirigidos por los fedayines de Saddam. No se sabe con certeza cuántos combatientes extranjeros lucharon en Irak en 2003, sin embargo, oficiales de inteligencia de la Primera División de Marines de los Estados Unidos estimaron que el 50% de todos los combatientes iraquíes en el centro de Irak eran extranjeros. [134] [135]

Además, el grupo militante islamista kurdo Ansar al-Islam controlaba una pequeña sección del norte de Irak en un área fuera del control de Saddam Hussein. Ansar al-Islam había estado luchando contra las fuerzas kurdas seculares desde 2001. En el momento de la invasión desplegaban alrededor de 600 a 800 combatientes. [136] Ansar al-Islam estaba dirigido por el militante nacido en Jordania Abu Musab al-Zarqawi , quien más tarde se convertiría en un líder importante en la insurgencia iraquí . Ansar al-Islam fue expulsado de Irak a fines de marzo por una fuerza conjunta estadounidense-kurda durante la Operación Viking Hammer .

Según la información proporcionada al Ministerio de Defensa holandés por las fuerzas estadounidenses, se estima que durante la invasión se dispararon más de 300.000 rondas de uranio empobrecido, muchas de ellas en o cerca de zonas pobladas de Irak, incluidas Samawah , Nasiriyah y Basora, la gran mayoría por fuerzas estadounidenses. En la información, las fuerzas estadounidenses proporcionaron al Ministerio de Defensa holandés las coordenadas GPS de las rondas de uranio empobrecido, junto con una lista de objetivos y números disparados. Luego, el Ministerio de Defensa holandés entregó los datos al grupo pacifista holandés Pax en virtud de la Ley de Libertad de Información . [137] [138]

Las fuerzas estadounidenses utilizaron fósforo blanco y napalm como armas incendiarias durante la batalla de Mosul y la segunda batalla de Faluya en 2004. En marzo de 2005, Field Artillery , una revista publicada por el ejército estadounidense, publicó informes sobre el uso de fósforo blanco en la batalla de Faluya. El Ministerio de Defensa británico confirmó el uso de la bomba Mark 77 por parte de las fuerzas estadounidenses durante la guerra. [139]

Las fuerzas de la coalición liderada por Estados Unidos utilizaron 61.000 municiones en racimo que contenían 20 millones de submuniciones durante la Guerra del Golfo de 1991, y 13.000 municiones en racimo que contenían dos millones de submuniciones durante la invasión de 2003 y la insurgencia posterior. [140] [141] Miles de municiones sin explotar de la invasión y guerras anteriores, incluidas municiones en racimo, minas y otras municiones sin explotar, todavía representaban una amenaza para los civiles en 2022. [142]

_listen_to_a_pre-flight_brief_in_one_of_the_squadron_ready_rooms_aboard_USS_Constellation_(CV_64).jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Desde la Guerra del Golfo de 1991 , Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido habían sido atacados por las defensas aéreas iraquíes mientras aplicaban las zonas de exclusión aérea iraquíes . [45] [46] Estas zonas, y los ataques para aplicarlas, fueron descritos como ilegales por el ex secretario general de la ONU, Boutros Boutros-Ghali , y el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores francés Hubert Vedrine . Otros países, en particular Rusia y China, también condenaron las zonas como una violación de la soberanía iraquí. [143] [144] [145] A mediados de 2002, Estados Unidos comenzó a seleccionar con más cuidado los objetivos en la parte sur del país para perturbar la estructura de mando militar en Irak. En ese momento se reconoció un cambio en las tácticas de aplicación, pero no se hizo público que esto era parte de un plan conocido como Operación Enfoque Sur .

La cantidad de municiones lanzadas sobre posiciones iraquíes por aviones de la coalición en 2001 y 2002 fue menor que en 1999 y 2000, durante la administración Clinton. [146] Sin embargo, la información obtenida por los Demócratas Liberales del Reino Unido mostró que el Reino Unido lanzó el doble de bombas sobre Irak en la segunda mitad de 2002 que durante todo el año 2001. El tonelaje de bombas británicas lanzadas aumentó de 0 en marzo de 2002 y 0,3 en abril de 2002 a entre 7 y 14 toneladas por mes en mayo-agosto, alcanzando un pico de preguerra de 54,6 toneladas en septiembre, antes de que el Congreso de los EE. UU. autorizara la invasión el 11 de octubre .

Los ataques del 5 de septiembre incluyeron un ataque con más de 100 aviones contra el principal emplazamiento de defensa aérea en el oeste de Irak. Según un editorial del New Statesman, este emplazamiento estaba "situado en el extremo más alejado de la zona de exclusión aérea del sur, lejos de las zonas que había que patrullar para impedir ataques contra los chiítas. Fue destruido no porque fuera una amenaza para las patrullas, sino para permitir que las fuerzas especiales aliadas que operaban desde Jordania entraran en Irak sin ser detectadas". [147]

Tommy Franks , que comandó la invasión de Irak, admitió posteriormente que el bombardeo tenía como objetivo "degradar" las defensas aéreas iraquíes de la misma manera que los ataques aéreos que iniciaron la Guerra del Golfo en 1991. Estos "picos de actividad" tenían como objetivo, en palabras del entonces Secretario de Defensa británico, Geoff Hoon , "ejercer presión sobre el régimen iraquí" o, como informó The Times , "provocar a Saddam Hussein para que diera a los aliados una excusa para la guerra". A este respecto, como provocaciones diseñadas para iniciar una guerra, el asesoramiento jurídico filtrado del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores británico concluyó que tales ataques eran ilegales según el derecho internacional. [148] [149]

Otro intento de provocar la guerra fue mencionado en un memorando filtrado de una reunión entre George W. Bush y Tony Blair el 31 de enero de 2003, en la que Bush supuestamente le dijo a Blair que "Estados Unidos estaba pensando en volar aviones de reconocimiento U2 con cobertura de combate sobre Irak, pintados con los colores de la ONU. Si Saddam les disparaba, estaría incumpliendo su obligación". [150] El 17 de marzo de 2003, el presidente estadounidense George W. Bush dio a Saddam Hussein 48 horas para abandonar el país, junto con sus hijos Uday y Qusay, o enfrentarse a la guerra. [151]

En la noche del 17 de marzo de 2003, la mayoría de los escuadrones B y D del 22º Regimiento SAS británico , designado como Task Force 14, cruzaron la frontera desde Jordania para llevar a cabo un asalto terrestre sobre un presunto emplazamiento de municiones químicas en una planta de tratamiento de agua en la ciudad de al-Qa'im . Se había informado de que el lugar podría haber sido un lugar de lanzamiento de misiles SCUD o un depósito; un oficial del SAS fue citado por el autor Mark Nicol diciendo que "era un lugar donde se habían disparado misiles contra Israel en el pasado, y un sitio de importancia estratégica para material de armas de destrucción masiva". Los 60 miembros del escuadrón D, junto con sus vehículos de patrulla del desierto "Pinkie" (la última vez que se utilizaron los vehículos antes de su retiro), volaron 120 km (75 millas) hacia Irak en 6 MH-47D en 3 oleadas. Tras su incorporación, el escuadrón D estableció un puesto de patrulla en un lugar remoto a las afueras de Al Qa'im y esperó la llegada del escuadrón B, que había viajado por tierra desde Jordania. Su aproximación a la planta se vio comprometida y se desató un tiroteo que terminó con un 'pinkie' que tuvo que ser abandonado y destruido. Los repetidos intentos de asaltar la planta fueron detenidos, lo que llevó al SAS a solicitar un ataque aéreo que silenció a la oposición. [152]

En la madrugada del 19 de marzo de 2003, las fuerzas estadounidenses abandonaron el plan de realizar ataques iniciales de decapitación no nucleares contra 55 altos funcionarios iraquíes, a la luz de los informes de que Saddam Hussein estaba visitando a sus hijos, Uday y Qusay , en las granjas de Dora, dentro de la comunidad agrícola de al-Dora en las afueras de Bagdad . [153] Aproximadamente a las 04:42 hora de Bagdad, [154] dos cazas furtivos F-117 Nighthawk del 8º Escuadrón de Cazas Expedicionarios [155] lanzaron cuatro ' Bunker Busters ' GBU-27 mejorados y guiados por satélite de 2.000 libras sobre el complejo. Como complemento al bombardeo aéreo se dispararon casi 40 misiles de crucero Tomahawk desde varios barcos, entre ellos el crucero de clase Ticonderoga USS Cowpens , considerado el primero en atacar, [156] los destructores de clase Arleigh Burke USS Donald Cook y USS Porter , así como dos submarinos en el mar Rojo y el golfo Pérsico . [157]

Una bomba no impactó en el complejo y las otras tres no alcanzaron su objetivo, cayendo al otro lado del muro del recinto del palacio. [158] Saddam Hussein no estaba presente, ni tampoco ningún miembro de la dirigencia iraquí. [153] [159] El ataque mató a un civil e hirió a otros catorce, incluidos cuatro hombres, nueve mujeres y un niño. [160] Fuentes posteriores indicaron que Saddam Hussein no había visitado la granja desde 1995, [157] mientras que otros afirmaron que Saddam había estado en el complejo esa mañana, pero se había ido antes del ataque, que Bush había ordenado retrasar hasta que expirara el plazo de 48 horas. [154]

El 19 de marzo de 2003, a las 21:00 horas, los miembros del 160º SOAR llevaron a cabo el primer ataque de la operación : un vuelo de DAP (Direct Action Penetrators) MH-60L y cuatro vuelos de "Black Swarm" (cada uno de ellos formado por un par de Little Birds AH-6M y un MH-6M equipado con FLIR para identificar objetivos para los AH-6 (cada vuelo de Black Swarm tenía asignado un par de A-10A ) atacaron puestos de observación visual iraquíes a lo largo de las fronteras sur y oeste de Irak. En siete horas, más de 70 sitios fueron destruidos, privando de hecho al ejército iraquí de cualquier advertencia temprana de la invasión venidera. A medida que se eliminaban los sitios, los primeros equipos SOF helitransportados despegaron desde la base aérea H-5 en Jordania, incluidas patrullas montadas en vehículos de los componentes británico y australiano transportados por los MH-47D del 160º SOAR. Elementos terrestres de las Fuerzas de Tareas Dagger, 20, 14 y 64 atravesaron los diques de arena a lo largo de la frontera iraquí con Jordania, Arabia Saudita y Kuwait en las primeras horas de la mañana y entraron en Irak. Extraoficialmente, los británicos, los australianos y la Fuerza de Tareas 20 habían estado en Irak semanas antes. [161] [162]

El 20 de marzo de 2003, aproximadamente a las 02:30 UTC , a las 05:34 hora local, se oyeron explosiones en Bagdad. Los comandos de operaciones especiales de la División de Actividades Especiales de la CIA del Elemento de Enlace del Norte de Irak se infiltraron en todo Irak y solicitaron los primeros ataques aéreos. [67] A las 03:16 UTC, o 10:16 pm EST, George W. Bush anunció que había ordenado un ataque contra "objetivos seleccionados de importancia militar" en Irak. [163] [164] Cuando se dio esta orden, las tropas en espera cruzaron la frontera hacia Irak.

Antes de la invasión, muchos observadores habían esperado una campaña más larga de bombardeos aéreos antes de cualquier acción terrestre, tomando como ejemplos la Guerra del Golfo Pérsico de 1991 o la invasión de Afganistán de 2001. En la práctica, los planes estadounidenses preveían ataques aéreos y terrestres simultáneos para incapacitar a las fuerzas iraquíes rápidamente, lo que dio como resultado una campaña militar de choque y pavor que intentaba eludir las unidades militares y las ciudades iraquíes en la mayoría de los casos. La suposición era que la movilidad y la coordinación superiores de las fuerzas de la coalición les permitirían atacar el corazón de la estructura de mando iraquí y destruirla en poco tiempo, y que esto minimizaría las muertes de civiles y los daños a la infraestructura. Se esperaba que la eliminación del liderazgo llevaría al colapso de las fuerzas iraquíes y del gobierno, y que gran parte de la población apoyaría a los invasores una vez que el gobierno se hubiera debilitado. La ocupación de ciudades y los ataques a unidades militares periféricas se consideraban distracciones indeseables.

Tras la decisión de Turquía de negar cualquier uso oficial de su territorio, la coalición se vio obligada a modificar el ataque simultáneo planeado desde el norte y el sur. [165] Las fuerzas de operaciones especiales de la CIA y el ejército de los EE. UU. lograron construir y dirigir a los peshmerga kurdos hasta convertirlos en una fuerza eficaz y atacar el norte. Las bases principales para la invasión estaban en Kuwait y otros estados del Golfo Pérsico . Un resultado de esto fue que una de las divisiones destinadas a la invasión se vio obligada a reubicarse y no pudo participar en la invasión hasta bien entrada la guerra. Muchos observadores sintieron que la coalición dedicó un número suficiente de tropas a la invasión, pero que demasiadas se retiraron después de que terminó, y que el hecho de no ocupar ciudades los puso en una gran desventaja para lograr la seguridad y el orden en todo el país cuando el apoyo local no estuvo a la altura de las expectativas.

Estados Unidos lanzó su invasión de Irak como una continuación operativa efectiva de la Primera Guerra del Golfo . Sus principales objetivos eran destruir el ejército iraquí, paralizar su capacidad de lucha y desmantelar el gobierno iraquí. [166] Sin embargo, los iraquíes se adaptaron de inmediato y comenzaron a utilizar tácticas no convencionales. Ya el 22 de marzo, apenas dos días después del inicio de la guerra, los estadounidenses experimentaron por primera vez las tácticas de insurgencia que luego definirían la guerra. El sargento de primera clase Anthony Broadhead, un sargento de pelotón de la tropa Crazy Horse de la unidad de caballería de la 3.ª División de Infantería, estaba en un tanque que se dirigía hacia un puente en Samawah en la ruta de la invasión. Saludó a un grupo de iraquíes, pero en lugar de devolverles el saludo, comenzaron a atacar a los tanques estadounidenses con rifles AK-47, granadas propulsadas por cohetes y morteros. Debido a que este tipo de fuerzas paramilitares estaban bien armadas, pero no se podían distinguir de los civiles, llegarían a representar un desafío significativo para las fuerzas estadounidenses durante la guerra de Irak. [167]

La invasión en sí fue rápida, y condujo al colapso del gobierno iraquí y del ejército de Irak en aproximadamente tres semanas. La infraestructura petrolera de Irak fue rápidamente tomada y asegurada con daños limitados en ese tiempo. Asegurar la infraestructura petrolera se consideró de gran importancia. En la primera Guerra del Golfo, mientras se retiraba de Kuwait, el ejército iraquí había incendiado muchos pozos de petróleo y había vertido petróleo en las aguas del Golfo; esto fue para disfrazar los movimientos de tropas y distraer a las fuerzas de la coalición. Antes de la invasión de 2003, las fuerzas iraquíes habían minado unos 400 pozos de petróleo alrededor de Basora y la península de Al-Faw con explosivos. [168] [169] [170] Las tropas de la coalición lanzaron un asalto aéreo y anfibio en la península de Al-Faw durante las últimas horas del 19 de marzo para asegurar los campos petrolíferos allí; el asalto anfibio fue apoyado por buques de guerra de la Marina Real , la Armada polaca y la Marina Real Australiana .

Mientras tanto, los Tornados de la Royal Air Force de los escuadrones 9 y 617 atacaron los sistemas de defensa de radar que protegían a Bagdad, pero perdieron un Tornado el 22 de marzo junto con el piloto y el navegante (Teniente de vuelo Kevin Main y Teniente de vuelo Dave Williams), derribados por un misil Patriot estadounidense cuando regresaban a su base aérea en Kuwait. [171] El 1 de abril, un F-14 del USS Kitty Hawk se estrelló en el sur de Irak, según se informa debido a una falla del motor, [172] y un S-3B Viking se precipitó desde la cubierta del USS Constellation después de un mal funcionamiento y un avión de salto AV-8B Harrier cayó al Golfo mientras intentaba aterrizar en el USS Nassau . [173]

La 3.ª Brigada de Comandos británica , con el Equipo Especial de Embarcaciones 22, Unidad de Tareas Dos de la Armada de los Estados Unidos , [174] así como la 15.ª Unidad Expedicionaria de Marines del Cuerpo de Marines de los Estados Unidos y la unidad de Fuerzas Especiales polacas GROM , atacaron el puerto de Umm Qasr . Allí se encontraron con una fuerte resistencia por parte de las tropas iraquíes. Un total de 14 tropas de la coalición y entre 30 y 40 tropas iraquíes murieron, y 450 iraquíes fueron hechos prisioneros. La 16.ª Brigada de Asalto Aéreo del Ejército británico junto con elementos del Regimiento de la Real Fuerza Aérea también aseguraron los campos petrolíferos en el sur de Irak en lugares como Rumaila , mientras que los comandos polacos capturaron plataformas petrolíferas en alta mar cerca del puerto, evitando su destrucción. A pesar del rápido avance de las fuerzas de invasión, unos 44 pozos petrolíferos fueron destruidos e incendiados por explosivos iraquíes o por fuego incidental. Sin embargo, los pozos fueron tapados rápidamente y los incendios apagados, evitando el daño ecológico y la pérdida de capacidad de producción de petróleo que se habían producido al final de la Guerra del Golfo.

Siguiendo el plan de avance rápido, la 3.ª División de Infantería de los EE. UU. se movió hacia el oeste y luego hacia el norte a través del desierto occidental hacia Bagdad, mientras que la 1.ª Fuerza Expedicionaria de Marines se movió por la Carretera 1 a través del centro del país, y la 1.ª División Blindada (del Reino Unido) se movió hacia el norte a través de las marismas del este.

Durante la primera semana de la guerra, las fuerzas iraquíes dispararon un misil Scud contra el centro de evaluación de la actualización del campo de batalla estadounidense en Camp Doha , Kuwait. El misil fue interceptado y derribado por un misil Patriot segundos antes de impactar en el complejo. Posteriormente, dos A-10 Warthog atacaron el lanzamisiles.

Inicialmente, la 1.ª División de Infantería de Marina (Estados Unidos) luchó en los campos petrolíferos de Rumaila y se trasladó al norte hasta Nasiriyah , una ciudad de tamaño moderado dominada por los chiítas con una importancia estratégica importante como cruce de carreteras principal y su proximidad al cercano aeródromo de Tallil . También estaba situada cerca de varios puentes estratégicamente importantes sobre el río Éufrates . La ciudad estaba defendida por una mezcla de unidades regulares del ejército iraquí, leales al Baaz y fedayines tanto de Irak como del extranjero. La 3.ª División de Infantería del Ejército de los Estados Unidos derrotó a las fuerzas iraquíes atrincheradas en el aeródromo y sus alrededores y pasó por alto la ciudad hacia el oeste.

El 23 de marzo, un convoy de la 3.ª División de Infantería, en el que se encontraban las soldados estadounidenses Jessica Lynch , Shoshana Johnson y Lori Piestewa , fue emboscado tras tomar un giro equivocado hacia la ciudad. Once soldados estadounidenses murieron y siete, entre ellos Lynch y Johnson, fueron capturados. [175] Piestewa murió por heridas poco después de su captura, mientras que los cinco prisioneros de guerra restantes fueron rescatados más tarde. Se cree que Piestewa, que era de Tuba City , Arizona , y miembro inscrito de la tribu Hopi , fue la primera mujer nativa americana muerta en combate en una guerra extranjera. [176] El mismo día, los marines estadounidenses de la 2.ª División de Marines entraron en Nasiriyah en masa, enfrentándose a una fuerte resistencia mientras avanzaban para asegurar dos puentes importantes en la ciudad. Varios marines murieron durante un tiroteo con fedayines en los combates urbanos. En el Canal de Saddam, otros 18 marines murieron en duros combates con soldados iraquíes. Un A-10 de la Fuerza Aérea se vio involucrado en un caso de fuego amigo que resultó en la muerte de seis marines cuando atacó accidentalmente un vehículo anfibio estadounidense. Otros dos vehículos fueron destruidos cuando una andanada de RPG y fuego de armas pequeñas mató a la mayoría de los marines que estaban en el interior. [177] Un marine del 28.º Grupo de Control Aéreo de Marines murió por fuego enemigo y dos ingenieros de marines se ahogaron en el Canal de Saddam. Los puentes fueron asegurados y la Segunda División de Marines estableció un perímetro alrededor de la ciudad.

En la tarde del 24 de marzo, el 2.º Batallón de Reconocimiento Blindado Ligero , que estaba adscrito al Equipo de Combate Regimental Uno (RCT-1) , avanzó a través de Nasiriyah y estableció un perímetro de 15 km (9,3 millas) al norte de la ciudad. Los refuerzos iraquíes de Kut lanzaron varios contraataques. Los marines lograron repelerlos utilizando fuego indirecto y apoyo aéreo cercano. El último ataque iraquí fue rechazado al amanecer. El batallón estimó que murieron entre 200 y 300 soldados iraquíes, sin una sola baja estadounidense. Nasiriyah fue declarada segura, pero los ataques de los fedayines iraquíes continuaron. Estos ataques no estaban coordinados y dieron lugar a tiroteos que mataron a muchos fedayines. Debido a la posición estratégica de Nasiriyah como cruce de carreteras, se produjo un importante atasco cuando las fuerzas estadounidenses que se movían hacia el norte convergieron en las carreteras circundantes de la ciudad.

Una vez asegurados los aeródromos de Nasiriyah y Tallil, las fuerzas de la coalición consiguieron un importante centro logístico en el sur de Irak y establecieron la base de operaciones de la Fuerza Aérea Jalibah, a unos 16 kilómetros de Nasiriyah. Pronto se trasladaron tropas y suministros adicionales a través de esta base de operaciones avanzada. La 101 División Aerotransportada continuó su ataque hacia el norte en apoyo de la 3.ª División de Infantería.

El 28 de marzo, una fuerte tormenta de arena frenó el avance de la coalición y la 3.ª División de Infantería detuvo su avance hacia el norte a mitad de camino entre Najaf y Karbala. Las operaciones aéreas con helicópteros, preparados para traer refuerzos de la 101.ª División Aerotransportada, quedaron bloqueadas durante tres días. Se produjeron combates especialmente intensos en el puente y sus alrededores, cerca de la ciudad de Kufl.

Otra batalla feroz fue en Najaf , donde las unidades aerotransportadas y blindadas estadounidenses con apoyo aéreo británico libraron una intensa batalla con las tropas regulares iraquíes, las unidades de la Guardia Republicana y las fuerzas paramilitares. Comenzó con los helicópteros artillados AH-64 Apache estadounidenses que partieron en una misión para atacar a las unidades blindadas de la Guardia Republicana; mientras volaban a baja altura, los Apaches fueron objeto de un intenso fuego antiaéreo, de armas pequeñas y de lanzacohetes que dañaron gravemente muchos helicópteros y derribaron uno, frustrando el ataque. [178] Atacaron de nuevo con éxito el 26 de marzo, esta vez después de un bombardeo de artillería previo a la misión y con el apoyo de los aviones F/A-18 Hornet , sin perder ningún helicóptero artillado. [179]