La historia de China abarca varios milenios en una amplia zona geográfica. Cada región que ahora se considera parte del mundo chino ha experimentado períodos de unidad, fractura, prosperidad y conflicto. La civilización china surgió por primera vez en el valle del río Amarillo , que junto con la cuenca del Yangtsé constituye el núcleo geográfico de la esfera cultural china . China mantiene una rica diversidad de grupos étnicos y lingüísticos. La lente tradicional para ver la historia china es el ciclo dinástico : las dinastías imperiales surgen y caen, y se les atribuyen ciertos logros. A lo largo de todo el relato está impregnado de que la civilización china puede rastrearse como un hilo ininterrumpido muchos miles de años en el pasado , lo que la convierte en una de las cunas de la civilización . En varias épocas, los estados representativos de una cultura china dominante han controlado directamente áreas que se extienden tan al oeste como Tian Shan , la cuenca del Tarim y el Himalaya , tan al norte como las montañas Sayan y tan al sur como el delta del río Rojo .

El Neolítico fue testigo del surgimiento de sistemas políticos cada vez más complejos a lo largo de los ríos Amarillo y Yangtsé . La cultura Erlitou, en las llanuras centrales de China , se identifica a veces con la dinastía Xia (tercer milenio a. C.) de la historiografía tradicional china . El chino escrito más antiguo que se conserva data de aproximadamente el año 1250 a. C. y consiste en adivinaciones inscritas en huesos oraculares . Las inscripciones chinas en bronce , textos rituales dedicados a los antepasados, forman otro gran corpus de la escritura china primitiva. Los primeros estratos de la literatura recibida en chino incluyen poesía , adivinación y registros de discursos oficiales . Se cree que China es uno de los pocos lugares de invención independiente de la escritura, y los registros más antiguos que se conservan muestran un lenguaje escrito ya maduro. La cultura recordada por la literatura existente más antigua es la de la dinastía Zhou ( c. 1046 – 256 a. C.), la Era Axial de China , durante la cual se introdujo el Mandato del Cielo y se sentaron las bases para filosofías como el confucianismo , el taoísmo , el legalismo y el wuxing .

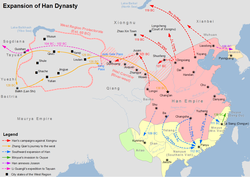

China fue unificada por primera vez bajo un solo estado imperial por Qin Shi Huang en el 221 a. C. Se estandarizaron la ortografía , los pesos, las medidas y las leyes. Poco después, China entró en su era clásica con la dinastía Han (202 a. C. - 220 d. C.), que marcó un período crítico. Un término para la lengua china todavía es "lengua Han", y el grupo étnico chino dominante es conocido como chino Han . El imperio chino alcanzó algunas de sus mayores extensiones geográficas durante este período. El confucianismo fue sancionado oficialmente y sus textos centrales fueron editados en sus formas recibidas. Las familias terratenientes ricas independientes de la antigua aristocracia comenzaron a ejercer un poder significativo. La tecnología Han puede considerarse a la par con la del Imperio Romano contemporáneo : la producción masiva de papel ayudó a la proliferación de documentos escritos, y el lenguaje escrito de este período se empleó durante milenios después. China se hizo conocida internacionalmente por su sericultura . Cuando el orden imperial Han finalmente colapsó después de cuatro siglos, China entró en un período igualmente largo de desunión, durante el cual el budismo comenzó a tener un impacto significativo en la cultura china, mientras que la caligrafía , el arte, la historiografía y la narración florecieron. Las familias ricas en algunos casos se volvieron más poderosas que el gobierno central. El valle del río Yangtze se incorporó a la esfera cultural dominante.

En 581 se inició un período de unidad con la dinastía Sui , que pronto dio paso a la longeva dinastía Tang (608-907), considerada otra época dorada china. La dinastía Tang vio florecientes desarrollos en ciencia, tecnología, poesía, economía e influencia geográfica. La única emperatriz oficialmente reconocida de China, Wu Zetian , reinó durante el primer siglo de la dinastía. El budismo fue adoptado por los emperadores Tang. "Pueblo Tang" es el otro gentilicio común para el grupo étnico Han. Después de la fractura de la dinastía Tang, la dinastía Song (960-1279) vio la máxima extensión del desarrollo cosmopolita imperial chino. Se introdujo la imprenta mecánica , y muchos de los primeros testigos sobrevivientes de ciertos textos son grabados en madera de esta era. El avance científico de Song lideró el mundo, y el sistema de exámenes imperial dio estructura ideológica a la burocracia política. El confucianismo y el taoísmo se unieron plenamente en el neoconfucianismo .

Finalmente, el Imperio mongol conquistó toda China y estableció la dinastía Yuan en 1271. El contacto con Europa comenzó a aumentar durante este tiempo. Los logros de la posterior dinastía Ming (1368-1644) incluyen la exploración global , la porcelana fina y muchos proyectos de obras públicas existentes, como los de restauración del Gran Canal y la Gran Muralla . Tres de las cuatro novelas clásicas chinas se escribieron durante la dinastía Ming. La dinastía Qing que sucedió a la Ming fue gobernada por personas de etnia manchú . El emperador Qianlong ( r. 1735-1796) encargó una enciclopedia completa de bibliotecas imperiales, con un total de casi mil millones de palabras. La China imperial alcanzó su mayor extensión territorial durante la dinastía Qing, pero China entró en crecientes conflictos con las potencias europeas, que culminaron en las Guerras del Opio y los posteriores tratados desiguales .

La Revolución Xinhai de 1911 , liderada por Sun Yat-sen y otros, creó la República de China moderna . Entre 1927 y 1949, se desató una costosa guerra civil entre el gobierno republicano de Chiang Kai-shek y el Ejército Rojo chino , de tendencia comunista, interrumpida por la invasión del país dividido por el Imperio industrializado de Japón hasta su derrota en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

Después de la victoria comunista , Mao Zedong proclamó el establecimiento de la República Popular China (RPC) en 1949, con la República retirándose a Taiwán. Ambos gobiernos todavía reclaman la legitimidad exclusiva de toda el área continental. La RPC ha acumulado lentamente la mayoría del reconocimiento diplomático, y el estatus de Taiwán sigue siendo disputado hasta el día de hoy. De 1966 a 1976, la Revolución Cultural en China continental ayudó a consolidar el poder de Mao hacia el final de su vida. Después de su muerte, el gobierno comenzó reformas económicas bajo Deng Xiaoping , y se convirtió en la economía principal de más rápido crecimiento del mundo . [ ¿Cuándo? ] China había sido la nación más poblada del mundo durante décadas desde su unificación, hasta que fue superada por la India en 2023.

La especie humana arcaica de Homo erectus llegó a Eurasia en algún momento entre hace 1,3 y 1,8 millones de años (Ma) y se han encontrado numerosos restos de su subespecie en lo que hoy es China. [1] El más antiguo de ellos es el Hombre de Yuanmou (元谋人; en Yunnan ), del suroeste, que data de c. 1,7 Ma, que vivió en un entorno mixto de matorrales y bosques junto a chalicoterios , ciervos , el elefante Stegodon , rinocerontes , ganado vacuno, cerdos y la hiena gigante de cara corta . [2] El más conocido Hombre de Pekín (北京猿人; cerca de Beijing) de 700.000–400.000 BP , [1] fue descubierto en la cueva de Zhoukoudian junto con raspadores , hachadoras y, fechados un poco más tarde, puntas, buriles y punzones. [3] Se han encontrado otros fósiles de Homo erectus en toda la región, incluido el Hombre de Lantian del noroeste en Shaanxi , así como especímenes menores en el noreste de Liaoning y el sur de Guangdong . [1] Las fechas de la mayoría de los sitios paleolíticos fueron debatidas durante mucho tiempo, pero se han establecido de manera más confiable basándose en la magnetoestratigrafía moderna : Majuangou en 1,66-1,55 Ma, Lanpo en 1,6 Ma, Xiaochangliang en 1,36 Ma, Xiantai en 1,36 Ma, Banshan en 1,32 Ma, Feiliang en 1,2 Ma y Donggutuo en 1,1 Ma. [4] La evidencia del uso del fuego por parte del Homo erectus ocurrió entre 1 y 1,8 millones de años AP en el sitio arqueológico de Xihoudu , provincia de Shanxi. [5]

Las circunstancias que rodearon la evolución del Homo erectus al H. sapiens contemporáneo son debatidas; las tres teorías principales incluyen la teoría dominante "Out of Africa" (OOA), el modelo de continuidad regional y la variante de mezcla de la hipótesis OOA. [1] De todos modos, los primeros humanos modernos han sido datados en China en 120.000-80.000 BP basándose en dientes fosilizados descubiertos en la cueva Fuyan del condado de Dao , Hunan. [6] Los animales más grandes que vivieron junto a estos humanos incluyen al panda extinto Ailuropoda baconi , la hiena Crocuta ultima , el Stegodon y el tapir gigante . [6] Se han encontrado evidencias de tecnología Levallois del Paleolítico Medio en el conjunto lítico del sitio de la cueva Guanyindong en el suroeste de China, que data de aproximadamente hace 170.000-80.000 años. [7]

Se considera que el Neolítico en China comenzó hace unos 10.000 años. [8] Dado que el Neolítico se define convencionalmente por la presencia de la agricultura, se deduce que comenzó en diferentes momentos en las diversas regiones de lo que hoy es China. La agricultura en China se desarrolló gradualmente, con la domesticación inicial de algunos granos y animales que se expandieron gradualmente con la incorporación de muchos otros durante los milenios posteriores. [9] La evidencia más temprana del arroz cultivado, encontrada junto al río Yangtze, fue datada por carbono en 8.000 años atrás. [10] La evidencia temprana de la agricultura del mijo en el valle del río Amarillo fue datada por radiocarbono en aproximadamente 7000 a. C. [11] El sitio de Jiahu es uno de los pueblos agrícolas tempranos mejor conservados (7000 a 5800 a. C.). En Damaidi , Ningxia, se han descubierto 3.172 grabados en acantilados que datan de entre 6000 y 5000 a. C., "que presentan 8.453 caracteres individuales como el sol, la luna, las estrellas, los dioses y escenas de caza o pastoreo", según el investigador Li Xiangshi. Se encontraron símbolos escritos, a veces llamados protoescritura , en el yacimiento de Jiahu, que data de alrededor de 7000 a. C., [12] Damaidi alrededor de 6000 a. C., Dadiwan de 5800 a. C. a 5400 a. C., [13] y Banpo , que data del quinto milenio a. C. Con la agricultura llegó el aumento de la población, la capacidad de almacenar y redistribuir las cosechas y el potencial para apoyar a artesanos y administradores especializados, que pueden haber existido en yacimientos del Neolítico tardío como Taosi y la cultura Liangzhu en el delta del Yangtze. [10] Las culturas del Neolítico medio y tardío en el valle central del río Amarillo se conocen, respectivamente, como la cultura Yangshao (5000 a. C. a 3000 a. C.) y la cultura Longshan (3000 a. C. a 2000 a. C.). Los cerdos y los perros fueron los primeros animales domesticados en la región, y después de aproximadamente el 3000 a. C. llegaron vacas y ovejas domesticadas desde Asia occidental. El trigo también llegó en esta época, pero siguió siendo un cultivo menor. Frutas como los melocotones , las cerezas y las naranjas , así como pollos y varias verduras, también fueron domesticadas en la China neolítica. [9]

Se han encontrado artefactos de bronce en el yacimiento de la cultura Majiayao (entre 3100 y 2700 a. C.). [14] [15] La Edad del Bronce también está representada en el yacimiento de la cultura Xiajiadian inferior (2200-1600 a. C.) [16] en el noreste de China. Se cree que Sanxingdui , ubicado en lo que ahora es Sichuan , es el sitio de una importante ciudad antigua, de una cultura de la Edad del Bronce previamente desconocida (entre 2000 y 1200 a. C.). El sitio fue descubierto por primera vez en 1929 y luego redescubierto en 1986. Los arqueólogos chinos han identificado la cultura Sanxingdui como parte del estado de Shu , vinculando los artefactos encontrados en el sitio a sus primeros reyes legendarios. [17] [18]

La metalurgia ferrosa comienza a aparecer a finales del siglo VI en el valle del Yangtze . [19] Un hacha de bronce con una hoja de hierro meteórico excavada cerca de la ciudad de Gaocheng en Shijiazhuang (ahora Hebei ) ha sido datada en el siglo XIV a. C. Una cultura de la Edad del Hierro de la meseta tibetana se ha asociado tentativamente con la cultura Zhang Zhung descrita en los primeros escritos tibetanos.

Los historiadores chinos de períodos posteriores estaban acostumbrados a la noción de que una dinastía sucedía a otra, pero la situación política en la China primitiva era mucho más complicada. Por lo tanto, como sugieren algunos estudiosos de China, los Xia y los Shang pueden referirse a entidades políticas que existieron simultáneamente, al igual que los primeros Zhou existieron al mismo tiempo que los Shang. [20] Esto guarda similitudes con la forma en que China, tanto contemporáneamente como posteriormente, se ha dividido en estados que no eran una región, legal o culturalmente. [21]

El período más antiguo que se considera histórico es la era legendaria de los sabios emperadores Yao , Shun y Yu . Tradicionalmente, el sistema de abdicación fue prominente en este período, [22] cuando Yao cedió su trono a Shun, quien abdicó ante Yu, quien fundó la dinastía Xia.

La dinastía Xia ( c. 2070 - c. 1600 a. C. ) es la más antigua de las tres dinastías descritas en la historiografía tradicional mucho más tardía, que incluye los Anales de Bambú y el Shiji de Sima Qian ( c. 91 a. C. ). Los eruditos occidentales generalmente consideran que Xia es mítica, pero en China generalmente se la asocia con el sitio de la Edad del Bronce temprana en Erlitou (1900-1500 a. C.) en Henan que fue excavado en 1959. Dado que no se excavó ningún escrito en Erlitou ni en ningún otro sitio contemporáneo, no hay suficiente evidencia para demostrar si la dinastía Xia alguna vez existió. Algunos arqueólogos afirman que el sitio de Erlitou fue la capital de Xia. [23] En cualquier caso, el sitio de Erlitou tenía un nivel de organización política que no sería incompatible con las leyendas de Xia registradas en textos posteriores. [24] Más importante aún, el sitio de Erlitou tiene la evidencia más temprana de una élite que realizaba rituales utilizando vasijas de bronce fundido, que luego serían adoptadas por los Shang y los Zhou. [25]

Tanto la evidencia arqueológica como los huesos y bronces de oráculo, así como los textos transmitidos atestiguan la existencia histórica de la dinastía Shang ( c. 1600 - c. 1046 a. C. ). Los hallazgos del período Shang anterior provienen de excavaciones en Erligang (actual Zhengzhou ). Se han encontrado hallazgos en Yinxu (cerca de la moderna Anyang , Henan), el sitio de la capital final de Shang durante el período Shang tardío ( c. 1250-1050 a. C. ). [26] Los hallazgos en Anyang incluyen el registro escrito más antiguo de los chinos descubierto hasta ahora: inscripciones de registros de adivinación en escritura china antigua en los huesos o caparazones de animales, los huesos de oráculo , que datan de c. 1250 - c. 1046 a. C. [ 27]

Una serie de al menos veintinueve reyes reinaron durante la dinastía Shang. [28] A lo largo de sus reinados, según el Shiji , la ciudad capital fue trasladada seis veces. [29] La mudanza final y más importante fue a Yin durante el reinado de Wu Ding alrededor del 1250 a. C. [ 30] El término dinastía Yin ha sido sinónimo de la dinastía Shang en la historia, aunque últimamente se ha utilizado para referirse específicamente a la segunda mitad de la dinastía Shang. [28]

Aunque los registros escritos encontrados en Anyang confirman la existencia de la dinastía Shang, [31] los académicos occidentales suelen dudar en asociar los asentamientos contemporáneos al asentamiento de Anyang con la dinastía Shang. Por ejemplo, los hallazgos arqueológicos en Sanxingdui sugieren una civilización tecnológicamente avanzada y culturalmente diferente a Anyang. La evidencia no es concluyente a la hora de demostrar hasta qué punto se extendió el reino Shang desde Anyang. La hipótesis principal es que Anyang, gobernado por el mismo Shang en la historia oficial, coexistió y comerció con numerosos otros asentamientos culturalmente diversos en el área que ahora se conoce como China propiamente dicha . [32]

La dinastía Zhou (1046 a. C. a aproximadamente 256 a. C.) es la dinastía más duradera de la historia china, aunque su poder disminuyó de manera constante durante los casi ocho siglos de su existencia. A fines del segundo milenio a. C., la dinastía Zhou surgió en el valle del río Wei de la moderna provincia occidental de Shaanxi, donde fueron designados protectores occidentales por los Shang . Una coalición liderada por el gobernante de los Zhou, el rey Wu , derrotó a los Shang en la batalla de Muye . Tomaron la mayor parte del valle central y bajo del río Amarillo y enfeudaron a sus parientes y aliados en estados semiindependientes en toda la región. [33] Varios de estos estados eventualmente se volvieron más poderosos que los reyes Zhou.

Los reyes de Zhou invocaron el concepto del Mandato del Cielo para legitimar su gobierno, un concepto que fue influyente para casi todas las dinastías posteriores. [34] Al igual que Shangdi, el Cielo ( tian ) gobernaba a todos los demás dioses y decidía quién gobernaría China. [35] Se creía que un gobernante perdía el Mandato del Cielo cuando se producían desastres naturales en gran número y cuando, de manera más realista, el soberano aparentemente había perdido su preocupación por el pueblo. En respuesta, la casa real sería derrocada y una nueva casa gobernaría, habiéndosele concedido el Mandato del Cielo.

Los Zhou establecieron dos capitales, Zongzhou (cerca de la actual Xi'an ) y Chengzhou ( Luoyang ), y la corte real se trasladaba entre ellas con regularidad. La alianza Zhou se expandió gradualmente hacia el este hasta Shandong, hacia el sureste hasta el valle del río Huai y hacia el sur hasta el valle del río Yangtze . [33]

En 771 a. C., el rey You y sus fuerzas fueron derrotados en la batalla del monte Li por los estados rebeldes y los bárbaros de Quanrong . Los aristócratas rebeldes establecieron un nuevo gobernante, el rey Ping , en Luoyang , [36] : 4 comenzando la segunda fase importante de la dinastía Zhou: el período Zhou Oriental, que se divide en los períodos de Primavera y Otoño y de los Estados Combatientes. El primer período recibe su nombre de los famosos Anales de Primavera y Otoño . La autoridad política drásticamente reducida de la casa real dejó un vacío de poder en el centro de la esfera de la cultura Zhou. Los reyes Zhou habían delegado la autoridad política local a cientos de estados de asentamiento , algunos de ellos tan grandes como una ciudad amurallada y la tierra circundante. Estos estados comenzaron a luchar entre sí y a competir por la hegemonía . Los estados más poderosos tendieron a conquistar e incorporar a los más débiles, por lo que el número de estados disminuyó con el tiempo. [37] Para el siglo VI a. C., la mayoría de los estados pequeños habían desaparecido al ser anexados y solo quedaban unos pocos principados grandes y poderosos. Algunos estados del sur, como Chu y Wu, reclamaron su independencia de los Zhou, quienes emprendieron guerras contra algunos de ellos (Wu y Yue). En este período se fundaron muchas ciudades nuevas y la sociedad se fue urbanizando y comercializando gradualmente. Muchos personajes famosos, como Laozi , Confucio y Sun Tzu, vivieron durante este período caótico.

En este período, los conflictos se produjeron tanto entre los estados como dentro de ellos. Las guerras entre estados obligaron a los estados supervivientes a desarrollar mejores administraciones para movilizar más soldados y recursos. Dentro de los estados, había constantes disputas entre las familias de la élite. Por ejemplo, las tres familias más poderosas del estado Jin (Zhao, Wei y Han) acabaron derrocando a la familia gobernante y se repartieron el estado entre ellas .

Durante este período y el posterior período de los Reinos Combatientes comenzaron a florecer las Cien Escuelas de Pensamiento de la filosofía clásica china . Se fundaron movimientos intelectuales tan influyentes como el confucianismo , el taoísmo , el legalismo y el moísmo , en parte como respuesta al cambiante mundo político. Las dos primeras corrientes filosóficas tendrían una enorme influencia en la cultura china.

Después de otras consolidaciones políticas, durante el siglo V a. C. quedaron siete estados importantes. Los años en que estos estados lucharon entre sí se conocen como el período de los Reinos Combatientes . Aunque el rey Zhou permaneció nominalmente como tal hasta el año 256 a. C., fue en gran medida una figura decorativa que ostentaba poco poder real.

Durante este período se produjeron numerosos avances en las áreas de la cultura y las matemáticas, entre ellos el Zuo Zhuan dentro de los Anales de Primavera y Otoño (una obra literaria que resume el período de Primavera y Otoño anterior), y el paquete de 21 hojas de bambú de la colección Tsinghua , que data del 305 a. C., que es el ejemplo más antiguo conocido en el mundo de una tabla de multiplicación de dos dígitos en base 10. La colección Tsinghua indica que la aritmética comercial sofisticada ya estaba establecida durante este período. [38]

A medida que se anexionaban los territorios vecinos de los siete estados (incluidas áreas de las actuales Sichuan y Liaoning ), estos debían ser gobernados por un sistema administrativo de comandancias y prefecturas . Este sistema se había utilizado en otros lugares desde el período de Primaveras y Otoños, y su influencia en la administración demostraría ser resistente: su terminología todavía se puede ver en los contemporáneos sheng y xian ("provincias" y "condados") de la China contemporánea.

El estado de Qin se volvió dominante en las décadas finales del período de los Reinos Combatientes, conquistando la capital Shu de Jinsha en la llanura de Chengdu; y luego eventualmente expulsando a Chu de su lugar en el valle del río Han. Qin imitó las reformas administrativas de los otros estados, convirtiéndose así en una potencia. [9] Su expansión final comenzó durante el reinado de Ying Zheng , unificando finalmente a las otras seis potencias regionales y permitiéndole proclamarse como el primer emperador de China , conocido en la historia como Qin Shi Huang .

El establecimiento de la dinastía Qin (秦朝) por parte de Ying Zheng en el 221 a. C. formalizó efectivamente la región como un verdadero imperio por primera vez en la historia china, en lugar de un estado, y su estatus fundamental probablemente llevó a que "Qin" (秦) evolucionara más tarde al término occidental "China". [39] Para enfatizar su gobierno único, Zheng se proclamó Shi Huangdi (始皇帝; "Primer Emperador"); el título Huangdi , derivado de la mitología china , se convirtió en el estándar para los gobernantes posteriores. [40] [a] Con sede en Xianyang , el imperio era una monarquía burocrática centralizada , un esquema de gobierno que dominó el futuro de la China imperial. [42] [43] En un esfuerzo por mejorar los fracasos percibidos de los Zhou, este sistema consistía en más de 36 comandancias (郡; jun ), [b] compuestas por condados (县; xian ) y divisiones progresivamente más pequeñas, cada una con un líder local. [46]

Muchos aspectos de la sociedad fueron influenciados por el legalismo , una ideología estatal promovida por el emperador y su canciller Li Si que fue introducida en un momento anterior por Shang Yang . [47] En asuntos legales, esta filosofía enfatizó la responsabilidad mutua en disputas y castigos severos por el crimen, mientras que las prácticas económicas incluyeron el estímulo general de la agricultura y la represión del comercio. [47] Se produjeron reformas en pesos y medidas, estilos de escritura ( escritura de sello ) y moneda de metal ( Ban Liang ), todos los cuales fueron estandarizados. [48] [49] Tradicionalmente, se considera que Qin Shi Huang ordenó una quema masiva de libros y el entierro vivo de eruditos bajo el disfraz del legalismo, aunque los eruditos contemporáneos expresan dudas considerables sobre la historicidad de este evento . [47] A pesar de su importancia, el legalismo probablemente fue complementado en asuntos no políticos por el confucianismo para las creencias sociales y morales y las teorías de cinco elementos Wuxing (五行) para el pensamiento cosmológico . [50]

La administración Qin mantuvo registros exhaustivos de su población, recopilando información sobre su sexo, edad, estatus social y residencia. [51] Los plebeyos, que constituían más del 90% de la población, [52] "sufrían un trato duro" según la historiadora Patricia Buckley Ebrey , ya que a menudo eran reclutados para trabajos forzados para los proyectos de construcción del imperio. [53] Esto incluía un sistema masivo de carreteras imperiales en 220 a. C., que se extendía alrededor de 4.250 millas (6.840 km) en total. [54] Otros proyectos de construcción importantes fueron asignados al general Meng Tian , que al mismo tiempo dirigió una exitosa campaña contra los pueblos xiongnu del norte (210 a. C.), según se informa con 300.000 tropas. [54] [c] Bajo las órdenes de Qin Shi Huang, Meng supervisó la combinación de numerosos muros antiguos en lo que llegó a conocerse como la Gran Muralla China y supervisó la construcción de una carretera recta de 500 millas (800 km) entre el norte y el sur de China. [56] El emperador también supervisó la construcción de su monumental mausoleo , que incluye el conocido Ejército de Terracota . [57]

Después de la muerte de Qin Shi Huang, el gobierno de Qin se deterioró drásticamente y finalmente capituló en el 207 a. C. después de que la capital de Qin fuera capturada y saqueada por rebeldes, lo que finalmente conduciría al establecimiento del Imperio Han. [58] [59]

La dinastía Han fue fundada por Liu Bang , quien salió victorioso de la disputa Chu-Han que siguió a la caída de la dinastía Qin. Una época dorada en la historia china, el largo período de estabilidad y prosperidad de la dinastía Han consolidó la base de China como un estado unificado bajo una burocracia imperial central, que duraría de manera intermitente durante la mayor parte de los siguientes dos milenios. Durante la dinastía Han, el territorio de China se extendió a la mayor parte de China propiamente dicha y a áreas del lejano oeste. El confucianismo fue elevado oficialmente a la categoría de ortodoxo y daría forma a la posterior civilización china. El arte, la cultura y la ciencia avanzaron a alturas sin precedentes. Con los profundos y duraderos impactos de este período de la historia china, el nombre de la dinastía "Han" había sido tomado como el nombre del pueblo chino, ahora el grupo étnico dominante en la China moderna, y había sido comúnmente utilizado para referirse al idioma chino y los caracteres escritos .

Después de las políticas iniciales de laissez-faire de los emperadores Wen y Jing , el ambicioso emperador Wu llevó al imperio a su apogeo. Para consolidar su poder, privó de sus derechos a la mayoría de los parientes imperiales, nombrando gobernadores militares para controlar sus antiguas tierras. [60] Como paso adicional, extendió el patrocinio al confucianismo, que enfatiza la estabilidad y el orden en una sociedad bien estructurada. Se establecieron universidades imperiales para apoyar su estudio. Sin embargo, a instancias de sus asesores legalistas, también fortaleció la estructura fiscal de la dinastía con monopolios gubernamentales .

Se lanzaron importantes campañas militares para debilitar al Imperio nómada Xiongnu , limitando su influencia al norte de la Gran Muralla. Junto con los esfuerzos diplomáticos liderados por Zhang Qian , la esfera de influencia del Imperio Han se extendió a los estados de la cuenca del Tarim , abrió la Ruta de la Seda que conectaba a China con el oeste, estimulando el comercio bilateral y el intercambio cultural. Al sur, varios pequeños reinos mucho más allá del valle del río Yangtze se incorporaron formalmente al imperio.

El emperador Wu también lanzó una serie de campañas militares contra las tribus Baiyue . Los Han se anexionaron Minyue en 135 a. C. y 111 a. C., Nanyue en 111 a. C. y Dian en 109 a. C. [ 61] La migración y las expediciones militares llevaron a la asimilación cultural del sur. [62] También puso a los Han en contacto con reinos del sudeste asiático, introduciendo la diplomacia y el comercio. [63]

Después del emperador Wu, el imperio se sumió en un estancamiento y decadencia graduales. En el plano económico, el tesoro estatal se vio afectado por campañas y proyectos excesivos, mientras que las adquisiciones de tierras por parte de familias de la élite fueron agotando gradualmente la base impositiva. Varios clanes consortes ejercieron un control cada vez mayor sobre una serie de emperadores incompetentes y, finalmente, la dinastía se vio brevemente interrumpida por la usurpación de Wang Mang .

En el año 9 d. C., el usurpador Wang Mang afirmó que el Mandato del Cielo exigía el fin de la dinastía Han y el ascenso de la suya, y fundó la efímera dinastía Xin. Wang Mang inició un amplio programa de reformas agrarias y económicas, que incluían la abolición de la esclavitud y la nacionalización y redistribución de la tierra. Sin embargo, estos programas nunca fueron apoyados por las familias terratenientes, porque favorecían a los campesinos. La inestabilidad del poder provocó caos, levantamientos y pérdida de territorios. A todo esto se sumó la inundación masiva del río Amarillo , que se dividió en dos canales debido a la acumulación de sedimentos y desplazó a un gran número de agricultores. Wang Mang fue finalmente asesinado en el palacio de Weiyang por una turba de campesinos enfurecida en el año 23 d. C.

El emperador Guangwu restableció la dinastía Han con el apoyo de las familias terratenientes y comerciantes de Luoyang , al este de la antigua capital Xi'an. Por lo tanto, esta nueva era se denomina dinastía Han del Este . Con las capaces administraciones de los emperadores Ming y Zhang , se recuperaron las antiguas glorias de la dinastía, con brillantes logros militares y culturales. El Imperio Xiongnu fue derrotado decisivamente . El diplomático y general Ban Chao expandió aún más las conquistas a través del Pamir hasta las orillas del Mar Caspio , [64] : 175 reabriendo así la Ruta de la Seda y trayendo comercio, culturas extranjeras, junto con la llegada del Budismo . Con amplias conexiones con Occidente, la primera de varias embajadas romanas a China se registraron en fuentes chinas, provenientes de la ruta marítima en el año 166 d. C., y una segunda en el año 284 d. C.

La dinastía Han del Este fue una de las épocas más prolíficas de la ciencia y la tecnología en la antigua China, en particular la histórica invención de la fabricación de papel por Cai Lun y las numerosas contribuciones científicas y matemáticas del famoso polímata Zhang Heng .

En el siglo II, el imperio decayó en medio de adquisiciones de tierras, invasiones y disputas entre clanes consortes y eunucos . La Rebelión de los Turbantes Amarillos estalló en el año 184 d. C., marcando el comienzo de una era de señores de la guerra . En la agitación que siguió, surgieron tres estados que intentaron obtener predominio y reunificar la tierra, lo que dio nombre a este período histórico. La novela histórica clásica Romance de los Tres Reinos dramatiza los acontecimientos de este período.

El caudillo Cao Cao reunificó el norte en 208, y en 220 su hijo aceptó la abdicación del emperador Xian de Han , iniciando así la dinastía Wei . Pronto, los rivales de Wei, Shu y Wu, proclamaron su independencia. Este período se caracterizó por una descentralización gradual del Estado que había existido durante las dinastías Qin y Han, y un aumento del poder de las grandes familias.

En 266, la dinastía Jin derrocó a la dinastía Wei y más tarde unificó el país en 280, pero esta unión duró poco.

La dinastía Jin reunificó a China por primera vez desde el final de la dinastía Han , poniendo fin a la era de los Tres Reinos . Sin embargo, la dinastía Jin se vio gravemente debilitada por la Guerra de los Ocho Príncipes y perdió el control del norte de China después de que los colonos chinos no Han se rebelaran y capturaran Luoyang y Chang'an . En 317, el príncipe Jin Sima Rui , con sede en la actual Nanjing , se convirtió en emperador y continuó la dinastía, ahora conocida como Jin del Este, que mantuvo el sur de China durante otro siglo. Antes de este movimiento, los historiadores se refieren a la dinastía Jin como Jin del Oeste.

El norte de China se fragmentó en una serie de estados independientes conocidos como los Dieciséis Reinos , la mayoría de los cuales fueron fundados por gobernantes xiongnu , xianbei , jie , di y qiang . Estos pueblos no han eran antepasados de los turcos , mongoles y tibetanos . Muchos de ellos habían sido, hasta cierto punto, " sinizados " mucho antes de su ascenso al poder. De hecho, a algunos de ellos, en particular los qiang y los xiongnu, ya se les había permitido vivir en las regiones fronterizas dentro de la Gran Muralla desde finales de la época Han. Durante este período, la guerra asoló el norte y provocó una migración china han a gran escala hacia el sur, a la cuenca y el delta del río Yangtsé.

A principios del siglo V, China entró en un período conocido como las dinastías del Norte y del Sur, en el que regímenes paralelos gobernaron las mitades norte y sur del país. En el sur, los Jin del Este dieron paso a los Liu Song , los Qi del Sur , los Liang y, finalmente, los Chen . Cada una de estas dinastías del Sur estaba liderada por familias gobernantes chinas Han y usaban Jiankang (la actual Nanjing) como capital. Resistieron los ataques del norte y preservaron muchos aspectos de la civilización china, mientras que los regímenes bárbaros del norte comenzaron a sinificarse .

En el norte, el último de los Dieciséis Reinos fue extinguido en 439 por el Wei del Norte , un reino fundado por los Xianbei , un pueblo nómada que unificó el norte de China. El Wei del Norte finalmente se dividió en el Wei Oriental y el Wei Occidental , que luego se convirtieron en el Qi del Norte y el Zhou del Norte . Estos regímenes estaban dominados por los chinos Xianbei o Han que se habían casado con miembros de familias Xianbei. Durante este período, la mayoría de los Xianbei adoptaron apellidos Han, lo que finalmente llevó a la asimilación completa en los Han.

A pesar de la división del país, el budismo se extendió por todo el territorio. En el sur de China, la corte real y los nobles solían celebrar intensos debates sobre si se debía permitir el budismo . Al final de la era, budistas y taoístas se habían vuelto mucho más tolerantes entre sí. [65]

La breve dinastía Sui fue un período crucial en la historia china. Fundada por el emperador Wen en 581 en sucesión de los Zhou del Norte , los Sui conquistaron los Chen del Sur en 589 para reunificar China, poniendo fin a tres siglos de división política. Los Sui fueron pioneros en muchas instituciones nuevas, incluido el sistema de gobierno de Tres Departamentos y Seis Ministerios , exámenes imperiales para seleccionar funcionarios de entre los plebeyos, al tiempo que mejoraron los sistemas de fubing , el sistema de reclutamiento militar, y el sistema de distribución de tierras en igualdad de condiciones . Estas políticas, que fueron adoptadas por dinastías posteriores, generaron un enorme crecimiento demográfico y acumularon una riqueza excesiva para el estado. La acuñación de monedas estandarizada se impuso en todo el imperio unificado. El budismo se arraigó como una religión prominente y recibió apoyo oficial. La China Sui era conocida por sus numerosos megaproyectos de construcción. El Gran Canal , destinado al transporte de cereales y tropas, unió las capitales Daxing (Chang'an) y Luoyang con la rica región del sudeste y, por otra ruta, con la frontera noreste. También se amplió la Gran Muralla , al tiempo que una serie de conquistas militares y maniobras diplomáticas pacificaban aún más sus fronteras. Sin embargo, las invasiones masivas de la península de Corea durante la guerra Goguryeo-Sui fracasaron desastrosamente, desencadenando revueltas generalizadas que llevaron a la caída de la dinastía .

La dinastía Tang fue una época dorada de la civilización china , un período próspero, estable y creativo con importantes avances en la cultura, el arte, la literatura (en particular la poesía ) y la tecnología. El budismo se convirtió en la religión predominante entre la gente común. Chang'an (la actual Xi'an ), la capital nacional, fue la ciudad más grande del mundo durante su época . [66]

El primer emperador, el emperador Gaozu , subió al trono el 18 de junio de 618, colocado allí por su hijo, Li Shimin, quien se convirtió en el segundo emperador, Taizong , uno de los emperadores más grandes de la historia china . Las conquistas militares combinadas y las maniobras diplomáticas redujeron las amenazas de las tribus de Asia Central, extendieron la frontera y unieron a los estados vecinos con un sistema tributario . Las victorias militares en la cuenca del Tarim mantuvieron abierta la Ruta de la Seda, conectando Chang'an con Asia Central y áreas lejanas al oeste. En el sur, las lucrativas rutas comerciales marítimas desde ciudades portuarias como Guangzhou conectaban con países distantes, y los comerciantes extranjeros se establecieron en China, fomentando una cultura cosmopolita . La cultura Tang y los sistemas sociales fueron observados y adaptados por los países vecinos, sobre todo Japón . Internamente, el Gran Canal conectaba el corazón político de Chang'an con los centros agrícolas y económicos en las partes oriental y meridional del imperio. Xuanzang , un monje budista chino , erudito, viajero y traductor, viajó a la India por su cuenta y regresó con "más de seiscientos textos Mahayana y Hinayana, siete estatuas de Buda y más de cien reliquias sarira ".

La prosperidad de la dinastía Tang temprana fue facilitada por una burocracia centralizada. El gobierno estaba organizado en " tres departamentos y seis ministerios " para elaborar, revisar e implementar políticas por separado. Estos departamentos estaban dirigidos por miembros de la familia real y aristócratas terratenientes, pero a medida que avanzaba la dinastía, se unieron o reemplazaron a funcionarios académicos seleccionados mediante exámenes imperiales , lo que estableció patrones para dinastías posteriores.

Bajo el " sistema de tierras iguales " de la dinastía Tang, toda la tierra era propiedad del Emperador y se concedía a cada familia según el tamaño de su unidad familiar. Los hombres a los que se concedían tierras eran reclutados para el servicio militar durante un período fijo cada año, una política militar conocida como el sistema fubing . Estas políticas estimularon un rápido crecimiento de la productividad y un ejército significativo sin mucha carga para el tesoro estatal. Sin embargo, hacia mediados de la dinastía, los ejércitos permanentes habían sustituido al reclutamiento, y la tierra caía continuamente en manos de propietarios privados y las instituciones religiosas a las que se concedían exenciones.

La dinastía continuó floreciendo bajo el gobierno de la emperatriz Wu Zetian , la única emperatriz gobernante oficial en la historia china, y alcanzó su apogeo durante el largo reinado del emperador Xuanzong , quien supervisó un imperio que se extendía desde el Pacífico hasta el mar de Aral con al menos 50 millones de personas. Hubo vibrantes creaciones artísticas y culturales, incluidas las obras de los más grandes poetas chinos , Li Bai y Du Fu .

En el apogeo de la prosperidad del imperio, la rebelión de An Lushan, que tuvo lugar entre 755 y 763, fue un acontecimiento decisivo. La guerra, las enfermedades y los trastornos económicos devastaron a la población y debilitaron drásticamente al gobierno imperial central. Tras la represión de la rebelión, los gobernadores militares regionales, conocidos como jiedushi , adquirieron un estatus cada vez más autónomo a medida que el gobierno central perdía su capacidad para controlarlos. Con la pérdida de ingresos procedentes del impuesto territorial, el gobierno imperial central pasó a depender en gran medida de su monopolio de la sal . En el exterior, los antiguos estados sumisos atacaron el imperio y los vastos territorios fronterizos se perdieron durante siglos. Sin embargo, la sociedad civil se recuperó y prosperó en medio de la debilitada burocracia imperial.

A finales del periodo Tang, el imperio se vio desgastado por las revueltas recurrentes de los gobernadores militares regionales, mientras los funcionarios académicos se enzarzaban en feroces luchas entre facciones y los eunucos corruptos acumulaban un inmenso poder . Catastróficamente, la Rebelión Huang Chao , de 874 a 884, devastó todo el imperio durante una década. El saqueo del puerto sureño de Cantón en 879 fue seguido por la masacre de la mayoría de sus habitantes, especialmente los grandes enclaves comerciales extranjeros. [68] [69] Para 881, ambas capitales, Luoyang y Chang'an , cayeron sucesivamente. La dependencia de los señores de la guerra étnicos Han y Turcos para reprimir la rebelión aumentó su poder e influencia. En consecuencia, la caída de la dinastía tras la usurpación de Zhu Wen condujo a una era de división .

In 808, 30,000 Shatuo under Zhuye Jinzhong defected from the Tibetans to Tang China and the Tibetans punished them by killing Zhuye Jinzhong as they were chasing them.[70] The Uyghurs also fought against an alliance of Shatuo and Tibetans at Beshbalik.[71] The Shatuo Turks under Zhuye Chixin (Li Guochang) served the Tang dynasty in fighting against their fellow Turkic people in the Uyghur Khaganate. In 839, when the Uyghur khaganate (Huigu) general Jueluowu (掘羅勿) rose against the rule of then-reigning Zhangxin Khan, he elicited the help from Zhuye Chixin by giving Zhuye 300 horses, and together, they defeated Zhangxin Khan, who then committed suicide, precipitating the subsequent collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate. In the next few years, when Uyghur Khaganate remnants tried to raid Tang borders, the Shatuo participated extensively in counterattacking the Uyghur Khaganate with other tribes loyal to Tang.[72] In 843, Zhuye Chixin, under the command of the Han Chinese officer Shi Xiong with Tuyuhun, Tangut and Han Chinese troops, participated in a raid against the Uyghur khaganate that led to the slaughter of Uyghur forces at Shahu mountain.[73]

The period of political disunity between the Tang and the Song, known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, lasted from 907 to 960. During this half-century, China was in all respects a multi-state system. Five regimes, namely, (Later) Liang, Tang, Jin, Han and Zhou, rapidly succeeded one another in control of the traditional Imperial heartland in northern China. Among the regimes, rulers of (Later) Tang, Jin and Han were sinicized Shatuo Turks, which ruled over an ethnic majority of Han Chinese in the north. More stable and smaller regimes of mostly ethnic Han rulers coexisted in south and western China over the period, cumulatively constituted the "Ten Kingdoms".

Amidst political chaos in the north, the strategic Sixteen Prefectures (region along today's Great Wall) were ceded to the emerging Khitan Liao dynasty, which drastically weakened the defense of China proper against northern nomadic empires. To the south, Vietnam gained lasting independence after being a Chinese prefecture for many centuries. With wars dominating in Northern China, there were mass southward migrations of population, which further enhanced the southward shift of cultural and economic centers in China. The era ended with the coup of Later Zhou general Zhao Kuangyin, and the establishment of the Song dynasty in 960, which eventually annihilated the remains of the "Ten Kingdoms" and reunified China.

In 960, the Song dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu, with its capital established in Kaifeng (then known as Bianjing). In 979, the Song dynasty reunified most of China proper, while large swaths of the outer territories were occupied by sinicized nomadic empires. The Khitan Liao dynasty, which lasted from 907 to 1125, ruled over Manchuria, Mongolia, and parts of Northern China. Meanwhile, in what are now the north-western Chinese provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi, and Ningxia, the Tangut tribes founded the Western Xia dynasty from 1032 to 1227.

Aiming to recover the strategic sixteen prefectures lost in the previous dynasty, campaigns were launched against the Liao dynasty in the early Song period, which all ended in failure. Then in 1004, the Liao cavalry swept over the exposed North China Plain and reached the outskirts of Kaifeng, forcing the Song's submission and then agreement to the Chanyuan Treaty, which imposed heavy annual tributes from the Song treasury. The treaty was a significant reversal of Chinese dominance of the traditional tributary system. Yet the annual outflow of Song's silver to the Liao was paid back through the purchase of Chinese goods and products, which expanded the Song economy, and replenished its treasury. This dampened the incentive for the Song to further campaign against the Liao. Meanwhile, this cross-border trade and contact induced further sinicization within the Liao Empire, at the expense of its military might which was derived from its nomadic lifestyle. Similar treaties and social-economical consequences occurred in Song's relations with the Jin dynasty.

Within the Liao Empire the Jurchen tribes revolted against their overlords to establish the Jin dynasty in 1115. In 1125, the devastating Jin cataphract annihilated the Liao dynasty, while remnants of Liao court members fled to Central Asia to found the Qara Khitai Empire (Western Liao dynasty). Jin's invasion of the Song dynasty followed swiftly. In 1127, Kaifeng was sacked, a massive catastrophe known as the Jingkang Incident, ending the Northern Song dynasty. Later the entire north of China was conquered. The survived members of Song court regrouped in the new capital city of Hangzhou, and initiated the Southern Song dynasty, which ruled territories south of the Huai River. In the ensuing years, the territory and population of China were divided between the Song dynasty, the Jin dynasty and the Western Xia dynasty. The era ended with the Mongol conquest, as Western Xia fell in 1227, the Jin dynasty in 1234, and finally the Southern Song dynasty in 1279.

Despite its military weakness, the Song dynasty is widely considered to be the high point of classical Chinese civilization. The Song economy, facilitated by technological advancement, had reached a level of sophistication probably unseen in world history before its time. The population soared to over 100 million and the living standards of common people improved tremendously due to improvements in rice cultivation and the wide availability of coal for production. The capital cities of Kaifeng and subsequently Hangzhou were both the most populous cities in the world for their time, and encouraged vibrant civil societies unmatched by previous Chinese dynasties. Although land trading routes to the far west were blocked by nomadic empires, there was extensive maritime trade with neighbouring states, such as in South-east Asia, which facilitated the use of Song coinage as the de facto currency of exchange. Giant wooden vessels equipped with compasses traveled throughout the China Seas and northern Indian Ocean. The concept of insurance was practised by merchants to hedge the risks of such long-haul maritime shipments. With prosperous economic activities, the historically first use of paper currency emerged in the western city of Chengdu, as a cheaper supplement to the existing copper coins.

The Song dynasty was considered to be the golden age of great advancements in science and technology of China, thanks to innovative scholar-officials such as Su Song (1020–1101) and Shen Kuo (1031–1095). Inventions such as the hydro-mechanical astronomical clock, the first continuous and endless power-transmitting chain, woodblock printing and paper money were all invented during the Song dynasty, further cementing its status.

There was court intrigue between the political reformers and conservatives, led by the chancellors Wang Anshi and Sima Guang, respectively. By the mid-to-late 13th century, the Chinese had adopted the dogma of Neo-Confucian philosophy formulated by Zhu Xi. Enormous literary works were compiled during the Song dynasty, such as the innovative historical narrative Zizhi Tongjian ("Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government"). The invention of movable-type printing further facilitated the spread of knowledge. Culture and the arts flourished, with grandiose artworks such as Along the River During the Qingming Festival and Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, along with great Buddhist painters such as the prolific Lin Tinggui.

The Song dynasty was also a period of major innovation in the history of warfare. Gunpowder, while invented in the Tang dynasty, was first put into practical use on the battlefield by the Song army, inspiring a succession of new firearms and siege engines designs. During the Southern Song dynasty, as its survival hinged decisively on guarding the Yangtze and Huai River against the cavalry forces from the north, the first standing navy in China was assembled in 1132, with its admiral's headquarters established at Dinghai. Paddle-wheel warships equipped with trebuchets could launch incendiary bombs made of gunpowder and lime to effect, as recorded in Song's victory over the invading Jin forces at the Battle of Tangdao in the East China Sea, and the Battle of Caishi on the Yangtze River in 1161.

The advances in civilisation during the Song dynasty came to an abrupt end following the devastating Mongol conquest of the North and subsequently other areas of the empire, during which the population sharply dwindled, with a marked contraction in economy. Despite viciously halting Mongol advances for more than three decades, the Southern Song capital Hangzhou fell in 1276, followed by the final annihilation of the Song standing navy at the Battle of Yamen in 1279.

The Yuan dynasty was formally proclaimed in 1271, when the Great Khan of Mongol, Kublai Khan, one of the grandsons of Genghis Khan, assumed the additional title of Emperor of China, and considered his inherited part of the Mongol Empire as a Chinese dynasty. In the preceding decades, the Mongols had conquered the Jin dynasty in Northern China, and the Southern Song dynasty fell in 1279 after a protracted and bloody war. The Mongol Yuan dynasty became the first conquest dynasty in Chinese history to rule the entire China proper and its population as an ethnic minority. The dynasty also directly controlled the Mongol heartland and other regions, inheriting the largest share of territory of the eastern Mongol empire, which roughly coincided with the modern area of China and nearby regions in East Asia. Further expansion of the empire was halted after defeats in the invasions of Japan and Vietnam. Following the previous Jin dynasty, the capital of Yuan dynasty was established at Khanbaliq (also known as Dadu, modern-day Beijing). The Grand Canal was reconstructed to connect the remote capital city to lively economic hubs in southern part of China, setting the precedence and foundation for Beijing to largely remain as the capital of the successive regimes of the unified Chinese mainland.

A series of Mongol civil wars in the late 13th century led to the division of the Mongol Empire. In 1304 the emperors of the Yuan dynasty were upheld as the nominal Khagan over western khanates (the Chagatai Khanate, the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate), which nonetheless remained de facto autonomous. The era was known as Pax Mongolica, when much of the Asian continent was ruled by the Mongols. For the first and only time in history, the Silk Road was controlled entirely by a single state, facilitating the flow of people, trade, and cultural exchange. A network of roads and a postal system were established to connect the vast empire. Lucrative maritime trade, developed from the previous Song dynasty, continued to flourish, with Quanzhou and Hangzhou emerging as the largest ports in the world. Adventurous travelers from the far west, most notably the Venetian, Marco Polo, would settle in China for decades. Upon his return, his detail travel record inspired generations of medieval Europeans with the splendors of the far East. The Yuan dynasty was the first ancient economy, where paper currency, known at the time as Jiaochao, was used as the predominant medium of exchange. Its unrestricted issuance in the late Yuan dynasty inflicted hyperinflation, which eventually brought the downfall of the dynasty.

While the Mongol rulers of the Yuan dynasty adopted substantially to Chinese culture, their sinicization was of lesser extent compared to earlier conquest dynasties in Chinese history. For preserving racial superiority as the conqueror and ruling class, traditional nomadic customs and heritage from the Mongolian Steppe were held in high regard. On the other hand, the Mongol rulers also adopted flexibly to a variety of cultures from many advanced civilizations within the vast empire. Traditional social structure and culture in China underwent immense transform during the Mongol dominance. Large groups of foreign migrants settled in China, who enjoyed elevated social status over the majority Han Chinese, while enriching Chinese culture with foreign elements. The class of scholar officials and intellectuals, traditional bearers of elite Chinese culture, lost substantial social status. This stimulated the development of culture of the common folks. There were prolific works in zaju variety shows and literary songs (sanqu), which were written in a distinctive poetry style known as qu. Novels of vernacular style gained unprecedented status and popularity.

Before the Mongol invasion, Chinese dynasties reported approximately 120 million inhabitants; after the conquest had been completed in 1279, the 1300 census reported roughly 60 million people.[74] This major decline is not necessarily due only to Mongol killings. Scholars such as Frederick W. Mote argue that the wide drop in numbers reflects an administrative failure to record rather than an actual decrease; others such as Timothy Brook argue that the Mongols created a system of enserfment among a huge portion of the Chinese populace, causing many to disappear from the census altogether; other historians including William McNeill and David Morgan consider that plague was the main factor behind the demographic decline during this period. In the 14th century China suffered additional depredations from epidemics of plague, estimated to have killed around a quarter of the population of China.[75]: 348–351

Throughout the Yuan dynasty, there was some general sentiment among the populace against the Mongol dominance. Yet rather than the nationalist cause, it was mainly strings of natural disasters and incompetent, corrupt governance that triggered widespread peasant uprisings since the 1340s. After the massive naval engagement at Lake Poyang, Zhu Yuanzhang prevailed over other rebel forces in the south. He proclaimed himself emperor and founded the Ming dynasty in 1368. The same year his northern expedition army captured the capital Khanbaliq. The Yuan remnants fled back to Mongolia and sustained the regime, but the period of Yuan dominance was effectively over for good. Other Mongol Khanates in Central Asia continued to exist after the fall of Yuan dynasty in China.

The Ming dynasty was founded by Zhu Yuanzhang in 1368, who proclaimed himself as the Hongwu Emperor. The capital was initially set at Nanjing, and was later moved to Beijing from Yongle Emperor's reign onward.

Urbanization increased as the population grew and as the division of labor grew more complex. Large urban centers, such as Nanjing and Beijing, also contributed to the growth of private industry. In particular, small-scale industries grew up, often specializing in paper, silk, cotton, and porcelain goods. For the most part, however, relatively small urban centers with markets proliferated around the country. Town markets mainly traded food, with some necessary manufactures such as pins or oil.

Despite the xenophobia and intellectual introspection characteristic of the increasingly popular new school of neo-Confucianism, China under the early Ming dynasty was not isolated. Foreign trade and other contacts with the outside world, particularly Japan, increased considerably. Chinese merchants explored all of the Indian Ocean, reaching East Africa with the voyages of Zheng He.

The Hongwu Emperor, being the only founder of a Chinese dynasty who was also of peasant origin, had laid the foundation of a state that relied fundamentally in agriculture. Commerce and trade, which flourished in the previous Song and Yuan dynasties, were less emphasized. Neo-feudal landholdings of the Song and Mongol periods were expropriated by the Ming rulers. Land estates were confiscated by the government, fragmented, and rented out. Private slavery was forbidden. Consequently, after the death of the Yongle Emperor, independent peasant landholders predominated in Chinese agriculture. These laws might have paved the way to removing the worst of the poverty during the previous regimes. Towards later era of the Ming dynasty, with declining government control, commerce, trade and private industries revived.

The dynasty had a strong and complex central government that unified and controlled the empire. The emperor's role became more autocratic, although Hongwu Emperor necessarily continued to use what he called the "Grand Secretariat" to assist with the immense paperwork of the bureaucracy, including memorials (petitions and recommendations to the throne), imperial edicts in reply, reports of various kinds, and tax records. It was this same bureaucracy that later prevented the Ming government from being able to adapt to changes in society, and eventually led to its decline.

The Yongle Emperor strenuously tried to extend China's influence beyond its borders by demanding other rulers send ambassadors to China to present tribute. A large navy was built, including four-masted ships displacing 1,500 tons. A standing army of 1 million troops was created. The Chinese armies conquered and occupied Vietnam for around 20 years, while the Chinese fleet sailed the China seas and the Indian Ocean, cruising as far as the east coast of Africa. The Chinese gained influence in eastern Moghulistan. Several maritime Asian nations sent envoys with tribute for the Chinese emperor. Domestically, the Grand Canal was expanded and became a stimulus to domestic trade. Over 100,000 tons of iron per year were produced. Many books were printed using movable type. The imperial palace in Beijing's Forbidden City reached its current splendor. It was also during these centuries that the potential of south China came to be fully exploited. New crops were widely cultivated and industries such as those producing porcelain and textiles flourished.

In 1449 Esen Tayisi led an Oirat Mongol invasion of northern China which culminated in the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor at Tumu. Since then, the Ming became on the defensive on the northern frontier, which led to the Ming Great Wall being built. Most of what remains of the Great Wall of China today was either built or repaired by the Ming. The brick and granite work was enlarged, the watchtowers were redesigned, and cannons were placed along its length.

At sea the Ming became increasingly isolationist after the death of the Yongle Emperor. The treasure voyages which sailed the Indian Ocean were discontinued, and the maritime prohibition laws were set in place banning the Chinese from sailing abroad. European traders who reached China in the midst of the Age of Discovery were repeatedly rebuked in their requests for trade, with the Portuguese being repulsed by the Ming navy at Tuen Mun in 1521 and again in 1522. Domestic and foreign demands for overseas trade, deemed illegal by the state, led to widespread wokou piracy attacking the southeastern coastline during the rule of the Jiajing Emperor (1507–1567), which only subsided after the opening of ports in Guangdong and Fujian and much military suppression.[76] In addition to raids from Japan by the wokou, raids from Taiwan and the Philippines by the Pisheye also ravaged the southern coasts.[77] The Portuguese were allowed to settle in Macau in 1557 for trade, which remained in Portuguese hands until 1999. After the Spanish invasion of the Philippines, trade with the Spanish at Manila imported large quantities of Mexican and Peruvian silver from the Spanish Americas to China.[78]: 144–145 The Dutch entry into the Chinese seas was also met with fierce resistance, with the Dutch being chased off the Penghu islands in the Sino-Dutch conflicts of 1622–1624 and were forced to settle in Taiwan instead. The Dutch in Taiwan fought with the Ming in the Battle of Liaoluo Bay in 1633 and lost, and eventually surrendered to the Ming loyalist Koxinga in 1662, after the fall of the Ming dynasty.

In 1556, during the rule of the Jiajing Emperor, the Shaanxi earthquake killed about 830,000 people, the deadliest earthquake of all time.

The Ming dynasty intervened deeply in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), which ended with the withdrawal of all invading Japanese forces in Korea, and the restoration of the Joseon dynasty, its traditional ally and tributary state. The regional hegemony of the Ming dynasty was preserved at a toll on its resources. Coincidentally, with Ming's control in Manchuria in decline, the Manchu (Jurchen) tribes, under their chieftain Nurhaci, broke away from Ming's rule, and emerged as a powerful, unified state, which was later proclaimed as the Qing dynasty. It went on to subdue the much weakened Korea as its tributary, conquered Mongolia, and expanded its territory to the outskirt of the Great Wall. The most elite army of the Ming dynasty was to station at the Shanhai Pass to guard the last stronghold against the Manchus, which weakened its suppression of internal peasants uprisings.

The Qing dynasty (1644–1912) was the last imperial dynasty in China. Founded by the Manchus, it was the second conquest dynasty to rule the entirety of China proper, and roughly doubled the territory controlled by the Ming. The Manchus were formerly known as Jurchens, residing in the northeastern part of the Ming territory outside the Great Wall. They emerged as the major threat to the late Ming dynasty after Nurhaci united all Jurchen tribes and his son, Hong Taiji, declared the founding of the Qing dynasty in 1636. The Qing dynasty set up the Eight Banners system that provided the basic framework for the Qing military conquest. Li Zicheng's peasant rebellion captured Beijing in 1644 and the Chongzhen Emperor, the last Ming emperor, committed suicide. The Manchus allied with the Ming general Wu Sangui to seize Beijing, which was made the capital of the Qing dynasty, and then proceeded to subdue the Ming remnants in the south. During the Ming-Qing transition, when the Ming dynasty and later the Southern Ming, the emerging Qing dynasty, and several other factions like the Shun dynasty and Xi dynasty founded by peasant revolt leaders fought against each another, which, along with innumerable natural disasters at that time such as those caused by the Little Ice Age[79] and epidemics like the Great Plague during the last decade of the Ming dynasty,[80] caused enormous loss of lives and significant harm to the economy. In total, these decades saw the loss of as many as 25 million lives, but the Qing appeared to have restored China's imperial power and inaugurate another flowering of the arts.[81] The early Manchu emperors combined traditions of Inner Asian rule with Confucian norms of traditional Chinese government and were considered a Chinese dynasty.

The Manchus enforced a 'queue order', forcing Han Chinese men to adopt the Manchu queue hairstyle. Officials were required to wear Manchu-style clothing Changshan (bannermen dress and Tangzhuang), but ordinary Han civilians were allowed to wear traditional Han clothing. Bannermen could not undertake trade or manual labor; they had to petition to be removed from banner status. They were considered aristocracy and were given annual pensions, land, and allotments of cloth. The Kangxi Emperor ordered the creation of the Kangxi Dictionary, the most complete dictionary of Chinese characters that had been compiled.

Over the next half-century, all areas previously under the Ming dynasty were consolidated under the Qing. Conquests in Central Asia in the eighteenth century extended territorial control. Between 1673 and 1681, the Kangxi Emperor suppressed the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, an uprising of three generals in Southern China who had been denied hereditary rule of large fiefdoms granted by the previous emperor. In 1683, the Qing staged an amphibious assault on southern Taiwan, bringing down the rebel Kingdom of Tungning, which was founded by the Ming loyalist Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) in 1662 after the fall of the Southern Ming, and had served as a base for continued Ming resistance in Southern China. The Qing defeated the Russians at Albazin, resulting in the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

By the end of Qianlong Emperor's long reign in 1796, the Qing Empire was at its zenith. The Qing ruled more than one-third of the world's population, and had the largest economy in the world. By area it was one of the largest empires ever.

In the 19th century the empire was internally restive and externally threatened by western powers. The defeat by the British Empire in the First Opium War (1840) led to the Treaty of Nanking (1842), under which Hong Kong was ceded to Britain and importation of opium (produced by British Empire territories) was allowed. Opium usage continued to grow in China, adversely affecting societal stability. Subsequent military defeats and unequal treaties with other western powers continued even after the fall of the Qing dynasty.

Internally the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864), a Christian religious movement led by the "Heavenly King" Hong Xiuquan swept from the south to establish the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom and controlled roughly a third of China proper for over a decade. The court in desperation empowered Han Chinese officials such as Zeng Guofan to raise local armies. After initial defeats, Zeng crushed the rebels in the Third Battle of Nanking in 1864.[82] This was one of the largest wars in the 19th century in troop involvement; there was massive loss of life, with a death toll of about 20 million.[83] A string of civil disturbances followed, including the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, Nian Rebellion, Dungan Revolt, and Panthay Rebellion.[84] All rebellions were ultimately put down, but at enormous cost and with millions dead, seriously weakening the central imperial authority. China never rebuilt a strong central army, and many local officials used their military power to effectively rule independently in their provinces.[82]

Yet the dynasty appeared to recover in the Tongzhi Restoration (1860–1872), led by Manchu royal family reformers and Han Chinese officials such as Zeng Guofan and his proteges Li Hongzhang and Zuo Zongtang. Their Self-Strengthening Movement made effective institutional reforms, imported Western factories and communications technology, with prime emphasis on strengthening the military. However, the reform was undermined by official rivalries, cynicism, and quarrels within the imperial family. The defeat of Yuan Shikai's modernized "Beiyang Fleet" in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) led to the formation of the New Army. The Guangxu Emperor, advised by Kang Youwei, then launched a comprehensive reform effort, the Hundred Days' Reform (1898). Empress Dowager Cixi, however, feared that precipitous change would lead to bureaucratic opposition and foreign intervention and quickly suppressed it.

In the summer of 1900, the Boxer Uprising opposed foreign influence and murdered Chinese Christians and foreign missionaries. When Boxers entered Beijing, the Qing government ordered all foreigners to leave, but they and many Chinese Christians were besieged in the foreign legations quarter. An Eight-Nation Alliance sent the Seymour Expedition of Japanese, Russian, British, Italian, German, French, American, and Austrian troops to relieve the siege, but they were routed and forced to retreat by Boxer and Qing troops at the Battle of Langfang. After the Alliance's attack on the Dagu Forts, the court declared war on the Alliance and authorised the Boxers to join with imperial armies. After fierce fighting at Tianjin, the Alliance formed the second, much larger Gaselee Expedition and finally reached Beijing; the Empress Dowager evacuated to Xi'an. The Boxer Protocol ended the war, exacting a tremendous indemnity.

The Qing court then instituted administrative and legal reforms known as the late Qing reforms, including abolition of the examination system. But young officials, military officers, and students debated reform, perhaps a constitutional monarchy, or the overthrow of the dynasty and the creation of a republic. They were inspired by an emerging public opinion formed by intellectuals such as Liang Qichao and the revolutionary ideas of Sun Yat-sen. A localised military uprising, the Wuchang uprising, began on 10 October 1911, in Wuchang (today part of Wuhan), and soon spread. The Republic of China was proclaimed on 1 January 1912, ending 2,000 years of dynastic rule.

The provisional government of the Republic of China was formed in Nanjing on 12 March 1912. Sun Yat-sen became President of the Republic of China, but he turned power over to Yuan Shikai, who commanded the New Army. Over the next few years, Yuan proceeded to abolish the national and provincial assemblies, and declared himself as the emperor of Empire of China in late 1915, in the style of an absolute monarchy. Yuan's imperial ambitions were fiercely opposed by his subordinates; faced with the rapidly growing prospect of violent rebellion, he abdicated in March 1916 and died of natural causes in June.

Yuan's death in 1916 left a power vacuum; the republican government (that had been nearly brought to its knees by his policies) was all but shattered. This opened the way for the Warlord Era, during which much of China was ruled by shifting coalitions of competing provincial military leaders and the Beiyang government, ushering in a short-lived period of uncertainty. Intellectuals, disappointed in the failure of the Republic, launched the New Culture Movement.

.jpg/440px-Beijing_students_protesting_the_Treaty_of_Versailles_(May_4,_1919).jpg)

In 1919, the May Fourth Movement began as a response to the pro-Japanese terms imposed on China by the Treaty of Versailles following World War I. It quickly became a nationwide protest movement. The protests were a moral success as the cabinet fell and China refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which had awarded German holdings of Shandong to Japan. Memory of the mistreatment at Versailles fuels resentment into the 21st century.[85]

Political and intellectual ferment waxed strong throughout the 1920s and 1930s. According to Patricia Ebrey:

In the 1920s Sun Yat-sen established a revolutionary base in Guangzhou and set out to unite the fragmented nation. He welcomed assistance from the Soviet Union (itself fresh from Lenin's Communist takeover) and he entered into an alliance with the fledgling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). After Sun's death from cancer in 1925, one of his protégés, Chiang Kai-shek, seized control of the Nationalist Party (KMT) and succeeded in bringing most of south and central China under its rule in the Northern Expedition (1926–1927). Having defeated the warlords in the south and central China by military force, Chiang was able to secure the nominal allegiance of the warlords in the North and establish the Nationalist government in Nanjing. In 1927, Chiang turned on the CCP and relentlessly purged the Communists elements in his NRA. In 1934, driven from their mountain bases such as the Chinese Soviet Republic, the CCP forces embarked on the Long March across China's most desolate terrain to the northwest, a feat transformed into legend, where they established a guerrilla base at Yan'an in Shaanxi. During the Long March, the communists reorganised under a new leader, Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung).

The bitter Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and the Communists continued, openly or clandestinely, through the 14-year-long Japanese occupation of various parts of the country (1931–1945). The two Chinese parties nominally formed a United Front to oppose the Japanese in 1937, during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), which became a part of World War II, although this alliance was tenuous at best and disagreements, sometimes violent, between the forces were still common. Japanese forces committed numerous war atrocities against the civilian population, including biological warfare (see Unit 731) and the Three Alls Policy (Sankō Sakusen), namely being: "Kill All, Burn All and Loot All".[87] During the war, China was recognized as one of the Allied "Big Four" in the Declaration by United Nations, as a tribute to its enduring struggle against the invading Japanese.[88] China was one of the four major Allies of World War II, and was later considered one of the primary victors in the war.[89]

Following the defeat of Japan in 1945, the war between the Nationalist government forces and the CCP resumed, after failed attempts at reconciliation and a negotiated settlement. By 1949, the CCP had established control over most of the country. Odd Arne Westad says the Communists won the Civil War because they made fewer military mistakes than Chiang, and because in his search for a powerful centralized government, Chiang antagonised too many interest groups in China. Furthermore, his party was weakened in the war against the Japanese. Meanwhile, the Communists told different groups, such as peasants, exactly what they wanted to hear, and cloaked themselves in the cover of Chinese Nationalism.[90] During the civil war both the Nationalists and Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants killed by both sides.[91] These included deaths from forced conscription and massacres.[92]

Now, rotten with internal corruption and compounding tactical error after error under crumbling leadership, the Nationalists were slowly routed towards the South. When the Nationalist government forces were defeated by CCP forces in mainland China in 1949, the Nationalist government fled to Taiwan with its forces, along with Chiang and a large number of their supporters; the Nationalist government had taken effective control of Taiwan at the end of WWII as part of the overall Japanese surrender, when Japanese troops in Taiwan surrendered to the Republic of China troops there.[93]

Until the early 1970s the ROC was recognised as the sole legitimate government of China by the United Nations, the United States and most Western nations, refusing to recognise the PRC on account of its status as a communist nation during the Cold War. This changed in 1971 when the PRC was seated in the United Nations, replacing the ROC. The KMT ruled Taiwan under martial law until 1987, with the stated goal of being vigilant against Communist infiltration and preparing to retake mainland China. Therefore, political dissent was not tolerated during that period, and crackdowns against dissidents were common.

In the 1990s the ROC underwent a major democratic reform, beginning with the 1991 resignation of the members of the Legislative Yuan and National Assembly elected in 1947. These groups were originally created to represent mainland China constituencies. Also lifted were the restrictions on the use of Taiwanese languages in the broadcast media and in schools. In 1996, the ROC held its first direct presidential election, and the incumbent president, KMT candidate Lee Teng-hui, was elected. In 2000, the KMT status as the ruling party ended when the DPP took power, only to regain its status in the 2008 election by Ma Ying-jeou.

Due to the controversial nature of Taiwan's political status, the ROC is currently recognised by merely 12 UN member states and the Holy See as of 2024 as the legitimate government of "China".

Major combat in the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949 with the KMT pulling out of the mainland, with the government relocating to Taipei and maintaining control only over a few islands. The CCP was left in control of mainland China. On 1 October 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China.[94] "Communist China" and "Red China" were two common names for the PRC.[95]

The PRC was shaped by a series of campaigns and five-year plans. The Great Leap Forward, a radical campaign that encompassed numerous attempted economic and social reforms, resulted in tens of millions of deaths.[96][better source needed] Mao's government carried out mass executions of landowners, instituted collectivisation and implemented the Laogai camp system. Execution, deaths from forced labor and other atrocities resulted in millions of deaths under Mao. In 1966 Mao and his allies launched the Cultural Revolution, which continued until Mao's death a decade later. The Cultural Revolution, motivated by power struggles within the Party and a fear of the Soviet Union, led to a major upheaval in Chinese society.

Following the Sino-Soviet split and motivated by concerns of invasion by either the Soviet Union or the United States, China initiated the Third Front campaign to develop national defense and industrial infrastructure in its rugged interior.[97]: 44 Through its distribution of infrastructure, industry, and human capital around the country, the Third Front created favorable conditions for subsequent market development and private enterprise.[97]: 177

In 1972, at the peak of the Sino-Soviet split, Mao and Zhou Enlai met U.S. president Richard Nixon in Beijing to establish relations with the US. In the same year, the PRC was admitted to the United Nations in place of the Republic of China, with permanent membership of the Security Council.

A power struggle followed Mao's death in 1976. The Gang of Four were arrested and blamed for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, marking the end of a turbulent political era in China. Deng Xiaoping outmaneuvered Mao's anointed successor chairman Hua Guofeng, and gradually emerged as the de facto leader over the next few years.