Afganistán , oficialmente Emirato Islámico de Afganistán , es un país sin salida al mar ubicado en la encrucijada de Asia Central y Asia Meridional . Limita con Pakistán al este y al sur , Irán al oeste , Turkmenistán al noroeste , Uzbekistán al norte , Tayikistán al noreste y China al noreste y al este . Ocupando 652.864 kilómetros cuadrados (252.072 millas cuadradas) de tierra, el país es predominantemente montañoso con llanuras en el norte y el suroeste , que están separadas por la cordillera del Hindu Kush . Kabul es la capital y la ciudad más grande del país. Según la revisión de la población mundial, a partir de 2023 [update], la población de Afganistán es de 43 millones. [6] La Autoridad Nacional de Información Estadística de Afganistán estimó que la población era de 32,9 millones en 2020. [update][ 27]

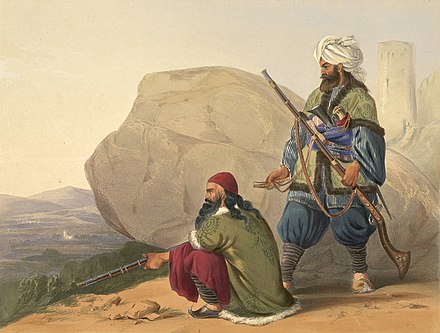

La presencia humana en Afganistán data del Paleolítico Medio . Popularmente conocida como el cementerio de imperios , [28] la tierra ha sido testigo de numerosas campañas militares , incluidas las de los persas , Alejandro Magno , el Imperio Maurya , los musulmanes árabes , los mongoles , los británicos , la Unión Soviética y una coalición liderada por Estados Unidos . Afganistán también sirvió como la fuente de la que los grecobactrianos y los mogoles , entre otros, surgieron para formar grandes imperios. [29] Debido a las diversas conquistas y períodos en las esferas culturales iraní e india , [30] [31] el área fue un centro para el zoroastrismo , el budismo, el hinduismo y más tarde el islam. [32] El estado moderno de Afganistán comenzó con el Imperio afgano durrani en el siglo XVIII, [33] aunque a veces se considera a Dost Mohammad Khan como el fundador del primer estado afgano moderno . [34] Afganistán se convirtió en un estado tapón en el Gran Juego entre el Imperio Británico y el Imperio Ruso . Desde la India, los británicos intentaron subyugar a Afganistán, pero fueron repelidos en la Primera Guerra Anglo-Afgana ; la Segunda Guerra Anglo-Afgana vio una victoria británica. Después de la Tercera Guerra Anglo-Afgana en 1919, Afganistán se liberó de la hegemonía política extranjera y emergió como el Reino independiente de Afganistán en 1926. Esta monarquía duró casi medio siglo, hasta que Zahir Shah fue derrocado en 1973 , tras lo cual se estableció la República de Afganistán .

Desde finales de la década de 1970, la historia de Afganistán ha estado dominada por una amplia guerra, que incluye golpes de Estado, invasiones, insurgencias y guerras civiles . El conflicto comenzó en 1978 cuando una revolución comunista estableció un estado socialista (en sí misma una respuesta a la dictadura establecida tras un golpe de Estado en 1973 ), y las luchas internas posteriores llevaron a la Unión Soviética a invadir Afganistán en 1979. Los muyahidines lucharon contra los soviéticos en la guerra soviético-afgana y continuaron luchando entre ellos después de la retirada de los soviéticos en 1989. Los talibanes controlaban la mayor parte del país en 1996, pero su Emirato Islámico de Afganistán recibió poco reconocimiento internacional antes de su derrocamiento en la invasión estadounidense de Afganistán en 2001. Los talibanes regresaron al poder en 2021 después de capturar Kabul , poniendo fin a la guerra de 2001-2021 . [35] El gobierno talibán sigue sin ser reconocido internacionalmente. [36]

Afganistán es rico en recursos naturales, incluidos litio , hierro, zinc y cobre. Es el segundo mayor productor de resina de cannabis , [37] y el tercero de azafrán [38] y cachemira . [39] El país es miembro de la Asociación del Asia Meridional para la Cooperación Regional y miembro fundador de la Organización de Cooperación Islámica . Debido a los efectos de la guerra en las últimas décadas, el país ha lidiado con altos niveles de terrorismo, pobreza y desnutrición infantil. Afganistán sigue estando entre los países menos desarrollados del mundo, ocupando el puesto 180 en el Índice de Desarrollo Humano . El producto interno bruto (PIB) de Afganistán es de $ 81 mil millones en paridad de poder adquisitivo y $ 20,1 mil millones en valores nominales. Per cápita, su PIB está entre los más bajos de cualquier país a partir de 2020 [update].

Algunos eruditos sugieren que el nombre raíz Afghān se deriva de la palabra sánscrita Aśvakan , que era el nombre utilizado para los antiguos habitantes del Hindu Kush . [40] Aśvakan significa literalmente "jinetes", "criadores de caballos" o " soldados de caballería " (de aśva , las palabras sánscritas y avésticas para "caballo"). [41]

Históricamente, el etnónimo Afghān se utilizó para referirse a los pastunes étnicos . [42] La forma árabe y persa del nombre, Afġān , fue atestiguada por primera vez en el libro de geografía del siglo X Hudud al-'Alam . [43] La última parte del nombre, " -stan ", es un sufijo persa que significa "lugar de". Por lo tanto, "Afganistán" se traduce como "tierra de los afganos", o "tierra de los pastunes" en un sentido histórico. Según la tercera edición de la Enciclopedia del Islam : [44]

El nombre Afganistán (Afghānistān, tierra de los afganos/pastunes, afāghina , sing. afghān ) se remonta a principios del siglo VIII/XIV, cuando designaba la parte más oriental del reino kartida . Este nombre se utilizó más tarde para ciertas regiones de los imperios safávida y mogol que estaban habitadas por afganos. Si bien se basaba en una élite de afganos abdālī/durrānī que apoyaba al Estado , el sistema político sadūzāʾī durrānī que surgió en 1160/1747 no se llamó Afganistán en su propia época. El nombre se convirtió en una designación estatal solo durante la intervención colonial del siglo XIX.

El término "Afganistán" se utilizó oficialmente en 1855, cuando los británicos reconocieron a Dost Mohammad Khan como rey de Afganistán . [45]

Las excavaciones de sitios prehistóricos sugieren que los humanos vivían en lo que ahora es Afganistán hace al menos 50.000 años, y que las comunidades agrícolas de la zona estaban entre las más antiguas del mundo. Un sitio importante de actividades históricas tempranas, muchos creen que Afganistán se compara con Egipto en el valor histórico de sus sitios arqueológicos. [46] [47] En Afganistán se han encontrado artefactos típicos del Paleolítico , Mesolítico , Neolítico , Edad del Bronce y Edad del Hierro . Se cree que la civilización urbana comenzó ya en el año 3000 a. C., y la antigua ciudad de Mundigak (cerca de Kandahar en el sur del país) fue un centro de la cultura de Helmand . Hallazgos más recientes establecieron que la Civilización del Valle del Indo se extendió hasta el actual Afganistán. Se ha encontrado un yacimiento del Valle del Indo en el río Oxus en Shortugai en el norte de Afganistán. [48] [49] [50]

Después del año 2000 a. C., sucesivas oleadas de pueblos seminómadas procedentes de Asia central comenzaron a desplazarse hacia el sur, hacia Afganistán; entre ellos había muchos indoiraníes de habla indoeuropea . Estas tribus migraron más tarde hacia el sur de Asia, Asia occidental y Europa a través del área al norte del mar Caspio . La región en ese momento se conocía como Ariana . [46] [51] A mediados del siglo VI a. C., los aqueménidas derrocaron a los medos e incorporaron Aracosia , Aria y Bactriana dentro de sus límites orientales. Una inscripción en la lápida de Darío I de Persia menciona el valle de Kabul en una lista de los 29 países que había conquistado. [52] La región de Aracosia , alrededor de Kandahar en el actual sur de Afganistán, solía ser principalmente zoroástrica y desempeñó un papel clave en la transferencia del Avesta a Persia y, por lo tanto, algunos la consideran la "segunda patria del zoroastrismo". [53] [54] [55]

Alejandro Magno y sus fuerzas macedonias llegaron a Afganistán en el 330 a. C. después de derrotar a Darío III de Persia un año antes en la batalla de Gaugamela . Tras la breve ocupación de Alejandro, el estado sucesor del Imperio seléucida controló la región hasta el 305 a. C., cuando cedió gran parte de ella al Imperio Maurya como parte de un tratado de alianza. Los Maurya controlaron la zona al sur del Hindu Kush hasta que fueron derrocados alrededor del 185 a. C. Su declive comenzó 60 años después de que terminara el gobierno de Ashoka , lo que llevó a la reconquista helenística por parte de los grecobactrianos . Gran parte de ella pronto se separó y pasó a formar parte del Reino indogriego . Fueron derrotados y expulsados por los indoescitas a finales del siglo II a. C. [56] [57] La Ruta de la Seda apareció durante el siglo I a. C., y Afganistán floreció con el comercio, con rutas a China, India, Persia y al norte a las ciudades de Bujará , Samarcanda y Jiva en la actual Uzbekistán. [58] En este punto central se intercambiaban bienes e ideas, como la seda china, la plata persa y el oro romano, mientras que la región del actual Afganistán extraía y comerciaba piedras de lapislázuli [59] principalmente de la región de Badakhshan .

Durante el siglo I a. C., el Imperio parto subyugó la región, pero la perdió ante sus vasallos indopartos . A mediados y finales del siglo I d. C., el vasto Imperio kushán , centrado en Afganistán, se convirtió en un gran mecenas de la cultura budista, lo que hizo que el budismo floreciera en toda la región. Los kushán fueron derrocados por los sasánidas en el siglo III d. C., aunque los indo-sasánidas continuaron gobernando al menos partes de la región. Fueron seguidos por los kidaritas que, a su vez, fueron reemplazados por los heftalitas . Fueron reemplazados por los turcos shahi en el siglo VII. El turco budista shahi de Kabul fue reemplazado por una dinastía hindú antes de que los saffaríes conquistaran el área en 870, esta dinastía hindú se llamó hindú shahi . [60] Gran parte de las áreas del noreste y sur del país permanecieron dominadas por la cultura budista . [61] [62]

Los musulmanes árabes trajeron el Islam a Herat y Zaranj en 642 d. C. y comenzaron a extenderse hacia el este; algunos de los habitantes nativos que encontraron lo aceptaron mientras que otros se rebelaron. Antes de la llegada del Islam , la región solía ser el hogar de varias creencias y cultos, lo que a menudo resultaba en sincretismo entre las religiones dominantes [63] [64] como el zoroastrismo , [53] [54] [55] el budismo o grecobudismo , las antiguas religiones iraníes , [65] el hinduismo , el cristianismo, [66] [67] y el judaísmo. [68] [69] Una ejemplificación del sincretismo en la región sería que las personas eran patrocinadores del budismo pero aún adoraban a dioses iraníes locales como Ahura Mazda , Lady Nana , Anahita o Mihr (Mitra) y retrataban a los dioses griegos como protectores de Buda. [70] [65] [71] Los Zunbils y Kabul Shahi fueron conquistados por primera vez en el año 870 d. C. por los musulmanes safaríes de Zaranj. Más tarde, los samánidas extendieron su influencia islámica al sur del Hindu Kush. Los gaznávidas subieron al poder en el siglo X. [72] [73] [74]

En el siglo XI, Mahmud de Ghazni había derrotado a los gobernantes hindúes restantes e islamizado efectivamente la región en general, [75] con la excepción de Kafiristán . [76] Mahmud convirtió a Ghazni en una ciudad importante y patrocinó a intelectuales como el historiador Al-Biruni y el poeta Ferdowsi . [77] La dinastía Ghaznavid fue derrocada por los Ghurids en 1186 , cuyos logros arquitectónicos incluyeron el remoto minarete de Jam . Los Ghurids controlaron Afganistán durante menos de un siglo antes de ser conquistados por la dinastía Khwarazmian en 1215. [78]

En 1219 d. C., Genghis Khan y su ejército mongol invadieron la región . Se dice que sus tropas aniquilaron las ciudades corasmias de Herat y Balkh , así como Bamiyán . [79] La destrucción causada por los mongoles obligó a muchos lugareños a regresar a una sociedad rural agraria. [80] El gobierno mongol continuó con el ilkhanate en el noroeste, mientras que la dinastía Khalji administró las áreas tribales afganas al sur del Hindu Kush hasta la invasión de Tamerlán (también conocido como Tamerlán), quien estableció el Imperio timúrida en 1370. Bajo el gobierno de Shah Rukh , la ciudad de Herat [81] sirvió como el punto focal del Renacimiento timúrida , cuya gloria igualó a la Florencia del Renacimiento italiano como centro de un renacimiento cultural. [82] [83]

A principios del siglo XVI, Babur llegó desde Ferghana y capturó Kabul de la dinastía Arghun . [84] Babur continuaría conquistando la dinastía afgana Lodi que había gobernado el Sultanato de Delhi en la Primera Batalla de Panipat . [85] Entre los siglos XVI y XVIII, el Kanato uzbeko de Bujará , los safávidas iraníes y los mogoles indios gobernaron partes del territorio. [86] Durante el período medieval, la zona noroeste de Afganistán era conocida con el nombre regional de Khorasan , que se usó comúnmente hasta el siglo XIX entre los nativos para describir su país. [87] [88] [89] [90]

En 1709, Mirwais Hotak , un líder tribal local Ghilzai , se rebeló con éxito contra los safávidas . Derrotó a Gurgin Khan , el gobernador georgiano de Kandahar bajo los safávidas, y estableció su propio reino. [91] Mirwais murió en 1715 y fue sucedido por su hermano Abdul Aziz , quien pronto fue asesinado por el hijo de Mirwais, Mahmud , por posiblemente planear firmar una paz con los safávidas. Mahmud dirigió al ejército afgano en 1722 a la capital persa de Isfahán , y capturó la ciudad después de la batalla de Gulnabad y se proclamó rey de Persia. [91] La dinastía afgana fue expulsada de Persia por Nader Shah después de la batalla de Damghan de 1729 .

En 1738, Nader Shah y sus fuerzas capturaron Kandahar en el asedio de Kandahar , el último bastión de Hotak, de Shah Hussain Hotak . Poco después, las fuerzas persas y afganas invadieron la India , Nader Shah había saqueado Delhi, junto con su comandante de 16 años, Ahmad Shah Durrani, quien lo había ayudado en estas campañas. Nader Shah fue asesinado en 1747. [92] [93]

Después de la muerte de Nader Shah en 1747, Ahmad Shah Durrani había regresado a Kandahar con un contingente de 4.000 pastunes . Los abdalíes habían "aceptado por unanimidad" a Ahmad Shah como su nuevo líder. Con su ascenso en 1747, Ahmad Shah había liderado múltiples campañas contra el imperio mogol , el imperio maratha y el imperio afsharí en retirada . Ahmad Shah había capturado Kabul y Peshawar del gobernador designado por los mogoles, Nasir Khan. Ahmad Shah había conquistado Herat en 1750 y también había capturado Cachemira en 1752. [94] Ahmad Shah había lanzado dos campañas en Jorasán , 1750-1751 y 1754-1755. [95] Su primera campaña había visto el asedio de Mashhad , sin embargo, se vio obligado a retirarse después de cuatro meses. En noviembre de 1750, se trasladó a sitiar Nishapur , pero no pudo capturar la ciudad y se vio obligado a retirarse a principios de 1751. Ahmad Shah regresó en 1754 ; capturó Tun , y el 23 de julio, sitió Mashhad una vez más. Mashhad había caído el 2 de diciembre, pero Shahrokh fue reelegido en 1755. Se vio obligado a entregar Torshiz , Bakharz , Jam , Khaf y Turbat-e Haidari a los afganos, así como a aceptar la soberanía afgana. Después de esto, Ahmad Shah sitió Nishapur una vez más y la capturó.

Ahmad Shah invadió la India ocho veces durante su reinado, [96] comenzando en 1748. Cruzando el río Indo, sus ejércitos saquearon y absorbieron Lahore en el Reino Durrani . Se enfrentó a los ejércitos mogoles en la batalla de Manupur (1748) , donde fue derrotado y obligado a retirarse a Afganistán. [97] Regresó al año siguiente en 1749 y capturó el área alrededor de Lahore y Punjab , presentándolo como una victoria afgana para esta campaña. [98] De 1749 a 1767, Ahmad Shah dirigió seis invasiones más, la más importante fue la última; la Tercera Batalla de Panipat creó un vacío de poder en el norte de la India, deteniendo la expansión maratha .

Ahmad Shah Durrani murió en octubre de 1772, y se produjo una guerra civil por la sucesión, con su sucesor designado, Timur Shah Durrani, sucediéndolo después de la derrota de su hermano, Suleiman Mirza. [99] Timur Shah Durrani ascendió al trono en noviembre de 1772, después de derrotar a una coalición liderada por Shah Wali Khan y Humayun Mirza. Timur Shah comenzó su reinado consolidando el poder hacia sí mismo y hacia la gente leal a él, purgando a los sardars durrani y a los líderes tribales influyentes en Kabul y Kandahar . Una de las reformas de Timur Shah fue trasladar la capital del Imperio durrani de Kandahar a Kabul . Timur Shah luchó contra múltiples series de rebeliones para consolidar el imperio, y también dirigió campañas en Punjab contra los sijs como su padre, aunque con más éxito. El ejemplo más destacado de sus batallas durante esta campaña fue cuando dirigió sus fuerzas bajo el mando de Zangi Khan Durrani (con más de 18.000 hombres en total de caballería afgana, qizilbash y mongol) contra más de 60.000 hombres sijs. Los sijs perdieron más de 30.000 en esta batalla y organizaron un resurgimiento durrani en la región de Punjab [100] . Los durranis perdieron Multan en 1772 después de la muerte de Ahmad Shah. Tras esta victoria, Timur Shah pudo sitiar Multan y recuperarla, [101] incorporándola una vez más al Imperio durrani, reintegrándola como provincia hasta el asedio de Multan (1818) . Timur Shah fue sucedido por su hijo Zaman Shah Durrani después de su muerte en mayo de 1793. El reinado de Timur Shah supervisó el intento de estabilización y consolidación del imperio. Sin embargo, Timur Shah tuvo más de 24 hijos, lo que sumió al imperio en una guerra civil por las crisis de sucesión. [102]

Zaman Shah Durrani sucedió al trono durrani tras la muerte de su padre, Timur Shah Durrani. Sus hermanos Mahmud Shah Durrani y Humayun Mirza se rebelaron contra él, con Humayun centrado en Kandahar y Mahmud Shah centrado en Herat . [103] Zaman Shah derrotaría a Humayun y forzaría la lealtad de Mahmud Shah Durrani. [103] Asegurando su posición en el trono, Zaman Shah dirigió tres campañas en Punjab . Las dos primeras campañas capturaron Lahore , pero se retiró debido a información sobre una posible invasión Qajar . Zaman Shah se embarcó en su tercera campaña por Punjab en 1800 para lidiar con un rebelde Ranjit Singh. [104] Sin embargo, se vio obligado a retirarse, y el reinado de Zaman Shah fue terminado por Mahmud Shah Durrani. [104] Sin embargo, poco menos de dos años después de su reinado, Mahmud Shah Durrani fue depuesto por su hermano Shah Shuja Durrani el 13 de julio de 1803. [105] Shah Shuja intentó consolidar el reino Durrani , pero fue depuesto por su hermano en la batalla de Nimla (1809) . [106] Mahmud Shah Durrani derrotó a Shah Shuja y lo obligó a huir, usurpando el trono nuevamente. Su segundo reinado comenzó el 3 de mayo de 1809. [107]

A principios del siglo XIX, el imperio afgano se encontraba amenazado por los persas en el oeste y el imperio sij en el este. Fateh Khan , líder de la tribu Barakzai , instaló a muchos de sus hermanos en puestos de poder en todo el imperio. Fateh Khan fue brutalmente asesinado en 1818 por Mahmud Shah . Como resultado, los hermanos de Fateh Khan y la tribu Barakzai se rebelaron y se gestó una guerra civil. Durante este período turbulento, Afganistán se dividió en muchos estados, incluido el Principado de Kandahar , el Emirato de Herat , el Kanato de Qunduz , el Kanato de Maimana y muchas otras entidades políticas en guerra. El estado más destacado fue el Emirato de Kabul , gobernado por Dost Mohammad Khan . [108] [109]

Con el colapso del Imperio Durrani y el exilio de la dinastía Sadozai para gobernar en Herat , Punjab y Cachemira se perdieron ante Ranjit Singh , gobernante del Imperio Sikh , quien invadió Khyber Pakhtunkhwa en marzo de 1823 y capturó la ciudad de Peshawar después de la Batalla de Nowshera . En 1834, Dost Mohammad Khan dirigió numerosas campañas, primero en Jalalabad y luego aliándose con sus hermanos rivales en Kandahar para derrotar a Shah Shuja Durrani y los británicos en la Expedición de Shuja ul-Mulk . [110] En 1837, Dost Mohammad Khan intentó conquistar Peshawar y envió una gran fuerza bajo su hijo Wazir Akbar Khan , lo que condujo a la Batalla de Jamrud . Akbar Khan y el ejército afgano no lograron capturar el Fuerte Jamrud del Ejército Sikh Khalsa , pero mataron al comandante sikh Hari Singh Nalwa , poniendo así fin a las guerras afgano-sij . En ese momento, los británicos avanzaban desde el este, aprovechando la decadencia del Imperio sikh después de que este tuviera su propio período de turbulencia tras la muerte de Ranjit Singh , que enfrentó al Emirato de Kabul en el primer conflicto importante durante " El Gran Juego ". [111]

En 1839, una fuerza expedicionaria británica marchó sobre Afganistán, invadiendo el Principado de Kandahar , y en agosto de 1839, tomó Kabul . Dost Mohammad Khan derrotó a los británicos en la campaña de Parwan , pero se rindió después de su victoria. Fue reemplazado por el ex gobernante durrani Shah Shuja Durrani como el nuevo gobernante de Kabul , un títere de facto de los británicos. [112] [113] Después de un levantamiento que vio el asesinato de Shah Shuja , la retirada de Kabul en 1842 de las fuerzas británico-indias y la aniquilación del ejército de Elphinstone , y la expedición punitiva de la Batalla de Kabul que llevó a su saqueo, los británicos renunciaron a sus intentos de tratar de subyugar Afganistán, lo que permitió que Dost Mohammad Khan regresara como gobernante. Después de esto, Dost Mohammad llevó a cabo una gran cantidad de campañas para unificar la mayor parte de Afganistán durante su reinado, lanzando numerosas incursiones, incluso contra los estados circundantes, como la campaña de Hazarajat , la conquista de Balkh , la conquista de Kunduz y la conquista de Kandahar . Dost Mohammad dirigió su campaña final contra Herat , conquistándola y reunificando Afganistán. Durante sus campañas de reunificación, mantuvo relaciones amistosas con los británicos a pesar de la Primera Guerra Anglo-Afgana, y afirmó su estatus en el Segundo tratado Anglo-Afgano de 1857, mientras que Bujará y los líderes religiosos internos presionaron a Dost Mohammad para que invadiera la India durante la Rebelión India de 1857. [ 114]

Dost Mohammad murió en junio de 1863, unas semanas después de su exitosa campaña a Herat. Después de su muerte, se produjo una guerra civil entre sus hijos, en particular Mohammad Afzal Khan , Mohammad Azam Khan y Sher Ali Khan . Sher Ali ganó la Guerra Civil Afgana resultante (1863-1869) y gobernó Afganistán hasta su muerte en 1879. En sus últimos años, los británicos regresaron a Afganistán en la Segunda Guerra Anglo-Afgana para luchar contra la percibida influencia rusa en la región. Sher Ali se retiró al norte de Afganistán, con la intención de crear una resistencia allí similar a la de sus predecesores, Dost Mohammad Khan y Wazir Akbar Khan. Sin embargo, su muerte prematura vio a Yaqub Khan declarado el nuevo Amir, lo que llevó a Gran Bretaña a obtener el control de las relaciones exteriores de Afganistán como parte del Tratado de Gandamak de 1879, convirtiéndolo oficialmente en un Estado Protegido Británico . [115] [116] Sin embargo, un levantamiento reanudó el conflicto y Yaqub Khan fue depuesto. Durante este tumultuoso período, Abdur Rahman Khan comenzó su ascenso al poder, convirtiéndose en un candidato elegible para convertirse en Amir después de apoderarse de gran parte del norte de Afganistán . Abdur Rahman marchó sobre Kabul y fue declarado Amir, siendo reconocido también por los británicos. Otro levantamiento de Ayub Khan amenazó a los británicos, donde los rebeldes se enfrentaron y derrotaron a las fuerzas británicas en la Batalla de Maiwand . Tras su victoria, Ayub Khan sitió Kandahar sin éxito , y su decisiva derrota supuso el fin de la Segunda Guerra Anglo-Afgana, con Abdur Rahman firmemente asegurado como Amir. [117] En 1893, Abdur Rahman firmó un acuerdo en el que los territorios étnicos pastún y baluchi fueron divididos por la Línea Durand , que forma la frontera actual entre Pakistán y Afganistán. El Hazarajat , dominado por los chiítas , y el Kafiristán pagano permanecieron políticamente independientes hasta que fueron conquistados por Abdur Rahman Khan entre 1891 y 1896. Era conocido como el "Emir de Hierro" por sus rasgos y sus métodos despiadados contra las tribus. [118] Murió en 1901, sucedido por su hijo, Habibullah Khan .

¿Cómo puede una pequeña potencia como Afganistán, que es como una cabra entre estos leones [Gran Bretaña y Rusia] o un grano de trigo entre dos fuertes piedras de molino, permanecer en medio de las piedras sin ser molida hasta convertirse en polvo?

— Abdur Rahman Khan , el "Emir de Hierro", en 1900 [119] [120]

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial , cuando Afganistán era neutral, Habibullah Khan fue recibido por funcionarios de las potencias centrales en la Expedición Niedermayer-Hentig . Llamaron a Afganistán a declarar la independencia total del Reino Unido, unirse a ellos y atacar la India británica, como parte de la Conspiración Hindú-Alemana . El esfuerzo por incorporar a Afganistán a las Potencias Centrales fracasó, pero provocó descontento entre la población sobre el mantenimiento de la neutralidad con los británicos. Habibullah fue asesinado en febrero de 1919, y Amanullah Khan finalmente asumió el poder. Un firme partidario de las expediciones de 1915-1916, Amanullah Khan invadió la India británica, comenzando la Tercera Guerra Anglo-Afgana y entrando en la India británica a través del Paso Khyber . [121]

Tras el final de la Tercera Guerra Anglo-Afgana y la firma del Tratado de Rawalpindi el 19 de agosto de 1919, el emir Amanullah Khan declaró al Emirato de Afganistán un estado soberano y completamente independiente . Se movió para poner fin al aislamiento tradicional de su país estableciendo relaciones diplomáticas con la comunidad internacional, particularmente con la Unión Soviética y la República de Weimar . [122] [123] Se proclamó Rey de Afganistán el 9 de junio de 1926, formando el Reino de Afganistán . Introdujo varias reformas destinadas a modernizar su nación. Una fuerza clave detrás de estas reformas fue Mahmud Tarzi , un ardiente partidario de la educación de las mujeres. Luchó por el Artículo 68 de la constitución de Afganistán de 1923 , que hizo obligatoria la educación primaria. La esclavitud fue abolida en 1923. [124] La esposa del rey Amanullah, la reina Soraya , fue una figura importante durante este período en la lucha por la educación de las mujeres y contra su opresión. [125]

Algunas de las reformas, como la abolición del burka tradicional para las mujeres y la apertura de escuelas mixtas, alejaron a muchos líderes tribales y religiosos, lo que llevó a la Guerra Civil Afgana (1928-1929) . El rey Amanullah abdicó en enero de 1929, y poco después Kabul cayó ante las fuerzas saqqawistas lideradas por Habibullah Kalakani . [126] Mohammed Nadir Shah , primo de Amanullah, derrotó y mató a Kalakani en octubre de 1929, y fue declarado rey Nadir Shah. [127] Abandonó las reformas del rey Amanullah en favor de un enfoque más gradual hacia la modernización, pero fue asesinado en 1933 por Abdul Khaliq . [128]

Mohammed Zahir Shah sucedió al trono y reinó como rey desde 1933 hasta 1973. Durante las revueltas tribales de 1944-1947 , el reinado del rey Zahir fue desafiado por los miembros de las tribus Zadran , Safi , Mangal y Wazir liderados por Mazrak Zadran , Salemai y Mirzali Khan , entre otros, muchos de los cuales eran leales a Amanullah . Afganistán se unió a la Liga de las Naciones en 1934. La década de 1930 vio el desarrollo de carreteras, infraestructura, la fundación de un banco nacional y el aumento de la educación. Las conexiones por carretera en el norte desempeñaron un papel importante en una creciente industria del algodón y los textiles. [129] El país construyó estrechas relaciones con las potencias del Eje , y la Alemania nazi tuvo la mayor participación en el desarrollo afgano en ese momento. [130]

Hasta 1946, el rey Zahir gobernó con la ayuda de su tío, que ocupó el puesto de primer ministro y continuó las políticas de Nadir Shah. Otro tío, Shah Mahmud Khan , se convirtió en primer ministro en 1946 y experimentó con permitir una mayor libertad política. Fue reemplazado en 1953 por Mohammed Daoud Khan , un nacionalista pastún que buscaba la creación de un Pastunistán , lo que llevó a relaciones muy tensas con Pakistán. [131] Daoud Khan presionó para reformas de modernización social y buscó una relación más cercana con la Unión Soviética . Después, se formó la constitución de 1964 y juró el primer primer ministro no real. [129]

Zahir Shah, al igual que su padre Nadir Shah, tenía una política de mantener la independencia nacional mientras perseguía una modernización gradual, creando un sentimiento nacionalista y mejorando las relaciones con el Reino Unido. Afganistán no participó en la Segunda Guerra Mundial ni se alineó con ninguno de los dos bloques de poder en la Guerra Fría . Sin embargo, fue un beneficiario de esta última rivalidad, ya que tanto la Unión Soviética como los Estados Unidos compitieron por la influencia mediante la construcción de las principales carreteras, aeropuertos y otras infraestructuras vitales de Afganistán. En términos per cápita, Afganistán recibió más ayuda soviética para el desarrollo que cualquier otro país. En 1973, mientras el rey estaba en Italia, Daoud Khan lanzó un golpe de estado incruento y se convirtió en el primer presidente de Afganistán , aboliendo la monarquía.

En abril de 1978, el Partido Democrático Popular de Afganistán (PDPA) comunista tomó el poder en un sangriento golpe de estado contra el entonces presidente Mohammed Daoud Khan , en lo que se llama la Revolución Saur . El PDPA declaró el establecimiento de la República Democrática de Afganistán , con su primer líder nombrado como el Secretario General del Partido Democrático Popular Nur Muhammad Taraki . [132] Esto desencadenaría una serie de eventos que convertirían dramáticamente a Afganistán de un país pobre y aislado (aunque pacífico) a un semillero de terrorismo internacional. [133] El PDPA inició varias reformas sociales, simbólicas y de distribución de tierras que provocaron una fuerte oposición, al mismo tiempo que oprimían brutalmente a los disidentes políticos. Esto causó disturbios y rápidamente se expandió a un estado de guerra civil en 1979, librada por guerrilleros muyahidines (y guerrillas maoístas más pequeñas ) contra las fuerzas del régimen en todo el país. Rápidamente se convirtió en una guerra por poderes , ya que el gobierno paquistaní proporcionó a estos rebeldes centros de entrenamiento encubiertos, Estados Unidos los apoyó a través de la Inteligencia Interservicios (ISI) de Pakistán , [134] y la Unión Soviética envió miles de asesores militares para apoyar al régimen del PDPA. [135] Mientras tanto, hubo una fricción cada vez más hostil entre las facciones rivales del PDPA: el dominante Khalq y el más moderado Parcham . [136]

En octubre de 1979, el secretario general del PDPA, Taraki, fue asesinado en un golpe interno orquestado por el entonces primer ministro Hafizullah Amin , quien se convirtió en el nuevo secretario general del Partido Democrático Popular . La situación en el país se deterioró bajo el gobierno de Amin y miles de personas desaparecieron. [137] Descontento con el gobierno de Amin, el ejército soviético invadió el país en diciembre de 1979, se dirigió a Kabul y mató a Amin. [138] Un régimen organizado por los soviéticos, dirigido por Babrak Karmal de Parcham pero que incluía a ambas facciones (Parcham y Khalq), llenó el vacío. Se desplegaron tropas soviéticas en cantidades más sustanciales para estabilizar Afganistán bajo Karmal, lo que marcó el comienzo de la guerra soviética-afgana . [139] La guerra, que duró nueve años, causó la muerte de entre 562.000 [140] y 2 millones de afganos, [141] [142] [143] [144] [145] [146] [147] [ citas excesivas ] y desplazó a unos 6 millones de personas que posteriormente huyeron de Afganistán, principalmente a Pakistán e Irán . [148] Los intensos bombardeos aéreos destruyeron muchas aldeas rurales, se colocaron millones de minas terrestres , [149] y algunas ciudades como Herat y Kandahar también resultaron dañadas por los bombardeos. Después de la retirada soviética , la guerra civil se prolongó hasta que el régimen comunista bajo el líder del Partido Democrático Popular Mohammad Najibullah se derrumbó en 1992. [150] [151] [152]

La guerra soviética-afgana tuvo efectos sociales drásticos en Afganistán. La militarización de la sociedad hizo que una policía fuertemente armada, guardaespaldas privados, grupos de defensa civil abiertamente armados y otras cosas similares se convirtieran en la norma en Afganistán durante décadas. [153] La estructura de poder tradicional había pasado del clero, los ancianos de la comunidad, la intelectualidad y el ejército a poderosos señores de la guerra . [154]

Otra guerra civil estalló después de la creación de un gobierno de coalición disfuncional entre los líderes de varias facciones muyahidines . En medio de un estado de anarquía y luchas internas entre facciones, [155] [156] [157] varias facciones muyahidines cometieron violaciones, asesinatos y extorsiones generalizadas, [156] [158] [159] mientras Kabul era fuertemente bombardeada y parcialmente destruida por los combates. [159] Se produjeron varias reconciliaciones y alianzas fallidas entre diferentes líderes. [160] Los talibanes surgieron en septiembre de 1994 como un movimiento y milicia de estudiantes ( talib ) de madrasas (escuelas) islámicas en Pakistán , [159] [161] que pronto tuvieron apoyo militar de Pakistán. [162] Tomando el control de la ciudad de Kandahar ese año, [159] conquistaron más territorios hasta finalmente expulsar al gobierno de Rabbani de Kabul en 1996, [163] [164] donde establecieron un emirato . [165] Los talibanes fueron condenados internacionalmente por la dura aplicación de su interpretación de la ley islámica sharia , que resultó en el tratamiento brutal de muchos afganos, especialmente mujeres . [166] [167] Durante su gobierno, los talibanes y sus aliados cometieron masacres contra civiles afganos, negaron suministros de alimentos de la ONU a civiles hambrientos y llevaron a cabo una política de tierra quemada , quemando vastas áreas de tierra fértil y destruyendo decenas de miles de hogares. [168] [169] [170] [171] [172] [173] [ citas excesivas ]

Tras la caída de Kabul ante los talibanes, Ahmad Shah Massoud y Abdul Rashid Dostum formaron la Alianza del Norte , a la que más tarde se sumaron otros, para resistir a los talibanes. Las fuerzas de Dostum fueron derrotadas por los talibanes durante las batallas de Mazar-i-Sharif en 1997 y 1998; el Jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército de Pakistán, Pervez Musharraf , comenzó a enviar miles de paquistaníes para ayudar a los talibanes a derrotar a la Alianza del Norte. [174] [162] [175] [176] [177] [ citas excesivas ] En 2000, la Alianza del Norte sólo controlaba el 10% del territorio, acorralado en el noreste. El 9 de septiembre de 2001, Massoud fue asesinado por dos atacantes suicidas árabes en el valle de Panjshir . Alrededor de 400.000 afganos murieron en conflictos internos entre 1990 y 2001. [178]

En octubre de 2001, Estados Unidos invadió Afganistán para expulsar a los talibanes del poder después de que se negaran a entregar a Osama bin Laden , el principal sospechoso de los ataques del 11 de septiembre , que era un "invitado" de los talibanes y operaba su red Al Qaeda en Afganistán. [179] [180] [181] La mayoría de los afganos apoyaron la invasión estadounidense. [182] [183] Durante la invasión inicial, las fuerzas estadounidenses y británicas bombardearon los campos de entrenamiento de Al Qaeda y, más tarde, trabajando con la Alianza del Norte, el régimen talibán llegó a su fin. [184]

En diciembre de 2001, después de que el gobierno talibán fuera derrocado, se formó la Administración Provisional Afgana bajo Hamid Karzai . La Fuerza Internacional de Asistencia para la Seguridad (ISAF) fue establecida por el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU para ayudar a asistir a la administración Karzai y proporcionar seguridad básica. [185] [186] En ese momento, después de dos décadas de guerra, así como una hambruna aguda en ese momento, Afganistán tenía una de las tasas de mortalidad infantil y de niños más altas del mundo, la esperanza de vida más baja, gran parte de la población estaba hambrienta, [187] [188] [189] y la infraestructura estaba en ruinas. [190] Muchos donantes extranjeros comenzaron a proporcionar ayuda y asistencia para reconstruir el país devastado por la guerra. [191] [192] Cuando las tropas de la coalición entraron en Afganistán para ayudar en el proceso de reconstrucción , [193] [194] los talibanes comenzaron una insurgencia para recuperar el control. Afganistán siguió siendo uno de los países más pobres del mundo debido a la falta de inversión extranjera, la corrupción gubernamental y la insurgencia talibán. [195] [196]

El gobierno afgano fue capaz de construir algunas estructuras democráticas, adoptando una constitución en 2004 con el nombre de República Islámica de Afganistán . Se hicieron intentos, a menudo con el apoyo de países donantes extranjeros, para mejorar la economía, la atención médica, la educación, el transporte y la agricultura del país. Las fuerzas de la ISAF también comenzaron a entrenar a las Fuerzas de Seguridad Nacional Afganas . Después de 2002, casi cinco millones de afganos fueron repatriados. [197] El número de tropas de la OTAN presentes en Afganistán alcanzó un máximo de 140.000 en 2011, [198] cayendo a alrededor de 16.000 en 2018. [199] En septiembre de 2014, Ashraf Ghani se convirtió en presidente después de las elecciones presidenciales de 2014, donde por primera vez en la historia de Afganistán el poder se transfirió democráticamente. [200] [201] [202] El 28 de diciembre de 2014, la OTAN terminó formalmente las operaciones de combate de la ISAF y transfirió la responsabilidad total de seguridad al gobierno afgano. El mismo día se formó la Operación Apoyo Decidido, dirigida por la OTAN, como sucesora de la ISAF. [203] [204] Miles de tropas de la OTAN permanecieron en el país para entrenar y asesorar a las fuerzas del gobierno afgano [205] y continuar su lucha contra los talibanes. [206] Un informe titulado Body Count concluyó que entre 106.000 y 170.000 civiles habían muerto como resultado de los combates en Afganistán a manos de todas las partes en el conflicto. [207]

El 19 de febrero de 2020, Estados Unidos y los talibanes firmaron en Qatar un acuerdo que fue uno de los acontecimientos críticos que provocaron el colapso de las Fuerzas Nacionales de Seguridad Afganas (ANSF, por sus siglas en inglés); [208] tras la firma del acuerdo, Estados Unidos redujo drásticamente el número de ataques aéreos y privó a las ANSF de una ventaja crítica en la lucha contra la insurgencia talibán , lo que llevó a los talibanes a tomar el control de Kabul. [209]

El secretario general de la OTAN, Jens Stoltenberg, anunció el 14 de abril de 2021 que la alianza había acordado comenzar a retirar sus tropas de Afganistán el 1 de mayo. [210] Poco después de que las tropas de la OTAN comenzaran a retirarse, los talibanes lanzaron una ofensiva contra el gobierno afgano y avanzaron rápidamente frente a las fuerzas gubernamentales afganas que estaban colapsando. [211] [212] Los talibanes capturaron la ciudad capital de Kabul el 15 de agosto de 2021, después de recuperar el control de la gran mayoría de Afganistán. Varios diplomáticos extranjeros y funcionarios del gobierno afgano, incluido el presidente Ashraf Ghani, [213] fueron evacuados del país, y muchos civiles afganos intentaron huir con ellos. [214] El 17 de agosto, el primer vicepresidente Amrullah Saleh se autoproclamó presidente interino y anunció la formación de un frente antitalibán con más de 6.000 tropas [215] [216] en el valle de Panjshir , junto con Ahmad Massoud . [217] [218] Sin embargo, el 6 de septiembre, los talibanes habían tomado el control de la mayor parte de la provincia de Panjshir , y los combatientes de la resistencia se retiraron a las montañas. [219] Los enfrentamientos en el valle cesaron a mediados de septiembre. [220]

Según el Costs of War Project , 176.000 personas murieron en el conflicto, incluidos 46.319 civiles, entre 2001 y 2021. [221] Según el Uppsala Conflict Data Program , al menos 212.191 personas murieron en el conflicto. [222] Aunque el estado de guerra en el país terminó en 2021, el conflicto armado persiste en algunas regiones [223] [224] [225] en medio de combates entre los talibanes y la rama local del Estado Islámico , así como una insurgencia republicana antitalibán . [226]

El gobierno talibán está dirigido por el líder supremo Hibatullah Akhundzada [227] y el primer ministro interino Hasan Akhund , quien asumió el cargo el 7 de septiembre de 2021. [228] [229] Akhund es uno de los cuatro fundadores de los talibanes [230] y fue viceprimer ministro del emirato anterior; su nombramiento fue visto como un compromiso entre moderados y de línea dura. [231] Se formó un nuevo gabinete, compuesto exclusivamente por hombres , que incluyó a Abdul Hakim Haqqani como ministro de Justicia. [232] [233] El 20 de septiembre de 2021, el Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas, António Guterres, recibió una carta del ministro interino de Asuntos Exteriores, Amir Khan Muttaqi, para reclamar formalmente el escaño de Afganistán como estado miembro para su portavoz oficial en Doha , Suhail Shaheen . Las Naciones Unidas no reconocieron al anterior gobierno talibán y optaron por trabajar con el entonces gobierno en el exilio. [234]

Las naciones occidentales suspendieron la mayor parte de su ayuda humanitaria a Afganistán tras la toma de posesión del país por los talibanes en agosto de 2021; el Banco Mundial y el Fondo Monetario Internacional también detuvieron sus pagos. [235] [236] Más de la mitad de los 39 millones de habitantes de Afganistán se enfrentaron a una grave escasez de alimentos en octubre de 2021. [237] Human Rights Watch informó el 11 de noviembre de 2021 que Afganistán se enfrentaba a una hambruna generalizada debido a una crisis económica y bancaria. [238] Los talibanes han abordado significativamente la corrupción, y ahora se ubican en el puesto 150 en el índice de percepción del organismo de control de la corrupción. Según se informa, los talibanes también han reducido el soborno y la extorsión en áreas de servicio público. [239] Al mismo tiempo, la situación de los derechos humanos en el país se ha deteriorado. [240] Después de la invasión de 2001, más de 5,7 millones de refugiados regresaron a Afganistán; [241] Sin embargo, en 2021, 2,6 millones de afganos seguían siendo refugiados, principalmente en Irán y Pakistán, y otros 4 millones estaban desplazados internos. [242]

En octubre de 2023, el gobierno paquistaní ordenó la expulsión de los afganos de Pakistán . [243] Irán también decidió deportar a los ciudadanos afganos a Afganistán. [244] Las autoridades talibanes condenaron las deportaciones de afganos como un "acto inhumano". [245] Afganistán enfrentó una crisis humanitaria a fines de 2023. [246]

Afganistán está situado en el centro-sur de Asia. [247] [248] [249] [250] [251] La región centrada en Afganistán se considera la "encrucijada de Asia", [252] y el país ha tenido el apodo de Corazón de Asia. [253] El famoso poeta urdu Allama Iqbal escribió una vez sobre el país:

Asia es un cuerpo de agua y tierra, cuyo corazón es la nación afgana. De su discordia, la discordia de Asia; y de su acuerdo, el acuerdo de Asia.

Con más de 652.864 km² ( 252.072 millas cuadradas), [254] Afganistán es el 41.º país más grande del mundo . [255] Es ligeramente más grande que Francia y más pequeño que Myanmar, y aproximadamente del tamaño de Texas en los Estados Unidos. No tiene costa, ya que Afganistán no tiene salida al mar . Afganistán comparte su frontera terrestre más larga (la Línea Durand ) con Pakistán al este y al sur, seguida de fronteras con Tayikistán al noreste, Irán al oeste, Turkmenistán al noroeste, Uzbekistán al norte y China al extremo noreste; India reconoce una frontera con Afganistán a través de Cachemira administrada por Pakistán . [256] En el sentido de las agujas del reloj desde el suroeste, Afganistán comparte fronteras con la provincia de Sistán y Baluchistán , la provincia de Jorasán del Sur y la provincia de Jorasán Razavi de Irán; la región de Ahal , la región de Mary y la región de Lebap de Turkmenistán; Región de Surxondaryo de Uzbekistán; Región de Khatlon y Región Autónoma de Gorno-Badakhshan de Tayikistán; Región Autónoma Uigur de Xinjiang de China; y el territorio de Gilgit-Baltistán , la provincia de Khyber Pakhtunkhwa y la provincia de Baluchistán de Pakistán. [257]

.jpg/440px-FrontLines_Environment_Photo_Contest_Winner_-5_(5808476109).jpg)

La geografía de Afganistán es variada, pero es mayormente montañosa y accidentada, con algunas crestas montañosas inusuales acompañadas de mesetas y cuencas fluviales. [258] Está dominada por la cordillera del Hindu Kush , la extensión occidental del Himalaya que se extiende hasta el este del Tíbet a través de las montañas Pamir y las montañas Karakoram en el extremo noreste de Afganistán. La mayoría de los puntos más altos están en el este y consisten en valles montañosos fértiles, a menudo considerados parte del " Techo del Mundo ". El Hindu Kush termina en las tierras altas del centro-oeste, creando llanuras en el norte y suroeste, a saber, las llanuras de Turkestán y la cuenca de Sistán ; estas dos regiones consisten en pastizales ondulados y semidesiertos, y desiertos cálidos y ventosos, respectivamente. [259] Existen bosques en el corredor entre las provincias de Nuristán y Paktika (ver bosques de coníferas de montaña del este de Afganistán ), [260] y tundra en el noreste. El punto más alto del país es Noshaq , a 7.492 m (24.580 pies) sobre el nivel del mar. [261] El punto más bajo se encuentra en la provincia de Jowzjan a lo largo de la orilla del río Amu, a 258 m (846 pies) sobre el nivel del mar.

A pesar de tener numerosos ríos y embalses , grandes partes del país son secas. La cuenca endorreica del Sistán es una de las regiones más secas del mundo. [262] El Amu Darya nace al norte del Hindu Kush, mientras que el cercano Hari Rud fluye al oeste hacia Herat , y el río Arghandab desde la región central hacia el sur. Al sur y al oeste del Hindu Kush fluyen varios arroyos que son afluentes del río Indo , [258] como el río Helmand . El río Kabul fluye en dirección este hasta el Indo y desemboca en el océano Índico. [263] Afganistán recibe fuertes nevadas durante el invierno en las montañas Hindu Kush y Pamir , y la nieve derretida en la temporada de primavera ingresa a los ríos, lagos y arroyos . [264] [265] Sin embargo, dos tercios del agua del país fluye hacia los países vecinos de Irán , Pakistán y Turkmenistán . Como se informó en 2010, el estado necesita más de 2.000 millones de dólares para rehabilitar sus sistemas de riego de manera que el agua se gestione adecuadamente. [266]

En Afganistán, la cubierta forestal representa alrededor del 2% de la superficie total del país, lo que equivale a 1.208.440 hectáreas (ha) de bosque en 2020, cifra que no ha variado respecto de 1990. En 2020, los bosques en regeneración natural cubrían 1.208.440 hectáreas (ha). Se informó que el 0% de los bosques en regeneración natural eran bosques primarios (es decir, especies de árboles nativos sin indicios claramente visibles de actividad humana) y alrededor del 0% de la superficie forestal se encontraba dentro de áreas protegidas. En el año 2015, se informó que el 100% de la superficie forestal era de propiedad pública . [267] [268]

La cordillera del Hindu Kush , en el noreste de Afganistán, se encuentra en una zona geológicamente activa en la que pueden producirse terremotos casi todos los años. [269] Pueden ser mortales y destructivos, provocando deslizamientos de tierra en algunas zonas o avalanchas durante el invierno. [270] En junio de 2022, un destructivo terremoto de 5,9 grados de magnitud sacudió la frontera con Pakistán, matando al menos a 1.150 personas y provocando temores de una importante crisis humanitaria. [271] El 7 de octubre de 2023, un terremoto de magnitud 6,3 sacudió el noroeste de Herat y mató a más de 1.400 personas. [272]

Afganistán tiene un clima continental con inviernos duros en las tierras altas centrales , el noreste glaciado (alrededor de Nuristán ) y el Corredor de Wakhan , donde la temperatura media en enero es inferior a -15 °C (5 °F) y puede alcanzar los -26 °C (-15 °F), [258] y veranos calurosos en las zonas bajas de la cuenca del Sistán en el suroeste, la cuenca de Jalalabad en el este y las llanuras del Turquestán a lo largo del río Amu en el norte, donde las temperaturas promedian más de 35 °C (95 °F) en julio [261] [274] y pueden superar los 43 °C (109 °F). [258] El país es generalmente árido en los veranos, y la mayor parte de las precipitaciones caen entre diciembre y abril. Las zonas más bajas del norte y el oeste de Afganistán son las más secas, con precipitaciones más comunes en el este. Aunque está cerca de la India, Afganistán se encuentra en su mayor parte fuera de la zona monzónica , [258] excepto la provincia de Nuristán , que ocasionalmente recibe lluvias monzónicas de verano. [275]

Existen varios tipos de mamíferos en todo Afganistán. Los leopardos de las nieves , los tigres siberianos y los osos pardos viven en las regiones de tundra alpina de gran altitud . Las ovejas Marco Polo viven exclusivamente en la región del Corredor Wakhan del noreste de Afganistán. Zorros, lobos , nutrias , ciervos , muflones , linces y otros grandes felinos pueblan la región forestal montañosa del este. En las llanuras semidesérticas del norte, la vida silvestre incluye una variedad de aves, erizos , tuzas y grandes carnívoros como chacales y hienas . [276]

Las gacelas , los jabalíes y los chacales pueblan las llanuras esteparias del sur y el oeste, mientras que las mangostas y los guepardos existen en el semidesierto del sur. [276] Las marmotas y las cabras montesas también viven en las altas montañas de Afganistán, y los faisanes existen en algunas partes del país. [277] El lebrel afgano es una raza de perro nativa conocida por su gran velocidad y su pelo largo; es relativamente conocido en el oeste. [278]

La fauna endémica de Afganistán incluye la ardilla voladora afgana , el pinzón de las nieves afgano , Paradactylodon (o la " salamandra de montaña de Paghman "), Stigmella kasyi , Vulcaniella kabulensis , el geco leopardo afgano , Wheeleria parviflorellus , entre otros. La flora endémica incluye Iris afghanica . Afganistán tiene una amplia variedad de aves a pesar de su clima relativamente árido: se estima que hay 460 especies, de las cuales 235 se reproducen allí. [278]

La región forestal de Afganistán tiene vegetación como pinos , piceas , abetos y alerces , mientras que las regiones de pastizales esteparios consisten en árboles de hoja ancha , pasto corto, plantas perennes y matorrales . Las regiones de gran altitud más frías están compuestas por pastos resistentes y pequeñas plantas con flores. [276] Varias regiones están designadas como áreas protegidas ; hay tres parques nacionales : Band-e Amir , Wakhan y Nuristan . Afganistán tuvo una puntuación media del Índice de Integridad del Paisaje Forestal de 2018 de 8,85/10, lo que lo ubica en el puesto 15 a nivel mundial entre 172 países. [279]

.jpg/440px-200229-D-AP390-1529_(49603221753).jpg)

Tras el colapso efectivo de la República Islámica de Afganistán durante la ofensiva talibán de 2021 , los talibanes declararon al país Emirato Islámico. El 7 de septiembre se anunció un nuevo gobierno provisional. [280] Al 8 de septiembre de 2021 [update], ningún otro país había reconocido formalmente al Emirato Islámico de Afganistán como gobierno de iure de Afganistán. [281] Según los índices de democracia de V-Dem , Afganistán en 2023 fue el tercer país menos democrático electoral de Asia . [282]

Un instrumento tradicional de gobierno en Afganistán es la loya jirga (gran asamblea), una reunión consultiva pastún que se organizaba principalmente para elegir un nuevo jefe de Estado , adoptar una nueva constitución o resolver cuestiones nacionales o regionales como la guerra. [283] Las loya jirgas se llevan celebrando desde al menos 1747, [284] y la más reciente tuvo lugar en agosto de 2020. [285] [286]

El 17 de agosto de 2021, el líder del partido Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin , afiliado a los talibanes, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar , se reunió con Hamid Karzai , expresidente de Afganistán , y Abdullah Abdullah , expresidente del Alto Consejo para la Reconciliación Nacional y exjefe del Ejecutivo , en Doha , Qatar , con el objetivo de formar un gobierno de unidad nacional . [287] [288] El presidente Ashraf Ghani , que había huido del país durante el avance de los talibanes hacia Tayikistán o Uzbekistán , apareció en los Emiratos Árabes Unidos y dijo que apoyaba esas negociaciones y que estaba en conversaciones para regresar a Afganistán. [289] [ 290] Muchas figuras dentro de los talibanes estuvieron de acuerdo en general en que la continuación de la Constitución de Afganistán de 2004 puede, si se aplica correctamente, ser viable como base para el nuevo estado religioso, ya que sus objeciones al gobierno anterior eran políticas y no religiosas. [291]

Horas después de que el último vuelo de tropas estadounidenses saliera de Kabul el 30 de agosto, un funcionario talibán entrevistado dijo que probablemente se anunciaría un nuevo gobierno tan pronto como el viernes 3 de septiembre después del Jumu'ah . Se agregó que Hibatullah Akhundzada sería nombrado oficialmente Emir , y que los ministros del gabinete serían revelados en el Arg en una ceremonia oficial. Abdul Ghani Baradar sería nombrado jefe de gobierno como Primer Ministro , mientras que otros puestos importantes irían a parar a Sirajuddin Haqqani y Mullah Yaqoob . Por debajo del líder supremo, la gobernanza diaria se confiará al gabinete . [292]

En un informe de CNN-News18, las fuentes dijeron que el nuevo gobierno iba a ser gobernado de manera similar a Irán con Hibatullah Akhundzada como líder supremo similar al papel de Saayid Ali Khamenei , y tendría su base en Kandahar . Baradar o Yaqoob sería el jefe de gobierno como Primer Ministro . Los ministerios y agencias del gobierno estarán bajo un gabinete presidido por el Primer Ministro. El Líder Supremo presidiría un órgano ejecutivo conocido como el Consejo Supremo con entre 11 y 72 miembros. Es probable que Abdul Hakim Haqqani sea ascendido a Presidente de la Corte Suprema . Según el informe, el nuevo gobierno se llevará a cabo en el marco de una Constitución de Afganistán enmendada de 1964. [ 293] La formación del gobierno se retrasó debido a las preocupaciones sobre la formación de un gobierno de base amplia aceptable para la comunidad internacional. [294] Sin embargo, más tarde se añadió que la Shura Rahbari de los talibanes, el consejo de dirección del grupo, estaba dividida entre la red Haqqani de línea dura y el moderado Abdul Ghani Baradar en lo que respecta a los nombramientos necesarios para formar un gobierno "inclusivo". Los informes afirmaron que esto culminó en una escaramuza que dio lugar a que Baradar resultara herido y recibiera tratamiento en Pakistán, pero el propio Baradar lo negó. [295] [296]

A principios de septiembre de 2021, los talibanes planeaban que el gabinete estuviera integrado únicamente por hombres. Periodistas y otros activistas de derechos humanos, en su mayoría mujeres, protestaron en Herat y Kabul para pedir que se incluyera a las mujeres. [297] El gabinete interino anunciado el 7 de septiembre estaba integrado únicamente por hombres, y se abolió el Ministerio de Asuntos de la Mujer . [280]

Hasta junio de 2024, ningún país ha reconocido al gobierno talibán como autoridad legítima de Afganistán, y la ONU agregó que el reconocimiento era imposible mientras persistieran las restricciones a la educación y el empleo femenino. [298] [299] El 16 de septiembre de 2024, los talibanes suspendieron las campañas de vacunación contra la polio en Afganistán, como lo informaron las Naciones Unidas, lo que representa un riesgo significativo para los esfuerzos mundiales de erradicación de la polio. [300]

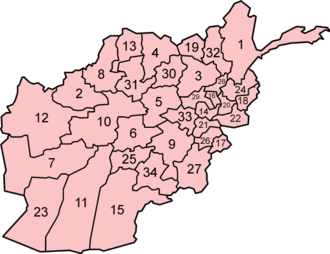

Afganistán se divide administrativamente en 34 provincias ( wilayat ). [301] Cada provincia tiene un gobernador y una capital. El país se divide además en casi 400 distritos provinciales , cada uno de los cuales normalmente abarca una ciudad o varias aldeas. Cada distrito está representado por un gobernador de distrito.

En la actualidad, los gobernadores provinciales son designados por el Primer Ministro del Afganistán , y los gobernadores de distrito son seleccionados por los gobernadores provinciales. [302] Los gobernadores provinciales son representantes del gobierno central en Kabul y son responsables de todas las cuestiones administrativas y formales dentro de sus provincias. También hay consejos provinciales que se eligen mediante elecciones directas y generales por cuatro años. [303] Las funciones de los consejos provinciales son participar en la planificación del desarrollo provincial y participar en el seguimiento y la evaluación de otras instituciones de gobernanza provincial.

Según el artículo 140 de la Constitución y el decreto presidencial sobre la ley electoral, los alcaldes de las ciudades deben ser elegidos mediante elecciones libres y directas por un período de cuatro años. Sin embargo, en la práctica, los alcaldes son designados por el gobierno. [304]

Las 34 provincias en orden alfabético son:

Afganistán se convirtió en miembro de las Naciones Unidas en 1946. [305] Históricamente, Afganistán tuvo fuertes relaciones con Alemania, uno de los primeros países en reconocer la independencia de Afganistán en 1919; la Unión Soviética, que proporcionó mucha ayuda y entrenamiento militar a las fuerzas de Afganistán e incluye la firma de un Tratado de Amistad en 1921 y 1978; y la India , con la que se firmó un tratado de amistad en 1950. [306] Las relaciones con Pakistán a menudo han sido tensas por diversas razones, como la cuestión fronteriza de la Línea Durand y la presunta participación paquistaní en grupos insurgentes afganos.

El actual Emirato Islámico de Afganistán actualmente no está reconocido internacionalmente , pero ha tenido notables vínculos no oficiales con China , Pakistán y Qatar. [307] [308] Bajo la anterior República Islámica de Afganistán, disfrutó de relaciones cordiales con varios países de la OTAN y aliados, en particular Estados Unidos , Canadá , Reino Unido , Alemania , Australia y Turquía . En 2012, Estados Unidos y la entonces república de Afganistán firmaron su Acuerdo de Asociación Estratégica en el que Afganistán se convirtió en un importante aliado no perteneciente a la OTAN . [309] Dicha calificación fue rescindida por el presidente estadounidense Joe Biden en julio de 2022. [310]

Las Fuerzas Armadas del Emirato Islámico de Afganistán capturaron una gran cantidad de armas, equipos, vehículos, aeronaves y equipos de las Fuerzas de Seguridad Nacional Afganas tras la ofensiva talibán de 2021 y la caída de Kabul . El valor total del equipo capturado se ha estimado en 83.000 millones de dólares. [311] [312]

La homosexualidad es un tabú en la sociedad afgana; [313] según el Código Penal, la intimidad homosexual se castiga con hasta un año de prisión. [314] Según la ley Sharia , los infractores pueden ser castigados con la muerte . [315] [316] Sin embargo, persiste una antigua tradición que implica actos homosexuales masculinos entre niños y hombres mayores (normalmente señores de la guerra ricos o personas de la élite) llamada bacha bazi .

Según se informa, minorías religiosas como los sijs, [317] los hindúes [318] y los cristianos han sufrido persecución. [319] [320]

Desde mayo de 2022, todas las mujeres de Afganistán están obligadas por ley a llevar una cobertura corporal completa cuando están en público (ya sea una burka o una abaya combinada con un niqab , que deja solo los ojos descubiertos). [321] [322] El primer vicepresidente Sirajuddin Haqqani afirmó que el decreto es solo consultivo y que ninguna forma de hijab es obligatoria en Afganistán, [323] aunque esto contradice la realidad. [324] Se ha especulado que existe una auténtica división política interna sobre los derechos de las mujeres entre los de línea dura, incluido el líder Hibatullah Akhundzada, y los pragmáticos, aunque públicamente presentan un frente unido. [325] Poco después del primero se emitió otro decreto, que exige que las presentadoras de televisión se cubran el rostro durante las transmisiones. [326] Desde la toma de poder de los talibanes, los suicidios entre mujeres se han vuelto más comunes, y el país podría ser ahora uno de los pocos donde la tasa de suicidio entre mujeres supera a la de los hombres. [327] [328] [329]

En mayo de 2022, los talibanes disolvieron la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de Afganistán junto con otros cuatro departamentos gubernamentales, citando el déficit presupuestario del país. [330]

El PIB nominal de Afganistán fue de 20.100 millones de dólares en 2020, o 81.000 millones de dólares en paridad de poder adquisitivo (PPA). [21] Su PIB per cápita es de 2.459 dólares (PPA) y de 611 dólares en nominal. [21] A pesar de tener 1 billón de dólares o más en depósitos minerales, [331] sigue siendo uno de los países menos desarrollados del mundo . La accidentada geografía física de Afganistán y su condición de país sin salida al mar se han citado como razones por las que el país siempre ha estado entre los menos desarrollados de la era moderna, un factor en el que el progreso también se ve frenado por el conflicto contemporáneo y la inestabilidad política. [258] El país importa más de 7.000 millones de dólares en bienes, pero exporta solo 784 millones, principalmente frutas y frutos secos . Tiene una deuda externa de 2.800 millones de dólares . [261] El sector servicios fue el que más contribuyó al PIB (55,9%), seguido de la agricultura (23%) y la industria (21,1%). [332]

El Banco Da Afghanistan es el banco central de la nación [333] y el afgani (AFN) es la moneda nacional, con un tipo de cambio de aproximadamente 75 afganis por 1 dólar estadounidense. [334] Varios bancos locales y extranjeros operan en el país, incluidos el Afghanistan International Bank , New Kabul Bank , Azizi Bank , Pashtany Bank , Standard Chartered Bank y First Micro Finance Bank .

Uno de los principales impulsores de la actual recuperación económica es el regreso de más de 5 millones de expatriados , que trajeron consigo habilidades empresariales y de creación de riqueza, así como fondos muy necesarios para poner en marcha empresas. Muchos afganos participan ahora en la construcción, que es una de las industrias más grandes del país. [335] Algunos de los principales proyectos de construcción nacionales incluyen la Nueva Ciudad de Kabul de 35 mil millones de dólares junto a la capital, el proyecto Aino Mena en Kandahar y la ciudad de Ghazi Amanullah Khan cerca de Jalalabad. [336] [337] [338] También se han iniciado proyectos de desarrollo similares en Herat , Mazar-e-Sharif y otras ciudades. [339] Se estima que 400.000 personas ingresan al mercado laboral cada año. [340]

Varias pequeñas empresas y fábricas comenzaron a operar en diferentes partes del país, lo que no solo genera ingresos para el gobierno sino que también crea nuevos empleos. Las mejoras en el entorno empresarial han dado como resultado una inversión en telecomunicaciones de más de 1.500 millones de dólares y han creado más de 100.000 puestos de trabajo desde 2003. [341] Las alfombras afganas están volviendo a ser populares, lo que permite a muchos comerciantes de alfombras de todo el país contratar a más trabajadores; en 2016-17 fue el cuarto grupo de artículos más exportado. [342]

Afganistán es miembro de la OMC , la SAARC , la OCE y la OCI . Tiene estatus de observador en la OCS . En 2018, la mayoría de las importaciones provienen de Irán, China, Pakistán y Kazajstán, mientras que el 84% de las exportaciones se destinan a Pakistán y la India. [343]

Desde que los talibanes tomaron el control del país en agosto de 2021, Estados Unidos ha congelado alrededor de 9.000 millones de dólares en activos pertenecientes al banco central afgano [344] , impidiendo a los talibanes acceder a miles de millones de dólares depositados en cuentas bancarias estadounidenses. [345] [346]

Se estima que el PIB de Afganistán cayó un 20% tras el regreso de los talibanes al poder. Después de esto, tras meses de caída libre, la economía afgana comenzó a estabilizarse, como resultado de las restricciones de los talibanes a las importaciones de contrabando, los límites a las transacciones bancarias y la ayuda de la ONU. En 2023, la economía afgana comenzó a ver signos de recuperación. A esto también le siguieron tipos de cambio estables, baja inflación, recaudación de ingresos estable y el aumento del comercio de exportaciones. [347] En el tercer trimestre de 2023, el afgani se convirtió en la moneda de mejor rendimiento del mundo, subiendo más del 9% frente al dólar estadounidense . [348]

La producción agrícola es la columna vertebral de la economía de Afganistán [349] y tradicionalmente ha dominado la economía, empleando a alrededor del 40% de la fuerza laboral en 2018. [350] El país es conocido por producir granadas , uvas, albaricoques, melones y varias otras frutas frescas y secas. Afganistán también se convirtió en el principal productor mundial de cannabis en 2010. [351] Sin embargo, en marzo de 2023, la producción de cannabis fue prohibida por un decreto de Hibatullah Akhundzada. [352]

El azafrán , la especia más cara, crece en Afganistán, particularmente en la provincia de Herat . En los últimos años, ha habido un repunte en la producción de azafrán, que las autoridades y los agricultores están utilizando para tratar de reemplazar el cultivo de adormidera. Entre 2012 y 2019, el azafrán cultivado y producido en Afganistán fue clasificado consecutivamente como el mejor del mundo por el Instituto Internacional de Sabor y Calidad. [353] [354] La producción alcanzó un récord en 2019 (19.469 kg de azafrán), y un kilogramo se vende en el país entre $ 634 y $ 1147. [355]

La disponibilidad de bombas de agua baratas impulsadas por diésel importadas de China y Pakistán, y en la década de 2010, de energía solar barata para bombear agua, resultó en la expansión de la agricultura y la población en los desiertos del suroeste de Afganistán en las provincias de Kandahar , Helmand y Nimruz en la década de 2010. Los pozos se han profundizado gradualmente, pero los recursos hídricos son limitados. El opio es el cultivo principal, pero a partir de 2022, estaba siendo atacado por el nuevo gobierno talibán que, para reprimir la producción de opio, estaba suprimiendo sistemáticamente el bombeo de agua. [356] [357] En un informe de 2023, el cultivo de adormidera en el sur de Afganistán se redujo en más del 80% como resultado de las campañas de los talibanes para detener su uso para el opio. Esto incluyó una reducción del 99% del crecimiento del opio en la provincia de Helmand . [358] En noviembre de 2023, un informe de la ONU mostró que en todo Afganistán, el cultivo de adormidera se redujo en más del 95%, lo que lo eliminó del puesto de mayor productor de opio del mundo. [359] [360]

Los recursos naturales del país incluyen: carbón, cobre, mineral de hierro, litio , uranio , tierras raras , cromita , oro, zinc , talco , barita , azufre , plomo, mármol , piedras preciosas y semipreciosas , gas natural y petróleo. [361] [362] En 2010, funcionarios del gobierno estadounidense y afgano estimaron que los depósitos minerales sin explotar ubicados en 2007 por el Servicio Geológico de Estados Unidos valen al menos $ 1 billón . [363]

Michael E. O'Hanlon, de la Brookings Institution, estimó que si Afganistán genera alrededor de 10 mil millones de dólares al año a partir de sus depósitos minerales , su producto nacional bruto se duplicaría y proporcionaría financiación a largo plazo para necesidades críticas. [364] El Servicio Geológico de los Estados Unidos (USGS) estimó en 2006 que el norte de Afganistán tiene un promedio de 460 millones de m3 ( 2,9 mil millones de bbl) de petróleo crudo , 440 mil millones de m3 ( 15,7 billones de pies cúbicos) de gas natural y 67 mil millones de l (562 millones de bbl estadounidenses) de líquidos de gas natural . [365] En 2011, Afganistán firmó un contrato de exploración petrolera con China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) para el desarrollo de tres campos petrolíferos a lo largo del río Amu Darya en el norte. [366]

El país tiene cantidades significativas de litio , cobre, oro, carbón, mineral de hierro y otros minerales . [361] [362] [367] La carbonatita Khanashin en la provincia de Helmand contiene 1.000.000 de toneladas (980.000 toneladas largas ; 1.100.000 toneladas cortas ) de elementos de tierras raras . [368] En 2007, se otorgó un contrato de arrendamiento de 30 años para la mina de cobre Aynak al Grupo Metalúrgico de China por $ 3 mil millones, [369] convirtiéndolo en la mayor inversión extranjera y empresa privada en la historia de Afganistán. [370] La Autoridad del Acero de la India, dirigida por el estado, ganó los derechos mineros para desarrollar el enorme depósito de mineral de hierro de Hajigak en el centro de Afganistán. [371] Los funcionarios del gobierno estiman que el 30% de los depósitos minerales sin explotar del país valen al menos $ 1 billón . [363] Un funcionario afirmó que "esto se convertirá en la columna vertebral de la economía afgana" y un memorando del Pentágono afirmó que Afganistán podría convertirse en la "Arabia Saudita del litio". [372] Las reservas de litio de 21 millones de toneladas podrían alcanzar las de Bolivia , que actualmente se considera el país con las mayores reservas de litio. [373] Otros depósitos más grandes son los de bauxita y cobalto . [373]

El acceso a la biocapacidad en Afganistán es inferior al promedio mundial. En 2016, Afganistán tenía 0,43 hectáreas globales [374] de biocapacidad por persona dentro de su territorio, mucho menos que el promedio mundial de 1,6 hectáreas globales por persona. [375] En 2016, Afganistán utilizó 0,73 hectáreas globales de biocapacidad por persona, es decir, su huella ecológica de consumo. Esto significa que utiliza casi el doble de biocapacidad que Afganistán. Como resultado, Afganistán tiene un déficit de biocapacidad. [374]

En septiembre de 2023, los talibanes firmaron contratos mineros por valor de 6.500 millones de dólares , con extracciones basadas en oro, hierro, plomo y zinc en las provincias de Herat, Ghor, Logar y Takhar. [376]

Según el Banco Mundial , el 98% de la población rural tiene acceso a la electricidad en 2018, frente al 28% en 2008. [377] En general, la cifra se sitúa en el 98,7%. [378] A partir de 2016, Afganistán produce 1.400 megavatios de energía, pero todavía importa la mayoría de la electricidad a través de líneas de transmisión de Irán y los estados de Asia Central. [379] La mayor parte de la producción de electricidad es a través de energía hidroeléctrica , ayudada por la cantidad de ríos y arroyos que fluyen desde las montañas. [380] Sin embargo, la electricidad no siempre es confiable y ocurren apagones, incluso en Kabul. [381] En los últimos años se ha construido un número cada vez mayor de plantas de energía solar , de biomasa y eólica. [382] Actualmente en desarrollo están el proyecto CASA-1000 que transmitirá electricidad desde Kirguistán y Tayikistán, y el gasoducto Turkmenistán-Afganistán-Pakistán-India (TAPI). [381] La energía es administrada por Da Afghanistan Breshna Sherkat (DABS, Compañía de Electricidad de Afganistán).

Entre las presas importantes se incluyen la presa Kajaki , la presa Dahla y la presa Sardeh Band . [263]

.jpg/440px-Contrasts_(4292970991).jpg)

El turismo es una industria pequeña en Afganistán debido a problemas de seguridad. Sin embargo, unos 20.000 turistas extranjeros visitan el país anualmente a partir de 2016. [383] En particular, una región importante para el turismo nacional e internacional es el pintoresco valle de Bamiyán , que incluye lagos, cañones y sitios históricos, ayudado por el hecho de que está en una zona segura lejos de la actividad insurgente. [384] [385] Un número menor de personas visitan y caminan en regiones como el valle de Wakhan , que también es una de las comunidades más remotas del mundo. [386] Desde finales de la década de 1960 en adelante, Afganistán fue una parada popular en la famosa ruta hippie , atrayendo a muchos europeos y estadounidenses. Procedente de Irán, la ruta atravesaba varias provincias y ciudades afganas, incluidas Herat , Kandahar y Kabul, antes de cruzar al norte de Pakistán, el norte de la India y Nepal . [387] [388] El turismo alcanzó su punto máximo en 1977, el año anterior al inicio de la inestabilidad política y el conflicto armado. [389]

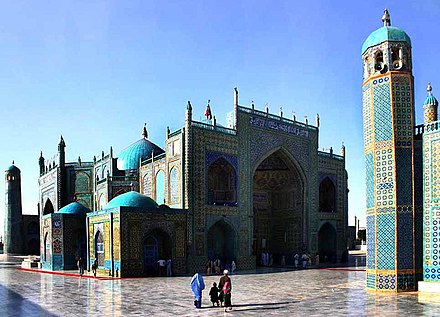

La ciudad de Ghazni tiene una historia y unos sitios históricos importantes, y junto con la ciudad de Bamiyán han sido votadas en los últimos años como Capital Cultural Islámica y Capital Cultural del Sur de Asia respectivamente. [390] Las ciudades de Herat , Kandahar , Balkh y Zaranj también son muy históricas. El minarete de Jam en el valle del río Hari es Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO . Una capa que supuestamente llevaba el profeta Mahoma se conserva en el Santuario de la Capa en Kandahar, una ciudad fundada por Alejandro Magno y la primera capital de Afganistán. La ciudadela de Alejandro en la ciudad occidental de Herat ha sido renovada en los últimos años y es una atracción popular. En el norte del país se encuentra el Santuario de Ali , que muchos creen que es el lugar donde fue enterrado Ali . [391] El Museo Nacional de Afganistán en Kabul alberga una gran cantidad de antigüedades budistas, griegas bactrianas e islámicas tempranas; el museo sufrió mucho por la guerra civil, pero se ha estado restaurando lentamente desde principios de la década de 2000. [392]

Inesperadamente, el turismo ha experimentado un desarrollo en Afganistán tras la toma de poder de los talibanes. Los esfuerzos activos de los talibanes han hecho que el turismo aumente de 691 turistas en 2021 a 2.300 en 2022. Se observó un fuerte aumento de más del 120% entre 2022 y 2023, llegando a casi 5.200 turistas, con algunas estimaciones de entre 7.000 y 10.000. [393] [394] [395] Sin embargo, esto se ve amenazado por el ISIS-K , que se responsabilizó de los ataques a turistas , como el tiroteo de Bamiyán en 2024. [396]

Los servicios de telecomunicaciones en Afganistán son proporcionados por Afghan Telecom , Afghan Wireless , Etisalat , MTN Group y Roshan . El país utiliza su propio satélite espacial llamado Afghansat 1 , que proporciona servicios a millones de suscriptores de teléfono, Internet y televisión. En 2001, tras años de guerra civil, las telecomunicaciones eran prácticamente un sector inexistente, pero en 2016 habían crecido hasta convertirse en una industria de 2.000 millones de dólares, con 22 millones de suscriptores de telefonía móvil y 5 millones de usuarios de Internet. El sector emplea al menos a 120.000 personas en todo el país. [397]

Debido a la geografía de Afganistán, el transporte entre las distintas partes del país ha sido históricamente difícil. La columna vertebral de la red vial de Afganistán es la carretera 1 , a menudo llamada la "carretera de circunvalación", que se extiende por 2.210 kilómetros (1.370 millas) y conecta cinco ciudades importantes: Kabul, Ghazni, Kandahar, Herat y Mazar-i-Sharif, [398] con ramales hacia Kunduz y Jalalabad y varios cruces fronterizos, mientras bordea las montañas del Hindu Kush. [399]

La carretera de circunvalación es de importancia crucial para el comercio nacional e internacional y la economía. [400] Una parte clave de la carretera de circunvalación es el túnel de Salang , terminado en 1964, que facilita el viaje a través de la cordillera del Hindu Kush y conecta el norte y el sur de Afganistán. [401] Es la única ruta terrestre que conecta Asia Central con el subcontinente indio . [402] Varios pasos de montaña permiten viajar entre el Hindu Kush y otras áreas. Los accidentes de tráfico graves son comunes en las carreteras y autopistas afganas, particularmente en la carretera Kabul-Kandahar y la carretera Kabul-Jalalabad . [403] Viajar en autobús en Afganistán sigue siendo peligroso debido a las actividades militantes. [404]

El transporte aéreo en Afganistán es proporcionado por la aerolínea nacional, Ariana Afghan Airlines , [405] y por la compañía privada Kam Air . Las aerolíneas de varios países también ofrecen vuelos dentro y fuera del país. Estas incluyen Air India , Emirates , Gulf Air , Iran Aseman Airlines , Pakistan International Airlines y Turkish Airlines . El país tiene cuatro aeropuertos internacionales: el Aeropuerto Internacional de Kabul (anteriormente Aeropuerto Internacional Hamid Karzai), el Aeropuerto Internacional de Kandahar , el Aeropuerto Internacional de Herat y el Aeropuerto Internacional de Mazar-e Sharif . Incluyendo los aeropuertos nacionales, hay 43. [261] La base aérea de Bagram es un importante aeródromo militar.

El país tiene tres enlaces ferroviarios: uno, una línea de 75 kilómetros (47 millas) desde Mazar-i-Sharif hasta la frontera con Uzbekistán ; [406] una línea de 10 kilómetros (6,2 millas) de largo desde Toraghundi hasta la frontera con Turkmenistán (donde continúa como parte de los Ferrocarriles Turcomanos ); y un enlace corto desde Aqina a través de la frontera con Turkmenistán hasta Kerki , que se planea extender más por Afganistán. [407] Estas líneas se utilizan solo para carga y no hay servicio de pasajeros. Una línea ferroviaria entre Khaf , Irán y Herat , oeste de Afganistán, destinada tanto para carga como para pasajeros, estaba en construcción en 2019. [408] [409] Aproximadamente 125 kilómetros (78 millas) de la línea estarán en el lado afgano. [410] [411]

La propiedad de vehículos privados ha aumentado sustancialmente desde principios de la década de 2000. Los taxis son amarillos y están compuestos tanto por automóviles como por rickshaws . [412] En las zonas rurales de Afganistán, los habitantes de las aldeas suelen utilizar burros, mulas o caballos para transportar o llevar mercancías. Los camellos son utilizados principalmente por los nómadas de Kochi. [278] Las bicicletas son populares en todo Afganistán. [413]

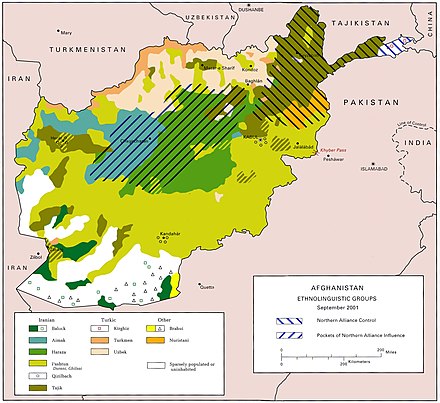

La Autoridad de Información y Estadísticas de Afganistán estimó en 32,9 millones de habitantes en 2019, [415] mientras que la ONU estima que supera los 38,0 millones. [416] En 1979, se informó que la población total era de unos 15,5 millones. [417] Alrededor del 23,9% de ellos son urbanitas , el 71,4% vive en zonas rurales y el 4,7% restante son nómadas. [418] Unos 3 millones de afganos adicionales están alojados temporalmente en los vecinos Pakistán e Irán , la mayoría de los cuales nacieron y crecieron en esos dos países. En 2013, Afganistán era el mayor país productor de refugiados del mundo, título que mantuvo durante 32 años.