La historia de la medicina es tanto un estudio de la medicina a lo largo de la historia como un campo de estudio multidisciplinario que busca explorar y comprender las prácticas médicas, tanto pasadas como presentes, en todas las sociedades humanas. [1]

La historia de la medicina es el estudio y la documentación de la evolución de los tratamientos, prácticas y conocimientos médicos a lo largo del tiempo. Los historiadores médicos a menudo recurren a otros campos de estudio de las humanidades , como la economía, las ciencias de la salud , la sociología y la política, para comprender mejor las instituciones, las prácticas, las personas, las profesiones y los sistemas sociales que han dado forma a la medicina. Cuando se trata de un período que es anterior o carece de fuentes escritas sobre medicina, la información se extrae de fuentes arqueológicas. [1] [2] Este campo rastrea la evolución del enfoque de las sociedades humanas hacia la salud, la enfermedad y las lesiones desde la prehistoria hasta la actualidad, los eventos que dan forma a estos enfoques y su impacto en las poblaciones.

Las tradiciones médicas tempranas incluyen las de Babilonia , China , Egipto e India . La invención del microscopio fue una consecuencia de la mejora de la comprensión, durante el Renacimiento. Antes del siglo XIX, se pensaba que el humorismo (también conocido como humoralismo) explicaba la causa de la enfermedad, pero fue reemplazado gradualmente por la teoría de los gérmenes de la enfermedad , lo que llevó a tratamientos efectivos e incluso curas para muchas enfermedades infecciosas. Los médicos militares avanzaron en los métodos de tratamiento de traumas y cirugía. Las medidas de salud pública se desarrollaron especialmente en el siglo XIX, ya que el rápido crecimiento de las ciudades requería medidas sanitarias sistemáticas. Los centros de investigación avanzados se abrieron a principios del siglo XX, a menudo conectados con los principales hospitales . La mitad del siglo XX se caracterizó por nuevos tratamientos biológicos, como los antibióticos . Estos avances, junto con los desarrollos en química , genética y radiografía, dieron lugar a la medicina moderna . La medicina se profesionalizó en gran medida en el siglo XX y se abrieron nuevas carreras para las mujeres como enfermeras (a partir de la década de 1870) y como médicas (especialmente después de 1970).

La medicina prehistórica es un campo de estudio centrado en comprender el uso de plantas medicinales , prácticas curativas, enfermedades y bienestar de los humanos antes de que existieran registros escritos. [4] Aunque se la denomina "medicina" prehistórica, las prácticas de atención médica prehistóricas eran muy diferentes de lo que entendemos por medicina en la era actual y se refiere con mayor precisión a los estudios y la exploración de las primeras prácticas curativas.

Este período se extiende desde el primer uso de herramientas de piedra por parte de los primeros humanos hace aproximadamente 3,3 millones de años [5] hasta el comienzo de los sistemas de escritura y la posterior historia registrada hace aproximadamente 5000 años.

Como las poblaciones humanas alguna vez estuvieron dispersas por todo el mundo, formando comunidades y culturas aisladas que interactuaban esporádicamente, se han desarrollado una variedad de períodos arqueológicos para dar cuenta de los diferentes contextos de tecnología, desarrollos socioculturales y adopción de sistemas de escritura en las primeras sociedades humanas. [6] [7] La medicina prehistórica es entonces altamente contextual a la ubicación y la gente en cuestión, [8] creando un período de estudio no uniforme para reflejar varios grados de desarrollo social.

Sin registros escritos, los conocimientos sobre la medicina prehistórica provienen indirectamente de la interpretación de la evidencia dejada por los humanos prehistóricos. Una rama de esto incluye la arqueología de la medicina; una disciplina que utiliza una variedad de técnicas arqueológicas, desde la observación de enfermedades en restos humanos, fósiles de plantas, hasta excavaciones para descubrir prácticas médicas. [3] [9] Hay evidencia de prácticas curativas entre los neandertales [10] y otras especies humanas tempranas. La evidencia prehistórica del compromiso humano con la medicina incluye el descubrimiento de fuentes de plantas psicoactivas como los hongos psilocibios en el Sahara alrededor del 6000 a . C. [11] hasta el cuidado dental primitivo en Riparo Fredian alrededor del 10 900 a. C. (13 000 a. C. ) [12] (actual Italia) [13] y Mehrgarh alrededor del 7000 a. C. (actual Pakistán ). [14] [15]

La antropología es otra rama académica que contribuye a la comprensión de la medicina prehistórica al descubrir las relaciones socioculturales, el significado y la interpretación de la evidencia prehistórica. [16] La superposición de la medicina como raíz de la curación del cuerpo y de lo espiritual a lo largo de los períodos prehistóricos resalta los múltiples propósitos que las prácticas curativas y las plantas podrían tener potencialmente. [17] [18] [19] Desde las proto-religiones hasta los sistemas espirituales desarrollados, las relaciones entre humanos y entidades sobrenaturales , desde los dioses hasta los chamanes , han jugado un papel entrelazado en la medicina prehistórica. [20] [21]

La historia antigua abarca el período comprendido entre el año 3000 a. C. y el año 500 d. C. , desde el desarrollo de los sistemas de escritura hasta el final de la era clásica y el comienzo del período posclásico . Esta periodización presenta la historia como si fuera la misma en todas partes, pero es importante señalar que los desarrollos socioculturales y tecnológicos pueden diferir localmente de un asentamiento a otro, así como globalmente de una sociedad a otra. [22]

La medicina antigua cubre un período de tiempo similar y presentó una variedad de teorías curativas similares de todo el mundo que conectan la naturaleza , la religión y los humanos dentro de las ideas de fluidos circulantes y energía. [23] Aunque académicos y textos destacados detallaron conocimientos médicos bien definidos, sus aplicaciones en el mundo real se vieron empañadas por la destrucción y pérdida de conocimiento, [24] mala comunicación, reinterpretaciones localizadas y aplicaciones inconsistentes posteriores. [25]

La región mesopotámica , que abarca gran parte de los actuales Irak , Kuwait , Siria , Irán y Turquía , estuvo dominada por una serie de civilizaciones, entre ellas Sumeria , la civilización más antigua conocida en la región de la Media Luna Fértil , [26] [27] junto con los acádios (incluidos los asirios y babilonios ). Las ideas superpuestas de lo que ahora entendemos como medicina, ciencia, magia y religión caracterizaron las primeras prácticas curativas mesopotámicas como un sistema híbrido de creencias naturalistas y sobrenaturales . [28] [29] [30]

Los sumerios , que habían desarrollado uno de los primeros sistemas de escritura conocidos en el tercer milenio a. C. , crearon numerosas tablillas de arcilla cuneiformes sobre su civilización que incluían relatos detallados de prescripciones de medicamentos , operaciones y exorcismos. Estos eran administrados y llevados a cabo por profesionales altamente definidos, incluidos bârû (videntes), âs[h]ipu (exorcistas) y asû (médicos-sacerdotes). [31] Un ejemplo de un medicamento temprano, similar a una prescripción, apareció en sumerio durante la Tercera Dinastía de Ur ( c. 2112 a. C. - c. 2004 a. C. ). [32]

Tras la conquista de la civilización sumeria por el Imperio acadio y el colapso final del imperio debido a una serie de factores sociales y ambientales, [33] la civilización babilónica comenzó a dominar la región. Entre los ejemplos de medicina babilónica se incluyen el extenso texto médico babilónico, el Manual de diagnóstico, escrito por el ummânū , o erudito principal, Esagil-kin-apli de Borsippa , [34] : 99 [35] a mediados del siglo XI a. C. durante el reinado del rey babilónico Adad-apla-iddina (1069-1046 a. C.). [36]

Este tratado médico prestó gran atención a la práctica del diagnóstico , pronóstico , examen físico y remedios. El texto contiene una lista de síntomas médicos y observaciones empíricas a menudo detalladas junto con reglas lógicas utilizadas para combinar los síntomas observados en el cuerpo de un paciente con su diagnóstico y pronóstico. [34] : 97–98 Aquí, se desarrollaron fundamentos claramente desarrollados para comprender las causas de las enfermedades y las lesiones, respaldados por teorías acordadas en ese momento sobre elementos que ahora podríamos entender como causas naturales, magia sobrenatural y explicaciones religiosas. [35]

La mayoría de los artefactos conocidos y recuperados de las antiguas civilizaciones mesopotámicas se centran en los períodos neoasirio ( c. 900 – 600 a. C. ) y neobabilónico ( c. 600 – 500 a. C. ), como los últimos imperios gobernados por gobernantes nativos de Mesopotamia. [37] Estos descubrimientos incluyen una gran variedad de tablillas de arcilla médicas de este período, aunque el daño a los documentos de arcilla crea grandes lagunas en nuestra comprensión de las prácticas médicas. [38]

A lo largo de las civilizaciones de Mesopotamia existe una amplia gama de innovaciones médicas que incluyen prácticas comprobadas de profilaxis , toma de medidas para prevenir la propagación de enfermedades, [28] relatos de accidentes cerebrovasculares, [ cita requerida ] y una conciencia de las enfermedades mentales. [39]

El antiguo Egipto , una civilización que se extendió a través del río Nilo (a lo largo de partes del actual Egipto , Sudán y Sudán del Sur ), existió desde su unificación en aproximadamente 3150 a. C. hasta su colapso a través de la conquista persa en 525 a. C. [40] y su caída final tras la conquista de Alejandro Magno en 332 a. C.

A lo largo de dinastías únicas, eras doradas y períodos intermedios de inestabilidad, los antiguos egipcios desarrollaron una tradición médica compleja, experimental y comunicativa que ha sido descubierta a través de documentos sobrevivientes, la mayoría hechos de papiro , como el Papiro Ginecológico de Kahun , el Papiro de Edwin Smith , el Papiro de Ebers , el Papiro Médico de Londres , hasta los Papiros Mágicos Griegos . [41]

Heródoto describió a los egipcios como "los más sanos de todos los hombres, después de los libios", [42] debido al clima seco y al notable sistema de salud pública que poseían. Según él, "la práctica de la medicina está tan especializada entre ellos que cada médico es un sanador de una enfermedad y no más". Aunque la medicina egipcia, en gran medida, se ocupaba de lo sobrenatural, [43] con el tiempo desarrolló un uso práctico en los campos de la anatomía, la salud pública y el diagnóstico clínico.

La información médica contenida en el Papiro de Edwin Smith puede datar de una época tan temprana como el año 3000 a. C. [44] A veces se atribuye a Imhotep , de la tercera dinastía, el mérito de ser el fundador de la medicina egipcia antigua y el de ser el autor original del Papiro de Edwin Smith , que detalla curas, dolencias y observaciones anatómicas . El Papiro de Edwin Smith se considera una copia de varias obras anteriores y fue escrito alrededor del año 1600 a. C. Es un antiguo libro de texto sobre cirugía casi completamente desprovisto de pensamiento mágico y describe con exquisito detalle el examen , el diagnóstico , el tratamiento y el pronóstico de numerosas dolencias. [45]

El Papiro Ginecológico de Kahun [46] trata las dolencias de las mujeres, incluidos los problemas de concepción . Sobreviven treinta y cuatro casos que detallan el diagnóstico y [47] el tratamiento, algunos de ellos de forma fragmentaria. [48] Data del año 1800 a. C. y es el texto médico más antiguo que se conserva de cualquier tipo.

Se sabe que las instituciones médicas, conocidas como Casas de Vida, se establecieron en el antiguo Egipto ya en el año 2200 a. C. [49]

El papiro de Ebers es el texto escrito más antiguo que menciona los enemas . Muchos medicamentos se administraban mediante enemas y uno de los muchos tipos de especialistas médicos era un Iri, el Pastor del Ano. [50]

El médico más antiguo conocido también se atribuye al antiguo Egipto : Hesy-Ra , "Jefe de dentistas y médicos" del rey Djoser en el siglo 27 a. C. [51] Además, la mujer médica más antigua conocida, Peseshet , ejerció en el Antiguo Egipto en la época de la IV dinastía . Su título era "Señora supervisora de las mujeres médicas". [52]

Las prácticas médicas y curativas en las primeras dinastías chinas estuvieron fuertemente influenciadas por la práctica de la medicina tradicional china (MTC). [53] A partir de la dinastía Zhou , se desarrollaron partes de este sistema y se demuestran en los primeros escritos sobre hierbas en el Clásico de los cambios ( Yi Jing ) y el Clásico de la poesía ( Shi Jing ). [54] [55]

China también desarrolló un amplio corpus de medicina tradicional. Gran parte de la filosofía de la medicina tradicional china se deriva de observaciones empíricas de enfermedades y dolencias realizadas por médicos taoístas y refleja la creencia china clásica de que las experiencias humanas individuales expresan principios causales que actúan en el entorno a todas las escalas. Estos principios causales, ya sean materiales, esenciales o místicos, se correlacionan como la expresión del orden natural del universo .

El texto fundacional de la medicina china es el Huangdi Neijing (o Canon Interno del Emperador Amarillo ), escrito entre el siglo V y el siglo III a. C. [56] Cerca del final del siglo II d. C., durante la dinastía Han, Zhang Zhongjing escribió un Tratado sobre el daño por frío , que contiene la referencia más antigua conocida al Neijing Suwen . El practicante de la dinastía Jin y defensor de la acupuntura y la moxibustión , Huangfu Mi (215-282), también cita al Emperador Amarillo en su Jiayi jing , c. 265. Durante la dinastía Tang , el Suwen fue ampliado y revisado y ahora es la mejor representación existente de las raíces fundamentales de la medicina tradicional china. La medicina tradicional china que se basa en el uso de la medicina herbal, la acupuntura, el masaje y otras formas de terapia se ha practicado en China durante miles de años.

Los críticos dicen que la teoría y la práctica de la medicina tradicional china no tienen base en la ciencia moderna , y los practicantes de la medicina tradicional china no están de acuerdo sobre qué diagnóstico y tratamientos se deben utilizar para cada persona en particular. [57] Un editorial de 2007 en la revista Nature escribió que la medicina tradicional china "sigue estando poco investigada y respaldada, y la mayoría de sus tratamientos no tienen un mecanismo de acción lógico " . [ 58 ] También describió a la medicina tradicional china como "plagada de pseudociencia ". [58] Una revisión de la literatura en 2008 encontró que los científicos "todavía no pueden encontrar una pizca de evidencia" de acuerdo con los estándares de la medicina basada en la ciencia para conceptos chinos tradicionales como el qi , los meridianos y los puntos de acupuntura, [59] y que los principios tradicionales de la acupuntura son profundamente defectuosos. [60] .Existen preocupaciones sobre una serie de plantas potencialmente tóxicas, partes de animales y compuestos minerales chinos, [61] así como la facilitación de enfermedades. Los animales traficados y criados en granjas utilizados en la medicina tradicional china son una fuente de varias enfermedades zoonóticas fatales . [62] Existen preocupaciones adicionales por el comercio y transporte ilegal de especies en peligro de extinción, incluidos los rinocerontes y los tigres, y el bienestar de los animales criados especialmente para esa especie, incluidos los osos. [63]

El Atharvaveda , un texto sagrado del hinduismo que data de la era védica media (c. 1200–900 a. C.), [64] es uno de los primeros textos indios que tratan sobre medicina. Es un texto lleno de amuletos mágicos, hechizos y encantamientos utilizados para diversos fines, como la protección contra los demonios, reavivar el amor, asegurar el parto y lograr el éxito en la batalla, el comercio e incluso el juego. También incluye numerosos amuletos destinados a curar enfermedades y varios remedios a base de hierbas medicinales, lo que lo convierte en una fuente clave de conocimiento médico durante el período védico . El uso de hierbas para tratar dolencias formaría más tarde una gran parte del Ayurveda . [5]

Ayurveda, que significa "conocimiento completo para una vida larga", es otro sistema médico de la India. Sus dos textos más famosos (samhitas) pertenecen a las escuelas de Charaka y Sushruta . Los Samhitas representan versiones revisadas (recensiones) posteriores de sus obras originales. Los primeros fundamentos del Ayurveda se construyeron sobre una síntesis de prácticas herbarias tradicionales junto con una enorme incorporación de conceptualizaciones teóricas, nuevas nosologías y nuevas terapias que datan de aproximadamente el año 600 a. C. en adelante y que surgieron de las comunidades de pensadores que incluían a Buda y otros. [65] [66]

Según el compendio de Charaka , el Charakasamhitā , la salud y la enfermedad no están predeterminadas y la vida puede prolongarse mediante el esfuerzo humano. El compendio de Suśruta , el Suśrutasamhitā, define el propósito de la medicina para curar las enfermedades de los enfermos, proteger a los sanos y prolongar la vida. Ambos compendios antiguos incluyen detalles del examen, diagnóstico, tratamiento y pronóstico de numerosas dolencias. El Suśrutasamhitā es notable por describir procedimientos en varias formas de cirugía, incluida la rinoplastia , la reparación de lóbulos de las orejas desgarrados, la litotomía perineal , la cirugía de cataratas y varias otras escisiones y otros procedimientos quirúrgicos. Lo más notable fue la cirugía de Susruta, especialmente la rinoplastia, por la que se le llama el padre de la cirugía plástica. Susruta también describió más de 125 instrumentos quirúrgicos en detalle. También es notable la inclinación de Sushruta por la clasificación científica: su tratado médico consta de 184 capítulos y enumera 1.120 afecciones, incluidas lesiones y enfermedades relacionadas con el envejecimiento y las enfermedades mentales. [ aclaración necesaria ]

Los clásicos ayurvédicos mencionan ocho ramas de la medicina: kāyācikitsā ( medicina interna ), śalyacikitsā (cirugía incluyendo anatomía ), śālākyacikitsā (enfermedades de ojos, oídos, nariz y garganta), kaumārabhṛtya ( pediatría con obstetricia y ginecología ), bhūtavidyā (medicina espiritual y psiquiátrica), agada tantra ( toxicología con tratamientos de picaduras y mordeduras), rasāyana (ciencia del rejuvenecimiento) y vājīkaraṇa ( afrodisíaco y fertilidad). Además de aprender estas, se esperaba que el estudiante de Ayurveda conociera diez artes que eran indispensables en la preparación y aplicación de sus medicinas: destilación , habilidades operativas, cocina, horticultura, metalurgia , fabricación de azúcar, farmacia , análisis y separación de minerales, composición de metales y preparación de álcalis . La enseñanza de varias materias se realizó durante la instrucción de las materias clínicas relevantes. Por ejemplo, la enseñanza de la anatomía era parte de la enseñanza de la cirugía, la embriología era parte de la formación en pediatría y obstetricia, y el conocimiento de la fisiología y la patología estaba entretejido en la enseñanza de todas las disciplinas clínicas. [ aclaración necesaria ]

Incluso hoy en día se practica el tratamiento ayurvédico, pero se considera pseudocientífico porque sus premisas no se basan en la ciencia; se ha descubierto que algunos medicamentos ayurvédicos contienen sustancias tóxicas. [67] [68] Se ha criticado tanto la falta de solidez científica en los fundamentos teóricos del ayurveda como la calidad de la investigación. [67] [69] [70] [71]

Humores

La teoría de los humores se derivó de obras médicas antiguas, dominó la medicina occidental hasta el siglo XIX y se le atribuye al filósofo y cirujano griego Galeno de Pérgamo (129– c. 216 d. C. ). [72] En la medicina griega, se cree que hay cuatro humores o fluidos corporales que están vinculados a la enfermedad: sangre, flema, bilis amarilla y bilis negra. [73] Los primeros científicos creían que los alimentos se digieren en sangre, músculo y huesos, mientras que los humores que no eran sangre se formaban a partir de materiales no digeribles que sobraban. Se teoriza que un exceso o escasez de cualquiera de los cuatro humores causa un desequilibrio que resulta en enfermedad; la declaración antes mencionada fue hipotetizada por fuentes anteriores a Hipócrates . [73] Hipócrates ( c. 400 a. C. ) dedujo que las cuatro estaciones del año y las cuatro edades del hombre afectan al cuerpo en relación con los humores. [72] Las cuatro edades del hombre son la infancia, la juventud, la madurez y la vejez. [73] Los cuatro humores asociados a las cuatro estaciones son la bilis negra (otoño), la bilis amarilla (verano), la flema (invierno) y la sangre (primavera). [74]

En De temperamentis, Galeno relacionó lo que él llamó temperamentos, o características de personalidad, con la mezcla natural de humores de una persona. También dijo que el mejor lugar para comprobar el equilibrio de los temperamentos era en la palma de la mano. Una persona que se considera flemática se dice que es introvertida, de temperamento equilibrado, tranquila y pacífica. [73] Esta persona tendría un exceso de flema, que se describe como una sustancia viscosa o mucosa. [75] De manera similar, un temperamento melancólico se relaciona con estar de mal humor, ansioso, deprimido, introvertido y pesimista. [73] Un temperamento melancólico es causado por un exceso de bilis negra, que es sedimentaria y de color oscuro. [75] Ser extrovertido, hablador, tolerante, despreocupado y sociable coincide con un temperamento sanguíneo, que está vinculado a un exceso de sangre. [73] Finalmente, el temperamento colérico se relaciona con demasiada bilis amarilla, que en realidad es de color rojo y tiene la textura de la espuma; se asocia con ser agresivo, excitable, impulsivo y también extrovertido.

Existen numerosas formas de tratar una desproporción de los humores. Por ejemplo, si se sospecha que alguien tiene demasiada sangre, entonces el médico realiza una sangría como tratamiento. Del mismo modo, si se cree que una persona tiene demasiada flema debe sentirse mejor después de expectorar, y alguien con demasiada bilis amarilla debe purgarse. [75] Otro factor a considerar en el equilibrio de los humores es la calidad del aire donde uno reside, como el clima y la altitud. También son importantes el nivel de comida y bebida, el equilibrio entre el sueño y la vigilia, el ejercicio y el descanso, la retención y la evacuación. Los estados de ánimo como la ira, la tristeza, la alegría y el amor pueden afectar el equilibrio. Durante esa época, la importancia del equilibrio quedó demostrada por el hecho de que las mujeres pierden sangre mensualmente durante la menstruación y tienen una menor incidencia de gota, artritis y epilepsia que los hombres. [75] Galeno también planteó la hipótesis de que hay tres facultades. La facultad natural afecta al crecimiento y la reproducción y se produce en el hígado. La facultad animal o vital controla la respiración y la emoción, que proviene del corazón. En el cerebro, la facultad psíquica comanda los sentidos y los pensamientos. [75] La estructura de las funciones corporales también está relacionada con los humores. Los médicos griegos entendían que la comida se cocinaba en el estómago; de ahí se extraían los nutrientes. Los mejores, más potentes y puros nutrientes de los alimentos se reservaban para la sangre, que se producía en el hígado y se transportaba por las venas hasta los órganos. La sangre enriquecida con pneuma, que significa viento o aliento, es transportada por las arterias. [73] El camino que sigue la sangre es el siguiente: la sangre venosa pasa por la vena cava y se desplaza hasta el ventrículo derecho del corazón; luego, la arteria pulmonar la lleva hasta los pulmones. [75] Más tarde, la vena pulmonar mezcla el aire de los pulmones con la sangre para formar la sangre arterial, que tiene diferentes características observables. [73] Después de salir del hígado, la mitad de la bilis amarilla que se produce viaja a la sangre, mientras que la otra mitad viaja a la vesícula biliar. De manera similar, la mitad de la bilis negra producida se mezcla con la sangre y la otra mitad es utilizada por el bazo. [75]

Gente

Alrededor del año 800 a. C., Homero, en la Ilíada, describe el tratamiento de heridas por parte de los dos hijos de Asclepio , los admirables médicos Podalirio y Macaón y un médico en funciones, Patroclo . Como Macaón está herido y Podalirio está en combate, Eurípilo le pide a Patroclo que "corte la punta de la flecha, lave la sangre oscura de mi muslo con agua tibia y espolvoree hierbas calmantes con poder para curar mi herida". [76] Asclepio, como Imhotep , llegó a ser asociado como un dios de la curación con el tiempo.

Los templos dedicados al dios sanador Asclepio , conocido como Asclepieia ( griego antiguo : Ἀσκληπιεῖα , sing. Ἀσκληπιεῖον , Asclepieion ), funcionaban como centros de asesoramiento médico, pronóstico y curación. [77] En estos santuarios, los pacientes entraban en un estado onírico de sueño inducido conocido como enkoimesis ( ἐγκοίμησις ), no muy diferente de la anestesia, en la que recibían orientación de la deidad en un sueño o eran curados mediante cirugía. [78] Asclepeia proporcionaba espacios cuidadosamente controlados propicios para la curación y cumplía varios de los requisitos de las instituciones creadas para la curación. [77] En el Asclepeion de Epidauro , tres grandes tableros de mármol datados en el 350 a. C. conservan los nombres, historias clínicas, quejas y curas de unos 70 pacientes que acudieron al templo con un problema y lo arrojaron allí. Algunas de las curas quirúrgicas enumeradas, como la apertura de un absceso abdominal o la eliminación de material extraño traumático, son lo suficientemente realistas como para haber tenido lugar, pero con el paciente en un estado de enkoimesis inducido con la ayuda de sustancias soporíferas como el opio. [78] Alcmeón de Crotona escribió sobre medicina entre el 500 y el 450 a. C. Sostuvo que los canales conectaban los órganos sensoriales con el cerebro, y es posible que descubriera un tipo de canal, los nervios ópticos, mediante disección. [79]

Hipócrates de Cos ( c. 460 – c. 370 a. C. ), considerado el "padre de la medicina moderna". [80] El Corpus Hipocrático es una colección de alrededor de setenta obras médicas tempranas de la antigua Grecia fuertemente asociadas con Hipócrates y sus estudiantes. El más famoso es el invento de los hipocráticos, el juramento hipocrático para los médicos. Los médicos contemporáneos juran un juramento de cargo que incluye aspectos que se encuentran en las primeras ediciones del juramento hipocrático.

Hipócrates y sus seguidores fueron los primeros en describir muchas enfermedades y afecciones médicas. Aunque el humorismo (humoralismo) como sistema médico es anterior a la medicina griega del siglo V, Hipócrates y sus estudiantes sistematizaron el pensamiento de que la enfermedad puede explicarse por un desequilibrio de sangre, flema, bilis negra y bilis amarilla. [81] A Hipócrates se le atribuye la primera descripción de los dedos en palillo de tambor, un signo diagnóstico importante en la enfermedad pulmonar supurativa crónica, el cáncer de pulmón y la enfermedad cardíaca cianótica . Por esta razón, a los dedos en palillo de tambor a veces se los denomina "dedos hipocráticos". [82] Hipócrates también fue el primer médico en describir el rostro hipocrático en Prognosis . Shakespeare alude famosamente a esta descripción cuando escribe sobre la muerte de Falstaff en el Acto II, Escena iii. de Enrique V. [83] Hipócrates comenzó a categorizar las enfermedades como agudas , crónicas , endémicas y epidémicas, y a utilizar términos como "exacerbación, recaída , resolución, crisis, paroxismo , pico y convalecencia ". [84] [85]

El griego Galeno (c. 129-216 d. C. ) fue uno de los médicos más importantes del mundo antiguo, ya que sus teorías dominaron todos los estudios médicos durante casi 1500 años. [86] Sus teorías y experimentos sentaron las bases de la medicina moderna en torno al corazón y la sangre. La influencia de Galeno y sus innovaciones en la medicina se pueden atribuir a los experimentos que realizó, que no se parecían a ningún otro experimento médico de su tiempo. Galeno creía firmemente que la disección médica era uno de los procedimientos esenciales para comprender verdaderamente la medicina. Comenzó a diseccionar diferentes animales que eran anatómicamente similares a los humanos, lo que le permitió aprender más sobre los órganos internos y extrapolar los estudios quirúrgicos al cuerpo humano. [86] Además, realizó muchas operaciones audaces, incluidas cirugías cerebrales y oculares, que no se volvieron a intentar durante casi dos milenios. A través de las disecciones y los procedimientos quirúrgicos, Galeno concluyó que la sangre puede circular por todo el cuerpo humano y que el corazón es el más similar al alma humana. [86] [87] En Ars medica ("Artes de la medicina"), explica con más detalle las propiedades mentales en términos de mezclas específicas de los órganos corporales. [88] [89] Si bien gran parte de su trabajo giró en torno a la anatomía física, también trabajó intensamente en la fisiología humoral.

La obra médica de Galeno fue considerada como una autoridad hasta bien entrada la Edad Media. Dejó un modelo fisiológico del cuerpo humano que se convirtió en el pilar del plan de estudios de anatomía de los médicos universitarios medievales. Aunque intentó extrapolar las disecciones animales al modelo del cuerpo humano, algunas de las teorías de Galeno eran incorrectas. Esto hizo que su modelo sufriera mucho de estancamiento intelectual. [90] Los tabúes griegos y romanos hicieron que la disección del cuerpo humano estuviera prohibida en la antigüedad, pero en la Edad Media esto cambió. [91] [92]

En 1523 se publicó en Londres De las facultades naturales de Galeno . En la década de 1530, el anatomista y médico belga Andreas Vesalio emprendió un proyecto para traducir muchos de los textos griegos de Galeno al latín. La obra más famosa de Vesalio, De humani corporis fabrica, estuvo muy influida por la escritura y la forma galénicas.

Herófilo y Erasístrato

Dos grandes alejandrinos sentaron las bases para el estudio científico de la anatomía y la fisiología: Herófilo de Calcedonia y Erasístrato de Ceos . [94] Otros cirujanos alejandrinos nos dieron la ligadura (hemostasia), la litotomía , las operaciones de hernia , la cirugía oftálmica , la cirugía plástica , los métodos de reducción de dislocaciones y fracturas, la traqueotomía y la mandrágora como anestésico . Parte de lo que sabemos de ellos proviene de Celso y Galeno de Pérgamo. [95]

Herófilo de Calcedonia , el famoso médico alejandrino, fue uno de los pioneros de la anatomía humana. Aunque su conocimiento de la estructura anatómica del cuerpo humano era vasto, se especializó en los aspectos de la anatomía neural. [96] Por lo tanto, su experimentación se centró en la composición anatómica del sistema vascular sanguíneo y las pulsaciones que se pueden analizar desde el sistema. [96] Además, la experimentación quirúrgica que administró hizo que se volviera muy prominente en todo el campo de la medicina, ya que fue uno de los primeros médicos en iniciar la exploración y disección del cuerpo humano. [97]

La práctica prohibida de la disección humana fue levantada durante su tiempo dentro de la comunidad escolástica. Este breve momento en la historia de la medicina griega le permitió estudiar más a fondo el cerebro, que creía que era el núcleo del sistema nervioso. [97] También distinguió entre venas y arterias , notando que estas últimas pulsan y las primeras no. Así, mientras trabajaba en la escuela de medicina de Alejandría , Herófilo colocó la inteligencia en el cerebro basándose en su exploración quirúrgica del cuerpo, y conectó el sistema nervioso con el movimiento y la sensación. Además, él y su contemporáneo, Erasístrato de Quíos , continuaron investigando el papel de las venas y los nervios . Después de realizar una extensa investigación, los dos alejandrinos trazaron el curso de las venas y los nervios en el cuerpo humano. Erasístrato conectó la mayor complejidad de la superficie del cerebro humano en comparación con otros animales a su inteligencia superior . A veces empleó experimentos para promover su investigación, en una ocasión pesando repetidamente un pájaro enjaulado y notando su pérdida de peso entre los tiempos de alimentación. [98] En la fisiología de Erasístrato , el aire entra en el cuerpo, es aspirado por los pulmones hasta el corazón, donde se transforma en espíritu vital y luego es bombeado por las arterias a todo el cuerpo. Parte de este espíritu vital llega al cerebro, donde se transforma en espíritu animal, que luego se distribuye por los nervios. [98]

Los romanos inventaron numerosos instrumentos quirúrgicos , incluidos los primeros instrumentos exclusivos de las mujeres, [99] así como los usos quirúrgicos de fórceps , bisturíes , cauterizadores , tijeras de hoja cruzada , la aguja quirúrgica , la sonda y los espéculos . [100] [101] Los romanos también realizaban cirugía de cataratas . [102]

Dioscórides ( c. 40-90 d. C.), médico militar romano , fue un botánico y farmacólogo griego. Escribió la enciclopedia De Materia Medica, en la que describía más de 600 remedios a base de hierbas, lo que dio origen a una farmacopea influyente que se utilizó ampliamente durante los siguientes 1500 años. [103]

Los primeros cristianos del Imperio Romano incorporaron la medicina a su teología, prácticas rituales y metáforas. [104]

Medicina bizantina

La medicina bizantina abarca las prácticas médicas comunes del Imperio bizantino desde aproximadamente el año 400 d. C. hasta el año 1453 d. C. La medicina bizantina se destacó por aprovechar la base de conocimientos desarrollada por sus predecesores grecorromanos. Al preservar las prácticas médicas de la antigüedad, la medicina bizantina influyó en la medicina islámica y fomentó el renacimiento occidental de la medicina durante el Renacimiento.

Los médicos bizantinos solían recopilar y estandarizar el conocimiento médico en libros de texto. Sus registros tendían a incluir tanto explicaciones diagnósticas como dibujos técnicos. El Compendio médico en siete libros , escrito por el destacado médico Pablo de Egina , sobrevivió como una fuente particularmente completa de conocimiento médico. Este compendio, escrito a fines del siglo VII, se siguió utilizando como libro de texto estándar durante los siguientes 800 años.

La Antigüedad tardía marcó el comienzo de una revolución en la ciencia médica, y los registros históricos a menudo mencionan hospitales civiles (aunque la medicina en el campo de batalla y el triaje en tiempos de guerra se registraron mucho antes de la Roma Imperial). Constantinopla se destacó como un centro de medicina durante la Edad Media, a lo que contribuyeron su ubicación en una encrucijada, su riqueza y el conocimiento acumulado.

El primer ejemplo conocido de separación de siameses se produjo en el Imperio bizantino en el siglo X. El siguiente ejemplo de separación de siameses se registraría muchos siglos después en Alemania en 1689. [105] [106]

Los vecinos del Imperio bizantino , el Imperio persa sasánida , también hicieron sus notables contribuciones principalmente con el establecimiento de la Academia de Gondeshapur , que fue "el centro médico más importante del mundo antiguo durante los siglos VI y VII". [107] Además, Cyril Elgood , médico británico e historiador de la medicina en Persia, comentó que gracias a centros médicos como la Academia de Gondeshapur, "en gran medida, el crédito por todo el sistema hospitalario debe atribuirse a Persia". [108]

Medicina islámica

La civilización islámica alcanzó la primacía en la ciencia médica a medida que sus médicos contribuyeron significativamente al campo de la medicina, incluida la anatomía , la oftalmología , la farmacología , la farmacia , la fisiología y la cirugía. La contribución de la civilización islámica a estos campos dentro de la medicina fue un proceso gradual que tomó cientos de años. Durante la época de la primera gran dinastía musulmana, el Califato Omeya (661-750 d. C.), estos campos estaban en sus primeras etapas de desarrollo y no se logró mucho progreso. [109] Una razón para el avance limitado en medicina durante el Califato Omeya fue el enfoque del Califato en la expansión después de la muerte de Mahoma (632 d. C.). [110] El enfoque en el expansionismo redirigió recursos de otros campos, como la medicina. La prioridad en estos factores llevó a un gran porcentaje de la población a creer que Dios proporcionará curas para sus enfermedades y dolencias debido a la atención en la espiritualidad. [110]

También hubo muchas otras áreas de interés durante ese tiempo antes de que hubiera un creciente interés en el campo de la medicina. Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan , el quinto califa de los Omeyas, desarrolló la administración gubernamental, adoptó el árabe como idioma principal y se centró en muchas otras áreas. [111] Sin embargo, este creciente interés en la medicina islámica creció significativamente cuando el califato abasí (750-1258 d. C.) derrocó al califato omeya en 750 d. C. [112] Este cambio de dinastía del califato omeya al califato abasí sirvió como un punto de inflexión hacia los desarrollos científicos y médicos. Un gran contribuyente a esto fue que bajo el gobierno abasí, gran parte del legado griego se transmitió al árabe, que para entonces era el idioma principal de las naciones islámicas. [110] Debido a esto, muchos médicos islámicos fueron fuertemente influenciados por las obras de los eruditos griegos de Alejandría y Egipto y pudieron expandir aún más esos textos para producir nuevas piezas de conocimiento médico. [113] Este período de tiempo también se conoce como la Edad de Oro Islámica , donde hubo un período de desarrollo y florecimiento de la tecnología, el comercio y las ciencias, incluida la medicina. Además, durante este tiempo, la creación del primer hospital islámico en 805 d. C. por el califa abasí Harun al-Rashid en Bagdad se relató como un evento glorioso de la Edad de Oro. [109] Este hospital en Bagdad contribuyó enormemente al éxito de Bagdad y también proporcionó oportunidades educativas para los médicos islámicos. Durante la Edad de Oro Islámica, hubo muchos médicos islámicos famosos que allanaron el camino para los avances y la comprensión médica. Sin embargo, esto no sería posible sin la influencia de muchas áreas diferentes del mundo que influyeron en los árabes.

Los árabes fueron influenciados por las antiguas prácticas médicas indias, persas, griegas, romanas y bizantinas, y ayudaron a que se desarrollaran aún más. [114] Galeno e Hipócrates fueron autoridades preeminentes. La traducción de 129 de las obras de Galeno al árabe por el cristiano nestoriano Hunayn ibn Ishaq y sus asistentes, y en particular la insistencia de Galeno en un enfoque sistemático racional de la medicina, sentó las bases para la medicina islámica , que se extendió rápidamente por todo el Imperio árabe . [115] Entre sus médicos más famosos se encontraban los eruditos persas Muhammad ibn Zakarīya al-Rāzi y Avicena , que escribió más de 40 obras sobre salud, medicina y bienestar. Siguiendo los pasos de Grecia y Roma, los eruditos islámicos mantuvieron vivos y en movimiento tanto el arte como la ciencia de la medicina. [116] El erudito persa Avicena también ha sido llamado el "padre de la medicina". [117] Escribió El canon de la medicina , que se convirtió en un texto médico estándar en muchas universidades europeas medievales, [118] considerado uno de los libros más famosos en la historia de la medicina. [119] El canon de la medicina presenta una descripción general del conocimiento médico contemporáneo del mundo islámico medieval , que había sido influenciado por tradiciones anteriores, incluida la medicina grecorromana (particularmente Galeno ), [120] la medicina persa , la medicina china y la medicina india . El médico persa al-Rāzi [121] fue uno de los primeros en cuestionar la teoría griega del humorismo , que sin embargo siguió siendo influyente tanto en la medicina occidental medieval como en la islámica medieval . [122] Algunos volúmenes de la obra de al-Rāzi Al-Mansuri , a saber, "Sobre la cirugía" y "Un libro general sobre terapia", se convirtieron en parte del plan de estudios de medicina en las universidades europeas. [123] Además, ha sido descrito como un médico de médicos, [124] el padre de la pediatría , [125] [126] y un pionero de la oftalmología . Por ejemplo, fue el primero en reconocer la reacción de la pupila del ojo a la luz. [ cita requerida ]

Además de las contribuciones a la comprensión de la anatomía humana por parte de la humanidad, los científicos y eruditos islámicos, específicamente los médicos, desempeñaron un papel invaluable en el desarrollo del sistema hospitalario moderno, creando las bases sobre las cuales los profesionales médicos más contemporáneos construirían modelos de sistemas de salud pública en Europa y en otros lugares. [127] Durante la época del imperio safávida (siglos XVI-XVIII) en Irán y el imperio mogol (siglos XVI-XIX) en la India, los eruditos musulmanes transformaron radicalmente la institución del hospital, creando un entorno en el que el conocimiento médico en rápido desarrollo de la época podía transmitirse entre estudiantes y profesores de una amplia gama de culturas. [128] Había dos escuelas principales de pensamiento con respecto al cuidado del paciente en ese momento. Estas incluían la fisiología humoral de los persas y la práctica ayurvédica. Después de que estas teorías se tradujeron del sánscrito al persa y viceversa, los hospitales podían tener una mezcla de cultura y técnicas. Esto permitió un sentido de medicina colaborativa. [ cita requerida ] Los hospitales se volvieron cada vez más comunes durante este período, ya que los patrocinadores ricos comúnmente los fundaban. Muchas características que todavía se utilizan hoy en día, como el énfasis en la higiene, un personal totalmente dedicado al cuidado de los pacientes y la separación de los pacientes entre sí, se desarrollaron en los hospitales islámicos mucho antes de que se pusieran en práctica en Europa. [129] En ese momento, los aspectos de atención al paciente de los hospitales en Europa no habían tenido efecto. Los hospitales europeos eran lugares de religión en lugar de instituciones científicas. Como fue el caso con gran parte del trabajo científico realizado por los eruditos islámicos, muchos de estos nuevos avances en la práctica médica se transmitieron a las culturas europeas cientos de años después de que se hubieran utilizado durante mucho tiempo en todo el mundo islámico. Aunque los científicos islámicos fueron responsables de descubrir gran parte del conocimiento que permite que el sistema hospitalario funcione de manera segura hoy en día, los eruditos europeos que se basaron en este trabajo aún reciben la mayor parte del crédito históricamente. [127]

Antes del desarrollo de las prácticas médicas científicas en los imperios islámicos, la atención médica era realizada principalmente por figuras religiosas como los sacerdotes. [127] Sin una comprensión profunda de cómo funcionaban las enfermedades infecciosas y por qué la enfermedad se propagaba de persona a persona, estos primeros intentos de cuidar a los enfermos y heridos a menudo hicieron más daño que bien. Por el contrario, con el desarrollo de prácticas nuevas y más seguras por parte de los eruditos y médicos islámicos en los hospitales árabes, se desarrollaron, aprendieron y transmitieron ampliamente ideas vitales para la atención eficaz de los pacientes. Los hospitales desarrollaron "conceptos y estructuras" novedosos que todavía se utilizan hoy en día: salas separadas para pacientes masculinos y femeninos, farmacias, mantenimiento de registros médicos y saneamiento e higiene personal e institucional. [127] Gran parte de este conocimiento se registró y se transmitió a través de textos médicos islámicos, muchos de los cuales fueron llevados a Europa y traducidos para el uso de los trabajadores médicos europeos. El Tasrif, escrito por el cirujano Abu Al-Qasim Al-Zahrawi, fue traducido al latín; Se convirtió en uno de los textos médicos más importantes en las universidades europeas durante la Edad Media y contenía información útil sobre técnicas quirúrgicas y propagación de infecciones bacterianas. [127]

El hospital era una institución típica de la mayoría de las ciudades musulmanas y, aunque a menudo estaba físicamente unido a instituciones religiosas, no era en sí mismo un lugar de práctica religiosa. [128] Más bien, servía como un lugar en el que la educación y la innovación científica podían florecer. Si tenían lugares de culto, eran secundarios con respecto al aspecto médico del hospital. Los hospitales islámicos, junto con los observatorios utilizados para la ciencia astronómica, eran algunos de los puntos de intercambio más importantes para la difusión del conocimiento científico. Sin duda, el sistema hospitalario desarrollado en el mundo islámico desempeñó un papel inestimable en la creación y evolución de los hospitales que conocemos como sociedad y de los que dependemos hoy.

Después del año 400 d. C., el estudio y la práctica de la medicina en el Imperio romano de Occidente entró en una profunda decadencia. Los servicios médicos se proporcionaban, especialmente para los pobres, en los miles de hospitales monásticos que surgieron en toda Europa, pero la atención era rudimentaria y principalmente paliativa. [130] La mayoría de los escritos de Galeno e Hipócrates se perdieron en Occidente, y los resúmenes y compendios de San Isidoro de Sevilla fueron el principal canal de transmisión de las ideas médicas griegas. [131] El Renacimiento carolingio trajo consigo un mayor contacto con Bizancio y un mayor conocimiento de la medicina antigua, [132] pero solo con el Renacimiento del siglo XII y las nuevas traducciones procedentes de fuentes musulmanas y judías en España, y la avalancha de recursos del siglo XV tras la caída de Constantinopla, Occidente recuperó por completo su conocimiento de la antigüedad clásica.

Los tabúes griegos y romanos habían significado que la disección estaba generalmente prohibida en la antigüedad, pero en la Edad Media esto cambió: los profesores y estudiantes de medicina en Bolonia comenzaron a abrir cuerpos humanos, y Mondino de Luzzi ( c. 1275-1326 ) produjo el primer libro de texto de anatomía conocido basado en la disección humana. [91] [92]

Wallis identifica una jerarquía de prestigio con médicos con educación universitaria en la cima, seguidos por cirujanos expertos, cirujanos con formación artesanal, cirujanos barberos, especialistas itinerantes como dentistas y oculistas, empíricos y parteras. [133]

Las primeras escuelas de medicina se abrieron en el siglo IX, sobre todo la Schola Medica Salernitana en Salerno, en el sur de Italia. Las influencias cosmopolitas de fuentes griegas, latinas, árabes y hebreas le dieron una reputación internacional como la ciudad hipocrática. Estudiantes de familias adineradas venían para tres años de estudios preliminares y cinco de estudios de medicina. La medicina, siguiendo las leyes de Federico II, que fundó en 1224 la universidad y mejoró la Schola Salernitana, en el período entre 1200 y 1400, tuvo en Sicilia (la llamada Edad Media siciliana) un desarrollo particular hasta el punto de crear una verdadera escuela de medicina judía. [134]

A raíz de lo cual, después de un examen legal, se confirió a una mujer judía siciliana, Virdimura , esposa de otro médico Pasquale de Catania, el registro histórico de antes de una mujer capacitada oficialmente para el ejercicio de la profesión médica. [135]

En la Universidad de Bolonia se inició la formación de médicos en 1219. La ciudad italiana atraía a estudiantes de toda Europa. Taddeo Alderotti construyó una tradición de educación médica que estableció los rasgos característicos de la medicina culta italiana y fue copiada por las escuelas de medicina de otros lugares. Turisano (fallecido en 1320) fue alumno suyo. [136]

La Universidad de Padua fue fundada alrededor de 1220 por estudiantes que abandonaron la Universidad de Bolonia y comenzó a enseñar medicina en 1222. Desempeñó un papel destacado en la identificación y el tratamiento de enfermedades y dolencias, especializándose en autopsias y el funcionamiento interno del cuerpo. [137] A partir de 1595, el famoso teatro anatómico de Padua atrajo a artistas y científicos que estudiaban el cuerpo humano durante disecciones públicas. El estudio intensivo de Galeno condujo a críticas a Galeno inspiradas en sus propios escritos, como en el primer libro de De humani corporis fabrica de Vesalio. Andreas Vesalio ocupó la cátedra de Cirugía y Anatomía ( explicator chirurgiae ) y en 1543 publicó sus descubrimientos anatómicos en De Humani Corporis Fabrica . Retrató el cuerpo humano como un sistema interdependiente de agrupaciones de órganos. El libro desencadenó un gran interés público en las disecciones e hizo que muchas otras ciudades europeas establecieran teatros anatómicos. [138]

En el siglo XIII, la escuela de medicina de Montpellier comenzó a eclipsar a la escuela salernitana. En el siglo XII, se fundaron universidades en Italia, Francia e Inglaterra, que pronto desarrollaron escuelas de medicina. La Universidad de Montpellier en Francia y la Universidad de Padua y la Universidad de Bolonia en Italia fueron las escuelas más importantes. Casi todo el aprendizaje se basaba en conferencias y lecturas de Hipócrates, Galeno, Avicena y Aristóteles. En siglos posteriores, la importancia de las universidades fundadas a fines de la Edad Media aumentó gradualmente, por ejemplo, la Universidad Carolina de Praga (fundada en 1348), la Universidad Jagellónica de Cracovia (1364), la Universidad de Viena (1365), la Universidad de Heidelberg (1386) y la Universidad de Greifswald (1456).

En 1376, en Sicilia, se dio históricamente, en relación con las leyes de Federico II que preveían un examen con regia misión de físicos, la primera habilitación para el ejercicio de la medicina a una mujer, Virdimura , judía de Catania, cuyo documento se conserva en Palermo en los archivos nacionales italianos. [139]

Inglaterra

En Inglaterra, después de 1550, sólo había tres hospitales pequeños. Pelling y Webster calculan que en Londres, en el período de 1580 a 1600, de una población de casi 200.000 personas, había unos 500 médicos. No se incluyen las enfermeras ni las parteras. Había unos 50 médicos, 100 cirujanos con licencia, 100 boticarios y 250 médicos adicionales sin licencia. En esta última categoría, alrededor del 25% eran mujeres. [140] En toda Inglaterra (y, de hecho, en todo el mundo), la gran mayoría de la gente de las ciudades, los pueblos y el campo dependía para su atención médica de aficionados locales sin formación profesional, pero con reputación de curanderos sabios que podían diagnosticar problemas y aconsejar a los enfermos qué hacer, y tal vez arreglar huesos rotos, sacar una muela, dar algunas hierbas o brebajes tradicionales o realizar un poco de magia para curar lo que les aquejaba.

El Renacimiento trajo consigo un intenso interés por la erudición en la Europa cristiana. Se produjo un gran esfuerzo por traducir las obras científicas árabes y griegas al latín. Los europeos se convirtieron gradualmente en expertos no sólo en los escritos antiguos de los romanos y los griegos, sino también en los escritos contemporáneos de los científicos islámicos. Durante los últimos siglos del Renacimiento se produjo un aumento de la investigación experimental, en particular en el campo de la disección y el examen corporal, lo que hizo avanzar nuestro conocimiento de la anatomía humana. [141]

_Venenbild.jpg/440px-William_Harvey_(1578-1657)_Venenbild.jpg)

En la Universidad de Bolonia el plan de estudios fue revisado y reforzado entre 1560 y 1590. [144] Un profesor representativo fue Julio César Aranzi (Arantius) (1530-1589). Se convirtió en profesor de Anatomía y Cirugía en la Universidad de Bolonia en 1556, donde estableció la anatomía como una rama importante de la medicina por primera vez. Aranzi combinó la anatomía con una descripción de procesos patológicos, basándose en gran medida en su propia investigación, Galeno y el trabajo de sus contemporáneos italianos. Aranzi descubrió los 'Nódulos de Aranzio' en las válvulas semilunares del corazón y escribió la primera descripción del elevador palpebral superior y los músculos coracobraquiales. Sus libros (en latín) cubrieron técnicas quirúrgicas para muchas afecciones, incluyendo hidrocefalia , pólipos nasales , bocio y tumores hasta fimosis , ascitis , hemorroides , abscesos anales y fístulas . [145]

Mujer

Las mujeres católicas desempeñaron un papel importante en la salud y la curación en la Europa medieval y moderna. [146] La vida como monja era un papel prestigioso; las familias ricas proporcionaban dotes para sus hijas, y estas financiaban los conventos, mientras que las monjas proporcionaban atención de enfermería gratuita a los pobres. [147]

Las élites católicas proporcionaban servicios hospitalarios debido a su teología de la salvación, según la cual las buenas obras eran el camino al cielo. Los reformadores protestantes rechazaban la idea de que los ricos podían ganar la gracia de Dios a través de las buenas obras (y así escapar del purgatorio) al proporcionar donaciones en efectivo a instituciones de caridad. También rechazaban la idea católica de que los pacientes pobres ganaban la gracia y la salvación a través de su sufrimiento. [148] Los protestantes generalmente cerraron todos los conventos [149] y la mayoría de los hospitales, enviando a las mujeres a sus casas para que se convirtieran en amas de casa, a menudo en contra de su voluntad. [150] Por otro lado, los funcionarios locales reconocieron el valor público de los hospitales, y algunos continuaron en tierras protestantes, pero sin monjes ni monjas y bajo el control de los gobiernos locales. [151]

En Londres, la corona permitió que dos hospitales continuaran con su labor caritativa, bajo el control no religioso de funcionarios de la ciudad. [152] Todos los conventos fueron cerrados, pero Harkness descubre que las mujeres (algunas de ellas ex monjas) formaban parte de un nuevo sistema que prestaba servicios médicos esenciales a personas ajenas a su familia. Eran empleadas por parroquias y hospitales, así como por familias privadas, y proporcionaban atención de enfermería, así como algunos servicios médicos, farmacéuticos y quirúrgicos. [153]

Mientras tanto, en países católicos como Francia, las familias ricas seguían financiando conventos y monasterios, e inscribían a sus hijas como monjas que prestaban servicios sanitarios gratuitos a los pobres. La enfermería era una función religiosa para la enfermera, y había poca demanda de ciencias. [154]

En el siglo XVIII, durante la dinastía Qing, proliferaron los libros populares y las enciclopedias más avanzadas sobre medicina tradicional. Los misioneros jesuitas introdujeron la ciencia y la medicina occidentales en la corte real, aunque los médicos chinos los ignoraron. [155]

La medicina unani , basada en el Canon de medicina de Avicena (ca. 1025), se desarrolló en la India durante los períodos medieval y moderno temprano. Su uso continuó, especialmente en las comunidades musulmanas, durante los períodos del sultanato indio y mogol . La medicina unani es en algunos aspectos similar a la ayurveda y a la medicina europea moderna temprana. Todas comparten una teoría sobre la presencia de los elementos (en la medicina unani, como en Europa, se considera que son fuego, agua, tierra y aire) y humores en el cuerpo humano. Según los médicos unani, estos elementos están presentes en diferentes fluidos humorales y su equilibrio conduce a la salud y su desequilibrio conduce a la enfermedad. [156]

La literatura médica sánscrita del período moderno temprano incluyó obras innovadoras como el Compendio de Śārṅgadhara (Skt. Śārṅgadharasaṃhitā , ca. 1350) y especialmente La iluminación de Bhāva ( Bhāvaprakāśa, de Bhāvamiśra , ca. 1550). Esta última obra también contenía un extenso diccionario de materia médica y se convirtió en un libro de texto estándar ampliamente utilizado por los médicos ayurvédicos en el norte de la India hasta el día de hoy (2024). Las innovaciones médicas de este período incluyeron el diagnóstico del pulso, el diagnóstico de orina, el uso de mercurio y raíz de china para tratar la sífilis y el uso creciente de ingredientes metálicos en los medicamentos. [157]

En el siglo XVIII, la terapia médica ayurvédica todavía se utilizaba ampliamente entre la mayoría de la población. Los gobernantes musulmanes construyeron grandes hospitales en Hyderabad en 1595 y en Delhi en 1719, y se escribieron numerosos comentarios sobre textos antiguos. [158]

La era de las Luces en Europa

Durante la época de las Luces , en el siglo XVIII, la ciencia gozaba de gran estima y los médicos mejoraron su estatus social al volverse más científicos. El campo de la salud estaba repleto de barberos-cirujanos autodidactas, boticarios, parteras, vendedores de drogas y charlatanes.

En toda Europa, las facultades de medicina dependían principalmente de conferencias y lecturas. El estudiante de último año tendría una experiencia clínica limitada al seguir al profesor por las salas. El trabajo de laboratorio era poco común y las disecciones rara vez se realizaban debido a las restricciones legales sobre los cadáveres. La mayoría de las facultades eran pequeñas y solo la Facultad de Medicina de Edimburgo , Escocia, con 11.000 exalumnos, produjo un gran número de graduados. [159] [160]

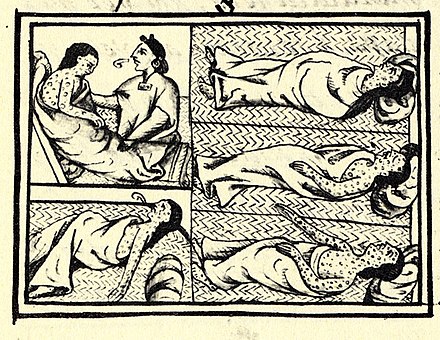

España y el Imperio Español

En el Imperio español , la capital virreinal de la Ciudad de México fue un sitio de formación médica para médicos y de creación de hospitales. Las enfermedades epidémicas habían diezmado las poblaciones indígenas a partir de la conquista española del imperio azteca a principios del siglo XVI , cuando un auxiliar negro en las fuerzas armadas del conquistador Hernán Cortés , con un caso activo de viruela , desencadenó una epidemia en tierra virgen entre los pueblos indígenas, aliados españoles y enemigos por igual. El emperador azteca Cuitláhuac murió de viruela. [161] [162] La enfermedad también fue un factor significativo en la conquista española en otros lugares. [163]

La educación médica instituida en la Real y Pontificia Universidad de México atendía principalmente las necesidades de las élites urbanas. Los curanderos o practicantes laicos, hombres y mujeres, atendían los males de las clases populares. La corona española comenzó a regular la profesión médica tan solo unos años después de la conquista, estableciendo el Tribunal Real del Protomedicato, una junta para otorgar licencias al personal médico en 1527. La concesión de licencias se volvió más sistemática después de 1646, y los médicos, farmacéuticos, cirujanos y sangradores necesitaban una licencia antes de poder ejercer públicamente. [164] La regulación de la corona de la práctica médica se volvió más general en el imperio español. [165]

Tanto las élites como las clases populares invocaban la intervención divina en las crisis sanitarias personales y de toda la sociedad, como la epidemia de 1737. La intervención de la Virgen de Guadalupe se representaba en una escena de indios muertos y moribundos, con las élites de rodillas rezando por su ayuda. A finales del siglo XVIII, la corona comenzó a aplicar políticas secularizadoras en la península ibérica y su imperio de ultramar para controlar las enfermedades de forma más sistemática y científica. [166] [167] [168]

La búsqueda española de especias medicinales

Botanical medicines also became popular during the 16th, 17th, and 18th Centuries. Spanish pharmaceutical books during this time contain medicinal recipes consisting of spices, herbs, and other botanical products. For example, nutmeg oil was documented for curing stomach ailments and cardamom oil was believed to relieve intestinal ailments.[169] During the rise of the global trade market, spices and herbs, along with many other goods, that were indigenous to different territories began to appear in different locations across the globe. Herbs and spices were especially popular for their utility in cooking and medicines. As a result of this popularity and increased demand for spices, some areas in Asia, like China and Indonesia, became hubs for spice cultivation and trade.[170] The Spanish Empire also wanted to benefit from the international spice trade, so they looked towards their American colonies.

The Spanish American colonies became an area where the Spanish searched to discover new spices and indigenous American medicinal recipes. The Florentine Codex, a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, is a major contribution to the history of Nahua medicine.[171] The Spanish did discover many spices and herbs new to them, some of which were reportedly similar to Asian spices. A Spanish physician by the name of Nicolás Monardes studied many of the American spices coming into Spain. He documented many of the new American spices and their medicinal properties in his survey Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales. For example, Monardes describes the "Long Pepper" (Pimienta luenga), found along the coasts of the countries that are now known Panama and Colombia, as a pepper that was more flavorful, healthy, and spicy in comparison to the Eastern black pepper.[169] The Spanish interest in American spices can first be seen in the commissioning of the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis, which was a Spanish-American codex describing indigenous American spices and herbs and describing the ways that these were used in natural Aztec medicines. The codex was commissioned in the year 1552 by Francisco de Mendoza, the son of Antonio de Mendoza, who was the first Viceroy of New Spain.[169] Francisco de Mendoza was interested in studying the properties of these herbs and spices, so that he would be able to profit from the trade of these herbs and the medicines that could be produced by them.

Francisco de Mendoza recruited the help of Monardez in studying the traditional medicines of the indigenous people living in what was then the Spanish colonies. Monardez researched these medicines and performed experiments to discover the possibilities of spice cultivation and medicine creation in the Spanish colonies. The Spanish transplanted some herbs from Asia, but only a few foreign crops were successfully grown in the Spanish Colonies. One notable crop brought from Asia and successfully grown in the Spanish colonies was ginger, as it was considered Hispaniola's number 1 crop at the end of the 16th Century.[169] The Spanish Empire did profit from cultivating herbs and spices, but they also introduced pre-Columbian American medicinal knowledge to Europe. Other Europeans were inspired by the actions of Spain and decided to try to establish a botanical transplant system in colonies that they controlled, however, these subsequent attempts were not successful.[170]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The London Dispensary opened in 1696, the first clinic in the British Empire to dispense medicines to poor sick people. The innovation was slow to catch on, but new dispensaries were open in the 1770s. In the colonies, small hospitals opened in Philadelphia in 1752, New York in 1771, and Boston (Massachusetts General Hospital) in 1811.[172]

Guy's Hospital, the first great British hospital with a modern foundation opened in 1721 in London, with funding from businessman Thomas Guy. It had been preceded by St Bartholomew's Hospital and St Thomas's Hospital, both medieval foundations. In 1821 a bequest of £200,000 by William Hunt in 1829 funded expansion for an additional hundred beds at Guy's. Samuel Sharp (1709–78), a surgeon at Guy's Hospital from 1733 to 1757, was internationally famous; his A Treatise on the Operations of Surgery (1st ed., 1739), was the first British study focused exclusively on operative technique.[173]

English physician Thomas Percival (1740–1804) wrote a comprehensive system of medical conduct, Medical Ethics; or, a Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conduct of Physicians and Surgeons (1803) that set the standard for many textbooks.[174]

In the 1830s in Italy, Agostino Bassi traced the silkworm disease muscardine to microorganisms. Meanwhile, in Germany, Theodor Schwann led research on alcoholic fermentation by yeast, proposing that living microorganisms were responsible. Leading chemists, such as Justus von Liebig, seeking solely physicochemical explanations, derided this claim and alleged that Schwann was regressing to vitalism.

In 1847 in Vienna, Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865), dramatically reduced the death rate of new mothers (due to childbed fever) by requiring physicians to clean their hands before attending childbirth, yet his principles were marginalized and attacked by professional peers.[175] At that time most people still believed that infections were caused by foul odors called miasmas.

French scientist Louis Pasteur confirmed Schwann's fermentation experiments in 1857 and afterwards supported the hypothesis that yeast were microorganisms. Moreover, he suggested that such a process might also explain contagious disease. In 1860, Pasteur's report on bacterial fermentation of butyric acid motivated fellow Frenchman Casimir Davaine to identify a similar species (which he called bacteridia) as the pathogen of the deadly disease anthrax. Others dismissed "bacteridia" as a mere byproduct of the disease. British surgeon Joseph Lister, however, took these findings seriously and subsequently introduced antisepsis to wound treatment in 1865.

German physician Robert Koch, noting fellow German Ferdinand Cohn's report of a spore stage of a certain bacterial species, traced the life cycle of Davaine's bacteridia, identified spores, inoculated laboratory animals with them, and reproduced anthrax—a breakthrough for experimental pathology and germ theory of disease. Pasteur's group added ecological investigations confirming spores' role in the natural setting, while Koch published a landmark treatise in 1878 on the bacterial pathology of wounds. In 1881, Koch reported discovery of the "tubercle bacillus", cementing germ theory and Koch's acclaim.

Upon the outbreak of a cholera epidemic in Alexandria, Egypt, two medical missions went to investigate and attend the sick, one was sent out by Pasteur and the other led by Koch.[177] Koch's group returned in 1883, having successfully discovered the cholera pathogen.[177] In Germany, however, Koch's bacteriologists had to vie against Max von Pettenkofer, Germany's leading proponent of miasmatic theory.[178] Pettenkofer conceded bacteria's casual involvement, but maintained that other, environmental factors were required to turn it pathogenic, and opposed water treatment as a misdirected effort amid more important ways to improve public health.[178] The massive cholera epidemic in Hamburg in 1892 devastated Pettenkoffer's position, and yielded German public health to "Koch's bacteriology".[178]

On losing the 1883 rivalry in Alexandria, Pasteur switched research direction, and introduced his third vaccine—rabies vaccine—the first vaccine for humans since Jenner's for smallpox.[177] From across the globe, donations poured in, funding the founding of Pasteur Institute, the globe's first biomedical institute, which opened in 1888.[177] Along with Koch's bacteriologists, Pasteur's group—which preferred the term microbiology—led medicine into the new era of "scientific medicine" upon bacteriology and germ theory.[177] Accepted from Jakob Henle, Koch's steps to confirm a species' pathogenicity became famed as "Koch's postulates". Although his proposed tuberculosis treatment, tuberculin, seemingly failed, it soon was used to test for infection with the involved species. In 1905, Koch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and remains renowned as the founder of medical microbiology.[179]

The breakthrough to professionalization based on knowledge of advanced medicine was led by Florence Nightingale in England. She resolved to provide more advanced training than she saw on the Continent. At Kaiserswerth, where the first German nursing schools were founded in 1836 by Theodor Fliedner, she said, "The nursing was nil and the hygiene horrible."[180]) Britain's male doctors preferred the old system, but Nightingale won out and her Nightingale Training School opened in 1860 and became a model. The Nightingale solution depended on the patronage of upper-class women, and they proved eager to serve. Royalty became involved. In 1902 the wife of the British king took control of the nursing unit of the British army, became its president, and renamed it after herself as the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps; when she died the next queen became president. Today its Colonel in Chief is Sophie, Countess of Wessex, the daughter-in-law of Queen Elizabeth II. In the United States, upper-middle-class women who already supported hospitals promoted nursing. The new profession proved highly attractive to women of all backgrounds, and schools of nursing opened in the late 19th century. Nurses were soon a part of large hospitals, where they provided a steady stream of low-paid idealistic workers. The International Red Cross began operations in numerous countries in the late 19th century, promoting nursing as an ideal profession for middle-class women.[181]

A major breakthrough in epidemiology came with the introduction of statistical maps and graphs. They allowed careful analysis of seasonality issues in disease incidents, and the maps allowed public health officials to identify critical loci for the dissemination of disease. John Snow in London developed the methods. In 1849, he observed that the symptoms of cholera, which had already claimed around 500 lives within a month, were vomiting and diarrhoea. He concluded that the source of contamination must be through ingestion, rather than inhalation as was previously thought. It was this insight that resulted in the removal of The Pump On Broad Street, after which deaths from cholera plummeted. English nurse Florence Nightingale pioneered analysis of large amounts of statistical data, using graphs and tables, regarding the condition of thousands of patients in the Crimean War to evaluate the efficacy of hospital services. Her methods proved convincing and led to reforms in military and civilian hospitals, usually with the full support of the government.[182][183][184]

By the late 19th and early 20th century English statisticians led by Francis Galton, Karl Pearson and Ronald Fisher developed the mathematical tools such as correlations and hypothesis tests that made possible much more sophisticated analysis of statistical data.[185]

During the U.S. Civil War the Sanitary Commission collected enormous amounts of statistical data, and opened up the problems of storing information for fast access and mechanically searching for data patterns. The pioneer was John Shaw Billings (1838–1913). A senior surgeon in the war, Billings built the Library of the Surgeon General's Office (now the National Library of Medicine), the centerpiece of modern medical information systems.[186] Billings figured out how to mechanically analyze medical and demographic data by turning facts into numbers and punching the numbers onto cardboard cards that could be sorted and counted by machine. The applications were developed by his assistant Herman Hollerith; Hollerith invented the punch card and counter-sorter system that dominated statistical data manipulation until the 1970s. Hollerith's company became International Business Machines (IBM) in 1911.[187]

Until the nineteenth century, the care of the insane was largely a communal and family responsibility rather than a medical one. The vast majority of the mentally ill were treated in domestic contexts with only the most unmanageable or burdensome likely to be institutionally confined.[188] This situation was transformed radically from the late eighteenth century as, amid changing cultural conceptions of madness, a new-found optimism in the curability of insanity within the asylum setting emerged.[189] Increasingly, lunacy was perceived less as a physiological condition than as a mental and moral one[190] to which the correct response was persuasion, aimed at inculcating internal restraint, rather than external coercion.[191] This new therapeutic sensibility, referred to as moral treatment, was epitomised in French physician Philippe Pinel's quasi-mythological unchaining of the lunatics of the Bicêtre Hospital in Paris[192] and realised in an institutional setting with the foundation in 1796 of the Quaker-run York Retreat in England.[47]

From the early nineteenth century, as lay-led lunacy reform movements gained in influence,[193] ever more state governments in the West extended their authority and responsibility over the mentally ill.[194] Small-scale asylums, conceived as instruments to reshape both the mind and behaviour of the disturbed,[195] proliferated across these regions.[196] By the 1830s, moral treatment, together with the asylum itself, became increasingly medicalised[197] and asylum doctors began to establish a distinct medical identity with the establishment in the 1840s of associations for their members in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and America, together with the founding of medico-psychological journals.[47] Medical optimism in the capacity of the asylum to cure insanity soured by the close of the nineteenth century as the growth of the asylum population far outstripped that of the general population.[a][198] Processes of long-term institutional segregation, allowing for the psychiatric conceptualisation of the natural course of mental illness, supported the perspective that the insane were a distinct population, subject to mental pathologies stemming from specific medical causes.[195] As degeneration theory grew in influence from the mid-nineteenth century,[199] heredity was seen as the central causal element in chronic mental illness,[200] and, with national asylum systems overcrowded and insanity apparently undergoing an inexorable rise, the focus of psychiatric therapeutics shifted from a concern with treating the individual to maintaining the racial and biological health of national populations.[201]

Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) introduced new medical categories of mental illness, which eventually came into psychiatric usage despite their basis in behavior rather than pathology or underlying cause. Shell shock among frontline soldiers exposed to heavy artillery bombardment was first diagnosed by British Army doctors in 1915. By 1916, similar symptoms were also noted in soldiers not exposed to explosive shocks, leading to questions as to whether the disorder was physical or psychiatric.[203] In the 1920s surrealist opposition to psychiatry was expressed in a number of surrealist publications. In the 1930s several controversial medical practices were introduced including inducing seizures (by electroshock, insulin or other drugs) or cutting parts of the brain apart (leucotomy or lobotomy). Both came into widespread use by psychiatry, but there were grave concerns and much opposition on grounds of basic morality, harmful effects, or misuse.[204]

In the 1950s new psychiatric drugs, notably the antipsychotic chlorpromazine, were designed in laboratories and slowly came into preferred use. Although often accepted as an advance in some ways, there was some opposition, due to serious adverse effects such as tardive dyskinesia. Patients often opposed psychiatry and refused or stopped taking the drugs when not subject to psychiatric control. There was also increasing opposition to the use of psychiatric hospitals, and attempts to move people back into the community on a collaborative user-led group approach ("therapeutic communities") not controlled by psychiatry. Campaigns against masturbation were done in the Victorian era and elsewhere. Lobotomy was used until the 1970s to treat schizophrenia. This was denounced by the anti-psychiatric movement in the 1960s and later.

It was very difficult for women to become doctors in any field before the 1970s. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to formally study and practice medicine in the United States. She was a leader in women's medical education. While Blackwell viewed medicine as a means for social and moral reform, her student Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842–1906) focused on curing disease. At a deeper level of disagreement, Blackwell felt that women would succeed in medicine because of their humane female values, but Jacobi believed that women should participate as the equals of men in all medical specialties using identical methods, values and insights.[205] In the Soviet Union although the majority of medical doctors were women, they were paid less than the mostly male factory workers.[206]

China

Finally in the 19th century, Western medicine was introduced at the local level by Christian medical missionaries from the London Missionary Society (Britain), the Methodist Church (Britain) and the Presbyterian Church (US). Benjamin Hobson (1816–1873) in 1839, set up a highly successful Wai Ai Clinic in Guangzhou, China.[207] The Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese was founded in 1887 by the London Missionary Society, with its first graduate (in 1892) being Sun Yat-sen, who later led the Chinese Revolution (1911). The Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese was the forerunner of the School of Medicine of the University of Hong Kong, which started in 1911.

Because of the social custom that men and women should not be near to one another, the women of China were reluctant to be treated by male doctors. The missionaries sent women doctors such as Dr. Mary Hannah Fulton (1854–1927). Supported by the Foreign Missions Board of the Presbyterian Church (US) she in 1902 founded the first medical college for women in China, the Hackett Medical College for Women, in Guangzhou.[208]

Japan

.jpg/440px-Doctor_(Kusakabe_Kimbei).jpg)