Irlanda del Norte ( irlandés : Tuaisceart Éireann [ˈt̪ˠuəʃcəɾˠt̪ˠ ˈeːɾʲən̪ˠ] ;[13] Ulster Scots:Norlin Airlann) es unapartedelReino Unidoen el noreste de la isla deIrlandaque se describe de diversas formas como un país, provincia o región.[14][15][16][17][18]Irlanda del Norte comparteuna frontera abiertaal sur y al oeste con laRepública de Irlanda. En elcenso de 2021, su población era de 1.903.175,[7]lo que representa alrededor del 3% de lapoblación del Reino Unidoy el 27% de la población de la isla deIrlanda. LaAsamblea de Irlanda del Norte, establecida por laLey de Irlanda del Norte de 1998, es responsable de una variedad dedelegadas, mientras que otras áreas están reservadas para elGobierno del Reino Unido. Elgobierno de Irlanda del Nortecoopera con elgobierno de Irlandaen varias áreas bajo los términos delAcuerdo de Belfast.[19]La República de Irlanda también tiene un papel consultivo en asuntos gubernamentales no delegados a través de la Conferencia Gubernamental Británico-Irlandesa (BIIG).[20]

Irlanda del Norte fue creada en 1921, cuando Irlanda fue dividida por la Ley de Gobierno de Irlanda de 1920 , creando un gobierno descentralizado para los seis condados del noreste . Como lo pretendían los unionistas y sus partidarios en Westminster , Irlanda del Norte tenía una mayoría unionista , que quería permanecer en el Reino Unido; [21] generalmente eran los descendientes protestantes de colonos de Gran Bretaña . Mientras tanto, la mayoría en Irlanda del Sur (que se convirtió en el Estado Libre Irlandés en 1922), y una minoría significativa en Irlanda del Norte, eran nacionalistas irlandeses (generalmente católicos ) que querían una Irlanda unida e independiente . [22] Hoy, los primeros generalmente se ven a sí mismos como británicos y los segundos generalmente se ven a sí mismos como irlandeses, mientras que una minoría significativa de todos los orígenes reivindica una identidad norirlandesa o del Ulster . [23]

La creación de Irlanda del Norte estuvo acompañada de violencia tanto en defensa como en contra de la partición. Durante el conflicto de 1920-22 , la capital, Belfast, fue escenario de una importante violencia comunal , principalmente entre civiles unionistas protestantes y nacionalistas católicos. [24] Más de 500 personas fueron asesinadas [25] y más de 10 000 se convirtieron en refugiados, en su mayoría católicos. [26] Durante los siguientes cincuenta años, Irlanda del Norte tuvo una serie ininterrumpida de gobiernos del Partido Unionista . [27] Hubo una segregación mutua informal por parte de ambas comunidades, [28] y los gobiernos unionistas fueron acusados de discriminación contra la minoría nacionalista irlandesa y católica. [29] A fines de la década de 1960, una campaña para poner fin a la discriminación contra los católicos y los nacionalistas fue rechazada por los leales , que la vieron como un frente republicano . [30] Estos disturbios desencadenaron los disturbios , un conflicto de treinta años en el que participaron paramilitares republicanos y leales y fuerzas estatales, que se cobró más de 3.500 vidas e hirió a otras 50.000. [31] [32] El Acuerdo de Viernes Santo de 1998 fue un paso importante en el proceso de paz , incluido el desarme paramilitar y la normalización de la seguridad, aunque el sectarismo y la segregación siguen siendo problemas sociales importantes y la violencia esporádica ha continuado. [33]

La economía de Irlanda del Norte era la más industrializada de Irlanda en el momento de la partición, pero pronto comenzó a declinar, exacerbada por la agitación política y social de los Problemas. [34] Su economía ha crecido significativamente desde finales de la década de 1990. El desempleo en Irlanda del Norte alcanzó un máximo del 17,2% en 1986, pero volvió a bajar por debajo del 10% en la década de 2010, [35] similar a la tasa del resto del Reino Unido. [36] Los vínculos culturales entre Irlanda del Norte, el resto de Irlanda y el resto del Reino Unido son complejos, ya que Irlanda del Norte comparte tanto la cultura de Irlanda como la cultura del Reino Unido . En muchos deportes, existe un organismo rector o equipo de toda Irlanda para toda la isla; la excepción más notable es el fútbol asociación. Irlanda del Norte compite por separado en los Juegos de la Commonwealth , y la gente de Irlanda del Norte puede competir por Gran Bretaña o Irlanda en los Juegos Olímpicos .

La región que ahora es Irlanda del Norte estuvo habitada durante mucho tiempo por gaélicos nativos que hablaban irlandés y eran predominantemente católicos. [37] Estaba formada por varios reinos y territorios gaélicos y era parte de la provincia de Ulster . En 1169, Irlanda fue invadida por una coalición de fuerzas bajo el mando de la corona inglesa que rápidamente invadió y ocupó la mayor parte de la isla, comenzando 800 años de autoridad central extranjera. Los intentos de resistencia fueron rápidamente aplastados en todas partes fuera del Ulster. A diferencia del resto del país, donde la autoridad gaélica continuó solo en lugares dispersos y remotos, los principales reinos del Ulster permanecerían intactos en su mayoría con la autoridad inglesa en la provincia contenida en áreas de la costa este más cercanas a Gran Bretaña. El poder inglés se erosionó gradualmente ante la tenaz resistencia irlandesa en los siglos siguientes; finalmente se redujo solo a la ciudad de Dublín y sus suburbios. Cuando Enrique VIII lanzó la reconquista Tudor de Irlanda en el siglo XVI , el Ulster una vez más resistió con mayor eficacia. En la Guerra de los Nueve Años (1594-1603), una alianza de jefes gaélicos liderados por los dos señores más poderosos del Ulster, Hugh Roe O'Donnell y el conde de Tyrone , luchó contra el gobierno inglés en Irlanda . La alianza dominada por el Ulster representó el primer frente unido irlandés; la resistencia anterior siempre había estado geográficamente localizada. A pesar de poder cimentar una alianza con España y obtener importantes victorias desde el principio, la derrota fue prácticamente inevitable después de la victoria de Inglaterra en el asedio de Kinsale . En 1607, los líderes de la rebelión huyeron a Europa continental junto con gran parte de la nobleza gaélica del Ulster. Sus tierras fueron confiscadas por la Corona y colonizadas con colonos protestantes de habla inglesa de Gran Bretaña, en la Plantación del Ulster . Esto llevó a la fundación de muchas de las ciudades del Ulster y creó una comunidad protestante del Ulster duradera con vínculos con Gran Bretaña. La Rebelión Irlandesa de 1641 comenzó en el Ulster. Los rebeldes querían poner fin a la discriminación anticatólica, un mayor autogobierno irlandés y hacer retroceder la Plantación. Se convirtió en un conflicto étnico entre los católicos irlandeses y los colonos protestantes británicos y se convirtió en parte de las Guerras de los Tres Reinos (1639-1653), que terminaron con la conquista parlamentaria inglesa . Otras victorias protestantes en la Guerra Williamita-Jacobita (1688-1691) consolidaron el protestantismo anglicano.gobernaron el Reino de Irlanda . Las victorias guillermitas del asedio de Derry (1689) y la batalla del Boyne (1690) todavía son celebradas por algunos protestantes en Irlanda del Norte. [38] Muchos más protestantes escoceses emigraron al Ulster durante la hambruna escocesa de la década de 1690 .

Tras la victoria guillermina, y en contra del Tratado de Limerick (1691), la clase dirigente protestante anglicana de Irlanda aprobó una serie de leyes penales con la intención de perjudicar a los católicos y, en menor medida, a los presbiterianos . Unos 250.000 presbiterianos del Ulster emigraron a las colonias británicas de Norteamérica entre 1717 y 1775. [39] Se estima que hay más de 27 millones de estadounidenses escoceses-irlandeses viviendo ahora en los Estados Unidos, [40] junto con muchos canadienses escoceses-irlandeses en Canadá. En el contexto de la discriminación institucional, el siglo XVIII vio cómo se desarrollaban sociedades secretas y militantes en el Ulster y actuaban sobre las tensiones sectarias en ataques violentos. Esto se intensificó a finales de siglo, especialmente durante los disturbios del condado de Armagh , donde los protestantes Peep o' Day Boys lucharon contra los Defensores Católicos . Esto llevó a la fundación de la Orden protestante de Orange . La rebelión irlandesa de 1798 fue liderada por los Irlandeses Unidos , un grupo republicano irlandés intercomunitario fundado por los presbiterianos de Belfast que buscaba la independencia de Irlanda. Después de esto, el gobierno del Reino de Gran Bretaña presionó para que los dos reinos se fusionaran, en un intento de sofocar el sectarismo violento, eliminar las leyes discriminatorias y evitar la propagación del republicanismo de estilo francés. El Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda se formó en 1801 y se gobernó desde Londres. Durante el siglo XIX, las reformas legales conocidas como la emancipación católica continuaron eliminando la discriminación contra los católicos, y los programas progresistas permitieron a los agricultores arrendatarios comprar tierras a los terratenientes.

A finales del siglo XIX, una gran y disciplinada cohorte de parlamentarios nacionalistas irlandeses en Westminster comprometió al Partido Liberal a la "autonomía irlandesa" (autogobierno para Irlanda, dentro del Reino Unido). Esto fue duramente rechazado por los unionistas irlandeses , la mayoría de los cuales eran protestantes, que temían un gobierno descentralizado irlandés dominado por nacionalistas irlandeses y católicos. El proyecto de ley de 1886 sobre el gobierno de Irlanda y el proyecto de ley de 1893 sobre el gobierno de Irlanda fueron derrotados. Sin embargo, el autogobierno se convirtió en una certeza casi absoluta en 1912 después de que se introdujera por primera vez la Ley de 1914 sobre el gobierno de Irlanda . El gobierno liberal dependía del apoyo nacionalista, y la Ley del Parlamento de 1911 impidió que la Cámara de los Lores bloqueara el proyecto de ley indefinidamente. [41]

En respuesta, los unionistas prometieron impedir el autogobierno irlandés, desde los líderes del Partido Conservador y Unionista como Bonar Law y el abogado Edward Carson , con sede en Dublín, hasta los sindicalistas militantes de la clase trabajadora en Irlanda. Esto desencadenó la Crisis del Autogobierno . En septiembre de 1912, más de 500.000 unionistas firmaron el Pacto del Ulster , comprometiéndose a oponerse al autogobierno por cualquier medio y a desafiar a cualquier gobierno irlandés. [42] En 1914, los unionistas contrabandearon miles de rifles y municiones de la Alemania imperial para su uso por parte de los Voluntarios del Ulster (UVF), una organización paramilitar formada para oponerse al autogobierno. Los nacionalistas irlandeses también habían formado una organización paramilitar, los Voluntarios Irlandeses . Buscaba garantizar la implementación del autogobierno, y contrabandeó sus propias armas a Irlanda unos meses después de los Voluntarios del Ulster. [43] Irlanda parecía estar al borde de una guerra civil. [44]

Los unionistas eran minoría en Irlanda en su conjunto, pero mayoría en la provincia del Ulster , especialmente en los condados de Antrim , Down , Armagh y Londonderry . [45] Los unionistas argumentaron que si no se podía detener el autogobierno, entonces todo o parte del Ulster debería ser excluido de él. [46] En mayo de 1914, el gobierno del Reino Unido presentó un proyecto de ley de enmienda para permitir que el "Ulster" fuera excluido del autogobierno. Luego hubo un debate sobre qué parte del Ulster debería excluirse y durante cuánto tiempo. Algunos unionistas del Ulster estaban dispuestos a tolerar la "pérdida" de algunas áreas principalmente católicas de la provincia. [47] La crisis fue interrumpida por el estallido de la Primera Guerra Mundial en agosto de 1914 y la participación de Irlanda en ella . El gobierno del Reino Unido abandonó el proyecto de ley de enmienda y, en su lugar, aprobó rápidamente un nuevo proyecto de ley, la Ley de Suspensión de 1914 , que suspendía el autogobierno durante la duración de la guerra, [48] con la exclusión del Ulster aún por decidir. [49]

Al final de la guerra (durante la cual tuvo lugar el Levantamiento de Pascua de 1916), la mayoría de los nacionalistas irlandeses ahora querían la independencia total en lugar de un gobierno autónomo. En septiembre de 1919, el primer ministro británico David Lloyd George encargó a un comité que planeara otro proyecto de ley de autonomía. Encabezado por el político unionista inglés Walter Long , se lo conocía como el "Comité Long". Decidió que se debían establecer dos gobiernos descentralizados, uno para los nueve condados del Ulster y otro para el resto de Irlanda, junto con un Consejo de Irlanda para el "fomento de la unidad irlandesa". [50] La mayoría de los unionistas del Ulster querían que el territorio del gobierno del Ulster se redujera a seis condados para que tuviera una mayoría unionista protestante más grande, lo que creían que garantizaría su longevidad. Los seis condados de Antrim , Down , Armagh , Londonderry , Tyrone y Fermanagh comprendían el área máxima que los unionistas creían que podían dominar. [51] El área que se convertiría en Irlanda del Norte incluía los condados de Fermanagh y Tyrone, a pesar de que tenían mayorías nacionalistas en las elecciones generales irlandesas de 1918. [ 52]

Los acontecimientos se apoderaron del gobierno. En las elecciones generales irlandesas de 1918, el partido independentista Sinn Féin ganó la abrumadora mayoría de los escaños irlandeses. Los miembros electos del Sinn Féin boicotearon el parlamento británico y fundaron un parlamento irlandés separado ( Dáil Éireann ), declarando una República Irlandesa independiente que abarcaba toda la isla. Muchos republicanos irlandeses culparon al establishment británico por las divisiones sectarias en Irlanda, y creían que el unionismo del Ulster se desvanecería una vez que terminara el dominio británico. [53] Las autoridades británicas ilegalizaron el Dáil en septiembre de 1919, [54] y se desarrolló un conflicto guerrillero cuando el Ejército Republicano Irlandés (IRA) comenzó a atacar a las fuerzas británicas. Esto se conoció como la Guerra de Independencia de Irlanda . [55]

.jpg/440px-Ulster_Welcomes_Her_King_&_Queen_(10990906846).jpg)

Mientras tanto, la Ley de Gobierno de Irlanda de 1920 pasó por el parlamento británico en 1920. Dividiría Irlanda en dos territorios británicos autónomos: los seis condados del noreste (Irlanda del Norte) gobernados desde Belfast , y los otros veintiséis condados ( Irlanda del Sur ) gobernados desde Dublín . Ambos tendrían un Lord Teniente de Irlanda compartido , que nombraría a ambos gobiernos y un Consejo de Irlanda , que el gobierno del Reino Unido pretendía convertir en un parlamento de toda Irlanda. [56] La ley recibió la sanción real ese diciembre, convirtiéndose en la Ley de Gobierno de Irlanda de 1920. Entró en vigor el 3 de mayo de 1921, [57] [58] dividiendo Irlanda y creando Irlanda del Norte. Las elecciones irlandesas de 1921 se celebraron el 24 de mayo, en las que los unionistas ganaron la mayoría de los escaños en el parlamento de Irlanda del Norte. Se reunió por primera vez el 7 de junio y formó su primer gobierno descentralizado , encabezado por el líder del Partido Unionista del Ulster, James Craig . Los miembros nacionalistas irlandeses se negaron a asistir. El rey Jorge V pronunció un discurso en la ceremonia inaugural del Parlamento del Norte el 22 de junio. [57]

Durante 1920-22, en lo que se convirtió en Irlanda del Norte, la partición estuvo acompañada de violencia "en defensa u oposición al nuevo asentamiento" [24] durante The Troubles (1920-1922) . El IRA llevó a cabo ataques contra las fuerzas británicas en el noreste, pero fue menos activo que en el resto de Irlanda. Los protestantes leales atacaron a los católicos en represalia por las acciones del IRA. En el verano de 1920, la violencia sectaria estalló en Belfast y Derry, y hubo incendios masivos de propiedades católicas en Lisburn y Banbridge . [59] El conflicto continuó de forma intermitente durante dos años, principalmente en Belfast , que vio una violencia comunitaria "salvaje y sin precedentes" entre protestantes y católicos, incluidos disturbios, tiroteos y bombardeos. Se atacaron casas, negocios e iglesias y se expulsó a personas de los lugares de trabajo y barrios mixtos. [24] Más de 500 personas murieron [25] y más de 10.000 se convirtieron en refugiados, la mayoría de ellos católicos. [60] Se desplegó el ejército británico y se formó la Policía Especial del Ulster (USC) para ayudar a la policía regular. La USC era casi totalmente protestante. Miembros de la USC y de la policía regular estuvieron involucrados en ataques de represalia contra civiles católicos. [61] Se estableció una tregua entre las fuerzas británicas y el IRA el 11 de julio de 1921, poniendo fin a los combates en la mayor parte de Irlanda. Sin embargo, la violencia comunitaria continuó en Belfast, y en 1922 el IRA lanzó una ofensiva guerrillera a lo largo de la nueva frontera irlandesa . [62]

El Tratado Anglo-Irlandés fue firmado entre representantes de los gobiernos del Reino Unido y la República de Irlanda el 6 de diciembre de 1921, estableciendo el proceso para la creación del Estado Libre Irlandés . Según los términos del tratado, Irlanda del Norte pasaría a ser parte del Estado Libre a menos que su gobierno optara por no hacerlo mediante una declaración dirigida al rey, aunque en la práctica la partición se mantuvo vigente. [63]

El Estado Libre Irlandés nació el 6 de diciembre de 1922 y, al día siguiente, el Parlamento de Irlanda del Norte decidió ejercer su derecho a optar por no formar parte del Estado Libre dirigiendo un discurso al rey Jorge V. [ 64] El texto del discurso fue el siguiente:

Gracioso Soberano, Nosotros, los súbditos más obedientes y leales de Vuestra Majestad, los Senadores y los Comunes de Irlanda del Norte reunidos en el Parlamento, habiendo sabido de la aprobación de la Ley de Constitución del Estado Libre Irlandés de 1922 , que es la Ley del Parlamento para la ratificación de los Artículos del Acuerdo para un Tratado entre Gran Bretaña e Irlanda, rogamos, por este humilde discurso, a Vuestra Majestad que los poderes del Parlamento y del Gobierno del Estado Libre Irlandés no se extiendan más a Irlanda del Norte. [65]

Poco después, se creó la Comisión de Límites Irlandeses para decidir sobre la frontera entre el Estado Libre Irlandés e Irlanda del Norte. Debido al estallido de la Guerra Civil Irlandesa , el trabajo de la comisión se retrasó hasta 1925. El gobierno del Estado Libre y los nacionalistas irlandeses esperaban una gran transferencia de territorio al Estado Libre, ya que muchas áreas fronterizas tenían mayorías nacionalistas. Muchos creían que esto dejaría el territorio restante de Irlanda del Norte demasiado pequeño para ser viable. [66] Sin embargo, el informe final de la comisión recomendó solo pequeñas transferencias de territorio, y en ambas direcciones. Los gobiernos del Estado Libre, Irlanda del Norte y el Reino Unido acordaron suprimir el informe y aceptar el statu quo , mientras que el gobierno del Reino Unido acordó que el Estado Libre ya no tendría que pagar una parte de la deuda nacional del Reino Unido. [67]

La frontera de Irlanda del Norte se trazó para darle "una mayoría protestante decisiva". En el momento de su creación, la población de Irlanda del Norte estaba compuesta por dos tercios de protestantes y un tercio de católicos. [21] La mayoría de los protestantes eran unionistas/leales que buscaban mantener a Irlanda del Norte como parte del Reino Unido, mientras que la mayoría de los católicos eran nacionalistas irlandeses/republicanos que buscaban una Irlanda Unida independiente. En Irlanda del Norte existía una segregación mutua autoimpuesta entre protestantes y católicos, como en la educación, la vivienda y, a menudo, el empleo. [68]

Durante sus primeros cincuenta años, Irlanda del Norte tuvo una serie ininterrumpida de gobiernos del Partido Unionista del Ulster . [69] Todos los primeros ministros y casi todos los ministros de estos gobiernos eran miembros de la Orden de Orange , al igual que todos menos 11 de los 149 diputados del Partido Unionista del Ulster (UUP) elegidos durante este tiempo. [70] Casi todos los jueces y magistrados eran protestantes, muchos de ellos estrechamente asociados con el UUP. La nueva fuerza policial de Irlanda del Norte fue la Real Policía del Ulster (RUC), que sucedió a la Real Policía Irlandesa (RIC). También era casi completamente protestante y carecía de independencia operativa, respondiendo a las instrucciones de los ministros del gobierno. La RUC y la reserva de la Policía Especial del Ulster (USC) eran fuerzas policiales militarizadas debido a la amenaza percibida del republicanismo militante. En 1936, el grupo de defensa británico, el Consejo Nacional para las Libertades Civiles, caracterizó al USC como "nada más que el ejército organizado del partido unionista". [71] "Tenían a su disposición la Ley de Poderes Especiales , una amplia ley que permitía arrestos sin orden judicial, internamientos sin juicio, poderes de búsqueda ilimitados y prohibiciones de reuniones y publicaciones". [72] Esta ley de 1922 se hizo permanente en 1933 y no fue derogada hasta 1973. [73]

El Partido Nacionalista fue el principal partido político de oposición a los gobiernos del UUP. Sin embargo, sus miembros electos a menudo protestaron absteniéndose en el parlamento de Irlanda del Norte, y muchos nacionalistas no votaron en las elecciones parlamentarias. [68] Otros grupos nacionalistas tempranos que hicieron campaña contra la partición incluyeron la Liga Nacional del Norte (formada en 1928), el Consejo Norteño para la Unidad (formado en 1937) y la Liga Antipartición Irlandesa (formada en 1945). [74]

La Ley de Gobierno Local (Irlanda del Norte) de 1922 permitió alterar los límites municipales y rurales. Esta ley condujo a la manipulación de los límites electorales locales en las ciudades de mayoría nacionalista de Derry City, Enniskillen, Omagh, Armagh y muchas otras ciudades y distritos rurales. Esa acción aseguró el control unionista sobre los consejos locales en áreas donde eran una minoría. [75] Los gobiernos del UUP, y algunas autoridades locales dominadas por el UUP, discriminaron a la minoría católica y nacionalista irlandesa; especialmente mediante la manipulación de los límites electorales locales, la asignación de vivienda pública, empleo en el sector público y la policía, mostrando "un patrón consistente e irrefutable de discriminación deliberada contra los católicos". [76] Muchos católicos/nacionalistas vieron la manipulación de los límites electorales locales y la abolición de la representación proporcional como prueba de discriminación patrocinada por el gobierno. Hasta 1969 estuvo en vigor un sistema llamado voto plural , que era una práctica por la cual una persona podía votar varias veces en una elección. Los propietarios de propiedades y negocios podían votar tanto en el distrito electoral donde se encontraba su propiedad como en el de su residencia, si ambos eran diferentes. Este sistema a menudo daba como resultado que una persona pudiera emitir varios votos. [77] Décadas más tarde, el Primer Ministro del UUP de Irlanda del Norte , David Trimble , dijo que Irlanda del Norte bajo el UUP había sido una "casa fría" para los católicos. [78]

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial , el reclutamiento en el ejército británico fue notablemente menor que los altos niveles alcanzados durante la Primera Guerra Mundial. En junio de 1940, para alentar al estado neutral irlandés a unirse a los Aliados , el primer ministro británico Winston Churchill indicó al Taoiseach Éamon de Valera que el gobierno británico alentaría la unidad irlandesa, pero creyendo que Churchill no podría cumplir, De Valera rechazó la oferta. [79] Los británicos no informaron al gobierno de Irlanda del Norte que habían hecho la oferta al gobierno de Dublín, y el rechazo de De Valera no se hizo público hasta 1970. Belfast fue una ciudad industrial clave en el esfuerzo bélico del Reino Unido, produciendo barcos, tanques, aviones y municiones. El desempleo que había sido tan persistente en la década de 1930 desapareció y apareció la escasez de mano de obra, lo que provocó la migración desde el Estado Libre. La ciudad estaba escasamente defendida y solo tenía 24 cañones antiaéreos. El ministro del Interior, Richard Dawson Bates , se había preparado demasiado tarde, asumiendo que Belfast estaba lo suficientemente lejos como para ser segura. El cuerpo de bomberos de la ciudad era inadecuado y, como el gobierno de Irlanda del Norte se había mostrado reacio a gastar dinero en refugios antiaéreos, solo comenzó a construirlos después del bombardeo de Londres durante el otoño de 1940. No había reflectores en la ciudad, lo que dificultaba el derribo de bombarderos enemigos. En abril-mayo de 1941, comenzó el bombardeo de Belfast cuando la Luftwaffe lanzó una serie de incursiones que fueron las más mortíferas vistas fuera de Londres. Las áreas de clase trabajadora en el norte y este de la ciudad fueron particularmente afectadas, y más de 1.000 personas murieron y cientos resultaron gravemente heridas. Decenas de miles de personas huyeron de la ciudad por temor a futuros ataques. En el ataque final, las bombas de la Luftwaffe infligieron grandes daños a los muelles y al astillero Harland & Wolff , cerrándolo durante seis meses. La mitad de las casas de la ciudad habían sido destruidas, lo que puso de relieve las terribles condiciones de vida de los barrios marginales de Belfast, y se produjeron daños por valor de unos 20 millones de libras. El gobierno de Irlanda del Norte fue duramente criticado por su falta de preparación, y el primer ministro de Irlanda del Norte, J. M. Andrews, dimitió. En 1944 se produjo una importante huelga de municiones. [80]

La Ley de Irlanda de 1949 dio la primera garantía legal de que la región no dejaría de ser parte del Reino Unido sin el consentimiento del Parlamento de Irlanda del Norte .

Entre 1956 y 1962, el Ejército Republicano Irlandés (IRA) llevó a cabo una campaña de guerrillas limitada en las zonas fronterizas de Irlanda del Norte, llamada Campaña Fronteriza . Su objetivo era desestabilizar Irlanda del Norte y poner fin a la partición, pero fracasó. [81]

En 1965, el primer ministro de Irlanda del Norte, Terence O'Neill, se reunió con el Taoiseach, Seán Lemass . Fue la primera reunión entre los dos jefes de gobierno desde la partición. [82]

Los disturbios, que comenzaron a fines de la década de 1960, consistieron en alrededor de 30 años de actos recurrentes de intensa violencia durante los cuales 3.254 personas fueron asesinadas [83] y más de 50.000 resultaron heridas. [84] Entre 1969 y 2003 hubo más de 36.900 incidentes con disparos y más de 16.200 atentados con bombas o intentos de atentados con bombas asociados con los disturbios. [32] El conflicto fue causado por las crecientes tensiones entre la minoría nacionalista irlandesa y la mayoría unionista dominante ; los nacionalistas irlandeses se oponen a que Irlanda del Norte permanezca dentro del Reino Unido. [85] Entre 1967 y 1972, la Asociación de Derechos Civiles de Irlanda del Norte (NICRA), que se inspiró en el movimiento de derechos civiles de los EE. UU., lideró una campaña de resistencia civil a la discriminación anticatólica en materia de vivienda, empleo, policía y procedimientos electorales. El sufragio para las elecciones del gobierno local incluía solo a los contribuyentes y sus cónyuges, y por lo tanto excluía a más de una cuarta parte del electorado. Aunque la mayoría de los electores privados de sus derechos eran protestantes, los católicos estaban sobrerrepresentados porque eran más pobres y tenían más adultos viviendo todavía en el hogar familiar. [86]

La campaña de NICRA, vista por muchos unionistas como un frente republicano irlandés , y la reacción violenta a la misma resultaron ser un precursor de un período más violento. [87] Ya en 1969, comenzaron las campañas armadas de grupos paramilitares, incluida la campaña del IRA Provisional de 1969-1997 que tenía como objetivo el fin del dominio británico en Irlanda del Norte y la creación de una Irlanda Unida , y la Fuerza de Voluntarios del Ulster , formada en 1966 en respuesta a la erosión percibida tanto del carácter británico como de la dominación unionista de Irlanda del Norte. Las fuerzas de seguridad del estado -el ejército británico y la policía (la Royal Ulster Constabulary )- también estuvieron involucradas en la violencia. La posición del gobierno del Reino Unido es que sus fuerzas fueron neutrales en el conflicto, tratando de defender la ley y el orden en Irlanda del Norte y el derecho del pueblo de Irlanda del Norte a la autodeterminación democrática. Los republicanos consideraban a las fuerzas estatales como combatientes en el conflicto, señalando la colusión entre las fuerzas estatales y los paramilitares leales como prueba de esto. La investigación "Ballast" del Defensor del Pueblo de la Policía de Irlanda del Norte ha confirmado que las fuerzas británicas, y en particular la RUC, sí conspiraron con paramilitares leales, estuvieron implicadas en asesinatos y obstruyeron el curso de la justicia cuando se habían investigado tales denuncias, [88] aunque todavía se discute hasta qué punto se produjo tal conspiración.

Como consecuencia del empeoramiento de la situación de seguridad, el gobierno regional autónomo de Irlanda del Norte fue suspendido en 1972. Junto a la violencia, hubo un punto muerto político entre los principales partidos políticos de Irlanda del Norte, incluidos los que condenaron la violencia, sobre el futuro estatus de Irlanda del Norte y la forma de gobierno que debería haber dentro de Irlanda del Norte. En 1973, Irlanda del Norte celebró un referéndum para determinar si debía permanecer en el Reino Unido o ser parte de una Irlanda unida. La votación fue mayoritariamente a favor (98,9%) de mantener el statu quo. Aproximadamente el 57,5% del electorado total votó a favor, pero solo el 1% de los católicos votó tras un boicot organizado por el Partido Socialdemócrata y Laborista (SDLP). [89]

Los disturbios tuvieron un final incómodo gracias a un proceso de paz que incluyó la declaración de alto el fuego por parte de la mayoría de las organizaciones paramilitares y el desmantelamiento completo de sus armas, la reforma de la policía y la correspondiente retirada de las tropas del ejército de las calles y zonas fronterizas sensibles como South Armagh y Fermanagh , según lo acordado por los firmantes del Acuerdo de Belfast (comúnmente conocido como el " Acuerdo de Viernes Santo "). Este reiteró la posición británica sostenida durante mucho tiempo, que nunca antes había sido plenamente reconocida por los sucesivos gobiernos irlandeses, de que Irlanda del Norte permanecerá dentro del Reino Unido hasta que una mayoría de votantes en Irlanda del Norte decida lo contrario. La Constitución de Irlanda fue enmendada en 1999 para eliminar una reivindicación de la "nación irlandesa" de soberanía sobre toda la isla (en el artículo 2). [90]

Los nuevos artículos 2 y 3 , añadidos a la Constitución para sustituir a los anteriores, reconocen implícitamente que el estatuto de Irlanda del Norte y sus relaciones con el resto del Reino Unido y con la República de Irlanda sólo se modificarían con el acuerdo de la mayoría de los votantes de cada jurisdicción. Este aspecto también fue central para el Acuerdo de Belfast, que se firmó en 1998 y se ratificó mediante referendos celebrados simultáneamente tanto en Irlanda del Norte como en la República. Al mismo tiempo, el Gobierno del Reino Unido reconoció por primera vez, como parte de la perspectiva, la denominada "dimensión irlandesa": el principio de que el pueblo de la isla de Irlanda en su conjunto tiene derecho, sin ninguna interferencia externa, a resolver los problemas entre el Norte y el Sur por consentimiento mutuo. [91] Esta última declaración fue clave para obtener el apoyo de los nacionalistas al acuerdo. Estableció un gobierno descentralizado de poder compartido, la Asamblea de Irlanda del Norte , situada en Stormont Estate , que debe estar formada por partidos unionistas y nacionalistas. Estas instituciones fueron suspendidas por el gobierno del Reino Unido en 2002 después de que el Servicio de Policía de Irlanda del Norte (PSNI) acusara a personas que trabajaban para el Sinn Féin de espionaje en la Asamblea ( Stormontgate ). El caso resultante contra el acusado miembro del Sinn Féin fracasó. [92]

El 28 de julio de 2005, el IRA Provisional declaró el fin de su campaña y desde entonces ha desmantelado lo que se cree que es todo su arsenal . Este acto final de desmantelamiento se llevó a cabo bajo la supervisión de la Comisión Internacional Independiente sobre Desmantelamiento (IICD) y dos testigos externos de la iglesia. Sin embargo, muchos unionistas se mantuvieron escépticos. La IICD confirmó más tarde que los principales grupos paramilitares leales, la Asociación de Defensa del Ulster , UVF y el Comando Mano Roja , habían desmantelado lo que se cree que son todos sus arsenales, en presencia del ex arzobispo Robin Eames y un ex alto funcionario público. [93]

Los políticos elegidos para la Asamblea en las elecciones de 2003 se reunieron el 15 de mayo de 2006, de conformidad con la Ley de Irlanda del Norte de 2006 [94], para elegir un Primer Ministro y un Viceprimer Ministro de Irlanda del Norte y elegir a los miembros de un Ejecutivo (antes del 25 de noviembre de 2006) como paso preliminar para la restauración del gobierno descentralizado.

Tras las elecciones del 7 de marzo de 2007 , el gobierno descentralizado volvió a funcionar el 8 de mayo de 2007, con el líder del Partido Unionista Democrático (DUP), Ian Paisley, y el vicelíder del Sinn Féin, Martin McGuinness, asumiendo el cargo de Primer Ministro y Viceprimer Ministro, respectivamente. [95] En su libro blanco sobre el Brexit , el gobierno del Reino Unido reiteró su compromiso con el Acuerdo de Belfast. En cuanto al estatus de Irlanda del Norte, afirmó que la "preferencia claramente declarada del gobierno del Reino Unido es mantener la posición constitucional actual de Irlanda del Norte: como parte del Reino Unido, pero con fuertes vínculos con Irlanda". [96]

El 3 de febrero de 2022, Paul Givan dimitió como primer ministro, lo que automáticamente supuso la dimisión de Michelle O'Neill como viceprimera ministra y el colapso del ejecutivo de Irlanda del Norte. [97] El 30 de enero de 2024, el líder del DUP, Jeffrey Donaldson, anunció que el DUP restablecería un gobierno ejecutivo con la condición de que la Cámara de los Comunes del Reino Unido aprobara una nueva legislación. [98]

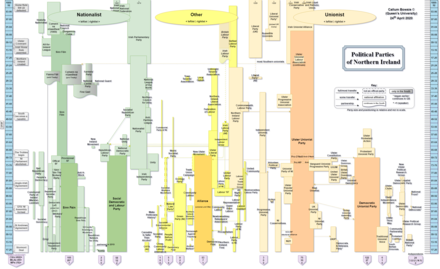

La principal división política en Irlanda del Norte es entre los unionistas, que desean que Irlanda del Norte continúe como parte del Reino Unido, y los nacionalistas, que desean ver a Irlanda del Norte unificada con la República de Irlanda, independiente del Reino Unido. Estas dos visiones opuestas están vinculadas a divisiones culturales más profundas. Los unionistas son predominantemente protestantes del Ulster , descendientes principalmente de colonos escoceses , ingleses y hugonotes , así como de gaélicos que se convirtieron a una de las denominaciones protestantes. Los nacionalistas son abrumadoramente católicos y descienden de la población anterior al asentamiento, con una minoría de las Tierras Altas de Escocia , así como algunos conversos del protestantismo. La discriminación contra los nacionalistas bajo el gobierno de Stormont (1921-1972) dio lugar al movimiento de derechos civiles en la década de 1960. [99]

Aunque algunos unionistas sostienen que la discriminación no se debía sólo a la intolerancia religiosa o política, sino también al resultado de factores socioeconómicos, sociopolíticos y geográficos más complejos, [100] su existencia y la forma en que se manejó la ira nacionalista fueron un factor importante que contribuyó a los disturbios. El malestar político atravesó su fase más violenta entre 1968 y 1994. [101]

En 2007, el 36% de la población se definió como unionista, el 24% como nacionalista y el 40% no se definió como ni lo uno ni lo otro. [102] Según una encuesta de opinión de 2015, el 70% expresa una preferencia a largo plazo por el mantenimiento de la membresía de Irlanda del Norte en el Reino Unido (ya sea gobernada directamente o con un gobierno descentralizado ), mientras que el 14% expresa una preferencia por la membresía de una Irlanda unida. [103] Esta discrepancia se puede explicar por la abrumadora preferencia entre los protestantes de seguir siendo parte del Reino Unido (93%), mientras que las preferencias católicas se extienden entre varias soluciones a la cuestión constitucional, incluyendo seguir siendo parte del Reino Unido (47%), una Irlanda unida (32%), Irlanda del Norte convirtiéndose en un estado independiente (4%) y los que "no saben" (16%). [104]

Las cifras oficiales de votación, que reflejan las opiniones sobre la "cuestión nacional" junto con cuestiones del candidato, la geografía, la lealtad personal y los patrones históricos de votación, muestran que el 54% de los votantes de Irlanda del Norte votan por partidos unionistas, el 42% vota por partidos nacionalistas y el 4% vota por "otros". Las encuestas de opinión muestran consistentemente que los resultados electorales no son necesariamente una indicación de la postura del electorado con respecto al estatus constitucional de Irlanda del Norte. La mayor parte de la población de Irlanda del Norte es al menos nominalmente cristiana, en su mayoría de denominaciones católicas romanas y protestantes. Muchos votantes (independientemente de su afiliación religiosa) se sienten atraídos por las políticas conservadoras del unionismo , mientras que otros votantes se sienten atraídos por el tradicionalmente izquierdista Sinn Féin y el SDLP y sus respectivas plataformas partidarias de socialismo democrático y socialdemocracia . [105]

En su mayoría, los protestantes sienten una fuerte conexión con Gran Bretaña y desean que Irlanda del Norte siga siendo parte del Reino Unido. Sin embargo, muchos católicos aspiran en general a una Irlanda unida o están menos seguros de cómo resolver la cuestión constitucional. Los católicos tienen una ligera mayoría en Irlanda del Norte, según el último censo de Irlanda del Norte. La composición de la Asamblea de Irlanda del Norte refleja los atractivos de los diversos partidos dentro de la población. De los 90 miembros de la Asamblea Legislativa , 37 son unionistas y 35 son nacionalistas (los 18 restantes están clasificados como "otros"). [106]

El Acuerdo de Viernes Santo de 1998 actúa como una constitución de facto para Irlanda del Norte. Desde 2015, el gobierno local de Irlanda del Norte se ha dividido entre 11 consejos con responsabilidades limitadas. [107] El Primer Ministro y el Viceprimer Ministro de Irlanda del Norte son los jefes conjuntos del gobierno de Irlanda del Norte. [108] [109]

.jpg/440px-Stormont_(49321598268).jpg)

Desde 1998, Irlanda del Norte ha tenido un gobierno descentralizado dentro del Reino Unido, presidido por la Asamblea de Irlanda del Norte y un gobierno intercomunitario (el Ejecutivo de Irlanda del Norte ). El Gobierno del Reino Unido y el Parlamento del Reino Unido son responsables de los asuntos reservados y exceptuados . Los asuntos reservados comprenden áreas de políticas enumeradas (como la aviación civil , las unidades de medida y la genética humana ) que el Parlamento puede delegar a la Asamblea en algún momento en el futuro. Nunca se espera que los asuntos exceptuados (como las relaciones internacionales , los impuestos y las elecciones) se consideren para la devolución. En todos los demás asuntos gubernamentales, el Ejecutivo junto con la Asamblea de 90 miembros pueden legislar y gobernar Irlanda del Norte. La devolución en Irlanda del Norte depende de la participación de los miembros del ejecutivo de Irlanda del Norte en el Consejo Ministerial Norte/Sur , que coordina áreas de cooperación (como la agricultura, la educación y la salud) entre Irlanda del Norte y la República de Irlanda. Además, "en reconocimiento del interés especial del Gobierno irlandés en Irlanda del Norte", el Gobierno de Irlanda y el Gobierno del Reino Unido cooperan estrechamente en asuntos no delegados a través de la Conferencia Intergubernamental Británico-Irlandesa .

Las elecciones a la Asamblea de Irlanda del Norte se realizan mediante voto único transferible y cinco miembros de la Asamblea Legislativa (MLA) son elegidos de cada una de las 18 circunscripciones parlamentarias . Además, dieciocho representantes (miembros del Parlamento, MP) son elegidos para la cámara baja del parlamento del Reino Unido de las mismas circunscripciones utilizando el sistema de mayoría simple . Sin embargo, no todos los elegidos ocupan sus escaños. Los parlamentarios del Sinn Féin, actualmente siete, se niegan a prestar el juramento de servir al Rey que se requiere antes de que se les permita ocupar sus escaños. Además, la cámara alta del parlamento del Reino Unido, la Cámara de los Lores , actualmente tiene unos 25 miembros designados de Irlanda del Norte .

La Oficina de Irlanda del Norte representa al Gobierno del Reino Unido en Irlanda del Norte en asuntos reservados y representa los intereses de Irlanda del Norte ante el Gobierno del Reino Unido. Además, el gobierno de la República también tiene derecho a "presentar opiniones y propuestas" sobre asuntos no delegados relacionados con Irlanda del Norte. La Oficina de Irlanda del Norte está dirigida por el Secretario de Estado para Irlanda del Norte , que forma parte del Gabinete del Reino Unido .

Irlanda del Norte es una jurisdicción legal distinta , separada de las otras dos jurisdicciones del Reino Unido ( Inglaterra y Gales y Escocia ). La ley de Irlanda del Norte se desarrolló a partir de la ley irlandesa que existía antes de la partición de Irlanda en 1921. Irlanda del Norte es una jurisdicción de derecho consuetudinario y su derecho consuetudinario es similar al de Inglaterra y Gales. Sin embargo, existen diferencias importantes en la ley y el procedimiento entre Irlanda del Norte e Inglaterra y Gales. El cuerpo de leyes estatutarias que afecta a Irlanda del Norte refleja la historia de Irlanda del Norte, incluidas las leyes del Parlamento del Reino Unido, la Asamblea de Irlanda del Norte , el antiguo Parlamento de Irlanda del Norte y el Parlamento de Irlanda , junto con algunas leyes del Parlamento de Inglaterra y del Parlamento de Gran Bretaña que se extendieron a Irlanda bajo la Ley de Poynings entre 1494 y 1782.

No existe un término generalmente aceptado para describir lo que es Irlanda del Norte. Se la ha descrito como país, provincia, región y otros términos oficialmente, en la prensa y en el habla común. La elección del término puede ser controvertida y puede revelar las preferencias políticas de uno. [17] Varios escritores sobre Irlanda del Norte han señalado este problema como tal, sin que exista una solución generalmente recomendada. [16] [17] [18]

La norma ISO 3166-2:GB define a Irlanda del Norte como una provincia. [15] La presentación del Reino Unido a la Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre la Normalización de los Nombres Geográficos de 2007 define al Reino Unido como un país formado por dos países (Inglaterra y Escocia), un principado (Gales) y una provincia (Irlanda del Norte). [110] Sin embargo, este término puede ser controvertido, en particular para los nacionalistas para quienes el título de provincia está reservado para la provincia tradicional del Ulster, de la que Irlanda del Norte comprende seis de los nueve condados. [111] [17] [112] Algunos autores han descrito el significado de este término como equívoco: se refiere a Irlanda del Norte como una provincia tanto del Reino Unido como del país tradicional de Irlanda. [113]

La Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas del Reino Unido y el sitio web de la Oficina del Primer Ministro del Reino Unido describen al Reino Unido como un país formado por cuatro países, uno de los cuales es Irlanda del Norte. [14] [114] Algunas guías de estilo de periódicos también consideran que el término país es aceptable para Irlanda del Norte. [111] Sin embargo, algunos autores rechazan el término. [112] [16] [18] [113]

El término "región" también ha sido utilizado por agencias gubernamentales del Reino Unido [115] y periódicos. [111] Algunos autores eligen esta palabra pero señalan que es "insatisfactoria". [17] [18] Irlanda del Norte también puede describirse simplemente como "parte del Reino Unido", incluso por las oficinas gubernamentales del Reino Unido. [114]

.jpg/440px-JAFFE_FOUNTAIN_OUTSIDE_VICTORIA_SQUARE_SHOPPING_CENTRE_-A_FAVOURITE_OF_MINE-_REF-104998_(17841282323).jpg)

Muchas personas, tanto dentro como fuera de Irlanda del Norte, utilizan otros nombres para referirse a Irlanda del Norte, según su punto de vista. El desacuerdo sobre los nombres y la interpretación del simbolismo político en el uso o no de una palabra también se dan en algunos centros urbanos. El ejemplo más notable es si la segunda ciudad más grande de Irlanda del Norte debería llamarse "Derry" o "Londonderry" .

La elección del idioma y la nomenclatura en Irlanda del Norte a menudo revelan la identidad cultural, étnica y religiosa del hablante. Aquellos que no pertenecen a ningún grupo pero se inclinan por un bando suelen utilizar el idioma de ese grupo. Los partidarios del unionismo en los medios británicos (en particular, The Daily Telegraph y Daily Express ) llaman regularmente a Irlanda del Norte "Ulster". [116] Muchos medios de comunicación de la República utilizan "Irlanda del Norte" (o simplemente "el Norte"), [117] [118] [119] [120] [121] así como los "Seis Condados". [122] The New York Times también ha utilizado "el Norte". [123]

Las organizaciones gubernamentales y culturales de Irlanda del Norte a menudo utilizan la palabra "Ulster" en sus títulos; por ejemplo, la Universidad del Ulster , el Museo del Ulster , la Orquesta del Ulster y la BBC Radio Ulster .

Aunque algunos boletines de noticias desde la década de 1990 han optado por evitar todos los términos polémicos y utilizar el nombre oficial, Irlanda del Norte, el término "el Norte" sigue siendo de uso común en los medios de difusión de la República. [117] [118] [119]

La actividad volcánica que creó la meseta de Antrim también formó los pilares geométricos de la Calzada del Gigante en la costa norte de Antrim. También en el norte de Antrim se encuentran el puente colgante de Carrick-a-Rede , el templo de Mussenden y los valles de Antrim . Irlanda del Norte estuvo cubierta por una capa de hielo durante la mayor parte de la última edad de hielo y en numerosas ocasiones anteriores, cuyo legado se puede ver en la amplia cobertura de drumlins en los condados de Fermanagh, Armagh, Antrim y, en particular, Down.

El centro de la geografía de Irlanda del Norte es Lough Neagh , con 151 millas cuadradas (391 km2 ) , el lago de agua dulce más grande tanto de la isla de Irlanda como de las Islas Británicas . Un segundo sistema de lagos extenso se centra en Lower y Upper Lough Erne en Fermanagh. La isla más grande de Irlanda del Norte es Rathlin , frente a la costa norte de Antrim. Strangford Lough es el mayor entrante de las Islas Británicas, con una superficie de 150 km2 ( 58 millas cuadradas).

Hay importantes tierras altas en las montañas Sperrin (una extensión del cinturón montañoso de Caledonia ) con extensos depósitos de oro, las montañas de granito de Mourne y la meseta basáltica de Antrim , así como cadenas montañosas más pequeñas en el sur de Armagh y a lo largo de la frontera entre Fermanagh y Tyrone. Ninguna de las colinas es especialmente alta, con Slieve Donard en las espectaculares montañas de Mourne que alcanza los 850 metros (2789 pies), el punto más alto de Irlanda del Norte. El pico más destacado de Belfast es Cavehill .

Los tramos inferior y superior del río Bann , el río Foyle y el río Blackwater forman extensas tierras bajas fértiles, con excelentes tierras cultivables también en el norte y el este de Down, aunque gran parte de la zona montañosa es marginal y adecuada principalmente para la cría de ganado. El valle del río Lagan está dominado por Belfast, cuya área metropolitana incluye más de un tercio de la población de Irlanda del Norte, con una fuerte urbanización e industrialización a lo largo del valle de Lagan y ambas orillas de Belfast Lough .

La gran mayoría de Irlanda del Norte tiene un clima marítimo templado ( Cfb en la clasificación climática de Köppen ), bastante más húmedo en el oeste que en el este, aunque la nubosidad es muy común en toda la región. El clima es impredecible en todas las épocas del año y, aunque las estaciones están diferenciadas, son considerablemente menos pronunciadas que en el interior de Europa o la costa este de América del Norte. Las temperaturas máximas diurnas promedio en Belfast son de 6,5 °C (43,7 °F) en enero y de 17,5 °C (63,5 °F) en julio. La temperatura máxima más alta registrada fue de 31,4 °C (88,5 °F), registrada en julio de 2021 en la estación meteorológica del Observatorio de Armagh . [134] La temperatura mínima más baja registrada fue de -18,7 °C (-1,7 °F) en Castlederg , condado de Tyrone, el 23 de diciembre de 2010. [135]

Hasta finales de la Edad Media , la tierra estaba densamente arbolada. Las especies nativas incluyen árboles de hoja caduca como el roble , el fresno , el avellano , el abedul , el aliso, el sauce , el álamo temblón , el olmo , el serbal y el espino , así como árboles de hoja perenne como el pino silvestre , el tejo y el acebo . [136] Hoy en día, solo el 8% de Irlanda del Norte es bosque, y la mayoría de ellos son plantaciones de coníferas no autóctonas . [137]

A partir del siglo XXI, Irlanda del Norte es la parte menos boscosa del Reino Unido e Irlanda, y uno de los países menos boscosos de Europa. [138]

El único reptil nativo de Irlanda del Norte es el lagarto vivíparo , o lagarto común, que está ampliamente distribuido, particularmente en brezales, pantanos y dunas de arena. La rana común es una especie muy extendida. Algunos lagos albergan poblaciones de aves de importancia internacional; Lough Neagh y Lough Beg albergan hasta 80.000 aves acuáticas invernantes de unas 20 especies, incluidos patos , gansos , cisnes y gaviotas . La nutria es el cuarto mamífero terrestre más grande de Irlanda del Norte. Se puede encontrar a lo largo de los sistemas fluviales, aunque rara vez se la ve y evitará el contacto con los humanos. [139] Se han registrado 356 especies de algas marinas en el noreste de Irlanda; 77 especies se consideran raras. [140]

Irlanda del Norte está formada por seis condados históricos : el condado de Antrim , el condado de Armagh , el condado de Down , el condado de Fermanagh , el condado de Londonderry [e] y el condado de Tyrone .

Estos condados ya no se utilizan para fines de gobierno local; en su lugar, hay once distritos de Irlanda del Norte que tienen diferentes extensiones geográficas. Estos se crearon en 2015, en sustitución de los veintiséis distritos que existían anteriormente. [141]

Aunque los condados ya no se utilizan para fines gubernamentales locales, siguen siendo un medio popular para describir dónde se encuentran los lugares. Se utilizan oficialmente al solicitar un pasaporte irlandés , que requiere que uno indique el condado de nacimiento. El nombre de ese condado aparece entonces tanto en irlandés como en inglés en la página de información del pasaporte, a diferencia de la ciudad o pueblo de nacimiento en el pasaporte del Reino Unido. La Asociación Atlética Gaélica todavía utiliza los condados como su principal medio de organización y presenta equipos representativos de cada condado de la GAA . El sistema original de números de registro de automóviles basado principalmente en los condados sigue en uso. En 2000, el sistema de numeración telefónica se reestructuró en un esquema de 8 dígitos con (excepto Belfast) el primer dígito reflejando aproximadamente el condado.

Los límites de los condados todavía aparecen en los mapas de Ordnance Survey de Irlanda del Norte y en los atlas de Philip's Street, entre otros. Con su declive en el uso oficial, a menudo hay confusión en torno a las ciudades y pueblos que se encuentran cerca de los límites de los condados, como Belfast y Lisburn , que se dividen entre los condados de Down y Antrim (la mayoría de ambas ciudades, sin embargo, se encuentran en Antrim).

En marzo de 2018, The Sunday Times publicó su lista de los mejores lugares para vivir en Gran Bretaña, incluidos los siguientes lugares en Irlanda del Norte: Ballyhackamore cerca de Belfast (el mejor en general para Irlanda del Norte), Holywood, County Down, Newcastle, County Down, Portrush, County Antrim, Strangford, County Down. [142]

La población de Irlanda del Norte ha aumentado anualmente desde 1978. La población en el momento del censo de 2021 era de 1,9 millones, habiendo crecido un 5% durante la década anterior. [145] La población en 2011 era de 1,8 millones, un aumento del 7,5% con respecto a la década anterior. [146] La población actual representa el 2,8% de la población del Reino Unido (67 millones) y el 27% de la población de la isla de Irlanda (7,03 millones). La densidad de población es de 135 habitantes/km 2 .

Según el censo de 2021, la población de Irlanda del Norte es casi en su totalidad blanca (96,6%). [147] En 2021, el 86,5% de la población nació en Irlanda del Norte, el 4,8% en Gran Bretaña, el 2,1% en la República de Irlanda y el 6,5% en otros lugares (más de la mitad de ellos en otro país europeo). [148] En 2021, los grupos étnicos no blancos más numerosos eran los negros (0,6%), los indios (0,5%) y los chinos (0,5%). [147] En 2011, el 88,8% de la población nació en Irlanda del Norte, el 4,5% en Gran Bretaña y el 2,9% en la República de Irlanda. El 4,3% nació en otros lugares, el triple de la cantidad que había en 2001. [149]

Según el censo de 2021, 1.165.168 (61,2 %) residentes vivían en un entorno urbano y 738.007 (38,8 %) vivían en un entorno no urbano. [150]

En los censos de Irlanda del Norte, los encuestados pueden elegir más de una identidad nacional. En 2021: [154]

Las principales identidades nacionales dadas en los censos recientes fueron:

Según el censo de 2021, en lo que respecta a la identidad nacional, cuatro de los seis condados tradicionales tenían una pluralidad irlandesa y dos tenían una pluralidad británica. [156] [157] [158] [159]

En el censo de 2021, el 42,3% de la población se identificó como católica romana , el 37,3% como protestante/otra cristiana, el 1,3% como de otras religiones, mientras que el 17,4% no se identificó con ninguna religión o no declaró ninguna. [160] Las mayores denominaciones protestantes/otras cristianas fueron la Iglesia Presbiteriana (16,6%), la Iglesia de Irlanda (11,5%) y la Iglesia Metodista (2,3%). [160] En el censo de 2011 , el 41,5% de la población se identificó como protestante/otra cristiana, el 41% como católica romana, el 0,8% como de otras religiones, mientras que el 17% no se identificó con ninguna religión o no declaró ninguna. [161] En términos de origen (es decir, religión o religión criada), en el censo de 2021 el 45,7% de la población provenía de un origen católico, el 43,5% de un origen protestante, el 1,5% de otros orígenes religiosos y el 5,6% de orígenes no religiosos. [160] Esta fue la primera vez desde la creación de Irlanda del Norte que había más personas de origen católico que protestante. [162] En el censo de 2011, el 48% provenía de un origen protestante, el 45% de un origen católico, el 0,9% de otros orígenes religiosos y el 5,6% de orígenes no religiosos. [161]

En censos recientes, los encuestados indicaron su identidad religiosa o educación religiosa de la siguiente manera: [163] [155] [160]

Según el censo de 2021, en cuanto a los antecedentes religiosos, cuatro de los seis condados tradicionales tenían una mayoría católica, uno tenía una pluralidad protestante y uno tenía una mayoría protestante. [164]

Varios estudios y encuestas realizados entre 1971 y 2006 han indicado que, en general, la mayoría de los protestantes en Irlanda del Norte se ven a sí mismos principalmente como británicos, mientras que la mayoría de los católicos se ven a sí mismos principalmente como irlandeses. [165] [166] [167 ] [168] [169] [170] [171] [172] Sin embargo, esto no explica las identidades complejas dentro de Irlanda del Norte , dado que muchos de los habitantes se consideran "ulsterianos" o "norirlandeses", ya sea como una identidad primaria o secundaria.

Una encuesta de 2008 reveló que el 57% de los protestantes se describían como británicos, mientras que el 32% se identificaban como norirlandeses, el 6% como ulsterianos y el 4% como irlandeses. En comparación con una encuesta similar de 1998, esto muestra una caída en el porcentaje de protestantes que se identificaban como británicos y ulsterianos y un aumento en los que se identificaban como norirlandeses. La encuesta de 2008 reveló que el 61% de los católicos se describían como irlandeses, mientras que el 25% se identificaban como norirlandeses, el 8% como británicos y el 1% como ulsterianos. Estas cifras se mantuvieron prácticamente sin cambios con respecto a los resultados de 1998. [173] [174]

Las personas nacidas en Irlanda del Norte son, con algunas excepciones, consideradas por la legislación del Reino Unido como ciudadanos del Reino Unido . También tienen derecho a ser ciudadanos de Irlanda , con excepciones similares. Este derecho fue reafirmado en el Acuerdo de Viernes Santo de 1998 entre los gobiernos británico e irlandés, que establece lo siguiente:

...es derecho de nacimiento de todos los habitantes de Irlanda del Norte identificarse y ser aceptados como irlandeses o británicos, o ambos, según elijan, y en consecuencia [los dos gobiernos] confirman que su derecho a poseer tanto la ciudadanía británica como la irlandesa es aceptado por ambos gobiernos y no se vería afectado por ningún cambio futuro en el estatus de Irlanda del Norte.

Como resultado del Acuerdo, se modificó la Constitución de la República de Irlanda . La redacción actual establece que las personas nacidas en Irlanda del Norte tienen derecho a ser ciudadanos irlandeses en las mismas condiciones que las personas de cualquier otra parte de la isla. [175]

Sin embargo, ninguno de los dos gobiernos extiende su ciudadanía a todas las personas nacidas en Irlanda del Norte. Ambos gobiernos excluyen a algunas personas nacidas en Irlanda del Norte, en particular a las personas nacidas sin un progenitor que sea ciudadano británico o irlandés. La restricción irlandesa entró en vigor mediante la vigésimo séptima enmienda a la Constitución irlandesa en 2004. La posición en la ley de nacionalidad del Reino Unido es que la mayoría de las personas nacidas en Irlanda del Norte son nacionales del Reino Unido, lo elijan o no. La renuncia a la ciudadanía británica requiere el pago de una tasa, que actualmente es de 372 libras esterlinas. [176]

En censos recientes, los residentes dijeron que tenían los siguientes pasaportes: [155] [177]

El irlandés es un idioma oficial de Irlanda del Norte desde el 6 de diciembre de 2022, cuando se promulgó la Ley de la lengua irlandesa ( Ley de identidad y lengua (Irlanda del Norte) de 2022 ). La Ley de la lengua irlandesa derogó oficialmente la legislación de 1737 que prohibía el uso del irlandés en los tribunales. [1] El inglés es un idioma oficial de facto . [ cita requerida ] El inglés también lo habla como primera lengua el 95,4% de la población de Irlanda del Norte. [178]

En virtud del Acuerdo de Viernes Santo , el irlandés y el escocés del Ulster (un dialecto del Ulster de la lengua escocesa , a veces conocido como Ullans ) son reconocidos como "parte de la riqueza cultural de Irlanda del Norte". [179] La Ley del idioma irlandés de 2022 también estableció comisionados para el irlandés y el escocés del Ulster. [1]

En virtud del Acuerdo se crearon dos organismos para la promoción de estas lenguas en toda la isla: Foras na Gaeilge , que promueve la lengua irlandesa, y la Agencia del Escocés del Ulster , que promueve el dialecto y la cultura del Escocés del Ulster. Estos organismos operan por separado bajo la égida del Organismo del Idioma Norte/Sur , que rinde cuentas al Consejo Ministerial Norte/Sur .

En 2001, el Gobierno del Reino Unido ratificó la Carta Europea de las Lenguas Regionales o Minoritarias . El irlandés (en Irlanda del Norte) se especificó en la Parte III de la Carta, con una serie de compromisos específicos sobre educación, traducción de estatutos, interacción con las autoridades públicas, uso de topónimos, acceso a los medios de comunicación, apoyo a actividades culturales y otros asuntos. Se concedió un nivel inferior de reconocimiento al escocés del Ulster, en virtud de la Parte II de la Carta. [180]

Según el censo de 2021, en el 94,74% de los hogares, todas las personas de 16 años o más hablaban inglés como lengua principal. [181] El dialecto del inglés hablado en Irlanda del Norte muestra influencia del idioma escocés de las tierras bajas . [182] Supuestamente hay algunas pequeñas diferencias en la pronunciación entre protestantes y católicos, por ejemplo; el nombre de la letra h , que los protestantes tienden a pronunciar como "aitch", como en inglés británico , y los católicos tienden a pronunciar como "haitch", como en inglés hiberno . [183] Sin embargo, la geografía es un determinante mucho más importante del dialecto que el trasfondo religioso.

El idioma irlandés ( en irlandés : an Ghaeilge ), o gaélico , es el segundo idioma más hablado en Irlanda del Norte y es una lengua nativa de Irlanda. [184] Se hablaba predominantemente en lo que hoy es Irlanda del Norte antes de las Plantaciones del Ulster en el siglo XVII y la mayoría de los nombres de lugares en Irlanda del Norte son versiones anglicanizadas de un nombre gaélico. Hoy en día, el idioma a menudo se asocia con el nacionalismo irlandés (y, por lo tanto, con los católicos). Sin embargo, en el siglo XIX, el idioma se consideraba una herencia común, y los protestantes del Ulster desempeñaron un papel principal en el renacimiento gaélico . [185]

En el censo de 2021, el 12,4% (en comparación con el 10,7% en 2011) de la población de Irlanda del Norte afirmó tener "algunos conocimientos de irlandés" y el 3,9% (en comparación con el 3,7% en 2011) afirmó poder "hablar, leer, escribir y comprender" el irlandés. [146] [178] En otra encuesta, de 1999, el 1% de los encuestados afirmó hablarlo como su lengua principal en casa. [186]

El dialecto hablado en Irlanda del Norte, el irlandés del Ulster, tiene dos tipos principales, el irlandés del Ulster oriental y el irlandés de Donegal (o irlandés del Ulster occidental), [187] es el más cercano al gaélico escocés (que se convirtió en una lengua separada del gaélico irlandés en el siglo XVII). Algunas palabras y frases son compartidas con el gaélico escocés, y los dialectos del este del Ulster (los de la isla de Rathlin y los Glens de Antrim ) eran muy similares al dialecto de Argyll , la parte de Escocia más cercana a Irlanda. Los dialectos de Armagh y Down también eran muy similares a los dialectos de Galloway.

The use of the Irish language in Northern Ireland today is politically sensitive. The erection by some district councils of bilingual street names in both English and Irish,[188] invariably in predominantly nationalist districts, is resisted by unionists who claim that it creates a "chill factor" and thus harms community relationships. Efforts by members of the Northern Ireland Assembly to legislate for some official uses of the language have failed to achieve the required cross-community support. In May 2022, the UK Government proposed a bill in the House of Lords to make Irish an official language (and support Ulster Scots) in Northern Ireland and to create an Irish Language Commissioner.[189][190] The bill has since been passed, and received royal assent in December 2022.[191] There has recently been an increase in interest in the language among unionists in East Belfast.[192]

Ulster Scots comprises varieties of the Scots language spoken in Northern Ireland. For a native English speaker, "[Ulster Scots] is comparatively accessible, and even at its most intense can be understood fairly easily with the help of a glossary."[193]

Along with the Irish language, the Good Friday Agreement recognised the dialect as part of Northern Ireland's unique culture and the St Andrews Agreement recognised the need to "enhance and develop the Ulster Scots language, heritage and culture".[194]

At the time of the 2021 census, approximately 1.1% (compared to 0.9% in 2011) of the population claimed to be able to speak, read, write and understand Ulster-Scots, while 10.4% (compared to 8.1% in 2011) professed to have "some ability".[146][178][186]

The most common sign language in Northern Ireland is Northern Ireland Sign Language (NISL). However, because in the past Catholic families tended to send their deaf children to schools in Dublin[citation needed] where Irish Sign Language (ISL) is commonly used, ISL is still common among many older deaf people from Catholic families.

Irish Sign Language (ISL) has some influence from the French family of sign language, which includes American Sign Language (ASL). NISL takes a large component from the British family of sign language (which also includes Auslan) with many borrowings from ASL. It is described as being related to Irish Sign Language at the syntactic level while much of the lexicon is based on British Sign Language (BSL).[195]

As of March 2004[update] the UK Government recognises only British Sign Language and Irish Sign Language as the official sign languages used in Northern Ireland.[196][197]

Unlike most areas of the United Kingdom, in the last year of primary school, many children sit entrance examinations for grammar schools. Integrated schools, which attempt to ensure a balance in enrolment between pupils of Protestant, Roman Catholic, and other faiths (or none), are becoming increasingly popular, although Northern Ireland still has a primarily de facto religiously segregated education system. In the primary school sector, 40 schools (8.9% of the total number) are integrated schools and 32 (7.2% of the total number) are Gaelscoileanna (Irish language-medium schools).

As with the island of Ireland as a whole, Northern Ireland has one of the youngest populations in Europe and, among the four UK nations, it has the highest proportion of children aged under 16 years (21% in mid-2019).[198]

In the most recent full academic year (2021–2022), the region's school education system comprised 1,124 schools (of all types) and around 346,000 pupils, including:

Enrolments in further and higher education were as follows (in 2019–2020) before disruption to enrolments and classes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic:

Statistics on education in Northern Ireland are published by the Department of Education and the Department for the Economy.

The main universities in Northern Ireland are Queen's University Belfast and Ulster University, and the distance learning Open University which has a regional office in Belfast.

Since 1948 Northern Ireland has a health care system similar to England, Scotland and Wales, though it provides not only health care, but also social care. Health care performance has been decreasing since the mid-2010s and reached crisis levels since 2022.[203]

Northern Ireland traditionally had an industrial economy, most notably featuring shipbuilding, rope manufacture, and textiles. In 2019, 53% of GVA was generated by services, 22% by the public sector, 15% by production, 8% by construction and 2% by agriculture.[204]

Belfast is the United Kingdom's second largest tech hub outside of London with more than 25% of their jobs being technology related. Many established multinational tech companies such as Fujitsu, SAP, IBM and Microsoft have a presence here. It is regarded an appealing place to live for tech professionals and has a low cost of living compared to other cities.[205][206]

In 2019 Northern Ireland welcomed 5.3m visitors, who spent over £1billion. A total of 167 cruise ships docked at Northern Ireland ports in 2019.[207] Tourism in recent years has been a major growth area with key attractions including the Giants Causeway and the many castles in the region with the historic towns and cities of Belfast, Derry, Armagh and Enniskillen being popular with tourists. Entertainment venues include the SSE Arena, Waterfront Hall, the Grand Opera House and Custom House Square. Tourists use various means of transport around Northern Ireland such as vehicle hire, guided tours, taxi tours, electric bikes, electric cars and public transport.[208]

Belfast currently has an 81-acre shipyard which was purposely developed to be able to take some of the world's largest vessels. It has the largest dry dock for ships in Europe measuring 556m x 93m and has 106m high cranes, it is ideally situated between the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea.[209] The shipyard can build ships and complete maintenance contracts such as the contracts awarded by P&O and Cunard cruise ships in 2022.[210]

Northern Ireland feeds around 10 million people when their population is only 1.8 million.[211] The predominant activity on Northern Ireland farms in 2022 was cattle and sheep. 79 per cent of farms in Northern Ireland have some cattle, 38 per cent have some sheep. Over three-quarters of farms in Northern Ireland are very small, in 2022 there were 26,089 farms in Northern Ireland with approximately one million hectares of land farmed.[212]

Northern Ireland is in a unique position where it can sell goods to the rest of the United Kingdom and the European Union tariff-free, free from customs declarations, rules of origin certificates and non-tariff barriers on the sale of goods to both regions.[213][214]

Below is a comparison of the goods being sold and purchased between Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom, compared with the goods being exported and imported between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland:

Northern Ireland has underdeveloped transport infrastructure, with most infrastructure concentrated around Greater Belfast, Greater Derry, and Craigavon. Northern Ireland is served by three airports—Belfast International near Antrim, George Best Belfast City integrated into the railway network at Sydenham in East Belfast, and City of Derry in County Londonderry. There are upgrade plans to transform the railway network in Northern Ireland including new lines from Derry to Portadown and Belfast to Newry, though it will take the best part of 25 years to deliver.[216] There are major seaports at Larne and Belfast which carry passengers and freight between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Passenger railways are operated by NI Railways. With Iarnród Éireann (Irish Rail), NI Railways co-operates in providing the joint Enterprise service between Dublin Connolly and Belfast Grand Central. The whole of Ireland has a mainline railway network with a gauge of 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm), which is unique in Europe and has resulted in distinct rolling stock designs. The only preserved line of this gauge on the island is the Downpatrick and County Down Railway, which operates heritage steam and diesel locomotives. Main railway lines linking to and from Belfast Grand Central Station and Lanyon Place railway station are:

The Derry line is the busiest single-track railway line in the United Kingdom, carrying 3 million passengers per annum, the Derry-Londonderry Line has also been described by Michael Palin as "one of the most beautiful rail journeys in the world".[217]

Main motorways are:

Additional short motorway spurs include:

The cross-border road connecting the ports of Larne in Northern Ireland and Rosslare Harbour in the Republic of Ireland is being upgraded as part of an EU-funded scheme. European route E01 runs from Larne through the island of Ireland, Spain, and Portugal to Seville.

Northern Ireland shares both the culture of Ulster and the culture of the United Kingdom.

Northern Ireland has witnessed rising numbers of tourists. Attractions include concert venues, cultural festivals, musical and artistic traditions, countryside and geographical sites of interest, public houses, welcoming hospitality, and sports (especially golf and fishing).[218] Since 1987 public houses have been allowed to open on Sundays, despite some opposition.

Parades are a prominent feature of Northern Ireland society,[219] more so than in the rest of Ireland or the United Kingdom. Most are held by Protestant fraternities such as the Orange Order, and Ulster loyalist marching bands. Each summer, during the "marching season", these groups have hundreds of parades, deck streets with British flags, bunting and specially-made arches, and light large towering bonfires in the "Eleventh Night" celebrations.[220] The biggest parades are held on 12 July (The Twelfth). There is often tension when these activities take place near Catholic neighbourhoods, which sometimes leads to violence.[221]

The Ulster Cycle is a large body of prose and verse centring on the traditional heroes of the Ulaid in what is now eastern Ulster. This is one of the four major cycles of Irish mythology. The cycle centres on the reign of Conchobar mac Nessa, who is said to have been the king of Ulster around the 1st century. He ruled from Emain Macha (now Navan Fort near Armagh), and had a fierce rivalry with queen Medb and king Ailill of Connacht and their ally, Fergus mac Róich, former king of Ulster. The foremost hero of the cycle is Conchobar's nephew Cúchulainn, who features in the epic prose/poem An Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley, a casus belli between Ulster and Connaught).

Northern Ireland comprises a patchwork of communities whose national loyalties are represented in some areas by flags flown from flagpoles or lamp posts. The Union Jack and the former Northern Ireland flag are flown in many loyalist areas, and the Tricolour, adopted by republicans as the flag of Ireland in 1916,[223] is flown in some republican areas. Even kerbstones in some areas are painted red-white-blue or green-white-orange, depending on whether local people express unionist/loyalist or nationalist/republican sympathies.[224]

The official flag is that of the state having sovereignty over the territory, i.e. the Union Flag.[225] The former Northern Ireland flag, also known as the "Ulster Banner" or "Red Hand Flag", is a banner derived from the coat of arms of the Government of Northern Ireland until 1972. Since 1972, it has had no official status. The Union Flag and the Ulster Banner are used exclusively by unionists. The UK flags policy states that in Northern Ireland, "The Ulster flag and the Cross of St Patrick have no official status and, under the Flags Regulations, are not permitted to be flown from Government Buildings."[226][227]

The Irish Rugby Football Union and the Church of Ireland have used the Saint Patrick's Saltire or "Cross of St Patrick". This red saltire on a white field was used to represent Ireland in the flag of the United Kingdom. It is still used by some British Army regiments. Foreign flags are also found, such as the Palestinian flags in some nationalist areas and Israeli flags in some unionist areas.[228]

The United Kingdom national anthem of "God Save the King" is often played at state events in Northern Ireland. At the Commonwealth Games and some other sporting events, the Northern Ireland team uses the Ulster Banner as its flag—notwithstanding its lack of official status—and the Londonderry Air (usually set to lyrics as Danny Boy), which also has no official status, as its national anthem.[229][230] The Northern Ireland national football team also uses the Ulster Banner as its flag but uses "God Save The King" as its anthem.[231]Major Gaelic Athletic Association matches are opened by the national anthem of the Republic of Ireland, "Amhrán na bhFiann (The Soldier's Song)", which is also used by most other all-Ireland sporting organisations.[232]Since 1995, the Ireland rugby union team has used a specially commissioned song, "Ireland's Call" as the team's anthem. The Irish national anthem is also played at Dublin home matches, being the anthem of the host country.[233]

Northern Irish murals have become well-known features of Northern Ireland, depicting past and present events and documenting peace and cultural diversity. Almost 2,000 murals have been documented in Northern Ireland since the 1970s.

.JPG/440px-BBC_Broadcasting_House,_Belfast,_October_2010_(01).JPG)

The BBC has a division called BBC Northern Ireland with headquarters in Belfast and operates BBC One Northern Ireland and BBC Two Northern Ireland. As well as broadcasting standard UK-wide programmes, BBC NI produces local content, including a news break-out called BBC Newsline. The ITV franchise in Northern Ireland is UTV. The state-owned Channel 4 and the privately owned Channel 5 also broadcast in Northern Ireland. Access is also available to satellite and cable services.[234] All Northern Ireland viewers must obtain a UK TV licence to watch live television transmissions or use BBC iPlayer.

RTÉ, the national broadcaster of the Republic of Ireland, is available over the air to most parts of Northern Ireland via reception overspill of the Republic's Saorview service,[235] or via satellite and cable. Since the digital TV switchover, RTÉ One, RTÉ2 and the Irish-language channel TG4, are now available over the air on the UK's Freeview system from transmitters within Northern Ireland.[236] Although they are transmitted in standard definition, a Freeview HD box or television is required for reception.

As well as the standard UK-wide radio stations from the BBC, Northern Ireland is home to many local radio stations, such as Cool FM, Q Radio, Downtown Radio and U105. The BBC has two regional radio stations which broadcast in Northern Ireland, BBC Radio Ulster and BBC Radio Foyle.

Besides the UK and Irish national newspapers, there are three main regional newspapers published in Northern Ireland. These are the Belfast Telegraph, The Irish News and The News Letter.[237] According to the Audit Bureau of Circulations (UK) the average daily circulation for these three titles in 2018 was: