Los iroqueses ( / ˈɪrəkwɔɪ , -kwɑː / IRR -ə-kwoy, -kwah ) , también conocidos como las Cinco Naciones , y más tarde como las Seis Naciones desde 1722 en adelante; alternativamente referidos por el endónimo Haudenosaunee [ a ] ( / ˌhoʊdɪnoʊˈʃoʊni / HOH - din -oh- SHOH - nee ; [ 8 ] lit. ' gente que está construyendo la casa comunal ' ) son una confederación de habla iroquesa de nativos americanos y pueblos de las Primeras Naciones en el noreste de América del Norte . Fueron conocidos por los franceses durante los años coloniales como la Liga Iroquesa , y más tarde como la Confederación Iroquesa , mientras que los ingleses simplemente los llamaron las "Cinco Naciones". Los pueblos iroqueses incluían (de este a oeste) a los mohawk , oneida , onondaga , cayuga y seneca . Después de 1722, el pueblo tuscarora de habla iroquesa del sureste fue aceptado en la confederación, a partir de ese momento se la conoció como las "Seis Naciones".

La Confederación probablemente surgió entre los años 1450 d. C. y 1660 d. C. como resultado de la Gran Ley de la Paz , que se dice que fue compuesta por Deganawidah el Gran Pacificador, Hiawatha y Jigonsaseh la Madre de las Naciones. Durante casi 200 años, la Confederación de las Seis Naciones/Haudenosaunee fue un factor poderoso en la política colonial de América del Norte, y algunos académicos defendieron el concepto de Punto Medio, [9] en el sentido de que los poderes europeos fueron utilizados por los iroqueses tanto como los europeos los utilizaron a ellos. [10] En su apogeo alrededor de 1700, el poder iroqués se extendió desde lo que hoy es el estado de Nueva York, al norte hasta el actual Ontario y Quebec a lo largo de los Grandes Lagos inferiores ( el alto San Lorenzo) , y al sur a ambos lados de las montañas Allegheny hasta las actuales Virginia y Kentucky y hasta el valle de Ohio .

Los iroqueses del San Lorenzo , los wendat (hurones), los erie y los susquehannock , todos pueblos independientes conocidos por los colonos europeos, también hablaban lenguas iroquesas . Se los considera iroqueses en un sentido cultural más amplio, ya que todos descienden del pueblo y la lengua protoiroqueses . Sin embargo, históricamente fueron competidores y enemigos de las naciones de la Confederación Iroquesa. [11]

En 2010, más de 45.000 personas inscritas en las Seis Naciones vivían en Canadá y más de 81.000 en los Estados Unidos . [12] [13]

Haudenosaunee ("Pueblo de la Casa Comunal") es el autónimo con el que las Seis Naciones se refieren a sí mismas. [14] Si bien su etimología exacta es debatida, el término iroqués es de origen colonial. Algunos estudiosos de la historia de los nativos americanos consideran que "iroqués" es un nombre despectivo adoptado de los enemigos tradicionales de los haudenosaunee. [15] Un autónimo menos común y más antiguo para la confederación es Ongweh'onweh , que significa "pueblo originario". [16] [17] [18]

Haudenosaunee deriva de dos palabras fonéticamente similares pero etimológicamente distintas en el idioma Séneca : Hodínöhšö:ni:h , que significa "los de la casa extendida", y Hodínöhsö:ni:h , que significa "constructores de casas". [19] [20] [21] El nombre "Haudenosaunee" aparece por primera vez en inglés en la obra de Lewis Henry Morgan (1851), donde lo escribe como Ho-dé-no-sau-nee . La ortografía "Hotinnonsionni" también está atestiguada a finales del siglo XIX. [19] [22] Ocasionalmente también se encuentra una designación alternativa, Ganonsyoni , [23] del mohawk kanǫhsyǫ́·ni "la casa extendida", o de una expresión cognada en una lengua iroquesa relacionada; En fuentes anteriores se escribe de diversas formas: "Kanosoni", "akwanoschioni", "Aquanuschioni", "Cannassoone", "Canossoone", "Ke-nunctioni" o "Konossioni". [19] De manera más transparente, a menudo se hace referencia a la confederación Haudenosaunee como las Seis Naciones (o, para el período anterior a la entrada de los Tuscarora en 1722, las Cinco Naciones). [19] [b] La palabra es Rotinonshón:ni en el idioma mohawk . [4]

Los orígenes del nombre Iroquois son algo oscuros, aunque el término ha sido históricamente más común entre los textos ingleses que Haudenosaunee. Su primera aparición escrita como "Irocois" está en el relato de Samuel de Champlain de su viaje a Tadoussac en 1603. [24] Otras grafías francesas tempranas incluyen "Erocoise", "Hiroquois", "Hyroquoise", "Irecoies", "Iriquois", "Iroquaes", "Irroquois" y "Yroquois", [19] pronunciado en ese momento como [irokwe] o [irokwɛ]. [c] Se han propuesto teorías en competencia para el origen de este término, pero ninguna ha ganado una aceptación generalizada. En 1978, Ives Goddard escribió: "No hay ninguna forma de este tipo atestiguada en ninguna lengua india como nombre para ningún grupo iroqués, y el origen y significado final del nombre son desconocidos". [19]

El sacerdote jesuita y misionero Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix escribió en 1744:

El nombre Iroquois es puramente francés, y se forma a partir del término [en lengua iroquesa] Hiro o Hero , que significa he dicho —con el que estos indios cierran todos sus discursos, como lo hacían antiguamente los latinos con su dixi— y de Koué , que es un grito a veces de tristeza, cuando se prolonga, y a veces de alegría, cuando se pronuncia más corto. [24]

En 1883, Horatio Hale escribió que la etimología de Charlevoix era dudosa y que "ninguna otra nación o tribu de la que tengamos conocimiento ha llevado jamás un nombre compuesto de esta manera caprichosa". [24] Hale sugirió en cambio que el término provenía del hurón y era cognado con el mohawk ierokwa "los que fuman", o cayuga iakwai "un oso". En 1888, JNB Hewitt expresó dudas de que cualquiera de esas palabras existiera en los respectivos idiomas. Prefirió la etimología de Montagnais irin "verdadero, real" y ako "serpiente", más el sufijo francés -ois . Más tarde revisó esto a Algonquin Iriⁿakhoiw como el origen. [24] [25]

En 1968, Gordon M. Day propuso una etimología más moderna, basándose en la de Charles Arnaud de 1880. Arnaud había afirmado que la palabra provenía del montañés irnokué , que significa «hombre terrible», a través de la forma reducida irokue . Day propuso una frase hipotética montañés irno kwédač , que significa «un hombre, un iroqués», como el origen de este término. Para el primer elemento irno , Day cita cognados de otros dialectos montañés atestiguados: irinou , iriniȣ e ilnu ; y para el segundo elemento kwédač , sugiere una relación con kouetakiou , kȣetat-chiȣin y goéṭètjg , nombres utilizados por las tribus algonquinas vecinas para referirse a los pueblos iroqués, hurones y lauretianos . [24]

La Enciclopedia Gale de América Multicultural atestigua el origen del iroqués como Iroqu , término algonquino que significa "serpiente de cascabel". [26] Los franceses fueron los primeros en encontrarse con las tribus de habla algonquina y habrían aprendido los nombres algonquinos de sus competidores iroqueses.

Se cree que la Confederación Iroquesa fue fundada por el Gran Pacificador en una fecha desconocida estimada entre 1450 y 1660, reuniendo a cinco naciones distintas en el área meridional de los Grandes Lagos en "La Gran Liga de la Paz". [27] Sin embargo, otras investigaciones sugieren que la fundación ocurrió en 1142. [28] Cada nación dentro de esta confederación iroquesa tenía un idioma, un territorio y una función distintos en la Liga.

La Liga está compuesta por un Gran Consejo, una asamblea de cincuenta jefes o sachems , cada uno de los cuales representa a un clan de una nación. [29]

Cuando los europeos llegaron por primera vez a América del Norte, los Haudenosaunee ( Liga Iroquesa para los franceses, Cinco Naciones para los británicos) tenían su base en lo que ahora es el centro y oeste del estado de Nueva York, incluida la región de Finger Lakes , ocupando grandes áreas al norte hasta el río San Lorenzo, al este hasta Montreal y el río Hudson , y al sur hasta lo que hoy es el noroeste de Pensilvania. En su apogeo alrededor de 1700, el poder iroqués se extendió desde lo que hoy es el estado de Nueva York, al norte hasta la actual Ontario y Quebec a lo largo de los Grandes Lagos inferiores - la parte superior del San Lorenzo , y al sur a ambos lados de las montañas Allegheny hasta la actual Virginia y Kentucky y hasta el valle del Ohio . De este a oeste, la Liga estaba compuesta por las naciones Mohawk , Oneida , Onondaga , Cayuga y Seneca . Alrededor de 1722, los Tuscarora de habla iroquesa se unieron a la Liga, habiendo emigrado hacia el norte desde las Carolinas después de un sangriento conflicto con los colonos blancos. Un trasfondo cultural compartido con las Cinco Naciones de los iroqueses (y un patrocinio de los oneida) llevó a los tuscarora a ser aceptados como la sexta nación de la confederación en 1722; los iroqueses pasaron a ser conocidos posteriormente como las Seis Naciones. [30] [31]

Otros pueblos independientes de habla iroquesa, como los erie , los susquehannock , los hurones (wendat) y los wyandot , vivieron en distintas épocas a lo largo del río San Lorenzo y alrededor de los Grandes Lagos . En el sudeste de Estados Unidos, los cherokee eran un pueblo de lengua iroquesa que había emigrado a esa zona siglos antes del contacto europeo. Ninguno de ellos formaba parte de la Liga Haudenosaunee. Los que vivían en las fronteras del territorio Haudenosaunee en la región de los Grandes Lagos competían y guerreaban con las naciones de la Liga.

Los colonos franceses, holandeses e ingleses, tanto en Nueva Francia (Canadá) como en lo que se convertiría en las Trece Colonias , reconocieron la necesidad de ganarse el favor del pueblo iroqués, que ocupaba una parte importante de las tierras al oeste de los asentamientos coloniales. Sus primeras relaciones fueron para el comercio de pieles , que se volvió muy lucrativo para ambas partes. Los colonos también buscaron establecer relaciones amistosas para asegurar las fronteras de sus asentamientos.

Durante casi 200 años, los iroqueses fueron un factor poderoso en la política colonial de América del Norte. La alianza con los iroqueses ofreció ventajas políticas y estratégicas a las potencias europeas, pero los iroqueses conservaron una independencia considerable. Algunos de sus habitantes se asentaron en aldeas misioneras a lo largo del río San Lorenzo , con lo que se vincularon más estrechamente a los franceses. Si bien participaron en las incursiones lideradas por los franceses en los asentamientos coloniales holandeses e ingleses, donde se asentaron algunos mohawks y otros iroqueses, en general los iroqueses se resistieron a atacar a sus propios pueblos.

Los iroqueses siguieron siendo un gran grupo político indígena americano unido hasta la Revolución estadounidense , cuando la Liga se dividió por sus opiniones conflictivas sobre cómo responder a las solicitudes de ayuda de la Corona británica. [32] Después de su derrota, los británicos cedieron territorio iroqués sin consultarles, y muchos iroqueses tuvieron que abandonar sus tierras en el valle Mohawk y en otros lugares y trasladarse a las tierras del norte que conservaban los británicos. La Corona les dio tierras en compensación por los cinco millones de acres que habían perdido en el sur, pero no era equivalente al territorio anterior.

Los estudiosos modernos de los iroqueses distinguen entre la Liga y la Confederación. [33] [34] [35] Según esta interpretación, la Liga Iroquesa se refiere a la institución ceremonial y cultural encarnada en el Gran Consejo, que todavía existe. La Confederación Iroquesa fue la entidad política y diplomática descentralizada que surgió en respuesta a la colonización europea, que se disolvió después de la derrota británica en la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos . [33] Los iroqueses/seis naciones de hoy no hacen tal distinción, usan los términos indistintamente, pero prefieren el nombre Confederación Haudenosaunee.

Tras la migración de la mayoría de los iroqueses a Canadá, los iroqueses que permanecieron en Nueva York se vieron obligados a vivir principalmente en reservas. En 1784, un total de 6.000 iroqueses se enfrentaban a 240.000 neoyorquinos, con habitantes de Nueva Inglaterra ávidos de tierras que estaban a punto de migrar al oeste. "Solo los oneidas, que eran sólo 600, poseían seis millones de acres, o alrededor de 2,4 millones de hectáreas. Los iroqueses eran una fiebre de tierras que estaba a punto de ocurrir". [36] Para la Guerra de 1812 , los iroqueses habían perdido el control de un territorio considerable.

El conocimiento de la historia iroquesa proviene de la tradición oral de los haudenosaunee , de la evidencia arqueológica , de los relatos de los misioneros jesuitas y de los historiadores europeos posteriores. El historiador Scott Stevens atribuye el valor que la Europa moderna temprana le dio a las fuentes escritas por sobre la tradición oral como una contribución a una perspectiva racializada y prejuiciosa sobre los iroqueses hasta el siglo XIX. [37] La historiografía de los pueblos iroqueses es un tema de mucho debate, especialmente en relación con el período colonial estadounidense. [38] [39]

Los relatos de los jesuitas franceses sobre los iroqueses los retrataban como salvajes que carecían de gobierno, leyes, letras y religión. [40] Pero los jesuitas hicieron un esfuerzo considerable por estudiar sus lenguas y culturas, y algunos llegaron a respetarlos. Una fuente de confusión para las fuentes europeas, que provenían de una sociedad patriarcal , era el sistema de parentesco matrilineal de la sociedad iroquesa y el poder asociado de las mujeres. [41] El historiador canadiense D. Peter MacLeod escribió sobre los iroqueses canadienses y los franceses en la época de la Guerra de los Siete Años:

Lo más grave es que los escritores patriarcales europeos pasaron por alto la importancia de las madres de clan , que tenían un poder económico y político considerable dentro de las comunidades iroquesas canadienses. Las referencias que existen muestran a las madres de clan reuniéndose en consejo con sus homólogos masculinos para tomar decisiones sobre la guerra y la paz y uniéndose a delegaciones para enfrentarse al Onontio [el término iroqués para el gobernador general francés] y a los líderes franceses en Montreal, pero solo insinúan la verdadera influencia que ejercían estas mujeres. [41]

La historiografía inglesa del siglo XVIII se centra en las relaciones diplomáticas con los iroqueses, complementadas con imágenes como Los cuatro reyes mohawk de John Verelst y publicaciones como las actas del tratado anglo-iroqués impresas por Benjamin Franklin . [42] Una narrativa persistente de los siglos XIX y XX presenta a los iroqueses como "una potencia militar y política expansiva... [que] subyugó a sus enemigos por la fuerza violenta y durante casi dos siglos actuó como punto de apoyo en el equilibrio de poder en la América del Norte colonial". [43]

El historiador Scott Stevens señaló que los propios iroqueses comenzaron a influir en la escritura de su historia en el siglo XIX, incluidos Joseph Brant (Mohawk) y David Cusick (Tuscarora, c. 1780-1840). John Arthur Gibson (Seneca, 1850-1912) fue una figura importante de su generación al relatar versiones de la historia iroquesa en epopeyas sobre el Pacificador . [44] En las décadas siguientes surgieron notables historiadoras entre los iroqueses, entre ellas Laura "Minnie" Kellogg (Oneida, 1880-1949) y Alice Lee Jemison (Seneca, 1901-1964). [45]

La Liga iroquesa se estableció antes del contacto europeo , con la unión de cinco de los muchos pueblos iroqueses que habían surgido al sur de los Grandes Lagos. [46] [d] Muchos arqueólogos y antropólogos creen que la Liga se formó alrededor de 1450, [47] [48] aunque se han presentado argumentos para una fecha anterior. [49] Una teoría sostiene que la Liga se formó poco después de un eclipse solar el 31 de agosto de 1142, un evento que se cree que se expresa en la tradición oral sobre los orígenes de la Liga. [50] [51] [52] Algunas fuentes vinculan un origen temprano de la confederación iroquesa a la adopción del maíz como cultivo básico. [53]

El arqueólogo Dean Snow sostiene que la evidencia arqueológica no respalda una fecha anterior a 1450. Ha dicho que las afirmaciones recientes de una fecha mucho más temprana "pueden tener fines políticos contemporáneos". [54] Otros académicos señalan que los investigadores antropológicos consultaron solo a informantes masculinos, perdiendo así la mitad de la historia histórica contada en las distintas tradiciones orales de las mujeres. [55] Por esta razón, los cuentos de origen tienden a enfatizar a los dos hombres Deganawidah y Hiawatha , mientras que la mujer Jigonsaseh , que juega un papel destacado en la tradición femenina, sigue siendo en gran parte desconocida. [55 ]

Los fundadores de la Liga son considerados tradicionalmente como Dekanawida el Gran Pacificador, Hiawatha y Jigonhsasee la Madre de las Naciones, cuyo hogar actuó como una especie de Naciones Unidas. Trajeron la Gran Ley de Paz del Pacificador a las naciones iroquesas en disputa que luchaban, atacaban y se peleaban entre sí y con otras tribus, tanto algonquinas como iroquesas . Cinco naciones se unieron originalmente a la Liga, dando lugar a las numerosas referencias históricas a las "Cinco Naciones de los Iroqueses". [e] [46] Con la incorporación de los Tuscarora del sur en el siglo XVIII, estas cinco tribus originales todavía componen los Haudenosaunee a principios del siglo XXI: los Mohawk , Onondaga , Oneida , Cayuga y Seneca .

Según la leyenda, un malvado jefe onondaga llamado Tadodaho fue el último en convertirse a los caminos de la paz gracias al Gran Pacificador y a Hiawatha. Se le ofreció el puesto de presidente titular del Consejo de la Liga, lo que representa la unidad de todas las naciones de la Liga. [56] Se dice que esto ocurrió en el lago Onondaga , cerca de la actual Syracuse, Nueva York . El título Tadodaho todavía se utiliza para el presidente de la Liga, el quincuagésimo jefe que se sienta con los onondaga en el consejo. [57]

Los iroqueses crearon posteriormente una sociedad sumamente igualitaria. Un administrador colonial británico declaró en 1749 que los iroqueses tenían "unas nociones de libertad tan absolutas que no permitían ningún tipo de superioridad de unos sobre otros y desterraban toda servidumbre de sus territorios". [58] A medida que las incursiones entre las tribus miembros terminaron y dirigieron la guerra contra los competidores, los iroqueses aumentaron en número mientras que sus rivales declinaron. La cohesión política de los iroqueses se convirtió rápidamente en una de las fuerzas más poderosas en el noreste de América del Norte de los siglos XVII y XVIII.

El Consejo de los Cincuenta de la Liga resolvía las disputas y buscaba el consenso. Sin embargo, la confederación no hablaba en nombre de las cinco tribus, que siguieron actuando de forma independiente y formando sus propias bandas de guerra. Alrededor de 1678, el consejo comenzó a ejercer más poder en las negociaciones con los gobiernos coloniales de Pensilvania y Nueva York, y los iroqueses se volvieron muy hábiles en la diplomacia, enfrentando a los franceses contra los británicos como tribus individuales habían enfrentado antes a los suecos, holandeses e ingleses. [46]

Los pueblos de lengua iroquesa participaban en guerras y comercio con miembros cercanos de la Liga Iroquesa. [46] El explorador Robert La Salle en el siglo XVII identificó a los Mosopelea como uno de los pueblos del valle de Ohio derrotados por los iroqueses a principios de la década de 1670. [59] Los pueblos de Erie y del valle superior de Allegheny declinaron antes durante las Guerras de los Castores . En 1676, el poder de los Susquehannock [f] se había roto por los efectos de tres años de enfermedades epidémicas , guerra con los iroqueses y batallas fronterizas, ya que los colonos se aprovecharon de la tribu debilitada. [46]

Según una teoría de la historia temprana de los iroqueses, después de unirse en la Liga, los iroqueses invadieron el valle del río Ohio en los territorios que se convertirían en el este del país de Ohio hasta el actual Kentucky en busca de terrenos de caza adicionales. Desplazaron a unos 1200 miembros de tribus de habla siouan del valle del río Ohio , como los quapaw (akansea), los ofo ( mosopelea ) y los tutelo y otras tribus estrechamente relacionadas fuera de la región. Estas tribus migraron a regiones alrededor del río Misisipi y las regiones del Piamonte de la costa este. [60]

Otros pueblos de lengua iroquesa, [61] incluidos los populosos wyandot (hurones) , con una organización social y culturas relacionadas, se extinguieron como tribus como resultado de las enfermedades y la guerra. [g] No se unieron a la Liga cuando se les invitó y se redujeron mucho después de las Guerras de los Castores y la alta mortalidad por enfermedades infecciosas euroasiáticas. Si bien las naciones indígenas a veces intentaron permanecer neutrales en las diversas guerras fronterizas coloniales, algunas también se aliaron con los europeos, como en la Guerra franco-india , el frente norteamericano de la Guerra de los Siete Años. Las Seis Naciones se dividieron en sus alianzas entre los franceses y los británicos en esa guerra.

En Reflections in Bullough's Pond , la historiadora Diana Muir sostiene que los iroqueses pre-contacto eran una cultura imperialista y expansionista cuyo cultivo del complejo agrícola maíz/frijoles/calabaza les permitió sustentar a una gran población. Hicieron la guerra principalmente contra los pueblos algonquinos vecinos . Muir utiliza datos arqueológicos para argumentar que la expansión iroquesa en tierras algonquinas fue frenada por la adopción algonquina de la agricultura. Esto les permitió sustentar a sus propias poblaciones lo suficientemente grandes como para resistir la conquista iroquesa. [62] El Pueblo de la Confederación disputa esta interpretación histórica, considerando a la Liga de la Gran Paz como la base de su herencia. [63]

Los iroqueses pueden ser los kwedech descritos en las leyendas orales de la nación mi'kmaq del este de Canadá. Estas leyendas cuentan que los mi'kmaq en el período tardío anterior al contacto habían expulsado gradualmente a sus enemigos, los kwedech , hacia el oeste a través de Nuevo Brunswick , y finalmente fuera de la región del bajo río San Lorenzo . Los mi'kmaq llamaron a la última tierra conquistada Gespedeg o "última tierra", de donde los franceses derivaron Gaspé . En general, se considera que los "kwedech" fueron iroqueses, específicamente los mohawk ; se estima que su expulsión de Gaspé por los mi'kmaq ocurrió alrededor de 1535-1600. [64] [ página requerida ]

Alrededor de 1535, Jacques Cartier informó sobre grupos de habla iroquesa en la península de Gaspé y a lo largo del río San Lorenzo. Los arqueólogos y antropólogos han definido a los iroqueses de San Lorenzo como un grupo distinto y separado (y posiblemente varios grupos discretos), que vivían en las aldeas de Hochelaga y otras cercanas (cerca de la actual Montreal), que habían sido visitadas por Cartier. En 1608, cuando Samuel de Champlain visitó el área, esa parte del valle del río San Lorenzo no tenía asentamientos, sino que estaba controlada por los mohawk como coto de caza. El destino del pueblo iroqués con el que se encontró Cartier sigue siendo un misterio, y todo lo que se puede decir con certeza es que cuando Champlain llegó, ya se habían ido. [65] En la península de Gaspé, Champlain se encontró con grupos de habla algonquina. La identidad precisa de cualquiera de estos grupos todavía se debate. El 29 de julio de 1609, Champlain ayudó a sus aliados a derrotar a un grupo de guerra mohawk en las orillas de lo que ahora se llama lago Champlain, y nuevamente en junio de 1610, Champlain luchó contra los mohawks. [66]

Los iroqueses se hicieron muy conocidos en las colonias del sur en el siglo XVII. Después del primer asentamiento inglés en Jamestown, Virginia (1607), numerosos relatos del siglo XVII describen a un pueblo poderoso conocido por la Confederación Powhatan como los massawomeck y por los franceses como los antouhonoron . Se decía que provenían del norte, más allá del territorio susquehannock . Los historiadores a menudo han identificado a los massawomeck/antouhonoron como los haudenosaunee.

En 1649, un grupo de guerra iroqués, formado principalmente por senecas y mohawks, destruyó la aldea huron de Wendake . A su vez, esto resultó en la desintegración de la nación hurona. Sin ningún enemigo del norte restante, los iroqueses dirigieron sus fuerzas contra las naciones neutrales en la costa norte de los lagos Erie y Ontario, los susquehannocks, su vecino del sur. Luego destruyeron otras tribus de lengua iroquesa, incluidos los erie , al oeste, en 1654, por la competencia por el comercio de pieles. [67] [ página requerida ] Luego destruyeron a los mohicanos . Después de sus victorias, reinaron supremos en un área desde el río Misisipi hasta el océano Atlántico; desde el río San Lorenzo hasta la bahía de Chesapeake .

Michael O. Varhola ha argumentado que su éxito en la conquista y sometimiento de las naciones vecinas había debilitado paradójicamente la respuesta nativa al crecimiento europeo, convirtiéndose así en víctimas de su propio éxito.

Las Cinco Naciones de la Liga establecieron una relación comercial con los holandeses en Fort Orange (actual Albany, Nueva York), intercambiando pieles por productos europeos, una relación económica que cambió profundamente su forma de vida y condujo a una caza excesiva de castores. [68]

Entre 1665 y 1670, los iroqueses establecieron siete aldeas en las costas septentrionales del lago Ontario , en la actual Ontario , conocidas colectivamente como las aldeas "Iroquois du Nord" . Todas las aldeas fueron abandonadas en 1701. [69]

Entre 1670 y 1710, las Cinco Naciones lograron el dominio político de gran parte de Virginia al oeste de la Fall Line y se extendieron hasta el valle del río Ohio en la actual Virginia Occidental y Kentucky. Como resultado de las Guerras de los Castores, expulsaron a las tribus de habla siouan y reservaron el territorio como coto de caza por derecho de conquista . Finalmente vendieron a los colonos británicos su reclamo restante sobre las tierras al sur de Ohio en 1768 en el Tratado de Fort Stanwix .

El historiador Pekka Hämäläinen escribe sobre la Liga: "Nunca había existido nada parecido a la Liga de las Cinco Naciones en América del Norte. Ninguna otra nación o confederación indígena había llegado tan lejos, llevado a cabo una política exterior tan ambiciosa o infundido tanto miedo y respeto. Las Cinco Naciones combinaron diplomacia, intimidación y violencia según lo dictaban las circunstancias, creando una inestabilidad mesurada que sólo ellas podían manejar. Su principio rector era evitar apegarse a una sola colonia, lo que restringiría sus opciones y los expondría a una manipulación externa". [70]

A partir de 1609, la Liga participó en las Guerras de los Castores, que duraron décadas, contra los franceses, sus aliados hurones y otras tribus vecinas, incluidos los petun , los erie y los susquehannock. [68] En un intento de controlar el acceso a la caza para el lucrativo comercio de pieles, invadieron a los pueblos algonquinos de la costa atlántica (los lenape o delaware ), los anishinaabe de la región boreal del Escudo Canadiense y, con no poca frecuencia, también las colonias inglesas. Durante las Guerras de los Castores, se dice que derrotaron y asimilaron a los hurones (1649), los petun (1650), la Nación Neutral (1651), [71] [72] la tribu Erie (1657) y los susquehannock (1680). [73] La visión tradicional es que estas guerras eran una forma de controlar el lucrativo comercio de pieles para comprar productos europeos de los que se habían vuelto dependientes. [74] [75] Starna cuestiona esta visión. [76]

Estudios recientes han profundizado en esta visión, argumentando que las Guerras de los Castores fueron una escalada de la tradición iroquesa de las "Guerras de Luto". [77] Esta visión sugiere que los iroqueses lanzaron ataques a gran escala contra tribus vecinas para vengar o reemplazar a los muchos muertos en batallas y epidemias de viruela .

En 1628, los mohawk derrotaron a los mahican para obtener un monopolio en el comercio de pieles con los holandeses en Fort Orange (actual Albany), Nueva Holanda . Los mohawk no permitieron que los pueblos nativos del norte comerciaran con los holandeses. [68] Para 1640, casi no quedaban castores en sus tierras, reduciendo a los iroqueses a intermediarios en el comercio de pieles entre los pueblos indígenas del oeste y el norte, y los europeos ávidos de las valiosas y gruesas pieles de castor. [68] En 1645, se forjó una paz tentativa entre los iroqueses y los hurones, algonquinos y franceses.

En 1646, los misioneros jesuitas de Sainte-Marie entre los hurones fueron como enviados a las tierras mohawk para proteger la precaria paz. Las actitudes mohawk hacia la paz se agriaron mientras los jesuitas viajaban, y sus guerreros atacaron al grupo en el camino. Los misioneros fueron llevados a la aldea de Ossernenon, Kanienkeh (nación mohawk) (cerca de la actual Auriesville , Nueva York), donde los clanes moderados Turtle y Wolf recomendaron liberarlos, pero miembros enojados del clan Bear mataron a Jean de Lalande e Isaac Jogues el 18 de octubre de 1646. [78] La Iglesia católica ha conmemorado a los dos sacerdotes franceses y al hermano laico jesuita René Goupil (asesinado el 29 de septiembre de 1642) [79] como entre los ocho mártires norteamericanos .

En 1649, durante las Guerras de los Castores, los iroqueses utilizaron armas holandesas recientemente adquiridas para atacar a los hurones, aliados de los franceses. Estos ataques, principalmente contra las ciudades hurones de Taenhatentaron (San Ignacio [80] ) y San Luis [81] en lo que ahora es el condado de Simcoe , Ontario , fueron las batallas finales que destruyeron efectivamente la Confederación Hurona . [82] Las misiones jesuitas en Huronia en las costas de la bahía Georgiana fueron abandonadas ante los ataques iroqueses, y los jesuitas lideraron a los hurones sobrevivientes hacia el este, hacia los asentamientos franceses en el río San Lorenzo. [78] Las Relaciones Jesuitas expresaron cierto asombro por el hecho de que las Cinco Naciones hubieran podido dominar el área "por quinientas leguas a la redonda, aunque sus números son muy pequeños". [78] Entre 1651 y 1652, los iroqueses atacaron a los susquehannock , al sur de la actual Pensilvania, sin éxito sostenido.

En 1653, la Nación Onondaga extendió una invitación de paz a Nueva Francia. Una expedición de jesuitas, liderada por Simon Le Moyne , estableció Sainte Marie de Ganentaa en su territorio en 1656. Se vieron obligados a abandonar la misión en 1658 cuando se reanudaron las hostilidades, posiblemente debido a la muerte repentina de 500 nativos a causa de una epidemia de viruela , una enfermedad infecciosa europea a la que no tenían inmunidad .

De 1658 a 1663, los iroqueses estuvieron en guerra con los susquehannock y sus aliados lenape y de la provincia de Maryland . En 1663, una gran fuerza de invasión iroquesa fue derrotada en el fuerte principal de los susquehannock. En 1663, los iroqueses estaban en guerra con la tribu sokoki del curso superior del río Connecticut . La viruela atacó de nuevo y, debido a los efectos de la enfermedad, el hambre y la guerra, los iroqueses estaban bajo amenaza de extinción. En 1664, un grupo oneida atacó a los aliados de los susquehannock en la bahía de Chesapeake .

En 1665, tres de las Cinco Naciones firmaron la paz con los franceses. Al año siguiente, el gobernador general de Nueva Francia, el marqués de Tracy , envió al regimiento Carignan a enfrentarse a los mohawk y oneida. [83] Los mohawk evitaron la batalla, pero los franceses quemaron sus aldeas, a las que se referían como "castillos", y sus cultivos. [83] En 1667, las dos naciones iroquesas restantes firmaron un tratado de paz con los franceses y acordaron permitir que los misioneros visitaran sus aldeas. Los misioneros jesuitas franceses eran conocidos como los "túnicas negras" por los iroqueses, quienes comenzaron a instar a los conversos católicos a trasladarse a Caughnawaga, Kanienkeh, en las afueras de Montreal. [83] Este tratado duró 17 años.

Alrededor de 1670, los iroqueses expulsaron a la tribu de habla sioux de los mannahoac de la región del Piamonte, en el norte de Virginia , y comenzaron a reclamar la propiedad del territorio. En 1672, fueron derrotados por un grupo de guerra de susquehannock, y los iroqueses pidieron apoyo al gobernador francés Frontenac:

Sería una vergüenza para él dejar que sus hijos fueran aplastados, como ellos mismos se veían... no teniendo ellos medios para ir a atacar su fuerte, que era muy fuerte, ni siquiera para defenderse si los otros venían a atacarlos en sus aldeas. [84]

Algunas historias antiguas afirman que los iroqueses derrotaron a los susquehannock, pero esto no está documentado y es dudoso. [85] En 1677, los iroqueses adoptaron a la mayoría de los susquehannock de habla iroquesa en su nación. [86]

En enero de 1676, el gobernador de la colonia de Nueva York, Edmund Andros , envió una carta a los jefes iroqueses pidiendo su ayuda en la Guerra del Rey Felipe , ya que los colonos ingleses en Nueva Inglaterra estaban teniendo muchas dificultades para luchar contra los wampanoag liderados por Metacom . A cambio de valiosas armas de los ingleses, un grupo de guerra iroqués devastó a los wampanoag en febrero de 1676, destruyendo aldeas y almacenes de alimentos mientras tomaba muchos prisioneros. [87]

En 1677, los iroqueses formaron una alianza con los ingleses a través de un acuerdo conocido como la Cadena del Pacto . En 1680, la Confederación iroquesa estaba en una posición fuerte, habiendo eliminado a los susquehannock y a los wampanoag, tomado un gran número de cautivos para aumentar su población y asegurado una alianza con los ingleses que les suministraban armas y municiones. [88] Juntos, los aliados lucharon hasta detener a los franceses y a sus aliados, los hurones , enemigos tradicionales de la Confederación. Los iroqueses colonizaron la costa norte del lago Ontario y enviaron grupos de asalto hacia el oeste hasta el Territorio de Illinois . Las tribus de Illinois finalmente fueron derrotadas, no por los iroqueses, sino por los potawatomi .

En 1679, los susquehannock, con ayuda de los iroqueses, atacaron a los aliados de Maryland, Piscataway y Mattawoman . [89] La paz no se alcanzó hasta 1685. Durante el mismo período, los misioneros jesuitas franceses estuvieron activos en Iroquoia, lo que llevó a una reubicación masiva voluntaria de muchos haudenosaunee al valle del San Lorenzo en Kahnawake y Kanesatake , cerca de Montreal. La intención de los franceses era utilizar a los haudenosaunee católicos en el valle del San Lorenzo como un amortiguador para mantener a las tribus haudenosaunee aliadas de los ingleses, en lo que ahora es el norte del estado de Nueva York , lejos del centro del comercio de pieles francés en Montreal. Los intentos tanto de los ingleses como de los franceses de hacer uso de sus aliados haudenosaunee fueron frustrados, ya que los dos grupos de haudenosaunee mostraron una "profunda renuencia a matarse entre sí". [90] Tras el traslado de los iroqueses católicos al valle del San Lorenzo, los historiadores suelen describir a los iroqueses que vivían fuera de Montreal como los iroqueses canadienses, mientras que a los que permanecieron en su núcleo histórico en el norte del estado de Nueva York moderno se los describe como los iroqueses de la Liga. [91]

En 1684, el gobernador general de Nueva Francia , Joseph-Antoine Le Febvre de La Barre, decidió lanzar una expedición punitiva contra los senecas, que atacaban a los comerciantes de pieles franceses y algonquinos en el valle del río Misisipi, y pidió a los católicos haudenosaunee que contribuyeran con hombres de combate. [92] La expedición de La Barre terminó en un fiasco en septiembre de 1684 cuando estalló la gripe entre las tropas francesas de la Marine , mientras que los guerreros iroqueses canadienses se negaron a luchar, y en su lugar solo se involucraron en batallas de insultos con los guerreros senecas. [93] El rey Luis XIV de Francia no se divirtió cuando se enteró del fracaso de La Barre, lo que llevó a su reemplazo por Jacques-René de Brisay, marqués de Denonville (gobernador general 1685-1689), quien llegó en agosto con órdenes del Rey Sol de aplastar a la confederación haudenosaunee y defender el honor de Francia incluso en las selvas de América del Norte. [93] Ese mismo año, los iroqueses invadieron nuevamente el territorio de Virginia e Illinois y atacaron sin éxito los puestos de avanzada franceses en este último. En un intento por reducir la guerra en el valle de Shenandoah en Virginia, más tarde ese año la colonia de Virginia acordó en una conferencia en Albany reconocer el derecho de los iroqueses a utilizar el camino norte-sur, conocido como el Gran Sendero de la Guerra , que discurría al este de Blue Ridge , siempre que no invadieran los asentamientos ingleses al este de Fall Line .

En 1687, el marqués de Denonville partió hacia Fort Frontenac (actual Kingston, Ontario ) con una fuerza bien organizada. En julio de 1687, Denonville llevó consigo en su expedición una fuerza mixta de tropas de la Marina , milicianos francocanadienses y 353 guerreros indios de los asentamientos de la misión jesuita, incluidos 220 haudenosaunee. [93] Se encontraron bajo una bandera de tregua con 50 sachems hereditarios del incendio del consejo de Onondaga , en la costa norte del lago Ontario en lo que ahora es el sur de Ontario. [93] Denonville recuperó el fuerte para Nueva Francia y capturó, encadenó y envió a los 50 jefes iroqueses a Marsella, Francia , para ser utilizados como esclavos de galeras . [93] Varios de los haudenosaunee católicos se indignaron por esta traición a un partido diplomático, lo que llevó a que al menos 100 de ellos desertaran a los seneca. [94] Denonville justificó la esclavitud de la gente que encontró, diciendo que como "europeo civilizado" no respetaba las costumbres de los "salvajes" y que haría lo que quisiera con ellos. El 13 de agosto de 1687, un grupo de avanzada de soldados franceses cayó en una emboscada de los senecas y casi murieron todos; sin embargo, los senecas huyeron cuando llegó la fuerza principal francesa. Los guerreros haudenosaunee católicos restantes se negaron a perseguir a los senecas en retirada. [93]

Denonville devastó la tierra de los senecas , desembarcando una armada francesa en la bahía de Irondequoit , atacando directamente la sede del poder seneca y destruyendo muchas de sus aldeas. Huyendo antes del ataque, los senecas se trasladaron más al oeste, este y sur por el río Susquehanna . Aunque se causó un gran daño a su tierra natal, el poder militar de los senecas no se debilitó apreciablemente. La Confederación y los senecas desarrollaron una alianza con los ingleses que se estaban asentando en el este. La destrucción de la tierra de los senecas enfureció a los miembros de la Confederación iroquesa. El 4 de agosto de 1689, tomaron represalias quemando Lachine , una pequeña ciudad adyacente a Montreal . Mil quinientos guerreros iroqueses habían estado hostigando las defensas de Montreal durante muchos meses antes de eso.

Finalmente, agotaron y derrotaron a Denonville y sus fuerzas. Su mandato fue seguido por el regreso de Frontenac durante los siguientes nueve años (1689-1698). Frontenac había organizado una nueva estrategia para debilitar a los iroqueses. Como acto de conciliación, localizó a los 13 sachems supervivientes de los 50 capturados originalmente y regresó con ellos a Nueva Francia en octubre de 1689. En 1690, Frontenac destruyó Schenectady, Kanienkeh y en 1693 quemó otras tres aldeas mohawk y tomó 300 prisioneros. [95]

En 1696, Frontenac decidió entrar en el campo de batalla contra los iroqueses, a pesar de tener setenta y seis años de edad. Decidió atacar a los oneida y onondaga, en lugar de a los mohawk que habían sido los enemigos favoritos de los franceses. [95] El 6 de julio, dejó Lachine a la cabeza de una fuerza considerable y viajó a la capital de Onondaga , donde llegó un mes después. Con el apoyo de los franceses, las naciones algonquinas expulsaron a los iroqueses de los territorios al norte del lago Erie y al oeste de la actual Cleveland, Ohio , regiones que habían conquistado durante las Guerras de los Castores. [86] Mientras tanto, los iroqueses habían abandonado sus aldeas. Como la persecución era impracticable, el ejército francés comenzó su marcha de regreso el 10 de agosto. Bajo el liderazgo de Frontenac, la milicia canadiense se volvió cada vez más experta en la guerra de guerrillas , llevando la guerra al territorio iroqués y atacando varios asentamientos ingleses. Los iroqueses nunca volvieron a amenazar a la colonia francesa. [96]

Durante la Guerra del Rey Guillermo (parte norteamericana de la Guerra de la Gran Alianza ), los iroqueses se aliaron con los ingleses. En julio de 1701, firmaron el " Tratado de Nanfan ", que otorgaba a los ingleses una gran extensión al norte del río Ohio. Los iroqueses afirmaban haber conquistado este territorio 80 años antes. Francia no reconoció el tratado, ya que tenía asentamientos en el territorio en ese momento y los ingleses prácticamente no tenían ninguno. Mientras tanto, los iroqueses estaban negociando la paz con los franceses; juntos firmaron la Gran Paz de Montreal ese mismo año.

Después del tratado de paz de 1701 con los franceses, los iroqueses permanecieron mayoritariamente neutrales. Durante el transcurso del siglo XVII, los iroqueses habían adquirido una reputación temible entre los europeos, y la política de las Seis Naciones era utilizar esta reputación para enfrentar a los franceses contra los británicos con el fin de extraer la máxima cantidad de recompensas materiales. [97] En 1689, la Corona inglesa proporcionó a las Seis Naciones bienes por valor de 100 libras a cambio de ayuda contra los franceses, en el año 1693 los iroqueses habían recibido bienes por valor de 600 libras, y en el año 1701 las Seis Naciones habían recibido bienes por valor de 800 libras. [98]

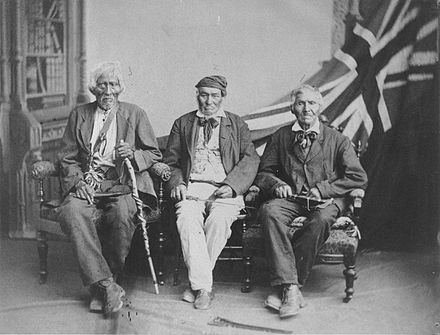

Durante la Guerra de la Reina Ana (parte norteamericana de la Guerra de Sucesión Española ), estuvieron involucrados en ataques planeados contra los franceses. Pieter Schuyler , alcalde de Albany, organizó que tres jefes mohawk y un jefe mahican (conocidos incorrectamente como los Cuatro Reyes Mohawk ) viajaran a Londres en 1710 para reunirse con la Reina Ana en un esfuerzo por sellar una alianza con los británicos. La Reina Ana quedó tan impresionada por sus visitantes que encargó sus retratos al pintor de la corte John Verelst . Se cree que los retratos son los primeros retratos al óleo sobrevivientes de pueblos aborígenes tomados de la vida. [99]

A principios del siglo XVIII, los tuscarora migraron gradualmente hacia el norte, en dirección a Pensilvania y Nueva York, después de un conflicto sangriento con los colonos blancos de Carolina del Norte y Carolina del Sur . Debido a las similitudes lingüísticas y culturales compartidas, los tuscarora se alinearon gradualmente con los iroqueses y entraron en la confederación como la sexta nación indígena en 1722, después de ser patrocinados por los oneida. [31]

El programa iroqués hacia las tribus derrotadas favorecía la asimilación dentro de la "Cadena del Pacto" y la Gran Ley de la Paz, en lugar de la matanza en masa. Tanto los Lenni Lenape como los Shawnee fueron tributarios durante un breve período de las Seis Naciones, mientras que las poblaciones iroquesas sometidas surgieron en el siguiente período como los Mingo , que hablaban un dialecto similar al de los Séneca, en la región de Ohio. Durante la Guerra de Sucesión Española, conocida por los estadounidenses como la "Guerra de la Reina Ana", los iroqueses se mantuvieron neutrales, aunque se inclinaron hacia los británicos. [95] Los misioneros anglicanos estuvieron activos con los iroqueses e idearon un sistema de escritura para ellos. [95]

En 1721 y 1722, el teniente gobernador de Virginia, Alexander Spotswood , concluyó un nuevo tratado en Albany con los iroqueses, renovando la cadena de pactos y acordando reconocer la cordillera Blue Ridge como la demarcación entre la colonia de Virginia y los iroqueses. Pero, cuando los colonos europeos comenzaron a trasladarse más allá de la cordillera Blue Ridge y al valle de Shenandoah en la década de 1730, los iroqueses se opusieron. Los funcionarios de Virginia les dijeron que la demarcación tenía como fin evitar que los iroqueses invadieran el este de la cordillera Blue Ridge, pero no evitaría que los ingleses se expandieran hacia el oeste. Las tensiones aumentaron durante las décadas siguientes y los iroqueses estuvieron a punto de entrar en guerra con la colonia de Virginia. En 1743, el gobernador Sir William Gooch les pagó la suma de 100 libras esterlinas por cualquier tierra colonizada en el valle que fuera reclamada por los iroqueses. Al año siguiente, en el Tratado de Lancaster , los iroqueses vendieron a Virginia todos sus reclamos restantes en el valle de Shenandoah por 200 libras en oro. [100]

Durante la Guerra franco-india (el teatro norteamericano de la Guerra de los Siete Años ), la Liga Iroquesa se puso del lado de los británicos contra los franceses y sus aliados algonquinos, que eran enemigos tradicionales. Los iroqueses esperaban que ayudar a los británicos también les reportaría favores después de la guerra. Pocos guerreros iroqueses se unieron a la campaña. Por el contrario, los iroqueses canadienses apoyaron a los franceses.

En 1711, los refugiados de lo que ahora es el suroeste de Alemania, conocidos como los Palatinos, pidieron permiso a las madres del clan iroqués para establecerse en sus tierras. [101] Para la primavera de 1713, alrededor de 150 familias palatinas habían arrendado tierras a los iroqueses. [102] Los iroqueses enseñaron a los palatinos cómo cultivar "las Tres Hermanas", como llamaban a sus cultivos básicos de frijoles, maíz y calabaza, y dónde encontrar nueces, raíces y bayas comestibles. [102] A cambio, los palatinos enseñaron a los iroqueses cómo cultivar trigo y avena, y cómo usar arados de hierro y azadas para cultivar. [102] Como resultado del dinero ganado con las tierras alquiladas a los palatinos, la élite iroquesa dejó de vivir en casas comunales y comenzó a vivir en casas de estilo europeo, teniendo un ingreso igual al de una familia inglesa de clase media. [102] A mediados del siglo XVIII, había surgido un mundo multicultural con los iroqueses viviendo junto a colonos alemanes y escoceses-irlandeses. [103] Los asentamientos de los Palatinos se mezclaron con las aldeas iroquesas. [104] En 1738, un irlandés, Sir William Johnson , que tuvo éxito como comerciante de pieles, se estableció con los iroqueses. [105] Johnson, que se hizo muy rico con el comercio de pieles y la especulación de tierras, aprendió las lenguas de los iroqueses y se convirtió en el principal intermediario entre los británicos y la Liga. [105] En 1745, Johnson fue nombrado superintendente del Norte de Asuntos Indígenas, formalizando su puesto. [106]

.jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

El 9 de julio de 1755, una fuerza de soldados regulares del ejército británico y la milicia de Virginia bajo el mando del general Edward Braddock que avanzaba hacia el valle del río Ohio fue destruida casi por completo por los franceses y sus aliados indios en la batalla de Monongahela . [106] Johnson, que tenía la tarea de alistar a la Liga Iroquesa en el lado británico, dirigió una fuerza mixta anglo-iroquesa a la victoria en Lac du St Sacrement, conocido por los británicos como Lake George. [106] En la batalla de Lake George , un grupo de mohawks católicos (de Kahnawake ) y fuerzas francesas emboscaron a una columna británica liderada por mohawks; los mohawks estaban profundamente perturbados ya que habían creado su confederación para la paz entre los pueblos y no habían tenido guerra entre ellos. Johnson intentó emboscar a una fuerza de 1.000 tropas francesas y 700 iroqueses canadienses bajo el mando del barón Dieskau, quien rechazó el ataque y mató al viejo jefe de guerra mohawk, Peter Hendricks. [106] El 8 de septiembre de 1755, Diskau atacó el campamento de Johnson, pero fue rechazado con grandes pérdidas. [106] Aunque la batalla del lago George fue una victoria británica, las grandes pérdidas sufridas por los mohawks y los oneida en la batalla hicieron que la Liga declarara neutralidad en la guerra. [106] A pesar de los mejores esfuerzos de Johnson, los iroqueses de la Liga permanecieron neutrales durante los siguientes años, y una serie de victorias francesas en Oswego, Louisbourg, Fort William Henry y Fort Carillon aseguraron que los iroqueses de la Liga no lucharan en lo que parecía ser el bando perdedor. [107]

En febrero de 1756, los franceses se enteraron por un espía, Oratory, un jefe oneida, que los británicos estaban almacenando suministros en el Oneida Carrying Place , un porteo crucial entre Albany y Oswego para apoyar una ofensiva en la primavera en lo que ahora es Ontario. Como las aguas congeladas se derretían al sur del lago Ontario en promedio dos semanas antes que las aguas al norte del lago Ontario, los británicos podrían moverse contra las bases francesas en Fort Frontenac y Fort Niagara antes de que las fuerzas francesas en Montreal pudieran llegar en su ayuda, lo que desde la perspectiva francesa requería un ataque preventivo en Oneida Carrying Place en el invierno. [108] Para llevar a cabo este ataque, el marqués de Vaudreuil , gobernador general de Nueva Francia, asignó la tarea a Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry, un oficial de las troupes de le Marine , que requirió y recibió la ayuda de los iroqueses canadienses para guiarlo al Oneida Carrying Place. [109] Los iroqueses canadienses se unieron a la expedición, que partió de Montreal el 29 de febrero de 1756, con el entendimiento de que sólo lucharían contra los británicos, no contra los iroqueses de la Liga, y que no asaltarían un fuerte. [110]

El 13 de marzo de 1756, un viajero indio de Oswegatchie informó a la expedición que los británicos habían construido dos fuertes en Oneida Carrying Place, lo que provocó que la mayoría de los iroqueses canadienses quisieran regresar, ya que argumentaron que los riesgos de asaltar un fuerte significarían demasiadas bajas, y muchos de hecho abandonaron la expedición. [111] El 26 de marzo de 1756, la fuerza de Léry de tropas de la Marina y milicianos francocanadienses, que no habían comido durante dos días, recibió comida muy necesaria cuando los iroqueses canadienses tendieron una emboscada a una caravana británica que llevaba suministros a Fort William y Fort Bull. [112] En lo que respecta a los iroqueses canadienses, la incursión fue un éxito, ya que capturaron 9 carros llenos de suministros y tomaron 10 prisioneros sin perder un hombre, y para ellos, emprender un ataque frontal contra los dos fuertes de madera como Léry quería hacer era irracional. [113] Los iroqueses canadienses informaron a Léry "si yo quería morir, yo era el amo de los franceses, pero no iban a seguirme". [114] Al final, unos 30 iroqueses canadienses se unieron de mala gana al ataque de Léry a Fort Bull en la mañana del 27 de marzo de 1756, cuando los franceses y sus aliados indios asaltaron el fuerte, abriéndose paso finalmente por la puerta principal con un ariete al mediodía. [115] De las 63 personas en Fort Bull, la mitad de las cuales eran civiles, solo 3 soldados, un carpintero y una mujer sobrevivieron a la batalla de Fort Bull como informó Léry "No pude contener el ardor de los soldados y los canadienses . Mataron a todos los que encontraron". [116] Después, los franceses destruyeron todos los suministros británicos y el propio Fort Bull, que aseguró el flanco occidental de Nueva Francia. Ese mismo día, la fuerza principal de los iroqueses canadienses tendió una emboscada a una fuerza de socorro de Fort William que venía en ayuda de Fort Bull, y no masacraron a sus prisioneros como lo hicieron los franceses en Fort Bull; para los iroqueses, los prisioneros eran muy valiosos ya que aumentaban el tamaño de la tribu. [117]

La diferencia crucial entre la forma de hacer la guerra en Europa y en las Primeras Naciones era que Europa tenía millones de habitantes, lo que significaba que los generales británicos y franceses estaban dispuestos a ver morir a miles de sus hombres en batalla con tal de asegurar la victoria, ya que sus pérdidas siempre podían compensarse; en cambio, los iroqueses tenían una población considerablemente menor y no podían permitirse grandes pérdidas que pudieran paralizar a una comunidad. La costumbre iroquesa de las "guerras de duelo" para tomar prisioneros que luego se convertirían en iroqueses reflejaba la necesidad continua de más gente en las comunidades iroquesas. Los guerreros iroqueses eran valientes, pero solo luchaban hasta la muerte si era necesario, normalmente para proteger a sus mujeres y niños; de lo contrario, la preocupación crucial de los jefes iroqueses era siempre ahorrar mano de obra. [118] El historiador canadiense D. Peter MacLeod escribió que el modo de guerra de los iroqueses se basaba en su filosofía de caza, donde un cazador exitoso derribaría un animal de manera eficiente sin ocasionar pérdidas a su grupo de caza y, de la misma manera, un líder de guerra exitoso infligiría pérdidas al enemigo sin sufrir pérdidas a cambio. [119]

Los iroqueses no volvieron a entrar en la guerra del lado británico hasta finales de 1758, después de que los británicos tomaran Louisbourg y Fort Frontenac. [107] En el Tratado de Fort Easton de octubre de 1758, los iroqueses obligaron a los lenape y shawnee, que habían estado luchando por los franceses, a declarar la neutralidad. [107] En julio de 1759, los iroqueses ayudaron a Johnson a tomar Fort Niagara. [107] En la campaña que siguió, la Liga Iroquesa ayudó al general Jeffrey Amherst a tomar varios fuertes franceses en los Grandes Lagos y el valle del San Lorenzo mientras avanzaba hacia Montreal, que tomó en septiembre de 1760. [107] El historiador británico Michael Johnson escribió que los iroqueses habían "desempeñado un papel de apoyo importante" en la victoria británica final en la Guerra de los Siete Años. [107] En 1763, Johnson dejó su antiguo hogar de Fort Johnson para mudarse a la lujosa propiedad, a la que llamó Johnson Hall, que se convirtió en un centro de la vida social de la región. [107] Johnson era cercano a dos familias blancas, los Butler y los Croghans, y tres familias Mohawk, los Brant, los Hills y los Peters. [107]

Después de la guerra, para proteger su alianza, el gobierno británico emitió la Proclamación Real de 1763 , prohibiendo el asentamiento de blancos más allá de los Montes Apalaches . Los colonos estadounidenses ignoraron en gran medida la orden y los británicos no contaban con suficientes soldados para hacerla cumplir. [120]

Ante los enfrentamientos, los iroqueses acordaron ajustar de nuevo la línea en el Tratado de Fort Stanwix (1768) . Sir William Johnson, primer baronet , superintendente británico de Asuntos Indígenas para el Distrito Norte, había convocado a las naciones iroquesas a una gran conferencia en el oeste de Nueva York, a la que asistieron un total de 3.102 indios. [36] Hacía tiempo que mantenían buenas relaciones con Johnson, que había comerciado con ellos y aprendido sus lenguas y costumbres. Como señaló Alan Taylor en su historia, The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (2006), los iroqueses eran pensadores creativos y estratégicos. Eligieron vender a la Corona británica todo su reclamo restante sobre las tierras entre los ríos Ohio y Tennessee, que no ocupaban, con la esperanza de al hacerlo aliviar la presión inglesa sobre sus territorios en la provincia de Nueva York. [36]

_by_Charles_Bird_King.jpg/440px-Joseph_Brant_(Mohawk)_by_Charles_Bird_King.jpg)

Durante la Guerra de Independencia de los Estados Unidos , los iroqueses intentaron primero mantenerse neutrales. El reverendo Samuel Kirkland, un ministro congregacionalista que trabajaba como misionero, presionó a los oneida y los tuscarora para que fueran neutrales a favor de los Estados Unidos, mientras que Guy Johnson y su primo John Johnson presionaron a los mohawk, los cayuga y los seneca para que lucharan por los británicos. [121] Presionados para unirse a un bando u otro, los tuscarora y los oneida se pusieron del lado de los colonos, mientras que los mohawk, los seneca, los onondaga y los cayuga se mantuvieron leales a Gran Bretaña, con quien tenían relaciones más sólidas. Joseph Louis Cook ofreció sus servicios a los Estados Unidos y recibió una comisión del Congreso como teniente coronel, el rango más alto alcanzado por cualquier nativo americano durante la guerra. [122] El jefe de guerra mohawk Joseph Brant junto con John Butler y John Johnson levantaron fuerzas irregulares racialmente mixtas para luchar por la Corona. [123] Molly Brant había sido la esposa de hecho de Sir William Johnson, y fue gracias a su patrocinio que su hermano Joseph llegó a ser jefe de guerra. [124]

El jefe de guerra mohawk Joseph Brant , otros jefes de guerra y aliados británicos llevaron a cabo numerosas operaciones contra los asentamientos fronterizos en el valle Mohawk, incluida la masacre del valle Cherry , destruyendo muchas aldeas y cultivos, y matando y capturando a los habitantes. Las incursiones destructivas de Brant y otros leales llevaron a apelaciones al Congreso en busca de ayuda. [124] Los continentales tomaron represalias y en 1779, George Washington ordenó la Campaña Sullivan , dirigida por el coronel Daniel Brodhead y el general John Sullivan , contra las naciones iroquesas para "no solo invadir, sino destruir", la alianza británico-india. Quemaron muchas aldeas y tiendas iroquesas en todo el oeste de Nueva York; los refugiados se mudaron al norte, a Canadá. Al final de la guerra, pocas casas y graneros en el valle habían sobrevivido a la guerra. Después de la expedición de Sullivan, Brant visitó la ciudad de Quebec para pedirle al general Sir Frederick Haildmand garantías de que los mohawk y los demás iroqueses leales recibirían una nueva patria en Canadá como compensación por su lealtad a la Corona si los británicos perdían. [124]

La Revolución estadounidense provocó una gran división entre los colonos, entre los patriotas y los leales, y una gran proporción (30-35%) de ellos eran neutrales; provocó una división entre las colonias y Gran Bretaña, y también provocó una ruptura que rompería la Confederación iroquesa. Al comienzo de la Revolución, las Seis Naciones de la Confederación iroquesa intentaron adoptar una postura de neutralidad. Sin embargo, casi inevitablemente, las naciones iroquesas finalmente tuvieron que tomar partido en el conflicto. Es fácil ver cómo la Revolución estadounidense habría causado conflicto y confusión entre las Seis Naciones. Durante años se habían acostumbrado a pensar en los ingleses y sus colonos como un solo y mismo pueblo. En la Revolución estadounidense, la Confederación iroquesa ahora tenía que lidiar con las relaciones entre dos gobiernos. [125]

La población de la Confederación Iroquesa había cambiado significativamente desde la llegada de los europeos. Las enfermedades habían reducido su población a una fracción de lo que había sido en el pasado. [126] Por lo tanto, les convenía estar del lado bueno de quien demostrara ser el bando ganador en la guerra, ya que el bando ganador dictaría cómo serían las relaciones futuras con los iroqueses en América del Norte. Tratar con dos gobiernos dificultaba mantener una postura neutral, porque los gobiernos podían ponerse celosos fácilmente si la Confederación interactuaba o comerciaba más con un lado que con el otro, o incluso si simplemente había una percepción de favoritismo. Debido a esta situación desafiante, las Seis Naciones tuvieron que elegir bando. Los oneida y tuscarora decidieron apoyar a los colonos estadounidenses, mientras que el resto de la Liga Iroquesa (los cayuga, mohawk, onondaga y seneca) se puso del lado de los británicos y sus leales entre los colonos.

Hubo muchas razones por las que las Seis Naciones no pudieron permanecer neutrales y no involucrarse en la Guerra Revolucionaria. Una de ellas fue la simple proximidad: la Confederación Iroquesa estaba demasiado cerca de la acción de la guerra como para no involucrarse. Las Seis Naciones estaban muy descontentas con la invasión de los ingleses y sus colonos en su territorio. Estaban particularmente preocupadas por la frontera establecida en la Proclamación de 1763 y el Tratado de Fort Stanwix en 1768. [127]

Durante la Revolución estadounidense, la autoridad del gobierno británico sobre la frontera fue muy disputada. Los colonos intentaron sacar provecho de ello tanto como pudieron buscando su propio beneficio y reclamando nuevas tierras. En 1775, las Seis Naciones todavía eran neutrales cuando "un soldado continental mató a un mohawk". [128] Un caso como éste muestra cómo la proximidad de las Seis Naciones a la guerra las atrajo a ella. Les preocupaba que las mataran y que les quitaran sus tierras. No podían mostrar debilidad y simplemente dejar que los colonos y los británicos hicieran lo que quisieran. Muchos de los ingleses y los colonos no respetaban los tratados hechos en el pasado. "Varios súbditos de Su Majestad en las colonias americanas vieron la proclamación como una prohibición temporal que pronto daría paso a la apertura de la zona para el asentamiento... y que era simplemente un acuerdo para calmar las mentes de los indios". [127] Las Seis Naciones tuvieron que tomar una postura para demostrar que no aceptarían ese trato, y buscaron construir una relación con un gobierno que respetara su territorio.

Además de estar muy cerca de la guerra, el nuevo estilo de vida y la economía de la Confederación Iroquesa desde la llegada de los europeos a América del Norte hicieron que fuera casi imposible para los iroqueses aislarse del conflicto. Para ese momento, los iroqueses se habían vuelto dependientes del comercio de bienes de los ingleses y los colonos y habían adoptado muchas costumbres, herramientas y armas europeas. Por ejemplo, dependían cada vez más de las armas de fuego para cazar. [125] Después de volverse tan dependientes, habría sido difícil siquiera considerar cortar el comercio que traía bienes que eran una parte central de la vida cotidiana.

Como afirmó Barbara Graymont, "su tarea era imposible: mantener la neutralidad. Sus economías y vidas se habían vuelto tan dependientes unas de otras para el intercambio de bienes y beneficios que era imposible ignorar el conflicto. Mientras tanto, tenían que tratar de equilibrar sus interacciones con ambos grupos. No querían que pareciera que favorecían a un grupo sobre el otro, porque eso provocaría celos y sospechas de ambas partes". Además, los ingleses habían hecho muchos acuerdos con las Seis Naciones a lo largo de los años, pero la mayor parte de la interacción diaria de los iroqueses había sido con los colonos. Esto hizo que la situación fuera confusa para los iroqueses porque no podían decir quiénes eran los verdaderos herederos del acuerdo y no podían saber si los acuerdos con Inglaterra seguirían siendo respetados por los colonos si lograban la independencia.

Apoyar a cualquiera de los dos bandos en la Guerra de la Independencia fue una decisión complicada. Cada nación sopesó individualmente sus opciones para llegar a una postura final que, en última instancia, rompiera la neutralidad y pusiera fin al acuerdo colectivo de la Confederación. Los británicos eran claramente los más organizados y, aparentemente, los más poderosos. En muchos casos, los británicos presentaron la situación a los iroqueses como si los colonos fueran simplemente "niños traviesos". Por otro lado, los iroqueses consideraban que "el gobierno británico estaba a tres mil millas de distancia. Esto los colocaba en desventaja a la hora de intentar hacer cumplir tanto la Proclamación de 1763 como el Tratado de Fort Stanwix de 1768 contra los colonos ávidos de tierras". [129] En otras palabras, aunque los británicos eran la facción más fuerte y mejor organizada, las Seis Naciones tenían dudas sobre si realmente serían capaces de hacer cumplir sus acuerdos desde tan lejos.

Los iroqueses también estaban preocupados por los colonos. Los británicos pidieron el apoyo iroqués en la guerra. "En 1775, el Congreso Continental envió una delegación a los iroqueses en Albany para pedir su neutralidad en la guerra que se avecinaba contra los británicos". [128] Había quedado claro en años anteriores que los colonos no habían respetado los acuerdos territoriales realizados en 1763 y 1768. La Confederación iroquesa estaba particularmente preocupada por la posibilidad de que los colonos ganaran la guerra, ya que si se producía una victoria revolucionaria, los iroqueses la veían como el precursor de que los colonos victoriosos les arrebataran sus tierras, ya que ya no tendrían a la Corona británica para contenerlos. [22] Oficiales del ejército continental como George Washington habían intentado destruir a los iroqueses. [126]

En cambio, los colonos eran los que habían establecido las relaciones más directas con los iroqueses debido a su proximidad y a sus vínculos comerciales. En su mayor parte, los colonos y los iroqueses habían vivido en relativa paz desde la llegada de los ingleses al continente un siglo y medio antes. Los iroqueses tenían que determinar si sus relaciones con los colonos eran fiables o si los ingleses resultarían más útiles a sus intereses. También tenían que determinar si realmente existían diferencias entre el trato que los ingleses y los colonos les daban.

La guerra estalló y los iroqueses rompieron su confederación. Cientos de años de precedentes y de gobierno colectivo fueron superados por la inmensidad de la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos. Los oneida y los tuscarora decidieron apoyar a los colonos, mientras que el resto de la Liga Iroquesa (cayuga, mohawk, onondaga y seneca) se alinearon con los británicos y los leales. Al concluir la guerra, el temor de que los colonos no respetaran las súplicas de los iroqueses se hizo realidad, especialmente después de que la mayoría de las Seis Naciones decidieran alinearse con los británicos y los estadounidenses recién independizados ya no los consideraran dignos de confianza. En 1783 se firmó el Tratado de París. Si bien el tratado incluía acuerdos de paz entre todas las naciones europeas involucradas en la guerra, así como con los recién nacidos Estados Unidos, no incluía disposiciones para los iroqueses, que quedaron a merced del nuevo gobierno estadounidense y fueron tratados como creyera conveniente. [125]

Después de la Guerra Revolucionaria, la antigua chimenea central de la Liga fue restablecida en Buffalo Creek . Los EE. UU. y los iroqueses firmaron el Tratado de Fort Stanwix en 1784, bajo el cual los iroqueses cedieron gran parte de su patria histórica a los estadounidenses, al que siguió otro tratado en 1794 en Canandaigua por el cual cedieron aún más tierra a los estadounidenses. [130] El gobernador del estado de Nueva York, George Clinton , presionaba constantemente a los iroqueses para que vendieran sus tierras a los colonos blancos, y como el alcoholismo se convirtió en un problema importante en las comunidades iroquesas, muchos vendieron sus tierras para comprar más alcohol, generalmente a agentes sin escrúpulos de compañías de tierras. [131] Al mismo tiempo, los colonos estadounidenses continuaron avanzando hacia las tierras más allá del río Ohio, lo que llevó a una guerra entre la Confederación Occidental y los EE. UU. [130] Uno de los jefes iroqueses, Cornplanter, persuadió a los iroqueses restantes en el estado de Nueva York para que permanecieran neutrales y no se unieran a la Confederación Occidental. [130] Al mismo tiempo, las políticas estadounidenses para hacer que los iroqueses se establecieran más comenzaron a tener algún efecto. Tradicionalmente, para los iroqueses la agricultura era trabajo de mujeres y la caza era trabajo de hombres; a principios del siglo XIX, las políticas estadounidenses para que los hombres cultivaran la tierra y dejaran de cazar estaban teniendo efecto. [132] Durante este tiempo, los iroqueses que vivían en el estado de Nueva York se desmoralizaron a medida que se vendían más tierras a especuladores de tierras, mientras que el alcoholismo, la violencia y las familias rotas se convirtieron en problemas importantes en sus reservas. [132] Los oneida y los cayuga vendieron casi todas sus tierras y se mudaron de sus tierras de origen tradicionales. [132]

En 1811, los misioneros metodistas y episcopalianos establecieron misiones para ayudar a los oneida y onondaga en el oeste de Nueva York. Sin embargo, los colonos blancos continuaron mudándose a la zona. En 1821, un grupo de oneida liderado por Eleazer Williams , hijo de una mujer mohawk, fue a Wisconsin para comprar tierras a los menominee y ho-chunk y así trasladar a su gente más al oeste. [133] En 1838, la Holland Land Company utilizó documentos falsificados para engañar a los senecas y quitarles casi todas sus tierras en el oeste de Nueva York, pero un misionero cuáquero, Asher Wright, inició demandas que llevaron a que una de las reservas senecas fuera devuelta en 1842 y otra en 1857. [132] Sin embargo, incluso en la década de 1950, tanto los gobiernos de Estados Unidos como de Nueva York confiscaron tierras pertenecientes a las Seis Naciones para caminos, represas y embalses, y las tierras que se le entregaron a Cornplanter para evitar que los iroqueses se unieran a la Confederación Occidental en la década de 1790 fueron compradas a la fuerza por dominio eminente e inundadas para la represa Kinzua. [132]

El capitán Joseph Brant y un grupo de iroqueses abandonaron Nueva York para establecerse en la provincia de Quebec (actual Ontario ). Para reemplazar parcialmente las tierras que habían perdido en el valle Mohawk y en otros lugares debido a su fatídica alianza con la Corona británica, la Proclamación Haldimand les otorgó una gran concesión de tierras en el río Grand , en Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation . El cruce del río por parte de Brant dio el nombre original a la zona: Brant's Ford. En 1847, los colonos europeos comenzaron a establecerse cerca y llamaron al pueblo Brantford . El asentamiento mohawk original estaba en el borde sur de la actual ciudad canadiense en una ubicación todavía favorable para el lanzamiento y desembarque de canoas. En la década de 1830, muchos onondaga, oneida, seneca, cayuga y tuscarora adicionales se trasladaron al territorio indio , la provincia del Alto Canadá y Wisconsin .

Muchos iroqueses (en su mayoría mohawks) y métis descendientes de iroqueses que vivían en el Bajo Canadá (principalmente en Kahnawake ) aceptaron empleo en la North West Company, con sede en Montreal , durante su existencia de 1779 a 1821 y se convirtieron en viajeros o comerciantes libres que trabajaban en el comercio de pieles de América del Norte hasta el oeste de las Montañas Rocosas. Se sabe que se establecieron en el área alrededor de Jasper's House [134] y posiblemente tan al oeste como el río Finlay [135] y al norte hasta las áreas de Pouce Coupe y Dunvegan , [136] donde fundaron nuevas comunidades aborígenes que han persistido hasta el día de hoy reivindicando la identidad de las Primeras Naciones o de los métis y los derechos indígenas. La Michel Band , los métis de montaña [137] y la Aseniwuche Winewak Nation of Canada [138] en Alberta y la comunidad de Kelly Lake en Columbia Británica reivindican ascendencia iroquesa.

Durante el siglo XVIII, los iroqueses canadienses católicos que vivían fuera de Montreal restablecieron lazos con la Liga Iroquesa. [139] Durante la Revolución Americana, los iroqueses canadienses declararon su neutralidad y se negaron a luchar por la Corona a pesar de las ofertas de Sir Guy Carleton , el gobernador de Quebec. [139] Muchos iroqueses canadienses trabajaron tanto para la Compañía de la Bahía de Hudson como para la Compañía del Noroeste como viajeros en el comercio de pieles a finales del siglo XVIII y principios del XIX. [139] En la Guerra de 1812, los iroqueses canadienses volvieron a declarar su neutralidad. [139] Las comunidades iroquesas canadienses de Oka y Kahnaweke eran asentamientos prósperos en el siglo XIX, que se mantenían a través de la agricultura y la venta de trineos, raquetas de nieve, barcos y cestas. [139] En 1884, el gobierno británico contrató a unos 100 iroqueses canadienses para que sirvieran como pilotos fluviales y barqueros para la expedición de socorro del general Charles Gordon, sitiado en Jartum, en Sudán, y llevaron la fuerza comandada por el mariscal de campo Wolsely por el Nilo desde El Cairo hasta Jartum. [139] En su camino de regreso a Canadá, los pilotos fluviales y barqueros iroqueses canadienses se detuvieron en Londres, donde la reina Victoria les agradeció personalmente sus servicios a la reina y al país. [139] En 1886, cuando se estaba construyendo un puente en el río San Lorenzo, se contrató a varios hombres iroqueses de Kahnawke para ayudar a construirlo y los trabajadores iroqueses demostraron ser tan hábiles como montadores de estructuras de acero que, desde entonces, los siderúrgicos iroqueses han construido varios puentes y rascacielos en Canadá y los EE. UU. [139]

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, la política canadiense fue alentar a los hombres de las Primeras Naciones a alistarse en la Fuerza Expedicionaria Canadiense (CEF), donde sus habilidades en la caza los hicieron excelentes como francotiradores y exploradores. [140] Como las Seis Naciones iroquesas eran consideradas las más belicosas de las Primeras Naciones de Canadá y, a su vez, los mohawks eran los más belicosos de las Seis Naciones, el gobierno canadiense alentó especialmente a los iroqueses, particularmente a los mohawks, a unirse. [141] Aproximadamente la mitad de los 4000 hombres de las Primeras Naciones que sirvieron en la CEF eran iroqueses. [142] Se animó a los hombres de la reserva de las Seis Naciones en Brantford a unirse al 114.º Batallón Haldimand (también conocido como "Rangers de Brock") de la CEF, donde dos compañías enteras, incluidos los oficiales, eran todos iroqueses. El 114.º Batallón se formó en diciembre de 1915 y se disolvió en noviembre de 1916 para proporcionar refuerzos a otros batallones. [140] Un mohawk de Brantford, William Forster Lickers, que se alistó en la CEF en septiembre de 1914, fue capturado en la Segunda Batalla de Ypres en abril de 1915, donde fue salvajemente golpeado por sus captores cuando un oficial alemán quería ver si "los indios podían sentir dolor". [143] Lickers fue golpeado tan brutalmente que quedó paralizado por el resto de su vida, aunque el oficial se alegró mucho de comprobar que los indios sí sentían dolor. [143]

El consejo de las Seis Naciones en Brantford tendía a verse a sí mismo como una nación soberana que estaba aliada a la Corona a través de la Cadena del Pacto que se remonta al siglo XVII y, por lo tanto, aliada personalmente al rey Jorge V en lugar de estar bajo la autoridad de Canadá. [144] Una madre de un clan iroqués, en una carta enviada en agosto de 1916 a un sargento de reclutamiento que se negó a permitir que su hijo adolescente se uniera a la CEF con el argumento de que era menor de edad, declaró que las Seis Naciones no estaban sujetas a las leyes de Canadá y que no tenía derecho a rechazar a su hijo porque las leyes canadienses no se aplicaban a ellas. [144] Como explicó, los iroqueses consideraban que la Cadena del Pacto todavía estaba en vigor, lo que significa que los iroqueses solo estaban luchando en la guerra en respuesta a un pedido de ayuda de su aliado, el rey Jorge V, que les había pedido que se alistaran en la CEF. [144]

El complejo entorno político que surgió en Canadá con los Haudenosaunee surgió de la era angloamericana de la colonización europea. Al final de la Guerra de 1812 , Gran Bretaña trasladó los asuntos indígenas del control militar al control civil. Con la creación de la Confederación Canadiense en 1867, la autoridad civil, y por lo tanto los asuntos indígenas, pasaron a manos de funcionarios canadienses, mientras que Gran Bretaña mantuvo el control de los asuntos militares y de seguridad. A principios de siglo, el gobierno canadiense comenzó a aprobar una serie de leyes que fueron enérgicamente objetadas por la Confederación iroquesa. Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, una ley intentó reclutar a los hombres de las Seis Naciones para el servicio militar. Bajo la Ley de Reubicación de Soldados , se introdujo una legislación para redistribuir las tierras nativas. Finalmente, en 1920, se propuso una ley para obligar a la ciudadanía a los "indios" con o sin su consentimiento, lo que eliminaría automáticamente su parte de cualquier tierra tribal del fideicomiso tribal y haría que la tierra y la persona estuvieran sujetas a las leyes de Canadá. [145]

Los haudenosaunee contrataron a un abogado para defender sus derechos en la Corte Suprema de Canadá. La Corte Suprema se negó a aceptar el caso, declarando que los miembros de las Seis Naciones eran ciudadanos británicos. En efecto, como Canadá era en ese momento una división del gobierno británico, no era un estado internacional, según lo define el derecho internacional. En contraste, la Confederación iroquesa había estado haciendo tratados y funcionando como un estado desde 1643 y todos sus tratados habían sido negociados con Gran Bretaña, no con Canadá. [145] Como resultado, en 1921 se tomó la decisión de enviar una delegación para presentar una petición al rey Jorge V , [146] tras lo cual la división de Asuntos Exteriores de Canadá bloqueó la emisión de pasaportes. En respuesta, los iroqueses comenzaron a emitir sus propios pasaportes y enviaron al general Levi , [145] al jefe cayuga "Deskaheh", [146] a Inglaterra con su abogado. Winston Churchill desestimó su queja alegando que estaba dentro del ámbito de la jurisdicción canadiense y los remitió de nuevo a los funcionarios canadienses.

El 4 de diciembre de 1922, Charles Stewart , superintendente de Asuntos Indígenas, y Duncan Campbell Scott , superintendente adjunto del Departamento Canadiense de Asuntos Indígenas, viajaron a Brantford para negociar un acuerdo sobre los problemas con las Seis Naciones. Después de la reunión, la delegación nativa llevó la oferta al consejo tribal, como era habitual bajo la ley Haudenosaunee. El consejo acordó aceptar la oferta, pero antes de que pudieran responder, la Real Policía Montada de Canadá realizó una redada de licor en el territorio iroqués del Grand River. El asedio duró tres días [145] e impulsó a los Haudenosaunee a enviar a Deskaheh a Washington, D.C., para reunirse con el encargado de negocios de los Países Bajos pidiendo a la Reina holandesa que los patrocinara para ser miembros de la Liga de las Naciones . [146] Bajo la presión de los británicos, los Países Bajos rechazaron a regañadientes el patrocinio. [147]