El río Misisipi [b] es el río principal y el segundo río más largo de la cuenca de drenaje más grande de los Estados Unidos . [c] [15] [16] Desde su fuente tradicional del lago Itasca en el norte de Minnesota , fluye generalmente hacia el sur por 2,340 millas (3,766 km) [16] hasta el delta del río Misisipi en el golfo de México . Con sus numerosos afluentes , la cuenca del Misisipi drena la totalidad o parte de 32 estados de EE. UU. y dos provincias canadienses entre las montañas Rocosas y los Apalaches . [17] El cauce principal está completamente dentro de los Estados Unidos; la cuenca de drenaje total es de 1,151,000 millas cuadradas (2,980,000 km 2 ), de los cuales solo alrededor del uno por ciento está en Canadá. El Misisipi se ubica como el decimotercer río más grande por descarga en el mundo. El río bordea o pasa por los estados de Minnesota , Wisconsin , Iowa , Illinois , Misuri , Kentucky , Tennessee , Arkansas , Misisipi y Luisiana . [18] [19]

Los nativos americanos han vivido a lo largo del río Misisipi y sus afluentes durante miles de años. La mayoría eran cazadores-recolectores , pero algunos, como los constructores de montículos , formaron prolíficas civilizaciones agrícolas y urbanas. La llegada de los europeos en el siglo XVI cambió el estilo de vida nativo, ya que primero los exploradores, luego los colonos, se aventuraron en la cuenca en cantidades cada vez mayores. [20] El río sirvió a veces como barrera, formando fronteras para Nueva España , Nueva Francia y los primeros Estados Unidos, y en todo momento como una arteria de transporte vital y un enlace de comunicaciones. En el siglo XIX, durante el apogeo de la ideología del destino manifiesto , el Misisipi y varios afluentes, sobre todo el más grande, el Ohio y el Misuri , formaron vías para la expansión occidental de los Estados Unidos. El río se convirtió en el tema de la literatura estadounidense , particularmente en los escritos de Mark Twain .

Formada a partir de gruesas capas de depósitos de limo del río , la ensenada del Misisipi es una de las regiones más fértiles de los Estados Unidos; los barcos de vapor se utilizaron ampliamente en los siglos XIX y principios del XX para enviar productos agrícolas e industriales. Durante la Guerra Civil estadounidense , la captura del Misisipi por las fuerzas de la Unión marcó un punto de inflexión hacia la victoria , debido a la importancia estratégica del río para el esfuerzo bélico confederado . Debido al crecimiento sustancial de las ciudades y los barcos y barcazas más grandes que reemplazaron a los barcos de vapor, las primeras décadas del siglo XX vieron la construcción de enormes obras de ingeniería como diques , esclusas y presas , a menudo construidas en combinación. Un enfoque principal de este trabajo ha sido evitar que el bajo Misisipi se desvíe hacia el canal del río Atchafalaya y pase por alto Nueva Orleans .

Desde el siglo XX, el río Misisipi también ha experimentado importantes problemas ambientales y de contaminación, en particular los elevados niveles de nutrientes y productos químicos provenientes de la escorrentía agrícola, principal causa de la zona muerta del Golfo de México .

La palabra Mississippi proviene de Misi zipi , la traducción francesa del nombre Anishinaabe ( Ojibwe o Algonquin ) para el río, Misi-ziibi (Gran Río). [21]

En el siglo XVIII, el río fue establecido por el Tratado de París como, en su mayor parte, la frontera occidental de los nuevos Estados Unidos. Con la Compra de Luisiana y la expansión del país hacia el oeste, se convirtió en una línea fronteriza conveniente entre las mitades occidental y oriental del país. [22] [23] Esto se refleja en el Gateway Arch en St. Louis, que fue diseñado para simbolizar la apertura del Oeste, [24] y el enfoque en la región " Trans-Mississippi " en la Exposición Trans-Mississippi . [25]

Los puntos de referencia regionales a menudo se clasifican en relación con el río, como "el pico más alto al este del Mississippi " [26] o "la ciudad más antigua al oeste del Mississippi". [27] La FCC también lo utiliza como línea divisoria para los indicativos de radiodifusión , que comienzan con W al este y K al oeste, superponiéndose en los mercados de medios a lo largo del río.

Debido a su tamaño e importancia, se le ha apodado El Poderoso Río Misisipi o simplemente El Poderoso Mississippi . [28]

El río Misisipi se puede dividir en tres secciones: el Alto Misisipi , el río desde su nacimiento hasta la confluencia con el río Misuri; el Medio Misisipi, que está río abajo desde el Misuri hasta el río Ohio; y el Bajo Misisipi , que fluye desde el Ohio hasta el Golfo de México.

El Alto Misisipi se extiende desde su nacimiento hasta su confluencia con el río Misuri en St. Louis, Misuri. Se divide en dos secciones:

La fuente del brazo superior del Misisipi se acepta tradicionalmente como el lago Itasca , a 1.475 pies (450 m) sobre el nivel del mar en el Parque Estatal Itasca en el condado de Clearwater, Minnesota . El nombre Itasca fue elegido para designar la "verdadera cabecera" del río Misisipi como una combinación de las últimas cuatro letras de la palabra latina para verdad ( ver itas ) y las primeras dos letras de la palabra latina para cabeza ( ca put ). [29] Sin embargo, el lago a su vez es alimentado por una serie de arroyos más pequeños.

Desde su origen en el lago Itasca hasta San Luis, Misuri , el caudal de la vía fluvial está moderado por 43 presas. Catorce de estas presas están situadas por encima de Minneapolis, en la región de las cabeceras , y sirven para múltiples propósitos, entre ellos la generación de energía y la recreación. Las 29 presas restantes, que comienzan en el centro de Minneapolis, contienen esclusas y se construyeron para mejorar la navegación comercial del curso superior del río. En conjunto, estas 43 presas dan forma de manera significativa a la geografía e influyen en la ecología del curso superior del río. Comenzando justo debajo de Saint Paul, Minnesota , y continuando a lo largo del curso superior e inferior del río, el Mississippi está controlado además por miles de diques laterales que moderan el caudal del río para mantener un canal de navegación abierto y evitar que el río erosione sus orillas.

La cabecera de la navegación en el Mississippi es la esclusa de St. Anthony Falls. [30] Antes de que se construyera la presa de Coon Rapids en Coon Rapids, Minnesota , en 1913, los barcos de vapor podían ocasionalmente ir río arriba hasta Saint Cloud, Minnesota , dependiendo de las condiciones del río.

La esclusa y presa más alta del Alto Misisipi es la esclusa y presa de las cataratas de San Antonio en Minneapolis. Por encima de la presa, la elevación del río es de 244 m (799 pies). Por debajo de la presa, la elevación del río es de 230 m (750 pies). Esta caída de 15 m (49 pies) es la más grande de todas las esclusas y presas del río Misisipi. El origen de la espectacular caída es una cascada preservada junto a la esclusa bajo una plataforma de hormigón. Las cataratas de San Antonio son la única cascada real de todo el río Misisipi. La elevación del agua continúa cayendo abruptamente a medida que pasa por el desfiladero tallado por la cascada.

Después de la finalización de la esclusa y presa de St. Anthony Falls en 1963, la cabecera de navegación del río se trasladó río arriba, a la presa de Coon Rapids . Sin embargo, las esclusas se cerraron en 2015 para controlar la propagación de la carpa asiática invasora , lo que convirtió a Minneapolis una vez más en el sitio de la cabecera de navegación del río. [30]

El Alto Misisipi tiene varios lagos naturales y artificiales, siendo su punto más ancho el lago Winnibigoshish , cerca de Grand Rapids, Minnesota , con más de 11 millas (18 km) de ancho. El lago Onalaska , creado por la esclusa y presa n.° 7 , cerca de La Crosse, Wisconsin , tiene más de 4 millas (6,4 km) de ancho. El lago Pepin , un lago natural formado detrás del delta del río Chippewa de Wisconsin cuando ingresa al Alto Misisipi, tiene más de 2 millas (3,2 km) de ancho. [31]

Cuando el Alto Misisipi llega a Saint Paul , Minnesota, por debajo de la esclusa y presa n.° 1, ha descendido más de la mitad de su elevación original y se encuentra a 209 m (687 pies) sobre el nivel del mar. Desde St. Paul hasta St. Louis, Missouri, la elevación del río desciende mucho más lentamente y se controla y gestiona como una serie de pozas creadas por 26 esclusas y presas. [32]

El Alto Misisipi se une al río Minnesota en Fort Snelling en las Twin Cities ; el río St. Croix cerca de Prescott, Wisconsin ; el río Cannon cerca de Red Wing, Minnesota ; el río Zumbro en Wabasha, Minnesota ; los ríos Black , La Crosse y Root en La Crosse, Wisconsin ; el río Wisconsin en Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin ; el río Rock en las Quad Cities ; el río Iowa cerca de Wapello, Iowa ; el río Skunk al sur de Burlington, Iowa ; y el río Des Moines en Keokuk, Iowa . Otros afluentes importantes del Alto Misisipi incluyen el río Crow en Minnesota, el río Chippewa en Wisconsin, el río Maquoketa y el río Wapsipinicon en Iowa, y el río Illinois en Illinois.

El Alto Misisipi es en gran parte un río de múltiples hilos con muchas barras e islas. Desde su confluencia con el río St. Croix río abajo hasta Dubuque, Iowa , el río está atrincherado, con altos acantilados de lecho rocoso a ambos lados. La altura de estos acantilados disminuye al sur de Dubuque, aunque todavía son significativos a través de Savanna, Illinois . Esta topografía contrasta fuertemente con el Bajo Misisipi, que es un río serpenteante en una zona amplia y plana, que solo rara vez fluye junto a un acantilado (como en Vicksburg, Mississippi ).

El río Misisipi se conoce como el Misisipi Medio desde la confluencia del Alto Misisipi con el río Misuri en San Luis, Misuri , durante 190 millas (310 km) hasta su confluencia con el río Ohio en El Cairo, Illinois . [33] [34]

El curso medio del río Misisipi es relativamente fluido. Desde San Luis hasta la confluencia con el río Ohio, el curso medio del río Misisipi cae 67 metros (220 pies) a lo largo de 290 kilómetros (180 millas) a una velocidad media de 23 centímetros por kilómetro (1,2 pies por milla). En su confluencia con el río Ohio, el curso medio del río Misisipi se encuentra a 96 metros (315 pies) sobre el nivel del mar. Aparte de los ríos Misuri y Meramec de Misuri y el río Kaskaskia de Illinois, no hay ningún afluente importante que desemboque en el curso medio del río Misisipi.

El río Misisipi se denomina río Misisipi inferior desde su confluencia con el río Ohio hasta su desembocadura en el golfo de México, una distancia de aproximadamente 1.600 km (1.000 millas). En la confluencia del Ohio y el Misisipi medio, el caudal medio a largo plazo del Ohio en Cairo, Illinois, es de 281.500 pies cúbicos por segundo (7.970 metros cúbicos por segundo), [35] mientras que el caudal medio a largo plazo del Misisipi en Thebes, Illinois (justo río arriba de Cairo) es de 208.200 pies cúbicos/s (5.900 m3 / s). [36] Por lo tanto, por volumen, el ramal principal del sistema del río Misisipi en Cairo puede considerarse el río Ohio (y el río Allegheny más arriba), en lugar del Misisipi medio.

Además del río Ohio , los principales afluentes del bajo río Misisipi son el río Blanco , que fluye en el Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre del Río Blanco en el centro-este de Arkansas; el río Arkansas , que se une al Misisipi en Arkansas Post ; el río Big Black en Misisipi; y el río Yazoo , que se encuentra con el Misisipi en Vicksburg, Misisipi .

La desviación deliberada del agua en la antigua estructura de control del río en Luisiana permite que el río Atchafalaya en Luisiana sea un distribuidor principal del río Misisipi, con el 30% del flujo combinado de los ríos Misisipi y Rojo fluyendo hacia el Golfo de México por esta ruta, en lugar de continuar por el canal actual del Misisipi pasando Baton Rouge y Nueva Orleans en una ruta más larga hacia el Golfo. [37] [38] [39] [40] Aunque el río Rojo alguna vez fue un afluente adicional, sus aguas ahora fluyen por separado hacia el Golfo de México a través del río Atchafalaya. [41]

El río Misisipi tiene la cuarta cuenca hidrográfica más grande del mundo ("cuenca hidrográfica" o "captación"). La cuenca cubre más de 1.245.000 millas cuadradas (3.220.000 km 2 ), incluyendo la totalidad o partes de 32 estados de EE. UU. y dos provincias canadienses. La cuenca de drenaje desemboca en el golfo de México , parte del océano Atlántico. La cuenca total del río Misisipi cubre casi el 40% de la masa continental de los Estados Unidos. El punto más alto dentro de la cuenca hidrográfica es también el punto más alto de las Montañas Rocosas , el monte Elbert a 14.440 pies (4.400 m). [42]

En Estados Unidos, el río Misisipi drena la mayor parte del área entre la cresta de las Montañas Rocosas y la cresta de los Apalaches , a excepción de varias regiones drenadas a la Bahía de Hudson por el Río Rojo del Norte ; al Océano Atlántico por los Grandes Lagos y el río San Lorenzo ; y al Golfo de México por el Río Grande , los ríos Alabama y Tombigbee , los ríos Chattahoochee y Appalachicola , y varias vías fluviales costeras más pequeñas a lo largo del Golfo.

El río Misisipi desemboca en el golfo de México a unos 160 km río abajo de Nueva Orleans. Las mediciones de la longitud del Misisipi desde el lago Itasca hasta el golfo de México varían un poco, pero la cifra del Servicio Geológico de los Estados Unidos es de 3766 km. El tiempo de retención desde el lago Itasca hasta el golfo suele ser de unos 90 días; [43] aunque la velocidad varía a lo largo del curso del río, esto da un promedio general de alrededor de 42 km por día, o 1,6 km por hora.

La pendiente del curso del río en su conjunto es del 0,01%, lo que supone un desnivel de 450 m en 3.766 km. [ cita requerida ]

El río Misisipi descarga a una tasa media anual de entre 200 y 700 mil pies cúbicos por segundo (6.000 y 20.000 m 3 /s). [44] El Misisipi es el decimocuarto río más grande del mundo por volumen. En promedio, el Misisipi tiene un 8% del caudal del río Amazonas , [45] que mueve casi 7 millones de pies cúbicos por segundo (200.000 m 3 /s) durante las estaciones húmedas.

Antes de 1900, el río Misisipi transportaba aproximadamente 440 millones de toneladas cortas (400 millones de toneladas métricas) de sedimentos por año desde el interior de los Estados Unidos hasta la costa de Luisiana y el Golfo de México. Durante las últimas dos décadas, esta cifra fue de solo 160 millones de toneladas cortas (145 millones de toneladas métricas) por año. La reducción de los sedimentos transportados por el río Misisipi es el resultado de la modificación de ingeniería de los ríos Misisipi, Misuri y Ohio y sus afluentes mediante presas, cortes de meandros , estructuras de encauzamiento del río y revestimientos de riberas y programas de control de la erosión del suelo en las áreas drenadas por ellos. [46]

El agua salada más densa del Golfo de México forma una cuña de sal a lo largo del fondo del río cerca de la desembocadura del río, mientras que el agua dulce fluye cerca de la superficie. En años de sequía, con menos agua dulce para expulsarla, el agua salada puede viajar muchos kilómetros río arriba (64 millas (103 km) en 2022), contaminando los suministros de agua potable y requiriendo el uso de desalinización . El Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército de los Estados Unidos construyó "umbrales de agua salada" o "diques submarinos" para contener esto en 1988, 1999, 2012 y 2022. Esto consiste en un gran montículo de arena que se extiende a lo ancho del río 55 pies por debajo de la superficie, lo que permite que pasen agua dulce y grandes barcos de carga. [47]

El agua dulce del río que fluye desde el Misisipi hacia el Golfo de México no se mezcla inmediatamente con el agua salada. Las imágenes del MODIS de la NASA muestran una gran columna de agua dulce, que aparece como una cinta oscura contra las aguas circundantes de color azul más claro. Estas imágenes demuestran que la columna no se mezcló con el agua del mar circundante de inmediato. En cambio, permaneció intacta mientras fluía a través del Golfo de México, hacia el Estrecho de Florida y entró en la Corriente del Golfo . El agua del río Misisipi rodeó la punta de Florida y viajó hacia la costa sureste hasta la latitud de Georgia antes de finalmente mezclarse tan completamente con el océano que ya no pudo ser detectada por MODIS.

A lo largo del tiempo geológico, el río Misisipi ha experimentado numerosos cambios grandes y pequeños en su curso principal, así como adiciones, eliminaciones y otros cambios entre sus numerosos afluentes, y el bajo río Misisipi ha utilizado diferentes vías como su canal principal hacia el Golfo de México a través de la región del delta.

Cuando Pangea comenzó a fragmentarse hace unos 95 millones de años, América del Norte pasó sobre un " punto caliente " volcánico en el manto de la Tierra (específicamente, el punto caliente de Bermudas ) que estaba atravesando un período de intensa actividad. El afloramiento de magma del punto caliente forzó una mayor elevación a una altura de quizás 2-3 km de parte de la cordillera Apalache-Ouachita , formando un arco que bloqueó los flujos de agua hacia el sur. La tierra elevada se erosionó rápidamente y, a medida que América del Norte se alejó del punto caliente y la actividad del punto caliente disminuyó, la corteza debajo de la región de la bahía se enfrió, se contrajo y se hundió a una profundidad de 2,6 km, y hace unos 80 millones de años, el Rift de Reelfoot formó una depresión que fue inundada por el Golfo de México . A medida que bajaban los niveles del mar, el Misisipi y otros ríos extendieron sus cursos hacia la bahía , que gradualmente se llenó de sedimentos con el río Misisipi en su centro. [48] [49]

A través de un proceso natural conocido como avulsión o cambio de delta, el curso inferior del río Misisipi ha cambiado su curso final hacia la desembocadura del Golfo de México cada mil años aproximadamente. Esto ocurre porque los depósitos de limo y sedimentos comienzan a obstruir su canal, elevando el nivel del río y haciendo que finalmente encuentre una ruta más empinada y directa hacia el Golfo de México. Los distribuidores abandonados disminuyen en volumen y forman lo que se conoce como bayous . Este proceso ha hecho que, durante los últimos 5.000 años, la línea costera del sur de Luisiana avance hacia el Golfo de 15 a 50 millas (24 a 80 km). El lóbulo del delta actualmente activo se llama Delta de Birdfoot, por su forma, o Delta de Balize, por La Balize, Luisiana , el primer asentamiento francés en la desembocadura del Misisipi.

La forma actual de la cuenca del río Misisipi se debió en gran medida a la capa de hielo Laurentide de la Edad de Hielo más reciente . La extensión más meridional de esta enorme glaciación se extendió hasta los Estados Unidos actuales y la cuenca del Misisipi. Cuando la capa de hielo comenzó a retroceder, se depositaron cientos de pies de sedimentos ricos, creando el paisaje llano y fértil del valle del Misisipi. Durante el derretimiento, ríos glaciares gigantes encontraron vías de drenaje en la cuenca del Misisipi, creando características como los valles del río Minnesota , el río James y el río Milk . Cuando la capa de hielo se retiró por completo, muchos de estos ríos "temporales" encontraron caminos hacia la bahía de Hudson o el océano Ártico, dejando la cuenca del Misisipi con muchas características "de gran tamaño" para que los ríos existentes las hubieran tallado en el mismo período de tiempo.

Las capas de hielo durante la Etapa Illinoiana , hace unos 300.000 a 132.000 años antes del presente, bloquearon el Misisipi cerca de Rock Island, Illinois, desviándolo hacia su actual cauce más al oeste, la actual frontera occidental de Illinois. El canal de Hennepin sigue aproximadamente el antiguo cauce del Misisipi río abajo desde Rock Island hasta Hennepin, Illinois . Al sur de Hennepin, hasta Alton, Illinois , el actual río Illinois sigue el antiguo cauce utilizado por el río Misisipi antes de la Etapa Illinoiana. [50] [51]

Cronología de los cambios en el curso del flujo de salida [52]

En marzo de 1876, el Mississippi cambió repentinamente de curso cerca del asentamiento de Reverie, Tennessee , dejando una pequeña parte del condado de Tipton, Tennessee , unida a Arkansas y separada del resto de Tennessee por el nuevo cauce del río. Dado que este evento fue una avulsión , en lugar del efecto de la erosión y la deposición incrementales, la frontera estatal todavía sigue el antiguo cauce. [53]

La ciudad de Kaskaskia, Illinois, estuvo alguna vez en una península en la confluencia de los ríos Misisipi y Kaskaskia (Okaw) . Fundada como una comunidad colonial francesa, más tarde se convirtió en la capital del Territorio de Illinois y fue la primera capital estatal de Illinois hasta 1819. A partir de 1844, las inundaciones sucesivas hicieron que el río Misisipi invadiera lentamente hacia el este. Una gran inundación en 1881 hizo que superara los 16 km (10 millas) inferiores del río Kaskaskia, formando un nuevo canal del Misisipi y separando a la ciudad del resto del estado. Las inundaciones posteriores destruyeron la mayor parte de la ciudad restante, incluida la Casa del Estado original. Hoy, la isla y la comunidad de 14 residentes restantes de 2300 acres (930 ha) se conocen como un enclave de Illinois y solo se puede acceder desde el lado de Misuri. [54]

La zona sísmica de New Madrid , a lo largo del río Mississippi cerca de New Madrid, Missouri , entre Memphis y St. Louis, está relacionada con un aulacógeno (rift fallido) que se formó al mismo tiempo que el Golfo de México. Esta área todavía es bastante activa sísmicamente. Cuatro grandes terremotos en 1811 y 1812 , estimados en 8 en la escala de Richter , tuvieron tremendos efectos locales en el área entonces escasamente poblada, y se sintieron en muchos otros lugares en el Medio Oeste y el este de los EE. UU. Estos terremotos crearon el lago Reelfoot en Tennessee a partir del paisaje alterado cerca del río.

Cuando se mide desde su fuente tradicional en el lago Itasca , el Misisipi tiene una longitud de 2340 millas (3766 km). Cuando se mide desde su fuente de corriente más larga (la fuente más distante del mar), Brower's Spring en Montana , la fuente del río Misuri , tiene una longitud de 3710 millas (5971 km), lo que lo convierte en el cuarto río más largo del mundo después del Nilo , el Amazonas y el Yangtsé . [55] Cuando se mide por la fuente de corriente más grande (por volumen de agua), el río Ohio , por extensión el río Allegheny , sería la fuente, y el Misisipi comenzaría en Pensilvania . [56]

En su nacimiento en el lago Itasca , el río Misisipi tiene unos 0,91 m de profundidad. La profundidad media del río Misisipi entre Saint Paul y Saint Louis es de entre 2,7 y 3,7 m, siendo la parte más profunda el lago Pepin , que tiene una media de 6 a 10 m y una profundidad máxima de 18 m. Entre el punto donde el río Misuri se une al Misisipi en Saint Louis (Misuri) y Cairo (Illinois), la profundidad media es de 9 m. Por debajo de Cairo, donde se une el río Ohio, la profundidad media es de 15 a 30 m. La parte más profunda del río está en Nueva Orleans, donde alcanza los 61 m. [57] [58]

El río Misisipi atraviesa o recorre diez estados, desde Minnesota hasta Luisiana , y se utiliza para definir partes de las fronteras de estos estados: Wisconsin , Illinois , Kentucky , Tennessee y Misisipi se encuentran a lo largo del lado este del río, y Iowa , Misuri y Arkansas a lo largo del lado oeste. Partes sustanciales de Minnesota y Luisiana se encuentran a ambos lados del río, aunque el Misisipi define parte del límite de cada uno de estos estados.

En todos estos casos, la mitad del lecho del río en el momento en que se establecieron las fronteras se utilizó como línea para definir las fronteras entre estados adyacentes. [59] [60] En varias áreas, el río se ha desplazado desde entonces, pero las fronteras estatales no han cambiado, y siguen siguiendo el antiguo lecho del río Misisipi en el momento de su establecimiento, dejando varias pequeñas áreas aisladas de un estado al otro lado del nuevo canal del río, contiguas al estado adyacente. Además, debido a un meandro en el río, una pequeña parte del oeste de Kentucky es contigua a Tennessee, pero aislada del resto de su estado.

A continuación se enumeran muchas de las comunidades que se encuentran a lo largo del río Misisipi; la mayoría tienen importancia histórica o tradición cultural que las vincula con el río. Están ordenadas desde el nacimiento del río hasta su desembocadura.

El cruce de caminos más alto en el Alto Misisipi es una simple alcantarilla de acero, a través de la cual el río (llamado localmente "Nicolet Creek") fluye hacia el norte desde el lago Nicolet bajo "Wilderness Road" hasta el brazo oeste del lago Itasca, dentro del Parque Estatal de Itasca . [61]

El primer puente que cruzó el río Misisipi se construyó en 1855. Cruzaba el río en Minneapolis , donde se encuentra el actual puente de la avenida Hennepin . [62] No hay carreteras ni túneles ferroviarios que crucen por debajo del río Misisipi.

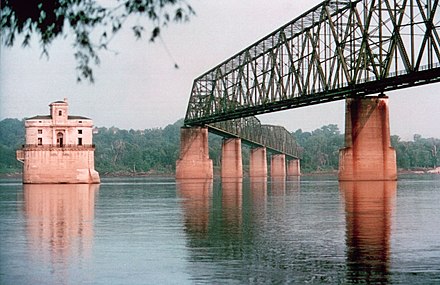

El primer puente ferroviario que cruzaba el Misisipi se construyó en 1856. Cruzaba el río entre el Rock Island Arsenal en Illinois y Davenport, Iowa. Los capitanes de los barcos de vapor de la época, temerosos de la competencia de los ferrocarriles, consideraron que el nuevo puente era un peligro para la navegación. Dos semanas después de su inauguración, el barco de vapor Effie Afton embistió parte del puente y le prendió fuego. Se iniciaron procedimientos legales, en los que Abraham Lincoln defendió al ferrocarril. La demanda llegó a la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos , que falló a favor del ferrocarril. [63]

A continuación se presenta una descripción general de puentes seleccionados de Mississippi que tienen una importancia histórica o de ingeniería notable, con sus ciudades o ubicaciones. Están ordenados desde la fuente del Alto Mississippi hasta la desembocadura del Bajo Mississippi.

.jpg/440px-Grant_River_Recreation_Area_along_the_Mississippi_River_-_Potosi,_Wisconsin_(24342209130).jpg)

Se necesita un canal despejado para las barcazas y otros buques que hacen del cauce principal del río Misisipi una de las grandes vías navegables comerciales del mundo. La tarea de mantener un canal de navegación es responsabilidad del Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército de los Estados Unidos , que se estableció en 1802. [66] Los proyectos anteriores comenzaron ya en 1829 para eliminar obstáculos, cerrar canales secundarios y excavar rocas y bancos de arena .

Las aguas estancadas superiores del Mississippi normalmente se congelan en diciembre, mientras que el canal principal se congela sólo en los años más fríos, históricamente tan al sur como St. Louis. [67]

Una serie de 29 esclusas y presas en el alto Misisipi, la mayoría de las cuales fueron construidas en la década de 1930, está diseñada principalmente para mantener un canal de 9 pies de profundidad (2,7 m) para el tráfico de barcazas comerciales. [68] [69] Los lagos formados también se utilizan para la navegación recreativa y la pesca. Las presas hacen que el río sea más profundo y ancho, pero no lo detienen. No se pretende controlar las inundaciones . Durante los períodos de alto flujo, las compuertas, algunas de las cuales son sumergibles, se abren completamente y las presas simplemente dejan de funcionar. Por debajo de St. Louis, el Misisipi fluye relativamente libremente, aunque está restringido por numerosos diques y dirigido por numerosas presas laterales . El alcance y la escala de los diques, construidos a lo largo de ambos lados del río para mantenerlo en su curso, a menudo se ha comparado con la Gran Muralla China . [37]

En el bajo Mississippi, desde Baton Rouge hasta la desembocadura del Mississippi, la profundidad de navegación es de 45 pies (14 m), lo que permite que los buques portacontenedores y cruceros atraquen en el puerto de Nueva Orleans y los buques de carga a granel de menos de 150 pies (46 m) de calado aéreo que caben debajo del puente Huey P. Long para atravesar el Mississippi hasta Baton Rouge. [70] Hay un estudio de viabilidad para dragar esta parte del río a 50 pies (15 m) para permitir profundidades de barcos New Panamax . [71]

En 1829 se realizaron estudios de los dos principales obstáculos del curso superior del Mississippi, los rápidos de Des Moines y los rápidos de Rock Island, donde el río era poco profundo y el lecho era rocoso. Los rápidos de Des Moines tenían una longitud de aproximadamente 11 millas (18 km) y se encontraban justo por encima de la desembocadura del río Des Moines en Keokuk, Iowa. Los rápidos de Rock Island estaban entre Rock Island y Moline, Illinois . Ambos rápidos se consideraban prácticamente intransitables.

En 1848, se construyó el canal de Illinois y Michigan para conectar el río Misisipi con el lago Michigan a través del río Illinois cerca de Peru, Illinois . El canal permitió el transporte marítimo entre estas importantes vías fluviales. En 1900, el canal fue reemplazado por el canal sanitario y marítimo de Chicago . El segundo canal, además del transporte marítimo, también permitió a Chicago abordar problemas de salud específicos ( fiebre tifoidea , cólera y otras enfermedades transmitidas por el agua) al enviar sus desechos por los sistemas de los ríos Illinois y Misisipi en lugar de contaminar su fuente de agua del lago Michigan.

El Cuerpo de Ingenieros recomendó la excavación de un canal de 1,5 m de profundidad en los rápidos de Des Moines, pero las obras no comenzaron hasta que el teniente Robert E. Lee aprobó el proyecto en 1837. Posteriormente, el Cuerpo también comenzó a excavar los rápidos de Rock Island. En 1866, se hizo evidente que la excavación no era práctica y se decidió construir un canal alrededor de los rápidos de Des Moines. El canal se inauguró en 1877, pero los rápidos de Rock Island siguieron siendo un obstáculo. En 1878, el Congreso autorizó al Cuerpo a establecer un canal de 1,4 m de profundidad que se obtendría mediante la construcción de presas laterales que dirigieran el río hacia un canal estrecho haciendo que cortara un canal más profundo, mediante el cierre de canales secundarios y mediante dragado. El proyecto del canal se completó cuando se inauguró la esclusa Moline, que pasaba por alto los rápidos de Rock Island, en 1907.

Para mejorar la navegación entre St. Paul, Minnesota, y Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin , el Cuerpo construyó varias represas en lagos en la zona de las cabeceras, incluidos el lago Winnibigoshish y el lago Pokegama . Las represas, que se construyeron a principios de la década de 1880, almacenaban el agua de escorrentía de los manantiales que se liberaba durante las aguas bajas para ayudar a mantener la profundidad del canal.

En 1907, el Congreso autorizó un proyecto de canal de 6 pies de profundidad (1,8 m) en el río Misisipi, que no se completó cuando fue abandonado a fines de la década de 1920 en favor del proyecto de canal de 9 pies de profundidad (2,7 m).

En 1913, se completó la construcción de la esclusa y presa n.º 19 en Keokuk, Iowa , la primera presa debajo de las cataratas St. Anthony. Construida por una empresa eléctrica privada ( Union Electric Company de St. Louis) para generar electricidad (originalmente para tranvías en St. Louis ), la presa de Keokuk era una de las plantas hidroeléctricas más grandes del mundo en ese momento. La presa también eliminó los rápidos de Des Moines. La esclusa y presa n.º 1 se completó en Minneapolis, Minnesota, en 1917. La esclusa y presa n.º 2 , cerca de Hastings, Minnesota , se completó en 1930.

Antes de la gran inundación del Mississippi de 1927 , la principal estrategia del Cuerpo de Ingenieros era cerrar tantos canales laterales como fuera posible para aumentar el caudal del río principal. Se creía que la velocidad del río arrastraría los sedimentos del fondo , lo que haría que el río se hiciera más profundo y disminuiría la posibilidad de inundaciones. La inundación de 1927 demostró que esto era tan erróneo que las comunidades amenazadas por la inundación comenzaron a crear sus propios diques para aliviar la fuerza de la crecida del río.

La Ley de Ríos y Puertos de 1930 autorizó el proyecto del canal de 2,7 m (9 pies), que requería un canal de navegación de 2,7 m (9 pies) de profundidad y 120 m (400 pies) de ancho para dar cabida a remolques de múltiples barcazas. [72] [73] Esto se logró mediante una serie de esclusas y presas, y mediante dragado. En la década de 1930 se construyeron veintitrés nuevas esclusas y presas en el alto Misisipi, además de las tres que ya existían.

Hasta la década de 1950, no había ninguna presa debajo de la esclusa y presa n.º 26 en Alton, Illinois. La esclusa Chain of Rocks (esclusa y presa n.º 27), que consta de una presa para aguas bajas y un canal de 13,5 km de largo, se añadió en 1953, justo debajo de la confluencia con el río Misuri, principalmente para sortear una serie de salientes rocosos en St. Louis. También sirve para proteger las tomas de agua de la ciudad de St. Louis durante épocas de aguas bajas.

U.S. government scientists determined in the 1950s that the Mississippi River was starting to switch to the Atchafalaya River channel because of its much steeper path to the Gulf of Mexico. Eventually, the Atchafalaya River would capture the Mississippi River and become its main channel to the Gulf of Mexico, leaving New Orleans on a side channel. As a result, the U.S. Congress authorized a project called the Old River Control Structure, which has prevented the Mississippi River from leaving its current channel that drains into the Gulf via New Orleans.[75]

Because the large scale of high-energy water flow threatened to damage the structure, an auxiliary flow control station was built adjacent to the standing control station. This $300 million project was completed in 1986 by the Corps of Engineers. Beginning in the 1970s, the Corps applied hydrological transport models to analyze flood flow and water quality of the Mississippi. Dam 26 at Alton, Illinois, which had structural problems, was replaced by the Mel Price Lock and Dam in 1990. The original Lock and Dam 26 was demolished.

The Corps now actively creates and maintains spillways and floodways to divert periodic water surges into backwater channels and lakes, as well as route part of the Mississippi's flow into the Atchafalaya Basin and from there to the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The main structures are the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway in Missouri; the Old River Control Structure and the Morganza Spillway in Louisiana, which direct excess water down the west and east sides (respectively) of the Atchafalaya River; and the Bonnet Carré Spillway, also in Louisiana, which directs floodwaters to Lake Pontchartrain (see diagram). Some experts blame urban sprawl for increases in both the risk and frequency of flooding on the Mississippi River.[76]

Some of the pre-1927 strategy remains in use today, with the Corps actively cutting the necks of horseshoe bends, allowing the water to move faster and reducing flood heights.[77]

Approximately 50,000 years ago, the Central United States was covered by an inland sea, which was drained by the Mississippi and its tributaries into the Gulf of Mexico—creating large floodplains and extending the continent further to the south in the process. The soil in areas such as Louisiana was thereafter found to be very rich.[78]

The area of the Mississippi River basin was first settled by hunting and gathering Native American peoples and is considered one of the few independent centers of plant domestication in human history.[79] Evidence of early cultivation of sunflower, a goosefoot, a marsh elder and an indigenous squash dates to the 4th millennium BC. The lifestyle gradually became more settled after around 1000 BC during what is now called the Woodland period, with increasing evidence of shelter construction, pottery, weaving and other practices.

A network of trade routes referred to as the Hopewell interaction sphere was active along the waterways between about 200 and 500 AD, spreading common cultural practices over the entire area between the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes. A period of more isolated communities followed, and agriculture introduced from Mesoamerica based on the Three Sisters (maize, beans and squash) gradually came to dominate. After around 800 AD there arose an advanced agricultural society today referred to as the Mississippian culture, with evidence of highly stratified complex chiefdoms and large population centers.

The most prominent of these, now called Cahokia, was occupied between about 600 and 1400 AD[80] and at its peak numbered between 8,000 and 40,000 inhabitants, larger than London, England of that time. At the time of first contact with Europeans, Cahokia and many other Mississippian cities had dispersed, and archaeological finds attest to increased social stress.[81][82][83]

Modern American Indian nations inhabiting the Mississippi basin include Cheyenne, Sioux, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Fox, Kickapoo, Tamaroa, Moingwena, Quapaw and Chickasaw.

The word Mississippi itself comes from Messipi, the French rendering of the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe or Algonquin) name for the river, Misi-ziibi (Great River).[84][85] The Ojibwe called Lake Itasca Omashkoozo-zaaga'igan (Elk Lake) and the river flowing out of it Omashkoozo-ziibi (Elk River). After flowing into Lake Bemidji, the Ojibwe called the river Bemijigamaag-ziibi (River from the Traversing Lake). After flowing into Cass Lake, the name of the river changes to Gaa-miskwaawaakokaag-ziibi (Red Cedar River) and then out of Lake Winnibigoshish as Wiinibiigoonzhish-ziibi (Miserable Wretched Dirty Water River), Gichi-ziibi (Big River) after the confluence with the Leech Lake River, then finally as Misi-ziibi (Great River) after the confluence with the Crow Wing River.[86] After the expeditions by Giacomo Beltrami and Henry Schoolcraft, the longest stream above the juncture of the Crow Wing River and Gichi-ziibi was named "Mississippi River". The Mississippi River Band of Chippewa Indians, known as the Gichi-ziibiwininiwag, are named after the stretch of the Mississippi River known as the Gichi-ziibi. The Cheyenne, one of the earliest inhabitants of the upper Mississippi River, called it the Máʼxe-éʼometaaʼe (Big Greasy River) in the Cheyenne language. The Arapaho name for the river is Beesniicíe.[87] The Pawnee name is Kickaátit.[88]

The Mississippi was spelled Mississipi or Missisipi during French Louisiana and was also known as the Rivière Saint-Louis.[89][90][91]

In 1519 Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda became the first recorded European to reach the Mississippi River, followed by Hernando de Soto who reached the river on May 8, 1541, and called it Río del Espíritu Santo ("River of the Holy Spirit"), in the area of what is now Mississippi.[92] In Spanish, the river is called Río Mississippi.[93]

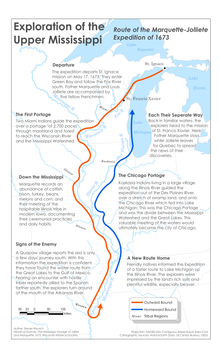

French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette began exploring the Mississippi in the 17th century. Marquette traveled with a Sioux Indian who named it Ne Tongo ("Big river" in Sioux language) in 1673. Marquette proposed calling it the River of the Immaculate Conception.

When Louis Jolliet explored the Mississippi Valley in the 17th century, natives guided him to a quicker way to return to French Canada via the Illinois River. When he found the Chicago Portage, he remarked that a canal of "only half a league" (less than 2 miles or 3 kilometers) would join the Mississippi and the Great Lakes.[94] In 1848, the continental divide separating the waters of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley was breached by the Illinois and Michigan canal via the Chicago River.[95] This both accelerated the development, and forever changed the ecology of the Mississippi Valley and the Great Lakes.

In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and Henri de Tonti claimed the entire Mississippi River valley for France, calling the river Colbert River after Jean-Baptiste Colbert and the region La Louisiane, for King Louis XIV. On March 2, 1699, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville rediscovered the mouth of the Mississippi, following the death of La Salle.[96] The French built the small fort of La Balise there to control passage.[97]

In 1718, about 100 miles (160 km) upriver, New Orleans was established along the river crescent by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, with construction patterned after the 1711 resettlement on Mobile Bay of Mobile, the capital of French Louisiana at the time.

In 1727, Étienne Perier begins work, using enslaved African laborers, on the first levees on the Mississippi River.

Following Britain's victory in the Seven Years War, the Mississippi became the border between the British and Spanish Empires. The Treaty of Paris (1763) gave Great Britain rights to all land east of the Mississippi and Spain rights to land west of the Mississippi. Spain also ceded Florida to Britain to regain Cuba, which the British occupied during the war. Britain then divided the territory into East and West Florida.

Article 8 of the Treaty of Paris (1783) states, "The navigation of the river Mississippi, from its source to the ocean, shall forever remain free and open to the subjects of Great Britain and the citizens of the United States". With this treaty, which ended the American Revolutionary War, Britain also ceded West Florida back to Spain to regain the Bahamas, which Spain had occupied during the war. Initial disputes around the ensuing claims of the U.S. and Spain were resolved when Spain was pressured into signing Pinckney's Treaty in 1795. However, in 1800, under duress from Napoleon of France, Spain ceded an undefined portion of West Florida to France in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso. The United States then secured effective control of the river when it bought the Louisiana Territory from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. This triggered a dispute between Spain and the U.S. on which parts of West Florida Spain had ceded to France in the first place, which would decide which parts of West Florida the U.S. had bought from France in the Louisiana Purchase, versus which were unceded Spanish property. Due to ongoing U.S. colonization creating facts on the ground, and U.S. military actions, Spain ceded both West and East Florida in their entirety to the United States in the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

The last serious European challenge to U.S. control of the river came at the conclusion of the War of 1812, when British forces mounted an attack on New Orleans just 15 days after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent. The attack was repulsed by an American army under the command of General Andrew Jackson.

In the Treaty of 1818, the U.S. and Great Britain agreed to fix the border running from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains along the 49th parallel north. In effect, the U.S. ceded the northwestern extremity of the Mississippi basin to the British in exchange for the southern portion of the Red River basin.

So many settlers traveled westward through the Mississippi river basin, as well as settled in it, that Zadok Cramer wrote a guidebook called The Navigator, detailing the features, dangers, and navigable waterways of the area. It was so popular that he updated and expanded it through 12 editions over 25 years.

The colonization of the area was barely slowed by the three earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, estimated at 8 on the Richter magnitude scale, that were centered near New Madrid, Missouri.

Mark Twain's book, Life on the Mississippi, covered the steamboat commerce, which took place from 1830 to 1870, before more modern ships replaced the steamer. Harper's Weekly first published the book as a seven-part serial in 1875. James R. Osgood & Company published the full version, including a passage from the then unfinished Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and works from other authors, in 1885.

The first steamboat to travel the full length of the Lower Mississippi from the Ohio River to New Orleans was the New Orleans in December 1811. Its maiden voyage occurred during the series of New Madrid earthquakes in 1811–12. The Upper Mississippi was treacherous, unpredictable and to make traveling worse, the area was not properly mapped out or surveyed. Until the 1840s, only two trips a year to the Twin Cities landings were made by steamboats, which suggests it was not very profitable.[98]

Steamboat transport remained a viable industry, both in terms of passengers and freight, until the end of the first decade of the 20th century. Among the several Mississippi River system steamboat companies was the noted Anchor Line, which, from 1859 to 1898, operated a luxurious fleet of steamers between St. Louis and New Orleans.

Italian explorer Giacomo Beltrami wrote about his journey on the Virginia, which was the first steamboat to make it to Fort St. Anthony in Minnesota. He referred to his voyage as a promenade that was once a journey on the Mississippi. The steamboat era changed the economic and political life of the Mississippi, as well as of travel itself. The Mississippi was completely changed by the steamboat era as it transformed into a flourishing tourist trade.[99]

Control of the river was a strategic objective of both sides in the American Civil War, forming a part of the U.S. Anaconda Plan. In 1862, Union forces coming down the river successfully cleared Confederate defenses at Island Number 10 and Memphis, Tennessee, while Naval forces coming upriver from the Gulf of Mexico captured New Orleans, Louisiana. One of the last major Confederate strongholds was on the heights overlooking the river at Vicksburg, Mississippi; the Union's Vicksburg Campaign (December 1862–July 1863), and the fall of Port Hudson, completed control of the lower Mississippi River. The Union victory ended the Siege of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, and was pivotal to the Union's final victory of the Civil War.[100]

The "Big Freeze" of 1918–19 blocked river traffic north of Memphis, Tennessee, preventing transportation of coal from southern Illinois. This resulted in widespread shortages, high prices, and rationing of coal in January and February.[101]

In the spring of 1927, the river broke out of its banks in 145 places, during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and inundated 27,000 sq mi (70,000 km2) to a depth of up to 30 feet (9.1 m).

In 1930, Fred Newton was the first person to swim the length of the river, from Minneapolis to New Orleans. The journey took 176 days and covered 1,836 miles.[102][103]

In 1962 and 1963, industrial accidents spilled 3.5 million US gallons (13,000 m3) of soybean oil into the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. The oil covered the Mississippi River from St. Paul to Lake Pepin, creating an ecological disaster and a demand to control water pollution.[104]

On October 20, 1976, the automobile ferry, MV George Prince, was struck by a ship traveling upstream as the ferry attempted to cross from Destrehan, Louisiana, to Luling, Louisiana. Seventy-eight passengers and crew died; only eighteen survived the accident.

In 1988, the water level of the Mississippi fell to 10 feet (3.0 m) below zero on the Memphis gauge. The remains of wooden-hulled water craft were exposed in an area of 4.5 acres (1.8 ha) on the bottom of the Mississippi River at West Memphis, Arkansas. They dated to the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The State of Arkansas, the Arkansas Archeological Survey, and the Arkansas Archeological Society responded with a two-month data recovery effort. The fieldwork received national media attention as good news in the middle of a drought.[105]

The Great Flood of 1993 was another significant flood, primarily affecting the Mississippi above its confluence with the Ohio River at Cairo, Illinois.

Two portions of the Mississippi were designated as American Heritage Rivers in 1997: the lower portion around Louisiana and Tennessee, and the upper portion around Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri and Wisconsin. The Nature Conservancy's project called "America's Rivershed Initiative" announced a 'report card' assessment of the entire basin in October 2015 and gave the grade of D+. The assessment noted the aging navigation and flood control infrastructure along with multiple environmental problems.[106]

In 2002, Slovenian long-distance swimmer Martin Strel swam the entire length of the river, from Minnesota to Louisiana, over the course of 68 days. In 2005, the Source to Sea Expedition[107] paddled the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers to benefit the Audubon Society's Upper Mississippi River Campaign.[108][109]

Geologists believe that the lower Mississippi could take a new course to the Gulf. Either of two new routes—through the Atchafalaya Basin or through Lake Pontchartrain—might become the Mississippi's main channel if flood-control structures are overtopped or heavily damaged during a severe flood.[110][111][112][113][114]

Failure of the Old River Control Structure, the Morganza Spillway, or nearby levees would likely re-route the main channel of the Mississippi through Louisiana's Atchafalaya Basin and down the Atchafalaya River to reach the Gulf of Mexico south of Morgan City in southern Louisiana. This route provides a more direct path to the Gulf of Mexico than the present Mississippi River channel through Baton Rouge and New Orleans.[112] While the risk of such a diversion is present during any major flood event, such a change has so far been prevented by active human intervention involving the construction, maintenance, and operation of various levees, spillways, and other control structures by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The Old River Control Structure, between the present Mississippi River channel and the Atchafalaya Basin, sits at the normal water elevation and is ordinarily used to divert 30% of the Mississippi flow to the Atchafalaya River. There is a steep drop here away from the Mississippi's main channel into the Atchafalaya Basin. If this facility were to fail during a major flood, there is a strong concern the water would scour and erode the river bottom enough to capture the Mississippi's main channel. The structure was nearly lost during the 1973 flood, but repairs and improvements were made after engineers studied the forces at play. In particular, the Corps of Engineers made many improvements and constructed additional facilities for routing water through the vicinity. These additional facilities give the Corps much more flexibility and potential flow capacity than they had in 1973, which further reduces the risk of a catastrophic failure in this area during other major floods, such as that of 2011.

Because the Morganza Spillway is slightly higher and well back from the river, it is normally dry on both sides.[115] Even if it failed at the crest during a severe flood, the floodwaters would have to erode to normal water levels before the Mississippi could permanently jump channel at this location.[116][117] During the 2011 floods, the Corps of Engineers opened the Morganza Spillway to 1/4 of its capacity to allow 150,000 cubic feet per second (4,200 m3/s) of water to flood the Morganza and Atchafalaya floodways and continue directly to the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing Baton Rouge and New Orleans.[118] In addition to reducing the Mississippi River crest downstream, this diversion reduced the chances of a channel change by reducing stress on the other elements of the control system.[119]

Some geologists have noted that the possibility for course change into the Atchafalaya also exists in the area immediately north of the Old River Control Structure. Army Corps of Engineers geologist Fred Smith once stated, "The Mississippi wants to go west. 1973 was a forty-year flood. The big one lies out there somewhere—when the structures can't release all the floodwaters and the levee is going to have to give way. That is when the river's going to jump its banks and try to break through."[120]

Another possible course change for the Mississippi River is a diversion into Lake Pontchartrain near New Orleans. This route is controlled by the Bonnet Carré Spillway, built to reduce flooding in New Orleans. This spillway and an imperfect natural levee about 12–20 ft (3.7–6.1 m) high are all that prevents the Mississippi from taking a new, shorter course through Lake Pontchartrain to the Gulf of Mexico.[121] Diversion of the Mississippi's main channel through Lake Pontchartrain would have consequences similar to an Atchafalaya diversion, but to a lesser extent, since the present river channel would remain in use past Baton Rouge and into the New Orleans area.

The sport of water skiing was invented on the river in a wide region between Minnesota and Wisconsin known as Lake Pepin.[122] Ralph Samuelson of Lake City, Minnesota, created and refined his skiing technique in late June and early July 1922. He later performed the first water ski jump in 1925 and was pulled along at 80 mph (130 km/h) by a Curtiss flying boat later that year.[122]

There are seven National Park Service sites along the Mississippi River. The Mississippi National River and Recreation Area is the National Park Service site dedicated to protecting and interpreting the Mississippi River itself. The other six National Park Service sites along the river are (listed from north to south):

The Mississippi basin is home to a highly diverse aquatic fauna and has been called the "mother fauna" of North American freshwater.[123]

About 375 fish species are known from the Mississippi basin, far exceeding other North Hemisphere river basins exclusively within temperate/subtropical regions,[123] except the Yangtze.[124] Within the Mississippi basin, streams that have their source in the Appalachian and Ozark highlands contain especially many species. Among the fish species in the basin are numerous endemics, as well as relicts such as paddlefish, sturgeon, gar and bowfin.[123]

Because of its size and high species diversity, the Mississippi basin is often divided into subregions. The Upper Mississippi River alone is home to about 120 fish species, including walleye, sauger, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, white bass, northern pike, bluegill, crappie, channel catfish, flathead catfish, common shiner, freshwater drum, and shovelnose sturgeon.[125][126]

A large number of reptiles are native to the river channels and basin, including American alligators, several species of turtle, aquatic amphibians,[127] and cambaridae crayfish, are native to the Mississippi basin.[128]

In addition, approximately 40% of the migratory birds in the US use the Mississippi River corridor during the Spring and Fall migrations; 60% of all migratory birds in North America (326 species) use the river basin as their flyway.[129]

Numerous introduced species are found in the Mississippi and some of these are invasive. Among the introductions are fish such as Asian carp, including the silver carp that have become infamous for out-competing native fish and their potentially dangerous jumping behavior. They have spread throughout much of the basin, even approaching (but not yet invading) the Great Lakes.[130] The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has designated much of the Mississippi River in the state as infested waters by the exotic species zebra mussels and Eurasian watermilfoil.[131]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)