Egipto ( árabe : مصر Miṣr [mesˁr] , pronunciación árabe egipcia: [mɑsˤr] ), oficialmente la República Árabe de Egipto , es un país transcontinental que abarca el extremo noreste de África y la península del Sinaí en el extremo suroeste de Asia . Limita con el mar Mediterráneo al norte , la Franja de Gaza de Palestina e Israel al noreste , el mar Rojo al este, Sudán al sur y Libia al oeste . El golfo de Áqaba en el noreste separa Egipto de Jordania y Arabia Saudita . El Cairo es la capital y la ciudad más grande de Egipto , mientras que Alejandría , la segunda ciudad más grande, es un importante centro industrial y turístico en la costa mediterránea . [20] Con aproximadamente 100 millones de habitantes, Egipto es el decimocuarto país más poblado del mundo y el tercero más poblado de África.

Egipto tiene una de las historias más largas de cualquier país, y su herencia a lo largo del delta del Nilo se remonta al sexto y cuarto milenio a. C. Considerado la cuna de la civilización , el Antiguo Egipto fue testigo de algunos de los primeros desarrollos de la escritura, la agricultura, la urbanización, la religión organizada y el gobierno central. [21] Egipto fue un centro temprano e importante del cristianismo , que luego adoptó el islam a partir del siglo VII en adelante. El Cairo se convirtió en la capital del califato fatimí en el siglo X y del sultanato mameluco en el siglo XIII. Luego, Egipto pasó a formar parte del Imperio otomano en 1517, antes de que su gobernante local Muhammad Ali estableciera el Egipto moderno como un Jedivato autónomo en 1867.

El país fue ocupado entonces por el Imperio Británico y obtuvo la independencia en 1922 como monarquía . Tras la revolución de 1952 , Egipto se declaró república . Durante un breve período entre 1958 y 1961, Egipto se fusionó con Siria para formar la República Árabe Unida . Egipto libró varios conflictos armados con Israel en 1948 , 1956 , 1967 y 1973 , y ocupó la Franja de Gaza de forma intermitente hasta 1967. En 1978, Egipto firmó los Acuerdos de Camp David , que reconocieron a Israel a cambio de su retirada del Sinaí ocupado. Después de la Primavera Árabe , que condujo a la revolución egipcia de 2011 y al derrocamiento de Hosni Mubarak , el país enfrentó un período prolongado de agitación política ; Esto incluyó la elección en 2012 de un breve y efímero gobierno islamista alineado con la Hermandad Musulmana y encabezado por Mohamed Morsi , y su posterior derrocamiento después de protestas masivas en 2013 .

El actual gobierno de Egipto, una república semipresidencial liderada por el presidente Abdel Fattah el-Sisi desde que fue elegido en 2014, ha sido descrito por varios organismos de control como autoritario y responsable de perpetuar el pobre historial de derechos humanos del país . El Islam es la religión oficial de Egipto y el árabe es su idioma oficial. [1] La gran mayoría de su gente vive cerca de las orillas del río Nilo , un área de unos 40.000 kilómetros cuadrados (15.000 millas cuadradas), donde se encuentra la única tierra cultivable . Las grandes regiones del desierto del Sahara , que constituyen la mayor parte del territorio de Egipto, están escasamente habitadas. Alrededor del 43% de los residentes de Egipto viven en las áreas urbanas del país, [22] y la mayoría se extiende por los centros densamente poblados del Gran Cairo, Alejandría y otras ciudades importantes en el delta del Nilo. Egipto es considerado una potencia regional en el norte de África , Oriente Medio y el mundo musulmán , y una potencia media a nivel mundial. [23] Es un país en desarrollo que tiene una economía diversificada, que es la más grande de África , la 38.ª economía más grande por PIB nominal y la 127.ª por PIB nominal per cápita. [24] Egipto es miembro fundador de las Naciones Unidas , el Movimiento de Países No Alineados , la Liga Árabe , la Unión Africana , la Organización de Cooperación Islámica , el Foro Mundial de la Juventud y miembro de los BRICS .

El nombre en inglés "Egipto" se deriva del griego antiguo " Aígyptos " (" Αἴγυπτος "), a través del francés medio "Egypte" y el latín " Aegyptus ". Se refleja en las primeras tablillas griegas en Lineal B como "a-ku-pi-ti-yo". [25] El adjetivo "aigýpti-"/"aigýptios" fue tomado prestado al copto como " gyptios ", y de allí al árabe como " qubṭī ", formado de nuevo en " قبط " (" qubṭ "), de donde proviene el inglés " Copt ". El destacado historiador y geógrafo griego antiguo , Estrabón , proporcionó una etimología popular que afirma que " Αἴγυπτος " (Aigýptios) había evolucionado originalmente como un compuesto de " Aἰγαίου ὑπτίως " Aegaeou huptiōs , que significa " Debajo del Egeo ". [26]

" Miṣr " ( pronunciación árabe: [misˤɾ] ; " مِصر ") es el nombre oficial moderno y árabe coránico clásico de Egipto, mientras que " Maṣr " ( pronunciación árabe egipcia: [mɑsˤɾ] ; مَصر ) es la pronunciación local en árabe egipcio . [27] El nombre actual de Egipto, Misr/Misir/Misru, proviene del antiguo nombre semítico para el mismo. El término originalmente connotaba " civilización " o " metrópolis ". [28] El árabe clásico Miṣr (árabe egipcio Maṣr ) es directamente cognado con el hebreo bíblico Mitsráyīm (מִצְרַיִם / מִצְרָיִם), que significa "los dos estrechos", una referencia a la separación predinástica del Alto y Bajo Egipto . También se menciona en varias lenguas semíticas como Mesru , Misir y Masar . [28] La atestación más antigua de este nombre para Egipto es el acadio "mi-iṣ-ru" ("miṣru") [29] [30] relacionado con miṣru/miṣirru/miṣaru , que significa "frontera" o "frontera". [31] El Imperio neoasirio utilizó el término derivado ![]() , Mu-sur . [32]

, Mu-sur . [32]

._Temple_dedicated_to_Pa_-_Horakhti.jpg/440px-Derr_(_125_miles_south_of_Aswan,_right_bank)._Temple_dedicated_to_Pa_-_Horakhti.jpg)

Hay evidencia de grabados rupestres a lo largo de las terrazas del Nilo y en los oasis del desierto. En el décimo milenio a. C. , una cultura de cazadores-recolectores y pescadores fue reemplazada por una cultura de molienda de granos . Los cambios climáticos o el pastoreo excesivo alrededor del 8000 a. C. comenzaron a desecar las tierras pastorales de Egipto, formando el Sahara . Los primeros pueblos tribales migraron al río Nilo, donde desarrollaron una economía agrícola sedentaria y una sociedad más centralizada . [39]

Hacia el año 6000 a. C., una cultura neolítica se arraigó en el valle del Nilo. [40] Durante la era neolítica, varias culturas predinásticas se desarrollaron de forma independiente en el Alto y el Bajo Egipto . La cultura badariense y la serie sucesora de Naqada se consideran generalmente precursoras del Egipto dinástico . El yacimiento más antiguo conocido del Bajo Egipto, Merimda, es anterior al badariense en unos setecientos años. Las comunidades contemporáneas del Bajo Egipto coexistieron con sus contrapartes del sur durante más de dos mil años, permaneciendo culturalmente distintas, pero manteniendo un contacto frecuente a través del comercio. La evidencia más antigua conocida de inscripciones jeroglíficas egipcias apareció durante el período predinástico en vasijas de cerámica de Naqada III, que datan de alrededor del 3200 a. C. [41]

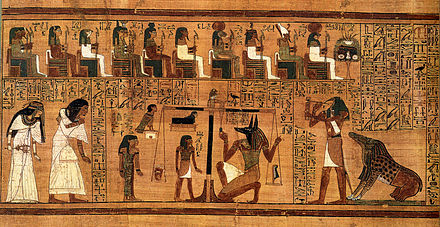

El rey Menes fundó un reino unificado alrededor del 3150 a. C. , lo que dio lugar a una serie de dinastías que gobernaron Egipto durante los tres milenios siguientes. La cultura egipcia floreció durante este largo período y siguió siendo distintivamente egipcia en su religión , artes , idioma y costumbres. Las dos primeras dinastías gobernantes de un Egipto unificado prepararon el terreno para el período del Imperio Antiguo , alrededor del 2700-2200 a . C., en el que se construyeron muchas pirámides , entre las que destacan la pirámide de Zoser de la Tercera Dinastía y las pirámides de Giza de la Cuarta Dinastía .

El Primer Período Intermedio marcó el comienzo de una época de agitación política que duró unos 150 años. [42] Sin embargo, las inundaciones más fuertes del Nilo y la estabilización del gobierno trajeron de vuelta una renovada prosperidad para el país en el Reino Medio alrededor del 2040 a. C., alcanzando su punto máximo durante el reinado del faraón Amenemhat III . Un segundo período de desunión anunció la llegada de la primera dinastía gobernante extranjera a Egipto, la de los hicsos semíticos . Los invasores hicsos tomaron gran parte del Bajo Egipto alrededor de 1650 a. C. y fundaron una nueva capital en Avaris . Fueron expulsados por una fuerza del Alto Egipto liderada por Ahmosis I , quien fundó la Dinastía XVIII y trasladó la capital de Menfis a Tebas .

El Imperio Nuevo (c. 1550-1070 a. C.) comenzó con la Dinastía XVIII, que marcó el ascenso de Egipto como potencia internacional que se expandió durante su mayor extensión hasta un imperio tan al sur como Tombos en Nubia , e incluyó partes del Levante en el este. Este período es conocido por algunos de los faraones más conocidos , entre ellos Hatshepsut , Tutmosis III , Akenatón y su esposa Nefertiti , Tutankamón y Ramsés II . La primera expresión históricamente atestiguada del monoteísmo llegó durante este período como Atenismo . Los contactos frecuentes con otras naciones trajeron nuevas ideas al Imperio Nuevo. El país fue posteriormente invadido y conquistado por libios , nubios y asirios , pero los egipcios nativos finalmente los expulsaron y recuperaron el control de su país. [43]

En 525 a. C., el Imperio aqueménida , liderado por Cambises II , comenzó su conquista de Egipto, y finalmente capturó al faraón Psamético III en la batalla de Pelusio . Cambises II asumió entonces el título formal de faraón , pero gobernó Egipto desde su hogar de Susa en Persia (actual Irán ), dejando Egipto bajo el control de una satrapía . Toda la Dinastía XXVII de Egipto , desde 525 hasta 402 a. C., a excepción de Petubastis III , fue un período gobernado enteramente por los aqueménidas, y a todos los emperadores aqueménidas se les concedió el título de faraón. Unas pocas revueltas temporalmente exitosas contra los aqueménidas marcaron el siglo V a. C., pero Egipto nunca pudo derrocar permanentemente a los aqueménidas. [44]

La Dinastía Trigésima fue la última dinastía gobernante nativa durante la época faraónica. Cayó en manos de los aqueménidas nuevamente en 343 a. C. después de que el último faraón nativo, el rey Nectanebo II , fuera derrotado en batalla. Sin embargo, esta Dinastía Trigésima Primera de Egipto no duró mucho, ya que los aqueménidas fueron derrocados varias décadas después por Alejandro Magno . El general griego macedonio de Alejandro, Ptolomeo I Sóter , fundó la dinastía ptolemaica . [45]

El reino ptolemaico era un poderoso estado helenístico que se extendía desde el sur de Siria en el este, hasta Cirene en el oeste y al sur hasta la frontera con Nubia. Alejandría se convirtió en la capital y en un centro de la cultura y el comercio griegos . Para ganar el reconocimiento de la población nativa egipcia, se autoproclamaron sucesores de los faraones. Los ptolemaicos posteriores adoptaron las tradiciones egipcias, se hicieron retratar en monumentos públicos con el estilo y la vestimenta egipcios y participaron en la vida religiosa egipcia. [46] [47]

La última gobernante de la línea ptolemaica fue Cleopatra VII , que se suicidó tras el entierro de su amante Marco Antonio , después de que Octavio hubiera capturado Alejandría y sus fuerzas mercenarias hubieran huido. Los ptolomeos se enfrentaron a rebeliones de egipcios nativos y estuvieron involucrados en guerras extranjeras y civiles que llevaron a la decadencia del reino y su anexión por parte de Roma.

El cristianismo llegó a Egipto de la mano de San Marcos Evangelista en el siglo I. [48] El reinado de Diocleciano (284-305 d. C.) marcó la transición de la era romana a la bizantina en Egipto, cuando un gran número de cristianos egipcios fueron perseguidos. Para entonces, el Nuevo Testamento ya había sido traducido al egipcio. Después del Concilio de Calcedonia en el año 451 d. C., se estableció firmemente una Iglesia copta egipcia distinta . [49]

Los bizantinos pudieron recuperar el control del país después de una breve invasión persa sasánida a principios del siglo VII en medio de la Guerra bizantino-sasánida de 602-628 durante la cual establecieron una nueva provincia de corta duración durante diez años conocida como Egipto sasánida , hasta 639-42, cuando Egipto fue invadido y conquistado por el califato islámico por los árabes musulmanes . Cuando derrotaron a los ejércitos bizantinos en Egipto, los árabes trajeron el Islam al país. En algún momento durante este período, los egipcios comenzaron a mezclar su nueva fe con creencias y prácticas indígenas, lo que dio lugar a varias órdenes sufíes que han florecido hasta el día de hoy. [48] Estos ritos anteriores habían sobrevivido al período del cristianismo copto . [50]

En 639, el segundo califa , Omar , envió un ejército a Egipto bajo el mando de Amr ibn al-As . Derrotaron a un ejército romano en la batalla de Heliópolis. A continuación, Amr se dirigió hacia Alejandría, que se rindió a él mediante un tratado firmado el 8 de noviembre de 641. Alejandría fue recuperada para el Imperio bizantino en 645, pero Amr la recuperó en 646. En 654, una flota invasora enviada por Constante II fue rechazada.

Los árabes fundaron la capital de Egipto, llamada Fustat , que luego fue incendiada durante las Cruzadas. Posteriormente, en el año 986, se construyó El Cairo, que creció hasta convertirse en la ciudad más grande y rica del califato árabe , superada solo por Bagdad .

El período abasí se caracterizó por la imposición de nuevos impuestos y los coptos se rebelaron de nuevo en el cuarto año de gobierno abasí. A principios del siglo IX se retomó la práctica de gobernar Egipto a través de un gobernador bajo Abdallah ibn Tahir , que decidió residir en Bagdad y envió un delegado a Egipto para que gobernara en su lugar. En 828 estalló otra revuelta egipcia y en 831 los coptos se unieron a los musulmanes nativos contra el gobierno. Finalmente, la pérdida de poder de los abasíes en Bagdad llevó a que un general tras otro asumiera el gobierno de Egipto; sin embargo, al estar bajo la lealtad abasí, la dinastía tuluní (868-905) y la dinastía ijshidí (935-969) estuvieron entre las más exitosas en desafiar al califa abasí.

Los gobernantes musulmanes mantuvieron el control de Egipto durante los siguientes seis siglos, con El Cairo como sede del califato fatimí . Con el fin de la dinastía ayubí , los mamelucos , una casta militar turco - circasiana , tomaron el control alrededor de 1250. A fines del siglo XIII, Egipto unía el Mar Rojo, la India, Malaya y las Indias Orientales. [51] La peste negra de mediados del siglo XIV mató a aproximadamente el 40% de la población del país. [52]

Egipto fue conquistado por los turcos otomanos en 1517, tras lo cual se convirtió en una provincia del Imperio otomano . La militarización defensiva dañó su sociedad civil y sus instituciones económicas. [51] El debilitamiento del sistema económico combinado con los efectos de la peste dejó a Egipto vulnerable a la invasión extranjera. Los comerciantes portugueses se hicieron cargo de su comercio. [51] Entre 1687 y 1731, Egipto experimentó seis hambrunas. [53] La hambruna de 1784 le costó aproximadamente una sexta parte de su población. [54] Egipto siempre fue una provincia difícil de controlar para los sultanes otomanos , debido en parte al continuo poder e influencia de los mamelucos , la casta militar egipcia que había gobernado el país durante siglos. Egipto permaneció semiautónomo bajo los mamelucos hasta que fue invadido por las fuerzas francesas de Napoleón Bonaparte en 1798. Después de que los franceses fueron derrotados por los británicos, se produjo una lucha de poder a tres bandas entre los turcos otomanos , los mamelucos egipcios que habían gobernado Egipto durante siglos y los mercenarios albaneses al servicio de los otomanos.

Tras la expulsión de los franceses, Muhammad Ali Pasha , un comandante militar albanés del ejército otomano en Egipto, tomó el poder en 1805. Muhammad Ali masacró a los mamelucos y estableció una dinastía que gobernaría Egipto hasta la revolución de 1952. La introducción en 1820 del algodón de fibra larga transformó su agricultura en un monocultivo comercial antes de finales de siglo, concentrando la propiedad de la tierra y desplazando la producción hacia los mercados internacionales. [55] Muhammad Ali anexó el norte de Sudán (1820-1824), Siria (1833) y partes de Arabia y Anatolia ; pero en 1841 las potencias europeas, temerosas de que derrocara al propio Imperio Otomano, lo obligaron a devolver la mayoría de sus conquistas a los otomanos. Su ambición militar le exigió modernizar el país: construyó industrias, un sistema de canales para irrigación y transporte, y reformó la administración pública . [55] Construyó un estado militar con alrededor del cuatro por ciento de la población sirviendo en el ejército para elevar a Egipto a una posición poderosa en el Imperio Otomano de una manera que muestra varias similitudes con las estrategias soviéticas (sin comunismo) llevadas a cabo en el siglo XX. [56]

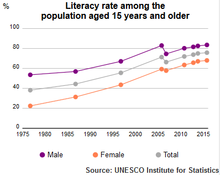

Muhammad Ali Pasha hizo evolucionar el ejército, que pasó de ser un ejército que se reunía bajo la tradición de la corvée a un gran ejército modernizado. Introdujo el reclutamiento del campesinado masculino en Egipto en el siglo XIX y adoptó un enfoque novedoso para crear su gran ejército, reforzándolo con número y habilidad. La educación y el entrenamiento de los nuevos soldados se volvieron obligatorios; además, los nuevos conceptos se reforzaron mediante el aislamiento. Los hombres fueron recluidos en cuarteles para evitar distracciones en su crecimiento como una unidad militar a tener en cuenta. El resentimiento por el estilo de vida militar finalmente se desvaneció de los hombres y se apoderó de una nueva ideología, una de nacionalismo y orgullo. Fue con la ayuda de esta unidad marcial recién renacida que Muhammad Ali impuso su gobierno sobre Egipto. [57] La política que siguió Mohammad Ali Pasha durante su reinado explica en parte por qué la capacidad numérica en Egipto, en comparación con otros países del norte de África y Oriente Medio, aumentó solo a un ritmo notablemente pequeño, ya que la inversión en educación superior solo se realizó en el sector militar e industrial. [58] Muhammad Ali fue sucedido brevemente por su hijo Ibrahim (en septiembre de 1848), luego por un nieto, Abbas I (en noviembre de 1848), luego por Said (en 1854) e Isma'il (en 1863), quien fomentó la ciencia y la agricultura y prohibió la esclavitud en Egipto. [56]

Egipto, bajo la dinastía Muhammad Ali , siguió siendo nominalmente una provincia otomana. En 1867 se le concedió el estatus de estado vasallo autónomo o Khedivate (1867-1914). El Canal de Suez , construido en colaboración con los franceses, se completó en 1869. Su construcción fue financiada por bancos europeos. Grandes sumas también se destinaron al clientelismo y la corrupción. Los nuevos impuestos provocaron el descontento popular. En 1875, Ismail evitó la quiebra vendiendo todas las acciones de Egipto en el canal al gobierno británico. En tres años, esto llevó a la imposición de controladores británicos y franceses que formaban parte del gabinete egipcio y, "con el poder financiero de los tenedores de bonos detrás de ellos, eran el poder real en el gobierno". [59] Otras circunstancias, como las enfermedades epidémicas (enfermedades del ganado en la década de 1880), las inundaciones y las guerras impulsaron la recesión económica y aumentaron aún más la dependencia de Egipto de la deuda externa. [60]

El descontento local con el Jedive y con la intrusión europea condujo a la formación de los primeros grupos nacionalistas en 1879, con Ahmed ʻUrabi como figura destacada. Después de aumentar las tensiones y las revueltas nacionalistas, el Reino Unido invadió Egipto en 1882, aplastando al ejército egipcio en la batalla de Tell El Kebir y ocupando militarmente el país. [61] Después de esto, el Jedive se convirtió en un protectorado británico de facto bajo soberanía otomana nominal. [62] En 1899 se firmó el Acuerdo de Condominio Anglo-Egipcio: el Acuerdo establecía que Sudán sería gobernado conjuntamente por el Jedive de Egipto y el Reino Unido. Sin embargo, el control real de Sudán estaba en manos únicamente británicas. En 1906, el incidente de Denshawai impulsó a muchos egipcios neutrales a unirse al movimiento nacionalista.

En 1914, el Imperio otomano entró en la Primera Guerra Mundial en alianza con los Imperios centrales; el Jedive Abbas II (que se había vuelto cada vez más hostil a los británicos en los años anteriores) decidió apoyar a la madre patria en la guerra. Tras tal decisión, los británicos lo destituyeron por la fuerza del poder y lo reemplazaron por su hermano Hussein Kamel . [63] [64] Hussein Kamel declaró la independencia de Egipto del Imperio otomano, asumiendo el título de sultán de Egipto . Poco después de la independencia, Egipto fue declarado protectorado del Reino Unido.

Después de la Primera Guerra Mundial , Saad Zaghlul y el Partido Wafd lideraron el movimiento nacionalista egipcio hasta lograr una mayoría en la Asamblea Legislativa local . Cuando los británicos exiliaron a Zaghlul y sus asociados a Malta el 8 de marzo de 1919, el país se levantó en su primera revolución moderna . La revuelta llevó al gobierno del Reino Unido a emitir una declaración unilateral de independencia de Egipto el 22 de febrero de 1922. [65] Después de la independencia del Reino Unido, el sultán Fuad I asumió el título de rey de Egipto ; a pesar de ser nominalmente independiente, el Reino todavía estaba bajo ocupación militar británica y el Reino Unido todavía tenía una gran influencia sobre el estado. El nuevo gobierno redactó e implementó una constitución en 1923 basada en un sistema parlamentario . El nacionalista Partido Wafd obtuvo una victoria aplastante en las elecciones de 1923-1924 y Saad Zaghloul fue designado como el nuevo primer ministro. En 1936 se firmó el Tratado anglo-egipcio y las tropas británicas se retiraron de Egipto, a excepción del Canal de Suez. El tratado no resolvió la cuestión de Sudán , que, según los términos del Acuerdo de Condominio Anglo-Egipcio existente de 1899, establecía que Sudán debería ser gobernado conjuntamente por Egipto y Gran Bretaña, pero que el poder real permanecería en manos británicas. [66]

Gran Bretaña utilizó Egipto como base para las operaciones aliadas en toda la región, especialmente las batallas en el norte de África contra Italia y Alemania. Sus mayores prioridades eran el control del Mediterráneo oriental y, especialmente, mantener abierto el Canal de Suez para los buques mercantes y para las conexiones militares con la India y Australia. Cuando comenzó la guerra en septiembre de 1939, Egipto declaró la ley marcial y rompió relaciones diplomáticas con Alemania. Rompió relaciones diplomáticas con Italia en 1940, pero nunca declaró la guerra, ni siquiera cuando el ejército italiano invadió Egipto. El ejército egipcio no combatió. En junio de 1940, el rey destituyó al primer ministro Aly Maher, que no se llevaba bien con los británicos. Se formó un nuevo gobierno de coalición con el independiente Hassan Pasha Sabri como primer ministro.

Tras una crisis ministerial en febrero de 1942, el embajador Sir Miles Lampson presionó a Farouk para que un gobierno del Wafd o de coalición del Wafd sustituyera al gobierno de Hussein Sirri Pasha . En la noche del 4 de febrero de 1942, tropas y tanques británicos rodearon el Palacio Abdeen en El Cairo y Lampson presentó un ultimátum a Farouk . Farouk capituló y Nahhas formó gobierno poco después.

La mayoría de las tropas británicas se retiraron a la zona del Canal de Suez en 1947 (aunque el ejército británico mantuvo una base militar en la zona), pero los sentimientos nacionalistas y antibritánicos continuaron creciendo después de la guerra. Los sentimientos antimonárquicos aumentaron aún más tras el desastroso desempeño del Reino en la Primera Guerra Árabe-Israelí . Las elecciones de 1950 vieron una victoria aplastante del Partido Nacionalista Wafd y el Rey se vio obligado a nombrar a Mostafa El-Nahas como nuevo primer ministro. En 1951, Egipto se retiró unilateralmente del Tratado Anglo-Egipcio de 1936 y ordenó a todas las tropas británicas restantes que abandonaran el Canal de Suez.

Como los británicos se negaron a abandonar su base en torno al Canal de Suez, el gobierno egipcio cortó el suministro de agua y se negó a permitir la entrada de alimentos a la base del Canal de Suez, anunció un boicot a los productos británicos, prohibió a los trabajadores egipcios entrar en la base y patrocinó ataques guerrilleros. El 24 de enero de 1952, las guerrillas egipcias organizaron un feroz ataque contra las fuerzas británicas en torno al Canal de Suez, durante el cual se observó a la Policía Auxiliar egipcia ayudando a las guerrillas. En respuesta, el 25 de enero, el general George Erskine envió tanques e infantería británicos para rodear la estación de policía auxiliar en Ismailia. El comandante de la policía llamó al ministro del Interior, Fouad Serageddin , la mano derecha de Nahas, para preguntarle si debía rendirse o luchar. Serageddin ordenó a la policía que luchara "hasta el último hombre y la última bala". La batalla resultante vio la estación de policía arrasada y 43 policías egipcios muertos junto con 3 soldados británicos. El incidente de Ismailia indignó a Egipto. Al día siguiente, el 26 de enero de 1952, se produjo el «Sábado Negro» , como se conoció a los disturbios antibritánicos, en los que se quemó gran parte del centro de El Cairo, que el Jedive Ismail el Magnífico había reconstruido al estilo de París. Farouk culpó al Wafd por los disturbios del Sábado Negro y destituyó a Nahas como primer ministro al día siguiente. Fue reemplazado por Aly Maher Pasha . [67]

El 22 y 23 de julio de 1952, el Movimiento de Oficiales Libres , encabezado por Muhammad Naguib y Gamal Abdel Nasser , lanzó un golpe de Estado ( Revolución egipcia de 1952 ) contra el rey. Faruk I abdicó el trono en favor de su hijo Fouad II , que en ese momento era un bebé de siete meses. La familia real abandonó Egipto unos días después y se formó el Consejo de Regencia, encabezado por el príncipe Muhammad Abdel Moneim . Sin embargo, el consejo solo tenía autoridad nominal y el poder real estaba en manos del Consejo del Comando Revolucionario , encabezado por Naguib y Nasser. Las expectativas populares de reformas inmediatas condujeron a los disturbios obreros en Kafr Dawar el 12 de agosto de 1952. Tras un breve experimento con el gobierno civil, los Oficiales Libres derogaron la monarquía y la constitución de 1923 y declararon a Egipto una república el 18 de junio de 1953. Naguib fue proclamado presidente, mientras que Nasser fue designado como nuevo primer ministro.

Tras la Revolución de 1952, impulsada por el Movimiento de Oficiales Libres , el gobierno de Egipto pasó a manos militares y se prohibieron todos los partidos políticos. El 18 de junio de 1953 se declaró la República de Egipto, con el general Muhammad Naguib como primer presidente de la República, cargo que ocupó durante poco menos de un año y medio. Se declaró la República de Egipto (1953-1958).

Naguib fue obligado a dimitir en 1954 por Gamal Abdel Nasser –un panarabista y el verdadero arquitecto del movimiento de 1952– y más tarde fue puesto bajo arresto domiciliario . Tras la dimisión de Naguib, el cargo de presidente quedó vacante hasta la elección de Nasser en 1956. [68] En octubre de 1954, Egipto y el Reino Unido acordaron abolir el Acuerdo de Condominio Anglo-Egipcio de 1899 y conceder la independencia a Sudán; el acuerdo entró en vigor el 1 de enero de 1956. Nasser asumió el poder como presidente en junio de 1956 y comenzó a dominar la historia del Egipto moderno . Las fuerzas británicas completaron su retirada de la Zona del Canal de Suez ocupada el 13 de junio de 1956. Nacionalizó el Canal de Suez el 26 de julio de 1956; Su actitud hostil hacia Israel y su nacionalismo económico provocaron el inicio de la Segunda Guerra Árabe-Israelí (Crisis de Suez), en la que Israel (con el apoyo de Francia y el Reino Unido) ocupó la península del Sinaí y el Canal. La guerra terminó gracias a la intervención diplomática de los Estados Unidos y la URSS y se restableció el statu quo .

En 1958, Egipto y Siria formaron una unión soberana conocida como la República Árabe Unida . La unión duró poco y terminó en 1961 cuando Siria se separó. Durante la mayor parte de su existencia, la República Árabe Unida también estuvo en una confederación flexible con Yemen del Norte (o el Reino Mutawakkilite de Yemen), conocido como los Estados Árabes Unidos . A principios de la década de 1960, Egipto se involucró de lleno en la Guerra Civil de Yemen del Norte . A pesar de varias maniobras militares y conferencias de paz, la guerra se hundió en un punto muerto. [69] A mediados de mayo de 1967, la Unión Soviética emitió advertencias a Nasser sobre un inminente ataque israelí a Siria. Aunque el jefe del Estado Mayor, Mohamed Fawzi, verificó que las afirmaciones eran "infundadas", [70] [71] Nasser tomó tres medidas sucesivas que hicieron que la guerra fuera prácticamente inevitable: el 14 de mayo desplegó sus tropas en el Sinaí, cerca de la frontera con Israel; el 19 de mayo expulsó a las fuerzas de paz de la ONU estacionadas en la frontera de la península del Sinaí con Israel, y el 23 de mayo cerró el estrecho de Tirán a la navegación israelí. [72] El 26 de mayo, Nasser declaró: "La batalla será general y nuestro objetivo básico será destruir a Israel". [73]

Esto provocó el comienzo de la Tercera Guerra Árabe Israelí (Guerra de los Seis Días) en la que Israel atacó a Egipto y ocupó la península del Sinaí y la Franja de Gaza , que Egipto había ocupado desde la Guerra Árabe-Israelí de 1948. Durante la guerra de 1967, se promulgó una Ley de Emergencia , que permaneció en vigor hasta 2012, con la excepción de una pausa de 18 meses en 1980/81. [74] Bajo esta ley, se ampliaron los poderes policiales, se suspendieron los derechos constitucionales y se legalizó la censura. [75] En el momento de la caída de la monarquía egipcia a principios de la década de 1950, menos de medio millón de egipcios eran considerados de clase alta y ricos, cuatro millones de clase media y 17 millones de clase baja y pobres. [76] Menos de la mitad de todos los niños en edad escolar primaria asistían a la escuela, la mayoría de ellos varones. Las políticas de Nasser cambiaron esto. La reforma y distribución de la tierra, el espectacular crecimiento de la educación universitaria y el apoyo gubernamental a las industrias nacionales mejoraron enormemente la movilidad social y aplanaron la curva social. Desde el año académico 1953-54 hasta 1965-66, la matrícula total en las escuelas públicas aumentó más del doble. Millones de egipcios que antes eran pobres, a través de la educación y los empleos en el sector público, se unieron a la clase media. Médicos, ingenieros, maestros, abogados y periodistas constituyeron la mayor parte de la creciente clase media en Egipto bajo Nasser. [76] Durante la década de 1960, la economía egipcia pasó de estar estancada al borde del colapso, la sociedad se volvió menos libre y el atractivo de Nasser disminuyó considerablemente. [77]

En 1970, el presidente Nasser murió y fue sucedido por Anwar Sadat . Durante su período , Sadat cambió la lealtad de Egipto de la Guerra Fría de la Unión Soviética a los Estados Unidos , expulsando a los asesores soviéticos en 1972. Egipto fue rebautizado como República Árabe de Egipto en 1971. Sadat lanzó la política de reforma económica Infitah , al tiempo que reprimió a la oposición religiosa y secular. En 1973, Egipto, junto con Siria, lanzó la Cuarta Guerra Árabe-Israelí (Guerra de Yom Kippur), un ataque sorpresa para recuperar parte del territorio del Sinaí que Israel había capturado 6 años antes. En 1975, Sadat cambió las políticas económicas de Nasser y trató de usar su popularidad para reducir las regulaciones gubernamentales y alentar la inversión extranjera a través de su programa Infitah. A través de esta política, incentivos como impuestos y aranceles de importación reducidos atrajeron a algunos inversores, pero las inversiones se dirigieron principalmente a empresas de bajo riesgo y rentables como el turismo y la construcción, abandonando las industrias incipientes de Egipto. [78] Debido a la eliminación de los subsidios a los alimentos básicos, condujo a los disturbios del pan egipcio de 1977. Sadat realizó una visita histórica a Israel en 1977 , que condujo al tratado de paz entre Egipto e Israel de 1979 a cambio de la retirada israelí del Sinaí. A cambio, Egipto reconoció a Israel como un estado soberano legítimo. La iniciativa de Sadat desató una enorme controversia en el mundo árabe y condujo a la expulsión de Egipto de la Liga Árabe , pero fue apoyada por la mayoría de los egipcios. [79] Sadat fue asesinado por un extremista islámico en octubre de 1981.

Hosni Mubarak llegó al poder tras el asesinato de Sadat en un referéndum en el que era el único candidato. [80] Se convirtió en otro líder que dominó la historia de Egipto . Hosni Mubarak reafirmó la relación de Egipto con Israel, pero alivió las tensiones con los vecinos árabes de Egipto. En el ámbito interno, Mubarak se enfrentó a graves problemas. La pobreza masiva y el desempleo llevaron a las familias rurales a irse a ciudades como El Cairo, donde terminaron en barrios marginales abarrotados, apenas logrando sobrevivir. El 25 de febrero de 1986 , la Policía de Seguridad comenzó a amotinarse, en protesta por los informes de que su período de servicio se extendería de 3 a 4 años. Hoteles, clubes nocturnos, restaurantes y casinos fueron atacados en El Cairo y hubo disturbios en otras ciudades. Se impuso un toque de queda durante el día. El ejército tardó 3 días en restablecer el orden. 107 personas murieron. [81]

En los decenios de 1980, 1990 y 2000, los ataques terroristas en Egipto se hicieron numerosos y graves, y comenzaron a tener como objetivo a cristianos coptos , turistas extranjeros y funcionarios del gobierno. [82] En los años 1990, un grupo islamista , Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya , participó en una extensa campaña de violencia, desde asesinatos e intentos de asesinato de escritores e intelectuales destacados hasta repetidos ataques contra turistas y extranjeros. Se causó un daño grave al mayor sector de la economía de Egipto, el turismo [83] , y a su vez al gobierno, pero también devastó los medios de vida de muchas de las personas de las que dependía el grupo para su sustento. [84] Durante el régimen de Mubarak, la escena política estaba dominada por el Partido Democrático Nacional , creado por Sadat en 1978. Aprobó la Ley de Sindicatos de 1993, la Ley de Prensa de 1995 y la Ley de Asociaciones No Gubernamentales de 1999, que obstaculizaron las libertades de asociación y expresión al imponer nuevas regulaciones y sanciones draconianas por las violaciones. [85] Como resultado, a fines de la década de 1990, la política parlamentaria se había vuelto virtualmente irrelevante y también se restringieron las vías alternativas para la expresión política. [86] El Cairo se convirtió en un área metropolitana con una población de más de 20 millones.

El 17 de noviembre de 1997, 62 personas, en su mayoría turistas, fueron masacradas cerca de Luxor . A finales de febrero de 2005, Mubarak anunció una reforma de la ley de elecciones presidenciales, allanando el camino para elecciones con múltiples candidatos por primera vez desde el movimiento de 1952. [87] Sin embargo, la nueva ley impuso restricciones a los candidatos y condujo a la fácil reelección de Mubarak. [88] La participación electoral fue inferior al 25%. [89] Los observadores electorales también denunciaron la interferencia del gobierno en el proceso electoral. [90] Después de la elección, Mubarak encarceló a Ayman Nour , el segundo candidato. [91]

El informe de 2006 de Human Rights Watch sobre Egipto detalló graves violaciones de los derechos humanos bajo el régimen de Mubarak, incluyendo torturas rutinarias , detenciones arbitrarias y juicios ante tribunales militares y de seguridad del Estado. [92] En 2007, Amnistía Internacional publicó un informe en el que afirmaba que Egipto se había convertido en un centro internacional de tortura, donde otras naciones envían sospechosos para interrogarlos, a menudo como parte de la Guerra contra el Terror . [93] El Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Egipto emitió rápidamente una refutación a este informe. [94] Los cambios constitucionales votados el 19 de marzo de 2007 prohibieron a los partidos utilizar la religión como base para la actividad política, permitieron la redacción de una nueva ley antiterrorista, autorizaron amplios poderes policiales de arresto y vigilancia, y dieron al presidente el poder de disolver el parlamento y poner fin a la supervisión judicial de las elecciones. [95] En 2009, el Dr. Ali El Deen Hilal Dessouki, Secretario de Medios del Partido Democrático Nacional ( NDP ), describió a Egipto como un sistema político " faraónico " y la democracia como un "objetivo a largo plazo". Dessouki también afirmó que "el verdadero centro del poder en Egipto es el ejército". [ cita requerida ]

El 25 de enero de 2011 comenzaron las protestas generalizadas contra el gobierno de Mubarak. El 11 de febrero de 2011, Mubarak dimitió y huyó de El Cairo. En la plaza Tahrir de El Cairo estallaron celebraciones jubilosas ante la noticia. [96] El ejército egipcio asumió entonces el poder de gobernar. [97] [98] Mohamed Hussein Tantawi , presidente del Consejo Supremo de las Fuerzas Armadas , se convirtió en el jefe de Estado interino de facto . [99] [100] El 13 de febrero de 2011, el ejército disolvió el parlamento y suspendió la constitución. [101]

El 19 de marzo de 2011 se celebró un referéndum constitucional. [102] El 28 de noviembre de 2011, Egipto celebró sus primeras elecciones parlamentarias desde que el régimen anterior estaba en el poder. La participación fue alta y no hubo informes de irregularidades importantes ni violencia. [103]

El 24 de junio de 2012 fue elegido presidente Mohamed Morsi , que estaba afiliado a la Hermandad Musulmana . [104] El 30 de junio de 2012, Mohamed Morsi juró como presidente de Egipto. [105] El 2 de agosto de 2012, el primer ministro egipcio, Hisham Qandil, anunció su gabinete de 35 miembros, compuesto por 28 recién llegados, incluidos cuatro de la Hermandad Musulmana. [106] Los grupos liberales y seculares abandonaron la Asamblea Constituyente porque creían que impondría estrictas prácticas islámicas, mientras que los partidarios de la Hermandad Musulmana dieron su apoyo a Morsi. [107] El 22 de noviembre de 2012, el presidente Morsi emitió una declaración temporal inmunizando sus decretos de ser impugnados y buscando proteger el trabajo de la Asamblea Constituyente. [108]

La medida provocó protestas masivas y acciones violentas en todo Egipto. [109] El 5 de diciembre de 2012, decenas de miles de partidarios y opositores del presidente Morsi se enfrentaron, en lo que se describió como la mayor batalla violenta entre islamistas y sus enemigos desde la revolución del país. [110] Mohamed Morsi ofreció un "diálogo nacional" con los líderes de la oposición, pero se negó a cancelar el referéndum constitucional de diciembre de 2012. [ 111] El 3 de julio de 2013, después de una ola de descontento público con los excesos autocráticos del gobierno de la Hermandad Musulmana de Morsi, [112] los militares destituyeron a Morsi de su cargo, disolvieron el Consejo de la Shura e instalaron un gobierno interino temporal. [113]

El 4 de julio de 2013, el presidente del Tribunal Constitucional Supremo de Egipto, Adly Mansour, de 68 años, juró como presidente interino del nuevo gobierno tras la destitución de Morsi. [114] Las nuevas autoridades egipcias tomaron medidas enérgicas contra los Hermanos Musulmanes y sus partidarios, encarcelando a miles de personas y dispersando por la fuerza las protestas a favor de Morsi y de la Hermandad. [115] [116] Muchos de los líderes y activistas de los Hermanos Musulmanes han sido condenados a muerte o cadena perpetua en una serie de juicios masivos. [117] [118] [119] El 18 de enero de 2014, el gobierno interino instituyó una nueva constitución tras un referéndum aprobado por una abrumadora mayoría de votantes (98,1%). El 38,6% de los votantes registrados participaron en el referéndum [120], un número mayor que el 33% que votó en un referéndum durante el mandato de Morsi. [121]

En las elecciones de junio de 2014, El Sisi ganó con un porcentaje del 96,1%. [122] El 8 de junio de 2014, Abdel Fatah El Sisi juró oficialmente como nuevo presidente de Egipto. [123] Bajo el Presidente El Sisi, Egipto ha implementado una política rigurosa de control de la frontera con la Franja de Gaza, incluido el desmantelamiento de túneles entre la Franja de Gaza y el Sinaí. [124] En abril de 2018, El Sisi fue reelegido por una mayoría aplastante en una elección sin oposición real. [125] En abril de 2019, el parlamento de Egipto extendió los mandatos presidenciales de cuatro a seis años. Al presidente Abdel Fattah Al Sisi también se le permitió postularse para un tercer mandato en las próximas elecciones de 2024. [126]

Se dice que Egipto ha vuelto al autoritarismo bajo el gobierno de El Sisi . Se han implementado nuevas reformas constitucionales que han reforzado el papel de los militares y limitado la oposición política. [127] Los cambios constitucionales fueron aceptados en un referéndum en abril de 2019. [128] En diciembre de 2020, los resultados finales de las elecciones parlamentarias confirmaron una clara mayoría de los escaños para el Partido Mostaqbal Watan ( Futuro de la Nación ) de Egipto , que apoya firmemente al presidente El Sisi. El partido incluso aumentó su mayoría, en parte debido a las nuevas reglas electorales. [129]

Egipto se encuentra principalmente entre las latitudes 22° y 32° N y las longitudes 25° y 35° E. Con 1.001.450 kilómetros cuadrados (386.660 millas cuadradas), es el 30.º país más grande del mundo. [130] Debido a la extrema aridez del clima de Egipto, los centros de población se concentran a lo largo del estrecho valle y del delta del Nilo, lo que significa que aproximadamente el 99% de la población utiliza aproximadamente el 5,5% de la superficie terrestre total. [131] El 98% de los egipcios vive en el 3% del territorio. [132]

Egipto limita al oeste con Libia, al sur con Sudán y al este con la Franja de Gaza e Israel. Es una nación transcontinental que posee un puente terrestre (el istmo de Suez) entre África y Asia, atravesado por una vía navegable (el canal de Suez ) que conecta el mar Mediterráneo con el océano Índico a través del mar Rojo.

Aparte del valle del Nilo, la mayor parte del paisaje de Egipto es desértico, con algunos oasis dispersos por todas partes. Los vientos crean prolíficas dunas de arena que alcanzan más de 30 metros de altura. Egipto incluye partes del desierto del Sahara y del desierto de Libia .

La península del Sinaí alberga la montaña más alta de Egipto, el monte Catalina, de 2.642 metros. La Riviera del Mar Rojo , al este de la península, es famosa por su riqueza en arrecifes de coral y vida marina.

Las ciudades y pueblos incluyen Alejandría , la segunda ciudad más grande; Asuán ; Asiut ; El Cairo , la capital egipcia moderna y la ciudad más grande; El Mahalla El Kubra ; Giza , el sitio de la pirámide de Keops; Hurghada ; Luxor ; Kom Ombo ; Port Safaga ; Port Said ; Sharm El Sheikh ; Suez , donde se encuentra el extremo sur del Canal de Suez; Zagazig ; y Minya . Los oasis incluyen Bahariya , Dakhla , Farafra , Kharga y Siwa . Los protectorados incluyen el Parque Nacional Ras Mohamed, el Protectorado de Zaranik y Siwa.

El 13 de marzo de 2015 se anunciaron los planes para una nueva capital de Egipto . [133]

.jpg/440px-Sand_Dunes_(Qattara_Depression).jpg)

La mayor parte de la lluvia en Egipto cae en los meses de invierno. [134] Al sur de El Cairo, la precipitación media es de sólo entre 2 y 5 mm (0,1 a 0,2 pulgadas) al año y en intervalos de muchos años. En una franja muy delgada de la costa norte la precipitación puede llegar a los 410 mm (16,1 pulgadas), [135] sobre todo entre octubre y marzo. La nieve cae en las montañas del Sinaí y en algunas de las ciudades costeras del norte como Damietta , Baltim y Sidi Barrani , y rara vez en Alejandría. Una cantidad muy pequeña de nieve cayó en El Cairo el 13 de diciembre de 2013, la primera vez en muchas décadas. [136] También se conocen heladas en el centro del Sinaí y en el centro de Egipto.

Egipto tiene un clima inusualmente cálido, soleado y seco. Las temperaturas máximas promedio son altas en el norte, pero muy altas en el resto del país durante el verano. Los vientos más frescos del Mediterráneo soplan constantemente sobre la costa norte del mar, lo que ayuda a obtener temperaturas más moderadas, especialmente en pleno verano. El Khamaseen es un viento cálido y seco que se origina en los vastos desiertos del sur y sopla en primavera o a principios del verano. Trae arena abrasadora y partículas de polvo, y generalmente trae temperaturas diurnas superiores a los 40 °C (104 °F) y, a veces, superiores a los 50 °C (122 °F) en el interior, mientras que la humedad relativa puede caer al 5% o incluso menos.

Antes de la construcción de la presa de Asuán , el Nilo se desbordaba todos los años, reabasteciendo el suelo egipcio, lo que le proporcionaba una cosecha constante a lo largo de los años.

El aumento potencial del nivel del mar debido al calentamiento global podría amenazar la franja costera densamente poblada de Egipto y tener graves consecuencias para la economía, la agricultura y la industria del país. Combinado con las crecientes presiones demográficas, un aumento significativo del nivel del mar podría convertir a millones de egipcios en refugiados ambientales para fines del siglo XXI, según algunos expertos en clima. [137] [138]

Egipto firmó el Convenio de Río sobre la Diversidad Biológica el 9 de junio de 1992 y se convirtió en parte de la convención el 2 de junio de 1994. [139] Posteriormente, elaboró una Estrategia y Plan de Acción Nacional sobre Biodiversidad , que fue recibida por la convención el 31 de julio de 1998. [140] Mientras que muchas Estrategias y Planes de Acción Nacionales sobre Biodiversidad del CDB descuidan reinos biológicos aparte de los animales y las plantas, [141]

En el plan se establecía que se habían registrado en Egipto las siguientes cantidades de especies de diferentes grupos: algas (1.483 especies), animales (unas 15.000 especies, de las cuales más de 10.000 eran insectos), hongos (más de 627 especies), moneras (319 especies), plantas (2.426 especies), protozoos (371 especies). En el caso de algunos grupos importantes, por ejemplo, los hongos formadores de líquenes y los gusanos nematodos, no se conocía la cantidad. Aparte de grupos pequeños y bien estudiados como los anfibios, las aves, los peces, los mamíferos y los reptiles, es probable que muchas de esas cantidades aumenten a medida que se registren más especies en Egipto. En el caso de los hongos, incluidas las especies formadoras de líquenes, por ejemplo, trabajos posteriores han demostrado que se han registrado más de 2.200 especies en Egipto, y se espera que la cifra final de todos los hongos que se dan realmente en el país sea mucho mayor. [142] En cuanto a las gramíneas, se han identificado y registrado en Egipto 284 especies nativas y naturalizadas. [143]

La Cámara de Representantes , cuyos miembros son elegidos para cumplir mandatos de cinco años, se especializa en legislación. Las elecciones se celebraron entre noviembre de 2011 y enero de 2012 , que luego se disolvieron. Se anunció que las siguientes elecciones parlamentarias se celebrarían dentro de los seis meses siguientes a la ratificación de la constitución el 18 de enero de 2014, y se celebraron en dos fases, del 17 de octubre al 2 de diciembre de 2015. [144] Originalmente, el parlamento se iba a formar antes de que se eligiera al presidente, pero el presidente interino Adly Mansour pospuso la fecha. [145] Las elecciones presidenciales egipcias de 2014 se celebraron del 26 al 28 de mayo. Las cifras oficiales mostraron una participación de 25.578.233 o el 47,5%, con Abdel Fattah el-Sisi ganando con 23,78 millones de votos, o el 96,9% en comparación con los 757.511 (3,1%) de Hamdeen Sabahi . [146]

Tras una ola de descontento público con los excesos autocráticos [ aclaración necesaria ] del gobierno de la Hermandad Musulmana del presidente Mohamed Morsi , [112] el 3 de julio de 2013 el entonces general Abdel Fattah el-Sisi anunció la destitución de Morsi de su cargo y la suspensión de la constitución . Se formó un comité constitucional de 50 miembros para modificar la constitución , que luego se publicó para votación pública y se adoptó el 18 de enero de 2014. [147]

En 2024, como parte de su informe Libertad en el Mundo , Freedom House calificó los derechos políticos en Egipto con un 6 (siendo 40 el más libre y 0 el menos libre), y las libertades civiles con un 12 (siendo 60 el puntaje más alto y 0 el más bajo), lo que le dio la calificación de libertad de "No libre". [148] Según los índices de democracia V-Dem de 2023, Egipto es el octavo país menos democrático de África . [149] La edición de 2023 del Índice de democracia de The Economist clasifica a Egipto como un "régimen autoritario", con una puntuación de 2,93. [150]

El nacionalismo egipcio es anterior a su homólogo árabe en muchas décadas, tiene raíces en el siglo XIX y se convirtió en el modo de expresión dominante de los activistas e intelectuales anticoloniales egipcios hasta principios del siglo XX. [151] La ideología defendida por islamistas como la Hermandad Musulmana es apoyada en su mayoría por los estratos medios-bajos de la sociedad egipcia. [152]

Egipto tiene la tradición parlamentaria continua más antigua del mundo árabe. [153] La primera asamblea popular se estableció en 1866. Se disolvió como resultado de la ocupación británica de 1882, y los británicos sólo permitieron que se reuniera un órgano consultivo. Sin embargo, en 1923, después de que se declarara la independencia del país, una nueva constitución preveía una monarquía parlamentaria. [153]

El ejército tiene influencia en la vida política y económica de Egipto y se exime de las leyes que se aplican a otros sectores. Goza de considerable poder, prestigio e independencia dentro del Estado y ha sido ampliamente considerado parte del " Estado profundo " egipcio. [80] [154] [155]

Israel especula que Egipto es el segundo país de la región con un satélite espía , EgyptSat 1 [156] además de EgyptSat 2 lanzado el 16 de abril de 2014. [157]

Estados Unidos proporciona a Egipto asistencia militar anual , que en 2015 ascendió a 1.300 millones de dólares. [158] En 1989, Egipto fue designado como un importante aliado no perteneciente a la OTAN de los Estados Unidos. [159] Sin embargo, los lazos entre los dos países se han deteriorado parcialmente desde el derrocamiento en julio de 2013 del presidente islamista Mohamed Morsi , [160] con la administración Obama denunciando a Egipto por su represión de la Hermandad Musulmana y cancelando futuros ejercicios militares que involucraran a los dos países. [161] Sin embargo, ha habido intentos recientes de normalizar las relaciones entre los dos, y ambos gobiernos han pedido con frecuencia apoyo mutuo en la lucha contra el terrorismo regional e internacional . [162] [163] [164] Sin embargo, tras la elección del republicano Donald Trump como presidente de los Estados Unidos , los dos países buscaban mejorar las relaciones egipcio-estadounidenses . El 3 de abril de 2017, Al Sisi se reunió con Trump en la Casa Blanca, lo que marcó la primera visita de un presidente egipcio a Washington en ocho años. Trump elogió a Al Sisi en lo que se informó como una victoria de relaciones públicas para el presidente egipcio, y señaló que era hora de normalizar las relaciones entre Egipto y Estados Unidos. [165]

Las relaciones con Rusia han mejorado significativamente tras la destitución de Mohamed Morsi [166] y desde entonces ambos países han trabajado para fortalecer los lazos militares [167] y comerciales [168], entre otros aspectos de la cooperación bilateral. Las relaciones con China también han mejorado considerablemente. En 2014, Egipto y China establecieron una “asociación estratégica integral” bilateral [169] .

La sede permanente de la Liga Árabe se encuentra en El Cairo y el secretario general del organismo ha sido tradicionalmente egipcio. Este cargo lo ocupa actualmente el ex ministro de Asuntos Exteriores Ahmed Aboul Gheit . La Liga Árabe se trasladó brevemente de Egipto a Túnez en 1978 para protestar por el tratado de paz entre Egipto e Israel , pero luego regresó a El Cairo en 1989. Las monarquías del Golfo, incluidos los Emiratos Árabes Unidos [170] y Arabia Saudita [171] , han prometido miles de millones de dólares para ayudar a Egipto a superar sus dificultades económicas desde el derrocamiento de Morsi. [172]

Tras la guerra de 1973 y el posterior tratado de paz, Egipto se convirtió en la primera nación árabe en establecer relaciones diplomáticas con Israel. A pesar de ello, la mayoría de los egipcios todavía considera a Israel como un Estado hostil. [173] Egipto ha desempeñado un papel histórico como mediador en la resolución de diversas disputas en Oriente Medio, en particular su gestión del conflicto israelí-palestino y el proceso de paz . [174] Los esfuerzos de Egipto por alcanzar un alto el fuego y una tregua en Gaza apenas han sido cuestionados tras la evacuación de los asentamientos israelíes de la Franja en 2005, a pesar de la creciente animosidad hacia el gobierno de Hamás en Gaza tras el derrocamiento de Mohamed Morsi, [175] y a pesar de los recientes intentos de países como Turquía y Qatar de asumir este papel. [176]

Los vínculos entre Egipto y otras naciones no árabes de Oriente Medio, entre ellas Irán y Turquía , han sido a menudo tensos. Las tensiones con Irán se deben principalmente al tratado de paz de Egipto con Israel y a la rivalidad de Irán con sus aliados tradicionales egipcios en el Golfo. [177] El reciente apoyo de Turquía a la ahora prohibida Hermandad Musulmana en Egipto y su presunta participación en Libia también convirtieron a ambos países en rivales regionales acérrimos. [178]

Egipto es miembro fundador del Movimiento de Países No Alineados y de las Naciones Unidas . También es miembro de la Organización Internacional de la Francofonía desde 1983. El ex viceprimer ministro egipcio Boutros Boutros-Ghali fue Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas entre 1991 y 1996.

En 2008, se calculaba que Egipto tenía dos millones de refugiados africanos, incluidos más de 20.000 nacionales sudaneses registrados en el ACNUR como refugiados que huían de conflictos armados o solicitantes de asilo. Egipto adoptó métodos de control fronterizo "duros, a veces letales". [179]

El sistema jurídico se basa en el derecho islámico y civil (en particular los códigos napoleónicos ) y en la revisión judicial por parte de un Tribunal Supremo, que acepta la jurisdicción obligatoria de la Corte Internacional de Justicia sólo con reservas. [67]

La jurisprudencia islámica es la principal fuente de legislación. Los tribunales de la sharia y los cadíes son administrados y autorizados por el Ministerio de Justicia . [180] La ley sobre el estado civil que regula cuestiones como el matrimonio, el divorcio y la custodia de los hijos se rige por la sharia. En un tribunal de familia, el testimonio de una mujer vale la mitad del testimonio de un hombre. [181]

El 26 de diciembre de 2012, los Hermanos Musulmanes intentaron institucionalizar una nueva y controvertida constitución. La misma fue aprobada por el público en un referéndum celebrado entre el 15 y el 22 de diciembre de 2012 con un apoyo del 64%, pero con una participación de apenas el 33% del electorado. [182] Reemplazó a la Constitución Provisional de Egipto de 2011 , adoptada tras la revolución.

El Código Penal era único, ya que contenía una " Ley de Blasfemia ". [183] El sistema judicial actual permite la pena de muerte, incluso contra una persona ausente que haya sido juzgada en ausencia . Varios estadounidenses y canadienses fueron condenados a muerte en 2012. [184]

El 18 de enero de 2014, el gobierno interino institucionalizó con éxito una constitución más secular . [185] El presidente es elegido por un período de cuatro años y puede cumplir dos mandatos. [185] El parlamento puede destituir al presidente. [185] Según la constitución, existe una garantía de igualdad de género y absoluta libertad de pensamiento . [185] El ejército conserva la capacidad de nombrar al Ministro de Defensa nacional para los próximos dos mandatos presidenciales completos desde que la constitución entró en vigor. [185] Según la constitución, los partidos políticos no pueden basarse en "religión, raza, género o geografía". [185]

En 2003, el gobierno creó el Consejo Nacional de Derechos Humanos. [186] Poco después de su fundación, el consejo fue objeto de fuertes críticas por parte de activistas locales, quienes sostienen que era una herramienta de propaganda del gobierno para excusar sus propias violaciones [187] y dar legitimidad a leyes represivas como la Ley de Emergencia. [188]

El Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life clasifica a Egipto como el quinto peor país del mundo en cuanto a libertad religiosa. [189] [190] La Comisión de los Estados Unidos para la Libertad Religiosa Internacional , una agencia independiente bipartidista del gobierno de los Estados Unidos, ha colocado a Egipto en su lista de vigilancia de países que requieren una estrecha vigilancia debido a la naturaleza y el alcance de las violaciones de la libertad religiosa cometidas o toleradas por el gobierno. [191] Según una encuesta de Pew Global Attitudes de 2010, el 84% de los egipcios encuestados apoyaba la pena de muerte para quienes abandonan el Islam ; el 77% apoyaba los azotes y el corte de manos por robo y hurto; y el 82% apoyaba la lapidación de una persona que comete adulterio. [192]

Los cristianos coptos se enfrentan a la discriminación en múltiples niveles del gobierno, que van desde la escasa representación en los ministerios gubernamentales hasta leyes que limitan su capacidad para construir o reparar iglesias. [193] La intolerancia hacia los seguidores de la fe baháʼí y los de las sectas musulmanas no ortodoxas, como los sufíes , los chiítas y los ahmadíes , también sigue siendo un problema. [92] Cuando el gobierno decidió informatizar las tarjetas de identificación, los miembros de minorías religiosas, como los baháʼís, no pudieron obtener documentos de identificación . [194] Un tribunal egipcio dictaminó a principios de 2008 que los miembros de otras religiones pueden obtener tarjetas de identidad sin enumerar sus creencias y sin ser reconocidos oficialmente. [195]

Continuaron los enfrentamientos entre la policía y los partidarios del ex presidente Mohamed Morsi. Durante los violentos enfrentamientos que se produjeron en el marco de la concentración para dispersar a los manifestantes en agosto de 2013 , 595 manifestantes fueron asesinados [196], y el 14 de agosto de 2013 se convirtió en el día más mortífero de la historia moderna de Egipto. [197]

Egipto practica activamente la pena capital . Las autoridades egipcias no publican cifras sobre sentencias de muerte y ejecuciones, a pesar de las reiteradas solicitudes a lo largo de los años de las organizaciones de derechos humanos. [198] La oficina de derechos humanos de las Naciones Unidas [199] y varias ONG [198] [200] expresaron "profunda alarma" después de que un tribunal penal egipcio de Minya condenara a muerte a 529 personas en una sola audiencia el 25 de marzo de 2014. Los partidarios condenados del ex presidente Mohamed Morsi iban a ser ejecutados por su presunto papel en la violencia tras su derrocamiento en julio de 2013. La sentencia fue condenada como una violación del derecho internacional . [201] En mayo de 2014, aproximadamente 16.000 personas (y hasta más de 40.000 según un recuento independiente, según The Economist ), [202] en su mayoría miembros o partidarios de la Hermandad, han sido encarceladas después de la destitución de Morsi [203] después de que el gobierno interino egipcio posterior a Morsi calificara a la Hermandad Musulmana de organización terrorista . [204] Según grupos de derechos humanos, hay unos 60.000 presos políticos en Egipto. [205] [206]

La homosexualidad es ilegal en Egipto. [208] Según una encuesta de 2013 del Pew Research Center , el 95% de los egipcios cree que la homosexualidad no debería ser aceptada por la sociedad. [209]

En 2017, una encuesta de la Fundación Thomson Reuters votó a El Cairo como la megaciudad más peligrosa para las mujeres, con más de 10 millones de habitantes . Se describió el acoso sexual como algo cotidiano. [210]

En su Índice Mundial de Libertad de Prensa 2017, Reporteros Sin Fronteras situó a Egipto en el puesto 160 entre 180 países. En agosto de 2015, al menos 18 periodistas estaban encarcelados en Egipto. [update]En agosto de 2015 se promulgó una nueva ley antiterrorista que amenaza a los miembros de los medios de comunicación con multas que van desde los 25.000 a los 60.000 dólares estadounidenses por la distribución de información errónea sobre actos terroristas dentro del país "que difieran de las declaraciones oficiales del Departamento de Defensa egipcio". [211]

Algunos críticos del gobierno han sido arrestados por supuestamente difundir información falsa sobre la pandemia de COVID-19 en Egipto . [212] [213]

Egipto está dividido en 27 gobernaciones, que a su vez se dividen en regiones, que contienen ciudades y pueblos. Cada gobernación tiene una capital, que a veces lleva el mismo nombre que la gobernación. [214]

La economía de Egipto depende principalmente de la agricultura, los medios de comunicación, las exportaciones de petróleo, el gas natural y el turismo. Además, hay más de tres millones de egipcios que trabajan en el extranjero, principalmente en Libia , Arabia Saudita , el Golfo Pérsico y Europa. La finalización de la presa de Asuán en 1970 y el lago Nasser resultante han alterado el lugar tradicional del río Nilo en la agricultura y la ecología de Egipto. Una población en rápido crecimiento, una tierra cultivable limitada y la dependencia del Nilo siguen sobrecargando los recursos y estresando la economía.

En 2022, la economía egipcia entró en una crisis continua, la libra egipcia fue una de las monedas con peor desempeño, [215] la inflación alcanzó el 32,6% y la inflación básica alcanzó casi el 40% en marzo. [216]

El gobierno ha invertido en comunicaciones e infraestructura física. Egipto ha recibido ayuda exterior de los Estados Unidos desde 1979 (un promedio de 2.200 millones de dólares al año) y es el tercer mayor receptor de este tipo de fondos de los Estados Unidos después de la guerra de Irak. La economía de Egipto depende principalmente de estas fuentes de ingresos: el turismo, las remesas de los egipcios que trabajan en el extranjero y los ingresos procedentes del Canal de Suez. [217]

En los últimos años, el ejército egipcio ha ampliado su influencia económica , dominando sectores como las gasolineras, la piscicultura, la fabricación de automóviles, los medios de comunicación, la infraestructura (carreteras y puentes) y la producción de cemento. Este control sobre diversas industrias ha dado lugar a una supresión de la competencia, disuadiendo la inversión privada y provocando efectos adversos para los egipcios comunes, como un crecimiento más lento, precios más altos y oportunidades limitadas. [218] La Organización Nacional de Productos de Servicio (NSPO) , propiedad de los militares, continúa su expansión estableciendo nuevas fábricas dedicadas a producir fertilizantes, equipos de riego y vacunas veterinarias. Las empresas operadas por los militares, como Wataniya y Safi, que gestionan gasolineras y agua embotellada, respectivamente, siguen siendo propiedad del gobierno. [219]

Las condiciones económicas han comenzado a mejorar considerablemente, después de un período de estancamiento, debido a la adopción de políticas económicas más liberales por parte del gobierno, así como al aumento de los ingresos procedentes del turismo y a un mercado de valores en auge . En su informe anual, el Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI) ha calificado a Egipto como uno de los principales países del mundo que emprende reformas económicas. [220] Algunas de las principales reformas económicas emprendidas por el gobierno desde 2003 incluyen una reducción drástica de las aduanas y los aranceles. Una nueva ley tributaria implementada en 2005 redujo los impuestos corporativos del 40% al 20% actual, lo que dio como resultado un aumento declarado del 100% en los ingresos fiscales para 2006.

Aunque uno de los principales obstáculos que aún enfrenta la economía egipcia es la limitada transferencia de riqueza a la población promedio, muchos egipcios critican a su gobierno por los precios más altos de los bienes básicos mientras que sus niveles de vida o poder adquisitivo permanecen relativamente estancados. Los egipcios a menudo citan la corrupción como el principal impedimento para un mayor crecimiento económico. [221] [222] El gobierno prometió una importante reconstrucción de la infraestructura del país, utilizando el dinero pagado por la tercera licencia de telefonía móvil recientemente adquirida (3 mil millones de dólares) por Etisalat en 2006. [223] En el Índice de Percepción de la Corrupción de 2013, Egipto ocupó el puesto 114 de 177. [224]

_in_the_Suez_canal_1981.jpg/440px-USS_America_(CV-66)_in_the_Suez_canal_1981.jpg)

Se estima que 2,7 millones de egipcios en el extranjero contribuyen activamente al desarrollo de su país a través de remesas (US$7.800 millones en 2009), así como de la circulación de capital humano y social y de la inversión. [225] Las remesas, dinero ganado por los egipcios que viven en el extranjero y enviado a casa, alcanzaron un récord de US$21.000 millones en 2012, según el Banco Mundial. [226]

La sociedad egipcia es moderadamente desigual en términos de distribución del ingreso: se estima que entre el 35 y el 40% de la población egipcia gana menos del equivalente a 2 dólares por día, mientras que sólo entre el 2 y el 3% puede considerarse rica. [227]

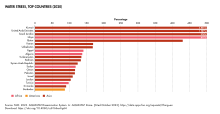

El turismo es uno de los sectores más importantes de la economía egipcia. Más de 12,8 millones de turistas visitaron Egipto en 2008, lo que generó ingresos por casi 11.000 millones de dólares. El sector turístico emplea a cerca del 12% de la fuerza laboral de Egipto. [228] El Ministro de Turismo Hisham Zaazou dijo a los profesionales del sector y a los periodistas que el turismo generó unos 9.400 millones de dólares en 2012, un ligero aumento respecto de los 9.000 millones de dólares registrados en 2011. [229]

La Necrópolis de Giza es una de las atracciones turísticas más conocidas de Egipto; es la única de las Siete Maravillas del Mundo Antiguo que aún existe.

Las playas de Egipto en el Mediterráneo y el Mar Rojo, que se extienden a lo largo de más de 3.000 kilómetros (1.900 millas), también son destinos turísticos populares; las playas del Golfo de Aqaba , Safaga , Sharm el-Sheikh , Hurghada , Luxor , Dahab , Ras Sidr y Marsa Alam son sitios populares.

Egipto tiene un mercado energético desarrollado basado en el carbón, el petróleo, el gas natural y la energía hidroeléctrica . En el noreste del Sinaí se extraen importantes depósitos de carbón a un ritmo de unas 600.000 toneladas (590.000 toneladas largas; 660.000 toneladas cortas) al año. En las regiones desérticas occidentales, el Golfo de Suez y el Delta del Nilo se produce petróleo y gas. Egipto tiene enormes reservas de gas, estimadas en 2.180 kilómetros cúbicos (520 millas cúbicas), [230] y GNL hasta 2012, exportado a muchos países. En 2013, la Compañía General de Petróleo de Egipto (EGPC) dijo que el país reduciría las exportaciones de gas natural y pediría a las principales industrias que redujeran la producción este verano para evitar una crisis energética y evitar disturbios políticos, según informó Reuters. Egipto cuenta con Qatar, el mayor exportador de gas natural licuado (GNL), para obtener volúmenes adicionales de gas en verano, al tiempo que alienta a las fábricas a planificar su mantenimiento anual para los meses de máxima demanda, dijo el presidente de la EGPC, Tarek El Barkatawy. Egipto produce su propia energía, pero ha sido un importador neto de petróleo desde 2008 y rápidamente se está convirtiendo en un importador neto de gas natural. [231]

Egipto produjo 691.000 bbl/d de petróleo y 2.141,05 Tcf de gas natural en 2013, lo que lo convierte en el mayor productor de petróleo no perteneciente a la OPEP y el segundo mayor productor de gas natural seco de África. En 2013, Egipto fue el mayor consumidor de petróleo y gas natural de África, con más del 20% del consumo total de petróleo y más del 40% del consumo total de gas natural seco de África. Además, Egipto posee la mayor capacidad de refinación de petróleo de África: 726.000 bbl/d (en 2012). [230]

Egipto está construyendo actualmente su primera planta de energía nuclear en El Dabaa , en la parte norte del país, con 25.000 millones de dólares de financiación rusa. [232]

El transporte en Egipto se centra en El Cairo y sigue en gran medida el patrón de asentamiento a lo largo del Nilo. La línea principal de la red ferroviaria de 40.800 kilómetros (25.400 millas) del país va de Alejandría a Asuán y está operada por los Ferrocarriles Nacionales Egipcios . La red de carreteras para vehículos se ha expandido rápidamente a más de 34.000 kilómetros (21.000 millas), que consta de 28 líneas, 796 estaciones, 1.800 trenes que cubren el valle y el delta del Nilo, las costas del Mediterráneo y del Mar Rojo, el Sinaí y los oasis occidentales.

El metro de El Cairo consta de tres líneas operativas y se espera una cuarta línea en el futuro.

EgyptAir, which is now the country's flag carrier and largest airline, was founded in 1932 by Egyptian industrialist Talaat Harb, today owned by the Egyptian government. The airline is based at Cairo International Airport, its main hub, operating scheduled passenger and freight services to more than 75 destinations in the Middle East, Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The Current EgyptAir fleet includes 80 aeroplanes.

The Suez Canal is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows ship transport between Europe and Asia without navigation around Africa. The northern terminus is Port Said and the southern terminus is Port Tawfiq at the city of Suez. Ismailia lies on its west bank, 3 kilometres (1+7⁄8 miles) from the half-way point.

The canal is 193.30 km (120+1⁄8 mi) long, 24 metres (79 feet) deep and 205 m (673 ft) wide as of 2010[update]. It consists of the northern access channel of 22 km (14 mi), the canal itself of 162.25 km (100+7⁄8 mi) and the southern access channel of 9 km (5+1⁄2 mi). The canal is a single lane with passing places in the Ballah By-Pass and the Great Bitter Lake. It contains no locks; seawater flows freely through the canal.

On 26 August 2014 a proposal was made for opening a New Suez Canal. Work on the New Suez Canal was completed in July 2015.[233][234] The channel was officially inaugurated with a ceremony attended by foreign leaders and featuring military flyovers on 6 August 2015, in accordance with the budgets laid out for the project.[235][236]

The piped water supply in Egypt increased between 1990 and 2010 from 89% to 100% in urban areas and from 39% to 93% in rural areas despite rapid population growth. Over that period, Egypt achieved the elimination of open defecation in rural areas and invested in infrastructure. Access to an improved water source in Egypt is now practically universal with a rate of 99%. About one half of the population is connected to sanitary sewers.[237]

Partly because of low sanitation coverage about 17,000 children die each year because of diarrhoea.[238] Another challenge is low cost recovery due to water tariffs that are among the lowest in the world. This in turn requires government subsidies even for operating costs, a situation that has been aggravated by salary increases without tariff increases after the Arab Spring. Poor operation of facilities, such as water and wastewater treatment plants, as well as limited government accountability and transparency, are also issues.

Due to the absence of appreciable rainfall, Egypt's agriculture depends entirely on irrigation. The main source of irrigation water is the river Nile of which the flow is controlled by the high dam at Aswan. It releases, on average, 55 cubic kilometres (45,000,000 acre·ft) water per year, of which some 46 cubic kilometres (37,000,000 acre·ft) are diverted into the irrigation canals.[239]

In the Nile valley and delta, almost 33,600 square kilometres (13,000 sq mi) of land benefit from these irrigation waters producing on average 1.8 crops per year.[239]

Egypt is the most populated country in the Arab world and the third most populous on the African continent, with about 95 million inhabitants as of 2017[update].[240] Its population grew rapidly from 1970 to 2010 due to medical advances and increases in agricultural productivity[241] enabled by the Green Revolution.[242] Egypt's population was estimated at 3 million when Napoleon invaded the country in 1798.[243]

Egypt's people are highly urbanised, being concentrated along the Nile (notably Cairo and Alexandria), in the Delta and near the Suez Canal. Egyptians are divided demographically into those who live in the major urban centres and the fellahin, or farmers, that reside in rural villages. The total inhabited area constitutes only 77,041 km², putting the physiological density at over 1,200 people per km2, similar to Bangladesh.

While emigration was restricted under Nasser, thousands of Egyptian professionals were dispatched abroad in the context of the Arab Cold War.[244] Egyptian emigration was liberalised in 1971, under President Sadat, reaching record numbers after the 1973 oil crisis.[245] An estimated 2.7 million Egyptians live abroad. Approximately 70% of Egyptian migrants live in Arab countries (923,600 in Saudi Arabia, 332,600 in Libya, 226,850 in Jordan, 190,550 in Kuwait with the rest elsewhere in the region) and the remaining 30% reside mostly in Europe and North America (318,000 in the United States, 110,000 in Canada and 90,000 in Italy).[225] The process of emigrating to non-Arab states has been ongoing since the 1950s.[246]

Ethnic Egyptians are by far the largest ethnic group in the country, constituting 99.7% of the total population.[67] Ethnic minorities include the Abazas, Turks, Greeks, Bedouin Arab tribes living in the eastern deserts and the Sinai Peninsula, the Berber-speaking Siwis (Amazigh) of the Siwa Oasis, and the Nubian communities clustered along the Nile. There are also tribal Beja communities concentrated in the southeasternmost corner of the country, and a number of Dom clans mostly in the Nile Delta and Faiyum who are progressively becoming assimilated as urbanisation increases.

Some 5 million immigrants live in Egypt, mostly Sudanese, "some of whom have lived in Egypt for generations".[247] Smaller numbers of immigrants come from Iraq, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan, and Eritrea.[247]

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that the total number of "people of concern" (refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people) was about 250,000. In 2015, the number of registered Syrian refugees in Egypt was 117,000, a decrease from the previous year.[247] Egyptian government claims that a half-million Syrian refugees live in Egypt are thought to be exaggerated.[247] There are 28,000 registered Sudanese refugees in Egypt.[247]

Jewish communities in Egypt have almost disappeared. Several important Jewish archaeological and historical sites are found in Cairo, Alexandria and other cities.

The official language of the Republic is Literary Arabic.[248] The spoken languages are: Egyptian Arabic (68%), Sa'idi Arabic (29%), Eastern Egyptian Bedawi Arabic (1.6%), Sudanese Arabic (0.6%), Domari (0.3%), Nobiin (0.3%), Beja (0.1%), Siwi and others.[citation needed] Additionally, Greek, Armenian and Italian, and more recently, African languages like Amharic and Tigrigna are the main languages of immigrants.

The main foreign languages taught in schools, by order of popularity, are English, French, German and Italian.

Historically Egyptian was spoken, the latest stage of which is Coptic Egyptian. Spoken Coptic was mostly extinct by the 17th century but may have survived in isolated pockets in Upper Egypt as late as the 19th century. It remains in use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.[249][250] It forms a separate branch among the family of Afroasiatic languages.

.jpg/440px-Mosque-Madrassa_of_Sultan_Hassan_(4).jpg)

Islam is the state religion of Egypt, and the country has the largest Muslim population in the Arab world and the world's sixth largest Muslim population, accounting for five percent of all Muslims worldwide.[251] Egypt also has the largest Christian population in the Middle East and North Africa.[252] Official data about religion is lacking due to social and political sensitivities.[253] An estimated 85–90% are identified as Muslim, 10–15% as Coptic Christians, and 1% as other Christian denominations; other estimates place the Christian population as high as 15–20%.[d]

Egypt was an early and leading center of Christianity into late antiquity; the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria was founded in the first century and remains the largest church in the country. With the arrival of Islam in the seventh century, the country was gradually Islamised into a majority-Muslim country.[259][260] It is unknown when Muslims reached a majority, variously estimated from c. 1000 CE to as late as the 14th century. Egypt emerged as a centre of politics and culture in the Muslim world. Under Anwar Sadat, Islam became the official state religion and Sharia the main source of law.[261]