La historia de Irán (o Persia , como se la conocía en el mundo occidental) está entrelazada con la del Gran Irán , una región sociocultural que se extiende desde Anatolia hasta el río Indo y desde el Cáucaso hasta el golfo Pérsico . En el centro de esta zona se encuentra el Irán actual , que cubre la mayor parte de la meseta iraní .

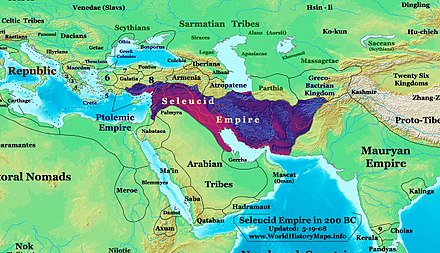

Irán es el hogar de una de las civilizaciones más antiguas del mundo, con asentamientos históricos y urbanos que datan del 4000 a. C. [1] La parte occidental de la meseta iraní participó en el antiguo Oriente Próximo tradicional con Elam (3200-539 a. C.), y más tarde con otros pueblos como los casitas , los maneos y los gutianos . Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel llamó a los persas el "primer pueblo histórico". [2] El Imperio iraní comenzó en la Edad del Hierro con el ascenso de los medos , que unificaron Irán como nación e imperio en el 625 a. C. [3] El Imperio aqueménida (550-330 a. C.), fundado por Ciro el Grande , fue el imperio más grande que el mundo haya visto, abarcando desde los Balcanes hasta el norte de África y Asia central . Fueron sucedidos por los imperios seléucida , parto y sasánida , que gobernaron Irán durante casi 1000 años, convirtiendo a Irán en una potencia líder una vez más. El archirrival de Persia durante este tiempo fue el Imperio Romano y su sucesor, el Imperio Bizantino .

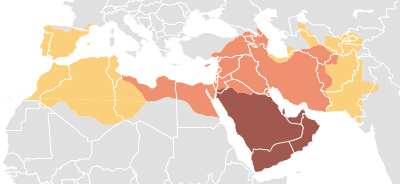

Irán soportó invasiones de macedonios , árabes , turcos y mongoles . A pesar de estas invasiones, Irán reafirmó continuamente su identidad nacional y se desarrolló como una entidad política y cultural distinta. La conquista musulmana de Persia (632-654) puso fin al Imperio sasánida y marcó un punto de inflexión en la historia iraní, lo que llevó a la islamización de Irán desde el siglo VIII al X y al declive del zoroastrismo . Sin embargo, los logros de las civilizaciones persas anteriores fueron absorbidos por la nueva política islámica . Irán sufrió invasiones de tribus nómadas durante la Baja Edad Media y el período moderno temprano , lo que afectó negativamente a la región. [4] Irán fue reunificado como un estado independiente en 1501 por la dinastía safávida , que estableció el Islam chiita como la religión oficial del imperio, [5] marcando un punto de inflexión significativo en la historia del Islam . [6] Irán funcionó nuevamente como una potencia mundial líder, especialmente en rivalidad con el Imperio otomano . En el siglo XIX, Irán perdió importantes territorios en el Cáucaso ante el Imperio ruso tras las guerras ruso-persas . [7]

Irán siguió siendo una monarquía hasta la Revolución iraní de 1979 , cuando se convirtió oficialmente en una república islámica el 1 de abril de 1979. [8] [9] Desde entonces, Irán ha experimentado importantes cambios políticos, sociales y económicos. El establecimiento de la República Islámica de Irán condujo a la reestructuración de su sistema político, con el Ayatolá Jomeini como Líder Supremo. Las relaciones exteriores de Irán han estado marcadas por la Guerra Irán-Irak (1980-1988), las tensiones en curso con los Estados Unidos y su programa nuclear, que ha sido un punto de discordia en la diplomacia internacional. A pesar de las sanciones económicas y los desafíos internos, Irán sigue siendo un actor clave en la geopolítica mundial y de Oriente Medio.

Los primeros artefactos arqueológicos en Irán se encontraron en los sitios de Kashafrud y Ganj Par que se cree que datan de hace 10.000 años en el Paleolítico Medio. [10] También se han encontrado herramientas de piedra musterienses hechas por neandertales . [11] Hay más restos culturales de neandertales que datan del período Paleolítico Medio , que se han encontrado principalmente en la región de Zagros y menos en el centro de Irán en sitios como Kobeh, Kunji, la cueva de Bisitun , Tamtama, Warwasi y la cueva de Yafteh . [12] En 1949, Carleton S. Coon descubrió un radio neandertal en la cueva de Bisitun. [13] La evidencia de los períodos Paleolítico superior y Epipaleolítico se conoce principalmente en los montes Zagros en las cuevas de Kermanshah y Khorramabad y en algunos sitios en Piranshahr y Alborz y el centro de Irán . Durante este tiempo, la gente comenzó a crear arte rupestre . [ cita requerida ]

Las primeras comunidades agrícolas como Chogha Golan en el año 10.000 a. C. [14] [15] junto con asentamientos como Chogha Bonut (la aldea más antigua de Elam) en el año 8000 a. C., [16] [17] comenzaron a florecer en la región de los montes Zagros y sus alrededores en el oeste de Irán. [18] Casi al mismo tiempo, las vasijas de arcilla y las figurillas de terracota modeladas con humanos y animales más antiguas que se conocen se produjeron en Ganj Dareh, también en el oeste de Irán. [18] También hay figurillas humanas y animales de 10.000 años de antigüedad de Tepe Sarab en la provincia de Kermanshah, entre muchos otros artefactos antiguos. [19]

La parte suroccidental de Irán era parte de la Media Luna Fértil , donde se cultivaban la mayoría de los primeros cultivos importantes de la humanidad, en aldeas como Susa (donde se fundó un asentamiento por primera vez posiblemente ya en 4395 cal AC) [20] : 46–47 y asentamientos como Chogha Mish , que data de 6800 AC; [21] [22] hay jarras de vino de 7000 años de antigüedad excavadas en los Montes Zagros [23] (ahora en exhibición en la Universidad de Pensilvania ) y ruinas de asentamientos de 7000 años de antigüedad como Tepe Sialk son otro testimonio de eso. Los dos principales asentamientos neolíticos iraníes fueron Ganj Dareh y la hipotética Cultura del Río Zayandeh . [24]

.JPG/440px-Choqa_Zanbil_Darafsh_1_(36).JPG)

Partes de lo que hoy es el noroeste de Irán formaban parte de la cultura Kura-Araxes (circa 3400 a. C. - ca. 2000 a. C.), que se extendía hasta las regiones vecinas del Cáucaso y Anatolia . [25] [26]

Susa es uno de los asentamientos más antiguos conocidos de Irán y del mundo. Según la datación C14, la fecha de fundación de la ciudad es tan temprana como 4395 a. C., [20] : 45–46 un momento justo después del establecimiento de la antigua ciudad sumeria de Uruk en 4500 a. C. La percepción general entre los arqueólogos es que Susa era una extensión de la ciudad-estado sumeria de Uruk , incorporando así muchos aspectos de la cultura mesopotámica. [27] [28] En su historia posterior, Susa se convirtió en la capital de Elam, que surgió como un estado fundado en 4000 a. C. [20] : 45–46 También hay docenas de sitios prehistóricos en la meseta iraní que apuntan a la existencia de culturas antiguas y asentamientos urbanos en el cuarto milenio a. C. [21] Una de las primeras civilizaciones en la meseta iraní fue la cultura Jiroft en el sureste de Irán en la provincia de Kerman .

Es uno de los sitios arqueológicos más ricos en artefactos de Oriente Medio. Las excavaciones arqueológicas en Jiroft condujeron al descubrimiento de varios objetos pertenecientes al cuarto milenio a. C. [29] Hay una gran cantidad de objetos decorados con grabados muy distintivos de animales, figuras mitológicas y motivos arquitectónicos. Los objetos y su iconografía se consideran únicos. Muchos están hechos de clorita , una piedra blanda de color verde grisáceo; otros son de cobre , bronce , terracota e incluso lapislázuli . Las excavaciones recientes en los sitios han producido la inscripción más antigua del mundo que es anterior a las inscripciones mesopotámicas. [30] [31]

Existen registros de numerosas civilizaciones antiguas en la meseta iraní antes del surgimiento de los pueblos iraníes durante la Edad del Hierro Temprana . La Edad del Bronce Temprana vio el surgimiento de la urbanización en ciudades-estado organizadas y la invención de la escritura (el período Uruk ) en Oriente Próximo. Si bien el Elam de la Edad del Bronce utilizó la escritura desde una época temprana, la escritura protoelamita sigue sin descifrarse y los registros de Sumer relacionados con el Elam son escasos.

El historiador ruso Igor M. Diakonoff afirmó que los habitantes modernos de Irán son descendientes de grupos principalmente no indoeuropeos, más específicamente de habitantes preiraníes de la meseta iraní: "Son los autóctonos de la meseta iraní, y no las tribus protoindoeuropeas de Europa, los que son, en lo principal, los antepasados, en el sentido físico de la palabra, de los iraníes actuales". [32]

Los registros se vuelven más tangibles con el surgimiento del Imperio neoasirio y sus registros de incursiones desde la meseta iraní. Ya en el siglo XX a. C., las tribus llegaron a la meseta iraní desde la estepa póntico-caspia . La llegada de iraníes a la meseta iraní obligó a los elamitas a renunciar a una zona de su imperio tras otra y a refugiarse en Elam, Juzestán y el área cercana, que solo entonces se convirtió en colindante con Elam. [33] Bahman Firuzmandi dice que los iraníes del sur podrían estar mezclados con los pueblos elamitas que viven en la meseta. [34] A mediados del primer milenio a. C., medos , persas y partos poblaban la meseta iraní. Hasta el surgimiento de los medos, todos permanecieron bajo la dominación asiria , como el resto del Cercano Oriente . En la primera mitad del primer milenio a. C., partes de lo que ahora es Azerbaiyán iraní se incorporaron a Urartu .

En el año 646 a. C., el rey asirio Asurbanipal saqueó Susa , lo que puso fin a la supremacía elamita en la región. [35] Durante más de 150 años, los reyes asirios de la cercana Mesopotamia del Norte habían querido conquistar las tribus medas del oeste de Irán. [36] Bajo la presión de Asiria, los pequeños reinos de la meseta occidental de Irán se fusionaron en estados cada vez más grandes y centralizados. [35]

En la segunda mitad del siglo VII a. C., los medos obtuvieron su independencia y fueron unificados por Deioces . En 612 a. C., Ciaxares , nieto de Deioces , y el rey babilónico Nabopolasar invadieron Asiria y sitiaron y finalmente destruyeron Nínive , la capital asiria, lo que llevó a la caída del Imperio neoasirio . [37] Urartu fue conquistada y disuelta más tarde también por los medos. [38] [39] A los medos se les atribuye la fundación de Irán como nación e imperio, y establecieron el primer imperio iraní, el más grande de su época hasta que Ciro el Grande estableció un imperio unificado de los medos y los persas, lo que condujo al Imperio aqueménida (c. 550-330 a. C.).

Ciro el Grande derrocó, a su vez, a los imperios medo, lidio y neobabilónico , creando un imperio mucho más grande que Asiria. Fue más capaz, mediante políticas más benignas, de reconciliar a sus súbditos con el gobierno persa; la longevidad de su imperio fue uno de los resultados. El rey persa, como el asirio , era también " rey de reyes ", xšāyaθiya xšāyaθiyānām ( shāhanshāh en persa moderno) - "gran rey", Megas Basileus , como lo conocían los griegos .

El hijo de Ciro, Cambises II , conquistó la última gran potencia de la región, el antiguo Egipto , provocando el colapso de la XXVI Dinastía de Egipto . Dado que enfermó y murió antes o mientras abandonaba Egipto , se desarrollaron historias, como las relata Heródoto , de que fue abatido por impiedad contra las antiguas deidades egipcias . Después de la muerte de Cambises II, Darío ascendió al trono derrocando al legítimo monarca aqueménida Bardiya , y luego sofocando rebeliones en todo su reino. Como vencedor, Darío I , basó su reclamo en la pertenencia a una línea colateral del Imperio aqueménida.

La primera capital de Darío fue Susa, y comenzó el programa de construcción en Persépolis . Reconstruyó un canal entre el Nilo y el Mar Rojo , un precursor del moderno Canal de Suez . Mejoró el extenso sistema de carreteras, y es durante su reinado que se menciona por primera vez el Camino Real (mostrado en el mapa), una gran carretera que se extendía desde Susa hasta Sardes con estaciones de correos a intervalos regulares. Bajo Darío se llevaron a cabo importantes reformas. La acuñación de monedas , en forma de dárico (moneda de oro) y siclo (moneda de plata), se estandarizó (la acuñación de monedas ya se había inventado más de un siglo antes en Lidia c. 660 a. C., pero no se estandarizó), [40] y aumentó la eficiencia administrativa.

El antiguo idioma persa aparece en inscripciones reales, escritas en una versión especialmente adaptada de la escritura cuneiforme . Bajo Ciro el Grande y Darío I , el Imperio persa acabó convirtiéndose en el mayor imperio de la historia humana hasta ese momento, gobernando y administrando la mayor parte del mundo conocido entonces, [41] además de abarcar los continentes de Europa , Asia y África. El mayor logro fue el propio imperio. El Imperio persa representó la primera superpotencia del mundo [42] [43] que se basó en un modelo de tolerancia y respeto por otras culturas y religiones. [44]

A finales del siglo VI a. C., Darío lanzó su campaña europea, en la que derrotó a los peonios , conquistó Tracia y sometió todas las ciudades griegas costeras, además de derrotar a los escitas europeos alrededor del río Danubio . [45] En 512/511 a. C., Macedonia se convirtió en un reino vasallo de Persia. [45]

En el año 499 a. C., Atenas prestó su apoyo a una revuelta en Mileto , que resultó en el saqueo de Sardes . Esto condujo a una campaña aqueménida contra la Grecia continental conocida como las Guerras greco-persas , que duraron la primera mitad del siglo V a. C. y se las conoce como una de las guerras más importantes de la historia europea . En la primera invasión persa de Grecia , el general persa Mardonio volvió a subyugar Tracia e hizo de Macedonia una parte completa de Persia. [45] Sin embargo, la guerra finalmente resultó en una derrota. El sucesor de Darío, Jerjes I, lanzó la segunda invasión persa de Grecia . En un momento crucial de la guerra, cerca de la mitad de Grecia continental fue invadida por los persas, incluyendo todos los territorios al norte del istmo de Corinto , [46] [47] sin embargo, esto también resultó en una victoria griega, después de las batallas de Platea y Salamina , por las cuales Persia perdió sus puntos de apoyo en Europa, y finalmente se retiró de ella. [48] Durante las guerras greco-persas, los persas obtuvieron importantes ventajas territoriales. Capturaron y arrasaron Atenas dos veces , una en 480 a. C. y otra en 479 a. C. Sin embargo, después de una serie de victorias griegas, los persas se vieron obligados a retirarse, perdiendo así el control de Macedonia , Tracia y Jonia . La lucha continuó durante varias décadas después del exitoso rechazo griego de la Segunda Invasión con numerosas ciudades-estado griegas bajo la recién formada Liga de Delos de Atenas , que finalmente terminó con la paz de Calias en 449 a. C., poniendo fin a las guerras greco-persas. En el año 404 a. C., tras la muerte de Darío II , Egipto se rebeló bajo el mando de Amirteo . Los faraones posteriores resistieron con éxito los intentos persas de reconquistar Egipto hasta el año 343 a. C., cuando Artajerjes III lo reconquistó .

Entre el 334 a. C. y el 331 a. C., Alejandro Magno derrotó a Darío III en las batallas de Gránico , Issos y Gaugamela , conquistando rápidamente el Imperio persa en el 331 a. C. El imperio de Alejandro se desintegró poco después de su muerte, y el general de Alejandro, Seleuco I Nicátor , intentó tomar el control de Irán, Mesopotamia y, más tarde , Siria y Anatolia . Su imperio fue el Imperio seléucida . Fue asesinado en el 281 a. C. por Ptolomeo Keraunos .

El Imperio parto , gobernado por los partos, un grupo de pueblos del noroeste de Irán, fue el reino de la dinastía arsácida. Esta última reunificó y gobernó la meseta iraní después de la conquista de Partia por los parnos y la derrota del Imperio seléucida a fines del siglo III a. C. Controló de manera intermitente Mesopotamia entre aproximadamente el 150 a. C. y el 224 d. C. y absorbió Arabia Oriental .

Partia era el archienemigo oriental del Imperio Romano y limitaba la expansión de Roma más allá de Capadocia (Anatolia central). Los ejércitos partos incluían dos tipos de caballería : los catafractos, fuertemente armados y acorazados, y los arqueros montados , ligeramente armados pero muy móviles .

Para los romanos, que dependían de la infantería pesada , los partos eran demasiado difíciles de derrotar, ya que ambos tipos de caballería eran mucho más rápidos y móviles que los soldados de a pie. El tiro parto utilizado por la caballería parta era especialmente temido por los soldados romanos, lo que resultó fundamental en la aplastante derrota romana en la batalla de Carras . Por otro lado, a los partos les resultó difícil ocupar las zonas conquistadas, ya que no eran expertos en la guerra de asedio . Debido a estas debilidades, ni los romanos ni los partos pudieron anexionarse completamente el territorio del otro.

El imperio parto subsistió durante cinco siglos, más que la mayoría de los imperios orientales. El fin de este imperio llegó finalmente en el año 224 d. C., cuando la organización del imperio se había debilitado y el último rey fue derrotado por uno de los pueblos vasallos del imperio, los persas bajo el mando de los sasánidas. Sin embargo, la dinastía arsácida continuó existiendo durante siglos en Armenia , la Península Ibérica y la Albania caucásica , que eran todas ramas epónimas de la dinastía.

El primer shah del Imperio sasánida, Ardashir I , comenzó a reformar el país económica y militarmente. Durante un período de más de 400 años, Irán volvió a ser una de las principales potencias del mundo, junto con su vecino rival, el Imperio romano y luego el bizantino . [49] [50] El territorio del imperio, en su apogeo, abarcó todo el actual Irán , Irak , Azerbaiyán , Armenia , Georgia , Abjasia , Daguestán , Líbano , Jordania , Palestina , Israel , partes de Afganistán , Turquía , Siria , partes de Pakistán , Asia Central , Arabia Oriental y partes de Egipto .

La mayor parte de la vida del Imperio sasánida se vio ensombrecida por las frecuentes guerras bizantino-sasánidas , una continuación de las guerras romano-partas y las guerras romano-persas que abarcaron todo el Imperio; la última fue el conflicto más duradero en la historia humana. Iniciada en el siglo I a. C. por sus predecesores, los partos y los romanos, la última guerra romano-persa se libró en el siglo VII. Los persas derrotaron a los romanos en la batalla de Edesa en 260 y tomaron prisionero al emperador Valeriano por el resto de su vida.

Arabia Oriental fue conquistada en un principio. Durante el gobierno de Cosroes II en 590-628, Egipto , Jordania , Palestina y Líbano también fueron anexados al Imperio. Los sasánidas llamaron a su imperio Erânshahr ("Dominio de los arios", es decir, de los iraníes ). [51]

Un capítulo de la historia de Irán siguió a unos seiscientos años de conflicto con el Imperio Romano. Durante este tiempo, los ejércitos sasánidas y romano-bizantinos se enfrentaron por la influencia en Anatolia, el Cáucaso occidental (principalmente Lazica y el Reino de Iberia ; las actuales Georgia y Abjasia ), Mesopotamia , Armenia y el Levante. Bajo el reinado de Justiniano I, la guerra desembocó en una paz precaria con el pago de tributos a los sasánidas.

Sin embargo, los sasánidas utilizaron la deposición del emperador bizantino Mauricio como casus belli para atacar al Imperio. Después de muchas victorias, los sasánidas fueron derrotados en Issos, Constantinopla y finalmente Nínive, lo que resultó en la paz. Con la conclusión de las guerras romano-persas que duraron más de 700 años hasta la culminante guerra bizantino-sasánida de 602-628 , que incluyó el mismísimo asedio de la capital bizantina de Constantinopla , los persas, exhaustos por la guerra, perdieron la batalla de al-Qādisiyyah (632) en Hilla (actual Irak ) ante las fuerzas musulmanas invasoras.

La era sasánida, que abarca la Antigüedad tardía , se considera uno de los períodos históricos más importantes e influyentes de Irán y tuvo un gran impacto en el mundo. En muchos sentidos, el período sasánida fue testigo del mayor logro de la civilización persa y constituye el último gran imperio iraní antes de la adopción del Islam. Persia influyó considerablemente en la civilización romana durante la época sasánida, [52] su influencia cultural se extendió mucho más allá de las fronteras territoriales del imperio, llegando hasta Europa occidental, [53] África, [54] China e India [55] y también desempeñó un papel destacado en la formación del arte medieval europeo y asiático. [56]

Esta influencia se trasladó al mundo musulmán . La cultura única y aristocrática de la dinastía transformó la conquista y destrucción islámica de Irán en un renacimiento persa. [53] Gran parte de lo que más tarde se conocería como cultura, arquitectura, escritura y otras contribuciones a la civilización islámicas fueron tomadas de los persas sasánidas y llevadas al mundo musulmán en general. [57]

En 633, cuando el rey sasánida Yazdegerd III gobernaba Irán, los musulmanes bajo el mando de Umar invadieron el país justo después de que éste hubiera estado envuelto en una sangrienta guerra civil. Varios nobles y familias iraníes, como el rey Dinar de la Casa de Karen y, posteriormente, los Kanarangiyans de Khorasan , se amotinaron contra sus señores sasánidas. Aunque la Casa de Mihran había reclamado el trono sasánida bajo el mando de dos generales prominentes, Bahrām Chōbin y Shahrbaraz , permaneció leal a los sasánidas durante su lucha contra los árabes, pero los Mihrans fueron finalmente traicionados y derrotados por sus propios parientes, la Casa de Ispahbudhan , bajo el mando de su líder Farrukhzad , que se había amotinado contra Yazdegerd III.

Yazdegerd III huyó de un distrito a otro hasta que un molinero local lo mató para robarle su dinero en Merv en 651. [58] En 674, los musulmanes habían conquistado el Gran Jorasán (que incluía la actual provincia iraní de Jorasán y el actual Afganistán y partes de Transoxiana ).

La conquista musulmana de Persia puso fin al Imperio sasánida y condujo a la decadencia de la religión zoroástrica en Persia. Con el tiempo, la mayoría de los iraníes se convirtieron al Islam. La mayoría de los aspectos de las civilizaciones persas anteriores no fueron descartados, sino que fueron absorbidos por la nueva política islámica . Como ha comentado Bernard Lewis :

“Estos acontecimientos han sido vistos de diversas maneras en Irán: por algunos como una bendición, el advenimiento de la verdadera fe, el fin de la era de la ignorancia y el paganismo; por otros como una humillante derrota nacional, la conquista y subyugación del país por invasores extranjeros. Ambas percepciones son, por supuesto, válidas, dependiendo del ángulo de visión de cada uno.” [59]

Tras la caída del Imperio sasánida en 651, los árabes del califato omeya adoptaron muchas costumbres persas, especialmente las administrativas y los modales de la corte. Los gobernadores provinciales árabes eran, sin duda, arameos persianos o persas étnicos; sin duda, el persa siguió siendo el idioma de los asuntos oficiales del califato hasta la adopción del árabe hacia finales del siglo VII, [60] cuando en 692 comenzó la acuñación en la capital, Damasco . Las nuevas monedas islámicas evolucionaron a partir de imitaciones de monedas sasánidas (así como de bizantinas ), y la escritura pahlavi en las monedas fue reemplazada por el alfabeto árabe .

Durante el califato omeya, los conquistadores árabes impusieron el árabe como lengua principal de los pueblos sometidos en todo su imperio. Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf , que no estaba contento con la prevalencia de la lengua persa en el diván , ordenó que la lengua oficial de las tierras conquistadas fuera reemplazada por el árabe, a veces por la fuerza. [61] En De los signos restantes de los siglos pasados de al-Biruni , por ejemplo, está escrito:

“Cuando Qutaibah bin Muslim, bajo el mando de Al-Hajjaj bin Yousef, fue enviado a Corasmia con una expedición militar y la conquistó por segunda vez, mató rápidamente a todo aquel que escribiera en la lengua nativa de Corasmia y que conociera la herencia, la historia y la cultura de Corasmia. Luego mató a todos sus sacerdotes zoroastrianos y quemó y destruyó sus libros, hasta que gradualmente sólo quedaron los analfabetos, que no sabían nada de escritura, y por lo tanto su historia fue en gran parte olvidada”. [62]

Hay varios historiadores que consideran que el gobierno de los Omeyas estableció la "dhimmah" para aumentar los impuestos de los dhimmis con el fin de beneficiar económicamente a la comunidad árabe musulmana y desalentar la conversión. [63] Los gobernadores presentaron quejas ante el califa cuando promulgó leyes que facilitaban la conversión, privando a las provincias de ingresos.

En el siglo VII, cuando muchos no árabes, como los persas , entraron al Islam, fueron reconocidos como mawali ("clientes") y tratados como ciudadanos de segunda clase por la élite árabe gobernante hasta el final del califato omeya. Durante esta era, el Islam se asoció inicialmente con la identidad étnica del árabe y requirió la asociación formal con una tribu árabe y la adopción del estatus de cliente de mawali . [63] Las políticas poco entusiastas de los últimos omeyas de tolerar a los musulmanes no árabes y a los chiítas no habían logrado sofocar el malestar entre estas minorías.

Sin embargo, todo Irán aún no estaba bajo control árabe, y la región de Daylam estaba bajo el control de los daylamitas , mientras que Tabaristán estaba bajo el control de los dabuyidas y paduspánidas , y la región del monte Damavand bajo el control de los masmughans de Damavand . Los árabes habían invadido estas regiones varias veces, pero no lograron un resultado decisivo debido al terreno inaccesible de las regiones. El gobernante más destacado de los dabuyidas, conocido como Farrukhan el Grande (r. 712-728), logró mantener sus dominios durante su larga lucha contra el general árabe Yazid ibn al-Muhallab , quien fue derrotado por un ejército combinado dailamita-dabuyida, y se vio obligado a retirarse de Tabaristán. [64]

Con la muerte del califa omeya Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik en 743, el mundo islámico se vio inmerso en una guerra civil. Abu Muslim fue enviado a Jorasán por el califato abasí, inicialmente como propagandista y luego para rebelarse en su nombre. Tomó Merv y derrotó al gobernador omeya allí, Nasr ibn Sayyar . Se convirtió en el gobernador abasí de facto de Jorasán. Durante el mismo período, el gobernante dabuyid Khurshid declaró la independencia de los omeyas, pero poco después se vio obligado a reconocer la autoridad abasí. En 750, Abu Muslim se convirtió en el líder del ejército abasí y derrotó a los omeyas en la batalla de Zab . Abu Muslim asaltó Damasco , la capital del califato omeya, más tarde ese año.

El ejército abasí estaba formado principalmente por jorasánes y estaba dirigido por un general iraní, Abu Muslim Khorasani . Contenía elementos tanto iraníes como árabes, y los abasíes disfrutaban del apoyo tanto iraní como árabe. Los abasíes derrocaron a los omeyas en 750. [65] Según Amir Arjomand, la Revolución abasí marcó esencialmente el fin del imperio árabe y el comienzo de un estado más inclusivo y multiétnico en Oriente Medio. [66]

Uno de los primeros cambios que realizaron los abasíes después de tomar el poder de los omeyas fue trasladar la capital del imperio desde Damasco , en el Levante , a Irak . Esta última región estaba influenciada por la historia y la cultura persas, y el traslado de la capital era parte de la demanda persa de influencia árabe en el imperio. La ciudad de Bagdad fue construida sobre el río Tigris , en 762, para servir como la nueva capital abasí. [67]

Los abasíes establecieron en su administración el cargo de visir , como el de Barmakids , que era el equivalente a un «vicecalifa» o segundo al mando. Con el tiempo, este cambio significó que muchos califas de los abasíes acabaron desempeñando un papel mucho más ceremonial que nunca, con el visir en el poder real. Una nueva burocracia persa empezó a sustituir a la antigua aristocracia árabe, y toda la administración reflejó estos cambios, demostrando que la nueva dinastía era diferente en muchos aspectos de los omeyas. [67]

En el siglo IX, el control abasí comenzó a debilitarse a medida que surgían líderes regionales en los rincones más alejados del imperio para desafiar la autoridad central del califato abasí. [67] Los califas abasíes comenzaron a reclutar a mamelucos , guerreros de habla turca, que habían estado saliendo de Asia Central hacia Transoxiana como guerreros esclavos ya en el siglo IX. Poco después, el poder real de los califas abasíes comenzó a menguar; finalmente, se convirtieron en figuras religiosas mientras los esclavos guerreros gobernaban. [65]

El siglo IX también fue testigo de la revuelta de los zoroastrianos nativos, conocidos como los khurramitas , contra el opresivo gobierno árabe. El movimiento fue liderado por un luchador por la libertad persa, Babak Khorramdin . La rebelión iranizante [68] de Babak , desde su base en Azerbaiyán en el noroeste de Irán , [69] exigía el regreso de las glorias políticas del pasado iraní [70] . La rebelión Khorramdin de Babak se extendió a las partes occidental y central de Irán y duró más de veinte años antes de ser derrotada cuando Babak fue traicionado por Afshin , un general de alto rango del califato abasí.

A medida que el poder de los califas abasíes disminuía, surgieron una serie de dinastías en varias partes de Irán, algunas con considerable influencia y poder. Entre las más importantes de estas dinastías superpuestas estaban los tahiríes en Jorasán (821-873); los saffaríes en Sistán (861-1003, su gobierno duró como maliks de Sistán hasta 1537); y los samánidas (819-1005), originalmente en Bujará . Los samánidas finalmente gobernaron un área desde el centro de Irán hasta Pakistán. [65]

A principios del siglo X, los abasíes casi perdieron el control ante la creciente facción persa conocida como la dinastía Buyid (934-1062). Dado que gran parte de la administración abasí había sido persa de todos modos, los Buyids pudieron asumir silenciosamente el poder real en Bagdad. Los Buyids fueron derrotados a mediados del siglo XI por los turcos selyúcidas , que continuaron ejerciendo influencia sobre los abasíes, al tiempo que les prometían lealtad públicamente. El equilibrio de poder en Bagdad se mantuvo así (con los abasíes en el poder solo de nombre) hasta que la invasión mongola de 1258 saqueó la ciudad y terminó definitivamente con la dinastía abasí. [67]

Durante el período abasí , los mawali experimentaron una emancipación y se produjo un cambio en la concepción política, desde la de un imperio principalmente árabe a la de un imperio musulmán [71] y alrededor del año 930 se promulgó un requisito que exigía que todos los burócratas del imperio fueran musulmanes. [63]

La islamización fue un largo proceso mediante el cual la mayoría de la población de Irán adoptó gradualmente el Islam . La "curva de conversión" de Richard Bulliet indica que sólo alrededor del 10% de Irán se convirtió al Islam durante el período omeya , relativamente centrado en los árabes . A partir del período abasí , con su mezcla de gobernantes persas y árabes, el porcentaje musulmán de la población aumentó. A medida que los musulmanes persas consolidaron su dominio del país, la población musulmana aumentó de aproximadamente el 40% a mediados del siglo IX a cerca del 90% a fines del siglo XI. [71] Seyyed Hossein Nasr sugiere que el rápido aumento de la conversión fue ayudado por la nacionalidad persa de los gobernantes. [72]

Aunque los persas adoptaron la religión de sus conquistadores, a lo largo de los siglos trabajaron para proteger y revivir su lengua y cultura distintivas, un proceso conocido como persianización . Árabes y turcos participaron en este intento. [73] [74] [75]

En los siglos IX y X, los súbditos no árabes de la Ummah crearon un movimiento llamado Shu'ubiyyah en respuesta al estatus privilegiado de los árabes. La mayoría de los impulsores del movimiento eran persas, pero hay referencias a egipcios , bereberes y arameos . [76] Citando como base las nociones islámicas de igualdad de razas y naciones, el movimiento se preocupaba principalmente por preservar la cultura persa y proteger la identidad persa, aunque dentro de un contexto musulmán.

La dinastía samánida lideró el resurgimiento de la cultura persa y el primer poeta persa importante después de la llegada del Islam, Rudaki , nació durante esta era y fue elogiado por los reyes samánidas. Los samánidas también revivieron muchos festivales persas antiguos. Su sucesor, los gaznawidas , que eran de origen turco no iraní, también contribuyeron decisivamente al resurgimiento de la cultura persa. [77]

La culminación del movimiento de persianización fue el Shahnameh , la epopeya nacional de Irán, escrita casi en su totalidad en persa. Esta voluminosa obra refleja la historia antigua de Irán, sus valores culturales únicos, su religión zoroástrica preislámica y su sentido de nacionalidad. Según Bernard Lewis : [59]

"Irán fue islamizado, pero no arabizado. Los persas siguieron siendo persas. Y después de un intervalo de silencio, Irán resurgió como un elemento separado, diferente y distintivo dentro del Islam, añadiendo con el tiempo un nuevo elemento incluso al propio Islam. Culturalmente, políticamente y, lo más notable de todo, incluso religiosamente, la contribución iraní a esta nueva civilización islámica es de inmensa importancia. La obra de los iraníes se puede ver en todos los campos de la actividad cultural, incluida la poesía árabe, a la que los poetas de origen iraní que compusieron sus poemas en árabe hicieron una contribución muy significativa. En cierto sentido, el Islam iraní es un segundo advenimiento del propio Islam, un nuevo Islam al que a veces se hace referencia como Islam-i Ajam. Fue este Islam persa, más que el Islam árabe original, el que se llevó a nuevas áreas y nuevos pueblos: a los turcos, primero en Asia Central y luego en Oriente Medio, en el país que llegó a llamarse Turquía, y por supuesto a la India. Los turcos otomanos trajeron una forma de civilización iraní a los muros de Viena..."

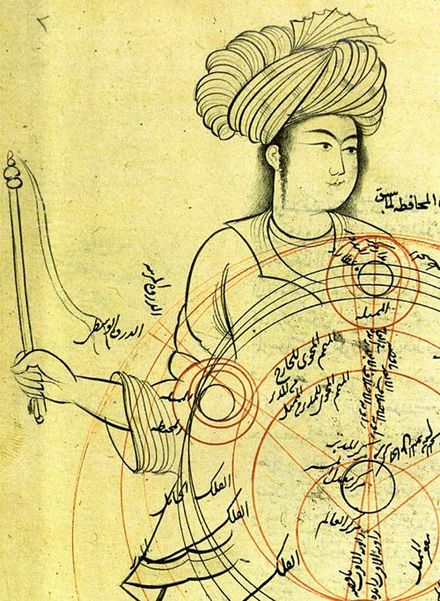

La islamización de Irán produjo profundas transformaciones en la estructura cultural, científica y política de la sociedad iraní: el florecimiento de la literatura , la filosofía , la medicina y el arte persas se convirtieron en elementos importantes de la nueva civilización musulmana. Al heredar una herencia de miles de años de civilización y estar en la "encrucijada de las principales vías culturales", [80] contribuyó a que Persia surgiera como lo que culminó en la " Edad de Oro Islámica ". Durante este período, cientos de eruditos y científicos contribuyeron enormemente a la tecnología, la ciencia y la medicina, influyendo más tarde en el auge de la ciencia europea durante el Renacimiento . [81]

Los eruditos más importantes de casi todas las sectas y escuelas de pensamiento islámicas eran persas o vivían en Irán, incluidos los recopiladores de hadices más notables y confiables de chiítas y sunitas como Shaikh Saduq , Shaikh Kulainy , Hakim al-Nishaburi , Imam Muslim e Imam Bukhari, los más grandes teólogos chiítas y sunitas como Shaykh Tusi , Imam Ghazali , Imam Fakhr al-Razi y Al-Zamakhshari , los más grandes médicos , astrónomos , lógicos , matemáticos , metafísicos , filósofos y científicos como Avicena y Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī , y los más grandes jeques del sufismo como Rumi y Abdul-Qadir Gilani .

En 977, un gobernador turco de los samánidas, Sabuktigin , conquistó Ghazna (en el actual Afganistán) y estableció una dinastía, los Ghaznavids , que duró hasta 1186. [65] El imperio Ghaznavid creció al tomar todos los territorios samánidas al sur del Amu Darya en la última década del siglo X, y finalmente ocupó partes del este de Irán, Afganistán, Pakistán y el noroeste de la India. [67]

En general, se atribuye a los gaznávidas la introducción del Islam en una India predominantemente hindú . La invasión de la India fue llevada a cabo en el año 1000 por el gobernante gaznávida Mahmud y continuó durante varios años. Sin embargo, no pudieron mantener el poder durante mucho tiempo, en particular después de la muerte de Mahmud en 1030. En 1040, los seléucidas habían tomado las tierras gaznávidas en Irán. [67]

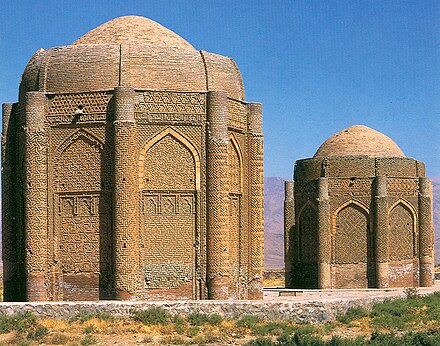

Los selyúcidas , que al igual que los gaznávidas eran de naturaleza persa y de origen turco, conquistaron lentamente Irán a lo largo del siglo XI. [65] La dinastía tuvo sus orígenes en las confederaciones tribales turcomanas de Asia Central y marcó el comienzo del poder turco en Oriente Medio. Establecieron un gobierno musulmán sunita sobre partes de Asia Central y Oriente Medio desde el siglo XI al XIV. Establecieron un imperio conocido como Gran Imperio Selyúcida que se extendía desde Anatolia en el oeste hasta Afganistán occidental en el este y las fronteras occidentales de China (actual) en el noreste; y fue el objetivo de la Primera Cruzada . Hoy en día se los considera los antepasados culturales de los turcos occidentales , los actuales habitantes de Turquía , Azerbaiyán y Turkmenistán , y se los recuerda como grandes mecenas de la cultura , el arte , la literatura y el idioma persas . [82] [83] [84]

El fundador de la dinastía, Tughril Beg , volvió su ejército contra los gaznávidas en Jorasán. Se trasladó al sur y luego al oeste, conquistando pero sin aniquilar las ciudades que se encontraba en su camino. En 1055, el califa de Bagdad le dio a Tughril Beg túnicas, regalos y el título de Rey del Este. Bajo el sucesor de Tughril Beg, Malik Shah (1072-1092), Irán disfrutó de un renacimiento cultural y científico, en gran parte atribuido a su brillante visir iraní, Nizam al Mulk . Estos líderes establecieron el observatorio donde Omar Khayyám realizó gran parte de su experimentación para un nuevo calendario, y construyeron escuelas religiosas en todas las ciudades principales. Trajeron a Abu Hamid Ghazali , uno de los más grandes teólogos islámicos, y otros eruditos eminentes a la capital selyúcida en Bagdad y alentaron y apoyaron su trabajo. [65]

Cuando Malik Shah I murió en 1092, el imperio se dividió cuando su hermano y cuatro hijos se pelearon por la distribución del imperio entre ellos. En Anatolia, Malik Shah I fue sucedido por Kilij Arslan I, quien fundó el Sultanato de Rûm , y en Siria por su hermano Tutush I. En Persia fue sucedido por su hijo Mahmud I, cuyo reinado fue disputado por sus otros tres hermanos Barkiyaruq en Irak , Muhammad I en Bagdad y Ahmad Sanjar en Jorasán . A medida que el poder selyúcida en Irán se debilitaba, otras dinastías comenzaron a ocupar su lugar, incluido un califato abasí resurgente y los khahs corasmitas . El Imperio corasmita fue una dinastía persa musulmana sunita, de origen turco oriental, que gobernó en Asia central. Originalmente vasallos de los selyúcidas, aprovecharon el declive de los selyúcidas para expandirse a Irán. [85] En 1194, el shah de Corasmia, Ala ad-Din Tekish, derrotó al sultán seléucida Toghrul III en batalla y el imperio seléucida en Irán se derrumbó. Del antiguo imperio seléucida sólo quedó el sultanato de Rum en Anatolia.

Una grave amenaza interna para los selyúcidas durante su reinado provino de los ismaelitas nizaríes , una secta secreta con sede en el castillo de Alamut , entre Rasht y Teherán . Controlaron la zona inmediata durante más de 150 años y esporádicamente enviaron adeptos para fortalecer su poder asesinando a funcionarios importantes. Varias de las diversas teorías sobre la etimología de la palabra asesino derivan de estos asesinos. [65]

Partes del noroeste de Irán fueron conquistadas a principios del siglo XIII d. C. por el Reino de Georgia , liderado por Tamar la Grande . [86]

La dinastía corasmia sólo duró unas décadas, hasta la llegada de los mongoles . Gengis Kan había unificado a los mongoles, y bajo su mando el Imperio mongol se expandió rápidamente en varias direcciones. En 1218, limitaba con Corasmia. En ese momento, el Imperio corasmio estaba gobernado por Ala ad-Din Muhammad (1200-1220). Muhammad, como Gengis, tenía la intención de expandir sus tierras y había conseguido la sumisión de la mayor parte de Irán. Se declaró shah y exigió el reconocimiento formal del califa abasí Al-Nasir . Cuando el califa rechazó su reclamación, Ala ad-Din Muhammad proclamó califa a uno de sus nobles e intentó sin éxito deponer a An-Nasir.

La invasión mongola de Irán comenzó en 1219, después de que dos misiones diplomáticas enviadas por Gengis Kan a Corasmia fueran masacradas. Durante 1220-21, Bujará , Samarcanda , Herat , Tus y Nishapur fueron arrasadas y todas las poblaciones fueron masacradas. El Sha de Corasmia huyó y murió en una isla frente a la costa del Caspio. [87] Durante la invasión de Transoxiana en 1219, junto con la principal fuerza mongola, Gengis Kan utilizó una unidad de catapultas especializada china en la batalla, que se volvió a utilizar en 1220 en Transoxiana. Es posible que los chinos hayan utilizado las catapultas para lanzar bombas de pólvora, ya que en ese momento ya las tenían. [88]

Mientras Gengis Kan conquistaba Transoxiana y Persia, varios chinos que estaban familiarizados con la pólvora servían en el ejército de Gengis. [89] Los mongoles utilizaron "regimientos enteros" compuestos enteramente por chinos para comandar trabuquetes que lanzaban bombas durante la invasión de Irán. [90] Los historiadores han sugerido que la invasión mongola había traído armas de pólvora chinas a Asia Central. Una de ellas era el huochong , un mortero chino. [91] Los libros escritos en la zona posteriormente describían armas de pólvora que se parecían a las de China. [92]

Antes de su muerte en 1227, Gengis había llegado al oeste de Azerbaiyán, saqueando y quemando muchas ciudades a lo largo del camino después de entrar en Irán por el noreste.

La invasión mongola fue en general desastrosa para los iraníes. Aunque los invasores mongoles finalmente se convirtieron al Islam y aceptaron la cultura de Irán, la destrucción mongola en Irán y otras regiones del corazón islámico (en particular la región histórica de Jorasán, principalmente en Asia Central) marcó un cambio de dirección importante para la región. Gran parte de los seis siglos de erudición, cultura e infraestructura islámicas fueron destruidas cuando los invasores arrasaron ciudades, quemaron bibliotecas y, en algunos casos, reemplazaron mezquitas por templos budistas . [93] [94] [95]

Los mongoles mataron a muchos civiles iraníes. La destrucción de los sistemas de irrigación de los qanats en el noreste de Irán destruyó el patrón de asentamientos relativamente continuos, lo que produjo muchas ciudades abandonadas que eran relativamente buenas en cuanto a irrigación y agricultura. [96]

Tras la muerte de Gengis, Irán quedó gobernado por varios comandantes mongoles. El nieto de Gengis, Hulagu Khan , fue el encargado de la expansión hacia el oeste del dominio mongol. Sin embargo, cuando ascendió al poder, el Imperio mongol ya se había disuelto, dividiéndose en diferentes facciones. Al llegar con un ejército, se estableció en la región y fundó el Ilkhanate , un estado escindido del Imperio mongol, que gobernaría Irán durante los siguientes ochenta años y se convertiría en persa en el proceso.

En 1258, Hulagu Khan tomó Bagdad y ejecutó al último califa abasí. Sin embargo, el avance de sus fuerzas hacia el oeste fue detenido por los mamelucos en la batalla de Ain Jalut, en Palestina , en 1260. Las campañas de Hulagu contra los musulmanes también enfurecieron a Berke , kan de la Horda de Oro y converso al Islam. Hulagu y Berke lucharon entre sí, demostrando el debilitamiento de la unidad del imperio mongol.

El gobierno del bisnieto de Hulagu, Ghazan (1295-1304), vio el establecimiento del Islam como la religión estatal del Ilkhanate. Ghazan y su famoso visir iraní, Rashid al-Din , trajeron a Irán una recuperación económica parcial y breve. Los mongoles redujeron los impuestos para los artesanos, fomentaron la agricultura, reconstruyeron y ampliaron las obras de irrigación y mejoraron la seguridad de las rutas comerciales. Como resultado, el comercio aumentó drásticamente.

Los objetos procedentes de la India, China e Irán pasaban fácilmente a través de las estepas asiáticas, y estos contactos enriquecieron culturalmente a Irán. Por ejemplo, los iraníes desarrollaron un nuevo estilo de pintura basado en una fusión única de la pintura mesopotámica sólida y bidimensional con las pinceladas ligeras y plumosas y otros motivos característicos de China. Sin embargo, después de que el sobrino de Ghazan, Abu Said, muriera en 1335, el Ilkhanate cayó en una guerra civil y se dividió en varias pequeñas dinastías, entre las que destacan los Jalayiridas , los Muzaffaridas , los Sarbadars y los Kartidas .

La Peste Negra de mediados del siglo XIV mató a aproximadamente el 30% de la población del país. [97]

Antes del ascenso del Imperio safávida, el Islam sunita era la religión dominante, representando alrededor del 90% de la población en ese momento. Según Mortaza Motahhari, la mayoría de los eruditos y las masas iraníes siguieron siendo sunitas hasta la época de los safávidas. [98] La dominación de los sunitas no significó que los chiítas estuvieran desarraigados en Irán. Los autores de Los cuatro libros del chiismo eran iraníes, así como muchos otros grandes eruditos chiítas.

La dominación del credo sunita durante los primeros nueve siglos islámicos caracterizó la historia religiosa de Irán durante este período. Sin embargo, hubo algunas excepciones a esta dominación general que surgieron en la forma de los zaydíes de Tabaristán (ver Dinastías alidas del norte de Irán ), los buyíes , los kakuyíes , el gobierno del sultán Muhammad Khudabandah (r. Shawwal 703-Shawwal 716/1304–1316) y los sarbedaran . [99]

Además de esta dominación, existieron, en primer lugar, a lo largo de estos nueve siglos, inclinaciones chiítas entre muchos sunitas de esta tierra y, en segundo lugar, el chiismo imamí original , así como el chiismo zaidí, prevalecieron en algunas partes de Irán. Durante este período, el chiismo en Irán se nutrió de Kufah , Bagdad y más tarde de Najaf y Hillah . [99] El chiismo fue la secta dominante en Tabaristán , Qom , Kashan , Avaj y Sabzevar . En muchas otras áreas, la población fusionada de chiítas y sunitas vivía junta. [ cita requerida ]

Durante los siglos X y XI, los fatimíes enviaron da'i (misioneros) ismaelitas a Irán y a otras tierras musulmanas. Cuando los ismaelitas se dividieron en dos sectas, los nizaríes establecieron su base en Irán. Hassan-i Sabbah conquistó fortalezas y capturó Alamut en 1090 d. C. Los nizaríes utilizaron esta fortaleza hasta una incursión mongola en 1256. [ cita requerida ]

Después de la incursión mongola y la caída de los abasíes, las jerarquías sunitas se tambalearon. No sólo perdieron el califato, sino también el estatus de madhhab oficial . Su pérdida fue la ganancia para los chiítas, cuyo centro no estaba en Irán en ese momento. Varias dinastías chiítas locales como los Sarbadars se establecieron durante esta época. [ cita requerida ]

El cambio principal ocurrió a principios del siglo XVI, cuando Ismail I fundó la dinastía safávida e inició una política religiosa para reconocer al Islam chiita como la religión oficial del Imperio safávida , y el hecho de que el Irán moderno siga siendo un estado oficialmente chiita es un resultado directo de las acciones de Ismail. [ cita requerida ]

Irán permaneció dividido hasta la llegada de Tamerlán , un turco-mongol [100] perteneciente a la dinastía Timúrida . Al igual que sus predecesores, el Imperio Timúrida también formaba parte del mundo persa. Tras establecer una base de poder en Transoxiana, Tamerlán invadió Irán en 1381 y acabó conquistando la mayor parte del país. Las campañas de Tamerlán fueron conocidas por su brutalidad; muchas personas fueron masacradas y varias ciudades fueron destruidas. [101]

Su régimen se caracterizó por la tiranía y el derramamiento de sangre, pero también por la inclusión de iraníes en funciones administrativas y la promoción de la arquitectura y la poesía. Sus sucesores, los timúridas, mantuvieron el control de la mayor parte de Irán hasta 1452, cuando perdieron la mayor parte del territorio ante los turcomanos ovejas negras . Los turcomanos ovejas negras fueron conquistados por los turcomanos ovejas blancas bajo el mando de Uzun Hasan en 1468; Uzun Hasan y sus sucesores fueron los amos de Irán hasta el ascenso de los safávidas. [101]

La popularidad del poeta sufí Hafez se estableció firmemente en la era timúrida, que vio la compilación y copia generalizada de su diván . Los sufíes fueron perseguidos a menudo por los musulmanes ortodoxos que consideraban blasfemas sus enseñanzas . El sufismo desarrolló un lenguaje simbólico rico en metáforas para oscurecer las referencias poéticas a enseñanzas filosóficas provocadoras. Hafez ocultó su propia fe sufí, al mismo tiempo que empleaba el lenguaje secreto del sufismo (desarrollado durante cientos de años) en su propia obra, y a veces se le atribuye haberlo "llevado a la perfección". [102] Su obra fue imitada por Jami , cuya propia popularidad creció hasta extenderse por todo el mundo persa. [103]

Los Kara Koyunlu eran una federación tribal turcomana [104] que gobernó el noroeste de Irán y las áreas circundantes desde 1374 hasta 1468 d. C. Los Kara Koyunlu expandieron su conquista a Bagdad, sin embargo, las luchas internas, las derrotas de los timúridas , las rebeliones de los armenios en respuesta a su persecución [105] y las luchas fallidas con los Ag Qoyunlu llevaron a su desaparición final. [106]

Los Aq Qoyunlu eran turcomanos [107] [108] bajo el liderazgo de la tribu Bayandur , [109] una federación tribal de musulmanes sunitas que gobernaron la mayor parte de Irán y grandes partes de las áreas circundantes desde 1378 hasta 1501 d. C. Los Aq Qoyunlu surgieron cuando Timur les concedió todo Diyar Bakr en la actual Turquía. Después, lucharon con sus rivales turcos oghuz, los Qara Qoyunlu . Si bien los Aq Qoyunlu tuvieron éxito en la derrota de Kara Koyunlu, su lucha con la emergente dinastía safávida condujo a su caída. [110]

Persia vivió un resurgimiento durante la dinastía safávida (1502-1736), cuya figura más destacada fue el sha Abbas I. Algunos historiadores atribuyen a la dinastía safávida la fundación del moderno estado-nación de Irán. El carácter chiita contemporáneo de Irán y segmentos significativos de las fronteras actuales de Irán tienen su origen en esta época ( por ejemplo , el Tratado de Zuhab ).

La dinastía safávida fue una de las dinastías gobernantes más importantes de Persia (actual Irán), y "a menudo se considera el comienzo de la historia persa moderna". [111] Gobernaron uno de los mayores imperios persas después de la conquista musulmana de Persia [112] y establecieron la escuela duodecimana del Islam chiita [5] como la religión oficial de su imperio, marcando uno de los puntos de inflexión más importantes en la historia musulmana . Los safávidas gobernaron desde 1501 hasta 1722 (experimentando una breve restauración de 1729 a 1736) y en su apogeo, controlaron todo el Irán moderno , Azerbaiyán y Armenia , la mayor parte de Georgia , el Cáucaso Norte , Irak , Kuwait y Afganistán , así como partes de Turquía , Siria , Pakistán , Turkmenistán y Uzbekistán . El Irán safávida fue uno de los " imperios de la pólvora " islámicos, junto con sus vecinos, su archirrival y principal enemigo, el Imperio Otomano , así como el Imperio Mogol .

La dinastía gobernante safávida fue fundada por Ismail, que se autodenominó Shāh Ismail I. [ 113] Prácticamente adorado por sus seguidores de Qizilbāsh , Ismail invadió Shirvan para vengar la muerte de su padre, Shaykh Haydar , que había sido asesinado durante su asedio a Derbent , en Daguestán. Después emprendió una campaña de conquista y, tras la captura de Tabriz en julio de 1501, se entronizó como el Shāh de Irán, [114] : 324 [115] [116] acuñó monedas en este nombre y proclamó el chiismo como la religión oficial de su dominio. [5]

Aunque inicialmente sólo dominaron Azerbaiyán y el sur de Daguestán, los safávidas habían ganado de hecho la lucha por el poder en Persia que se había prolongado durante casi un siglo entre varias dinastías y fuerzas políticas tras la fragmentación de Kara Koyunlu y Aq Qoyunlu . Un año después de su victoria en Tabriz, Ismail proclamó la mayor parte de Persia como su dominio y [5] rápidamente conquistó y unificó Irán bajo su gobierno. Poco después, el nuevo Imperio safávida conquistó rápidamente regiones, naciones y pueblos en todas las direcciones, incluyendo Armenia , Azerbaiyán , partes de Georgia , Mesopotamia (Irak), Kuwait , Siria , Daguestán , grandes partes de lo que hoy es Afganistán , partes de Turkmenistán y grandes porciones de Anatolia, sentando las bases de su carácter multiétnico que influiría fuertemente en el propio imperio (sobre todo en el Cáucaso y sus pueblos ).

Tahmasp I , hijo y sucesor de Ismail I , llevó a cabo múltiples invasiones en el Cáucaso que había sido incorporado al imperio safávida desde Shah Ismail I y durante muchos siglos después, y comenzó con la tendencia de deportar y trasladar a cientos de miles de circasianos , georgianos y armenios al corazón de Irán. Inicialmente, solo incluyó a los harenes reales, guardias reales y otras secciones menores del Imperio, Tahmasp creía que eventualmente podría reducir el poder de los Qizilbash , creando e integrando completamente una nueva capa en la sociedad iraní. Como afirma la Encyclopædia Iranica , para Tahmasp, el problema giraba en torno a la élite tribal militar del imperio, los Qizilbash, que creían que la proximidad física y el control de un miembro de la familia safávida inmediata garantizaban ventajas espirituales, fortuna política y avance material. [117] Con esta nueva capa caucásica en la sociedad iraní, el poder indiscutible de los Qizilbash (que funcionaban de manera muy similar a los ghazis del vecino Imperio Otomano ) sería cuestionado y completamente disminuido a medida que la sociedad se volvería completamente meritocrática .

Shah Abbas I y sus sucesores ampliarían significativamente esta política y plan iniciado por Tahmasp, deportando durante su reinado a unos 200.000 georgianos , 300.000 armenios y entre 100.000 y 150.000 circasianos a Irán, completando la fundación de una nueva capa en la sociedad iraní. Con esto, y la desorganización sistemática completa del Qizilbash por sus órdenes personales, finalmente logró reemplazar el poder del Qizilbash por el de los ghulams caucásicos . Estos nuevos elementos caucásicos (los llamados ghilman / غِلْمَان / "sirvientes" ), casi siempre después de la conversión al chiismo dependiendo de la función dada, serían, a diferencia del Qizilbash, completamente leales solo al Sha. Las demás masas de caucásicos fueron desplegadas en todas las demás funciones y posiciones posibles disponibles en el imperio, así como en el harén , el ejército regular, los artesanos, los agricultores, etc. Este sistema de utilización masiva de súbditos caucásicos siguió existiendo hasta la caída de la dinastía Qajar .

El mayor de los monarcas safávidas, Shah Abbas I el Grande (1587-1629), llegó al poder en 1587 a los 16 años. Abbas I luchó primero contra los uzbekos, recuperando Herat y Mashhad en 1598, que había perdido su predecesor Mohammad Khodabanda en la guerra otomano-safávida (1578-1590) . Después se volvió contra los otomanos, los archirrivales de los safávidas, recuperando Bagdad, el este de Irak, las provincias del Cáucaso y más allá en 1618 . Entre 1616 y 1618, tras la desobediencia de sus súbditos georgianos más leales, Teimuraz I y Luarsab II , Abbas llevó a cabo una campaña punitiva en sus territorios de Georgia, devastando Kajetia y Tbilisi y llevándose entre 130.000 [118] y 200.000 [119] [120] cautivos georgianos hacia el Irán continental. Su nuevo ejército, que había mejorado drásticamente con la llegada de Robert Shirley y sus hermanos tras la primera misión diplomática a Europa , consiguió la primera victoria aplastante sobre los archirrivales de los safávidas, los otomanos en la guerra de 1603-1618 antes mencionada y superaría a los otomanos en fuerza militar. También utilizó su nueva fuerza para desalojar a los portugueses de Bahréin (1602) y Ormuz (1622) con la ayuda de la marina inglesa, en el Golfo Pérsico.

Amplió los vínculos comerciales con la Compañía Holandesa de las Indias Orientales y estableció vínculos firmes con las casas reales europeas, que Ismail I había iniciado anteriormente mediante la alianza Habsburgo-Persa . De este modo, Abbas I pudo romper la dependencia de los Qizilbash para el poder militar y, por lo tanto, pudo centralizar el control. La dinastía safávida ya se había establecido durante el Sha Ismail I, pero bajo Abbas I realmente se convirtió en una gran potencia en el mundo junto con su archirrival, el Imperio Otomano, contra el que pudo competir en igualdad de condiciones. También comenzó la promoción del turismo en Irán. Bajo su gobierno, la arquitectura persa floreció de nuevo y vio muchos monumentos nuevos en varias ciudades iraníes, de las cuales Isfahán es el ejemplo más notable.

A excepción de Shah Abbas el Grande , Shah Ismail I , Shah Tahmasp I y Shah Abbas II , muchos de los gobernantes safávidas fueron ineficaces, a menudo estando más interesados en sus mujeres, el alcohol y otras actividades de ocio. El final del reinado de Abbas II en 1666, marcó el comienzo del fin de la dinastía safávida. A pesar de la caída de los ingresos y las amenazas militares, muchos de los sahs posteriores tuvieron estilos de vida lujosos. Shah Soltan Hosain (1694-1722), en particular, fue conocido por su amor al vino y su desinterés en el gobierno. [121]

El país en decadencia fue atacado repetidamente en sus fronteras. Finalmente, el jefe pastún Ghilzai llamado Mir Wais Khan comenzó una rebelión en Kandahar y derrotó al ejército safávida bajo el gobernador georgiano iraní sobre la región, Gurgin Khan . En 1722, Pedro el Grande de la vecina Rusia Imperial lanzó la Guerra Ruso-Persa (1722-1723) , capturando muchos de los territorios caucásicos de Irán, incluidos Derbent , Shaki , Bakú , pero también Gilan , Mazandaran y Astrabad . En medio del caos, en el mismo año de 1722, un ejército afgano dirigido por el hijo de Mir Wais, Mahmud , marchó a través del este de Irán, sitió y tomó Isfahán . Mahmud se proclamó a sí mismo 'Shah' de Persia. Mientras tanto, los rivales imperiales de Persia, los otomanos y los rusos, aprovecharon el caos en el país para apoderarse de más territorio para sí mismos. [122] Con estos acontecimientos, la dinastía safávida había llegado a su fin. En 1724, en virtud del Tratado de Constantinopla , los otomanos y los rusos acordaron dividirse entre ellos los territorios recién conquistados de Irán. [123]

La integridad territorial de Irán fue restaurada por un señor de la guerra turco afshar iraní nativo de Khorasan, Nader Shah . Derrotó y desterró a los afganos, derrotó a los otomanos , reinstaló a los safávidas en el trono y negoció la retirada rusa de los territorios caucásicos de Irán, con el Tratado de Resht y el Tratado de Ganja . En 1736, Nader se había vuelto tan poderoso que pudo deponer a los safávidas y hacerse coronar shah. Nader fue uno de los últimos grandes conquistadores de Asia y presidió brevemente lo que probablemente fue el imperio más poderoso del mundo. Para apoyar financieramente sus guerras contra el archirrival de Persia, el Imperio Otomano , fijó su mirada en el débil pero rico Imperio Mogol al este. En 1739, acompañado por sus leales súbditos caucásicos, incluido Erekle II , [124] [125] : 55 invadió la India mogol , derrotó a un ejército mogol numéricamente superior en menos de tres horas y saqueó y robó por completo Delhi , trayendo de vuelta una inmensa riqueza a Persia. En su camino de regreso, también conquistó todos los kanatos uzbekos, excepto Kokand , e hizo a los uzbekos sus vasallos. También restableció firmemente el dominio persa sobre todo el Cáucaso, Bahréin, así como grandes partes de Anatolia y Mesopotamia. Invicto durante años, su derrota en Daguestán , tras las rebeliones guerrilleras de los lezguinos y el intento de asesinato contra él cerca de Mazandaran, a menudo se considera el punto de inflexión en la impresionante carrera de Nader. Para su frustración, los daguestaníes recurrieron a la guerra de guerrillas, y Nader con su ejército convencional pudo avanzar poco contra ellos. [126] En la batalla de Andalal y la batalla de Avaria, el ejército de Nader fue derrotado aplastantemente y perdió la mitad de toda su fuerza, lo que lo obligó a huir a las montañas. [127] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] Aunque Nader logró tomar la mayor parte de Daguestán durante su campaña, la efectiva guerra de guerrillas desplegada por los lezguinos, pero también por los ávaros y los laks hizo que la reconquista iraní de la región particular del Cáucaso del Norte esta vez fuera de corta duración; varios años después, Nader se vio obligado a retirarse.. Casi al mismo tiempo, se produjo un intento de asesinato contra él cerca de Mazandaran, lo que aceleró el curso de la historia; poco a poco enfermó y se volvió megalómano, cegando a sus hijos, de quienes sospechaba que habían intentado asesinarlo, y mostrando una crueldad cada vez mayor contra sus súbditos y oficiales. En sus últimos años, esto acabó provocando múltiples revueltas y, finalmente, el asesinato de Nader en 1747. [128]

La muerte de Nader fue seguida por un período de anarquía en Irán mientras los comandantes rivales del ejército luchaban por el poder . La propia familia de Nader, los Afsharids, pronto se vieron reducidos a aferrarse a un pequeño dominio en Khorasan. Muchos de los territorios del Cáucaso se separaron en varios kanatos del Cáucaso . Los otomanos recuperaron los territorios perdidos en Anatolia y Mesopotamia. Omán y los kanatos uzbekos de Bujará y Jiva recuperaron la independencia. Ahmad Shah Durrani , uno de los oficiales de Nader, fundó un estado independiente que finalmente se convirtió en el moderno Afganistán. Erekle II y Teimuraz II , quienes, en 1744, habían sido nombrados reyes de Kajetia y Kartli respectivamente por el propio Nader por su leal servicio, [125] : 55 capitalizaron la erupción de inestabilidad y declararon la independencia de facto . Erekle II asumió el control de Kartli después de la muerte de Teimuraz II, unificando así los dos como el Reino de Kartli-Kakheti , convirtiéndose en el primer gobernante georgiano en tres siglos en presidir una Georgia oriental políticamente unificada, [129] y debido al frenético giro de los acontecimientos en el Irán continental, podría seguir siendo autónomo de facto durante el período Zand . [130] Desde su capital Shiraz , Karim Khan de la dinastía Zand gobernó "una isla de relativa calma y paz en un período por lo demás sangriento y destructivo", [131] sin embargo, el alcance del poder Zand se limitó al Irán contemporáneo y partes del Cáucaso. La muerte de Karim Khan en 1779 condujo a otra guerra civil en la que la dinastía Qajar finalmente triunfó y se convirtió en reyes de Irán. Durante la guerra civil, Irán perdió permanentemente Basora en 1779 ante los otomanos, que habían sido capturados durante la guerra otomano-persa (1775-76) , [132] y Bahréin ante la familia Al Khalifa después de la invasión de Bani Utbah en 1783. [ cita requerida ]

Agha Mohammad Khan emerged victorious out of the civil war that commenced with the death of the last Zand king. His reign is noted for the reemergence of a centrally led and united Iran. After the death of Nader Shah and the last of the Zands, most of Iran's Caucasian territories had broken away into various Caucasian khanates. Agha Mohammad Khan, like the Safavid kings and Nader Shah before him, viewed the region as no different from the territories in mainland Iran. Therefore, his first objective after having secured mainland Iran, was to reincorpate the Caucasus region into Iran.[133] Georgia was seen as one of the most integral territories.[130] For Agha Mohammad Khan, the resubjugation and reintegration of Georgia into the Iranian Empire was part of the same process that had brought Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tabriz under his rule.[130] As the Cambridge History of Iran states, its permanent secession was inconceivable and had to be resisted in the same way as one would resist an attempt at the separation of Fars or Gilan.[130] It was therefore natural for Agha Mohammad Khan to perform whatever necessary means in the Caucasus in order to subdue and reincorporate the recently lost regions following Nader Shah's death and the demise of the Zands, including putting down what in Iranian eyes was seen as treason on the part of the wali (viceroy) of Georgia, namely the Georgian king Erekle II (Heraclius II) who was appointed viceroy of Georgia by Nader Shah himself.[130]

Agha Mohammad Khan subsequently demanded that Heraclius II renounce its 1783 treaty with Russia, and to submit again to Persian suzerainty,[133] in return for peace and the security of his kingdom. The Ottomans, Iran's neighboring rival, recognized the latter's rights over Kartli and Kakheti for the first time in four centuries.[134] Heraclius appealed then to his theoretical protector, Empress Catherine II of Russia, pleading for at least 3,000 Russian troops,[134] but he was ignored, leaving Georgia to fend off the Persian threat alone.[135] Nevertheless, Heraclius II still rejected the Khan's ultimatum.[136] As a response, Agha Mohammad Khan invaded the Caucasus region after crossing the Aras river, and, while on his way to Georgia, he re-subjugated Iran's territories of the Erivan Khanate, Shirvan, Nakhchivan Khanate, Ganja khanate, Derbent Khanate, Baku khanate, Talysh Khanate, Shaki Khanate, Karabakh Khanate, which comprise modern-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, Dagestan, and Igdir. Having reached Georgia with his large army, he prevailed in the Battle of Krtsanisi, which resulted in the capture and sack of Tbilisi, as well as the effective resubjugation of Georgia.[137][138] Upon his return from his successful campaign in Tbilisi and in effective control over Georgia, together with some 15,000 Georgian captives that were moved back to mainland Iran,[135] Agha Mohammad was formally crowned Shah in 1796 in the Mughan plain, just as his predecessor Nader Shah was about sixty years earlier.

Agha Mohammad Shah was later assassinated while preparing a second expedition against Georgia in 1797 in Shusha[139] (now part of the Republic of Azerbaijan) and the seasoned king Heraclius died early in 1798. The reassertion of Iranian hegemony over Georgia did not last long; in 1799 the Russians marched into Tbilisi.[140] The Russians were already actively occupied with an expansionist policy towards its neighboring empires to its south, namely the Ottoman Empire and the successive Iranian kingdoms since the late 17th/early 18th century. The next two years following Russia's entrance into Tbilisi were a time of confusion, and the weakened and devastated Georgian kingdom, with its capital half in ruins, was easily absorbed by Russia in 1801.[135][136] As Iran could not permit or allow the cession of Transcaucasia and Dagestan, which had been an integral part of Iran for centuries,[141] this would lead directly to the wars of several years later, namely the Russo-Persian Wars of 1804-1813 and 1826–1828. The outcome of these two wars (in the Treaty of Gulistan and the Treaty of Turkmenchay, respectively) proved for the irrevocable forced cession and loss of what is now eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan to Imperial Russia.[142][137]

The area to the north of the river Aras, among which the territory of the contemporary republic of Azerbaijan, eastern Georgia, Dagestan, and Armenia were Iranian territory until they were occupied by Russia in the course of the 19th century.[143]

Following the official loss of vast territories in the Caucasus, major demographic shifts were bound to take place. Following the 1804–1814 war, but also per the 1826–1828 war which ceded the last territories, large migrations, so-called Caucasian Muhajirs, set off to migrate to mainland Iran. Some of these groups included the Ayrums, Qarapapaqs, Circassians, Shia Lezgins, and other Transcaucasian Muslims.[144]

After the Battle of Ganja of 1804 during the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813), many thousands of Ayrums and Qarapapaqs were settled in Tabriz. During the remaining part of the 1804–1813 war, as well as through the 1826–1828 war, a large number of the Ayrums and Qarapapaqs that were still remaining in newly conquered Russian territories were settled in and migrated to Solduz (in modern-day Iran's West Azerbaijan province).[145] As the Cambridge History of Iran states; "The steady encroachment of Russian troops along the frontier in the Caucasus, General Yermolov's brutal punitive expeditions and misgovernment, drove large numbers of Muslims, and even some Georgian Christians, into exile in Iran."[146]

From 1864 until the early 20th century, another mass expulsion took place of Caucasian Muslims as a result of the Russian victory in the Caucasian War. Others simply voluntarily refused to live under Christian Russian rule, and thus departed for Turkey or Iran. These migrations once again, towards Iran, included masses of Caucasian Azerbaijanis, other Transcaucasian Muslims, as well as many North Caucasian Muslims, such as Circassians, Shia Lezgins and Laks.[144][147]Many of these migrants would prove to play a pivotal role in further Iranian history, as they formed most of the ranks of the Persian Cossack Brigade, which was established in the late 19th century.[148] The initial ranks of the brigade would be entirely composed of Circassians and other Caucasian Muhajirs.[148] This brigade would prove decisive in the following decades in Qajar history.

Furthermore, the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay included the official rights for the Russian Empire to encourage settling of Armenians from Iran in the newly conquered Russian territories.[149][150] Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[151] At the close of the fourteenth century, after Timur's campaigns, the Timurid Renaissance flourished, and Islam had become the dominant faith, and Armenians became a minority in Eastern Armenia. [151] After centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian Plateau, many Armenians chose to emigrate and settle elsewhere. Following Shah Abbas I's massive relocation of Armenians and Muslims in 1604–05,[152] their numbers dwindled even further.

At the time of the Russian invasion of Iran, some 80% of the population of Iranian Armenia were Muslims (Persians, Turkics, and Kurds) whereas Christian Armenians constituted a minority of about 20%.[153] As a result of the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede Iranian Armenia (which also constituted the present-day Armenia), to the Russians.[154][155] After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[156] The new Russian administration encouraged the settling of ethnic Armenians from Iran proper and Ottoman Turkey. As a result, by 1832, the number of ethnic Armenians had matched that of the Muslims.[153] It would be only after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, which brought another influx of Turkish Armenians, that ethnic Armenians once again established a solid majority in Eastern Armenia.[157] Nevertheless, the city of Erivan retained a Muslim majority up to the twentieth century.[157] According to the traveller H. F. B. Lynch, the city of Erivan was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Tatars[a] i.e. Azeris and Persians) in the early 1890s.[160]

Fath Ali Shah's reign saw increased diplomatic contacts with the West and the beginning of intense European diplomatic rivalries over Iran. His grandson Mohammad Shah, who succeeded him in 1834, fell under the Russian influence and made two unsuccessful attempts to capture Herat. When Mohammad Shah died in 1848 the succession passed to his son Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, who proved to be the ablest and most successful of the Qajar sovereigns. He founded the first modern hospital in Iran.[161]

The Great Persian Famine of 1870–1871 is believed to have caused the death of two million people.[162]

A new era in the history of Persia dawned with the Persian Constitutional Revolution against the Shah in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Shah managed to remain in power, granting a limited constitution in 1906 (making the country a constitutional monarchy). The first Majlis (parliament) was convened on 7 October 1906.

The discovery of petroleum in 1908 by the British in Khuzestan spawned intense renewed interest in Persia by the British Empire (see William Knox D'Arcy and Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now BP). Control of Persia remained contested between the United Kingdom and Russia, in what became known as The Great Game, and codified in the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which divided Persia into spheres of influence, regardless of her national sovereignty.

During World War I, the country was occupied by British, Ottoman and Russian forces but was essentially neutral (see Persian Campaign). In 1919, after the Russian Revolution and their withdrawal, Britain attempted to establish a protectorate in Persia, which was unsuccessful.

Finally, the Constitutionalist movement of Gilan and the central power vacuum caused by the instability of the Qajar government resulted in the rise of Reza Khan, who was later to become Reza Shah Pahlavi, and the subsequent establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925. In 1921, a military coup established Reza Khan, an officer of the Persian Cossack Brigade, as the dominant figure for the next 20 years. Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabai was also a leader and important figure in the perpetration of the coup. The coup was not actually directed at the Qajar monarchy; according to Encyclopædia Iranica, it was targeted at officials who were in power and actually had a role in controlling the government — the cabinet and others who had a role in governing Persia.[163] In 1925, after being prime minister for two years, Reza Khan became the first shah of the Pahlavi dynasty.

Reza Shah ruled for almost 16 years until 16 September 1941, when he was forced to abdicate by the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. He established an authoritarian government that valued nationalism, militarism, secularism and anti-communism combined with strict censorship and state propaganda.[164] Reza Shah introduced many socio-economic reforms, reorganizing the army, government administration, and finances.[165]

To his supporters, his reign brought "law and order, discipline, central authority, and modern amenities – schools, trains, buses, radios, cinemas, and telephones".[166] However, his attempts of modernisation have been criticised for being "too fast"[167] and "superficial",[168] and his reign a time of "oppression, corruption, taxation, lack of authenticity" with "security typical of police states."[166]

Many of the new laws and regulations created resentment among devout Muslims and the clergy. For example, mosques were required to use chairs; most men were required to wear western clothing, including a hat with a brim; women were encouraged to discard the hijab—hijab was eventually banned in 1936; men and women were allowed to congregate freely, violating Islamic mixing of the sexes. Tensions boiled over in 1935, when bazaaris and villagers rose up in rebellion at the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad to protest against plans for the hijab ban, chanting slogans such as 'The Shah is a new Yezid.' Dozens were killed and hundreds were injured when troops finally quelled the unrest.[169]

While German armies were highly successful against the Soviet Union, the Iranian government expected Germany to win the war and establish a powerful force on its borders. It rejected British and Soviet demands to expel German residents from Iran. In response, the two Allies invaded in August 1941 and easily overwhelmed the weak Iranian army in Operation Countenance. Iran became the major conduit of Allied Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union. The purpose was to secure Iranian oil fields and ensure Allied supply lines (see Persian Corridor). Iran remained officially neutral. Its monarch Rezā Shāh was deposed during the subsequent occupation and replaced with his young son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[170]

At the Tehran Conference of 1943, the Allies issued the Tehran Declaration which guaranteed the post-war independence and boundaries of Iran. However, when the war actually ended, Soviet troops stationed in northwestern Iran not only refused to withdraw but backed revolts that established short-lived, pro-Soviet separatist national states in the northern regions of Azerbaijan and Iranian Kurdistan, the Azerbaijan People's Government and the Republic of Kurdistan respectively, in late 1945. Soviet troops did not withdraw from Iran proper until May 1946 after receiving a promise of oil concessions. The Soviet republics in the north were soon overthrown and the oil concessions were revoked.[171][172]

Initially there were hopes that post-occupation Iran could become a constitutional monarchy. The new, young Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi initially took a very hands-off role in government, and allowed parliament to hold a lot of power. Some elections were held in the first shaky years, although they remained mired in corruption. Parliament became chronically unstable, and from the 1947 to 1951 period Iran saw the rise and fall of six different prime ministers. Pahlavi increased his political power by convening the Iran Constituent Assembly, 1949, which finally formed the Senate of Iran—a legislative upper house allowed for in the 1906 constitution but never brought into being. The new senators were largely supportive of Pahlavi, as he had intended.

In 1951 Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq received the vote required from the parliament to nationalize the British-owned oil industry, in a situation known as the Abadan Crisis. Despite British pressure, including an economic blockade, the nationalization continued. Mosaddeq was briefly removed from power in 1952 but was quickly re-appointed by the Shah, due to a popular uprising in support of the premier, and he, in turn, forced the Shah into a brief exile in August 1953 after a failed military coup by Imperial Guard Colonel Nematollah Nassiri.

Shortly thereafter on 19 August a successful coup was headed by retired army general Fazlollah Zahedi, aided by the United States (CIA)[173] with the active support of the British (MI6) (known as Operation Ajax and Operation Boot to the respective agencies).[174] The coup—with a black propaganda campaign designed to turn the population against Mosaddeq [175] — forced Mosaddeq from office. Mosaddeq was arrested and tried for treason. Found guilty, his sentence was reduced to house arrest on his family estate while his foreign minister, Hossein Fatemi, was executed. Zahedi succeeded him as prime minister, and suppressed opposition to the Shah, specifically the National Front and Communist Tudeh Party.