El Monte del Templo ( hebreo : הַר הַבַּיִת , romanizado: Har haBayīt , lit. 'Monte del Templo'), también conocido como Haram al -Sharif ( árabe : الحرم الشريف, lit. ' El Noble Santuario'), recinto de la mezquita al-Aqsa , o simplemente al-Aqsa ( / ælˈæksə / ; المسجد الأقصى , al-Masjid al-Aqṣā , lit. 'La Mezquita Más Lejana'), [ 2] y a veces como la explanada sagrada de Jerusalén , [ 3] [4] es una colina en la Ciudad Vieja de Jerusalén que ha sido venerada como un lugar sagrado durante miles de años, incluso en el judaísmo . , Cristianismo e Islam . [5] [6]

El sitio actual es una plaza plana rodeada de muros de contención (incluido el Muro Occidental ), que fueron construidos originalmente por el rey Herodes en el siglo I a. C. para una expansión del Segundo Templo judío . La plaza está dominada por dos estructuras monumentales construidas originalmente durante los califatos Rashidun y Omeya temprano después de la captura de la ciudad en 637 d. C.: [7] la sala de oración principal de la mezquita de al-Aqsa y la Cúpula de la Roca , cerca del centro de la colina, que se completó en 692 d. C., lo que la convierte en una de las estructuras islámicas existentes más antiguas del mundo. Los muros y puertas herodianos , con añadidos de los períodos bizantino tardío , musulmán temprano , mameluco y otomano , flanquean el sitio, al que se puede llegar a través de once puertas , diez reservadas para musulmanes y una para no musulmanes, con puestos de guardia de la Policía de Israel en las proximidades de cada una. [8] El patio está rodeado al norte y al oeste por dos pórticos de la época mameluca ( riwaq ) y cuatro minaretes .

El Monte del Templo es el lugar más sagrado del judaísmo, [9] [10] [a] y donde una vez estuvieron dos templos judíos. [12] [13] [14] Según la tradición y las escrituras judías, [15] el Primer Templo fue construido por el rey Salomón , hijo del rey David , en 957 a. C., y fue destruido por el Imperio neobabilónico , junto con Jerusalén , en 587 a. C. No se ha encontrado evidencia arqueológica que verifique la existencia del Primer Templo, y las excavaciones científicas han sido limitadas debido a sensibilidades religiosas. [16] [17] [18] El Segundo Templo, construido bajo Zorobabel en 516 a. C., fue renovado más tarde por el rey Herodes y finalmente destruido por el Imperio romano en 70 d. C. La tradición judía ortodoxa sostiene que es aquí donde se construirá el tercer y último Templo cuando venga el Mesías . [19] El Monte del Templo es el lugar hacia el que los judíos se vuelven durante la oración. Las actitudes judías hacia la entrada al sitio varían. Debido a su extrema santidad, muchos judíos no caminan sobre el Monte mismo, para evitar entrar involuntariamente en el área donde se encontraba el Lugar Santísimo , ya que, según la ley rabínica, todavía hay algún aspecto de la presencia divina en el lugar. [20] [21] [22]

El recinto de la mezquita de Al-Aqsa , en la cima del sitio, es la segunda mezquita más antigua del Islam , [23] y una de las tres Mezquitas Sagradas, los lugares más sagrados del Islam ; es venerada como "el Noble Santuario". [24] Su patio ( sahn ) [25] puede albergar a más de 400.000 fieles, lo que la convierte en una de las mezquitas más grandes del mundo . [23] Tanto para los musulmanes sunitas como para los chiítas , se ubica como el tercer lugar más sagrado del Islam . La plaza incluye el lugar considerado como el lugar donde el profeta islámico Mahoma ascendió al cielo , [26] y sirvió como la primera " qibla ", la dirección hacia la que se giran los musulmanes cuando rezan. Al igual que en el judaísmo, los musulmanes también asocian el sitio con Salomón y otros profetas que también son venerados en el Islam. [27] El sitio, y el término "al-Aqsa", en relación con toda la plaza, también es un símbolo de identidad central para los palestinos , incluidos los cristianos palestinos . [28] [29] [30]

Desde las Cruzadas , la comunidad musulmana de Jerusalén ha administrado el sitio a través del Waqf islámico de Jerusalén . El sitio, junto con toda Jerusalén Este (que incluye la Ciudad Vieja), estuvo controlado por Jordania desde 1948 hasta 1967 y ha estado ocupado por Israel desde la Guerra de los Seis Días de 1967. Poco después de capturar el sitio, Israel devolvió su administración al Waqf bajo la custodia hachemita jordana , al tiempo que mantuvo el control de seguridad israelí. [31] El gobierno israelí aplica una prohibición de la oración a los no musulmanes como parte de un acuerdo generalmente conocido como el "statu quo". [32] [33] [34] El sitio sigue siendo un importante punto focal del conflicto israelí-palestino . [35]

El nombre del sitio es objeto de controversia, principalmente entre musulmanes y judíos, en el contexto del actual conflicto entre israelíes y palestinos . Algunos comentaristas y eruditos árabes musulmanes intentan negar la conexión judía con el Monte del Templo , mientras que algunos comentaristas y eruditos judíos intentan menospreciar la importancia del sitio en el Islam. [36] [37] Durante una disputa de 2016 sobre el nombre del sitio, la Directora General de la UNESCO, Irina Bokova, declaró: "Distintos pueblos adoran los mismos lugares, a veces bajo diferentes nombres. El reconocimiento, uso y respeto de estos nombres es primordial". [38]

El término Har haBayīt –comúnmente traducido como «Monte del Templo» en español– fue utilizado por primera vez en los libros de Miqueas (4:1) y Jeremías (26:18), literalmente como «Monte de la Casa», una variación literaria de la frase más larga «Monte de la Casa del Señor». La abreviatura no se volvió a utilizar en los libros posteriores de la Biblia hebrea [39] ni en el Nuevo Testamento . [40] El término siguió utilizándose durante todo el período del Segundo Templo , aunque el término «Monte Sión», que hoy se refiere a la colina oriental de la antigua Jerusalén, se utilizó con más frecuencia. Ambos términos se utilizan en el Libro de los Macabeos . [41] El término Har haBayīt se utiliza en toda la Mishná y en textos talmúdicos posteriores. [42] [43]

El momento exacto en el que surgió por primera vez el concepto del Monte como una característica topográfica separada del Templo o de la ciudad misma es un tema de debate entre los eruditos. [41] Según Eliav, fue durante el siglo I d.C., después de la destrucción del Segundo Templo. [44] Shahar y Shatzman llegaron a conclusiones diferentes. [45] [46] En los Libros de Crónicas , editados al final del período persa , ya se hace referencia al monte como una entidad distinta. En 2 Crónicas, el Templo de Salomón se construyó en el Monte Moriah (3:1), y la expiación de Manasés por sus pecados se asocia con el Monte de la Casa del Señor (33:15). [47] [48] [41] La concepción del Templo como ubicado en una montaña sagrada que posee cualidades especiales se encuentra repetidamente en los Salmos, y el área circundante se considera una parte integral del Templo mismo. [49]

La organización gubernamental que administra el sitio, el Waqf Islámico de Jerusalén (parte del gobierno jordano), ha declarado que el nombre "Monte del Templo" es un "nombre extraño y ajeno" y un "término de judaización de nueva creación". [50] En 2014, la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina (OLP) emitió un comunicado de prensa instando a los periodistas a no utilizar el término "Monte del Templo" al referirse al sitio. [51] En 2017, se informó de que los funcionarios del Waqf acosaron a arqueólogos como Gabriel Barkay y guías turísticos que utilizaron el término en el sitio. [52] Según Jan Turek y John Carman, en el uso moderno, el término Monte del Templo puede implicar potencialmente apoyo al control israelí del sitio. [53]

2 Crónicas 3:1 [47] se refiere al Monte del Templo en el tiempo anterior a la construcción del templo como el Monte Moriah ( en hebreo : הַר הַמֹּורִיָּה , har ha-Môriyyāh ).

Varios pasajes de la Biblia hebrea indican que durante la época en que fueron escritos, el Monte del Templo se identificaba como el Monte Sión. [54] El Monte Sión mencionado en las partes posteriores del Libro de Isaías (Isaías 60:14), [55] en el Libro de los Salmos y el Primer Libro de los Macabeos ( c. siglo II a. C. ) parece referirse a la cima de la colina, generalmente conocida como el Monte del Templo. [54] Según el Libro de Samuel , el Monte Sión era el sitio de la fortaleza jebusea llamada la "fortaleza de Sión", pero una vez que se erigió el Primer Templo, según la Biblia, en la cima de la Colina Oriental ("Monte del Templo"), el nombre "Monte Sión" migró allí también. [54] El nombre migró más tarde por última vez, esta vez a la Colina Occidental de Jerusalén. [54]

.jpg/440px-Mesjid_el-Aksa_and_Jami_el-Aksa_in_the_1841_Aldrich_and_Symonds_map_of_Jerusalem_(cropped).jpg)

El término inglés "Mezquita al-Aqsa" es una traducción de al-Masjid al-'Aqṣā ( árabe : ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ ) o al-Jâmi' al-Aqṣā ( árabe : ٱلْـجَـامِـع الْأَقْـصّى ). [56] [57] [58] Al-Masjid al-'Aqṣā – "la mezquita más lejana" – se deriva de la Sura 17 del Corán ("El viaje nocturno") que escribe que Mahoma viajó desde La Meca a la mezquita, desde donde posteriormente ascendió al Cielo . [59] [60] Escritores árabes y persas como el geógrafo del siglo X Al-Maqdisi , [61] el erudito del siglo XI Nasir Khusraw , [61] el geógrafo del siglo XII Muhammad al-Idrisi [62] y el erudito islámico del siglo XV Mujir al-Din , [63] [64] así como los orientalistas estadounidenses y británicos del siglo XIX Edward Robinson , [56] Guy Le Strange y Edward Henry Palmer explicaron que el término Masjid al-Aqsa se refiere a toda la explanada de la plaza que es el tema de este artículo - toda el área incluyendo la Cúpula de la Roca , las fuentes, las puertas y los cuatro minaretes - porque ninguno de estos edificios existía en el momento en que se escribió el Corán. [57] [65] [66]

Al-Jâmi' al-Aqṣá se refiere al sitio específico del edificio de la mezquita congregacional con cúpula plateada , [56] [57] [58] también conocida como Mezquita Qibli o Capilla Qibli ( al-Jami' al-Aqsa o al-Qibli , o Masjid al-Jumah o al-Mughata ), en referencia a su ubicación en el extremo sur del complejo como resultado del traslado de la qibla islámica de Jerusalén a La Meca. [67] Los dos términos árabes diferentes traducidos como "mezquita" en inglés son paralelos a los dos términos griegos diferentes traducidos como "templo" en el Nuevo Testamento : griego : ίερόν , romanizado : hieron (equivalente a Masjid) y griego : ναός , romanizado : naos (equivalente a Jami'a), [56] [63] [68] y el uso del término "mezquita" para todo el complejo sigue el uso del mismo término para otros sitios islámicos tempranos con grandes patios como la Mezquita de Ibn Tulun en El Cairo, la Mezquita Omeya en Damasco y la Gran Mezquita de Kairuán . [69] Otras fuentes y mapas han utilizado el término al-Masjid al-'Aqṣā para referirse a la mezquita congregacional en sí. [70] [71] [72]

.jpg/440px-Solomon's_Stables_in_the_1936_Old_City_of_Jerusalem_map_by_Survey_of_Palestine_map_1-2,500_(cropped).jpg)

El término "al-Aqsa" como símbolo y marca se ha vuelto popular y prevaleciente en la región. [73] Por ejemplo, la Intifada de Al-Aqsa (el levantamiento de septiembre de 2000), las Brigadas de los Mártires de Al-Aqsa (una coalición de milicias nacionalistas palestinas en Cisjordania), Al-Aqsa TV (el canal de televisión oficial dirigido por Hamás), la Universidad de Al-Aqsa (universidad palestina establecida en 1991 en la Franja de Gaza), Jund al-Aqsa (una organización yihadista salafista que estuvo activa durante la Guerra Civil Siria), el periódico militar jordano publicado desde principios de la década de 1970, y las asociaciones de las ramas sur y norte del Movimiento Islámico en Israel se llaman Al-Aqsa en honor a este sitio. [73]

Durante el período de los mamelucos [74] (1260-1517) y el dominio otomano (1517-1917), el complejo más amplio comenzó a ser conocido popularmente como Haram al-Sharif, o al-Ḥaram ash-Sharīf (árabe: اَلْـحَـرَم الـشَّـرِيْـف ), que se traduce como el "Santuario Noble". Refleja la terminología de la Masjid al-Haram en La Meca ; [75] [76] [77] [78] Este término elevó el complejo a la categoría de Haram , que anteriormente había estado reservado para la Masjid al-Haram en La Meca y la Al-Masjid an-Nabawi en Medina . Otras figuras islámicas disputaron el estatus de haram del sitio. [73] El uso del nombre Haram al-Sharif por los palestinos locales ha disminuido en las últimas décadas, en favor del nombre tradicional de Mezquita Al-Aqsa. [73]

Algunos eruditos han utilizado los términos Explanada Sagrada o Explanada Sagrada como un "término estrictamente neutral" para el sitio. [5] [6] Un ejemplo notable de este uso es la obra de 2009 Donde el Cielo y la Tierra se encuentran: la Explanada Sagrada de Jerusalén , escrita como un proyecto conjunto de 21 eruditos judíos, musulmanes y cristianos. [79] [80]

En los últimos años, el término "Santa Explanada" ha sido utilizado por las Naciones Unidas , por su Secretario General y por los órganos subsidiarios de la ONU. [81]

El Monte del Templo forma la parte norte de un estrecho espolón de colina que desciende abruptamente de norte a sur. Elevándose sobre el valle de Cedrón al este y el valle de Tiropeón al oeste, [82] su pico alcanza una altura de 740 m (2428 pies) sobre el nivel del mar. [83] Alrededor del año 19 a. C., Herodes el Grande extendió la meseta natural del Monte al encerrar el área con cuatro enormes muros de contención y rellenar los vacíos. Esta expansión artificial dio como resultado una gran extensión plana que hoy forma la sección oriental de la Ciudad Vieja de Jerusalén . La plataforma con forma de trapecio mide 488 m (1601 pies) a lo largo del oeste, 470 m (1540 pies) a lo largo del este, 315 m (1033 pies) a lo largo del norte y 280 m (920 pies) a lo largo del sur, lo que da un área total de aproximadamente 150 000 m 2 (37 acres). [84] El muro norte del Monte, junto con la sección norte del muro occidental, está oculto detrás de edificios residenciales. La sección sur del flanco occidental está expuesta y contiene lo que se conoce como el Muro Occidental . Los muros de contención en estos dos lados descienden muchos metros por debajo del nivel del suelo. Una parte norte del muro occidental se puede ver desde dentro del Túnel del Muro Occidental , que fue excavado a través de edificios adyacentes a la plataforma. En los lados sur y este, los muros son visibles casi en toda su altura. La plataforma en sí está separada del resto de la Ciudad Vieja por el Valle de Tyropeon, aunque este valle, una vez profundo, ahora está en gran parte oculto debajo de depósitos posteriores y es imperceptible en algunos lugares. Se puede llegar a la plataforma a través de la Puerta de la Calle de las Cadenas, una calle en el Barrio Musulmán al nivel de la plataforma, que en realidad se asienta sobre un puente monumental; [85] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] el puente ya no es visible externamente debido al cambio en el nivel del suelo, pero se puede ver desde abajo a través del Túnel del Muro Occidental. [86]

En 1980, Jordania propuso que la Ciudad Vieja fuera incluida en la Lista del Patrimonio Mundial de la UNESCO [87] y fue añadida a la Lista en 1981. [88] En 1982, fue añadida a la Lista del Patrimonio Mundial en Peligro . [89]

El 26 de octubre de 2016, la UNESCO aprobó la Resolución sobre la Palestina ocupada , que condenaba lo que describía como "la escalada de las agresiones israelíes" y las medidas ilegales contra el waqf, pedía la restauración del acceso musulmán y exigía que Israel respetara el statu quo histórico [90] [91] [92] y también criticaba a Israel por su continua "negativa a permitir que los expertos del organismo accedan a los lugares sagrados de Jerusalén para determinar su estado de conservación". [93] [94] Si bien el texto reconocía la "importancia de la Ciudad Vieja de Jerusalén y sus murallas para las tres religiones monoteístas", se refería al recinto sagrado de la cima de la colina en la Ciudad Vieja de Jerusalén solo por su nombre musulmán Al-Haram al-Sharif.

En respuesta, Israel denunció la resolución de la UNESCO por su omisión de las palabras "Monte del Templo" o "Har HaBayit", afirmando que negaba los vínculos judíos con el sitio. [92] [95] Israel congeló todos los vínculos con la UNESCO. [96] [97] En octubre de 2017, Israel y los Estados Unidos anunciaron que se retirarían de la UNESCO, citando un sesgo antiisraelí. [98] [99]

El 6 de abril de 2022, la UNESCO adoptó por unanimidad una resolución que reiteraba las 21 resoluciones anteriores relativas a Jerusalén. [100]

El Monte del Templo tiene importancia histórica y religiosa para las tres principales religiones abrahámicas : el judaísmo, el cristianismo y el islam. Tiene una importancia religiosa particular para el judaísmo y el islam.

El Monte del Templo es considerado el lugar más sagrado del judaísmo. [101] [102] [11] Según la tradición judía, ambos Templos se encontraban en el Monte del Templo. [103] La tradición judía además ubica al Monte del Templo como el lugar de una serie de eventos importantes que ocurrieron en la Biblia, incluyendo la Atadura de Isaac , el sueño de Jacob y la oración de Isaac y Rebeca . [104] Según el Talmud, la Piedra Fundacional es el lugar desde donde el mundo fue creado y se expandió a su forma actual. [105] [106] La tradición judía ortodoxa sostiene que es aquí donde se construirá el tercer y último Templo cuando venga el Mesías . [107]

El Monte del Templo es el lugar al que se dirigen los judíos durante la oración. Las actitudes de los judíos respecto de entrar en el lugar varían. Debido a su extrema santidad, muchos judíos no caminan por el Monte mismo, para evitar entrar sin querer en la zona donde se encontraba el Santo de los Santos , ya que, según la ley rabínica, todavía hay algún aspecto de la presencia divina en el lugar. [108] [109] [110]

Según la Biblia hebrea , el Monte del Templo era originalmente una era propiedad de Arauna , un jebuseo . [111] La Biblia narra cómo David unió a las doce tribus israelitas , conquistó Jerusalén y trajo el artefacto central de los israelitas , el Arca de la Alianza , a la ciudad. [112] Cuando una gran plaga azotó a Israel, un ángel destructor apareció en la era de Arauna. El profeta Gad sugirió entonces a David la zona como un lugar apropiado para la erección de un altar a Yahvé . [113] David compró la propiedad a Arauna, por cincuenta piezas de plata, y erigió el altar. Dios respondió a sus oraciones y detuvo la plaga. Posteriormente, David eligió el sitio para un futuro templo para reemplazar el Tabernáculo y albergar el Arca de la Alianza; [114] [115] Sin embargo, Dios le prohibió construirlo, porque había "derramado mucha sangre". [116]

El Primer Templo fue construido bajo el mando del hijo de David , Salomón , [117] quien se convirtió en un ambicioso constructor de obras públicas en el antiguo Israel : [118]

Entonces Salomón comenzó a edificar la casa de Jehová en Jerusalén, en el monte Moriah, donde Jehová se había aparecido a David su padre; para lo cual se había preparado en la casa de David, en la era de Ornán jebuseo.

— 2 Crónicas 3:1 [119]

Salomón colocó el Arca en el Lugar Santísimo, el santuario más interior y sin ventanas y la zona más sagrada del templo en la que reposaba la presencia de Dios; [120] la entrada al Lugar Santísimo estaba muy restringida, y solo el Sumo Sacerdote de Israel entraba en el santuario una vez al año en Yom Kippur , llevando la sangre de un cordero sacrificial y quemando incienso . [120] Según la Biblia, el sitio funcionaba como el centro de toda la vida nacional: un centro gubernamental, judicial y religioso. [121]

El Génesis Rabba , que probablemente fue escrito entre 300 y 500 d.C., afirma que este sitio es uno de los tres sobre los cuales las naciones del mundo no pueden burlarse de Israel y decir: "los has robado", ya que fue comprado "por su precio completo" por David. [122]

El Primer Templo fue destruido en 587/586 a. C. por el Imperio Neobabilónico bajo el segundo rey babilónico, Nabucodonosor II , quien posteriormente exilió a los judíos a Babilonia tras la caída del Reino de Judá y su anexión como provincia babilónica . A los judíos que habían sido deportados tras la conquista babilónica de Judá finalmente se les permitió regresar tras una proclamación del rey persa Ciro el Grande que se emitió después de la caída de Babilonia ante el Imperio aqueménida . En 516 a. C., la población judía que regresó a Judá, bajo el gobierno provincial persa , reconstruyó el Templo de Jerusalén bajo los auspicios de Zorobabel , produciendo lo que se conoce como el Segundo Templo .

Durante el Período del Segundo Templo , Jerusalén era el centro de la vida religiosa y nacional de los judíos, incluidos los de la diáspora . [123] Se cree que el Segundo Templo atrajo a decenas y tal vez cientos de miles de personas durante las Tres Fiestas de Peregrinación . [123] La festividad de Hanukkah conmemora la rededicación del Templo al comienzo de la revuelta macabea en el siglo II a. C. Durante el siglo I a. C., el Templo fue renovado por Herodes . Fue destruido por el Imperio Romano en el apogeo de la Primera Guerra Judeo-Romana en el año 70 d. C. Tisha B'Av , un día de ayuno anual en el judaísmo , marca la destrucción del Primer y Segundo Templos, que según la tradición judía, ocurrió el mismo día en el calendario hebreo .

El libro de Isaías predice la importancia internacional del Monte del Templo:

Y acontecerá en lo postrero de los tiempos, que será confirmado el monte de la casa de Jehová como cabeza de los montes, y será exaltado sobre los collados, y correrán a él todas las naciones. Y vendrán muchos pueblos, y dirán: Venid, y subamos al monte de Jehová, a la casa del Dios de Jacob; y nos enseñará sus caminos, y andaremos por sus sendas. Porque de Sión saldrá la ley, y de Jerusalén la palabra de Jehová.

— Isaías 2:2–3 [124]

En la tradición judía, también se cree que el Monte del Templo es el lugar donde Abraham ató a Isaac . 2 Crónicas 3:1 [47] se refiere al Monte del Templo en la época anterior a la construcción del templo como Monte Moriah ( en hebreo : הַר הַמֹּורִיָּה , har ha-Môriyyāh ). La « tierra de Moriah » ( אֶרֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּה , eretṣ ha-Môriyyāh ) es el nombre dado por el Génesis al lugar donde ataron a Isaac. [125] Desde al menos el siglo I d. C., los dos sitios han sido identificados entre sí en el judaísmo, y esta identificación ha sido posteriormente perpetuada por la tradición judía y cristiana . La erudición moderna tiende a considerarlos distintos (véase Moriah ).

Según los sabios rabínicos cuyos debates produjeron el Talmud , la Piedra Fundacional , que se encuentra debajo de la Cúpula de la Roca , fue el lugar desde donde se creó el mundo y se expandió hasta su forma actual, [105] [106] y donde Dios reunió el polvo utilizado para crear al primer ser humano, Adán . [125]

Los textos judíos predicen que el Monte será el sitio de un Tercer y último Templo , que será reconstruido con la llegada del Mesías . La reconstrucción del Templo siguió siendo un tema recurrente entre generaciones, particularmente en la Amidá (oración de pie) tres veces al día, la oración central de la liturgia judía , que contiene una petición para la construcción de un Tercer Templo y la restauración de los servicios sacrificiales . Varios grupos judíos vocales ahora abogan por la construcción del Tercer Templo sin demora para hacer realidad los "planes proféticos de Dios para el fin de los tiempos para Israel y el mundo entero". [126]

El Templo era de importancia central en el culto judío en el Tanaj ( Antiguo Testamento ). En el Nuevo Testamento , el Templo de Herodes fue el lugar de varios eventos en la vida de Jesús , y la lealtad cristiana al sitio como punto focal permaneció mucho después de su muerte. [127] [128] [129] Después de la destrucción del Templo en el año 70 d. C., que llegó a ser considerada por los primeros cristianos, como lo fue por Josefo y los sabios del Talmud de Jerusalén , como un acto divino de castigo por los pecados del pueblo judío, [130] [131] el Monte del Templo perdió su importancia para el culto cristiano y los cristianos lo consideraron un cumplimiento de la profecía de Cristo en, por ejemplo, Mateo 23:38 [132] y Mateo 24:2. [133] Fue con este fin, prueba de una profecía bíblica cumplida y de la victoria del cristianismo sobre el judaísmo con el Nuevo Pacto , [134] que los primeros peregrinos cristianos también visitaron el sitio. [135] Los cristianos bizantinos, a pesar de algunos signos de trabajo constructivo en la explanada, [136] generalmente descuidaron el Monte del Templo, especialmente cuando un intento judío de reconstruir el Templo fue destruido por el terremoto de 363. [ 137] Se convirtió en un vertedero de basura local desolado, tal vez fuera de los límites de la ciudad, [138] cuando el culto cristiano en Jerusalén se trasladó a la Iglesia del Santo Sepulcro , y la centralidad de Jerusalén fue reemplazada por Roma. [139]

Durante la era bizantina , Jerusalén era principalmente cristiana y los peregrinos acudían por decenas de miles para experimentar los lugares por los que caminó Jesús. [ cita requerida ] Después de la invasión persa en 614, muchas iglesias fueron arrasadas y el sitio se convirtió en un vertedero. Los árabes conquistaron la ciudad del Imperio bizantino que la había retomado en 629. La prohibición bizantina sobre los judíos se levantó y se les permitió vivir dentro de la ciudad y visitar los lugares de culto. Los peregrinos cristianos pudieron venir y experimentar el área del Monte del Templo. [140] La guerra entre los selyúcidas y el Imperio bizantino y la creciente violencia musulmana contra los peregrinos cristianos a Jerusalén instigaron las Cruzadas . Los cruzados capturaron Jerusalén en 1099 y la Cúpula de la Roca fue entregada a los agustinos , quienes la convirtieron en una iglesia, y la Mezquita al-Aqsa se convirtió en el palacio real de Balduino I de Jerusalén en 1104. Los Caballeros Templarios , que creían que la Cúpula de la Roca era el sitio del Templo de Salomón , le dieron el nombre de " Templum Domini " y establecieron su cuartel general en la Mezquita al-Aqsa adyacente a la Cúpula durante gran parte del siglo XII. [ cita requerida ]

En el arte cristiano , la circuncisión de Jesús fue representada convencionalmente como ocurriendo en el Templo, aunque hasta hace poco los artistas europeos no tenían forma de saber cómo era el Templo y los Evangelios no afirman que el evento tuvo lugar en el Templo. [141]

Aunque algunos cristianos creen que el Templo será reconstruido antes o al mismo tiempo que la Segunda Venida de Jesús (véase también dispensacionalismo ), la peregrinación al Monte del Templo no se considera importante en las creencias y el culto de la mayoría de los cristianos. El Nuevo Testamento relata la historia de una mujer samaritana que le preguntó a Jesús cuál era el lugar apropiado para adorar, Jerusalén (como lo era para los judíos) o el Monte Gerizim (como lo era para los samaritanos ), a lo que Jesús responde:

Mujer, créeme, llega la hora en que ni en este monte ni en Jerusalén adoraréis al Padre. Vosotros adoráis lo que no sabéis; nosotros adoramos lo que conocemos, porque la salvación viene de los judíos. Pero llega la hora, y ya está aquí, en que los verdaderos adoradores adorarán al Padre en espíritu y en verdad, porque el Padre tales adoradores busca. Dios es Espíritu, y los que le adoran deben adorar en espíritu y en verdad.

— Juan 4:21–24 [142]

Esto se ha interpretado en el sentido de que Jesús prescindió de la ubicación física para el culto, que era más bien una cuestión de espíritu y verdad. [143]

.jpg/440px-Dan_Hadani_collection_(990040387040205171).jpg)

Entre los musulmanes sunitas y chiítas , [ cita requerida ] toda la plaza, conocida como la mezquita al-Aqsa, también conocida como Haram al-Sharif o "el Noble Santuario", se considera el tercer lugar más sagrado del Islam . [24] Según la tradición islámica, la plaza es el lugar de la ascensión de Mahoma al cielo desde Jerusalén , y sirvió como la primera " qibla ", la dirección hacia la que se giran los musulmanes cuando rezan. Al igual que en el judaísmo, los musulmanes también asocian el sitio con Abraham y otros profetas que también son venerados en el Islam. [27] Los musulmanes ven el sitio como uno de los primeros y más notables lugares de adoración a Dios . Prefirieron usar la explanada como el corazón del barrio musulmán, ya que había sido abandonada por los cristianos, para evitar perturbar los barrios cristianos de Jerusalén. [144] Los califas omeyas encargaron la construcción de la mezquita al-Aqsa en el sitio, incluido el santuario conocido como la " Cúpula de la Roca ". [145] La Cúpula se completó en el año 692 d. C., lo que la convierte en una de las estructuras islámicas más antiguas que aún se conservan en el mundo. La Mezquita Al-Aqsa , a veces conocida como la Mezquita Qibli, se encuentra en el extremo sur del Monte, frente a La Meca .

El Islam primitivo consideraba que la Piedra Fundamental era la ubicación del Templo de Salomón, y las primeras iniciativas arquitectónicas en el Monte del Templo buscaban glorificar a Jerusalén presentando al Islam como una continuación del judaísmo y el cristianismo. [36] Casi inmediatamente después de la conquista musulmana de Jerusalén en 638 d. C., el califa 'Omar ibn al Khatab , al parecer disgustado por la suciedad que cubría el lugar, lo hizo limpiar a fondo, [146] y concedió a los judíos el acceso al lugar. [147] Según los primeros intérpretes coránicos y lo que generalmente se acepta como tradición islámica, en 638 d. C. Umar, al entrar en una Jerusalén conquistada, consultó con Ka'ab al-Ahbar -un judío convertido al Islam que vino con él desde Medina- sobre cuál sería el mejor lugar para construir una mezquita. Al-Ahbar le sugirió que debería estar detrás de la Roca "... para que toda Jerusalén estuviera ante ti". Umar respondió: "¡Tú correspondes al judaísmo!" Inmediatamente después de esta conversación, Umar comenzó a limpiar el lugar –que estaba lleno de basura y escombros– con su manto, y otros seguidores musulmanes lo imitaron hasta que el lugar quedó limpio. Luego, Umar rezó en el lugar donde se creía que Mahoma había rezado antes de su viaje nocturno, recitando la sura coránica Sad . [148] Así, según esta tradición, Umar volvió a consagrar el lugar como mezquita. [149]

Las interpretaciones musulmanas del Corán coinciden en que el Monte es el sitio del Templo construido originalmente por Salomón , considerado un profeta en el Islam , que luego fue destruido. [150] [151] Después de la construcción, creen los musulmanes, el templo fue utilizado para la adoración del único Dios por muchos profetas del Islam, incluido Jesús. [152] [153] [154] Otros eruditos musulmanes han utilizado la Torá (llamada Tawrat en árabe) para ampliar los detalles del templo. [155] El término Bayt al-Maqdis (o Bayt al-Muqaddas ), que aparece con frecuencia como nombre de Jerusalén en las primeras fuentes islámicas, es un cognado del término hebreo bēt ha-miqdāsh (בית המקדש), el Templo en Jerusalén. [156] [157] [158] Mujir al-Din , un cronista jerosolimitano del siglo XV, menciona una tradición anterior relatada por al-Wasti, según la cual "después de que David construyó muchas ciudades y la situación de los hijos de Israel mejoró, quiso construir Bayt al-Maqdis y construir una cúpula sobre la roca en el lugar que Alá santificó en Aelia". [36]

Según el Corán , Mahoma fue transportado a un sitio llamado Mezquita Al-Aqsa - "el lugar más alejado de la oración" ( al-Masjid al-'Aqṣā ) durante su Viaje Nocturno ( Isra y Mi'raj ). [159] El Corán describe cómo Mahoma fue llevado por el corcel milagroso Buraq desde la Gran Mezquita de La Meca a la Mezquita al-Aqsa donde oró. [160] [159] [161] Después de que Mahoma terminó sus oraciones, el ángel Jibril ( Gabriel ) viajó con él al cielo, donde conoció a varios otros profetas y los guió en la oración: [162] [163] [164]

¡Gloria a Aquel que llevó a Su siervo Muhammad de noche desde la Mezquita Sagrada a la Mezquita más alejada, cuyos alrededores bendecimos, para mostrarle algunos de Nuestros signos! En verdad, sólo Él es Quien todo lo oye, Quien todo lo ve.

— Sura Al-Isra 17:1

El Corán no menciona la ubicación exacta del «lugar de oración más alejado», y la ciudad de Jerusalén no es mencionada por ninguno de sus nombres en el Corán. [165] [151] Según la Enciclopedia del Islam , la frase se entendió originalmente como una referencia a un sitio en los cielos. [166] Un grupo de eruditos islámicos entendió la historia de la ascensión de Mahoma desde la mezquita de Al-Aqsa como relacionada con el Templo judío en Jerusalén . Otro grupo no estuvo de acuerdo con esta identificación y prefirió el significado del término como una referencia al cielo. [167] Se cree que Al-Bujari y Al-Tabari , por ejemplo, rechazaron la identificación con Jerusalén. [166] [168] Finalmente, surgió un consenso en torno a la identificación del «lugar de oración más alejado» con Jerusalén, y por implicación el Monte del Templo. [167] [169] Los hadices posteriores se refirieron a Jerusalén como el sitio de la mezquita de Al-Aqsa: [170]

Narró Jabir bin `Abdullah:

Que escuchó al Mensajero de Allah decir: "Cuando la gente de Quraish no me creyó (es decir, la historia de mi Viaje Nocturno), me puse de pie en Al-Hijr y Allah mostró Jerusalén frente a mí, y comencé a describírsela mientras la miraba".— Sahih al-Bujari 3886

Algunos estudiosos señalan los motivos políticos de la dinastía Omeya que llevaron a la santificación de Jerusalén en el Islam. Según la Enciclopedia del Islam, los omeyas asociaron el Viaje Nocturno con Jerusalén como un medio político para promover la gloria de Jerusalén y competir con la gloria del santuario de La Meca, entonces controlado por Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr . [166] [171] La construcción de la Cúpula de la Roca fue interpretada por Ya'qubi , un historiador abasí del siglo IX , como un intento omeya de redirigir el Hajj desde La Meca a Jerusalén creando un rival para la Kaaba . [172]

Otros académicos atribuyen la santidad de Jerusalén al surgimiento y expansión de un cierto tipo de género literario, conocido como al-Fadhail o historia de las ciudades. El Fadhail de Jerusalén inspiró a los musulmanes, especialmente durante el período omeya, a embellecer la santidad de la ciudad más allá de su estatus en los textos sagrados. [173] Basándose en los escritos de los historiadores del siglo VIII Al-Waqidi [174] y al-Azraqi , algunos eruditos han sugerido que la mezquita de al-Aqsa mencionada en el Corán no está en Jerusalén sino en el pueblo de al-Ju'ranah , a 18 millas al noreste de La Meca. [168] [175] [176]

Los escritos medievales posteriores, así como los tratados políticos modernos, tienden a clasificar la mezquita de Al-Aqsa como el tercer lugar más sagrado del Islam. [177]

La importancia histórica de la mezquita de al-Aqsa en el Islam se enfatiza aún más por el hecho de que los musulmanes se volvieron hacia al-Aqsa cuando oraron durante un período de 16 o 17 meses después de la migración a Medina en 624; por lo tanto, se convirtió en la qibla ("dirección") a la que los musulmanes se orientaban para la oración. [178] Mahoma más tarde oró hacia la Kaaba en La Meca después de recibir una revelación durante una sesión de oración [179] [180] en la Masjid al-Qiblatayn . [181] [182] La qibla fue reubicada en la Kaaba, donde los musulmanes han sido dirigidos a orar desde entonces. [183]

La Organización para la Cooperación Islámica se refiere a la Mezquita Al-Aqsa como el tercer lugar más sagrado del Islam (y pide la soberanía árabe sobre ella). [184]

Se cree que la colina ha estado habitada desde el cuarto milenio a . C. [ cita requerida ] En 2012, el Proyecto de Cribado del Monte del Templo descubrió en el sitio un amuleto con el cartucho de Tutmosis III (r. 1479-1425 a. C.). [ 185 ]

Según los arqueólogos, el Monte del Templo sirvió como centro de la vida religiosa de la Jerusalén bíblica, así como acrópolis real del Reino de Judá . [186] Se cree que el Primer Templo alguna vez fue parte de un complejo real mucho más grande. [187] La Biblia también menciona varios otros edificios construidos por Salomón en el sitio, incluido el palacio real, la "Casa del Bosque del Líbano", el "Salón de los Pilares", el "Salón del Trono" y la "Casa de la Hija del Faraón". [41] [188] Algunos eruditos creen que, de acuerdo con los relatos bíblicos, el complejo real y religioso en el Monte del Templo fue construido por Salomón durante el siglo X a. C. como una entidad separada, que luego se incorporó a la ciudad. [186] Knauf argumentó que el Monte del Templo ya servía como centro de culto y gobierno de Jerusalén ya en la Edad del Bronce Tardío . [189] Alternativamente, Naamán sugirió que Salomón construyó el Templo en una escala mucho más pequeña que la descrita en la Biblia, que fue ampliada o reconstruida durante el siglo VIII a. C. [190] En 2014, Finkelstein , Koch y Lipschits propusieron que el testimonio de la antigua Jerusalén se encuentra debajo del complejo moderno, en lugar del sitio arqueológico cercano conocido como la Ciudad de David , como cree la arqueología convencional; [191] sin embargo, esta propuesta fue rechazada por otros estudiosos del tema. [192]

Todos los eruditos coinciden en que el Monte del Templo de la Edad de Hierro era más pequeño que el complejo herodiano aún visible hoy en día. Algunos eruditos, como Kenyon y Ritmeyer , argumentaron que los muros del complejo del Primer Templo se extendían hacia el este hasta el Muro Oriental . [186] [187] Ritmeyer identifica hiladas específicas de sillares visibles ubicados al norte y al sur de la Puerta Dorada como de estilo de la Edad de Hierro de Judea, y los data de la construcción de este muro por Ezequías . Se supone que más piedras de este tipo sobreviven bajo tierra. [193] [194] Ritmeyer también ha sugerido que uno de los escalones que conducen a la Cúpula de la Roca es en realidad la parte superior de una hilera de piedras restante del muro occidental del complejo de la Edad de Hierro. [195] [196]

El Primer Templo fue destruido en 587/586 a. C. por el Imperio Neobabilónico bajo el mando de Nabucodonosor II .

La construcción del Segundo Templo comenzó bajo el reinado de Ciro alrededor del año 538 a. C. y se completó en el año 516 a. C. Se construyó en el sitio original del Templo de Salomón. [197] [41]

Según Patrich y Edelcopp, el área ideal del complejo, descrita en Ezequiel como 50x50 codos, fue alcanzada por los asmoneos , quizás bajo Juan Hircano ; este es el mismo tamaño mencionado más tarde por la Mishná . [41]

El arqueólogo Leen Ritmeyer ha recuperado evidencia de una expansión asmonea del Monte del Templo .

En el año 67 a. C. estalló una disputa entre Aristóbulo II e Hircano II por el trono asmoneo. El general romano Pompeyo , que había sido invitado a intervenir en el conflicto, se puso del lado de Hircano; Aristóbulo y sus seguidores se atrincheraron dentro del Monte del Templo y destruyeron el puente que lo unía a la ciudad. Cuando el ejército romano llegó a Jerusalén, Pompeyo ordenó que se rellenara el foso que defendía el Monte del Templo desde el norte. Para lograrlo, Pompeyo esperó a que llegaran los sabbats , para que los defensores no interrumpieran el trabajo. Después de un asedio de tres meses , los romanos pudieron derribar una de las torres de vigilancia y asaltar el Monte del Templo. El propio Pompeyo entró en el Lugar Santísimo , pero no dañó el Templo y permitió que los sacerdotes continuaran con su trabajo como de costumbre. [198] [199] [200]

Alrededor del año 19 a. C., Herodes el Grande amplió aún más el Monte del Templo y reconstruyó el templo . El ambicioso proyecto, que implicó el empleo de 10.000 trabajadores, [201] duplicó con creces el tamaño del Monte del Templo hasta aproximadamente 36 acres (150.000 m2 ) . Herodes niveló el área cortando la roca en el lado noroeste y elevando el terreno inclinado hacia el sur. Logró esto construyendo enormes muros de contrafuerte y bóvedas y rellenando las secciones necesarias con tierra y escombros. [202] El resultado fue el temenos más grande del mundo antiguo. [203]

Las entradas principales al Monte del Templo herodiano eran dos juegos de puertas construidas en el muro sur, junto con otras cuatro puertas a las que se podía llegar desde el lado occidental por escaleras y puentes. Grandes stoas rodeaban la plataforma por tres lados, y en su lado sur se encontraba una magnífica basílica a la que Josefo se refirió como la Stoa Real . [203] La Stoa Real servía como centro para las transacciones comerciales y legales de la ciudad, y tenía acceso independiente a la ciudad de abajo a través del paso elevado del Arco de Robinson . [204] El Templo en sí y sus patios estaban ubicados en una plataforma elevada en medio del complejo más grande. Además de la restauración del Templo, sus patios y pórticos, Herodes también construyó la Fortaleza Antonia , que dominaba la esquina noroeste del Monte del Templo, y un depósito de agua de lluvia, Birket Israel , en el noreste. Una calle monumental, hoy conocida como la " Calle Escalonada ", llevaba a los peregrinos desde la puerta sur de la ciudad a través del Valle de Tiropeón hasta el lado occidental del Monte del Templo. En 2019 se propuso que Poncio Pilato construyó la carretera durante los años 30. [205]

Durante las primeras fases de la Primera Guerra Judeo-Romana (66-70 d. C.), el Monte del Templo se convirtió en un centro de lucha para varias facciones judías que luchaban por el control de la ciudad, con diferentes facciones que controlaban el área durante el conflicto. En abril del 70, el ejército romano bajo el mando de Tito llegó a Jerusalén y comenzó a sitiar la ciudad . Los romanos tardaron cuatro meses en derrotar a los defensores del Monte del Templo y tomar el sitio. Los romanos destruyeron por completo el Templo y todas las demás estructuras en la plataforma. [206] Se descubrieron enormes derrumbes de piedra de los muros superiores sobre la calle Herodiana que corre a lo largo de la parte sur del Muro Occidental, [207] con algunas de las piedras quemadas a temperaturas que alcanzaron los 800 °C (1472 °F). [208] La inscripción del Lugar de las Trompetas , una inscripción hebrea monumental que fue arrojada por legionarios romanos, fue encontrada en una de estas pilas de piedras. [209]

La ciudad de Aelia Capitolina fue construida en el año 130 d. C. por el emperador romano Adriano y ocupada por una colonia romana en el sitio de Jerusalén, que todavía estaba en ruinas desde la Primera Revuelta Judía en el año 70 d. C. Aelia proviene del nomen gentile de Adriano , Aelius , mientras que Capitolina significaba que la nueva ciudad estaba dedicada a Júpiter Capitolino , a quien se le construyó un templo superpuesto al sitio del anterior segundo templo judío, el Monte del Templo. [210]

Adriano había pensado en la construcción de la nueva ciudad como un regalo a los judíos, pero como había construido una estatua gigante de sí mismo frente al Templo de Júpiter y el Templo de Júpiter tenía una enorme estatua de Júpiter en su interior, había ahora en el Monte del Templo dos enormes imágenes esculpidas , que los judíos consideraban idólatras. También era costumbre en los ritos romanos sacrificar un cerdo en las ceremonias de purificación de la tierra. [211] Después de la Tercera Revuelta Judía , a todos los judíos se les prohibió bajo pena de muerte entrar en la ciudad o en el territorio circundante a la ciudad. [212]

Desde el siglo I hasta el VII, el cristianismo se extendió por todo el Imperio Romano, se convirtió gradualmente en la religión predominante de Palestina y, bajo los bizantinos, la propia Jerusalén era casi completamente cristiana, y la mayor parte de la población era cristiana jacobita de rito sirio . [134] [137]

El emperador Constantino I promovió la cristianización de la sociedad romana, dándole prioridad sobre los cultos paganos. [213] Una consecuencia fue que el Templo de Júpiter de Adriano en el Monte del Templo fue demolido inmediatamente después del Primer Concilio de Nicea en el año 325 d. C. por orden de Constantino. [214]

El peregrino de Burdeos , que visitó Jerusalén en 333-334, durante el reinado del emperador Constantino I, escribió que «hay dos estatuas de Adriano y, no lejos de ellas, una piedra horadada a la que los judíos acuden cada año y se ungen. Se lamentan y rasgan sus vestiduras, y luego se van». [215] Se supone que la ocasión fue Tisha b'Av , ya que décadas después Jerónimo relató que ese era el único día en el que se permitía a los judíos entrar en Jerusalén. [216]

En el año 363, el emperador Juliano , sobrino de Constantino , concedió permiso a los judíos para reconstruir el Templo. [216] [217] En una carta atribuida a Juliano, escribió a los judíos: «Debéis hacer esto para que, cuando haya concluido con éxito la guerra en Persia, pueda reconstruir con mis propios esfuerzos la ciudad sagrada de Jerusalén, que durante tantos años habéis anhelado ver habitada, y pueda traer colonos allí y, junto con vosotros, glorificar allí al Dios Altísimo». [216] Juliano veía al Dios judío como un miembro adecuado del panteón de dioses en los que creía, y también era un fuerte oponente del cristianismo. [216] [218] Los historiadores de la Iglesia escribieron que los judíos comenzaron a limpiar las estructuras y los escombros del Monte del Templo, pero se vieron frustrados, primero por un gran terremoto y luego por milagros que incluyeron fuego que brotó de la tierra. [219] Sin embargo, ninguna fuente judía contemporánea menciona este episodio directamente. [216]

Durante sus excavaciones en la década de 1930, Robert Hamilton descubrió porciones de un piso de mosaico multicolor con patrones geométricos dentro de la mezquita al-Aqsa, pero no las publicó. [220] La fecha del mosaico es discutida: Zachi Dvira considera que son del período bizantino preislámico, mientras que Baruch, Reich y Sandhaus favorecen un origen omeya mucho más posterior debido a su similitud con un mosaico omeya conocido. [220]

En el año 610, el Imperio sasánida expulsó al Imperio bizantino de Oriente Medio, lo que permitió a los judíos controlar Jerusalén por primera vez en siglos. A los judíos de Palestina se les permitió establecer un estado vasallo bajo el Imperio sasánida llamado la Mancomunidad Judía Sasánida , que duró cinco años. Los rabinos judíos ordenaron que se reanudaran los sacrificios de animales por primera vez desde la época del Segundo Templo y comenzaron a reconstruir el Templo judío. Poco antes de que los bizantinos recuperaran la zona cinco años después, en el año 615, los persas cedieron el control a la población cristiana, que derribó el edificio parcialmente construido del Templo judío y lo convirtió en un vertedero de basura, [221] que era cuando el califa Umar tomó la ciudad en el año 637 .

En 637, los árabes sitiaron y capturaron la ciudad del Imperio bizantino, que había derrotado a las fuerzas persas y sus aliados, y reconquistaron la ciudad. No hay registros contemporáneos, pero sí muchas tradiciones, sobre el origen de los principales edificios islámicos en el monte. [222] [223] Un relato popular de siglos posteriores es que el califa Rashidun Umar fue llevado al lugar de mala gana por el patriarca cristiano Sofronio . [224] Lo encontró cubierto de escombros, pero la Roca sagrada fue encontrada con la ayuda de un judío converso, Ka'b al-Ahbar . [224] Al-Ahbar le aconsejó a Umar que construyera una mezquita al norte de la roca, para que los fieles estuvieran de cara tanto a la roca como a La Meca, pero en cambio Umar eligió construirla al sur de la roca. [224] Se conoció como la mezquita de al-Aqsa. Según fuentes musulmanas, los judíos participaron en la construcción del haram, sentando las bases tanto para al-Aqsa como para la mezquita de la Cúpula de la Roca. [225] El primer testimonio conocido de un testigo ocular es el del peregrino Arculf , que lo visitó alrededor del año 670. Según el relato de Arculf registrado por Adomnán , vio una casa de oración rectangular de madera construida sobre unas ruinas, lo suficientemente grande como para albergar a 3.000 personas. [222] [226]

En 691, el califa Abd al-Malik construyó un edificio islámico octogonal coronado por una cúpula alrededor de la roca, por una miríada de razones políticas, dinásticas y religiosas, basándose en tradiciones locales y coránicas que articulaban la santidad del lugar, un proceso en el que las narrativas textuales y arquitectónicas se reforzaban mutuamente. [227] El santuario llegó a ser conocido como la Cúpula de la Roca ( قبة الصخرة , Qubbat as-Sakhra ). (La cúpula misma fue cubierta de oro en 1920.) En 715, los omeyas, liderados por el califa al-Walid I , construyeron la mezquita de al-Aqsa ( المسجد الأقصى , al-Masjid al-'Aqṣā , lit. "Mezquita más alejada"), correspondiente a la creencia islámica del milagroso viaje nocturno de Mahoma tal como se relata en el Corán y los hadices . El término "Noble Santuario" o "Haram al-Sharif", como lo llamaron más tarde los mamelucos y los otomanos , se refiere a toda el área que rodea esa Roca. [228]

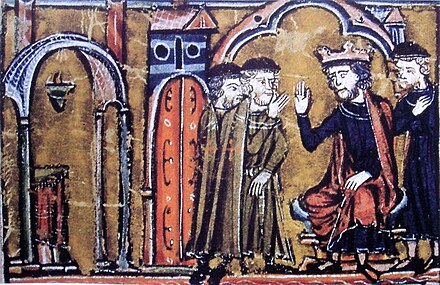

El período de las Cruzadas comenzó en 1099 con la toma de Jerusalén por parte de la Primera Cruzada . Después de la conquista de la ciudad, a la orden de las Cruzadas conocida como los Caballeros Templarios se le concedió el uso de la Mezquita de Al-Aqsa para que la utilizara como su cuartel general. Esto fue probablemente otorgado por Balduino II de Jerusalén y Warmund, Patriarca de Jerusalén en el Concilio de Nablus en enero de 1120. [229] El Monte del Templo tenía una mística porque estaba sobre lo que se creía que eran las ruinas del Templo de Salomón . [230] [231] Por lo tanto, los Cruzados se referían a la Mezquita de Al-Aqsa como el Templo de Salomón, y fue de esta ubicación que la nueva Orden tomó el nombre de "Pobres Caballeros de Cristo y del Templo de Salomón", o caballeros "Templarios".

En 1187, una vez que recuperó Jerusalén, Saladino eliminó todo rastro de culto cristiano del Monte del Templo y devolvió la Cúpula de la Roca y la mezquita de Al-Aqsa a sus usos musulmanes. A partir de entonces, la mezquita permaneció en manos musulmanas, incluso durante los períodos relativamente breves de dominio cruzado posteriores a la Sexta Cruzada .

Hay varios edificios mamelucos en la explanada del Haram y sus alrededores, como la madrasa al-Ashrafiyya de finales del siglo XV y la fuente Sabil de Qaytbay . Los mamelucos también elevaron el nivel del valle central o tirolés de Jerusalén, que bordea el Monte del Templo por el oeste, construyendo enormes subestructuras sobre las que luego construyeron a gran escala. Las subestructuras y los edificios sobre el suelo del período mameluco cubren así gran parte del muro occidental herodiano del Monte del Templo.

Tras la conquista otomana de Palestina en 1516, las autoridades otomanas continuaron con la política de prohibir a los no musulmanes poner un pie en el Monte del Templo hasta principios del siglo XIX, cuando se les permitió nuevamente visitar el lugar. [232] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ]

En 1867, un equipo de los Ingenieros Reales , dirigido por el teniente Charles Warren y financiado por el Fondo de Exploración de Palestina ( PEF), descubrió una serie de túneles cerca del Monte del Templo. Warren excavó en secreto algunos túneles cerca de los muros del Monte del Templo y fue el primero en documentar sus cursos inferiores. Warren también realizó algunas excavaciones a pequeña escala dentro del Monte del Templo, retirando escombros que bloqueaban los pasajes que conducían a la cámara de la Puerta Doble .

Entre 1922 y 1924, el Consejo Superior Islámico restauró la Cúpula de la Roca. [233] El movimiento sionista de la época se oponía firmemente a cualquier idea de que se pudiera reconstruir el Templo. De hecho, su brazo armado, la milicia Haganah , asesinó a un judío cuando su plan de volar los lugares islámicos del Haram llegó a su conocimiento en 1931. [234]

Jordan llevó a cabo dos renovaciones de la Cúpula de la Roca: reemplazó la cúpula interior de madera con goteras por una cúpula de aluminio en 1952 y, cuando la nueva cúpula comenzó a gotear, realizó una segunda restauración entre 1959 y 1964. [233]

Ni los árabes israelíes ni los judíos israelíes pudieron visitar sus lugares sagrados en los territorios jordanos durante este período. [235] [236]

El 7 de junio de 1967, durante la Guerra de los Seis Días , las fuerzas israelíes avanzaron más allá de la Línea del Acuerdo de Armisticio de 1949 hacia territorios de Cisjordania , tomando el control de la Ciudad Vieja de Jerusalén , incluido el Monte del Templo.

El Gran Rabino de las Fuerzas de Defensa de Israel , Shlomo Goren , dirigió a los soldados en las celebraciones religiosas en el Monte del Templo y en el Muro Occidental. El Gran Rabinato israelí también declaró una festividad religiosa en el aniversario, llamada " Yom Yerushalayim " (Día de Jerusalén), que se convirtió en una fiesta nacional para conmemorar la reunificación de Jerusalén . Muchos vieron la captura de Jerusalén y el Monte del Templo como una liberación milagrosa de proporciones bíblicas-mesiánicas. [237] Unos días después de la guerra, más de 200.000 judíos acudieron al Muro Occidental en la primera peregrinación judía masiva cerca del Monte desde la destrucción del Templo en el año 70 d. C. Las autoridades islámicas no molestaron a Goren cuando fue a rezar al Monte hasta que, el noveno día de Av , trajo a 50 seguidores e introdujo un shofar y un arca portátil para rezar, una innovación que alarmó a las autoridades del Waqf y provocó un deterioro de las relaciones entre las autoridades musulmanas y el gobierno israelí. [238]

En junio de 1969, un australiano prendió fuego a la mezquita Jami'a al-Aqsa . El 11 de abril de 1982, un judío se escondió en la Cúpula de la Roca y disparó, matando a 2 palestinos e hiriendo a 44; en 1974, 1977 y 1983, grupos liderados por Yoel Lerner conspiraron para hacer estallar tanto la Cúpula de la Roca como al-Aqsa. El 26 de enero de 1984, los guardias del Waqf detectaron a miembros de B'nei Yehuda, un culto mesiánico de antiguos gánsteres convertidos en místicos con sede en Lifta , que intentaban infiltrarse en la zona para hacerla estallar. [239] [240] [241]

El 15 de enero de 1988, durante la Primera Intifada , las tropas israelíes dispararon balas de goma y gases lacrimógenos contra los manifestantes que se encontraban fuera de la mezquita, hiriendo a 40 fieles. [242] [243]

El 8 de octubre de 1990, las fuerzas israelíes que patrullaban el lugar impidieron que los fieles llegaran al mismo. Se detonó una bomba de gas lacrimógeno entre las mujeres fieles, lo que provocó una escalada de los acontecimientos. El 12 de octubre de 1990, los musulmanes palestinos protestaron violentamente por la intención de algunos judíos extremistas de colocar una piedra angular en el sitio para un Nuevo Templo como preludio a la destrucción de las mezquitas musulmanas. El intento fue bloqueado por las autoridades israelíes, pero se informó ampliamente de que los manifestantes habían apedreado a los judíos en el Muro Occidental. [239] [244] Según el historiador palestino Rashid Khalidi , el periodismo de investigación ha demostrado que esta acusación es falsa. [245] Finalmente, se lanzaron piedras, mientras que las fuerzas de seguridad dispararon ráfagas que mataron a 21 personas e hirieron a otras 150. [239] Una investigación israelí encontró a las fuerzas israelíes culpables, pero también concluyó que no se podían presentar cargos contra ningún individuo en particular. [246]

El 8 de octubre de 1990, 22 palestinos fueron asesinados y más de 100 heridos por la policía fronteriza israelí durante las protestas que se desencadenaron por el anuncio de los Fieles del Monte del Templo , un grupo de judíos religiosos, de que iban a colocar la piedra angular del Tercer Templo. [247] [248] Entre 1992 y 1994, el gobierno jordano emprendió la medida sin precedentes de dorar la cúpula de la Cúpula de la Roca, cubriéndola con 5000 placas de oro, y restaurando y reforzando la estructura. También se reconstruyó el minbar de Saladino . El proyecto fue pagado personalmente por el rey Hussein , con un costo de $8 millones. [233] El Monte del Templo permanece, según los términos del tratado de paz entre Israel y Jordania de 1994 , bajo custodia jordana . [249] En diciembre de 1997, los servicios de seguridad israelíes frustraron un intento de extremistas judíos de arrojar una cabeza de cerdo envuelta en las páginas del Corán a la zona, con el fin de provocar un motín y avergonzar al gobierno. [239]

El 28 de septiembre de 2000, el entonces líder de la oposición israelí Ariel Sharon y miembros del partido Likud , junto con 1.000 guardias armados, visitaron el complejo de Al-Aqsa. La visita fue vista como un gesto provocador por muchos palestinos, que se congregaron alrededor del lugar. Después de que Sharon y los miembros del partido Likud se marcharan, estalló una manifestación y los palestinos que se encontraban en el recinto de Haram al-Sharif comenzaron a arrojar piedras y otros proyectiles a la policía antidisturbios israelí. La policía disparó gases lacrimógenos y balas de goma contra la multitud, hiriendo a 24 personas. La visita desencadenó un levantamiento palestino que duró cinco años, comúnmente conocido como la Intifada de Al-Aqsa , aunque algunos comentaristas, citando discursos posteriores de funcionarios de la Autoridad Palestina, en particular Imad Falouji y Yasar Arafat , afirman que la Intifada había sido planeada con meses de antelación, ya en julio, tras el regreso de Arafat de las conversaciones de Camp David en los Estados Unidos. [250] [251] [252] El 29 de septiembre, el gobierno israelí desplegó 2.000 policías antidisturbios en la mezquita. Cuando un grupo de palestinos abandonó la mezquita después de las oraciones del viernes ( Yumu'ah ), lanzaron piedras a la policía. La policía irrumpió entonces en el recinto de la mezquita, disparando munición real y balas de goma contra el grupo de palestinos, matando a cuatro e hiriendo a unos 200. [253]

El 3 de enero de 2023, el ministro de Seguridad Nacional israelí, Itamar Ben-Gvir , visitó el Monte del Templo en Jerusalén , lo que provocó protestas de los palestinos y la condena de varios países árabes . [254]

A los judíos no se les permitió visitar el país durante aproximadamente mil años. [ ¿Cuándo? ] [255]

En los primeros diez años del gobierno británico en Palestina, a todos se les permitía la entrada al complejo del Monte del Templo/Haram al-Sharif. A veces estallaba violencia en la entrada entre judíos y musulmanes. Durante los disturbios palestinos de 1929 , se acusó a los judíos de violar el statu quo. [256] [257] Después de los disturbios, el Consejo Supremo Musulmán y el Waqf Islámico de Jerusalén prohibieron a los judíos entrar por las puertas del sitio. Durante el período del mandato, los líderes judíos celebraron antiguas prácticas religiosas en el Muro Occidental. La prohibición a los visitantes continuó hasta 1948 [258]

Aunque el Acuerdo de Armisticio de 1949 preveía "la reanudación del funcionamiento normal de las instituciones culturales y humanitarias del Monte Scopus y el libre acceso a las mismas; el libre acceso a los Santos Lugares y a las instituciones culturales y el uso del cementerio del Monte de los Olivos", en la práctica, las barreras de alambre y hormigón eran la realidad. Los lugares culturales y religiosos de ambos lados de la ciudad fueron destruidos y abandonados y la comunidad judía fue excluida de sus lugares sagrados. [259]

Unos días después de la Guerra de los Seis Días , el 17 de junio de 1967, se celebró una reunión en la mezquita de al-Aqsa entre Moshe Dayan y las autoridades religiosas musulmanas de Jerusalén para reformular el statu quo. [260] A los judíos se les dio el derecho de visitar el Monte del Templo sin obstáculos y de forma gratuita si respetaban los sentimientos religiosos de los musulmanes y actuaban decentemente, pero no se les permitió rezar. El Muro Occidental seguiría siendo el lugar de oración judío. La "soberanía religiosa" seguiría siendo de los musulmanes mientras que la "soberanía general" pasaría a ser israelí. [238] Los musulmanes se opusieron a la oferta de Dayan, ya que rechazaban por completo la conquista israelí de Jerusalén y el Monte del Templo. Algunos judíos, encabezados por Shlomo Goren , entonces rabino jefe militar, también se habían opuesto, alegando que la decisión entregaba el complejo a los musulmanes, ya que la santidad del Muro Occidental se deriva del Monte y simboliza el exilio, mientras que rezar en el Monte simboliza la libertad y el regreso del pueblo judío a su patria. [260] El presidente del Tribunal Superior de Justicia, Aharon Barak , en respuesta a una apelación en 1976 contra la interferencia policial con el supuesto derecho de un individuo a rezar en el sitio, expresó la opinión de que, si bien los judíos tenían derecho a rezar allí, no era absoluto sino que estaba sujeto al interés público y a los derechos de otros grupos. Los tribunales de Israel han considerado la cuestión como algo que estaba más allá de su competencia y, dada la delicadeza del asunto, bajo jurisdicción política. [260] Barak escribió:

El principio básico es que todo judío tiene derecho a entrar en el Monte del Templo, a rezar allí y a tener comunión con su Creador. Esto forma parte de la libertad religiosa de culto y de la libertad de expresión. Sin embargo, como ocurre con todo derecho humano, no es un derecho absoluto, sino relativo... De hecho, en un caso en el que existe una certeza casi absoluta de que se puede causar daño al interés público si se respetan los derechos de culto religioso y de libertad de expresión de una persona, es posible limitar los derechos de la persona a fin de defender el interés público. [238]

La policía siguió prohibiendo a los judíos rezar en el Monte del Templo. [260] Posteriormente, varios primeros ministros también intentaron cambiar el statu quo, pero fracasaron. En octubre de 1986, un acuerdo entre los Fieles del Monte del Templo , el Consejo Supremo Musulmán y la policía, que permitiría visitas breves en grupos pequeños, se ejerció una vez y nunca se repitió, después de que 2.000 musulmanes armados con piedras y botellas atacaran al grupo y apedrearan a los fieles en el Muro Occidental. Durante la década de 1990, se hicieron intentos adicionales de oración judía en el Monte del Templo, que fueron detenidos por la policía israelí. [260]

Hasta el año 2000, los visitantes no musulmanes podían entrar en la Cúpula de la Roca, la Mezquita de Al-Aqsa y el Museo Islámico con una entrada en el Waqf . Este procedimiento terminó cuando estalló la Segunda Intifada . Quince años después, las negociaciones entre Israel y Jordania podrían dar como resultado [ necesita actualización ] la reapertura de esos lugares una vez más. [261]

En la década de 2010, surgió entre los palestinos el temor de que Israel planeara cambiar el statu quo y permitir las oraciones judías o que Israel pudiera dañar o destruir la mezquita de Al-Aqsa. Al-Aqsa se utilizó como base para ataques contra los visitantes y la policía desde donde se arrojaron piedras, bombas incendiarias y fuegos artificiales. La policía israelí nunca había entrado en la mezquita de Al-Aqsa hasta el 5 de noviembre de 2014, cuando fracasó el diálogo con los líderes del Waqf y los alborotadores. Esto resultó en la imposición de estrictas limitaciones a la entrada de visitantes al Monte del Templo. El liderazgo israelí declaró repetidamente que el statu quo no cambiaría. [262] Según el entonces comisionado de policía de Jerusalén, Yohanan Danino, el lugar está en el centro de una "guerra santa" y "cualquiera que quiera cambiar el statu quo en el Monte del Templo no debería ser permitido subir allí", citando una "agenda de extrema derecha para cambiar el statu quo en el Monte del Templo"; Hamás y la Yihad Islámica siguieron afirmando erróneamente que el gobierno israelí planeaba destruir la mezquita de Al-Aqsa, lo que dio lugar a ataques terroristas crónicos y disturbios. [263]

Se han producido varios cambios en el status quo:

Muchos palestinos creen que el statu quo está amenazado, ya que los israelíes de derechas lo han estado desafiando con más fuerza y frecuencia, afirmando un derecho religioso a rezar allí. Hasta que Israel los prohibió, los miembros de Murabitat , un grupo de mujeres, gritaban "Alá Akbar" a los grupos de visitantes judíos para recordarles que el Monte del Templo todavía estaba en manos musulmanas. [264] [265] En octubre de 2021, un tribunal israelí anuló la prohibición de un hombre judío, Aryeh Lippo, a quien la policía israelí prohibió la entrada al Monte del Templo durante quince días después de ser sorprendido rezando en silencio, con el argumento de que su comportamiento no había violado las instrucciones de la policía. [266] Hamás calificó la sentencia como "una clara declaración de guerra". [267] Un tribunal superior israelí revocó rápidamente la sentencia del tribunal inferior. [268]

Un Waqf islámico ha administrado el Monte del Templo de manera continua desde la reconquista musulmana del Reino Latino de Jerusalén en 1187. El 7 de junio de 1967, poco después de que Israel tomara el control de la zona durante la Guerra de los Seis Días , el Primer Ministro Levi Eshkol aseguró que "no se causará daño alguno a los lugares sagrados para todas las religiones". Junto con la extensión de la jurisdicción y administración israelíes sobre Jerusalén oriental, el Knesset aprobó la Ley de Preservación de los Lugares Santos [269], asegurando la protección de los Lugares Santos contra la profanación, así como la libertad de acceso a los mismos. [270] El sitio permanece dentro del área controlada por el Estado de Israel , y la administración del sitio permanece en manos del Waqf islámico de Jerusalén.

Aunque la libertad de acceso estaba consagrada en la ley, como medida de seguridad, el gobierno israelí ahora aplica una prohibición a la oración de los no musulmanes en el lugar. Los no musulmanes que son vistos rezando en el lugar están sujetos a expulsión por la policía. [271] En varias ocasiones, cuando existe el temor de disturbios árabes en el monte que resulten en el lanzamiento de piedras desde arriba hacia la Plaza del Muro Occidental, Israel ha impedido que los hombres musulmanes menores de 45 años recen en el complejo, citando estas preocupaciones. [272] A veces, tales restricciones han coincidido con las oraciones de los viernes durante el mes sagrado islámico del Ramadán . [273] Normalmente, a los palestinos de Cisjordania se les permite el acceso a Jerusalén solo durante las festividades islámicas, y el acceso generalmente está restringido a los hombres mayores de 35 años y a las mujeres de cualquier edad que reúnan los requisitos para obtener permisos para ingresar a la ciudad. [274] Los residentes palestinos de Jerusalén, que debido a la anexión de Jerusalén por parte de Israel, tienen tarjetas de residencia permanente israelíes, y los árabes israelíes, tienen permitido el acceso sin restricciones al Monte del Templo. [ cita requerida ] La Puerta de los Magrebíes es la única entrada al Monte del Templo accesible para los no musulmanes. [275] [276] [277]

Due to religious restrictions on entering the most sacred areas of the Temple Mount (see following section), the Western Wall, a retaining wall for the Temple Mount and remnant of the Second Temple structure, is considered by some rabbinical authorities to be the holiest accessible site for Jews to pray. A 2013 Knesset committee hearing considered allowing Jews to pray at the site, amidst heated debate. Arab-Israeli MPs were ejected for disrupting the hearing, after shouting at the chairman, calling her a "pyromaniac". Religious Affairs Minister Eli Ben-Dahan of Jewish Home said his ministry was seeking legal ways to enable Jews to pray at the site.[278]

During Temple times, entry to the Mount was limited by a complex set of purity laws. Persons suffering from corpse uncleanness were not allowed to enter the inner court.[279] Non-Jews were also prohibited from entering the inner court of the Temple.[280] A hewn stone measuring 60 cm × 90 cm (24 in × 35 in) and engraved with Greek uncials was discovered in 1871 near a court on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem in which it outlined this prohibition:

ΜΗΟΕΝΑΑΛΛΟΓΕΝΗΕΙΣΠΟ

ΡΕΥΕΣΟΑΙΕΝΤΟΣΤΟΥΠΕ

ΡΙΤΟΙΕΡΟΝΤΡΥΦΑΚΤΟΥΚΑΙ

ΠΕΡΙΒΟΛΟΥΟΣΔΑΝΛΗ

ΦΘΗΕΑΥΤΩΙΑΙΤΙΟΣΕΣ

ΤΑΙΔΙΑΤΟΕΞΑΚΟΛΟΥ

ΘΕΙΝΘΑΝΑΤΟΝ

Translation: "Let no foreigner enter within the parapet and the partition which surrounds the Temple precincts. Anyone caught [violating] will be held accountable for his ensuing death." Today, the stone is preserved in Istanbul's Museum of Antiquities.

Maimonides wrote that it was only permitted to enter the site to fulfill a religious precept. After the destruction of the Temple there was discussion as to whether the site, bereft of the Temple, still maintained its holiness. Jewish codifiers accepted the opinion of Maimonides who ruled that the holiness of the Temple sanctified the site for eternity and consequently the restrictions on entry to the site remain in force.[232] While secular Jews ascend freely, the question of whether ascending is permitted is a matter of some debate among religious authorities, with a majority holding that it is permitted to ascend to the Temple Mount, but not to step on the site of the inner courtyards of the ancient Temple.[232] The question then becomes whether the site can be ascertained accurately.[232][better source needed]

There is debate over whether reports that Maimonides himself ascended the Mount are reliable.[281] One such report[citation needed] claims that he did so on Thursday, October 21, 1165, during the Crusader period. Some early scholars however, claim that entry onto certain areas of the Mount is permitted. It appears that Radbaz also entered the Mount and advised others how to do this. He permits entry from all the gates into the 135 x 135 cubits of the Women's Courtyard in the east, since the biblical prohibition only applies to the 187 x 135 cubits of the Temple in the west.[282] There are also Christian and Islamic sources which indicate that Jews visited the site,[283] but these visits may have been made under duress.[284]

A few hours after the Temple Mount came under Israeli control during the Six-Day War, a message from the Chief Rabbis of Israel, Isser Yehuda Unterman and Yitzhak Nissim was broadcast, warning that Jews were not permitted to enter the site.[285] This warning was reiterated by the Council of the Chief Rabbinate a few days later, which issued an explanation written by Rabbi Bezalel Jolti (Zolti) that "Since the sanctity of the site has never ended, it is forbidden to enter the Temple Mount until the Temple is built."[285] The signatures of more than 300 prominent rabbis were later obtained.[286]

A major critic of the decision of the Chief Rabbinate was Rabbi Shlomo Goren, the chief rabbi of the IDF.[285] According to General Uzi Narkiss, who led the Israeli force that conquered the Temple Mount, Goren proposed to him that the Dome of the Rock be immediately blown up.[286] After Narkiss refused, Goren unsuccessfully petitioned the government to close off the Mount to Jews and non-Jews alike.[286] Later he established his office on the Mount and conducted a series of demonstrations on the Mount in support of the right of Jewish men to enter there.[285] His behavior displeased the government, which restricted his public actions, censored his writings, and in August prevented him from attending the annual Oral Law Conference at which the question of access to the Mount was debated.[287] Although there was considerable opposition, the conference consensus was to confirm the ban on entry to Jews.[287] The ruling said "We have been warned, since time immemorial [lit. 'for generations and generations'], against entering the entire area of the Temple Mount and have indeed avoided doing so."[286][287] According to Ron Hassner, the ruling "brilliantly" solved the government's problem of avoiding ethnic conflict, since those Jews who most respected rabbinical authority were those most likely to clash with Muslims on the Mount.[287]

Rabbinical consensus in the post-1967 period, held that it is forbidden for Jews to enter any part of the Temple Mount,[288] and in January 2005, a declaration was signed confirming the 1967 decision.[289]

Most Haredi rabbis are of the opinion that the Mount is off limits to Jews and non-Jews alike.[290] Their opinions against entering the Temple Mount are based on the current political climate surrounding the Mount,[291] along with the potential danger of entering the hallowed area of the Temple courtyard and the impossibility of fulfilling the ritual requirement of cleansing oneself with the ashes of a red heifer.[292][293] The boundaries of the areas which are completely forbidden, while having large portions in common, are delineated differently by various rabbinic authorities.

However, there is a growing body of Modern Orthodox and national religious rabbis who encourage visits to certain parts of the Mount, which they believe are permitted according to most medieval rabbinical authorities.[232][better source needed] These rabbis include: Shlomo Goren (former Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel); Chaim David Halevi (former Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv and Yafo); Dov Lior (Rabbi of Kiryat Arba); Yosef Elboim; Yisrael Ariel; She'ar Yashuv Cohen (Chief Rabbi of Haifa); Yuval Sherlo (rosh yeshiva of the hesder yeshiva of Petah Tikva); Meir Kahane. One of them, Shlomo Goren, held that it is possible that Jews are even allowed to enter the heart of the Dome of the Rock in time of war, according to Jewish Law of Conquest.[294] These authorities demand an attitude of veneration on the part of Jews ascending the Temple Mount, ablution in a mikveh prior to the ascent, and the wearing of non-leather shoes.[232][better source needed] Some rabbinic authorities are now of the opinion that it is imperative for Jews to ascend in order to halt the ongoing process of Islamization of the Temple Mount. Maimonides, perhaps the greatest codifier of Jewish Law, wrote in Laws of the Chosen House ch 7 Law 15 "One may bring a dead body in to the (lower sanctified areas of the) Temple Mount and there is no need to say that the ritually impure (from the dead) may enter there, because the dead body itself can enter". One who is ritually impure through direct or in-direct contact of the dead cannot walk in the higher sanctified areas. For those who are visibly Jewish, they have no choice, but to follow a peripheral route[295] as it has become unofficially part of the status quo on the Mount. Many of these recent opinions rely on archaeological evidence.[232][better source needed]

In December 2013, the two Chief Rabbis of Israel, David Lau and Yitzhak Yosef, reiterated the ban on Jews entering the Temple Mount.[296] They wrote, "In light of [those] neglecting [this ruling], we once again warn that nothing has changed and this strict prohibition remains in effect for the entire area [of the Temple Mount]".[296] In November 2014, the Sephardic chief rabbi Yitzhak Yosef reiterated the point of view held by many rabbinic authorities that Jews should not visit the Mount.[249]

On the occasion of an upsurge in Palestinian knifing attacks on Israelis, associated with fears that Israel was changing the status quo on the Mount, the Haredi newspaper Mishpacha ran a notification in Arabic asking, 'their cousins', Palestinians, to stop trying to murder members of their congregation, since they were vehemently opposed to ascending the Mount and consider such visits proscribed by Jewish law.[297]

The large courtyard (sahn)[25] can host more than 400,000 worshippers, making it one of the largest mosques in the world.[23]

The upper platform surrounds the Dome of the Rock, beneath which lies the Well of Souls, originally accessible only by a narrow hole in the Sakhrah, the foundation stone on which the Dome of the Rock site and after which it is named, until the Crusaders dug a new entrance to the cave from the south.[298] The platform is accessible via eight staircases, each of which is topped by a free-standing arcade known in Arabic as the qanatir or mawazin. The arcades were erected in different periods from the 10th to 15th centuries.[299]

There is also a smaller domed building on the upper platform, to the east of the Dome of the Rock, known as the Dome of the Chain (Qubbat al-Sisila in Arabic).[300][301] Its exact origin and purpose is uncertain but historical sources indicate it was built under the reign of Abd al-Malik, the same Umayyad caliph who built the Dome of the Rock.[302] Two other small domes stand to the northwest of the Dome of the Rock. The Dome of the Ascension (Qubbat al-Miraj in Arabic) has an inscription with a date corresponding to 1201 CE.[299][303] It may have been a former Crusader structure, possibly a baptistery, that was repurposed at this time,[303] or it may be a structure that was built after Saladin's capture of the city and reused some Crusader-era materials, including its columns.[304] Per its name, this dome commemorates the spot where, according to some, Muhammad ascended to heaven.[305] The Dome of the Spirits or Dome of the Winds (Qubbat al-Arwah in Arabic) stands a little further north and is dated to the 16th century.[306][299]

.jpg/440px-Jerusalem_Temple_Mount_(43195424811).jpg)

In the southwest corner of the upper platform is a quadrangular structure which includes a portion topped by another dome. It is known as the Dome of Literature (Qubba Nahwiyya in Arabic) and dated to 1208.[299] Standing further east, close to one of the southern entrance arcades, is a stone minbar known as the "Summer Pulpit" or Minbar of Burhan al-Din, used for open-air prayers. It appears to be an older ciborium from the Crusader period, as attested by its sculptural decoration, which was then reused under the Ayyubids. Sometime after 1345, a Mamluk judge named Burhan al-Din (d. 1388) restored it and added a stone staircase, giving it its present form.[307][308]

The lower platform – which constitutes most of the surface of the Temple Mount – has at its southern end al-Aqsa Mosque, which takes up most of the width of the Mount. Gardens take up the eastern and most of the northern side of the platform; the far north of the platform houses an Islamic school.[309]

The lower platform also houses an ablution fountain (known as al-Kas), originally supplied with water via a long narrow aqueduct leading from the so-called Solomon's Pools near Bethlehem, but now supplied from Jerusalem's water mains.

There are several cisterns beneath the lower platform, designed to collect rainwater as a water supply. These have various forms and structures, seemingly built in different periods, ranging from vaulted chambers built in the gap between the bedrock and the platform, to chambers cut into the bedrock itself. Of these, the most notable are (numbering traditionally follows Wilson's scheme[310]):