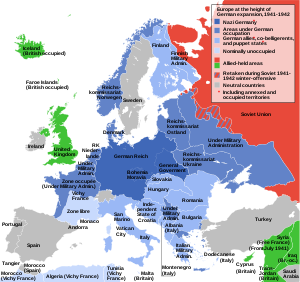

El Frente Oriental , también conocido como la Gran Guerra Patria [n] en la Unión Soviética y sus estados sucesores, y la Guerra Germano-Soviética [o] en la actual Alemania y Ucrania, fue un teatro de operaciones de la Segunda Guerra Mundial que se libró entre las potencias del Eje europeo y los Aliados , incluida la Unión Soviética (URSS) y Polonia . Abarcó Europa Central , Europa del Este , Europa del Noreste ( Báltico ) y Europa del Sudeste ( Balcanes ), y duró desde el 22 de junio de 1941 hasta el 9 de mayo de 1945. De las aproximadamente 70–85 millones de muertes atribuidas a la Segunda Guerra Mundial, alrededor de 30 millones ocurrieron en el Frente Oriental, incluidos 9 millones de niños. [2] [3] El Frente Oriental fue decisivo para determinar el resultado en el teatro de operaciones europeo en la Segunda Guerra Mundial , y eventualmente sirvió como la razón principal de la derrota de la Alemania nazi y las naciones del Eje. [4] El historiador Geoffrey Roberts señala que «más del 80 por ciento de todos los combates durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial tuvieron lugar en el Frente Oriental». [5]

Las fuerzas del Eje, lideradas por la Alemania nazi, comenzaron su avance hacia la Unión Soviética bajo el nombre en clave de Operación Barbarroja el 22 de junio de 1941, la fecha de apertura del Frente Oriental. Inicialmente, las fuerzas soviéticas no pudieron detener a las fuerzas del Eje, que se acercaron a Moscú . A pesar de sus muchos intentos, el Eje no logró capturar Moscú y pronto se centró en los campos petrolíferos del Cáucaso . Las fuerzas alemanas invadieron el Cáucaso bajo el plan Fall Blau ("Caso Azul") el 28 de junio de 1942. Los soviéticos detuvieron con éxito el avance del Eje en Stalingrado , la batalla más sangrienta de la guerra, lo que le costó la moral a las potencias del Eje y se consideró uno de los puntos de inflexión clave del frente.

Al ver el revés del Eje en Stalingrado, la Unión Soviética desplegó sus fuerzas y recuperó territorios a sus expensas. La derrota del Eje en Kursk puso fin a la fuerza ofensiva alemana y despejó el camino para las ofensivas soviéticas. Sus reveses hicieron que muchos países amigos de Alemania desertaran y se unieran a los Aliados, como Rumania y Bulgaria . El Frente Oriental concluyó con la captura de Berlín , seguida de la firma del Instrumento de Rendición alemán el 8 de mayo, un día que marcó el final del Frente Oriental y de la Guerra en Europa.

Las batallas en el Frente Oriental de la Segunda Guerra Mundial constituyeron la confrontación militar más grande de la historia. [6] En pos de su agenda colonial de asentamiento " Lebensraum ", la Alemania nazi libró una guerra de aniquilación ( Vernichtungskrieg ) en toda Europa del Este. Las operaciones militares nazis se caracterizaron por una brutalidad despiadada, tácticas de tierra arrasada , destrucción gratuita, deportaciones masivas, hambrunas forzadas, terrorismo generalizado y masacres. Estas también incluyeron las campañas genocidas del Generalplan Ost y el Hunger Plan , que apuntaban al exterminio y la limpieza étnica de más de cien millones de nativos de Europa del Este. El historiador alemán Ernst Nolte llamó al Frente Oriental "la guerra más atroz de conquista, esclavitud y aniquilación conocida en la historia moderna", [7] mientras que el historiador británico Robin Cross expresó que "En la Segunda Guerra Mundial ningún teatro fue más agotador y destructivo que el Frente Oriental, y en ningún lugar la lucha fue más encarnizada". [8]

Las dos principales potencias beligerantes en el Frente Oriental fueron Alemania y la Unión Soviética, junto con sus respectivos aliados. Aunque nunca enviaron tropas terrestres al Frente Oriental, Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido proporcionaron ayuda material sustancial a la Unión Soviética en forma del programa de Préstamo y Arriendo , junto con apoyo naval y aéreo. Las operaciones conjuntas germano-finlandesas en la frontera más septentrional entre Finlandia y la Unión Soviética y en la región de Murmansk se consideran parte del Frente Oriental. Además, la Guerra de Continuación soviético-finlandesa generalmente también se considera el flanco norte del Frente Oriental.

Alemania y la Unión Soviética no estaban satisfechas con el resultado de la Primera Guerra Mundial (1914-1918). La Rusia soviética había perdido un territorio sustancial en Europa del Este como resultado del Tratado de Brest-Litovsk (marzo de 1918), donde los bolcheviques en Petrogrado cedieron a las demandas alemanas y cedieron el control de Polonia, Lituania, Estonia, Letonia, Finlandia y otras áreas a las Potencias Centrales . Posteriormente, cuando Alemania a su vez se rindió a los Aliados (noviembre de 1918) y estos territorios se convirtieron en estados independientes bajo los términos de la Conferencia de Paz de París de 1919 en Versalles , la Rusia soviética estaba en medio de una guerra civil y los Aliados no reconocieron al gobierno bolchevique, por lo que no asistió ninguna representación rusa soviética. [9]

Adolf Hitler había declarado su intención de invadir la Unión Soviética el 11 de agosto de 1939 a Carl Jacob Burckhardt , Comisionado de la Sociedad de Naciones , diciendo:

Todo lo que emprendo está dirigido contra los rusos . Si Occidente es demasiado estúpido y ciego para comprenderlo, me veré obligado a llegar a un acuerdo con los rusos, derrotar a Occidente y, después de su derrota, volverme contra la Unión Soviética con todas mis fuerzas. Necesito a Ucrania para que no puedan matarnos de hambre, como ocurrió en la última guerra. [10]

El Pacto Ribbentrop-Mólotov, firmado en agosto de 1939, fue un acuerdo de no agresión entre Alemania y la Unión Soviética. Contenía un protocolo secreto cuyo objetivo era devolver a Europa Central al status quo anterior a la Primera Guerra Mundial dividiéndola entre Alemania y la Unión Soviética. Finlandia, Estonia, Letonia y Lituania volverían al control soviético, mientras que Polonia y Rumania quedarían divididas. [ cita requerida ] El Frente Oriental también fue posible gracias al Acuerdo Fronterizo y Comercial Alemán-Soviético , en el que la Unión Soviética le dio a Alemania los recursos necesarios para lanzar operaciones militares en Europa del Este. [11]

El 1 de septiembre de 1939 , Alemania invadió Polonia , lo que dio inicio a la Segunda Guerra Mundial . El 17 de septiembre, la Unión Soviética invadió Polonia oriental y, como resultado, Polonia fue dividida entre Alemania, la Unión Soviética y Lituania. Poco después, la Unión Soviética exigió concesiones territoriales significativas a Finlandia y, después de que Finlandia rechazara las demandas soviéticas, la Unión Soviética atacó a Finlandia el 30 de noviembre de 1939 en lo que se conoció como la Guerra de Invierno , un amargo conflicto que resultó en un tratado de paz el 13 de marzo de 1940, con Finlandia manteniendo su independencia pero perdiendo sus partes orientales en Carelia . [12]

En junio de 1940, la Unión Soviética ocupó y anexó ilegalmente los tres estados bálticos (Estonia, Letonia y Lituania). [12] El Pacto Mólotov-Ribbentrop aparentemente proporcionó seguridad a los soviéticos en la ocupación tanto del Báltico como de las regiones del norte y noreste de Rumania ( Bucovina del Norte y Besarabia , junio-julio de 1940), aunque Hitler, al anunciar la invasión de la Unión Soviética, citó las anexiones soviéticas de territorio báltico y rumano como una violación de la interpretación alemana del pacto. Moscú repartió el territorio rumano anexado entre las Repúblicas Socialistas Soviéticas de Ucrania y Moldavia .

Hitler había defendido en su autobiografía Mein Kampf (1925) la necesidad de Lebensraum ("espacio vital"): adquirir nuevo territorio para los alemanes en Europa del Este, en particular Rusia. [13] Preveía asentar allí a los alemanes, ya que según la ideología nazi el pueblo germánico constituía la " raza superior ", mientras que exterminaba o deportaba a la mayoría de los habitantes existentes a Siberia y utilizaba al resto como mano de obra esclava . [14] Hitler ya en 1917 se había referido a los rusos como inferiores, creyendo que la Revolución bolchevique había puesto a los judíos en el poder sobre la masa de eslavos , que eran, en opinión de Hitler, incapaces de gobernarse a sí mismos y, por lo tanto, habían terminado siendo gobernados por amos judíos. [15]

Los líderes nazis , incluido Heinrich Himmler , [16] vieron la guerra contra la Unión Soviética como una lucha entre las ideologías del nazismo y el bolchevismo judío , asegurando la expansión territorial de los Übermenschen (superhumanos) germánicos -que según la ideología nazi eran los Herrenvolk ("raza superior") arios- a expensas de los Untermenschen (subhumanos) eslavos. [17] Los oficiales de la Wehrmacht ordenaron a sus tropas que atacaran a las personas que eran descritas como "subhumanos bolcheviques judíos", las "hordas mongoles", la "inundación asiática" y la "bestia roja". [18] La gran mayoría de los soldados alemanes vieron la guerra en términos nazis, viendo al enemigo soviético como subhumano. [19] [ necesita cita para verificar ]

Hitler se refirió a la guerra en términos radicales, llamándola una " guerra de aniquilación " ( en alemán : Vernichtungskrieg ) que era tanto una guerra ideológica como racial. La visión nazi para el futuro de Europa del Este fue codificada más claramente en el Generalplan Ost . Las poblaciones de la Europa Central ocupada y la Unión Soviética debían ser deportadas parcialmente a Siberia Occidental, esclavizadas y finalmente exterminadas; los territorios conquistados debían ser colonizados por colonos alemanes o "germanizados". [20] Además, los nazis también buscaron librarse de la gran población judía de Europa Central y Oriental [21] como parte de su programa destinado a exterminar a todos los judíos europeos . [22]

Psicológicamente, la ofensiva alemana hacia el Este en 1941 marcó un punto culminante en el sentimiento de Ostrausch de algunos alemanes : una intoxicación con la idea de colonizar el Este. [23]

Tras el éxito inicial de Alemania en la batalla de Kiev en 1941, Hitler consideró que la Unión Soviética era militarmente débil y madura para una conquista inmediata. En un discurso pronunciado en el Sportpalast de Berlín el 3 de octubre, anunció: "Sólo tenemos que derribar la puerta a patadas y toda la estructura podrida se derrumbará". [24] Así pues, las autoridades alemanas esperaban otra breve Blitzkrieg y no hicieron preparativos serios para una guerra prolongada. Sin embargo, tras la decisiva victoria soviética en la batalla de Stalingrado en 1943 y la terrible situación militar alemana resultante, la propaganda nazi empezó a presentar la guerra como una defensa alemana de la civilización occidental contra la destrucción por parte de las enormes " hordas bolcheviques " que estaban invadiendo Europa.

Durante la década de 1930, la Unión Soviética experimentó una industrialización masiva y un crecimiento económico bajo el liderazgo de Joseph Stalin . El principio central de Stalin, " el socialismo en un solo país ", se manifestó como una serie de planes quinquenales centralizados a nivel nacional a partir de 1929. Esto representó un cambio ideológico en la política soviética, alejándose de su compromiso con la revolución comunista internacional , y eventualmente conduciendo a la disolución de la organización Comintern (Tercera Internacional) en 1943. La Unión Soviética inició un proceso de militarización con el primer plan quinquenal que comenzó oficialmente en 1928, aunque fue solo hacia el final del segundo plan quinquenal a mediados de la década de 1930 que el poder militar se convirtió en el foco principal de la industrialización soviética. [25]

En febrero de 1936, las elecciones generales españolas llevaron a muchos líderes comunistas al gobierno del Frente Popular en la Segunda República Española , pero en cuestión de meses un golpe militar de derecha inició la Guerra Civil Española de 1936-1939. Este conflicto pronto adquirió las características de una guerra por poderes que involucró a la Unión Soviética y voluntarios de izquierda de diferentes países del lado de la Segunda República Española predominantemente socialista y liderada por los comunistas [26] ; [27] mientras que la Alemania nazi , la Italia fascista y el Estado Novo de Portugal se pusieron del lado de los nacionalistas españoles , el grupo militar rebelde liderado por el general Francisco Franco . [28] Sirvió como un campo de pruebas útil tanto para la Wehrmacht como para el Ejército Rojo para experimentar con equipos y tácticas que luego emplearían a mayor escala en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

La Alemania nazi, que era un régimen anticomunista , formalizó su posición ideológica el 25 de noviembre de 1936 al firmar el Pacto Anti-Comintern con el Japón Imperial . [29] La Italia fascista se unió al Pacto un año después. [27] [30] La Unión Soviética negoció tratados de asistencia mutua con Francia y con Checoslovaquia con el objetivo de contener la expansión de Alemania. [31] El Anschluss alemán de Austria en 1938 y el desmembramiento de Checoslovaquia (1938-1939) demostraron la imposibilidad de establecer un sistema de seguridad colectiva en Europa, [32] una política defendida por el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores soviético bajo Maxim Litvinov . [33] [34] Esto, así como la renuencia de los gobiernos británico y francés a firmar una alianza política y militar antialemana a gran escala con la URSS, [35] condujo al Pacto Mólotov-Ribbentrop entre la Unión Soviética y Alemania a fines de agosto de 1939. [36] El Pacto Tripartito separado entre las que se convirtieron en las tres principales potencias del Eje no se firmaría hasta unos cuatro años después del Pacto Anti-Comintern.

La guerra se libró entre Alemania, sus aliados y Finlandia , contra la Unión Soviética y sus aliados. El conflicto comenzó el 22 de junio de 1941 con la ofensiva de la Operación Barbarroja , cuando las fuerzas del Eje cruzaron las fronteras descritas en el Pacto de No Agresión germano-soviético , invadiendo así la Unión Soviética. La guerra terminó el 9 de mayo de 1945, cuando las fuerzas armadas alemanas se rindieron incondicionalmente tras la Batalla de Berlín (también conocida como la Ofensiva de Berlín ), una operación estratégica ejecutada por el Ejército Rojo.

Los estados que proporcionaron fuerzas y otros recursos para el esfuerzo bélico alemán incluyeron a las Potencias del Eje, principalmente Rumania, Hungría, Italia, Eslovaquia pronazi y Croacia. La Finlandia antisoviética , que había luchado en la Guerra de Invierno contra la Unión Soviética, también se unió a la ofensiva. Las fuerzas de la Wehrmacht también recibieron ayuda de partisanos anticomunistas en lugares como Ucrania occidental y los estados bálticos. Entre las formaciones del ejército voluntario más destacadas se encontraba la División Azul española , enviada por el dictador español Francisco Franco para mantener intactos sus vínculos con el Eje. [37]

La Unión Soviética ofreció apoyo a los partisanos anti-Eje en muchos países ocupados por la Wehrmacht en Europa Central, en particular los de Eslovaquia y Polonia . Además, las Fuerzas Armadas polacas en el Este , en particular el Primer y el Segundo Ejércitos polacos, fueron armadas y entrenadas, y eventualmente lucharían junto al Ejército Rojo. Las fuerzas de la Francia Libre también contribuyeron al Ejército Rojo mediante la formación de la unidad GC3 ( Groupe de Chasse 3 o 3er Grupo de Cazas) para cumplir con el compromiso de Charles de Gaulle , líder de la Francia Libre, que pensaba que era importante que los militares franceses sirvieran en todos los frentes.

Las cifras anteriores incluyen todo el personal del ejército alemán, es decir, las fuerzas terrestres en servicio activo del Heer , las Waffen SS y la Luftwaffe , el personal de la artillería costera naval y las unidades de seguridad. [41] [42] En la primavera de 1940, Alemania había movilizado 5.500.000 hombres. [43] En el momento de la invasión de la Unión Soviética, la Wehrmacht estaba formada por unos 3.800.000 hombres del Heer, 1.680.000 de la Luftwaffe, 404.000 de la Kriegsmarine , 150.000 de las Waffen-SS y 1.200.000 del Ejército de Reemplazo (que contenía 450.400 reservistas activos, 550.000 nuevos reclutas y 204.000 en servicios administrativos, vigiles y/o en convalecencia). En 1941, la Wehrmacht contaba con una fuerza total de 7.234.000 hombres. Para la Operación Barbarroja, Alemania movilizó 3.300.000 tropas del Heer, 150.000 de las Waffen-SS [44] y aproximadamente 250.000 efectivos de la Luftwaffe fueron seleccionados activamente. [45]

En julio de 1943, la Wehrmacht contaba con 6.815.000 soldados. De ellos, 3.900.000 estaban desplegados en Europa del Este, 180.000 en Finlandia, 315.000 en Noruega, 110.000 en Dinamarca, 1.370.000 en Europa Occidental, 330.000 en Italia y 610.000 en los Balcanes. [46] Según una presentación de Alfred Jodl , la Wehrmacht contaba con 7.849.000 efectivos en abril de 1944. 3.878.000 estaban desplegados en Europa del Este, 311.000 en Noruega/Dinamarca, 1.873.000 en Europa Occidental, 961.000 en Italia y 826.000 en los Balcanes. [47] Entre el 15 y el 20% de la fuerza total alemana eran tropas extranjeras (de países aliados o territorios conquistados). El punto álgido de la ofensiva alemana se produjo justo antes de la batalla de Kursk , a principios de julio de 1943: 3.403.000 tropas alemanas y 650.000 tropas finlandesas, húngaras, rumanas y de otros países. [39] [40]

Durante casi dos años la frontera estuvo tranquila mientras Alemania conquistaba Dinamarca, Noruega, Francia, los Países Bajos y los Balcanes . Hitler siempre había tenido la intención de renegar de su pacto con la Unión Soviética, y finalmente tomó la decisión de invadirla en la primavera de 1941. [10] [48]

Algunos historiadores sostienen que Stalin temía una guerra con Alemania, o simplemente no esperaba que Alemania iniciara una guerra en dos frentes , y se mostraba reacio a hacer nada que pudiera provocar a Hitler. Otro punto de vista es que Stalin esperaba una guerra en 1942 (el momento en que todos sus preparativos estarían completos) y se negó obstinadamente a creer que llegaría antes de tiempo. [49]

Los historiadores británicos Alan S. Milward y M. Medlicott demuestran que la Alemania nazi, a diferencia de la Alemania imperial, estaba preparada sólo para una guerra de corta duración (Blitzkrieg). [50] Según Edward Ericson, aunque los recursos propios de Alemania fueron suficientes para las victorias en Occidente en 1940, los envíos masivos soviéticos obtenidos durante un corto período de colaboración económica nazi-soviética fueron fundamentales para que Alemania lanzara la Operación Barbarroja. [51]

Alemania había estado reuniendo un gran número de tropas en el este de Polonia y realizando repetidos vuelos de reconocimiento sobre la frontera; la Unión Soviética respondió reuniendo sus divisiones en su frontera occidental, aunque la movilización soviética fue más lenta que la de Alemania debido a la red de carreteras menos densa del país. Al igual que en el conflicto chino-soviético en el Ferrocarril Oriental de China o en los conflictos fronterizos soviético-japoneses , las tropas soviéticas en la frontera occidental recibieron una directiva, firmada por el mariscal Semyon Timoshenko y el general del ejército Georgy Zhukov , que ordenaba (como exigió Stalin): "no responder a ninguna provocación" y "no emprender ninguna acción (ofensiva) sin órdenes específicas" [ cita requerida ] , lo que significaba que las tropas soviéticas solo podían abrir fuego en su suelo y prohibían el contraataque en suelo alemán. [ cita requerida ] Por lo tanto, la invasión alemana tomó al liderazgo militar y civil soviético en gran medida por sorpresa.

El alcance de las advertencias recibidas por Stalin sobre una invasión alemana es controvertido, y la afirmación de que hubo una advertencia de que "Alemania atacaría el 22 de junio sin declaración de guerra" ha sido descartada como un "mito popular". Sin embargo, algunas fuentes citadas en los artículos sobre los espías soviéticos Richard Sorge y Willi Lehmann , dicen que habían enviado advertencias de un ataque el 20 o 22 de junio, que fueron tratadas como "desinformación". La red de espionaje Lucy en Suiza también envió advertencias, posiblemente derivadas del descifrado de códigos Ultra en Gran Bretaña. Suecia tuvo acceso a las comunicaciones internas alemanas a través del descifrado de la criptografía utilizada en la máquina de cifrado Siemens y Halske T52 también conocida como Geheimschreiber e informó a Stalin sobre la próxima invasión mucho antes del 22 de junio, pero no reveló sus fuentes. [ cita requerida ]

La inteligencia soviética fue engañada por la desinformación alemana, por lo que envió falsas alarmas a Moscú sobre una invasión alemana en abril, mayo y principios de junio. La inteligencia soviética informó que Alemania preferiría invadir la URSS después de la caída del Imperio Británico [52] o después de un ultimátum inaceptable exigiendo la ocupación alemana de Ucrania durante la invasión alemana de Gran Bretaña. [53]

Una ofensiva aérea estratégica de la Fuerza Aérea del Ejército de los Estados Unidos y la Real Fuerza Aérea desempeñó un papel importante en dañar la industria alemana y en paralizar los recursos de la fuerza aérea y la defensa aérea alemanas; algunos bombardeos, como el de la ciudad de Dresde, en el este de Alemania , se realizaron para facilitar objetivos operativos soviéticos específicos. Además de Alemania, se lanzaron cientos de miles de toneladas de bombas sobre sus aliados orientales de Rumania y Hungría , principalmente en un intento de paralizar la producción petrolera rumana .

Las fuerzas británicas y de la Commonwealth también contribuyeron directamente a los combates en el Frente Oriental a través de su servicio en los convoyes del Ártico y el entrenamiento de los pilotos de la Fuerza Aérea Roja , así como proporcionando apoyo material y de inteligencia temprano.

Entre otros bienes, Lend-Lease suministró: [55] : 8–9

La ayuda de préstamo y arriendo de equipos, componentes y bienes militares a la Unión Soviética constituyó el 20% de la asistencia. [55] : 122 El resto fueron alimentos, metales no ferrosos (por ejemplo, cobre, magnesio, níquel, zinc, plomo, estaño, aluminio), sustancias químicas, petróleo (gasolina de aviación de alto octanaje) y maquinaria industrial. La ayuda de equipos y maquinaria de línea de producción fue crucial y ayudó a mantener niveles adecuados de producción de armamento soviético durante toda la guerra. [55] : 122 Además, la URSS recibió innovaciones en tiempos de guerra, incluyendo penicilina, radar, cohetes, tecnología de bombardeo de precisión, el sistema de navegación de largo alcance Loran y muchas otras innovaciones. [55] : 123

De las 800.000 toneladas de metales no ferrosos embarcados, [55] : 124 unas 350.000 toneladas eran de aluminio. [55] : 135 El envío de aluminio no sólo representaba el doble de la cantidad de metal que poseía Alemania, sino que también constituía la mayor parte del aluminio que se utilizaba en la fabricación de aviones soviéticos, cuyo suministro había disminuido críticamente. [55] : 135 Las estadísticas soviéticas muestran que sin estos envíos de aluminio, la producción de aviones habría sido menos de la mitad (o alrededor de 45.000 menos) del total de 137.000 aviones producidos. [55] : 135

Stalin señaló en 1944 que dos tercios de la industria pesada soviética se habían construido con la ayuda de los Estados Unidos, y el tercio restante, con la ayuda de otras naciones occidentales como Gran Bretaña y Canadá. [55] : 129 La transferencia masiva de equipos y personal calificado de los territorios ocupados ayudó a impulsar aún más la base económica. [55] : 129 Sin la ayuda de Préstamo y Arriendo, la disminuida base económica de la Unión Soviética después de la invasión no habría producido suministros adecuados de armamento, aparte de centrarse en máquinas herramienta, alimentos y bienes de consumo. [ aclaración necesaria ] [55] : 129

En el último año de guerra, los datos de Préstamo y Arriendo muestran que alrededor de 5,1 millones de toneladas de alimentos salieron de los Estados Unidos con destino a la Unión Soviética. [55] : 123 Se estima que todos los suministros de alimentos enviados a Rusia podrían alimentar a un ejército de 12.000.000 de hombres con media libra de alimentos concentrados por día, durante toda la duración de la guerra. [55] : 122–3

Se ha estimado que la ayuda total de Préstamo y Arriendo proporcionada durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial estuvo entre 42 y 50 mil millones de dólares. [55] : 128 La Unión Soviética recibió envíos de material bélico, equipo militar y otros suministros por valor de 12.500 millones de dólares, aproximadamente una cuarta parte de la ayuda de Préstamo y Arriendo estadounidense proporcionada a otros países aliados. [55] : 123 Sin embargo, las negociaciones de posguerra para liquidar toda la deuda nunca concluyeron, [55] : 133 y, hasta la fecha, los problemas de la deuda siguen siendo objeto de futuras cumbres y conversaciones entre Estados Unidos y Rusia. [55] : 133–4

El profesor Dr. Albert L. Weeks concluyó: "En cuanto a los intentos de resumir la importancia de esos envíos de préstamos y arriendos de cuatro años de duración para la victoria rusa en el frente oriental durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el jurado aún no se ha pronunciado, es decir, en cualquier sentido definitivo para establecer exactamente cuán crucial fue esta ayuda". [55] : 123

En aquel momento, las capacidades económicas, científicas, de investigación e industriales de Alemania se contaban entre las más avanzadas técnicamente del mundo. Sin embargo, el acceso a los recursos , las materias primas y la capacidad de producción necesarios para alcanzar objetivos a largo plazo (como el control de Europa, la expansión territorial alemana y la destrucción de la URSS) y su control eran limitados. Las exigencias políticas exigían que Alemania ampliara su control de los recursos naturales y humanos, la capacidad industrial y las tierras agrícolas más allá de sus fronteras (territorios conquistados). La producción militar alemana estaba vinculada a los recursos que se encontraban fuera de su área de control, una dinámica que no se daba entre los aliados.

Durante la guerra, a medida que Alemania adquiría nuevos territorios (ya sea por anexión directa o instalando gobiernos títeres en los países derrotados), estos nuevos territorios se vieron obligados a vender materias primas y productos agrícolas a compradores alemanes a precios extremadamente bajos. En general, Francia hizo la mayor contribución al esfuerzo bélico alemán. Dos tercios de todos los trenes franceses en 1941 se utilizaron para transportar mercancías a Alemania. En 1943-44, los pagos franceses a Alemania pueden haber aumentado hasta el 55% del PIB francés. [58] Noruega perdió el 20% de su ingreso nacional en 1940 y el 40% en 1943. [59] Los aliados del Eje como Rumania e Italia , Hungría , Finlandia, Croacia y Bulgaria se beneficiaron de las importaciones netas de Alemania. En general, Alemania importó el 20% de sus alimentos y el 33% de sus materias primas de los territorios conquistados y los aliados del Eje. [60]

El 27 de mayo de 1940, Alemania firmó el "Pacto del Petróleo" con Rumania, por el cual Alemania intercambiaría armas por petróleo. La producción petrolera de Rumania ascendió a aproximadamente 6.000.000 de toneladas anuales. Esta producción representa el 35% de la producción total de combustible del Eje, incluidos los productos sintéticos y sustitutos, y el 70% de la producción total de petróleo crudo. [61] En 1941, Alemania sólo tenía el 18% del petróleo que tenía en tiempos de paz. Rumania suministró a Alemania y sus aliados aproximadamente 13 millones de barriles de petróleo (unos 4 millones por año) entre 1941 y 1943. La producción máxima de petróleo de Alemania en 1944 ascendió a unos 12 millones de barriles de petróleo por año. [62]

Rolf Karlbom estimó que la participación sueca en el consumo total de hierro de Alemania podría haber sido del 43% durante el período de 1933 a 1943. También es probable que "el mineral sueco constituyera la materia prima de cuatro de cada diez cañones alemanes" durante la era de Hitler. [63]

El uso de mano de obra extranjera forzada y esclavitud en Alemania y en toda la Europa ocupada por Alemania durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial tuvo lugar en una escala sin precedentes. [64] Fue una parte vital de la explotación económica alemana de los territorios conquistados. También contribuyó al exterminio masivo de poblaciones en la Europa ocupada por Alemania. Los alemanes secuestraron aproximadamente a 12 millones de personas extranjeras de casi veinte países europeos; alrededor de dos tercios provenían de Europa central y oriental. [65] Contando las muertes y la rotación, alrededor de 15 millones de hombres y mujeres fueron trabajadores forzados en algún momento durante la guerra. [66] Por ejemplo, 1,5 millones de soldados franceses fueron mantenidos en campos de prisioneros de guerra en Alemania como rehenes y trabajadores forzados y, en 1943, 600.000 civiles franceses fueron obligados a mudarse a Alemania para trabajar en plantas de guerra. [67]

La derrota de Alemania en 1945 liberó a aproximadamente 11 millones de extranjeros (clasificados como "personas desplazadas"), la mayoría de los cuales eran trabajadores forzados y prisioneros de guerra. En tiempos de guerra, las fuerzas alemanas habían traído al Reich 6,5 millones de civiles, además de prisioneros de guerra soviéticos, para trabajos forzados en fábricas. [65] En total, 5,2 millones de trabajadores extranjeros y prisioneros de guerra fueron repatriados a la Unión Soviética, 1,6 millones a Polonia, 1,5 millones a Francia y 900.000 a Italia, junto con 300.000 a 400.000 a Yugoslavia, Checoslovaquia, los Países Bajos, Hungría y Bélgica. [68]

Aunque los historiadores alemanes no aplican ninguna periodización específica a la conducción de las operaciones en el Frente Oriental, todos los historiadores soviéticos y rusos dividen la guerra contra Alemania y sus aliados en tres períodos, que se subdividen a su vez en ocho campañas principales del Teatro de guerra: [69]

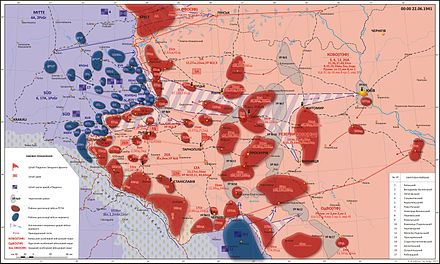

La Operación Barbarroja comenzó justo antes del amanecer del 22 de junio de 1941. Los alemanes cortaron la red de cables en todos los distritos militares occidentales soviéticos para socavar las comunicaciones del Ejército Rojo. [70] Las transmisiones de pánico de las unidades soviéticas de primera línea a sus cuarteles generales fueron captadas así: "Nos están disparando. ¿Qué debemos hacer?". La respuesta fue igualmente confusa: "Debes estar loco. ¿Y por qué tu señal no está en código?". [71]

A las 03:15 del 22 de junio de 1941, 99 de las 190 divisiones alemanas, incluidas catorce divisiones panzer y diez motorizadas, se desplegaron contra la Unión Soviética desde el Báltico hasta el mar Negro. Estaban acompañadas por diez divisiones rumanas, tres divisiones italianas, dos divisiones eslovacas y nueve brigadas rumanas y cuatro húngaras . [72] El mismo día, los distritos militares especiales del Báltico , Occidental y de Kiev fueron renombrados como Frentes Noroeste , Occidental y Sudoeste respectivamente. [70]

Para establecer la supremacía aérea, la Luftwaffe comenzó a atacar de inmediato los aeródromos soviéticos, destruyendo gran parte de las flotas de aeródromos de la Fuerza Aérea Soviética desplegadas en la vanguardia, que consistían en modelos en gran parte obsoletos, antes de que sus pilotos tuvieran la oportunidad de despegar. [73] Durante un mes, la ofensiva llevada a cabo en tres ejes fue completamente imparable, ya que las fuerzas panzer rodearon a cientos de miles de tropas soviéticas en enormes bolsas que luego fueron reducidas por ejércitos de infantería de movimiento más lento mientras los panzer continuaban la ofensiva. La Luftwaffe también lanzó cientos de paracaidistas de habla rusa detrás de las líneas ofensivas para traer información sobre la disposición de las reservas de las tropas soviéticas. [74]

El objetivo del Grupo de Ejércitos Norte era Leningrado a través de los estados bálticos. Esta formación, compuesta por los ejércitos 16 y 18 y el 4.º Grupo Panzer , avanzó a través de los estados bálticos y las regiones rusas de Pskov y Nóvgorod . Los insurgentes locales aprovecharon el momento y controlaron la mayor parte de Lituania, el norte de Letonia y el sur de Estonia antes de la llegada de las fuerzas alemanas. [75] [76]

Los dos grupos panzer del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro (el 2.º y el 3.º ) avanzaron al norte y al sur de Brest-Litovsk y convergieron al este de Minsk , seguidos por los ejércitos 2.º , 4.º y 9.º. La fuerza panzer combinada alcanzó el río Beresina en sólo seis días, a 650 km (400 millas) de sus líneas de partida. El siguiente objetivo era cruzar el río Dniéper , lo que se logró el 11 de julio. Su siguiente objetivo era Smolensk , que cayó el 16 de julio, pero la feroz resistencia soviética en el área de Smolensk y la ralentización del avance de la Wehrmacht por parte de los Grupos de Ejércitos Norte y Sur obligaron a Hitler a detener un avance central en Moscú y a desviar al 3.º Grupo Panzer hacia el norte. Críticamente, el 2.º Grupo Panzer de Guderian recibió la orden de moverse hacia el sur en una gigantesca maniobra de pinza con el Grupo de Ejércitos Sur que avanzaba hacia Ucrania. Las divisiones de infantería del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro quedaron relativamente sin apoyo blindado para continuar su lento avance hacia Moscú. [77]

Esta decisión provocó una grave crisis de liderazgo. Los comandantes de campo alemanes abogaron por una ofensiva inmediata hacia Moscú, pero Hitler los desestimó , citando la importancia de los recursos agrícolas, mineros e industriales ucranianos, así como la concentración de reservas soviéticas en el área de Gomel entre el flanco sur del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro y el flanco norte del empantanado Grupo de Ejércitos Sur. Se cree que esta decisión, la "pausa de verano" de Hitler, [77] tuvo un impacto severo en el resultado de la Batalla de Moscú más tarde ese año, al frenar el avance sobre Moscú a favor de rodear a un gran número de tropas soviéticas alrededor de Kiev. [78]

El Grupo de Ejércitos Sur , con el 1.er Grupo Panzer y los ejércitos 6.º , 11.º y 17.º , recibió la misión de avanzar a través de Galicia y hacia Ucrania. Sin embargo, su avance fue bastante lento y sufrieron fuertes bajas en la batalla de Brody . A principios de julio, el 3.er y 4.º Ejércitos rumanos, ayudados por elementos del 11.º Ejército alemán, se abrieron paso a través de Besarabia hacia Odessa . El 1.er Grupo Panzer se alejó de Kiev por el momento y avanzó hacia la curva del Dniéper (al oeste del óblast de Dnipropetrovsk ). Cuando se unió a los elementos meridionales del Grupo de Ejércitos Sur en Uman , el Grupo capturó a unos 100.000 prisioneros soviéticos en un enorme cerco. Las divisiones blindadas del Grupo de Ejércitos Sur que avanzaban se encontraron con el 2.º Grupo Panzer de Guderian cerca de Lokhvytsa el 16 de septiembre, cortando el paso a un gran número de tropas del Ejército Rojo en la bolsa al este de Kiev. [77] 400.000 prisioneros soviéticos fueron capturados cuando Kiev se rindió el 19 de septiembre. [77]

El 26 de septiembre, las fuerzas soviéticas al este de Kiev se rindieron y la batalla de Kiev terminó.

Mientras el Ejército Rojo se retiraba tras los ríos Dnieper y Dvina , el Stavka (alto mando) soviético centró su atención en evacuar la mayor parte posible de la industria de las regiones occidentales. Se desmantelaron fábricas y se las trasladó en vagones plataforma lejos de la línea del frente para restablecerlas en zonas más remotas de los montes Urales , el Cáucaso , Asia central y el sudeste de Siberia. La mayoría de los civiles tuvieron que abrirse camino hacia el este por sus propios medios, y sólo los trabajadores relacionados con la industria fueron evacuados con el equipo; gran parte de la población quedó a merced de las fuerzas invasoras.

Stalin ordenó al Ejército Rojo en retirada que iniciara una política de tierra arrasada para negar a los alemanes y sus aliados los suministros básicos a medida que avanzaban hacia el este. Para llevar a cabo esa orden, se formaron batallones de destrucción en las áreas de primera línea, con autoridad para ejecutar sumariamente a cualquier persona sospechosa. Los batallones de destrucción quemaron aldeas, escuelas y edificios públicos. [79] Como parte de esta política, la NKVD masacró a miles de prisioneros antisoviéticos . [80]

Hitler decidió entonces reanudar el avance sobre Moscú, rebautizando a los grupos panzer como ejércitos panzer para la ocasión. La Operación Tifón, que se puso en marcha el 30 de septiembre, vio al 2.º Ejército Panzer avanzar a toda velocidad por la carretera pavimentada desde Oriol (capturada el 5 de octubre) hasta el río Oka en Plavsk , mientras que el 4.º Ejército Panzer (transferido del Grupo de Ejércitos Norte al Centro) y el 3.º Ejército Panzer rodearon a las fuerzas soviéticas en dos enormes bolsas en Vyazma y Briansk . [81] El Grupo de Ejércitos Norte se posicionó frente a Leningrado e intentó cortar el enlace ferroviario en Mga al este. [82] Esto dio comienzo al asedio de Leningrado de 900 días . Al norte del Círculo Polar Ártico , una fuerza germano-finlandesa partió hacia Múrmansk, pero no pudo llegar más allá del río Zapadnaya Litsa , donde se estableció. [83]

El Grupo de Ejércitos Sur avanzó desde el Dniéper hasta la costa del mar de Azov , también atravesando Járkov , Kursk y Stalino . Las fuerzas combinadas alemanas y rumanas avanzaron hacia Crimea y tomaron el control de toda la península en otoño (excepto Sebastopol , que resistió hasta el 3 de julio de 1942). El 21 de noviembre, la Wehrmacht tomó Rostov , la puerta de entrada al Cáucaso. Sin embargo, las líneas alemanas estaban demasiado extendidas y los defensores soviéticos contraatacaron la punta de lanza del 1.er Ejército Panzer desde el norte, obligándolos a retirarse de la ciudad y detrás del río Mius ; la primera retirada alemana significativa de la guerra. [84] [85]

El inicio de la helada invernal provocó una última embestida alemana que se abrió el 15 de noviembre, cuando la Wehrmacht intentó rodear Moscú. El 27 de noviembre, el 4.º Ejército Panzer llegó a 30 km (19 mi) del Kremlin cuando alcanzó la última parada de tranvía de la línea moscovita en Jimki . Mientras tanto, el 2.º Ejército Panzer no logró tomar Tula , la última ciudad soviética que se interponía en su camino hacia la capital. Después de una reunión celebrada en Orsha entre el jefe del OKH ( Estado Mayor del Ejército ), el general Franz Halder y los jefes de tres grupos de ejércitos y ejércitos, decidieron avanzar hacia Moscú ya que era mejor, como argumentó el jefe del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro , el mariscal de campo Fedor von Bock , que probaran suerte en el campo de batalla en lugar de simplemente sentarse y esperar mientras su oponente reunía más fuerzas. [86]

Sin embargo, el 6 de diciembre se hizo evidente que la Wehrmacht no tenía fuerzas suficientes para capturar Moscú, por lo que se suspendió el ataque. El mariscal Shaposhnikov comenzó su contraataque , empleando reservas recién movilizadas , [87] así como algunas divisiones del Lejano Oriente bien entrenadas transferidas desde el este tras recibir información de que Japón permanecería neutral . [88]

La contraofensiva soviética durante la batalla de Moscú había eliminado la amenaza alemana inmediata a la ciudad. Según Zhukov , "el éxito de la contraofensiva de diciembre en la dirección estratégica central fue considerable. Tras sufrir una importante derrota, las fuerzas de ataque alemanas del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro se estaban retirando". El objetivo de Stalin en enero de 1942 era "negar a los alemanes cualquier respiro, empujarlos hacia el oeste sin descanso, hacer que agotaran sus reservas antes de que llegara la primavera..." [89]

El golpe principal se daría mediante un doble envolvimiento orquestado por el Frente Noroeste, el Frente Kalinin y el Frente Occidental. El objetivo general según Zhukov era el "subsiguiente envolvimiento y destrucción de las principales fuerzas del enemigo en el área de Rzhev , Vyazma y Smolensk. El Frente de Leningrado , el Frente Volkhov y las fuerzas del ala derecha del Frente Noroeste debían derrotar al Grupo de Ejércitos Norte". El Frente Sudoeste y el Frente Sur debían derrotar al Grupo de Ejércitos Sur. El Frente Caucásico y la Flota del Mar Negro debían recuperar Crimea. [89] : 53

El 20.º Ejército, parte del 1.º Ejército de Choque soviético , la 22.ª Brigada de Tanques y cinco batallones de esquí lanzaron su ataque el 10 de enero de 1942. Para el 17 de enero, los soviéticos habían capturado Lotoshino y Shakhovskaya. Para el 20 de enero, los 5.º y 33.º Ejércitos habían capturado Ruza, Dorokhovo, Mozhaisk y Vereya, mientras que los 43.º y 49.º Ejércitos estaban en Domanovo. [89] : 58–59

La Wehrmacht se reorganizó y mantuvo un saliente en Rzhev. El 18 y el 22 de enero, dos batallones de la 201.ª Brigada Aerotransportada y el 250.º Regimiento Aerotransportado lanzaron paracaidistas soviéticos para "cortar las comunicaciones del enemigo con la retaguardia". El 33.º Ejército del teniente general Mijail Grigorievich Yefremov , con la ayuda del 1.º Cuerpo de Caballería del general Belov y de partisanos soviéticos , intentó apoderarse de Vyazma. A esta fuerza se unieron paracaidistas adicionales de la 8.ª Brigada Aerotransportada a finales de enero. Sin embargo, a principios de febrero, los alemanes lograron cortar el paso a esta fuerza, separando a los soviéticos de su fuerza principal en la retaguardia de los alemanes. Recibieron suministros por aire hasta abril, cuando se les dio permiso para recuperar las principales líneas soviéticas. Sin embargo, sólo una parte del Cuerpo de Caballería de Belov logró ponerse a salvo, mientras que los hombres de Yefremov libraron "una batalla perdida". [89] : 59–62

En abril de 1942, el Mando Supremo Soviético acordó asumir la defensa para "consolidar el terreno capturado". Según Zhukov, "Durante la ofensiva de invierno, las fuerzas del Frente Occidental habían avanzado de 70 a 100 km, lo que mejoró un poco la situación operativa y estratégica general en el sector occidental". [89] : 64

Al norte, el Ejército Rojo rodeó una guarnición alemana en Demyansk , que resistió con suministro aéreo durante cuatro meses , y se estableció frente a Kholm , Velizh y Velikie Luki . Más al norte aún, el 2.º Ejército de Choque soviético se desplegó en el río Volkhov . Inicialmente, esto hizo algún progreso; sin embargo, no recibió apoyo, y en junio un contraataque alemán cortó y destruyó el ejército. El comandante soviético, el teniente general Andrey Vlasov , más tarde desertó a Alemania y formó el ROA o Ejército de Liberación Ruso . En el sur, el Ejército Rojo se lanzó sobre el río Donets en Izyum y avanzó un saliente de 100 km (62 mi) de profundidad. La intención era inmovilizar al Grupo de Ejércitos Sur contra el mar de Azov, pero cuando el invierno amainó, la Wehrmacht contraatacó y cortó el paso a las tropas soviéticas sobreextendidas en la Segunda Batalla de Járkov .

Aunque se hicieron planes para atacar Moscú de nuevo, el 28 de junio de 1942, la ofensiva se reanudó en una dirección diferente. El Grupo de Ejércitos Sur tomó la iniciativa, anclando el frente con la Batalla de Voronezh y luego siguiendo el río Don hacia el sudeste. El gran plan era asegurar el Don y el Volga primero y luego avanzar hacia el Cáucaso en dirección a los campos petrolíferos , pero consideraciones operativas y la vanidad de Hitler le hicieron ordenar que se intentaran ambos objetivos simultáneamente. Rostov fue recapturada el 24 de julio cuando el 1.er Ejército Panzer se unió a ellos, y luego ese grupo avanzó hacia el sur en dirección a Maikop . Como parte de esto, se ejecutó la Operación Shamil, un plan por el cual un grupo de comandos de Brandeburgo se disfrazaron de tropas soviéticas de la NKVD para desestabilizar las defensas de Maikop y permitir que el 1.er Ejército Panzer entrara en la ciudad petrolera con poca oposición.

Mientras tanto, el 6.º Ejército avanzaba hacia Stalingrado , sin el apoyo del 4.º Ejército Panzer, que había sido desviado para ayudar al 1.º Ejército Panzer a cruzar el Don durante un largo período. Cuando el 4.º Ejército Panzer se reincorporó a la ofensiva de Stalingrado, la resistencia soviética (que comprendía al 62.º Ejército al mando de Vasily Chuikov ) se había endurecido. Un salto a través del Don llevó a las tropas alemanas al Volga el 23 de agosto, pero durante los tres meses siguientes la Wehrmacht estaría luchando en la batalla de Stalingrado calle por calle.

Hacia el sur, el 1.er Ejército Panzer había alcanzado las estribaciones del Cáucaso y el río Malka . A finales de agosto, las tropas de montaña rumanas se unieron a la punta de lanza del Cáucaso, mientras que los ejércitos rumanos 3.er y 4.º fueron redistribuidos de su exitosa tarea de limpiar el litoral de Azov . Tomaron posiciones a ambos lados de Stalingrado para liberar a las tropas alemanas para la ofensiva principal. Conscientes del continuo antagonismo entre los aliados del Eje, Rumania y Hungría, por Transilvania , el ejército rumano en la curva del Don fue separado del 2.º ejército húngaro por el 8.º ejército italiano. De este modo, todos los aliados de Hitler estuvieron involucrados, incluido un contingente eslovaco con el 1.er Ejército Panzer y un regimiento croata adscrito al 6.º Ejército.

El avance hacia el Cáucaso se estancó y los alemanes no pudieron abrirse paso más allá de Malgobek y llegar a Grozni , el principal objetivo . En lugar de ello, cambiaron la dirección de su avance para acercarse a él desde el sur, cruzando el río Malka a finales de octubre y entrando en Osetia del Norte y en los suburbios de Ordzhonikidze el 2 de noviembre.

Mientras los ejércitos Panzer 6 y 4 alemanes se abrían paso hacia Stalingrado, los ejércitos soviéticos se habían concentrado a ambos lados de la ciudad, concretamente en las cabezas de puente del Don , y fue desde ellas desde donde atacaron en noviembre de 1942. La Operación Urano comenzó el 19 de noviembre. Dos frentes soviéticos atravesaron las líneas rumanas y convergieron en Kalach el 23 de noviembre, atrapando a 300.000 tropas del Eje tras ellos. [90] Se suponía que una ofensiva simultánea en el sector de Rzhev conocida como Operación Marte avanzaría hasta Smolensk, pero fue un costoso fracaso, ya que las defensas tácticas alemanas impidieron cualquier avance.

Los alemanes se apresuraron a transferir tropas a la Unión Soviética en un intento desesperado por aliviar Stalingrado, pero la ofensiva no pudo comenzar hasta el 12 de diciembre, momento en el que el 6.º Ejército en Stalingrado estaba hambriento y demasiado débil para avanzar hacia él. La Operación Tormenta de Invierno , con tres divisiones panzer transferidas, avanzó rápidamente desde Kotelnikovo hacia el río Aksai, pero se estancó a 65 km (40 millas) de su objetivo. Para desviar el intento de rescate, el Ejército Rojo decidió aplastar a los italianos y descender detrás del intento de socorro si podían; esa operación comenzó el 16 de diciembre. Lo que sí logró fue destruir muchos de los aviones que habían estado transportando suministros de socorro a Stalingrado. El alcance bastante limitado de la ofensiva soviética, aunque finalmente todavía se centró en Rostov, también le dio tiempo a Hitler para entrar en razón y sacar al Grupo de Ejércitos A del Cáucaso y volver a cruzar el Don. [91]

El 31 de enero de 1943, los 90.000 supervivientes del 6.º Ejército, formado por 300.000 hombres, se rindieron. Para entonces, el 2.º Ejército húngaro también había sido aniquilado. El Ejército Rojo avanzó desde el Don 500 km (310 millas) al oeste de Stalingrado, marchando a través de Kursk (recuperada el 8 de febrero de 1943) y Járkov (recuperada el 16 de febrero de 1943). Para salvar la posición en el sur, los alemanes decidieron abandonar el saliente de Rzhev en febrero, liberando tropas suficientes para dar una respuesta exitosa en el este de Ucrania. La contraofensiva de Manstein , reforzada por un Cuerpo Panzer de las SS especialmente entrenado y equipado con tanques Tiger , comenzó el 20 de febrero de 1943 y se abrió paso desde Poltava hasta Járkov en la tercera semana de marzo, cuando llegó el deshielo primaveral. Esto dejó un evidente bulto soviético en el frente centrado en Kursk.

Tras el fracaso del intento de capturar Stalingrado, Hitler había delegado la autoridad de planificación para la próxima temporada de campaña al Alto Mando del Ejército alemán y reinstaló a Heinz Guderian en un papel destacado, esta vez como Inspector de Tropas Panzer. El debate en el Estado Mayor estaba polarizado, e incluso Hitler estaba nervioso por cualquier intento de apoderarse del saliente de Kursk. Sabía que en los seis meses intermedios la posición soviética en Kursk había sido reforzada fuertemente con cañones antitanque , trampas para tanques , minas terrestres , alambre de púas , trincheras , fortines , artillería y morteros . [92]

Sin embargo, si se pudiera montar una última gran ofensiva relámpago , entonces la atención podría centrarse en la amenaza aliada al frente occidental . Ciertamente, las negociaciones de paz en abril no habían llevado a ninguna parte. [92] El avance se ejecutaría desde el saliente de Orel al norte de Kursk y desde Belgorod al sur. Ambas alas convergerían en el área al este de Kursk y, por ese medio, restablecerían las líneas del Grupo de Ejércitos Sur en los puntos exactos que mantuvo durante el invierno de 1941-1942.

En el norte, todo el 9.º Ejército alemán se había redesplegado desde el saliente de Rzhev al saliente de Orel y debía avanzar desde Maloarkhangelsk hasta Kursk. Pero sus fuerzas ni siquiera pudieron pasar el primer objetivo en Olkhovatka , a solo 8 km (5,0 mi) de avance. El 9.º Ejército embotó su punta de lanza contra los campos de minas soviéticos, frustrantemente teniendo en cuenta que el terreno elevado allí era la única barrera natural entre ellos y el terreno llano de los tanques hasta Kursk. La dirección del avance se cambió entonces a Ponyri , al oeste de Olkhovatka, pero el 9.º Ejército tampoco pudo abrirse paso allí y pasó a la defensiva. El Ejército Rojo lanzó entonces una contraofensiva, la Operación Kutuzov .

El 12 de julio, el Ejército Rojo atravesó la línea de demarcación entre las divisiones 211 y 293 en el río Zhizdra y avanzó hacia Karachev , justo detrás de ellas y detrás de Orel. La ofensiva del sur, encabezada por el 4.º Ejército Panzer , dirigido por el general coronel Hoth , con tres cuerpos de tanques, avanzó más. Avanzando a ambos lados del alto Donets por un estrecho corredor, el II Cuerpo Panzer SS y las divisiones Panzergrenadier de Großdeutschland se abrieron paso a través de campos de minas y sobre terreno relativamente alto hacia Oboyan . La dura resistencia provocó un cambio de dirección de este a oeste del frente, pero los tanques avanzaron 25 km (16 millas) antes de encontrarse con las reservas del 5.º Ejército de Tanques de la Guardia soviético en las afueras de Prokhorovka . La batalla se inició el 12 de julio, con unos mil tanques en combate.

Después de la guerra, la batalla cerca de Prochorovka fue idealizada por los historiadores soviéticos como la batalla de tanques más grande de todos los tiempos. El enfrentamiento en Prochorovka fue un éxito defensivo soviético, aunque a un alto costo. El 5.º Ejército de Tanques de la Guardia soviético, con unos 800 tanques ligeros y medianos, atacó elementos del II Cuerpo Panzer SS. Las pérdidas de tanques en ambos bandos han sido fuente de controversia desde entonces. Aunque el 5.º Ejército de Tanques de la Guardia no logró sus objetivos, el avance alemán había sido detenido.

Al final del día, ambos bandos habían luchado hasta el punto muerto, pero a pesar del fracaso alemán en el norte, Manstein propuso continuar el ataque con el 4.º Ejército Panzer. El Ejército Rojo inició la fuerte operación ofensiva en el saliente norte de Orel y logró abrirse paso por el flanco del 9.º Ejército alemán. Preocupado también por el desembarco de los aliados en Sicilia el 10 de julio, Hitler tomó la decisión de detener la ofensiva, incluso cuando el 9.º Ejército alemán estaba cediendo terreno rápidamente en el norte. La última ofensiva estratégica de los alemanes en la Unión Soviética terminó con su defensa contra una importante contraofensiva soviética que duró hasta agosto.

La ofensiva de Kursk fue la última de la escala de las de 1940 y 1941 que la Wehrmacht pudo lanzar; las ofensivas posteriores representarían sólo una sombra del poderío ofensivo alemán anterior.

La ofensiva soviética de verano en varias etapas comenzó con el avance hacia el saliente de Orel. La desviación de la bien equipada División Großdeutschland de Belgorod a Karachev no pudo contrarrestarla, y la Wehrmacht comenzó una retirada de Orel (recuperada por el Ejército Rojo el 5 de agosto de 1943), retrocediendo a la línea Hagen frente a Briansk. Al sur, el Ejército Rojo rompió las posiciones del Grupo de Ejércitos Sur en Belgorod y se dirigió a Járkov una vez más. Aunque las intensas batallas de movimiento a lo largo de finales de julio y agosto de 1943 vieron a los Tigres frenar los ataques de tanques soviéticos en un eje, pronto fueron flanqueados en otra línea hacia el oeste mientras las fuerzas soviéticas avanzaban por el Psel , y Járkov fue abandonada por última vez el 22 de agosto.

Las fuerzas alemanas en el Mius , que ahora comprendían el 1.er Ejército Panzer y un 6.º Ejército reconstituido, en agosto eran demasiado débiles para rechazar un ataque soviético en su propio frente, y cuando el Ejército Rojo las atacó, se retiraron a través de la región industrial del Donbass hasta el Dnieper, perdiendo la mitad de las tierras agrícolas que Alemania había invadido la Unión Soviética para explotar. En ese momento, Hitler aceptó una retirada general a la línea del Dnieper, a lo largo de la cual se suponía que estaría el Ostwall , una línea de defensa similar al Muro Occidental (Línea Sigfrido) de fortificaciones a lo largo de la frontera alemana en el oeste.

El principal problema para la Wehrmacht era que estas defensas aún no se habían construido; cuando el Grupo de Ejércitos Sur había evacuado el este de Ucrania y había comenzado a retirarse a través del Dnieper en septiembre, las fuerzas soviéticas los habían seguido de cerca. Tenazmente, pequeñas unidades remaron a través del río de 3 km de ancho y establecieron cabezas de puente. Un segundo intento del Ejército Rojo de ganar terreno utilizando paracaidistas, realizado en Kaniv el 24 de septiembre, resultó tan decepcionante como el de Dorogobuzh dieciocho meses antes. Los paracaidistas fueron repelidos pronto, pero no hasta que aún más tropas del Ejército Rojo utilizaron la cobertura que les proporcionaban para cruzar el Dnieper y atrincherarse de forma segura.

A finales de septiembre y principios de octubre, los alemanes se encontraron con que era imposible mantener la línea del Dniéper, ya que las cabezas de puente soviéticas crecían. Las ciudades importantes del Dniéper comenzaron a caer, siendo Zaporozhye la primera en caer, seguida por Dnepropetrovsk . Finalmente, a principios de noviembre, el Ejército Rojo salió de sus cabezas de puente a ambos lados de Kiev y capturó la capital ucraniana, en ese momento la tercera ciudad más grande de la Unión Soviética.

A 130 kilómetros al oeste de Kiev, el 4.º Ejército Panzer, convencido todavía de que el Ejército Rojo estaba agotado, fue capaz de preparar una respuesta exitosa en Zhytomyr a mediados de noviembre, debilitando la cabeza de puente soviética mediante un atrevido ataque de flanqueo lanzado por el Cuerpo Panzer de las SS a lo largo del río Teterev. Esta batalla también permitió al Grupo de Ejércitos Sur recuperar Korosten y ganar algo de tiempo para descansar. Sin embargo, en Nochebuena la retirada comenzó de nuevo cuando el Primer Frente Ucraniano (rebautizado como Frente Voronezh) los atacó en el mismo lugar. El avance soviético continuó a lo largo de la línea ferroviaria hasta que se alcanzó la frontera polaco-soviética de 1939 el 3 de enero de 1944.

Al sur, el Segundo Frente Ucraniano (antiguo Frente de la Estepa ) había cruzado el Dnieper en Kremenchug y continuaba hacia el oeste. En la segunda semana de enero de 1944, viró hacia el norte y se encontró con las fuerzas de tanques de Vatutin, que habían virado hacia el sur desde su penetración en Polonia y habían rodeado a diez divisiones alemanas en Korsun-Shevchenkovsky, al oeste de Cherkassy . La insistencia de Hitler en mantener la línea del Dnieper, incluso cuando se enfrentaba a la perspectiva de una derrota catastrófica, se vio agravada por su convicción de que la bolsa de Cherkassy podía escapar e incluso avanzar hacia Kiev, pero a Manstein le preocupaba más poder avanzar hasta el borde de la bolsa y luego implorar a las fuerzas rodeadas que escaparan.

El 16 de febrero se había completado la primera etapa, con los panzer separados de la bolsa de Cherkasy que se estaba contrayendo sólo por el crecido río Gniloy Tikich. Bajo el fuego de artillería y perseguidas por los tanques soviéticos, las tropas alemanas rodeadas, entre las que se encontraba la 5.ª División Panzer SS Wiking , se abrieron paso a través del río hasta ponerse a salvo, aunque a costa de la mitad de su número y todo su equipo. Supusieron que el Ejército Rojo no atacaría de nuevo, ya que se acercaba la primavera, pero el 3 de marzo el Frente Ucraniano Soviético pasó a la ofensiva. Habiendo aislado ya Crimea cortando el istmo de Perekop , las fuerzas de Malinovsky avanzaron a través del barro hasta la frontera rumana, sin detenerse en el río Prut .

Un último movimiento en el sur completó la campaña de 1943-44, que había puesto fin a un avance soviético de más de 800 kilómetros. En marzo, 20 divisiones alemanas del 1.er Ejército Panzer del Generaloberst Hans-Valentin Hube fueron rodeadas en lo que se conocería como la Bolsa de Hube cerca de Kamenets-Podolskiy. Después de dos semanas de duros combates, el 1.er Ejército Panzer logró escapar de la bolsa, a costa de perder casi todo el equipo pesado. En este punto, Hitler destituyó a varios generales destacados, incluido Manstein. En abril, el Ejército Rojo recuperó Odessa, seguido de la campaña del 4.º Frente Ucraniano para restaurar el control sobre Crimea, que culminó con la captura de Sebastopol el 10 de mayo.

En agosto de 1943, el Grupo de Ejércitos Centro fue empujando lentamente a esta fuerza desde la línea de Hagen, cediendo relativamente poco territorio, pero la pérdida de Bryansk, y más importante aún, de Smolensk, el 25 de septiembre, le costó a la Wehrmacht la piedra angular de todo el sistema defensivo alemán. Los ejércitos 4º y 9º y el 3º Ejército Panzer todavía se mantenían firmes al este del alto Dnieper, sofocando los intentos soviéticos de llegar a Vitebsk. En el frente del Grupo de Ejércitos Norte, apenas hubo combates hasta enero de 1944, cuando, de la nada, atacaron los frentes Volkhov y el Segundo Báltico. [93]

En una campaña relámpago, los alemanes fueron rechazados de Leningrado y Nóvgorod fue capturada por las fuerzas soviéticas. Después de un avance de 120 kilómetros (75 millas) en enero y febrero, el Frente de Leningrado había alcanzado las fronteras de Estonia. Para Stalin, el mar Báltico parecía la forma más rápida de llevar las batallas al territorio alemán en Prusia Oriental y tomar el control de Finlandia. [93] Las ofensivas del Frente de Leningrado hacia Tallin , un puerto importante del Báltico , fueron detenidas en febrero de 1944. El grupo de ejército alemán "Narwa" incluía reclutas estonios , defendiendo el restablecimiento de la independencia de Estonia . [94] [95]

Los planificadores de la Wehrmacht estaban convencidos de que el Ejército Rojo atacaría de nuevo en el sur, donde el frente estaba a 80 kilómetros de Lviv y ofrecía la ruta más directa a Berlín . En consecuencia, retiraron tropas del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro, cuyo frente aún sobresalía profundamente en la Unión Soviética. Los alemanes habían transferido algunas unidades a Francia para contrarrestar la invasión de Normandía dos semanas antes. La Ofensiva Bielorrusa (nombre en código Operación Bagration ), que fue acordada por los Aliados en la Conferencia de Teherán en diciembre de 1943 y lanzada el 22 de junio de 1944, fue un ataque soviético masivo, que consistió en cuatro grupos de ejército soviéticos que sumaban más de 120 divisiones que aplastaron una línea alemana débilmente defendida.

Concentraron sus ataques masivos en el Grupo de Ejércitos Centro, no en el Grupo de Ejércitos del Norte de Ucrania, como los alemanes habían esperado originalmente. Más de 2,3 millones de tropas soviéticas entraron en acción contra el Grupo de Ejércitos Centro alemán, que tenía una fuerza de menos de 800.000 hombres. En los puntos de ataque, las ventajas numéricas y cualitativas de las fuerzas soviéticas eran abrumadoras. El Ejército Rojo logró una proporción de diez a uno en tanques y siete a uno en aviones sobre su enemigo. Los alemanes se derrumbaron. La capital de Bielorrusia , Minsk, fue tomada el 3 de julio, atrapando a unos 100.000 alemanes. Diez días después, el Ejército Rojo llegó a la frontera polaca de antes de la guerra. Bagration fue, desde cualquier punto de vista, una de las operaciones individuales más grandes de la guerra.

A finales de agosto de 1944, los alemanes habían perdido unos 400.000 muertos, heridos, desaparecidos y enfermos, de los que 160.000 fueron capturados, así como 2.000 tanques y 57.000 vehículos más. En la operación, el Ejército Rojo perdió unos 180.000 muertos y desaparecidos (765.815 en total, incluidos los heridos y enfermos más 5.073 polacos), [96] así como 2.957 tanques y cañones de asalto. La ofensiva en Estonia se cobró la vida de otros 480.000 soldados soviéticos, 100.000 de ellos clasificados como muertos. [97] [98]

El 17 de julio de 1944 se lanzó la operación Lviv-Sandomierz , en la que el Ejército Rojo derrotó a las fuerzas alemanas en Ucrania occidental y recuperó Lviv. El avance soviético en el sur continuó hasta Rumania y, tras un golpe de Estado contra el gobierno de Rumania, aliado del Eje, el 23 de agosto, el Ejército Rojo ocupó Bucarest el 31 de agosto. Rumania y la Unión Soviética firmaron un armisticio el 12 de septiembre. [99] [100]

El rápido avance de la Operación Bagration amenazó con aislar a las unidades alemanas del Grupo de Ejércitos Norte, que resistían con tenacidad el avance soviético hacia Tallin . A pesar de un feroz ataque en las colinas de Sinimäed , Estonia, el Frente de Leningrado soviético no logró atravesar la defensa del destacamento militar más pequeño y bien fortificado "Narwa" en un terreno no apto para operaciones a gran escala . [101] [102]

En el istmo de Carelia , el Ejército Rojo lanzó una ofensiva de Vyborg-Petrozavodsk contra las líneas finlandesas el 9 de junio de 1944 (coordinada con la invasión aliada occidental de Normandía). Tres ejércitos se enfrentaron allí contra los finlandeses, entre ellos varias formaciones de fusileros de guardia con experiencia. El ataque rompió la línea de frente de defensa finlandesa en Valkeasaari el 10 de junio y las fuerzas finlandesas se retiraron a su línea de defensa secundaria, la línea VT . El ataque soviético fue apoyado por un bombardeo de artillería pesada, bombardeos aéreos y fuerzas blindadas. La línea VT fue violada el 14 de junio y después de un contraataque fallido en Kuuterselkä por parte de la división blindada finlandesa, la defensa finlandesa tuvo que retroceder a la línea VKT . Después de duros combates en las batallas de Tali-Ihantala e Ilomantsi , las tropas finlandesas finalmente lograron detener el ataque soviético. [ cita requerida ]

En Polonia, cuando el Ejército Rojo se acercaba, el Ejército Nacional Polaco (AK) lanzó la Operación Tempestad . Durante el Levantamiento de Varsovia , se ordenó al Ejército Rojo detenerse en el río Vístula . No se sabe si Stalin no pudo o no quiso acudir en ayuda de la resistencia polaca. [103]

En Eslovaquia, el Levantamiento Nacional Eslovaco comenzó como una lucha armada entre las fuerzas de la Wehrmacht alemana y las tropas rebeldes eslovacas entre agosto y octubre de 1944. Tuvo su epicentro en Banská Bystrica . [104]

En el otoño de 1944, los soviéticos detuvieron su ofensiva hacia Berlín para ganar primero el control de los Balcanes.

El 8 de septiembre de 1944, el Ejército Rojo inició un ataque al paso de Dukla, en la frontera entre Eslovaquia y Polonia. Dos meses después, las fuerzas soviéticas ganaron la batalla y entraron en Eslovaquia. El saldo fue alto: murieron 20.000 soldados del Ejército Rojo, además de varios miles de alemanes, eslovacos y checos.

Bajo la presión de la Ofensiva Soviética del Báltico , el Grupo de Ejércitos Alemán del Norte se retiró para luchar en los asedios de Saaremaa , Courland y Memel .

La Unión Soviética entró finalmente en Varsovia el 17 de enero de 1945, después de que la ciudad fuera destruida y abandonada por los alemanes. Durante tres días, en un frente amplio que incorporaba cuatro frentes de ejército , el Ejército Rojo lanzó la Ofensiva Vístula-Óder a través del río Narew y desde Varsovia. Los soviéticos superaban en número a los alemanes en un promedio de 5-6:1 en tropas, 6:1 en artillería, 6:1 en tanques y 4:1 en artillería autopropulsada . Después de cuatro días, el Ejército Rojo estalló y comenzó a moverse de treinta a cuarenta kilómetros por día, tomando los estados bálticos, Danzig , Prusia Oriental, Poznań y trazando una línea a sesenta kilómetros al este de Berlín a lo largo del río Óder . Durante el curso completo de la operación Vístula-Óder (23 días), las fuerzas del Ejército Rojo sufrieron 194.191 bajas totales (muertos, heridos y desaparecidos) y perdieron 1.267 tanques y cañones de asalto.

El 25 de enero de 1945, Hitler cambió el nombre de tres grupos de ejércitos: el Grupo de Ejércitos Norte pasó a llamarse Grupo de Ejércitos Curlandia , el Grupo de Ejércitos Centro pasó a llamarse Grupo de Ejércitos Norte y el Grupo de Ejércitos A pasó a llamarse Grupo de Ejércitos Centro. El Grupo de Ejércitos Norte (antiguo Grupo de Ejércitos Centro) fue empujado hacia una bolsa cada vez más pequeña alrededor de Königsberg, en Prusia Oriental.

Un contraataque limitado (con nombre en código Operación Solsticio ) por parte del recién creado Grupo de Ejércitos Vístula , bajo el mando del Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, había fracasado el 24 de febrero, y el Ejército Rojo avanzó hacia Pomerania y despejó la orilla derecha del río Óder. En el sur, los intentos alemanes, en la Operación Konrad , de aliviar la guarnición rodeada de Budapest fracasaron y la ciudad cayó el 13 de febrero. El 6 de marzo, los alemanes lanzaron lo que sería su última gran ofensiva de la guerra, la Operación Despertar de Primavera , que fracasó el 16 de marzo. El 30 de marzo, el Ejército Rojo entró en Austria y capturó Viena el 13 de abril.

El OKW - Oberkommando der Wehrmacht o Alto Mando del Ejército Alemán - afirmó que las pérdidas alemanas fueron de 77.000 muertos, 334.000 heridos y 192.000 desaparecidos, con un total de 603.000 hombres, en el Frente Oriental durante enero y febrero de 1945. [105]

El 9 de abril de 1945, Königsberg, en Prusia Oriental, finalmente cayó ante el Ejército Rojo, aunque los restos destrozados del Grupo de Ejércitos Centro continuaron resistiendo en el Vístula y la península de Hel hasta el final de la guerra en Europa. La operación de Prusia Oriental , aunque a menudo eclipsada por la operación Vístula-Oder y la posterior batalla de Berlín, fue de hecho una de las operaciones más grandes y costosas que libró el Ejército Rojo durante toda la guerra. Durante el período que duró (del 13 de enero al 25 de abril), le costó al Ejército Rojo 584.788 bajas y 3.525 tanques y cañones de asalto.

La caída de Königsberg permitió a la Stavka liberar al 2.º Frente Bielorruso (2BF) del general Konstantin Rokossovsky para que se desplazara hacia el oeste, a la orilla oriental del Oder. Durante las dos primeras semanas de abril, el Ejército Rojo realizó su redespliegue de frente más rápido de la guerra. El general Georgy Zhukov concentró su 1.er Frente Bielorruso (1BF), que había sido desplegado a lo largo del río Oder desde Frankfurt en el sur hasta el Báltico, en un área frente a los Altos de Seelow . El 2BF se trasladó a las posiciones que estaba dejando el 1BF al norte de los Altos de Seelow. Mientras se desarrollaba este redespliegue, se dejaron huecos en las líneas y los restos del 2.º Ejército alemán, que se había quedado atrapado en una bolsa cerca de Danzig, lograron escapar a través del Oder. Al sur, el general Ivan Konev trasladó el peso principal del 1.er Frente Ucraniano (1UF) desde la Alta Silesia al noroeste hasta el río Neisse . [106] Los tres frentes soviéticos tenían en total unos 2,5 millones de hombres (incluidos 78.556 soldados del 1.er Ejército polaco); 6.250 tanques; 7.500 aviones; 41.600 piezas de artillería y morteros; 3.255 lanzacohetes Katyusha montados en camiones (apodados "Órganos de Stalin"); y 95.383 vehículos de motor, muchos de los cuales fueron fabricados en los Estados Unidos. [106]

La ofensiva soviética tenía dos objetivos. Debido a las sospechas de Stalin sobre las intenciones de los aliados occidentales de entregar el territorio que ocupaban en la esfera de influencia soviética de posguerra , la ofensiva debía ser en un frente amplio y moverse lo más rápidamente posible hacia el oeste, para encontrarse con los aliados occidentales lo más al oeste posible. Pero el objetivo primordial era capturar Berlín. Los dos eran complementarios porque la posesión de la zona no podía ganarse rápidamente a menos que se tomara Berlín. Otra consideración era que Berlín en sí tenía activos estratégicos, incluido Adolf Hitler y parte del programa alemán de bombas atómicas . [107]

La ofensiva para capturar el centro de Alemania y Berlín comenzó el 16 de abril con un asalto a las líneas del frente alemán en los ríos Oder y Neisse . Después de varios días de duros combates, la 1BF y la 1UF soviéticas abrieron brecha en la línea del frente alemana y se desplegaron por el centro de Alemania. El 24 de abril, elementos de la 1BF y la 1UF habían completado el cerco de la capital alemana y la batalla de Berlín entró en sus etapas finales. El 25 de abril, la 2BF atravesó la línea del 3.er Ejército Panzer alemán al sur de Stettin . Ahora eran libres de moverse al oeste hacia el 21.er Grupo de Ejércitos británico y al norte hacia el puerto báltico de Stralsund . La 58.ª División de Fusileros de la Guardia del 5.º Ejército de la Guardia hizo contacto con la 69.ª División de Infantería estadounidense del Primer Ejército cerca de Torgau , Alemania, en el río Elba . [108] [109]

El 29 y 30 de abril, mientras las fuerzas soviéticas se abrían paso hacia el centro de Berlín, Adolf Hitler se casó con Eva Braun y luego se suicidó tomando cianuro y pegándose un tiro . En su testamento, Hitler nombró al Gran Almirante Karl Dönitz como nuevo Presidente del Reich y al Ministro de Propaganda Joseph Goebbels como nuevo Canciller del Reich ; sin embargo, Goebbels también se suicidó, junto con su esposa Magda y sus hijos , el 1 de mayo de 1945. Helmuth Weidling , comandante de defensa de Berlín, entregó la ciudad a las fuerzas soviéticas el 2 de mayo. [110] En total, la operación de Berlín (16 de abril - 2 de mayo) le costó al Ejército Rojo 361.367 bajas (muertos, heridos, desaparecidos y enfermos) y 1.997 tanques y cañones de asalto. Las pérdidas alemanas en este período de la guerra siguen siendo imposibles de determinar con alguna fiabilidad. [111]

Al enterarse de la muerte de Hitler y Goebbels, Dönitz (ahora presidente del Reich) nombró a Johann Ludwig Schwerin von Krosigk como nuevo "ministro principal" del Reich alemán. [112] Las fuerzas aliadas que avanzaban rápidamente limitaron la jurisdicción del nuevo gobierno alemán a un área alrededor de Flensburg cerca de la frontera danesa , donde se encontraban las oficinas centrales de Dönitz, junto con Mürwik . En consecuencia, esta administración fue conocida como el gobierno de Flensburg . [113] Dönitz y Schwerin von Krosigk intentaron negociar un armisticio con los aliados occidentales mientras continuaban resistiendo al ejército soviético, pero finalmente se vieron obligados a aceptar una rendición incondicional en todos los frentes. [114]

A las 2:41 am del 7 de mayo de 1945, en el cuartel general del SHAEF , el jefe del Estado Mayor alemán, general Alfred Jodl, firmó los documentos de rendición incondicional de todas las fuerzas alemanas a los aliados en Reims , Francia. Incluía la frase Todas las fuerzas bajo control alemán cesarán las operaciones activas a las 23:01 horas, hora de Europa Central, el 8 de mayo de 1945. Al día siguiente, poco antes de la medianoche, el mariscal de campo Wilhelm Keitel repitió la firma en Berlín en el cuartel general de Zhukov, ahora conocido como el Museo Alemán-Ruso . La guerra en Europa había terminado . [115]

En la Unión Soviética, el fin de la guerra se considera el 9 de mayo, fecha en la que se hizo efectiva la rendición, hora de Moscú. Esta fecha se celebra como fiesta nacional ( el Día de la Victoria ) en Rusia (como parte de un feriado de dos días, el 8 y el 9 de mayo) y en algunos otros países postsoviéticos. El desfile ceremonial de la Victoria se celebró en Moscú el 24 de junio.

El Grupo de Ejércitos Centro alemán se negó inicialmente a rendirse y continuó combatiendo en Checoslovaquia hasta aproximadamente el 11 de mayo. [116] Una pequeña guarnición alemana en la isla danesa de Bornholm se negó a rendirse hasta que fue bombardeada e invadida por los soviéticos. La isla fue devuelta al gobierno danés cuatro meses después.

La última batalla de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en el Frente Oriental, la batalla de Slivice, estalló el 11 de mayo y terminó con una victoria soviética el día 12.

El 13 de mayo de 1945 cesaron todas las ofensivas soviéticas y los combates en el Frente Oriental de la Segunda Guerra Mundial llegaron a su fin.

Tras la derrota alemana, Stalin prometió a sus aliados Truman y Churchill que atacaría a los japoneses en los 90 días siguientes a la rendición alemana. La invasión soviética de Manchuria comenzó el 8 de agosto de 1945, con un asalto a los estados títeres japoneses de Manchukuo y el vecino Mengjiang ; la mayor ofensiva eventualmente incluiría el norte de Corea , el sur de Sajalín y las islas Kuriles . Aparte de las batallas de Jaljin Gol , marcó la única acción militar de la Unión Soviética contra el Japón imperial; en la Conferencia de Yalta , había aceptado las súplicas de los Aliados de terminar el pacto de neutralidad con Japón y entrar en el teatro del Pacífico de la Segunda Guerra Mundial dentro de los tres meses posteriores al final de la guerra en Europa. Si bien no es parte de las operaciones del Frente Oriental, se incluye aquí porque los comandantes y gran parte de las fuerzas utilizadas por el Ejército Rojo provenían del Teatro de operaciones europeo y se beneficiaron de la experiencia adquirida allí. [117]

El Frente Oriental fue el teatro más grande y sangriento de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. En general, se acepta que fue el conflicto más mortífero de la historia de la humanidad, con más de 30 millones de muertos como resultado. [3] Las fuerzas armadas alemanas sufrieron el 80% de sus muertes militares en el Frente Oriental. [118] Implicó más combates terrestres que todos los demás teatros de la Segunda Guerra Mundial juntos. [5] La operación militar más grande de la historia, la Operación Barbarroja , la batalla más sangrienta de la historia, Stalingrado , el asedio más letal de la historia, Leningrado , [119] y la batalla más grande de la historia, Kursk , ocurrieron todas en el Frente Oriental. [120] La naturaleza distintivamente brutal de la guerra en el Frente Oriental se ejemplificó por un desprecio a menudo deliberado por la vida humana por parte de ambos lados. También se reflejó en la premisa ideológica de la guerra, que vio un choque trascendental entre dos ideologías directamente opuestas.

Aparte del conflicto ideológico, la mentalidad de los líderes de Alemania y la Unión Soviética, Hitler y Stalin, respectivamente, contribuyó a la escalada del terror y el asesinato a una escala sin precedentes. Tanto Stalin como Hitler hicieron caso omiso de la vida humana con tal de alcanzar su objetivo de la victoria. Esto incluyó la aterrorización de su propio pueblo, así como las deportaciones masivas de poblaciones enteras. Todos estos factores dieron lugar a una tremenda brutalidad tanto para los combatientes como para los civiles que no encontró paralelo en el Frente Occidental . Según la revista Time : "En términos de mano de obra, duración, alcance territorial y bajas, el Frente Oriental fue hasta cuatro veces la escala del conflicto en el Frente Occidental que se inició con la invasión de Normandía ". [121] Por el contrario, el general George Marshall , jefe del Estado Mayor del Ejército de los Estados Unidos , calculó que sin el Frente Oriental, Estados Unidos habría tenido que duplicar el número de sus soldados en el Frente Occidental. [122]

Memorándum para el asistente especial del presidente , Harry Hopkins , Washington, DC, 10 de agosto de 1943:

En la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Rusia ocupa una posición dominante y es el factor decisivo para la derrota del Eje en Europa. Mientras en Sicilia las fuerzas de Gran Bretaña y los Estados Unidos se enfrentan a dos divisiones alemanas, el frente ruso recibe la atención de aproximadamente 200 divisiones alemanas. Siempre que los Aliados abran un segundo frente en el continente, será decididamente un frente secundario al de Rusia; el suyo seguirá siendo el esfuerzo principal. Sin Rusia en la guerra, el Eje no puede ser derrotado en Europa, y la posición de las Naciones Unidas se vuelve precaria. De manera similar, la posición de Rusia en Europa después de la guerra será dominante. Con Alemania aplastada, no hay poder en Europa para oponerse a sus tremendas fuerzas militares. [123]