El sionismo [a] es un movimiento nacionalista etnocultural [1] [fn 1] que surgió en Europa a fines del siglo XIX y tenía como objetivo el establecimiento de un estado judío a través de la colonización de una tierra fuera de Europa. [4] [5] [6] Con el rechazo de propuestas alternativas para un estado judío , finalmente se centró en el establecimiento de una patria judía en Palestina , [7] [8] una región correspondiente a la Tierra de Israel en el judaísmo , [9] [10] y de importancia central en la historia judía . Los sionistas querían crear un estado judío en Palestina con la mayor cantidad de tierra, tantos judíos y la menor cantidad posible de árabes palestinos . [11] Tras el establecimiento del Estado de Israel en 1948, el sionismo se convirtió en la ideología nacional o estatal de Israel . [12] [7] [13]

El sionismo surgió inicialmente en Europa central y oriental como un movimiento nacionalista a fines del siglo XIX, en reacción a nuevas olas de antisemitismo y en respuesta a la Haskalah o Ilustración judía. [1] [14] Durante este período, Palestina fue parte del Imperio otomano . [15] La llegada de colonos sionistas a Palestina durante este período es ampliamente vista como el inicio del conflicto israelí-palestino . A lo largo de la primera década del movimiento sionista, algunas figuras sionistas, incluido el fundador del movimiento Theodor Herzl , consideraron alternativas a Palestina, como bajo el " Esquema de Uganda " (entonces parte del África Oriental Británica , y hoy en Kenia ), o en Argentina , Chipre , Mesopotamia , Mozambique o la península del Sinaí , [16] pero esto fue rechazado por la mayoría del movimiento. El proceso de traslado o "retorno" de los judíos a la tierra (alrededor de la actual Palestina e Israel) de la que habían sido exiliados, fue visto por el emergente movimiento sionista como una " reunión de exiliados " ( kibbutz galuyot ), un esfuerzo por poner fin a los éxodos y persecuciones que han marcado la historia judía al traer al pueblo judío de regreso a su patria histórica . [17]

De 1897 a 1948, el objetivo principal del movimiento sionista fue establecer las bases para una patria judía en Palestina y, posteriormente, consolidarla. El propio movimiento reconoció que la posición del sionismo de que una población extraterritorial tenía el reclamo más fuerte sobre Palestina iba en contra de la interpretación comúnmente aceptada del principio de autodeterminación . [18] En 1884, grupos protosionistas establecieron los Amantes de Sión , y en 1897 se organizó el primer congreso sionista . A fines del siglo XIX y principios del XX, un gran número de judíos emigraron primero al Imperio Otomano y luego al Mandato Británico de Palestina . Al mismo tiempo, se obtuvo cierto reconocimiento y apoyo internacional, en particular en la Declaración Balfour de 1917 del Reino Unido . Desde el establecimiento del Estado de Israel en 1948, el sionismo ha seguido principalmente abogando en nombre de Israel y abordando las amenazas a su existencia y seguridad continuas .

El término "sionismo" se ha aplicado a diversos enfoques para abordar los problemas que enfrentaban los judíos europeos a fines del siglo XIX. [19] El sionismo político moderno, diferente del sionismo religioso , es un movimiento formado por diversos grupos políticos cuyas estrategias y tácticas han cambiado con el tiempo. La ideología común entre las principales facciones sionistas es el apoyo a la concentración territorial y una mayoría demográfica judía en Palestina, a través de la colonización . [5] La corriente principal sionista ha incluido históricamente al sionismo liberal , laboral , revisionista y cultural , mientras que grupos como Brit Shalom e Ihud han sido facciones disidentes dentro del movimiento. [20] Las diferencias dentro de los principales grupos sionistas radican principalmente en su presentación y ethos, habiendo adoptado estrategias similares para lograr sus objetivos políticos, en particular en el uso de la violencia y el traslado obligatorio para lidiar con la presencia de la población palestina local, no judía. [21] [22] Los defensores del sionismo lo han visto como un movimiento de liberación nacional para la repatriación de un pueblo indígena (que fue objeto de persecución y comparte una identidad nacional a través de la conciencia nacional ), a la tierra natal de sus antepasados como se señala en la historia antigua . [23] [24] [25] De manera similar, el antisionismo tiene muchos aspectos, que incluyen la crítica del sionismo como una ideología colonialista , [26] racista , [27] o excepcionalista o como un movimiento colonialista de asentamiento . [28] [29] Los defensores del sionismo no necesariamente rechazan la caracterización del sionismo como colonial de asentamiento o excepcionalista. [b] [30] [31] [32]

El término "sionismo" se deriva de la palabra Sión ( hebreo : ציון , romanizado : Tzi-yon ) o Monte Sión , una colina en Jerusalén , que simboliza ampliamente la Tierra de Israel. [33] Monte Sión también es un término utilizado en la Biblia hebrea . [34] [35] En toda Europa del Este a fines del siglo XIX, numerosos grupos de base promovieron el reasentamiento nacional de los judíos en su tierra natal, [36] así como la revitalización y el cultivo de la lengua hebrea . Estos grupos fueron llamados colectivamente los " Amantes de Sión " y fueron vistos como opositores a un creciente movimiento judío hacia la asimilación. El primer uso del término se atribuye al austriaco Nathan Birnbaum , fundador del movimiento nacionalista de estudiantes judíos Kadimah ; utilizó el término en 1890 en su revista Selbst-Emancipation ( Autoemancipación ), [37] [38] cuyo nombre es casi idéntico al del libro de Leon Pinsker de 1882 Autoemancipación .

El sionismo se originó como un movimiento nacionalista destinado a crear un estado judío independiente. [39] [40] El denominador común entre todos los sionistas modernos es una reivindicación de Palestina, una tierra conocida en la tradición judía como la Tierra de Israel (" Eretz Israel "), como patria nacional de los judíos y como foco de la autodeterminación nacional judía . [41] Históricamente, el consenso en la ideología sionista ha sido que un hogar nacional judío requiere una mayoría judía. [20] El sionismo se basa en lazos históricos y tradiciones religiosas que vinculan al pueblo judío con la Tierra de Israel. [42] El sionismo no tiene una ideología uniforme, pero el sionismo político moderno se asocia típicamente con el sionismo laborista y el sionismo revisionista, que no son fundamentalmente diferentes. [43] [44] [ página necesaria ] [20]

Durante aproximadamente 1.700 años después de la última mayoría judía registrada en la región, la mayoría de los judíos vivían en varios países sin un estado nacional como parte del capítulo posromano de la diáspora judía . [45] El movimiento sionista fue fundado a fines del siglo XIX por judíos seculares , en gran parte como una respuesta de los judíos asquenazíes al creciente antisemitismo en Europa, ejemplificado por el caso Dreyfus en Francia y los pogromos antijudíos en el Imperio ruso . [46] El movimiento político fue establecido formalmente por el periodista austrohúngaro Theodor Herzl en 1897 después de la publicación de su libro Der Judenstaat ( El Estado judío ). [47] En ese momento, Herzl creía que la migración judía a la Palestina otomana , particularmente entre las comunidades judías pobres, no asimiladas y cuya presencia "flotante" causaba inquietud, sería beneficiosa para los judíos y cristianos europeos asimilados. [48] El sionismo político fue en algunos aspectos una ruptura drástica con los dos mil años de tradición judía y rabínica. El sionismo, que se inspiró en otros movimientos nacionalistas europeos, se inspiró en particular en una versión alemana del pensamiento de la Ilustración europea, y los principios nacionalistas alemanes se convirtieron en características clave del nacionalismo sionista. El historiador judío del nacionalismo Hans Kohn sostuvo que el nacionalismo sionista "no tenía nada que ver con las tradiciones judías; en muchos sentidos se oponía a ellas". Desde el principio, el sionismo tuvo sus críticos: el sionista cultural Ahad Ha'am , a principios del siglo XX, escribió que no había creatividad en el movimiento sionista de Herzl y que su cultura era europea y específicamente alemana. Consideraba que el movimiento representaba a los judíos como simples transmisores de la cultura imperialista europea. [49]

Aunque inicialmente fue uno de los varios movimientos políticos judíos que ofrecían respuestas alternativas a la asimilación judía y al antisemitismo, el sionismo se expandió rápidamente. En sus primeras etapas, sus partidarios consideraron la creación de un Estado judío en el territorio histórico de Palestina. Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la destrucción de la vida judía en Europa central y oriental, donde estos movimientos alternativos tenían sus raíces, se convirtió en un movimiento dominante en el pensamiento sobre un Estado nacional judío. Durante este período, el sionismo desarrollaría un discurso en el que los judíos religiosos, no sionistas, del Antiguo Yishuv que vivían en ciudades mixtas de árabes y judíos eran vistos como atrasados en comparación con el Nuevo Yishuv sionista secular . [49]

Desde el comienzo del desarrollo del movimiento sionista, el apoyo de las potencias europeas fue visto como necesario por los líderes sionistas (Herzl, Chaim Weizmann y David Ben-Gurion ). Creando una alianza con Gran Bretaña y asegurando apoyo durante algunos años para la emigración judía a Palestina, los sionistas también reclutaron judíos europeos para inmigrar allí, especialmente judíos que vivían en áreas del Imperio ruso donde el antisemitismo estaba en auge. La alianza con Gran Bretaña se tensó cuando este último se dio cuenta de las implicaciones del movimiento judío para los árabes en Palestina, pero los sionistas persistieron. El movimiento finalmente logró establecer Israel el 14 de mayo de 1948 (5 de Iyar de 5708 en el calendario hebreo ) como la patria del pueblo judío . La proporción de judíos del mundo que viven en Israel ha crecido de manera constante desde que surgió el movimiento. Entonces se conoció un consenso sionista como un paraguas ideológico generalmente atribuido a dos factores principales: una historia trágica compartida (como el Holocausto ) y la amenaza común planteada por los enemigos vecinos de Israel. [50] [51] A principios del siglo XXI, más del 40% de los judíos del mundo vivían en Israel, más que en cualquier otro país. En algunos estudios académicos, el sionismo ha sido analizado tanto en el contexto más amplio de la política de la diáspora como un ejemplo de los movimientos de liberación nacional modernos y como un ejemplo de colonialismo de asentamiento . [52] [53] Algunas figuras prominentes en el movimiento sionista temprano se refirieron al movimiento como colonialista, como Ze'ev Jabotinsky . [c] [54] [55] [32]

El sionismo moderno surgió a finales del siglo XIX en Europa, a raíz de los intentos infructuosos de los judíos de integrarse en la sociedad occidental, así como del creciente antisemitismo en Europa. El sionismo veía el nacionalismo como un problema para los judíos, que los excluía por considerarlos una minoría "no deseada" o "extraña". El sionismo también veía el nacionalismo como una solución a la difícil situación de los judíos europeos, al establecer un estado en el que los judíos serían mayoría. [56] [ página requerida ] El sionismo no buscaba resolver el antisemitismo, sino que lo veía como una realidad inevitable. Leo Pinsker describió el antisemitismo como una enfermedad hereditaria e incurable, y concluyó en su Autoemancipación que "un pueblo sin territorio es como un hombre sin sombra: algo antinatural, espectral". [57] Los judíos llamados "asimilacionistas" deseaban una integración completa en la sociedad europea. Estaban dispuestos a restar importancia a su identidad judía y, en algunos casos, a abandonar las opiniones y puntos de vista tradicionales en un intento de modernización y asimilación al mundo moderno. Una forma menos extrema de asimilación se denominaba síntesis cultural. Quienes estaban a favor de la síntesis cultural deseaban la continuidad y sólo una evolución moderada, y les preocupaba que los judíos no perdieran su identidad como pueblo. Los "sintetistas culturales" enfatizaban tanto la necesidad de mantener los valores y la fe judíos tradicionales como la necesidad de adaptarse a una sociedad modernista, por ejemplo, cumpliendo con los días y las reglas de trabajo. [58] [ página necesaria ]

En 1975, la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas aprobó la Resolución 3379 , que calificaba al sionismo de «una forma de racismo y discriminación racial». La Resolución 3379 fue derogada en 1991, cuando Israel condicionó su participación en las conversaciones de paz de Madrid a la aprobación de la Resolución 46/86 , que «revocaba la determinación contenida en» la 3379. [59]

El sionismo considera fundamental la creencia de que los judíos constituyen una nación y tienen el derecho moral e histórico de autodeterminarse en Palestina . [d] Esta creencia surgió de las experiencias de los judíos europeos, que según los primeros sionistas demostraban el peligro inherente a su condición de minoría. En contraste con la noción sionista de nacionalidad, el sentido judío de ser una nación se basaba en creencias religiosas de elección única y providencia divina, más que en la etnicidad. Las oraciones diarias enfatizaban la distinción con respecto a otras naciones; la conexión con Eretz Israel y la expectativa de la restauración se basaban en creencias mesiánicas y prácticas religiosas, no en concepciones nacionalistas materiales. [61]

La reivindicación sionista sobre Palestina se basaba en la idea de que los judíos tenían un derecho histórico a la tierra que superaba los derechos de los árabes, que no tenían "ninguna importancia moral o histórica". [20] [60] Según la historiadora israelí Simha Flapan, la visión expresada en la proclamación de que " no existían los palestinos " era una piedra angular de la política sionista iniciada por Ben-Gurion, Weizmann y continuada por sus sucesores. Flapan escribe además que el no reconocimiento de los palestinos sigue siendo un principio básico de la política israelí. [62] Esta perspectiva también era compartida por aquellos en la extrema izquierda del movimiento sionista, incluyendo a Martin Buber y otros miembros de Brit Shalom. [e] [f] [g] Los funcionarios británicos que apoyaban el esfuerzo sionista también tenían creencias similares con respecto a los derechos judíos y árabes en Palestina. [h] [i] [65] [63] [66]

A diferencia de otras formas de nacionalismo, la reivindicación sionista sobre Palestina era aspiracional y requería un mecanismo por el cual la reivindicación pudiera realizarse. [67] La concentración territorial de judíos en Palestina y el objetivo posterior de establecer una mayoría judía allí fue el principal mecanismo por el cual los grupos sionistas buscaron hacer realidad esta reivindicación. [68] En el momento de la Revuelta Árabe de 1936 , las diferencias políticas entre los diversos grupos sionistas se habían reducido aún más, y casi todos los grupos sionistas buscaban un estado judío en Palestina. [69] [70] Si bien no todos los grupos sionistas pidieron abiertamente el establecimiento de un estado judío en Palestina, todos los grupos de la corriente principal sionista estaban casados con la idea de establecer una mayoría demográfica judía allí. [71]

Desde la perspectiva de los primeros pensadores sionistas, los judíos que viven entre no judíos son anormales y sufren impedimentos que solo pueden abordarse rechazando la identidad judía que se desarrolló mientras vivían entre no judíos . En consecuencia, los primeros sionistas buscaron desarrollar una vida política judía nacionalista en un territorio donde los judíos constituyen una mayoría demográfica. [61] [72] [j] Los primeros pensadores sionistas vieron la integración de los judíos en la sociedad no judía como poco realista (o insuficiente para abordar las deficiencias asociadas con el estatus de minoría demográfica de los judíos en Europa) e indeseable, ya que la asimilación estaba acompañada por la dilución de la distinción cultural judía. [41] Moses Hess , un precursor líder del sionismo, comentó sobre la insuficiencia percibida de la asimilación: "El alemán odia a la raza judía más que a la religión; se opone menos a las creencias peculiares de los judíos que a sus narices peculiares". Líderes destacados del movimiento sionista expresaron una "comprensión" del antisemitismo , haciéndose eco de sus creencias:

El antisemitismo no es una psicosis... ni tampoco una mentira. El antisemitismo es el resultado necesario de una colisión entre dos tipos de identidad [o "esencia"]. El odio depende de la cantidad de "agentes de fermentación" que se introducen en el organismo general [es decir, el grupo no judío], ya sea que estén activos en él y lo irriten, o que sean neutralizados en él. [72]

En este sentido, el sionismo no intentó desafiar el antisemitismo, sino más bien aceptarlo como una realidad. La solución sionista a las deficiencias percibidas de la vida diaspórica (o la " cuestión judía ") dependía de la concentración territorial de los judíos en Palestina, con el objetivo a largo plazo de establecer una mayoría demográfica judía allí. [20] [73] [41]

Los primeros sionistas fueron los principales partidarios judíos de la idea de que los judíos son una raza, ya que "ofrecía una 'prueba' científica del mito etnonacionalista de la descendencia común". [74] Según Raphael Falk , ya en la década de 1870 los pensadores sionistas y presionistas concebían a los judíos como pertenecientes a un grupo biológico distinto. [75] Esta reconceptualización del judaísmo presentó al " volk " de la comunidad judía como una raza-nación, en contraste con concepciones centenarias del pueblo judío como una agrupación sociocultural religiosa. [75] A los historiadores judíos Heinrich Graetz y Simon Dubnow se les atribuye en gran medida esta creación del sionismo como un proyecto nacionalista. Se basaron en fuentes judías religiosas y textos no judíos para reconstruir una identidad y conciencia nacionales. Esta nueva historiografía judía se divorció de la memoria colectiva judía tradicional y, a veces, entró en desacuerdo con ella. [49]

Fue particularmente importante en la construcción temprana de la nación en Israel, porque los judíos en Israel son étnicamente diversos y los orígenes de los judíos asquenazíes no eran conocidos. [76] [77] Entre los defensores notables de esta idea racial se encontraban Max Nordau , cofundador de la Organización Sionista original junto con Herzl , Ze'ev Jabotinsky , el destacado arquitecto del sionismo estatista temprano y fundador de lo que se convirtió en el partido Likud de Israel , [78] y Arthur Ruppin , considerado el "padre de la sociología israelí". [79] Birnbaum, a quien se le atribuye ampliamente el primer uso del término "sionismo" en referencia a un movimiento político, veía la raza como la base de la nacionalidad, [80] Jabotinsky escribió que la integridad nacional judía se basa en la "pureza racial", [78] [k] y que "(e)l sentimiento de autoidentidad nacional está arraigado en la 'sangre' del hombre, en su tipo físico-racial, y sólo en él". [81]

Según Hassan S. Haddad, la aplicación de los conceptos bíblicos de los judíos como el pueblo elegido y la " Tierra Prometida " en el sionismo, particularmente a los judíos seculares, requiere la creencia de que los judíos modernos son los descendientes primarios de los judíos bíblicos y los israelitas. [82] Esto se considera importante para el Estado de Israel, porque su narrativa fundacional se centra en el concepto de una " Reunión de los exiliados " y el " Retorno a Sión ", bajo el supuesto de que todos los judíos modernos son los descendientes lineales directos de los judíos bíblicos. [83] La cuestión ha sido así centrada tanto por los partidarios del sionismo como por los antisionistas , [84] ya que en ausencia de esta primacía bíblica, "el proyecto sionista cae presa de la categorización peyorativa de 'colonialismo de asentamiento' perseguida bajo suposiciones falsas, haciendo el juego a los críticos de Israel y alimentando la indignación del pueblo palestino desplazado y apátrida", [83] mientras que los israelíes de derecha buscan "una manera de demostrar que la ocupación es legítima, de autentificar el ethnos como un hecho natural y de defender al sionismo como un retorno". [85] Una "autodefinición biológica" judía se ha convertido en una creencia estándar para muchos nacionalistas judíos, y la mayoría de los investigadores demográficos israelíes nunca han dudado de que algún día se encontrarán pruebas, aunque hasta ahora las pruebas de la afirmación han "permanecido siempre elusivas". [86]

El sionismo rechazó las definiciones judías tradicionales de lo que significa ser judío, pero luchó por ofrecer una nueva interpretación de la identidad judía independiente de la tradición rabínica. La religión judía es vista como un factor esencialmente negativo, incluso en la ideología religiosa sionista, y se la considera responsable de la disminución del estatus de los judíos que viven como minoría. [72] En respuesta a los desafíos de la modernidad, el sionismo buscó reemplazar las instituciones religiosas y comunitarias por una secular-nacionalista, definiendo al judaísmo en "términos cristianos". [87] De hecho, el sionismo mantuvo principalmente los símbolos externos de la tradición judía, redefiniéndolos en un contexto nacionalista. Adaptó los conceptos religiosos judíos tradicionales, como la devoción al Dios de Israel, la reverencia por la Tierra de Israel bíblica y la creencia en un futuro retorno judío durante la era mesiánica, a un marco nacionalista moderno. Sin duda, el anhelo por un retorno a la tierra de Israel "era enteramente quietista" y las oraciones diarias por un retorno a Sión estaban acompañadas por una apelación a Dios, en lugar de un llamado a los judíos a tomar la iniciativa de apropiarse de la tierra. [61] [88] El sionismo se veía a sí mismo como el encargado de traer a los judíos al mundo moderno al redefinir lo que significa ser judío en términos de identificación con un estado soberano, en lugar de la fe y la tradición judías. [87]

El sionismo pretendía reconfigurar la identidad y la cultura judías en términos nacionalistas y seculares. Esta nueva identidad se basaría en el rechazo de la vida en el exilio. El sionismo retrataba al judío de la diáspora como mentalmente inestable, físicamente frágil y propenso a involucrarse en negocios transitorios como la venta ambulante o la intermediación. Se lo veía como alguien separado de la naturaleza, puramente materialista y centrado únicamente en sus ganancias personales. En cambio, la visión del nuevo judío era radicalmente diferente: un individuo de fuertes valores morales y estéticos, no encadenado a la religión, impulsado por ideales y dispuesto a desafiar las circunstancias degradantes; una persona liberada, digna y ansiosa por defender tanto el orgullo personal como el nacional. [72] [41]

El objetivo sionista de reformular la identidad judía en términos seculares-nacionalistas significó principalmente el declive del estatus de la religión en la comunidad judía. [72] Los pensadores sionistas prominentes enmarcan este desarrollo como el nacionalismo que cumple el mismo papel que la religión, reemplazándola funcionalmente. [87] El sionismo buscó hacer del nacionalismo étnico judío el rasgo distintivo de los judíos en lugar de su compromiso con el judaísmo. [41] El sionismo en cambio adoptó una comprensión racial de la identidad judía, que paradójicamente reflejaba puntos de vista antisemitas al sugerir que el judaísmo es un rasgo inherente e inmutable que se encuentra en la "sangre" de uno. [72] Enmarcada de esta manera, la identidad judía es solo secundariamente una cuestión de tradición o cultura. [89] El nacionalismo sionista abrazó ideologías pangermánicas, que enfatizaban el concepto de das völk : las personas de ascendencia compartida deben buscar la separación y establecer un estado unificado. Los pensadores sionistas ven el movimiento como una “rebelión contra una tradición de muchos siglos” de vivir como parásitos al margen de la sociedad occidental. De hecho, el sionismo se sentía incómodo con el término “judío”, asociándolo con la pasividad, la espiritualidad y la mancha del “galut”. En cambio, los pensadores sionistas preferían el término “hebreo” para describir su identidad, que asociaban con la sabra saludable y moderna. En el pensamiento sionista, el nuevo judío sería productivo y trabajaría la tierra, en contraste con el judío de la diáspora que, reflejando las representaciones antisemitas, era representado como holgazán y parásito de la sociedad. El sionismo vinculó el término “judío” con estas características negativas prevalecientes en los estereotipos antisemitas europeos, que los sionistas creían que podrían remediarse solo a través de la soberanía. [90]

La académica israelí-irlandesa Ronit Lentin ha sostenido que la construcción de la identidad sionista como un nacionalismo militarizado surgió en contraste con la identidad imputada del judío de la diáspora como un Otro "feminizado" . Ella describe esto como una relación de desprecio hacia la identidad previa de la diáspora judía vista como incapaz de resistir el antisemitismo y el Holocausto. Lentin sostiene que el rechazo del sionismo a esta identidad "feminizada" y su obsesión por construir una nación se refleja en la naturaleza del simbolismo del movimiento, que se extrae de fuentes modernas y se apropia como sionista, citando como ejemplo el hecho de que la melodía del himno Hatikvah se basó en la versión compuesta por el compositor checo Bedřich Smetana . [49]

El rechazo a la vida en la diáspora no se limitaba al sionismo secular; muchos sionistas religiosos compartían esta opinión, pero no todos los sionistas religiosos lo hacían. Abraham Isaac Kook , considerado uno de los pensadores sionistas religiosos más importantes, caracterizó la diáspora como una existencia imperfecta y alienada marcada por la decadencia, la estrechez, el desplazamiento, la soledad y la fragilidad. Creía que el modo de vida de la diáspora se opone diametralmente a un "renacimiento nacional", que se manifiesta no sólo en el retorno a Sión, sino también en el retorno a la naturaleza y la creatividad, el resurgimiento de los valores heroicos y estéticos y el resurgimiento del poder individual y social. [91]

.jpg/440px-Portrait_of_Eliezer_Ben-Yehuda_(cropped).jpg)

El resurgimiento del hebreo como lengua literaria secular en Europa del Este marcó un cambio cultural significativo entre los judíos, quienes, según la tradición judía, utilizaban el hebreo sólo con fines religiosos. Esta secularización del hebreo, que incluyó su uso en novelas, poemas y periodismo, se encontró con la resistencia de los rabinos, que la consideraban una profanación de la lengua sagrada. Si bien algunas autoridades rabínicas apoyaron el desarrollo del hebreo como lengua vernácula común, lo hicieron sobre la base de ideas nacionalistas, en lugar de sobre la base de la tradición judía. [61] Eliezer Ben Yehuda, una figura clave en el resurgimiento, imaginó que el hebreo serviría a un "espíritu nacional" y al renacimiento cultural en la Tierra de Israel. [93] El principal motivador para establecer el hebreo moderno como lengua nacional fue el sentido de legitimidad que le dio al movimiento, al sugerir una conexión entre los judíos del antiguo Israel y los judíos del movimiento sionista. [94] Estos acontecimientos se consideran en la historiografía sionista como una rebelión contra la tradición, en la que el desarrollo del hebreo moderno proporciona la base sobre la que podría desarrollarse un renacimiento cultural judío. [61]

Los sionistas generalmente preferían hablar hebreo , una lengua semítica que floreció como lengua hablada en los antiguos reinos de Israel y Judá durante el período de aproximadamente 1200 a 586 a. C., [95] y continuó usándose en algunas partes de Judea durante el período del Segundo Templo y hasta el año 200 d. C. Es el idioma de la Biblia hebrea y la Mishná , textos centrales del judaísmo . El hebreo se conservó en gran medida a lo largo de la historia posterior como el principal idioma litúrgico del judaísmo.

Los sionistas trabajaron para modernizar el hebreo y adaptarlo para el uso cotidiano. A veces se negaban a hablar yiddish , un idioma que creían que se había desarrollado en el contexto de la persecución europea . Una vez que se mudaron a Israel, muchos sionistas se negaron a hablar sus lenguas maternas (diaspóricas) y adoptaron nuevos nombres hebreos . El hebreo fue preferido no solo por razones ideológicas, sino también porque permitía a todos los ciudadanos del nuevo estado tener un idioma común, lo que fomentaba los vínculos políticos y culturales entre los sionistas. [ cita requerida ]

El resurgimiento de la lengua hebrea y el establecimiento del hebreo moderno están estrechamente asociados con el lingüista Eliezer Ben-Yehuda y el Comité de la Lengua Hebrea (posteriormente reemplazado por la Academia de la Lengua Hebrea ). [96]

La transformación de una conexión religiosa y principalmente pasiva entre los judíos y Palestina en un movimiento activo, secular y nacionalista surgió en el contexto de los desarrollos ideológicos dentro de las naciones europeas modernas en el siglo XIX. El concepto del "retorno" siguió siendo un símbolo poderoso dentro de la creencia religiosa judía que enfatizaba que su retorno debería ser determinado por la Providencia Divina en lugar de la acción humana. [87] El destacado historiador sionista Shlomo Avineri describe esta conexión: "Los judíos no se relacionaron con la visión del Retorno de una manera más activa de lo que la mayoría de los cristianos vieron la Segunda Venida". La noción religiosa judaica de ser una nación era distinta de la noción europea moderna de nacionalismo. [41] Los judíos ultraortodoxos se opusieron firmemente al asentamiento colectivo judío en Palestina, [l] viéndolo como una violación de los tres juramentos hechos a Dios: no forzar su entrada en la patria, no apresurar el fin de los tiempos y no rebelarse contra otras naciones . Creían que cualquier intento de lograr la redención a través de acciones humanas, en lugar de la intervención divina y la venida del Mesías , constituía una rebelión contra la voluntad divina y una herejía peligrosa. [m]

La memoria cultural de los judíos en la diáspora reverenciaba la Tierra de Israel. La tradición religiosa sostenía que una futura era mesiánica marcaría el comienzo de su retorno como pueblo. [97] , un "retorno a Sión" conmemorado particularmente en las oraciones de Pascua y de Yom Kippur . A fines de la época medieval, surgió entre los ashkenazíes un augurio - " El año que viene en Jerusalén " - que se incluía en la Amidá (oración de pie) tres veces al día. [98] La profecía bíblica de las Galuyot del Kibutz , la reunión de los exiliados en la Tierra de Israel según lo predicho por los profetas , se convirtió en una idea central en el sionismo. [99] [100] [101]

Los precursores del sionismo, en lugar de estar relacionados causalmente con el desarrollo posterior del sionismo, son pensadores y activistas que expresaron alguna noción de conciencia nacional judía o abogaron por la migración de judíos a Palestina. Estos intentos no fueron continuos como suelen serlo los movimientos nacionales. [102] [103] Los precursores más notables del sionismo fueron pensadores como Judah Alkalai y Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (ambos figuras rabínicas), así como Moses Hess , considerado el primer nacionalista judío moderno. [104]

Hess abogó por el establecimiento de un estado judío independiente en pos de la normalización económica y social del pueblo judío. [105] Hess creía que la emancipación por sí sola no era una solución suficiente a los problemas que enfrentaba el judaísmo europeo; percibía un cambio del sentimiento antijudío de una base religiosa a una base racial. Para Hess, la conversión religiosa no solucionaría esta hostilidad antijudía. [103] En contraste con Hess, Alkalai y Kalischer desarrollaron sus ideas como una reinterpretación del mesianismo según líneas tradicionalistas en las que la intervención humana prepararía (y específicamente solo prepararía) para la redención final. En consecuencia, la inmigración judía en esta línea tenía la intención de ser selectiva, involucrando solo a los judíos más devotos. [104] Su idea de los judíos como un colectivo estaba fuertemente ligada a nociones religiosas distintas del movimiento secular conocido como sionismo que se desarrolló a fines del siglo. [102]

Las ideas restauracionistas cristianas que promovían la migración de judíos a Palestina contribuyeron al contexto ideológico e histórico que dio un sentido de credibilidad a estas iniciativas presionistas. [103] Las ideas restauracionistas fueron un prerrequisito para el éxito del sionismo, ya que desde el principio el sionismo dependió del apoyo cristiano. [102]

En el siglo XVII, Sabbatai Zevi (1626-1676) se anunció como el Mesías y ganó a muchos judíos para su lado, formando una base en Salónica. Primero intentó establecer un asentamiento en Gaza, pero luego se mudó a Esmirna . Después de derrocar al viejo rabino Aaron Lapapa en la primavera de 1666, la comunidad judía de Aviñón, Francia , se preparó para emigrar al nuevo reino. [106] [107] [108]

Otras figuras protosionistas incluyen a los rabinos Yehuda Bibas (1789-1852), Tzvi Kalischer (1795-1874) y Judah Alkalai (1798-1878). [109]

La idea de regresar a Palestina fue rechazada por las conferencias de rabinos celebradas en esa época. Esfuerzos individuales apoyaron la emigración de grupos de judíos a Palestina, antes de la aliyá sionista , incluso antes del Primer Congreso Sionista en 1897, año considerado como el inicio del sionismo práctico. [110]

Los judíos reformistas rechazaron esta idea de un retorno a Sión. La conferencia de rabinos celebrada en Frankfurt am Main del 15 al 28 de julio de 1845 suprimió del ritual todas las oraciones por el retorno a Sión y la restauración de un estado judío. La Conferencia de Filadelfia de 1869 siguió el ejemplo de los rabinos alemanes y decretó que la esperanza mesiánica de Israel es "la unión de todos los hijos de Dios en la confesión de la unidad de Dios". En 1885, la Conferencia de Pittsburgh reiteró esta interpretación de la idea mesiánica del judaísmo reformista, expresando en una resolución que "ya no nos consideramos una nación, sino una comunidad religiosa; y por lo tanto no esperamos ni un retorno a Palestina, ni un culto sacrificial bajo los hijos de Aarón, ni la restauración de ninguna de las leyes relativas a un estado judío". [111]

En 1819, WD Robinson propuso el establecimiento de asentamientos judíos en la región del Alto Misisipi. [112] [ cita completa necesaria ]

En Praga , Abraham Benisch y Moritz Steinschneider realizaron esfuerzos morales, pero no prácticos, para organizar una emigración judía en 1835. En los Estados Unidos, Mordecai Noah intentó establecer un refugio judío frente a Buffalo, Nueva York , en Grand Isle, en 1825. Estos primeros esfuerzos de construcción de una nación judía de Cresson, Benisch, Steinschneider y Noah fracasaron. [113] [ página necesaria ] [114]

Sir Moses Montefiore , famoso por su intervención en favor de los judíos de todo el mundo, incluido el intento de rescatar a Edgardo Mortara , estableció una colonia para judíos en Palestina. En 1854, su amigo Judah Touro legó dinero para financiar el asentamiento residencial judío en Palestina. Montefiore fue designado albacea de su testamento y utilizó los fondos para una variedad de proyectos, incluida la construcción en 1860 del primer asentamiento residencial judío y asilo de beneficencia fuera de la antigua ciudad amurallada de Jerusalén, hoy conocida como Mishkenot Sha'ananim . Laurence Oliphant fracasó en un intento similar de traer a Palestina al proletariado judío de Polonia, Lituania, Rumania y el Imperio turco (1879 y 1882).

Las ideas de unidad cultural judía adquirieron una expresión específicamente política en la década de 1860, cuando los intelectuales judíos comenzaron a promover la idea del nacionalismo judío. El sionismo sería sólo uno de los varios movimientos nacionales judíos que se desarrollarían; otros incluían grupos nacionalistas de la diáspora como el Bund . [115]

El sionismo surgió hacia el final del "mejor siglo" [87] para los judíos, a quienes por primera vez se les permitió entrar en igualdad de condiciones en la sociedad europea. Durante este tiempo, los judíos tendrían igualdad ante la ley y obtendrían acceso a escuelas, universidades y profesiones que antes les estaban vedadas. [87] En la década de 1870, los judíos habían logrado una emancipación cívica casi completa en todos los estados de Europa occidental y central. [41] En 1914, un siglo después del comienzo de la emancipación , los judíos habían pasado de los márgenes a la vanguardia de la sociedad europea. En los centros urbanos de Europa y América, los judíos desempeñaron un papel influyente en la vida profesional e intelectual, considerada en proporción a su número. [87] Durante este período, cuando la asimilación judía todavía progresaba de manera muy prometedora, algunos intelectuales judíos y tradicionalistas religiosos enmarcaron la asimilación como una negación humillante de la distinción cultural judía. El desarrollo del sionismo y otros movimientos nacionalistas judíos surgió de estos sentimientos, que comenzaron a surgir incluso antes de la aparición del antisemitismo moderno como un factor importante. [41] En este sentido, el sionismo puede leerse como una respuesta a la Haskalá y a los desafíos de la modernidad y el liberalismo, más que puramente una respuesta al antisemitismo. [87]

La emancipación en Europa del Este progresó más lentamente, [116] hasta el punto que Deickoff escribe que "las condiciones sociales eran tales que hacían inútil la idea de la asimilación individual". El antisemitismo, los pogromos y las políticas oficiales en la Rusia zarista llevaron a la emigración de tres millones de judíos entre 1882 y 1914, de los cuales sólo el 1% fue a Palestina. Los que fueron a Palestina lo hicieron principalmente impulsados por ideas de autodeterminación e identidad judía, más que como respuesta a los pogromos o la inseguridad económica. [87] El surgimiento del sionismo a finales del siglo XIX se produjo entre los judíos asimilados de Europa central que, a pesar de su emancipación formal, todavía se sentían excluidos de la alta sociedad. Muchos de estos judíos se habían alejado de las observancias religiosas tradicionales y eran en gran medida seculares, lo que refleja una tendencia más amplia de secularización en Europa. A pesar de sus esfuerzos por integrarse, los judíos de Europa central y oriental se vieron frustrados por la continua falta de aceptación por parte de los movimientos nacionales locales que tendían hacia la intolerancia y la exclusividad. [61] Para los primeros sionistas, si bien el nacionalismo planteaba un desafío al judaísmo europeo, también proponía una solución. [44]

El inicio oficial de la construcción del Nuevo Yishuv en Palestina suele datarse con la llegada del grupo Bilu en 1882, que inició la Primera Aliá . En los años siguientes, la inmigración judía a Palestina comenzó en serio. La mayoría de los inmigrantes provenían del Imperio ruso, escapando de los frecuentes pogromos y la persecución dirigida por el estado en lo que ahora son Ucrania y Polonia. [ cita requerida ] Fundaron una serie de asentamientos agrícolas con el apoyo financiero de filántropos judíos en Europa occidental. Aliá adicionales siguieron a la Revolución rusa y su estallido de violentos pogromos. A fines del siglo XIX, los judíos eran una pequeña minoría en Palestina. [ 117 ]

.jpg/440px-PikiWiki_Israel_5628_Synagogue_(cropped).jpg)

En la década de 1890, Theodor Herzl (el padre del sionismo político) infundió al sionismo una nueva ideología y urgencia práctica, lo que llevó al Primer Congreso Sionista en Basilea en 1897, que creó la Organización Sionista (ZO), rebautizada en 1960 como Organización Sionista Mundial (WZO). [118] En Der Judenstaat , Herzl fue explícito al mencionar que el "estado de los judíos" solo podría establecerse con el apoyo de una potencia europea. Describió al estado judío como un "puesto de avanzada de la civilización contra la barbarie". En un escrito separado, Herzl se comparó con Cecil Rhodes , quien era un firme partidario de las ideologías colonialistas e imperialistas británicas. [49] : 327

En 1896, Theodor Herzl expresó en Der Judenstaat sus puntos de vista sobre "la restauración del estado judío". [119] Herzl consideraba que el antisemitismo era una característica eterna de todas las sociedades en las que los judíos vivían como minorías, y que sólo una soberanía podría permitir a los judíos escapar de la persecución eterna: "¡Que nos den soberanía sobre un pedazo de la superficie de la Tierra, justo lo suficiente para las necesidades de nuestro pueblo, luego haremos el resto!" proclamó exponiendo su plan. [120] En 1902, Herzl publicó Altneuland , que retrata un estado judío donde judíos y árabes viven juntos en armonía. Laqueur describe Altneuland como un reflejo de la creencia de Herzl en la importancia de la coexistencia y el respeto mutuo entre diferentes comunidades. [121] [ página necesaria ]

Antes de la Primera Guerra Mundial, aunque liderado por judíos austriacos y alemanes, el sionismo estaba compuesto principalmente por judíos rusos. [122] Inicialmente, los sionistas eran una minoría, tanto en Rusia como en todo el mundo. [123] [124] [125] [126] El sionismo ruso rápidamente se convirtió en una fuerza importante dentro del movimiento, constituyendo aproximadamente la mitad de los delegados en los congresos sionistas. [127]

A pesar de su éxito en atraer seguidores, el sionismo ruso se enfrentó a una feroz oposición por parte de la intelectualidad rusa de todo el espectro político y las clases socioeconómicas. Fue condenado por diferentes grupos como reaccionario, mesiánico y poco realista, argumentando que aislaría a los judíos y exacerbaría sus circunstancias en lugar de integrarlos a las sociedades europeas. [127] Los judíos religiosos como el rabino Joel Teitelbaum vieron en el sionismo una profanación de sus creencias sagradas y un complot satánico, mientras que otros no pensaban que mereciera una atención seria. [128] Para ellos, el sionismo era visto como un intento de desafiar el orden divino de esperar la llegada del Mesías. [129] Sin embargo, muchos de estos judíos religiosos todavía creían en la pronta venida del Mesías. Por ejemplo, el rabino Israel Meir Kahan "estaba tan convencido de la inminente llegada del Mesías que instó a sus estudiantes a estudiar las leyes del sacerdocio para que los sacerdotes estuvieran preparados para llevar a cabo sus deberes cuando se reconstruyera el Templo de Jerusalén". [128]

Las críticas no se limitaban a los judíos religiosos. Los socialistas bundistas y los liberales del periódico Voskhod atacaron al sionismo por distraer de la lucha de clases y bloquear el camino hacia la emancipación judía en Rusia, respectivamente. [127] Figuras como el historiador Simon Dubnow vieron un valor potencial en el sionismo al promover la identidad judía, pero rechazaron fundamentalmente un estado judío por mesiánico e inviable. [130] Propusieron soluciones emancipadoras alternativas, como la asimilación, la emigración y el nacionalismo de la diáspora. [131] La oposición al sionismo, arraigada en la visión racionalista del mundo de la intelectualidad, debilitó su atractivo entre posibles adeptos como la clase trabajadora y la intelectualidad judías. [127] En última instancia, la intelectualidad rusa estaba unida en la opinión de que el sionismo era una ideología aberrante que iba en contra de sus creencias en la asimilación judía.

.jpg/440px-THEODOR_HERZL_AT_THE_FIRST_ZIONIST_CONGRESS_IN_BASEL_ON_25.8.1897._תאודור_הרצל_בקונגרס_הציוני_הראשון_-_1897.8.25_(cropped).jpg)

La empresa sionista se financió principalmente por grandes benefactores que hicieron grandes contribuciones, simpatizantes de comunidades judías de todo el mundo (véase, por ejemplo, las cajas de donaciones del Fondo Nacional Judío ) y los propios colonos. El movimiento estableció un banco para administrar sus finanzas, el Jewish Colonial Trust (fundado en 1888, constituido en Londres en 1899). En 1902 se formó una filial local en Palestina, el Anglo-Palestine Bank .

Una lista de grandes contribuyentes pre-estatales a empresas pre-sionistas y sionistas incluiría, en orden alfabético,

Una lista de organizaciones paramilitares y de defensa judías preestatales en Palestina incluiría:

No sancionado por la administración sionista central

A lo largo de la primera década del movimiento sionista, hubo varios casos en los que algunas figuras sionistas, incluido Herzl, consideraron un estado judío en lugares fuera de Palestina, como "Uganda" (en realidad partes del África Oriental Británica hoy en Kenia ), Argentina , Chipre , Mesopotamia , Mozambique y la península del Sinaí . [16] Herzl, el fundador del sionismo político, inicialmente se contentó con cualquier estado judío autogobernado. [135] El asentamiento judío de Argentina fue el proyecto de Maurice de Hirsch . [136] No está claro si Herzl consideró seriamente este plan alternativo, [137] sin embargo, más tarde reafirmó que Palestina tendría un mayor atractivo debido a los lazos históricos de los judíos con esa área. [138]

Una de las principales preocupaciones y la razón principal para considerar otros territorios fueron los pogromos rusos, en particular la masacre de Kishinev , y la necesidad resultante de un reasentamiento rápido en un lugar más seguro. [139] Sin embargo, otros sionistas enfatizaron la memoria, la emoción y la tradición que vinculan a los judíos con la Tierra de Israel. [140] Sión se convirtió en el nombre del movimiento, en honor al lugar donde el rey David estableció su reino, luego de su conquista de la fortaleza jebusea allí (2 Samuel 5:7, 1 Reyes 8:1). El nombre Sión era sinónimo de Jerusalén. Palestina solo se convirtió en el foco principal de Herzl después de que se publicara su manifiesto sionista ' Der Judenstaat ' en 1896, pero incluso entonces dudó en concentrar sus esfuerzos únicamente en el reasentamiento en Palestina cuando la velocidad era esencial. [141]

En 1903, el secretario colonial británico Joseph Chamberlain ofreció a Herzl 5.000 millas cuadradas (13.000 km² ) en el Protectorado de Uganda para el asentamiento judío en las colonias de Gran Bretaña en África Oriental. [142] Herzl aceptó evaluar la propuesta de Joseph Chamberlain, [143] : 55–56 y se presentó el mismo año al Congreso de la Organización Sionista Mundial en su sexta reunión, donde se produjo un feroz debate. Algunos grupos sintieron que aceptar el plan haría más difícil establecer un estado judío en Palestina , la tierra africana fue descrita como una " antesala de la Tierra Santa". Se decidió enviar una comisión para investigar la tierra propuesta por 295 a 177 votos, con 132 abstenciones. Al año siguiente, el Congreso envió una delegación para inspeccionar la meseta. Se pensó que un clima templado debido a su gran altitud era adecuado para el asentamiento europeo. Sin embargo, la zona estaba poblada por un gran número de masai , a quienes no parecía agradar la llegada de europeos. Además, la delegación descubrió que estaba llena de leones y otros animales.

Después de la muerte de Herzl en 1904, el Congreso decidió el cuarto día de su séptima sesión en julio de 1905 rechazar la oferta británica y, según Adam Rovner, "dirigir todos los esfuerzos futuros de asentamiento únicamente a Palestina". [142] [144] La Organización Territorialista Judía de Israel Zangwill tenía como objetivo un estado judío en cualquier lugar, habiendo sido establecida en 1903 en respuesta al Plan de Uganda. Fue apoyada por varios delegados del Congreso. Después de la votación, que había sido propuesta por Max Nordau , Zangwill acusó a Nordau de que "será acusado ante el tribunal de la historia", y sus partidarios culparon al bloque de votantes rusos de Menachem Ussishkin por el resultado de la votación. [144]

La posterior salida del JTO de la Organización Sionista tuvo poco impacto. [142] [145] [146] El Partido Socialista Obrero Sionista también fue una organización que favoreció la idea de una autonomía territorial judía fuera de Palestina . [147]

Como alternativa al sionismo, las autoridades soviéticas (URSS) establecieron una Óblast Autónoma Judía en 1934, que sigue existiendo como la única Óblast Autónoma de Rusia. [148]

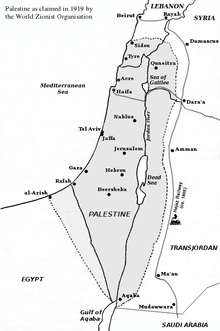

Según Elaine Hagopian, en las primeras décadas se previó que la patria de los judíos se extendería no sólo por la región de Palestina, sino también por el Líbano, Siria, Jordania y Egipto, con sus fronteras coincidiendo más o menos con las principales zonas fluviales y ricas en agua del Levante. [149]

El cabildeo del inmigrante judío ruso Chaim Weizmann, junto con el temor de que los judíos estadounidenses alentaran a Estados Unidos a apoyar a Alemania en la guerra contra Rusia, culminó en la Declaración Balfour del gobierno británico de 1917.

Aprobó la creación de una patria judía en Palestina, de la siguiente manera:

El Gobierno de Su Majestad ve con buenos ojos el establecimiento en Palestina de un hogar nacional para el pueblo judío y hará todo lo posible para facilitar el logro de este objetivo, quedando claramente entendido que no se hará nada que pueda perjudicar los derechos civiles y religiosos de las comunidades no judías existentes en Palestina, o los derechos y el estatus político de que gozan los judíos en cualquier otro país. [150]

En 1922, la Sociedad de Naciones adoptó la declaración y concedió a Gran Bretaña el Mandato de Palestina:

El Mandato garantizará el establecimiento del hogar nacional judío... y el desarrollo de instituciones autónomas, y también salvaguardará los derechos civiles y religiosos de todos los habitantes de Palestina, independientemente de su raza y religión. [151]

El papel de Weizmann en la obtención de la Declaración Balfour condujo a su elección como líder del movimiento sionista. Permaneció en ese cargo hasta 1948, y luego fue elegido como el primer presidente de Israel después de que la nación obtuviera la independencia.

En el Primer Congreso Mundial de Mujeres Judías , que se celebró en Viena (Austria) en mayo de 1923, participaron representantes de alto nivel de la comunidad internacional de mujeres judías. Una de las principales resoluciones fue: "Parece... que es deber de todos los judíos cooperar en la reconstrucción socioeconómica de Palestina y ayudar al asentamiento de los judíos en ese país". [152]

En 1927, el judío ucraniano Yitzhak Lamdan escribió un poema épico titulado Masada para reflejar la difícil situación de los judíos y pedir una "última resistencia". [153]

En 1933, Adolf Hitler llegó al poder en Alemania y en 1935 se promulgaron las Leyes de Núremberg . Muchos aliados nazis en Europa aplicaron reglas similares . El posterior crecimiento de la migración judía fomentó la revuelta árabe de 1936-1939 en Palestina . Gran Bretaña estableció la Comisión Peel para investigar la situación. La comisión pidió una solución de dos estados y el traslado obligatorio de poblaciones . Los árabes se opusieron al plan de partición y Gran Bretaña rechazó más tarde esta solución y en su lugar implementó el Libro Blanco de 1939. Este planificaba poner fin a la inmigración judía en 1944 y no permitir más de 75.000 inmigrantes judíos adicionales. Al final del período de cinco años en 1944, solo se habían utilizado 51.000 de los 75.000 certificados de inmigración previstos, y los británicos ofrecieron permitir que la inmigración continuara más allá de la fecha límite de 1944, a un ritmo de 1500 por mes, hasta que se completara el cupo restante. [154] [155] Según Arieh Kochavi, al final de la guerra, el Gobierno Mandatario tenía 10.938 certificados restantes y da más detalles sobre la política gubernamental en ese momento. [154] Los británicos mantuvieron las políticas del Libro Blanco de 1939 hasta el final del Mandato. [156]

El crecimiento de la comunidad judía en Palestina y la devastación de la vida judía europea marginaron a la Organización Sionista Mundial (OSM). La Agencia Judía para Palestina, bajo el liderazgo de David Ben-Gurion, dictaba cada vez más políticas con el apoyo de los sionistas estadounidenses que proporcionaban financiación e influencia en Washington, DC, incluso a través del Comité Palestino Americano . [ cita requerida ] En 1938, Ben-Gurion sostuvo que una fuente importante de temor para los sionistas era la fuerza política defensiva de la posición palestina, afirmando: [158]

Un pueblo que lucha contra la usurpación de su tierra no se cansará tan fácilmente... Cuando decimos que los árabes son los agresores y nosotros nos defendemos, eso es sólo la mitad de la verdad... Políticamente, nosotros somos los agresores y ellos se defienden. El país es suyo porque lo habitan, mientras que nosotros queremos venir aquí y establecernos, y en su opinión queremos quitarles su país.

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, cuando se conocieron los horrores del Holocausto , el liderazgo sionista formuló el Plan del Millón , una reducción del objetivo anterior de Ben-Gurion de dos millones de inmigrantes. Tras el final de la guerra, muchos refugiados apátridas , principalmente sobrevivientes del Holocausto , comenzaron a migrar a Palestina en pequeñas embarcaciones desafiando las reglas británicas. El Holocausto unió a gran parte del resto del judaísmo mundial detrás del proyecto sionista. [159] Los británicos encarcelaron a estos judíos en Chipre o los enviaron a las Zonas de Ocupación Aliadas controladas por los británicos en Alemania . Los británicos, después de haber enfrentado revueltas árabes, ahora enfrentaban la oposición de los grupos sionistas en Palestina por las restricciones posteriores a la inmigración judía. En enero de 1946, el Comité Angloamericano de Investigación, un comité conjunto británico y estadounidense , recibió la tarea de examinar las condiciones políticas, económicas y sociales en la Palestina del Mandato y el bienestar de los pueblos que ahora vivían allí; consultar a representantes de árabes y judíos, y hacer otras recomendaciones 'según sea necesario' para un manejo provisional de estos problemas, así como para su solución final. [160] Tras el fracaso de la Conferencia de Londres sobre Palestina de 1946-47 , en la que Estados Unidos se negó a apoyar a los británicos, lo que llevó a que tanto el Plan Morrison-Grady como el Plan Bevin fueran rechazados por todas las partes, los británicos decidieron remitir la cuestión a la ONU el 14 de febrero de 1947. [161] [fn 2]

Con la invasión alemana de la URSS en 1941, Stalin revirtió su oposición de larga data al sionismo y trató de movilizar el apoyo judío mundial para el esfuerzo bélico soviético. Se creó un Comité Judío Antifascista en Moscú. Muchos miles de refugiados judíos huyeron de los nazis y entraron en la Unión Soviética durante la guerra, donde revitalizaron las actividades religiosas judías y abrieron nuevas sinagogas. [162] En mayo de 1947, el viceministro soviético de Asuntos Exteriores, Andrei Gromyko, dijo a las Naciones Unidas que la URSS apoyaba la partición de Palestina en un estado judío y otro árabe. La URSS votó formalmente de esa manera en la ONU en noviembre de 1947. [163] Sin embargo, una vez que se estableció Israel, Stalin revirtió sus posiciones, favoreció a los árabes, arrestó a los líderes del Comité Judío Antifascista y lanzó ataques contra los judíos en la URSS. [164]

En 1947, el Comité Especial de la ONU sobre Palestina recomendó que Palestina occidental se dividiera en un estado judío, un estado árabe y un territorio controlado por la ONU, Corpus separatum , alrededor de Jerusalén . [165] Este plan de partición fue adoptado el 29 de noviembre de 1947, con la Resolución 181 de la Asamblea General de la ONU, con 33 votos a favor, 13 en contra y 10 abstenciones. La votación provocó celebraciones en las comunidades judías y protestas en las comunidades árabes de toda Palestina. [166] La violencia en todo el país, anteriormente una insurgencia árabe y judía contra los británicos, la violencia comunitaria entre judíos y árabes , desembocó en la guerra de Palestina de 1947-1949 . Según varias evaluaciones de la ONU , el conflicto provocó un éxodo de 711.000 a 957.000 árabes palestinos , [167] fuera de los territorios de Israel. Más de una cuarta parte ya había huido durante la guerra civil de 1947-1948 en el Mandato Británico de Palestina , antes de la Declaración de Independencia de Israel y el estallido de la Guerra Árabe-Israelí de 1948. Después de los Acuerdos de Armisticio de 1949 , una serie de leyes aprobadas por el primer gobierno israelí impidieron a los palestinos desplazados reclamar propiedades privadas o regresar a los territorios del estado. Ellos y muchos de sus descendientes siguen siendo refugiados apoyados por la UNRWA . [168] [169]

.jpg/440px-Op_Magic_Carpet_(Yemenites).jpg)

Desde la creación del Estado de Israel, la Organización Sionista Mundial ha funcionado principalmente como una organización dedicada a ayudar y alentar a los judíos a migrar a Israel. Ha brindado apoyo político a Israel en otros países, pero desempeña un papel pequeño en la política interna israelí. El mayor éxito del movimiento desde 1948 fue brindar apoyo logístico a los inmigrantes y refugiados judíos y, lo más importante, ayudar a los judíos soviéticos en su lucha con las autoridades por el derecho a abandonar la URSS y practicar su religión en libertad, y el éxodo de 850.000 judíos del mundo árabe, en su mayoría a Israel. En 1944-45, Ben-Gurion describió el Plan del Millón a funcionarios extranjeros como el "objetivo principal y la máxima prioridad del movimiento sionista". [170] Las restricciones a la inmigración del Libro Blanco británico de 1939 significaron que un plan de este tipo no podía implementarse a gran escala hasta la Declaración de Independencia de Israel en mayo de 1948. La política de inmigración del nuevo país encontró cierta oposición dentro del nuevo gobierno israelí, como aquellos que argumentaban que no había "justificación para organizar una emigración a gran escala entre judíos cuyas vidas no estaban en peligro, particularmente cuando el deseo y la motivación no eran los propios" [171] así como aquellos que argumentaban que el proceso de absorción causaba "dificultades excesivas". [172] Sin embargo, la fuerza de la influencia y la insistencia de Ben-Gurion aseguraron que su política de inmigración se llevara a cabo. [173] [174]

La Guerra de Junio de 1967 fue seguida por el surgimiento del " sionismo religioso ". La conquista israelí de Cisjordania , a la que los sionistas se refieren como Judea y Samaria , indicó a los sionistas religiosos que estaban viviendo en una era mesiánica . Para ellos, la guerra fue una demostración de la obra de la Mano Divina y el "inicio de la redención". Los rabinos que siguieron esta línea de pensamiento inmediatamente comenzaron a venerar la tierra como sagrada, haciendo de su santidad un principio central del sionismo religioso. En consecuencia, cualquiera que estuviera dispuesto a ceder partes de esta tierra era visto como un traidor al pueblo judío. Esta creencia contribuyó al asesinato por motivos religiosos de Yitzhak Rabin , que se llevó a cabo con la aprobación de algunos rabinos ortodoxos. [44] El rabino Kook , un importante líder y pensador religioso sionista, declararía en 1967 después de la guerra de junio en presencia de los dirigentes israelíes, incluido el presidente, ministros, miembros del Knesset , jueces, rabinos principales y altos funcionarios públicos:

Os lo digo explícitamente... que la Torá prohíbe ceder ni siquiera una pulgada de nuestra tierra liberada. Aquí no hay conquistas ni ocupamos tierras extranjeras; volvemos a nuestra casa, a la herencia de nuestros antepasados. Aquí no hay tierra árabe, sólo la herencia de nuestro Dios. Cuanto más se acostumbre el mundo a esta idea, mejor será para él y para todos nosotros. [175]

Para los sionistas religiosos, el sionismo secular y las políticas estatales seculares eran sagradas: “El espíritu de Israel... está tan estrechamente vinculado al espíritu de Dios que un nacionalista judío, no importa cuán secularista pueda ser su intención, está, a pesar de sí mismo, imbuido del espíritu divino incluso contra su propia voluntad”. [116] Los sionistas religiosos ven el asentamiento de Cisjordania como un mandamiento de Dios, necesario para la redención del pueblo judío. [64]

La llegada de colonos sionistas a Palestina a finales del siglo XIX se considera ampliamente como el inicio del conflicto palestino-israelí . [49] : 70 [176] [177] Los sionistas querían crear un estado judío en Palestina con tanta tierra, tantos judíos y tan pocos árabes palestinos como fuera posible. [11] En respuesta a la cita de Ben-Gurion de 1938 de que "políticamente somos los agresores y ellos [los palestinos] se defienden", el historiador israelí Benny Morris dice: "Ben-Gurion, por supuesto, tenía razón. El sionismo era una ideología y un movimiento colonizadores y expansionistas", y que "la ideología y la práctica sionistas eran necesariamente y elementalmente expansionistas". Morris describe el objetivo sionista de establecer un estado judío en Palestina como necesariamente desplazar y desposeer a la población árabe. [117] La cuestión práctica de establecer un Estado judío en una región mayoritariamente no judía y árabe era una cuestión fundamental para el movimiento sionista. [117] Los sionistas utilizaban el término "transferencia" como un eufemismo para la eliminación, o limpieza étnica , de la población árabe palestina. [fn 3] [178] Según Benny Morris, "la idea de transferir a los árabes fuera... era vista como el principal medio de asegurar la estabilidad del 'judaísmo' del propuesto Estado judío". [117]

De hecho, el concepto de expulsar por la fuerza a la población no judía de Palestina fue una noción que cosechó apoyo en todo el espectro de grupos sionistas, incluidas sus facciones más izquierdistas [fn 4] , desde el comienzo del desarrollo del movimiento. [64] [179] [180] [117] [181] [73] El concepto de traslado no sólo era visto como deseable sino también como una solución ideal por los líderes sionistas. [73] [60] [ página necesaria ] [20] La noción de traslado forzoso era tan atractiva para estos líderes que se consideró la disposición más atractiva de la Comisión Peel. De hecho, este sentimiento estaba profundamente arraigado hasta el punto de que la aceptación de la partición por parte de Ben Gurion estaba supeditada a la expulsión de la población palestina. Llegaría a decir que el traslado era una solución tan ideal que "debe suceder algún día". Fue el ala derecha del movimiento sionista la que presentó los principales argumentos contra la transferencia; sus objeciones se basaban principalmente en motivos prácticos más que morales. [64] [62] [ página necesaria ]

Según Morris, la idea de limpiar étnicamente la tierra de Palestina iba a desempeñar un papel importante en la ideología sionista desde el inicio del movimiento. Explica que la "transferencia" era "inevitable y estaba incorporada al sionismo" y que una tierra que era principalmente árabe no podía transformarse en un estado judío sin desplazar a la población árabe. [fn 5] Además, no se podía garantizar la estabilidad del estado judío dado el temor de la población árabe al desplazamiento. Explica que esta sería la principal fuente de conflicto entre el movimiento sionista y la población árabe. [178]

El movimiento sionista, multinacional y mundial, está estructurado sobre principios democráticos representativos . Los congresos se celebran cada cuatro años (antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial se celebraban cada dos años) y los delegados al congreso son elegidos por los miembros. Los miembros deben pagar una cuota conocida como shekel . En el congreso, los delegados eligen un consejo ejecutivo de 30 miembros, que a su vez elige al líder del movimiento. [ cita requerida ] El movimiento fue democrático desde su inicio y las mujeres tenían derecho a voto. [ 183 ]

Hasta 1917, la Organización Sionista Mundial siguió una estrategia de construcción de un hogar nacional judío mediante una inmigración persistente en pequeña escala y la fundación de organismos como el Fondo Nacional Judío (1901, una organización benéfica que compraba tierras para el asentamiento judío) y el Banco Anglo-Palestino (1903, que otorgaba préstamos a empresas y agricultores judíos). En 1942, en la Conferencia de Biltmore , el movimiento incluyó por primera vez un objetivo expreso de establecimiento de un estado judío en la Tierra de Israel. [184]

El 28º Congreso Sionista , reunido en Jerusalén en 1968, adoptó los cinco puntos del "Programa de Jerusalén" como objetivos del sionismo actual. Son los siguientes: [185]

Desde la creación del Israel moderno, el papel del movimiento ha disminuido. Ahora es un factor periférico en la política israelí , aunque diferentes percepciones del sionismo siguen desempeñando un papel en el debate político israelí y judío. [186] Después de la creación del Estado, el sionismo ha llegado a ser descrito como la ideología nacional o estatal de Israel. [187]

El sionismo obrero se originó en Europa del Este . Los sionistas socialistas creían que siglos de opresión en sociedades antisemitas habían reducido a los judíos a una existencia sumisa, vulnerable y desesperanzada que invitaba a un mayor antisemitismo, una visión estipulada originalmente por Theodor Herzl. [189] [190] Argumentaban que una revolución del alma y la sociedad judía era necesaria y alcanzable en parte si los judíos se mudaban a Israel y se convertían en agricultores, trabajadores y soldados en un país propio. La mayoría de los sionistas socialistas rechazaban la observancia del judaísmo religioso tradicional por perpetuar una "mentalidad de diáspora" entre el pueblo judío, y establecieron comunas rurales en Israel llamadas " kibutzim ". [191] El kibutz comenzó como una variación de un plan de "granja nacional", una forma de agricultura cooperativa donde el Fondo Nacional Judío contrataba a trabajadores judíos bajo supervisión capacitada. Los kibutz eran un símbolo de la Segunda Aliá , ya que ponían gran énfasis en el comunalismo y el igualitarismo, representando en cierta medida el socialismo utópico . Además, hacían hincapié en la autosuficiencia, que se convirtió en un aspecto esencial del sionismo laborista. [192] [193] Aunque el sionismo socialista se inspira y se basa filosóficamente en los valores fundamentales y la espiritualidad del judaísmo, su expresión progresista de ese judaísmo a menudo ha fomentado una relación antagónica con el judaísmo ortodoxo . [193] [194]

La historiadora israelí tradicionalista Anita Shapira describe el uso de la violencia del sionismo obrero contra los palestinos con fines políticos como esencialmente el mismo que el de los grupos sionistas conservadores radicales. Por ejemplo, Shapira señala que durante la revuelta palestina de 1936 , el Irgun Zvai Leumi se dedicó al "uso desinhibido del terror", "asesinatos masivos indiscriminados de ancianos, mujeres y niños", "ataques contra británicos sin ninguna consideración de posibles lesiones a transeúntes inocentes y el asesinato de británicos a sangre fría". Shapira sostiene que sólo había diferencias marginales en el comportamiento militar entre el Irgun y el sionismo obrero Palmah . Siguiendo las políticas establecidas por Ben-Gurion, el método predominante entre los escuadrones de campo era que si una banda árabe había utilizado un pueblo como escondite, se consideraba aceptable responsabilizar colectivamente a todo el pueblo. Las líneas que delineaban lo que era aceptable e inaceptable al tratar con estos aldeanos eran "vagas e intencionadamente borrosas". Como sugiere Shapira, estos límites ambiguos prácticamente no diferían de los del grupo abiertamente terrorista Irgun. [43]

El sionismo obrero se convirtió en la fuerza dominante en la vida política y económica del Yishuv durante el Mandato Británico de Palestina y fue la ideología dominante del establishment político en Israel hasta las elecciones de 1977 , cuando el Partido Laborista israelí fue derrotado. El Partido Laborista israelí continúa la tradición, aunque el partido más popular en los kibutzim es Meretz . [195] La principal institución del sionismo obrero es la Histadrut (organización general de sindicatos), que comenzó proporcionando rompehuelgas contra una huelga de trabajadores palestinos en 1920 y hasta la década de 1970 fue el mayor empleador en Israel después del gobierno israelí. [196]

General Zionism (or Liberal Zionism) was initially the dominant trend within the Zionist movement from the First Zionist Congress in 1897 until after the First World War. General Zionists identified with the liberal European middle class to which many Zionist leaders such as Herzl and Chaim Weizmann aspired. Liberal Zionism, although not associated with any single party in modern Israel, remains a strong trend in Israeli politics advocating free market principles, democracy and adherence to human rights. Their political arm was one of the ancestors of the modern-day Likud. Kadima, the main centrist party during the 2000s that split from Likud and is now defunct, however, did identify with many of the fundamental policies of Liberal Zionist ideology, advocating among other things the need for Palestinian statehood in order to form a more democratic society in Israel, affirming the free market, and calling for equal rights for Arab citizens of Israel. In 2013, Ari Shavit suggested that the success of the then-new Yesh Atid party (representing secular, middle-class interests) embodied the success of "the new General Zionists."[197][better source needed]

Dror Zeigerman writes that the traditional positions of the General Zionists—"liberal positions based on social justice, on law and order, on pluralism in matters of State and Religion, and on moderation and flexibility in the domain of foreign policy and security"—are still favored by important circles and currents within certain active political parties.[198]

Philosopher Carlo Strenger describes a modern-day version of Liberal Zionism (supporting his vision of "Knowledge-Nation Israel"), rooted in the original ideology of Herzl and Ahad Ha'am, that stands in contrast to both the romantic nationalism of the right and the Netzah Yisrael of the ultra-Orthodox. It is marked by a concern for democratic values and human rights, freedom to criticize government policies without accusations of disloyalty, and rejection of excessive religious influence in public life. "Liberal Zionism celebrates the most authentic traits of the Jewish tradition: the willingness for incisive debate; the contrarian spirit of davka; the refusal to bow to authoritarianism."[199][200] Liberal Zionists see that "Jewish history shows that Jews need and are entitled to a nation-state of their own. But they also think that this state must be a liberal democracy, which means that there must be strict equality before the law independent of religion, ethnicity or gender."[201]

Revisionist Zionists, led by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, believed that a Jewish state must expand to both sides of the Jordan River, i.e. taking Transjordan in addition to all of Palestine.[202][203] The movement developed what became known as Nationalist Zionism, whose guiding principles were outlined in the 1923 essay Iron Wall, a term denoting the force needed to prevent Palestinian resistance against colonization.[204] Jabotinsky wrote that

Zionism is a colonising adventure and it therefore stands or falls by the question of armed force. It is important to build, it is important to speak Hebrew, but, unfortunately, it is even more important to be able to shoot—or else I am through with playing at colonization.

— Zeev Jabotinsky[205][206]

Historian Avi Shlaim describes Jabotinsky's perspective[207]

Although the Jews originated in the East, they belonged to the West culturally, morally, and spiritually. Zionism was conceived by Jabotinsky not as the return of the Jews to their spiritual homeland but as an offshoot or implant of Western civilization in the East. This worldview translated into a geostrategic conception in which Zionism was to be permanently allied with European colonialism against all the Arabs in the eastern Mediterranean.

In 1935 the Revisionists left the WZO because it refused to state that the creation of a Jewish state was an objective of Zionism.[citation needed] The Revisionists advocated the formation of a Jewish Army in Palestine to force the Arab population to accept mass Jewish migration.

Supporters of Revisionist Zionism developed the Likud Party in Israel, which has dominated most governments since 1977. It advocates Israel's maintaining control of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and takes a hard-line approach in the Arab–Israeli conflict. In 2005, the Likud split over the issue of creation of a Palestinian state in the occupied territories. Party members advocating peace talks helped form the Kadima Party.[208]

Religious Zionism is an ideology that combines Zionism and observant Judaism. Before the establishment of the state of Israel, Religious Zionists were mainly observant Jews who supported Zionist efforts to build a Jewish state in the Land of Israel. One of the core ideas in Religious Zionism is the belief that the ingathering of exiles in the Land of Israel and the establishment of Israel is Atchalta De'Geulah ("the beginning of the redemption"), the initial stage of the geula.[209]

After the Six-Day War and the capture of the West Bank, a territory referred to in Jewish terms as Judea and Samaria, right-wing components of the Religious Zionist movement integrated nationalist revindication and evolved into what is sometimes known as Neo-Zionism. Their ideology revolves around three pillars: the Land of Israel, the People of Israel and the Torah of Israel.[210]

The French government, through Minister M. Cambon, formally committed itself to "... the renaissance of the Jewish nationality in that Land from which the people of Israel were exiled so many centuries ago."[211]

In China, top figures of the Nationalist government, including Sun Yat-sen, expressed their sympathy with the aspirations of the Jewish people for a National Home.[212]

Some Christians actively supported the return of Jews to Palestine even prior to the rise of Zionism, as well as subsequently. Anita Shapira, a history professor emerita at Tel Aviv University, suggests that evangelical Christian restorationists of the 1840s "passed this notion on to Jewish circles".[214] Evangelical Christian anticipation of and political lobbying within the UK for Restorationism was widespread in the 1820s and common beforehand.[215] It was common among the Puritans to anticipate and frequently to pray for a Jewish return to their homeland.[216][217][218]

One of the principal Protestant teachers who promoted the biblical doctrine that the Jews would return to their national homeland was John Nelson Darby. His doctrine of dispensationalism is credited with promoting Zionism, following his 11 lectures on the hopes of the church, the Jew and the gentile given in Geneva in 1840.[219] However, others like C H Spurgeon,[220] both Horatius[221] and Andrew Bonar, Robert Murray M'Chyene,[222] and J C Ryle[223] were among a number of prominent proponents of both the importance and significance of a Jewish return, who were not dispensationalist. Pro-Zionist views were embraced by many evangelicals and also affected international foreign policy.

The Russian Orthodox ideologue Hippolytus Lutostansky, also known as the author of multiple antisemitic tracts, insisted in 1911 that Russian Jews should be "helped" to move to Palestine "as their rightful place is in their former kingdom of Palestine".[224]

Notable early supporters of Zionism include British Prime Ministers David Lloyd George and Arthur Balfour, American President Woodrow Wilson and British Major-General Orde Wingate, whose activities in support of Zionism led the British Army to ban him from ever serving in Palestine. According to Charles Merkley of Carleton University, Christian Zionism strengthened significantly after the Six-Day War of 1967, and many dispensationalist and non-dispensationalist evangelical Christians, especially Christians in the United States, now strongly support Zionism.[citation needed]

Martin Luther King Jr. was a strong supporter of Israel and Zionism,[213] although the Letter to an Anti-Zionist Friend is a work falsely attributed to him.

In the last years of his life, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, Joseph Smith, declared, "the time for Jews to return to the land of Israel is now." In 1842, Smith sent Orson Hyde, an Apostle of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, to Jerusalem to dedicate the land for the return of the Jews.[225]

Some Arab Christians publicly supporting Israel include US author Nonie Darwish, and former Muslim Magdi Allam, author of Viva Israele,[226] both born in Egypt. Brigitte Gabriel, a Lebanese-born Christian US journalist and founder of the American Congress for Truth, urges Americans to "fearlessly speak out in defense of America, Israel and Western civilization".[227]

The largest Zionist organisation is Christians United for Israel, which has 10 million members and is led by John Hagee.[228][229][230]

Muslims who have publicly defended Zionism include Tawfik Hamid, Islamic thinker and reformer[232] and former member of al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, an Islamist militant group that is designated as a terrorist organization by the European Union[233] and United Kingdom,[234] Sheikh Prof. Abdul Hadi Palazzi, Director of the Cultural Institute of the Italian Islamic Community[235] and Tashbih Sayyed, a Pakistani-American scholar, journalist, and author.[236]

On occasion, some non-Arab Muslims such as some Kurds and Berbers have also voiced support for Zionism.[237][238][239]

While most Israeli Druze identify as ethnically Arab,[240] today, tens of thousands of Israeli Druze belong to "Druze Zionist" movements.[231]

During the Palestine Mandate era, As'ad Shukeiri, a Muslim scholar ('alim) of the Acre area, and the father of PLO founder Ahmad Shukeiri, rejected the values of the Palestinian Arab national movement and was opposed to the anti-Zionist movement.[241] He met routinely with Zionist officials and had a part in every pro-Zionist Arab organization from the beginning of the British Mandate, publicly rejecting Mohammad Amin al-Husayni's use of Islam to attack Zionism.[242]