El pueblo portugués ( en portugués : portugueses – masculino – o portuguesas ) es un grupo étnico y nación de habla romance indígena de Portugal , un país en el oeste de la península Ibérica en el suroeste de Europa , que comparte una cultura , ascendencia y lengua comunes . [87] [88] [89]

El origen político del Estado portugués se remonta a la fundación del Condado de Portugal en 868. Sin embargo, no fue hasta la Batalla de São Mamede (1128) cuando Portugal obtuvo el reconocimiento internacional como reino a través del Tratado de Zamora y la bula papal Manifestis Probatum . Este establecimiento del Estado portugués en el siglo XII allanó el camino para que el pueblo portugués se uniera como nación. [90] [91] [92]

Los portugueses desempeñaron un papel importante en la navegación, y exploraron varias tierras lejanas previamente desconocidas para los europeos en América, África, Asia y Oceanía (sudoeste del océano Pacífico). En 1415, con la conquista de Ceuta , los portugueses comenzaron a desempeñar un papel significativo en la Era de los Descubrimientos , que culminó en un imperio colonial , considerado como uno de los primeros imperios globales y una de las principales potencias económicas, políticas y militares del mundo en los siglos XV y XVI, con territorios que ahora forman parte de numerosos países. [93] [94] [95] Portugal ayudó a la posterior dominación de la civilización occidental por otras naciones europeas vecinas . [96] [97] [98] [95]

Debido a la gran extensión histórica del Imperio portugués desde el siglo XVI y la posterior colonización de territorios en Asia, África y América, así como la emigración histórica y reciente, los portugueses se dispersaron por diferentes partes del mundo. [99]

La herencia del pueblo portugués se deriva en gran parte de los pueblos indoeuropeos ( lusitanos , conii ) [100] [101] [102] y celtas ( galaecos , túrdulos y celtas ), [103] [104] [105] que fueron romanizados más tarde tras la conquista de la región por los antiguos romanos . [106] [107] [108] Como resultado de la colonización romana , el idioma portugués (la lengua materna de la abrumadora mayoría de los portugueses) proviene del latín vulgar . [109]

Varios linajes masculinos descienden de tribus germánicas que llegaron como élites gobernantes después del período romano, a partir de 409. [ 110] Entre ellos se encontraban los suevos , los buri , los asdingos , los vándalos y los visigodos . Los alanos, pastores del norte del Cáucaso, dejaron pequeñas huellas en algunas áreas del centro y sur (por ejemplo, Alenquer , de " Alen Kerke " o "Templo de los alanos"). [111] [112] [113] [114]

La conquista omeya de Iberia , entre principios del siglo VIII hasta el siglo XII , también dejó pequeñas aportaciones genéticas moriscas , judías y saqaliba en el país. [115] [116] [106] [107] [117] Otras influencias menores, así como posteriores, incluyen pequeños asentamientos vikingos entre los siglos IX y XI , realizados por escandinavos que invadieron las zonas costeras principalmente en las regiones septentrionales del Duero y el Miño . [118] [119] [120] [121] También hay una influencia prerromana de baja incidencia de los antiguos fenicios y griegos en las zonas costeras del sur. [122]

El nombre Portugal, del que toman su nombre los portugueses, es un nombre compuesto que proviene de la palabra latina Portus (que significa puerto) y una segunda palabra Cale , cuyo significado y origen no están claros. Cale es probablemente un recordatorio de los Gallaeci (también conocidos como Callaeci), una tribu celta que vivía en el área que hoy forma parte del norte de Portugal .

También existe la posibilidad de que el nombre provenga del asentamiento primitivo de Cale (actual Gaia ), situado en la desembocadura del río Duero en la costa atlántica ( Portus Cale ). El nombre Cale parece provenir de los celtas -quizás de una de sus especificaciones, Cailleach- pero que, en la vida cotidiana, era sinónimo de refugio, fondeadero o puerta. [123] Entre otras teorías, algunos sugieren que Cale puede provenir de la palabra griega para "bello" kalós . Otra teoría para Portugal postula una derivación francesa, Portus Gallus [124] "puerto de los galos".

Durante la Edad Media , la zona de Cale pasó a ser conocida por los visigodos como Portucale . Portucale podría haber evolucionado en los siglos VII y VIII, para convertirse en Portugale , o Portugal, a partir del siglo IX. El término designaba la zona entre los ríos Duero y Miño . [125]

Los portugueses son una población del suroeste de Europa, con orígenes predominantemente del sur y oeste de Europa. Se cree que los primeros humanos modernos que habitaron Portugal fueron pueblos paleolíticos que podrían haber llegado a la península Ibérica hace entre 35.000 y 40.000 años. La interpretación actual de los datos del cromosoma Y y del ADN mitocondrial sugiere que los portugueses actuales remontan una proporción de estos linajes a los pueblos paleolíticos que comenzaron a asentarse en el continente europeo entre el final de la última glaciación, hace unos 45.000 años.

Se cree que el norte de Iberia fue un importante refugio de la Edad de Hielo desde el que los humanos del Paleolítico colonizaron Europa posteriormente. Las migraciones desde lo que hoy es el norte de Iberia durante el Paleolítico y el Mesolítico vinculan a los íberos modernos con las poblaciones de gran parte de Europa occidental, y en particular las Islas Británicas y la Europa atlántica . [126]

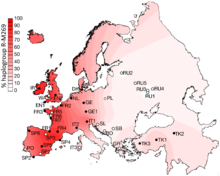

El haplogrupo R1b del cromosoma Y es el haplogrupo más común en prácticamente toda la península Ibérica y Europa occidental. [127] Dentro del haplogrupo R1b existen haplotipos modales . Uno de los mejor caracterizados de estos haplotipos es el haplotipo modal atlántico (AMH). Este haplotipo alcanza las frecuencias más altas en la península Ibérica y en las Islas Británicas. En Portugal se estima que supone un 65% en el sur y un 87% en el norte, y en algunas regiones un 96%. [128]

La colonización neolítica de Europa desde Asia occidental y Oriente Medio, que comenzó hace unos 10.000 años, llegó a Iberia , así como anteriormente había llegado al resto del continente, aunque según el modelo de difusión démica su impacto fue mayor en las regiones sur y este del continente europeo. [129]

A partir del tercer milenio a. C., durante la Edad del Bronce , se produjo la primera ola de migraciones de hablantes de lenguas indoeuropeas hacia Iberia. Los principales estudios genéticos, realizados desde 2015, han demostrado ahora que la expansión del haplogrupo R1b en Europa occidental, más común en muchas áreas de la Europa atlántica , se debe principalmente a migraciones masivas desde la estepa póntico-caspia de Europa del Este durante la Edad del Bronce , junto con portadores de lenguas indoeuropeas como el protocelta y el protoitálico . A diferencia de estudios más antiguos sobre marcadores uniparentales, se analizaron grandes cantidades de ADN autosómico además del ADN-Y paterno . Se detectó un componente autosómico en los europeos modernos que no estaba presente en el Neolítico o el Mesolítico, y que entró en Europa con los linajes paternos R1b y R1a, así como las lenguas indoeuropeas. [130] [131] [132]

Las primeras inmigraciones de hablantes de lenguas indoeuropeas fueron seguidas posteriormente por oleadas de celtas . Los celtas llegaron al territorio que hoy es Portugal hace unos 3.000 años [133], aunque el fenómeno migratorio fue especialmente intenso entre los siglos VII y V a. C. [134] [135]

Estos dos procesos definieron el paisaje cultural de Iberia y Portugal: « Continental en el noroeste y mediterráneo hacia el sureste », como lo describe el historiador José Mattoso . [136]

El cambio cultural noroeste-sureste también se refleja en las diferencias genéticas: según los hallazgos de 2016, [137] el haplogrupo H, un grupo que se encuentra dentro de la categoría del haplogrupo R, es más frecuente a lo largo de la fachada atlántica , incluida la costa cantábrica y Portugal. Muestra la frecuencia más alta en Galicia (esquina noroeste de Iberia). La frecuencia del haplogrupo H muestra una tendencia decreciente desde la fachada atlántica hacia las regiones mediterráneas.

Este hallazgo añade una prueba sólida de que Galicia y el norte de Portugal eran una población en un callejón sin salida, una especie de frontera europea para una importante migración antigua de Europa central. Por lo tanto, existe un patrón interesante de continuidad genética a lo largo de la costa de Cantabria y Portugal, un patrón que se ha observado anteriormente cuando se examinaron subclados menores de la filogenia del ADNmt. [138]

Teniendo en cuenta los orígenes de los colonizadores del Paleolítico y Neolítico, así como de las migraciones indoeuropeas de la Edad del Bronce y de la Edad del Hierro , se puede decir que el origen étnico portugués es principalmente una mezcla de preceltas o paraceltas , como los lusitanos [139] de Lusitania , y pueblos celtas como los galaicos de Gallaecia , los celtas [140] y los cinetes [141] del Alentejo y del Algarve .

Los lusitanos (o Lusitānus –singular– Lusitani –plural– en latín ) eran un pueblo de habla indoeuropea que vivía en la península Ibérica occidental mucho antes de que se convirtiera en la provincia romana de Lusitania (actual Portugal , Extremadura y una pequeña parte de Salamanca ). Hablaban la lengua lusitana , de la que solo sobreviven unos pocos fragmentos escritos breves. La mayoría de los portugueses consideran a los lusitanos como sus antepasados, aunque las regiones del norte ( Miño , Duero , Trás-os-Montes ) se identifican más con los galaicos . Destacados lingüistas modernos como Ellis Evans creen que el galaico -lusitano era una lengua (por lo tanto, no lenguas separadas) de la variante celta "p" . [142] [143] Eran una gran tribu que vivía entre los ríos Duero y Tajo .

Se ha planteado la hipótesis de que los lusitanos pueden haberse originado en los Alpes y haberse establecido en la región en el siglo VI a. C. Algunos estudiosos modernos como Dáithí Ó hÓgáin los consideran indígenas [144] del país. También afirma que inicialmente estuvieron dominados por los celtas , antes de obtener la independencia total de ellos. El arqueólogo rumano Scarlat Lambrino , activo en Portugal durante muchos años, propuso que originalmente eran un grupo tribal celta , relacionado con los lusones . [145]

La primera zona colonizada por los lusitanos fue probablemente el valle del Duero y la región de Beira Alta ; posteriormente se desplazaron hacia el sur, expandiéndose a ambas orillas del río Tajo , antes de ser conquistados por los romanos .

La etnogénesis lusitana y, en particular, su lengua, aún no se comprenden por completo. Se originaron a partir de poblaciones protoceltas o protoitálicas que se extendieron desde Europa central a Europa occidental después de nuevas migraciones yamnas al valle del Danubio , mientras que el protogermánico y el protobaltoeslavo pueden haberse desarrollado al este de los montes Cárpatos , en la actual Ucrania , desplazándose hacia el norte y extendiéndose con la cultura de la cerámica cordada en Europa central (tercer milenio a. C.). Una teoría postula que una rama europea de dialectos indoeuropeos, denominada "indoeuropeo del noroeste" y asociada con la cultura del vaso campaniforme , puede haber sido ancestral no solo del celta y el itálico, sino también del germánico y el baltoeslavo. [146]

La raíz celta de los lusitanos y de su lengua se ve reforzada por una reciente investigación del Instituto Max Planck sobre los orígenes de las lenguas indoeuropeas. Este exhaustivo estudio genético-lingüístico identifica una rama celta común de pueblos y lenguas que se extiende por la mayor parte de la Europa atlántica, incluida Lusitania, alrededor del año 7000 a. C. Este nuevo trabajo contradice teorías anteriores que excluían al lusitano de la familia lingüística celta. [147]

En la época romana, la provincia romana original de Lusitania se extendió al norte de las áreas ocupadas por los lusitanos para incluir los territorios de Asturias y Gallaecia, pero estos pronto fueron cedidos a la jurisdicción de la Provincia Tarraconensis en el norte, mientras que el sur permaneció como Provincia Lusitania et Vettones . Después de esto, la frontera norte de Lusitania fue a lo largo del río Duero, mientras que su frontera oriental pasó por Salmantica y Caesarobriga hasta el río Anas ( Guadiana ).

En la lucha de los lusitanos contra los romanos por su independencia, el nombre de Lusitania fue adoptado por los galaicos , tribus que vivían al norte del Duero, y otras tribus de los alrededores, extendiéndose con el tiempo como una etiqueta para todos los pueblos cercanos que luchaban contra el dominio romano en el oeste de Iberia. Fue por esta razón que los romanos llegaron a denominar a su provincia original en el área, que inicialmente cubría todo el lado occidental de la península Ibérica, Lusitania.

A continuación se presenta una lista de las tribus, a menudo conocidas por sus nombres en latín, que vivían en el área del Portugal moderno antes del dominio romano:

La República Romana conquistó la Península Ibérica durante los siglos II y I a.C. al vasto imperio marítimo de Cartago durante las Guerras Púnicas .

Los lusitanos llevaban años combatiendo a Roma y a su expansión por la península tras la derrota y ocupación de Cartago en el norte de África. Se defendieron con valentía durante años, provocando graves derrotas a los invasores romanos , aunque finalmente fueron severamente castigados por el pretor Servio Galba en el año 150 a. C., quien, con una astuta trampa, mató a 9.000 lusitanos y vendió posteriormente a 20.000 más como esclavos más al noreste, en las recién conquistadas provincias romanas de la Galia (la actual Francia).

Tres años después (147 a. C.), Viriato se convirtió en el líder de los lusitanos y dañó gravemente el dominio romano en Lusitania y más allá. Dirigió una confederación de tribus celtas [152] e impidió la expansión romana mediante la guerra de guerrillas. En 139 a. C. Viriato fue traicionado y asesinado mientras dormía por sus compañeros (que habían sido enviados como emisarios a los romanos ), Audax, Ditalco y Minuro , sobornados por Marco Popilio Laenas . Sin embargo, cuando Audax, Ditalco y Minuro regresaron para recibir su recompensa por parte de los romanos, el cónsul Quinto Servilio Cepión ordenó su ejecución, declarando que "Roma no paga a los traidores" .

Viriato [154] es el primer « héroe nacional » y tiene, para los portugueses, la misma importancia que Vercingétorix [155] tiene para los franceses o Boudicca [156] disfruta entre los ingleses. Después del gobierno de Viriato, los lusitanos celtizados se romanizaron en gran medida , adoptando la cultura romana y la lengua latina .

Los habitantes de las ciudades lusitanas, de forma similar a los del resto de la península romano-ibérica, acabaron adquiriendo el estatus de " ciudadanos de Roma ". Durante los últimos siglos de la colonización romana surgieron del territorio del actual Portugal numerosos santos venerados por la Iglesia católica, entre ellos Santa Engrácia , Santa Quitéria y Santa Marina de Aguas Santas , entre otros.

Los romanos también dejaron un gran impacto en la población, tanto genéticamente como en la cultura portuguesa ; la lengua portuguesa deriva principalmente del latín , dado que la lengua en sí es en su mayoría una evolución local posterior de la lengua romana después de la caída del Imperio Romano de Occidente . [106] [107] Según Mario Pei , la distancia fonética encontrada hoy en día entre el portugués y el latín es del 31%. [157] [158] La dominación romana duró desde el siglo II a. C. hasta el siglo V d. C.

Después de los romanos, los pueblos germánicos , a saber, los suevos ( ver Reino suevo ), los buri y los visigodos (que se estima que formaban el 2-3% de la población), [160] [161] [162] [163] gobernaron la península como élites durante varios siglos y se asimilaron a las poblaciones locales. Algunos de los vándalos ( silingos y asdingos ) y alanos [164] también permanecieron. Los suevos del norte y centro de Portugal y de Galicia fueron las tribus germánicas más numerosas. Portugal y Galicia (junto con Cataluña , que formaba parte del Reino franco ), son las regiones con las mayores proporciones actuales de ADN-Y germánico en la península Ibérica . [ cita requerida ]

Otras influencias menores, así como posteriores, incluyen pequeños asentamientos vikingos entre los siglos IX y XI , hechos por nórdicos que invadieron las zonas costeras principalmente en las regiones del norte del Duero y el Miño . [165] [119] [166] [121]

Los moros ocuparon lo que hoy es Portugal desde el siglo VIII hasta que el movimiento de Reconquista los expulsó del Algarve en 1249. Parte de su población, principalmente bereberes y judíos, se convirtieron al cristianismo y se convirtieron en cristianos nuevos ( Cristãos novos ); algunos descendientes de estas personas aún son identificables por sus nuevos apellidos . [167] Varios estudios genéticos, incluidos los estudios de genoma completos más completos publicados sobre poblaciones históricas y modernas de la península Ibérica , concluyen que la ocupación morisca dejó poca o ninguna influencia genética judía , árabe y bereber en la mayor parte de Iberia, con mayor incidencia en el sur y el oeste, y menor incidencia en el noreste; casi inexistente en el País Vasco . [168] [169] [106] [107]

Tras el fin de la Reconquista y la conquista de Faro , minorías religiosas y étnicas como los llamados "nuevos cristianos" o los " ciganos " ( gitanos romaníes ) [170] sufrirían posteriormente persecución por parte del Estado y de la Santa Inquisición . Como consecuencia, muchos fueron expulsados y condenados en virtud de la sentencia del Auto de Fe [171] o huyeron del país, creándose una diáspora judía en los Países Bajos , [172] Inglaterra, los actuales Estados Unidos, [173] Brasil, [174] los Balcanes [175] así como otras partes del mundo.

El origen político del Estado portugués se encuentra en la fundación del Condado de Portugal en 868 ( en portugués : Condado Portucalense ; en documentos de la época el nombre utilizado era Portugalia [176] ). Fue la primera vez en su historia que surgió un nacionalismo cohesionado, ya que incluso durante la época romana, las poblaciones indígenas eran de diversos orígenes étnicos y culturales.

Aunque el país se estableció como condado en 868, fue solo después de la Batalla de São Mamede el 24 de junio de 1128 que Portugal fue reconocido oficialmente como reino en virtud del Tratado de Zamora y la bula papal Manifestis Probatum del Papa Alejandro III . El establecimiento del estado portugués en el siglo XII allanó el camino para que los portugueses se agruparan como nación. [90] [91] [92]

Un punto de inflexión posterior en el nacionalismo portugués fue la batalla de Aljubarrota en 1385, ligada a la figura de Brites de Almeida que puso fin a cualquier ambición castellana de apoderarse del trono portugués .

Los portugueses comparten un grado de características étnicas con los vascos , [177] desde tiempos antiguos. Los resultados del presente estudio HLA en poblaciones portuguesas muestran que tienen características en común con los vascos y algunos españoles de Madrid : se encuentra una alta frecuencia de los haplotipos HLA A29-B44-DR7 (antiguos europeos occidentales) y A1-B8-DR3 como características comunes. Muchos portugueses y vascos no muestran el haplotipo mediterráneo A33-B14-DR1 , lo que confirma una menor mezcla con los mediterráneos . [138]

Los portugueses tienen una característica única entre las poblaciones del mundo: una alta frecuencia de HLA-A25-B18-DR15 y A26-B38-DR13, que puede reflejar un efecto fundador aún detectable que proviene de los portugueses antiguos, es decir, Oestriminis y Cynetes . [178] Según un estudio genético temprano, los portugueses son una población relativamente distinta según los datos de HLA, ya que tienen una alta frecuencia de los genes HLA-A25-B18-DR15 y A26-B38-DR13, siendo este último un marcador portugués único. En Europa, el gen A25-B18-DR15 solo se encuentra en Portugal, y también se observa en norteamericanos blancos y en brasileños (muy probablemente de ascendencia portuguesa). [179]

El haplotipo paneuropeo A1-B8-DR3 y el haplotipo europeo occidental A29-B44-DR7 son compartidos por portugueses, vascos y españoles . Este último también es común en poblaciones irlandesas, del sur de Inglaterra y del oeste de Francia. [179]

Según un estudio genético del haplogrupo del cromosoma Y humano entre los portugueses realizado en 2005, los hombres de Portugal continental , las Azores y Madeira pertenecían al 78-83% del haplogrupo "europeo occidental" R1b y los J y E3b mediterráneos . [180]

La tabla comparativa muestra estadísticas por haplogrupos de hombres portugueses con hombres de países y comunidades europeas .

Cultural y lingüísticamente, los portugueses son cercanos a los gallegos que viven en el noroeste de España. [181] [182] [183] [184] Las similitudes entre los dos grupos son muy pronunciadas y algunas personas afirman que el gallego y el portugués son, de hecho, el mismo idioma ( ver también: Reintegracionismo ). [185] [186]

Hay alrededor de 9,15 millones de personas nacidas en Portugal, [187] de una población total de 10,467 millones [188] (87,4%).

En cuanto a la ciudadanía, hay alrededor de 782.000 extranjeros viviendo legalmente en el país (7,47%), por lo que aproximadamente 9,685 millones de personas que viven en Portugal tienen ciudadanía portuguesa o residencia legal. [189]

El envejecimiento es un problema importante en Portugal, donde la edad media se sitúa en 46,8 años (mientras que en la UE en su conjunto es de 44,4 años) [190] y las personas de 65 años o más representan ahora el 23,4% de la población total. [191] Esto se debe a una baja tasa de fertilidad total (1,35 frente a la media de la UE de 1,53) [191] , así como a una esperanza de vida al nacer muy alta (82,65). [192] Debido al alto porcentaje de ciudadanos de edad avanzada, la tasa bruta de mortalidad (12%) [193] supera la tasa bruta de natalidad (7,6%). [194]

En lo que respecta a la tasa de mortalidad infantil , Portugal cuenta con una de las más bajas del mundo (2,6%), lo que demuestra una mejora significativa de las condiciones de vida desde 1961, cuando moría el 8,9% de los recién nacidos . [195] La edad media de las mujeres en el momento del primer parto se sitúa en 29,9 años, en contraste con la media de la UE de 28,2. [196]

Alrededor del 66,85% de la población vive en entornos urbanos, con una distribución desigual de la población y concentrándose a lo largo de la costa y en el área metropolitana de Lisboa , donde viven 2.883.645 personas, es decir, el 27,67% de la población. [197] [198]

Alrededor del 64,88% de la población nacional, o 6.760.989 personas, vive en los 56 municipios con más de 50.000 habitantes, alrededor del 18,2% de todos los municipios nacionales . Por otro lado, hay 122 municipios, alrededor del 39,6% de todos los municipios nacionales, con una población de 10.000 habitantes o menos, que suman un total de 678.855 habitantes, alrededor del 6,51% de la población nacional.

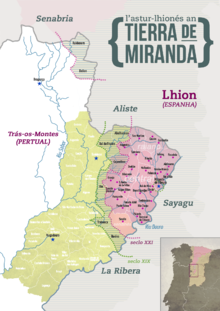

El idioma principal hablado como primera lengua por la abrumadora mayoría de la población es el portugués . [199] Otras lenguas autóctonas habladas incluyen:

Desde el siglo XX, personas procedentes de las antiguas colonias , en particular Brasil, el África portuguesa (especialmente afroportuguesa ), Macao , la India portuguesa y Timor Oriental , han estado migrando a Portugal.

Un gran número de eslavos , especialmente ucranianos (ahora una de las mayores minorías étnicas [215] [216] ) y rusos , así como moldavos , rumanos , búlgaros y georgianos , han estado migrando a Portugal desde finales del siglo XX. Una nueva ola de ucranianos llegó a Portugal después de la invasión rusa de Ucrania , y ahora hay aproximadamente 60.000 refugiados ucranianos en Portugal, lo que los convierte en la segunda comunidad migrante más grande de Portugal, después de la de Brasil. [217] [218]

Existe una minoría china de origen cantonés de Macao , así como de China continental .

Otras comunidades asiáticas relevantes en número incluyen a los indios , nepaleses , bangladesíes y paquistaníes , mientras que, en cuanto a los latinoamericanos , los venezolanos , cuyo número es de unos 27.700, están particularmente presentes. [219]

Además, hay una pequeña minoría de romaníes : unos 52.000 en número. [220] [221]

Portugal también es el hogar de otros nacionales de la UE y del EEE / AELC (franceses, alemanes, holandeses, suecos, españoles). El Reino Unido y Francia representaban las comunidades de residentes de la tercera edad más grandes del país en 2019, y forman parte de una comunidad de expatriados más grande que también incluye a alemanes , holandeses , belgas y suecos . [222]

Los extranjeros registrados oficialmente representaban el 7,3% de la población, [189] con tendencia a aumentar aún más. [223] Entre ellos se incluyen tanto los ciudadanos nacidos en Portugal con ciudadanía extranjera como los inmigrantes extranjeros. Se excluyen los descendientes de inmigrantes (Portugal, como muchos países europeos, no recoge datos sobre etnicidad) y aquellos que, independientemente del lugar de nacimiento o la ciudadanía al nacer, eran ciudadanos portugueses ( véase también la ley de nacionalidad portuguesa ).

En cuanto a las minorías religiosas, también hay alrededor de 100.000 musulmanes [224] [225] y una minoría aún más pequeña de judíos de alrededor de 5.000 a 6.000 personas (la mayoría son sefardíes , como los judíos de Belmonte , mientras que algunos otros son asquenazíes ). [226] [227] [228] [229]

Un apellido portugués suele estar compuesto por un número variable de apellidos (raramente uno, a menudo dos o tres, a veces más). Los primeros nombres adicionales suelen ser el apellido de la madre y el del padre. Por cuestiones prácticas, normalmente solo se utiliza el último apellido ( excluidas las preposiciones ) en los saludos formales.

Portugal tiene un sistema de nombres muy adaptable que cumple con el marco jurídico del país. La ley exige que cada niño reciba al menos un nombre propio y un apellido de uno de los padres. Además, existe un límite al número de nombres que se pueden dar, que se establece en un máximo de dos nombres propios y cuatro apellidos. [231]

En la época prerromana, los habitantes de lo que hoy es Portugal tenían un nombre único o un nombre seguido de un patronímico, que reflejaba su etnia o la tribu/región a la que pertenecían. Estos nombres podían ser celtas , lusitanos , ibéricos o conii . Sin embargo, el sistema onomástico romano comenzó a ganar popularidad lentamente después del siglo I d. C. Este sistema implicaba la adopción de un nombre romano o tria nomina, que consistía en un praenomen (nombre de pila), nomen (gentil) y cognomen . Hoy en día, la mayoría de los apellidos portugueses tienen un patronímico germánico (como Henriques , Pires , Rodrigues , Lopes , Nunes , Mendes , Fernandes , etc. donde la terminación -es significa "hijo de" ) , locativo ( Gouveia , Guimarães , Lima , Maia , Mascarenhas , Serpa , Montes , Fonseca , Barroso ), origen religioso ( Cruz , Reis , De Jesus , sés , Nascimento ) , ocupacional ( Carpinteiro (carpintero), Malheiro (lanero, trillador), Jardineiro (jardinero), o derivado de la apariencia física ( Branco (blanco), Trigueiro (moreno, bronceado), Louraço (rubio). Los apellidos toponímicos, locativos y derivados de la religión suelen ir precedidos por la preposición 'de' en sus diversas formas: ( De, de ), ( Do, do - masculino), ( Da, da - femenino) o 'de los' ( dos, Dos, das, Das – plural) como De Carvalho , Da Silva , de Gouveia , Da Costa , da Maia , do Nascimento , dos Santos , das Mercês . Si la preposición va seguida de una vocal, a veces se utilizan apóstrofes en apellidos (o nombres artísticos) como D'Oliveira , d'Abranches , d'Eça . En algunas colonias portuguesas anteriores en Asia (India, Malasia, Timor Oriental) existen grafías alternativas como 'D'Souza, Desouza , De Cunha , Ferrao , Dessais., Balsemao , Conceicao , Gurjao , Mathias , Thomaz .

A continuación se muestra una lista de los 25 apellidos más frecuentes en Portugal; las cifras de "frecuencia porcentual" son más altas de lo que cabría esperar porque la mayoría de los portugueses tienen varios apellidos. Para ilustrarlo, si suponemos que la distribución de apellidos es relativamente uniforme (al menos para aquellos con alta frecuencia), podemos inferir que aproximadamente el 0,5626% (9,44 x 0,0596) de la población portuguesa lleva simultáneamente los apellidos Silva y Santos. [232] [233] [234]

Portugal ha sido tradicionalmente una tierra de emigración: según las estimaciones, en todo el mundo podría haber fácilmente más de cien millones de personas con antepasados portugueses reconocibles, con diásporas portuguesas encontradas en todas partes, en muchas regiones diversas alrededor del mundo en todos los continentes . Debido a la magnitud del fenómeno y la falta de fuentes que se ocupen de estadísticas que datan de hace cientos de años, el número total de personas de ascendencia portuguesa es difícil de estimar. [235] [236] [237]

La extensión del fenómeno se debe a las exploraciones realizadas en los siglos XV y XVI, así como a la posterior expansión colonial . La colonización alentó la emigración mundial de portugueses a partir del siglo XV al sur de Asia, las Américas, Macao, Timor Oriental , Malasia , Indonesia , Myanmar [238] y África, particularmente a las antiguas colonias ( ver Lusoafricanos ). La emigración portuguesa también contribuyó al asentamiento de las islas atlánticas , la población de Brasil (donde la mayoría de la población actual es de ascendencia portuguesa) y la formación de comunidades de origen étnico-cultural parcialmente portugués, como en Goa los católicos goanos , en Sri Lanka los burgueses portugueses , en Malaca los Kristang y en Macao los Macaense . El Imperio portugués , que duró casi 600 años, terminó cuando Macao fue devuelto a China en 1999. Como consecuencia, durante esos 600 años, millones de personas abandonaron Portugal. Como resultado del matrimonio interétnico y de las influencias culturales, han surgido dialectos basados en el portugués tanto en las antiguas colonias (por ejemplo, el forro ) como en otros países (por ejemplo, el papiamento ).

Además, una parte considerable de las comunidades portuguesas en el extranjero se debe a fenómenos recientes de emigración masiva, impulsados principalmente por razones económicas, que datan de los siglos XIX y XX. De hecho, entre 1886 y 1966 Portugal, después de Irlanda, fue el segundo país de Europa occidental que perdió más personas debido a la emigración. [239]

Desde mediados del siglo XIX hasta finales de la década de 1950, casi dos millones de portugueses abandonaron Europa para vivir principalmente en Brasil y, en cantidades significativas, en Estados Unidos, Canadá y el Caribe . [240] Alrededor de 1,2 millones de ciudadanos brasileños son portugueses nativos. [241] Existen importantes minorías portuguesas verificadas en varios países ( véase la tabla siguiente ). [242]

En 1989, unos 4.000.000 de ciudadanos portugueses vivían en el extranjero, principalmente en Francia, Alemania, Brasil, Sudáfrica, Canadá, Venezuela y Estados Unidos. [243] Estimaciones de 2021 indican que hasta 5 millones de ciudadanos portugueses (sin tener en cuenta a los descendientes o ciudadanos no registrados ante las autoridades consulares portuguesas) podrían estar viviendo en el extranjero. [244]

En Europa, se pueden encontrar concentraciones importantes de portugués en países francófonos como Francia, Luxemburgo y Suiza, estimuladas en parte por la proximidad lingüística que existe entre el portugués y el francés. De hecho, según datos de la Dirección General de Asuntos Consulares y Comunidades Portuguesas del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores portugués, los países con las comunidades portuguesas más numerosas son, en orden ascendente de importancia demográfica, Francia, el Reino Unido y Suiza. [245]

En términos generales, las comunidades portuguesas diásporicas suelen sentir un fuerte vínculo con la tierra de sus antepasados, su lengua, su cultura y sus platos nacionales como el bacalao .

Desde hace muchos siglos, los descendientes de judíos sefardíes portugueses se encuentran en todas partes del mundo, con comunidades notables que se han establecido en cantidades significativas en Israel, los Países Bajos , los Estados Unidos, Francia, Venezuela , Brasil y Turquía .

La diáspora judía portuguesa fue principalmente el resultado del decreto de expulsión [246] emitido en 1496 por la monarquía portuguesa , que tenía como objetivo a los judíos que vivían en Portugal . Este decreto obligó a muchos judíos a convertirse al cristianismo (lo que llevó al surgimiento de los Cristão-novos y de las prácticas criptojudías ) o a abandonar el país, lo que llevó a una diáspora de judíos portugueses en toda Europa y Brasil. En Brasil [247] muchos de los primeros colonos también eran originalmente judíos sefardíes que, después de su conversión, fueron conocidos como cristianos nuevos (ver Anusim ) . [248] [249]

La emigración

.JPG/440px-Expulsao_judeus_Olival_(Porto).JPG)

Se cree que hasta 10.000 judíos portugueses podrían haber emigrado a Francia a partir de 1497; este fenómeno se mantuvo visible hasta el siglo XVII, cuando los Países Bajos se convirtieron en la opción favorita. [250] [251]

Los Países Bajos e Inglaterra se convirtieron de hecho en los principales destinos para los emigrantes judíos portugueses debido a la ausencia de la Inquisición . Además de agregar a los aspectos económicos y culturales de sus países de acogida, [252] los judíos portugueses también establecieron instituciones que todavía están presentes, como la Esnoga , en Ámsterdam , la Congregación Shearith Israel -la congregación judía más antigua de los Estados Unidos-, la Sinagoga Bevis Marks -la sinagoga más antigua del Reino Unido-, la Sinagoga Española y Portuguesa de Montreal -la sinagoga más antigua de Canadá-, el Hospital Monte Sinaí en Nueva York, City Lights Booksellers & Publishers o la Academia David Cardozo en Jerusalén .

Pequeñas comunidades prosperaron en los Balcanes , [253] Italia, [254] el Imperio Otomano [255] [256] y Alemania, especialmente en Hamburgo ( véase Elijah Aboab Cardoso, Joan d'Acosta y Samuel ben Abraham Aboab ). [257]

Los judíos portugueses también fueron responsables de la aparición del papiamento [258] (un criollo basado en el portugués con 300.000 hablantes [259], que ahora es idioma oficial en Aruba , Curazao y Bonaire ) y del sranan tongo , un criollo basado en el inglés influenciado por el portugués hablado por más de 500.000 personas en Surinam . [260] [261]

La Shoah

Durante la Shoah , casi 4.000 judíos de ascendencia portuguesa residentes en los Países Bajos perdieron la vida, lo que constituye el grupo más grande de víctimas con antecedentes portugueses en el genocidio nazi alemán . [262] [263] Entre las famosas víctimas judías portuguesas de la Shoah se encuentra el pintor Baruch Lopes Leão de Laguna . Vale la pena destacar que, aunque oficialmente neutral , el régimen portugués en ese momento, Estado Novo , se alineó con la ideología de Alemania y no protegió por completo a sus ciudadanos y otras personas judías que vivían en el extranjero. [264] [265] [266] A pesar de la falta de apoyo de las autoridades portuguesas, algunos judíos de ascendencia portuguesa [267] y no portuguesa, se salvaron gracias a las acciones de ciudadanos individuales como Carlos Sampaio Garrido , Joaquim Carreira, José Brito Mendes y el conocido caso de Aristides de Sousa Mendes , [268] quien solo ayudó a 34.000 judíos a escapar de la violencia nazi . [269]

Los judíos portugueses en la actualidad

Más de 500 años después del decreto de expulsión, en 2015 el parlamento portugués reconoció oficialmente la expulsión de sus ciudadanos de ascendencia judía como injusta. Para intentar compensar las injusticias históricas de larga duración, el gobierno aprobó una ley conocida como " Ley del Retorno ". [270] La ley tenía como objetivo corregir los errores históricos de la Inquisición portuguesa , que resultaron en la expulsión o conversión forzada de miles de judíos de Portugal en los siglos XV y XVI. La ley otorga la ciudadanía a cualquier descendiente de esos judíos perseguidos que pueda confirmar su ascendencia judía sefardí y una "conexión" con Portugal. Tiene como objetivo proporcionar una medida de justicia y reconocimiento a aquellos cuyas familias sufrieron discriminación y persecución cinco siglos antes. [271] [272] [273] [274]

Desde 2015, más de 140.000 personas de ascendencia sefardí, de 60 países (en su mayoría de Israel o Turquía ) solicitaron la ciudadanía portuguesa . [275] [276] [277] [278] Desafortunadamente, poco después de que se aprobara esta ley, se supo que a varios extranjeros sin vínculos históricos sefardíes legítimos se les concedió la ciudadanía portuguesa, entre ellos, el oligarca ruso Roman Abramovich se convirtió en ciudadano portugués (es decir, de la UE ) bajo la nueva ley. Debido a los casos de abuso y las lagunas en esta ley, que se concibió como una reparación hacia una minoría, el poder judicial se vio obligado a intervenir y revisar esta ley. [279] [280] [281] [282]

Entre las personas notables de ascendencia judía portuguesa se incluyen:

Estados Unidos

Estados Unidos ha mantenido relaciones bilaterales con Portugal desde sus primeros años. Después de la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos , Portugal se convirtió en el primer país neutral en reconocer a los Estados Unidos. [286]

A pesar de que Portugal nunca colonizó (ni intentó colonizar) el actual territorio de los Estados Unidos de América, navegantes como João Fernandes Lavrador , Miguel Corte-Real y João Rodrigues Cabrilho se encuentran entre los primeros exploradores europeos documentados. El Dighton Rock , en el sureste de Massachusetts , es un testimonio de la temprana presencia portuguesa en el país. [287] [288] [289] [290]

Se cree que Mathias de Sousa , que era potencialmente un judío sefardí de origen africano mixto, fue el primer residente portugués documentado de los Estados Unidos coloniales . [291] Además, uno de los primeros judíos portugueses en los Estados Unidos, Isaac Touro , es conmemorado en nombre de la sinagoga más antigua del país, la Sinagoga Touro .

Despite the relations between the two countries dating hundreds of years, the Portuguese started to settle in significant numbers only in the 19th century, with major migration waves occurring in the first half of the 20th century, especially from the Azores.[292][293][294][295] Of the 1,4 million Portuguese Americans found in the nation today (0.4% of the US population) the majority of them are originally from the Azores. Not only the arrival of Azorean emigrants was easier because of geographic proximity, but it was also encouraged by the Azorean Refugee Act of 1958, sponsored by Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy and Rhode Island senator John Pastore so as to help the population affected by the 1957–58, the Capelinhos volcano eruption.[296][297][298] Moreover, it is noteworthy that the 1965 Immigration Act stated that if someone had legal or American relatives in the United States who could serve as a sponsor, they could be given the status of legal aliens. This act dramatically increased Portuguese immigration into the 1970s and 1980s.[299]

Major Portuguese communities are found in New Jersey (particularly in Newark), the New England states, California and along the Gulf Coast (Louisiana). Springfield, Illinois once possessed the largest Portuguese community in the Midwest.[300] In the Pacific, Hawaii (see Portuguese immigration to Hawaii) has a sizable Portuguese population, encouraged by the availability of labor contracts on the islands 150 years ago.[301]

The Portuguese community in the US is the second largest in the Americas after the one found in Brazil.

Canada

Canada, particularly Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, has developed a significant Portuguese community since the 1940s. The availability of more job opportunities in Canada attracted a significant number of Portuguese migrants, leading to the flourishing of Portuguese culture in the subsequent decade. Many Portuguese residents took the initiative to purchase homes and establish their own businesses, resulting in contributing to the Canadian cultural landscape.

According to the 2016 Census, there were 482,610, or 1.4% of Canadians, who claimed full or partial Portuguese ancestry.[302]

Two major neighbourhoods where the Portuguese heritage is particularly present include Little Portugal, in both Toronto and Montréal. Montréal's Little Portugal, known as "Petit Portugal" in French, is adorned with numerous Portuguese shops, restaurants, and cafes, and it is also home to "Parc du Portugal" (Portugal's park), embellished with vibrant murals and elements inspired by Portuguese design.[303][304]

Portuguese Canadians are proud of their heritage and, despite the geographical distance between the two countries, interest towards the language remains vivid.[305][306][307] Recent statistics reveal that the Portuguese language is spoken by over 330,000 Canadians, making up around 1% of the population.[308] It is considered one of the most significant cultural contributions that the Portuguese have made to Canada, adding to its diversity and enriching the country as a whole.[309][310][311]

Despite the growth the community has seen in the 20th century, significant testimonies of the Portuguese presence in Canada include the name of one of the 10 provinces of Canada: Newfoundland and Labrador. King Henry VII coined the name "New found land" for the territory explored by Sebastian and John Cabot.. In Portuguese, the land is known as Terra Nova, which translates to "new land," and is also referred to as Terre-Neuve in French, the name for the province's island region. The name Terra Nova is commonly used on the island, including in the name of Terra Nova National Park. The influence of early Portuguese exploration is evident in the name of Labrador, which is derived from the surname of Portuguese navigator João Fernandes Lavrador.[312] Other remnants of early Portuguese exploration include toponyms such as Baccalieu (from bacalhau, Portuguese for codfish) and Portugal Cove. Portuguese cartographer Diogo Ribeiro is responsible for one of the earliest maps depicting the territory of modern-day Canada.[313]

The Caribbean

There are Portuguese influenced people with their own Portuguese-influenced culture and Portuguese-based dialects in parts of the world other than former Portuguese colonies. In the Caribbean, in particular, although never colonized by the Portuguese, the Lusitanian heritage remains strong thanks to the migrants that from the 1830s came as indentured labourers, especially from Madeira. In fact, although the first Portuguese who settled in the region were merchants or Portuguese-Jews fleeing the Portuguese Inquisition,[314] the mass migration that took place in the 19th century coincided with the abolition of slavery in the British colonies. As a result, the Portuguese, along with Indians and Chinese, were called upon to replace slave labor. The Portuguese took a prominent part in shaping the population of the West Indies and today their descendants form an active minority in many countries across the region.

As part of a larger system of low-wage labour, about 2,500 Portuguese left for Antigua and Barbuda[315] (where, as of today, little more than 1,000 people still speak the language),[316] 30,000 to Guyana (4.3% of the population in 1891)[317] (see Portuguese immigrants in Guyana) and another 2,000 settled in Trinidad and Tobago (see Portuguese immigrants in Trinidad and Tobago)[318][319][320] between the mid-1800s and the mid-1900s.[321][322][323] With regards to Guyana the Portuguese heritage is still alive in the numerous enterprises established by members of the community. Despite today numbering about 2,000 people, the Portuguese community's contributions are recognized and recently (2016) the second international airport of the country was renamed after a Portuguese Guyanese individual.[321][324]

Portuguese fishermen, farmers and indentured labourers dispersed also across other Caribbean countries, especially in Jamaica (about 5,700 people, primarily of Portuguese-Jewish descent),[325][326][327][328][329] St. Vincent and the Grenadines (0.7% of the population),[330] the briefly reclaimed by the Portuguese Empire island of Barbados – where there is still high influence from the Portuguese community[331] and Suriname (see Portuguese immigrants in Suriname). Dealing with Suriname, it is noteworthy that its first capital, Torarica (literally "rich Torah" in Portuguese), was established by Portuguese-Jewish settlers. Minor communities exist in Grenada,[332] Saint Lucia,[333] Saint Kitts and Nevis[334] and the Cayman Islands[335]

In the Caribbean territories of Overseas France there are about 4,000 Portuguese people, especially in Saint Barthélemy (where they constitute about a third of the population), Guadeloupe and Martinique.[336][337][338]

Portuguese heritage is still very tangible in Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao. In the three territories, the official language, Papiamentu, retains numerous Portuguese elements.

Moreover, the North Atlantic archipelago of Bermuda (10%[339] to 25%[340] of the population) has had sustained immigration especially from the Azores, as well as from Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands since the 1840s.[341]

Latin America (excluding Brazil)

.JPG/440px-Charrería_en_Tequixquiac_(18).JPG)

Mexico (see Portuguese Mexicans) has had flows of Portuguese immigration since the colonial period until the early 20th century, the most important settlements are in north eastern cities,[342] such as Saltillo, Monterrey, Durango and Torreon. Santiago Tequixquiac, due to its natural conditions and its lime and stone mining deposits, was a place of settlement for Portuguese Crypto-Jews during the colonial period, they were brought there together with the Tlaxcalans and peninsular Spaniards to appease the Otomi indigenous people, in that town. Many Lusitanian cultural traits were preserved throughout the 19th century, such as forcados, gastronomy, some Sephardic customs and the surnames of its inhabitants. Every year dozens of young people seek to experience the adventure of catching a bull in the bullring, and one of the Portuguese traditions that prevail in Mexico.[343] A notable Portuguese-Mexican Jew was Francisca Nuñez de Carabajal, executed by burning at the stake by the Inquisition for judaizing in 1596.

Portuguese communities are also present in Central American countries such as Cuba, Dominican Republic or Puerto Rico.[344] Notable members of the community include activist Ada Bello, businesswoman Alexis Victoria Yeb, former Nicaraguan First Lady Lila Teresita Abaunza and Felipa Colón de Toledo.

Venezuela has the biggest number of Portuguese people in Latin America after Brazil (see Portuguese Venezuelans) . Portuguese started arriving to Venezuela in the early and middle 20th century as economic immigrants particularly from Madeira.[345] In Venezuela about 1.3 million people (4.61% of the population) is of Portuguese descent.[345] The emigration towards Venezuela occurred mainly in the 1940s and 1950s. The extense Luso-Venezuelan community includes personalities such as María Gabriela de Faría, Marjorie de Sousa, Vanessa Gonçalves, Kimberly Dos Ramos and Laura Gonçalves.

Colombia did not witness mass Portuguese immigration, since the Portuguese tended to move to countries where immigration was not curbed but promoted, such as Brazil and Venezuela. Although Portuguese may have explored the area during the Age of Discovery, there is not evidence that they established communities in nowadays Colombia. It is noteworthy that Colombia was under full Spanish sovereignty, as defined by the Treaty of Tordesillas. The Portuguese embassy in Bogota estimates that there are around 800 Portuguese nationals who live in Colombia, although the numbers could be much higher as Portuguese are not obliged to register their presence within consulates abroad. The number of people of Portuguese ancestry is not known, but it is safe to assume that they have integrated very well in the Colombian society and are indistinguishable, except for some surnames, from other Colombians.[346][347]

In Peru, Portuguese immigration gradually began at the time of the Viceroyalty of Peru until the beginning of the 19th century, without being massive. Many sailors who traveled along the Peruvian coast, and later entered the country following the route from the Atlantic through the Amazon River established themselves in Peru, intermarrying with local people. There are also records of Luso-Brazilians in the cities surrounding the Brazil-Peru border. Although the number of Portuguese citizens in Peru is not high (about 2,000 people),[348] Peruvians with Portuguese ancestors could easily be as much as 1 million people, including direct and indirect descendants, which represents about 3% of the national total.[349] A famous Peruvian of Portuguese descent is popular TV presenter Janet Barboza.

The Cono Sur region had Portuguese immigration since the early 20th century. The community in Argentina (See Portuguese Argentines and Cape Verdean Argentines), Uruguay (see Portuguese Uruguayans) and Chile numbers around 255,000 people combined[350][351][352] (0.37% of the population of the region).

In particular, Portuguese Uruguayans are mainly of Azorean descent[353] even though Portuguese presence in the country dates back to the colonal times, in particular to the establishment of Colonia del Sacramento by the Portuguese in 1680,[354] which eventually turned into a regional center of smuggling. Other Portuguese entered Uruguay as Brazilians of Portuguese descent, who crossed the border into the country ever since it became independent from Brazil itself. During the second half of the 19th century and part of the 20th, several additional Portuguese immigrants arrived; the last wave was during 1930–1965.[355][356] As of 2021, 3,069[357] Portuguese citizens have registered as residing in Uruguay within Portuguese authorities. In addition to Portuguese citizens, there are also many luso-descendants (lusodescendentes) whose numbers are hard to estimate.[358][350]

Argentina-Portugal relations date back to the early European explorations in the region, as the Río de la Plata (literally, silver river) was first explored by the Portuguese in the 1510s. In Argentina, Portuguese immigration has been relatively limited due to a preference for the Portuguese-speaking neighboring Brazil. However, the Portuguese constituted the second-largest immigrant group after the Spanish before 1816 and continued to arrive throughout the 19th century. While a significant number settled in the interior of the country, with the primary destination for Portuguese immigrants being Buenos Aires. Many men from Lisbon, Porto, and coastal regions of Portugal, with diverse occupations but predominantly in maritime professions such as sailors, stevedores, and porters, were already present in these areas. During the 1970s, they began to organize themselves ethnically, and over the following decades, community life, including mutual support organizations, clubs, and newspapers, became more active.[359][360] A popular member of the Portuguese community in Argentina was best-selling author Silvina Bullrich.

In the early twentieth century the Portuguese government encouraged white emigration to Angola and Mozambique, and by the 1970s, there were up to 1 million Portuguese settlers living in their overseas African provinces.[361] Minor communities also settled in Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe, Portuguese influences are still found in these countries, where Portuguese enjoys the status of official language.

Following the Carnation Revolution, as the country's African possessions gained independence in 1975, An estimated 800,000 Portuguese returned to Portugal or moved to other countries. For many, Portugal was more an historical homeland than the actual country of birth. Despite this, thousands of people left and went to a country they had never been to.[362] These people are often referred as Retornados (literally, those who came back).

Other Portuguese moved to South Africa, Brazil, Botswana and Algeria.[363][364][365][366][367] In particular, in South Africa there is now the largest Portuguese community in the continent, numbering about 700,000 people (more than the city of Lisbon itself).

Portuguese descendants still make up a significant minority in the former colonies where, as a result of intermarriage and cultural influences, they form the bulk of Mestiços (Mixed African-European people).[368][369][370][371]

France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Monaco, Andorra and Switzerland

_vue_de_la_cité_universitaire.jpg/440px-Eglise_du_Sacré_Coeur_de_Gentilly_(92)_vue_de_la_cité_universitaire.jpg)

.jpg/440px-Portuguese_WWI_Memorial_(1324658430).jpg)

Due to the linguistic proximity between Portuguese and French and the plurality of schools in Portugal which promotes French as foreign language many Portuguese nationals started migrating towards French speaking countries in Europe (namely, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Monaco and the French-speaking part of Switzerland) in the 1960s, for economic reasons and to avoid conscription to fight in Portuguese Overseas provinces. Interestingly, migration to Andorra - where, although Catalan is the sole official language, French is widely spoken - made the Portuguese the third largest ethnic group in the state, after Andorrans and Spaniards.[372][373][374][375]

According to the most recent estimates of both Eurostat and INE, around 15.4% of Portuguese people are fluent in French.[376][377] Although relatively popular still, French has been dwindling, and English is taught in schools as a global language. For instance, in 2005 the proportion of Portuguese adults fluent in French stood at 24%[378] which indicates a clear decline in younger speakers. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy noticing that 70% of middle school students study French.[379] French media are widely available in Portugal (newspapers, magazines, radio stations and TV channels) and many libraries still offer a French-language section.

Some Portuguese migration to the more affluent French speaking countries in Europe exists, although not as significant as in post-WWII decades.

Between France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Monaco, Andorra and Switzerland there are more than 2,260,000 Portuguese citizens and, taking int account People with Portuguese ancestry not holding Portuguese nationality their numbers could easily soar up to 2,7 million: for instance, France alone hosts 450,000 Luso-descendants or lusodescendentes. In fact, with more than 1,55 million Portuguese citizens[380] and up to 2 million people of Portuguese descent,[381] France hosts, by far, the largest community of Portuguese people outside of Portugal, second only to Brazil (see Portuguese in France).

There are records of Portuguese people living in France since the early centuries of the Portuguese kingdom, notably merchants but also Portuguese-Jews and Portuguese nobles: even Louis XIV or "le Roi Soleil" was of Portuguese descent through his grandfather Philip II. Despite their being present in the country for centuries, Portuguese nationals have only relatively recently started to move to France in large numbers: for comparison, there were less than 40,000 Portuguese in France on the eve of WWII.[382][383]

From the 1960s, the economic stagnation of Brazil, a traditional destination, measures taken by France to attract Portuguese workers, António de Oliveira Salazar's dictatorship and the colonial wars, were all factors that contributed to 1,000,000 people fleeing Portugal and going to France from 1960 to 1974.[384][385][386][387][388] After 1974, despite remaining a major destination for Portuguese migrants, Portuguese nationals have started moving to Luxembourg and Monaco (1980s), Switzerland (1990s) and – increasingly – Belgium and Andorra (2000s). This is also due to the tightening control of immigration by French authorities following the 1973 oil crisis.[389][390][391][392]

Portuguese constitute 23.4% of the population of Luxembourg, which makes them one of the largest ethnic groups as a proportion of the total national population, second only to native Luxembourgers (see Portuguese in Luxembourg). Andorra is inhabited by 16,300 Portuguese nationals (19.4% of the population)[393][394], Monaco hosts around 1,000 Portuguese nationals (3.3% of the Population)[395] while Belgium is home to around 80,000 Portuguese nationals (0.7% of the population).[396]

In Switzerland, Portuguese have settled mainly in Romandy. In fact, while official figures suggest that Portuguese is spoken by 5% of the population of Switzerland as a whole at home - by comparison Italian, an official language of Switzerland, is spoken by 8.8% - the figure rises to 10.1% in French speaking Switzerland, thus making Portuguese the most spoken language in the region's households, second only to French. Around 460,000 Portuguese nationals live in the country according to the latest estimates (5.3% of Switzerland's population).[397]

Famous Swiss people of Portuguese descent include snooker player Alexander Ursenbacher, models Pedro Mendes and Nomi Fernandes, actress Yaël Boon and Olympic medalist Stéphane Lambiel.

Notable Belgians of Portuguese descent include – apart from nobles such as Queen Elizabeth or King Leopold III – fashion designer Veronique Branquinho, footballer Yannick Carrasco, actress Rose Bertram, sprinter Jonathan Sacoor and actress Helena Noguerra.

Despite Portuguese migration towards these countries has steadily declined over the years, from 2003 to 2022 around 615,000 Portuguese nationals have moved towards these countries, especially during the years following the 2008 financial crisis. Interestingly, as of 2021 around 40% has returned to Portugal, in particular after 2015, when the economic outlook the Mediterranean country bettered significantly.[398]

Germany

In the post-war period, Hundreds of thousands of Portuguese settled as guest workers in other European countries, especially in Western Europe. On 17 March 1964, the recruitment agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and Portugal was signed under the Erhard I cabinet. The Portuguese Armando Rodrigues de Sá was officially welcomed in 1964 as the millionth "guest worker" in Germany and was given a certificate of honor and a two-seater Zündapp Sport Combinette – Mokick.[400] The number of Portuguese citizens living in Germany is estimated at 245,000 as of 2021.[401]The largest Portuguese community is located in Hamburg with about 25,000 people with Portuguese descent. There is also a Portugiesenviertel (Portuguese quarter) in Hamburg near the Port of Hamburg and between the subway stations of Landungsbrücken and Baumwall where many Portuguese restaurants and cafes are located there.

The United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, people of Portuguese origin were estimated at 400,000 in 2021 by Portuguese authorities (see Portuguese in the United Kingdom).[402][403] Although unconfirmed, other sources claim that there might be as much as 500,000 Portuguese in the country,[404] a considerably higher than the estimated 170,000 Portuguese-born people residing in the country in 2021[405] (this figure does not include British-born people of Portuguese descent).

In areas such as Thetford and the crown dependencies of Jersey and Guernsey, the Portuguese form the largest ethnic minority groups at 30% of the population, 9.03% and 3.13% respectively.

The British capital London is home to the largest number of Portuguese people in the UK, with the majority being found in the Western boroughs of Kensington and Chelsea, Lambeth and Westminster.[406]

Due to the emigration of a significant part of the Portuguese towards Brazil, they played a particularly important role in the formation of Brazilians as a nation, becoming one of its main components. In fact, given the shared past and the fact that Portuguese deeply influenced the formation of Brazilians as a nation, the Portuguese are the largest European immigrant group in Brazil. In colonial times, over 700,000 Portuguese settled in Brazil, and most of them went there during the gold rush of the 18th century.[407]Brazil received more European settlers during its colonial era than any other country in the Americas. Between 1500 and 1760, about 700,000 Europeans immigrated to Brazil, compared to 530,000 European immigrants in the United States.[408][409] They managed to be the only significant European population to populate the country during colonization, even though there were French and Dutch invasions. The Portuguese migration was strongly marked by the predominance of men (colonial reports from the 16th and 17th centuries almost always report the absence or rarity of Portuguese women). This lack of women worried the Jesuits, who asked the Portuguese King to send any kind of Portuguese women to Brazil, even the socially undesirable (e.g. prostitutes or women with mental maladies such as Down Syndrome) if necessary.[410][411] The Crown responded by sending groups of Iberian orphan maidens to marry both cohorts of marriageable men, the nobles and the peasants. Some of which were even primarily studying to be nuns.[410][412]

The Crown also shipped over many Órfãs do Rei of what was considered "good birth" to colonial Brazil to marry Portuguese settlers of high rank. Órfãs do Rei literally translates to "Orphans of the King", and they were Portuguese female orphans in nubile age. There were noble and non-noble maidens and they were daughters of military compatriots who died in battle for the king or noblemen who died overseas and whose upbringing was paid by the Crown. Bahia's port in the East received one of the first groups of orphans in 1551.[413]In colonial Brazil, the Portuguese men competed for women, because among the African slaves and the female component of Indigenous peoples of the Americas were minorities.[414] This explains why the Portuguese men left more descendants in Brazil than the Amerindian or African men did. The Indigenous and African women were "dominated" by the Portuguese men, preventing men of color to find partners with whom they could have children. Added to this, White people had a much better quality of life and therefore a lower mortality rate than the black and indigenous population. Then, even though the Portuguese migration during colonial Brazil was smaller (3.2 million Indians estimated at the beginning of colonization and 4.8 million Africans brought since then, compared to the descendants of the over 700,000 Portuguese immigrants) the "white" population (whose ancestry was predominantly Portuguese) was as large as the "non-white" population in the early 19th century, just before independence from Portugal.[415][416][414] After independence from Portugal in 1822, around 1.7 million Portuguese immigrants settled in Brazil.[414]

Portuguese immigration into Brazil in the 19th and 20th centuries was marked by its concentration in the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The immigrants opted mostly for urban centers. Portuguese women appeared with some regularity among immigrants, with percentage variation in different decades and regions of the country. However, even among the more recent influx of Portuguese immigrants at the turn of the 20th century, there were 319 men to each 100 women among them.[417] The Portuguese were different from other immigrants in Brazil, like the Germans,[418] or Italians[419] who brought many women along with them (even though the proportion of men was higher in any immigrant community). Despite the small female proportion, Portuguese men married mainly Portuguese women. Female immigrants rarely married Brazilian men. In this context, the Portuguese had a rate of endogamy which was higher than any other European immigrant community, and behind only the Japanese among all immigrants.[420]

Even with Portuguese heritage, many Portuguese-Brazilians identify themselves as being simply Brazilians, since Portuguese culture was a dominant cultural influence in the formation of Brazil (like many British Americans in the United States, who will never describe themselves as of British extraction, but only as "Americans", since British culture was a dominant cultural influence in the formation of The United States).

In 1872, there were 3.7 million Whites in Brazil (the vast majority of them of Portuguese ancestry), 4.1 million mixed-race people (mostly of Portuguese-African-Amerindian ancestry) and 1.9 million Blacks. These numbers give the percentage of 80% of people with total or partial Portuguese ancestry in Brazil in the 1870s.[421]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a new large wave of immigrants from Portugal arrived. From 1881 to 1991, over 1.5 million Portuguese immigrated to Brazil. In 1906, for example, there were 133,393 Portuguese-born people living in Rio de Janeiro, comprising 16% of the city's population. Rio is, still today, considered the largest "Portuguese city" outside of Portugal itself, with 1% Portuguese-born people.[408][422]

Genetic studies also confirm the strong Portuguese genetic influence in Brazilians. According to a study, at least half of the Brazilian population's Y Chromosome (male inheritance) comes from Portugal. Black Brazilians have an average of 48% non-African genes, most of them may come from Portuguese ancestors. On the other hand, 33% Amerindian and 28% African contribution to the total mtDNA (female inheritance) of white Brazilians was found[423][424]

An autosomal study from 2013, with nearly 1300 samples from all of the Brazilian regions, found a predominant degree of European ancestry (mostly Portuguese, due to the dominant Portuguese influx among European colonization and immigration to Brazil) combined with African and Native American contributions, in varying degrees. 'Following an increasing North to South gradient, European ancestry was the most prevalent in all urban populations (with values from 51% to 74%). The populations in the North consisted of a significant proportion of Native American ancestry that was about two times higher than the African contribution. Conversely, in the Northeast, Center-West and Southeast, African ancestry was the second most prevalent. At an intrapopulation level, all urban populations were highly admixed, and most of the variation in ancestry proportions was observed between individuals within each population rather than among population'.[425]

A large community-based multicenter autosomal study from 2015, considering representative samples from three different urban communities located in the Northeast (Salvador, capital of Bahia), Southeast (Bambuí, interior of Minas Gerais) and South Brazilian (Pelotas, interior of Rio Grande do Sul) regions, estimated European ancestry to be 42.4%, 83.8% and 85.3%, respectively.[426] In all three cities, European ancestors were mainly Iberian.

It was estimated that around 5 million Brazilians (2.3% of the country's population) can acquire Portuguese citizenship, due to the last Portuguese nationality law that grants citizenship to grandchildren of Portuguese nationals.[427]

Australia and New Zealand have sizeable Portuguese communities.

In Australia, although their numbers are relatively small in comparison to the Greek and Italian communities, the Portuguese constitute a highly organized, self-aware, and active community across various aspects of Australian life. Despite being among the early settlers, with some (unproven) theories that state they might have discovered Australia, their numbers have never been massive, when compared to major communities. The Portuguese immigration to Australia experienced a boom after the Carnation Revolution and the Indonesian Invasion of Timor-Leste. The Portuguese are dispersed throughout the country and engage in activities such as sports teams, social clubs, radio programs, newspapers, cultural festivals, culinary events, and even have a designated Portuguese neighborhood. The 73,903 people of Portuguese descent constitute about 0.28% of the Australian population. Portuguese cuisine has gained popularity within mainstream Australian society, exemplified by the rapid expansion and establishment of restaurants and fast-food outlets such as "Nando's", "Oporto," and "Ogalo." The delectable Portuguese pastry known as "pastel de nata" is widely enjoyed and readily available throughout the country. Many of the Portuguese are from Madeira.[428][429][430][431][432] Notable Portuguese Australians include Naomi Sequeira, Kate DeAraugo, Junie Morosi, Lyndsey Rodrigues, Sophie Masson and Irina Dunn.

The community in New Zealand is much smaller and the 1,500 Portuguese people living there (although the numbers could be significantly higher) constitute about 0.03% of the population. On 22 April 2010, the Office of Ethnic Affairs officially recognized Portuguese New Zealanders as a distinct community in New Zealand. A symbolic act of tying the 70th ribbon to Parliament's mooring stone in the Parliament House Galleria marked this recognition. In addition to their official recognition, the Portuguese community in New Zealand organizes various annual gatherings and celebrations, such as Portugal Day, and maintains a friendship association. Portuguese individuals were among the early settlers in New Zealand, although immigration from Portugal declined gradually until the 1960s. After the Carnation Revolution, the community started to increase again.[433][434]

In addition, about 900 Portuguese live in the French collectivity of New Caledonia (0.38% of the population).[435]

Portuguese influences are found throughout Asia, especially in Macau (see Macanese people), Timor-Leste and India (see Luso-Indian), all territories where the Portuguese maintained colonies up to the 20th century.[436][437]

Southeast Asia

.jpg/440px-Khanom_Farang_Kudi_Chin,_2020-10-10_(1).jpg)

Luso-Asian communities have had a strong presence in Southeast Asia since the 15th century. As a result of inter-ethnic marriage, dialects based on Portuguese have occurred in the former Portuguese territories now part of Malaysia (see Kristang people) and Singapore (see Eurasian Singaporeans). In particular, notable Kristang people from Malaysia include Kimberley Leggett, Jojo Sturys, Joan Margaret Marbeck, Elaine Daly, Nor Aliah Lee, Melissa Tan, Andrea Fonseka, Anna Jobling and Cheryl Samad. People of Portuguese descent from Singapore include personalities such as Pilar Arlando, Mary Klass and Vernetta Lopez.

Other communities are found in Indonesia (see Portuguese Indonesians and Mardjiker), with significant populations of Portuguese descent living in Lamno (the so-called "mata biru" or blue-eyed people), Aceh, Maluku Islands and Kampung Tugu.[438][439][440][441][442][443] Portuguese vestiges in Indonesia include dozens of loanwords as well as the introduction of Roman Catholicism (3.12% of the population but still the major religion in NTT) and Keroncong, similar to Portuguese cavaquinho.[444][445][446][447] In recent years many Indonesians of Portuguese descent have been active in the entertainment industry such as, among others, Puteri Indonesia Elfin Pertiwi Rappa or actress Millane Fernandez. In neighbouring Philippines, actress Sophie Albert is another example of Portuguese-South Asian working in the said industry.

Due to early Portuguese explorers, communities of Portuguese descent are also found in Myanmar (see Bayingyi people)[448][449] and Thailand (see Kudi Chin).[450][451] In Thailand, during the reign of King Narai the Great the Portuguese community in Ayutthaya is thought to have peaked at 6,000 people.[452] Notable Thai of Portuguese descent include Francis Chit, known for being the first Thai photographer, Maria Guyomar de Pinha, responsible for introducing Fios de ovos (or Foi Thong in Thai) and sangkhaya into Thai cuisine or actresses such as Kung Nang Pattamasuta, Krystal Vee or Neon Issara.

Indian Subcontinent

In Sri Lanka (see Burgher people, Portuguese Burghers and Mestiços), home to around 40,000 Burghers. A notable Portuguese Burger was the best-selling author Rosemary Rogers. In addition, as a consequence of the Portuguese invasion of Sri Lanka, during the 16th and 17th centuries, many Portuguese language surnames were adopted among the Sinhalese people. As a result, Perera and Fernando eventually became the most common names in Sri Lanka.[453][454][455] Afro Sri-Lankans also retain a Portuguese identity.[456] Major Portuguese contributions to Sri Lanka, dating to the colonial period, include, apart from archaeological vestiges, about 1,000 loanwords in Sinhala of Portuguese origin,[457] Baila music (from the Portuguese bailar, meaning to dance), culinary innovations such as "Bolo di amor" (literally Love cake) or "Bolo Folhado" (literally Puff Pastry)[458] as well as the introduction of Roman Catholicism (approximately 6.1% of the population identifies as Catholic) and the endangered Sri Lankan Portuguese creole.[459][460]

In Pakistan (see Portuguese in Pakistan) there is a small Portuguese community numbering about 64 people,[461] even though other estimates point at 400 people of Portuguese origin in Karachi alone.[462] Notable Portuguese Pakistani include actress Dilshad Vadsaria and scholar Bernadette Louise Dean. Despite today not being numerically visible[463] it is noteworthy to remember that, before the partition of India, it is estimated that the Goan community in Karachi numbered up to 15,000. The majority of them after 1947 moved back to Goa or went to other territories controlled by the Portuguese, as well as to the UK.[464] The Portuguese community has greatly contributed to the musical scene of the pre-1947 Karachi.[463] As of today, about 6,000 Goans remain in Pakistan, mainly in Karachi.[462]

Portuguese heritage is also present in Bangladesh, where they were the first Europeans to arrive:[465] not only did the Portuguese introduce Catholicism, a religion now professed by about 375,000 Bangladeshis,[466] but their heritage extends also to more than 1,500 words in Bengali that are of Portuguese origin.[467] In colonial times, the Portuguese population in Bangladesh may have reached 40,000 people[468][469] but, as time went by, many resettled to other colonies. Those who remained are now perfectly integrated in the larger Bangladeshi society. Notable examples of Portuguese influence in Bangladesh are the surnames bore by a large part of the Catholics, as well as Bangladesh's oldest church, the Holy Rosary Church in Dhaka.[470] As of now, the Portuguese community in Bangladesh is almost no existent with only a few expatriates[471] and some descendants of the early settlers.

Nevertheless, the most important Portuguese community found today in the Indian subcontinent – as well as in Asia as a whole when taking into account people with distant Portuguese ancestry – remains the one that has settled in India, especially in Goa, Damão e Diu and Dadrá e Nagar Aveli.[472]

East Asia

A small but growing Portuguese community – consisting mainly of recent expats and numbering about 3,500 people – is found in Japan,[473][474] South Korea,[475] China[476][477] and Taiwan, whose name used by European literature until the 20th century – Formosa, meaning "Beautiful (island)" - came from Portuguese.[478]

A 20,700 people-strong community also exists in Hong Kong, mainly of Macanese descent.[479] Notable people of Portuguese descent from Hong Kong include personalities such as Joe Junior, Michelle Reis, Rowan Varty, Rita Carpio and Ray Cordeiro.

Due to the shared past, the most important Portuguese community in Eastern Asia is the one in Macau, that was, until 1999, a Portuguese colony. With more than 150,000 Portuguese citizens, accounting for 22.34% of the total population, Portuguese influence in Macau is still very visible and Macau still has, as of today, the largest concentration of Portuguese nationals in Asia as well as one of the most important in the world.[480] Notable people from Macau of Portuguese descent include personalities such as singer Germano Guilherme.

Portuguese literature has a long and varied history, with roots in the Middle Ages when troubadours dominated the literary world. In the 16th century, Portugal's literature entered its "Golden Age", during which time poets like Luís de Camões and Francisco de Sá de Miranda were some of the nation's most renowned literary figures.[607] Portuguese is often referred as to the "língua de Camões" (Camões's language), highlighting the importance the author had in forging the national identity as well as the domestic literary production.[608]

Famous Portuguese authors from the Age of Discoveries include Públia Hortênsia de Castro, Gomes Eanes de Zurara, Joana Vaz, Fernão Mendes Pinto (author of Peregrinação), Joana da Gama, Fernão Lopes and Violante do Céu.[609]

A new generation of authors appeared in the 19th century, including Almeida Garrett, who is credited with founding modern Portuguese literature. His writings reflect the political and social revolutions taking place in Portugal at the time, and his writing style is recognized as exceptionally original and unique for the time.[610]

Portuguese authors like Fernando Pessoa and Guerra Junqueiro gained international acclaim for their writings in the 20th century. In this century there was a great rise in the country's literary production. It is worth mentioning that Pessoa, due to him being considered very innovative and ground-breaking for his time, is often referred to as one of the most emblematic 20th-century Portuguese authors and his contributions to the nation's literary production are among the most notable ones.[611][612]

With modern authors like José Saramago and António Lobo Antunes, receiving both home and foreign critical recognition, Portuguese literature is still thriving today. These authors write about identity, culture, and society, and their writing reflects Portugal's rich and varied cultural legacy.