La pena capital , también conocida como pena de muerte y antiguamente llamada homicidio judicial , [1] [2] es el asesinato sancionado por el estado de una persona como castigo por una mala conducta real o supuesta. [3] La sentencia que ordena que un delincuente sea castigado de esa manera se conoce como sentencia de muerte , y el acto de llevar a cabo la sentencia se conoce como ejecución . Un prisionero que ha sido sentenciado a muerte y espera la ejecución es condenado y comúnmente se lo conoce como "en el corredor de la muerte ". Etimológicamente, el término capital ( lit. ' de la cabeza ' , derivado a través del latín capitalis de caput , "cabeza") se refiere a la ejecución por decapitación , [4] pero las ejecuciones se llevan a cabo por muchos métodos , incluidos el ahorcamiento , el fusilamiento , la inyección letal , la lapidación , la electrocución y el gas .

Los delitos que se castigan con la muerte se conocen como delitos capitales , delitos capitales o delitos graves capitales , y varían según la jurisdicción, pero comúnmente incluyen delitos graves contra una persona, como asesinato , asesinato , asesinato en masa , asesinato de niños , violación agravada , terrorismo , secuestro de aeronaves , crímenes de guerra , crímenes contra la humanidad y genocidio , junto con delitos contra el Estado como intento de derrocar al gobierno , traición , espionaje , sedición y piratería . Además, en algunos casos, los actos de reincidencia , robo agravado y secuestro , además del tráfico de drogas, el tráfico de drogas y la posesión de drogas, son delitos capitales o agravantes. Sin embargo, los estados también han impuesto ejecuciones punitivas, por una amplia gama de conductas, por creencias y prácticas políticas o religiosas, por un estado fuera del control de uno o sin emplear ningún procedimiento significativo de debido proceso. [3] El asesinato judicial es el asesinato intencional y premeditado de una persona inocente mediante la pena capital. [5] Por ejemplo, las ejecuciones posteriores a los juicios-espectáculo en la Unión Soviética durante la Gran Purga de 1936-1938 fueron un instrumento de represión política.

Los 3 países principales por número de ejecuciones son China , Irán y Arabia Saudita . [6] En 2021, 56 países conservan la pena capital , 111 países la han abolido por completo de iure para todos los delitos, siete la han abolido para los delitos comunes (aunque la mantienen para circunstancias especiales como los crímenes de guerra) y 24 son abolicionistas en la práctica. [7] Aunque la mayoría de los países han abolido la pena capital, más de la mitad de la población mundial vive en países donde se mantiene la pena de muerte, incluidos India, Estados Unidos, Indonesia, Pakistán, Bangladesh, Japón, Vietnam, Egipto, Nigeria, Etiopía y la República Democrática del Congo. En 2023, solo 2 de los 38 países miembros de la OCDE ( Estados Unidos y Japón ) permiten la pena capital. [8]

La pena capital es controvertida, y muchas personas, organizaciones y grupos religiosos tienen opiniones diferentes sobre si es éticamente permisible. Amnistía Internacional declara que la pena de muerte viola los derechos humanos, específicamente "el derecho a la vida y el derecho a vivir libre de torturas o tratos o penas crueles, inhumanos o degradantes". [9] Estos derechos están protegidos por la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos , adoptada por las Naciones Unidas en 1948. [9] En la Unión Europea (UE), el artículo 2 de la Carta de los Derechos Fundamentales de la Unión Europea prohíbe el uso de la pena capital. [10] El Consejo de Europa , que tiene 46 estados miembros, ha trabajado para poner fin a la pena de muerte y no se ha llevado a cabo ninguna ejecución en sus actuales estados miembros desde 1997. La Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas ha adoptado, a lo largo de los años de 2007 a 2020, [11] ocho resoluciones no vinculantes que piden una moratoria global de las ejecuciones , con vistas a una eventual abolición. [12]

La ejecución de criminales y disidentes ha sido utilizada por casi todas las sociedades desde el comienzo de las civilizaciones en la Tierra. [13] Hasta el siglo XIX, sin sistemas penitenciarios desarrollados, con frecuencia no había una alternativa viable para garantizar la disuasión e incapacitación de los criminales. [14] En tiempos premodernos, las ejecuciones en sí mismas a menudo implicaban tortura con métodos dolorosos, como la rueda de romper , el arrastre de quilla , el aserrado , el ahorcamiento, el descuartizamiento , la quema en la hoguera , la crucifixión , el desollamiento , el corte lento , la cocción viva , el empalamiento , el mazzatello , el soplo de un arma , el schwedentrunk y el escafismo . Otros métodos que aparecen solo en la leyenda incluyen el águila ensangrentada y el toro de bronce . [ cita requerida ]

El uso de la ejecución formal se remonta al comienzo de la historia registrada. La mayoría de los registros históricos y diversas prácticas tribales primitivas indican que la pena de muerte formaba parte de su sistema de justicia. Los castigos comunitarios por las malas acciones generalmente incluían una compensación monetaria por sangre para el malhechor, castigos corporales, exclusión , destierro y ejecución. En las sociedades tribales, la compensación y la exclusión a menudo se consideraban suficientes como forma de justicia. [15] La respuesta a los crímenes cometidos por tribus, clanes o comunidades vecinas incluía una disculpa formal, una compensación, enemistades sangrientas y guerras tribales .

Una venganza de sangre o venganza ocurre cuando el arbitraje entre familias o tribus fracasa o no existe un sistema de arbitraje. Esta forma de justicia era común antes de que surgiera un sistema de arbitraje basado en el Estado o en una religión organizada. Puede ser resultado de un crimen, de disputas por tierras o de un código de honor. “Los actos de represalia subrayan la capacidad del colectivo social para defenderse y demostrar a los enemigos (así como a los aliados potenciales) que los daños a la propiedad, a los derechos o a la persona no quedarán impunes”. [16]

En la mayoría de los países que practican la pena capital, ahora está reservada para el asesinato, el terrorismo, los crímenes de guerra, el espionaje, la traición o como parte de la justicia militar. En algunos países, los delitos sexuales , como la violación, la fornicación , el adulterio , el incesto , la sodomía y la bestialidad conllevan la pena de muerte, al igual que los delitos religiosos como el hudud , la zina y los delitos qisas , como la apostasía (renuncia formal a la religión del estado ), la blasfemia , el moharebeh , el hirabah , el fasad , el mofsed-e-filarz y la brujería. En muchos países que utilizan la pena de muerte , el tráfico de drogas y, a menudo, la posesión de drogas también es un delito capital. En China, la trata de personas y los casos graves de corrupción y delitos financieros se castigan con la pena de muerte. En los ejércitos de todo el mundo, los tribunales marciales han impuesto sentencias de muerte por delitos como la cobardía, la deserción , la insubordinación y el motín . [17]

Las elaboraciones del arbitraje tribal de las disputas incluían acuerdos de paz a menudo realizados en un contexto religioso y un sistema de compensación. La compensación se basaba en el principio de sustitución que podía incluir compensación material (por ejemplo, ganado, esclavos, tierra), intercambio de novias o novios, o pago de la deuda de sangre. Las reglas de liquidación podían permitir que la sangre animal reemplazara a la sangre humana, o transferencias de propiedad o dinero de sangre o, en algunos casos, una oferta de una persona para su ejecución. La persona ofrecida para la ejecución no tenía que ser un perpetrador original del crimen porque el sistema social se basaba en tribus y clanes, no en individuos. Las disputas de sangre podían regularse en reuniones, como las cosas de los nórdicos . [18] Los sistemas derivados de las disputas de sangre pueden sobrevivir junto con sistemas legales más avanzados o recibir reconocimiento de los tribunales (por ejemplo, juicio por combate o dinero de sangre). Uno de los refinamientos más modernos de la disputa de sangre es el duelo .

En ciertas partes del mundo surgieron naciones en forma de antiguas repúblicas, monarquías u oligarquías tribales. Estas naciones a menudo estaban unidas por lazos lingüísticos, religiosos o familiares comunes. Además, la expansión de estas naciones a menudo se produjo mediante la conquista de tribus o naciones vecinas. En consecuencia, surgieron varias clases de realeza, nobleza, diversos plebeyos y esclavos. En consecuencia, los sistemas de arbitraje tribal se sumergieron en un sistema de justicia más unificado que formalizó la relación entre las diferentes "clases sociales" en lugar de "tribus". El ejemplo más antiguo y famoso es el Código de Hammurabi , que establece diferentes castigos y compensaciones, según la diferente clase o grupo de víctimas y perpetradores. La Torá/Antiguo Testamento establece la pena de muerte para el asesinato, [19] el secuestro, la práctica de la magia, la violación del Shabat , la blasfemia y una amplia gama de delitos sexuales, aunque la evidencia [ especificar ] sugiere que las ejecuciones reales fueron extremadamente raras, si es que ocurrieron. [20] [ página necesaria ]

Otro ejemplo proviene de la Antigua Grecia , donde el sistema legal ateniense que reemplazó al derecho oral consuetudinario fue escrito por primera vez por Dracón alrededor del 621 a. C.: la pena de muerte se aplicó para una gama particularmente amplia de delitos, aunque Solón luego derogó el código de Dracón y publicó nuevas leyes, manteniendo la pena capital solo para el homicidio intencional y solo con el permiso de la familia de la víctima. [21] La palabra draconiano deriva de las leyes de Dracón. Los romanos también usaban la pena de muerte para una amplia gama de delitos. [22]

Protágoras (cuyo pensamiento recoge Platón ) critica el principio de venganza, porque una vez producido el daño no puede ser anulado por ninguna acción. Así pues, si la pena de muerte ha de ser impuesta por la sociedad, es sólo para protegerla del criminal o con un fin disuasorio. [23] "El único derecho que Protágoras conoce es, pues, el derecho humano, que, establecido y sancionado por una colectividad soberana, se identifica con la ley positiva o vigente en la ciudad. De hecho, encuentra su garantía en la pena de muerte que amenaza a todos los que no la respetan." [24] [25]

Platón veía la pena de muerte como un medio de purificación, porque los crímenes son una “mancilla”. Así, en las Leyes , consideraba necesaria la ejecución del animal o la destrucción del objeto que causaba la muerte de un hombre por accidente. Para los asesinos, consideraba que el acto del homicidio no es natural ni está plenamente consentido por el criminal. El homicidio es, pues, una enfermedad del alma , que debe ser reeducada lo más posible y, en última instancia, condenada a muerte si no es posible la rehabilitación. [26]

Según Aristóteles , para quien el libre albedrío es propio del hombre, la persona es responsable de sus actos. Si se ha cometido un delito, el juez debe definir la pena que permita anular el delito mediante una indemnización. Así, la indemnización pecuniaria aparece para los delincuentes menos recalcitrantes y cuya rehabilitación se considera posible. Sin embargo, para los demás, sostiene, la pena de muerte es necesaria. [27]

Esta filosofía, que pretende por un lado proteger a la sociedad y por otro compensar para cancelar las consecuencias del delito cometido, inspiró el derecho penal occidental hasta el siglo XVII, época en la que aparecieron las primeras reflexiones sobre la abolición de la pena de muerte. [28]

Las Doce Tablas , el conjunto de leyes dictadas desde la Roma arcaica, prescriben la pena de muerte para una variedad de delitos, entre ellos la difamación, el incendio provocado y el robo. [29] Durante la Baja República , hubo consenso entre el público y los legisladores para reducir la incidencia de la pena capital. Esta opinión llevó a que se prescribiera el exilio voluntario en lugar de la pena de muerte, por el cual un convicto podía elegir entre irse al exilio o enfrentarse a la ejecución. [30]

En el Senado romano se celebró un debate histórico, seguido de una votación, para decidir el destino de los aliados de Catilina cuando intentó hacerse con el poder en diciembre del 63 a. C. Cicerón, entonces cónsul romano , argumentó a favor de matar a los conspiradores sin juicio por decisión del Senado ( Senatus consultum ultimum ) y fue apoyado por la mayoría de los senadores; entre las voces minoritarias opuestas a la ejecución, la más notable fue la de Julio César . [31] La costumbre era diferente para los extranjeros que no tenían derechos como ciudadanos romanos , y especialmente para los esclavos, que eran propiedad transferible. [ cita requerida ]

La crucifixión era una forma de castigo empleada por primera vez por los romanos contra los esclavos que se rebelaban , y durante la era republicana estuvo reservada para esclavos , bandidos y traidores . Con la intención de ser un castigo, una humillación y un elemento disuasorio, los condenados podían tardar hasta unos días en morir. Los cadáveres de los crucificados solían dejarse en las cruces para que se descompusieran y fueran comidos por los animales. [32]

Hubo una época en la dinastía Tang (618-907) en la que se abolió la pena de muerte. [33] Esto fue en el año 747, promulgada por el emperador Xuanzong de Tang (r. 712-756). Al abolir la pena de muerte, Xuanzong ordenó a sus funcionarios que se remitieran a la regulación más cercana por analogía al sentenciar a los culpables de delitos para los cuales el castigo prescrito era la ejecución. Así, dependiendo de la gravedad del delito, un castigo de flagelación severa con la vara gruesa o el exilio a la remota región de Lingnan podría sustituir a la pena capital. Sin embargo, la pena de muerte fue restaurada solo 12 años después, en 759, en respuesta a la Rebelión de An Lushan . [34] En esta época de la dinastía Tang, solo el emperador tenía la autoridad para sentenciar a los criminales a ejecución. Bajo el régimen de Xuanzong la pena capital era relativamente poco frecuente, con sólo 24 ejecuciones en el año 730 y 58 ejecuciones en el año 736. [33]

Las dos formas más comunes de ejecución en la dinastía Tang eran el estrangulamiento y la decapitación, que eran los métodos de ejecución prescritos para 144 y 89 delitos respectivamente. El estrangulamiento era la sentencia prescrita para presentar una acusación contra los padres o abuelos ante un magistrado, planear secuestrar a una persona y venderla como esclava y abrir un ataúd mientras se profanaba una tumba. La decapitación era el método de ejecución prescrito para delitos más graves, como la traición y la sedición. A pesar de la gran incomodidad que implicaba, la mayoría de los chinos Tang preferían el estrangulamiento a la decapitación, como resultado de la creencia tradicional china Tang de que el cuerpo es un regalo de los padres y que, por lo tanto, es una falta de respeto a los antepasados morir sin devolver el cuerpo intacto a la tumba.

En la dinastía Tang se practicaban otras formas de pena capital, de las cuales al menos las dos primeras que siguen eran extralegales. [ aclaración necesaria ] La primera de ellas era la flagelación hasta la muerte con la vara gruesa [ aclaración necesaria ] que era común durante toda la dinastía Tang, especialmente en casos de corrupción grave. La segunda era el truncamiento, en el que la persona condenada era cortada en dos por la cintura con un cuchillo de forraje y luego se la dejaba desangrar hasta morir. [35] Otra forma de ejecución llamada Ling Chi ( corte lento ), o muerte por/de mil cortes, se utilizó desde el final de la dinastía Tang (alrededor de 900) hasta su abolición en 1905.

Cuando un ministro de quinto grado o superior recibía una sentencia de muerte, el emperador podía concederle una dispensa especial que le permitía suicidarse en lugar de ser ejecutado. Incluso cuando no se concedía este privilegio, la ley exigía que los guardianes del ministro condenado le proporcionaran comida y cerveza y lo transportaran al lugar de la ejecución en un carro en lugar de tener que ir a pie.

Casi todas las ejecuciones durante la dinastía Tang se llevaban a cabo en público como advertencia a la población. Las cabezas de los ejecutados se exhibían en postes o lanzas. Cuando las autoridades locales decapitaban a un criminal convicto, la cabeza era encajonada y enviada a la capital como prueba de identidad y de que la ejecución había tenido lugar. [35]

En la Europa medieval y moderna, antes del desarrollo de los sistemas penitenciarios modernos, la pena de muerte también se utilizaba como una forma generalizada de castigo incluso para delitos menores. [36]

En la Europa moderna temprana, un pánico masivo en relación con la brujería se extendió por toda Europa y más tarde por las colonias europeas en América del Norte . Durante este período, hubo afirmaciones generalizadas de que las malévolas brujas satánicas operaban como una amenaza organizada para la cristiandad . Como resultado, decenas de miles de mujeres fueron procesadas por brujería y ejecutadas a través de los juicios por brujería del período moderno temprano (entre los siglos XV y XVIII).

La pena de muerte también se aplicaba a delitos sexuales como la sodomía . En la historia temprana del Islam (siglos VII-XI), hay una serie de "informes supuestos (pero mutuamente inconsistentes)" ( athar ) sobre los castigos de la sodomía ordenados por algunos de los primeros califas . [37] [38] Abu Bakr , el primer califa del califato Rashidun , aparentemente recomendó derribar un muro sobre el culpable, o bien quemarlo vivo , [38] mientras que se dice que Ali ibn Abi Talib ordenó la muerte por lapidación para un sodomita y tiró a otro de cabeza desde lo alto del edificio más alto de la ciudad; según Ibn Abbas , este último castigo debe ser seguido por la lapidación. [38] [39] Otros líderes musulmanes medievales, como los califas abasíes en Bagdad (más notablemente al-Mu'tadid ), a menudo eran crueles en sus castigos. [40] [ página necesaria ] En la Inglaterra moderna temprana, la Ley de Sodomía de 1533 estipulaba la horca como castigo por " sodomía ". James Pratt y John Smith fueron los dos últimos ingleses ejecutados por sodomía en 1835. [41] En 1636, las leyes de la colonia puritana de Plymouth incluían una sentencia de muerte para la sodomía y la sodomía. [42] La colonia de la bahía de Massachusetts siguió su ejemplo en 1641. A lo largo del siglo XIX, los estados de EE. UU. derogaron las sentencias de muerte de sus leyes de sodomía, siendo Carolina del Sur el último en hacerlo en 1873. [43]

Los historiadores reconocen que durante la Alta Edad Media , las poblaciones cristianas que vivían en las tierras invadidas por los ejércitos árabes musulmanes entre los siglos VII y X sufrieron discriminación religiosa , persecución religiosa , violencia religiosa y martirio en múltiples ocasiones a manos de funcionarios y gobernantes árabes musulmanes. [44] [45] Como Pueblo del Libro , los cristianos bajo el dominio musulmán estaban sujetos al estatus de dhimmi (junto con los judíos , samaritanos , gnósticos , mandeos y zoroastrianos), que era inferior al estatus de los musulmanes. [45] [46] Por tanto, los cristianos y otras minorías religiosas se enfrentaron a la discriminación religiosa y la persecución religiosa , ya que se les prohibió hacer proselitismo (para los cristianos, estaba prohibido evangelizar o difundir el cristianismo ) en las tierras invadidas por los musulmanes árabes bajo pena de muerte, se les prohibió portar armas, ejercer determinadas profesiones y se les obligó a vestirse de forma diferente para distinguirse de los árabes. [46] Bajo la sharia , los no musulmanes estaban obligados a pagar impuestos jizya y kharaj , [45] [46] junto con fuertes rescates periódicos impuestos a las comunidades cristianas por los gobernantes musulmanes para financiar campañas militares, todo lo cual contribuía con una proporción significativa de ingresos a los estados islámicos mientras que, a la inversa, reducía a muchos cristianos a la pobreza, y estas dificultades financieras y sociales obligaron a muchos cristianos a convertirse al Islam. [46] Los cristianos que no podían pagar estos impuestos se vieron obligados a entregar a sus hijos a los gobernantes musulmanes como pago, quienes los venderían como esclavos a hogares musulmanes donde fueron obligados a convertirse al Islam . [46] Muchos mártires cristianos fueron ejecutados bajo la pena de muerte islámica por defender su fe cristiana a través de dramáticos actos de resistencia como negarse a convertirse al Islam, repudio a la religión islámica y posterior reconversión al cristianismo , y blasfemia hacia las creencias musulmanas . [44]

A pesar del uso generalizado de la pena de muerte, no eran desconocidos los reclamos de reforma. El erudito jurista judío del siglo XII, Moisés Maimónides, escribió: "Es mejor y más satisfactorio absolver a mil personas culpables que condenar a muerte a un solo inocente". Sostenía que ejecutar a un criminal acusado sin tener una certeza absoluta conduciría a una pendiente resbaladiza de disminución de la carga de la prueba , hasta que acabaríamos condenando simplemente "según el capricho del juez". La preocupación de Maimónides era mantener el respeto popular por la ley, y consideraba que los errores de comisión eran mucho más amenazantes que los errores de omisión. [47]

Si en la Edad Media se tenía en cuenta el aspecto expiatorio de la pena de muerte, ya no es así con los Lumières . Estos definen el lugar del hombre en la sociedad, no según una regla divina, sino como un contrato establecido al nacer entre el ciudadano y la sociedad, es decir, el contrato social . A partir de ese momento, la pena capital debe ser vista como útil a la sociedad por su efecto disuasorio, pero también como un medio de protección de ésta frente a los criminales. [48]

En los últimos siglos, con el surgimiento de los estados nacionales modernos , la justicia pasó a asociarse cada vez más con el concepto de derechos naturales y legales . El período vio un aumento de las fuerzas policiales permanentes y las instituciones penitenciales permanentes. La teoría de la elección racional , un enfoque utilitarista de la criminología que justifica el castigo como una forma de disuasión en lugar de la retribución, se remonta a Cesare Beccaria , cuyo influyente tratado Sobre los delitos y las penas (1764) fue el primer análisis detallado de la pena capital para exigir la abolición de la pena de muerte. [49] En Inglaterra, Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), el fundador del utilitarismo moderno, pidió la abolición de la pena de muerte. [50] Beccaria, y más tarde Charles Dickens y Karl Marx notaron la incidencia del aumento de la criminalidad violenta en los momentos y lugares de las ejecuciones. El reconocimiento oficial de este fenómeno llevó a que las ejecuciones se llevaran a cabo dentro de las cárceles, lejos de la vista del público.

En Inglaterra, en el siglo XVIII, cuando no había policía, el Parlamento aumentó drásticamente el número de delitos capitales a más de 200. Se trataba principalmente de delitos contra la propiedad, como por ejemplo cortar un cerezo en un huerto. [51] En 1820, había 160, incluidos delitos como el hurto en tiendas, el hurto menor o el robo de ganado. [52] La severidad del llamado Código Sangriento era a menudo atenuada por los jurados que se negaban a condenar, o por los jueces, en el caso del hurto menor, que arbitrariamente fijaban el valor robado por debajo del nivel legal para un delito capital. [53]

En la Alemania nazi , había tres tipos de pena capital: ahorcamiento, decapitación y muerte por fusilamiento. [54] Además, las organizaciones militares modernas emplearon la pena capital como un medio para mantener la disciplina militar. En el pasado, la cobardía , la ausencia sin permiso, la deserción , la insubordinación , eludir el fuego enemigo y desobedecer las órdenes eran a menudo delitos castigados con la muerte (véase diezmación y correr el guante ). Un método de ejecución, desde que las armas de fuego se volvieron de uso común, también ha sido el pelotón de fusilamiento, aunque algunos países utilizan la ejecución con un solo disparo en la cabeza o el cuello.

Varios estados autoritarios emplearon la pena de muerte como un potente medio de opresión política . [55] El autor antisoviético Robert Conquest afirmó que más de un millón de ciudadanos soviéticos fueron ejecutados durante la Gran Purga de 1936 a 1938, casi todos de un tiro en la nuca. [56] [57] Mao Zedong declaró públicamente que "800.000" personas habían sido ejecutadas en China durante la Revolución Cultural (1966-1976). En parte como respuesta a tales excesos, las organizaciones de derechos civiles comenzaron a poner cada vez más énfasis en el concepto de derechos humanos y en la abolición de la pena de muerte. [ cita requerida ]

Por continente, todos los países europeos menos uno han abolido la pena capital; [nota 1] muchos países de Oceanía la han abolido; [nota 2] la mayoría de los países de las Américas han abolido su uso, [nota 3] mientras que unos pocos la mantienen activamente; [nota 4] menos de la mitad de los países de África la mantienen; [nota 5] y la mayoría de los países de Asia la mantienen, por ejemplo, China , Japón e India . [58]

La abolición se adoptó a menudo debido a cambios políticos, como cuando los países pasaron del autoritarismo a la democracia o cuando se convirtió en una condición de entrada a la UE. Estados Unidos es una notable excepción: algunos estados han prohibido la pena capital durante décadas; el primero fue Michigan , donde se abolió en 1846, mientras que otros estados todavía la utilizan activamente en la actualidad. La pena de muerte en Estados Unidos sigue siendo un tema polémico que se debate acaloradamente .

En los países retencionistas, el debate se reaviva a veces cuando se produce un error judicial, aunque esto tiende a provocar esfuerzos legislativos para mejorar el proceso judicial en lugar de abolir la pena de muerte. En los países abolicionistas, el debate se reaviva a veces por asesinatos particularmente brutales, aunque pocos países la han restablecido después de abolirla. Sin embargo, un aumento de los delitos graves y violentos, como asesinatos o ataques terroristas, ha llevado a algunos países a poner fin de hecho a la moratoria sobre la pena de muerte. Un ejemplo notable es Pakistán , que en diciembre de 2014 levantó una moratoria de seis años sobre las ejecuciones después de la masacre de la escuela de Peshawar durante la cual 132 estudiantes y 9 miembros del personal de la Escuela Pública del Ejército y la Facultad de Grado de Peshawar fueron asesinados por terroristas de Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan , un grupo distinto de los talibanes afganos , que condenaron el ataque. [59] Desde entonces, Pakistán ha ejecutado a más de 400 convictos. [60]

En 2017, dos países importantes, Turquía y Filipinas , vieron a sus ejecutivos tomar medidas para restablecer la pena de muerte. [61] Ese mismo año, la aprobación de la ley en Filipinas no logró obtener la aprobación del Senado. [62]

El 29 de diciembre de 2021, después de una moratoria de 20 años, el gobierno de Kazajstán promulgó la "Ley sobre enmiendas y adiciones a ciertos actos legislativos de la República de Kazajstán sobre la abolición de la pena de muerte", firmada por el presidente Kassym-Jomart Tokayev como parte de una serie de reformas ómnibus del sistema jurídico kazajo bajo la iniciativa "Estado que escucha". [63]

En 724 d. C., en Japón, la pena de muerte fue prohibida durante el reinado del emperador Shōmu , pero la abolición solo duró unos pocos años. [64] En 818, el emperador Saga abolió la pena de muerte bajo la influencia del sintoísmo y duró hasta 1156. [65] [66] En China, la pena de muerte fue prohibida por el emperador Xuanzong de Tang en 747 , reemplazándola por el exilio o la flagelación . Sin embargo, la prohibición solo duró 12 años. [64] Después de su conversión al cristianismo en 988, Vladimir el Grande abolió la pena de muerte en la Rus de Kiev , junto con la tortura y la mutilación; el castigo corporal también rara vez se utilizó. [67]

En Inglaterra, se incluyó una declaración pública de oposición en Las doce conclusiones de los lolardos , escrita en 1395. En la República posclásica de Poljica , la vida se garantizó como un derecho básico en su Estatuto de Poljica de 1440. La Utopía de Sir Thomas More , publicada en 1516, debatió los beneficios de la pena de muerte en forma de diálogo, sin llegar a ninguna conclusión firme. El propio More fue ejecutado por traición en 1535.

La oposición más reciente a la pena de muerte surgió del libro del italiano Cesare Beccaria Dei Delitti e Delle Pene (" Sobre los crímenes y las penas "), publicado en 1764. En este libro, Beccaria pretendía demostrar no sólo la injusticia, sino incluso la inutilidad desde el punto de vista del bienestar social , de la tortura y la pena de muerte. Influenciado por el libro, el gran duque Leopoldo II de Habsburgo, futuro emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico , abolió la pena de muerte en el entonces independiente Gran Ducado de Toscana , la primera abolición en los tiempos modernos. El 30 de noviembre de 1786, después de haber bloqueado de facto las ejecuciones (la última fue en 1769), Leopoldo promulgó la reforma del código penal que abolió la pena de muerte y ordenó la destrucción de todos los instrumentos para la ejecución capital en su tierra. En 2000, las autoridades regionales de Toscana instituyeron un feriado anual el 30 de noviembre para conmemorar el evento. El evento es conmemorado en este día por 300 ciudades de todo el mundo que celebran el Día de las Ciudades por la Vida . El hermano de Leopoldo , José , el entonces emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico, abolió en sus tierras inmediatas en 1787 la pena capital, que aunque solo duró hasta 1795, después de que ambos habían muerto y el hijo de Leopoldo, Francisco, la abolió en sus tierras inmediatas. En Toscana se reintrodujo en 1790 después de la partida de Leopoldo convirtiéndose en emperador. Solo después de 1831 la pena capital volvió a suspenderse en ocasiones, aunque hubo que esperar hasta 2007 para abolirla por completo en Italia .

El Reino de Tahití (cuando la isla era independiente) fue la primera asamblea legislativa del mundo en abolir la pena de muerte en 1824. Tahití conmutó la pena de muerte por el destierro. [68]

En Estados Unidos, Michigan fue el primer estado en prohibir la pena de muerte, el 18 de mayo de 1846. [69]

La efímera República revolucionaria romana prohibió la pena capital en 1849. Venezuela siguió su ejemplo y abolió la pena de muerte en 1863 [70] [71] y San Marino lo hizo en 1865. La última ejecución en San Marino había tenido lugar en 1468. En Portugal, después de propuestas legislativas en 1852 y 1863, la pena de muerte fue abolida en 1867. La última ejecución en Brasil fue en 1876; desde entonces todas las condenas fueron conmutadas por el emperador Pedro II hasta su abolición para delitos civiles y militares en tiempo de paz en 1891. La pena por delitos cometidos en tiempo de paz fue luego restablecida y abolida nuevamente dos veces (1938-1953 y 1969-1978), pero en esas ocasiones se restringió a actos de terrorismo o subversión considerados "guerra interna" y todas las sentencias fueron conmutadas y no ejecutadas.

Muchos países han abolido la pena capital, ya sea en la ley o en la práctica. Desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial , ha habido una tendencia hacia la abolición de la pena capital. La pena capital ha sido abolida completamente por 108 países, otros siete lo han hecho para todos los delitos, excepto en circunstancias especiales, y otros 26 la han abolido en la práctica porque no la han utilizado durante al menos 10 años y se cree que tienen una política o una práctica establecida contra la realización de ejecuciones. [72]

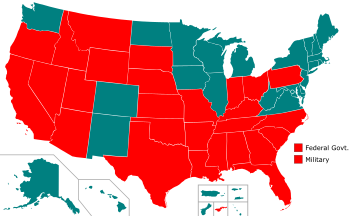

En los Estados Unidos, entre 1972 y 1976, la pena de muerte fue declarada inconstitucional a raíz del caso Furman contra Georgia , pero en 1976 el caso Gregg contra Georgia volvió a permitir la pena de muerte en determinadas circunstancias. En los casos Atkins contra Virginia (2002; pena de muerte inconstitucional para personas con discapacidad intelectual ) y Roper contra Simmons (2005; pena de muerte inconstitucional si el acusado era menor de 18 años en el momento de cometer el delito) se impusieron más limitaciones a la pena de muerte. En los Estados Unidos, 23 de los 50 estados y Washington, DC prohíben la pena capital.

En el Reino Unido, se abolió por asesinato (dejando solo la traición, la piratería con violencia , el incendio en los astilleros reales y una serie de delitos militares en tiempos de guerra como crímenes capitales) para un experimento de cinco años en 1965 y de forma permanente en 1969, la última ejecución tuvo lugar en 1964. Fue abolida para todos los delitos en 1998. [73] El Protocolo 13 del Convenio Europeo de Derechos Humanos, que entró en vigor por primera vez en 2003, prohíbe la pena de muerte en todas las circunstancias para los Estados que son parte del mismo, incluido el Reino Unido desde 2004.

La abolición se produjo en Canadá en 1976 (excepto en el caso de algunos delitos militares, que se abolieron por completo en 1998); en Francia en 1981 ; y en Australia en 1973 (aunque el estado de Australia Occidental mantuvo la pena hasta 1984). En Australia del Sur, bajo el mandato del entonces primer ministro Dunstan, se modificó la Ley de Consolidación del Derecho Penal de 1935 (SA) de modo que la pena de muerte se sustituyó por la de cadena perpetua en 1976.

En 1977, la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas afirmó en una resolución formal que en todo el mundo es deseable "restringir progresivamente el número de delitos por los cuales pueda imponerse la pena de muerte, con miras a la conveniencia de abolir este castigo". [74]

La mayoría de las naciones, incluidos casi todos los países desarrollados , han abolido la pena capital ya sea en la ley o en la práctica; las excepciones notables son Estados Unidos , Japón , Taiwán y Singapur . Además, la pena capital también se lleva a cabo en China , India y la mayoría de los estados islámicos . [75] [76] [77] [78] [79] [80]

Desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial , ha habido una tendencia hacia la abolición de la pena de muerte. 54 países mantienen la pena de muerte en uso activo, 112 países han abolido la pena capital por completo, 7 lo han hecho para todos los delitos excepto en circunstancias especiales, y 22 más la han abolido en la práctica porque no la han utilizado durante al menos 10 años y se cree que tienen una política o práctica establecida contra la realización de ejecuciones. [81]

According to Amnesty International, 20 countries are known to have performed executions in 2022.[82] There are countries which do not publish information on the use of capital punishment, most significantly China and North Korea. According to Amnesty International, around 1,000 prisoners were executed in 2017.[83] Amnesty reported in 2004 and 2009 that Singapore and Iraq respectively had the world's highest per capita execution rate.[84][85] According to Al Jazeera and UN Special Rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed, Iran has had the world's highest per capita execution rate.[86][87] A 2012 EU report from the Directorate-General for External Relations' policy department pointed to Gaza as having the highest per capita execution rate in the MENA region.[88]

The use of the death penalty is becoming increasingly restrained in some retentionist countries including Taiwan and Singapore.[90][better source needed] Indonesia carried out no executions between November 2008 and March 2013.[91] Singapore, Japan and the United States are the only developed countries that are classified by Amnesty International as 'retentionist' (South Korea is classified as 'abolitionist in practice').[92][93] Nearly all retentionist countries are situated in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean.[92] The only retentionist country in Europe is Belarus and in March 2023 Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko signed a law which allows to use capital punishment against officials and soldiers convicted of high treason.[94] During the 1980s, the democratisation of Latin America swelled the ranks of abolitionist countries.[95]

This was soon followed by the overthrow of the socialist states in Europe. Many of these countries aspired to enter the EU, which strictly requires member states not to practice the death penalty, as does the Council of Europe (see Capital punishment in Europe). Public support for the death penalty in the EU varies.[96] The last execution in a member state of the present-day Council of Europe took place in 1997 in Ukraine.[97][98] In contrast, the rapid industrialisation in Asia has seen an increase in the number of developed countries which are also retentionist. In these countries, the death penalty retains strong public support, and the matter receives little attention from the government or the media; in China there is a small but significant and growing movement to abolish the death penalty altogether.[99] This trend has been followed by some African and Middle Eastern countries where support for the death penalty remains high.

Some countries have resumed practising the death penalty after having previously suspended the practice for long periods. The United States suspended executions in 1972 but resumed them in 1976; there was no execution in India between 1995 and 2004; and Sri Lanka declared an end to its moratorium on the death penalty on 20 November 2004,[100] although it has not yet performed any further executions. The Philippines re-introduced the death penalty in 1993 after abolishing it in 1987, but again abolished it in 2006.[101]

The United States and Japan are the only developed countries to have recently carried out executions. The U.S. federal government, the U.S. military, and 27 states have a valid death penalty statute, and over 1,400 executions have been carried in the United States since it reinstated the death penalty in 1976. Japan has 108 inmates with finalized death sentences as of February 2, 2024[update], after Yuki Endo, who was sentenced to death on 18 January, by the Kofu District Court for murdering the parents of his love interest and setting fire to their home in Yamanashi prefecture on 12 October 2021, when Endo was 19 years old at the time of the double murder,[102] withdrew the appeal to the High Court, which was filed by his attorney, thus Endo's death sentence was finalized.

The most recent country to abolish the death penalty was Kazakhstan on 2 January 2021 after a moratorium dating back 2 decades.[103][104]

According to an Amnesty International report released in April 2020, Egypt ranked regionally third and globally fifth among the countries that carried out most executions in 2019. The country increasingly ignored international human rights concerns and criticism. In March 2021, Egypt executed 11 prisoners in a jail, who were convicted in cases of "murder, theft, and shooting".[105]

According to Amnesty International's 2021 report, at least 483 people were executed in 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure excluded the countries that classify death penalty data as state secret. The top five executioners for 2020 were China, Iran, Egypt, Iraq and Saudi Arabia.[106]

The public opinion on the death penalty varies considerably by country and by the crime in question. Countries where a majority of people are against execution include Norway, where only 25% support it.[107] Most French, Finns, and Italians also oppose the death penalty.[108] In 2020, 55% of Americans supported the death penalty for an individual convicted of murder, down from 60% in 2016, 64% in 2010, 65% in 2006, and 68% in 2001.[109][110][111][112] In 2020, 43% of Italians expressed support for the death penalty.[113][114][115]

In Taiwan, polls and research have consistently shown strong support for the death penalty at 80%. This includes a survey conducted by the National Development Council of Taiwan in 2016, showing that 88% of Taiwanese people disagree with abolishing the death penalty.[116][117][118] Its continuation of the practice drew criticism from local rights groups.[119]

The support and sentencing of capital punishment has been growing in India in the 2010s[120] due to anger over several recent brutal cases of rape, even though actual executions are comparatively rare.[120] While support for the death penalty for murder is still high in China, executions have dropped precipitously, with 3,000 executed in 2012 versus 12,000 in 2002.[121] A poll in South Africa, where capital punishment is abolished, found that 76% of millennial South Africans support re-introduction of the death penalty due to increasing incidents of rape and murder.[122][123]A 2017 poll found younger Mexicans are more likely to support capital punishment than older ones.[124] 57% of Brazilians support the death penalty. The age group that shows the greatest support for execution of those condemned is the 25 to 34-year-old category, in which 61% say they support it.[125]

A 2023 poll by Research Co. found that 54% of Canadians support reinstating the death penalty for murder in their country.[126] In April 2021 a poll found that 54% of Britons said they would support reinstating the death penalty for those convicted of terrorism in the UK, while 23% of respondents said they would be opposed.[127] In 2020, an Ipsos/Sopra Steria survey showed that 55% of the French people support re-introduction of the death penalty; this was an increase from 44% in 2019.[128]

The death penalty for juvenile offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime although the legal or accepted definition of juvenile offender may vary from one jurisdiction to another) has become increasingly rare. Considering the age of majority is not 18 in some countries or has not been clearly defined in law, since 1990 ten countries have executed offenders who were considered juveniles at the time of their crimes: China, Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United States, and Yemen.[129] China, Pakistan, the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen have since raised the minimum age to 18.[130] Amnesty International has recorded 61 verified executions since then, in several countries, of both juveniles and adults who had been convicted of committing their offences as juveniles.[131] China does not allow for the execution of those under 18, but child executions have reportedly taken place.[132]

.jpg/440px-Martyrs_of_Guernsey_(cropped).jpg)

One of the youngest children ever to be executed was the infant son of Perotine Massey on or around 18 July 1556. His mother was one of the Guernsey Martyrs who was executed for heresy, and his father had previously fled the island. At less than one day old, he was ordered to be burned by Bailiff Hellier Gosselin, with the advice of priests nearby who said the boy should burn due to having inherited moral stain from his mother, who had given birth during her execution.[133]

Since 1642 in Colonial America and in the United States, an estimated 365[134] juvenile offenders were executed by various colonial authorities and (after the American Revolution) the federal government.[135] The U.S. Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), and for all juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005).

In Prussia, children under the age of 14 were exempted from the death penalty in 1794.[136] Capital punishment was cancelled by the Electorate of Bavaria in 1751 for children under the age of 11[137] and by the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1813 for children and youth under 16 years.[138] In Prussia, the exemption was extended to youth under the age of 16 in 1851.[139] For the first time, all juveniles were excluded for the death penalty by the North German Confederation in 1871,[140] which was continued by the German Empire in 1872.[141] In Nazi Germany, capital punishment was reinstated for juveniles between 16 and 17 years in 1939.[142] This was broadened to children and youth from age 12 to 17 in 1943.[143] The death penalty for juveniles was abolished by West Germany, also generally, in 1949 and by East Germany in 1952.

In the Hereditary Lands, Austrian Silesia, Bohemia and Moravia within the Habsburg monarchy, capital punishment for children under the age of 11 was no longer foreseen by 1770.[144] The death penalty was, also for juveniles, nearly abolished in 1787 except for emergency or military law, which is unclear in regard of those. It was reintroduced for juveniles above 14 years by 1803,[145] and was raised by general criminal law to 20 years in 1852[146] and this exemption[147] and the alike one of military law in 1855,[148] which may have been up to 14 years in wartime,[149] were also introduced into all of the Austrian Empire.

In the Helvetic Republic, the death penalty for children and youth under the age of 16 was abolished in 1799[150] yet the country was already dissolved in 1803 whereas the law could remain in force if it was not replaced on cantonal level. In the canton of Bern, all juveniles were exempted from the death penalty at least in 1866.[151] In Fribourg, capital punishment was generally, including for juveniles, abolished by 1849. In Ticino, it was abolished for youth and young adults under the age of 20 in 1816.[152] In Zurich, the exclusion from the death penalty was extended for juveniles and young adults up to 19 years of age by 1835.[153] In 1942, the death penalty was almost deleted in criminal law, as well for juveniles, but since 1928 persisted in military law during wartime for youth above 14 years.[154] If no earlier change was made in the given subject, by 1979 juveniles could no longer be subject to the death penalty in military law during wartime.[155]

Between 2005 and May 2008, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Yemen were reported to have executed child offenders, the largest number occurring in Iran.[156]

During Hassan Rouhani's tenure as president of Iran from 2013 until 2021, at least 3,602 death sentences have been carried out. This includes the executions of 34 juvenile offenders.[157][158]

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which forbids capital punishment for juveniles under article 37(a), has been signed by all countries and subsequently ratified by all signatories with the exception of the United States (despite the US Supreme Court decisions abolishing the practice).[159] The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to a jus cogens of customary international law. A majority of countries are also party to the U.N. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (whose Article 6.5 also states that "Sentence of death shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age...").

Iran, despite its ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, was the world's largest executioner of juvenile offenders, for which it has been the subject of broad international condemnation; the country's record is the focus of the Stop Child Executions Campaign. But on 10 February 2012, Iran's parliament changed controversial laws relating to the execution of juveniles. In the new legislation the age of 18 (solar year) would be applied to accused of both genders and juvenile offenders must be sentenced pursuant to a separate law specifically dealing with juveniles.[160][161] Based on the Islamic law which now seems to have been revised, girls at the age of 9 and boys at 15 of lunar year (11 days shorter than a solar year) are deemed fully responsible for their crimes.[160] Iran accounted for two-thirds of the global total of such executions, and currently[needs update] has approximately 140 people considered as juveniles awaiting execution for crimes committed (up from 71 in 2007).[162][163] The past executions of Mahmoud Asgari, Ayaz Marhoni and Makwan Moloudzadeh became the focus of Iran's child capital punishment policy and the judicial system that hands down such sentences.[164][165] In 2023 Iran executed a minor who had knifed a man that fought him for following a girl in the street.[166]

Saudi Arabia also executes criminals who were minors at the time of the offence.[167][168] In 2013, Saudi Arabia was the center of an international controversy after it executed Rizana Nafeek, a Sri Lankan domestic worker, who was believed to have been 17 years old at the time of the crime.[169] Saudi Arabia banned execution for minors, except for terrorism cases, in April 2020.[170]

Japan has not executed juvenile criminals after August 1997, when they executed Norio Nagayama, a spree killer who had been convicted of shooting four people dead in the late 1960s. Nagayama's case created the eponymously named Nagayama standards, which take into account factors such as the number of victims, brutality and social impact of the crimes. The standards have been used in determining whether to apply the death sentence in murder cases. Teruhiko Seki, convicted of murdering four family members including a 4-year-old daughter and raping a 15-year-old daughter of a family in 1992, became the second inmate to be hanged for a crime committed as a minor in the first such execution in 20 years after Nagayama on 19 December 2017.[171] Takayuki Otsuki, who was convicted of raping and strangling a 23-year-old woman and subsequently strangling her 11-month-old daughter to death on 14 April 1999, when he was 18, is another inmate sentenced to death, and his request for retrial has been rejected by the Supreme Court of Japan.[172]

There is evidence that child executions are taking place in the parts of Somalia controlled by the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). In October 2008, a girl, Aisha Ibrahim Dhuhulow was buried up to her neck at a football stadium, then stoned to death in front of more than 1,000 people. Somalia's established Transitional Federal Government announced in November 2009 (reiterated in 2013)[173] that it plans to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This move was lauded by UNICEF as a welcome attempt to secure children's rights in the country.[174]

The following methods of execution have been used by various countries:[175][176][177][178][179]

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend". This definition excludes the presence of a small number of witnesses randomly selected to assure executive accountability.[180] While today the great majority of the world considers public executions to be distasteful and most countries have outlawed the practice, throughout much of history executions were performed publicly as a means for the state to demonstrate "its power before those who fell under its jurisdiction be they criminals, enemies, or political opponents". Additionally, it afforded the public a chance to witness "what was considered a great spectacle".[181]

Social historians note that beginning in the 20th century in the U.S. and western Europe, death in general became increasingly shielded from public view, occurring more and more behind the closed doors of the hospital.[182] Executions were likewise moved behind the walls of the penitentiary.[182] The last formal public executions occurred in 1868 in Britain, in 1936 in the U.S. and in 1939 in France.[182]

According to Amnesty International, in 2012, "public executions were known to have been carried out in Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia and Somalia".[183] There have been reports of public executions carried out by state and non-state actors in Hamas-controlled Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen.[184][185][186] Executions which can be classified as public were also carried out in the U.S. states of Florida and Utah as of 1992[update].[180]

Atrocity crimes such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide are usually punishable by death in countries retaining capital punishment.[187] Death sentences for such crimes were handed down and carried out during the Nuremberg Trials in 1946 and the Tokyo Trials in 1948, but starting in the 1990s, ad hoc tribunals such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) forbade the death penalty and can only impose life imprisonment as a maximum penalty.[188] This tradition is carried on by the current International Criminal Court.[188][189]

Intentional homicide is punishable by death in most countries retaining capital punishment, but generally provided it involves an aggravating factor required by statute or judicial precedents.[citation needed]

Some countries, including Singapore and Malaysia, made the death penalty mandatory for murder, though Singapore later changed its laws since 2013 to reserve the mandatory death sentence for intentional murder while providing an alternative sentence of life imprisonment with/without caning for murder with no intention to cause death, which allowed some convicted murderers on death row in Singapore (including Kho Jabing) to apply for the reduction of their death sentences after the courts in Singapore confirmed that they committed murder without the intention to kill and thus eligible for re-sentencing under the new death penalty laws in Singapore.[190][191] In October 2018 the Malaysian Government imposed a moratorium on all executions until the passage of a new law that would abolish the death penalty.[192][193][194] In April 2023, legislation abolishing the mandatory death penalty was passed in Malaysia. The death penalty would be retained, but courts have the discretion to replace it with other punishments, including whipping and imprisonment of 30–40 years.[195]

In 2018, at least 35 countries retained the death penalty for drug trafficking, drug dealing, drug possession and related offences. People had been regularly sentenced to death and executed for drug-related offences in China, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Vietnam. Other countries may retain the death penalty for symbolic purposes.[196]

The death penalty was mandated for drug trafficking in Singapore and Malaysia. Since 2013, Singapore ruled that those who were certified to have diminished responsibility (e.g. major depressive disorder) or acting as drug couriers and had assisted the authorities in tackling drug-related activities, would be sentenced to life imprisonment instead of death, with the offender liable to at least 15 strokes of the cane if he was not sentenced to death and was simultaneously sentenced to caning as well.[190][191] Notably, drug couriers like Yong Vui Kong and Cheong Chun Yin successfully applied to have their death sentences replaced with life imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane in 2013 and 2015 respectively.[197][198]

In April 2023, legislation abolishing the mandatory death penalty was passed in Malaysia.[195]

Other crimes that are punishable by death in some countries include:

Death penalty opponents regard the death penalty as inhumane[206] and criticize it for its irreversibility.[207] They argue also that capital punishment lacks deterrent effect,[208][209][210] or has a brutalization effect,[211][212] discriminates against minorities and the poor, and that it encourages a "culture of violence".[213] There are many organizations worldwide, such as Amnesty International,[214] and country-specific, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), whose main purpose includes abolition of the death penalty.[215][216]

Advocates of the death penalty argue that it deters crime,[217][218] is a good tool for police and prosecutors in plea bargaining,[219] makes sure that convicted criminals do not offend again, and that it ensures justice for crimes such as homicide, where other penalties will not inflict the desired retribution demanded by the crime itself. Capital punishment for non-lethal crimes is usually considerably more controversial, and abolished in many of the countries that retain it.[220][221]

Supporters of the death penalty argued that death penalty is morally justified when applied in murder especially with aggravating elements such as for murder of police officers, child murder, torture murder, multiple homicide and mass killing such as terrorism, massacre and genocide. This argument is strongly defended by New York Law School's Professor Robert Blecker,[222] who says that the punishment must be painful in proportion to the crime. Eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant defended a more extreme position, according to which every murderer deserves to die on the grounds that loss of life is incomparable to any penalty that allows them to remain alive, including life imprisonment.[223]

Some abolitionists argue that retribution is simply revenge and cannot be condoned. Others while accepting retribution as an element of criminal justice nonetheless argue that life without parole is a sufficient substitute. It is also argued that the punishing of a killing with another death is a relatively unusual punishment for a violent act, because in general violent crimes are not punished by subjecting the perpetrator to a similar act (e.g. rapists are, typically, not punished by corporal punishment, although it may be inflicted in Singapore, for example).[224]

Abolitionists believe capital punishment is the worst violation of human rights, because the right to life is the most important, and capital punishment violates it without necessity and inflicts to the condemned a psychological torture. Human rights activists oppose the death penalty, calling it "cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment". Amnesty International considers it to be "the ultimate irreversible denial of Human Rights".[225] Albert Camus wrote in a 1956 book called Reflections on the Guillotine, Resistance, Rebellion & Death:

An execution is not simply death. It is just as different from the privation of life as a concentration camp is from prison. [...] For there to be an equivalency, the death penalty would have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death on him and who, from that moment onward, had confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster is not encountered in private life.[226]

In the classic doctrine of natural rights as expounded by for instance Locke and Blackstone, on the other hand, it is an important idea that the right to life can be forfeited, as most other rights can be given due process is observed, such as the right to property and the right to freedom, including provisionally, in anticipation of an actual verdict.[227] As John Stuart Mill explained in a speech given in Parliament against an amendment to abolish capital punishment for murder in 1868:

And we may imagine somebody asking how we can teach people not to inflict suffering by ourselves inflicting it? But to this I should answer – all of us would answer – that to deter by suffering from inflicting suffering is not only possible, but the very purpose of penal justice. Does fining a criminal show want of respect for property, or imprisoning him, for personal freedom? Just as unreasonable is it to think that to take the life of a man who has taken that of another is to show want of regard for human life. We show, on the contrary, most emphatically our regard for it, by the adoption of a rule that he who violates that right in another forfeits it for himself, and that while no other crime that he can commit deprives him of his right to live, this shall.[228]

In one of the most recent cases relating to the death penalty in Singapore, activists like Jolovan Wham, Kirsten Han and Kokila Annamalai and even the international groups like the United Nations and European Union argued for Malaysian drug trafficker Nagaenthran K. Dharmalingam, who has been on death row at Singapore's Changi Prison since 2010, should not be executed due to an alleged intellectual disability, as they argued that Nagaenthran has low IQ of 69 and a psychiatrist has assessed him to be mentally impaired to an extent that he should not be held liable to his crime and execution. They also cited international law where a country should be prohibiting the execution of mentally and intellectually impaired people in order to push for Singapore to commute Nagaenthran's death penalty to life imprisonment based on protection of human rights. However, the Singapore government and both Singapore's High Court and Court of Appeal maintained their firm stance that despite his certified low IQ, it is confirmed that Nagaenthran is not mentally or intellectually disabled based on the joint opinion of three government psychiatrists as he is able to fully understand the magnitude of his actions and has no problem in his daily functioning of life.[229][230][231] Despite the international outcry, Nagaenthran was executed on 27 April 2022.[232]

Trends in most of the world have long been to move to private and less painful executions. France adopted the guillotine for this reason in the final years of the 18th century, while Britain banned hanging, drawing, and quartering in the early 19th century. Hanging by turning the victim off a ladder or by kicking a stool or a bucket, which causes death by strangulation, was replaced by long drop "hanging" where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar, Shah of Persia (1896–1907) introduced throat-cutting and blowing from a gun (close-range cannon fire) as quick and relatively painless alternatives to more torturous methods of executions used at that time.[233] In the United States, electrocution and gas inhalation were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging, but have been almost entirely superseded by lethal injection. A small number of countries, for example Iran and Saudi Arabia, still employ slow hanging methods, decapitation, and stoning.

A study of executions carried out in the United States between 1977 and 2001 indicated that at least 34 of the 749 executions, or 4.5%, involved "unanticipated problems or delays that caused, at least arguably, unnecessary agony for the prisoner or that reflect gross incompetence of the executioner". The rate of these "botched executions" remained steady over the period of the study.[234] A separate study published in The Lancet in 2005 found that in 43% of cases of lethal injection, the blood level of hypnotics was insufficient to guarantee unconsciousness.[235] However, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2008 (Baze v. Rees) and again in 2015 (Glossip v. Gross) that lethal injection does not constitute cruel and unusual punishment.[236] In Bucklew v. Precythe, the majority verdict – written by Judge Neil Gorsuch – further affirmed this principle, stating that while the ban on cruel and unusual punishment affirmatively bans penalties that deliberately inflict pain and degradation, it does in no sense limit the possible infliction of pain in the execution of a capital verdict.[237]

It is frequently argued that capital punishment leads to miscarriage of justice through the wrongful execution of innocent persons.[238] Many people have been proclaimed innocent victims of the death penalty.[239][240][241]

Some have claimed that as many as 39 executions have been carried out in the face of compelling evidence of innocence or serious doubt about guilt in the US from 1992 through 2004. Newly available DNA evidence prevented the pending execution of more than 15 death row inmates during the same period in the US,[242] but DNA evidence is only available in a fraction of capital cases.[243] As of 2017[update], 159 prisoners on death row have been exonerated by DNA or other evidence, which is seen as an indication that innocent prisoners have almost certainly been executed.[244][245] The National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty claims that between 1976 and 2015, 1,414 prisoners in the United States have been executed while 156 sentenced to death have had their death sentences vacated.[246] It is impossible to assess how many have been wrongly executed, since courts do not generally investigate the innocence of a dead defendant, and defense attorneys tend to concentrate their efforts on clients whose lives can still be saved; however, there is strong evidence of innocence in many cases.[247]

Improper procedure may also result in unfair executions. For example, Amnesty International argues that in Singapore "the Misuse of Drugs Act contains a series of presumptions which shift the burden of proof from the prosecution to the accused. This conflicts with the universally guaranteed right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty".[248] Singapore's Misuse of Drugs Act presumes one is guilty of possession of drugs if, as examples, one is found to be present or escaping from a location "proved or presumed to be used for the purpose of smoking or administering a controlled drug", if one is in possession of a key to a premises where drugs are present, if one is in the company of another person found to be in possession of illegal drugs, or if one tests positive after being given a mandatory urine drug screening. Urine drug screenings can be given at the discretion of police, without requiring a search warrant. The onus is on the accused in all of the above situations to prove that they were not in possession of or consumed illegal drugs.[249]

Some prisoners have volunteered or attempted to expedite capital punishment, often by waiving all appeals. Prisoners have made requests or committed further crimes in prison as well. In the United States, execution volunteers constitute approximately 11% of prisoners on death row. Volunteers often bypass legal procedures which are designed to designate the death penalty for the "worst of the worst" offenders. Opponents of execution volunteering cited the prevalence of mental illness among volunteers comparing it to suicide. Execution volunteers have received considerably less attention and effort at legal reform than those who were exonerated after execution.[250]

Opponents of the death penalty argue that this punishment is being used more often against perpetrators from racial and ethnic minorities and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, than against those criminals who come from a privileged background; and that the background of the victim also influences the outcome.[251][252][253] Researchers have shown that white Americans are more likely to support the death penalty when told that it is mostly applied to black Americans,[254] and that more stereotypically black-looking or dark-skinned defendants are more likely to be sentenced to death if the case involves a white victim.[255] However, a study published in 2018 failed to replicate the findings of earlier studies that had concluded that white Americans are more likely to support the death penalty if informed that it is largely applied to black Americans; according to the authors, their findings "may result from changes since 2001 in the effects of racial stimuli on white attitudes about the death penalty or their willingness to express those attitudes in a survey context."[256]

In Alabama in 2019, a death row inmate named Domineque Ray was denied his imam in the room during his execution, instead only offered a Christian chaplain.[257] After filing a complaint, a federal court of appeals ruled 5–4 against Ray's request. The majority cited the "last-minute" nature of the request, and the dissent stated that the treatment went against the core principle of denominational neutrality.[257]

In July 2019, two Shiite men, Ali Hakim al-Arab, 25, and Ahmad al-Malali, 24, were executed in Bahrain, despite the protests from the United Nations and rights group. Amnesty International stated that the executions were being carried out on confessions of "terrorism crimes" that were obtained through torture.[258]

On 30 March 2022, despite the appeals by the United Nations and rights activists, 68-year-old Malay Singaporean Abdul Kahar Othman was hanged at Singapore's Changi Prison for illegally trafficking diamorphine, which marked the first execution in Singapore since 2019 as a result of an informal moratorium caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier, there were appeals made to advocate for Abdul Kahar's death penalty be commuted to life imprisonment on humanitarian grounds, as Abdul Kahar came from a poor family and has struggled with drug addiction. He was also revealed to have been spending most of his life going in and out of prison, including a ten-year sentence of preventive detention from 1995 to 2005, and has not been given much time for rehabilitation, which made the activists and groups arguing that Abdul Kahar should be given a chance for rehabilitation instead of subjecting him to execution.[259][260][261] Both the European Union (EU) and Amnesty International criticised Singapore for finalizing and carrying out Abdul Kahar's execution, and about 400 Singaporeans protested against the government's use of the death penalty merely days after Abdul Kahar's death sentence was authorised.[262][263][264][230] Still, over 80% of the public supported the use of the death penalty in Singapore.[265]

The United Nations introduced a resolution during the General Assembly's 62nd sessions in 2007 calling for a universal ban.[266][267] The approval of a draft resolution by the Assembly's third committee, which deals with human rights issues, voted 99 to 52, with 33 abstentions, in support of the resolution on 15 November 2007 and was put to a vote in the Assembly on 18 December.[268][269][270]

Again in 2008, a large majority of states from all regions adopted, on 20 November in the UN General Assembly (Third Committee), a second resolution calling for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty; 105 countries voted in support of the draft resolution, 48 voted against and 31 abstained.

The moratorium resolution has been presented for a vote each year since 2007. On 15 December 2022, 125 countries voted in support of the moratorium, with 37 countries opposing, and 22 abstentions. The countries voting against the moratorium included the United States, People's Republic of China, North Korea, and Iran.[271]

A range of amendments proposed by a small minority of pro-death penalty countries were overwhelmingly defeated. It had in 2007 passed a non-binding resolution (by 104 to 54, with 29 abstentions) by asking its member states for "a moratorium on executions with a view to abolishing the death penalty".[272]

A number of regional conventions prohibit the death penalty, most notably, the Protocol 6 (abolition in time of peace) and Protocol 13 (abolition in all circumstances) to the European Convention on Human Rights. The same is also stated under Protocol 2 in the American Convention on Human Rights, which, however, has not been ratified by all countries in the Americas, most notably Canada[273] and the United States. Most relevant operative international treaties do not require its prohibition for cases of serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This instead has, in common with several other treaties, an optional protocol prohibiting capital punishment and promoting its wider abolition.[274]

Several international organizations have made abolition of the death penalty (during time of peace, or in all circumstances) a requirement of membership, most notably the EU and the Council of Europe. The Council of Europe are willing to accept a moratorium as an interim measure. Thus, while Russia was a member of the Council of Europe, and the death penalty remains codified in its law, it has not made use of it since becoming a member of the council – Russia has not executed anyone since 1996. With the exception of Russia (abolitionist in practice) and Belarus (retentionist), all European countries are classified as abolitionist.[92]

Latvia abolished de jure the death penalty for war crimes in 2012, becoming the last EU member to do so.[275]

Protocol 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights calls for the abolition of the death penalty in all circumstances (including for war crimes). The majority of European countries have signed and ratified it. Some European countries have not done this, but all of them except Belarus have now abolished the death penalty in all circumstances (de jure, and Russia de facto). Armenia is the most recent country to ratify the protocol, on 19 October 2023.[276]

Protocol 6, which prohibits the death penalty during peacetime, has been ratified by all members of the Council of Europe. It had been signed but not ratified by Russia at the time of its expulsion in 2022.

There are also other international abolitionist instruments, such as the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which has 90 parties;[277] and the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty (for the Americas; ratified by 13 states).[278]

In Turkey, over 500 people were sentenced to death after the 1980 Turkish coup d'état. About 50 of them were executed, the last one 25 October 1984. Then there was a de facto moratorium on the death penalty in Turkey. As a move towards EU membership, Turkey made some legal changes. The death penalty was removed from peacetime law by the National Assembly in August 2002, and in May 2004 Turkey amended its constitution to remove capital punishment in all circumstances. It ratified Protocol 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights in February 2006.[279] As a result, Europe is a continent free of the death penalty in practice, all states, having ratified Protocol 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights, with the exceptions of Russia (which has entered a moratorium) and Belarus, which are not members of the Council of Europe.[citation needed] The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has been lobbying for Council of Europe observer states who practice the death penalty, the U.S. and Japan, to abolish it or lose their observer status. In addition to banning capital punishment for EU member states, the EU has also banned detainee transfers in cases where the receiving party may seek the death penalty.[280]

Sub-Saharan African countries that have recently abolished the death penalty include Burundi, which abolished the death penalty for all crimes in 2009,[281] and Gabon which did the same in 2010.[282] On 5 July 2012, Benin became part of the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prohibits the use of the death penalty.[283]

The newly created South Sudan is among the 111 UN member states that supported the resolution passed by the United Nations General Assembly that called for the removal of the death penalty, therefore affirming its opposition to the practice. South Sudan, however, has not yet abolished the death penalty and stated that it must first amend its Constitution, and until that happens it will continue to use the death penalty.[284]

Among non-governmental organizations (NGOs), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are noted for their opposition to capital punishment.[285][286] A number of such NGOs, as well as trade unions, local councils, and bar associations, formed a World Coalition Against the Death Penalty in 2002.[287]

An open letter led by Danish Member of the European Parliament, Karen Melchior was sent to the European Commission ahead of the 26 January 2021 meeting of the Bahraini Minister of Foreign Affairs, Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani with the members of the European Union for the signing of a Cooperation Agreement. A total of 16 MEPs undersigned the letter expressing their grave concern towards the extended abuse of human rights in Bahrain following the arbitrary arrest and detention of activists and critics of the government. The attendees of the meeting were requested to demand from their Bahraini counterparts to take into consideration the concerns raised by the MEPs, particularly for the release of Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja and Sheikh Mohammed Habib Al-Muqdad, the two European-Bahraini dual citizens on death row.[288][289]

The world's major faiths have differing views depending on the religion, denomination, sect and the individual adherent.[290][291] The Catholic Church considers the death penalty as "inadmissible" in any circumstance and denounces it as an "attack" on the "inviolability and dignity of the person."[292][293] Both the Baháʼí and Islamic faiths support capital punishment.[294][295]

Capital punishment, or 'the death penalty,' is an institutionalized practice designed to result in deliberately executing persons in response to actual or supposed misconduct and following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that the person is responsible for violating norms that warrant execution.

When this country was founded, memories of the Stuart horrors were fresh and severe corporal punishments were common. Death was not then a unique punishment. The practice of punishing criminals by death, moreover, was widespread and by and large acceptable to society. Indeed, without developed prison systems, there was frequently no workable alternative. Since that time, successive restrictions, imposed against the background of a continuing moral controversy, have drastically curtailed the use of this punishment.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)Kazakhstan has abolished the death penalty, making permanent a nearly two-decade freeze on capital punishment in the Central Asian country.

[31] In Nagaenthran (CM) (at [71] and [75]), the High Court found that the appellant had borderline intellectual functioning; not that he was suffering from mild intellectual disability.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)With 400 condemned on death row, Florida is an extremely aggressive death penalty state, a state that will even execute for drug trafficking.

Human Rights Watch opposes the death penalty in all cases as a violation of fundamental rights – the right to life and the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman, and degrading punishment.