Los británicos negros son un grupo multiétnico de británicos de ascendencia africana subsahariana o afrocaribeña . [7] El término británico negro se desarrolló en la década de 1950, refiriéndose a los antillanos británicos negros de las antiguas colonias británicas caribeñas en las Indias Occidentales (es decir, la Nueva Commonwealth ), a veces denominados Generación Windrush , y a los británicos negros descendientes de África .

El término negro ha tenido históricamente varias aplicaciones como etiqueta racial y política y puede usarse en un contexto sociopolítico más amplio para abarcar una gama más amplia de poblaciones de minorías étnicas no europeas en Gran Bretaña. Esta se ha convertido en una definición controvertida. [8] El término británico negro es una de las diversas entradas de autodenominación utilizadas en las clasificaciones étnicas oficiales del Reino Unido .

En 2021, alrededor del 3,7 por ciento de la población del Reino Unido era negra. Las cifras han aumentado desde el censo de 1991, cuando el 1,63 por ciento de la población estaba registrada como negra o británica negra, hasta 1,15 millones de residentes en 2001, o el 2 por ciento de la población, y esta cifra aumentó aún más hasta poco más de 1,9 millones en 2011, lo que representa el 3 por ciento. Casi el 96 por ciento de los británicos negros viven en Inglaterra, especialmente en las áreas urbanas más grandes de Inglaterra, y cerca de 1,2 millones viven en el Gran Londres .

El término británico negro se ha utilizado con mayor frecuencia para referirse a las personas negras originarias de la Nueva Commonwealth , tanto de ascendencia de África occidental como del sur de Asia. Por ejemplo, la organización Southall Black Sisters se estableció en 1979 "para satisfacer las necesidades de las mujeres negras (asiáticas y afrocaribeñas)". [9] Obsérvese que "asiático" en el contexto británico suele referirse a personas de ascendencia del sur de Asia . [10] [11] El término "negro" se utilizó en este sentido político inclusivo para significar " británico no blanco ". [12]

En la década de 1970, una época de creciente activismo contra la discriminación racial, las principales comunidades así descritas eran las de las Indias Occidentales Británicas y el subcontinente indio . La solidaridad contra el racismo y la discriminación a veces extendió el término en esa época también a la población irlandesa de Gran Bretaña . [13] [14]

Varias organizaciones siguen utilizando el término de forma inclusiva, como la Black Arts Alliance , [15] [16] que extiende su uso del término a los latinoamericanos y a todos los refugiados, [17] y la National Black Police Association . [18] El censo oficial del Reino Unido tiene entradas de autodesignación separadas para que los encuestados se identifiquen como "británicos asiáticos", "británicos negros" y "otro grupo étnico". [2] Debido a la diáspora india y, en particular, a la expulsión de asiáticos de Uganda por parte de Idi Amin en 1972, muchos asiáticos británicos provienen de familias que habían vivido anteriormente durante varias generaciones en las Indias Occidentales Británicas o las Comoras . [19] Varios asiáticos británicos, incluidas celebridades como Riz Ahmed y Zayn Malik, todavía utilizan el término "negro" y "asiático" indistintamente. [20]

El censo de 1991 del Reino Unido fue el primero en incluir una pregunta sobre la etnia . A partir del censo de 2011 del Reino Unido , la Oficina de Estadísticas Nacionales (ONS) y la Agencia de Investigación y Estadísticas de Irlanda del Norte (NISRA) permiten a las personas de Inglaterra, Gales e Irlanda del Norte que se identifican como "negras" seleccionar las casillas de verificación "Africano negro", "Caribeño negro" o "Cualquier otro origen negro/africano/caribeño". [2] Para el censo escocés de 2011 , la Oficina General de Registro de Escocia (GOS) también estableció nuevas casillas de verificación separadas "Africano, escocés africano o británico africano" y "Caribeño, escocés caribeño o británico caribeño" para las personas en Escocia de África y el Caribe, respectivamente, que no se identifican como "negros, escoceses negros o británicos negros". [21] El censo de 2021 en Inglaterra y Gales mantuvo las opciones de origen caribeño, africano y cualquier otro origen negro, británico negro o caribeño, agregando una respuesta por escrito para el grupo "Africano negro". En Irlanda del Norte, el censo de 2021 tenía casillas para marcar Negro africano y Otros negros. En Escocia, las opciones eran Africano, Africano escocés o Africano británico, y Caribeño o Negro, cada una acompañada de una casilla para escribir la respuesta. [22]

En todos los censos del Reino Unido, las personas con múltiples ascendencias familiares pueden escribir sus respectivas etnias en la opción "Grupos étnicos mixtos o múltiples", que incluye casillas adicionales de "Caribeños blancos y negros" o "Africanos blancos y negros" en Inglaterra, Gales e Irlanda del Norte. [2]

El término británico negro o inglés negro también se usaba para designar a las personas negras y mestizas de Sierra Leona (conocidas como criollos o krio(s) ) que eran descendientes de inmigrantes de Inglaterra y Canadá y se identificaban como británicos. [23] Por lo general, son descendientes de personas negras que vivieron en Inglaterra en el siglo XVIII y liberaron a los esclavos negros estadounidenses que lucharon por la Corona en la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos (véase también leales negros ). En 1787, cientos de pobres negros de Londres (una categoría que incluía a los marineros de las Indias Orientales conocidos como lascars ) aceptaron ir a esta colonia de África occidental con la condición de que conservaran el estatus de súbditos británicos , vivieran en libertad bajo la protección de la Corona británica y fueran defendidos por la Marina Real . Junto con ellos se encontraban algunas personas blancas (véase también Comité para el Socorro de los Negros Pobres ), incluidas amantes, esposas y viudas de los hombres negros. [24] Además, casi 1200 leales negros, antiguos esclavos estadounidenses que habían sido liberados y reasentados en Nueva Escocia , y 550 cimarrones jamaicanos también eligieron unirse a la nueva colonia. [25] [26]

Según la Historia de Augusto , el emperador romano del norte de África Septimio Severo supuestamente visitó el Muro de Adriano en el año 210 d. C. Cuando regresaba de una inspección del muro, se dice que un soldado etíope que sostenía una guirnalda de ramas de ciprés se burló de él. Severo le ordenó que se fuera, supuestamente "asustado" [27] por el color oscuro de su piel [27] [28] [29] y viendo su acto y apariencia como un presagio. Se dice que el etíope dijo: "Has sido todas las cosas, has conquistado todas las cosas, ahora, oh conquistador, sé un dios". [30] [31]

Se descubrió que una niña enterrada en Updown , cerca de Eastry en Kent a principios del siglo VII tenía un 33% de su ADN de tipo africano occidental, muy similar al de los grupos Esan o Yoruba . [32]

En 2013, [33] [34] se descubrió un esqueleto en Fairford , Gloucestershire , que la antropología forense reveló que se trataba de una mujer del África subsahariana. Sus restos han sido datados entre los años 896 y 1025. [34] Los historiadores locales creen que probablemente era una esclava o una sirvienta . [35]

Un músico negro se encuentra entre los seis trompetistas representados en el séquito real de Enrique VIII en el Westminster Tournament Roll, un manuscrito iluminado que data de 1511. Lleva la librea real y está montado a caballo. El hombre generalmente se identifica como " John Blanke , el trompetista negro", que figura en las cuentas de pago tanto de Enrique VIII como de su padre, Enrique VII . [36] [37] Un grupo de africanos en la corte de Jacobo IV de Escocia , incluía a Ellen More y un baterista conocido como el " More taubronar ". Tanto él como John Blanke recibieron salarios por sus servicios. [38] Un pequeño número de africanos negros trabajaron como dueños de negocios independientes en Londres a fines del siglo XVI, incluido el tejedor de seda Reasonable Blackman . [39] [40] [41]

Cuando comenzaron a abrirse líneas comerciales entre Londres y África occidental, personas de esta zona empezaron a llegar a Gran Bretaña a bordo de barcos mercantes y de esclavos. Por ejemplo, el comerciante John Lok trajo varios cautivos a Londres en 1555 desde Guinea. El relato del viaje en Hakluyt informa que: "eran hombres altos y fuertes, y podían soportar nuestras comidas y bebidas. El aire frío y húmedo los ofende un poco". [42]

Durante el final del siglo XVI y las dos primeras décadas del siglo XVII, 25 personas nombradas en los registros de la pequeña parroquia de St. Botolph's en Aldgate están identificadas como "moros negros". [43] En el período de la guerra con España, entre 1588 y 1604, hubo un aumento en el número de personas que llegaban a Inglaterra procedentes de las expediciones coloniales españolas en partes de África. Los ingleses liberaron a muchos de estos cautivos de la esclavitud en los barcos españoles. Llegaron a Inglaterra en gran medida como un subproducto de la trata de esclavos; algunos eran de raza mixta africana y española, y se convirtieron en intérpretes o marineros. [44] El historiador estadounidense Ira Berlin clasificó a estas personas como criollos del Atlántico o la Generación de la Carta de esclavos y trabajadores multirraciales en América del Norte. [45] El esclavista John Hawkins llegó a Londres con 300 cautivos de África occidental. [44] Sin embargo, el comercio de esclavos no se consolidó hasta el siglo XVII y Hawkins sólo se embarcó en tres expediciones.

Jacques Francis , que ha sido descrito como un esclavo por algunos historiadores, [46] [47] [48] pero se describió a sí mismo en latín como un " famulus ", que significa sirviente, esclavo o asistente. [49] [50] Francis nació en una isla frente a la costa de Guinea, probablemente la isla Arguin , frente a la costa de Mauritania . [51] [52] [53] Trabajó como buzo para Pietro Paulo Corsi en sus operaciones de salvamento en el hundido St Mary y St Edward de Southampton y otros barcos, como el Mary Rose , que se había hundido en el puerto de Portsmouth . Cuando Corsi fue acusado de robo, Francis lo apoyó en un tribunal inglés. Con la ayuda de un intérprete, apoyó las afirmaciones de inocencia de su amo. Algunas de las declaraciones en el caso mostraron actitudes negativas hacia los esclavos o las personas negras como testigos. [54] En marzo de 2019, se descubrió que dos de los esqueletos encontrados en el Mary Rose tenían ascendencia del sur de Europa o del norte de África; Se cree que uno de ellos, que llevaba una muñequera de cuero con el escudo de Catalina de Aragón y el escudo real de Inglaterra, posiblemente era español o norteafricano; se cree que el otro, conocido como "Henry", también tenía una composición genética similar. El ADN mitocondrial de Henry mostró que su ascendencia podría haber venido del sur de Europa, Oriente Próximo o el norte de África, aunque el Dr. Sam Robson, de la Universidad de Portsmouth, "descartó" que Henry fuera negro o que fuera de origen africano subsahariano . El Dr. Onyeka Nubia advirtió que el número de personas a bordo del Mary Rose que tenían herencia fuera de Gran Bretaña no era necesariamente representativo de toda Inglaterra en ese momento, aunque definitivamente no era un "caso único". [55] Se cree que es probable que hayan viajado por España o Portugal antes de llegar a Gran Bretaña. [55]

Los sirvientes moros eran vistos como una novedad de moda y trabajaban en los hogares de varios isabelinos prominentes, incluidos los de la reina Isabel I, William Pole , Francis Drake , [56] [57] [44] y Ana de Dinamarca en Escocia . [58] Entre estos sirvientes estaba "John Come-quick, un moreno negro", sirviente del capitán Thomas Love. [44] Otros incluidos en los registros parroquiales incluyen a Domingo "un sirviente negro negro de Sir William Winter ", enterrado el día 27 de agosto [1587] y "Frauncis un sirviente negro de Thomas Parker", enterrado en enero de 1591. [59] Algunos eran trabajadores libres, aunque la mayoría estaban empleados como sirvientes domésticos y artistas. Algunos trabajaban en puertos, pero invariablemente se los describía como mano de obra en propiedad. [60]

La población africana puede haber sido de varios cientos durante el período isabelino, sin embargo, no todos eran africanos subsaharianos. [55] El historiador Michael Wood señaló que los africanos en Inglaterra eran "en su mayoría libres... [y] tanto hombres como mujeres, se casaron con ingleses nativos". [61] La evidencia de archivo muestra registros de más de 360 africanos entre 1500 y 1640 en Inglaterra y Escocia. [62] [63] [64] En reacción a la tez más oscura de las personas con ascendencia birracial, George Best argumentó en 1578 que la piel negra no estaba relacionada con el calor del sol (en África ) sino que era causada por la condenación bíblica. Reginald Scot señaló que las personas supersticiosas asociaban la piel negra con demonios y fantasmas, escribiendo (en su libro escéptico Discoverie of Witchcraft ) "Pero en nuestra infancia, las doncellas de nuestras madres nos aterrorizaban con un ouglie divell que tenía cuernos en la cabeza y una cola en el trasero, ojos como un bason, colmillos como un perro, garras como un oso, una piel como un Níger y una voz rugiente como un león"; el historiador Ian Mortimer afirmó que tales puntos de vista "se notan en todos los niveles de la sociedad". [65] [66] Las opiniones sobre las personas negras estaban "afectadas por nociones preconcebidas del Jardín del Edén y la Caída en desgracia ". [64] Además, en este período, Inglaterra no tenía el concepto de naturalización como un medio para incorporar inmigrantes a la sociedad. Concebía a los súbditos ingleses como aquellas personas nacidas en la isla. Aquellos que no lo eran eran considerados por algunos como incapaces de convertirse en súbditos o ciudadanos. [67]

En 1596, la reina Isabel I envió cartas a los alcaldes de las principales ciudades afirmando que "últimamente se han traído a este reino diversos negros y moros, de los cuales ya hay aquí un gran número...". Durante su visita a la corte inglesa, Casper Van Senden , un comerciante alemán de Lübeck , solicitó permiso para transportar a los "negros y moros" que vivían en Inglaterra a Portugal o España, presumiblemente para venderlos allí. Posteriormente, Isabel I emitió una orden real a Van Senden, otorgándole el derecho a hacerlo. [68] Sin embargo, Van Senden y Sherley no tuvieron éxito en este esfuerzo, como reconocieron en la correspondencia con Sir Robert Cecil. [69] En 1601, Isabel I emitió otra proclamación expresando que estaba "muy descontenta de entender la gran cantidad de negros y moros que (según se le informó) son llevados a este reino", [70] y nuevamente autorizó a van Senden a deportarlos. Su proclamación de 1601 afirmaba que los moros eran "fomentados y alimentados aquí, para gran disgusto del propio pueblo vasallo [de la reina], que codicia el socorro que esa gente consume". Afirmaba además que "la mayoría de ellos son infieles, que no entienden a Cristo ni su Evangelio". [71] [72]

Los estudios sobre los africanos en la Gran Bretaña moderna temprana indican una presencia continua y menor. Entre estos estudios se incluyen Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500–1677: Imprints of the Invisible (Ashgate, 2008) de Imtiaz Habib, [ 73 ] Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, Their Presence, Status and Origins (Narrative Eye, 2013) de Onyeka, [74] la tesis de doctorado en Oxford de Miranda Kaufmann Africans in Britain, 1500–1640 [ 75] y su Black Tudors: The Untold Story ( Oneworld Publications , 2017). [76]

_-_double_portrait_-_circa_1650.jpg/440px-Anon_(English_School)_-_double_portrait_-_circa_1650.jpg)

Gran Bretaña participó en el comercio tricontinental de esclavos entre Europa, África y las Américas. Muchos de los involucrados en las actividades coloniales británicas, como capitanes de barcos , funcionarios coloniales , comerciantes, traficantes de esclavos y dueños de plantaciones, trajeron esclavos negros como sirvientes de regreso a Gran Bretaña con ellos. Esto provocó una creciente presencia negra en las áreas norte, este y sur de Londres. Uno de los esclavos más famosos que asistió a un capitán de barco era conocido como Sambo. Cayó enfermo poco después de llegar a Inglaterra y, en consecuencia, fue enterrado en Lancashire. Su placa y lápida aún se mantienen en pie hasta el día de hoy. También hubo un pequeño número de esclavos libres y marineros de África occidental y el sur de Asia. Muchas de estas personas se vieron obligadas a mendigar debido a la falta de trabajo y la discriminación racial. [78] [79] En 1687, un "moro" recibió la libertad de la ciudad de York . Aparece en las listas de hombres libres como "John Moore - blacke". Es la única persona negra que se ha encontrado hasta la fecha en las listas de York . [80]

La participación de los comerciantes de Gran Bretaña [81] en el comercio transatlántico de esclavos fue el factor más importante en el desarrollo de la comunidad negra británica. Estas comunidades florecieron en ciudades portuarias fuertemente involucradas en el comercio de esclavos, como Liverpool [81] y Bristol . Algunos liverpoolianos pueden rastrear su herencia negra en la ciudad hasta diez generaciones atrás. [81] Los primeros colonos negros en la ciudad incluyeron marineros, los hijos mestizos de los comerciantes enviados a educarse en Inglaterra, sirvientes y esclavos liberados. Las referencias erróneas a que los esclavos que ingresaron al país después de 1722 se consideraron hombres libres se derivan de una fuente en la que 1722 es un error de imprenta para 1772, a su vez basado en un malentendido de los resultados del caso Somerset al que se hace referencia a continuación. [82] [83] Como resultado, Liverpool es el hogar de la comunidad negra más antigua de Gran Bretaña, que data al menos de la década de 1730. En 1795, Liverpool poseía el 62,5 por ciento del comercio europeo de esclavos. [81]

Durante esta época, Lord Mansfield declaró que un esclavo que huía de su amo no podía ser tomado por la fuerza en Inglaterra ni vendido en el extranjero. Sin embargo, Mansfield se esforzó en señalar que su sentencia no comentaba la legalidad de la esclavitud en sí. [84] Este veredicto impulsó el número de negros que escaparon de la esclavitud y ayudó a que la esclavitud entrara en decadencia. Durante este mismo período, muchos ex soldados esclavos estadounidenses, que habían luchado del lado de los británicos en la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos , fueron reasentados como hombres libres en Londres. Nunca se les concedieron pensiones y muchos de ellos cayeron en la pobreza y se vieron reducidos a mendigar en las calles. Los informes de la época afirmaban que "no tenían ninguna perspectiva de subsistir en este país excepto mediante la depredación del público o la caridad común". Un observador comprensivo escribió que "un gran número de negros y personas de color, muchos de ellos refugiados de Estados Unidos y otros que habían estado al servicio de Su Majestad por tierra o por mar, estaban... en gran apuro". Incluso hacia los leales blancos había poca buena voluntad hacia los recién llegados de Estados Unidos. [85]

Oficialmente, la esclavitud no era legal en Inglaterra. [86] La decisión Cartwright de 1569 resolvió que Inglaterra era "un aire demasiado puro para que un esclavo lo respirara". Sin embargo, los esclavos africanos negros continuaron siendo comprados y vendidos en Inglaterra durante el siglo XVIII. [87] La cuestión de la esclavitud no fue cuestionada legalmente hasta el caso Somerset de 1772, que involucraba a James Somersett, un esclavo negro fugitivo de Virginia . El Lord Presidente del Tribunal Supremo William Murray, primer conde de Mansfield, concluyó que no se podía obligar a Somerset a abandonar Inglaterra contra su voluntad. Más tarde reiteró: "Las determinaciones no van más allá de que el amo no puede obligarlo por la fuerza a salir del reino". [88] A pesar de los fallos anteriores, como la declaración de 1706 (que se aclaró un año después) del Lord Presidente del Tribunal Supremo Holt [89] sobre que la esclavitud no era legal en Gran Bretaña, a menudo se ignoraba, y los dueños de esclavos argumentaban que los esclavos eran propiedad y, por lo tanto, no podían considerarse personas. [90] El dueño de esclavos Thomas Papillon fue uno de los muchos que tomaron a su sirviente negro "por ser de la naturaleza y calidad de mis bienes y muebles". [91] [92]

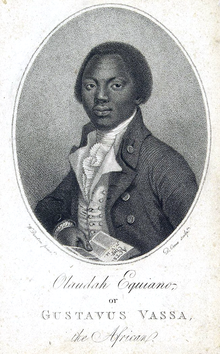

Los negros vivían entre los blancos en Londres en áreas de Mile End , Stepney , Paddington y St Giles . Después del gobierno de Mansfield, muchos ex esclavos continuaron trabajando para sus antiguos amos como empleados remunerados. Entre 14.000 y 15.000 (según las estimaciones contemporáneas de entonces) esclavos fueron liberados inmediatamente en Inglaterra. [93] Muchos de estos individuos emancipados fueron etiquetados como los "pobres negros", los pobres negros fueron definidos como antiguos soldados esclavos desde que se emanciparon, marineros, como los lascars del sur de Asia, [94] antiguos sirvientes contratados y antiguos trabajadores de plantaciones contratados. [95] Alrededor de la década de 1750, Londres se convirtió en el hogar de muchos negros, así como judíos, irlandeses, alemanes y hugonotes . Según Gretchen Gerzina en su Londres negro , a mediados del siglo XVIII, los negros representaban entre el 1% y el 3% de la población de Londres. [96] [97] Se ha encontrado evidencia del número de residentes negros en la ciudad a través de entierros registrados. Algunas personas negras en Londres resistieron la esclavitud mediante la huida. [96] Los principales activistas negros de esta era incluyeron a Olaudah Equiano , Ignatius Sancho y Quobna Ottobah Cugoano . La mestiza Dido Elizabeth Belle, que nació esclava en el Caribe, se mudó a Gran Bretaña con su padre blanco en la década de 1760. En 1764, The Gentleman's Magazine informó que "se suponía que había cerca de 20.000 sirvientes negros". [98]

John Ystumllyn (c. 1738 - 1786) fue la primera persona negra de Gales del Norte de la que se tiene constancia . Es posible que fuera víctima de la trata de esclavos del Atlántico y que procediera de África occidental o de las Indias Occidentales . La familia Wynn lo llevó a su finca Ystumllyn en Criccieth y lo bautizó con el nombre galés de John Ystumllyn. Los lugareños le enseñaron inglés y galés , se convirtió en jardinero de la finca y "se convirtió en un joven apuesto y vigoroso". Su retrato fue pintado en la década de 1750. Se casó con una mujer local, Margaret Gruffydd, en 1768 y sus descendientes todavía viven en la zona. [99]

En el Morning Gazette se informó de que había 30.000 en todo el país, aunque se pensó que las cifras eran exageraciones "alarmistas". Ese mismo año, una fiesta para hombres y mujeres negros en un pub de Fleet Street fue lo suficientemente inusual como para que se escribiera sobre ella en los periódicos. Su presencia en el país fue lo suficientemente llamativa como para iniciar acalorados brotes de desagrado por las colonias de hotentotes . [100] Los historiadores modernos estiman, basándose en listas parroquiales, registros de bautismo y matrimonio, así como en contratos penales y de compraventa, que alrededor de 10.000 personas negras vivieron en Gran Bretaña durante el siglo XVIII. [101] [102] [91] [103] Otras estimaciones sitúan la cifra en 15.000. [104] [105] [106]

En 1772, Lord Mansfield estimó que el número de personas negras en el país era de hasta 15.000, aunque la mayoría de los historiadores modernos consideran que 10.000 es lo más probable. [91] [109] Se estimó que la población negra era de alrededor de 10.000 en Londres, lo que hace que los negros sean aproximadamente el 1% de la población total de Londres. La población negra constituía alrededor del 0,1% de la población total de Gran Bretaña en 1780. [110] [111] Se estima que la población femenina negra apenas alcanzó el 20% de la población afrocaribeña total del país. [111] En la década de 1780, con el final de la Guerra de la Independencia de los Estados Unidos, cientos de leales negros de Estados Unidos se reasentaron en Gran Bretaña. [112] Se cree que Marcus Thomas fue traído en ese momento desde Jamaica cuando era un niño por la familia Stanhope, donde trabajó como sirviente en su casa, fue bautizado a los 19 años y luego se unió a la Milicia de Westminster como baterista. [107] [108] Más tarde, algunos emigraron a Sierra Leona , con la ayuda del Comité para el Socorro de los Pobres Negros después de sufrir la indigencia, para formar la identidad étnica criolla de Sierra Leona . [113] [114] [115]

En 1731, el alcalde de Londres dictaminó que "ningún negro podrá ser aprendiz de ningún comerciante o artesano de esta ciudad". Debido a esta decisión, la mayoría se vio obligada a trabajar como sirvientes domésticos y otras profesiones serviles. [116] [91] Los londinenses negros que eran sirvientes no remunerados eran, en efecto, esclavos en todo menos en el nombre. [117] En 1787, Thomas Clarkson , un abolicionista inglés, señaló en un discurso en Manchester: "También me sorprendió encontrar una gran multitud de negros de pie alrededor del púlpito. Podría haber cuarenta o cincuenta de ellos". [118] Hay evidencia de que los hombres y mujeres negros fueron discriminados ocasionalmente cuando se trataba de la ley debido a su color de piel. En 1737, George Scipio fue acusado de robar la ropa de Anne Godfrey, el caso dependía completamente de si Scipio era o no el único hombre negro en Hackney en ese momento. [119] Ignacio Sancho , escritor, compositor, comerciante y votante negro en Westminster escribió que, a pesar de haber estado en Gran Bretaña desde los dos años, sentía que era "sólo un inquilino, y no eso". [120] Sancho se quejaba de "la antipatía nacional y el prejuicio" de los británicos blancos nativos "hacia sus hermanos de cabeza lanuda". [121] Sancho estaba frustrado porque muchos recurrían a estereotipar a sus vecinos negros. [122] Como jefe de familia económicamente independiente, se convirtió en la primera persona negra de origen africano en votar en las elecciones parlamentarias en Gran Bretaña, en una época en la que sólo el 3% de la población británica tenía permitido votar. [123]

Los marineros de ascendencia africana sufrieron muchos menos prejuicios que los negros en ciudades como Londres. Los marineros negros compartían los mismos alojamientos, deberes y paga que sus compañeros blancos. Existen algunas controversias en cuanto a la estimación de los marineros negros: las estimaciones conservadoras la sitúan entre el 6% y el 8% de los marineros de la marina de la época, una proporción considerablemente mayor que la de la población en su conjunto. Ejemplos notables son Olaudah Equiano y Francis Barber . [124]

Con el apoyo de otros británicos, estos activistas exigieron que los negros fueran liberados de la esclavitud. Entre los partidarios de estos movimientos se encontraban trabajadores y otras nacionalidades de los pobres urbanos. Entre los negros de Londres que apoyaban el movimiento abolicionista se encontraban Cugoano y Equiano. En esa época, la esclavitud en Gran Bretaña no contaba con el apoyo del derecho consuetudinario, pero su estatus legal definitivo no se definió claramente hasta el siglo XIX. [ cita requerida ]

A finales del siglo XVIII se escribieron numerosas publicaciones y memorias sobre los "pobres negros". Un ejemplo son los escritos de Olaudah Equiano , un ex esclavo que escribió unas memorias tituladas The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano .

En 1786, Equiano se convirtió en la primera persona negra empleada por el gobierno británico, cuando fue nombrado comisario de provisiones y tiendas para las 350 personas negras que sufrían pobreza y que habían decidido aceptar la oferta del gobierno de un pasaje asistido a Sierra Leona. [125] Al año siguiente, en 1787, alentados por el Comité para el Socorro de los Negros Pobres , alrededor de 400 [126] londinenses negros recibieron ayuda para emigrar a Sierra Leona en África Occidental, fundando la primera colonia británica en el continente. [127] Pidieron que se reconociera su condición de súbditos británicos , junto con solicitudes de que la Marina Real les diera protección militar . [128] Sin embargo, aunque el comité inscribió a unos 700 miembros de los Negros Pobres, solo 441 abordaron los tres barcos que zarparon de Londres a Portsmouth. [129] Muchos londinenses negros ya no estaban interesados en el plan, y la coerción empleada por el comité y el gobierno para reclutarlos solo reforzó su oposición. Equiano, que originalmente participó en el plan, se convirtió en uno de sus críticos más acérrimos. Otro londinense negro prominente, Ottobah Cugoano , también criticó el plan. [130] [131] [132]

En 2007, los científicos encontraron el raro haplogrupo paterno A1 en unos pocos hombres británicos vivos con apellidos de Yorkshire. Este clado se encuentra hoy casi exclusivamente entre los hombres de África occidental , donde también es raro. Se cree que el haplogrupo llegó a Gran Bretaña a través de soldados alistados durante la Britania romana, o mucho más tarde a través del comercio moderno de esclavos . Turi King, coautor del estudio, señaló que la "conjetura" más probable era el comercio de esclavos de África occidental. Algunos de los individuos conocidos que llegaron a través de la ruta de los esclavos, como Ignatius Sancho y Olaudah Equiano, alcanzaron un rango social muy alto. Algunos se casaron con miembros de la población general. [133]

A finales del siglo XVIII, el comercio británico de esclavos decayó como respuesta al cambio de opinión popular. Tanto Gran Bretaña como los Estados Unidos abolieron el comercio de esclavos en el Atlántico en 1808 y cooperaron para liberar a los esclavos de los barcos mercantes ilegales en las costas de África occidental. Muchos de estos esclavos liberados fueron llevados a Sierra Leona para establecerse allí. La esclavitud fue abolida por completo en el Imperio británico en 1834, aunque había sido rentable en las plantaciones del Caribe. Se trajeron menos negros a Londres desde las Indias Occidentales y África occidental. [95] La población negra británica residente, principalmente masculina, ya no crecía a partir del goteo de esclavos y sirvientes de las Indias Occidentales y América. [134]

La abolición significó un alto virtual a la llegada de personas negras a Gran Bretaña, justo cuando la inmigración desde Europa estaba aumentando. [135] La población negra de la Gran Bretaña victoriana era tan pequeña que aquellos que vivían fuera de los puertos comerciales más grandes estaban aislados de la población negra. [136] [137] La mención de personas negras y descendientes en los registros parroquiales disminuyó notablemente a principios del siglo XIX. Es posible que los investigadores simplemente no recopilaran los datos o que la población masculina mayoritariamente negra de finales del siglo XVIII se hubiera casado con mujeres blancas. [138] [136] Todavía hoy se pueden encontrar pruebas de tales matrimonios con descendientes de sirvientes negros como Francis Barber , un sirviente nacido en Jamaica que vivió en Gran Bretaña durante el siglo XVIII. Sus descendientes todavía viven en Inglaterra hoy y son blancos. [116] La abolición de la esclavitud en 1833, puso fin de manera efectiva al período de inmigración negra en pequeña escala a Londres y Gran Bretaña. Aunque hubo algunas excepciones: los marineros negros y chinos comenzaron a establecerse en pequeñas comunidades en los puertos británicos, sobre todo porque fueron abandonados allí por sus empleadores. [135]

A finales del siglo XIX, la discriminación racial se vio fomentada por las teorías del racismo científico , que sostenían que los blancos eran la raza superior y que los negros eran menos inteligentes que los blancos. Los intentos de apoyar estas teorías citaban "pruebas científicas", como el tamaño del cerebro. James Hunt, presidente de la Sociedad Antropológica de Londres, en 1863, en su artículo "Sobre el lugar del negro en la naturaleza", escribió que "el negro es intelectualmente inferior al europeo... [y] solo puede ser humanizado y civilizado por los europeos". [139] En la década de 1880, hubo una acumulación de pequeños grupos de comunidades negras en los muelles de ciudades como Canning Town , [140] Liverpool y Cardiff .

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Sara_Forbes_Bonetta_(15_September_1862)_(cropped).jpg)

A pesar de los prejuicios sociales y la discriminación en la Inglaterra victoriana, algunos británicos negros del siglo XIX lograron un éxito excepcional. Pablo Fanque , nacido pobre como William Darby en Norwich , llegó a ser el propietario de uno de los circos victorianos más exitosos de Gran Bretaña. Está inmortalizado en la letra de la canción de The Beatles " Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite! " Treinta años después de su muerte en 1871, el capellán del Showman's Guild dijo:

"En la gran hermandad del mundo ecuestre no hay barreras raciales, pues, aunque Pablo Fanque era de origen africano, rápidamente llegó a la cima de su profesión. La camaradería en el ruedo sólo tiene una prueba: la habilidad". [141]

Otro gran artista de circo fue el jinete Joseph Hillier, quien se hizo cargo y dirigió la compañía de circo de Andrew Ducrow después de su muerte. [142]

Desde principios de siglo, los estudiantes de ascendencia africana fueron admitidos en las universidades británicas. Uno de ellos, por ejemplo, fue el afroamericano James McCune Smith, que viajó desde la ciudad de Nueva York a la Universidad de Glasgow para estudiar medicina. En 1837 obtuvo el doctorado en medicina y publicó dos artículos científicos en la London Medical Gazette . Estos artículos son los primeros que se sabe que fueron publicados por un médico afroamericano en una revista científica. [143]

Un británico indio, Dadabhai Naoroji , se presentó a las elecciones al parlamento por el Partido Liberal en 1886. Fue derrotado, lo que llevó al líder del Partido Conservador , Lord Salisbury, a comentar que "por grande que haya sido el progreso de la humanidad y por mucho que hayamos avanzado en la superación de los prejuicios, dudo que hayamos llegado aún al punto de vista en el que un distrito electoral británico elija a un negro". [144] Naoroji fue elegido para el parlamento en 1892, convirtiéndose en el segundo miembro del Parlamento (MP) de ascendencia india después de David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre .

Según el abogado y escritor criollo de Sierra Leona , Augustus Merriman-Labor , en su libro de 1909 Britons Through Negro Spectacles , la población negra de Londres en ese momento "no superaba con creces las cien" personas y "por cada una [persona negra en Londres], hay más de sesenta mil blancos". [145]

La Primera Guerra Mundial vio un pequeño crecimiento en el tamaño de las comunidades negras de Londres con la llegada de marineros mercantes y soldados. En ese momento, también hubo pequeños grupos de estudiantes de África y el Caribe que migraron a Londres. Estas comunidades se encuentran ahora entre las comunidades negras más antiguas de Londres. [146] Las comunidades negras más grandes se encontraban en las grandes ciudades portuarias del Reino Unido: East End de Londres , Liverpool, Bristol y Tiger Bay de Cardiff , con otras comunidades en South Shields en Tyne & Wear y Glasgow . En 1914, la población negra se estimó en 10.000 y se centró principalmente en Londres. [147] [148]

En 1918, puede haber habido hasta 20.000 [149] o 30.000 [147] personas negras viviendo en Gran Bretaña. Sin embargo, la población negra era mucho menor en relación con la población británica total de 45 millones y los documentos oficiales no estaban adaptados para registrar la etnicidad. [150] Los residentes negros habían emigrado en su mayor parte de partes del Imperio Británico. Se desconoce el número de soldados negros que sirvieron en el ejército británico (en lugar de regimientos coloniales) antes de la Primera Guerra Mundial, pero es probable que haya sido insignificantemente bajo. [148] Uno de los soldados británicos negros durante la Primera Guerra Mundial fue Walter Tull , un futbolista profesional inglés, nacido de un carpintero barbadense , Daniel Tull, y Alice Elizabeth Palmer, nacida en Kent. Su abuelo era esclavo en Barbados . [151] Tull se convirtió en el primer oficial de infantería de ascendencia mixta nacido en Gran Bretaña en un regimiento regular del ejército británico, a pesar de que el Manual de Derecho Militar de 1914 excluía específicamente a los soldados que no fueran "de ascendencia europea pura" de convertirse en oficiales comisionados. [152] [153] [154]

Los soldados coloniales y los marineros de ascendencia afrocaribeña sirvieron en el Reino Unido durante la Primera Guerra Mundial y algunos se establecieron en ciudades británicas. La comunidad de South Shields, que también incluía a otros marineros "de color" conocidos como lascars, que eran del sur de Asia y del mundo árabe , fueron víctimas del primer motín racial del Reino Unido en 1919. [155] Pronto otras ocho ciudades con importantes comunidades no blancas también se vieron afectadas por motines raciales. [156] Debido a estos disturbios, muchos de los residentes del mundo árabe, así como algunos otros inmigrantes, fueron evacuados a sus países de origen. [157] En ese primer verano de posguerra, también tuvieron lugar otros motines raciales de blancos contra personas "de color" en numerosas ciudades de los Estados Unidos, pueblos del Caribe y Sudáfrica. [156] Fueron parte de la dislocación social después de la guerra, ya que las sociedades luchaban por integrar a los veteranos en las fuerzas laborales nuevamente y los grupos competían por empleos y vivienda. Ante la insistencia de Australia, los británicos se negaron a aceptar la Propuesta de Igualdad Racial presentada por los japoneses en la Conferencia de Paz de París de 1919 .

La Segunda Guerra Mundial marcó otro período de crecimiento para las comunidades negras en Londres, Liverpool y otras partes de Gran Bretaña. Muchos negros del Caribe y África Occidental llegaron en pequeños grupos como trabajadores en tiempos de guerra, marineros mercantes y militares del ejército, la marina y las fuerzas aéreas. [158] Por ejemplo, en febrero de 1941, 345 antillanos llegaron a trabajar en fábricas en Liverpool y sus alrededores, fabricando municiones. [159] Entre los caribeños que se unieron a la Real Fuerza Aérea (RAF) y prestaron un servicio distinguido se encuentran Ulric Cross [160] de Trinidad, Cy Grant [161] de Guyana y Billy Strachan [162] de Jamaica. El African and Caribbean War Memorial fue instalado en Brixton , Londres, en 2017 por el Nubian Jak Community Trust para honrar a los militares de África y el Caribe que sirvieron junto a las fuerzas británicas y de la Commonwealth tanto en la Primera Guerra Mundial como en la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [163]

A finales de 1943, había 3.312 soldados afroamericanos estacionados en Maghull y Huyton , cerca de Liverpool. [164] Se estimó que la población negra en el verano de 1944 era de 150.000, en su mayoría soldados negros de los Estados Unidos. Sin embargo, en 1948 se estimó que la población negra era inferior a 20.000 y no alcanzó el pico anterior de 1944 hasta 1958. [165]

Learie Constantine , un jugador de críquet de las Indias Occidentales, era un funcionario de bienestar social del Ministerio de Trabajo cuando se le negó el servicio en un hotel de Londres. Presentó una demanda por incumplimiento de contrato y se le concedieron daños y perjuicios. Este ejemplo en particular es utilizado por algunos para ilustrar el lento cambio del racismo hacia la aceptación e igualdad de todos los ciudadanos en Londres. [166] En 1943, la rama de Essex del Ejército de Tierra de Mujeres le negó trabajo a Amelia King porque era negra. La decisión fue revocada después de que su causa fuera asumida por el Consejo de Comercio de Holborn, [167] lo que llevó a su diputado, Walter Edwards , a plantear el asunto en la Cámara de los Comunes . Finalmente aceptó un puesto en Frith Farm, Wickham , Hampshire y se alojó con una familia en el pueblo. [168]

En 1950, probablemente había menos de 20.000 residentes no blancos en Gran Bretaña, casi todos nacidos en el extranjero. [169] Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, se produjo la mayor afluencia de personas negras, principalmente de las Indias Occidentales Británicas . Más de un cuarto de millón de antillanos, la abrumadora mayoría de ellos de Jamaica , se establecieron en Gran Bretaña en menos de una década. En 1951, la población de personas nacidas en el Caribe y África en Gran Bretaña se estimó en 20.900. [170] A mediados de la década de 1960, Gran Bretaña se había convertido en el centro de la mayor población de antillanos en el extranjero. [171] Este evento migratorio a menudo se etiqueta como "Windrush", una referencia al HMT Empire Windrush , el barco que transportó al primer grupo importante de migrantes caribeños al Reino Unido en 1948. [172]

El término "caribeño" no es en sí mismo una identidad étnica o política; por ejemplo, algunos de los inmigrantes de esta ola eran indocaribeños . El término más utilizado en esa época era "antillano" (o, a veces, "de color" ). El término "negro británico" no se generalizó hasta que nació la segunda generación de estos inmigrantes de posguerra en el Reino Unido. Aunque eran británicos por nacionalidad, debido a la fricción entre ellos y la mayoría blanca, a menudo nacieron en comunidades relativamente cerradas, lo que creó las raíces de lo que se convertiría en una identidad negra británica distintiva . En la década de 1950, había una conciencia de los negros como un grupo separado que no había existido durante 1932-1938. [171] La creciente conciencia de los pueblos negros británicos estuvo profundamente influenciada por la afluencia de la cultura negra estadounidense importada por los militares negros durante y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, siendo la música un ejemplo central de lo que Jacqueline Nassy-Brown llama "recursos diaspóricos". Estas estrechas interacciones entre estadounidenses y británicos negros no sólo fueron materiales, sino que también inspiraron la expatriación de algunas mujeres británicas negras a Estados Unidos después de casarse con militares (algunos de los cuales luego fueron repatriados al Reino Unido). [173]

En 1961, la población de personas nacidas en África o el Caribe se estimó en 191.600, poco menos del 0,4% de la población total del Reino Unido. [170] La Ley de Inmigrantes de la Commonwealth de 1962 se aprobó en Gran Bretaña junto con una sucesión de otras leyes en 1968 , 1971 y 1981 , que restringieron severamente la entrada de inmigrantes negros a Gran Bretaña. Durante este período se argumenta ampliamente que los negros y asiáticos emergentes lucharon en Gran Bretaña contra el racismo y los prejuicios. Durante la década de 1970, y en parte como respuesta tanto al aumento de la intolerancia racial como al auge del movimiento Black Power en el extranjero, el negro se desprendió de sus connotaciones negativas y se recuperó como un marcador de orgullo: el negro es hermoso. [171] En 1975, David Pitt fue nombrado miembro de la Cámara de los Lores . Habló contra el racismo y a favor de la igualdad con respecto a todos los residentes de Gran Bretaña. En los años siguientes, varios miembros negros fueron elegidos para el Parlamento británico . En 1981, se estimaba que la población negra en el Reino Unido representaba el 1,2% de todos los países de nacimiento, de los cuales el 0,8% eran negros caribeños, el 0,3% negros de otros países y el 0,1% negros africanos residentes. [174]

Desde la década de 1980, la mayoría de los inmigrantes negros en el país provienen directamente de África, en particular, Nigeria y Ghana en África occidental, Uganda y Kenia en África oriental, Zimbabwe y Sudáfrica en África meridional. [ cita requerida ] Los nigerianos y ghaneses se han acostumbrado especialmente rápido a la vida británica, y los jóvenes nigerianos y ghaneses obtienen algunos de los mejores resultados en GCSE y A-Level , a menudo a la par o por encima del rendimiento de los alumnos blancos. [175] La tasa de matrimonio interracial entre ciudadanos británicos nacidos en África y británicos nativos sigue siendo bastante baja, en comparación con los del Caribe.

A finales del siglo XX, el número de londinenses negros ascendía a medio millón, según el censo de 1991. El censo de 1991 fue el primero en incluir una pregunta sobre la etnicidad, y la población negra de Gran Bretaña (es decir, el Reino Unido excluyendo Irlanda del Norte, donde no se hizo la pregunta) se registró como 890.727, o el 1,6% de la población total. Esta cifra incluía 499.964 personas en la categoría Negro-caribeño (0,9%), 212.362 en la categoría Negro-africano (0,4%) y 178.401 en la categoría Negro-Otro (0,3%). [176] [177] Un número cada vez mayor de londinenses negros nacieron en Londres o en Gran Bretaña. Incluso con esta población en crecimiento y los primeros negros elegidos para el Parlamento, muchos argumentan que todavía había discriminación y un desequilibrio socioeconómico en Londres entre los negros. En 1992, el número de negros en el Parlamento aumentó a seis, y en 1997, aumentó su número a nueve. Los londinenses negros aún enfrentan muchos problemas; la nueva revolución informática global y de alta tecnología está cambiando la economía urbana y algunos sostienen que está aumentando las tasas de desempleo entre los negros en relación con los no negros, [95] algo que, se sostiene, amenaza con erosionar el progreso logrado hasta ahora. [95] En 2001, la población británica negra se registró en 1.148.738 (2,0%) en el censo de 2001. [ 178]

Desde finales de la década de 1950 hasta finales de la década de 1980 se produjeron una serie de conflictos callejeros masivos entre jóvenes afrocaribeños y agentes de policía británicos en ciudades inglesas, principalmente como resultado de tensiones entre miembros de las comunidades negras locales y los blancos.

El primer incidente importante ocurrió en 1958 en Notting Hill , cuando bandas de entre 300 y 400 jóvenes blancos atacaron a afrocaribeños y sus casas en todo el vecindario, lo que provocó que varios hombres afrocaribeños quedaran inconscientes en las calles. [179] Al año siguiente, Kelso Cochrane, nacido en Antigua, murió después de ser atacado y apuñalado por una pandilla de jóvenes blancos mientras caminaba hacia su casa en Notting Hill.

Durante la década de 1970, las fuerzas policiales de toda Inglaterra comenzaron a utilizar cada vez más la ley Sus , lo que provocó la sensación de que los jóvenes negros estaban siendo discriminados por la policía [180]. El siguiente brote de peleas callejeras digno de mención ocurrió en 1976 en el Carnaval de Notting Hill, cuando varios cientos de policías y jóvenes se vieron involucrados en peleas y riñas televisadas, con piedras arrojadas a la policía, cargas con porras y una serie de lesiones menores y arrestos. [181]

En 1980, en los disturbios de St Pauls en Bristol, se produjeron enfrentamientos entre jóvenes locales y agentes de policía, que se saldaron con numerosos heridos menores, daños a la propiedad y arrestos. En Londres, en 1981, se produjo un nuevo conflicto, con una fuerza policial percibida como racista tras la muerte de 13 jóvenes negros que asistían a una fiesta de cumpleaños que terminó en el devastador incendio de New Cross . Muchos consideraron que el incendio era una masacre racista [179] y se celebró una importante manifestación política, conocida como el Día de Acción de los Negros , para protestar contra los propios ataques, la percepción de un aumento del racismo y la percepción de hostilidad e indiferencia por parte de la policía, los políticos y los medios de comunicación. [179] Las tensiones se incrementaron aún más cuando, en la cercana Brixton , la policía lanzó la operación Swamp 81, una serie de detenciones y registros masivos de jóvenes negros. [179] La ira estalló cuando hasta 500 personas se vieron involucradas en una pelea callejera entre la Policía Metropolitana y la comunidad afrocaribeña local, lo que llevó a que se incendiaran varios automóviles y tiendas, se lanzaran piedras a la policía y cientos de arrestos y lesiones menores. Un patrón similar ocurrió más al norte de Inglaterra ese año, en Toxteth , Liverpool, y Chapeltown, Leeds . [182]

A pesar de las recomendaciones del Informe Scarman (publicado en noviembre de 1981), [179] las relaciones entre los jóvenes negros y la policía no mejoraron significativamente y una nueva ola de conflictos a nivel nacional ocurrió en Handsworth , Birmingham, en 1985, cuando la comunidad local del sur de Asia también se involucró. El fotógrafo y artista Pogus Caesar documentó extensamente los disturbios. [180] Después del tiroteo policial de una abuela negra, Cherry Groce, en Brixton, y la muerte de Cynthia Jarrett durante una redada en su casa en Tottenham , en el norte de Londres, las protestas celebradas en las comisarías de policía locales no terminaron pacíficamente y estallaron más batallas callejeras con la policía, [179] los disturbios se extendieron más tarde al Moss Side de Manchester . [179] Las batallas callejeras en sí (que implicaron más lanzamiento de piedras, la descarga de un arma de fuego y varios incendios) llevaron a dos muertes (en el motín de Broadwater Farm ) y Brixton.

En 1999, tras la investigación Macpherson sobre el asesinato de Stephen Lawrence en 1993 , Sir Paul Condon , comisario de la Policía Metropolitana, aceptó que su organización era institucionalmente racista . Algunos miembros de la comunidad negra británica estuvieron implicados en los disturbios raciales de Harehills de 2001 y en los disturbios raciales de Birmingham de 2005 .

En la década de 1950, el gobierno británico comenzó a preocuparse por la radicalización dentro de las comunidades de inmigrantes negros y comenzó a tomar medidas para vigilarlas en general. Por ejemplo, en Sheffield, se autorizó a los agentes de policía a "observar, visitar e informar" sobre la comunidad negra de la ciudad, y se les autorizó a crear un fichero con datos como la dirección y el lugar de trabajo de los 534 residentes de la ciudad en ese momento.

Los documentos de los Archivos Nacionales muestran que las prácticas continuaron hasta la década de 1960, cuando la policía de Manchester creó informes sobre la "mezcla, el mestizaje y la ilegitimidad" de las comunidades inmigrantes, enumerando el número de niños por raza. [183]

En 2011, tras el tiroteo de un hombre mestizo, Mark Duggan , por parte de la policía en Tottenham, se celebró una protesta en la comisaría local. La protesta terminó con un brote de enfrentamientos entre jóvenes locales y agentes de policía que provocaron disturbios generalizados en varias ciudades inglesas .

Algunos analistas afirmaron que la población negra estuvo desproporcionadamente representada en los disturbios de 2011 en Inglaterra. [184] Las investigaciones sugieren que las relaciones raciales en Gran Bretaña se deterioraron en el período posterior a los disturbios y que el prejuicio hacia las minorías étnicas aumentó. [185] Se dijo que grupos como la EDL y el BNP estaban explotando la situación. [186] Las tensiones raciales entre negros y asiáticos en Birmingham aumentaron después de la muerte de tres hombres asiáticos a manos de un joven negro. [187]

En un debate en Newsnight del 12 de agosto de 2011, el historiador David Starkey culpó a la cultura del rap y de los gangsters negros, diciendo que habían influenciado a los jóvenes de todas las razas. [188] Las cifras mostraron que el 46 por ciento de las personas llevadas ante un tribunal por arrestos relacionados con los disturbios de 2011 eran negras. [189]

Durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en el Reino Unido, los primeros diez trabajadores de la salud que murieron a causa del virus provenían de orígenes negros y de minorías étnicas (BAME), lo que llevó al director de la Asociación Médica Británica a pedir al gobierno que comenzara a investigar si las minorías se estaban viendo afectadas desproporcionadamente y por qué. [190] Las primeras estadísticas encontraron que las personas negras y asiáticas se estaban viendo más afectadas que las personas blancas, con cifras que mostraban que el 35% de los pacientes de COVID-19 no eran blancos, [191] y estudios similares en los EE. UU. habían mostrado una clara disparidad racial. [192] El gobierno anunció que iniciará una investigación oficial sobre el impacto desproporcionado del coronavirus en las comunidades negras, asiáticas y de minorías étnicas, y el Ministro de Comunidades, Robert Jenrick, reconoció que "parece haber un impacto desproporcionado del virus en las comunidades BAME en el Reino Unido". [193]

Una campaña en las redes sociales en respuesta a la campaña Clap for our Carers , destacó el papel de los trabajadores sanitarios y clave negros y minoritarios y pidió al público que continuara su apoyo después de la pandemia obtuvo más de 12 millones de visitas en línea. [194] [195] [196] Se informó que el 72 por ciento del personal del NHS que murió por COVID-19 pertenecía a grupos étnicos negros y minoritarios, mucho más que el número de personal de orígenes BAME que trabaja en el NHS, que se situó en el 44%. [197] Las estadísticas mostraron que las personas negras estaban significativamente sobrerrepresentadas, pero que a medida que avanzaba la pandemia, la disparidad en estas cifras se estaba reduciendo. [198] Los informes analizaron una serie de factores contribuyentes complejos, incluida la desigualdad de salud e ingresos, y los factores sociales y ambientales estaban exacerbando y contribuyendo a la propagación de la enfermedad de manera desigual. [199] En abril de 2020, después de que la pareja de su hermana muriera a causa del virus, Patrick Vernon creó una iniciativa de recaudación de fondos llamada "The Majonzi Fund", que proporcionará a las familias acceso a pequeñas subvenciones financieras que pueden utilizarse para acceder a asesoramiento sobre duelo y organizar eventos conmemorativos y homenajes después de que se haya levantado el bloqueo social. [200]

Después del Brexit , los ciudadanos de la UE que trabajaban en el sector de la salud y la asistencia social fueron reemplazados por inmigrantes de países no pertenecientes a la UE, como Nigeria . [201] [202] Alrededor de 141.000 personas vinieron de Nigeria en 2023. [203]

Año de llegada (censo de 2021, Inglaterra y Gales) [c] [218]

En el censo de 2021 , se registraron 2.409.278 personas en Inglaterra y Gales como de etnia negra, británica negra, galesa negra, caribeña o africana, lo que representa el 4,0% de la población. [219] En Irlanda del Norte, 11.032, o el 0,6% de la población, se identificaron como africana negra o negra otra. [4] El censo en Escocia se retrasó un año y se llevó a cabo en 2022, la cifra equivalente fue de 65.414, lo que representa el 1,2% de la población. [3] Las diez autoridades locales con la mayor proporción de personas que se identificaron como negras estaban ubicadas en Londres: Lewisham (26,77%), Southwark (25,13%), Lambeth (23,97%), Croydon (22,64%), Barking y Dagenham (21,39%), Hackney (21,09%), Greenwich (20,96%), Enfield (18,34%), Haringey (17,58%) y Brent (17,51%). Fuera de Londres, Manchester tenía la mayor proporción, con un 11,94%. En Escocia, la proporción más alta estaba en Aberdeen , con un 4,20%; en Gales, la concentración más alta estaba en Cardiff, con un 3,84%; y en Irlanda del Norte, la concentración más alta estaba en Belfast, con un 1,34%. [220]

El censo del Reino Unido de 2011 registró 1.904.684 residentes que se identificaron como "negros/africanos/caribeños/británicos negros", lo que representa el 3 por ciento de la población total del Reino Unido. [221] Este fue el primer censo del Reino Unido en el que el número de residentes negros africanos que se autodeclararon residentes superó al de caribeños negros. [222]

En Inglaterra y Gales, 989.628 personas especificaron su origen étnico como "africano negro", 594.825 como "caribeño negro" y 280.437 como "otro negro". [223] En Irlanda del Norte, 2.345 personas se identificaron como "africanos negros", 372 como "caribeños negros" y 899 como "otro negro", lo que hace un total de 3.616 residentes "negros". [224] En Escocia, 29.638 personas se identificaron como "africanas" y eligieron la casilla "africano, escocés africano o británico africano" o la casilla "otro africano" y el área para escribir. 6.540 personas también se identificaron como "caribeñas o negras" y seleccionaron la casilla "caribeño, escocés caribeño o británico caribeño", la casilla "negro, escocés negro o británico negro" o la casilla "otro caribeño o negro" y el área para escribir. [225] Para comparar los resultados de todo el Reino Unido, la Oficina de Estadísticas Nacionales combinó las entradas "africanas" y "caribeñas o negras" en el nivel superior, [2] y reportó un total de 36.178 residentes "negros" en Escocia. [221] Según la ONS, las personas en Escocia con etnias "africanas", "blancas" y "asiáticas", así como identidades "negras", podrían así potencialmente ser capturadas dentro de este resultado combinado. [2] La Oficina del Registro General de Escocia, que diseñó las categorías y administra el censo de Escocia, no combina las entradas "africanas" y "caribeñas o negras", manteniéndolas separadas para las personas que no se identifican como "negras" (ver clasificación del censo ). [21]

En el censo de 2001 , 575.876 personas en el Reino Unido habían declarado su etnia como "caribeños negros", 485.277 como "africanos negros" y 97.585 como "otros negros", lo que hace un total de 1.148.738 residentes "negros o británicos negros". Esto equivalía al 2 por ciento de la población del Reino Unido en ese momento. [178]

La mayoría de los británicos negros se encuentran en las grandes ciudades y áreas metropolitanas del país. El censo de 2011 encontró que 1,85 millones de una población negra total de 1,9 millones vivían en Inglaterra, con 1,09 millones de ellos en Londres , donde representaban el 13,3 por ciento de la población, en comparación con el 3,5 por ciento de la población de Inglaterra y el 3 por ciento de la población del Reino Unido. Las diez autoridades locales con la mayor proporción de sus poblaciones que se describen a sí mismas como negras en el censo estaban todas en Londres: Lewisham (27,2 por ciento), Southwark (26,9 por ciento), Lambeth (25,9 por ciento), Hackney (23,1 por ciento), Croydon (20,2 por ciento), Barking y Dagenham (20,0 por ciento), Newham (19,6 por ciento), Greenwich (19,1 por ciento), Haringey (18,8 por ciento) y Brent (18,8 por ciento). [221] Más específicamente, para los africanos negros la autoridad local más alta fue Southwark (16,4 por ciento), seguida de Barking y Dagenham (15,4 por ciento) y Greenwich (13,8 por ciento), mientras que para los caribeños negros la más alta fue Lewisham (11,2 por ciento), seguida de Lambeth (9,5 por ciento) y Croydon (8,6 por ciento). [221]

Fuera de Londres, las siguientes poblaciones más grandes se encuentran en Birmingham (125.760, 11%) / Coventry (30.723, 9%) / Sandwell (29.779, 8,7%) / Wolverhampton (24.636, 9,3%), Manchester (65.893, 12%), Nottingham (32.215, 10%), Leicester (28.766, 8%), Bristol (27.890, 6%), Leeds (25.893, 5,6%), Sheffield (25.512, 4,6%) y Luton (22.735, 10%). [1]

Un artículo de una revista académica publicado en 2005, que cita fuentes de 1997 y 2001, estimó que casi la mitad de los hombres afrocaribeños nacidos en Gran Bretaña , un tercio de las mujeres afrocaribeñas nacidas en Gran Bretaña y una quinta parte de los hombres africanos tienen parejas blancas. [228] En 2014, The Economist informó que, según la Encuesta de la Fuerza Laboral , el 48 por ciento de los hombres negros caribeños y el 34 por ciento de las mujeres negras caribeñas en pareja tienen parejas de un grupo étnico diferente. Además, los niños mestizos menores de diez años con padres negros caribeños y blancos superan en número a los niños negros caribeños en una proporción de dos a uno. [229]

El inglés multicultural de Londres es una variedad del idioma inglés hablado por una gran cantidad de la población negra británica de ascendencia afrocaribeña. [230] El dialecto negro británico ha sido influenciado por el patois jamaicano debido a la gran cantidad de inmigrantes de Jamaica, pero también lo hablan o imitan personas de diferente ascendencia.

El habla negra británica también está fuertemente influenciada por la clase social y el dialecto regional ( cockney , mancuniano , brummie , scouse , etc.).

Los inmigrantes nacidos en África hablan lenguas africanas y francés además de inglés.

La música negra británica es una parte influyente y de larga data de la música británica . Su presencia en el Reino Unido se remonta al siglo XVIII, abarcando a artistas de conciertos como George Bridgetower y músicos callejeros como Billy Waters . Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) alcanzó un gran éxito como compositor a finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX. La era del jazz también había tenido un efecto en la generación. [231]

A finales de los años 1970 y 1980, 2 Tone se hizo popular entre la juventud británica , especialmente en West Midlands . Una mezcla de punk , ska y pop lo convirtió en un favorito entre el público blanco y negro. Entre las bandas famosas del género se incluyen Selecter , Specials , Beat y Bodysnatchers .

La música jungle , dubstep , drum and bass , UK garage y grime se originaron en Londres.

Los Premios MOBO reconocen a los intérpretes de "Música de origen negro".

Black Lives in Music (BLiM) se formó después de que sus fundadores se percataran del racismo institucionalizado en la industria del entretenimiento británica. BLiM trabaja por la igualdad de oportunidades para las personas negras, asiáticas y de diversas etnias en la industria del jazz y la música clásica, oportunidades que incluyen la posibilidad de aprender a tocar un instrumento musical, asistir a una escuela de música, seguir una carrera en la música y alcanzar niveles superiores dentro del sector sin sufrir discriminación. [232] [233] [234] [235]

La comunidad negra en Gran Bretaña tiene varias publicaciones importantes. La publicación clave más importante es el periódico The Voice , fundado por Val McCalla en 1982, y el único periódico semanal negro nacional de Gran Bretaña. The Voice se dirige principalmente a la diáspora caribeña y se ha impreso durante más de 35 años. [236] En segundo lugar, la revista Black History Month es un punto central de atención que lidera la celebración nacional de la historia, las artes y la cultura negras en todo el Reino Unido. [237] Pride Magazine , publicada desde 1991, es la revista mensual más grande que se dirige a las mujeres negras británicas, mestizas, africanas y afrocaribeñas en el Reino Unido. En 2007, The Guardian informó que la revista había dominado el mercado de revistas para mujeres negras durante más de 15 años. [238] La revista Keep The Faith es una revista multipremiada para la comunidad negra y de minorías étnicas que se produce trimestralmente desde 2005. [239] Los colaboradores editoriales de Keep The Faith son algunos de los agitadores y emprendedores más poderosos e influyentes dentro de las comunidades BME.

Muchas de las principales publicaciones británicas negras se gestionan a través de Diverse Media Group, [240] que se especializa en ayudar a las organizaciones a llegar a la comunidad negra y de minorías étnicas de Gran Bretaña a través de los principales medios de comunicación que consumen. El equipo directivo superior está compuesto por muchos directores ejecutivos y propietarios de las publicaciones mencionadas anteriormente.

Entre las editoriales lideradas por negros establecidas en el Reino Unido se encuentran New Beacon Books (cofundada en 1966 por John La Rose ), Allison and Busby (cofundada en 1967 por Margaret Busby ), Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications (cofundada en 1969 por Jessica Huntley y Eric Huntley), Hansib (fundada en 1970), Karnak House (fundada en 1975 por Amon Saba Saakana ), Black Ink Collective (fundada en 1978), Black Womantalk (fundada en 1983), Karnak House (fundada por Buzz Johnson ), Tamarind Books (fundada en 1987 por Verna Wilkins ), y otras. [241] [242] [243] [244] La Feria Internacional del Libro de Libros Radicales Negros y del Tercer Mundo (1982-1995) fue una iniciativa lanzada por New Beacon Books, Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications y el Race Today Collective. [245]

La ola de inmigrantes negros que llegó a Gran Bretaña desde el Caribe en la década de 1950 se enfrentó a cantidades significativas de racismo . Para muchos inmigrantes caribeños, su primera experiencia de discriminación llegó cuando intentaban encontrar alojamiento privado. Por lo general, no eran elegibles para viviendas sociales porque solo las personas que habían residido en el Reino Unido durante un mínimo de cinco años calificaban para ello. En ese momento, no había una legislación antidiscriminación que impidiera que los propietarios se negaran a aceptar inquilinos negros. Una encuesta realizada en Birmingham en 1956 encontró que solo 15 de un total de 1.000 personas blancas encuestadas alquilarían una habitación a un inquilino negro. Como resultado, muchos inmigrantes negros se vieron obligados a vivir en áreas marginales de las ciudades, donde la vivienda era de mala calidad y había problemas de delincuencia, violencia y prostitución. [246] [247] Uno de los propietarios de barrios marginales más notorios fue Peter Rachman , que poseía alrededor de 100 propiedades en el área de Notting Hill de Londres. Los inquilinos negros normalmente pagaban el doble del alquiler que los inquilinos blancos y vivían en condiciones de hacinamiento extremo. [246]

El historiador Winston James sostiene que la experiencia del racismo en Gran Bretaña fue un factor importante en el desarrollo de una identidad caribeña compartida entre inmigrantes negros de diferentes orígenes insulares y de clase. [248]

En las décadas de 1970 y 1980, los negros en Gran Bretaña fueron víctimas de violencia racista perpetrada por grupos de extrema derecha como el Frente Nacional . [249] Durante este período, también era común que los futbolistas negros fueran objeto de cánticos racistas por parte de los miembros de la multitud. [250] [251]

Se considera que el racismo en Gran Bretaña en general, incluso contra las personas negras, ha disminuido con el tiempo. El académico Robert Ford demuestra que la distancia social , medida mediante preguntas de la encuesta British Social Attitudes sobre si a las personas les importaría tener un jefe de una minoría étnica o que un pariente cercano se case con un cónyuge de una minoría étnica, disminuyó durante el período 1983-1996. Estas disminuciones se observaron en las actitudes hacia las minorías étnicas negras y asiáticas. Gran parte de este cambio de actitudes ocurrió en la década de 1990. En la década de 1980, la oposición al matrimonio interracial fue significativa. [252] [253] No obstante, Ford sostiene que "el racismo y la discriminación racial siguen siendo parte de la vida cotidiana de las minorías étnicas de Gran Bretaña. Los británicos negros y asiáticos... tienen menos probabilidades de estar empleados y es más probable que trabajen en peores empleos, vivan en peores casas y sufran peor salud que los británicos blancos". [252] El proyecto Minorities at Risk (MAR) de la Universidad de Maryland señaló en 2006 que, si bien los afrocaribeños en el Reino Unido ya no enfrentan discriminación formal, siguen estando subrepresentados en la política y enfrentando barreras discriminatorias en el acceso a la vivienda y en las prácticas de empleo. El proyecto también señala que el sistema escolar británico "ha sido acusado en numerosas ocasiones de racismo y de socavar la confianza en sí mismos de los niños negros y de difamar la cultura de sus padres". El perfil del MAR sobre los afrocaribeños en el Reino Unido señala "una creciente violencia 'entre negros' entre personas del Caribe e inmigrantes de África". [254]

Existe la preocupación de que los asesinatos con cuchillos no reciben la atención suficiente porque la mayoría de las víctimas son negras. Martin Hewitt, de la Policía Metropolitana, dijo: "A veces temo que, como la mayoría de las personas que resultan heridas o mueren provienen de ciertas comunidades y, muy a menudo, de las comunidades negras de Londres, no se genere el sentido de indignación colectiva que debería generarse y que realmente haga que todos hagamos todo lo posible para evitar que esto suceda. Es un esfuerzo enorme de nuestra parte. Estamos destinando enormes recursos para tratar de detener el flujo de la violencia y estamos teniendo cierto éxito en ese sentido, pero colectivamente todos deberíamos analizar esto y ver cómo podemos prevenirlo". [255] [256]

Una encuesta de la Universidad de Cambridge de 2023 que incluyó la muestra más grande de personas negras en Gran Bretaña encontró que el 88% había denunciado discriminación racial en el trabajo, el 79% creía que la policía atacaba injustamente a las personas negras con poderes de detención y registro y el 80% definitivamente o algo estaba de acuerdo en que la discriminación racial era la mayor barrera para el logro académico de los jóvenes estudiantes negros . [257]

Los jóvenes nigerianos y ghaneses obtuvieron algunos de los mejores resultados en GCSE y A-Level según un informe del gobierno publicado en 2006, a menudo a la par o por encima del rendimiento de los alumnos blancos. [175] Según las estadísticas del Departamento de Educación para el año académico 2021-22, los alumnos británicos negros obtuvieron un rendimiento académico inferior al promedio nacional tanto en el nivel A-Level como en el GCSE . El 12,3% de los alumnos británicos negros obtuvieron al menos 3 A en el nivel A [258] y se logró una puntuación media de 48,6 en la puntuación de Attainment 8 en el nivel GCSE. [259] Existe una disparidad en el rendimiento académico entre los alumnos negros africanos y los alumnos negros caribeños en el nivel GCSE. Los alumnos negros africanos obtuvieron mejores resultados que los alumnos blancos y que el promedio nacional, con una puntuación media de 50,9 y el 54,5% de los alumnos obtuvieron el grado 5 o superior tanto en inglés como en matemáticas GCSE. Mientras tanto, los alumnos negros del Caribe obtuvieron una puntuación media de 41,7 y solo el 34,6% de los alumnos alcanzaron el grado 5 o superior tanto en inglés como en matemáticas GCSE. [260]

Un informe de 2019 de Universities UK concluyó que la raza y la etnia de los estudiantes afectan significativamente los resultados de sus títulos. Según este informe de 2017-18, había una brecha del 13 % entre la probabilidad de que los estudiantes blancos y los estudiantes de minorías étnicas (BAME) se graduaran con una clasificación de primer o segundo grado en las universidades británicas. [261] [262]

Según el informe de la TUC de 2005 Trabajadores negros, empleos y pobreza , las personas negras y de minorías étnicas (BME) tenían más probabilidades de estar desempleadas que la población blanca. La tasa de desempleo entre la población blanca era del 5%, pero entre los grupos de minorías étnicas era del 17% entre los bangladesíes, del 15% entre los paquistaníes, del 15% entre los mestizos, del 13% entre los británicos negros, del 12% entre los de otras etnias y del 7% entre los indios. De los diferentes grupos étnicos estudiados, los asiáticos tenían la tasa de pobreza más alta, del 45% (después de los costos de la vivienda), los británicos negros del 38% y los chinos/otros del 32% (en comparación con una tasa de pobreza del 20% para la población blanca). Sin embargo, el informe admitió que las cosas estaban mejorando lentamente. [263]

Según datos de 2012 compilados por la Oficina de Estadísticas Nacionales , el 50% de los hombres negros jóvenes de entre 16 y 24 años estaban desempleados entre el cuarto trimestre de 2011 y el primer trimestre de 2012. [264]

Un estudio de 2014 realizado por el Black Training and Enterprise Group (BTEG), financiado por Trust for London , exploró las opiniones de los hombres negros jóvenes de Londres sobre por qué su grupo demográfico tiene una tasa de desempleo más alta que cualquier otro grupo de jóvenes, y descubrió que muchos hombres negros jóvenes de Londres creen que el racismo y los estereotipos negativos son las principales razones de su alta tasa de desempleo. [265]

En 2021, el 67% de los negros de entre 16 y 64 años estaban empleados, en comparación con el 76% de los blancos británicos y el 69% de los británicos asiáticos. La tasa de empleo de los negros de entre 16 y 24 años fue del 31%, en comparación con el 56% de los blancos británicos y el 37% de los británicos asiáticos. [266] El salario medio por hora de los negros británicos en 2021 fue uno de los más bajos de todos los grupos étnicos, con 12,55 libras esterlinas, solo por delante de los británicos paquistaníes y bangladesíes. [267] En 2023, la Oficina de Estadísticas Nacionales publicó un análisis más granular y descubrió que los empleados negros nacidos en el Reino Unido (15,18 libras esterlinas) ganaron más que los empleados blancos nacidos en el Reino Unido (14,26 libras esterlinas) en 2022, mientras que los empleados negros no nacidos en el Reino Unido ganaron menos (12,95 libras esterlinas). En general, los empleados negros tenían un salario medio por hora de £13,53 en 2022. [268] Según los datos del Departamento de Trabajo y Pensiones para el período 2018-2021, el 24% de las familias negras recibían beneficios relacionados con los ingresos , en comparación con el 16% de las familias británicas blancas y el 8% de las familias chinas e indias británicas. Las familias negras también eran la etnia con más probabilidades de recibir beneficios de vivienda, reducción de impuestos municipales y residir en viviendas sociales. [269] [270] Sin embargo, las familias británicas blancas (54%) eran las que tenían más probabilidades de recibir apoyo estatal de todos los grupos étnicos, con un 27% de las familias británicas blancas recibiendo la pensión estatal . [269]

Tanto los delitos racistas como los delitos relacionados con las bandas siguen afectando a las comunidades negras, hasta el punto de que la Policía Metropolitana lanzó la Operación Trident para abordar los delitos cometidos entre negros. Las numerosas muertes de hombres negros bajo custodia policial han generado una desconfianza general hacia la policía entre los negros urbanos del Reino Unido. [271] [272] Según la Autoridad de la Policía Metropolitana, en 2002-03 de las 17 muertes bajo custodia policial, 10 eran de negros o asiáticos; los convictos negros tienen una tasa de encarcelamiento desproporcionadamente más alta que otras etnias. El gobierno informa [273] que el número total de incidentes racistas registrados por la policía aumentó un 7 por ciento, de 49.078 en 2002/03 a 52.694 en 2003/04.

La representación mediática de los jóvenes negros británicos se ha centrado especialmente en las "pandillas" con miembros negros y en los delitos violentos que implican a víctimas y perpetradores negros. [274] Según un informe del Ministerio del Interior, [273] el 10 por ciento de todas las víctimas de asesinato entre 2000 y 2004 eran negras. De ellas, el 56 por ciento fueron asesinadas por otras personas negras (el 44 por ciento de los negros fueron asesinados por blancos y asiáticos, lo que hace que los negros sean desproporcionadamente más víctimas de asesinatos a manos de personas de otras etnias). Además, una solicitud de Libertad de Información realizada por The Daily Telegraph muestra datos internos de la policía que proporcionan un desglose de la etnia de los 18.091 hombres y niños contra los que la policía tomó medidas por una serie de delitos en Londres en octubre de 2009. Entre los procesados por delitos callejeros, el 54 por ciento eran negros; por robo, el 59 por ciento; y por delitos con armas de fuego, el 67 por ciento. [275] Según la Oficina de Estadísticas Nacionales, el 18,4% de los sospechosos de homicidio en Inglaterra y Gales entre marzo de 2019 y marzo de 2021 eran negros. [276]

Los negros, que según las estadísticas gubernamentales [277] representan el 2 por ciento de la población, son los principales sospechosos en el 11,7 por ciento de los asesinatos, es decir, en 252 de los 2163 asesinatos cometidos en 2001/2, 2002/3 y 2003/4. [278] A juzgar por la población carcelaria, una minoría sustancial (alrededor del 35%) de los delincuentes negros en el Reino Unido no son ciudadanos británicos sino extranjeros . [279] En noviembre de 2009, el Ministerio del Interior publicó un estudio que mostraba que, una vez que se habían tenido en cuenta otras variables , la etnicidad no era un predictor significativo de la delincuencia, el comportamiento antisocial o el abuso de drogas entre los jóvenes. [280]

Después de varias investigaciones de alto perfil como la del asesinato de Stephen Lawrence , la policía ha sido acusada de racismo, tanto desde dentro como desde fuera del servicio. Cressida Dick , jefa de la unidad antirracismo de la Policía Metropolitana en 2003, comentó que era "difícil imaginar una situación en la que digamos que ya no somos institucionalmente racistas ". [281] Las personas negras tenían siete veces más probabilidades de ser detenidas y registradas por la policía en comparación con las personas blancas, según el Ministerio del Interior. Un estudio independiente dijo que las personas negras tenían más de nueve veces más probabilidades de ser registradas. [282]

En 2010, los británicos negros representaban alrededor del 2,2% de la población general del Reino Unido, pero constituían el 15% de la población carcelaria británica , lo que, según los expertos, es "resultado de décadas de prejuicio racial en el sistema de justicia penal y un enfoque excesivamente punitivo de los asuntos penales". [283] Esta proporción disminuyó al 12,4% a finales de 2022, aunque los británicos negros ahora representan alrededor del 3-4% de la población británica. [284] En el entorno penitenciario, los presos negros son los más propensos a estar involucrados en incidentes violentos. En 2020, los presos negros eran los más propensos de todos los grupos étnicos a ser agresores (319 incidentes por cada 1.000 presos) o a estar involucrados en incidentes violentos sin una víctima o agresor claro (185 incidentes por cada 1.000 presos). [285] En el mismo año, el 32% de los niños en prisión eran negros, en contraste con el 47% de los presos menores de 18 años que eran blancos. [286] La Revisión Lammy , dirigida por el diputado David Lammy , proporcionó posibles razones para el número desproporcionado de niños negros en las cárceles, incluidas la austeridad en los servicios públicos, la falta de diversidad en el poder judicial y el sistema escolar que no presta un servicio adecuado a la comunidad negra al no identificar las dificultades de aprendizaje. [287] [288]