Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin [c] [d] (nacido el 7 de octubre de 1952) es un político ruso y ex oficial de inteligencia que es el presidente de Rusia . Putin ha ocupado cargos continuos como presidente o primer ministro desde 1999: [e] como primer ministro de 1999 a 2000 y de 2008 a 2012, y como presidente de 2000 a 2008 y desde 2012. [f] [7] Es el líder ruso o soviético con más años en el cargo desde Joseph Stalin .

Putin trabajó como oficial de inteligencia extranjera de la KGB durante 16 años, ascendiendo al rango de teniente coronel antes de renunciar en 1991 para comenzar una carrera política en San Petersburgo . En 1996, se mudó a Moscú para unirse a la administración del presidente Boris Yeltsin . Se desempeñó brevemente como director del Servicio Federal de Seguridad (FSB) y luego como secretario del Consejo de Seguridad de Rusia antes de ser nombrado primer ministro en agosto de 1999. Tras la renuncia de Yeltsin, Putin se convirtió en presidente interino y, en menos de cuatro meses, fue elegido para su primer mandato como presidente. Fue reelegido en 2004. Debido a las limitaciones constitucionales de dos mandatos presidenciales consecutivos, Putin se desempeñó como primer ministro nuevamente de 2008 a 2012 bajo Dmitri Medvédev . Regresó a la presidencia en 2012, luego de una elección marcada por acusaciones de fraude y protestas , y fue reelegido en 2018 .

Durante el mandato presidencial inicial de Putin, la economía rusa creció en promedio un siete por ciento anual, [8] impulsada por reformas económicas y un aumento de cinco veces en el precio del petróleo y el gas. [9] [10] Además, Putin lideró a Rusia en un conflicto contra los separatistas chechenos , restableciendo el control federal sobre la región. [11] [12] Mientras se desempeñaba como primer ministro bajo Medvedev, supervisó un conflicto militar con Georgia y promulgó reformas militares y policiales . En su tercer mandato presidencial, Rusia anexó Crimea y apoyó una guerra en el este de Ucrania a través de varias incursiones militares, lo que resultó en sanciones internacionales y una crisis financiera en Rusia . También ordenó una intervención militar en Siria para apoyar a su aliado Bashar al-Assad durante la guerra civil siria , asegurando finalmente bases navales permanentes en el Mediterráneo oriental . [13] [14] [15]

En febrero de 2022, durante su cuarto mandato presidencial, Putin lanzó una invasión a gran escala de Ucrania , que provocó la condena internacional y condujo a la ampliación de las sanciones . En septiembre de 2022, anunció una movilización parcial y anexó por la fuerza cuatro óblasts ucranianos, juntos aproximadamente del tamaño de Portugal, a Rusia . En marzo de 2023, la Corte Penal Internacional emitió una orden de arresto contra Putin por crímenes de guerra [16] relacionados con su presunta responsabilidad penal por secuestros ilegales de niños durante la guerra . [17] En abril de 2021, después de un referéndum , firmó enmiendas constitucionales que incluían una que le permitía postularse a la reelección dos veces más, lo que potencialmente extendería su presidencia hasta 2036. [18] [19] En marzo de 2024, fue reelegido para otro mandato.

Bajo el gobierno de Putin , el sistema político ruso se ha transformado en una dictadura autoritaria con culto a la personalidad . [20] [21] [22] Su gobierno ha estado marcado por una corrupción endémica y violaciones generalizadas de los derechos humanos , incluido el encarcelamiento y la represión de opositores políticos , la intimidación y la censura de los medios independientes en Rusia y la falta de elecciones libres y justas . [23] [24] [25] Bajo el gobierno de Putin, Rusia ha recibido constantemente puntuaciones muy bajas en el Índice de Percepción de la Corrupción de Transparencia Internacional , el Índice de Democracia de The Economist , el índice de Libertad en el Mundo de Freedom House y el Índice de Libertad de Prensa de Reporteros sin Fronteras .

Putin nació el 7 de octubre de 1952 en Leningrado, Unión Soviética (hoy San Petersburgo, Rusia), [26] el menor de los tres hijos de Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin (1911-1999) y Maria Ivanovna Putina ( née Shelomova; 1911-1998). Su abuelo, Spiridon Putin (1879-1965), fue cocinero personal de Vladimir Lenin y Joseph Stalin . [27] [28] El nacimiento de Putin fue precedido por la muerte de dos hermanos: Albert, nacido en la década de 1930, murió en la infancia, y Viktor, nacido en 1940, murió de difteria y hambre en 1942 durante el Sitio de Leningrado por las fuerzas de la Alemania nazi en la Segunda Guerra Mundial . [29] [30]

La madre de Putin era trabajadora de fábrica y su padre era un recluta de la Armada Soviética , sirviendo en la flota de submarinos a principios de la década de 1930. Durante la primera etapa de la invasión nazi de la Unión Soviética , su padre sirvió en el batallón de destrucción de la NKVD . [31] [32] [33] Más tarde, fue transferido al ejército regular y resultó gravemente herido en 1942. [34] La abuela materna de Putin fue asesinada por los ocupantes alemanes de la región de Tver en 1941, y sus tíos maternos desaparecieron en el Frente Oriental durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. [35]

El 1 de septiembre de 1960, Putin comenzó a asistir a la Escuela Nº 193 de Baskov Lane, cerca de su casa. Era uno de los pocos de su clase de unos 45 alumnos que aún no eran miembros de la organización de Jóvenes Pioneros ( Komsomol ). A la edad de 12 años, comenzó a practicar sambo y judo. [36] En su tiempo libre, disfrutaba leyendo las obras de Karl Marx , Friedrich Engels y Lenin. [37] Putin asistió a la Escuela Secundaria 281 de San Petersburgo con un programa de inmersión en el idioma alemán. [38] Habla alemán con fluidez y a menudo da discursos y entrevistas en ese idioma. [39] [40]

Putin estudió derecho en la Universidad Estatal de Leningrado que lleva el nombre de Andrei Zhdanov (ahora Universidad Estatal de San Petersburgo ) en 1970 y se graduó en 1975. [41] Su tesis fue sobre "El principio comercial de la nación más favorecida en el derecho internacional". [42] Mientras estuvo allí, se le pidió que se uniera al Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética (PCUS); permaneció como miembro hasta que dejó de existir en 1991. [43] Putin conoció a Anatoly Sobchak , un profesor asistente que enseñaba derecho comercial , [g] y que más tarde se convirtió en el coautor de la constitución rusa . Putin fue influyente en la carrera de Sobchak en San Petersburgo, y Sobchak fue influyente en la carrera de Putin en Moscú. [44]

En 1997, Putin se licenció en economía ( kandidat ekonomicheskikh nauk ) en la Universidad de Minería de San Petersburgo por una tesis sobre las dependencias energéticas y su instrumentalización en la política exterior. [45] [46] Su supervisor fue Vladimir Litvinenko , quien en 2000 y nuevamente en 2004 dirigió sus campañas electorales presidenciales en San Petersburgo. [47] Igor Danchenko y Clifford Gaddy consideran que Putin es un plagiador según los estándares occidentales. Un libro del que copió párrafos enteros es la edición en ruso de Planificación estratégica y política de King y Cleland (1978). [47] Balzer escribió sobre la tesis de Putin y la política energética rusa y concluye junto con Olcott que "La primacía del estado ruso en el sector energético del país no es negociable", y cita la insistencia en la propiedad rusa mayoritaria de cualquier empresa conjunta, particularmente desde que BASF firmó el acuerdo Gazprom Nord Stream - Yuzhno-Russkoye en 2004 con una estructura 49-51, a diferencia de la antigua división 50-50 del proyecto TNK-BP de British Petroleum . [48]

En 1975, Putin se unió a la KGB y se entrenó en la 401.ª Escuela de la KGB en Okhta, Leningrado . [49] [50] Después del entrenamiento, trabajó en la Segunda Dirección General ( contrainteligencia ), antes de ser transferido a la Primera Dirección General , donde monitoreaba a extranjeros y funcionarios consulares en Leningrado. [49] [51] [52] En septiembre de 1984, Putin fue enviado a Moscú para recibir capacitación adicional en el Instituto Bandera Roja Yuri Andropov . [53] [54] [55]

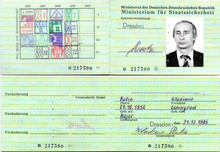

De 1985 a 1990, sirvió en Dresde , Alemania del Este , [56] utilizando una identidad encubierta como traductor. [57] Mientras estuvo destinado en Dresde, Putin trabajó como uno de los oficiales de enlace de la KGB con la policía secreta Stasi y, según se informa, fue ascendido a teniente coronel . Según el sitio oficial presidencial del Kremlin, el régimen comunista de Alemania del Este elogió a Putin con una medalla de bronce por "fiel servicio al Ejército Popular Nacional ". Putin ha expresado públicamente su alegría por sus actividades en Dresde, relatando una vez sus enfrentamientos con manifestantes anticomunistas de 1989 que intentaron la ocupación de edificios de la Stasi en la ciudad. [58]

"Putin y sus colegas se redujeron principalmente a recopilar recortes de prensa , contribuyendo así a las montañas de información inútil producida por la KGB", escribió la ruso-estadounidense Masha Gessen en su biografía de Putin de 2012. [57] Su trabajo también fue minimizado por el exjefe de espionaje de la Stasi Markus Wolf y el ex colega de Putin en la KGB, Vladimir Usoltsev. La periodista Catherine Belton escribió en 2020 que esta minimización era en realidad una tapadera para la participación de Putin en la coordinación y el apoyo de la KGB a la terrorista Fracción del Ejército Rojo , cuyos miembros se escondían con frecuencia en Alemania del Este con el apoyo de la Stasi. Dresde fue preferida como una ciudad "marginal" con solo una pequeña presencia de servicios de inteligencia occidentales. [59] Según una fuente anónima que afirmó ser un ex miembro de la RAF, en una de estas reuniones en Dresde los militantes le presentaron a Putin una lista de armas que luego fueron entregadas a la RAF en Alemania Occidental. Klaus Zuchold, que afirmó haber sido reclutado por Putin, dijo que Putin trató con un neonazi , Rainer Sonntag, e intentó reclutar a un autor de un estudio sobre venenos. [59] Según se informa, Putin se reunió con alemanes para ser reclutados para asuntos de comunicaciones inalámbricas junto con un intérprete. Estuvo involucrado en tecnologías de comunicaciones inalámbricas en el sudeste asiático debido a viajes de ingenieros alemanes, reclutados por él, allí y a Occidente. [52] Sin embargo, una investigación de 2023 de Der Spiegel informó que la fuente anónima nunca había sido miembro de la RAF y es "considerado un fabulista notorio" con "varias condenas previas, incluso por hacer declaraciones falsas". [60]

Según la biografía oficial de Putin, durante la caída del Muro de Berlín , que comenzó el 9 de noviembre de 1989, él guardó los archivos del Centro Cultural Soviético (Casa de la Amistad) y de la villa de la KGB en Dresde para las autoridades oficiales de la futura Alemania unificada, con el fin de impedir que los manifestantes, incluidos los agentes de la KGB y la Stasi, los obtuvieran y destruyeran. Luego supuestamente quemó sólo los archivos de la KGB, en unas pocas horas, pero guardó los archivos del Centro Cultural Soviético para las autoridades alemanas. No se dice nada sobre los criterios de selección durante esta quema; por ejemplo, sobre los archivos de la Stasi o sobre los archivos de otras agencias de la República Democrática Alemana o de la URSS. Explicó que muchos documentos se dejaron en Alemania sólo porque el horno estalló, pero muchos documentos de la villa de la KGB fueron enviados a Moscú. [62]

Tras el colapso del gobierno comunista de Alemania Oriental , Putin tuvo que dimitir del servicio activo en la KGB debido a las sospechas que se despertaron sobre su lealtad durante las manifestaciones en Dresde y antes, aunque la KGB y el ejército soviético todavía operaban en Alemania Oriental. Regresó a Leningrado a principios de 1990 como miembro de las "reservas activas", donde trabajó durante unos tres meses con la sección de Asuntos Internacionales de la Universidad Estatal de Leningrado , reportando al vicerrector Yuriy Molchanov , mientras trabajaba en su tesis doctoral. [52]

Allí, buscó nuevos reclutas para la KGB, observó al estudiantado y renovó su amistad con su antiguo profesor, Anatoly Sobchak , que pronto sería alcalde de Leningrado . [63] Putin afirma que dimitió con el rango de teniente coronel el 20 de agosto de 1991, [63] el segundo día del intento de golpe de Estado soviético de 1991 contra el presidente soviético Mijail Gorbachov . [64] Putin dijo: "Tan pronto como empezó el golpe, decidí inmediatamente de qué lado estaba", aunque señaló que la elección fue difícil porque había pasado la mayor parte de su vida con "los órganos". [65]

En mayo de 1990, Putin fue nombrado asesor en asuntos internacionales del alcalde de Leningrado, Anatoly Sobchak . En una entrevista de 2017 con Oliver Stone , Putin dijo que renunció a la KGB en 1991, tras el golpe de Estado contra Mijail Gorbachov, ya que no estaba de acuerdo con lo sucedido y no quería formar parte de la inteligencia en la nueva administración. [66] Según las declaraciones de Putin en 2018 y 2021, es posible que haya trabajado como taxista privado para ganar dinero extra, o haya considerado ese trabajo. [67] [68]

El 28 de junio de 1991, Putin se convirtió en jefe del Comité de Relaciones Exteriores de la Oficina del Alcalde , con la responsabilidad de promover las relaciones internacionales y las inversiones extranjeras [70] y registrar las empresas comerciales. En el plazo de un año, Putin fue investigado por el consejo legislativo de la ciudad dirigido por Marina Salye . Se concluyó que había subestimado los precios y permitido la exportación de metales valorados en 93 millones de dólares a cambio de ayuda alimentaria extranjera que nunca llegó. [71] [41] A pesar de la recomendación de los investigadores de que Putin fuera despedido, Putin siguió siendo jefe del Comité de Relaciones Exteriores hasta 1996. [72] [73] De 1994 a 1996, ocupó varios otros cargos políticos y gubernamentales en San Petersburgo.

En marzo de 1994, Putin fue nombrado primer vicepresidente del Gobierno de San Petersburgo . En mayo de 1995, organizó la filial en San Petersburgo del partido político progubernamental Nuestra Casa – Rusia , el partido liberal en el poder fundado por el primer ministro Viktor Chernomyrdin . En 1995, dirigió la campaña de las elecciones legislativas de ese partido y, desde 1995 hasta junio de 1997, fue el líder de su filial en San Petersburgo.

En junio de 1996, Sobchak perdió su intento de reelección en San Petersburgo y Putin, que había encabezado su campaña electoral, dimitió de sus cargos en la administración de la ciudad. Se trasladó a Moscú y fue nombrado subdirector del Departamento de Gestión de la Propiedad Presidencial dirigido por Pavel Borodin . Ocupó este puesto hasta marzo de 1997. Era responsable de la propiedad extranjera del Estado y organizó la transferencia de los antiguos activos de la Unión Soviética y el PCUS a la Federación Rusa. [44]

El 26 de marzo de 1997, el presidente Boris Yeltsin nombró a Putin subdirector del Estado Mayor Presidencial , cargo que ocupó hasta mayo de 1998, y jefe de la Dirección Principal de Control del Departamento de Gestión de la Propiedad Presidencial (hasta junio de 1998). Su predecesor en este puesto fue Alexei Kudrin y su sucesor fue Nikolai Patrushev , ambos futuros políticos destacados y asociados de Putin. [44] El 3 de abril de 1997, Putin fue ascendido a consejero de Estado activo de primera clase de la Federación de Rusia , el rango más alto del servicio civil estatal federal . [74]

El 27 de junio de 1997, en el Instituto de Minería de San Petersburgo , dirigido por el rector Vladimir Litvinenko , Putin defendió su disertación de Candidato a la Ciencia en economía, titulada Planificación estratégica de la reproducción de la base de recursos minerales de una región bajo condiciones de formación de relaciones de mercado . [75] Esto ejemplificó la costumbre en Rusia por la cual un funcionario joven en ascenso escribía un trabajo académico a mitad de su carrera. [76] La tesis de Putin fue plagiada . [77] Los investigadores de la Brookings Institution descubrieron que 15 páginas fueron copiadas de un libro de texto estadounidense. [78] [79]

El 25 de mayo de 1998, Putin fue nombrado primer jefe adjunto del Estado Mayor Presidencial para las regiones, en sucesión de Viktoriya Mitina . El 15 de julio, fue nombrado jefe de la comisión para la preparación de acuerdos sobre la delimitación del poder de las regiones y jefe del centro federal adjunto al presidente, en sustitución de Sergey Shakhray . Después del nombramiento de Putin, la comisión no completó ningún acuerdo de ese tipo, aunque durante el mandato de Shakhray como jefe de la Comisión se habían firmado 46 acuerdos de ese tipo. [80] Más tarde, después de convertirse en presidente, Putin canceló los 46 acuerdos. [44] El 25 de julio de 1998, Yeltsin nombró a Putin director del Servicio Federal de Seguridad (FSB), la principal organización de inteligencia y seguridad de la Federación Rusa y sucesora del KGB. [81] En 1999, Putin describió el comunismo como "un callejón sin salida, lejos de la corriente principal de la civilización". [82]

El 9 de agosto de 1999, Putin fue designado uno de los tres primeros viceprimeros ministros y, más tarde ese mismo día, fue designado primer ministro interino del Gobierno de la Federación Rusa por el presidente Yeltsin . [83] Yeltsin también anunció que quería ver a Putin como su sucesor. Más tarde ese mismo día, Putin aceptó postularse para la presidencia. [84]

El 16 de agosto, la Duma Estatal aprobó su nombramiento como primer ministro con 233 votos a favor (frente a 84 en contra y 17 abstenciones), [85] mientras que se requería una mayoría simple de 226, lo que lo convirtió en el quinto primer ministro de Rusia en menos de dieciocho meses. Tras su nombramiento, pocos esperaban que Putin, prácticamente desconocido para el público en general, durara más que sus predecesores. Inicialmente se lo consideró un leal a Yeltsin; al igual que otros primeros ministros de Boris Yeltsin , Putin no elegía a sus ministros él mismo, su gabinete lo determinaba la administración presidencial. [86]

Los principales oponentes de Yeltsin y sus posibles sucesores ya estaban haciendo campaña para reemplazar al enfermo presidente y lucharon arduamente para evitar que Putin surgiera como un sucesor potencial. Después de los atentados con bombas en los apartamentos rusos de septiembre de 1999 y la invasión de Daguestán por muyahidines , incluidos los ex agentes de la KGB, con base en la República Chechena de Ichkeria , la imagen de Putin de ley y orden y su enfoque implacable en la Segunda Guerra Chechena pronto se combinaron para aumentar su popularidad y le permitieron superar a sus rivales.

Aunque no estaba asociado formalmente con ningún partido, Putin prometió su apoyo al recién formado Partido de la Unidad , [87] que obtuvo el segundo mayor porcentaje del voto popular (23,3%) en las elecciones a la Duma de diciembre de 1999 , y a su vez apoyó a Putin.

El 31 de diciembre de 1999, Yeltsin dimitió inesperadamente y, según la Constitución de Rusia , Putin se convirtió en presidente interino de la Federación Rusa . Al asumir este papel, Putin realizó una visita previamente programada a las tropas rusas en Chechenia. [88]

El primer decreto presidencial que Putin firmó el 31 de diciembre de 1999 se titulaba "Sobre garantías para el ex presidente de la Federación Rusa y los miembros de su familia". [89] [90] En él se garantizaba que no se presentarían "acusaciones de corrupción contra el presidente saliente y sus familiares". [91] El decreto se dirigía, en particular, al caso de soborno de Mabetex en el que estaban implicados los miembros de la familia de Yeltsin. El 30 de agosto de 2000 se desestimó una investigación penal (número 18/238278-95) en la que el propio Putin, [92] [93] como miembro del gobierno de la ciudad de San Petersburgo , era uno de los sospechosos.

El 30 de diciembre de 2000, otro caso contra el fiscal general fue desestimado "por falta de pruebas", a pesar de que los fiscales suizos habían presentado miles de documentos. [94] El 12 de febrero de 2001, Putin firmó una ley federal similar que sustituyó al decreto de 1999. Marina Salye reabrió un caso sobre la presunta corrupción de Putin en las exportaciones de metales a partir de 1992 , pero fue silenciada y obligada a abandonar San Petersburgo. [95]

Mientras sus oponentes se preparaban para una elección en junio de 2000, la renuncia de Yeltsin dio lugar a que las elecciones presidenciales se celebraran el 26 de marzo de 2000; Putin ganó en la primera vuelta con el 53% de los votos. [96] [97]

La toma de posesión del presidente Putin se produjo el 7 de mayo de 2000. Nombró al ministro de finanzas , Mijaíl Kasyanov , como primer ministro. [98] El primer desafío importante a la popularidad de Putin llegó en agosto de 2000, cuando fue criticado por la supuesta mala gestión del desastre del submarino Kursk . [99] Esa crítica se debió en gran medida a que Putin tardó varios días en regresar de sus vacaciones, y varios más antes de que visitara el lugar. [99]

Entre 2000 y 2004, Putin se dedicó a reconstruir la situación de pobreza del país, aparentemente ganando una lucha de poder con los oligarcas rusos y alcanzando un “gran pacto” con ellos, que les permitió conservar la mayor parte de sus poderes a cambio de su apoyo explícito al gobierno de Putin y su alineamiento con él. [100] [101]

La crisis de los rehenes en el teatro de operaciones de Moscú se produjo en octubre de 2002. Muchos medios de comunicación rusos e internacionales advirtieron de que la muerte de 130 rehenes en la operación de rescate de las fuerzas especiales durante la crisis dañaría gravemente la popularidad del presidente Putin. Sin embargo, poco después de que terminara el asedio, el presidente ruso disfrutaba de índices de aprobación pública récord: el 83% de los rusos se declararon satisfechos con Putin y su gestión del asedio. [102]

En 2003, se celebró un referéndum en Chechenia , adoptando una nueva constitución que declara que la República de Chechenia es parte de Rusia; por otra parte, la región adquirió autonomía. [103] Chechenia se ha estabilizado gradualmente con el establecimiento de las elecciones parlamentarias y un gobierno regional. [104] [105] A lo largo de la Segunda Guerra Chechena , Rusia desactivó gravemente el movimiento rebelde checheno; sin embargo, los ataques esporádicos de los rebeldes continuaron ocurriendo en todo el norte del Cáucaso. [106]

El 14 de marzo de 2004, Putin fue elegido presidente para un segundo mandato, recibiendo el 71% de los votos. [108] La crisis de los rehenes en la escuela de Beslán tuvo lugar del 1 al 3 de septiembre de 2004; murieron más de 330 personas, incluidos 186 niños. [109]

El período de casi 10 años previo al ascenso de Putin tras la disolución del régimen soviético fue una época de agitación en Rusia. [110] En un discurso en el Kremlin en 2005 , Putin caracterizó el colapso de la Unión Soviética como la "mayor catástrofe geopolítica del siglo XX". [111] Putin explicó: "Además, la epidemia de desintegración infectó a la propia Rusia". [112] La red de seguridad social del país desde la cuna hasta la tumba había desaparecido y la esperanza de vida disminuyó en el período anterior al gobierno de Putin. [113] En 2005, se lanzaron los Proyectos de Prioridad Nacional para mejorar la atención sanitaria , la educación , la vivienda y la agricultura de Rusia . [114] [115]

La continua persecución penal del hombre más rico de Rusia en ese momento, el presidente de la compañía de petróleo y gas Yukos , Mikhail Khodorkovsky , por fraude y evasión fiscal fue vista por la prensa internacional como una represalia por las donaciones de Khodorkovsky a opositores liberales y comunistas del Kremlin. [116] Khodorkovsky fue arrestado, Yukos se declaró en quiebra y los activos de la compañía fueron subastados a un valor inferior al del mercado, y la mayor parte fue adquirida por la empresa estatal Rosneft . [117] El destino de Yukos fue visto como una señal de un cambio más amplio de Rusia hacia un sistema de capitalismo de Estado . [118] [119] Esto se subrayó en julio de 2014, cuando los accionistas de Yukos recibieron 50 mil millones de dólares en compensación por parte del Tribunal Permanente de Arbitraje de La Haya . [120]

El 7 de octubre de 2006, Anna Politkovskaya , una periodista que expuso la corrupción en el ejército ruso y su conducta en Chechenia , fue asesinada a tiros en el vestíbulo de su edificio de apartamentos, el día del cumpleaños de Putin. La muerte de Politkovskaya desencadenó críticas internacionales, con acusaciones de que Putin no había protegido a los nuevos medios independientes del país. [121] [122] El propio Putin dijo que su muerte causó al gobierno más problemas que sus escritos. [123]

En enero de 2007, Putin se reunió con la canciller alemana Angela Merkel en su residencia del Mar Negro en Sochi , dos semanas después de que Rusia cortara los suministros de petróleo a Alemania. Putin llevó a su labrador negro Konni frente a Merkel, que tiene una notoria fobia a los perros y parecía visiblemente incómoda en su presencia, y agregó: "Estoy seguro de que se comportará", lo que provocó un furor entre el cuerpo de prensa alemán. [124] [125] Cuando se le preguntó sobre el incidente en una entrevista de enero de 2016 con Bild , Putin afirmó que no estaba al tanto de su fobia y agregó: "Quería hacerla feliz. Cuando descubrí que no le gustaban los perros, por supuesto me disculpé". [126] Merkel dijo más tarde a un grupo de periodistas: "Entiendo por qué tiene que hacer esto: para demostrar que es un hombre. Tiene miedo de su propia debilidad. Rusia no tiene nada, ni política ni economía exitosas. Todo lo que tienen es esto". [125]

En un discurso pronunciado en febrero de 2007 en la Conferencia de Seguridad de Munich , Putin se quejó del sentimiento de inseguridad engendrado por la posición dominante en la geopolítica de los Estados Unidos y observó que un ex funcionario de la OTAN había hecho promesas retóricas de no expandirse a nuevos países de Europa del Este.

El 14 de julio de 2007, Putin anunció que Rusia suspendería la implementación de sus obligaciones en virtud del Tratado sobre Fuerzas Armadas Convencionales en Europa , con efecto a los 150 días, [127] [128] y suspendería su ratificación del Tratado Adaptado sobre Fuerzas Armadas Convencionales en Europa , tratado que fue rechazado por los miembros de la OTAN en espera de la retirada rusa de Transnistria y la República de Georgia . Moscú siguió participando en el grupo consultivo conjunto, porque esperaba que el diálogo pudiera llevar a la creación de un nuevo y efectivo régimen de control de armas convencionales en Europa. [129] Rusia especificó los pasos que la OTAN podría tomar para poner fin a la suspensión. "Entre ellas, los miembros de la OTAN recortaron sus asignaciones de armas y restringieron aún más los despliegues temporales de armas en el territorio de cada uno de sus miembros. Rusia también quería que se eliminaran las restricciones sobre el número de fuerzas que puede desplegar en sus flancos sur y norte. Además, está presionando a los miembros de la OTAN para que ratifiquen una versión actualizada de 1999 del acuerdo, conocida como el Tratado CFE Adaptado , y está exigiendo que los cuatro miembros de la alianza que no forman parte del tratado original, Estonia, Letonia, Lituania y Eslovenia, se unan a él". [128]

A principios de 2007, el grupo opositor La Otra Rusia [130] , liderado por el ex campeón de ajedrez Garry Kasparov y el líder nacional-bolchevique Eduard Limonov , organizó las « Marchas de los disidentes » . Tras advertencias previas, las manifestaciones en varias ciudades rusas se enfrentaron a la acción policial, que incluyó la interferencia en el desplazamiento de los manifestantes y la detención de hasta 150 personas que intentaron romper las líneas policiales. [131]

El 12 de septiembre de 2007, Putin disolvió el gobierno a petición del primer ministro Mijail Fradkov . Fradkov comentó que era para darle al presidente "mano libre" de cara a las elecciones parlamentarias. Viktor Zubkov fue nombrado nuevo primer ministro. [132] El 19 de septiembre de 2007, los bombarderos con capacidad nuclear de Putin comenzaron ejercicios cerca de los EE. UU., por primera vez desde la caída de la URSS. [133]

En diciembre de 2007, Rusia Unida —el partido gobernante que apoya las políticas de Putin— ganó el 64,24% del voto popular en su campaña para la Duma Estatal según los resultados preliminares de las elecciones. [134] La victoria de Rusia Unida en las elecciones de diciembre de 2007 fue vista por muchos como una indicación del fuerte apoyo popular al entonces liderazgo ruso y sus políticas. [135] [136] El 11 de febrero de 2008, mientras Putin se dirigía a la fiesta del 15º aniversario de Gazprom , sus empleados amenazaron a Ucrania con detener el flujo. [133]

El 4 de abril de 2008, en la cumbre de la OTAN en Bucarest , el invitado Putin dijo a George W. Bush y a otros delegados de la conferencia: "Consideramos la aparición de un poderoso bloque militar en nuestra frontera como una amenaza directa a la seguridad de nuestra nación. La afirmación de que este proceso no está dirigido contra Rusia no basta. La seguridad nacional no se basa en promesas". [133]

La Constitución prohibía a Putin ejercer un tercer mandato consecutivo . El primer viceprimer ministro, Dmitri Medvédev , fue elegido su sucesor. En una operación de alternancia de poderes el 8 de mayo de 2008 , sólo un día después de entregar la presidencia a Medvédev, Putin fue nombrado primer ministro de Rusia , manteniendo su dominio político. [137]

Putin ha dicho que superar las consecuencias de la crisis económica mundial fue uno de los dos principales logros de su segundo mandato como primer ministro. [115] El otro fue estabilizar el tamaño de la población de Rusia entre 2008 y 2011 tras un largo período de colapso demográfico que comenzó en la década de 1990. [115]

La guerra ruso-georgiana que comenzó y terminó en agosto de 2008 fue imaginada por Putin y comunicada a su personal a principios de 2006. [138]

Según Andriy Kobolyev , que en ese momento era asesor del director ejecutivo de la empresa de servicios públicos ucraniana Naftogaz , Putin controlaba el tablero de ajedrez de Gazprom durante su mandato como primer ministro . En 2010, Putin observó en una feria comercial alemana que si sus anfitriones no querían el gas natural ni la energía nuclear de Rusia, siempre podrían calentarse con madera y para eso tendrían que talar Siberia . [133]

En el Congreso de Rusia Unida celebrado en Moscú el 24 de septiembre de 2011, Medvedev propuso oficialmente a Putin que se presentase a la presidencia en 2012, oferta que Putin aceptó. Dado el dominio casi total de Rusia Unida en la política rusa, muchos observadores creían que Putin tenía asegurado un tercer mandato. Se esperaba que esta medida viera a Medvedev como candidato de Rusia Unida a las elecciones parlamentarias de diciembre, con el objetivo de convertirse en primer ministro al final de su mandato presidencial. [139]

Tras las elecciones parlamentarias del 4 de diciembre de 2011, decenas de miles de rusos participaron en protestas contra un supuesto fraude electoral, las mayores protestas en la era de Putin. Los manifestantes criticaron a Putin y a Rusia Unida y exigieron la anulación de los resultados electorales. [140] Esas protestas despertaron el temor de una revolución de colores en la sociedad. [141] Putin supuestamente organizó una serie de grupos paramilitares leales a él y al partido Rusia Unida en el período comprendido entre 2005 y 2012. [142]

Poco después de que Medvedev asumiera el cargo en 2008, los mandatos presidenciales se ampliaron de cuatro a seis años, a partir de las elecciones de 2012. [143]

El 24 de septiembre de 2011, durante un discurso en el congreso del partido Rusia Unida , Medvedev anunció que recomendaría al partido que nominara a Putin como su candidato presidencial. También reveló que los dos hombres habían llegado a un acuerdo hacía tiempo para permitir que Putin se postulara a la presidencia en 2012. [144] Este cambio fue denominado por muchos en los medios como "Rokirovka", el término ruso para la jugada de ajedrez " enroque ". [145]

El 4 de marzo de 2012, Putin ganó las elecciones presidenciales rusas de 2012 en la primera vuelta, con el 63,6% de los votos, a pesar de las acusaciones generalizadas de fraude electoral. [146] [147] [148] Los grupos de oposición acusaron a Putin y al partido Rusia Unida de fraude. [149] Aunque se hicieron públicos los esfuerzos por hacer transparentes las elecciones, incluido el uso de cámaras web en los centros de votación, la votación fue criticada por la oposición rusa y por los observadores internacionales de la Organización para la Seguridad y la Cooperación en Europa por irregularidades de procedimiento. [150]

Las protestas contra Putin tuvieron lugar durante y directamente después de la campaña presidencial. La protesta más notoria fue la actuación de Pussy Riot el 21 de febrero y el juicio posterior. [151] Se estima que entre 8.000 y 20.000 manifestantes se reunieron en Moscú el 6 de mayo, [152] [153] cuando ochenta personas resultaron heridas en enfrentamientos con la policía, [154] y 450 fueron arrestadas, y al día siguiente se produjeron otras 120 detenciones. [155] Se produjo una contraprotesta de partidarios de Putin que culminó con una reunión de unos 130.000 partidarios en el Estadio Luzhniki , el estadio más grande de Rusia. [156] Algunos de los asistentes afirmaron que les habían pagado para venir, que sus empleadores les obligaron a venir o que les hicieron creer erróneamente que iban a asistir a un festival folclórico. [157] [158] [159] Se considera que la manifestación es la más grande en apoyo de Putin hasta la fecha. [160]

La presidencia de Putin fue inaugurada en el Kremlin el 7 de mayo de 2012. [161] En su primer día como presidente, Putin emitió 14 decretos presidenciales , que a veces son llamados los "Decretos de Mayo" por los medios, incluyendo uno extenso que establece objetivos de amplio alcance para la economía rusa . Otros decretos se referían a la educación , la vivienda, la capacitación de mano de obra calificada, las relaciones con la Unión Europea , la industria de defensa , las relaciones interétnicas y otras áreas políticas tratadas en los artículos del programa de Putin emitidos durante la campaña presidencial. [162]

En 2012 y 2013, Putin y el partido Rusia Unida respaldaron una legislación más estricta contra la comunidad LGBT en San Petersburgo , Arjánguelsk y Novosibirsk ; una ley llamada ley rusa de propaganda gay , que está en contra de la "propaganda homosexual" (que prohíbe símbolos como la bandera del arcoíris , [163] [164] así como obras publicadas que contengan contenido homosexual) fue adoptada por la Duma Estatal en junio de 2013. [165] [166] En respuesta a las preocupaciones internacionales sobre la legislación de Rusia, Putin pidió a los críticos que señalaran que la ley era una "prohibición de la propaganda de la pedofilia y la homosexualidad" y afirmó que los visitantes homosexuales a los Juegos Olímpicos de Invierno de 2014 deberían "dejar a los niños en paz", pero negó que hubiera alguna "discriminación profesional, de carrera o social" contra los homosexuales en Rusia. [167]

En junio de 2013, Putin asistió a un mitin televisado del Frente Popular de toda Rusia , donde fue elegido jefe del movimiento, [168] que se creó en 2011. [169] Según el periodista Steve Rosenberg , el movimiento tiene como objetivo "reconectar el Kremlin con el pueblo ruso" y un día, si es necesario, reemplazar al cada vez más impopular partido Rusia Unida que actualmente respalda a Putin. [170]

_Summit_meeting_of_the_leaders_of_Russia,_Ukraine,_Germany_and_France,_October_2014.jpg/440px-Asia-Europe_(ASEM)_Summit_meeting_of_the_leaders_of_Russia,_Ukraine,_Germany_and_France,_October_2014.jpg)

En febrero de 2014, Rusia realizó varias incursiones militares en territorio ucraniano. Después de las protestas de Euromaidán y la caída del presidente ucraniano Viktor Yanukovych , soldados rusos sin insignias tomaron el control de posiciones estratégicas e infraestructura dentro del territorio ucraniano de Crimea. Rusia luego anexó Crimea y Sebastopol después de un referéndum en el que, según los resultados oficiales, los crimeos votaron para unirse a la Federación Rusa. [171] [172] [173] Posteriormente, las manifestaciones contra las acciones legislativas de la Rada ucraniana por parte de grupos prorrusos en el área de Donbas de Ucrania se intensificaron en la Guerra Ruso-Ucraniana entre el gobierno ucraniano y las fuerzas separatistas respaldadas por Rusia de las autoproclamadas Repúblicas Populares de Donetsk y Luhansk . En agosto de 2014, [174] vehículos militares rusos cruzaron la frontera en varios lugares del óblast de Donetsk. [175] [176] [177] Las autoridades ucranianas consideraron que la incursión del ejército ruso fue responsable de la derrota de las fuerzas ucranianas a principios de septiembre. [178] [179]

En octubre de 2014, Putin abordó las preocupaciones de seguridad rusas en Sochi en el Club de Discusión Internacional Valdai . En noviembre de 2014, el ejército ucraniano informó de un intenso movimiento de tropas y equipos desde Rusia hacia las partes controladas por los separatistas del este de Ucrania. [180] Associated Press informó de 80 vehículos militares sin distintivos en movimiento en zonas controladas por los rebeldes. [181] Una Misión Especial de Observación de la OSCE observó convoyes de armas pesadas y tanques en territorio controlado por la RPD sin insignias. [182] Los observadores de la OSCE afirmaron además que observaron vehículos que transportaban municiones y cadáveres de soldados cruzando la frontera entre Rusia y Ucrania bajo la apariencia de convoyes de ayuda humanitaria . [183]

A principios de agosto de 2015, la OSCE observó más de 21 de esos vehículos marcados con el código militar ruso para los soldados muertos en acción. [184] Según The Moscow Times , Rusia ha tratado de intimidar y silenciar a los trabajadores de derechos humanos que hablan de las muertes de soldados rusos en el conflicto. [185] La OSCE informó en repetidas ocasiones que a sus observadores se les negó el acceso a las zonas controladas por "fuerzas combinadas ruso-separatistas". [186]

En octubre de 2015, The Washington Post informó que Rusia había redistribuido algunas de sus unidades de élite de Ucrania a Siria en las últimas semanas para apoyar al presidente sirio Bashar al-Assad . [187] En diciembre de 2015, Putin admitió que oficiales de inteligencia militar rusos estaban operando en Ucrania. [188]

El académico prorruso Andrei Tsygankov , citado por el periódico Moscow Times, afirmó que muchos miembros de la comunidad internacional asumieron que la anexión de Crimea por parte de Putin había iniciado un tipo completamente nuevo de política exterior rusa [189] [190] y que su política exterior había pasado de ser una política exterior impulsada por el Estado a adoptar una postura ofensiva para recrear la Unión Soviética. En julio de 2015, opinó que este cambio de política podía entenderse como un intento de Putin de defender a las naciones en la esfera de influencia de Rusia de la "invasión del poder occidental". [191]

_04.jpg/440px-Vladimir_Putin_and_Barack_Obama_(2015-09-29)_04.jpg)

_02.jpg/440px-Vladimir_Putin_and_Bashar_al-Assad_(2017-11-21)_02.jpg)

El 30 de septiembre de 2015, el presidente Putin autorizó la intervención militar rusa en la guerra civil siria , tras una solicitud formal del gobierno sirio de ayuda militar contra los grupos rebeldes y yihadistas. [192]

Las actividades militares rusas consistieron en ataques aéreos, ataques con misiles de crucero y el uso de asesores de primera línea y fuerzas especiales rusas contra grupos militantes opuestos al gobierno sirio , incluida la oposición siria , así como el Estado Islámico de Irak y el Levante (EIIL), el Frente al-Nusra (al-Qaeda en el Levante), Tahrir al-Sham , Ahrar al-Sham y el Ejército de la Conquista . [193] [194] Después del anuncio de Putin el 14 de marzo de 2016 de que la misión que había establecido para el ejército ruso en Siria se había "cumplido en gran medida" y ordenó la retirada de la "parte principal" de las fuerzas rusas de Siria, [195] las fuerzas rusas desplegadas en Siria continuaron operando activamente en apoyo del gobierno sirio. [196]

En enero de 2017, una evaluación de la comunidad de inteligencia estadounidense expresó alta confianza en que Putin ordenó personalmente una campaña de influencia, inicialmente para denigrar a Hillary Clinton y dañar sus posibilidades electorales y su posible presidencia, y luego desarrollar "una clara preferencia" por Donald Trump . [197] Trump negó constantemente cualquier interferencia rusa en las elecciones estadounidenses, [198] [199] [200] como lo hizo Putin en diciembre de 2016, [201] marzo de 2017, [202] junio de 2017, [203] [204] [205] y julio de 2017. [206]

Putin declaró más tarde que la interferencia era "teóricamente posible" y podría haber sido perpetrada por piratas informáticos rusos "de mentalidad patriótica", [207] y en otra ocasión afirmó que "ni siquiera rusos, sino ucranianos, tártaros o judíos, pero con ciudadanía rusa" podrían haber sido los responsables. [208] En julio de 2018, The New York Times informó que la CIA había nutrido durante mucho tiempo a una fuente rusa que finalmente ascendió a una posición cercana a Putin, lo que le permitió a la fuente pasar información clave en 2016 sobre la participación directa de Putin. [ 209] Putin continuó con intentos similares en las elecciones presidenciales estadounidenses de 2020. [210]

Putin ganó las elecciones presidenciales rusas de 2018 con más del 76% de los votos. [211] Su cuarto mandato comenzó el 7 de mayo de 2018, [212] y durará hasta 2024. [213] El mismo día, Putin invitó a Dmitri Medvédev a formar un nuevo gobierno . [214] El 15 de mayo de 2018, Putin participó en la apertura del movimiento a lo largo de la sección de la autopista del puente de Crimea . [215] El 18 de mayo de 2018, Putin firmó decretos sobre la composición del nuevo Gobierno. [216] El 25 de mayo de 2018, Putin anunció que no se postularía a la presidencia en 2024, justificándolo en cumplimiento de la Constitución rusa. [217] El 14 de junio de 2018, Putin inauguró la 21.ª Copa Mundial de la FIFA , que tuvo lugar en Rusia por primera vez. El 18 de octubre de 2018, Putin dijo que los rusos "irían al cielo como mártires" en caso de una guerra nuclear , ya que solo usaría armas nucleares en represalia. [218] En septiembre de 2019, la administración de Putin interfirió en los resultados de las elecciones regionales nacionales de Rusia y las manipuló eliminando a todos los candidatos de la oposición. El evento, que tenía como objetivo contribuir a la victoria del partido gobernante, Rusia Unida , también contribuyó a incitar protestas masivas por la democracia, lo que condujo a arrestos a gran escala y casos de brutalidad policial. [219]

El 15 de enero de 2020, Medvedev y todo su gobierno dimitieron tras el discurso presidencial de 2020 de Putin ante la Asamblea Federal . Putin sugirió importantes enmiendas constitucionales que podrían ampliar su poder político después de la presidencia. [220] [221] Al mismo tiempo, en nombre de Putin, continuó ejerciendo sus poderes hasta la formación de un nuevo gobierno. [222] Putin sugirió que Medvedev asumiera el puesto recién creado de vicepresidente del Consejo de Seguridad . [223]

Ese mismo día, Putin nominó a Mijaíl Mishustin , jefe del Servicio Fiscal Federal del país , para el puesto de primer ministro. Al día siguiente, fue confirmado por la Duma Estatal en el cargo, [224] [225] y nombrado primer ministro por decreto de Putin. [226] Esta fue la primera vez en la historia que un primer ministro fue confirmado sin ningún voto en contra. El 21 de enero de 2020, Mishustin presentó a Putin un proyecto de estructura de su Gabinete . Ese mismo día, el presidente firmó un decreto sobre la estructura del Gabinete y nombró a los ministros propuestos. [227] [228] [229]

El 15 de marzo de 2020, Putin dio instrucciones para formar un grupo de trabajo del Consejo de Estado para contrarrestar la propagación del COVID-19. Putin nombró al alcalde de Moscú, Serguéi Sobianin, como jefe del grupo. [230]

El 22 de marzo de 2020, tras una llamada telefónica con el primer ministro italiano Giuseppe Conte , Putin organizó el envío por parte del ejército ruso de médicos militares, vehículos especiales de desinfección y otros equipos médicos a Italia, el país europeo más afectado por la pandemia de COVID-19 . [231] Putin comenzó a trabajar de forma remota desde su oficina en Novo-Ogaryovo . Según Dmitry Peskov , Putin pasó pruebas diarias de COVID-19 y su salud no estaba en peligro. [232] [233]

El 25 de marzo, el presidente Putin anunció en un discurso televisado a la nación que el referéndum constitucional del 22 de abril se pospondría debido al COVID-19. [234] Añadió que la próxima semana sería un feriado nacional pagado e instó a los rusos a quedarse en casa. [235] [236] Putin también anunció una lista de medidas de protección social , apoyo a las pequeñas y medianas empresas y cambios en la política fiscal . [237] Putin anunció las siguientes medidas para las microempresas, las pequeñas y medianas empresas: aplazamiento de los pagos de impuestos (excepto el impuesto al valor agregado de Rusia ) durante los próximos seis meses, reducción a la mitad del tamaño de las contribuciones a la seguridad social, aplazamiento de las contribuciones a la seguridad social, aplazamiento de los reembolsos de préstamos durante los próximos seis meses, una moratoria de seis meses sobre multas, cobro de deudas y solicitudes de quiebra de las empresas deudoras por parte de los acreedores. [238] [239]

El 2 de abril de 2020, Putin volvió a emitir un discurso en el que anunció la prolongación del tiempo no laboral hasta el 30 de abril. [240] Putin comparó la lucha de Rusia contra el COVID-19 con las batallas de Rusia contra los nómadas esteparios pechenegos y cumanos invasores en los siglos X y XI. [241] En una encuesta de Levada del 24 al 27 de abril , el 48% de los encuestados rusos dijeron que desaprobaban el manejo de Putin de la pandemia de COVID-19, [242] y su estricto aislamiento y falta de liderazgo durante la crisis fue ampliamente comentado como una señal de pérdida de su imagen de "hombre fuerte". [243] [244]

_Organising_Committee_2019-12-11_(4).jpg/440px-Meeting_of_Russian_Pobeda_(Victory)_Organising_Committee_2019-12-11_(4).jpg)

En junio de 2021, Putin dijo que estaba completamente vacunado contra la enfermedad con la vacuna Sputnik V , enfatizando que si bien las vacunas deben ser voluntarias, hacerlas obligatorias en algunas profesiones frenaría la propagación de la COVID-19. [246] En septiembre, Putin entró en autoaislamiento después de que personas de su círculo íntimo dieron positivo en la prueba de la enfermedad. [247] Según un informe del Wall Street Journal , el círculo íntimo de asesores de Putin se redujo durante el confinamiento por la COVID-19 a un pequeño número de asesores de línea dura. [248]

El 3 de julio de 2020, Putin firmó una orden ejecutiva para introducir oficialmente enmiendas en la Constitución rusa que le permitirían presentarse como candidato a dos mandatos adicionales de seis años. Estas enmiendas entraron en vigor el 4 de julio de 2020. [249]

En 2020 y 2021, se llevaron a cabo protestas en el Krai de Jabárovsk, en el Lejano Oriente de Rusia, en apoyo del gobernador regional arrestado, Sergei Furgal . [250] Las protestas de 2020 en el Krai de Jabárovsk se volvieron cada vez más anti-Putin con el tiempo. [251] [252] Una encuesta de Levada de julio de 2020 encontró que el 45% de los rusos encuestados apoyaban las protestas. [253] El 22 de diciembre de 2020, Putin firmó un proyecto de ley que otorga inmunidad procesal de por vida a los expresidentes rusos. [254] [255]

Putin se reunió con el presidente iraní, Ebrahim Raisi, en enero de 2022 para sentar las bases de un acuerdo de 20 años entre las dos naciones. [256]

En julio de 2021, Putin publicó un ensayo titulado Sobre la unidad histórica de rusos y ucranianos , en el que afirma que los bielorrusos, ucranianos y rusos deberían estar en una nación panrusa como parte del mundo ruso y son "un pueblo" al que "las fuerzas que siempre han buscado socavar nuestra unidad" querían "dividir y gobernar". [257] El ensayo niega la existencia de Ucrania como nación independiente. [258] [259]

El 30 de noviembre de 2021, Putin declaró que una ampliación de la OTAN en Ucrania sería una cuestión de "línea roja" para Rusia. [260] [261] [262] El Kremlin negó repetidamente que tuviera planes de invadir Ucrania, [263] [264] [265] y el propio Putin descartó esos temores como "alarmistas". [266] El 21 de febrero de 2022, Putin firmó un decreto que reconocía a las dos repúblicas separatistas autoproclamadas en el Donbás como estados independientes y pronunció un discurso sobre los acontecimientos en Ucrania . [267]

Putin fue persuadido para invadir Ucrania por un pequeño grupo de sus colaboradores más cercanos, especialmente Nikolai Patrushev , Yury Kovalchuk y Alexander Bortnikov . [268] Según fuentes cercanas al Kremlin, la mayoría de los asesores y colaboradores de Putin se opusieron a la invasión, pero Putin los desestimó. La invasión de Ucrania había sido planeada durante casi un año. [269]

El 24 de febrero, Putin anunció en un discurso televisado una " operación militar especial " [270] (SMO) en Ucrania, [271] [272] lanzando una invasión a gran escala del país. [273] Citando un propósito de " desnazificación ", afirmó que estaba haciendo esto para proteger a la gente en la región predominantemente rusoparlante de Donbas que, según Putin, se enfrentó a "humillación y genocidio" por parte de Ucrania durante ocho años. [274] Minutos después del discurso, lanzó una guerra para obtener el control del resto del país y derrocar al gobierno electo bajo el pretexto de que estaba dirigido por nazis. [275] [276]

.jpg/440px-Manifestation_contre_guerre_en_Ukraine_Nice_27_02_2022_(51907203661).jpg)

La invasión rusa fue recibida con condena internacional. [277] [278] [279] Se impusieron sanciones internacionales ampliamente contra Rusia, incluso contra Putin personalmente. [280] [281] La invasión también dio lugar a numerosos llamamientos para que Putin fuera perseguido con cargos de crímenes de guerra. [282] [283] [284] [285] La Corte Penal Internacional (CPI) declaró que investigaría la posibilidad de crímenes de guerra en Ucrania desde finales de 2013, [286] y Estados Unidos se comprometió a ayudar a la CPI a procesar a Putin y otros por crímenes de guerra cometidos durante la invasión de Ucrania. [287] En respuesta a estas condenas, Putin puso en alerta máxima a las unidades de disuasión nuclear de las Fuerzas de Cohetes Estratégicos . [288] A principios de marzo, las agencias de inteligencia estadounidenses determinaron que Putin estaba "frustrado" por el lento progreso debido a una defensa ucraniana inesperadamente fuerte. [289]

_01.jpg/440px-Vladimir_Putin_in_Ryazan_Oblast_(2022-10-20)_01.jpg)

El 4 de marzo, Putin firmó una ley que introducía penas de prisión de hasta 15 años para quienes publicaran "información deliberadamente falsa" sobre el ejército ruso y sus operaciones, lo que llevó a algunos medios de comunicación en Rusia a dejar de informar sobre Ucrania. [290] El 7 de marzo, como condición para poner fin a la invasión, el Kremlin exigió la neutralidad de Ucrania , el reconocimiento de Crimea como territorio ruso y el reconocimiento de las autoproclamadas repúblicas de Donetsk y Luhansk como estados independientes. [291] [292] El 8 de marzo, Putin prometió que no se utilizarían reclutas en el SMO. [293] El 16 de marzo, Putin lanzó una advertencia a los "traidores" rusos que, según él, Occidente quería utilizar como una " quinta columna " para destruir a Rusia. [294] [295] Tras la invasión de Ucrania en 2022, [296] la crisis demográfica a largo plazo de Rusia se profundizó debido a la emigración , las tasas de fertilidad más bajas y las bajas relacionadas con la guerra . [297]

Ya el 25 de marzo, la Oficina del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos informó que Putin ordenó una política de "secuestro", mediante la cual los ciudadanos ucranianos que no cooperaron con la toma de posesión rusa de su patria fueron víctimas de agentes del FSB. [298] [299] El 28 de marzo, el presidente ucraniano Volodymyr Zelenskyy dijo que estaba "99,9 por ciento seguro" de que Putin pensaba que los ucranianos darían la bienvenida a las fuerzas invasoras con "flores y sonrisas", mientras abría la puerta a las negociaciones sobre la oferta de que Ucrania sería de ahora en adelante un estado no alineado . [300]

El 21 de septiembre, Putin anunció una movilización parcial , tras una exitosa contraofensiva ucraniana en Járkov y el anuncio de referendos de anexión en la Ucrania ocupada por Rusia . [301]

El 30 de septiembre, Putin firmó decretos que anexaban las provincias de Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhia y Kherson de Ucrania a la Federación Rusa. Las anexiones no están reconocidas por la comunidad internacional y son ilegales según el derecho internacional. [302] El 11 de noviembre del mismo año, Ucrania liberó Kherson . [303]

En diciembre de 2022, dijo que una guerra contra Ucrania podría ser un "largo proceso" [304]. Cientos de miles de personas han muerto en la guerra ruso-ucraniana desde febrero de 2022. [305] [306] En enero de 2023, Putin citó el reconocimiento de la soberanía de Rusia sobre los territorios anexados como condición para las conversaciones de paz con Ucrania. [307]

Del 20 al 22 de marzo de 2023, el presidente chino, Xi Jinping, visitó Rusia y se reunió con Vladimir Putin tanto de manera oficial como no oficial. [308] Fue la primera reunión internacional de Vladimir Putin desde que la Corte Penal Internacional emitió una orden de arresto en su contra. [309]

.jpg/440px-Putin-Xi_press_conference_(2023).jpg)

En mayo de 2023, Sudáfrica anunció que otorgaría inmunidad diplomática a Vladimir Putin para asistir a la 15ª Cumbre BRICS en Johannesburgo a pesar de la orden de arresto de la CPI. [310] En julio de 2023, el presidente sudafricano Cyril Ramaphosa anunció que Putin no asistiría a la cumbre "de mutuo acuerdo" y en su lugar enviaría al ministro de Relaciones Exteriores, Sergei Lavrov . [311]

.jpg/440px-Vladimir_Putin_and_Cyril_Ramaphosa_(2023-06-17).jpg)

En julio de 2023, Putin amenazó con tomar "acciones recíprocas" si Ucrania usaba municiones en racimo suministradas por Estados Unidos durante una contraofensiva ucraniana contra las fuerzas rusas en el sureste de Ucrania ocupado. [312] El 17 de julio de 2023, Putin se retiró de un acuerdo que permitía a Ucrania exportar granos a través del Mar Negro a pesar de un bloqueo en tiempos de guerra, [313] arriesgándose a profundizar la crisis alimentaria mundial y antagonizar a los países neutrales en el Sur Global . [314]

Los días 27 y 28 de julio, Putin fue el anfitrión de la Cumbre Rusia-África 2023 en San Petersburgo, [315] a la que asistieron delegaciones de más de 40 países africanos. [316] En agosto de 2023, el número total de soldados rusos y ucranianos muertos o heridos durante la invasión rusa de Ucrania era de casi 500.000. [317]

Putin condenó el ataque liderado por Hamás en 2023 contra Israel que desencadenó la guerra entre Israel y Hamás y dijo que Israel tenía derecho a defenderse, pero también criticó la respuesta de Israel y dijo que Israel no debería sitiar la Franja de Gaza de la forma en que la Alemania nazi sitió Leningrado . Putin sugirió que Rusia podría ser un mediador en el conflicto. [318] [319] Putin culpó de la guerra a la fallida política exterior de los Estados Unidos en Oriente Medio y expresó su preocupación por el sufrimiento de los niños palestinos en la Franja de Gaza. [320] En una llamada de diciembre de 2023 entre el primer ministro israelí , Benjamin Netanyahu, y Putin, Netanyahu expresó su descontento por la conducta de Rusia en las Naciones Unidas y describió sus crecientes vínculos con Irán como peligrosos. [321]

El 22 de noviembre de 2023, Putin afirmó que Rusia siempre estuvo "dispuesta a dialogar" para poner fin a la "tragedia" de la guerra en Ucrania, y acusó a los dirigentes ucranianos de rechazar las conversaciones de paz con Rusia. [322] Sin embargo, el 14 de diciembre de 2023, Putin dijo que "solo habrá paz en Ucrania cuando logremos nuestros objetivos", que según él son "la desnazificación, la desmilitarización y un estatus neutral" de Ucrania. [323] El 23 de diciembre de 2023, The New York Times informó que Putin ha estado señalando a través de intermediarios desde al menos septiembre de 2022 que "está abierto a un alto el fuego que congele los combates en las líneas actuales". [324]

El 17 de marzo de 2023, la Corte Penal Internacional emitió una orden de arresto contra Putin , [325] [326] [327] [328] alegando que Putin tenía responsabilidad penal en la deportación y traslado ilegal de niños de Ucrania a Rusia durante la invasión rusa de Ucrania. [329] [330] [331]

Fue la primera vez que la CPI emitió una orden de arresto contra el jefe de Estado de uno de los cinco miembros permanentes del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas [325] ( las cinco principales potencias nucleares del mundo). [332]

La CPI emitió simultáneamente una orden de arresto contra Maria Lvova-Belova , Comisionada para los Derechos del Niño en la Oficina del Presidente de la Federación Rusa. Ambas están acusadas de:

:...el crimen de guerra de deportación ilegal de población (niños) y el de traslado ilegal de población (niños) de zonas ocupadas de Ucrania a la Federación de Rusia,... [327] ...por su programa publicitado, desde el 24 de febrero de 2022, de deportaciones forzadas de miles de niños ucranianos no acompañados a Rusia, desde zonas del este de Ucrania bajo control ruso. [325] [327]

Rusia ha sostenido que las deportaciones eran esfuerzos humanitarios para proteger a los huérfanos y otros niños abandonados en la región del conflicto. [325]

.jpg/440px-Vladimir_Putin_(24.06.2023).jpg)

El 23 de junio de 2023, el Grupo Wagner , una organización paramilitar rusa, se rebeló contra el gobierno de Rusia . La revuelta surgió en medio de una creciente tensión entre el Ministerio de Defensa ruso y Yevgeny Prigozhin , el líder de Wagner. [333]

Prigozhin describió la rebelión como una respuesta a un supuesto ataque a sus fuerzas por parte del ministerio. [334] [335] Desestimó la justificación del gobierno para invadir Ucrania , [336] culpó al ministro de Defensa, Sergei Shoigu, por las deficiencias militares del país, [337] y lo acusó de librar la guerra en beneficio de los oligarcas rusos . [338] [339] En un discurso televisado el 24 de junio, el presidente ruso Vladimir Putin denunció las acciones de Wagner como traición y se comprometió a sofocar la rebelión. [335] [340]

Las fuerzas de Prigozhin tomaron el control de Rostov del Don y del cuartel general del Distrito Militar Sur y avanzaron hacia Moscú en una columna blindada. [341] Tras las negociaciones con el presidente bielorruso Alexander Lukashenko , [342] Prigozhin aceptó dimitir [343] y, a última hora del 24 de junio, comenzó a retirarse de Rostov del Don. [344]

El 23 de agosto de 2023, exactamente dos meses después de la rebelión, Prigozhin murió junto con otras nueve personas cuando un avión comercial se estrelló en el óblast de Tver , al norte de Moscú. [345] La inteligencia occidental informó que el accidente probablemente fue causado por una explosión a bordo, y se sospecha ampliamente que el estado ruso estuvo involucrado. [346]

.jpg/440px-President_of_Vietnam_To_Lam_held_an_official_welcoming_ceremony_for_Vladimir_Putin_(2024).jpg)

Putin ganó las elecciones presidenciales rusas de 2024 con el 88,48% de los votos. Los observadores internacionales no consideraron que las elecciones fueran libres ni justas , [347] y Putin aumentó la represión política después de lanzar su guerra a gran escala con Ucrania en 2022. [348] [349] Las elecciones también se celebraron en los territorios de Ucrania ocupados por Rusia . [349] Hubo informes de irregularidades , incluido el relleno de urnas y la coerción, [350] y el análisis estadístico sugirió niveles sin precedentes de fraude en las elecciones de 2024. [351]

El 22 de marzo de 2024 se produjo el atentado contra el Ayuntamiento de Crocus , que causó la muerte de al menos 145 personas y heridas al menos a 551 más. [352] [353] Fue el ataque terrorista más mortífero en suelo ruso desde el asedio a la escuela de Beslán en 2004. [354] [355]

El 7 de mayo de 2024, Putin fue investido presidente de Rusia por quinta vez. [356] Según los analistas, la sustitución de Sergei Shoigu por Andrey Belousov como ministro de Defensa indica que Putin quiere transformar la economía rusa en una economía de guerra y se está "preparando para muchos más años de guerra". [357] [358] En mayo de 2024, cuatro fuentes rusas dijeron a Reuters que Putin estaba dispuesto a poner fin a la guerra en Ucrania con un alto el fuego negociado que reconocería las ganancias bélicas de Rusia y congelaría la guerra en las líneas del frente actuales, ya que Putin quería evitar medidas impopulares como una mayor movilización a nivel nacional y un mayor gasto de guerra. [359]

El 2 de agosto de 2024, Putin recibió al asesino del FSB Vadim Krasikov y a los espías Artem Dultsev y Anna Dultseva, así como a otros, que fueron repatriados en un intercambio de prisioneros con países occidentales. Putin indultó al periodista estadounidense Evan Gershkovich , a los opositores Vladimir Kara-Murza , Ilya Yashin y a otros en el intercambio. [360] [361] [362]

Fue el intercambio de prisioneros más extenso entre Rusia y Estados Unidos desde el final de la Guerra Fría , que implicó la liberación de veintiséis personas. [363] Se realizó después de al menos seis meses de negociaciones multilaterales secretas. [364] [365]

Las políticas internas de Putin, en particular al comienzo de su primera presidencia, apuntaban a crear una estructura de poder vertical . El 13 de mayo de 2000, emitió un decreto que organizaba los 89 sujetos federales de Rusia en siete distritos federales administrativos y nombró un enviado presidencial responsable de cada uno de esos distritos (cuyo título oficial es Representante Plenipotenciario). [366]

Según Stephen White , bajo la presidencia de Putin, Rusia dejó en claro que no tenía intención de establecer una "segunda edición" del sistema político estadounidense o británico, sino más bien un sistema que fuera más cercano a las propias tradiciones y circunstancias de Rusia. [367] Algunos comentaristas han descrito la administración de Putin como una " democracia soberana ". [368] [369] [370] Según los defensores de esa descripción (principalmente Vladislav Surkov ), las acciones y políticas del gobierno deberían sobre todo disfrutar del apoyo popular dentro de la propia Rusia y no ser dirigidas o influenciadas desde fuera del país. [371]

El economista sueco Anders Åslund describe la práctica del sistema como una gestión manual, al comentar: "Después de que Putin volviera a la presidencia en 2012, su gobierno se puede describir mejor como 'gestión manual', como les gusta decir a los rusos. Putin hace lo que quiere, sin tener en cuenta las consecuencias, con una salvedad importante. Durante la crisis financiera rusa de agosto de 1998, Putin aprendió que las crisis financieras son políticamente desestabilizadoras y deben evitarse a toda costa. Por lo tanto, le preocupa la estabilidad financiera". [372]

The period after 2012 saw mass protests against the falsification of elections, censorship and toughening of free assembly laws. In July 2000, according to a law proposed by Putin and approved by the Federal Assembly of Russia, Putin gained the right to dismiss the heads of the 89 federal subjects. In 2004, the direct election of those heads (usually called "governors") by popular vote was replaced with a system whereby they would be nominated by the president and approved or disapproved by regional legislatures.[373][374]

This was seen by Putin as a necessary move to stop separatist tendencies and get rid of those governors who were connected with organised crime.[375] This and other government actions effected under Putin's presidency have been criticized by many independent Russian media outlets and Western commentators as anti-democratic.[376][377]

During his first term in office, Putin opposed some of the Yeltsin-era business oligarchs, as well as his political opponents, resulting in the exile or imprisonment of such people as Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, and Mikhail Khodorkovsky; other oligarchs such as Roman Abramovich and Arkady Rotenberg are friends and allies with Putin.[378] Putin succeeded in codifying land law and tax law and promulgated new codes on labor, administrative, criminal, commercial and civil procedural law.[379] Under Medvedev's presidency, Putin's government implemented some key reforms in the area of state security, the Russian police reform and the Russian military reform.[380]

Sergey Guriyev, when talking about Putin's economic policy, divided it into four distinct periods: the "reform" years of his first term (1999–2003); the "statist" years of his second term (2004—the first half of 2008); the world economic crisis and recovery (the second half of 2008–2013); and the Russo-Ukrainian War, Russia's growing isolation from the global economy, and stagnation (2014–present).[381]

In 2000, Putin launched the "Programme for the Socio-Economic Development of the Russian Federation for the Period 2000–2010", but it was abandoned in 2008 when it was 30% complete.[382] Fueled by the 2000s commodities boom including record-high oil prices,[9][10] under the Putin administration from 2000 to 2016, an increase in income in USD terms was 4.5 times.[383] During Putin's first eight years in office, industry grew substantially, as did production, construction, real incomes, credit, and the middle class.[384][385] A fund for oil revenue allowed Russia to repay Soviet Union's debts by 2005. Russia joined the World Trade Organization in August 2012.[386]

In 2006, Putin launched an industry consolidation programme to bring the main aircraft-producing companies under a single umbrella organization, the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC).[387][388] In September 2020, the UAC general director announced that the UAC will receive the largest-ever post-Soviet government support package for the aircraft industry in order to pay and renegotiate the debt.[389][390]

In 2014, Putin signed a deal to supply China with 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year. Power of Siberia, which Putin has called the "world's biggest construction project," was launched in 2019 and is expected to continue for 30 years at an ultimate cost to China of $400bn.[392] The ongoing financial crisis began in the second half of 2014 when the Russian ruble collapsed due to a decline in the price of oil and international sanctions against Russia. These events in turn led to loss of investor confidence and capital flight, although it has also been argued that the sanctions had little to no effect on Russia's economy.[393][394][395] In 2014, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project named Putin their Person of the Year for furthering corruption and organized crime.[396][397]

According to Meduza, Putin has since 2007 predicted on a number of occasions that Russia will become one of the world's five largest economies. In 2013, he said Russia was one of the five biggest economies in terms of gross domestic product but still lagged behind other countries on indicators such as labour productivity.[398] By the end of 2023, Putin planned to spend almost 40% of public expenditures on defense and security.[399]

In 2004, Putin signed the Kyoto Protocol treaty designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[400] However, Russia did not face mandatory cuts, because the Kyoto Protocol limits emissions to a percentage increase or decrease from 1990 levels and Russia's greenhouse-gas emissions fell well below the 1990 baseline due to a drop in economic output after the breakup of the Soviet Union.[401]

Putin regularly attends the most important services of the Russian Orthodox Church on the main holy days and has established a good relationship with Patriarchs of the Russian Church, the late Alexy II of Moscow and the current Kirill of Moscow. As president, Putin took an active personal part in promoting the Act of Canonical Communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, signed 17 May 2007, which restored relations between the Moscow-based Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia after the 80-year schism.[402]

Under Putin, the Hasidic Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia became increasingly influential within the Jewish community, partly due to the influence of Federation-supporting businessmen mediated through their alliances with Putin, notably Lev Leviev and Roman Abramovich.[403][404] According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Putin is popular amongst the Russian Jewish community, who see him as a force for stability. Russia's chief rabbi, Berel Lazar, said Putin "paid great attention to the needs of our community and related to us with a deep respect".[405] In 2016, Ronald S. Lauder, the president of the World Jewish Congress, also praised Putin for making Russia "a country where Jews are welcome".[406]

Human rights organizations and religious freedom advocates have criticized the state of religious freedom in Russia.[407] In 2016, Putin oversaw the passage of legislation that prohibited missionary activity in Russia.[407] Nonviolent religious minority groups have been repressed under anti-extremism laws, especially Jehovah's Witnesses.[408] One of the 2020 amendments to the Constitution of Russia has a constitutional reference to God.[409]

_23.jpg/440px-Vostok-2018_military_manoeuvres_(2018-09-13)_23.jpg)

The resumption of long-distance flights of Russia's strategic bombers was followed by the announcement by Russian Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov during his meeting with Putin on 5 December 2007, that 11 ships, including the aircraft carrier Kuznetsov, would take part in the first major navy sortie into the Mediterranean since Soviet times.[410][411]

Key elements of the reform included reducing the armed forces to a strength of one million, reducing the number of officers, centralising officer training from 65 military schools into 10 systemic military training centres, creating a professional NCO corps, reducing the size of the central command, introducing more civilian logistics and auxiliary staff, elimination of cadre-strength formations, reorganising the reserves, reorganising the army into a brigade system, and reorganising air forces into an airbase system instead of regiments.[412]

According to the Kremlin, Putin embarked on a build-up of Russia's nuclear capabilities because of U.S. President George W. Bush's unilateral decision to withdraw from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.[414] To counter what Putin sees as the United States' goal of undermining Russia's strategic nuclear deterrent, Moscow has embarked on a program to develop new weapons capable of defeating any new American ballistic missile defense or interception system. Some analysts believe that this nuclear strategy under Putin has brought Russia into violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.[415]

Accordingly, U.S. President Donald Trump announced the U.S. would no longer consider itself bound by the treaty's provisions, raising nuclear tensions between the two powers.[415] This prompted Putin to state that Russia would not launch first in a nuclear conflict but that "an aggressor should know that vengeance is inevitable, that he will be annihilated, and we would be the victims of the aggression. We will go to heaven as martyrs".[416]

Putin has also sought to increase Russian territorial claims in the Arctic and its military presence there. In August 2007, Russian expedition Arktika 2007, part of research related to the 2001 Russian territorial extension claim, planted a flag on the seabed at the North Pole.[417] Both Russian submarines and troops deployed in the Arctic have been increasing.[418][419]

.jpg/440px-Sun_in_the_flags_of_protesters_(50096710531).jpg)

New York City-based NGO Human Rights Watch, in a report entitled Laws of Attrition, authored by Hugh Williamson, the British director of HRW's Europe & Central Asia Division, has claimed that since May 2012, when Putin was reelected as president, Russia has enacted many restrictive laws, started inspections of non-governmental organizations, harassed, intimidated and imprisoned political activists, and started to restrict critics. The new laws include the "foreign agents" law, which is widely regarded as over-broad by including Russian human rights organizations which receive some international grant funding, the treason law, and the assembly law which penalizes many expressions of dissent.[420][421] Human rights activists have criticized Russia for censoring speech of LGBT activists due to "the gay propaganda law"[422] and increasing violence against LGBT+ people due to the law.[423][424][425]

In 2020, Putin signed a law on labelling individuals and organizations receiving funding from abroad as "foreign agents". The law is an expansion of "foreign agent" legislation adopted in 2012.[426][427]

As of June 2020, per Memorial Human Rights Center, there were 380 political prisoners in Russia, including 63 individuals prosecuted, directly or indirectly, for political activities (including Alexey Navalny) and 245 prosecuted for their involvement with one of the Muslim organizations that are banned in Russia. 78 individuals on the list, i.e., more than 20% of the total, are residents of Crimea.[428][429] As of December 2022, more than 4,000 people were prosecuted for criticizing the war in Ukraine under Russia's war censorship laws.[430]

Scott Gehlbach, a professor of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, has claimed that since 1999, Putin has systematically punished journalists who challenge his official point of view.[432] Maria Lipman, an American writing in Foreign Affairs claims, "The crackdown that followed Putin's return to the Kremlin in 2012 extended to the liberal media, which had until then been allowed to operate fairly independently."[433] The Internet has attracted Putin's attention because his critics have tried to use it to challenge his control of information.[434] Marian K. Leighton, who worked for the CIA as a Soviet analyst in the 1980s says, "Having muzzled Russia's print and broadcast media, Putin focused his energies on the Internet."[435]

Robert W. Orttung and Christopher Walker reported that "Reporters Without Borders, for instance, ranked Russia 148 in its 2013 list of 179 countries in terms of freedom of the press. It particularly criticized Russia for the crackdown on the political opposition and the failure of the authorities to vigorously pursue and bring to justice criminals who have murdered journalists. Freedom House ranks Russian media as "not free", indicating that basic safeguards and guarantees for journalists and media enterprises are absent.[436] About two-thirds of Russians use television as their primary source of daily news.[437]

In the early 2000s, Putin and his circle began promoting the idea in Russian media that they are the modern-day version of the 17th-century Romanov tsars who ended Russia's "Time of Troubles", meaning they claim to be the peacemakers and stabilizers after the fall of the Soviet Union.[438]

_03.jpg/440px-Vladimir_Putin_in_Pokrova_Church_(Turginovo)_03.jpg)

Putin has promoted explicitly conservative policies in social, cultural, and political matters, both at home and abroad. Putin has attacked globalism and neoliberalism and is identified by scholars with Russian conservatism.[439] Putin has promoted new think tanks that bring together like-minded intellectuals and writers. For example, the Izborsky Club, founded in 2012 by the conservative right-wing journalist Alexander Prokhanov, stresses (i) Russian nationalism, (ii) the restoration of Russia's historical greatness, and (iii) systematic opposition to liberal ideas and policies.[440] Vladislav Surkov, a senior government official, has been one of the key economics consultants during Putin's presidency.[441]

In cultural and social affairs Putin has collaborated closely with the Russian Orthodox Church. Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, head of the Church, endorsed his election in 2012 stating Putin's terms were like "a miracle of God".[442] Steven Myers reports, "The church, once heavily repressed, had emerged from the Soviet collapse as one of the most respected institutions... Now Kiril led the faithful directly into an alliance with the state."[443]

Mark Woods, a Baptist Union of Great Britain minister and contributing editor to Christian Today, provides specific examples of how the Church has backed the expansion of Russian power into Crimea and eastern Ukraine.[444] Some Russian Orthodox believers consider Putin a corrupt and brutal strongman or even a tyrant. Others do not admire him but appreciate that he aggravates their political opponents. Still others appreciate that Putin defends some although not all Orthodox teachings, whether or not he believes in them himself.[445]

On abortion, Putin stated: "In the modern world, the decision is up to the woman herself."[446] This put him at odds with the Russian Orthodox Church.[447] In 2020, he supported efforts to reduce the number of abortions instead of prohibiting it.[448] On 28 November 2023, during a speech to the World Russian People's Council, Putin urged Russian women to have "seven, eight, or even more children" and said "large families must become the norm, a way of life for all of Russia's people".[449]

Putin supported the 2020 Russian constitutional referendum, which passed and defined marriage as a relationship between one man and one woman in the Constitution of Russia.[450][451][452]

In 2007, Putin led a successful effort on behalf of Sochi for the 2014 Winter Olympics and the 2014 Winter Paralympics,[453] the first Winter Olympic Games to ever be hosted by Russia. In 2008, the city of Kazan won the bid for the 2013 Summer Universiade; on 2 December 2010, Russia won the right to host the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup and 2018 FIFA World Cup, also for the first time in Russian history. In 2013, Putin stated that gay athletes would not face any discrimination at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.[454]