El referéndum de 2016 sobre la permanencia en la Unión Europea del Reino Unido , comúnmente conocido como referéndum de la UE o referéndum del Brexit , fue un referéndum que tuvo lugar el 23 de junio de 2016 en el Reino Unido (RU) y Gibraltar de conformidad con las disposiciones de la Ley del Referéndum de la Unión Europea de 2015 para preguntar al electorado si el país debía seguir siendo miembro de la Unión Europea (UE) o abandonarla. El resultado fue un voto a favor de abandonar la UE, lo que desencadenó llamamientos para iniciar el proceso de retirada del país de la UE, comúnmente denominado " Brexit ".

Desde 1973 , el Reino Unido ha sido un estado miembro de la UE y su predecesora, las Comunidades Europeas (principalmente la Comunidad Económica Europea ), junto con otros organismos internacionales. Las implicaciones constitucionales de la membresía para el Reino Unido se convirtieron en un tema de debate a nivel nacional, particularmente en lo que respecta a la soberanía. En 1975 se celebró un referéndum sobre la membresía continua de las Comunidades Europeas (CE) para tratar de resolver el problema, lo que resultó en que el Reino Unido siguiera siendo miembro. [1] Entre 1975 y 2016, a medida que se profundizaba la integración europea , el Parlamento del Reino Unido ratificó los tratados y acuerdos CE/UE posteriores . Tras la victoria del Partido Conservador en las elecciones generales de 2015 como promesa principal del manifiesto, la base legal para el referéndum de la UE se estableció a través de la Ley del Referéndum de la Unión Europea de 2015. El primer ministro David Cameron también supervisó una renegociación de los términos de la membresía de la UE , con la intención de implementar estos cambios en caso de un resultado de permanencia. El referéndum no fue jurídicamente vinculante debido al antiguo principio de soberanía parlamentaria , aunque el gobierno prometió implementar el resultado. [2]

La campaña oficial tuvo lugar entre el 15 de abril y el 23 de junio de 2016. El grupo oficial a favor de permanecer en la UE fue Britain Stronger in Europe, mientras que Vote Leave fue el grupo oficial que apoyó la salida. [3] Otros grupos de campaña, partidos políticos, empresas, sindicatos, periódicos y personas prominentes también estuvieron involucrados, y ambos lados tenían partidarios de todo el espectro político. Los partidos a favor de permanecer incluyeron al Partido Laborista , los Demócratas Liberales , el Partido Nacional Escocés , Plaid Cymru y el Partido Verde ; [4] [5] [6] [7] mientras que el Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido hizo campaña a favor de la salida; [8] y el Partido Conservador se mantuvo neutral. [9] A pesar de las posiciones oficiales del Partido Conservador y Laborista, ambos partidos permitieron a sus miembros del Parlamento hacer campaña públicamente para cualquiera de los lados del tema. [10] [11] Los temas de la campaña incluyeron los costos y beneficios de la membresía para la economía del Reino Unido, la libertad de movimiento y la migración. Varias acusaciones de campaña ilegal e interferencia rusa surgieron durante y después del referéndum.

Los resultados registraron un 51,9% de los votos emitidos a favor de abandonar la UE. La mayoría de las áreas de Inglaterra y Gales tuvieron una mayoría a favor de abandonar la UE, y la mayoría de los votantes en Escocia , Irlanda del Norte , Gran Londres y Gibraltar eligieron permanecer en la UE. La preferencia de los votantes se correlacionó con la edad, el nivel de educación y los factores socioeconómicos. Las causas y el razonamiento del resultado del Brexit han sido objeto de análisis y comentarios. Inmediatamente después del resultado , los mercados financieros reaccionaron negativamente en todo el mundo y Cameron anunció que dimitiría como primer ministro y líder del Partido Conservador , lo que hizo en julio. El referéndum provocó una serie de reacciones internacionales . Jeremy Corbyn se enfrentó a un desafío de liderazgo del Partido Laborista como resultado del referéndum. En 2017, el Reino Unido notificó formalmente su intención de retirarse de la UE, y la retirada se formalizó en 2020.

Las Comunidades Europeas se formaron en la década de 1950: la Comunidad Europea del Carbón y del Acero (CECA) en 1952, y la Comunidad Europea de la Energía Atómica (CEEA o Euratom) y la Comunidad Económica Europea (CEE) en 1957. [12] La CEE, la más ambiciosa de las tres, llegó a conocerse como el "Mercado Común". El Reino Unido solicitó por primera vez unirse a ellas en 1961, pero Francia lo vetó. [12] Una solicitud posterior tuvo éxito y el Reino Unido se unió en 1973; dos años más tarde, un referéndum nacional sobre la continuidad de la membresía en la CE dio como resultado un 67,2% de votos "Sí" a favor de la membresía continua, con una participación nacional del 64,6%. [12] Sin embargo, no se celebraron más referendos sobre la cuestión de la relación del Reino Unido con Europa y los sucesivos gobiernos británicos se integraron aún más en el proyecto europeo, que ganó atención cuando el Tratado de Maastricht estableció la Unión Europea (UE) en 1993, que incorporó (y después del Tratado de Lisboa , sucedió) a las Comunidades Europeas. [12] [13]

En la cumbre de la OTAN de mayo de 2012 , el Primer Ministro del Reino Unido , David Cameron , el Ministro de Asuntos Exteriores, William Hague, y Ed Llewellyn discutieron la idea de utilizar un referéndum de la Unión Europea como una concesión al ala euroescéptica del Partido Conservador. [14] El 20 de junio de 2012, el entonces diputado euroescéptico Douglas Carswell presentó un proyecto de ley de iniciativa parlamentaria de tres cláusulas en la Cámara de los Comunes para poner fin a la pertenencia del Reino Unido a la UE y derogar la Ley de las Comunidades Europeas de 1972, pero sin contener ningún compromiso de celebrar ningún referéndum. Recibió una segunda lectura en un debate de media hora en la cámara el 26 de octubre de 2012, pero no avanzó más. [15]

En enero de 2013, Cameron pronunció el discurso de Bloomberg y prometió que, si los conservadores ganaban una mayoría parlamentaria en las elecciones generales de 2015 , el gobierno británico negociaría acuerdos más favorables para la continuidad de la membresía británica en la UE, antes de celebrar un referéndum sobre si el Reino Unido debía permanecer o salir de la UE. [16] El Partido Conservador publicó un proyecto de ley de referéndum de la UE en mayo de 2013, y esbozó sus planes para la renegociación seguida de una votación de entrada-salida (es decir, un referéndum que diera opciones solo de salir y de permanecer en la UE bajo los términos actuales, o bajo nuevos términos si estos estuvieran disponibles), si el partido fuera reelegido en 2015. [17] El proyecto de ley establecía que el referéndum debía celebrarse a más tardar el 31 de diciembre de 2017. [18]

El proyecto de ley fue presentado como proyecto de ley de iniciativa parlamentaria por el diputado conservador James Wharton , conocido como Proyecto de Ley de la Unión Europea (Referéndum) de 2013. [ 19] La primera lectura del proyecto de ley en la Cámara de los Comunes tuvo lugar el 19 de junio de 2013. [20] Un portavoz dijo que Cameron estaba "muy satisfecho" y que se aseguraría de que el proyecto de ley recibiera "el pleno apoyo del Partido Conservador". [21]

En relación con la capacidad del proyecto de ley para vincular al Gobierno del Reino Unido en el Parlamento 2015-20 (que indirectamente, como resultado del propio referéndum, resultó durar solo dos años) a la celebración de dicho referéndum, un documento de investigación parlamentaria señaló que:

El proyecto de ley simplemente prevé un referéndum sobre la permanencia en la UE para fines de diciembre de 2017 y no especifica de otro modo el calendario, salvo exigir al Secretario de Estado que presente las órdenes para fines de 2016. [...] Si ningún partido obtiene una mayoría en las [próximas elecciones generales previstas para 2015], podría haber cierta incertidumbre sobre la aprobación de las órdenes en el próximo Parlamento. [22]

El proyecto de ley recibió su segunda lectura el 5 de julio de 2013, aprobándose por 304 votos a favor y ninguno en contra después de que casi todos los parlamentarios laboristas y todos los parlamentarios liberaldemócratas se abstuvieran, fue aprobado por la Cámara de los Comunes en noviembre de 2013 y luego presentado a la Cámara de los Lores en diciembre de 2013, donde los miembros votaron para bloquear el proyecto de ley. [23]

El diputado conservador Bob Neill presentó entonces un proyecto de ley de referéndum alternativo a la Cámara de los Comunes. [24] [25] Después de un debate el 17 de octubre de 2014, pasó al Comité de Proyectos de Ley Públicos , pero debido a que la Cámara de los Comunes no logró aprobar una resolución monetaria, el proyecto de ley no pudo avanzar más antes de la disolución del parlamento el 27 de marzo de 2015. [26] [27]

En las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2014 , el Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido (UKIP) obtuvo más votos y más escaños que cualquier otro partido, la primera vez que un partido distinto de los conservadores o el laborismo encabezaba una encuesta nacional en 108 años, dejando a los conservadores en tercer lugar. [28]

Bajo el liderazgo de Ed Miliband entre 2010 y 2015, el Partido Laborista descartó un referéndum de entrada o salida a menos que y hasta que se propusiera una nueva transferencia de poderes del Reino Unido a la UE. [29] En su manifiesto para las elecciones generales de 2015, los Demócratas Liberales se comprometieron a celebrar un referéndum de entrada o salida solo en caso de que hubiera un cambio en los tratados de la UE. [30] El Partido de la Independencia del Reino Unido (UKIP), el Partido Nacional Británico (BNP), el Partido Verde [31] , el Partido Unionista Democrático [32] y el Partido del Respeto [33] apoyaron el principio de un referéndum.

Cuando el Partido Conservador ganó la mayoría de escaños en la Cámara de los Comunes en las elecciones generales de 2015 , Cameron reiteró el compromiso del manifiesto de su partido de celebrar un referéndum sobre la pertenencia del Reino Unido a la UE a finales de 2017, pero sólo después de "negociar un nuevo acuerdo para Gran Bretaña en la UE". [34]

A principios de 2014, David Cameron esbozó los cambios que pretendía introducir en la UE y en la relación del Reino Unido con ella. [35] Estos eran: controles migratorios adicionales, especialmente para los ciudadanos de los nuevos estados miembros de la UE; normas migratorias más estrictas para los ciudadanos actuales de la UE; nuevos poderes para que los parlamentos nacionales veten colectivamente las leyes propuestas por la UE; nuevos acuerdos de libre comercio y una reducción de la burocracia para las empresas; una disminución de la influencia del Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos sobre la policía y los tribunales británicos; más poder para los estados miembros individuales y menos para la UE central; y el abandono de la noción de la UE de una "unión cada vez más estrecha". [35] Tenía la intención de introducir estos cambios durante una serie de negociaciones con otros líderes de la UE y luego, si era reelegido, anunciar un referéndum. [35]

En noviembre de ese año, Cameron dio una actualización sobre las negociaciones y dio más detalles de sus objetivos. [36] Las demandas clave hechas a la UE fueron: sobre gobernanza económica, reconocer oficialmente que las leyes de la eurozona no se aplicarían necesariamente a los miembros de la UE no pertenecientes a la eurozona y que estos últimos no tendrían que rescatar a las economías de la eurozona en problemas; sobre competitividad, expandir el mercado único y establecer un objetivo de reducción de la burocracia para las empresas; sobre soberanía, que el Reino Unido estuviera legalmente exento de una "unión cada vez más estrecha" y que los parlamentos nacionales pudieran vetar colectivamente las leyes propuestas por la UE; y, sobre inmigración, que los ciudadanos de la UE que fueran al Reino Unido para trabajar no pudieran solicitar vivienda social o beneficios por trabajo hasta que hubieran trabajado allí durante cuatro años, y que no pudieran enviar pagos de subsidios por hijo al extranjero. [36] [37]

El resultado de las renegociaciones se anunció en febrero de 2016. [38] Los términos renegociados se sumaron a las exclusiones existentes del Reino Unido en la Unión Europea y el reembolso del Reino Unido . La importancia de los cambios en el acuerdo UE-Reino Unido fue cuestionada y especulada, y ninguno de los cambios se consideró fundamental, pero algunos se consideraron importantes para muchos británicos. [38] Se acordaron algunos límites a los beneficios laborales para los inmigrantes de la UE, pero estos se aplicarían en una escala móvil durante cuatro años y serían solo para nuevos inmigrantes; antes de que pudieran aplicarse, un país tendría que obtener el permiso del Consejo Europeo . [38] Los pagos de beneficios por hijo aún podrían realizarse en el extranjero, pero estos estarían vinculados al costo de vida en el otro país. [39] En cuanto a la soberanía, se aseguró al Reino Unido que no estaría obligado a participar en una "unión cada vez más estrecha"; estas garantías estaban "en línea con la legislación vigente de la UE". [38] La exigencia de Cameron de permitir a los parlamentos nacionales vetar las leyes propuestas de la UE fue modificada para permitir a los parlamentos nacionales objetar colectivamente las leyes propuestas de la UE, en cuyo caso el Consejo Europeo reconsideraría la propuesta antes de decidir por sí mismo qué hacer. [38] En materia de gobernanza económica, se reforzarían las normas antidiscriminación para los miembros no pertenecientes a la eurozona, pero no podrían vetar ninguna legislación. [40] Las dos últimas áreas cubiertas fueron las propuestas de "excluir del ámbito de aplicación de los derechos de libre circulación a los nacionales de terceros países que no tuvieran residencia legal previa en un Estado miembro antes de casarse con un ciudadano de la Unión" [41] y de facilitar a los Estados miembros la deportación de nacionales de la UE por razones de orden público o seguridad pública. [42] El grado en que las distintas partes del acuerdo serían jurídicamente vinculantes es complejo; ninguna parte del acuerdo en sí cambió la legislación de la UE, pero algunas partes podrían ser aplicables en el derecho internacional. [43]

Según se informa, la UE había ofrecido a David Cameron un llamado "freno de emergencia", que habría permitido al Reino Unido retener los beneficios sociales a los nuevos inmigrantes durante los primeros cuatro años después de su llegada; este freno podría haberse aplicado por un período de siete años. [44] Esa oferta todavía estaba sobre la mesa en el momento del referéndum del Brexit, pero expiró cuando la votación determinó que el Reino Unido abandonaría la UE. Cameron afirmó que "podría haber evitado el Brexit si los líderes europeos le hubieran dejado controlar la migración", según el Financial Times . [45] [46] Sin embargo, Angela Merkel dijo que la oferta no había sido hecha por la UE. Merkel declaró en el Parlamento alemán: "Si deseas tener libre acceso al mercado único, entonces tienes que aceptar los derechos fundamentales europeos, así como las obligaciones que se derivan de él. Esto es tan cierto para Gran Bretaña como para cualquier otro". [47]

El referéndum planeado fue incluido en el Discurso de la Reina el 27 de mayo de 2015. [48] Se sugirió en ese momento que Cameron estaba planeando celebrar el referéndum en octubre de 2016, [49] pero la Ley de Referéndum de la Unión Europea de 2015, que lo autorizó, fue presentada ante la Cámara de los Comunes al día siguiente, solo tres semanas después de la elección. [50] En la segunda lectura del proyecto de ley el 9 de junio, los miembros de la Cámara de los Comunes votaron por 544 a 53 a favor, respaldando el principio de celebrar un referéndum, con solo el Partido Nacional Escocés votando en contra. [51] En contraste con la posición del Partido Laborista antes de las elecciones generales de 2015 bajo Miliband, la líder laborista en funciones Harriet Harman comprometió a su partido a apoyar los planes para un referéndum de la UE para 2017, una posición mantenida por el líder electo Jeremy Corbyn . [52]

Para que el referéndum pudiera celebrarse, el Parlamento del Reino Unido aprobó la Ley del Referéndum de la Unión Europea [53] , que se amplió para incluir y surtir efecto legislativo en Gibraltar [54] [ 55] y recibió la sanción real el 17 de diciembre de 2015. La Ley, a su vez, fue confirmada, promulgada e implementada en Gibraltar por la Ley de la Unión Europea (Referéndum) de 2016 (Gibraltar) [56] , que fue aprobada por el Parlamento de Gibraltar y entró en vigor tras recibir la sanción del Gobernador de Gibraltar el 28 de enero de 2016.

La Ley del Referéndum de la Unión Europea exigía que se celebrara un referéndum sobre la cuestión de la permanencia del Reino Unido en la Unión Europea (UE) antes de finales de 2017. No contenía ningún requisito para que el Gobierno del Reino Unido implementara los resultados del referéndum. En cambio, estaba diseñada para medir la opinión del electorado sobre la pertenencia a la UE. Los referendos celebrados en Escocia, Gales e Irlanda del Norte en 1997 y 1998 son ejemplos de este tipo, en los que se puso a prueba la opinión antes de introducir la legislación. El Reino Unido no tiene disposiciones constitucionales que exijan que se implementen los resultados de un referéndum , a diferencia, por ejemplo, de la República de Irlanda , donde las circunstancias en las que debe celebrarse un referéndum vinculante están establecidas en su constitución . Por el contrario, la legislación que preveía el referéndum celebrado en AV en mayo de 2011 habría aplicado el nuevo sistema de votación sin más legislación, siempre que se aplicaran también los cambios de límites previstos en la Ley del Sistema de Votación Parlamentaria y de Circunscripciones de 2011 . En el caso de la votación, hubo una mayoría sustancial en contra de cualquier cambio. El referéndum de 1975 se celebró después de que todos los Estados miembros de la CE acordaran los términos renegociados de la membresía del Reino Unido en la CE, y los términos se establecieran en un documento de instrucciones y fueran aprobados por ambas Cámaras. [57] Después del referéndum de 2016, el Tribunal Superior confirmó que el resultado no era jurídicamente vinculante, debido a los principios constitucionales de soberanía parlamentaria y democracia representativa, y la legislación que autorizaba el referéndum no contenía palabras claras en sentido contrario. [58]

La investigación de la Comisión Electoral confirmó que la pregunta recomendada "era clara y directa para los votantes, y era la redacción más neutral de la gama de opciones... consideradas y probadas", citando las respuestas a su consulta por parte de una amplia gama de consultados. [59] La pregunta propuesta fue aceptada por el gobierno en septiembre de 2015, poco antes de la tercera lectura del proyecto de ley. [60] La pregunta que apareció en las papeletas de votación en el referéndum bajo la Ley fue:

¿Debe el Reino Unido seguir siendo miembro de la Unión Europea o abandonarla?

con las respuestas a la pregunta (a marcar con una sola (X)):

Seguir siendo miembro de la Unión Europea

Salir de la Unión Europea

y en galés :

A ddylai'r Deyrnas Unedig aros yn aelod o'r Undeb Ewropeaidd neu adael yr Undeb Ewropeaidd?

con las respuestas (a marcar con una sola (X)):

Aros yn aelod o'r Undeb Ewropeaidd

Gadael yr Undeb Ewropeaidd

Antes de que se anunciara oficialmente, se especuló ampliamente que una fecha de junio para el referéndum era una posibilidad seria. Los primeros ministros de Irlanda del Norte, Escocia y Gales firmaron una carta a Cameron el 3 de febrero de 2016 pidiéndole que no celebrara el referéndum en junio, ya que las elecciones descentralizadas estaban programadas para el mes anterior, el 5 de mayo. Estas elecciones se habían pospuesto durante un año para evitar un choque con las elecciones generales de 2015, después de que Westminster hubiera implementado la Ley de Parlamento de Plazo Fijo . Cameron rechazó esta solicitud, diciendo que la gente podía tomar sus propias decisiones en múltiples elecciones espaciadas al menos seis semanas entre sí. [61] [62]

El 20 de febrero de 2016, Cameron anunció que el Gobierno del Reino Unido recomendaría formalmente al pueblo británico que el país siguiera siendo miembro de una Unión Europea reformada y que el referéndum se celebraría el 23 de junio, lo que marcaría el lanzamiento oficial de la campaña. También anunció que el Parlamento promulgaría legislación secundaria el 22 de febrero relacionada con la Ley del Referéndum de la Unión Europea de 2015. Con el lanzamiento oficial, los ministros del Gobierno del Reino Unido quedaron libres de hacer campaña a favor o en contra de cualquiera de los dos bandos, en una rara excepción a la responsabilidad colectiva del Gabinete . [63]

El derecho a votar en el referéndum en el Reino Unido está definido por la legislación como limitado a los residentes del Reino Unido que también fueran ciudadanos de la Commonwealth según la Sección 37 de la Ley de Nacionalidad Británica de 1981 (que incluye a los ciudadanos británicos y otros nacionales británicos ), o aquellos que también fueran ciudadanos de la República de Irlanda , o ambos. Los miembros de la Cámara de los Lores , que no pudieron votar en las elecciones generales, pudieron votar en el referéndum. El electorado de 46.500.001 representó el 70,8% de la población de 65.678.000 ( Reino Unido y Gibraltar ). [64] Aparte de los residentes de Gibraltar, los ciudadanos de los Territorios Británicos de Ultramar que residían en los Territorios Británicos de Ultramar no pudieron votar en el referéndum. [65] [66]

Los residentes del Reino Unido que eran ciudadanos de otros países de la UE no podían votar a menos que fueran ciudadanos (o también ciudadanos) de la República de Irlanda, de Malta o de la República de Chipre . [67]

Las Leyes de Representación del Pueblo de 1983 (1983 c. 2) y 1985 (1985 c. 50) , en su forma enmendada, también permiten votar a ciertos ciudadanos británicos (pero no a otros nacionales británicos) que alguna vez vivieron en el Reino Unido, pero que desde entonces y mientras tanto vivieron fuera del Reino Unido, pero por un período no mayor a 15 años. [68]

El día del referéndum, la votación se celebró de 07:00 a 22:00 BST ( hora del este de Inglaterra ) (de 07:00 a 22:00 CEST en Gibraltar) en unos 41.000 colegios electorales atendidos por más de 100.000 trabajadores electorales . Se especificó que cada colegio electoral no tuviera más de 2.500 votantes registrados. [ cita requerida ] Según las disposiciones de la Ley de Representación del Pueblo de 2000 , también se permitieron las papeletas de voto por correo en el referéndum y se enviaron a los votantes elegibles unas tres semanas antes de la votación (2 de junio de 2016).

La edad mínima para votar en el referéndum se fijó en 18 años, de conformidad con la Ley de Representación del Pueblo, en su forma enmendada. Una enmienda de la Cámara de los Lores que proponía reducir la edad mínima a 16 años fue rechazada. [69]

La fecha límite para registrarse para votar fue inicialmente la medianoche del 7 de junio de 2016; sin embargo, esta fecha se extendió 48 horas debido a problemas técnicos con el sitio web oficial de registro el 7 de junio, causados por un tráfico web inusualmente alto. Algunos partidarios de la campaña a favor del Brexit, incluido el diputado conservador Sir Gerald Howarth , criticaron la decisión del gobierno de extender la fecha límite, alegando que daba una ventaja a los partidarios de la permanencia porque muchos de los que se registraron tarde eran jóvenes que se consideraba que tenían más probabilidades de votar por la permanencia. [70] Según cifras provisionales de la Comisión Electoral, casi 46,5 millones de personas estaban habilitadas para votar. [71]

El Ayuntamiento de Nottingham envió un correo electrónico a un partidario del voto por el Brexit para decirle que el ayuntamiento no podía comprobar si la nacionalidad que las personas indicaban en su formulario de registro para votar era verdadera y que, por lo tanto, simplemente tenían que asumir que la información presentada era, de hecho, correcta. [72]

3.462 ciudadanos de la UE recibieron por error tarjetas de votación por correo debido a un problema informático que tuvo Xpress, un proveedor de software electoral para varios ayuntamientos. En un principio, Xpress no pudo confirmar el número exacto de afectados. El asunto se resolvió con la emisión de un parche de software que hizo que los electores registrados por error no pudieran votar el 23 de junio. [72]

Los residentes de las Dependencias de la Corona (que no forman parte del Reino Unido), a saber, la Isla de Man y los Bailiazgos de Jersey y Guernsey , incluso si eran ciudadanos británicos, fueron excluidos del referéndum a menos que también fueran residentes anteriores del Reino Unido (es decir: Inglaterra y Gales, Escocia e Irlanda del Norte). [73]

Algunos residentes de la Isla de Man protestaron porque, como ciudadanos británicos de pleno derecho en virtud de la Ley de Nacionalidad Británica de 1981 y residentes en las Islas Británicas , también se les debería haber dado la oportunidad de votar en el referéndum, ya que la Isla y los Bailiaces, aunque no estaban incluidos como si fueran parte del Reino Unido a los efectos de la membresía en la Unión Europea (y el Espacio Económico Europeo (EEE)) (como es el caso de Gibraltar), también se habrían visto significativamente afectados por el resultado y el impacto del referéndum. [73]

En octubre de 2015, se formó Britain Stronger in Europe , un grupo multipartidario que hacía campaña para que Gran Bretaña siguiera siendo miembro de la UE. [74] Había dos grupos rivales que promovían la retirada británica de la UE y que buscaban convertirse en la campaña oficial a favor del Brexit: Leave.EU (que fue respaldada por la mayoría del UKIP , incluido Nigel Farage ) y Vote Leave (respaldada por los euroescépticos del Partido Conservador). En enero de 2016, Nigel Farage y la campaña Leave.EU se convirtieron en parte del movimiento Grassroots Out , que nació de las luchas internas entre los activistas de Vote Leave y Leave.EU. [75] [76] En abril, la Comisión Electoral anunció que Britain Stronger in Europe y Vote Leave iban a ser designadas como las campañas oficiales a favor de la permanencia y del Brexit respectivamente. [77] Esto les dio el derecho a gastar hasta £7 000 000, un correo gratuito, transmisiones televisivas y £600 000 en fondos públicos. La postura oficial del Gobierno del Reino Unido era apoyar la campaña a favor de la permanencia en la UE. Sin embargo, Cameron anunció que los ministros y parlamentarios conservadores tenían libertad para hacer campaña a favor de la permanencia en la UE o de la salida, según su conciencia. Esta decisión se produjo tras la creciente presión para que se votara libremente a los ministros. [78] En una excepción a la regla habitual de responsabilidad colectiva del gabinete , Cameron permitió a los ministros del gabinete hacer campaña públicamente a favor de la retirada de la UE. [79] En abril se lanzó una campaña respaldada por el Gobierno. [80] El 16 de junio, toda la campaña nacional oficial se suspendió hasta el 19 de junio tras el asesinato de Jo Cox . [81]

Después de que las encuestas internas sugirieran que el 85% de la población del Reino Unido quería más información sobre el referéndum por parte del gobierno, se envió un folleto a todos los hogares del Reino Unido. [82] Contenía detalles sobre por qué el gobierno creía que el Reino Unido debía permanecer en la UE. Este folleto fue criticado por aquellos que querían salir porque daban al bando de la permanencia una ventaja injusta; también se describió como inexacto y un desperdicio de dinero de los contribuyentes (costó 9,3 millones de libras en total). [83] Durante la campaña, Nigel Farage sugirió que habría una demanda pública de un segundo referéndum si el resultado era una victoria por una diferencia menor al 52-48%, porque el folleto significaba que se había permitido al bando de la permanencia gastar más dinero que al bando de la salida. [84]

En la semana que comenzó el 16 de mayo, la Comisión Electoral envió una guía de votación sobre el referéndum a todos los hogares del Reino Unido y Gibraltar para concienciar sobre el próximo referéndum. La guía de ocho páginas contenía detalles sobre cómo votar, así como una muestra de la papeleta electoral real, y se entregó una página entera a cada uno de los grupos de campaña Britain Stronger in Europe y Vote Leave para que presentaran su caso. [85] [86]

La campaña Vote Leave argumentó que si el Reino Unido abandonaba la UE, se protegería la soberanía nacional , se podrían imponer controles de inmigración y el Reino Unido podría firmar acuerdos comerciales con el resto del mundo. El Reino Unido también podría dejar de pagar a la UE cada semana como miembro. [87] [nota 1] La campaña Britain Stronger in Europe argumentó que abandonar la Unión Europea dañaría la economía del Reino Unido y que el estatus del Reino Unido como influencia mundial dependía de su membresía. [90]

Las tablas enumeran los partidos políticos con representación en la Cámara de los Comunes o la Cámara de los Lores , el Parlamento Europeo , el Parlamento Escocés , la Asamblea de Irlanda del Norte , el Parlamento Galés o el Parlamento de Gibraltar en el momento del referéndum.

Entre los partidos minoritarios, el Partido Laborista Socialista , el Partido Comunista de Gran Bretaña , Britain First , [113] el Partido Nacional Británico (BNP), [114] Éirígí [Irlanda], [115] el Partido del Respeto , [116] la Coalición Sindicalista y Socialista (TUSC), [117] el Partido Socialdemócrata , [118] el Partido Liberal , [119] Independence from Europe , [120] y el Partido de los Trabajadores [Irlanda] [121] apoyaron la salida de la UE.

El Partido Socialista Escocés (SSP), Left Unity y Mebyon Kernow [Cornualles] apoyaron la permanencia en la UE. [122] [123] [124]

El Partido Socialista de Gran Bretaña no apoyaba ni el abandono ni la permanencia y el Partido para la Igualdad de la Mujer no tenía una posición oficial sobre el tema. [125] [126] [127] [128]

El Gabinete del Reino Unido es un organismo responsable de tomar decisiones sobre políticas y organizar los departamentos gubernamentales ; está presidido por el Primer Ministro y contiene la mayoría de los jefes ministeriales del gobierno. [129] Tras el anuncio del referéndum en febrero, 23 de los 30 ministros del Gabinete (incluidos los asistentes) apoyaron la permanencia del Reino Unido en la UE. [130] Iain Duncan Smith , a favor de salir, renunció el 19 de marzo y fue reemplazado por Stephen Crabb , quien estaba a favor de permanecer. [130] [131] Crabb ya era miembro del gabinete, como Secretario de Estado para Gales , y su reemplazo, Alun Cairns , estaba a favor de permanecer, lo que elevó el número total de miembros del Gabinete a favor de la permanencia a 25.

Varias multinacionales del Reino Unido han declarado que no les gustaría que el Reino Unido abandonara la UE debido a la incertidumbre que causaría, como Shell , [132] BT [133] y Vodafone , [134] y algunas han evaluado los pros y los contras de la salida de Gran Bretaña. [135] El sector bancario fue uno de los que más abogó por permanecer en la UE, y la Asociación de Banqueros Británicos dijo: "A las empresas no les gusta ese tipo de incertidumbre". [136] RBS advirtió sobre el daño potencial a la economía. [137] Además, HSBC y los bancos extranjeros JP Morgan y Deutsche Bank afirman que un Brexit podría resultar en un cambio de domicilio de los bancos. [138] [139] Según Goldman Sachs y el jefe de políticas de la City de Londres , todos estos factores podrían afectar el estatus actual de la City de Londres como líder del mercado europeo y mundial en servicios financieros. [140] En febrero de 2016, los líderes de 36 de las empresas del índice FTSE 100 , entre ellas Shell, BAE Systems , BT y Rio Tinto , apoyaron oficialmente la permanencia en la UE. [141] Además, el 60% de los miembros del Instituto de Directores y del EEF apoyaron la permanencia. [142]

Muchas empresas con sede en el Reino Unido, incluida Sainsbury's , se mantuvieron firmemente neutrales, preocupadas de que tomar partido en esta cuestión divisiva pudiera provocar una reacción negativa de los clientes. [143]

Richard Branson declaró que tenía "mucho miedo" de las consecuencias de una salida del Reino Unido de la UE. [144] Alan Sugar expresó una preocupación similar. [145]

James Dyson , fundador de la empresa Dyson , argumentó en junio de 2016 que la introducción de aranceles sería menos perjudicial para los exportadores británicos que la apreciación de la libra frente al euro, argumentando que, debido a que Gran Bretaña tenía un déficit comercial de 100 mil millones de libras con la UE, los aranceles podrían representar una fuente de ingresos significativa para el Tesoro. [146] Señalando que los idiomas, los enchufes y las leyes difieren entre los estados miembros de la UE, Dyson dijo que el bloque de 28 países no era un mercado único y argumentó que los mercados de más rápido crecimiento estaban fuera de la UE. [146] La empresa de ingeniería Rolls-Royce escribió a los empleados para decirles que no quería que el Reino Unido abandonara la UE. [147]

Las encuestas realizadas a grandes empresas del Reino Unido mostraron que una gran mayoría estaba a favor de que el Reino Unido permaneciera en la UE. [148] Las pequeñas y medianas empresas del Reino Unido estaban más divididas. [148] Las encuestas realizadas a empresas extranjeras revelaron que aproximadamente la mitad tendría menos probabilidades de hacer negocios en el Reino Unido, mientras que el 1% aumentaría su inversión en el Reino Unido. [149] [150] [151] Dos grandes fabricantes de automóviles, Ford y BMW , advirtieron en 2013 contra el Brexit, sugiriendo que sería "devastador" para la economía. [152] Por el contrario, en 2015, otros ejecutivos de fabricación dijeron a Reuters que no cerrarían sus plantas si el Reino Unido abandonara la UE, aunque las inversiones futuras podrían correr riesgo. [153] El director ejecutivo de Vauxhall declaró que un Brexit no afectaría materialmente a su negocio. [154] El director ejecutivo de Toyota, con sede en el extranjero , Akio Toyoda, confirmó que, independientemente de que Gran Bretaña abandonara o no la UE, Toyota seguiría fabricando automóviles en Gran Bretaña como lo había hecho antes. [155]

En la semana siguiente a la conclusión de la renegociación del Reino Unido (y especialmente después de que Boris Johnson anunciara que apoyaría la salida del Reino Unido), la libra cayó a un mínimo de siete años frente al dólar y los economistas de HSBC advirtieron que podría caer aún más. [156] Al mismo tiempo, Daragh Maher, director de HSBC, sugirió que si la libra esterlina perdía valor, también lo haría el euro. Los analistas bancarios europeos también citaron las preocupaciones por el Brexit como la razón de la caída del euro. [157] Inmediatamente después de que una encuesta en junio de 2016 mostrara que la campaña a favor del Brexit iba 10 puntos por delante, la libra cayó un 1 por ciento más. [158] En el mismo mes, se anunció que el valor de los bienes exportados desde el Reino Unido en abril había mostrado un aumento intermensual del 11,2%, "el mayor aumento desde que comenzaron los registros en 1998". [159] [160]

La incertidumbre sobre el resultado del referéndum, junto con varios otros factores (el aumento de las tasas de interés en Estados Unidos, los bajos precios de las materias primas, el bajo crecimiento de la eurozona y las preocupaciones sobre los mercados emergentes como China) contribuyeron a un alto nivel de volatilidad del mercado de valores en enero y febrero de 2016. [ cita requerida ] El 14 de junio, las encuestas que mostraban que un Brexit era más probable llevaron a que el FTSE 100 cayera un 2%, perdiendo 98 mil millones de libras en valor. [161] [162] Después de que otras encuestas sugirieran un movimiento de regreso hacia la permanencia, la libra y el FTSE se recuperaron. [163]

El día del referéndum, la libra esterlina alcanzó un máximo de 2016 de 1,5018 dólares por 1 libra esterlina y el FTSE 100 también subió a un máximo de 2016, ya que una nueva encuesta sugirió una victoria de la campaña Remain. [164] Los resultados iniciales sugirieron un voto por "Remain" y el valor de la libra se mantuvo. Sin embargo, cuando se anunció el resultado de Sunderland , indicó un giro inesperado hacia "Leave". Los resultados posteriores parecieron confirmar este giro y la libra esterlina cayó en valor a 1,3777 dólares, su nivel más bajo desde 1985. El lunes siguiente, cuando abrieron los mercados, 1 libra esterlina cayó a un nuevo mínimo de 1,32 dólares. [165]

Muhammad Ali Nasir y Jamie Morgan, dos economistas británicos, diferenciaron y reflexionaron sobre la debilidad de la libra esterlina debido a la débil posición externa de la economía del Reino Unido y el papel adicional desempeñado por la incertidumbre en torno al Brexit [166]. Informaron que durante la semana del referéndum, hasta la declaración del resultado, la depreciación del tipo de cambio se desvió de la tendencia de largo plazo en aproximadamente un 3,5 por ciento, pero el efecto inmediato real sobre el tipo de cambio fue una depreciación del 8 por ciento. Además, durante el período desde el anuncio del referéndum, el tipo de cambio fluctuó notablemente alrededor de su tendencia y también se puede identificar un efecto mayor basado en el "mal paso" de los mercados en el momento en que se anunció el resultado. [166]

Cuando la Bolsa de Valores de Londres abrió en la mañana del 24 de junio, el FTSE 100 cayó de 6338,10 a 5806,13 en los primeros diez minutos de negociación. Se recuperó a 6091,27 después de otros 90 minutos, antes de recuperarse aún más a 6162,97 al final de la jornada de negociación. Cuando los mercados reabrieron el lunes siguiente, el FTSE 100 mostró una caída constante perdiendo más del 2% a media tarde. [167] Al abrir más tarde el viernes después del referéndum, el Promedio Industrial Dow Jones de EE. UU. cayó casi 450 puntos o alrededor del 2½% en menos de media hora. Associated Press calificó la repentina caída del mercado de valores mundial como un colapso del mercado de valores . [168] Los inversores en los mercados de valores de todo el mundo perdieron más del equivalente a US$ 2 billones el 24 de junio de 2016, lo que la convirtió en la peor pérdida de un solo día en la historia, en términos absolutos . [169] Las pérdidas del mercado ascendieron a 3 billones de dólares estadounidenses al 27 de junio. [170] La libra esterlina cayó a un mínimo de 31 años frente al dólar estadounidense. [171] Las calificaciones crediticias de la deuda soberana del Reino Unido y la UE también fueron rebajadas a AA por Standard & Poor's . [172] [173]

A media tarde del 27 de junio de 2016, la libra esterlina estaba en su nivel más bajo en 31 años, tras haber caído un 11% en dos días de negociación, y el FTSE 100 había perdido 85.000 millones de libras; [174] sin embargo, el 29 de junio había recuperado todas sus pérdidas desde que los mercados cerraron el día de las elecciones y el valor de la libra había comenzado a subir. [175] [176]

El referéndum fue generalmente bien aceptado por la extrema derecha europea. [177] Marine Le Pen , líder del Frente Nacional francés , describió la posibilidad de un Brexit como "como la caída del Muro de Berlín " y comentó que "el Brexit sería maravilloso -extraordinario- para todos los pueblos europeos que anhelan la libertad". [178] Una encuesta en Francia en abril de 2016 mostró que el 59% de los franceses estaban a favor de que Gran Bretaña permaneciera en la UE. [179] El político holandés Geert Wilders , líder del Partido por la Libertad , dijo que los Países Bajos deberían seguir el ejemplo de Gran Bretaña: "Como en la década de 1940, una vez más Gran Bretaña podría ayudar a liberar a Europa de otro monstruo totalitario, esta vez llamado 'Bruselas'. Una vez más, podríamos ser salvados por los británicos". [180]

El presidente polaco, Andrzej Duda, apoyó la permanencia del Reino Unido en la UE. [181] El primer ministro moldavo, Pavel Filip, pidió a todos los ciudadanos moldavos que viven en el Reino Unido que hablen con sus amigos británicos y los convenzan de votar a favor de que el Reino Unido permanezca en la UE. [182] El ministro de Asuntos Exteriores español, José García-Margallo, dijo que España exigiría el control de Gibraltar "al día siguiente" de la retirada británica de la UE. [183] Margallo también amenazó con cerrar la frontera con Gibraltar si Gran Bretaña abandonaba la UE. [184]

La ministra sueca de Asuntos Exteriores, Margot Wallström, dijo el 11 de junio de 2016 que si Gran Bretaña abandonaba la UE, otros países celebrarían referendos sobre si abandonar la UE, y que si Gran Bretaña permanecía en la UE, otros países negociarían, pedirían y exigirían un trato especial. [185] El primer ministro checo, Bohuslav Sobotka, sugirió en febrero de 2016 que la República Checa iniciaría conversaciones sobre la salida de la UE si el Reino Unido votaba a favor de una salida de la UE. [186]

Christine Lagarde , directora gerente del Fondo Monetario Internacional , advirtió en febrero de 2016 que la incertidumbre sobre el resultado del referéndum sería mala "en sí misma" para la economía británica. [187] En respuesta, la activista a favor del Brexit, Priti Patel, dijo que una advertencia previa del FMI sobre el plan de déficit del gobierno de coalición para el Reino Unido resultó ser incorrecta y que el FMI "se equivocó entonces y se equivoca ahora". [188]

En octubre de 2015, el Representante Comercial de los Estados Unidos, Michael Froman, declaró que Estados Unidos no estaba interesado en buscar un acuerdo de libre comercio (ALC) separado con Gran Bretaña si abandonara la UE, socavando así, según el periódico The Guardian , un argumento económico clave de los defensores de quienes dicen que Gran Bretaña prosperaría por sí sola y podría asegurar TLC bilaterales con socios comerciales. [189] También en octubre de 2015, el Embajador de los Estados Unidos en el Reino Unido, Matthew Barzun, dijo que la participación del Reino Unido en la OTAN y la UE hacía que cada grupo fuera "mejor y más fuerte" y que, si bien la decisión de permanecer o irse es una elección del pueblo británico, era de interés para los Estados Unidos que permaneciera. [190] En abril de 2016, ocho exsecretarios del Tesoro de los Estados Unidos , que habían servido a presidentes demócratas y republicanos , instaron a Gran Bretaña a permanecer en la UE. [191]

En julio de 2015, el presidente Barack Obama confirmó la preferencia de larga data de Estados Unidos por que el Reino Unido permanezca en la UE. Obama dijo: "Tener al Reino Unido en la UE nos da mucha más confianza sobre la fortaleza de la unión transatlántica, y es parte de la piedra angular de las instituciones construidas después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial que han hecho que el mundo sea más seguro y más próspero. Queremos asegurarnos de que el Reino Unido siga teniendo esa influencia". [192] Algunos parlamentarios conservadores acusaron al presidente estadounidense Barack Obama de interferir en la votación del Brexit, [193] [194] y Boris Johnson calificó la intervención como una "muestra de hipocresía escandalosa y exorbitante" [195] y el líder del UKIP, Nigel Farage , lo acusó de "interferencia monstruosa", diciendo "No esperaría que el Primer Ministro británico interviniera en su elección presidencial, no esperaría que el Primer Ministro respaldara a un candidato u otro". [196] La intervención de Obama fue criticada por el senador republicano Ted Cruz como "una bofetada a la autodeterminación británica ya que el presidente, típicamente, elevó una organización internacional por encima de los derechos de un pueblo soberano", y declaró que "Gran Bretaña estará al frente de la fila para un acuerdo de libre comercio con Estados Unidos", si se produjera el Brexit. [197] [198] Más de 100 parlamentarios de los conservadores, laboristas, UKIP y el DUP escribieron una carta al embajador de Estados Unidos en Londres pidiendo al presidente Obama que no interviniera en la votación del Brexit ya que "hace mucho tiempo que la práctica establecida es no interferir en los asuntos políticos internos de nuestros aliados y esperamos que esto siga siendo así". [199] [200] Dos años después, uno de los ex asistentes de Obama contó que la intervención pública se realizó a raíz de una solicitud de Cameron. [201]

Antes de la votación, el candidato presidencial republicano Donald Trump anticipó que Gran Bretaña se iría debido a sus preocupaciones sobre la migración, [202] mientras que la candidata presidencial demócrata Hillary Clinton esperaba que Gran Bretaña permaneciera en la UE para fortalecer la cooperación transatlántica. [203]

En octubre de 2015, el presidente chino Xi Jinping declaró su apoyo a la permanencia de Gran Bretaña en la UE, diciendo que "China espera ver una Europa próspera y una UE unida, y espera que Gran Bretaña, como miembro importante de la UE, pueda desempeñar un papel aún más positivo y constructivo en la promoción del desarrollo cada vez más profundo de los lazos entre China y la UE". Los diplomáticos chinos han declarado "extraoficialmente" que la República Popular ve a la UE como un contrapeso al poder económico estadounidense, y que una UE sin Gran Bretaña significaría unos Estados Unidos más fuertes. [ cita requerida ]

En febrero de 2016, los ministros de finanzas de las principales economías del G20 advirtieron que la salida del Reino Unido de la UE provocaría un "shock" en la economía mundial. [204] [205]

En mayo de 2016, el primer ministro australiano, Malcolm Turnbull, dijo que Australia preferiría que el Reino Unido permaneciera en la UE, pero que era un asunto que debía resolver el pueblo británico y que "sea cual sea el juicio que tomen, las relaciones entre Gran Bretaña y Australia serán muy, muy estrechas". [206]

El presidente indonesio, Joko Widodo, declaró durante un viaje a Europa que no estaba a favor del Brexit. [207]

El primer ministro de Sri Lanka, Ranil Wickremesinghe, emitió una declaración de motivos por los que estaba “muy preocupado” por la posibilidad del Brexit. [208]

El presidente ruso, Vladimir Putin, dijo: “Quiero decir que no es asunto nuestro, es asunto del pueblo del Reino Unido”. [209] Maria Zakharova , portavoz oficial del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores ruso, dijo: “Rusia no tiene nada que ver con el Brexit. No estamos involucrados en este proceso de ninguna manera. No tenemos ningún interés en él”. [210]

En noviembre de 2015, el gobernador del Banco de Inglaterra, Mark Carney, dijo que el Banco de Inglaterra haría lo que fuera necesario para ayudar a la economía del Reino Unido si el pueblo británico votaba a favor de abandonar la UE. [211] En marzo de 2016, Carney dijo a los parlamentarios que una salida de la UE era el "mayor riesgo interno" para la economía del Reino Unido, pero que seguir siendo miembro también conllevaba riesgos relacionados con la Unión Monetaria Europea , de la que el Reino Unido no es miembro. [212] En mayo de 2016, Carney dijo que una "recesión técnica" era uno de los posibles riesgos de que el Reino Unido abandonara la UE. [213] Sin embargo, Iain Duncan Smith dijo que el comentario de Carney debería tomarse con "una pizca de sal", diciendo que "todos los pronósticos al final son incorrectos". [214]

En diciembre de 2015, el Banco de Inglaterra publicó un informe sobre el impacto de la inmigración en los salarios. El informe concluyó que la inmigración ejercía una presión a la baja sobre los salarios de los trabajadores, en particular de los trabajadores poco calificados: un aumento de 10 puntos porcentuales en la proporción de inmigrantes que trabajaban en servicios poco calificados hizo bajar los salarios promedio de los trabajadores poco calificados en aproximadamente un 2 por ciento. [215] El aumento de 10 puntos porcentuales citado en el documento es mayor que todo el aumento observado desde el período 2004-2006 en el sector de servicios semicalificados y no calificados, que es de aproximadamente 7 puntos porcentuales. [216]

En marzo de 2016, el economista ganador del premio Nobel Joseph Stiglitz argumentó que podría reconsiderar su apoyo a la permanencia del Reino Unido en la UE si se aprobaba la propuesta Asociación Transatlántica para el Comercio y la Inversión (TTIP). [217] Stiglitz advirtió que, en virtud de la disposición sobre solución de controversias entre inversores y Estados incluida en los borradores actuales de la TTIP, los gobiernos corrían el riesgo de ser demandados por pérdida de beneficios resultantes de nuevas regulaciones, incluidas las regulaciones de salud y seguridad para limitar el uso de amianto o tabaco. [217]

El economista alemán Clemens Fuest escribió que en la UE había un bloque liberal de libre comercio que comprendía al Reino Unido, los Países Bajos, la República Checa, Suecia, Dinamarca, Irlanda, Eslovaquia, Finlandia, Estonia, Letonia y Lituania, que controlaba el 32% de los votos en el Consejo Europeo y se oponía a las políticas dirigistas y proteccionistas favorecidas por Francia y sus aliados. [218] Alemania, con su economía de "mercado social", se encuentra a medio camino entre el modelo económico dirigista francés y el modelo económico británico de libre mercado. Desde el punto de vista alemán, la existencia del bloque liberal le permite a Alemania oponer a la Gran Bretaña de libre mercado contra la Francia dirigista , y que si Gran Bretaña se fuera, el bloque liberal se debilitaría severamente, lo que permitiría a los franceses llevar a la UE en una dirección mucho más dirigista que sería poco atractiva desde el punto de vista de Berlín. [218]

Un estudio de Oxford Economics para la Law Society of England and Wales ha sugerido que el Brexit tendría un impacto negativo particularmente grande en la industria de servicios financieros del Reino Unido y los bufetes de abogados que la apoyan, lo que podría costar al sector legal hasta £1.700 millones por año para 2030. [219] El propio informe de la Law Society sobre los posibles efectos del Brexit señala que abandonar la UE probablemente reduciría el papel desempeñado por el Reino Unido como centro para resolver disputas entre empresas extranjeras, mientras que una posible pérdida de derechos de "pasaporte" requeriría que las empresas de servicios financieros transfirieran departamentos responsables de la supervisión regulatoria al extranjero. [220]

El director del Foro Mundial de Pensiones , M. Nicolas J. Firzli, ha sostenido que el debate sobre el Brexit debería considerarse en el contexto más amplio del análisis económico de la legislación y la reglamentación de la UE en relación con el derecho consuetudinario inglés , argumentando: "Cada año, el Parlamento británico se ve obligado a aprobar decenas de nuevos estatutos que reflejan las últimas directivas de la UE procedentes de Bruselas, un proceso altamente antidemocrático conocido como ' transposición '... Lenta pero seguramente, estas nuevas leyes dictadas por los comisarios de la UE están conquistando el derecho consuetudinario inglés, imponiendo a las empresas y los ciudadanos del Reino Unido una colección cada vez mayor de regulaciones fastidiosas en todos los campos". [221]

Thiemo Fetzer, profesor de economía de la Universidad de Warwick , analizó las reformas del sistema de bienestar en el Reino Unido desde el año 2000 y sugiere que numerosas reformas inducidas por la austeridad a partir de 2010 han dejado de contribuir a mitigar las diferencias de ingresos a través de los pagos de transferencias. Esto podría ser un factor clave que active las preferencias anti-UE que están detrás del desarrollo de quejas económicas y la falta de apoyo en una victoria del Remain. [222]

Michael Jacobs, actual director de la Comisión de Justicia Económica del Instituto de Investigación de Políticas Públicas, y Mariana Mazzucato, profesora de Economía de la Innovación y Valor Público en el University College de Londres, han descubierto que la campaña del Brexit tendía a culpar a fuerzas externas de los problemas económicos internos y han argumentado que los problemas dentro de la economía no se debían a las "fuerzas imparables de la globalización", sino más bien al resultado de decisiones políticas y empresariales activas. En cambio, afirman que la teoría económica ortodoxa ha guiado una política económica deficiente, como la inversión, y que esa ha sido la causa de los problemas dentro de la economía británica. [223]

En mayo de 2016, el Instituto de Estudios Fiscales dijo que una salida de la UE podría significar dos años más de recortes de austeridad, ya que el gobierno tendría que compensar una pérdida estimada de entre 20.000 y 40.000 millones de libras esterlinas en ingresos fiscales. El director del IFS, Paul Johnson, dijo que el Reino Unido "podría decidir perfectamente razonablemente que estamos dispuestos a pagar un pequeño precio por abandonar la UE y recuperar cierta soberanía y control sobre la inmigración, etc., pero creo que ahora casi no cabe duda de que habría algún precio". [224]

Una encuesta de abogados realizada por una empresa de contratación legal a finales de mayo de 2016 sugirió que el 57% de los abogados querían permanecer en la UE. [225]

Durante una reunión del Comité del Tesoro celebrada poco después de la votación, los expertos económicos coincidieron en general en que el voto a favor de abandonar la UE sería perjudicial para la economía del Reino Unido. [226]

Michael Dougan , profesor de Derecho Europeo y titular de la Cátedra Jean Monnet de Derecho de la UE en la Universidad de Liverpool y abogado constitucionalista, describió la campaña a favor del Brexit como "una de las campañas políticas más deshonestas que este país [el Reino Unido] haya visto jamás", por utilizar argumentos basados en el derecho constitucional que, según él, eran fácilmente demostrables como falsos. [227]

En mayo de 2016, Simon Stevens, director del Servicio Nacional de Salud de Inglaterra, advirtió que una recesión tras el Brexit sería "muy peligrosa" para el Servicio Nacional de Salud, y dijo que "cuando la economía británica estornuda, el NHS se resfría". [228] Tres cuartas partes de una muestra de líderes del NHS estuvieron de acuerdo en que abandonar la UE tendría un efecto negativo en el NHS en su conjunto. En particular, ocho de cada diez encuestados consideraron que abandonar la UE tendría un impacto negativo en la capacidad de los fideicomisos para contratar personal sanitario y de asistencia social. [229] En abril de 2016, un grupo de casi 200 profesionales de la salud e investigadores advirtió que el NHS estaría en peligro si Gran Bretaña abandonara la Unión Europea. [230] La campaña a favor del Brexit reaccionó diciendo que habría más dinero disponible para gastar en el NHS si el Reino Unido abandonara la UE.

Según fuentes anónimas consultadas por The Lancet, las directrices de la Charity Commission for England and Wales que prohíben la actividad política a las organizaciones benéficas registradas han limitado los comentarios de las organizaciones sanitarias del Reino Unido sobre la encuesta de la UE. [231] Según Simon Wessely , jefe de medicina psicológica en el Instituto de Psiquiatría del King's College de Londres, ni una revisión especial de las directrices a partir del 7 de marzo de 2016 ni el estímulo de Cameron han hecho que las organizaciones sanitarias estén dispuestas a hablar. [231] La Genetic Alliance UK, el Royal College of Midwives , la Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry y el Director Ejecutivo del Servicio Nacional de Salud habían declarado posiciones a favor de la permanencia a principios de junio de 2016. [231]

Una encuesta realizada en junio de 2016 a pescadores británicos reveló que el 92 % tenía la intención de votar a favor de abandonar la UE. [232] La Política Pesquera Común de la UE fue mencionada como una razón central para su casi unanimidad. [232] Más de tres cuartas partes creían que podrían desembarcar más pescado, y el 93 % afirmó que abandonar la UE beneficiaría a la industria pesquera. [233]

En mayo de 2016, más de 300 historiadores escribieron en una carta conjunta a The Guardian que Gran Bretaña podría desempeñar un papel más importante en el mundo como parte de la UE. Dijeron: "Como historiadores de Gran Bretaña y de Europa, creemos que Gran Bretaña ha tenido en el pasado, y tendrá en el futuro, un papel irreemplazable que desempeñar en Europa". [234] Por otro lado, muchos historiadores argumentaron a favor de la salida, viéndola como un retorno a la soberanía propia. [235] [236]

Tras el anuncio de David Cameron de un referéndum sobre la salida de la UE, en julio de 2013 el Instituto de Asuntos Económicos (AIE) anunció el "Premio Brexit", un concurso para encontrar el mejor plan para la salida del Reino Unido de la Unión Europea, y declaró que una salida era una "posibilidad real" tras las elecciones generales de 2015. [237] Iain Mansfield, un graduado de Cambridge y diplomático del UKTI , presentó la tesis ganadora: Un plan para Gran Bretaña: apertura, no aislamiento . [238] La presentación de Mansfield se centró en abordar cuestiones comerciales y regulatorias con los estados miembros de la UE, así como con otros socios comerciales globales . [239] [240]

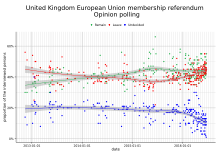

Las encuestas de opinión realizadas a partir de 2010 sugirieron que el público británico estaba dividido de manera relativamente uniforme sobre la cuestión, con la oposición a la pertenencia a la UE alcanzando su punto máximo en noviembre de 2012 con un 56% en comparación con un 30% que prefería permanecer en la UE, [241] mientras que en junio de 2015 los que estaban a favor de que Gran Bretaña permaneciera en la UE alcanzaron el 43% frente a los que se oponían al 36%. [242] La encuesta más grande jamás realizada (de 20.000 personas, en marzo de 2014) mostró que el público estaba dividido de manera uniforme sobre el tema, con un 41% a favor de la retirada, un 41% a favor de la pertenencia y un 18% indeciso. [243] Sin embargo, cuando se les preguntó cómo votarían si Gran Bretaña renegociara los términos de su pertenencia a la UE y el Gobierno del Reino Unido declarara que los intereses británicos habían sido protegidos satisfactoriamente, más del 50% indicó que votaría por la permanencia de Gran Bretaña. [244]

El análisis de las encuestas sugirió que los votantes jóvenes tendían a apoyar la permanencia en la UE, mientras que los mayores tienden a apoyar la salida, pero no había una división de género en las actitudes. [245] [246] En febrero de 2016, YouGov también encontró que el euroescepticismo se correlacionaba con las personas de menores ingresos y que "los estratos sociales más altos están más claramente a favor de permanecer en la UE", pero señaló que el euroescepticismo también tenía bastiones en "los condados más ricos y conservadores". [247] Escocia, Gales y muchas áreas urbanas inglesas con grandes poblaciones estudiantiles eran más pro-UE. [247] Las grandes empresas estaban ampliamente a favor de permanecer en la UE, aunque la situación entre las empresas más pequeñas era menos clara. [248] En las encuestas de economistas, abogados y científicos, claras mayorías vieron la membresía del Reino Unido en la UE como beneficiosa. [249] [250] [251] [252] [253] El día del referéndum, la casa de apuestas Ladbrokes ofrecía unas probabilidades de 6/1 en contra de que el Reino Unido abandonara la UE. [254] Mientras tanto, la empresa de apuestas Spreadex ofrecía un spread de porcentaje de votos a favor del Brexit de 45-46, un spread de porcentaje de votos a favor de la permanencia de 53,5-54,5 y un spread de índice binario de permanencia de 80-84,7, donde la victoria de la permanencia se compensaría con 100 y una derrota con 0. [255]

Poco después de que cerraran las urnas a las 22 horas del 23 de junio, la empresa británica de sondeos YouGov publicó una encuesta realizada entre casi 5.000 personas ese mismo día; en ella se sugería una estrecha ventaja para el "Remain", que obtuvo el 52% de los votos, frente al 48% para el "Leave". Más tarde fue criticada por sobrestimar el margen del voto "Remain", [256] cuando unas horas más tarde se hizo evidente que el Reino Unido había votado con un 51,9% frente a un 48,1% a favor de abandonar la Unión Europea.

El número de empleos perdidos o ganados por una salida fue un tema dominante; el esquema de cuestiones de la BBC advirtió que era difícil encontrar una cifra precisa. La campaña a favor del Brexit sostuvo que una reducción de la burocracia asociada con las regulaciones de la UE crearía más empleos y que las pequeñas y medianas empresas que comercian dentro del país serían las mayores beneficiarias. Quienes defendían permanecer en la UE afirmaban que se perderían millones de empleos. La importancia de la UE como socio comercial y el resultado de su estatus comercial si se fuera fue un tema controvertido. Mientras que quienes querían quedarse citaron que la mayor parte del comercio del Reino Unido se hacía con la UE, quienes defendían la salida dijeron que su comercio no era tan importante como solía ser. Los escenarios de las perspectivas económicas para el país si salía de la UE eran generalmente negativos. El Reino Unido también pagó más al presupuesto de la UE de lo que recibió. [257]

Los ciudadanos de los países de la UE, incluido el Reino Unido, tienen derecho a viajar, vivir y trabajar en otros países de la UE, ya que la libre circulación es uno de los cuatro principios fundadores de la UE. [258] Los activistas a favor de la permanencia dijeron que la inmigración de la UE tuvo impactos positivos en la economía del Reino Unido, citando que las previsiones de crecimiento del país se basaban en parte en los altos niveles continuos de inmigración neta. [257] La Oficina de Responsabilidad Presupuestaria también afirmó que los impuestos de los inmigrantes impulsan la financiación pública. [257] Un reciente [ ¿cuándo? ] artículo académico sugiere que la migración desde Europa del Este ejerce presión sobre el crecimiento salarial en el extremo inferior de la distribución salarial, al mismo tiempo que aumenta las presiones sobre los servicios públicos y la vivienda. [259] La campaña a favor del Brexit creía que una inmigración reducida aliviaría la presión en los servicios públicos como las escuelas y los hospitales, además de dar a los trabajadores británicos más puestos de trabajo y salarios más altos. [257] Según datos oficiales de la Oficina de Estadísticas Nacionales , la migración neta en 2015 fue de 333.000, el segundo nivel más alto registrado, muy por encima del objetivo de David Cameron de decenas de miles. [260] [261] La migración neta desde la UE fue de 184.000. [261] Las cifras también mostraron que 77.000 inmigrantes de la UE que llegaron a Gran Bretaña estaban buscando trabajo. [260] [261]

Después de que se anunció el resultado del referéndum, Rowena Mason, corresponsal política de The Guardian, ofreció la siguiente evaluación: "Las encuestas sugieren que el descontento con la escala de la migración al Reino Unido ha sido el principal factor que ha empujado a los británicos a votar en contra, y la contienda se ha convertido en un referéndum sobre si la gente está dispuesta a aceptar la libre circulación a cambio del libre comercio". [262] Un columnista de The Times , Philip Collins , fue un paso más allá en su análisis: "Este fue un referéndum sobre la inmigración disfrazado de referéndum sobre la Unión Europea". [263]

El eurodiputado conservador ( miembro del Parlamento Europeo ) que representa al sureste de Inglaterra, Daniel Hannan , predijo en el programa Newsnight de la BBC que el nivel de inmigración se mantendría alto después del Brexit. [264] "Francamente, si la gente que está viendo la votación piensa que ya ha votado y que ahora no habrá inmigración de la UE, se sentirá decepcionada... buscarán en vano cualquier cosa que la campaña del Brexit haya dicho en algún momento que sugiera que alguna vez habrá algún tipo de cierre de fronteras o de levantamiento del puente levadizo". [265]

La UE había ofrecido a David Cameron un llamado "freno de emergencia" que habría permitido al Reino Unido retener los beneficios sociales a los nuevos inmigrantes durante los primeros cuatro años después de su llegada; este freno podría haberse aplicado por un período de siete años". [266] Esa oferta todavía estaba sobre la mesa en el momento del referéndum del Brexit, pero expiró cuando la votación determinó que el Reino Unido abandonaría la UE. [267]

La posibilidad de que los países constituyentes más pequeños del Reino Unido pudieran votar por permanecer dentro de la UE pero encontrarse retirados de la UE condujo a un debate sobre el riesgo para la unidad del Reino Unido. [268] La Primera Ministra de Escocia, Nicola Sturgeon , dejó en claro que creía que los escoceses "casi con toda seguridad" exigirían un segundo referéndum de independencia si el Reino Unido votaba por abandonar la UE pero Escocia no lo hacía. [269] El Primer Ministro de Gales , Carwyn Jones , dijo: "Si Gales vota por permanecer en [la UE] pero el Reino Unido vota por salir, habrá una... crisis constitucional. El Reino Unido no puede continuar en su forma actual si Inglaterra vota por salir y todos los demás votan por quedarse". [270]

Existía la preocupación de que la Asociación Transatlántica de Comercio e Inversión (TTIP), un acuerdo comercial propuesto entre los Estados Unidos y la UE, sería una amenaza para los servicios públicos de los estados miembros de la UE. [271] [272] [273] [274] Jeremy Corbyn , del lado de los partidarios de permanecer en la UE, dijo que se comprometió a vetar el TTIP en el Gobierno. [275] John Mills , del lado de los partidarios de abandonar la UE, dijo que el Reino Unido no podía vetar el TTIP porque los pactos comerciales se decidían por votación por mayoría cualificada en el Consejo Europeo . [276]

Se debatió hasta qué punto la pertenencia a la Unión Europea contribuía a la seguridad y la defensa en comparación con la pertenencia del Reino Unido a la OTAN y a las Naciones Unidas. [277] También se plantearon preocupaciones en materia de seguridad sobre la política de libre circulación de la unión, porque era poco probable que las personas con pasaportes de la UE recibieran controles detallados en los controles fronterizos. [278]

El 15 de marzo de 2016, The Guardian celebró un debate en el que participaron el líder del UKIP, Nigel Farage , la diputada conservadora Andrea Leadsom , el líder de la campaña del "sí" del Partido Laborista, Alan Johnson, y el exlíder de los Demócratas Liberales, Nick Clegg . [279]

A principios de la campaña, el 11 de enero, tuvo lugar un debate entre Nigel Farage y Carwyn Jones , que en ese momento era el Primer Ministro de Gales y líder del Partido Laborista galés . [280] [281] La renuencia a que los miembros del Partido Conservador discutan entre sí ha provocado que algunos debates se dividan, y los candidatos a favor y en contra del Brexit sean entrevistados por separado. [282]

El Spectator celebró un debate presentado por Andrew Neil el 26 de abril, en el que participaron Nick Clegg , Liz Kendall y Chuka Umunna defendiendo el voto a favor de permanecer en la UE, y Nigel Farage , Daniel Hannan y la parlamentaria laborista Kate Hoey defendiendo el voto a favor de abandonar la UE. [283] El Daily Express celebró un debate el 3 de junio, en el que participaron Nigel Farage , Kate Hoey y el parlamentario conservador Jacob Rees-Mogg debatiendo con los parlamentarios laboristas Siobhain McDonagh y Chuka Umunna y el empresario Richard Reed , cofundador de Innocent Drinks . [284] Andrew Neil presentó cuatro entrevistas antes del referéndum. Los entrevistados fueron Hilary Benn , George Osborne , Nigel Farage e Iain Duncan Smith los días 6, 8, 10 y 17 de mayo, respectivamente, en BBC One . [285]

Los debates y sesiones de preguntas programados incluyeron una serie de sesiones de preguntas y respuestas con varios activistas. [286] [287] y un debate en ITV celebrado el 9 de junio en el que participaron Angela Eagle , Amber Rudd y Nicola Sturgeon a favor de permanecer en la UE, Boris Johnson , Andrea Leadsom y Gisela Stuart a favor de salir. [288]

El referéndum de la UE: el gran debate se celebró en el Wembley Arena el 21 de junio y fue presentado por David Dimbleby , Mishal Husain y Emily Maitlis frente a una audiencia de 6.000 personas. [289] La audiencia se dividió de manera uniforme entre ambos lados. Sadiq Khan , Ruth Davidson y Frances O'Grady estuvieron a favor de la permanencia. El Brexit estuvo representado por el mismo trío que en el debate de ITV del 9 de junio (Johnson, Leadsom y Stuart). [290] Europa: el debate final con Jeremy Paxman se celebró al día siguiente en el Canal 4. [ 291]

.jpg/440px-Brexit_(27240041144).jpg)

La votación tuvo lugar desde las 07:00 BST (hora del oeste) hasta las 22:00 BST (las mismas horas CEST en Gibraltar) en 41.000 colegios electorales repartidos en 382 áreas de votación, y cada colegio electoral tenía un límite de 2.500 votantes como máximo. [292] El referéndum se celebró en los cuatro países del Reino Unido, así como en Gibraltar, como una votación por mayoría simple. Las 382 áreas de votación se agruparon en doce recuentos regionales y hubo declaraciones separadas para cada uno de los recuentos regionales.

En Inglaterra, como sucedió en el referéndum sobre el AV de 2011 , los 326 distritos se utilizaron como áreas de votación locales y los resultados de estos se incorporaron a nueve recuentos regionales ingleses . En Escocia, las áreas de votación locales fueron los 32 consejos locales que luego incorporaron sus resultados al recuento nacional escocés, y en Gales, los 22 consejos locales fueron sus áreas de votación locales antes de que los resultados se incorporaran al recuento nacional galés. Irlanda del Norte, como fue el caso en el referéndum sobre el AV, fue un área de votación única y de recuento nacional, aunque se anunciaron los totales locales por áreas de circunscripción parlamentaria de Westminster.

Gibraltar era una zona de votación única, pero como Gibraltar debía ser tratado e incluido como si fuera parte del suroeste de Inglaterra, sus resultados se incluyeron junto con el recuento regional del suroeste de Inglaterra. [292]

La siguiente tabla muestra el desglose de las zonas de votación y los recuentos regionales que se utilizaron para el referéndum. [292]

British expat Harry Shindler, a World War II veteran living in Italy, took legal action as the UK does not permit citizens residing abroad who have not lived in the UK for over 15 years to vote in elections. Shindler believed this prohibition violated his rights as he wished to vote in the referendum.[293] He had previously raised a case in 2009 (Shindler v. the United Kingdom 19840/09) regarding his rights to vote in UK general elections that the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) deemed did not violate his rights.[294]

Shindler first sued the UK government before the referendum, claiming that his disenfranchisement was a penalty against UK citizens who live abroad, exercising their EU right of free movement, thus violating his right as an EU citizen. This 15-year prohibition on voting, Shindler argued, discourages British citizens from continuing to exercise their free movement rights as they are required to return to the UK to vote in the EU referendum.[295]

The High Court, on 20 April 2016, rejected Shindler’s claims, saying that it is "totally unrealistic" that the 15-year prohibition would deter citizens from settling in another Member State. The court also found that "significant practical difficulties" in allowing residents abroad for more than 15 years to vote permits the government to enact this restriction.[295]

Further, the High Court found that this prohibition, even if it did violate EU rights, is a parliamentary prerogative as "Parliament could legitimately take the view that electors who satisfy the test of closeness of connection set by the 15 year rule form an appropriate group to vote on the question whether the United Kingdom should remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union."[295]

After the referendum, Shindler brought a case against the Council of the EU in the General Court. He argued that the Council's decision (Decision XT 21016/17) to recognize the referendum was illegal as his disenfranchisement invalidated the referendum.[296] Shindler argued that the decision lacked “definite constitutional authorization based on the votes of all UK citizens” as not all citizens were permitted to vote. He claims the Council should have "sought judicial review of the constitutionality of the notification of the intention to withdraw” because depriving UK citizens to vote in the referendum is contrary to EU law. Shindler claimed that “the Council should have refused or stayed the opening of negotiations” between the EU and the UK.[297]

In November 2018, however, the court found Shindler's arguments unconvincing as the decision to recognize the referendum did not "directly affect the legal situation of the applicants." The Council's action merely recognized and began the withdrawal procedures and did not violate Shinder's rights.[297]

On 16 June 2016, a pro-EU Labour MP, Jo Cox, was shot and killed in Birstall, West Yorkshire the week before the referendum by a man calling out "death to traitors, freedom for Britain", and a man who intervened was injured.[298] The two rival official campaigns agreed to suspend their activities as a mark of respect to Cox.[81] After the referendum, evidence emerged that Leave.EU had continued to put out advertising the day after Jo Cox's murder.[299][300] David Cameron cancelled a planned rally in Gibraltar supporting British EU membership.[301] Campaigning resumed on 19 June.[302][303] Polling officials in the Yorkshire and Humber region also halted counting of the referendum ballots on the evening of 23 June to observe a minute of silence.[304] The Conservative Party, Liberal Democrats, UK Independence Party and the Green Party all announced that they would not contest the ensuing by-election in Cox's constituency as a mark of respect.[305]

On polling day itself two polling stations in Kingston upon Thames were flooded by rain and had to be relocated.[306] In advance of polling day, concern had been expressed that the courtesy pencils provided in polling booths could allow votes to be later altered. Although this was widely dismissed as a conspiracy theory (see: Voting pencil conspiracy theory), some Leave campaigners advocated that voters should instead use pens to mark their ballot papers. On polling day in Winchester an emergency call was made to police about "threatening behaviour" outside the polling station. After questioning a woman who had been offering to lend her pen to voters, the police decided that no offence was being committed.[307]

The final result was announced on Friday 24 June 2016 at 07:20 BST by then-Electoral Commission Chairwoman Jenny Watson at Manchester Town Hall after all 382 voting areas and the twelve UK regions had declared their totals. With a national turnout of 72% across the United Kingdom and Gibraltar (representing 33,577,342 people), at least 16,788,672 votes were required to win a majority. The electorate voted to "Leave the European Union", with a majority of 1,269,501 votes (3.8%) over those who voted "Remain a member of the European Union".[308] The national turnout of 72% was the highest ever for a UK-wide referendum, and the highest for any national vote since the 1992 general election.[309][310][311][312] Roughly 38% of the UK population voted to leave the EU and roughly 35% voted to remain.[313]

Voting figures from local referendum counts and ward-level data (using local demographic information collected in the 2011 census) suggests that Leave votes were strongly correlated with lower qualifications and higher age.[315][316][317][318] The data were obtained from about one in nine wards in England and Wales, with very little information from Scotland and none from Northern Ireland.[315] A YouGov survey reported similar findings; these are summarised in the charts below.[319][320]

Researchers based at the University of Warwick found that areas with "deprivation in terms of education, income and employment were more likely to vote Leave". The Leave vote tended to be greater in areas which had lower incomes and high unemployment, a strong tradition of manufacturing employment, and in which the population had fewer qualifications.[321] It also tended to be greater where there was a large flow of Eastern European migrants (mainly low-skilled workers) into areas with a large share of native low-skilled workers.[321] Those in lower social grades (especially the 'working class') were more likely to vote Leave, while those in higher social grades (especially the 'upper middle class') were more likely to vote Remain.[322]

Polls by Ipsos MORI, YouGov and Lord Ashcroft all assert that 70–75% of under 25s voted 'remain'.[323] Additionally according to YouGov, only 54% of 25- to 49-year-olds voted 'remain', whilst 60% of 50- to 64-year-olds and 64% of over-65s voted 'leave', meaning that the support for 'remain' was not as strong outside the youngest demographic.[324] Also, YouGov found that around 87% of under-25s in 2018 would now vote to stay in the EU.[325] Opinion polling by Lord Ashcroft Polls found that Leave voters believed leaving the EU was "more likely to bring about a better immigration system, improved border controls, a fairer welfare system, better quality of life, and the ability to control our own laws", while Remain voters believed EU membership "would be better for the economy, international investment, and the UK's influence in the world".[326] Immigration is thought to be a particular worry for older people that voted Leave, who consider it a potential threat to national identity and culture.[327] The polling found that the main reasons people had voted Leave were "the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK", and that leaving "offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders". The main reason people voted Remain was that "the risks of voting to leave the EU looked too great when it came to things like the economy, jobs and prices".[326]

One analysis suggests that in contrast to the general correlation between age and likelihood of having voted to leave the EU, those who experienced the majority of their formative period (between the ages of 15 and 25) during the Second World War are more likely to oppose Brexit than the rest of the over-65 age group,[failed verification] for they are more likely to associate the EU with bringing peace.[328]