La era de la Reconstrucción fue un período en la historia de los Estados Unidos y de la historia del sur de los Estados Unidos que siguió a la Guerra Civil estadounidense y estuvo dominada por los desafíos legales, sociales y políticos de la abolición de la esclavitud y la reintegración de los once antiguos Estados Confederados de América a los Estados Unidos. Durante este período, se añadieron tres enmiendas a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos para otorgar ciudadanía e igualdad de derechos civiles a los esclavos recién liberados . Para eludir estos logros legales, los antiguos estados confederados impusieron impuestos electorales y pruebas de alfabetización y recurrieron al terrorismo para intimidar y controlar a las personas de color y disuadirlas o impedirles votar. [2]

Durante toda la guerra, la Unión se enfrentó al problema de cómo administrar las áreas que capturaba y cómo manejar el flujo constante de esclavos que escapaban hacia las líneas de la Unión. En muchos casos, el Ejército de los Estados Unidos desempeñó un papel vital en el establecimiento de una economía de trabajo libre en el Sur, protegiendo los derechos legales de los libertos y creando instituciones educativas y religiosas. A pesar de su renuencia a interferir con la institución de la esclavitud, el Congreso aprobó las Leyes de Confiscación para apoderarse de los esclavos de los confederados, proporcionando un precedente para que el presidente Abraham Lincoln emitiera la Proclamación de Emancipación . Posteriormente, el Congreso estableció una Oficina de Libertos para proporcionar alimentos y refugio muy necesarios a los esclavos recién liberados.

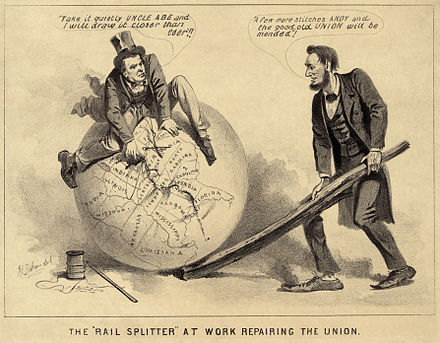

Cuando se hizo evidente que la guerra terminaría con una victoria de la Unión, el Congreso debatió el proceso de readmisión de los estados secesionistas. Los republicanos radicales y moderados discreparon sobre la naturaleza de la secesión, las condiciones para la readmisión y la conveniencia de reformas sociales como consecuencia de la derrota confederada. Lincoln favoreció el " plan del diez por ciento " y vetó el proyecto de ley radical Wade-Davis , que proponía condiciones estrictas para la readmisión.

Lincoln fue asesinado el 14 de abril de 1865, justo cuando la lucha estaba llegando a su fin . Fue reemplazado por el presidente Andrew Johnson . Johnson vetó numerosos proyectos de ley republicanos radicales , indultó a miles de líderes confederados y permitió que los estados del Sur aprobaran códigos negros draconianos que restringían los derechos de los libertos. Sus acciones indignaron a muchos norteños y avivaron los temores de que la élite sureña recuperara su poder político. Los candidatos republicanos radicales llegaron al poder en las elecciones de mitad de período de 1866, obteniendo grandes mayorías en ambas cámaras del Congreso .

En 1867 y 1868, los republicanos radicales aprobaron las Leyes de Reconstrucción a pesar de los vetos de Johnson, estableciendo los términos por los cuales los antiguos estados confederados podían ser readmitidos en la Unión. Las convenciones constitucionales celebradas en todo el Sur dieron a los hombres negros el derecho a votar. Se establecieron nuevos gobiernos estatales por una coalición de libertos, sureños blancos solidarios y trasplantados del Norte . Se les opusieron los " redentores ", que buscaban restaurar la supremacía blanca y restablecer el control del Partido Demócrata de los gobiernos y la sociedad del Sur. Grupos violentos, incluido el Ku Klux Klan , la Liga Blanca y los Camisas Rojas , participaron en la insurgencia paramilitar y el terrorismo para interrumpir los esfuerzos de los gobiernos de la Reconstrucción y aterrorizar a los republicanos. [3] La ira del Congreso por los repetidos intentos del presidente Johnson de vetar la legislación radical condujo a su impeachment , pero no fue destituido de su cargo.

Bajo el sucesor de Johnson, el presidente Ulysses S. Grant , los republicanos radicales aprobaron leyes adicionales para hacer cumplir los derechos civiles, como la Ley del Ku Klux Klan y la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1875. Sin embargo, la continua resistencia a la Reconstrucción por parte de los blancos sureños y su alto costo contribuyeron a que perdiera apoyo en el Norte durante la administración de Grant. La elección presidencial de 1876 estuvo marcada por una supresión generalizada del voto negro en el Sur, y el resultado fue ajustado y disputado. Una Comisión Electoral dio como resultado el Compromiso de 1877 , que otorgó la elección al republicano Rutherford B. Hayes con el entendimiento de que las tropas federales se retirarían del Sur, poniendo fin de manera efectiva a la Reconstrucción. Los esfuerzos posteriores a la Guerra Civil para hacer cumplir las protecciones federales de los derechos civiles en el Sur terminaron en 1890 con el fracaso de la Ley Lodge .

Los historiadores siguen discrepando sobre el legado de la Reconstrucción. Las críticas a la misma se centran en el fracaso inicial en la prevención de la violencia, la corrupción, el hambre, las enfermedades y otros problemas. Algunos consideran que la política de la Unión hacia los esclavos liberados es inadecuada y su política hacia los antiguos propietarios de esclavos es demasiado indulgente. [4] Sin embargo, se atribuye a la Reconstrucción la restauración de la Unión federal, la limitación de las represalias contra el Sur y el establecimiento de un marco legal para la igualdad racial a través de los derechos constitucionales a la ciudadanía por nacimiento , el debido proceso , la igualdad de protección de las leyes y el sufragio masculino independientemente de la raza. [5]

La era de la Reconstrucción se fecha típicamente desde la Proclamación de Emancipación en 1863 hasta la retirada de las últimas tropas federales estacionadas en el Sur en 1877. [6] [7] Sin embargo, los historiadores han propuesto diferentes fechas de inicio y fin para la era de la Reconstrucción, y el período exacto de la Reconstrucción puede variar dependiendo del estado o del tema. [ cita requerida ]

En el siglo XX, la mayoría de los estudiosos de la era de la Reconstrucción comenzaron su revisión en 1865, con el fin de las hostilidades formales entre el Norte y el Sur. Sin embargo, en su monografía emblemática Reconstruction , el historiador Eric Foner propuso 1863, comenzando con la Proclamación de la Emancipación , el Experimento de Port Royal y el serio debate sobre las políticas de Reconstrucción durante la Guerra Civil. [8] [9] Muchos historiadores [¿ quiénes? ] ahora siguen esta periodización de 1863. [7]

El Parque Histórico Nacional de la Era de la Reconstrucción propuso 1861 como fecha de inicio, interpretando la Reconstrucción como el comienzo "tan pronto como la Unión capturó territorio en la Confederación" en Fort Monroe en Virginia y en las Islas del Mar de Carolina del Sur . Según los historiadores Downs y Masur, "la Reconstrucción comenzó cuando los primeros soldados estadounidenses llegaron al territorio esclavista y las personas esclavizadas escaparon de las plantaciones y granjas, algunas de ellas huyendo a estados libres y otras tratando de encontrar seguridad con las fuerzas estadounidenses". Poco después, comenzaron los primeros discursos y experimentos en serio con respecto a las políticas de Reconstrucción. Las políticas de Reconstrucción brindaron oportunidades a las poblaciones esclavizadas Gullah en las Islas del Mar que se liberaron de la noche a la mañana el 7 de noviembre de 1861, después de la Batalla de Port Royal , cuando todos los residentes blancos y los propietarios de esclavos huyeron del área después de la llegada de la Unión. Después de la Batalla de Port Royal, se implementaron políticas de reconstrucción bajo el Experimento de Port Royal que fueron la educación , la propiedad de la tierra y la reforma laboral. Esta transición a una sociedad libre se llamó "Ensayo para la Reconstrucción". [10] [11] [12] [13]

El final convencional de la Reconstrucción es 1877, cuando el gobierno federal retiró las últimas tropas estacionadas en el Sur como parte del Compromiso de 1877. [7] Sin embargo, algunos académicos [¿ quiénes? ] ofrecen fechas posteriores, como 1890, cuando los republicanos no lograron aprobar el Proyecto de Ley Lodge para asegurar los derechos de voto en el Sur. [13]

En la Guerra Civil estadounidense , once estados del Sur, todos los cuales permitían la esclavitud , se separaron de los Estados Unidos después de la elección del presidente Abraham Lincoln y formaron los Estados Confederados de América . Aunque Lincoln inicialmente declaró que la secesión era "legalmente nula" [14] y se negó a negociar con los delegados confederados en Washington, después del asalto confederado a la guarnición de la Unión en Fort Sumter , Lincoln declaró que existía "una ocasión extraordinaria" en el Sur y levantó un ejército para sofocar "combinaciones demasiado poderosas para ser suprimidas por el curso ordinario de los procedimientos judiciales". [15] Durante los siguientes cuatro años, se libraron 237 batallas con nombre entre los ejércitos de la Unión y la Confederación, lo que resultó en la disolución de los Estados Confederados en 1865. Durante la guerra, Lincoln emitió la Proclamación de Emancipación, que declaraba que "todas las personas mantenidas como esclavas" dentro del territorio confederado "son, y de ahora en adelante serán libres". [16]

La Guerra Civil tuvo inmensas implicaciones sociales para los Estados Unidos. La emancipación había alterado el estatus legal de 3,5 millones de personas, amenazaba con el fin de la economía de plantación del Sur y suscitaba preguntas sobre la desigualdad legal y social de las razas en los Estados Unidos. El fin de la guerra estuvo acompañado de una gran migración de personas recién liberadas a las ciudades, [17] donde fueron relegadas a los trabajos peor pagados, como el trabajo no calificado y el de servicios. Los hombres trabajaban como trabajadores ferroviarios, trabajadores de laminadores y aserraderos y trabajadores de hoteles. Las mujeres negras se limitaban en gran medida al trabajo doméstico, empleadas como cocineras, mucamas y niñeras, o en hoteles y lavanderías. La gran población de artesanos esclavos durante el período anterior a la guerra no se tradujo en un gran número de artesanos libres durante la Reconstrucción. [18] Los desplazamientos tuvieron un impacto negativo severo en la población negra, con una gran cantidad de enfermedades y muertes. [19]

Durante la guerra, Lincoln experimentó con la reforma agraria al otorgar tierras a los afroamericanos en Carolina del Sur . Habiendo perdido su enorme inversión en esclavos, los dueños de las plantaciones tenían un capital mínimo para pagar a los trabajadores libertos para que trajeran las cosechas. Como resultado, se desarrolló un sistema de aparcería , en el que los terratenientes dividían grandes plantaciones y alquilaban pequeñas parcelas a los libertos y sus familias. De este modo, la estructura principal de la economía sureña cambió de una minoría de élite de aristócratas terratenientes a un sistema de agricultura de arrendatarios . [20]

El historiador David W. Blight identificó tres visiones de las implicaciones sociales de la Reconstrucción: [21] [ página necesaria ]

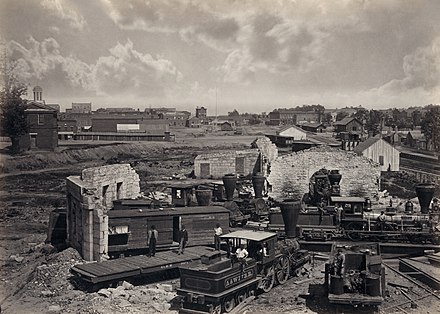

La Guerra Civil tuvo un impacto económico y material devastador en el Sur, donde ocurrió la mayoría de los combates.

El enorme costo de la guerra confederada tuvo un alto costo para la infraestructura económica de la región. Los costos directos en capital humano , gastos gubernamentales y destrucción física totalizaron 3.300 millones de dólares. A principios de 1865, el dólar confederado tenía un valor casi nulo y el sistema bancario del Sur estaba en colapso al final de la guerra. En los lugares donde no se podían obtener los escasos dólares de la Unión, los residentes recurrían a un sistema de trueque . [20]

En 1861, los Estados Confederados contaban con 297 pueblos y ciudades, con una población total de 835.000 habitantes; de ellos, 162, con 681.000 habitantes, estuvieron ocupados en algún momento por las fuerzas de la Unión. Once ciudades fueron destruidas o gravemente dañadas por la acción militar, entre ellas Atlanta, Charleston, Columbia y Richmond, aunque la tasa de daños en los pueblos más pequeños fue mucho menor. [22] Las granjas estaban en mal estado y el ganado, las mulas y los caballos que había antes de la guerra se habían agotado. El cuarenta por ciento del ganado del Sur había muerto. [23] Las granjas del Sur no estaban muy mecanizadas, pero el valor de los aperos y la maquinaria agrícola, según el censo de 1860, era de 81 millones de dólares y se había reducido en un 40% en 1870. [24] La infraestructura de transporte estaba en ruinas y había pocos servicios de ferrocarril o barco fluvial disponibles para trasladar los cultivos y los animales al mercado. [25] La mayor parte de las líneas ferroviarias se encontraban en zonas rurales; más de dos tercios de los rieles, puentes, patios ferroviarios, talleres de reparación y material rodante del Sur se encontraban en áreas alcanzadas por los ejércitos de la Unión, que destruyeron sistemáticamente todo lo que pudieron. Incluso en áreas vírgenes, la falta de mantenimiento y reparación, la ausencia de nuevos equipos, el uso excesivo y la reubicación deliberada de equipos por parte de los confederados desde áreas remotas a la zona de guerra aseguraron que el sistema se arruinaría al final de la guerra. [22] Restaurar la infraestructura, especialmente el sistema ferroviario, se convirtió en una alta prioridad para los gobiernos estatales de la Reconstrucción. [26]

Más de una cuarta parte de los hombres blancos sureños en edad militar (la columna vertebral de la fuerza laboral blanca) murieron durante la guerra, dejando a sus familias en la indigencia [23] y el ingreso per cápita de los sureños blancos disminuyó de $125 en 1857 a un mínimo de $80 en 1879. A fines del siglo XIX y hasta bien entrado el siglo XX, el Sur estaba atrapado en un sistema de pobreza. En qué medida este fracaso fue causado por la guerra y por la dependencia previa de la esclavitud sigue siendo tema de debate entre economistas e historiadores [27] . Tanto en el Norte como en el Sur, la modernización y la industrialización fueron el foco de la recuperación de posguerra, basada en el crecimiento de las ciudades, los ferrocarriles, las fábricas y los bancos y liderada por republicanos radicales y ex whigs [28] [29]

.jpg/440px-Wealth,_per_capita,_in_the_United_States,_from_9th_US_Census_(1872).jpg)

Desde sus orígenes, existieron dudas sobre la importancia legal de la Guerra Civil, si la secesión había ocurrido realmente y qué medidas, si las hubiera, eran necesarias para restaurar los gobiernos de los Estados Confederados. Por ejemplo, durante todo el conflicto, el gobierno de los Estados Unidos reconoció la legitimidad de un gobierno unionista en Virginia dirigido por Francis Harrison Pierpont desde Wheeling . (Este reconocimiento se volvió discutible cuando el gobierno de Pierpont separó los condados del noroeste del estado y solicitó la admisión como Virginia Occidental .) A medida que más territorios quedaron bajo el control de la Unión, se establecieron gobiernos reconstruidos en Tennessee, Arkansas y Luisiana. Los debates sobre la reconstrucción legal se centraron en si la secesión era legalmente válida, las implicaciones de la secesión para la naturaleza de los estados secesionistas y el método legítimo de su readmisión a la Unión. [ cita requerida ]

El primer plan de reconstrucción legal fue presentado por Lincoln en su Proclamación de Amnistía y Reconstrucción, el llamado " plan del diez por ciento ", según el cual se establecería un gobierno estatal unionista leal cuando el diez por ciento de sus votantes de 1860 juraran lealtad a la Unión, con un perdón completo para aquellos que prometieran tal juramento. En 1864, Luisiana, Tennessee y Arkansas habían establecido gobiernos unionistas en pleno funcionamiento bajo este plan. Sin embargo, el Congreso aprobó la Ley Wade-Davis en oposición, que en su lugar proponía que una mayoría de votantes debía jurar que nunca había apoyado al gobierno confederado y privaba del derecho al voto a todos los que lo habían hecho. Lincoln vetó la Ley Wade-Davis, pero estableció un conflicto duradero entre las visiones presidencial y del Congreso de la reconstrucción. [30] [31] [32]

Además del estatus legal de los estados secesionistas, el Congreso debatió las consecuencias legales para los veteranos confederados y otros que habían participado en "insurrecciones y rebeliones" contra el gobierno y los derechos legales de aquellos liberados de la esclavitud. Estos debates dieron como resultado las Enmiendas de Reconstrucción a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos. [ cita requerida ]

Durante la Guerra Civil, los líderes republicanos radicales argumentaron que la esclavitud y el poder esclavista debían ser destruidos de manera permanente. Los moderados dijeron que esto podría lograrse fácilmente tan pronto como el Ejército de los Estados Confederados se rindiera y los estados del Sur derogaran la secesión y aceptaran la Decimotercera Enmienda , lo cual ocurrió en su mayor parte en diciembre de 1865. [34]

Lincoln rompió con los radicales en 1864. La ley Wade-Davis de 1864 aprobada en el Congreso por los radicales fue diseñada para privar permanentemente de sus derechos al elemento confederado en el Sur. La ley pedía al gobierno que otorgara a los hombres afroamericanos el derecho a votar y que se le negara el derecho a votar a cualquiera que voluntariamente entregara armas para la lucha contra los Estados Unidos. La ley requería que los votantes, el cincuenta y uno por ciento de los varones blancos, hicieran el juramento de hierro en el que juraran que nunca habían apoyado a la Confederación ni habían sido uno de sus soldados. Este juramento también implicaba que juraran lealtad a la Constitución y a la Unión antes de poder tener reuniones constitucionales estatales. Lincoln lo bloqueó. Siguiendo una política de "malicia hacia nadie" anunciada en su segundo discurso inaugural, [35] Lincoln pidió a los votantes que solo apoyaran a la Unión en el futuro, independientemente del pasado. [31] Lincoln vetó de bolsillo la ley Wade-Davis, que era mucho más estricta que el plan del diez por ciento.

Tras el veto de Lincoln, los radicales perdieron apoyo pero recuperaron fuerza después del asesinato de Lincoln en abril de 1865. [ cita requerida ]

Tras el asesinato del presidente Lincoln en abril de 1865, el vicepresidente Andrew Johnson se convirtió en presidente. Los radicales consideraban a Johnson un aliado, pero al convertirse en presidente rechazó el programa radical de reconstrucción. Mantenía buenas relaciones con los ex confederados del sur y los ex Copperheads del norte. Designó a sus propios gobernadores e intentó cerrar el proceso de reconstrucción a fines de 1865. Thaddeus Stevens se opuso vehementemente a los planes de Johnson de poner fin abruptamente a la reconstrucción, insistiendo en que ésta debía "revolucionar las instituciones, los hábitos y las costumbres del sur... Los cimientos de sus instituciones... deben ser destruidos y reconstruidos, o toda nuestra sangre y nuestro tesoro se habrán gastado en vano". [36] Johnson rompió decisivamente con los republicanos en el Congreso cuando vetó la Ley de Derechos Civiles el 27 de marzo de 1866. Mientras los demócratas celebraban, los republicanos se unieron, aprobaron nuevamente el proyecto de ley y anularon el veto repetido de Johnson. [37] Ahora existía una guerra política a gran escala entre Johnson (ahora aliado con los demócratas) y los republicanos radicales. [38] [39]

Como la guerra había terminado, el Congreso rechazó el argumento de Johnson de que tenía el poder de guerra para decidir qué hacer. El Congreso decidió que tenía la autoridad primaria para decidir cómo debía proceder la Reconstrucción, porque la Constitución establecía que Estados Unidos tenía que garantizar a cada estado una forma republicana de gobierno . Los radicales insistieron en que eso significaba que el Congreso decidía cómo debía lograrse la Reconstrucción. Las cuestiones eran múltiples: ¿Quién debía decidir, el Congreso o el presidente? ¿Cómo debía operar el republicanismo en el Sur? ¿Cuál era el estatus de los antiguos estados confederados? ¿Cuál era el estatus de ciudadanía de los líderes de la Confederación? ¿Cuál era el estatus de ciudadanía y sufragio de los libertos? [40]

Después de terminar la guerra, el presidente Andrew Johnson devolvió la mayor parte de las tierras a los antiguos propietarios de esclavos blancos. [ cita requerida ]

En 1866, la facción de republicanos radicales liderada por el representante Thaddeus Stevens y el senador Charles Sumner estaba convencida de que los designados sureños de Johnson eran desleales a la Unión, hostiles a los unionistas leales y enemigos de los libertos. Los radicales utilizaron como prueba los brotes de violencia de las turbas contra los negros, como los disturbios de Memphis de 1866 y la masacre de Nueva Orleans de 1866. Los republicanos radicales exigieron una respuesta federal rápida y contundente para proteger a los libertos y frenar el racismo sureño. [41]

Stevens y sus seguidores consideraron que la secesión había dejado a los estados en un estatus similar al de los nuevos territorios. Sumner argumentó que la secesión había destruido la condición de estado, pero que la Constitución aún extendía su autoridad y su protección sobre los individuos, como en los territorios estadounidenses existentes . Los republicanos intentaron evitar que los políticos sureños de Johnson "restauraran la subordinación histórica de los negros". Dado que se abolió la esclavitud, el Compromiso de los Tres Quintos ya no se aplicaba al recuento de la población de negros. Después del censo de 1870, el Sur obtendría numerosos representantes adicionales en el Congreso, en base a la población total de libertos. [i] Un republicano de Illinois expresó un temor común de que si se permitía al Sur simplemente restaurar sus poderes establecidos previamente, la "recompensa de la traición sería una mayor representación". [42] [43] [ página necesaria ]

Las elecciones de 1866 cambiaron decisivamente el equilibrio de poder, dando a los republicanos mayorías de dos tercios en ambas cámaras del Congreso y votos suficientes para superar los vetos de Johnson. Decidieron enjuiciar a Johnson debido a sus constantes intentos de frustrar las medidas de Reconstrucción Radical, utilizando la Ley de Duración del Cargo . Johnson fue absuelto por un voto, pero perdió la influencia para dar forma a la política de Reconstrucción. [44]

En 1867, el Congreso aprobó las Leyes de Reconstrucción de 1867 que delineaban los términos en los que los estados rebeldes serían readmitidos en la Unión. Bajo estas leyes, el Congreso republicano estableció distritos militares en el Sur y utilizó personal del Ejército para administrar la región hasta que pudieran establecerse nuevos gobiernos leales a la Unión, que aceptaran la Decimocuarta Enmienda y el derecho de los libertos a votar. El Congreso suspendió temporalmente la capacidad de votar de aproximadamente 10.000 a 15.000 ex funcionarios confederados y altos oficiales, mientras que las enmiendas constitucionales dieron ciudadanía plena a todos los afroamericanos y sufragio a los hombres adultos. [45] Con el poder de votar, los libertos comenzaron a participar en la política. Si bien muchas personas esclavizadas eran analfabetas, los negros educados (incluidos los esclavos fugitivos ) se mudaron desde el Norte para ayudarlos, y los líderes naturales también dieron un paso al frente. Eligieron a hombres blancos y negros para que los representaran en las convenciones constitucionales. Una coalición republicana de libertos, sureños partidarios de la Unión (a los que los demócratas blancos llamaban despectivamente " scalawags ") y norteños que habían emigrado al Sur (a los que los demócratas blancos llamaban despectivamente " carpetbaggers ") —algunos de los cuales eran nativos que regresaban, pero en su mayoría veteranos de la Unión— se organizaron para crear convenciones constitucionales. Crearon nuevas constituciones estatales para fijar nuevos rumbos para los estados del Sur. [46]

El Congreso tuvo que estudiar cómo restaurar el estatus y la representación plenos dentro de la Unión a aquellos estados del Sur que habían declarado su independencia de los Estados Unidos y habían retirado su representación. El sufragio de los antiguos confederados era una de las dos preocupaciones principales. Había que decidir si se permitía votar (y ocupar cargos) sólo a algunos o a todos los antiguos confederados. Los moderados del Congreso querían que votaran prácticamente todos, pero los radicales se resistieron. Impusieron repetidamente el Juramento de Hierro, que en la práctica no habría permitido votar a ningún antiguo confederado. El historiador Harold Hyman dice que en 1866 los congresistas "describieron el juramento como el último baluarte contra el regreso de los antiguos rebeldes al poder, la barrera tras la cual se protegían los unionistas y los negros del Sur". [47]

El líder republicano radical Thaddeus Stevens propuso, sin éxito, que todos los ex confederados perdieran el derecho a votar durante cinco años. El compromiso al que se llegó privó del derecho al voto a muchos líderes civiles y militares confederados. Nadie sabe cuántos perdieron temporalmente el derecho al voto, pero una estimación situó la cifra en entre 10.000 y 15.000. [48] Sin embargo, los políticos radicales asumieron la tarea a nivel estatal. Sólo en Tennessee, más de 80.000 ex confederados fueron privados del derecho al voto. [49]

En segundo lugar, y estrechamente relacionado con esto, estaba la cuestión de si los 4 millones de libertos iban a ser recibidos como ciudadanos: ¿podrían votar? Si se los iba a contar plenamente como ciudadanos, se tenía que determinar algún tipo de representación para la distribución de los escaños en el Congreso. Antes de la guerra, la población de esclavos se había contabilizado como tres quintos de un número correspondiente de blancos libres. Al tener 4 millones de libertos contabilizados como ciudadanos de pleno derecho, el Sur ganaría escaños adicionales en el Congreso. Si a los negros se les negaba el voto y el derecho a ocupar cargos públicos, entonces sólo los blancos los representarían. Muchos, incluida la mayoría de los sureños blancos, los demócratas del Norte y algunos republicanos del Norte, se oponían al derecho al voto de los afroamericanos. La pequeña fracción de votantes republicanos opuestos al sufragio negro contribuyó a las derrotas de varias medidas de sufragio votadas en la mayoría de los estados del Norte. [50] Algunos estados del Norte que tuvieron referendos sobre el tema limitaron la capacidad de sus propias pequeñas poblaciones de negros para votar.

Lincoln había apoyado una posición intermedia: permitir que algunos hombres negros votaran, especialmente los veteranos del ejército estadounidense . Johnson también creía que ese servicio debía ser recompensado con la ciudadanía. Lincoln propuso dar el voto a "los muy inteligentes, y especialmente a aquellos que han luchado valientemente en nuestras filas". [51] En 1864, el gobernador Johnson dijo: "La clase más pudiente de ellos irá a trabajar y se mantendrá a sí misma, y a esa clase se le debe permitir votar, sobre la base de que un negro leal es más digno que un hombre blanco desleal". [52]

Como presidente en 1865, Johnson escribió al hombre que nombró gobernador de Mississippi, recomendándole: "Si pudiera extender el derecho al voto a todas las personas de color que pueden leer la Constitución en inglés y escribir sus nombres, y a todas las personas de color que poseen bienes raíces valuados al menos en doscientos cincuenta dólares y pagan impuestos sobre ellos, desarmaría completamente al adversario [los radicales en el Congreso] y daría un ejemplo que los demás estados seguirán". [53]

Charles Sumner y Thaddeus Stevens, líderes de los republicanos radicales, se mostraron inicialmente reticentes a conceder el derecho al voto a los libertos, en su mayoría analfabetos. Sumner prefirió en un principio establecer requisitos imparciales que impusieran restricciones a la alfabetización de negros y blancos. Creía que no lograría aprobar una legislación que privara del derecho al voto a los blancos analfabetos que ya tenían derecho a voto. [54]

En el Sur, muchos blancos pobres eran analfabetos, ya que antes de la guerra casi no había educación pública . En 1880, por ejemplo, la tasa de analfabetismo entre los blancos era de alrededor del 25% en Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Carolina del Sur y Georgia, y de hasta el 33% en Carolina del Norte. Esto se compara con la tasa nacional del 9% y una tasa de analfabetismo entre los negros que superaba el 70% en el Sur. [55] Sin embargo, en 1900, con el énfasis puesto en la educación dentro de la comunidad negra, la mayoría de los negros habían alcanzado la alfabetización. [56]

Sumner pronto concluyó que "no había protección sustancial para el liberto excepto en el derecho al voto". Esto era necesario, afirmó, "(1) para su propia protección; (2) para la protección del unionista blanco; y (3) para la paz del país. Pusimos el mosquete en sus manos porque era necesario; por la misma razón debemos darle el derecho al voto". El apoyo al derecho al voto fue un compromiso entre republicanos moderados y radicales. [57]

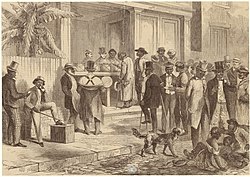

Los republicanos creían que la mejor manera de que los hombres adquirieran experiencia política era poder votar y participar en el sistema político. Aprobaron leyes que permitían votar a todos los hombres libertos. En 1867, los hombres negros votaron por primera vez. Durante la Reconstrucción, más de 1.500 afroamericanos ocuparon cargos públicos en el Sur; algunos de ellos eran hombres que habían escapado al Norte y obtenido educación, y regresaron al Sur. No ocupaban cargos en cantidades representativas de su proporción en la población, pero a menudo elegían a blancos para que los representaran. [58] [ página requerida ] También se debatió la cuestión del sufragio femenino , pero fue rechazada. [59] [ página requerida ] Las mujeres finalmente obtuvieron el derecho a votar con la Decimonovena Enmienda a la Constitución de los Estados Unidos en 1920. [ cita requerida ]

Entre 1890 y 1908, los estados del Sur aprobaron nuevas constituciones y leyes estatales que privaron del derecho al voto a la mayoría de los negros y a decenas de miles de blancos pobres, con nuevas normas electorales y de registro de votantes. Al establecer nuevos requisitos, como pruebas de alfabetización administradas de forma subjetiva , en algunos estados se utilizaron " cláusulas de exención " para permitir que los blancos analfabetos votaran. [60]

Las cinco tribus civilizadas que habían sido reubicadas en el Territorio Indio (ahora parte de Oklahoma ) tenían esclavos negros y firmaron tratados de apoyo a la Confederación. Durante la guerra, se desató una guerra entre los nativos americanos pro-Unión y los anti-Unión. El Congreso aprobó una ley que le dio al presidente la autoridad para suspender las asignaciones de cualquier tribu si la tribu está "en un estado de hostilidad real hacia el gobierno de los Estados Unidos... y, mediante proclamación, declarar que todos los tratados con dicha tribu son derogados por dicha tribu". [61] [62]

Como parte de la Reconstrucción, el Departamento del Interior ordenó una reunión de representantes de todas las tribus indígenas que se habían afiliado a la Confederación. [63] El consejo, la Comisión del Tratado del Sur , se celebró por primera vez en Fort Smith, Arkansas , en septiembre de 1865, y asistieron cientos de nativos americanos que representaban a docenas de tribus. Durante los siguientes años, la comisión negoció tratados con las tribus que dieron como resultado reubicaciones adicionales en el Territorio Indio y la creación de facto (inicialmente por tratado) de un Territorio de Oklahoma no organizado . [ cita requerida ]

El presidente Lincoln firmó dos leyes de confiscación , la primera el 6 de agosto de 1861 y la segunda el 17 de julio de 1862, que protegían a los esclavos fugitivos que cruzaban las fronteras de la Unión desde la Confederación y les otorgaban una emancipación indirecta si sus amos continuaban la insurrección contra los Estados Unidos. Las leyes permitían la confiscación de tierras para la colonización de quienes ayudaron y apoyaron la rebelión. Sin embargo, estas leyes tuvieron un efecto limitado, ya que estaban mal financiadas por el Congreso y eran mal aplicadas por el fiscal general Edward Bates . [64] [65] [66]

En agosto de 1861, el mayor general John C. Frémont , comandante de la Unión del Departamento Occidental, declaró la ley marcial en Misuri , confiscó las propiedades confederadas y emancipó a sus esclavos. Lincoln ordenó inmediatamente a Frémont que rescindiera su declaración de emancipación, afirmando: "Creo que existe un gran peligro de que ... la liberación de esclavos de propietarios traidores, alarme a nuestros amigos de la Unión del Sur y los vuelva contra nosotros, tal vez arruinando nuestra justa perspectiva para Kentucky". Después de que Frémont se negara a rescindir la orden de emancipación, Lincoln lo despidió del servicio activo el 2 de noviembre de 1861. A Lincoln le preocupaba que los estados fronterizos se separaran de la Unión si se les daba la libertad a los esclavos. El 26 de mayo de 1862, el mayor general de la Unión David Hunter emancipó a los esclavos en Carolina del Sur, Georgia y Florida, declarando a todas las "personas ... hasta ahora mantenidas como esclavas ... libres para siempre". Lincoln, avergonzado por la orden, anuló la declaración de Hunter y canceló la emancipación. [67]

El 16 de abril de 1862, Lincoln firmó una ley que prohibía la esclavitud en Washington, DC, y liberaba a los aproximadamente 3.500 esclavos que había en la ciudad. El 19 de junio de 1862, firmó una ley que prohibía la esclavitud en todos los territorios de los Estados Unidos. El 17 de julio de 1862, en virtud de la autoridad de las Leyes de Confiscación y una Ley de Fuerza enmendada de 1795, autorizó el reclutamiento de esclavos liberados en el Ejército de los Estados Unidos y la confiscación de cualquier propiedad confederada para fines militares. [66] [68] [69]

En un esfuerzo por mantener a los estados fronterizos en la Unión, Lincoln, ya en 1861, diseñó programas de emancipación gradual compensada pagados por bonos del gobierno. Lincoln deseaba que Delaware , Maryland , Kentucky y Missouri "adoptaran un sistema de emancipación gradual que debería lograr la extinción de la esclavitud en veinte años". El 26 de marzo de 1862, Lincoln se reunió con el senador Charles Sumner y recomendó que se convocara una sesión conjunta especial del Congreso para discutir la concesión de ayuda financiera a cualquier estado fronterizo que iniciara un plan de emancipación gradual . En abril de 1862, se reunió la sesión conjunta del Congreso; sin embargo, los estados fronterizos no estaban interesados y no respondieron a Lincoln ni a ninguna propuesta de emancipación del Congreso. [70] Lincoln abogó por la emancipación compensada durante la Conferencia de Hampton Roads . [ cita requerida ]

En agosto de 1862, Lincoln se reunió con líderes afroamericanos y los instó a colonizar algún lugar de América Central . Lincoln planeaba liberar a los esclavos del Sur en la Proclamación de Emancipación y le preocupaba que los libertos no fueran bien tratados en los Estados Unidos por los blancos tanto del Norte como del Sur. Aunque Lincoln dio garantías de que el gobierno de los Estados Unidos apoyaría y protegería cualquier colonia que se estableciera para los antiguos esclavos, los líderes rechazaron la oferta de colonización. Muchos negros libres se habían opuesto a los planes de colonización en el pasado porque querían permanecer en los Estados Unidos. Lincoln persistió en su plan de colonización en la creencia de que la emancipación y la colonización eran parte del mismo programa. En abril de 1863, Lincoln logró enviar colonos negros a Haití , así como 453 a Chiriquí en América Central; sin embargo, ninguna de las colonias pudo seguir siendo autosuficiente. Frederick Douglass , un destacado activista de los derechos civiles estadounidense del siglo XIX , criticó a Lincoln al afirmar que estaba "mostrando todas sus inconsistencias, su orgullo de raza y sangre, su desprecio por los negros y su hipócrita hipocresía". Los afroamericanos, según Douglass, querían ciudadanía y derechos civiles en lugar de colonias. Los historiadores no están seguros de si Lincoln abandonó la idea de la colonización afroamericana a fines de 1863 o si realmente planeó continuar con esta política hasta 1865. [66] [70] [71]

A partir de marzo de 1862, en un esfuerzo por impedir la Reconstrucción por parte de los radicales en el Congreso, Lincoln instaló gobernadores militares en ciertos estados rebeldes bajo control militar de la Unión. [72] Aunque los estados no serían reconocidos por los radicales hasta un tiempo indeterminado, la instalación de gobernadores militares mantuvo la administración de la Reconstrucción bajo el control presidencial, en lugar de la del cada vez más antipático Congreso Radical. El 3 de marzo de 1862, Lincoln instaló a un demócrata leal, el senador Andrew Johnson, como gobernador militar con el rango de general de brigada en su estado natal de Tennessee. [73] En mayo de 1862, Lincoln nombró a Edward Stanly gobernador militar de la región costera de Carolina del Norte con el rango de general de brigada. Stanly renunció casi un año después cuando enfureció a Lincoln al cerrar dos escuelas para niños negros en New Bern . Después de que Lincoln instalara al general de brigada George Foster Shepley como gobernador militar de Luisiana en mayo de 1862, Shepley envió a dos representantes antiesclavistas, Benjamin Flanders y Michael Hahn , elegidos en diciembre de 1862, a la Cámara, que capituló y votó para que se sentaran. En julio de 1862, Lincoln instaló al coronel John S. Phelps como gobernador militar de Arkansas, aunque renunció poco después debido a problemas de salud. [74] [ página requerida ]

En julio de 1862, Lincoln se convenció de que era "una necesidad militar" luchar contra la esclavitud para ganar la Guerra Civil para la Unión. Las Leyes de Confiscación sólo estaban teniendo un efecto mínimo para poner fin a la esclavitud. El 22 de julio, escribió un primer borrador de la Proclamación de Emancipación que liberaba a los esclavos en los estados en rebelión. Después de mostrarle el documento a su Gabinete, se hicieron ligeras modificaciones en la redacción. Lincoln decidió que la derrota de la invasión confederada del Norte en Sharpsburg era una victoria en el campo de batalla suficiente para permitirle publicar la Proclamación de Emancipación preliminar que daba a los rebeldes 100 días para regresar a la Unión o se emitiría la proclamación real. [ cita requerida ]

El 1 de enero de 1863 se promulgó la Proclamación de Emancipación, que nombraba específicamente 10 estados en los que los esclavos serían "libres para siempre". La proclama no mencionaba los estados de Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland y Delaware, y excluía específicamente numerosos condados de otros estados. Finalmente, a medida que el ejército estadounidense avanzaba hacia la Confederación, millones de esclavos fueron liberados. Muchos de estos libertos se unieron al ejército estadounidense y lucharon en batallas contra las fuerzas confederadas. [66] [71] [75] Sin embargo, cientos de miles de esclavos liberados murieron durante la emancipación a causa de enfermedades que devastaron los regimientos del ejército. Los esclavos liberados sufrieron viruela, fiebre amarilla y desnutrición. [76]

Lincoln estaba decidido a lograr una rápida restauración de los estados confederados a la Unión después de la Guerra Civil. En 1863, propuso un plan moderado para la reconstrucción del estado confederado capturado de Luisiana. El plan otorgaba amnistía a los rebeldes que hicieran un juramento de lealtad a la Unión. Los trabajadores negros libertos estaban atados a trabajar en las plantaciones durante un año a un salario de 10 dólares al mes. [77] Solo el 10% del electorado del estado tenía que hacer el juramento de lealtad para que el estado fuera readmitido en el Congreso de los EE. UU. El estado estaba obligado a abolir la esclavitud en su nueva constitución estatal. Se adoptarían planes de reconstrucción idénticos en Arkansas y Tennessee. En diciembre de 1864, el plan de reconstrucción de Lincoln se había promulgado en Luisiana y la legislatura envió a dos senadores y cinco representantes a ocupar sus escaños en Washington. Sin embargo, el Congreso se negó a contar ninguno de los votos de Luisiana, Arkansas y Tennessee, rechazando en esencia el plan de reconstrucción moderado de Lincoln. El Congreso, en ese momento controlado por los radicales, propuso el proyecto de ley Wade-Davis que exigía que la mayoría de los electorados estatales prestaran juramento de lealtad para ser admitidos en el Congreso. Lincoln vetó el proyecto de ley y la brecha se amplió entre los moderados, preocupados principalmente por preservar la Unión y ganar la guerra, y los radicales, que querían lograr un cambio más completo dentro de la sociedad sureña. [78] [79] Frederick Douglass denunció el plan de Lincoln de un electorado del 10% como antidemocrático, ya que la admisión y la lealtad a los estados solo dependían del voto de una minoría. [80]

Antes de 1864, los matrimonios de esclavos no habían sido reconocidos legalmente; la emancipación no los afectó. [17] Cuando fueron liberados, muchos buscaron matrimonios oficiales. Antes de la emancipación, los esclavos no podían celebrar contratos, incluido el contrato matrimonial. No todas las personas libres formalizaron sus uniones. Algunos continuaron teniendo matrimonios de hecho o relaciones reconocidas por la comunidad. [81] El reconocimiento del matrimonio por parte del estado aumentó el reconocimiento del estado de las personas liberadas como actores legales y eventualmente ayudó a defender los derechos parentales de las personas liberadas contra la práctica del aprendizaje de los niños negros. [82] Estos niños fueron separados legalmente de sus familias con el pretexto de "proporcionarles tutela y hogares 'buenos' hasta que alcanzaran la edad de consentimiento a los veintiún años" en virtud de leyes como la Ley de Aprendices de Georgia de 1866. [83] Estos niños generalmente eran utilizados como fuentes de trabajo no remunerado.

El 3 de marzo de 1865, se promulgó la Ley de la Oficina de los Libertos , patrocinada por los republicanos para ayudar a los libertos y a los refugiados blancos. Se creó una oficina federal para proporcionar alimentos, ropa, combustible y asesoramiento sobre la negociación de contratos laborales. Intentó supervisar las nuevas relaciones entre los libertos y sus antiguos amos en un mercado laboral libre. La ley, sin deferencia hacia el color de la piel de una persona, autorizó a la oficina a arrendar tierras confiscadas por un período de tres años y a venderlas en porciones de hasta 40 acres (16 ha) por comprador. La oficina expiraría un año después de la finalización de la guerra. Lincoln fue asesinado antes de que pudiera nombrar a un comisionado de la oficina. [ cita requerida ]

Con la ayuda de la oficina, los esclavos recientemente liberados comenzaron a votar, a formar partidos políticos y a asumir el control de la mano de obra en muchas áreas. La oficina ayudó a iniciar un cambio de poder en el Sur que atrajo la atención nacional de los republicanos del Norte a los demócratas del Sur. Esto es especialmente evidente en la elección entre Grant y Seymour (Johnson no obtuvo la nominación demócrata), donde casi 700.000 votantes negros votaron e inclinaron la elección 300.000 votos a favor de Grant. [ cita requerida ]

A pesar de los beneficios que les otorgaba a los libertos, la Oficina de los Libertos no podía operar de manera efectiva en ciertas áreas. El Ku Klux Klan era el enemigo de la Oficina de los Libertos, pues aterrorizaba a los libertos por intentar votar, ocupar un cargo político o poseer tierras. [84] [85] [86]

Se firmó otra legislación que amplió la igualdad y los derechos de los afroamericanos. Lincoln prohibió la discriminación por motivos de color, en el transporte de correo de Estados Unidos, en los tranvías públicos de Washington, DC y en el pago de los salarios de los soldados. [87]

El 3 de febrero de 1865, Lincoln y el secretario de Estado William H. Seward se reunieron con tres representantes del Sur para discutir la reconstrucción pacífica de la Unión y la Confederación en Hampton Roads , Virginia. La delegación del Sur incluía al vicepresidente confederado Alexander H. Stephens , John Archibald Campbell y Robert MT Hunter . Los sureños propusieron el reconocimiento de la Confederación por parte de la Unión, un ataque conjunto de la Unión y la Confederación a México para derrocar al emperador Maximiliano I y un estatus alternativo de subordinación de servidumbre para los negros en lugar de esclavitud. Lincoln rechazó de plano el reconocimiento de la Confederación y dijo que los esclavos amparados por su Proclamación de Emancipación no serían esclavizados de nuevo. Dijo que los estados de la Unión estaban a punto de aprobar la Decimotercera Enmienda, que proscribía la esclavitud. Lincoln instó al gobernador de Georgia a retirar las tropas confederadas y "ratificar esta enmienda constitucional de forma prospectiva , para que entre en vigor, digamos en cinco años... La esclavitud está condenada". Lincoln también instó a una emancipación compensatoria para los esclavos, pues pensaba que el Norte debería estar dispuesto a compartir los costos de la libertad. Aunque la reunión fue cordial, las partes no llegaron a acuerdos. [88]

Lincoln siguió defendiendo su Plan de Luisiana como modelo para todos los estados hasta su asesinato el 15 de abril de 1865. El plan inició con éxito el proceso de Reconstrucción al ratificar la Decimotercera Enmienda en todos los estados. Lincoln es retratado típicamente como alguien que toma una posición moderada y lucha contra las posiciones radicales. Existe un considerable debate sobre cuán bien Lincoln, si hubiera vivido, habría manejado al Congreso durante el proceso de Reconstrucción que tuvo lugar después de que terminó la Guerra Civil. Un grupo histórico sostiene que la flexibilidad, el pragmatismo y las habilidades políticas superiores de Lincoln con el Congreso habrían resuelto la Reconstrucción con mucha menos dificultad. El otro grupo cree que los radicales habrían intentado destituir a Lincoln, tal como lo hicieron con su sucesor, Andrew Johnson, en 1868. [31] [78]

La ira del Norte por el asesinato de Lincoln y el inmenso costo humano de la guerra condujo a demandas de políticas punitivas. El vicepresidente Andrew Johnson había adoptado una línea dura y habló de ahorcar a los confederados, pero cuando sucedió a Lincoln como presidente, Johnson adoptó una posición mucho más suave, perdonando a muchos líderes confederados y otros ex confederados. [39] El ex presidente confederado Jefferson Davis fue encarcelado durante dos años, pero otros líderes confederados no. No hubo juicios por cargos de traición. Solo tres personas —el capitán Henry Wirz , comandante del campo de prisioneros en Andersonville, Georgia , y los líderes guerrilleros Champ Ferguson y Henry C. Magruder— fueron ejecutadas por crímenes de guerra. La visión racista de Andrew Johnson de la Reconstrucción no incluía la participación de los negros en el gobierno, y se negó a prestar atención a las preocupaciones del Norte cuando las legislaturas estatales del Sur implementaron los Códigos Negros que establecían el estatus de los libertos mucho más bajo que el de los blancos. [30]

Smith sostiene que "Johnson intentó llevar adelante lo que él consideraba los planes de Lincoln para la Reconstrucción". [89] McKitrick dice que en 1865 Johnson tenía un fuerte apoyo en el Partido Republicano, diciendo: "Fue naturalmente del gran sector moderado de la opinión unionista en el Norte de donde Johnson pudo sacar su mayor consuelo". [90] Ray Allen Billington dice: "Una facción, los republicanos moderados bajo el liderazgo de los presidentes Abraham Lincoln y Andrew Johnson, favorecieron una política suave hacia el Sur". [91] David A. Lincove, citando a los biógrafos de Lincoln James G. Randall y Richard N. Current , argumentó que: [92]

Es probable que, si hubiera vivido, Lincoln hubiera seguido una política similar a la de Johnson, que se hubiera enfrentado a los radicales del Congreso, que hubiera producido un resultado mejor para los libertos que el que obtuvo y que sus habilidades políticas lo hubieran ayudado a evitar los errores de Johnson.

Los historiadores generalmente coinciden en que el presidente Johnson era un político inepto que perdió todas sus ventajas por maniobras inexpertas. Rompió con el Congreso a principios de 1866 y luego se volvió desafiante e intentó bloquear la aplicación de las leyes de Reconstrucción aprobadas por el Congreso de los EE. UU. Estuvo en constante conflicto constitucional con los radicales en el Congreso sobre el estatus de los libertos y los blancos en el Sur derrotado. [93] Aunque se resignaron a la abolición de la esclavitud, muchos ex confederados no estaban dispuestos a aceptar tanto los cambios sociales como la dominación política por parte de los ex esclavos. En palabras de Benjamin Franklin Perry , la elección del presidente Johnson como gobernador provisional de Carolina del Sur: "Primero, el negro debe ser investido con todo el poder político, y luego el antagonismo de intereses entre el capital y el trabajo debe resolver el resultado". [94]

Sin embargo, los temores de la élite de los plantadores y otros ciudadanos blancos importantes se vieron parcialmente apaciguados por las acciones del presidente Johnson, que se aseguró de que no se produjera una redistribución masiva de tierras de los plantadores a los libertos. El presidente Johnson ordenó que las tierras confiscadas o abandonadas administradas por la Oficina de los Libertos no se redistribuirían a los libertos, sino que se devolverían a los propietarios indultados. Se devolvieron tierras que habrían sido confiscadas en virtud de las Leyes de Confiscación aprobadas por el Congreso en 1861 y 1862. [ cita requerida ]

Los gobiernos de los estados del sur promulgaron rápidamente los restrictivos " Códigos Negros ". Sin embargo, fueron abolidos en 1866 y rara vez tuvieron efecto, porque la Oficina de los Libertos (no los tribunales locales) se ocupaba de los asuntos legales de los libertos.

Los Códigos Negros indicaban los planes de los blancos sureños para los antiguos esclavos. [95] Los libertos tendrían más derechos que los negros libres antes de la guerra, pero seguirían teniendo sólo derechos civiles de segunda clase, sin derecho a voto ni ciudadanía. No podrían poseer armas de fuego, formar parte de un jurado en un juicio que involucrara a blancos ni desplazarse sin empleo. [96] Los Códigos Negros indignaron a la opinión norteña. Fueron derrocados por la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1866 que dio a los libertos más igualdad legal (aunque todavía sin derecho a voto). [97]

Los libertos, con el fuerte respaldo de la Oficina de Libertos, rechazaron los patrones de trabajo en cuadrillas que se habían utilizado en la esclavitud. En lugar del trabajo en cuadrillas, las personas liberadas preferían los grupos de trabajo basados en la familia. [98] Obligaron a los plantadores a negociar su trabajo. Dicha negociación pronto condujo al establecimiento del sistema de aparcería , que dio a los libertos mayor independencia económica y autonomía social que el trabajo en cuadrillas. Sin embargo, debido a que carecían de capital y los plantadores seguían siendo dueños de los medios de producción (herramientas, animales de tiro y tierra), los libertos se vieron obligados a producir cultivos comerciales (principalmente algodón) para los terratenientes y comerciantes, y entraron en un sistema de gravámenes sobre los cultivos . La pobreza generalizada, la perturbación de una economía agrícola demasiado dependiente del algodón y la caída del precio del algodón llevaron en cuestión de décadas al endeudamiento rutinario de la mayoría de los libertos y a la pobreza de muchos plantadores. [99]

Los funcionarios del Norte dieron informes variados sobre las condiciones de los libertos en el Sur. Una evaluación dura provino de Carl Schurz , quien informó sobre la situación en los estados a lo largo de la Costa del Golfo. Su informe documentó docenas de ejecuciones extrajudiciales y afirmó que cientos o miles de afroamericanos más fueron asesinados: [100]

El número de asesinatos y agresiones perpetrados contra los negros es muy grande; sólo podemos hacernos una idea aproximada de lo que ocurre en aquellas partes del Sur que no están fuertemente guarnecidas y de las que no se reciben informes regulares, basándonos en lo que ocurre ante los propios ojos de nuestras autoridades militares. En cuanto a mi experiencia personal, sólo mencionaré que durante mi estancia de dos días en Atlanta, un negro fue apuñalado con efecto fatal en la calle y tres fueron envenenados, uno de los cuales murió. Mientras estuve en Montgomery, un negro fue cortado en la garganta evidentemente con la intención de matar, y otro recibió un disparo, pero ambos escaparon con vida. Varios documentos adjuntos a este informe dan cuenta del número de casos de pena capital que ocurrieron en ciertos lugares durante un período de tiempo determinado. Es un hecho triste que la perpetración de esos actos no se limita a esa clase de gente que podría llamarse la chusma.

El informe incluía testimonios jurados de soldados y funcionarios de la Oficina de Libertos. En Selma, Alabama , el mayor JP Houston señaló que los blancos que mataron a 12 afroamericanos en su distrito nunca fueron juzgados. Muchos otros asesinatos nunca se convirtieron en casos oficiales. El capitán Poillon describió las patrullas blancas en el suroeste de Alabama: [100]

Los libertos, desconcertados y aterrorizados, no saben qué hacer: irse es la muerte; quedarse es sufrir la carga aumentada que les impone el cruel capataz, cuyo único interés es su trabajo, arrancado de ellos por todos los medios que un ingenio inhumano puede idear; por eso se recurre al látigo y al asesinato para intimidar a aquellos a quienes el solo temor a una muerte terrible hace que se queden, mientras patrullas, perros negros y espías, disfrazados de yanquis, mantienen una vigilancia constante sobre esta gente desafortunada.

Gran parte de la violencia que se perpetró contra los afroamericanos estuvo determinada por los prejuicios de género con respecto a ellos. Las mujeres negras estaban en una situación particularmente vulnerable. Condenar a un hombre blanco por agredir sexualmente a mujeres negras en este período era extremadamente difícil. [101] [ página requerida ] El sistema judicial del Sur había sido completamente reconfigurado para hacer que uno de sus propósitos principales fuera la coerción de los afroamericanos para que cumplieran con las costumbres sociales y las demandas laborales de los blancos. [ más explicación necesaria ] [ cita requerida ] Se desalentaron los juicios y era difícil encontrar abogados para los acusados de delitos menores negros. El objetivo de los tribunales del condado era un juicio rápido y sin complicaciones con una condena resultante. La mayoría de los negros no podían pagar sus multas o fianzas, y "la pena más común era de nueve meses a un año en una mina de esclavos o un campamento maderero". [102] El sistema judicial del Sur estaba amañado para generar tarifas y reclamar recompensas, no para garantizar la protección pública. Las mujeres negras eran percibidas socialmente como sexualmente avaras y, dado que se las retrataba como personas con pocas virtudes, la sociedad sostenía que no podían ser violadas. [103] Un informe indica que dos mujeres liberadas, Frances Thompson y Lucy Smith, describieron su violenta agresión sexual durante los disturbios de Memphis de 1866. [ 104] Sin embargo, las mujeres negras eran vulnerables incluso en tiempos de relativa normalidad. Las agresiones sexuales a mujeres afroamericanas eran tan generalizadas, particularmente por parte de sus empleadores blancos, que los hombres negros buscaban reducir el contacto entre hombres blancos y mujeres negras haciendo que las mujeres de su familia evitaran hacer trabajos que fueran supervisados de cerca por blancos. [105] Los hombres negros eran considerados extremadamente agresivos sexualmente y sus supuestas o rumoreadas amenazas a las mujeres blancas a menudo se usaban como pretexto para linchamientos y castraciones. [18]

Durante el otoño de 1865, en respuesta a los Códigos Negros y a las preocupantes señales de recalcitrancia sureña, los republicanos radicales bloquearon la readmisión de los antiguos estados rebeldes en el Congreso. Sin embargo, Johnson se conformó con permitir la entrada de los antiguos estados confederados en la Unión siempre que sus gobiernos estatales adoptaran la Decimotercera Enmienda que abolía la esclavitud. El 6 de diciembre de 1865, la enmienda fue ratificada y Johnson consideró que la Reconstrucción había terminado. Según James Schouler, que escribió en 1913, Johnson estaba siguiendo la política moderada de reconstrucción presidencial de Lincoln para conseguir que los estados fueran readmitidos lo antes posible. [106]

Sin embargo, el Congreso, controlado por los radicales, tenía otros planes. Los radicales estaban liderados por Charles Sumner en el Senado y Thaddeus Stevens en la Cámara de Representantes. El 4 de diciembre de 1865, el Congreso rechazó la moderada Reconstrucción presidencial de Johnson y organizó el Comité Conjunto de Reconstrucción , un panel de 15 miembros para diseñar los requisitos de Reconstrucción para que los estados del Sur fueran reinstaurados en la Unión. [106]

En enero de 1866, el Congreso renovó la Oficina de los Libertos; sin embargo, Johnson vetó el proyecto de ley de la Oficina de los Libertos en febrero de 1866. Aunque Johnson simpatizaba con la difícil situación de los libertos, [ cita requerida ] estaba en contra de la asistencia federal. Un intento de anular el veto fracasó el 20 de febrero de 1866. Este veto sorprendió a los radicales del Congreso. En respuesta, tanto el Senado como la Cámara aprobaron una resolución conjunta para no permitir la admisión de ningún senador o representante hasta que el Congreso decidiera cuándo terminaría la Reconstrucción. [106]

El senador Lyman Trumbull de Illinois , líder de los republicanos moderados, se opuso a los Códigos Negros. Propuso la primera Ley de Derechos Civiles , porque la abolición de la esclavitud era vana si: [107]

Se deben promulgar y aplicar leyes que priven a las personas de ascendencia africana de privilegios que son esenciales para los hombres libres... Una ley que no permite a una persona de color ir de un condado a otro, y una que no le permite tener propiedades, enseñar, predicar, son ciertamente leyes que violan los derechos de un hombre libre... El propósito de este proyecto de ley es destruir todas estas discriminaciones.

La clave del proyecto de ley estaba en su primera parte: [ Esta cita necesita una cita ]

Todas las personas nacidas en los Estados Unidos... son por la presente declaradas ciudadanos de los Estados Unidos; y dichos ciudadanos de cualquier raza y color, sin tener en cuenta ninguna condición previa de esclavitud... tendrán el mismo derecho en cada estado... a hacer y hacer cumplir contratos, a demandar, ser partes y dar testimonio, a heredar, comprar, arrendar, vender, poseer y transferir bienes inmuebles y personales, y al beneficio pleno e igual de todas las leyes y procedimientos para la seguridad de la persona y la propiedad, como lo disfrutan los ciudadanos blancos, y estarán sujetos a castigos, penas y sanciones similares y a ningún otro, no obstante cualquier ley, estatuto, ordenanza, reglamento o costumbre en contrario.

El proyecto de ley no concedió a los libertos el derecho a votar. El Congreso aprobó rápidamente el proyecto de ley de derechos civiles; el 2 de febrero, el Senado votó por 33 a 12; el 13 de marzo, la Cámara de Representantes votó por 111 a 38.

Aunque los moderados del Congreso lo instaron enérgicamente a firmar la ley de derechos civiles, Johnson rompió decisivamente con ellos al vetarla el 27 de marzo de 1866. Su mensaje de veto objetaba la medida porque confería la ciudadanía a los libertos en un momento en que 11 de los 36 estados no estaban representados y pretendía fijar mediante una ley federal "una igualdad perfecta de las razas blanca y negra en todos los estados de la Unión". Johnson dijo que era una invasión por parte de la autoridad federal de los derechos de los estados; no tenía justificación en la Constitución y era contraria a todos los precedentes. Era un "paso hacia la centralización y la concentración de todo el poder legislativo en el gobierno nacional". [109]

El Partido Demócrata, que se proclamaba el partido de los hombres blancos, del Norte y del Sur, apoyó a Johnson. [39] Sin embargo, los republicanos en el Congreso anularon su veto (el Senado por una ajustada votación de 33 a 15, y la Cámara de Representantes por 122 a 41) y el proyecto de ley de derechos civiles se convirtió en ley. El Congreso también aprobó un proyecto de ley diluido sobre la Oficina de los Libertos; Johnson lo vetó rápidamente como lo había hecho con el proyecto de ley anterior. Una vez más, sin embargo, el Congreso tenía suficiente apoyo y anuló el veto de Johnson. [37]

La última propuesta moderada fue la Decimocuarta Enmienda , cuyo principal redactor fue el representante John Bingham . Fue diseñada para incluir las disposiciones clave de la Ley de Derechos Civiles en la Constitución, pero fue mucho más allá. Extendió la ciudadanía a todos los nacidos en los Estados Unidos (excepto los indios en reservas), penalizó a los estados que no dieron el voto a los libertos y, lo más importante, creó nuevos derechos civiles federales que podrían ser protegidos por los tribunales federales. Garantizaba que se pagaría la deuda federal de guerra (y prometía que nunca se pagaría la deuda confederada). Johnson usó su influencia para bloquear la enmienda en los estados ya que se requerían tres cuartas partes de los estados para la ratificación (la enmienda fue ratificada más tarde). El esfuerzo moderado para llegar a un acuerdo con Johnson había fracasado, y estalló una lucha política entre los republicanos (tanto radicales como moderados) por un lado, y por el otro, Johnson y sus aliados en el Partido Demócrata en el Norte, y las agrupaciones (que usaban nombres diferentes) en cada estado del Sur. [ cita requerida ]

Preocupados por los múltiples informes de abusos a los libertos negros por parte de funcionarios blancos sureños y dueños de plantaciones, los republicanos en el Congreso tomaron el control de las políticas de Reconstrucción después de la elección de 1866. [110] Johnson ignoró el mandato de la política y alentó abiertamente a los estados del Sur a negar la ratificación de la Decimocuarta Enmienda (excepto Tennessee, todos los antiguos estados confederados se negaron a ratificarla, al igual que los estados fronterizos de Delaware, Maryland y Kentucky). Los republicanos radicales en el Congreso, liderados por Stevens y Sumner, abrieron el camino al sufragio para los libertos varones. En general, tenían el control, aunque tuvieron que comprometerse con los republicanos moderados (los demócratas en el Congreso casi no tenían poder). Los historiadores se refieren a este período como "Reconstrucción Radical" o "Reconstrucción del Congreso". [111] Los portavoces empresariales en el Norte generalmente se opusieron a las propuestas radicales. El análisis de 34 periódicos económicos importantes mostró que 12 discutían política y solo uno, Iron Age , apoyaba el radicalismo. Los otros 11 se opusieron a una política de reconstrucción "dura", favorecieron el rápido retorno de los estados del Sur a la representación en el Congreso, se opusieron a la legislación diseñada para proteger a los libertos y deploraron el impeachment del presidente Andrew Johnson. [112]

Los dirigentes blancos del Sur, que ostentaron el poder en la era inmediatamente posterior a la guerra, antes de que se concediera el derecho al voto a los libertos, renunciaron a la secesión y a la esclavitud, pero no a la supremacía blanca. La gente que había ostentado el poder anteriormente se enfadó en 1867 cuando se celebraron nuevas elecciones. Los nuevos legisladores republicanos fueron elegidos por una coalición de unionistas blancos, libertos y norteños que se habían establecido en el Sur. Algunos dirigentes del Sur intentaron adaptarse a las nuevas condiciones.

Se aprobaron tres enmiendas constitucionales, conocidas como enmiendas de la Reconstrucción. La Decimotercera Enmienda, que abolía la esclavitud, fue ratificada en 1865. La Decimocuarta Enmienda fue propuesta en 1866 y ratificada en 1868, garantizando la ciudadanía estadounidense a todas las personas nacidas o naturalizadas en los Estados Unidos y otorgándoles derechos civiles federales. La Decimoquinta Enmienda, propuesta a fines de febrero de 1869 y aprobada a principios de febrero de 1870, decretó que el derecho al voto no podía ser negado por "raza, color o condición previa de servidumbre". No se afectó a que los estados aún determinaran el registro de votantes y las leyes electorales. Las enmiendas estaban dirigidas a terminar con la esclavitud y proporcionar ciudadanía plena a los libertos. Los congresistas del Norte creían que proporcionar a los hombres negros el derecho al voto sería el medio más rápido de educación y capacitación política. [ cita requerida ]

Muchos negros participaron activamente en las elecciones y en la vida política, y rápidamente continuaron construyendo iglesias y organizaciones comunitarias. Después de la Reconstrucción, los demócratas blancos y los grupos insurgentes utilizaron la fuerza para recuperar el poder en las legislaturas estatales y aprobar leyes que privaron de sus derechos a la mayoría de los negros y a muchos blancos pobres del Sur. Entre 1890 y 1910, los estados del Sur aprobaron nuevas constituciones estatales que completaron la privación de derechos a los negros. Los fallos de la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos sobre estas disposiciones confirmaron muchas de estas nuevas constituciones y leyes de los estados del Sur, y a la mayoría de los negros se les impidió votar en el Sur hasta la década de 1960. La aplicación federal completa de las Enmiendas Decimocuarta y Decimoquinta no se produjo hasta después de la aprobación de la legislación a mediados de la década de 1960 como resultado del movimiento por los derechos civiles . [ cita requerida ]

Para más detalles, consulte:

The Reconstruction Acts, as originally passed, were initially called "An act to provide for the more efficient Government of the Rebel States".[115] The legislation was enacted by the 39th Congress, on March 2, 1867. It was vetoed by President Johnson, and the veto then overridden by a two-thirds majority, in both the House and the Senate, the same day. Congress also clarified the scope of the federal writ of habeas corpus, to allow federal courts to vacate unlawful state court convictions or sentences, in 1867.[116]

With the Radicals in control, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts on July 19, 1867. The first Reconstruction Act, authored by Oregon Sen. George Henry Williams, a Radical Republican, placed 10 of the former Confederate states—all but Tennessee—under military control, grouping them into five military districts:[117]

20,000 U.S. troops were deployed to enforce the act.

The five border states that had not joined the Confederacy were not subject to military Reconstruction. West Virginia, which had seceded from Virginia in 1863, and Tennessee, which had already been re-admitted in 1866, were not included in the military districts. Federal troops, however, were kept in West Virginia through 1868 in order to control civil unrest in several areas throughout the state.[118] Federal troops were removed from Kentucky and Missouri in 1866.[119]

The 10 Southern state governments were re-constituted under the direct control of the United States Army. One major purpose was to recognize and protect the right of African Americans to vote.[120] There was little to no combat, but rather a state of martial law in which the military closely supervised local government, supervised elections, and tried to protect office holders and freedmen from violence.[121] Blacks were enrolled as voters; former Confederate leaders were excluded for a limited period.[122] No one state was entirely representative. Randolph Campbell describes what happened in Texas:[123][124]

The first critical step ... was the registration of voters according to guidelines established by Congress and interpreted by Generals Sheridan and Charles Griffin. The Reconstruction Acts called for registering all adult males, white and black, except those who had ever sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States and then engaged in rebellion.... Sheridan interpreted these restrictions stringently, barring from registration not only all pre-1861 officials of state and local governments who had supported the Confederacy but also all city officeholders and even minor functionaries such as sextons of cemeteries. In May Griffin ... appointed a three-man board of registrars for each county, making his choices on the advice of known scalawags and local Freedmen's Bureau agents. In every county where practicable a freedman served as one of the three registrars.... Final registration amounted to approximately 59,633 whites and 49,479 blacks. It is impossible to say how many whites were rejected or refused to register (estimates vary from 7,500 to 12,000), but blacks, who constituted only about 30 percent of the state's population, were significantly over-represented at 45 percent of all voters.

The 11 Southern states held constitutional conventions giving Black men the right to vote,[125] where the factions divided into the Radical, "conservative", and in-between delegates.[126] The Radicals were a coalition: 40% were Southern White Republicans; 25% were White and 34% were Black.[127] In addition to expanding the franchise, they pressed for provisions designed to promote economic growth, especially financial aid to rebuild the ruined railroad system.[128][129] The conventions set up systems of free public schools funded by tax dollars, but did not require them to be racially integrated.[130]

Until 1872, most former Confederate or prewar Southern office holders were disqualified from voting or holding office; all but 500 top Confederate leaders were pardoned by the Amnesty Act of 1872.[131] "Proscription" was the policy of disqualifying as many ex-Confederates as possible. For example, in 1865 Tennessee had disenfranchised 80,000 ex-Confederates.[132] However, proscription was soundly rejected by the Black element, which insisted on universal suffrage.[133][134] The issue would come up repeatedly in several states, especially in Texas and Virginia. In Virginia, an effort was made to disqualify for public office every man who had served in the Confederate Army even as a private, and any civilian farmer who sold food to the Confederate States Army.[135][136] Disenfranchising Southern Whites was also opposed by moderate Republicans in the North, who felt that ending proscription would bring the South closer to a republican form of government based on the consent of the governed, as called for by the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Strong measures that were called for in order to forestall a return to the defunct Confederacy increasingly seemed out of place, and the role of the United States Army and controlling politics in the state was troublesome. Historian Mark Summers states that increasingly "the disenfranchisers had to fall back on the contention that denial of the vote was meant as punishment, and a lifelong punishment at that ... Month by month, the un-republican character of the regime looked more glaring."[137]

During the Civil War, many in the North believed that fighting for the Union was a noble cause—for the preservation of the Union and the end of slavery. After the war ended, with the North victorious, the fear among Radicals was that President Johnson too quickly assumed that slavery and Confederate nationalism were dead and that the Southern states could return. The Radicals sought out a candidate for president who represented their viewpoint.[138]

In May 1868, the Republicans unanimously chose Ulysses S. Grant as their presidential candidate, and Schuyler Colfax as their vice-presidential candidate.[139] Grant won favor with the Radicals after he allowed Edwin Stanton, a Radical, to be reinstated as secretary of war. As early as 1862, during the Civil War, Grant had appointed the Ohio military chaplain John Eaton to protect and gradually incorporate refugee slaves in west Tennessee and northern Mississippi into the Union war effort and pay them for their labor. It was the beginning of his vision for the Freedmen's Bureau.[140] Grant opposed President Johnson by supporting the Reconstruction Acts passed by the Radicals.[141]

In northern cities Grant contended with a strong immigrant, and particularly in New York City an Irish, anti-Reconstructionist Democratic bloc.[142][143] Republicans sought to make inroads campaigning for the Irish taken prisoner in the Fenian raids into Canada, and calling on the Johnson administration to recognize a lawful state of war between Ireland and England. In 1867 Grant personally intervened with David Bell and Michael Scanlon to move their paper, the Irish Republic, articulate in its support for black equality, to New York from Chicago.[144][145]

The Democrats, having abandoned Johnson, nominated former governor Horatio Seymour of New York for president and Francis P. Blair of Missouri for vice president.[146] The Democrats advocated the immediate restoration of former Confederate states to the Union and amnesty from "all past political offenses".[147]

Grant won the popular vote by 300,000 votes out of 5,716,082 votes cast, receiving an Electoral College landslide of 214 votes to Seymour's 80.[148] Seymour received a majority of white votes, but Grant was aided by 500,000 votes cast by blacks,[146] winning him 52.7 percent of the popular vote.[149] He lost Louisiana and Georgia primarily due to Ku Klux Klan violence against African-American voters.[150] At the age of 46, Grant was the youngest president yet elected, and the first president elected after the nation had outlawed slavery.[151][148][152]

President Ulysses S. Grant was considered an effective civil rights executive, concerned about the plight of African Americans.[153][154] Grant met with prominent black leaders for consultation and signed a bill into law, on March 18, 1869, that guaranteed equal rights to both blacks and whites, to serve on juries, and hold office, in Washington D.C.[153][155] In 1870 Grant signed into law a Naturalization Act that opened a path to citizenship for foreign-born Black residents in the US.[153] Additionally, Grant's Postmaster General, John Creswell used his patronage powers to integrate the postal system and appointed a record number of African-American men and women as postal workers across the nation, while also expanding many of the mail routes.[156][157] Grant appointed Republican abolitionist and champion of black education Hugh Lennox Bond as U.S. Circuit Court judge.[158]

Immediately upon inauguration in 1869, Grant bolstered Reconstruction by prodding Congress to readmit Virginia, Mississippi, and Texas into the Union, while ensuring their state constitutions protected every citizen's voting rights.[155]

Grant advocated the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment that said states could not disenfranchise African Americans.[159] Within a year, the three remaining states—Mississippi, Virginia, and Texas—adopted the new amendment—and were admitted to Congress.[160] Grant put military pressure on Georgia to reinstate its black legislators and adopt the new amendment.[161] Georgia complied, and on February 24, 1871, its senators were seated in Congress, with all the former Confederate states represented.[162] Southern Reconstructed states were controlled by Republicans and former slaves. Eight years later, in 1877, the Democratic Party had full control of the region and Reconstruction was dead.[163]

In 1870, to enforce Reconstruction, Congress and Grant created the Justice Department that allowed the Attorney General Amos Akerman and the first Solicitor General Benjamin Bristow to prosecute the Klan.[164][165] In Grant's two terms he strengthened Washington's legal capabilities to directly intervene to protect citizenship rights even if the states ignored the problem.[166]

Congress and Grant passed a series (three) of powerful civil rights Enforcement Acts between 1870 and 1871, designed to protect blacks and Reconstruction governments.[167] These were criminal codes that protected the freedmen's right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protection of laws. Most important, they authorized the federal government to intervene when states did not act. Urged by Grant and his Attorney General Amos T. Akerman, the strongest of these laws was the Ku Klux Klan Act, passed on April 20, 1871, that authorized the president to impose martial law and suspend the writ of habeas corpus.[167][168][169]

Grant was so adamant about the passage of the Ku Klux Klan Act, he earlier had sent a message to Congress, on March 23, 1871, in which he said:

"A condition of affairs now exists in some of the States of the Union rendering life and property insecure, and the carrying of the mails and the collection of the revenue dangerous. The proof that such a, condition of affairs exists in some localities is now before the Senate. That the power to correct these evils is beyond the control of State authorities, I do not doubt. That the power of the Executive of the United States, acting within the limits of existing laws, is sufficient for present emergencies, is not clear."[170]

Grant also recommended the enforcement of laws in all parts of the United States to protect life, liberty, and property.[170]