La legislación laboral de los Estados Unidos establece los derechos y deberes de los empleados, los sindicatos y los empleadores en los EE. UU. El objetivo básico de la legislación laboral es remediar la " desigualdad del poder de negociación " entre empleados y empleadores, especialmente los empleadores "organizados en la corporación u otras formas de asociación de propiedad". [1] Durante el siglo XX, la ley federal creó derechos sociales y económicos mínimos y alentó a las leyes estatales a ir más allá del mínimo para favorecer a los empleados. [2] La Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 requiere un salario mínimo federal , actualmente $ 7.25 pero más alto en 29 estados y DC, y desalienta las semanas laborales de más de 40 horas a través del pago de horas extras de tiempo y medio . No hay leyes federales, y pocas leyes estatales, que requieran vacaciones pagadas o licencia familiar paga . La Ley de Licencia Médica y Familiar de 1993 crea un derecho limitado a 12 semanas de licencia sin goce de sueldo en los empleadores más grandes. No existe un derecho automático a una pensión ocupacional más allá de la Seguridad Social garantizada por el gobierno federal [3] , pero la Ley de Seguridad de Ingresos de Jubilación de Empleados de 1974 exige estándares de gestión prudente y buena gobernanza si los empleadores aceptan proporcionar pensiones, planes de salud u otros beneficios. La Ley de Seguridad y Salud Ocupacional de 1970 exige que los empleados tengan un sistema de trabajo seguro.

Un contrato de trabajo siempre puede crear mejores condiciones que los derechos mínimos legales. Pero para aumentar su poder de negociación y conseguir mejores condiciones, los empleados organizan sindicatos para la negociación colectiva . La Ley Clayton de 1914 garantiza a todas las personas el derecho a organizarse, [4] y la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935 crea derechos para que la mayoría de los empleados se organicen sin perjuicios a través de prácticas laborales injustas . Según la Ley de Información y Divulgación de la Gestión Laboral de 1959 , la gobernanza de los sindicatos sigue principios democráticos. Si la mayoría de los empleados de un lugar de trabajo apoyan a un sindicato, las entidades empleadoras tienen el deber de negociar de buena fe . Los sindicatos pueden emprender acciones colectivas para defender sus intereses, incluida la retirada de su mano de obra en huelga. Todavía no existen derechos generales para participar directamente en la gobernanza empresarial, pero muchos empleados y sindicatos han experimentado con la obtención de influencia a través de fondos de pensiones, [5] y representación en los consejos corporativos . [6]

Desde la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1964 , todas las entidades empleadoras y los sindicatos tienen el deber de tratar a los empleados por igual, sin discriminación basada en "raza, color, religión, sexo u origen nacional". [7] Existen reglas separadas para la discriminación sexual en la remuneración según la Ley de Igualdad Salarial de 1963. Se agregaron grupos adicionales con "estatus protegido" mediante la Ley de Discriminación por Edad en el Empleo de 1967 y la Ley de Estadounidenses con Discapacidades de 1990. No existe una ley federal que prohíba toda discriminación por orientación o identidad sexual , pero 22 estados habían aprobado leyes en 2016. Estas leyes de igualdad generalmente previenen la discriminación en la contratación y los términos de empleo, y hacen que el despido debido a una característica protegida sea ilegal. En 2020, la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos dictaminó en Bostock v. Clayton County que la discriminación basada únicamente en la orientación sexual o la identidad de género viola el Título VII de la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1964. No existe una ley federal contra el despido injustificado , y la mayoría de los estados tampoco tienen una ley con plena protección contra el despido injustificado del empleo . [8] Los convenios colectivos realizados por los sindicatos y algunos contratos individuales exigen que las personas solo sean despedidas por una " causa justa ". La Ley de Notificación de Ajuste y Reentrenamiento de Trabajadores de 1988 exige que las entidades empleadoras den un aviso de 60 días si más del 50 o un tercio de la fuerza laboral puede perder su trabajo. La ley federal ha tenido como objetivo alcanzar el pleno empleo a través de la política monetaria y el gasto en infraestructura. La política comercial ha intentado poner los derechos laborales en los acuerdos internacionales, para garantizar que los mercados abiertos en una economía global no socaven el empleo justo y pleno .

La legislación laboral estadounidense moderna proviene principalmente de estatutos aprobados entre 1935 y 1974 , y de interpretaciones cambiantes de la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos . [9] Sin embargo, las leyes regulaban los derechos de las personas en el trabajo y de los empleadores desde la época colonial en adelante. Antes de la Declaración de Independencia en 1776, el derecho consuetudinario era incierto u hostil a los derechos laborales. [10] Los sindicatos se clasificaban como conspiraciones y potencialmente criminales. [11] Toleraba la esclavitud y la servidumbre por contrato . Desde la Guerra Pequot en Connecticut desde 1636 en adelante, los nativos americanos fueron esclavizados por colonos europeos. Más de la mitad de los inmigrantes europeos llegaron como prisioneros o en servidumbre por contrato , [12] donde no eran libres de dejar a sus empleadores hasta que se hubiera pagado un bono de deuda . Hasta su abolición, la trata de esclavos del Atlántico llevó a millones de africanos a realizar trabajos forzados en las Américas.

Sin embargo, en 1772, el Tribunal de King's Bench de Inglaterra sostuvo en Somerset v Stewart que la esclavitud debía presumirse ilegal según el derecho consuetudinario. [13] Charles Stewart de Boston , Massachusetts, había comprado a James Somerset como esclavo y lo había llevado a Inglaterra . Con la ayuda de los abolicionistas , Somerset escapó y demandó un recurso de hábeas corpus (que "retener su cuerpo" había sido ilegal). Lord Mansfield , después de declarar que debería " dejar que se haga justicia sea cual sea la consecuencia ", sostuvo que la esclavitud era "tan odiosa" que nadie podía tomar "un esclavo por la fuerza para venderlo" por ninguna "razón". Esta fue una de las principales quejas de los estados esclavistas del sur, que condujo a la Revolución estadounidense en 1776. [14] El censo de los Estados Unidos de 1790 registró 694.280 esclavos (17,8 por ciento) de una población total de 3.893.635. Después de la independencia, el Imperio Británico detuvo el comercio de esclavos en el Atlántico en 1807 , [15] y abolió la esclavitud en sus propios territorios , pagando a los dueños de esclavos en 1833. [16] En los EE. UU., los estados del norte abolieron progresivamente la esclavitud. Sin embargo, los estados del sur no lo hicieron. En Dred Scott v. Sandford, la Corte Suprema sostuvo que el gobierno federal no podía regular la esclavitud, y también que las personas que eran esclavas no tenían derechos legales en los tribunales. [17] La Guerra Civil estadounidense fue el resultado. La Proclamación de Emancipación del presidente Lincoln en 1863 convirtió la abolición de la esclavitud en un objetivo de guerra, y la Decimotercera Enmienda de 1865 consagró la abolición de la mayoría de las formas de esclavitud en la Constitución. Los antiguos dueños de esclavos también tenían prohibido mantener a las personas en servidumbre involuntaria por deudas por la Ley de Peonaje de 1867 . [18] En 1868, la Decimocuarta Enmienda garantizó la igualdad de acceso a la justicia, y la Decimoquinta Enmienda exigió que todos tuvieran derecho a votar. La Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1875 también pretendía garantizar la igualdad en el acceso a la vivienda y al transporte, pero en los Casos de Derechos Civiles , la Corte Suprema la consideró "inconstitucional", asegurando que la segregación racial continuaría. En su opinión discrepante, el Juez Harlan dijo que la mayoría estaba dejando a la gente "prácticamente a merced de las corporaciones". [19]Incluso si las personas eran formalmente libres, en los hechos seguían dependiendo de los propietarios para obtener trabajo, ingresos y servicios básicos.

El trabajo es anterior e independiente del capital . El capital es sólo el fruto del trabajo, y nunca podría haber existido si el trabajo no hubiera existido primero. El trabajo es superior al capital, y merece una consideración mucho más alta... El principiante prudente y sin dinero en el mundo trabaja por un salario durante un tiempo, ahorra un excedente con el que comprar herramientas o tierra para sí mismo, luego trabaja por cuenta propia otro tiempo, y al final contrata a otro principiante nuevo para que lo ayude. Este es el sistema justo, generoso y próspero que abre el camino a todos, da esperanza a todos y, en consecuencia, energía, progreso y mejora de la condición de todos. No hay hombres vivos más dignos de confianza que aquellos que trabajan duro desde la pobreza ; ninguno está menos inclinado a tomar o tocar algo que no han ganado honestamente. Que tengan cuidado de no entregar un poder político que ya poseen, y que, si lo entregaran, seguramente se utilizaría para cerrar la puerta del progreso a los que son como ellos y para fijarles nuevas discapacidades y cargas hasta que se pierda toda la libertad .

— Abraham Lincoln , Primer mensaje anual (1861)

Al igual que la esclavitud, la represión de los sindicatos por parte del derecho consuetudinario tardó en deshacerse. [20] En 1806, Commonwealth v. Pullis sostuvo que un sindicato de zapateros de Filadelfia que se declaraba en huelga por salarios más altos era una "conspiración" ilegal, [21] aunque las corporaciones (combinaciones de empleadores) eran legales. Los sindicatos todavía se formaban y actuaban. La primera federación de sindicatos, la National Trades Union , se estableció en 1834 para lograr una jornada laboral de 10 horas , pero no sobrevivió al creciente desempleo del pánico financiero de 1837. En 1842, Commonwealth v. Hunt sostuvo que Pullis estaba equivocado, después de que la Boston Journeymen Bootmakers' Society hiciera huelga por salarios más altos. [22] El juez de primera instancia dijo que los sindicatos "volverían insegura la propiedad y la convertirían en el botín de la multitud, aniquilarían la propiedad y envolverían a la sociedad en una ruina común". Pero en la Corte Suprema Judicial de Massachusetts , Shaw CJ sostuvo que las personas "son libres de trabajar para quien quieran, o de no trabajar, si así lo prefieren" y podían "acordar juntos ejercer sus propios derechos reconocidos, de tal manera que mejor sirva a sus propios intereses". Esto detuvo los casos penales, aunque los casos civiles persistieron. [23] En 1869 una organización llamada Knights of Labor fue fundada por artesanos de Filadelfia, a la que se unieron los mineros en 1874 y los comerciantes urbanos a partir de 1879. Tenía como objetivo la igualdad racial y de género, la educación política y la empresa cooperativa, [24] pero apoyó la Ley de Contrato Laboral Extranjero de 1885 que suprimía a los trabajadores que migraban a los EE. UU. bajo un contrato de trabajo.

Los conflictos industriales en los ferrocarriles y telégrafos a partir de 1883 llevaron a la fundación de la Federación Estadounidense del Trabajo en 1886, con el simple objetivo de mejorar los salarios de los trabajadores, la vivienda y la seguridad laboral "aquí y ahora". [25] También pretendía ser la única federación, para crear un movimiento laboral fuerte y unificado. Las empresas reaccionaron con litigios. La Ley Antimonopolio Sherman de 1890 , que pretendía sancionar a los cárteles empresariales que actuaban en restricción del comercio , [26] se aplicó a los sindicatos. En 1895, la Corte Suprema de los EE. UU. en In re Debs afirmó una orden judicial, basada en la Ley Sherman, contra los trabajadores en huelga de la Pullman Company . El líder de la huelga, Eugene Debs, fue encarcelado. [27] En un notable disenso entre los jueces, [28] Holmes J argumentó en Vegelahn v. Guntner que cualquier sindicato que tomara acción colectiva de buena fe era legal: incluso si las huelgas causaban pérdidas económicas, esto era igualmente legítimo que la pérdida económica de las corporaciones que competían entre sí. [29] Holmes J fue elevado a la Corte Suprema de los EE. UU ., pero nuevamente estaba en minoría en materia de derechos laborales. En 1905, Lochner v. New York sostuvo que Nueva York limitando la jornada laboral de los panaderos a 60 horas semanales violaba la libertad de contrato de los empleadores . La mayoría de la Corte Suprema supuestamente desenterró este "derecho" en la Decimocuarta Enmienda , de que ningún Estado debería "privar a ninguna persona de la vida, la libertad o la propiedad, sin el debido proceso legal". [30] Con Harlan J , Holmes J disintió, argumentando que "la constitución no está destinada a incorporar una teoría económica particular" sino que está "hecha para personas con puntos de vista fundamentalmente diferentes". En cuestiones de política social y económica, los tribunales nunca deberían declarar que una legislación es "inconstitucional". Sin embargo, la Corte Suprema aceleró su ataque al trabajo en Loewe v. Lawlor , al sostener que un sindicato en huelga debía pagar daños triples a sus empleadores en virtud de la Ley Sherman de 1890. [ 31] Esta línea de casos fue finalmente anulada por la Ley Clayton de 1914 §6. Esta eliminó al trabajo de la legislación antimonopolio , afirmando que "el trabajo de un ser humano no es una mercancía".o artículo de comercio" y nada "en las leyes antimonopolio" prohibiría el funcionamiento de las organizaciones laborales "con fines de ayuda mutua". [32]

A lo largo de los primeros años del siglo XX, los estados promulgaron derechos laborales para promover el progreso social y económico. Pero a pesar de la Ley Clayton y los abusos de los empleadores documentados por la Comisión de Relaciones Industriales a partir de 1915, la Corte Suprema anuló los derechos laborales por inconstitucionales, dejando a los poderes de gestión virtualmente irresponsables. [33] En esta era de Lochner , los tribunales sostuvieron que los empleadores podían obligar a los trabajadores a no pertenecer a sindicatos, [34] que un salario mínimo para mujeres y niños era nulo, [35] que los estados no podían prohibir que las agencias de empleo cobraran honorarios por el trabajo, [36] que los trabajadores no podían hacer huelga en solidaridad con colegas de otras empresas, [37] e incluso que el gobierno federal no podía prohibir el trabajo infantil. [38] También encarceló a activistas socialistas que se opusieron a los combates en la Primera Guerra Mundial , lo que significa que Eugene Debs se presentó como candidato del Partido Socialista a la presidencia en 1920 desde la prisión. [39] Críticamente, los tribunales sostuvieron que los intentos estatales y federales de crear la Seguridad Social eran inconstitucionales. [40] Debido a que no pudieron ahorrar en pensiones públicas seguras, millones de personas compraron acciones de corporaciones, lo que provocó un crecimiento masivo en el mercado de valores . [41] Debido a que la Corte Suprema impidió la regulación de la buena información sobre lo que la gente estaba comprando, los promotores corporativos engañaron a las personas para que pagaran más de lo que realmente valían las acciones. El desplome de Wall Street de 1929 acabó con los ahorros de millones de personas. Las empresas perdieron inversiones y despidieron a millones de trabajadores. Las personas desempleadas tenían menos para gastar en las empresas. Las empresas despidieron a más personas. Hubo una espiral descendente hacia la Gran Depresión .

Esto llevó a la elección de Franklin D. Roosevelt como presidente en 1932, quien prometió un " New Deal ". El gobierno se comprometió a crear pleno empleo y un sistema de derechos sociales y económicos consagrados en la ley federal. [42] Pero a pesar de la abrumadora victoria electoral del Partido Demócrata , la Corte Suprema continuó anulando la legislación, en particular la Ley de Recuperación Industrial Nacional de 1933 , que regulaba la empresa en un intento de garantizar salarios justos y prevenir la competencia desleal . [43] Finalmente, después de la segunda victoria abrumadora de Roosevelt en 1936, y la amenaza de Roosevelt de crear más puestos judiciales si sus leyes no se mantenían, un juez de la Corte Suprema cambió de posición . En West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, la Corte Suprema encontró que la legislación del salario mínimo era constitucional, [44] permitiendo que el New Deal continuara. En derecho laboral, la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935 garantizó a todos los empleados el derecho a sindicalizarse, negociar colectivamente salarios justos y emprender acciones colectivas, incluso en solidaridad con los empleados de otras empresas. La Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 creó el derecho a un salario mínimo y al pago de horas extras de tiempo y medio si los empleadores pedían a los trabajadores que trabajaran más de 40 horas semanales. La Ley de Seguridad Social de 1935 dio a todos el derecho a una pensión básica y a recibir seguro si estaban desempleados, mientras que la Ley de Valores de 1933 y la Ley de Intercambio de Valores de 1934 garantizaron que los compradores de valores en el mercado de valores tuvieran buena información. La Ley Davis-Bacon de 1931 y la Ley de Contratos Públicos Walsh-Healey de 1936 exigían que, en los contratos del gobierno federal, todos los empleadores pagaran a sus trabajadores salarios justos, más allá del mínimo, a las tarifas locales vigentes. [45] Para alcanzar el pleno empleo y salir de la depresión, la Ley de Asignación de Ayuda de Emergencia de 1935 permitió al gobierno federal gastar enormes sumas de dinero en la construcción y creación de puestos de trabajo. Esto se aceleró cuando comenzó la Segunda Guerra Mundial . En 1944, cuando su salud se estaba deteriorando, Roosevelt instó al Congreso a trabajar en pos de una " Segunda Carta de Derechos " mediante una acción legislativa, porque "a menos que haya seguridad aquí en casa no puede haber una paz duradera en el mundo" y "habremos cedido al espíritu deEl fascismo aquí en casa." [46]

Aunque el New Deal había creado una red de seguridad mínima de derechos laborales y tenía como objetivo permitir un salario justo a través de la negociación colectiva , un Congreso dominado por los republicanos se rebeló cuando Roosevelt murió. Contra el veto del presidente Truman , la Ley Taft-Hartley de 1947 limitó el derecho de los sindicatos a tomar medidas de solidaridad y permitió a los estados prohibir los sindicatos exigiendo que todas las personas en un lugar de trabajo se conviertan en miembros del sindicato. Una serie de decisiones de la Corte Suprema, sostuvo que la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935 no solo creó estándares mínimos, sino que detuvo o " preemptó " a los estados que permitieran mejores derechos sindicales, a pesar de que no existía tal disposición en el estatuto. [47] Los sindicatos fueron ampliamente regulados por la Ley de Informes y Divulgación de Gestión Laboral de 1959. La prosperidad de la posguerra había elevado los niveles de vida de las personas, pero la mayoría de los trabajadores que no tenían sindicato o derechos de seguridad laboral seguían siendo vulnerables al desempleo. Además de la crisis desencadenada por Brown v. Board of Education , [48] y la necesidad de desmantelar la segregación, la pérdida de empleos en la agricultura, particularmente entre los afroamericanos , fue una de las principales razones del movimiento por los derechos civiles , que culminó en la Marcha sobre Washington por el Empleo y la Libertad liderada por Martin Luther King Jr. Aunque la Orden Ejecutiva 8802 de Roosevelt de 1941 había prohibido la discriminación racial en la industria de defensa nacional, las personas aún sufrían discriminación debido a su color de piel en otros lugares de trabajo. Además, a pesar del creciente número de mujeres en el trabajo, la discriminación sexual era endémica. El gobierno de John F. Kennedy introdujo la Ley de Igualdad Salarial de 1963 , que exigía la igualdad salarial para mujeres y hombres. Lyndon B. Johnson introdujo la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1964 , que finalmente prohibía la discriminación contra las personas por "raza, color, religión, sexo u origen nacional". Lentamente, se extendió una nueva generación de leyes de igualdad de derechos. A nivel federal, esto incluyó la Ley de Discriminación por Edad en el Empleo de 1967 , la Ley de Discriminación por Embarazo de 1978 y la Ley de Estadounidenses con Discapacidades de 1990 , ahora supervisada por la Comisión de Igualdad de Oportunidades en el Empleo .

Aunque las personas, en campos limitados, podían reclamar un trato igualitario, los mecanismos para un salario y un trato justos fueron desmantelados después de la década de 1970. La última ley laboral importante, la Ley de Seguridad de Ingresos de Jubilación de Empleados de 1974 creó derechos a pensiones ocupacionales bien reguladas , aunque solo cuando un empleador ya había prometido proporcionar una: esto generalmente dependía de la negociación colectiva de los sindicatos. Pero en 1976, la Corte Suprema en Buckley v. Valeo sostuvo que cualquiera podía gastar cantidades ilimitadas de dinero en campañas políticas, como parte del derecho de la Primera Enmienda a la " libertad de expresión ". Después de que el presidente republicano Reagan asumiera el cargo en 1981, despidió a todo el personal de control de tráfico aéreo que se declaró en huelga y reemplazó a los miembros de la Junta Nacional de Relaciones Laborales por hombres pro-gerencia. Dominada por los republicanos, la Corte Suprema suprimió los derechos laborales, eliminando los derechos de los profesores, maestros de escuelas religiosas o inmigrantes ilegales a organizarse en un sindicato, [50] permitiendo que los empleados fueran registrados en el trabajo, [51] y eliminando los derechos de los empleados a demandar por mala praxis médica en su propia atención médica. [52] Sólo se hicieron cambios estatutarios limitados. La Ley de Reforma y Control de la Inmigración de 1986 criminalizó a un gran número de inmigrantes. La Ley de Notificación de Ajuste y Reentrenamiento de Trabajadores de 1988 garantizó a los trabajadores algún aviso antes de un despido masivo de sus trabajos. La Ley de Licencia Familiar y Médica de 1993 garantizó el derecho a 12 semanas de licencia para cuidar a los niños después del nacimiento, todas sin remuneración. La Ley de Protección del Empleo de las Pequeñas Empresas de 1996 redujo el salario mínimo, al permitir a los empleadores tomar las propinas de su personal para subsidiar el salario mínimo. Una serie de propuestas de políticos demócratas e independientes para promover los derechos laborales no se implementaron, [53] y Estados Unidos comenzó a quedarse atrás de la mayoría de los demás países desarrollados en materia de derechos laborales. [54]

En relación con la contratación del gobierno federal , el presidente Barack Obama emitió el 31 de julio de 2014 la Orden Ejecutiva 13673, titulada Pago justo y lugares de trabajo seguros . Contenía "nuevos requisitos diseñados para aumentar la eficiencia y el ahorro de costos en el proceso de contratación federal", [55] refiriéndose específicamente a "contratar con fuentes responsables que cumplan con las leyes laborales". [56] La Administración de Seguridad y Salud Ocupacional publicó una guía el 25 de agosto de 2016. [55] La orden enumeraba 14 leyes federales que se definían como "leyes laborales" y ampliaba la cobertura a "leyes estatales equivalentes". Una violación de cualquiera de estas leyes durante el período de tres años anterior a la adjudicación del contrato se trataba como incumplimiento; para un contrato valorado en más de $500,000, los funcionarios de contratación debían considerar dichas violaciones, y cualquier acción correctiva tomada por la empresa en cuestión, al determinar la adjudicación del contrato. Se incorporaron disposiciones similares en los acuerdos de subcontratación. Para respaldar el cumplimiento, cada agencia federal debía designar un "Asesor de Cumplimiento Laboral". [56] : Sec. 3 La orden fue revocada por el presidente Donald Trump el 27 de marzo de 2017 bajo la Orden Ejecutiva 13782. [ 57]

Los contratos entre empleados y empleadores (en su mayoría corporaciones ) generalmente inician una relación laboral, pero a menudo no son suficientes para un sustento decente. Debido a que las personas carecen de poder de negociación , especialmente contra corporaciones ricas, la ley laboral crea derechos legales que anulan los resultados arbitrarios del mercado. Históricamente, la ley hizo cumplir fielmente los derechos de propiedad y la libertad de contrato en cualquier condición, [59] ya sea que esto fuera ineficiente, explotador e injusto o no. A principios del siglo XX, a medida que más personas favorecían la introducción de derechos económicos y sociales determinados democráticamente por sobre los derechos de propiedad y contrato, los gobiernos estatales y federales introdujeron reformas legales. Primero, la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 creó un salario mínimo (ahora $ 7.25 a nivel federal, más alto en 28 estados) y un pago de horas extra de una vez y media. Segundo, la Ley de Licencia Familiar y Médica de 1993 crea derechos muy limitados para tomar licencia sin goce de sueldo. En la práctica, los buenos contratos de empleo mejoran estos mínimos. En tercer lugar, si bien no existe el derecho a una pensión laboral ni a otros beneficios, la Ley de Seguridad de Ingresos de Jubilación de Empleados de 1974 garantiza que los empleadores garanticen esos beneficios si se los prometen. En cuarto lugar, la Ley de Seguridad y Salud Ocupacional de 1970 exige un sistema de trabajo seguro, respaldado por inspectores profesionales. A menudo, los estados individuales están facultados para ir más allá del mínimo federal y funcionar como laboratorios de democracia en materia de derechos sociales y económicos, donde no han sido limitados por la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos .

El derecho consuetudinario , los estatutos estatales y federales suelen otorgar derechos laborales a los "empleados", pero no a las personas que son autónomas y tienen suficiente poder de negociación para ser "contratistas independientes". En 1994, la Comisión Dunlop sobre el futuro de las relaciones entre trabajadores y dirección: Informe final recomendó una definición unificada de empleado en todas las leyes laborales federales, para reducir los litigios, pero esto no se implementó. Tal como están las cosas, los casos de la Corte Suprema han establecido varios principios generales, que se aplicarán según el contexto y el propósito del estatuto en cuestión. En NLRB v. Hearst Publications, Inc. , [60] los repartidores de periódicos que vendían periódicos en Los Ángeles afirmaron que eran "empleados", por lo que tenían derecho a negociar colectivamente según la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935. Las corporaciones periodísticas argumentaron que los repartidores de periódicos eran "contratistas independientes" y que no tenían el deber de negociar de buena fe . La Corte Suprema sostuvo que los repartidores de periódicos eran empleados y que las pruebas de empleo de derecho consuetudinario, en particular el resumen en la Restatement of the Law of Agency, Second §220, ya no eran apropiadas. No eran "contratistas independientes" debido al grado de control que tenían los empleadores. Pero la Junta Nacional de Relaciones Laborales podía decidir por sí misma quién estaba cubierto si tenía "una base legal razonable". El Congreso reaccionó, primero, modificando explícitamente el NLRA §2(1) para que los contratistas independientes estuvieran exentos de la ley y, segundo, desaprobó que el derecho consuetudinario fuera irrelevante. Al mismo tiempo, la Corte Suprema decidió United States v. Silk , [61] sosteniendo que se debe tener en cuenta la "realidad económica" al decidir quién es un empleado según la Ley de Seguridad Social de 1935. Esto significaba que un grupo de cargadores de carbón eran empleados, teniendo en cuenta su posición económica, incluida su falta de poder de negociación , el grado de discreción y control, y el riesgo que asumían en comparación con las empresas de carbón para las que trabajaban. Por el contrario, la Corte Suprema encontró que los camioneros que poseían sus propios camiones y brindaban servicios a una empresa de transporte eran contratistas independientes. [62] Por lo tanto, ahora se acepta que múltiples factores de las pruebas tradicionales de derecho consuetudinario no pueden reemplazarse si una ley no brinda una definición adicional de "empleado" (como es habitual, por ejemplo, la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 , la Ley de Seguridad de Ingresos de Jubilación de Empleados de 1974 , la Ley de Licencia Familiar y Médica de 1993).). Junto con el propósito de la legislación laboral de mitigar la desigualdad del poder de negociación y corregir la realidad económica de la posición de un trabajador, deben considerarse los múltiples factores que se encuentran en la Restatement of Agency , aunque ninguno es necesariamente decisivo. [63]

Las pruebas de la agencia de derecho consuetudinario para determinar quién es un "empleado" tienen en cuenta el control del empleador, si el empleado está en un negocio distinto, el grado de dirección, la habilidad, quién proporciona las herramientas, la duración del empleo, el método de pago, el negocio regular del empleador, lo que creen las partes y si el empleador tiene un negocio. [65] Algunas leyes también hacen exclusiones específicas que reflejan el derecho consuetudinario, como para los contratistas independientes, y otras hacen excepciones adicionales. En particular, la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935 §2(11) exime a los supervisores con "autoridad, en interés del empleador", para ejercer discreción sobre los trabajos y términos de otros empleados. Esta fue originalmente una excepción limitada. Polémicamente, en NLRB v. Yeshiva University , [66] una mayoría de 5 a 4 de la Corte Suprema sostuvo que los profesores de tiempo completo en una universidad estaban excluidos de los derechos de negociación colectiva, sobre la teoría de que ejercían discreción "gerencial" en asuntos académicos. Los jueces disidentes señalaron que la gestión estaba en realidad en manos de la administración de la universidad, no de los profesores. En NLRB v. Kentucky River Community Care, Inc. , [67] la Corte Suprema sostuvo, nuevamente por 5 a 4, que seis enfermeras registradas que ejercían estatus de supervisión sobre otras personas caían dentro de la exención "profesional". Stevens J , por la disidencia, argumentó que si "el 'supervisor' se interpreta demasiado ampliamente", sin tener en cuenta el propósito de la Ley, la protección "se anula efectivamente". [68] De manera similar, bajo la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 , en Christopher v. SmithKline Beecham Corp. , [69] la Corte Suprema sostuvo por 5 a 4 que un vendedor médico viajero de GSK durante cuatro años era un "vendedor externo", y por lo tanto no podía reclamar horas extra. Las personas que trabajan ilegalmente a menudo se consideran cubiertas, para no alentar a los empleadores a explotar a los empleados vulnerables. Por ejemplo, en Lemmerman v. AT Williams Oil Co. [70], bajo la Ley de Compensación de los Trabajadores de Carolina del Norte, un niño de ocho años estaba protegido como empleado, aunque era ilegal que los niños menores de ocho años trabajaran. Sin embargo, en Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. v. NLRB [71] , la Corte Suprema sostuvo por 5 a 4 que un trabajador indocumentado no podía reclamar el pago retroactivo de su salario, después de haber sido despedido por organizarse en un sindicato. La retirada gradual de cada vez más personas del ámbito de aplicación de la legislación laboral, por una escasa mayoría de la Corte Suprema desde 1976, significa que Estados Unidos está por debajo de los estándares del derecho internacional y de los estándares de otros países democráticos.sobre los derechos laborales fundamentales, incluidoslibertad de asociación . [72]

Las pruebas de derecho consuetudinario eran a menudo importantes para determinar quién era, no sólo un empleado, sino los empleadores relevantes que tenían " responsabilidad indirecta ". Potencialmente puede haber múltiples empleadores conjuntos que compartan la responsabilidad, aunque la responsabilidad en el derecho de responsabilidad civil puede existir independientemente de una relación laboral. En Ruiz v. Shell Oil Co , [74] el Quinto Circuito sostuvo que era relevante qué empleador tenía más control, de quién era el trabajo que se estaba realizando, si había acuerdos en vigor, quién proporcionaba las herramientas, tenía derecho a despedir al empleado o tenía la obligación de pagar. [75] En Local 217, Hotel & Restaurant Employees Union v. MHM Inc [76] surgió la cuestión bajo la Ley de Notificación de Ajuste y Reentrenamiento de Trabajadores de 1988 de si una subsidiaria o corporación matriz era responsable de notificar a los empleados que el hotel cerraría. El Segundo Circuito sostuvo que la subsidiaria era el empleador, aunque el tribunal de primera instancia había encontrado responsable a la matriz al tiempo que señalaba que la subsidiaria sería el empleador bajo la NLRA . En virtud de la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 , 29 USC §203(r), cualquier "empresa" que esté bajo control común contará como entidad empleadora. Otros estatutos no adoptan explícitamente este enfoque, aunque la NLRB ha determinado que una empresa es empleadora si tiene "una gestión, un propósito comercial, una operación, un equipo, clientes y una supervisión sustancialmente idénticos". [77] En South Prairie Const. Co. v. Local No. 627, International Union of Operating Engineers, AFL-CIO , [78] la Corte Suprema determinó que el Circuito de DC había identificado legítimamente a dos corporaciones como un único empleador dado que tenían un "grado cualitativo muy sustancial de control centralizado de la mano de obra", [79] pero que la determinación adicional de la unidad de negociación relevante debería haberse remitido a la NLRB . Cuando se contratan empleados a través de una agencia, es probable que el empleador final sea considerado responsable de los derechos legales en la mayoría de los casos, aunque la agencia puede ser considerada como un empleador conjunto. [80]

Cuando las personas comienzan a trabajar, casi siempre habrá un contrato de trabajo que rige la relación del empleado y la entidad empleadora (generalmente una corporación , pero ocasionalmente un ser humano). [81] Un "contrato" es un acuerdo exigible por ley. Muy a menudo puede escribirse o firmarse, pero un acuerdo oral también es un contrato completamente exigible. Debido a que los empleados tienen un poder de negociación desigual en comparación con casi todas las entidades empleadoras, la mayoría de los contratos de trabajo son " estándar ". [82] La mayoría de los términos y condiciones son fotocopiados o reproducidos para muchas personas. La negociación genuina es rara, a diferencia de las transacciones comerciales entre dos corporaciones comerciales. Esta ha sido la principal justificación para la promulgación de derechos en la ley federal y estatal. El derecho federal a la negociación colectiva , por parte de un sindicato elegido por sus empleados, tiene como objetivo reducir el poder de negociación inherentemente desigual de los individuos contra las organizaciones para hacer convenios colectivos . [83] El derecho federal a un salario mínimo y a un aumento de las horas extras por trabajar más de 40 horas semanales fue diseñado para garantizar un "nivel mínimo de vida necesario para la salud, la eficiencia y el bienestar general de los trabajadores", incluso cuando una persona no pudiera obtener un salario lo suficientemente alto mediante la negociación individual. [84] Estos y otros derechos, incluidos los permisos familiares , los derechos contra la discriminación o los estándares básicos de seguridad laboral , fueron diseñados por el Congreso de los Estados Unidos y las legislaturas estatales para reemplazar las disposiciones de los contratos individuales. Los derechos legales prevalecen incluso sobre un término escrito expreso de un contrato, generalmente a menos que el contrato sea más beneficioso para un empleado. Algunas leyes federales también prevén que los derechos de la ley estatal pueden mejorar los derechos mínimos. Por ejemplo, la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 faculta a los estados y municipios a establecer salarios mínimos más allá del mínimo federal. Por el contrario, otras leyes como la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935, la Ley de Seguridad y Salud Ocupacional de 1970 , [85] y la Ley de Seguridad de Ingresos de Jubilación de los Empleados de 1974 , [86] han sido interpretadas en una serie de sentencias polémicas por la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos para " prevenir " las promulgaciones de leyes estatales. [87]Estas interpretaciones han tenido el efecto de "detener la experimentación en cuestiones sociales y económicas" y detener a los estados que quieren "servir como laboratorio" mejorando los derechos laborales. [88] Cuando no existen derechos mínimos en los estatutos federales o estatales, se aplicarán los principios del derecho contractual y, potencialmente , los de responsabilidad civil civil .

Además de los términos de los acuerdos orales o escritos, los términos pueden incorporarse por referencia. Dos fuentes principales son los convenios colectivos y los manuales de la empresa. En JI Case Co v. National Labor Relations Board, una corporación empleadora argumentó que no debería tener que negociar de buena fe con un sindicato y que no cometió una práctica laboral injusta al negarse, porque había firmado recientemente contratos individuales con sus empleados. [90] La Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos sostuvo por unanimidad que el "propósito mismo" de la negociación colectiva y la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935 era "sustituir los términos de los acuerdos separados de los empleados con términos que reflejen la fuerza y el poder de negociación y sirvan al bienestar del grupo". Por lo tanto, los términos de los convenios colectivos, en beneficio de los empleados individuales, sustituyen a los contratos individuales. De manera similar, si un contrato escrito establece que los empleados no tienen derechos, pero un supervisor le ha dicho a un empleado que los tiene, o los derechos están asegurados en un manual de la empresa, generalmente tendrá derecho a un reclamo. [91] Por ejemplo, en Torosyan v. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., la Corte Suprema de Connecticut sostuvo que una promesa en un manual de que un empleado podía ser despedido sólo por una buena razón (o "causa justa") era vinculante para la corporación empleadora. Además, un empleador no tenía derecho a cambiar unilateralmente los términos. [92] La mayoría de los demás tribunales estatales han llegado a la misma conclusión, que los contratos no pueden ser alterados, excepto para beneficio de los empleados, sin una nueva contraprestación y un verdadero acuerdo. [93] Por el contrario, una ligera mayoría en la Corte Suprema de California , designada por gobernadores republicanos, sostuvo en Asmus v. Pacific Bell que una política de la empresa de duración indefinida puede ser alterada después de un tiempo razonable con un aviso razonable, si no afecta a los beneficios adquiridos. [94] Los cuatro jueces disidentes, designados por gobernadores demócratas, sostuvieron que este era un "resultado patentemente injusto, de hecho desmesurado, que permite a un empleador que hizo una promesa de seguridad laboral continua ... repudiar esa promesa con impunidad varios años después". Además, en todos los estados, el common law o la equidad implican un término básico de buena fe que no puede renunciarse. Este suele exigir, como principio general, que "ninguna de las partes hará nada que tenga el efecto de destruir o lesionar el derecho de la otra parte a recibir los frutos del contrato". [95] El término de buena fepersiste durante toda la relación laboral. Todavía no ha sido utilizado ampliamente por los tribunales estatales, en comparación con otras jurisdicciones. La Corte Suprema de Montana ha reconocido que podrían estar disponibles daños extensos e incluso punitivos por el incumplimiento de las expectativas razonables de un empleado. [96] Sin embargo, otros, como la Corte Suprema de California , limitan cualquier recuperación de daños a los incumplimientos contractuales, pero no a los daños relacionados con la forma de terminación. [97] Por el contrario, en el Reino Unido se ha encontrado que el requisito de " buena fe " [98] limita el poder de despido excepto por razones justas [99] (pero no entra en conflicto con la ley [100] ), en Canadá puede limitar el despido injusto también para los trabajadores autónomos, [101] y en Alemania puede impedir el pago de salarios significativamente inferiores a la media. [102]

Por último, tradicionalmente se ha creído que las cláusulas de arbitraje no pueden desplazar ningún derecho laboral y, por lo tanto, limitar el acceso a la justicia en los tribunales públicos. [103] Sin embargo, en 14 Penn Plaza LLC v. Pyett , [104] en una decisión de 5 a 4 en virtud de la Ley Federal de Arbitraje de 1925, las cláusulas de arbitraje de los contratos de trabajo individuales deben ser ejecutadas de acuerdo con sus términos. Los cuatro jueces disidentes argumentaron que esto eliminaría derechos de una manera que la ley nunca pretendió. [105]

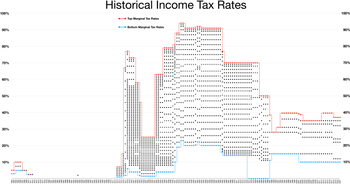

Aunque los contratos suelen determinar los salarios y las condiciones de empleo, la ley se niega a hacer cumplir los contratos que no observan los estándares básicos de equidad para los empleados. [106] Hoy, la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 tiene como objetivo crear un salario mínimo nacional, y una voz en el trabajo, especialmente a través de la negociación colectiva, debería lograr salarios justos. Un creciente cuerpo de leyes también regula el pago de los ejecutivos , aunque actualmente no está en vigor un sistema de regulación del " salario máximo ", por ejemplo mediante la antigua Ley de Estabilización de 1942. Históricamente, la ley en realidad suprimía los salarios , no de los altamente pagados, de los trabajadores ordinarios. Por ejemplo, en 1641 la legislatura de la Colonia de la Bahía de Massachusetts (dominada por los propietarios y la iglesia oficial) exigió reducciones salariales y dijo que el aumento de los salarios "tiende a la ruina de las Iglesias y la Commonwealth ". [107] A principios del siglo XX, la opinión democrática exigía que todos tuvieran un salario mínimo y pudieran negociar salarios justos más allá del mínimo. Pero cuando los estados intentaron introducir nuevas leyes, la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos las declaró inconstitucionales. La mayoría sostuvo que el derecho a la libertad de contrato podía interpretarse a partir de la protección que otorgan la Quinta y la Decimocuarta Enmienda contra la privación "de la vida, la libertad o la propiedad sin el debido proceso legal". Los jueces disidentes argumentaron que el "debido proceso" no afectaba al poder legislativo para crear derechos sociales o económicos, porque los empleados "no gozan de un nivel pleno de igualdad de elección con su empleador". [108]

Después del desplome de Wall Street y el New Deal con la elección de Franklin D. Roosevelt , la mayoría en la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos cambió. En West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish Hughes CJ sostuvo (sobre cuatro disidentes que todavía argumentaban a favor de la libertad de contrato ) que una ley de Washington que establecía salarios mínimos para mujeres era constitucional porque las legislaturas estatales deberían estar habilitadas para adoptar leyes en interés público. [111] Esto puso fin a la " era Lochner ", y el Congreso promulgó la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938. [ 112] Según el §202(a), el salario mínimo federal tiene como objetivo garantizar un "nivel de vida necesario para la salud, la eficiencia y el bienestar general". [113] Según el §207(a)(1), la mayoría de los empleados (pero con muchas excepciones) que trabajan más de 40 horas a la semana deben recibir un 50 por ciento más de pago de horas extras en su salario por hora. [114] Nadie puede pagar un salario inferior al mínimo, pero en virtud del artículo 218(a), los estados y los gobiernos municipales pueden establecer salarios más altos. [115] Esto se hace con frecuencia para reflejar la productividad local y los requisitos de una vida digna en cada región. [116] Sin embargo, el salario mínimo federal no tiene un mecanismo automático para actualizarse con la inflación. Debido a que el Partido Republicano se ha opuesto a aumentar los salarios, el salario mínimo federal real es hoy más de un 33 por ciento inferior al de 1968, uno de los más bajos del mundo industrializado.

.jpg/440px-Fight_for_$15_on_4-15_(17160512642).jpg)

Aunque existe un salario mínimo federal, se ha restringido en (1) el alcance de quién cubre, (2) el tiempo que cuenta para calcular el salario mínimo por hora y (3) la cantidad que los empleadores pueden tomar de las propinas de sus empleados o deducir para gastos. Primero, cinco jueces de la Corte Suprema de los EE. UU. sostuvieron en Alden v. Maine que el salario mínimo federal no puede hacerse cumplir para los empleados de los gobiernos estatales, a menos que el estado haya consentido, porque eso violaría la Undécima Enmienda . [117] Souter J , junto con tres jueces disidentes, [118] sostuvo que no existía tal "inmunidad soberana" en la Undécima Enmienda . [119] Sin embargo, veintiocho estados tenían leyes de salario mínimo más altas que el nivel federal en 2016. Además, debido a que la Constitución de los EE. UU. , artículo uno , sección 8, cláusula 3 solo permite al gobierno federal "regular el comercio ... entre los varios estados", los empleados de cualquier "empresa" de menos de $500,000 que fabrique bienes o servicios que no ingresen al comercio no están cubiertos: deben confiar en las leyes estatales de salario mínimo. [120] FLSA 1938 §203(s) exime explícitamente a los establecimientos cuyos únicos empleados son familiares cercanos. [121] Según §213, el salario mínimo no se puede pagar a 18 categorías de empleados y el pago de horas extras a 30 categorías de empleados. [122] Esto incluye según §213(a)(1) a los empleados de " capacidad ejecutiva, administrativa o profesional de buena fe ". En el caso de Auer v. Robbins, los sargentos y tenientes de policía del Departamento de Policía de St. Louis , Missouri, afirmaron que no deberían ser clasificados como ejecutivos o empleados profesionales y que deberían recibir un pago por horas extras. [123] El Juez Scalia sostuvo que, siguiendo las directrices del Departamento de Trabajo , los comisionados de policía de St. Louis tenían derecho a eximirlos. Esto ha alentado a los empleadores a intentar definir al personal como más "senior" y hacerlos trabajar más horas mientras evitan el pago de horas extras. [124] Otra exención en el §213(a)(15) es para las personas "empleadas en empleos de servicio doméstico para proporcionar servicios de compañía". En Long Island Care at Home, Ltd. v. Coke , una corporación solicitó la exención, aunque el Juez Breyer por una corte unánime estuvo de acuerdo con el Departamento de Trabajo en que solo estaba destinada a los cuidadores en hogares privados. [125]

En segundo lugar, debido a que el §206(a)(1)(C) dice que el salario mínimo es de $7.25 por hora, los tribunales han tenido que lidiar con qué horas cuentan como "trabajo". [126] Los primeros casos establecieron que el tiempo de viaje al trabajo no contaba como trabajo, a menos que estuviera controlado por, requerido por y para el beneficio de un empleador, como viajar a través de una mina de carbón. [127] Por ejemplo, en Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co. una mayoría de cinco a dos jueces sostuvo que los empleados tenían que ser pagados por la larga caminata al trabajo a través de la instalación de Mount Clemens Pottery Co. de un empleador. [128] Según Murphy J este tiempo, y el tiempo de instalación de estaciones de trabajo, involucraba "esfuerzo de naturaleza física, controlado o requerido por el empleador y buscado necesariamente y principalmente para el beneficio del empleador". [129] En Armour & Co. v. Wantock los bomberos afirmaron que se les debía pagar completamente mientras estaban de guardia en su estación para incendios. El Tribunal Supremo sostuvo que, aunque los bomberos podían dormir o jugar a las cartas, debido a que "la disposición para servir puede ser contratada tanto como el servicio en sí" y el tiempo de espera de guardia era "un beneficio para el empleador". [130] Por el contrario, en 1992 el Sexto Circuito sostuvo polémicamente que la necesidad de estar disponible con poca frecuencia por teléfono o buscapersonas, donde el movimiento no estaba restringido, no era tiempo de trabajo. [131] El tiempo dedicado a realizar una limpieza inusual, por ejemplo ducharse para quitarse sustancias tóxicas, cuenta como tiempo de trabajo, [132] y también el tiempo que se pasa poniéndose el equipo de protección especial. [133] De acuerdo con el §207(e), el pago de las horas extras debe ser una vez y media el pago regular. En Walling v. Helmerich & Payne, Inc. , el Tribunal Supremo sostuvo que el plan de un empleador de pagar salarios más bajos por la mañana y salarios más altos por la tarde, para argumentar que las horas extras solo debían calcularse sobre los salarios (más bajos) de la mañana era ilegal. Las horas extras deben calcularse en función del salario regular promedio. [134] Sin embargo, en Christensen v. Harris County, seis jueces de la Corte Suprema sostuvieron que la policía del condado de Harris, Texas, podía verse obligada a utilizar su "tiempo compensatorio" acumulado (permitiéndole tiempo libre con salario completo) antes de reclamar horas extras. [135] En su escrito de disidencia, Stevens J dijo que la mayoría había malinterpretado el §207(o)(2), que requiere un "acuerdo" entre empleadores, sindicatos o empleados sobre las reglas aplicables, y la policía de Texas no había estado de acuerdo. [136]En tercer lugar, el §203(m) permite a los empleadores deducir de los salarios sumas por concepto de comida o alojamiento que se "proporciona habitualmente" a los empleados. El Secretario de Trabajo puede determinar qué se considera un valor justo. Lo más problemático es que, fuera de los estados que han prohibido la práctica, pueden deducir dinero de un "empleado que recibe propinas" por el dinero que supere el "salario en efectivo que se le debía pagar a ese empleado el 20 de agosto de 1996", que era de 2,13 dólares por hora. Si un empleado no gana lo suficiente en propinas, el empleador debe pagar igualmente el salario mínimo de 7,25 dólares. Pero esto significa que en muchos estados las propinas no van a los trabajadores: los empleadores las toman para subsidiar los salarios bajos. Según el §216(b)-(c) de la FLSA 1938 , el Secretario de Estado puede hacer cumplir la ley, o los individuos pueden reclamar en su propio nombre. La aplicación federal es poco frecuente, por lo que la mayoría de los empleados tienen éxito si están en un sindicato. La Ley de Protección del Crédito al Consumidor de 1968 limita las deducciones o "embargos" por parte de los empleadores al 25 por ciento de los salarios, [137] aunque muchos estados son considerablemente más protectores. Finalmente, en virtud de la Ley Portal to Portal de 1947 , donde el Congreso limitó las leyes de salario mínimo de diversas maneras, el §254 establece un límite de tiempo de dos años para hacer cumplir las reclamaciones, o de tres años si una entidad empleadora es culpable de una violación intencional. [138]

En Estados Unidos, la gente trabaja una de las más largas horas semanales del mundo industrializado y tiene la menor cantidad de vacaciones anuales. [140] El artículo 24 de la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos de 1948 establece: "Toda persona tiene derecho al descanso, al ocio, a una limitación razonable de la duración del trabajo y a vacaciones periódicas pagadas ". Sin embargo, no existe una legislación federal o estatal general que exija vacaciones anuales pagadas. El Título 5 del Código de los Estados Unidos §6103 especifica diez días festivos para los empleados del gobierno federal y establece que las vacaciones serán pagadas. [141] Muchos estados hacen lo mismo, sin embargo, ninguna ley estatal exige que los empleadores del sector privado proporcionen vacaciones pagadas. Muchos empleadores privados siguen las normas del gobierno federal y estatal, pero el derecho a vacaciones anuales, si lo hay, dependerá de los convenios colectivos y los contratos de trabajo individuales. Se han hecho propuestas de leyes estatales para introducir vacaciones anuales pagadas. Un proyecto de ley de Washington de 2014 presentado por la miembro de la Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos Gael Tarleton habría exigido un mínimo de 3 semanas de vacaciones pagadas cada año a los empleados de empresas con más de 20 empleados, después de 3 años de trabajo. Según el Convenio sobre vacaciones pagadas de 1970 de la Organización Internacional del Trabajo [142], tres semanas es el mínimo indispensable. El proyecto de ley no recibió suficientes votos. [143] En cambio, los empleados de todos los países de la Unión Europea tienen derecho a al menos 4 semanas (es decir, 28 días) de vacaciones anuales pagadas cada año. [144] Además, no existe ninguna ley federal o estatal que limite la duración de la semana laboral. En cambio, la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 , §207, crea un desincentivo financiero para las horas de trabajo más largas. Bajo el título "Horas máximas", el §207 establece que se debe pagar tiempo y medio a los empleados que trabajen más de 40 horas a la semana. [114] Sin embargo, no establece un límite real, y hay al menos 30 excepciones para categorías de empleados que no reciben pago por horas extras. [145] La reducción del tiempo de trabajo fue una de las demandas originales del movimiento obrero. Desde las primeras décadas del siglo XX, la negociación colectiva produjo la práctica de tener, y la palabra para, un "fin de semana" de dos días. [146] Sin embargo, la legislación estatal para limitar el tiempo de trabajo fue suprimida por la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos en Lochner v. New York . [147] La Legislatura del Estado de Nueva Yorkhabía aprobado la Ley de Panaderías de 1895, que limitaba el trabajo en las panaderías a 10 horas diarias o 60 horas semanales, para mejorar la salud, la seguridad y las condiciones de vida de las personas. Después de ser procesado por hacer que su personal trabajara más tiempo en su Utica , el Sr. Lochner afirmó que la ley violaba la Decimocuarta Enmienda sobre el " debido proceso ". A pesar del disenso de cuatro jueces, una mayoría de cinco jueces sostuvo que la ley era inconstitucional. Sin embargo, la Corte Suprema confirmó el estatuto de jornada laboral minera de Utah en 1898. [148] La Corte Suprema del Estado de Mississippi confirmó un estatuto de jornada laboral de diez horas en 1912 cuando falló en contra de los argumentos del debido proceso de una empresa maderera interestatal. [149] Toda la era de jurisprudencia de Lochner fue revocada por la Corte Suprema de los EE. UU. en 1937, [150] pero la experimentación para mejorar los derechos de tiempo de trabajo y el " equilibrio entre el trabajo y la vida " aún no se ha recuperado.

Así como no existen derechos a vacaciones anuales pagadas o a un máximo de horas, no existen derechos a tiempo libre pagado para el cuidado de niños o licencia familiar en la ley federal. Hay derechos mínimos en algunos estados. La mayoría de los convenios colectivos, y muchos contratos individuales, prevén tiempo libre pagado, pero los empleados que carecen de poder de negociación a menudo no lo obtienen. [152] Sin embargo, existen derechos federales limitados a licencia sin goce de sueldo por razones familiares y médicas. La Ley de Licencia Familiar y Médica de 1993 generalmente se aplica a los empleadores de 50 o más empleados en 20 semanas del último año, y otorga derechos a los empleados que han trabajado más de 12 meses y 1250 horas en el último año. [153] Los empleados pueden tener hasta 12 semanas de licencia sin goce de sueldo por nacimiento de un hijo, adopción, para cuidar a un pariente cercano con mala salud o por la propia mala salud del empleado. [154] La licencia por cuidado de niños debe tomarse en un solo pago, a menos que se acuerde lo contrario. [155] Los empleados deben dar aviso de 30 días a los empleadores si el nacimiento o la adopción son "previsibles", [156] y para condiciones de salud graves si es factible. Los tratamientos deben organizarse "de manera que no interrumpan indebidamente las operaciones del empleador" de acuerdo con el consejo médico. [157] Los empleadores deben proporcionar beneficios durante la licencia sin goce de sueldo. [158] Según el §2652(b), los estados están facultados para proporcionar "derechos mayores de licencia familiar o médica". En 2016, California, Nueva Jersey , Rhode Island y Nueva York tenían leyes para los derechos de licencia familiar paga. Según el §2612(2)(A), un empleador puede hacer que un empleado sustituya el derecho a 12 semanas de licencia sin goce de sueldo por "licencia de vacaciones paga acumulada, licencia personal o licencia familiar" en la política de personal de un empleador. Originalmente, el Departamento de Trabajo tenía una sanción para que los empleadores notificaran a los empleados que esto podría suceder. Sin embargo, cinco jueces de la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos en Ragsdale v. Wolverine World Wide, Inc. sostuvieron que la ley impedía el derecho del Departamento de Trabajo a hacerlo. Cuatro jueces disidentes habrían sostenido que nada impedía la regla y que era tarea del Departamento de Trabajo hacer cumplir la ley. [159] Después de una licencia sin goce de sueldo, un empleado generalmente tiene derecho a regresar a su trabajo, excepto los empleados que se encuentran en el 10% superior de los mejor pagados y el empleador puede argumentar que la negativa "es necesaria para evitar un daño económico sustancial y grave a las operaciones del empleador". [160] Los empleados o el Secretario de Trabajo pueden presentar acciones de cumplimiento, [161]pero no existe el derecho a un jurado para las demandas de reincorporación. Los empleados pueden reclamar daños y perjuicios por los salarios y beneficios perdidos, o el costo del cuidado infantil, más una cantidad igual de daños y perjuicios liquidados a menos que un empleador pueda demostrar que actuó de buena fe y con causa razonable para creer que no estaba infringiendo la ley. [162] Hay un límite de dos años para presentar demandas, o de tres años para violaciones intencionales. [163] A pesar de la falta de derechos a licencia, no existe el derecho a guarderías o guarderías gratuitas . Esto ha alentado varias propuestas para crear un sistema público de guarderías gratuitas, o para que el gobierno subvencione los costos de los padres. [164]

A principios del siglo XX, la posibilidad de tener una "jubilación" se hizo real a medida que las personas vivían más tiempo, [165] y creían que los ancianos no deberían tener que trabajar o depender de la caridad hasta que murieran. [166] La ley mantiene un ingreso en la jubilación de tres maneras (1) a través de un programa público de seguridad social creado por la Ley de Seguridad Social de 1935, [167] (2) pensiones ocupacionales administradas a través de la relación laboral, y (3) pensiones privadas o seguros de vida que las personas compran por sí mismas. En el trabajo, la mayoría de los planes de pensiones ocupacionales originalmente resultaron de la negociación colectiva durante los años 1920 y 1930. [168] Los sindicatos generalmente negociaban con los empleadores de un sector para juntar fondos, de modo que los empleados pudieran mantener sus pensiones si cambiaban de trabajo. Los planes de jubilación de múltiples empleadores, establecidos por acuerdo colectivo , se conocieron como " planes Taft-Hartley " después de que la Ley Taft-Hartley de 194] exigiera la gestión conjunta de los fondos por parte de empleados y empleadores. [169] Muchos empleadores también eligen voluntariamente proporcionar pensiones. Por ejemplo, la pensión para profesores, ahora llamada TIAA , fue establecida por iniciativa de Andrew Carnegie en 1918 con el requisito expreso de que los participantes tuvieran derechos de voto para los fideicomisarios del plan. [170] Estos podrían ser esquemas de beneficio definido y colectivo : un porcentaje de los ingresos de una persona (por ejemplo, el 67%) se reemplaza para la jubilación, sin importar cuánto tiempo viva la persona. Pero más recientemente, más empleadores solo han proporcionado planes individuales " 401(k) ". Estos reciben su nombre del Código de Rentas Internas § 401(k) [171] , que permite a los empleadores y empleados no pagar impuestos sobre el dinero que se ahorra en el fondo, hasta que un empleado se jubila. La misma regla de aplazamiento de impuestos se aplica a todas las pensiones. Pero a diferencia de un plan de " beneficio definido ", un 401(k) solo contiene lo que el empleador y el empleado aportan . Se agotará si una persona vive demasiado tiempo, lo que significa que el jubilado puede tener solo un mínimo de seguridad social. La Ley de Protección de Pensiones de 2006, §902, codificó un modelo para que los empleadores inscriban automáticamente a sus empleados en una pensión, con derecho a optar por no hacerlo. [172] Sin embargo, no existe el derecho a una pensión ocupacional. La Ley de Seguridad de Ingresos de Jubilación de Empleados de 1974En efecto, si se establece un seguro, se crean una serie de derechos para los empleados. También se aplica a la atención sanitaria o a cualquier otro plan de "beneficios para empleados". [173]

.jpg/440px-The_Morgan_Stanley_Building_(WTM_by_official-ly_cool_112).jpg)

Cinco derechos principales para los beneficiarios en ERISA 1974 incluyen información, financiación , adquisición de derechos , antidiscriminación y deberes fiduciarios . Primero, cada beneficiario debe recibir una "descripción resumida del plan" en 90 días de unirse, los planes deben presentar informes anuales al Secretario de Trabajo , y si los beneficiarios hacen reclamos, cualquier rechazo debe justificarse con una "revisión completa y justa". [175] Si la "descripción resumida del plan" es más beneficiosa que los documentos del plan real, porque el fondo de pensiones comete un error, un beneficiario puede hacer cumplir los términos de cualquiera de los dos. [176] Si un empleador tiene pensiones u otros planes, todos los empleados deben tener derecho a participar después de un máximo de 12 meses, si trabajan más de 1000 horas. [177] Segundo, todas las promesas deben financiarse por adelantado. [178] La Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation fue establecida por el gobierno federal para ser una aseguradora de último recurso, pero solo hasta $ 60,136 por año para cada empleador. En tercer lugar, los beneficios de los empleados normalmente no pueden ser retirados (se " adquieren ") después de 5 años, [179] y las contribuciones deben acumularse (es decir, el empleado posee contribuciones) a una tasa proporcional. [180] Si los empleadores y los fondos de pensiones se fusionan, no puede haber reducción en los beneficios, [181] y si un empleado se declara en quiebra, sus acreedores no pueden tomar su pensión ocupacional. [182] Sin embargo, la Corte Suprema de los EE. UU. ha permitido que los empleadores retiren los beneficios simplemente modificando los planes. En Lockheed Corp. v. Spink una mayoría de siete jueces sostuvo que un empleador podía alterar un plan, para privar a un hombre de 61 años de los beneficios completos cuando fuera recontratado, sin estar sujeto a deberes fiduciarios de preservar lo que se le había prometido originalmente al empleado. [183] En disidencia, Breyer J y Souter J se reservaron cualquier opinión sobre esos "asuntos altamente técnicos e importantes". [184] Los pasos para terminar un plan dependen de si es individual o multipatronal, y en Mead Corp. v. Tilley una mayoría de la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos sostuvo que los empleadores podían recuperar los beneficios excedentes pagados a los planes de pensiones una vez que se cumplieran las condiciones de la PBGC . Stevens J , en su opinión disidente, sostuvo que se deben satisfacer todos los pasivos contingentes y futuros. [185]En cuarto lugar, como principio general, los empleados o beneficiarios no pueden sufrir discriminación o perjuicio alguno por "la consecución de ningún derecho" en virtud de un plan. [186] En quinto lugar, los administradores están sujetos a responsabilidades de competencia y lealtad, llamadas " deberes fiduciarios ". [187] Según el §1102, un fiduciario es cualquier persona que administra un plan, sus fideicomisarios y los administradores de inversiones a quienes se les delega el control. Según el §1104, los fiduciarios deben seguir un estándar de persona " prudente ", que involucra tres componentes principales. Primero, un fiduciario debe actuar "de acuerdo con los documentos e instrumentos que rigen el plan". [188] Segundo, deben actuar con "cuidado, habilidad y diligencia", incluyendo "diversificar las inversiones del plan" para "minimizar el riesgo de grandes pérdidas". [189] La responsabilidad por descuido se extiende a hacer declaraciones engañosas sobre los beneficios, [190] y ha sido interpretada por el Departamento de Trabajo como que implica un deber de votar sobre los poderes cuando se compran acciones corporativas y publicar una declaración de política de inversión. [191] En tercer lugar, y codificando principios equitativos fundamentales, un fiduciario debe evitar cualquier posibilidad de un conflicto de intereses . [192] Los fiduciarios deben actuar "únicamente en interés de los participantes ... con el propósito exclusivo de proporcionar beneficios" con "gastos razonables", [193] y evitando específicamente el trato en beneficio propio con una "parte interesada" relacionada. [194] Por ejemplo, en Donovan v. Bierwirth , el Segundo Circuito sostuvo que los fideicomisarios de un fondo de pensiones que poseía acciones en la empresa de los empleados cuando se lanzó una oferta pública de adquisición , debido a que enfrentaban un posible conflicto de intereses , tenían que obtener asesoramiento legal independiente sobre cómo votar o posiblemente abstenerse. [195] Sin embargo, la Corte Suprema ha restringido los recursos para estos deberes a fin de desfavorecer los daños. [196] En estos campos, según el §1144, ERISA 1974 "reemplazará todas y cada una de las leyes estatales en la medida en que puedan estar ahora o en el futuro relacionadas con cualquier plan de beneficios para empleados". [197] Por lo tanto, ERISA no siguió el modelo de la Ley de Normas Laborales Justas de 1938 o la Ley de Licencia Familiar y Médica de 1993 , que alientan a los estados a legislar para mejorar la protección de los empleados, más allá del mínimo.La regla de prelación llevó a la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidospara derribar una ley de Nueva York que requería dar beneficios a empleadas embarazadas en los planes ERISA . [198] Sostuvo que un caso bajo la ley de Texas por daños y perjuicios por negar la adquisición de los beneficios fue preempted, por lo que el demandante solo tenía recursos ERISA . [199] Derribó una ley de Washington que alteraba quién recibiría la designación de seguro de vida en caso de muerte. [200] Sin embargo, bajo §1144(b)(2)(A) esto no afecta a "ninguna ley de ningún Estado que regule seguros, banca o valores ". Así, la Corte Suprema también ha declarado válida una ley de Massachusetts que requería que la salud mental estuviera cubierta por las pólizas de salud grupales del empleador. [201] Pero derribó un estatuto de Pensilvania que prohibía a los empleadores subrogarse en reclamos (potencialmente más valiosos) de los empleados por seguros después de accidentes. [202] Más recientemente, los tribunales han mostrado una mayor voluntad de evitar que las leyes sean reemplazadas, [203] sin embargo, los tribunales aún no han adoptado el principio de que la ley estatal no es reemplazada o "reemplazada" si es más protectora para los empleados que un mínimo federal.

.jpg/440px-Bernie_Sanders_in_East_Los_Angeles_(27211671695).jpg)

Los derechos más importantes que no cubría la ERISA de 1974 eran los de quién controla las inversiones y los valores que compran los beneficiarios con sus ahorros para la jubilación. La forma más grande de fondo de jubilación se ha convertido en el 401(k) . A menudo, se trata de una cuenta individual que establece un empleador y luego se delega en una empresa de gestión de inversiones , como Vanguard , Fidelity , Morgan Stanley o BlackRock , la tarea de negociar los activos del fondo. Por lo general, también votan sobre las acciones corporativas, con la ayuda de una empresa de "asesoramiento por poder" como ISS o Glass Lewis . Según la ERISA de 1974 §1102(a), [206] un plan simplemente debe tener fiduciarios nombrados que tengan "autoridad para controlar y gestionar la operación y administración del plan", seleccionados por "una organización de empleadores o empleados" o ambos conjuntamente. Por lo general, estos fiduciarios o administradores delegarán la gestión a una empresa profesional, en particular porque, según la §1105(d), si lo hacen, no serán responsables de los incumplimientos de las obligaciones de un administrador de inversiones. [207] Estos gestores de inversiones compran una gama de activos, en particular acciones corporativas que tienen derechos de voto, así como bonos del gobierno , bonos corporativos , materias primas , bienes raíces o derivados . Los derechos sobre esos activos están en la práctica monopolizados por los gestores de inversiones, a menos que los fondos de pensiones se hayan organizado para realizar la votación internamente o para instruir a sus gestores de inversiones. Dos tipos principales de fondos de pensiones que hacen esto son los planes Taft-Hartley organizados por sindicatos y los planes de pensiones públicos estatales . Según la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales enmendada de 1935 §302(c)(5)(B), un plan negociado por un sindicato tiene que ser gestionado conjuntamente por representantes de empleadores y empleados. [208] Aunque muchos fondos de pensiones locales no están consolidados y han tenido avisos de financiación críticos del Departamento de Trabajo , [209] más fondos con representación de los empleados garantizan que los derechos de voto corporativos se emitan de acuerdo con las preferencias de sus miembros. Las pensiones públicas estatales suelen ser más grandes y tienen un mayor poder de negociación para utilizar en nombre de sus miembros. Los planes de pensiones estatales revelan invariablemente la forma en que se seleccionan los fideicomisarios. En 2005, en promedio, más de un tercio de los fideicomisarios fueron elegidos por empleados o beneficiarios. [210] Por ejemplo, el Código de Gobierno de California§20090 requiere que su fondo de pensiones de empleados públicos, CalPERS, tenga 13 miembros en su junta, 6 elegidos por empleados y beneficiarios. Sin embargo, solo los fondos de pensiones de tamaño suficiente han actuado para reemplazar la votación de los gerentes de inversiones . Además, ninguna legislación general requiere derechos de voto para los empleados en los fondos de pensiones, a pesar de varias propuestas. [211] Por ejemplo, la Ley de Democracia en el Lugar de Trabajo de 1999 , patrocinada por Bernie Sanders entonces en la Cámara de Representantes de los EE. UU ., habría requerido que todos los planes de pensiones de un solo empleador tuvieran fideicomisarios designados de manera igualitaria por los empleadores y los representantes de los empleados. [204] Además, actualmente no existe ninguna legislación que impida que los gerentes de inversiones voten con el dinero de otras personas, ya que la Ley Dodd-Frank de 2010 §957 prohibió a los corredores-distribuidores votar sobre cuestiones significativas sin instrucciones. [212] Esto significa que los votos en las corporaciones más grandes que compran los ahorros para la jubilación de las personas son ejercidos abrumadoramente por administradores de inversiones, cuyos intereses potencialmente entran en conflicto con los intereses de los beneficiarios en materia de derechos laborales , salarios justos , seguridad laboral o política de pensiones.

La Ley de Seguridad y Salud Ocupacional , [213] promulgada en 1970 por el presidente Richard Nixon , crea normas específicas para la seguridad en el lugar de trabajo. La ley ha generado años de litigios por parte de grupos industriales que han desafiado las normas que limitan la cantidad de exposición permitida a sustancias químicas como el benceno . La ley también prevé la protección de los "denunciantes" que se quejan a las autoridades gubernamentales sobre condiciones inseguras, al tiempo que permite a los trabajadores el derecho a negarse a trabajar en condiciones inseguras en determinadas circunstancias. La ley permite a los estados asumir la administración de la OSHA en sus jurisdicciones, siempre que adopten leyes estatales al menos tan protectoras de los derechos de los trabajadores como las de la ley federal. Más de la mitad de los estados lo han hecho.

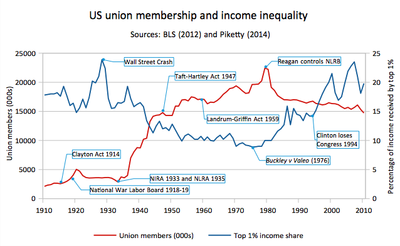

El derecho central en la ley laboral , más allá de los estándares mínimos de salario, horas, pensiones, seguridad o privacidad, es participar y votar en la gobernanza del lugar de trabajo. [215] El modelo estadounidense se desarrolló a partir de la Ley Antimonopolio Clayton de 1914 , [216] que declaró que "el trabajo de un ser humano no es una mercancía o artículo de comercio" y tenía como objetivo sacar las relaciones laborales del alcance de los tribunales hostiles a la negociación colectiva. Al carecer de éxito, la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935 cambió el modelo básico, que se mantuvo durante el siglo XX. Reflejando la " desigualdad del poder de negociación entre los empleados ... y los empleadores que están organizados en la corporación u otras formas de asociación de propiedad", [217] la NLRA de 1935 codificó los derechos básicos de los empleados para organizar un sindicato , requiere que los empleadores negocien de buena fe (al menos en el papel) después de que un sindicato tenga apoyo mayoritario, vincula a los empleadores a los convenios colectivos y protege el derecho a emprender acciones colectivas , incluida la huelga. La afiliación sindical, la negociación colectiva y el nivel de vida aumentaron rápidamente hasta que el Congreso impuso la Ley Taft-Hartley de 1947. Sus enmiendas permitieron a los estados aprobar leyes que restringían los acuerdos para que todos los empleados de un lugar de trabajo se sindicalizaran, prohibían las acciones colectivas contra los empleadores asociados e introdujeron una lista de prácticas laborales injustas para los sindicatos, así como para los empleadores. Desde entonces, la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos decidió desarrollar una doctrina según la cual las reglas de la NLRA de 1935 prevalecían sobre cualquier otra regla estatal si una actividad estaba "discutiblemente sujeta" a sus derechos y deberes. [218] Si bien se les prohibió a los estados actuar como " laboratorios de la democracia ", y en particular porque los sindicatos fueron objeto de ataques a partir de 1980 y la afiliación disminuyó, la NLRA de 1935 ha sido criticada como un "estatuto fallido" a medida que la legislación laboral estadounidense se "osificaba". [219] Esto ha llevado a experimentos más innovadores entre los estados, las corporaciones progresistas y los sindicatos para crear derechos de participación directa, incluido el derecho a votar o codeterminar a los directores de las juntas corporativas y elegir consejos de trabajo con derechos vinculantes sobre cuestiones del lugar de trabajo.

La libertad de asociación en los sindicatos siempre ha sido fundamental para el desarrollo de la sociedad democrática y está protegida por la Primera Enmienda de la Constitución . [220] En la historia colonial temprana , los sindicatos fueron suprimidos rutinariamente por el gobierno. Los casos registrados incluyen conductores de carros que fueron multados por hacer huelga en 1677 en la ciudad de Nueva York, y carpinteros procesados como criminales por hacer huelga en Savannah , Georgia en 1746. [221] Sin embargo, después de la Revolución estadounidense , los tribunales se apartaron de los elementos represivos del derecho consuetudinario inglés . El primer caso reportado, Commonwealth v. Pullis en 1806, encontró a los zapateros de Filadelfia culpables de "una combinación para aumentar sus salarios". [222] Sin embargo, los sindicatos continuaron y la primera federación de sindicatos se formó en 1834, el National Trades' Union , con el objetivo principal de una jornada laboral de 10 horas. [223] En 1842, la Corte Suprema de Massachusetts sostuvo en Commonwealth v. Hunt que una huelga de la Boston Journeymen Bootmakers' Society para obtener salarios más altos era legal. [224] El presidente de la Corte Suprema Shaw sostuvo que las personas "son libres de trabajar para quien quieran, o de no trabajar, si así lo prefieren" y "de acordar juntos ejercer sus propios derechos reconocidos". La abolición de la esclavitud por la Proclamación de Emancipación de Abraham Lincoln durante la Guerra Civil estadounidense fue necesaria para crear derechos genuinos para organizarse, pero no fue suficiente para garantizar la libertad de asociación. Usando la Ley Sherman de 1890 , que tenía como objetivo romper los cárteles comerciales, la Corte Suprema impuso una orden judicial a los trabajadores en huelga de la Pullman Company y encarceló al líder y futuro candidato presidencial, Eugene Debs . [225] La Corte también permitió que los sindicatos fueran demandados por daños triples en Loewe v. Lawlor , un caso que involucraba a un sindicato de fabricantes de sombreros en Danbury, Connecticut . [226] El Presidente y el Congreso de los Estados Unidos respondieron aprobando la Ley Clayton de 1914 para eliminar a los trabajadores de la legislación antimonopolio . Luego, después de la Gran Depresión, se aprobó la Ley Nacional de Relaciones Laborales de 1935.para proteger positivamente el derecho a organizarse y emprender acciones colectivas. Después de eso, la ley se dedicó cada vez más a regular los asuntos internos de los sindicatos. La Ley Taft-Hartley de 1947 reguló cómo los miembros podían afiliarse a un sindicato, y la Ley de Información y Divulgación de Información Laboral de 1959 creó una "carta de derechos" para los miembros de los sindicatos.