Haití , [b] oficialmente la República de Haití , [c] [d] es un país en la isla de La Española en el mar Caribe , al este de Cuba y Jamaica , y al sur de las Bahamas . Ocupa las tres octavas partes occidentales de la isla, que comparte con la República Dominicana . [17] [18] Haití es el tercer país más grande del Caribe , y con una población estimada de 11,4 millones, es el país caribeño más poblado. [19] [20] La capital y ciudad más grande es Puerto Príncipe .

La isla fue habitada originalmente por el pueblo taíno . [21] Los primeros europeos llegaron en diciembre de 1492 durante el primer viaje de Cristóbal Colón , [22] estableciendo el primer asentamiento europeo en América , La Navidad , en lo que ahora es la costa noreste de Haití. [23] [24] [25] [26] La isla formó parte del Imperio español hasta 1697, cuando la parte occidental fue cedida a Francia y posteriormente rebautizada como Saint-Domingue . Los colonos franceses establecieron plantaciones de caña de azúcar , trabajadas por esclavos traídos de África, lo que convirtió a la colonia en una de las más ricas del mundo. [ cita requerida ]

En medio de la Revolución Francesa , personas esclavizadas, cimarrones y personas libres de color lanzaron la Revolución Haitiana (1791-1804), liderada por un ex esclavo y general del ejército francés , Toussaint Louverture . Las fuerzas de Napoleón fueron derrotadas por el sucesor de Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines (más tarde emperador Jacques I), quien declaró la soberanía de Haití el 1 de enero de 1804, lo que llevó a una masacre de los franceses . Haití se convirtió en el primer estado independiente del Caribe , la segunda república de las Américas, el primer país de las Américas en abolir oficialmente la esclavitud y el único país en la historia establecido por una revuelta de esclavos . [27] [28] [29]

El primer siglo de la independencia se caracterizó por la inestabilidad política, el aislamiento internacional, los agobiantes pagos de la deuda a Francia y una costosa guerra con la vecina República Dominicana. La volatilidad política y la influencia económica extranjera provocaron una ocupación estadounidense de 1915 a 1934. [30] Una serie de presidencias inestables dieron paso a casi tres décadas de dictadura bajo la familia Duvalier (1957-1986), que trajo consigo violencia sancionada por el Estado, corrupción y estancamiento económico. Tras un golpe de Estado en 2004 , las Naciones Unidas intervinieron para estabilizar el país. En 2010, Haití sufrió un catastrófico terremoto , seguido de un brote mortal de cólera . Con su situación económica en deterioro, [31] el país ha experimentado una crisis socioeconómica y política marcada por disturbios y protestas, hambre generalizada y aumento de la actividad de las pandillas. [32] A mayo de 2024, Haití no tiene funcionarios gubernamentales electos restantes y ha sido descrito como un estado fallido . [33] [34]

Haití es miembro fundador de las Naciones Unidas , la Organización de los Estados Americanos (OEA), [35] la Asociación de Estados del Caribe [36] y la Organización Internacional de la Francofonía . Además de CARICOM , es miembro del Fondo Monetario Internacional , [37] la Organización Mundial del Comercio [38] y la Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños . Históricamente pobre y políticamente inestable, Haití tiene el índice de desarrollo humano más bajo de las Américas. [39]

Haití (también anteriormente Hayti ) [d] proviene de la lengua indígena taína y significa "tierra de altas montañas"; [40] era el nombre nativo [e] de toda la isla de La Española . El nombre fue restaurado por el revolucionario haitiano Jean-Jacques Dessalines como el nombre oficial de Saint-Domingue independiente, como un tributo a los predecesores amerindios. [44]

En francés, la ï en Ha ï ti tiene una marca diacrítica (usada para mostrar que la segunda vocal se pronuncia por separado, como en la palabra na ï ve ), mientras que la H es muda. [45] (En inglés, esta regla para la pronunciación a menudo se ignora, por lo que se usa la ortografía Haití ). Hay diferentes anglicizaciones para su pronunciación, como HIGH-ti , high-EE-ti y haa-EE-ti , que todavía se usan, pero HAY-ti es la más extendida y mejor establecida. [46] En francés, el apodo de Haití significa la "Perla de las Antillas" ( La Perle des Antilles ) debido tanto a su belleza natural [47] como a la cantidad de riqueza que acumuló para el Reino de Francia . [48] En criollo haitiano , se escribe y se pronuncia con y pero sin H : Ayiti . Otra teoría sobre el nombre Haití es su origen en la tradición africana; En lengua fon, una de las más habladas por los bossales (haitianos nacidos en África), Ayiti-Tomè significa: “Desde hoy esta tierra es nuestra tierra”. [ cita requerida ]

En la comunidad haitiana el país tiene múltiples apodos: Ayiti-Toma (por su origen en Ayiti Tomè), Ayiti-Cheri (Ayiti mi querida), Tè-Desalin (Tierra de Dessalines) o Lakay (Hogar). [ cita requerida ]

La isla de La Española , de la que Haití ocupa las tres octavas partes occidentales, [17] [18] ha estado habitada desde hace unos 6.000 años por nativos americanos que se cree que llegaron desde América Central o del norte de América del Sur. Se cree que estos pueblos de la Edad Arcaica eran en gran parte cazadores-recolectores. Durante el primer milenio a. C. , los antepasados de habla arahuaca del pueblo taíno comenzaron a migrar al Caribe. A diferencia de los pueblos arcaicos, practicaban la producción intensiva de cerámica y la agricultura. La evidencia más temprana de los antepasados del pueblo taíno en La Española es la cultura ostionoide, que data de alrededor del año 600 d. C. [49]

En la sociedad taína, la unidad más grande de organización política estaba liderada por un cacique , o jefe, como los entendían los europeos. En el momento del contacto europeo, la isla de La Española estaba dividida entre cinco caciques: los Magua en el noreste, los Marien en el noroeste, los Jaragua en el suroeste, los Maguana en las regiones centrales del Cibao y los Higüey en el sureste. [50] [51]

Entre los artefactos culturales taínos se encuentran pinturas rupestres en varios lugares del país, que se han convertido en símbolos nacionales de Haití y atracciones turísticas. La actual Léogâne , que comenzó como una ciudad colonial francesa en el suroeste, se encuentra al lado de la antigua capital del cacique de Xaragua. [52]

El navegante Cristóbal Colón desembarcó en Haití el 6 de diciembre de 1492, en una zona que llamó Môle-Saint-Nicolas , [53] y reclamó la isla para la Corona de Castilla . Diecinueve días después, su barco, el Santa María, encalló cerca del actual emplazamiento de Cap-Haïtien . Colón dejó 39 hombres en la isla, que fundaron el asentamiento de La Navidad el 25 de diciembre de 1492. [54] Las relaciones con los pueblos nativos, inicialmente buenas, se rompieron y los colonos fueron posteriormente asesinados por los taínos. [55]

Los marineros eran portadores de enfermedades infecciosas endémicas de Eurasia , que causaron epidemias que mataron a un gran número de nativos. [56] [57] La primera epidemia de viruela registrada en América estalló en La Española en 1507. [58] Sus números se redujeron aún más por la dureza del sistema de encomiendas , en el que los españoles obligaban a los nativos a trabajar en minas de oro y plantaciones. [59] [55]

Los españoles aprobaron las Leyes de Burgos (1512-1513), que prohibían el maltrato a los indígenas, avalaban su conversión al catolicismo [60] y daban un marco legal a las encomiendas . Los indígenas eran llevados a estos sitios para trabajar en plantaciones o industrias específicas. [61]

A medida que los españoles reorientaron sus esfuerzos de colonización hacia las mayores riquezas de América Central y del Sur, La Española se redujo en gran medida a un puesto comercial y de reabastecimiento de combustible. Como resultado, la piratería se generalizó, alentada por las potencias europeas hostiles a España, como Francia (con base en Île de la Tortue ) e Inglaterra. [55] Los españoles abandonaron en gran medida el tercio occidental de la isla, centrando su esfuerzo de colonización en los dos tercios orientales. [62] [54] Así, la parte occidental de la isla fue poblada gradualmente por bucaneros franceses ; entre ellos se encontraba Bertrand d'Ogeron, que logró cultivar tabaco y reclutó a muchas familias coloniales francesas de Martinica y Guadalupe . [63] En 1697, Francia y España resolvieron sus hostilidades en la isla mediante el Tratado de Ryswick de 1697, que dividió La Española entre ellos. [64] [54]

Francia recibió el tercio occidental y posteriormente lo llamó Saint-Domingue, el equivalente francés de Santo Domingo , la colonia española en La Española . [65] Los franceses comenzaron a crear plantaciones de azúcar y café, trabajadas por un gran número de esclavos importados de África , y Saint-Domingue creció hasta convertirse en su posesión colonial más rica, [64] [54] generando el 40% del comercio exterior de Francia y duplicando la generación de riqueza de todas las colonias de Inglaterra, juntas. [66]

Los colonos franceses eran superados en número por los esclavos en una proporción de casi 10 a 1. [64] Según el censo de 1788, la población de Haití estaba formada por casi 25.000 europeos, 22.000 negros libres y 700.000 africanos esclavos. [67] En contraste, en 1763 la población blanca del Canadá francés , un territorio mucho más grande, contaba con sólo 65.000 personas. [68] En el norte de la isla, los esclavos pudieron conservar muchos vínculos con las culturas, la religión y el idioma africanos; estos vínculos se renovaban continuamente con los africanos recién importados. Algunos africanos occidentales esclavos se aferraron a sus creencias tradicionales vudú sincretizándolas en secreto con el catolicismo. [54]

Los franceses promulgaron el Code Noir ("Código Negro"), preparado por Jean-Baptiste Colbert y ratificado por Luis XIV , que establecía reglas sobre el tratamiento de los esclavos y las libertades permisibles. [69] Saint-Domingue ha sido descrita como una de las colonias esclavistas más brutalmente eficientes; a fines del siglo XVIII suministraba dos tercios de los productos tropicales de Europa, mientras que un tercio de los africanos recién importados moría en pocos años. [70] Muchas personas esclavizadas murieron de enfermedades como la viruela y la fiebre tifoidea . [71] Tenían bajas tasas de natalidad , [72] y hay evidencia de que algunas mujeres abortaron fetos en lugar de dar a luz a niños dentro de los lazos de la esclavitud . [73] El medio ambiente de la colonia también sufrió, ya que los bosques fueron talados para dar paso a plantaciones y la tierra fue trabajada en exceso para extraer el máximo beneficio para los propietarios de plantaciones franceses. [54]

Al igual que en su colonia de Luisiana , el gobierno colonial francés permitió algunos derechos a las personas libres de color ( gens de couleur ), los descendientes de raza mixta de los colonos europeos varones y las mujeres esclavizadas africanas (y más tarde, las mujeres de raza mixta). [64] Con el tiempo, muchos fueron liberados de la esclavitud y establecieron una clase social separada . Los padres blancos criollos franceses con frecuencia enviaban a sus hijos mestizos a Francia para su educación. Algunos hombres de color fueron admitidos en el ejército. Más personas libres de color vivían en el sur de la isla, cerca de Puerto Príncipe , y muchos se casaron entre sí dentro de su comunidad. [64] Con frecuencia trabajaban como artesanos y comerciantes, y comenzaron a poseer algunas propiedades, incluidas personas esclavizadas. [54] [64] Las personas libres de color solicitaron al gobierno colonial que ampliara sus derechos. [64]

La brutalidad de la vida esclava llevó a muchas personas en cautiverio a escapar a regiones montañosas, donde establecieron sus propias comunidades autónomas y se hicieron conocidos como cimarrones . [54] Un líder cimarrón, François Mackandal , lideró una rebelión en la década de 1750; sin embargo, más tarde fue capturado y ejecutado por los franceses. [64]

Inspirados por la Revolución Francesa de 1789 y los principios de los derechos del hombre , los colonos franceses y las personas libres de color presionaron por una mayor libertad política y más derechos civiles . [69] Las tensiones entre estos dos grupos llevaron al conflicto, ya que Vincent Ogé creó una milicia de personas de color libres en 1790 , lo que resultó en su captura, tortura y ejecución. [54] Al percibir una oportunidad, en agosto de 1791 se establecieron los primeros ejércitos de esclavos en el norte de Haití bajo el liderazgo de Toussaint Louverture inspirado por el houngan (sacerdote) vudú Boukman, y respaldado por los españoles en Santo Domingo; pronto estalló una rebelión de esclavos en toda regla en toda la colonia. [54]

En 1792, el gobierno francés envió tres comisionados con tropas para restablecer el control; para construir una alianza con la gens de couleur y las personas esclavizadas, los comisionados Léger-Félicité Sonthonax y Étienne Polverel abolieron la esclavitud en la colonia. [69] Seis meses después, la Convención Nacional , liderada por Maximilien de Robespierre y los jacobinos , aprobó la abolición y la extendió a todas las colonias francesas. [74]

Estados Unidos , que era una nueva república en sí misma, osciló entre apoyar o no a Toussaint Louverture y al país emergente de Haití, dependiendo de quién fuera presidente de los EE. UU. Washington, que era un poseedor de esclavos y aislacionista, mantuvo a los Estados Unidos neutral, aunque los ciudadanos estadounidenses privados a veces brindaron ayuda a los plantadores franceses que intentaban sofocar la revuelta. John Adams, un opositor vocal de la esclavitud, apoyó plenamente la revuelta de esclavos al proporcionar reconocimiento diplomático, apoyo financiero, municiones y buques de guerra (incluido el USS Constitution ) a partir de 1798. Este apoyo terminó en 1801 cuando Jefferson, otro presidente esclavista, asumió el cargo y llamó a la Marina de los EE. UU. [75] [76] [77]

Con la abolición de la esclavitud, Toussaint Louverture juró lealtad a Francia y luchó contra las fuerzas británicas y españolas que se habían aprovechado de la situación e invadieron Saint-Domingue. [78] [79] Los españoles se vieron obligados más tarde a ceder su parte de la isla a Francia según los términos de la Paz de Basilea en 1795, unificando la isla bajo un solo gobierno. Sin embargo, estalló una insurgencia contra el dominio francés en el este, y en el oeste hubo combates entre las fuerzas de Louverture y la gente libre de color liderada por André Rigaud en la Guerra de los Cuchillos (1799-1800). [80] [81] El apoyo de los Estados Unidos a los negros en la guerra contribuyó a su victoria sobre los mulatos. [82] Más de 25.000 blancos y negros libres abandonaron la isla como refugiados. [83]

Después de que Louverture creara una constitución separatista y se proclamara gobernador general vitalicio, Napoleón Bonaparte envió en 1802 una expedición de 20.000 soldados y otros tantos marineros [84] bajo el mando de su cuñado, Charles Leclerc , para reafirmar el control francés. Los franceses lograron algunas victorias, pero en pocos meses la mayor parte de su ejército había muerto de fiebre amarilla . [85] Finalmente, más de 50.000 soldados franceses murieron en un intento de recuperar la colonia, incluidos 18 generales. [86] Los franceses lograron capturar a Louverture, transportándolo a Francia para ser juzgado. Fue encarcelado en Fort de Joux , donde murió en 1803 por exposición y posiblemente tuberculosis . [70] [87]

Las personas esclavizadas, junto con las gens de couleur libres y sus aliados, continuaron su lucha por la independencia, lideradas por los generales Jean-Jacques Dessalines , Alexandre Pétion y Henry Christophe . [87] Los rebeldes finalmente lograron derrotar decisivamente a las tropas francesas en la batalla de Vertières el 18 de noviembre de 1803, estableciendo el primer estado en obtener con éxito la independencia a través de una revuelta de esclavos. [88] Bajo el mando general de Dessalines, los ejércitos haitianos evitaron la batalla abierta y, en su lugar, llevaron a cabo una exitosa campaña de guerrillas contra las fuerzas napoleónicas, trabajando con enfermedades como la fiebre amarilla para reducir el número de soldados franceses. [89] Más tarde ese año, Francia retiró sus 7.000 tropas restantes de la isla y Napoleón abandonó su idea de restablecer un imperio norteamericano, vendiendo Luisiana (Nueva Francia) a los Estados Unidos , en la Compra de Luisiana . [87]

A lo largo de la revolución, se estima que 20.000 soldados franceses sucumbieron a la fiebre amarilla, mientras que otros 37.000 murieron en acción , [90] superando el total de soldados franceses muertos en acción en varias campañas coloniales del siglo XIX en Argelia, México, Indochina, Túnez y África Occidental, que resultaron en aproximadamente 10.000 soldados franceses muertos en acción combinados. [91] Los británicos sufrieron 45.000 muertos. [92] Además, murieron 350.000 haitianos exesclavizados. [93] En el proceso, Dessalines se convirtió posiblemente en el comandante militar más exitoso en la lucha contra la Francia napoleónica. [94]

La independencia de Saint-Domingue fue proclamada bajo el nombre nativo 'Haití' por Jean-Jacques Dessalines el 1 de enero de 1804 en Gonaïves [95] [96] y fue proclamado "Emperador vitalicio" como Emperador Jacques I por sus tropas. [97] Dessalines al principio ofreció protección a los plantadores blancos y otros. [98] Sin embargo, una vez en el poder, ordenó el genocidio de casi todos los hombres, mujeres y niños blancos restantes; entre enero y abril de 1804, entre 3.000 y 5.000 blancos fueron asesinados, incluidos aquellos que habían sido amistosos y simpatizantes de la población negra. [99] Solo tres categorías de personas blancas fueron seleccionadas como excepciones y perdonadas: soldados polacos , la mayoría de los cuales habían desertado del ejército francés y luchado junto a los rebeldes haitianos; el pequeño grupo de colonos alemanes invitados a la región noroeste ; y un grupo de médicos y profesionales. [100] Según se informa, también se salvaron las personas que tenían conexiones con oficiales del ejército haitiano, así como las mujeres que aceptaron casarse con hombres no blancos. [101]

Temeroso del impacto potencial que la rebelión de esclavos podría tener en los estados esclavistas , el presidente estadounidense Thomas Jefferson se negó a reconocer la nueva república. Los políticos sureños, que eran un poderoso bloque de votantes en el Congreso estadounidense, impidieron el reconocimiento de Estados Unidos durante décadas hasta que se retiraron en 1861 para formar la Confederación . [102]

La revolución provocó una ola de emigración. [103] En 1809, 9.000 refugiados de Saint-Domingue, tanto plantadores blancos como personas de color, se establecieron en masa en Nueva Orleans , duplicando la población de la ciudad, tras haber sido expulsados de su refugio inicial en Cuba por las autoridades españolas. [104] Además, las personas esclavizadas recién llegadas se sumaron a la población africana de la ciudad. [105]

El sistema de plantación se restableció en Haití, aunque a cambio de un salario; sin embargo, muchos haitianos fueron marginados y resentidos por la forma autoritaria con que esto se aplicó en la política de la nueva nación. [87] El movimiento rebelde se dividió y Dessalines fue asesinado por sus rivales el 17 de octubre de 1806. [106] [ Enlace a la página exacta ] [87]

Después de la muerte de Dessalines, Haití se dividió en dos, con el Reino de Haití en el norte dirigido por Henri Christophe, que más tarde se declaró Enrique I , y una república en el sur centrada en Puerto Príncipe, dirigida por Alexandre Pétion , un homme de couleur . [108] [109] [110] [111] [87] Christophe estableció un sistema de corvée semifeudal , con un código educativo y económico rígido. [112] La república de Pétion era menos absolutista e inició una serie de reformas agrarias que beneficiaron a la clase campesina. [87] El presidente Pétion también brindó asistencia militar y financiera al líder revolucionario Simón Bolívar , que fueron fundamentales para permitirle liberar el Virreinato de Nueva Granada . [113] Mientras tanto, los franceses, que habían logrado mantener un control precario del este de La Española, fueron derrotados por los insurgentes liderados por Juan Sánchez Ramírez , y el área volvió al dominio español en 1809 después de la Batalla de Palo Hincado . [114]

_Portrait.jpg/440px-President_Jean-Pierre_Boyer_of_Haiti_(Hispaniola_Unification_Regime)_Portrait.jpg)

A partir de 1821, el presidente Jean-Pierre Boyer , también homme de couleur y sucesor de Pétion, reunificó la isla tras el suicidio de Henry Christophe. [54] [115] Después de que Santo Domingo declarara su independencia de España el 30 de noviembre de 1821, Boyer invadió, buscando unir toda la isla por la fuerza y poner fin a la esclavitud en Santo Domingo. [116]

En su esfuerzo por reactivar la economía agrícola para producir cultivos básicos , Boyer aprobó el Código Rural, que negaba a los trabajadores campesinos el derecho a abandonar la tierra, entrar en las ciudades o iniciar granjas o tiendas propias, lo que provocó mucho resentimiento ya que la mayoría de los campesinos deseaban tener sus propias granjas en lugar de trabajar en plantaciones. [117] [118]

A partir de septiembre de 1824, más de 6.000 afroamericanos emigraron a Haití, con transporte pagado por un grupo filantrópico estadounidense similar en función a la Sociedad Americana de Colonización y sus esfuerzos en Liberia . [119] Muchos encontraron las condiciones demasiado duras y regresaron a los Estados Unidos. [ cita requerida ]

En julio de 1825, el rey Carlos X de Francia , durante un período de restauración de la monarquía francesa , envió una flota para reconquistar Haití. Bajo presión, el presidente Boyer aceptó un tratado por el cual Francia reconoció formalmente la independencia del estado a cambio de un pago de 150 millones de francos . [54] Por una orden del 17 de abril de 1826, el rey de Francia renunció a sus derechos de soberanía y reconoció formalmente la independencia de Haití. [120] [121] [122] Los pagos forzados a Francia obstaculizaron el crecimiento económico de Haití durante años, exacerbados por el hecho de que muchos estados occidentales continuaron negándose al reconocimiento diplomático formal a Haití; Gran Bretaña reconoció la independencia haitiana en 1833, y Estados Unidos no hasta 1862. [54] Haití pidió préstamos importantes a bancos occidentales a tasas de interés extremadamente altas para pagar la deuda. Aunque el monto de las reparaciones se redujo a 90 millones en 1838, en 1900 el 80% del gasto del gobierno de Haití era pago de la deuda y el país no terminó de pagarla hasta 1947. [123] [87]

Después de perder el apoyo de la élite de Haití, Boyer fue derrocado en 1843, y Charles Rivière-Hérard lo reemplazó como presidente. [54] Las fuerzas nacionalistas dominicanas en el este de La Española lideradas por Juan Pablo Duarte tomaron el control de Santo Domingo el 27 de febrero de 1844. [54] Las fuerzas haitianas, que no estaban preparadas para un levantamiento significativo, capitularon ante los rebeldes, poniendo fin de manera efectiva al dominio haitiano en el este de La Española. En marzo, Rivière-Hérard intentó reimponer su autoridad, pero los dominicanos infligieron grandes pérdidas. [124] Rivière-Hérard fue destituido de su cargo por la jerarquía mulata y reemplazado por el anciano general Philippe Guerrier , quien asumió la presidencia el 3 de mayo de 1844. [ cita requerida ]

Guerrier murió en abril de 1845 y fue sucedido por el general Jean-Louis Pierrot . [125] El deber más urgente de Pierrot como nuevo presidente era controlar las incursiones de los dominicanos, que estaban acosando a las tropas haitianas. [125] Las cañoneras dominicanas también estaban haciendo depredaciones en las costas de Haití. [125] El presidente Pierrot decidió abrir una campaña contra los dominicanos, a quienes consideraba simplemente como insurgentes; sin embargo, la ofensiva haitiana de 1845 fue detenida en la frontera. [124]

El 1 de enero de 1846, Pierrot anunció una nueva campaña para restablecer la soberanía haitiana sobre la parte oriental de La Española, pero sus oficiales y hombres recibieron esta nueva convocatoria con desprecio. [124] Así, un mes después, febrero de 1846, cuando Pierrot ordenó a sus tropas marchar contra los dominicanos, el ejército haitiano se amotinó y sus soldados proclamaron su derrocamiento como presidente de la república. [124] Como la guerra contra los dominicanos se había vuelto muy impopular en Haití, estaba más allá del poder del nuevo presidente, el general Jean-Baptiste Riché , organizar otra invasión. [124]

El 27 de febrero de 1847, el presidente Riché murió después de sólo un año en el poder y fue reemplazado por un oscuro oficial, el general Faustin Soulouque . [54] Durante los primeros dos años de la administración de Soulouque, las conspiraciones y la oposición que enfrentó para retener el poder fueron tan múltiples que los dominicanos tuvieron un respiro adicional para consolidar su independencia. [124] Pero, cuando en 1848 Francia finalmente reconoció a la República Dominicana como un estado libre e independiente y firmó provisionalmente un tratado de paz, amistad, comercio y navegación, Haití protestó de inmediato, alegando que el tratado era un ataque a su propia seguridad. [124] Soulouque decidió invadir la nueva República antes de que el gobierno francés pudiera ratificar el tratado. [124]

El 21 de marzo de 1849, los soldados haitianos atacaron la guarnición dominicana en Las Matas . Los desmoralizados defensores no ofrecieron casi resistencia antes de abandonar sus armas. Soulouque siguió adelante y capturó San Juan . Esto dejó solo la ciudad de Azua como el bastión dominicano restante entre el ejército haitiano y la capital. El 6 de abril, Azua cayó ante el ejército haitiano de 18.000 hombres, con un contraataque dominicano de 5.000 hombres que no logró expulsarlos. [78] El camino a Santo Domingo ahora estaba despejado. Pero las noticias del descontento existente en Puerto Príncipe, que llegaron a Soulouque, detuvieron su avance y lo obligaron a regresar con el ejército a su capital. [126]

Envalentonados por la repentina retirada del ejército haitiano, los dominicanos contraatacaron. Su flotilla llegó hasta Dame-Marie , en la costa oeste de Haití, donde saquearon e incendiaron la ciudad. [126] Después de otra campaña haitiana en 1855, Gran Bretaña y Francia intervinieron y obtuvieron un armisticio en favor de los dominicanos, que declararon su independencia como República Dominicana. [126]

Los sufrimientos que padecieron los soldados durante la campaña de 1855, y las pérdidas y sacrificios infligidos al país sin que se produjeran compensaciones ni resultados prácticos, provocaron un gran descontento. [126] En 1858 comenzó una revolución, liderada por el general Fabre Geffrard , duque de Tábara. En diciembre de ese año, Geffrard derrotó al ejército imperial y tomó el control de la mayor parte del país. [54] Como resultado, el emperador abdicó de su trono el 15 de enero de 1859. Faustin fue llevado al exilio y el general Geffrard lo sucedió como presidente. [ cita requerida ]

El período que siguió al derrocamiento de Soulouque y que se prolongó hasta el cambio de siglo fue turbulento para Haití, con repetidos episodios de inestabilidad política. El presidente Geffrard fue derrocado en un golpe de Estado en 1867, [127] al igual que su sucesor, Sylvain Salnave , en 1869. [128] Bajo la presidencia de Michel Domingue (1874-1876), las relaciones con la República Dominicana mejoraron drásticamente con la firma de un tratado en el que ambas partes reconocían la independencia de la otra. En este período también se produjo cierta modernización de la economía y la infraestructura, especialmente bajo las presidencias de Lysius Salomon (1879-1888) y Florvil Hyppolite (1889-1896). [129]

Las relaciones de Haití con las potencias extranjeras fueron a menudo tensas. En 1889, Estados Unidos intentó obligar a Haití a permitir la construcción de una base naval en Môle Saint-Nicolas , a lo que el presidente Hyppolite se resistió firmemente. [130] En 1892, el gobierno alemán apoyó la supresión del movimiento reformista de Anténor Firmin , y en 1897, los alemanes utilizaron la diplomacia de las cañoneras para intimidar y luego humillar al gobierno haitiano del presidente Tirésias Simon Sam (1896-1902) durante el asunto Lüders . [131]

En las primeras décadas del siglo XX, Haití atravesó una gran inestabilidad política y se encontraba endeudado con Francia, Alemania y los Estados Unidos. Se sucedieron una serie de presidencias de corta duración: el presidente Pierre Nord Alexis fue derrocado en 1908, [132] [133] al igual que su sucesor François C. Antoine Simon en 1911; [134] el presidente Cincinnatus Leconte (1911-12) murió en una explosión (posiblemente deliberada) en el Palacio Nacional; [135] Michel Oreste (1913-14) fue derrocado en un golpe de Estado, al igual que su sucesor Oreste Zamor en 1914. [136]

Alemania aumentó su influencia en Haití en este período, con una pequeña comunidad de colonos alemanes que ejercían una influencia desproporcionada en la economía de Haití. [137] [138] La influencia alemana provocó ansiedad en los Estados Unidos, que también habían invertido mucho en el país y cuyo gobierno defendía su derecho a oponerse a la interferencia extranjera en las Américas bajo la Doctrina Monroe . [54] [138] En diciembre de 1914, los estadounidenses retiraron $ 500,000 del Banco Nacional de Haití, pero en lugar de confiscarlos para ayudar a pagar la deuda, fueron retirados para su custodia en Nueva York, lo que le dio a los Estados Unidos el control del banco e impidió que otras potencias lo hicieran. Esto proporcionó una base financiera estable sobre la cual construir la economía y permitir que se pagara la deuda. [139]

En 1915, el nuevo presidente de Haití, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, intentó fortalecer su tenue gobierno con una ejecución masiva de 167 prisioneros políticos. La indignación por los asesinatos condujo a disturbios, y Sam fue capturado y asesinado por una turba de linchadores. [138] [140] Temiendo una posible intervención extranjera, o el surgimiento de un nuevo gobierno dirigido por el político haitiano antiestadounidense Rosalvo Bobo , el presidente Woodrow Wilson envió marines estadounidenses a Haití en julio de 1915. El USS Washington , bajo el mando del contralmirante Caperton , llegó a Puerto Príncipe en un intento de restablecer el orden y proteger los intereses estadounidenses. En cuestión de días, los marines habían tomado el control de la capital y sus bancos y aduanas. Los marines declararon la ley marcial y censuraron severamente a la prensa. En cuestión de semanas, se instaló un nuevo presidente haitiano pro-estadounidense, Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave , y se redactó una nueva constitución favorable a los intereses de los Estados Unidos. La constitución (redactada por el futuro presidente estadounidense Franklin D. Roosevelt ) incluía una cláusula que permitía, por primera vez, la propiedad extranjera de tierras en Haití, a lo que se oponía tenazmente la legislatura y la ciudadanía haitianas. [138] [141]

La ocupación mejoró algunas de las infraestructuras de Haití y centralizó el poder en Puerto Príncipe. [138] Se hicieron utilizables 1700 km de carreteras, se construyeron 189 puentes, se rehabilitaron muchos canales de irrigación, se construyeron hospitales, escuelas y edificios públicos y se llevó agua potable a las principales ciudades. [ cita requerida ] Se organizó la educación agrícola, con una escuela central de agricultura y 69 granjas en el país. [142] [ cita corta incompleta ] Sin embargo, muchos proyectos de infraestructura se construyeron utilizando el sistema de corvée que permitía al gobierno/fuerzas de ocupación sacar a las personas de sus hogares y granjas, a punta de pistola si era necesario, para construir carreteras, puentes, etc. por la fuerza, un proceso que fue profundamente resentido por los haitianos comunes. [143] [138] También se introdujo el sisal en Haití, y la caña de azúcar y el algodón se convirtieron en exportaciones importantes, impulsando la prosperidad. [144] Los tradicionalistas haitianos, con base en áreas rurales, se resistieron fuertemente a los cambios apoyados por Estados Unidos, mientras que las élites urbanas, típicamente mestizas, recibieron con agrado la creciente economía, pero querían un mayor control político. [54] Juntos ayudaron a asegurar el fin de la ocupación en 1934, bajo la presidencia de Sténio Vincent (1930-1941). [54] [145] Las deudas todavía estaban pendientes, aunque menos debido a la creciente prosperidad, y el asesor financiero general de los Estados Unidos manejó el presupuesto hasta 1941. [146] [54]

Los marines estadounidenses estaban imbuidos de un paternalismo especial hacia los haitianos, "expresado en la metáfora de la relación de un padre con sus hijos". [147] La oposición armada a la presencia estadounidense estuvo liderada por los cacos bajo el mando de Charlemagne Péralte ; su captura y ejecución en 1919 le valió el estatus de mártir nacional. [148] [54] [138] Durante las audiencias del Senado en 1921, el comandante del Cuerpo de Marines informó que, en los 20 meses de disturbios activos, 2.250 haitianos habían sido asesinados. Sin embargo, en un informe al Secretario de la Marina, informó que el número de muertos era de 3.250. [149] Los historiadores haitianos han afirmado que el número real era mucho mayor, pero la mayoría de los historiadores fuera de Haití no lo respaldan. [150]

Después de que las fuerzas estadounidenses se marcharan en 1934, el dictador dominicano Rafael Trujillo utilizó el sentimiento antihaitiano como herramienta nacionalista. En un suceso que se conoció como la Masacre del Perejil , ordenó a su ejército matar a los haitianos que vivían en el lado dominicano de la frontera. [151] [152] Se utilizaron pocas balas; en su lugar, entre 20.000 y 30.000 haitianos fueron apaleados y apuñalados con bayonetas, para luego ser conducidos al mar, donde los tiburones acabaron con lo que Trujillo había empezado. [153] La masacre indiscriminada se produjo durante un período de cinco días.

El presidente Vincent se volvió cada vez más dictatorial y renunció bajo presión estadounidense en 1941, siendo reemplazado por Élie Lescot (1941-1946). [154] En 1941, durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial , Lescot declaró la guerra a Japón (8 de diciembre), Alemania (12 de diciembre), Italia (12 de diciembre), Bulgaria (24 de diciembre), Hungría (24 de diciembre) y Rumania (24 de diciembre). [155] De estos seis países del Eje , solo Rumania correspondió, declarando la guerra a Haití el mismo día (24 de diciembre de 1941). [156] El 27 de septiembre de 1945, [157] Haití se convirtió en miembro fundador de las Naciones Unidas (la sucesora de la Liga de las Naciones , de la que Haití también fue miembro fundador). [158] [159]

En 1946 Lescot fue derrocado por los militares, y Dumarsais Estimé se convirtió más tarde en el nuevo presidente (1946-1950). [54] Intentó mejorar la economía y la educación, e impulsar el papel de los haitianos negros; sin embargo, mientras buscaba consolidar su gobierno, él también fue derrocado en un golpe de estado dirigido por Paul Magloire , quien lo reemplazó como presidente (1950-1956). [54] [160] Firmemente anticomunista, fue apoyado por los Estados Unidos; con una mayor estabilidad política, los turistas comenzaron a visitar Haití. [161] La zona costera de Puerto Príncipe fue remodelada para permitir que los pasajeros de cruceros caminaran hasta las atracciones culturales.

En 1956-57 Haití atravesó una grave agitación política; Magloire se vio obligado a dimitir y abandonar el país en 1956 y fue seguido por cuatro presidencias de corta duración. [54] En las elecciones de septiembre de 1957, François Duvalier fue elegido presidente de Haití. Conocido como 'Papa Doc' e inicialmente popular, Duvalier permaneció como presidente hasta su muerte en 1971. [162] Promovió los intereses negros en el sector público, donde con el tiempo, la gente de color había predominado como la élite urbana educada. [54] [163] Al no confiar en el ejército, a pesar de sus frecuentes purgas de oficiales considerados desleales, Duvalier creó una milicia privada conocida como Tontons Macoutes ("Cocos"), que mantenía el orden aterrorizando a la población y a los oponentes políticos. [162] [164] En 1964 Duvalier se proclamó 'Presidente vitalicio'; Un levantamiento contra su gobierno ese año en Jérémie fue violentamente reprimido, con los cabecillas ejecutados públicamente y cientos de ciudadanos mestizos de la ciudad asesinados. [162] La mayor parte de la clase educada y profesional comenzó a abandonar el país, y la corrupción se generalizó. [54] [162] Duvalier trató de crear un culto a la personalidad, identificándose con el barón Samedi , uno de los loa (o lwa ), o espíritus, del vudú haitiano . A pesar de los abusos bien publicitados bajo su gobierno, el firme anticomunismo de Duvalier le valió el apoyo de los estadounidenses, que proporcionaron ayuda al país. [162] [165]

En 1971, Duvalier murió y fue sucedido por su hijo Jean-Claude Duvalier , apodado "Baby Doc", quien gobernó hasta 1986. [166] [162] Continuó en gran medida las políticas de su padre, aunque frenó algunos de los peores excesos para cortejar la respetabilidad internacional. [54] El turismo, que había caído en picada en la época de Papa Doc, volvió a convertirse en una industria en crecimiento. [167] Sin embargo, a medida que la economía continuó decayendo, el control de Baby Doc sobre el poder comenzó a debilitarse. La población de cerdos de Haití fue sacrificada después de un brote de peste porcina a fines de la década de 1970, lo que causó dificultades a las comunidades rurales que los utilizaron como inversión. [54] [168] La oposición se hizo más vocal, reforzada por una visita al país del Papa Juan Pablo II en 1983, quien criticó públicamente al presidente. [169] Se produjeron manifestaciones en Gonaïves en 1985 que luego se extendieron por todo el país; Bajo presión de los Estados Unidos, Duvalier abandonó el país rumbo a Francia en febrero de 1986. [ cita requerida ]

En total, se estima que entre 40.000 y 60.000 haitianos fueron asesinados durante el reinado de los Duvalier. [170] Gracias a sus tácticas de intimidación y ejecuciones, muchos intelectuales haitianos huyeron, dejando al país con una fuga masiva de cerebros de la que todavía no se ha recuperado. [171]

Tras la marcha de Duvalier, el general Henri Namphy, líder del ejército, encabezó un nuevo Consejo Nacional de Gobierno . [54] Las elecciones previstas para noviembre de 1987 se cancelaron después de que decenas de habitantes fueran baleados en la capital por soldados y Tontons Macoutes . [172] [54] En 1988 se celebraron elecciones fraudulentas , en las que sólo votó el 4% de la ciudadanía. [ 173] [54] El presidente recién elegido, Leslie Manigat , fue derrocado unos meses después en el golpe de Estado haitiano de junio de 1988. [54] [174]

En septiembre de 1988 se produjo otro golpe , tras la masacre de San Juan Bosco , en la que murieron entre 13 y 50 personas que asistían a una misa dirigida por el destacado crítico del gobierno y sacerdote católico Jean-Bertrand Aristide . [174] [175] Posteriormente, el general Prosper Avril dirigió un régimen militar hasta marzo de 1990. [54] [176] [177]

Avril transfirió el poder al jefe del Estado Mayor del ejército, el general Hérard Abraham , el 10 de marzo de 1990. Abraham renunció al poder tres días después, convirtiéndose en el único líder militar de Haití durante el siglo XX en renunciar voluntariamente al poder. Posteriormente, Abraham ayudó a asegurar las elecciones generales haitianas de 1990-91 . [ cita requerida ]

En diciembre de 1990, Jean-Bertrand Aristide fue elegido presidente en las elecciones generales haitianas . Sin embargo, su ambiciosa agenda reformista preocupó a las élites y en septiembre del año siguiente fue derrocado por los militares, encabezados por Raoul Cédras , en el golpe de Estado haitiano de 1991. [54] [178] En medio de la agitación continua, muchos haitianos intentaron huir del país. [ 162] [54]

En septiembre de 1994, Estados Unidos negoció la salida de los líderes militares de Haití y la entrada pacífica de 20.000 tropas estadounidenses bajo la Operación Defender la Democracia . [162] Esto permitió la restauración del democráticamente elegido Jean-Bertrand Aristide como presidente, quien regresó a Haití en octubre para completar su mandato. [179] [180] Como parte del acuerdo, Aristide tuvo que implementar reformas de libre mercado en un intento de mejorar la economía haitiana, con resultados mixtos. [181] [54] En noviembre de 1994, el huracán Gordon azotó Haití, arrojando fuertes lluvias y creando inundaciones repentinas que provocaron deslizamientos de tierra. Gordon mató a unas 1.122 personas, aunque algunas estimaciones llegan hasta 2.200. [182] [183]

En 1995 se celebraron elecciones que ganó René Préval , con el 88% del voto popular, aunque con una baja participación. [184] [185] [54] Posteriormente, Aristide formó su propio partido, Fanmi Lavalas , y se produjo un estancamiento político; las elecciones de noviembre de 2000 devolvieron a Aristide a la presidencia con el 92% de los votos. [186] La elección había sido boicoteada por la oposición, entonces organizada en la Convergencia Democrática , debido a una disputa en las elecciones legislativas de mayo . En los años siguientes, hubo un aumento de la violencia entre facciones políticas rivales y abusos de los derechos humanos . [187] [188] Aristide pasó años negociando con la Convergencia Democrática sobre nuevas elecciones, pero la incapacidad de la Convergencia para desarrollar una base electoral suficiente hizo que las elecciones fueran poco atractivas. [ cita requerida ]

En 2004, estalló una revuelta contra Aristide en el norte de Haití. La rebelión llegó finalmente a la capital y Aristide se vio obligado a exiliarse. [187] [54] La naturaleza precisa de los acontecimientos es objeto de controversia; algunos, incluidos Aristide y su guardaespaldas, Franz Gabriel, afirmaron que fue víctima de un "nuevo golpe de Estado o secuestro moderno" por parte de las fuerzas estadounidenses. [187] [189] [190] Estas acusaciones fueron negadas por el gobierno estadounidense. [191] [187] A medida que la violencia política y el crimen seguían aumentando, se envió una Misión de Estabilización de las Naciones Unidas (MINUSTAH) para mantener el orden. [192] Sin embargo, la MINUSTAH resultó controvertida, ya que su enfoque periódicamente de mano dura para mantener la ley y el orden y varios casos de abusos, incluido el presunto abuso sexual de civiles, provocaron resentimiento y desconfianza entre los haitianos comunes. [193] [194] [54]

Boniface Alexandre asumió la autoridad interina hasta 2006, cuando René Préval fue reelegido presidente tras las elecciones . [192] [54] [195]

En medio del continuo caos político, una serie de desastres naturales azotaron Haití. En 2004, la tormenta tropical Jeanne rozó la costa norte, dejando 3.006 personas muertas en inundaciones y deslizamientos de tierra , principalmente en la ciudad de Gonaïves . [196] En 2008, Haití fue golpeado nuevamente por tormentas tropicales; la tormenta tropical Fay , el huracán Gustav , el huracán Hanna y el huracán Ike produjeron fuertes vientos y lluvias, lo que resultó en 331 muertes y alrededor de 800.000 personas necesitadas de ayuda humanitaria. [197] La situación producida por estas tormentas se intensificó por los precios ya altos de los alimentos y el combustible que habían causado una crisis alimentaria y disturbios políticos en abril de 2008. [198] [199] [54]

El 12 de enero de 2010, a las 16:53 hora local, Haití fue golpeado por un terremoto de magnitud -7,0 . Este fue el terremoto más severo del país en más de 200 años. [200] Se informó que el terremoto dejó entre 160.000 y 300.000 personas muertas y hasta 1,6 millones sin hogar, lo que lo convirtió en uno de los desastres naturales más mortíferos jamás registrados . [201] [202] También es uno de los terremotos más mortíferos jamás registrados. [203] La situación se vio agravada por un brote masivo de cólera posterior que se desencadenó cuando los desechos infectados con cólera de una estación de mantenimiento de la paz de las Naciones Unidas contaminaron el principal río del país, el Artibonite . [192] [204] [205] En 2017, se informó que aproximadamente 10.000 haitianos habían muerto y casi un millón habían enfermado. Tras años de negación, las Naciones Unidas pidieron disculpas en 2016, pero a partir de 2017 se han negado a reconocer la culpa, evitando así la responsabilidad financiera. [206][update]

Las elecciones generales estaban previstas para enero de 2010, pero se pospusieron debido al terremoto. [54] El 28 de noviembre de 2010 se celebraron elecciones para el senado, el parlamento y la primera vuelta de las elecciones presidenciales. La segunda vuelta entre Michel Martelly y Mirlande Manigat tuvo lugar el 20 de marzo de 2011, y los resultados preliminares, publicados el 4 de abril, nombraron a Michel Martelly como ganador. [207] [208] En 2011, tanto el ex dictador Jean-Claude Duvalier como Jean-Bertrand Aristide regresaron a Haití; los intentos de juzgar a Duvalier por crímenes cometidos bajo su gobierno fueron archivados tras su muerte en 2014. [209] [210] [211] [207] En 2013, el gobierno haitiano pidió a los gobiernos europeos que pagaran reparaciones por la esclavitud y establecieran una comisión oficial para la solución de los delitos pasados. [212] [213] Mientras tanto, después de continuar las disputas políticas con la oposición y las acusaciones de fraude electoral, Martelly aceptó dimitir en 2016 sin un sucesor en su lugar. [207] [214] Después de numerosos aplazamientos, en parte debido a los efectos del devastador huracán Matthew , se celebraron elecciones en noviembre de 2016. [215] [216] El vencedor, Jovenel Moïse del Partido Haitiano Tèt Kale , juró como presidente en 2017. [217] [218] Las protestas comenzaron el 7 de julio de 2018, en respuesta al aumento de los precios del combustible. Con el tiempo, estas protestas se convirtieron en demandas de renuncia del presidente Moïse. [219]

El 7 de julio de 2021, el presidente Moïse fue asesinado en un ataque a su residencia privada y la primera dama Martine Moïse fue hospitalizada. [220] En medio de la crisis política, el gobierno de Haití instaló a Ariel Henry como primer ministro interino y presidente interino el 20 de julio de 2021. [221] [222] El 14 de agosto de 2021, Haití sufrió otro gran terremoto , con muchas víctimas. [223] El terremoto también dañó las condiciones económicas de Haití y provocó un aumento de la violencia de las pandillas que, en septiembre de 2021, se había convertido en una guerra de pandillas de larga duración y otros delitos violentos dentro del país. [224] [225] En marzo de 2022, Haití todavía no tenía presidente, ni quórum parlamentario y un tribunal superior disfuncional debido a la falta de jueces. [221] En 2022, se intensificaron las protestas contra el gobierno y el aumento de los precios del combustible . [226] [227]

En 2023, los secuestros aumentaron un 72% con respecto al primer trimestre del año anterior. [228] Médicos, abogados y otros miembros ricos de la sociedad fueron secuestrados y retenidos para pedir rescate. [229] Muchas víctimas fueron asesinadas cuando no se cumplieron las demandas de rescate, lo que llevó a quienes tenían los medios para hacerlo a huir del país, lo que obstaculizó aún más los esfuerzos para sacar al país de la crisis. [229] Se estima que, en medio de la crisis, hasta el 20% del personal médico calificado había abandonado Haití a fines de 2023. [230]

En marzo de 2024, las pandillas le impidieron a Ariel Henry regresar a Haití, luego de una visita a Kenia . [231] Henry aceptó renunciar una vez que se formara un gobierno de transición. A partir de ese mes, casi la mitad de la población de Haití vivía bajo una inseguridad alimentaria aguda , según el Programa Mundial de Alimentos . [25] El 25 de abril de 2024, el Consejo Presidencial de Transición de Haití asumió el gobierno de Haití y está previsto que permanezca en el poder hasta 2026. [232] Michel Patrick Boisvert fue nombrado primer ministro interino. [232] El 3 de junio de 2024, el consejo nombró a Garry Conille como primer ministro interino.

Haití ocupa las tres octavas partes occidentales de La Española , la segunda isla más grande de las Antillas Mayores . Con 27 750 km² ( 10 710 millas cuadradas), Haití es el tercer país más grande del Caribe, detrás de Cuba y la República Dominicana , esta última comparte una frontera de 360 kilómetros (224 millas) con Haití. El país tiene una forma similar a la de una herradura y, debido a esto, tiene una costa desproporcionadamente larga, segunda en longitud (1771 km o 1100 millas) detrás de Cuba en las Antillas Mayores. [233] [234]

Haití es el país más montañoso del Caribe, su terreno está formado por montañas intercaladas con pequeñas llanuras costeras y valles fluviales. [235] El clima es tropical, con algunas variaciones según la altitud. El punto más alto es Pic la Selle , a 2.680 metros (8.793 pies). [22] [235] [54]

La región norte o Región Marien está formada por el Macizo del Norte y la Llanura del Norte . El Macizo del Norte es una extensión de la Cordillera Central en la República Dominicana. [54] Comienza en la frontera oriental de Haití, al norte del río Guayamouc , y se extiende hacia el noroeste a través de la península norte. Las tierras bajas de la Llanura del Norte se encuentran a lo largo de la frontera norte con la República Dominicana, entre el Macizo del Norte y el Océano Atlántico Norte.

La región central o Región de Artibonite está formada por dos llanuras y dos conjuntos de cadenas montañosas. La Meseta Central (Plateau Central) se extiende a lo largo de ambos lados del río Guayamouc, al sur del Macizo del Norte . Corre de sureste a noroeste. Al suroeste de la Meseta Central se encuentran las Montagnes Noires , cuya parte más noroccidental se fusiona con el Macizo del Norte . El valle más importante de Haití en términos de cultivos es la Plaine de l'Artibonite, que se encuentra entre las Montagnes Noires y la Chaîne des Matheux. [54] Esta región sostiene el río más largo del país, el Riviere l'Artibonite , que comienza en la región occidental de la República Dominicana y continúa durante la mayor parte de su longitud por el centro de Haití, donde luego desemboca en el Golfo de la Gonâve . [54] También en este valle se encuentra el segundo lago más grande de Haití, el Lago de Péligre , formado como resultado de la construcción de la presa de Péligre a mediados de la década de 1950. [236]

La región sur o región de Xaragua está formada por la Plaine du Cul-de-Sac (el sureste) y la montañosa península sur (la península de Tiburón ). La Plaine du Cul-de-Sac es una depresión natural que alberga los lagos salinos del país, como Trou Caïman y el lago más grande de Haití, Étang Saumatre . La cordillera de Chaîne de la Selle , una extensión de la cadena montañosa del sur de la República Dominicana (la Sierra de Baoruco), se extiende desde el Massif de la Selle en el este hasta el Massif de la Hotte en el oeste. [54]

Haití también incluye varias islas cercanas a la costa. La isla de Tortuga se encuentra frente a la costa norte de Haití. El distrito de La Gonâve se encuentra en la isla del mismo nombre, en el Golfo de la Gonâve ; la isla más grande de Haití, Gonâve, está moderadamente poblada por aldeanos rurales. Île à Vache se encuentra frente a la costa suroeste; también forman parte de Haití las Cayemites , ubicadas en el Golfo de Gonâve al norte de Pestel . La isla Navassa , ubicada a 40 millas náuticas (46 mi; 74 km) al oeste de Jérémie en la península suroeste de Haití, [237] está sujeta a una disputa territorial en curso con los Estados Unidos, que actualmente administran la isla. [238]

El clima de Haití es tropical con algunas variaciones según la altitud. [235] En Puerto Príncipe, la temperatura mínima promedio en enero varía de 23 °C (73,4 °F) a una máxima promedio de 31 °C (87,8 °F); en julio, de 25 a 35 °C (77 a 95 °F). El patrón de precipitaciones es variado, con lluvias más intensas en algunas de las tierras bajas y las laderas norte y este de las montañas. La estación seca de Haití ocurre de noviembre a enero.

Puerto Príncipe recibe una precipitación anual media de 1.370 mm (53,9 pulgadas). Hay dos estaciones lluviosas, de abril a junio y de octubre a noviembre. Haití sufre sequías periódicas e inundaciones, agravadas por la deforestación. Los huracanes son una amenaza y el país también es propenso a inundaciones y terremotos. [235]

Existen fallas ciegas asociadas al sistema de fallas Enriquillo-Plantain Garden sobre el que se encuentra Haití. [239] Después del terremoto de 2010, no hubo evidencia de ruptura superficial y los hallazgos de los geólogos se basaron en datos sismológicos, geológicos y de deformación del suelo. [240]

El límite norte de la falla es donde la placa tectónica del Caribe se desplaza hacia el este unos 20 mm (0,79 pulgadas) por año en relación con la placa norteamericana . El sistema de fallas de rumbo de la región tiene dos ramas en Haití, la falla Septentrional-Oriente en el norte y la falla Enriquillo-Plantain Garden en el sur. [ cita requerida ]

Un estudio de riesgo sísmico de 2007 señaló que la zona de falla Enriquillo-Plantain Garden podría estar al final de su ciclo sísmico y concluyó que un pronóstico del peor caso implicaría un terremoto de 7,2 Mw , similar en tamaño al terremoto de Jamaica de 1692. [241] Un equipo de estudio que realizó una evaluación de riesgo del sistema de fallas recomendó estudios de ruptura geológica histórica de "alta prioridad", ya que la falla estaba completamente bloqueada y había registrado pocos terremotos en los 40 años anteriores. [ 242] El terremoto de magnitud 7,0 de Haití de 2010 ocurrió en esta zona de falla el 12 de enero de 2010. [243]

Haití también tiene elementos raros como el oro , que se puede encontrar en la mina de oro de Mont Organisé . [244]

Haití no tiene volcanes activos en la actualidad. "En las montañas Terre-Neuve, a unos 12 kilómetros de Eaux Boynes, se conocen pequeñas intrusiones al menos del Oligoceno y probablemente del Mioceno . No se conoce ninguna otra actividad volcánica de una fecha tan reciente cerca de ninguna de las otras fuentes termales". [245]

La erosión del suelo liberada desde las cuencas superiores y la deforestación han causado inundaciones periódicas y graves, como la ocurrida, por ejemplo, el 17 de septiembre de 2004. A principios de mayo de ese año, las inundaciones habían matado a más de 3.000 personas en la frontera sur de Haití con la República Dominicana. [246]

Hace apenas 50 años, los bosques de Haití cubrían el 60% del país, pero esa cifra se ha reducido a la mitad, hasta llegar a una estimación actual de una cobertura arbórea del 30%. Esta estimación supone una marcada diferencia con la cifra errónea del 2% que se ha citado a menudo en el discurso sobre la condición ambiental del país. [247] Haití obtuvo una puntuación media en el Índice de Integridad del Paisaje Forestal de 2019 de 4,01/10, lo que lo situó en el puesto 137 a nivel mundial entre 172 países. [248]

Los científicos del Centro para la Red Internacional de Información sobre Ciencias de la Tierra de la Universidad de Columbia y del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente están trabajando en la Iniciativa Regenerativa de Haití, una iniciativa que tiene como objetivo reducir la pobreza y la vulnerabilidad a los desastres naturales mediante la restauración de los ecosistemas y la gestión sostenible de los recursos. [249]

Haití alberga cuatro ecorregiones: los bosques húmedos de La Española , los bosques secos de La Española , los bosques de pinos de La Española y los manglares de las Antillas Mayores . [250]

A pesar de su pequeño tamaño, el terreno montañoso de Haití y las múltiples zonas climáticas resultantes han dado lugar a una amplia variedad de vida vegetal. [251] Las especies de árboles notables incluyen el árbol del pan , el árbol de mango , la acacia , la caoba , la palma cocotera , la palma real y el cedro de las Indias Occidentales . [251] Los bosques antes eran mucho más extensos, pero han estado sujetos a una grave deforestación. [54]

La mayoría de las especies de mamíferos no son nativas, ya que fueron traídas a la isla desde la época colonial. [251] Sin embargo, hay varias especies nativas de murciélagos , así como la jutía endémica de La Española y el solenodonte de La Española . [251] También se pueden encontrar especies de ballenas y delfines en las costas de Haití.

Hay más de 260 especies de aves, 31 endémicas de La Española. [252] Las especies endémicas notables incluyen el trogón de La Española , el periquito de La Española , la tángara coronigris y la amazona de La Española . [252] También hay varias aves rapaces , así como pelícanos, ibis, colibríes y patos.

Los reptiles son comunes, con especies como la iguana rinoceronte , la boa haitiana , el cocodrilo americano y el geco . [253]

El gobierno de Haití es una república semipresidencial , un sistema multipartidista en el que el presidente de Haití es el jefe de Estado y es elegido directamente en elecciones populares celebradas cada cinco años. [54] [254] El primer ministro de Haití actúa como jefe de gobierno y es designado por el presidente, elegido del partido mayoritario en la Asamblea Nacional. [54] El poder ejecutivo es ejercido por el presidente y el primer ministro, quienes juntos constituyen el gobierno. [255]

El poder legislativo reside tanto en el gobierno como en las dos cámaras de la Asamblea Nacional de Haití , el Senado (Sénat) y la Cámara de Diputados (Chambre des Députés). [54] [235] El gobierno está organizado de manera unitaria , por lo que el gobierno central delega poderes a los departamentos sin necesidad de consentimiento constitucional. La estructura actual del sistema político de Haití fue establecida en la Constitución de Haití el 29 de marzo de 1987. [235]

La política haitiana ha sido polémica: desde su independencia, Haití ha sufrido 32 golpes de estado . [256] Haití es el único país del hemisferio occidental que ha experimentado una revolución esclavista exitosa ; sin embargo, una larga historia de opresión por parte de dictadores como François Duvalier y su hijo Jean-Claude Duvalier ha afectado notablemente la gobernanza y la sociedad de la república. Desde el final de la era Duvalier, Haití ha estado en transición hacia un sistema democrático. [54]

Administrativamente, Haití está dividido en diez departamentos . [235] Los departamentos se enumeran a continuación, con las capitales departamentales entre paréntesis.

Los departamentos se dividen a su vez en 42 distritos , 145 comunas y 571 secciones comunales , que sirven como divisiones administrativas de segundo y tercer nivel, respectivamente. [257] [258] [259]

Haití es miembro de una amplia gama de organizaciones internacionales y regionales, como las Naciones Unidas, CARICOM, la Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños , el Fondo Monetario Internacional , la Organización de los Estados Americanos , la Organización Internacional de la Francofonía , OPANAL y la Organización Mundial del Comercio . [235]

En febrero de 2012, Haití señaló que buscaría mejorar su estatus de observador a miembro asociado pleno de la Unión Africana (UA). [260] Se informó que la UA estaba planeando mejorar el estatus de Haití de observador a asociado en su cumbre de junio de 2013 [261] pero la solicitud aún no había sido ratificada en mayo de 2016. [262]

Haití tiene una fuerte historia militar que se remonta a la lucha anterior a la independencia. El Ejército Indígena es esencial en la construcción del Estado, la gestión de la tierra y las finanzas públicas. Hasta el siglo XX, todos los presidentes haitianos eran oficiales del ejército. Durante la intervención estadounidense, el ejército fue remodelado como Gendarmería de Haití y más tarde como Fuerza Armada de Haití (FAdH). A principios de la década de 1990, el ejército fue desmantelado inconstitucionalmente y reemplazado por la Policía Nacional de Haití (PNH). En 2018, el presidente Jovenel Moise reactivó la FAdH. [ cita requerida ]

El Ministerio de Defensa de Haití es el principal órgano de las fuerzas armadas. [263] Las antiguas Fuerzas Armadas de Haití se desmovilizaron en 1995; sin embargo, actualmente se están realizando esfuerzos para reconstituirlas . [264] La fuerza de defensa actual de Haití es la Policía Nacional de Haití , que cuenta con un equipo SWAT altamente capacitado y trabaja junto con la Guardia Costera de Haití . En 2010, la fuerza de la Policía Nacional de Haití contaba con 7.000 efectivos. [265]

A partir de 2023, el ejército haitiano incluye un batallón de infantería que está en proceso de formación, con 700 efectivos. [266]

El sistema jurídico se basa en una versión modificada del Código napoleónico . [267] [54]

Haití ha sido clasificado consistentemente entre los países más corruptos del mundo en el Índice de Percepción de la Corrupción . [268] Según un informe de 2006 del Índice de Percepción de la Corrupción , existe una fuerte correlación entre la corrupción y la pobreza en Haití. La república ocupó el primer lugar de todos los países encuestados por los niveles de corrupción interna percibida. [269] Se estima que el presidente "Baby Doc" Duvalier , su esposa Michele y sus agentes robaron US $ 504 millones del tesoro entre 1971 y 1986. [270] De manera similar, después de que el Ejército haitiano se derrumbó en 1995, la Policía Nacional Haitiana (PNH) obtuvo poder exclusivo de autoridad sobre los ciudadanos haitianos. Muchos haitianos, así como observadores, creen que este poder monopolizado podría haber dado paso a una fuerza policial corrupta. [271] Algunos medios de comunicación afirmaron que el ex presidente Jean-Bertrand Aristide robó millones . [272] [273] [274] [275] La BBC también describió los esquemas piramidales , en los que los haitianos perdieron cientos de millones en 2002, como la "única iniciativa económica real" de los años de Aristide. [276]

Por el contrario, según el informe de 2013 de la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito ( ONUDD ), las tasas de homicidios (10,2 por 100.000) están muy por debajo del promedio regional (26 por 100.000); menos de 1/4 la de Jamaica (39,3 por 100.000) y casi 1/2 la de la República Dominicana (22,1 por 100.000), lo que la convierte en uno de los países más seguros de la región. [277] [278] En gran parte, esto se debe a la capacidad del país para cumplir una promesa de aumentar su policía nacional anualmente en un 50%, una iniciativa de cuatro años que se inició en 2012. Además de los reclutas anuales, la Policía Nacional de Haití (PNH) ha estado utilizando tecnologías innovadoras para acabar con el crimen. Una redada notable en los últimos años [ ¿cuándo? ] condujo al desmantelamiento de la red de secuestros más grande del país con el uso de un programa de software avanzado desarrollado por un funcionario haitiano entrenado en West Point que resultó ser tan eficaz que ha llevado a sus asesores extranjeros a realizar averiguaciones. [279] [280]

En 2010, el Departamento de Policía de la Ciudad de Nueva York (NYPD) envió un equipo de oficiales a Haití para ayudar a reconstruir su fuerza policial con capacitación especial en técnicas de investigación, estrategias antisecuestro y extensión comunitaria. También ha ayudado a la PNH a establecer una unidad policial en Delmas , un barrio de Puerto Príncipe. [281] [282] [283] [284]

En 2012 y 2013, 150 oficiales de la PNH recibieron capacitación especializada financiada por el gobierno de los Estados Unidos, que también contribuyó al apoyo de infraestructura y comunicaciones mejorando la capacidad de radio y construyendo nuevas estaciones de policía desde los barrios más propensos a la violencia de Cité Soleil y Grande Ravine en Puerto Príncipe hasta el nuevo parque industrial del norte en Caracol . [282]

La penitenciaría de Puerto Príncipe alberga a la mitad de los presos de Haití. La prisión tiene una capacidad para 1.200 detenidos , pero en noviembre de 2017 [update]la penitenciaría estaba obligada a mantener a 4.359 detenidos, un nivel de ocupación del 363%. [285] La incapacidad de recibir fondos suficientes ha provocado casos mortales de desnutrición , combinados con las estrictas condiciones de vida, que aumentan el riesgo de enfermedades infecciosas como la tuberculosis . [285]

La ley haitiana establece que una vez arrestado, uno debe presentarse ante un juez dentro de las 48 horas siguientes; sin embargo, esto es muy poco frecuente. En una entrevista con Unreported World , el director de la prisión afirmó que alrededor de 529 detenidos nunca fueron sentenciados, y hay 3.830 detenidos que se encuentran en detención preventiva prolongada. Por lo tanto, el 80% no son condenados. [286] A menos que las familias puedan proporcionar los fondos necesarios para que los reclusos comparezcan ante un juez, hay una probabilidad muy pequeña de que el recluso tenga un juicio, en promedio, dentro de los 10 años. [287]

Los reclusos, que viven en espacios reducidos durante 22 o 23 horas al día, no cuentan con letrinas y se ven obligados a defecar en bolsas de plástico. Estas condiciones fueron consideradas inhumanas por la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos en 2008. [288]

El 3 de marzo de 2024, bandas armadas irrumpieron en la prisión principal de Puerto Príncipe y alrededor de 3.700 reclusos escaparon, mientras que 12 personas murieron. [289]

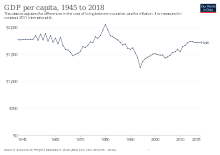

Haiti has a highly regulated, predominantly state-controlled economy, ranking 145th out of the 177 countries given a "freedom index" by the Heritage Foundation.[290] Haiti's per capita GDP is $1,800 and its GDP is $19.97 billion (2017 estimates).[235] The country uses the Haitian gourde as its currency. Despite its tourism industry, Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the Americas, with corruption, political instability, poor infrastructure, lack of health care and lack of education cited as the main causes.[235] Unemployment is high and many Haitians seek to emigrate. Trade declined dramatically after the 2010 earthquake and subsequent outbreak of cholera, with the country's purchasing power parity GDP falling by 8% (from US$12.15 billion to US$11.18 billion).[4] Haiti ranked 145th of 182 countries in the 2010 United Nations Human Development Index, with 57.3% of the population being deprived in at least three of the HDI's poverty measures.[291]

Following the disputed 2000 election and accusations about President Aristide's rule,[292] US aid to the Haitian government was cut off between 2001 and 2004.[293] After Aristide's departure in 2004, aid was restored and the Brazilian army led a United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti peacekeeping operation. After almost four years of recession, the economy grew by 1.5% in 2005.[294] In September 2009, Haiti met the conditions set out by the IMF and World Bank's Heavily Indebted Poor Countries program to qualify for cancellation of its external debt.[295]

More than 90 percent of the government's budget comes from an agreement with Petrocaribe, a Venezuela-led oil alliance.[296]

Haiti received more than US$4 billion in aid from 1990 to 2003, including US$1.5 billion from the United States.[297] The largest donor is the US, followed by Canada and the European Union.[298] In January 2010, following the earthquake, US President Barack Obama promised US$1.15 billion in assistance.[299] The European Union pledged more than €400 million (US$616 million).[300] Neighboring Dominican Republic has also provided extensive humanitarian aid to Haiti, including the funding and construction of a public university,[301] human capital, free healthcare services in the border region, and logistical support after the 2010 earthquake.[302]

The United Nations states that US$13.34 billion has been earmarked for post-earthquake reconstruction through 2020, though two years after the 2010 quake, less than half of that amount had actually been released. As of 2015[update], the US government has allocated US$4 billion, US$3 billion has already been spent, and the rest is dedicated to longer-term projects.[303]

According to the 2015 CIA World Factbook, Haiti's main import partners are: Dominican Republic 35%, US 26.8%, Netherlands Antilles 8.7%, China 7% (est. 2013). Haiti's main export partner is the US 83.5% (est. 2013).[304] Haiti had a trade deficit of US$3 billion in 2011, or 41% of GDP.[305]

Haiti relies heavily on an oil alliance with Petrocaribe for much of its energy requirements. In recent years, hydroelectric, solar and wind energy have been explored as possible sustainable energy sources.[306]

As of 2017, among all the countries in the Americas, Haiti is producing the least energy. Less than a quarter of the country has electric coverage.[307] Most regions of Haiti that do have energy are powered by generators. These generators are often expensive and produce a lot of pollution. The areas that do get electricity experience power cuts on a daily basis, and some areas are limited to 12 hours of electricity a day. Electricity is provided by a small number of independent companies: Sogener, E-power, and Haytrac.[308] There is no national electricity grid.[309] The most common source of energy is wood, along with charcoal. About 4 million metric tons of wood products are consumed yearly.[310] Like charcoal and wood, petroleum is also an important source of energy. Since Haiti cannot produce its own fuel, all fuel is imported. Yearly, around 691,000 tons of oil is imported into the country.[309]

In 2018, a 24-hour electricity project was announced; for this purpose 236 MW needs to installed in Port-au-Prince alone, with an additional 75 MW needed in all other regions. Presently only 27.5% of the population has access to electricity; moreover, the national energy agency l'Électricité d'Haïti (Ed'H) is only able to meet 62% of overall electricity demand.[311]

Haiti suffers from a shortage of skilled labor, widespread unemployment, and underemployment. Most Haitians in the labor force have informal jobs. Three-quarters of the population lives on US$2 or less per day.[312]

Remittances from Haitians living abroad are the primary source of foreign exchange, equaling one-fifth (20%) of GDP and more than five times the earnings from exports as of 2012.[313] In 2004, 80% or more of college graduates from Haiti were living abroad.[314]

Occasionally, families who are unable to care for children may send them to live with a wealthier family as a restavek, or house servant. In return the family are supposed to ensure that the child is educated and provided with food and shelter; however, the system is open to abuse and has proved controversial, with some likening it to child slavery.[315][316]

In rural areas, people often live in wooden huts with corrugated iron roofs. Outhouses are located in back of the huts. In Port-au-Prince, colorful shantytowns surround the central city and go up the mountainsides.[317]

The middle and upper classes live in suburbs, or in the central part of the bigger cities in apartments, where there is urban planning. Many of the houses they live in are like miniature fortresses, located behind walls embedded with metal spikes, barbed wire, broken glass, and sometimes all three. The houses have backup generators, because the electrical grid is unreliable. Some even have rooftop reservoirs for water.[317]

Haiti is the world's leading producer of vetiver, a root plant used to make luxury perfumes, essential oils and fragrances, providing for half the world's supply.[318][319][320] Roughly 40–50% of Haitians work in the agricultural sector.[235][321] However, according to soil surveys by the United States Department of Agriculture in the early 1980s, only 11.3 percent of the land was highly suitable for crops. Haiti relies upon imports for half its food needs and 80% of its rice.[321]

Haiti exports crops such as mangoes, cacao, coffee, papayas, mahogany nuts, spinach, and watercress.[322] Agricultural products constitute 6% of all exports.[305] In addition, local agricultural products include maize, beans, cassava, sweet potato, peanuts, pistachios, bananas, millet, pigeon peas, sugarcane, rice, sorghum, and wood.[322][323]

The Haitian gourde (HTG) is the national currency. The "Haitian dollar" equates to 5 gourdes (goud), which is a fixed exchange rate that exists in concept only, but are commonly used as informal prices.[324] The vast majority of the business sector and individuals will also accept US dollars, though at the outdoor markets gourdes may be preferred. Locals may refer to the USD as "dollar américain" (dola ameriken) or "dollar US" (pronounced oo-es).[325]

The tourism market in Haiti is undeveloped and the government is heavily promoting this sector. Haiti has many of the features that attract tourists to other Caribbean destinations, such as white sand beaches, mountainous scenery and a year-round warm climate. However, the country's poor image overseas, at times exaggerated, has hampered the development of this sector.[54] In 2014, the country received 1,250,000 tourists (mostly from cruise ships), and the industry generated US$200 million in 2014.[citation needed]

Several hotels were opened in 2014, including an upscale Best Western Premier,[326][327] a five-star Royal Oasis hotel by Occidental Hotel and Resorts in Pétion-Ville,[328][329][330] a four-star Marriott Hotel in the Turgeau area of Port-au-Prince[331] and other new hotel developments in Port-au-Prince, Les Cayes, Cap-Haïtien and Jacmel.[citation needed]

On 21 October 2012, Haitian President Michel Martelly, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Bill Clinton, Richard Branson, Ben Stiller and Sean Penn inaugurated the 240-hectare (600-acre) Caracol industrial park, the largest in the Caribbean.[332] The project cost US$300 million and included a 10-megawatt power plant, a water-treatment plant and worker housing.[332] The plan for the park pre-dated the 2010 earthquake but was fast-tracked as part of US foreign aid strategy to help Haiti recover.[333] The park was part of a "master plan" for Haiti's North and North-East departments, including the expansion of the Cap-Haïtien International Airport to accommodate large international flights, the construction of an international seaport in Fort-Liberté and the opening of the $50 million Roi Henri Christophe Campus of a new university in Limonade (near Cap-Haïtien) on 12 January 2012.[334]

In 2012, USAID believed the park had the potential to create as many as 65,000 jobs once fully developed.[335][336] South Korean clothing manufacturer Sae-A Trading Co. Ltd, the park's only major tenant, created 5,000 permanent jobs out of the 20,000 it had projected and promised to build 5,000 houses yet only 750 homes had been built near Caracol by 2014.[333]

Ten years later, the park was considered to have failed to uphold its promise to deliver the transformation the Clintons had promised.[337] The US invested tens of millions of dollars into the port project but eventually abandoned it.[337] In order to establish the park, hundreds of families of small farmers had to be removed from the land, approximately 3,500 people overall.[338] An audit by the United States Government Accountability Office uncovered that the port project lacked "staff with technical expertise in planning, construction, and oversight of a port" and revealed that USAid hadn't constructed a port anywhere since the 1970s.[337] A USAid feasibility study in 2015 found that "a new port was not viable for a variety of technical, environmental and economic reasons", that the US was short US$72m in funds to cover the majority of the projected costs, and that private companies USAid had wanted to attract "had no interest in supporting the construction of a new port in northern Haiti".[337]

Haiti has two main highways that run from one end of the country to the other. The northern highway, Route Nationale No. 1 (National Highway One), originates in Port-au-Prince, winding through the coastal towns of Montrouis and Gonaïves, before reaching its terminus at the northern port Cap-Haïtien. The southern highway, Route Nationale No. 2, links Port-au-Prince with Les Cayes via Léogâne and Petit-Goâve. The state of Haiti's roads are generally poor, many being potholed and becoming impassable in rough weather.[54]

The port at Port-au-Prince, Port international de Port-au-Prince, has more registered shipping than any of the other dozen ports in the country. The port's facilities include cranes, large berths, and warehouses, but these facilities are not in good condition. The port is underused, possibly due to the substantially high port fees. The port of Saint-Marc is currently the preferred port of entry for consumer goods.[citation needed]

In the past, Haiti used rail transport; however, the rail infrastructure was poorly maintained when in use and cost of rehabilitation is beyond the means of the Haitian economy. In 2018 the Regional Development Council of the Dominican Republic proposed a "trans-Hispaniola" railway between both countries.[339]

Toussaint Louverture International Airport, located ten kilometers (six miles) north-northeast of Port-au-Prince proper in the commune of Tabarre, is the primary hub for entry and exit into the country. It has Haiti's main jetway, and along with Cap-Haïtien International Airport handles the vast majority of the country's international flights. Cities such as Jacmel, Jérémie, Les Cayes, and Port-de-Paix have smaller, less accessible airports that are serviced by regional airlines and private aircraft.[citation needed]

In 2013, plans for the development of an international airport on Île-à-Vache were introduced by the Prime Minister.[340]

In May 2024 the airport reopened following 3 months closure following violence, and is expected to help ease a shortage of medications and basic supplies.[341][342]

Tap tap buses are colorfully painted buses or pick-up trucks that serve as shared taxis. The "tap tap" name comes from the sound of passengers tapping on the metal bus body to indicate they want off.[343] These vehicles for hire are often privately owned and extensively decorated. They follow fixed routes, do not leave until filled with passengers, and riders can usually disembark at any point. The decorations are a typically Haitian form of art.[344]