El mandato de Barack Obama como el 44.º presidente de los Estados Unidos comenzó con su primera toma de posesión el 20 de enero de 2009 y terminó el 20 de enero de 2017. Obama, un demócrata de Illinois , asumió el cargo tras su victoria sobre el candidato republicano John McCain en las elecciones presidenciales de 2008. Cuatro años después, en las elecciones presidenciales de 2012 , derrotó al candidato republicano Mitt Romney , para ganar la reelección. Obama es el primer presidente afroamericano , el primer presidente multirracial , el primer presidente no blanco, [a] y el primer presidente nacido en Hawái. Obama fue sucedido por el republicano Donald Trump , quien ganó las elecciones presidenciales de 2016. Los historiadores y politólogos lo ubican entre los primeros puestos en las clasificaciones históricas de los presidentes estadounidenses .

Los logros de Obama durante los primeros 100 días de su presidencia incluyeron la firma de la Ley de Salario Justo Lilly Ledbetter de 2009, que relaja el plazo de prescripción de las demandas por igualdad salarial; [2] la promulgación de la ley del Programa de Seguro Médico Infantil ampliado (S-CHIP); la obtención de la aprobación de una resolución presupuestaria del Congreso que dejó constancia de que el Congreso estaba dedicado a abordar importantes leyes de reforma del sistema de salud en 2009; la implementación de nuevas directrices éticas diseñadas para reducir significativamente la influencia de los grupos de presión en el poder ejecutivo; la ruptura con la administración Bush en varios frentes políticos, excepto en Irak, en el que siguió adelante con la retirada de las tropas estadounidenses de Irak por parte de Bush; [3] el apoyo a la declaración de la ONU sobre la orientación sexual y la identidad de género ; y el levantamiento de la prohibición de siete años y medio de financiación federal para la investigación con células madre embrionarias . [4] Obama también ordenó el cierre del campo de detención de la bahía de Guantánamo , en Cuba , aunque sigue abierto. Levantó algunas restricciones de viaje y dinero a la isla. [3]

Obama firmó muchos proyectos de ley emblemáticos durante sus primeros dos años en el cargo. Las principales reformas incluyen: la Ley de Atención Médica Asequible , a veces denominada "ACA" u "Obamacare", la Ley de Reforma de Wall Street y Protección al Consumidor Dodd-Frank y la Ley de Derogación de No Preguntes, No Digas de 2010. La Ley de Recuperación y Reinversión Estadounidense y la Ley de Alivio Fiscal, Reautorización del Seguro de Desempleo y Creación de Empleo sirvieron como estímulos económicos en medio de la Gran Recesión . Después de un largo debate sobre el límite de la deuda nacional , firmó la Ley de Control Presupuestario de 2011 y la Ley de Alivio al Contribuyente Estadounidense de 2012. En política exterior, aumentó los niveles de tropas estadounidenses en Afganistán , redujo las armas nucleares con el tratado New START entre Estados Unidos y Rusia y puso fin a la participación militar en la Guerra de Irak . Recibió elogios generalizados por ordenar la Operación Neptune Spear , la incursión que mató a Osama bin Laden , quien fue responsable de los ataques del 11 de septiembre . En 2011, Obama ordenó el asesinato mediante un ataque con drones en Yemen del miembro de Al Qaeda Anwar al Awlaki , que era ciudadano estadounidense. Ordenó la intervención militar en Libia para implementar la Resolución 1973 del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas , contribuyendo así al derrocamiento de Muammar Gaddafi .

Después de ganar la reelección al derrotar a su oponente republicano Mitt Romney, Obama juró su cargo para un segundo mandato el 20 de enero de 2013. Durante este mandato, condenó las filtraciones de Snowden de 2013 como antipatrióticas, pero pidió más restricciones a la Agencia de Seguridad Nacional (NSA) para abordar cuestiones de privacidad. Obama también promovió la inclusión de los estadounidenses LGBT . Su administración presentó escritos que instaron a la Corte Suprema a anular las prohibiciones al matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo por inconstitucionales ( Estados Unidos v. Windsor y Obergefell v. Hodges ); el matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo se legalizó en todo el país en 2015 después de que la Corte dictaminara así en Obergefell . Abogó por el control de armas en respuesta al tiroteo de la escuela primaria Sandy Hook , indicando su apoyo a la prohibición de las armas de asalto , y emitió acciones ejecutivas de amplio alcance sobre el calentamiento global y la inmigración. En política exterior, ordenó intervenciones militares en Irak y Siria en respuesta a los avances logrados por el EI después de la retirada de Irak en 2011, promovió las discusiones que llevaron al Acuerdo de París de 2015 sobre el cambio climático global, retiró las tropas estadounidenses en Afganistán en 2016, inició sanciones contra Rusia después de su anexión de Crimea y nuevamente después de la interferencia en las elecciones estadounidenses de 2016 , negoció el acuerdo nuclear del Plan de Acción Integral Conjunto con Irán y normalizó las relaciones de Estados Unidos con Cuba . Obama nominó a tres jueces para la Corte Suprema : Sonia Sotomayor y Elena Kagan fueron confirmadas como magistradas, mientras que a Merrick Garland se le negaron audiencias o una votación del Senado de mayoría republicana .

Después de ganar las elecciones para representar a Illinois en el Senado de los Estados Unidos en 2004 , Barack Obama anunció su candidatura para la nominación demócrata en las elecciones presidenciales de 2008 el 10 de febrero de 2007. [5] Obama se enfrentó a la senadora y ex primera dama Hillary Clinton en las primarias demócratas. Varios otros candidatos, incluido el senador Joe Biden de Delaware y el ex senador John Edwards de Carolina del Norte , también se postularon para la nominación, pero estos candidatos abandonaron después de las primarias iniciales. En junio, el día de las primarias finales, Obama aseguró la nominación al ganar la mayoría de los delegados, incluidos los delegados comprometidos y los superdelegados . [6] Obama seleccionó a Biden como su compañero de fórmula, y fueron nominados oficialmente como la candidatura demócrata en la Convención Nacional Demócrata de 2008 .

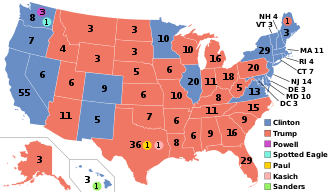

Con el mandato del presidente republicano George W. Bush limitado, los republicanos nominaron al senador John McCain de Arizona para presidente y a la gobernadora Sarah Palin de Alaska para vicepresidenta. Obama ganó la elección presidencial con 365 de los 538 votos electorales totales y el 52,9% del voto popular. En las elecciones concurrentes al Congreso , los demócratas aumentaron sus mayorías tanto en la Cámara de Representantes como en el Senado , y la presidenta de la Cámara de Representantes Nancy Pelosi y el líder de la mayoría del Senado Harry Reid permanecieron en sus puestos. Los republicanos John Boehner y Mitch McConnell continuaron desempeñándose como líder de la minoría de la Cámara de Representantes y líder de la minoría del Senado, respectivamente.

El período de transición presidencial comenzó tras la victoria de Obama en las elecciones presidenciales de Estados Unidos de 2008 , aunque Obama había elegido a Chris Lu para comenzar a planificar la transición en mayo de 2008. [7] John Podesta , Valerie Jarrett y Pete Rouse copresidieron el Proyecto de Transición Obama-Biden. Durante el período de transición, Obama anunció nominaciones para su gabinete y administración . En noviembre de 2008, el congresista Rahm Emanuel aceptó la oferta de Obama de servir como jefe de gabinete de la Casa Blanca . [8]

Obama asumió el cargo el 20 de enero de 2009, en reemplazo de George W. Bush . Obama asumió oficialmente la presidencia a las 12:00 p. m., hora del este de EE. UU. , [9] y completó el juramento del cargo a las 12:05 p. m., hora del este de EE. UU. Pronunció su discurso inaugural inmediatamente después de su juramento. [10] El equipo de transición de Obama elogió mucho al equipo de transición saliente de la administración Bush, en particular en lo que respecta a la seguridad nacional, y algunos elementos de la transición Bush-Obama se codificaron posteriormente en la ley. [7]

![]() El texto completo del primer discurso inaugural de Barack Obama en Wikisource.

El texto completo del primer discurso inaugural de Barack Obama en Wikisource.

A los pocos minutos de que Obama asumiera el cargo, su jefe de gabinete, Rahm Emanuel , emitió una orden suspendiendo regulaciones de último minuto y órdenes ejecutivas firmadas por su predecesor George W. Bush . [11] Algunas de las primeras acciones de la presidencia de Obama se centraron en revertir las medidas adoptadas por la administración Bush tras los ataques del 11 de septiembre . [12] En su primera semana en el cargo, Obama firmó la Orden Ejecutiva 13492 suspendiendo todos los procedimientos en curso de las comisiones militares de Guantánamo y ordenando que el centro de detención de Guantánamo se cerrara dentro del año. [13] Otra orden, la Orden Ejecutiva 13491 , prohibió la tortura y otras técnicas coercitivas, como el ahogamiento simulado . [14] Obama también emitió una orden ejecutiva que imponía restricciones más estrictas al cabildeo en la Casa Blanca, [15] y anuló la Política de la Ciudad de México , que prohibía las subvenciones federales a grupos internacionales que brindan servicios de aborto o asesoramiento. [16]

El 29 de enero, Obama firmó un proyecto de ley por primera vez en su presidencia; la Ley de Salario Justo Lilly Ledbetter de 2009 revisó el estatuto de limitaciones para presentar demandas por discriminación salarial . [17] El 3 de febrero, firmó la Ley de Reautorización del Programa de Seguro Médico para Niños (CHIP), ampliando la cobertura de atención médica del CHIP de 7 millones de niños a 11 millones de niños. [18] El 9 de marzo de 2009, Obama levantó las restricciones a la financiación federal de la investigación con células madre embrionarias . [19] Obama declaró que, al igual que Bush, emplearía declaraciones firmadas si considera que una parte de un proyecto de ley es inconstitucional, [20] y posteriormente emitió varias declaraciones firmadas. [21] Obama también firmó la Ley Ómnibus de Gestión de Tierras Públicas de 2009 , que añadió 2 millones de acres (8100 km2 ) de tierra al Sistema Nacional de Preservación de la Naturaleza , [22] así como una ley que aumenta el impuesto a los paquetes de cigarrillos en 62 centavos (equivalente a $0,88 en 2023). [23]

El 17 de febrero de 2009, Obama firmó la Ley de Recuperación y Reinversión Estadounidense (ARRA, por sus siglas en inglés) para abordar la Gran Recesión . La ARRA había sido aprobada, después de mucho debate, tanto por la Cámara de Representantes como por el Senado cuatro días antes. Si bien originalmente se pretendía que fuera un proyecto de ley bipartidista , la aprobación del proyecto de ley en el Congreso dependió en gran medida de los votos demócratas, aunque tres senadores republicanos votaron a favor. [24] La falta de apoyo republicano al proyecto de ley, y la incapacidad de los demócratas para obtener ese apoyo, presagiaron el estancamiento y el partidismo que continuaron durante toda la presidencia de Obama. [24] [25] [26] El proyecto de ley de 787 mil millones de dólares combinaba exenciones fiscales con gasto en proyectos de infraestructura, extensión de los beneficios sociales y educación. [27] [28]

Tras su investidura, Obama y el Senado trabajaron para confirmar a sus nominados para el Gabinete de los Estados Unidos . Tres funcionarios de nivel de Gabinete no requirieron confirmación: el vicepresidente Joe Biden , a quien Obama había elegido como su compañero de fórmula en la Convención Nacional Demócrata de 2008 , el jefe de Gabinete Rahm Emanuel y el secretario de Defensa Robert Gates , a quien Obama decidió retener de la administración anterior. [29] Una lista temprana de sugerencias provino de Michael Froman , entonces ejecutivo de Citigroup . [30] Obama describió sus elecciones de Gabinete como un " equipo de rivales ", y Obama eligió a varios funcionarios públicos prominentes para puestos de Gabinete, incluida la rival derrotada Hillary Clinton como Secretaria de Estado. [31] Obama nominó a varios ex funcionarios de la administración Clinton para el Gabinete y para otros puestos. [32] El 28 de abril de 2009, el Senado confirmó a la ex gobernadora de Kansas Kathleen Sebelius como Secretaria de Salud y Servicios Humanos, completando el Gabinete inicial de Obama. [33] Durante la presidencia de Obama, cuatro republicanos sirvieron en su gabinete: Ray LaHood como Secretario de Transporte, Robert McDonald como Secretario de Asuntos de Veteranos, y Gates y Chuck Hagel como Secretarios de Defensa.

†Designado por el presidente Bush

‡Designado originalmente por el presidente Bush, designado nuevamente por el presidente Obama

Durante el mandato de Obama hubo tres vacantes en la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos , pero Obama sólo realizó dos nombramientos exitosos. Durante el 111.º Congreso , cuando los demócratas tenían mayoría en el Senado, Obama nominó con éxito a dos jueces de la Corte Suprema:

El juez Antonin Scalia murió en febrero de 2016, durante el 114.º Congreso , que tenía una mayoría republicana en el Senado. En marzo de 2016, Obama nominó al juez principal Merrick Garland del Circuito de DC para ocupar el puesto de Scalia. [34] Sin embargo, el líder de la mayoría del Senado Mitch McConnell , el presidente del Comité Judicial Chuck Grassley y otros republicanos del Senado argumentaron que las nominaciones a la Corte Suprema no deberían hacerse durante un año de elecciones presidenciales y que el ganador de las elecciones presidenciales de 2016 debería designar al reemplazo de Scalia. [34] [35] La nominación de Garland permaneció ante el Senado durante más tiempo que cualquier otra nominación a la Corte Suprema en la historia, [36] y la nominación expiró con el final del 114.º Congreso. [37] El presidente Donald Trump nominó más tarde a Neil Gorsuch para el antiguo escaño de Scalia en la Corte Suprema, y Gorsuch fue confirmado por el Senado en abril de 2017.

La presidencia de Obama vio la continuación de las batallas entre ambos partidos sobre la confirmación de los nominados judiciales . Los demócratas acusaron continuamente a los republicanos de estancar a los nominados durante el mandato de Obama. [39] Después de varias batallas de nominación, los demócratas del Senado en 2013 reformaron el uso del obstruccionismo para que ya no pudiera usarse en nominaciones ejecutivas o judiciales (excluyendo la Corte Suprema). [40] Los republicanos tomaron el control del Senado después de las elecciones de 2014 , dándoles el poder de bloquear a cualquier nominado judicial, [41] y el 114.º Congreso confirmó solo a 20 nominados judiciales, el número más bajo de confirmaciones desde el 82.º Congreso . [42] Los nominados judiciales de Obama fueron significativamente más diversos que los de las administraciones anteriores, con más nombramientos para mujeres y minorías. [39]

Una vez que el proyecto de ley de estímulo fue promulgado en febrero de 2009, la reforma del sistema de salud se convirtió en la principal prioridad nacional de Obama, y el 111.º Congreso aprobó un importante proyecto de ley que finalmente se conoció ampliamente como " Obamacare ". La reforma del sistema de salud había sido durante mucho tiempo una prioridad máxima del Partido Demócrata, y los demócratas estaban ansiosos por implementar un nuevo plan que reduciría los costos y aumentaría la cobertura. [44] En contraste con el plan de 1993 de Bill Clinton para reformar el sistema de salud, Obama adoptó una estrategia de dejar que el Congreso impulsara el proceso, con la Cámara y el Senado escribiendo sus propios proyectos de ley. [45] En el Senado, un grupo bipartidista de senadores en el Comité de Finanzas conocido como la Banda de los Seis comenzó a reunirse con la esperanza de crear un proyecto de ley bipartidista de reforma del sistema de salud, [46] a pesar de que los senadores republicanos involucrados en la elaboración del proyecto de ley finalmente terminaron oponiéndose a él. [45] En noviembre de 2009, la Cámara aprobó la Ley de Atención Médica Asequible para Estados Unidos con una votación de 220 a 215, con solo un republicano votando a favor del proyecto de ley. [47] En diciembre de 2009, el Senado aprobó su propio proyecto de ley de reforma de la atención médica, la Ley de Protección al Paciente y Atención Médica Asequible (PPACA o ACA), en una votación partidaria de 60 a 39. [48] Ambos proyectos de ley ampliaron Medicaid y proporcionaron subsidios para la atención médica; también establecieron un mandato individual , bolsas de seguros de salud y una prohibición de negar cobertura en función de condiciones preexistentes . [49] Sin embargo, el proyecto de ley de la Cámara incluía un aumento de impuestos a las familias que ganan más de $1 millón por año y una opción de seguro de salud público , mientras que el plan del Senado incluía un impuesto especial sobre los planes de salud de alto costo . [49]

La victoria de Scott Brown en las elecciones especiales del Senado de Massachusetts de 2010 puso en serio peligro las perspectivas de un proyecto de ley de reforma de la atención sanitaria, ya que los demócratas perdieron su supermayoría de 60 escaños en el Senado . [50] [51] La Casa Blanca y la presidenta de la Cámara de Representantes, Nancy Pelosi, participaron en una extensa campaña para convencer tanto a los centristas como a los liberales de la Cámara de Representantes de que aprobaran el proyecto de ley de atención sanitaria del Senado, la Ley de Protección al Paciente y Atención Médica Asequible. [52] En marzo de 2010, después de que Obama anunciara una orden ejecutiva que reforzaba la ley actual contra el gasto de fondos federales para servicios de aborto electivo, [53] la Cámara de Representantes aprobó la Ley de Protección al Paciente y Atención Médica Asequible. [54] El proyecto de ley, que había sido aprobado por el Senado en diciembre de 2009, no recibió un solo voto republicano en ninguna de las cámaras. [54] El 23 de marzo de 2010, Obama firmó la PPACA como ley. [55] El New York Times describió la PPACA como "la legislación social más expansiva promulgada en décadas", [55] mientras que el Washington Post señaló que fue la mayor expansión de la cobertura de seguro de salud desde la creación de Medicare y Medicaid en 1965. [54] Ambas cámaras del Congreso también aprobaron una medida de reconciliación para realizar cambios y correcciones significativas a la PPACA; este segundo proyecto de ley se convirtió en ley el 30 de marzo de 2010. [56] [57] La Ley de Protección al Paciente y Atención Médica Asequible se hizo ampliamente conocida como la Ley de Atención Médica Asequible (ACA) u "Obamacare". [58]

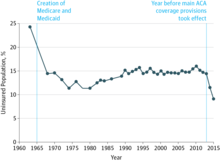

La Ley de Atención Médica Asequible enfrentó considerables desafíos y oposición después de su aprobación, y los republicanos continuamente intentaron derogar la ley. [60] La ley también sobrevivió a dos importantes desafíos que llegaron a la Corte Suprema. [61] En National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius , una mayoría de 5 a 4 confirmó la constitucionalidad de la Ley de Atención Médica Asequible, a pesar de que hizo voluntaria la expansión estatal de Medicaid . En King v. Burwell , una mayoría de 6 a 3 permitió el uso de créditos fiscales en los intercambios operados por el estado. El lanzamiento en octubre de 2013 de HealthCare.gov , un sitio web de intercambio de seguros de salud creado bajo las disposiciones de la ACA, fue ampliamente criticado, [62] a pesar de que muchos de los problemas se solucionaron a fines de año. [63] El número de estadounidenses sin seguro disminuyó del 20,2% de la población en 2010 al 13,3% de la población en 2015, [64] aunque los republicanos continuaron oponiéndose a Obamacare como una expansión no deseada del gobierno. [65] Muchos liberales siguieron presionando a favor de un sistema de atención sanitaria de pagador único o una opción pública, [52] y Obama respaldó esta última propuesta, así como una expansión de los créditos fiscales para el seguro de salud, en 2016. [66]

Las prácticas riesgosas entre las principales instituciones financieras de Wall Street fueron ampliamente vistas como contribuyentes a la crisis de las hipotecas de alto riesgo , la crisis financiera de 2007-08 y la posterior Gran Recesión , por lo que Obama hizo de la reforma de Wall Street una prioridad en su primer mandato. [67] El 21 de julio de 2010, Obama firmó la Ley Dodd-Frank de Reforma de Wall Street y Protección del Consumidor , la mayor revisión regulatoria financiera desde el New Deal . [68] La ley aumentó la regulación y los requisitos de información sobre los derivados (en particular los swaps de incumplimiento crediticio ), y tomó medidas para limitar los riesgos sistémicos para la economía estadounidense con políticas como mayores requisitos de capital , la creación de la Autoridad de Liquidación Ordenada para ayudar a liquidar las grandes instituciones financieras en quiebra, y la creación del Consejo de Supervisión de Estabilidad Financiera para monitorear los riesgos sistémicos. [69] Dodd-Frank también estableció la Oficina de Protección Financiera del Consumidor , que se encargó de proteger a los consumidores contra prácticas financieras abusivas. [70] Al firmar el proyecto de ley, Obama declaró que el proyecto de ley "empoderaría a los consumidores e inversores", "sacaría a la luz los acuerdos oscuros que causaron la crisis" y "pondría fin a los rescates de los contribuyentes de una vez por todas". [71] Algunos liberales estaban decepcionados de que la ley no dividiera los bancos más grandes del país ni restableciera la Ley Glass-Steagall , mientras que muchos conservadores criticaron el proyecto de ley como una extralimitación del gobierno que podría hacer que el país fuera menos competitivo. [71] Según el proyecto de ley, la Reserva Federal y otras agencias reguladoras debían proponer e implementar varias nuevas normas regulatorias , y las batallas sobre estas normas continuaron durante la presidencia de Obama. [72] Obama pidió una mayor reforma de Wall Street después de la aprobación de Dodd-Frank, diciendo que los bancos deberían tener un papel más pequeño en la economía y menos incentivos para realizar operaciones riesgosas. [73] Obama también firmó la Ley de Tarjetas de Crédito de 2009 , que creó nuevas reglas para las compañías de tarjetas de crédito. [74]

Durante su presidencia, Obama describió el calentamiento global como la mayor amenaza a largo plazo que enfrenta el mundo. [75] Obama tomó varias medidas para combatir el calentamiento global, pero no pudo aprobar un proyecto de ley importante que abordara el tema, en parte porque muchos republicanos y algunos demócratas cuestionaron si el calentamiento global está ocurriendo y si la actividad humana contribuye a él. [76] Después de su toma de posesión, Obama pidió que el Congreso aprobara un proyecto de ley para poner un límite a las emisiones nacionales de carbono. [77] Después de que la Cámara de Representantes aprobara la Ley de Energía Limpia y Seguridad Estadounidense en 2009, Obama trató de convencer al Senado para que también aprobara el proyecto de ley. [78] La legislación habría requerido que Estados Unidos redujera las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero en un 17 por ciento para 2020 y en un 83 por ciento para mediados del siglo XXI. [78] Sin embargo, el proyecto de ley fue fuertemente rechazado por los republicanos y ni éste ni un compromiso bipartidista propuesto por separado [77] llegaron a ser sometidos a votación en el Senado. [79] En 2013, Obama anunció que pasaría por alto al Congreso al ordenar a la EPA que implementara nuevos límites a las emisiones de carbono. [80] El Clean Power Plan , presentado en 2015, busca reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero de los EE. UU. entre un 26 y un 28 por ciento para 2025. [81] Obama también impuso regulaciones sobre el hollín, el azufre y el mercurio que alentaron una transición para abandonar el carbón como fuente de energía, pero la caída del precio de las fuentes de energía eólica, solar y de gas natural también contribuyó al declive del carbón. [82] Obama alentó esta exitosa transición para abandonar el carbón en gran parte debido al hecho de que el carbón emite más carbono que otras fuentes de energía, incluido el gas natural. [82]

La campaña de Obama para combatir el calentamiento global tuvo más éxito a nivel internacional que en el Congreso. Obama asistió a la Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático de 2009 , que redactó el Acuerdo de Copenhague no vinculante como sucesor del Protocolo de Kioto . El acuerdo preveía el monitoreo de las emisiones de carbono entre los países en desarrollo , pero no incluía la propuesta de Obama de comprometerse a reducir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero a la mitad para 2050. [83] En 2014, Obama llegó a un acuerdo con China en el que China se comprometió a alcanzar niveles máximos de emisiones de carbono para 2030, mientras que Estados Unidos se comprometió a reducir sus emisiones en un 26-28 por ciento en comparación con sus niveles de 2005. [84] El acuerdo proporcionó impulso para un posible acuerdo multilateral sobre el calentamiento global entre los mayores emisores de carbono del mundo. [85] Muchos republicanos criticaron los objetivos climáticos de Obama como una posible sangría para la economía. [85] [86] En la Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático de 2015 , casi todos los países del mundo acordaron un acuerdo climático histórico en el que cada nación se comprometió a reducir sus emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero. [87] [88] El Acuerdo de París creó un sistema de contabilidad universal para las emisiones, requirió que cada país monitoreara sus emisiones y requirió que cada país creara un plan para reducir sus emisiones. [87] [89] Varios negociadores climáticos señalaron que el acuerdo climático entre Estados Unidos y China y los límites de emisiones de la EPA ayudaron a hacer posible el acuerdo. [87] En 2016, la comunidad internacional acordó el acuerdo de Kigali, una enmienda al Protocolo de Montreal que buscaba reducir el uso de HFC , compuestos orgánicos que contribuyen al calentamiento global. [90]

Desde el comienzo de su presidencia, Obama tomó varias medidas para aumentar la eficiencia de combustible de los vehículos en los Estados Unidos. En 2009, Obama anunció un plan para aumentar la Economía de Combustible Promedio Corporativo a 35 millas por galón estadounidense (6,7 L/100 km)], un aumento del 40 por ciento con respecto a los niveles de 2009. [91] Tanto los ambientalistas como los funcionarios de la industria automotriz acogieron con agrado la medida, ya que el plan elevaba los estándares nacionales de emisiones pero proporcionaba el estándar nacional único de eficiencia que el grupo de funcionarios de la industria automotriz había deseado durante mucho tiempo. [91] En 2012, Obama estableció estándares aún más altos, ordenando una eficiencia de combustible promedio de 54,5 millas por galón estadounidense (4,32 L/100 km). [92] Obama también firmó el proyecto de ley "dinero por chatarra" , que brindaba incentivos a los consumidores para cambiar los automóviles más viejos y menos eficientes en combustible por automóviles más eficientes. La Ley de Recuperación y Reinversión Estadounidense de 2009 proporcionó 54 mil millones de dólares en fondos para fomentar la producción nacional de energía renovable , hacer que los edificios federales sean más eficientes energéticamente, mejorar la red eléctrica , reparar viviendas públicas y acondicionar los hogares de ingresos modestos. [93] Obama también promovió el uso de vehículos eléctricos enchufables y, a fines de 2015, se habían vendido 400.000 automóviles eléctricos. [94]

Según un informe de la Asociación Pulmonar Americana, hubo una "mejora importante" en la calidad del aire durante el gobierno de Obama. [95]

Al asumir el cargo, Obama se centró en la gestión de la crisis financiera mundial y la posterior Gran Recesión que había comenzado antes de su elección, [100] [101] que en general se consideró como la peor crisis económica desde la Gran Depresión . [102] El 17 de febrero de 2009, Obama firmó una ley de estímulo económico de 787 mil millones de dólares que incluía gastos para atención sanitaria, infraestructura, educación, varias exenciones e incentivos fiscales y asistencia directa a las personas. Las disposiciones fiscales de la ley, incluido un recorte del impuesto sobre la renta de 116 mil millones de dólares, redujeron temporalmente los impuestos para el 98% de los contribuyentes, lo que llevó las tasas impositivas a sus niveles más bajos en 60 años. [103] [104] La administración Obama argumentaría más tarde que el estímulo salvó a los Estados Unidos de una recesión de "doble caída". [105] Obama pidió un segundo paquete de estímulo importante en diciembre de 2009, [106] pero no se aprobó ningún segundo proyecto de ley de estímulo importante. Obama también lanzó un segundo rescate de los fabricantes de automóviles estadounidenses, posiblemente salvando a General Motors y Chrysler de la bancarrota a un costo de $ 9.3 mil millones. [107] [108] Para los propietarios de viviendas en peligro de incumplir su hipoteca debido a la crisis de las hipotecas de alto riesgo , Obama lanzó varios programas, incluidos HARP y HAMP . [109] [110] Obama volvió a nombrar a Ben Bernanke como presidente de la Junta de la Reserva Federal en 2009, [111] y nombró a Janet Yellen para suceder a Bernanke en 2013. [112] Las tasas de interés a corto plazo se mantuvieron cerca de cero durante gran parte de la presidencia de Obama, y la Reserva Federal no aumentó las tasas de interés durante la presidencia de Obama hasta diciembre de 2015. [113]

Hubo un aumento sostenido de la tasa de desempleo en Estados Unidos durante los primeros meses de la administración, [114] a medida que continuaban los esfuerzos de estímulo económico plurianuales. [115] [116] La tasa de desempleo alcanzó un pico en octubre de 2009 con un 10,0%. [117] Sin embargo, la economía agregó empleos no agrícolas durante un récord de 75 meses consecutivos entre octubre de 2010 y diciembre de 2016, y la tasa de desempleo cayó al 4,7% en diciembre de 2016. [118] La recuperación de la Gran Recesión estuvo marcada por una menor tasa de participación en la fuerza laboral, algunos economistas atribuyeron la menor tasa de participación parcialmente a una población que envejece y a que las personas permanecen en la escuela por más tiempo, así como a cambios demográficos estructurales a largo plazo. [119] La recuperación también dejó al descubierto la creciente desigualdad de ingresos en los Estados Unidos , [120] que la administración Obama destacó como un problema importante. [121] El salario mínimo federal aumentó durante la presidencia de Obama a $7,25 por hora; [122] En su segundo mandato, Obama abogó por otro aumento a 12 dólares por hora. [123]

El crecimiento del PIB regresó en el tercer trimestre de 2009, expandiéndose a un ritmo del 1,6%, seguido de un aumento del 5,0% en el cuarto trimestre. [124] El crecimiento continuó en 2010, registrando un aumento del 3,7% en el primer trimestre, con ganancias menores durante el resto del año. [124] El PIB real del país creció alrededor del 2% en 2011, 2012, 2013 y 2014, alcanzando un máximo del 2,9% en 2015. [125] [126] Como consecuencia de la recesión, el ingreso familiar medio (ajustado a la inflación) disminuyó durante el primer mandato de Obama, antes de recuperarse a un nuevo récord en su último año. [127] La tasa de pobreza alcanzó un máximo del 15,1% en 2010, pero disminuyó al 12,7% en 2016, cifra que seguía siendo superior a la del 12,5% registrada antes de la recesión en 2007. [128] [129] [130] Las tasas de crecimiento del PIB relativamente pequeñas en los Estados Unidos y otros países desarrollados tras la Gran Recesión dejaron a los economistas y a otros preguntándose si las tasas de crecimiento de los Estados Unidos volverían alguna vez a los niveles observados en la segunda mitad del siglo XX. [131] [132]

La presidencia de Obama fue testigo de una prolongada batalla por los impuestos que finalmente condujo a la extensión permanente de la mayoría de los recortes impositivos de Bush , que se habían promulgado entre 2001 y 2003. Esos recortes impositivos debían expirar durante la presidencia de Obama, ya que se aprobaron originalmente mediante una maniobra del Congreso conocida como reconciliación , y tenían que cumplir con los requisitos de déficit a largo plazo de la "regla Byrd". Durante la sesión de los legisladores salientes del 111.º Congreso , Obama y los republicanos discutieron sobre el destino final de los recortes. Obama quería extender los recortes impositivos para los contribuyentes que ganaban menos de 250.000 dólares al año, mientras que los republicanos del Congreso querían una extensión total de los recortes impositivos y se negaron a apoyar cualquier proyecto de ley que no extendiera los recortes impositivos para los que más ganan. [134] [135] Obama y el liderazgo republicano del Congreso llegaron a un acuerdo que incluía una extensión de dos años de todos los recortes de impuestos, una extensión de 13 meses del seguro de desempleo , una reducción de un año en el impuesto a la nómina FICA y otras medidas. [136] Obama finalmente persuadió a muchos demócratas cautelosos para que apoyaran el proyecto de ley, aunque muchos liberales como Bernie Sanders continuaron oponiéndose. [137] [138] La Ley de Alivio de Impuestos, Reautorización del Seguro de Desempleo y Creación de Empleo de 858 mil millones de dólares de 2010 se aprobó con mayorías bipartidistas en ambas cámaras del Congreso y fue firmada como ley por Obama el 17 de diciembre de 2010. [137] [139]

Poco después de la reelección de Obama en 2012, los republicanos del Congreso y Obama volvieron a enfrentarse por el destino final de los recortes de impuestos de Bush. Los republicanos buscaban hacer permanentes todos los recortes de impuestos, mientras que Obama buscaba extender los recortes de impuestos solo para aquellos que ganaran menos de $250.000. [140] Obama y los republicanos del Congreso llegaron a un acuerdo sobre la Ley de Alivio al Contribuyente Estadounidense de 2012 , que hizo permanentes los recortes de impuestos para las personas que ganaban menos de $400.000 al año (o menos de $450.000 para parejas). [140] Para los ingresos superiores a esa cantidad, el impuesto a la renta aumentó del 35% al 39,6%, que era la tasa máxima antes de la aprobación de los recortes de impuestos de Bush. [141] El acuerdo también indexó permanentemente el impuesto mínimo alternativo a la inflación, limitó las deducciones para individuos que ganaran más de $250,000 ($300,000 para parejas), fijó permanentemente la exención del impuesto a las herencias en $5.12 millones (indexado a la inflación), y aumentó la tasa máxima del impuesto a las herencias del 35% al 40%. [141] Aunque a muchos republicanos no les gustó el acuerdo, el proyecto de ley fue aprobado por la Cámara Republicana en gran parte debido al hecho de que el hecho de no aprobar ningún proyecto de ley habría resultado en la expiración total de los recortes de impuestos de Bush. [140] [142]

La deuda del gobierno estadounidense creció sustancialmente durante la Gran Recesión , a medida que caían los ingresos del gobierno. Obama rechazó en gran medida las políticas de austeridad seguidas por muchos países europeos. [143] La deuda del gobierno estadounidense creció del 52% del PIB cuando Obama asumió el cargo en 2009 al 74% en 2014, y la mayor parte del crecimiento de la deuda se produjo entre 2009 y 2012. [125] En 2010, Obama ordenó la creación de la Comisión Nacional de Responsabilidad Fiscal y Reforma (también conocida como la "Comisión Simpson-Bowles") para encontrar formas de reducir la deuda del país. [144] La comisión finalmente publicó un informe que pedía una combinación de recortes de gastos y aumentos de impuestos. [144] Las recomendaciones notables del informe incluyen un recorte en el gasto militar , una reducción de las deducciones fiscales para hipotecas y seguros de salud proporcionados por el empleador, un aumento de la edad de jubilación de la Seguridad Social y una reducción del gasto en Medicare, Medicaid y empleados federales. [144] La propuesta nunca recibió votación en el Congreso, pero sirvió como modelo para planes futuros para reducir la deuda nacional. [145]

Después de tomar el control de la Cámara en las elecciones de 2010 , los republicanos del Congreso exigieron recortes de gasto a cambio de elevar el techo de la deuda de los Estados Unidos , el límite legal sobre la cantidad total de deuda que el Departamento del Tesoro puede emitir. La crisis del techo de la deuda de 2011 se desarrolló cuando Obama y los demócratas del Congreso exigieron un aumento "limpio" del techo de la deuda que no incluyera recortes de gasto. [146] Aunque algunos demócratas argumentaron que Obama podía elevar unilateralmente el techo de la deuda bajo los términos de la Decimocuarta Enmienda , [147] Obama eligió negociar con los republicanos del Congreso. Obama y el presidente de la Cámara de Representantes, John Boehner, intentaron negociar un "gran acuerdo" para reducir el déficit, reformar los programas de prestaciones sociales y reescribir el código tributario, pero las negociaciones finalmente colapsaron debido a las diferencias ideológicas entre los líderes demócratas y republicanos. [148] [149] [150] En cambio, el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Control Presupuestario de 2011 , que aumentó el techo de la deuda, previó recortes del gasto interno y militar y estableció el Comité Selecto Conjunto bipartidista sobre la Reducción del Déficit para proponer más recortes del gasto. [151] Como el Comité Selecto Conjunto sobre la Reducción del Déficit no logró llegar a un acuerdo sobre más recortes, los recortes del gasto interno y militar conocidos como el "secuestro" entraron en vigor a partir de 2013. [152]

En octubre de 2013, el gobierno cerró durante dos semanas porque los republicanos y los demócratas no pudieron ponerse de acuerdo sobre un presupuesto. Los republicanos de la Cámara de Representantes aprobaron un presupuesto que desfinanciaría Obamacare , pero los demócratas del Senado se negaron a aprobar cualquier presupuesto que desfinanciara Obamacare. [153] Mientras tanto, el país se enfrentaba a otra crisis del techo de la deuda . Finalmente, las dos partes acordaron una resolución continua que reabrió el gobierno y suspendió el techo de la deuda. [154] Meses después de aprobar la resolución continua, el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Presupuesto Bipartidista de 2013 y un proyecto de ley de gastos ómnibus para financiar al gobierno hasta 2014. [155] En 2015, después de que John Boehner anunciara que renunciaría como presidente de la Cámara de Representantes, el Congreso aprobó un proyecto de ley que establecía objetivos de gasto gubernamental y suspendía el límite de la deuda hasta después de que Obama dejara el cargo. [156]

Durante su presidencia, Obama, el Congreso y la Corte Suprema contribuyeron a una importante expansión de los derechos LGBT . En 2009, Obama firmó la Ley de Prevención de Crímenes de Odio Matthew Shepard y James Byrd Jr. , que amplió las leyes de crímenes de odio para cubrir los crímenes cometidos debido a la orientación sexual de la víctima. [157] En diciembre de 2010, Obama firmó la Ley de Derogación de No Preguntes, No Digas de 2010 , que puso fin a la política militar de prohibir que las personas abiertamente homosexuales y lesbianas sirvan abiertamente en las Fuerzas Armadas de los Estados Unidos . [158] Obama también apoyó la aprobación de ENDA , que prohibiría la discriminación contra los empleados por motivos de género o identidad sexual para todas las empresas con 15 o más empleados, [159] y la Ley de Igualdad similar pero más completa . [160] Ninguno de los proyectos de ley fue aprobado por el Congreso. En mayo de 2012, Obama se convirtió en el primer presidente en funciones en apoyar el matrimonio entre personas del mismo sexo , poco después de que el vicepresidente Joe Biden también hubiera expresado su apoyo a la institución. [161] Al año siguiente, Obama nombró a Todd M. Hughes para el Tribunal de Apelaciones del Circuito Federal , convirtiendo a Hughes en el primer juez federal abiertamente gay en la historia de los EE. UU. [162] En 2015, la Corte Suprema dictaminó que la Constitución garantiza a las parejas del mismo sexo el derecho a casarse en el caso de Obergefell v. Hodges . La administración Obama presentó un escrito amicus en apoyo del matrimonio homosexual y Obama felicitó personalmente al demandante. [163] Obama también emitió docenas de órdenes ejecutivas destinadas a ayudar a los estadounidenses LGBT, [164] incluida una orden de 2010 que extendió los beneficios completos a las parejas del mismo sexo de los empleados federales. [165] Una orden de 2014 prohibió la discriminación contra los empleados de contratistas federales por motivos de orientación sexual o identidad de género. [165] En 2015, el secretario de Defensa Ash Carter puso fin a la prohibición de que las mujeres desempeñaran funciones de combate , [166] y en 2016, puso fin a la prohibición de que las personas transgénero sirvieran abiertamente en el ejército. [167] En el escenario internacional, Obama abogó por los derechos de los homosexuales, particularmente en África. [168]

La Gran Recesión de 2008-09 provocó una marcada caída de los ingresos fiscales en todas las ciudades y estados. La respuesta fue recortar los presupuestos de educación. El paquete de estímulo de 800 mil millones de dólares de Obama incluía 100 mil millones de dólares para las escuelas públicas, que cada estado utilizó para proteger su presupuesto educativo. Sin embargo, en términos de patrocinio de la innovación, Obama y su Secretario de Educación, Arne Duncan, impulsaron la reforma de la educación K-12 a través del programa de subvenciones Race to the Top . Con más de 15 mil millones de dólares de subvenciones en juego, 34 estados revisaron rápidamente sus leyes educativas de acuerdo con las propuestas de reformadores educativos avanzados. En la competencia se otorgaron puntos por permitir que las escuelas charter se multiplicaran, por compensar a los maestros en función de los méritos, incluyendo las puntuaciones de las pruebas de los estudiantes, y por adoptar estándares educativos más altos. Hubo incentivos para que los estados establecieran estándares de preparación para la universidad y la carrera profesional, lo que en la práctica significó adoptar la Iniciativa de Estándares Estatales Básicos Comunes que había sido desarrollada de manera bipartidista por la Asociación Nacional de Gobernadores y el Consejo de Directores de Escuelas Estatales . Los criterios no eran obligatorios, sino incentivos para mejorar las oportunidades de obtener una subvención. La mayoría de los estados revisaron sus leyes en consecuencia, aunque se dieron cuenta de que era poco probable que lo hicieran cuando se trataba de una nueva subvención muy competitiva. Race to the Top tuvo un fuerte apoyo bipartidista, con elementos centristas de ambos partidos. Se opuso a él el ala izquierda del Partido Demócrata y el ala derecha del Partido Republicano, y fue criticado por centralizar demasiado el poder en Washington. También hubo quejas de familias de clase media, que estaban molestas por el creciente énfasis en enseñar para el examen, en lugar de alentar a los maestros a mostrar creatividad y estimular la imaginación de los estudiantes. [169] [170] [171]

Obama también abogó por programas universales de preescolar , [172] y dos años gratuitos de colegio comunitario para todos. [173] A través de su programa Let's Move y la defensa de almuerzos escolares más saludables, la Primera Dama Michelle Obama centró la atención en la obesidad infantil , que era tres veces mayor en 2008 que en 1974. [174] En diciembre de 2015, Obama firmó la Ley Every Student Succeeds Act , un proyecto de ley bipartidista que reautorizó las pruebas obligatorias a nivel federal pero redujo el papel del gobierno federal en la educación, especialmente con respecto a las escuelas con problemas. [175] La ley también puso fin al uso de exenciones por parte del Secretario de Educación. [175] En materia de educación postsecundaria, Obama firmó la Ley de Reconciliación de la Atención Sanitaria y la Educación de 2010 , que puso fin al papel de los bancos privados en la concesión de préstamos estudiantiles asegurados por el gobierno federal , [176] creó un nuevo plan de pago de préstamos basado en los ingresos conocido como Pay as You Earn y aumentó la cantidad de becas Pell otorgadas cada año. [177] También instituyó nuevas regulaciones sobre las universidades con fines de lucro , incluida una regla de "empleo remunerado" que restringía la financiación federal de las universidades que no preparaban adecuadamente a los graduados para sus carreras. [178]

Desde el comienzo de su presidencia, Obama apoyó una reforma migratoria integral, que incluía una vía a la ciudadanía para muchos inmigrantes que residían ilegalmente en los Estados Unidos. [179] Sin embargo, el Congreso no aprobó un proyecto de ley migratorio integral durante el mandato de Obama, y Obama recurrió a medidas ejecutivas. En la sesión saliente de 2010, Obama apoyó la aprobación de la Ley DREAM , que fue aprobada por la Cámara de Representantes pero no logró superar una obstrucción del Senado en una votación de 55 a 41 a favor del proyecto de ley. [180] En 2013, el Senado aprobó un proyecto de ley migratorio con una vía a la ciudadanía, pero la Cámara de Representantes no votó sobre el proyecto de ley. [181] [182] En 2012, Obama implementó la política DACA , que protegió a aproximadamente 700.000 inmigrantes ilegales de la deportación; la política se aplica solo a aquellos que fueron traídos a los Estados Unidos antes de cumplir 16 años. [183] En 2014, Obama anunció una nueva orden ejecutiva que habría protegido a otros cuatro millones de inmigrantes ilegales de la deportación, [184] pero la orden fue bloqueada por la Corte Suprema en una votación de 4 a 4 que confirmó el fallo de un tribunal inferior. [185] A pesar de las acciones ejecutivas para proteger a algunas personas, las deportaciones de inmigrantes ilegales continuaron bajo Obama. Un récord de 400.000 deportaciones ocurrió en 2012, aunque el número de deportaciones cayó durante el segundo mandato de Obama. [186] En la continuación de una tendencia que comenzó con la aprobación de la Ley de Inmigración y Nacionalidad de 1965 , el porcentaje de personas nacidas en el extranjero que viven en los Estados Unidos alcanzó el 13,7% en 2015, más alto que en cualquier otro momento desde principios del siglo XX. [187] [188] Después de haber aumentado desde 1990, el número de inmigrantes ilegales que viven en los Estados Unidos se estabilizó en alrededor de 11,5 millones de personas durante la presidencia de Obama, por debajo de un pico de 12,2 millones en 2007. [189] [190]

La población inmigrante del país alcanzó un récord de 42,2 millones en 2014. [191] En noviembre de 2015, Obama anunció un plan para reasentar al menos a 10.000 refugiados sirios en Estados Unidos. [192]

La producción de energía experimentó un auge durante la administración Obama. [193] Un aumento en la producción de petróleo fue impulsado en gran medida por un auge del fracking impulsado por la inversión privada en tierras privadas, y la administración Obama jugó solo un papel pequeño en este desarrollo. [193] La administración Obama promovió el crecimiento de la energía renovable , [194] y la generación de energía solar se triplicó durante la presidencia de Obama. [195] Obama también emitió numerosos estándares de eficiencia energética, contribuyendo a un aplanamiento del crecimiento de la demanda total de energía de Estados Unidos. [196] En mayo de 2010, Obama extendió una moratoria sobre los permisos de perforación en alta mar después del derrame de petróleo de Deepwater Horizon de 2010 , que fue el peor derrame de petróleo en la historia de Estados Unidos. [197] [198] En diciembre de 2016, el presidente Obama invocó la Ley de Tierras de la Plataforma Continental Exterior para prohibir la exploración de petróleo y gas en alta mar en grandes partes de los océanos Ártico y Atlántico. [199]

Durante el mandato de Obama, la batalla por el oleoducto Keystone XL se convirtió en un tema importante, con defensores argumentando que contribuiría al crecimiento económico y ambientalistas argumentando que su aprobación contribuiría al calentamiento global. [200] El oleoducto propuesto de 1,000 millas (1,600 km) habría conectado las arenas petrolíferas de Canadá con el Golfo de México . [200] Debido a que el oleoducto cruzaba fronteras internacionales, su construcción requirió la aprobación del gobierno federal de los EE. UU., y el Departamento de Estado de los EE. UU. participó en un largo proceso de revisión. [200] El presidente Obama vetó un proyecto de ley para construir el oleoducto Keystone en febrero de 2015, argumentando que la decisión de aprobación debería recaer en el poder ejecutivo. [201] Fue el primer veto importante de su presidencia, y el Congreso no pudo anularlo. [202] En noviembre de 2015, Obama anunció que no aprobaría la construcción del oleoducto. [200] Al vetar el proyecto de ley, afirmó que el oleoducto desempeñaba un "papel exagerado" en el discurso político estadounidense y habría tenido un impacto relativamente pequeño en la creación de empleo o el cambio climático. [200]

La administración Obama tomó algunas medidas para reformar el sistema de justicia penal en un momento en que muchos en ambos partidos sentían que Estados Unidos había ido demasiado lejos en el encarcelamiento de delincuentes de drogas, [203] y Obama fue el primer presidente desde la década de 1960 en presidir una reducción en la población carcelaria federal. [204] El mandato de Obama también vio una disminución continua de la tasa nacional de delitos violentos desde su pico en 1991, aunque hubo un repunte en la tasa de delitos violentos en 2015. [205] [206] En octubre de 2009, el Departamento de Justicia de los EE. UU. emitió una directiva a los fiscales federales en estados con leyes de marihuana medicinal para que no investigaran ni procesaran casos de uso o producción de marihuana realizados en cumplimiento de esas leyes. [207] En 2009, el presidente Obama firmó la Ley de Asignaciones Consolidadas de 2010 , que derogó una prohibición de 21 años de antigüedad sobre la financiación federal de programas de intercambio de agujas . [208] En agosto de 2010, Obama firmó la Ley de Sentencias Justas , que redujo la disparidad de sentencias entre el crack y la cocaína en polvo . [209] En 2012, Colorado y Washington se convirtieron en los primeros estados en legalizar la marihuana no medicinal , [210] y seis estados más legalizaron la marihuana recreativa cuando Obama dejó el cargo. [211] Aunque cualquier uso de marihuana siguió siendo ilegal según la ley federal , la administración Obama generalmente optó por no procesar a quienes consumían marihuana en los estados que optaron por legalizarla. [212] En 2016, Obama anunció que el gobierno federal eliminaría gradualmente el uso de prisiones privadas . [213] Obama conmutó las sentencias de más de 1000 personas, un número mayor de conmutaciones que cualquier otro presidente, y la mayoría de las conmutaciones de Obama se destinaron a delincuentes no violentos por drogas. [214] [215]

Durante la presidencia de Obama, hubo un marcado aumento de la mortalidad por opioides . Muchas de las muertes, tanto entonces como ahora, son consecuencia del consumo de fentanilo, en el que es más probable que se produzca una sobredosis que en el caso del consumo de heroína . Y muchas personas murieron porque no eran conscientes de esta diferencia o porque pensaban que se administrarían heroína o una mezcla de drogas, pero en realidad consumían fentanilo puro. [216] Los expertos en salud criticaron la respuesta del gobierno por lenta y débil. [217] [218]

Al asumir el cargo en 2009, Obama expresó su apoyo a la reinstauración de la Prohibición Federal de Armas de Asalto ; pero no hizo un fuerte esfuerzo para aprobarla, ni ninguna nueva legislación de control de armas al principio de su presidencia. [219] Durante su primer año en el cargo, Obama firmó dos proyectos de ley que contenían enmiendas que reducían las restricciones a los propietarios de armas, uno que permitía transportar armas en el equipaje facturado en los trenes de Amtrak [220] y otro que permitía el porte oculto de armas de fuego cargadas en los Parques Nacionales , ubicados en estados donde se permitía el porte oculto . [221] [222]

Tras el tiroteo de la escuela primaria Sandy Hook en diciembre de 2012 , Obama esbozó una serie de propuestas de amplio alcance para el control de armas, instando al Congreso a reintroducir una prohibición vencida sobre las armas de asalto "de estilo militar" , imponer límites a los cargadores de munición a 10 balas, exigir verificaciones de antecedentes universales para todas las ventas de armas nacionales, prohibir la posesión y venta de balas perforantes e introducir penas más severas para los traficantes de armas. [223] A pesar de la defensa de Obama y los tiroteos masivos posteriores , ningún proyecto de ley importante sobre control de armas fue aprobado por el Congreso durante la presidencia de Obama. Los senadores Joe Manchin (demócrata por Virginia Occidental) y Pat Toomey (republicano por Pensilvania) intentaron aprobar una medida de control de armas más limitada que habría ampliado las verificaciones de antecedentes, pero el proyecto de ley fue bloqueado en el Senado. [224]

La ciberseguridad surgió como un tema importante durante la presidencia de Obama. En 2009, la administración Obama estableció el Comando Cibernético de los Estados Unidos , un comando subunificado de las fuerzas armadas encargado de defender al ejército contra ataques cibernéticos. [225] Sony Pictures sufrió un importante ataque informático en 2014, que el gobierno de los EE. UU. alega que se originó en Corea del Norte en represalia por el lanzamiento de la película The Interview . [226] China también desarrolló sofisticadas fuerzas de guerra cibernética. [227] En 2015, Obama declaró los ataques cibernéticos en los EE. UU. una emergencia nacional. [226] Más tarde ese año, Obama firmó la Ley de Intercambio de Información de Ciberseguridad . [228] En 2016, el Comité Nacional Demócrata y otras organizaciones estadounidenses fueron hackeadas , [229] y el FBI y la CIA concluyeron que Rusia patrocinó el ataque informático con la esperanza de ayudar a Donald Trump a ganar las elecciones presidenciales de 2016. [230] Las cuentas de correo electrónico de otras personas prominentes, incluido el exsecretario de Estado Colin Powell y el director de la CIA John O. Brennan , también fueron pirateadas, lo que generó nuevos temores sobre la confidencialidad de los correos electrónicos. [231]

En sus discursos como presidente, Obama no hizo referencias más abiertas a las relaciones raciales que sus predecesores, [232] [233] pero según un estudio, implementó acciones políticas más fuertes en favor de los afroamericanos que cualquier presidente desde la era de Nixon. [234]

Tras la elección de Obama, muchos reflexionaron sobre la existencia de una "América postracial". [235] [236] Sin embargo, las tensiones raciales persistentes se hicieron evidentes rápidamente, [235] [237] y muchos afroamericanos expresaron su indignación por lo que vieron como "veneno racial" dirigido a la presidencia de Obama. [238] En julio de 2009, el destacado profesor afroamericano de Harvard Henry Louis Gates, Jr. , fue arrestado en su casa de Cambridge, Massachusetts , por un oficial de policía local, lo que desató una controversia después de que Obama declarara que la policía actuó "estúpidamente" al manejar el incidente. Para reducir las tensiones, Obama invitó a Gates y al oficial de policía a la Casa Blanca en lo que se conoció como la "Cumbre de la Cerveza". [239] Varios otros incidentes durante la presidencia de Obama provocaron indignación en la comunidad afroamericana y/o la comunidad policial, y Obama buscó generar confianza entre los funcionarios encargados de hacer cumplir la ley y los activistas de los derechos civiles. [240] La absolución de George Zimmerman tras el asesinato de Trayvon Martin desató la indignación nacional, lo que llevó a Obama a pronunciar un discurso en el que señaló que "Trayvon Martin podría haber sido yo hace 35 años". [241] El tiroteo de Michael Brown en Ferguson, Missouri, desató una ola de protestas . [242] Estos y otros acontecimientos llevaron al nacimiento del movimiento Black Lives Matter , que hace campaña contra la violencia y el racismo sistémico hacia los negros . [242] Algunos miembros de la comunidad policial criticaron la condena de Obama al sesgo racial después de los incidentes en los que la acción policial provocó la muerte de hombres afroamericanos, mientras que algunos activistas por la justicia racial criticaron las expresiones de empatía de Obama hacia la policía. [240] Aunque Obama asumió el cargo reacio a hablar sobre la raza, en 2014 comenzó a discutir abiertamente las desventajas que enfrentan muchos miembros de grupos minoritarios. [243] En una encuesta de Gallup de marzo de 2016, casi un tercio de los estadounidenses dijeron que estaban preocupados "mucho" por las relaciones raciales, una cifra más alta que en cualquier encuesta de Gallup anterior desde 2001. [244]

In July 2009, Obama appointed Charles Bolden, a former astronaut, as NASA Administrator.[245] That same year, Obama set up the Augustine panel to review the Constellation program. In February 2010, Obama announced that he was cutting the program from the 2011 United States federal budget, describing it as "over budget, behind schedule, and lacking in innovation."[246][247] After the decision drew criticism in the United States, a new "Flexible path to Mars" plan was unveiled at a space conference in April 2010.[248][249] It included new technology programs, increased R&D spending, an increase in NASA's 2011 budget from $18.3 billion to $19 billion, a focus on the International Space Station, and plans to contract future transportation to Low Earth orbit to private companies.[248] During Obama's presidency, NASA designed the Space Launch System and developed the Commercial Crew Development and Commercial Orbital Transportation Services to cooperate with private space flight companies.[250][251] These private companies, including SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin, Boeing, and Bigelow Aerospace, became increasingly active during Obama's presidency.[252] The Space Shuttle program ended in 2011, and NASA relied on the Russian space program to launch its astronauts into orbit for the remainder of the Obama administration.[250][253] Obama's presidency also saw the launch of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Mars Science Laboratory. In 2016, Obama called on the United States to land a human on Mars by the 2030s.[252]

Obama promoted various technologies and the technological prowess of the United States. The number of American adults using the internet grew from 74% in 2008 to 84% in 2013,[254] and Obama pushed programs to extend broadband internet to lower income Americans.[255] Over the opposition of many Republicans, the Federal Communications Commission began regulating internet providers as public utilities, with the goal of protecting "net neutrality".[256] Obama launched 18F and the United States Digital Service, two organizations devoted to modernizing government information technology.[257][258] The stimulus package included money to build high-speed rail networks such as the proposed Florida High Speed Corridor, but political resistance and funding problems stymied those efforts.[259] In January 2016, Obama announced a plan to invest $4 billion in the development of self-driving cars, as well as an initiative by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to develop regulations for self-driving cars.[260] That same month, Obama called for a national effort led by Vice President Biden to develop a cure for cancer.[261] On October 19, 2016, Biden spoke at the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate at the University of Massachusetts Boston to speak about the administration's cancer initiative.[262] A 2020 study in the American Economic Review found that the decision by the Obama administration to issue press releases that named and shamed facilities that violated OSHA safety and health regulations led other facilities to increase their compliance and to experience fewer workplace injuries. The study estimated that each press release had the same effect on compliance as 210 inspections.[263][264]

The Obama administration inherited a war in Afghanistan, a war in Iraq, and a global "War on Terror", all launched by Congress during the term of President Bush in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. Upon taking office, Obama called for a "new beginning" in relations between the Muslim world and the United States,[266][267] and he discontinued the use of the term "War on Terror" in favor of the term "Overseas Contingency Operation".[268] Obama pursued a "light footprint" military strategy in the Middle East that emphasized special forces, drone strikes, and diplomacy over large ground troop occupations.[269] However, American forces continued to clash with Islamic militant organizations such as al-Qaeda, ISIL, and al-Shabaab[270] under the terms of the AUMF passed by Congress in 2001.[271] Though the Middle East remained important to American foreign policy, Obama pursued a "pivot" to East Asia.[272][273] Obama also emphasized closer relations with India, and was the first president to visit the country twice.[274] An advocate for nuclear non-proliferation, Obama successfully negotiated arms-reduction deals with Iran and Russia.[275] In 2015, Obama described the Obama Doctrine, saying "we will engage, but we preserve all our capabilities."[276] Obama also described himself as an internationalist who rejected isolationism and was influenced by realism and liberal interventionism.[277]

During the 2008 presidential election, Obama strongly criticized the Iraq War,[290] and Obama withdrew the vast majority of US soldiers in Iraq by late 2011. On taking office, Obama announced that US combat forces would leave Iraq by August 2010, with 35,000–50,000 American soldiers remaining in Iraq as advisers and trainers,[291] down from the roughly 150,000 American soldiers in Iraq in early 2009.[292] In 2008, President Bush had signed the US–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, in which the United States committed to withdrawing all forces by late 2011.[293][294] Obama attempted to convince Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to allow US soldiers to stay past 2011, but the large presence of American soldiers was unpopular with most Iraqis.[293] By late-December 2011, only 150 American soldiers remained to serve at the US embassy.[280] However, in 2014, the US began a campaign against ISIL, an Islamic extremist terrorist group operating in Iraq and Syria that grew dramatically after the withdrawal of US soldiers from Iraq and the start of the Syrian Civil War.[295][296] By June 2015, there were about 3500 American soldiers in Iraq serving as advisers to anti-ISIL forces in the Iraqi Civil War,[297] and Obama left office with roughly 5,262 US soldiers in Iraq and 503 of them in Syria.[298]

It is unacceptable that almost seven years after nearly 3,000 Americans were killed on our soil, the terrorists who attacked us on 9/11 are still at large. Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahari are recording messages to their followers and plotting more terror. The Taliban controls parts of Afghanistan. Al Qaeda has an expanding base in Pakistan that is probably no farther from their old Afghan sanctuary than a train ride from Washington to Philadelphia. If another attack on our homeland comes, it will likely come from the same region where 9/11 was planned. And yet today, we have five times more troops in Iraq than Afghanistan.[299]

— Obama during his 2008 presidential campaign speech

Obama increased the number of American soldiers in Afghanistan during his first term before withdrawing most military personnel in his second term. On taking office, Obama announced that the US military presence in Afghanistan would be bolstered by 17,000 new troops by Summer 2009,[300] on top of the roughly 30,000 soldiers already in Afghanistan at the start of 2009.[301] Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chair Michael Mullen all argued for further troops, and Obama dispatched additional soldiers after a lengthy review process.[302][303] During this time, his administration had used the neologism AfPak to denote Afghanistan and Pakistan as a single theater of operations in the war on terror.[304] The number of American soldiers in Afghanistan would peak at 100,000 in 2010.[279] In 2012, the US and Afghanistan signed a strategic partnership agreement in which the US agreed to hand over major combat operation to Afghan forces.[305] That same year, the Obama administration designated Afghanistan as a major non-NATO ally.[306] In 2014, Obama announced that most troops would leave Afghanistan by late 2016, with a small force remaining at the US embassy.[307] In September 2014, Ashraf Ghani succeeded Hamid Karzai as the President of Afghanistan after the US helped negotiate a power-sharing agreement between Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah.[308] On January 1, 2015, the US military ended Operation Enduring Freedom and began Resolute Support Mission, in which the US shifted to more of a training role, although some combat operations continued.[309] In October 2015, Obama announced that US soldiers would remain in Afghanistan indefinitely in order support the Afghan government in the civil war against the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and ISIL.[310] Joint Chiefs of Staff Chair Martin Dempsey framed the decision to keep soldiers in Afghanistan as part of a long-term counter-terrorism operation stretching across Central Asia.[311] Obama left office with roughly 8,400 US soldiers remaining in Afghanistan.[289]

Though other areas of the world remained important to American foreign policy, Obama pursued a "pivot" to East Asia, focusing the US's diplomacy and trade in the region.[272][273] China's continued emergence as a major power was a major issue of Obama's presidency; while the two countries worked together on issues such as climate change, the China-United States relationship also experienced tensions regarding territorial claims in the South China Sea and the East China Sea.[312] In 2016, the United States hosted a summit with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) for the first time, reflecting the Obama administration's pursuit of closer relations with ASEAN and other Asian countries.[313] After helping to encourage openly contested elections in Myanmar, Obama lifted many US sanctions on Myanmar.[314][315] Obama also increased US military ties with Vietnam,[316] Australia, and the Philippines, increased aid to Laos, and contributed to a warming of relations between South Korea and Japan.[317] Obama designed the Trans-Pacific Partnership as the key economic pillar of the Asian pivot, though the agreement remains unratified.[317] Obama made little progress with relations with North Korea, a long-time adversary of the United States, and North Korea continued to develop its WMD program.[318]

On taking office, Obama called for a "reset" in relations with Russia, which had declined following the 2008 Russo-Georgian War.[319] While President Bush had successfully pushed for NATO expansion into former Eastern bloc states, the early Obama era saw NATO put more of an emphasis on creating a long-term partnership with Russia.[320] Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev worked together on a new treaty to reduce and monitor nuclear weapons, Russian accession to the World Trade Organization, and counterterrorism.[319] On April 8, 2010, Obama and Medvedev signed the New START treaty, a major nuclear arms control agreement that reduced the nuclear weapons stockpiles of both countries and provided for a monitoring regime.[321] In December 2010, the Senate ratified New START in a 71–26 vote, with 13 Republicans and all Democrats voting in favor of the treaty.[322] In 2012, Russia joined the World Trade Organization and Obama normalized trade relations with Russia.[323]

US–Russia relations declined after Vladimir Putin returned to the presidency in 2012.[319] Russia's invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea in response to the Euromaidan movement led to a strong condemnation by Obama and other Western leaders, who imposed sanctions on Russian leaders.[319][324] The sanctions contributed to a Russian financial crisis.[325] Some members of Congress from both parties also called for the US to arm Ukrainian forces, but Obama resisted becoming closely involved in the War in Donbass.[326] In 2016, following several cybersecurity incidents, the Obama administration formally accused Russia of engaging in a campaign to undermine the 2016 election, and the administration imposed sanctions on some Russian-linked people and organizations.[327][328] In 2017, after Obama left office, Robert Mueller was appointed as special counsel to investigate Russian's involvement in the 2016 election, including the myriad links between Trump associates and Russian officials and spies.[329] The Mueller Report, released in 2019, concludes that Russia undertook a sustained social media campaign and cyberhacking operation to bolster the Trump campaign.[330] The report did not reach a conclusion on allegations that the Trump campaign had colluded with Russia, but, according to Mueller, his investigation did not find evidence "sufficient to charge any member of the [Trump] campaign with taking part in a criminal conspiracy."[331]

The relationship between Obama and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (who held office for all but two months of Obama's presidency) was notably icy, with many commenting on their mutual distaste for each other.[332][333] On taking office, Obama appointed George J. Mitchell as a special envoy to the Middle East to work towards a settlement of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but Mitchell made little progress before stepping down in 2011.[334] In March 2010, Secretary of State Clinton criticized the Israeli government for approving expansion of settlements in East Jerusalem.[335] Netanyahu strongly opposed Obama's efforts to negotiate with Iran and was seen as favoring Mitt Romney in the 2012 US presidential election.[332] However, Obama continued the US policy of vetoing UN resolutions calling for a Palestinian state, and the administration continued to advocate for a negotiated two-state solution.[336] Obama also increased aid to Israel, including a $225 million emergency aid package for the Iron Dome air defense program.[337]

During Obama's last months in office, his administration chose not to veto United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334, which urged the end of Israeli settlement in the territories that Israel captured in the Six-Day War of 1967. The Obama administration argued that the abstention was consistent with long-standing American opposition to the expansion of settlements, while critics of the abstention argued that it abandoned a close US ally.[338]

Like his predecessor, Obama pursued free trade agreements, in part due to the lack of progress at the Doha negotiations in lowering trade barriers worldwide.[339] In October 2011, the United States entered into free trade agreements with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea. Congressional Republicans overwhelmingly supported the agreements, while Congressional Democrats cast a mix of votes.[340] The three agreements had originally been negotiated by the Bush administration, but Obama re-opened negotiations with each country and changed some terms of each deal.[340]

Obama promoted two significantly larger, multilateral free trade agreements: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with eleven Pacific Rim countries, including Japan, Mexico, and Canada, and the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the European Union.[341] TPP negotiations began under President Bush, and Obama continued them as part of a long-term strategy that sought to refocus on rapidly growing economies in East Asia.[342] The chief administration goals in the TPP, included: (1) establishing free market capitalism as the main normative platform for economic integration in the region; (2) guaranteeing standards for intellectual property rights, especially regarding copyright, software, and technology; (3) underscore American leadership in shaping the rules and norms of the emerging global order; (4) and blocking China from establishing a rival network.[343]

After years of negotiations, the 12 countries reached a final agreement on the content of the TPP in October 2015,[344] and the full text of the treaty was made public in November 2015.[345] The Obama administration was criticized from the left for a lack of transparency in the negotiations, as well as the presence of corporate representatives who assisted in the drafting process.[346][347][348] In July 2015, Congress passed a bill giving trade promotion authority to the president until 2021; trade promotion authority requires Congress to vote up or down on trade agreements signed by the president, with no possibility of amendments or filibusters.[349] The TPP became a major campaign issue in the 2016 elections, with both major party presidential nominees opposing its ratification.[350] After Obama left office, President Trump pulled the United States out of the TPP negotiations, and the remaining TPP signatories later concluded a separate free trade agreement known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.[351]

In June 2011, it was reported that the US Embassy aided Levi's, Hanes contractors in their fight against an increase in Haiti's minimum wage.[352]

In 2002, the Bush administration established the Guantanamo Bay detention camp to hold alleged "enemy combatants" in a manner that did not treat the detainees as conventional prisoners of war.[353] Obama repeatedly stated his desire to close the detention camp, arguing that the camp's extrajudicial nature provided a recruitment tool for terrorist organizations.[353] On his first day in office, Obama instructed all military prosecutors to suspend proceedings so that the incoming administration could review the military commission process.[354] On January 22, 2009, Obama signed an executive order restricting interrogators to methods listed and authorized by an Army Field Manual,[355] ending the use of "enhanced interrogation techniques".[356] In March 2009, the administration announced that it would no longer refer to prisoners at Guantanamo Bay as enemy combatants, but it also asserted that the president had the authority to detain terrorism suspects there without criminal charges.[357] The prisoner population of the detention camp fell from 242 in January 2009 to 91 in January 2016, in part due to the Periodic Review Boards that Obama established in 2011.[358] Many members of Congress strongly opposed plans to transfer Guantanamo detainees to prisons in US states, and the Obama administration was reluctant to send potentially dangerous prisoners to other countries, especially unstable countries such as Yemen.[359] Though Obama continued to advocate for the closure of the detention camp,[359] 41 inmates remained in Guantanamo when Obama left office.[360][361]

The Obama administration launched a successful operation that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaeda, a global Sunni Islamist militant organization responsible for the September 11 attacks and several other terrorist attacks.[362] Starting with information received in July 2010, the CIA located Osama bin Laden in a large compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, a suburban area 35 miles (56 km) from Islamabad.[363] CIA head Leon Panetta reported this intelligence to Obama in March 2011. Meeting with his national security advisers over the course of the next six weeks, Obama rejected a plan to bomb the compound, and authorized a "surgical raid" to be conducted by United States Navy SEALs. The operation took place on May 1, 2011, resulting in the death of bin Laden and the seizure of papers and computer drives and disks from the compound.[364] Bin Laden's body was identified through DNA testing, and buried at sea several hours later.[365] Reaction to the announcement was positive across party lines, including from his two predecessors George W. Bush and Bill Clinton,[366] and from many countries around the world.[367]

Obama expanded the drone strike program begun by the Bush administration, and the Obama administration conducted drone strikes against targets in Yemen, Somalia, and, most prominently, Pakistan.[368] Though the drone strikes killed high-ranking terrorists, they were also criticized for resulting in civilian casualties.[369] A 2013 Pew research poll showed that the strikes were broadly unpopular in Pakistan,[370] and some former members of the Obama administration have criticized the strikes for causing a backlash against the United States.[369] However, based on 147 interviews conducted in 2015, professor Aqil Shah argued that the strikes were popular in North Waziristan, the area in which most of the strikes take place, and that little blowback occurred.[371] In 2009, the UN special investigator on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions called the United States' reliance on drones "increasingly common" and "deeply troubling", and called on the US to justify its use of targeted assassinations rather than attempting to capture al Qaeda or Taliban suspects.[372][373]

Starting in 2011, in response to Obama's attempts to avoid civilian casualties, the Hellfire R9X "flying Ginsu" missile was developed. It is usually fired from drones. It does not have an explosive warhead that causes a large area of destruction but kills by using six rotating blades that cut the target into shreds. On July 31, 2022, Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed by an R9X missile.[374] In 2013, Obama appointed John Brennan as the new CIA Director and announced a new policy that required CIA operatives to determine with a "near-certainty" that no civilians would be hurt in a drone strike.[368] The number of drone strikes fell substantially after the announcement of the new policy.[368][369]