Las migraciones indoeuropeas son migraciones hipotéticas de pueblos que hablaban protoindoeuropeo (PIE) y las lenguas indoeuropeas derivadas , que tuvieron lugar entre aproximadamente el 4000 y el 1000 a. C., lo que potencialmente explica cómo estas lenguas relacionadas llegaron a hablarse en una gran área de Eurasia que abarca desde el subcontinente indio y la meseta iraní hasta la Europa atlántica , en un proceso de difusión cultural .

Aunque estas lenguas tempranas y sus hablantes son prehistóricos (carecen de evidencia documental), una síntesis de lingüística , arqueología , antropología y genética ha establecido la existencia del protoindoeuropeo y la propagación de sus dialectos hijos a través de migraciones de grandes poblaciones de sus hablantes, así como el reclutamiento de nuevos hablantes a través de la emulación de las élites conquistadoras. La lingüística comparada describe las similitudes entre varias lenguas regidas por leyes de cambio sistemático , que permiten la reconstrucción del habla ancestral (ver estudios indoeuropeos ). La arqueología rastrea la propagación de artefactos, viviendas y lugares de enterramiento que se presume fueron creados por hablantes de protoindoeuropeo en varias etapas, desde su hipotética patria protoindoeuropea hasta su diáspora por toda Europa occidental, Asia central y el sur de Asia, con incursiones en el este de Asia. [1] [2] La investigación genética reciente, incluida la paleogenética , ha delineado cada vez más los grupos de parentesco involucrados en este movimiento.

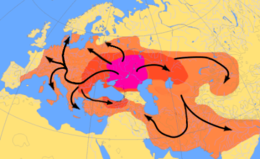

Según la hipótesis ampliamente aceptada de los kurganes o la renovada hipótesis de la estepa, la migración indoeuropea más antigua se separó de la comunidad de habla protoindoeuropea más antigua (la PIE arcaica) que habitaba la cuenca del Volga y produjo las lenguas anatolias ( el hitita y el luvita ). La segunda rama más antigua, el tocario , se hablaba en la cuenca del Tarim (hoy en día, el oeste de China ), después de separarse de la PIE temprana hablada en la estepa póntica oriental. La cultura PIE tardía, dentro del horizonte yamna en la estepa póntico-caspia alrededor del 3000 a. C., se ramificó luego para producir la mayor parte de las lenguas indoeuropeas a través de migraciones hacia el oeste y el sureste.

El albanés , el griego y otras lenguas paleobalcánicas tuvieron su núcleo formativo en los Balcanes después de las migraciones indoeuropeas en la región. [3] [4] El protocelta y el protoitálico pueden haberse desarrollado a partir de lenguas indoeuropeas que llegaron de Europa central a Europa occidental después de las migraciones yamna del tercer milenio a. C. al valle del Danubio, [5] [6] mientras que el protogermánico y el protobaltoeslavo pueden haberse desarrollado al este de los montes Cárpatos , en la actual Ucrania , [7] moviéndose hacia el norte y extendiéndose con la cultura de la cerámica cordada en Europa central (tercer milenio a. C.). [8] [9] [web 1] [10] [web 2] [11]

La lengua y cultura protoindoiraníes probablemente surgieron dentro de la cultura Sintashta ( c. 2100-1800 a. C.), en la frontera oriental de la cultura Abashevo , que a su vez se desarrolló a partir de la cultura Fatyanovo-Balanovo relacionada con la cerámica cordada . [12] [13] [1] [14] [15] [16] La cultura Sintashta se convirtió en la cultura Andronovo [12] [13] [1] [14] [15] [16] ( c. 1900 [17] -800 a. C.), siendo las dos primeras fases la cultura Fedorovo Andronovo ( c. 1900-1400 a. C.) [17] y la cultura Alakul Andronovo ( c. 1800-1500 a. C.). [18] Los indoarios se trasladaron al complejo arqueológico Bactria-Margiana ( c. 2400-1600 a. C.) y se extendieron al Levante ( Mitanni ), norte de la India ( pueblo védico , c. 1700 a. C. ). [2] Las lenguas iraníes se extendieron por las estepas con los escitas , y al antiguo Irán con los medos , partos y persas desde c. 800 a. C. [ 2]

Se han propuesto varias teorías alternativas. La hipótesis anatolia de Colin Renfrew sugiere una fecha mucho más temprana para las lenguas indoeuropeas, proponiendo un origen en Anatolia y una difusión inicial con los primeros agricultores que migraron a Europa. Ha sido la única alternativa seria para la teoría de la estepa, pero carece de poder explicativo.

Además, la hipótesis armenia propone que el Urheimat de la lengua indoeuropea se encontraba al sur del Cáucaso. Si bien la hipótesis armenia ha sido criticada por razones arqueológicas y cronológicas, las investigaciones genéticas recientes han reavivado el debate.

El erudito holandés Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn (1612-1653) notó extensas similitudes entre varias lenguas europeas , el sánscrito y el persa . Más de un siglo después, después de aprender sánscrito en la India, Sir William Jones detectó correspondencias sistemáticas; las describió en su Discurso del Tercer Aniversario ante la Sociedad Asiática en 1786, concluyendo que todas estas lenguas se originaron de la misma fuente. [19] [web 3] A partir de sus intuiciones iniciales se desarrolló la hipótesis de una familia de lenguas indoeuropeas que consta de varios cientos de lenguas y dialectos relacionados . El Ethnologue de 2009 estima un total de alrededor de 439 lenguas y dialectos indoeuropeos, aproximadamente la mitad de estos (221) pertenecientes a la subrama indoaria con base en la subregión del sur de Asia . [web 4] La familia indoeuropea incluye la mayoría de las principales lenguas actuales de Europa , de la meseta iraní , de la mitad norte del subcontinente indio y de Sri Lanka , con lenguas afines que también se hablaban antiguamente en partes de la antigua Anatolia y Asia central. Con testimonios escritos que aparecen desde la Edad del Bronce en forma de lenguas anatolias y griego micénico , la familia indoeuropea es significativa en la lingüística histórica por poseer la segunda historia registrada más larga , después de la familia afroasiática .

Casi 3 mil millones de hablantes nativos utilizan lenguas indoeuropeas, [web 5] lo que las convierte, con diferencia, en la familia lingüística más numerosa. De las 20 lenguas del mundo con mayor número de hablantes nativos , doce son indoeuropeas ( español , inglés , hindi , portugués , bengalí , ruso , alemán , panyabí , maratí , francés , urdu e italiano ), lo que representa más de 1.700 millones de hablantes nativos. [web 6] [ necesita actualización ]

El idioma protoindoeuropeo (PIE) (tardío) es la reconstrucción lingüística de un ancestro común de las lenguas indoeuropeas , tal como lo hablaban los protoindoeuropeos después de la separación del anatolio y el tocario. El PIE fue el primer protolenguaje propuesto que fue ampliamente aceptado por los lingüistas. Se ha dedicado mucho más trabajo a reconstruirlo que a cualquier otro protolenguaje y es, con mucho, el más comprendido de todos los protolenguajes de su época. Durante el siglo XIX, la gran mayoría del trabajo lingüístico se dedicó a la reconstrucción del protoindoeuropeo o de sus protolenguas hijas , como el protogermánico , y la mayoría de las técnicas actuales de lingüística histórica (por ejemplo, el método comparativo y el método de reconstrucción interna ) se desarrollaron como resultado.

Los expertos estiman que el PIE puede haber sido hablado como una sola lengua (antes de que comenzara la divergencia) alrededor del 3500 a. C., aunque las estimaciones de diferentes autoridades pueden variar en más de un milenio. La hipótesis más popular sobre el origen y la difusión de la lengua es la hipótesis kurgana , que postula un origen en la estepa póntico-caspia de Europa del Este.

La existencia del PIE fue postulada por primera vez en el siglo XVIII por Sir William Jones , quien observó las similitudes entre el sánscrito , el griego antiguo y el latín . A principios del siglo XX, se habían desarrollado descripciones bien definidas del PIE que todavía se aceptan hoy en día (con algunas mejoras). Los avances más importantes del siglo XX han sido el descubrimiento de las lenguas anatolias y tocarios y la aceptación de la teoría laríngea . Las lenguas anatolias también han impulsado una importante reevaluación de las teorías sobre el desarrollo de varias características lingüísticas indoeuropeas compartidas y el grado en que estas características estaban presentes en el propio PIE.

Se cree que el PIE tenía un sistema complejo de morfología que incluía flexiones (sufijos de raíces, como en who, whom, whose ) y ablaut (alteraciones vocálicas, como en sing, sang, sung ). Los sustantivos utilizaban un sistema sofisticado de declinación y los verbos utilizaban un sistema de conjugación igualmente sofisticado .

Se han propuesto relaciones con otras familias lingüísticas, incluidas las lenguas urálicas , pero siguen siendo controvertidas. No hay evidencia escrita del protoindoeuropeo, por lo que todo el conocimiento de la lengua se deriva de la reconstrucción a partir de lenguas posteriores utilizando técnicas lingüísticas como el método comparativo y el método de reconstrucción interna . La mayoría de los lingüistas reconocen que existe un límite a la reconstrucción lingüística y que reconstruir una lengua ancestral al protoindoeuropeo podría no ser posible. [1]

La hipótesis indohitita postula un predecesor común del que proceden tanto las lenguas anatolias como las demás lenguas indoeuropeas, llamado protoindohitita. [1] Aunque el IPE tuvo lógicamente predecesores, [21] la hipótesis indohitita no es ampliamente aceptada, y hay pocos indicios de que sea posible reconstruir una etapa protoindohitita que difiera sustancialmente de lo que ya se ha reconstruido para el IPE. [22]

Frederik Kortlandt postula un ancestro común compartido del indoeuropeo y el urálico, el protoindourálico , como un posible pre-PIE. [23] Según Kortlandt, "el indoeuropeo es una rama del indourálico que se transformó radicalmente bajo la influencia de un sustrato del Cáucaso Norte cuando sus hablantes se trasladaron del área al norte del Mar Caspio al área al norte del Mar Negro". [23] [subnota 1]

El proto-ugrio fino y el PIE tienen un léxico en común, generalmente relacionado con el comercio, como las palabras para "precio" y "extraer, conducir". De manera similar, "vender" y "lavar" fueron préstamos del proto-ugrio . Aunque algunos han propuesto un ancestro común (la macrofamilia nostrática hipotética ), esto generalmente se considera como el resultado de un préstamo intensivo, lo que sugiere que sus países de origen estaban ubicados cerca uno del otro. El protoindoeuropeo también exhibe préstamos léxicos hacia o desde las lenguas caucásicas , particularmente el protocaucásico del noroeste y el protokartveliano , lo que sugiere una ubicación cercana al Cáucaso. [21] [24]

Gramkelidze e Ivanov , utilizando la teoría glotálica de la fonología indoeuropea, que ahora carece de respaldo , también propusieron préstamos semíticos en protoindoeuropeo, sugiriendo una patria más meridional para explicar estos préstamos. Según Mallory y Adams, algunos de estos préstamos pueden ser demasiado especulativos o de una fecha posterior, pero consideran que los préstamos semíticos propuestos *táwros 'toro' y *wéyh₁on- 'vino; vid' son más probables. [25] Anthony señala que esos préstamos semíticos también pueden haber ocurrido a través del avance de las culturas agrícolas de Anatolia a través del valle del Danubio hacia la zona de la estepa. [1]

Según Anthony, se puede utilizar la siguiente terminología: [1]

Las lenguas anatolias son la primera familia de lenguas indoeuropeas que se ha separado del grupo principal. Debido a los elementos arcaicos conservados en las lenguas anatolias ahora extintas, es posible que sean un "primo" del protoindoeuropeo, en lugar de una "hija", pero el anatolio se considera generalmente como una rama temprana del grupo de lenguas indoeuropeas. [1]

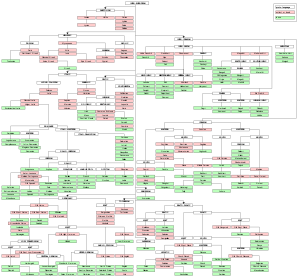

A partir de un análisis matemático tomado de la biología evolutiva, pero basándose en un vocabulario comparativo, varios investigadores han intentado estimar las fechas de la división de las distintas lenguas indoeuropeas. Según el último estudio de Kassian et al. (2021), el hitita fue la primera lengua que se separó del resto, alrededor del 4139-3450 a. C., seguida por el tocario alrededor del 3727-2262 a. C. Posteriormente, el indoeuropeo se dividió en cuatro ramas alrededor del 3357-2162 a. C.: (1) greco-armenio, (2) albanés, (3) itálico-germánico-celta, (4) baltoeslavo-indoiraní. El baltoeslavo se separó del indoiraní alrededor de 2723-1790 a. C., el itálico-germánico-celta se separó alrededor de 2655-1537 a. C., y el indoiraní se separó alrededor de 2044-1458 a. C. La posición del albanés no está completamente clara debido a la insuficiencia de evidencias.

Los autores señalan que estas fechas, que son sólo aproximadas, no son incompatibles con las fechas establecidas por otros métodos para las diversas culturas arqueológicas que se cree que están asociadas con las lenguas indoeuropeas. Por ejemplo, la fecha de la ruptura tocario corresponde a la migración que dio origen a la cultura Afanasievo; la fecha de la ruptura baltoeslava-indoiraní puede correlacionarse con el final de la cultura de la cerámica cordada alrededor de 2100 o 2000 a. C.; y la fecha del indoiraní corresponde a la de la cultura arqueológica Sintashta, frecuentemente asociada con hablantes de protoindoiraní.

La investigación arqueológica ha desenterrado una amplia gama de culturas históricas que pueden relacionarse con la difusión de las lenguas indoeuropeas. Varias culturas esteparias muestran fuertes similitudes con el horizonte de Yamna en la estepa póntica, mientras que el rango temporal de varias culturas asiáticas también coincide con la trayectoria y el rango temporal propuestos de las migraciones indoeuropeas. [28] [1]

Según la hipótesis de los kurganes o teoría de la estepa , ampliamente aceptada , la lengua y la cultura indoeuropeas se difundieron en varias etapas desde el Urheimat protoindoeuropeo en las estepas pónticas euroasiáticas hasta Europa occidental , Asia central y meridional , a través de migraciones populares y el llamado reclutamiento de élites. [1] [2] Este proceso comenzó con la introducción del ganado en las estepas euroasiáticas alrededor del 5200 a. C., y la movilización de las culturas de pastores esteparios con la introducción de carros con ruedas y la equitación, lo que condujo a un nuevo tipo de cultura. Entre el 4500 y el 2500 a. C., este " horizonte ", que incluye varias culturas distintivas que culminaron en la cultura Yamnaya , se extendió por las estepas pónticas y fuera de Europa y Asia. [1] Anthony considera que la cultura Khvalynsk es la cultura que estableció las raíces del protoindoeuropeo temprano alrededor del 4500 a. C. en el bajo y medio Volga. [29]

Las primeras migraciones, en torno al 4200 a. C., trajeron pastores esteparios al valle inferior del Danubio , lo que provocó o aprovechó el colapso de la Vieja Europa . [30] Según Antonio, la rama anatolia, [31] [32] a la que pertenecen los hititas , [33] probablemente llegó a Anatolia desde el valle del Danubio . [34] [35] [web 7] [36] [37] [38]

Las migraciones hacia el este desde la cultura Repin fundaron la cultura Afanasevo [1] [39] que se desarrolló hasta convertirse en los Tocarios . [40] Se pensaba que las momias de Tarim representaban una migración de hablantes de Tocario de la cultura Afanasevo a la cuenca del Tarim . [41] Sin embargo, un estudio de 2021 demuestra que las momias son restos de lugareños descendientes de antiguos euroasiáticos del norte y antiguos asiáticos del noreste ; mientras tanto, el estudio sugiere en cambio que los migrantes de Afanasevo podrían haber introducido el prototocario en Dzungaria durante la Edad del Bronce Temprano antes de que las lenguas Tocario se registraran en textos budistas que datan de 500-1000 d. C. en la cuenca del Tarim. [42] Las migraciones hacia el sur pueden haber fundado la cultura Maykop , [43] pero los orígenes de Maykop también podrían haber estado en el Cáucaso. [44] [web 8]

El PIE tardío está relacionado con la cultura Yamnaya. Las propuestas sobre su origen apuntan tanto a la cultura de Khvalynsk oriental como a la de Sredny Stog occidental; [45] según Anthony, se originó en la zona del Don-Volga alrededor del 3400 a. C. [46]

Las lenguas indoeuropeas occidentales ( germánica , celta , itálica ) probablemente se extendieron a Europa desde el complejo balcánico-danubiano, un conjunto de culturas en el sudeste de Europa . [5] Hacia el año 3000 a. C., tuvo lugar una migración de hablantes protoindoeuropeos de la cultura yamna hacia el oeste a lo largo del río Danubio, [6] el eslavo y el báltico se desarrollaron un poco más tarde en el Dniepr medio (actual Ucrania), [7] moviéndose hacia el norte hacia la costa báltica . [47] La cultura de la cerámica cordada en Europa central (tercer milenio a. C.), [web 1] que surgió en la zona de contacto al este de los montes Cárpatos, se materializó con una migración masiva desde las estepas euroasiáticas a Europa central , [10] [web 2] [11] probablemente jugó un papel central en la difusión de los dialectos pregermánicos y prebaltoeslavos. [8] [9]

La parte oriental de la cultura de la cerámica cordada contribuyó a la cultura Sintashta ( c. 2100-1800 a. C.), donde surgieron la lengua y la cultura indoiraníes y donde se inventó el carro . [1] La lengua y la cultura indoiraníes se desarrollaron aún más en la cultura Andronovo ( c. 1800-800 a. C.), e influenciadas por el Complejo Arqueológico Bactria-Margiana ( c. 2400-1600 a. C.). Los indoarios se separaron alrededor de 1800-1600 a. C. de los iraníes, [48] después de lo cual los grupos indoarios se trasladaron al Levante ( Mitanni ), el norte de la India ( pueblo védico , c. 1500 a. C. ) y China ( Wusun ). [2] Las lenguas iraníes se extendieron por las estepas con los escitas y en Irán con los medos , partos y persas desde c. 800 a . C. [2]

Según Marija Gimbutas , el proceso de " indoeuropeización " de Europa fue esencialmente una transformación cultural, no física. [49] Se entiende como una migración del pueblo Yamnaya a Europa, como vencedores militares, que impusieron con éxito un nuevo sistema administrativo, idioma y religión a los grupos indígenas, a los que Gimbutas se refiere como viejos europeos . [50] [nota 1] La organización social del pueblo Yamnaya , especialmente una estructura patriarcal y patrilineal , facilitó enormemente su eficacia en la guerra. [51] Según Gimbutas, la estructura social de la Vieja Europa "contrastaba con los kurgans indoeuropeos que eran móviles y no igualitarios" y que tenían una estructura social tripartita organizada jerárquicamente ; los IE eran guerreros, vivían en aldeas más pequeñas a veces y tenían una ideología que se centraba en el varón viril, reflejada también en su panteón. En contraste, los grupos indígenas de la Vieja Europa no tenían ni una clase guerrera ni caballos. [52] [nota 2]

Las lenguas indoeuropeas probablemente se propagaron a través de cambios lingüísticos. [53] [54] Los grupos pequeños pueden cambiar un área cultural más grande, [55] [1] y el dominio masculino de élite por parte de grupos pequeños puede haber llevado a un cambio lingüístico en el norte de la India. [56] [57] [58]

Se cree que cuando los indoeuropeos se expandieron hacia Europa desde la estepa póntico-caspia, se encontraron con poblaciones existentes que hablaban lenguas diferentes y no relacionadas. Basándose en la evidencia de un léxico presumiblemente no indoeuropeo en las ramas europeas del indoeuropeo, Iversen y Kroonen (2017) postulan un grupo de lenguas del "Neolítico europeo temprano" que está asociado con la expansión neolítica de los agricultores en Europa. Las lenguas neolíticas europeas tempranas fueron suplantadas con la llegada de los indoeuropeos, pero según Iversen y Kroonen dejaron su rastro en una capa de vocabulario principalmente agrícola en las lenguas indoeuropeas de Europa. [59]

Según Edgar Polomé , el 30% del alemán moderno deriva de una lengua de sustrato no indoeuropeo hablada por personas de la cultura Funnelbeaker indígena del sur de Escandinavia. [60] Cuando los hablantes indoeuropeos yamna entraron en contacto con los pueblos indígenas durante el tercer milenio a. C., llegaron a dominar las poblaciones locales, pero partes del léxico indígena persistieron en la formación del protogermánico , lo que le dio a las lenguas germánicas el estatus de lenguas indoeuropeizadas . [61] De manera similar, según Marija Gimbutas , la cultura de la cerámica cordada , después de migrar a Escandinavia, se sintetizó con la cultura Funnelbeaker , dando origen a la lengua protogermánica. [49]

David Anthony, en su "hipótesis revisada de la estepa", [62] conjetura que la difusión de las lenguas indoeuropeas probablemente no ocurrió a través de "migraciones populares en cadena", sino por la introducción de estas lenguas por élites rituales y políticas, que fueron emuladas por grandes grupos de personas, [63] [nota 3] un proceso que él llama "reclutamiento de élite". [65]

Según Parpola, las élites locales se unieron a "pequeños pero poderosos grupos" de inmigrantes de habla indoeuropea. [53] Estos inmigrantes tenían un sistema social atractivo y buenas armas y bienes de lujo que marcaban su estatus y poder. Unirse a estos grupos era atractivo para los líderes locales, ya que fortalecía su posición y les otorgaba ventajas adicionales. [66] Estos nuevos miembros se incorporaron aún más mediante alianzas matrimoniales . [67] [54]

Según Joseph Salmons, el cambio lingüístico se ve facilitado por la "dislocación" de las comunidades lingüísticas, en las que la élite toma el control. [68] Observa que este cambio se ve facilitado por "cambios sistemáticos en la estructura de la comunidad", en los que una comunidad local se incorpora a una estructura social más amplia. [68] [nota 4]

Desde la década de 2000, los estudios genéticos han asumido un papel destacado en la investigación sobre las migraciones indoeuropeas. Los estudios de genoma completo revelan las relaciones entre las personas asociadas con varias culturas y el rango de tiempo en el que se establecieron esas relaciones. La investigación de Haak et al. (2015) mostró que aproximadamente el 75% de la ascendencia de las personas relacionadas con la cerámica cordada provenía de poblaciones relacionadas con Yamna, [10] mientras que Allentoft et al. (2015) muestra que las personas de la cultura Sintashta están relacionadas genéticamente con las de la cultura de la cerámica cordada. [72]

El cambio climático y la sequía pueden haber desencadenado tanto la dispersión inicial de los hablantes indoeuropeos como la migración de los indoeuropeos desde las estepas del centro-sur de Asia y la India.

Alrededor de 4200–4100 a. C. se produjo un cambio climático , que se manifestó en inviernos más fríos en Europa. [73] Los pastores esteparios, hablantes arcaicos del protoindoeuropeo, se extendieron al valle inferior del Danubio alrededor de 4200–4000 a. C., ya sea causando o aprovechando el colapso de la Vieja Europa . [30]

El horizonte Yamnaya fue una adaptación a un cambio climático ocurrido entre 3500 y 3000 a. C., en el que las estepas se volvieron más secas y frías. Los rebaños debían trasladarse con frecuencia para alimentarlos lo suficiente, y el uso de carros y la equitación lo hicieron posible, dando lugar a "una nueva forma de pastoreo más móvil". [74]

En el segundo milenio a. C., la aridización generalizada provocó escasez de agua y cambios ecológicos tanto en las estepas euroasiáticas como en el sur de Asia. [web 10] [75] En las estepas, la humidificación provocó un cambio de vegetación, lo que desencadenó "una mayor movilidad y la transición a la cría de ganado nómada". [75] [nota 5] [nota 6] La escasez de agua también tuvo un fuerte impacto en el sur de Asia, "causando el colapso de las culturas urbanas sedentarias en el centro-sur de Asia, Afganistán, Irán y la India, y desencadenando migraciones a gran escala". [web 10]

Las hipótesis Urheimat protoindoeuropeas son identificaciones tentativas de la Urheimat , o patria primaria, de la hipotética lengua protoindoeuropea . Tales identificaciones intentan ser consistentes con la glotocronología del árbol lingüístico y con la arqueología de esos lugares y tiempos. Las identificaciones se realizan sobre la base de qué tan bien, si es que lo hacen, las rutas de migración proyectadas y los tiempos de migración se ajustan a la distribución de las lenguas indoeuropeas, y qué tan cerca se ajusta el modelo sociológico de la sociedad original reconstruido a partir de elementos léxicos protoindoeuropeos al perfil arqueológico. Todas las hipótesis suponen un período significativo (al menos 1500-2000 años) entre la época de la lengua protoindoeuropea y los primeros textos atestiguados, en Kültepe , c. siglo XIX a. C.

Desde principios de la década de 1980, [76] el consenso general entre los indoeuropeos favorece la " hipótesis de los kurganes " de Marija Gimbutas, [77] [78] [15] [21] o, más recientemente, la "hipótesis revisada de la estepa" de David Anthony, derivada del trabajo pionero de Gimbutas, [1] que sitúa la patria indoeuropea en la estepa póntica , más específicamente, entre el Dniepr (Ucrania) y el río Ural (Rusia), del período Calcolítico (milenio IV a V a. C.), [77] donde se desarrollaron varias culturas relacionadas. [77] [1]

La estepa póntica es una gran zona de pastizales en el extremo oriental de Europa , situada al norte del mar Negro , las montañas del Cáucaso y el mar Caspio , e incluye partes del este de Ucrania , el sur de Rusia y el noroeste de Kazajistán . Esta es la época y el lugar de la primera domesticación del caballo , que según esta hipótesis fue obra de los primeros indoeuropeos, lo que les permitió expandirse hacia el exterior y asimilar o conquistar muchas otras culturas. [1]

La hipótesis de los kurganes (también llamada teoría o modelo) sostiene que los habitantes de una «cultura kurgan» arqueológica (un término que agrupa a la cultura Yamnaya o de las tumbas de pozo y sus predecesores y sucesores en la estepa póntica desde el VI hasta finales del IV milenio a. C.) fueron los hablantes más probables de la lengua protoindoeuropea . El término se deriva de kurgan ( курган ), un préstamo turco en ruso para un túmulo o túmulo funerario. Un origen en las estepas póntico-caspías es el escenario más ampliamente aceptado de los orígenes indoeuropeos . [79] [80] [15] [21] [nota 7]

Marija Gimbutas formuló su hipótesis sobre los kurganes en la década de 1950, agrupando varias culturas relacionadas en las estepas pónticas. Definió la "cultura kurgan" como compuesta por cuatro períodos sucesivos, de los cuales el más antiguo (Kurgan I) incluye las culturas de Samara y Seroglazovo de la región del Dniéper / Volga en la Edad del Cobre (principios del IV milenio a. C.). Los portadores de estas culturas eran pastores nómadas que, según el modelo, a principios del III milenio se expandieron por toda la estepa póntico-caspia y hacia Europa del Este . [81]

En la actualidad, se considera que la agrupación de Gimbutas fue demasiado amplia. Según Anthony, es mejor hablar de la cultura Yamnaya o de un "horizonte Yamnaya", que incluía varias culturas relacionadas, como la cultura protoindoeuropea definitoria en la estepa póntica. [1] David Anthony ha incorporado desarrollos recientes en su "hipótesis esteparia revisada", que también apoya un origen estepario de las lenguas indoeuropeas. [1] [83] Anthony enfatiza la cultura Yamnaya (3300-2500 a. C.), [1] que según él comenzó en el Don medio y el Volga, como el origen de la dispersión indoeuropea, [1] [83] pero considera la cultura arqueológica de Khvalynsk desde alrededor del 4500 a. C. como la fase más antigua del protoindoeuropeo en el bajo y medio Volga, una cultura que mantenía ovejas, cabras, ganado y tal vez caballos domesticados. [29] Investigaciones recientes de Haak et al. (2015) confirma la migración del pueblo Yamnaya a Europa occidental, formando la cultura de cerámica cordada. [10]

Un análisis reciente de Anthony (2019) también sugiere un origen genético de los protoindoeuropeos (de la cultura Yamnaya) en la estepa de Europa del Este al norte del Cáucaso, que deriva de una mezcla de cazadores-recolectores de Europa del Este (EHG) y cazadores-recolectores del Cáucaso (CHG). Anthony sugiere además que la lengua protoindoeuropea se formó principalmente a partir de una base de lenguas habladas por EHG con influencias de lenguas de CHG del norte, además de una posible influencia posterior y menor de la lengua de la cultura Maykop al sur (que se supone que perteneció a la familia del Cáucaso del Norte ) en el Neolítico tardío o la Edad del Bronce con poco impacto genético. [84]

El principal competidor es la hipótesis anatolia propuesta por Colin Renfrew , [78] [21] que afirma que las lenguas indoeuropeas comenzaron a propagarse pacíficamente en Europa desde Asia Menor (la actual Turquía ) alrededor del 7000 a. C. con el avance de la agricultura por difusión demica (difusión a través de la migración) durante la Revolución Neolítica . [77] En consecuencia, la mayoría de los habitantes de la Europa neolítica habrían hablado lenguas indoeuropeas y las migraciones posteriores, en el mejor de los casos, habrían reemplazado estas variedades indoeuropeas por otras variedades indoeuropeas. [85] La principal fortaleza de la hipótesis de la agricultura radica en su vinculación de la difusión de las lenguas indoeuropeas con un evento conocido arqueológicamente (la difusión de la agricultura) que a menudo se supone que implica cambios significativos de población. Sin embargo, en estos días la hipótesis anatolia es generalmente rechazada, ya que es incompatible con los datos crecientes sobre la historia genética del pueblo Yamnaya. [21]

Otra hipótesis que ha atraído considerable y renovada atención es la hipótesis de la meseta armenia de Gamkrelidze e Ivanov, quienes han argumentado que el Urheimat estaba al sur del Cáucaso, específicamente, "dentro de Anatolia oriental, el Cáucaso meridional y Mesopotamia septentrional" en el quinto al cuarto milenio a. C. [86] [77] [78] [21] Su propuesta se basaba en una hipótesis controvertida de consonantes glotales en PIE. Según Gamkrelidze e Ivanov, las palabras PIE para objetos de cultura material implican contacto con pueblos más avanzados del sur, la existencia de préstamos semíticos en PIE, préstamos kartvelianos de PIE y algún contacto con el sumerio , elamita y otros. Sin embargo, dado que la hipótesis glotálica nunca se impuso y hubo poco apoyo arqueológico para ella, la hipótesis de Gamkrelidze e Ivanov no ganó apoyo hasta que la hipótesis anatolia de Renfrew revivió aspectos de su propuesta. [21]

Los protoindoeuropeos eran hablantes de la lengua protoindoeuropea (PIE), una lengua prehistórica reconstruida de Eurasia . El conocimiento sobre ellos proviene principalmente de la reconstrucción lingüística, junto con evidencia material de la arqueología y la arqueogenética .

Según algunos arqueólogos, no se puede suponer que los hablantes de lenguas indígenas persas hayan sido un pueblo o tribu único e identificable, sino un grupo de poblaciones vagamente relacionadas, ancestrales de los indoeuropeos de la Edad del Bronce , posteriores y todavía parcialmente prehistóricos . Esta opinión es sostenida especialmente por aquellos arqueólogos que postulan una patria original de vasta extensión y una inmensa profundidad temporal. Sin embargo, esta opinión no es compartida por los lingüistas, ya que las protolenguas generalmente ocupan pequeñas áreas geográficas durante un lapso de tiempo muy limitado, y generalmente son habladas por comunidades muy unidas, como una única y pequeña tribu. [87]

Es probable que los protoindoeuropeos hayan vivido a finales del Neolítico , o aproximadamente en el cuarto milenio a. C. Los estudios más extendidos los sitúan en la zona de estepa forestal inmediatamente al norte del extremo occidental de la estepa póntico-caspia en Europa del Este . Algunos arqueólogos extenderían la profundidad temporal de la EIP hasta el Neolítico medio (5500 a 4500 a. C.) o incluso el Neolítico temprano (7500 a 5500 a. C.), y sugieren patrias originales protoindoeuropeas alternativas .

A finales del tercer milenio a. C., las ramificaciones de los protoindoeuropeos habían llegado a Anatolia ( hititas ), el Egeo ( Grecia micénica ), Europa occidental y el sur de Siberia ( cultura de Afanasevo ). [88]

Los protoindoeuropeos, es decir, el pueblo Yamnaya y las culturas relacionadas, parecen haber sido una mezcla de cazadores-recolectores de Europa del Este; y personas relacionadas con el Cercano Oriente, [89] es decir, cazadores-recolectores del Cáucaso (CHG) [90] es decir, personas del Calcolítico de Irán con un componente de cazadores-recolectores caucásicos. [91] Se desconoce de dónde vino este componente CHG; la mezcla de EHG y CHG puede ser el resultado de "un gradiente genético natural existente que va desde EHG lejos al norte hasta CHG/Irán en el sur", [92] o puede explicarse como "el resultado de la ascendencia iraní/relacionada con CHG que llegó a la zona de la estepa de forma independiente y antes de una corriente de ascendencia AF [agricultores de Anatolia]", [92] que llegó a las estepas con personas que migraron hacia el norte a las estepas entre 5.000 y 3.000 a. C. [32] [84] [nota 9]

Existen diferentes posibilidades con respecto a la génesis del PIE arcaico. [36] [84] [23] [93] Si bien el consenso es que las lenguas PIE tempranas y tardías se originaron en las estepas pónticas, la ubicación del origen del PIE arcaico se ha convertido en el foco de renovada atención, debido a la pregunta de dónde vino el componente CHG y si fueron los portadores del PIE arcaico. [36] Algunos sugieren un origen del PIE arcaico a partir de las lenguas de los cazadores-recolectores (EHG) de la estepa de Europa del Este/Eurasia, algunos sugieren un origen en el Cáucaso o al sur del mismo, y otros sugieren un origen mixto de las lenguas de ambas regiones mencionadas anteriormente.

Algunas investigaciones recientes sobre el ADN han dado lugar a nuevas sugerencias, en particular por parte de David Reich, de una patria caucásica para los indoeuropeos arcaicos o "protoprotoindoeuropeos", desde donde los pueblos de habla PIE arcaica migraron a Anatolia, donde se desarrollaron las lenguas anatolias, mientras que en las estepas el PIE arcaico se convirtió en el PIE temprano y tardío. [10] [93] [94] [95 ] [36] [37] [38] [96] [nota 11]

Anthony (2019, 2020) critica las propuestas de origen sureño/caucásico de Reich y Kristiansen, y rechaza la posibilidad de que el pueblo Maykop de la Edad de Bronce del Cáucaso fuera una fuente meridional de lengua y genética indoeuropea. Según Anthony, refiriéndose a Wang et al. (2018), [nota 12] la cultura Maykop tuvo poco impacto genético en los Yamnaya, cuyos linajes paternos diferían de los encontrados en los restos de Maykop, pero estaban relacionados con los de los cazadores-recolectores de Europa del Este anteriores. Además, los Maykop (y otras muestras contemporáneas del Cáucaso), junto con CHG de esta fecha, tenían una ascendencia significativa de agricultores de Anatolia "que se había extendido al Cáucaso desde el oeste después de aproximadamente 5000 a. C.", mientras que los Yamnaya tenían un porcentaje menor que no encaja con un origen Maykop. En parte por estas razones, Anthony concluye que los grupos del Cáucaso de la Edad de Bronce como los maykop "sólo desempeñaron un papel menor, si es que tuvieron alguno, en la formación de la ascendencia yamna". Según Anthony, las raíces del protoindoeuropeo (arcaico o protoindoeuropeo) se encontraban principalmente en la estepa, más que en el sur. Anthony considera probable que los maykop hablaran una lengua caucásica septentrional no ancestral del indoeuropeo. [101] [84]

La hipótesis alternativa del sustrato caucásico de Bomhard propone un Urheimat " indo-urálico del norte del Caspio ", que implica un origen del PIE a partir del contacto de dos lenguas: una lengua esteparia euroasiática del norte del Caspio (relacionada con el urálico ) que adquirió una influencia de sustrato de una lengua del noroeste del Cáucaso. [102] [nota 13] Según Anthony (2019), una relación genética con el urálico es poco probable y no se puede probar de manera confiable; las similitudes entre el urálico y el indoeuropeo se explicarían por préstamos e influencias tempranas. [84]

Anthony sostiene que el protoindoeuropeo se formó principalmente a partir de las lenguas de los cazadores-recolectores de Europa del Este con influencias de las de los cazadores-recolectores del Cáucaso, [101] y sugiere que la lengua protoindoeuropea arcaica se formó en la cuenca del Volga (en la estepa de Europa del Este). [84] Se desarrolló a partir de una base de lenguas habladas por los cazadores-recolectores de Europa del Este en las llanuras de la estepa del Volga, con algunas influencias de las lenguas de los cazadores-recolectores del norte del Cáucaso que migraron del Cáucaso al bajo Volga. Además, es posible que exista una influencia posterior, con poco impacto genético, en el Neolítico tardío o la Edad del Bronce de la lengua de la cultura Maykop al sur, que se plantea como perteneciente a la familia del Cáucaso del Norte . [84] Según Anthony, los campamentos de caza y pesca del bajo Volga, que datan de 6200-4500 a. C., podrían ser los restos de personas que aportaron el componente CHG, similar a la cueva Hotu, que migraron desde el noroeste de Irán o Azerbaiyán a través de la costa occidental del Caspio. Se mezclaron con personas EHG de las estepas del norte del Volga, formando la cultura Khvalynsk , que "podría representar la fase más antigua de PIE". [84] [36] [nota 14] La cultura resultante contribuyó a la cultura Sredny Stog, [111] un predecesor de la cultura Yamnaya.

Según Anthony, el desarrollo de las culturas protoindoeuropeas comenzó con la introducción del ganado en las estepas póntico-caspías. [112] Hasta ca. 5200-5000 a. C., las estepas póntico-caspías estaban pobladas por cazadores-recolectores. [113] Según Anthony, los primeros pastores de ganado llegaron desde el valle del Danubio alrededor del 5800-5700 a. C., descendientes de los primeros agricultores europeos . [114] Formaron la cultura Criş (5800-5300 a. C.), creando una frontera cultural en la cuenca del Prut-Dniéster. [115] La cultura adyacente Bug-Dniéster (6300-5500 a. C.) fue una cultura local, desde donde la cría de ganado se extendió a los pueblos esteparios. [116] El área de los rápidos del Dniéster fue la siguiente parte de las estepas póntico-caspías en cambiar al pastoreo de ganado. En aquella época era una zona densamente poblada de las estepas póntico-caspias y había estado habitada por varias poblaciones de cazadores-recolectores desde el final de la Edad de Hielo. Entre los años 5800 y 5200 estuvo habitada por la primera fase de la cultura Dniéper-Donets , una cultura de cazadores-recolectores contemporánea a la cultura Bug-Dniéster. [117]

Hacia el 5200-5000 a. C., la cultura Cucuteni-Trypillia (6000-3500 a. C.) (también conocida como cultura Tripolye), que se presume que no hablaba indoeuropeo, aparece al este de los montes Cárpatos, [118] desplazando la frontera cultural al valle del Bug meridional, [119] mientras que los recolectores de los rápidos del Dniéper pasaron a la cría de ganado, lo que marca el cambio a Dniéper-Donets II (5200/5000 – 4400/4200 a. C.). [120] La cultura del Dniéper-Donets tenía ganado no solo para sacrificios rituales, sino también para su dieta diaria. [121] La cultura Jvalynsk (4700–3800 a. C.), [121] situada en el curso medio del Volga, que estaba conectada con el valle del Danubio por redes comerciales, [122] también tenía ganado vacuno y ovino, pero eran "más importantes en los sacrificios rituales que en la dieta". [123] La cultura Samara (principios del V milenio a. C.), [nota 15] al norte de la cultura Jvalynsk, interactuó con esta última, [124] mientras que los hallazgos arqueológicos parecen estar relacionados con los de la cultura Dniéper-Donets II . [124]

La cultura Sredny Stog (4400–3300 a. C.) [125] aparece en el mismo lugar que la cultura Dniepr-Donets, pero muestra influencias de personas que vinieron de la región del río Volga. [111] Según Vasiliev, las culturas Khvalynsk y Sredny Stog muestran fuertes similitudes, lo que sugiere "un amplio horizonte Sredny Stog-Khvalynsk que abarca todo el Póntico-Caspio durante el Eneolítico". [126] De este horizonte surgió la cultura Yamnaya, que también se extendió por toda la estepa Póntico-Caspio. [126]

Según Anthony, los pastores esteparios preyamnaya, hablantes arcaicos del protoindoeuropeo, se extendieron al valle inferior del Danubio alrededor del 4200-4000 a. C., ya sea causando o aprovechando el colapso de la Vieja Europa , [30] sus lenguas "probablemente incluían dialectos protoindoeuropeos arcaicos del tipo parcialmente preservado más tarde en Anatolia". [127] Véase la cultura Suvorovo y la cultura Ezero para más detalles.

Los anatolios eran un grupo de pueblos indoeuropeos distintos que hablaban las lenguas anatolias y compartían una cultura común. [128] [129] [ 130] [131] [132] Los primeros testimonios lingüísticos e históricos de los anatolios son los nombres mencionados en textos mercantiles asirios del siglo XIX a. C. Kanesh . [128]

Las lenguas anatolias eran una rama de la gran familia de lenguas indoeuropeas . El descubrimiento arqueológico de los archivos de los hititas y la clasificación de la lengua hitita como una rama anatolia separada de las lenguas indoeuropeas causó sensación entre los historiadores, obligando a una reevaluación de la historia del Cercano Oriente y la lingüística indoeuropea . [132]

Damgaard et al. (2018) señalan que "[e]ntre los lingüistas comparativos, una ruta balcánica para la introducción del idioma inglés de Anatolia se considera generalmente más probable que un paso por el Cáucaso, debido, por ejemplo, a una mayor presencia del idioma inglés de Anatolia y a la diversidad lingüística en Occidente". [32]

Mathieson et al. señalan la ausencia de "grandes cantidades" de ascendencia esteparia en la península de los Balcanes y Anatolia, lo que puede indicar que el PIE arcaico se originó en el Cáucaso o Irán, pero también afirman que "sigue siendo posible que las lenguas indoeuropeas se extendieran a través del sudeste de Europa hasta Anatolia sin un movimiento o mezcla de población a gran escala". [98]

Damgaard et al. (2018), no encontraron "ninguna correlación entre la ascendencia genética y las identidades étnicas o políticas exclusivas entre las poblaciones de la Edad del Bronce de Anatolia Central, como se había planteado anteriormente". [32] Según ellos, los hititas carecían de ascendencia esteparia, argumentando que "el clado anatolio de lenguas IE no derivó de un movimiento poblacional a gran escala de la Edad del Cobre/Edad del Bronce Temprano desde la estepa", contrariamente a la propuesta de Anthony de una migración a gran escala a través de los Balcanes, como se propuso en 2007. [32] Los primeros hablantes de IE pueden haber llegado a Anatolia "a través de contactos comerciales y movimientos a pequeña escala durante la Edad del Bronce". [32] Afirman además que sus hallazgos son "coherentes con los modelos históricos de hibridez cultural y 'término medio' en una Anatolia de la Edad del Bronce multicultural y multilingüe pero genéticamente homogénea", como propusieron otros investigadores. [32]

Según Kroonen et al. (2018), en el suplemento lingüístico de Damgaard et al. (2018), los estudios de ADNa en Anatolia "no muestran ninguna indicación de una intrusión a gran escala de una población esteparia", pero sí "encajan en el consenso desarrollado recientemente entre lingüistas e historiadores de que los hablantes de las lenguas anatolias se establecieron en Anatolia mediante una infiltración gradual y una asimilación cultural". [133] Además, señalan que esto respalda la hipótesis indohitita , según la cual tanto el protoanatolio como el protoindoeuropeo se separaron de una lengua materna común "a más tardar en el cuarto milenio a. C.". [134]

Aunque los hititas están atestiguados por primera vez en el segundo milenio a. C., [33] la rama anatolia parece haberse separado en una etapa muy temprana del protoindoeuropeo, o puede haberse desarrollado a partir de un ancestro preprotoindoeuropeo más antiguo . [135] Considerando un origen estepario para el PIE arcaico, junto con los tocarios, los anatolios constituyeron la primera dispersión conocida del indoeuropeo fuera de la estepa euroasiática . [136] Aunque esos hablantes arcaicos del PIE tenían carros, probablemente llegaron a Anatolia antes de que los indoeuropeos hubieran aprendido a usar carros para la guerra. [136] Es probable que su llegada fuera una de asentamiento gradual y no como un ejército invasor. [128]

Según Mallory, es probable que los anatolios llegaran al Cercano Oriente desde el norte, ya sea a través de los Balcanes o el Cáucaso en el tercer milenio a. C. [132] Según Anthony, si se separó del protoindoeuropeo, probablemente lo hizo entre 4500 y 3500 a. C. [137] Según Anthony, los descendientes de los pastores esteparios protoindoeuropeos arcaicos, que se trasladaron al valle inferior del Danubio alrededor de 4200-4000 a. C., se trasladaron más tarde a Anatolia, en un momento desconocido, pero tal vez tan pronto como 3000 a. C. [138] Según Parpola, la aparición de hablantes indoeuropeos de Europa en Anatolia, y la aparición del hitita, está relacionada con migraciones posteriores de hablantes protoindoeuropeos de la cultura yamna al valle del Danubio en c. 2800 a. C. , [35] [6] lo que coincide con la suposición "habitual" de que la lengua indoeuropea de Anatolia se introdujo en Anatolia en algún momento del tercer milenio a. C. [web 7]

Los hititas, que establecieron un extenso imperio en Oriente Medio en el segundo milenio a. C., son con diferencia los miembros más conocidos del grupo de Anatolia. La historia de la civilización hitita se conoce sobre todo a partir de textos cuneiformes encontrados en la zona de su reino, y de la correspondencia diplomática y comercial hallada en varios archivos de Egipto y Oriente Medio . A pesar del uso de Hatti como territorio central, los hititas deben distinguirse de los hatianos , un pueblo anterior que habitó la misma región (hasta principios del segundo milenio). El ejército hitita hizo un uso exitoso de los carros . Aunque pertenecen a la Edad del Bronce , fueron los precursores de la Edad del Hierro , desarrollando la fabricación de artefactos de hierro desde el siglo XIV a. C., cuando las cartas a los gobernantes extranjeros revelan la demanda de estos últimos de productos de hierro. El imperio hitita alcanzó su apogeo a mediados del siglo XIV a. C. bajo Suppiluliuma I , cuando abarcaba un área que incluía la mayor parte de Asia Menor , así como partes del norte del Levante y la Alta Mesopotamia . Después de 1180 a. C., en medio del Colapso de la Edad de Bronce en el Levante asociado con la llegada repentina de los Pueblos del Mar , el reino se desintegró en varias ciudades-estado " neohititas " independientes, algunas de las cuales sobrevivieron hasta el siglo VIII a. C. Las tierras de los pueblos de Anatolia fueron invadidas sucesivamente por varios pueblos e imperios con alta frecuencia: los frigios , los bitinios , los medos , los persas , los griegos , los celtas gálatas , los romanos y los turcos oghuz . Muchos de estos invasores se establecieron en Anatolia, en algunos casos causando la extinción de las lenguas anatolias. En la Edad Media , todas las lenguas anatolias (y las culturas que las acompañaban) se habían extinguido, aunque puede que todavía quedaran influencias en los habitantes modernos de Anatolia, sobre todo los armenios . [139]

La cultura Maikop, c. 3700–3000 a. C., [140] fue una importante cultura arqueológica de la Edad del Bronce en la región del Cáucaso occidental del sur de Rusia. Se extiende a lo largo del área desde la península de Tamán en el estrecho de Kerch hasta cerca de la frontera moderna de Daguestán y hacia el sur hasta el río Kura . La cultura toma su nombre de un entierro real encontrado en el túmulo de Maikop en el valle del río Kuban .

Según Mallory y Adams, las migraciones hacia el sur fundaron la cultura Maykop ( c. 3500-2500 a. C.). [43] Sin embargo, según Mariya Ivanova, los orígenes de Maykop estaban en la meseta iraní, [44] mientras que los kurganes de principios del cuarto milenio en Soyuqbulaq en Azerbaiyán , que pertenecen a la cultura Leyla-Tepe , muestran paralelismos con los kurganes de Maykop. Según Museyibli, "las tribus de la cultura Leylatepe migraron al norte a mediados del cuarto milenio y desempeñaron un papel importante en el surgimiento de la cultura Maykop del Cáucaso Norte". [web 8] Este modelo fue confirmado por un estudio genético publicado en 2018, que atribuyó el origen de los individuos de Maykop a una migración de agricultores eneolíticos desde el oeste de Georgia hacia el lado norte del Cáucaso. [141] Se ha sugerido que el pueblo Maykop hablaba una lengua del Cáucaso Norte , en lugar de una indoeuropea. [84] [142]

La cultura Afanasievo (3300 a 2500 a. C.) es la cultura arqueológica eneolítica más antigua encontrada hasta ahora en el sur de Siberia , que ocupa la cuenca de Minusinsk , Altay y el este de Kazajstán . Se originó con una migración de personas de la cultura pre-Yamnaya Repin , en el río Don, [144] y está relacionada con los tocarios. [145]

El radiocarbono proporciona fechas tan tempranas como 3705 a. C. en herramientas de madera y 2874 a. C. en restos humanos de la cultura Afanasievo. [146] La más temprana de estas fechas ha sido rechazada, dando una fecha de alrededor de 3300 a. C. para el inicio de la cultura. [147]

"Estos movimientos tanto de tocarios como de iraníes hacia el este de Asia central no fueron una mera nota a pie de página en la historia de China, sino que... fueron parte de un panorama mucho más amplio que involucraba los cimientos mismos de la civilización sobreviviente más antigua del mundo". [148]

Los tocarios , o "tokharianos" ( / təˈkɛəriənz / o / təˈkɑːriənz / ) eran habitantes de ciudades-estado medievales en el extremo norte de la cuenca del Tarim ( actual Sinkiang , China ). Sus lenguas tocarios ( una rama de la familia indoeuropea ) se conocen a partir de manuscritos de los siglos VI al VIII d. C., después de lo cual fueron suplantadas por las lenguas túrquicas de las tribus uigures . A finales del siglo XIX, los eruditos llamaron a este pueblo "tocarios" y los identificaron con los tókharoi descritos por las fuentes griegas antiguas como habitantes de Bactria . Aunque esta identificación se considera generalmente errónea, el nombre se ha vuelto habitual.

Se cree que los tocarios se desarrollaron a partir de la cultura Afanasevo de Siberia ( c. 3500-2500 a. C.). [145] Se cree que las momias de Tarim , que datan de 1800 a. C., representan una migración de hablantes de tocarios de la cultura Afanasevo en la cuenca del Tarim a principios del segundo milenio a. C.; [41] Sin embargo, un estudio genético de 2021 demostró que las momias de Tarim son restos de lugareños que descienden de antiguos euroasiáticos del norte y asiáticos del noreste , y en cambio sugirió que " el tocario puede haber sido introducido plausiblemente en la cuenca de Dzungaria por migrantes de Afanasievo" -es decir, "los pastores de Afanasievo de la región de Altai-Sayan en el sur de Siberia (3150-2750 a. C.), quienes a su vez tienen estrechos vínculos genéticos con los yamna (3500-2500 a. C.) de la estepa póntico-caspia ubicada a 3000 km al oeste"- antes de ser registrados en las escrituras budistas de 500-1000 d . C. [42]

La expansión indoeuropea hacia el este en el segundo milenio a. C. dejó una influencia en la cultura china, introduciendo vehículos con ruedas y el caballo domesticado . [149] Aunque mucho menos seguro, también puede haber introducido tecnología del hierro , [150] [web 12] estilos de lucha, rituales de cabeza y pezuña, motivos artísticos y mitos. [151] A fines del segundo milenio a. C., los pueblos dominantes tan al este como las montañas de Altai hacia el sur hasta las salidas septentrionales de la meseta tibetana eran antropológicamente caucásicos , con la parte norte hablando lenguas escitas iraníes y las partes sur lenguas tocarios, teniendo poblaciones mongoloides como sus vecinos del noreste. [152] [web 13] Estos dos grupos competían entre sí hasta que el último venció al primero. [web 13] El punto de inflexión se produjo alrededor de los siglos V al IV a. C. con una mongolización gradual de Siberia, mientras que el este de Asia central (Turkestán oriental) siguió siendo de habla caucásica e indoeuropea hasta bien entrado el primer milenio d. C. [153]

“La historia política de los indoeuropeos del Asia interior, desde el siglo II a. C. hasta el siglo V d. C., es sin duda un período glorioso. Fue su movimiento el que puso a China en contacto con el mundo occidental y con la India. Estos indoeuropeos tuvieron la llave del comercio mundial durante un largo período... En el proceso de su propia transformación, estos indoeuropeos influyeron en el mundo que los rodeaba más que cualquier otro pueblo antes del surgimiento del Islam”. [154]

El sinólogo Edwin G. Pulleyblank ha sugerido que los yuezhi , los wusun , los dayuan , los kangju y los pueblos de Yanqi podrían haber sido de habla tocario. [156] De estos, se considera generalmente que los yuezhi eran tocarios. [157] Los yuezhi se asentaron originalmente en las praderas áridas de la zona oriental de la cuenca del Tarim , en lo que hoy es Xinjiang y el oeste de Gansu , en China .

En el apogeo de su poder en el siglo III a. C., se cree que los yuezhi dominaron las áreas al norte de las montañas Qilian (incluidas la cuenca del Tarim y Dzungaria ), la región de Altai , [158] la mayor parte de Mongolia y las aguas superiores del río Amarillo . [159] [160] [161] Este territorio ha sido denominado el Imperio Yuezhi . [162] Sus vecinos orientales eran los donghu . [160] Mientras los yuezhi presionaban a los xiongnu desde el oeste, los donghu hacían lo mismo desde el este. [160] Un gran número de pueblos, incluidos los wusun , los estados de la cuenca del Tarim y posiblemente los qiang , [161] estaban bajo el control de los yuezhi. [160] Se los consideraba la potencia predominante en Asia Central . [161] La evidencia de los registros chinos indica que los pueblos de Asia Central hasta el oeste del Imperio parto estaban bajo el dominio de los Yuezhi. [161] Esto significa que el territorio del Imperio Yuezhi correspondía aproximadamente al del posterior Primer Khaganato Turco . [161] Los entierros de Pazyryk de la meseta de Ukok coinciden con el apogeo del poder de los Yuezhi, y por lo tanto los entierros se les han atribuido, lo que significa que la región de Altai era parte del Imperio Yuezhi. [158]

Después de que los yuezhi fueran derrotados por los xiongnu , en el siglo II a. C., un pequeño grupo, conocido como los pequeños yuezhi, huyó al sur, dando lugar más tarde al pueblo jie . A principios del siglo IV d. C., los jie dominaron el norte de China bajo el Zhao Posterior (319-351 d. C.) hasta su completo exterminio por la orden de sacrificio de Ran Min y las guerras en medio del colapso de su estado. Sin embargo, la mayoría de los yuezhi emigraron al oeste, al valle de Ili , donde desplazaron a los sakas ( escitas ). Expulsados del valle de Ili poco después por los wusun, los yuezhi emigraron a Sogdia y luego a Bactria , donde a menudo se los identifica con los tókharoi (Τοχάριοι) y los asioi de las fuentes clásicas. Luego se expandieron al norte de Asia meridional , donde una rama de los yuezhi fundó el Imperio kushán . El imperio kushán se extendió desde Turfán , en la cuenca del Tarim , hasta Pataliputra, en la llanura del Ganges , en su punto más alto, y desempeñó un papel importante en el desarrollo de la Ruta de la Seda y la transmisión del budismo a China . Las lenguas tocarios continuaron hablándose en las ciudades-estado de la cuenca del Tarim, y solo se extinguieron en la Edad Media .

El PIE tardío está relacionado con la cultura y expansión Yamnaya, de la que descienden todas las lenguas IE, excepto las lenguas anatolias y el tocario.

According to Mallory, "The origin of the Yamnaya culture is still a topic of debate," with proposals for its origins pointing to both Khvalynsk and Sredny Stog.[45] The Khvalynsk culture (4700–3800 BCE)[121] (middle Volga) and the Don-based Repin culture (ca.3950–3300 BCE)[144] in the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe, and the closely related Sredny Stog culture (c. 4500–3500 BCE) in the western Pontic-Caspian steppe, preceded the Yamnaya culture (3300–2500 BCE).[163][164] According to Anthony, the Yamnaya culture originated in the Don-Volga area at ca. 3400 BCE,[46] arguing that late pottery from these two cultures can barely be distinguished from early Yamnaya pottery.[165]

The Yamnaya horizon (a.k.a. Pit Grave culture) spread quickly across the Pontic-Caspian steppes between ca. 3400 and 3200 BCE.[46] It was an adaptation to a climate change that occurred between 3500 and 3000 BCE, in which the steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved frequently to feed them sufficiently, and the use of wagons and horse-back riding made this possible, leading to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism".[74] It was accompanied by new social rules and institutions, to regulate the local migrations in the steppes, creating a new social awareness of a distinct culture, and of "cultural Others" who did not participate in these new institutions.[163]

According to Anthony, "the spread of the Yamnaya horizon was the material expression of the spread of late Proto-Indo-European across the Pontic-Caspian steppes."[166] Anthony further notes that "the Yamnaya horizon is the visible archaeological expression of a social adjustment to high mobility – the invention of the political infrastructure to manage larger herds from mobile homes based in the steppes."[167] The Yamnaya horizon represents the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practising animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. According to Gimbutas, contact of the Yamnaya horizon with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures.[168] Anthony excludes the Globular Amphora culture.[1]

The Maykop culture (3700–3000) emerges somewhat earlier in the northern Caucasus. Although considered by Gimbutas as an outgrowth of the steppe cultures, it is related to the development of Mesopotamia, and Anthony does not consider it to be a Proto-Indo-European culture.[1] The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to the Yamnaya horizon.

Between 3100 and 2600 BCE the Yamnaya people spread into the Danube Valley as far as Hungary.[169] According to Anthony, this migration probably gave rise to Proto-Celtic[170] and Pre-Italic.[170] Pre-Germanic dialects may have developed between the Dniestr (west Ukraine) and the Vistula (Poland) at c. 3100–2800 BCE, and spread with the Corded Ware culture.[171] Slavic and Baltic developed at the middle Dniepr (present-day Ukraine)[7] at c. 2800 BCE, also spreading with the Corded Ware horizon.[47]

In the northern Don-Volga area the Yamnaya horizon was followed by the Poltavka culture (2700–2100 BCE), while the Corded Ware culture extended eastwards, giving rise to the Sintashta culture (2100–1800). The Sintashta culture extended the Indo-European culture zone east of the Ural mountains, giving rise to Proto-Indo-Iranian and the subsequent spread of the Indo-Iranian languages toward India and the Iranian plateau.[1]

Between ca. 4000 and 3000 BCE, Neolithic populations in western Europe declined, probably due to the plague and other viral hemorrhagic fevers. This decline was followed by the migrations of Indo-European-speaking populations into western Europe, transforming the genetic make-up of the western populations.[172][note 16] Haak et al. (2015), Allentoft et al. (2015), and Mathieson et al. (2015) concluded that subclades of Y-DNA haplogroups R1b and R1a and an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans were introduced by Yamnaya-related populations from the West Eurasian Steppe, along with the Indo-European languages.[173][72][174]

During the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Age, the cultures of Europe derived from Early European Farmers (EEF) were overwhelmed by successive invasions of Western Steppe Herders (WSHs) from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, who carried about 60% Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) and 40% Caucasus Hunter-Gatherer (CHG) admixture. These invasions led to EEF paternal DNA lineages in Europe being almost entirely replaced with EHG/WSH paternal DNA (mainly R1b and R1a). EEF maternal DNA (mainly haplogroup N) also heavily declined, being supplanted by steppe lineages,[175][176] suggesting the migrations involved both males and females from the steppe. The study argues that more than 90% of Britain's Neolithic gene pool was replaced with the coming of the Beaker people,[177] who were around 50% WSH ancestry.[178] Danish archaeologist Kristian Kristiansen said he is "increasingly convinced there must have been a kind of genocide."[179] According to evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev, "There was a heavy reduction of Neolithic DNA in temperate Europe, and a dramatic increase of the new Yamnaya genomic component that was only marginally present in Europe prior to 3000 BC."[82]

The origins of Italo-Celtic, Germanic and Balto-Slavic have often been associated with the spread of the Corded Ware horizon and the Bell Beakers, but the specifics remain unsolved. A complicating factor is the association of haplogroup R1b with the Yamnaya horizon and the Bell Beakers, while the Corded Ware horizon is strongly associated with haplogroup R1a. Ancestors of Germanic and Balto-Slavic may have spread with the Corded Ware, originating east of the Carpatians, while the Danube Valley was ancestral to Italo-Celtic.

According to David Anthony, pre-Germanic split off earliest (3300 BCE), followed by pre-Italic and pre-Celtic (3000 BCE), pre-Armenian (2800 BCE), pre-Balto-Slavic (2800 BCE) and pre-Greek (2500 BCE).[180]

Mallory notes that the Italic, Celtic and Germanic languages are closely related, which accords with their historic distribution. The Germanic languages are also related to the Baltic and Slavic languages, which in turn share similarities with the Indo-Iranic languages.[181] The Greek, Armenian and Indo-Iranian languages are also related, which suggests "a chain of central Indo-European dialects stretching from the Balkans across the Black sea to the east Caspian".[181] And the Celtic, Italic, Anatolian and Tocharian languages preserve archaisms which are preserved only in those languages.[181]

Although Corded Ware is presumed to be largely derived from the Yamnaya culture, most Corded Ware males carried R1a Y-DNA, while males of the Yamnaya primarily carried R1b-M269.[note 17] According to Sjögren et al. (2020), R1b-M269 "is the major lineage associated with the arrival of Steppe ancestry in western Europe after 2500 BC[E],"[184] and is strongly related to the Bell Beaker expansion.

The Balkan-Danubian complex is a set of cultures in Southeast Europe, east and west of the Carpathian mountains, from which the western Indo-European languages probably spread into western Europe from c. 3500 BCE.[5] The area east of the Carpathian mountains formed a contact zone between the expanding Yamnaya culture and the northern European farmer cultures. According to Anthony, Pre-Italic and Pre-Celtic (related by Anthony to the Danube valley), and Pre-Germanic and Balto-Slavic (related by Anthony to the east-Carpathian contact zone) may have split off here from Proto-Indo-European.[185]

Anthony (2007) postulates the Usatovo culture as the origin of the pre-Germanic branch.[186] It developed east of the Carpathian mountains, south-eastern Central Europe, at around 3300–3200 BCE at the Dniestr river.[187] Although closely related to the Tripolye culture, it is contemporary with the Yamnaya culture, and resembles it in significant ways.[188] According to Anthony, it may have originated with "steppe clans related to the Yamnaya horizon who were able to impose a patron-client relationship on Tripolye farming villages".[189]

According to Anthony, the Pre-Germanic dialects may have developed in this culture between the Dniestr (west Ukraine) and the Vistula (Poland) at c. 3100–2800 BCE, and spread with the Corded Ware culture.[171] Slavic and Baltic developed at the middle Dniepr (present-day Ukraine)[7] at c. 2800 BCE, spreading north from there.[47]

Anthony (2017) relates the origins of the Corded Ware to the Yamnaya migrations into Hungary.[190] Between 3100 and 2800/2600 BCE, when the Yamnaya horizon spread fast across the Pontic Steppe, a real folk migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture took place into the Danube Valley,[6] moving along Usatovo territory toward specific destinations, reaching as far as Hungary,[191] where as many as 3,000 kurgans may have been raised.[192] According to Anthony (2007), Bell Beaker sites at Budapest, dated c. 2800–2600 BCE, may have aided in spreading Yamnaya dialects into Austria and southern Germany at their west, where Proto-Celtic may have developed.[170] Pre-Italic may have developed in Hungary, and spread toward Italy via the Urnfield culture and Villanovan culture.[170]

According to Parpola, this migration into the Danube Valley is related to the appearance of Indo-European speakers from Europe into Anatolia, and the appearance of Hittite.[35]

According to Lazaridis et al. (2022), the speakers of Albanian, Greek and other Paleo-Balkan languages, go back directly to the migration of Yamnaya steppe pastoralists into the Balkans about 5000 to 4500 years ago, admixting with the local populations.[193] Latin expanded after the Roman conquest of the Balkans, and in the early Middle Ages the territory was occupied by migrating Slavic people, and by east Asian steppe peoples. After the spread of Latin and Slavic, Albanian is the only surviving representative of the poorly attested ancient Balkan languages.[4]

The Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (c. 3200[194] or 2,900[web 1]–2450 or 2350 cal.[web 1][194] BCE) probably played an essential role in the origin and spread of the Indo-European languages in Europe during the Copper and Bronze Ages.[8][9] David Anthony states that "Childe (1953:133-38) and Gimbutas (1963) speculated that migrants from the steppe Yamnaya horizon (3300–2600 BCE) might have been the creators of the Corded Ware culture and carried IE languages into Europe from the steppes."[195]

According to Anthony (2007), the Corded Ware originated north-east of the Carpathian mountains, and spread across northern Europe after 3000 BCE, with an "initial rapid spread" between 2900 and 2700 BCE.[170] While Anthony (2007) situates the development of pre-Germanic dialects east of the Carpathians, arguing for a migration up the Dniestr,[171] Anthony (2017) relates the origins of the Corded Ware to the early third century Yamna-migrations into the Danube-valley, stating that "[t]he migration stream that created these intrusive cemeteries now can be seen to have continued from eastern Hungary across the Carpathians into southern Poland, where the earliest material traits of the Corded ware horizon appeared."[196] In southern Poland, interaction between Scandinavian and Global Amphora resulted in a new culture, absorbed by the incoming Yamnaya pastoralists.[197][note 18][note 19]

According to Mallory (1999), the Corded Ware culture may be postulated as "the common prehistoric ancestor of the later Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, and possibly some of the Indo-European languages of Italy". Yet, Mallory also notes that the Corded Ware can not account for Greek, Illyrian, Thracian and East Italic, which may be derived from Southeast Europe.[200] According to Anthony, the Corded Ware horizon may have introduced Germanic, Baltic and Slavic into northern Europe.[170]

According to Gimbutas, the Corded Ware culture was preceded by the Globular Amphora culture (3400–2800 BCE), which she also regarded to be an Indo-European culture. The Globular Amphora culture stretched from central Europe to the Baltic sea, and emerged from the Funnelbeaker culture.[201] According to Mallory, around 2400 BCE the people of the Corded Ware replaced their predecessors and expanded to Danubian and northern areas of western Germany. A related branch invaded the territories of present-day Denmark and southern Sweden. In places a continuity between Funnelbeaker and Corded Ware can be demonstrated, whereas in other areas Corded Ware heralds a new culture and physical type.[77] According to Cunliffe, most of the expansion was clearly intrusive.[202] Yet, according to Furholt, the Corded Ware culture was an indigenous development,[195] connecting local developments into a larger network.[196]

Recent research by Haak et al. found that four late Corded Ware people (2500–2300 BCE) buried at Esperstadt, Germany, were genetically very close to the Yamna-people, suggesting that a massive migration took place from the Eurasian steppes to Central Europe.[10][web 2][11][203] According to Haak et al. (2015), German Corded Ware "trace ~75% of their ancestry to the Yamna."[204] In supplementary information to Haak et al. (2015) Anthony, together with Lazaridis, Haak, Patterson, and Reich, notes that the mass migration of Yamnaya people to northern Europe shows that "the languages could have been introduced simply by strength of numbers: via major migration in which both sexes participated."[205][note 20]

Volker Heyd has cautioned to be careful with drawing too strong conclusions from those genetic similarities between Corded Ware and Yamna, noting the small number of samples; the late dates of the Esperstadt graves, which could also have undergone Bell Beaker admixture; the presence of Yamna-ancestry in western Europe before the Danube-expansion; and the risks of extrapolating "the results from a handful of individual burials to whole ethnically interpreted populations."[206] Heyd confirms the close connection between Corded Ware and Yamna, but also states that "neither a one-to-one translation from Yamnaya to CWC, nor even the 75:25 ratio as claimed (Haak et al. 2015:211) fits the archaeological record."[206]

The Bell Beaker-culture (c. 2900–1800 BCE[208][209]) may be ancestral to proto-Celtic,[210] which spread westward from the Alpine regions and formed a "North-west Indo-European" Sprachbund with Italic, Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[211][note 21]

The initial moves of the Bell Beakers from the Tagus estuary, Portugal were maritime. A southern move led to the Mediterranean where 'enclaves' were established in southwestern Spain and southern France around the Golfe du Lion and into the Po valley in Italy, probably via ancient western Alpine trade routes used to distribute jadeite axes. A northern move incorporated the southern coast of Armorica. The enclave established in southern Brittany was linked closely to the riverine and landward route, via the Loire, and across the Gâtinais valley to the Seine valley, and thence to the lower Rhine. This was a long-established route reflected in early stone axe distributions and it was via this network that Maritime Bell Beakers first reached the Lower Rhine in about 2600 BCE.[209][212]

The Germanic peoples (also called Teutonic, Suebian or Gothic in older literature)[214] were an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic starting during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.[web 14]

According to Mallory, Germanicists "generally agree" that the Urheimat ('original homeland') of the Proto-Germanic language, the ancestral idiom of all attested Germanic dialects, was primarily situated in an area corresponding to the extent of the Jastorf culture,[215][216][217][note 22] situated in Denmark and northern Germany.[218]

According to Herrin, the Germanic peoples are believed to have emerged about 1800 BCE with the Nordic Bronze Age (c. 1700-500 BCE).[web 15] The Nordic Bronze Age developed from the absorption of the hunter-gatherer Pitted Ware culture (c. 3500-2300 BCE) into the agricultural Battle Axe culture (c. 2800-2300 BCE),[219][220] which in turn developed from the superimposition of the Corded Ware culture (c. 3100-2350 BCE) upon the Funnelbeaker culture (c. 4300-2800 BCE) on the North European Plain, adjacent to the north of the Bell Beaker culture (c. 2800–2300 BCE).[web 15] Pre-Germanic may have been related to the Slavo-Baltic and Indo-Iranian languages, but reoriented towards the Italo-Celtic languages.[web 16]

By the early 1st millennium BC, Proto-Germanic is believed to have been spoken in the areas of present-day Denmark, southern Sweden, southern Norway and Northern Germany. Over time this area was expanded to include and a strip of land on the North European plain stretching from Flanders to the Vistula. Around 28% of the Germanic vocabulary is of non-Indo-European origin.[221]

By the 3rd century BC, the Pre-Roman Iron Age arose among the Germanic peoples, who were at the time expanding southwards at the expense of the Celts and Illyrians.[web 17] During the subsequent centuries, migrating Germanic peoples reached the banks of the Rhine and the Danube along the Roman border, and also expanded into the territories of Iranian peoples north of the Black Sea.[web 18]

In the late 4th century, the Huns invaded the Germanic territories from the east, forcing many Germanic tribes to migrate into the Western Roman Empire.[web 19] During the Viking Age, which began in the 8th century, the North Germanic peoples of Scandinavia migrated throughout Europe, establishing settlements as far as North America. The migrations of the Germanic peoples in the 1st millennium were a formative element in the distribution of peoples in modern Europe.[web 15]

Italic and Celtic languages are commonly grouped together on the basis of features shared by these two branches and no others. This could imply that they are descended from a common ancestor and/or Proto-Celtic and Proto-Italic developed in close proximity over a long period of time. The Italic languages, like Celtic ones, are split into P and Q forms: P-Italic includes Oscan and Umbrian, while Latin and Faliscan are included in the Q-Italic branch.[222]

The link to the Yamnaya-culture, in the contact zone of western and central Europe between Rhine and Vistula (Poland),[223] is as follows: Yamnaya culture (c. 3300–2600 BC) – Corded Ware culture (c. 3100–2350 BCE) – Bell Beaker culture (c. 2800–1800 BC) – Unetice culture (c. 2300–1680 BCE) – Tumulus culture (c. 1600–1200 BCE) – Urnfield culture (c. 1300–750 BCE). At the Balkan, the Vučedol culture (c. 3000–2200 BCE) formed a contact zone between post-Yamnaya and Bell Beaker culture.

The Italic languages are a subfamily of the Indo-European language family originally spoken by Italic peoples. They include the Romance languages derived from Latin (Italian, Sardinian, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, French, Romanian, Occitan, etc.); a number of extinct languages of the Italian Peninsula, including Umbrian, Oscan, Faliscan, South Picene; and Latin itself. At present, Latin and its daughter Romance languages are the only surviving languages of the Italic language family.

The most widely accepted theory suggests that Latins and other proto-Italic tribes first entered in Italy with the late Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture (12th–10th cent. BCE), then part of the central European Urnfield culture system (1300–750 BCE).[224][225] In particular various authors, like Marija Gimbutas, had noted important similarities between Proto-Villanova, the South-German Urnfield culture of Bavaria-Upper Austria[226] and Middle-Danube Urnfield culture.[226][227][228] According to David W. Anthony, proto-Latins originated in today's eastern Hungary, kurganized around 3100 BCE by the Yamnaya culture,[229] while Kristian Kristiansen associated the Proto-Villanovans with the Velatice-Baierdorf culture of Moravia and Austria.[230]

Today the Romance languages, which comprise all languages that descended from Latin, are spoken by more than 800 million native speakers worldwide, mainly in the Americas, Europe, and Africa. Romance languages are either official, co-official, or significantly used in 72 countries around the globe.[231][232][233][234][235]

The Celts (/ˈkɛlts/, occasionally /ˈsɛlts/, see pronunciation of Celtic) or Kelts were an ethnolinguistic group of tribal societies in Iron Age and Medieval Europe who spoke Celtic languages and had a similar culture,[236] although the relationship between the ethnic, linguistic and cultural elements remains uncertain and controversial.

The earliest archaeological culture that may justifiably be considered Proto-Celtic is the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture of Central Europe, which flourished from around 1200 BCE.[237]

Their fully Celtic[237] descendants in central Europe were the people of the Iron Age Hallstatt culture (c. 800–450 BCE) named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria.[238] By the later La Tène period (c. 450 BCE up to the Roman conquest), this Celtic culture had expanded by diffusion or migration to the British Isles (Insular Celts), France and The Low Countries (Gauls), Bohemia, Poland and much of Central Europe, the Iberian Peninsula (Celtiberians, Celtici and Gallaeci) and Italy (Golaseccans, Lepontii, Ligures and Cisalpine Gauls)[239] and, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BCE, as far east as central Anatolia (Galatians).[240]

The Celtic languages (usually pronounced /ˈkɛltɪk/ but sometimes /ˈsɛltɪk/)[241] are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707.[242]

Modern Celtic languages are mostly spoken on the northwestern edge of Europe, notably in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall, and the Isle of Man, and can be found spoken on Cape Breton Island. There are also a substantial number of Welsh speakers in the Patagonia area of Argentina. Some people speak Celtic languages in the other Celtic diaspora areas of the United States,[243] Canada, Australia,[244] and New Zealand.[245] In all these areas, the Celtic languages are now only spoken by minorities though there are continuing efforts at revitalization. Welsh is the only Celtic language not classified as "endangered" by UNESCO.