A través de las redes sociales , los mensajes de texto [1] y los medios de comunicación masivos se ha difundido información falsa , incluida desinformación intencional y teorías conspirativas , sobre la escala de la pandemia de COVID-19 y el origen , la prevención, el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la enfermedad . Celebridades, políticos y otras figuras públicas prominentes han propagado información falsa. Muchos países han aprobado leyes contra las " noticias falsas " y miles de personas han sido arrestadas por difundir información errónea sobre la COVID-19. La difusión de información errónea sobre la COVID-19 por parte de los gobiernos también ha sido significativa.

En las estafas comerciales se afirma que se ofrecen pruebas caseras, supuestos preventivos y curas "milagrosas" . [2] Varios grupos religiosos han afirmado que su fe los protegerá del virus. [3] Sin pruebas, algunas personas han afirmado que el virus es un arma biológica filtrada accidental o deliberadamente de un laboratorio, un plan de control de la población , el resultado de una operación de espionaje o el efecto secundario de las actualizaciones 5G a las redes celulares. [4]

La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) declaró una " infodemia " de información incorrecta sobre el virus que plantea riesgos para la salud mundial. [5] Si bien la creencia en teorías conspirativas no es un fenómeno nuevo, en el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19, esto puede conducir a efectos adversos para la salud. Los sesgos cognitivos, como el de sacar conclusiones precipitadas y el sesgo de confirmación , pueden estar relacionados con la aparición de creencias conspirativas. [6] La incertidumbre entre los expertos, cuando se combina con una falta de comprensión del proceso científico por parte de los legos, también ha sido un factor que amplifica las teorías conspirativas sobre la pandemia de COVID-19. [7] Además de los efectos sobre la salud, los daños resultantes de la difusión de información errónea y el respaldo de teorías conspirativas incluyen una creciente desconfianza en las organizaciones de noticias y las autoridades médicas, así como divisiones y fragmentación política. [8]

En enero de 2020, la BBC informó sobre el creciente problema de las teorías conspirativas y los malos consejos de salud con respecto al COVID-19. Los ejemplos en ese momento incluían consejos de salud falsos compartidos en las redes sociales y chats privados, así como teorías conspirativas como la de que el brote se estaba planeando con la participación del Instituto Pirbright . [9] [10] En enero, The Guardian enumeró siete casos de desinformación, agregando las teorías conspirativas sobre armas biológicas y el vínculo con la tecnología 5G , e incluyendo diversos consejos de salud falsos. [11]

En un intento por acelerar el intercambio de investigaciones, muchos investigadores han recurrido a servidores de preprints como arXiv , bioRxiv , medRxiv y SSRN . Los artículos se suben a estos servidores sin revisión por pares ni ningún otro proceso editorial que garantice la calidad de la investigación. Algunos de estos artículos han contribuido a la difusión de teorías conspirativas. [12] [13] [14] Los preprints sobre COVID-19 se han compartido ampliamente en línea y algunos datos sugieren que los medios los han utilizado casi 10 veces más que los preprints sobre otros temas. [15]

Según un estudio publicado por el Instituto Reuters para el Estudio del Periodismo , la mayor parte de la desinformación relacionada con el COVID-19 implica "diversas formas de reconfiguración, donde la información existente y a menudo verdadera se manipula, tuerce, recontextualiza o reelabora"; menos desinformación "fue completamente inventada". El estudio también encontró que "la desinformación de arriba hacia abajo de políticos, celebridades y otras figuras públicas prominentes", si bien representa una minoría de las muestras, captó la mayoría de la interacción en las redes sociales. Según su clasificación, la categoría más grande de desinformación (39%) fue "afirmaciones engañosas o falsas sobre las acciones o políticas de las autoridades públicas, incluidos los organismos gubernamentales e internacionales como la OMS o la ONU". [16]

Además de las redes sociales, la televisión y la radio han sido percibidas como fuentes de desinformación. En las primeras etapas de la pandemia de COVID-19 en los Estados Unidos , Fox News adoptó una línea editorial de que la respuesta de emergencia a la pandemia tenía motivaciones políticas o era injustificada de otro modo, [17] [18] y el presentador Sean Hannity afirmó en el aire que la pandemia era un "engaño" (más tarde emitió un desmentido). [19] Cuando lo evaluaron los analistas de medios, se encontró que el efecto de la desinformación transmitida influye en los resultados de salud en la población. En un experimento natural (un experimento que se lleva a cabo de forma espontánea, sin diseño o intervención humana), se compararon dos programas de noticias de televisión similares que se emitieron en la cadena Fox News en febrero-marzo de 2020. Un programa informó sobre los efectos de COVID-19 de forma más grave, mientras que un segundo programa restó importancia a la amenaza de COVID-19. El estudio encontró que las audiencias que estuvieron expuestas a las noticias que restaron importancia a la amenaza fueron estadísticamente más susceptibles a un aumento de las tasas de infección y muerte por COVID-19. [20] En agosto de 2021, la emisora de televisión Sky News Australia fue criticada por publicar videos en YouTube que contenían afirmaciones médicas engañosas sobre la COVID-19. [21] La radio hablada conservadora en los EE. UU. también ha sido percibida como una fuente de comentarios inexactos o engañosos sobre la COVID-19. En agosto y septiembre de 2021, varios presentadores de radio que habían desalentado la vacunación contra la COVID-19, o habían expresado escepticismo hacia la vacuna contra la COVID-19, murieron posteriormente por complicaciones de la COVID-19, entre ellos Dick Farrel , Phil Valentine y Bob Enyart . [22] [23]

En muchos países, los políticos, los grupos de interés y los agentes estatales han utilizado la desinformación sobre el COVID-19 con fines políticos: para evitar responsabilidades, convertir a otros países en chivos expiatorios y evitar las críticas por sus decisiones anteriores. A veces, también hay un motivo financiero. [24] [25] [26] Se ha acusado a varios países de difundir desinformación con operaciones respaldadas por el Estado en las redes sociales de otros países para generar pánico, sembrar desconfianza y socavar el debate democrático en otros países, o para promover sus modelos de gobierno. [27] [28] [29] [30]

Un estudio de la Universidad de Cornell sobre 38 millones de artículos en medios de comunicación en inglés de todo el mundo concluyó que el presidente estadounidense Donald Trump era el principal impulsor de la desinformación. [31] [32] Un análisis publicado por la Radio Pública Nacional en diciembre de 2021 concluyó que, a medida que los condados estadounidenses mostraban mayores porcentajes de votos para Trump en 2020, las tasas de vacunación contra la COVID-19 disminuyeron significativamente y las tasas de mortalidad aumentaron significativamente. La NPR atribuyó los hallazgos a la desinformación. [33]

El consenso entre los virólogos es que el origen más probable del virus SARS-CoV-2 es un cruce natural desde animales , habiéndose extendido a la población humana desde los murciélagos, posiblemente a través de un huésped animal intermediario, aunque no se ha determinado la vía de transmisión exacta. [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] La evidencia genómica sugiere que un virus ancestral del SARS-CoV-2 se originó en los murciélagos de herradura . [35]

Una hipótesis alternativa que se está investigando, considerada poco probable por la mayoría de los virólogos dada la falta de evidencia, es que el virus puede haberse escapado accidentalmente del Instituto de Virología de Wuhan en el curso de una investigación estándar. [36] [39] Una encuesta realizada en julio de 2021 encontró que el 52% de los adultos estadounidenses creen que el COVID-19 se escapó de un laboratorio. [40]

Durante la pandemia, han ganado popularidad las especulaciones sin fundamento y las teorías conspirativas relacionadas con este tema. Las teorías conspirativas más comunes afirman que el virus fue diseñado intencionalmente, ya sea como arma biológica o para obtener ganancias con la venta de vacunas. Según la Organización Mundial de la Salud, el análisis genómico ha descartado la manipulación genética. [41] [36] [42] También se han contado muchas otras historias sobre el origen, que van desde afirmaciones de complots secretos por parte de oponentes políticos hasta una teoría conspirativa sobre los teléfonos móviles. En marzo de 2020, el Pew Research Center descubrió que un tercio de los estadounidenses creía que el COVID-19 había sido creado en un laboratorio y una cuarta parte pensaba que había sido diseñado intencionalmente. [43] La propagación de estas teorías conspirativas se ve magnificada por la desconfianza y la animosidad mutuas, así como por el nacionalismo y el uso de campañas de propaganda con fines políticos. [44]

La promoción de desinformación ha sido utilizada por grupos estadounidenses de extrema derecha como QAnon , por medios de comunicación de derecha como Fox News, por el expresidente estadounidense Donald Trump y también otros republicanos prominentes para avivar los sentimientos anti-China, [45] [46] [43] y ha llevado a un aumento de la actividad anti-asiática en las redes sociales y en el mundo real. [47] Esto también ha resultado en el acoso a científicos y funcionarios de salud pública, tanto en línea como en persona, [54] alimentado por un debate altamente político y a menudo tóxico sobre muchos temas. [35] [55] Tal difusión de desinformación y teorías conspirativas tiene el potencial de afectar negativamente a la salud pública y disminuir la confianza en los gobiernos y los profesionales médicos. [56]

El resurgimiento de la fuga de laboratorio y otras teorías fue impulsado en parte por la publicación, en mayo de 2021, de los primeros correos electrónicos entre el director del Instituto Nacional de Alergias y Enfermedades Infecciosas (NIAID), Anthony Fauci , y científicos que discutían el tema. Según los correos electrónicos en cuestión, Kristian Andersen (autor de un estudio que desacredita las teorías de manipulación genómica) había considerado seriamente la posibilidad y envió un correo electrónico a Fauci proponiendo posibles mecanismos, antes de descartar la manipulación deliberada con un análisis técnico más profundo. [57] [58] Estos correos electrónicos fueron posteriormente malinterpretados y utilizados por los críticos para afirmar que se estaba produciendo una conspiración. [59] [60] La controversia resultante se conoció como el " Origen Proximal ". [61] [62] Sin embargo, a pesar de las afirmaciones en contrario en algunos periódicos estadounidenses, no ha surgido ninguna evidencia nueva que respalde ninguna teoría de un accidente de laboratorio, y la mayoría de las investigaciones revisadas por pares apuntan a un origen natural. Esto es similar a brotes anteriores de nuevas enfermedades, como el VIH, el SARS y el H1N1, que también han sido objeto de acusaciones de origen de laboratorio. [63] [64]

Una de las primeras fuentes de la teoría del origen de las armas biológicas fue la ex oficial del servicio secreto israelí Dany Shoham, quien concedió una entrevista a The Washington Times sobre el laboratorio de nivel de bioseguridad 4 (BSL-4) del Instituto de Virología de Wuhan . [65] [66] Una científica de Hong Kong, Li-Meng Yan , huyó de China y publicó una preimpresión que afirmaba que el virus se modificó en un laboratorio en lugar de tener una evolución natural. En una revisión por pares ad hoc (ya que el artículo no se presentó para la revisión por pares tradicional como parte del proceso de publicación científica estándar), sus afirmaciones fueron etiquetadas como engañosas, no científicas y una promoción poco ética de "teorías esencialmente conspirativas que no están fundadas en hechos". [67] El artículo de Yan fue financiado por la Rule of Law Society y la Rule of Law Foundation, dos organizaciones sin fines de lucro vinculadas a Steve Bannon , un ex estratega de Trump, y Guo Wengui , un multimillonario chino expatriado . [68] Esta desinformación fue aprovechada por la extrema derecha estadounidense, conocida por promover la desconfianza hacia China . En efecto, esto formó "una cámara de resonancia de rápido crecimiento para la desinformación". [45] La idea de que el SARS-CoV-2 es un arma diseñada en un laboratorio es un elemento de la teoría de la conspiración de Plandemic , que propone que fue liberado deliberadamente por China. [64]

The Epoch Times , un periódico anti- Partido Comunista Chino (PCCh) afiliado a Falun Gong , ha difundido información errónea relacionada con la pandemia de COVID-19 en forma impresa y a través de redes sociales como Facebook y YouTube. [69] [70] Ha promovido la retórica anti-PCCh y teorías conspirativas en torno al brote de coronavirus, por ejemplo a través de una edición especial de 8 páginas llamada "Cómo el Partido Comunista Chino puso en peligro al mundo", que se distribuyó sin que nadie lo solicitara en abril de 2020 a clientes de correo en áreas de los Estados Unidos, Canadá y Australia. [71] [72] En el periódico, el virus SARS-CoV-2 se conoce como el " virus del PCCh ", y un comentario en el periódico planteó la pregunta: "¿es el brote del nuevo coronavirus en Wuhan un accidente ocasionado por la militarización del virus en ese laboratorio [de virología de Wuhan P4]?" [69] [71] El consejo editorial del artículo sugirió que los pacientes de COVID-19 se curarían a sí mismos “condenando al PCCh ” y “tal vez ocurrirá un milagro”. [73]

En respuesta a la propagación de teorías en los EE. UU. sobre un origen de laboratorio de Wuhan, el gobierno chino promulgó la teoría de la conspiración de que el virus fue desarrollado por el ejército de los Estados Unidos en Fort Detrick . [74] [75] La teoría de la conspiración también fue promovida por el diputado británico Andrew Bridgen en marzo de 2023. [75]

Una idea utilizada para apoyar el origen de laboratorio invoca investigaciones previas sobre ganancia de función en coronavirus. La viróloga Angela Rasmussen sostuvo que esto es poco probable, debido al intenso escrutinio y supervisión gubernamental a la que está sujeta la investigación sobre ganancia de función, y que es improbable que la investigación sobre coronavirus difíciles de obtener pueda ocurrir bajo el radar. [76] El significado exacto de "ganancia de función" es objeto de controversia entre los expertos. [77] [78]

En mayo de 2020, el presentador de Fox News, Tucker Carlson, acusó a Anthony Fauci de haber "financiado la creación de COVID" a través de una investigación de ganancia de función en el Instituto de Virología de Wuhan (WIV). [77] Citando un ensayo del escritor científico Nicholas Wade , Carlson alegó que Fauci había dirigido una investigación para hacer que los virus de murciélago fueran más infecciosos para los humanos. [79] En una audiencia al día siguiente, el senador estadounidense Rand Paul alegó que los Institutos Nacionales de Salud de EE. UU. (NIH) habían estado financiando una investigación de ganancia de función en Wuhan, acusando a investigadores, incluido el epidemiólogo Ralph Baric , de crear "supervirus". [77] [80] Tanto Fauci como el director del NIH, Francis Collins, han negado que el gobierno de EE. UU. haya apoyado dicha investigación. [77] [78] [79] Baric también rechazó las acusaciones de Paul, diciendo que la investigación de su laboratorio sobre el potencial de los coronavirus de murciélago para la transmisión entre especies no fue considerada como ganancia de función por el NIH o la Universidad de Carolina del Norte, donde trabaja. [80]

Un estudio de 2017 sobre coronavirus quiméricos de murciélagos en el WIV incluyó a los NIH como patrocinadores; sin embargo, la financiación de los NIH solo estaba relacionada con la recolección de muestras. Basándose en esta y otras pruebas, The Washington Post calificó la afirmación de una conexión de los NIH con la investigación de ganancia de función sobre coronavirus como "dos pinochos", [80] [81] lo que representa "omisiones y/o exageraciones significativas". [82]

Otra teoría sugiere que el virus surgió en los humanos a partir de una infección accidental de trabajadores de laboratorio por una muestra natural. [39] En Internet se han difundido especulaciones infundadas sobre este escenario. [36]

En marzo de 2021, un informe de investigación publicado por la OMS describió este escenario como "extremadamente improbable" y no respaldado por ninguna evidencia disponible. [83] El informe reconoció, sin embargo, que la posibilidad no se puede descartar sin más pruebas. [39] La investigación detrás de este informe funcionó como una colaboración conjunta entre científicos chinos e internacionales. [84] [85] En la sesión informativa de publicación del informe, el Director General de la OMS, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, reiteró los llamados del informe para una investigación más profunda de todas las posibilidades evaluadas, incluido el escenario del origen de laboratorio. [86] El estudio y el informe fueron criticados por jefes de estado de los EE. UU., la UE y otros países miembros de la OMS por la falta de transparencia y el acceso incompleto a los datos. [87] [88] [89] Algunos científicos también han solicitado más investigaciones, incluido Anthony Fauci y los firmantes de una carta publicada en Science . [90]

Desde mayo de 2021, algunos medios de comunicación suavizaron el lenguaje que había utilizado anteriormente para describir la teoría de la fuga de laboratorio como "desacreditada" o una "teoría de la conspiración". [91] Por otro lado, la opinión científica de que una fuga accidental es posible, pero poco probable, se ha mantenido firme. [92] [35] Varios periodistas y científicos han dicho que descartaron o evitaron discutir la teoría de la fuga de laboratorio durante el primer año de la pandemia como resultado de la polarización percibida que resultó de la aceptación de la teoría por parte de Donald Trump. [91] [46] [93] [94]

Algunos usuarios de las redes sociales han alegado que científicos chinos robaron el COVID-19 de un laboratorio canadiense de investigación de virus. Health Canada y la Agencia de Salud Pública de Canadá dijeron que esto "no tenía base fáctica". [95] Las historias parecen haber sido derivadas de un artículo de noticias de CBC de julio de 2019 que afirmaba que a algunos investigadores chinos se les revocó el acceso de seguridad al Laboratorio Nacional de Microbiología en Winnipeg, un laboratorio de virología de nivel 4 , después de una investigación de la Real Policía Montada de Canadá . [96] [97] Los funcionarios canadienses describieron esto como un asunto administrativo y dijeron que no había ningún riesgo para el público canadiense. [96]

En respuesta a las teorías de conspiración, la CBC afirmó que sus artículos "nunca afirmaron que los dos científicos fueran espías, o que trajeron alguna versión de [un] coronavirus al laboratorio de Wuhan". Si bien las muestras de patógenos se transfirieron del laboratorio de Winnipeg a Beijing en marzo de 2019, ninguna de las muestras contenía un coronavirus. La Agencia de Salud Pública de Canadá ha declarado que el envío se ajustaba a todas las políticas federales y que los investigadores en cuestión aún están bajo investigación, por lo que no se puede confirmar ni negar que estos dos fueran responsables de enviar el envío. Tampoco se ha publicado la ubicación de los investigadores que están siendo investigados por la Real Policía Montada de Canadá. [95] [98] [99]

En una conferencia de prensa de enero de 2020, el secretario general de la OTAN , Jens Stoltenberg , cuando se le preguntó sobre el caso, declaró que no podía hacer comentarios específicos al respecto, pero expresó su preocupación por los "aumentos de los esfuerzos de las naciones para espiar a los aliados de la OTAN de diferentes maneras". [100]

Según The Economist , existen teorías conspirativas en Internet de China sobre que la CIA creó el COVID-19 para "mantener a China abajo". [101] Según una investigación de ProPublica , tales teorías conspirativas y desinformación se han propagado bajo la dirección de China News Service , el segundo medio de comunicación gubernamental más grande del país controlado por el Departamento de Trabajo del Frente Unido . [102] Global Times y la Agencia de Noticias Xinhua también han sido implicadas en la propagación de desinformación relacionada con los orígenes del COVID-19. [103] Sin embargo, NBC News ha señalado que también ha habido esfuerzos para desacreditar teorías conspirativas relacionadas con los EE. UU. publicadas en línea, y se informa que una búsqueda en WeChat de "Coronavirus [enfermedad de 2019] es de los EE. UU." arroja principalmente artículos que explican por qué tales afirmaciones son irrazonables. [104] [a]

En marzo de 2020, dos portavoces del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de China, Zhao Lijian y Geng Shuang , afirmaron en una conferencia de prensa que las potencias occidentales podrían haber "biodiseñado" el COVID-19. Aludieron a que el Ejército de los EE. UU. creó y propagó el COVID-19, supuestamente durante los Juegos Mundiales Militares de 2019 en Wuhan , donde se informaron numerosos casos de enfermedad similar a la gripe . [117] [118]

Una integrante de la delegación de atletismo militar estadounidense con base en Fort Belvoir, que compitió en la carrera de 50 millas en los Juegos de Wuhan, se convirtió en objeto de ataques en línea por parte de internautas que la acusaron de ser la "paciente cero" del brote de COVID-19 en Wuhan, y luego fue entrevistada por CNN, para limpiar su nombre de las "falsas acusaciones de iniciar la pandemia". [119]

En enero de 2021, Hua Chunying renovó la teoría de la conspiración de Zhao Lijian y Geng Shuang de que el virus SARS-CoV-2 se originó en los Estados Unidos en el laboratorio estadounidense de armas biológicas Fort Detrick . Esta teoría de la conspiración rápidamente se volvió tendencia en la plataforma de redes sociales china Weibo, y Hua Chunying continuó citando evidencia en Twitter, mientras pedía al gobierno de los Estados Unidos que abriera Fort Detrick para una mayor investigación para determinar si es la fuente del virus SARS-CoV-2. [120] [121] En agosto de 2021, un portavoz del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de China utilizó repetidamente un podio oficial para elevar la idea de que el origen no probado de Fort Detrick. [122]

Según un informe de Foreign Policy , diplomáticos y funcionarios gubernamentales chinos, en concierto con el aparato de propaganda de China y redes encubiertas de agitadores e influenciadores en línea, han respondido, centrándose en repetir la acusación de Zhao Lijian relacionada con Fort Detrick en Maryland y los "más de 200 biolaboratorios estadounidenses" en todo el mundo. [123]

En febrero de 2020, funcionarios estadounidenses afirmaron que Rusia está detrás de una campaña de desinformación en curso, utilizando miles de cuentas de redes sociales en Twitter, Facebook e Instagram para promover deliberadamente teorías de conspiración infundadas, afirmando que el virus es un arma biológica fabricada por la CIA y que Estados Unidos está librando una guerra económica contra China utilizando el virus. [124] [125] [126] [b]

En marzo de 2022, en medio de la invasión rusa de Ucrania en 2022 , el Ministerio de Defensa ruso declaró que el hijo del presidente estadounidense Joe Biden , Hunter Biden , así como el multimillonario George Soros , estaban estrechamente vinculados a los laboratorios biológicos ucranianos. Personalidades de los medios de comunicación de derecha estadounidenses, como Tucker Carlson , destacaron la historia, mientras que el tabloide Global Times, propiedad del Partido Comunista Chino, afirmó además que los laboratorios habían estado estudiando coronavirus de murciélago, que se difundieron ampliamente en Internet chino por insinuar que Estados Unidos había creado el SARS-CoV-19 en laboratorios ucranianos. [132] [133]

Según el Middle East Media Research Institute , una organización sin fines de lucro con sede en Washington, DC, numerosos escritores de la prensa árabe han promovido la teoría de la conspiración de que el COVID-19, así como el SARS y el virus de la gripe porcina, fueron creados y propagados deliberadamente para vender vacunas contra estas enfermedades, y es "parte de una guerra económica y psicológica librada por Estados Unidos contra China con el objetivo de debilitarla y presentarla como un país atrasado y una fuente de enfermedades". [134] [c]

En Turquía se han recibido acusaciones de que los estadounidenses crearon el virus como arma [135] [136] y una encuesta de YouGov de agosto de 2020 encontró que el 37% de los encuestados turcos creían que el gobierno de los EE. UU. era responsable de crear y propagar el virus. [137]

Un clérigo iraní en Qom dijo que Donald Trump había atacado la ciudad con el coronavirus "para dañar su cultura y su honor". [138] Reza Malekzadeh , viceministro de salud de Irán y exministro de Salud, rechazó las afirmaciones de que el virus fuera un arma biológica, señalando que Estados Unidos sufriría mucho por ello. Dijo que Irán se vio muy afectado porque sus estrechos vínculos con China y su renuencia a cortar los vínculos aéreos introdujeron el virus, y porque los primeros casos se habían confundido con influenza. [139] [d]

En Irak, los usuarios de las redes sociales proiraníes lanzaron una campaña en Twitter durante la presidencia de Trump para poner fin a la presencia estadounidense en el país, culpándolo del virus. La campaña se centró en hashtags como #Bases_de_la_pandemia_estadounidense y #El_coronavirus_es_el_arma_de_Trump. Una encuesta realizada en marzo de 2020 por USCENTCOM concluyó que el 67% de los encuestados iraquíes creía que una fuerza extranjera estaba detrás del COVID-19, y el 72% de ellos nombró a Estados Unidos como esa fuerza. [148]

En Filipinas, [e] Venezuela [f] y Pakistán también han circulado teorías que culpan a los EE. UU. [153] Una encuesta de Globsec de octubre de 2020 en países de Europa del Este encontró que el 38% de los encuestados en Montenegro y Serbia, el 37% de los de Macedonia del Norte y el 33% de los de Bulgaria creían que los EE. UU. crearon deliberadamente el COVID-19. [154] [155]

El canal de televisión iraní Press TV afirmó que « elementos sionistas desarrollaron una cepa más letal de coronavirus contra Irán». [156] De manera similar, algunos medios de comunicación árabes acusaron a Israel y a los Estados Unidos de crear y propagar el COVID-19, la gripe aviar y el SARS . [157] Los usuarios de las redes sociales ofrecieron otras teorías, incluida la acusación de que los judíos habían fabricado el COVID-19 para precipitar un colapso del mercado bursátil mundial y, por lo tanto, beneficiarse mediante el uso de información privilegiada , [158] mientras que un invitado en la televisión turca postuló un escenario más ambicioso en el que los judíos y los sionistas habían creado el COVID-19, la gripe aviar y la fiebre hemorrágica de Crimea-Congo para «diseñar el mundo, apoderarse de países [y] castrar a la población mundial». [159] Según se informa, el político turco Fatih Erbakan dijo en un discurso: «Aunque no tenemos pruebas ciertas, este virus sirve a los objetivos del sionismo de disminuir el número de personas y evitar que aumente, y una investigación importante lo expresa». [160]

Los intentos israelíes de desarrollar una vacuna contra la COVID-19 provocaron reacciones negativas en Irán. El gran ayatolá Naser Makarem Shirazi negó los informes iniciales de que había dictaminado que una vacuna fabricada por sionistas sería halal [161] y un periodista de Press TV tuiteó que "prefiero correr el riesgo de contraer el virus que consumir una vacuna israelí". [162] Un columnista del periódico turco Yeni Akit afirmó que una vacuna de ese tipo podría ser una artimaña para llevar a cabo una esterilización masiva . [163]

Una alerta de la Oficina Federal de Investigaciones de Estados Unidos sobre la posible amenaza de que extremistas de extrema derecha propaguen intencionalmente el COVID-19 mencionó que se culpa a los judíos y a los líderes judíos de causar la pandemia y varios cierres estatales. [164]

Se han encontrado volantes en tranvías alemanes que culpan falsamente a los judíos por la pandemia. [165]

En abril de 2022, dos miembros del movimiento Reichsbürger (más tarde implicados en el complot del golpe de Estado alemán de 2022 ) fueron acusados de conspirar para secuestrar al ministro de salud alemán Karl Lauterbach . [166]

Según un estudio realizado por la Universidad de Oxford a principios de 2020, casi una quinta parte de los encuestados en Inglaterra creía en cierta medida que los judíos eran responsables de crear o propagar el virus con el motivo de obtener ganancias económicas. [167] [168]

En la India, se ha culpado a los musulmanes de propagar la infección tras la aparición de casos vinculados a una reunión religiosa de Tablighi Jamaat . [169] Hay informes de difamación de musulmanes en las redes sociales y ataques a personas en la India. [170] Se ha afirmado que los musulmanes están vendiendo alimentos contaminados con SARS-CoV-2 y que una mezquita en Patna estaba albergando a personas de Italia e Irán. [171] Se ha demostrado que estas afirmaciones son falsas. [172] En el Reino Unido, hay informes de grupos de extrema derecha que culpan a los musulmanes por la pandemia y afirman falsamente que las mezquitas permanecieron abiertas después de la prohibición nacional de grandes reuniones. [173]

Según la BBC, Jordan Sather, un YouTuber que apoya la teoría de la conspiración QAnon y el movimiento antivacunas , ha afirmado falsamente que el brote fue un plan de control de la población creado por el Instituto Pirbright en Inglaterra y por el ex director ejecutivo de Microsoft, Bill Gates . [9] [174] [175]

La médica y presentadora Hilary Jones calificó a Piers Corbyn de “peligroso” durante su entrevista conjunta en Good Morning Britain a principios de septiembre de 2020. Corbyn describió al COVID-19 como una “operación psicológica para cerrar la economía en beneficio de las megacorporaciones” y afirmó que “las vacunas causan muerte”. [176]

Las primeras teorías conspirativas que vinculaban la COVID-19 con las redes móviles 5G ya habían aparecido a finales de enero de 2020. Esas afirmaciones se propagaron rápidamente en las redes sociales, lo que dio lugar a una propagación de desinformación que se ha comparado con un "incendio digital". [177]

En marzo de 2020, Thomas Cowan, un médico holístico que se formó como médico y trabaja en libertad condicional en la Junta Médica de California , afirmó que la COVID-19 es causada por la tecnología 5G. Basó su afirmación en las afirmaciones de que los países africanos no se habían visto afectados significativamente por la pandemia y que África no era una región 5G. [178] [179] Cowan también afirmó falsamente que los virus eran desechos de células envenenadas por campos electromagnéticos y que las pandemias virales históricas coincidieron con importantes avances en la tecnología de radio. [179]

El video de las afirmaciones de Cowan se volvió viral y fue recirculado por celebridades, entre ellas Woody Harrelson , John Cusack y la cantante Keri Hilson . [180] Las afirmaciones también pueden haber sido recirculadas por una supuesta "campaña de desinformación coordinada", similar a las campañas utilizadas por la Agencia de Investigación de Internet en San Petersburgo , Rusia. [181] Las afirmaciones fueron criticadas en las redes sociales y desacreditadas por Reuters , [182] USA Today , [183] Full Fact [184] y el director ejecutivo de la Asociación Estadounidense de Salud Pública, Georges C. Benjamin . [178] [185]

Las afirmaciones de Cowan fueron repetidas por Mark Steele , un teórico de la conspiración que afirmó tener conocimiento de primera mano de que 5G era de hecho un sistema de armas capaz de causar síntomas idénticos a los producidos por el virus. [186] Kate Shemirani , una ex enfermera que había sido eliminada del registro de enfermería del Reino Unido y se había convertido en promotora de teorías de la conspiración, afirmó repetidamente que estos síntomas eran idénticos a los producidos por la exposición a campos electromagnéticos. [187] [188]

Steve Powis, director médico nacional del Servicio Nacional de Salud de Inglaterra , describió las teorías que vinculan las redes de telefonía móvil 5G con la COVID-19 como el "peor tipo de noticia falsa". [189] Los virus no pueden transmitirse por ondas de radio , y la COVID-19 se ha propagado y sigue propagándose en muchos países que no tienen redes 5G. [190]

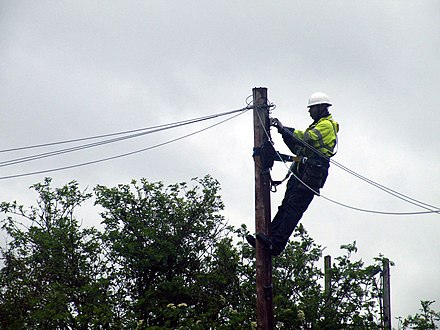

Hubo 20 presuntos ataques incendiarios en antenas de telefonía en el Reino Unido durante el fin de semana de Pascua de 2020. [189] Estos incluyeron un incidente en Dagenham donde tres hombres fueron arrestados bajo sospecha de incendio provocado, un incendio en Huddersfield que afectó a una antena utilizada por los servicios de emergencia y un incendio en una antena que proporciona conectividad móvil al Hospital NHS Nightingale de Birmingham . [189] Algunos ingenieros de telecomunicaciones denunciaron amenazas de violencia, incluidas amenazas de apuñalarlos y asesinarlos, por parte de personas que creen que están trabajando en redes 5G. [191] En abril de 2020, los servicios de Gardaí y bomberos fueron llamados a incendios en antenas 5G en el condado de Donegal , Irlanda. [192] Los Gardaí estaban tratando los incendios como incendios provocados. [192] Después de los ataques incendiarios, el ministro de la Oficina del Gabinete británico, Michael Gove, dijo que la teoría de que el virus COVID-19 puede propagarse por la comunicación inalámbrica 5G es "simplemente una tontería, una tontería peligrosa también". [193] El proveedor de telecomunicaciones Vodafone anunció que dos antenas de Vodafone y dos que comparte con O2 , otro proveedor, habían sido atacadas. [194] [195]

En abril de 2020, al menos 20 antenas de telefonía móvil en el Reino Unido habían sido vandalizadas. [196] Debido a la lenta implementación de 5G en el Reino Unido, muchas de las antenas dañadas solo tenían equipos 3G y 4G. [196] Los operadores de telefonía móvil y banda ancha doméstica estimaron que hubo al menos 30 incidentes en los que los ingenieros que realizaban el mantenimiento de los equipos se enfrentaron en la semana hasta el 6 de abril. [196] Al 30 de mayo, se habían producido 29 incidentes de intentos de incendio en antenas de telefonía móvil en los Países Bajos, incluido un caso en el que estaba escrito "Fuck 5G". [197] [198] También ha habido incidentes en Irlanda y Chipre. [199] Facebook ha eliminado mensajes que fomentaban los ataques a los equipos 5G. [196]

Los ingenieros que trabajan para Openreach , una división de British Telecom , publicaron súplicas en grupos de Facebook anti-5G pidiendo que se les evite el abuso, ya que no están involucrados en el mantenimiento de las redes móviles. [200] El grupo de presión de la industria Mobile UK dijo que los incidentes estaban afectando el mantenimiento de las redes que respaldan el trabajo desde casa y brindan conexiones críticas a clientes vulnerables, servicios de emergencia y hospitales. [200] Un video ampliamente circulado mostró a una mujer acusando a los empleados de la empresa de banda ancha Community Fiber de instalar 5G como parte de un plan para matar a la población. [200]

De aquellos que creían que las redes 5G causaban los síntomas de COVID-19, el 60% afirmó que gran parte de su conocimiento sobre el virus provenía de YouTube. [201] En abril de 2020, YouTube anunció que reduciría la cantidad de contenido que afirmaba vínculos entre 5G y COVID-19. [194] Los videos conspirativos sobre 5G que no mencionan COVID-19 no se eliminarían, aunque podrían considerarse "contenido límite" y, por lo tanto, eliminarse de las recomendaciones de búsqueda, perdiendo ingresos publicitarios. [194] Las afirmaciones desacreditadas habían sido circuladas por el teórico de la conspiración británico David Icke en videos (posteriormente eliminados) en YouTube y Vimeo , y una entrevista de la cadena de televisión London Live , lo que provocó llamados a la acción por parte de Ofcom . [202] [203] YouTube tardó en promedio 41 días en eliminar videos relacionados con Covid que contenían información falsa en la primera mitad de 2020. [204]

Ofcom emitió una guía para ITV tras los comentarios de Eamonn Holmes sobre 5G y COVID-19 en This Morning . [205] Ofcom dijo que los comentarios eran "ambiguos" e "imprudentes" y que "corrían el riesgo de socavar la confianza de los espectadores en el asesoramiento de las autoridades públicas y la evidencia científica". [205] Ofcom también encontró que el canal local London Live incumplió las normas por una entrevista que tuvo con David Icke. Dijo que había "expresado opiniones que tenían el potencial de causar un daño significativo a los espectadores en Londres durante la pandemia". [205]

En abril de 2020, The Guardian reveló que Jonathan Jones, un pastor evangélico de Luton , había proporcionado la voz masculina en una grabación que culpaba al 5G por las muertes causadas por COVID-19. [206] Afirmó haber dirigido anteriormente la unidad de negocios más grande de Vodafone, pero personas con información privilegiada de la empresa dijeron que fue contratado para un puesto de ventas en 2014 cuando el 5G no era una prioridad para la empresa y que el 5G no habría sido parte de su trabajo. [206] Había dejado Vodafone después de menos de un año. [206]

Un tuit dio origen a un meme en Internet en el que se afirmaba que los billetes de 20 libras del Banco de Inglaterra contenían una imagen de una antena 5G y del virus SARS-CoV-2 . Facebook y YouTube eliminaron los artículos que promocionaban esta historia, y las organizaciones de verificación de datos establecieron que la imagen es del faro de Margate y que el "virus" es la escalera de la Tate Britain . [207] [208] [209]

En abril de 2020, circularon rumores en Facebook que afirmaban que el gobierno de Estados Unidos había "acabado de descubrir y arrestado" a Charles Lieber , director del Departamento de Química y Biología Química de la Universidad de Harvard, por "fabricar y vender" el nuevo coronavirus (COVID-19) a China. Según un informe de Reuters , las publicaciones que difundían el rumor se compartieron en varios idiomas más de 79.000 veces en Facebook. [210] Lieber fue arrestado en enero de 2020 y luego acusado de dos cargos federales por hacer una declaración supuestamente falsa sobre sus vínculos con una universidad china, no relacionada con el virus. El rumor de que Lieber, un químico en un área completamente ajena a la investigación del virus, desarrolló COVID-19 y lo vendió a China ha sido desacreditado. [211]

En 2020, un grupo de investigadores que incluía a Edward J. Steele y Chandra Wickramasinghe , el principal defensor vivo de la panspermia , especuló en diez artículos de investigación que el COVID-19 se originó a partir de un meteorito visto como una bola de fuego brillante sobre la ciudad de Songyuan en el noreste de China en octubre de 2019 y que un fragmento del meteorito aterrizó en el área de Wuhan, lo que inició los primeros brotes de COVID-19. Sin embargo, el grupo de investigadores no proporcionó ninguna evidencia directa que probara esta conjetura. [212]

En un artículo de agosto de 2020, Astronomy.com calificó la conjetura del origen del meteorito como "tan notable que hace que las demás parezcan aburridas en comparación". [212]

En abril de 2020, ABC News informó que, en noviembre de 2019, "los funcionarios de inteligencia de Estados Unidos advirtieron que un contagio estaba arrasando la región china de Wuhan, cambiando los patrones de vida y negocios y representando una amenaza para la población". El artículo afirmaba que el Centro Nacional de Inteligencia Médica (NCMI, por sus siglas en inglés) había elaborado un informe de inteligencia en noviembre de 2019 que planteaba inquietudes sobre la situación. El director del NCMI, el coronel R. Shane Day, dijo que "los informes de los medios sobre la existencia/publicación de un producto/evaluación relacionado con el coronavirus del Centro Nacional de Inteligencia Médica en noviembre de 2019 no son correctos. No existe tal producto del NCMI". [213] [214]

Las publicaciones en las redes sociales han afirmado falsamente que Kary Mullis , el inventor de la reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (PCR), dijo que las pruebas de PCR para el SARS-CoV-2 no funcionan. Mullis, quien recibió el Premio Nobel de Química por la invención de la PCR, murió en agosto de 2019 antes de la aparición del virus SARS-CoV-2 y nunca hizo estas declaraciones. [215] [216] [217] Varias publicaciones afirman que Mullis dijo que "las pruebas de PCR no pueden detectar virus infecciosos libres en absoluto", [215] que las pruebas de PCR fueron diseñadas para detectar cualquier ADN no humano [216] o el ADN y ARN de la persona que se está probando, [217] o que el proceso de amplificación de ADN utilizado en la PCR conducirá a la contaminación de las muestras. [216] También ha circulado ampliamente un video de una entrevista de 1997 con Mullis, en la que Mullis dice que la PCR encontrará "cualquier cosa"; la descripción del video afirma que esto significa que la PCR no se puede utilizar para detectar de manera confiable el SARS-CoV-2. [218]

En realidad, la prueba de reacción en cadena de la polimerasa con transcripción inversa (RT-PCR) para el SARS-CoV-2 es muy sensible al virus, y los laboratorios de pruebas tienen controles establecidos para prevenir y detectar la contaminación. [215] [216] Sin embargo, las pruebas solo revelan la presencia del virus y no si sigue siendo infeccioso. [215]

En Filipinas se ha popularizado una afirmación atribuida a la Oficina Federal de Salud Pública de Suiza de que las pruebas PCR son fraudulentas y sigue siendo una creencia generalizada. Según un informe de AFP , el investigador asociado Joshua Miguel Danac, del Instituto Nacional de Biología Molecular y Biotecnología de la Universidad de Filipinas , desmintió la afirmación y calificó las pruebas PCR como "el estándar de oro para el diagnóstico". [219] Las pruebas falsas y la percepción de que son falsas siguen siendo un problema en Filipinas. [220]

A principios de 2020, aparecieron varias fotos y vídeos virales que se caracterizaron erróneamente como una muestra de una extrema gravedad de la exposición a la COVID-19. En enero y febrero de 2020, circularon en las redes sociales varios vídeos procedentes de China que pretendían mostrar a personas infectadas con la COVID-19 desplomándose de repente o ya desplomándose en la calle. [221] Algunos de estos vídeos fueron republicados o citados por algunos periódicos sensacionalistas, como el Daily Mail y The Sun. [ 221] Sin embargo, se cree que las personas que aparecen en estos vídeos padecían algo distinto de la COVID-19, como una persona que estaba borracha. [222]

Un video de febrero de 2020 que supuestamente mostraba a víctimas muertas de COVID-19 en China era en realidad un video de Shenzhen de personas durmiendo en la calle. [223] De manera similar, una foto que circuló en marzo de 2020 de docenas de personas acostadas en la calle, que supuestamente eran víctimas de COVID-19 en China o Italia, era de hecho una foto de personas vivas de un proyecto de arte de 2014 en Alemania. [224]

Informar correctamente el número de personas enfermas o fallecidas fue difícil, especialmente durante los primeros días de la pandemia. [225]

Los documentos filtrados muestran que los informes públicos de casos de China dieron una imagen incompleta durante las primeras etapas de la pandemia. Por ejemplo, en febrero de 2020, China informó públicamente 2.478 nuevos casos confirmados. Sin embargo, documentos internos confidenciales que luego se filtraron a CNN mostraron 5.918 nuevos casos en febrero. Estos se desglosaron en 2.345 casos confirmados [ aclaración necesaria ] , 1.772 casos diagnosticados clínicamente y 1.796 casos sospechosos. [226] [227]

En enero de 2020, circuló en Internet un vídeo en el que aparecía una enfermera llamada Jin Hui [228] en Hubei , en el que se describía una situación mucho más grave en Wuhan que la que informaron los funcionarios chinos. Sin embargo, la BBC dijo que, contrariamente a los subtítulos en inglés de una de las versiones existentes del vídeo, la mujer no afirma ser ni enfermera ni médica en el vídeo y que su traje y su mascarilla no coinciden con los que lleva el personal médico en Hubei. [9]

El vídeo afirmaba que más de 90.000 personas habían sido infectadas con el virus en China, que el virus podía propagarse de una persona a 14 personas ( R 0 = 14 ) y que el virus estaba iniciando una segunda mutación. [229] El vídeo atrajo millones de visitas en varias plataformas de redes sociales y fue mencionado en numerosos informes en línea. La BBC señaló que el supuesto R 0 de 14 en el vídeo era incoherente con la estimación de los expertos de 1,4 a 2,5 en ese momento. [230] Se señaló que la afirmación del vídeo de 90.000 casos infectados "no estaba fundamentada". [9] [229]

En febrero de 2020, Taiwan News publicó un artículo en el que afirmaba que Tencent podría haber filtrado accidentalmente las cifras reales de muertes e infecciones en China. Taiwan News sugirió que el Tencent Epidemic Situation Tracker había mostrado brevemente casos infectados y cifras de muertes muchas veces superiores a la cifra oficial, citando una publicación en Facebook de un propietario de una tienda de bebidas taiwanés de 38 años y un internauta taiwanés anónimo . [231] El artículo, al que hacen referencia otros medios de comunicación como el Daily Mail y que circuló ampliamente en Twitter, Facebook y 4chan, provocó una amplia gama de teorías conspirativas de que la captura de pantalla indica la cifra real de muertos en lugar de las publicadas por los funcionarios de salud. [232]

El autor del artículo periodístico original defendió la autenticidad y el valor noticioso de la filtración del programa WION . [232]

En febrero de 2020, apareció un informe en Twitter que afirmaba que los datos mostraban un aumento masivo de las emisiones de azufre sobre Wuhan, China. El hilo de Twitter luego afirmó que la razón se debía a la cremación masiva de quienes murieron por COVID-19. La historia fue compartida en varios medios de comunicación, incluidos Daily Express , Daily Mail y Taiwan News . [233] [232] Snopes desacreditó la información errónea, señalando que los mapas utilizados por las afirmaciones no eran observaciones en tiempo real de las concentraciones de dióxido de azufre (SO 2 ) sobre Wuhan. En cambio, los datos eran un modelo generado por computadora basado en información histórica y pronóstico sobre las emisiones de SO 2 . [234]

En febrero de 2020, The Epoch Times publicó un artículo en el que se compartía un mapa de Internet que afirmaba falsamente que se habían producido liberaciones masivas de dióxido de azufre en los crematorios durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en China, y se especulaba que podrían haberse quemado 14.000 cuerpos. [235] Una verificación de datos realizada por AFP informó que el mapa era un pronóstico de la NASA sacado de contexto. [235]

Hubo una disminución de casi 21 millones de suscripciones de teléfonos celulares entre los tres operadores de telefonía celular más grandes de China, lo que dio lugar a desinformación de que esto es evidencia de millones de muertes debido a COVID-19 en China. [236] La caída se atribuye a las cancelaciones de servicios telefónicos debido a una desaceleración de la vida social y económica durante el brote. [236]

Se han formulado acusaciones de que no se informa lo suficiente, de que se informa demasiado y de que hay otros problemas. En algunos lugares, por ejemplo, a nivel estatal en los Estados Unidos, se corrompieron datos necesarios. [237]

El manejo de la pandemia por parte de la salud pública se ha visto obstaculizado por el uso de tecnología arcaica (incluidas máquinas de fax y formatos incompatibles), [225] un flujo y una gestión deficientes de los datos (o incluso la falta de acceso a los datos) y una falta general de estandarización y liderazgo. [238] Las leyes de privacidad obstaculizaron el rastreo de contactos y los esfuerzos de detección de casos , lo que dio lugar a un subdiagnóstico y una subnotificación. [239]

En agosto de 2020, el presidente Donald Trump retuiteó una teoría conspirativa que alegaba que las muertes por COVID-19 se contabilizan sistemáticamente en exceso y que solo el 6% de las muertes reportadas en los Estados Unidos fueron en realidad por la enfermedad. [240] Este número del 6% se basa en contar solo los certificados de defunción donde COVID-19 es la única condición enumerada. El estadístico principal de mortalidad del Centro Nacional de Estadísticas de Salud de los Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC) dijo que esos certificados de defunción probablemente no incluían todos los pasos que llevaron a la muerte y, por lo tanto, estaban incompletos. Los CDC recopilan datos basados en la vigilancia de casos, registros vitales y exceso de muertes . [241] Un artículo de FactCheck.org sobre el tema informó que, si bien el 6% de los certificados de defunción incluían COVID-19 exclusivamente como causa de muerte y el 94% tenía condiciones adicionales que contribuyeron a ello, COVID-19 figuraba como la causa subyacente de muerte en el 92% de ellos, ya que puede causar directamente otras afecciones graves como neumonía o síndrome de dificultad respiratoria aguda. [242]

Entre febrero de 2020 y enero de 2022, Estados Unidos registró 882.000 “muertes en exceso” (es decir, muertes por encima de la línea de base esperada a partir de la mortalidad normal en años anteriores), lo que es algo más alto que la mortalidad por COVID-19 registrada oficialmente durante ese período (835.000 muertes). El análisis de los datos semanales de cada estado de Estados Unidos muestra que las muertes en exceso calculadas están fuertemente correlacionadas con las infecciones por COVID-19, lo que debilita la idea de que las muertes fueron causadas principalmente por algún factor distinto de la enfermedad. [243]

En noviembre de 2020, Genevieve Briand (directora adjunta del programa de maestría en Economía Aplicada de la JHU) [244] publicó un artículo en el Johns Hopkins News-Letter, dirigido por estudiantes , en el que afirmaba no haber encontrado "ninguna evidencia de que la COVID-19 haya creado un exceso de muertes". [245] El artículo fue posteriormente retractado después de que se utilizara para promover teorías conspirativas en cuentas de redes sociales de derecha y sitios web de desinformación, [246] pero la presentación no fue eliminada de YouTube, donde había sido vista más de 58.000 veces hasta el 3 de diciembre de 2020. [247]

Briand comparó los datos de la primavera de 2020 y enero de 2018, ignorando las variaciones estacionales esperadas en la mortalidad y los picos inusuales en la primavera y el verano de 2020 en comparación con los meses de primavera y verano anteriores. [245] El artículo de Briand no tuvo en cuenta el exceso total de mortalidad por todas las causas notificado durante la pandemia, [248] con 300.000 muertes asociadas al virus según los datos de los CDC en 2020. [248] Las muertes por grupo de edad también se mostraron como un porcentaje de proporción en lugar de como números brutos, lo que oscurece los efectos de la pandemia cuando el número de muertes aumenta pero las proporciones se mantienen. [248] El artículo también sugirió que las muertes atribuidas a enfermedades cardíacas y respiratorias en personas infectadas se categorizaron incorrectamente como muertes debidas a COVID-19. Este punto de vista no reconoce que quienes padecen tales afecciones son más vulnerables al virus y, por lo tanto, tienen más probabilidades de morir a causa de él. [245] La retractación del artículo de Briand se volvió viral en las redes sociales bajo falsas afirmaciones de censura. [249]

En febrero de 2020, la Agencia Central de Noticias de Taiwán informó que había aparecido una gran cantidad de información errónea en Facebook que afirmaba que la pandemia en Taiwán estaba fuera de control, que el gobierno taiwanés había encubierto el número total de casos y que la presidenta Tsai Ing-wen había sido infectada. La organización de verificación de datos de Taiwán había sugerido que la información errónea en Facebook compartía similitudes con la de China continental debido al uso de caracteres chinos simplificados y vocabulario de China continental. La organización advirtió que el propósito de la información errónea es atacar al gobierno. [250] [251] [252]

En marzo de 2020, la Oficina de Investigación del Ministerio de Justicia de Taiwán advirtió que China estaba tratando de socavar la confianza en las noticias veraces al presentar los informes del gobierno taiwanés como noticias falsas. Se ha ordenado a las autoridades taiwanesas que utilicen todos los medios posibles para rastrear si los mensajes estaban vinculados a instrucciones dadas por el Partido Comunista Chino. La Oficina de Asuntos de Taiwán de la República Popular China negó las acusaciones, calificándolas de mentiras, y dijo que el Partido Progresista Democrático de Taiwán estaba "incitando al odio" entre las dos partes. Luego afirmó que "el DPP continúa manipulando políticamente el virus". [253] Según The Washington Post , China ha utilizado campañas de desinformación organizadas contra Taiwán durante décadas. [254]

Nick Monaco, director de investigación del Laboratorio de Inteligencia Digital del Institute for the Future , analizó las publicaciones y concluyó que la mayoría parecen provenir de usuarios comunes de China, no del estado. Sin embargo, criticó la decisión del gobierno chino de permitir que la información se difundiera más allá del Gran Cortafuegos de China , que describió como "maliciosa". [255] Según Taiwan News , se cree que casi uno de cada cuatro casos de desinformación está relacionado con China. [256]

En marzo de 2020, el Instituto Americano en Taiwán anunció que se asociaría con el Centro FactCheck de Taiwán para ayudar a combatir la desinformación sobre el brote de COVID-19. [257]

A principios de febrero de 2020, un mapa de hace una década que ilustraba un brote viral hipotético publicado por el Proyecto de Población Mundial (parte de la Universidad de Southampton ) fue apropiado indebidamente por varios medios de comunicación australianos (y los tabloides británicos The Sun , Daily Mail y Metro ) [258] que afirmaban que el mapa representaba la pandemia de COVID-19. Esta desinformación se difundió luego a través de las cuentas de redes sociales de los mismos medios de comunicación y, si bien algunos medios eliminaron posteriormente el mapa, la BBC informó, en febrero, que varios sitios de noticias aún no se habían retractado del mapa. [258]

Los negacionistas del COVID-19 utilizan la palabra casedemia como una forma abreviada de referirse a una teoría conspirativa que sostiene que el COVID-19 es inofensivo y que las cifras de la enfermedad reportadas son simplemente el resultado del aumento de las pruebas. El concepto es particularmente atractivo para los activistas antivacunas , quienes lo utilizan para argumentar que no se necesitan medidas de salud pública, y en particular vacunas, para contrarrestar lo que ellos dicen que es una epidemia falsa. [259] [260] [261] [262]

David Gorski escribe que la palabra casedemia fue aparentemente acuñada por Ivor Cummins, un ingeniero cuyas opiniones son populares entre los negacionistas del COVID-19, en agosto de 2020. [259]

El término ha sido adoptado por el defensor de la medicina alternativa Joseph Mercola , quien ha exagerado el efecto de los falsos positivos en las pruebas de reacción en cadena de la polimerasa (PCR) para construir una narrativa falsa de que las pruebas no son válidas porque no son perfectamente precisas . En realidad, los problemas con las pruebas de PCR son bien conocidos y las autoridades de salud pública los tienen en cuenta. Tales afirmaciones también ignoran la posibilidad de propagación asintomática , el número de casos potencialmente no detectados durante las fases iniciales de la pandemia en comparación con el presente debido al aumento de las pruebas y el conocimiento desde entonces, y otras variables que pueden influir en las pruebas de PCR. [259]

Al principio de la pandemia, se sabía poco sobre cómo se propaga el virus, cuándo enfermaron las primeras personas o quiénes eran más vulnerables a la infección, a las complicaciones graves o a la muerte. Durante 2020, quedó claro que la principal vía de propagación era la exposición a las gotitas respiratorias cargadas de virus producidas por una persona infectada. [263] También hubo algunas preguntas iniciales sobre si la enfermedad podría haber estado presente antes de lo que se informó; sin embargo, investigaciones posteriores refutaron esta idea. [264] [265]

En marzo de 2020, Victor Davis Hanson publicó una teoría de que el COVID-19 podría haber estado en California en el otoño de 2019, lo que resultó en un nivel de inmunidad colectiva que explica al menos parcialmente las diferencias en las tasas de infección en ciudades como la ciudad de Nueva York frente a Los Ángeles. [266] Jeff Smith, del condado de Santa Clara, afirmó que la evidencia indicaba que el virus podría haber estado en California desde diciembre de 2019. [267] Los primeros análisis genéticos y de anticuerpos refutan la idea de que el virus estuviera en los Estados Unidos antes de enero de 2020. [264] [265] [268] [269] [ necesita actualización ]

En marzo de 2020, los teóricos de la conspiración comenzaron el falso rumor de que Maatje Benassi, una reservista del ejército estadounidense, era la " Paciente Cero " de la pandemia, la primera persona infectada con COVID-19. [270] Benassi fue atacada debido a su participación en los Juegos Mundiales Militares de 2019 en Wuhan antes de que comenzara la pandemia, a pesar de que nunca dio positivo en la prueba del virus. Los teóricos de la conspiración incluso conectaron a su familia con el DJ Benny Benassi como un complot del virus Benassi, a pesar de que no están relacionados y Benny tampoco había tenido el virus. [271]

Antes de mediados de 2021, la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) negó que el COVID se propagara fácilmente por el aire; [272] aunque, reconocieron que dicha propagación podría ocurrir durante ciertos procedimientos médicos a partir de julio de 2020. [273] En febrero de 2020, el Director General de la OMS, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus , inicialmente declaró que el COVID se transmitía por el aire durante una conferencia de prensa, solo para retractarse de esta declaración unos minutos después. [274] En marzo de 2020, la OMS tuiteó "HECHO: #COVID19 NO se transmite por el aire". [275] [276]

La investigadora de calidad del aire Lidia Morawska consideró que su posición inicial era "difundir información errónea". [272] A mediados de 2020, cientos de científicos consideraban que se estaba produciendo una propagación por vía aérea y pidieron a la OMS que cambiara su posición. [277] Se expresó la preocupación de que las "voces conservadoras" dentro del comité de la OMS encargado de estas directrices estaban impidiendo que se incorporaran nuevas pruebas. [277] [278]

Al principio de la pandemia se afirmó que la COVID-19 podía propagarse por contacto con superficies o fómites contaminados , aunque esta es una vía de transmisión poco común para otros virus respiratorios. Esto llevó a recomendar que las superficies de alto contacto (como los equipos de juegos o los pupitres de la escuela) se limpiaran a fondo con frecuencia y que ciertos artículos (como los alimentos o los paquetes enviados por correo) se desinfectaran. [279] Finalmente, los Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC) de EE. UU. concluyeron que la probabilidad de transmisión en estos escenarios era inferior a 1 en 10 000. [280] Además, concluyeron que el lavado de manos reducía el riesgo de exposición a la COVID-19, pero la desinfección de superficies no. [280]

Se ha afirmado que determinadas etnias son más o menos vulnerables al COVID-19. El COVID-19 es una nueva enfermedad zoonótica , por lo que ninguna población ha tenido tiempo aún de desarrollar inmunidad . [ cita médica necesaria ]

A partir de febrero de 2020, se difundieron rápidamente informes a través de Facebook que daban a entender que un estudiante camerunés en China se había curado completamente del virus debido a su genética africana. Si bien un estudiante fue tratado con éxito, otros medios de comunicación han indicado que no hay evidencia que sugiera que los africanos sean más resistentes al virus y han etiquetado tales afirmaciones como información falsa. [281] El secretario de Salud de Kenia, Mutahi Kagwe, refutó explícitamente los rumores de que "aquellos con piel negra no pueden contraer el coronavirus [enfermedad de 2019]", al anunciar el primer caso de Kenia en marzo. [282] Esta afirmación falsa fue citada como un factor que contribuyó a las tasas desproporcionadamente altas de infección y muerte observadas entre los afroamericanos. [283] [284]

Se ha dicho que existe una “inmunidad india”: que la población de la India tiene más inmunidad al virus COVID-19 debido a las condiciones de vida en el país. Anand Krishnan, profesor del Centro de Medicina Comunitaria del Instituto de Ciencias Médicas de la India (AIIMS), calificó esta idea de “absoluta tontería”. Krishnan dijo que todavía no había inmunidad de la población al virus COVID-19, ya que es nuevo, y ni siquiera está claro si las personas que se han recuperado de la COVID-19 tendrán inmunidad duradera, ya que esto sucede con algunos virus pero no con otros. [285]

El líder supremo de Irán, el ayatolá Ali Khamenei, afirmó que el virus había sido genéticamente dirigido a los iraníes por Estados Unidos, dando esta explicación de por qué la pandemia había afectado gravemente a Irán . No ofreció ninguna prueba. [286] [287]

Un grupo de investigadores jordanos publicó un informe en el que se afirma que los árabes son menos vulnerables al COVID-19 debido a una variación genética específica de los de ascendencia de Oriente Medio. Este artículo no había sido desmentido hasta noviembre de 2020. [288]

Se han producido ataques xenófobos relacionados con la COVID-19 contra personas, en los que el atacante culpa a la víctima de la COVID-19 basándose en su origen étnico. En muchos otros países, personas que se consideran de apariencia china han sido objeto de ataques verbales y físicos relacionados con la COVID-19, a menudo por parte de personas que las acusan de transmitir el virus. [289] [290] [291] Dentro de China, ha habido discriminación (como desalojos y negativa de servicio en tiendas) contra personas de cualquier lugar más cercano a Wuhan (donde comenzó la pandemia) y contra cualquier persona percibida como no china (especialmente aquellas consideradas africanas), ya que el gobierno chino ha atribuido los casos continuos a la reintroducción del virus desde el extranjero (el 90% de los casos reintroducidos fueron de titulares de pasaportes chinos). Los países vecinos también han discriminado a personas consideradas occidentales. [292] [293] [294]

La gente también ha culpado simplemente a otros grupos locales en función de tensiones y divisiones sociales preexistentes, a veces citando informes de casos de COVID-19 dentro de ese grupo. Por ejemplo, los musulmanes han sido ampliamente culpados, rechazados y discriminados en la India (incluidos algunos ataques violentos), en medio de afirmaciones infundadas de que los musulmanes están propagando deliberadamente la COVID-19, y un evento musulmán en el que la enfermedad se propagó ha recibido mucha más atención pública que muchos eventos similares organizados por otros grupos y el gobierno. [295] Los grupos supremacistas blancos han culpado a los no blancos de la COVID-19 y han abogado por infectar deliberadamente a las minorías que no les gustan, como los judíos. [296]

Algunos medios de comunicación, incluidos Daily Mail y RT , así como individuos, difundieron un video que mostraba a una mujer china comiendo un murciélago, sugiriendo falsamente que fue filmado en Wuhan y conectándolo con el brote. [297] [298] Sin embargo, el video ampliamente circulado contiene imágenes no relacionadas de un vlogger de viajes chino , Wang Mengyun, comiendo sopa de murciélago en el país insular de Palau en 2016. [297] [298] [299] [300] Wang publicó una disculpa en Weibo , [299] [300] en la que dijo que había sido abusada y amenazada, [299] y que solo había querido mostrar la cocina palauana . [299] [300] La difusión de información errónea sobre el consumo de murciélagos se ha caracterizado por un sentimiento xenófobo y racista hacia los asiáticos. [301] [302] [303] Por el contrario, los científicos sugieren que el virus se originó en los murciélagos y migró a un animal huésped intermediario antes de infectar a las personas. [301] [304]

El "populista conservador" surcoreano Jun Kwang-hun dijo a sus seguidores que no había riesgo en las reuniones públicas multitudinarias, ya que era imposible contraer el virus al aire libre. Muchos de sus seguidores son ancianos. [305]

Se ha difundido información errónea según la cual la vida útil del SARS-CoV-2 es de solo 12 horas y que quedarse en casa durante 14 horas durante el toque de queda de Janata rompería la cadena de transmisión. [306] Otro mensaje afirmaba que observar el toque de queda de Janata resultaría en una reducción de los casos de COVID-19 en un 40%. [306]

Se ha afirmado que los mosquitos transmiten el COVID-19, pero no hay pruebas de que esto sea cierto. [190]

En las redes sociales circuló un aviso falso de retirada de productos de Costco que afirmaba que el papel higiénico de la marca Kirkland había sido contaminado con COVID-19 (es decir, SARS-CoV-2) debido a que el artículo se fabricaba en China. No hay evidencia que respalde que el SARS-CoV-2 pueda sobrevivir en superficies durante períodos prolongados de tiempo (como podría suceder durante el envío), y Costco no ha emitido tal retirada. [307] [308] [309]

Una advertencia que supuestamente proviene del Departamento de Salud de Australia decía que el COVID-19 se propaga a través de los surtidores de gasolina y que todos deberían usar guantes al cargar gasolina en sus autos. [310]

Se afirmó que el uso de zapatos en el hogar era la causa de la propagación del COVID-19 en Italia. [311]

En marzo de 2020, el Miami New Times informó que los gerentes de Norwegian Cruise Line habían preparado un conjunto de respuestas destinadas a convencer a los clientes cautelosos de que reservaran cruceros, incluidas afirmaciones "descaradamente falsas" de que el COVID-19 "solo puede sobrevivir en temperaturas frías, por lo que el Caribe es una opción fantástica para su próximo crucero", que "los científicos y los profesionales médicos han confirmado que el clima cálido de la primavera será el fin del coronavirus [ sic ]", y que el virus "no puede vivir en las temperaturas increíblemente cálidas y tropicales a las que navegará su crucero". [312]

La gripe es estacional (se vuelve menos frecuente en el verano) en algunos países, pero no en otros. Si bien es posible que la COVID-19 también muestre cierta estacionalidad, esto aún no se ha determinado. [313] [314] [315] [ cita médica necesaria ] Cuando la COVID-19 se propagó a lo largo de las rutas aéreas internacionales, no pasó por alto las zonas tropicales. [316] Los brotes en los cruceros , donde una población de mayor edad vive en espacios reducidos y toca con frecuencia superficies que otros han tocado, fueron comunes. [317] [318]

Parece que el COVID-19 puede transmitirse en todos los climas. [190] Ha afectado gravemente a muchos países de clima cálido. Por ejemplo, Dubái , con una temperatura máxima diaria promedio anual de 28,0 °C (82,3 °F) y el aeropuerto que se dice tiene el mayor tráfico internacional del mundo , ha tenido miles de casos . [ cita médica requerida ]

Si bien las empresas comerciales que elaboran sucedáneos de la leche materna promocionan sus productos durante la pandemia, la OMS y el UNICEF recomiendan que las mujeres sigan amamantando durante la pandemia de COVID-19 incluso si tienen COVID-19 confirmado o sospechoso. La evidencia hasta mayo de 2020 [update]indica que es poco probable que la COVID-19 pueda transmitirse a través de la leche materna. [319]

La COVID-19 puede persistir en el semen de los hombres incluso después de que hayan comenzado a recuperarse, aunque el virus no puede replicarse en el sistema reproductivo . [320]

Los investigadores chinos que encontraron el virus en el semen de hombres infectados con COVID-19 afirmaron que esto abría una pequeña posibilidad de que la enfermedad pudiera transmitirse sexualmente, aunque esta afirmación ha sido cuestionada por otros académicos ya que esto se ha demostrado con muchos otros virus como el ébola y el zika . [321]

Un equipo de investigadores italianos descubrió que 11 de 43 hombres que se recuperaron de infecciones, o una cuarta parte de los sujetos de prueba, tenían azoospermia (ausencia de espermatozoides en el semen) u oligospermia (bajo recuento de espermatozoides). Los mecanismos a través de los cuales las enfermedades infecciosas afectan a los espermatozoides se dividen aproximadamente en dos categorías. Una implica que los virus ingresen a los testículos, donde atacan a las espermatogonias . La otra implica que la fiebre alta exponga los testículos al calor y, por lo tanto, mate a los espermatozoides. [321]

Las personas probaron muchas cosas diferentes para prevenir la infección. A veces, la desinformación consistía en afirmaciones falsas sobre la eficacia, como las afirmaciones de que el virus no podía propagarse durante las ceremonias religiosas, y en otras ocasiones, la desinformación consistía en afirmaciones falsas sobre la ineficacia, como la afirmación de que el desinfectante de manos a base de alcohol no funcionaba. En otros casos, especialmente en lo que respecta a los consejos de salud pública sobre el uso de mascarillas , la evidencia científica adicional dio lugar a diferentes consejos con el tiempo. [322]

Las afirmaciones de que el desinfectante de manos es simplemente "antibacteriano, no antiviral", y, por lo tanto, ineficaz contra la COVID-19, se han extendido ampliamente en Twitter y otras redes sociales. Si bien la eficacia del desinfectante depende de los ingredientes específicos, la mayoría de los desinfectantes de manos que se venden comercialmente inactivan el SARS-CoV-2, que causa la COVID-19. [324] [325] El desinfectante de manos se recomienda contra la COVID-19, [190] aunque, a diferencia del jabón, no es eficaz contra todos los tipos de gérmenes. [326] Los Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC) de EE. UU. recomiendan lavarse con agua y jabón durante al menos 20 segundos como la mejor manera de limpiar las manos en la mayoría de las situaciones. Sin embargo, si no hay agua y jabón disponibles, se puede usar un desinfectante de manos que contenga al menos un 60% de alcohol, a menos que las manos estén visiblemente sucias o grasosas. [323] [327] Tanto los CDC como la Administración de Alimentos y Medicamentos recomiendan el jabón común; No hay evidencia de que los jabones antibacterianos sean mejores, y hay evidencia limitada de que podrían ser peores a largo plazo. [328] [329]

Las autoridades, especialmente en Asia, recomendaron el uso de mascarillas en público al comienzo de la pandemia. En otras partes del mundo, las autoridades hicieron declaraciones contradictorias (o contradictorias). [330] Varios gobiernos e instituciones, como en los Estados Unidos, inicialmente desestimaron el uso de mascarillas por parte de la población en general, a menudo con información engañosa o incompleta sobre su efectividad. [331] [332] [333] Algunos comentaristas han atribuido los mensajes anti-mascarillas a los intentos de controlar la escasez de mascarillas causada por la inacción inicial, señalando que las afirmaciones iban más allá de la ciencia o eran simplemente mentiras. [333] [334] [335] [336]

.jpg/440px-White_House_Coronavirus_Update_Briefing_(49810101702).jpg)

En febrero de 2020, el director general de sanidad de Estados Unidos , Jerome Adams, tuiteó: "En serio, gente: ¡DEJEN DE COMPRAR MASCARILLAS! NO son efectivas para evitar que el público en general se contagie de #Coronavirus [enfermedad de 2019]"; más tarde revirtió su posición con la creciente evidencia de que las mascarillas pueden limitar la propagación de COVID-19. [338] [339] En junio de 2020, Anthony Fauci (un miembro clave del Grupo de Trabajo sobre el Coronavirus de la Casa Blanca ) confirmó que al público estadounidense se le dijo desde el principio que no usara mascarillas, debido a la escasez de mascarillas, y luego explicó que las mascarillas realmente funcionan. [340] [341] [342] [343]

Algunos medios de comunicación afirmaron que las polainas para el cuello eran peores que no usar mascarillas en absoluto durante la pandemia de COVID-19, malinterpretando un estudio que pretendía demostrar un método para evaluar las mascarillas (y no determinar realmente la eficacia de los diferentes tipos de mascarillas). [344] [345] [346] El estudio también solo examinó a un usuario que llevaba la polaina para el cuello hecha de una mezcla de poliéster/ spandex , lo que no es evidencia suficiente para respaldar la afirmación sobre las polainas hecha en los medios de comunicación. [345] El estudio encontró que la polaina para el cuello, que estaba hecha de un material delgado y elástico, parecía ser ineficaz para limitar las gotitas en el aire expulsadas del usuario; Isaac Henrion, uno de los coautores, sugiere que el resultado probablemente se debió al material más que al estilo, afirmando que "Cualquier mascarilla hecha de esa tela probablemente tendría el mismo resultado, sin importar el diseño". [347] Warren S. Warren , un coautor, dijo que intentaron ser cuidadosos con su lenguaje en las entrevistas, pero agregó que la cobertura de prensa "se ha salido de control" para un estudio que prueba una técnica de medición. [344]

Se han difundido afirmaciones falsas de que el uso de mascarillas causa problemas de salud adversos , como niveles bajos de oxígeno en sangre [348] , niveles altos de dióxido de carbono en sangre [349] y un sistema inmunológico debilitado [ 350] . Algunos también afirmaron falsamente que las mascarillas causan neumonía resistente a los antibióticos al impedir que los organismos patógenos se exhalen fuera del cuerpo [351] .

Algunas personas han reclamado engañosamente exenciones legales o médicas para evitar cumplir con los mandatos de uso de mascarillas. [352] Por ejemplo, algunas personas han afirmado que la Ley de Estadounidenses con Discapacidades (ADA, diseñada para prohibir la discriminación basada en discapacidades) permite la exención de los requisitos de uso de mascarillas. El Departamento de Justicia de los Estados Unidos (DOJ) respondió que la Ley "no proporciona una exención general a las personas con discapacidades para cumplir con los requisitos de seguridad legítimos necesarios para operaciones seguras". [353] El DOJ también emitió una advertencia sobre las tarjetas (que a veces presentan logotipos del DOJ o avisos de la ADA) que afirman "eximir" a sus titulares de usar mascarillas, afirmando que estas tarjetas son fraudulentas y no fueron emitidas por ninguna agencia gubernamental. [354] [355]

Contrariamente a algunos informes, beber alcohol no protege contra la COVID-19 y puede aumentar los riesgos para la salud a corto y largo plazo . [190] El alcohol para beber se elabora con etanol puro . Otras sustancias, como el desinfectante para manos , el alcohol de madera y el alcohol desnaturalizado , contienen otros alcoholes, como el isopropanol o el metanol . Estos otros alcoholes son venenosos y pueden causar úlceras gástricas, ceguera, insuficiencia hepática o la muerte. Estos productos químicos suelen estar presentes en bebidas alcohólicas fermentadas o destiladas de forma inadecuada. [356]

Varios países, incluidos Irán [357] y Turquía [358] [359] han informado de incidentes de intoxicación por metanol, causados por la falsa creencia de que beber alcohol curaría o protegería contra el COVID-19. [357] [360] [361] El alcohol está prohibido en Irán y el alcohol de contrabando puede contener metanol . [360] Según Associated Press en marzo de 2020, 480 personas habían muerto y 2.850 enfermaron debido a la intoxicación por metanol. [361] Esa cifra llegó a 700 en abril. [362]

En Kenia, en abril de 2020, el gobernador de Nairobi, Mike Sonko , fue objeto de escrutinio por incluir pequeñas botellas de coñac Hennessy en paquetes de ayuda, afirmando falsamente que el alcohol sirve como "desinfectante de garganta". [363] [364]

En 2020, el tabaquismo se difundió en las redes sociales como un falso remedio contra la COVID-19 después de que se publicaran unos pequeños estudios observacionales en los que se demostraba que el tabaquismo era preventivo contra el SARS-CoV-2. En abril de 2020, investigadores de un hospital de París observaron una relación inversa entre el tabaquismo y las infecciones por COVID-19, lo que provocó un aumento de las ventas de tabaco en Francia. Estos resultados fueron al principio tan sorprendentes que el gobierno francés inició un ensayo clínico con parches transdérmicos de nicotina . Evidencias clínicas más recientes basadas en estudios más amplios demuestran claramente que los fumadores tienen una mayor probabilidad de infección por COVID-19 y experimentan síntomas respiratorios más graves. [365] [366]

In early 2020, several viral tweets spread around Europe and Africa, suggesting that snorting cocaine would sterilize one's nostrils of SARS-CoV-2. In response, the French Ministry of Health released a public service announcement debunking this claim, saying "No, cocaine does NOT protect against COVID-19. It is an addictive drug that causes serious side effects and is harmful to people's health." The World Health Organization also debunked the claim.[367]

There were several claims that drinking warm drinks at a temperature of around 30 °C (86 °F) protects one from COVID-19, most notably by Alberto Fernández, the president of Argentina said "The WHO recommends that one drink many hot drinks because heat kills the virus." Scientists commented that the WHO had made no such recommendation, and that drinking hot water can damage the oral mucosa.[368]

A number of religious groups have claimed protection due to their faith. Some refused to stop practices, such as gatherings of large groups, that promoted the transmission of the virus.