En la mitología y religión griega antigua , Perséfone ( / p ər ˈ s ɛ f ə n iː / pər - SEF -ə-nee ; griego : Περσεφόνη , romanizado : Persephónē , pronunciación clásica: [per.se.pʰó.nɛː] ), También llamada Kore ( / ˈk ɔːr iː / KOR -ee ; griego : Κόρη , romanizado : Kórē , lit. ' la doncella') o Cora , es hija de Zeus y Deméter . Se convirtió en la reina del inframundo después de ser secuestrada por su tío Hades , el rey del inframundo, quien más tarde también la tomaría en matrimonio. [6]

El mito de su rapto, su estancia en el inframundo y su retorno cíclico a la superficie representa sus funciones como encarnación de la primavera y personificación de la vegetación, especialmente de los cereales, que desaparecen en la tierra cuando se siembran, brotan de la tierra en primavera y se cosechan cuando están completamente desarrollados. En el arte griego clásico , Perséfone es representada invariablemente con túnica, a menudo portando una gavilla de trigo. Puede aparecer como una divinidad mística con un cetro y una pequeña caja, pero la mayoría de las veces se la representaba en el proceso de ser raptada por Hades.

Perséfone, como diosa de la vegetación , y su madre Deméter eran las figuras centrales de los Misterios de Eleusis , que prometían a los iniciados una feliz vida después de la muerte . Los orígenes de su culto son inciertos, pero se basaba en antiguos cultos agrarios de las comunidades agrícolas. En Atenas, los misterios celebrados en el mes de Anthesterion estaban dedicados a ella. La ciudad de Locri Epizephyrii , en la actual Calabria (sur de Italia ), era famosa por su culto a Perséfone, donde es diosa del matrimonio y el parto en esta región.

Su nombre tiene numerosas variantes históricas, entre ellas Perséfala ( Περσεφάσσα ) y Perséfata ( Περσεφάττα ). En latín, su nombre se traduce como Proserpina . Los romanos la identificaron como la diosa itálica Libera , que se confundió con Proserpina. Mitos similares al descenso y regreso de Perséfone a la tierra también aparecen en los cultos de dioses masculinos, incluidos Atis , Adonis y Osiris , [7] y en la Creta minoica .

En una inscripción griega micénica lineal B en una tablilla encontrada en Pilos fechada entre 1400 y 1200 a. C., John Chadwick reconstruyó [a] el nombre de una diosa, *Preswa , que podría identificarse con Perse , hija de Océano , y encontró especulativa la identificación adicional con el primer elemento de Perséfone. [9] [b] Persephonē ( griego : Περσεφόνη ) es su nombre en el griego jónico de la literatura épica . La forma homérica de su nombre es Persephoneia ( Περσεφονεία , [11] Persephoneia ). En otros dialectos, se la conocía con nombres variantes: Persephassa ( Περσεφάσσα ), Persephatta ( Περσεφάττα ), o simplemente Korē ( Κόρη , "muchacha, doncella"). [12] En los vasos áticos del siglo V se encuentra a menudo la forma ( Φερρϖφάττα ). Platón la llama Pherepapha ( Φερέπαφα ) en su Cratilo , "porque es sabia y toca lo que está en movimiento". También existen las formas Periphona ( Πηριφόνα ) y Phersephassa ( Φερσέφασσα ). La existencia de tantas formas diferentes muestra lo difícil que era para los griegos pronunciar la palabra en su propia lengua y sugiere que el nombre puede tener un origen pregriego . [13]

La etimología de la palabra «Perséfone» es oscura. Según una hipótesis reciente propuesta por Rudolf Wachter, el primer elemento del nombre ( Perso- ( Περσο- ) bien puede reflejar un término muy raro, atestiguado en el Rig Veda (sánscrito parṣa- ) y el Avesta , que significa «gavilla de trigo»/«espiga [de grano]». El segundo constituyente, phatta , conservado en la forma Persephatta ( Περσεφάττα ), reflejaría en esta visión el protoindoeuropeo *-gʷn-t-ih , de la raíz *gʷʰen- «golpear/batir/matar». El sentido combinado sería, por tanto, «la que golpea las espigas de trigo», es decir, una «trilladora de grano». [14] [15]

Se cree que el nombre de la diosa albanesa del amanecer, diosa del amor y protectora de las mujeres, Premtë o P(ë)rende , corresponde regularmente a su contraparte griega antigua Περσεφάττα ( Persephatta ), una variante de Περσεφόνη ( Perséfone ). [16] [17] Los teónimos se remontan al indoeuropeo *pers-é-bʰ(h₂)n̥t-ih₂ ("la que trae la luz"). [16]

Una etimología popular proviene de φέρειν φόνον , pherein phonon , "traer (o causar) la muerte". [18]

Los epítetos de Perséfone revelan su doble función como diosa ctónica y de la vegetación. Los sobrenombres que le dieron los poetas hacen referencia a su papel de reina del mundo inferior y de los muertos y al poder que brota y se retira hacia la tierra. Su nombre común como diosa de la vegetación es Kore, y en Arcadia era adorada bajo el título de Despoina , "la señora", una divinidad ctónica muy antigua. [18] Günther Zuntz considera a "Perséfone" y "Kore" como deidades distintas y escribe que "ningún granjero rezaba a Perséfone para que le diera trigo; ningún doliente pensaba que los muertos estuvieran con Kore". Sin embargo, los escritores griegos antiguos no fueron tan consistentes como afirma Zuntz. [19]

Plutarco escribe que Perséfone era identificada con la estación primaveral, [20] y Cicerón la llama la semilla de los frutos de los campos. En los Misterios de Eleusis , su regreso del inframundo cada primavera es un símbolo de inmortalidad, y era representada con frecuencia en sarcófagos .

En las religiones de los órficos y los platónicos , se describe a Kore como la diosa omnipresente de la naturaleza [21] que produce y destruye todo, y por lo tanto se la menciona junto con otras divinidades similares, o se la identifica con ellas, como Isis , Rea , Ge , Hestia , Pandora , Artemisa y Hécate . [22] En la tradición órfica, se dice que Perséfone es la hija de Zeus y su madre Rea, que se convirtió en Deméter después de ser seducida por su hijo. [23] Se dice que la Perséfone órfica se convirtió, por Zeus, en la madre de Dioniso / Yaco / Zagreo , [18] y de la poco documentada Melinoe . [c]

En la mitología y la literatura se la suele llamar la temible Perséfone y reina del inframundo, dentro de cuya tradición estaba prohibido pronunciar su nombre. Esta tradición proviene de su fusión con la antiquísima divinidad ctónica Despoina ("[la] señora"), cuyo verdadero nombre no podía ser revelado a nadie excepto a aquellos iniciados en sus misterios. [25] Como diosa de la muerte, también se la llamaba hija de Zeus y Estigia , [26] el río que formaba el límite entre la Tierra y el inframundo. En las epopeyas de Homero , siempre aparece junto con Hades en el inframundo, aparentemente compartiendo con Hades el control sobre los muertos. [27] [28] En la Odisea de Homero , Odiseo se encuentra con la "temible Perséfone" en el Tártaro cuando visita a su madre muerta. Odiseo sacrifica un carnero a la diosa ctónica Perséfone y a los fantasmas de los muertos, que beben la sangre del animal sacrificado. En la reformulación de la mitología griega expresada en los Himnos órficos , Dioniso y Melinoe son llamados por separado hijos de Zeus y Perséfone. [29] Los bosques consagrados a ella se encontraban en el extremo occidental de la tierra, en las fronteras del mundo inferior, que a su vez era llamado "casa de Perséfone". [30]

Su mito central sirvió de contexto para los ritos secretos de regeneración en Eleusis, [31] que prometían la inmortalidad a los iniciados.

En un texto del período clásico atribuido a Empédocles , c. 490–430 a. C., [d] que describe una correspondencia entre cuatro deidades y los elementos clásicos , el nombre Nestis para el agua aparentemente se refiere a Perséfone:

De las cuatro deidades de los elementos de Empédocles, el nombre de Perséfone es el único tabú ( Nestis es un título de culto eufemístico [e] ), pues también era la terrible Reina de los Muertos, cuyo nombre no era seguro pronunciar en voz alta, que era llamada eufemísticamente simplemente Kore o "la Doncella", un vestigio de su papel arcaico como la deidad que gobernaba el inframundo. Nestis significa "la que ayuna" en griego antiguo. [33]

_480-460_BC_(Sk_1761)_1.JPG/440px-Throning_goddess_(Persephone)_480-460_BC_(Sk_1761)_1.JPG)

Como diosa del inframundo, Perséfone recibió nombres eufemísticamente amistosos. [34] Sin embargo, es posible que algunos de ellos fueran los nombres de diosas originales:

Como diosa de la vegetación, se la llamaba: [35] [37]

Deméter y su hija Perséfone eran llamadas habitualmente: [37] [39]

.JPG/440px-Sarcophagus_with_the_Abduction_of_Persephone_by_Hades_(detail).JPG)

El rapto de Perséfone por Hades [f] se menciona brevemente en la Teogonía de Hesíodo , [41] y se cuenta con considerable detalle en el Himno homérico a Deméter . Se dice que Zeus permitió a Hades, que estaba enamorado de la bella Perséfone, raptarla ya que su madre Deméter no era probable que permitiera que su hija bajara al Hades. Perséfone estaba recogiendo flores, junto con las Oceánides , Palas y Artemisa , como dice el Himno homérico , en un campo cuando Hades vino a raptarla, irrumpiendo a través de una hendidura en la tierra. [42] En otra versión del mito, Perséfone tenía sus propias compañeras personales a quienes Deméter convirtió en las sirenas mitad pájaro como castigo por no haber podido evitar el rapto de su hija. [43]

Varias tradiciones locales sitúan el rapto de Perséfone en diferentes lugares. Los sicilianos , entre quienes su culto fue probablemente introducido por los colonos corintios y megarianos, creían que Hades la encontró en los prados cerca de Enna , y que un pozo surgió en el lugar donde descendió con ella al mundo inferior. Los cretenses pensaban que su propia isla había sido el escenario del rapto, y los eleusinos mencionaron la llanura de Nisia en Beocia, y dijeron que Perséfone había descendido con Hades al mundo inferior en la entrada del Océano occidental. Relatos posteriores sitúan el rapto en Ática , cerca de Atenas , o cerca de Eleusis. [44] El himno homérico menciona Nysion (o Mysion), que probablemente era un lugar mítico. La ubicación de este lugar mítico puede ser simplemente una convención para mostrar que se pretendía una tierra ctónica mágicamente distante del mito en el pasado remoto. [37]

Tras la desaparición de Perséfone, Deméter la buscó por toda la tierra con las antorchas de Hécate . En la mayoría de las versiones, ella prohíbe a la tierra producir, o la descuida y, en lo más profundo de su desesperación, no hace que nada crezca. Helios , el Sol, que todo lo ve, acabó contándole a Deméter lo que había sucedido y ella descubrió por fin dónde habían llevado a su hija. Zeus, presionado por los gritos del pueblo hambriento y por las otras deidades que también oían su angustia, obligó a Hades a devolver a Perséfone. [44]

Cuando Hades fue informado de la orden de Zeus de devolver a Perséfone, cumplió con la petición, pero primero la engañó para que comiera semillas de granada . [g] Hermes fue enviado a recuperar a Perséfone pero, debido a que había probado la comida del inframundo, se vio obligada a pasar un tercio de cada año (los meses de invierno) allí, y la parte restante del año con los dioses de arriba. [47] Con los escritores posteriores Ovidio e Higinio, el tiempo de Perséfone en el inframundo se convierte en la mitad del año. [48] Se le explicó a Deméter, su madre, que sería liberada, siempre y cuando no probara la comida del inframundo, ya que ese era un ejemplo de tabú de la Antigua Grecia .

En algunas versiones, Ascálafo informó a las demás deidades que Perséfone había comido las semillas de granada. Como castigo por informar a Hades, Perséfone o Deméter lo inmovilizaron bajo una pesada roca en el inframundo hasta que Hércules lo liberó más tarde, lo que provocó que Deméter lo convirtiera en un búho real . [49]

En una versión anterior, Hécate rescató a Perséfone. En una crátera campanular ática de figuras rojas de alrededor del 440 a. C. que se encuentra en el Museo Metropolitano de Arte , Perséfone se eleva como si estuviera subiendo unas escaleras desde una hendidura en la tierra, mientras Hermes se mantiene a un lado; Hécate, sosteniendo dos antorchas, mira hacia atrás mientras la conduce hacia Deméter, entronizada. [50]

Antes de que Perséfone fuera raptada por Hades, el pastor Eumolpo y el porquero Eubuleo vieron a una muchacha en un carro negro conducido por un conductor invisible que era llevada hacia la tierra que se había abierto violentamente. Eubuleo estaba alimentando a sus cerdos en la abertura del inframundo, y sus cerdos fueron tragados por la tierra junto con ella. Este aspecto del mito es una etiología de la relación de los cerdos con los antiguos ritos en las Tesmoforias [51] y en Eleusis.

En el himno, Perséfone finalmente regresa del inframundo y se reúne con su madre cerca de Eleusis. Los eleusinos construyeron un templo cerca del manantial de Calícoro, y Deméter establece allí sus misterios. [52]

Independientemente de cómo y cuántas semillas de granada hubiera comido, los antiguos griegos contaron el mito de Perséfone para explicar el origen de las cuatro estaciones . Los antiguos griegos creían que la primavera y el verano ocurrían durante los meses en que Perséfone permanecía con Deméter, quien haría que las flores florecieran y las cosechas crecieran abundantemente. Durante los otros meses en los que Perséfone debía vivir en el inframundo con Hades, Deméter expresaba su tristeza dejando que la tierra se volviera estéril y cubriéndola de nieve, lo que dio lugar al otoño y al invierno . [53]

Según la tradición griega, una diosa de la caza precedió a la diosa de la cosecha. [54] En Arcadia , a Deméter y Perséfone se las llamaba a menudo Despoinai ( Δέσποιναι , «las amantes»). Son las dos grandes diosas de los cultos arcadios, y evidentemente provienen de una religión más primitiva. [37] El dios griego Poseidón probablemente sustituyó al compañero ( Paredros , Πάρεδρος ) de la gran diosa minoica [55] en los misterios arcadios. En el mito arcadio, mientras Deméter buscaba a Perséfone secuestrada, llamó la atención de su hermano menor Poseidón. Deméter se convirtió en una yegua para escapar de él, pero luego Poseidón se convirtió en un semental para perseguirla. La atrapó y la violó. Posteriormente, Deméter dio a luz al caballo parlante Arión y a la diosa Despoina ("la señora"), una diosa de los misterios de Arcadia. [56]

En la Teogonía Rapsódica órfica (siglo I a. C./d. C.), [57] Perséfone es descrita como la hija de Zeus y Rea . Zeus estaba lleno de deseo por su madre, Rea, con la intención de casarse con ella. Persiguió a Rea, que no estaba dispuesta, pero ella se transformó en una serpiente.

Zeus también se transformó en serpiente y violó a Rea, lo que dio lugar al nacimiento de Perséfone. [58] Después, Rea se convirtió en Deméter . [59] Perséfone nació tan deformada que Rea huyó asustada de ella y no la amamantó. [58] Zeus se aparea con Perséfone, quien da a luz a Dioniso . Más tarde, ella se queda en la casa de su madre, custodiada por los Curetes . Rea-Deméter profetiza que Perséfone se casará con Apolo .

Sin embargo, esta profecía no se cumple, ya que mientras teje un vestido, Perséfone es raptada por Hades para ser su esposa. Ella se convierte en la madre de las Erinias por Hades. [60] En las Dionisíacas de Nonnus , los dioses del Olimpo quedaron hechizados por la belleza de Perséfone y la desearon.

Hermes , Apolo , Ares y Hefesto le ofrecieron a Perséfone un regalo para cortejarla. Deméter, preocupada de que Perséfone pudiera terminar casándose con Hefesto, consulta al dios astrológico Astreo . Astreo le advierte que Perséfone será violada y embarazada por una serpiente. Deméter luego esconde a Perséfone en una cueva; pero Zeus, en forma de serpiente, entra en la cueva y viola a Perséfone. Perséfone queda embarazada y da a luz a Zagreo . [61]

Se decía que mientras Perséfone jugaba con la ninfa Hercina, Hercina le puso un ganso en la mano y lo soltó. El ganso voló hasta una cueva hueca y se escondió debajo de una piedra; cuando Perséfone tomó la piedra para recuperar el pájaro, brotó agua de ese lugar, y de ahí que el río recibiera el nombre de Hercina. [62] Fue entonces cuando fue raptada por Hades según la leyenda beocia; un jarrón muestra aves acuáticas acompañando a las diosas Deméter y Hécate en busca de la desaparecida Perséfone. [63]

_(12853680765).jpg/440px-Fragment_of_a_marble_relief_depicting_a_Kore,_3rd_century_BC,_from_Panticapaeum,_Taurica_(Crimea)_(12853680765).jpg)

El rapto de Perséfone es un mito etiológico que proporciona una explicación para el cambio de las estaciones. Como Perséfone había consumido semillas de granada en el inframundo, se vio obligada a pasar cuatro meses, o en otras versiones seis meses por seis semillas, con Hades. [64] [65] Cuando Perséfone regresara al inframundo , la desesperación de Deméter por perder a su hija haría que la vegetación y la flora del mundo se marchitaran, lo que significa las estaciones de otoño e invierno. Cuando el tiempo de Perséfone terminara y se reuniera con su madre, la alegría de Deméter haría que la vegetación de la tierra floreciera y se desarrollara, lo que significa las estaciones de primavera y verano. Esto también explica por qué Perséfone está asociada con la primavera: su reaparición del inframundo significa el comienzo de la primavera. Por lo tanto, la reunión anual de Perséfone y Deméter no solo simboliza el cambio de estaciones y el comienzo de un nuevo ciclo de crecimiento para los cultivos, sino que también simboliza la muerte y la regeneración de la vida. [66] [67]

En otra interpretación del mito, el rapto de Perséfone por Hades, en la forma de Pluto ( πλούτος , riqueza), representa la riqueza del grano contenido y almacenado en silos subterráneos o jarras de cerámica ( pithoi ) durante las estaciones de verano (ya que esa era la temporada de sequía en Grecia). [68] En este relato, Perséfone como doncella del grano simboliza el grano dentro del pithoi que está atrapado bajo tierra dentro del reino de Hades. A principios del otoño, cuando el grano de la vieja cosecha se coloca en los campos, ella asciende y se reúne con su madre Deméter. [69] [66] [67] Esta interpretación del mito del rapto de Perséfone simboliza el ciclo de vida y muerte, ya que Perséfone muere cuando ella (el grano) es enterrada en el pithoi (ya que se usaban pithoi similares en la antigüedad para prácticas funerarias) y renace con la exhumación y esparcimiento del grano.

Lincoln sostiene que el mito es una descripción de la pérdida de la virginidad de Perséfone, donde su epíteto koure significa "una niña en edad iniciática", y donde Hades es el opresor masculino que se acosta con una joven por primera vez. [70]

Adonis era un hombre mortal sumamente bello de quien Perséfone se enamoró. [71] [72] [73] Después de que nació, Afrodita se lo confió a Perséfone para que lo criara. Pero cuando Perséfone vio al hermoso Adonis, al encontrarlo tan atractivo como Afrodita, se negó a devolvérselo. El asunto fue llevado ante Zeus , y él decretó que Adonis pasaría un tercio del año con cada diosa y tendría el último tercio para él. Adonis eligió pasar su propia parte del año con Afrodita. [74] Alternativamente, Adonis tuvo que pasar la mitad del año con cada diosa por sugerencia de la musa Calíope . [75] De ellos, Eliano escribió que la vida de Adonis estaba dividida entre dos diosas: una que lo amaba bajo la tierra y otra arriba, [76] mientras que el autor satírico Luciano de Samosata hace que Afrodita se queje a la diosa lunar Selene de que Eros hizo que Perséfone se enamorara de su propio amado, y ahora tiene que compartir a Adonis con ella. [77] En otra variación, Perséfone conoció a Adonis sólo después de que este hubiera sido asesinado por un jabalí; Afrodita descendió al Inframundo para recuperarlo. Pero Perséfone, enamorada de él, no lo dejó ir hasta que llegaron a un acuerdo de que Adonis alternaría entre la tierra de los vivos y la tierra de los muertos cada año. [78]

Después de que una plaga azotara Aonia , sus habitantes consultaron al oráculo de Apolo Gortinius, y les dijeron que necesitaban apaciguar la ira del rey y la reina del inframundo mediante el sacrificio de dos doncellas voluntarias. Se eligieron dos doncellas, Menipe y Metioche (que eran las hijas de Orión ), y aceptaron ser ofrecidas a los dos dioses para salvar a su país. Después de que las dos muchachas se sacrificaran con sus lanzaderas, Perséfone y Hades se compadecieron de ellas y convirtieron sus cadáveres en cometas . [79]

Minthe era una ninfa náyade del río Cocito que se convirtió en la amante de Hades , el esposo de Perséfone . Perséfone no tardó en darse cuenta y, por celos, pisoteó a la ninfa, matándola y convirtiéndola en una planta de menta . [80] [81] Alternativamente, Perséfone despedazó a Minthe por acostarse con Hades, y fue él quien convirtió a su ex amante en la planta de dulce olor. [82] En otra versión, Minthe había sido la amante de Hades antes de conocer a Perséfone. Cuando Minthe afirma que Hades regresará con ella debido a su belleza, la madre de Perséfone, Deméter, mata a Minthe por el insulto hecho a su hija. [83]

Teófila era una muchacha que afirmaba que Hades la amaba y que ella era mejor que Perséfone. [84] [85]

Una vez, Hermes persiguió a Perséfone (o Hécate ) con el objetivo de violarla; pero la diosa roncaba o rugía de ira, asustándolo y haciendo que desistiera, de ahí que se ganara el nombre de " Brimo " ("enojada"). [86]

El héroe Orfeo descendió una vez al inframundo con la intención de llevar de vuelta a la tierra de los vivos a su difunta esposa Eurídice , que murió cuando una serpiente la mordió. La música que tocó fue tan encantadora que encantó a Perséfone e incluso al severo Hades. [87] Perséfone quedó tan fascinada por la dulce melodía de Orfeo que convenció a su esposo para que dejara que el desafortunado héroe volviera a llevarse a su esposa. [88]

Sísifo , el astuto rey de Corinto , logró evitar permanecer muerto, después de que la Muerte fuera a recogerlo, apelando a Perséfone y engañando a ésta para que lo dejara ir; así Sísifo regresó a la luz del sol en la superficie. [89]

Cuando Echemeia , reina de Cos , dejó de rendir culto a Artemisa , la diosa le disparó una flecha. Perséfone, al presenciarlo, atrapó a Euthemia, que aún estaba viva, y la llevó al inframundo. [90]

Cuando Dioniso, el dios del vino, descendió al inframundo acompañado de Deméter para recuperar a su madre muerta Sémele y traerla de vuelta a la tierra de los vivos, se dice que ofreció una planta de mirto a Perséfone a cambio de Sémele. [91] [ verificación fallida ] En un ánfora de cuello de Atenas, Dioniso está representado montado en un carro con su madre, junto a Perséfone sosteniendo un mirto que está con su propia madre Deméter; muchos jarrones de Atenas representan a Dioniso en compañía de Perséfone y Deméter. [92]

Perséfone también convenció a Hades para que permitiera al héroe Protesilao regresar al mundo de los vivos por un período de tiempo limitado para ver a su esposa. [93]

Sócrates en el Cratilo de Platón menciona previamente que Hades se junta con Perséfone debido a su sabiduría. [94]

Perséfone era adorada junto con su madre Deméter y en los mismos misterios. Sus cultos incluían magia agraria, danzas y rituales. Los sacerdotes utilizaban vasos especiales y símbolos sagrados, y el pueblo participaba con rimas. En Eleusis hay evidencia de leyes sagradas y otras inscripciones. [95]

El culto a Deméter y a la doncella se encuentra en el Ática, en las principales fiestas de las Tesmoforias y los misterios de Eleusis y en numerosos cultos locales. Estas fiestas se celebraban casi siempre en la siembra de otoño y en la luna llena según la tradición griega. En algunos cultos locales las fiestas estaban dedicadas a Deméter.

El mito de una diosa raptada y llevada al inframundo es probablemente de origen pregriego. Samuel Noah Kramer , el renombrado erudito de la antigua Sumeria , ha postulado que la historia griega del rapto de Perséfone puede derivar de una antigua historia sumeria en la que Ereshkigal , la antigua diosa sumeria del inframundo, es raptada por Kur , el dragón primigenio de la mitología sumeria , y obligada a convertirse en gobernante del inframundo contra su propia voluntad. [96]

The location of Persephone's abduction is different in each local cult. The Homeric Hymn to Demeter mentions the "plain of Nysa".[97] The locations of this probably mythical place may simply be conventions to show that a magically distant chthonic land of myth was intended in the remote past.[98][h] Demeter found and met her daughter in Eleusis, and this is the mythical disguise of what happened in the mysteries.[100]

In his 1985 book on Greek Religion, Walter Burkert claimed that Persephone is an old chthonic deity of the agricultural communities, who received the souls of the dead into the earth, and acquired powers over the fertility of the soil, over which she reigned. The earliest depiction of a goddess Burkert claims may be identified with Persephone growing out of the ground, is on a plate from the Old-Palace period in Phaistos. According to Burkert, the figure looks like a vegetable because she has snake lines on other side of her. On either side of the vegetable person there is a dancing girl.[101] A similar representation, where the goddess appears to come down from the sky, is depicted on the Minoan ring of Isopata.

The cults of Persephone and Demeter in the Eleusinian mysteries and in the Thesmophoria were based on old agrarian cults.[102] The beliefs of these cults were closely-guarded secrets, kept hidden because they were believed to offer believers a better place in the afterlife than in miserable Hades. There is evidence that some practices were derived from the religious practices of the Mycenaean age.[103][101] Kerenyi asserts that these religious practices were introduced from Minoan Crete.[104][105] The idea of immortality which appears in the syncretistic religions of the Near East did not exist in the Eleusinian mysteries at the very beginning.[106][i]

Walter Burkert believed that elements of the Persephone myth had origins in the Minoan religion. This belief system had unique characteristics, particularly the appearance of the goddess from above in the dance. Dance floors have been discovered in addition to "vaulted tombs", and it seems that the dance was ecstatic. Homer memorializes the dance floor which Daedalus built for Ariadne in the remote past.[108] A gold ring from a tomb in Isopata depicts four women dancing among flowers, the goddess floating above them.[109] An image plate from the first palace of Phaistos seems to depict the ascent of Persephone: a figure grows from the ground, with a dancing girl on each side and stylized flowers all around.[101] The depiction of the goddess is similar to later images of "Anodos of Pherephata". On the Dresden vase, Persephone is growing out of the ground, and she is surrounded by the animal-tailed agricultural gods Silenoi.[110]

Despoina and "Hagne" were probably euphemistic surnames of Persephone, therefore Karl Kerenyi theorizes that the cult of Persephone was the continuation of the worship of a Minoan Great goddess.[111][112] It is possible that some religious practices, especially the mysteries, were transferred from a Cretan priesthood to Eleusis, where Demeter brought the poppy from Crete.[113] Besides these similarities, Burkert explains that up to now it is not known to what extent one can and must differentiate between Minoan and Mycenean religion.[j] In the Anthesteria Dionysos is the "divine child".

There is evidence of a cult in Eleusis from the Mycenean period;[115] however, there are not sacral finds from this period. The cult was private and there is no information about it. As well as the names of some Greek gods in the Mycenean Greek inscriptions, names of goddesses who do not have Mycenean origin appear, such as "the divine Mother" (the mother of the gods) or "the Goddess (or priestess) of the winds".[100] In historical times, Demeter and Kore were usually referred to as "the goddesses" or "the mistresses" (Arcadia) in the mysteries .[116] In the Mycenean Greek tablets dated 1400–1200 BC, the "two queens and the king" are mentioned. John Chadwick believes that these were the precursor divinities of Demeter, Persephone and Poseidon.[117][k]

Some information can be obtained from the study of the cult of Eileithyia at Crete, and the cult of Despoina. In the cave of Amnisos at Crete, Eileithyia is related with the annual birth of the divine child and she is connected with Enesidaon (The earth shaker), who is the chthonic aspect of the god Poseidon.[103]Persephone was conflated with Despoina, "the mistress", a chthonic divinity in West-Arcadia.[105] The megaron of Eleusis is quite similar to the "megaron" of Despoina at Lycosura.[100] Demeter is united with her, the god Poseidon, and she bears him a daughter, the unnameable Despoina.[119] Poseidon appears as a horse, as usually happens in Northern European folklore. The goddess of nature and her companion survived in the Eleusinian cult, where the words "Mighty Potnia bore a great sun" were uttered.[103] In Eleusis, in a ritual, one child ("pais") was initiated from the hearth. The name pais (the divine child) appears in the Mycenean inscriptions.[100]

In Greek mythology Nysa is a mythical mountain with an unknown location.[h] Nysion (or Mysion), the place of the abduction of Persephone was also probably a mythical place which did not exist on the map, a magically distant chthonic land of myth which was intended in the remote past.[120]

Persephone and Demeter were intimately connected with the Thesmophoria, a widely-spread Greek festival of secret women-only rituals. These rituals, which were held in the month Pyanepsion, commemorated marriage and fertility, as well as the abduction and return of Persephone.

They were also involved in the Eleusinian mysteries, a festival celebrated at the autumn sowing in the city of Eleusis. Inscriptions refer to "the Goddesses" accompanied by the agricultural god Triptolemos (probably son of Gaia and Oceanus),[121] and "the God and the Goddess" (Persephone and Plouton) accompanied by Eubuleus who probably led the way back from the underworld.[122]

The Romans first heard of her from the Aeolian and Dorian cities of Magna Graecia, who used the dialectal variant Proserpinē (Προσερπίνη). Hence, in Roman mythology she was called Proserpina, a name erroneously derived by the Romans from proserpere, "to shoot forth"[123] and as such became an emblematic figure of the Renaissance.[124] In 205 BC, Rome officially identified Proserpina with the local Italic goddess Libera, who, along with Liber, were closely associated with the Roman grain goddess Ceres (considered equivalent to the Greek Demeter). The Roman author Gaius Julius Hyginus also considered Proserpina equivalent to the Cretan goddess Ariadne, who was the bride of Liber's Greek equivalent, Dionysus.[125][126]

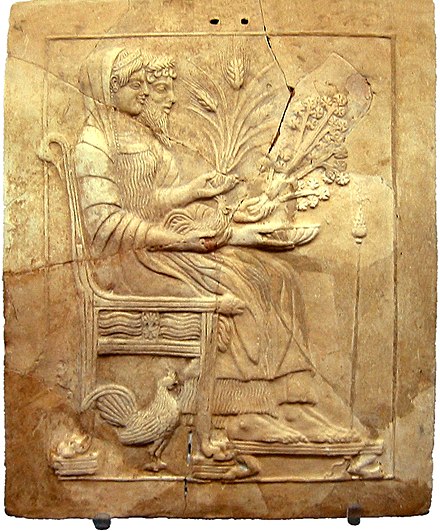

At Locri Epizephyrii, a city of Magna Graecia situated on the coast of the Ionian Sea in Calabria (a region of southern Italy), perhaps uniquely, Persephone was worshiped as protector of marriage and childbirth, a role usually assumed by Hera (in fact, Hera seems to have played no role in the public worship of the city[127]); in the iconography of votive plaques at Locri Epizephyrii, her abduction and marriage to Hades served as an emblem of the marital state, children of the town were dedicated to Proserpina, and maidens about to be wed brought their peplos to be blessed.[128] Diodorus Siculus knew the temple there as the most illustrious in Italy.[129] During the 5th century BC, votive pinakes in terracotta were often dedicated as offerings to the goddess, made in series and painted with bright colors, animated by scenes connected to the myth of Persephone. Many of these pinakes are now on display in the National Museum of Magna Græcia in Reggio Calabria. Locrian pinakes represent one of the most significant categories of objects from Magna Graecia, both as documents of religious practice and as works of art.[130]

For most Greeks, the marriage of Persephone was a marriage with death, and could not serve as a role for human marriage; the Locrians, not fearing death, painted her destiny in a uniquely positive light.[131] While the return of Persephone to the world above was crucial in Panhellenic tradition, in southern Italy Persephone apparently accepted her new role as queen of the underworld, of which she held extreme power, and perhaps did not return above;[132] Virgil for example in Georgics writes that "Proserpina cares not to follow her mother",[133] – though note that references to Proserpina serve as a warning, since the soil is only fertile when she is above it.[134] Although her importance stems from her marriage to Hades, in Locri Epizephyrii she seems to have the supreme power over the land of the dead, and Hades is not mentioned in the Pelinna tablets found in the area.[135] Many pinakes found in the cult are near Epizephyrian Locri depict the abduction of Persephone by Hades, and others show her enthroned next to her beardless, youthful husband, indicating that in there Persephone's abduction was taken as a model of transition from girlhood to marriage for young women; a terrifying change, but one nonetheless that provides the bride with status and position in society. Those representations thus show both the terror of marriage and the triumph of the girl who transitions from bride to matron.[136]

It had been suggested that Persephone's cult at Locri Epizephyrii was entirely independent from that of Demeter, who supposedly was not venerated there,[19] but a sanctuary of Demeter Thesmophoros has been found in a different region of the colony, ruling against the notion that she was completely excluded from the Locrian pantheon.[127]

The temple at Locri Epizephyrii was looted by Pyrrhus.[137] The importance of the regionally powerful Epizephyrian Locrian Persephone influenced the representation of the goddess in Magna Graecia. Pinakes, terracotta tablets with brightly painted sculptural scenes in relief were founded in Locri. The scenes are related to the myth and cult of Persephone and other deities. They were produced in Locri during the first half of the 5th century BC and offered as votive dedications at the Locrian sanctuary of Persephone. More than 5,000, mostly fragmentary, pinakes are stored in the National Museum of Magna Græcia in Reggio Calabria and in the museum of Locri.[130] Representations of myth and cult on the clay tablets (pinakes) dedicated to this goddess reveal not only a 'Chthonian Queen,' but also a deity concerned with the spheres of marriage and childbirth.[129]

The Italian archaeologist Paolo Orsi, between 1908 and 1911, carried out a meticulous series of excavations and explorations in the area which allowed him to identify the site of the renowned Persephoneion, an ancient temple dedicated to Persephone in Calabria which Diodorus in his own time knew as the most illustrious in Italy.[138]

The place where the ruins of the Sanctuary of Persephone were brought to light is located at the foot of the Mannella hill, near the walls (upstream side) of the polis of Epizephyrian Locri. Thanks to the finds that have been retrieved and to the studies carried on, it has been possible to date its use to a period between the 7th century BC and the 3rd century BC.

Archaeological finds suggest that worship of Demeter and Persephone was widespread in Sicily and Greek Italy.

Evidence from both the Orphic Hymns and the Orphic Gold Leaves demonstrate that Persephone was one of the most important deities worshiped in Orphism.[139] In the Orphic religion, gold leaves with verses intended to help the deceased enter into an optimal afterlife were often buried with the dead. Persephone is mentioned frequently in these tablets, along with Demeter and Euklês, which may be another name for Plouton.[139] The ideal afterlife destination believers strive for is described on some leaves as the "sacred meadows and groves of Persephone". Other gold leaves describe Persephone's role in receiving and sheltering the dead, in such lines as "I dived under the kolpos [portion of a Peplos folded over the belt] of the Lady, the Chthonian Queen", an image evocative of a child hiding under its mother's apron.[139]

In Orphism, Persephone is believed to be the mother of the first Dionysus. In Orphic myth, Zeus came to Persephone in her bedchamber in the underworld and impregnated her with the child who would become his successor. The infant Dionysus was later dismembered by the Titans, before being reborn as the second Dionysus, who wandered the earth spreading his mystery cult before ascending to the heavens with his second mother, Semele.[24] The first, "Orphic" Dionysus is sometimes referred to with the alternate name Zagreus (Greek: Ζαγρεύς). The earliest mentions of this name in literature describe him as a partner of Gaia and call him the highest god. The Greek poet Aeschylus considered Zagreus either an alternate name for Hades, or his son (presumably born to Persephone).[140] Scholar Timothy Gantz noted that Hades was often considered an alternate, cthonic form of Zeus, and suggested that it is likely Zagreus was originally the son of Hades and Persephone, who was later merged with the Orphic Dionysus, the son of Zeus and Persephone, owing to the identification of the two fathers as the same being.[141] However, no known Orphic sources use the name "Zagreus" to refer to Dionysus. It is possible that the association between the two was known by the 3rd century BC, when the poet Callimachus may have written about it in a now-lost source.[142] In Orphic myth, the Eumenides are attributed as daughters of Persephone and Zeus.[143] Whereas Melinoë was conceived as the result of rape when Zeus disguised himself as Hades in order to mate with Persephone, the Eumenides' origin is unclear.[144]

There were local cults of Demeter and Kore in Greece, Asia Minor, Sicily, Magna Graecia, and Libya.

Persephone also appears many times in popular culture. Modern retellings of the myth sometimes depict Persephone as at first unhappy with Hades abducting and marrying her, but eventually loving him when he treated her as his equal.[157] Featured in a variety of novels such as Persephone [158] by Kaitlin Bevis, A Touch of Darkness by Scarlett St. Clair, Persephone's Orchard[159] by Molly Ringle, The Goddess Test by Aimee Carter, The Goddess Letters by Carol Orlock, Abandon by Meg Cabot, Neon Gods by Katee Robert and Lore Olympus by Rachel Smythe, her story has also been treated by Suzanne Banay Santo in Persephone Under the Earth in the light of women's spirituality; portraying Persephone not as a victim but as a woman in quest of sexual depth and power, transcending the role of daughter, though ultimately returning to it as an awakened Queen.[160]

Elizabeth Eowyn Nelson, in "Embodying Persephone’s Desire: Authentic Movement and Underworld",[161] interprets the Persephone myth through Jungian psychology. She focuses on the dual nature of Persephone as both maiden and queen of the underworld, symbolizing the Jungian themes of life, death, and rebirth, and the complexity of the human psyche. Nelson also examines the mother-daughter relationship between Persephone and Demeter, emphasizing its significance in the myth as an embodiment of the cyclical nature of life and the process of transformation. This interpretation views Persephone's descent into the underworld as a metaphor for the journey into the unconscious, highlighting self-discovery and confrontation with deeper aspects of the self.