.jpg/440px-Israel_CHOD_visit_150108-D-HU462-018_(16231906515).jpg)

Estados Unidos fue el primer país en reconocer al naciente Estado de Israel . [1] Desde la década de 1960, la relación entre Israel y Estados Unidos se ha convertido en una alianza mutuamente beneficiosa en aspectos económicos, estratégicos y militares. [1] Estados Unidos ha brindado un fuerte apoyo a Israel. Ha desempeñado un papel clave en la promoción de buenas relaciones entre Israel y sus estados árabes vecinos —en particular Jordania , Líbano y Egipto— al tiempo que mantiene a raya la hostilidad de países como Siria e Irán . A su vez, Israel proporciona un punto de apoyo estratégico estadounidense en la región, así como inteligencia y asociaciones tecnológicas avanzadas tanto en el mundo civil como en el militar. Durante la Guerra Fría , Israel fue un contrapeso vital a la influencia soviética en la región. [2] Las relaciones con Israel son un factor importante en la política exterior general del gobierno estadounidense en Oriente Medio , y el Congreso de Estados Unidos ha otorgado considerable importancia al mantenimiento de una relación de apoyo.

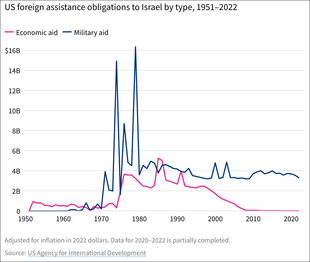

Israel es el mayor receptor acumulado de ayuda exterior estadounidense : hasta febrero de 2022, Estados Unidos había proporcionado a Israel 150.000 millones de dólares (sin ajustar a la inflación) en asistencia. [3] El primer acuerdo de libre comercio de Estados Unidos fue con Israel, en 1985. El acuerdo de libre comercio con Israel crea la mayor cantidad de empleos estadounidenses por dólar de exportación de todos los acuerdos de libre comercio de Estados Unidos. [4] En 1999, el gobierno de Estados Unidos firmó un compromiso para proporcionar a Israel al menos 2.700 millones de dólares en ayuda militar anualmente durante diez años; en 2009 se elevó a 3.000 millones de dólares; y en 2019 se elevó a un mínimo de 3.800 millones de dólares . [3] Desde 1972, Estados Unidos también ha otorgado garantías de préstamos a Israel para ayudar con la escasez de viviendas, la absorción de nuevos inmigrantes judíos y la recuperación económica. [3] Además, Israel es el 23.º socio comercial más importante de Estados Unidos, mientras que Estados Unidos es el mayor socio comercial de Israel; El comercio bilateral totalizó casi 50 mil millones de dólares en 2023. [5] 300 empresas estadounidenses, principalmente orientadas a la tecnología, han establecido centros de I+D en Israel, mientras que 650 empresas tecnológicas israelíes operan en los Estados Unidos. [6] [7] Las asociaciones israelí-estadounidenses tienden a contribuir a sectores relativamente nicho de la economía estadounidense y el efecto se multiplica positivamente hacia la economía en general. [8]

Además de la ayuda financiera y militar, Estados Unidos proporciona apoyo político a gran escala, habiendo utilizado su poder de veto en el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas 42 veces contra resoluciones que condenaban a Israel , de las 83 veces en las que se ha utilizado su veto . Entre 1991 y 2011, de los 24 vetos invocados por Estados Unidos, 15 se utilizaron para proteger a Israel. [9] [10] A partir de 2021 [update], Estados Unidos sigue siendo el único miembro permanente del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas que ha reconocido los Altos del Golán como territorio soberano israelí no ocupado, reconoció a Jerusalén como la capital de Israel y trasladó su embajada allí desde Tel Aviv en 2018. [11] Los funcionarios israelíes presionaron a Estados Unidos para que reconociera la "soberanía israelí" sobre los Altos del Golán. [12] Israel está designado por Estados Unidos como un importante aliado no perteneciente a la OTAN , el único país de Oriente Medio aparte de Egipto que tiene esta designación.

Las relaciones bilaterales han evolucionado desde una política inicial estadounidense de simpatía y apoyo a la creación de una patria judía en 1948, a una asociación que vincula a un estado pequeño pero poderoso con una superpotencia que intenta equilibrar su influencia contra intereses en competencia en la región, a saber, Rusia y sus aliados. [13] [14] Algunos analistas sostienen que Israel es un aliado particularmente estratégico para los Estados Unidos, y que las relaciones con el primero fortalecen la influencia del segundo en el Medio Oriente. [15] Argumentan que la presencia militar ofrecida por Israel justifica el gasto de la ayuda militar estadounidense, refiriéndose a Israel como " el portaaviones de Estados Unidos en el Medio Oriente". [16] [17]

El apoyo al sionismo entre los judíos estadounidenses fue mínimo, hasta la participación de Louis Brandeis en la Federación de Sionistas Estadounidenses , [18] a partir de 1912 y el establecimiento del Comité Ejecutivo Provisional para Asuntos Sionistas Generales en 1914; fue autorizado por la Organización Sionista "para ocuparse de todos los asuntos sionistas, hasta que lleguen tiempos mejores". [19]

Woodrow Wilson , que simpatizaba con la difícil situación de los judíos en Europa y era favorable a los objetivos sionistas (dando su asentimiento al texto de la Declaración Balfour poco antes de su publicación) declaró el 2 de marzo de 1919: "Estoy convencido de que las naciones aliadas, con el pleno consentimiento de nuestro propio gobierno y pueblo, están de acuerdo en que en Palestina se sentarán las bases de una futura comunidad judía" y el 16 de abril de 1919 corroboró la "expresada aquiescencia" del gobierno de los EE. UU. en la Declaración Balfour. [20] Las declaraciones de Wilson no resultaron en un cambio en la política del Departamento de Estado de los EE. UU. a favor de los objetivos sionistas. Sin embargo, el Congreso de los EE. UU. aprobó la resolución Lodge-Fish, [21] la primera resolución conjunta que declaraba su apoyo al "establecimiento en Palestina de un hogar nacional para el pueblo judío" el 21 de septiembre de 1922. [22] [23] El mismo día, el Mandato de Palestina fue aprobado por el Consejo de la Liga de las Naciones .

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial , mientras que las decisiones de política exterior de Estados Unidos eran a menudo movimientos ad hoc y soluciones dictadas por las demandas de la guerra, el movimiento sionista se apartó fundamentalmente de la política sionista tradicional y de sus objetivos declarados, en la Conferencia de Biltmore en mayo de 1942. [24] La política declarada anterior hacia el establecimiento de un "hogar nacional" judío en Palestina había desaparecido; estas fueron reemplazadas por su nueva política de "que Palestina se establezca como una Commonwealth judía" como otras naciones, en cooperación con los Estados Unidos, no con Gran Bretaña. [25] Dos intentos del Congreso en 1944 de aprobar resoluciones que declararan el apoyo del gobierno estadounidense al establecimiento de un estado judío en Palestina fueron objetados por los Departamentos de Guerra y Estado, debido a consideraciones de tiempos de guerra y a la oposición árabe a la creación de un estado judío. Las resoluciones fueron desechadas permanentemente. [26]

Después de la guerra, la "nueva era de posguerra fue testigo de una intensa participación de los Estados Unidos en los asuntos políticos y económicos de Oriente Medio , en contraste con la actitud de no intervención característica del período anterior a la guerra. En la administración de Truman, Estados Unidos tuvo que enfrentar y definir su política en los tres sectores que proporcionaban las causas profundas de los intereses estadounidenses en la región: la amenaza soviética , el nacimiento de Israel y el petróleo ". [27]

Los presidentes estadounidenses anteriores, aunque alentados por el apoyo activo de los miembros de las comunidades judías estadounidenses y mundiales, así como de grupos cívicos nacionales, sindicatos y partidos políticos, apoyaron el concepto de patria judía, al que se alude en la Declaración Balfour de Gran Bretaña de 1917 , oficialmente continuaron "aceptándolo". A lo largo de las administraciones de Roosevelt y Truman, los Departamentos de Guerra y Estado reconocieron la posibilidad de una conexión soviético-árabe y la potencial restricción árabe de los suministros de petróleo a los EE. UU., y desaconsejaron la intervención estadounidense en nombre de los judíos. [28] Con el conflicto continuo en el área y el empeoramiento de las condiciones humanitarias entre los sobrevivientes del Holocausto en Europa, el 29 de noviembre de 1947, y con el apoyo de los EE. UU., la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas adoptó como Resolución 181, el Plan de Partición de las Naciones Unidas para Palestina , que recomendaba la adopción e implementación de un Plan de Partición con Unión Económica . [29] La votación fue fuertemente presionada por los partidarios sionistas, lo que el propio Truman señaló más tarde, [30] y rechazada por los árabes.

A medida que se acercaba el final del mandato, la decisión de reconocer al Estado judío siguió siendo polémica, con un desacuerdo significativo entre el presidente Truman , su asesor interno y de campaña, Clark Clifford , y tanto el Departamento de Estado como el de Defensa . Truman, aunque simpatizaba con la causa sionista , estaba más preocupado por aliviar la difícil situación de las personas desplazadas ; el secretario de Estado George Marshall temía que el respaldo de Estados Unidos a un Estado judío dañara las relaciones con el mundo musulmán , limitara el acceso al petróleo de Oriente Medio y desestabilizara la región. El 12 de mayo de 1948, Truman se reunió en la Oficina Oval con el secretario de Estado Marshall, el subsecretario de Estado Robert A. Lovett , el asesor del presidente Clark Clifford y varios otros para discutir la situación de Palestina. Clifford argumentó a favor de reconocer el nuevo Estado judío de acuerdo con la resolución de partición. Marshall se opuso a los argumentos de Clifford, alegando que se basaban en consideraciones políticas internas en el año electoral. Marshall dijo que, si Truman seguía el consejo de Clifford y reconocía al Estado judío, votaría en su contra en las elecciones. Truman no expresó claramente sus opiniones en la reunión. [31]

Dos días después, el 14 de mayo de 1948, Estados Unidos, bajo el mando de Truman, se convirtió en el primer país en otorgar algún tipo de reconocimiento. Esto ocurrió pocas horas después de que el Consejo del Pueblo Judío se reuniera en el Museo de Tel Aviv y David Ben-Gurion declarara "el establecimiento de un Estado judío en Eretz Israel , que se conocería como el Estado de Israel ". La frase "en Eretz Israel" es el único lugar en la Declaración del Establecimiento del Estado de Israel que contiene alguna referencia a la ubicación del nuevo Estado. [32]

El texto de la comunicación del gobierno provisional de Israel a Truman fue el siguiente:

Estimado señor presidente: Tengo el honor de informarle que el Estado de Israel ha sido proclamado como una república independiente dentro de las fronteras aprobadas por la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas en su Resolución del 29 de noviembre de 1947, y que se ha encomendado a un gobierno provisional asumir los derechos y deberes de gobierno para preservar la ley y el orden dentro de las fronteras de Israel, defender al Estado contra agresiones externas y cumplir con las obligaciones de Israel para con las demás naciones del mundo de conformidad con el derecho internacional. El Acta de Independencia entrará en vigor un minuto después de las seis de la tarde del 14 de mayo de 1948, hora de Washington.

Con pleno conocimiento del profundo vínculo de simpatía que ha existido y se ha fortalecido durante los últimos treinta años entre el Gobierno de los Estados Unidos y el pueblo judío de Palestina, he sido autorizado por el gobierno provisional del nuevo Estado a presentar este mensaje y expresar la esperanza de que su gobierno reconozca y dé la bienvenida a Israel en la comunidad de naciones.

Muy respetuosamente suyo,

Eliahu Epstein

Agente del Gobierno provisional de Israel [33]

El texto del reconocimiento de los Estados Unidos fue el siguiente:

Este Gobierno ha sido informado de que se ha proclamado un Estado judío en Palestina y de que el Gobierno provisional del mismo ha solicitado su reconocimiento.

Estados Unidos reconoce al gobierno provisional como la autoridad de facto del nuevo Estado de Israel.

(Significado) Harry Truman

Aprobado,

14 de mayo de 1948

6.11 [34]

Con esta inesperada decisión, el representante de Estados Unidos ante las Naciones Unidas, Warren Austin , cuyo equipo había estado trabajando en una propuesta de administración fiduciaria alternativa , abandonó poco después su oficina en la ONU y se fue a casa. El secretario de Estado Marshall envió a un funcionario del Departamento de Estado a las Naciones Unidas para evitar que toda la delegación de los Estados Unidos renunciara. [31] El reconocimiento de iure se produjo el 31 de enero de 1949.

Tras la mediación de la ONU por parte del estadounidense Ralph Bunche , los Acuerdos de Armisticio de 1949 pusieron fin a la Guerra Árabe-Israelí de 1948. En relación con la aplicación del armisticio, Estados Unidos firmó la Declaración Tripartita de 1950 con Gran Bretaña y Francia. En ella, se comprometieron a tomar medidas dentro y fuera de las Naciones Unidas para impedir las violaciones de las fronteras o líneas de armisticio; expusieron su compromiso con la paz y la estabilidad en la zona y su oposición al uso o la amenaza de la fuerza; y reiteraron su oposición al desarrollo de una carrera armamentista en la región.

En circunstancias geopolíticas rápidamente cambiantes, la política estadounidense en Oriente Medio se orientó en general a apoyar la independencia de los estados árabes, ayudar al desarrollo de los países productores de petróleo, impedir que la influencia soviética se afianzara en Grecia , Turquía e Irán , y prevenir una carrera armamentista y mantener una postura neutral en el conflicto árabe-israelí . Al principio, las autoridades estadounidenses utilizaron la ayuda exterior para apoyar estos objetivos.

Durante estos años de austeridad , Estados Unidos proporcionó a Israel cantidades moderadas de ayuda económica, principalmente en forma de préstamos para alimentos básicos; una porción mucho mayor de los ingresos estatales derivados de las reparaciones de guerra alemanas (86% del PIB israelí en 1956) se utilizó para el desarrollo interno.

Francia se convirtió en el principal proveedor de armas de Israel en ese momento y proporcionó a Israel equipo y tecnología militar avanzados. Israel vio este apoyo como una forma de contrarrestar la amenaza percibida de Egipto bajo el presidente Gamal Abdel Nasser con respecto al " trato de armas checo " de septiembre de 1955. Durante la Crisis de Suez de 1956 , las Fuerzas de Defensa de Israel invadieron Egipto y pronto fueron seguidas por fuerzas francesas y británicas. Por diferentes razones, Francia, Israel y Gran Bretaña firmaron un acuerdo secreto para derrocar a Nasser recuperando el control del Canal de Suez, luego de su nacionalización, y para ocupar partes del Sinaí occidental asegurando el libre paso de barcos (para Israel) en el Golfo de Aqaba . [35] En respuesta, Estados Unidos, con el apoyo de la Unión Soviética en la ONU, intervino en nombre de Egipto para forzar una retirada. Posteriormente, Nasser expresó su deseo de establecer relaciones más estrechas con Estados Unidos. Ansioso por aumentar su influencia en la región y evitar que Nasser se pasara al bloque soviético, la política estadounidense fue permanecer neutral y no aliarse demasiado con Israel. En ese momento, la única ayuda que Estados Unidos brindaba a Israel era ayuda alimentaria. A principios de los años 1960, Estados Unidos comenzó a vender armas avanzadas, pero defensivas, a Israel, Egipto y Jordania , incluidos misiles antiaéreos Hawk .

Como presidente, Kennedy inició la creación de vínculos de seguridad con Israel y fue el fundador de la alianza militar entre Estados Unidos e Israel . Kennedy, basando sus decisiones políticas en sus asesores de la Casa Blanca, evitó el Departamento de Estado con su mayor interés en el mundo árabe. Un tema central fue el estatus de los palestinos, dividido entre Israel, Egipto y Jordania . En 1961 había 1,2 millones de refugiados palestinos viviendo en Jordania, Siria, Líbano y Egipto. La Unión Soviética, aunque inicialmente apoyó la creación de Israel, ahora era un oponente y miraba al mundo árabe para generar apoyo. La Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas era en general antiisraelí , pero todas las decisiones estaban sujetas al poder de veto estadounidense en el Consejo de Seguridad. Según el derecho internacional, las resoluciones de la AGNU no son jurídicamente vinculantes, mientras que las resoluciones del CSNU sí lo son. Kennedy intentó ser imparcial, pero las presiones políticas internas lo empujaron a apoyar a Israel. [36]

Yo había previsto que, una vez terminada la guerra de Argelia , Francia abandonaría a Israel como si fuera un carbón caliente y renovaría sus vínculos con el mundo árabe. Y eso, por supuesto, es exactamente lo que ocurrió: Israel adoptó a Estados Unidos en su lugar.

Uri Avnery [37]

Kennedy puso fin al embargo de armas que las administraciones de Eisenhower y Truman habían impuesto a Israel. Al describir la protección de Israel como un compromiso moral y nacional, fue el primero en introducir el concepto de una "relación especial" (como lo describió a Golda Meir ) entre Estados Unidos e Israel. [38]

En 1962, el presidente John F. Kennedy vendió a Israel un importante sistema de armas, el misil antiaéreo Hawk. El profesor Abraham Ben-Zvi, de la Universidad de Tel Aviv, sostiene que la venta fue el resultado de la "necesidad de Kennedy de mantener -y preferiblemente ampliar y consolidar- la base de apoyo judío a la administración en vísperas de las elecciones al Congreso de noviembre de 1962". Tan pronto como se tomó la decisión, los funcionarios de la Casa Blanca se lo comunicaron a los líderes judíos estadounidenses. Sin embargo, el historiador Zachary Wallace sostiene que la nueva política fue impulsada principalmente por la admiración de Kennedy por el Estado judío. Merecía el apoyo estadounidense para lograr la estabilidad en Oriente Medio. [39]

Kennedy advirtió al gobierno israelí contra la producción de materiales nucleares en Dimona , que creía que podría instigar una carrera armamentista nuclear en Oriente Medio. Después de que el gobierno israelí negara inicialmente la existencia de una planta nuclear, David Ben-Gurion declaró en un discurso ante el Knesset israelí el 21 de diciembre de 1960 que el propósito de la planta nuclear en Beersheba era "la investigación de los problemas de las zonas áridas y la flora y fauna del desierto". [40] Cuando Ben-Gurion se reunió con Kennedy en Nueva York, afirmó que Dimona, por el momento, se estaba desarrollando para proporcionar energía nuclear para la desalinización y otros fines pacíficos. En 1962, los gobiernos israelí y estadounidense acordaron un régimen de inspección anual. A pesar de esta política de inspección [acuerdo], Rodger Davies , el director de la Oficina de Asuntos del Cercano Oriente del Departamento de Estado, concluyó en marzo de 1965 que Israel estaba desarrollando armas nucleares . Informó que la fecha objetivo de Israel para lograr la capacidad nuclear era 1968-1969. [41] En 1966, cuando el piloto iraquí desertor Munir Redfa aterrizó en Israel volando un avión de combate MiG-21 de fabricación soviética , la información sobre el avión se compartió inmediatamente con los Estados Unidos.

Durante la presidencia de Lyndon B. Johnson , la política estadounidense cambió hacia un apoyo incondicional, pero no incuestionable, a Israel. En el período previo a la Guerra de los Seis Días de 1967, si bien la administración Johnson comprendía la necesidad de Israel de defenderse de los ataques extranjeros, a Estados Unidos le preocupaba que la respuesta de Israel fuera desproporcionada y potencialmente desestabilizadora. La incursión de Israel en Jordania después del Incidente de Samu de 1966 fue muy preocupante para Estados Unidos porque Jordania también era un aliado y había recibido más de 500 millones de dólares en ayuda para la construcción del Canal Principal de East Ghor , que quedó prácticamente destruido en incursiones posteriores.

La principal preocupación de la administración Johnson era que, en caso de que estallara una guerra en la región, Estados Unidos y la Unión Soviética se verían arrastrados a ella. Las intensas negociaciones diplomáticas con las naciones de la región y los soviéticos, incluido el primer uso de la línea directa , no lograron evitar la guerra. Cuando Israel lanzó ataques preventivos contra la fuerza aérea egipcia, el Secretario de Estado Dean Rusk se sintió decepcionado, ya que pensaba que podría haber sido posible una solución diplomática.

Durante la Guerra de los Seis Días, aviones de combate y torpederos israelíes atacaron al USS Liberty , un buque espía de la Armada de Estados Unidos en aguas egipcias, matando a 34 personas e hiriendo a 171. Israel declaró que el Liberty fue confundido con el buque egipcio El Quseir y que se trató de un caso de fuego amigo . El gobierno estadounidense lo aceptó como tal, aunque el incidente generó mucha controversia y algunos todavía creen que fue deliberado. [ ¿ Quién? ]

Antes de la Guerra de los Seis Días, las administraciones estadounidenses habían tomado considerables precauciones para evitar dar la impresión de favoritismo. En su artículo American Presidents and the Middle East , George Lenczowski señala que "la presidencia de Johnson fue una presidencia desafortunada, prácticamente trágica", en relación con "la posición y la postura de Estados Unidos en Oriente Medio", y marcó un punto de inflexión en las relaciones entre Estados Unidos e Israel y entre Estados Unidos y los países árabes. [42] Caracteriza la percepción que los países de Oriente Medio tienen de Estados Unidos como una que pasó de ser "el más popular de los países occidentales" antes de 1948 a "haber disminuido su glamour, pero la posición de Eisenhower durante la crisis árabe-israelí del canal de Suez convenció a muchos moderados de Oriente Medio de que, si bien no era realmente adorable, Estados Unidos era al menos un país justo con el que tratar; esta visión de la justicia e imparcialidad de Estados Unidos todavía prevaleció durante la presidencia de Kennedy; pero durante la presidencia de Lyndon B. Johnson la política estadounidense dio un giro definitivo en la dirección pro-israelí". Añadió: "La guerra de junio de 1967 confirmó esta impresión, y desde 1967 en adelante [escribiendo en 1990] Estados Unidos emergió como el país más desconfiado, si no odiado, en Medio Oriente".

Después de la guerra, la percepción en Washington era que muchos estados árabes (especialmente Egipto) habían derivado permanentemente hacia los soviéticos. En 1968, con un fuerte apoyo del Congreso, Johnson aprobó la venta de cazas Phantom a Israel, sentando el precedente del apoyo estadounidense a la ventaja militar cualitativa de Israel sobre sus vecinos. Sin embargo, Estados Unidos siguió proporcionando equipo militar a estados árabes como Líbano y Arabia Saudita , para contrarrestar las ventas de armas soviéticas en la región.

Durante la Guerra de Desgaste entre Israel y Egipto, los comandos israelíes capturaron una estación de radar P-12 de fabricación soviética en una operación denominada Rooster 53. Posteriormente, se compartió con los EE. UU. información previamente desconocida. [44]

Cuando el gobierno francés impuso un embargo de armas a Israel en 1967, los espías israelíes consiguieron diseños del Dassault Mirage 5 de un ingeniero judío suizo para construir el IAI Kfir . Estos diseños también se compartieron con los Estados Unidos.

La ventaja militar cualitativa (QME, por sus siglas en inglés) es un concepto de la política exterior estadounidense . Estados Unidos se compromete a mantener la ventaja militar cualitativa (QME, por sus siglas en inglés) de Israel , es decir, las ventajas tecnológicas , tácticas y de otro tipo que le permiten disuadir a adversarios numéricamente superiores. [45] Esta política está definida en la legislación estadounidense vigente . [46] [47] [48]

El periódico israelí Haaretz informó en 2019 que, durante la primavera y el verano de 1963, los líderes de Estados Unidos e Israel (el presidente John F. Kennedy y los primeros ministros David Ben-Gurion y Levi Eshkol ) estuvieron involucrados en una batalla de voluntades de alto riesgo sobre el programa nuclear de Israel . Las tensiones eran invisibles para el público de ambos países, y solo unos pocos funcionarios de alto rango, de ambos lados, eran conscientes de la gravedad de la situación. Según Yuval Ne'eman , Eshkol , el sucesor de Ben-Gurion, y sus asociados vieron a Kennedy como si le presentara a Israel un verdadero ultimátum. Según Ne'eman, el ex comandante de la Fuerza Aérea de Israel, el mayor general (res.) Dan Tolkowsky , abrigaba seriamente el temor de que Kennedy pudiera enviar tropas aerotransportadas estadounidenses a Dimona , el hogar del complejo nuclear de Israel . [49]

El 25 de marzo de 1963, el presidente Kennedy y el director de la CIA, John A. McCone, discutieron el programa nuclear israelí. Según McCone, Kennedy planteó la "cuestión de que Israel adquiera capacidad nuclear", y McCone proporcionó a Kennedy la estimación de Kent sobre las consecuencias negativas previstas de la nuclearización israelí. Según McCone, Kennedy entonces ordenó al asesor de seguridad nacional McGeorge Bundy que orientara al secretario de estado Dean Rusk , en colaboración con el director de la CIA y el presidente de la AEC, para que presentara una propuesta "sobre cómo se podría instituir alguna forma de salvaguardas internacionales o bilaterales de los EE. UU. para protegerse contra la contingencia mencionada". Eso también significaba que la "próxima inspección informal del complejo de reactores israelí [debe] ... realizarse rápidamente y ... ser lo más exhaustiva posible". [49]

Esta petición presidencial se tradujo en una acción diplomática: el 2 de abril de 1963, el embajador Barbour se reunió con el primer ministro Ben-Gurion y le presentó la petición estadounidense de su "aprobación para visitas semestrales a Dimona, tal vez en mayo y noviembre, con pleno acceso a todas las partes e instrumentos de la instalación, por científicos estadounidenses calificados". Ben-Gurion, aparentemente tomado por sorpresa, respondió diciendo que el asunto tendría que posponerse hasta después de la Pascua , que ese año terminó el 15 de abril. Para resaltar aún más el punto, dos días después, el secretario adjunto Talbot convocó al embajador israelí Harman al Departamento de Estado y le presentó una gestión diplomática sobre las inspecciones. Este mensaje a Ben-Gurion fue la primera salva en lo que se convertiría en "la confrontación estadounidense-israelí más dura sobre el programa nuclear israelí". [49]

El 26 de abril de 1963, más de tres semanas después de la demanda original de los EE.UU. sobre Dimona, Ben-Gurion respondió a Kennedy con una carta de siete páginas que se centraba en cuestiones generales de seguridad israelí y estabilidad regional. Afirmando que Israel se enfrentaba a una amenaza sin precedentes, Ben-Gurion invocó el espectro de "otro Holocausto" e insistió en que la seguridad de Israel debía ser protegida por garantías externas conjuntas de seguridad, que serían otorgadas por los EE.UU. y la Unión Soviética. Kennedy, sin embargo, estaba decidido a no permitir que Ben-Gurion cambiara de tema. El 4 de mayo de 1963, respondió al primer ministro, asegurándole que "estamos siguiendo de cerca los acontecimientos actuales en el mundo árabe". En cuanto a la propuesta de Ben-Gurion de una declaración conjunta de superpotencias, Kennedy descartó tanto su viabilidad como su sabiduría política. A Kennedy le preocupaba mucho menos un "ataque árabe temprano" que "un desarrollo exitoso de sistemas ofensivos avanzados que, como usted dice, no podrían ser controlados por los medios actualmente disponibles". [49]

Kennedy no cedió en Dimona y los desacuerdos se convirtieron en un "dolor de cabeza" para él, como escribió posteriormente Robert Komer . La confrontación con Israel se intensificó cuando el Departamento de Estado transmitió la última carta de Kennedy a la embajada de Tel Aviv el 15 de junio para que el embajador Barbour la entregara de inmediato a Ben-Gurion. En la carta, Kennedy detallaba su insistencia en visitas bianuales con un conjunto de condiciones técnicas detalladas. La carta era algo así como un ultimátum: si el gobierno estadounidense no podía obtener "información fiable" sobre el estado del proyecto de Dimona, el "compromiso y apoyo de Washington a Israel" podría verse "seriamente comprometido". Pero la carta nunca fue presentada a Ben-Gurion. El telegrama con la carta de Kennedy llegó a Tel Aviv el sábado 15 de junio, el día antes del anuncio de la dimisión de Ben-Gurion, una decisión que sorprendió a su país y al mundo. Ben-Gurion nunca explicó, ni por escrito ni de palabra, qué le llevó a dimitir, más allá de citar "razones personales". Se cree que el asunto Lavon , una misión de espionaje israelí fallida en Egipto, fue el motivo de su dimisión. Negó que su decisión estuviera relacionada con cuestiones políticas específicas, pero la cuestión de hasta qué punto influyó la presión de Kennedy en Dimona sigue abierta a debate hasta el día de hoy. [49]

El 5 de julio, menos de diez días después de que Levi Eshkol sucediera a Ben-Gurion como primer ministro, el embajador Barbour le entregó una primera carta del presidente Kennedy. La carta era prácticamente una copia de la carta no entregada del 15 de junio a Ben-Gurion. [50] Como afirmó Yuval Ne'eman, a Eshkol y a sus asesores les resultó inmediatamente evidente que las exigencias de Kennedy eran similares a un ultimátum y, por lo tanto, constituían una crisis en ciernes. En su primera respuesta provisional, el 17 de julio, Eshkol, atónito, pidió más tiempo para estudiar el tema y para realizar consultas. El primer ministro señaló que, si bien esperaba que la amistad entre Estados Unidos e Israel creciera bajo su supervisión, "Israel haría lo que tuviera que hacer por su seguridad nacional y para salvaguardar sus derechos soberanos". Barbour, aparentemente queriendo mitigar la franqueza de la carta, aseguró a Eshkol que la declaración de Kennedy era "factual": Los críticos de las fuertes relaciones entre Estados Unidos e Israel podrían complicar la relación diplomática si Dimona no fuera inspeccionada. [49]

El 19 de agosto, después de seis semanas de consultas que generaron al menos ocho borradores diferentes, Eshkol entregó a Barbour su respuesta escrita a las demandas de Kennedy. Empezaba reiterando las garantías anteriores de Ben-Gurion de que el propósito de Dimona era pacífico. En cuanto a la petición de Kennedy, Eshkol escribió que, dada la relación especial entre los dos países, había decidido permitir visitas regulares de representantes estadounidenses al sitio de Dimona. Sobre la cuestión específica del calendario, Eshkol sugirió –como Ben-Gurion había hecho en su última carta a Kennedy– que a finales de 1963 sería el momento de la primera visita: para entonces, escribió, “el grupo francés nos habrá entregado el reactor y éste estará realizando pruebas generales y mediciones de sus parámetros físicos a potencia cero”. [49]

Eshkol no se explayó sobre la frecuencia de las visitas. Desestimó la exigencia de Kennedy de visitas bianuales, aunque evitó cuestionar frontalmente su pedido. "Tras haber considerado esta petición, creo que podremos llegar a un acuerdo sobre el futuro programa de visitas", escribió Eshkol. En resumen, el primer ministro dividió las diferencias: para poner fin a la confrontación, asintió a las "visitas regulares" de científicos estadounidenses, pero no aceptó la idea de la visita inmediata que Kennedy quería y evitó hacer un compromiso explícito de inspecciones bianuales. La respuesta apreciativa de Kennedy no mencionó estas divergencias, pero supuso un acuerdo básico sobre las "visitas regulares". [49]

A raíz de la carta de Eshkol, la primera de las visitas de inspección regulares a Dimona, largamente solicitadas, tuvo lugar a mediados de enero de 1964, dos meses después del asesinato de Kennedy . Los israelíes dijeron a los visitantes estadounidenses que el reactor había entrado en estado crítico sólo unas semanas antes, pero esa afirmación no era exacta. Israel reconoció años después que el reactor de Dimona entró en funcionamiento a mediados de 1963, como había supuesto originalmente la administración Kennedy. [49]

Resultó que la insistencia de Kennedy en realizar visitas bianuales a Dimona no se implementó después de su muerte. Los funcionarios del gobierno de los EE. UU. siguieron interesados en dicho programa, y el presidente Lyndon B. Johnson planteó el tema a Eshkol, pero nunca presionó tanto sobre el tema como Kennedy. [49]

Al final, el enfrentamiento entre el presidente Kennedy y dos primeros ministros israelíes dio lugar a una serie de seis inspecciones estadounidenses del complejo nuclear de Dimona, una al año entre 1964 y 1969. Nunca se llevaron a cabo bajo las estrictas condiciones que Kennedy expuso en sus cartas. Si bien el sucesor de Kennedy siguió comprometido con la causa de la no proliferación nuclear y apoyó las visitas de inspección estadounidenses a Dimona, estaba mucho menos preocupado por obligar a los israelíes a cumplir las condiciones de Kennedy. En retrospectiva, este cambio de actitud puede haber salvado el programa nuclear israelí. [49]

El 19 de junio de 1970, el Secretario de Estado William P. Rogers propuso formalmente el Plan Rogers , que exigía un alto el fuego de 90 días y una zona de estancamiento militar a cada lado del Canal de Suez, para calmar la Guerra de Desgaste en curso . Fue un esfuerzo por llegar a un acuerdo específicamente sobre el marco de la Resolución 242 de la ONU , que exigía la retirada israelí de los territorios ocupados en 1967 y el reconocimiento mutuo de la soberanía e independencia de cada estado. [51] Los egipcios aceptaron el Plan Rogers, pero los israelíes estaban divididos y no lo hicieron; no lograron obtener suficiente apoyo dentro del "gobierno de unidad". A pesar de los alineamientos dominantes por los laboristas , la aceptación formal de la 242 de la ONU y la "paz para la retirada" a principios de ese año, Menachem Begin y la alianza de derecha Gahal se opusieron rotundamente a la retirada de los Territorios Palestinos ; El segundo partido más grande en el gobierno renunció el 5 de agosto de 1970. [52] Finalmente, el plan también fracasó debido al apoyo insuficiente de Nixon al plan de su Secretario de Estado, prefiriendo en cambio la posición de su Asesor de Seguridad Nacional , Henry Kissinger , de no seguir adelante con la iniciativa.

No se produjo ningún avance ni siquiera después de que en 1972 el presidente egipcio Sadat expulsara inesperadamente a los asesores soviéticos de Egipto y volviera a manifestar a Washington su voluntad de negociar. [53]

El 28 de febrero de 1973, durante una visita a Washington, DC , la entonces primera ministra israelí Golda Meir acordó con el entonces asesor de seguridad nacional de Estados Unidos Henry Kissinger la propuesta de paz basada en "seguridad versus soberanía": Israel aceptaría la soberanía egipcia sobre todo el Sinaí , mientras que Egipto aceptaría la presencia israelí en algunas de las posiciones estratégicas del Sinaí. [54] [55] [56] [57] [58]

Ante esta falta de avances en el frente diplomático, y con la esperanza de obligar a la administración Nixon a intervenir más, Egipto se preparó para un conflicto militar. En octubre de 1973, Egipto y Siria atacaron simultáneamente a Israel, iniciando así la Guerra del Yom Kippur .

A pesar de que los servicios de inteligencia indicaban un ataque de Egipto y Siria, la primera ministra Golda Meir tomó la controvertida decisión de no lanzar un ataque preventivo. Meir, entre otras preocupaciones, temía distanciarse de Estados Unidos si se consideraba que Israel estaba iniciando otra guerra, ya que Israel sólo confiaba en que Estados Unidos acudiera en su ayuda. En retrospectiva, la decisión de no atacar fue probablemente acertada, aunque se debate vigorosamente en Israel hasta el día de hoy. Más tarde, según el secretario de Estado Henry Kissinger , si Israel hubiera atacado primero, no habría recibido "ni un clavo". El 6 de octubre de 1973, durante la festividad judía de Yom Kippur , Egipto y Siria, con el apoyo de las fuerzas expedicionarias árabes y con el respaldo de la Unión Soviética, lanzaron ataques simultáneos contra Israel. El conflicto resultante se conoce como la Guerra de Yom Kippur. El ejército egipcio fue capaz inicialmente de romper las defensas israelíes, avanzar hacia el Sinaí y establecer posiciones defensivas a lo largo de la orilla este del Canal de Suez , pero luego fueron rechazados en una batalla masiva de tanques cuando intentaron avanzar más para desviar la presión de Siria. Los israelíes luego cruzaron el Canal de Suez. Se produjeron importantes batallas con grandes pérdidas para ambos lados. Al mismo tiempo, los sirios casi rompieron las delgadas defensas de Israel en los Altos del Golán, pero finalmente fueron detenidos por refuerzos y rechazados, seguidos por un avance israelí exitoso en Siria. Israel también ganó la ventaja en el aire y en el mar al principio de la guerra. Días después de la guerra, se ha sugerido que Meir autorizó el ensamblaje de bombas nucleares israelíes. Esto se hizo abiertamente, tal vez para llamar la atención estadounidense, pero Meir autorizó su uso contra objetivos egipcios y sirios solo si las fuerzas árabes lograban avanzar demasiado. [59] [60] Los soviéticos comenzaron a reabastecer a las fuerzas árabes, predominantemente sirias. Meir le pidió ayuda a Nixon con el suministro militar. Después de que Israel se pusiera en alerta nuclear total y cargara sus ojivas en los aviones que lo esperaban, Nixon ordenó el inicio a gran escala de una operación de transporte aéreo estratégico para entregar armas y suministros a Israel; esta última medida a veces se denomina "el puente aéreo que salvó a Israel". Sin embargo, cuando llegaron los suministros, Israel estaba ganando terreno.

Nuevamente, Estados Unidos y los soviéticos temieron verse arrastrados a un conflicto en Oriente Medio. Después de que los soviéticos amenazaran con intervenir en nombre de Egipto, tras los avances israelíes más allá de las líneas de alto el fuego, Estados Unidos aumentó el Estado de Defensa (DEFCON) de cuatro a tres, el nivel más alto en tiempos de paz. Esto se produjo después de que Israel atrapara al Tercer Ejército de Egipto al este del canal de Suez.

Kissinger se dio cuenta de que la situación presentaba una tremenda oportunidad para Estados Unidos: Egipto dependía totalmente de Estados Unidos para impedir que Israel destruyera el ejército, que ahora no tenía acceso a alimentos ni agua. La posición podría aprovecharse más tarde para permitir que Estados Unidos mediara en la disputa y expulsara a Egipto de la influencia soviética. Como resultado, Estados Unidos ejerció una enorme presión sobre los israelíes para que se abstuvieran de destruir el ejército atrapado. En una llamada telefónica con el embajador israelí Simcha Dinitz , Kissinger le dijo al embajador que la destrucción del Tercer Ejército egipcio "es una opción que no existe". Los egipcios retiraron más tarde su solicitud de apoyo y los soviéticos accedieron.

Después de la guerra, Kissinger presionó a los israelíes para que se retiraran de los territorios árabes, lo que contribuyó a las primeras fases de una paz duradera entre Israel y Egipto. El apoyo estadounidense a Israel durante la guerra contribuyó al embargo de la OPEP de 1973 contra Estados Unidos, que se levantó en marzo de 1974.

A principios de 1975, el gobierno israelí rechazó una iniciativa estadounidense para un mayor redespliegue de tropas en el Sinaí. El presidente Ford respondió el 21 de marzo de 1975 enviando al primer ministro Rabin una carta en la que afirmaba que la intransigencia israelí había complicado los intereses mundiales de Estados Unidos y que, por lo tanto, la administración "reevaluaría" sus relaciones con el gobierno israelí. Además, se detuvieron los envíos de armas a Israel. La crisis de la reevaluación llegó a su fin con el acuerdo de retirada de fuerzas entre Israel y Egipto del 4 de septiembre de 1975. [61]

.jpg/440px-Carter_and_Begin,_September_5,_1978_(10729514294).jpg)

La administración Carter se caracterizó por una participación muy activa de Estados Unidos en el proceso de paz de Oriente Medio. Con la elección en mayo de 1977 de Menachem Begin del Likud como primer ministro, después de 29 años de liderar la oposición del gobierno israelí, se produjeron cambios importantes con respecto a la retirada israelí de los territorios ocupados . [15] Esto provocó fricciones en las relaciones bilaterales entre Estados Unidos e Israel. Los dos marcos incluidos en el proceso de Camp David iniciado por Carter fueron vistos por elementos de derecha en Israel como la creación de presiones estadounidenses sobre Israel para retirarse de los territorios palestinos capturados , así como obligarlo a tomar riesgos en aras de la paz con Egipto. El tratado de paz israelí-egipcio se firmó en la Casa Blanca el 26 de marzo de 1979. Condujo a la retirada israelí del Sinaí en 1982. Desde entonces, los gobiernos del Likud han argumentado que su aceptación de la retirada total del Sinaí como parte de estos acuerdos y el eventual tratado de paz entre Egipto e Israel cumplieron la promesa israelí de retirarse del Sinaí. [15] El apoyo del presidente Carter a una patria palestina y a los derechos políticos palestinos creó tensiones en particular con el gobierno del Likud, y se lograron pocos avances en ese frente.

Los partidarios israelíes expresaron su preocupación al comienzo del primer mandato de Ronald Reagan sobre las posibles dificultades en las relaciones entre Estados Unidos e Israel, en parte porque varios de los designados presidenciales tenían vínculos o asociaciones comerciales pasadas con países árabes clave (por ejemplo, los secretarios Caspar Weinberger y George P. Shultz eran funcionarios de la Bechtel Corporation , que tiene fuertes vínculos con el mundo árabe; véase lobby árabe en los Estados Unidos ). Sin embargo, el apoyo personal del presidente Reagan a Israel y la compatibilidad entre las perspectivas israelíes y de Reagan sobre el terrorismo , la cooperación en materia de seguridad y la amenaza soviética llevaron a un fortalecimiento considerable de las relaciones bilaterales. [62]

En 1981, Weinberger y el Ministro de Defensa israelí, Ariel Sharon , firmaron el Acuerdo de Cooperación Estratégica , estableciendo un marco para la consulta y cooperación continuas con el fin de mejorar la seguridad nacional de ambos países. En noviembre de 1983, las dos partes formaron un Grupo Político Militar Conjunto , que se reúne dos veces al año, para implementar la mayoría de las disposiciones de ese acuerdo. Los ejercicios militares conjuntos aéreos y marítimos comenzaron en junio de 1984, y Estados Unidos construyó dos instalaciones de Reserva de Guerra en Israel para almacenar equipo militar. Aunque estaba destinado a las fuerzas estadounidenses en Oriente Medio, el equipo puede transferirse para uso israelí si es necesario. [62]

Los lazos entre Estados Unidos e Israel se fortalecieron durante el segundo mandato de Reagan. En 1989, Israel obtuvo el estatus de " aliado importante no perteneciente a la OTAN ", lo que le dio acceso a sistemas de armas ampliados y oportunidades para presentar ofertas en contratos de defensa estadounidenses. Estados Unidos mantuvo la ayuda en forma de subvenciones a Israel en 3.000 millones de dólares anuales e implementó un acuerdo de libre comercio en 1985. Desde entonces, se han eliminado todos los aranceles aduaneros entre los dos socios comerciales. Sin embargo, las relaciones se deterioraron cuando Israel llevó a cabo la Operación Opera , un ataque aéreo israelí al reactor nuclear de Osirak en Bagdad . Reagan suspendió un envío de aviones militares a Israel y criticó duramente la acción. Las relaciones también se deterioraron durante la Guerra del Líbano de 1982 , cuando Estados Unidos incluso contempló sanciones para detener el asedio israelí a Beirut . Estados Unidos recordó a Israel que el armamento proporcionado por Estados Unidos debía usarse solo con fines defensivos y suspendió los envíos de municiones de racimo a Israel. Aunque la guerra puso de manifiesto algunas diferencias graves entre las políticas israelí y estadounidense, como el rechazo por parte de Israel del plan de paz de Reagan del 1 de septiembre de 1982, no alteró el favoritismo de la Administración hacia Israel ni el énfasis que ponía en la importancia de Israel para los Estados Unidos. Aunque criticó las acciones israelíes, Estados Unidos vetó una resolución del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas propuesta por los soviéticos para imponer un embargo de armas a Israel. [62]

En 1985, Estados Unidos apoyó la estabilización económica de Israel mediante aproximadamente 1.500 millones de dólares en garantías de préstamos a dos años para la creación de un foro económico bilateral entre Estados Unidos e Israel llamado Grupo de Desarrollo Económico Conjunto Estados Unidos-Israel (JEDG). [62]

El segundo mandato de Reagan terminó con lo que muchos israelíes consideraron una nota amarga cuando Estados Unidos inició un diálogo con la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina (OLP) en diciembre de 1988. Pero, a pesar del diálogo entre Estados Unidos y la OLP, el caso del espionaje de Pollard y el rechazo israelí a la iniciativa de paz de Shultz en la primavera de 1988, las organizaciones pro israelíes en Estados Unidos caracterizaron a la administración Reagan (y al 100º Congreso) como la "más pro israelí de la historia", y elogiaron el tono general positivo de las relaciones bilaterales. [62]

En medio de la primera Intifada , el Secretario de Estado James Baker dijo a una audiencia del Comité de Asuntos Públicos de Estados Unidos e Israel (AIPAC, un grupo de presión pro-Israel ) el 22 de mayo de 1989 que Israel debería abandonar sus "políticas expansionistas". El Presidente Bush provocó la ira del gobierno del Likud cuando dijo en una conferencia de prensa el 3 de marzo de 1991 que Jerusalén Oriental era un territorio ocupado y no una parte soberana de Israel como Israel afirma. Israel había anexado Jerusalén Oriental en 1980, una acción que no obtuvo reconocimiento internacional. Estados Unidos e Israel discreparon sobre la interpretación israelí del plan israelí de celebrar elecciones para una delegación palestina a la conferencia de paz en el verano de 1989, y también discreparon sobre la necesidad de una investigación del incidente de Jerusalén del 8 de octubre de 1990, en el que la policía israelí mató a 17 palestinos. [62]

En medio de la crisis entre Irak y Kuwait y las amenazas iraquíes contra Israel generadas por ella, el ex presidente Bush reiteró el compromiso de Estados Unidos con la seguridad de Israel. La tensión entre Israel y Estados Unidos se alivió después del inicio de la guerra del Golfo Pérsico el 16 de enero de 1991, cuando Israel se convirtió en blanco de los misiles Scud iraquíes , sufriendo más de 30 ataques durante la guerra. Estados Unidos instó a Israel a no tomar represalias contra Irak por los ataques porque se creía que Irak quería arrastrar a Israel al conflicto y obligar a otros miembros de la coalición, Egipto y Siria en particular, a abandonar la coalición y unirse a Irak en una guerra contra Israel. Israel no tomó represalias y recibió elogios por su moderación. [62]

Tras la Guerra del Golfo, la administración volvió inmediatamente a la pacificación árabe-israelí, creyendo que había una ventana de oportunidad para utilizar el capital político generado por la victoria estadounidense para revitalizar el proceso de paz árabe-israelí. El 6 de marzo de 1991, el presidente Bush se dirigió al Congreso en un discurso que a menudo se cita como la principal declaración política de la administración sobre el nuevo orden en relación con Oriente Medio, tras la expulsión de las fuerzas iraquíes de Kuwait. [63] [64] Michael Oren resume el discurso diciendo: "El presidente procedió a esbozar su plan para mantener una presencia naval estadounidense permanente en el Golfo, para proporcionar fondos para el desarrollo de Oriente Medio y para instituir salvaguardas contra la proliferación de armas no convencionales. La pieza central de su programa, sin embargo, era el logro de un tratado árabe-israelí basado en el principio de territorio por paz y el cumplimiento de los derechos palestinos". Como primer paso, Bush anunció su intención de volver a convocar la conferencia internacional de paz en Madrid . [63]

Sin embargo, a diferencia de anteriores esfuerzos de paz estadounidenses, no se utilizarían nuevos compromisos de ayuda. Esto se debió tanto a que el presidente Bush y el secretario Baker consideraron que la victoria de la coalición y el aumento del prestigio de Estados Unidos inducirían por sí mismos un nuevo diálogo árabe-israelí, como a que su iniciativa diplomática se centró en el proceso y el procedimiento en lugar de en acuerdos y concesiones. Desde la perspectiva de Washington, los incentivos económicos no serían necesarios, aunque éstos entraron en el proceso cuando Israel los inyectó en mayo. La solicitud del primer ministro israelí Yitzhak Shamir de 10.000 millones de dólares en garantías de préstamos estadounidenses añadió una nueva dimensión a la diplomacia estadounidense y desencadenó un enfrentamiento político entre su gobierno y la administración Bush. [65]

Bush y Baker fueron decisivos para convocar la conferencia de paz de Madrid en octubre de 1991 y para persuadir a todas las partes a participar en las negociaciones de paz posteriores. Se informó ampliamente que la administración Bush no compartía una relación amistosa con el gobierno del Likud de Yitzhak Shamir . Sin embargo, el gobierno israelí logró la revocación de la Resolución 3379 de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas , que equiparaba el sionismo con el racismo. Después de la conferencia, en diciembre de 1991, la ONU aprobó la Resolución 46/86 de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas ; Israel había hecho de la revocación de la resolución 3379 una condición para su participación en la conferencia de paz de Madrid. [66] Después de que el Partido Laborista ganara las elecciones de 1992, las relaciones entre Estados Unidos e Israel parecieron mejorar. La coalición laborista aprobó una congelación parcial de la construcción de viviendas en los territorios ocupados el 19 de julio, algo que el gobierno de Shamir no había hecho a pesar de los llamamientos de la administración Bush para una congelación como condición para las garantías de los préstamos.

Israel y la OLP intercambiaron cartas de reconocimiento mutuo el 10 de septiembre y firmaron la Declaración de Principios el 13 de septiembre de 1993. El presidente Bill Clinton anunció el 10 de septiembre que Estados Unidos y la OLP restablecerían su diálogo. El 26 de octubre de 1994, el presidente Clinton fue testigo de la firma del tratado de paz entre Jordania e Israel , y el presidente Clinton, el presidente egipcio Mubarak y el rey Hussein de Jordania fueron testigos de la firma en la Casa Blanca del Acuerdo Interino entre Israel y los palestinos el 28 de septiembre de 1995. [62]

El presidente Clinton asistió al funeral del asesinado primer ministro Yitzhak Rabin en Jerusalén en noviembre de 1995. Después de una visita a Israel en marzo de 1996, el presidente Clinton ofreció 100 millones de dólares en ayuda para las actividades antiterroristas de Israel, otros 200 millones para el despliegue del sistema antimisiles Arrow y unos 50 millones para un arma láser antimisiles. [62]

El presidente Clinton no estaba de acuerdo con la política del primer ministro Benjamin Netanyahu de expandir los asentamientos judíos en los territorios palestinos, y se informó que el presidente creía que el primer ministro estaba retrasando el proceso de paz. El presidente Clinton fue anfitrión de las negociaciones en el Centro de Conferencias de Wye River en Maryland, que terminaron con la firma de un acuerdo el 23 de octubre de 1998. Israel suspendió la implementación del acuerdo de Wye a principios de diciembre de 1998, cuando los palestinos violaron el Acuerdo de Wye al amenazar con declarar un estado (la condición de Estado palestino no se mencionó en Wye). En enero de 1999, el Acuerdo de Wye se retrasó hasta las elecciones israelíes en mayo. [62]

Ehud Barak fue elegido Primer Ministro el 17 de mayo de 1999 y obtuvo un voto de confianza para su gobierno el 6 de julio de 1999. El Presidente Clinton y el Primer Ministro Barak parecieron establecer estrechas relaciones personales durante cuatro días de reuniones entre el 15 y el 20 de julio. El Presidente Clinton medió en las reuniones entre el Primer Ministro Barak y el Presidente Arafat en la Casa Blanca, Oslo , Shepherdstown , Camp David y Sharm al-Shaykh en la búsqueda de la paz. [62]

El presidente George W. Bush y el primer ministro Ariel Sharon establecieron buenas relaciones en sus reuniones de marzo y junio de 2001. El 4 de octubre de 2001, poco después de los ataques del 11 de septiembre , Sharon acusó a la administración Bush de apaciguar a los palestinos a expensas de Israel en un intento de obtener el apoyo árabe para la campaña antiterrorista estadounidense. [67] La Casa Blanca dijo que el comentario era inaceptable. En lugar de disculparse por el comentario, Sharon dijo que Estados Unidos no lo entendió. Además, Estados Unidos criticó la práctica israelí de asesinar a palestinos que se cree que participan en el terrorismo, lo que a algunos israelíes les pareció incompatible con la política estadounidense de perseguir a Osama bin Laden "vivo o muerto". [68] No obstante, más tarde se reveló que Sharon obtuvo un entendimiento de la administración Bush de que el gobierno estadounidense brindaría apoyo a Israel mientras emprendía una amplia campaña de asesinatos selectivos contra militantes palestinos , a cambio de un compromiso israelí de desistir de continuar con la creación de más asentamientos en Cisjordania . [69]

En 2003, en medio de la Segunda Intifada y una fuerte crisis económica en Israel, Estados Unidos proporcionó a Israel 9.000 millones de dólares en garantías de préstamos condicionales, disponibles hasta 2011 y negociadas cada año en el Grupo de Desarrollo Económico Conjunto Estados Unidos-Israel. [70]

Todas las administraciones estadounidenses recientes han desaprobado la actividad de asentamiento de Israel, por considerar que prejuzga el estatuto final y posiblemente impide el surgimiento de un Estado palestino contiguo. Sin embargo, el Presidente Bush señaló en un Memorándum del 14 de abril de 2002 que llegó a llamarse "la Hoja de Ruta de Bush " (y que establecía los parámetros para las posteriores negociaciones entre Israel y Palestina) la necesidad de tener en cuenta los cambios "realidades sobre el terreno, incluidos los importantes centros de población israelíes ya existentes", así como las preocupaciones de seguridad de Israel, afirmando que "es poco realista esperar que el resultado de las negociaciones sobre el estatuto final sea un retorno total y completo a las líneas de armisticio de 1949". [71] Más tarde subrayó que, dentro de esos parámetros, los detalles de las fronteras eran temas de negociación entre las partes.

En momentos de violencia, los funcionarios estadounidenses han instado a Israel a retirarse lo más rápidamente posible de las zonas palestinas recuperadas en operaciones de seguridad. La administración Bush insistió en que las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas debían ser "equilibradas" y criticar tanto la violencia palestina como la israelí, y vetó las resoluciones que no cumplían con ese criterio. [72]

La Secretaria de Estado Condoleezza Rice no nombró a un Enviado Especial para Oriente Medio ni dijo que no participaría en negociaciones directas entre israelíes y palestinos sobre cuestiones de interés. Dijo que prefería que los israelíes y los palestinos trabajaran juntos, y viajó a la región varias veces en 2005. La Administración apoyó la retirada de Israel de Gaza como una forma de volver al proceso de la Hoja de Ruta para lograr una solución basada en dos Estados, Israel y Palestina, que vivan uno al lado del otro en paz y seguridad. [73] La evacuación de los colonos de la Franja de Gaza y de cuatro pequeños asentamientos en el norte de Cisjordania se completó el 23 de agosto de 2005.

El 14 de julio de 2006, cuando estalló la Guerra del Líbano , el Congreso de los Estados Unidos fue notificado de una posible venta de combustible para aviones a Israel por valor de 210 millones de dólares. La Agencia de Cooperación para la Seguridad de la Defensa señaló que la venta del combustible JP-8, en caso de que se completara, "permitiría a Israel mantener la capacidad operativa de su inventario de aeronaves", y que "el combustible para aviones se consumiría mientras las aeronaves estuvieran en uso para mantener la paz y la seguridad en la región". [74] El 24 de julio se informó de que Estados Unidos estaba en proceso de proporcionar a Israel bombas " antibúnkeres ", que supuestamente se utilizarían para atacar al líder del grupo guerrillero libanés Hezbolá y destruir sus trincheras. [75]

Los medios estadounidenses también cuestionaron si Israel violó un acuerdo de no usar bombas de racimo contra objetivos civiles. Aunque muchas de las bombas de racimo utilizadas eran municiones avanzadas M-85 desarrolladas por Israel Military Industries , Israel también utilizó municiones más antiguas compradas a los EE. UU. durante el conflicto, golpeando áreas civiles, aunque la población civil había huido en su mayoría. Israel afirma que el daño civil era inevitable, ya que Hezbollah se atrincheró en áreas altamente pobladas. Simultáneamente, el fuego indiscriminado de cohetes de Hezbollah convirtió muchas de sus ciudades del norte en ciudades fantasmas virtuales, en violación del derecho internacional. Muchas bombas pequeñas quedaron sin detonar después de la guerra, causando peligro para los civiles libaneses. Israel dijo que no había violado ninguna ley internacional porque las bombas de racimo no son ilegales y se utilizaron solo en objetivos militares. [76]

El 15 de julio, el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas volvió a rechazar las peticiones del Líbano de que exigiera un alto el fuego inmediato entre Israel y el Líbano. El periódico israelí Haaretz informó de que Estados Unidos era el único miembro de los 15 países que integran el organismo de la ONU que se oponía a cualquier acción del Consejo. [77]

El 19 de julio, la administración Bush rechazó los llamados a un alto el fuego inmediato. [78] La Secretaria de Estado Condoleezza Rice dijo que se debían cumplir ciertas condiciones, sin especificar cuáles eran. John Bolton , embajador de los Estados Unidos ante las Naciones Unidas, rechazó el llamado a un alto el fuego, con el argumento de que tal acción abordaba el conflicto sólo superficialmente: "La idea de simplemente declarar un alto el fuego y actuar como si eso fuera a resolver el problema, creo que es simplista". [79]

El 26 de julio, los ministros de Asuntos Exteriores de Estados Unidos, Europa y Oriente Medio reunidos en Roma prometieron "trabajar de inmediato para alcanzar con la máxima urgencia un alto el fuego que ponga fin a la violencia y las hostilidades actuales". Sin embargo, Estados Unidos mantuvo su firme apoyo a la campaña israelí y se informó de que los resultados de la conferencia no estuvieron a la altura de las expectativas de los líderes árabes y europeos. [80]

En septiembre de 2008, The Guardian informó que Estados Unidos había vetado el plan del primer ministro israelí Ehud Olmert de bombardear las instalaciones nucleares iraníes el mes de mayo anterior. [81]

.jpg/440px-President_Barack_Obama_talks_with_Israeli_Prime_Minister_Benjamin_Netanyahu_in_the_Oval_Office_-_18_May_2009_-_P051809PS-0069_(3544160604).jpg)

Las relaciones entre Israel y Estados Unidos se vieron sometidas a una tensión cada vez mayor durante el segundo gobierno del Primer Ministro Netanyahu y el nuevo gobierno de Obama . Después de asumir el cargo, el Presidente Barack Obama se propuso como objetivo principal lograr un acuerdo de paz entre Israel y los palestinos y presionó al Primer Ministro Netanyahu para que aceptara un Estado palestino y entrara en negociaciones. Netanyahu finalmente cedió el 14 de julio de 2009. De acuerdo con los deseos de Estados Unidos, Israel impuso una congelación de diez meses en la construcción de asentamientos en Cisjordania. Como la congelación no incluía Jerusalén Oriental , que Israel considera su territorio soberano, ni 3.000 unidades de vivienda aprobadas previamente que ya estaban en construcción, así como el hecho de que no se desmantelaran los asentamientos israelíes ya construidos , los palestinos rechazaron la congelación por inadecuada y se negaron a entrar en negociaciones durante nueve meses. Los negociadores palestinos señalaron su voluntad de entrar en negociaciones semanas antes del final de la congelación de la construcción si se prorrogaban, pero los israelíes lo rechazaron.

En 2009, Obama se convirtió en el primer presidente estadounidense que autorizó la venta de bombas antibúnkeres a Israel. La transferencia se mantuvo en secreto para evitar la impresión de que Estados Unidos estaba armando a Israel para un ataque contra Irán. [82]

En febrero de 2011, la administración Obama vetó una resolución de la ONU que declaraba ilegales los asentamientos israelíes en Cisjordania. [83] En 2011, la administración Obama allanó el camino para el desarrollo y la producción del sistema de defensa antimisiles Iron Dome para Israel, contribuyendo con 235 millones de dólares a su financiación. [84] [85]

En marzo de 2010, Israel anunció que continuaría construyendo 1.600 nuevas viviendas que ya estaban en construcción en el barrio de Ramat Shlomo , en Jerusalén oriental , durante la visita del vicepresidente Joe Biden a Israel. El incidente fue descrito como "una de las disputas más graves entre los dos aliados en las últimas décadas". [86] La secretaria de Estado Hillary Clinton dijo que la medida de Israel era "profundamente negativa" para las relaciones entre Estados Unidos e Israel. [87] La comunidad internacional considera ampliamente que Jerusalén Oriental es un territorio ocupado, mientras que Israel lo niega, ya que anexó el territorio en 1980. [86] Se informó que Obama estaba "furioso" por el anuncio. [88]

Poco después, el presidente Obama dio instrucciones a la secretaria de Estado Hillary Clinton para que presentara a Netanyahu un ultimátum en cuatro partes: que Israel cancelara la aprobación de las unidades habitacionales, congelara todas las construcciones judías en Jerusalén Este , hiciera un gesto a los palestinos de que quiere la paz con una recomendación sobre la liberación de cientos de prisioneros palestinos y aceptara discutir una partición de Jerusalén y una solución al problema de los refugiados palestinos durante las negociaciones. Obama amenazó con que ni él ni ningún alto funcionario de la administración se reunirían con Netanyahu y sus ministros de alto rango durante su próxima visita a Washington. [89]

El 26 de marzo de 2010, Netanyahu y Obama se reunieron en la Casa Blanca . La reunión se llevó a cabo sin fotógrafos ni declaraciones de prensa. Durante la reunión, Obama exigió que Israel extendiera la congelación de los asentamientos después de su expiración, impusiera una congelación de la construcción judía en Jerusalén Este y retirara las tropas a las posiciones ocupadas antes del inicio de la Segunda Intifada . Netanyahu no dio concesiones por escrito sobre estos temas y le presentó a Obama un diagrama de flujo sobre cómo se otorga el permiso para construir en la Municipalidad de Jerusalén para reiterar que no tenía conocimiento previo de los planes. Obama luego sugirió que Netanyahu y su personal se quedaran en la Casa Blanca para considerar sus propuestas de modo que pudiera informar a Obama de inmediato si cambiaba de opinión, y fue citado diciendo: "Todavía estoy aquí, avíseme si hay algo nuevo". Netanyahu y sus ayudantes fueron a la Sala Roosevelt , pasaron media hora más con Obama y extendieron su estadía por un día de conversaciones de emergencia para reiniciar las negociaciones de paz, pero se fueron sin ninguna declaración oficial de ninguna de las partes. [88] [90]

En julio de 2010, apareció un vídeo de 2001 del ciudadano Netanyahu, en el que hablaba con un grupo de familias en duelo en Ofra sobre las relaciones con Estados Unidos y el proceso de paz, y al parecer no sabía que lo estaban grabando. Dijo: "Sé lo que es Estados Unidos; Estados Unidos es algo que se puede mover muy fácilmente, moverlo en la dirección correcta. No se interpondrán en su camino". También se jactó de cómo socavó el proceso de paz cuando era primer ministro durante la administración Clinton. "Me preguntaron antes de las elecciones si honraría [los acuerdos de Oslo ]", dijo. "Dije que lo haría, pero... voy a interpretar los acuerdos de tal manera que me permitan poner fin a este avance galopante hacia las fronteras de 1967". [91] [92] Aunque generó poco revuelo en la prensa, fue muy criticado entre la izquierda en Israel. [93]

El 19 de mayo de 2011, Obama pronunció un discurso sobre política exterior en el que pidió el regreso a las fronteras israelíes anteriores a 1967 con intercambios de tierras mutuamente acordados, a lo que Netanyahu se opuso. [94] Los republicanos criticaron a Obama por el discurso. [95] [96] El discurso se produjo un día antes de que Obama y Netanyahu tuvieran previsto reunirse. [97] En un discurso ante el Comité de Asuntos Públicos Estados Unidos-Israel el 22 de mayo, Obama dio más detalles sobre su discurso del 19 de mayo:

La mayor parte de la atención, incluso ahora, se centró en mi referencia a las líneas de 1967, con canjes mutuamente acordados. Y como mi posición ha sido tergiversada varias veces, permítanme reafirmar lo que significa "líneas de 1967 con canjes mutuamente acordados".

Por definición, significa que las propias partes –israelíes y palestinos– negociarán una frontera distinta a la que existía el 4 de junio de 1967. Eso es lo que significan los intercambios mutuamente acordados. Es una fórmula bien conocida por todos los que han trabajado en esta cuestión durante una generación. Permite a las propias partes dar cuenta de los cambios que han tenido lugar en los últimos 44 años.

Permite a las partes tomar en cuenta esos cambios, incluidas las nuevas realidades demográficas sobre el terreno, y las necesidades de ambas partes. El objetivo final es dos Estados para dos pueblos: Israel como Estado judío y patria del pueblo judío y el Estado de Palestina como patria del pueblo palestino, cada Estado en un marco de libre determinación, reconocimiento mutuo y paz. [98]

En su discurso ante una sesión conjunta del Congreso el 24 de mayo, Netanyahu adoptó algunos de los términos anteriores de Obama:

Ahora hay que negociar la delimitación precisa de esas fronteras. Seremos generosos en cuanto al tamaño del futuro Estado palestino, pero, como dijo el presidente Obama, la frontera será diferente a la que existía el 4 de junio de 1967. Israel no volverá a las fronteras indefendibles de 1967. [98]

El 20 de septiembre de 2011, el presidente Obama declaró que Estados Unidos vetaría cualquier solicitud palestina de reconocimiento como Estado en las Naciones Unidas, afirmando que "no puede haber atajos hacia la paz". [99]

En octubre de 2011, el nuevo secretario de Defensa de Estados Unidos, Leon Panetta , sugirió que las políticas israelíes eran en parte responsables de su aislamiento diplomático en Oriente Medio. El gobierno israelí respondió que el problema era el creciente radicalismo en la región, más que sus propias políticas. [100]

En 2012, el presidente Obama firmó una ley que ampliaría por otros tres años el programa de garantías de Estados Unidos para la deuda del gobierno israelí. [101]

En 2012, Antony Blinken , asesor de seguridad nacional del entonces vicepresidente estadounidense Joe Biden , lamentó la tendencia de los políticos estadounidenses a utilizar el debate sobre la política hacia Israel con fines políticos. Hasta entonces, Israel había sido un bastión del consenso bipartidista en Estados Unidos. [102]

En 2010 y nuevamente en julio y agosto de 2012, las exportaciones israelíes a los Estados Unidos superaron a las de la Unión Europea , habitualmente el principal destino de las exportaciones israelíes. [103]

En Israel, el acuerdo provisional de Ginebra sobre el programa nuclear iraní generó reacciones encontradas . El primer ministro Netanyahu lo criticó duramente como un "error histórico", [104] y el ministro de finanzas Naftali Bennett lo calificó de "un muy mal acuerdo". [105] Sin embargo, el líder del partido Kadima Shaul Mofaz , [106] el líder de la oposición Isaac Herzog , [107] y el ex jefe de Aman Amos Yadlin expresaron cierto apoyo al acuerdo y sugirieron que era más importante mantener buenos lazos con Washington que criticar públicamente el acuerdo. [108]

.jpg/440px-Secretary_Kerry_in_Israel_(23172858152).jpg)

El 2 de abril de 2014, la embajadora de Estados Unidos ante la ONU, Samantha Power, reafirmó la postura de la administración de que Estados Unidos se opone a todas las iniciativas unilaterales palestinas para obtener la condición de Estado. [109]

Durante el conflicto de 2014 entre Israel y Gaza , Estados Unidos suspendió temporalmente el suministro de misiles Hellfire a Israel, lo que desató tensiones entre los dos países. [110]

En diciembre de 2014, el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Asociación Estratégica entre Estados Unidos e Israel de 2013. [ 111] Esta nueva categoría está un nivel por encima de la clasificación de Principal Aliado No-OTAN y añade apoyo adicional para defensa, energía y fortalece la cooperación empresarial y académica. [112] El proyecto de ley también exige que Estados Unidos aumente su stock de reservas de guerra en Israel en 1.800 millones de dólares. [113]

En noviembre de 2014, el Centro de Estudios Estratégicos Begin-Sadat de Bar Ilan realizó un estudio que mostraba que el 96% de la población israelí considera que las relaciones del país con Estados Unidos son importantes o muy importantes. También se consideraba que Washington es un aliado leal y que Estados Unidos acudirá en ayuda de Israel ante amenazas existenciales. Por otra parte, sólo el 37% cree que el presidente Obama tiene una actitud positiva hacia Israel (y el 24% dice que su actitud es neutral). [114]

On December 23, 2016, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution calling for an end to Israeli settlements; the Obama administration's UN ambassador, Samantha Power, was instructed to abstain—although the U.S. had previously vetoed a comparable resolution in 2011. President-elect Donald Trump attempted to intercede by publicly advocating the resolution be vetoed and successfully persuading Egypt's Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to temporarily withdraw it from consideration. The resolution was then "proposed again by Malaysia, New Zealand, Senegal and Venezuela"—and passed 14 to 0. Netanyahu's office alleged that "the Obama administration not only failed to protect Israel against this gang-up at the UN, it colluded with it behind the scenes," adding: "Israel looks forward to working with President-elect Trump and with all our friends in Congress, Republicans and Democrats alike, to negate the harmful effects of this absurd resolution."[115][116][117]

On December 28, 2016, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry strongly criticized Israel and its settlement policies in a speech.[118] Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu strongly criticized the UN Resolution[119] and Kerry's speech.[120] On January 6, 2017, the Israeli government withdrew its annual dues from the organization, which totaled $6 million in United States dollars.[121] On January 5, 2017, the United States House of Representatives voted 342–80 to condemn the UN Resolution.[122][123]

According to Army Radio, the U.S. has reportedly pledged to sell Israel materials used to produce electricity, nuclear technology, and other supplies.[124]

.jpg/440px-President_Donald_Trump_and_Prime_Minister_Benjamin_Netanyahu_Joint_Press_Conference,_February_15,_2017_(02).jpg)

Trump was inaugurated as U.S. president on January 20, 2017; he appointed a new ambassador to Israel, David M. Friedman. On January 22, 2017, in response to Trump's inauguration, the Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced his intention to lift all restrictions on construction in the West Bank.[125]

Former United States Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has said that on May 22, 2017, Benjamin Netanyahu showed Donald Trump a fake and altered video of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas calling for the killing of children. This was at a time when Trump was considering if Israel was the obstacle to peace. Netanyahu had showed Trump the fake video to change his position in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[126] In September 2017 it was announced that the U.S. would open their first permanent military base in Israel.[127]

On December 6, 2017, President Trump recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.[128] The U.S. Embassy was opened in Jerusalem on May 14, 2018, the 70th anniversary of the Independence of Israel.[129]

In May 2018, President Trump withdrew the United States from the Iran nuclear deal a few days after Netanyahu gave a presentation in which he revealed documents that Mossad smuggled out of Tehran, purportedly showing that Iran lied about its nuclear program.[130] This was followed by a renewal of U.S. sanctions on Iran.[131]

On March 25, 2019, President Trump signed the United States recognition of the Golan Heights as part of Israel, in a joint press conference in Washington with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, making the U.S. the first country other than Israel themselves to recognize Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights.[132] Israeli officials had lobbied the United States into recognizing "Israeli sovereignty" over the territory.[12]

In August 2020, Trump, Netanyahu and Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan jointly announced the establishment of formal Israel–United Arab Emirates relations.[133] This was followed by Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco establishing relations with Israel through U.S. mediation.[134]

Early in the Biden administration, the White House confirmed that the U.S. Embassy would remain in Jerusalem, which would remain recognised as the Capital. The administration also expressed support for the Abraham Accords while wanting to expand on them, although it shied away from using that name, instead referring to it simply as "the normalization process".[135][136][137]

On 13 May 2021, in the aftermath of the Al-Aqsa mosque conflict, the Biden administration was accused of being indifferent towards the violent conflict between Israeli statehood and the Palestinian minority there. Critics on both sides have identified the reaction by the White House as "lame and late".[138]

On 21 May 2021, a ceasefire was brokered between Israel and Hamas after eleven days of clashes. According to Biden, the U.S. will be playing a key role to rebuild damaged infrastructure in the Gaza alongside the Palestinian authority.[139][140]

In July 2022, President Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Israel as part of a trip to the Middle East. During the official state visit in Jerusalem, Biden and then-Prime Minister Yair Lapid signed a joint declaration extending a 10-year, $38 billion defense package to Israel that had been signed in 2016 under the Obama administration. In addition, the declaration addressed global security issues, such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine and committed both sides to preventing Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon.[141]

In an interview on Israel's Channel 12, Biden stated that "if that was the last resort" the United States would use force to achieve this[142] and that Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps would remain on the United States' Foreign Terrorist Organizations list even if that meant Iran did not return to the JCPOA under which Iran limited its nuclear program to slow its nuclear weapon program, in return for relief from economic sanctions.[143]

Biden and Lapid also opened the first meeting of I2U2 forum, together with the President of the United Arab Emirates, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, and the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, in a virtual conference during which the four countries agreed to collaborate further on issues including food security, clean energy, technology and trade, and reaffirmed their support for the Abraham Accords and other peace and normalization arrangements with Israel. The UAE pledged $2 billion for agricultural development in India using Israeli technologies.[141][144]

On 29 December 2022, after Netanyahu's right-wing government took office and approved the plan to change the structure of the Israeli judiciary, the value gap between many American Jews and Israel increased.[145] On 22 March 2023, the Biden administration summoned Israel's ambassador to the United States to the State Department, voicing its displeasure following the Knesset's passage of a law allowing the resettlement of illegal settlements in critical areas of the occupied West Bank that were evacuated in 2005.[146] The Israeli press considered such a meeting between the two countries very unusual and it reflects the deterioration of relations between the Biden government and the Netanyahu government.[146][147] On 29 March 2023, Biden announced that he does not intend to invite Netanyahu to the White House "in the near term".[148]