Salónica ( / ˌ θ ɛ s ə l ə ˈ n iː k i / ; griego : Θεσσαλονίκη [θesaloˈnici] ) , también conocida como Tesalónica (en español : / ˌθɛsələˈnaɪkə , ˌθɛsəˈlɒnɪkə / ) , Salónica , SalónicaoSalónica(/ səˈlɒnɪkə , ˌsæləˈniːkə/ ) , es lasegunda ciudad más grandedeGrecia , con un poco másde un millón de habitantes ensuáreametropolitana , y la capital de la región geográfica de Macedonia , laregión administrativa de Macedonia Central y la Administración Descentralizada de Macedonia y Tracia . [7][8]También se la conoce engriegocomo "η Συμπρωτεύουσα" (i Symprotévousa), literalmente "la co-capital",[9]una referencia a su estatus histórico comoΣυμβασιλεύουσα(Symvasilévousa) o ciudad "co-reinante" delImperio bizantinojunto aConstantinopla.[10]

Salónica está situada en el golfo de Tesalónica , en la esquina noroeste del mar Egeo . Limita al oeste con el delta del Axios . El municipio de Salónica , el centro histórico, tenía una población de 319.045 habitantes en 2021, [5] mientras que el área metropolitana de Salónica tenía 1.006.112 habitantes y la región en general tenía 1.092.919. [4] [3] Es el segundo centro económico, industrial, comercial y político más importante de Grecia, y un importante centro de transporte para Grecia y el sudeste de Europa, en particular a través del puerto de Salónica . [11] La ciudad es famosa por sus festivales, eventos y vibrante vida cultural en general. [12] Anualmente se celebran eventos como la Feria Internacional de Salónica y el Festival Internacional de Cine de Salónica . Salónica fue la Capital Europea de la Juventud 2014 . La principal universidad de la ciudad, la Universidad Aristóteles , es la más grande de Grecia y los Balcanes . [13]

La ciudad fue fundada en el año 315 a. C. por Casandro de Macedonia , quien la bautizó con el nombre de su esposa Tesalónica , hija de Filipo II de Macedonia y hermana de Alejandro Magno . Fue construida a 40 km al sureste de Pella , la capital del Reino de Macedonia . Tesalónica, una importante metrópolis en la época romana, fue la segunda ciudad más grande y rica del Imperio bizantino . Fue conquistada por los otomanos en 1430 y siguió siendo un importante puerto marítimo y una metrópolis multiétnica durante los casi cinco siglos de dominio turco , con iglesias, mezquitas y sinagogas coexistiendo una al lado de la otra. Desde el siglo XVI hasta el XX fue la única ciudad de mayoría judía en Europa . Pasó del Imperio Otomano al Reino de Grecia el 8 de noviembre de 1912. Salónica exhibe arquitectura bizantina , incluyendo numerosos monumentos paleocristianos y bizantinos , Patrimonio de la Humanidad , y varias estructuras romanas , otomanas y judías sefardíes .

En 2013, la revista National Geographic incluyó a Tesalónica entre sus principales destinos turísticos a nivel mundial, [14] mientras que en 2014 la revista Financial Times FDI (Inversiones Extranjeras Directas) declaró a Tesalónica como la mejor ciudad europea de tamaño medio del futuro para capital humano y estilo de vida. [15] [16]

El nombre original de la ciudad era Θεσσαλονίκη Thessaloníkē . Recibía el nombre de la princesa Tesalónica de Macedonia , media hermana de Alejandro Magno , cuyo nombre significa «victoria tesalia», de Θεσσαλός Thessalos y Νίκη «victoria» ( Nike ), en honor a la victoria macedonia en la batalla del Campo del Azafrán (353/352 a. C.).

También se encuentran variantes menores, incluidas Θετταλονίκη Thettaloníkē , [17] [18] Θεσσαλονίκεια Thessaloníkeia , [19] Θεσσαλονείκη Thessaloneíkē y Θε. σσαλονικέων Tesalónica . [20] [21]

El nombre Σαλονίκη Saloníki aparece por primera vez en griego en la Crónica de Morea (siglo XIV), y es común en canciones populares , pero debe haberse originado antes, ya que al-Idrisi lo llamó Salunik ya en el siglo XII. Es la base del nombre de la ciudad en otros idiomas: Солѹнъ ( Solunŭ ) en antiguo eslavo eclesiástico , סאלוניקו [22] [23] ( Saloniko ) en judeoespañol (שאלוניקי antes del siglo XIX [23] ), סלוניקי ( Saloniki ) en hebreo , Selenik en lengua albanesa , سلانیك ( Selânik ) en turco otomano y Selanik en turco moderno , Salonicco en italiano , Solun o Солун en las lenguas eslavas meridionales locales y vecinas , Салоники ( Saloníki ) en ruso , Sãrunã en arrumano. [24] y Săruna en megleno-rumano . [25]

En español, la ciudad puede llamarse Tesalónica, Salónica, Thessalonica, Salonica, Thessalonika, Saloniki, Thessalonike o Thessalonice. En los textos impresos, el nombre y la ortografía más común hasta principios del siglo XX era Tesalónica, que coincidía con el nombre en latín; durante la mayor parte del resto del siglo XX, fue Salónica. Hacia 1985, el nombre individual más común pasó a ser Tesalónica. [26] [27] Las formas con la terminación latina -a tomadas en conjunto siguen siendo más comunes que aquellas con la terminación fonética griega -i y mucho más comunes que la antigua transliteración -e . [28]

Tesalónica fue revivida como el nombre oficial de la ciudad en 1912, cuando se unió al Reino de Grecia durante las Guerras de los Balcanes . [29] En el habla local, el nombre de la ciudad se pronuncia típicamente con una L oscura y profunda , característica del acento del dialecto macedonio moderno del griego . [30] [31] El nombre a menudo se abrevia como Θεσ/νίκη . [ cita requerida ]

La ciudad fue fundada alrededor del 315 a. C. por el rey Casandro de Macedonia , en o cerca del sitio de la antigua ciudad de Terma y otras 26 aldeas locales. [32] [33] La nombró en honor a su esposa Tesalónica , [34] media hermana de Alejandro Magno y princesa de Macedonia como hija de Filipo II . Bajo el reino de Macedonia, la ciudad conservó su propia autonomía y parlamento [35] y evolucionó hasta convertirse en la ciudad más importante de Macedonia. [34]

Veinte años después de la caída del Reino de Macedonia en 168 a. C., en 148 a. C., Tesalónica se convirtió en la capital de la provincia romana de Macedonia . [36] Tesalónica se convirtió en una ciudad libre de la República romana bajo Marco Antonio en 41 a. C. [34] [37] Se convirtió en un importante centro comercial ubicado en la Vía Egnatia , [38] la carretera que conectaba Dirraquio con Bizancio , [39] lo que facilitaba el comercio entre Tesalónica y grandes centros de comercio como Roma y Bizancio . [40] Tesalónica también se encuentra en el extremo sur de la principal ruta norte-sur a través de los Balcanes a lo largo de los valles de los ríos Morava y Axios , uniendo así los Balcanes con el resto de Grecia. [41] La ciudad se convirtió en la capital de uno de los cuatro distritos romanos de Macedonia;. [38]

En la época del Imperio Romano, alrededor del año 50 d. C., Tesalónica también fue uno de los primeros centros del cristianismo ; durante su segundo viaje misionero, el apóstol Pablo visitó la sinagoga principal de esta ciudad durante tres sábados y sembró las semillas de la primera iglesia cristiana de Tesalónica. Más tarde, Pablo escribió cartas a la nueva iglesia de Tesalónica, y dos cartas a la iglesia bajo su nombre aparecen en el canon bíblico como Primera y Segunda Epístola a los Tesalonicenses . Algunos eruditos sostienen que la Primera Epístola a los Tesalonicenses es el primer libro escrito del Nuevo Testamento . [42]

En el año 306 d. C., Tesalónica adquirió un santo patrono, San Demetrio , un cristiano al que se dice que Galerio condenó a muerte. La mayoría de los estudiosos están de acuerdo con la teoría de Hippolyte Delehaye de que Demetrio no era nativo de Tesalónica, pero su veneración se trasladó a Tesalónica cuando reemplazó a Sirmio como la principal base militar en los Balcanes. [43] Una iglesia basilical dedicada a San Demetrio, Hagios Demetrios , se construyó por primera vez en el siglo V d. C. y ahora es Patrimonio de la Humanidad de la UNESCO .

Cuando el Imperio Romano se dividió en la tetrarquía , Tesalónica se convirtió en la capital administrativa de una de las cuatro porciones del Imperio bajo Galerio Maximiano César , [44] [45] donde Galerio encargó un palacio imperial, un nuevo hipódromo , un arco de triunfo y un mausoleo , entre otras estructuras. [45] [46] [47]

En 379, cuando la prefectura romana de Iliria se dividió entre los imperios romanos de Oriente y Occidente, Tesalónica se convirtió en la capital de la nueva prefectura de Iliria. [38] Al año siguiente, el Edicto de Tesalónica convirtió al cristianismo en la religión estatal del Imperio romano . [48] En 390, las tropas bajo el mando del emperador romano Teodosio I lideraron una masacre contra los habitantes de Tesalónica , que se habían rebelado contra la detención de un auriga favorito. En el momento de la caída de Roma en 476, Tesalónica era la segunda ciudad más grande del Imperio romano de Oriente . [40]

_(4._Jhdt.)_(47052790724).jpg/440px-Thessaloniki,_Nördliche_Stadtmauer_(Τείχη_της_Θεσσαλονίκης)_(4._Jhdt.)_(47052790724).jpg)

Desde los primeros años del Imperio bizantino , Salónica fue considerada la segunda ciudad del Imperio después de Constantinopla , [49] [50] [51] tanto en términos de riqueza como de tamaño, [49] con una población de 150.000 habitantes a mediados del siglo XII. [52] La ciudad mantuvo este estatus hasta su transferencia al control veneciano en 1423. En el siglo XIV, la población de la ciudad superó los 100.000 a 150.000, [53] [54] [55] lo que la hizo más grande que Londres en ese momento. [56]

Durante los siglos VI y VII, la zona alrededor de Tesalónica fue invadida por ávaros y eslavos, que sitiaron la ciudad sin éxito varias veces, como se narra en los Milagros de San Demetrio . [57] La historiografía tradicional estipula que muchos eslavos se establecieron en el interior de Tesalónica; [58] sin embargo, los eruditos modernos consideran que esta migración fue en una escala mucho menor de lo que se pensaba anteriormente. [58] [59] En el siglo IX, los misioneros bizantinos Cirilo y Metodio , ambos nativos de la ciudad, crearon la primera lengua literaria de los eslavos, el antiguo eslavo eclesiástico , muy probablemente basado en el dialecto eslavo utilizado en el interior de su ciudad natal. [60] [61] [62] [63] [64]

Un ataque naval dirigido por bizantinos conversos al Islam (incluido León de Trípoli ) en 904 resultó en el saqueo de la ciudad . [65]

La expansión económica de la ciudad continuó durante el siglo XII a medida que el gobierno de los emperadores Comnenoi expandió el control bizantino hacia el norte. Tesalónica dejó de estar en manos bizantinas en 1204, [66] cuando Constantinopla fue capturada por las fuerzas de la Cuarta Cruzada e incorporó la ciudad y sus territorios circundantes al Reino de Tesalónica [67] , que luego se convirtió en el mayor vasallo del Imperio latino . En 1224, el Reino de Tesalónica fue invadido por el Despotado de Epiro , un remanente del antiguo Imperio bizantino, bajo Teodoro Comneno Ducas , quien se coronó emperador, [68] y la ciudad se convirtió en la capital del efímero Imperio de Tesalónica . [68] [69] [70] [71] Sin embargo, tras su derrota en Klokotnitsa en 1230, [68] [72] el Imperio de Tesalónica se convirtió en un estado vasallo del Segundo Imperio Búlgaro hasta que fue recuperado nuevamente en 1246, esta vez por el Imperio de Nicea . [68]

En 1342, [73] la ciudad vio surgir la Comuna de los Zelotes , un partido antiaristocrático formado por marineros y pobres, [74] que hoy en día se describe como social-revolucionario. [73] La ciudad era prácticamente independiente del resto del Imperio, [73] [74] [75] ya que tenía su propio gobierno, una forma de república. [73] El movimiento zelote fue derrocado en 1350 y la ciudad se reunificó con el resto del Imperio. [73]

La captura de Galípoli por los otomanos en 1354 dio inicio a una rápida expansión turca en el sur de los Balcanes , llevada a cabo tanto por los propios otomanos como por bandas de guerreros turcos semiindependientes, los ghazi . En 1369, los otomanos pudieron conquistar Adrianópolis (la moderna Edirne ), que se convirtió en su nueva capital hasta 1453. [76] Tesalónica, gobernada por Manuel II Paleólogo (r. 1391-1425), se rindió después de un largo asedio en 1383-1387 , junto con la mayor parte de Macedonia oriental y central, a las fuerzas del sultán Murad I. [ 77] Inicialmente, a las ciudades rendidas se les permitió una autonomía completa a cambio del pago del impuesto electoral kharaj . Sin embargo, tras la muerte del emperador Juan V Paleólogo en 1391, Manuel II escapó de la custodia otomana y fue a Constantinopla, donde fue coronado emperador, sucediendo a su padre. Esto enfureció al sultán Bayaceto I , que arrasó los territorios bizantinos restantes y luego se volvió contra Crisópolis, que fue capturada por asalto y destruida en gran parte. [78] Tesalónica también se sometió nuevamente al dominio otomano en este momento, posiblemente después de una breve resistencia, pero fue tratada con más indulgencia: aunque la ciudad quedó bajo pleno control otomano, la población cristiana y la Iglesia conservaron la mayoría de sus posesiones, y la ciudad conservó sus instituciones. [79] [80]

Tesalónica permaneció en manos otomanas hasta 1403, cuando el emperador Manuel II se puso del lado del hijo mayor de Bayaceto, Solimán, en la lucha por la sucesión otomana que estalló tras la aplastante derrota y captura de Bayaceto en la batalla de Ankara contra Tamerlán en 1402. A cambio de su apoyo, en el Tratado de Galípoli, el emperador bizantino consiguió la devolución de Tesalónica, parte de su interior, la península de Calcídica y la región costera entre los ríos Estrimón y Pineio . [81] [82] Tesalónica y la región circundante fueron entregadas como un infantazgo autónomo a Juan VII Paleólogo . Después de su muerte en 1408, fue sucedido por el tercer hijo de Manuel, el déspota Andrónico Paleólogo , que fue supervisado por Demetrio Leontares hasta 1415. Tesalónica disfrutó de un período de relativa paz y prosperidad después de 1403, ya que los turcos estaban preocupados con su propia guerra civil , pero fue atacada por los pretendientes otomanos rivales en 1412 (por Musa Çelebi [83] ) y 1416 (durante el levantamiento de Mustafa Çelebi contra Mehmed I [84] ). [85] [86] Una vez que terminó la guerra civil otomana, la presión turca sobre la ciudad comenzó a aumentar nuevamente. Al igual que durante el asedio de 1383-1387, esto llevó a una marcada división de opiniones dentro de la ciudad entre facciones que apoyaban la resistencia, si era necesario con ayuda occidental, o la sumisión a los otomanos. [87]

En 1423, el déspota Andrónico Paleólogo la cedió a la República de Venecia con la esperanza de que pudiera protegerse de los otomanos que estaban asediando la ciudad . Los venecianos mantuvieron Tesalónica hasta que fue capturada por el sultán otomano Murad II el 29 de marzo de 1430. [88]

Cuando el sultán Murad II capturó Tesalónica y la saqueó en 1430, [89] informes contemporáneos estimaron que aproximadamente una quinta parte de la población de la ciudad estaba esclavizada. [90] La artillería otomana se utilizó para asegurar la captura de la ciudad y eludir sus murallas dobles. [89] Tras la conquista de Tesalónica, algunos de sus habitantes escaparon, [91] incluidos intelectuales como Teodoro Gaza "Thessalonicensis" y Andrónico Calixto . [92] Sin embargo, el cambio de soberanía del Imperio bizantino al otomano no afectó al prestigio de la ciudad como una importante ciudad imperial y centro comercial. [93] [94] Tesalónica y Esmirna , aunque de menor tamaño que Constantinopla , eran los centros comerciales más importantes del Imperio Otomano. [93] La importancia de Tesalónica residía principalmente en el ámbito del transporte marítimo , [93] pero también en la industria manufacturera, [94] mientras que la mayoría de los comerciantes de la ciudad eran judíos . [93]

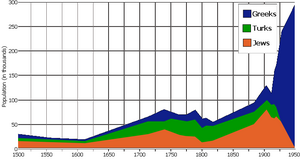

Durante el período otomano, la población de musulmanes otomanos (incluidos los de origen turco , así como los musulmanes albaneses , musulmanes búlgaros , especialmente los pomacos y los musulmanes griegos de origen converso) y los gitanos musulmanes como los sepečides romani creció sustancialmente. Según el censo de 1478, Selânik ( turco otomano : سلانیك ), como llegó a conocerse a la ciudad en turco otomano, tenía 6.094 hogares cristianos ortodoxos , 4.320 musulmanes y algunos católicos. No se registraron judíos en el censo, lo que sugiere que la posterior afluencia de población judía no estaba vinculada [96] a la comunidad romaniota ya existente. [97] Sin embargo, poco después del cambio del siglo XV al XVI, casi 20.000 judíos sefardíes inmigraron a Grecia desde la península Ibérica tras su expulsión de España por el Decreto de la Alhambra de 1492 . [98] Hacia el año 1500, el número de hogares había aumentado a 7.986 cristianos, 8.575 musulmanes y 3.770 judíos. En 1519, los hogares judíos sefardíes sumaban 15.715, el 54% de la población de la ciudad. Algunos historiadores consideran que la invitación del régimen otomano al asentamiento judío fue una estrategia para evitar que la población cristiana dominara la ciudad. [99] La ciudad se convirtió en la ciudad judía más grande del mundo y la única ciudad con mayoría judía en el mundo en el siglo XVI. Como resultado, Tesalónica atrajo a judíos perseguidos de todo el mundo. [100]

Salónica fue la capital del Sanjak de Selanik dentro del Eyalet de Rumelia (Balcanes) [101] hasta 1826, y posteriormente la capital del Eyalet de Selanik (después de 1867, el Vilayet de Selanik ). [102] [103] Este consistía en los sanjaks de Selanik, Serres y Drama entre 1826 y 1912. [104]

En la primavera de 1821, cuando estalló la Guerra de Independencia griega , el gobernador Yusuf Bey encarceló en su cuartel general a más de 400 rehenes. El 18 de mayo, cuando Yusuf se enteró de la insurrección en los pueblos de Calcídica , ordenó que la mitad de sus rehenes fueran masacrados ante sus ojos. El mulá de Tesalónica, Hayrıülah, da la siguiente descripción de las represalias de Yusuf: «Todos los días y todas las noches no se oye nada en las calles de Tesalónica más que gritos y gemidos. Parece que Yusuf Bey, los Yeniceri Agasi, los Subaşı, los hocas y los ulemas se han vuelto locos de atar». [105] La comunidad griega de la ciudad tardaría hasta finales de siglo en recuperarse. [106]

Salónica también era un bastión jenízaro donde se entrenaban los novatos. En junio de 1826, soldados otomanos regulares atacaron y destruyeron la base jenízara en Salónica, matando a más de 10.000 jenízaros, un evento conocido como el Incidente Auspicioso en la historia otomana. [107] Entre 1870 y 1917, impulsada por el crecimiento económico, la población de la ciudad se expandió en un 70%, alcanzando los 135.000 habitantes en 1917. [108]

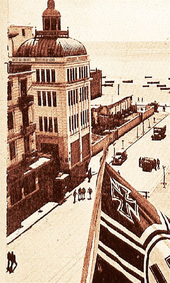

Las últimas décadas del control otomano sobre la ciudad fueron una época de renacimiento, en particular en lo que respecta a la infraestructura de la ciudad. Fue en esa época cuando la administración otomana de la ciudad adquirió un rostro "oficial" con la creación de la Casa de Gobierno [109], mientras que se construyeron varios edificios públicos nuevos de estilo ecléctico para proyectar el rostro europeo tanto de Tesalónica como del Imperio Otomano. [109] [110] Las murallas de la ciudad fueron derribadas entre 1869 y 1889, [111] los esfuerzos para una expansión planificada de la ciudad son evidentes ya en 1879, [112] el primer servicio de tranvía comenzó en 1888 [113] y las calles de la ciudad fueron iluminadas con farolas eléctricas en 1908. [114] En 1888, el Ferrocarril Oriental conectó Tesalónica con Europa Central a través del ferrocarril a través de Belgrado y a Monastir en 1893, mientras que el Ferrocarril de Unión Tesalónica-Estambul la conectó con Constantinopla en 1896. [112]

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk , fundador de la moderna república de Turquía , nació en Salónica (entonces conocida como Selânik en turco otomano) en 1881. Su lugar de nacimiento en İslahhane Caddesi (ahora calle Apostolou 24) es ahora el Museo Atatürk y forma parte del complejo del consulado turco. [115]

A principios del siglo XX, Salónica se convirtió en el centro de las actividades radicales de varios grupos: la Organización Revolucionaria Interna de Macedonia , fundada en 1897, [116] y el Comité Griego Macedonio , fundado en 1903. [117] En 1903, un grupo anarquista búlgaro conocido como los Barqueros de Salónica colocó bombas en varios edificios de Salónica, incluido el Banco Otomano , con cierta ayuda de la IMRO. El consulado griego en la Salónica otomana (ahora el Museo de la Lucha Macedonia ) sirvió como centro de operaciones para las guerrillas griegas.

Durante este período, y desde el siglo XVI, el elemento judío de Tesalónica fue el más dominante; fue la única ciudad en Europa donde los judíos eran mayoría de la población total. [118] La ciudad era étnicamente diversa y cosmopolita . En 1890, su población había aumentado a 118.000, de los cuales el 47% eran judíos, seguidos de turcos (22%), griegos (14%), búlgaros (8%), romaníes (2%) y otros (7%). [119] Para 1913, la composición étnica de la ciudad había cambiado de modo que la población era de 157.889, con judíos en el 39%, seguidos de nuevo por turcos (29%), griegos (25%), búlgaros (4%), romaníes (2%) y otros en el 1%. [120] Se practicaban muchas religiones variadas y se hablaban muchos idiomas, incluido el judeoespañol , un dialecto del español hablado por los judíos de la ciudad.

Salónica también fue el centro de actividades de los Jóvenes Turcos , un movimiento de reforma política cuyo objetivo era reemplazar la monarquía absoluta del Imperio Otomano por un gobierno constitucional. Los Jóvenes Turcos comenzaron como un movimiento clandestino, hasta que finalmente en 1908, iniciaron la Revolución de los Jóvenes Turcos desde la ciudad de Salónica, que los llevó a obtener el control del Imperio Otomano y poner fin al poder de los sultanes otomanos. [121] La plaza Eleftherias (Libertad) , donde los Jóvenes Turcos se reunieron al estallar la revolución, debe su nombre al evento. [122] El primer presidente de Turquía, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk , que nació y se crió en Salónica, fue miembro de los Jóvenes Turcos en sus días de soldado y también participó en la Revolución de los Jóvenes Turcos.

Cuando estalló la Primera Guerra de los Balcanes , Grecia declaró la guerra al Imperio otomano y expandió sus fronteras. Cuando se le preguntó a Eleftherios Venizelos , primer ministro en ese momento, si el ejército griego debía avanzar hacia Salónica o Monastir (ahora Bitola , República de Macedonia del Norte ), Venizelos respondió " Θεσσαλονίκη με κάθε κόστος! " ( ¡Salónica, a toda costa! ). [123] Con el ejército otomano superado en número luchando en una acción de retaguardia contra fuerzas griegas bien preparadas en Yenidje , tropas búlgaras avanzando cerca y la base naval otomana en Salónica bloqueada por la Armada griega, el general Hasan Tahsin Pasha pronto se dio cuenta de que se había vuelto insostenible defender la ciudad. El hundimiento del acorazado otomano Feth-i Bülend en el puerto de Salónica el 31 de octubre de 1912, aunque militarmente insignificante, dañó aún más la moral otomana. Como tanto Grecia como Bulgaria querían Salónica, la guarnición otomana de la ciudad entró en negociaciones con ambos ejércitos. [124] El 8 de noviembre de 1912 (26 de octubre al estilo antiguo ), el día festivo del santo patrón de la ciudad, San Demetrio , el ejército griego aceptó la rendición de la guarnición otomana en Salónica. [125] El ejército búlgaro llegó un día después de la rendición de la ciudad a Grecia y Hasan Tahsin Pasha, comandante de las defensas de la ciudad, dijo a los funcionarios búlgaros que "sólo tengo una Salónica, que he rendido". [124] Después de la Segunda Guerra de los Balcanes , Salónica y el resto de la parte griega de Macedonia fueron anexadas oficialmente a Grecia por el Tratado de Bucarest en 1913. [126] El 18 de marzo de 1913, Jorge I de Grecia fue asesinado en la ciudad por Alexandros Schinas . [127]

En 1915, durante la Primera Guerra Mundial , una gran fuerza expedicionaria aliada estableció una base en Salónica para operaciones [128] contra la pro-alemana Bulgaria. [129] Esto culminó con el establecimiento del Frente Macedonio , también conocido como el frente de Salónica. [130] [131] Y se instaló un hospital temporal dirigido por los Hospitales de Mujeres Escocesas para el Servicio Exterior en una fábrica en desuso. En 1916, oficiales del ejército griego pro- venizelista y civiles, con el apoyo de los Aliados, lanzaron un levantamiento, [132] creando un gobierno temporal pro-aliado [133] con el nombre de " Gobierno Provisional de Defensa Nacional " [132] [134] que controlaba las "Nuevas Tierras" (tierras que Grecia ganó en las Guerras de los Balcanes , la mayor parte del norte de Grecia, incluida la Macedonia griega, el norte del Egeo y la isla de Creta ); [132] [134] El gobierno oficial del rey en Atenas , el "Estado de Atenas", [132] controlaba la "Antigua Grecia" [132] [134] , que tradicionalmente era monárquica. El Estado de Tesalónica se disolvió con la unificación de los dos gobiernos griegos opuestos bajo Venizelos, tras la abdicación del rey Constantino en 1917. [129] [134]

El 30 de diciembre de 1915, un ataque aéreo austríaco sobre Salónica alarmó a muchos civiles de la ciudad y mató al menos a una persona, y en respuesta, las tropas aliadas estacionadas allí arrestaron a los vicecónsules alemán, austríaco, búlgaro y turco y a sus familias y dependientes y los pusieron en un acorazado, y alojaron tropas en los edificios de sus consulados en Salónica. [135]

La mayor parte del casco antiguo de la ciudad fue destruida por el Gran Incendio de Tesalónica de 1917 , que se inició accidentalmente por un incendio en una cocina sin vigilancia el 18 de agosto de 1917. [136] El fuego arrasó el centro de la ciudad, dejando a 72.000 personas sin hogar; según el Informe Pallis, la mayoría de ellos eran judíos (50.000). Muchos negocios fueron destruidos, como resultado, el 70% de la población estaba desempleada. [136] Se perdieron dos iglesias y muchas sinagogas y mezquitas. Más de una cuarta parte de la población total de aproximadamente 271.157 se quedó sin hogar. [136] Después del incendio, el gobierno prohibió la reconstrucción rápida, para poder implementar el nuevo rediseño de la ciudad de acuerdo con el plan urbano de estilo europeo [10] preparado por un grupo de arquitectos, incluido el británico Thomas Mawson , y encabezado por el arquitecto francés Ernest Hébrard . [136] Los valores de las propiedades cayeron de 6,5 millones de dracmas griegas a 750.000. [137]

Tras la derrota de Grecia en la guerra greco-turca y durante la desintegración del Imperio otomano, se produjo un intercambio de población entre Grecia y Turquía. [133] Más de 160.000 griegos étnicos deportados del antiguo Imperio otomano , en particular griegos de Asia Menor [138] y Tracia Oriental , se reasentaron en la ciudad, [133] lo que cambió su demografía. Además, muchos de los musulmanes de la ciudad, incluidos los musulmanes griegos otomanos , fueron deportados a Turquía, en un número aproximado de 20.000 personas. [139] Esto hizo que el elemento griego fuera dominante, [140] mientras que la población judía se redujo a una minoría por primera vez desde el siglo XVI. [141]

Esto fue parte de un proceso general de helenización moderna, que afectó a casi todas las minorías dentro de Grecia, convirtiendo la región en un foco de nacionalismo étnico. [142]

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Salónica fue fuertemente bombardeada por la Italia fascista (con 232 personas muertas, 871 heridas y más de 800 edificios dañados o destruidos solo en noviembre de 1940), [144] y, habiendo fracasado los italianos en su invasión de Grecia , cayó en manos de las fuerzas de la Alemania nazi el 8 de abril de 1941 [145] y quedó bajo ocupación alemana. Los nazis pronto obligaron a los residentes judíos a vivir en un gueto cerca de los ferrocarriles y el 15 de marzo de 1943 comenzaron la deportación de los judíos de la ciudad a los campos de concentración de Auschwitz y Bergen-Belsen . [146] [147] [148] La mayoría fueron asesinados inmediatamente en las cámaras de gas . De los 45.000 judíos deportados a Auschwitz, solo el 4% sobrevivió. [149] [150]

Durante un discurso en el Reichstag , Hitler afirmó que la intención de su campaña en los Balcanes era impedir que los aliados establecieran "un nuevo frente macedonio", como lo habían hecho durante la Primera Guerra Mundial. La importancia de Salónica para la Alemania nazi se puede demostrar por el hecho de que, inicialmente, Hitler había planeado incorporarla directamente a la Alemania nazi [151] y no dejarla controlada por un estado títere como el Estado helénico o un aliado de Alemania (Salónica había sido prometida a Yugoslavia como recompensa por unirse al Eje el 25 de marzo de 1941). [152]

Como fue la primera ciudad importante de Grecia en caer ante las fuerzas de ocupación, en Salónica se formó el primer grupo de resistencia griego (bajo el nombre de Ελευθερία , Elefthería , "Libertad") [153] así como el primer periódico antinazi en un territorio ocupado en cualquier parte de Europa, [154] también con el nombre de Eleftheria . Salónica también fue el hogar de un campo militar convertido en campo de concentración, conocido en alemán como "Konzentrationslager Pavlo Mela" ( Campo de concentración Pavlos Melas ), [155] donde miembros de la resistencia y otros antifascistas [155] fueron retenidos para ser asesinados o enviados a otros campos de concentración. [155] En septiembre de 1943, los alemanes establecieron el campo de tránsito Dulag 410 para los internados militares italianos en la ciudad. [156] El 30 de octubre de 1944, después de batallas con el ejército alemán en retirada y los Batallones de Seguridad de Poulos , las fuerzas del ELAS entraron en Salónica como liberadores encabezados por Markos Vafiadis (que no obedeció las órdenes de la dirección del ELAS en Atenas de no entrar en la ciudad). Celebraciones y manifestaciones a favor del EAM siguieron en la ciudad. [157] [158] En el referéndum de la monarquía de 1946 , la mayoría de los lugareños votaron a favor de una república, al contrario del resto de Grecia. [159]

Después de la guerra, Tesalónica fue reconstruida con un desarrollo a gran escala de nuevas infraestructuras e industrias durante las décadas de 1950, 1960 y 1970. Muchos de sus tesoros arquitectónicos aún permanecen, agregando valor a la ciudad como destino turístico, mientras que varios monumentos paleocristianos y bizantinos de Tesalónica fueron agregados a la lista del Patrimonio Mundial de la UNESCO en 1988. [160] En 1997, Tesalónica fue celebrada como Capital Europea de la Cultura , [161] patrocinando eventos en toda la ciudad y la región. La agencia establecida para supervisar las actividades culturales de ese año 1997 todavía existía en 2010. [162] En 2004, la ciudad albergó varios eventos de fútbol como parte de los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 2004. [ 163]

Hoy en día, Salónica se ha convertido en uno de los centros comerciales y de negocios más importantes del sudeste de Europa , con su puerto, el Puerto de Salónica, siendo uno de los más grandes del Egeo y facilitando el comercio en todo el interior de los Balcanes. [11] El 26 de octubre de 2012, la ciudad celebró su centenario desde su incorporación a Grecia. [164] La ciudad también forma uno de los centros estudiantiles más grandes del sudeste de Europa, alberga la mayor población estudiantil de Grecia y fue la Capital Europea de la Juventud en 2014. [165] [166]

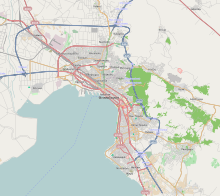

Tesalónica está situada a 502 kilómetros (312 millas) al norte de Atenas .

El área urbana de Tesalónica se extiende a lo largo de 30 kilómetros (19 millas) desde Oraiokastro en el norte hasta Thermi en el sur en dirección a Calcídica .

Tesalónica se encuentra en la franja norte del golfo de Tesalónica , en su costa oriental, y está limitada por el monte Chortiatis en su sureste. Su proximidad a imponentes cadenas montañosas , colinas y fallas geológicas, especialmente hacia el sureste, han hecho que la ciudad sea propensa a cambios geológicos.

Desde la época medieval, Salónica ha sido golpeada por fuertes terremotos , en particular en 1759, 1902, 1978 y 1995. [167] El 19 y 20 de junio de 1978, la ciudad sufrió una serie de poderosos terremotos , registrándose 5,5 y 6,5 en la escala de Richter . [168] [169] Los temblores causaron daños considerables a varios edificios y monumentos antiguos, [168] pero la ciudad resistió la catástrofe sin mayores problemas. [169] Un edificio de apartamentos en el centro de Salónica se derrumbó durante el segundo terremoto, matando a muchos y elevando el número final de muertos a 51. [168] [169]

El clima de Tesalónica es de transición, y se encuentra en la periferia de múltiples zonas climáticas. Según la clasificación climática de Köppen , la ciudad generalmente tiene un clima semiárido frío ( BSk ) mientras que un clima semiárido cálido ( BSh ) se encuentra en el centro. Las influencias mediterráneas ( Csa ) y subtropicales húmedas ( Cfa ) también se encuentran en el clima de la ciudad. [170] [171] La cordillera del Pindo contribuye en gran medida al clima generalmente seco del área al secar sustancialmente los vientos del oeste. [172] De hecho, la estación de la Feria Internacional de Tesalónica del Observatorio Nacional de Atenas es la estación más septentrional del mundo con un clima semiárido cálido ( BSh ). [173]

Los inviernos son algo secos, con heladas matinales ocasionales. Las nevadas ocurren más o menos cada invierno, pero la capa de nieve no dura más que unos pocos días. Durante los inviernos más fríos, las temperaturas pueden bajar a -10 °C (14 °F). [174] La temperatura mínima récord en Tesalónica fue de -14 °C (7 °F). [175] En promedio, Tesalónica experimenta heladas (temperaturas bajo cero) 32 días al año, [174] aunque eso es menos común cerca del centro de la ciudad, debido al efecto de isla de calor urbano que caracteriza a la ciudad y es más pronunciado durante los meses de invierno. [176] Los días de niebla ocurren escasamente, aproximadamente 17 días al año, principalmente en los meses de otoño e invierno. [177] El mes más frío del año en el centro de Tesalónica es enero, con una temperatura promedio de 24 horas de 8 °C (46 °F). [178] La ciudad también es bastante ventosa en los meses de invierno, con enero y febrero con una velocidad media del viento de unos 11 km/h (7 mph). [174]

Los veranos de Tesalónica son calurosos y moderadamente secos. [174] Las temperaturas máximas suelen superar los 30 °C (86 °F), [174] pero rara vez superan los 40 °C (104 °F); [174] mientras que el número medio de días en los que la temperatura supera los 32 °C (90 °F) es de 32. [174] Generalmente, la brisa marina que sopla desde el golfo de Tesalónica ayuda a moderar las temperaturas de la ciudad. [179] La temperatura máxima registrada en la ciudad fue de 44 °C (111 °F). [174] [175] Ocasionalmente llueve en verano, principalmente durante las tormentas eléctricas, mientras que las olas de calor ocurren esporádicamente, aunque pocas de ellas son intensas. [180] Los meses más calurosos del año en el centro de Tesalónica son julio y agosto, con una temperatura media de 24 horas de alrededor de 28,0 °C (82 °F). [178]

En 2021, la Comisión Europea reprendió a Grecia por no haber logrado frenar los niveles sistemáticamente elevados de contaminación del aire en Salónica. [181]

Según la reforma Kallikratis , a partir del 1 de enero de 2011 el Área Urbana de Salónica ( griego : Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Θεσσαλονίκης ) que conforma la "Ciudad de Salónica", está formada por seis municipios autónomos ( griego : Δήμοι ) y una unidad municipal ( griego : Δημοτική ενότητα ). Los municipios que están incluidos en el área urbana de Tesalónica son los de Tesalónica (el centro de la ciudad y el de mayor tamaño de población), Kalamaria , Neapoli-Sykies , Pavlos Melas , Kordelio-Evosmos , Ampelokipoi-Menemeni y las unidades municipales de Pylaia y Panorama. , parte del municipio de Pylaia-Chortiatis . [3] Antes de la reforma de Kallikratis , el área urbana de Tesalónica estaba formada por el doble de municipios, considerablemente más pequeños en tamaño, lo que creaba problemas burocráticos. [192]

El municipio de Tesalónica ( en griego : Δήμος Θεσαλονίκης ) es el segundo más poblado de Grecia, después de Atenas , con una población residente de 317.778 [5] (en 2021) y una superficie de 19.307 kilómetros cuadrados (7.454 millas cuadradas). El municipio forma el núcleo del área urbana de Tesalónica , con su distrito central (el centro de la ciudad), conocido como Kentro , que significa 'centro' o 'centro urbano'. [193]

El primer alcalde de la ciudad, Osman Sait Bey, fue nombrado cuando se inauguró la institución de la alcaldía bajo el Imperio Otomano en 1912. El alcalde actual es Stelios Angeloudis. En 2011, el municipio de Tesalónica tenía un presupuesto de 464,33 millones de euros [194] , mientras que el presupuesto de 2012 asciende a 409,00 millones de euros. [195]

Salónica es la segunda ciudad más grande de Grecia. Es una ciudad influyente para las zonas del norte del país y es la capital de la región de Macedonia Central y de la unidad regional de Salónica . El Ministerio de Macedonia y Tracia también tiene su sede en Salónica, ya que la ciudad es la capital de facto de la región griega de Macedonia . [ cita requerida ]

Es costumbre cada año que el Primer Ministro de Grecia anuncie las políticas de su administración sobre una serie de temas, como la economía, en la noche de apertura de la Feria Internacional de Tesalónica . En 2010, durante los primeros meses de la crisis de la deuda griega de 2010 , todo el gabinete de Grecia se reunió en Tesalónica para discutir el futuro del país. [196]

En el Parlamento griego , la zona urbana de Salónica constituye una circunscripción de 17 escaños. En las elecciones legislativas griegas de junio de 2023, el partido más votado en Salónica es Nueva Democracia , con el 35,28 % de los votos, seguido de Syriza (17,52 %). [197] La siguiente tabla resume los resultados de las últimas elecciones.

La arquitectura de Tesalónica es el resultado directo de la posición de la ciudad en el centro de todos los acontecimientos históricos de los Balcanes. Además de su importancia comercial, Tesalónica también fue durante muchos siglos el centro militar y administrativo de la región y, más allá de esto, el enlace de transporte entre Europa y el Levante . Mercaderes, comerciantes y refugiados de toda Europa se establecieron en la ciudad. La necesidad de edificios comerciales y públicos en esta nueva era de prosperidad llevó a la construcción de grandes edificios en el centro de la ciudad. Durante este tiempo, la ciudad vio la construcción de bancos, grandes hoteles, teatros, almacenes y fábricas. Los arquitectos que diseñaron algunos de los edificios más notables de la ciudad, a finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, incluyen a Vitaliano Poselli , Pietro Arrigoni , Xenophon Paionidis , Salvatore Poselli, Leonardo Gennari, Eli Modiano, Moshé Jacques, Joseph Pleyber, Frederic Charnot, Ernst Ziller , Max Rubens, Filimon Paionidis, Dimitris Andronikos, Levi Ernst, Angelos Siagas, Alexandros Tzonis y más, utilizando principalmente los estilos del eclecticismo , el art nouveau y el neobarroco .

El trazado de la ciudad cambió después de 1870, cuando las fortificaciones costeras dieron paso a extensos muelles y se derribaron muchas de las murallas más antiguas de la ciudad, incluidas las que rodeaban la Torre Blanca , que hoy en día se alza como el principal punto de referencia de la ciudad. La demolición de partes de las primeras murallas bizantinas permitió que la ciudad se expandiera hacia el este y el oeste a lo largo de la costa. [198]

La ampliación de la plaza Eleftherias hacia el mar completó el nuevo centro comercial de la ciudad y en su momento se consideró una de las plazas más vibrantes de la ciudad. A medida que la ciudad crecía, los trabajadores se mudaron a los distritos occidentales, debido a su proximidad a las fábricas y las actividades industriales; mientras que las clases medias y altas se mudaron gradualmente del centro de la ciudad a los suburbios orientales, abandonando principalmente las empresas. En 1917, un incendio devastador arrasó la ciudad y ardió sin control durante 32 horas. [108] Destruyó el centro histórico de la ciudad y una gran parte de su patrimonio arquitectónico, pero allanó el camino para el desarrollo moderno con avenidas diagonales más amplias y plazas monumentales. [108] [199]

.jpg/440px-Θεσσαλονίκη_2014_-_panoramio_(2).jpg)

Tras el gran incendio de Tesalónica de 1917, un equipo de arquitectos y urbanistas, entre los que se encontraban Thomas Mawson y Ernest Hebrard , un arquitecto francés, eligieron la era bizantina como base de sus diseños de (re)construcción para el centro de la ciudad de Tesalónica. El nuevo plan de la ciudad incluía ejes, calles diagonales y plazas monumentales, con una cuadrícula de calles que canalizaría el tráfico sin problemas. El plan de 1917 incluía disposiciones para futuras expansiones de población y una red de calles y carreteras que sería, y sigue siendo, suficiente en la actualidad. [108] Contenía sitios para edificios públicos y preveía la restauración de iglesias bizantinas y mezquitas otomanas.

También llamado centro histórico , se divide en varios distritos, entre ellos la Plaza Dimokratias (Plaza de la Democracia, también conocida como Vardaris ) , Ladadika (donde se encuentran muchos lugares de entretenimiento y tabernas), Kapani (donde se encuentra el mercado central Modiano de la ciudad ), Diagonios , Navarinou , Rotonda , Agia Sofia e Hippodromio , que se encuentran todos alrededor del punto más central de Tesalónica, la Plaza Aristóteles .

Varias stoas comerciales alrededor de Aristóteles reciben nombres del pasado de la ciudad y de personalidades históricas de la ciudad, como stoa Hirsch , stoa Carasso / Ermou, Pelosov, Colombou, Levi, Modiano , Morpurgo, Mordoch, Simcha, Kastoria, Malakopi, Olympios, Emboron, Rogoti, Vyzantio, Tatti, Agiou Mina, Karipi, etc. [200]

La parte occidental del centro de la ciudad alberga los tribunales de justicia de Tesalónica, su estación central internacional de trenes y el puerto , mientras que su lado oriental alberga las dos universidades de la ciudad, el Centro Internacional de Exposiciones de Tesalónica , el estadio principal de la ciudad , sus museos arqueológicos y bizantinos, el nuevo ayuntamiento y sus parques y jardines centrales, a saber, los del ΧΑΝΘ y Pedion tou Areos .

Ano Poli (también llamada Ciudad Vieja y literalmente Ciudad Alta ) es el distrito declarado Patrimonio de la Humanidad al norte del centro de la ciudad de Tesalónica que no fue engullido por el gran incendio de 1917 y fue declarado Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO a través de las acciones ministeriales de Melina Merkouri , durante la década de 1980. Consiste en la parte más tradicional de la ciudad de Tesalónica, que aún cuenta con pequeñas calles adoquinadas, antiguas plazas y casas de antigua arquitectura griega y otomana . Es la zona favorita de los poetas, intelectuales y bohemios de Tesalónica.

Ano Poli es también el punto más alto de Tesalónica y, como tal, es el lugar donde se encuentran la acrópolis de la ciudad, su fortaleza bizantina, el Heptapyrgion , gran parte de las murallas restantes de la ciudad y muchas de sus estructuras otomanas y bizantinas adicionales aún en pie. Con la captura de Tesalónica por los otomanos en 1430, después de un largo asedio de la ciudad desde 1422 hasta 1430, los otomanos se establecieron en Ano Poli. Esta elección geográfica se atribuyó al nivel más alto de Ano Poli, que era conveniente para controlar al resto de la población a distancia, y al microclima de la zona, que favorecía mejores condiciones de vida en términos de higiene en comparación con las áreas del centro.

En la actualidad, la zona ofrece acceso al Parque Nacional Forestal Seich Sou [201] y ofrece vistas panorámicas de toda la ciudad y del golfo de Tesalónica . En días claros , también se puede ver el monte Olimpo , a unos 100 km (62 mi) de distancia al otro lado del golfo, elevándose en el horizonte.

En el Municipio de Tesalónica, además del centro histórico y la Ciudad Alta, se incluyen los siguientes distritos: Xirokrini, Dikastiria (Tribunales), Ichthioskala, Palaios Stathmos, Lachanokipoi, Behtsinari, Panagia Faneromeni, Doxa, Saranta Ekklisies, Evangelistria, Triandria. , Agia Triada-Faliro, Ippokrateio, Charilaou, Analipsi, Depot y Toumba.

En la zona de la antigua estación de tren (Palaios Stathmos) comenzó la construcción del Museo del Holocausto de Grecia . [202] [203] En esta zona se encuentran el Museo del Ferrocarril de Tesalónica , el Museo del Abastecimiento de Agua y grandes lugares de ocio de la ciudad, como Milos , Fix , Vilka (que se encuentran en antiguas fábricas reconvertidas). La estación de tren de Tesalónica se encuentra en la calle Monastiriou.

Otras zonas residenciales extensas y densamente edificadas son Charilaou y Toumba , que se divide en "Ano Toumpa" y "Kato Toumpa". Toumba debe su nombre a la colina homónima de Toumba, donde se llevan a cabo extensas investigaciones arqueológicas. Fue creada por refugiados después del desastre de Asia Menor de 1922 y el intercambio de población (1923-24). En la avenida Exochon ( Rue des Campagnes , hoy avenidas Vasilissis Olgas y Vasileos Georgiou), fue hasta la década de 1920 el hogar de los residentes más adinerados de la ciudad y formó los suburbios más externos de la ciudad en ese momento, con el área cercana al Golfo Termaico , de las villas de vacaciones del siglo XIX que definieron el área. [204] [205]

Otros distritos de la zona urbana más amplia de Tesalónica son Ampelokipi, Eleftherio – Kordelio, Menemeni, Evosmos, Ilioupoli, Stavroupoli, Nikopoli, Neapoli, Polichni, Paeglos, Meteora, Agios Pavlos, Kalamaria, Pylaia y Sykies. En el noroeste de Tesalónica se encuentra Moni Lazariston , ubicado en Stavroupoli , que hoy constituye uno de los centros culturales más importantes de la ciudad, incluyendo MOMus–Museo de Arte Moderno–Colección Costakis y dos teatros del Teatro Nacional del Norte de Grecia . [206] [207]

En el noroeste de Tesalónica existen numerosos espacios culturales, como el teatro al aire libre Manos Katrakis en Sykies, el Museo del Helenismo Refugiado en Neapolis, el teatro municipal y el teatro al aire libre en Neapoli y el Nuevo Centro Cultural de Menemeni (calle Ellis Alexiou). [208] El Jardín Botánico de Stavroupolis en la calle Perikleous incluye 1.000 especies de plantas y es un oasis de vegetación de 5 acres (2,0 ha). El Centro de Educación Ambiental en Kordelio fue diseñado en 1997 y es uno de los pocos edificios públicos de diseño bioclimático en Tesalónica. [209]

El noroeste de Tesalónica constituye el principal punto de entrada a la ciudad de Tesalónica, atravesado por las avenidas Monastiriou, Lagkada y 26is Octovriou, así como por la prolongación de la autopista A1, que desemboca en el centro de la ciudad de Tesalónica. En esta zona se encuentran la terminal de autobuses interurbanos de Macedonia ( KTEL ), la estación de tren de Tesalónica y el cementerio militar conmemorativo de los aliados de Zeitenlik .

También se han erigido monumentos en honor de los combatientes de la Resistencia griega , ya que en estas zonas la Resistencia fue muy activa: el monumento de la Resistencia Nacional Griega en Sykies, el monumento de la Resistencia Nacional Griega en Stavroupolis, la Estatua de la Madre Luchadora en la Plaza Eptalofos y el monumento de los jóvenes griegos que fueron ejecutados por los nazis el 11 de mayo de 1944 en Xirokrini. En Eptalofos, el 15 de mayo de 1941, un mes después de la ocupación del país, se fundó la primera organización de resistencia en Grecia, "Eleftheria", con su periódico y la primera imprenta ilegal en la ciudad de Tesalónica. [210] [211]

En la actualidad, el sureste de Tesalónica se ha convertido de alguna manera en una extensión del centro de la ciudad, con las avenidas Megalou Alexandrou, Georgiou Papandreou (Antheon), Vasileos Georgiou, Vasilissis Olgas, Delfon, Konstantinou Karamanli (Nea Egnatia) y Papanastasiou pasando por ella, encierra un área tradicionalmente llamada Ντεπώ ( Depó , lit. Dépôt), del nombre de la antigua estación de tranvía, propiedad de una empresa francesa.

El municipio de Kalamaria también está situado en el sureste de Tesalónica y, en un principio, estuvo habitado principalmente por refugiados griegos de Asia Menor y Tracia Oriental después de 1922. [212] Allí se construyeron el Comando Naval del Norte de Grecia y el antiguo palacio real (llamado Palataki ), ubicado en el punto más occidental del cabo Mikro Emvolo .

Debido a la importancia de Tesalónica durante los primeros períodos cristiano y bizantino , la ciudad alberga varios monumentos paleocristianos que han contribuido significativamente al desarrollo del arte y la arquitectura bizantina en todo el Imperio bizantino , así como en Serbia . [160] La evolución de la arquitectura bizantina imperial y la prosperidad de Tesalónica van de la mano, especialmente durante los primeros años del Imperio, [160] cuando la ciudad continuó floreciendo. Fue en esa época cuando se construyó el Complejo del emperador romano Galerio , así como la primera iglesia de Hagios Demetrios . [160]

En el siglo VIII, la ciudad se había convertido en un importante centro administrativo del Imperio bizantino y manejaba gran parte de los asuntos del Imperio en los Balcanes . [213] Durante ese tiempo, la ciudad vio la creación de iglesias cristianas más notables que ahora son parte del Patrimonio de la Humanidad de la UNESCO de Tesalónica, como la Iglesia de Santa Catalina , la Santa Sofía de Tesalónica , la Iglesia de Acheiropoietos y la Iglesia de Panagia Chalkeon . [160] Cuando el Imperio Otomano tomó el control de Tesalónica en 1430, la mayoría de las iglesias de la ciudad se convirtieron en mezquitas , [160] pero han sobrevivido hasta nuestros días. Viajeros como Paul Lucas y Abdulmejid I [160] documentan la riqueza de la ciudad en monumentos cristianos durante los años de control otomano de la ciudad.

La iglesia de San Demetrio se quemó durante el Gran Incendio de Tesalónica de 1917 , al igual que muchos otros monumentos de la ciudad, pero fue reconstruida. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial , la ciudad fue bombardeada extensamente y, como tal, muchos de los monumentos paleocristianos y bizantinos de Tesalónica resultaron gravemente dañados. [213] Algunos de los sitios no fueron restaurados hasta la década de 1980. Tesalónica tiene más monumentos catalogados como Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO que cualquier otra ciudad de Grecia, un total de 15 monumentos. [160] Han estado listados desde 1988. [160]

_-_panoramio_(2).jpg/440px-Θεσσαλονίκη_2014_(The_Statue_of_Alexander_the_Great)_-_panoramio_(2).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Aristotelous_Square_-_panoramio_(1).jpg)

There are around 150 statues or busts in the city.[214] Probably the most famous one is the equestrian statue of Alexander the Great on the promenade, placed in 1973 and created by sculptor Evangelos Moustakas. An equestrian statue of Constantine I, by sculptor Georgios Dimitriades, is located in Demokratias Square. Other notable statues include that of Eleftherios Venizelos by sculptor Giannis Pappas, Pavlos Melas by Natalia Mela, the statue of Emmanouel Pappas by Memos Makris, Chrysostomos of Smyrna by Athanasios Apartis, Aristotle on Aristotelous Square and such as various creations by George Zongolopoulos.

With the 100th anniversary of the 1912 incorporation of Thessaloniki into Greece, the government announced a large-scale redevelopment programme for the city of Thessaloniki, which aims in addressing the current environmental and spatial problems[215] that the city faces. More specifically, the programme will drastically change the physiognomy of the city[215] by relocating the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre and grounds of the Thessaloniki International Fair outside the city centre and turning the current location into a large metropolitan park,[216] redeveloping the coastal front of the city,[216] relocating the city's numerous military camps and using the grounds and facilities to create large parklands and cultural centres;[216] and the complete redevelopment of the harbour and the Lachanokipoi and Dendropotamos districts (behind and near the Port of Thessaloniki) into a commercial business district,[216] with possible highrise developments.[217]

The plan also envisions the creation of new wide avenues in the outskirts of the city[216] and the creation of pedestrian-only zones in the city centre.[216] Furthermore, the program includes plans to expand the jurisdiction of Seich Sou Forest National Park[215] and the improvement of accessibility to and from the Old Town.[215] The ministry has said that the project will take an estimated 15 years to be completed, in 2025.[216]

Part of the plan has been implemented with extensive pedestrianisations within the city centre by the municipality of Thessaloniki and the revitalisation the eastern urban waterfront/promenade, Νέα Παραλία (Néa Paralía, lit. new promenade), with a modern and vibrant design. Its first section opened in 2008, having been awarded as the best public project in Greece of the last five years by the Hellenic Institute of Architecture.[218]

The municipality of Thessaloniki's budget for the reconstruction of important areas of the city and the completion of the waterfront, opened in January 2014, was estimated at €28.2 million (US$39.9 million) for the year 2011 alone.[219]

Thessaloniki rose to economic prominence as a major economic hub in the Balkans during the years of the Roman Empire. The Pax Romana and the city's strategic position allowed for the facilitation of trade between Rome and Byzantium (later Constantinople and now Istanbul) through Thessaloniki by means of the Via Egnatia.[223] The Via Egnatia also functioned as an important line of communication between the Roman Empire and the nations of Asia,[223] particularly in relation to the Silk Road. With the partition of the Roman Empire into East (Byzantine) and West, Thessaloniki became the second-largest city of the Eastern Roman Empire after New Rome (Constantinople) in terms of economic might.[49][223] Under the Empire, Thessaloniki was the largest port in the Balkans.[224] As the city passed from Byzantium to the Republic of Venice in 1423, it was subsequently conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Under Ottoman rule the city retained its position as the most important trading hub in the Balkans.[93] Manufacturing, shipping and trade were the most important components of the city's economy during the Ottoman period,[93] and the majority of the city's trade at the time was controlled by ethnic Greeks.[93] Plus, the Jewish community was also an important factor in the trade sector.[citation needed]

Historically important industries for the economy of Thessaloniki included tobacco (in 1946 35% of all tobacco companies in Greece were headquartered in the city, and 44% in 1979)[225] and banking (in Ottoman years Thessaloniki was a major centre for investment from western Europe, with the Banque de Salonique having a capital of 20 million French francs in 1909).[93]

The service sector accounts for nearly two-thirds of the total labour force of Thessaloniki.[226] Of those working in services, 20% were employed in trade; 13% in education and healthcare; 7.1% in real estate; 6.3% in transport, communications and storage; 6.1% in the finance industry and service-providing organizations; 5.7% in public administration and insurance services; and 5.4% in hotels and restaurants.[226]

The city's port, the Port of Thessaloniki, is one of the largest ports in the Aegean and as a free port, it functions as a major gateway to the Balkan hinterland.[11][227] In 2010, more than 15.8 million tons of products went through the city's port,[228] making it the second-largest port in Greece after Aghioi Theodoroi, surpassing Piraeus. At 273,282 TEUs, it is also Greece's second-largest container port after Piraeus.[229] As a result, the city is a major transportation hub for the whole of south-eastern Europe,[230] carrying, among other things, trade to and from the neighbouring countries.[citation needed]

In recent years Thessaloniki has begun to turn into a major port for cruising in the eastern Mediterranean.[227] The Greek ministry of tourism considers Thessaloniki to be Greece's second most important commercial port,[231] and companies such as Royal Caribbean International have expressed interest in adding the Port of Thessaloniki to their destinations.[231] A total of 30 cruise ships are expected to arrive at Thessaloniki in 2011.[231]

After WWII and the Greek Civil War, heavy industrialization of the city's suburbs began in the mid-1950s.[232]

During the 1980s, a spate of factory shutdowns occurred, mostly of automobile manufacturers, such as Agricola, AutoDiana, EBIAM, Motoemil, Pantelemidis-TITAN and C.AR. Since the 1990s, companies took advantage of cheaper labour markets and more lax regulations than in other countries, and among the largest companies to shut down factories were Goodyear,[233] AVEZ pasta industry (one of the first industrial factories in northern Greece, built in 1926),[234] Philkeram Johnson, AGNO dairy and VIAMIL.

However, Thessaloniki still remains a major business hub in the Balkans and Greece, with a number of important Greek companies headquartered in the city, such as the Hellenic Vehicle Industry (ELVO), Namco, Astra Airlines, Ellinair, Pyramis and MLS Multimedia, which introduced the first Greek-built smartphone in 2012.[235]

In early 1960s, with the collaboration of Standard Oil and ESSO-Pappas, a large industrial zone was created, containing refineries, oil refinery and steel production (owned by Hellenic Steel Co.). The zone attracted also a series of different factories during the next decades.

Titan Cement has also facilities outside the city, on the road to Serres,[236] such as the AGET Heracles, a member of the Lafarge group, and Alumil SA.

Multinational companies such as Air Liquide, Cyanamid, Nestlé, Pfizer, Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company and Vivartia have also industrial facilities in the suburbs of the city.[237]

Foodstuff or drink companies headquartered in the city include the Macedonian Milk Industry (Mevgal), Allatini, Barbastathis, Hellenic Sugar Industry, Haitoglou Bros, Mythos Brewery, Malamatina, while the Goody's chain started from the city.[citation needed]

The American Farm School also is an important contributor to local food production.[238]

In 2011, the regional unit of Thessaloniki had a Gross Domestic Product of €18.293 billion (ranked second amongst the country's regional units),[220] comparable to Bahrain or Cyprus, and a per capita of €15,900 (ranked 16th).[220] In Purchasing Power Parity, the same indicators are €19,851 billion (2nd)[220] and €17,200 (15th) respectively.[220] In terms of comparison with the European Union average, Thessaloniki's GDP per capita indicator stands at 63% the EU average[220] and 69% in PPP[220] – this is comparable to the German state of Brandenburg.[220] Overall, Thessaloniki accounts for 8.9% of the total economy of Greece.[220] Between 1995 and 2008 Thessaloniki's GDP saw an average growth rate of 4.1% per annum (ranging from +14.5% in 1996 to −11.1% in 2005) while in 2011 the economy contracted by −7.8%.[220]

The tables below show the ethnic statistics of Thessaloniki during the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

The municipality of Thessaloniki is the most populous in the Thessaloniki Urban Area. Its population has increased in the latest census and the metropolitan area's population rose to over one million. The city forms the base of the Thessaloniki metropolitan area, with latest census in 2021 giving it a population of 1,091,424.[239]

The Jewish population in Greece is the oldest in mainland Europe (see Romaniotes). When Paul the Apostle came to Thessaloniki, he taught in the area of what today is called Upper City. Later, during the Ottoman period, with the coming of Sephardic Jews from Spain, the community of Thessaloniki became mostly Sephardic. Thessaloniki became the largest centre in Europe of the Sephardic Jews, who nicknamed the city la madre de Israel (Israel's mother)[147] and "Jerusalem of the Balkans".[244] It also included the historically significant and ancient Greek-speaking Romaniote community. During the Ottoman era, Thessaloniki's Sephardic community was half of the population according to the Ottoman Census of 1902 and almost 40% the city's population of 157,000 about 1913; Jewish merchants were prominent in commerce until the ethnic Greek population increased after Thessaloniki was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece in 1913. By the 1680s, about 300 families of Sephardic Jews, followers of Sabbatai Zevi, had converted to Islam, becoming a sect known as the Dönmeh (convert), and migrated to Salonika, whose population was majority Jewish. They established an active community that thrived for about 250 years. Many of their descendants later became prominent in trade.[245] Many Jewish inhabitants of Thessaloniki spoke Judeo-Spanish, the Romance language of the Sephardic Jews.[246]

From the second half of the 19th century with the Ottoman reforms, the Jewish community had a new revival. Many French and especially Italian Jews (from Livorno and other cities), influential in introducing new methods of education and developing new schools and intellectual environments for the Jewish population, were established in Thessaloniki. Such modernists introduced also new techniques and ideas from the industrialised Western Europe and from the 1880s the city began to industrialize. The Italian-Jewish Allatini brothers led Jewish entrepreneurship, establishing milling and other food industries, brickmaking and processing plants for tobacco. Several traders supported the introduction of a large textile-production industry, superseding the weaving of cloth in a system of artisanal production. Notable names of the era include among others the Italo-Jewish Modiano family and the Allatini. Benrubis founded also in 1880 one of the first retail companies in the Balkans.

After the Balkan Wars, Thessaloniki was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece in 1913. At first, the community feared that the annexation would lead to difficulties and during the first years its political stance was, in general, anti-Venizelist and pro-royalist/conservative. The Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 during World War I burned much of the centre of the city and left 50,000 Jews homeless of the total of 72,000 residents who were burned out.[137] Having lost homes and their businesses, many Jews emigrated to the United States, Palestine, and Paris. They could not wait for the government to create a new urban plan for rebuilding, which was eventually done.[247]

After the Greco-Turkish War in 1922 and the bilateral population exchange between Greece and Turkey, many refugees came to Greece. Nearly 100,000 ethnic Greeks resettled in Thessaloniki, reducing the proportion of Jews in the total community. After this, Jews made up about 20% of the city's population. During the interwar period, Greece granted Jewish citizens the same civil rights as other Greek citizens.[137] In March 1926, Greece re-emphasized that all citizens of Greece enjoyed equal rights, and a considerable proportion of the city's Jews decided to stay. During the Metaxas regime, the stance towards Jews improved even more.

World War II brought disaster for the Jewish Greeks, since in 1941 the Germans occupied Greece and began actions against the Jewish population. Greeks of the Resistance helped save some of the Jewish residents.[147] By the 1940s, the great majority of the Jewish Greek community firmly identified as both Greek and Jewish. According to Misha Glenny, such Greek Jews had largely not encountered "anti-Semitism as in its North European form."[248]

In 1943, the Nazis began brutal actions against the historic Jewish population in Thessaloniki, forcing them into a ghetto near the railroad lines and beginning deportation to concentration and labor camps. They deported and exterminated approximately 94% of Thessaloniki's Jews of all ages during the Holocaust.[249] The Thessaloniki Holocaust memorial in Eleftherias ("Freedom") Square was built in 1997 in memory of all the Jewish people from Thessaloniki murdered in the Holocaust. The site was chosen because it was the place where Jewish residents were rounded up before embarking on trains for concentration camps.[250][251] Today, a community of around 1,200 remains in the city.[147] Communities of descendants of Thessaloniki Jews – both Sephardic and Romaniote – live in other areas, mainly the United States and Israel.[249] Israeli singer Yehuda Poliker recorded a song about the Jewish people of Thessaloniki, called "Wait for me, Thessaloniki".

Since the late 19th century, many merchants from Western Europe (mainly from France and Italy) were established in the city. They had an important role in the social and economic life of the city and introduced new industrial techniques. Their main district was what is known today as the "Frankish district" (near Ladadika), where the Catholic church designed by Vitaliano Poselli is also situated.[253][254] A part of them left after the incorporation of the city into the Greek kingdom, while others, who were of Jewish faith, were exterminated by the Nazis.

The Bulgarian community of the city increased during the late 19th century.[255] The community had a Men's High School, a Girl's High School, a trade union and a gymnastics society. A large part of them were Catholics, as a result of actions by the Lazarists society, which had its base in the city.

Another group is the Armenian community which dates back to the Byzantine and Ottoman periods. During the 20th century, after the Armenian genocide and the defeat of the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22), many fled to Greece including Thessaloniki. There is also an Armenian cemetery and an Armenian church at the centre of the city.[256]

Thessaloniki is regarded not only as the cultural and entertainment capital of northern Greece[213][257] but also the cultural capital of the country as a whole.[12] The city's main theaters, run by the National Theatre of Northern Greece (Greek: Κρατικό Θέατρο Βορείου Ελλάδος) which was established in 1961,[258] include the Theater of the Society of Macedonian Studies, where the National Theater is based, the Royal Theater (Βασιλικό Θέατρο) - the first base of the National Theater - Moni Lazariston, and the Earth Theater and Forest Theater, both amphitheatrical open-air theatres overlooking the city.[258]

The title of the European Capital of Culture in 1997 saw the birth of the city's first opera[259] and today forms an independent section of the National Theatre of Northern Greece.[260] The opera is based at the Thessaloniki Concert Hall, one of the largest concert halls in Greece. Recently a second building was also constructed and designed by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki. Thessaloniki is also the seat of two symphony orchestras, the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra and the Symphony Orchestra of the Municipality of Thessaloniki.Olympion Theater, the site of the Thessaloniki International Film Festival and the Plateia Assos Odeon multiplex are the two major cinemas in downtown Thessaloniki. The city also has a number of multiplex cinemas in major shopping malls in the suburbs, most notably in Mediterranean Cosmos, the largest retail and entertainment development in the Balkans.

Thessaloniki is renowned for its major shopping streets and lively laneways. Tsimiski Street, Mitropoleos and Proxenou Koromila avenue are the city's most famous shopping streets and are among Greece's most expensive and exclusive high streets. The city is also home to one of Greece's most famous and prestigious hotels, Makedonia Palace hotel, the Hyatt Regency Casino and hotel (the biggest casino in Greece and one of the biggest in Europe) and Waterland, the largest water park in southeastern Europe.

The city has long been known in Greece for its vibrant city culture, including having the most cafes and bars per capita of any city in Europe; and as having some of the best nightlife and entertainment in the country, thanks to its large young population and multicultural feel. Lonely Planet listed Thessaloniki among the world's "ultimate party cities".[261]

Although Thessaloniki is not renowned for its parks and greenery throughout its urban area, where green spaces are few, it has several large open spaces around its waterfront, namely the central city gardens of Palios Zoologikos Kipos (which is recently being redeveloped to also include rock climbing facilities, a new skatepark and paintball range),[262] the park of Pedion tou Areos, which also holds the city's annual floral expo; and the parks of the Nea Paralia (waterfront) that span for 3 km (2 mi) along the coast, from the White Tower to the concert hall.

The Nea Paralia parks are used throughout the year for a variety of events, while they open up to the Thessaloniki waterfront, which is lined up with several cafés and bars; and during summer is full of Thessalonians enjoying their long evening walks (referred to as "the volta" and is embedded into the culture of the city). Having undergone an extensive revitalization, the city's waterfront today features a total of 12 thematic gardens/parks.[263]

Thessaloniki's proximity to places such as the national parks of Pieria and beaches of Chalkidiki often allow its residents to easily have access to some of the best outdoor recreation in Europe; however, the city is also right next to the Seich Sou forest national park, just 3.5 km (2 mi) away from Thessaloniki's city centre; and offers residents and visitors alike, quiet viewpoints towards the city, mountain bike trails and landscaped hiking paths.[264] The city's zoo, which is operated by the municipality of Thessaloniki, is also located nearby the national park.[265]

Other recreation spaces throughout the Thessaloniki metropolitan area include the Fragma Thermis, a landscaped parkland near Thermi and the Delta wetlands west of the city centre; while urban beaches that have continuously been awarded the blue flags,[266] are located along the 10 km (6 mi) coastline of Thessaloniki's southeastern suburbs of Thermaikos, about 20 km (12 mi) away from the city centre.

Because of the city's rich and diverse history, Thessaloniki houses many museums dealing with many different eras in history. Two of the city's most famous museums include the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of Byzantine Culture.

The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki was established in 1962 and houses some of the most important ancient Macedonian artifacts,[267] including an extensive collection of golden artwork from the royal palaces of Aigai and Pella.[268] It also houses exhibits from Macedon's prehistoric past, dating from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.[269] The Prehistoric Antiquities Museum of Thessaloniki has exhibits from those periods as well.

The Museum of Byzantine Culture is one of the city's most famous museums, showcasing the city's glorious Byzantine past.[270] The museum was also awarded Council of Europe's museum prize in 2005.[271] The museum of the White Tower of Thessaloniki houses a series of galleries relating to the city's past, from the creation of the White Tower until recent years.[272]

One of the most modern museums in the city is the Thessaloniki Science Centre and Technology Museum and is one of the most high-tech museums in Greece and southeastern Europe.[273] It features the largest planetarium in Greece, a cosmotheatre with the country's largest flat screen, an amphitheater, a motion simulator with 3D projection and 6-axis movement and exhibition spaces.[273] Other industrial and technological museums in the city include the Railway Museum of Thessaloniki, which houses an original Orient Express train, the War Museum of Thessaloniki and others. The city also has a number of educational and sports museums, including the Thessaloniki History Centre and the Thessaloniki Olympic Museum.

The Atatürk Museum in Thessaloniki is the historic house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern-day Turkey, was born. The house is now part of the Turkish consulate complex, but admission to the museum is free.[274] The museum contains historic information about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his life, especially while he was in Thessaloniki.[274] Other ethnological museums of the sort include the Historical Museum of the Balkan Wars, the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, containing information about the anti-Ottoman rebellions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[275] Construction on the Holocaust Museum of Greece began in the city in 2018.[203]

The city also has a number of important art galleries. Such include the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, housing exhibitions from a number of well-known Greek and foreign artists.[276] The Teloglion Foundation of Art is part of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and includes an extensive collection of works by important artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, including works by prominent Greeks and native Thessalonians.[277] The Thessaloniki Museum of Photography also houses a number of important exhibitions, and is located within the old port of Thessaloniki.[278]

Thessaloniki is home to a number of prominent archaeological sites. Apart from its recognized UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Thessaloniki features a large two-terraced Roman forum[279] featuring two-storey stoas,[280] dug up by accident in the 1960s.[279] The forum complex also boasts two Roman baths,[281] one of which has been excavated while the other is buried underneath the city.[281] The forum also features a small theater,[279][281] which was also used for gladiatorial games.[280] Although the initial complex was not built in Roman times, it was largely refurbished in the second century.[281] It is believed that the forum and the theater continued to be used until at least the sixth century.[282]

Another important archaeological site is the imperial palace complex which Roman emperor Galerius, located at Navarinou Square, commissioned when he made Thessaloniki the capital of his portion of the Roman Empire.[44][45] The large octagonal portion of the complex, most of which survives to this day, is believed to have been an imperial throne room.[280] Various mosaics from the palatial complex have also survived.[283] Some historians believe that the complex must have been in use as an imperial residence until the 11th century.[282]

Not far from the palace itself is the Arch of Galerius,[283] known colloquially as the Kamara. The arch was built to commemorate the emperor's campaigns against the Persians.[280][283] The original structure featured three arches;[280] however, only two full arches and part of the third survive to this day. Many of the arches' marble parts survive as well,[280] although it is mostly the brick interior that can be seen today.

Other monuments of the city's past, such as Las Incantadas, a Caryatid portico from the ancient forum, have been removed or destroyed over the years. Las Incantadas in particular are on display at the Louvre.[279][284] Thanks to a private donation of €180,000, it was announced on 6 December 2011 that a replica of Las Incantadas would be commissioned and later put on display in Thessaloniki.[284]

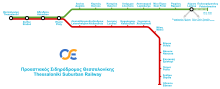

The construction of the Thessaloniki Metro inadvertently started the largest archaeological dig not only of the city, but of Northern Greece; the dig spans 20 km2 (7.7 sq mi) and has unearthed 300,000 individual artefacts from as early as the Roman Empire and as late as the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917.[285][286] Ancient Thessaloniki's Decumanus Maximus was also found and 75 metres (246 ft) of the marble-paved and column-lined road were unearthed along with shops, other buildings, and plumbing, prompting one scholar to describe the discovery as "the Byzantine Pompeii".[287] Some of the artefacts will be put on display inside the metro stations, while Venizelou will feature the world's first open archaeological site located within a metro station.[288][289]

Thessaloniki is home of a number of festivals and events.[290] The Thessaloniki International Fair is the most important event to be hosted in the city annually, by means of economic development. It was first established in 1926[291] and takes place every year at the 180,000 m2 (1,900,000 sq ft) Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre. The event attracts major political attention and it is customary for the Prime Minister of Greece to outline his administration's policies for the next year during the event. Over 250,000 visitors attended the exposition in 2010.[292] The new Art Thessaloniki, is starting first time 29.10. – 1 November 2015 as an international contemporary art fair. The Thessaloniki International Film Festival is established as one of the most important film festivals in Southern Europe,[293] with a number of notable filmmakers such as Francis Ford Coppola, Faye Dunaway, Catherine Deneuve, Irene Papas and Fatih Akın taking part, and was established in 1960.[294] The Documentary Festival, founded in 1999, has focused on documentaries that explore global social and cultural developments, with many of the films presented being candidates for FIPRESCI and Audience Awards.[295]

The Dimitria festival, founded in 1966 and named after the city's patron saint of St. Demetrius, has focused on a wide range of events including music, theatre, dance, local happenings, and exhibitions.[296] The DMC DJ Championship has been hosted at the International Trade Fair of Thessaloniki, has become a worldwide event for aspiring DJs and turntablists. The International Festival of Photography has taken place every February to mid-April.[297] Exhibitions for the event are sited in museums, heritage landmarks, galleries, bookshops and cafés. Thessaloniki also holds an annual International Book Fair.[298]

Between 1962–1997 and 2005–2008, the city also hosted the Thessaloniki Song Festival,[299] Greece's most important music festival, at Alexandreio Melathron.[300]

In 2012, the city hosted its first pride parade, Thessaloniki Pride, which took place between 22 and 23 June.[301] It has been held every year ever since, however in 2013 transgender people participating in the parade became victims of police brutality. The issue was soon settled by the government.[302] The city's Greek Orthodox Church leadership has consistently rallied against the event, but mayor Boutaris sided with Thessaloniki Pride, saying also that Thessaloniki would seek to host EuroPride 2020.[303] The event was given to Thessaloniki in September 2017, beating Bergen, Brussels, and Hamburg.[304]Since 1998, the city host Thessaloniki International G.L.A.D. Film Festival, the first LGBT film festival in Greece.