Xinjiang , [a] oficialmente la Región Autónoma Uygur de Xinjiang , [11] [12] es una región autónoma de la República Popular China (RPC), ubicada en el noroeste del país en la encrucijada de Asia Central y Asia Oriental . Siendo la división a nivel de provincia más grande de China por área y la octava subdivisión de país más grande del mundo, Xinjiang se extiende por más de 1,6 millones de kilómetros cuadrados (620.000 millas cuadradas) y tiene alrededor de 25 millones de habitantes. [1] [13] Xinjiang limita con los países de Afganistán , India , Kazajistán , Kirguistán , Mongolia , Pakistán , Rusia y Tayikistán . Las escarpadas cadenas montañosas de Karakoram , Kunlun y Tian Shan ocupan gran parte de las fronteras de Xinjiang, así como sus regiones occidental y meridional. Las regiones de Aksai Chin y Trans-Karakoram Tract son reclamadas por India pero administradas por China. [14] [15] [16] Xinjiang también limita con la Región Autónoma del Tíbet y las provincias de Gansu y Qinghai . La ruta más conocida de la histórica Ruta de la Seda atravesaba el territorio desde el este hasta su frontera noroccidental.

Xinjiang está dividida en la cuenca de Dzungaria ( Dzungaria ) en el norte y la cuenca de Tarim en el sur por una cadena montañosa y solo alrededor del 9,7 por ciento de la superficie terrestre de Xinjiang es apta para la habitación humana. [17] [¿ Fuente poco confiable? ] Es el hogar de varios grupos étnicos, incluidos los tayikos chinos ( Pamiris ), los chinos Han , los hui , los kazajos , los kirguisos , los mongoles , los rusos , los sibe , los tibetanos y los uigures . [18] Hay más de una docena de prefecturas y condados autónomos para minorías en Xinjiang. Las obras de referencia más antiguas en idioma inglés a menudo se refieren al área como Turkestán chino , [19] [20] Turkestán chino, [21] Turkestán oriental [22] y Turkestán oriental. [23]

Con una historia documentada de al menos 2.500 años, una sucesión de personas e imperios han competido por el control de todo o parte de este territorio. El territorio quedó bajo el gobierno de la dinastía Qing en el siglo XVIII, que luego fue reemplazada por la República de China . Desde 1949 y la Guerra Civil China , ha sido parte de la República Popular China. En 1954, el Partido Comunista Chino (PCCh) estableció el Cuerpo de Producción y Construcción de Xinjiang (XPCC) para fortalecer la defensa fronteriza contra la Unión Soviética y promover la economía local mediante el asentamiento de soldados en la región. [24] En 1955, Xinjiang pasó de ser una provincia a una región autónoma administrativamente . En las últimas décadas, se han encontrado abundantes reservas de petróleo y minerales en Xinjiang y actualmente es la región productora de gas natural más grande de China.

Desde la década de 1990 hasta la de 2010, el movimiento independentista del Turkestán Oriental , el conflicto separatista y la influencia del Islam radical han provocado disturbios en la región con ocasionales ataques terroristas y enfrentamientos entre fuerzas separatistas y gubernamentales. [25] [26] Estos conflictos llevaron al gobierno chino a cometer una serie de continuos abusos de los derechos humanos contra los uigures y otras minorías étnicas y religiosas en la provincia, incluido, según algunos, el genocidio. [27] [28]

La región general de Xinjiang ha sido conocida por muchos nombres diferentes a lo largo del tiempo. Estos nombres incluyen Altishahr , el nombre uigur histórico para la mitad sur de la región que hace referencia a "las seis ciudades" de la cuenca del Tarim , así como Khotan, Khotay, Tartaria china , Alta Tartaria, Chagatay Oriental (era la parte oriental del Kanato de Chagatai ), Moghulistan ("tierra de los mongoles"), Kashgaria, Pequeña Bukhara, Serindia (debido a la influencia cultural india) [30] y, en chino, Xiyu (西域), que significa " Regiones occidentales ". [31]

Entre el siglo II a. C. y el siglo II d. C., el Imperio Han estableció el Protectorado de las Regiones Occidentales o Protectorado Xiyu (西域都護府) en un esfuerzo por asegurar las rutas rentables de la Ruta de la Seda . [32] Las regiones occidentales durante la era Tang se conocían como Qixi (磧西). Qi se refiere al desierto de Gobi, mientras que Xi se refiere al oeste. El Imperio Tang había establecido el Protectorado General para Pacificar el Oeste o Protectorado Anxi (安西都護府) en 640 para controlar la región.

Durante la dinastía Qing , la parte norte de Xinjiang, Dzungaria , era conocida como Zhunbu (準部, " región de Dzungar ") y la cuenca meridional del Tarim era conocida como Huijiang (回疆, "frontera musulmana"). Ambas regiones se fusionaron después de que la dinastía Qing reprimiera la revuelta de Altishahr Khojas en 1759 y se convirtieron en la región de "Xiyu Xinjiang" (西域新疆, literalmente "Nueva frontera de las regiones occidentales"), más tarde simplificada como "Xinjiang" (新疆; anteriormente romanizado como "Sinkiang"). El nombre oficial fue dado durante el reinado del emperador Guangxu en 1878. [33] Puede traducirse como "nueva frontera" o "nuevo territorio". [34] De hecho, el término "Xinjiang" se utilizó en muchos otros lugares conquistados, pero nunca fueron gobernados directamente por los imperios chinos hasta la reforma administrativa gradual de Gaitu Guiliu , incluidas las regiones del sur de China. [35] Por ejemplo, el actual condado de Jinchuan en Sichuan se conocía entonces como "Jinchuan Xinjiang", Zhaotong en Yunnan se nombró directamente como "Xinjiang", la región de Qiandongnan , Anshun y Zhenning se denominaron "Liangyou Xinjiang", etc. [36]

En 1955, la provincia de Xinjiang pasó a llamarse "Región Autónoma Uigur de Xinjiang". El nombre que se propuso originalmente fue simplemente "Región Autónoma de Xinjiang" porque ese era el nombre del territorio imperial. Esta propuesta no fue bien recibida por los uigures en el Partido Comunista, quienes encontraron el nombre colonialista en su naturaleza ya que significaba "nuevo territorio". Saifuddin Azizi , el primer presidente de Xinjiang, expresó sus fuertes objeciones al nombre propuesto ante Mao Zedong , argumentando que "la autonomía no se da a las montañas y los ríos. Se da a nacionalidades particulares". Algunos comunistas uigures propusieron en cambio el nombre " Región Autónoma Uigur de Tian Shan ". Los comunistas Han en el gobierno central negaron que el nombre Xinjiang fuera colonialista y negaron que el gobierno central pudiera ser colonialista tanto porque eran comunistas como porque China era víctima del colonialismo. Sin embargo, debido a las quejas de los uigures, la región administrativa se llamaría " Región Autónoma Uigur de Xinjiang ". [37] [34]

Xinjiang consta de dos regiones principales geográfica, histórica y étnicamente distintas con diferentes nombres históricos, Dzungaria al norte de las montañas Tianshan y la cuenca del Tarim al sur de las montañas Tianshan, antes de que la China Qing las unificara en una entidad política llamada Provincia de Xinjiang en 1884. En el momento de la conquista Qing en 1759, Dzungaria estaba habitada por el pueblo budista tibetano nómada Dzungar que vivía en las estepas, mientras que la cuenca del Tarim estaba habitada por agricultores musulmanes sedentarios que vivían en oasis y hablaban turco, ahora conocidos como uigures, que fueron gobernados por separado hasta 1884.

La dinastía Qing era muy consciente de las diferencias entre la antigua zona mongol budista al norte de Tian Shan y la zona musulmana turca al sur de Tian Shan y las gobernó en unidades administrativas separadas al principio. [38] Sin embargo, la gente Qing comenzó a pensar en ambas áreas como parte de una región distinta llamada Xinjiang. [39] El concepto mismo de Xinjiang como una identidad geográfica distinta fue creado por los Qing. [40] Durante el gobierno Qing, la gente común de Xinjiang no tenía ningún sentido de "identidad regional", más bien, la identidad distintiva de Xinjiang fue dada a la región por los Qing, ya que tenía una geografía, historia y cultura distintas, mientras que al mismo tiempo fue creada por los chinos, multicultural, colonizada por Han y Hui y separada de Asia Central durante más de un siglo y medio. [41]

A finales del siglo XIX, algunas personas todavía proponían crear dos regiones separadas a partir de Xinjiang, la zona al norte de Tianshan y la zona al sur de Tianshan, mientras se debatía si convertir Xinjiang en una provincia. [42]

Xinjiang es una zona extensa y escasamente poblada, que abarca más de 1,6 millones de km2 ( comparable en tamaño a Irán ), que ocupa aproximadamente una sexta parte del territorio del país. Xinjiang limita con la Región Autónoma del Tíbet y el distrito Leh de la India en Ladakh al sur, las provincias de Qinghai y Gansu al este, Mongolia ( provincias de Bayan-Ölgii , Govi-Altai y Khovd ) al este, la República de Altái de Rusia al norte y Kazajstán ( regiones de Almaty y Kazajstán Oriental ), Kirguistán ( regiones de Issyk-Kul , Naryn y Osh ), la Región Autónoma de Gorno-Badakhshan de Tayikistán , la provincia de Badakhshan de Afganistán y Gilgit-Baltistán de Pakistán al oeste.

La cadena este-oeste de Tian Shan separa Dzungaria, en el norte, de la cuenca de Tarim, en el sur. Dzungaria es una estepa seca y la cuenca de Tarim contiene el enorme desierto de Taklamakán , rodeado de oasis. En el este se encuentra la depresión de Turpan . En el oeste, Tian Shan se dividió y formó el valle del río Ili .

Los primeros habitantes de la región que hoy comprende Xinjiang eran genéticamente de origen euroasiático antiguo y nororiental , con un flujo genético posterior durante la Edad del Bronce vinculado a la expansión de los primeros indoeuropeos . Estas dinámicas poblacionales dieron lugar a una composición demográfica heterogénea. Las muestras de la Edad del Hierro de Xinjiang muestran niveles intensificados de mezcla entre pastores esteparios y asiáticos nororientales, con Xinjiang del norte y el este mostrando más afinidades con los asiáticos nororientales, y Xinjiang del sur mostrando más afinidad con los asiáticos centrales. [43] [44]

Entre 2009 y 2015, se analizaron los restos de 92 individuos del cementerio de Xiaohe en busca de marcadores de ADN mitocondrial y cromosoma Y. Los análisis genéticos de las momias mostraron que los linajes paternos del pueblo Xiaohe eran casi todos de origen europeo [45] , mientras que los linajes maternos de la población primitiva eran diversos, presentando linajes tanto de Eurasia oriental como de Eurasia occidental , así como un número menor de linajes indios /del sur de Asia. Con el tiempo, los linajes maternos de Eurasia occidental fueron reemplazados gradualmente por linajes maternos de Eurasia oriental. Los matrimonios con mujeres de comunidades siberianas llevaron a la pérdida de la diversidad original de los linajes de ADNmt observados en la población Xiaohe anterior. [46] [47] [48]

Por lo tanto, la población de Tarim siempre fue notablemente diversa, lo que refleja una historia compleja de mezcla entre personas de ascendencia del norte de Eurasia antigua , el sur de Asia y el noreste de Asia . Las momias de Tarim se han encontrado en varios lugares de la cuenca occidental de Tarim, como Loulan , el complejo de tumbas de Xiaohe y Qäwrighul . Anteriormente se ha sugerido que estas momias eran hablantes de tocario o indoeuropeo, pero evidencia reciente sugiere que las primeras momias pertenecían a una población distinta no relacionada con los pastores indoeuropeos y hablaban una lengua desconocida, probablemente una lengua aislada . [49]

Aunque muchos de los antropólogos clasificaron las momias del Tarim como caucásicas , los sitios de la cuenca del Tarim también contienen restos "caucasoides" y "mongoloides", lo que indica contacto entre los nómadas occidentales recién llegados y las comunidades agrícolas del este. [50] Se han encontrado momias en varios lugares de la cuenca occidental del Tarim, como Loulan , el complejo de tumbas de Xiaohe y Qäwrighul .

Las tribus nómadas como los yuezhi , los saka y los wusun probablemente formaron parte de la migración de hablantes indoeuropeos que se habían establecido en la cuenca del Tarim de Xinjiang mucho antes que los chinos xiongnu y han. Cuando la dinastía Han bajo el emperador Wu (r. 141-87 a. C.) arrebató la cuenca occidental del Tarim a sus señores anteriores (los xiongnu), estaba habitada por varios pueblos que incluían a los tocarios de habla indoeuropea en Turfan y Kucha , los pueblos saka centrados en el reino Shule y el reino de Khotan , los diversos grupos tibeto-birmanos (especialmente personas relacionadas con los qiang ), así como el pueblo chino han. [51] Algunos lingüistas postulan que la lengua tocario tuvo grandes cantidades de influencia de las lenguas paleosiberianas , [52] como las lenguas urálicas y yeniseanas .

La cultura yuezhi está documentada en la región. La primera referencia conocida a los yuezhi data del año 645 a. C. y la hizo el canciller chino Guan Zhong en su obra Guanzi (管子, Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). Describió a los yúshì ,禺氏(o niúshì ,牛氏), como un pueblo del noroeste que suministraba jade a los chinos desde las montañas cercanas (también conocidas como yushi) en Gansu. [53] El suministro de jade desde hace mucho tiempo [54] de la cuenca del Tarim está bien documentado arqueológicamente: "Es bien sabido que los antiguos gobernantes chinos tenían un fuerte apego al jade. Todos los objetos de jade excavados en la tumba de Fuhao de la dinastía Shang , más de 750 piezas, eran de Khotan en la actual Xinjiang. Ya a mediados del primer milenio a. C., los Yuezhi se dedicaban al comercio de jade, cuyos principales consumidores eran los gobernantes de la China agrícola". [55]

Atravesadas por la Ruta de la Seda del Norte , [56] las regiones de Tarim y Dzungaria eran conocidas como las Regiones Occidentales. A principios de la dinastía Han, la región estaba gobernada por los Xiongnu, un poderoso pueblo nómada. [57] : 148 Durante el siglo II a. C., la dinastía Han se preparó para la guerra contra los Xiongnu cuando el emperador Wu de Han envió a Zhang Qian para explorar los misteriosos reinos del oeste y formar una alianza con los Yuezhi contra los Xiongnu. Como resultado de la guerra, los chinos controlaron la región estratégica desde el corredor de Ordos y Gansu hasta Lop Nor . Separaron a los Xiongnu del pueblo Qiang en el sur y obtuvieron acceso directo a las Regiones Occidentales. La China Han envió a Zhang Qian como enviado a los estados de la región, lo que dio inicio a varias décadas de lucha entre los Xiongnu y la China Han en la que China finalmente prevaleció. Durante los años 100 a. C., la Ruta de la Seda trajo consigo una creciente influencia económica y cultural china a la región. [57] : 148 En el año 60 a. C., la China Han estableció el Protectorado de las Regiones Occidentales (西域都護府) en Wulei (烏壘, cerca de la moderna Luntai ), para supervisar la región hasta el oeste de las montañas Pamir . El protectorado fue tomado durante la guerra civil contra Wang Mang (r. 9-23 d. C.), y volvió al control Han en el año 91 debido a los esfuerzos del general Ban Chao .

La dinastía Jin Occidental sucumbió a sucesivas oleadas de invasiones de nómadas del norte a principios del siglo IV. Los efímeros reinos que gobernaron el noroeste de China uno tras otro, incluidos Antiguo Liang , Antiguo Qin , Liang Posterior y Liáng Occidental , intentaron todos mantener el protectorado, con distintos grados de éxito. Después de la reunificación final del norte de China bajo el imperio Wei del Norte , su protectorado controlaba lo que ahora es la región sudoriental de Xinjiang. Los estados locales como Shule, Yutian , Guizi y Qiemo controlaban la región occidental, mientras que la región central alrededor de Turpan estaba controlada por Gaochang , remanentes de un estado ( Liang del Norte ) que una vez gobernó parte de lo que ahora es la provincia de Gansu en el noroeste de China.

Durante la dinastía Tang, se llevaron a cabo una serie de expediciones contra el Khaganato turco occidental y sus vasallos: los estados oasis del sur de Xinjiang. [58] Las campañas contra los estados oasis comenzaron bajo el emperador Taizong con la anexión de Gaochang en 640. [59] El cercano reino de Karasahr fue capturado por los Tang en 644 y el reino de Kucha fue conquistado en 649. [ 60] La dinastía Tang luego estableció el Protectorado General para Pacificar Occidente (安西都護府) o Protectorado de Anxi, en 640 para controlar la región.

Durante la Rebelión de Anshi , que casi destruyó la dinastía Tang, el Tíbet invadió la dinastía Tang en un frente amplio desde Xinjiang hasta Yunnan . Ocupó la capital Tang de Chang'an en 763 durante 16 días y controló el sur de Xinjiang a fines de siglo. El Kanato uigur tomó el control del norte de Xinjiang, gran parte de Asia Central y Mongolia al mismo tiempo.

A medida que el Tíbet y el Kanato uigur declinaban a mediados del siglo IX, el Kanato Kara-Khanid (una confederación de tribus turcas que incluía a los karluks , chigils y yaghmas) [61] controló Xinjiang occidental durante los siglos X y XI. Después de que el Kanato uigur en Mongolia fuera destruido por los kirguises en 840, ramas de los uigures se establecieron en Qocha (Karakhoja) y Beshbalik (cerca de las actuales Turfan y Ürümqi). El estado uigur permaneció en Xinjiang oriental hasta el siglo XIII, aunque fue gobernado por señores extranjeros. Los Kara-Khanids se convirtieron al Islam. El estado uigur en Xinjiang oriental, inicialmente maniqueo , se convirtió más tarde al budismo .

Los restos de la dinastía Liao de Manchuria entraron en Xinjiang en 1132, huyendo de la rebelión de los vecinos Jurchens . Establecieron un nuevo imperio, el Qara Khitai (Liao occidental), que gobernó las partes de la cuenca del Tarim en manos de los Kara-Khanid y los Uyghur durante el siglo siguiente. Aunque el Khitan y el chino eran las principales lenguas administrativas, también se utilizaban el persa y el uigur. [62]

La actual Xinjiang estaba formada por la cuenca del Tarim y Dzungaria y originalmente estaba habitada por tocarios indoeuropeos y sakas iraníes que practicaban el budismo y el zoroastrismo . Las cuencas de Turfan y Tarim estaban habitadas por hablantes de lenguas tocarios, [63] con momias caucásicas encontradas en la región. [64] La zona se islamizó durante el siglo X con la conversión del kanato karakhanida , que ocupó Kashgar. A mediados del siglo X, el reino budista saka de Khotan fue atacado por el gobernante musulmán turco karakhanida Musa; el líder karakhanida Yusuf Qadir Khan conquistó Khotan alrededor de 1006. [65]

Después de que Gengis Kan unificara Mongolia y comenzara su avance hacia el oeste, el estado uigur de la región de Turpan-Urumchi ofreció su lealtad a los mongoles en 1209, contribuyendo con impuestos y tropas al esfuerzo imperial mongol. A cambio, los gobernantes uigures mantuvieron el control de su reino; el Imperio mongol de Gengis Kan conquistó Qara Khitai en 1218. Xinjiang era un bastión de Ögedei Kan y más tarde quedó bajo el control de su descendiente, Kaidu . Esta rama de la familia mongol mantuvo a raya a la dinastía Yuan hasta que terminó su gobierno.

Durante la era del Imperio mongol, la dinastía Yuan compitió con el Kanato Chagatai por el gobierno de la región y este último controló la mayor parte de ella. Después de que el Kanato Chagatai se dividiera en kanatos más pequeños a mediados del siglo XIV, la región políticamente fracturada fue gobernada por una serie de kanes mongoles persianizados, incluidos los de Moghulistán (con la ayuda de los emires locales Dughlat ), Uigurstan (más tarde Turpan) y Kashgaria. Estos líderes guerrearon entre sí y con los timúridas de Transoxiana al oeste y los oiratas al este: el sucesor del régimen Chagatai con base en Mongolia y China. Durante el siglo XVII, los Dzungar establecieron un imperio sobre gran parte de la región.

Los dzungars mongoles eran la identidad colectiva de varias tribus oirates que formaron y mantuvieron uno de los últimos imperios nómadas . El kanato dzungar cubría Dzungaria, extendiéndose desde la Gran Muralla China occidental hasta el actual Kazajistán oriental y desde el actual norte de Kirguistán hasta el sur de Siberia . La mayor parte de la región fue rebautizada como "Xinjiang" por los chinos después de la caída del Imperio dzungar, que existió desde principios del siglo XVII hasta mediados del siglo XVIII. [66]

Los musulmanes turcos sedentarios de la cuenca del Tarim fueron gobernados originalmente por el Kanato Chagatai y los mongoles budistas nómadas de Oirat en Dzungaria gobernaron el Kanato Dzungar. Los Naqshbandi Sufi Khojas , descendientes de Mahoma , habían reemplazado a los Chagatayid Khans como gobernantes de la cuenca del Tarim a principios del siglo XVII. Hubo una lucha entre dos facciones Khoja: los Afaqi (Montaña Blanca) y los Ishaqi (Montaña Negra). Los Ishaqi derrotaron a los Afaqi y los Afaq Khoja invitaron al quinto Dalai Lama (el líder de los tibetanos ) a intervenir en su nombre en 1677. El Dalai Lama luego llamó a sus seguidores budistas Dzungar en el Kanato Dzungar a actuar en respuesta a la invitación. El Kanato Dzungar conquistó la cuenca del Tarim en 1680, estableciendo a los Afaqi Khoja como su gobernante títere. Después de convertirse al Islam, los descendientes de los uigures anteriormente budistas de Turfán creyeron que los "kalmuks infieles" (dzungars) construyeron monumentos budistas en su región. [67]

Los musulmanes turcos de los oasis de Turfan y Kumul se sometieron a la dinastía Qing y pidieron a China que los liberara de los dzungars; los Qing aceptaron a sus gobernantes como vasallos. Lucharon contra los dzungars durante décadas antes de derrotarlos; los abanderados manchúes de la dinastía Qing llevaron a cabo el genocidio dzungar , casi erradicándolos y despoblando Dzungaria. Los Qing liberaron al líder afaqi khoja Burhan-ud-din y a su hermano, Khoja Jihan, del encarcelamiento de Dzungar y los designaron para gobernar la cuenca del Tarim como vasallos Qing. Los hermanos Khoja incumplieron el acuerdo, declarándose líderes independientes de la cuenca del Tarim. Los Qing y el líder de Turfan Emin Khoja aplastaron su revuelta, y en 1759 China controlaba Dzungaria y la cuenca del Tarim. [68]

La dinastía Qing manchú obtuvo el control de Xinjiang oriental como resultado de una larga lucha con los dzungar que comenzó durante el siglo XVII. En 1755, con la ayuda del noble oirat Amursana , los Qing atacaron Ghulja y capturaron al kan dzungar. Después de que la solicitud de Amursana de ser declarado kan dzungar no fuera respondida, lideró una revuelta contra los Qing. Los ejércitos Qing destruyeron los restos del kanato dzungar durante los siguientes dos años, y muchos chinos han y hui se trasladaron a las áreas pacificadas. [69]

Los mongoles oirat nativos de Dzungar sufrieron mucho a causa de las brutales campañas y de una epidemia de viruela simultánea . El escritor Wei Yuan describió la desolación resultante en el actual norte de Xinjiang como "una llanura vacía de varios miles de li , sin ninguna yurta oirat excepto las de los rendidos". [70] Se ha estimado que el 80 por ciento de los 600.000 (o más) dzungars murieron a causa de una combinación de enfermedades y guerra, [71] y la recuperación tardó generaciones. [72]

Al principio, a los comerciantes han y hui solo se les permitía comerciar en la cuenca del Tarim; su asentamiento en la cuenca del Tarim estuvo prohibido hasta la invasión de Muhammad Yusuf Khoja en 1830 , cuando los Qing recompensaron a los comerciantes por luchar contra Khoja permitiéndoles establecerse en la cuenca. [73] El rebelde musulmán uigur sayyid y sufí naqshbandi de la suborden afaqi, Jahangir Khoja, fue asesinado a cuchilladas (lingchi) en 1828 por los manchúes por liderar una rebelión contra los Qing . Según Robert Montgomery Martin , muchos chinos con diversas ocupaciones se establecieron en Dzungaria en 1870; en Turkestán (la cuenca del Tarim), sin embargo, solo unos pocos comerciantes chinos y soldados de guarnición se intercalaron con la población musulmana. [74]

La rebelión de Ush de 1765 por parte de los uigures contra los manchúes comenzó después de que las mujeres uigures fueran violadas por los sirvientes y el hijo del funcionario manchú Su-cheng. [75] Se dijo que "los musulmanes ush habían querido durante mucho tiempo dormir sobre las pieles [de Sucheng y su hijo] y comer su carne" debido al abuso que duró meses. [76] El emperador manchú ordenó la masacre de la ciudad rebelde uigur; las fuerzas Qing esclavizaron a los niños y mujeres uigures y mataron a los hombres uigures. [77] El abuso sexual de mujeres uigures por parte de soldados y funcionarios manchúes desencadenó una profunda hostilidad uigur contra el gobierno manchú. [78]

En la década de 1860, Xinjiang llevaba un siglo bajo el dominio de la dinastía Qing . En 1759, la región fue arrebatada al kanato de Dzungar , [79] cuya población (los oirats ) se convirtió en blanco de genocidio. Xinjiang era principalmente semiárida o desértica y poco atractiva para los colonos han no comerciantes , y otros (incluidos los uigures) se establecieron allí.

La rebelión de los dunganes , protagonizada por los hui y otros grupos étnicos musulmanes, se libró en las provincias chinas de Shaanxi , Ningxia y Gansu y en Xinjiang entre 1862 y 1877. El conflicto provocó 20,77 millones de muertes debido a la migración y la guerra, y muchos refugiados murieron de hambre. [80] [ verificación fallida ] Miles de refugiados musulmanes de Shaanxi huyeron a Gansu; algunos formaron batallones en el este de Gansu, con la intención de reconquistar sus tierras en Shaanxi. Mientras los rebeldes hui se preparaban para atacar Gansu y Shaanxi, Yaqub Beg (un comandante uzbeko o tayiko del Kanato de Kokand ) huyó del kanato en 1865 después de perder Tashkent ante los rusos . Beg se instaló en Kashgar y pronto controló Xinjiang. Aunque fomentó el comercio, construyó caravasares , canales y otros sistemas de irrigación, su régimen fue considerado duro. Los chinos tomaron medidas decisivas contra Yettishar; un ejército al mando del general Zuo Zongtang se acercó rápidamente a Kashgaria y la reconquistó el 16 de mayo de 1877. [81]

Después de reconquistar Xinjiang a fines de la década de 1870 de manos de Yaqub Beg, [82] la dinastía Qing estableció Xinjiang ("nueva frontera") como provincia en 1884 [83] , convirtiéndola en parte de China y eliminando los antiguos nombres de Zhunbu (準部, Región de Dzungar) y Huijiang (Tierra Musulmana). [84] [85]

Después de que Xinjiang se convirtió en una provincia china, el gobierno Qing alentó a los uigures a migrar desde el sur de Xinjiang a otras áreas de la provincia (como la región entre Qitai y la capital, habitada en gran parte por chinos han, y Ürümqi, Tacheng (Tabarghatai), Yili, Jinghe, Kur Kara Usu, Ruoqiang, Lop Nor y el bajo río Tarim. [86]

En 1912, la dinastía Qing fue reemplazada por la República de China . La República de China continuó tratando el territorio Qing como propio, incluido Xinjiang. [87] : 69 Yuan Dahua, el último gobernador Qing de Xinjiang, huyó. Uno de sus subordinados, Yang Zengxin , tomó el control de la provincia y accedió en nombre a la República de China en marzo de ese año. Equilibrando los distritos electorales étnicos mixtos, Yang controló Xinjiang hasta su asesinato en 1928 después de la Expedición al Norte del Kuomintang . [88]

La Rebelión Kumul y otras estallaron en todo Xinjiang a principios de la década de 1930 contra Jin Shuren , el sucesor de Yang, involucrando a uigures, otros grupos turcos y chinos hui (musulmanes). Jin reclutó a los rusos blancos para aplastar las revueltas. En la región de Kashgar , el 12 de noviembre de 1933, la efímera Primera República del Turquestán Oriental se autoproclamó después del debate sobre si debería llamarse "Turquestán Oriental" o "Uiguristán". [89] [90] La región reclamada por la ETR abarcaba las prefecturas de Kashgar , Khotan y Aksu en el suroeste de Xinjiang. [91] La 36.ª División del Kuomintang musulmán chino (Ejército Nacional Revolucionario) derrotó al ejército de la Primera República del Turquestán Oriental en la Batalla de Kashgar de 1934 , poniendo fin a la república después de que los musulmanes chinos ejecutaran a sus dos emires: Abdullah Bughra y Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra . La Unión Soviética invadió la provincia ; quedó bajo el control del caudillo Han del noreste Sheng Shicai después de la Guerra de Xinjiang de 1937. Sheng gobernó Xinjiang durante la siguiente década con el apoyo de la Unión Soviética , muchas de cuyas políticas étnicas y de seguridad instituyó. La Unión Soviética mantuvo una base militar en la provincia y desplegó varios asesores militares y económicos. Sheng invitó a un grupo de comunistas chinos a Xinjiang (incluido el hermano de Mao Zedong, Mao Zemin ), [92] : 111 pero los ejecutó a todos en 1943 por temor a una conspiración. En 1944, el presidente y primer ministro de China Chiang Kai-shek , informado por la Unión Soviética de la intención de Shicai de unirse a ella, lo transfirió a Chongqing como Ministro de Agricultura y Silvicultura al año siguiente. [93] Durante la Rebelión de Ili , la Unión Soviética apoyó a los separatistas uigures para formar la Segunda República del Turkestán Oriental (ETR) en la región de Ili, mientras que la mayor parte de Xinjiang permaneció bajo el control del Kuomintang. [89]

El Ejército Popular de Liberación entró en Xinjiang en 1949 , cuando el comandante del Kuomintang Tao Zhiyue y el presidente del gobierno Burhan Shahidi les entregaron la provincia. [90] Cinco líderes del ETR que iban a negociar con los chinos sobre la soberanía del ETR murieron en un accidente aéreo ese año en las afueras de Kabansk en la RSFS de Rusia . [94] La República Popular de China continuó el sistema de colonialismo de asentamiento y asimilación forzada que había definido el expansionismo chino anterior en Xinjiang. [95]

La región autónoma de la República Popular China se estableció el 1 de octubre de 1955, en sustitución de la provincia; [90] ese año (el primer censo moderno de China se realizó en 1953), los uigures eran el 73 por ciento de la población total de Xinjiang, de 5,11 millones. [37] Aunque Xinjiang fue designada como "Región Autónoma Uigur" desde 1954, más del 50 por ciento de su área está designada como áreas autónomas para 13 grupos nativos no uigures. [96] Los uigures modernos desarrollaron la etnogénesis en 1955, cuando la República Popular China reconoció a los pueblos oasis que antes se autoidentificaban por separado. [ 97 ]

En el sur de Xinjiang vive la mayor parte de la población uigur, unos nueve millones de personas, de una población total de veinte millones; el cincuenta y cinco por ciento de la población han de Xinjiang, principalmente urbana, vive en el norte. [98] [99] Esto creó un desequilibrio económico, ya que la cuenca norte de Junghar (Dzungaria) está más desarrollada que el sur. [100]

La reforma agraria y la colectivización se produjeron en las zonas agrícolas uigures al mismo ritmo general que en la mayor parte de China. [101] : 134 El hambre en Xinjiang no era tan grande como en otras partes de China durante el Gran Salto Adelante y un millón de chinos Han que huían de la hambruna se reasentaron en Xinjiang. [101] : 134

En 1980, China permitió a Estados Unidos establecer estaciones de escucha electrónica en Xinjiang para que Estados Unidos pudiera monitorear los lanzamientos de cohetes soviéticos en Asia central a cambio de que Estados Unidos autorizara la venta de tecnología civil y militar de doble uso y equipo militar no letal a China. [102]

Desde que la reforma económica china de finales de los años 1970 ha exacerbado el desarrollo regional desigual, más uigures han emigrado a las ciudades de Xinjiang y algunos han han emigrado a Xinjiang en busca de progreso económico. El líder chino Deng Xiaoping hizo una visita de nueve días a Xinjiang en 1981 y describió la región como "inestable". [103] Las reformas de la era Deng alentaron a las minorías étnicas de China, incluidos los uigures, a establecer pequeñas empresas privadas para el transporte de mercancías, el comercio minorista y los restaurantes. [104] A principios de los años 1990, se habían gastado un total de 19 mil millones de yuanes en la construcción de proyectos industriales de tamaño grande y mediano en Xinjiang, con énfasis en el desarrollo de transporte moderno, infraestructura de comunicaciones y apoyo a las industrias del petróleo y el gas. [57] : 149

El comercio transfronterizo entre uigures se desarrolló aún más después de la perestroika de la Unión Soviética . [104]

El aumento del contacto étnico y la competencia laboral coincidieron con el terrorismo uigur desde la década de 1990 , como los atentados con bombas en los autobuses de Ürümqi en 1997. [105]

En 2000, los uigures eran el 45 por ciento de la población de Xinjiang y el 13 por ciento de la población de Ürümqi. Con el nueve por ciento de la población de Xinjiang, Ürümqi representa el 25 por ciento del PIB de la región; muchos uigures rurales han emigrado a la ciudad para trabajar en sus industrias ligera , pesada y petroquímica . [106] Los han en Xinjiang son mayores, mejor educados y trabajan en profesiones mejor pagadas que sus contrapartes uigures. Es más probable que los han citen razones comerciales para mudarse a Ürümqi, mientras que algunos uigures citan problemas legales en el hogar y razones familiares para mudarse a la ciudad. [107] Los han y los uigures están igualmente representados en la población flotante de Ürümqi , que trabaja principalmente en el comercio. La autosegregación en la ciudad está generalizada en la concentración residencial, las relaciones laborales y la endogamia . [108] En 2010, los uigures eran mayoría en la cuenca del Tarim y pluralidad en Xinjiang en su conjunto. [109]

Xinjiang cuenta con 81 bibliotecas públicas y 23 museos, frente a ninguno en 1949. Tiene 98 periódicos en 44 idiomas, frente a cuatro en 1952. Según las estadísticas oficiales, la proporción de médicos, trabajadores médicos, clínicas y camas de hospital con respecto a la población general supera la media nacional; la tasa de inmunización ha alcanzado el 85 por ciento. [5]

El conflicto actual en Xinjiang [110] [111] incluye la incursión en Xinjiang de 2007 , [112] un intento frustrado de atentado suicida en un vuelo de China Southern Airlines en 2008 , [113] el ataque de Kashgar de 2008 que mató a 16 agentes de policía cuatro días antes de los Juegos Olímpicos de Pekín , [114] [115] los ataques con jeringas de agosto de 2009 , [116] el ataque de Hotan de 2011 , [117] el ataque de Kunming de 2014 , [118] el ataque de Ürümqi de abril de 2014 , [119] y el ataque de Ürümqi de mayo de 2014 . [120] Varios de los ataques fueron orquestados por el Partido Islámico de Turkestán (anteriormente Movimiento Islámico de Turkestán Oriental), identificado como grupo terrorista por varias entidades (entre ellas Rusia, [121] Turquía, [122] [123] el Reino Unido, [124] los Estados Unidos hasta octubre de 2020, [125] [126] y las Naciones Unidas). [127]

En 2014, el liderazgo del Partido Comunista Chino (PCCh) en Xinjiang inició una Guerra Popular contra las "Tres Fuerzas del Mal" del separatismo, el terrorismo y el extremismo. Desplegaron doscientos mil cuadros del partido en Xinjiang y lanzaron el programa de emparejamiento de funcionarios públicos y familias . [128] [129] El líder del Partido Comunista Chino, Xi Jinping, no estaba satisfecho con los resultados iniciales de la Guerra Popular y reemplazó a Zhang Chunxian por Chen Quanguo como secretario del Comité del Partido en 2016. Después de su nombramiento, Chen supervisó el reclutamiento de decenas de miles de oficiales de policía adicionales y la división de la sociedad en tres categorías: confiables, promedio y no confiables. Instruyó a sus subordinados a "tomar esta ofensiva como el proyecto principal" y "adelantarse al enemigo, atacar desde el principio". Después de una reunión con Xi en Beijing, Chen Quanguo celebró un mitin en Ürümqi con diez mil tropas, helicópteros y vehículos blindados. Mientras desfilaban, anunció una "ofensiva aplastante y arrasadora" y declaró que "enterrarían los cadáveres de los terroristas y las bandas terroristas en el vasto mar de la Guerra Popular". [128]

Las autoridades chinas han operado campos de internamiento para adoctrinar a los uigures y otros musulmanes como parte de la Guerra Popular desde al menos 2017. [130] [27] Los campos han sido criticados por varios gobiernos y organizaciones de derechos humanos por patrones de abuso y maltrato , con diversas caracterizaciones hasta incluyendo la de un genocidio perpetrado por el gobierno chino. [131] En 2020, el secretario general del PCCh , Xi Jinping, dijo: "La práctica ha demostrado que la estrategia del partido para gobernar Xinjiang en la nueva era es completamente correcta". [132]

En 2021, las autoridades condenaron a muerte a Sattar Sawut y Shirzat Bawudun —exdirectores de los departamentos de educación y justicia de Xinjiang respectivamente— con una suspensión de dos años por cargos de separatismo y soborno. [133] Esta sentencia suele conmutarse por cadena perpetua. [134] Las autoridades dijeron que Sawut fue declarado culpable de incorporar contenido de separatismo étnico, violencia y extremismo religioso en los libros de texto en lengua uigur, lo que había influido en varias personas para participar en los ataques en Urumqi . Dijeron que Bawudun fue declarado culpable de conspirar con el ETIM y llevar a cabo "actividades religiosas ilegales en la boda de su hija". [133] [135] Otros tres educadores fueron condenados a cadena perpetua. [136] Chen fue reemplazado como secretario del Partido Comunitario para Xinjiang por Ma Xingrui en diciembre de 2021. [137]

Xi Jinping realizó una visita de cuatro días a Xinjiang en julio de 2022, donde Kompas TV había documentado grupos de uigures dando la bienvenida a su llegada. [138] Xi pidió a los funcionarios locales que hicieran más para preservar la cultura de las minorías étnicas [139] y, tras una inspección del Cuerpo de Producción y Construcción de Xinjiang , elogió el "gran progreso" de la organización en la reforma y el desarrollo. [140] Durante otra visita a Xinjiang en agosto de 2023, Xi dijo en un discurso que la región debería abrirse más al turismo para atraer visitantes nacionales y extranjeros. [141] [142]

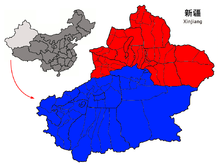

Xinjiang está dividida en trece divisiones a nivel de prefectura : cuatro ciudades a nivel de prefectura , seis prefecturas y cinco prefecturas autónomas (incluida la prefectura autónoma subprovincial de Ili, que a su vez tiene dos de las siete prefecturas dentro de su jurisdicción) para las minorías mongol , kazaja , kirguisa y hui. [143]

Estas se dividen en 13 distritos, 29 ciudades a nivel de condado, 60 condados y 6 condados autónomos. Doce de las ciudades a nivel de condado no pertenecen a ninguna prefectura y están administradas de facto por el Cuerpo de Producción y Construcción de Xinjiang (XPCC). Las subdivisiones de la Región Autónoma Uygur de Xinjiang se muestran en la imagen adyacente y se describen en la tabla siguiente:

Xinjiang es la subdivisión política más grande de China y representa más de una sexta parte del territorio total de China y una cuarta parte de la longitud de sus fronteras. Xinjiang está cubierta principalmente por desiertos inhabitables y pastizales secos, con oasis dispersos propicios para la habitación que representan el 9,7 por ciento del área total de Xinjiang en 2015 [17] al pie de Tian Shan , las montañas Kunlun y las montañas Altai , respectivamente.

Xinjiang está dividida por la cordillera Tian Shan ( تەڭرى تاغ , Tengri Tagh, Тңри Тағ), que la divide en dos grandes cuencas: la cuenca de Dzungarian en el norte y la cuenca de Tarim en el sur. Una pequeña cuña en forma de V entre estas dos cuencas principales, limitada por la cordillera principal de Tian Shan en el sur y las montañas Borohoro en el norte, es la cuenca del río Ili , que desemboca en el lago Balkhash de Kazajstán ; una cuña aún más pequeña más al norte es el valle de Emin .

Otras importantes cadenas montañosas de Xinjiang son las montañas Pamir y Karakoram en el suroeste, las montañas Kunlun en el sur (a lo largo de la frontera con el Tíbet) y las montañas Altai en el noreste (compartidas con Mongolia). El punto más alto de la región es el monte K2 , un ochomil ubicado a 8.611 metros (28.251 pies) sobre el nivel del mar en las montañas Karakoram en la frontera con Pakistán .

Gran parte de la cuenca del Tarim está dominada por el desierto de Taklamakán. Al norte de ella se encuentra la depresión de Turfán, que contiene el punto más bajo de Xinjiang y de toda la República Popular China, a 155 metros (509 pies) por debajo del nivel del mar.

La cuenca de Dzungaria es ligeramente más fría y recibe algo más de precipitaciones que la cuenca de Tarim. No obstante, también tiene un gran desierto de Gurbantünggüt (también conocido como Dzoosotoyn Elisen) en su centro.

La cordillera de Tian Shan marca la frontera entre Xinjiang y Kirguistán en el Paso de Torugart (3752 m). La carretera del Karakorum (KKH) une Islamabad , Pakistán, con Kashgar a través del Paso de Khunjerab .

De sur a norte, los pasos de montaña que bordean Xinjiang son:

Xinjiang is geologically young. Collision of the Indian and the Eurasian plates formed the Tian Shan, Kunlun Shan, and Pamir mountain ranges; said tectonics render it a very active earthquake zone. Older geological formations are located in the far north, where Kazakhstania is geologically part of Kazakhstan, and in the east, where is part of the North China Craton.[citation needed]

Xinjiang has within its borders, in the Gurbantünggüt Desert, the location in Eurasia that is furthest from the sea in any direction (a continental pole of inaccessibility): 46°16.8′N 86°40.2′E / 46.2800°N 86.6700°E / 46.2800; 86.6700 (Eurasian pole of inaccessibility). It is at least 2,647 km (1,645 mi) (straight-line distance) from any coastline.

In 1992, local geographers determined another point within Xinjiang – 43°40′52″N 87°19′52″E / 43.68111°N 87.33111°E / 43.68111; 87.33111 in the southwestern suburbs of Ürümqi, Ürümqi County – to be the "center point of Asia". A monument to this effect was then erected there and the site has become a local tourist attraction.[151]

Having hot summer and low precipitation, most of Xinjiang is endorheic. Its rivers either disappear in the desert, or terminate in salt lakes (within Xinjiang itself, or in neighboring Kazakhstan), instead of running towards an ocean. The northernmost part of the region, with the Irtysh River rising in the Altai Mountains, that flows (via Kazakhstan and Russia) toward the Arctic Ocean, is the only exception. But even so, a significant part of the Irtysh's waters were artificially diverted via the Irtysh–Karamay–Ürümqi Canal to the drier regions of southern Dzungarian Basin.

Elsewhere, most of Xinjiang's rivers are comparatively short streams fed by the snows of the several ranges of the Tian Shan. Once they enter the populated areas in the mountains' foothills, their waters are extensively used for irrigation, so that the river often disappears in the desert instead of reaching the lake to whose basin it nominally belongs. This is the case even with the main river of the Tarim Basin, the Tarim, which has been dammed at a number of locations along its course, and whose waters have been completely diverted before they can reach the Lop Lake. In the Dzungarian basin, a similar situation occurs with most rivers that historically flowed into Lake Manas. Some of the salt lakes, having lost much of their fresh water inflow, are now extensively use for the production of mineral salts (used e.g., in the manufacturing of potassium fertilizers); this includes the Lop Lake and the Manas Lake.

Deserts include:

Due to water scarcity, most of Xinjiang's population lives within fairly narrow belts that are stretched along the foothills of the region's mountain ranges in areas conducive to irrigated agriculture. It is in these belts where most of the region's cities are found.

A semiarid or desert climate (Köppen BSk or BWk, respectively) prevails in Xinjiang. The entire region has great seasonal differences in temperature with cold winters. The Turpan Depression often records some of the hottest temperatures nationwide in summer,[152] with air temperatures easily exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). Winter temperatures regularly fall below −20 °C (−4 °F) in the far north and highest mountain elevations. On 18 February 2024, a record low temperature for the region of −52.3 °C (−62.1 °F) was recorded.[153]

Continuous permafrost is typically found in the Tian Shan starting at the elevation of about 3,500–3,700 m above sea level. Discontinuous alpine permafrost usually occurs down to 2,700–3,300 m, but in certain locations, due to the peculiarity of the aspect and the microclimate, it can be found at elevations as low as 2,000 m.[154]

Despite the province's easternmost point being more than 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) west of Beijing, Xinjiang, like the rest of China, is officially in the UTC+8 time zone, known by residents as Beijing Time. Despite this, some residents, local organizations and governments observe UTC+6 as the standard time and refer to this zone as Xinjiang Time.[155] Han people tend to use Beijing Time, while Uyghurs tend to use Xinjiang Time as a form of resistance to Beijing.[156] Time zones notwithstanding, most schools and businesses open and close two hours later than in the other regions of China.[157]

.jpg/440px-Kashgar_(23968353536).jpg)

Like all governing institutions in mainland China, Xinjiang has a parallel party-government system. The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Regional Committee of the CCP acts as the top policy-formulation body, and exercises control over the Regional People's Government. The CCP Committee Secretary, generally a member of the Han ethnic group, outranks the Government Chairman, always an Uyghur. The Government Chairman typically serves as a Deputy Committee Secretary.[158]

Xinjiang maintains the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), an economic and paramilitary organization administered by the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It plays a critical role in the region's economy, owning or being otherwise connected to many companies in the region as well as dominating Xinjiang's agricultural output.[159] It additionally directly administers cities throughout Xinjiang, mainly concentrated in the northern parts. It is headed by the CCP secretary of Xinjiang, while the CCP secretary of the XPCC is considered the second most powerful person in the region.[159]

Local governments in Xinjiang seek to address ethnic tensions in the region through poverty alleviation and redistributive programs.[160]: 189 These efforts include working with state-owned enterprises and private enterprises in the mining sector.[160]: 189 For example, during the Targeted Poverty Alleviation Campaign, officials paired 1,000 villages with 1,000 enterprises for economic development projects.[160]: 189

Human Rights Watch has documented the denial of due legal process and fair trials and failure to hold genuinely open trials as mandated by law e.g. to suspects arrested following ethnic violence in the city of Ürümqi's 2009 riots.[161]

The Chinese government, under Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping's administration,[27] launched the Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism in 2014, which involved mass detention and surveillance of ethnic Uyghurs there;[162] the program was massively expanded by Chen Quanguo when he was appointed as CCP Xinjiang secretary in 2016.[163] The campaign included the detainment of 1.8 million people in internment camps, mostly Uyghurs, but also including other ethnic and religious minorities, by 2020.[163] An October 2018 exposé by BBC News claimed, based on analysis of satellite imagery collected over time, that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs were likely interned in the camps, and they are rapidly being expanded.[164] In 2019, The Art Newspaper reported that "hundreds" of writers, artists, and academics had been imprisoned in (what the magazine qualified as) an attempt to "punish any form of religious or cultural expression" among Uyghurs.[165] China has also been accused of targeting Muslim religious figures, Mosques and tombs in the region. [166] This program has been called a genocide by some observers, while a report by the UN Human Rights Office said they may amount to crimes against humanity.[167][168]

On 28 June 2020, the Associated Press published a report which stated the Chinese government was taking draconian measures to slash birth rates among Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, even as it encouraged some of the country's Han majority to have more children.[169] While individual women have spoken out before about forced birth control, the practice was far more widespread and systematic than previously known, according to an AP investigation based on government statistics, state documents and interviews with 30 ex-detainees, family members and a former detention camp instructor. The campaign over the past four years in Xinjiang has been labeled by some experts as a form of "demographic genocide."[169] The allegation of Uyghur birth rates being lower than those of Han Chinese have been disputed by pundits from Pakistan Observer,[170] Antara,[171] and Detik.com.[172]

Some factions in Xinjiang, most prominently Uyghur nationalists, advocate establishing an independent country named East Turkestan (also sometimes called "Uyghuristan"),[173] which has led to tension, conflict,[174] and ethnic strife in the region.[175][176][177] Autonomous regions in China do not have a legal right to secede, and each one is considered to be an "inseparable part of the People's Republic of China" by the government.[178][179] The separatist movement claims that the region is not part of China, but was invaded by the CCP in 1949 and has been under occupation since then. The Chinese government asserts that the region has been part of China since ancient times,[180] and has engaged in "strike hard" campaigns targeted at separatists.[181] The movement has been supported by both militant Islamic extremist groups such as the Turkistan Islamic Party,[182] as well as advocacy groups with no connection to extremist groups.

According to the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, the two main sources for separatism in the Xinjiang Province are religion and ethnicity. Religiously, the most Uyghur peoples of Xinjiang follow Islam; in the rest of China, many are Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian, although many follow Islam as well, such as the Hui ethnic subgroup of the Han ethnicity, comprising some 10 million people. Thus, the major difference and source of friction with eastern China is ethnicity and religious doctrinal differences that differentiate them politically from other Muslim minorities elsewhere in the country.[181]

The GDP of Xinjiang was about CN¥1.774 trillion (US$263 billion) as of 2022[update].[184] Economic growth has been fueled by to discovery of the abundant reserves of coal, oil, gas as well as the China Western Development policy introduced by the State Council to boost economic development in Western China.[185] Its per capita GDP for 2022 was CN¥68,552 (US$10,191). Southern Xinjiang, with 95 percent non-Han population, has an average per capita income half that of Xinjiang as a whole.[184] XPCC plays an outsized role in Xinjiang's economy, with the organization producing CN¥350 billion (US$52 billion), or around 19.7% of Xinjiang's economy, while the per capita GDP was CN¥98,748 (US$14,680).[186]

Economic development of Xinjiang is a priority for China.[187] In 1997, the 26,000 km Uzbek-Kyrgyz-Chinese highway became operational.[57]: 150 In 1998, the Turpan–Ürümqi–Dahuangshan Expressway was completed, linking several key areas in Xinjiang.[57]: 150 In 2000, the government articulated its strategy for developing the western regions of the country, and that plan made Xinjiang a major focus.[187] Accelerating development in Xinjiang is intended by China to achieve a number of objectives, including narrowing the economic gap between Xinjiang and the more developed eastern provinces, as well as alleviating political discontent and security problems by alleviating poverty and raising the standard of living in order to increase stability.[187] From 2014 to 2020, fiscal transfers from China's central government to Xinjiang grew by an average of 10.4% per year.[188]: 110

In July 2010, state media outlet China Daily reported that:

Local governments in China's 19 provinces and municipalities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Zhejiang and Liaoning, are engaged in the commitment of "pairing assistance" support projects in Xinjiang to promote the development of agriculture, industry, technology, education and health services in the region.[189]

Xinjiang has traditionally been an agricultural region, but is also rich in minerals and oil. Xinjiang is a major producer of solar panel components due to its large production of the base material polysilicon. In 2020 45 percent of global production of solar-grade polysilicon occurred in Xinjiang. Concerns have been raised both within the solar industry and outside it that forced labor may occur in the Xinjiang part of the supply chain.[190] The global solar panel industry are under pressure to move sourcing away from the region due to human rights and liability concerns.[191] China's solar association claimed the allegations were baseless and unfairly stigmatized firms with operations there.[192] A 2021 investigation in the United Kingdom found that 40 percent of solar farms in the UK had been built using panels from Chinese companies linked to forced labor in Xinjiang.[193]

Main area is of irrigated agriculture. By 2015, the agricultural land area of the region is 631 thousand km2 or 63.1 million ha, of which 6.1 million ha is arable land.[194] In 2016, the total cultivated land rose to 6.2 million ha, with the crop production reaching 15.1 million tons.[195] Agriculture in Xinjiang is dominated by the XPCC, which employs a majority of the organization's workforce.[196] Wheat was the main staple crop of the region, maize grown as well, millet found in the south, while only a few areas (in particular, Aksu) grew rice.[197]

Cotton became an important crop in several oases, notably Hotan, Yarkand and Turpan by the late 19th century.[197] Sericulture is also practiced.[198] The Xinjiang cotton industry is the world's largest cotton exporter, producing 84 percent of Chinese cotton while the country provides 26 percent of global cotton export.[199] Xinjiang also produces peppers and pepper pigments used in cosmetics such lipstick for export.[200]

Xinjiang is famous for its tomatoes, grapes and melons, particularly Hami melons and Turpan raisins.[201] The region is a leading source for tomato paste, which it supplies for international brands.[199]

The main livestock of the region have traditionally been sheep. Much of the region's pasture land is in its northern part, where more precipitation is available,[202] but there are mountain pastures throughout the region.[203]: 29

Due to the lack of access to the ocean and limited amount of inland water, Xinjiang's fish resources are somewhat limited. Nonetheless, there is a significant amount of fishing in Lake Ulungur and Lake Bosten and in the Irtysh River. A large number of fish ponds have been constructed since the 1970s, their total surface exceeding 10,000 hectares by the 1990s. In 2000, the total of 58,835 tons of fish was produced in Xinjiang, 85 percent of which came from aquaculture.[204] The Sayram Lake is both the largest alpine lake and highest altitude lake in Xinjiang, and is the location of a major cold-water fishery.[citation needed] Originally Sayram had no fish but in 1998, northern whitefish (Coregonus peled) from Russia were introduced and investment in breeding infrastructure and technology has consequently made Sayram into the country's largest exporter of northern whitefish with an annual output of over 400 metric tons.[205][better source needed]

Mining-related industries are a major part of Xinjiang's economy.[160]: 23

Xinjiang was known for producing salt, soda, borax, gold, and jade in the 19th century.[206]

The Lop Lake was once a large brackish lake during the end of the Pleistocene but has slowly dried up in the Holocene where average annual precipitation in the area has declined to just 31.2 millimeters (1.2 inches), and experiences annual evaporation rate of 2,901 millimeters (114 inches). The area is rich in brine potash, a key ingredient in fertilizer and is the second-largest source of potash in the country. Discovery of potash in the mid-1990s, has transformed Lop Nur into a major potash mining industry.[207]

The oil and gas extraction industry in Aksu and Karamay is growing, with the West–East Gas Pipeline linking to Shanghai. The oil and petrochemical sector get up to 60 percent of Xinjiang's economy.[208] The region contains over a fifth of China's hydrocarbon resources and has the highest concentration of fossil fuel reserves of any region in the country.[209] The region is rich in coal and contains 40 percent of the country's coal reserves or around 2.2 trillion tonnes, which is enough to supply China's thermal coal demand for more than 100 years even if only 15 percent of the estimated coal reserve prove recoverable.[210][211]

Tarim basin is the largest oil and gas bearing area in the country with about 16 billion tonnes of oil and gas reserves discovered.[212] The area is still actively explored and in 2021, China National Petroleum Corporation found a new oil field reserve of 1 billion tons (about 907 million tonnes). That find is regarded as being the largest one in recent decades. As of 2021, the basin produces hydrocarbons at an annual rate of 2 million tons, up from 1.52 million tons from 2020.[213]

Trade with Central Asian countries is crucial to Xinjiang's economy.[214] Most of the overall import/export volume in Xinjiang was directed to and from Kazakhstan through Ala Pass. China's first border free trade zone (Horgos Free Trade Zone) was located at the Xinjiang-Kazakhstan border city of Horgos.[215] Horgos is the largest "land port" in China's western region and it has easy access to the Central Asian market. Xinjiang also opened its second border trade market to Kazakhstan in March 2006, the Jeminay Border Trade Zone.[216]

Vietnam is a major importer of Xinjiang cotton.[217]: 45

The Xinjiang Networking Transmission Limited operates the Urumqi People's Broadcasting Station and the Xinjiang People Broadcasting Station, broadcasting in Mandarin, Uyghur, Kazakh and Mongolian.

In 1995[update], there were 50 minority-language newspapers published in Xinjiang, including the Qapqal News, the world's only Xibe language newspaper.[225] The Xinjiang Economic Daily is considered one of China's most dynamic newspapers.[226]

For a time after the July 2009 riots, authorities placed restrictions on the internet and text messaging, gradually permitting access to state-controlled websites like Xinhua News Agency,[227] until restoring Internet to the same level as the rest of China on 14 May 2010.[228][229][230]

The earliest Tarim mummies, dated to 1800 BC, are of a Caucasoid physical type.[242] East Asian migrants arrived in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin about 3000 years ago and the Uyghur peoples appeared after the collapse of the Orkhon Uyghur Kingdom, based in modern-day Mongolia, around 842 AD.[243][244]

The Islamization of Xinjiang started around 1000 AD. Xinjiang Muslim Turkic peoples contain Uyghurs, Kazaks, Kyrgyz, Tatars, Uzbeks; Muslim Iranian peoples comprise Tajiks, Sarikolis/Wakhis (often conflated as Tajiks); Muslim Sino-Tibetan peoples are such as the Hui. Other ethnic groups in the region are Hans, Mongols (Oirats, Daurs, Dongxiangs), Russians, Xibes, Manchus. Around 70,000 Russian immigrants were living in Xinjiang in 1945.[245]

The Han Chinese of Xinjiang arrived at different times from different directions and social backgrounds. There are now descendants of criminals and officials who had been exiled from China during the second half of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries; descendants of families of military and civil officers from Hunan, Yunnan, Gansu and Manchuria; descendants of merchants from Shanxi, Tianjin, Hubei and Hunan; and descendants of peasants who started immigrating into the region in 1776.[246]

Some Uyghur scholars claim descent from both the Turkic Uyghurs and the pre-Turkic Tocharians (or Tokharians, whose language was Indo-European); also, Uyghurs often have relatively-fair skin, hair and eyes and other Caucasoid physical traits.

In 2002, there were 9,632,600 males (growth rate of 1.0 percent) and 9,419,300 females (growth rate of 2.2 percent). The population overall growth rate was 1.09 percent, with 1.63 percent of birth rate and 0.54 percent mortality rate.

The Qing began a process of settling Han, Hui, and Uyghur settlers into Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria) in the 18th century. At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in Southern Xinjiang.[247] A census of Xinjiang under Qing rule in the early 19th century tabulated ethnic shares of the population as 30 percent Han and 60 percent Turkic and it dramatically shifted to 6 percent Han and 75 percent Uyghur in the 1953 census. However, a situation similar to the Qing era's demographics with a large number of Han had been restored by 2000, with 40.57 percent Han and 45.21 percent Uyghur.[248] Professor Stanley W. Toops noted that today's demographic situation is similar to that of the early Qing period in Xinjiang.[249] Before 1831, only a few hundred Chinese merchants lived in Southern Xinjiang oases (Tarim Basin), and only a few Uyghurs lived in Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria).[250]

After 1831, the Qing encouraged Han Chinese migration into the Tarim Basin, in southern Xinjiang, but with very little success, and permanent troops were stationed on the land there as well.[251] Political killings and expulsions of non-Uyghur populations during the uprisings in the 1860s[251] and the 1930s saw them experience a sharp decline as a percentage of the total population[252] though they rose once again in the periods of stability from 1880, which saw Xinjiang increase its population from 1.2 million,[253][254] to 1949. From a low of 7 percent in 1953, the Han began to return to Xinjiang between then and 1964, where they comprised 33 percent of the population (54 percent Uyghur), like in Qing times. A decade later, at the beginning of the Chinese economic reform in 1978, the demographic balance was 46 percent Uyghur and 40 percent Han,[248] which did not change drastically until the 2000 Census, when the Uyghur population had reduced to 42 percent.[255] In 2010, the population of Xinjiang was 45.84 percent Uyghur and 40.48 percent Han. The 2020 Census showed the share of the Uyghur population decline slightly to 44.96 percent, and the Han population rise to 42.24 percent[256][257]

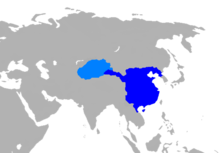

Military personnel are not counted and national minorities are undercounted in the Chinese census, as in some other censuses.[258] 3.6 million people reside in XPCC administered areas, around 14 percent of Xinjiang's population.[186] While some of the shift has been attributed to an increased Han presence,[18] Uyghurs have also emigrated to other parts of China, where their numbers have increased steadily. Uyghur independence activists express concern over the Han population changing the Uyghur character of the region though the Han and Hui Chinese mostly live in Northern Xinjiang Dzungaria and are separated from areas of historic Uyghur dominance south of the Tian Shan mountains (Southwestern Xinjiang), where Uyghurs account for about 90 percent of the population.[259]

In general, Uyghurs are the majority in Southwestern Xinjiang, including the prefectures of Kashgar, Khotan, Kizilsu and Aksu (about 80 percent of Xinjiang's Uyghurs live in those four prefectures) as well as Turpan Prefecture, in Eastern Xinjiang. The Han are the majority in Eastern and Northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria), including the cities of Ürümqi, Karamay, Shihezi and the prefectures of Changjyi, Bortala, Bayin'gholin, Ili (especially the cities of Kuitun) and Kumul. Kazakhs are mostly concentrated in Ili Prefecture in Northern Xinjiang. Kazakhs are the majority in the northernmost part of Xinjiang.

The major religions in Xinjiang are Islam, practiced largely by Uyghurs and the Hui Chinese minority, as well as Chinese folk religions, Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, practiced essentially by the Han Chinese. Christianity in Xinjiang is practiced by 1 percent of the population according to the Chinese General Social Survey of 2009.[264] According to a demographic analysis of the year 2010, Muslims formed 58 percent of the province's population.[265] In 1950, there were 29,000 mosques and 54,000 imams in Xinjiang, which fell to 14,000 mosques and 29,000 imams by 1966. Following the Cultural Revolution, there were only about 1,400 remaining mosques. By the mid-1980's, the number of mosques had returned to 1950 levels.[266] According to a 2020 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, since 2017, Chinese authorities have destroyed or damaged 16,000 mosques in Xinjiang – 65 percent of the region's total.[267][268]

According to a DeWereldMorgen report in March 2024, there are more than 100 Islamic associations in Xinjiang where imams have lessons in theology, Arabic and Mandarin.[201] A majority of the Uyghur Muslims adhere to Sunni Islam of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence or madhab.[citation needed] A minority of Shias, almost exclusively of the Nizari Ismaili (Seveners) rites are located in the higher mountains of Tajik and Tian Shan. In the western mountains (the Tajiks), almost the entire population of Tajiks (Sarikolis and Wakhis), are Nizari Ismaili Shia.[18] In the north, in the Tian Shan, the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz are Sunni.

Afaq Khoja Mausoleum and Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar are most important Islamic Xinjiang sites. Emin Minaret in Turfan is a key Islamic site. Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves is a notable Buddhist site. In Awat County also lies a huge park with a statue of Turkish-Muslim philosopher Nasreddin.[269]

Xinjiang is home to the Xinjiang Flying Tigers professional basketball team of the Chinese Basketball Association, and to Xinjiang Tianshan Leopard F.C., a football team that plays in China League One.

The capital, Ürümqi, is home to the Xinjiang University baseball team, an integrated Uyghur and Han group profiled in the documentary film Diamond in the Dunes.

In 2008, according to the Xinjiang Transportation Network Plan, the government has focused construction on State Road 314, Alar-Hotan Desert Highway, State Road 218, Qingshui River Line-Yining Highway and State Road 217, as well as other roads.

The construction of the first expressway in the mountainous area of Xinjiang began a new stage in its construction on 24 July 2007. The 56 km (35 mi) highway linking Sayram Lake and Guozi Valley in Northern Xinjiang area had cost 2.39 billion yuan. The expressway is designed to improve the speed of national highway 312 in northern Xinjiang. The project started in August 2006 and several stages have been fully operational since March 2007. Over 3,000 construction workers have been involved. The 700 m-long Guozi Valley Cable Bridge over the expressway is now currently being constructed, with the 24 main pile foundations already completed. Highway 312 national highway Xinjiang section, connects Xinjiang with China's east coast, Central and West Asia, plus some parts of Europe. It is a key factor in Xinjiang's economic development. The population it covers is around 40 percent of the overall in Xinjiang, who contribute half of the GDP in the area.

Zulfiya Abdiqadir, head of the Transport Department was quoted as saying that 24,800,000,000 RMB had been invested into Xinjiang's road network in 2010 alone and, by this time, the roads covered approximately 152,000 km (94,000 mi).[270]

Xinjiang's rail hub is Ürümqi. To the east, a conventional and a high-speed rail line runs through Turpan and Hami to Lanzhou in Gansu Province. A third outlet to the east connects Hami and Inner Mongolia.

To the west, the Northern Xinjiang runs along the northern footslopes of the Tian Shan range through Changji, Shihezi, Kuytun and Jinghe to the Kazakh border at Alashankou, where it links up with the Turkestan–Siberia Railway. Together, the Northern Xinjiang and the Lanzhou-Xinjiang lines form part of the Trans-Eurasian Continental Railway, which extends from Rotterdam, on the North Sea, to Lianyungang, on the East China Sea. The Northern Xinjiang railway provides additional rail transport capacity to Jinghe, from which the Jinghe–Yining–Khorgos railway heads into the Ili River Valley to Yining, Huocheng and Khorgos, a second rail border crossing with Kazakhstan. The Kuytun–Beitun railway runs from Kuytun north into the Junggar Basin to Karamay and Beitun, near Altay.

In the south, the Southern Xinjiang railway from Turpan runs southwest along the southern footslopes of the Tian Shan into the Tarim Basin, with stops at Yanqi, Korla, Kuqa, Aksu, Maralbexi (Bachu), Artux and Kashgar. From Kashgar, the Kashgar–Hotan railway, follows the southern rim of the Tarim to Hotan, with stops at Shule, Akto, Yengisar, Shache (Yarkant), Yecheng (Karghilik), Moyu (Karakax). There are also the Hotan–Ruoqiang railway and Golmud–Korla railway.

The Ürümqi–Dzungaria railway connects Ürümqi with coal fields in the eastern Junggar Basin. The Hami–Lop Nur railway connects Hami with potassium salt mines in and around Lop Nur. The Golmud–Korla railway, opened in 2020, provides an outlet to Qinghai. Planning is underway on additional intercity railways.[271] Railways to Pakistan and Kyrgyzstan have been proposed.[citation needed]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)In contemporary geographic terminology, Chinese Turkestan refers to Xinjiang (Sinkiang), the Uighur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China.

For most of their history, the Uyghurs lived as tribes in a loosely affiliated nation on the northern Chinese border (sometimes called East Turkestan).

The general boundaries of East Turkistan are the Altai range on the northeast, Mongolia on the east, the Kansu corridor or the Su-lo-ho basin on the southeast, the K'un-lun system on the south, the Sarygol and Muztay-ata on the west, the main range of the T'ien-shan system on the north to the approximate longitude of Aqsu (80 deg. E), then generally northeast to the Altai system which the boundary joins in the vicinity of the Khrebët Nalinsk and Khrebët Sailjuginsk.

The Qianlong emperor (1736–1796) named the region Xinjiang, for New Territory.

In the Iron Age, in general, Steppe-related and northeastern Asian admixture intensified, with North and East Xinjiang populations showing more affinity with northeastern Asians and South Xinjiang populations showing more affinity with Central Asians. The genetic structure observed in the Historical Era of Xinjiang is similar to that in the Iron Age, demonstrating genetic continuity since the Iron Age with some additional genetic admixture with populations surrounding the Xinjiang region.

Using qpAdm, we modelled the Tarim Basin individuals as a mixture of two ancient autochthonous Asian genetic groups: the ANE, represented by an Upper Palaeolithic individual from the Afontova Gora site in the upper Yenisei River region of Siberia (AG3) (about 72%), and ancient Northeast Asians, represented by Baikal_EBA (about 28%) (Supplementary Data 1E and Fig. 3a). Tarim_EMBA2 from Beifang can also be modelled as a mixture of Tarim_EMBA1 (about 89%) and Baikal_EBA (about 11%).

Since the Ghulja Incident, numerous attacks including attacks on buses, clashes between ETIM militants and Chinese security forces, assassination attempts, attempts to attack Chinese key installations and government buildings have taken place, though many cases go unreported.

The Subcommittee heard that the Government of China has been employing various strategies to persecute Muslim groups living in Xinjiang, including mass detentions, forced labour, pervasive state surveillance and population control. Witnesses were clear that the Government of China's actions are a clear attempt to eradicate Uyghur culture and religion. Some witnesses stated that the Government of China's actions meet the definition of genocide as set out in Article II of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention).

Selama 4 hari, Xi Jinping mengunjungi sejumlah situs di Xinjiang termasuk perkebunan kapas, zona perdagangan dan museum. Penduduk Uighur pun menyambut Presiden Xi Jinping.

Our visit came on the heels of Chinese President Xi Jinping's visit to Ürümqi, where he reportedly stressed on the positive promotion of the region to show an open and confident Xinjiang. Xi also called for Xinjiang to be opened more widely for tourism to encourage visits from domestic and foreign tourists.

But amid growing global attention on Xinjiang, China has been eager to portray the region as a "success story" by welcoming more tourists. In a speech that he made while visiting the region last month, Xi said Xinjiang was "no longer a remote area" and should open up more to domestic and foreign tourism.

Pada 2018, misalnya, persentase kelahiran Uighur adalah 11,9‰, sedangkan Han cuma 9,42‰. Secara keseluruhan, total populasi Uighur di Xinjiang naik dari yang sekitar 8,346 juta pada 2000, ke 11,624 juta lebih pada 2020. Alias rata-rata naik 1,71% tiap tahunnya. Jauh lebih tinggi ketimbang populasi suku minoritas lain di seluruh China yang saban warsa hanya naik 0,83%.

Based on China's Constitution, any sub-national unit, either a province or an ethnic minority autonomous region, does not legally have the right to secede from China.

各民族自治地方都是中华人民共和国不可分离的部分 – Each and every ethnic autonomous region is an inseparable part of the People's Republic of China.

In Awat county near Aksu, a huge park, with a statue of 13th century Turkish philosopher Nasiruddin Hodza at the entrance, preserves the tradition of Daolang tribe and their forest of Euphrates poplar, known locally as king of desert.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter |agency= ignored (help){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)