Hawái ( / h ə ˈ w aɪ . i / hə-WY-ee;[9] Hawái:Hawái [həˈvɐjʔi, həˈwɐjʔi]estadoinsularde losEstados Unidos, en elocéano Pacíficoa unas 2000 millas (3200 km) al suroeste del territorio continental de Estados Unidos . Es el único estado que no está en elnorteamericano, el único estado que es unarchipiélagoy el único estado en lostrópicos. También alberga10 de los 14 climas(la tasa más alta para cualquier subdivisión de país) y es uno de los dos estados de EE. UU. conclima tropical.

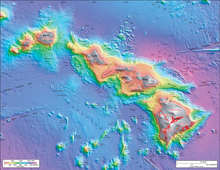

Hawái está formado por 137 islas volcánicas que comprenden casi todo el archipiélago hawaiano (la excepción, que está fuera del estado, es el atolón Midway ). Con una extensión de 2400 km (1500 millas), el estado es fisiográfica y etnológicamente parte de la subregión polinesia de Oceanía . [10] La costa oceánica de Hawái es, en consecuencia, la cuarta más larga de los EE. UU. , con aproximadamente 1210 km (750 millas). [d] Las ocho islas principales, de noroeste a sureste, son Niʻihau , Kauaʻi , Oʻahu , Molokaʻi , Lānaʻi , Kahoʻolawe , Maui y Hawaiʻi , de la que toma el nombre el estado; a esta última a menudo se la llama "Isla Grande" o "Isla de Hawái" para evitar confusiones con el estado o el archipiélago. Las islas deshabitadas del noroeste de Hawái constituyen la mayor parte del Monumento Nacional Marino Papahānaumokuākea , el área protegida más grande de los EE. UU. y la cuarta más grande del mundo.

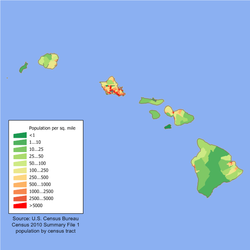

De los 50 estados de EE. UU. , Hawái es el octavo más pequeño en superficie y el undécimo menos poblado ; pero con 1,4 millones de residentes, ocupa el puesto 13 en densidad de población . Dos tercios de los residentes de Hawái viven en O'ahu, hogar de la capital y ciudad más grande del estado, Honolulu . Hawái se encuentra entre los estados más diversos del país, debido a su ubicación central en el Pacífico y más de dos siglos de migración. Como uno de los únicos siete estados de mayoría minoritaria , tiene la única pluralidad asiático-estadounidense, la comunidad budista más grande [ 11 ] y la mayor proporción de personas multirraciales en los EE. UU. [12] En consecuencia, Hawái es un crisol único de culturas de América del Norte y Asia Oriental , además de su herencia hawaiana indígena .

Hawái, colonizada por polinesios en algún momento entre 1000 y 1200 d. C., fue el hogar de numerosos cacicazgos independientes. [13] En 1778, el explorador británico James Cook fue el primer no polinesio conocido en llegar al archipiélago; la influencia británica temprana se refleja en la bandera del estado , que lleva una Union Jack . Pronto llegó una afluencia de exploradores, comerciantes y balleneros europeos y estadounidenses, lo que llevó a la aniquilación de la comunidad indígena, una vez aislada, mediante la introducción de enfermedades como la sífilis, la tuberculosis, la viruela y el sarampión; la población nativa hawaiana disminuyó de entre 300.000 y un millón a menos de 40.000 en 1890. [14] [15] [16] Hawái se convirtió en un reino unificado y reconocido internacionalmente en 1810, permaneciendo independiente hasta que los empresarios estadounidenses y europeos derrocaron a la monarquía en 1893; Esto llevó a la anexión por parte de los EE. UU. en 1898. Como territorio estadounidense de valor estratégico , Hawái fue atacado por Japón el 7 de diciembre de 1941, lo que le dio importancia global e histórica, y contribuyó a la entrada de Estados Unidos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Hawái es el estado más reciente en unirse a la unión , el 21 de agosto de 1959. [17] En 1993, el gobierno de los EE. UU. se disculpó formalmente por su papel en el derrocamiento del gobierno de Hawái, que había impulsado el movimiento de soberanía hawaiana y ha llevado a esfuerzos en curso para obtener reparación para la población indígena.

Históricamente dominado por una economía de plantación , Hawái sigue siendo un importante exportador agrícola debido a su suelo fértil y su clima tropical único en los EE. UU. Su economía se ha diversificado gradualmente desde mediados del siglo XX, y el turismo y la defensa militar se han convertido en los dos sectores más grandes. El estado atrae visitantes, surfistas y científicos con su diverso paisaje natural, clima tropical cálido, abundantes playas públicas, entorno oceánico, volcanes activos y cielos despejados en la Gran Isla. Hawái alberga la Flota del Pacífico de los Estados Unidos , el comando naval más grande del mundo, así como 75.000 empleados del Departamento de Defensa. [18] El aislamiento de Hawái da como resultado uno de los costos de vida más altos de los EE. UU. Sin embargo, Hawái es el tercer estado más rico, [18] y los residentes tienen la esperanza de vida más larga de todos los estados de EE. UU., con 80,7 años. [19]

El nombre del estado de Hawái deriva del nombre de su isla más grande, Hawái . Una explicación común del nombre de Hawái es que recibió su nombre de Hawaiʻiloa , un personaje de la tradición oral hawaiana. Se dice que descubrió las islas cuando se establecieron por primera vez. [20] [21]

La palabra hawaiana Hawaiʻi es muy similar a la protopolinesia Sawaiki , con el significado reconstruido de "patria". [e] Se encuentran cognados de Hawaiʻi en otras lenguas polinesias, incluyendo el maorí ( Hawaiki ), el rarotongano ( ʻAvaiki ) y el samoano ( Savaiʻi ). Según los lingüistas Pukui y Elbert, [23] "en otras partes de Polinesia, Hawaiʻi o un cognado es el nombre del inframundo o del hogar ancestral, pero en Hawái, el nombre no tiene significado". [24]

En 1978, el hawaiano se agregó a la Constitución del Estado de Hawái como idioma oficial del estado junto con el inglés. [25] El título de la constitución estatal es Constitución del Estado de Hawái . El Artículo XV, Sección 1 de la Constitución utiliza El Estado de Hawái . [26] No se utilizaron diacríticos porque el documento, redactado en 1949, [27] es anterior al uso de ʻokina ⟨ʻ⟩ y el kahakō en la ortografía hawaiana moderna. La ortografía exacta del nombre del estado en el idioma hawaiano es Hawaiʻi . [f] En la Ley de Admisión de Hawái que otorgó la condición de estado a Hawái, el gobierno federal utilizó Hawái como nombre del estado. Las publicaciones oficiales del gobierno, los títulos de departamentos y oficinas y el Sello de Hawái utilizan la ortografía sin símbolos para las oclusiones glotales o la longitud de las vocales. [28] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ]

Hay ocho islas principales en Hawái. Siete están habitadas, pero solo seis están abiertas a turistas y lugareños. Niʻihau está gestionada de forma privada por los hermanos Bruce y Keith Robinson ; el acceso está restringido a quienes tienen su permiso. Esta isla también es el hogar de hawaianos nativos. El acceso a la isla deshabitada de Kahoʻolawe también está restringido y cualquiera que entre sin permiso será arrestado. Esta isla también puede ser peligrosa, ya que fue una base militar durante las guerras mundiales y aún podría tener munición sin explotar.

El archipiélago hawaiano se encuentra a 3200 km (2000 mi) al suroeste de los Estados Unidos continentales. [38] Hawái es el estado más meridional de los EE. UU. y el segundo más occidental después de Alaska . Al igual que Alaska, Hawái no limita con ningún otro estado de los EE. UU. Es el único estado de los EE. UU. que no está en América del Norte y el único completamente rodeado de agua y enteramente un archipiélago.

Además de las ocho islas principales, el estado tiene muchas islas e islotes más pequeños. Kaʻula es una pequeña isla cerca de Niʻihau. Las islas del noroeste de Hawái son un grupo de nueve islas pequeñas y más antiguas al noroeste de Kauaʻi que se extienden desde Nihoa hasta el atolón de Kure ; son restos de montañas volcánicas que alguna vez fueron mucho más grandes. A lo largo del archipiélago hay alrededor de 130 pequeñas rocas e islotes, como Molokini , que están formados por roca sedimentaria volcánica o marina. [39]

La montaña más alta de Hawái, Mauna Kea , tiene 4205 m (13 796 pies) sobre el nivel medio del mar; [40] es más alta que el Monte Everest si se mide desde la base de la montaña, que se encuentra en el fondo del Océano Pacífico y se eleva unos 10 200 m (33 500 pies). [41]

Las islas hawaianas se formaron por la actividad volcánica iniciada en una fuente de magma submarina llamada punto caliente de Hawái . El proceso continúa formando islas; la placa tectónica debajo de gran parte del océano Pacífico se mueve continuamente hacia el noroeste y el punto caliente permanece estacionario, creando lentamente nuevos volcanes. Debido a la ubicación del punto caliente, todos los volcanes terrestres activos están en la mitad sur de la isla de Hawái. El volcán más nuevo, Kamaʻehuakanaloa (anteriormente Lōʻihi), está al sur de la costa de la isla de Hawái.

La última erupción volcánica fuera de la isla de Hawái ocurrió en Haleakalā en Maui antes de finales del siglo XVIII, posiblemente cientos de años antes. [42] En 1790, el Kilauea explotó ; es la erupción más mortal conocida que haya ocurrido en la era moderna en lo que ahora es Estados Unidos. [43] Hasta 5405 guerreros y sus familias que marchaban sobre el Kilauea murieron por la erupción. [44] La actividad volcánica y la erosión posterior han creado características geológicas impresionantes. La isla de Hawái tiene el segundo punto más alto entre las islas del mundo. [45]

En los flancos de los volcanes, la inestabilidad de las laderas ha generado terremotos dañinos y tsunamis relacionados , particularmente en 1868 y 1975. [46] Las catastróficas avalanchas de escombros en los flancos sumergidos de los volcanes de las islas oceánicas han creado acantilados escarpados. [ 47] [48]

El Kilauea entró en erupción en mayo de 2018, abriendo 22 fisuras en suzona de rift.Leilani Estatesy Lanipuna Gardens se encuentran dentro de este territorio. La erupción destruyó al menos 36 edificios y esto, sumado a losflujosde lavade dióxido de azufre, obligó a evacuar a más de 2000 habitantes de sus barrios.[49]

Las islas de Hawái están alejadas de otros hábitats terrestres, y se cree que la vida llegó allí por el viento, las olas (es decir, las corrientes oceánicas) y las alas (es decir, las aves, los insectos y las semillas que pudieran haber llevado en sus plumas). Hawái tiene más especies en peligro de extinción y ha perdido un mayor porcentaje de sus especies endémicas que cualquier otro estado de los EE. UU. [50] La planta endémica Brighamia ahora requiere polinización manual porque se presume que su polinizador natural está extinto. [51] Las dos especies de Brighamia , B. rockii y B. insignis , están representadas en la naturaleza por alrededor de 120 plantas individuales. Para garantizar que estas plantas produzcan semillas, los biólogos descienden en rápel por acantilados de 3000 pies (910 m) para cepillar el polen sobre sus estigmas. [52]

Las islas principales existentes del archipiélago han estado sobre la superficie del océano por menos de 10 millones de años, una fracción del tiempo en que la colonización y evolución biológica han ocurrido allí. Las islas son bien conocidas por la diversidad ambiental que ocurre en altas montañas dentro de un campo de vientos alisios. Los nativos hawaianos desarrollaron prácticas hortícolas complejas para utilizar el ecosistema circundante para la agricultura. Las prácticas culturales desarrolladas para consagrar los valores de la gestión ambiental y la reciprocidad con el mundo natural, dieron como resultado una biodiversidad generalizada y relaciones sociales y ambientales intrincadas que persisten hasta el día de hoy. [53] En una sola isla, el clima alrededor de las costas puede variar de tropical seco (menos de 20 pulgadas o 510 milímetros de lluvia anual) a tropical húmedo; en las laderas, los ambientes varían desde la selva tropical (más de 200 pulgadas o 5,100 milímetros por año), pasando por un clima templado , hasta condiciones alpinas con un clima frío y seco. El clima lluvioso impacta el desarrollo del suelo , que determina en gran medida la permeabilidad del suelo, afectando la distribución de arroyos y humedales . [54] [55] [56]

Varias áreas de Hawái están bajo la protección del Servicio de Parques Nacionales . [57] Hawái tiene dos parques nacionales: el Parque Nacional Haleakalā , cerca de Kula en Maui, que presenta el volcán inactivo Haleakalā que se formó al este de Maui; y el Parque Nacional de los Volcanes de Hawái , en la región sureste de la isla de Hawái, que incluye el volcán activo Kīlauea y sus zonas de ruptura.

Existen tres parques históricos nacionales : el Parque Histórico Nacional de Kalaupapa en Kalaupapa, Molokaʻi, el sitio de una antigua colonia de leprosos; el Parque Histórico Nacional de Kaloko-Honokōhau en Kailua-Kona en la isla de Hawái; y el Parque Histórico Nacional de Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau , un antiguo lugar de refugio en la costa oeste de la isla de Hawái. Otras áreas bajo el control del Servicio de Parques Nacionales incluyen el Sendero Histórico Nacional Ala Kahakai en la isla de Hawái y el USS Arizona Memorial en Pearl Harbor en Oʻahu.

El presidente George W. Bush proclamó el Monumento Nacional Marino Papahānaumokuākea el 15 de junio de 2006. El monumento cubre aproximadamente 140.000 millas cuadradas (360.000 km 2 ) de arrecifes, atolones y mar profundo y poco profundo hasta 50 millas (80 km) de la costa en el Océano Pacífico, un área más grande que todos los parques nacionales de los EE. UU. juntos. [58]

Hawái tiene un clima tropical . Las temperaturas y la humedad tienden a ser menos extremas debido a los vientos alisios casi constantes del este. Las máximas de verano alcanzan alrededor de 88 °F (31 °C) durante el día, con mínimas de 75 °F (24 °C) por la noche. Las temperaturas diurnas de invierno suelen rondar los 83 °F (28 °C); a baja altitud, rara vez bajan de los 65 °F (18 °C) por la noche. La nieve, que no suele asociarse con los trópicos, cae a 13.800 pies (4.200 m) en Mauna Kea y Mauna Loa en la isla de Hawái en algunos meses de invierno. La nieve rara vez cae en Haleakalā. El monte Waiʻaleʻale en Kauaʻi tiene la segunda precipitación media anual más alta de la Tierra, alrededor de 460 pulgadas (12.000 mm) por año. La mayor parte de Hawái experimenta solo dos estaciones: la estación seca va de mayo a octubre y la estación lluviosa va de octubre a abril. [60]

En general, con el cambio climático , Hawái se está volviendo más seco y caluroso . [61] [62] La temperatura más cálida registrada en el estado, en Pahala el 27 de abril de 1931, es de 100 °F (38 °C), empatada con Alaska como la temperatura máxima más baja registrada en un estado de EE. UU. [63] La temperatura mínima récord de Hawái es de 12 °F (−11 °C) observada en mayo de 1979, en la cima de Mauna Kea . Hawái es el único estado que nunca ha registrado temperaturas bajo cero Fahrenheit. [63]

Los climas varían considerablemente en cada isla; se pueden dividir en zonas de barlovento y de sotavento ( Koʻolau y Kona , respectivamente) según su ubicación en relación con las montañas más altas. Los lados de barlovento se enfrentan a una cubierta de nubes. [64]

Hawái tiene una historia de décadas de albergar más espacio militar para los Estados Unidos que cualquier otro territorio o estado. [65] Este historial de actividad militar ha tenido un alto costo para la salud ambiental del archipiélago hawaiano, degradando sus playas y suelo, y haciendo que algunos lugares sean completamente inseguros debido a municiones sin detonar . [66] Según la académica Winona LaDuke : "La vasta militarización de Hawái ha dañado profundamente la tierra. Según la Agencia de Protección Ambiental, hay más sitios federales de desechos peligrosos en Hawái -31- que en cualquier otro estado de EE. UU." [67] El representante estatal de Hawái, Roy Takumi, escribe en "Challenging US Militarism in Hawai'i and Okinawa" que estas bases militares y sitios de desechos peligrosos han significado "la confiscación de grandes extensiones de tierra de los pueblos nativos" y cita al difunto activista hawaiano George Helm preguntando: "¿Qué es la defensa nacional cuando lo que se está destruyendo es precisamente lo que se le confía a los militares defender, la tierra sagrada de Hawái?" [65] Los indígenas hawaianos contemporáneos siguen protestando por la ocupación de sus tierras natales y la degradación ambiental debido a la creciente militarización a raíz del 11 de septiembre. [68]

Tras el auge de las plantaciones de caña de azúcar a mediados del siglo XIX, la ecología de las islas cambió drásticamente. Las plantaciones requieren cantidades masivas de agua, y los propietarios de plantaciones europeos y estadounidenses transformaron la tierra para poder acceder a ella, principalmente construyendo túneles para desviar el agua de las montañas a las plantaciones, construyendo embalses y cavando pozos. [69] Estos cambios han tenido efectos duraderos en la tierra y siguen contribuyendo a la escasez de recursos para los nativos hawaianos en la actualidad. [69] [70]

Según la científica y académica de Stanford Sibyl Diver, los hawaianos indígenas mantienen una relación recíproca con la tierra, "basada en principios de cuidado mutuo, reciprocidad y compartición". [71] Esta relación garantiza la longevidad, la sostenibilidad y los ciclos naturales de crecimiento y decadencia, además de cultivar un sentido de respeto por la tierra y humildad hacia el lugar que uno ocupa en un ecosistema. [71]

La expansión continua de la industria del turismo y su presión sobre los sistemas locales de ecología, tradición cultural e infraestructura están creando un conflicto entre la salud económica y ambiental. [72] En 2020, el Centro para la Diversidad Biológica informó sobre la contaminación plástica de la playa Kamilo de Hawái, citando "enormes pilas de desechos plásticos". [73] Las especies invasoras se están propagando y los vertidos químicos y patógenos están contaminando las aguas subterráneas y costeras. [74]

Hawái es uno de los dos estados de Estados Unidos, junto con Texas , que fueron naciones soberanas reconocidas internacionalmente antes de convertirse en estados de Estados Unidos. El Reino de Hawái fue soberano desde 1810 hasta 1893, cuando los capitalistas y terratenientes estadounidenses y europeos residentes derrocaron a la monarquía . Hawái fue una república independiente desde 1894 hasta el 12 de agosto de 1898, cuando se convirtió oficialmente en territorio estadounidense. Hawái fue admitido como estado de Estados Unidos el 21 de agosto de 1959. [75]

Según la evidencia arqueológica, la primera ocupación de las islas hawaianas parece datar entre 1000 y 1200 d. C. La primera ola probablemente estuvo formada por colonos polinesios de las islas Marquesas , [13] [ dudoso – discutir ] y una segunda ola de migración desde Raiatea y Bora Bora tuvo lugar en el siglo XI. La fecha del descubrimiento y ocupación humana de las islas hawaianas es objeto de debate académico. [76] Algunos arqueólogos e historiadores creen que fue una ola posterior de inmigrantes de Tahití alrededor del año 1000 d. C. quienes introdujeron una nueva línea de altos jefes, el sistema kapu , la práctica del sacrificio humano y la construcción de heiau . [77] Esta inmigración posterior se detalla en la mitología hawaiana ( moʻolelo ) sobre Paʻao . Otros autores dicen que no hay evidencia arqueológica o lingüística de una afluencia posterior de colonos tahitianos y que Paʻao debe considerarse un mito. [77]

La historia de las islas está marcada por un crecimiento lento y constante de la población y del tamaño de los cacicazgos , que crecieron hasta abarcar islas enteras. Los jefes locales, llamados aliʻi , gobernaban sus asentamientos y lanzaban guerras para extender su influencia y defender a sus comunidades de rivales depredadores. El antiguo Hawái era una sociedad basada en castas , muy similar a la de los hindúes en la India. [78] El crecimiento de la población se vio facilitado por prácticas ecológicas y agrícolas que combinaban la agricultura de las tierras altas ( manuka ), la pesca oceánica ( makai ), los estanques de peces y los sistemas de jardinería. Estos sistemas se sustentaban en creencias espirituales y religiosas, como el lokahi , que vinculaban la continuidad cultural con la salud del mundo natural. [53] Según el erudito hawaiano Mililani Trask , el lokahi simboliza "la más grande de las tradiciones, valores y prácticas de nuestro pueblo... Hay tres puntos en el triángulo: el Creador, Akua ; los pueblos de la tierra, Kanaka Maoli ; y la tierra, los ʻaina . Estas tres cosas tienen una relación recíproca". [53] [79]

La llegada en 1778 del explorador británico, el capitán James Cook, marcó el primer contacto documentado de un explorador europeo con Hawái; la influencia británica temprana se puede ver en el diseño de la bandera de Hawái , que lleva la Union Jack en la esquina superior izquierda. Cook nombró al archipiélago "las islas Sandwich" en honor a su patrocinador John Montagu, cuarto conde de Sandwich , publicando la ubicación de las islas y traduciendo el nombre nativo como Owyhee . La forma " Owyhee" u "Owhyhee" se conserva en los nombres de ciertas ubicaciones en la parte estadounidense del noroeste del Pacífico, entre ellas el condado de Owyhee y las montañas Owyhee en Idaho , llamadas así en honor a tres miembros nativos hawaianos de un grupo de tramperos que desaparecieron en el área. [80]

Los exploradores españoles podrían haber llegado a las islas hawaianas en el siglo XVI, 200 años antes de la primera visita documentada de Cook en 1778. Ruy López de Villalobos comandó una flota de seis barcos que partieron de Acapulco en 1542 con destino a Filipinas, con un marinero español llamado Juan Gaetano a bordo como piloto. Los informes de Gaetano describen un encuentro con Hawái o las Islas Marshall . [81] [82] [ se necesita una mejor fuente ] Si la tripulación de López de Villalobos avistó Hawái, Gaetano sería el primer europeo en ver las islas. La mayoría de los académicos han descartado estas afirmaciones debido a la falta de credibilidad. [83] [84] [85]

Sin embargo, los archivos españoles contienen un mapa que muestra islas en la misma latitud que Hawái, pero con una longitud de diez grados al este de las islas. En este manuscrito, Maui se llama La Desgraciada (La Isla Desafortunada), y lo que parece ser la isla de Hawái se llama La Mesa (La Mesa). Las islas que se parecen a Kahoʻolawe' , Lānaʻi y Molokaʻi se llaman Los Monjes (Los Monjes). [86] Durante dos siglos y medio, los galeones españoles cruzaron el Pacífico desde México por una ruta que pasaba al sur de Hawái en su camino a Manila . La ruta exacta se mantuvo en secreto para proteger el monopolio comercial español contra las potencias competidoras. Hawái mantuvo así su independencia, a pesar de estar en una ruta marítima de este a oeste entre naciones que eran súbditos del Virreinato de Nueva España , un imperio que ejercía jurisdicción sobre muchas civilizaciones y reinos sometidos en ambos lados del Pacífico. [87]

.jpg/440px-Entrevue_de_l'expedition_de_M._Kotzebue_avec_le_roi_Tammeamea_dans_l'ile_d'Ovayhi,_Iles_Sandwich_(detailed).jpg)

A pesar de estas afirmaciones controvertidas, Cook es considerado generalmente el primer europeo en desembarcar en Hawái, habiendo visitado las islas hawaianas dos veces. Mientras se preparaba para partir después de su segunda visita en 1779, se produjo una pelea cuando tomó ídolos del templo y cercas como "leña", [88] y un jefe menor y su grupo robaron un bote de su barco. Cook secuestró al rey de la isla de Hawái , Kalaniʻōpuʻu , y lo retuvo a bordo de su barco para pedir un rescate para recuperar el bote de Cook, ya que esta táctica había funcionado anteriormente en Tahití y otras islas. [89] En cambio, los partidarios de Kalaniʻōpuʻu atacaron, matando a Cook y cuatro marineros mientras el grupo de Cook se retiraba por la playa hacia su barco. El barco partió sin recuperar el bote robado.

Después de la visita de Cook y la publicación de varios libros que relataban sus viajes, las islas hawaianas atrajeron a muchos exploradores, comerciantes y balleneros europeos y estadounidenses, que encontraron en las islas un puerto conveniente y una fuente de suministros. Estos visitantes introdujeron enfermedades en las islas, que alguna vez estuvieron aisladas, lo que provocó que la población hawaiana cayera precipitadamente. [90] Los hawaianos nativos no tenían resistencia a las enfermedades euroasiáticas, como la gripe , la viruela y el sarampión . En 1820, las enfermedades, el hambre y las guerras entre los jefes mataron a más de la mitad de la población hawaiana nativa. [91] Durante la década de 1850, el sarampión mató a una quinta parte de la población de Hawái. [92]

Los registros históricos indican que los primeros inmigrantes chinos en Hawái procedían de la provincia de Guangdong ; unos pocos marineros llegaron en 1778 con el viaje de Cook, y más en 1789 con un comerciante estadounidense que se instaló en Hawái a finales del siglo XVIII. Se dice que los trabajadores chinos introdujeron la lepra en 1830 y, al igual que con las otras nuevas enfermedades infecciosas, resultó perjudicial para los hawaianos. [93]

Durante las décadas de 1780 y 1790, los jefes lucharon a menudo por el poder. Después de una serie de batallas que terminaron en 1795, todas las islas habitadas fueron subyugadas bajo un solo gobernante, que pasó a ser conocido como el rey Kamehameha el Grande . Estableció la Casa de Kamehameha , una dinastía que gobernó el reino hasta 1872. [94]

Después de que Kamehameha II heredara el trono en 1819, los misioneros protestantes estadounidenses en Hawái convirtieron a muchos hawaianos al cristianismo. Los misioneros han argumentado que una de las funciones del trabajo misionero era "civilizar" y "purificar" el paganismo percibido en el Nuevo Mundo. Esto se trasladó a Hawái. [95] [96] [97] [98] [99] [100] Según el arqueólogo histórico James L. Flexner, "los misioneros proporcionaron los medios morales para racionalizar la conquista y la conversión generalizada al cristianismo". [95] Pero en lugar de abandonar las creencias tradicionales por completo, la mayoría de los hawaianos nativos fusionaron su religión indígena con el cristianismo. [95] [97] [96] Los misioneros utilizaron su influencia para poner fin a muchas prácticas tradicionales, incluido el sistema kapu , el sistema legal predominante antes del contacto europeo, y los heiau , o "templos" a figuras religiosas. [95] [101] [102] Kapu , que normalmente se traduce como "lo sagrado", se refiere a las regulaciones sociales (como las restricciones de género y clase) que se basaban en creencias espirituales. Bajo la guía de los misioneros, se promulgaron leyes contra el juego, el consumo de alcohol, el baile del hula , la violación del sabbat y la poligamia. [96] Sin el sistema kapu , muchos templos y estatus sacerdotales se vieron amenazados, se quemaron ídolos y aumentó la participación en el cristianismo. [96] [98] Cuando Kamehameha III heredó el trono a los 12 años, sus asesores lo presionaron para que fusionara el cristianismo con las formas tradicionales hawaianas. Bajo la guía de su kuhina nui (su madre y corregente Elizabeth Kaʻahumanu ) y aliados británicos, Hawái se convirtió en una monarquía cristiana con la firma de la Constitución de 1840 . [103] [98] Hiram Bingham I , un destacado misionero protestante, fue un consejero de confianza de la monarquía durante este período. Otros misioneros y sus descendientes se volvieron activos en asuntos comerciales y políticos, lo que llevó a conflictos entre la monarquía y sus inquietos súbditos estadounidenses. [104] Los misioneros de la Iglesia Católica Romana y de La Iglesia de Jesucristo de los Santos de los Últimos Días también estuvieron activos en el reino, inicialmente convirtiendo a una minoría de la población nativa hawaiana, pero luego se convirtieron en la primera y segunda denominaciones religiosas más grandes de las islas, respectivamente. [105] [106] [107] [108]Los misioneros de cada grupo principal administraron la colonia de leprosos de Kalaupapa en Molokaʻi, que se estableció en 1866 y funcionó hasta bien entrado el siglo XX. Los más conocidos fueron el padre Damián y la madre Marianne Cope , ambos canonizados a principios del siglo XXI como santos católicos romanos .

La muerte del rey soltero Kamehameha V —que no nombró heredero— dio lugar a la elección popular de Lunalilo en lugar de Kalākaua . Lunalilo murió al año siguiente, también sin nombrar heredero. En 1874, la elección fue disputada dentro de la legislatura entre Kalākaua y Emma, reina consorte de Kamehameha IV . Después de que estallaran los disturbios, Estados Unidos y Gran Bretaña desembarcaron tropas en las islas para restablecer el orden. La Asamblea Legislativa eligió al rey Kalākaua como monarca por una votación de 39 a 6 el 12 de febrero de 1874. [109]

En 1887, Kalākaua se vio obligado a firmar la Constitución del Reino de Hawái de 1887. Redactada por empresarios y abogados blancos, el documento despojó al rey de gran parte de su autoridad. Estableció una calificación de propiedad para votar que privó de sus derechos a la mayoría de los hawaianos y trabajadores inmigrantes y favoreció a la élite blanca más rica. Los blancos residentes podían votar, pero los asiáticos residentes no. Como la Constitución de 1887 se firmó bajo amenaza de violencia, se la conoce como la Constitución de la Bayoneta. El rey Kalākaua, reducido a una figura decorativa, reinó hasta su muerte en 1891. Su hermana, la reina Liliʻuokalani , lo sucedió; ella fue la última monarca de Hawái. [110]

En 1893, Liliʻuokalani anunció planes para una nueva constitución para proclamarse monarca absoluta. El 14 de enero de 1893, un grupo de líderes empresariales y residentes, en su mayoría euroamericanos, formó el Comité de Seguridad para dar un golpe de estado contra el reino y buscar la anexión por parte de los Estados Unidos. El ministro de gobierno de los EE. UU., John L. Stevens , en respuesta a una solicitud del Comité de Seguridad, convocó a una compañía de marines estadounidenses. Los soldados de la reina no se resistieron. Según el historiador William Russ, la monarquía no pudo protegerse a sí misma. [111] En Autonomía hawaiana , Liliʻuokalani afirma:

Si no resistimos por la fuerza su último ultraje, fue porque no podíamos hacerlo sin atacar la fuerza militar de los Estados Unidos. Cualquiera que sea la obligación que pueda tener el ejecutivo de este gran país para reconocer al actual gobierno de Honolulu, no le ha sido impuesta por ningún acto nuestro, sino por los actos ilegales de sus propios agentes. Los intentos de repudiar esos actos son vanos. [112] [113]

En un mensaje a Sanford B. Dole, Liliʻuokalani afirma:

Ahora bien, para evitar cualquier colisión de fuerzas armadas y tal vez la pérdida de vidas, bajo esta protesta, e impulsado por dicha fuerza, cedo mi autoridad hasta el momento en que el Gobierno de los Estados Unidos, al presentarse los hechos, deshaga la acción de sus representantes y me restablezca en la autoridad que reclamo como soberano constitucional de las Islas Hawaianas. [114] [115]

Los juicios por traición de 1892 reunieron a los principales protagonistas del derrocamiento de 1893. El ministro estadounidense John L. Stevens expresó su apoyo a los revolucionarios nativos hawaianos; William R. Castle, miembro del Comité de Seguridad, actuó como abogado defensor en los juicios por traición; Alfred Stedman Hartwell, el comisionado de anexión de 1893, dirigió la defensa; y Sanford B. Dole falló como juez de la Corte Suprema contra los actos de conspiración y traición. [116]

El 17 de enero de 1893, un pequeño grupo de empresarios azucareros y productores de piña, ayudados por el ministro estadounidense en Hawái y respaldados por soldados y marines estadounidenses fuertemente armados, depusieron a la reina Liliʻuokalani e instalaron un gobierno provisional compuesto por miembros del Comité de Seguridad. [117] Según la académica Lydia Kualapai y el representante estatal de Hawái Roy Takumi, este comité se formó contra la voluntad de los votantes indígenas hawaianos, que constituían la mayoría de los votantes en ese momento, y estaba formado por "trece hombres blancos" según el académico J Kehaulani Kauanui. [118] [65] [68] El ministro de los Estados Unidos en el Reino de Hawái ( John L. Stevens ) conspiró con ciudadanos estadounidenses para derrocar a la monarquía. [119] Después del derrocamiento, Sanford B. Dole , ciudadano de Hawái y primo de James Dole, propietario de Hawaiian Fruit Company, una empresa que se benefició de la anexión de Hawái, se convirtió en presidente de la república cuando el Gobierno Provisional de Hawái terminó el 4 de julio de 1894. [120] [121]

En los años siguientes se desató una controversia cuando la reina intentó recuperar su trono. La académica Lydia Kualapai escribe que Liliʻuokalani había "cedido bajo protesta no al falso Gobierno Provisional de Hawái sino a la fuerza superior de los Estados Unidos de América" y escribió cartas de protesta al presidente solicitando un reconocimiento de la alianza y una restitución de su soberanía contra las recientes acciones del Gobierno Provisional de Hawái. [118] Después del golpe de enero de 1893 que depuso a Liliʻuokalani, muchos realistas se preparaban para derrocar a la oligarquía de la República de Hawái liderada por los blancos. Cientos de rifles fueron enviados de forma encubierta a Hawái y escondidos en cuevas cercanas. Mientras las tropas armadas iban y venían, una patrulla de la República de Hawái descubrió al grupo rebelde. El 6 de enero de 1895, comenzaron los disparos en ambos lados y más tarde los rebeldes fueron rodeados y capturados. Durante los siguientes diez días se produjeron varias escaramuzas, hasta que los últimos opositores armados se rindieron o fueron capturados. La República de Hawái tomó a 123 soldados bajo custodia como prisioneros de guerra. El arresto masivo de casi 300 hombres y mujeres más, incluida la reina Liliʻuokalani, como prisioneros políticos tenía como objetivo incapacitar la resistencia política contra la oligarquía gobernante. En marzo de 1895, un tribunal militar condenó a 170 prisioneros por traición y condenó a seis soldados a ser "colgados del cuello" hasta la muerte, según el historiador Ronald Williams Jr. Los demás prisioneros fueron sentenciados a penas de entre cinco y treinta y cinco años de prisión con trabajos forzados, mientras que los condenados por cargos menores recibieron sentencias de entre seis meses y seis años de prisión con trabajos forzados. [122] La reina fue sentenciada a cinco años de prisión, pero pasó ocho meses bajo arresto domiciliario hasta que fue puesta en libertad condicional. [123] El número total de arrestos relacionados con el Kaua Kūloko de 1895 fue de 406 personas según una lista resumida de estadísticas publicada por el gobierno de la República de Hawái. [122]

La administración del presidente Grover Cleveland encargó el Informe Blount , que concluyó que la destitución de Liliʻuokalani había sido ilegal. El comisionado Blount declaró a los EE. UU. y a su ministro culpables de todos los cargos, incluidos el derrocamiento, el desembarco de los marines y el reconocimiento del gobierno provisional. [114] En un mensaje al Congreso, Cleveland escribió:

Y, por último, si no hubiera sido por la ocupación ilegal de Honolulu bajo falsos pretextos por las fuerzas de los Estados Unidos, y si no hubiera sido por el reconocimiento del Ministro Stevens del gobierno provisional cuando las fuerzas de los Estados Unidos eran su único apoyo y constituían su única fuerza militar, la Reina y su Gobierno nunca se hubieran rendido ante el gobierno provisional, ni siquiera por un tiempo y con el único propósito de someter su caso a la justicia ilustrada de los Estados Unidos. [114] [117] Mediante un acto de guerra, cometido con la participación de un representante diplomático de los Estados Unidos y sin la autorización del Congreso, el Gobierno de un pueblo débil pero amistoso y confiado ha sido derrocado. Se ha cometido así un daño sustancial que, teniendo en cuenta nuestro carácter nacional y los derechos del pueblo perjudicado, debemos esforzarnos por reparar. El gobierno provisional no ha asumido una forma republicana ni de otra constitución, sino que ha seguido siendo un mero consejo ejecutivo u oligarquía, establecido sin el consentimiento del pueblo. No ha tratado de encontrar una base permanente de apoyo popular y no ha dado ninguna prueba de intención de hacerlo. [117] [114]

El gobierno de los Estados Unidos exigió en un primer momento que se restituyera a la reina Liliʻuokalani, pero el gobierno provisional se negó. El 23 de diciembre de 1893, la respuesta del gobierno provisional de Hawái, redactada por el presidente Sanford B. Dole, fue recibida por el ministro representante de Cleveland, Albert S. Willis, y en ella se subrayaba que el gobierno provisional de Hawái había rechazado "sin vacilar" la demanda de la administración de Cleveland. [118]

El Congreso llevó a cabo una investigación independiente y el 26 de febrero de 1894 presentó el Informe Morgan , que encontró a todas las partes, incluido el ministro Stevens (con excepción de la reina) "no culpables" y no responsables del golpe. [124] Los partidarios de ambos lados del debate cuestionaron la precisión e imparcialidad de los informes Blount y Morgan sobre los acontecimientos de 1893. [111] [125] [126] [127]

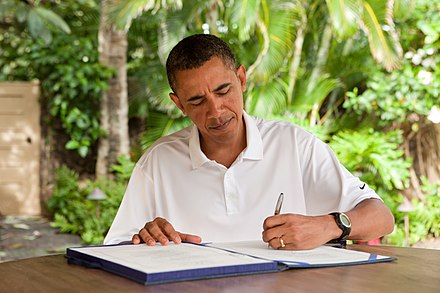

En 1993, el Congreso aprobó una Resolución de Disculpas conjunta en relación con el derrocamiento, que fue firmada por el presidente Bill Clinton . La resolución se disculpaba y decía que el derrocamiento era ilegal en la siguiente frase: "El Congreso, con ocasión del centenario del derrocamiento ilegal del Reino de Hawái el 17 de enero de 1893, reconoce la importancia histórica de este acontecimiento que dio lugar a la supresión de la soberanía inherente del pueblo nativo hawaiano". [119] La Resolución de Disculpas también "reconoce que el derrocamiento del Reino de Hawái se produjo con la participación activa de agentes y ciudadanos de los Estados Unidos y reconoce además que el pueblo nativo hawaiano nunca cedió directamente a los Estados Unidos sus reclamaciones a su soberanía inherente como pueblo sobre sus tierras nacionales, ni a través del Reino de Hawái ni a través de un plebiscito o referéndum". [127] [119]

Después de que William McKinley ganara las elecciones presidenciales de Estados Unidos en 1896, los defensores presionaron para anexar la República de Hawái. El presidente anterior, Grover Cleveland, era amigo de la reina Liliʻuokalani. McKinley estaba abierto a la persuasión de los expansionistas estadounidenses y de los anexionistas de Hawái. Se reunió con tres anexionistas no nativos: Lorrin A. Thurston , Francis March Hatch y William Ansel Kinney . Después de las negociaciones en junio de 1897, el Secretario de Estado John Sherman acordó un tratado de anexión con estos representantes de la República de Hawái. [128] El Senado de Estados Unidos nunca ratificó el tratado. A pesar de la oposición de la mayoría de los hawaianos nativos, [129] la Resolución Newlands se utilizó para anexar la república a los EE. UU.; se convirtió en el Territorio de Hawái . La Resolución de Newlands fue aprobada por la Cámara el 15 de junio de 1898, por 209 votos a favor y 91 en contra, y por el Senado el 6 de julio de 1898, por 42 votos a 21. [130] [131] [132]

La mayoría de los nativos hawaianos se opusieron a la anexión, expresada principalmente por Liliʻuokalani, a quien la hawaiana Haunani-Kay Trask describió como querida y respetada por su pueblo. [133] Liliʻuokalani escribió: "No se nos había ocurrido creer que estos amigos y aliados de los Estados Unidos... llegarían tan lejos como para derrocar absolutamente nuestra forma de gobierno, apoderarse de nuestra nación por el cuello y entregársela a una potencia extranjera" en su relato del derrocamiento de su gobierno. [134] Según Trask, los periódicos de la época argumentaron que los hawaianos sufrirían "una esclavitud virtual bajo la anexión", incluida una mayor pérdida de tierras y libertades, en particular para los propietarios de plantaciones de azúcar. [135] Estas plantaciones estaban protegidas por la Marina de los EE. UU. como intereses económicos, lo que justificaba una presencia militar continua en las islas. [135]

En 1900, Hawái obtuvo el autogobierno y conservó el Palacio Iolani como capital territorial. A pesar de varios intentos de convertirse en estado, Hawái siguió siendo territorio durante 60 años. Los propietarios de plantaciones y los capitalistas, que mantenían el control a través de instituciones financieras como las Cinco Grandes , encontraron conveniente el estatus territorial porque seguían pudiendo importar mano de obra extranjera barata. Tales prácticas de inmigración y trabajo estaban prohibidas en muchos estados. [136]

La inmigración puertorriqueña a Hawái comenzó en 1899, cuando la industria azucarera de Puerto Rico fue devastada por un huracán , lo que provocó una escasez mundial de azúcar y una enorme demanda de azúcar de Hawái. Los propietarios de plantaciones de caña de azúcar hawaianas comenzaron a reclutar trabajadores experimentados y desempleados en Puerto Rico. En el siglo XX se produjeron dos oleadas de inmigración coreana a Hawái . La primera ola llegó entre 1903 y 1924; la segunda ola comenzó en 1965 después de que el presidente Lyndon B. Johnson firmara la Ley de Inmigración y Nacionalidad de 1965 , que eliminó las barreras raciales y nacionales y resultó en una alteración significativa de la mezcla demográfica en los EE. UU. [137]

Oʻahu fue el objetivo de un ataque sorpresa a Pearl Harbor por parte del Japón Imperial el 7 de diciembre de 1941. El ataque a Pearl Harbor y otras instalaciones militares y navales, llevado a cabo por aviones y por submarinos enanos , llevó a Estados Unidos a la Segunda Guerra Mundial .

En la década de 1950, el poder de los dueños de las plantaciones fue quebrado por los descendientes de trabajadores inmigrantes, que nacieron en Hawái y eran ciudadanos estadounidenses. Votaron en contra del Partido Republicano de Hawái , fuertemente apoyado por los dueños de las plantaciones. La nueva mayoría votó por el Partido Demócrata de Hawái , que dominó la política territorial y estatal durante más de 40 años. Ansiosos por obtener una representación plena en el Congreso y el Colegio Electoral, los residentes hicieron campaña activamente por la estadidad. En Washington, se habló de que Hawái sería un bastión del Partido Republicano. Como resultado, la admisión de Hawái coincidió con la admisión de Alaska, que era vista como un bastión del Partido Demócrata. Estas predicciones resultaron inexactas; a partir de 2017, Hawái generalmente vota por los demócratas, mientras que Alaska generalmente vota por los republicanos. [138] [139] [140] [141]

Durante la Guerra Fría, Hawái se convirtió en un sitio importante para la diplomacia cultural , el entrenamiento militar y la investigación de los EE. UU., y como base de operaciones para la guerra de Estados Unidos en Vietnam . [142] : 105

En marzo de 1959, el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Admisiones de Hawái , que el presidente estadounidense Dwight D. Eisenhower convirtió en ley. [143] La ley excluía al atolón Palmyra de la condición de estado; había sido parte del Reino y Territorio de Hawái. El 27 de junio de 1959, un referéndum pidió a los residentes de Hawái que votaran sobre el proyecto de ley de estadidad; el 94,3% votó a favor de la estadidad y el 5,7% se opuso. [144] El referéndum pidió a los votantes que eligieran entre aceptar la Ley y seguir siendo un territorio estadounidense. El Comité Especial de Descolonización de las Naciones Unidas más tarde eliminó a Hawái de su lista de territorios no autónomos .

Después de alcanzar la categoría de estado, Hawái se modernizó rápidamente a través de la construcción y una economía turística en rápido crecimiento. Más tarde, los programas estatales promovieron la cultura hawaiana. [ ¿Cuáles? ] La Convención Constitucional del Estado de Hawái de 1978 creó instituciones como la Oficina de Asuntos Hawaianos para promover la lengua y la cultura indígenas. [145]

En 1897, más de 21.000 nativos, que representaban la abrumadora mayoría de los hawaianos adultos, firmaron peticiones contra la anexión en uno de los primeros ejemplos de protesta contra el derrocamiento del gobierno de la reina Liliʻuokalani. [146] Casi 100 años después, en 1993, 17.000 hawaianos marcharon para exigir acceso y control sobre las tierras fiduciarias hawaianas y como parte del movimiento moderno de soberanía hawaiana. [147] La propiedad y el uso de las tierras fiduciarias hawaianas todavía son ampliamente controvertidos como consecuencia de la anexión. Según la académica Winona LaDuke, en 2015, el 95% de las tierras de Hawái eran propiedad o estaban controladas por solo 82 terratenientes, incluido más del 50% por los gobiernos federal y estatal, así como por las empresas azucareras y de piña establecidas. [147] Está previsto construir el Telescopio de Treinta Metros en tierras fiduciarias hawaianas, pero ha encontrado resistencia porque el proyecto interfiere con la indigeneidad kanaka. [ aclarar ] [148]

Después de que los europeos y los estadounidenses continentales llegaron por primera vez durante el período del Reino de Hawái , la población general de Hawái, que hasta ese momento estaba compuesta únicamente por hawaianos indígenas, disminuyó drásticamente. Muchas personas de la población hawaiana indígena murieron a causa de enfermedades extranjeras, disminuyendo de 300.000 en la década de 1770, a 60.000 en la década de 1850, a 24.000 en 1920. Otras estimaciones para la población anterior al contacto varían de 150.000 a 1,5 millones. [14] La población de Hawái comenzó a aumentar finalmente después de una afluencia de colonos principalmente asiáticos que llegaron como trabajadores migrantes a fines del siglo XIX. [152] En 1923, el 42% de la población era de ascendencia japonesa, el 9% era de ascendencia china y el 16% era de ascendencia nativa. [153]

La población indígena hawaiana no mezclada aún no ha recuperado el nivel de 300.000 personas que tenía antes del contacto. En 2010 [update], solo 156.000 personas declararon tener ascendencia exclusivamente hawaiana, poco más de la mitad de la población hawaiana nativa del nivel anterior al contacto, aunque otras 371.000 personas declararon poseer ascendencia hawaiana nativa en combinación con una o más razas (incluidos otros grupos polinesios, pero principalmente asiáticos o caucásicos ).

En 2018 [update], la Oficina del Censo de los Estados Unidos estimó que la población de Hawái era de 1.420.491 habitantes, una disminución de 7.047 respecto del año anterior y un aumento de 60.190 (4,42 %) desde 2010. Esto incluye un aumento natural de 48.111 (96.028 nacimientos menos 47.917 muertes) y un aumento debido a la migración neta de 16.956 personas al estado. La inmigración desde fuera de los Estados Unidos resultó en un aumento neto de 30.068; la migración dentro del país produjo una pérdida neta de 13.112 personas. [154] [ necesita actualización ]

El centro de población de Hawái se encuentra en la isla de O'ahu . Un gran número de hawaianos nativos se han mudado a Las Vegas , que se ha denominado la "novena isla" de Hawái. [155] [156]

Hawái tiene una población de facto de más de 1,4 millones, debido en parte a una gran cantidad de personal militar y residentes turistas. O'ahu es la isla más poblada; tiene la densidad de población más alta con una población residente de poco menos de un millón en 597 millas cuadradas (1546 km 2 ), aproximadamente 1650 personas por milla cuadrada. [g] [157] Los 1,4 millones de residentes de Hawái , distribuidos en 6000 millas cuadradas (15 500 km 2 ) de tierra, dan como resultado una densidad de población promedio de 188,6 personas por milla cuadrada. [158] El estado tiene una densidad de población menor que Ohio e Illinois . [159]

La esperanza de vida promedio proyectada para las personas nacidas en Hawái en 2000 es de 79,8 años; 77,1 años si son hombres, 82,5 si son mujeres, más larga que la esperanza de vida promedio de cualquier otro estado de los EE. UU. [160] En 2011, [update]el ejército estadounidense informó que tenía 42.371 efectivos en las islas. [161]

Según el Informe Anual de Evaluación de Personas sin Hogar de 2022 del HUD , se estima que había 5.967 personas sin hogar en Hawái. [162] [163]

En 2018, los principales países de origen de los inmigrantes en Hawái fueron Filipinas , China , Japón , Corea y las Islas Marshall . [164]

Según el censo de los Estados Unidos de 2020, Hawái tenía una población de 1.455.271 habitantes. La población del estado se identificó como 37,2% asiática ; 25,3% multirracial ; 22,9% blanca ; 10,8% nativa hawaiana y otras islas del Pacífico ; 9,5% hispana y latina de cualquier raza; 1,6% negra o afroamericana ; 1,8% de alguna otra raza; y 0,3% nativa americana y nativa de Alaska . [165]

Hawái tiene el porcentaje más alto de estadounidenses de origen asiático y multirracial y el porcentaje más bajo de estadounidenses blancos de todos los estados. Es el único estado donde las personas que se identifican como estadounidenses de origen asiático son el grupo étnico más numeroso. En 2012, el 14,5 % de la población residente menor de 1 año era blanca no hispana. [169] La población asiática de Hawái se compone principalmente de 198 000 (14,6 %) estadounidenses de origen filipino, 185 000 (13,6 %) estadounidenses de origen japonés, aproximadamente 55 000 (4,0 %) estadounidenses de origen chino y 24 000 (1,8 %) estadounidenses de origen coreano . [170]

Más de 120.000 (8,8%) hispanoamericanos y latinoamericanos viven en Hawái. Los mexicanoamericanos suman más de 35.000 (2,6%); los puertorriqueños superan los 44.000 (3,2%). Los estadounidenses multirraciales constituyen casi el 25% de la población de Hawái, superando las 320.000 personas. Hawái es el único estado que tiene un grupo trirracial como su grupo multirracial más grande, uno que incluye blancos, asiáticos y nativos hawaianos/isleños del Pacífico (22% de toda la población multirracial). [171] La población blanca no hispana asciende a alrededor de 310.000, poco más del 20% de la población. La población multirracial supera a la población blanca no hispana en aproximadamente 10.000 personas. [170] En 1970, la Oficina del Censo informó que la población de Hawái era 38,8% blanca y 57,7% asiática e isleña del Pacífico. [172]

Hay más de 80.000 hawaianos indígenas, el 5,9% de la población. [170] Incluyendo a aquellos con ascendencia parcial, los estadounidenses de origen samoano constituyen el 2,8% de la población de Hawái, y los estadounidenses de origen tongano constituyen el 0,6%. [173]

Las cinco ascendencias europeas más numerosas en Hawái son la alemana (7,4%), la irlandesa (5,2%), la inglesa (4,6%), la portuguesa (4,3%) y la italiana (2,7%). Alrededor del 82,2% de los residentes del estado nacieron en los Estados Unidos. Aproximadamente el 75% de los residentes nacidos en el extranjero son originarios de Asia. Hawái es un estado de mayoría minoritaria . Se esperaba que fuera uno de los tres estados que no tendrían una pluralidad blanca no hispana en 2014; los otros dos son California y Nuevo México . [174]

El tercer grupo de extranjeros que llegó a Hawái procedía de China. Los trabajadores chinos de los barcos comerciales occidentales se establecieron en Hawái a partir de 1789. En 1820, llegaron los primeros misioneros estadounidenses para predicar el cristianismo y enseñar a los hawaianos las costumbres occidentales. [177] A partir de 2015 [update], una gran proporción de la población de Hawái tiene ascendencia asiática, especialmente filipina, japonesa y china. Muchos son descendientes de inmigrantes traídos para trabajar en las plantaciones de caña de azúcar a mediados y fines del siglo XIX. Los primeros 153 inmigrantes japoneses llegaron a Hawái el 19 de junio de 1868. No fueron aprobados por el entonces gobierno japonés porque el contrato era entre un intermediario y el shogunato Tokugawa , para entonces reemplazado por la Restauración Meiji . Los primeros inmigrantes japoneses aprobados por el actual gobierno llegaron el 9 de febrero de 1885, después de la petición de Kalākaua al emperador Meiji cuando Kalākaua visitó Japón en 1881. [178] [179]

En 1899 habían llegado casi 13.000 inmigrantes portugueses, que también trabajaban en las plantaciones de caña de azúcar. [180] En 1901, más de 5.000 puertorriqueños vivían en Hawái. [181]

El inglés y el hawaiano figuran como idiomas oficiales de Hawái en la constitución del estado de 1978, en el artículo XV, sección 4. [182] Sin embargo, el uso del hawaiano es limitado porque la constitución especifica que "el hawaiano será necesario para actos y transacciones públicas solo según lo disponga la ley". El inglés criollo hawaiano , conocido localmente como "pidgin", es el idioma nativo de muchos residentes nativos y es un segundo idioma para muchos otros. [183]

Según el censo de 2000, el 73,4% de los residentes de Hawái de 5 años o más hablan exclusivamente inglés en casa. [184] Según la Encuesta sobre la comunidad estadounidense de 2008, el 74,6% de los residentes de Hawái mayores de 5 años hablan solo inglés en casa. [175] En sus hogares, el 21,0% de los residentes del estado hablan un idioma asiático adicional , el 2,6% habla español, el 1,6% habla otros idiomas indoeuropeos y el 0,2% habla otro idioma. [175]

Después del inglés, otros idiomas hablados popularmente en el estado son el tagalo , el ilocano y el japonés. [185] El 5,4% de los residentes habla tagalo, que incluye hablantes no nativos de filipino , una lengua nacional y cooficial de Filipinas basada en el tagalo; el 5,0% habla japonés y el 4,0% habla ilocano; el 1,2% habla chino, el 1,7% habla hawaiano; el 1,7% habla español; el 1,6% habla coreano ; y el 1,0% habla samoano . [184]

El idioma hawaiano tiene alrededor de 2000 hablantes nativos, aproximadamente el 0,15% de la población total. [186] Según el censo de los Estados Unidos , había más de 24 000 hablantes totales del idioma en Hawái en 2006-2008. [187] El hawaiano es un miembro polinesio de la familia de lenguas austronesias . [186] Está estrechamente relacionado con otras lenguas polinesias , como el marquesano , el tahitiano , el maorí , el rapa nui (el idioma de la Isla de Pascua ), y menos estrechamente con el samoano y el tongano . [188]

Según Schütz, los marqueses colonizaron el archipiélago aproximadamente en el año 300 d. C. [189] y luego fueron seguidos por oleadas de navegantes de las Islas de la Sociedad , Samoa y Tonga . [190] Estos polinesios permanecieron en las islas; finalmente se convirtieron en el pueblo hawaiano y sus lenguas evolucionaron hasta convertirse en el idioma hawaiano. [191] Kimura y Wilson dicen: "[l]os lingüistas coinciden en que el hawaiano está estrechamente relacionado con el polinesio oriental, con un vínculo particularmente fuerte en las Marquesas del Sur y un vínculo secundario en Tahití, que puede explicarse por los viajes entre las islas hawaianas y de la Sociedad". [192]

Antes de la llegada del capitán James Cook, el idioma hawaiano no tenía forma escrita. Esa forma fue desarrollada principalmente por misioneros protestantes estadounidenses entre 1820 y 1826, quienes asignaron a los fonemas hawaianos letras del alfabeto latino. El interés por el hawaiano aumentó significativamente a fines del siglo XX. Con la ayuda de la Oficina de Asuntos Hawaianos, se establecieron escuelas de inmersión especialmente designadas en las que todas las materias se enseñarían en hawaiano. La Universidad de Hawái desarrolló un programa de estudios de posgrado en idioma hawaiano. Se modificaron los códigos municipales para favorecer los nombres de lugares y calles hawaianos para los nuevos desarrollos cívicos. [193]

El hawaiano distingue entre sonidos vocálicos largos y cortos . En la práctica moderna, la longitud de la vocal se indica con un macrón ( kahakō ). Los periódicos en lengua hawaiana ( nūpepa ) publicados entre 1834 y 1948 y los hablantes nativos tradicionales de hawaiano generalmente omiten las marcas en su propia escritura. El ʻokina y el kahakō tienen como objetivo capturar la pronunciación correcta de las palabras hawaianas. [194] El idioma hawaiano utiliza la oclusión glotal ( ʻOkina ) como consonante. Se escribe como un símbolo similar al apóstrofo o comilla simple colgante izquierda (de apertura). [195]

La distribución del teclado utilizada para el hawaiano es QWERTY . [196]

Algunos residentes de Hawái hablan inglés criollo hawaiano (HCE), llamado endonímicamente pidgin o inglés pidgin . El léxico del HCE deriva principalmente del inglés, pero también utiliza palabras derivadas del hawaiano, chino, japonés, portugués, ilocano y tagalo. Durante el siglo XIX, el aumento de la inmigración, principalmente de China, Japón, Portugal, especialmente de las Azores y Madeira , y España, catalizó el desarrollo de una variante híbrida del inglés conocida por sus hablantes como pidgin . A principios del siglo XX, los hablantes de pidgin tuvieron hijos que lo adquirieron como su primera lengua. Los hablantes de HCE utilizan algunas palabras hawaianas sin que esas palabras se consideren arcaicas. [ aclaración necesaria ] La mayoría de los nombres de lugares se conservan del hawaiano, al igual que algunos nombres de plantas y animales. Por ejemplo, el atún a menudo se llama por su nombre hawaiano, ahi . [197]

Los hablantes del HCE han modificado el significado de algunas palabras inglesas. Por ejemplo, "aunty" y "uncle" pueden referirse a cualquier adulto que sea amigo o usarse para mostrar respeto a un anciano. La sintaxis y la gramática siguen reglas distintivas diferentes de las del inglés general estadounidense. Por ejemplo, en lugar de "it is hot today, isn't it?", un hablante del HCE diría simplemente "stay hot, eh?" [h] El término da kine se usa como relleno ; un sustituto de prácticamente cualquier palabra o frase. Durante el auge del surf en Hawái, el HCE se vio influenciado por la jerga de los surfistas. Algunas expresiones del HCE, como brah y da kine , han encontrado su camino en otros lugares a través de las comunidades de surfistas. [198]

El lenguaje de señas hawaiano , un lenguaje de señas para sordos basado en el idioma hawaiano, se ha utilizado en las islas desde principios del siglo XIX. Su uso está disminuyendo debido a que el lenguaje de señas americano ha sustituido al HSL en la enseñanza y en otros ámbitos. [199]

.tif/lossy-page1-440px-Perspective_view_of_northwest_elevation_-_Makiki_Christian_Church,_829_Pensacola_Street,_Honolulu,_Honolulu_County,_HI_HABS_HI-533-1_(cropped).tif.jpg)

Autoidentificación religiosa, según la Encuesta de valores estadounidenses de 2022 del Public Religion Research Institute [200]

Religión en Hawái (2014) [201]

Hawaii is among the most religiously diverse states in the U.S., with one in ten residents practicing a non-Christian faith.[202] Roughly one-quarter to half the population identify as unaffiliated and nonreligious, making Hawaii one of the most secular states as well.

Christianity remains the majority religion, represented mainly by various Protestant groups and Roman Catholicism. The second-largest religion is Buddhism, which comprises a larger proportion of the population than in any other state; it is concentrated in the Japanese community. Native Hawaiians continue to engage in traditional religious and spiritual practices today, often adhering to Christian and traditional beliefs at the same time.[53][97][95][79][96]

The Cathedral Church of Saint Andrew in Honolulu was formally the seat of the Hawaiian Reformed Catholic Church, a province of the Anglican Communion that had been the state church of the Kingdom of Hawaii; it subsequently merged into the Episcopal Church in the 1890s following the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, becoming the seat of the Episcopal Diocese of Hawaii. The Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Peace and the Co-Cathedral of Saint Theresa of the Child Jesus serve as seats of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu. The Eastern Orthodox community is centered around the Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Cathedral of the Pacific.

The largest religious denominations by membership were the Roman Catholic Church with 249,619 adherents in 2010;[203] the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 68,128 adherents in 2009;[204] the United Church of Christ with 115 congregations and 20,000 members; and the Southern Baptist Convention with 108 congregations and 18,000 members.[205] Nondenominational churches collectively have 128 congregations and 32,000 members.

According to data provided by religious establishments, religion in Hawaii in 2000 was distributed as follows:[206][207]

However, a Pew poll found that the religious composition was as follows:

Note: Births in this table do not add up, because Hispanic peoples are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

Hawaii has had a long history of LGBTQIA+ identities. Māhū ("in the middle") were a precolonial third gender with traditional spiritual and social roles, widely respected as healers. Homosexual relationships known as aikāne were widespread and normal in ancient Hawaiian society.[219][220][221] Among men, aikāne relationships often began as teens and continued throughout their adult lives, even if they also maintained heterosexual partners.[222] While aikāne usually refers to male homosexuality, some stories also refer to women, implying that women may have been involved in aikāne relationships as well.[223] Journals written by Captain Cook's crew record that many aliʻi (hereditary nobles) also engaged in aikāne relationships, and Kamehameha the Great, the founder and first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii, was also known to participate. Cook's second lieutenant and co-astronomer James King observed that "all the chiefs had them", and recounts that Cook was actually asked by one chief to leave King behind, considering the role a great honor.

Hawaiian scholar Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa notes that aikāne served a practical purpose of building mutual trust and cohesion; "If you didn't sleep with a man, how could you trust him when you went into battle? How would you know if he was going to be the warrior that would protect you at all costs, if he wasn't your lover?"[224]

As Western colonial influences intensified in the late 19th and early 20th century, the word aikāne was expurgated of its original sexual meaning, and in print simply meant "friend". Nonetheless, in Hawaiian language publications its metaphorical meaning can still mean either "friend" or "lover" without stigmatization.[225]

A 2012 Gallup poll found that Hawaii had the largest proportion of LGBTQIA+ adults in the U.S., at 5.1%, an estimated 53,966 individuals. The number of same-sex couple households in 2010 was 3,239, representing a 35.5% increase from a decade earlier.[226][227] In 2013, Hawaii became the fifteenth U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage; this reportedly boosted tourism by $217 million.[228]

.jpg/440px-Pineapple_field_near_Honolulu,_Hawaii,_1907_(CHS-418).jpg)

The history of Hawaii's economy can be traced through a succession of dominant industries: sandalwood,[229] whaling,[230] sugarcane, pineapple, the military, tourism and education. By the 1840s, sugar plantations had gained a strong foothold in the Hawaiian economy, due to a high demand of sugar in the United States and rapid transport via steamships.[69] Sugarcane plantations were tightly controlled by American missionary families and businessmen known as "the Big Five", who monopolized control of the sugar industry's profits.[69][70] By the time Hawaiian annexation was being considered in 1898, sugarcane producers turned to cultivating tropical fruits like pineapple, which became the principal export for Hawaiʻi's plantation economy.[70][69] Since statehood in 1959, tourism has been the largest industry, contributing 24.3% of the gross state product (GSP) in 1997, despite efforts to diversify. The state's gross output for 2003 was US$47 billion; per capita income for Hawaii residents in 2014 was US$54,516.[231] Hawaiian exports include food and clothing. These industries play a small role in the Hawaiian economy, due to the shipping distance to viable markets, such as the West Coast of the United States. The state's food exports include coffee, macadamia nuts, pineapple, livestock, sugarcane and honey.[232]

By weight, honey bees may be the state's most valuable export.[233] According to the Hawaii Agricultural Statistics Service, agricultural sales were US$370.9 million from diversified agriculture, US$100.6 million from pineapple, and US$64.3 million from sugarcane. Hawaii's relatively consistent climate has attracted the seed industry, which is able to test three generations of crops per year on the islands, compared with one or two on the mainland.[234] Seeds yielded US$264 million in 2012, supporting 1,400 workers.[235]

As of December 2015[update], the state's unemployment rate was 3.2%.[236] In 2009, the United States military spent US$12.2 billion in Hawaii, accounting for 18% of spending in the state for that year. 75,000 United States Department of Defense personnel live in Hawaii.[237] According to a 2013 study by Phoenix Marketing International, Hawaii at that time had the fourth-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States, with a ratio of 7.2%.[238]

Tax is collected by the Hawaii Department of Taxation.[239] Most government revenue comes from personal income taxes and a general excise tax (GET) levied primarily on businesses; there is no statewide tax on sales,[240] personal property, or stock transfers,[241] while the effective property tax rate is among the lowest in the country.[242] The high rate of tourism means that millions of visitors generate public revenue through GET and the hotel room tax.[243] However, Hawaii residents generally pay among the most state taxes per person in the U.S.[243]

The Tax Foundation of Hawaii considers the state's tax burden too high, claiming that it contributes to higher prices and the perception of an unfriendly business climate.[243] The nonprofit Tax Foundation ranks Hawaii third in income tax burden and second in its overall tax burden, though notes that a significant portion of taxes are borne by tourists.[244] Former State Senator Sam Slom attributed Hawaii's comparatively high tax rate to the fact that the state government is responsible for education, health care, and social services that are usually handled at a county or municipal level in most other states.[243]

The cost of living in Hawaii, specifically Honolulu, is high compared to that of most major U.S. cities, although it is 6.7% lower than in New York City and 3.6% lower than in San Francisco.[245] These numbers may not take into account some costs, such as increased travel costs for flights, additional shipping fees, and the loss of promotional participation opportunities for customers outside the contiguous U.S. While some online stores offer free shipping on orders to Hawaii, many merchants exclude Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico and certain other U.S. territories.[246][247]

Hawaiian Electric Industries, a privately owned company, provides 95% of the state's population with electricity, mostly from fossil-fuel power stations. Average electricity prices in October 2014 (36.41 cents per kilowatt-hour) were nearly three times the national average (12.58 cents per kilowatt-hour) and 80% higher than the second-highest state, Connecticut.[248]

The median home value in Hawaii in the 2000 U.S. Census was US$272,700, while the national median home value was US$119,600. Hawaii home values were the highest of all states, including California with a median home value of US$211,500.[249] Research from the National Association of Realtors places the 2010 median sale price of a single family home in Honolulu, Hawaii, at US$607,600 and the U.S. median sales price at US$173,200. The sale price of single family homes in Hawaii was the highest of any U.S. city in 2010, just above that of the Silicon Valley area of California (US$602,000).[250]

Hawaii's very high cost of living is the result of several interwoven factors of the global economy in addition to domestic U.S. government trade policy. Like other regions with desirable weather year-round, such as California, Arizona and Florida, Hawaii's residents can be considered to be subject to a "sunshine tax". This situation is further exacerbated by the natural factors of geography and world distribution that lead to higher prices for goods due to increased shipping costs, a problem which many island states and territories suffer from as well.

The higher costs to ship goods across an ocean may be further increased by the requirements of the Jones Act, which generally requires that goods be transported between places within the U.S., including between the mainland U.S. west coast and Hawaii, using only U.S.-owned, built, and crewed ships. Jones Act-compliant vessels are often more expensive to build and operate than foreign equivalents, which can drive up shipping costs. While the Jones Act does not affect transportation of goods to Hawaii directly from Asia, this type of trade is nonetheless not common; this is a result of other primarily economic reasons including additional costs associated with stopping over in Hawaii (e.g. pilot and port fees), the market size of Hawaii, and the economics of using ever-larger ships that cannot be handled in Hawaii for transoceanic voyages. Therefore, Hawaii relies on receiving most inbound goods on Jones Act-qualified vessels originating from the U.S. west coast, which may contribute to the increased cost of some consumer goods and therefore the overall cost of living.[251][252] Critics of the Jones Act contend that Hawaii consumers ultimately bear the expense of transporting goods imposed by the Jones Act.[253]

The aboriginal culture of Hawaii is Polynesian. Hawaii represents the northernmost extension of the vast Polynesian Triangle of the south and central Pacific Ocean. While traditional Hawaiian culture remains as vestiges in modern Hawaiian society, there are re-enactments of the ceremonies and traditions throughout the islands. Some of these cultural influences, including the popularity (in greatly modified form) of lūʻau and hula, are strong enough to affect the wider United States.

The cuisine of Hawaii is a fusion of many foods brought by immigrants to the Hawaiian Islands, including the earliest Polynesians and Native Hawaiian cuisine, and American, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Polynesian, Puerto Rican, and Portuguese origins. Plant and animal food sources are imported from around the world for agricultural use in Hawaii. Poi, a starch made by pounding taro, is one of the traditional foods of the islands. Many local restaurants serve the ubiquitous plate lunch, which features two scoops of rice, a simplified version of American macaroni salad and a variety of toppings including hamburger patties, a fried egg, and gravy of a loco moco, Japanese style tonkatsu or the traditional lūʻau favorites, including kālua pork and laulau. Spam musubi is an example of the fusion of ethnic cuisine that developed on the islands among the mix of immigrant groups and military personnel. In the 1990s, a group of chefs developed Hawaii regional cuisine as a contemporary fusion cuisine.

Some key customs and etiquette in Hawaii are as follows: when visiting a home, it is considered good manners to bring a small gift for one's host (for example, a dessert). Thus, parties are usually in the form of potlucks. Most locals take their shoes off before entering a home. It is customary for Hawaiian families, regardless of ethnicity, to hold a luau to celebrate a child's first birthday. It is also customary at Hawaiian weddings, especially at Filipino weddings, for the bride and groom to do a money dance (also called the pandanggo). Print media and local residents recommend that one refer to non-Hawaiians as "locals of Hawaii" or "people of Hawaii".

Hawaiian mythology includes the legends, historical tales, and sayings of the ancient Hawaiian people. It is considered a variant of a more general Polynesian mythology that developed a unique character for several centuries before c. 1800. It is associated with the Hawaiian religion, which was officially suppressed in the 19th century but was kept alive by some practitioners to the modern day.[254] Prominent figures and terms include Aumakua, the spirit of an ancestor or family god and Kāne, the highest of the four major Hawaiian deities.[citation needed]

Polynesian mythology is the oral traditions of the people of Polynesia, a grouping of Central and South Pacific Ocean island archipelagos in the Polynesian triangle together with the scattered cultures known as the Polynesian outliers. Polynesians speak languages that descend from a language reconstructed as Proto-Polynesian that was probably spoken in the area around Tonga and Samoa in around 1000 BC.[255]

Prior to the 15th century, Polynesian people migrated east to the Cook Islands, and from there to other island groups such as Tahiti and the Marquesas. Their descendants later discovered the islands Tahiti, Rapa Nui, and later the Hawaiian Islands and New Zealand.[256]

The Polynesian languages are part of the Austronesian language family. Many are close enough in terms of vocabulary and grammar to be mutually intelligible. There are also substantial cultural similarities between the various groups, especially in terms of social organization, childrearing, horticulture, building and textile technologies. Their mythologies in particular demonstrate local reworkings of commonly shared tales. The Polynesian cultures each have distinct but related oral traditions; legends or myths are traditionally considered to recount ancient history (the time of "pō") and the adventures of gods ("atua") and deified ancestors.[citation needed]

There are many Hawaiian state parks.

The literature of Hawaii is diverse and includes authors Kiana Davenport, Lois-Ann Yamanaka, and Kaui Hart Hemmings. Hawaiian magazines include Hana Hou!, Hawaii Business and Honolulu, among others.

The music of Hawaii includes traditional and popular styles, ranging from native Hawaiian folk music to modern rock and hip hop.

Styles such as slack-key guitar are well known worldwide, while Hawaiian-tinged music is a frequent part of Hollywood soundtracks. Hawaii also made a major contribution to country music with the introduction of the steel guitar.[257]

Traditional Hawaiian folk music is a major part of the state's musical heritage. The Hawaiian people have inhabited the islands for centuries and have retained much of their traditional musical knowledge. Their music is largely religious in nature, and includes chanting and dance music.

Hawaiian music has had an enormous impact on the music of other Polynesian islands; according to Peter Manuel, the influence of Hawaiian music is a "unifying factor in the development of modern Pacific musics".[258] Native Hawaiian musician and Hawaiian sovereignty activist Israel Kamakawiwoʻole, famous for his medley of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World", was named "The Voice of Hawaii" by NPR in 2010 in its 50 great voices series.[259]

Due to its distance from the continental United States, team sports in Hawaii are characterised by youth, collegial and amateur teams over professional teams, although some professional teams sports teams have at one time played in the state. Notable professional teams include The Hawaiians, which played at the World Football League in 1974 and 1975; the Hawaii Islanders, a Triple-A minor league baseball team that played at the Pacific Coast League from 1961 to 1987; and Team Hawaii, a North American Soccer League team that played in 1977.

Notable college sports events in Hawaii include the Maui Invitational Tournament, Diamond Head Classic (basketball) and Hawaii Bowl (football). The only NCAA Division I team in Hawaii is the Hawaii Rainbow Warriors and Rainbow Wahine, which competes at the Big West Conference (major sports), Mountain West Conference (football) and Mountain Pacific Sports Federation (minor sports). There are three teams in NCAA Division II: Chaminade Silverswords, Hawaii Pacific Sharks and Hawaii-Hilo Vulcans, all of which compete at the Pacific West Conference.

Surfing has been a central part of Polynesian culture for centuries. Since the late 19th century, Hawaii has become a major site for surfists from around the world. Notable competitions include the Triple Crown of Surfing and The Eddie. Likewise, Hawaii has produced elite-level swimmers, including five-time Olympic medalist Duke Kahanamoku and Buster Crabbe, who set 16 swimming world records.

Hawaii has hosted the Sony Open in Hawaii golf tournament since 1965, the Tournament of Champions golf tournament since 1999, the Lotte Championship golf tournament since 2012, the Honolulu Marathon since 1973, the Ironman World Championship triathlon race since 1978, the Ultraman triathlon since 1983, the National Football League's Pro Bowl from 1980 to 2016, the 2000 FINA World Open Water Swimming Championships, and the 2008 Pan-Pacific Championship and 2012 Hawaiian Islands Invitational soccer tournaments.

Hawaii has produced a number of notable Mixed Martial Arts fighters, such as former UFC Lightweight Champion and UFC Welterweight Champion B.J. Penn, and former UFC Featherweight Champion Max Holloway. Other notable Hawaiian Martial Artists include Travis Browne, K. J. Noons, Brad Tavares and Wesley Correira.

Hawaiians have found success in the world of sumo wrestling. Takamiyama Daigorō was the first foreigner to ever win a sumo title in Japan, while his protege Akebono Tarō became a top-level sumo wrestler in Japan during the 1990s before transitioning into a successful professional wrestling career in the 2000s. Akebono was the first foreign-born Sumo to reach Yokozuna in history and helped fuel a boom in interest in Sumo during his career.

Tourism is an important part of the Hawaiian economy as it represents ¼ of the economy. According to the Hawaii Tourism: 2019 Annual Visitor Research Report, a total of 10,386,673 visitors arrived in 2019 which increased 5% from the previous year, with expenditures of almost $18 billion.[260] In 2019, tourism provided over 216,000 jobs statewide and contributed more than $2 billion in tax revenue.[261] Due to mild year-round weather, tourist travel is popular throughout the year. Tourists across the globe visited Hawaii in 2019 with over 1 million tourists from the U.S. East, almost 2 million Japanese tourists, and almost 500,000 Canadian tourists.

It was with statehood in 1959 that the Hawaii tourism industry began to grow.[262]