.jpg/440px-Lynching_of_Jesse_Washington,_1916_(cropped).jpg)

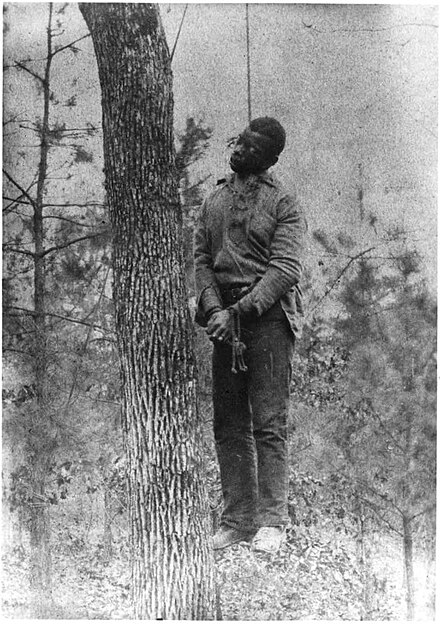

_(NBY_7660).jpg/440px-Hanging_in_Georgia_(black_man_hung_by_a_white_mob)_(NBY_7660).jpg)

Los linchamientos fueron una práctica generalizada de asesinatos extrajudiciales que comenzó en el sur de los Estados Unidos antes de la Guerra Civil en la década de 1830, se desaceleró durante el movimiento por los derechos civiles en las décadas de 1950 y 1960 y continuó hasta 1981. Aunque las víctimas de los linchamientos eran miembros de varias etnias, después de que aproximadamente 4 millones de afroamericanos esclavizados se emanciparon, se convirtieron en los principales objetivos de los sureños blancos . Los linchamientos en los EE. UU. alcanzaron su apogeo entre la década de 1890 y la de 1920, y victimizaron principalmente a minorías étnicas . La mayoría de los linchamientos ocurrieron en el sur de Estados Unidos , ya que la mayoría de los afroamericanos vivían allí, pero también ocurrieron linchamientos por motivos raciales en el Medio Oeste y los estados fronterizos . [2] En 1891, el linchamiento masivo más grande en la historia de Estados Unidos se perpetró en Nueva Orleans contra inmigrantes italianos . [3] [4]

Los linchamientos siguieron a los afroamericanos con la Gran Migración ( c. 1916-1970 ) fuera del sur de Estados Unidos, y a menudo se perpetraron para imponer la supremacía blanca e intimidar a las minorías étnicas junto con otros actos de terrorismo racial. [5] Un número significativo de víctimas de linchamientos fueron acusadas de asesinato o intento de asesinato . La violación , el intento de violación u otras formas de agresión sexual fueron la segunda acusación más común; estas acusaciones a menudo se usaban como pretexto para linchar a los afroamericanos que fueron acusados de violar la etiqueta de la era de Jim Crow o participar en la competencia económica con los blancos . Un estudio determinó que hubo "4.467 víctimas de linchamientos en total entre 1883 y 1941. De estas víctimas, 4.027 eran hombres, 99 eran mujeres y 341 eran de género no identificado (aunque probablemente varones); 3.265 eran negros, 1.082 eran blancos, 71 eran mexicanos o de ascendencia mexicana, 38 eran indios americanos, 10 eran chinos y 1 era japonés". [6]

Una percepción común de los linchamientos en los EE. UU. es que fueron solo ahorcamientos , debido a la visibilidad pública del lugar, lo que facilitó a los fotógrafos fotografiar a las víctimas. Algunos linchamientos fueron fotografiados profesionalmente y luego las fotos se vendieron como postales , que se convirtieron en recuerdos populares en algunas partes de los Estados Unidos. Las víctimas de linchamiento también fueron asesinadas de diversas maneras: a balazos, quemadas vivas, arrojadas desde un puente, arrastradas detrás de un automóvil, etc. Ocasionalmente, se extrajeron partes del cuerpo de las víctimas y se vendieron como recuerdos. Los linchamientos no siempre fueron fatales; los linchamientos "simulados", que implicaban poner una cuerda alrededor del cuello de alguien sospechoso de ocultar información, a veces se usaban para obligar a las personas a hacer "confesiones". Las turbas de linchadores variaban en tamaño desde unos pocos hasta miles.

Los linchamientos aumentaron de manera constante después de la Guerra Civil, alcanzando su punto máximo en 1892. Los linchamientos siguieron siendo comunes hasta principios del siglo XX, acelerándose con la aparición del Segundo Ku Klux Klan . Los linchamientos disminuyeron considerablemente en la época de la Gran Depresión . El linchamiento de 1955 de Emmett Till , un niño afroamericano de 14 años , galvanizó el movimiento por los derechos civiles y marcó el último linchamiento clásico (según lo registrado por el Instituto Tuskegee ). La abrumadora mayoría de los perpetradores de linchamientos nunca se enfrentaron a la justicia. La supremacía blanca y los jurados totalmente blancos aseguraron que los perpetradores, incluso si eran juzgados, no fueran condenados. Las campañas contra los linchamientos cobraron impulso a principios del siglo XX, defendidas por grupos como la NAACP . Se presentaron unos 200 proyectos de ley contra los linchamientos en el Congreso entre el final de la Guerra Civil y el movimiento por los derechos civiles, pero ninguno fue aprobado. Finalmente, en 2022, 67 años después del asesinato de Emmett Till y el fin de la era de los linchamientos, el Congreso de los Estados Unidos aprobó una legislación contra los linchamientos en forma de la Ley Antilinchamientos Emmett Till .

La violencia colectiva era un aspecto familiar del panorama legal estadounidense temprano, y la violencia grupal en la América colonial era generalmente no letal en intención y resultado. En el siglo XVII, en el contexto de las Guerras de los Tres Reinos en las Islas Británicas y las condiciones sociales y políticas inestables en las colonias estadounidenses, los linchamientos se convirtieron en una forma frecuente de "justicia de masas" cuando se percibía que las autoridades no eran confiables. [7] En los Estados Unidos, durante las décadas posteriores a la Guerra Civil , los afroamericanos fueron las principales víctimas de linchamientos raciales, pero en el suroeste estadounidense , los mexicanos estadounidenses también fueron blanco de linchamientos. [8]

En el primer linchamiento registrado, ocurrido en San Luis en 1835, un hombre negro llamado McIntosh (que mató a un ayudante del sheriff mientras era llevado a la cárcel) fue capturado, encadenado a un árbol y quemado vivo en una esquina del centro de la ciudad frente a una multitud de más de 1000 personas. [9]

Según el historiador Michael J. Pfeifer, la prevalencia de los linchamientos en los Estados Unidos posteriores a la Guerra Civil reflejó la falta de confianza de la gente en el " debido proceso " del sistema judicial estadounidense. Pfeifer vincula la disminución de los linchamientos a principios del siglo XX con "la llegada de la pena de muerte moderna", y sostiene que "los legisladores renovaron la pena de muerte... por preocupación directa por la alternativa de la violencia de las turbas". Entre 1901 y 1964, Georgia ahorcó y electrocutó a 609 personas. El ochenta y dos por ciento de los ejecutados eran hombres negros, a pesar de que Georgia era mayoritariamente blanca. Pfeifer también citó "los excesos racializados modernos de las fuerzas policiales urbanas en el siglo XX y después" como características de los linchamientos. [10]

Un motivo importante de los linchamientos, particularmente en el Sur, fueron los esfuerzos de la sociedad blanca por mantener la supremacía blanca después de la emancipación de las personas esclavizadas tras la Guerra Civil estadounidense . Los linchamientos castigaban las violaciones percibidas de las costumbres, más tarde institucionalizadas como leyes de Jim Crow , que ordenaban la segregación racial de blancos y negros, y un estatus de segunda clase para los negros. Un artículo de 2017 encontró que los condados con mayor segregación racial tenían más probabilidades de ser lugares donde los blancos realizaban linchamientos. [12]

Los linchamientos enfatizaron el nuevo orden social que se construyó bajo las leyes de Jim Crow; los blancos actuaron juntos, reforzando su identidad colectiva junto con el estatus desigual de los negros a través de estos actos grupales de violencia. [13]

Los linchamientos también fueron (en parte) una herramienta para suprimir el voto . Un estudio de 2019 concluyó que los linchamientos ocurrían con mayor frecuencia en las proximidades de las elecciones, en particular en zonas donde el Partido Demócrata enfrentaba desafíos. [14]

El Instituto Tuskegee, ahora Universidad Tuskegee , definió las condiciones que constituían un linchamiento reconocido, una definición que fue generalmente aceptada por otros compiladores de la época:

1. Debe haber evidencia legal de que una persona fue asesinada.

2. Esa persona debe haber encontrado la muerte ilegalmente.

3. Un grupo de tres o más personas debe haber participado en el asesinato.

4. El grupo debe haber actuado bajo el pretexto de servir a la justicia, la raza o la tradición. [15] [16]

Las estadísticas sobre linchamientos proceden tradicionalmente de tres fuentes principalmente, ninguna de las cuales cubre todo el período histórico de linchamientos en los Estados Unidos. Antes de 1882, no se habían recopilado estadísticas contemporáneas a nivel nacional. En 1882, el Chicago Tribune comenzó a tabular sistemáticamente los linchamientos a nivel nacional. En 1908, el Instituto Tuskegee comenzó una recopilación sistemática de informes sobre linchamientos bajo la dirección de Monroe Work en su Departamento de Registros, extraídos principalmente de informes de periódicos. Monroe Work publicó sus primeras tabulaciones independientes en 1910, aunque su informe también se remontaba al año de inicio de 1882. [17] Finalmente, en 1912, la Asociación Nacional para el Progreso de la Gente de Color comenzó un registro independiente de linchamientos. Las cifras de linchamientos de cada fuente varían ligeramente, y algunos historiadores consideran que las cifras del Instituto Tuskegee son "conservadoras". [18]

Según la fuente, las cifras varían según las fuentes citadas, los años que se consideran en ellas y las definiciones que se dan a incidentes específicos en ellas. El Instituto Tuskegee ha registrado los linchamientos de 3.446 negros y los linchamientos de 1.297 blancos, todos los cuales ocurrieron entre 1882 y 1968, con el pico en la década de 1890, en un momento de estrés económico en el Sur y creciente represión política de los negros. [19] Un estudio de seis años publicado en 2017 por la Iniciativa de Justicia Igualitaria encontró que 4.084 hombres, mujeres y niños negros fueron víctimas de "linchamientos por terror racial" en doce estados del Sur entre 1877 y 1950, además de 300 que tuvieron lugar en otros estados. Durante este período, los 654 linchamientos de Mississippi lideraron los linchamientos que ocurrieron en todos los estados del Sur. [20] [2] [21]

Los registros del Instituto Tuskegee siguen siendo la fuente más completa de estadísticas y registros sobre este delito desde 1882 para todos los estados, aunque la investigación moderna ha arrojado luz sobre nuevos incidentes en estudios centrados en estados específicos de forma aislada. [16] En 1959, que fue la última vez que se publicó el informe anual del Instituto Tuskegee, un total de 4.733 personas habían muerto por linchamiento desde 1882. El último linchamiento registrado por el Instituto Tuskegee fue el de Emmett Till en 1955. En los 65 años previos a 1947, se informó de al menos un linchamiento cada año. El período de 1882 a 1901 vio el apogeo de los linchamientos, con un promedio de más de 150 cada año. 1892 vio el mayor número de linchamientos en un año: 231 o 3,25 por cada millón de personas. Después de 1924, los casos disminuyeron de manera constante, hasta llegar a menos de 30 al año. [22] [23] [24] La tasa decreciente de linchamientos anuales fue más rápida fuera del Sur y entre las víctimas blancas. El linchamiento se convirtió en un fenómeno más sureño y racial que afectó abrumadoramente a las víctimas negras. [25] Hubo variaciones mensurables en las tasas de linchamientos entre estados y dentro de ellos. [26]

Según el Instituto Tuskegee, el 38% de las víctimas de linchamiento fueron acusadas de asesinato, el 16% de violación, el 7% de intento de violación, el 6% de agresión con agravantes, el 7% de robo, el 2% de insultos a personas blancas y el 24% de delitos varios o sin delito. [25] En 1940, el sociólogo Arthur F. Raper investigó cien linchamientos posteriores a 1929 y estimó que aproximadamente un tercio de las víctimas fueron acusadas falsamente. [25]

El método del Instituto Tuskegee de clasificar a la mayoría de las víctimas de linchamientos como negros o blancos en publicaciones y resúmenes de datos significó que los asesinatos de algunos grupos minoritarios e inmigrantes quedaron ocultos. En Occidente, por ejemplo, los mexicanos, los nativos americanos y los chinos fueron blancos de linchamientos con mayor frecuencia que los afroamericanos, pero sus muertes fueron incluidas entre las de otros blancos. De manera similar, aunque los inmigrantes italianos fueron el foco de la violencia en Luisiana cuando comenzaron a llegar en mayor número, sus muertes no fueron tabuladas por separado de las de los blancos. En años anteriores, los blancos que eran objeto de linchamientos a menudo eran el blanco debido a sospechas de actividades políticas o apoyo a los libertos, pero generalmente se los consideraba miembros de la comunidad de una manera en que no se lo era con los nuevos inmigrantes. [27]

Otras víctimas fueron inmigrantes blancos y, en el suroeste, latinos . De las 468 víctimas de linchamientos en Texas entre 1885 y 1942, 339 eran negros, 77 blancos, 53 hispanos y 1 nativo americano. [28]

También hubo linchamientos de negros contra negros, con 125 registrados entre 1882 y 1903, y hubo cuatro casos de blancos asesinados por turbas de negros. La tasa de linchamientos de negros contra negros aumentó y disminuyó siguiendo un patrón similar al de los linchamientos generales. También hubo más de 200 casos de linchamientos de blancos contra blancos en el Sur antes de 1930. [24]

Las conclusiones de numerosos estudios realizados desde mediados del siglo XX han encontrado las siguientes variables que afectan la tasa de linchamientos en el Sur: "los linchamientos fueron más numerosos donde la población afroamericana era relativamente grande, la economía agrícola se basaba predominantemente en el algodón, la población blanca estaba estresada económicamente, el Partido Demócrata era más fuerte y múltiples organizaciones religiosas competían por los feligreses". [29]

._Southern_Justice_._Harper's_Weekly_combined.jpg/440px-Nast,_Thomas_(1867-03-23)._Southern_Justice_._Harper's_Weekly_combined.jpg)

Después de la Guerra Civil estadounidense , los blancos sureños lucharon por mantener su dominio. Grupos de vigilantes secretos y terroristas como el Ku Klux Klan (KKK) instigaron ataques extrajudiciales y asesinatos para disuadir a los libertos de votar, trabajar y educarse. [18] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] También atacaron a veces a norteños, maestros y agentes de la Oficina de Libertos . La magnitud de la violencia extralegal que ocurrió durante las campañas electorales alcanzó proporciones epidémicas, lo que llevó al historiador William Gillette a etiquetarla como " guerra de guerrillas ", [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] y al historiador Thomas E. Smith a entenderla como una forma de " violencia colonial ". [37]

Los linchadores a veces asesinaban a sus víctimas, pero en otras ocasiones las azotaban o las agredían físicamente para recordarles su antigua condición de esclavos. [38] A menudo se realizaban redadas nocturnas en los hogares de los afroamericanos con el fin de confiscar armas de fuego. Los linchamientos para impedir que los libertos y sus aliados votaran y portaran armas eran formas extralegales de intentar imponer el sistema anterior de dominio social y los Códigos Negros , que habían sido invalidados por las Enmiendas 14 y 15 en 1868 y 1870.

La periodista, educadora y líder de los derechos civiles, Ida B. Wells, comentó en un panfleto que publicó en 1892 titulado Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases que "las únicas ocasiones en las que un afroamericano que fue agredido logró escapar fue cuando tenía un arma y la usó en defensa propia". [39] Un estudio publicado en agosto de 2022 por investigadores de la Universidad de Clemson afirmó que "... las tasas de linchamientos de negros disminuyeron con un mayor acceso de los negros a las armas de fuego..." [40]

Desde mediados de la década de 1870 en adelante, la violencia aumentó a medida que los grupos paramilitares insurgentes en el sur profundo trabajaron para suprimir el voto negro y expulsar a los republicanos del cargo. En Luisiana, las Carolinas y Florida especialmente, el Partido Demócrata se basó en grupos paramilitares de la "Línea Blanca", como la Camelia Blanca , la Liga Blanca y las Camisas Rojas para aterrorizar, intimidar y asesinar a los republicanos afroamericanos y blancos en una campaña organizada para recuperar el poder. En Mississippi y las Carolinas, capítulos paramilitares de las Camisas Rojas llevaron a cabo violencia abierta y perturbaron las elecciones. En Luisiana, la Liga Blanca tenía numerosos capítulos; llevaron a cabo los objetivos del Partido Demócrata de suprimir el voto negro. El deseo de Grant de mantener a Ohio en el pasillo republicano y las maniobras de su fiscal general llevaron a un fracaso en el apoyo al gobernador de Mississippi con tropas federales. [41] La campaña de terror funcionó. En el condado de Yazoo, Mississippi , por ejemplo, con una población afroamericana de 12.000 personas, solo se emitieron siete votos para los republicanos en 1874. En 1875, los demócratas arrasaron en la legislatura del estado de Mississippi. [41]

Los linchamientos contra afroamericanos, especialmente en el sur , aumentaron drásticamente después de la Reconstrucción. El pico de linchamientos ocurrió en 1892, después de que los demócratas blancos del sur recuperaran el control de las legislaturas estatales. Muchos incidentes estaban relacionados con problemas económicos y competencia. A principios del siglo XX, los estados del sur aprobaron nuevas constituciones o leyes que privaron de derechos a la mayoría de las personas negras y a muchos blancos pobres , establecieron la segregación de las instalaciones públicas por raza y separaron a las personas negras de la vida pública común y las instalaciones a través de las leyes de Jim Crow . La tasa de linchamientos en el sur ha sido fuertemente asociada con tensiones económicas, [44] aunque la naturaleza causal de este vínculo no está clara. [45] Los bajos precios del algodón, la inflación y el estrés económico están asociados con mayores frecuencias de linchamientos.

Según el Instituto Tuskegee , Georgia fue el estado con mayor número de linchamientos entre 1900 y 1931, con 302 incidentes. Sin embargo, Florida fue el estado con mayor número de linchamientos per cápita entre 1900 y 1930. [46] [47] [48] Los linchamientos alcanzaron su punto máximo en muchas áreas cuando llegó el momento de que los terratenientes saldaran cuentas con los aparceros . [49]

La frecuencia de los linchamientos aumentó durante los años de mala economía y precios bajos del algodón, lo que demuestra que no fueron las tensiones sociales las que generaron los catalizadores de la acción de las turbas contra las clases bajas. [44] Los investigadores han estudiado varios modelos para determinar qué motivó los linchamientos. Un estudio de las tasas de linchamientos de negros en los condados del sur entre 1889 y 1931 encontró una relación con la concentración de negros en partes del sur profundo: donde se concentraba la población negra, las tasas de linchamientos eran más altas. Esas áreas también tenían una mezcla particular de condiciones socioeconómicas, con una alta dependencia del cultivo de algodón. [50]

Henry Smith , un manitas afroamericano acusado de asesinar a la hija de un policía, fue una víctima de linchamiento conocida debido a la ferocidad del ataque contra él y la enorme multitud que se reunió. [51] Fue linchado en París, Texas , en 1893 por matar a Myrtle Vance, la hija de tres años de un policía de Texas, después de que el policía hubiera agredido a Smith. [52] Smith no fue juzgado en un tribunal de justicia. Una gran multitud siguió el linchamiento, como era común entonces en el estilo de ejecuciones públicas. Henry Smith fue atado a una plataforma de madera, torturado durante 50 minutos con marcas de hierro al rojo vivo y quemado vivo mientras más de 10.000 espectadores vitoreaban. [51]

Menos del uno por ciento de los participantes en los linchamientos fueron condenados por los tribunales locales y rara vez fueron procesados o llevados a juicio. A finales del siglo XIX, los jurados de los juicios en la mayor parte del sur de los Estados Unidos eran todos blancos porque los afroamericanos habían sido privados del derecho al voto y sólo los votantes registrados podían actuar como jurados. A menudo, los jurados nunca dejaban que el asunto pasara de la investigación.

Casos similares ocurrieron también en el Norte. En 1892, un policía de Port Jervis, Nueva York , intentó detener el linchamiento de un hombre negro que había sido acusado injustamente de agredir a una mujer blanca. La turba respondió colocando la soga alrededor del cuello del policía como una forma de asustarlo, y terminó matando al otro hombre. Aunque en la investigación el policía identificó a ocho personas que habían participado en el linchamiento, incluido el exjefe de policía, el jurado determinó que el asesinato había sido llevado a cabo "por una persona o personas desconocidas". [53]

En Duluth, Minnesota , el 15 de junio de 1920, tres jóvenes afroamericanos que trabajaban en un circo ambulante fueron linchados tras ser acusados de haber violado a una mujer blanca y encarcelados a la espera de una audiencia ante un gran jurado. Un examen médico posterior de la mujer no encontró evidencia de violación o agresión. [ se necesita más explicación ] [54]

En 1903, el St. Louis Post-Dispatch informó sobre un nuevo y popular juego de simulación para niños: "El juego del linchamiento". "Un alcalde imaginario da la orden de no hacer daño a una turba imaginaria, y a continuación se produce un ahorcamiento imaginario. El fuego aporta un toque realista". "Ha desplazado al béisbol" y, si continúa, "puede privar al fútbol de parte de su prestigio". [55]

La película de 1915 de D. W. Griffith , El nacimiento de una nación , glorificó al Ku Klux Klan original como protector de las mujeres blancas del sur durante la Reconstrucción, que retrató como una época de violencia y corrupción , siguiendo la interpretación de la historia de la Escuela Dunning . La película despertó una gran controversia. Fue popular entre los blancos de todo el país, pero fue objeto de protestas por parte de activistas negros, la NAACP y otros grupos de derechos civiles . [56] [57]

El 25 de noviembre de 1915, un grupo de hombres liderado por William J. Simmons quemó una cruz en la cima de Stone Mountain , inaugurando así el resurgimiento del Ku Klux Klan. Al evento asistieron 15 miembros fundadores y algunos exmiembros del Klan original que ya estaban envejeciendo. [58]

El Klan y su uso del linchamiento fueron apoyados por algunos funcionarios públicos como John Trotwood Moore , el bibliotecario y archivista estatal de Tennessee de 1919 a 1929. [59] Moore "se convirtió en uno de los defensores más estridentes del linchamiento en el Sur". [59]

1919 fue uno de los peores años en cuanto a linchamientos, con al menos setenta y seis personas asesinadas en actos violentos relacionados con turbas o justicieros. De ellos, más de once veteranos afroamericanos que habían servido en la guerra recientemente terminada fueron linchados ese año . [60] : 232 La violencia de la supremacía blanca culminó en la masacre racial de Tulsa de 1921, en la que el distrito de Greenwood, de mayoría negra, fue arrasado hasta los cimientos.

La NAACP organizó una fuerte campaña nacional de protestas y educación pública contra El nacimiento de una nación . Como resultado, algunos gobiernos municipales prohibieron el estreno de la película. Además, la NAACP publicitó la producción y ayudó a crear audiencias para los estrenos de 1919, El nacimiento de una raza y Dentro de nuestras puertas , películas dirigidas por afroamericanos que presentaban imágenes más positivas de los negros.

Si bien la frecuencia de los linchamientos disminuyó en la década de 1930, hubo un aumento en 1930 durante la Gran Depresión. Por ejemplo, solo en el norte de Texas y el sur de Oklahoma, cuatro personas fueron linchadas en incidentes separados en menos de un mes. Un aumento en los linchamientos ocurrió después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , cuando surgieron tensiones después de que los veteranos regresaran a casa. Los blancos intentaron reimponer la supremacía blanca sobre los veteranos negros que regresaban. El último linchamiento masivo documentado ocurrió en el condado de Walton, Georgia , en 1946, cuando los terratenientes blancos locales mataron a dos veteranos de guerra y sus esposas.

Los medios soviéticos frecuentemente cubrían la discriminación racial en los EE. UU. [61] Al considerar las críticas estadounidenses a los abusos de los derechos humanos de la Unión Soviética en ese momento como hipocresía, los rusos respondieron con " Y ustedes están linchando a los negros ". [62] En Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (2001), la historiadora Mary L. Dudziak escribió que las críticas comunistas soviéticas a la discriminación racial y la violencia en los Estados Unidos influyeron en el gobierno federal para apoyar la legislación de derechos civiles. [63]

La mayoría de los linchamientos cesaron en la década de 1960. [19] [64] Sin embargo, en 2021 hubo afirmaciones de que todavía ocurren linchamientos racistas en los Estados Unidos, que se encubren como suicidios. [65]

Los opositores a la legislación solían decir que los linchamientos prevenían el asesinato y la violación. Como documentó Ida B. Wells , la acusación más frecuente contra las víctimas de linchamientos era el asesinato o el intento de asesinato. Los cargos o rumores de violación estaban presentes en menos de un tercio de los linchamientos; dichos cargos eran a menudo pretextos para linchar a los negros que violaban la etiqueta de Jim Crow o participaban en la competencia económica con los blancos. Otras razones comunes dadas incluían incendio provocado, robo, asalto y robo; transgresiones sexuales ( mestizaje , adulterio, cohabitación); "prejuicio racial", "odio racial", "disturbios raciales"; informar sobre otros; "amenazas contra los blancos"; y violaciones de la línea de color ("atender a una chica blanca", "propuestas a una mujer blanca"). [66]

Aunque la retórica que rodeaba los linchamientos sugería con frecuencia que se llevaban a cabo para proteger la virtud y la seguridad de las mujeres blancas, las acciones surgieron básicamente de los intentos de los blancos de mantener la dominación en una sociedad que cambiaba rápidamente y de sus temores al cambio social. [18]

Las turbas solían alegar delitos por los que linchaban a los negros. Sin embargo, a finales del siglo XIX, la periodista Ida B. Wells demostró que muchos de los presuntos delitos eran exagerados o ni siquiera habían ocurrido. [67]

La ideología detrás del linchamiento, directamente relacionada con la negación de la igualdad política y social, fue enunciada abiertamente en 1900 por el senador estadounidense Benjamin Tillman , quien anteriormente fue gobernador de Carolina del Sur :

Nosotros, los del Sur, nunca hemos reconocido el derecho del negro a gobernar a los hombres blancos, y nunca lo haremos. Nunca hemos creído que sea igual al hombre blanco, y no nos someteremos a que satisfaga su lujuria con nuestras esposas e hijas sin lincharlo. [68] [69]

Los linchamientos disminuyeron brevemente después de que los supremacistas blancos, los llamados " Redentores ", asumieran los gobiernos de los estados del sur en la década de 1870. A fines del siglo XIX, con las luchas por el trabajo y la privación de derechos, y la continua depresión agrícola, los linchamientos aumentaron nuevamente. Entre 1882 y 1968, el Instituto Tuskegee registró 1297 linchamientos de personas blancas y 3446 linchamientos de personas negras. [71] [72] Los linchamientos se concentraron en el Cinturón de Algodón ( Misisipi , Georgia , Alabama , Texas y Luisiana ). [73] [74] Sin embargo, los linchamientos de mexicanos fueron subcontabilizados en los registros del Instituto Tuskegee, [75] y algunos de los linchamientos masivos más grandes en la historia estadounidense fueron la masacre china de 1871 y el linchamiento de once inmigrantes italianos en 1891 en Nueva Orleans . [76] Durante la fiebre del oro en California , el resentimiento de los blancos hacia los mineros mexicanos y chilenos más exitosos resultó en el linchamiento de al menos 160 mexicanos entre 1848 y 1860. [77] [78]

Los miembros de las turbas que participaban en los linchamientos solían tomar fotografías de lo que habían hecho a sus víctimas para difundir la conciencia y el miedo a su poder. No era raro llevarse recuerdos, como trozos de cuerda, ropa, ramas y, a veces, partes del cuerpo . Algunas de esas fotografías se publicaron y se vendieron como postales. En 2000, James Allen publicó una colección de 145 fotografías de linchamientos en forma de libro y en línea [79] , con palabras escritas y videos para acompañar las imágenes.

Los asesinatos reflejaban las tensiones de los cambios laborales y sociales, a medida que los blancos imponían las leyes de Jim Crow , la segregación legal y la supremacía blanca. Los linchamientos también eran un indicador de la prolongada tensión económica debida a la caída de los precios del algodón durante gran parte del siglo XIX, así como a la depresión financiera de la década de 1890. En las tierras bajas del Mississippi, por ejemplo, los linchamientos aumentaron cuando se suponía que se debían saldar las cosechas y las cuentas. [49]

A finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, en el delta del Mississippi se observó la influencia de la frontera y las acciones dirigidas a reprimir a los afroamericanos. Después de la Guerra Civil, el 90% del delta todavía no estaba urbanizado. [49] Tanto los blancos como los negros migraron allí en busca de la oportunidad de comprar tierras en el interior del país. Era una zona desértica fronteriza, densamente arbolada y sin carreteras durante años. [49] Antes de principios del siglo XX, los linchamientos solían adoptar la forma de justicia fronteriza dirigida tanto a los trabajadores transitorios como a los residentes. [49] Los plantadores trajeron a miles de trabajadores para que trabajaran en la tala de árboles y en los diques. [ cita requerida ]

Los blancos representaban poco más del 12 por ciento de la población de la región del Delta, pero representaban casi el 17 por ciento de las víctimas de linchamiento. Por lo tanto, en esta región, fueron linchados a una tasa que era más del 35 por ciento más alta que su proporción en la población, principalmente debido a que fueron acusados de delitos contra la propiedad (principalmente robo). Por el contrario, los negros fueron linchados a una tasa, en el Delta, menor que su proporción en la población. Esto era diferente al resto del Sur, donde los negros constituían la mayoría de las víctimas de linchamiento. En el Delta, fueron acusados con mayor frecuencia de asesinato o intento de asesinato, en la mitad de los casos, y el 15 por ciento de las veces, fueron acusados de violación, lo que significa que otro 15 por ciento de las veces fueron acusados de una combinación de violación y asesinato, o violación e intento de asesinato. [49]

Los linchamientos se producían de forma estacional, siendo los meses más fríos los más mortales. Como se ha señalado, los precios del algodón cayeron durante las décadas de 1880 y 1890, lo que aumentó las presiones económicas. "De septiembre a diciembre, se recogía el algodón, se revelaban las deudas y se obtenían beneficios (o pérdidas)... Ya fuera para cerrar contratos antiguos o para discutir nuevos acuerdos, [los propietarios y los arrendatarios] entraban con frecuencia en conflicto en estos meses y, a veces, acababan a golpes". [49] Durante el invierno, el asesinato era la causa más citada de los linchamientos. Después de 1901, cuando la economía cambió y más negros se convirtieron en arrendatarios y aparceros en el Delta, con pocas excepciones, solo los afroamericanos fueron linchados. La frecuencia aumentó de 1901 a 1908 después de que se privara de sus derechos a los afroamericanos. "En el siglo XX, el vigilantismo en el Delta finalmente se unió, como era previsible, a la supremacía blanca". [80]

Según el Instituto Tuskegee , de las 4.743 personas linchadas entre 1882 y 1968, 1.297 fueron catalogadas como "blancas". El Instituto Tuskegee, que mantuvo los registros más completos, documentó a las víctimas internamente como "negras", "blancas", "chinas" y, ocasionalmente, como "mexicanas" o "indias", pero las fusionó en solo dos categorías de negras o blancas en los recuentos que publicó. Las víctimas de linchamiento mexicanas, chinas y nativas americanas fueron contabilizadas como blancas. Particularmente en Occidente, minorías como los chinos, los nativos americanos , los mexicanos y otros también fueron víctimas de linchamiento. El linchamiento de mexicanos y mexicano-americanos en el suroeste fue pasado por alto durante mucho tiempo en la historia estadounidense, cuando la atención se centró en el tratamiento de los afroamericanos en el sur. [23] [27] [81]

En los estudios modernos, los investigadores estiman que 597 mexicanos fueron linchados entre 1848 y 1928. Los mexicanos fueron linchados a una tasa de 27,4 por cada 100.000 habitantes entre 1880 y 1930. Esta estadística fue superada sólo por la de la comunidad afroamericana, que soportó un promedio de 37,1 por cada 100.000 habitantes durante ese período. Entre 1848 y 1879, los mexicanos fueron linchados a una tasa sin precedentes de 473 por cada 100.000 habitantes. [27]

Después de su creciente inmigración a los EE. UU. a fines del siglo XIX, los italoamericanos en el sur fueron reclutados para trabajos manuales. El 14 de marzo de 1891, 11 inmigrantes italianos fueron linchados en Nueva Orleans, Luisiana . [82] Este incidente fue uno de los linchamientos masivos más grandes en la historia de los EE. UU. [83] Un total de veinte italianos fueron linchados durante la década de 1890. Aunque la mayoría de los linchamientos de italoamericanos ocurrieron en el sur, los italianos no comprendían una porción importante de los inmigrantes o una porción importante de la población en su conjunto. También ocurrieron linchamientos aislados de italianos en Nueva York , Pensilvania y Colorado .

El 21 de febrero de 1909, se produjo un motín contra los estadounidenses de origen griego en Omaha, Nebraska . Muchos griegos fueron saqueados, golpeados y sus negocios quemados.

En 1915, Leo Frank , un judío estadounidense , fue linchado cerca de Atlanta, Georgia . En 1913, Frank había sido condenado por el asesinato de Mary Phagan, una niña de trece años que trabajaba en su fábrica de lápices. Se presentaron una serie de apelaciones en nombre de Frank, pero todas fueron denegadas. La apelación final fue denegada después de que la Corte Suprema de los Estados Unidos tomara una decisión de 7 a 2. Después de que el gobernador John M. Slaton conmutara la sentencia de Frank a cadena perpetua , un grupo de hombres, que se hacían llamar los Caballeros de Mary Phagan, secuestraron a Frank de una granja prisión en Milledgeville en un evento planificado que incluía cortar los cables telefónicos de la prisión. Lo transportaron 175 millas de regreso a Marietta , cerca de Atlanta, donde lo lincharon frente a una turba.

Después del linchamiento de Leo Frank, aproximadamente la mitad de los 3.000 judíos de Georgia abandonaron el estado. [84] Según el autor Steve Oney, "lo que esto le hizo a los judíos del sur no se puede descartar... Los llevó a un estado de negación de su judaísmo. Se volvieron aún más asimilados , antiisraelíes y episcopalianos . El Templo eliminó las jupás en las bodas, cualquier cosa que pudiera llamar la atención". [85]

Entre los años 1830 y 1850, la mayoría de los linchados eran blancos. Entre 1882 y 1885, se lincharon más blancos que negros. En la década de 1890, el número de negros linchados anualmente aumentó a un número significativamente mayor que el de blancos, y la gran mayoría de las víctimas fueron negras a partir de entonces. Los blancos fueron linchados principalmente en los estados y territorios del oeste, aunque hubo más de 200 casos en el sur. Según el Instituto Tuskegee, en 1884 cerca de Georgetown, Colorado , hubo un caso de 17 "hombres blancos desconocidos" que fueron ahorcados por ladrones de ganado en un solo día. En el oeste, los linchamientos se hacían a menudo para establecer la ley y el orden. [18] [19] [24]

Los linchamientos solían considerarse un deporte para espectadores, en el que grandes multitudes se reunían para participar o presenciar la tortura y mutilación de las víctimas. Los asistentes solían considerarlos eventos festivos, con comida, fotos familiares y recuerdos. [86] Los blancos utilizaban estos eventos para demostrar su poder y control. Esto a menudo conducía al éxodo de la población negra restante y desalentaba futuros asentamientos. [2]

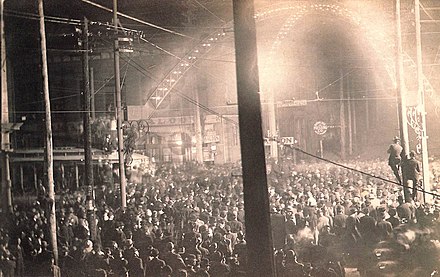

En la era posterior a la Reconstrucción, las fotografías de linchamientos se imprimían con diversos fines, incluidas postales, periódicos y recuerdos de eventos. [87] Por lo general, estas imágenes mostraban a una víctima afroamericana de linchamiento y a toda o parte de la multitud presente. Entre los espectadores a menudo había mujeres y niños. Los perpetradores de los linchamientos no fueron identificados. [88] El linchamiento de Jesse Washington en Waco, Texas, en 1916, atrajo a casi 15.000 espectadores. [87] A menudo, los linchamientos se anunciaban en los periódicos antes del evento para darles tiempo a los fotógrafos de llegar temprano y preparar su equipo fotográfico. [89]

A principios del siglo XX, en Estados Unidos, los linchamientos eran un deporte fotográfico. La gente enviaba postales con fotografías de los linchamientos que había presenciado. Un escritor de la revista Time señaló en 2000:

Ni siquiera los nazis se rebajaron a vender recuerdos de Auschwitz , pero las escenas de linchamientos se convirtieron en un floreciente subdepartamento de la industria de las postales. En 1908, el negocio había crecido tanto y la práctica de enviar postales con las víctimas de los asesinos de la mafia se había vuelto tan repugnante que el director general de Correos de Estados Unidos prohibió las tarjetas en el correo. [90]

Después del linchamiento, los fotógrafos vendían sus fotografías tal como estaban o como postales, a veces costando hasta cincuenta centavos cada una, o $9, en 2016. [88] Aunque algunas fotografías se vendían como impresiones simples, otras contenían subtítulos. Estos subtítulos eran detalles sencillos, como la hora, la fecha y las razones del linchamiento, mientras que otras contenían polémicas o poemas con comentarios racistas o amenazantes. [89] Un ejemplo de esto es una postal fotográfica adjunta al poema "Dogwood Tree", que dice: "El negro ahora / Por la gracia eterna / Debe aprender a quedarse en el lugar del negro / En el soleado sur, la tierra de los libres / Que el BLANCO SUPREMO sea para siempre". [92] Este tipo de postales con retórica explícita como "Dogwood Tree" generalmente circulaban de forma privada o se enviaban por correo en un sobre cerrado. [93] Otras veces, estas imágenes simplemente incluían la palabra "ADVERTENCIA". [89]

En 1873 se aprobó la Ley Comstock , que prohibía la publicación de «material obsceno, así como su circulación por correo». [89] En 1908, se añadió la Sección 3893 a la Ley Comstock, que establecía que la prohibición incluía material «que tendiera a incitar al incendio, al asesinato o al asesinato». [89] Aunque esta ley no prohibía explícitamente las fotografías o postales de linchamientos, sí prohibía los textos y poemas racistas explícitos inscritos en ciertas impresiones. Según algunos, estos textos se consideraban «más incriminatorios» y provocaron su eliminación del correo en lugar de la fotografía en sí porque el texto hacía «demasiado explícito lo que siempre estaba implícito en los linchamientos». [89] Algunas ciudades impusieron la «autocensura» a las fotografías de linchamientos, pero la Sección 3893 fue el primer paso hacia una censura nacional. [89] A pesar de la enmienda, la distribución de fotografías y postales de linchamientos continuó. Aunque no se vendían abiertamente, la censura se eludía cuando la gente enviaba el material en sobres o envoltorios de correo. [93]

Los afroamericanos se resistieron a los linchamientos de numerosas formas. Los intelectuales y periodistas fomentaron la educación pública, protestando activamente y presionando contra la violencia de las turbas que linchaban y la complicidad del gobierno. La Asociación Nacional para el Progreso de las Personas de Color (NAACP) y grupos relacionados organizaron el apoyo de los estadounidenses blancos y negros, dando a conocer las injusticias, investigando los incidentes y trabajando por la aprobación de una legislación federal contra los linchamientos (que finalmente se aprobó como la Ley Antilinchamientos Emmett Till el 29 de marzo de 2022). [94] Los clubes de mujeres afroamericanas recaudaron fondos y llevaron a cabo campañas de petición, cartas, reuniones y manifestaciones para destacar los problemas y combatir los linchamientos. [95] En la gran migración , en particular de 1910 a 1940, 1,5 millones de afroamericanos abandonaron el sur, principalmente hacia destinos en ciudades del norte y el medio oeste, tanto para conseguir mejores trabajos y educación como para escapar de la alta tasa de violencia. En particular, entre 1910 y 1930, más negros emigraron de condados con altos números de linchamientos. [96]

Los escritores afroamericanos utilizaron su talento de diversas maneras para dar publicidad y protestar contra los linchamientos. En 1914, Angelina Weld Grimké ya había escrito su obra Rachel para abordar la violencia racial. Se representó en 1916. En 1915, WEB Du Bois , destacado académico y director de la recién formada NAACP, pidió que se escribieran más obras de autores negros.

Las dramaturgas afroamericanas respondieron con fuerza. Escribieron diez de las catorce obras contra los linchamientos producidas entre 1916 y 1935. La NAACP creó un Comité de Teatro para fomentar ese tipo de obras. Además, la Universidad Howard , la principal universidad históricamente negra, estableció un departamento de teatro en 1920 para alentar a los dramaturgos afroamericanos. A partir de 1924, las principales publicaciones de la NAACP, The Crisis and Opportunity, patrocinaron concursos para alentar la producción literaria negra. [97]

Los afroamericanos salieron de la Guerra Civil con la experiencia política y la estatura necesarias para resistir los ataques, pero la privación de derechos y la imposición de las leyes de segregación racial en el Sur a principios del siglo XX los excluyeron del sistema político y judicial de muchas maneras. Las organizaciones de defensa de los derechos de los afroamericanos recopilaron estadísticas y dieron a conocer las atrocidades, además de trabajar por la aplicación de los derechos civiles y una ley federal contra los linchamientos. Desde principios de la década de 1880, el Chicago Tribune reimprimió relatos de linchamientos de otros periódicos y publicó estadísticas anuales. Estas proporcionaron la principal fuente para las compilaciones del Instituto Tuskegee para documentar los linchamientos, una práctica que continuó hasta 1968. [98]

En 1892, la periodista Ida B. Wells-Barnett se sorprendió cuando tres amigos en Memphis, Tennessee , fueron linchados . Se enteró de que fue porque su tienda de comestibles había competido con éxito contra una tienda propiedad de blancos. Indignada, Wells-Barnett comenzó una campaña mundial contra los linchamientos que creó conciencia sobre estos asesinatos. También investigó los linchamientos y desmintió la idea común de que se basaban en crímenes sexuales de negros, como se discutía popularmente; descubrió que los linchamientos eran más un esfuerzo para reprimir a los negros que competían económicamente con los blancos, especialmente si tenían éxito. Como resultado de sus esfuerzos en materia de educación, las mujeres negras en los EE. UU. se volvieron activas en la cruzada contra los linchamientos, a menudo en forma de clubes que recaudaban dinero para publicitar los abusos. Cuando se formó la Asociación Nacional para el Progreso de las Personas de Color (NAACP) en 1909, Wells se convirtió en parte de su liderazgo multirracial y continuó activa contra los linchamientos. La NAACP comenzó a publicar estadísticas de linchamientos en su oficina de la ciudad de Nueva York.

En 1898, Alexander Manly de Wilmington, Carolina del Norte , desafió directamente las ideas populares sobre el linchamiento en un editorial en su periódico The Daily Record . Señaló que las relaciones consensuales tenían lugar entre mujeres blancas y hombres negros, y dijo que muchos de estos últimos tenían padres blancos (como él). Sus referencias al mestizaje levantaron el velo de la negación. Los blancos estaban indignados. Una turba destruyó su imprenta y su negocio, expulsó a los líderes negros de la ciudad y mató a muchos otros, y derrocó al gobierno municipal populista-republicano birracial , encabezado por un alcalde blanco y un consejo de mayoría blanca. Manly escapó y finalmente se estableció en Filadelfia , Pensilvania .

En 1903, el escritor Charles W. Chesnutt de Ohio publicó el artículo "La privación de derechos de los negros", en el que detallaba los abusos de los derechos civiles que se habían producido cuando los estados del Sur aprobaron leyes y constituciones que, en esencia , privaban de sus derechos a los afroamericanos , excluyéndolos por completo del sistema político. Chesnutt difundió la necesidad de un cambio en el Sur. Numerosos escritores apelaron al público culto. [99]

En 1904, Mary Church Terrell , la primera presidenta de la Asociación Nacional de Mujeres de Color , publicó un artículo en la revista North American Review para responder al sureño Thomas Nelson Page . Analizó y refutó con datos su intento de justificación de los linchamientos como respuesta a las agresiones de hombres negros a mujeres blancas. Terrell mostró cómo los apologistas como Page habían tratado de racionalizar lo que eran acciones violentas de turbas que rara vez se basaban en agresiones. [101] Los periódicos afroamericanos como el periódico de Chicago Illinois The Chicago Whip [102] y la revista de la NAACP The Crisis no solo informaban sobre los linchamientos, sino que también los denunciaban. De hecho, en 1919, la NAACP publicaría "Treinta años de linchamientos" y colgaría una bandera negra fuera de su oficina. [ cita requerida ]

La resistencia afroamericana a los linchamientos conllevaba riesgos sustanciales. En 1921, en Tulsa, Oklahoma , un grupo de 75 ciudadanos afroamericanos intentó impedir que una turba de linchadores sacara de la cárcel a Dick Rowland , un joven de 19 años sospechoso de agresión . En una pelea entre un hombre blanco y un veterano afroamericano armado, el hombre blanco recibió un disparo, lo que provocó un tiroteo entre los dos grupos, que dejó dos afroamericanos y diez blancos muertos. Los blancos tomaron represalias con disturbios, durante los cuales quemaron 1.256 casas y hasta 200 negocios en el distrito segregado de Greenwood , destruyendo lo que había sido una zona próspera. Una comisión estatal de 2001 confirmó 39 muertos, 26 muertes de negros y 13 de blancos. La comisión dio varias estimaciones que oscilaban entre 75 y 300 muertos en total. [103] Sin embargo, Rowland se salvó y más tarde fue exonerado.

Las redes cada vez más numerosas de grupos de mujeres afroamericanas fueron fundamentales para recaudar fondos para apoyar las campañas de educación pública y cabildeo de la NAACP. También crearon organizaciones comunitarias. En 1922, Mary Talbert encabezó la cruzada contra los linchamientos para crear un movimiento integrado de mujeres contra los linchamientos. [101] Estaba afiliada a la NAACP, que montó una campaña multifacética. Durante años, la NAACP utilizó campañas de petición, cartas a periódicos, artículos, carteles, cabildeo en el Congreso y marchas para protestar contra los abusos en el Sur y mantener el tema ante el público.

Un estudio de 2022 concluyó que las comunidades afroamericanas que tenían un mayor acceso a las armas de fuego tenían menos probabilidades de ser linchadas. Los autores del estudio escriben: "En los estados y años en los que los residentes negros tenían más acceso a las armas de fuego, hubo menos linchamientos... En las tres variantes de la estrategia de estimación, el efecto negativo estimado del acceso de los negros a las armas de fuego sobre los linchamientos es bastante grande y estadísticamente significativo. Un aumento de una desviación estándar en el acceso a las armas de fuego, por ejemplo, se asocia con una reducción de los linchamientos de entre 0,8 y 1,4 por año, aproximadamente la mitad de una desviación estándar". [104]

En 1930, las mujeres blancas del Sur respondieron en gran número al liderazgo de Jessie Daniel Ames y formaron la Asociación de Mujeres del Sur para la Prevención de los Linchamientos . Ella y sus cofundadoras obtuvieron las firmas de 40.000 mujeres para su compromiso contra los linchamientos y a favor de un cambio en el Sur. El compromiso incluía la declaración:

A la luz de los hechos, ya no nos atrevemos a... permitir que quienes buscan la venganza personal y el salvajismo cometan actos de violencia y anarquía en nombre de las mujeres.

A pesar de las amenazas físicas y la oposición hostil, las mujeres líderes persistieron con campañas de peticiones, cartas, reuniones y manifestaciones para resaltar los problemas. [95] En la década de 1930, el número de linchamientos había disminuido a unos diez por año en los estados del Sur.

En octubre de 1905, el cardenal James Gibbons condenó el linchamiento, calificándolo de mancha en la civilización estadounidense y contrario a las enseñanzas de Jesucristo . [105]

La rápida llegada de negros durante la Gran Migración alteró el equilibrio racial en las ciudades del norte, exacerbando la hostilidad entre los blancos y los negros del norte. El Verano Rojo de 1919 estuvo marcado por cientos de muertes y un mayor número de víctimas en todo Estados Unidos como resultado de los disturbios raciales que ocurrieron en más de tres docenas de ciudades, como los disturbios raciales de Chicago de 1919 y los disturbios raciales de Omaha de 1919. [ 106]

A principios del siglo XX, hubo un esfuerzo republicano concertado para restringir la distribución de escaños en el Sur [107] y dejar de lado los casos de resultados electorales debidos a la privación del derecho al voto de los negros . Estos esfuerzos fracasaron.

El presidente Theodore Roosevelt hizo declaraciones públicas contra los linchamientos en 1903, tras el asesinato de George White en Delaware , y en el discurso sobre el Estado de la Unión de 1906 , el 4 de diciembre de 1906. Cuando Roosevelt sugirió que se estaban produciendo linchamientos en Filipinas, los senadores del Sur (todos demócratas blancos) demostraron su poder mediante una maniobra obstruccionista en 1902 durante la revisión del "Proyecto de ley de Filipinas". En 1903, Roosevelt se abstuvo de hacer comentarios sobre los linchamientos durante sus campañas políticas en el Sur.

Los esfuerzos de Roosevelt le costaron el apoyo político entre los blancos, especialmente en el Sur. Las amenazas contra él aumentaron, de modo que el Servicio Secreto aumentó el número de guardaespaldas. [108]

Entre 1882 y 1968, "se presentaron en el Congreso casi 200 proyectos de ley contra los linchamientos, y tres de ellos fueron aprobados por la Cámara de Representantes. Siete presidentes, entre 1890 y 1952, solicitaron al Congreso que aprobara una ley federal". [109] Ninguno logró ser aprobado, bloqueado por el Caucus Sureño , la delegación de poderosos sureños blancos en el Senado, que controlaba, debido a su antigüedad , muchas de las poderosas presidencias de comités. [109] En 2005, mediante una resolución patrocinada por los senadores Mary Landrieu de Luisiana y George Allen de Virginia, y aprobada por votación oral, el Senado se disculpó formalmente por no haber aprobado una ley contra los linchamientos "cuando más se necesitaba". [109]

El proyecto de ley Dyer contra los linchamientos fue presentado por primera vez en el Congreso de los Estados Unidos el 1 de abril de 1918 por el congresista republicano Leonidas C. Dyer de St. Louis, Missouri, en la Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos . El representante Dyer estaba preocupado por el aumento de los linchamientos, la violencia de las turbas y el desprecio por el "estado de derecho" en el Sur. El proyecto de ley convirtió el linchamiento en un delito federal y quienes participaran en él serían procesados por el gobierno federal. No se aprobó debido a una maniobra obstruccionista del Sur . En 1919, la nueva NAACP organizó la Conferencia Nacional sobre Linchamientos para aumentar el apoyo al proyecto de ley Dyer.

The bill was passed by the United States House of Representatives in 1922, and in the same year it was given a favorable report by the United States Senate Committee. Its passage was blocked by White Democratic senators from the Solid South, the only representatives elected since the southern states had disfranchised African Americans around the start of the 20th century.[110] The Dyer Bill influenced later anti-lynching legislation, including the Costigan-Wagner Bill, which was also defeated in the US Senate.[111]

As passed by the House, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill stated:

"To assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every State the equal protection of the laws, and to punish the crime of lynching.... Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the phrase 'mob or riotous assemblage,' when used in this act, shall mean an assemblage composed of three or more persons acting in concert for the purpose of depriving any person of his life without authority of law as a punishment for or to prevent the commission of some actual or supposed public offense."[112]

In 1920, the Black community succeeded in getting its most important priority in the Republican Party's platform at the National Convention: support for an anti-lynching bill. The Black community supported Warren G. Harding in that election, but were disappointed as his administration moved slowly on a bill.[113]

Dyer revised his bill and re-introduced it to the House in 1921. It passed the House, 230 to 119,[114] on January 26, 1922, due to "insistent country-wide demand",[113] and was favorably reported out by the Senate Judiciary Committee. Action in the Senate was delayed, and ultimately the Democratic Solid South filibuster defeated the bill in the Senate in December.[115] In 1923, Dyer went on a Midwestern and Western state tour promoting the anti-lynching bill; he praised the NAACP's work for continuing to publicize lynching in the South and for supporting the federal bill. Dyer's anti-lynching motto was "We have just begun to fight", and he helped generate additional national support. His bill was defeated twice more in the Senate by Southern Democratic filibuster. The Republicans were unable to pass a bill in the 1920s.[116]

Anti-lynching advocates such as Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White campaigned for presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. They hoped he would lend public support to their efforts against lynching. Senators Robert F. Wagner and Edward P. Costigan drafted the Costigan–Wagner Bill in 1934 to require local authorities to protect prisoners from lynch mobs. Like the Dyer Bill, it made lynching a Federal crime in order to take it out of state administration.

Southerners had a disproportionate influence on Congress. Because of the Southern Democrats' disfranchisement of African Americans in Southern states at the start of the 20th century, Southern Whites for decades had nearly double the representation in Congress beyond their own population. Southern states had Congressional representation based on total population, but essentially only Whites could vote and only their issues were supported. Due to seniority achieved through one-party Democratic rule in their region, Southern Democrats controlled many important committees in both houses. As a result, Southern white Democrats were a formidable power in Congress until the 1960s and they consistently opposed any legislation related to putting lynching under Federal oversight.

In the 1930s, virtually all Southern senators blocked the proposed Costigan–Wagner Bill. Southern senators used a filibuster to prevent a vote on the bill. Some Republican senators, such as the conservative William Borah from Idaho, opposed the bill for constitutional reasons (he had also opposed the Dyer Bill). He felt it encroached on state sovereignty and, by the 1930s, thought that social conditions had changed so that the bill was less needed.[117] He spoke at length in opposition to the bill in 1935 and 1938. 1934 saw 15 lynchings of African Americans with 21 lynchings in 1935, 8 in 1936, and 2 in 1939.

A lynching in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, changed the political climate in Washington.[118] On July 19, 1935, Rubin Stacy, a homeless African-American tenant farmer, knocked on doors begging for food. After resident complaints, deputies took Stacy into custody. While he was in custody, a lynch mob took Stacy from the deputies and murdered him. Although the faces of his murderers could be seen in a photo taken at the lynching site, the state did not prosecute the murder.[119]

Stacy's murder galvanized anti-lynching activists, but President Roosevelt did not support the federal anti-lynching bill. He feared that support would cost him Southern votes in the 1936 election.

In 1937, the lynching of Roosevelt Townes and Robert McDaniels gained national publicity, and its brutality was widely condemned.[120] Such publicity enabled Joseph A. Gavagan (D-New York) to gain support for anti-lynching legislation he had put forward in the House of Representatives; it was supported in the Senate by Democrats Robert F. Wagner (New York) and Frederick Van Nuys (Indiana). The legislation eventually passed in the House, but the emerging Democratic Southern caucus blocked it in the Senate.[121][122] Senator Allen Ellender (D-Louisiana) proclaimed: "We shall at all cost preserve the white supremacy of America."[121]

In 1939, Roosevelt created the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department. It started prosecutions to combat lynching, but failed to win any convictions until 1946.[123]

In 1946, the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department gained its first conviction under federal civil rights laws against a lyncher. Florida constable Tom Crews was sentenced to a $1,000 fine (equivalent to $15,600 in 2023) and one year in prison for civil rights violations in the killing of an African-American farm worker.

In 1946, a mob of white men shot and killed two young African American couples near Moore's Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia, 60 miles east of Atlanta. This lynching of four young sharecroppers, one a World War II veteran, shocked the nation. The attack was a key factor in President Harry S. Truman's making civil rights a priority of his administration. Although the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigated the crime, they were unable to prosecute. It was the last documented lynching of so many people in one incident.[123]

In 1947, the Truman administration published a report entitled To Secure These Rights which advocated making lynching a federal crime, abolishing poll taxes, and other civil rights reforms. The Southern Democratic bloc of senators and congressmen continued to obstruct attempts at federal legislation.[124]

In the 1940s, the Klan openly criticized Truman for his efforts to promote civil rights. Later historians documented that Truman had briefly made an attempt to join the Klan as a young man in 1924, when it was near its peak of social influence in promoting itself as a fraternal organization. When a Klan officer demanded that Truman pledge not to hire any Catholics if he were re-elected as county judge, Truman refused. He personally knew their worth from his World War I experience. His membership fee was returned and he never joined the Klan.[citation needed][a]

International media, including the media in the Soviet Union, covered racial discrimination in the U.S.[128][129]

In a meeting with President Harry Truman in 1946, Paul Robeson urged him to take action against lynching. In 1951, Robeson and the Civil Rights Congress made a presentation entitled "We Charge Genocide" to the United Nations a document which argued that the U.S. government's failure to act against lynchings meant it was guilty of genocide under Article II of the United Nations Genocide Convention. Based on his commissions report To Secure There Rights, Truman introduced in Congress the first presidentially proposed comprehensive Civil Rights Bill - it included legislation making lynching a federal crime. The first year on record with no lynchings reported in the United States was 1952.[130]

In the early Cold War years, the FBI was worried more about possible communist connections among anti-lynching groups than about the lynching crimes. For instance, the FBI branded Albert Einstein a communist sympathizer for joining Robeson's American Crusade Against Lynching.[131]

By the 1950s, the civil rights movement was gaining momentum. Membership in the NAACP increased in states across the country. The NAACP achieved a significant U.S. Supreme Court victory in 1954 ruling that segregated education was unconstitutional. A 1955 lynching that sparked public outrage about injustice was that of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago. Spending the summer with relatives in Money, Mississippi, Till was killed by a mob of white men. Till had been badly beaten, one of his eyes was gouged out, and he was shot in the head before being thrown into the Tallahatchie River, his body weighed down with a 70-pound (32 kg) cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. His mother insisted on a public funeral with an open casket, to show people how badly Till's body had been disfigured. News photographs circulated around the country, and drew intense public reaction. The visceral response to his mother's decision to have an open-casket funeral mobilized the Black community throughout the U.S.[132] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted by an all-white jury.[133][134]

In the 1960s, the civil rights movement attracted students to the South from all over the country to work on voter registration and integration. The intervention of people from outside the communities and threat of social change aroused fear and resentment among many Whites. In June 1964, three civil rights workers disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. They had been investigating the arson of a Black church being used as a "Freedom School". Six weeks later, their bodies were found in a partially constructed dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi. James Chaney of Meridian, Mississippi, and Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman of New York City had been members of the Congress of Racial Equality. They had been dedicated to non-violent direct action against racial discrimination. The investigation also unearthed the bodies of numerous anonymous victims of past lynchings and murders.

The United States prosecuted 18 men for a Ku Klux Klan conspiracy to deprive the victims of their civil rights under 19th century federal law, in order to prosecute the crime in a federal court. Seven men were convicted but received light sentences, two men were released because of a deadlocked jury, and the remainder were acquitted. In 2005, 80-year-old Edgar Ray Killen, one of the men who had earlier gone free, was retried by the state of Mississippi, convicted of three counts of manslaughter in a new trial, and sentenced to 60 years in prison. Killen died in 2018 after serving 12+1⁄2 years.

Because of J. Edgar Hoover's and others' hostility to the civil rights movement, agents of the FBI resorted to outright lying to smear civil rights workers and other opponents of lynching. For example, the FBI leaked false information in the press about the lynching victim Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered in 1965 in Alabama. The FBI said Liuzzo had been a member of the Communist Party USA, had abandoned her five children, and was involved in sexual relationships with African Americans in the movement.[135]

Although lynchings have become rare following the civil rights movement and the resulting changes in American social norms, some lynchings have still occurred. In 1981, two Klan members in Alabama randomly selected a 19-year-old Black man, Michael Donald, and murdered him, in order to retaliate for a jury's acquittal of a Black man who was accused of murdering a white police officer. The Klansmen were caught, prosecuted, and convicted (one of the Klansmen, Henry Hayes, was sentenced to death and executed on June 6, 1997). A $7 million judgment in a civil suit against the Klan bankrupted the local Klan subgroup, the United Klans of America.[136]

In 1998, Shawn Allen Berry, Lawrence Russel Brewer, and ex-convict John William King murdered James Byrd Jr. in Jasper, Texas. Byrd was a 49-year-old father of three, who had accepted an early-morning ride home with the three men. They attacked him and dragged him to his death behind their truck.[137] The three men dumped their victim's mutilated remains in the town's segregated African-American cemetery and then went to a barbecue.[138] Local authorities immediately treated the murder as a hate crime and requested FBI assistance. The murderers (two of whom turned out to be members of a white supremacist prison gang) were caught and stood trial. Brewer and King were both sentenced to death (with Brewer being executed in 2011, and King being executed in 2019). Berry was sentenced to life in prison.

On June 13, 2005, the U.S. Senate formally apologized for its failure to enact a federal anti-lynching law in the early 20th century, "when it was most needed". Before the vote, Louisiana senator Mary Landrieu noted: "There may be no other injustice in American history for which the Senate so uniquely bears responsibility."[139] The resolution was passed on a voice vote with 80 senators cosponsoring, with Mississippians Thad Cochran and Trent Lott being among the twenty U.S. senators abstaining.[139] The resolution expressed "the deepest sympathies and most solemn regrets of the Senate to the descendants of victims of lynching, the ancestors of whom were deprived of life, human dignity and the constitutional protections accorded all citizens of the United States".[139]

In February 2014, a noose was placed on the statue of James Meredith, the first African American student at the University of Mississippi.[140] A number of nooses appeared in 2017, primarily in or near Washington, D.C.[141][142][143]

In August 2014, Lennon Lacy, a teenager from Bladenboro, North Carolina, who had been dating a white girl, was found dead, hanging from a swing set. His family believes that he was lynched, but the FBI stated, after an investigation, that it found no evidence of a hate crime. The case is featured in a 2019 documentary about lynching in America, Always in Season.[144]

In May 2017, Mississippi Republican state representative Karl Oliver of Winona stated that Louisiana lawmakers who supported the removal of Confederate monuments from their state should be lynched. Oliver's district includes Money, Mississippi, where Emmett Till was murdered in 1955. Mississippi's leaders from both the Republican and Democratic parties quickly condemned Oliver's statement.[145]

In 2018, the Senate attempted to pass new anti-lynching legislation (the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act), but this failed.

On April 26, 2018, in Montgomery, Alabama, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened. Founded by the Equal Justice Initiative of that city, it is the first memorial created specifically to document lynchings of African Americans.

In 2019, Goodloe Sutton, then editor of a small Alabama newspaper, The Democrat-Reporter, received national publicity after he said in an editorial that the Ku Klux Klan was needed to "clean up D.C."[146] When he was asked what he meant by "cleaning up D.C.", he stated: "We'll get the hemp ropes out, loop them over a tall limb and hang all of them." "When he was asked if he felt that it was appropriate for the publisher of a newspaper to call for the lynching of Americans, Sutton doubled down on his position by stating: …'It's not calling for the lynchings of Americans. These are socialist-communists we're talking about. Do you know what socialism and communism is?'" He denied that the Klan was a racist and violent organization, comparing it to the NAACP.[147]

On January 6, 2021, during the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol, the rioters shouted "Hang Mike Pence!" in an attempt to find and lynch the vice president of the United States for refusing to overturn the 2020 United States Presidential Election in favor of President Donald Trump, and a rudimentary gallows was built on the Capitol lawn.[148][149]

As of 2021, the Equal Justice Initiative claims that lynchings never stopped, listing 8 deaths in Mississippi that law-enforcement deemed suicides, but the civil rights organization Julian believes were lynchings. According to Jill Jefferson, "There is a pattern to how these cases are investigated", "When authorities arrive on the scene of a hanging, it's treated as a suicide almost immediately. The crime scene is not preserved. The investigation is shoddy. And then there is a formal ruling of suicide, despite evidence to the contrary. And the case is never heard from again unless someone brings it up."[150]

Historians have debated the history of lynchings on the western frontier, which has been obscured by the mythology of the American Old West. In unorganized territories or sparsely settled states, law enforcement was limited, often provided only by a U.S. Marshal who might, despite the appointment of deputies, be hours, or days, away by horseback.

People often carried out lynchings in the Old West against accused criminals in custody. Lynching did not so much substitute for an absent legal system as constitute an alternative system dominated by a particular social class or racial group. Historian Michael J. Pfeifer writes, "Contrary to the popular understanding, early territorial lynching did not flow from an absence or distance of law enforcement but rather from the social instability of early communities and their contest for property, status, and the definition of social order."[151]

The exact number of people in the Western states/territories killed in lynchings is unknown. There were 571 lynchings of Mexicans between 1848 and 1928. The most recorded deaths were in Texas, with up to 232 killings, then followed by California (143 deaths), New Mexico (87 deaths), and Arizona (48 deaths). Lynch mobs killed Mexicans for a variety of reasons, with the most common accusations being murder and robbery. Others were killed as suspected bandits or rebels.[152]

Many of the Mexicans who were native to what would become a state within the United States were experienced miners, and they had great success mining gold in California.[27] Their success aroused animosity by white prospectors, who intimidated Mexican miners with the threat of violence and committed violence against some. Between 1848 and 1860, white Americans lynched at least 163 Mexicans in California.[27] On July 5, 1851, a mob in Downieville, California, lynched a Mexican woman named Josefa Segovia.[153] She was accused of killing a white man who had attempted to assault her after breaking into her home.[154][155]

The San Francisco Vigilance Movement has traditionally been portrayed as a positive response to government corruption and rampant crime, but revisionist historians have argued that it created more lawlessness than it eliminated.[156] Four men were executed by the 1851 Committee of Vigilance before it disbanded. When the second Committee of Vigilance was instituted in 1856, in response to the murder of publisher James King of William, it hanged a total of four men, all accused of murder.[157]

During the same year of 1851, just after the beginning of the Gold Rush, these Committees lynched an unnamed thief in northern California. The Gold Rush and the economic prosperity of Mexican-born people was one of the main reasons for mob violence against them. Other factors include land and livestock, since they were also a form of economic success. In conjunction with lynching, mobs also attempted to expel Mexicans, and other groups such as the indigenous peoples of the region, from areas with great mining activity and gold. As a result of the violence against Mexicans, many formed bands of bandits and would raid towns. One case, in 1855, was when a group of bandits went into Rancheria and killed six people. When the news of this incident spread, a mob of 1,500 people formed, rounded up 38 Mexicans, and executed Puertanino.[who?] The mob also expelled all the Mexicans in Rancheria and nearby towns as well, burning their homes.[citation needed][158]

On October 24, 1871, a mob rampaged through Old Chinatown, Los Angeles and killed at least 18 Chinese Americans, after a white businessman had inadvertently been killed there in the crossfire of a tong battle within the Chinese community.

After the body of Brooke Hart was found on November 26, 1933, Thomas Harold Thurman and John Holmes, who had confessed to kidnapping and murdering Hart, were lynched on November 26 or November 27, 1933.[159][160]

Four lynchings are included in a book of 12 case studies of the prosecution of homicides in the early years of statehood of Minnesota.[161] In 1858 the institutions of justice in the new state, such as jails, were scarce and the lynching of Charles J. Reinhart at Lexington on December 19 was not prosecuted. The following year, the lynching of Oscar Jackson at Minnehaha Falls on April 25 resulted in a later charging of Aymer Moore for the homicide.

In 1866, when Alexander Campbell and George Liscomb were lynched at Mankato on Christmas Day, the state returned an indictment of John Gut on September 18 the following year. Then in 1872 when Bobolink, a Native American, was accused and imprisoned pending trial in Saint Paul, the state avoided his lynching despite a public outcry against Natives.

"Lynching in Texas", a project of Sam Houston State University, maintains a database of over 600 lynchings committed in Texas between 1882 and 1942.[162] Many of the lynchings were of people of Mexican heritage.

During the early 1900s, hostilities between Anglos and Mexicans along the "Brown Belt" were common. In Rocksprings, Antonio Rodriguez, a Mexican, was burned at the stake. This event was widely publicized and protests against the treatment of Mexicans in the U.S. erupted within the interior of Mexico, namely in Guadalajara and Mexico City.[163]

Members of the Texas Rangers were charged in 1918 with the murder of Florencio Garcia. Two rangers had taken Garcia into custody for a theft investigation. The next day they let Garcia go, and were last seen escorting him on a mule. Garcia was never seen again. A month after the interrogation, bones and Garcia's clothing were found beside the road where the Rangers claimed to have let Garcia go. The Rangers were arrested for murder, freed on bail, and acquitted due to lack of evidence. The case became part of the Canales investigation into criminal conduct by the Rangers.[164]: 80

In 1859, white settlers began to expel Mexicans from Arizona. The mob was able to chase Mexicans out of many towns, southward. Even though they were successful in doing so, the mob followed and killed many of the people that had been chased out. The Sonoita massacre was a result of these expulsions, where white settlers killed four Mexicans and one Native American.[citation needed]

On April 19, 1915, the Leon brothers were lynched by hanging in Pima Country by deputies Robert Fenter and Frank Moore. This lynching was unusual, since the perpetrators were arrested, tried, and convicted for the murders. Fenter and Moore were both found guilty of second degree murder and each sentenced to 10 years to life in prison. However, they were both pardoned by Governor George W. P. Hunt upon his departure from office in February 1917.[165][166]

Another well-documented episode in the history of the American West is the Johnson County War, a dispute in the 1890s over land use in Wyoming. Large-scale ranchers hired mercenaries to lynch the small ranchers.

Alonzo Tucker was a traveling boxer who was heading north from California to Washington. Part of his travels led him to stay in Coos Bay, Oregon, where he was lynched by a mob on September 18, 1902. He was accused by Mrs. Dennis for assault. After the lynching, Dennis and her family quickly left town and headed to California. Tucker is the only documented lynching of a Black man in Oregon.[167]

Other lynchings include many Native Americans.[168]

For most of the history of the United States, lynching was rarely prosecuted, as the same people who would have had to prosecute and sit on juries were generally on the side of the action or related to the perpetrators in the small communities where many lived. When the crime was prosecuted, it was under state murder statutes. In one example in 1907–09, the U.S. Supreme Court tried its only criminal case in history, 203 U.S. 563 (U.S. v. Sheriff Shipp). Shipp was found guilty of criminal contempt for doing nothing to stop the mob in Chattanooga, Tennessee that lynched Ed Johnson, who was in jail for rape.[169] In the South, Blacks generally were not able to serve on juries, as they could not vote, having been disfranchised by discriminatory voter registration and electoral rules passed by majority-white legislatures in the late 19th century, who also imposed Jim Crow laws.

Starting in 1909, federal legislators introduced more than 200 bills in Congress to make lynching a federal crime, but they failed to pass, chiefly because of Southern legislators' opposition.[170] Because Southern states had effectively disfranchised African Americans at the start of the 20th century, the white Southern Democrats controlled all the apportioned seats of the South, nearly double the Congressional representation that white residents alone would have been entitled to. They were a powerful voting bloc for decades and controlled important committee chairmanships. The Senate Democrats formed a bloc that filibustered for a week in December 1922, holding up all national business, to defeat the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. It had passed the House in January 1922 with broad support except for the South. Representative Leonidas C. Dyer of St. Louis, the chief sponsor, undertook a national speaking tour in support of the bill in 1923, but the Southern Senators defeated it twice more in the next two sessions.