La aplicación de la ley en el Reino Unido está organizada por separado en cada uno de los sistemas jurídicos del Reino Unido: Inglaterra y Gales , Escocia e Irlanda del Norte . [nb 1] La mayoría de las funciones de aplicación de la ley las llevan a cabo quienes ocupan el cargo de agente de policía de una fuerza policial territorial .

En 2021, había 39 fuerzas policiales territoriales en Inglaterra, 4 en Gales, una sola fuerza policial en Escocia y una sola fuerza policial en Irlanda del Norte . [1] Estas fuerzas policiales territoriales son responsables de la mayor parte de la aplicación de la ley y la reducción del crimen en sus respectivas áreas policiales . [nb 2] En términos de gobierno nacional, las fuerzas policiales territoriales de Inglaterra y Gales están supervisadas por el Ministerio del Interior , aunque son operativamente independientes del gobierno. La Policía de Transporte Británica (BTP), la Policía del Ministerio de Defensa (MDP) y la Policía Nuclear Civil (CNC) brindan servicios policiales especializados en Inglaterra, Escocia y Gales. La Agencia Nacional contra el Crimen (NCA) se encarga principalmente de abordar el crimen organizado y ha sido comparada con la Oficina Federal de Investigaciones (FBI) en los Estados Unidos . [2] [3]

Los agentes de policía tienen determinados poderes que les permiten llevar a cabo sus funciones. Sus principales funciones son la protección de la vida y la propiedad, la preservación de la paz y la prevención y detección de delitos penales. [4] En el modelo británico de actuación policial, los agentes de policía ejercen sus poderes policiales con el consentimiento implícito del público. " Policía por consentimiento " es la frase que se utiliza para describir esto. Expresa que la legitimidad de la actuación policial a los ojos del público se basa en un consenso general de apoyo que se desprende de la transparencia sobre sus poderes, su integridad en el ejercicio de esos poderes y su responsabilidad por hacerlo. [5] [6]

La mayoría de los agentes de policía de Inglaterra, Escocia y Gales no llevan armas de fuego . En 2022, había 142.526 agentes de policía en Inglaterra y Gales, de los cuales 6.192 estaban autorizados a portar armas de fuego. [7]

En el siglo XVIII, la aplicación de la ley y la vigilancia policial estaban organizadas por comunidades locales basadas en vigilantes y alguaciles; el gobierno no participaba directamente en la vigilancia. La Policía de la ciudad de Glasgow , la primera policía profesional, se estableció tras una ley del Parlamento en 1800. [8] La primera fuerza policial organizada centralmente en el mundo se creó en Irlanda, entonces parte del Reino Unido, tras la Ley de Preservación de la Paz en 1814, de la que Sir Robert Peel fue en gran medida responsable. [9]

Londres tenía una población de casi un millón y medio de personas a principios del siglo XIX, pero estaba vigilada por solo 450 agentes y 4.500 serenos. [10] El concepto de policía profesional fue retomado por Sir Robert Peel cuando se convirtió en Ministro del Interior en 1822. La Ley de Policía Metropolitana de Peel de 1829 estableció una fuerza policial de tiempo completo, profesional y organizada centralmente para el área metropolitana de Londres, conocida como la Policía Metropolitana . [11] En marzo de 1839, Sir Edwin Chadwick presentó la Comisión Real sobre Fuerzas Policiales al Parlamento. Este informe debía evaluar cómo la creciente fuerza policial trabajaría con la "ley de pobres", así como también defender la necesidad de establecer una fuerza nacional basada en la Policía Metropolitana. Gran parte de su argumento se basaba en la necesidad de proteger el capitalismo en desarrollo que estaba creciendo en Inglaterra en ese momento. Chadwick también abordó la preocupación de que la creación de un poderoso estado policial podría llevar a una reducción de las libertades civiles y personales, pero argumentó que el miedo al crimen convertía a los ciudadanos ingleses en esclavos y, por lo tanto, eran menos libres sin una policía agresiva. [12] La legislación de la década de 1830 introdujo la policía en los distritos y muchos condados y, en la década de 1850, la policía se estableció a nivel nacional.

Los principios peelianos describen la filosofía que desarrolló Sir Robert Peel para definir una fuerza policial ética. Los principios tradicionalmente atribuidos a Peel establecen que: [13] [14]

En las "Instrucciones generales" que se entregaron a todos los nuevos agentes de policía de la Policía Metropolitana a partir de 1829 se establecieron nueve principios de actuación policial. El Ministerio del Interior ha sugerido que es más probable que esta lista haya sido escrita por Charles Rowan y Richard Mayne, los primeros y comisionados de la Policía Metropolitana. [15] [16]

El historiador policial Charles Reith explicó en su Nuevo estudio de la historia policial (1956) que estos principios constituían una filosofía de la actuación policial "única en la historia y en todo el mundo porque no derivaba del miedo sino casi exclusivamente de la cooperación pública con la policía, inducida por ellos deliberadamente mediante un comportamiento que asegura y mantiene para ellos la aprobación, el respeto y el afecto del público". [15] [17] Este enfoque de la actuación policial llegó a conocerse como " vigilancia por consentimiento ". [16]

Otros historiadores, como Robert Storch, David Philips y Roger Swift, sostienen que la Policía Metropolitana de Peel se construyó a partir de su experiencia con la Real Policía Irlandesa. [18] La opinión de Storch es que la fuerza policial inglesa no es diferente a las de otras naciones y, de hecho, sigue un desarrollo bastante típico como fuerza de mantenimiento de la paz colonial. Existe una amplia documentación de la brutalidad policial en el siglo XIX, que incluye el uso excesivo de la fuerza, la discriminación racial y varias acusaciones de asesinato. Las controversias que plagaron los primeros años de la fuerza policial fueron muy similares a las quejas actuales contra la policía moderna. [19]

Las primeras mujeres policías fueron contratadas durante la Primera Guerra Mundial. Hull y Southampton fueron dos de las primeras ciudades en emplear mujeres policías, aunque Grantham fue la primera en tener una mujer policía autorizada. [20]

Desde la década de 1940, las fuerzas policiales del Reino Unido se han fusionado y modernizado.

La corrupción en la Brigada Móvil de la Policía Metropolitana dio lugar a una condena y a dimisiones en 1977, tras las investigaciones de la Operación Countryman . Como respuesta, se creó una Junta de Quejas contra la Policía para ocuparse de las denuncias de mala praxis.

En la década de 1980 se produjeron cambios para endurecer los procedimientos policiales, en respuesta al Informe Scarman , para garantizar que las pruebas y las entrevistas fueran sólidas, con la introducción de la Ley de Policía y Pruebas Penales de 1984. En 1989, la Brigada de Delitos Graves de West Midlands se disolvió cuando una serie de alrededor de 100 casos penales fracasaron o fueron posteriormente anulados en West Midlands, después de que nuevas técnicas forenses mostraran que los agentes de policía habían estado manipulando pruebas de declaraciones para asegurar condenas, incluidas las de los Seis de Birmingham .

En 1985, la Junta de Quejas contra la Policía fue sustituida por la Autoridad de Quejas contra la Policía , que a su vez fue reemplazada por la Comisión Independiente de Quejas contra la Policía (IPCC) en 2004. El 8 de enero de 2018, la IPCC fue sustituida por la Oficina Independiente de Conducta Policial (IOPC). [21]

La mayoría de los agentes de policía son miembros de fuerzas policiales territoriales . Una persona debe hacer una declaración antes de asumir el cargo de agente y tener poderes; aunque esto a veces todavía se conoce como el juramento policial , y el proceso a veces se denomina "juramento", ahora toma la forma de una "atentación" (en Inglaterra y Gales e Irlanda del Norte ) o una "declaración" (en Escocia ). El proceso se lleva a cabo en presencia de un magistrado y generalmente va seguido de la emisión de una tarjeta de autorización . Esto otorga al agente todos los poderes y privilegios, deberes y responsabilidades de un agente en uno de los tres sistemas legales distintos: ya sea Inglaterra y Gales, Escocia o Irlanda del Norte, y las aguas territoriales de ese país. Las circunstancias limitadas en las que sus poderes se extienden a través de la frontera se describen en la sección anterior.

Hay muchos agentes de policía que no son miembros de las fuerzas policiales territoriales. Los más notables son los miembros de las tres fuerzas conocidas como fuerzas policiales especiales : la Policía de Transporte Británica , la Policía del Ministerio de Defensa y la Policía Nuclear Civil . Estos oficiales tienen los "poderes y privilegios de un agente de policía" en asuntos relacionados con su trabajo. [22] [23] [24] Los oficiales de la BTP y del MDP tienen jurisdicción adicional cuando lo solicita un agente de otra fuerza, en cuyo caso asumen la jurisdicción de ese agente. [25] [26] A petición del jefe de policía de una fuerza policial, los miembros de una de las tres fuerzas anteriores pueden recibir los plenos poderes de los agentes de policía en el área policial de la fuerza solicitante. [25] [27] Esto se utilizó para complementar los números de policías en las áreas circundantes a la cumbre del G8 de 2005 en Gleneagles.

Muchas leyes permiten a las empresas o ayuntamientos emplear agentes de policía para un propósito específico. Hay diez empresas cuyos empleados son juramentados como agentes de policía en virtud del artículo 79 de la Ley de Cláusulas de Puertos, Muelles y Embarcaderos de 1847. [ 28] Como resultado, tienen plenos poderes de un agente de policía en terrenos propiedad del puerto, muelle o puerto y en cualquier lugar dentro de una milla de cualquier terreno de su propiedad. También hay fuerzas creadas por legislación específica, como la Policía del Puerto de Tilbury ( Ley del Puerto de Londres de 1968 ), la Policía de los Túneles de Mersey (Ley del Condado de Merseyside de 1989) y los Guardianes del Bosque de Epping ( Ley del Bosque de Epping de 1878 ).

En virtud del artículo 18 de la Ley de Confirmación de la Orden Provisional del Ministerio de Vivienda y Gobierno Local (Parques y Espacios Abiertos del Gran Londres) de 1967, los Ayuntamientos de los distritos de Londres pueden tomar juramento a los funcionarios del consejo como agentes de policía para "garantizar el cumplimiento de las disposiciones de todas las leyes relativas a los espacios abiertos bajo su control o gestión y de las ordenanzas y reglamentos dictados en virtud de las mismas". Los agentes de parques de las autoridades locales tienen todos los poderes de un agente en relación con los reglamentos y ordenanzas locales y todas las disposiciones relativas a los espacios abiertos. El artículo 19 de la Ley fue derogado por la sección 26(1) de la Ley de policía y pruebas penales de 1984 (Leyes locales) y el poder de arresto de los agentes de parques ahora está contenido en la sección 24 de PACE 1984. Las modificaciones adicionales al artículo 19 que cubrían la ayuda y asistencia de un agente o funcionario fueron derogadas por SOCPA 2005, ya que esta disposición ya está cubierta en PACE 1984 (Legal Counsel 2007,2012). Ningún organismo de ejecución con un poder de arresto o detención puede operar fuera de las disposiciones de PACE 1984; por lo tanto, todos los poderes locales de arresto y detención se alinearon con la sección 26(1) de PACE 1984.

Las fuerzas policiales emplean personal que realiza muchas funciones para ayudar a los agentes y apoyar el buen funcionamiento de su fuerza policial. No tienen el cargo de agente de policía. En Inglaterra y Gales, el jefe de policía de una fuerza policial territorial puede designar a cualquier persona que esté empleada por la autoridad policial que mantiene esa fuerza y que esté bajo la dirección y el control de ese jefe de policía, como una de las siguientes:

Los PCSO fueron creados por la Ley de Reforma Policial de 2002 [30] , con una serie de poderes estándar, así como poderes adicionales que pueden ser conferidos a discreción de su jefe de policía. A diferencia de un agente de policía , un PCSO solo tiene poderes cuando está de servicio y uniformado, y dentro del área vigilada por su respectiva fuerza.

El rol de oficial de apoyo policial originalmente estaba dividido en tres roles separados en la Ley de Reforma Policial de 2002 , cada uno con una lista específica de poderes discrecionales que podía otorgar un jefe de policía:

La Ley de Policía y Delincuencia de 2017 reformó esto y lo simplificó a los dos roles anteriores, y dio poderes discrecionales completos a los jefes de policía, de modo que pueden asignar cualquier poder, excepto los poderes reservados solo para los agentes , a cualquier miembro del personal o voluntario de la policía.

Hasta 1991, la vigilancia del estacionamiento estaba a cargo principalmente de agentes de tráfico contratados por la policía . Desde la aprobación de la Ley de Tráfico por Carretera de 1991, la despenalización de la vigilancia del estacionamiento ha permitido a las autoridades locales asumir esta función y, en la actualidad, muy pocas fuerzas policiales emplean a agentes de tráfico de la policía. Entre ellas se encuentra el Servicio de Policía Metropolitana; sin embargo, han combinado la función con los agentes de policía de tráfico como agentes de apoyo comunitario en materia de tráfico .

En Escocia, los agentes de custodia y seguridad policiales tienen poderes similares a los de los agentes de detención y de escolta en Inglaterra y Gales. [32] En Irlanda del Norte existen poderes similares. [33]

Los jefes de policía de las fuerzas policiales territoriales [34] (y la Policía de Transporte Británica [35] ) también pueden otorgar poderes limitados [36] a personas no empleadas por la autoridad policial, en virtud de los Esquemas de Acreditación de Seguridad Comunitaria . Un ejemplo notable son los funcionarios de la Agencia de Normas para Conductores y Vehículos , a quienes se les han otorgado poderes para detener vehículos. [37] Esta práctica ha sido criticada por la Federación de Policía , que la calificó de "a medias". [38]

Sólo en Irlanda del Norte , los miembros de las Fuerzas Armadas de Su Majestad tienen poderes para detener a personas [39] o vehículos, [40] arrestar y detener a personas durante tres horas [41] y entrar en edificios para mantener la paz [42] o buscar a personas que hayan sido secuestradas. [43] Además, los oficiales comisionados pueden cerrar carreteras. [44] Si es necesario, pueden usar la fuerza al ejercer estos poderes siempre que sea razonable. [45]

En virtud de la Ley de Gestión Aduanera de 1979, los miembros de las Fuerzas Armadas Británicas pueden detener a personas si creen que han cometido un delito conforme a las leyes de Aduanas e Impuestos Especiales, y pueden confiscar bienes si creen que están sujetos a decomiso conforme a las mismas leyes. [46]

La policía militar y de servicio no son agentes de policía según la legislación del Reino Unido y no tienen poderes de policía sobre el público en general; sin embargo, tienen toda la gama de poderes policiales que poseen los agentes de policía cuando tratan con personal de servicio o civiles sujetos a la Ley de Servicio, obteniendo sus poderes de la Ley de Fuerzas Armadas de 2006. La policía de servicio ayuda a las fuerzas policiales territoriales en las ciudades del Reino Unido con cuarteles militares cercanos donde es probable que haya un número significativo de personal de servicio fuera de servicio. En los Territorios de Ultramar, a veces prestan juramento como agentes de policía para ayudar y/o actuar como fuerza policial (por ejemplo, la Policía del Territorio Británico del Océano Índico, que está formada por policías de tres servicios y se conocen como "Oficiales de Policía Real de Ultramar" [47] ) y en cualquier lugar donde las Fuerzas Británicas estén estacionadas o desplegadas. Generalmente, cuando llevan a cabo esta asistencia, los policías de servicio están desarmados, pero llevan una variedad de EPI que incluyen una porra, esposas y un chaleco protector.

En el Reino Unido , cada persona tiene poderes limitados de arresto si ve que se está cometiendo un delito: en el derecho consuetudinario en Escocia, y en Inglaterra y Gales si el delito es procesable [57] , estos se denominan "poderes de cada persona", comúnmente conocidos como " arresto ciudadano ". En Inglaterra y Gales, la gran mayoría de los agentes de policía certificados disfrutan de plenos poderes de arresto y registro según lo otorgado por la Ley de Policía y Pruebas Penales de 1984. Para los fines de esta legislación, "agentes de policía" se define como todos los oficiales de policía, independientemente de su rango . Aunque los oficiales de policía tienen amplios poderes, aún están sujetos a las mismas leyes que los miembros del público (aparte de exenciones específicas como el porte de armas de fuego y cierta legislación de tránsito). Existen restricciones legales adicionales impuestas a los oficiales de policía, como las prohibiciones de acción industrial y de participar en política activa.

Cada lugar geográfico del Reino Unido está definido por ley como parte de una determinada zona policial . En Inglaterra y Gales, esto se define actualmente en la sección 1 de la Ley de Policía de 1996. Una zona policial define el área geográfica de la que una fuerza policial territorial es responsable de la vigilancia policial. Esto es diferente a la jurisdicción legal (véase más abajo). Las fuerzas policiales especiales (como la BTP) no tienen zonas policiales y, en última instancia, el jefe de policía de una fuerza policial territorial es responsable de mantener la ley y el orden en toda su zona policial, incluso si, por ejemplo, la BTP tiene presencia en las estaciones de tren dentro del área policial. Escocia e Irlanda del Norte tienen fuerzas policiales nacionales (véase más abajo).

En Inglaterra, las fuerzas policiales se financian mediante una combinación de fuentes, incluido el gobierno central y mediante el impuesto "precepto policial" recaudado como parte del impuesto municipal que cobran los gobiernos locales. [58] El precepto de la fuerza policial local se puede aumentar mediante referéndum . Desde 2013, las fuerzas policiales en Inglaterra (y Gales) han sido supervisadas por un comisionado de policía y delincuencia (PCC) elegido directamente que hace que la fuerza rinda cuentas al público. Los PCC no tienen control operativo de la fuerza policial, y la gestión operativa de la fuerza policial es responsabilidad del jefe de policía en la mayoría de las fuerzas policiales inglesas, aunque el puesto equivalente se conoce como comisionado en la Policía Metropolitana de Londres y la Policía de la Ciudad de Londres. La administración de los asuntos policiales generalmente no se ve afectada por la Ley del Gobierno de Gales de 2006 .

En 1981, James Anderton , jefe de policía de la Gran Mánchester , pidió que el número de fuerzas se redujera a nueve en Inglaterra (una para cada región ) y una para Gales. [60] Una propuesta de 2004 de la Asociación de Superintendentes de Policía para la creación de una única fuerza policial nacional, similar a la Garda Síochána , fue objetada por la Asociación de Jefes de Policía . El gobierno no aceptó la propuesta en ese momento. [61]

Entre 2005 y 2006, el gobierno consideró la posibilidad de fusionar varias fuerzas policiales territoriales en Inglaterra y Gales. La revisión sólo afectó a la policía fuera de Escocia, Irlanda del Norte y el Gran Londres. Del mismo modo, las principales fuerzas no territoriales ( Policía de Transporte Británica , Policía Nuclear Civil , Policía del Ministerio de Defensa ) son responsables ante otros departamentos gubernamentales y tampoco se habrían visto afectadas. El principal argumento para la fusión de fuerzas es que las fuerzas con 4.000 o más agentes tendrían un mejor rendimiento y podrían ahorrar costes. [62] La opinión fue apoyada por la Inspección de Policía de Su Majestad , que dijo en septiembre de 2005 que la estructura existente "ya no funcionaba". [63]

El Ministro del Interior anunció propuestas de fusión a principios de 2006. Proponía reducir el número de fuerzas policiales a menos de 25, y que Gales y varias regiones de Inglaterra tuvieran una fuerza cada una. [64] [65] [66] [67] [68] [69] El período de consulta sobre este segundo lote de fusiones comenzó el 11 de abril de 2006 y habría finalizado el 11 de agosto, con el objetivo de abril de 2008 para que las fusiones entraran en vigor. [70]

El 20 de junio de 2006, el entonces Ministro del Interior, John Reid , anunció que las fusiones en disputa se retrasarían para su posterior debate. [71] La única fusión acordada fue la de la policía de Lancashire y la policía de Cumbria . El 12 de julio de 2006, el Ministerio del Interior confirmó que se abandonarían todas las fusiones y que se llevaría a consulta toda la propuesta. [72]

En 2013, las 8 fuerzas policiales territoriales de Escocia se fusionaron en una sola fuerza policial escocesa, llamada "El Servicio de Policía de Escocia", o coloquialmente Policía de Escocia . La fusión de estas fuerzas se había planteado por primera vez en 2010, y fue apoyada por el Partido Nacional Escocés , el Partido Laborista Escocés y el Partido Conservador Escocés antes de las elecciones al Parlamento escocés de 2011. [ 73] Después de un proceso de consulta, [74] [75] el Gobierno escocés confirmó el 8 de septiembre de 2011 que se crearía un solo servicio policial en Escocia. [76] El Gobierno escocés declaró que "la reforma salvaguardará la vigilancia de primera línea en las comunidades mediante la creación de oficiales superiores locales designados para cada área del consejo con el deber legal de trabajar con los consejos para dar forma a los servicios locales. El establecimiento de un servicio único tiene como objetivo garantizar un acceso más igualitario a los servicios y conocimientos nacionales y especializados, como los principales equipos de investigación y los equipos de armas de fuego, cuando y donde sea necesario". [77] El proyecto de ley de reforma de la policía y los bomberos (Escocia) se publicó en enero de 2012 [78] y se aprobó el 27 de junio de 2012 después del escrutinio en el Parlamento escocés . [77] El proyecto de ley recibió la sanción real como Ley de reforma de la policía y los bomberos (Escocia) de 2012. Esto creó una fuerza de aproximadamente 17.000 agentes de policía, la segunda más grande del Reino Unido después de la Policía Metropolitana de Londres. [79] [80]

En marzo de 2015, tras la transferencia de poderes de supervisión policial al Gobierno escocés, [81] el Secretario de Justicia anunció propuestas para unificar aún más la policía en Escocia fusionando las operaciones de la Policía de Transporte Británica al norte de la frontera con la Policía de Escocia. [82]

Los agentes de policía territorial tienen ciertos poderes de arresto en otra de las tres jurisdicciones legales del Reino Unido en las que fueron atestiguados. Hay cuatro disposiciones principales para que lo hagan: arresto con una orden judicial, arresto sin una orden judicial por un delito cometido en su jurisdicción de origen mientras se encuentra en otra jurisdicción, arresto sin una orden judicial por un delito cometido en otra jurisdicción mientras se encuentra en esa jurisdicción, y ayuda mutua. Un quinto poder de arresto transjurisdiccional fue introducido por la sección 116 de la Ley de Policía y Delito de 2017 que llena un vacío legal en los poderes de arresto en ciertas situaciones. Este poder entró en vigor en marzo de 2018. [83] Este nuevo poder permite a un agente de policía de una jurisdicción arrestar sin orden judicial a una persona sospechosa de un delito en otra jurisdicción mientras se encuentra en su jurisdicción de origen. Este poder está relacionado con los delitos más graves enumerados en la ley. La Ley establece durante cuánto tiempo la "fuerza que realiza la detención" puede detener a una persona en una jurisdicción hasta que los agentes de la "fuerza investigadora" de otra jurisdicción puedan viajar para volver a detenerla y tomar las medidas correspondientes. [84] A continuación se presenta un resumen de estos cinco poderes con un ejemplo práctico debido a la naturaleza complicada de esta área del derecho. Nota: esta sección se aplica únicamente a los agentes de policía territoriales, y no a otros, excepto a la Policía de Transporte Británica, que también tiene ciertos poderes transfronterizos además de sus poderes naturales.

Ciertas órdenes judiciales pueden ser ejecutadas por agentes de policía incluso si se encuentran fuera de su jurisdicción: órdenes de arresto y órdenes de encarcelamiento (todas); y una orden para arrestar a un testigo (Inglaterra, Gales o Irlanda del Norte); una orden de encarcelamiento, una orden de encarcelamiento (o de aprehender y encarcelar) y una orden para arrestar a un testigo (Escocia). [85] Una orden judicial emitida en una jurisdicción legal puede ser ejecutada en cualquiera de las otras dos jurisdicciones por un agente de policía de la jurisdicción donde fue emitida o de la jurisdicción donde se ejecuta. [85]

When executing a warrant issued in Scotland, the constable executing it shall have the same powers and duties, and the person arrested the same rights, as they would have had if execution had been in Scotland by a constable of a police force in Scotland. When executing a warrant issued in England & Wales or Northern Ireland, a constable may use reasonable force and has specified search powers provided by section 139 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.[86]

In very simple terms, this power allows constables of one jurisdiction to travel to another jurisdiction and arrest a person they suspect of committing an offence in their home jurisdiction. For example, constables from Cumbria Police investigating an offence of assault that occurred in their police area could travel over the border into Scotland and arrest the suspect without warrant found in Gretna.

If a constable suspects that a person has committed or attempted to commit an offence in their legal jurisdiction, and that person is now in another jurisdiction, the constable may arrest them in that other jurisdiction.[87]

A constable from England & Wales is subject to the same necessity tests for arrest (as under section 24 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984[88]) as they would be in England & Wales, a constable from Scotland may arrest if it would have been lawful to do so in Scotland and a constable from Northern Ireland is subject to the same necessity tests for arrest (as under Article 26 of the Police and Criminal Evidence (Northern Ireland) Order 1989.[89]) as they would be in Northern Ireland.[87]

A person arrested under the above powers:[87]

In simple terms, this power gives a constable of one jurisdiction whilst in another jurisdiction the same power of arrest as a constable of the jurisdiction they are visiting. As a practical example, if constables from Police Scotland are over the border in Cumbria on enquiries and come across a burglary in progress they can arrest the suspect on suspicion of burglary using the same arrest powers as a constable of England or Wales.

A constable from one legal jurisdiction has, in the other jurisdictions, the same powers of arrest as a constable of that jurisdiction would have.[90]

A constable from England or Wales has:[90]

A constable from Scotland has:[90]

A constable from Northern Ireland has:[90]

When a constable arrests a person in England & Wales, the constable is subject to the requirements of section 28 (informing of arrest),[94] section 30 (taking to a designated police station)[95] and section 32 (search on arrest).[90][96] When a constable arrests a person in Scotland, the arrested person shall have the same rights and the constable the same powers and duties as they would have were the constable a constable of a police force in Scotland.[90] When a constable arrests a person in Northern Ireland, the constable is subject to the requirements of Article 30 (informing of arrest),[97] Article 32 (taking to a designated police station)[98] and Article 34 (search on arrest).[90][99]

This power allows a constable of one jurisdiction to arrest without warrant a person suspected of an offence in another jurisdiction whilst in their home jurisdiction. The Policing and Crime Act 2017 sets out which offences this power of arrest will apply to in each jurisdiction (generally serious offences), and how long the person arrested can be kept in custody, with relevant authorities, by the "arresting force" to allow sufficient time for officers from the "investigating force" in another jurisdiction to travel and re-arrest the detained person for the purposes of their investigation.[84]

This relatively new power came into force in March 2018.[83] Until the introduction of this power, there was an issue whereby a constable in his home jurisdiction could not arrest a person suspected of an offence in another jurisdiction without a warrant.[100]

Police forces often support each other with large-scale operations, such as those that require specialist skills or expertise and those that require policing levels that the host-forces cannot provide. Referred to as mutual aid, constables loaned from one force to another have the powers and privileges of a constable of the host force.[101] Constables from the Metropolitan Police who are on protection duties in Scotland or Northern Ireland have all the powers and privileges of a constable of the host police force.[102] A constable who is taking a person to or from a prison retains all the powers, authority, protection and privileges of his office regardless of his location.[103] Regardless of where they are in the United Kingdom, a constable may arrest under section 41[104] and may stop and search under section 43[105] of the Terrorism Act 2000 on suspicion of terrorism (defined by section 40[106])

From 22 November 2012, police authorities outside London were replaced by directly elected Police and Crime Commissioners or Police, Fire and Crime Commissioners. In London, the City of London Police continued to be overseen by City of London Corporation, whilst the Mayor of London has responsibility for the governance of the Metropolitan Police.[107] The mayors of Greater Manchester and West Yorkshire also have responsibility for governance.

In Northern Ireland, the Police Service of Northern Ireland is supervised by the Northern Ireland Policing Board.

In Scotland, Police Scotland is overseen by the Scottish Police Authority.

The British Transport Police and the Civil Nuclear Constabulary had their own police authority established in 2004. These forces operate across the United Kingdom and their responsibility is to the specific activities they were established to police.

The official bodies responsible for the examination and assessment of police forces to ensure their requirements are met as intended are:

As of June 2022 in addition to the london Metropolitan Police six police forces are in special measures because they are failing. They are Cleveland, Greater Manchester police, Gloucestershire. Staffordshire and Wiltshire forces. London mayor, Sadiq Khan said "(...) after 12 years of massive cuts. We've lost 21,000 experienced officers around the country, many of them in London. Because of City Hall funding we've managed to replace many of them, but clearly, with newer, inexperienced officers."[108]

Throughout the United Kingdom, the rank structure of police forces is identical up to the rank of chief superintendent. At higher ranks, structures are distinct within London where the Metropolitan Police Service and the City of London Police have a series of commander and commissioner ranks as their top ranks whereas other UK police forces have assistants, deputies and a chief constable as their top ranks. All commissioners and chief constables are equal in rank.

Police community support officers (PCSOs) were introduced following the passing of the Police Reform Act 2002, although some have criticised these as for being a cheap alternative to fully trained police officers.[109]

Uniforms, the issuing of firearms, type of patrol cars, and other equipment, varies by force.

The custodian helmet which is synonymous with the "bobby on the beat" image is frequently worn by male officers in England and Wales (and formerly in Scotland), while the equivalent for female officers is the "bowler" hat. The flat peaked cap is worn by officers on mobile patrol and higher-ranking officers.[110]

Unlike police in most other developed countries, the vast majority of British police officers do not carry firearms on standard patrol; they carry an ASP baton and CS gas or PAVA spray. Officers are becoming increasingly trained in the use of and equipped with the TASER X2 as another tactical option.[111]

Every territorial force has a specialist Firearms Unit,[112] which maintains armed response vehicles to respond to firearms-related emergency calls. The Police Service of Northern Ireland, Belfast International Airport Constabulary, Belfast Harbour Police, Civil Nuclear Constabulary and the Ministry of Defence Police are routinely armed.

London's Metropolitan Police firearms unit is the Specialist Firearms Command (SCO19), but every force in the United Kingdom maintains its own armed unit. Metropolitan and City of London Police operate with three officers per armed response vehicle, composed of a driver, a navigator, and an observer who gathers information about the incident and liaises with other units. Other police forces carry two authorised firearms officers instead of three.

Armed police carry various weapons, ranging from semi-automatic carbines to sniper rifles, baton guns (which fire baton rounds) and shotguns. All officers also carry a sidearm. Since 2009, Tasers have been issued to armed officers as an alternative to deadly force.[citation needed]

The majority of officers on mobile patrol will do so in a marked police vehicle, namely an Incident Response Vehicle (IRV). Officers typically hold a 'response' permit, allowing them to utilise blue lights and sirens to make an emergency response. Some officers may not have undergone the additional training, and as such are only permitted to use emergency equipment when positioned at a scene or to pull over a vehicle. Officers who have undergone additional training to reach 'initial pursuit phase' standard are allowed to pursue vehicles, should they fail to stop. Vans are used as IRVs and, more specifically, to transport arrested suspects in a cage, who are unsuitable to be taken to custody in a car.

Some forces utilise Area Cars in addition to IRVs. Like IRVs, they respond to 999 calls and are manned by officers from response teams. However, officers are trained as 'advanced' drivers – allowing them to drive high-performance vehicles and pursue fleeing vehicles in the tactical phase of a pursuit. Some drivers may also be trained in skills like Tactical Pursuit and Containment (TPAC).

In addition, forces' specialist units utilise a wide variety of vehicles to help perform their role effectively. Roads Policing Units (RPU) utilise performance vehicles to primarily enforce traffic laws and pursue fleeing suspects. Armed Response Vehicles (ARV) are used to transport armed officers and carry weaponry. Tactical/operational support units use larger vans, equipped with windscreen cages and/or reinforced glass, to transport officers into public order situations.

Forces also utilise unmarked vehicles for a wide-variety of roles. Covert surveillance vehicles are typically not fitted with any emergency equipment, as it is not necessary. Some forces utilise unmarked response vehicles to aid in proactive work. Similarly, some roads policing vehicles and ARVs are unmarked to help officers identity offences and use pre-emptive tactics to stop a suspect fleeing. Additionally, some forces have dedicated road crime units who use high-performance vehicles to primarily focus on organised criminals using the road committing offences.

The College of Policing defines six curricula for new police constables, special constables and police community support officers:[113]

A number of alternative programmes exist to join police forces, including Police Now and Fast Track programmes to the rank of Inspector and Superintendent for those with substantial management experience in other sectors.

Derived from the IPLDP and although not linked to a formal qualification as such; IL4SC requires the learning outcomes and National Occupational Standards (NOSs) are met in order to become compliant. This curriculum will bring an officer to the 'point of safe and lawful accompanied patrol'.[115] This course equates to roughly 3.5 weeks of direct learning.

Successfully completion of the PCSO NLP over a period of six months to a year will result in a non-mandatory Certificate in Policing and this equates to 10 weeks of direct learning and consists of six mandatory units. Four of these units also feature within the IPLDP and being a QCF qualification, this can allow for officers wishing to become police officers for 'Recognition of Prior Learning' (RPL) and the transfer of such units to the IPLDP scheme.[113]

All initial probationer training in Scotland is undertaken at the Scottish Police College (or SPC) at Tulliallan Castle. Recruits initially spend 12 weeks at the SPC before being posted to their divisions and over the next two years return to the SPC a number of times to complete examinations and fitness tests.[116] Training is composed of four distinct modules undertaken at various locations with some parts being delivered locally and some centrally at the SPC.[117]

Training for Special Constables is delivered locally at seven locations throughout Scotland over a series of evenings and/or weekends. The training is split into two parts, with the first phase being delivered in a classroom environment before being sworn in as a Special Constable and the second phase is delivered after being sworn in. Upon successful completion of both parts of the training programme Special Constables are awarded a certificate of achievement and would be eligible to complete an abbreviated course at the Scottish Police College should they later wish to join the Police Service of Scotland as a regular officer.[118]

As all police forces are autonomous organisations there is much variation in organisation and nomenclature; however, outlined below are the main strands of policing that makes up police forces:

In the United Kingdom, the Fixated Threat Assessment Centre is a joint police/mental health unit set up in October 2006 by the Home Office, the Department of Health and Metropolitan Police Service to identify and address those individuals considered to pose a threat to VIPs or the Royal Family.[119] They may then be referred to local health services for further assessment and potential involuntary commitment. In some cases, they may be detained by police under the section 136 powers of the Mental Health Act 1983 prior to referral.

.jpg/440px-Searcher_-_Border_Force_ship_(cropped).jpg)

As part of the wide-ranging review of the Home Office, the then Home Secretary, John Reid, announced in July 2006 that all British immigration officers would be uniformed. On 1 April 2007 the Border and Immigration Agency (BIA) was created and commenced operation. However, there were no police officers in the Agency, a matter that attracted considerable criticism when the Agency was established - agency officers have limited powers of arrest. Further powers for designated officers within the Agency, including powers of detention pending the arrival of a police officer, were introduced by the UK Borders Act 2007.[120]

The Government has effectively admitted the shortcomings of the Agency by making a number of fundamental changes within a year of its commencement. On 1 April 2008 the BIA became the UK Border Agency following a merger with UKvisas, the port of entry functions of HM Revenue and Customs. The Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith, announced that the UK Border Agency (UKBA) "...will bring together the work of the Border and Immigration Agency, UK Visas and parts of HM Revenue and Customs at the border, [and] will work closely with the police and other law enforcement agencies to improve border controls and security."[121]

Within months of this, the Home Secretary revealed (in a 16-page response to a report by Lord Carlile, the independent reviewer of UK terrorism legislation), that the Home Office would issue a Green Paper proposing to take forward proposals by the Association of Chief Police Officers (England & Wales) for the establishment of a new 3,000-strong national border police force to work alongside the Agency.[122][123]

Following a major enquiry into the UK Border Agency that exposed significant flaws in the operation of border controls, the Home Secretary, Theresa May, announced in 2012 that the Border Force, which is responsible for manning all points of entry into the United Kingdom, would be split from the control of the UKBA and become a separate organisation with direct accountability to ministers and a "law-enforcement ethos".[124] Brian Moore, the former Chief Constable of Wiltshire Police, was appointed as the first head of the new UKBF.[125]

There are certain instances where police forces of other nations operate in a limited degree in the United Kingdom:

UK police officers have often served overseas as part of secondments to United Nations Police (UNPOL), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and European Union Police (EUPOL). These are typically training and mentoring posts, but sometimes involve carrying out executive policing duties.[130]

One of the most common merger proposals is to merge the City of London Police and London operations of the British Transport Police into the Metropolitan Police.

The 2005-06 merger proposals had not included Greater London. This was due to two separate reviews of policing in the capital - the first was a review by the Department of Transport into the future role and function of the British Transport Police. The second was a review by the Attorney-General into national measures for combating fraud (the City of London Police is one of the major organisations for combating economic crime).[131] Both the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Ian Blair, and the Mayor, Ken Livingstone, stated that they would like to see a single police force in London, with the Metropolitan Police also absorbing the functions of the British Transport Police in London.[132] However, the proposal to merge both the BTP and City forces with the Met caused significant criticism from several areas; the House of Commons Transport Select Committee severely criticised the idea of the Metropolitan Police taking over policing of the rail network in a report published on 16 May 2006,[133] while the City of London Corporation and several major financial institutions in The City made public their opposition to the City Police merging with the Met.[134] In a statement on 20 July 2006, the Transport Secretary announced that there would be no structural or operational changes to the British Transport Police, effectively ruling out any merger[135] The interim report by the Attorney General's fraud review recognised the role taken by the City Police as the lead force in London and the South-East for tackling fraud, and made a recommendation that, should a national lead force be required, the City Police, with its expertise, would be an ideal candidate to take this role.[136] This view was confirmed on the publication of the final report, which recommended that the City of London Police's Fraud Squad should be the national lead force in combatting fraud, to "act as a centre of excellence, disseminate best practice, give advice on complex inquiries in other regions, and assist with or direct the most complex of such investigations"[137]

Separate from the proposals raised by the Mayor of London and Metropolitan Police Commissioner was a plan by the government to reform policing in the Royal Parks. Since 1872 this had been the responsibility of the Royal Parks Constabulary. A report by former Metropolitan Police Assistant Commissioner Anthony Speed provided three options to reform the RPC, with the decision taken that it should be merged with the Metropolitan Police.[138] The Met took over responsibility for policing the Royal Parks on 1 April 2004 with the formation of the Royal Parks Operational Command Unit. The full merger and abolition of the Royal Parks Constabulary took place in May 2006.[139]

In May 2016, following his election, the Mayor of London Sadiq Khan ordered a review, led by Lord Harris, of London's preparedness in the face of potential terror attacks. Amongst the recommendations, which were published in October 2016, was a revisiting of the idea of merging the Metropolitan Police, City of London Police and British Transport Police. In commenting, both the City Police and BTP cautioned against the proposal.[140]

.jpg/440px-New_Scotland_Yard_¦_Embankment_Chic_%3F_(33219232590).jpg)

The police are funded both by central government and by local government.[141] Central government funding is calculated based by a formula, based on several population and socio-economic factors which are used to determine the expected cost of policing the area.[141]

For the 2017/18 fiscal year, the budget for local Police and Crime Commissioners to spend on police is £11 billion, with an extra £1.5 billion allocated to counter-terrorism and other special programmes.[142] The combined funding will reduce from £12.3 billion in 2017/18 to £11.6 billion in 2020/21. His Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) estimates that officer numbers will fall by around 2%.

According to the National Audit Office, funding was decreased between 2011 and 2016 by 22% in real terms[141] and police officer numbers fell by 20,000 from 2010 to 2017.[143] Funding levels stayed the same in real terms between 2015 and 2018, with a decrease in central government funding made up for by an increase in local government funding.[144] Increased spending in some areas such as counter-terrorism has been offset by decreased spending in other departments.[145] In 2018 further funding cuts will force further cuts in the numbers of police officers.[146] 80% of UK people believe Britain is less safe due to cuts to police funding.[147]

In 2017, a report from the Inspectorate found that most police forces were providing a good service, though it noted that some aspects such as investigations and neighbourhood policing were being compromised by "rationing" and cutbacks.[145] A report from the Inspectorate in March 2018 had similar findings; it reported improvement in neighbourhood policing and highlighted issues with response policing.[148][149] Several current and former chief constables were raising concerns about whether the police can meet foreseeable challenges with current levels of funding.[145][150][151]

The police service is sometimes criticised for incidents that result in deaths due to police firearms usage or in police custody, as well as the lack of competence and impartiality in investigations (in England and Wales only) by the Independent Police Complaints Commission after these events.[152] The Economist stated in 2009:

Bad apples ... are seldom brought to justice: no policeman has ever been convicted of murder or manslaughter for a death following police contact, though there have been more than 400 such deaths in the past ten years alone. The IPCC is at best overworked and at worst does not deserve the "I" in its name.

— The Economist[152]

In the year 2011/12 there were 15 deaths in or following police custody. There were two fatal police shootings and 39 people died from apparent suicide following contact with the police.[153]

In the year 2012/13 there were 15 deaths in police custody. Nearly half of those who died had known mental health issue and four of those who died had been restrained by police officers. There were 64 deaths by apparent suicide within 48 hours of release from police custody.[154]

In the year 2013/14 there were 11 deaths in or following police custody. The number of people recorded as having apparently committed suicide within 48 hours of release from police custody was 68, a ten-year high.[155]

In the year 2014/15 there were 17 deaths in or following police custody. There was one fatal police shooting and there were 69 apparent suicides following custody.[156]

The policy under which police officers in England and Wales use firearms has resulted in controversy. Notorious examples include the Stephen Waldorf shooting in 1983, the deliberate fatal shootings of James Ashley in 1998, Harry Stanley in 1999, and Jean Charles de Menezes in 2005, and the accidental non-fatal shooting of Abdul Kahar in 2006.

From 1990 to July 2012, 950 deaths occurred in police custody.[157]

In 1997/98, 69 people died in police custody or following contact with the police across England and Wales; 26 resulted from deliberate self-harm.[158]

There are two defined categories of death in custody issued by the Home Office:[159]

Category A: This category also encompasses deaths of those under arrest who are held in temporary police accommodation or have been taken to hospital following arrest. It also includes those who die, following arrest, whilst in a police vehicle.

Category B: Where the deceased was otherwise in the hands of the police or death resulted from the actions of a police officer in the purported execution of his duty.

Hundreds of people kill themselves within 48 hours of being released from police custody.[160]

The Macpherson Report coined the phrase "institutionalised racism" to describe policies and procedures that adversely affect persons from ethnic minority groups after the death of Stephen Lawrence.

In 2003, ten police officers from Greater Manchester Police, North Wales Police and Cheshire Constabulary were forced to resign after a BBC documentary, The Secret Policeman, shown on 21 October, alleged racism among recruits at Bruche Police National Training Centre at Warrington.[162][163] In March 2005 it was reported that minor disciplinary action would be taken against twelve other officers in connection with the programme, but that they would not lose their jobs.[163] In November 2003, allegations were made that some police officers were members of the British National Party.[citation needed]

In June 2015, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, said there was "some justification" in claims that the Metropolitan Police Service is "institutionally racist":

I have always said if other people think we are institutionally racist then we are. It is no good me saying we are not and then saying you must believe me, it's nonsense, if they believe that. I think it is a label but in some sense there is a truth there for some people ... You're very much more likely to be stopped and searched if you're a young black man. I can't explain that fully. I can give you reasons but I can't fully explain it. So there is some justification ... I think in some ways society is institutionally racist. We see lack of representation in many fields, of which the police are one.[164][165]

At the beginning of 2005 it was announced that the Police Information Technology Organisation (PITO) had signed an eight-year £122 m contract to introduce biometric identification technology.[166] PITO are also planning to use CCTV facial recognition systems to identify known suspects; a future link to the proposed National Identity Register has been suggested by some.[167]

The police have sometimes been accused of infringing on free speech. In December 2005, author Lynette Burrows was interviewed by police after expressing her opinion on BBC Radio 5 Live that homosexuals should not be allowed to adopt children.[168] The following month, Sir Iqbal Sacranie was investigated by police for stating the Islamic view that homosexuality is a sin.[169]

Section 76 of the Counter-Terrorism Act 2008 came into force on 15 February 2009[170] making it an offence to elicit, attempt to elicit, or publish information "...of a kind likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism" about:[171] a member of His Majesty's Armed Forces; a constable, the Security Service, the Secret Intelligence Service, or Government Communications Headquarters. Any person found guilty faces 10 years imprisonment and an unlimited fine.[171] It is a defence for a person charged with this offence to prove that they had a reasonable excuse for their action.[171] It is not otherwise illegal to photograph or film a police officer in a public place per se.[172][173] Any film or photography recorded whilst a constable is dealing with an incident may be seized as it becomes evidence under section 19 of PACE 1984.

Public order policing presents challenges to the approach of policing by consent.[174][175] In April 2009, a total of 145 complaints were made following clashes between police and protesters at the G20 summit.[176] Incidents including the death of 47-year-old Ian Tomlinson,[177] minutes after an alleged assault by a police officer,[178] and a separate alleged assault on a woman by a police officer,[179] has led to criticism of police tactics during protests.[180] In response, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Paul Stephenson asked Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Constabulary (HMIC) to review policing tactics,[181] including the practice of kettling.[182] These events sparked a debate in the UK about the relationship between the police, media and public, and the independence of the Independent Police Complaints Commission.[183] In response to the concerns, the Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Denis O'Connor, published a 150-page report in November 2009 that aimed to restore Britain's consent-based model of policing.[184]

During 2010 and 2011, it emerged that, while engaged in covert infiltration of protest groups, undercover police officers had entered into intimate relationships with a number of people on false pretences and under assumed aliases, in some cases sharing a home, making plans for weddings, or fathering children, only to vanish after some years when their role was complete. In 2015 a public inquiry under a senior judge was announced. In November 2015 the Metropolitan Police published an unreserved apology in which it exonerated and apologised to those women who had been deceived and stated the methodology had constituted abuse and a "gross violation" with severely harmful effects, as part of a settlement of their cases. In 2016 new cases continued to come to light.

Recorded crime rose by almost a third in the three years to 2018, but charges or summons dropped by 26%, and arrests also fell. Neighbourhood policing capacity has fallen on average by at least a fifth since 2010. Neighbourhood policing is important in dealing with terrorism and gang crime, especially in communities where the police are distrusted. Yvette Cooper said the police were "performing a remarkable public service in increasingly difficult circumstances", though they were "badly overstretched" and responding with difficulty to increasing challenges like online fraud and online child abuse. Only a very small proportion of online fraud cases are investigated and the police are "woefully under-resourced" for the number of online child sexual abuse investigations they must undertake. Che Donald of the Police Federation of England and Wales said the government should acknowledge the "true cost of policing" or officers would be unable to keep the public safe.[185]

In 2016, allegations of serious sexual abuse were made against hundreds of police officers in England and Wales. Several forces in England and Wales received 436 allegations of abuse of power for sexual gain against 436 police officers, including 20 police community support officers and eight staff in the two years to March 2016.[186][187] Mike Cunningham, inspector of constabulary and former chief constable of Staffordshire police said: "It's the most serious form of corruption. It is an exploitation of power where the guardian becomes an abuser. What can be worse than a guardian abusing the trust and confidence of an abused person? There can be no greater violation of public trust".[186]

Prior to Brexit there were concerns that the UK may lose access to important cross border databases of criminals, which would make it harder for the police to keep the public safe. Police leaders warned of "a significant loss of operational capacity" if the UK were to leave the EU without an agreement on policing.[188] The Association of Police and Crime Commissioners sent a letter to Home Secretary Sajid Javid stressing the need for co-operation with European policing and justice organisations after March 2019. The letter stated that 32 measures were used daily including the European Arrest Warrant, the Schengen Information System (SIS) – a database giving alerts about individuals – and the European Criminal Records Information System. The letter stressed the importance and mutual benefit of continued cooperation between the UK and Europe to face mutual threats[188][189]

The loss of access to SIS has led to police officers being unable to see alerts on criminals from EU countries, and vice versa. UK police agencies have replaced these with Interpol, but this comes with additional administrative overhead and reduced powers, and they are unable to know if they are missing any entries that are in SIS but not Interpol systems.[190][191] The loss of access to European Investigation Orders has been especially damaging.[191] However, the UK has retained access to DNA, fingerprint, vehicle and flight data.[192]

"Two-tier policing" is a far-right conspiracy theory claiming that either; white working class British people are being treated more harshly than minority groups and immigrants, or that right-wing political groups are being treated more harshly than left-wing political groups.[193][194][195]

During the 2024 United Kingdom riots, MP and Reform UK leader Nigel Farage accused the police services of two-tier policing after suggesting the riots have been dealt with more harshly than other recent protests. This claim was later denied by Prime Minister Keir Starmer.[196][197] Conservative former Home Secretary Priti Patel called Farage's comments deeply misleading and "simply not relevant right now". She told Times Radio: "There's a clear difference between effectively blocking streets or roads being closed to burning down libraries, hotels, food banks and attacking places of worship. What we have seen is thuggery, violence, racism."[198]

When asked by a Sky News journalist whether the Metropolitan Police would "end two-tier policing", Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley responded by grabbing the journalist’s microphone and throwing it to the ground.[199][200]

A YouGov poll of 2070 people conducted over 7-8 August 2024 found partisan differences in beliefs in police bias, with voters of Reform UK and the Conservative Party more likely to believe that the police were more lenient towards Muslims, black people, the far left and climate activists. Labour and Liberal Democrat voters were more likely to disagree with this, and more likely to believe the police were more strict with black people.[201]

Mike Neville, a retired Scotland Yard detective chief inspector described the 2024 Notting Hill Carnival, a celebration of Afro-Caribbean culture, as the "ultimate example of two-tier policing", and that if the same disorderly behaviour was replicated at football matches or elsewhere it would be banned. Scotland Yard strongly rejected claims of two-tier policing at the event.[202]

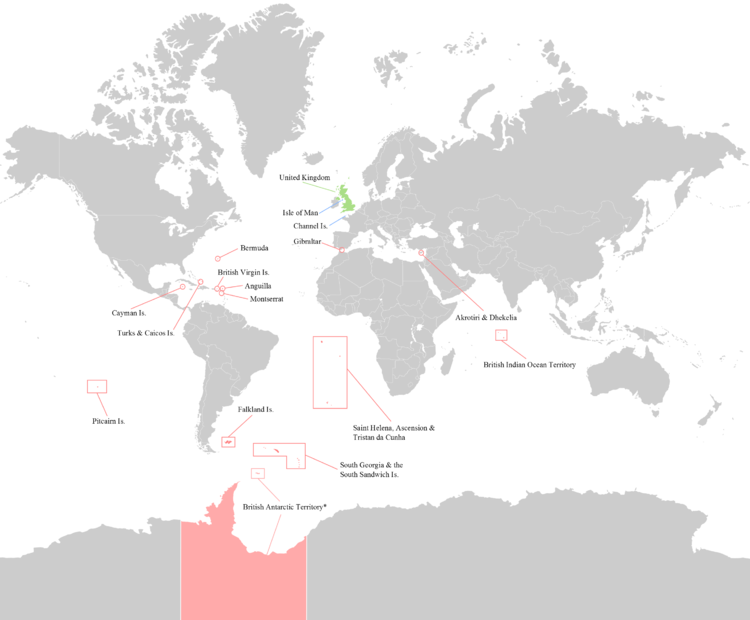

The Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories have their own police forces, the majority of which use the British model. Because they are not part of the United Kingdom, they are not answerable to the British Government; instead they are organised by and are responsible to their own governments (an exception to this is the Sovereign Base Areas Police; as the SBAs' existence is solely for the benefit of the British armed forces and do not have full overseas territory status, the SBA Police are responsible to the Ministry of Defence). Because they are based on the British model of policing, these police forces conform to the standards set out by the British government, which includes voluntarily submitting themselves to inspection by the HMIC.[203] Their vehicles share similarities with the vehicles owned by forces based in the UK, such as the use of Battenburg markings.

The fourteen British Overseas Territories are:[204]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)It is of course a vital element of police legitimacy, based on the theory 'policing by consent' that predominates in the UK context, that public protest is policed impartially, and in a politically neutral manner

Elon Musk has called the prime minister "two-tier Keir" in reference to the conspiracy theory that police are treating white far-right "protesters" more harshly than minority groups.

In another post, Musk used the hashtag #twotierKeir, in reference to "two-tier policing". This is a claim often used by the far-right to suggest that police treat certain groups of people in different ways.

In particular, he has played a hand in fuelling the "two-tier policing" narrative on X. This is a debunked theory spread by far-right actors that argues that U.K. police are lenient on minority groups and immigrants who commit crimes but heavy-handed with white British people.