Leipzig ( / ˈ l aɪ p s ɪ ɡ , - s ɪ x / LYPE -sig, -sikh , [4] [5] [6] [7] Alemán: [ˈlaɪptsɪç] ;Alto sajón:Leibz'sch;Alto sorabo:Lipsk) es la ciudad más poblada delestadodeSajonia. La ciudad tiene una población de 628.718 habitantes en 2023.[8]Es laoctava ciudad más grandede Alemania y forma parte de laRegión Metropolitana de Alemania Central. El nombre de la ciudad suele interpretarse como un término eslavo que significalugar detilos, en consonancia con muchos otros topónimos eslavos de la región.[9]

Leipzig está situada a unos 150 km (90 mi) al suroeste de Berlín, en la parte más meridional de la llanura del norte de Alemania (la bahía de Leipzig ), en la confluencia del río Elster blanco y sus afluentes Pleiße y Parthe , que forman un extenso delta interior en la ciudad conocido como Leipziger Gewässerknoten , a lo largo del cual se ha desarrollado el Bosque Ribereño de Leipzig , el bosque ribereño intraurbano más grande de Europa . Leipzig está en el centro de Neuseenland ( nuevo distrito de los lagos ), que consta de varios lagos artificiales creados a partir de antiguas minas a cielo abierto de lignito .

Leipzig ha sido una ciudad comercial desde al menos la época del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico . [10] La ciudad se encuentra en la intersección de la Vía Regia y la Vía Imperii , dos importantes rutas comerciales medievales. La feria comercial de Leipzig se remonta a 1190. Entre 1764 y 1945, la ciudad fue un centro editorial. [11] Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y durante el período de la República Democrática Alemana (Alemania del Este), Leipzig siguió siendo un importante centro urbano en Alemania del Este, pero su importancia cultural y económica disminuyó. [11]

Los acontecimientos de Leipzig en 1989 desempeñaron un papel importante en precipitar la caída del comunismo en Europa central y oriental, principalmente a través de manifestaciones que comenzaron en la iglesia de San Nicolás . Los efectos inmediatos de la reunificación de Alemania incluyeron el colapso de la economía local (que había llegado a depender de una industria pesada altamente contaminante ), un desempleo severo y el deterioro urbano. A principios de la década de 2000 , la tendencia se había revertido y, desde entonces, Leipzig ha experimentado algunos cambios significativos, incluido el rejuvenecimiento urbano y económico y la modernización de la infraestructura de transporte. [12] [13]

Leipzig es el hogar de una de las universidades más antiguas de Europa ( la Universidad de Leipzig ). Es la sede principal de la Biblioteca Nacional Alemana (la segunda es la de Fráncfort ), la sede del Archivo Alemán de Música , así como del Tribunal Administrativo Federal Alemán . El Zoológico de Leipzig es uno de los zoológicos más modernos de Europa y a fecha de 2018 ocupa el primer lugar en Alemania y el segundo en Europa. [14]

La arquitectura de finales del siglo XIX de Leipzig se compone de unos 12.500 edificios. [15] [16] La terminal ferroviaria central de la ciudad, Leipzig Hauptbahnhof, es, con 83.460 metros cuadrados (898.400 pies cuadrados), la estación ferroviaria más grande de Europa en términos de superficie. Desde que el Leipzig City Tunnel entró en funcionamiento en 2013, ha formado la pieza central del sistema de transporte público S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland ( S-Bahn Central Germany ), la red de S-Bahn más grande de Alemania, con una longitud de sistema de 802 km (498 mi). [17]

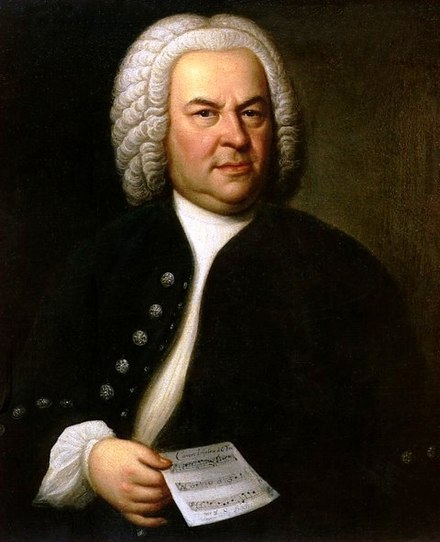

Leipzig ha sido durante mucho tiempo un importante centro de música, incluyendo la clásica y la moderna dark wave . El Thomanerchor (en español: Coro de Santo Tomás de Leipzig), un coro de niños, fue fundado en 1212. La Orquesta de la Gewandhaus de Leipzig , establecida en 1743, es una de las orquestas sinfónicas más antiguas del mundo. Varios compositores famosos vivieron y trabajaron en Leipzig, entre ellos Johann Sebastian Bach (1723 a 1750) y Felix Mendelssohn (1835 a 1847). La Universidad de Música y Teatro "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" fue fundada en 1843. La Ópera de Leipzig , uno de los teatros de ópera más importantes de Alemania, fue fundada en 1693. Durante una estancia en Gohlis , que ahora es parte de la ciudad, Friedrich Schiller escribió su poema " Oda a la alegría ".

En inglés, Leipzig se escribe más antiguamente como Leipsic . También se utilizaba el nombre latino Lipsia . [18]

El nombre Leipzig se considera comúnmente que deriva de lipa , la designación eslava común para los tilos , lo que hace que el nombre de la ciudad esté relacionado etimológicamente con Lipetsk, Rusia y Liepaja, Letonia . Basándose en testimonios medievales como Lipzk (c. 1190), el nombre eslavo original de la ciudad ha sido reconstruido como *Lipьsko , que también se refleja en formas similares en las lenguas eslavas modernas vecinas (sorbio/polaco Lipsk , checo Lipsko ). Sin embargo, esto ha sido cuestionado por investigaciones onomásticas más recientes basadas en las formas más antiguas como Libzi (c. 1015). [19]

Debido a la etimología mencionada anteriormente, Lindenstadt o Stadt der Linden (Ciudad de los tilos) son epítetos poéticos comunes para la ciudad. [20]

Otro epíteto un tanto anticuado es Pleiß-Athen ( Atenas en el río Pleiße ), que hace alusión a la larga tradición académica y literaria de Leipzig, como sede de una de las universidades alemanas más antiguas y centro del comercio del libro. [21]

En 1937, el gobierno nazi rebautizó oficialmente la ciudad como Reichsmessestadt Leipzig (Ciudad Ferial del Reich de Leipzig). [22]

En 1989 Leipzig fue bautizada como Ciudad Héroe ( Heldenstadt ), en alusión al título honorífico otorgado en la antigua Unión Soviética a ciertas ciudades que desempeñaron un papel clave en la victoria de los Aliados durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, en reconocimiento al papel que las manifestaciones de los lunes allí desempeñaron en la caída del régimen de Alemania del Este. [23]

Más recientemente, la ciudad ha recibido el sobrenombre de Hypezig , la "ciudad en auge del este de Alemania" o "el mejor Berlín" ( Das bessere Berlin ) y los medios de comunicación la celebran como un centro urbano de moda por su vibrante estilo de vida y su escena creativa con muchas empresas emergentes . [24] [25] [26] [27]

Leipzig está situada en la bahía de Leipzig , la parte más meridional de la llanura del norte de Alemania , que es la parte de la llanura del norte de Europa en Alemania. La ciudad se asienta sobre el Elster blanco , un río que nace en la República Checa y desemboca en el Saale al sur de Halle. El Pleiße y el Parthe se unen al Elster blanco en Leipzig, y el gran paisaje interior similar a un delta que forman los tres ríos se llama Leipziger Gewässerknoten . El sitio se caracteriza por áreas pantanosas como el bosque ribereño de Leipzig ( Leipziger Auenwald ), aunque también hay algunas áreas de piedra caliza al norte de la ciudad. El paisaje es mayoritariamente plano, aunque también hay alguna evidencia de morrena y drumlins .

Aunque existen algunos parques forestales dentro de los límites de la ciudad, la zona que rodea Leipzig está relativamente desforestada. Durante el siglo XX, hubo varias minas a cielo abierto en la región, muchas de las cuales se han convertido en lagos. [28] Véase también: Neuseenland

Leipzig también está situada en la intersección de las antiguas carreteras conocidas como la Vía Regia (carretera del Rey), que atravesaba Alemania en dirección este-oeste, y la Vía Imperii (carretera Imperial), una carretera de norte a sur.

Leipzig fue una ciudad amurallada en la Edad Media y la actual carretera de circunvalación que rodea el centro histórico de la ciudad sigue la línea de las antiguas murallas.

Desde 1992 Leipzig está dividida administrativamente en diez distritos ( Stadtbezirke ), que a su vez contienen un total de 63 localidades ( Ortsteile ). Algunas de ellas corresponden a pueblos periféricos que han sido anexados a Leipzig.

Como muchas ciudades de Alemania del Este, Leipzig tiene un clima oceánico ( Köppen : Cfb ), con importantes influencias continentales debido a su ubicación en el interior. Los inviernos son fríos, con una temperatura media de alrededor de 1 °C (34 °F). Los veranos son generalmente cálidos, con un promedio de 19 °C (66 °F) con temperaturas diurnas de 24 °C (75 °F). Las precipitaciones en invierno son aproximadamente la mitad de las del verano. La cantidad de sol difiere significativamente entre invierno y verano, con un promedio de alrededor de 51 horas de sol en diciembre (1,7 horas por día) en comparación con 229 horas de sol en julio (7,4 horas por día). [32]

Leipzig fue mencionada por primera vez en 1015 en las crónicas del obispo Thietmar de Merseburg como urbs Libzi ( Chronicon , VII, 25) y fue dotada de privilegios de ciudad y mercado en 1165 por Otón el Rico . La Feria de Leipzig , que comenzó en la Edad Media , se ha convertido en un evento de importancia internacional y es la feria comercial más antigua que se conserva en el mundo. Esto fomentó el crecimiento de la burguesía comercial de Leipzig .

Hay registros de operaciones de pesca comercial en el río Pleiße que, muy probablemente, se refieren a Leipzig y que se remontan a 1305, cuando el margrave Dietrich el Joven concedió los derechos de pesca a la iglesia y al convento de Santo Tomás. [35]

En la ciudad y sus alrededores había varios monasterios , entre ellos un monasterio franciscano que da nombre al Barfußgäßchen (Callejón de los Descalzos) y un monasterio de monjes irlandeses ( Jacobskirche , destruido en 1544) cerca de la actual Ranstädter Steinweg (la antigua Via Regia ).

La Universidad de Leipzig fue fundada en 1409 y Leipzig se convirtió en un importante centro del derecho alemán y de la industria editorial en Alemania, dando lugar a que en los siglos XIX y XX el Reichsgericht (Tribunal Imperial de Justicia) y la Biblioteca Nacional Alemana se ubicaran aquí.

Durante la Guerra de los Treinta Años , se libraron dos batallas en Breitenfeld , a unos 8 km de las murallas de la ciudad de Leipzig. La primera batalla de Breitenfeld tuvo lugar en 1631 y la segunda en 1642. Ambas batallas resultaron en victorias para el bando liderado por los suecos.

El 24 de diciembre de 1701, siendo alcalde Franz Conrad Romanus , se implantó un sistema de alumbrado público alimentado con petróleo . La ciudad contaba con guardias de luz que debían cumplir un horario específico para garantizar el encendido puntual de los 700 faroles.

La región de Leipzig fue escenario de la Batalla de Leipzig de 1813 entre la Francia napoleónica y una coalición aliada de Prusia , Rusia , Austria y Suecia. Fue la batalla más grande en Europa antes de la Primera Guerra Mundial y la victoria de la coalición puso fin a la presencia de Napoleón en Alemania y, en última instancia, conduciría a su primer exilio en Elba . El Monumento a la Batalla de las Naciones que celebra el centenario de este evento se completó en 1913. Además de estimular el nacionalismo alemán, la guerra tuvo un gran impacto en la movilización de un espíritu cívico en numerosas actividades de voluntariado. Se formaron muchas milicias voluntarias y asociaciones cívicas, que colaboraron con iglesias y la prensa para apoyar a las milicias locales y estatales, la movilización patriótica en tiempos de guerra, la ayuda humanitaria y las prácticas y rituales conmemorativos de posguerra. [36]

Cuando en 1839 se convirtió en terminal del primer ferrocarril alemán de larga distancia a Dresde (la capital de Sajonia), Leipzig se convirtió en un centro de tráfico ferroviario de Europa Central, siendo la estación terminal de Leipzig la más grande en superficie de Europa. La estación de trenes tiene dos grandes vestíbulos de entrada, el oriental para los Ferrocarriles Reales del Estado Sajón y el occidental para los Ferrocarriles del Estado Prusiano .

En el siglo XIX, Leipzig fue un centro de los movimientos liberales alemanes y sajones. [37] El primer partido obrero alemán , la Asociación General de Trabajadores Alemanes ( Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein , ADAV) fue fundada en Leipzig el 23 de mayo de 1863 por Ferdinand Lassalle ; alrededor de 600 trabajadores de toda Alemania viajaron hasta la fundación en el nuevo ferrocarril. Leipzig se expandió rápidamente a más de 700.000 habitantes. Se construyeron enormes áreas de Gründerzeit , que en su mayoría sobrevivieron tanto a la guerra como a la demolición de posguerra.

Con la apertura de una quinta nave de producción en 1907, la Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei se convirtió en la mayor fábrica de tejidos de algodón del continente, con más de 240.000 husos y una producción anual que superaba los 5 millones de kilogramos de hilo. [38]

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial , en 1917, el Consulado estadounidense fue cerrado y su edificio se convirtió en un lugar de estancia temporal para estadounidenses y refugiados aliados de Serbia , Rumania y Japón . [39]

Durante los años 30 y 40, la música era un tema destacado en Leipzig. Muchos estudiantes asistían a la Escuela Superior de Música y Teatro Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (en aquel entonces llamada Landeskonservatorium). Sin embargo, en 1944 cerró debido a la Segunda Guerra Mundial . Volvió a abrir poco después de que terminara la guerra en 1945.

El 22 de mayo de 1930, Carl Friedrich Goerdeler fue elegido alcalde de Leipzig. Más tarde se convirtió en un opositor al régimen nazi . [40] Dimitió en 1937 cuando, en su ausencia, su adjunto nazi ordenó la destrucción de la estatua de Felix Mendelssohn de la ciudad . En la Noche de los Cristales Rotos de 1938, la sinagoga de Leipzig de estilo neomorisco de 1855 , uno de los edificios arquitectónicamente más significativos de la ciudad, fue destruida deliberadamente. Goerdeler fue ejecutado más tarde por los nazis el 2 de febrero de 1945.

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial varios miles de trabajadores forzados fueron destinados a Leipzig.

A partir de 1933, muchos ciudadanos judíos de Leipzig eran miembros de la Gemeinde , una gran comunidad religiosa judía extendida por Alemania, Austria y Suiza. En octubre de 1935, la Gemeinde ayudó a fundar la Lehrhaus (en español: una casa de estudio) en Leipzig para proporcionar diferentes formas de estudios a los estudiantes judíos a quienes se les prohibía asistir a cualquier institución en Alemania. Se hizo hincapié en los estudios judíos y gran parte de la comunidad judía de Leipzig se involucró. [41]

Como todas las demás ciudades reclamadas por los nazis, Leipzig fue objeto de arianización . A partir de 1933 y en 1939, los dueños de negocios judíos se vieron obligados a renunciar a sus posesiones y tiendas. Esto se intensificó hasta el punto en que los funcionarios nazis fueron lo suficientemente fuertes como para desalojar a los judíos de sus propios hogares. También tenían el poder de obligar a muchos de los judíos que vivían en la ciudad a vender sus casas. Muchas personas que vendieron sus casas emigraron a otros lugares, fuera de Leipzig. Otros se mudaron a Judenhäuser, que eran casas más pequeñas que actuaban como guetos, albergando a grandes grupos de personas. [41]

Los judíos de Leipzig se vieron muy afectados por las Leyes de Núremberg . Sin embargo, debido a la Feria de Muestras de Leipzig y a la atención internacional que despertó, Leipzig se mostró especialmente cautelosa con respecto a su imagen pública. A pesar de ello, las autoridades de Leipzig no temieron aplicar y hacer cumplir estrictamente las medidas antisemitas. [41]

El 20 de diciembre de 1937, después de que los nazis tomaran el control de la ciudad, la rebautizaron como Reichsmessestadt Leipzig, que significa "Ciudad Imperial de Ferias de Comercio de Leipzig". [22] A principios de 1938, Leipzig vio un aumento del sionismo a través de ciudadanos judíos. Muchos de estos sionistas intentaron huir antes de que comenzaran las deportaciones. [41] El 28 de octubre de 1938, Heinrich Himmler ordenó la deportación de judíos polacos de Leipzig a Polonia. [41] [42] El consulado polaco albergó a 1.300 judíos polacos, impidiendo su deportación. [43]

El 9 de noviembre de 1938, en el marco de la Noche de los Cristales Rotos , en la Gottschedstrasse se incendiaron sinagogas y comercios. [41] Sólo un par de días después, el 11 de noviembre de 1938, muchos judíos de la zona de Leipzig fueron deportados al campo de concentración de Buchenwald. [44] Cuando la Segunda Guerra Mundial llegó a su fin, gran parte de Leipzig quedó destruida. Después de la guerra, el Partido Comunista de Alemania proporcionó ayuda para la reconstrucción de la ciudad. [45]

En 1933, un censo registró que más de 11.000 judíos vivían en Leipzig. En el censo de 1939, el número había caído a aproximadamente 4.500, y para enero de 1942 solo quedaban 2.000. En ese mes, estos 2.000 judíos comenzaron a ser deportados. [41] El 13 de julio de 1942, 170 judíos fueron deportados de Leipzig al campo de concentración de Auschwitz . El 19 de septiembre de 1942, 440 judíos fueron deportados de Leipzig al campo de concentración de Theresienstadt . El 18 de junio de 1943, los 18 judíos restantes que todavía estaban en Leipzig fueron deportados de Leipzig a Auschwitz. Según los registros de las dos oleadas de deportaciones a Auschwitz, no hubo sobrevivientes. Según los registros de la deportación de Theresienstadt, solo sobrevivieron 53 judíos. [41] [46]

Durante la invasión alemana de Polonia al inicio de la Segunda Guerra Mundial , en septiembre de 1939, la Gestapo llevó a cabo arrestos de destacados polacos locales , [47] y se apoderó del Consulado polaco y su biblioteca. [43] En 1941, el Consulado estadounidense también fue cerrado por orden de las autoridades alemanas. [39] Durante la guerra, Leipzig fue la ubicación de cinco subcampos del campo de concentración de Buchenwald , en el que fueron encarcelados más de 8.000 hombres, mujeres y niños, en su mayoría polacos, judíos, soviéticos y franceses, pero también italianos, checos y belgas. [48] En abril de 1945, la mayoría de los prisioneros sobrevivientes fueron enviados a marchas de la muerte a varios destinos en Sajonia y Checoslovaquia ocupada por Alemania , mientras que los prisioneros del subcampo de Leipzig-Thekla que no pudieron marchar fueron quemados vivos, fusilados o golpeados hasta la muerte por la Gestapo, las SS , la Volkssturm y civiles alemanes en la masacre de Abtnaundorf. [49] [50] Algunos fueron rescatados por trabajadores forzados polacos de otro campo; al menos 67 personas sobrevivieron. [49] [50] 84 víctimas fueron enterradas el 27 de abril de 1945, sin embargo, el número total de víctimas sigue siendo desconocido. [49] [50]

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Leipzig fue bombardeada repetidamente por los aliados , comenzando en 1943 y durando hasta 1945. El primer ataque ocurrió en la mañana del 4 de diciembre de 1943, cuando 442 bombarderos de la Real Fuerza Aérea (RAF) arrojaron una cantidad total de casi 1.400 toneladas de explosivos e incendiarios sobre la ciudad, destruyendo grandes partes del centro de la ciudad. [51] Este bombardeo fue el más grande hasta ese momento. Debido a la proximidad de muchos de los edificios afectados, se produjo una tormenta de fuego. Esto llevó a los bomberos a acudir rápidamente a la ciudad; sin embargo, no pudieron controlar los incendios. A diferencia del bombardeo incendiario de la vecina ciudad de Dresde , este fue un bombardeo en gran parte convencional con explosivos de alta potencia en lugar de incendiarios. El patrón resultante de pérdida fue un mosaico, en lugar de una pérdida total de su centro, pero sin embargo fue extenso.

El avance terrestre aliado en Alemania llegó a Leipzig a finales de abril de 1945. La 2.ª División de Infantería de los EE. UU. y la 69.ª División de Infantería de los EE. UU. se abrieron paso hasta la ciudad el 18 de abril y completaron su captura después de una feroz acción urbana, en la que los combates eran a menudo casa por casa y bloque por bloque, el 19 de abril de 1945. [52] En abril de 1945, el alcalde de Leipzig, el SS- Gruppenführer Alfred Freyberg , su esposa e hija, junto con el vicealcalde y tesorero de la ciudad Ernest Kurt Lisso, su esposa, hija y el mayor de la Volkssturm y ex alcalde Walter Dönicke, se suicidaron en el Ayuntamiento de Leipzig.

Los Estados Unidos entregaron la ciudad al Ejército Rojo cuando este se retiró de la línea de contacto con las fuerzas soviéticas en julio de 1945 hacia los límites de la zona de ocupación designada. Leipzig se convirtió en una de las principales ciudades de la República Democrática Alemana ( Alemania del Este ).

Tras el final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1945, Leipzig vio un lento regreso de los judíos a la ciudad. [41] [53] A ellos se unieron grandes cantidades de refugiados alemanes que habían sido expulsados de Europa central y oriental de acuerdo con el Acuerdo de Potsdam . [54]

A mediados del siglo XX, la feria comercial de la ciudad adquirió una importancia renovada como punto de contacto con el bloque económico de Europa del Este (Comecon) , del que Alemania del Este era miembro. En esa época, las ferias comerciales se celebraban en un recinto al sur de la ciudad, cerca del Monumento a la Batalla de las Naciones .

Sin embargo, la economía planificada de la República Democrática Alemana no fue benévola con Leipzig. Antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Leipzig había desarrollado una mezcla de industria, negocios creativos (notablemente editoriales) y servicios (incluidos los servicios jurídicos). Durante el período de la República Democrática Alemana, los servicios pasaron a ser una preocupación del estado, concentrándose en Berlín Oriental ; los negocios creativos se trasladaron a Alemania Occidental ; y Leipzig se quedó solo con la industria pesada. Para empeorar las cosas, esta industria era extremadamente contaminante, lo que hacía de Leipzig una ciudad aún menos atractiva para vivir. [55] Entre 1950 y el final de la República Democrática Alemana, la población de Leipzig cayó de 600.000 a 500.000. [13]

En octubre de 1989, después de las oraciones por la paz en la iglesia de San Nicolás , establecida en 1983 como parte del movimiento por la paz, comenzaron las manifestaciones de los lunes como la protesta masiva más destacada contra el gobierno de Alemania del Este . [56] [57] Sin embargo, la reunificación de Alemania al principio no fue buena para Leipzig. La industria pesada de planificación centralizada que se había convertido en la especialidad de la ciudad era, en términos de la economía avanzada de la Alemania reunificada, casi completamente inviable y cerró. En solo seis años, el 90% de los empleos en la industria habían desaparecido. [13] A medida que el desempleo se disparó, la población cayó drásticamente; unas 100.000 personas abandonaron Leipzig en los diez años posteriores a la reunificación, y las viviendas vacías y abandonadas se convirtieron en un problema urgente. [13]

A partir de 2000, un ambicioso plan de renovación urbana detuvo primero el declive demográfico de Leipzig y luego lo revirtió. El plan se centró en salvar y mejorar el atractivo centro histórico de la ciudad y, en particular, su parque inmobiliario de principios del siglo XX, y en atraer nuevas industrias, en parte mediante la mejora de la infraestructura. Sin embargo, la renovación ha provocado la gentrificación de partes de la ciudad y no ha detenido el declive de Leipzig-East. [55] [13]

Leipzig es un importante centro económico de Alemania. Desde la década de 2010, los medios de comunicación han celebrado la ciudad como un centro urbano de moda con una calidad de vida muy alta. [58] [59] [60] A menudo se la llama "El nuevo Berlín". [61] Leipzig es también la ciudad de más rápido crecimiento de Alemania. [62] Leipzig fue la candidata alemana para los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 2012 , pero no tuvo éxito. Después de diez años de construcción, el túnel de la ciudad de Leipzig se inauguró el 14 de diciembre de 2013. [63] Leipzig forma la pieza central del sistema de transporte público S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland , que opera en los cuatro estados alemanes de Sajonia , Sajonia-Anhalt, Turingia y Brandeburgo .

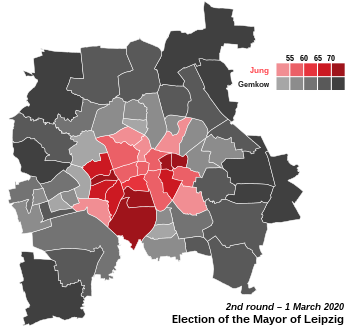

El primer alcalde elegido libremente después de la reunificación alemana fue Hinrich Lehmann-Grube, del Partido Socialdemócrata (SDP), que ocupó el cargo entre 1990 y 1998. En un principio, el alcalde era elegido por el ayuntamiento, pero desde 1994 se elige directamente. Wolfgang Tiefensee , también del SDP, ocupó el cargo desde 1998 hasta su dimisión en 2005 para convertirse en ministro federal de Transporte. Le sucedió su compañero político del SPD Burkhard Jung , que fue elegido en enero de 2006 y reelegido en 2013 y 2020. La última elección de alcalde se celebró el 2 de febrero de 2020, con una segunda vuelta el 1 de marzo, y los resultados fueron los siguientes:

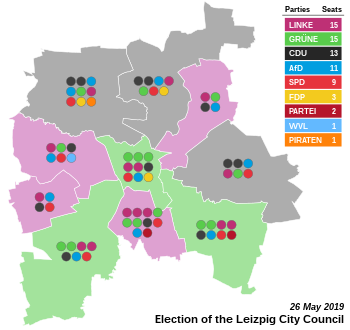

Las últimas elecciones municipales se celebraron el 26 de mayo de 2019 y los resultados fueron los siguientes:

Leipzig está representada en el Bundestag por tres distritos electorales : Leipzig I , Leipzig II y Leipzig-Land .

_11_ies.jpg/440px-Leipzig_(Rathausturm,_Neues_Rathaus)_11_ies.jpg)

Leipzig tiene una población de aproximadamente 620.000 habitantes. [65] En 1930, la población alcanzó su pico histórico de más de 700.000. Disminuyó de manera constante desde 1950 hasta aproximadamente 530.000 en 1989. En la década de 1990, la población disminuyó con bastante rapidez hasta 437.000 en 1998. Esta reducción se debió principalmente a la migración hacia el exterior y la suburbanización. Después de casi duplicar el área de la ciudad mediante la incorporación de pueblos circundantes en 1999, el número se estabilizó y comenzó a aumentar de nuevo, con un aumento de 1.000 en 2000. [66] A partir de 2015 [update], Leipzig es la ciudad de más rápido crecimiento en Alemania con más de 500.000 habitantes. [67] El crecimiento de los últimos 10 a 15 años se ha debido principalmente a la migración interna. En los últimos años, la migración interna se aceleró y alcanzó un aumento de 12.917 en 2014. [68]

En los años posteriores a la reunificación alemana, muchas personas en edad laboral aprovecharon la oportunidad de trasladarse a los estados de la antigua Alemania Occidental en busca de oportunidades de empleo. Este fue un factor que contribuyó a la caída de las tasas de natalidad. Los nacimientos cayeron de 7.000 en 1988 a menos de 3.000 en 1994. [69] Sin embargo, el número de niños nacidos en Leipzig ha aumentado desde finales de los años 1990. En 2011, alcanzó los 5.490 nacimientos, lo que resultó en un RNI de -17,7 (-393,7 en 1995). [70]

La tasa de desempleo disminuyó del 18,2% en 2003 al 9,8% en 2014 y al 7,6% en junio de 2017. [71] [72] [73]

El porcentaje de población de origen inmigrante es bajo en comparación con otras ciudades alemanas. En 2012 [update], solo el 5,6% de la población era extranjera, en comparación con el promedio nacional alemán del 7,7%. [74]

El número de personas de origen inmigrante (inmigrantes y sus hijos) aumentó de 49.323 en 2012 a 77.559 en 2016, lo que los convierte en el 13,3% de la población de la ciudad (la población de Leipzig era de 579.530 en 2016). [75]

Las minorías más numerosas (de primera y segunda generación) en Leipzig por país de origen a 31 de diciembre de 2021 son: [76]

En la década de 2010, Leipzig fue a menudo llamada Hypezig , ya que se hicieron comparaciones exageradas con Berlín en los años 1990 y principios de los 2000. La asequibilidad, la diversidad y la apertura de la ciudad han atraído a muchos jóvenes de toda Europa, lo que ha dado lugar a una atmósfera alternativa que marca tendencias y da como resultado una escena innovadora de música, danza y arte. [77]

El centro histórico de Leipzig cuenta con un conjunto de edificios de estilo renacentista del siglo XVI, entre los que se encuentra el antiguo ayuntamiento en la plaza del mercado. También hay varias casas comerciales de la época barroca y antiguas residencias de ricos comerciantes. Como Leipzig creció considerablemente durante el auge económico de finales del siglo XIX, la ciudad cuenta con muchos edificios de estilo historicista representativos de la época de los cimientos . Aproximadamente el 35% de las viviendas de Leipzig se encuentran en edificios de este tipo. El nuevo ayuntamiento , terminado en 1905, está construido en el mismo estilo.

Durante el régimen comunista en Alemania del Este, en Leipzig se construyeron alrededor de 90.000 apartamentos en edificios Plattenbau . [78] Aunque algunos de ellos han sido demolidos y el número de personas que viven en este tipo de alojamiento ha disminuido en los últimos años, una minoría significativa de personas todavía vive en alojamientos Plattenbau; en Grünau, por ejemplo, en 2016 había alrededor de 43.600 personas viviendo en este tipo de alojamiento. [79]

La iglesia de San Pablo fue destruida por el gobierno comunista en 1968 para dejar espacio a un nuevo edificio principal para la universidad. Después de algún debate, la ciudad decidió establecer un nuevo edificio, principalmente secular, en el mismo lugar, llamado Paulinum , que se terminó en 2012. Su arquitectura alude al aspecto de la antigua iglesia e incluye espacio para uso religioso de la facultad de teología, incluido el altar original de la antigua iglesia y dos órganos de nueva construcción.

Muchos edificios comerciales se construyeron en la década de 1990 como resultado de las exenciones fiscales tras la reunificación alemana.

La estructura más alta de Leipzig es la chimenea de la Stahl- und Hartgusswerk Bösdorf GmbH, con una altura de 205 m. El edificio más alto de Leipzig es la City-Hochhaus Leipzig , con 142 m . Entre 1972 y 1973 fue el edificio más alto de Alemania .

Uno de los puntos culminantes de las artes contemporáneas de la ciudad fue la retrospectiva Neo Rauch , inaugurada en abril de 2010 en el Museo de Bellas Artes de Leipzig . Se trata de una muestra dedicada al padre de la Nueva Escuela de Leipzig [80] de artistas. Según The New York Times [81] , esta escena "ha sido el centro de atención del mundo del arte contemporáneo" durante la última década. Además, hay once galerías en la llamada Spinnerei [82] .

El complejo del Museo Grassi contiene otras tres importantes colecciones de Leipzig: [83] el Museo Etnográfico , el Museo de Artes Aplicadas y el Museo de Instrumentos Musicales (este último administrado por la Universidad de Leipzig). La universidad también administra el Museo de Antigüedades . [84]

Fundada en marzo de 2015, la G2 Kunsthalle alberga la Colección Hildebrand. [85] Esta colección privada se centra en la llamada Nueva Escuela de Leipzig . El primer museo privado de Leipzig dedicado al arte contemporáneo en Leipzig después del cambio de milenio se encuentra en el centro de la ciudad, cerca de la famosa iglesia de Santo Tomás, en el tercer piso del antiguo centro de procesamiento de la RDA. [86] También dedicada al arte contemporáneo está la Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig . [87]

Otros museos en Leipzig incluyen los siguientes:

Leipzig es conocida por sus grandes parques. El Leipziger Auwald ( bosque de ribera ) se encuentra en su mayor parte dentro de los límites de la ciudad. Neuseenland es una zona al sur de Leipzig donde las antiguas minas a cielo abierto se están convirtiendo en un enorme distrito de lagos. Está previsto que esté terminado en 2060.

Johann Sebastian Bach spent the longest phase of his career in Leipzig, from 1723 until his death in 1750, conducting the Thomanerchor (St. Thomas Church Choir), at the St. Thomas Church, the St. Nicholas Church and the Paulinerkirche, the university church of Leipzig (destroyed in 1968). The composer Richard Wagner was born in Leipzig in 1813, in the Brühl. Robert Schumann was also active in Leipzig music, having been invited by Felix Mendelssohn when the latter established Germany's first musical conservatoire in the city in 1843. Gustav Mahler was second conductor (working under Artur Nikisch) at the Leipzig Opera from June 1886 until May 1888, and achieved his first significant recognition while there by completing and publishing Carl Maria von Weber's opera Die Drei Pintos. Mahler also completed his own 1st Symphony while living in Leipzig.

Today the conservatory is the University of Music and Theatre Leipzig.[89] A broad range of subjects are taught, including artistic and teacher training in all orchestral instruments, voice, interpretation, coaching, piano chamber music, orchestral conducting, choir conducting and musical composition in various musical styles. The drama departments teach acting and scriptwriting.

The Bach-Archiv Leipzig, an institution for the documentation and research of the life and work of Bach (and also of the Bach family), was founded in Leipzig in 1950 by Werner Neumann. The Bach-Archiv organizes the prestigious International Johann Sebastian Bach Competition, initiated in 1950 as part of a music festival marking the bicentennial of Bach's death. The competition is now held every two years in three changing categories. The Bach-Archiv also organizes performances, especially the international festival Bachfest Leipzig and runs the Bach-Museum.

The city's musical tradition is also reflected in the worldwide fame of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, under its chief conductor Andris Nelsons, and the Thomanerchor.

The MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra is Leipzig's second largest symphony orchestra. Its current chief conductor is Kristjan Järvi. Both the Gewandhausorchester and the MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra make use of in the Gewandhaus concert hall.

For over sixty years Leipzig has been offering a "school concert"[90] programme for children in Germany, with over 140 concerts every year in venues such as the Gewandhaus and over 40,000 children attending.

Leipzig is known for its independent music scene and subcultural events. Leipzig has for thirty years been home to the Wave-Gotik-Treffen (WGT), which is currently the world's largest Gothic festival, where thousands of fans of goth music gather in the early summer. The first Wave Gotik Treffen was held at the Eiskeller club, today known as Conne Island, in the Connewitz district. Mayhem's notorious album Live in Leipzig was also recorded at the Eiskeller club.

Leipzig Pop Up was an annual music trade fair for the independent music scene as well as a music festival taking place on Pentecost weekend.[91] Its most famous indie-labels are Moon Harbour Recordings (House) and Kann Records (House/Techno/Psychedelic). Several venues offer live music frequently, including the Moritzbastei,[92] Tonelli's, and Noch Besser Leben.

Die Prinzen ("The Princes") is a German band founded in Leipzig. With almost six million records sold, they are one of the most successful German bands.

The cover photo for the Beirut band's 2005 album Gulag Orkestar, according to the sleeve notes, was stolen from a Leipzig library by Zach Condon.

The city of Leipzig is also the birthplace of Till Lindemann, best known as the lead vocalist of Rammstein, a band formed in 1994.

There are more than 300 sport clubs in the city, representing 78 different disciplines. Over 400 athletic facilities are available to citizens and club members.[99]

The German Football Association (DFB) was founded in Leipzig in 1900. The city was the venue for the 2006 FIFA World Cup draw, and hosted four first-round matches and one match in the round of 16 in the central stadium.

VfB Leipzig won the first national Association football championship in 1903. The club was dissolved in 1946 and the remains reformed as SG Probstheida. The club was eventually reorganized as football club 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig in 1966. 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig has had a glorious past in international competition as well, having been champions of the 1965–66 Intertoto Cup, semi-finalists in the 1973–74 UEFA Cup, and runners-up in the 1986–87 European Cup Winners' Cup.

Red Bull took over a local 5th division football club SSV Markranstädt in May 2009, having previously been denied the right to buy into FC Sachsen Leipzig in 2006. The club was renamed RB Leipzig and came up through the ranks of German football, winning promotion to the Bundesliga, the highest division of German football in 2016.[100] The club finished runners-up in its first-ever Bundesliga season and made its debut in the UEFA Champions League in 2017 and the Semi-Final in 2020.

RB Leipzig won the DFB-Pokal football cup twice, in 2022 and 2023.

List of Leipzig men and women's football clubs playing at state level and above:

Note 1: The RB Leipzig women's football team was formed in 2016 and began play in the 2016–17 season.

Note 2: The club began play in the 2008–09 season.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, ice hockey has gained popularity, and several local clubs established departments dedicated to that sport.[101]

SC DHfK Leipzig is the men's handball club in Leipzig and were six times (1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1965 and 1966) the champion of East Germany handball league and was winner of EHF Champions League in 1966. They finally promoted to Handball-Bundesliga as champions of 2. Bundesliga in 2014–15 season. They play in the Arena Leipzig which has a capacity of 6,327 spectators in HBL games but can take up to 7,532 spectators for handball in maximum capacity.

Handball-Club Leipzig is one of the most successful women's handball clubs in Germany, winning 21 domestic championships since 1953 and 2 Champions League titles. The team was however relegated to the third tier league in 2017 due to failing to achieve the economic standard demanded by the league licence.

Leipzig Kings is an American football team playing in the European League of Football (ELF), which is a planned professional league, that is set to become the first fully professional league in Europe since the demise of NFL Europe.[102] The Kings will start playing games against teams from Germany, Spain and Poland in June 2021.[103] They play their home games at Alfred-Kunze-Sportpark.

The Motodrom am Cottaweg is a motorcycle speedway stadium on the west side of the Neue Luppe, located on the Cottaweg road.[104][105] The venue is used by the speedway club called Motorsport Club Post Leipzig e.V.[106] and held the East German Speedway Championship in 1978 and a qualifying round of the Speedway World Team Cup in 1991.[107]

From 1950 to 1990 Leipzig was host of the Deutsche Hochschule für Körperkultur (DHfK, German College of Physical Culture), the national sports college of the GDR.

Leipzig also hosted the Fencing World Cup in 2005 and hosts a number of international competitions in a variety of sports each year.

Leipzig made a bid to host the 2012 Summer Olympics. The bid did not make the shortlist after the International Olympic Committee pared the bids down to 5.

Markkleeberger See is a new lake next to Markkleeberg, a suburb on the south side of Leipzig. A former open-pit coal mine, it was flooded in 1999 with groundwater and developed in 2006 as a tourist area. On its southeastern shore is Germany's only pump-powered artificial whitewater slalom course, Markkleeberg Canoe Park (Kanupark Markkleeberg), a venue which rivals the Eiskanal in Augsburg for training and international canoe/kayak competition.

Leipzig Rugby Club competes in the German Rugby Bundesliga but finished at the bottom of their group in 2013.[108]

Leipzig hosted the Indoor Hockey World Cup in 2015. All matches were played in Leipzig Arena, with the Netherlands coming out victorious in both the men's and women's tournaments.

Leipzig University, founded 1409, is one of Europe's oldest universities. Karl Bücher, a German economist, founded the Institut für Zeitungswissenschaften (Institute for Newspaper Science) at the University of Leipzig in 1916. It was the first institute of its kind to be established in Europe, and it marks the commencement of academic study of media communication in Germany.[109]

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a philosopher and mathematician, was born in Leipzig in 1646, and attended the university from 1661 to 1666. Nobel Prize laureate Werner Heisenberg worked at the university as a physics professor (from 1927 to 1942), as did Nobel Prize laureates Gustav Ludwig Hertz (physics), Wilhelm Ostwald (chemistry) and Theodor Mommsen (Nobel Prize in literature). The 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine went to Svante Pääbo, an honorary professor at the university. Other former university staff include mineralogist Georg Agricola, writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, philosopher Ernst Bloch, founder of psychophysics Gustav Theodor Fechner, and founder of modern psychology, Wilhelm Wundt. The university's notable former students include writers Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Erich Kästner, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, political activist Karl Liebknecht, and composer Richard Wagner. Angela Merkel, former German chancellor, studied physics at Leipzig University.[110] The university has about 30,000 students.

A part of Leipzig University is the German Institute for Literature which was founded in 1955 under the name "Johannes R. Becher-Institut". Many noted writers have graduated from this school, including Heinz Czechowski, Kurt Drawert, Adolf Endler, Ralph Giordano, Kerstin Hensel, Sarah and Rainer Kirsch, Angela Krauß, Erich Loest, and Fred Wander. After its closure in 1990 the institute was refounded in 1995 with new teachers.

The Academy of Visual Arts (Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst) was established in 1764. Its 600 students (as of 2018[update]) are enrolled in courses in painting and graphics, book design/graphic design, photography and media art. The school also houses an Institute for Theory.

The University of Music and Theatre offers a broad range of subjects ranging from training in orchestral instruments, voice, interpretation, coaching, piano chamber music, orchestral conducting, choir conducting and musical composition to acting and scriptwriting.

The Leipzig University of Applied Sciences (HTWK)[111] has approximately 6,200 students (as of 2007[update]) and is (as of 2007[update]) the second biggest institution of higher education in Leipzig. It was founded in 1992, merging several older schools. As a university of applied sciences (German: Fachhochschule) its status is slightly below that of a university, with more emphasis on the practical parts of education. The HTWK offers many engineering courses, as well as courses in computer science, mathematics, business administration, librarianship, museum studies, and social work. It is mainly located in the south of the city.

The private Leipzig Graduate School of Management, (in German Handelshochschule Leipzig (HHL)), is the oldest business school in Germany. According to The Economist, HHL is one of the best schools in the world, ranked at number six overall.[112][113]

Branch campus of Lancaster University, it is the first public UK university with a campus in Germany. Lancaster University Leipzig was founded in 2020 and currently has a diverse international student body with more than 45 nationalities.

Leipzig is currently the home of twelve research institutes and the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Leipzig is home to one of the world's oldest schools, Thomasschule zu Leipzig (St. Thomas' School, Leipzig), which gained fame for its long association with the Bach family of musicians and composers.

The Lutheran Theological Seminary is a seminary of the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church in Leipzig.[114][115] The seminary trains students to become pastors for the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church or for member church bodies of the Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference.[116]

The city is a location for automobile manufacturing by BMW and Porsche in large plants north of the city. In 2011 and 2012 DHL transferred the bulk of its European air operations from Brussels Airport to Leipzig/Halle Airport. Kirow Ardelt AG, the world market leader in breakdown cranes, is based in Leipzig. The city also houses the European Energy Exchange, the leading energy exchange in Central Europe. VNG – Verbundnetz Gas AG, one of Germany's large natural gas suppliers, is headquartered at Leipzig. In addition, inside its larger metropolitan area, Leipzig has developed an important petrochemical centre.

Some of the largest employers in the area (outside of manufacturing) include software companies such as Spreadshirt and the various schools and universities in and around the Leipzig/Halle region. The University of Leipzig attracts millions of euros of investment yearly and celebrated its 600th birthday in 2009.

Leipzig also benefits from world-leading medical research (Leipzig Heart Centre) and a growing biotechnology industry.[117]

Many bars, restaurants and stores in the downtown area are patronized by German and foreign tourists. Leipzig Main Train Station is the location of a shopping mall.[118] Leipzig is one of Germany's most visited cities with over 3 million overnight stays in 2017.[119]

In 2010, Leipzig was included in the top 10 cities to visit by The New York Times,[81] and ranked 39th globally out of 289 cities for innovation in the 4th Innovation Cities Index published by Australian agency 2thinknow.[120] In 2015, Leipzig have among the 30 largest German cities the third best prospects for the future.[121] In recent years Leipzig has often been nicknamed the "Boomtown of eastern Germany" or "Hypezig".[25] As of 2013[update] it had the highest rate of population growth of any German city.[26]

Companies with operations in or around Leipzig include:

Leipzig has a dense network of socio-ecological infrastructures. Worth mentioning in the food sector are the Fairteiler of foodsharing[122] and the numerous Community-supported agricultures,[123] in the textile sector the Umsonstladen in Plagwitz,[124] in the bicycle self-help workshops the Radsfatz,[125] in the computer sector the Hackerspace Die Dezentrale,[126] and in the repair sector the Café kaputt.[127]

In December 2013, according to a study by GfK, Leipzig was ranked as the most livable city in Germany.[132][133]

In 2015/2016, Leipzig was named by the consumer portal verbraucherzentrale.de as the second-best city for students in Germany (after Munich).[134]

In a 2017 study from the Institut für Handelsforschung Köln, the Leipzig inner city ranked first among all large cities in Germany due to its urban aesthetics, gastronomy, and shopping opportunities.[135][136]

According to HWWI/Berenberg-Städteranking, since 2018 it also has the second-best future prospects of all cities in Germany, second to Munich in 2018 and Berlin in 2019.[137][138]

According to a 2017 Global Least & Most Stressful Cities Ranking by Zipjet, a London-based online laundry service, Leipzig was one of the least stressful cities in the World. It was ranked 25th out of 150 cities worldwide and above Dortmund, Cologne, Frankfurt, and Berlin.[139]

Leipzig was named European City of the Year at the 2019 Urbanism Awards.[140]

According to the 2019 study by Forschungsinstitut Prognos, Leipzig is the most dynamic region in Germany. Within 15 years, the city climbed 230 places and occupied in 2019 rank 104 of all 401 German regions.[141][142]

Leipzig was listed as one of 52 places to go in 2020 by The New York Times and the highest-ranking German destination.[143]

Leipzig Hauptbahnhof has been ranked the best railway station in Germany and the third-best in Europe in a consumer organisation poll, surpassed only by St Pancras railway station and Zürich Hauptbahnhof.[144]

Founded at the crossing of Via Regia and Via Imperii, Leipzig has been a major interchange of inter-European traffic and commerce since medieval times. After the Reunification of Germany, immense efforts to restore and expand the traffic network have been undertaken and left the city area with an excellent infrastructure.

Opened in 1915, Leipzig Hauptbahnhof (lit. main station) is the largest overhead railway station in Europe in terms of its built-up area. At the same time, it is an important supra-regional junction in the Intercity-Express (ICE) and Intercity network of the Deutsche Bahn as well as a connection point for S-Bahn and regional traffic in the Halle/Leipzig area.

In Leipzig the Intercity Express routes (Hamburg–)Berlin–Leipzig–Nuremberg–Munich and Dresden–Leipzig–Erfurt–Frankfurt am Main–(Wiesbaden/Saarbrücken) intersect. Leipzig is also the starting point for the intercity lines Leipzig-Halle (Saale)–Magdeburg–Hannover–Dortmund–Köln and –Bremen–Oldenburg(–Norddeich Mole). Both lines complement each other at hourly intervals and also stop at Leipzig/Halle Airport. The only international connection is the daily EuroCity Leipzig-Prague.

Most major and medium-sized towns in Saxony and southern Saxony-Anhalt can be reached without changing trains. There are also direct connections via regional express lines to Falkenberg/Elster-Cottbus, Hoyerswerda and Dessau-Magdeburg as well as Chemnitz. Neighbouring Halle (Saale) can be reached via three S-Bahn lines, two of which run via Leipzig/Halle Airport. The surrounding area of Leipzig is served by numerous regional and S-Bahn lines.

The city's railway connections are currently being greatly improved by major construction projects, particularly within the framework of the German Unity transport projects. The line to Berlin has been extended and has been passable at 200 km/h (120 mph) since 2006. On 13 December 2015, the high-speed line from Leipzig to Erfurt, designed for 300 km/h (190 mph), was put into operation. Its continuation to Nuremberg followed in December 2017. This integration into the high-speed network considerably reduced the journey times of the ICE from Leipzig to Nuremberg, Munich and Frankfurt am Main. The Leipzig-Dresden railway line, which was the first German long-distance railway to go into operation in 1839, is also undergoing expansion for 200 km/h. The most important construction project in regional transport was the four-kilometer-long city tunnel, which went into operation in December 2013 as the main line of the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland.

There are freight stations in the districts of Wahren and Engelsdorf. In addition, a freight traffic centre has been set up near the Schkeuditzer Kreuz junction for goods handling between road and rail, as well as a freight station on the site of the DHL hub at Leipzig/Halle Airport.

Leipzig is the core of the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland line network. Together with the tram, six of the ten lines form the backbone of local public transport and an important link to the region and the neighbouring Halle. The main line of the S-Bahn consists of the underground S-Bahn stations Hauptbahnhof, Markt, Wilhelm-Leuschner-Platz and Bayerischer Bahnhof leading through the City Tunnel as well as the above-ground station Leipzig MDR. There are a total of 30 S-Bahn stations in the Leipzig city area. Endpoints of the S-Bahn lines include Wurzen, Zwickau, Dessau, and Lutherstadt Wittenberg. Two lines run to Halle, one of them via Leipzig/Halle Airport.

With the timetable change in December 2004, the networks of Leipzig and Halle were combined to form the Leipzig-Halle S-Bahn. However, this network only served as a transitional solution and was replaced by the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland on 15 December 2013. At the same time, the main line tunnel, marketed as the Leipzig City Tunnel, went into operation. The tunnel, which is almost four kilometres long, crosses the entire city centre from the main railway station to the Bavarian railway station. The S-Bahn stations are up to 22 metres underground. This construction was the first to create a continuous north–south axis, which had not existed until now due to the north-facing terminus station. The connection to the south of the city and the federal state will thus be greatly improved.

The Leipziger Verkehrsbetriebe, existing since 1 January 1917, operate a total of 15 tram lines and 47 bus lines in the city.

The total length of the tram network is 146 km (91 mi), making it the largest in Saxony ahead of Dresden (134.4 km (83.5 mi)) and the second largest in Germany after Berlin (196 km (122 mi)).

The longest line in the Leipzig network is line 11, which connects Schkeuditz with Markkleeberg over 22 kilometres and is the only tram line in Leipzig to run in three tariff zones of the Central German Transport Association.

Night bus lines N1 to N9 and the night tram N17 operate in the night traffic. On Saturdays, Sundays and holidays the tram line N10 and the bus line N60 also operate. The central transfer point between the bus and tram lines as well as to the S-Bahn is Leipzig Central Station.

Like most German cities, Leipzig has a traffic layout designed to be bicycle-friendly. There is an extensive cycle network. In most of the one-way central streets, cyclists are explicitly allowed to cycle both ways. A few cycle paths have been built or declared since 1990. According to the data from the 2021/22 traffic count, the Saxons' Bridge has the highest traffic occupancy with over 15,000 cyclists per day in cycling in Leipzig.[145]

Since 2004 there is a bicycle-sharing system. Bikes can be borrowed and returned via smartphone app or by telephone. Since 2018, the system has enabled flexible borrowing and returning of bicycles in the inner city; in this zone, bicycles can be handed in and borrowed from almost any street corner. Outside these zones, there are stations where the bikes are waiting. The current locations of the bikes can be seen via the app. There are cooperation offers with the Leipzig public transport companies and car sharing in order to offer as complete a mobility chain as possible.

Several federal motorways pass by Leipzig: the A 14 in the north, the A 9 in the west, and the A 38 in the south. The three motorways form a triangular partial ring of the double ring Mitteldeutsche Schleife around Halle and Leipzig. To the south towards Chemnitz, the A 72 is also partly under construction.

The federal roads B 2, B 6, B 87, B 181, and B 184 lead through the city area.

The ring road (Innenstadtring), which corresponds to the course of the old city fortification, surrounds the city centre of Leipzig, which today is largely traffic-calmed.

Leipzig has a dense network of carsharing stations. Additionally, since 2018 there is also a stationless car sharing system in Leipzig. Here the cars can be parked and booked anywhere in the inner city without having to define a specific car or period in advance. Finding and booking is done via a smartphone app.

Leipzig is one of the few cities in Germany with vehicle for hire services that can be booked via a mobile app. In contrast to taxicab services, the start and destination must be defined beforehand and other passengers can be taken along at the same time if they share a route.

Since March 2018 there has been a central bus station directly east of Leipzig Central Station.

In addition to a large number of national lines, several international lines also serve Leipzig. The cities of Bregenz, Budapest, Milan, Prague, Sofia and Zurich, among others, can be reached without having to change trains. Around 30,000 journeys and 1.5 million passengers a year are expected at the new bus station.

Some lines also use Leipzig/Halle Airport, located at the A 9/A 14 motorway junction, and Leipziger Messe for a stop. Passengers can take the S-Bahn from there to the city centre.

Leipzig/Halle Airport is the international commercial airport of the region. It is located at the Schkeuditzer Kreuz junction northwest of Leipzig, halfway between the two major cities. The easternmost section of the new Erfurt-Leipzig/Halle line under construction gave the airport a long-distance railway station, which was also integrated into the ICE network when the railway line was completed in 2015.

Passenger flights are operated to and from the major German hub airports, European metropolises and holiday destinations, especially to the Mediterranean region and North Africa. The airport is of international importance in the cargo sector. In Germany, it ranks second behind Frankfurt am Main, fifth in Europe and 26th worldwide (as of 2011). DHL uses the airport as its central European hub. It is also the home base of the freight airlines Aerologic and European Air Transport Leipzig.

The former military airport near Altenburg, Thuringia, called Leipzig-Altenburg Airport, about a half-hour drive from Leipzig, was served by Ryanair until 2010.

In the first half of the 20th century, the construction of the Elster-Saale canal, White Elster, and Saale was started in Leipzig in order to connect to the network of waterways. The outbreak of the Second World War stopped most of the work, though some may have continued through the use of forced labor. The Lindenauer port was almost completed but not yet connected to the Elster-Saale and Karl Heine Canal respectively. The Leipzig rivers (White Elster, New Luppe, Pleiße, and Parthe) in the city have largely artificial river beds and are supplemented by some channels. These waterways are suitable only for small leisure boat traffic.

Through the renovation and reconstruction of existing mill races and watercourses in the south of the city and flooded disused open cast mines, the city's navigable water network is being expanded. A link between Karl Heine Canal and the disused Lindenauer port was opened in 2015. Still more work was scheduled to complete the Elster-Saale canal. Such a move would allow small boats to reach the Elbe from Leipzig. The intended completion date has been postponed because of an unacceptable cost-benefit ratio.

Mein Leipzig lob' ich mir! Es ist ein klein Paris und bildet seine Leute. ("I praise my Leipzig! It is a small Paris and educates its people.") – Frosch, a university student in Goethe's Faust, Part One

Ich komme nach Leipzig, an den Ort, wo man die ganze Welt im Kleinen sehen kann. ("I'm coming to Leipzig, to the place where one can see the whole world in miniature.") – Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Extra Lipsiam vivere est miserrime vivere. ("To live outside Leipzig is to live miserably.") – Benedikt Carpzov the Younger

Das angenehme Pleis-Athen, Behält den Ruhm vor allen, Auch allen zu gefallen, Denn es ist wunderschön. ("The pleasurable Pleiss-Athens, earns its fame above all, appealing to every one, too, for it is mightily beauteous.") – Johann Sigismund Scholze

Leipzig is twinned with:[146]

.jpg/440px-Christoph_Bernhard_Francke_-_Bildnis_des_Philosophen_Leibniz_(ca._1695).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Riccardo_Chailly_(1986).jpg)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)...Clara Schumann (1819–1896).....had a brilliant career as a pianist...