Malappuram ( malayalam: [mɐlɐpːurɐm] ), es uno de los14 distritosdelestado indiodeKerala, con una costa de 70 km (43 mi). El distrito más poblado de Kerala, Malappuram, alberga alrededor del 13% de la población total del estado. El distrito se formó el 16 de junio de 1969, abarcando un área de aproximadamente 3.554 km²(1.372 millas cuadradas). Es el tercer distrito más grande de Kerala por área. Está delimitado porlos Ghats occidentalesy elmar Arábigoa ambos lados. El distrito está dividido en sietetaluks:Eranad,Kondotty,Nilambur,Perinthalmanna,Ponnani,TiruryTirurangadi.

El malabar es el idioma más hablado. El distrito ha sido testigo de una emigración significativa, especialmente a los estados árabes del Golfo Pérsico durante el auge del Golfo de los años 1970 y principios de los años 1980, y su economía depende significativamente de las remesas de una gran comunidad de expatriados malayos . [6] Malappuram fue el primer distrito alfabetizado electrónicamente , así como el primer distrito alfabetizado cibernéticamente de la India. [7] [8] El distrito tiene cuatro ríos principales, a saber, Bharathappuzha , Chaliyar , Kadalundippuzha y Tirur Puzha , de los cuales los tres primeros también se encuentran entre los cinco ríos más largos de Kerala .

El área metropolitana de Malappuram es la cuarta aglomeración urbana más grande de Kerala después de las áreas urbanas de Kochi, Calicut y Thrissur y la 25.ª más grande de la India con una población total de 1,7 millones. [9] El 44,2% de la población del distrito reside en las áreas urbanas según el censo de la India de 2011. Al ser el hogar de 4 universidades en el estado, incluida la Universidad de Calicut , Malappuram es un centro de educación superior en Kerala. El distrito comprende 2 divisiones de ingresos , 7 taluks , 12 municipios , 15 bloques , 94 Grama Panchayats y 16 distritos electorales de la Asamblea Legislativa de Kerala . [10] [11] [12] [13]

Durante el Raj británico , Malappuram se convirtió en el cuartel general de las tropas europeas y británicas y más tarde de la Policía Especial de Malabar (MSP), anteriormente conocida como Fuerza Especial de Malappuram formada en 1885, que también es el batallón de policía armada más antiguo del estado. [14] [15] La plantación de teca más antigua del mundo en la parcela de Conolly está situada en el valle de Chaliyar en Nilambur . La línea ferroviaria más antigua del estado se colocó de Tirur a Chaliyam en 1861, pasando por Tanur , Parappanangadi y Vallikkunnu . [16] La segunda línea ferroviaria del estado también se colocó el mismo año de Tirur a Kuttippuram a través de Tirunavaya . [16] La línea Nilambur-Shoranur , también colocada en la era colonial, es una de las líneas ferroviarias de vía corta más cortas y pintorescas de la India.

.jpg/440px-Valamangalam_Pulpetta_(386717435).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Chaliyar_Edavanna_(251932360).jpg)

El término, Malappuram , que significa "sobre la colina" en malabar , deriva de la geografía de Malappuram , la sede administrativa del distrito. [17] [18] El área central del distrito se caracteriza por varias colinas onduladas como las colinas Arimbra , las colinas Amminikkadan , la colina Oorakam , las colinas Cheriyam , las colinas Pandalur y las colinas Chekkunnu , todas las cuales se encuentran alejadas de los Ghats occidentales . [19] Sin embargo, la llanura costera arenosa bordeada de cocoteros es una excepción a la naturaleza montañosa general.

Los restos de símbolos prehistóricos, incluidos dólmenes , menhires y cuevas excavadas en la roca, se han encontrado en varias partes del distrito. Se han encontrado cuevas excavadas en la roca en Puliyakkode , Thrikkulam , Oorakam , Melmuri , Ponmala , Vallikunnu y Vengara . [20] El antiguo puerto marítimo de Tyndis , que entonces era un centro de comercio con la Antigua Roma , se identifica aproximadamente con Ponnani , Tanur y la región de Kadalundi - Vallikkunnu - Chaliyam - Beypore . Tyndis era un importante centro de comercio, solo superado por Muziris, entre los Cheras y el Imperio Romano . [21] Plinio el Viejo (siglo I d. C.) afirma que el puerto de Tyndis estaba ubicado en la frontera noroeste de Keprobotos ( dinastía Chera ). [22] La región, que se encuentra al norte del puerto de Tyndis , fue gobernada por el reino de Ezhimala durante el período Sangam . [23] Según el Periplus of the Erythraean Sea , una región conocida como Limyrike comenzaba en Naura y Tyndis . Sin embargo, Ptolomeo menciona solo Tyndis como el punto de partida de Limyrike . La región probablemente terminaba en Kanyakumari ; por lo tanto, corresponde aproximadamente a la actual Costa de Malabar . El valor del comercio anual de Roma con la región se estimó en alrededor de 50.000.000 de sestercios . [24] Plinio el Viejo mencionó que Limyrike era propensa a los piratas. [25] Cosmas Indicopleustes mencionó que Limyrike era una fuente de pimientas. [26] [27] El río Bharathappuzha (río Ponnani) tuvo importancia desde el período Sangam (siglos I-IV d.C.), debido a la presencia de Palakkad Gap que conectaba la costa de Malabar con la costa de Coromandel a través del interior. [28]

La inscripción de Kurumathur encontrada cerca de Areekode se remonta al 871 d. C. [29] Tres inscripciones escritas en malabar antiguo que datan del 932 d. C., que se encontraron en Triprangode (cerca de Tirunavaya ), Kottakkal y Chaliyar , mencionan el nombre de Goda Ravi de la dinastía Chera . [30] La inscripción de Triprangode habla del acuerdo de Thavanur . [30] Varias inscripciones escritas en malabar antiguo que datan del siglo X d. C. se han encontrado en Sukapuram cerca de Edappal , que era una de las 64 antiguas aldeas Nambudiri de Kerala.

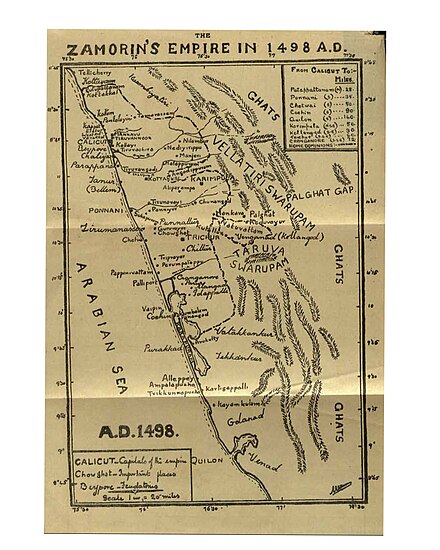

Descripciones sobre los gobernantes de las regiones de Eranad y Valluvanad se pueden ver en las placas de cobre judías de Bhaskara Ravi Varman (alrededor de 1000 d. C.) y las placas de cobre de Viraraghava de Veera Raghava Chakravarthy (alrededor de 1225 d. C.). [20] El Zamorin de Calicut originalmente pertenecía a Nediyiruppu en Kondotty en Eranad antes de que trasladara su sede al vecino Kozhikode . [31] Eranad estaba gobernada por un clan Samanthan Nair conocido como Eradis , similar a los Vellodis del vecino Valluvanad y Nedungadis de Nedunganad . [31] Los gobernantes de Eranad eran conocidos por el título de Eralppad / Eradi . [31] Fue el gobernante de Eranad ( Eradi de Nediyiruppu ) quien estableció el reino de Calicut y desarrolló Kozhikode como una importante ciudad portuaria en la costa de Malabar . [31] Justo después de eso, los gobernantes de Parappanad ( Parappanangadi ) y Vettathunadu ( Tanur ) se convirtieron en vasallos de Zamorin. La familia real Parappanad es una dinastía prima de la familia real Travancore . [31] Además, una porción mayor de Valluvanad Kovilakams (Nilambur, Manjeri, Malappuram, Kottakkal y Ponnani) también se convirtieron en vasallos de Zamorin. [31]

La sede original de los Swaroopam de Perumbadappu , que más tarde se convertirían en el Reino de Cochin , estaba en Chithrakoodam en Vanneri, Perumpadappu , que se encuentra a 10 km al sur de Puthuponnani , en el taluk de Ponnani . [31] Cuando Perumpadappu quedó bajo el reino de los Zamorin de Calicut , los gobernantes de Perumpadappu huyeron a Kodungallur , y más tarde se mudaron a Kochi , donde establecieron el Reino de Cochin . [31] Entre 1250 y 1300 d. C., casi todo el distrito quedó bajo el gobierno de los Zamorin. [31] [20]

El festival Mamankam , que tuvo una importancia política especial en el Kerala medieval, se celebró en Tirunavaya , que se encuentra en la orilla norte del río Bharathappuzha , en el distrito. [31] La rivalidad que existía entre los Nambudiris en las aldeas Nambudiri de Panniyoor y Chowwara (Sukapuram) también fue de gran importancia política en el Kerala medieval. [31] Panniyoor está situado frente a la ciudad de Kuttippuram , mientras que Sukapuram se encuentra en Edappal . Los Zamorins se vieron intervenidos en el llamado Koormatsaram entre los Nambudiris de Panniyurkur y Chovvarakur. En el evento más reciente, los Thirumanasseri Nambudiri habían asaltado y quemado la aldea rival cercana. Los gobernantes de Valluvanadu y Perumpadappu vinieron a ayudar a los Chovvaram y asaltaron Panniyur simultáneamente. Thirumanasseri Nadu fue invadido por sus vecinos del sur y el este. El Thirumanasseri Nambudiri pidió ayuda al Zamorin y prometió cederle el puerto de Ponnani , donde el río Bharathappuzha se une con el mar Arábigo , como precio por su protección. Thirumanassery Nambudiri, el Koya de Kozhikode y gobernante de Vettathunadu apoyó al Zamorin. Zamorin, buscando una oportunidad así, aceptó con gusto la oferta. [32] En sus campañas militares en Valluvanadu, el Zamorin recibió una ayuda inequívoca de los marineros musulmanes de Oriente Medio de Beypore , Chaliyam , Tanur y Kodungallur , y del Koya de Kozhikode. [33] Como recompensa por parte del Zamorin, el puerto de Ponnani se convirtió en un importante centro comercial y cultural de los marineros de Oriente Medio. Parece que el juez musulmán de Kozhikode ofreció toda la ayuda en "dinero y material" a los Samoothiri para atacar Tirunavaya . [32] El Zamorin continuó su conquista hasta Valluvanadu y conquistó las regiones de Kottakkal , Malappuram , Manjeri y Nilambur . Fue así como Perumpadappu y una porción más grande de Valluvanad quedaron bajo el gobierno de Zamorin. Así, Zamorin se convirtió en el Raksha Purusha de Mamankam y el gobernante de Tirunavaya , vecino de Triprangode yPonnani . [31]

Bajo el gobierno de los Zamorin, las regiones incluidas en el distrito surgieron como importantes centros de comercio marítimo exterior en la Kerala medieval. Los Zamorin obtuvieron la mayor parte de sus ingresos gravando el comercio de especias a través de sus puertos. Los principales puertos del reino de Zamorin incluían Parappanangadi , Tanur y Ponnani . [34] [35] Parappanangadi ( Barburankad ), Tirurangadi ( Tiruwarankad ), Tanur y Ponnani ( Funan ) también fueron importantes entre los asentamientos comerciales bajo el gobierno de los Zamorin, según la obra histórica del siglo XVI Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen . [36] Thrikkavil Kovilakam en Ponnani sirvió como segundo hogar para los Zamorin. Ponnani actuó como sede naval de su reino. [34] Malappuram fue la sede de Para Nambi , que era un jefe local de los Zamorin. [37] Otros Kovilakams de Zamorin incluyeron Kizhakke Kovilakam en Kottakkal , Manjeri Kovilakam en Manjeri , [38] y Nilambur Kovilakam en Nilambur . Parappanad Kovilakam en Parappanangadi y Tanur Kovilakam en Tanur eran casas reales vasallas de Zamorin. Sin embargo, Mankada Kovilakam en Mankada, cerca de Angadipuram, era la sede de la familia gobernante de Valluvanad Rajas . Azhvanchery Mana , que era la sede de Azhvanchery Thamprakkal , quien era el jefe supremo de los brahmanes Nambudiri de Kerala, está ubicado en Athavanad cerca de Kuttippuram , en Tirur Taluk . Azhvanchery Thamprakkal y el señor de Kalpakanchery en el Reino de Tanur solían estar presentes en la Ariyittu Vazhcha (Coronación) de un nuevo Zamorin. [38] Los árabes tenían el monopolio del comercio a principios de la Edad Media. [38] La sede original de los Raja de Palakkad también estaba en Athavanad . [39]

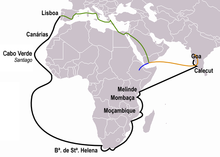

La escuadra de Vasco da Gama salió de Portugal en 1497, rodeó el Cabo y continuó a lo largo de la costa de África Oriental, donde se llevó a bordo un piloto local que los guió a través del Océano Índico , llegando a Calicut en mayo de 1498. [40] En el momento de la llegada de Vasco da Gama y su flota portuguesa a Calicut, el Zamorin de Calicut residía en Ponnani. [41] El Zamorin había proporcionado a los portugueses todas las facilidades para el comercio. [20] Sin embargo, las provocaciones portuguesas en las propiedades árabes llevaron a un conflicto entre el Zamorin y los portugueses. Además, Ponnani , que era la segunda sede del Zamorin, era un objetivo importante de los portugueses. [20] El gobernante del Reino de Tanur , que era vasallo del Zamorin de Calicut , se puso del lado de los portugueses, contra su señor supremo en Kozhikode . [31] Como resultado, el Reino de Tanur ( Vettathunadu ) se convirtió en una de las primeras colonias portuguesas en la India. El gobernante de Tanur también se puso del lado de Cochin . [31] Muchos de los miembros de la familia real de Cochin en los siglos XVI y XVII fueron seleccionados de Vettom . [31] Sin embargo, las fuerzas de Tanur bajo el rey lucharon por el Zamorin de Calicut en la Batalla de Cochin (1504) . [42] Sin embargo, la lealtad de los comerciantes de Mappila en la región de Tanur todavía permaneció bajo el Zamorin de Calicut . [36] Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan , considerado el padre de la literatura malayalam moderna , nació en Tirur ( Vettathunadu ) durante el período portugués. [31] La escuela medieval de astronomía y matemáticas de Kerala que floreció entre los siglos XIV y XVI, también se basó principalmente en Vettathunadu ( región de Tirur ). [43] [44]

En 1507, el virrey portugués Francisco de Almeida atacó Ponnani y comenzó a construir una fortaleza allí en 1585. [20] El distrito fue testigo de varias batallas entre los jefes navales de Kozhikode, conocidos como Kunhali Marakkars , y los portugueses por el monopolio del comercio de especias. A los Kunjali Marakkars se les atribuye la organización de la primera defensa naval de la costa india. [45] [46] La ciudad de Tanur fue una de las primeras colonias portuguesas en el subcontinente indio. Las ciudades de Ponnani y Parappanangadi fueron quemadas por los portugueses en los años 1525 y 1573-74 respectivamente. [34] Algunos de los reyes del Reino de Cochin en el siglo XVI d. C., cuando Cochin se convirtió en una potencia importante en la costa de Malabar, generalmente fueron seleccionados de la familia real del Reino de Tanur . [31] Los portugueses fueron expulsados del Reino de Tanur en la Batalla del Fuerte Chaliyam de 1571. Chaliyam era la frontera norte de Vettathunadu . Durante esa batalla, los zamorines recibieron ayuda inequívoca de los mappilas de Ponnani , Tanur y Parappanangadi .

El Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen escrito por Zainuddin Makhdoom II (nacido alrededor de 1532) en Ponnani durante el siglo XVI d. C. es el primer libro conocido basado íntegramente en la historia de Kerala, escrito por un keralita. Está escrito en árabe y contiene información sobre la resistencia que opuso la armada de Kunjali Marakkar junto con el Zamorin de Calicut desde 1498 hasta 1583 contra los intentos portugueses de colonizar la costa de Malabar . [47] Se imprimió y publicó por primera vez en Lisboa . Se ha conservado una copia de esta edición en la biblioteca de la Universidad Al-Azhar , El Cairo . [48] [49] [50] En 1532, con la ayuda del gobernante de Tanur , se construyó una capilla en Chaliyam , junto con una casa para el comandante, cuarteles para los soldados y almacenes para el comercio. Diego de Pereira, que había negociado el tratado con el Zamorín, quedó al mando de esta nueva fortaleza, con una guarnición de 250 hombres; y Manuel de Sousa tenía órdenes de asegurar su seguridad por mar, con un escuadrón de veintidós buques. [51] El Zamorín pronto se arrepintió de haber permitido que se construyera este fuerte en sus dominios, y utilizó esfuerzos ineficaces para inducir al gobernante de Parappanangadi , Caramanlii (¿Rey de Beypore ?) (Algunos registros dicen que el gobernante de Tanur también estaba con ellos [51] ) a romper con los portugueses, incluso yendo a la guerra contra ellos. [36] En 1571, los portugueses fueron derrotados por las fuerzas del Zamorín en la batalla del Fuerte Chaliyam . [52] Las continuas guerras lideradas por los portugueses por un lado y los zamorines, que contaban con el apoyo de los comerciantes árabes , y las fuerzas locales de Nair y Mappila por el otro, finalmente llevaron al declive del monopolio árabe del comercio exterior en las ciudades costeras. Sin tener en cuenta la oposición portuguesa, los zamorines firmaron un tratado con la Compañía Holandesa de las Indias Orientales el 11 de noviembre de 1604. [20] A esto le siguió otro tratado en 1608, que confirmó el tratado anterior y los holandeses aseguraron asistencia a los zamorines para expulsar a los portugueses. [20] El ascenso del monopolio holandés provocó que el dominio portugués también decayera. El renacimiento cultural seguido por los disturbios del siglo XVI produjo poetas como Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan y Poonthanam Nambudiri , que fueron fundamentales en el desarrollo de la literatura malayalam.en su forma actual, y Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri , quien también fue miembro de la escuela medieval de astronomía y matemáticas de Kerala .

A mediados del siglo XVII, los holandeses tenían el monopolio del comercio exterior en los puertos de Kerala, a excepción de las pequeñas fábricas inglesas en Ponnani y Kozhikode . [20] Aunque la llegada de William Keeling en 1650 fue el comienzo del monopolio de la Compañía Británica de las Indias Orientales en la región, no pudieron establecer la supremacía hasta 1792. [20] Durante el siglo XVIII, los gobernantes de facto del reino de Mysore, Hyder Ali y Tipu Sultan, unificaron todos los estados feudales más pequeños en el norte de Kerala y pasaron a formar parte del Reino de Mysore . Durante un breve período de tiempo en 1766, Manjeri fue la sede del sultán Hyder Ali . [53] Cuando el Samutiri Kovilakam en Calicut fue asediado por el sultán de Mysore Haidar 'Ali (siglo XVIII d. C.), el Zamorin envió a los miembros de su familia a Thrikkavil Kovilakam en Ponnani. [54] La batalla de Tirurangadi fue una serie de enfrentamientos que tuvieron lugar entre el ejército británico y Tipu Sultan entre el 7 y el 12 de diciembre de 1790 en Tirurangadi , durante la Tercera Guerra Anglo-Mysore . [55] En 1792, Tipu Sultan fue derrotado por la Compañía Inglesa de las Indias Orientales a través de la Tercera Guerra Anglo-Mysore, y se acordó el Tratado de Seringapatam . Según este tratado, la mayor parte de la Región de Malabar , incluido el actual distrito de Malappuram, se integró en la Compañía Inglesa de las Indias Orientales. Los Koyi Thampurans de Travancore pertenecen a la Familia Real Parappanad . Era de esta familia de la que generalmente se seleccionaban los consortes de la familia Travancore de Rani. [53] La plantación de teca más antigua del mundo en la parcela de Conolly está a solo 2 km (1,2 millas) de la ciudad de Nilambur . Fue nombrada en memoria de Henry Valentine Conolly , el entonces recaudador de distrito de Malabar. [56] La primera línea ferroviaria del estado comenzó a funcionar desde Tirur a Chaliyam el 12 de marzo de 1861, con la estación ferroviaria más antigua en Tirur . [57] [16]

El distrito fue escenario de muchas de las revueltas de Mappila (levantamientos contra la Compañía Británica de las Indias Orientales en Kerala) entre 1792 y 1921. Se estima que hubo alrededor de 830 disturbios, grandes y pequeños, durante este período. Durante 1841-1921 hubo más de 86 revueltas solo contra los funcionarios británicos. [58] El distrito estuvo incluido en los subdistritos de Eranad, Valluvanad y Ponnani en el sur de Malabar durante el gobierno británico. La Policía Especial de Malabar tenía su sede en Malappuram . La MSP es también el batallón de policía armada más antiguo del estado. Los británicos habían establecido el cuartel Haig en la parte superior de la ciudad de Malappuram, en la orilla del río Kadalundi , para estacionar sus fuerzas. [59]

La conferencia política del distrito de Malabar del Congreso Nacional Indio celebrada en Manjeri el 28 de abril de 1920 fortaleció el movimiento de independencia de la India y el movimiento nacional en Malabar británica . [60] Esa conferencia declaró que las Reformas de Montagu-Chelmsford no eran capaces de satisfacer las necesidades de la India británica . También abogó por una reforma agraria para buscar soluciones a los problemas causados por el arrendamiento que existía en Malabar. Sin embargo, la decisión amplió la deriva entre extremistas y moderados dentro del Congreso. La conferencia dio lugar a la insatisfacción de los terratenientes con el Congreso Nacional Indio. Hizo que el liderazgo del Comité del Congreso del distrito de Malabar quedara bajo el control de los extremistas que representaban a los trabajadores y la clase media. [31]

.jpg/440px-മലപ്പുറം_ജില്ലയിൽ_പൊന്നാനിയിലെ_ഹാർബർ_(1930-37).jpg)

La rebelión de Malabar fue la última y más importante de las revueltas. La batalla de Pookkottur desempeñó un papel importante en la rebelión. [61] [62] Después de que el ejército, la policía y las autoridades británicas huyeran, la declaración de independencia tuvo lugar en más de 200 aldeas en los taluks de Eranad , Valluvanad , Ponnani y Kozhikode el 28 de agosto de 1921. [63] Sin embargo, menos de seis meses después de la declaración de autonomía, la Compañía de las Indias Orientales recuperó el territorio y lo anexó al Raj británico . La tragedia de Wagon tuvo lugar después de la rebelión de Malabar, donde murieron 64 prisioneros el 20 de noviembre de 1921. [64]

La antigua presidencia de Madrás se convirtió en el estado de Madrás después de la independencia de la India en 1947. La división de ingresos de Malappuram fue una de las cinco divisiones de ingresos en el antiguo distrito de Malabar con la jurisdicción de Eranad (Manjeri) y Valluvanad (Perinthalmanna) Taluks. Las otras cuatro divisiones de ingresos en el distrito de Malabar fueron Thalassery , Kozhikode , Palakkad y Fort Cochin . [65] El 1 de noviembre de 1956, se formó el estado de Kerala sobre una base lingüística. El distrito de Malappuram se formó con cuatro subdistritos (Eranad, Perinthalmanna, Tirur y Ponnani), cuatro ciudades, catorce bloques de desarrollo y 95 Gram panchayats en ese momento. [66] Más tarde, Tirur Taluk se bifurcó para formar Tirurangadi Taluk, y Eranad Taluk se trifurcó para formar dos Taluks más, a saber, Nilambur y Kondotty. La Universidad de Calicut , que también es la segunda universidad más antigua existente en Kerala, y el Aeropuerto Internacional de Calicut , que también es el segundo aeropuerto más antiguo existente en el estado, comenzaron a funcionar en Tenhipalam y Karipur , en los años 1968 y 1988, respectivamente. [67] En la década de 1970, las reservas de petróleo en los países del Golfo Pérsico se abrieron a la extracción comercial y miles de trabajadores no calificados emigraron al golfo. Enviaron dinero a casa, apoyando la economía rural, y para fines del siglo XX, la región alcanzó estándares de salud del Primer Mundo y alfabetización casi universal. [68]

.JPG/440px-Cherumb_eco_tourism_village,_Karuvarakundu_India_(3).JPG)

.JPG/440px-Puthuponnani_(2).JPG)

Malappuram, que limita al noroeste con el distrito de Kozhikode , al noreste con el distrito de Wayanad , al este con las colinas de Nilgiri , al sureste con el distrito de Palakkad , al suroeste con el distrito de Thrissur y al oeste con el mar Arábigo , tiene una superficie geográfica total de 3.554 km2 , lo que lo sitúa en tercer lugar en el estado en cuanto a superficie. El distrito posee el 9,15% de la superficie total del estado. El distrito está situado en la longitud 75°E – 77°E y en la latitud 10°N – 12°N en el mapa geográfico. Al igual que otras partes de Kerala, Malappuram también tiene una zona costera (tierras bajas) delimitada por el mar Arábigo al oeste, una zona media en el centro y una zona montañosa (tierras altas), delimitada por los Ghats occidentales al este. A diferencia de otros distritos de Kerala, las zonas montañosas también se ven ampliamente en la zona media. El pico Mukurthi de 2.554 m de altura , que está situado en la frontera de Nilambur Taluk y Ooty Taluk, y también es el quinto pico más alto en el sur de la India , así como el tercero más alto en Kerala después de Anamudi (2.696 m) y Meesapulimala (2.651 m), es el punto de elevación más alto en el distrito de Malappuram. También es el pico más alto en Kerala fuera del distrito de Idukki . El pico Anginda de 2.383 m de altura , que se encuentra más cerca de la frontera del distrito de Malappuram- Palakkad - Nilgiris es el segundo pico más alto. Vavul Mala , un pico de 2.339 m de altura situado en la triunión de Nilambur Taluk de Malappuram, Wayanad y Thamarassery Taluk de los distritos de Kozhikode , es el tercer punto de elevación más alto en el distrito.

El distrito de Malappuram comparte su frontera con los siguientes 12 taluks de 5 distritos.

Sobre la base de la topografía, geología, suelos, clima y vegetación natural, el distrito se divide en cinco submicro regiones:

La costa de Malappuram se extiende a lo largo de la franja costera de Malappuram desde Vallikkunnu al norte hasta Perumpadappu al sur. Limita con la costa de Kozhikode al norte, la llanura ondulada de Malappuram al este, la costa de Thrissur al sur y el mar de Lakshadweep al oeste. La región está drenada por los principales ríos como Chaliyar, Kadalundi, Bharathappuzha, Tirurpuzha, etc. canales y remansos. La región está bordeada de cocoteros. La llanura costera se inclina hacia el oeste muy suavemente. [69] Las principales ciudades, incluidas Ponnani , Edappal , Tirur , Valanchery , Kuttippuram , Tanur , Tirurangadi y Parappanangadi , se encuentran en esta región. La altura máxima de esta región se encuentra en el pueblo de Kalpakanchery (104 m) en Tirur Taluk. [69]

La llanura ondulada de Malappuram, paralela a la costa, limita con las llanuras onduladas de Nadapuram - Mavur al norte, la cuenca del río Chaliyar y las tierras altas onduladas de Perinthalmanna al este, la llanura ondulada de Pattambi al sur y la costa de Malappuram al oeste. La colina Nenmini (478 m) en Kannamangalam es el punto más alto y el Vazhayur en la parte norte (95 m) es el más bajo de la región. Aquí se ven algunas colinas y laderas. [69]

La cuenca del río Chaliyar está delimitada por las colinas boscosas de Nilambur al norte y al este, las tierras altas onduladas de Perinthalmanna al sur y la llanura ondulada de Malappuram al este. Se encuentra en el curso medio del Chaliyar y presenta subidas y bajadas en forma de colinas aisladas. [69]

Las colinas boscosas de Nilambur, también conocidas como el valle de Nilambur en los registros coloniales, forman su límite con las colinas boscosas de Kozhikode y Wayanad al norte, Tamil Nadu al este, las colinas boscosas de Mannarkad -Palakkad al sur y la cuenca del río Chaliyar al oeste. Es una parte de los Ghats occidentales. Aquí se ven varios picos que tienen una elevación de más de 1000 m desde el nivel del mar. [69] La altitud más alta de esta región está en Mukurthi (2594 m), que se encuentra al este del Santuario de Vida Silvestre Karimpuzha en la frontera de Kerala con Tamil Nadu. El punto más bajo se encuentra en Mampad (115 m). [69] La zona boscosa montañosa de Nilambur forma parte de la Reserva de la Biosfera de Nilgiri .

Las onduladas tierras altas de Perinthalmanna forman su límite con la cuenca del río Chaliyar al norte, las colinas boscosas de Mannarkad-Palakkad al este, el paso de Palakkad al sur y la llanura ondulada de Malappuram al oeste. Aquí se ven varias colinas pequeñas y aisladas. Kodikuthimala es una de ellas. El río Kadalundi drena esta región. La altura máxima de la región es de 610 m en Makkaraparamba . [69]

Malappuram ocupa el quinto lugar en cuanto a longitud de costa entre los distritos de Kerala, con una costa de 70 km (11,87% de la costa total del estado). [70] El cinturón costero de Malappuram se encuentra en tres ciudades municipales, a saber, Tanur , Ponnani y Parappanangadi , y ocho Gram panchayats, a saber, Vallikkunnu , Tanalur , Niramaruthur , Vettom , Mangalam , Purathur , Veliyankode y Perumbadappu . Ponnani, Tanur, Parappanangadi y Padinjarekkara Beach , todos ellos situados en la parte occidental del distrito, son los principales centros pesqueros. La costa marítima del distrito está llena de riqueza marina. [69] Además de ser un destino favorito de los comerciantes árabes en el pasado, Ponnani también fue un destino cautivador para muchos líderes espirituales musulmanes , que fueron fundamentales en la propagación del Islam aquí. La ciudad portuaria también es conocida como La pequeña meca de Malabar , así como La ciudad de las monedas de oro . [71] [72] Durante los meses de febrero/abril, miles de aves migratorias llegan aquí. Situado cerca de Ponnani se encuentra Biyyam Kayal, una tranquila vía fluvial rodeada de verde con instalaciones para deportes acuáticos. El canal de Conolly se encuentra con el mar Arábigo en Puthuponnani . La ciudad costera de Tanur fue la capital del Reino de Vettathunad en el período medieval temprano, y es conocida por el Templo de Keraladeshpuram . Parappanangadi fue la sede de las familias gobernantes del reino de Parappanad en el período medieval temprano.

Los principales ríos que fluyen a través del distrito son Chaliyar , Kadalundi , Bharathappuzha y Tirur . Chaliyar tiene una longitud total de unos 168 km y un área de drenaje de 2.818 km2 ( 1.088 millas cuadradas). Pasa por Nilambur , Mampad , Edavanna , Areekode y Vazhakkad en el distrito y luego fluye a través de la frontera del distrito de Kozhikode-Malappuram y desemboca en el mar Arábigo en Chaliyam . Varios afluentes más grandes y más pequeños de Chaliyar están allí en el valle de Nilambur Taluk. [69] [73] Karimpuzha , el afluente más grande de Chaliyar, y Thuthapuzha , uno de los afluentes más grandes de Bharathappuzha, y Olipuzha, uno de los afluentes más grandes del río Kadalundi, también fluyen a través del distrito. El río Kadalundi pasa por Melattur , Keezhattur , Pandikkad , Manjeri , Malappuram , Panakkad , Parappur , Vengara , Tirurangadi , Parappanangadi , Vallikkunnu y desemboca en el mar Arábigo en Kadalundi Nagaram en Vallikkunnu en la frontera noroeste del distrito. Está formado por la confluencia del río Olippuzha y el río Veliyar. El río Kadalundi se origina en los Ghats occidentales en la frontera occidental del Valle Silencioso y fluye a través del distrito. Olippuzha y Veliyar se fusionan para formar el río Kadalundi en Keezhattur . El río Kadalundi pasa por las regiones de Eranad y Valluvanad . Tiene una longitud de 130 km, con una zona de captación de 1.114 km2 ( 430 millas cuadradas) y una escorrentía total de 2189 millones de pies cúbicos. [69] [73] Bharathappuzha tiene una longitud total de 209 km. Fluye como su afluente el río Thuthapuzha a través de Thootha, Elamkulam , Pulamanthole en la frontera del distrito de Malappuram-Palakkad, y se une al río principal en Pallippuram. Luego llega nuevamente al distrito desde Thiruvegappura y llega a Kuttippuram después de fluir a través de algunos distritos vecinos. Luego fluye completamente a través del distrito. Bharathappuzha desemboca en el mar Arábigo en Ponnani .Tirunavaya , Kuttippuram , Triprangode , Irimbiliyam , Thavanur y Ponnani son algunas ciudades importantes en la orilla de Bharathappuzha. [69] [73] El río Tirur tiene 48 km de largo. Se une con Bharathappuzha en Padinjarekara cerca de Ponnani. [69] [73] Además de estos grandes ríos, el distrito tiene un pequeño río llamado río Purapparamba, que tiene solo 8 km de largo. Está conectado a los ríos principales a través del Canal Conolly . [69] [73] Varios afluentes y arroyos más grandes y más pequeños de los principales ríos descritos anteriormente también fluyen a través del distrito.

Hay cuatro estuarios: Padinjarekara Azhimukham en Purathur , donde los ríos Bharathappuzha y Tirur se fusionan para unirse al Mar Arábigo, el promontorio Puthuponnani donde el canal Conolly desemboca en el mar, Purappuzha Azhimukham en Tanur y Kadalundi Nagaram Azhimukham en Vallikkunnu en el límite noroeste del distrito. . [69] [73] Los remansos como Biyyam, Veliyankode, Manur y Kodinhi se encuentran en la costa de Taluks. [69] [73] El canal Ponnani se construyó para el transporte de mercancías desde Ponnani a la estación de tren de Tirur durante el Raj británico . Aquí hay una descripción sobre el Canal Ponnani realizada por empleados de la Misión de Basilea en Kodakkal . [74]

...hoy en día, un barco de vapor viaja entre Ponnani y Tirur a través del canal, donde se encuentra la estación de tren más conveniente para Ponnani. El billete cuesta sólo 4 annas, aunque la distancia es de 10 km...

La temperatura del distrito es casi constante durante todo el año. Tiene un clima tropical. Recibe precipitaciones significativas en la mayoría de los meses, con una corta estación seca. Según Köppen y Geiger, este clima se clasifica como Am. La temperatura media anual en Malappuram es de 27,3 °C. En un año, la precipitación media es de 2.952 milímetros (116,2 pulgadas). El verano suele durar de marzo a mayo; el monzón comienza en junio y termina en septiembre. Malappuram recibe monzones tanto del suroeste como del noreste. El invierno va de diciembre a febrero. [75]

El distrito contiene una vida salvaje diversa y una serie de pequeñas colinas, bosques, ríos y arroyos que fluyen hacia el oeste, remansos y plantaciones de arroz , nuez de areca , anacardo , pimienta , jengibre , legumbres , coco , plátano , tapioca , té y caucho . La parcela de Conolly, la plantación de teca más antigua del mundo , se encuentra en Nilambur . Nilambur también es conocido por el Museo de la Teca . Los árboles de bambú se ven ampliamente cerca de las plantaciones de teca de Nilambur. Un parque natural de recursos biológicos está asociado con el Museo de la Teca. En los antiguos registros administrativos de la Presidencia de Madrás , se registra que la plantación más notable propiedad del Gobierno en la antigua Presidencia de Madrás fue la plantación de teca en Nilambur plantada en 1844. [77]

De los 3.554 km2 de superficie del distrito, 1.034 km2 ( 399 millas cuadradas) (29%) constituyen zona forestal. Puede ser más o menos densa. [78] La parte noreste del distrito tiene una vasta superficie forestal de 758,87 km2 ( 293,00 millas cuadradas). En esta, 325,33 km2 ( 125,61 millas cuadradas) son bosques reservados y el resto son bosques adquiridos. De estos, el 80% son caducifolios, mientras que el resto son perennes . La zona forestal se concentra principalmente en el subdistrito de Nilambur, que comparte su límite con el distrito montañoso de Wayanad , los Ghats occidentales y las zonas montañosas ( Nilgiris ) de Tamil Nadu . En la zona forestal de Nilambur se ven árboles como la teca , el palo de rosa y la caoba . Las colinas de bambú se ven ampliamente en el bosque. El santuario de vida silvestre Karimpuzha en el distrito es el santuario de vida silvestre más grande del estado. [79] [80] El Bosque Reservado New Amarambalam , que es parte del Santuario de Vida Silvestre Karimpuzha , tiene una variedad de fauna. Una variedad de animales, incluidos elefantes, ciervos, tigres, monos azules, osos, jabalíes, conejos, pájaros y reptiles, se encuentran en los bosques. También se recolectan productos forestales como miel, hierbas medicinales y especias de aquí. La selva tropical Nedumkayam también existe en el valle de Nilambur. Los bosques están protegidos por dos divisiones: Nilambur norte y Nilambur sur. El Instituto de Investigación Forestal de Kerala tiene un subcentro en Nilambur. Los tipos importantes de peces que se encuentran en las áreas costeras e interiores del distrito incluyen camarones , sardinas de aceite , panza plateada , tiburones , bagres , caballas , rayas , chemba, peces soll, peces vidente y peces cinta . [69]

La teca de Nilambur es el primer producto forestal que obtiene su propia etiqueta IG . [81] Tirur Vettila , un tipo de betel que se encuentra en Tirur , también ha obtenido la etiqueta IG . [82] Alrededor de 50 acres de bosque de manglares se encuentran en Vallikkunnu , ubicado en la zona costera del distrito. Los manglares también se ven ampliamente en las otras regiones costeras. El santuario de aves de Kadalundi se encuentra en Vallikkunnu Grama Panchayat del distrito. [83] La reserva comunitaria de Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu es la primera reserva comunitaria en Kerala. Ahora ha sido declarada como un centro de ecoturismo. [84] Un santuario de aves en el estuario de Padinjarekkara en Purathur se propuso en 2010. [85] Tirunavaya es conocida por sus campos de loto. [86]

La sede de la administración del distrito está en Uphill, Malappuram . La administración del distrito está encabezada por el recaudador del distrito . Cuenta con la asistencia de cinco recaudadores adjuntos responsables de asuntos generales, adquisición de tierras, recuperación de ingresos, reformas agrarias y elecciones. Un magistrado de distrito adicional con rango de recaudador adjunto (general) brinda apoyo al recaudador del distrito en todas las actividades administrativas. [87]

El distrito de ingresos de Malappuram tiene dos divisiones: Tirur y Perinthalmanna. El distrito se divide a su vez en 138 aldeas que juntas forman 7 subdistritos (taluks). [88] Para la administración rural, 94 Gram Panchayats se combinan en 15 Block Panchayats, que juntos forman el Panchayat del Distrito de Malappuram. Además de esto, para realizar mejor la administración urbana, existen 12 municipios . [89]

Hay dos divisiones de ingresos en el distrito: Perinthalmanna y Tirur . Los subdistritos de Ponnani , Tirur , Tirurangadi y Kondotty están incluidos en la división de ingresos de Tirur, mientras que los restantes Nilambur , Eranad y Perinthalmanna se combinan para formar la división de ingresos de Perinthalmanna. La oficina de la división de ingresos está dirigida por un Oficial de la División de Ingresos / Subrecaudador (RDO), que también es el magistrado de la subdivisión de la división de ingresos. Las oficinas de la división de ingresos están en Tirur y Perinthalmanna respectivamente.

Un taluk (subdistrito) es una división administrativa dentro de un distrito. Hay 7 taluks en el distrito de Malappuram, y cada taluk está encabezado por un Tahsildar, que es responsable de la administración de los ingresos de la tierra y las funciones magistrales ejecutivas. Nilambur es el subdistrito ( Taluk ) más grande de Kerala. Los subdistritos de Ponnani , Tirur y Tirurangadi se encuentran en la región costera. Perinthalmanna , Eranad y Kondotty se encuentran en la región central, mientras que el subdistrito de Nilambur se encuentra en la cordillera alta. Además de la Estación Civil en Malappuram para coordinar la administración a nivel de distrito, hay Mini-Estaciones Civiles en Manjeri , Nilambur , Perinthalmanna , Tirurangadi , Tanur , Tirur , Kuttippuram y Ponnani para coordinar las actividades administrativas a nivel de Taluk . [90]

Las aldeas de ingresos son la subdivisión de los taluks y la institución más baja de administración de ingresos del distrito. Cada taluk consta de varias aldeas bajo su jurisdicción. Hay 138 aldeas de ingresos en el distrito de Malappuram. Las aldeas de ingresos se dividen a su vez en desoms para asuntos de ingresos territoriales.

El Comité de Planificación del Distrito de Malappuram está integrado por dos miembros de los municipios, diez miembros del Panchayat del Distrito y un miembro designado por el Panchayat, además de un presidente y un secretario. El puesto de presidente está reservado para un Panchayat del Distrito ex officio y el de secretario para un Recaudador del Distrito ex officio. [93]

La sede judicial del distrito está en Manjeri . 24 tribunales funcionan bajo el distrito judicial de Manjeri, incluidos Manjeri, Malappuram , Tirur , Perinthalmanna , Parappanangadi , Ponnani y Nilambur . [94] Después del establecimiento del Distrito de Malappuram el 16 de junio de 1969, un Tribunal de Distrito comenzó a funcionar en Kozhikode el 25 de mayo de 1970. Posteriormente, el 1 de febrero de 1974, el tribunal se trasladó al Complejo de Tribunales de Manjeri.

En el Distrito Judicial de Manjeri, actualmente hay 24 tribunales en funcionamiento distribuidos en varias localidades del distrito, entre ellas Manjeri, Malappuram, Tirur, Perinthalmanna , Parappanagadi, Ponnani, Tirur y Nilambur. La sede judicial de Malappuram está situada en Manjeri.

El distrito cuenta con tres juzgados de distrito y de sesiones adicionales, dos juzgados de familia (uno en Malappuram y el otro en Tirur), así como dos tribunales de reclamaciones por accidentes de tráfico (uno en Manjeri y el otro en Tirur). Además, hay dos tribunales secundarios, uno en Manjeri y el otro en Tirur . El distrito también alberga dos juzgados de primera instancia de Munsiff, uno en Ponnani y el otro en Perinthalmanna. Por último, hay nueve juzgados de primera instancia judiciales que funcionan en el distrito de Malappuram.

La Policía del Distrito de Malappuram, una división de la Policía de Kerala , se encarga de hacer cumplir la ley y de realizar investigaciones dentro del distrito. La Oficina de Policía del Distrito está situada en Malappuram y está dirigida por un Jefe de Policía del Distrito con el rango de Superintendente de Policía (SP). Hay seis subdivisiones de policía y 36 comisarías de policía en el distrito de Malappuram. Las sedes de estas subdivisiones de policía se encuentran en las siguientes áreas: Malappuram , Kondotty , Perinthalmanna , Tirur , Tanur y Nilambur . Cada subdivisión de policía está dirigida por un Superintendente Adjunto de Policía y cada comisaría está supervisada por un Oficial de la Comisaría con el rango de Inspector de Policía .

El Distrito de Policía de Malappuram, junto con los distritos de policía de Palakkad, la ciudad de Thrissur y la zona rural de Thrissur, está bajo la jurisdicción de la Policía de la Cordillera de Thrissur . [95] La Oficina de Policía del Distrito, la Sección Especial del Distrito, la Oficina de Registros Criminales del Distrito, la Sección "C" del Distrito, la Célula de Narcóticos, la Sala de Control de la Policía del Distrito, la Célula Cibernética, la Célula de Mujeres y la Unidad de Telecomunicaciones se encuentran en Malappuram . La estación de policía costera está en Ponnani , mientras que el Campamento de Reserva Armada del Distrito está situado en Padinhattummuri. Las Unidades de tráfico de la policía de Malappuram están centradas en Malappuram, Manjeri, Kondotty , Perinthalmanna y Tirur. [96]

La sede de la Policía Especial de Malabar (formada en 1884), un batallón de policía armada dependiente de la Policía de Kerala , está en Malappuram . También es el batallón de policía armada más antiguo del estado. [94]

Las instituciones de autogobierno local se dividen en dos categorías: órganos locales urbanos y panchayats (órganos locales rurales).

El distrito comprende 12 municipios establecidos para administrar áreas urbanas ( ciudades estatutarias ). Cada municipio tiene su propio consejo electo y es responsable de la gobernanza local, la planificación urbana y la prestación de servicios esenciales dentro de su respectiva jurisdicción. Un presidente y vicepresidente, elegidos por los concejales, encabezan cada municipio. Estos municipios se dividen en 479 distritos, de cada uno de los cuales se elige un concejal por un período de cinco años. [97]

El Panchayat del Distrito de Malappuram es el órgano máximo de gobernanza rural en el distrito de Malappuram. El Panchayat del Distrito tiene 32 divisiones, con miembros elegidos de cada división. Está encabezado por un Presidente y un Vicepresidente, elegidos por los miembros. El área jurisdiccional del Panchayat del Distrito abarca los gram panchayats dentro del distrito.

Para la gobernanza a nivel de bloque, hay 15 panchayats de bloque en el distrito.

El distrito rural está dividido en 94 Gram Panchayats que se incluyen en 15 bloques, a saber, Areekode, Kalikavu, Kondotty, Kuttippuram , Malappuram, Mankada, Nilambur, Perinthalmanna, Perumpadappu, Ponnani, Tanur, Tirur, Tirurangadi, Vengara y Wandoor. [104] Estos bloques se combinan para formar el distrito Panchayat de Malappuram, que es el órgano distrital de máxima autoridad de la gobernanza rural. De los 32 distritos del distrito Panchayat, la UDF ganó 27 en las elecciones de 2020 , mientras que el LDF ganó los 5 restantes . [105] El distrito Panchayat de Malappuram es el distrito Panchayat más grande, así como el organismo local más grande del estado. Los 94 Gram Panchayats se dividen nuevamente en 1.778 distritos. [106] Las ciudades censales (pequeñas ciudades con características urbanas) también están bajo la jurisdicción de los Gram Panchayats. Aunque las notificaciones preliminares para la formación de nuevos Gram Panchayats, a saber, Anamangad , Ananthavoor , Arakkuparamba , Ariyallur , Chembrassery , Elankur , Karipur , Kootayi, Kurumbalangode, Marutha , Pang , Vaniyambalam y Velimukku se publicaron en 2015, aún no se han formado. [107] Con su formación, el número de Gram Panchayats en el distrito será de 106.

Para la representación de Malappuram en la Asamblea Legislativa de Kerala , hay 16 distritos electorales de la asamblea legislativa en el distrito. Estos están incluidos en 3 distritos electorales de Lok Sabha. Malappuram tiene el mayor número de distritos electorales de la asamblea en el estado. De estos, los distritos electorales de la asamblea de Eranad , Nilambur y Wandoor juntos forman parte de Wayanad (distrito electoral de Lok Sabha) , mientras que Tirurangadi , Tanur , Tirur , Kottakkal , Thavanur y Ponnani están incluidos en Ponnani (distrito electoral de Lok Sabha) . Los siete distritos electorales restantes de la asamblea juntos forman Malappuram (distrito electoral de Lok Sabha) . [89] [109] 16 de los 140 miembros de la Asamblea Legislativa de Kerala son elegidos del distrito. [110] En las elecciones de 2021 , la UDF ganó 12 de ellos, mientras que la LDF se llevó los escaños restantes.

El distrito de Malappuram tiene dos distritos electorales de Lok Sabha: Malappuram y Ponnani . El distrito también tiene una pequeña parte del distrito electoral de Wayanad Lok Sabha . [111]

El Valor Agregado Distrital Bruto (GDVA) del distrito en el año fiscal 2018-19 se estima en ₹ 698.37 mil millones, y el crecimiento en GDVA, comparado con el del año anterior fue del 11.30%. El distrito ocupa el tercer lugar en GDVA entre los distritos de Kerala, después de Ernakulam y Thiruvananthapuram , a partir de 2018-19. [112] El Valor Agregado Distrital Neto (NDVA) del distrito en el año 2018-19 fue de ₹ 631.90 mil millones y la tasa de crecimiento anual fue del 11.59%. El GDVA per cápita se calcula en ₹ 154,463 en el año fiscal. La tasa de crecimiento del VAB fue del 18,12 % en 2017-18, del 9,49 % en 2016-17, del 7,86 % en 2015-16, del 8,83 % en 2014-15, del 14,08 % en 2013-14 y del 9,70 % en 2012-13. Muestra una tendencia en zigzag. [112]

La economía de Malappuram depende en gran medida de los emigrantes. Malappuram es el estado con más emigrantes. Según el informe de revisión económica de 2016 publicado por el Gobierno de Kerala , 54 de cada 100 hogares del distrito son hogares de emigrantes. [113] La mayoría de ellos trabajan en Oriente Medio y son importantes contribuyentes a la economía del distrito. La sede de la KGB está situada en Malappuram. [114]

Laterite stone is widely seen in midland area of the district. The Angadipuram Laterite has gained recognition as a National Geo-heritage Monument.[115] Archean Gneiss is the most seen geological formation of the district. Quartz magnetite, which is seen in Porur is one among the minerals found in the district having economical importance. Quartz gneisses are seen in the regions of Nilambur, Edavanna, and Pandikkad. Garneliforus Quartz is seen in the areas of Manjeri and Kondotty. Charnockite rocks are found in Nilambur and Edavanna. Dykes consisting of plagioclase, feldspar, and pyroxene in typical laterite texture are there at Manjeri. Deposits of good quality iron ore have reported from Eranad region. The deposits of lime shells have found from the coastal areas of Ponnani and Kadalundinagaram. The coastal sands of Ponnani and Veliyankode contain a high amount of heavy minerals, ilmenite and monazite. Kaolinite have been found from the Taluks of Ponnani and Perinthalmanna. The deposits of Ball clay have found from Thekkummuri village. Parts of Nilambur subdistrict are included in the hidden goldfields of Wayanad. The Nilambur Taluk, along with the adjoining regions of Wayanad and Attappadi Valley are known for natural Gold fields. Explorations done at the valley of the river Chaliyar in Nilambur has shown reserves of the order of 2.5 million cubic meters of placers with 0.1 gram per cubic meter of gold.[69] Bauxite was discovered from some parts of the district like Kottakkal, Parappil, Oorakam, and Melmuri.[116] Karuvarakundu, which means Place of the Blacksmith, derives its name from iron-ore cutting and blacksmithy.[117]

Kodakkal Tile Factory at Tirunavaya, established in 1887, was the second tile factory in India. The first tile factory in India was at Feroke, which was then part of Eranad Taluk. According to the census conducted in 2011, there are 10,629 industrial units registered under SSI/MMSE, and 396 units among these are promoted by Scheduled castes, 83 by Scheduled tribes, and the remaining units by general category. About 1,000 people are aided annually under a self-employment program. There are KINFRA food-processing and IT industrial estates in Kakkancherry near Tenhipalam,[118] INKEL SME Park at Malappuram for Small and Medium Industries and a rubber plant and industrial estate at Payyanad in Manjeri. INKEL Greens, spread over 168 acres at Malappuram, contains an industrial zone, 'SME Park', and an educational zone, 'Educity'.[119]

MALCOSPIN (Malappuram Spinning Mills Limited) is one of the oldest industrial establishments in the district under the state government. Wood-related industries are common in Kottakkal, Edavanna, Vaniyambalam, Karulai, Nilambur and Mampad. Sawmills, furniture manufacturers and timber trade were the most important businesses in the district until the last decades. Tirur is a major regional trading centre for electronics, mobile phones and other gadgets. Employees' State Insurance has its branch office at Malappuram.[69] KELTRON Electro Ceramics (KELCERA) at Kuttippuram,[120] KELTRON tool room at Kuttippuram, Edarikode Textiles at Edarikode, KSRTC body workshop at Edappal, MALCOTEX (Malabar Co-operative Textiles Limited) at Athavanad,[121] and KELTEX (Kerala Hi-Tech Textile Cooperative Limited) at Athavanad,[122] are other major industrial centres under public sector.[123] The Kerala State Detergents and Chemicals Ltd. and the Kerala State Wood Industries Ltd. have their headquarters at Kuttippuram and Nilambur respectively.[124][125] Popees baby care, one of the largest baby clothes manufacturer brands in the world, is primarily based at Malappuram.[126]

_kerala_infia.jpg/440px-Edappal_malappuram(district)_kerala_infia.jpg)

Coconut, palms and paddy are mainly found in the Malappuram coast. Cashew, coconut, and tapioca are seen in the undulating plain. Rubber, cashew, pepper, and coconut are the important vegetation found in the Chaliyar river basin. Nilambur valley contain the cultivation of a wide variety of species. Teak is mostly seen in the region. Perinthalmanna undulating uplands contain the cultivation of species coconut, palm trees, pepper, rubber, and cashew. This region is drained by the Kadalundi River. Besides casual crops, species like mango, jackfruit, banana, etc. are also cultivated.[69] The general hilly nature of the district supports terrace farming. A portion of the Thrissur-Ponnani Kole Wetlands lie in Ponnani taluk of the district, which is favourable for highly productive cultivation of paddy.

According to the statistics of 2016–17, the gross cropped area was 237,860 hectares, while the net cropped area was 173,178 hectares. The cropping intensity of the district is 137 hectares. The most produced uncountable crop in 2016–17 was tapioca (185,880 Metric Tonnes), followed by banana (58,564 MT), and rubber (40,000 MT). 878 million coconuts and 19 million jackfruits were produced in 2016–17. However, the land use was maximum for the cultivation of coconut (102,836 hectares), followed by rubber (42,770 hectares), and areca nut (18,379 hectares).[127] An agricultural research station functions at Anakkayam. The Seed Garden Complex at Munderi, is said to be one of the biggest farms in Asia. State seed farms are there at Chokkad, Thavanur, and Anakkayam. A district agricultural farm functions at Chungathara and a coconut nursery functions at Parappanangadi.[128] The KCAET at Thavanur is the only agricultural engineering institute in the state.[129]

.jpg/440px-Bridge_-bharatappuzha_-kuttippuram_(1).jpg)

Malappuram is well connected by roads. There are four KSRTC stations in district.[130] 2 National highways pass through district- NH 66 and NH 966. NH 66 reaches the district through Ramanattukara and connects the cities/towns including Tirurangadi, Kakkad, Kottakkal, Valanchery, Kuttippuram, and Ponnani and goes out from district through Chavakkad. Major cities/towns those are connected through NH 966 include Kondotty (Karipur Airport), Malappuram, and Perinthalmanna. The State Highways in the district are SH 23 (Shornur-Perinthalmanna), SH 28 (Malappuram-Vazhikadavu), SH 34 (Quilandy-Edavanna), SH 39 (Perumbilavu-Nilambur), SH 53 (Mundur-Perinthalmanna), Hill Highway, SH 60 (Angadipuram-Cherukara), SH 62 (Guruvayur-Ponnani), SH 65 (Parappanangadi-Areekode), SH 69 (Thrissur-Kuttipuram), SH 70 (Karuvarakundu – Melattur), SH 71 (Tirur-Manjeri), SH 72 (Malappuram – Tirurangadi), and SH 73 (Valanchery-Nilambur). The length of road maintained by Kerala PWD in district is 2,680 km. Out of this, 2,305 km constitute district roads. The remaining 375 km consists of State Highways.[131] The Nadukani Churam Ghat Road connects Malappuram with Nilgiris.[132]

The Nadukani-Parappanangadi Road connects the coastal area of Malappuram district with the easternmost hilly border at Nadukani Churam bordering Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu, near Nilambur.[133] Beginning from Parappanangadi, it passes through other major towns such as Tirurangadi, Malappuram, Manjeri, and Nilambur, before reaching the Nadukani Ghat Road.[133]

The first modern kind of road in the district was laid in eighteenth century by Tipu Sultan.[16] The road from Tirur to Chaliyam via Tanur, Parappanangadi, and Vallikkunnu was projected by him.[16] Tipu had also projected the roads from Malappuram to Thamarassery, from Malappuram to Western Ghats, from Feroke to Kottakkal via Tirurangadi, and from Kottakkal to Angadipuram.[53]

.jpg/440px-Angadipuram_Railway_station_(2356310689).jpg)

Total length of railway line that passes through the district is 142 km.[134] The railway in the district comes under the Palakkad Railway Division, which is one of the six divisions under the Southern Railway. The history of railways in Kerala traces back to the district. The oldest railway station in the state is at Tirur.[16] The stations at Tanur, Parappanangadi, and Vallikkunnu also form parts of the oldest railway line in the state laid from Tirur to Chaliyam.[16] The line was inaugurated on 12 March 1861.[57] In the same year, it was extended from Tirur to Kuttippuram via Tirunavaya.[16] Later, it was further extended from Kuttippuram to Pattambi in 1862, and was again extended from Pattambi to Podanur in the same year.[16] The current Chennai-Mangalore railway line was later formed as an extension of the Beypore – Podanur line thus constructed.[16]

The Nilambur–Shoranur line is among the shortest as well as picturesque broad gauge railway lines in India.[135] It was laid by the British in colonial era for the transportation of Nilambur Teak logs into United Kingdom through Kozhikode. The Nilambur–Nanjangud line is a proposed railway line, which connects Nilambur with the districts of Wayanad, Nilgiris, and Mysore.[136][137] Guruvayur-Tirunavaya Railway line is another proposed project.[138] The Ministry of Railways has included the railway line connecting Kozhikode-Malappuram-Angadipuram in its Vision 2020 as a socially desirable railway line. Multiple surveys have been done on the line already. Indian Railway computerized reservation counter is available at Friends Janasevana Kendram, Down Hill. Reservation for any train can be done from here. Malappuram city is served by the railway stations at Angadipuram (17 km (11 mi) away), Tirur, and Parappanangadi (both 26 km, 40-minute drive away).

Malappuram is served by Calicut International Airport (IATA: CCJ, ICAO: VOCL) located at Karipur, about 25 kilometre away from Malappuram City. The airport started operation in April 1988. It has two terminals, one for domestic flights and another for international flights.[139] The airport serves as an operating base for Air India Express and operates Hajj Pilgrimage services to Medina and Jeddah from Kerala. Domestic flight services are available to major cities including Bangalore, Chennai, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Goa, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, Mangalore and Coimbatore while International flight services connects Malappuram with Dubai, Jeddah, Riyadh, Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, Al Ain, Bahrain, Dammam, Doha, Muscat, Salalah and Kuwait. There are direct buses to the airport for transportation. Other than buses, Taxis, Auto Rickshaws available for transportation.

According to the statistics provided by the Airports Authority of India in 2019–20, it is the 17th busiest airport in the country and the third-busiest in the state.

According to the 2018 Statistics Report, the district had a population of 4,494,998,[1] which is roughly equal to the population of Mauritania or the US state of Kentucky. 12.98% of the total population of Kerala resides in Malappuram.[1] It is the most populous district in Kerala and also the 50th most populous of India's 640 districts, with a population density of 1,265 inhabitants per square kilometre (3,280/sq mi). Its population-growth rate from 2001 to 2011 was 13.39 per cent. According to the 2011 Census of India, Malappuram has a sex ratio of 1098 women to 1000 men, and its literacy rate is 93.57 per cent, which is almost equal to the average literacy rate of the state (93.91%). Out of the total Malappuram population for 2011 census, 44.18 percent lives in the urban regions of district. In 2011, children under 0–6 formed 13.96 percent of the total population, compared to the 15.21 percent in 2001. Child Sex Ratio as per census 2011 was 965 compared to 960 of census 2001. According to the census 2011, only 0.02% of the total population of the district is houseless. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes make up 7.50% and 0.56% of the population respectively.[4]

Ponnani municipality is most densely populated local body in the district having 3,646 residents per square kilometre, which is followed by the municipalities of Tanur (3,568/km2) and Tirur (3,387/km2), as of census conducted in the year 2011.[4] The least densely populated local bodies are located in the eastern hilly region.[4] Chaliyar has the least with only 167 residents per square kilometre, which is followed by the Gram panchayats of Karulai (177/km2) and Chungathara (280/km2).[4] Among the Taluks, Tirurangadi is most densely populated while Nilambur has the least density of population.[4] The Malappuram metropolitan area has a population of 1.7 million.[9] According to a report published by The Economist in January 2020, Malappuram is the fastest growing metropolitan area in the world.[141][142][143]

The Malappuram Urban Agglomeration (UA) is the 4th most populous UA in the state. Malappuram is placed 25th in the list of most populous urban agglomerations in India. The total urban population of the entire district is 44.18% of district's population.[4] The metropolitan area of Malappuram includes Abdu Rahiman Nagar, Alamkode, Ariyallur, Chelembra, Cheriyamundam, Cherukavu, Edappal, Irimbiliyam, Kalady, Kannamangalam, Kodur, Kondotty, Koottilangadi, Kottakkal, Kuttippuram, Manjeri, Maranchery, Moonniyur, Naduvattom, Nannambra, Neduva, Oorakam, Othukkungal, Pallikkal Bazar, Parappur, Perumanna, Peruvallur, Ponnani, Ponmundam, Tanalur, Tenhipalam, Thalakkad, Thennala, Tirunavaya, Tirur, Tirurangadi, Trikkalangode, Triprangode, Valanchery, Vazhayur, and Vengara.[144]

Modern medicine, Ayurveda, and Homeopathy are available in the district. A general hospital, 3 district hospitals, and 6 Taluk hospitals are functioning under the Government of Kerala for Allopathy. The Government Medical College, Manjeri, established in 2013, is the apex medical college in the district.[145] A network of local health centers function under the public sector. It includes 66 Primary Health Centres, 20 All-time functioning primary health centers, 20 Community health centers, and 2 TBC's. 5 Major public health centers, 77 mini public health centers, and 565 sub-centers are there. 3 Leprosy control units, 2 Filaria control units, etc. also function under the public sector. The total bed strength of government hospitals is 1500. Many private hospitals with super-specialty units are also there in the district under Allopathy.[146][147]

The Govt Ayurveda Research Institute for Mental Disease at Pottippara near Kottakkal is the only government Ayurvedic mental hospital in Kerala. It is also the first of its type under the public sector in the country. Kottakkal is also home to the Arya Vaidya Sala, the renowned Ayurvedic health center. Under the government sector, a district Ayurvedic hospital functions at Edarikode. Government Ayurvedic hospitals also function in Manjeri, Velimukku, Perinthalmanna, Malappuram, Vengara, Kalpakanchery, Thiruvali, and Chelembra. Homeopathic hospitals under public sector function at Malappuram, Manjeri, Wandoor, and Kuttippuram.[147][148] Many hospitals function under the private sector.

As of 2003, Malappuram has the least suicide rate among the districts of Kerala (13.3), which is much lesser than the state average (32.8).[5]

The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics flourished between the 14th and 16th centuries. In attempting to solve astronomical problems, the Kerala school independently created a number of important mathematics concepts, including series expansion for trigonometric functions.[43][44] The Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics was based at Vettathunadu (Tirur region).[43]

The district has the most schools in Kerala as per the school statistics of 2019–20. There are 898 Lower primary schools,[149] 363 Upper primary schools,[150] 355 High schools,[151] 248 Higher secondary schools,[152] and 27 Vocational Higher secondary schools[153] in the district. Hence there are 1620 schools in the district.[154] Besides these, there are 120 CBSE schools and 3 ICSE schools.

554 government schools, 810 Aided schools, and 1 unaided school, recognised by the Government of Kerala have been digitalised.[155] In the academic year 2019–20, the total number of students studying in the schools recognised by Government of Kerala is 739,966 – 407,690 in the aided schools, 245,445 in the government schools, and 86,831 in the recognised unaided schools.[156]

The district plays a significant role in the higher education sector of the state. It is home to two of the main universities in the state- the University of Calicut centered at Tenhipalam which was established in 1968 as the second university in Kerala,[157] and the Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University centered at Tirur which was established in the year 2012.[158] AMU Malappuram, one of the three off-campus centres of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) is situated in Cherukara, which was established in 2010.[159][160] An off-campus of the English and Foreign Languages University functions at Panakkad.[161] The district is also home to a subcentre of Kerala Agricultural University at Thavanur, and a subcentre of Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit at Tirunavaya. The headquarters of Darul Huda Islamic University is at Chemmad, Tirurangadi. INKEL Greens at Malappuram provides an educational zone with the industrial zone.[162] Eranad Knowledge City at Manjeri is a first of its kind project in the state.[163]

The areas that come under the Malappuram district have been multi-ethnic and multi-religious since the early medieval period. The centuries of trade across the Arabian Sea has given Malappuram a cosmopolitan population.[165] Religions practised in district include Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, and other minor religions.[166] Malappuram is one of the two districts with a Muslim majority in South India, the other being Lakshadweep district. Most of Christians in the district are descendants of Saint Thomas Christians who migrated from Northern Travancore to Malabar in the 20th century (Malabar Migration).[167]

The principal language used in the district is Malayalam. Arabi Malayalam script, also known as Ponnani Script, was used widely in the district in the past centuries. Minority Dravidian languages are Allar (around 350 speakers)[168] and Aranadan, (around 200 speakers).[169] Tamil is spoken by a small fraction of the people.

Malayalam is the predominant language, spoken by 99.46% of the population.[170]

The currently adopted Malayalam alphabet was first accepted by Thunchath Ezhuthachan, who was born at Tirur and is known as the father of the modern Malayalam language.[15] Tirur is the headquarters of the Malayalam Research Centre. Moyinkutty Vaidyar, the most renowned Mappila paattu poet was born at Kondotty. He is considered as one of the Mahakavis (a title for 'great poet') of Mappila songs.[15]

Besides Thunchath Ezhuthachan and Moyinkutty Vaidyar, the renowned writers of Malayalam including Achyutha Pisharadi, Alamkode Leelakrishnan, Edasseri Govindan Nair, K. P. Ramanunni, Kuttikrishna Marar, Kuttippuram Kesavan Nair, Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, N. Damodaran, Nandanar, Poonthanam Nambudiri, Pulikkottil Hyder, Uroob, V. C. Balakrishna Panicker, Vallathol Gopala Menon, and Vallathol Narayana Menon were natives of the district.[15] M. Govindan, M. T. Vasudevan Nair, and Akkitham Achuthan Namboothiri were the writers hailed from Ponnani Kalari based at Ponnani.[15] Nalapat Narayana Menon, Balamani Amma, V. T. Bhattathiripad, and Kamala Surayya, also hail from the erstwhile Ponnani taluk.

Malappuram was also the main centre of Mappila Paattu literature in the state.[15] Besides Moyinkutty Vaidyar and Pulikkottil Hyder, several Mappila Paattu poets including Kulangara Veettil Moidu Musliyar (popularly known as Chakkeeri Shujayi), Chakkeeri Moideenkutty, Manakkarakath Kunhikoya, Nallalam Beeran, K. K. Muhammad Abdul Kareem, Balakrishnan Vallikunnu, Punnayurkulam Bapu, Veliyankode Umar Qasi, etc., chose Malappuram as their working platform.[15]

The district has also given its own deposits to Kathakali, the classical art form of Kerala, and Ayurveda.[15] Kottakkal Chandrasekharan, Kottakkal Sivaraman, and Kottakkal Madhu are famous Kathakali artists hailed from Kottakkal Natya Sangam established by Vaidyaratnam P. S. Warrier in Kottakkal. The Veṭṭathunāṭu rulers, who had the control over parts of present-day Tirurangadi, Tirur, and Ponnani Taluks, were noted patrons of arts and learning. A Veṭṭathunāṭu Raja (r. 1630–1640) is said to have introduced innovations in the art form Kathakali, which has come to be known as the "Veṭṭathu Tradition".[171] Thunchath Ezhuthachchan and Vallathol Narayana Menon hail from Vettathunad. Vallathol Narayana Menon is also considered as the resurrector of Kathakali in the modern period through the establishment of Kerala Kalamandalam at Cheruthuruthi.[15] Vazhenkada Kunchu Nair, a major Kathakali trainer, and Sankaran Embranthiri and Tirur Nambissan, who were among the most popular Kathakali singers, were also from Malappuram.[15] Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma, who played a major role in resurrecting Mohiniyattam in the modern Kerala, hails from Tirunavaya in the district.[15] Mrinalini Sarabhai, an Indian classical dancer, hailed from erstwhile Ponnani taluk. Arya Vaidya Sala at Kottakkal is one of the largest Ayurvedic medicinal networks in the world.[15] Zainuddin Makhdoom II, the first known Keralite historian, also hails from the district.[15]

Kerala Varma Valiya Koyi Thampuran (Kerala Kalidasan), Raja Raja Varma (Kerala Panini) and Raja Ravi Varma (Famous Painter) are from different branches of Parappanad Royal Family, who later migrated from Parappanangadi to Harippad, Changanassery, Mavelikkara and Kilimanoor.[172] According to some scholars, the ancestors of Velu Thampi Dalawa also belong to Vallikkunnu near Parappanangadi. The Chief Editor of the daily "The Hindu" (1898 to 1905) and Founder Chief Editor of "The Indian Patriot" Divan Bahadur C. Karunakara Menon (1863–1922) was also from Parappanangadi.[173] O. Chandu Menon wrote his novels Indulekha and Saradha while he was the judge at Parappanangadi Munciff Court. Indulekha is also the first Major Novel written in Malayalam language. K. Madhavan Nair, the founder of Mathrubhumi Daily, comes from Malappuram. Ponnani region was the working platform of K. Kelappan, popularly known as Kerala Gandhi, A. V. Kuttimalu Amma, and Mohammed Abdur Rahiman, and several other freedom fighters.[15] Other independence activists from Ponnani taluk included Lakshmi Sehgal, V. T. Bhattathiripad, and Ammu Swaminathan. The ashes of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Lal Bahadur Shastri, were deposited in Kerala at Tirunavaya, on the bank of the river Bharathappuzha.[31][15] K. Madhavanar, who was the translator of Mahatma Gandhi's autobiography into Malayalam, was also a native of Malappuram.

Ponnani's trade relations with foreign countries since ancient times paved the way for a cultural exchange.[15] Persian-Arab art forms and North Indian culture came to Ponnani that way. There were resonances in the language as well. This is how the hybrid language Arabi-Malayalam came to be.[15] Many poems have been written in this hybrid language.[15] Qawwali and Ghazals from Hindustani, who came here as part of their cultural exchange, still thrive in Ponnani. EK Aboobacker, Main and Khalil Bhai (Khalil Rahman) are some of the famous Qawwali singers of Ponnani.

The headquarters of the Azhvanchery Thamprakkal, who were considered as the supreme religious head of Kerala Nambudiri Brahmins, was at Athavanad.[15] The original headquarters of the Palakkad Rajas were also at Athavanad.[39] Several aristocratic Nambudiri Manas are present in the Taluks of Tirur, Perinthalmanna, and Ponnani. Tirunavaya, the seat of the medieval Mamankam festival, is also present in the district. Perumpadappu, the ancestral headquarters of the Kingdom of Cochin, and Nediyiruppu, the ancestral headquarters of the Zamorin of Calicut, are also present in the district. The Kunhali Marakkars had close relationship with the port towns of Ponnani, Tanur, and Parappanangadi.[15] Some of the kings of Kingdom of Cochin in the 16th century CE, when Cochin became a major power on the Malabar Coast, were usually borrowed from the royal family of Kingdom of Tanur.[31] Many of the consorts of the queens of Travancore were usually selected from the Parappanad Royal family. E. M. S. Namboodiripad, the first Chief Minister of Kerala, hails from Perinthalmanna in the district.[15] Angadipuram and Mankada, the seats of the ruling families of the medieval Kingdom of Valluvanad, lie adjacent to Perinthalmanna.

During the medieval period, the district was a centre of Vedic as well as Islamic studies.[15] It is believed that Malik Dinar had visited the port town of Ponnani.[174] The Valiya Juma Masjid at Ponnani was one of the largest Islamic studies centre in Asia during the medieval period. Parameshvara, Nilakantha Somayaji, Jyeṣṭhadeva, Achyutha Pisharadi, and Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, who were the main members of the Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics hailed from Tirur region.[15] The Arabi Malayalam script, otherwise known as the Ponnani script, took its birth during the late 16th century and early 17th century.[15] The script was widely used in the district during the last centuries.[15]

Playwrights and actors from the district include K. T. Muhammed, Nilambur Balan, Nilambur Ayisha, Adil Ibrahim, Aneesh G. Menon, Aparna Nair, Baby Anikha, Dhanish Karthik, Hemanth Menon, Rashin Rahman, Ravi Vallathol, Sangita Madhavan Nair, Shwetha Menon, Sooraj Thelakkad, etc. Sukumaran, who is also the father of two notable actors as well as playback singers of Malayalam film industry namely Prithviraj Sukumaran and Indrajith Sukumaran, also was a native of the district. Playback singers including Krishnachandran, Parvathy Jayadevan, Shahabaz Aman, Sithara Krishnakumar, Sudeep Palanad, and Unni Menon also hail from the district. The district has also produced some notable film producers, lyricists, cinematographers, and directors including Aryadan Shoukath, Deepu Pradeep, Hari Nair, Iqbal Kuttippuram, Mankada Ravi Varma, Muhammad Musthafa, Muhsin Parari, Rajeev Nair, Salam Bappu, Shanavas K Bavakutty, Shanavas Naranippuzha, T. A. Razzaq, T. A. Shahid, Vinay Govind, and Zakariya Mohammed. Most notable painters from district include Artist Namboothiri, K. C. S. Paniker, and T. K. Padmini.[15] Another painter Akkitham Narayanan was from Kumaranellur. M. G. S. Narayanan, one among the most notable historians of Kerala, also hail from here.[15] Social reformers from the district include Veliyankode Umar Khasi (1757–1852), Chalilakath Kunahmed Haji, E. Moidu Moulavi, and Sayyid Sanaullah Makti Tangal (1847–1912).[15]

The centuries of maritime trade has given the Malappuram a cosmopolitan cuisine. The cuisine is a blend of traditional Kerala, Persian, Yemenese and Arab food culture.[175] One of the main elements of this cuisine is Pathiri, a pancake made of rice flour. Variants of Pathiri include Neypathiri (made with ghee), Poricha Pathiri (fried rather than baked), Meen Pathiri (stuffed with fish), and Irachi Pathiri (stuffed with beef). Spices like Black pepper, Cardamom, and Clove are widely used in the cuisine of Malappuram. The main item used in the festivals is the Malabar style of Biryani. Sadhya is also seen in marriage and festival occasions. Ponnani region of the district has a wide variety of indigenous dishes. Snacks such as Arikadukka, Chattipathiri, Muttamala, Pazham Nirachathu, and Unnakkaya have their own style in Ponnani. Besides these, other common food items of Kerala are also seen in the cuisine of Malappuram.[176] The Malabar version of Biryani, popularly known as Kuzhi Mandi in Malayalam is another popular item, which has an influence from Yemen.[175]

Malayala Manorama, Mathrubhumi, Madhyamam, Chandrika, Deshabhimani, Suprabhaatham, and Siraj dailies have their printing centres in and around the Malappuram city. The Hindu has an edition and printing press at Malappuram. A few periodicals-monthlies, fortnightlies and weeklies-mostly devoted to religion and culture are also published. Almost all Malayalam channels and newspapers have their bureau at Up Hill. There are so many local cable visions and their regional media. Malappuram Press Club is also situated at Uphill adjacent to Municipal Town Hall. Doordarshan has two major relay stations in the district at Malappuram and Manjeri. The government of India's Prasar Bharati National Public Service Broadcaster has an FM station in the district (AIR Manjeri FM), broadcasting on 102.7 Mhtz. Even without any private FM stations, Malappuram, Ponnani, and Tirur find their own places in the ten towns with the highest radio listenership in India.[177]

Malappuram is often known as The Mecca of Kerala Football.[178][179] Malappuram District Sports Complex & Football Academy is situated at Payyanad in Manjeri. MDSC Stadium was selected as one of two stadiums, along with the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, to host the group stages of the 2013–14 Indian Federation Cup.[180] The stadium hosted groups B and D.[180] Kottappadi Football Stadium is a historic football stadium. Other major stadiums include the Rajiv Gandhi Municipal Stadium at Tirur, and the Perinthalmanna Cricket Stadium at Perinthalmanna. A synthetic track is there along with the Tirur Municipal Stadium. Malabar Premier League was initiated in 2015 to strengthen football in the district.[181] The Calicut University Synthetic Track at Tenhipalam is the apex synthetic track in the district. It is associated with the C. H. Muhammad Koya Stadium at Tenhipalam.[182] Other major stadiums of district include those at Areekode, Kottakkal, and Ponnani. A football hub to internationalise the eight major football stadiums of district is proposed.[183] The construction works of two new stadium complexes are being processed in Tanur and Nilambur.[184]

For a few years, the demand to create a new coastal district called Tirur district, centered at Tirur is being strengthened.[252] They argue that it is imperative from the development perspective to split the district, with double the population and size of the Alappuzha district, into two. No other district in Kerala has seven subdistricts, 94 Village Panchayats, and 12 municipalities together. As for its extent, if one travels from Perumbadappu which borders Thrissur district to Vazhikkadavu bordering Tamil Nadu, normally it takes more than three hours to cover that distance of 115 km. They also point out that the problems in the health and educational sectors that require solutions are not trivial. The issue was raised again by the IUML MLA K. N. A. Khader in 2019.[252] The demand is to bifurcate the existing Malappuram district into two districts by carving out a new one called Tirur district from it.[252] Kerala Congress (M) campaigns for a new district centred at Edappal.[253] Some people including Veteran Congress leader Aryadan Muhammad, and IUML district secretary U. A. Latheef oppose the bifurcation of Malappuram.[254][255]

However, the demand was rejected by the two successive governments who ruled Kerala in 2013 and in 2019.[254][255] But the studies regarding the bifurcation of the district are still in the consideration of the Government of Kerala.

One example I can give you relates to the Indian Mādhava's demonstration, in about 1400 A.D., of the infinite power series of trigonometrical functions using geometrical and algebraic arguments. When this was first described in English by Charles Whish, in the 1830s, it was heralded as the Indians' discovery of the calculus. This claim and Mādhava's achievements were ignored by Western historians, presumably at first because they could not admit that an Indian discovered the calculus, but later because no one read anymore the Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society, in which Whish's article was published. The matter resurfaced in the 1950s, and now we have the Sanskrit texts properly edited, and we understand the clever way that Mādhava derived the series without the calculus, but many historians still find it impossible to conceive of the problem and its solution in terms of anything other than the calculus and proclaim that the calculus is what Mādhava found. In this case, the elegance and brilliance of Mādhava's mathematics are being distorted as they are buried under the current mathematical solution to a problem to which he discovered an alternate and powerful solution.