El Gulag [c] [d] fue un sistema de campos de trabajos forzados en la Unión Soviética . [10] [11] [12] [9] La palabra Gulag originalmente se refería solo a la división de la policía secreta soviética que estaba a cargo de administrar los campos de trabajos forzados desde la década de 1930 hasta principios de la década de 1950 durante el gobierno de Joseph Stalin , pero en la literatura inglesa el término se usa popularmente para el sistema de trabajo forzado durante la era soviética . La abreviatura GULAG (ГУЛАГ) significa " Г ла́вное У правле́ние исправи́тельно-трудовы́х ЛАГ ере́й" (Dirección Principal de Campos de Trabajo Correccionales ), pero el nombre oficial completo de la agencia cambió varias veces.

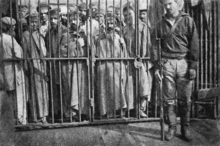

El Gulag es reconocido como un importante instrumento de represión política en la Unión Soviética . Los campos albergaban tanto a delincuentes comunes como a prisioneros políticos , un gran número de los cuales fueron condenados mediante procedimientos simplificados, como las troikas de la NKVD u otros instrumentos de castigo extrajudicial . En 1918-1922, la agencia fue administrada por la Cheka , seguida por la GPU (1922-1923), la OGPU (1923-1934), más tarde conocida como NKVD (1934-1946), y el Ministerio del Interior (MVD) en los últimos años. El campo de prisioneros de Solovki , el primer campo de trabajo correccional que se construyó después de la revolución, fue inaugurado en 1918 y legalizado por un decreto, "Sobre la creación de los campos de trabajos forzados", el 15 de abril de 1919.

El sistema de internamiento creció rápidamente, alcanzando una población de 100.000 personas en la década de 1920. A finales de 1940, la población de los campos de Gulag ascendía a 1,5 millones. [13] El consenso emergente entre los académicos es que, de los 14 millones de prisioneros que pasaron por los campos de Gulag y los 4 millones de prisioneros que pasaron por las colonias de Gulag entre 1930 y 1953, aproximadamente entre 1,5 y 1,7 millones de prisioneros perecieron allí o murieron poco después de ser liberados. [1] [2] [3] Algunos periodistas y escritores que cuestionan la fiabilidad de tales datos se basan en gran medida en fuentes de memorias que llegan a estimaciones más altas. [1] [7] Los investigadores de archivos no han encontrado "ningún plan de destrucción" de la población del gulag ni ninguna declaración de intención oficial de matarlos, y las liberaciones de prisioneros excedieron ampliamente el número de muertes en el gulag. [1] Esta política puede atribuirse en parte a la práctica común de liberar a prisioneros que padecían enfermedades incurables, así como a prisioneros que estaban cerca de morir. [13] [14]

Casi inmediatamente después de la muerte de Stalin , el establishment soviético comenzó a desmantelar el sistema Gulag. Una amnistía general masiva fue otorgada inmediatamente después de la muerte de Stalin, pero sólo se ofreció a los presos no políticos y a los presos políticos que habían sido sentenciados a un máximo de cinco años de prisión. Poco después, Nikita Khrushchev fue elegido Primer Secretario , iniciando los procesos de desestalinización y el deshielo de Khrushchev , desencadenando una liberación masiva y rehabilitación de presos políticos. Seis años después, el 25 de enero de 1960, el sistema Gulag fue abolido oficialmente cuando los restos de su administración fueron disueltos por Khrushchev. La práctica legal de condenar a los convictos a trabajos forzados sigue existiendo en la Federación Rusa , pero su capacidad se ha reducido considerablemente. [15] [16]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn , ganador del Premio Nobel de Literatura , que sobrevivió ocho años de encarcelamiento en el Gulag, dio al término su reputación internacional con la publicación de El archipiélago Gulag en 1973. El autor comparó los campos dispersos con " una cadena de islas ", y como testigo ocular, describió el Gulag como un sistema donde la gente trabajaba hasta la muerte. [17] En marzo de 1940, había 53 direcciones de campos Gulag (simplemente denominados "campos") y 423 colonias de trabajo en la Unión Soviética. [4] Muchas ciudades y pueblos mineros e industriales en el norte de Rusia, el este de Rusia y Kazajstán, como Karaganda , Norilsk , Vorkuta y Magadan , eran bloques de campos que originalmente fueron construidos por prisioneros y posteriormente administrados por ex prisioneros. [18]

GULAG (ГУЛАГ) significa "Гла́вное управле́ние испави́тельно-трудовы́х лагере́й" (Dirección Principal de Campos de Trabajo Correccionales ) . Se le cambió el nombre varias veces, por ejemplo, a Dirección Principal de Colonias de Trabajo Correccional ( Главное управление исправительно-трудовых колоний (ГУИТК) ), cuyos nombres se pueden ver en los documentos que describen la subordinación de varios campos. [19]

Algunos historiadores estiman que 14 millones de personas fueron encarceladas en los campos de trabajo del Gulag entre 1929 y 1953 (las estimaciones para el período de 1918 a 1929 son más difíciles de calcular). [20] Otros cálculos, del historiador Orlando Figes , se refieren a 25 millones de prisioneros del Gulag entre 1928 y 1953. [21] Otros 6-7 millones fueron deportados y exiliados a áreas remotas de la URSS , y 4-5 millones pasaron por colonias de trabajo , más3,5 millonesque ya estaban en asentamientos laborales o habían sido enviados a ellos . [20]

Según algunas estimaciones, la población total de los campos varió de 510.307 en 1934 a 1.727.970 en 1953. [4] Según otras estimaciones, a principios de 1953 el número total de prisioneros en los campos de prisioneros era más de 2,4 millones, de los cuales más de 465.000 eran prisioneros políticos. [22] [23] Entre los años 1934 y 1953, entre el 20% y el 40% de la población del Gulag en cada año determinado fue liberada. [24] [25]

El análisis institucional del sistema de concentración soviético se complica por la distinción formal entre GULAG y GUPVI. GUPVI (ГУПВИ) era la Administración Principal para Asuntos de Prisioneros de Guerra e Internos ( Главное управление по делам военнопленных и интернированных , Glavnoye upravleniye po delam voyennoplennyh i internirovannyh ), un departamento de NKVD (más tarde MVD) a cargo del manejo de los internados civiles extranjeros y prisioneros de guerra (prisioneros de guerra) en la Unión Soviética durante y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial (1939-1953). En muchos aspectos, el sistema GUPVI era similar al GULAG. [26]

Su función principal era la organización del trabajo forzado extranjero en la Unión Soviética . La alta dirección del GUPVI provenía del sistema GULAG. La principal distinción que se observa en las memorias con respecto al GULAG era la ausencia de criminales convictos en los campos del GUPVI. Por lo demás, las condiciones en ambos sistemas de campos eran similares: trabajos forzados, mala nutrición y malas condiciones de vida, y alta tasa de mortalidad. [27]

En el caso de los prisioneros políticos soviéticos, como Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn , todos los detenidos civiles extranjeros y los prisioneros de guerra extranjeros fueron encarcelados en el GULAG; los civiles extranjeros y prisioneros de guerra supervivientes se consideraban prisioneros del GULAG. Según las estimaciones, en total, durante todo el período de existencia del GUPVI, hubo más de 500 campos de prisioneros de guerra (dentro de la Unión Soviética y en el extranjero), que encarcelaron a más de 4.000.000 de prisioneros de guerra. [28] La mayoría de los reclusos del Gulag no eran prisioneros políticos, aunque se podía encontrar un número significativo de prisioneros políticos en los campos en cualquier momento. [22]

Los delitos menores y las bromas sobre el gobierno soviético y sus funcionarios se castigaban con prisión. [29] [30] Aproximadamente la mitad de los prisioneros políticos en los campos de Gulag fueron encarcelados " por medios administrativos ", es decir, sin juicio en los tribunales; los datos oficiales sugieren que hubo más de 2,6 millones de sentencias de prisión en casos investigados por la policía secreta entre 1921 y 1953. [31] Las sentencias máximas variaban según el tipo de delito y cambiaban con el tiempo. A partir de 1953, la sentencia máxima por hurto menor era de seis meses, [32] habiendo sido anteriormente de un año y siete años. Sin embargo, el robo de propiedad estatal tenía una sentencia mínima de siete años y una máxima de veinticinco. [33] En 1958, la sentencia máxima por cualquier delito se redujo de veinticinco a quince años. [34]

En 1960, el Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores dejó de funcionar como administración de los campos a nivel soviético y se convirtió en una institución independiente en la República. Las administraciones centralizadas de detención dejaron de funcionar temporalmente. [35] [36]

Aunque el término Gulag se utilizó originalmente en referencia a una agencia gubernamental, en inglés y en muchos otros idiomas, el acrónimo adquirió las cualidades de un sustantivo común, que denota el sistema soviético de trabajo no libre basado en prisiones . [37]

En un sentido más amplio, "Gulag" ha llegado a significar el propio sistema represivo soviético, el conjunto de procedimientos que los prisioneros alguna vez llamaron la "picadora de carne": los arrestos, los interrogatorios, el transporte en vagones de ganado sin calefacción, el trabajo forzado, la destrucción de familias, los años pasados en el exilio, las muertes tempranas e innecesarias.

Los autores occidentales utilizan el término Gulag para designar todas las prisiones y campos de internamiento de la Unión Soviética. El uso contemporáneo del término a veces no está directamente relacionado con la URSS, como en la expresión " Gulag de Corea del Norte " [38] para los campos que funcionan hoy en día. [39]

La palabra gulag no se utilizaba mucho en ruso, ni oficialmente ni en el lenguaje cotidiano; los términos predominantes eran campos (лагеря, lagerya ) y zona (зона, zona ), normalmente en singular, para referirse al sistema de campos de trabajo y a los campos individuales. El término oficial, " campo de trabajo correccional ", fue propuesto para su uso oficial por el Politburó del Partido Comunista de la Unión Soviética en la sesión del 27 de julio de 1929.

Tanto el zar como el Imperio ruso utilizaban el exilio forzado y el trabajo forzado como formas de castigo judicial. La katorga , una categoría de castigo que estaba reservada para aquellos que eran condenados por los delitos más graves, tenía muchas de las características que se asociaban con el encarcelamiento en campos de trabajo: confinamiento, instalaciones simplificadas (a diferencia de las instalaciones que existían en las cárceles) y trabajo forzado, que generalmente implicaba trabajo duro, no calificado o semicalificado. Según la historiadora Anne Applebaum , la katorga no era una sentencia común; aproximadamente 6.000 convictos de katorga cumplían sentencias en 1906 y 28.600 en 1916. [40] Bajo el sistema penal imperial ruso, aquellos que eran condenados por delitos menos graves eran enviados a prisiones correctivas y también eran obligados a trabajar. [41]

El exilio forzado a Siberia se había utilizado para una amplia gama de delitos desde el siglo XVII y era un castigo común para los disidentes políticos y revolucionarios. En el siglo XIX, los miembros de la fallida revuelta decembrista y los nobles polacos que resistieron el dominio ruso fueron enviados al exilio. Fiódor Dostoievski fue condenado a muerte por leer literatura prohibida en 1849, pero la sentencia fue conmutada por el destierro a Siberia. Los miembros de varios grupos revolucionarios socialistas, incluidos bolcheviques como Sergo Ordzhonikidze , Vladímir Lenin , León Trotski y José Stalin también fueron enviados al exilio. [42]

Los presos que cumplían condenas de trabajos forzados y exiliados eran enviados a las zonas despobladas de Siberia y el Lejano Oriente ruso , regiones que carecían de ciudades o fuentes de alimentos, así como de sistemas de transporte organizados. A pesar de las condiciones de aislamiento, algunos prisioneros lograron escapar a zonas pobladas. El propio Stalin escapó tres de las cuatro veces que fue enviado al exilio. [43] Desde entonces, Siberia adquirió su temible connotación de lugar de castigo, una reputación que se vio reforzada aún más por el sistema soviético GULAG. Las propias experiencias de los bolcheviques con el exilio y el trabajo forzado les proporcionaron un modelo en el que podían basar su propio sistema, incluida la importancia de la aplicación estricta de las normas.

Entre 1920 y 1950, los dirigentes del Partido Comunista y del Estado soviético consideraron la represión como una herramienta que debían utilizar para asegurar el funcionamiento normal del sistema estatal soviético y preservar y fortalecer sus posiciones dentro de su base social, la clase obrera (cuando los bolcheviques tomaron el poder, los campesinos representaban el 80% de la población). [44]

En medio de la Guerra Civil Rusa , Lenin y los bolcheviques establecieron un sistema de campos de prisioneros "especiales", separado de su sistema penitenciario tradicional y bajo el control de la Cheka . [45] Estos campos, como los imaginó Lenin, tenían un propósito claramente político. [46] Estos primeros campos del sistema GULAG se introdujeron para aislar y eliminar elementos ajenos a la clase, socialmente peligrosos, disruptivos, sospechosos y otros elementos desleales, cuyos actos y pensamientos no contribuían al fortalecimiento de la dictadura del proletariado . [44]

El trabajo forzado como "método de reeducación" se aplicó en el campo de prisioneros de Solovki ya en la década de 1920, [47] basándose en los experimentos de Trotsky con campos de trabajos forzados para prisioneros de guerra checos a partir de 1918 y sus propuestas de introducir el "servicio de trabajo obligatorio" expresadas en Terrorismo y comunismo . [47] [48] Estos campos de concentración no eran idénticos a los campos estalinistas o hitlerianos, sino que se introdujeron para aislar a los prisioneros de guerra dada la situación histórica extrema posterior a la Primera Guerra Mundial . [49]

Se definieron varias categorías de prisioneros: delincuentes menores, prisioneros de guerra de la Guerra Civil Rusa , funcionarios acusados de corrupción, sabotaje y malversación de fondos, enemigos políticos, disidentes y otras personas consideradas peligrosas para el Estado. En la primera década del régimen soviético, los sistemas judicial y penal no estaban unificados ni coordinados, y existía una distinción entre presos criminales y presos políticos o "especiales".

El sistema judicial y penitenciario "tradicional", que se ocupaba de los presos criminales, fue supervisado primero por el Comisariado Popular de Justicia hasta 1922, después de lo cual fue supervisado por el Comisariado Popular de Asuntos Internos, también conocido como NKVD . [50] La Cheka y sus organizaciones sucesoras, la GPU o Dirección Política Estatal y la OGPU , supervisaban a los presos políticos y los campos "especiales" a los que eran enviados. [51] En abril de 1929, se eliminaron las distinciones judiciales entre presos criminales y políticos, y el control de todo el sistema penal soviético pasó a manos de la OGPU. [52] En 1928, había 30.000 personas internadas; las autoridades se oponían al trabajo forzado. En 1927, el funcionario a cargo de la administración penitenciaria escribió:

La explotación del trabajo penitenciario, el sistema de exprimirles "sudor dorado", la organización de la producción en los lugares de confinamiento, que si bien es rentable desde un punto de vista comercial, carece fundamentalmente de importancia correctiva, son completamente inadmisibles en los lugares de confinamiento soviéticos. [53]

La base legal y la orientación para la creación del sistema de "campos de trabajo correctivo" ( исправи́тельно-трудовые лагеря , Ispravitel'no-trudovye lagerya ), la columna vertebral de lo que comúnmente se conoce como el "Gulag", fue un decreto secreto del Sovnarkom del 11 de julio de 1929, sobre el uso del trabajo penal que duplicaba el apéndice correspondiente a las actas de la reunión del Politburó del 27 de junio de 1929. [ cita requerida ] [54]

Uno de los fundadores del sistema Gulag fue Naftaly Frenkel . En 1923, fue arrestado por cruzar fronteras ilegalmente y contrabando. Fue sentenciado a 10 años de trabajos forzados en Solovki , que más tarde se conocería como el "primer campo del Gulag". Mientras cumplía su condena, escribió una carta a la administración del campo detallando una serie de propuestas de "mejora de la productividad", incluido el infame sistema de explotación laboral por el cual las raciones de comida de los reclusos debían estar vinculadas a su tasa de producción, una propuesta conocida como escala de nutrición (шкала питания). Este notorio sistema de "comer mientras se trabaja" a menudo mataba a los prisioneros más débiles en semanas y causaba innumerables bajas. La carta llamó la atención de varios altos funcionarios comunistas, incluido Genrikh Yagoda , y Frenkel pronto pasó de ser un recluso a convertirse en comandante del campo y en un importante funcionario del Gulag. Sus propuestas pronto fueron ampliamente adoptadas en el sistema Gulag. [55]

Después de haber aparecido como instrumento y lugar de aislamiento de elementos contrarrevolucionarios y criminales, el Gulag, gracias a su principio de "corrección mediante trabajos forzados", se convirtió rápidamente, de hecho, en una rama independiente de la economía nacional, asegurada gracias a la mano de obra barata proporcionada por los prisioneros. De ahí otra razón importante para la constancia de la política represiva: el interés del Estado en recibir sin cesar una mano de obra barata que se utilizaba por la fuerza, sobre todo en las condiciones extremas del este y del norte. [44] El Gulag tenía funciones tanto punitivas como económicas. [56]

El Gulag era un organismo administrativo que vigilaba los campos; con el tiempo su nombre se utilizaría para estos campos de forma retroactiva. Después de la muerte de Lenin en 1924, Stalin pudo tomar el control del gobierno y comenzó a formar el sistema de gulag. El 27 de junio de 1929, el Politburó creó un sistema de campos autosuficientes que eventualmente reemplazarían a las cárceles existentes en todo el país. [57] Estas cárceles estaban destinadas a recibir a los reclusos que recibieron una sentencia de prisión que excediera los tres años. Los prisioneros que tenían una sentencia de prisión más corta que tres años debían permanecer en el sistema penitenciario que todavía estaba bajo la jurisdicción de la NKVD .

El propósito de estos nuevos campos era colonizar los entornos remotos e inhóspitos de toda la Unión Soviética. Estos cambios se produjeron casi al mismo tiempo que Stalin empezó a instituir la colectivización y el rápido desarrollo industrial. La colectivización dio lugar a una purga a gran escala de campesinos y de los llamados kulaks . Los kulaks eran supuestamente ricos, en comparación con otros campesinos soviéticos, y el Estado los consideraba capitalistas y, por extensión, enemigos del socialismo. El término también se asociaría con cualquiera que se opusiera o pareciera insatisfecho con el gobierno soviético.

A finales de 1929, Stalin inició un programa conocido como deskulakización . Stalin exigió que la clase kulak fuera completamente aniquilada, lo que resultó en el encarcelamiento y ejecución de campesinos soviéticos. En apenas cuatro meses, 60.000 personas fueron enviadas a los campos y otras 154.000 exiliadas. Sin embargo, esto fue sólo el comienzo del proceso de deskulakización . Sólo en 1931, 1.803.392 personas fueron exiliadas. [58]

Aunque estos procesos de reubicación masiva tuvieron éxito en conseguir que una gran cantidad de mano de obra forzada libre llegara a donde necesitaba estar, eso fue todo lo que lograron. Los " colonos especiales ", como los llamaba el gobierno soviético, vivían todos con raciones de hambre, y mucha gente murió de hambre en los campos, y cualquiera que estaba lo suficientemente sano como para escapar trató de hacerlo. Esto dio como resultado que el gobierno tuviera que dar raciones a un grupo de personas a las que no les hacía casi ningún uso, y que solo le costaba dinero al gobierno soviético. La Administración Política Estatal Unificada (OGPU) se dio cuenta rápidamente del problema y comenzó a reformar el proceso de deskulakización . [59]

Para ayudar a prevenir las fugas en masa, la OGPU comenzó a reclutar gente dentro de la colonia para ayudar a detener a la gente que intentaba irse, y preparó emboscadas alrededor de las rutas de escape más conocidas. La OGPU también intentó mejorar las condiciones de vida en estos campos para que no animaran a la gente a intentar escapar activamente, y se prometió a los kulaks que recuperarían sus derechos después de cinco años. Incluso estas revisiones finalmente no lograron resolver el problema, y el proceso de deskulakización fue un fracaso en proporcionar al gobierno una fuerza laboral forzada estable. Estos prisioneros también tuvieron suerte de estar en el gulag a principios de la década de 1930. Los prisioneros estaban relativamente bien en comparación con lo que tendrían que pasar los prisioneros en los años finales del gulag. [59] El gulag se estableció oficialmente el 25 de abril de 1930, como GULAG por la orden 130/63 de la OGPU de acuerdo con la orden 22 p. 248 del 7 de abril de 1930. En noviembre de ese año pasó a llamarse GULAG. [60]

La hipótesis de que las consideraciones económicas fueron responsables de los arrestos masivos durante el período del estalinismo ha sido refutada sobre la base de antiguos archivos soviéticos que se han vuelto accesibles desde la década de 1990, aunque algunas fuentes de archivo también tienden a apoyar una hipótesis económica. [61] [62] En cualquier caso, el desarrollo del sistema de campos siguió líneas económicas. El crecimiento del sistema de campos coincidió con el auge de la campaña de industrialización soviética . La mayoría de los campos establecidos para acomodar a las masas de prisioneros entrantes fueron asignados a tareas económicas distintas. [ cita requerida ] Estas incluían la explotación de los recursos naturales y la colonización de áreas remotas, así como la realización de enormes instalaciones de infraestructura y proyectos de construcción industrial. El plan para lograr estos objetivos con " asentamientos especiales " en lugar de campos de trabajo fue abandonado después de la revelación del asunto Nazino en 1933.

Los archivos de 1931-32 indican que el Gulag tenía aproximadamente 200.000 prisioneros en los campos; mientras que en 1935, aproximadamente 800.000 estaban en campos y 300.000 en colonias. [63] La población del Gulag alcanzó un valor máximo (1,5 millones) en 1941, disminuyó gradualmente durante la guerra y luego comenzó a crecer de nuevo, alcanzando un máximo en 1953. [4] Además de los campos del Gulag, una cantidad significativa de prisioneros, que confinaban a los prisioneros que cumplían condenas cortas. [4]

A principios de la década de 1930, un endurecimiento de la política penal soviética provocó un crecimiento significativo de la población de los campos de prisioneros. [64]

Durante la Gran Purga de 1937-38, las detenciones masivas provocaron otro aumento del número de reclusos. Cientos de miles de personas fueron detenidas y condenadas a largas penas de prisión en virtud de uno de los múltiples pasajes del famoso artículo 58 de los Códigos Penales de las repúblicas de la Unión, que definía el castigo para diversas formas de "actividades contrarrevolucionarias". En virtud de la Orden Nº 00447 de la NKVD , decenas de miles de reclusos del Gulag fueron ejecutados en 1937-38 por "continuar con actividades contrarrevolucionarias".

Entre 1934 y 1941, el número de prisioneros con educación superior aumentó más de ocho veces, y el número de prisioneros con educación superior aumentó cinco veces. [44] Esto resultó en un aumento de su participación en la composición general de los prisioneros del campo. [44] Entre los prisioneros del campo, el número y la participación de la intelectualidad estaba creciendo al ritmo más rápido. [44] La desconfianza, la hostilidad e incluso el odio hacia la intelectualidad era una característica común de los líderes soviéticos. [44] La información sobre las tendencias de encarcelamiento y las consecuencias para la intelectualidad proviene de las extrapolaciones de Viktor Zemskov a partir de una recopilación de datos sobre los movimientos de población de los campos de prisioneros. [44] [65]

En vísperas de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los archivos soviéticos indican que la población combinada de los campos y colonias superaba los 1,6 millones en 1939, según VP Kozlov. [63] Anne Applebaum y Steven Rosefielde estiman que entre 1,2 y 1,5 millones de personas estaban en los campos de prisioneros y colonias del sistema Gulag cuando comenzó la guerra. [66] [67]

Después de la invasión alemana de Polonia que marcó el inicio de la Segunda Guerra Mundial en Europa, la Unión Soviética invadió y anexó partes orientales de la Segunda República Polaca . En 1940, la Unión Soviética ocupó Estonia , Letonia , Lituania , Besarabia (ahora la República de Moldavia) y Bucovina . Según algunas estimaciones, cientos de miles de ciudadanos polacos [68] [69] y habitantes de las otras tierras anexadas, independientemente de su origen étnico, fueron arrestados y enviados a los campos de Gulag. Sin embargo, según los datos oficiales, el número total de sentencias por delitos políticos y contra el Estado (espionaje, terrorismo) en la URSS en 1939-41 fue de 211.106. [31]

Aproximadamente 300.000 prisioneros de guerra polacos fueron capturados por la URSS durante y después de la "Guerra Defensiva Polaca" . [70] Casi todos los oficiales capturados y un gran número de soldados rasos fueron asesinados (véase la masacre de Katyn ) o enviados al Gulag. [71] De los 10.000–12.000 polacos enviados a Kolymá en 1940–41, la mayoría prisioneros de guerra , solo sobrevivieron 583 hombres, liberados en 1942 para unirse a las Fuerzas Armadas Polacas en el Este . [72] De los 80.000 evacuados del general Anders de la Unión Soviética reunidos en Gran Bretaña, solo 310 se ofrecieron como voluntarios para regresar a la Polonia controlada por los soviéticos en 1947. [73]

Durante la Gran Guerra Patria , la población de los gulags disminuyó drásticamente debido a un pronunciado aumento de la mortalidad en 1942-43. En el invierno de 1941, una cuarta parte de la población del gulag murió de hambre . [74] 516.841 prisioneros murieron en los campos de prisioneros entre 1941 y 1943, [75] [76] debido a una combinación de sus duras condiciones de trabajo y la hambruna causada por la invasión alemana. Este período representa aproximadamente la mitad de todas las muertes en los gulags, según las estadísticas rusas.

En 1943 se volvió a introducir el término « trabajos de catorce días » ( каторжные работы ). En un principio, se destinaban a los colaboradores nazis , pero luego también se condenaba a «trabajos de catorce días» a otras categorías de presos políticos (por ejemplo, miembros de pueblos deportados que huían del exilio). Los presos condenados a «trabajos de catorce días» eran enviados a campos de prisioneros del gulag con el régimen más severo y muchos de ellos perecían. [76]

Hasta la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el sistema de gulag se expandió drásticamente para crear una "economía de campo" soviética. Justo antes de la guerra, el trabajo forzado proveía el 46,5% del níquel , el 76% del estaño , el 40% del cobalto , el 40,5% del mineral de cromo y hierro, el 60% del oro y el 25,3% de la madera del país. [77] Y, en preparación para la guerra, la NKVD construyó muchas más fábricas y carreteras y ferrocarriles.

El Gulag pasó rápidamente a la producción de armas y suministros para el ejército después de que comenzaran los combates. Al principio, el transporte siguió siendo una prioridad. En 1940, la NKVD centró la mayor parte de su energía en la construcción de ferrocarriles. [78] Esto resultaría extremadamente importante cuando comenzó el avance alemán en la Unión Soviética en 1941. Además, las fábricas se reconvirtieron para producir municiones, uniformes y otros suministros. Además, la NKVD reunió a trabajadores cualificados y especialistas de todo el Gulag en 380 colonias especiales que producían tanques, aviones, armamento y municiones. [77]

A pesar de sus bajos costos de capital, la economía de los campos adolecía de graves defectos. Por un lado, la productividad real casi nunca coincidía con las estimaciones: éstas resultaban demasiado optimistas. Además, la escasez de maquinaria y herramientas asolaba los campos y las herramientas que tenían se estropeaban rápidamente. El Trust de Siberia Oriental de la Administración Principal de Campos para la Construcción de Carreteras destruyó noventa y cuatro camiones en sólo tres años. [77] Pero el mayor problema era simple: el trabajo forzado era menos eficiente que el trabajo libre. De hecho, los prisioneros del Gulag eran, en promedio, la mitad de productivos que los trabajadores libres en la URSS en ese momento, [77] lo que puede explicarse en parte por la desnutrición.

Para compensar esta disparidad, la NKVD hizo trabajar a los prisioneros más duro que nunca. Para satisfacer la creciente demanda, los prisioneros trabajaban cada vez más horas y con raciones de comida más bajas que nunca. Un administrador del campo dijo en una reunión: "Hay casos en los que a un prisionero sólo se le dan cuatro o cinco horas de veinticuatro para descansar, lo que reduce significativamente su productividad". En palabras de un ex prisionero del Gulag: "En la primavera de 1942, el campo dejó de funcionar. Era difícil encontrar personas que fueran capaces incluso de recoger leña o enterrar a los muertos". [77]

La escasez de alimentos se debió en parte a la tensión general que atravesaba toda la Unión Soviética, pero también a la falta de ayuda central al Gulag durante la guerra. El gobierno central centró toda su atención en el ejército y dejó que los campos se las arreglaran solos. En 1942, el Gulag creó la Administración de Suministros para encontrar sus propios alimentos y productos industriales. Durante este tiempo, no sólo escaseó la comida, sino que la NKVD limitó las raciones en un intento de motivar a los prisioneros a trabajar más duro para conseguir más comida, una política que duró hasta 1948. [79]

Además de la escasez de alimentos, el Gulag sufrió escasez de mano de obra al comienzo de la guerra. El Gran Terror de 1936-1938 había proporcionado una gran cantidad de mano de obra gratuita, pero al comienzo de la Segunda Guerra Mundial las purgas se habían ralentizado. Para completar todos sus proyectos , los administradores de los campos trasladaron a los prisioneros de un proyecto a otro. [78] Para mejorar la situación, a mediados de 1940 se implementaron leyes que permitían dar sentencias cortas en los campos (4 meses o un año) a los condenados por robo menor, vandalismo o infracciones a la disciplina laboral. En enero de 1941, la fuerza laboral del Gulag había aumentado en aproximadamente 300.000 prisioneros. [78] Pero en 1942, comenzó una grave escasez de alimentos y la población de los campos volvió a descender. Los campos perdieron aún más prisioneros en el esfuerzo bélico cuando la Unión Soviética entró en pie de guerra total en junio de 1941. Muchos trabajadores recibieron liberaciones anticipadas para que pudieran ser reclutados y enviados al frente. [79]

Aunque el número de trabajadores se reducía, la demanda de productos seguía creciendo rápidamente. Como resultado, el gobierno soviético presionó al Gulag para que "hiciera más con menos". Con menos trabajadores aptos para trabajar y pocos suministros provenientes de fuera del sistema de campos, los administradores de los campos tuvieron que encontrar una manera de mantener la producción. La solución que encontraron fue presionar aún más a los prisioneros que quedaban. La NKVD empleó un sistema de establecer metas de producción irrealmente altas, agotando los recursos en un intento de alentar una mayor productividad. A medida que los ejércitos del Eje avanzaron en territorio soviético a partir de junio de 1941, los recursos laborales se vieron aún más limitados y muchos de los campos tuvieron que evacuarse de Rusia occidental. [79]

Desde el comienzo de la guerra hasta mediados de 1944, se establecieron 40 campos y se desmantelaron 69. Durante las evacuaciones, la maquinaria tuvo prioridad, dejando a los prisioneros para que llegaran a salvo a pie. La velocidad del avance de la Operación Barbarroja impidió la evacuación de todos los prisioneros a tiempo, y la NKVD masacró a muchos para evitar que cayeran en manos alemanas . Si bien esta práctica negó a los alemanes una fuente de mano de obra gratuita, también restringió aún más la capacidad del Gulag para satisfacer las demandas del Ejército Rojo. Sin embargo, cuando cambió el rumbo de la guerra y los soviéticos comenzaron a hacer retroceder a los invasores del Eje, nuevos grupos de trabajadores reabastecieron los campos. A medida que el Ejército Rojo recuperaba territorios de los alemanes, una afluencia de ex prisioneros de guerra soviéticos aumentó enormemente la población del Gulag. [79]

Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el número de reclusos en campos de prisioneros y colonias aumentó bruscamente nuevamente, llegando a aproximadamente 2,5 millones de personas a principios de la década de 1950 (de las cuales alrededor de 1,7 millones estaban en campos).

Cuando la guerra en Europa terminó en mayo de 1945, hasta dos millones de antiguos ciudadanos rusos fueron repatriados por la fuerza a la URSS . [80] El 11 de febrero de 1945, al concluir la Conferencia de Yalta , Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido firmaron un Acuerdo de Repatriación con la Unión Soviética. [81] Una interpretación de este acuerdo resultó en la repatriación forzosa de todos los soviéticos. Las autoridades civiles británicas y estadounidenses ordenaron a sus fuerzas militares en Europa que deportaran a la Unión Soviética hasta dos millones de antiguos residentes de la Unión Soviética, incluidas personas que habían abandonado el Imperio ruso y establecido una ciudadanía diferente años antes. Las operaciones de repatriación forzosa tuvieron lugar entre 1945 y 1947. [82]

Varias fuentes afirman que los prisioneros de guerra soviéticos , a su regreso a la Unión Soviética, fueron tratados como traidores (ver Orden No. 270 ). [83] [84] [85] Según algunas fuentes, más de 1,5 millones de soldados supervivientes del Ejército Rojo encarcelados por los alemanes fueron enviados al Gulag. [86] [87] [88] Sin embargo, eso es una confusión con otros dos tipos de campos. Durante y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los prisioneros de guerra liberados fueron a campos especiales de "filtración". De estos, en 1944, más del 90 por ciento fueron absueltos y alrededor del 8 por ciento fueron arrestados o condenados a batallones penales. En 1944, fueron enviados directamente a formaciones militares de reserva para ser absueltos por la NKVD.

Además, en 1945 se establecieron unos 100 campos de filtración para los Ostarbeiter repatriados , prisioneros de guerra y otras personas desplazadas, en los que se procesaron más de 4.000.000 de personas. En 1946, la NKVD había desalojado a la mayor parte de la población de estos campos y la había enviado a casa o reclutado (véase la tabla para más detalles). [89] 226.127 de los 1.539.475 prisioneros de guerra fueron transferidos a la NKVD, es decir, al Gulag. [89] [90]

Tras la derrota de la Alemania nazi , en la zona de ocupación soviética de la Alemania de posguerra se establecieron diez "campos especiales" dirigidos por la NKVD, subordinados al Gulag . Estos "campos especiales" eran antiguos Stalags , prisiones o campos de concentración nazis como Sachsenhausen ( campo especial número 7 ) y Buchenwald ( campo especial número 2 ). Según estimaciones del gobierno alemán, "65.000 personas murieron en esos campos dirigidos por los soviéticos o durante el transporte a ellos". [91] Según investigadores alemanes, Sachsenhausen, donde se han descubierto 12.500 víctimas de la era soviética, debería considerarse parte integral del sistema Gulag. [92]

Sin embargo, la principal razón del aumento del número de prisioneros después de la guerra fue el endurecimiento de la legislación sobre delitos contra la propiedad en el verano de 1947 (en ese momento había una hambruna en algunas partes de la Unión Soviética que se cobró alrededor de un millón de vidas), lo que dio lugar a cientos de miles de condenas a largas penas de prisión, a veces sobre la base de casos de robo o malversación de fondos. A principios de 1953, el número total de prisioneros en los campos de prisioneros era de más de 2,4 millones, de los cuales más de 465.000 eran presos políticos. [76]

En 1948 se estableció el sistema de "campos especiales" exclusivamente para un "contingente especial" de presos políticos , condenados según los subartículos más severos del artículo 58 (Enemigos del pueblo): traición, espionaje, terrorismo, etc., por diversos oponentes políticos reales, como trotskistas , "nacionalistas" ( nacionalismo ucraniano ), emigrados blancos , así como por los inventados.

El Estado continuó manteniendo el extenso sistema de campos durante un tiempo después de la muerte de Stalin en marzo de 1953, aunque en ese período se debilitó el control de las autoridades del campo y se produjeron varios conflictos y levantamientos ( véase Guerras de perras ; Levantamiento de Kengir ; Levantamiento de Vorkuta ).

La amnistía de 1953 se limitó a los presos no políticos y a los presos políticos condenados a no más de5 años, therefore mostly those convicted for common crimes were then freed. The release of political prisoners started in 1954 and became widespread, and also coupled with mass rehabilitations, after Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalinism in his Secret Speech at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956.

The Gulag institution was closed by the MVD order No 020 of January 25, 1960,[60] but forced labor colonies for political and criminal prisoners continued to exist. Political prisoners continued to be kept in one of the most famous camps Perm-36[93] until 1987 when it was closed.[94]

The Russian penal system, despite reforms and a reduction in prison population, informally or formally continues many practices endemic to the Gulag system, including forced labor, inmates policing inmates, and prisoner intimidation.[16]

In the late 2000s, some human rights activists accused authorities of gradual removal of Gulag remembrance from places such as Perm-36 and Solovki prison camp.[95]

According to Encyclopædia Britannica,

At its height the Gulag consisted of many hundreds of camps, with the average camp holding 2,000–10,000 prisoners. Most of these camps were "corrective labour colonies" in which prisoners felled timber, laboured on general construction projects (such as the building of canals and railroads), or worked in mines. Most prisoners laboured under the threat of starvation or execution if they refused. It is estimated that the combination of very long working hours, harsh climatic and other working conditions, inadequate food, and summary executions killed tens of thousands of prisoners each year. Western scholarly estimates of the total number of deaths in the Gulag in the period from 1918 to 1956 ranged from 1.2 to 1.7 million.[96]

Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, estimates of Gulag victims ranged from 2.3 to 17.6 million (see History of Gulag population estimates). Mortality in Gulag camps in 1934–40 was 4–6 times higher than average in the Soviet Union. Post-1991 research by historians accessing archival materials brought this range down considerably.[97][98] In a 1993 study of archival Soviet data, a total of 1,053,829 people died in the Gulag from 1934 to 1953.[4]: 1024

It was common practice to release prisoners who were either suffering from incurable diseases or near death,[13][14] so a combined statistics on mortality in the camps and mortality caused by the camps was higher. The tentative historical consensus is that, of the 18 million people who passed through the gulag from 1930 to 1953, between 1.6 million[2][3] and 1.76 million[99] perished as a result of their detention,[1] and about half of all deaths occurred between 1941 and 1943 following the German invasion.[99][100] Timothy Snyder writes that "with the exception of the war years, a very large majority of people who entered the Gulag left alive".[101] If prisoner deaths from labor colonies and special settlements are included, the death toll rises to 2,749,163, according to J. Otto Pohl's incomplete data.[14][5]

In her 2018 study, Golfo Alexopoulos attempted to challenge this consensus figure by encompassing those whose life was shortened due to GULAG conditions.[1] Alexopoulos concluded from her research that a systematic practice of the Gulag was to release sick prisoners on the verge of death; and that all prisoners who received the health classification "invalid", "light physical labor", "light individualised labor", or "physically defective" that together according to Alexopoulos encompassed at least one third of all inmates who passed through the Gulag died or had their lives shortened due to detention in the Gulag in captivity or shortly after release.[102]

The GULAG mortality estimated in this way yields the figure of 6 million deaths.[6] Historian Orlando Figes and Russian writer Vadim Erlikman have posited similar estimates.[7][8] The estimate of Alexopoulos, however, has obvious methodological difficulties[1] and is supported by misinterpreted evidence, such as presuming that hundreds of thousands of prisoners "directed to other places of detention" in 1948 was a euphemism for releasing prisoners on the verge of death into labor colonies, when it was really referring to internal transport in the Gulag rather than release.[103]

In a University of Oxford doctoral dissertation, in 2020, the problem of medical release ('aktirovka') and of mortality among 'certified invalids' ('aktirovannye') was considered in detail by Mikhail Nakonechnyi. He concluded that the number of terminally ill people discharged early on medical grounds from the Gulag was about 1 million. Mikhail added 800,000–850,000 excess deaths to the death toll directly caused by the results of GULAG incarceration, which brings the death toll to 2.5 million people.[104]

In 2009, Steven Rosefielde stated more complete archival data increases camp deaths by 19.4 percent to 1,258,537, "the best archivally-based estimate of Gulag excess deaths at present is 1.6 million from 1929 to 1953."[3] Dan Healey in 2018 also stated the same thing "New studies using declassified Gulag archives have provisionally established a consensus on mortality and "inhumanity." The tentative consensus says that once secret records of the Gulag administration in Moscow show a lower death toll than expected from memoir sources, generally between 1.5 and 1.7 million (out of 18 million who passed through) for the years from 1930 to 1953."[105]

Certificates of death in the Gulag system for the period from 1930 to 1956[106]

Living and working conditions in the camps varied significantly across time and place, depending, among other things, on the impact of broader events (World War II, countrywide famines and shortages, waves of terror, sudden influx or release of large numbers of prisoners) and the type of crime committed. Instead of being used for economic gain, political prisoners were typically given the worst work or were dumped into the less productive parts of the gulag. For example Victor Herman, in his memoirs, compares the Burepolom and the Nuksha 2 camps, which were both near Vyatka.[110][111]

In Burepolom there were roughly 3,000 prisoners, all non-political, in the central compound. They could walk around at will, were lightly guarded, had unlocked barracks with mattresses and pillows, and watched western movies[clarification needed]. However Nuksha 2, which housed serious criminals and political prisoners, featured guard towers with machine guns and locked barracks.[111] In some camps prisoners were only permitted to send one letter a year and were not allowed to have photos of loved ones.[112]

Some prisoners were released early if they displayed good performance.[111] There were several productive activities for prisoners in the camps. For example, in early 1935, a course in livestock raising was held for prisoners at a state farm; those who took it had their workday reduced to four hours.[111] During that year the professional theater group in the camp complex gave 230 performances of plays and concerts to over 115,000 spectators.[111] Camp newspapers also existed.[111]

Andrei Vyshinsky, chief procurator of the Soviet Union, wrote a memorandum to NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov in 1938, during the Great Purge, which stated:[113]

Among the prisoners there are some so ragged and lice-ridden that they pose a sanitary danger to the rest. These prisoners have deteriorated to the point of losing any resemblance to human beings. Lacking food…they collect orts [refuse] and, according to some prisoners, eat rats and dogs.

According to prisoner Yevgenia Ginzburg, Gulag inmates could tell when Yezhov was no longer in charge as one day the conditions relaxed. A few days later Beria's name appeared in official prison notices.[114]

In general, the central administrative bodies showed a discernible interest in maintaining the labor force of prisoners in a condition allowing the fulfilment of construction and production plans handed down from above. Besides a wide array of punishments for prisoners refusing to work (which, in practice, were sometimes applied to prisoners that were too enfeebled to meet production quota), they instituted a number of positive incentives intended to boost productivity. These included monetary bonuses (since the early 1930s) and wage payments (from 1950 onward), cuts of individual sentences, general early-release schemes for norm fulfilment and overfulfilment (until 1939, again in selected camps from 1946 onward), preferential treatment, sentence reduction and privileges for the most productive workers (shock workers or Stakhanovites in Soviet parlance).[115][111]

Inmates were used as camp guards and could purchase camp newspapers as well as bonds. Robert W. Thurston writes that this was "at least an indication that they were still regarded as participants in society to some degree."[111] Sports team, particularly football teams were set up by the prison authorities.[116]

Boris Sulim, a former prisoner who had worked in the Omsuchkan camp, close to Magadan, when he was a teenager stated:[117]

I was 18 years old and Magadan seemed a very romantic place to me. I got 880 rubles a month and a 3000 ruble installation grant, which was a hell of a lot of money for a kid like me. I was able to give my mother some of it. They even gave me membership in the Komsomol. There was a mining and ore-processing plant which sent out parties to dig for tin. I worked at the radio station which kept contact with the parties. [...] If the inmates were good and disciplined they had almost the same rights as the free workers. They were trusted and they even went to the movies. As for the reason they were in the camps, well, I never poked my nose into details. We all thought the people were there because they were guilty.

Immediately after the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 the conditions in camps worsened drastically: quotas were increased, rations cut, and medical supplies came close to none, all of which led to a sharp increase in mortality. The situation slowly improved in the final period and after the end of the war.

Considering the overall conditions and their influence on inmates, it is important to distinguish three major strata of Gulag inmates:

The Soviet famine of 1932–1933 swept across many different regions of the Soviet Union. During this time, it is estimated that around six to seven million people starved to death.[118] On 7 August 1932, a new decree drafted by Stalin (Law of Spikelets) specified a minimum sentence of ten years or execution for theft from collective farms or of cooperative property. Over the next few months, prosecutions rose fourfold. A large share of cases prosecuted under the law were for the theft of small quantities of grain worth less than fifty rubles. The law was later relaxed on 8 May 1933.[119] Overall, during the first half of 1933, prisons saw more new incoming inmates than the three previous years combined.

Prisoners in the camps faced harsh working conditions. One Soviet report stated that, in early 1933, up to 15% of the prison population in Soviet Uzbekistan died monthly. During this time, prisoners were getting around 300 calories (1,300 kJ) worth of food a day. Many inmates attempted to flee, causing an upsurge in coercive and violent measures. Camps were directed "not to spare bullets".[120]

The convicts in such camps were actively involved in all kinds of labor with one of them being logging. The working territory of logging presented by itself a square and was surrounded by forest clearing. Thus, all attempts to exit or escape from it were well observed from the four towers set at each of its corners.

Locals who captured a runaway were given rewards.[121] It is also said that camps in colder areas were less concerned with finding escaped prisoners as they would die anyhow from the severely cold winters. In such cases prisoners who did escape without getting shot were often found dead kilometres away from the camp.

In the early days of Gulag, the locations for the camps were chosen primarily for the isolated conditions involved. Remote monasteries in particular were frequently reused as sites for new camps. The site on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea is one of the earliest and also most noteworthy, taking root soon after the Revolution in 1918.[17] The colloquial name for the islands, "Solovki", entered the vernacular as a synonym for the labor camp in general. It was presented to the world as an example of the new Soviet method for "re-education of class enemies" and reintegrating them through labor into Soviet society. Initially the inmates, largely Russian intelligentsia, enjoyed relative freedom within the natural confinement of the islands.[122]

Local newspapers and magazines were published. Even some scientific research was carried out, e.g., a local botanical garden was maintained but unfortunately later lost completely. Eventually, Solovki turned into an ordinary Gulag camp. Some historians maintain that it was a pilot camp of this type. In 1929, Maxim Gorky visited the camp and published an apology for it. The report of Gorky's trip to Solovki was included in the cycle of impressions titled "Po Soiuzu Sovetov", Part V, subtitled "Solovki." In the report, Gorky wrote that "camps such as 'Solovki' were absolutely necessary."[122]

With the new emphasis on Gulag as the means of concentrating cheap labor, new camps were then constructed throughout the Soviet sphere of influence, wherever the economic task at hand dictated their existence, or was designed specifically to avail itself of them, such as the White Sea–Baltic Canal or the Baikal–Amur Mainline, including facilities in big cities — parts of the famous Moscow Metro and the Moscow State University new campus were built by forced labor. Many more projects during the rapid industrialisation of the 1930s, war-time and post-war periods were fulfilled on the backs of convicts. The activity of Gulag camps spanned a wide cross-section of Soviet industry. Gorky organized in 1933 a trip of 120 writers and artists to the White Sea–Baltic Canal, 36 of them wrote a propaganda book about the construction published in 1934 and destroyed in 1937.

The majority of Gulag camps were positioned in extremely remote areas of northeastern Siberia (the best known clusters are Sevvostlag (The North-East Camps) along Kolyma river and Norillag near Norilsk) and in the southeastern parts of the Soviet Union, mainly in the steppes of Kazakhstan (Luglag, Steplag, Peschanlag). A detailed map was made by the Memorial Foundation.[123]

These were vast and sparsely inhabited regions with no roads or sources of food, but rich in minerals and other natural resources, such as timber. The construction of the roads was assigned to the inmates of specialised railway camps. Camps were generally spread throughout the entire Soviet Union, including the European parts of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

There were several camps outside the Soviet Union, in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Mongolia, which were under the direct control of the Gulag.[citation needed]

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, there were at least 476 separate camp administrations.[124][125] The Russian researcher Galina Ivanova stated that,[125]

to date, Russian historians have discovered and described 476 camps that existed at different times on the territory of the USSR. It is well known that practically every one of them had several branches, many of which were quite large. In addition to the large numbers of camps, there were no less than 2,000 colonies. It would be virtually impossible to reflect the entire mass of Gulag facilities on a map that would also account for the various times of their existence.

Since many of these existed only for short periods, the number of camp administrations at any given point was lower. It peaked in the early 1950s when there were more than 100 camp administrations across the Soviet Union. Most camp administrations oversaw several single camp units, some as many as dozens or even hundreds.[126] The infamous complexes were those at Kolyma, Norilsk, and Vorkuta, all in arctic or subarctic regions. However, prisoner mortality in Norilsk in most periods was actually lower than across the camp system as a whole.[127]

According to historian Stephen Barnes, the origins and functions of the Gulag can be looked at in four major ways:[128]

Hannah Arendt argues that as part of a totalitarian system of government, the camps of the Gulag system were experiments in "total domination." In her view, the goal of a totalitarian system was not merely to establish limits on liberty, but rather to abolish liberty entirely in service of its ideology. She argues that the Gulag system was not merely political repression because the system survived and grew long after Stalin had wiped out all serious political resistance. Although the various camps were initially filled with criminals and political prisoners, eventually they were filled with prisoners who were arrested irrespective of anything relating to them as individuals, but rather only on the basis of their membership in some ever shifting category of imagined threats to the state.[129]: 437–59

She also argues that the function of the Gulag system was not truly economic. Although the Soviet government deemed them all "forced labor" camps, this in fact highlighted that the work in the camps was deliberately pointless, since all Russian workers could be subject to forced labor.[129]: 444–5 The only real economic purpose they typically served was financing the cost of their own supervision. Otherwise the work performed was generally useless, either by design or made that way through extremely poor planning and execution; some workers even preferred more difficult work if it was actually productive. She differentiated between "authentic" forced-labor camps, concentration camps, and "annihilation camps".[129]: 444–5

In authentic labor camps, inmates worked in "relative freedom and are sentenced for limited periods." Concentration camps had extremely high mortality rates and but were still "essentially organized for labor purposes." Annihilation camps were those where the inmates were "systematically wiped out through starvation and neglect." She criticizes other commentators' conclusion that the purpose of the camps was a supply of cheap labor. According to her, the Soviets were able to liquidate the camp system without serious economic consequences, showing that the camps were not an important source of labor and were overall economically irrelevant.[129]: 444–5

Arendt argues that together with the systematized, arbitrary cruelty inside the camps, this served the purpose of total domination by eliminating the idea that the arrestees had any political or legal rights. Morality was destroyed by maximizing cruelty and by organizing the camps internally to make the inmates and guards complicit. The terror resulting from the operation of the Gulag system caused people outside of the camps to cut all ties with anyone who was arrested or purged and to avoid forming ties with others for fear of being associated with anyone who was targeted. As a result, the camps were essential as the nucleus of a system that destroyed individuality and dissolved all social bonds. Thereby, the system attempted to eliminate any capacity for resistance or self-directed action in the greater population.[129]: 437–59

Statistical reports made by the OGPU–NKVD–MGB–MVD between the 1930s and 1950s are kept in the State Archive of the Russian Federation formerly called Central State Archive of the October Revolution (CSAOR). These documents were highly classified and inaccessible. Amid glasnost and democratization in the late 1980s, Viktor Zemskov and other Russian researchers managed to gain access to the documents and published the highly classified statistical data collected by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD and related to the number of the Gulag prisoners, special settlers, etc. In 1995, Zemskov wrote that foreign scientists have begun to be admitted to the restricted-access collection of these documents in the State Archive of the Russian Federation since 1992.[130] However, only one historian, namely Zemskov, was admitted to these archives, and later the archives were again "closed", according to Leonid Lopatnikov.[131] Pressure from the Putin administration has exacerbated the difficulties of Gulag researchers.[132]

While considering the issue of reliability of the primary data provided by corrective labor institutions, it is necessary to take into account the following two circumstances. On the one hand, their administration was not interested to understate the number of prisoners in its reports, because it would have automatically led to a decrease in the food supply plan for camps, prisons, and corrective labor colonies. The decrement in food would have been accompanied by an increase in mortality that would have led to wrecking of the vast production program of the Gulag. On the other hand, overstatement of data of the number of prisoners also did not comply with departmental interests, because it was fraught with the same (i.e., impossible) increase in production tasks set by planning bodies. In those days, people were highly responsible for non-fulfilment of plan. It seems that a resultant of these objective departmental interests was a sufficient degree of reliability of the reports.[133]

Between 1990 and 1992, the first precise statistical data on the Gulag based on the Gulag archives were published by Viktor Zemskov.[134] These had been generally accepted by leading Western scholars,[20][13] despite the fact that a number of inconsistencies were found in this statistics.[135] Not all the conclusions drawn by Zemskov based on his data have been generally accepted. Thus, Sergei Maksudov alleged that although literary sources, for example the books of Lev Razgon or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, did not envisage the total number of the camps very well and markedly exaggerated their size. On the other hand, Viktor Zemskov, who published many documents by the NKVD and KGB, was far from understanding of the Gulag essence and the nature of socio-political processes in the country. He added that without distinguishing the degree of accuracy and reliability of certain figures, without making a critical analysis of sources, without comparing new data with already known information, Zemskov absolutizes the published materials by presenting them as the ultimate truth. As a result, Maksudov charges that Zemskov's attempts to make generalized statements with reference to a particular document, as a rule, do not hold water.[136]

In response, Zemskov wrote that the charge that he allegedly did not compare new data with already known information could not be called fair. In his words, the trouble with most western writers is that they do not benefit from such comparisons. Zemskov added that when he tried not to overuse the juxtaposition of new information with "old" one, it was only because of a sense of delicacy, not to once again psychologically traumatize the researchers whose works used incorrect figures, as it turned out after the publication of the statistics by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD.[130]

According to French historian Nicolas Werth, the mountains of the materials of the Gulag archives, which are stored in funds of the State Archive of the Russian Federation and were being constantly exposed during the last fifteen years, represent only a very small part of bureaucratic prose of immense size left over after the decades of "creativity" by the "dull and reptile" organization managing the Gulag. In many cases, local camp archives, which had been stored in sheds, barracks, or other rapidly disintegrating buildings, simply disappeared in the same way as most of the camp buildings did.[137]

In 2004 and 2005, some archival documents were published in the edition Istoriya Stalinskogo Gulaga. Konets 1920-kh — Pervaya Polovina 1950-kh Godov. Sobranie Dokumentov v 7 Tomakh (The History of Stalin's Gulag. From the Late 1920s to the First Half of the 1950s. Collection of Documents in Seven Volumes), wherein each of its seven volumes covered a particular issue indicated in the title of the volume:

The edition contains the brief introductions by the two "patriarchs of the Gulag science", Robert Conquest and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and 1,431 documents, the overwhelming majority of which were obtained from funds of the State Archive of the Russian Federation.[145]

During the decades before the dissolution of the USSR, the debates about the population size of GULAG failed to arrive at generally accepted figures; wide-ranging estimates have been offered,[146] and the bias toward higher or lower side was sometimes ascribed to political views of the particular author.[146] Some of those earlier estimates (both high and low) are shown in the table below.

The glasnost political reforms in the late 1980s and the subsequent dissolution of the USSR, led to the release of a large amount of formerly classified archival documents[157] including new demographic and NKVD data.[13] Analysis of the official GULAG statistics by Western scholars immediately demonstrated that, despite their inconsistency, they do not support previously published higher estimates.[146] Importantly, the released documents made possible to clarify terminology used to describe different categories of forced labor population, because the use of the terms "forced labor", "GULAG", "camps" interchangeably by early researchers led to significant confusion and resulted in significant inconsistencies in the earlier estimates.[146]

Archival studies revealed several components of the NKVD penal system in the Stalinist USSR: prisons, labor camps, labor colonies, as well as various "settlements" (exile) and of non-custodial forced labor.[4] Although most of them fit the definition of forced labor, only labor camps, and labor colonies were associated with punitive forced labor in detention.[4] Forced labor camps ("GULAG camps") were hard regime camps, whose inmates were serving more than three-year terms. As a rule, they were situated in remote parts of the USSR, and labor conditions were extremely hard there. They formed a core of the GULAG system. The inmates of "corrective labor colonies" served shorter terms; these colonies were located in less remote parts of the USSR, and they were run by local NKVD administration.[4]

Preliminary analysis of the GULAG camps and colonies statistics (see the chart on the right) demonstrated that the population reached the maximum before the World War II, then dropped sharply, partially due to massive releases, partially due to wartime high mortality, and then was gradually increasing until the end of Stalin era, reaching the global maximum in 1953, when the combined population of GULAG camps and labor colonies amounted to 2,625,000.[158]

The results of these archival studies convinced many scholars, including Robert Conquest[20] or Stephen Wheatcroft to reconsider their earlier estimates of the size of the GULAG population, although the 'high numbers' of arrested and deaths are not radically different from earlier estimates.[20] Although such scholars as Rosefielde or Vishnevsky point at several inconsistencies in archival data with Rosefielde pointing out the archival figure of 1,196,369 for the population of the Gulag and labor colonies combined on December 31, 1936, is less than half the 2.75 million labor camp population given to the Census Board by the NKVD for the 1937 census,[159][135] it is generally believed that these data provide more reliable and detailed information that the indirect data and literary sources available for the scholars during the Cold War era.[13] Although Conquest cited Beria's report to the Politburo of the labor camp numbers at the end of 1938 stating there were almost 7 million prisoners in the labor camps, more than three times the archival figure for 1938 and an official report to Stalin by the Soviet minister of State Security in 1952 stating there were 12 million prisoners in the labor camps.[160]

These data allowed scholars to conclude that during the period of 1928–53, about 14 million prisoners passed through the system of GULAG labor camps and 4–5 million passed through the labor colonies.[20] Thus, these figures reflect the number of convicted persons, and do not take into account the fact that a significant part of Gulag inmates had been convicted more than one time, so the actual number of convicted is somewhat overstated by these statistics.[13] From other hand, during some periods of Gulag history the official figures of GULAG population reflected the camps' capacity, not the actual number of inmates, so the actual figures were 15% higher in, e.g. 1946.[20]

The USSR implemented a number of labor disciplinary measures, due to the lack of productivity of its labour force in the early 1930s. 1.8 million workers were sentenced to 6 months in forced labor with a quarter of their original pay, 3.3 million faced sanctions, and 60k were imprisoned for absentees in 1940 alone. The conditions of Soviet workers worsened in WW2 as 1.3 million were punished in 1942, and 1 million each were punished in subsequent 1943 and 1944 with the reduction of 25% of food rations. Further more, 460 thousand were imprisoned throughout these years.[161]

The Gulag spanned nearly four decades of Soviet and East European history and affected millions of individuals. Its cultural impact was enormous.

The Gulag has become a major influence on contemporary Russian thinking, and an important part of modern Russian folklore. Many songs by the authors-performers known as the bards, most notably Vladimir Vysotsky and Alexander Galich, neither of whom ever served time in the camps, describe life inside the Gulag and glorified the life of "zeks". Words and phrases which originated in the labor camps became part of the Russian/Soviet vernacular in the 1960s and 1970s. The memoirs of Alexander Dolgun, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Varlam Shalamov and Yevgenia Ginzburg, among others, became a symbol of defiance in Soviet society. These writings harshly chastised the Soviet people for their tolerance and apathy regarding the Gulag, but at the same time provided a testament to the courage and resolve of those who were imprisoned.

Another cultural phenomenon in the Soviet Union linked with the Gulag was the forced migration of many artists and other people of culture to Siberia. This resulted in a Renaissance of sorts in places like Magadan, where, for example, the quality of theatre production was comparable to Moscow's and Eddie Rosner played jazz.

Many eyewitness accounts of Gulag prisoners have been published:

Soviet state documents show that the goals of the gulag included colonization of sparsely populated remote areas and exploiting its resources using forced labor. In 1929, OGPU was given the task to colonize these areas.[164] To this end, the notion of "free settlement" was introduced. On 12 April 1930 Genrikh Yagoda wrote to the OGPU Commission:

The camps must be transformed into colonizing settlements, without waiting for the end of periods of confinement... Here is my plan: to turn all the prisoners into a settler population until they have served their sentences.[164]

When well-behaved persons had served the majority of their terms, they could be released for "free settlement" (вольное поселение, volnoye poseleniye) outside the confinement of the camp. They were known as "free settlers" (вольнопоселенцы, volnoposelentsy; not to be confused with the term ссыльнопоселенцы, ssyl'noposelentsy, "exile settlers"). In addition, for persons who served full term, but who were denied the free choice of place of residence, it was recommended to assign them for "free settlement" and give them land in the general vicinity of the place of confinement.

The gulag inherited this approach from the katorga system.

It is estimated that of the 40,000 people collecting state pensions in Vorkuta, 32,000 are trapped former gulag inmates, or their descendants.[165]

Persons who served a term in a camp or prison were restricted from taking a wide range of jobs. Concealment of a previous imprisonment was a triable offence. Persons who served terms as "politicals" were nuisances for "First Departments" (Первый Отдел, Pervyj Otdel, outlets of the secret police at all enterprises and institutions), because former "politicals" had to be monitored.[citation needed]

Many people who were released from camps were restricted from settling in larger cities.

_-_59.jpg/440px-State_Museum_of_Gulag_History_(2017-12-12)_-_59.jpg)

Both Moscow and St. Petersburg have memorials to the victims of the Gulag made of boulders from the Solovki camp — the first prison camp in the Gulag system. Moscow's memorial is on Lubyanka Square, the site of the headquarters of the NKVD. People gather at these memorials every year on the Day of Victims of the Repression (October 30).

Moscow has the State Gulag Museum whose first director was Anton Antonov-Ovseyenko.[166][167][168][169] In 2015, another museum dedicated to the Gulag was opened in Moscow.[170]

New studies using declassified Gulag archives have provisionally established a consensus on mortality and "inhumanity." The tentative consensus says that once secret records of the Gulag administration in Moscow show a lower death toll than expected from memoir sources, generally between 1.5 and 1.7 million (out of 18 million who passed through) for the years from 1930 to 1953.

Хотя даже по самым консервативным оценкам, от 20 до 25 млн человек стали жертвами репрессий, из которых, возможно, от пяти до шести миллионов погибли в результате пребывания в ГУЛАГе. Translation: 'The most conservative calculations speak of 20–25 million victims of repression, 5 to 6 million of whom died in the Gulag.'

Orlando Figes Estimates that 25 million people circulated through the Gulag system between 1928 and 1953

The long-awaited archival evidence on repression in the period of the Great Purges shows that levels of arrests, political prisoners, executions, and general camp populations tend to confirm the orders of magnitude indicated by those labeled as "revisionists" and mocked by those proposing high estimates.

To ensure that the preferred version of history prevailed, the Kremlin has squeezed historians, researchers and rights groups that focus on gulag research and memory.