Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun (German: [ˌvɛʁnheːɐ̯ fɔn ˈbʁaʊ̯n]; US: /ˌvɜːrnər vɒn ˈbraʊn/ VUR-nər von BROWN;[3] 23 March 1912 – 16 June 1977) was a German-American aerospace engineer[4] and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, the leading figure in the development of rocket technology in Nazi Germany, and later a pioneer of rocket and space technology in the United States.[5]

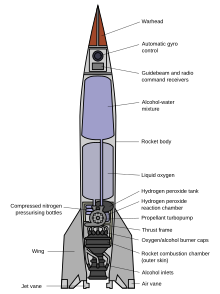

As a young man, von Braun worked in Nazi Germany's rocket development program. He helped design and co-developed the V-2 rocket at Peenemünde during World War II. The V-2 became the first artificial object to travel into space on 20 June 1944. Following the war, he was secretly moved to the United States, along with about 1,600 other German scientists, engineers, and technicians, as part of Operation Paperclip.[6] He worked for the United States Army on an intermediate-range ballistic missile program, and he developed the rockets that launched the United States' first space satellite Explorer 1 in 1958. He worked with Walt Disney on a series of films, which popularized the idea of human space travel in the U.S. and beyond from 1955 to 1957.[7]

In 1960, his group was assimilated into NASA, where he served as director of the newly formed Marshall Space Flight Center and as the chief architect of the Saturn V super heavy-lift launch vehicle that propelled the Apollo spacecraft to the Moon.[8][9] In 1967, von Braun was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering, and in 1975, he received the National Medal of Science.

Von Braun is a highly controversial figure widely seen as escaping justice for his Nazi war crimes due to the Americans' desire to beat the Soviets in the Cold War.[10][11][5] He is also sometimes described by others as the "father of space travel",[12] the "father of rocket science",[13] or the "father of the American lunar program".[10] He advocated a human mission to Mars.

Wernher von Braun was born on 23 March 1912, in the small town of Wirsitz in the Province of Posen, Kingdom of Prussia, then German Empire and now Poland.[14]

His father, Magnus Freiherr von Braun (1878–1972), was a civil servant and conservative politician; he served as Minister of Agriculture in the federal government during the Weimar Republic. His mother, Emmy von Quistorp (1886–1959), traced her ancestry through both parents to medieval European royalty and was a descendant of Philip III of France, Valdemar I of Denmark, Robert III of Scotland, and Edward III of England.[15][16] He had an older brother, the West German diplomat Sigismund von Braun, who served as Secretary of State in the Foreign Office in the 1970s, and a younger brother, Magnus von Braun, who was a rocket scientist and later a senior executive with Chrysler.[17]

The family moved to Berlin, Brandenburg, in 1915, where his father worked at the Ministry of the Interior. After his Confirmation, his mother gave him a telescope, and he developed a passion for astronomy.[18] Von Braun learned to play both the cello and the piano at an early age and at one time wanted to become a composer. He took lessons from the composer Paul Hindemith. The few pieces of von Braun's youthful compositions that exist are reminiscent of Hindemith's style.[19]: 11 He could play piano pieces of Beethoven and Bach from memory. Beginning in 1925, he attended a boarding school at Ettersburg Castle near Weimar, Free State of Thuringia, where he did not do well in physics and mathematics. There he acquired a copy of Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (1923, By Rocket into Planetary Space)[20] by rocket pioneer Hermann Oberth. In 1928, his parents moved him to the Hermann-Lietz-Internat (also a residential school) on the East Frisian North Sea island of Spiekeroog. Space travel had always fascinated him, and from then on he applied himself to physics and mathematics to pursue his interest in rocket engineering.[21][22]

In 1928 the Raketenrummel or "Rocket Rumble" fad initiated by Fritz von Opel and Max Valier was highly influential on von Braun as a teenage space enthusiast. He was so enthusiastic after seeing one of the public Opel-RAK rocket car demonstrations, that he constructed his own homemade toy rocket car and caused a disruption in a crowded sidewalk by launching the toy wagon, to which he had attached the largest firework rockets he could purchase. He was later taken in for questioning by the local police, until released to his father for disciplinary action. The incident highlighted the young von Braun's determination to "dedicate his life to space travel".[4]: 62-64

In 1930, von Braun attended the Technische Hochschule Berlin, where he joined the Spaceflight Society (Verein für Raumschiffahrt or VfR), co-founded by Valier, and worked with Willy Ley in his liquid-fueled rocket motor tests in conjunction with others such as Rolf Engel, Rudolf Nebel, Hermann Oberth or Paul Ehmayr.[23] In spring 1932, he graduated with a diploma in mechanical engineering.[24] His early exposure to rocketry convinced him that the exploration of space would require far more than applications of the current engineering technology. Wanting to learn more about physics, chemistry, and astronomy, von Braun entered the Friedrich-Wilhelm University of Berlin for doctoral studies and graduated with a doctorate in physics in 1934.[25] He also studied at ETH Zürich for a term from June to October 1931.[25]

In 1930, von Braun attended a presentation given by Auguste Piccard. After the talk, the young student approached the famous pioneer of high-altitude balloon flight, and stated to him: "You know, I plan on traveling to the Moon at some time." Piccard is said to have responded with encouraging words.[26]

Von Braun was greatly influenced by Oberth, of whom he said:

Hermann Oberth was the first who, when thinking about the possibility of spaceships, grabbed a slide-rule and presented mathematically analyzed concepts and designs... I, myself, owe to him not only the guiding-star of my life, but also my first contact with the theoretical and practical aspects of rocketry and space travel. A place of honor should be reserved in the history of science and technology for his ground-breaking contributions in the field of astronautics.[27]

According to historian Norman Davies, von Braun was able to pursue a career as a rocket scientist in Germany due to a "curious oversight" in the Treaty of Versailles which did not include rocketry in its list of weapons forbidden to Germany.[28]

Von Braun was an opportunist who joined the Nazi Party to continue his work on rockets for Nazi Germany.[6] He applied for membership in the Party on 12 November 1937, and was issued membership number 5,738,692.[29]: 96

Michael J. Neufeld, an author of aerospace history and chief of the Space History Division at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, wrote that ten years after von Braun obtained his Nazi Party membership, he signed an affidavit for the U.S. Army, though he stated the incorrect year:[29]: 96

In 1939, I was officially demanded to join the National Socialist Party. At this time I was already Technical Director at the Army Rocket Center at Peenemünde (Baltic Sea). The technical work carried out there had, in the meantime, attracted more and more attention in higher levels. Thus, my refusal to join the party would have meant that I would have to abandon the work of my life. Therefore, I decided to join. My membership in the party did not involve any political activity.[29]: 96

It has not been ascertained whether von Braun's error with regard to the year was deliberate or a simple mistake.[29]: 96 Neufeld wrote:

Von Braun, like other Peenemünders, was assigned to the local group in Karlshagen; there is no evidence that he did more than send in his monthly dues. But he is seen in some photographs with the party's swastika pin in his lapel – it was politically useful to demonstrate his membership.[29]: 96

Von Braun's later attitude toward the Nazi regime of the late 1930s and early 1940s was complex. He said that he had been so influenced by the early Nazi promise of release from the post–World War I economic effects, that his patriotic feelings had increased.[30] In a 1952 memoir article he admitted that, at that time, he "fared relatively rather well under totalitarianism".[29]: 96–97 Yet, he also wrote that "to us, Hitler was still only a pompous fool with a Charlie Chaplin moustache"[31] and that he perceived him as "another Napoleon" who was "wholly without scruples, a godless man who thought himself the only god".[32]

Later examination of von Braun's background, conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation, suggests that his background check file contained no derogatory information pertaining to his involvement in the party, but it was found that he had numerous letters of commendation for outstanding performance of duties during his time working under the Nazi party.[33] Overall FBI conclusions point to von Braun's involvement in the Nazi Party to be purely for the advancement of his academic career, or out of fear of imprisonment or execution.[33]

Von Braun joined the SS horseback riding school on 1 November 1933 as an SS-Anwärter. He left the following year.[34]: 63 In 1940, von Braun joined the SS[35]: 47 [36] and was given the rank of Untersturmführer in the Allgemeine-SS and issued membership number 185,068.: 121 In 1947, he gave the U.S. War Department this explanation:

In spring 1940, one SS-Standartenführer (SS-Colonel) Müller from Greifswald, a bigger town in the vicinity of Peenemünde, looked me up in my office...and told me that Reichsführer-SS Himmler had sent him with the order to urge me to join the SS. I told him I was so busy with my rocket work that I had no time to spare for any political activity. He then told me, that...the SS would cost me no time at all. I would be awarded the rank of a[n] "Untersturmfuehrer" (lieutenant) and it were [sic] a very definite desire of Himmler that I attend his invitation to join.

I asked Müller to give me some time for reflection. He agreed.

Realizing that the matter was of highly political significance for the relation between the SS and the Army, I called immediately on my military superior, Dr. Dornberger. He informed me that the SS had for a long time been trying to get their "finger in the pie" of the rocket work. I asked him what to do. He replied on the spot that if I wanted to continue our mutual work, I had no alternative but to join.[37]

When shown a picture of himself standing behind Himmler, von Braun said that he had only worn the SS uniform that one time,[38] but in 2002 a former SS officer at Peenemünde told the BBC that von Braun had regularly worn the SS uniform to official meetings. He began as an Untersturmführer (Second lieutenant) and was promoted three times by Himmler, the last time in June 1943 to SS-Sturmbannführer (Major). Von Braun later stated that these were simply technical promotions received each year regularly by mail.[38][39]

In 1932, von Braun received a Bachelor of Science Degree in Mechanical Engineering from Technische Hochschule Berlin (now Technische Universität Berlin), Germany. During a period in 1931, von Braun attended the ETH Zürich in Switzerland. During this time in Switzerland, von Braun assisted Professor Hermann Oberth in writing a book concerning the possibilities of creating and manufacturing liquid-propellant rockets. Shortly after this, von Braun founded his own private rocket development business in Berlin, and through which he made the first rocket fired by gasoline and liquid oxygen.[33]

In 1932, having caught wind of von Braun's rocket business, the German Army connected with von Braun to pursue basic missile research and weather data experimentation.[33] Von Braun said that the German government financed the development of test stands and facilities for experimentation in Darmstadt, Germany. In 1939, von Braun was appointed a technical advisor at Peenemünde Army Research Center on the Baltic Sea.[33]

In 1933, von Braun was working on his creative doctorate when the Nazi Party came to power in a coalition government in Germany; rocketry was almost immediately moved onto the national agenda. An artillery captain, Walter Dornberger, arranged an Ordnance Department research grant for von Braun, who then worked next to Dornberger's existing solid-fuel rocket test site at Kummersdorf.[40]

Von Braun received his doctorate in physics (aerospace engineering) on 27 July 1934, from the University of Berlin for a thesis titled "About Combustion Tests." His doctoral supervisor was Erich Schumann.[29]: 61 However, this thesis represented only the public aspect of von Braun's work. His actual thesis, entitled "Construction, Theoretical, and Experimental Solution to the Problem of the Liquid Propellant Rocket" (dated 16 April 1934), detailed the construction and design of the A2 rocket. It remained classified by the German army until its publication in 1960.[41][42] By the end of 1934, his group had successfully launched two liquid fuel A2 rockets that rose to heights of 2.2 and 3.5 km (2 mi).[43]

Von Braun continued his guided missile work throughout World War Two, and met with Adolf Hitler on several occasions, being formally decorated by Hitler twice, including being awarded the Iron Cross.[44]

At the time, Germany was highly interested in American physicist Robert H. Goddard's research. Before 1939, German scientists occasionally contacted Goddard directly with technical questions. Von Braun used Goddard's plans from various journals and incorporated them into the building of the Aggregat (A) series of rockets. The first successful launch of an A-4 took place on 3 October 1942.[45] The A-4 rocket became well known as the V-2.[46] In 1963, von Braun reflected on the history of rocketry, and said of Goddard's work: "His rockets ... may have been rather crude by present-day standards, but they blazed the trail and incorporated many features used in our most modern rockets and space vehicles."[25]

Goddard confirmed his work was used by von Braun in 1944, shortly before the Nazis began firing V-2s at England. A V-2 crashed in Sweden and some parts were sent to an Annapolis lab where Goddard was doing research for the Navy. If this was the so-called Bäckebo Bomb, it had been procured by the British in exchange for Spitfires; Annapolis would have received some parts from them. Goddard is reported to have recognized components he had invented and inferred that his brainchild had been turned into a weapon.[47] Later, von Braun said: "I have very deep and sincere regret for the victims of the V-2 rockets, but there were victims on both sides...A war is a war, and when my country is at war, my duty is to help win that war."[4]: 351

The engineer who designed the V2, Wernher von Braun, came to be feted as a hero of the space age. The Allies realised that the V-2 was a machine, unlike anything they had developed themselves.

—V-2: The Nazi rocket that launched the space age, BBC, September 2014.[48]

In response to Goddard's statements, von Braun said "at no time in Germany did I or any of my associates ever see a Goddard patent". This was independently confirmed. He wrote that statements that he had lifted Goddard's work were the furthest from the truth, noting that Goddard's paper "A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes", which was studied by von Braun and Oberth, lacked the specificity of liquid-fuel experimentation with rockets. It was also confirmed that he was responsible for an estimated 20 patentable innovations related to rocketry, as well as receiving U.S. patents after the war concerning the advancement of rocketry. Documented accounts also stated he provided solutions to a host of aerospace engineering problems in the 1950s and 1960s.[49]

On 22 December 1942, Adolf Hitler ordered the production of the A-4 as a "vengeance weapon", and the Peenemünde group developed it to target London. Following von Braun's 7 July 1943 presentation of a color movie showing an A-4 taking off, Hitler was so enthusiastic that he personally made von Braun a professor shortly thereafter.[50]

By that time, the British and Soviet intelligence agencies were aware of the rocket program and von Braun's team at Peenemünde, based on the intelligence provided by the Polish underground Home Army. Over the nights of 17–18 August 1943, RAF Bomber Command's Operation Hydra dispatched raids on the Peenemünde camp consisting of 596 aircraft, and dropped 1,800 tons of explosives.[51] The facility was salvaged and most of the engineering team remained unharmed; however, the raids killed von Braun's engine designer Walter Thiel and Chief Engineer Walther, and the rocket program was delayed.[52][53]

The V-2 became the first artificial object to travel into space by crossing the Kármán line with the vertical launch of MW 18014 on 20 June 1944.[54]

The first combat A-4, renamed the V-2 (Vergeltungswaffe 2 "Retaliation/Vengeance Weapon 2") for propaganda purposes, was launched toward England on 7 September 1944, only 21 months after the project had been officially commissioned.[4]: 184 Doug Millard of the Science Museum, London states:

The V-2 was a quantum leap of technological change. We got to the Moon using V-2 technology but this was technology that was developed with massive resources, including some particularly grim ones. The V-2 programme was hugely expensive in terms of lives, with the Nazis using slave labour to manufacture these rockets.[48]

In 1936, von Braun's rocketry team working at Kummersdorf investigated installing liquid-fuelled rockets in aircraft. Ernst Heinkel enthusiastically supported their efforts, supplying a He-72 and later two He-112s for the experiments. Later in 1936, Erich Warsitz was seconded by the RLM to von Braun and Heinkel, because he had been recognized as one of the most experienced test pilots of the time, and because he also had an extraordinary fund of technical knowledge.[55]: 30 After he familiarized Warsitz with a test-stand run, showing him the corresponding apparatus in the aircraft, he asked: "Are you with us and will you test the rocket in the air? Then, Warsitz, you will be a famous man. And later we will fly to the Moon – with you at the helm!"[55]: 35

In June 1937, at Neuhardenberg (a large field about 70 km (43 mi) east of Berlin, listed as a reserve airfield in the event of war), one of these latter aircraft was flown with its piston engine shut down during flight by Warsitz, at which time it was propelled by von Braun's rocket power alone. Despite a wheels-up landing and the fuselage having been on fire, it proved to official circles that an aircraft could be flown satisfactorily with a back-thrust system through the rear.[55]: 51

At the same time, Hellmuth Walter's experiments into hydrogen peroxide based rockets were leading toward light and simple rockets that appeared well-suited for aircraft installation. Also, the firm of Hellmuth Walter at Kiel had been commissioned by the RLM to build a rocket engine for the He-112, so there were two different new rocket motor designs at Neuhardenberg: whereas von Braun's engines were powered by alcohol and liquid oxygen, Walter engines had hydrogen peroxide and calcium permanganate as a catalyst. Von Braun's engines used direct combustion and created fire, while the Walter devices used hot vapors from a chemical reaction, but both created thrust and provided high speed.[55]: 41 The subsequent flights with the He-112 used the Walter-rocket instead of von Braun's; it was more reliable, simpler to operate, and safer for the test pilot, Warsitz.[55]: 55

SS General Hans Kammler, who as an engineer had constructed several concentration camps, including Auschwitz, had a reputation for brutality and had conceived the idea of using concentration camp prisoners as slave laborers in the rocket program. Arthur Rudolph, chief engineer of the V-2 rocket factory at Peenemünde, endorsed this idea in April 1943 when a labor shortage developed. More people died building the V-2 rockets than were killed by it as a weapon.[56] Von Braun admitted visiting the plant at Mittelwerk on many occasions,[6] and called conditions at the plant "repulsive", but stated that he had never personally witnessed any deaths or beatings, although it had become clear to him by 1944 that deaths had occurred.[57] He denied ever having visited the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, where 20,000 died from illness, beatings, hangings, and intolerable working conditions.[58]

Some prisoners state that von Braun engaged in brutal treatment or approved of it. Guy Morand, a French resistance fighter who was a prisoner in Dora, testified in 1995 that, after an apparent sabotage attempt, von Braun ordered a prisoner to be flogged,[59] while Robert Cazabonne, another French prisoner, stated that von Braun stood by as prisoners were hanged by chains suspended by cranes.[59]: 123–124 However, these accounts may have been a case of mistaken identity.[60] Former Buchenwald inmate Adam Cabala stated that von Braun went to the concentration camp to pick slave laborers:

... also the German scientists led by Prof. Wernher von Braun were aware of everything daily. As they went along the corridors, they saw the exhaustion of the inmates, their arduous work and their pain. Not one single time did Prof. Wernher von Braun protest against this cruelty during his frequent stays at Dora. Even the aspect of corpses did not touch him: On a small area near the ambulance shed, inmates tortured to death by slave labor and the terror of the overseers were piling up daily. But, Prof. Wernher von Braun passed them so close that he was almost touching the corpses.[61]

Von Braun later stated that he was aware of the treatment of prisoners, but felt helpless to change the situation.[62] When asked if von Braun could have protested against the brutal treatment of the slave laborers, von Braun team member Konrad Dannenberg (a member of the Nazi party since 1932) told The Huntsville Times: "If he had done it, in my opinion, he would have been shot on the spot."[63]

According to André Sellier, a French historian and survivor of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, Heinrich Himmler had von Braun come to his Feldkommandostelle Hochwald HQ in East Prussia in February 1944.[64] To increase his power-base within the Nazi regime, Himmler was conspiring to use Kammler to gain control of all German armament programs, including the V-2 program at Peenemünde.[19]: 38–40 He therefore recommended that von Braun work more closely with Kammler to solve the problems of the V-2. Von Braun stated that he replied that the problems were merely technical and he was confident that they would be solved with Dornberger's assistance.[65]

Von Braun had been under SD surveillance since October 1943. A secret report stated that he and his colleagues Klaus Riedel and Helmut Gröttrup were said to have expressed regret at an engineer's house one evening in early March 1944 that they were not working on a spaceship[6] and that they felt the war was not going well; this was considered a "defeatist" attitude. A young female dentist who was an SS spy reported their comments. Himmler's unfounded allegations branding von Braun and his colleagues as communist sympathizers and accusing them of sabotaging the V-2 program, coupled with von Braun's regular piloting of a government-provided airplane that could facilitate an escape to Britain, led to their arrest by the Gestapo.[19]: 38–40

The unsuspecting von Braun was detained on 14 March (or 15 March),[66] 1944, and was taken to a Gestapo cell in Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland).[19]: 38–40 where he was held for two weeks without knowing the charges against him.[67]

Through Major Hans Georg Klamroth, in charge of the Abwehr for Peenemünde, Dornberger obtained von Braun's conditional release and Albert Speer, Reichsminister for Munitions and War Production, persuaded Hitler to reinstate von Braun so that the V-2 program could continue[6][19]: 38–40 [68] or turn into a "V-4 program" (the Rheinbote as a short-range ballistic rocket) which in their view would be impossible without von Braun's leadership.[32] In his memoirs, Speer states Hitler had finally conceded that von Braun was to be "protected from all prosecution as long as he is indispensable, difficult though the general consequences arising from the situation."[69]

Upon investigation by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation on 1 May 1961 advised that "there was no record of an arrest in their respective files"[70] suggesting that Von Braun's imprisonment was wiped from German prison records at a point after his conditional release or after the Nazi regime had fallen.

The Soviet Army was about 160 km (100 mi) from Peenemünde in early 1945 when von Braun assembled his planning staff and asked them to decide how and to whom they should surrender. Unwilling to go to the Soviets, von Braun and his staff decided to try to surrender to the Americans. Kammler had ordered the relocation of his team to central Germany; however, a conflicting order from an army chief ordered them to join the army and fight. Deciding that Kammler's order was their best bet to defect to the Americans, von Braun fabricated documents and transported 500 of his affiliates to the area around Mittelwerk, where they resumed their work in Bleicherode and surrounding towns after the middle of February 1945. For fear of their documents being destroyed by the SS, von Braun ordered the blueprints to be hidden in an abandoned iron mine in the Harz mountain range near Goslar.[71] The U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps managed to unveil the location after lengthy interrogations of von Braun, Walter Dornberger, Bernhard Tessmann and Dieter Huzel and recovered 14 tons of V-2 documents by 15 May 1945, from the British Occupation Zone.[29][72]

While on an official trip in March, von Braun suffered a complicated fracture of his left arm and shoulder in a car accident after his driver fell asleep at the wheel. His injuries were serious, but he insisted that his arm be set in a cast so that he could leave the hospital. Due to this neglect of the injury, he had to be hospitalized again a month later when his bones had to be rebroken and realigned.[71]

In early April, as the Allied forces advanced deeper into Germany, Kammler ordered the engineering team, around 450 specialists, to be moved by train into the town of Oberammergau in the Bavarian Alps, where they were closely guarded by the SS with orders to execute the team if they were about to fall into enemy hands. However, von Braun managed to convince SS Major Kummer to order the dispersal of the group into nearby villages so that they would not be an easy target for U.S. bombers.[71] On 29 April 1945, Oberammergau was captured by the Allied forces who seized the majority of the engineering team.[73]

Nearing the end of the war, Hitler instructed SS troops to gas all technical men concerned with rocket development.[70] Upon hearing this, von Braun commandeered a train and fled with other "technical men" to a location in the mountains of South Germany. After some time, von Braun and many of the others who made it to the mountains left their location to flee to advancing American lines in Austria.[33]

Von Braun and several members of the engineering team, including Dornberger, made it to Austria.[74] On 2 May 1945, upon finding an American private from the U.S. 44th Infantry Division, von Braun's brother and fellow rocket engineer, Magnus, approached the soldier on a bicycle, calling out in broken English: "My name is Magnus von Braun. My brother invented the V-2. We want to surrender."[17][75] After the surrender, Wernher von Braun spoke to the press:

We knew that we had created a new means of warfare, and the question as to what nation, to what victorious nation we were willing to entrust this brainchild of ours was a moral decision more than anything else. We wanted to see the world spared another conflict such as Germany had just been through, and we felt that only by surrendering such a weapon to people who are guided not by the laws of materialism but by Christianity and humanity could such an assurance to the world be best secured.[76]

The American high command was well aware of how important their catch was: von Braun had been at the top of the Black List, the code name for the list of German scientists and engineers targeted for immediate interrogation by U.S. military experts. On 9 June 1945, two days before the originally scheduled handover of the Nordhausen and Bleicherode area in Thuringia to the Soviets, U.S. Army Major Robert B. Staver, Chief of the Jet Propulsion Section of the Research and Intelligence Branch of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps in London, and Lieutenant Colonel R. L. Williams took von Braun and his department chiefs by Jeep from Garmisch to Munich, from where they were flown to Nordhausen. In the following days, a larger group of rocket engineers, among them Helmut Gröttrup, was evacuated from Bleicherode 40 miles (64 km) southwest to Witzenhausen, a small town in the American Zone.[77]

According to Dornberger, there the Soviets tried to kidnap von Braun at night using English uniforms: Americans recognized this and didn't let them in.[78]

Von Braun was briefly detained at the "Dustbin" interrogation center at Kransberg Castle, where the elite of Nazi Germany's economic, scientific and technological sectors were debriefed by U.S. and British intelligence officials.[79] Initially, he was recruited to the U.S. under a program called Operation Overcast, subsequently known as Operation Paperclip. There is evidence, however, that British intelligence and scientists were the first to interview him in depth, eager to gain information that they knew U.S. officials would deny them.[80][81] The team included the young L.S. Snell, then the leading British rocket engineer, later chief designer of Rolls-Royce Limited and inventor of the Concorde's engines. The specific information the British gleaned remained top secret, both from the Americans and from the other allies.[82]

On 20 June 1945, U.S. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius Jr. approved the transfer of von Braun and his specialists to the United States as one of his last acts in office. This was announced to the public on 1 October 1945.[83]

In September 1945, von Braun and other members of the Peenemünde team signed a work contract with the United States Army Ordnance Corps.[84] On 20 September 1945, the first seven technicians arrived in the United States at New Castle Army Air Field, just south of Wilmington, Delaware. They were then flown to Boston, Massachusetts, and taken by boat to the Army Intelligence Service post at Fort Strong in Boston Harbor. Later, with the exception of von Braun, the men were transferred to Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland to sort out the Peenemünde documents, enabling the scientists to continue their rocketry experiments.[85]

Finally, von Braun and his remaining Peenemünde staff (see List of German rocket scientists in the United States) were transferred to their new home at Fort Bliss, a large Army installation just north of El Paso, Texas. Von Braun later wrote that he found it hard to develop a "genuine emotional attachment" to his new surroundings.[86] His chief design engineer Walther Reidel became the subject of a December 1946 article, "German Scientist Says American Cooking Tasteless; Dislikes Rubberized Chicken", exposing the presence of von Braun's team in the country and drawing criticism from Albert Einstein and John Dingell.[86] Requests to improve their living conditions such as laying linoleum over their cracked wood flooring were rejected.[86] Von Braun was hypercritical of the slowness of the United States' development of guided missiles. His lab was never able to get sufficient funds to go on with their programs.[33] Von Braun remarked "at Peenemünde we had been coddled, here you were counting pennies".[86] Whereas von Braun had thousands of engineers who answered to him at Peenemünde, he was now subordinate to "pimply" 26-year-old Jim Hamill, an Army major who possessed only an undergraduate degree in engineering.[86] His loyal Germans still addressed him as "Herr Professor", but Hamill addressed him as "Wernher" and never responded to von Braun's request for more materials. Every proposal for new rocket ideas was dismissed.[86]

While at Fort Bliss, they trained military, industrial, and university personnel in the intricacies of rockets and guided missiles. As part of the Hermes project, they helped refurbish, assemble, and launch a number of V-2s that had been shipped from Allied-occupied Germany to the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico. They also continued to study the future potential of rockets for military and research applications. Since they were not permitted to leave Fort Bliss without military escort, von Braun and his colleagues began to refer to themselves only half-jokingly as "PoPs" – "Prisoners of Peace".[4]: 218

In 1950, at the start of the Korean War, von Braun and his team were transferred to Huntsville, Alabama, his home for the next 20 years. From 1952 to 1956,[87] von Braun led the Army's rocket development team at Redstone Arsenal, resulting in the Redstone rocket, which was used for the first live nuclear ballistic missile tests conducted by the United States. He personally witnessed this historic launch and detonation.[88] Work on the Redstone led to the development of the first high-precision inertial guidance system on the Redstone rocket.[89] By 1953 von Braun's title was, "Chief, Guided Missiles Development Division, Redstone Arsenal."[90]

As director of the Development Operations Division of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, von Braun, with his team, then developed the Jupiter-C, a modified Redstone rocket.[91] The Jupiter-C was the basis for the Juno I rocket that successfully launched the West's first satellite, Explorer 1, on 31 January 1958. This event signaled the birth of America's space program.[92]

Repeating the pattern he had established during his earlier career in Germany, von Braun – while directing military rocket development in the real world – continued to entertain his engineer-scientist's dream of a future in which rockets would be used for space exploration. However, he was no longer at risk of being fired. As American public opinion of Germans began to recover, von Braun found himself increasingly in a position to popularize his ideas. The 14 May 1950 headline of The Huntsville Times ("Dr. von Braun Says Rocket Flights Possible to Moon") might have marked the beginning of these efforts. Von Braun's ideas rode a publicity wave that was created by science fiction movies and stories.[7]

In 1952, von Braun first published his concept of a crewed space station in a Collier's Weekly magazine series of articles titled "Man Will Conquer Space Soon!". These articles were illustrated by the space artist Chesley Bonestell and were influential in spreading his ideas. Frequently, von Braun worked with fellow German-born space advocate and science writer Willy Ley to publish his concepts, which, unsurprisingly, were heavy on the engineering side and anticipated many technical aspects of space flight that later became reality.[93]

The space station (to be constructed using rockets with recoverable and reusable ascent stages) was a toroid structure, with a diameter of 250 feet (76 m); this built on the concept of a rotating wheel-shaped station introduced in 1929 by Herman Potočnik in his book The Problem of Space Travel – The Rocket Motor. The space station spun around a central docking nave to provide artificial gravity, and was assembled in a 1,075-mile (1,730 km) two-hour, high-inclination Earth orbit allowing observation of essentially every point on Earth on at least a daily basis. The ultimate purpose of the space station was to provide an assembly platform for crewed lunar expeditions. More than a decade later, the movie version of 2001: A Space Odyssey drew heavily on the design concept in its visualization of an orbital space station.[94]

Von Braun envisioned these expeditions as very large-scale undertakings, with a total of 50 astronauts traveling in three huge spacecraft (two for crew, one primarily for cargo), each 49 m (160.76 ft) long and 33 m (108.27 ft) in diameter and driven by a rectangular array of 30 rocket propulsion engines.[95] Upon arrival, astronauts would establish a permanent lunar base in the Sinus Roris region by using the emptied cargo holds of their craft as shelters, and would explore their surroundings for eight weeks. This would include a 400 km (249 mi) expedition in pressurized rovers to the crater Harpalus and the Mare Imbrium foothills.[96]

At this time, von Braun also worked out preliminary concepts for a human mission to Mars that used the space station as a staging point. His initial plans, published in The Mars Project (1952), had envisaged a fleet of 10 spacecraft (each with a mass of 3,720 metric tonnes), three of them uncrewed and each carrying one 200-tonne winged lander[95] in addition to cargo, and nine crew vehicles transporting a total of 70 astronauts. The engineering and astronautical parameters of this gigantic mission were thoroughly calculated. A later project was much more modest, using only one purely orbital cargo ship and one crewed craft. In each case, the expedition used minimum-energy Hohmann transfer orbits for its trips to Mars and back to Earth.[97]

Before technically formalizing his thoughts on human spaceflight to Mars, von Braun had written a science fiction novel on the subject, set in the year 1980. However, 18 publishers rejected the manuscript.[98] Von Braun later published small portions of this opus in magazines, to illustrate selected aspects of his Mars project popularizations. The complete manuscript, titled Project Mars: A Technical Tale, did not appear as a printed book until December 2006.[99]

In the hope that its involvement would bring about greater public interest in the future of the space program, von Braun also began working with Walt Disney and the Disney studios as a technical director, initially for three television films about space exploration. The initial broadcast devoted to space exploration was Man in Space, which first went on air on 9 March 1955, drawing 40 million viewers.[86][100][101]

Later (in 1959) von Braun published a short booklet, condensed from episodes that had appeared in This Week Magazine before – describing his updated concept of the first crewed lunar landing.[102] The scenario included only a single and relatively small spacecraft – a winged lander with a crew of only two experienced pilots who had already circumnavigated the Moon on an earlier mission. The brute-force direct ascent flight schedule used a rocket design with five sequential stages, loosely based on the Nova designs that were under discussion at this time. After a night launch from a Pacific island, the first three stages brought the spacecraft (with the two remaining upper stages attached) to terrestrial escape velocity, with each burn creating an acceleration of 8–9 times standard gravity. The residual propellant in the third stage was used for the deceleration intended to commence only a few hundred kilometers above the landing site in a crater near the lunar north pole. The fourth stage provided acceleration to lunar escape velocity, and the fifth stage was responsible for a deceleration during return to the Earth to a residual speed that allows aerocapture of the spacecraft ending in a runway landing, much in the way of the Space Shuttle. One remarkable feature of this technical tale is that the engineer von Braun anticipated a medical phenomenon that became apparent only years later: being a veteran astronaut with no history of serious adverse reactions to weightlessness offers no protection against becoming unexpectedly and violently spacesick.[check quotation syntax][citation needed]

In the first half of his life, von Braun was a nonpracticing, perfunctory Lutheran.[4]: 4 : 230 As described by Ernst Stuhlinger and Frederick I. Ordway III: "Throughout his younger years, von Braun did not show signs of religious devotion, or even an interest in things related to the church or to biblical teachings. In fact, he was known to his friends as a 'merry heathen' (fröhlicher Heide)."[103] Nevertheless, in 1945 he explained his decision to surrender to the Western Allies, rather than Russians, as being influenced by a desire to share rocket technology with people who followed the Bible. In 1946,[4]: 469 he attended church in El Paso, El Paso County, Texas, and underwent a religious conversion to Evangelical Christianity.[104] In an unnamed religious magazine he stated:

One day in Fort Bliss, a neighbor called and asked if I would like to go to church with him. I accepted, because I wanted to see if the American church was just a country club as I'd been led to expect. Instead, I found a small, white frame building... in the hot Texas sun on a browned-grass lot... Together, these people make a live, vibrant community. This was the first time I really understood that religion was not a cathedral inherited from the past, or a quick prayer at the last minute. To be effective, a religion has to be backed up by discipline and effort.[4]: 229–230

On the motives behind this conversion, Michael J. Neufeld is of the opinion that he turned to religion "to pacify his own conscience",[105] and University of Southampton scholar Kendrick Oliver said that von Braun was presumably moved "by a desire to find a new direction for his life after the moral chaos of his service for the Third Reich".[106] Having "concluded one bad bargain with the Devil, perhaps now he felt a need to have God securely at his side".[107]

At a Gideons conference in 2004, W. Albert Wilson, a former pilot and NASA employee, stated that he had talked with von Braun about the Christian faith while von Braun was working for NASA, and believed that conversation had been instrumental in von Braun's conversion.[108]

Later in life, he joined an Episcopal congregation,[104] and became increasingly religious.[109] He publicly spoke and wrote about the complementarity of science and religion, the afterlife of the soul, and his belief in God.[110][111] He stated, "Through science man strives to learn more of the mysteries of creation. Through religion he seeks to know the Creator."[112] He was interviewed by the Assemblies of God pastor C. M. Ward and stated that "The farther we probe into space, the greater my faith."[113] In addition, he met privately with evangelist Billy Graham and with the civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.[114]

Von Braun developed and published his space station concept during the time of the Cold War when the U.S. government put the containment of the Soviet Union above everything else. The fact that his space station – if armed with missiles that could be easily adapted from those already available at this time – would give the United States space superiority in both orbital and orbit-to-ground warfare did not escape him. In his popular writings, von Braun elaborated on them in several of his books and articles, but he took care to qualify such military applications as "particularly dreadful". This much-less-peaceful aspect of von Braun's "drive for space" has been reviewed by Michael J. Neufeld from the Space History Division of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington.[115]

The U.S. Navy had been tasked with building a rocket to lift satellites into orbit, but the resulting Vanguard rocket launch system was unreliable. In 1957, with the launch of Sputnik 1, a belief grew within the United States that it lagged behind the Soviet Union in the emerging Space Race. American authorities then chose to use von Braun and his German team's experience with missiles to create an orbital launch vehicle. Von Braun had originally proposed such an idea in 1954, but it was denied at the time.[86]

NASA was established by law on 29 July 1958. One day later, the 50th Redstone rocket was successfully launched from Johnston Atoll in the south Pacific as part of Operation Hardtack I. Two years later, NASA opened the Marshall Space Flight Center at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, and the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) development team led by von Braun was transferred to NASA. In a face-to-face meeting with Herb York at the Pentagon, von Braun made it clear he would go to NASA only if development of the Saturn were allowed to continue.[116] Von Braun became the center's first director on 1 July 1960 and held the position until 27 January 1970.[117]

Von Braun's early years at NASA included a failed "4 inch mission." On 21 November 1960 during which the first uncrewed Mercury-Redstone rocket, the rocket only rose up a mere 4 inches before settling back down onto the launch pad. The unfortunate and untimely failure of the rocket launch created a "nadir of morale in Project Mercury." The launch failure was later determined to be the result of a "power plug with one prong shorter than the other because a worker filed it to make it fit."[citation needed] Because of the difference in the length of one prong, the launch system detected the difference in the power disconnection as a "cut-off signal to the engine." The safety system in fact stopped the launch.[118]

After the success of the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission in January 1961, a mere 2 months after the failed "4 inch mission," NASA morale was improved. Still, a new string of problems emerged. Von Braun insisted on one more test before the Redstone could be deemed man-rated. His overly cautious nature brought about clashes with other people involved in the program, who argued that MR-2's technical issues were simple and had been resolved shortly after the flight. He overruled them, so a test mission involving a Redstone on a boilerplate capsule was flown successfully in March. Von Braun's stubbornness was blamed for the inability of the U.S. to launch a crewed space mission before the Soviet Union, which ended up putting the first man in space the following month.[119] Three weeks later on 5 May, von Braun's team successfully launched Alan Shepard into space. He named his Mercury-Redstone 3 Freedom 7.[120]

The Marshall Center's first major program was the development of Saturn rockets to carry heavy payloads into and beyond Earth orbit. From this, the Apollo program for crewed Moon flights was developed. Von Braun initially pushed for a flight engineering concept that called for an Earth orbit rendezvous technique (the approach he had argued for building his space station), but in 1962, he converted to the lunar orbit rendezvous concept that was subsequently realized.[121][122] During Apollo, he worked closely with former Peenemünde teammate, Kurt H. Debus, the first director of the Kennedy Space Center. His dream to help mankind set foot on the Moon became a reality on 16 July 1969, when a Marshall-developed Saturn V rocket launched the crew of Apollo 11 on its historic eight-day mission. Over the course of the program, Saturn V rockets enabled six teams of astronauts to reach the surface of the Moon.[123]

During the late 1960s, von Braun was instrumental in the development of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville. The desk from which he guided America's entry into the Space Race remains on display there. He also was instrumental in the launching of the experimental Applications Technology Satellite. He traveled to India and hoped that the program would be helpful in bringing a massive educational television project to help the poorest people in that country.[124]

During the local summer of 1966–67, von Braun participated in a field trip to Antarctica, organized for him and several other members of top NASA management.[125] The goal of the field trip was to determine whether the experience gained by the U.S. scientific and technological community during the exploration of Antarctic wastelands would be useful for the crewed exploration of space. Von Braun was mainly interested in the management of the scientific effort on Antarctic research stations, logistics, habitation, and life support, and in using the barren Antarctic terrain like the glacial dry valleys to test the equipment that one day was used to look for signs of life on Mars and other worlds.[126]

In an internal memo dated 16 January 1969,[127] von Braun had confirmed to his staff that he would stay on as a center director at Huntsville to head the Apollo Applications Program. He referred to this time as a moment in his life when he felt the strong need to pray, stating "I certainly prayed a lot before and during the crucial Apollo flights".[128] A few months later, on the occasion of the first Moon landing, he publicly expressed his optimism that the Saturn V carrier system would continue to be developed, advocating human missions to Mars in the 1980s.[129]

Nonetheless, on 1 March 1970, von Braun and his family relocated to Washington, D.C., when he was assigned the post of NASA's Deputy Associate Administrator for Planning at NASA Headquarters. After a series of conflicts associated with the truncation of the Apollo program, and facing severe budget constraints, von Braun retired from NASA on 26 May 1972. Not only had it become evident by this time that NASA and his visions for future U.S. space flight projects were incompatible, but also it was perhaps even more frustrating for him to see popular support for a continued presence of man in space wane dramatically once the goal to reach the Moon had been accomplished.[130]

Von Braun also developed the idea of a Space Camp that would train children in fields of science and space technologies, as well as help their mental development much the same way sports camps aim at improving physical development.[29]: 354–355 [131]

After leaving NASA, von Braun moved to the Washington, D.C. area and became vice president for Engineering and Development at the aerospace company Fairchild Industries in Germantown, Maryland on 1 July 1972.[131]

In 1973, during a routine physical examination, von Braun was diagnosed with kidney cancer, which could not be controlled with the medical techniques available at the time.[132]

Von Braun helped establish and promote the National Space Institute, a precursor of the present-day National Space Society, in 1975, and became its first president and chairman. In 1976, he became a scientific consultant to Lutz Kayser, the CEO of OTRAG, and a member of the Daimler-Benz board of directors. However, his deteriorating health forced him to retire from Fairchild on 31 December 1976. When the 1975 National Medal of Science was awarded to him in early 1977, he had been hospitalized, and was unable to attend the White House ceremony.[133]

Von Braun's insistence on more tests after Mercury-Redstone 2 flew higher than planned has been identified as contributing to the Soviet Union's success in launching the first human in space.[134] The successful Mercury-Redstone BD flight took the launch slot that might have put Alan Shepard into space, three weeks ahead of Yuri Gagarin. His Soviet counterpart Sergei Korolev insisted on two successful flights with dogs before risking Gagarin's life on a crewed attempt. The second test flight took place one day after the Mercury-Redstone BD mission.[29]

Von Braun took a conservative approach to engineering, designing with ample safety factors and redundant structure. This became a point of contention with other engineers, who struggled to keep vehicle weight down so that payload could be maximized. As noted above, his caution likely led to the U.S. losing the race to put a man into space before the Soviets. Krafft Ehricke likened von Braun's approach to building the Brooklyn Bridge.[135]: 208 Many at NASA headquarters jokingly referred to Marshall as the "Chicago Bridge and Iron Works", but acknowledged that the designs worked.[136] The conservative approach paid off when a fifth engine was added to the Saturn C-4, producing the Saturn V. The C-4 design had a large crossbeam that could easily absorb the thrust of an additional engine.[29]: 371

Von Braun did not indicate interest in politics or political philosophy during his onboarding working for the U.S. Army. He was primarily focused on his work in guided missiles for the purpose of advancing science and technology. According to FBI background checks, "any political activity he may have engaged in was a means to an end to provide him with the necessary freedom to conduct his experiments."[33] This included time spent in the Nazi party during World War 2.

During his time in NASA, he opposed racial segregation which brought him into conflict with George Wallace, who advocated racial discrimination in Alabama and wanted to continue segregation.[137] Von Braun accused segregationist policies as obstructing the development of Alabama. His statements were considered "unusual for a space scientist, particularly in the south, but well within agency and national policy.[138]

Von Braun had a charismatic personality and was known as a ladies' man. As a student in Berlin, he often was seen in the evenings in the company of two girlfriends at once.[29]: 63 He later had a succession of affairs within the secretarial and computer pool at Peenemünde.[29]: 92–94

In January 1943, von Braun became engaged to Dorothee Brill, a physical education teacher in Berlin, and he sought permission to marry from the SS Race and Settlement Main Office. However, the engagement was broken due to his mother's opposition.[29]: 146–147 Later in 1943, he had an affair with a French woman while in Paris preparing V-2 launch sites in northeastern France. She was imprisoned for collaboration after the war and became destitute.[29]: 147–148

During his stay at Fort Bliss, von Braun proposed marriage to Maria Luise von Quistorp, his maternal first cousin, in a letter to his father. He married her in a Lutheran church in Landshut, Bavaria, on 1 March 1947, having received permission to go back to Germany and return with his bride. He was 35, and his new bride was 18.[139] Shortly after, he converted to Evangelicalism.[140] He returned to Manhattan on 26 March 1947, with his wife, father, and mother. On 8 December 1948, the von Brauns' first daughter together, Iris Careen, was born at Fort Bliss Army Hospital.[45] The couple had two more children: Margrit Cécile, born in 1952,[141] and Peter Constantine, born in 1960.[141]

On 15 April 1955, von Braun became a naturalized citizen of the United States.[142]

In 1973, von Braun was diagnosed with kidney cancer during a routine medical examination. However, he continued to work unrestrained for a number of years. In January 1977, then very ill, he resigned from Fairchild Industries. Later in 1977, President Gerald R. Ford awarded him the country's highest science honor, the National Medal of Science in Engineering. He was too ill to attend the White House ceremony.[143]

Von Braun died on 16 June 1977 of pancreatic cancer in Alexandria, Virginia, at age 65.[144][145] He is buried on Valley Road at the Ivy Hill Cemetery in Alexandria. His gravestone cites Psalm 19:1: "The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork" (KJV).[146]

(left SS after graduation from the school; commissioned in 1940 with date of entry backdated to 1934)

Film and television

Von Braun has been featured in a number of films and television shows or series:

Several fictional characters have been modeled on von Braun:

In print media:

In literature:

In theatre:

In music:

In video games:

It would be a blow to U.S. prestige if we did not [launch a satellite] first.[184]

During the time he was in Huntsville, Dr. Braun told everyone that his name was pronounced like the color Brown.

Magnus von Braun, the brother of rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun who worked in Huntsville from 1950–1955, died Saturday in Phoenix, Ariz. He was 84. Though not as famous as his older brother, who died in 1977, Magnus von Braun made the first contact with U.S. Army troops to arrange the German rocket team's surrender at the end of World War II.

Von Braun was a right-wing nationalist by upbringing but seems to have taken little interest in Nazi ideology or anti-Semitism. As money began flowing into rearmament and eventually into the rocket program, he became more enthusiastic about the regime. In 1933–34, he was a member of an SS riding group in Berlin, but National Socialist organizations were then pressing non-member students to participate in paramilitary activities. In 1937, now the technical director at age 25 of the new Army rocket center at Peenemünde on the Baltic, he received a letter asking him to join the Party. Since it required little commitment, and it might damage his career to say no, he went along.

It had been thought that he publicly wore his uniform with swastika armband just once, during one of two formal...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)Even as man prepared to take his first tentative extraterrestrial steps, other celestial adventures beckoned him. The shape and scope of the post-Apollo crewed space program remained hazy, and a great deal depends on the safe and successful outcome of Apollo 11. Well before the lunar flight was launched, though, NASA was casting eyes on targets far beyond the Moon. The most inviting: the earth's close, and probably most hospitable, planetary neighbor. Given the same energy and dedication that took them to the Moon, says Wernher von Braun, Americans could land on Mars as early as 1982.

Wernher von Braun, the master rocket builder and pioneer of space travel, died of cancer Thursday morning. He was 65 years old.