El mariscal de campo Sir Henry Hughes Wilson, primer baronet , GCB , DSO (5 de mayo de 1864 - 22 de junio de 1922) fue uno de los oficiales de estado mayor de mayor rango del ejército británico durante la Primera Guerra Mundial y fue brevemente un político unionista irlandés .

Wilson se desempeñó como comandante de la Escuela Superior de Camberley y luego como director de operaciones militares en el Ministerio de Guerra , donde desempeñó un papel fundamental en la elaboración de planes para desplegar una fuerza expedicionaria en Francia en caso de guerra. Se ganó la reputación de intrigante político por su papel en la campaña a favor de la introducción del servicio militar obligatorio y por el incidente de Curragh de 1914.

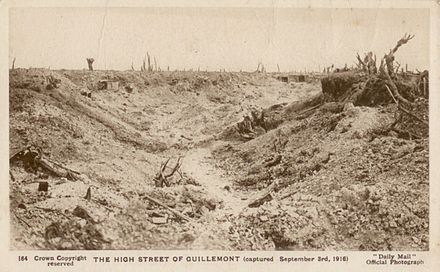

Como subjefe del Estado Mayor de la Fuerza Expedicionaria Británica (BEF), Wilson fue el asesor más importante de Sir John French durante la campaña de 1914, pero sus malas relaciones con Haig y Robertson lo dejaron al margen de la toma de decisiones de alto nivel en los años intermedios de la guerra. Desempeñó un papel importante en las relaciones militares anglo-francesas en 1915 y, después de su única experiencia de mando de campo como comandante de cuerpo en 1916 [1] , como aliado del controvertido general francés Robert Nivelle a principios de 1917. Más tarde, en 1917, fue asesor militar informal del primer ministro británico David Lloyd George y luego representante militar permanente británico en el Consejo Supremo de Guerra en Versalles. En 1918, Wilson sirvió como jefe del Estado Mayor Imperial (el jefe profesional del Ejército británico). Continuó ocupando este puesto después de la guerra, una época en la que el ejército se estaba reduciendo drásticamente en tamaño mientras intentaba contener el malestar industrial en el Reino Unido y el malestar nacionalista en Mesopotamia y Egipto. También jugó un papel importante en la Guerra de Independencia de Irlanda .

Después de retirarse del ejército, Wilson sirvió brevemente como miembro del Parlamento y asesor de seguridad del gobierno de Irlanda del Norte . Fue asesinado por dos pistoleros del IRA en 1922.

La familia Wilson afirmó haber llegado a Carrickfergus con Guillermo de Orange en 1690, pero bien pudo haber vivido en la zona antes de eso. Prosperaron, como protestantes del Ulster , en el negocio naviero de Belfast a finales del siglo XVIII y principios del XIX y, tras la Ley de Fincas Gravadas de 1849, se convirtieron en terratenientes. El padre de Wilson, James, el más joven de cuatro hijos, heredó Currygrane en Ballinalee (1200 acres, valorado en 835 libras en 1878), lo que lo convirtió en un terrateniente de rango medio. James Wilson sirvió como alto sheriff , juez de paz y teniente adjunto de Longford, y asistió al Trinity College de Dublín . Incluso en la década de 1960, el líder del IRA Seán Mac Eoin recordaba a los Wilson como terratenientes y empleadores justos. [2] Los Wilson también eran dueños de Frascati, una casa del siglo XVIII en Blackrock, Dublín . [3]

Nacido en Currygrane, Henry Wilson fue el segundo de los cuatro hijos de James y Constant Wilson (también tenía tres hermanas). Asistió a la escuela pública de Marlborough entre septiembre de 1877 y Pascua de 1880, antes de irse a estudiar para prepararse para el ejército. Uno de los hermanos menores de Wilson también se convirtió en oficial del ejército y el otro en agente inmobiliario. [4]

Wilson hablaba con acento irlandés y a veces se consideraba británico, irlandés o ulsteriano. Como muchos de su época, incluidos los angloirlandeses o los escoceses del Ulster , a menudo se refería a Gran Bretaña como "Inglaterra". Su biógrafo Keith Jeffery sugiere que bien podría, como muchos angloirlandeses, haber exagerado su "irlandesidad" en Inglaterra y haberse considerado más "anglo-" mientras estuvo en Irlanda, y también podría haber estado de acuerdo con la opinión de su hermano Jemmy de que Irlanda no era lo suficientemente "homogénea" para ser "una nación". [5] Wilson era un miembro devoto de la Iglesia de Irlanda y en ocasiones asistía a servicios católicos , pero no le gustaba el ritual "romano". [5]

Entre 1881 y 1882, Wilson intentó varias veces sin éxito entrar en las instituciones de formación de oficiales del ejército británico : dos para entrar en la Real Academia Militar (Woolwich) y tres para el Real Colegio Militar . [6] Los exámenes de ingreso a ambas instituciones dependían en gran medida del aprendizaje de memoria. Sir John Fortescue afirmó más tarde que esto se debía a que, como era un muchacho alto, necesitaba "tiempo para que su cerebro se desarrollara". [7] [6] [8]

Al igual que French y Spears , entre otros, Wilson adquirió su comisión "por la puerta de atrás", como se conocía entonces, convirtiéndose primero en un oficial de la milicia . En diciembre de 1882 se unió a la Milicia de Longford, que también era el 6.º Batallón (de la Milicia) de la Brigada de Fusileros . [6] También se entrenó con el 5.º Batallón de los Fusileros Reales de Munster . [9] [10] Después de dos períodos de entrenamiento, fue elegible para solicitar una comisión regular, y después de estudiar más a fondo en el invierno de 1883-84, y de viajes a Argel y Darmstadt para aprender francés y alemán, se presentó al examen del Ejército en julio de 1884. Fue comisionado en el Regimiento Real Irlandés , pero pronto fue transferido a la más prestigiosa Brigada de Fusileros. [9] [11] [12]

A principios de 1885, Wilson fue destinado a la India con el 1.er Batallón de la Brigada de Fusileros , donde se dedicó al polo y a la caza mayor. En noviembre de 1886 fue destinado al Alto Irawaddy, al sur de Mandalay, en la Birmania recientemente anexionada, para participar en la Tercera Guerra Birmana , cuyas operaciones de contrainsurgencia en las colinas de Arakan se conocieron como "la guerra de los subalternos". Las tropas británicas se organizaron en infantería montada, acompañadas por la "policía Goorkha". Wilson trabajó con Henry Rawlinson , del Real Cuerpo de Fusileros del Rey (KRRC), quien lo describió en su diario como "un muy buen tipo". El 5 de mayo de 1887 fue herido por encima del ojo izquierdo. La herida no sanó y, tras seis meses en Calcuta, pasó casi todo 1888 recuperándose en Irlanda hasta que fue declarado apto para el servicio del regimiento. Quedó desfigurado. [13] Su herida le valió los apodos de "Ugly Wilson" y "el hombre más feo del ejército británico". [8]

Mientras estuvo en Irlanda, Wilson comenzó a cortejar a Cecil Mary Wray, que era dos años mayor que él. Su familia, que había llegado a Irlanda a finales del reinado de Isabel I , había sido propietaria de una finca llamada Ardamona cerca de Lough Eske , Donegal , cuya rentabilidad nunca se había recuperado de la Gran Hambruna de Irlanda de la década de 1840. El 26 de diciembre de 1849, dos barriles de explosivos fueron detonados fuera de la casa, después de lo cual la familia solo pasó allí un invierno más. Desde 1850, el padre de Cecil, George Wray, había trabajado como agente inmobiliario, últimamente para las propiedades de Lord Drogheda en Kildare, hasta su muerte en 1878. Cecil creció en circunstancias difíciles y sus opiniones sobre la política irlandesa parecen haber sido bastante más duras que las de su marido. Se casaron el 3 de octubre de 1891. [14]

Los Wilson no tenían hijos. [15] Wilson les prodigaba cariño a sus mascotas (incluido un perro llamado Paddles) y a los hijos de otras personas. Le dieron un hogar al joven Lord Guilford en 1895-1896 y a la sobrina de Cecil, Leonora ("Little Trench"), a partir de diciembre de 1902. [16]

Mientras contemplaba la posibilidad de casarse, Wilson comenzó a estudiar para el Staff College, Camberley , en 1888, posiblemente porque asistir al Staff College no solo era más barato que servir en un regimiento elegante, sino que también abría la posibilidad de un ascenso. En ese momento, Wilson tenía un ingreso privado de £200 al año proveniente de un fondo fiduciario de £6000. A fines de 1888, Wilson fue declarado apto para el servicio en el país (pero no en el extranjero) y se unió al 2.º batallón en Dover a principios de 1889. [17] Wilson fue elegido miembro de White's en 1889. [18]

Después de un destino en Aldershot, Wilson fue destinado a Belfast en mayo de 1890. En mayo de 1891, pasó en el puesto 15 (de 25) en el Staff College. El francés y el alemán estaban entre sus peores materias, y comenzó a estudiar allí en enero de 1892. [17] Después de su dificultad para entrar en el ejército, aprobar el examen de ingreso demostró que no le faltaba cerebro. [8]

El coronel Henry Hildyard se convirtió en comandante del Staff College en agosto de 1893, iniciando una reforma de la institución, poniendo más énfasis en la evaluación continua (incluyendo ejercicios al aire libre) en lugar de los exámenes. Wilson también estudió con el coronel George Henderson . [19] Mientras estaba en el College, visitó los campos de batalla de la guerra franco-prusiana en marzo de 1893. [20] Rawlinson y Thomas D'Oyly Snow fueron a menudo sus compañeros de estudio. Rawlinson y Wilson se hicieron amigos cercanos, a menudo se alojaban y socializaban juntos, y Rawlinson presentó a Wilson a Lord Roberts en mayo de 1893, mientras ambos hombres trabajaban en un plan para la defensa de la India. [19] Wilson se convirtió en un protegido de Roberts. [8]

Wilson se graduó en la Escuela Superior de Estado Mayor en diciembre de 1893 y fue inmediatamente ascendido a capitán . [21] Debía ser destinado con el 3.er Batallón a la India a principios de 1894, pero después de una extensa e infructuosa presión obtuvo un aplazamiento médico. Luego se enteró de que debía unirse al 1.er Batallón en Hong Kong durante dos años, pero lo intercambió con otro capitán, que luego murió en su período de servicio. No hay evidencia clara de por qué Wilson estaba tan interesado en evitar el servicio en el extranjero. Repington , entonces capitán del personal en la Sección de Inteligencia del Ministerio de Guerra, llevó a Wilson a una gira por las instalaciones militares y navales francesas en julio. Después de un servicio muy breve con su regimiento en septiembre, con la ayuda de Repington, Wilson llegó a trabajar en el Ministerio de Guerra en noviembre de 1894, inicialmente como asistente no remunerado, y luego sucedió en el propio trabajo de Repington. [22]

La División de Inteligencia había sido desarrollada por el general Henry Brackenbury a fines de la década de 1880 como una especie de Estado Mayor sustituto; Brackenbury había sido sucedido por el protegido de Roberts, el general Edward Chapman, en abril de 1891. [23] Wilson trabajó allí durante tres años a partir de noviembre de 1894. [24] [23] [25] [26] A partir de noviembre de 1895, Wilson encontró tiempo para ayudar a Rawlinson con su "Libro de notas del oficial" basado en un libro anterior de Lord Wolseley , y que inspiró el "Libro de bolsillo del servicio de campo" oficial. [23]

Wilson trabajó en la Sección A (Francia, Bélgica, Italia, España, Portugal y América Latina). En abril de 1895, a pesar de recibir clases intensivas de hasta tres horas casi todos los días, suspendió un examen de alemán para un destino en Berlín. El 5 de mayo de 1895, reemplazó a Repington como capitán de Estado Mayor de la Sección A, lo que lo convirtió en el oficial de Estado Mayor más joven del Ejército británico. Sus funciones lo llevaron a París (junio de 1895, para informarse sobre la expedición a Borgu en el Alto Níger) y Bruselas. [27] En enero de 1896 parecía probable que lo nombraran mayor de brigada de la 2.ª brigada en Aldershot si el titular actual, Jack Cowans, un notorio mujeriego con una inclinación por el "comercio rudo", renunciaba, aunque en realidad esto no sucedió hasta principios de septiembre. [28]

Wilson, que creía que la guerra con el Transvaal era "muy probable" desde la primavera de 1897, hizo campaña para conseguir un lugar en alguna fuerza expedicionaria. Esa primavera ayudó al mayor HP Northcott, jefe de la sección del Imperio Británico en la División de Inteligencia, a trazar un plan "para decapitar a Kruger ". Leo Amery afirmó más tarde que Wilson y el teniente Dawnay ayudaron a Roberts a trazar lo que se convertiría en su plan final para invadir las repúblicas bóer desde el oeste. Recibió una medalla por participar en la procesión del Jubileo de Diamante de la Reina Victoria , pero lamentó no haber ganado una medalla de guerra. [29] Para su pesar, y a diferencia de su amigo Rawlinson, Wilson no consiguió un destino en la Expedición a Sudán de 1898 . [28] Cuando las tensiones volvieron a aumentar en el verano de 1899, [29] Wilson fue nombrado mayor de brigada de la 3.ª brigada, ahora rebautizada como 4.ª o brigada "ligera" en Aldershot , [30] que desde el 9 de octubre estuvo bajo el mando de Neville Lyttelton . Se declaró la guerra el 11 de octubre de 1899 y llegó a Ciudad del Cabo el 18 de noviembre. [29]

La brigada de Wilson estaba entre las tropas enviadas a Natal ; a fines de noviembre estaba acampada en el río Mooi , a 509 millas de la sitiada Ladysmith . La brigada de Wilson tomó parte en la batalla de Colenso (15 de diciembre), en la que las tropas británicas, que avanzaban después de un bombardeo de artillería inadecuado, fueron derribadas por bóers atrincherados y en gran parte ocultos, armados con fusiles de carga. [31] Buller , que todavía estaba al mando en Natal a pesar de haber sido reemplazado por Roberts como comandante en jefe, estaba esperando la llegada de la 5.ª División de Sir Charles Warren . El fuego de artillería en el asedio de Ladysmith todavía se podía escuchar desde las posiciones de Buller, pero rechazó una propuesta de Wilson de que la Brigada Ligera cruzara el río Tugela en Potgieter's Drift, 15 millas río arriba. Wilson criticó tanto la demora desde el 16 de diciembre como el hecho de que Buller no compartiera información con Lyttelton y otros oficiales superiores. Buller permitió a Lyttleton cruzar en ese lugar el 16 de enero, y la mayor parte de sus fuerzas reforzadas cruzaron sin oposición en Trikhardt's Drift, cinco millas río arriba, al día siguiente. [32] Wilson se atribuyó el mérito del fuego de artillería de distracción de la Brigada Ligera durante el cruce de Trikhardt's Drift. [33]

Durante la batalla de Spion Kop (24 de enero), Wilson criticó a Buller por su falta de personal adecuado, su falta de comunicación y su interferencia con Warren, a quien había puesto a cargo. En un relato escrito después de la batalla, afirmó haber querido aliviar la presión enviando dos batallones (los Scottish Rifles (cameronianos) y el 60th King's Royal Rifle Corps , así como los Buccaneers de Bethune (una unidad de infantería montada )) para ocupar Sugar Loaf, dos millas al este-noreste de Spion Kop, donde los hombres de Warren estaban bajo fuego desde tres lados. Lyttelton, 25 años después, afirmó que Wilson le había sugerido enviar refuerzos para ayudar a Warren. El diario contemporáneo de Wilson es ambiguo, afirmando que "nosotros" habíamos enviado al 60.º a tomar Sugar Loaf, mientras que los hombres de Bethune y los rifles fueron a ayudar a Warren, y que cuando el Kop se llenó de gente, Lyttelton rechazó la solicitud de Wilson de enviar los rifles a Sugar Loaf para ayudar al 60.º. [34]

Después de la derrota, Wilson volvió a burlarse de la falta de progreso de Buller y de sus predicciones de que estaría en Ladysmith el 5 de febrero. Leo Amery contó más tarde una historia maliciosa de que Wilson había sugerido reunir a los mayores de brigada para arrestar a su comandante general, aunque Wilson de hecho parece haber tenido una buena opinión de Lyttelton en ese momento. También fue muy crítico con Fitzroy Hart ("perfecta desgracia... bastante loco e incapaz bajo fuego"), comandante general de la Brigada Irlandesa, por atacar Inniskilling Hill en orden cerrado el 24 de febrero (ver Batalla de las Alturas de Tugela ) y, el mismo día, dejar a la Infantería Ligera de Durham (parte de la Brigada Ligera) expuesta al ataque (Wilson visitó la posición, y se retiraron el 27 de febrero después de que Wilson presionara a Lyttelton y Warren), y por dejar a Wilson para organizar una defensa contra un ataque nocturno de los bóers al Cuartel General de la Brigada Ligera después de rechazar las solicitudes de la Brigada Ligera de colocar piquetes. La Brigada Ligera finalmente tomó Inniskilling Hill el 27 de febrero y Ladysmith fue relevada al día siguiente, lo que permitió a Wilson reunirse nuevamente con su viejo amigo Rawlinson, quien había sido asediado allí. [35] Después del relevo de Ladysmith, Wilson continuó siendo muy crítico del mal estado de la logística y del débil liderazgo de Buller y Dundonald . Después de la caída de Pretoria, predijo correctamente que los bóers recurrirían a la guerra de guerrillas , aunque no esperaba que la guerra durara hasta la primavera de 1902. [36]

En agosto de 1900, Wilson fue convocado para ver al "Jefe" y designado para ayudar a Rawlinson en la rama del Ayudante General, y optó por quedarse allí en lugar de regresar a su puesto de mayor de brigada (que pasó a su hermano Tono). Parte de la motivación de Wilson era su deseo de volver a casa antes. Compartía una casa en Pretoria con Rawlinson y Eddie Stanley (más tarde Lord Derby ), el secretario de Roberts; todos tenían unos treinta y cinco años y socializaban con las hijas de Roberts, que entonces tenían 24 y 29 años. [37] Wilson fue nombrado Ayudante General Adjunto Adjunto (1 de septiembre de 1900) [38] y secretario militar adjunto de Roberts en septiembre, lo que significó que regresó a casa con Roberts en diciembre. Lyttelton lo había querido en Sudáfrica en su personal, mientras que Kelly-Kenny lo quería en el personal del Comando Sur , que esperaba obtener. [37]

El 9 de octubre de 1899, el teniente coronel Repington , por el bien de su carrera, le dio a Wilson su promesa escrita de renunciar a su amante Mary Garstin. Wilson había sido amigo del padre de Mary Garstin, que había muerto en 1893, y ella era prima de su amiga Lady Guilford, quien le pidió a Wilson que se involucrara en la Navidad de 1898. El 12 de febrero de 1900, Repington le dijo que se consideraba absuelto de su libertad condicional después de enterarse de que su esposo había estado difundiendo rumores de sus otras infidelidades. Durante las audiencias de divorcio, Wilson rechazó la solicitud de Repington de firmar un relato de lo que se había dicho en su reunión, y no pudo acceder a la solicitud de Kelly-Kenny ( Ayudante General de las Fuerzas Armadas ) de un relato de la reunión, ya que no había escrito detalles de ella en su diario (Lady Guilford había destruido la carta que le había escrito conteniendo los detalles). Por lo tanto, no pudo o no quiso confirmar la afirmación de Repington de que lo había liberado de su libertad condicional. Repington creía que Wilson había "delatado" a un compañero soldado. Los rumores del ejército posteriores afirmaron que Wilson había delatado deliberadamente a un potencial rival de carrera. Repington tuvo que renunciar a su cargo. [39] [40]

En 1901, Wilson pasó nueve meses trabajando bajo las órdenes de Ian Hamilton en el Ministerio de Guerra, donde se encargaba de asignar honores y premios de la reciente guerra sudafricana. Él mismo recibió una Mención en Despachos [41] y una Orden de Servicio Distinguido [24] [42] , que Aylmer Haldane afirmó posteriormente que Wilson había insistido en recibir por celos de que se la hubieran concedido. [43] También se recomendó a Wilson para un ascenso breve a teniente coronel al alcanzar una mayoría sustancial . [44]

Entre marzo y mayo de 1901, a instancias del diputado unionista liberal Sir William Rattigan , y en el contexto de las reformas del ejército propuestas por St John Brodrick , Wilson, escribiendo anónimamente como "oficial del Estado Mayor", publicó una serie de doce artículos sobre la reforma del ejército en el Lahore Civil and Military Gazette . Sostuvo que, dado el gran crecimiento reciente del tamaño del Imperio, Gran Bretaña ya no podía depender solo de la Marina Real. Wilson sostuvo que las tres funciones principales del ejército eran la defensa interior, la defensa de la India (contra Rusia), Egipto y Canadá (contra los EE. UU., con quienes Wilson esperaba, no obstante, que Gran Bretaña mantuviera una relación amistosa) y la defensa de las principales estaciones de carbón y puertos para uso de la Marina Real. A diferencia de St John Brodrick, Wilson en esta etapa descartó explícitamente que Gran Bretaña se involucrara en una guerra europea. Sin sus principales colonias, argumentó, Gran Bretaña sufriría " el destino de España ". Quería que se pusieran a disposición 250.000 hombres para el servicio en el extranjero, no los 120.000 propuestos por Brodrick, y contempló la introducción del servicio militar obligatorio (que había sido descartado por la Oposición Liberal). [45] En privado, Wilson –en parte motivado por el pobre desempeño de las unidades de Yeomanry mal entrenadas en Sudáfrica– y otros oficiales del Ministerio de Guerra fueron menos elogiosos con respecto a las reformas propuestas por Brodrick. [46]

Wilson obtuvo tanto el ascenso sustancial a mayor como el brevet prometido en diciembre de 1901, [47] y en 1902 se convirtió en comandante del 9.º Batallón Provisional de la Brigada de Fusileros en Colchester , [24] [48] destinado a suministrar reclutas para la Guerra de Sudáfrica, que entonces todavía estaba en curso. El batallón se disolvió en febrero de 1903. [49]

Wilson regresó al Ministerio de Guerra como asistente de Rawlinson en el Departamento de Educación y Entrenamiento Militar bajo el mando del general Sir Henry Hildyard. Los tres hombres dirigieron un comité que trabajó en un "Manual de Entrenamiento Combinado" y un "Manual de Estado Mayor" que formaron la base de las Regulaciones del Servicio de Campaña Parte II, que entrarían en vigor cuando el Ejército entrara en guerra en agosto de 1914. [50] Con £1.600 prestados por su padre, Wilson compró una casa en Marylebone Road . [50] En 1903 se convirtió en Ayudante General Adjunto . [51]

En esa época Wilson se estaba haciendo amigo de figuras políticas como Arthur Balfour , Winston Churchill , Leo Amery y Leo Maxse . [16] Algunas de las reformas propuestas por St. John Brodrick fueron criticadas por el Informe Elgin en agosto de 1903. Brodrick estaba siendo atacado en el Parlamento por parlamentarios conservadores, incluido Amery, a quien Wilson estaba proporcionando información. [52]

Por sugerencia de Leo Amery, el colega de Wilson, Gerald Ellison, fue nombrado secretario del Comité de Reconstitución del Ministerio de Guerra (véase el Informe Esher ), que estaba formado por Esher , el almirante John Fisher y Sir George Clarke . Wilson aprobó los objetivos de Esher, pero no la velocidad vertiginosa con la que comenzó a hacer cambios en el Ministerio de Guerra. Wilson impresionó a Esher y fue puesto a cargo del nuevo departamento que gestionaba la Escuela Superior, la RMA, la RMC y los exámenes de ascenso de los oficiales. [53] Wilson viajaba a menudo por Gran Bretaña e Irlanda para supervisar el entrenamiento de los oficiales y los exámenes de ascenso. [54]

Wilson asistió a la primera Conferencia del Estado Mayor y a la primera Marcha del Estado Mayor en Camberley en enero de 1905. [55] Continuó presionando para que se estableciera un Estado Mayor, especialmente después del incidente del Dogger Bank de octubre de 1904. Wilson propuso un Jefe del Estado Mayor fuerte que sería el único asesor del Secretario de Estado para la Guerra en cuestiones de estrategia, irónicamente el puesto que ocuparía el rival de Wilson, Robertson, durante la Primera Guerra Mundial. [56] A pesar de la presión de Repington, Esher y Sir George Clarke, el progreso en el Estado Mayor fue muy lento. En agosto, el sucesor de Brodrick, Arnold-Forster, emitió un acta similar a la de Wilson de tres meses antes. Lyttelton (Jefe del Estado Mayor), que desconocía el papel de Wilson, expresó su apoyo. En noviembre, Wilson publicó el memorando de Arnold-Forster a la prensa, afirmando que se le había ordenado hacerlo; Arnold-Forster inicialmente expresó "asombro", pero luego estuvo de acuerdo en que la filtración "no había hecho más que bien". [57]

Los Wilson cenaron en Navidad con Roberts en 1904 y 1905. Wilson ayudó a Roberts con sus discursos en la Cámara de los Lores , y la cercanía de su relación atrajo la desaprobación de Lyttelton, y posiblemente de French y Arnold-Forster. Las relaciones con Lyttelton se volvieron más tensas en 1905-06, posiblemente por celos o influenciado por Repington. [58] Wilson había predicho un Parlamento sin mayoría absoluta en enero de 1906 , pero para su disgusto, "ese traidor de CB " había ganado por una mayoría aplastante. [55] [59]

En mayo de 1906 hubo un temor de guerra cuando los turcos ocuparon un antiguo fuerte egipcio en la cabecera del Golfo de Aqaba . Wilson señaló que Grierson (Director de Operaciones Militares) y Lyttelton ("absolutamente incapaz... positivamente un tonto peligroso") habían aprobado el plan propuesto para la acción militar, pero ni el Ayudante General ni el Intendente General habían sido consultados. [60] Repington escribió a Esher que Wilson era un "impostor intrigante" y "un conspirador de clase baja cuya única aptitud es adorar soles nacientes, una aptitud expresada por aquellos que lo conocen en un lenguaje más vulgar". [61 ] El 12 de septiembre de 1906, la Orden del Ejército 233 creó un Estado Mayor para supervisar la educación y el entrenamiento y para elaborar planes de guerra (Wilson había redactado una Orden del Ejército a fines de 1905, pero se había retrasado por disputas sobre si los oficiales del Estado Mayor debían ser designados por el Jefe del Estado Mayor, como prefería Wilson, o por una junta de selección de once hombres). [60]

Wilson ya había esperado, en marzo de 1905, suceder a Rawlinson como comandante en la Escuela Superior de Estado Mayor de Camberley . En julio, Lyttelton ( Jefe del Estado Mayor ), a quien Wilson no parecía gustarle, elevó el puesto a general de brigada, para el que Wilson aún no tenía la edad suficiente. [62]

El 16 de julio de 1906, Rawlinson le comunicó a Wilson que quería que lo sucediera a finales de año, y la noticia apareció en la prensa en agosto entre elogios a Rawlinson, sugiriendo que él, y no Wilson, había sido quien la había filtrado. El mariscal de campo Roberts escribió a Richard Haldane (secretario de Estado para la Guerra) y a Esher recomendando a Wilson sobre la base de su excelente trabajo en Sudáfrica y como un hombre de carácter fuerte que era necesario para mantener las mejoras de Rawlinson en Camberley. Wilson, que se enteró indirectamente de Aylmer Haldane el 24 de octubre de que iba a conseguir el puesto, escribió para agradecer a Roberts, y no tenía ninguna duda de que su apoyo le había asegurado el puesto. Wilson se mantuvo muy cercano a Roberts, a menudo acompañándolo en la cena de Navidad y asistiendo a sus Bodas de Oro en mayo de 1909. [63] French (que entonces comandaba el 1.er Cuerpo de Ejército en el Comando de Aldershot ) inicialmente había sospechado de Wilson como protegido de Roberts, pero ahora apoyaba su candidatura, y en 1912 Wilson se había convertido en su asesor de mayor confianza. [64]

Wilson fue ascendido a coronel sustantivo el 1 de enero de 1907 [65] y su nombramiento como general de brigada temporal y comandante del Estado Mayor de Camberley se anunció el 8 de enero de 1907. [66] Al principio le faltaba dinero: tuvo que pedir prestado 350 libras (46 768 libras en 2016) para cubrir los gastos de mudarse a Camberley, donde su salario oficial no era suficiente para cubrir el coste del entretenimiento esperado, e inicialmente tuvo que recortar las vacaciones en el extranjero y los viajes sociales a Londres, pero después de heredar 1300 libras tras la muerte de su padre en agosto de 1907, pudo comprar caballos de polo y un segundo coche en los años siguientes. [67] Su sueldo como comandante aumentó de 1200 libras en 1907 a 1350 libras en 1910. [68]

En sus discursos a los estudiantes, Wilson hizo hincapié en la necesidad de conocimientos administrativos ("la monotonía del trabajo de estado mayor"), aptitud física, imaginación, "un juicio sólido sobre los hombres y los asuntos" y "una lectura y reflexión constantes sobre las campañas de los grandes maestros". Brian Bond sostuvo que la "escuela de pensamiento" de Wilson no sólo implicaba un entrenamiento común para los oficiales de estado mayor, sino también la defensa del reclutamiento y el compromiso militar de enviar una fuerza de defensa británica a Francia en caso de guerra. Keith Jeffery sostiene que esto es un malentendido por parte de Bond: no hay evidencia en los escritos de Wilson que confirme que él haya querido decir la frase de esa manera. [69]

Aunque Wilson estaba menos obsesionado con los peligros del espionaje que Edmonds, en marzo de 1908 hizo que dos barberos alemanes fueran expulsados del Staff College por ser espías potenciales. [70]

Wilson fue nombrado Compañero de la Orden del Baño en los honores de cumpleaños de junio de 1908. [68]

En 1908, Wilson hizo que su clase superior preparara un plan para el despliegue de una fuerza expedicionaria en Francia, suponiendo que Alemania hubiera invadido Bélgica. Se hicieron preguntas en la Cámara de los Comunes cuando se filtraron noticias de esto, y al año siguiente no se hizo ninguna suposición de una invasión alemana de Bélgica, y se recordó a los estudiantes con firmeza que el ejercicio era "SECRETO". [71] Wilson conoció a Foch por primera vez en una visita a la Escuela Superior de Guerra (diciembre de 1909). Entablaron una buena relación, y ambos pensaron que los alemanes atacarían entre Verdún y Namur . [72] [73] Wilson organizó que Foch y Victor Huguet visitaran Gran Bretaña en junio de 1910, y copió su práctica de organizar ejercicios al aire libre para los estudiantes en los que los instructores los distraían gritando "¡Allez! Allez!" y "¡Vite! Vite!" mientras intentaban trazar planes con poca antelación. [72]

Acompañado por el coronel Harper , Wilson reconoció el probable futuro teatro de operaciones de la guerra. En agosto de 1908, junto con Edward Percival ("Perks"), exploraron el sur de Namur en tren y bicicleta. En agosto de 1909, Harper y Wilson viajaron desde Mons y luego bajaron por la frontera francesa casi hasta Suiza. En la primavera de 1910, esta vez en automóvil, viajaron desde Rotterdam hasta Alemania, luego exploraron el lado alemán de la frontera, notando las nuevas líneas ferroviarias y "muchos apartaderos" que se habían construido cerca de St Vith y Bitburg (para permitir la concentración de tropas alemanas cerca de las Ardenas). [74] [75]

Wilson apoyó en privado el reclutamiento al menos desde 1905. Pensaba que el plan de Haldane de fusionar la milicia , la caballería y los voluntarios en un nuevo ejército territorial no sería suficiente para igualar el entrenamiento y la eficiencia alemanes. [76] Wilson presionó con éxito a Haldane para que se aumentara el tamaño de la Escuela Superior para proporcionar oficiales para el nuevo ejército territorial. Durante el mandato de Wilson, el número de instructores aumentó de 7 a 16 y el número de estudiantes de 64 a 100. En total, 224 oficiales del ejército y 22 de la marina real estudiaron con él. [68]

Wilson votó por primera vez para el Parlamento en enero de 1910 (por los unionistas). [77] [78] Señaló que "las mentiras dichas por los radicales desde Asquith hacia abajo son repugnantes". [79]

Launcelot Kiggell escribió que Wilson fue un conferenciante "fascinante" como comandante en Camberley. [8] Durante su tiempo como comandante, Wilson dio 33 conferencias. Varios estudiantes, de los cuales el más famoso fue Archibald Wavell , contrastaron más tarde las conferencias expansivas de Wilson, que abarcaban amplia e ingeniosamente la geopolítica, con el enfoque más práctico de su sucesor Robertson. Muchos de estos recuerdos no son confiables en sus detalles, bien pueden exagerar las diferencias entre los dos hombres y pueden haber sido influenciados por los diarios indiscretos de Wilson publicados en la década de 1920. [80]

Berkeley Vincent , que había sido observador en la guerra ruso-japonesa (era un protegido de Ian Hamilton , a quien Wilson aparentemente no le gustaba), tenía una visión más crítica de Wilson. Se oponía a sus opiniones tácticas (Wilson era escéptico ante las afirmaciones de que la moral japonesa había permitido a su infantería superar la potencia de fuego defensiva rusa) y a su estilo de dar conferencias: "una especie de bufonería ingeniosa... una especie de irlandés inglés de teatro". [81]

En mayo y junio de 1909, Wilson había sido considerado como el sucesor de Haig como Director de Funciones del Estado Mayor, aunque él hubiera preferido el mando de una brigada. [68] En abril y mayo de 1910, cuando su mandato en Camberley todavía estaba oficialmente vigente hasta enero de 1911, el Jefe del Estado Mayor Imperial (CIGS), William Nicholson , le dijo a Wilson que iba a suceder a Spencer Ewart como Director de Operaciones Militares ese verano y le vetó la aceptación de la oferta de Horace Smith-Dorrien de una brigada en Aldershot. [82] El rey Jorge V completó el mandato de Wilson en Camberley con una visita oficial en julio de 1910. [68]

Wilson recomendó a Kiggell como su sucesor y consideró que el nombramiento de William Robertson era "una apuesta tremenda". Es posible que pensara que la falta de medios personales de Robertson no lo hacía adecuado para un puesto que requería recibir invitados. [83] Robertson visitó Camberley con Lord Kitchener (28 de julio de 1910), quien criticó a Wilson; esta puede haber sido una de las causas de las malas relaciones entre Wilson y Kitchener en agosto de 1914. [84] Edmonds contó más tarde una historia de cómo Wilson había dejado una factura por 250 libras para muebles y mejoras en la residencia del comandante, y que el predecesor de Wilson, Rawlinson, cuando Robertson le pidió consejo, había comentado que muchas de estas mejoras habían sido realizadas por su propia esposa o por comandantes anteriores. Cualquiera que sea la verdad del asunto, las relaciones entre Wilson y Robertson se deterioraron a partir de entonces. [85]

Repington (a quien Wilson consideraba un "mentiroso bruto") atacó los estándares actuales de los oficiales del Estado Mayor británicos en The Times el 27 de septiembre de 1910, argumentando que Wilson había educado a los oficiales del Estado Mayor para que fueran "chupadores de Napoleones " y que Robertson era un "hombre de primera" que lo solucionaría. [86]

En 1910, Wilson se convirtió en Director de Operaciones Militares del Ministerio de Guerra británico . [75] [87] Wilson creía que su deber más importante como DMO era la elaboración de planes detallados para el despliegue de una fuerza expedicionaria en Francia. Se habían logrado pocos avances en esta área desde los planes de Grierson durante la Primera Crisis Marroquí . [8] [88] De los 36 documentos que Wilson escribió como DMO, 21 se ocuparon de asuntos relacionados con la Fuerza Expedicionaria. También esperaba que se introdujera el reclutamiento, pero esto no llegó a nada. [89]

Wilson describió el tamaño de la Fuerza Expedicionaria planeada por Haldane como simplemente una "reorganización" de las tropas disponibles en Gran Bretaña. [90] Ferdinand Foch estaba ansioso por conseguir ayuda militar británica. Invitó a Wilson y al coronel Fairholme, agregado militar británico en París, a la boda de su hija en octubre de 1910. En una visita a Londres (6 de diciembre de 1910), Wilson lo llevó a una reunión con Sir Arthur Nicolson , subsecretario permanente del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores. [91]

En 1910, Wilson compró el número 36 de Eaton Place en un contrato de arrendamiento de 13 años por 2.100 libras esterlinas. Su salario era entonces de 1.500 libras esterlinas. La casa era una carga financiera y los Wilson la alquilaban a menudo. [92]

Wilson y su personal pasaron el invierno de 1910-11 realizando un "gran juego de guerra estratégico" para predecir lo que harían las grandes potencias cuando estallara la guerra. [93]

Wilson consideró que los planes existentes para el despliegue de la BEF (conocido como el plan "WF" -que significaba "With France" (Con Francia) pero a veces se pensaba erróneamente que significaba "Wilson-Foch") eran "vergonzosos. Un acuerdo puramente académico, de papel, sin ningún valor terrenal". Envió a Nicholson un largo minuto exigiendo autoridad sobre la planificación del transporte. Se lo dieron después de un almuerzo con Haldane. [94]

El 27 y 28 de enero de 1911, Wilson visitó Bruselas, cenó con miembros del Estado Mayor belga y, más tarde, exploró la parte del país al sur del Mosa con el agregado militar, el coronel Tom Bridges . [95] Entre el 17 y el 27 de febrero, visitó Alemania, donde se reunió con el canciller Bethmann Hollweg y el almirante Tirpitz en una cena en la embajada británica. En el viaje de regreso cenó en París con Foch, a quien advirtió que no escuchara a Repington, y con el jefe del Estado Mayor francés, el general Laffort de Ladibat. [96] El almirante John Fisher se mostró hostil a los planes de Wilson de desplegar fuerzas en el continente. [97] El 21 de marzo, Wilson estaba preparando planes para embarcar a la infantería de la BEF el día 4 de la movilización, seguida por la caballería el día 7 y la artillería el día 9. [98] Al rechazar la solicitud de Nicholson (abril de 1911) de que ayudara con la nueva Army Review de Repington , lo declaró "un hombre falto de honor y un mentiroso". [96]

Wilson se sentó hasta la medianoche del 4 de julio (tres días después de que el cañonero alemán Panther llegara a Agadir en un intento de intimidar a los franceses) escribiendo un largo acta al CIGS. El 19 de julio fue a París para hablar con Adolphe Messimy (ministro de Guerra francés) y el general Dubail (jefe del Estado Mayor francés). El memorando Wilson-Dubail, aunque dejaba explícito que ninguno de los dos gobiernos se comprometía a actuar, prometía que en caso de guerra la Marina Real transportaría 150.000 hombres a Rouen, Le Havre y Boulogne, y que la BEF se concentraría entre Arras, Cambrai y Saint Quentin el decimotercer día de movilización. En realidad, los planes de transporte no estaban listos ni de lejos, aunque no está claro que los franceses lo supieran. [99] [100] Los franceses llamaron a la Fuerza Expedicionaria "l'Armee Wilson" [101] aunque parece que se quedaron con una idea inflada del tamaño del compromiso que enviaría Gran Bretaña. [102]

Wilson aprobó el discurso de Lloyd George en Mansion House (apoyando a Francia). [103] Almorzó con Grey y Sir Eyre Crowe (subsecretario adjunto del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores) el 9 de agosto, instándolos a que Gran Bretaña debía movilizarse el mismo día que Francia y enviar las seis divisiones completas. [104]

Hankey se quejó de la "obsesión perfecta de Wilson por las operaciones militares en el continente", burlándose de sus viajes en bicicleta por las fronteras francesa y belga, y acusándolo de llenar el Ministerio de Guerra con oficiales con ideas afines. [105] A petición de Nicholson, Wilson preparó un documento en el que argumentaba que la ayuda británica sería necesaria para evitar que Alemania derrotara a Francia y lograra dominar el continente. Argumentó que para el día 13 de la movilización Francia tendría la ventaja, superando en número a los alemanes, pero para el día 17 Alemania superaría en número a Francia. Sin embargo, debido a los cuellos de botella en las carreteras en las partes transitables del teatro de guerra, los alemanes podrían desplegar como máximo 54 divisiones en la fase inicial, lo que permitiría a las 6 divisiones de infantería de la BEF un efecto desproporcionado en el resultado. Ernest R. May afirmó más tarde que Wilson había "manipulado" estas cifras, pero sus argumentos fueron cuestionados por Edward Bennett, quien consideró que las cifras de Wilson no estaban muy equivocadas. [106]

Esta se convirtió en la posición del Estado Mayor para la reunión del CID del 23 de agosto. Sir Arthur Wilson propuso que 5 divisiones protegieran a Gran Bretaña mientras una desembarcaba en la costa del Báltico, o posiblemente en Amberes , creyendo que los alemanes estarían a medio camino de París para cuando una Fuerza Expedicionaria estuviera lista, y que las cuatro a seis divisiones que se esperaba que Gran Bretaña pudiera reunir tendrían poco efecto. Wilson pensó que el plan de la Marina Real era "uno de los documentos más infantiles que he leído". [107] Henry Wilson expuso sus propios planes, aparentemente la primera vez que el CID los había escuchado. [75] Hankey registró que la lúcida presentación de Wilson triunfó a pesar de que el propio Hankey no estaba del todo de acuerdo con ella. El Primer Ministro HH Asquith ordenó a la Marina que se uniera a los planes del Ejército. Hankey también registró que Morley y Burns renunciaron al Gabinete porque no pudieron aceptar la decisión, y Churchill y Lloyd George nunca aceptaron por completo las implicaciones de comprometer una gran fuerza militar en Francia. Después de la reunión, Hankey comenzó a redactar el Libro de Guerra detallando los planes de movilización, y sin embargo, el despliegue exacto de la BEF todavía no estaba decidido hasta el 4 de agosto de 1914. [101]

Wilson había recomendado desplegarse en Maubeuge. Pensó (erróneamente, como se vio después) que los alemanes sólo violarían el territorio belga al sur del Mosa. Durante las semanas siguientes, Wilson mantuvo varias reuniones con Churchill, Grey y Lloyd George, que estaban interesados en obtener un acuerdo con Bélgica. Esto atrajo la oposición de Haldane y Nicholson, que suprimieron un extenso documento de Wilson en el que abogaba por un acuerdo con Bélgica; el documento fue finalmente distribuido al CID por el sucesor de Nicholson, Sir John French, en abril de 1912. [108]

Durante la crisis de Agadir, Wilson se esforzó por transmitir a Churchill la información más reciente. Churchill y Grey fueron a la casa de Wilson (4 de septiembre) para discutir la situación hasta pasada la medianoche. Wilson (18 de septiembre) registró cuatro informes separados de espías sobre tropas alemanas que se concentraban frente a la frontera belga. Wilson también era responsable de la Inteligencia Militar, que entonces estaba en pañales. Esto incluía el MO5 (bajo el mando de George Macdonogh , que sucedió a Edmonds) y el embrionario MI5 (bajo el mando del coronel Vernon Kell ) y el MI6 (bajo el mando del "C", el comandante Mansfield Cumming ). No está claro a partir de los documentos supervivientes cuánto tiempo dedicó Wilson a estas agencias, aunque cenó con Haldane, Kell y Cumming el 26 de noviembre de 1911. [109]

En octubre de 1911, Wilson emprendió otro viaje en bicicleta por Bélgica al sur del Mosa, inspeccionando el lado francés de la frontera, visitando Verdún, el campo de batalla de Mars-La-Tour y Fort St Michel en Toul (cerca de Nancy). De regreso a casa, todavía ansioso por "capturar a esos belgas", visitó al agregado militar británico en Bruselas. [110] [111]

Los miembros radicales del gabinete presionaron para la destitución de Wilson, pero fue defendido firmemente por Haldane, que tenía el respaldo de los ministros más influyentes: Asquith, Grey y Lloyd George, así como Churchill. [112]

Después de Agadir, la sección MO1 bajo el mando de Harper se convirtió en una rama clave en la preparación para la guerra. Churchill, recién nombrado para el Almirantazgo , se mostró más receptivo a la cooperación entre el Ejército y la Marina. La inteligencia sugirió que Alemania se estaba preparando para la guerra en abril de 1912. [112] En febrero de 1912, Wilson inspeccionó los muelles de Rouen, se reunió en París con Joffre , de Castelnau y Millerand (ministro de Guerra), visitó Foch, ahora al mando de una división en Chaumont, e inspeccionó el sur de Bélgica y el apéndice de Maastricht. [113] Sir John French, el nuevo CIGS, se mostró receptivo a los deseos de Wilson de prepararse para la guerra. [114] En abril, Wilson jugó al golf con Tom Bridges, instruyéndolo para las conversaciones con los belgas, a quienes Wilson quería reforzar en Lieja y Namur. [115]

A través de su hermano Jemmy, Wilson forjó vínculos con el nuevo líder conservador Bonar Law . Jemmy había estado en la tribuna en Belfast en abril de 1912 cuando Law se dirigió a una reunión masiva contra el Home Rule , y en el verano de 1912 llegó a Londres para trabajar para la Liga de Defensa del Ulster (dirigida por Walter Long y Charlie Hunter). [116] Wilson cenó con Law y quedó impresionado por él, discutiendo sobre Irlanda y asuntos de defensa. Ese verano comenzó a tener conversaciones regulares con Long, quien utilizó a Wilson como conducto para tratar de establecer un acuerdo de defensa entre partidos con Churchill. [116]

Wilson pensó que Haldane era un tonto por pensar que Gran Bretaña tendría una ventana de tiempo de hasta seis meses para desplegar la BEF. [115] En septiembre de 1912 inspeccionó Varsovia con Alfred Knox , agregado militar británico en Rusia, luego se reunió con Zhilinsky en San Petersburgo, antes de visitar el campo de batalla de Borodino y Kiev, luego - en Austria-Hungría - Lemburgo, Cracovia y Viena. Los planes para visitar Constantinopla tuvieron que ser archivados debido a la Primera Guerra de los Balcanes , aunque Wilson registró sus preocupaciones de que los búlgaros habían derrotado a los turcos un mes después de la declaración de guerra, evidencia de que la BEF debe ser comprometida con la guerra de inmediato, no dentro de los seis meses como esperaba Haldane. [115]

El 14 de noviembre de 1912, los horarios de los trenes, elaborados por el Ministerio de Guerra de Harper, estaban listos, después de dos años de trabajo. Un comité conjunto del Ministerio de Guerra y el Almirantazgo, que incluía a representantes de la industria naviera mercante, se reunió quincenalmente a partir de febrero de 1913 y elaboró un plan viable en la primavera de 1914. En ese caso, el transporte de la BEF desde sólo tres puertos (Southampton para las tropas, Avonmouth para el transporte mecánico y Newhaven para los suministros) se llevaría a cabo sin problemas. [114] Brian Bond sostuvo que el mayor logro de Wilson como DMO fue la provisión de caballos y transporte y otras medidas que permitieron que la movilización se llevara a cabo sin problemas. [117]

Repington y Wilson seguían matándose mutuamente cada vez que se encontraban. En noviembre de 1912, Repington, que quería utilizar el Ejército Territorial como base para el reclutamiento, instó a Haldane (ahora Lord Canciller ) a que despidiera a Wilson y lo reemplazara Robertson. [118]

En 1912, Wilson fue nombrado coronel honorario del 3.er Batallón de los Royal Irish Rifles . [119]

El apoyo de Wilson al reclutamiento le hizo amigo de Leo Amery , Arthur Lee , Charlie Hunter , Earl Percy , (Lord) Simon Lovat , Garvin de The Observer , Gwynne de The Morning Post y FS Oliver , propietario de los grandes almacenes Debenham and Freebody . Wilson informó a Oliver y Lovat, que eran miembros activos de la Liga Nacional de Servicio . En diciembre de 1912, Wilson cooperó con Gwynne y Oliver en una campaña para destruir la Fuerza Territorial. [120]

En la primavera de 1913, Roberts, tras la insistencia previa de Lovat, consiguió una reconciliación entre Repington y Wilson. Repington escribió una carta a The Times en junio de 1913, exigiendo saber por qué Wilson no estaba desempeñando un papel más destacado en los debates de 1913-1914 sobre si se debían mantener en el país algunas divisiones regulares británicas para derrotar una posible invasión. [118] En mayo de 1913, Wilson sugirió que Earl Percy escribiera un artículo contra el "principio voluntario" para la National Review y lo ayudó a escribirlo. También estaba redactando discursos a favor del reclutamiento para Lord Roberts. [120]

Wilson visitó Francia siete veces en 1913, incluida una visita en agosto para observar las maniobras francesas. Wilson hablaba francés con fluidez, pero no a la perfección, y a veces recurría al inglés para asuntos delicados a fin de no correr el riesgo de hablar de forma imprecisa. [121]

En octubre de 1913, Wilson visitó Constantinopla. No le impresionaron el ejército turco ni la infraestructura vial y ferroviaria, y pensaba que la introducción de un gobierno constitucional sería el golpe final al Imperio otomano. Estas opiniones pueden haber contribuido a que se subestimara la fuerza defensiva de Turquía en Galípoli . [122]

Roberts había estado presionando a French para que promoviera a Wilson a mayor general, un rango apropiado para su trabajo como DMO, desde finales de 1912. En abril de 1913, cuando un mando de brigada estaba a punto de quedar vacante, Wilson recibió la garantía de French de que sería ascendido a mayor general más adelante ese año, y que el hecho de no haber comandado una brigada no le impediría comandar una división más tarde. [123] Wilson creía que French quería que se convirtiera en jefe de personal designado de la BEF después de las maniobras de 1913, pero que era demasiado joven. En su lugar, se nombró a Murray. [124]

Wilson fue ascendido a mayor general en noviembre de 1913. [125] French confió que tenía la intención de que su propio mandato como CIGS se extendiera por dos años hasta 1918, y que Murray lo sucediera , momento en el que Wilson sucedería a Murray como sub-CIGS. [123] Después de una reunión del 17 de noviembre de 1913 de los oficiales superiores de la BEF, Wilson registró en privado sus preocupaciones por la falta de intelecto de French y esperaba que no hubiera una guerra todavía. [126]

A principios de 1914, en un ejercicio en la Escuela Superior, Wilson actuó como jefe de Estado Mayor. Edmonds escribió más tarde que Robertson, en calidad de director de ejercicios, llamó la atención de Wilson sobre su ignorancia de ciertos procedimientos y le dijo a French en un susurro teatral: "si vas a la guerra con ese personal de operaciones, estás prácticamente derrotado". [127]

Wilson y su familia habían participado activamente en la política unionista durante mucho tiempo. Su padre se había presentado como candidato al Parlamento por Longford Sur en 1885 , mientras que su hermano mayor James Mackay ("Jemmy") se había presentado contra Justin McCarthy por Longford Norte en 1885 y 1892 , siendo derrotado por un margen de más de 10:1 cada vez. [128]

En 1893, durante la aprobación de la segunda ley de autonomía de Gladstone , Wilson había participado en una propuesta para reclutar entre 2.000 y 4.000 hombres para entrenar como soldados en el Ulster, aunque quería que también se reclutaran católicos. En febrero de 1895, Henry y Cecil escucharon y "disfrutaron inmensamente" un discurso "muy bueno" de Joseph Chamberlain sobre cuestiones municipales de Londres en Stepney, y Wilson escuchó otro discurso de Chamberlain en mayo. En 1903, el padre de Wilson formó parte de la delegación de la Convención de Propietarios de Tierras para observar la aprobación de la legislación agraria irlandesa en el Parlamento. En 1906, su hermano menor Tono fue agente conservador en Swindon . [129]

Wilson apoyó a los opositores unionistas del Ulster al Tercer Proyecto de Ley de Autonomía Irlandesa , que debía convertirse en ley en 1914. [1] Wilson había oído de su hermano Jemmy (13 de abril de 1913) sobre los planes para reclutar 25.000 hombres armados y 100.000 "agentes de policía", y para formar un Gobierno Provisional en el Ulster para tomar el control de los bancos y los ferrocarriles, lo que él pensaba "todo muy sensato". Cuando Roberts (16 de abril de 1913) le pidió que fuera jefe de personal del "Ejército del Ulster", Wilson respondió que si era necesario lucharía por el Ulster en lugar de contra él. [130]

En una reunión en el Ministerio de Guerra (4 de noviembre de 1913), Wilson le dijo a French que "no podía abrir fuego contra el norte siguiendo los dictados de Redmond" y que "Inglaterra, como Inglaterra, se opone al autogobierno local, e Inglaterra debe aceptarlo... No puedo creer que Asquith esté tan loco como para emplear la fuerza". French, a quien Wilson instó a decirle al rey que no podía depender de la lealtad de todo el ejército, no sabía que Wilson estaba filtrando el contenido de estas reuniones al líder conservador Bonar Law . [131] [132]

Wilson se reunió con Bonar Law y le dijo que no estaba de acuerdo con que el porcentaje de deserciones en el cuerpo de oficiales fuera tan alto como el 40%, la cifra sugerida por el consejero del Rey, Lord Stamfordham . Le transmitió el consejo de su esposa Cecil de que la UVF debía adoptar una postura patriótica y comprometerse a luchar por el Rey y la Patria en caso de guerra. [133] Bonar Law intentó inmediatamente comunicarse con Carson por teléfono para transmitirle esta sugerencia. Wilson también le aconsejó a Bonar Law que se asegurara de que las negociaciones fracasaran de una manera que hiciera que los nacionalistas irlandeses parecieran intransigentes. [134]

El 14 de noviembre cenó con Charlie Hunter y Lord Milner , quienes le dijeron que cualquier oficial que dimitiera por el Ulster sería reinstalado por el próximo gobierno conservador. Wilson también advirtió a Edward Sclater que la UVF no debía tomar ninguna acción hostil al ejército. Wilson encontró "ominoso" el discurso de Asquith en Leeds, en el que el primer ministro prometió "llevar esto a buen puerto" sin elecciones, y el 28 de noviembre John du Cane se presentó en el Ministerio de Guerra "furioso" con Asquith y afirmó que habría que conceder al Ulster el estatus de beligerante como a los Estados Confederados de América . [135]

Las familias Wilson y Rawlinson pasaron la Navidad con Lord Roberts, que se oponía firmemente a la legislación prevista, al igual que el general de brigada Johnnie Gough, con quien Wilson jugó al golf el día de Navidad, y Leo Amery, con quien almorzó en White's el día de Año Nuevo. La principal preocupación de Wilson era "que el ejército no se viera involucrado", y el 5 de enero tuvo "una larga y seria conversación sobre el Ulster y sobre si no podíamos hacer algo para mantener al ejército fuera de él" con Joey Davies (director de funciones del Estado Mayor desde octubre de 1913) y Robertson (director de entrenamiento militar), y los tres hombres acordaron sondear la opinión del ejército en la conferencia anual del Colegio del Estado Mayor en Camberley la semana siguiente. A fines de febrero, Wilson fue a Belfast, donde visitó el Cuartel General Unionista en el Old Town Hall. Su misión no era secreta –el propósito oficial era inspeccionar el 3.er Regimiento de Fusileros Reales Irlandeses y dar una conferencia sobre los Balcanes en el cuartel Victoria , e informó su opinión sobre la situación del Ulster al Secretario de Estado y a Sir John French– pero atrajo especulaciones de la prensa. [136] Wilson estaba encantado con los Voluntarios del Ulster (ahora 100.000 efectivos), [137] a quienes también estaba filtrando información. [138]

Después de que se le había dicho a Paget que se preparara para desplegar tropas en el Ulster, Wilson intentó en vano persuadir a French de que cualquier medida de ese tipo tendría graves repercusiones no sólo en Glasgow sino también en Egipto y la India. [139] Wilson ayudó al anciano Lord Roberts (por la mañana del 20 de marzo) a redactar una carta al Primer Ministro, instándole a no causar una división en el ejército. Wilson fue llamado a casa por su esposa para ver a Johnnie Gough , que había venido de Aldershot, y le contó la amenaza de Hubert Gough de dimitir (véase el incidente de Curragh ). Wilson le aconsejó a Johnnie que no "enviara sus papeles" (dimitiera) todavía, y telefoneó a French, quien cuando le comunicaron la noticia "dijo lugares comunes hasta que (Wilson) estuvo casi enfermo". [140] [141]

El sábado 21 por la mañana, Wilson hablaba de dimitir e instaba a su personal a hacer lo mismo, aunque en realidad nunca lo hizo y perdió el respeto al hablar demasiado de derribar al gobierno. [142] [143] Mientras el Parlamento debatía una moción conservadora de censura al gobierno por utilizar el ejército en el Ulster, [143] Repington telefoneó a Wilson (21 de abril de 1914) para preguntar qué línea debería adoptar The Times . [118] Recién llegado de una visita a Bonar Law (21 de marzo), Wilson sugirió instar a Asquith a tomar "acciones inmediatas" para evitar las dimisiones del personal general. A petición de Seely (Secretario de Estado para la Guerra), Wilson escribió un resumen de "lo que el ejército aceptaría", es decir, una promesa de que el ejército no sería utilizado para coaccionar al Ulster, pero esto no era aceptable para el gobierno. A pesar del cálido apoyo de Robertson, Wilson no pudo persuadir a French para que advirtiera al gobierno de que el ejército no actuaría contra el Ulster. [144]

Hubert Gough desayunó con Wilson el 23 de marzo, antes de su reunión con French y Ewart en el Ministerio de Guerra, donde exigió una garantía escrita de que el Ejército no sería utilizado contra el Ulster. [145] Wilson también estuvo presente en la reunión de las 4:00 p. m. en la que Gough, siguiendo su consejo, insistió en modificar un documento del Gabinete para aclarar que el Ejército no sería utilizado para imponer el Home Rule en el Ulster , a lo que French también accedió por escrito. Wilson se fue entonces, diciendo a la gente del Ministerio de Guerra que el Ejército había hecho lo que la Oposición no había hecho (es decir, evitar la coerción del Ulster). Wilson le dijo a French que sospechaba que él (French) sería despedido por el Gobierno, en cuyo caso "el Ejército estaría de su lado". [146] Para diversión de su hermano, Johnnie Gough "calentó" (se burló) de Wilson fingiendo creer que realmente iba a dimitir. [147] Wilson estaba preocupado de que un futuro gobierno de Dublín pudiera emitir "órdenes legales" para coaccionar al Ulster. En la parte superior de la página de su diario del 23 de marzo escribió: "Nosotros, los soldados, derrotamos a Asquith y sus viles trucos". [148]

Asquith repudió públicamente las enmiendas al documento del Gabinete, pero al principio se negó a aceptar las renuncias de French y Ewart, aunque Wilson le advirtió a French que debía renunciar "a menos que estuvieran en condiciones de justificar su permanencia en el cargo a los ojos de los oficiales". French finalmente renunció después de que Wilson probara el clima en un encuentro de punto a punto en la Escuela de Estado Mayor. [138] [149]

Wilson telegrafió a Gough dos veces y le aconsejó que se mantuviera firme y se quedara con el documento, pero no recibió respuesta. Milner pensó que Wilson había "salvado al Imperio", lo que Wilson consideró "demasiado halagador". Pensó que Morley (que había asesorado a Seely) y Haldane (que asesoró a French) también tendrían que dimitir, lo que haría caer al gobierno. Gough estaba enojado porque Wilson no se había ofrecido a dimitir y culpó a Wilson por no haber hecho nada para detener los planes del gobierno de coaccionar al Ulster hasta que Gough y sus oficiales amenazaron con dimitir. [142] Los hermanos Gough posteriormente despidieron a Wilson. [138] [149] [150]

Entre el 21 de marzo y finales de mes, Wilson vio a Law nueve veces, a Amery cuatro veces, a Gwynne tres veces y a Milner y Arthur Lee dos veces. No parece que considerara estos contactos con la oposición como secretos. Roberts también filtraba información que le proporcionaban Wilson y los hermanos Gough. Gough prometió mantener confidencial el Tratado del 23 de marzo, pero pronto se filtró a la prensa; parece que tanto Gough como French se lo filtraron a Gwynne, mientras que Wilson se lo filtró a Amery y Bonar Law. [151]

Wilson visitó Francia cuatro veces para discutir los planes de guerra entre enero y mayo de 1914. Como el CID había recomendado que dos de las seis divisiones de la BEF se mantuvieran en casa para protegerse contra una invasión, Wilson presionó con éxito a Asquith, que era Secretario de Estado de Guerra, para que enviara al menos cinco divisiones a Francia. [152]

Durante la Crisis de Julio, Wilson se preocupó principalmente por la aparente inminencia de una guerra civil en Irlanda y presionó en vano al nuevo CIGS Charles Douglas para que inundara toda Irlanda con tropas. [153] A fines de julio, estaba claro que el continente estaba al borde de las hostilidades. [153] Wilson llamó a de la Panouse (agregado militar francés) y a Paul Cambon (embajador francés) para discutir la situación militar. [154] Es posible que Wilson haya estado manteniendo informados a los líderes conservadores de las discusiones entre Cambon y el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores Grey. [155] [156] La invasión alemana de Bélgica proporcionó un casus belli y Gran Bretaña se movilizó el 3 de agosto y declaró la guerra el 4 de agosto. [157]

A Wilson se le ofreció inicialmente el trabajo de "General de Brigada de Operaciones", pero como ya era un general de división, negoció una mejora en su título a "Subjefe de Estado Mayor". [158] Edmonds , Kirke y Murray afirmaron después de la guerra que French había querido a Wilson como Jefe de Estado Mayor, pero esto había sido vetado debido a su papel en el Motín de Curragh ; ninguna evidencia contemporánea, ni siquiera el diario de Wilson, confirma esto. [159]

Wilson se reunió con Victor Huguet (7 de agosto), un oficial de enlace francés convocado a Londres a petición de Kitchener, y lo envió de vuelta a Francia para obtener más información de Joffre , habiéndole contado los planes británicos de iniciar el movimiento de tropas el 9 de agosto. Kitchener, enojado porque Wilson había actuado sin consultarle, lo citó a su oficina para una reprimenda. Wilson estaba enojado porque Kitchener estaba confundiendo los planes de movilización al desplegar tropas de Aldershot a Grimsby en caso de invasión alemana, y registró en su diario que "le respondí porque no tengo intención de dejarme intimidar por él, especialmente cuando dice esas tonterías... el hombre es un tonto... Es un tonto de mierda". A su regreso (12 de agosto) Huguet se reunió con French, Murray y Wilson. Acordaron desplegar la BEF en Maubeuge , pero Kitchener, en una reunión de tres horas que fue, según Wilson, "memorable al mostrar la colosal ignorancia y vanidad de K", trató de insistir en un despliegue en Amiens, donde la BEF estaría en menor peligro de ser invadida por los alemanes que venían al norte del Mosa . [160] Wilson escribió no sólo sobre las dificultades y demoras que Kitchener estaba creando, sino también sobre "la cobardía de ello", aunque el historiador John Terraine argumentó más tarde que la oposición de Kitchener a un despliegue avanzado se demostró completamente correcta por la proximidad con la que la BEF estuvo al desastre. [161] El choque de personalidades entre Wilson y Kitchener empeoró las relaciones entre Kitchener y Sir John French, quien a menudo seguía el consejo de Wilson. [162]

Wilson, French y Murray cruzaron a Francia el 14 de agosto. [163] Wilson era escéptico ante la invasión alemana de Bélgica, pensando que sería desviada para enfrentar los avances franceses en Lorena y las Ardenas. [164] Al reconocer el área con Harper en agosto de 1913, Wilson había querido desplegar la BEF justo al este de Namur . Aunque la predicción de Wilson sobre el avance alemán fue menos profética que la de Kitchener, de haberse hecho esto, es posible que las fuerzas anglo-francesas hubieran atacado al norte, amenazando con cortar el paso a los ejércitos alemanes que se movían hacia el oeste al norte del Mosa. [163]

Al igual que otros comandantes británicos, Wilson, al principio, subestimó el tamaño de las fuerzas alemanas frente a la BEF, aunque Terraine y Holmes son muy críticos con el consejo que Wilson le estaba dando a Sir John el 22 de agosto, alentando más avances de la BEF y "calculando" que la BEF se enfrentaba solo a un cuerpo alemán y una división de caballería, aunque Macdonogh estaba proporcionando estimaciones más realistas. [165] [166] Wilson incluso emitió una reprimenda a la División de Caballería por informar que fuertes fuerzas alemanas se dirigían a Mons desde Bruselas, alegando que estaban equivocados y que solo la caballería alemana y los Jaegers estaban frente a ellos. [167]

.jpg/440px-German_advance_(1914).jpg)

El 23 de agosto, el día de la Batalla de Mons , Wilson inicialmente redactó órdenes para que el II Cuerpo y la división de caballería atacaran al día siguiente, que Sir John canceló (después de recibir un mensaje de Joffre a las 8 p.m. advirtiendo de al menos 2 ½ cuerpos alemanes enfrente [168] - de hecho había tres cuerpos alemanes frente a la BEF con un cuarto moviéndose alrededor del flanco izquierdo británico, y luego se ordenó una retirada a las 11 p.m. cuando llegó la noticia de que el Quinto Ejército de Lanrezac a la derecha estaba retrocediendo). El 24 de agosto, el día después de la batalla, lamentó que no hubiera sido necesaria ninguna retirada si la BEF hubiera tenido 6 divisiones de infantería como se planeó originalmente. Terraine describe el relato del diario de Wilson sobre estos eventos como "un resumen ridículo... por un hombre en una posición de responsabilidad", y sostiene que aunque los temores de Kitchener de una invasión alemana de Gran Bretaña habían sido exagerados, su consiguiente decisión de retener dos divisiones salvó a la BEF de un desastre mayor que podría haber sido provocado por el exceso de confianza de Wilson. [165] [166] [169]

El personal de la BEF tuvo un desempeño pobre durante los días siguientes. Varios testigos oculares informaron que Wilson era uno de los miembros más tranquilos del GHQ, pero estaba preocupado por la incapacidad médica de Murray y la aparente incapacidad de French para comprender la situación. Wilson se opuso a la decisión de Smith-Dorrien de permanecer y luchar en Le Cateau (26 de agosto). [166] Sin embargo, cuando Smith-Dorrien le dijo que no sería posible separarse y retroceder hasta el anochecer, según su propio relato le deseó suerte. [170] El recuerdo ligeramente diferente de Smith-Dorrien fue que Wilson le había advertido que corría el riesgo de ser rodeado como los franceses en Sedán en 1870. [171]

Baker-Carr recordó a Wilson de pie, en bata y zapatillas, profiriendo "bromas sardónicas a todo el que estuviera al alcance del oído" mientras el Cuartel General preparaba el equipaje para evacuar, un comportamiento que, según comenta el historiador Dan Todman, probablemente fue "tranquilizador para algunos, pero profundamente irritante para otros". [172] Macready registró a Wilson (27 de agosto) "caminando lentamente de un lado a otro" por la sala de Noyon que había sido requisada como cuartel general con una "expresión cómica y caprichosa", aplaudiendo y cantando "Nunca llegaremos allí, nunca llegaremos allí... al mar, al mar, al mar", aunque también registró que esto probablemente tenía la intención de mantener en alto el ánimo de los oficiales más jóvenes. Su infame orden " sauve qui peut " a Snow , GOC 4th Division , (27 de agosto) ordenando que se desecharan las municiones innecesarias y los equipos de los oficiales para que los soldados cansados y heridos pudieran ser transportados, fue, según Swinton , probablemente intencionada por preocupación por los soldados más que por pánico. Smith-Dorrien fue posteriormente reprendido por French por revocarla. [166] [173] Lord Loch pensó que la orden mostraba que "el GHQ había perdido la cabeza", mientras que el general Haldane pensó que era "una orden loca" (ambos en sus diarios del 28 de agosto). [174] El mayor general Pope-Hennessey alegó más tarde (en la década de 1930) que Wilson había ordenado la destrucción de las órdenes emitidas durante la retirada para ocultar el grado de pánico. [175]

Después de la guerra, Wilson afirmó que los alemanes deberían haber ganado en 1914 si no hubiera sido por la mala suerte. Bartholomew , que había sido capitán de Estado Mayor en ese momento, le dijo más tarde a Liddell Hart que Wilson había sido "el hombre que salvó al ejército británico" al ordenar a Smith-Dorrien que se retirara hacia el sur después de Le Cateau, rompiendo así el contacto con los alemanes que esperaban que se retirara al suroeste. Wilson jugó un papel importante como enlace con los franceses, y también parece haber disuadido a Joffre de nuevos ataques de Lanrezac , con los que los británicos no habrían podido ayudar (29 de agosto). [176] Mientras Murray mantenía una reunión importante (4 de septiembre) con Gallieni ( gobernador militar de París ) y Maunoury (comandante del Sexto Ejército francés ) para discutir el planeado contraataque aliado que se convertiría en la Primera Batalla del Marne , Wilson mantenía una reunión simultánea con Franchet d'Esperey ( Quinto Ejército , a la derecha británica), que preveía que el Sexto Ejército atacara al norte del Marne. [177] Wilson más tarde persuadió a Sir John French para que cancelara sus órdenes de retirarse más al sur (4 de septiembre) y ayudó a persuadirlo para que se uniera a la Batalla del Marne (6 de septiembre). [176] Como muchos líderes aliados, Wilson creyó después de la victoria en el Marne que la guerra estaba prácticamente ganada. [178]

Wilson actuó como jefe de personal de la BEF cuando Murray visitó el Ministerio de Guerra en octubre. [179] Al igual que muchos oficiales aliados de alto rango, Wilson creía que la guerra se ganaría en la primavera siguiente y sentía que Kitchener estaba poniendo en peligro la victoria al retener oficiales en Gran Bretaña para lo que Wilson llamó sus "ejércitos en la sombra" . [180] Wilson no previó que las tropas británicas lucharan bajo el mando francés y se opuso a la petición de Foch de que Allenby y dos batallones participaran en un ataque francés. [181] Murray (4-5 de noviembre) se quejó y amenazó con dimitir cuando Wilson modificó una de sus órdenes sin decírselo. [182] Wilson estuvo presente en el lecho de muerte de su antiguo patrón Lord Roberts , volviendo a casa para el funeral en la catedral de San Pablo. [180]

French le dijo a Wilson que estaba pensando en trasladar a Murray a un mando de cuerpo e insistió en que Wilson lo sustituyera, pero Asquith le prohibió que promoviera a "ese rufián venenoso aunque inteligente de Wilson que se comportó... tan mal... en lo que respecta al Ulster". Wilson afirmó haber oído a Joffre quejarse de que era "una lástima" que no se hubiera destituido a Murray, pero cuando se enteró de ello, Asquith lo atribuyó a "las constantes intrigas de esa serpiente de Wilson" a quien él y Kitchener estaban decididos a bloquear. [182] Asquith sentía que era demasiado francófilo y demasiado aficionado a las "travesuras" (intrigas políticas), pero a pesar de que Wilson le advirtió a French que las razones de sus objeciones eran en gran medida personales, no pudo disuadirlos de bloquear el nombramiento. [102] En una visita a Londres a principios de enero, Wilson escuchó del secretario asistente del rey, Clive Wigram, que era Asquith y no Kitchener quien estaba bloqueando el ascenso, que Carson y Law estaban ansiosos por que tuviera. [182]

Jeffery sostiene que hay pocas pruebas específicas de que Wilson intrigara para reemplazar a Murray, simplemente que era ampliamente sospechoso de haberlo hecho, y que su postura pro francesa era vista con profunda sospecha por otros oficiales británicos. [183] Cuando Murray fue finalmente destituido como jefe del estado mayor de la BEF en enero de 1915, su puesto pasó al intendente general de la BEF "Wully" Robertson . Robertson se negó a tener a Wilson como su adjunto, por lo que Wilson fue designado en su lugar como oficial de enlace principal con los franceses y ascendido a teniente general temporal . [184] [185] French técnicamente no tenía autoridad para hacer esta promoción, pero le dijo a Wilson que renunciaría si el Gabinete o el Ministerio de Guerra se oponían. Los franceses habían estado presionando tanto para el nombramiento de Wilson que incluso Sir John pensó que deberían ocuparse de sus propios asuntos. [186] Asquith y Haig comentaron que esto estaba poniendo a Wilson fuera de peligro. [182]

Wilson estaba "bastante molesto por los cambios que se hicieron en su ausencia" mientras estaba de gira por el frente francés: Robertson destituyó al aliado de Wilson, el general de brigada George Harper, "de una manera muy poco diplomática". El diario de Wilson hace varias referencias a que Robertson se mostraba "sospechoso y hostil" hacia él. [187] Se sospechaba que Wilson había intrigado para conseguir la destitución de Robertson. [187]

Wilson veía a Foch cada dos o tres días [188] y a veces suavizaba las tensas reuniones con una (mala) traducción creativa. [189] Wilson se opuso a la Campaña de Galípoli y dejó constancia de su enfado porque, después de que se hubieran tenido que enviar proyectiles a Galípoli, la BEF, que entonces contaba con 12 divisiones, apenas tenía suficientes proyectiles de alto poder explosivo para la Batalla de Festubert , que él pensaba que podría ser "una de las acciones decisivas de la guerra". [190]

El fracaso en alcanzar un éxito rápido en Galípoli, y la escasez de proyectiles a la que contribuyó esa campaña, llevaron a los ministros conservadores a unirse al nuevo gobierno de coalición en mayo, lo que impulsó las perspectivas de Wilson. [191] Wilson fue nombrado Caballero Comendador de la Orden del Baño en los Honores del Cumpleaños del Rey de junio de 1915 , [192] después de haber sido pasado por alto para el honor en febrero. [193] Fue invitado a hablar en una reunión del Gabinete en el verano de 1915. [194] A partir de julio de 1915, Asquith y Kitchener comenzaron a consultar a Wilson regularmente [194] y sus relaciones personales con ambos hombres parecen haberse vuelto más cordiales. [191]

Wilson deploró el fallido desembarco de agosto en la bahía de Suvla en Galípoli, escribiendo que "Winston primero y otros después" deberían ser juzgados por asesinato. [190] En el verano de 1915, Wilson creyó que el gobierno francés podría caer, o que Francia misma buscara la paz, a menos que los británicos se comprometieran con la ofensiva de Loos . [195] Sus esfuerzos por ser el principal intermediario entre French y Joffre terminaron en septiembre de 1915, cuando se decidió que estos contactos deberían pasar por Sidney Clive , el oficial de enlace británico en GQG . [188] Leo Maxse , HA Gwynne y el diputado radical Josiah Wedgwood , impresionados por el apoyo de Wilson al reclutamiento [196] y al abandono de Galípoli, lo señalaron como un potencial CIGS en lugar de James Wolfe-Murray , pero Archibald Murray fue designado en su lugar (septiembre de 1915). [191]

Después de la batalla de Loos , los días de Sir John French como comandante en jefe estaban contados. Robertson le dijo al rey el 27 de octubre que Wilson debería ser destituido por no ser "leal"; Robertson había criticado anteriormente a Wilson por su cercanía a los franceses. [197] Wilson era visto como "un asesor no oficial" de "rango similar" pero "temperamento totalmente diferente" a Robertson. [187] Sir John French, Milner, Lloyd George y Arthur Lee plantearon la posibilidad de que Wilson se convirtiera en Jefe del Estado Mayor Imperial (CIGS) en lugar de Murray. Hankey pensó que podría haber llegado a ser CIGS si no fuera por la desconfianza persistente por el incidente de Curragh, pero no hay evidencia explícita en el diario de Wilson de que codiciara el trabajo. Joffre sugirió que Wilson debería reemplazar a Kitchener como Secretario de Estado para la Guerra. [198]

Wilson también recibió el nombramiento honorario de coronel de los Royal Irish Rifles el 11 de noviembre de 1915, [199] y fue nombrado comandante y más tarde gran oficial de la Légion d'honneur por sus servicios. [200] [201] [202] Wilson asistió a la Conferencia anglo-francesa de Chantilly (6-8 de diciembre de 1915) junto con Murray (CIGS), French y Robertson , así como Joffre, Maurice Pellé y Victor Huguet por Francia, Zhilinski e Ignatieff por Rusia, Cadorna por Italia y un representante serbio y belga. Wilson desaprobaba las grandes reuniones y pensaba que los ministros de guerra británicos y franceses, los comandantes en jefe y los ministros de asuntos exteriores (6 hombres en total) deberían reunirse regularmente, lo que podría desalentar iniciativas como Amberes , Galípoli y Salónica . [203]

Ante la inminente "dimisión" de French, Wilson, que parece haber permanecido leal a él, intentó dimitir y cobrar la mitad del sueldo (10 de diciembre) porque sentía que no podía servir bajo el mando de Haig o Robertson; Bonar Law y Charles E. Callwell intentaron disuadirle. [1] [198] Haig pensó que esto era inaceptable para un oficial tan capaz en tiempos de guerra, y Robertson le aconsejó que Wilson "haría menos daño" en Francia que en Inglaterra. [204] Haig pensó (12 de diciembre) que Wilson debería comandar una división antes de comandar un cuerpo, a pesar de su creencia de que Wilson se había criticado a sí mismo ya otros generales británicos, y había instigado un artículo en The Observer sugiriendo que la BEF se pusiera bajo el mando del general Foch (comandante del Grupo del Ejército del Norte de Francia) [205] (Charteris le escribió a su esposa (12 de diciembre) a propósito de los artículos que "ni DH ni Robertson quieren a Wilson cerca de ellos"). [206]

Rawlinson , del que se rumoreaba que iba a ser ascendido para suceder a Haig como Primer Ejército del GOC, ofreció a Wilson la oportunidad de sucederlo como IV Cuerpo del GOC, pero Wilson prefirió no servir bajo Rawlinson, prefiriendo en su lugar el nuevo XIV Cuerpo , parte del Tercer Ejército de Allenby y que incluía la 36.ª División (Ulster) . Asquith convocó a Wilson a Londres y le ofreció personalmente un cuerpo, y Kitchener le dijo que el mando del cuerpo sería "sólo temporal en espera de algo mejor", aunque Wilson pensó que no era práctica su sugerencia de que simultáneamente continuara realizando tareas de enlace anglo-francesas. Jeffery sugiere que Kitchener puede haber visto a Wilson como un aliado potencial contra Robertson. [206]

Al igual que muchos conservadores, Wilson estaba insatisfecho con la falta de un liderazgo firme por parte de Asquith y con la demora en implementar el servicio militar obligatorio, y desde diciembre de 1915 instó a Bonar Law a derrocar al gobierno (Law se negó, señalando que las elecciones generales resultantes serían divisivas y el apoyo de los parlamentarios radicales e irlandeses se perdería en el esfuerzo bélico). [207]